User login

Simulation training on management of shoulder dystocia reduces incidence of permanent BPBI

Key clinical point: Weekly 3-hour simulation-based training of midwives and doctors on shoulder dystocia (SD) management significantly reduced the incidence of permanent brachial plexus birth injury (BPBI).

Major finding: Despite an increase in the incidence of SD cases (0.1% vs 0.3%; P < .001) and risk factors in pre-training vs post-training period, the incidence of permanent BPBI decreased significantly (0.05% vs 0.02%; P < .001), with the risk for permanent BPBI among those with SD reducing (43.5% vs 6.0%; P < .001) and the rate of successful posterior arm delivery increasing (11.3% vs 23.4%; P = .04) significantly after the implementation of systematic simulation-based training.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective observational study including 113,785 vertex deliveries performed by a team of doctors and midwives after receiving the weekly 3-hour simulation-based training.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Helsinki University State Research Funding. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Kaijomaa M et al. Impact of simulation training on the management of shoulder dystocia and incidence of permanent brachial plexus birth injury: An observational study. BJOG. 2022 (Aug 10). Doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17278

Key clinical point: Weekly 3-hour simulation-based training of midwives and doctors on shoulder dystocia (SD) management significantly reduced the incidence of permanent brachial plexus birth injury (BPBI).

Major finding: Despite an increase in the incidence of SD cases (0.1% vs 0.3%; P < .001) and risk factors in pre-training vs post-training period, the incidence of permanent BPBI decreased significantly (0.05% vs 0.02%; P < .001), with the risk for permanent BPBI among those with SD reducing (43.5% vs 6.0%; P < .001) and the rate of successful posterior arm delivery increasing (11.3% vs 23.4%; P = .04) significantly after the implementation of systematic simulation-based training.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective observational study including 113,785 vertex deliveries performed by a team of doctors and midwives after receiving the weekly 3-hour simulation-based training.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Helsinki University State Research Funding. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Kaijomaa M et al. Impact of simulation training on the management of shoulder dystocia and incidence of permanent brachial plexus birth injury: An observational study. BJOG. 2022 (Aug 10). Doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17278

Key clinical point: Weekly 3-hour simulation-based training of midwives and doctors on shoulder dystocia (SD) management significantly reduced the incidence of permanent brachial plexus birth injury (BPBI).

Major finding: Despite an increase in the incidence of SD cases (0.1% vs 0.3%; P < .001) and risk factors in pre-training vs post-training period, the incidence of permanent BPBI decreased significantly (0.05% vs 0.02%; P < .001), with the risk for permanent BPBI among those with SD reducing (43.5% vs 6.0%; P < .001) and the rate of successful posterior arm delivery increasing (11.3% vs 23.4%; P = .04) significantly after the implementation of systematic simulation-based training.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective observational study including 113,785 vertex deliveries performed by a team of doctors and midwives after receiving the weekly 3-hour simulation-based training.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Helsinki University State Research Funding. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Kaijomaa M et al. Impact of simulation training on the management of shoulder dystocia and incidence of permanent brachial plexus birth injury: An observational study. BJOG. 2022 (Aug 10). Doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17278

November 2022 - ICYMI

Gastroenterology

August 2022

Johnson-Laghi KA, Mattar MC. Integrating cognitive apprenticeship into gastroenterology clinical training. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):364-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.013.

Wood LD et al. Pancreatic cancer: Pathogenesis, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):386-402.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.056.

Calderwood AH and Robertson DJ. Stopping surveillance in gastrointestinal conditions: Thoughts on the scope of the problem and potential solutions. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):345-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.009.

September 2022

Donnangelo LL et al. Disclosure and reflection after an adverse event: Tips for training and practice. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):568-71. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.07.003.

Chey WD et al. Vonoprazan triple and dual therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in the United States and Europe: Randomized clinical trial. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):608-19. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.055.

Bushyhead D and Quigley EMM. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth-pathophysiology and its implications for definition and management. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):593-607. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.002.

Long MT et al. AGA Clinical practice update: Diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in lean individuals: Expert review. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):764-74.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.023.

CGH

August 2022

Lennon AM and Vege SS. Pancreatic cyst surveillance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1663-7.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.002.

Crockett SD et al. Large Polyp Study Group Consortium. Clip closure does not reduce risk of bleeding after resection of large serrated polyps: Results from a randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1757-17--65.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.036.

Martin P et al. Treatment algorithm for managing chronic hepatitis b virus infection in the United States: 2021 update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1766-75. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.036.

September 2022

Pawlak KM et al. How to train the next generation to provide high-quality peer-reviews. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):1902-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.018.

Choung RS et al. Collagenous gastritis: Characteristics and response to topical budesonide. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):1977-85.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.11.033.

Basnayake C et al. Long-term outcome of multidisciplinary versus standard gastroenterologist care for functional gastrointestinal disorders: A randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):2102-11.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.005.

Deutsch-Link S et al. Alcohol-associated liver disease mortality increased from 2017 to 2020 and accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):2142-4.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.017.

TIGE

Nakamatsu, Dai et al. Safety of cold snare polypectomy for small colorectal polyps in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2022 Apr 8;24[3]:246-53. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2022.03.008.

Gastro Hep Advances

Brindusa Truta et al. Outcomes of continuation vs. discontinuation of adalimumab therapy during third trimester of pregnancy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastro Hep Advances. 2022 Jan 1;1[5]:785-91. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2022.04.009.

Gastroenterology

August 2022

Johnson-Laghi KA, Mattar MC. Integrating cognitive apprenticeship into gastroenterology clinical training. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):364-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.013.

Wood LD et al. Pancreatic cancer: Pathogenesis, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):386-402.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.056.

Calderwood AH and Robertson DJ. Stopping surveillance in gastrointestinal conditions: Thoughts on the scope of the problem and potential solutions. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):345-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.009.

September 2022

Donnangelo LL et al. Disclosure and reflection after an adverse event: Tips for training and practice. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):568-71. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.07.003.

Chey WD et al. Vonoprazan triple and dual therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in the United States and Europe: Randomized clinical trial. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):608-19. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.055.

Bushyhead D and Quigley EMM. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth-pathophysiology and its implications for definition and management. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):593-607. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.002.

Long MT et al. AGA Clinical practice update: Diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in lean individuals: Expert review. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):764-74.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.023.

CGH

August 2022

Lennon AM and Vege SS. Pancreatic cyst surveillance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1663-7.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.002.

Crockett SD et al. Large Polyp Study Group Consortium. Clip closure does not reduce risk of bleeding after resection of large serrated polyps: Results from a randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1757-17--65.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.036.

Martin P et al. Treatment algorithm for managing chronic hepatitis b virus infection in the United States: 2021 update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1766-75. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.036.

September 2022

Pawlak KM et al. How to train the next generation to provide high-quality peer-reviews. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):1902-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.018.

Choung RS et al. Collagenous gastritis: Characteristics and response to topical budesonide. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):1977-85.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.11.033.

Basnayake C et al. Long-term outcome of multidisciplinary versus standard gastroenterologist care for functional gastrointestinal disorders: A randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):2102-11.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.005.

Deutsch-Link S et al. Alcohol-associated liver disease mortality increased from 2017 to 2020 and accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):2142-4.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.017.

TIGE

Nakamatsu, Dai et al. Safety of cold snare polypectomy for small colorectal polyps in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2022 Apr 8;24[3]:246-53. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2022.03.008.

Gastro Hep Advances

Brindusa Truta et al. Outcomes of continuation vs. discontinuation of adalimumab therapy during third trimester of pregnancy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastro Hep Advances. 2022 Jan 1;1[5]:785-91. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2022.04.009.

Gastroenterology

August 2022

Johnson-Laghi KA, Mattar MC. Integrating cognitive apprenticeship into gastroenterology clinical training. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):364-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.013.

Wood LD et al. Pancreatic cancer: Pathogenesis, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):386-402.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.056.

Calderwood AH and Robertson DJ. Stopping surveillance in gastrointestinal conditions: Thoughts on the scope of the problem and potential solutions. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):345-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.009.

September 2022

Donnangelo LL et al. Disclosure and reflection after an adverse event: Tips for training and practice. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):568-71. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.07.003.

Chey WD et al. Vonoprazan triple and dual therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in the United States and Europe: Randomized clinical trial. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):608-19. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.055.

Bushyhead D and Quigley EMM. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth-pathophysiology and its implications for definition and management. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):593-607. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.002.

Long MT et al. AGA Clinical practice update: Diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in lean individuals: Expert review. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):764-74.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.023.

CGH

August 2022

Lennon AM and Vege SS. Pancreatic cyst surveillance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1663-7.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.002.

Crockett SD et al. Large Polyp Study Group Consortium. Clip closure does not reduce risk of bleeding after resection of large serrated polyps: Results from a randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1757-17--65.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.036.

Martin P et al. Treatment algorithm for managing chronic hepatitis b virus infection in the United States: 2021 update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1766-75. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.036.

September 2022

Pawlak KM et al. How to train the next generation to provide high-quality peer-reviews. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):1902-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.018.

Choung RS et al. Collagenous gastritis: Characteristics and response to topical budesonide. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):1977-85.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.11.033.

Basnayake C et al. Long-term outcome of multidisciplinary versus standard gastroenterologist care for functional gastrointestinal disorders: A randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):2102-11.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.005.

Deutsch-Link S et al. Alcohol-associated liver disease mortality increased from 2017 to 2020 and accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):2142-4.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.017.

TIGE

Nakamatsu, Dai et al. Safety of cold snare polypectomy for small colorectal polyps in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2022 Apr 8;24[3]:246-53. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2022.03.008.

Gastro Hep Advances

Brindusa Truta et al. Outcomes of continuation vs. discontinuation of adalimumab therapy during third trimester of pregnancy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastro Hep Advances. 2022 Jan 1;1[5]:785-91. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2022.04.009.

The role of repeat uterine curettage in postmolar gestational trophoblastic neoplasia

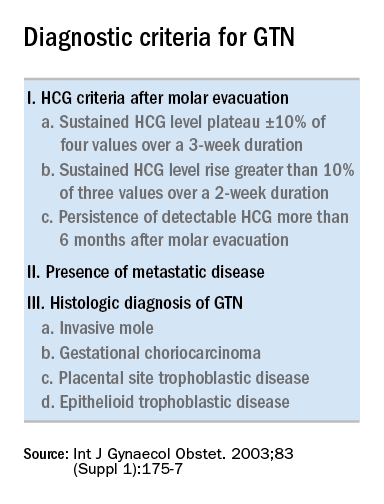

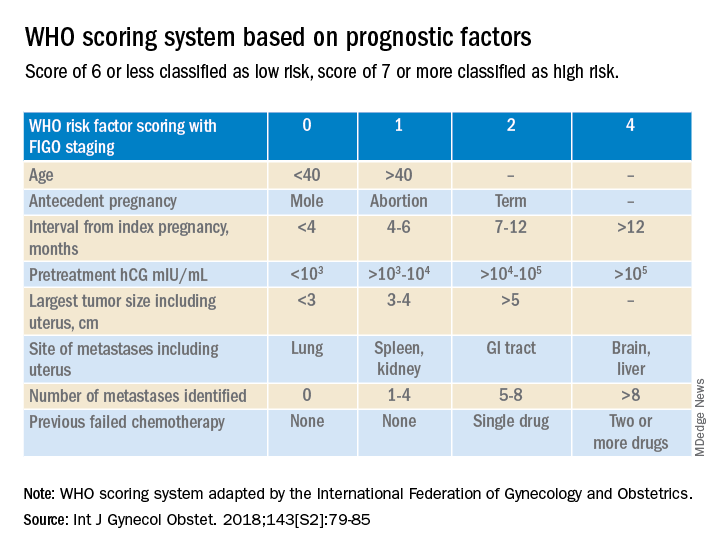

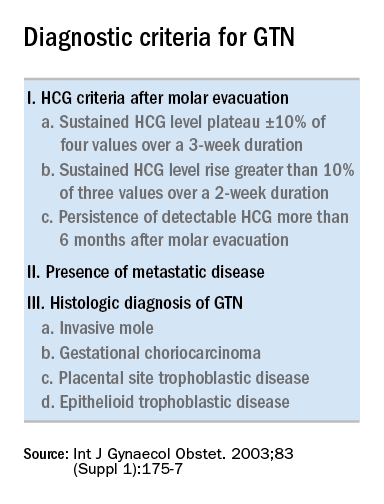

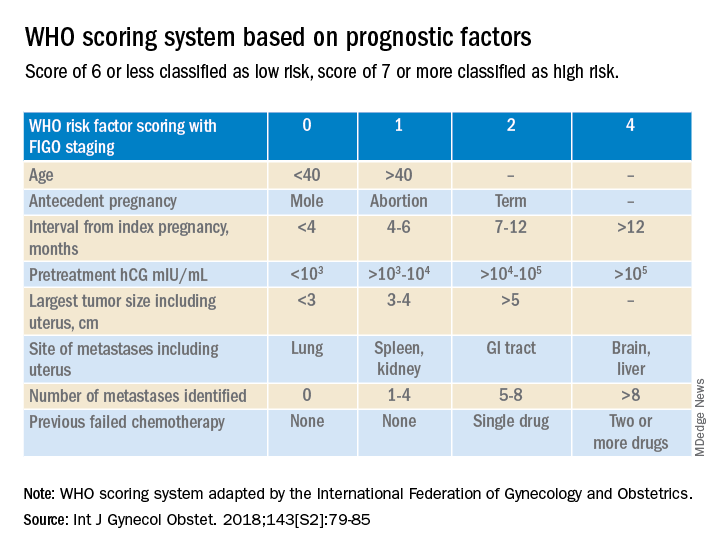

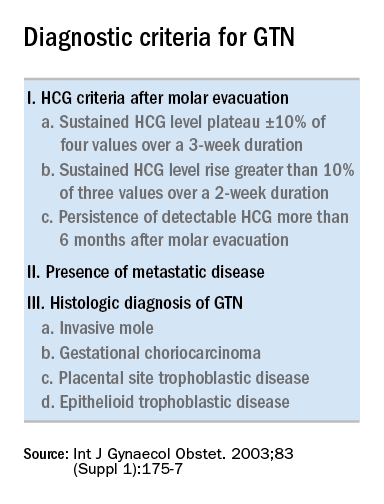

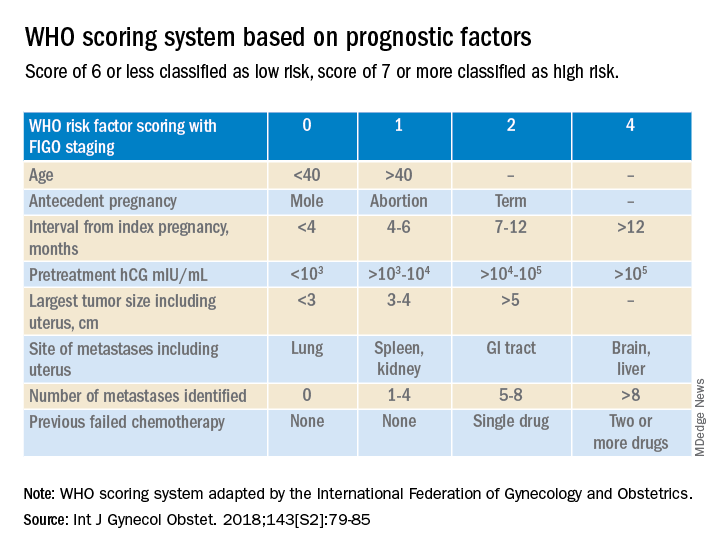

Trophoblastic tissue is responsible for formation of the placenta during pregnancy. Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), a group comprising benign (hydatidiform moles) and malignant tumors, occurs when gestational trophoblastic tissue behaves in an abnormal manner. Hydatidiform moles, which are thought to be caused by errors in fertilization, occur in approximately 1 in 1,200 pregnancies in the United States. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) refers to the subgroup of these trophoblastic or placental tumors with malignant behavior and includes postmolar GTN, invasive mole, gestational choriocarcinoma, placental-site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT), and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Postmolar GTN arises after evacuation of a molar pregnancy and is most frequently diagnosed by a plateau or increase in human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).1 The risk of postmolar GTN is much higher after a complete mole (7%-30%) compared with a partial mole (2.5%-7.5%).2 Once postmolar GTN is diagnosed, a World Health Organization score is assigned to determine if patients have low- or high-risk disease.3 The primary treatment for most GTN is chemotherapy. A patient’s WHO score helps determine whether they would benefit from single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy. The standard of care for low-risk disease is single-agent chemotherapy with either methotrexate or actinomycin D.

The role of a second uterine curettage, after the diagnosis of low-risk postmolar GTN, has been controversial because of the limited data and disparate outcomes reported. In older retrospective series, a second curettage affected treatment or produced remission in only 9%-20% of patients and caused uterine perforation or major hemorrhage in 5%-8% of patients.4,5 Given relatively high rates of major complications compared with surgical cure or decreased chemotherapy cycles needed, only a limited number of patients seemed to benefit from a second procedure. On the other hand, an observational study of 544 patients who underwent second uterine evacuation after a presumed diagnosis of persistent GTD found that up to 60% of patients did not require chemotherapy afterward.6 Those with hCG levels greater than 1,500 IU/L or histologic evidence of GTD were less likely to have a surgical cure after second curettage. The indications for uterine evacuations were varied across these studies and make it nearly impossible to compare their results.

More recently, there have been two prospective trials that have tackled the question of the utility of second uterine evacuation in low-risk, nonmetastatic GTN. The Gynecologic Oncology Group performed a single-arm prospective study in the United States that enrolled patients with postmolar GTN to undergo second curettage as initial treatment of their disease.7 Of 60 eligible patients, 40% had a surgical cure (defined as normalization of hCG followed by at least 6 months of subsequent normal hCG values). Overall, 47% of patients were able to avoid chemotherapy. All surgical cures were seen in patients with WHO scores between 0 and 4. Importantly, three women were diagnosed with PSTT, which tends to be resistant to methotrexate and actinomycin D (treatment for nonmetastatic PSTT is definitive surgery with hysterectomy). The study found that hCG was a poor discriminator for achieving surgical cure. While age appeared to have an association with surgical cure (cure less likely for younger and older ages, younger than 19 and older than 40), patient numbers were too small to make a statistical conclusion. There were no uterine perforations and one patient had a grade 3 hemorrhage (requiring transfusion).

In the second prospective trial, performed in Iran, 62 patients were randomized to either second uterine evacuation or standard treatment after diagnosis of postmolar GTN.8 All patients in the surgical arm received a cervical ripening agent prior to their procedure, had their procedure under ultrasound guidance, and received misoprostol afterward to prevent uterine bleeding. Among those undergoing second uterine evacuation, 50% were cured (no need for chemotherapy). Among those needing chemotherapy after surgery, the mean number of cycles of chemotherapy needed (3.07 vs. 6.69) and the time it took to achieve negative hCG (3.23 vs. 9.19 weeks) were significantly less compared with patients who did not undergo surgery. hCG prior to second uterine evacuation could distinguish response to surgery compared with those needing chemotherapy (hCG of 1,983 IU/L or less was the level determined to best predict response). No complications related to surgery were reported.

Given prospective data available, second uterine evacuation for treatment of nonmetastatic, low-risk postmolar GTN is a reasonable treatment option and one that should be considered and discussed with patients given the potential to avoid chemotherapy or decrease the number of cycles needed. It may be prudent to limit the procedure to patients with an hCG less than 1,500-2,000 IU/L and to those between the ages of 20 and 40. While uterine hemorrhage and perforation have been reported in the literature, more recent data suggest low rates of these complications. Unfortunately, given the rarity of the disease and the historically controversial use of second curettage, little is known about the effects on future fertility that this procedure may have, including the development of uterine synechiae.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Ngan HY et al, FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003 Oct;83 Suppl 1:175-7. Erratum in: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Dec;155(3):563.

2. Soper JT. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Feb.;137(2):355-70.

3. Ngan HY et al. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:79-85.

4. Schlaerth JB et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Jun;162(6):1465-70.

5. van Trommel NE et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Oct;99(1):6-13.

6. Pezeshki M et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Dec;95(3):423-9.

7. Osborne RJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):535-42.

8. Ayatollahi H et al. Int J Womens Health. 2017 Sep 21;9:665-71.

Trophoblastic tissue is responsible for formation of the placenta during pregnancy. Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), a group comprising benign (hydatidiform moles) and malignant tumors, occurs when gestational trophoblastic tissue behaves in an abnormal manner. Hydatidiform moles, which are thought to be caused by errors in fertilization, occur in approximately 1 in 1,200 pregnancies in the United States. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) refers to the subgroup of these trophoblastic or placental tumors with malignant behavior and includes postmolar GTN, invasive mole, gestational choriocarcinoma, placental-site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT), and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Postmolar GTN arises after evacuation of a molar pregnancy and is most frequently diagnosed by a plateau or increase in human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).1 The risk of postmolar GTN is much higher after a complete mole (7%-30%) compared with a partial mole (2.5%-7.5%).2 Once postmolar GTN is diagnosed, a World Health Organization score is assigned to determine if patients have low- or high-risk disease.3 The primary treatment for most GTN is chemotherapy. A patient’s WHO score helps determine whether they would benefit from single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy. The standard of care for low-risk disease is single-agent chemotherapy with either methotrexate or actinomycin D.

The role of a second uterine curettage, after the diagnosis of low-risk postmolar GTN, has been controversial because of the limited data and disparate outcomes reported. In older retrospective series, a second curettage affected treatment or produced remission in only 9%-20% of patients and caused uterine perforation or major hemorrhage in 5%-8% of patients.4,5 Given relatively high rates of major complications compared with surgical cure or decreased chemotherapy cycles needed, only a limited number of patients seemed to benefit from a second procedure. On the other hand, an observational study of 544 patients who underwent second uterine evacuation after a presumed diagnosis of persistent GTD found that up to 60% of patients did not require chemotherapy afterward.6 Those with hCG levels greater than 1,500 IU/L or histologic evidence of GTD were less likely to have a surgical cure after second curettage. The indications for uterine evacuations were varied across these studies and make it nearly impossible to compare their results.

More recently, there have been two prospective trials that have tackled the question of the utility of second uterine evacuation in low-risk, nonmetastatic GTN. The Gynecologic Oncology Group performed a single-arm prospective study in the United States that enrolled patients with postmolar GTN to undergo second curettage as initial treatment of their disease.7 Of 60 eligible patients, 40% had a surgical cure (defined as normalization of hCG followed by at least 6 months of subsequent normal hCG values). Overall, 47% of patients were able to avoid chemotherapy. All surgical cures were seen in patients with WHO scores between 0 and 4. Importantly, three women were diagnosed with PSTT, which tends to be resistant to methotrexate and actinomycin D (treatment for nonmetastatic PSTT is definitive surgery with hysterectomy). The study found that hCG was a poor discriminator for achieving surgical cure. While age appeared to have an association with surgical cure (cure less likely for younger and older ages, younger than 19 and older than 40), patient numbers were too small to make a statistical conclusion. There were no uterine perforations and one patient had a grade 3 hemorrhage (requiring transfusion).

In the second prospective trial, performed in Iran, 62 patients were randomized to either second uterine evacuation or standard treatment after diagnosis of postmolar GTN.8 All patients in the surgical arm received a cervical ripening agent prior to their procedure, had their procedure under ultrasound guidance, and received misoprostol afterward to prevent uterine bleeding. Among those undergoing second uterine evacuation, 50% were cured (no need for chemotherapy). Among those needing chemotherapy after surgery, the mean number of cycles of chemotherapy needed (3.07 vs. 6.69) and the time it took to achieve negative hCG (3.23 vs. 9.19 weeks) were significantly less compared with patients who did not undergo surgery. hCG prior to second uterine evacuation could distinguish response to surgery compared with those needing chemotherapy (hCG of 1,983 IU/L or less was the level determined to best predict response). No complications related to surgery were reported.

Given prospective data available, second uterine evacuation for treatment of nonmetastatic, low-risk postmolar GTN is a reasonable treatment option and one that should be considered and discussed with patients given the potential to avoid chemotherapy or decrease the number of cycles needed. It may be prudent to limit the procedure to patients with an hCG less than 1,500-2,000 IU/L and to those between the ages of 20 and 40. While uterine hemorrhage and perforation have been reported in the literature, more recent data suggest low rates of these complications. Unfortunately, given the rarity of the disease and the historically controversial use of second curettage, little is known about the effects on future fertility that this procedure may have, including the development of uterine synechiae.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Ngan HY et al, FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003 Oct;83 Suppl 1:175-7. Erratum in: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Dec;155(3):563.

2. Soper JT. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Feb.;137(2):355-70.

3. Ngan HY et al. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:79-85.

4. Schlaerth JB et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Jun;162(6):1465-70.

5. van Trommel NE et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Oct;99(1):6-13.

6. Pezeshki M et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Dec;95(3):423-9.

7. Osborne RJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):535-42.

8. Ayatollahi H et al. Int J Womens Health. 2017 Sep 21;9:665-71.

Trophoblastic tissue is responsible for formation of the placenta during pregnancy. Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), a group comprising benign (hydatidiform moles) and malignant tumors, occurs when gestational trophoblastic tissue behaves in an abnormal manner. Hydatidiform moles, which are thought to be caused by errors in fertilization, occur in approximately 1 in 1,200 pregnancies in the United States. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) refers to the subgroup of these trophoblastic or placental tumors with malignant behavior and includes postmolar GTN, invasive mole, gestational choriocarcinoma, placental-site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT), and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Postmolar GTN arises after evacuation of a molar pregnancy and is most frequently diagnosed by a plateau or increase in human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).1 The risk of postmolar GTN is much higher after a complete mole (7%-30%) compared with a partial mole (2.5%-7.5%).2 Once postmolar GTN is diagnosed, a World Health Organization score is assigned to determine if patients have low- or high-risk disease.3 The primary treatment for most GTN is chemotherapy. A patient’s WHO score helps determine whether they would benefit from single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy. The standard of care for low-risk disease is single-agent chemotherapy with either methotrexate or actinomycin D.

The role of a second uterine curettage, after the diagnosis of low-risk postmolar GTN, has been controversial because of the limited data and disparate outcomes reported. In older retrospective series, a second curettage affected treatment or produced remission in only 9%-20% of patients and caused uterine perforation or major hemorrhage in 5%-8% of patients.4,5 Given relatively high rates of major complications compared with surgical cure or decreased chemotherapy cycles needed, only a limited number of patients seemed to benefit from a second procedure. On the other hand, an observational study of 544 patients who underwent second uterine evacuation after a presumed diagnosis of persistent GTD found that up to 60% of patients did not require chemotherapy afterward.6 Those with hCG levels greater than 1,500 IU/L or histologic evidence of GTD were less likely to have a surgical cure after second curettage. The indications for uterine evacuations were varied across these studies and make it nearly impossible to compare their results.

More recently, there have been two prospective trials that have tackled the question of the utility of second uterine evacuation in low-risk, nonmetastatic GTN. The Gynecologic Oncology Group performed a single-arm prospective study in the United States that enrolled patients with postmolar GTN to undergo second curettage as initial treatment of their disease.7 Of 60 eligible patients, 40% had a surgical cure (defined as normalization of hCG followed by at least 6 months of subsequent normal hCG values). Overall, 47% of patients were able to avoid chemotherapy. All surgical cures were seen in patients with WHO scores between 0 and 4. Importantly, three women were diagnosed with PSTT, which tends to be resistant to methotrexate and actinomycin D (treatment for nonmetastatic PSTT is definitive surgery with hysterectomy). The study found that hCG was a poor discriminator for achieving surgical cure. While age appeared to have an association with surgical cure (cure less likely for younger and older ages, younger than 19 and older than 40), patient numbers were too small to make a statistical conclusion. There were no uterine perforations and one patient had a grade 3 hemorrhage (requiring transfusion).

In the second prospective trial, performed in Iran, 62 patients were randomized to either second uterine evacuation or standard treatment after diagnosis of postmolar GTN.8 All patients in the surgical arm received a cervical ripening agent prior to their procedure, had their procedure under ultrasound guidance, and received misoprostol afterward to prevent uterine bleeding. Among those undergoing second uterine evacuation, 50% were cured (no need for chemotherapy). Among those needing chemotherapy after surgery, the mean number of cycles of chemotherapy needed (3.07 vs. 6.69) and the time it took to achieve negative hCG (3.23 vs. 9.19 weeks) were significantly less compared with patients who did not undergo surgery. hCG prior to second uterine evacuation could distinguish response to surgery compared with those needing chemotherapy (hCG of 1,983 IU/L or less was the level determined to best predict response). No complications related to surgery were reported.

Given prospective data available, second uterine evacuation for treatment of nonmetastatic, low-risk postmolar GTN is a reasonable treatment option and one that should be considered and discussed with patients given the potential to avoid chemotherapy or decrease the number of cycles needed. It may be prudent to limit the procedure to patients with an hCG less than 1,500-2,000 IU/L and to those between the ages of 20 and 40. While uterine hemorrhage and perforation have been reported in the literature, more recent data suggest low rates of these complications. Unfortunately, given the rarity of the disease and the historically controversial use of second curettage, little is known about the effects on future fertility that this procedure may have, including the development of uterine synechiae.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Ngan HY et al, FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003 Oct;83 Suppl 1:175-7. Erratum in: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Dec;155(3):563.

2. Soper JT. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Feb.;137(2):355-70.

3. Ngan HY et al. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:79-85.

4. Schlaerth JB et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Jun;162(6):1465-70.

5. van Trommel NE et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Oct;99(1):6-13.

6. Pezeshki M et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Dec;95(3):423-9.

7. Osborne RJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):535-42.

8. Ayatollahi H et al. Int J Womens Health. 2017 Sep 21;9:665-71.

Add PCSK9 inhibitor to high-intensity statin at primary PCI, proposes sham-controlled EPIC-STEMI

It’s best to have patients on aggressive lipid-lowering therapy before discharge after an acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), so why not start it right away – even in the cath lab – using some of the most potent LDL cholesterol–lowering agents available?

That was a main idea behind the randomized, sham-controlled EPIC-STEMI trial, in which STEMI patients were started on a PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) inhibitor immediately before direct percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and on top of high-intensity statins.

Those in the trial getting the active agent showed a 22% drop in LDL cholesterol levels by 6 weeks, compared with the control group given a sham injection along with high-intensity statins. They were also more likely to meet LDL cholesterol goals specified in some guidelines, including reduction by at least 50%. And those outcomes were achieved regardless of baseline LDL cholesterol levels or prior statin use.

Adoption of the trial’s early, aggressive LDL cholesterolreduction strategy in practice “has the potential to substantially reduce morbidity and mortality” in such cases “by further reducing LDL beyond statins in a much greater number of high-risk patients than are currently being treated with these agents,” suggested principal investigator Shamir R. Mehta, MD, MSc, when presenting the findings at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Adherence to secondary prevention measures in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) is much better if they are started before hospital discharge, explained Dr. Mehta, senior scientist with Population Health Research Institute and professor of medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. But “as soon as the patient has left the hospital, it is much more difficult to get these therapies on board.”

Routine adoption of such aggressive in-hospital, lipid-lowering therapy for the vast population with ACS would likely mean far fewer deaths and cardiovascular events “across a broader patient population.”

EPIC-STEMI is among the first studies to explore the strategy. “I think that’s the point of the trial that we wanted to make, that we don’t yet have data on this. We’re treading very carefully with PCSK9 inhibitors, and it’s just inching forward in populations. And I think we need a bold trial to see whether or not this changes things.”

The PCSK9 inhibitor alirocumab (Praluent) was used in EPIC-STEMI, which was published in EuroIntervention, with Dr. Mehta as lead author, the same day as his presentation. The drug and its sham injection were given on top of either atorvastatin 40-80 mg or rosuvastatin 40 mg.

Early initiation of statins in patients with acute STEMI has become standard, but there’s good evidence from intracoronary imaging studies suggesting that the addition of PCSK9 inhibitors might promote further stabilization of plaques that could potentially cause recurrent ischemic events.

Treatment with the injectable drugs plus statins led to significant coronary lesion regression in the GLAGOV trial of patients with stable coronary disease. And initiation of PCSK9 inhibitors with high-intensity statins soon after PCI for ACS improved atheroma shrinkage in non–infarct-related arteries over 1 year in the recent, placebo-controlled PACMAN-AMI trial.

Dr. Mehta pointed out that LDL reductions on PCSK9 inhibition, compared with the sham control, weren’t necessarily as impressive as might be expected from the major trials of long-term therapy with the drugs.

“You need longer [therapy] in order to see a difference in LDL levels when you use a PCSK9 inhibitor acutely. This is shown also on measures of infarct size.” There was no difference between treatment groups in infarct size as measured by levels of the MB fraction of creatine kinase, he reported.

“What this is telling us is that the acute use of a PCSK9 inhibitor did not modify the size or the severity of the baseline STEMI event.”

And EPIC-STEMI was too small and never intended to assess clinical outcomes; it was more about feasibility and what degree of LDL cholesterol lowering might be expected.

The trial was needed, Dr. Mehta said, because the PCSK9 inhibitors haven’t been extensively adopted into clinical practice and are not getting to the patients who could most benefit. One of the reasons for that is quite clear to him. “We are missing the high-risk patients because we are not treating them acutely,” Dr. Mehta said in an interview.

The strategy “has not yet been evaluated, and there have been barriers,” he observed. “Cost has been a barrier. Access to the drug has been a barrier. But in terms of the science, in terms of reducing cardiovascular events, this is a strategy that has to be tested.”

The aggressive, early LDL cholesterol reduction strategy should be evaluated for its effect on long-term outcomes, “especially knowing that in the first 30 days to 6 months post STEMI there’s a tremendous uptick in ischemic events, including recurrent myocardial infarction,” Roxana Mehran, MD, said at a media briefing on EPIC-STEMI held before Dr. Mehta’s formal presentation.

The “fantastic reduction acutely” with a PCSK9 inhibitor on top of statins, “hopefully reducing inflammation” similarly to what’s been observed in past trials, “absolutely warrants” a STEMI clinical outcomes trial, said Dr. Mehran, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, who isn’t connected with EPIC-STEMI.

If better post-discharge medication adherence is one of the acute strategy’s goals, it will be important to consider the potential influence of prescribing a periodically injected drug, proposed Eric A. Cohen, MD, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center, Toronto, at the press conference.

“Keep in mind that STEMI patients typically come to the hospital on zero medications and leave 2 days later on five medications,” Dr. Cohen observed. “I’m curious whether having one of those as a sub-Q injection every 2 weeks, and reducing the pill burden, will help or deter adherence to therapy. I think it’s worth studying.”

The trial originally included 97 patients undergoing PCI for STEMI who were randomly assigned to receive the PCSK9 inhibitor or a sham injection on top of high-intensity statins, without regard to LDL cholesterol levels. Randomization took place after diagnostic angiography but before PCI.

The analysis, however, subsequently excluded 29 patients who could not continue with the study, “mainly because of hospital research clinic closure due to the COVID-19 pandemic,” the published report states.

That left 68 patients who had received at least one dose of PCSK9 inhibitor, alirocumab 150 mg subcutaneously, or the sham injection, and had at least one blood draw for LDL cholesterol response which, Dr. Mehta said, still left adequate statistical power for the LDL cholesterol–based primary endpoint.

By 6 weeks, LDL cholesterol levels had fallen 72.9% in the active-therapy group and by 48.1% in the control group (P < .001). Also, 92.1% and 56.7% of patients, respectively (P = .002), had achieved levels below the 1.4 mmol/L (54 mg/dL) goal in the European guidelines, Dr. Mehta reported.

Levels fell more than 50% compared with baseline in 89.5% of alirocumab patients and 60% (P = .007) of controls, respectively.

There was no significant difference in rates of attaining LDL cholesterol levels below the 70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L) threshold specified in U.S. guidelines for very high-risk patients: 94.7% of alirocumab patients and 83.4% of controls (P = .26).

Nor did the groups differ significantly in natriuretic peptide levels, which reflect ventricular remodeling; or in 6-week change in the inflammatory biomarker high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

An open-label, randomized trial scheduled to launch before the end of 2022 will explore similarly early initiation of a PCSK9 inhibitor, compared with standard lipid management, in an estimated 4,000 patients hospitalized with STEMI or non-STEMI.

The EVOLVE MI trial is looking at the monoclonal antibody evolocumab (Repatha) for its effect on the primary endpoint of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, arterial revascularization, or death from any cause over an expected 3-4 years.

EPIC-STEMI was supported in part by Sanofi. Dr. Mehta reported an unrestricted grant from Sanofi to Hamilton Health Sciences for the present study and consulting fees from Amgen, Sanofi, and Novartis. Dr. Cohen disclosed receiving grant support from and holding research contracts with Abbott Vascular; and receiving fees for consulting, honoraria, or serving on a speaker’s bureau for Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, and Baylis. Dr. Mehran disclosed receiving grants or research support from numerous pharmaceutical companies; receiving consultant fee or honoraria or serving on a speaker’s bureau for Novartis, Abbott Vascular, Janssen, Medtronic, Medscape/WebMD, and Cine-Med Research; and holding equity, stock, or stock options with Control Rad, Applied Therapeutics, and Elixir Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s best to have patients on aggressive lipid-lowering therapy before discharge after an acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), so why not start it right away – even in the cath lab – using some of the most potent LDL cholesterol–lowering agents available?

That was a main idea behind the randomized, sham-controlled EPIC-STEMI trial, in which STEMI patients were started on a PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) inhibitor immediately before direct percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and on top of high-intensity statins.

Those in the trial getting the active agent showed a 22% drop in LDL cholesterol levels by 6 weeks, compared with the control group given a sham injection along with high-intensity statins. They were also more likely to meet LDL cholesterol goals specified in some guidelines, including reduction by at least 50%. And those outcomes were achieved regardless of baseline LDL cholesterol levels or prior statin use.

Adoption of the trial’s early, aggressive LDL cholesterolreduction strategy in practice “has the potential to substantially reduce morbidity and mortality” in such cases “by further reducing LDL beyond statins in a much greater number of high-risk patients than are currently being treated with these agents,” suggested principal investigator Shamir R. Mehta, MD, MSc, when presenting the findings at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Adherence to secondary prevention measures in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) is much better if they are started before hospital discharge, explained Dr. Mehta, senior scientist with Population Health Research Institute and professor of medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. But “as soon as the patient has left the hospital, it is much more difficult to get these therapies on board.”

Routine adoption of such aggressive in-hospital, lipid-lowering therapy for the vast population with ACS would likely mean far fewer deaths and cardiovascular events “across a broader patient population.”

EPIC-STEMI is among the first studies to explore the strategy. “I think that’s the point of the trial that we wanted to make, that we don’t yet have data on this. We’re treading very carefully with PCSK9 inhibitors, and it’s just inching forward in populations. And I think we need a bold trial to see whether or not this changes things.”

The PCSK9 inhibitor alirocumab (Praluent) was used in EPIC-STEMI, which was published in EuroIntervention, with Dr. Mehta as lead author, the same day as his presentation. The drug and its sham injection were given on top of either atorvastatin 40-80 mg or rosuvastatin 40 mg.

Early initiation of statins in patients with acute STEMI has become standard, but there’s good evidence from intracoronary imaging studies suggesting that the addition of PCSK9 inhibitors might promote further stabilization of plaques that could potentially cause recurrent ischemic events.

Treatment with the injectable drugs plus statins led to significant coronary lesion regression in the GLAGOV trial of patients with stable coronary disease. And initiation of PCSK9 inhibitors with high-intensity statins soon after PCI for ACS improved atheroma shrinkage in non–infarct-related arteries over 1 year in the recent, placebo-controlled PACMAN-AMI trial.

Dr. Mehta pointed out that LDL reductions on PCSK9 inhibition, compared with the sham control, weren’t necessarily as impressive as might be expected from the major trials of long-term therapy with the drugs.

“You need longer [therapy] in order to see a difference in LDL levels when you use a PCSK9 inhibitor acutely. This is shown also on measures of infarct size.” There was no difference between treatment groups in infarct size as measured by levels of the MB fraction of creatine kinase, he reported.

“What this is telling us is that the acute use of a PCSK9 inhibitor did not modify the size or the severity of the baseline STEMI event.”

And EPIC-STEMI was too small and never intended to assess clinical outcomes; it was more about feasibility and what degree of LDL cholesterol lowering might be expected.

The trial was needed, Dr. Mehta said, because the PCSK9 inhibitors haven’t been extensively adopted into clinical practice and are not getting to the patients who could most benefit. One of the reasons for that is quite clear to him. “We are missing the high-risk patients because we are not treating them acutely,” Dr. Mehta said in an interview.

The strategy “has not yet been evaluated, and there have been barriers,” he observed. “Cost has been a barrier. Access to the drug has been a barrier. But in terms of the science, in terms of reducing cardiovascular events, this is a strategy that has to be tested.”

The aggressive, early LDL cholesterol reduction strategy should be evaluated for its effect on long-term outcomes, “especially knowing that in the first 30 days to 6 months post STEMI there’s a tremendous uptick in ischemic events, including recurrent myocardial infarction,” Roxana Mehran, MD, said at a media briefing on EPIC-STEMI held before Dr. Mehta’s formal presentation.

The “fantastic reduction acutely” with a PCSK9 inhibitor on top of statins, “hopefully reducing inflammation” similarly to what’s been observed in past trials, “absolutely warrants” a STEMI clinical outcomes trial, said Dr. Mehran, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, who isn’t connected with EPIC-STEMI.

If better post-discharge medication adherence is one of the acute strategy’s goals, it will be important to consider the potential influence of prescribing a periodically injected drug, proposed Eric A. Cohen, MD, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center, Toronto, at the press conference.

“Keep in mind that STEMI patients typically come to the hospital on zero medications and leave 2 days later on five medications,” Dr. Cohen observed. “I’m curious whether having one of those as a sub-Q injection every 2 weeks, and reducing the pill burden, will help or deter adherence to therapy. I think it’s worth studying.”

The trial originally included 97 patients undergoing PCI for STEMI who were randomly assigned to receive the PCSK9 inhibitor or a sham injection on top of high-intensity statins, without regard to LDL cholesterol levels. Randomization took place after diagnostic angiography but before PCI.

The analysis, however, subsequently excluded 29 patients who could not continue with the study, “mainly because of hospital research clinic closure due to the COVID-19 pandemic,” the published report states.

That left 68 patients who had received at least one dose of PCSK9 inhibitor, alirocumab 150 mg subcutaneously, or the sham injection, and had at least one blood draw for LDL cholesterol response which, Dr. Mehta said, still left adequate statistical power for the LDL cholesterol–based primary endpoint.

By 6 weeks, LDL cholesterol levels had fallen 72.9% in the active-therapy group and by 48.1% in the control group (P < .001). Also, 92.1% and 56.7% of patients, respectively (P = .002), had achieved levels below the 1.4 mmol/L (54 mg/dL) goal in the European guidelines, Dr. Mehta reported.

Levels fell more than 50% compared with baseline in 89.5% of alirocumab patients and 60% (P = .007) of controls, respectively.

There was no significant difference in rates of attaining LDL cholesterol levels below the 70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L) threshold specified in U.S. guidelines for very high-risk patients: 94.7% of alirocumab patients and 83.4% of controls (P = .26).

Nor did the groups differ significantly in natriuretic peptide levels, which reflect ventricular remodeling; or in 6-week change in the inflammatory biomarker high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

An open-label, randomized trial scheduled to launch before the end of 2022 will explore similarly early initiation of a PCSK9 inhibitor, compared with standard lipid management, in an estimated 4,000 patients hospitalized with STEMI or non-STEMI.

The EVOLVE MI trial is looking at the monoclonal antibody evolocumab (Repatha) for its effect on the primary endpoint of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, arterial revascularization, or death from any cause over an expected 3-4 years.

EPIC-STEMI was supported in part by Sanofi. Dr. Mehta reported an unrestricted grant from Sanofi to Hamilton Health Sciences for the present study and consulting fees from Amgen, Sanofi, and Novartis. Dr. Cohen disclosed receiving grant support from and holding research contracts with Abbott Vascular; and receiving fees for consulting, honoraria, or serving on a speaker’s bureau for Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, and Baylis. Dr. Mehran disclosed receiving grants or research support from numerous pharmaceutical companies; receiving consultant fee or honoraria or serving on a speaker’s bureau for Novartis, Abbott Vascular, Janssen, Medtronic, Medscape/WebMD, and Cine-Med Research; and holding equity, stock, or stock options with Control Rad, Applied Therapeutics, and Elixir Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s best to have patients on aggressive lipid-lowering therapy before discharge after an acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), so why not start it right away – even in the cath lab – using some of the most potent LDL cholesterol–lowering agents available?

That was a main idea behind the randomized, sham-controlled EPIC-STEMI trial, in which STEMI patients were started on a PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) inhibitor immediately before direct percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and on top of high-intensity statins.

Those in the trial getting the active agent showed a 22% drop in LDL cholesterol levels by 6 weeks, compared with the control group given a sham injection along with high-intensity statins. They were also more likely to meet LDL cholesterol goals specified in some guidelines, including reduction by at least 50%. And those outcomes were achieved regardless of baseline LDL cholesterol levels or prior statin use.

Adoption of the trial’s early, aggressive LDL cholesterolreduction strategy in practice “has the potential to substantially reduce morbidity and mortality” in such cases “by further reducing LDL beyond statins in a much greater number of high-risk patients than are currently being treated with these agents,” suggested principal investigator Shamir R. Mehta, MD, MSc, when presenting the findings at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Adherence to secondary prevention measures in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) is much better if they are started before hospital discharge, explained Dr. Mehta, senior scientist with Population Health Research Institute and professor of medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. But “as soon as the patient has left the hospital, it is much more difficult to get these therapies on board.”

Routine adoption of such aggressive in-hospital, lipid-lowering therapy for the vast population with ACS would likely mean far fewer deaths and cardiovascular events “across a broader patient population.”

EPIC-STEMI is among the first studies to explore the strategy. “I think that’s the point of the trial that we wanted to make, that we don’t yet have data on this. We’re treading very carefully with PCSK9 inhibitors, and it’s just inching forward in populations. And I think we need a bold trial to see whether or not this changes things.”

The PCSK9 inhibitor alirocumab (Praluent) was used in EPIC-STEMI, which was published in EuroIntervention, with Dr. Mehta as lead author, the same day as his presentation. The drug and its sham injection were given on top of either atorvastatin 40-80 mg or rosuvastatin 40 mg.

Early initiation of statins in patients with acute STEMI has become standard, but there’s good evidence from intracoronary imaging studies suggesting that the addition of PCSK9 inhibitors might promote further stabilization of plaques that could potentially cause recurrent ischemic events.

Treatment with the injectable drugs plus statins led to significant coronary lesion regression in the GLAGOV trial of patients with stable coronary disease. And initiation of PCSK9 inhibitors with high-intensity statins soon after PCI for ACS improved atheroma shrinkage in non–infarct-related arteries over 1 year in the recent, placebo-controlled PACMAN-AMI trial.

Dr. Mehta pointed out that LDL reductions on PCSK9 inhibition, compared with the sham control, weren’t necessarily as impressive as might be expected from the major trials of long-term therapy with the drugs.

“You need longer [therapy] in order to see a difference in LDL levels when you use a PCSK9 inhibitor acutely. This is shown also on measures of infarct size.” There was no difference between treatment groups in infarct size as measured by levels of the MB fraction of creatine kinase, he reported.

“What this is telling us is that the acute use of a PCSK9 inhibitor did not modify the size or the severity of the baseline STEMI event.”

And EPIC-STEMI was too small and never intended to assess clinical outcomes; it was more about feasibility and what degree of LDL cholesterol lowering might be expected.

The trial was needed, Dr. Mehta said, because the PCSK9 inhibitors haven’t been extensively adopted into clinical practice and are not getting to the patients who could most benefit. One of the reasons for that is quite clear to him. “We are missing the high-risk patients because we are not treating them acutely,” Dr. Mehta said in an interview.

The strategy “has not yet been evaluated, and there have been barriers,” he observed. “Cost has been a barrier. Access to the drug has been a barrier. But in terms of the science, in terms of reducing cardiovascular events, this is a strategy that has to be tested.”

The aggressive, early LDL cholesterol reduction strategy should be evaluated for its effect on long-term outcomes, “especially knowing that in the first 30 days to 6 months post STEMI there’s a tremendous uptick in ischemic events, including recurrent myocardial infarction,” Roxana Mehran, MD, said at a media briefing on EPIC-STEMI held before Dr. Mehta’s formal presentation.

The “fantastic reduction acutely” with a PCSK9 inhibitor on top of statins, “hopefully reducing inflammation” similarly to what’s been observed in past trials, “absolutely warrants” a STEMI clinical outcomes trial, said Dr. Mehran, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, who isn’t connected with EPIC-STEMI.

If better post-discharge medication adherence is one of the acute strategy’s goals, it will be important to consider the potential influence of prescribing a periodically injected drug, proposed Eric A. Cohen, MD, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center, Toronto, at the press conference.

“Keep in mind that STEMI patients typically come to the hospital on zero medications and leave 2 days later on five medications,” Dr. Cohen observed. “I’m curious whether having one of those as a sub-Q injection every 2 weeks, and reducing the pill burden, will help or deter adherence to therapy. I think it’s worth studying.”

The trial originally included 97 patients undergoing PCI for STEMI who were randomly assigned to receive the PCSK9 inhibitor or a sham injection on top of high-intensity statins, without regard to LDL cholesterol levels. Randomization took place after diagnostic angiography but before PCI.

The analysis, however, subsequently excluded 29 patients who could not continue with the study, “mainly because of hospital research clinic closure due to the COVID-19 pandemic,” the published report states.

That left 68 patients who had received at least one dose of PCSK9 inhibitor, alirocumab 150 mg subcutaneously, or the sham injection, and had at least one blood draw for LDL cholesterol response which, Dr. Mehta said, still left adequate statistical power for the LDL cholesterol–based primary endpoint.

By 6 weeks, LDL cholesterol levels had fallen 72.9% in the active-therapy group and by 48.1% in the control group (P < .001). Also, 92.1% and 56.7% of patients, respectively (P = .002), had achieved levels below the 1.4 mmol/L (54 mg/dL) goal in the European guidelines, Dr. Mehta reported.

Levels fell more than 50% compared with baseline in 89.5% of alirocumab patients and 60% (P = .007) of controls, respectively.

There was no significant difference in rates of attaining LDL cholesterol levels below the 70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L) threshold specified in U.S. guidelines for very high-risk patients: 94.7% of alirocumab patients and 83.4% of controls (P = .26).

Nor did the groups differ significantly in natriuretic peptide levels, which reflect ventricular remodeling; or in 6-week change in the inflammatory biomarker high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

An open-label, randomized trial scheduled to launch before the end of 2022 will explore similarly early initiation of a PCSK9 inhibitor, compared with standard lipid management, in an estimated 4,000 patients hospitalized with STEMI or non-STEMI.

The EVOLVE MI trial is looking at the monoclonal antibody evolocumab (Repatha) for its effect on the primary endpoint of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, arterial revascularization, or death from any cause over an expected 3-4 years.

EPIC-STEMI was supported in part by Sanofi. Dr. Mehta reported an unrestricted grant from Sanofi to Hamilton Health Sciences for the present study and consulting fees from Amgen, Sanofi, and Novartis. Dr. Cohen disclosed receiving grant support from and holding research contracts with Abbott Vascular; and receiving fees for consulting, honoraria, or serving on a speaker’s bureau for Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, and Baylis. Dr. Mehran disclosed receiving grants or research support from numerous pharmaceutical companies; receiving consultant fee or honoraria or serving on a speaker’s bureau for Novartis, Abbott Vascular, Janssen, Medtronic, Medscape/WebMD, and Cine-Med Research; and holding equity, stock, or stock options with Control Rad, Applied Therapeutics, and Elixir Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM TCT 2022

Gender-affirming mastectomy boosts image and quality of life in gender-diverse youth

Adolescents and young adults who undergo “top surgery” for gender dysphoria overwhelmingly report being satisfied with the procedure in the near-term, new research shows.

The results of the prospective cohort study, reported recently in JAMA Pediatrics, suggest that the surgery can help facilitate gender congruence and comfort with body image for transmasculine and nonbinary youth. The authors, from Northwestern University, Chicago, said the findings may “help dispel misconceptions that gender-affirming treatment is experimental and support evidence-based practices of top surgery.”

Sumanas Jordan, MD, PhD, assistant professor of plastic surgery at Northwestern University, Chicago, and a coauthor of the study, said the study was the first prospective, matched cohort analysis showing that chest surgery improves outcomes in this age group.

“We focused our study on chest dysphoria, the distress due to the presence of breasts, and gender congruence, the feeling of alignment between identity and physical characteristics,” Dr. Jordan said. “We will continue to study the effect of surgery in other areas of health, such as physical functioning and quality of life, and follow our patients longer term.”

As many as 9% of adolescents and young adults identify as transgender or nonbinary - a group underrepresented in the pediatric literature, Dr. Jordan’s group said. Chest dysphoria often is associated with psychosocial issues such as depression and anxiety.

“Dysphoria can lead to a range of negative physical and emotional consequences, such as avoidance of exercise and sports, harmful chest-binding practices, functional limitations, and suicidal ideation, said M. Brett Cooper, MD, MEd, assistant professor of pediatrics, and adolescent and young adult medicine, at UT Southwestern Medical Center/Children’s Health, Dallas. “These young people often bind for several hours a day to reduce the presence of their chest.”

The study

The Northwestern team recruited 81 patients with a mean age of 18.6 years whose sex at birth was assigned female. Patients were overwhelmingly White (89%), and the majority (59%) were transgender male, the remaining patients nonbinary.

The population sample included patients aged 13-24 who underwent top surgery from December 2019 to April 2021 and a matched control group of those who did not have surgery.

Outcomes measures were assessed preoperatively and 3 months after surgery.

Thirty-six surgical patients and 34 of those in the control arm completed the outcomes measures. Surgical complications were minimal. Propensity analyses suggested an association between surgery and substantial improvements in scores on the following study endpoints:

- Chest dysphoria measure (–25.58 points, 95% confidence interval [CI], –29.18 to –21.98).

- Transgender congruence scale (7.78 points, 95%: CI, 6.06-9.50)

- Body image scale (–7.20 points, 95% CI, –11.68 to –2.72).

The patients who underwent top surgery reported significant improvements in scores of chest dysphoria, transgender congruence, and body image. The results for patients younger than age 18 paralleled those for older participants in the study.

While the results corroborate other studies showing that gender-affirming therapy improves mental health and quality of life among these young people, the researchers cautioned that some insurers require testosterone therapy for 1 year before their plans will cover the costs of gender-affirming surgery.

This may negatively affect those nonbinary patients who do not undergo hormone therapy,” the researchers wrote. They are currently collecting 1-year follow-up data to determine the long-term effects of top surgery on chest dysphoria, gender congruence, and body image.

As surgical patients progress through adult life, does the risk of regret increase? “We did not address regret in this short-term study,” Dr. Jordan said. “However, previous studies have shown very low levels of regret.”

An accompanying editorial concurred that top surgery is effective and medically necessary in this population of young people.

Calling the study “an important milestone in gender affirmation research,” Kishan M. Thadikonda, MD, and Katherine M. Gast, MD, MS, of the school of medicine and public health at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, said it will be important to follow this young cohort to prove these benefits will endure as patients age.

They cautioned, however, that nonbinary patients represented just 13% of the patient total and only 8% of the surgical cohort. Nonbinary patients are not well understood as a patient population when it comes to gender-affirmation surgery and are often included in studies with transgender patients despite clear differences, they noted.

Current setbacks

According to Dr. Cooper, politics is already affecting care in Texas. “Due to the sociopolitical climate in my state in regard to gender-affirming care, I have also seen a few young people have their surgeries either canceled or postponed by their parents,” he said. “This has led to a worsening of mental health in these patients.”

Dr. Cooper stressed the need for more research on the perspective of non-White and socioeconomically disadvantaged youth.

“This study also highlights the disparity between patients who have commercial insurance versus those who are on Medicaid,” he said. “Medicaid plans often do not cover this, so those patients usually have to continue to suffer or pay for this surgery out of their own pocket.”

This study was supported by the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, funded in part by the National Institutes of Health. Funding also came from the Plastic Surgery Foundation and American Association of Pediatric Plastic Surgery. Dr. Jordan received grants from the Plastic Surgery Foundation during the study. One coauthor reported consultant fees from CVS Caremark for consulting outside the submitted work, and another reported grants from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. Dr. Cooper disclosed no competing interests relevant to his comments. The editorial commentators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Adolescents and young adults who undergo “top surgery” for gender dysphoria overwhelmingly report being satisfied with the procedure in the near-term, new research shows.

The results of the prospective cohort study, reported recently in JAMA Pediatrics, suggest that the surgery can help facilitate gender congruence and comfort with body image for transmasculine and nonbinary youth. The authors, from Northwestern University, Chicago, said the findings may “help dispel misconceptions that gender-affirming treatment is experimental and support evidence-based practices of top surgery.”

Sumanas Jordan, MD, PhD, assistant professor of plastic surgery at Northwestern University, Chicago, and a coauthor of the study, said the study was the first prospective, matched cohort analysis showing that chest surgery improves outcomes in this age group.

“We focused our study on chest dysphoria, the distress due to the presence of breasts, and gender congruence, the feeling of alignment between identity and physical characteristics,” Dr. Jordan said. “We will continue to study the effect of surgery in other areas of health, such as physical functioning and quality of life, and follow our patients longer term.”

As many as 9% of adolescents and young adults identify as transgender or nonbinary - a group underrepresented in the pediatric literature, Dr. Jordan’s group said. Chest dysphoria often is associated with psychosocial issues such as depression and anxiety.

“Dysphoria can lead to a range of negative physical and emotional consequences, such as avoidance of exercise and sports, harmful chest-binding practices, functional limitations, and suicidal ideation, said M. Brett Cooper, MD, MEd, assistant professor of pediatrics, and adolescent and young adult medicine, at UT Southwestern Medical Center/Children’s Health, Dallas. “These young people often bind for several hours a day to reduce the presence of their chest.”

The study

The Northwestern team recruited 81 patients with a mean age of 18.6 years whose sex at birth was assigned female. Patients were overwhelmingly White (89%), and the majority (59%) were transgender male, the remaining patients nonbinary.

The population sample included patients aged 13-24 who underwent top surgery from December 2019 to April 2021 and a matched control group of those who did not have surgery.

Outcomes measures were assessed preoperatively and 3 months after surgery.

Thirty-six surgical patients and 34 of those in the control arm completed the outcomes measures. Surgical complications were minimal. Propensity analyses suggested an association between surgery and substantial improvements in scores on the following study endpoints:

- Chest dysphoria measure (–25.58 points, 95% confidence interval [CI], –29.18 to –21.98).

- Transgender congruence scale (7.78 points, 95%: CI, 6.06-9.50)

- Body image scale (–7.20 points, 95% CI, –11.68 to –2.72).

The patients who underwent top surgery reported significant improvements in scores of chest dysphoria, transgender congruence, and body image. The results for patients younger than age 18 paralleled those for older participants in the study.

While the results corroborate other studies showing that gender-affirming therapy improves mental health and quality of life among these young people, the researchers cautioned that some insurers require testosterone therapy for 1 year before their plans will cover the costs of gender-affirming surgery.

This may negatively affect those nonbinary patients who do not undergo hormone therapy,” the researchers wrote. They are currently collecting 1-year follow-up data to determine the long-term effects of top surgery on chest dysphoria, gender congruence, and body image.

As surgical patients progress through adult life, does the risk of regret increase? “We did not address regret in this short-term study,” Dr. Jordan said. “However, previous studies have shown very low levels of regret.”

An accompanying editorial concurred that top surgery is effective and medically necessary in this population of young people.

Calling the study “an important milestone in gender affirmation research,” Kishan M. Thadikonda, MD, and Katherine M. Gast, MD, MS, of the school of medicine and public health at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, said it will be important to follow this young cohort to prove these benefits will endure as patients age.

They cautioned, however, that nonbinary patients represented just 13% of the patient total and only 8% of the surgical cohort. Nonbinary patients are not well understood as a patient population when it comes to gender-affirmation surgery and are often included in studies with transgender patients despite clear differences, they noted.

Current setbacks

According to Dr. Cooper, politics is already affecting care in Texas. “Due to the sociopolitical climate in my state in regard to gender-affirming care, I have also seen a few young people have their surgeries either canceled or postponed by their parents,” he said. “This has led to a worsening of mental health in these patients.”

Dr. Cooper stressed the need for more research on the perspective of non-White and socioeconomically disadvantaged youth.

“This study also highlights the disparity between patients who have commercial insurance versus those who are on Medicaid,” he said. “Medicaid plans often do not cover this, so those patients usually have to continue to suffer or pay for this surgery out of their own pocket.”

This study was supported by the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, funded in part by the National Institutes of Health. Funding also came from the Plastic Surgery Foundation and American Association of Pediatric Plastic Surgery. Dr. Jordan received grants from the Plastic Surgery Foundation during the study. One coauthor reported consultant fees from CVS Caremark for consulting outside the submitted work, and another reported grants from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. Dr. Cooper disclosed no competing interests relevant to his comments. The editorial commentators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Adolescents and young adults who undergo “top surgery” for gender dysphoria overwhelmingly report being satisfied with the procedure in the near-term, new research shows.

The results of the prospective cohort study, reported recently in JAMA Pediatrics, suggest that the surgery can help facilitate gender congruence and comfort with body image for transmasculine and nonbinary youth. The authors, from Northwestern University, Chicago, said the findings may “help dispel misconceptions that gender-affirming treatment is experimental and support evidence-based practices of top surgery.”

Sumanas Jordan, MD, PhD, assistant professor of plastic surgery at Northwestern University, Chicago, and a coauthor of the study, said the study was the first prospective, matched cohort analysis showing that chest surgery improves outcomes in this age group.

“We focused our study on chest dysphoria, the distress due to the presence of breasts, and gender congruence, the feeling of alignment between identity and physical characteristics,” Dr. Jordan said. “We will continue to study the effect of surgery in other areas of health, such as physical functioning and quality of life, and follow our patients longer term.”

As many as 9% of adolescents and young adults identify as transgender or nonbinary - a group underrepresented in the pediatric literature, Dr. Jordan’s group said. Chest dysphoria often is associated with psychosocial issues such as depression and anxiety.

“Dysphoria can lead to a range of negative physical and emotional consequences, such as avoidance of exercise and sports, harmful chest-binding practices, functional limitations, and suicidal ideation, said M. Brett Cooper, MD, MEd, assistant professor of pediatrics, and adolescent and young adult medicine, at UT Southwestern Medical Center/Children’s Health, Dallas. “These young people often bind for several hours a day to reduce the presence of their chest.”

The study

The Northwestern team recruited 81 patients with a mean age of 18.6 years whose sex at birth was assigned female. Patients were overwhelmingly White (89%), and the majority (59%) were transgender male, the remaining patients nonbinary.

The population sample included patients aged 13-24 who underwent top surgery from December 2019 to April 2021 and a matched control group of those who did not have surgery.

Outcomes measures were assessed preoperatively and 3 months after surgery.

Thirty-six surgical patients and 34 of those in the control arm completed the outcomes measures. Surgical complications were minimal. Propensity analyses suggested an association between surgery and substantial improvements in scores on the following study endpoints:

- Chest dysphoria measure (–25.58 points, 95% confidence interval [CI], –29.18 to –21.98).

- Transgender congruence scale (7.78 points, 95%: CI, 6.06-9.50)

- Body image scale (–7.20 points, 95% CI, –11.68 to –2.72).

The patients who underwent top surgery reported significant improvements in scores of chest dysphoria, transgender congruence, and body image. The results for patients younger than age 18 paralleled those for older participants in the study.

While the results corroborate other studies showing that gender-affirming therapy improves mental health and quality of life among these young people, the researchers cautioned that some insurers require testosterone therapy for 1 year before their plans will cover the costs of gender-affirming surgery.

This may negatively affect those nonbinary patients who do not undergo hormone therapy,” the researchers wrote. They are currently collecting 1-year follow-up data to determine the long-term effects of top surgery on chest dysphoria, gender congruence, and body image.

As surgical patients progress through adult life, does the risk of regret increase? “We did not address regret in this short-term study,” Dr. Jordan said. “However, previous studies have shown very low levels of regret.”

An accompanying editorial concurred that top surgery is effective and medically necessary in this population of young people.

Calling the study “an important milestone in gender affirmation research,” Kishan M. Thadikonda, MD, and Katherine M. Gast, MD, MS, of the school of medicine and public health at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, said it will be important to follow this young cohort to prove these benefits will endure as patients age.

They cautioned, however, that nonbinary patients represented just 13% of the patient total and only 8% of the surgical cohort. Nonbinary patients are not well understood as a patient population when it comes to gender-affirmation surgery and are often included in studies with transgender patients despite clear differences, they noted.

Current setbacks

According to Dr. Cooper, politics is already affecting care in Texas. “Due to the sociopolitical climate in my state in regard to gender-affirming care, I have also seen a few young people have their surgeries either canceled or postponed by their parents,” he said. “This has led to a worsening of mental health in these patients.”

Dr. Cooper stressed the need for more research on the perspective of non-White and socioeconomically disadvantaged youth.

“This study also highlights the disparity between patients who have commercial insurance versus those who are on Medicaid,” he said. “Medicaid plans often do not cover this, so those patients usually have to continue to suffer or pay for this surgery out of their own pocket.”