User login

Crohn’s disease: Risankizumab maintenance therapy shows promise in phase 3NF

Key Clinical Point: Maintenance therapy with subcutaneous risankizumab showed superior efficacy than withdrawal from risankizumab to receive subcutaneous placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease (CD). It also had a tolerable safety profile.

Major finding: At week 52, patients receiving maintenance 360 mg risankizumab vs. placebo showed higher rates of Crohn’s Disease Activity Index clinical remission (adjusted difference [Δ] 15%; 95% CI 4%-25%) and endoscopic response (Δ 28%; 95% CI 19%-37%), with findings being similar for 180 mg risankizumab. The incidence of adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 FORTIFY trial including 542 patients with moderate-to-severe CD who showed a clinical response to risankizumab in the ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials and were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous risankizumab (180 or 360 mg) or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie. Some authors declared being employees or holding stocks at AbbVie, and other authors reported receiving grants, speakers’ fees, consulting fees, or serving as advisory board members for various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Ferrante M et al. Risankizumab as maintenance therapy for moderately to severely active Crohn's disease: Results from the multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, withdrawal phase 3 FORTIFY maintenance trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2031-2046 (May 28). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00466-4

Key Clinical Point: Maintenance therapy with subcutaneous risankizumab showed superior efficacy than withdrawal from risankizumab to receive subcutaneous placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease (CD). It also had a tolerable safety profile.

Major finding: At week 52, patients receiving maintenance 360 mg risankizumab vs. placebo showed higher rates of Crohn’s Disease Activity Index clinical remission (adjusted difference [Δ] 15%; 95% CI 4%-25%) and endoscopic response (Δ 28%; 95% CI 19%-37%), with findings being similar for 180 mg risankizumab. The incidence of adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 FORTIFY trial including 542 patients with moderate-to-severe CD who showed a clinical response to risankizumab in the ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials and were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous risankizumab (180 or 360 mg) or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie. Some authors declared being employees or holding stocks at AbbVie, and other authors reported receiving grants, speakers’ fees, consulting fees, or serving as advisory board members for various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Ferrante M et al. Risankizumab as maintenance therapy for moderately to severely active Crohn's disease: Results from the multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, withdrawal phase 3 FORTIFY maintenance trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2031-2046 (May 28). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00466-4

Key Clinical Point: Maintenance therapy with subcutaneous risankizumab showed superior efficacy than withdrawal from risankizumab to receive subcutaneous placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease (CD). It also had a tolerable safety profile.

Major finding: At week 52, patients receiving maintenance 360 mg risankizumab vs. placebo showed higher rates of Crohn’s Disease Activity Index clinical remission (adjusted difference [Δ] 15%; 95% CI 4%-25%) and endoscopic response (Δ 28%; 95% CI 19%-37%), with findings being similar for 180 mg risankizumab. The incidence of adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 FORTIFY trial including 542 patients with moderate-to-severe CD who showed a clinical response to risankizumab in the ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials and were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous risankizumab (180 or 360 mg) or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie. Some authors declared being employees or holding stocks at AbbVie, and other authors reported receiving grants, speakers’ fees, consulting fees, or serving as advisory board members for various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Ferrante M et al. Risankizumab as maintenance therapy for moderately to severely active Crohn's disease: Results from the multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, withdrawal phase 3 FORTIFY maintenance trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2031-2046 (May 28). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00466-4

Crohn’s disease: Risankizumab maintenance therapy shows promise in phase 3NF

Key Clinical Point: Maintenance therapy with subcutaneous risankizumab showed superior efficacy than withdrawal from risankizumab to receive subcutaneous placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease (CD). It also had a tolerable safety profile.

Major finding: At week 52, patients receiving maintenance 360 mg risankizumab vs. placebo showed higher rates of Crohn’s Disease Activity Index clinical remission (adjusted difference [Δ] 15%; 95% CI 4%-25%) and endoscopic response (Δ 28%; 95% CI 19%-37%), with findings being similar for 180 mg risankizumab. The incidence of adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 FORTIFY trial including 542 patients with moderate-to-severe CD who showed a clinical response to risankizumab in the ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials and were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous risankizumab (180 or 360 mg) or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie. Some authors declared being employees or holding stocks at AbbVie, and other authors reported receiving grants, speakers’ fees, consulting fees, or serving as advisory board members for various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Ferrante M et al. Risankizumab as maintenance therapy for moderately to severely active Crohn's disease: Results from the multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, withdrawal phase 3 FORTIFY maintenance trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2031-2046 (May 28). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00466-4

Key Clinical Point: Maintenance therapy with subcutaneous risankizumab showed superior efficacy than withdrawal from risankizumab to receive subcutaneous placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease (CD). It also had a tolerable safety profile.

Major finding: At week 52, patients receiving maintenance 360 mg risankizumab vs. placebo showed higher rates of Crohn’s Disease Activity Index clinical remission (adjusted difference [Δ] 15%; 95% CI 4%-25%) and endoscopic response (Δ 28%; 95% CI 19%-37%), with findings being similar for 180 mg risankizumab. The incidence of adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 FORTIFY trial including 542 patients with moderate-to-severe CD who showed a clinical response to risankizumab in the ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials and were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous risankizumab (180 or 360 mg) or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie. Some authors declared being employees or holding stocks at AbbVie, and other authors reported receiving grants, speakers’ fees, consulting fees, or serving as advisory board members for various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Ferrante M et al. Risankizumab as maintenance therapy for moderately to severely active Crohn's disease: Results from the multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, withdrawal phase 3 FORTIFY maintenance trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2031-2046 (May 28). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00466-4

Key Clinical Point: Maintenance therapy with subcutaneous risankizumab showed superior efficacy than withdrawal from risankizumab to receive subcutaneous placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease (CD). It also had a tolerable safety profile.

Major finding: At week 52, patients receiving maintenance 360 mg risankizumab vs. placebo showed higher rates of Crohn’s Disease Activity Index clinical remission (adjusted difference [Δ] 15%; 95% CI 4%-25%) and endoscopic response (Δ 28%; 95% CI 19%-37%), with findings being similar for 180 mg risankizumab. The incidence of adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 FORTIFY trial including 542 patients with moderate-to-severe CD who showed a clinical response to risankizumab in the ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials and were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous risankizumab (180 or 360 mg) or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie. Some authors declared being employees or holding stocks at AbbVie, and other authors reported receiving grants, speakers’ fees, consulting fees, or serving as advisory board members for various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Ferrante M et al. Risankizumab as maintenance therapy for moderately to severely active Crohn's disease: Results from the multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, withdrawal phase 3 FORTIFY maintenance trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2031-2046 (May 28). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00466-4

Ulcerative colitis: Tofacitinib more effective than vedolizumab in patients refractory to anti-TNF

Key clinical point: Tofacitinib showed higher efficacy and comparable safety to vedolizumab in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) with prior treatment failure with anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy.

Major finding: Patients treated with tofacitinib vs. vedolizumab were more likely to achieve corticosteroid-free remission at weeks 12 (odds ratio [OR] 6.33; P < .01), 24 (OR 3.02; P < .01), and 52 (OR 1.86; P = .01). The overall risk for adverse events (AE) was higher in patients treated with vedolizumab (OR 1.83; P = .02), whereas the risk for serious AE was similar in both the groups.

Study details: This was a prospective cohort study of 148 patients with UC from the Initiative on Crohn and Colitis (ICC) registry who were treated with vedolizumab (n = 83) or tofacitinib (n = 65) after the failure of treatment with at least one anti-TNF agent.

Disclosures: The ICC fellowship was sponsored by AbbVie, Pfizer, and others. Some authors reported receiving grants, consulting fees, speakers’ fees, presentation fees from, or serving on advisory boards for various sources, including the sponsors of the ICC Fellowship.

Source: Straatmijer T et al. Superior effectiveness of tofacitinib compared to vedolizumab in anti-TNF experienced ulcerative colitis patients: A nationwide Dutch Registry study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 (May 26). Doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.04.038

Key clinical point: Tofacitinib showed higher efficacy and comparable safety to vedolizumab in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) with prior treatment failure with anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy.

Major finding: Patients treated with tofacitinib vs. vedolizumab were more likely to achieve corticosteroid-free remission at weeks 12 (odds ratio [OR] 6.33; P < .01), 24 (OR 3.02; P < .01), and 52 (OR 1.86; P = .01). The overall risk for adverse events (AE) was higher in patients treated with vedolizumab (OR 1.83; P = .02), whereas the risk for serious AE was similar in both the groups.

Study details: This was a prospective cohort study of 148 patients with UC from the Initiative on Crohn and Colitis (ICC) registry who were treated with vedolizumab (n = 83) or tofacitinib (n = 65) after the failure of treatment with at least one anti-TNF agent.

Disclosures: The ICC fellowship was sponsored by AbbVie, Pfizer, and others. Some authors reported receiving grants, consulting fees, speakers’ fees, presentation fees from, or serving on advisory boards for various sources, including the sponsors of the ICC Fellowship.

Source: Straatmijer T et al. Superior effectiveness of tofacitinib compared to vedolizumab in anti-TNF experienced ulcerative colitis patients: A nationwide Dutch Registry study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 (May 26). Doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.04.038

Key clinical point: Tofacitinib showed higher efficacy and comparable safety to vedolizumab in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) with prior treatment failure with anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy.

Major finding: Patients treated with tofacitinib vs. vedolizumab were more likely to achieve corticosteroid-free remission at weeks 12 (odds ratio [OR] 6.33; P < .01), 24 (OR 3.02; P < .01), and 52 (OR 1.86; P = .01). The overall risk for adverse events (AE) was higher in patients treated with vedolizumab (OR 1.83; P = .02), whereas the risk for serious AE was similar in both the groups.

Study details: This was a prospective cohort study of 148 patients with UC from the Initiative on Crohn and Colitis (ICC) registry who were treated with vedolizumab (n = 83) or tofacitinib (n = 65) after the failure of treatment with at least one anti-TNF agent.

Disclosures: The ICC fellowship was sponsored by AbbVie, Pfizer, and others. Some authors reported receiving grants, consulting fees, speakers’ fees, presentation fees from, or serving on advisory boards for various sources, including the sponsors of the ICC Fellowship.

Source: Straatmijer T et al. Superior effectiveness of tofacitinib compared to vedolizumab in anti-TNF experienced ulcerative colitis patients: A nationwide Dutch Registry study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 (May 26). Doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.04.038

Risankizumab induction therapy safe and effective in moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease

Key Clinical Point: Intravenous risankizumab induction therapy is safe and effective in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease (CD).

Major finding: In the ADVANCE trial, Crohn’s Disease Activity Index clinical remission at week 12 was higher with 600 mg risankizumab (adjusted difference [Δ] 21%) and 1200 mg (Δ 17%) vs. placebo, with the endoscopic response being higher with 600 mg risankizumab (Δ 28%) and 1200 mg (Δ 20%; all P < .0001) vs. placebo. The MOTIVATE trial reported similar findings. The incidence of adverse events was similar across all treatment groups.

Study details: This study included patients with moderate-to-severe CD and intolerance/inadequate response to biologics or conventional therapy from the phase 3 ADVANCE (n=931) and MOTIVATE (n = 618) trials who were randomly assigned to receive risankizumab (600 or 1200 mg) or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie. Some authors declared being employees or holding stocks at AbbVie, and other authors reported receiving grants, speaker’s fees, or consulting fees or serving as advisory board members for various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: D’Haens G et al. Risankizumab as induction therapy for Crohn's disease: Results from the phase 3 ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2015-2030 (May 28). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00467-6

Key Clinical Point: Intravenous risankizumab induction therapy is safe and effective in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease (CD).

Major finding: In the ADVANCE trial, Crohn’s Disease Activity Index clinical remission at week 12 was higher with 600 mg risankizumab (adjusted difference [Δ] 21%) and 1200 mg (Δ 17%) vs. placebo, with the endoscopic response being higher with 600 mg risankizumab (Δ 28%) and 1200 mg (Δ 20%; all P < .0001) vs. placebo. The MOTIVATE trial reported similar findings. The incidence of adverse events was similar across all treatment groups.

Study details: This study included patients with moderate-to-severe CD and intolerance/inadequate response to biologics or conventional therapy from the phase 3 ADVANCE (n=931) and MOTIVATE (n = 618) trials who were randomly assigned to receive risankizumab (600 or 1200 mg) or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie. Some authors declared being employees or holding stocks at AbbVie, and other authors reported receiving grants, speaker’s fees, or consulting fees or serving as advisory board members for various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: D’Haens G et al. Risankizumab as induction therapy for Crohn's disease: Results from the phase 3 ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2015-2030 (May 28). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00467-6

Key Clinical Point: Intravenous risankizumab induction therapy is safe and effective in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease (CD).

Major finding: In the ADVANCE trial, Crohn’s Disease Activity Index clinical remission at week 12 was higher with 600 mg risankizumab (adjusted difference [Δ] 21%) and 1200 mg (Δ 17%) vs. placebo, with the endoscopic response being higher with 600 mg risankizumab (Δ 28%) and 1200 mg (Δ 20%; all P < .0001) vs. placebo. The MOTIVATE trial reported similar findings. The incidence of adverse events was similar across all treatment groups.

Study details: This study included patients with moderate-to-severe CD and intolerance/inadequate response to biologics or conventional therapy from the phase 3 ADVANCE (n=931) and MOTIVATE (n = 618) trials who were randomly assigned to receive risankizumab (600 or 1200 mg) or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie. Some authors declared being employees or holding stocks at AbbVie, and other authors reported receiving grants, speaker’s fees, or consulting fees or serving as advisory board members for various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: D’Haens G et al. Risankizumab as induction therapy for Crohn's disease: Results from the phase 3 ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2015-2030 (May 28). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00467-6

At-home colorectal cancer testing and follow-up vary by ethnicity

Doctors were significantly less likely to order colorectal cancer screening with the at-home test Cologuard (Exact Sciences) for Black patients and were more likely to order the test for Asian patients, new evidence reveals.

Investigators retrospectively studied 557,156 patients in the Mayo Clinic health system from 2012 to 2022. They found that Cologuard was ordered for 8.7% of Black patients, compared to 11.9% of White patients and 13.1% of Asian patients.

Both minority groups were less likely than White patients to undergo a follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year of Cologuard testing. Cologuard tests the stool for blood and DNA markers associated with colorectal cancer.

Although the researchers did not examine the reasons driving the disparities, lead investigator Ahmed Ouni, MD, told this news organization that “it could be patient preferences ... or there could be some bias as providers ourselves in how we present the data to patients.”

Dr. Ouni presented the findings on May 22 at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW), held in person in San Diego and virtually.

Breakdown by physician specialty

“We looked at the specialty of physicians ordering these because we wanted to see where the disparity was coming from, if there was a disparity,” said Dr. Ouni, a gastroenterologist at Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida.

Just over half (51%) of the patients received care from family medicine physicians, 27% received care from internists, and 22% were seen by gastroenterologists.

Family physicians ordered Cologuard testing for 8.7% of Black patients, compared with 16.1% of White patients, a significant difference (P < .001). Internists ordered the test for 10.5% of Black patients and 11.1% of White patients (P < .001). Gastroenterologists ordered Cologuard screening for 2.4% of Black patients and 3.2% of White patients (P = .009).

Gastroenterologists were 47% more likely to order Cologuard for Asian patients, and internists were 16% more likely to order it for this population than for White patients. However, the findings were not statistically significant for the overall cohort of Asian patients when the researchers adjusted for age and sex (P = 0.52).

Black patients were 25% less likely to have a follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year of undergoing a Cologuard test (odds ratio, 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.94), and Asian patients were 35% less likely (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.52-0.82).

Ongoing and future research

Of the total study population, only 2.9% self-identified as Black; according to the 2020 U.S. Census, 12.4% of the population of the United States are Black persons.

When asked about the relatively low proportion of Black persons in the study, Dr. Ouni replied that the investigators are partnering with a Black physician group in the Jacksonville, Fla., area to expand the study to a more diverse population.

Additional plans include assessing how many positive Cologuard test results led to follow-up colonoscopies.

The investigators are also working with family physicians at the Mayo Clinic to examine how physicians explain colorectal cancer screening options to patients and are studying patient preferences regarding screening options, which include Cologuard, fecal immunochemical test (FIT)/fecal occult blood testing, CT colonography, and colonoscopy.

“We’re analyzing the data by ZIP code to see if this could be related to finances,” Dr. Ouni added. “So, if you’re Black or White and more financially impoverished, how does that affect how you view Cologuard and colorectal cancer screening?”

Some unanswered questions

“Overall this study supports other studies of a disparity in colorectal cancer screening for African Americans,” John M. Carethers, MD, told this news organization when asked to comment. “This is known for FIT and colonoscopy, and Cologuard, which is a genetic test in addition to FIT, appears to be in that same realm.”

“Noninvasive tests will have a role to reach populations who may not readily have access to colonoscopy,” said Dr. Carethers, John G. Searle Professor and chair of the department of internal medicine and professor of human genetics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and president of the American Gastroenterological Association. “The key here is if the test is positive, it needs to be followed up with a colonoscopy.”

Dr. Carethers added that the study raises some unanswered questions; for example, does the cost difference between testing options make a difference?

“FIT is under $20, but Cologuard is generally $300 or more,” he said. What percentage of the study population were offered other options, such as FIT? How does insurance status affect screening in different populations?”

“The findings should be taken in context of what other screening options were offered to or elected by patients,” agreed Gregory S. Cooper, MD, professor of medicine and population and quantitative health sciences at Case Western Reserve University and a gastroenterologist at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

According to guidelines, patients can be offered a menu of options, including FIT, colonoscopy, and Cologuard, Dr. Cooper said in an interview.

“If more African Americans elected colonoscopy, for example, the findings may balance out,” said Dr. Cooper, who was not affiliated with the study. “It would also be of interest to know if the racial differences changed over time. With the pandemic, the use of noninvasive options, such as Cologuard, have increased.”

“I will note that specifically for colonoscopy in the United States, the disparity gap had been closing from about 15% to 18% 20 years ago to about 3% in 2020 pre-COVID,” Dr. Carethers added. “I am fearful that COVID may have led to a widening of that gap again as we get more data.”

“It is important that noninvasive tests for screening be a part of the portfolio of offerings to patients, as about 35% of eligible at-risk persons who need to be screened are not screened in the United States,” Dr. Carethers said.

The study was not industry sponsored. Dr. Ouni and Dr. Carethers report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Cooper has received consulting fees from Exact Sciences.

To help your patients understand their colorectal cancer screening options, send them to the AGA GI Patient Center.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctors were significantly less likely to order colorectal cancer screening with the at-home test Cologuard (Exact Sciences) for Black patients and were more likely to order the test for Asian patients, new evidence reveals.

Investigators retrospectively studied 557,156 patients in the Mayo Clinic health system from 2012 to 2022. They found that Cologuard was ordered for 8.7% of Black patients, compared to 11.9% of White patients and 13.1% of Asian patients.

Both minority groups were less likely than White patients to undergo a follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year of Cologuard testing. Cologuard tests the stool for blood and DNA markers associated with colorectal cancer.

Although the researchers did not examine the reasons driving the disparities, lead investigator Ahmed Ouni, MD, told this news organization that “it could be patient preferences ... or there could be some bias as providers ourselves in how we present the data to patients.”

Dr. Ouni presented the findings on May 22 at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW), held in person in San Diego and virtually.

Breakdown by physician specialty

“We looked at the specialty of physicians ordering these because we wanted to see where the disparity was coming from, if there was a disparity,” said Dr. Ouni, a gastroenterologist at Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida.

Just over half (51%) of the patients received care from family medicine physicians, 27% received care from internists, and 22% were seen by gastroenterologists.

Family physicians ordered Cologuard testing for 8.7% of Black patients, compared with 16.1% of White patients, a significant difference (P < .001). Internists ordered the test for 10.5% of Black patients and 11.1% of White patients (P < .001). Gastroenterologists ordered Cologuard screening for 2.4% of Black patients and 3.2% of White patients (P = .009).

Gastroenterologists were 47% more likely to order Cologuard for Asian patients, and internists were 16% more likely to order it for this population than for White patients. However, the findings were not statistically significant for the overall cohort of Asian patients when the researchers adjusted for age and sex (P = 0.52).

Black patients were 25% less likely to have a follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year of undergoing a Cologuard test (odds ratio, 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.94), and Asian patients were 35% less likely (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.52-0.82).

Ongoing and future research

Of the total study population, only 2.9% self-identified as Black; according to the 2020 U.S. Census, 12.4% of the population of the United States are Black persons.

When asked about the relatively low proportion of Black persons in the study, Dr. Ouni replied that the investigators are partnering with a Black physician group in the Jacksonville, Fla., area to expand the study to a more diverse population.

Additional plans include assessing how many positive Cologuard test results led to follow-up colonoscopies.

The investigators are also working with family physicians at the Mayo Clinic to examine how physicians explain colorectal cancer screening options to patients and are studying patient preferences regarding screening options, which include Cologuard, fecal immunochemical test (FIT)/fecal occult blood testing, CT colonography, and colonoscopy.

“We’re analyzing the data by ZIP code to see if this could be related to finances,” Dr. Ouni added. “So, if you’re Black or White and more financially impoverished, how does that affect how you view Cologuard and colorectal cancer screening?”

Some unanswered questions

“Overall this study supports other studies of a disparity in colorectal cancer screening for African Americans,” John M. Carethers, MD, told this news organization when asked to comment. “This is known for FIT and colonoscopy, and Cologuard, which is a genetic test in addition to FIT, appears to be in that same realm.”

“Noninvasive tests will have a role to reach populations who may not readily have access to colonoscopy,” said Dr. Carethers, John G. Searle Professor and chair of the department of internal medicine and professor of human genetics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and president of the American Gastroenterological Association. “The key here is if the test is positive, it needs to be followed up with a colonoscopy.”

Dr. Carethers added that the study raises some unanswered questions; for example, does the cost difference between testing options make a difference?

“FIT is under $20, but Cologuard is generally $300 or more,” he said. What percentage of the study population were offered other options, such as FIT? How does insurance status affect screening in different populations?”

“The findings should be taken in context of what other screening options were offered to or elected by patients,” agreed Gregory S. Cooper, MD, professor of medicine and population and quantitative health sciences at Case Western Reserve University and a gastroenterologist at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

According to guidelines, patients can be offered a menu of options, including FIT, colonoscopy, and Cologuard, Dr. Cooper said in an interview.

“If more African Americans elected colonoscopy, for example, the findings may balance out,” said Dr. Cooper, who was not affiliated with the study. “It would also be of interest to know if the racial differences changed over time. With the pandemic, the use of noninvasive options, such as Cologuard, have increased.”

“I will note that specifically for colonoscopy in the United States, the disparity gap had been closing from about 15% to 18% 20 years ago to about 3% in 2020 pre-COVID,” Dr. Carethers added. “I am fearful that COVID may have led to a widening of that gap again as we get more data.”

“It is important that noninvasive tests for screening be a part of the portfolio of offerings to patients, as about 35% of eligible at-risk persons who need to be screened are not screened in the United States,” Dr. Carethers said.

The study was not industry sponsored. Dr. Ouni and Dr. Carethers report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Cooper has received consulting fees from Exact Sciences.

To help your patients understand their colorectal cancer screening options, send them to the AGA GI Patient Center.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctors were significantly less likely to order colorectal cancer screening with the at-home test Cologuard (Exact Sciences) for Black patients and were more likely to order the test for Asian patients, new evidence reveals.

Investigators retrospectively studied 557,156 patients in the Mayo Clinic health system from 2012 to 2022. They found that Cologuard was ordered for 8.7% of Black patients, compared to 11.9% of White patients and 13.1% of Asian patients.

Both minority groups were less likely than White patients to undergo a follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year of Cologuard testing. Cologuard tests the stool for blood and DNA markers associated with colorectal cancer.

Although the researchers did not examine the reasons driving the disparities, lead investigator Ahmed Ouni, MD, told this news organization that “it could be patient preferences ... or there could be some bias as providers ourselves in how we present the data to patients.”

Dr. Ouni presented the findings on May 22 at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW), held in person in San Diego and virtually.

Breakdown by physician specialty

“We looked at the specialty of physicians ordering these because we wanted to see where the disparity was coming from, if there was a disparity,” said Dr. Ouni, a gastroenterologist at Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida.

Just over half (51%) of the patients received care from family medicine physicians, 27% received care from internists, and 22% were seen by gastroenterologists.

Family physicians ordered Cologuard testing for 8.7% of Black patients, compared with 16.1% of White patients, a significant difference (P < .001). Internists ordered the test for 10.5% of Black patients and 11.1% of White patients (P < .001). Gastroenterologists ordered Cologuard screening for 2.4% of Black patients and 3.2% of White patients (P = .009).

Gastroenterologists were 47% more likely to order Cologuard for Asian patients, and internists were 16% more likely to order it for this population than for White patients. However, the findings were not statistically significant for the overall cohort of Asian patients when the researchers adjusted for age and sex (P = 0.52).

Black patients were 25% less likely to have a follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year of undergoing a Cologuard test (odds ratio, 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.94), and Asian patients were 35% less likely (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.52-0.82).

Ongoing and future research

Of the total study population, only 2.9% self-identified as Black; according to the 2020 U.S. Census, 12.4% of the population of the United States are Black persons.

When asked about the relatively low proportion of Black persons in the study, Dr. Ouni replied that the investigators are partnering with a Black physician group in the Jacksonville, Fla., area to expand the study to a more diverse population.

Additional plans include assessing how many positive Cologuard test results led to follow-up colonoscopies.

The investigators are also working with family physicians at the Mayo Clinic to examine how physicians explain colorectal cancer screening options to patients and are studying patient preferences regarding screening options, which include Cologuard, fecal immunochemical test (FIT)/fecal occult blood testing, CT colonography, and colonoscopy.

“We’re analyzing the data by ZIP code to see if this could be related to finances,” Dr. Ouni added. “So, if you’re Black or White and more financially impoverished, how does that affect how you view Cologuard and colorectal cancer screening?”

Some unanswered questions

“Overall this study supports other studies of a disparity in colorectal cancer screening for African Americans,” John M. Carethers, MD, told this news organization when asked to comment. “This is known for FIT and colonoscopy, and Cologuard, which is a genetic test in addition to FIT, appears to be in that same realm.”

“Noninvasive tests will have a role to reach populations who may not readily have access to colonoscopy,” said Dr. Carethers, John G. Searle Professor and chair of the department of internal medicine and professor of human genetics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and president of the American Gastroenterological Association. “The key here is if the test is positive, it needs to be followed up with a colonoscopy.”

Dr. Carethers added that the study raises some unanswered questions; for example, does the cost difference between testing options make a difference?

“FIT is under $20, but Cologuard is generally $300 or more,” he said. What percentage of the study population were offered other options, such as FIT? How does insurance status affect screening in different populations?”

“The findings should be taken in context of what other screening options were offered to or elected by patients,” agreed Gregory S. Cooper, MD, professor of medicine and population and quantitative health sciences at Case Western Reserve University and a gastroenterologist at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

According to guidelines, patients can be offered a menu of options, including FIT, colonoscopy, and Cologuard, Dr. Cooper said in an interview.

“If more African Americans elected colonoscopy, for example, the findings may balance out,” said Dr. Cooper, who was not affiliated with the study. “It would also be of interest to know if the racial differences changed over time. With the pandemic, the use of noninvasive options, such as Cologuard, have increased.”

“I will note that specifically for colonoscopy in the United States, the disparity gap had been closing from about 15% to 18% 20 years ago to about 3% in 2020 pre-COVID,” Dr. Carethers added. “I am fearful that COVID may have led to a widening of that gap again as we get more data.”

“It is important that noninvasive tests for screening be a part of the portfolio of offerings to patients, as about 35% of eligible at-risk persons who need to be screened are not screened in the United States,” Dr. Carethers said.

The study was not industry sponsored. Dr. Ouni and Dr. Carethers report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Cooper has received consulting fees from Exact Sciences.

To help your patients understand their colorectal cancer screening options, send them to the AGA GI Patient Center.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More evidence the flu vaccine may guard against Alzheimer’s

In a large propensity-matched cohort of older adults, those who had received at least one influenza inoculation were 40% less likely than unvaccinated peers to develop AD over the course of 4 years.

“Influenza infection can cause serious health complications, particularly in adults 65 and older. Our study’s findings – that vaccination against the flu virus may also reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s dementia for at least a few years – adds to the already compelling reasons get the flu vaccine annually,” Avram Bukhbinder, MD, of the University of Texas, Houston, said in an interview.

The new findings support earlier work by the same researchers that also suggested a protective effect of flu vaccination on dementia risk.

The latest study was published online in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

40% lower risk

Prior studies have found a lower risk of dementia of any etiology following influenza vaccination in selected populations, including veterans and patients with serious chronic health conditions.

However, the effect of influenza vaccination on AD risk in a general cohort of older U.S. adults has not been characterized.

Dr. Bukhbinder and colleagues used claims data to create a propensity-matched cohort of 935,887 influenza-vaccinated adults and a like number of unvaccinated adults aged 65 and older.

The median age of the persons in the matched sample was 73.7 years, and 57% were women. All were free of dementia during the 6-year look-back study period.

During median follow-up of 46 months, 47,889 (5.1%) flu-vaccinated adults and 79,630 (8.5%) unvaccinated adults developed AD.

The risk of AD was 40% lower in the vaccinated group (relative risk, 0.60; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.61). The absolute risk reduction was 0.034 (95% CI, 0.033-0.035), corresponding to a number needed to treat of 29.4.

Mechanism unclear

“Our study does not address the mechanism(s) underlying the apparent effect of influenza vaccination on Alzheimer’s risk, but we look forward to future research investigating this important question,” Dr. Bukhbinder said.

“One possible mechanism is that, by helping to prevent or mitigate infection with the flu virus and the systemic inflammation that follows such an infection, the flu vaccine helps to decrease the systemic inflammation that may have otherwise occurred,” he explained.

It’s also possible that influenza vaccination may trigger non–influenza-specific changes in the immune system that help to reduce the damage caused by AD pathology, including amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, he said.

“For example, the influenza vaccine may alter the brain’s immune cells such that they are better at clearing Alzheimer’s pathologies, an effect that has been seen in mice, or it may reprogram these immune cells to respond to Alzheimer’s pathologies in ways that are less likely to damage nearby healthy brain cells, or it may do both,” Dr. Bukhbinder noted.

Alzheimer’s expert weighs in

Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations for the Alzheimer’s Association, said this study “suggests that flu vaccination may be valuable for maintaining cognition and memory as we age. This is even more relevant today in the COVID-19 environment.

“It is too early to tell if getting flu vaccine, on its own, can reduce risk of Alzheimer’s. More research is needed to understand the biological mechanisms behind the results in this study,” Dr. Snyder said in an interview.

“For example, it is possible that people who are getting vaccinated also take better care of their health in other ways, and these things add up to lower risk of Alzheimer’s and other dementias,” she noted.

“It is also possible that there are issues related to unequal access and/or vaccine hesitancy and how this may influence the study population and the research results,” Dr. Snyder said.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Bukhbinder and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a large propensity-matched cohort of older adults, those who had received at least one influenza inoculation were 40% less likely than unvaccinated peers to develop AD over the course of 4 years.

“Influenza infection can cause serious health complications, particularly in adults 65 and older. Our study’s findings – that vaccination against the flu virus may also reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s dementia for at least a few years – adds to the already compelling reasons get the flu vaccine annually,” Avram Bukhbinder, MD, of the University of Texas, Houston, said in an interview.

The new findings support earlier work by the same researchers that also suggested a protective effect of flu vaccination on dementia risk.

The latest study was published online in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

40% lower risk

Prior studies have found a lower risk of dementia of any etiology following influenza vaccination in selected populations, including veterans and patients with serious chronic health conditions.

However, the effect of influenza vaccination on AD risk in a general cohort of older U.S. adults has not been characterized.

Dr. Bukhbinder and colleagues used claims data to create a propensity-matched cohort of 935,887 influenza-vaccinated adults and a like number of unvaccinated adults aged 65 and older.

The median age of the persons in the matched sample was 73.7 years, and 57% were women. All were free of dementia during the 6-year look-back study period.

During median follow-up of 46 months, 47,889 (5.1%) flu-vaccinated adults and 79,630 (8.5%) unvaccinated adults developed AD.

The risk of AD was 40% lower in the vaccinated group (relative risk, 0.60; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.61). The absolute risk reduction was 0.034 (95% CI, 0.033-0.035), corresponding to a number needed to treat of 29.4.

Mechanism unclear

“Our study does not address the mechanism(s) underlying the apparent effect of influenza vaccination on Alzheimer’s risk, but we look forward to future research investigating this important question,” Dr. Bukhbinder said.

“One possible mechanism is that, by helping to prevent or mitigate infection with the flu virus and the systemic inflammation that follows such an infection, the flu vaccine helps to decrease the systemic inflammation that may have otherwise occurred,” he explained.

It’s also possible that influenza vaccination may trigger non–influenza-specific changes in the immune system that help to reduce the damage caused by AD pathology, including amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, he said.

“For example, the influenza vaccine may alter the brain’s immune cells such that they are better at clearing Alzheimer’s pathologies, an effect that has been seen in mice, or it may reprogram these immune cells to respond to Alzheimer’s pathologies in ways that are less likely to damage nearby healthy brain cells, or it may do both,” Dr. Bukhbinder noted.

Alzheimer’s expert weighs in

Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations for the Alzheimer’s Association, said this study “suggests that flu vaccination may be valuable for maintaining cognition and memory as we age. This is even more relevant today in the COVID-19 environment.

“It is too early to tell if getting flu vaccine, on its own, can reduce risk of Alzheimer’s. More research is needed to understand the biological mechanisms behind the results in this study,” Dr. Snyder said in an interview.

“For example, it is possible that people who are getting vaccinated also take better care of their health in other ways, and these things add up to lower risk of Alzheimer’s and other dementias,” she noted.

“It is also possible that there are issues related to unequal access and/or vaccine hesitancy and how this may influence the study population and the research results,” Dr. Snyder said.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Bukhbinder and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a large propensity-matched cohort of older adults, those who had received at least one influenza inoculation were 40% less likely than unvaccinated peers to develop AD over the course of 4 years.

“Influenza infection can cause serious health complications, particularly in adults 65 and older. Our study’s findings – that vaccination against the flu virus may also reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s dementia for at least a few years – adds to the already compelling reasons get the flu vaccine annually,” Avram Bukhbinder, MD, of the University of Texas, Houston, said in an interview.

The new findings support earlier work by the same researchers that also suggested a protective effect of flu vaccination on dementia risk.

The latest study was published online in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

40% lower risk

Prior studies have found a lower risk of dementia of any etiology following influenza vaccination in selected populations, including veterans and patients with serious chronic health conditions.

However, the effect of influenza vaccination on AD risk in a general cohort of older U.S. adults has not been characterized.

Dr. Bukhbinder and colleagues used claims data to create a propensity-matched cohort of 935,887 influenza-vaccinated adults and a like number of unvaccinated adults aged 65 and older.

The median age of the persons in the matched sample was 73.7 years, and 57% were women. All were free of dementia during the 6-year look-back study period.

During median follow-up of 46 months, 47,889 (5.1%) flu-vaccinated adults and 79,630 (8.5%) unvaccinated adults developed AD.

The risk of AD was 40% lower in the vaccinated group (relative risk, 0.60; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.61). The absolute risk reduction was 0.034 (95% CI, 0.033-0.035), corresponding to a number needed to treat of 29.4.

Mechanism unclear

“Our study does not address the mechanism(s) underlying the apparent effect of influenza vaccination on Alzheimer’s risk, but we look forward to future research investigating this important question,” Dr. Bukhbinder said.

“One possible mechanism is that, by helping to prevent or mitigate infection with the flu virus and the systemic inflammation that follows such an infection, the flu vaccine helps to decrease the systemic inflammation that may have otherwise occurred,” he explained.

It’s also possible that influenza vaccination may trigger non–influenza-specific changes in the immune system that help to reduce the damage caused by AD pathology, including amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, he said.

“For example, the influenza vaccine may alter the brain’s immune cells such that they are better at clearing Alzheimer’s pathologies, an effect that has been seen in mice, or it may reprogram these immune cells to respond to Alzheimer’s pathologies in ways that are less likely to damage nearby healthy brain cells, or it may do both,” Dr. Bukhbinder noted.

Alzheimer’s expert weighs in

Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations for the Alzheimer’s Association, said this study “suggests that flu vaccination may be valuable for maintaining cognition and memory as we age. This is even more relevant today in the COVID-19 environment.

“It is too early to tell if getting flu vaccine, on its own, can reduce risk of Alzheimer’s. More research is needed to understand the biological mechanisms behind the results in this study,” Dr. Snyder said in an interview.

“For example, it is possible that people who are getting vaccinated also take better care of their health in other ways, and these things add up to lower risk of Alzheimer’s and other dementias,” she noted.

“It is also possible that there are issues related to unequal access and/or vaccine hesitancy and how this may influence the study population and the research results,” Dr. Snyder said.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Bukhbinder and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Acute hepatitis cases in children show declining trend; adenovirus, COVID-19 remain key leads

LONDON – Case numbers of acute hepatitis in children show “a declining trajectory,” and COVID-19 and adenovirus remain the most likely, but as yet unproven, causative agents, said experts in an update at the annual International Liver Congress sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

Philippa Easterbrook, MD, medical expert at the World Health Organization Global HIV, Hepatitis, and STI Programme, shared the latest case numbers and working hypotheses of possible causative agents in the outbreak of acute hepatitis among children in Europe and beyond.

Global data across the five WHO regions show there were 244 cases in the past month, bringing the total to 894 probable cases reported since October 2021 from 33 countries.

“It’s important to remember that this includes new cases, as well as retrospectively identified cases,” Dr.Easterbrook said. “Over half (52%) are from the European region, while 262 cases (30% of the global total) are from the United Kingdom.”

Data from Europe and the United States show a declining trajectory of reports of new cases. “This is a positive development,” she said.

The second highest reporting region is the Americas, she said, with 368 cases total, 290 cases of which come from the United States, accounting for 35% of the global total.

“Together the United Kingdom and the United States make up 65% of the global total,” she said.

Dr. Easterbrook added that 17 of the 33 reporting countries had more than five cases. Most cases (75%) are in young children under 5 years of age.

Serious cases are relatively few, but 44 (5%) children have required liver transplantation. Data from the European region show that 30% have required intensive care at some point during their hospitalization. There have been 18 (2%) reported deaths.

Possible post-COVID phenomenon, adenovirus most commonly reported

Dr. Easterbrook acknowledged the emerging hypothesis of a post-COVID phenomenon.

“Is this a variant of the rare but recognized multisystem inflammatory syndrome condition in children that’s been reported, often 1-2 months after COVID, causing widespread organ damage?” But she pointed out that the reported COVID cases with hepatitis “don’t seem to fit these features.”

Adenovirus remains the most commonly detected virus in acute hepatitis in children, found in 53% of cases overall, she said. The adenovirus detection rate is higher in the United Kingdom, at 68%.

“There are quite high rates of detection, but they’re not in all cases. There does seem to be a high rate of detection in the younger age groups and in those who are developing severe disease, so perhaps there is some link to severity,” Dr. Easterbrook said.

The working hypotheses continue to favor adenovirus together with past or current SARS-CoV-2 infection, as proposed early in the outbreak, she said. “These either work independently or work together as cofactors in some way to result in hepatitis. And there has been some clear progress on this. WHO is bringing together the data from different countries on some of these working hypotheses.”

Dr. Easterbrook highlighted the importance of procuring global data, especially given that two countries are reporting the majority of cases and in high numbers. “It’s a mixed picture with different rates of adenovirus detection and of COVID,” she said. “We need good-quality data collected in a standardized way.” WHO is requesting that countries provide these data.

She also highlighted the need for good in-depth studies, citing the UK Health Security Agency as an example of this. “There’s only a few countries that have the capacity or the patient numbers to look at this in detail, for example, the U.K. and the UKHSA.”

She noted that the UKHSA had laid out a comprehensive, systematic set of further investigations. For example, a case-control study is trying to establish whether there is a difference in the rate of adenovirus detection in children with hepatitis compared with other hospitalized children at the same time. “This aims to really tease out whether adenovirus is a cause or just a bystander,” she said.

She added that there were also genetic studies investigating whether genes were predisposing some children to develop a more severe form of disease. Other studies are evaluating the immune response of the patients.

Dr. Easterbrook added that the WHO will soon launch a global survey asking whether the reports of acute hepatitis are greater than the expected background rate for cases of hepatitis of unknown etiology.

Acute hepatitis is not new, but high caseload is

Also speaking at the ILC special briefing was Maria Buti, MD, PhD, policy and public health chair for the European Association for the Study of the Liver, and chief of the internal medicine and hepatology department at Hospital General Universitari Valle Hebron in Barcelona.

Dr. Buti drew attention to the fact that severe acute hepatitis of unknown etiology in children is not new.

“We have cases of acute hepatitis that even needed liver transplantation some years ago, and every year in our clinics we see these type of patients,” Dr. Buti remarked. What is really new, she added, is the amount of cases, particularly in the United Kingdom.

Dr. Easterbrook and Dr. Buti have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LONDON – Case numbers of acute hepatitis in children show “a declining trajectory,” and COVID-19 and adenovirus remain the most likely, but as yet unproven, causative agents, said experts in an update at the annual International Liver Congress sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

Philippa Easterbrook, MD, medical expert at the World Health Organization Global HIV, Hepatitis, and STI Programme, shared the latest case numbers and working hypotheses of possible causative agents in the outbreak of acute hepatitis among children in Europe and beyond.

Global data across the five WHO regions show there were 244 cases in the past month, bringing the total to 894 probable cases reported since October 2021 from 33 countries.

“It’s important to remember that this includes new cases, as well as retrospectively identified cases,” Dr.Easterbrook said. “Over half (52%) are from the European region, while 262 cases (30% of the global total) are from the United Kingdom.”

Data from Europe and the United States show a declining trajectory of reports of new cases. “This is a positive development,” she said.

The second highest reporting region is the Americas, she said, with 368 cases total, 290 cases of which come from the United States, accounting for 35% of the global total.

“Together the United Kingdom and the United States make up 65% of the global total,” she said.

Dr. Easterbrook added that 17 of the 33 reporting countries had more than five cases. Most cases (75%) are in young children under 5 years of age.

Serious cases are relatively few, but 44 (5%) children have required liver transplantation. Data from the European region show that 30% have required intensive care at some point during their hospitalization. There have been 18 (2%) reported deaths.

Possible post-COVID phenomenon, adenovirus most commonly reported

Dr. Easterbrook acknowledged the emerging hypothesis of a post-COVID phenomenon.

“Is this a variant of the rare but recognized multisystem inflammatory syndrome condition in children that’s been reported, often 1-2 months after COVID, causing widespread organ damage?” But she pointed out that the reported COVID cases with hepatitis “don’t seem to fit these features.”

Adenovirus remains the most commonly detected virus in acute hepatitis in children, found in 53% of cases overall, she said. The adenovirus detection rate is higher in the United Kingdom, at 68%.

“There are quite high rates of detection, but they’re not in all cases. There does seem to be a high rate of detection in the younger age groups and in those who are developing severe disease, so perhaps there is some link to severity,” Dr. Easterbrook said.

The working hypotheses continue to favor adenovirus together with past or current SARS-CoV-2 infection, as proposed early in the outbreak, she said. “These either work independently or work together as cofactors in some way to result in hepatitis. And there has been some clear progress on this. WHO is bringing together the data from different countries on some of these working hypotheses.”

Dr. Easterbrook highlighted the importance of procuring global data, especially given that two countries are reporting the majority of cases and in high numbers. “It’s a mixed picture with different rates of adenovirus detection and of COVID,” she said. “We need good-quality data collected in a standardized way.” WHO is requesting that countries provide these data.

She also highlighted the need for good in-depth studies, citing the UK Health Security Agency as an example of this. “There’s only a few countries that have the capacity or the patient numbers to look at this in detail, for example, the U.K. and the UKHSA.”

She noted that the UKHSA had laid out a comprehensive, systematic set of further investigations. For example, a case-control study is trying to establish whether there is a difference in the rate of adenovirus detection in children with hepatitis compared with other hospitalized children at the same time. “This aims to really tease out whether adenovirus is a cause or just a bystander,” she said.

She added that there were also genetic studies investigating whether genes were predisposing some children to develop a more severe form of disease. Other studies are evaluating the immune response of the patients.

Dr. Easterbrook added that the WHO will soon launch a global survey asking whether the reports of acute hepatitis are greater than the expected background rate for cases of hepatitis of unknown etiology.

Acute hepatitis is not new, but high caseload is

Also speaking at the ILC special briefing was Maria Buti, MD, PhD, policy and public health chair for the European Association for the Study of the Liver, and chief of the internal medicine and hepatology department at Hospital General Universitari Valle Hebron in Barcelona.

Dr. Buti drew attention to the fact that severe acute hepatitis of unknown etiology in children is not new.

“We have cases of acute hepatitis that even needed liver transplantation some years ago, and every year in our clinics we see these type of patients,” Dr. Buti remarked. What is really new, she added, is the amount of cases, particularly in the United Kingdom.

Dr. Easterbrook and Dr. Buti have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LONDON – Case numbers of acute hepatitis in children show “a declining trajectory,” and COVID-19 and adenovirus remain the most likely, but as yet unproven, causative agents, said experts in an update at the annual International Liver Congress sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

Philippa Easterbrook, MD, medical expert at the World Health Organization Global HIV, Hepatitis, and STI Programme, shared the latest case numbers and working hypotheses of possible causative agents in the outbreak of acute hepatitis among children in Europe and beyond.

Global data across the five WHO regions show there were 244 cases in the past month, bringing the total to 894 probable cases reported since October 2021 from 33 countries.

“It’s important to remember that this includes new cases, as well as retrospectively identified cases,” Dr.Easterbrook said. “Over half (52%) are from the European region, while 262 cases (30% of the global total) are from the United Kingdom.”

Data from Europe and the United States show a declining trajectory of reports of new cases. “This is a positive development,” she said.

The second highest reporting region is the Americas, she said, with 368 cases total, 290 cases of which come from the United States, accounting for 35% of the global total.

“Together the United Kingdom and the United States make up 65% of the global total,” she said.

Dr. Easterbrook added that 17 of the 33 reporting countries had more than five cases. Most cases (75%) are in young children under 5 years of age.

Serious cases are relatively few, but 44 (5%) children have required liver transplantation. Data from the European region show that 30% have required intensive care at some point during their hospitalization. There have been 18 (2%) reported deaths.

Possible post-COVID phenomenon, adenovirus most commonly reported

Dr. Easterbrook acknowledged the emerging hypothesis of a post-COVID phenomenon.

“Is this a variant of the rare but recognized multisystem inflammatory syndrome condition in children that’s been reported, often 1-2 months after COVID, causing widespread organ damage?” But she pointed out that the reported COVID cases with hepatitis “don’t seem to fit these features.”

Adenovirus remains the most commonly detected virus in acute hepatitis in children, found in 53% of cases overall, she said. The adenovirus detection rate is higher in the United Kingdom, at 68%.

“There are quite high rates of detection, but they’re not in all cases. There does seem to be a high rate of detection in the younger age groups and in those who are developing severe disease, so perhaps there is some link to severity,” Dr. Easterbrook said.

The working hypotheses continue to favor adenovirus together with past or current SARS-CoV-2 infection, as proposed early in the outbreak, she said. “These either work independently or work together as cofactors in some way to result in hepatitis. And there has been some clear progress on this. WHO is bringing together the data from different countries on some of these working hypotheses.”

Dr. Easterbrook highlighted the importance of procuring global data, especially given that two countries are reporting the majority of cases and in high numbers. “It’s a mixed picture with different rates of adenovirus detection and of COVID,” she said. “We need good-quality data collected in a standardized way.” WHO is requesting that countries provide these data.

She also highlighted the need for good in-depth studies, citing the UK Health Security Agency as an example of this. “There’s only a few countries that have the capacity or the patient numbers to look at this in detail, for example, the U.K. and the UKHSA.”

She noted that the UKHSA had laid out a comprehensive, systematic set of further investigations. For example, a case-control study is trying to establish whether there is a difference in the rate of adenovirus detection in children with hepatitis compared with other hospitalized children at the same time. “This aims to really tease out whether adenovirus is a cause or just a bystander,” she said.

She added that there were also genetic studies investigating whether genes were predisposing some children to develop a more severe form of disease. Other studies are evaluating the immune response of the patients.

Dr. Easterbrook added that the WHO will soon launch a global survey asking whether the reports of acute hepatitis are greater than the expected background rate for cases of hepatitis of unknown etiology.

Acute hepatitis is not new, but high caseload is

Also speaking at the ILC special briefing was Maria Buti, MD, PhD, policy and public health chair for the European Association for the Study of the Liver, and chief of the internal medicine and hepatology department at Hospital General Universitari Valle Hebron in Barcelona.

Dr. Buti drew attention to the fact that severe acute hepatitis of unknown etiology in children is not new.

“We have cases of acute hepatitis that even needed liver transplantation some years ago, and every year in our clinics we see these type of patients,” Dr. Buti remarked. What is really new, she added, is the amount of cases, particularly in the United Kingdom.

Dr. Easterbrook and Dr. Buti have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ILC 2022

Rapidly Evolving Papulonodular Eruption in the Axilla

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

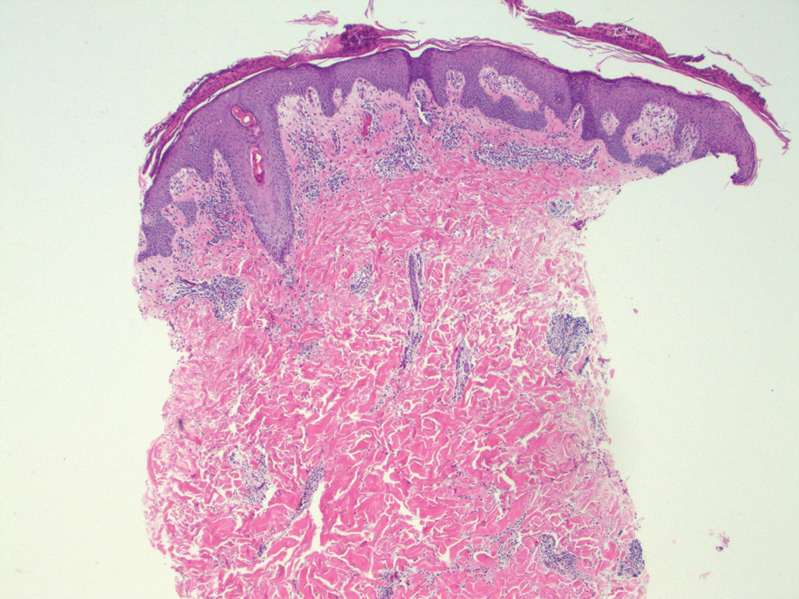

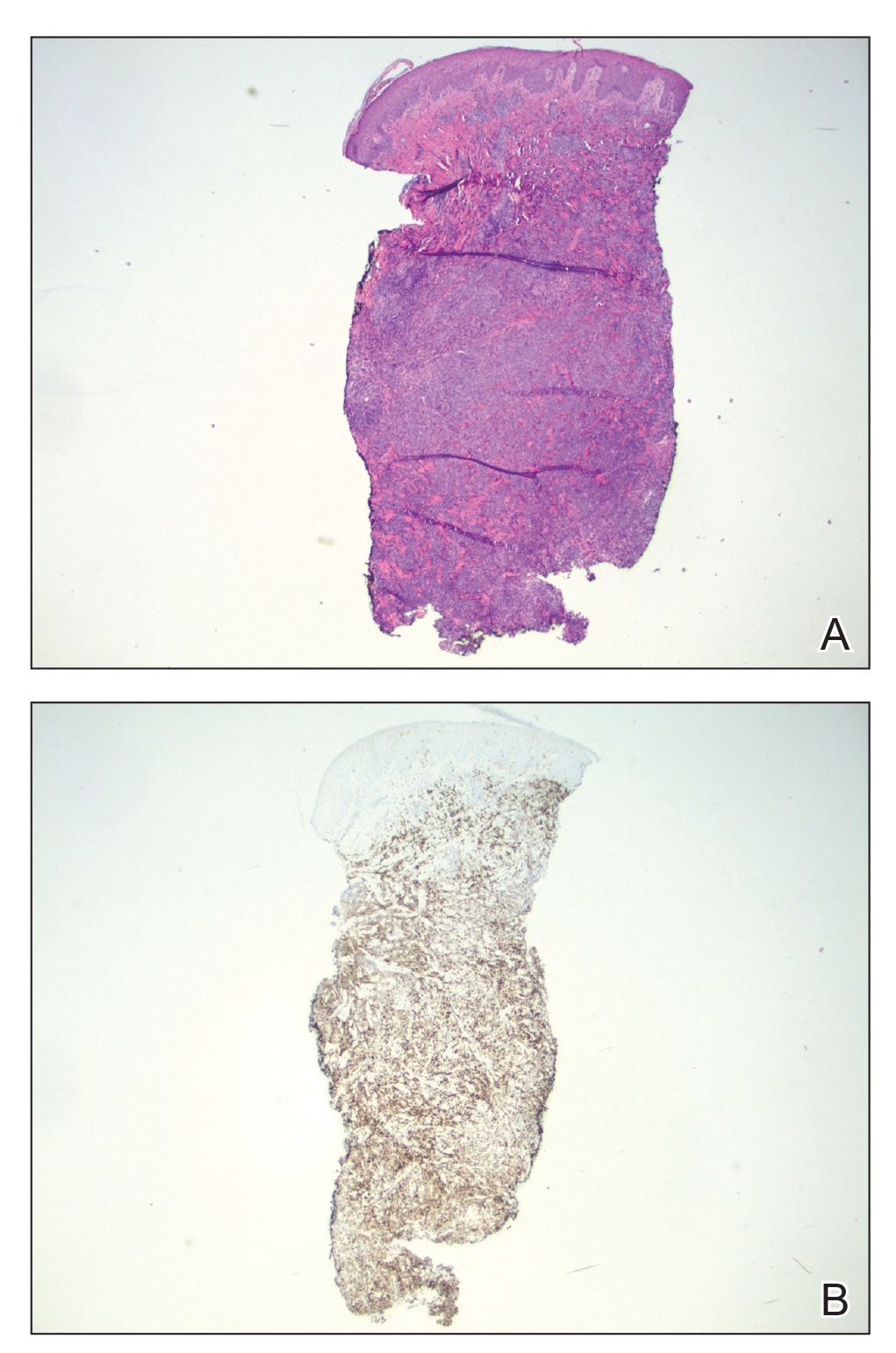

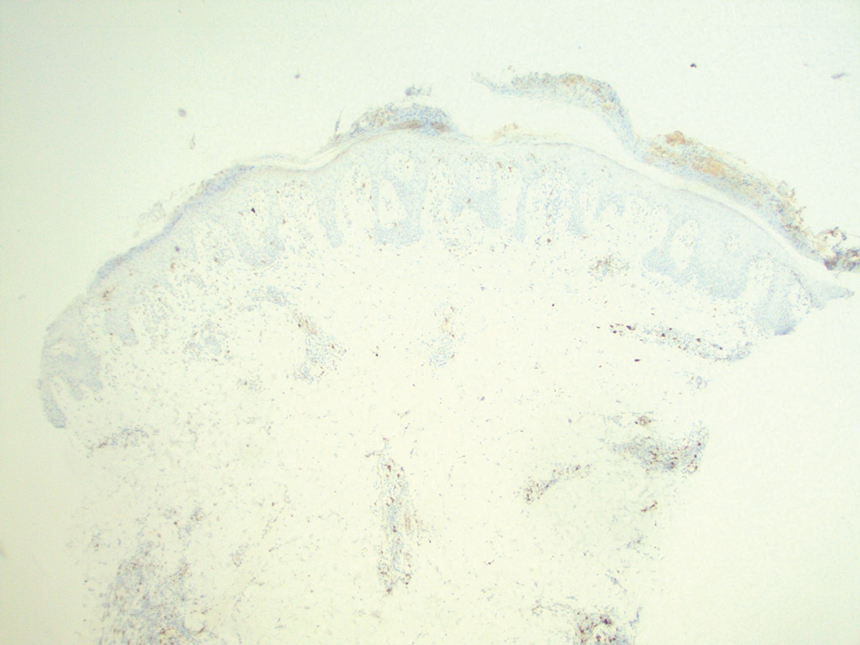

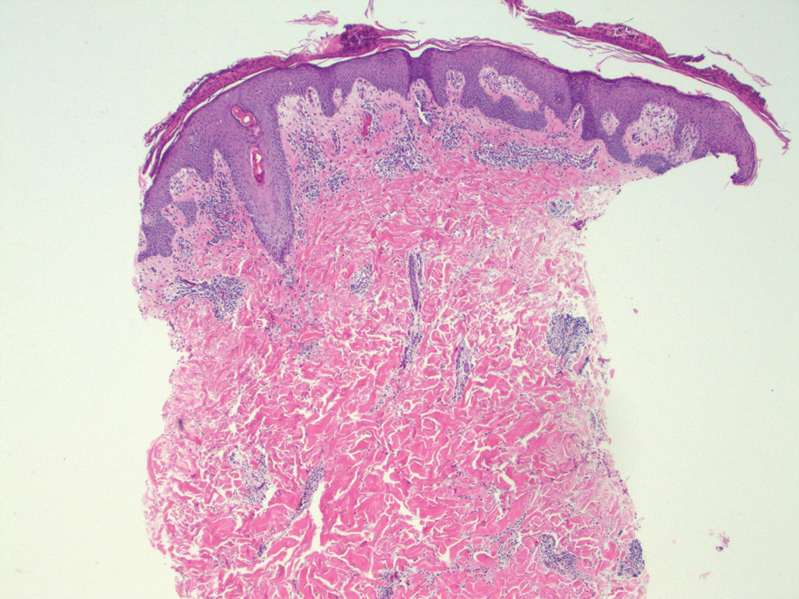

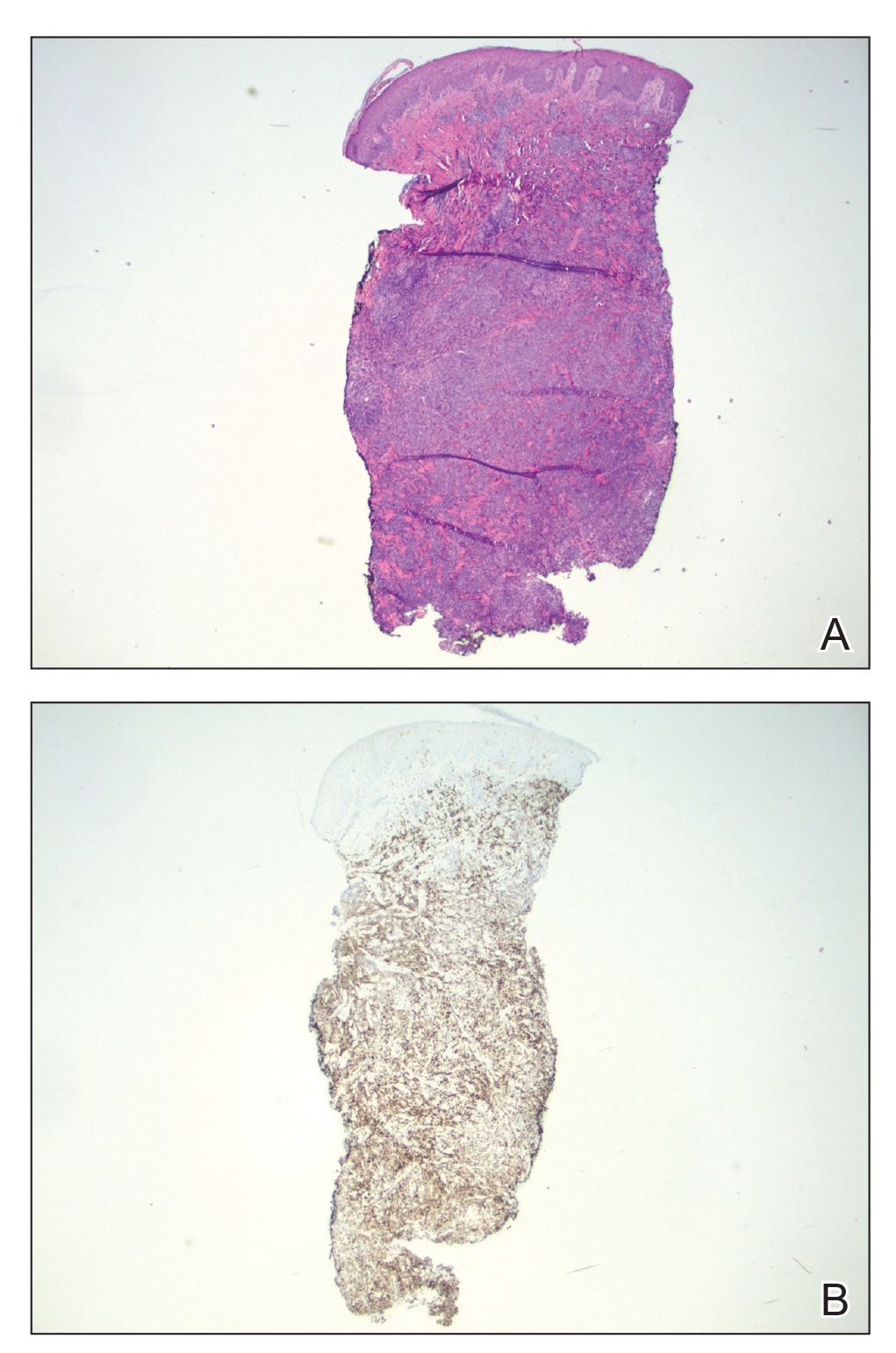

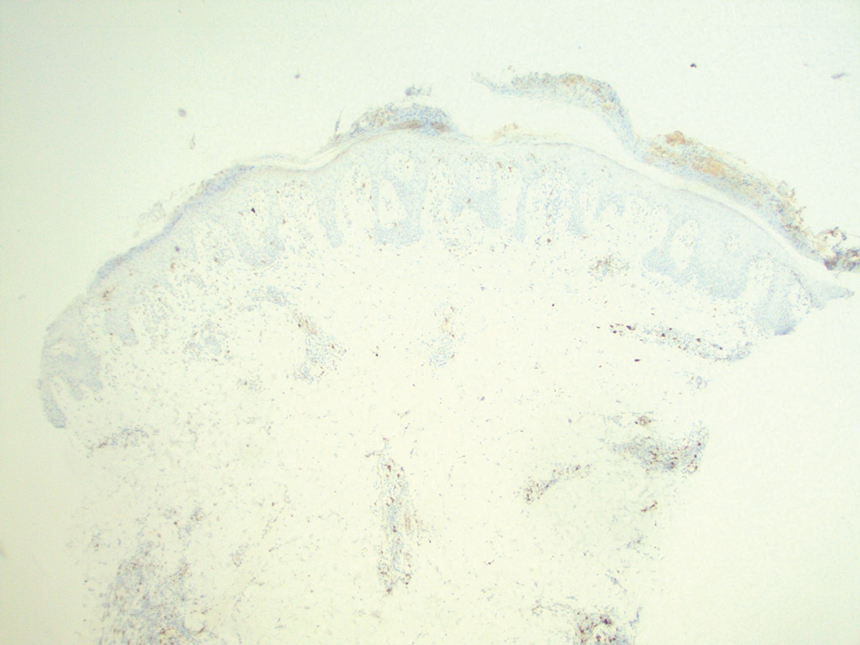

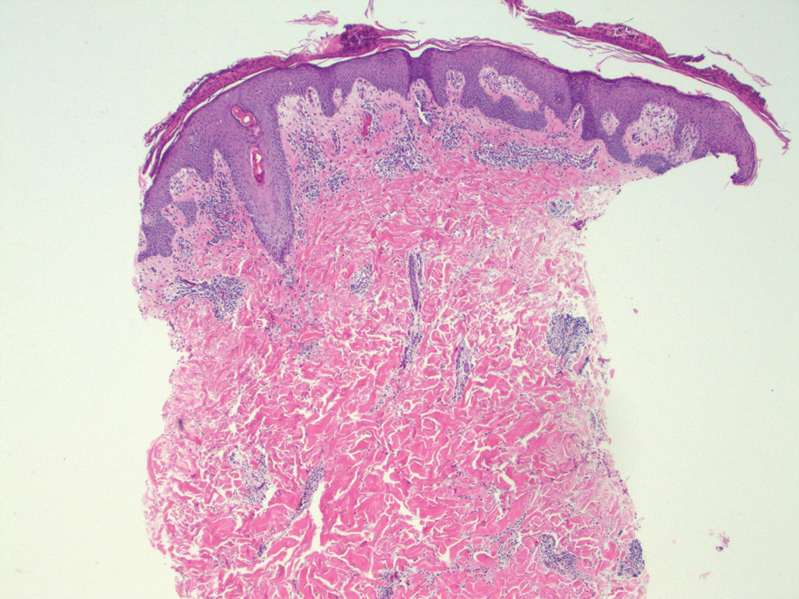

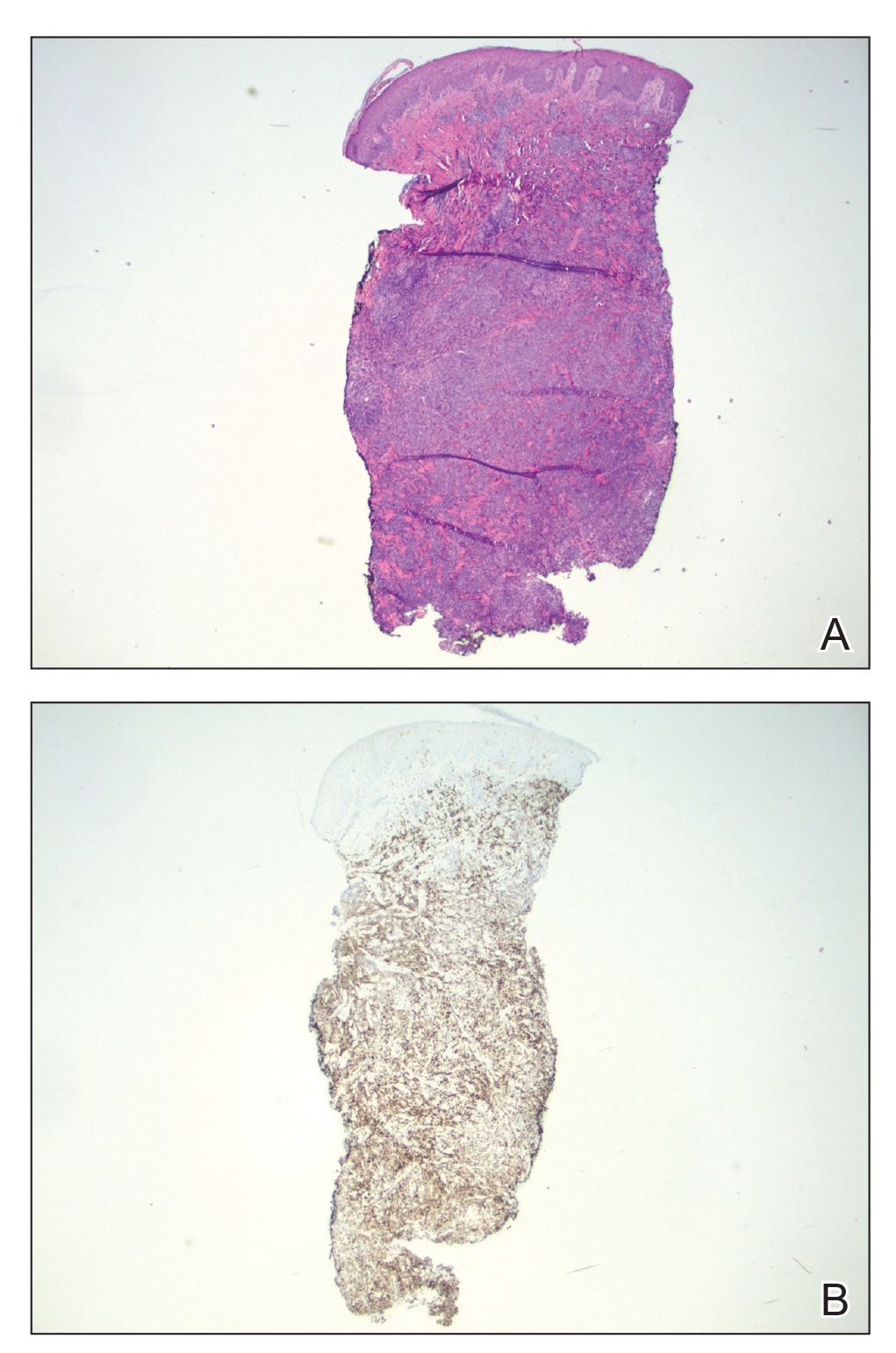

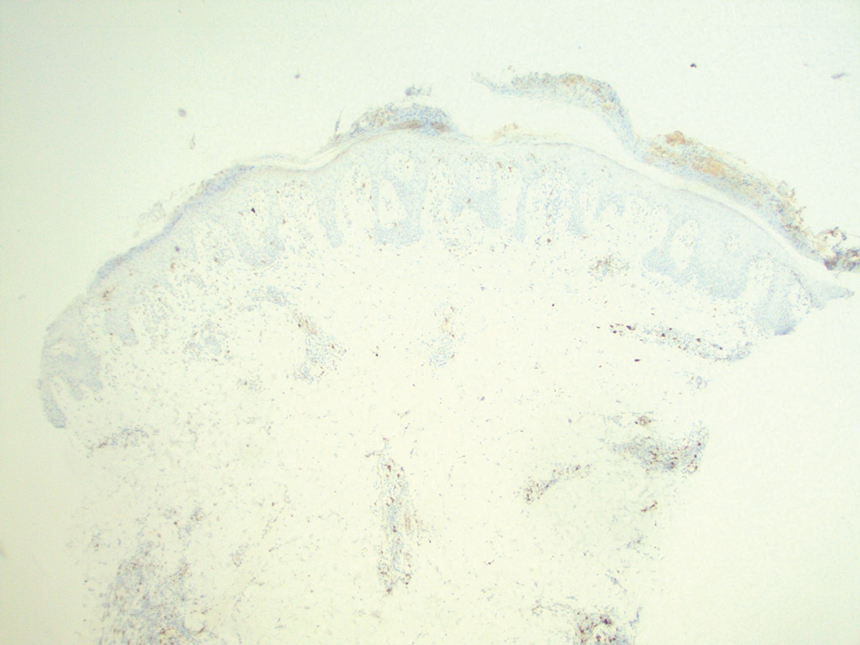

At the time of the initial visit, a punch biopsy was performed on the posterior shoulder girdle. Histopathology revealed mild epidermal spongiosis and acanthosis with associated parakeratosis and a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes consistent with pityriasis rosea (Figure 1). Two weeks after the biopsy, the patient returned for suture removal and to discuss the biopsy results. The patient reported more evolving lesions despite completing the prescribed course of dicloxacillin. At this time, physical examination revealed the persistence of several reddishbrown papules along with new nodular lesions on the arms and thighs, some with central ulceration and crusting (Figure 2). A second biopsy of a nodular lesion on the right distal forearm was performed at this visit along with a superficial tissue culture, which was negative for bacterial or fungal elements. The biopsy revealed an atypical CD30+ lymphoid proliferation (Figure 3). These cells were strongly PD-L1 positive and also positive for CD3, CD4, and granzyme-B. Ki67 showed a high proliferation rate, and T-cell gene rearrangement studies were positive. Given these histologic findings and the clinical context of rapidly evolving skin lesions from small papules to nodular skin tumors, a diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) was established.

Because of the notable pathologic discordance between the 2 biopsy specimens, re-evaluation of the initial specimen was requested. The initial biopsy was subsequently found to be CD30+ with an identical peak on gene rearrangement studies as the second biopsy, further validating the diagnosis of LyP (Figure 4). Our patient was offered low-dose methotrexate therapy but declined the treatment plan, as the skin lesions had begun to resolve.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder with a characteristic recurrent and self-remitting disease course.1,2 Although it typically has a benign clinical course, it is histologically malignant and considered a low-grade variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. 2,3 The classic clinical presentation of LyP involves the presence of reddish-brown papules and nodules typically measuring less than 2.0 cm, which may show evidence of central ulceration, hemorrhage, necrosis, and/or crust formation.1-5 It is characteristic that a patient may present with these skin lesions in different stages of evolution and that biopsies of these lesions may reflect different histologic features depending on the age of the lesion, making a definitive diagnosis more difficult to obtain if not clinically correlated.1,2 Any part of the body may be involved; however, there appears to be a predilection for the trunk and extremities in most cases.1-3,5 The skin eruptions usually are asymptomatic, but pruritus is a commonly associated concern.1,2,4,5

Lymphomatoid papulosis can have a localized, clustered, or generalized distribution pattern and typically will spontaneously regress without treatment within 3 to 12 weeks of symptom onset.2,3 Lymphomatoid papulosis has a slight male predominance with a male to female ratio of 1.5:1. It occurs most commonly between 35 and 45 years of age, though it can present at any age. The overall duration of the disease can range from months to decades.2,3 Lymphomatoid papulosis makes up approximately 15% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.2,3 Although the overall prognosis is excellent, patients with LyP are at an increased risk of developing cutaneous or systemic lymphoma, most commonly mycosis fungoides, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, or Hodgkin lymphoma.1-3 This increased lifelong risk is the reason that patients with LyP must be followed long-term every 6 to 12 months for surveillance of emerging malignancy.1,2,6

The pathogenesis of LyP remains unknown. Some have hypothesized a possible viral trigger; however, there is insufficient data to support this theory.2,6 A diagnostic hallmark of LyP is its CD30 positivity, which is a known marker for T-cell activation.6 The spontaneous regression of skin lesions that is characteristic of LyP is believed to involve the interactions between CD30 and its ligand (CD30L), which may contribute to apoptosis of neoplastic T cells.2,3,6 With regards to the possible mechanisms contributing to tumor progression in LyP, a mutation in the transforming growth factor β receptor gene on CD30+ tumor cells within LyP lesions may allow for these cells to evade growth regulation and progress to lymphoma.2,6 A large percentage of LyP biopsy specimens show evidence of T-cell receptor gene monoclonal rearrangement, which can aid in establishing a diagnosis.1,2

The histologic features of LyP can vary greatly depending on the age of the lesion sampled.1,2 Histologic subtypes of LyP have been established, with type A being the most common (approximately 75% of cases), displaying a wedge-shaped infiltrate of scattered or clustered, large, atypical CD30+ T cells.1,2 Types B through E vary in histologic features, with the exception that all subtypes contain a CD30+ lymphocytic infiltrate.2,3

Treatment of LyP depends on the symptom/disease burden that the patient is experiencing. For patients with a limited number of nonscarring skin lesions in areas that are not cosmetically sensitive, observation is recommended. 1-3 For symptomatic patients with an extensive number of lesions, particularly those that may be scarring and/or in cosmetically sensitive areas, low-dose oral methotrexate therapy is considered first-line treatment.1-4 A methotrexate dose of 5 to 20 mg weekly can be effective in reducing the number and severity of lesions, with duration of treatment depending on clinical response.1,2 For patients who have contraindications to or who cannot tolerate oral methotrexate, phototherapy using psoralen plus UVA twice weekly for 6 to 8 weeks is another treatment option.1,2 Topical corticosteroids also can be used in children or for patients experiencing substantial pruritus.1,2,4 Oral or topical retinoids, topical carmustine or mechlorethamine, and brentuximab (an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody) are all alternative therapies that have shown some beneficial effects.1,2 In the event that any of the skin lesions do not spontaneously regress within a 3- to 12-week time frame, surgical excision or radiotherapy can be performed on those lesions.2

Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (C-ALCL) is another CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder with overlapping clinical and histopathological features of LyP. Recurrent crops of multiple lesions favor a diagnosis of LyP, whereas solitary lesions favor C-ALCL; however, multifocal C-ALCL cases may occur.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that characteristically presents in a patch, plaque, tumor progression. Although mycosis fungoides eventually may transform into a CD30+ lymphoma, our patient did not display the characteristic clinical progression to suggest this diagnosis. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and pityriasis lichenoides chronica also fall into the spectrum of clonal T-cell cutaneous disorders that more commonly affect the pediatric population. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta has a marked CD8+ lymphocyte infiltrate, whereas pityriasis lichenoides chronica has more CD4+ lymphocytes. These disorders typically do not stain positive for CD30.2

All patients with a diagnosis of LyP should maintain lifelong, regular, 6- to 12-month follow-up visits to monitor disease status and screen for any evidence of developing malignancy.1,2,6 A thorough review of clinical history, complete skin examination, and physical examination with a particular focus on detection of lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly should be included at every followup visit.1 Systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, or weight loss are not typical features of LyP; therefore, patients who begin to develop these symptoms should be promptly evaluated for systemic lymphoma.1

- Kadin ME. Lymphomatoid papulosis. UpToDate website. Accessed June 4, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lymphomatoid-papulosis

- Willemze R. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2017:2141-2143.

- Wiznia LE, Cohen JM, Beasley JM, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt4xt046c9.

- Wieser I, Oh CW, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.013

- Wolff K, Johnson RA, Saavedra AP, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2017.

- Kunishige JH, McDonald H, Alvarez G, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis and associated lymphomas: a retrospective case series of 84 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:576-581. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2230.2008.03024.x

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

At the time of the initial visit, a punch biopsy was performed on the posterior shoulder girdle. Histopathology revealed mild epidermal spongiosis and acanthosis with associated parakeratosis and a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes consistent with pityriasis rosea (Figure 1). Two weeks after the biopsy, the patient returned for suture removal and to discuss the biopsy results. The patient reported more evolving lesions despite completing the prescribed course of dicloxacillin. At this time, physical examination revealed the persistence of several reddishbrown papules along with new nodular lesions on the arms and thighs, some with central ulceration and crusting (Figure 2). A second biopsy of a nodular lesion on the right distal forearm was performed at this visit along with a superficial tissue culture, which was negative for bacterial or fungal elements. The biopsy revealed an atypical CD30+ lymphoid proliferation (Figure 3). These cells were strongly PD-L1 positive and also positive for CD3, CD4, and granzyme-B. Ki67 showed a high proliferation rate, and T-cell gene rearrangement studies were positive. Given these histologic findings and the clinical context of rapidly evolving skin lesions from small papules to nodular skin tumors, a diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) was established.

Because of the notable pathologic discordance between the 2 biopsy specimens, re-evaluation of the initial specimen was requested. The initial biopsy was subsequently found to be CD30+ with an identical peak on gene rearrangement studies as the second biopsy, further validating the diagnosis of LyP (Figure 4). Our patient was offered low-dose methotrexate therapy but declined the treatment plan, as the skin lesions had begun to resolve.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder with a characteristic recurrent and self-remitting disease course.1,2 Although it typically has a benign clinical course, it is histologically malignant and considered a low-grade variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. 2,3 The classic clinical presentation of LyP involves the presence of reddish-brown papules and nodules typically measuring less than 2.0 cm, which may show evidence of central ulceration, hemorrhage, necrosis, and/or crust formation.1-5 It is characteristic that a patient may present with these skin lesions in different stages of evolution and that biopsies of these lesions may reflect different histologic features depending on the age of the lesion, making a definitive diagnosis more difficult to obtain if not clinically correlated.1,2 Any part of the body may be involved; however, there appears to be a predilection for the trunk and extremities in most cases.1-3,5 The skin eruptions usually are asymptomatic, but pruritus is a commonly associated concern.1,2,4,5

Lymphomatoid papulosis can have a localized, clustered, or generalized distribution pattern and typically will spontaneously regress without treatment within 3 to 12 weeks of symptom onset.2,3 Lymphomatoid papulosis has a slight male predominance with a male to female ratio of 1.5:1. It occurs most commonly between 35 and 45 years of age, though it can present at any age. The overall duration of the disease can range from months to decades.2,3 Lymphomatoid papulosis makes up approximately 15% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.2,3 Although the overall prognosis is excellent, patients with LyP are at an increased risk of developing cutaneous or systemic lymphoma, most commonly mycosis fungoides, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, or Hodgkin lymphoma.1-3 This increased lifelong risk is the reason that patients with LyP must be followed long-term every 6 to 12 months for surveillance of emerging malignancy.1,2,6