User login

Childhood cow’s milk allergy raises health care costs

Managing children’s cow’s milk allergy is costly to families and to health care systems, largely owing to costs of prescriptions, according to an industry-sponsored study based on data from the United Kingdom.

“This large cohort study provides novel evidence of a significant health economic burden of cow’s milk allergy in children,” Abbie L. Cawood, PhD, RNutr, MICR, head of scientific affairs at Nutricia Ltd in Trowbridge, England, and colleagues wrote in Clinical and Translational Allergy.

“Management of cow’s milk allergy necessitates the exclusion of cow’s milk protein from the diet. Whilst breastmilk remains the ideal nutrient source in infants with cow’s milk allergy, infants who are not exclusively breastfed require a hypoallergenic formula,” added Dr. Cawood, a visiting research fellow at University of Southampton, and her coauthors.

Cow’s milk allergy, an immune‐mediated response to one or more proteins in cow’s milk, is one of the most common childhood food allergies and affects 2%-5% of infants in Europe. Management involves avoiding cow’s milk protein and treating possible related gastrointestinal, skin, respiratory, and other allergic conditions, the authors explained.

In their retrospective matched cohort study, Dr. Cawood and colleagues turned to The Health Improvement Network (THIN), a Cegedim Rx proprietary database of 2.9 million anonymized active patient records. They extracted data from nearly 7,000 case records covering 5 years (2015-2020).

They examined medication prescriptions and health care professional contacts based on diagnosis read-codes and hypoallergenic formula prescriptions and compared health care costs for children with cow’s milk allergy with the costs for those without.

They matched 3,499 children aged 1 year or younger who had confirmed or suspected cow’s milk allergy with the same number of children without cow’s milk allergy. Around half of the participants were boys, and the mean observation period was 4.2 years.

Children with cow’s milk allergy need more, costly health care

The researchers found:

- Medications were prescribed to significantly more children with cow’s milk allergy (CMA), at a higher rate, than to those without CMA. In particular, prescriptions for antireflux medication increased by almost 500%.

- Children with CMA needed significantly more health care contacts and at a higher rate than those without CMA.

- CMA was linked with additional potential health care costs of £1381.53 per person per year. Assuming a 2.5% prevalence from the estimated 2%-5% CMA prevalence range and extrapolating to the UK infant population, CMA may have added more than £25.7 million in annual health care costs nationwide.

“Several conditions in infancy necessitate the elimination of cow milk–based formulas and require extensively hydrolyzed or amino acid formulas or, if preferred or able, exclusive breast milk,” Kara E. Coffey, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh, said by email.

“This study shows that, regardless of the reason for cow milk–based avoidance, these infants require more healthcare service utilizations (clinic visits, nutritional assessments, prescriptions) than [do] their peers, which is certainly a commitment of a lot of time and money for their families to ensure their ability to grow and thrive,” added Dr. Coffey, who was not involved in the study.

Jodi A. Shroba, MSN, APRN, CPNP, the coordinator for the Food Allergy Program at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, Mo., did not find these numbers surprising.

“Children with food allergies typically have other atopic comorbidities that require more visits to primary care physicians and specialists and more prescriptions,” Ms. Shroba, who was not involved in the study, said by email.

“An intriguing statement is that the U.K. guidelines recommend the involvement of a dietitian for children with cow’s milk allergy,” she noted. “In the United States, having a dietitian involved would be a wonderful addition to care, as avoidance of cow’s milk can cause nutritional and growth deficiencies. But not all healthcare practices have those resources available.

“The higher rate of antibiotic use and the almost 500% increase of antireflux prescriptions by the children with cow’s milk allergy warrant additional research,” she added.

Nutricia Ltd. funded the study. Dr. Cawood and one coauthor are employed by Nutricia, and all other coauthors have been employees of or have other financial relationships with Nutricia. One coauthor is employed by Cegedim Rx, which was funded for this research by Nutricia. Ms. Shroba and Dr. Coffey report no conflicts of interest with the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Managing children’s cow’s milk allergy is costly to families and to health care systems, largely owing to costs of prescriptions, according to an industry-sponsored study based on data from the United Kingdom.

“This large cohort study provides novel evidence of a significant health economic burden of cow’s milk allergy in children,” Abbie L. Cawood, PhD, RNutr, MICR, head of scientific affairs at Nutricia Ltd in Trowbridge, England, and colleagues wrote in Clinical and Translational Allergy.

“Management of cow’s milk allergy necessitates the exclusion of cow’s milk protein from the diet. Whilst breastmilk remains the ideal nutrient source in infants with cow’s milk allergy, infants who are not exclusively breastfed require a hypoallergenic formula,” added Dr. Cawood, a visiting research fellow at University of Southampton, and her coauthors.

Cow’s milk allergy, an immune‐mediated response to one or more proteins in cow’s milk, is one of the most common childhood food allergies and affects 2%-5% of infants in Europe. Management involves avoiding cow’s milk protein and treating possible related gastrointestinal, skin, respiratory, and other allergic conditions, the authors explained.

In their retrospective matched cohort study, Dr. Cawood and colleagues turned to The Health Improvement Network (THIN), a Cegedim Rx proprietary database of 2.9 million anonymized active patient records. They extracted data from nearly 7,000 case records covering 5 years (2015-2020).

They examined medication prescriptions and health care professional contacts based on diagnosis read-codes and hypoallergenic formula prescriptions and compared health care costs for children with cow’s milk allergy with the costs for those without.

They matched 3,499 children aged 1 year or younger who had confirmed or suspected cow’s milk allergy with the same number of children without cow’s milk allergy. Around half of the participants were boys, and the mean observation period was 4.2 years.

Children with cow’s milk allergy need more, costly health care

The researchers found:

- Medications were prescribed to significantly more children with cow’s milk allergy (CMA), at a higher rate, than to those without CMA. In particular, prescriptions for antireflux medication increased by almost 500%.

- Children with CMA needed significantly more health care contacts and at a higher rate than those without CMA.

- CMA was linked with additional potential health care costs of £1381.53 per person per year. Assuming a 2.5% prevalence from the estimated 2%-5% CMA prevalence range and extrapolating to the UK infant population, CMA may have added more than £25.7 million in annual health care costs nationwide.

“Several conditions in infancy necessitate the elimination of cow milk–based formulas and require extensively hydrolyzed or amino acid formulas or, if preferred or able, exclusive breast milk,” Kara E. Coffey, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh, said by email.

“This study shows that, regardless of the reason for cow milk–based avoidance, these infants require more healthcare service utilizations (clinic visits, nutritional assessments, prescriptions) than [do] their peers, which is certainly a commitment of a lot of time and money for their families to ensure their ability to grow and thrive,” added Dr. Coffey, who was not involved in the study.

Jodi A. Shroba, MSN, APRN, CPNP, the coordinator for the Food Allergy Program at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, Mo., did not find these numbers surprising.

“Children with food allergies typically have other atopic comorbidities that require more visits to primary care physicians and specialists and more prescriptions,” Ms. Shroba, who was not involved in the study, said by email.

“An intriguing statement is that the U.K. guidelines recommend the involvement of a dietitian for children with cow’s milk allergy,” she noted. “In the United States, having a dietitian involved would be a wonderful addition to care, as avoidance of cow’s milk can cause nutritional and growth deficiencies. But not all healthcare practices have those resources available.

“The higher rate of antibiotic use and the almost 500% increase of antireflux prescriptions by the children with cow’s milk allergy warrant additional research,” she added.

Nutricia Ltd. funded the study. Dr. Cawood and one coauthor are employed by Nutricia, and all other coauthors have been employees of or have other financial relationships with Nutricia. One coauthor is employed by Cegedim Rx, which was funded for this research by Nutricia. Ms. Shroba and Dr. Coffey report no conflicts of interest with the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Managing children’s cow’s milk allergy is costly to families and to health care systems, largely owing to costs of prescriptions, according to an industry-sponsored study based on data from the United Kingdom.

“This large cohort study provides novel evidence of a significant health economic burden of cow’s milk allergy in children,” Abbie L. Cawood, PhD, RNutr, MICR, head of scientific affairs at Nutricia Ltd in Trowbridge, England, and colleagues wrote in Clinical and Translational Allergy.

“Management of cow’s milk allergy necessitates the exclusion of cow’s milk protein from the diet. Whilst breastmilk remains the ideal nutrient source in infants with cow’s milk allergy, infants who are not exclusively breastfed require a hypoallergenic formula,” added Dr. Cawood, a visiting research fellow at University of Southampton, and her coauthors.

Cow’s milk allergy, an immune‐mediated response to one or more proteins in cow’s milk, is one of the most common childhood food allergies and affects 2%-5% of infants in Europe. Management involves avoiding cow’s milk protein and treating possible related gastrointestinal, skin, respiratory, and other allergic conditions, the authors explained.

In their retrospective matched cohort study, Dr. Cawood and colleagues turned to The Health Improvement Network (THIN), a Cegedim Rx proprietary database of 2.9 million anonymized active patient records. They extracted data from nearly 7,000 case records covering 5 years (2015-2020).

They examined medication prescriptions and health care professional contacts based on diagnosis read-codes and hypoallergenic formula prescriptions and compared health care costs for children with cow’s milk allergy with the costs for those without.

They matched 3,499 children aged 1 year or younger who had confirmed or suspected cow’s milk allergy with the same number of children without cow’s milk allergy. Around half of the participants were boys, and the mean observation period was 4.2 years.

Children with cow’s milk allergy need more, costly health care

The researchers found:

- Medications were prescribed to significantly more children with cow’s milk allergy (CMA), at a higher rate, than to those without CMA. In particular, prescriptions for antireflux medication increased by almost 500%.

- Children with CMA needed significantly more health care contacts and at a higher rate than those without CMA.

- CMA was linked with additional potential health care costs of £1381.53 per person per year. Assuming a 2.5% prevalence from the estimated 2%-5% CMA prevalence range and extrapolating to the UK infant population, CMA may have added more than £25.7 million in annual health care costs nationwide.

“Several conditions in infancy necessitate the elimination of cow milk–based formulas and require extensively hydrolyzed or amino acid formulas or, if preferred or able, exclusive breast milk,” Kara E. Coffey, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh, said by email.

“This study shows that, regardless of the reason for cow milk–based avoidance, these infants require more healthcare service utilizations (clinic visits, nutritional assessments, prescriptions) than [do] their peers, which is certainly a commitment of a lot of time and money for their families to ensure their ability to grow and thrive,” added Dr. Coffey, who was not involved in the study.

Jodi A. Shroba, MSN, APRN, CPNP, the coordinator for the Food Allergy Program at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, Mo., did not find these numbers surprising.

“Children with food allergies typically have other atopic comorbidities that require more visits to primary care physicians and specialists and more prescriptions,” Ms. Shroba, who was not involved in the study, said by email.

“An intriguing statement is that the U.K. guidelines recommend the involvement of a dietitian for children with cow’s milk allergy,” she noted. “In the United States, having a dietitian involved would be a wonderful addition to care, as avoidance of cow’s milk can cause nutritional and growth deficiencies. But not all healthcare practices have those resources available.

“The higher rate of antibiotic use and the almost 500% increase of antireflux prescriptions by the children with cow’s milk allergy warrant additional research,” she added.

Nutricia Ltd. funded the study. Dr. Cawood and one coauthor are employed by Nutricia, and all other coauthors have been employees of or have other financial relationships with Nutricia. One coauthor is employed by Cegedim Rx, which was funded for this research by Nutricia. Ms. Shroba and Dr. Coffey report no conflicts of interest with the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CLINICAL AND TRANSLATIONAL ALLERGY

Legacy of neutral renal denervation trial recast by long-term outcomes: SYMPLICITY HTN-3

BOSTON – There’s an intriguing plot twist in the story of SYMPLICITY HTN-3, the sham-controlled clinical trial that nearly put the kibosh on renal denervation (RDN) therapy as a promising approach to treatment-resistant hypertension (HTN).

The trial famously showed no benefit for systolic blood pressure (BP) from the invasive procedure at 6 months and 12 months, dampening enthusiasm for RDN in HTN for both physicians and industry. But it turns out that disappointment in the study may have been premature.

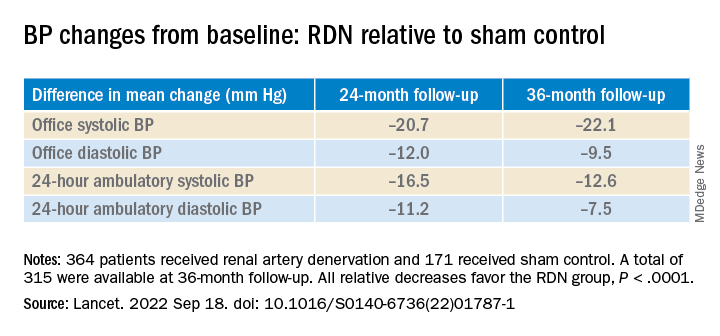

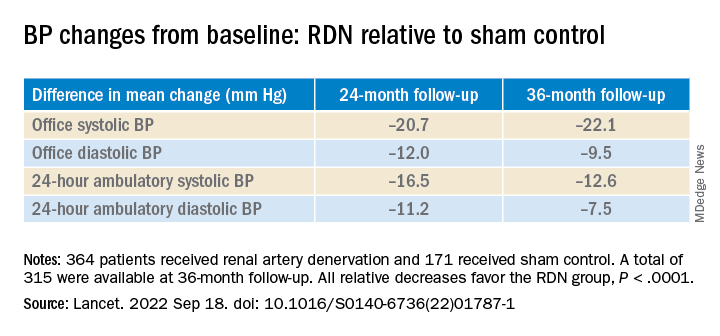

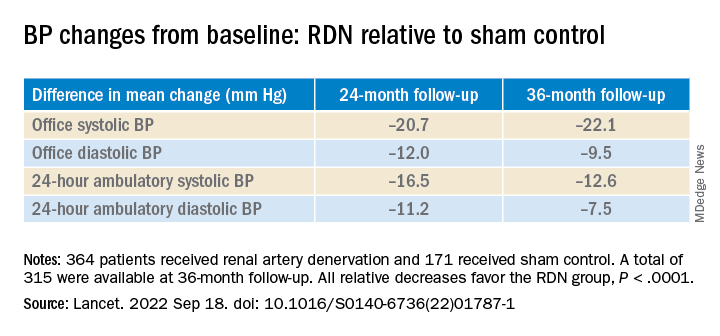

The procedure led to significant improvements in systolic BP, whether in-office or ambulatory, compared with a sham control procedure, in a new analysis that followed the trial’s patients out to 3 years. Those who underwent RDN also required less intense antihypertensive drug therapy.

“These findings support that durable blood pressure reductions with radiofrequency renal artery denervation, in the presence of lifestyle modification and maximal medical therapy, are safely achievable,” Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, said in a Sept. 18 presentation at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, which was sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Dr. Bhatt, of Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, is lead author on the report published in The Lancet simultaneously with his presentation.

Strides in RDN technology and trial design since the neutral primary SYMPLICITY HTN-3 results were reported in 2014 have long since restored faith in the procedure, which is currently in advanced stages of clinical trials and expected to eventually make a mark on practice.

But Roxana Mehran, MD, not connected to SYMPLICITY HTN-3, expressed caution in interpreting the current analysis based on secondary endpoints and extended follow-up time.

And elsewhere at the TCT sessions, observers of the trial as well as Dr. Bhatt urged similar cautions interpreting “positive” secondary results from trials that were “negative” in their primary analyses.

Still, “I believe there is no question that we have now enough evidence to say that renal denervation on top of medications is probably something that we’re going to be seeing in the future,” Dr. Mehran, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, told this news organization.

Importantly, and a bit controversially, the RDN group in the 36-month SYMPLICITY HTN-3 analysis includes patients originally assigned to the sham control group who crossed over to receive RDN after the trial was unblinded. Their “control” BP responses were thereafter imputed by accepted statistical methodology that Dr. Bhatt characterized as “last observation carried forward.”

That’s another reason to be circumspect about the current results, observed Naomi Fisher, MD, also of Brigham and Women’s and Harvard Medical School, as a panelist following Dr. Bhatt’s formal presentation.

“With all the missing data and imputational calculations,” she said, “I think we have to apply caution in the interpretation.”

She also pointed out that blinding in the trial was lifted at 6 months, allowing patients to learn their treatment assignment, and potentially influencing subsequent changes to medications.

They were prescribed, on average, about five antihypertensive meds, Dr. Fisher noted, and “that’s already a red flag. Patients taking that many medications generally aren’t universally taking them. There’s very high likelihood that there could have been variable adherence.”

Patients who learned they were in the sham control group, for example, could have “fallen off” taking their medications, potentially worsening outcomes and amplifying the apparent benefit of RDN. Such an effect, Dr. Fisher said, “could have contributed” to the study’s long-term results.

As previously reported, the single-blind SYMPLICITY HTN-3 had randomly assigned 535 patients to either RDN or a sham control procedure, 364 and 171 patients respectively, at 88 U.S. centers. The trial used the Symplicity Flex RDN radiofrequency ablation catheter (Medtronic).

For study entry, patients were required to have office systolic BP of at least 160 mm Hg and 24-hour ambulatory systolic BP of at least 135 mm Hg despite stable, maximally tolerated dosages of a diuretic plus at least two other antihypertensive agents.

Blinding was lifted at 6 months, per protocol, after which patients in the sham control group who still met the trial’s BP entry criteria were allowed to cross over and undergo RDN. The 101 controls who crossed over were combined with the original active-therapy cohort for the current analysis.

From baseline to 36 months, mean number of medication classes per patient maintained between 4.5 and 5, with no significant difference between groups at any point.

However, medication burden expressed as number of doses daily held steady between 9.7 to 10.2 for controls while the RDN group showed a steady decline from 10.2 to 8.4. Differences between RDN patients and controls were significant at both 24 months (P = .01) and 36 months (P = .005), Dr. Bhatt reported.

All relative decreases favor the RDN group, P < .0001

The RDN group spent a longer percentage of time with systolic BP at goal compared to those in the sham control group in an analysis that did not involve imputation of data, Dr. Bhatt reported. The proportions of time in therapeutic range were 18% for RDN patients and 9% for controls (P < .0001).

As in the 6- and 12-month analyses, there was no adverse safety signal associated with RDN in follow-up out to both 36 and 48 months. As Dr. Bhatt reported, the rates of the composite safety endpoint in RDN patients, crossovers, and noncrossover controls were 15%, 14%, and 14%, respectively.

The safety endpoint included death, new end-stage renal disease, significant embolic events causing end-organ damage, vascular complications, renal-artery reintervention, and “hypertensive emergency unrelated to nonadherence to medications,” Dr. Bhatt reported.

There are many patients with “out of control” HTN “who cannot remain compliant on their medications,” Dr. Mehran observed for this news organization. “I believe having an adjunct to medical management of these patients,” that is RDN, “is going to be tremendously important.”

SYMPLICITY HTN-3 was funded by Medtronic. Dr. Bhatt has disclosed ties with many companies, as well as WebMD, Medscape Cardiology, and other publications or organizations. Dr. Mehran disclosed ties to Abbott Vascular, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Daiichi-Sankyo/Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Novartis, OrbusNeich, Abiomed; Boston Scientific, Alleviant, Amgen, AM-Pharma, Applied Therapeutics, Arena, BAIM, Biosensors, Biotronik, CardiaWave, CellAegis, Concept Medical, CeloNova, CERC, Chiesi, Cytosorbents, Duke University, Element Science, Faraday, Humacyte, Idorsia, Insel Gruppe, Philips, RenalPro, Vivasure, and Zoll; as well as Medscape/WebMD, and Cine-Med Research; and holding equity, stock, or stock options with Control Rad, Applied Therapeutics, and Elixir Medical. Dr. Fisher disclosed ties to Medtronic, Recor Medical, and Aktiia; and receiving grants or hold research contracts with Recor Medical and Aktiia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BOSTON – There’s an intriguing plot twist in the story of SYMPLICITY HTN-3, the sham-controlled clinical trial that nearly put the kibosh on renal denervation (RDN) therapy as a promising approach to treatment-resistant hypertension (HTN).

The trial famously showed no benefit for systolic blood pressure (BP) from the invasive procedure at 6 months and 12 months, dampening enthusiasm for RDN in HTN for both physicians and industry. But it turns out that disappointment in the study may have been premature.

The procedure led to significant improvements in systolic BP, whether in-office or ambulatory, compared with a sham control procedure, in a new analysis that followed the trial’s patients out to 3 years. Those who underwent RDN also required less intense antihypertensive drug therapy.

“These findings support that durable blood pressure reductions with radiofrequency renal artery denervation, in the presence of lifestyle modification and maximal medical therapy, are safely achievable,” Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, said in a Sept. 18 presentation at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, which was sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Dr. Bhatt, of Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, is lead author on the report published in The Lancet simultaneously with his presentation.

Strides in RDN technology and trial design since the neutral primary SYMPLICITY HTN-3 results were reported in 2014 have long since restored faith in the procedure, which is currently in advanced stages of clinical trials and expected to eventually make a mark on practice.

But Roxana Mehran, MD, not connected to SYMPLICITY HTN-3, expressed caution in interpreting the current analysis based on secondary endpoints and extended follow-up time.

And elsewhere at the TCT sessions, observers of the trial as well as Dr. Bhatt urged similar cautions interpreting “positive” secondary results from trials that were “negative” in their primary analyses.

Still, “I believe there is no question that we have now enough evidence to say that renal denervation on top of medications is probably something that we’re going to be seeing in the future,” Dr. Mehran, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, told this news organization.

Importantly, and a bit controversially, the RDN group in the 36-month SYMPLICITY HTN-3 analysis includes patients originally assigned to the sham control group who crossed over to receive RDN after the trial was unblinded. Their “control” BP responses were thereafter imputed by accepted statistical methodology that Dr. Bhatt characterized as “last observation carried forward.”

That’s another reason to be circumspect about the current results, observed Naomi Fisher, MD, also of Brigham and Women’s and Harvard Medical School, as a panelist following Dr. Bhatt’s formal presentation.

“With all the missing data and imputational calculations,” she said, “I think we have to apply caution in the interpretation.”

She also pointed out that blinding in the trial was lifted at 6 months, allowing patients to learn their treatment assignment, and potentially influencing subsequent changes to medications.

They were prescribed, on average, about five antihypertensive meds, Dr. Fisher noted, and “that’s already a red flag. Patients taking that many medications generally aren’t universally taking them. There’s very high likelihood that there could have been variable adherence.”

Patients who learned they were in the sham control group, for example, could have “fallen off” taking their medications, potentially worsening outcomes and amplifying the apparent benefit of RDN. Such an effect, Dr. Fisher said, “could have contributed” to the study’s long-term results.

As previously reported, the single-blind SYMPLICITY HTN-3 had randomly assigned 535 patients to either RDN or a sham control procedure, 364 and 171 patients respectively, at 88 U.S. centers. The trial used the Symplicity Flex RDN radiofrequency ablation catheter (Medtronic).

For study entry, patients were required to have office systolic BP of at least 160 mm Hg and 24-hour ambulatory systolic BP of at least 135 mm Hg despite stable, maximally tolerated dosages of a diuretic plus at least two other antihypertensive agents.

Blinding was lifted at 6 months, per protocol, after which patients in the sham control group who still met the trial’s BP entry criteria were allowed to cross over and undergo RDN. The 101 controls who crossed over were combined with the original active-therapy cohort for the current analysis.

From baseline to 36 months, mean number of medication classes per patient maintained between 4.5 and 5, with no significant difference between groups at any point.

However, medication burden expressed as number of doses daily held steady between 9.7 to 10.2 for controls while the RDN group showed a steady decline from 10.2 to 8.4. Differences between RDN patients and controls were significant at both 24 months (P = .01) and 36 months (P = .005), Dr. Bhatt reported.

All relative decreases favor the RDN group, P < .0001

The RDN group spent a longer percentage of time with systolic BP at goal compared to those in the sham control group in an analysis that did not involve imputation of data, Dr. Bhatt reported. The proportions of time in therapeutic range were 18% for RDN patients and 9% for controls (P < .0001).

As in the 6- and 12-month analyses, there was no adverse safety signal associated with RDN in follow-up out to both 36 and 48 months. As Dr. Bhatt reported, the rates of the composite safety endpoint in RDN patients, crossovers, and noncrossover controls were 15%, 14%, and 14%, respectively.

The safety endpoint included death, new end-stage renal disease, significant embolic events causing end-organ damage, vascular complications, renal-artery reintervention, and “hypertensive emergency unrelated to nonadherence to medications,” Dr. Bhatt reported.

There are many patients with “out of control” HTN “who cannot remain compliant on their medications,” Dr. Mehran observed for this news organization. “I believe having an adjunct to medical management of these patients,” that is RDN, “is going to be tremendously important.”

SYMPLICITY HTN-3 was funded by Medtronic. Dr. Bhatt has disclosed ties with many companies, as well as WebMD, Medscape Cardiology, and other publications or organizations. Dr. Mehran disclosed ties to Abbott Vascular, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Daiichi-Sankyo/Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Novartis, OrbusNeich, Abiomed; Boston Scientific, Alleviant, Amgen, AM-Pharma, Applied Therapeutics, Arena, BAIM, Biosensors, Biotronik, CardiaWave, CellAegis, Concept Medical, CeloNova, CERC, Chiesi, Cytosorbents, Duke University, Element Science, Faraday, Humacyte, Idorsia, Insel Gruppe, Philips, RenalPro, Vivasure, and Zoll; as well as Medscape/WebMD, and Cine-Med Research; and holding equity, stock, or stock options with Control Rad, Applied Therapeutics, and Elixir Medical. Dr. Fisher disclosed ties to Medtronic, Recor Medical, and Aktiia; and receiving grants or hold research contracts with Recor Medical and Aktiia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BOSTON – There’s an intriguing plot twist in the story of SYMPLICITY HTN-3, the sham-controlled clinical trial that nearly put the kibosh on renal denervation (RDN) therapy as a promising approach to treatment-resistant hypertension (HTN).

The trial famously showed no benefit for systolic blood pressure (BP) from the invasive procedure at 6 months and 12 months, dampening enthusiasm for RDN in HTN for both physicians and industry. But it turns out that disappointment in the study may have been premature.

The procedure led to significant improvements in systolic BP, whether in-office or ambulatory, compared with a sham control procedure, in a new analysis that followed the trial’s patients out to 3 years. Those who underwent RDN also required less intense antihypertensive drug therapy.

“These findings support that durable blood pressure reductions with radiofrequency renal artery denervation, in the presence of lifestyle modification and maximal medical therapy, are safely achievable,” Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, said in a Sept. 18 presentation at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, which was sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Dr. Bhatt, of Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, is lead author on the report published in The Lancet simultaneously with his presentation.

Strides in RDN technology and trial design since the neutral primary SYMPLICITY HTN-3 results were reported in 2014 have long since restored faith in the procedure, which is currently in advanced stages of clinical trials and expected to eventually make a mark on practice.

But Roxana Mehran, MD, not connected to SYMPLICITY HTN-3, expressed caution in interpreting the current analysis based on secondary endpoints and extended follow-up time.

And elsewhere at the TCT sessions, observers of the trial as well as Dr. Bhatt urged similar cautions interpreting “positive” secondary results from trials that were “negative” in their primary analyses.

Still, “I believe there is no question that we have now enough evidence to say that renal denervation on top of medications is probably something that we’re going to be seeing in the future,” Dr. Mehran, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, told this news organization.

Importantly, and a bit controversially, the RDN group in the 36-month SYMPLICITY HTN-3 analysis includes patients originally assigned to the sham control group who crossed over to receive RDN after the trial was unblinded. Their “control” BP responses were thereafter imputed by accepted statistical methodology that Dr. Bhatt characterized as “last observation carried forward.”

That’s another reason to be circumspect about the current results, observed Naomi Fisher, MD, also of Brigham and Women’s and Harvard Medical School, as a panelist following Dr. Bhatt’s formal presentation.

“With all the missing data and imputational calculations,” she said, “I think we have to apply caution in the interpretation.”

She also pointed out that blinding in the trial was lifted at 6 months, allowing patients to learn their treatment assignment, and potentially influencing subsequent changes to medications.

They were prescribed, on average, about five antihypertensive meds, Dr. Fisher noted, and “that’s already a red flag. Patients taking that many medications generally aren’t universally taking them. There’s very high likelihood that there could have been variable adherence.”

Patients who learned they were in the sham control group, for example, could have “fallen off” taking their medications, potentially worsening outcomes and amplifying the apparent benefit of RDN. Such an effect, Dr. Fisher said, “could have contributed” to the study’s long-term results.

As previously reported, the single-blind SYMPLICITY HTN-3 had randomly assigned 535 patients to either RDN or a sham control procedure, 364 and 171 patients respectively, at 88 U.S. centers. The trial used the Symplicity Flex RDN radiofrequency ablation catheter (Medtronic).

For study entry, patients were required to have office systolic BP of at least 160 mm Hg and 24-hour ambulatory systolic BP of at least 135 mm Hg despite stable, maximally tolerated dosages of a diuretic plus at least two other antihypertensive agents.

Blinding was lifted at 6 months, per protocol, after which patients in the sham control group who still met the trial’s BP entry criteria were allowed to cross over and undergo RDN. The 101 controls who crossed over were combined with the original active-therapy cohort for the current analysis.

From baseline to 36 months, mean number of medication classes per patient maintained between 4.5 and 5, with no significant difference between groups at any point.

However, medication burden expressed as number of doses daily held steady between 9.7 to 10.2 for controls while the RDN group showed a steady decline from 10.2 to 8.4. Differences between RDN patients and controls were significant at both 24 months (P = .01) and 36 months (P = .005), Dr. Bhatt reported.

All relative decreases favor the RDN group, P < .0001

The RDN group spent a longer percentage of time with systolic BP at goal compared to those in the sham control group in an analysis that did not involve imputation of data, Dr. Bhatt reported. The proportions of time in therapeutic range were 18% for RDN patients and 9% for controls (P < .0001).

As in the 6- and 12-month analyses, there was no adverse safety signal associated with RDN in follow-up out to both 36 and 48 months. As Dr. Bhatt reported, the rates of the composite safety endpoint in RDN patients, crossovers, and noncrossover controls were 15%, 14%, and 14%, respectively.

The safety endpoint included death, new end-stage renal disease, significant embolic events causing end-organ damage, vascular complications, renal-artery reintervention, and “hypertensive emergency unrelated to nonadherence to medications,” Dr. Bhatt reported.

There are many patients with “out of control” HTN “who cannot remain compliant on their medications,” Dr. Mehran observed for this news organization. “I believe having an adjunct to medical management of these patients,” that is RDN, “is going to be tremendously important.”

SYMPLICITY HTN-3 was funded by Medtronic. Dr. Bhatt has disclosed ties with many companies, as well as WebMD, Medscape Cardiology, and other publications or organizations. Dr. Mehran disclosed ties to Abbott Vascular, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Daiichi-Sankyo/Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Novartis, OrbusNeich, Abiomed; Boston Scientific, Alleviant, Amgen, AM-Pharma, Applied Therapeutics, Arena, BAIM, Biosensors, Biotronik, CardiaWave, CellAegis, Concept Medical, CeloNova, CERC, Chiesi, Cytosorbents, Duke University, Element Science, Faraday, Humacyte, Idorsia, Insel Gruppe, Philips, RenalPro, Vivasure, and Zoll; as well as Medscape/WebMD, and Cine-Med Research; and holding equity, stock, or stock options with Control Rad, Applied Therapeutics, and Elixir Medical. Dr. Fisher disclosed ties to Medtronic, Recor Medical, and Aktiia; and receiving grants or hold research contracts with Recor Medical and Aktiia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT TCT 2022

Minorities hit especially hard by overdose deaths during COVID

The results underscore the “urgency of expanding prevention, treatment, and harm reduction interventions tailored to specific populations, especially American Indian or Alaska Native and Black populations, given long-standing structural racism and inequities in accessing these services,” the researchers note.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

‘Urgent need’ for education

From February 2020 to August 2021, drug overdose deaths in the United States rose 37%, and these deaths were largely due to synthetic opioids other than methadone – primarily fentanyl or analogs – and methamphetamine.

Yet, data are lacking regarding racial and ethnic disparities in overdose death rates.

To investigate, Beth Han, MD, PhD, with the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and colleagues analyzed federal drug overdose death data for individuals aged 15-34 and 35-64 from March 2018 to August 2021.

Among individuals aged 15-34, from March 2018 to August 2021, overdose death rates involving any drug, fentanyl, and methamphetamine with or without fentanyl, increased overall.

For the 6 months from March to August 2021, non-Hispanic Native American or Alaska Native men had the highest rates overall involving any drug, fentanyl, and methamphetamine without fentanyl, with rates of 42.0, 30.2, and 6.0 per 100,000, respectively.

The highest rates (per 100,000) of drug overdose deaths involving methamphetamine with fentanyl were for Native American or Alaska Native men (9.2) and women (8.0) and non-Hispanic White men (6.7).

Among people aged 35-64, from March to August 2021, overall drug overdose rates (per 100,000) were highest among non-Hispanic Black men (61.2) and Native American or Alaska Native men (60.0), and fentanyl-involved death rates were highest among Black men (43.3).

Rates involving methamphetamine with fentanyl were highest among Native American or Alaska Native men (12.6) and women (9.4) and White men (9.5).

Rates involving methamphetamine without fentanyl were highest among Native American or Alaska Native men (22.9).

The researchers note the findings highlight the “urgent need” for education on dangers of methamphetamine and fentanyl.

Expanding access to naloxone, fentanyl test strips, and treatments for substance use disorders to disproportionately affected populations is also critical to help curb disparities in drug overdose deaths, they add.

Limitations of the study are that overdose deaths may be underestimated because of the use of 2021 provisional data and that racial or ethnic identification may be misclassified, especially for Native American or Alaska Native people.

This study was sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors report no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The results underscore the “urgency of expanding prevention, treatment, and harm reduction interventions tailored to specific populations, especially American Indian or Alaska Native and Black populations, given long-standing structural racism and inequities in accessing these services,” the researchers note.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

‘Urgent need’ for education

From February 2020 to August 2021, drug overdose deaths in the United States rose 37%, and these deaths were largely due to synthetic opioids other than methadone – primarily fentanyl or analogs – and methamphetamine.

Yet, data are lacking regarding racial and ethnic disparities in overdose death rates.

To investigate, Beth Han, MD, PhD, with the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and colleagues analyzed federal drug overdose death data for individuals aged 15-34 and 35-64 from March 2018 to August 2021.

Among individuals aged 15-34, from March 2018 to August 2021, overdose death rates involving any drug, fentanyl, and methamphetamine with or without fentanyl, increased overall.

For the 6 months from March to August 2021, non-Hispanic Native American or Alaska Native men had the highest rates overall involving any drug, fentanyl, and methamphetamine without fentanyl, with rates of 42.0, 30.2, and 6.0 per 100,000, respectively.

The highest rates (per 100,000) of drug overdose deaths involving methamphetamine with fentanyl were for Native American or Alaska Native men (9.2) and women (8.0) and non-Hispanic White men (6.7).

Among people aged 35-64, from March to August 2021, overall drug overdose rates (per 100,000) were highest among non-Hispanic Black men (61.2) and Native American or Alaska Native men (60.0), and fentanyl-involved death rates were highest among Black men (43.3).

Rates involving methamphetamine with fentanyl were highest among Native American or Alaska Native men (12.6) and women (9.4) and White men (9.5).

Rates involving methamphetamine without fentanyl were highest among Native American or Alaska Native men (22.9).

The researchers note the findings highlight the “urgent need” for education on dangers of methamphetamine and fentanyl.

Expanding access to naloxone, fentanyl test strips, and treatments for substance use disorders to disproportionately affected populations is also critical to help curb disparities in drug overdose deaths, they add.

Limitations of the study are that overdose deaths may be underestimated because of the use of 2021 provisional data and that racial or ethnic identification may be misclassified, especially for Native American or Alaska Native people.

This study was sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors report no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The results underscore the “urgency of expanding prevention, treatment, and harm reduction interventions tailored to specific populations, especially American Indian or Alaska Native and Black populations, given long-standing structural racism and inequities in accessing these services,” the researchers note.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

‘Urgent need’ for education

From February 2020 to August 2021, drug overdose deaths in the United States rose 37%, and these deaths were largely due to synthetic opioids other than methadone – primarily fentanyl or analogs – and methamphetamine.

Yet, data are lacking regarding racial and ethnic disparities in overdose death rates.

To investigate, Beth Han, MD, PhD, with the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and colleagues analyzed federal drug overdose death data for individuals aged 15-34 and 35-64 from March 2018 to August 2021.

Among individuals aged 15-34, from March 2018 to August 2021, overdose death rates involving any drug, fentanyl, and methamphetamine with or without fentanyl, increased overall.

For the 6 months from March to August 2021, non-Hispanic Native American or Alaska Native men had the highest rates overall involving any drug, fentanyl, and methamphetamine without fentanyl, with rates of 42.0, 30.2, and 6.0 per 100,000, respectively.

The highest rates (per 100,000) of drug overdose deaths involving methamphetamine with fentanyl were for Native American or Alaska Native men (9.2) and women (8.0) and non-Hispanic White men (6.7).

Among people aged 35-64, from March to August 2021, overall drug overdose rates (per 100,000) were highest among non-Hispanic Black men (61.2) and Native American or Alaska Native men (60.0), and fentanyl-involved death rates were highest among Black men (43.3).

Rates involving methamphetamine with fentanyl were highest among Native American or Alaska Native men (12.6) and women (9.4) and White men (9.5).

Rates involving methamphetamine without fentanyl were highest among Native American or Alaska Native men (22.9).

The researchers note the findings highlight the “urgent need” for education on dangers of methamphetamine and fentanyl.

Expanding access to naloxone, fentanyl test strips, and treatments for substance use disorders to disproportionately affected populations is also critical to help curb disparities in drug overdose deaths, they add.

Limitations of the study are that overdose deaths may be underestimated because of the use of 2021 provisional data and that racial or ethnic identification may be misclassified, especially for Native American or Alaska Native people.

This study was sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors report no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Commentary: Preventing and Predicting T2D Complications, October 2022

Diabetes guidelines recommend sodium-glucose transport protein 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors to reduce kidney disease progression in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and moderate-to-severe albuminuric kidney disease on the basis of renal outcomes trials, such as CREDENCE and DAPA-CKD. However, these trials did not include patients who are at low risk for kidney disease progression.

Mozenson and colleagues published a post hoc analysis of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial and focused on patients with low kidney risk. They demonstated that dapagliflozin slowed the progression of kidney disease in patients with T2D at high cardiovascular risk, including those who are at low risk for kidney progression. The absolute benefit for slowing kidney progression was much lower in patients with low kidney risk compared with those who are at high or very high risk (number needed to treat 177 vs 13-23). Though dapagliflozin does provide kidney protection across a spectrum of patients with kidney risk, clinicians should consider the level of risk when starting an SGLT2 inhibitor for slowing kidney disease.

SGLT2 inhibitor outcome trials and meta-analyses have mainly shown neutral results for ischemic stroke, except for sotagliflozin vs placebo in the SCORED trial. In this trial, sotagliflozin was shown to reduce total stroke. Recently, in a retrospective longitudinal cohort study of patients with T2D in Taiwan, Lin and colleagues have shown a significant reduction in new onset stroke among those who use SGLT2 inhibitor compared with those who don't. A 15% relative risk reduction in stroke was shown in an analysis that adjusted for age, sex, and duration of T2D, with a similar reduction in a propensity score-matched analysis. Although limited by its observational design, this study suggests that further research should be continued regarding the impact of SGLT2 inhibitors on stroke outcomes.

Severe hypoglycemia is a serious complication of insulin and insulin secretagogue therapy. There have been few studies regarding the association between long-term glycemic variability of A1c and fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and the risk for severe hypoglycemia. Long and colleagues performed a post hoc analysis of the ACCORD study and found that both A1c and FPG variability were associated with a greater risk for severe hypoglycemia in T2D, with FPG being a more sensitive indicator than is A1c variability. Clinicians need to be aware that A1c and FPG variability in insulin- or insulin secretagogue–treated patients with T2D places them at greater risk for severe hypoglycemia and such variability should be considered a potential target of treatment.

Although a higher mean A1c has been linked to diabetes microvascular and macrovascular complications, there is a paucity of data comparing mean A1c and A1c variability and diabetes complications. In a prospective study from Taiwan, Wu and colleagues demonstrated that both mean A1c and A1c variability predicted most diabetes-related complications, with mean A1c being more effective at predicting retinopathy and A1c variability being more effective at predicting a decline in kidney function and cardiovascular and total mortality. Perhaps physicians need to pay more attention to A1c variability and not just the mean A1c over time when assessing an individual and their overall risk for diabetes complications.

Diabetes guidelines recommend sodium-glucose transport protein 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors to reduce kidney disease progression in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and moderate-to-severe albuminuric kidney disease on the basis of renal outcomes trials, such as CREDENCE and DAPA-CKD. However, these trials did not include patients who are at low risk for kidney disease progression.

Mozenson and colleagues published a post hoc analysis of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial and focused on patients with low kidney risk. They demonstated that dapagliflozin slowed the progression of kidney disease in patients with T2D at high cardiovascular risk, including those who are at low risk for kidney progression. The absolute benefit for slowing kidney progression was much lower in patients with low kidney risk compared with those who are at high or very high risk (number needed to treat 177 vs 13-23). Though dapagliflozin does provide kidney protection across a spectrum of patients with kidney risk, clinicians should consider the level of risk when starting an SGLT2 inhibitor for slowing kidney disease.

SGLT2 inhibitor outcome trials and meta-analyses have mainly shown neutral results for ischemic stroke, except for sotagliflozin vs placebo in the SCORED trial. In this trial, sotagliflozin was shown to reduce total stroke. Recently, in a retrospective longitudinal cohort study of patients with T2D in Taiwan, Lin and colleagues have shown a significant reduction in new onset stroke among those who use SGLT2 inhibitor compared with those who don't. A 15% relative risk reduction in stroke was shown in an analysis that adjusted for age, sex, and duration of T2D, with a similar reduction in a propensity score-matched analysis. Although limited by its observational design, this study suggests that further research should be continued regarding the impact of SGLT2 inhibitors on stroke outcomes.

Severe hypoglycemia is a serious complication of insulin and insulin secretagogue therapy. There have been few studies regarding the association between long-term glycemic variability of A1c and fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and the risk for severe hypoglycemia. Long and colleagues performed a post hoc analysis of the ACCORD study and found that both A1c and FPG variability were associated with a greater risk for severe hypoglycemia in T2D, with FPG being a more sensitive indicator than is A1c variability. Clinicians need to be aware that A1c and FPG variability in insulin- or insulin secretagogue–treated patients with T2D places them at greater risk for severe hypoglycemia and such variability should be considered a potential target of treatment.

Although a higher mean A1c has been linked to diabetes microvascular and macrovascular complications, there is a paucity of data comparing mean A1c and A1c variability and diabetes complications. In a prospective study from Taiwan, Wu and colleagues demonstrated that both mean A1c and A1c variability predicted most diabetes-related complications, with mean A1c being more effective at predicting retinopathy and A1c variability being more effective at predicting a decline in kidney function and cardiovascular and total mortality. Perhaps physicians need to pay more attention to A1c variability and not just the mean A1c over time when assessing an individual and their overall risk for diabetes complications.

Diabetes guidelines recommend sodium-glucose transport protein 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors to reduce kidney disease progression in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and moderate-to-severe albuminuric kidney disease on the basis of renal outcomes trials, such as CREDENCE and DAPA-CKD. However, these trials did not include patients who are at low risk for kidney disease progression.

Mozenson and colleagues published a post hoc analysis of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial and focused on patients with low kidney risk. They demonstated that dapagliflozin slowed the progression of kidney disease in patients with T2D at high cardiovascular risk, including those who are at low risk for kidney progression. The absolute benefit for slowing kidney progression was much lower in patients with low kidney risk compared with those who are at high or very high risk (number needed to treat 177 vs 13-23). Though dapagliflozin does provide kidney protection across a spectrum of patients with kidney risk, clinicians should consider the level of risk when starting an SGLT2 inhibitor for slowing kidney disease.

SGLT2 inhibitor outcome trials and meta-analyses have mainly shown neutral results for ischemic stroke, except for sotagliflozin vs placebo in the SCORED trial. In this trial, sotagliflozin was shown to reduce total stroke. Recently, in a retrospective longitudinal cohort study of patients with T2D in Taiwan, Lin and colleagues have shown a significant reduction in new onset stroke among those who use SGLT2 inhibitor compared with those who don't. A 15% relative risk reduction in stroke was shown in an analysis that adjusted for age, sex, and duration of T2D, with a similar reduction in a propensity score-matched analysis. Although limited by its observational design, this study suggests that further research should be continued regarding the impact of SGLT2 inhibitors on stroke outcomes.

Severe hypoglycemia is a serious complication of insulin and insulin secretagogue therapy. There have been few studies regarding the association between long-term glycemic variability of A1c and fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and the risk for severe hypoglycemia. Long and colleagues performed a post hoc analysis of the ACCORD study and found that both A1c and FPG variability were associated with a greater risk for severe hypoglycemia in T2D, with FPG being a more sensitive indicator than is A1c variability. Clinicians need to be aware that A1c and FPG variability in insulin- or insulin secretagogue–treated patients with T2D places them at greater risk for severe hypoglycemia and such variability should be considered a potential target of treatment.

Although a higher mean A1c has been linked to diabetes microvascular and macrovascular complications, there is a paucity of data comparing mean A1c and A1c variability and diabetes complications. In a prospective study from Taiwan, Wu and colleagues demonstrated that both mean A1c and A1c variability predicted most diabetes-related complications, with mean A1c being more effective at predicting retinopathy and A1c variability being more effective at predicting a decline in kidney function and cardiovascular and total mortality. Perhaps physicians need to pay more attention to A1c variability and not just the mean A1c over time when assessing an individual and their overall risk for diabetes complications.

‘Concerning’ rate of benzo/Z-drug use in IBD

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are 70% more likely to use benzodiazepines and “Z-drugs” than are the general population, a large study from Canada suggests.

Mood/anxiety disorders and sleep disorders are common in patients with IBD, but few studies have looked at use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs (such as zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone) in this patient population.

The results are “concerning, and especially as the IBD population ages, these drugs are associated with health risks, including something as simple as falls,” first author Charles Bernstein, MD, of the IBD clinical and research centre, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, told this news organization.

“Clinicians need to find better strategies to deal with anxiety disorders and sleep disorders in the IBD population,” Dr. Bernstein said.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

High burden of use

Using administrative data from Manitoba, Dr. Bernstein and colleagues identified 5,741 patients with IBD (2,381 with Crohn’s disease and 3,360 with ulcerative colitis) and matched them (1:5) to 28,661 population controls without IBD.

Over a 20-year period (1997-2017), there was a “high burden” of benzodiazepine and Z-drug use in the IBD population. In 2017, roughly 20% of Manitobans with IBD were using benzodiazepines, and 20% were using Z-drugs, the study team reports.

The benzodiazepine use rate (per 1,000) was 28.06 in the IBD cohort vs. 16.83 in the non-IBD population (adjusted rate ratio, 1.67). The use rate for Z-drugs was 21.07 in the IBD cohort vs. 11.26 in the non-IBD population (adjusted RR, 1.87).

Benzodiazepine use declined from 1997 to 2016, but it remained at least 50% higher in patients with IBD than in the general population over this period, the researchers found. The rate of Z-drug use also was higher in the IBD population than in the general population but remained stable over the 20-year study period.

Regardless of age, men and women had similarly high use rates for benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, and joint use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs. The highest incidence rates for joint benzodiazepine and Z-drug use were in young adults (age 18-44 years), and these rates were similar among men and women.

Patients with IBD and a mood/anxiety disorder also were more likely to use benzodiazepines and Z-drugs and to be continuous users than were those without a mood/anxiety disorder.

Mental health and IBD go hand in hand

“The results are not very surprising, but they highlight the importance of mental health and mood disturbances in patients with IBD,” Ashwin Ananthakrishnan, MBBS, MPH, with Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, who wasn’t involved in the study, told this news organization.

“It is important for treating physicians to be aware of the important mental health implications of IBD diagnosis and disease activity, to screen patients for these disturbances, and to institute early effective interventions,” Dr. Ananthakrishnan said.

Also offering perspective, Laurie Keefer, PhD, academic health psychologist and director of psychobehavioral research within the division of gastroenterology, Mount Sinai Health System, New York, said that she is “concerned but not surprised” by the results of this study.

“One in three patients with IBD meets criteria for an anxiety disorder,” Dr. Keefer told this news organization.

And with the ongoing mental health crisis and shortage of mental health providers, “gastroenterologists are, unfortunately, in the position where they may have to manage these issues,” she said.

Dr. Keefer noted that when patients are first diagnosed with IBD, they will likely be on prednisone, and “an antidote” for the side effects of prednisone are benzodiazepines and sleeping medications because prednisone itself causes insomnia. “However, that’s really just a band-aid,” she said.

A major concern, said Dr. Keefer, is that young men and women who are diagnosed with IBD in their 20s may start using these drugs and become reliant on them.

“People do build up a tolerance to these drugs, so they need more and more to receive the same effect,” she said.

A better approach is to figure out why patients are so anxious and teach them skills to manage their anxiety and sleep problems so that they’re not dependent on these drugs, Dr. Keefer said.

“There are behavioral strategies that can help. These are harder to do, and they’re not a quick fix. However, they are skills you can learn in your 20s and so when you have an IBD flare at 50, you have the skills to deal with it,” she said.

“We just have to be a little more proactive in really encouraging patients to learn disease management skills,” Dr. Keefer added.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Crohn’s and Colitis Canada. Dr. Bernstein has disclosed relationships with AbbVie Canada, Amgen Canada, Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada, Roche Canada, Janssen Canada, Sandoz Canada, Takeda and Takeda Canada, Pfizer Canada, Mylan Pharmaceuticals, and Medtronic Canada. Dr. Ananthakrishnan and Dr. Keefer report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are 70% more likely to use benzodiazepines and “Z-drugs” than are the general population, a large study from Canada suggests.

Mood/anxiety disorders and sleep disorders are common in patients with IBD, but few studies have looked at use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs (such as zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone) in this patient population.

The results are “concerning, and especially as the IBD population ages, these drugs are associated with health risks, including something as simple as falls,” first author Charles Bernstein, MD, of the IBD clinical and research centre, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, told this news organization.

“Clinicians need to find better strategies to deal with anxiety disorders and sleep disorders in the IBD population,” Dr. Bernstein said.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

High burden of use

Using administrative data from Manitoba, Dr. Bernstein and colleagues identified 5,741 patients with IBD (2,381 with Crohn’s disease and 3,360 with ulcerative colitis) and matched them (1:5) to 28,661 population controls without IBD.

Over a 20-year period (1997-2017), there was a “high burden” of benzodiazepine and Z-drug use in the IBD population. In 2017, roughly 20% of Manitobans with IBD were using benzodiazepines, and 20% were using Z-drugs, the study team reports.

The benzodiazepine use rate (per 1,000) was 28.06 in the IBD cohort vs. 16.83 in the non-IBD population (adjusted rate ratio, 1.67). The use rate for Z-drugs was 21.07 in the IBD cohort vs. 11.26 in the non-IBD population (adjusted RR, 1.87).

Benzodiazepine use declined from 1997 to 2016, but it remained at least 50% higher in patients with IBD than in the general population over this period, the researchers found. The rate of Z-drug use also was higher in the IBD population than in the general population but remained stable over the 20-year study period.

Regardless of age, men and women had similarly high use rates for benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, and joint use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs. The highest incidence rates for joint benzodiazepine and Z-drug use were in young adults (age 18-44 years), and these rates were similar among men and women.

Patients with IBD and a mood/anxiety disorder also were more likely to use benzodiazepines and Z-drugs and to be continuous users than were those without a mood/anxiety disorder.

Mental health and IBD go hand in hand

“The results are not very surprising, but they highlight the importance of mental health and mood disturbances in patients with IBD,” Ashwin Ananthakrishnan, MBBS, MPH, with Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, who wasn’t involved in the study, told this news organization.

“It is important for treating physicians to be aware of the important mental health implications of IBD diagnosis and disease activity, to screen patients for these disturbances, and to institute early effective interventions,” Dr. Ananthakrishnan said.

Also offering perspective, Laurie Keefer, PhD, academic health psychologist and director of psychobehavioral research within the division of gastroenterology, Mount Sinai Health System, New York, said that she is “concerned but not surprised” by the results of this study.

“One in three patients with IBD meets criteria for an anxiety disorder,” Dr. Keefer told this news organization.

And with the ongoing mental health crisis and shortage of mental health providers, “gastroenterologists are, unfortunately, in the position where they may have to manage these issues,” she said.

Dr. Keefer noted that when patients are first diagnosed with IBD, they will likely be on prednisone, and “an antidote” for the side effects of prednisone are benzodiazepines and sleeping medications because prednisone itself causes insomnia. “However, that’s really just a band-aid,” she said.

A major concern, said Dr. Keefer, is that young men and women who are diagnosed with IBD in their 20s may start using these drugs and become reliant on them.

“People do build up a tolerance to these drugs, so they need more and more to receive the same effect,” she said.

A better approach is to figure out why patients are so anxious and teach them skills to manage their anxiety and sleep problems so that they’re not dependent on these drugs, Dr. Keefer said.

“There are behavioral strategies that can help. These are harder to do, and they’re not a quick fix. However, they are skills you can learn in your 20s and so when you have an IBD flare at 50, you have the skills to deal with it,” she said.

“We just have to be a little more proactive in really encouraging patients to learn disease management skills,” Dr. Keefer added.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Crohn’s and Colitis Canada. Dr. Bernstein has disclosed relationships with AbbVie Canada, Amgen Canada, Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada, Roche Canada, Janssen Canada, Sandoz Canada, Takeda and Takeda Canada, Pfizer Canada, Mylan Pharmaceuticals, and Medtronic Canada. Dr. Ananthakrishnan and Dr. Keefer report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are 70% more likely to use benzodiazepines and “Z-drugs” than are the general population, a large study from Canada suggests.

Mood/anxiety disorders and sleep disorders are common in patients with IBD, but few studies have looked at use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs (such as zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone) in this patient population.

The results are “concerning, and especially as the IBD population ages, these drugs are associated with health risks, including something as simple as falls,” first author Charles Bernstein, MD, of the IBD clinical and research centre, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, told this news organization.

“Clinicians need to find better strategies to deal with anxiety disorders and sleep disorders in the IBD population,” Dr. Bernstein said.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

High burden of use

Using administrative data from Manitoba, Dr. Bernstein and colleagues identified 5,741 patients with IBD (2,381 with Crohn’s disease and 3,360 with ulcerative colitis) and matched them (1:5) to 28,661 population controls without IBD.

Over a 20-year period (1997-2017), there was a “high burden” of benzodiazepine and Z-drug use in the IBD population. In 2017, roughly 20% of Manitobans with IBD were using benzodiazepines, and 20% were using Z-drugs, the study team reports.

The benzodiazepine use rate (per 1,000) was 28.06 in the IBD cohort vs. 16.83 in the non-IBD population (adjusted rate ratio, 1.67). The use rate for Z-drugs was 21.07 in the IBD cohort vs. 11.26 in the non-IBD population (adjusted RR, 1.87).

Benzodiazepine use declined from 1997 to 2016, but it remained at least 50% higher in patients with IBD than in the general population over this period, the researchers found. The rate of Z-drug use also was higher in the IBD population than in the general population but remained stable over the 20-year study period.

Regardless of age, men and women had similarly high use rates for benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, and joint use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs. The highest incidence rates for joint benzodiazepine and Z-drug use were in young adults (age 18-44 years), and these rates were similar among men and women.

Patients with IBD and a mood/anxiety disorder also were more likely to use benzodiazepines and Z-drugs and to be continuous users than were those without a mood/anxiety disorder.

Mental health and IBD go hand in hand

“The results are not very surprising, but they highlight the importance of mental health and mood disturbances in patients with IBD,” Ashwin Ananthakrishnan, MBBS, MPH, with Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, who wasn’t involved in the study, told this news organization.

“It is important for treating physicians to be aware of the important mental health implications of IBD diagnosis and disease activity, to screen patients for these disturbances, and to institute early effective interventions,” Dr. Ananthakrishnan said.

Also offering perspective, Laurie Keefer, PhD, academic health psychologist and director of psychobehavioral research within the division of gastroenterology, Mount Sinai Health System, New York, said that she is “concerned but not surprised” by the results of this study.

“One in three patients with IBD meets criteria for an anxiety disorder,” Dr. Keefer told this news organization.

And with the ongoing mental health crisis and shortage of mental health providers, “gastroenterologists are, unfortunately, in the position where they may have to manage these issues,” she said.

Dr. Keefer noted that when patients are first diagnosed with IBD, they will likely be on prednisone, and “an antidote” for the side effects of prednisone are benzodiazepines and sleeping medications because prednisone itself causes insomnia. “However, that’s really just a band-aid,” she said.

A major concern, said Dr. Keefer, is that young men and women who are diagnosed with IBD in their 20s may start using these drugs and become reliant on them.

“People do build up a tolerance to these drugs, so they need more and more to receive the same effect,” she said.

A better approach is to figure out why patients are so anxious and teach them skills to manage their anxiety and sleep problems so that they’re not dependent on these drugs, Dr. Keefer said.

“There are behavioral strategies that can help. These are harder to do, and they’re not a quick fix. However, they are skills you can learn in your 20s and so when you have an IBD flare at 50, you have the skills to deal with it,” she said.

“We just have to be a little more proactive in really encouraging patients to learn disease management skills,” Dr. Keefer added.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Crohn’s and Colitis Canada. Dr. Bernstein has disclosed relationships with AbbVie Canada, Amgen Canada, Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada, Roche Canada, Janssen Canada, Sandoz Canada, Takeda and Takeda Canada, Pfizer Canada, Mylan Pharmaceuticals, and Medtronic Canada. Dr. Ananthakrishnan and Dr. Keefer report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AMERICAN JOURNAL OF GASTROENTEROLOGY

Docs gain new flexibility treating osteoporosis from steroids

Doctors caring for patients taking steroids now have broader flexibility for which drugs to use to prevent osteoporosis associated with the medications.

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has released an updated guideline that advises treatment providers on when and how long to prescribe therapies that prevent or treat glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (GIOP). Since the ACR last updated the guideline in 2017, the Food and Drug Administration has approved new treatments for osteoporosis, which are now included in the recommendations.

The new guideline also advises physicians that they may need to transition patients to a second treatment after concluding a first course – so-called sequential therapy – to better protect them against bone loss and fracture. It also offers detailed instructions for which drugs to use, when, and how long these medications should be administered for patients taking glucocorticoids over a long period of time.

The guideline’s inclusion of sequential therapy is significant and will be helpful to practicing clinicians, according to S.B. Tanner IV, MD, director of the Osteoporosis Clinic at Vanderbilt Health, Nashville, Tenn.

“For the first time, the ACR has offered guidance for starting and stopping treatments,” Dr. Tanner said. “This guideline supports awareness that osteoporosis is lifelong – something that will consistently need monitoring.”

An estimated 2.5 million Americans use glucocorticoids, according to a 2013 study in Arthritis Care & Research. Meanwhile, a 2019 study of residents in Denmark found 3% of people in the country were prescribed glucocorticoids annually. That study estimated 54% of glucocorticoid users were female and found the percentage of people taking glucocorticoids increased with age.

Glucocorticoids are used to treat a variety of inflammatory conditions, from multiple sclerosis to lupus, and often are prescribed to transplant patients to prevent their immune systems from rejecting new organs. When taken over time these medications can cause osteoporosis, which in turn raises the risk of fracture.

More than 10% of patients who receive long-term glucocorticoid treatment are diagnosed with clinical fractures. In addition, even low-dose glucocorticoid therapy is associated with a bone loss rate of 10% per year for a patient.

Osteoporosis prevention

After stopping some prevention therapies for GIOP, a high risk of bone loss or fracture still persists, according to Linda A. Russell, MD, director of the Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Health Center for the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and co-principal investigator of the new guideline.

“We wanted to be sure the need for sequential treatment is adequately communicated, including to patients who might not know they need to start a second medication,” Dr. Russell said.

Physicians and patients must be aware that when completing a course of one GIOP treatment, another drug for the condition should be started, as specified in the guideline.

“Early intervention can prevent glucocorticoid-induced fractures that can lead to substantial morbidity and increased mortality,” said Mary Beth Humphrey, MD, PhD, interim vice president for research at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City and co-principal investigator of the ACR guideline.

Janet Rubin, MD, vice chair for research in the Department of medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said she is hopeful the guideline will change practice.”The risk of bone loss, fractures, and osteoporosis due to glucocorticoids has been known since the beginning of time, but the guideline reinforces the risk and treatment strategies for rheumatologists,” she said. “Such recommendations are known to influence doctor prescribing habits.”

Anyone can fracture

While age and other risk factors, including menopause, increase the risk of developing GIOP, bone loss can occur rapidly for a patient of any age.

Even a glucocorticoid dose as low as 2.5 mg will increase the risk of vertebral fractures, with some occurring as soon as 3 months after treatment starts, Dr. Humphrey said. For patients taking up to 7.5 mg daily, the risk of vertebral fracture doubles. Doses greater than 10 mg daily for more than 3 months raise the likelihood of a vertebral fracture by a factor of 14, and result in a 300% increase in the likelihood of hip fractures, according to Dr. Humphrey.

“When on steroids, even patients with high bone density scores can fracture,” Dr. Tanner said. “The 2017 guideline was almost too elaborate in its effort to calculate risk. The updated guideline acknowledges moderate risk and suggests that this is a group of patients who need treatment.”

Rank ordering adds flexibility

The updated ACR guideline no longer ranks medications based on patient fracture data, side effects, cost care, and whether the drug is provided through injection, pill, or IV.

All of the preventive treatments the panel recommends reduce the risk of steroid-induced bone loss, Dr. Humphrey said.

“We thought the 2017 guideline was too restrictive,” Dr. Russell said. “We’re giving physicians and patients more leeway to choose a medication based on their preferences.”

Patient preference of delivery mechanism – such as a desire for pills only – can now be weighed more heavily into drug treatment decisions.

“In the exam room, there are three dynamics going on: What the patient wants, what the doctor knows is most effective, and what the insurer will pay,” Dr. Tanner said. “Doing away with rank ordering opens up the conversation beyond cost to consider all those factors.”

The guideline team conducted a systematic literature review for clinical questions on nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment addressed in the 2017 guideline, and for questions on new pharmacologic treatments, discontinuation of medications, and sequential and combination therapy. The voting panel consisted of two patient representatives and 13 experts representing adult and pediatric rheumatology and endocrinology, nephrology, and gastroenterology.

A full manuscript has been submitted for publication in Arthritis & Rheumatology and Arthritis Care and Research for peer review, and is expected to publish in early 2023.

Dr. Humphrey and Dr. Russell, the co-principal investigators for the guideline, and Dr. Rubin have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tanner reported a current research grant funded by Amgen through the University of Alabama at Birmingham and being a paid course instructor for the International Society for Clinical Densitometry bone density course, Osteoporosis Essentials.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctors caring for patients taking steroids now have broader flexibility for which drugs to use to prevent osteoporosis associated with the medications.

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has released an updated guideline that advises treatment providers on when and how long to prescribe therapies that prevent or treat glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (GIOP). Since the ACR last updated the guideline in 2017, the Food and Drug Administration has approved new treatments for osteoporosis, which are now included in the recommendations.