User login

Poor evidence for vaginal laser therapy

Despite a lack of evidence and high cost, laser therapy continues to attract many women seeking “vaginal rejuvenation” to help reverse the physical symptoms of menopause.

Recent reviews of the medical literature continue to show that laser treatment appears to be less effective than estrogen at improving vaginal dryness and pain during sex, according to Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD, a professor of ob.gyn. and urology at Georgetown University, Washington.

“Laser for GSM [genitourinary syndrome of menopause] is showing some promise, but patients need to be offered [Food and Drug Administration]–approved treatments prior to considering laser, and users need to know how to do speculum and pelvic exams and understand vulvovaginal anatomy and pathology,” Dr. Iglesia, who directs the section of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery at MedStar Washington Hospital Center, said in an interview, adding that patients should avoid “vaginal rejuvenation” treatments offered at med-spas.

Dr. Iglesia reviewed how these lasers work and then discussed the controversy over their marketing and the evidence for their use at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

By 3 years after menopause, more than half of women experience atrophy in their vagina resulting from a lack of estrogen. Marked by a thinning of the epithelium, reduced blood supply, and loss of glycogen, vulvovaginal atrophy is to blame for GSM.

Vaginal laser therapy has been a popular option for women for the last decade, despite a lack of evidence supporting its use or approval from regulators.

The FDA has issued broad clearance for laser therapy for incision, ablation, vaporization, and coagulation of body soft tissues, such as dysplasia, vulvar or anal neoplasia, endometriosis, condylomas, and other disorders. However, the agency has not approved the use of laser therapy for vulvovaginal atrophy, GSM, vaginal dryness, or dyspareunia.

Evidence regarding vaginal laser therapy

According to Dr. Iglesia, the evidence for vaginal laser therapy is mixed and of generally low quality. A systematic review published in the Journal of Sexual Medicine (2022 Jan 29. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.12.010) presented mostly low-quality evidence from 25 studies and found promising data for genitourinary symptoms but not enough to justify its use for genitourinary symptoms just yet. Dr. Iglesia discussed her own small, multisite study of 62 participants, which compared vaginal laser with vaginal estrogen and found no differences between the two for multiple outcomes. (The study would have been larger if not for interruption from an FDA warning for an Investigational Device Exemption.)

A JAMA study from Australia found no difference between laser therapy and sham laser therapy, but the most recent systematic review, from JAMA Network Open, found no significant difference between vaginal laser and vaginal estrogen for vaginal and sexual function symptoms. This review, however, covered only the six existing randomized controlled trials, including Dr. Iglesia’s, which were small and had a follow-up period of only 3-6 months.

“There have only been a few randomized controlled trials comparing laser to vaginal estrogen therapy, and most of those did not include a placebo or sham arm,” Monica Christmas, MD, director of the Center for Women’s Integrated Health at the University of Chicago Medicine, said in an interview. “This is extremely important, as most of the trials that did include a sham arm did not find that laser was better than the sham.” Dr. Christmas was not a part of the presentation but attended it at NAMS.

The bottom line, she said, is that “current evidence is not sufficient to make conclusions on long-term safety or sustainability, nor is there compelling evidence to make claims on equivalence to vaginal estrogen therapy.” Currently, committee opinions from a half-dozen medical societies, including NAMS, oppose using vaginal laser therapy until rigorous, robust trials on long-term safety and efficacy have been conducted. The International Continence Society and International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease issued a joint statement in 2018 that emphasized that histologic changes from lasers do not necessarily equate with changes in function. The statement noted the lack of evidence for laser treatment of incontinence and prolapse and stated that it should not be used for vulvodynia or lichen sclerosus.

A 2020 statement from NAMS found “insufficient placebo-controlled trials of energy-based therapies, including laser, to draw conclusions of efficacy or safety or to make treatment recommendations.” A slightly more optimistic statement from the American Urogynecologic Society concluded that energy-based devices have shown short-term efficacy for menopause-related vaginal atrophy and dyspareunia, including effects lasting up to 1 year from fractionated laser for treat dyspareunia, but also noted that studies up to that time were small and measure various outcomes.

Recommendations on vaginal laser therapy

Given this landscape of uneven and poor-quality evidence, Dr. Iglesia provided several “common sense” recommendations for energy-based therapies, starting with the need for any practitioner to have working knowledge of vulvovaginal anatomy. Contraindications for laser therapy include any malignancy – especially gynecologic – undiagnosed bleeding, active herpes or other infections, radiation, and vaginal mesh, particularly transvaginal mesh. The provider also must discuss the limited data on long-term function and treatment alternatives, including FDA-approved therapies like topical estrogen, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), ospemifene, and moisturizers, Dr. Iglesia said.

Adverse events associated with laser therapy, such as scarring or burning, are rare but do occur, and cost remains an issue, Dr. Iglesia said.

“Vaginal estrogen therapy is well established as a safe and effective treatment option based on high quality evidence,” Dr. Christmas said. “This is not the case for laser therapy. Rare, but serious harms are reported with vaginal laser, including burns, scarring, dyspareunia, pain, and potential irreversible damage.”

Dr. Iglesia also cautioned that clinicians should take extra care with vulnerable populations, particularly cancer patients and others with contraindications for estrogen treatment.

For those in whom vaginal estrogen is contraindicated, Dr. Christmas recommended vaginal moisturizers, lubricants, dilators, and physical therapy for the pelvic floor.

“In patients who fail those nonhormonal approaches, short courses of vaginal estrogen therapy or DHEA-S suppository may be employed with approval from their oncologist,” Dr. Christmas said.

Dr. Iglesia finally reviewed the major research questions that remain with laser therapy:

- What are outcomes for laser versus sham studies?

- What are long-term outcomes (beyond 6 months)

- What pretreatment is necessary?

- Could laser be used as a drug delivery mechanism for estrogen, and could this provide a synergistic effect?

- What is the optimal number and interval for laser treatments?

Dr. Iglesia had no industry disclosures but received honoraria for consulting at UpToDate. Dr. Christmas is a consultant for Materna. The presentation did not rely on any external funding.

Despite a lack of evidence and high cost, laser therapy continues to attract many women seeking “vaginal rejuvenation” to help reverse the physical symptoms of menopause.

Recent reviews of the medical literature continue to show that laser treatment appears to be less effective than estrogen at improving vaginal dryness and pain during sex, according to Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD, a professor of ob.gyn. and urology at Georgetown University, Washington.

“Laser for GSM [genitourinary syndrome of menopause] is showing some promise, but patients need to be offered [Food and Drug Administration]–approved treatments prior to considering laser, and users need to know how to do speculum and pelvic exams and understand vulvovaginal anatomy and pathology,” Dr. Iglesia, who directs the section of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery at MedStar Washington Hospital Center, said in an interview, adding that patients should avoid “vaginal rejuvenation” treatments offered at med-spas.

Dr. Iglesia reviewed how these lasers work and then discussed the controversy over their marketing and the evidence for their use at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

By 3 years after menopause, more than half of women experience atrophy in their vagina resulting from a lack of estrogen. Marked by a thinning of the epithelium, reduced blood supply, and loss of glycogen, vulvovaginal atrophy is to blame for GSM.

Vaginal laser therapy has been a popular option for women for the last decade, despite a lack of evidence supporting its use or approval from regulators.

The FDA has issued broad clearance for laser therapy for incision, ablation, vaporization, and coagulation of body soft tissues, such as dysplasia, vulvar or anal neoplasia, endometriosis, condylomas, and other disorders. However, the agency has not approved the use of laser therapy for vulvovaginal atrophy, GSM, vaginal dryness, or dyspareunia.

Evidence regarding vaginal laser therapy

According to Dr. Iglesia, the evidence for vaginal laser therapy is mixed and of generally low quality. A systematic review published in the Journal of Sexual Medicine (2022 Jan 29. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.12.010) presented mostly low-quality evidence from 25 studies and found promising data for genitourinary symptoms but not enough to justify its use for genitourinary symptoms just yet. Dr. Iglesia discussed her own small, multisite study of 62 participants, which compared vaginal laser with vaginal estrogen and found no differences between the two for multiple outcomes. (The study would have been larger if not for interruption from an FDA warning for an Investigational Device Exemption.)

A JAMA study from Australia found no difference between laser therapy and sham laser therapy, but the most recent systematic review, from JAMA Network Open, found no significant difference between vaginal laser and vaginal estrogen for vaginal and sexual function symptoms. This review, however, covered only the six existing randomized controlled trials, including Dr. Iglesia’s, which were small and had a follow-up period of only 3-6 months.

“There have only been a few randomized controlled trials comparing laser to vaginal estrogen therapy, and most of those did not include a placebo or sham arm,” Monica Christmas, MD, director of the Center for Women’s Integrated Health at the University of Chicago Medicine, said in an interview. “This is extremely important, as most of the trials that did include a sham arm did not find that laser was better than the sham.” Dr. Christmas was not a part of the presentation but attended it at NAMS.

The bottom line, she said, is that “current evidence is not sufficient to make conclusions on long-term safety or sustainability, nor is there compelling evidence to make claims on equivalence to vaginal estrogen therapy.” Currently, committee opinions from a half-dozen medical societies, including NAMS, oppose using vaginal laser therapy until rigorous, robust trials on long-term safety and efficacy have been conducted. The International Continence Society and International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease issued a joint statement in 2018 that emphasized that histologic changes from lasers do not necessarily equate with changes in function. The statement noted the lack of evidence for laser treatment of incontinence and prolapse and stated that it should not be used for vulvodynia or lichen sclerosus.

A 2020 statement from NAMS found “insufficient placebo-controlled trials of energy-based therapies, including laser, to draw conclusions of efficacy or safety or to make treatment recommendations.” A slightly more optimistic statement from the American Urogynecologic Society concluded that energy-based devices have shown short-term efficacy for menopause-related vaginal atrophy and dyspareunia, including effects lasting up to 1 year from fractionated laser for treat dyspareunia, but also noted that studies up to that time were small and measure various outcomes.

Recommendations on vaginal laser therapy

Given this landscape of uneven and poor-quality evidence, Dr. Iglesia provided several “common sense” recommendations for energy-based therapies, starting with the need for any practitioner to have working knowledge of vulvovaginal anatomy. Contraindications for laser therapy include any malignancy – especially gynecologic – undiagnosed bleeding, active herpes or other infections, radiation, and vaginal mesh, particularly transvaginal mesh. The provider also must discuss the limited data on long-term function and treatment alternatives, including FDA-approved therapies like topical estrogen, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), ospemifene, and moisturizers, Dr. Iglesia said.

Adverse events associated with laser therapy, such as scarring or burning, are rare but do occur, and cost remains an issue, Dr. Iglesia said.

“Vaginal estrogen therapy is well established as a safe and effective treatment option based on high quality evidence,” Dr. Christmas said. “This is not the case for laser therapy. Rare, but serious harms are reported with vaginal laser, including burns, scarring, dyspareunia, pain, and potential irreversible damage.”

Dr. Iglesia also cautioned that clinicians should take extra care with vulnerable populations, particularly cancer patients and others with contraindications for estrogen treatment.

For those in whom vaginal estrogen is contraindicated, Dr. Christmas recommended vaginal moisturizers, lubricants, dilators, and physical therapy for the pelvic floor.

“In patients who fail those nonhormonal approaches, short courses of vaginal estrogen therapy or DHEA-S suppository may be employed with approval from their oncologist,” Dr. Christmas said.

Dr. Iglesia finally reviewed the major research questions that remain with laser therapy:

- What are outcomes for laser versus sham studies?

- What are long-term outcomes (beyond 6 months)

- What pretreatment is necessary?

- Could laser be used as a drug delivery mechanism for estrogen, and could this provide a synergistic effect?

- What is the optimal number and interval for laser treatments?

Dr. Iglesia had no industry disclosures but received honoraria for consulting at UpToDate. Dr. Christmas is a consultant for Materna. The presentation did not rely on any external funding.

Despite a lack of evidence and high cost, laser therapy continues to attract many women seeking “vaginal rejuvenation” to help reverse the physical symptoms of menopause.

Recent reviews of the medical literature continue to show that laser treatment appears to be less effective than estrogen at improving vaginal dryness and pain during sex, according to Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD, a professor of ob.gyn. and urology at Georgetown University, Washington.

“Laser for GSM [genitourinary syndrome of menopause] is showing some promise, but patients need to be offered [Food and Drug Administration]–approved treatments prior to considering laser, and users need to know how to do speculum and pelvic exams and understand vulvovaginal anatomy and pathology,” Dr. Iglesia, who directs the section of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery at MedStar Washington Hospital Center, said in an interview, adding that patients should avoid “vaginal rejuvenation” treatments offered at med-spas.

Dr. Iglesia reviewed how these lasers work and then discussed the controversy over their marketing and the evidence for their use at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

By 3 years after menopause, more than half of women experience atrophy in their vagina resulting from a lack of estrogen. Marked by a thinning of the epithelium, reduced blood supply, and loss of glycogen, vulvovaginal atrophy is to blame for GSM.

Vaginal laser therapy has been a popular option for women for the last decade, despite a lack of evidence supporting its use or approval from regulators.

The FDA has issued broad clearance for laser therapy for incision, ablation, vaporization, and coagulation of body soft tissues, such as dysplasia, vulvar or anal neoplasia, endometriosis, condylomas, and other disorders. However, the agency has not approved the use of laser therapy for vulvovaginal atrophy, GSM, vaginal dryness, or dyspareunia.

Evidence regarding vaginal laser therapy

According to Dr. Iglesia, the evidence for vaginal laser therapy is mixed and of generally low quality. A systematic review published in the Journal of Sexual Medicine (2022 Jan 29. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.12.010) presented mostly low-quality evidence from 25 studies and found promising data for genitourinary symptoms but not enough to justify its use for genitourinary symptoms just yet. Dr. Iglesia discussed her own small, multisite study of 62 participants, which compared vaginal laser with vaginal estrogen and found no differences between the two for multiple outcomes. (The study would have been larger if not for interruption from an FDA warning for an Investigational Device Exemption.)

A JAMA study from Australia found no difference between laser therapy and sham laser therapy, but the most recent systematic review, from JAMA Network Open, found no significant difference between vaginal laser and vaginal estrogen for vaginal and sexual function symptoms. This review, however, covered only the six existing randomized controlled trials, including Dr. Iglesia’s, which were small and had a follow-up period of only 3-6 months.

“There have only been a few randomized controlled trials comparing laser to vaginal estrogen therapy, and most of those did not include a placebo or sham arm,” Monica Christmas, MD, director of the Center for Women’s Integrated Health at the University of Chicago Medicine, said in an interview. “This is extremely important, as most of the trials that did include a sham arm did not find that laser was better than the sham.” Dr. Christmas was not a part of the presentation but attended it at NAMS.

The bottom line, she said, is that “current evidence is not sufficient to make conclusions on long-term safety or sustainability, nor is there compelling evidence to make claims on equivalence to vaginal estrogen therapy.” Currently, committee opinions from a half-dozen medical societies, including NAMS, oppose using vaginal laser therapy until rigorous, robust trials on long-term safety and efficacy have been conducted. The International Continence Society and International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease issued a joint statement in 2018 that emphasized that histologic changes from lasers do not necessarily equate with changes in function. The statement noted the lack of evidence for laser treatment of incontinence and prolapse and stated that it should not be used for vulvodynia or lichen sclerosus.

A 2020 statement from NAMS found “insufficient placebo-controlled trials of energy-based therapies, including laser, to draw conclusions of efficacy or safety or to make treatment recommendations.” A slightly more optimistic statement from the American Urogynecologic Society concluded that energy-based devices have shown short-term efficacy for menopause-related vaginal atrophy and dyspareunia, including effects lasting up to 1 year from fractionated laser for treat dyspareunia, but also noted that studies up to that time were small and measure various outcomes.

Recommendations on vaginal laser therapy

Given this landscape of uneven and poor-quality evidence, Dr. Iglesia provided several “common sense” recommendations for energy-based therapies, starting with the need for any practitioner to have working knowledge of vulvovaginal anatomy. Contraindications for laser therapy include any malignancy – especially gynecologic – undiagnosed bleeding, active herpes or other infections, radiation, and vaginal mesh, particularly transvaginal mesh. The provider also must discuss the limited data on long-term function and treatment alternatives, including FDA-approved therapies like topical estrogen, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), ospemifene, and moisturizers, Dr. Iglesia said.

Adverse events associated with laser therapy, such as scarring or burning, are rare but do occur, and cost remains an issue, Dr. Iglesia said.

“Vaginal estrogen therapy is well established as a safe and effective treatment option based on high quality evidence,” Dr. Christmas said. “This is not the case for laser therapy. Rare, but serious harms are reported with vaginal laser, including burns, scarring, dyspareunia, pain, and potential irreversible damage.”

Dr. Iglesia also cautioned that clinicians should take extra care with vulnerable populations, particularly cancer patients and others with contraindications for estrogen treatment.

For those in whom vaginal estrogen is contraindicated, Dr. Christmas recommended vaginal moisturizers, lubricants, dilators, and physical therapy for the pelvic floor.

“In patients who fail those nonhormonal approaches, short courses of vaginal estrogen therapy or DHEA-S suppository may be employed with approval from their oncologist,” Dr. Christmas said.

Dr. Iglesia finally reviewed the major research questions that remain with laser therapy:

- What are outcomes for laser versus sham studies?

- What are long-term outcomes (beyond 6 months)

- What pretreatment is necessary?

- Could laser be used as a drug delivery mechanism for estrogen, and could this provide a synergistic effect?

- What is the optimal number and interval for laser treatments?

Dr. Iglesia had no industry disclosures but received honoraria for consulting at UpToDate. Dr. Christmas is a consultant for Materna. The presentation did not rely on any external funding.

FROM NAMS 2022

Chest reconstruction surgeries up nearly fourfold among adolescents

The number of chest reconstruction surgeries performed for adolescents rose nearly fourfold between 2016 and 2019, researchers report in a study published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“To our knowledge, this study is the largest investigation to date of gender-affirming chest reconstruction in a pediatric population. The results demonstrate substantial increases in gender-affirming chest reconstruction for adolescents,” the authors report.

The researchers, from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn., used the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample to identify youth with gender dysphoria who underwent top surgery to remove, or, in rare cases, to add breasts.

The authors identified 829 chest surgeries. They adjusted the number to a weighted figure of 1,130 patients who underwent chest reconstruction during the study period. Of those, 98.6% underwent masculinizing surgery to remove breasts, and 1.4% underwent feminizing surgery. Roughly 100 individuals received gender-affirming chest surgeries in 2016. In 2019, the number had risen to 489 – a 389% increase, the authors reported.

Approximately 44% of the patients in the study were aged 17 years at the time of surgery, while 5.5% were younger than 14.

Around 78% of the individuals who underwent chest surgeries in 2019 were White, 2.7% were Black, 12.2% were Hispanic, and 2.5% were Asian or Pacific Islander. Half of the patients who underwent surgery had a household income of $82,000 or more, according to the researchers.

“Most transgender adolescents had either public or private health insurance coverage for these procedures, contrasting with the predominance of self-payers reported in earlier studies on transgender adults,” write the researchers, citing a 2018 study of trends in transgender surgery.

Masculinizing chest reconstruction, such as mastectomy, and feminizing chest reconstruction, such as augmentation mammaplasty, can be performed as outpatient procedures or as ambulatory surgeries, according to another study .

The study was supported by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program. One author has reported receiving grant funding from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The number of chest reconstruction surgeries performed for adolescents rose nearly fourfold between 2016 and 2019, researchers report in a study published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“To our knowledge, this study is the largest investigation to date of gender-affirming chest reconstruction in a pediatric population. The results demonstrate substantial increases in gender-affirming chest reconstruction for adolescents,” the authors report.

The researchers, from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn., used the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample to identify youth with gender dysphoria who underwent top surgery to remove, or, in rare cases, to add breasts.

The authors identified 829 chest surgeries. They adjusted the number to a weighted figure of 1,130 patients who underwent chest reconstruction during the study period. Of those, 98.6% underwent masculinizing surgery to remove breasts, and 1.4% underwent feminizing surgery. Roughly 100 individuals received gender-affirming chest surgeries in 2016. In 2019, the number had risen to 489 – a 389% increase, the authors reported.

Approximately 44% of the patients in the study were aged 17 years at the time of surgery, while 5.5% were younger than 14.

Around 78% of the individuals who underwent chest surgeries in 2019 were White, 2.7% were Black, 12.2% were Hispanic, and 2.5% were Asian or Pacific Islander. Half of the patients who underwent surgery had a household income of $82,000 or more, according to the researchers.

“Most transgender adolescents had either public or private health insurance coverage for these procedures, contrasting with the predominance of self-payers reported in earlier studies on transgender adults,” write the researchers, citing a 2018 study of trends in transgender surgery.

Masculinizing chest reconstruction, such as mastectomy, and feminizing chest reconstruction, such as augmentation mammaplasty, can be performed as outpatient procedures or as ambulatory surgeries, according to another study .

The study was supported by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program. One author has reported receiving grant funding from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The number of chest reconstruction surgeries performed for adolescents rose nearly fourfold between 2016 and 2019, researchers report in a study published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“To our knowledge, this study is the largest investigation to date of gender-affirming chest reconstruction in a pediatric population. The results demonstrate substantial increases in gender-affirming chest reconstruction for adolescents,” the authors report.

The researchers, from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn., used the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample to identify youth with gender dysphoria who underwent top surgery to remove, or, in rare cases, to add breasts.

The authors identified 829 chest surgeries. They adjusted the number to a weighted figure of 1,130 patients who underwent chest reconstruction during the study period. Of those, 98.6% underwent masculinizing surgery to remove breasts, and 1.4% underwent feminizing surgery. Roughly 100 individuals received gender-affirming chest surgeries in 2016. In 2019, the number had risen to 489 – a 389% increase, the authors reported.

Approximately 44% of the patients in the study were aged 17 years at the time of surgery, while 5.5% were younger than 14.

Around 78% of the individuals who underwent chest surgeries in 2019 were White, 2.7% were Black, 12.2% were Hispanic, and 2.5% were Asian or Pacific Islander. Half of the patients who underwent surgery had a household income of $82,000 or more, according to the researchers.

“Most transgender adolescents had either public or private health insurance coverage for these procedures, contrasting with the predominance of self-payers reported in earlier studies on transgender adults,” write the researchers, citing a 2018 study of trends in transgender surgery.

Masculinizing chest reconstruction, such as mastectomy, and feminizing chest reconstruction, such as augmentation mammaplasty, can be performed as outpatient procedures or as ambulatory surgeries, according to another study .

The study was supported by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program. One author has reported receiving grant funding from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

FDA OKs Medtronic lead for left bundle branch pacing

Labeling for a Medtronic pacing lead, already indicated for stimulation of the His bundle, has been expanded to include the left bundle branch (LBB), the company announced on Oct. 17.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration previously expanded the Medtronic SelectSecure MRI SureScan Model 3830 lead’s approval in 2018 to include His-bundle pacing. “Now this cardiac lead is approved for pacing and sensing at the bundle of His or in the left bundle branch area as an alternative to apical pacing in the right ventricle in a single- or dual-chamber pacing system,” Medtronic states in a press release.

The Model 3830 lead was initially approved for atrial or right ventricular pacing and sensing, the announcement says, and now “has more than 20 years of proven performance and reliability.”

The newly expanded conduction system pacing indication is “based on evidence from multiple sources spanning more than 20,000 treated patients,” for which the company cited “Medtronic data on file.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Labeling for a Medtronic pacing lead, already indicated for stimulation of the His bundle, has been expanded to include the left bundle branch (LBB), the company announced on Oct. 17.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration previously expanded the Medtronic SelectSecure MRI SureScan Model 3830 lead’s approval in 2018 to include His-bundle pacing. “Now this cardiac lead is approved for pacing and sensing at the bundle of His or in the left bundle branch area as an alternative to apical pacing in the right ventricle in a single- or dual-chamber pacing system,” Medtronic states in a press release.

The Model 3830 lead was initially approved for atrial or right ventricular pacing and sensing, the announcement says, and now “has more than 20 years of proven performance and reliability.”

The newly expanded conduction system pacing indication is “based on evidence from multiple sources spanning more than 20,000 treated patients,” for which the company cited “Medtronic data on file.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Labeling for a Medtronic pacing lead, already indicated for stimulation of the His bundle, has been expanded to include the left bundle branch (LBB), the company announced on Oct. 17.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration previously expanded the Medtronic SelectSecure MRI SureScan Model 3830 lead’s approval in 2018 to include His-bundle pacing. “Now this cardiac lead is approved for pacing and sensing at the bundle of His or in the left bundle branch area as an alternative to apical pacing in the right ventricle in a single- or dual-chamber pacing system,” Medtronic states in a press release.

The Model 3830 lead was initially approved for atrial or right ventricular pacing and sensing, the announcement says, and now “has more than 20 years of proven performance and reliability.”

The newly expanded conduction system pacing indication is “based on evidence from multiple sources spanning more than 20,000 treated patients,” for which the company cited “Medtronic data on file.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nonblanching Rash on the Legs and Chest

The Diagnosis: Leukemia Cutis

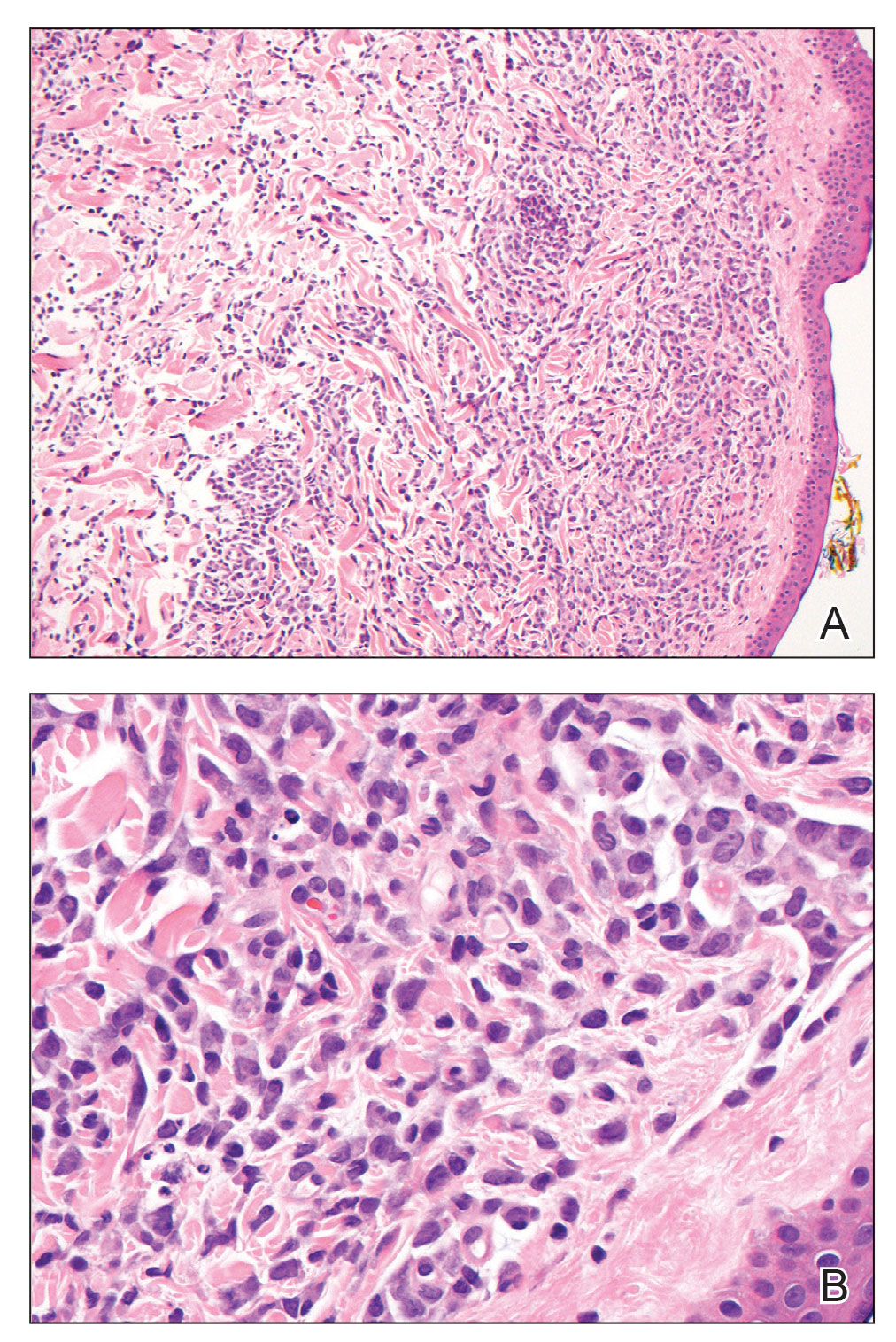

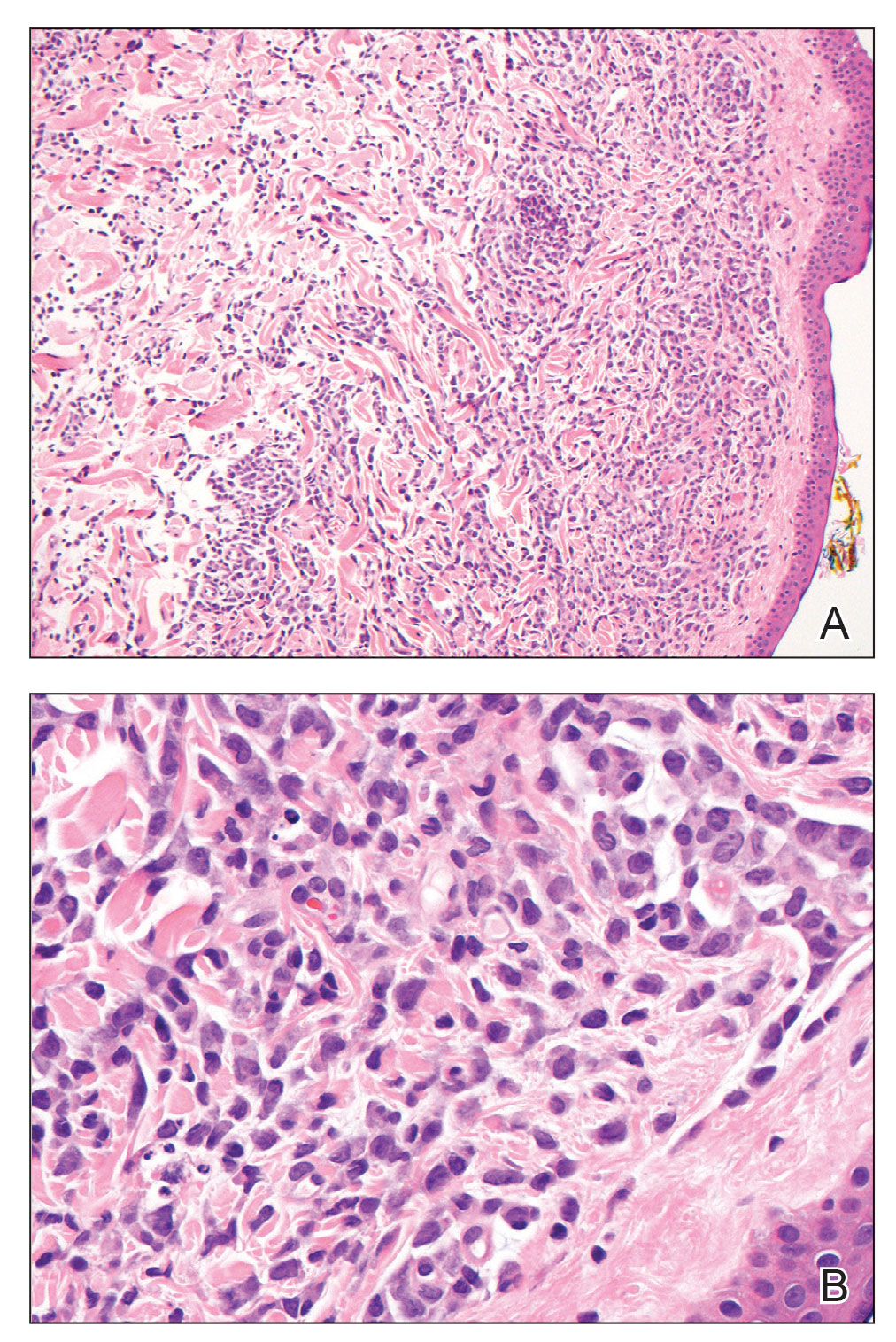

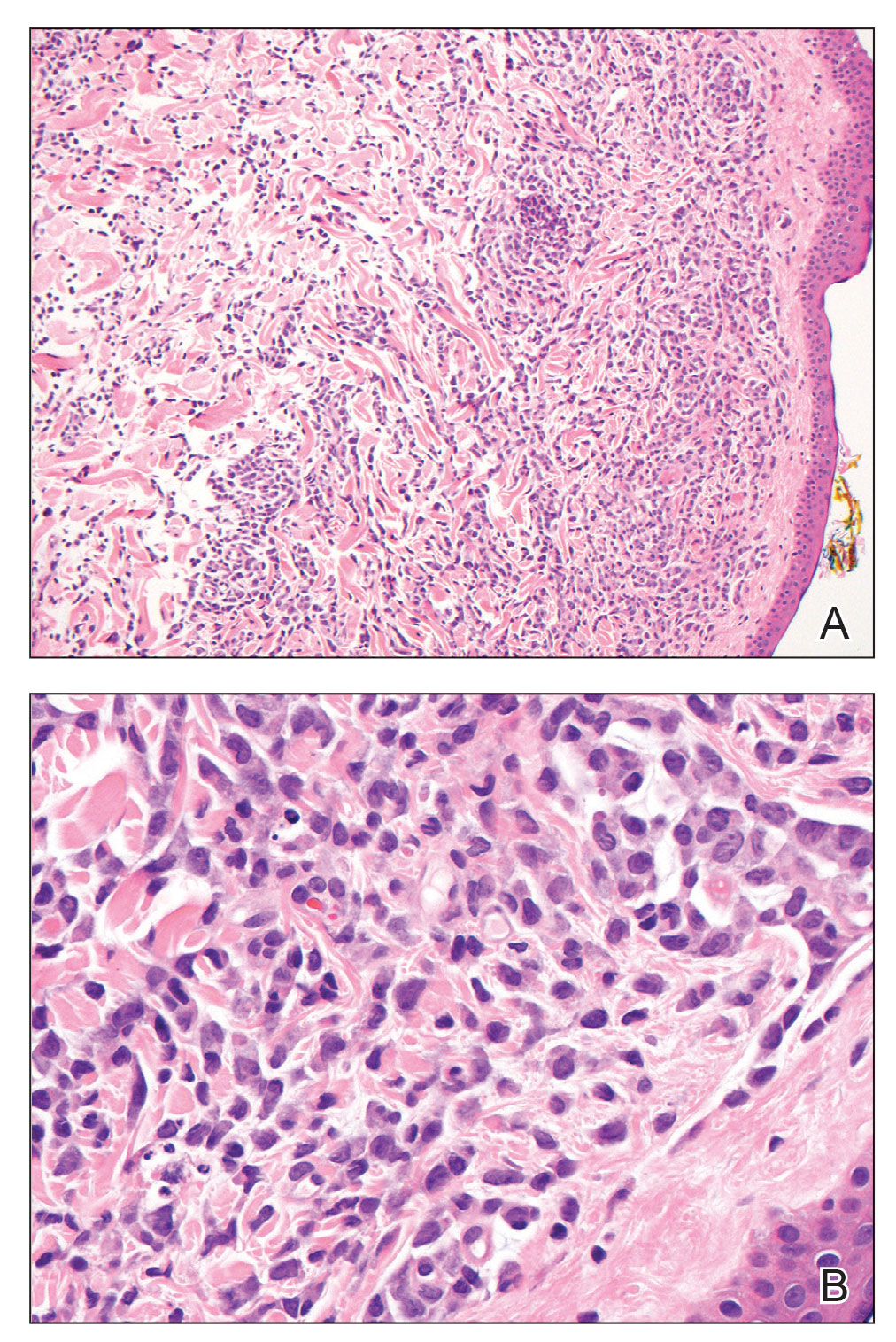

Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed an infiltration of monomorphic atypical myeloid cells with cleaved nuclei within the dermis, with a relatively uninvolved epidermis (Figure, A). The cells formed aggregates in single-file lines along dermal collagen bundles. Occasional Auer rods, which are crystal aggregates of the enzyme myeloperoxidase, a marker unique to cells of the myeloid lineage (Figure, B) were appreciated.

Immunohistochemical staining for myeloperoxidase was weakly positive; however, flow cytometric evaluation of the bone marrow aspirate revealed that approximately 20% of all CD45+ cells were myeloid blasts. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of recurrent acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The diagnosis of AML can be confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy demonstrating more than 20% of the total cells in blast form as well as evidence that the cells are of myeloid origin, which can be inferred by the presence of Auer rods, positive myeloperoxidase staining, or immunophenotyping. In our patient, the Auer rods, myeloperoxidase staining, and atypical myeloid cells on skin biopsy, in conjunction with the bone marrow biopsy results, confirmed leukemia cutis.

Leukemia cutis is the infiltration of neoplastic proliferating leukocytes in the epidermis, dermis, or subcutis from a primary or more commonly metastatic malignancy. Leukemic cutaneous involvement is seen in up to 13% of leukemia patients and most commonly is seen in monocytic or myelomonocytic forms of AML.1 It may present anywhere on the body but mostly is found on the back, trunk, and head. It also may have a predilection for areas with a history of trauma or inflammation. The lesions most often are firm, erythematous to violaceous papules and nodules, though leukemia cutis can present with hemorrhagic ulcers, purpura, or other cutaneous manifestations of concomitant thrombocytopenia such as petechiae and ecchymoses.2 Involvement of the lower extremities mimicking venous stasis dermatitis has been described.3,4

Treatment of leukemia cutis requires targeting the underlying leukemia2 under the guidance of hematology and oncology as well as the use of chemotherapeutic agents.5 The presence of leukemia cutis is a poor prognostic sign, and a discussion regarding goals of care often is appropriate. Our patient initially responded to FLAG (fludarabine, cytarabine, filgrastim) chemotherapy induction and consolidation, which was followed by midostaurin maintenance. However, she ultimately regressed, requiring decitabine and gilteritinib treatment, and died 9 months later from the course of the disease.

Although typically asymptomatic and presenting on the lower limbs, capillaritis (also known as the pigmented purpuric dermatoses) consists of a set of cutaneous conditions that often are chronic and relapsing in nature, as opposed to our patient’s subacute presentation. These benign conditions have several distinct morphologies; some are characterized by pigmented macules or pinpoint red-brown petechiae that most often are found on the legs but also are seen on the trunk and upper extremities.6 Of the various clinical presentations of capillaritis, our patient’s skin findings may be most consistent with pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis of Gougerot and Blum, in which purpuric red-brown papules coalesce into plaques, though her lesions were not raised. The other pigmented purpuric dermatoses can present with cayenne pepper–colored petechiae, golden-brown macules, pruritic purpuric patches, or red-brown annular patches,6 which were not seen in our patient.

Venous stasis dermatitis also favors the lower extremities7; however, it classically includes the medial malleolus and often presents with scaling and hyperpigmentation from hemosiderin deposition.8 It often is associated with pruritus, as opposed to the nonpruritic nonpainful lesions in leukemia cutis. Other signs of venous insufficiency also may be appreciated, including edema or varicose veins,7 which were not evident in our patient.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, a small vessel vasculitis, also appears as palpable or macular purpura, which classically is asymptomatic and erupts on the shins approximately 1 week after an inciting exposure,9 such as medications, pathogens, or autoimmune diseases. One of the least distinctive vasculitides is polyarteritis nodosa, a form of medium vessel vasculitis, which presents most often with palpable purpura or painful nodules on the lower extremities and may be accompanied by livedo reticularis or digital necrosis.9 Acute leukemia may be accompanied by inflammatory paraneoplastic conditions including vasculitis, which is thought to be due to leukemic cells infiltrating and damaging blood vessels.10

Pretibial myxedema is closely associated with Graves disease and shares some features seen in the presentation of our patient’s leukemia cutis. It is asymptomatic, classically affects the pretibial regions, and most commonly affects older adults and women.11,12 Pretibial myxedema presents with thick indurated plaques rather than patches. Our patient did not demonstrate ophthalmopathy, which nearly always precedes pretibial myxedema.12 The most common form of pretibial myxedema is nonpitting, though nodular, plaquelike, polypoid, and elephantiasic forms also exist.11 Pretibial myxedema classically favors the shins; however, it also can affect the ankles, dorsal aspects of the feet, and toes. The characteristic induration of the skin is believed to be the result of excess fibroblast production of glycosaminoglycans in the dermis and subcutis likely triggered by stimulation of fibroblast thyroid stimulating hormone receptors.11

- Bakst RL, Tallman MS, Douer D, et al. How I treat extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:3785-3793.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2014:973-977.

- Papadavid E, Panayiotides I, Katoulis A, et al. Stasis dermatitis-like leukaemic infiltration in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:298-300.

- Chang HY, Wong KM, Bosenberg M, et al. Myelogenous leukemia cutis resembling stasis dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:128-129.

- Aguilera SB, Zarraga M, Rosen L. Leukemia cutis in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;85:31-36.

- Kim DH, Seo SH, Ahn HH, et al. Characteristics and clinical manifestations of pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:404-410.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other eczematous eruptions. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2014:103-108.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Wetter DA, Dutz JP, Shinkai K, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Lorenzo C, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:409-439.

- Jones D, Dorfman DM, Barnhill RL, et al. Leukemic vasculitis: a feature of leukemia cutis in some patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;107:637-642.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- Fatourechi V, Pajouhi M, Fransway AF. Dermopathy of Graves disease (pretibial myxedema). review of 150 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:1-7.

The Diagnosis: Leukemia Cutis

Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed an infiltration of monomorphic atypical myeloid cells with cleaved nuclei within the dermis, with a relatively uninvolved epidermis (Figure, A). The cells formed aggregates in single-file lines along dermal collagen bundles. Occasional Auer rods, which are crystal aggregates of the enzyme myeloperoxidase, a marker unique to cells of the myeloid lineage (Figure, B) were appreciated.

Immunohistochemical staining for myeloperoxidase was weakly positive; however, flow cytometric evaluation of the bone marrow aspirate revealed that approximately 20% of all CD45+ cells were myeloid blasts. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of recurrent acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The diagnosis of AML can be confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy demonstrating more than 20% of the total cells in blast form as well as evidence that the cells are of myeloid origin, which can be inferred by the presence of Auer rods, positive myeloperoxidase staining, or immunophenotyping. In our patient, the Auer rods, myeloperoxidase staining, and atypical myeloid cells on skin biopsy, in conjunction with the bone marrow biopsy results, confirmed leukemia cutis.

Leukemia cutis is the infiltration of neoplastic proliferating leukocytes in the epidermis, dermis, or subcutis from a primary or more commonly metastatic malignancy. Leukemic cutaneous involvement is seen in up to 13% of leukemia patients and most commonly is seen in monocytic or myelomonocytic forms of AML.1 It may present anywhere on the body but mostly is found on the back, trunk, and head. It also may have a predilection for areas with a history of trauma or inflammation. The lesions most often are firm, erythematous to violaceous papules and nodules, though leukemia cutis can present with hemorrhagic ulcers, purpura, or other cutaneous manifestations of concomitant thrombocytopenia such as petechiae and ecchymoses.2 Involvement of the lower extremities mimicking venous stasis dermatitis has been described.3,4

Treatment of leukemia cutis requires targeting the underlying leukemia2 under the guidance of hematology and oncology as well as the use of chemotherapeutic agents.5 The presence of leukemia cutis is a poor prognostic sign, and a discussion regarding goals of care often is appropriate. Our patient initially responded to FLAG (fludarabine, cytarabine, filgrastim) chemotherapy induction and consolidation, which was followed by midostaurin maintenance. However, she ultimately regressed, requiring decitabine and gilteritinib treatment, and died 9 months later from the course of the disease.

Although typically asymptomatic and presenting on the lower limbs, capillaritis (also known as the pigmented purpuric dermatoses) consists of a set of cutaneous conditions that often are chronic and relapsing in nature, as opposed to our patient’s subacute presentation. These benign conditions have several distinct morphologies; some are characterized by pigmented macules or pinpoint red-brown petechiae that most often are found on the legs but also are seen on the trunk and upper extremities.6 Of the various clinical presentations of capillaritis, our patient’s skin findings may be most consistent with pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis of Gougerot and Blum, in which purpuric red-brown papules coalesce into plaques, though her lesions were not raised. The other pigmented purpuric dermatoses can present with cayenne pepper–colored petechiae, golden-brown macules, pruritic purpuric patches, or red-brown annular patches,6 which were not seen in our patient.

Venous stasis dermatitis also favors the lower extremities7; however, it classically includes the medial malleolus and often presents with scaling and hyperpigmentation from hemosiderin deposition.8 It often is associated with pruritus, as opposed to the nonpruritic nonpainful lesions in leukemia cutis. Other signs of venous insufficiency also may be appreciated, including edema or varicose veins,7 which were not evident in our patient.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, a small vessel vasculitis, also appears as palpable or macular purpura, which classically is asymptomatic and erupts on the shins approximately 1 week after an inciting exposure,9 such as medications, pathogens, or autoimmune diseases. One of the least distinctive vasculitides is polyarteritis nodosa, a form of medium vessel vasculitis, which presents most often with palpable purpura or painful nodules on the lower extremities and may be accompanied by livedo reticularis or digital necrosis.9 Acute leukemia may be accompanied by inflammatory paraneoplastic conditions including vasculitis, which is thought to be due to leukemic cells infiltrating and damaging blood vessels.10

Pretibial myxedema is closely associated with Graves disease and shares some features seen in the presentation of our patient’s leukemia cutis. It is asymptomatic, classically affects the pretibial regions, and most commonly affects older adults and women.11,12 Pretibial myxedema presents with thick indurated plaques rather than patches. Our patient did not demonstrate ophthalmopathy, which nearly always precedes pretibial myxedema.12 The most common form of pretibial myxedema is nonpitting, though nodular, plaquelike, polypoid, and elephantiasic forms also exist.11 Pretibial myxedema classically favors the shins; however, it also can affect the ankles, dorsal aspects of the feet, and toes. The characteristic induration of the skin is believed to be the result of excess fibroblast production of glycosaminoglycans in the dermis and subcutis likely triggered by stimulation of fibroblast thyroid stimulating hormone receptors.11

The Diagnosis: Leukemia Cutis

Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed an infiltration of monomorphic atypical myeloid cells with cleaved nuclei within the dermis, with a relatively uninvolved epidermis (Figure, A). The cells formed aggregates in single-file lines along dermal collagen bundles. Occasional Auer rods, which are crystal aggregates of the enzyme myeloperoxidase, a marker unique to cells of the myeloid lineage (Figure, B) were appreciated.

Immunohistochemical staining for myeloperoxidase was weakly positive; however, flow cytometric evaluation of the bone marrow aspirate revealed that approximately 20% of all CD45+ cells were myeloid blasts. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of recurrent acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The diagnosis of AML can be confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy demonstrating more than 20% of the total cells in blast form as well as evidence that the cells are of myeloid origin, which can be inferred by the presence of Auer rods, positive myeloperoxidase staining, or immunophenotyping. In our patient, the Auer rods, myeloperoxidase staining, and atypical myeloid cells on skin biopsy, in conjunction with the bone marrow biopsy results, confirmed leukemia cutis.

Leukemia cutis is the infiltration of neoplastic proliferating leukocytes in the epidermis, dermis, or subcutis from a primary or more commonly metastatic malignancy. Leukemic cutaneous involvement is seen in up to 13% of leukemia patients and most commonly is seen in monocytic or myelomonocytic forms of AML.1 It may present anywhere on the body but mostly is found on the back, trunk, and head. It also may have a predilection for areas with a history of trauma or inflammation. The lesions most often are firm, erythematous to violaceous papules and nodules, though leukemia cutis can present with hemorrhagic ulcers, purpura, or other cutaneous manifestations of concomitant thrombocytopenia such as petechiae and ecchymoses.2 Involvement of the lower extremities mimicking venous stasis dermatitis has been described.3,4

Treatment of leukemia cutis requires targeting the underlying leukemia2 under the guidance of hematology and oncology as well as the use of chemotherapeutic agents.5 The presence of leukemia cutis is a poor prognostic sign, and a discussion regarding goals of care often is appropriate. Our patient initially responded to FLAG (fludarabine, cytarabine, filgrastim) chemotherapy induction and consolidation, which was followed by midostaurin maintenance. However, she ultimately regressed, requiring decitabine and gilteritinib treatment, and died 9 months later from the course of the disease.

Although typically asymptomatic and presenting on the lower limbs, capillaritis (also known as the pigmented purpuric dermatoses) consists of a set of cutaneous conditions that often are chronic and relapsing in nature, as opposed to our patient’s subacute presentation. These benign conditions have several distinct morphologies; some are characterized by pigmented macules or pinpoint red-brown petechiae that most often are found on the legs but also are seen on the trunk and upper extremities.6 Of the various clinical presentations of capillaritis, our patient’s skin findings may be most consistent with pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis of Gougerot and Blum, in which purpuric red-brown papules coalesce into plaques, though her lesions were not raised. The other pigmented purpuric dermatoses can present with cayenne pepper–colored petechiae, golden-brown macules, pruritic purpuric patches, or red-brown annular patches,6 which were not seen in our patient.

Venous stasis dermatitis also favors the lower extremities7; however, it classically includes the medial malleolus and often presents with scaling and hyperpigmentation from hemosiderin deposition.8 It often is associated with pruritus, as opposed to the nonpruritic nonpainful lesions in leukemia cutis. Other signs of venous insufficiency also may be appreciated, including edema or varicose veins,7 which were not evident in our patient.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, a small vessel vasculitis, also appears as palpable or macular purpura, which classically is asymptomatic and erupts on the shins approximately 1 week after an inciting exposure,9 such as medications, pathogens, or autoimmune diseases. One of the least distinctive vasculitides is polyarteritis nodosa, a form of medium vessel vasculitis, which presents most often with palpable purpura or painful nodules on the lower extremities and may be accompanied by livedo reticularis or digital necrosis.9 Acute leukemia may be accompanied by inflammatory paraneoplastic conditions including vasculitis, which is thought to be due to leukemic cells infiltrating and damaging blood vessels.10

Pretibial myxedema is closely associated with Graves disease and shares some features seen in the presentation of our patient’s leukemia cutis. It is asymptomatic, classically affects the pretibial regions, and most commonly affects older adults and women.11,12 Pretibial myxedema presents with thick indurated plaques rather than patches. Our patient did not demonstrate ophthalmopathy, which nearly always precedes pretibial myxedema.12 The most common form of pretibial myxedema is nonpitting, though nodular, plaquelike, polypoid, and elephantiasic forms also exist.11 Pretibial myxedema classically favors the shins; however, it also can affect the ankles, dorsal aspects of the feet, and toes. The characteristic induration of the skin is believed to be the result of excess fibroblast production of glycosaminoglycans in the dermis and subcutis likely triggered by stimulation of fibroblast thyroid stimulating hormone receptors.11

- Bakst RL, Tallman MS, Douer D, et al. How I treat extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:3785-3793.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2014:973-977.

- Papadavid E, Panayiotides I, Katoulis A, et al. Stasis dermatitis-like leukaemic infiltration in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:298-300.

- Chang HY, Wong KM, Bosenberg M, et al. Myelogenous leukemia cutis resembling stasis dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:128-129.

- Aguilera SB, Zarraga M, Rosen L. Leukemia cutis in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;85:31-36.

- Kim DH, Seo SH, Ahn HH, et al. Characteristics and clinical manifestations of pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:404-410.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other eczematous eruptions. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2014:103-108.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Wetter DA, Dutz JP, Shinkai K, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Lorenzo C, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:409-439.

- Jones D, Dorfman DM, Barnhill RL, et al. Leukemic vasculitis: a feature of leukemia cutis in some patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;107:637-642.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- Fatourechi V, Pajouhi M, Fransway AF. Dermopathy of Graves disease (pretibial myxedema). review of 150 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:1-7.

- Bakst RL, Tallman MS, Douer D, et al. How I treat extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:3785-3793.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2014:973-977.

- Papadavid E, Panayiotides I, Katoulis A, et al. Stasis dermatitis-like leukaemic infiltration in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:298-300.

- Chang HY, Wong KM, Bosenberg M, et al. Myelogenous leukemia cutis resembling stasis dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:128-129.

- Aguilera SB, Zarraga M, Rosen L. Leukemia cutis in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;85:31-36.

- Kim DH, Seo SH, Ahn HH, et al. Characteristics and clinical manifestations of pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:404-410.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other eczematous eruptions. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2014:103-108.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Wetter DA, Dutz JP, Shinkai K, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Lorenzo C, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:409-439.

- Jones D, Dorfman DM, Barnhill RL, et al. Leukemic vasculitis: a feature of leukemia cutis in some patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;107:637-642.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- Fatourechi V, Pajouhi M, Fransway AF. Dermopathy of Graves disease (pretibial myxedema). review of 150 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:1-7.

A 67-year-old woman with history of atrial fibrillation and leukemia presented with a nonpruritic nonpainful rash of 10 days' duration that began on the distal lower extremities (top) and then spread superiorly. She reported having a sore throat and mouth, cough, night sweats, unintentional weight loss, and lymphadenopathy. Physical examination revealed pink-purple nonblanching macules and patches on the lower extremities extending from the ankles to the knees. She also had firm pink papules on the chest (bottom) and back. Punch biopsies of the skin on the chest and leg were obtained for histologic examination and immunohistochemical staining.

Insulin rationing common, ‘surprising’ even among privately insured

Insulin rationing due to cost in the United States is common even among people with diabetes who have private health insurance, new data show.

The findings from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) suggest that about one in six people with insulin-treated diabetes in the United States practice insulin rationing – skipping doses, taking less insulin than needed, or delaying the purchase of insulin – because of the price.

Not surprisingly, those without insurance had the highest rationing rate, at nearly a third. However, those with private insurance also had higher rates, at nearly one in five, than those of the overall diabetes population. And those with public insurance – Medicare and Medicaid – had lower rates.

The finding regarding privately insured individuals was “somewhat surprising,” lead author Adam Gaffney, MD, told this news organization. But he noted that the finding likely reflects issues such as copays and deductibles, along with other barriers patients experience within the private health insurance system.

The authors pointed out that the $35 copay cap on insulin included in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 might improve insulin access for Medicare beneficiaries but a similar cap for privately insured people was removed from the bill. Moreover, copay caps don’t help people who are uninsured.

And, although some states have also passed insulin copay caps that apply to privately insured people, “even a monthly cost of $35 can be a lot of money for people with low incomes. That isn’t negligible. It’s important to keep that in mind,” said Dr. Gaffney, a pulmonary and critical care physician at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance.

“Insulin rationing is frequently harmful and sometimes deadly. In the ICU, I have cared for patients who have life-threatening complications of diabetes because they couldn’t afford this life-saving drug. Universal access to insulin, without cost barriers, is urgently needed,” Dr. Gaffney said in a Public Citizen statement.

Senior author Steffie Woolhandler, MD, agrees. “Drug companies have ramped up prices on insulin year after year, even for products that remain completely unchanged,” she noted.

“Drug firms are making vast profits at the expense of the health, and even the lives, of patients,” noted Dr. Woolhandler, a distinguished professor at Hunter College, City University of New York, a lecturer in medicine at Harvard, and a research associate at Public Citizen.

Uninsured, privately insured, and younger people more likely to ration

Dr. Gaffney and colleagues’ findings were published online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The study is the first to examine insulin rationing across the United States among people with all diabetes types treated with insulin using the nationally representative NHIS data.

The results are consistent with those of previous studies, which have found similar rates of insulin rationing at a single U.S. institution and internationally among just those with type 1 diabetes, Dr. Gaffney noted.

In 2021, questions about insulin rationing were added to the NHIS for the first time.

The sample included 982 insulin users with diabetes, representing about 1.4 million U.S. adults with type 1 diabetes, 5.8 million with type 2 diabetes, and 0.4 million with other/unknown types.

Overall, 16.5% of participants – 1.3 million nationwide – reported skipping or reducing insulin doses or delaying the purchase of it in the past year. Delaying purchase was the most common type of rationing, reported by 14.2%, while taking less than needed was the most common practice among those with type 1 diabetes (16.5%).

Age made a difference, with 11.2% of adults aged 65 or older versus 20.4% of younger people reporting rationing. And by income level, even among those at the top level examined – 400% or higher of the federal poverty line – 10.8% reported rationing.

“The high-income group is not necessarily rich. Many would be considered middle-income,” Dr. Gaffney pointed out.

By race, 23.2% of Black participants reported rationing compared with 16.0% of White and Hispanic individuals.

People without insurance had the highest rationing rate (29.2%), followed by those with private insurance (18.8%), other coverage (16.1%), Medicare (13.5%), and Medicaid (11.6%).

‘It’s a complicated system’

Dr. Gaffney noted that even when the patient has private insurance, it’s challenging for the clinician to know in advance whether there are formulary restrictions on what type of insulin can be prescribed or what the patient’s copay or deductible will be.

“Often the prescription gets written without clear knowledge of coverage beforehand ... Coverage differs from patient to patient, from insurance to insurance. It’s a complicated system.”

He added, though, that some electronic health records (EHRs) incorporate this information. “Currently, some EHRs give real-time feedback. I see no reason why, for all the money we plug into these EHRs, there couldn’t be real-time feedback for every patient so you know what the copay is and whether it’s covered at the time you’re prescribing it. To me that’s a very straightforward technological fix that we could achieve. We have the information, but it’s hard to act on it.”

But beyond the EHR, “there are also problems when the patient’s insurance changes or their network changes, and what insulin is covered changes. And they don’t necessarily get that new prescription in time. And suddenly they have a gap. Gaps can be dangerous.”

What’s more, Dr. Gaffney noted: “The study raises concerning questions about what happens when the public health emergency ends and millions of people with Medicaid lose their coverage. Where are they going to get insulin? That’s another population we have to be worried about.”

All of this puts clinicians in a difficult spot, he said.

“They want the best for their patients but they’re working in a system that’s not letting them focus on practicing medicine and instead is forcing them to think about these economic issues that are in large part out of their control.”

Dr. Gaffney is a member of Physicians for a National Health Program, which advocates for a single-payer health system in the United States.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Insulin rationing due to cost in the United States is common even among people with diabetes who have private health insurance, new data show.

The findings from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) suggest that about one in six people with insulin-treated diabetes in the United States practice insulin rationing – skipping doses, taking less insulin than needed, or delaying the purchase of insulin – because of the price.

Not surprisingly, those without insurance had the highest rationing rate, at nearly a third. However, those with private insurance also had higher rates, at nearly one in five, than those of the overall diabetes population. And those with public insurance – Medicare and Medicaid – had lower rates.

The finding regarding privately insured individuals was “somewhat surprising,” lead author Adam Gaffney, MD, told this news organization. But he noted that the finding likely reflects issues such as copays and deductibles, along with other barriers patients experience within the private health insurance system.

The authors pointed out that the $35 copay cap on insulin included in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 might improve insulin access for Medicare beneficiaries but a similar cap for privately insured people was removed from the bill. Moreover, copay caps don’t help people who are uninsured.

And, although some states have also passed insulin copay caps that apply to privately insured people, “even a monthly cost of $35 can be a lot of money for people with low incomes. That isn’t negligible. It’s important to keep that in mind,” said Dr. Gaffney, a pulmonary and critical care physician at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance.

“Insulin rationing is frequently harmful and sometimes deadly. In the ICU, I have cared for patients who have life-threatening complications of diabetes because they couldn’t afford this life-saving drug. Universal access to insulin, without cost barriers, is urgently needed,” Dr. Gaffney said in a Public Citizen statement.

Senior author Steffie Woolhandler, MD, agrees. “Drug companies have ramped up prices on insulin year after year, even for products that remain completely unchanged,” she noted.

“Drug firms are making vast profits at the expense of the health, and even the lives, of patients,” noted Dr. Woolhandler, a distinguished professor at Hunter College, City University of New York, a lecturer in medicine at Harvard, and a research associate at Public Citizen.

Uninsured, privately insured, and younger people more likely to ration

Dr. Gaffney and colleagues’ findings were published online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The study is the first to examine insulin rationing across the United States among people with all diabetes types treated with insulin using the nationally representative NHIS data.

The results are consistent with those of previous studies, which have found similar rates of insulin rationing at a single U.S. institution and internationally among just those with type 1 diabetes, Dr. Gaffney noted.

In 2021, questions about insulin rationing were added to the NHIS for the first time.

The sample included 982 insulin users with diabetes, representing about 1.4 million U.S. adults with type 1 diabetes, 5.8 million with type 2 diabetes, and 0.4 million with other/unknown types.

Overall, 16.5% of participants – 1.3 million nationwide – reported skipping or reducing insulin doses or delaying the purchase of it in the past year. Delaying purchase was the most common type of rationing, reported by 14.2%, while taking less than needed was the most common practice among those with type 1 diabetes (16.5%).

Age made a difference, with 11.2% of adults aged 65 or older versus 20.4% of younger people reporting rationing. And by income level, even among those at the top level examined – 400% or higher of the federal poverty line – 10.8% reported rationing.

“The high-income group is not necessarily rich. Many would be considered middle-income,” Dr. Gaffney pointed out.

By race, 23.2% of Black participants reported rationing compared with 16.0% of White and Hispanic individuals.

People without insurance had the highest rationing rate (29.2%), followed by those with private insurance (18.8%), other coverage (16.1%), Medicare (13.5%), and Medicaid (11.6%).

‘It’s a complicated system’

Dr. Gaffney noted that even when the patient has private insurance, it’s challenging for the clinician to know in advance whether there are formulary restrictions on what type of insulin can be prescribed or what the patient’s copay or deductible will be.

“Often the prescription gets written without clear knowledge of coverage beforehand ... Coverage differs from patient to patient, from insurance to insurance. It’s a complicated system.”

He added, though, that some electronic health records (EHRs) incorporate this information. “Currently, some EHRs give real-time feedback. I see no reason why, for all the money we plug into these EHRs, there couldn’t be real-time feedback for every patient so you know what the copay is and whether it’s covered at the time you’re prescribing it. To me that’s a very straightforward technological fix that we could achieve. We have the information, but it’s hard to act on it.”

But beyond the EHR, “there are also problems when the patient’s insurance changes or their network changes, and what insulin is covered changes. And they don’t necessarily get that new prescription in time. And suddenly they have a gap. Gaps can be dangerous.”

What’s more, Dr. Gaffney noted: “The study raises concerning questions about what happens when the public health emergency ends and millions of people with Medicaid lose their coverage. Where are they going to get insulin? That’s another population we have to be worried about.”

All of this puts clinicians in a difficult spot, he said.

“They want the best for their patients but they’re working in a system that’s not letting them focus on practicing medicine and instead is forcing them to think about these economic issues that are in large part out of their control.”

Dr. Gaffney is a member of Physicians for a National Health Program, which advocates for a single-payer health system in the United States.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Insulin rationing due to cost in the United States is common even among people with diabetes who have private health insurance, new data show.

The findings from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) suggest that about one in six people with insulin-treated diabetes in the United States practice insulin rationing – skipping doses, taking less insulin than needed, or delaying the purchase of insulin – because of the price.

Not surprisingly, those without insurance had the highest rationing rate, at nearly a third. However, those with private insurance also had higher rates, at nearly one in five, than those of the overall diabetes population. And those with public insurance – Medicare and Medicaid – had lower rates.

The finding regarding privately insured individuals was “somewhat surprising,” lead author Adam Gaffney, MD, told this news organization. But he noted that the finding likely reflects issues such as copays and deductibles, along with other barriers patients experience within the private health insurance system.

The authors pointed out that the $35 copay cap on insulin included in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 might improve insulin access for Medicare beneficiaries but a similar cap for privately insured people was removed from the bill. Moreover, copay caps don’t help people who are uninsured.

And, although some states have also passed insulin copay caps that apply to privately insured people, “even a monthly cost of $35 can be a lot of money for people with low incomes. That isn’t negligible. It’s important to keep that in mind,” said Dr. Gaffney, a pulmonary and critical care physician at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance.

“Insulin rationing is frequently harmful and sometimes deadly. In the ICU, I have cared for patients who have life-threatening complications of diabetes because they couldn’t afford this life-saving drug. Universal access to insulin, without cost barriers, is urgently needed,” Dr. Gaffney said in a Public Citizen statement.

Senior author Steffie Woolhandler, MD, agrees. “Drug companies have ramped up prices on insulin year after year, even for products that remain completely unchanged,” she noted.

“Drug firms are making vast profits at the expense of the health, and even the lives, of patients,” noted Dr. Woolhandler, a distinguished professor at Hunter College, City University of New York, a lecturer in medicine at Harvard, and a research associate at Public Citizen.

Uninsured, privately insured, and younger people more likely to ration

Dr. Gaffney and colleagues’ findings were published online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The study is the first to examine insulin rationing across the United States among people with all diabetes types treated with insulin using the nationally representative NHIS data.

The results are consistent with those of previous studies, which have found similar rates of insulin rationing at a single U.S. institution and internationally among just those with type 1 diabetes, Dr. Gaffney noted.

In 2021, questions about insulin rationing were added to the NHIS for the first time.

The sample included 982 insulin users with diabetes, representing about 1.4 million U.S. adults with type 1 diabetes, 5.8 million with type 2 diabetes, and 0.4 million with other/unknown types.

Overall, 16.5% of participants – 1.3 million nationwide – reported skipping or reducing insulin doses or delaying the purchase of it in the past year. Delaying purchase was the most common type of rationing, reported by 14.2%, while taking less than needed was the most common practice among those with type 1 diabetes (16.5%).

Age made a difference, with 11.2% of adults aged 65 or older versus 20.4% of younger people reporting rationing. And by income level, even among those at the top level examined – 400% or higher of the federal poverty line – 10.8% reported rationing.

“The high-income group is not necessarily rich. Many would be considered middle-income,” Dr. Gaffney pointed out.

By race, 23.2% of Black participants reported rationing compared with 16.0% of White and Hispanic individuals.

People without insurance had the highest rationing rate (29.2%), followed by those with private insurance (18.8%), other coverage (16.1%), Medicare (13.5%), and Medicaid (11.6%).

‘It’s a complicated system’

Dr. Gaffney noted that even when the patient has private insurance, it’s challenging for the clinician to know in advance whether there are formulary restrictions on what type of insulin can be prescribed or what the patient’s copay or deductible will be.

“Often the prescription gets written without clear knowledge of coverage beforehand ... Coverage differs from patient to patient, from insurance to insurance. It’s a complicated system.”

He added, though, that some electronic health records (EHRs) incorporate this information. “Currently, some EHRs give real-time feedback. I see no reason why, for all the money we plug into these EHRs, there couldn’t be real-time feedback for every patient so you know what the copay is and whether it’s covered at the time you’re prescribing it. To me that’s a very straightforward technological fix that we could achieve. We have the information, but it’s hard to act on it.”

But beyond the EHR, “there are also problems when the patient’s insurance changes or their network changes, and what insulin is covered changes. And they don’t necessarily get that new prescription in time. And suddenly they have a gap. Gaps can be dangerous.”

What’s more, Dr. Gaffney noted: “The study raises concerning questions about what happens when the public health emergency ends and millions of people with Medicaid lose their coverage. Where are they going to get insulin? That’s another population we have to be worried about.”

All of this puts clinicians in a difficult spot, he said.

“They want the best for their patients but they’re working in a system that’s not letting them focus on practicing medicine and instead is forcing them to think about these economic issues that are in large part out of their control.”

Dr. Gaffney is a member of Physicians for a National Health Program, which advocates for a single-payer health system in the United States.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

VA Center Dramatically Shrinks Wait Times for Bone Marrow Biopsies

SAN DIEGO–The Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center in Ohio dramatically reduced wait times for bone marrow biopsies and treatment by ditching the radiology department and opening a weekly clinic devoted to the procedures, a cancer care team reported at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) September 16 to 18, 2022.

The average time from biopsy order to procedure fell by more than two-thirds from 23.1 days to 7.0 days, and the time from order to diagnosis dipped from 27.8 days to 11.6 days. The time from treatment fell from 54.8 days to 20.2 days.

The new strategy aims to avoid sending patients to the radiology department and treat them in a clinic within the cancer center instead. “It’s great to be able to keep as many hematology/oncology–related things such as infusion, scheduling, and procedures within our department. It provides continuity for the veteran, and it’s helpful for them from that aspect,” said nurse practitioner Kyle Stimpert, MSN, RN, ACNP, of VA Northeast Ohio Healthcare System.

As the cancer team reported in an abstract presented at the AVAHO meeting, “bone marrow biopsies often need to be performed expeditiously to alleviate patient concerns and quickly determine a diagnosis and treatment plan. However, with increasing subspecialization, there are fewer hematology/oncology providers available to perform this procedure.”

The Cleveland VA tried to address this problem by sending patients to interventional radiology, but it still took weeks for bone marrow biopsies to be performed: From August 4, 2020, to August 12, 2021, when 140 biopsies were performed, the average time from order to procedure was 23.1 days. The time from order to diagnosis was 27.8 days, and from order to treatment was 54.8 days.

The bone marrow biopsies provide insight into diseases such as hematologic malignancies and myelodysplastic syndromes, Stimpert said. The procedures may lead to diagnoses or reveal how treatment is progressing.

In 2021, new leadership sought to shrink the wait times. “We put together a small team and started brainstorming,” said oncology clinical nurse specialist Alecia Smalheer, MSN, APRN, OCN, in an interview. With the help of staff who’d come from other facilities, she said, “we were able to see what was being done in surrounding community hospitals and come up with a model and a checklist.”

The team modified a space to create a new weekly, half-day bone marrow biopsy clinic. They also worked on procedures, documentation, education of patients, and training of staff, Smalheer said.

After implementation in the summer of 2021, the biopsy clinic performed 89 procedures through August 31, 2022. The average time from order to procedure was 7.0 days. The time to diagnosis was 11.6 days, and the time to treatment was 20.2 days. The differences between the pre-implementation and postimplementation periods were statistically significant. (P < .001 for each).

The biopsy clinic now sees about 3 to 4 patients a week. “Just yesterday, I had a vet whose cancer was going down. I was able to just do this bone marrow right there, and it was amazing. He didn’t have to go home [and come back],” Stimpert said. “A lot of patients travel a far distance or on oxygen, or it’s hard for them to get around. Coming to the facility for repeat appointments can just take a lot out of them. So it’s really nice to be able to get it all done in one visit.”

There are multiple benefits to shortening wait times, Smalheer said. “They can start treatment much sooner… but it also alleviates some of the emotional distress of waiting. They still have some waiting to do, but it’s definitely not as long.”

And, Stimpert added, patients are familiar with the infusion center and will see faces they know.