User login

Tinea capitis

THE COMPARISON

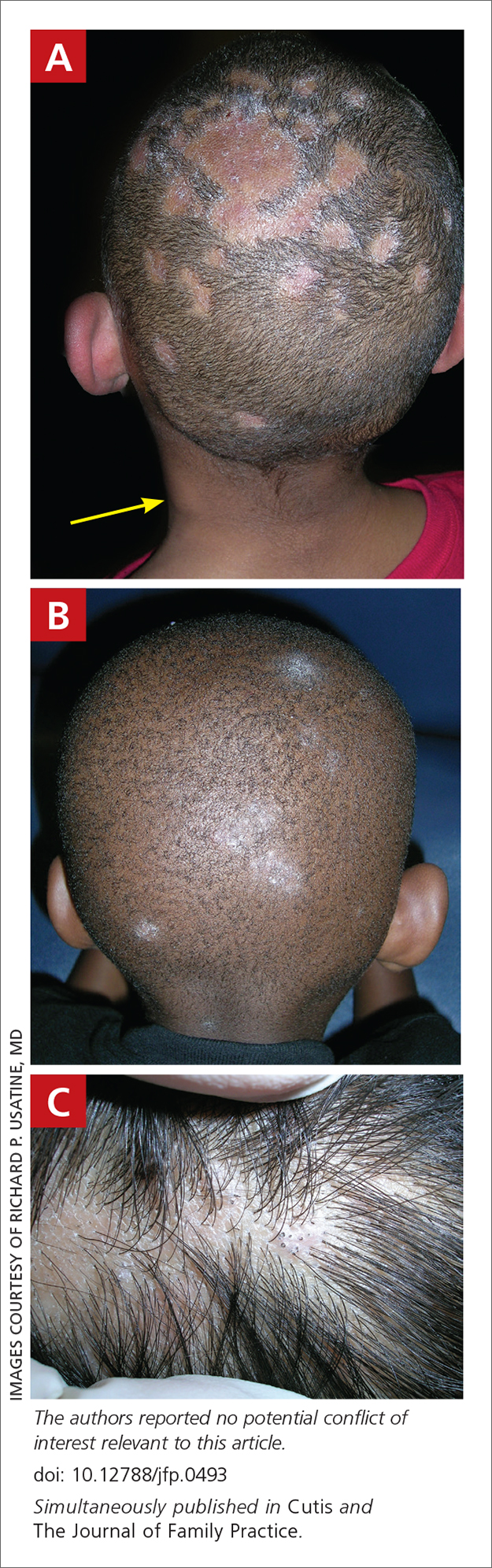

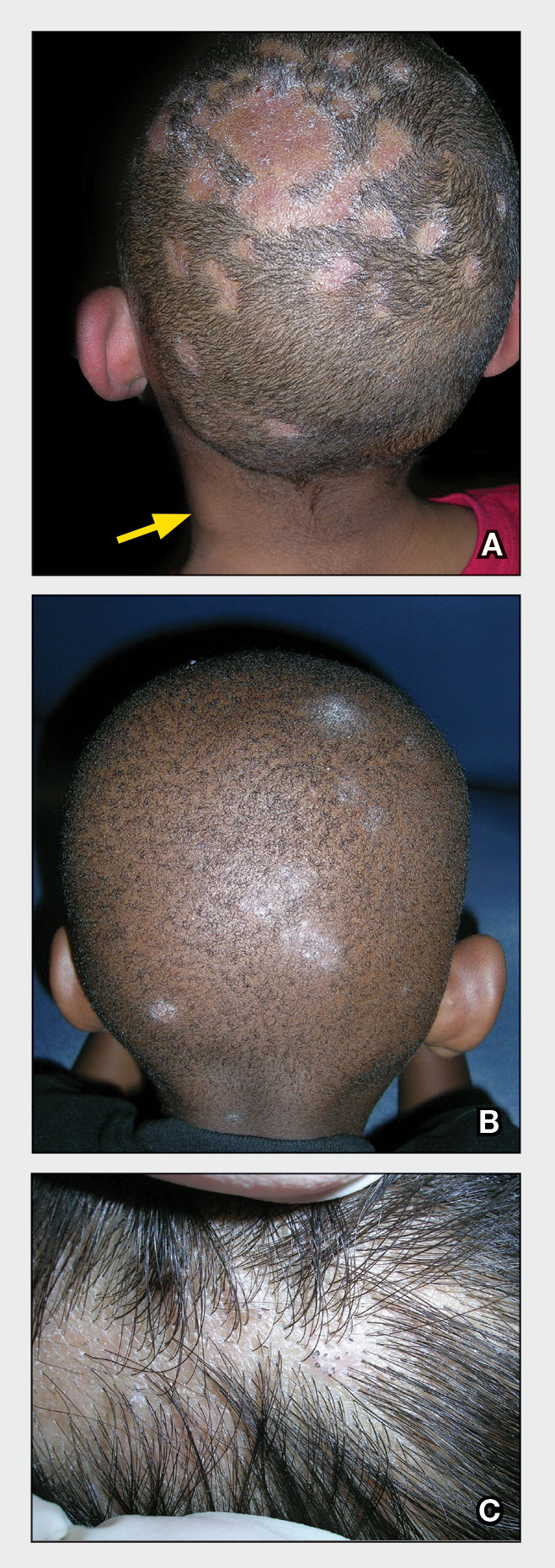

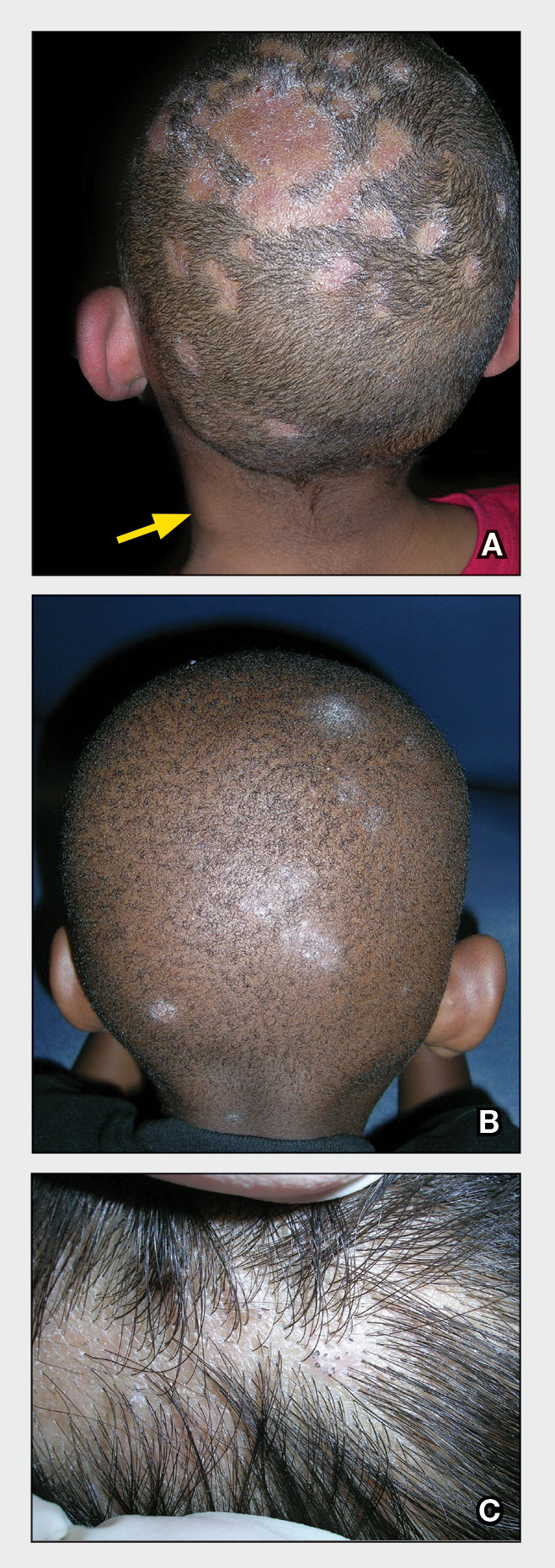

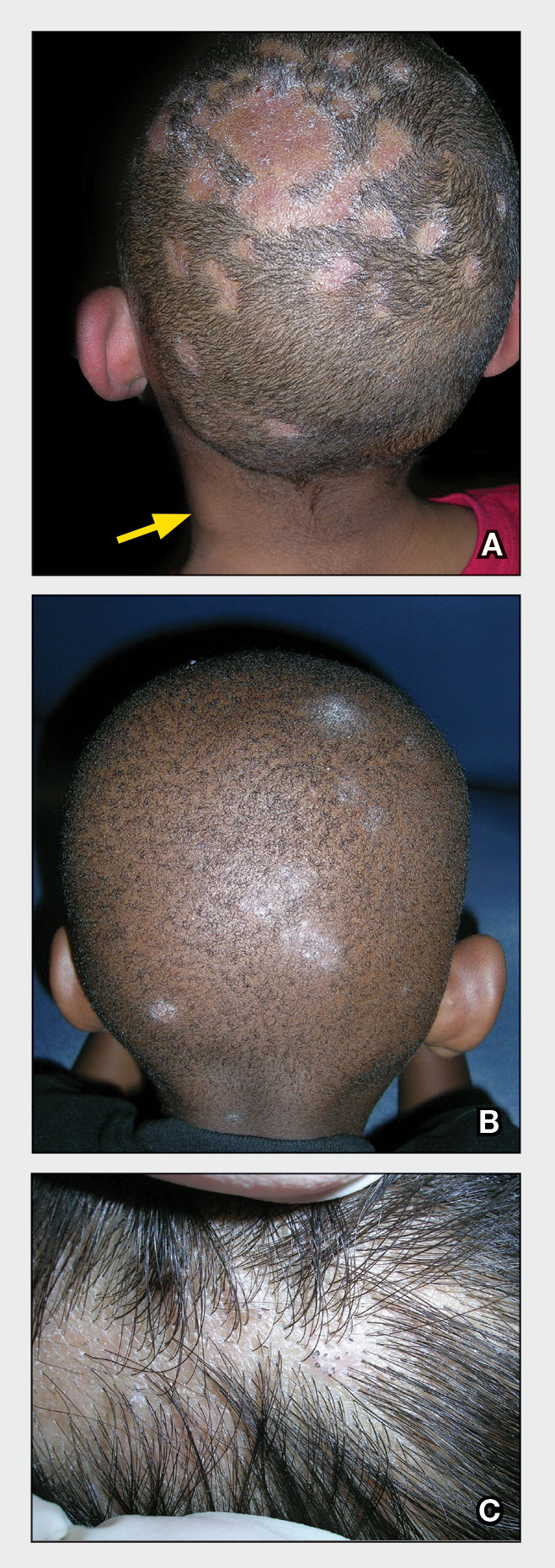

A Areas of alopecia with erythema and scale in a young Black boy with tinea capitis. He also had an enlarged posterior cervical lymph node (arrow) from this fungal infection.

B White patches of scale from tinea capitis in a young Black boy with no obvious hair loss; however, a potassium hydroxide preparation from the scale was positive for fungus.

C A subtle area of tinea capitis on the scalp of a Latina girl showed comma hairs.

Tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp in school-aged children. The infection is spread by close contact with infected people or with their personal items, including combs, brushes, pillowcases, and hats, as well as animals. It is uncommon in adults.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection among school-aged children worldwide.1 In a US-based study of more than 10,000 school-aged children, the prevalence of tinea capitis ranged from 0% to 19.4%, with Black children having the highest rates of infection at 12.9%.2 However, people of all races and ages may develop tinea capitis.3

Tinea capitis most commonly is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. Dermatophyte scalp infections caused by T tonsurans produce fungal spores that may occur within the hair shaft (endothrix) or with fungal elements external to the hair shaft (exothrix) caused by M canis. M canis usually fluoresces an apple green color on Wood lamp examination because of the location of the spores.

Key clinical features

Tinea capitis has a variety of clinical presentations:

- broken hairs that appear as black dots on the scalp

- diffuse scale mimicking seborrheic dermatitis

- well-demarcated annular plaques

- exudate and tenderness caused by inflammation

- scalp pruritus

- occipital scalp lymphadenopathy.

Worth noting

Tinea capitis impacts all patient groups, not just Black patients. In the United States, Black and Hispanic children are most commonly affected.4 Due to a tendency to have dry hair and hair breakage, those with more tightly coiled, textured hair may routinely apply oil and/or grease to the scalp. However, the application of heavy emollients, oils, and grease to camouflage scale contributes to false-negative fungal cultures of the scalp if applied within 1 week of the fungal culture, which may delay diagnosis. If tinea capitis is suspected, occipital lymphadenopathy on physical examination should prompt treatment for tinea capitis, even without a fungal culture.5

Health disparity highlight

A risk factor for tinea capitis is crowded living environments. Some families may live in crowded environments due to economic and housing disparities. This close contact increases the risk for conditions such as tinea capitis.6 Treatment delays may occur due to some cultural practices of applying oils and grease to the hair and scalp, camouflaging the clinical signs of tinea capitis.

1. Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2264-2274. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15088

2. Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966-973. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2522

3. Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Tinea capitis: focus on African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S120-S124. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120793

4. Alvarez MS, Silverberg NB. Tinea capitis. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:246-255.

5. Nguyen CV, Collier S, Merten AH, et al. Tinea capitis: a singleinstitution retrospective review from 2010 to 2015. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:305-310. doi: 10.1111/pde.14092

6. Emele FE, Oyeka CA. Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria. Mycoses. 2008;51:536-541. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01507.x

THE COMPARISON

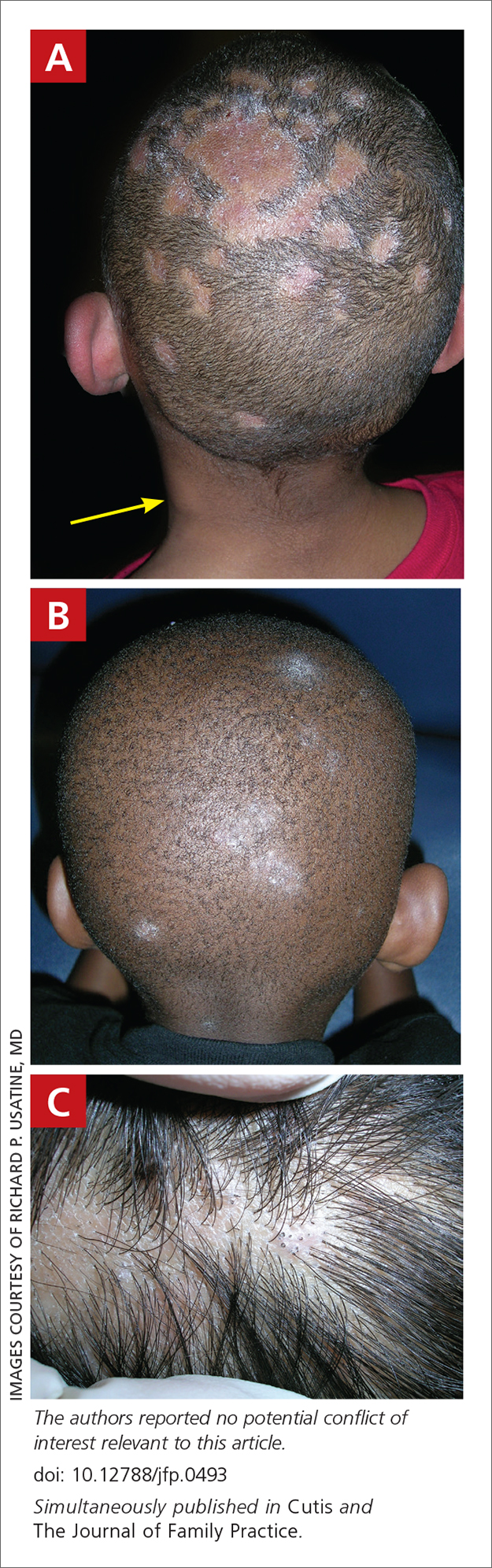

A Areas of alopecia with erythema and scale in a young Black boy with tinea capitis. He also had an enlarged posterior cervical lymph node (arrow) from this fungal infection.

B White patches of scale from tinea capitis in a young Black boy with no obvious hair loss; however, a potassium hydroxide preparation from the scale was positive for fungus.

C A subtle area of tinea capitis on the scalp of a Latina girl showed comma hairs.

Tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp in school-aged children. The infection is spread by close contact with infected people or with their personal items, including combs, brushes, pillowcases, and hats, as well as animals. It is uncommon in adults.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection among school-aged children worldwide.1 In a US-based study of more than 10,000 school-aged children, the prevalence of tinea capitis ranged from 0% to 19.4%, with Black children having the highest rates of infection at 12.9%.2 However, people of all races and ages may develop tinea capitis.3

Tinea capitis most commonly is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. Dermatophyte scalp infections caused by T tonsurans produce fungal spores that may occur within the hair shaft (endothrix) or with fungal elements external to the hair shaft (exothrix) caused by M canis. M canis usually fluoresces an apple green color on Wood lamp examination because of the location of the spores.

Key clinical features

Tinea capitis has a variety of clinical presentations:

- broken hairs that appear as black dots on the scalp

- diffuse scale mimicking seborrheic dermatitis

- well-demarcated annular plaques

- exudate and tenderness caused by inflammation

- scalp pruritus

- occipital scalp lymphadenopathy.

Worth noting

Tinea capitis impacts all patient groups, not just Black patients. In the United States, Black and Hispanic children are most commonly affected.4 Due to a tendency to have dry hair and hair breakage, those with more tightly coiled, textured hair may routinely apply oil and/or grease to the scalp. However, the application of heavy emollients, oils, and grease to camouflage scale contributes to false-negative fungal cultures of the scalp if applied within 1 week of the fungal culture, which may delay diagnosis. If tinea capitis is suspected, occipital lymphadenopathy on physical examination should prompt treatment for tinea capitis, even without a fungal culture.5

Health disparity highlight

A risk factor for tinea capitis is crowded living environments. Some families may live in crowded environments due to economic and housing disparities. This close contact increases the risk for conditions such as tinea capitis.6 Treatment delays may occur due to some cultural practices of applying oils and grease to the hair and scalp, camouflaging the clinical signs of tinea capitis.

THE COMPARISON

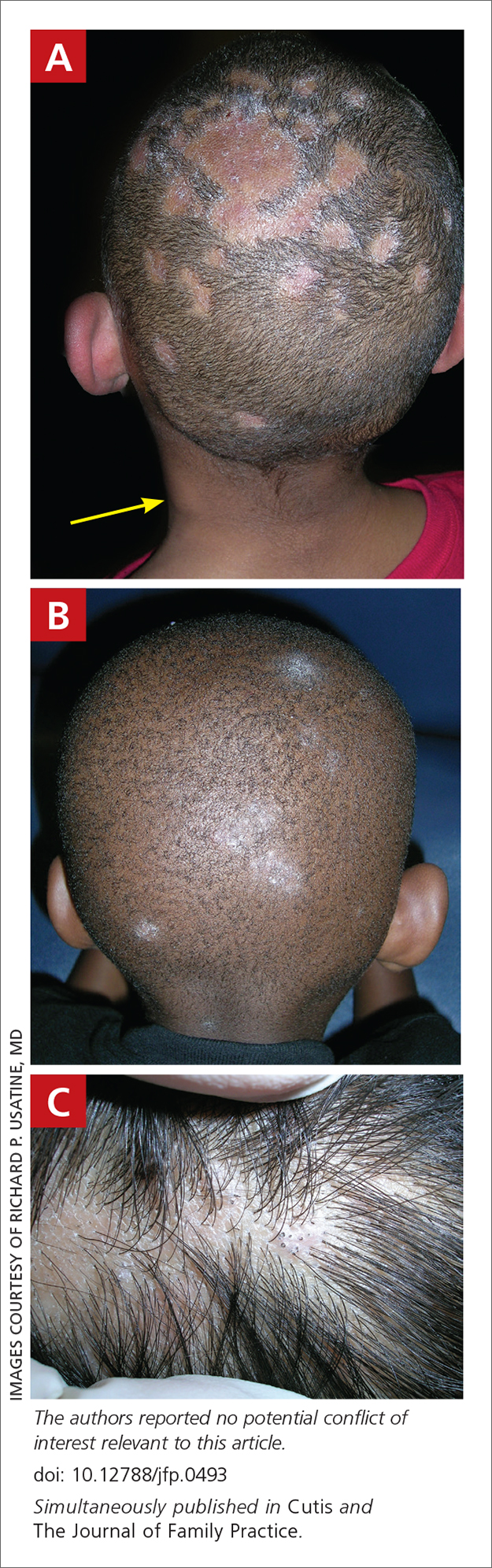

A Areas of alopecia with erythema and scale in a young Black boy with tinea capitis. He also had an enlarged posterior cervical lymph node (arrow) from this fungal infection.

B White patches of scale from tinea capitis in a young Black boy with no obvious hair loss; however, a potassium hydroxide preparation from the scale was positive for fungus.

C A subtle area of tinea capitis on the scalp of a Latina girl showed comma hairs.

Tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp in school-aged children. The infection is spread by close contact with infected people or with their personal items, including combs, brushes, pillowcases, and hats, as well as animals. It is uncommon in adults.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection among school-aged children worldwide.1 In a US-based study of more than 10,000 school-aged children, the prevalence of tinea capitis ranged from 0% to 19.4%, with Black children having the highest rates of infection at 12.9%.2 However, people of all races and ages may develop tinea capitis.3

Tinea capitis most commonly is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. Dermatophyte scalp infections caused by T tonsurans produce fungal spores that may occur within the hair shaft (endothrix) or with fungal elements external to the hair shaft (exothrix) caused by M canis. M canis usually fluoresces an apple green color on Wood lamp examination because of the location of the spores.

Key clinical features

Tinea capitis has a variety of clinical presentations:

- broken hairs that appear as black dots on the scalp

- diffuse scale mimicking seborrheic dermatitis

- well-demarcated annular plaques

- exudate and tenderness caused by inflammation

- scalp pruritus

- occipital scalp lymphadenopathy.

Worth noting

Tinea capitis impacts all patient groups, not just Black patients. In the United States, Black and Hispanic children are most commonly affected.4 Due to a tendency to have dry hair and hair breakage, those with more tightly coiled, textured hair may routinely apply oil and/or grease to the scalp. However, the application of heavy emollients, oils, and grease to camouflage scale contributes to false-negative fungal cultures of the scalp if applied within 1 week of the fungal culture, which may delay diagnosis. If tinea capitis is suspected, occipital lymphadenopathy on physical examination should prompt treatment for tinea capitis, even without a fungal culture.5

Health disparity highlight

A risk factor for tinea capitis is crowded living environments. Some families may live in crowded environments due to economic and housing disparities. This close contact increases the risk for conditions such as tinea capitis.6 Treatment delays may occur due to some cultural practices of applying oils and grease to the hair and scalp, camouflaging the clinical signs of tinea capitis.

1. Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2264-2274. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15088

2. Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966-973. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2522

3. Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Tinea capitis: focus on African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S120-S124. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120793

4. Alvarez MS, Silverberg NB. Tinea capitis. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:246-255.

5. Nguyen CV, Collier S, Merten AH, et al. Tinea capitis: a singleinstitution retrospective review from 2010 to 2015. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:305-310. doi: 10.1111/pde.14092

6. Emele FE, Oyeka CA. Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria. Mycoses. 2008;51:536-541. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01507.x

1. Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2264-2274. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15088

2. Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966-973. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2522

3. Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Tinea capitis: focus on African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S120-S124. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120793

4. Alvarez MS, Silverberg NB. Tinea capitis. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:246-255.

5. Nguyen CV, Collier S, Merten AH, et al. Tinea capitis: a singleinstitution retrospective review from 2010 to 2015. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:305-310. doi: 10.1111/pde.14092

6. Emele FE, Oyeka CA. Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria. Mycoses. 2008;51:536-541. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01507.x

IVIG proves effective for dermatomyositis in phase 3 trial

With use of intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of adults with dermatomyositis, a significantly higher percentage of patients experienced at least minimal improvement in disease activity in comparison with placebo in the first-ever phase 3 trial of the blood-product therapy for the condition.

Until this trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, there had not been an extensive evaluation of IVIG for the treatment of dermatomyositis, the study’s authors noted.

Glucocorticoids are typically offered as first-line therapy, followed by various immunosuppressants. IVIG is composed of purified liquid IgG concentrates from human plasma. It has been prescribed off label as second- or third-line therapy for dermatomyositis, usually along with immunosuppressive drugs. In European guidelines, it has been recommended as a glucocorticoid-sparing agent for patients with this condition.

“The study provides support that IVIG is effective in treating the signs and symptoms of patients with dermatomyositis, at least in the short term,” said David Fiorentino, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and associate residency program director at Stanford Health Care, Stanford, California, who was not involved in the study.

“IVIG appears to be effective for patients with any severity level and works relatively quickly [within 1 month of therapy],” he added. “IVIG is effective in treating both the muscle symptoms as well as the rash of dermatomyositis, which is important, as both organ systems can cause significant patient morbidity in this disease.”

Time to improvement was shorter with IVIG than with placebo (a median of 35 days vs. 115 days), said Kathryn H. Dao, MD, associate professor in the division of rheumatic diseases at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, who was not involved in the study.

The study’s greatest strengths are its international, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled design, Dr. Dao said. In addition, “these patients were permitted to be on background medicines that we typically use in real-world situations.”

Study methodology

Researchers led by Rohit Aggarwal, MD, of the division of rheumatology and clinical immunology at the University of Pittsburgh, recruited patients aged 18-80 years with active dermatomyositis. Individuals were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive either IVIG at a dose of 2.0 g/kg of body weight or placebo (0.9% sodium chloride) every 4 weeks for 16 weeks.

Those who were administered placebo and those who did not experience confirmed clinical deterioration while receiving IVIG could participate in an open-label extension phase for another 24 weeks.

The primary endpoint was a response, defined as a Total Improvement Score (TIS) of at least 20 (indicating at least minimal improvement) at week 16 and no confirmed deterioration up to week 16. The TIS is a weighted composite score that reflects the change in a core set of six measures of myositis activity over time. Scores span from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more significant improvement.

Secondary endpoints

Key secondary endpoints included moderate improvement (TIS ≥ 40) and major improvement (TIS ≥ 60) and change in score on the Cutaneous Dermatomyositis Disease Area and Severity Index.

A total of 95 patients underwent randomization; 47 patients received IVIG and 48 received placebo. At 16 weeks, a TIS of at least 20 occurred in 37 of 47 (79%) patients who received IVIG and in 21 of 48 (44%) patients with placebo (difference, 35%; 95% confidence interval, 17%-53%; P < .001).

The results with respect to the secondary endpoints, including at least moderate improvement and major improvement, were generally in the same direction as the results of the primary endpoint analysis, except for change in creatine kinase (CK) level (an individual core measure of the TIS), which did not differ meaningfully between the two groups.

Adverse events

Over the course of 40 weeks, 282 treatment-related adverse events were documented among patients who received IVIG. Headache was experienced by 42%, pyrexia by 19%, and nausea by 16%. Nine serious adverse events occurred and were believed to be associated with IVIG, including six thromboembolic events.

Despite the favorable outcome observed with IVIG, in an editorial that accompanied the study, Anthony A. Amato, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, noted that “most of the core components of the TIS are subjective. Because of the high percentage of patients who had a response with placebo, large numbers of patients will be needed in future trials to show a significant difference between trial groups, or the primary endpoint would need to be set higher (e.g., a TIS of ≥40).”

Dr. Dao thought it was significant that the study proactively assessed patients for venous thrombotic events (VTEs) after each infusion. There were eight events in six patients who received IVIG. “Of interest and possibly practice changing is the finding that slowing the IVIG infusion rate from 0.12 to 0.04 mL/kg per minute reduced the incidence of VTEs from 1.54/100 patient-months to 0.54/100 patient-months,” she said. “This is important, as it informs clinicians that IVIG infusion rates should be slower for patients with active dermatomyositis to reduce the risk for blood clots.”

Study weaknesses

A considerable proportion of patients with dermatomyositis do not have clinical muscle involvement but do have rash and do not substantially differ in any other ways from those with classic dermatomyositis, Dr. Fiorentino said.

“These patients were not eligible to enter the trial, and so we have no data on the efficacy of IVIG in this population,” he said. “Unfortunately, these patients might now be denied insurance reimbursement for IVIG therapy, given that they are not part of the indicated patient population in the label.”

In addition, there is limited information about Black, Asian, or Hispanic patients because few of those patients participated in the study. That is also the case for patients younger than 18, which for this disease is relevant because incidence peaks in younger patients (juvenile dermatomyositis), Dr. Fiorentino noted.

Among the study’s weaknesses, Dr. Dao noted that more than 70% of participants were women. The study was short in duration, fewer than half of patients underwent muscle biopsy to confirm myositis, and only two thirds of patients underwent electromyography/nerve conduction studies to show evidence of myositis. There was a high placebo response (44%), the CK values were not high at the start of the trial, and they did not change with treatment.

No analysis was performed to evaluate the efficacy of IVIG across dermatomyositis subgroups – defined by autoantibodies – but the study likely was not powered to do so. These subgroups might respond differently to IVIG, yielding important information, Fiorentino said.

The study provided efficacy data for only one formulation of IVIG, Octagam 10%, which was approved for dermatomyositis by the Food and Drug Administration in 2021 on the basis of this trial. However, in the United States, patients with dermatomyositis are treated with multiple brands of IVIG. “The decision around IVIG brand is largely determined by third-party payers, and for the most part, the different brands are used interchangeably from the standpoint of the treating provider,” Dr. Fiorentino said. “This will likely continue to be the case, as the results of this study are generally being extrapolated to all brands of IVIG.”

Multiple IVIG brands that have been used for immune-mediated diseases differ in concentration, content of IgA, sugar concentration, additives, and preparations (for example, the need for reconstitution vs. being ready to use), Dr. Dao said. Octagam 10% is the only brand approved by the FDA for adult dermatomyositis; hence, cost can be an issue for patients if other brands are used off label. The typical cost of IVIG is $100-$400 per gram; a typical course of treatment is estimated to be $30,000-$40,000 per month. “However, if Octagam is not available or a patient has a reaction to it, clinicians may use other IVIG brands as deemed medically necessary to treat their patients,” she said.

Dr. Aggarwal has financial relationships with more than 15 pharmaceutical companies, including Octapharma, which provided financial support for this trial. Some of the coauthors were employees of Octapharma or had financial relationships with the company. Dr. Dao disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Fiorentino has conducted sponsored research for Pfizer and Argenyx, has received research funding from Serono, and is a paid adviser to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Acelyrin, and Corbus.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With use of intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of adults with dermatomyositis, a significantly higher percentage of patients experienced at least minimal improvement in disease activity in comparison with placebo in the first-ever phase 3 trial of the blood-product therapy for the condition.

Until this trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, there had not been an extensive evaluation of IVIG for the treatment of dermatomyositis, the study’s authors noted.

Glucocorticoids are typically offered as first-line therapy, followed by various immunosuppressants. IVIG is composed of purified liquid IgG concentrates from human plasma. It has been prescribed off label as second- or third-line therapy for dermatomyositis, usually along with immunosuppressive drugs. In European guidelines, it has been recommended as a glucocorticoid-sparing agent for patients with this condition.

“The study provides support that IVIG is effective in treating the signs and symptoms of patients with dermatomyositis, at least in the short term,” said David Fiorentino, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and associate residency program director at Stanford Health Care, Stanford, California, who was not involved in the study.

“IVIG appears to be effective for patients with any severity level and works relatively quickly [within 1 month of therapy],” he added. “IVIG is effective in treating both the muscle symptoms as well as the rash of dermatomyositis, which is important, as both organ systems can cause significant patient morbidity in this disease.”

Time to improvement was shorter with IVIG than with placebo (a median of 35 days vs. 115 days), said Kathryn H. Dao, MD, associate professor in the division of rheumatic diseases at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, who was not involved in the study.

The study’s greatest strengths are its international, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled design, Dr. Dao said. In addition, “these patients were permitted to be on background medicines that we typically use in real-world situations.”

Study methodology

Researchers led by Rohit Aggarwal, MD, of the division of rheumatology and clinical immunology at the University of Pittsburgh, recruited patients aged 18-80 years with active dermatomyositis. Individuals were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive either IVIG at a dose of 2.0 g/kg of body weight or placebo (0.9% sodium chloride) every 4 weeks for 16 weeks.

Those who were administered placebo and those who did not experience confirmed clinical deterioration while receiving IVIG could participate in an open-label extension phase for another 24 weeks.

The primary endpoint was a response, defined as a Total Improvement Score (TIS) of at least 20 (indicating at least minimal improvement) at week 16 and no confirmed deterioration up to week 16. The TIS is a weighted composite score that reflects the change in a core set of six measures of myositis activity over time. Scores span from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more significant improvement.

Secondary endpoints

Key secondary endpoints included moderate improvement (TIS ≥ 40) and major improvement (TIS ≥ 60) and change in score on the Cutaneous Dermatomyositis Disease Area and Severity Index.

A total of 95 patients underwent randomization; 47 patients received IVIG and 48 received placebo. At 16 weeks, a TIS of at least 20 occurred in 37 of 47 (79%) patients who received IVIG and in 21 of 48 (44%) patients with placebo (difference, 35%; 95% confidence interval, 17%-53%; P < .001).

The results with respect to the secondary endpoints, including at least moderate improvement and major improvement, were generally in the same direction as the results of the primary endpoint analysis, except for change in creatine kinase (CK) level (an individual core measure of the TIS), which did not differ meaningfully between the two groups.

Adverse events

Over the course of 40 weeks, 282 treatment-related adverse events were documented among patients who received IVIG. Headache was experienced by 42%, pyrexia by 19%, and nausea by 16%. Nine serious adverse events occurred and were believed to be associated with IVIG, including six thromboembolic events.

Despite the favorable outcome observed with IVIG, in an editorial that accompanied the study, Anthony A. Amato, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, noted that “most of the core components of the TIS are subjective. Because of the high percentage of patients who had a response with placebo, large numbers of patients will be needed in future trials to show a significant difference between trial groups, or the primary endpoint would need to be set higher (e.g., a TIS of ≥40).”

Dr. Dao thought it was significant that the study proactively assessed patients for venous thrombotic events (VTEs) after each infusion. There were eight events in six patients who received IVIG. “Of interest and possibly practice changing is the finding that slowing the IVIG infusion rate from 0.12 to 0.04 mL/kg per minute reduced the incidence of VTEs from 1.54/100 patient-months to 0.54/100 patient-months,” she said. “This is important, as it informs clinicians that IVIG infusion rates should be slower for patients with active dermatomyositis to reduce the risk for blood clots.”

Study weaknesses

A considerable proportion of patients with dermatomyositis do not have clinical muscle involvement but do have rash and do not substantially differ in any other ways from those with classic dermatomyositis, Dr. Fiorentino said.

“These patients were not eligible to enter the trial, and so we have no data on the efficacy of IVIG in this population,” he said. “Unfortunately, these patients might now be denied insurance reimbursement for IVIG therapy, given that they are not part of the indicated patient population in the label.”

In addition, there is limited information about Black, Asian, or Hispanic patients because few of those patients participated in the study. That is also the case for patients younger than 18, which for this disease is relevant because incidence peaks in younger patients (juvenile dermatomyositis), Dr. Fiorentino noted.

Among the study’s weaknesses, Dr. Dao noted that more than 70% of participants were women. The study was short in duration, fewer than half of patients underwent muscle biopsy to confirm myositis, and only two thirds of patients underwent electromyography/nerve conduction studies to show evidence of myositis. There was a high placebo response (44%), the CK values were not high at the start of the trial, and they did not change with treatment.

No analysis was performed to evaluate the efficacy of IVIG across dermatomyositis subgroups – defined by autoantibodies – but the study likely was not powered to do so. These subgroups might respond differently to IVIG, yielding important information, Fiorentino said.

The study provided efficacy data for only one formulation of IVIG, Octagam 10%, which was approved for dermatomyositis by the Food and Drug Administration in 2021 on the basis of this trial. However, in the United States, patients with dermatomyositis are treated with multiple brands of IVIG. “The decision around IVIG brand is largely determined by third-party payers, and for the most part, the different brands are used interchangeably from the standpoint of the treating provider,” Dr. Fiorentino said. “This will likely continue to be the case, as the results of this study are generally being extrapolated to all brands of IVIG.”

Multiple IVIG brands that have been used for immune-mediated diseases differ in concentration, content of IgA, sugar concentration, additives, and preparations (for example, the need for reconstitution vs. being ready to use), Dr. Dao said. Octagam 10% is the only brand approved by the FDA for adult dermatomyositis; hence, cost can be an issue for patients if other brands are used off label. The typical cost of IVIG is $100-$400 per gram; a typical course of treatment is estimated to be $30,000-$40,000 per month. “However, if Octagam is not available or a patient has a reaction to it, clinicians may use other IVIG brands as deemed medically necessary to treat their patients,” she said.

Dr. Aggarwal has financial relationships with more than 15 pharmaceutical companies, including Octapharma, which provided financial support for this trial. Some of the coauthors were employees of Octapharma or had financial relationships with the company. Dr. Dao disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Fiorentino has conducted sponsored research for Pfizer and Argenyx, has received research funding from Serono, and is a paid adviser to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Acelyrin, and Corbus.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With use of intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of adults with dermatomyositis, a significantly higher percentage of patients experienced at least minimal improvement in disease activity in comparison with placebo in the first-ever phase 3 trial of the blood-product therapy for the condition.

Until this trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, there had not been an extensive evaluation of IVIG for the treatment of dermatomyositis, the study’s authors noted.

Glucocorticoids are typically offered as first-line therapy, followed by various immunosuppressants. IVIG is composed of purified liquid IgG concentrates from human plasma. It has been prescribed off label as second- or third-line therapy for dermatomyositis, usually along with immunosuppressive drugs. In European guidelines, it has been recommended as a glucocorticoid-sparing agent for patients with this condition.

“The study provides support that IVIG is effective in treating the signs and symptoms of patients with dermatomyositis, at least in the short term,” said David Fiorentino, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and associate residency program director at Stanford Health Care, Stanford, California, who was not involved in the study.

“IVIG appears to be effective for patients with any severity level and works relatively quickly [within 1 month of therapy],” he added. “IVIG is effective in treating both the muscle symptoms as well as the rash of dermatomyositis, which is important, as both organ systems can cause significant patient morbidity in this disease.”

Time to improvement was shorter with IVIG than with placebo (a median of 35 days vs. 115 days), said Kathryn H. Dao, MD, associate professor in the division of rheumatic diseases at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, who was not involved in the study.

The study’s greatest strengths are its international, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled design, Dr. Dao said. In addition, “these patients were permitted to be on background medicines that we typically use in real-world situations.”

Study methodology

Researchers led by Rohit Aggarwal, MD, of the division of rheumatology and clinical immunology at the University of Pittsburgh, recruited patients aged 18-80 years with active dermatomyositis. Individuals were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive either IVIG at a dose of 2.0 g/kg of body weight or placebo (0.9% sodium chloride) every 4 weeks for 16 weeks.

Those who were administered placebo and those who did not experience confirmed clinical deterioration while receiving IVIG could participate in an open-label extension phase for another 24 weeks.

The primary endpoint was a response, defined as a Total Improvement Score (TIS) of at least 20 (indicating at least minimal improvement) at week 16 and no confirmed deterioration up to week 16. The TIS is a weighted composite score that reflects the change in a core set of six measures of myositis activity over time. Scores span from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more significant improvement.

Secondary endpoints

Key secondary endpoints included moderate improvement (TIS ≥ 40) and major improvement (TIS ≥ 60) and change in score on the Cutaneous Dermatomyositis Disease Area and Severity Index.

A total of 95 patients underwent randomization; 47 patients received IVIG and 48 received placebo. At 16 weeks, a TIS of at least 20 occurred in 37 of 47 (79%) patients who received IVIG and in 21 of 48 (44%) patients with placebo (difference, 35%; 95% confidence interval, 17%-53%; P < .001).

The results with respect to the secondary endpoints, including at least moderate improvement and major improvement, were generally in the same direction as the results of the primary endpoint analysis, except for change in creatine kinase (CK) level (an individual core measure of the TIS), which did not differ meaningfully between the two groups.

Adverse events

Over the course of 40 weeks, 282 treatment-related adverse events were documented among patients who received IVIG. Headache was experienced by 42%, pyrexia by 19%, and nausea by 16%. Nine serious adverse events occurred and were believed to be associated with IVIG, including six thromboembolic events.

Despite the favorable outcome observed with IVIG, in an editorial that accompanied the study, Anthony A. Amato, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, noted that “most of the core components of the TIS are subjective. Because of the high percentage of patients who had a response with placebo, large numbers of patients will be needed in future trials to show a significant difference between trial groups, or the primary endpoint would need to be set higher (e.g., a TIS of ≥40).”

Dr. Dao thought it was significant that the study proactively assessed patients for venous thrombotic events (VTEs) after each infusion. There were eight events in six patients who received IVIG. “Of interest and possibly practice changing is the finding that slowing the IVIG infusion rate from 0.12 to 0.04 mL/kg per minute reduced the incidence of VTEs from 1.54/100 patient-months to 0.54/100 patient-months,” she said. “This is important, as it informs clinicians that IVIG infusion rates should be slower for patients with active dermatomyositis to reduce the risk for blood clots.”

Study weaknesses

A considerable proportion of patients with dermatomyositis do not have clinical muscle involvement but do have rash and do not substantially differ in any other ways from those with classic dermatomyositis, Dr. Fiorentino said.

“These patients were not eligible to enter the trial, and so we have no data on the efficacy of IVIG in this population,” he said. “Unfortunately, these patients might now be denied insurance reimbursement for IVIG therapy, given that they are not part of the indicated patient population in the label.”

In addition, there is limited information about Black, Asian, or Hispanic patients because few of those patients participated in the study. That is also the case for patients younger than 18, which for this disease is relevant because incidence peaks in younger patients (juvenile dermatomyositis), Dr. Fiorentino noted.

Among the study’s weaknesses, Dr. Dao noted that more than 70% of participants were women. The study was short in duration, fewer than half of patients underwent muscle biopsy to confirm myositis, and only two thirds of patients underwent electromyography/nerve conduction studies to show evidence of myositis. There was a high placebo response (44%), the CK values were not high at the start of the trial, and they did not change with treatment.

No analysis was performed to evaluate the efficacy of IVIG across dermatomyositis subgroups – defined by autoantibodies – but the study likely was not powered to do so. These subgroups might respond differently to IVIG, yielding important information, Fiorentino said.

The study provided efficacy data for only one formulation of IVIG, Octagam 10%, which was approved for dermatomyositis by the Food and Drug Administration in 2021 on the basis of this trial. However, in the United States, patients with dermatomyositis are treated with multiple brands of IVIG. “The decision around IVIG brand is largely determined by third-party payers, and for the most part, the different brands are used interchangeably from the standpoint of the treating provider,” Dr. Fiorentino said. “This will likely continue to be the case, as the results of this study are generally being extrapolated to all brands of IVIG.”

Multiple IVIG brands that have been used for immune-mediated diseases differ in concentration, content of IgA, sugar concentration, additives, and preparations (for example, the need for reconstitution vs. being ready to use), Dr. Dao said. Octagam 10% is the only brand approved by the FDA for adult dermatomyositis; hence, cost can be an issue for patients if other brands are used off label. The typical cost of IVIG is $100-$400 per gram; a typical course of treatment is estimated to be $30,000-$40,000 per month. “However, if Octagam is not available or a patient has a reaction to it, clinicians may use other IVIG brands as deemed medically necessary to treat their patients,” she said.

Dr. Aggarwal has financial relationships with more than 15 pharmaceutical companies, including Octapharma, which provided financial support for this trial. Some of the coauthors were employees of Octapharma or had financial relationships with the company. Dr. Dao disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Fiorentino has conducted sponsored research for Pfizer and Argenyx, has received research funding from Serono, and is a paid adviser to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Acelyrin, and Corbus.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Water exchange boosts colonoscopy training experience

A new study finds that colonoscopy trainees had a better experience with and performed better when using water exchange (WE) than when using air insufflation. The new study was published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

According to study author Felix W. Leung, MD, from the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System in North Hills, Calif., and the University of California, Los Angeles, WE is less painful than air insufflation and increases cecal intubation rate because it reduces loop formation. He added that it also increases polyp and adenoma detection rates.

Although WE has compared favorably with air insufflation for ADR and pain, there is little evidence regarding how trainees view WE versus air insufflation. Dr. Leung pointed out that the issue could be particularly important among millennial trainees, who may have a different learning style than previous generations. He also noted that previous studies of WE versus air insufflation among trainees measured the perspective of trainers, and did not include the trainees’ opinions of the learning process or trainee outcomes like polyp detection rate.

Seeking to fill this knowledge gap, Dr. Leung conducted a prospective observational study at a Veterans Administration Hospital. Trainees conducted unsedated colonoscopies using WE, as well as WE and air insufflation colonoscopies in alternating order in sedated patients. A total of 83 air insufflation and 119 WE colonoscopies were performed. Trainees rated their experiences on a 1- to 5-point scale, with 1 being “strongly agree” and 5 “strongly disagree” to two statements: “My colonoscopy experience was better than expected” then “I was confident with my technical skills using this method.”

On average, trainees using WE reported a better than expected experience when using WE, compared with air insufflation (2.02 vs. 2.43; P = .0087), but no significant difference in the ensuing confidence in their technical skills (2.76 vs. 2.85; P = .48). There was a longer insertion time for WE (40 minutes vs. 30 minutes; P = .0008). WE was associated with a significantly higher adjusted cecal intubation rate (99% vs. 89%; P = .0031) and a significantly higher polyp detection rate (54% vs. 32%; P = .0447). Overall insertion time was longer with WE than air insufflation (40 minutes vs. 30 minutes; P = .0008), but withdrawal times were similar (22 minutes vs. 20 minutes; P = .3369).

The reduction in pain associated with WE can potentially improve training, in which cases procedures are typically performed on patients under moderate sedation, according to John Allen, MD, who was asked to comment on the study.

He also said that WE can sometimes do a better job than air of opening the lumen. It can help clean the colon surface, and even improve visibility. “Viewing the mucosa under water is like having a lens that helps view the surface and enhance polyp detection,” said Dr. Allen, who is a retired clinical professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Allen noted that either air sufflation or WE can be used to overcome the inexperience of the trainee, and that there shouldn’t be much difference between the two methods for sedated colonoscopies. The time of exam is similar, and WE does not require use of carbon dioxide or other gases, which avoids extra costs. “A highly skilled colonoscopist can perform exams using any of the available media. That said, WE is proving to be helpful no matter what your skill level. The only disadvantage I can see is that many trainers do not know how WE works and are unused to this process, although it is easy to learn,” said Dr. Allen.

The study is limited by the fact that it was conducted at a single institution in a nonblinded, nonrandomized population.

Dr. Leung declared there are no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Allen has no relevant financial disclosures.

A new study finds that colonoscopy trainees had a better experience with and performed better when using water exchange (WE) than when using air insufflation. The new study was published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

According to study author Felix W. Leung, MD, from the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System in North Hills, Calif., and the University of California, Los Angeles, WE is less painful than air insufflation and increases cecal intubation rate because it reduces loop formation. He added that it also increases polyp and adenoma detection rates.

Although WE has compared favorably with air insufflation for ADR and pain, there is little evidence regarding how trainees view WE versus air insufflation. Dr. Leung pointed out that the issue could be particularly important among millennial trainees, who may have a different learning style than previous generations. He also noted that previous studies of WE versus air insufflation among trainees measured the perspective of trainers, and did not include the trainees’ opinions of the learning process or trainee outcomes like polyp detection rate.

Seeking to fill this knowledge gap, Dr. Leung conducted a prospective observational study at a Veterans Administration Hospital. Trainees conducted unsedated colonoscopies using WE, as well as WE and air insufflation colonoscopies in alternating order in sedated patients. A total of 83 air insufflation and 119 WE colonoscopies were performed. Trainees rated their experiences on a 1- to 5-point scale, with 1 being “strongly agree” and 5 “strongly disagree” to two statements: “My colonoscopy experience was better than expected” then “I was confident with my technical skills using this method.”

On average, trainees using WE reported a better than expected experience when using WE, compared with air insufflation (2.02 vs. 2.43; P = .0087), but no significant difference in the ensuing confidence in their technical skills (2.76 vs. 2.85; P = .48). There was a longer insertion time for WE (40 minutes vs. 30 minutes; P = .0008). WE was associated with a significantly higher adjusted cecal intubation rate (99% vs. 89%; P = .0031) and a significantly higher polyp detection rate (54% vs. 32%; P = .0447). Overall insertion time was longer with WE than air insufflation (40 minutes vs. 30 minutes; P = .0008), but withdrawal times were similar (22 minutes vs. 20 minutes; P = .3369).

The reduction in pain associated with WE can potentially improve training, in which cases procedures are typically performed on patients under moderate sedation, according to John Allen, MD, who was asked to comment on the study.

He also said that WE can sometimes do a better job than air of opening the lumen. It can help clean the colon surface, and even improve visibility. “Viewing the mucosa under water is like having a lens that helps view the surface and enhance polyp detection,” said Dr. Allen, who is a retired clinical professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Allen noted that either air sufflation or WE can be used to overcome the inexperience of the trainee, and that there shouldn’t be much difference between the two methods for sedated colonoscopies. The time of exam is similar, and WE does not require use of carbon dioxide or other gases, which avoids extra costs. “A highly skilled colonoscopist can perform exams using any of the available media. That said, WE is proving to be helpful no matter what your skill level. The only disadvantage I can see is that many trainers do not know how WE works and are unused to this process, although it is easy to learn,” said Dr. Allen.

The study is limited by the fact that it was conducted at a single institution in a nonblinded, nonrandomized population.

Dr. Leung declared there are no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Allen has no relevant financial disclosures.

A new study finds that colonoscopy trainees had a better experience with and performed better when using water exchange (WE) than when using air insufflation. The new study was published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

According to study author Felix W. Leung, MD, from the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System in North Hills, Calif., and the University of California, Los Angeles, WE is less painful than air insufflation and increases cecal intubation rate because it reduces loop formation. He added that it also increases polyp and adenoma detection rates.

Although WE has compared favorably with air insufflation for ADR and pain, there is little evidence regarding how trainees view WE versus air insufflation. Dr. Leung pointed out that the issue could be particularly important among millennial trainees, who may have a different learning style than previous generations. He also noted that previous studies of WE versus air insufflation among trainees measured the perspective of trainers, and did not include the trainees’ opinions of the learning process or trainee outcomes like polyp detection rate.

Seeking to fill this knowledge gap, Dr. Leung conducted a prospective observational study at a Veterans Administration Hospital. Trainees conducted unsedated colonoscopies using WE, as well as WE and air insufflation colonoscopies in alternating order in sedated patients. A total of 83 air insufflation and 119 WE colonoscopies were performed. Trainees rated their experiences on a 1- to 5-point scale, with 1 being “strongly agree” and 5 “strongly disagree” to two statements: “My colonoscopy experience was better than expected” then “I was confident with my technical skills using this method.”

On average, trainees using WE reported a better than expected experience when using WE, compared with air insufflation (2.02 vs. 2.43; P = .0087), but no significant difference in the ensuing confidence in their technical skills (2.76 vs. 2.85; P = .48). There was a longer insertion time for WE (40 minutes vs. 30 minutes; P = .0008). WE was associated with a significantly higher adjusted cecal intubation rate (99% vs. 89%; P = .0031) and a significantly higher polyp detection rate (54% vs. 32%; P = .0447). Overall insertion time was longer with WE than air insufflation (40 minutes vs. 30 minutes; P = .0008), but withdrawal times were similar (22 minutes vs. 20 minutes; P = .3369).

The reduction in pain associated with WE can potentially improve training, in which cases procedures are typically performed on patients under moderate sedation, according to John Allen, MD, who was asked to comment on the study.

He also said that WE can sometimes do a better job than air of opening the lumen. It can help clean the colon surface, and even improve visibility. “Viewing the mucosa under water is like having a lens that helps view the surface and enhance polyp detection,” said Dr. Allen, who is a retired clinical professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Allen noted that either air sufflation or WE can be used to overcome the inexperience of the trainee, and that there shouldn’t be much difference between the two methods for sedated colonoscopies. The time of exam is similar, and WE does not require use of carbon dioxide or other gases, which avoids extra costs. “A highly skilled colonoscopist can perform exams using any of the available media. That said, WE is proving to be helpful no matter what your skill level. The only disadvantage I can see is that many trainers do not know how WE works and are unused to this process, although it is easy to learn,” said Dr. Allen.

The study is limited by the fact that it was conducted at a single institution in a nonblinded, nonrandomized population.

Dr. Leung declared there are no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Allen has no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY

Resistance training tied to improvements in Parkinson’s disease symptoms

, new research suggests.

A meta-analysis, which included 18 randomized controlled trials and more than 1,000 patients with Parkinson’s disease, showed that those who underwent resistance training had significantly greater improvement in motor impairment, muscle strength, and mobility/balance than their peers who underwent passive or placebo interventions.

However, there was no significant difference between patients who participated in resistance training and those who participated in other active physical interventions, including yoga.

Overall, the results highlight the importance that these patients should participate in some type of physical exercise, said the study’s lead author, Romina Gollan, MSc, an assistant researcher in the division of medical psychology, University of Cologne, Germany. “Patients should definitely be doing exercises, including resistance training, if they want to. But the type of exercise is of secondary interest,” she said.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Positive but inconsistent

Previous reviews have suggested resistance training has positive effects on motor function in Parkinson’s disease. However, results from the included studies were inconsistent; and few reviews have examined nonmotor outcomes of resistance training in this population, the investigators noted.

After carrying out a literature search of studies that examined the effects of resistance training in Parkinson’s disease, the researchers included 18 randomized controlled trials in their current review. Among the 1,134 total participants, the mean age was 66 years, the mean Hoehn & Yahr stage was 2.3 (range 0-4), and the mean duration of Parkinson’s disease was 7.5 years.

The investigation was grouped into two meta-analysis groups: one examining resistance training versus a passive or placebo intervention and the other assessing resistance training versus active physical interventions, such as yoga.

During resistance training, participants use their full strength to do a repetition, working muscles to overcome a certain threshold, said Ms. Gollan. In contrast, a placebo intervention is “very low intensity” and involves a much lower threshold, she added.

Passive interventions include such things as stretching where the stimulus “is not high enough for muscles to adapt” and build strength, Ms. Gollan noted.

A passive intervention might also include “treatment as usual” or normal daily routines.

Patient preference important

The meta-analysis comparing resistance training groups with passive control groups showed significant large effects on muscle strength (standard mean difference, –0.84; 95% confidence interval, –1.29 to –0.39; P = .0003), motor impairment (SMD, –0.81; 95% CI, –1.34 to –0.27; P = .003), and mobility and balance (SMD, –1.80; 95% CI, –3.13 to –0.49; P = .007).

The review also showed significant but small effects on quality of life.

However, the meta-analysis that assessed resistance training versus other physical interventions showed no significant between-group differences.

Ms. Gollan noted that although there were some assessments of cognition and depression, the data were too limited to determine the impact of resistance training on these outcomes.

“We need more studies, especially randomized controlled trials, to investigate the effects of resistance training on nonmotor outcomes like depression and cognition,” she said.

Co-investigator Ann-Kristin Folkerts, PhD, who heads the University of Cologne medical psychology working group, noted that although exercise in general is beneficial for patients with Parkinson’s disease, the choice of activity should take patient preferences into consideration.

It is important that patients choose an exercise they enjoy “because otherwise they probably wouldn’t adhere to the treatment,” Dr. Folkerts said. “It’s important to have fun.”

Specific goals or objectives, such as improving quality of life or balance, should also be considered, she added.

Oversimplification?

Commenting on the research, Alice Nieuwboer, PhD, professor in the department of rehabilitation sciences and head of the neurorehabilitation research group at the University of Leuven, Belgium, disagreed that exercise type is of secondary importance in Parkinson’s disease.

“In my view, it’s of primary interest, especially at the mid- to later stages,” said Dr. Nieuwboer, who was not involved with the research.

She noted it is difficult to carry out meta-analyses of resistance training versus other interventions because studies comparing different exercise types “are rather scarce.”

“Another issue is that the dose may differ, so you’re comparing apples with pears,” said Dr. Nieuwboer.

She did agree that all patients should exercise, because it is “better than no exercise,” and they should be “free to choose a mode that interests them.”

However, she stressed that exercise requires significant effort on the part of patients with Parkinson’s disease, requires “sustained motivation,” and has to become habit-forming. This makes “exercise targeting” very important, with the target changing over the disease course, Dr. Nieuwboer said.

For example, for a patient at an early stage of the disease who can still move quite well, both resistance training and endurance training can improve fitness and health; but at a mid-stage, it is perhaps better for patients to work on balance and walking quality “to preempt the risk of falls and developing freezing,” she noted.

Later on, as movement becomes very difficult, “the exercise menu is even more restricted,” said Dr. Nieuwboer.

The bottom line is that a message saying “any movement counts” is an oversimplification, she added.

The study was funded by a grant from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. The investigators and Dr. Nieuwboer have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

A meta-analysis, which included 18 randomized controlled trials and more than 1,000 patients with Parkinson’s disease, showed that those who underwent resistance training had significantly greater improvement in motor impairment, muscle strength, and mobility/balance than their peers who underwent passive or placebo interventions.

However, there was no significant difference between patients who participated in resistance training and those who participated in other active physical interventions, including yoga.

Overall, the results highlight the importance that these patients should participate in some type of physical exercise, said the study’s lead author, Romina Gollan, MSc, an assistant researcher in the division of medical psychology, University of Cologne, Germany. “Patients should definitely be doing exercises, including resistance training, if they want to. But the type of exercise is of secondary interest,” she said.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Positive but inconsistent

Previous reviews have suggested resistance training has positive effects on motor function in Parkinson’s disease. However, results from the included studies were inconsistent; and few reviews have examined nonmotor outcomes of resistance training in this population, the investigators noted.

After carrying out a literature search of studies that examined the effects of resistance training in Parkinson’s disease, the researchers included 18 randomized controlled trials in their current review. Among the 1,134 total participants, the mean age was 66 years, the mean Hoehn & Yahr stage was 2.3 (range 0-4), and the mean duration of Parkinson’s disease was 7.5 years.

The investigation was grouped into two meta-analysis groups: one examining resistance training versus a passive or placebo intervention and the other assessing resistance training versus active physical interventions, such as yoga.

During resistance training, participants use their full strength to do a repetition, working muscles to overcome a certain threshold, said Ms. Gollan. In contrast, a placebo intervention is “very low intensity” and involves a much lower threshold, she added.

Passive interventions include such things as stretching where the stimulus “is not high enough for muscles to adapt” and build strength, Ms. Gollan noted.

A passive intervention might also include “treatment as usual” or normal daily routines.

Patient preference important

The meta-analysis comparing resistance training groups with passive control groups showed significant large effects on muscle strength (standard mean difference, –0.84; 95% confidence interval, –1.29 to –0.39; P = .0003), motor impairment (SMD, –0.81; 95% CI, –1.34 to –0.27; P = .003), and mobility and balance (SMD, –1.80; 95% CI, –3.13 to –0.49; P = .007).

The review also showed significant but small effects on quality of life.

However, the meta-analysis that assessed resistance training versus other physical interventions showed no significant between-group differences.

Ms. Gollan noted that although there were some assessments of cognition and depression, the data were too limited to determine the impact of resistance training on these outcomes.

“We need more studies, especially randomized controlled trials, to investigate the effects of resistance training on nonmotor outcomes like depression and cognition,” she said.

Co-investigator Ann-Kristin Folkerts, PhD, who heads the University of Cologne medical psychology working group, noted that although exercise in general is beneficial for patients with Parkinson’s disease, the choice of activity should take patient preferences into consideration.

It is important that patients choose an exercise they enjoy “because otherwise they probably wouldn’t adhere to the treatment,” Dr. Folkerts said. “It’s important to have fun.”

Specific goals or objectives, such as improving quality of life or balance, should also be considered, she added.

Oversimplification?

Commenting on the research, Alice Nieuwboer, PhD, professor in the department of rehabilitation sciences and head of the neurorehabilitation research group at the University of Leuven, Belgium, disagreed that exercise type is of secondary importance in Parkinson’s disease.

“In my view, it’s of primary interest, especially at the mid- to later stages,” said Dr. Nieuwboer, who was not involved with the research.

She noted it is difficult to carry out meta-analyses of resistance training versus other interventions because studies comparing different exercise types “are rather scarce.”

“Another issue is that the dose may differ, so you’re comparing apples with pears,” said Dr. Nieuwboer.

She did agree that all patients should exercise, because it is “better than no exercise,” and they should be “free to choose a mode that interests them.”

However, she stressed that exercise requires significant effort on the part of patients with Parkinson’s disease, requires “sustained motivation,” and has to become habit-forming. This makes “exercise targeting” very important, with the target changing over the disease course, Dr. Nieuwboer said.

For example, for a patient at an early stage of the disease who can still move quite well, both resistance training and endurance training can improve fitness and health; but at a mid-stage, it is perhaps better for patients to work on balance and walking quality “to preempt the risk of falls and developing freezing,” she noted.

Later on, as movement becomes very difficult, “the exercise menu is even more restricted,” said Dr. Nieuwboer.

The bottom line is that a message saying “any movement counts” is an oversimplification, she added.

The study was funded by a grant from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. The investigators and Dr. Nieuwboer have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

A meta-analysis, which included 18 randomized controlled trials and more than 1,000 patients with Parkinson’s disease, showed that those who underwent resistance training had significantly greater improvement in motor impairment, muscle strength, and mobility/balance than their peers who underwent passive or placebo interventions.

However, there was no significant difference between patients who participated in resistance training and those who participated in other active physical interventions, including yoga.

Overall, the results highlight the importance that these patients should participate in some type of physical exercise, said the study’s lead author, Romina Gollan, MSc, an assistant researcher in the division of medical psychology, University of Cologne, Germany. “Patients should definitely be doing exercises, including resistance training, if they want to. But the type of exercise is of secondary interest,” she said.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Positive but inconsistent

Previous reviews have suggested resistance training has positive effects on motor function in Parkinson’s disease. However, results from the included studies were inconsistent; and few reviews have examined nonmotor outcomes of resistance training in this population, the investigators noted.

After carrying out a literature search of studies that examined the effects of resistance training in Parkinson’s disease, the researchers included 18 randomized controlled trials in their current review. Among the 1,134 total participants, the mean age was 66 years, the mean Hoehn & Yahr stage was 2.3 (range 0-4), and the mean duration of Parkinson’s disease was 7.5 years.

The investigation was grouped into two meta-analysis groups: one examining resistance training versus a passive or placebo intervention and the other assessing resistance training versus active physical interventions, such as yoga.

During resistance training, participants use their full strength to do a repetition, working muscles to overcome a certain threshold, said Ms. Gollan. In contrast, a placebo intervention is “very low intensity” and involves a much lower threshold, she added.

Passive interventions include such things as stretching where the stimulus “is not high enough for muscles to adapt” and build strength, Ms. Gollan noted.

A passive intervention might also include “treatment as usual” or normal daily routines.

Patient preference important

The meta-analysis comparing resistance training groups with passive control groups showed significant large effects on muscle strength (standard mean difference, –0.84; 95% confidence interval, –1.29 to –0.39; P = .0003), motor impairment (SMD, –0.81; 95% CI, –1.34 to –0.27; P = .003), and mobility and balance (SMD, –1.80; 95% CI, –3.13 to –0.49; P = .007).

The review also showed significant but small effects on quality of life.

However, the meta-analysis that assessed resistance training versus other physical interventions showed no significant between-group differences.

Ms. Gollan noted that although there were some assessments of cognition and depression, the data were too limited to determine the impact of resistance training on these outcomes.

“We need more studies, especially randomized controlled trials, to investigate the effects of resistance training on nonmotor outcomes like depression and cognition,” she said.

Co-investigator Ann-Kristin Folkerts, PhD, who heads the University of Cologne medical psychology working group, noted that although exercise in general is beneficial for patients with Parkinson’s disease, the choice of activity should take patient preferences into consideration.

It is important that patients choose an exercise they enjoy “because otherwise they probably wouldn’t adhere to the treatment,” Dr. Folkerts said. “It’s important to have fun.”

Specific goals or objectives, such as improving quality of life or balance, should also be considered, she added.

Oversimplification?

Commenting on the research, Alice Nieuwboer, PhD, professor in the department of rehabilitation sciences and head of the neurorehabilitation research group at the University of Leuven, Belgium, disagreed that exercise type is of secondary importance in Parkinson’s disease.

“In my view, it’s of primary interest, especially at the mid- to later stages,” said Dr. Nieuwboer, who was not involved with the research.

She noted it is difficult to carry out meta-analyses of resistance training versus other interventions because studies comparing different exercise types “are rather scarce.”

“Another issue is that the dose may differ, so you’re comparing apples with pears,” said Dr. Nieuwboer.

She did agree that all patients should exercise, because it is “better than no exercise,” and they should be “free to choose a mode that interests them.”

However, she stressed that exercise requires significant effort on the part of patients with Parkinson’s disease, requires “sustained motivation,” and has to become habit-forming. This makes “exercise targeting” very important, with the target changing over the disease course, Dr. Nieuwboer said.

For example, for a patient at an early stage of the disease who can still move quite well, both resistance training and endurance training can improve fitness and health; but at a mid-stage, it is perhaps better for patients to work on balance and walking quality “to preempt the risk of falls and developing freezing,” she noted.

Later on, as movement becomes very difficult, “the exercise menu is even more restricted,” said Dr. Nieuwboer.

The bottom line is that a message saying “any movement counts” is an oversimplification, she added.

The study was funded by a grant from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. The investigators and Dr. Nieuwboer have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MDS 2022

How do patients with chronic urticaria fare during pregnancy?

In addition, the rates of preterm births and medical problems of newborns in patients with CU are similar to those of the normal population and not linked to treatment used during pregnancy.

Those are the key findings from an analysis of new data from PREG-CU, an international, multicenter study of the Urticaria Centers of Reference and Excellence (UCARE) network. Results from the first PREG-CU analysis published in 2021 found that CU improved in about half of patients with CU during pregnancy. “However, two in five patients reported acute exacerbations of CU especially at the beginning and end of pregnancy,” investigators led by Emek Kocatürk, MD, of the department of dermatology and UCARE at Koç University School of Medicine, Istanbul, wrote in the new study, recently published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“In addition, 1 in 10 pregnant CU patients required urticaria emergency care and 1 of 6 had angioedema during pregnancy,” they said. Risk factors for worsening CU during pregnancy, they added, were “mild disease and no angioedema before pregnancy, not taking treatment before pregnancy, chronic inducible urticaria, CU worsening during a previous pregnancy, stress as a driver of exacerbations, and treatment during pregnancy.”

Analysis involved 288 pregnant women

To optimize treatment of CU during pregnancy and to better understand how treatment affects pregnancy outcomes, the researchers analyzed 288 pregnancies in 288 women with CU from 13 countries and 21 centers worldwide. Their mean age at pregnancy was 32.1 years, and their mean duration of CU was 84.9 months. Prior to pregnancy, 35.7% of patients rated the severity of their CU symptoms as mild, 34.2% rated it as moderate, and 29.7% rated it as severe.

The researchers found that during pregnancy, 60% of patients used urticaria medication, including standard-dose second-generation H1-antihistamines (35.1%), first-generation H1-antihistamines (7.6%), high-dose second-generation H1-antihistamines (5.6%), and omalizumab (5.6%). The preterm birth rate was 10.2%, which was similar between patients who did and did not receive treatment during pregnancy (11.6% vs. 8.7%, respectively; P = .59).

On multivariate logistic regression, two predictors for preterm birth emerged: giving birth to twins (a 13.3-fold increased risk; P = .016) and emergency referrals for CU (a 4.3-fold increased risk; P =.016). The cesarean delivery rate was 51.3%, and more than 90% of newborns were healthy at birth. There was no link between any patient or disease characteristics or treatments and medical problems at birth.

In other findings, 78.8% of women with CU breastfed their babies. Of the 58 patients who did not breastfeed, 20.7% indicated severe urticaria/angioedema and/or taking medications as the main reason for not breastfeeding.

“Most CU patients use treatment during pregnancy and such treatments, especially second generation H1 antihistamines, seem to be safe during pregnancy regardless of the trimester,” the researchers concluded. “Outcomes of pregnancy in patients with CU were similar compared to the general population and not linked to treatment used during pregnancy. Notably, emergency referral for CU was an independent risk factor for preterm birth,” and the high cesarean delivery rate was “probably linked to comorbidities associated with the disease,” they added. “Overall, these findings suggest that patients should continue their treatments using an individualized dose to provide optimal symptom control.”

International guidelines

The authors noted that international guidelines for the management of urticaria published in 2022 suggest that modern second-generation H1-antihistamines should be used for pregnant patients, preferably loratadine with a possible extrapolation to desloratadine, cetirizine, or levocetirizine.

“Similarly, in this population, we found that cetirizine and loratadine were the most commonly used antihistamines, followed by levocetirizine and fexofenadine,” Dr. Kocatürk and colleagues wrote.

“Guidelines also suggest that the use of first-generation H1-antihistamines should be avoided given their sedative effects; but if these are to be given, it would be wise to know that use of first-generation H1-antihistamines immediately before parturition could cause respiratory depression and other adverse effects in the neonate,” they added, noting that chlorpheniramine and diphenhydramine are the first-generation H1-antihistamines with the greatest evidence of safety in pregnancy.

They acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its retrospective design and the fact that there were no data on low birth weight, small for gestational age, or miscarriage rates. In addition, disease activity or severity during pregnancy and after birth were not monitored.

Asked to comment on these results, Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, who directs the center for eczema and itch in the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, noted that despite a higher prevalence of CU among females compared with males, very little is known about how the condition is managed during pregnancy. “This retrospective study shows that most patients continue to utilize CU treatment during pregnancy (primarily second-generation antihistamines), with similar birth outcomes as the general population,” he said. “Interestingly, cesarean rates were higher among mothers with CU, and emergency CU referral was a risk factor for preterm birth. While additional prospective studies are needed, these results suggest that CU patients should be carefully managed, particularly during pregnancy, when treatment should be optimized.”

Dr. Kocatürk reported having received personal fees from Novartis, Ibrahim Etem-Menarini, and Sanofi, outside the submitted work. Many coauthors reported having numerous financial disclosures. Dr. Chovatiya disclosed that he is a consultant to, a speaker for, and/or a member of the advisory board for AbbVie, Arcutis, Arena, Incyte, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi Genzyme.

In addition, the rates of preterm births and medical problems of newborns in patients with CU are similar to those of the normal population and not linked to treatment used during pregnancy.

Those are the key findings from an analysis of new data from PREG-CU, an international, multicenter study of the Urticaria Centers of Reference and Excellence (UCARE) network. Results from the first PREG-CU analysis published in 2021 found that CU improved in about half of patients with CU during pregnancy. “However, two in five patients reported acute exacerbations of CU especially at the beginning and end of pregnancy,” investigators led by Emek Kocatürk, MD, of the department of dermatology and UCARE at Koç University School of Medicine, Istanbul, wrote in the new study, recently published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“In addition, 1 in 10 pregnant CU patients required urticaria emergency care and 1 of 6 had angioedema during pregnancy,” they said. Risk factors for worsening CU during pregnancy, they added, were “mild disease and no angioedema before pregnancy, not taking treatment before pregnancy, chronic inducible urticaria, CU worsening during a previous pregnancy, stress as a driver of exacerbations, and treatment during pregnancy.”

Analysis involved 288 pregnant women

To optimize treatment of CU during pregnancy and to better understand how treatment affects pregnancy outcomes, the researchers analyzed 288 pregnancies in 288 women with CU from 13 countries and 21 centers worldwide. Their mean age at pregnancy was 32.1 years, and their mean duration of CU was 84.9 months. Prior to pregnancy, 35.7% of patients rated the severity of their CU symptoms as mild, 34.2% rated it as moderate, and 29.7% rated it as severe.

The researchers found that during pregnancy, 60% of patients used urticaria medication, including standard-dose second-generation H1-antihistamines (35.1%), first-generation H1-antihistamines (7.6%), high-dose second-generation H1-antihistamines (5.6%), and omalizumab (5.6%). The preterm birth rate was 10.2%, which was similar between patients who did and did not receive treatment during pregnancy (11.6% vs. 8.7%, respectively; P = .59).

On multivariate logistic regression, two predictors for preterm birth emerged: giving birth to twins (a 13.3-fold increased risk; P = .016) and emergency referrals for CU (a 4.3-fold increased risk; P =.016). The cesarean delivery rate was 51.3%, and more than 90% of newborns were healthy at birth. There was no link between any patient or disease characteristics or treatments and medical problems at birth.

In other findings, 78.8% of women with CU breastfed their babies. Of the 58 patients who did not breastfeed, 20.7% indicated severe urticaria/angioedema and/or taking medications as the main reason for not breastfeeding.

“Most CU patients use treatment during pregnancy and such treatments, especially second generation H1 antihistamines, seem to be safe during pregnancy regardless of the trimester,” the researchers concluded. “Outcomes of pregnancy in patients with CU were similar compared to the general population and not linked to treatment used during pregnancy. Notably, emergency referral for CU was an independent risk factor for preterm birth,” and the high cesarean delivery rate was “probably linked to comorbidities associated with the disease,” they added. “Overall, these findings suggest that patients should continue their treatments using an individualized dose to provide optimal symptom control.”

International guidelines