User login

Dermatologist arrested for allegedly poisoning radiologist husband

It is a story that has quickly gone viral around the world:

Yue Yu, MD, aged 45, was booked into the Orange County Jail on Aug. 4, after Irvine Police had been called to her residence that day by her husband, Jack Chen, MD, 53, a radiologist. Dr. Chen provided the police with video evidence that he said showed Dr. Yu pouring a drain-opening chemical into his hot lemonade drink.

“The victim sustained significant internal injuries but is expected to recover,” the Irvine police department said in a statement.

Dr. Yu was released after paying a $30,000 bond and has not been formally charged, according to the New York Post.

In a statement to the court on Aug. 5, Dr. Chen said he and the couple’s two children had long suffered verbal abuse from his wife and her mother, according to the Post. Multiple news organizations reported that Dr. Chen filed for divorce and also for a restraining order against Dr. Yu on that day.

After feeling ill for months – and being diagnosed with ulcers and esophageal inflammation – Dr. Chen reportedly set up video cameras in the couple’s house. He said he caught Dr. Yu on camera pouring something into his drink on several occasions in July.

According to NBC News, Dr. Yu’s attorney, David E. Wohl, said that Dr. Yu “vehemently and unequivocally denies ever attempting to poison her husband or anyone else.”

Dr. Yu received her medical degree from Washington University in St. Louis in 2006 and has no disciplinary actions against her, according to the Medical Board of California. She was head of dermatology at Mission Heritage Medical Group, but her name and information have been scrubbed from that group’s website. Mission Heritage is affiliated with Providence Mission Hospital. A spokesperson for the hospital told NBC News that it is cooperating with the police investigation and that no patients are in danger.

The dermatologist is due to report back to court in November, NBC News said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It is a story that has quickly gone viral around the world:

Yue Yu, MD, aged 45, was booked into the Orange County Jail on Aug. 4, after Irvine Police had been called to her residence that day by her husband, Jack Chen, MD, 53, a radiologist. Dr. Chen provided the police with video evidence that he said showed Dr. Yu pouring a drain-opening chemical into his hot lemonade drink.

“The victim sustained significant internal injuries but is expected to recover,” the Irvine police department said in a statement.

Dr. Yu was released after paying a $30,000 bond and has not been formally charged, according to the New York Post.

In a statement to the court on Aug. 5, Dr. Chen said he and the couple’s two children had long suffered verbal abuse from his wife and her mother, according to the Post. Multiple news organizations reported that Dr. Chen filed for divorce and also for a restraining order against Dr. Yu on that day.

After feeling ill for months – and being diagnosed with ulcers and esophageal inflammation – Dr. Chen reportedly set up video cameras in the couple’s house. He said he caught Dr. Yu on camera pouring something into his drink on several occasions in July.

According to NBC News, Dr. Yu’s attorney, David E. Wohl, said that Dr. Yu “vehemently and unequivocally denies ever attempting to poison her husband or anyone else.”

Dr. Yu received her medical degree from Washington University in St. Louis in 2006 and has no disciplinary actions against her, according to the Medical Board of California. She was head of dermatology at Mission Heritage Medical Group, but her name and information have been scrubbed from that group’s website. Mission Heritage is affiliated with Providence Mission Hospital. A spokesperson for the hospital told NBC News that it is cooperating with the police investigation and that no patients are in danger.

The dermatologist is due to report back to court in November, NBC News said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It is a story that has quickly gone viral around the world:

Yue Yu, MD, aged 45, was booked into the Orange County Jail on Aug. 4, after Irvine Police had been called to her residence that day by her husband, Jack Chen, MD, 53, a radiologist. Dr. Chen provided the police with video evidence that he said showed Dr. Yu pouring a drain-opening chemical into his hot lemonade drink.

“The victim sustained significant internal injuries but is expected to recover,” the Irvine police department said in a statement.

Dr. Yu was released after paying a $30,000 bond and has not been formally charged, according to the New York Post.

In a statement to the court on Aug. 5, Dr. Chen said he and the couple’s two children had long suffered verbal abuse from his wife and her mother, according to the Post. Multiple news organizations reported that Dr. Chen filed for divorce and also for a restraining order against Dr. Yu on that day.

After feeling ill for months – and being diagnosed with ulcers and esophageal inflammation – Dr. Chen reportedly set up video cameras in the couple’s house. He said he caught Dr. Yu on camera pouring something into his drink on several occasions in July.

According to NBC News, Dr. Yu’s attorney, David E. Wohl, said that Dr. Yu “vehemently and unequivocally denies ever attempting to poison her husband or anyone else.”

Dr. Yu received her medical degree from Washington University in St. Louis in 2006 and has no disciplinary actions against her, according to the Medical Board of California. She was head of dermatology at Mission Heritage Medical Group, but her name and information have been scrubbed from that group’s website. Mission Heritage is affiliated with Providence Mission Hospital. A spokesperson for the hospital told NBC News that it is cooperating with the police investigation and that no patients are in danger.

The dermatologist is due to report back to court in November, NBC News said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long COVID’s grip will likely tighten as infections continue

COVID-19 is far from done in the United States, with more than 111,000 new cases being recorded a day in the second week of August, according to Johns Hopkins University, and 625 deaths being reported every day. , a condition that already has affected between 7.7 million and 23 million Americans, according to U.S. government estimates.

“It is evident that long COVID is real, that it already impacts a substantial number of people, and that this number may continue to grow as new infections occur,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) said in a research action plan released Aug. 4.

“We are heading towards a big problem on our hands,” says Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research and development at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in St. Louis. “It’s like if we are falling in a plane, hurtling towards the ground. It doesn’t matter at what speed we are falling; what matters is that we are all falling, and falling fast. It’s a real problem. We needed to bring attention to this, yesterday,” he said.

Bryan Lau, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and co-lead of a long COVID study there, says whether it’s 5% of the 92 million officially recorded U.S. COVID-19 cases, or 30% – on the higher end of estimates – that means anywhere between 4.5 million and 27 million Americans will have the effects of long COVID.

Other experts put the estimates even higher.

“If we conservatively assume 100 million working-age adults have been infected, that implies 10 to 33 million may have long COVID,” Alice Burns, PhD, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, wrote in an analysis.

And even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says only a fraction of cases have been recorded.

That, in turn, means tens of millions of people who struggle to work, to get to school, and to take care of their families – and who will be making demands on an already stressed U.S. health care system.

The HHS said in its Aug. 4 report that long COVID could keep 1 million people a day out of work, with a loss of $50 billion in annual pay.

Dr. Lau said health workers and policymakers are woefully unprepared.

“If you have a family unit, and the mom or dad can’t work, or has trouble taking their child to activities, where does the question of support come into play? Where is there potential for food issues, or housing issues?” he asked. “I see the potential for the burden to be extremely large in that capacity.”

Dr. Lau said he has yet to see any strong estimates of how many cases of long COVID might develop. Because a person has to get COVID-19 to ultimately get long COVID, the two are linked. In other words, as COVID-19 cases rise, so will cases of long COVID, and vice versa.

Evidence from the Kaiser Family Foundation analysis suggests a significant impact on employment: Surveys showed more than half of adults with long COVID who worked before becoming infected are either out of work or working fewer hours. Conditions associated with long COVID – such as fatigue, malaise, or problems concentrating – limit people’s ability to work, even if they have jobs that allow for accommodations.

Two surveys of people with long COVID who had worked before becoming infected showed that between 22% and 27% of them were out of work after getting long COVID. In comparison, among all working-age adults in 2019, only 7% were out of work. Given the sheer number of working-age adults with long COVID, the effects on employment may be profound and are likely to involve more people over time. One study estimates that long COVID already accounts for 15% of unfilled jobs.

The most severe symptoms of long COVID include brain fog and heart complications, known to persist for weeks for months after a COVID-19 infection.

A study from the University of Norway published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found 53% of people tested had at least one symptom of thinking problems 13 months after infection with COVID-19. According to the HHS’ latest report on long COVID, people with thinking problems, heart conditions, mobility issues, and other symptoms are going to need a considerable amount of care. Many will need lengthy periods of rehabilitation.

Dr. Al-Aly worries that long COVID has already severely affected the labor force and the job market, all while burdening the country’s health care system.

“While there are variations in how individuals respond and cope with long COVID, the unifying thread is that with the level of disability it causes, more people will be struggling to keep up with the demands of the workforce and more people will be out on disability than ever before,” he said.

Studies from Johns Hopkins and the University of Washington estimate that 5%-30% of people could get long COVID in the future. Projections beyond that are hazy.

“So far, all the studies we have done on long COVID have been reactionary. Much of the activism around long COVID has been patient led. We are seeing more and more people with lasting symptoms. We need our research to catch up,” Dr. Lau said.

Theo Vos, MD, PhD, professor of health sciences at University of Washington, Seattle, said the main reasons for the huge range of predictions are the variety of methods used, as well as differences in sample size. Also, much long COVID data is self-reported, making it difficult for epidemiologists to track.

“With self-reported data, you can’t plug people into a machine and say this is what they have or this is what they don’t have. At the population level, the only thing you can do is ask questions. There is no systematic way to define long COVID,” he said.

Dr. Vos’s most recent study, which is being peer-reviewed and revised, found that most people with long COVID have symptoms similar to those seen in other autoimmune diseases. But sometimes the immune system can overreact, causing the more severe symptoms, such as brain fog and heart problems, associated with long COVID.

One reason that researchers struggle to come up with numbers, said Dr. Al-Aly, is the rapid rise of new variants. These variants appear to sometimes cause less severe disease than previous ones, but it’s not clear whether that means different risks for long COVID.

“There’s a wide diversity in severity. Someone can have long COVID and be fully functional, while others are not functional at all. We still have a long way to go before we figure out why,” Dr. Lau said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID-19 is far from done in the United States, with more than 111,000 new cases being recorded a day in the second week of August, according to Johns Hopkins University, and 625 deaths being reported every day. , a condition that already has affected between 7.7 million and 23 million Americans, according to U.S. government estimates.

“It is evident that long COVID is real, that it already impacts a substantial number of people, and that this number may continue to grow as new infections occur,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) said in a research action plan released Aug. 4.

“We are heading towards a big problem on our hands,” says Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research and development at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in St. Louis. “It’s like if we are falling in a plane, hurtling towards the ground. It doesn’t matter at what speed we are falling; what matters is that we are all falling, and falling fast. It’s a real problem. We needed to bring attention to this, yesterday,” he said.

Bryan Lau, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and co-lead of a long COVID study there, says whether it’s 5% of the 92 million officially recorded U.S. COVID-19 cases, or 30% – on the higher end of estimates – that means anywhere between 4.5 million and 27 million Americans will have the effects of long COVID.

Other experts put the estimates even higher.

“If we conservatively assume 100 million working-age adults have been infected, that implies 10 to 33 million may have long COVID,” Alice Burns, PhD, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, wrote in an analysis.

And even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says only a fraction of cases have been recorded.

That, in turn, means tens of millions of people who struggle to work, to get to school, and to take care of their families – and who will be making demands on an already stressed U.S. health care system.

The HHS said in its Aug. 4 report that long COVID could keep 1 million people a day out of work, with a loss of $50 billion in annual pay.

Dr. Lau said health workers and policymakers are woefully unprepared.

“If you have a family unit, and the mom or dad can’t work, or has trouble taking their child to activities, where does the question of support come into play? Where is there potential for food issues, or housing issues?” he asked. “I see the potential for the burden to be extremely large in that capacity.”

Dr. Lau said he has yet to see any strong estimates of how many cases of long COVID might develop. Because a person has to get COVID-19 to ultimately get long COVID, the two are linked. In other words, as COVID-19 cases rise, so will cases of long COVID, and vice versa.

Evidence from the Kaiser Family Foundation analysis suggests a significant impact on employment: Surveys showed more than half of adults with long COVID who worked before becoming infected are either out of work or working fewer hours. Conditions associated with long COVID – such as fatigue, malaise, or problems concentrating – limit people’s ability to work, even if they have jobs that allow for accommodations.

Two surveys of people with long COVID who had worked before becoming infected showed that between 22% and 27% of them were out of work after getting long COVID. In comparison, among all working-age adults in 2019, only 7% were out of work. Given the sheer number of working-age adults with long COVID, the effects on employment may be profound and are likely to involve more people over time. One study estimates that long COVID already accounts for 15% of unfilled jobs.

The most severe symptoms of long COVID include brain fog and heart complications, known to persist for weeks for months after a COVID-19 infection.

A study from the University of Norway published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found 53% of people tested had at least one symptom of thinking problems 13 months after infection with COVID-19. According to the HHS’ latest report on long COVID, people with thinking problems, heart conditions, mobility issues, and other symptoms are going to need a considerable amount of care. Many will need lengthy periods of rehabilitation.

Dr. Al-Aly worries that long COVID has already severely affected the labor force and the job market, all while burdening the country’s health care system.

“While there are variations in how individuals respond and cope with long COVID, the unifying thread is that with the level of disability it causes, more people will be struggling to keep up with the demands of the workforce and more people will be out on disability than ever before,” he said.

Studies from Johns Hopkins and the University of Washington estimate that 5%-30% of people could get long COVID in the future. Projections beyond that are hazy.

“So far, all the studies we have done on long COVID have been reactionary. Much of the activism around long COVID has been patient led. We are seeing more and more people with lasting symptoms. We need our research to catch up,” Dr. Lau said.

Theo Vos, MD, PhD, professor of health sciences at University of Washington, Seattle, said the main reasons for the huge range of predictions are the variety of methods used, as well as differences in sample size. Also, much long COVID data is self-reported, making it difficult for epidemiologists to track.

“With self-reported data, you can’t plug people into a machine and say this is what they have or this is what they don’t have. At the population level, the only thing you can do is ask questions. There is no systematic way to define long COVID,” he said.

Dr. Vos’s most recent study, which is being peer-reviewed and revised, found that most people with long COVID have symptoms similar to those seen in other autoimmune diseases. But sometimes the immune system can overreact, causing the more severe symptoms, such as brain fog and heart problems, associated with long COVID.

One reason that researchers struggle to come up with numbers, said Dr. Al-Aly, is the rapid rise of new variants. These variants appear to sometimes cause less severe disease than previous ones, but it’s not clear whether that means different risks for long COVID.

“There’s a wide diversity in severity. Someone can have long COVID and be fully functional, while others are not functional at all. We still have a long way to go before we figure out why,” Dr. Lau said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID-19 is far from done in the United States, with more than 111,000 new cases being recorded a day in the second week of August, according to Johns Hopkins University, and 625 deaths being reported every day. , a condition that already has affected between 7.7 million and 23 million Americans, according to U.S. government estimates.

“It is evident that long COVID is real, that it already impacts a substantial number of people, and that this number may continue to grow as new infections occur,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) said in a research action plan released Aug. 4.

“We are heading towards a big problem on our hands,” says Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research and development at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in St. Louis. “It’s like if we are falling in a plane, hurtling towards the ground. It doesn’t matter at what speed we are falling; what matters is that we are all falling, and falling fast. It’s a real problem. We needed to bring attention to this, yesterday,” he said.

Bryan Lau, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and co-lead of a long COVID study there, says whether it’s 5% of the 92 million officially recorded U.S. COVID-19 cases, or 30% – on the higher end of estimates – that means anywhere between 4.5 million and 27 million Americans will have the effects of long COVID.

Other experts put the estimates even higher.

“If we conservatively assume 100 million working-age adults have been infected, that implies 10 to 33 million may have long COVID,” Alice Burns, PhD, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, wrote in an analysis.

And even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says only a fraction of cases have been recorded.

That, in turn, means tens of millions of people who struggle to work, to get to school, and to take care of their families – and who will be making demands on an already stressed U.S. health care system.

The HHS said in its Aug. 4 report that long COVID could keep 1 million people a day out of work, with a loss of $50 billion in annual pay.

Dr. Lau said health workers and policymakers are woefully unprepared.

“If you have a family unit, and the mom or dad can’t work, or has trouble taking their child to activities, where does the question of support come into play? Where is there potential for food issues, or housing issues?” he asked. “I see the potential for the burden to be extremely large in that capacity.”

Dr. Lau said he has yet to see any strong estimates of how many cases of long COVID might develop. Because a person has to get COVID-19 to ultimately get long COVID, the two are linked. In other words, as COVID-19 cases rise, so will cases of long COVID, and vice versa.

Evidence from the Kaiser Family Foundation analysis suggests a significant impact on employment: Surveys showed more than half of adults with long COVID who worked before becoming infected are either out of work or working fewer hours. Conditions associated with long COVID – such as fatigue, malaise, or problems concentrating – limit people’s ability to work, even if they have jobs that allow for accommodations.

Two surveys of people with long COVID who had worked before becoming infected showed that between 22% and 27% of them were out of work after getting long COVID. In comparison, among all working-age adults in 2019, only 7% were out of work. Given the sheer number of working-age adults with long COVID, the effects on employment may be profound and are likely to involve more people over time. One study estimates that long COVID already accounts for 15% of unfilled jobs.

The most severe symptoms of long COVID include brain fog and heart complications, known to persist for weeks for months after a COVID-19 infection.

A study from the University of Norway published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found 53% of people tested had at least one symptom of thinking problems 13 months after infection with COVID-19. According to the HHS’ latest report on long COVID, people with thinking problems, heart conditions, mobility issues, and other symptoms are going to need a considerable amount of care. Many will need lengthy periods of rehabilitation.

Dr. Al-Aly worries that long COVID has already severely affected the labor force and the job market, all while burdening the country’s health care system.

“While there are variations in how individuals respond and cope with long COVID, the unifying thread is that with the level of disability it causes, more people will be struggling to keep up with the demands of the workforce and more people will be out on disability than ever before,” he said.

Studies from Johns Hopkins and the University of Washington estimate that 5%-30% of people could get long COVID in the future. Projections beyond that are hazy.

“So far, all the studies we have done on long COVID have been reactionary. Much of the activism around long COVID has been patient led. We are seeing more and more people with lasting symptoms. We need our research to catch up,” Dr. Lau said.

Theo Vos, MD, PhD, professor of health sciences at University of Washington, Seattle, said the main reasons for the huge range of predictions are the variety of methods used, as well as differences in sample size. Also, much long COVID data is self-reported, making it difficult for epidemiologists to track.

“With self-reported data, you can’t plug people into a machine and say this is what they have or this is what they don’t have. At the population level, the only thing you can do is ask questions. There is no systematic way to define long COVID,” he said.

Dr. Vos’s most recent study, which is being peer-reviewed and revised, found that most people with long COVID have symptoms similar to those seen in other autoimmune diseases. But sometimes the immune system can overreact, causing the more severe symptoms, such as brain fog and heart problems, associated with long COVID.

One reason that researchers struggle to come up with numbers, said Dr. Al-Aly, is the rapid rise of new variants. These variants appear to sometimes cause less severe disease than previous ones, but it’s not clear whether that means different risks for long COVID.

“There’s a wide diversity in severity. Someone can have long COVID and be fully functional, while others are not functional at all. We still have a long way to go before we figure out why,” Dr. Lau said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: Hearing, Vision, and Balance

- Lucas JW, Zelaya CE. Hearing difficulty, vision trouble, and balance problems among male veterans and nonveterans. Natl Health Stat Report. 2020;(142):1-8. Accessed March 30, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr142-508.pdf

- Shrauner W, Lord EM, Nguyen XMT, et al. Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US veterans. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):818-826. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850

- Defense Health Agency, Vision Center of Excellence (email, March 23, 2022).

- Frick KD, Singman EL. Cost of military eye injury and vision impairment related to traumatic brain injury: 2001–2017. Mil Med. 2019;184(5-6):e338. http://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy420

- Hussain SF, Raza Z, Cash ATG, et al. Traumatic brain injury and sight loss in military and veteran populations – a review. Mil Med Res. 2021;8(1):42. http://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-021-00334-3

- Lucas JW, Zelaya CE. Hearing difficulty, vision trouble, and balance problems among male veterans and nonveterans. Natl Health Stat Report. 2020;(142):1-8. Accessed March 30, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr142-508.pdf

- Shrauner W, Lord EM, Nguyen XMT, et al. Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US veterans. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):818-826. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850

- Defense Health Agency, Vision Center of Excellence (email, March 23, 2022).

- Frick KD, Singman EL. Cost of military eye injury and vision impairment related to traumatic brain injury: 2001–2017. Mil Med. 2019;184(5-6):e338. http://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy420

- Hussain SF, Raza Z, Cash ATG, et al. Traumatic brain injury and sight loss in military and veteran populations – a review. Mil Med Res. 2021;8(1):42. http://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-021-00334-3

- Lucas JW, Zelaya CE. Hearing difficulty, vision trouble, and balance problems among male veterans and nonveterans. Natl Health Stat Report. 2020;(142):1-8. Accessed March 30, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr142-508.pdf

- Shrauner W, Lord EM, Nguyen XMT, et al. Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US veterans. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):818-826. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850

- Defense Health Agency, Vision Center of Excellence (email, March 23, 2022).

- Frick KD, Singman EL. Cost of military eye injury and vision impairment related to traumatic brain injury: 2001–2017. Mil Med. 2019;184(5-6):e338. http://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy420

- Hussain SF, Raza Z, Cash ATG, et al. Traumatic brain injury and sight loss in military and veteran populations – a review. Mil Med Res. 2021;8(1):42. http://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-021-00334-3

‘Shocking’ and persistent gap in treatment for opioid addiction

The vast majority of Americans with opioid use disorder (OUD) do not receive potentially lifesaving medications.

Drugs such as methadone, buprenorphine, and extended-release naltrexone have been shown to reduce opioid overdoses by more than 50%. Yet a new analysis shows that only about 1 in 10 people living with OUD receive these medications.

“Even though it’s not especially surprising, it’s still disturbing and shocking in a way that we have just made such little progress on this huge issue,” study investigator Noa Krawczyk, PhD, with the Center for Opioid Epidemiology and Policy, department of population health, NYU Langone, told this news organization.

The study was published online in the International Journal of Drug Policy.

Increased urgency

Despite efforts to increase capacity for OUD treatment in the United States, how receipt of treatment compares to need for treatment remains unclear.

Dr. Krawczyk and colleagues examined the gap between new estimates of OUD prevalence and treatment at the national and state levels from 2010 through 2019.

“,” the investigators write.

Adjusted estimates suggest that past-year OUD affected roughly 7.63 million individuals in the United States (2,773 per 100,000), yet only about 1.02 million received medication (365 per 100,000), they note.

Overall, there was a 106% increase in receipt of medications for OUD across the United States from 2010 to 2019 and a 5% increase from 2018 to 2019.

Yet, as of 2019, 87% of people with OUD were not receiving medication.

“While the number of people getting treatment doubled over the last decade, it’s nowhere near the amount of people who are still struggling with an opioid use disorder, and the urgency of the problem has become much worse because of the worsening fentanyl crisis and the lethality of the drug supply,” said Dr. Krawczyk.

The study also showed wide variation in past-year OUD prevalence and treatment across the United States.

Past-year OUD rates were highest in Washington, D.C., and lowest in Minnesota. Receipt of treatment was lowest in South Dakota and highest in Vermont.

However, in all 50 states and Washington, D.C., past-year OUD prevalence was greater than rates of medication use. As of 2019, the largest treatment gaps were in Iowa, North Dakota, and Washington, D.C. The smallest treatment gaps were in Connecticut, Maryland, and Rhode Island.

Long road ahead

“Even in states with the smallest treatment gaps, at least 50% of people who could benefit from medications for opioid use disorder are still not receiving them,” senior author Magdalena Cerdá, DrPH, director of the Center for Opioid Epidemiology and Policy in the department of population health at NYU Langone Health, said in a statement.

“We have a long way to go in reducing stigma surrounding treatment and in devising the types of policies and programs we need to ensure these medications reach the people who need them the most,” Dr. Cerdá added.

Access to OUD treatment is an ongoing problem in the United States.

“A lot of areas don’t have specialty treatment programs that provide methadone, or they might not have addiction-trained providers who are willing to prescribe buprenorphine or have a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, so a lot places are really struggling with where people can get treatment,” said Dr. Krawczyk.

Recent data show that 46% of counties lack an OUD medication provider, and 32% have no specialty programs to treat substance use disorders.

Dr. Krawczyk and colleagues note that COVID-19–related policy changes and recently proposed legislation to allow more flexible and convenient access to OUD treatment may be a first step toward expanding access to this lifesaving treatment.

But improving initial access to medication for OUD is “only the first step – our research and health systems have a long way to go in addressing the needs of people with OUD to support retention in treatment and services to effectively reduce overdose and improve long-term health and well-being,” the researchers write.

The study was supported by the NYU Center for Epidemiology and Policy. Dr. Krawczyk has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The vast majority of Americans with opioid use disorder (OUD) do not receive potentially lifesaving medications.

Drugs such as methadone, buprenorphine, and extended-release naltrexone have been shown to reduce opioid overdoses by more than 50%. Yet a new analysis shows that only about 1 in 10 people living with OUD receive these medications.

“Even though it’s not especially surprising, it’s still disturbing and shocking in a way that we have just made such little progress on this huge issue,” study investigator Noa Krawczyk, PhD, with the Center for Opioid Epidemiology and Policy, department of population health, NYU Langone, told this news organization.

The study was published online in the International Journal of Drug Policy.

Increased urgency

Despite efforts to increase capacity for OUD treatment in the United States, how receipt of treatment compares to need for treatment remains unclear.

Dr. Krawczyk and colleagues examined the gap between new estimates of OUD prevalence and treatment at the national and state levels from 2010 through 2019.

“,” the investigators write.

Adjusted estimates suggest that past-year OUD affected roughly 7.63 million individuals in the United States (2,773 per 100,000), yet only about 1.02 million received medication (365 per 100,000), they note.

Overall, there was a 106% increase in receipt of medications for OUD across the United States from 2010 to 2019 and a 5% increase from 2018 to 2019.

Yet, as of 2019, 87% of people with OUD were not receiving medication.

“While the number of people getting treatment doubled over the last decade, it’s nowhere near the amount of people who are still struggling with an opioid use disorder, and the urgency of the problem has become much worse because of the worsening fentanyl crisis and the lethality of the drug supply,” said Dr. Krawczyk.

The study also showed wide variation in past-year OUD prevalence and treatment across the United States.

Past-year OUD rates were highest in Washington, D.C., and lowest in Minnesota. Receipt of treatment was lowest in South Dakota and highest in Vermont.

However, in all 50 states and Washington, D.C., past-year OUD prevalence was greater than rates of medication use. As of 2019, the largest treatment gaps were in Iowa, North Dakota, and Washington, D.C. The smallest treatment gaps were in Connecticut, Maryland, and Rhode Island.

Long road ahead

“Even in states with the smallest treatment gaps, at least 50% of people who could benefit from medications for opioid use disorder are still not receiving them,” senior author Magdalena Cerdá, DrPH, director of the Center for Opioid Epidemiology and Policy in the department of population health at NYU Langone Health, said in a statement.

“We have a long way to go in reducing stigma surrounding treatment and in devising the types of policies and programs we need to ensure these medications reach the people who need them the most,” Dr. Cerdá added.

Access to OUD treatment is an ongoing problem in the United States.

“A lot of areas don’t have specialty treatment programs that provide methadone, or they might not have addiction-trained providers who are willing to prescribe buprenorphine or have a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, so a lot places are really struggling with where people can get treatment,” said Dr. Krawczyk.

Recent data show that 46% of counties lack an OUD medication provider, and 32% have no specialty programs to treat substance use disorders.

Dr. Krawczyk and colleagues note that COVID-19–related policy changes and recently proposed legislation to allow more flexible and convenient access to OUD treatment may be a first step toward expanding access to this lifesaving treatment.

But improving initial access to medication for OUD is “only the first step – our research and health systems have a long way to go in addressing the needs of people with OUD to support retention in treatment and services to effectively reduce overdose and improve long-term health and well-being,” the researchers write.

The study was supported by the NYU Center for Epidemiology and Policy. Dr. Krawczyk has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The vast majority of Americans with opioid use disorder (OUD) do not receive potentially lifesaving medications.

Drugs such as methadone, buprenorphine, and extended-release naltrexone have been shown to reduce opioid overdoses by more than 50%. Yet a new analysis shows that only about 1 in 10 people living with OUD receive these medications.

“Even though it’s not especially surprising, it’s still disturbing and shocking in a way that we have just made such little progress on this huge issue,” study investigator Noa Krawczyk, PhD, with the Center for Opioid Epidemiology and Policy, department of population health, NYU Langone, told this news organization.

The study was published online in the International Journal of Drug Policy.

Increased urgency

Despite efforts to increase capacity for OUD treatment in the United States, how receipt of treatment compares to need for treatment remains unclear.

Dr. Krawczyk and colleagues examined the gap between new estimates of OUD prevalence and treatment at the national and state levels from 2010 through 2019.

“,” the investigators write.

Adjusted estimates suggest that past-year OUD affected roughly 7.63 million individuals in the United States (2,773 per 100,000), yet only about 1.02 million received medication (365 per 100,000), they note.

Overall, there was a 106% increase in receipt of medications for OUD across the United States from 2010 to 2019 and a 5% increase from 2018 to 2019.

Yet, as of 2019, 87% of people with OUD were not receiving medication.

“While the number of people getting treatment doubled over the last decade, it’s nowhere near the amount of people who are still struggling with an opioid use disorder, and the urgency of the problem has become much worse because of the worsening fentanyl crisis and the lethality of the drug supply,” said Dr. Krawczyk.

The study also showed wide variation in past-year OUD prevalence and treatment across the United States.

Past-year OUD rates were highest in Washington, D.C., and lowest in Minnesota. Receipt of treatment was lowest in South Dakota and highest in Vermont.

However, in all 50 states and Washington, D.C., past-year OUD prevalence was greater than rates of medication use. As of 2019, the largest treatment gaps were in Iowa, North Dakota, and Washington, D.C. The smallest treatment gaps were in Connecticut, Maryland, and Rhode Island.

Long road ahead

“Even in states with the smallest treatment gaps, at least 50% of people who could benefit from medications for opioid use disorder are still not receiving them,” senior author Magdalena Cerdá, DrPH, director of the Center for Opioid Epidemiology and Policy in the department of population health at NYU Langone Health, said in a statement.

“We have a long way to go in reducing stigma surrounding treatment and in devising the types of policies and programs we need to ensure these medications reach the people who need them the most,” Dr. Cerdá added.

Access to OUD treatment is an ongoing problem in the United States.

“A lot of areas don’t have specialty treatment programs that provide methadone, or they might not have addiction-trained providers who are willing to prescribe buprenorphine or have a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, so a lot places are really struggling with where people can get treatment,” said Dr. Krawczyk.

Recent data show that 46% of counties lack an OUD medication provider, and 32% have no specialty programs to treat substance use disorders.

Dr. Krawczyk and colleagues note that COVID-19–related policy changes and recently proposed legislation to allow more flexible and convenient access to OUD treatment may be a first step toward expanding access to this lifesaving treatment.

But improving initial access to medication for OUD is “only the first step – our research and health systems have a long way to go in addressing the needs of people with OUD to support retention in treatment and services to effectively reduce overdose and improve long-term health and well-being,” the researchers write.

The study was supported by the NYU Center for Epidemiology and Policy. Dr. Krawczyk has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF DRUG POLICY

Pro-life ob.gyns. say Dobbs not end of abortion struggle

After 49 years of labor, abortion foes received the ultimate victory in June when the United States Supreme Court struck down a federal right to terminate pregnancy. Among those most heartened by the ruling was a small organization of doctors who specialize in women’s reproductive health. The group’s leader, while grateful for the win, isn’t ready for a curtain call. Instead, she sees her task as moving from a national stage to 50 regional ones.

The decision in Dobbs v. Jackson, which overturned a woman’s constitutional right to obtain an abortion, was the biggest but not final quarry for the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists (AAPLOG). “It actually doesn’t change anything except to turn the whole discussion on abortion back to the states, which in our opinion is where it should have been 50 years ago,” Donna Harrison, MD, the group’s chief executive officer, said in a recent interview.

Dr. Harrison, an obstetrician-gynecologist and adjunct professor of bioethics at Trinity International University in Deerfield, Ind., said she was proud of “our small role in bringing science” to the top court’s attention, noting that the ruling incorporated some of AAPLOG’s medical arguments in reversing Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision that created a right to abortion – and prompted her group’s founding. The ruling, for instance, agreed – in a departure from the generally accepted science – that a fetus is viable at 15 weeks, and the procedure is risky for mothers thereafter. “You could congratulate us for perseverance and for bringing that information, which has been in the peer-reviewed literature for a long time, to the justices’ attention,” she said.

Dr. Harrison said she was pleased that the Supreme Court agreed with the “science” that guided its decision to overturn Roe. That the court was willing to embrace that evidence troubles the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the nation’s leading professional group for reproductive health experts.

Defending the ‘second patient’

AAPLOG operates under the belief that life begins at the moment of fertilization, at which point “we defend the life of our second patient, the human being in the womb,” Dr. Harrison said. “For a very long time, ob.gyns. who valued both patients were not given a voice, and I think now we’re finding our voice.” The group will continue supporting abortion restrictions at the state level.

AAPLOG, with 6,000 members, was considered a “special interest” group within ACOG until the college discontinued such subgroups in 2013. ACOG, numbering 60,000 members, calls the Dobbs ruling “a huge step back for women and everyone who is seeking access to ob.gyn. care,” said Molly Meegan, JD, ACOG’s chief legal officer. Ms. Meegan expressed concern over the newfound influence of AAPLOG, which she called “a single-issue, single-topic, single-advocacy organization.”

Pro-choice groups, including ACOG, worry that the reversal of Roe has provided AAPLOG with an undeserved veneer of medical expertise. The decision also allowed judges and legislators to “insert themselves into nuanced and complex situations” they know little about and will rely on groups like AAPLOG to exert influence, Ms. Meegan said.

In turn, Dr. Harrison described ACOG as engaging in “rabid, pro-abortion activism.”

The number of abortions in the United States had steadily declined from a peak of 1.4 million per year in 1990 until 2017, after which it has risen slightly. In 2019, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 625,000 abortions occurred nationally. Of those, 42.3% were medication abortions performed in the first 9 weeks, using a combination of the drugs mifepristone and misoprostol. Medication abortions now account for more than half of all pregnancy terminations in the United States, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

Dr. Harrison said that medication abortions put women at an elevated risk of serious, sometimes deadly bleeding, while ACOG points to evidence that the risk of childbirth to women is significantly higher. She also is no fan of Plan B, the “morning after” pill, which is available to women without having to consult a doctor. She described abortifacients as “a huge danger to women being harmed” by medications available over the counter.

In Dr. Harrison’s view, the 10-year-old Ohio girl who traveled to Indiana to obtain an abortion after she became pregnant as the result of rape should have continued her pregnancy. So, too, should young girls who are the victims of incest. “Incest is a horrific crime,” she said, “but aborting a girl because of incest doesn’t make her un-raped. It just adds another trauma.”

When told of Dr. Harrison’s comment, Ms. Meegan paused for 5 seconds before saying, “I think that statement speaks for itself.”

Louise Perkins King, MD, JD, an ob.gyn. and director of reproductive bioethics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said she had the “horrific” experience of delivering a baby to an 11-year-old girl.

“Children are not fully developed, and they should not be having children,” Dr. King said.

Anne-Marie E. Amies Oelschlager, MD, vice chair of ACOG’s Clinical Consensus Committee and an ob.gyn. at Seattle Children’s in Washington, said in a statement that adolescents who are sexually assaulted are at extremely high risk of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. “Do we expect a fourth-grader to carry a pregnancy to term, deliver, and expect that child to carry on after this horror?,” she asked.

Dr. Harrison dismissed such concerns. “Somehow abortion is a mental health treatment? Abortion doesn’t treat mental health problems,” she said. “Is there any proof that aborting in those circumstances improves their mental health? I would tell you there is very little research about it. …There are human beings involved, and this child who was raped, who also had a child, who was a human being, who is no longer.”

Dr. Harrison said the Dobbs decision would have no effect on up to 93% of ob.gyns. who don’t perform abortions. Dr. King said the reason that most don’t perform the procedure is the “stigma” attached to abortion. “It’s still frowned upon,” she said. “We don’t talk about it as health care.”

Ms. Meegan added that ob.gyns. are fearful in the wake of the Dobbs decision because “they might find themselves subject to civil and criminal penalties.”

Dr. Harrison said that Roe was always a political decision and the science was always behind AAPLOG – something both Ms. Meegan and Dr. King dispute. Ms. Meegan and Dr. King said they are concerned about the chilling effects on both women and their clinicians, especially with laws that prevent referrals and travel to other states.

“You can’t compel me to give blood or bone marrow,” Dr. King said. “You can’t even compel me to give my hair for somebody, and you can’t compel me to give an organ. And all of a sudden when I’m pregnant, all my rights are out the window?”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After 49 years of labor, abortion foes received the ultimate victory in June when the United States Supreme Court struck down a federal right to terminate pregnancy. Among those most heartened by the ruling was a small organization of doctors who specialize in women’s reproductive health. The group’s leader, while grateful for the win, isn’t ready for a curtain call. Instead, she sees her task as moving from a national stage to 50 regional ones.

The decision in Dobbs v. Jackson, which overturned a woman’s constitutional right to obtain an abortion, was the biggest but not final quarry for the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists (AAPLOG). “It actually doesn’t change anything except to turn the whole discussion on abortion back to the states, which in our opinion is where it should have been 50 years ago,” Donna Harrison, MD, the group’s chief executive officer, said in a recent interview.

Dr. Harrison, an obstetrician-gynecologist and adjunct professor of bioethics at Trinity International University in Deerfield, Ind., said she was proud of “our small role in bringing science” to the top court’s attention, noting that the ruling incorporated some of AAPLOG’s medical arguments in reversing Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision that created a right to abortion – and prompted her group’s founding. The ruling, for instance, agreed – in a departure from the generally accepted science – that a fetus is viable at 15 weeks, and the procedure is risky for mothers thereafter. “You could congratulate us for perseverance and for bringing that information, which has been in the peer-reviewed literature for a long time, to the justices’ attention,” she said.

Dr. Harrison said she was pleased that the Supreme Court agreed with the “science” that guided its decision to overturn Roe. That the court was willing to embrace that evidence troubles the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the nation’s leading professional group for reproductive health experts.

Defending the ‘second patient’

AAPLOG operates under the belief that life begins at the moment of fertilization, at which point “we defend the life of our second patient, the human being in the womb,” Dr. Harrison said. “For a very long time, ob.gyns. who valued both patients were not given a voice, and I think now we’re finding our voice.” The group will continue supporting abortion restrictions at the state level.

AAPLOG, with 6,000 members, was considered a “special interest” group within ACOG until the college discontinued such subgroups in 2013. ACOG, numbering 60,000 members, calls the Dobbs ruling “a huge step back for women and everyone who is seeking access to ob.gyn. care,” said Molly Meegan, JD, ACOG’s chief legal officer. Ms. Meegan expressed concern over the newfound influence of AAPLOG, which she called “a single-issue, single-topic, single-advocacy organization.”

Pro-choice groups, including ACOG, worry that the reversal of Roe has provided AAPLOG with an undeserved veneer of medical expertise. The decision also allowed judges and legislators to “insert themselves into nuanced and complex situations” they know little about and will rely on groups like AAPLOG to exert influence, Ms. Meegan said.

In turn, Dr. Harrison described ACOG as engaging in “rabid, pro-abortion activism.”

The number of abortions in the United States had steadily declined from a peak of 1.4 million per year in 1990 until 2017, after which it has risen slightly. In 2019, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 625,000 abortions occurred nationally. Of those, 42.3% were medication abortions performed in the first 9 weeks, using a combination of the drugs mifepristone and misoprostol. Medication abortions now account for more than half of all pregnancy terminations in the United States, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

Dr. Harrison said that medication abortions put women at an elevated risk of serious, sometimes deadly bleeding, while ACOG points to evidence that the risk of childbirth to women is significantly higher. She also is no fan of Plan B, the “morning after” pill, which is available to women without having to consult a doctor. She described abortifacients as “a huge danger to women being harmed” by medications available over the counter.

In Dr. Harrison’s view, the 10-year-old Ohio girl who traveled to Indiana to obtain an abortion after she became pregnant as the result of rape should have continued her pregnancy. So, too, should young girls who are the victims of incest. “Incest is a horrific crime,” she said, “but aborting a girl because of incest doesn’t make her un-raped. It just adds another trauma.”

When told of Dr. Harrison’s comment, Ms. Meegan paused for 5 seconds before saying, “I think that statement speaks for itself.”

Louise Perkins King, MD, JD, an ob.gyn. and director of reproductive bioethics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said she had the “horrific” experience of delivering a baby to an 11-year-old girl.

“Children are not fully developed, and they should not be having children,” Dr. King said.

Anne-Marie E. Amies Oelschlager, MD, vice chair of ACOG’s Clinical Consensus Committee and an ob.gyn. at Seattle Children’s in Washington, said in a statement that adolescents who are sexually assaulted are at extremely high risk of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. “Do we expect a fourth-grader to carry a pregnancy to term, deliver, and expect that child to carry on after this horror?,” she asked.

Dr. Harrison dismissed such concerns. “Somehow abortion is a mental health treatment? Abortion doesn’t treat mental health problems,” she said. “Is there any proof that aborting in those circumstances improves their mental health? I would tell you there is very little research about it. …There are human beings involved, and this child who was raped, who also had a child, who was a human being, who is no longer.”

Dr. Harrison said the Dobbs decision would have no effect on up to 93% of ob.gyns. who don’t perform abortions. Dr. King said the reason that most don’t perform the procedure is the “stigma” attached to abortion. “It’s still frowned upon,” she said. “We don’t talk about it as health care.”

Ms. Meegan added that ob.gyns. are fearful in the wake of the Dobbs decision because “they might find themselves subject to civil and criminal penalties.”

Dr. Harrison said that Roe was always a political decision and the science was always behind AAPLOG – something both Ms. Meegan and Dr. King dispute. Ms. Meegan and Dr. King said they are concerned about the chilling effects on both women and their clinicians, especially with laws that prevent referrals and travel to other states.

“You can’t compel me to give blood or bone marrow,” Dr. King said. “You can’t even compel me to give my hair for somebody, and you can’t compel me to give an organ. And all of a sudden when I’m pregnant, all my rights are out the window?”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After 49 years of labor, abortion foes received the ultimate victory in June when the United States Supreme Court struck down a federal right to terminate pregnancy. Among those most heartened by the ruling was a small organization of doctors who specialize in women’s reproductive health. The group’s leader, while grateful for the win, isn’t ready for a curtain call. Instead, she sees her task as moving from a national stage to 50 regional ones.

The decision in Dobbs v. Jackson, which overturned a woman’s constitutional right to obtain an abortion, was the biggest but not final quarry for the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists (AAPLOG). “It actually doesn’t change anything except to turn the whole discussion on abortion back to the states, which in our opinion is where it should have been 50 years ago,” Donna Harrison, MD, the group’s chief executive officer, said in a recent interview.

Dr. Harrison, an obstetrician-gynecologist and adjunct professor of bioethics at Trinity International University in Deerfield, Ind., said she was proud of “our small role in bringing science” to the top court’s attention, noting that the ruling incorporated some of AAPLOG’s medical arguments in reversing Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision that created a right to abortion – and prompted her group’s founding. The ruling, for instance, agreed – in a departure from the generally accepted science – that a fetus is viable at 15 weeks, and the procedure is risky for mothers thereafter. “You could congratulate us for perseverance and for bringing that information, which has been in the peer-reviewed literature for a long time, to the justices’ attention,” she said.

Dr. Harrison said she was pleased that the Supreme Court agreed with the “science” that guided its decision to overturn Roe. That the court was willing to embrace that evidence troubles the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the nation’s leading professional group for reproductive health experts.

Defending the ‘second patient’

AAPLOG operates under the belief that life begins at the moment of fertilization, at which point “we defend the life of our second patient, the human being in the womb,” Dr. Harrison said. “For a very long time, ob.gyns. who valued both patients were not given a voice, and I think now we’re finding our voice.” The group will continue supporting abortion restrictions at the state level.

AAPLOG, with 6,000 members, was considered a “special interest” group within ACOG until the college discontinued such subgroups in 2013. ACOG, numbering 60,000 members, calls the Dobbs ruling “a huge step back for women and everyone who is seeking access to ob.gyn. care,” said Molly Meegan, JD, ACOG’s chief legal officer. Ms. Meegan expressed concern over the newfound influence of AAPLOG, which she called “a single-issue, single-topic, single-advocacy organization.”

Pro-choice groups, including ACOG, worry that the reversal of Roe has provided AAPLOG with an undeserved veneer of medical expertise. The decision also allowed judges and legislators to “insert themselves into nuanced and complex situations” they know little about and will rely on groups like AAPLOG to exert influence, Ms. Meegan said.

In turn, Dr. Harrison described ACOG as engaging in “rabid, pro-abortion activism.”

The number of abortions in the United States had steadily declined from a peak of 1.4 million per year in 1990 until 2017, after which it has risen slightly. In 2019, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 625,000 abortions occurred nationally. Of those, 42.3% were medication abortions performed in the first 9 weeks, using a combination of the drugs mifepristone and misoprostol. Medication abortions now account for more than half of all pregnancy terminations in the United States, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

Dr. Harrison said that medication abortions put women at an elevated risk of serious, sometimes deadly bleeding, while ACOG points to evidence that the risk of childbirth to women is significantly higher. She also is no fan of Plan B, the “morning after” pill, which is available to women without having to consult a doctor. She described abortifacients as “a huge danger to women being harmed” by medications available over the counter.

In Dr. Harrison’s view, the 10-year-old Ohio girl who traveled to Indiana to obtain an abortion after she became pregnant as the result of rape should have continued her pregnancy. So, too, should young girls who are the victims of incest. “Incest is a horrific crime,” she said, “but aborting a girl because of incest doesn’t make her un-raped. It just adds another trauma.”

When told of Dr. Harrison’s comment, Ms. Meegan paused for 5 seconds before saying, “I think that statement speaks for itself.”

Louise Perkins King, MD, JD, an ob.gyn. and director of reproductive bioethics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said she had the “horrific” experience of delivering a baby to an 11-year-old girl.

“Children are not fully developed, and they should not be having children,” Dr. King said.

Anne-Marie E. Amies Oelschlager, MD, vice chair of ACOG’s Clinical Consensus Committee and an ob.gyn. at Seattle Children’s in Washington, said in a statement that adolescents who are sexually assaulted are at extremely high risk of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. “Do we expect a fourth-grader to carry a pregnancy to term, deliver, and expect that child to carry on after this horror?,” she asked.

Dr. Harrison dismissed such concerns. “Somehow abortion is a mental health treatment? Abortion doesn’t treat mental health problems,” she said. “Is there any proof that aborting in those circumstances improves their mental health? I would tell you there is very little research about it. …There are human beings involved, and this child who was raped, who also had a child, who was a human being, who is no longer.”

Dr. Harrison said the Dobbs decision would have no effect on up to 93% of ob.gyns. who don’t perform abortions. Dr. King said the reason that most don’t perform the procedure is the “stigma” attached to abortion. “It’s still frowned upon,” she said. “We don’t talk about it as health care.”

Ms. Meegan added that ob.gyns. are fearful in the wake of the Dobbs decision because “they might find themselves subject to civil and criminal penalties.”

Dr. Harrison said that Roe was always a political decision and the science was always behind AAPLOG – something both Ms. Meegan and Dr. King dispute. Ms. Meegan and Dr. King said they are concerned about the chilling effects on both women and their clinicians, especially with laws that prevent referrals and travel to other states.

“You can’t compel me to give blood or bone marrow,” Dr. King said. “You can’t even compel me to give my hair for somebody, and you can’t compel me to give an organ. And all of a sudden when I’m pregnant, all my rights are out the window?”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: Sleep Disorders

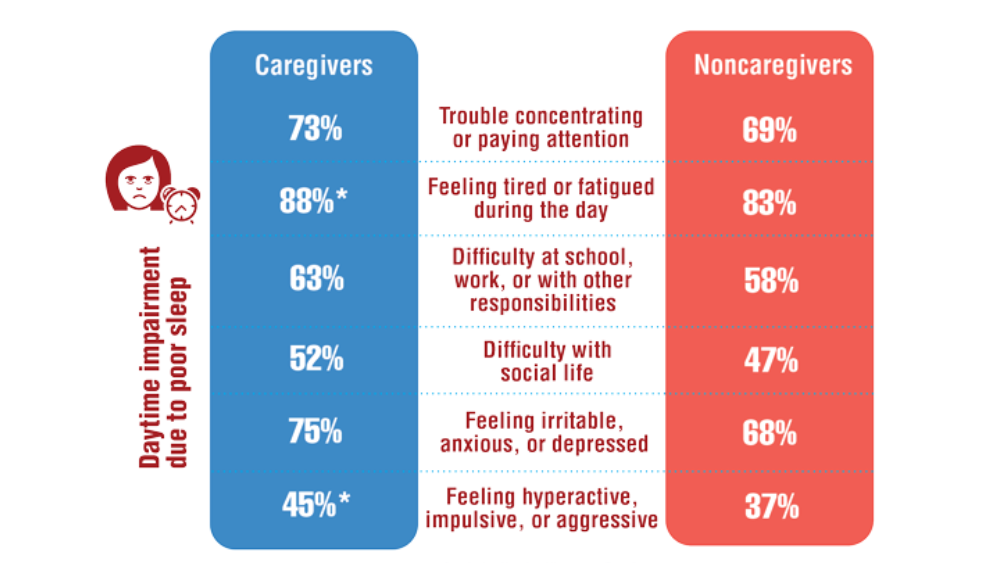

- Song Y, Carlson GC, McGowan SK, et al. Sleep disruption due to stress in women veterans: a comparison between caregivers and noncaregivers. Behav Sleep Med. 2021;19(2):243-254. http://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2020.1732981

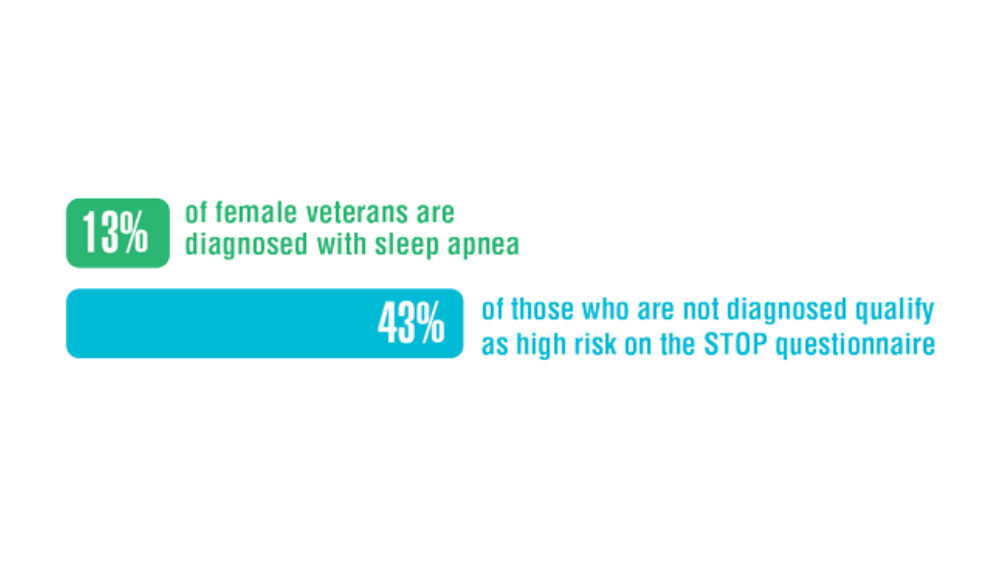

- Martin JL, Carlson G, Kelly M, et al. Sleep apnea in women veterans: results of a national survey of VA health care users. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(3):555-565. http://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8956

- Song Y, Carlson GC, McGowan SK, et al. Sleep disruption due to stress in women veterans: a comparison between caregivers and noncaregivers. Behav Sleep Med. 2021;19(2):243-254. http://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2020.1732981

- Martin JL, Carlson G, Kelly M, et al. Sleep apnea in women veterans: results of a national survey of VA health care users. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(3):555-565. http://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8956

- Song Y, Carlson GC, McGowan SK, et al. Sleep disruption due to stress in women veterans: a comparison between caregivers and noncaregivers. Behav Sleep Med. 2021;19(2):243-254. http://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2020.1732981

- Martin JL, Carlson G, Kelly M, et al. Sleep apnea in women veterans: results of a national survey of VA health care users. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(3):555-565. http://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8956

Impact of Race on Outcomes of High-Risk Patients With Prostate Cancer Treated With Moderately Hypofractionated Radiotherapy in an Equal Access Setting

Although moderately hypofractionated radiotherapy (MHRT) is an accepted treatment for localized prostate cancer, its adaptation remains limited in the United States.1,2 MHRT theoretically exploits α/β ratio differences between the prostate (1.5 Gy), bladder (5-10 Gy), and rectum (3 Gy), thereby reducing late treatment-related adverse effects compared with those of conventional fractionation at biologically equivalent doses.3-8 Multiple randomized noninferiority trials have demonstrated equivalent outcomes between MHRT and conventional fraction with no appreciable increase in patient-reported toxicity.9-14 Although these studies have led to the acceptance of MHRT as a standard treatment, the majority of these trials involve individuals with low- and intermediate-risk disease.

There are less phase 3 data addressing MHRT for high-risk prostate cancer (HRPC).10,12,14-17 Only 2 studies examined predominately high-risk populations, accounting for 83 and 292 patients, respectively.15,16 Additional phase 3 trials with small proportions of high-risk patients (n = 126, 12%; n = 53, 35%) offer limited additional information regarding clinical outcomes and toxicity rates specific to high-risk disease.10-12 Numerous phase 1 and 2 studies report various field designs and fractionation plans for MHRT in the context of high-risk disease, although the applicability of these data to off-trial populations remains limited.18-20

Furthermore, African American individuals are underrepresented in the trials establishing the role of MHRT despite higher rates of prostate cancer incidence, more advanced disease stage at diagnosis, and higher rates of prostate cancer–specific survival (PCSS) when compared with White patients.21 Racial disparities across patients with prostate cancer and their management are multifactorial across health care literacy, education level, access to care (including transportation issues), and issues of adherence and distrust.22-25 Correlation of patient race to prostate cancer outcomes varies greatly across health care systems, with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) equal access system providing robust mental health services and transportation services for some patients, while demonstrating similar rates of stage-adjusted PCSS between African American and White patients across a broad range of treatment modalities.26-28 Given the paucity of data exploring outcomes following MHRT for African American patients with HRPC, the present analysis provides long-term clinical outcomes and toxicity profiles for an off-trial majority African American population with HRPC treated with MHRT within the VA.

Methods

Records were retrospectively reviewed under an institutional review board–approved protocol for all patients with HRPC treated with definitive MHRT at the Durham Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in North Carolina between November 2008 and August 2018. Exclusion criteria included < 12 months of follow-up or elective nodal irradiation. Demographic variables obtained included age at diagnosis, race, clinical T stage, pre-MHRT prostate-specific antigen (PSA), Gleason grade group at diagnosis, favorable vs unfavorable high-risk disease, pre-MHRT international prostate symptom score (IPSS), and pre-MHRT urinary medication usage (yes/no).29

Concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was initiated 6 to 8 weeks before MHRT unless medically contraindicated per the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist. Patients generally received 18 to 24 months of ADT, with those with favorable HRPC (ie, T1c disease with either Gleason 4+4 and PSA < 10 mg/mL or Gleason 3+3 and PSA > 20 ng/mL) receiving 6 months after 2015.29 Patients were simulated supine in either standard or custom immobilization with a full bladder and empty rectum. MHRT fractionation plans included 70 Gy at 2.5 Gy per fraction and 60 Gy at 3 Gy per fraction. Radiotherapy targets included the prostate and seminal vesicles without elective nodal coverage per institutional practice. Treatments were delivered following image guidance, either prostate matching with cone beam computed tomography or fiducial matching with kilo voltage imaging. All patients received intensity-modulated radiotherapy. For plans delivering 70 Gy at 2.5 Gy per fraction, constraints included bladder V (volume receiving) 70 < 10 cc, V65 ≤ 15%, V40 ≤ 35%, rectum V70 < 10 cc, V65 ≤ 10%, V40 ≤ 35%, femoral heads maximum point dose ≤ 40 Gy, penile bulb mean dose ≤ 50 Gy, and small bowel V40 ≤ 1%. For plans delivering 60 Gy at 3 Gy per fraction, constraints included rectum V57 ≤ 15%, V46 ≤ 30%, V37 ≤ 50%, bladder V60 ≤ 5%, V46 ≤ 30%, V37 ≤ 50%, and femoral heads V43 ≤ 5%.

Gastrointestinal (GI) and genitourinary (GU) toxicities were graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 5.0, with acute toxicity defined as on-treatment < 3 months following completion of MHRT. Late toxicity was defined as ≥ 3 months following completion of MHRT. Individuals were seen in follow-up at 6 weeks and 3 months with PSA and testosterone after MHRT completion, then every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and annually thereafter. Each follow-up visit included history, physical examination, IPSS, and CTCAE grading for GI and GU toxicity.

The Wilcoxon rank sum test and χ2 test were used to compare differences in demographic data, dosimetric parameters, and frequency of toxicity events with respect to patient race. Clinical endpoints including biochemical recurrence-free survival (BRFS; defined by Phoenix criteria as 2.0 above PSA nadir), distant metastases-free survival (DMFS), PCSS, and overall survival (OS) were estimated from time of radiotherapy completion by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between African American and White race by log-rank testing.30 Late GI and GU toxicity-free survival were estimated by Kaplan-Meier plots and compared between African American and White patients by the log-rank test. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4.

Results

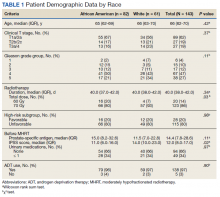

We identified 143 patients with HRPC treated with definitive MHRT between November 2008 and August 2018 (Table 1). Mean age was 65 years (range, 36-80 years); 57% were African American men. Eighty percent of individuals had unfavorable high-risk disease. Median (IQR) PSA was 14.4 (7.8-28.6). Twenty-six percent had grade group 1-3 disease, 47% had grade group 4 disease, and 27% had grade group 5 disease. African American patients had significantly lower pre-MHRT IPSS scores than White patients (mean IPSS, 11 vs 14, respectively; P = .02) despite similar rates of preradiotherapy urinary medication usage (66% and 66%, respectively).

Eighty-six percent received 70 Gy over 28 fractions, with institutional protocol shifting to 60 Gy over 20 fractions (14%) in June 2017. The median (IQR) duration of radiotherapy was 39 (38-42) days, with 97% of individuals undergoing ADT for a median (IQR) duration of 24 (24-36) months. The median follow-up time was 38 months, with 57 (40%) patients followed for at least 60 months.

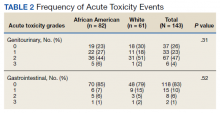

Grade 3 GI and GU acute toxicity events were observed in 1% and 4% of all individuals, respectively (Table 2). No acute GI or GU grade 4+ events were observed. No significant differences in acute GU or GI toxicity were observed between African American and White patients.

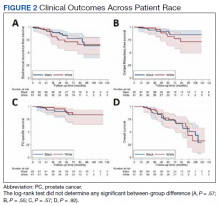

No significant differences between African American and White patients were observed for late grade 2+ GI (P = .19) or GU (P = .55) toxicity. Late grade 2+ GI toxicity was observed in 17 (12%) patients overall (Figure 1A). One grade 3 and 1 grade 4 late GI event were observed following MHRT completion: The latter involved hospitalization for bleeding secondary to radiation proctitis in the context of cirrhosis predating MHRT. Late grade 2+ GU toxicity was observed in 80 (56%) patients, with late grade 2 events steadily increasing over time (Figure 1B). Nine late grade 3 GU toxicity events were observed at a median of 13 months following completion of MHRT, 2 of which occurred more than 24 months after MHRT completion. No late grade 4 or 5 GU events were observed. IPSS values both before MHRT and at time of last follow-up were available for 65 (40%) patients, with a median (IQR) IPSS of 10 (6-16) before MHRT and 12 (8-16) at last follow-up at a median (IQR) interval of 36 months (26-76) from radiation completion.

No significant differences were observed between African American and White patients with respect to BRFS, DMFS, PCSS, or OS (Figure 2). Overall, 21 of 143 (15%) patients experienced biochemical recurrence: 5-year BRFS was 77% (95% CI, 67%-85%) for all patients, 83% (95% CI, 70%-91%) for African American patients, and 71% (95% CI, 53%-82%) for White patients. Five-year DMFS was 87% (95% CI, 77%-92%) for all individuals, 91% (95% CI, 80%-96%) for African American patients, and 81% (95% CI, 62%-91%) for White patients. Five-year PCSS was 89% (95% CI, 80%-94%) for all patients, with 5-year PCSS rates of 90% (95% CI, 79%-95%) for African American patients and 87% (95% CI, 70%-95%) for White patients. Five-year OS was 75% overall (95% CI, 64%-82%), with 5-year OS rates of 73% (95% CI, 58%-83%) for African American patients and 77% (95% CI, 60%-87%) for White patients.

Discussion

In this study, we reported acute and late GI and GU toxicity rates as well as clinical outcomes for a majority African American population with predominately unfavorable HRPC treated with MHRT in an equal access health care environment. We found that MHRT was well tolerated with high rates of biochemical control, PCSS, and OS. Additionally, outcomes were not significantly different across patient race. To our knowledge, this is the first report of MHRT for HRPC in a majority African American population.

We found that MHRT was an effective treatment for patients with HRPC, in particular those with unfavorable high-risk disease. While prior prospective and randomized studies have investigated the use of MHRT, our series was larger than most and had a predominately unfavorable high-risk population.12,15-17 Our biochemical and PCSS rates compare favorably with those of HRPC trial populations, particularly given the high proportion of unfavorable high-risk disease.12,15,16 Despite similar rates of biochemical control, OS was lower in the present cohort than in HRPC trial populations, even with a younger median age at diagnosis. The similarly high rates of non–HRPC-related death across race may reflect differences in baseline comorbidities compared with trial populations as well as reported differences between individuals in the VA and the private sector.31 This suggests that MHRT can be an effective treatment for patients with unfavorable HRPC.

We did not find any differences in outcomes between African American and White individuals with HRPC treated with MHRT. Furthermore, our study demonstrates long-term rates of BRFS and PCSS in a majority African American population with predominately unfavorable HRPC that are comparable with those of prior randomized MHRT studies in high-risk, predominately White populations.12,15,16 Prior reports have found that African American men with HRPC may be at increased risk for inferior clinical outcomes due to a number of socioeconomic, biologic, and cultural mediators.26,27,32 Such individuals may disproportionally benefit from shorter treatment courses that improve access to radiotherapy, a well-documented disparity for African American men with localized prostate cancer.33-36 The VA is an ideal system for studying racial disparities within prostate cancer, as accessibility of mental health and transportation services, income, and insurance status are not barriers to preventative or acute care.37 Our results are concordant with those previously seen for African American patients with prostate cancer seen in the VA, which similarly demonstrate equal outcomes with those of other races.28,36 Incorporation of the earlier mentioned VA services into oncologic care across other health care systems could better characterize determinants of racial disparities in prostate cancer, including the prognostic significance of shortening treatment duration and number of patient visits via MHRT.

Despite widespread acceptance in prostate cancer radiotherapy guidelines, routine use of MHRT seems limited across all stages of localized prostate cancer.1,2 Late toxicity is a frequently noted concern regarding MHRT use. Higher rates of late grade 2+ GI toxicity were observed in the hypofractionation arm of the HYPRO trial.17 While RTOG 0415 did not include patients with HRPC, significantly higher rates of physician-reported (but not patient-reported) late grade 2+ GI and GU toxicity were observed using the same MHRT fractionation regimen used for the majority of individuals in our cohort.9 In our study, the steady increase in late grade 2 GU toxicity is consistent with what is seen following conventionally fractionated radiotherapy and is likely multifactorial.38 The mean IPSS difference of 2/35 from pre-MHRT baseline to the time of last follow-up suggests minimal quality of life decline. The relatively stable IPSSs over time alongside the > 50% prevalence of late grade 2 GU toxicity per CTCAE grading seems consistent with the discrepancy noted in RTOG 0415 between increased physician-reported late toxicity and favorable patient-reported quality of life scores.9 Moreover, significant variance exists in toxicity grading across scoring systems, revised editions of CTCAE, and physician-specific toxicity classification, particularly with regard to the use of adrenergic receptor blocker medications. In light of these factors, the high rate of late grade 2 GU toxicity in our study should be interpreted in the context of largely stable post-MHRT IPSSs and favorable rates of late GI grade 2+ and late GU grade 3+ toxicity.

Limitations