User login

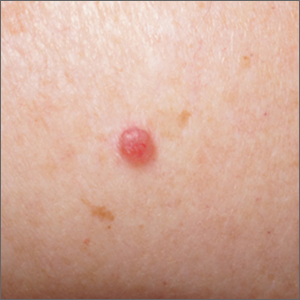

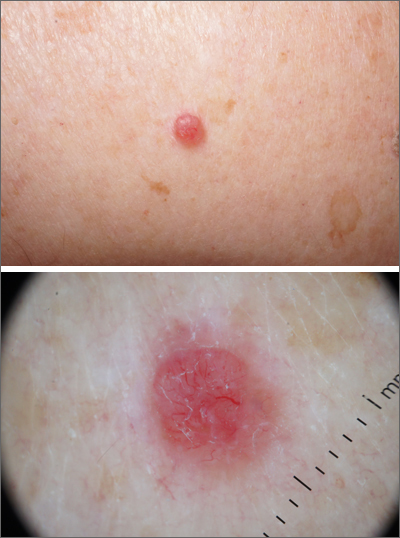

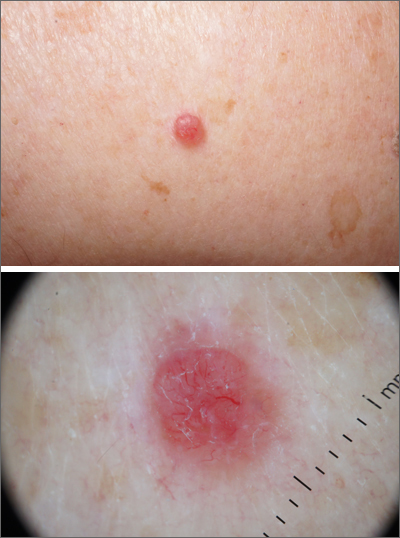

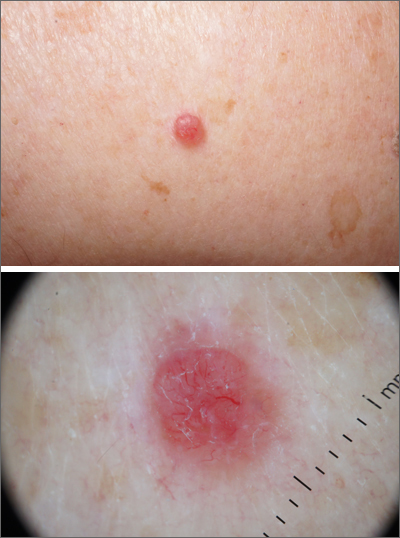

Pink shoulder lesion

A scoop shave biopsy was performed and histology was consistent with a nodular basal cell carcinoma. BCC is the most common skin cancer in the United States, occurring in approximately 30% of patients with skin types I and II.1 In patients who are Black, squamous cell carcinoma is more common than BCC.2 The overall incidence of BCC is increasing by 4% to 8% every year in the United States.1

BCC most often affects sun-damaged areas—especially on the head and neck—and frequently causes significant tissue damage. It is, however, associated with a low risk of metastasis and mortality.

BCCs may appear as a pink, brown, blue, or white papule or macule. The surface is frequently shiny or pearly in appearance with a rolled border. Dilated, angulated, tree-branch like vessels termed “arborizing vessels” are common. Infiltrative BCC subtypes may look like melted candlewax and extend beyond the area that is clinically apparent.

Partial shave biopsies of a lesion can confirm the diagnosis. A punch biopsy can make it easier to evaluate flat (or even sunken) lesions.

The patient described here was treated with electrodessication and curettage (EDC)—a fast, economical, and effective treatment for the low-risk subtypes of superficial or nodular BCCs on the trunk or extremities. EDC should be avoided with higher risk subtypes of micronodular and infiltrative BCC. With these subtypes, excision (with 4- to 6-mm margins) or Mohs microsurgery is recommended.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. References

1. Kim DP, Kus KJB, Ruiz E. Basal cell carcinoma review. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:13-24. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.09.004

2. Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;21:170-177, 206.

A scoop shave biopsy was performed and histology was consistent with a nodular basal cell carcinoma. BCC is the most common skin cancer in the United States, occurring in approximately 30% of patients with skin types I and II.1 In patients who are Black, squamous cell carcinoma is more common than BCC.2 The overall incidence of BCC is increasing by 4% to 8% every year in the United States.1

BCC most often affects sun-damaged areas—especially on the head and neck—and frequently causes significant tissue damage. It is, however, associated with a low risk of metastasis and mortality.

BCCs may appear as a pink, brown, blue, or white papule or macule. The surface is frequently shiny or pearly in appearance with a rolled border. Dilated, angulated, tree-branch like vessels termed “arborizing vessels” are common. Infiltrative BCC subtypes may look like melted candlewax and extend beyond the area that is clinically apparent.

Partial shave biopsies of a lesion can confirm the diagnosis. A punch biopsy can make it easier to evaluate flat (or even sunken) lesions.

The patient described here was treated with electrodessication and curettage (EDC)—a fast, economical, and effective treatment for the low-risk subtypes of superficial or nodular BCCs on the trunk or extremities. EDC should be avoided with higher risk subtypes of micronodular and infiltrative BCC. With these subtypes, excision (with 4- to 6-mm margins) or Mohs microsurgery is recommended.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. References

A scoop shave biopsy was performed and histology was consistent with a nodular basal cell carcinoma. BCC is the most common skin cancer in the United States, occurring in approximately 30% of patients with skin types I and II.1 In patients who are Black, squamous cell carcinoma is more common than BCC.2 The overall incidence of BCC is increasing by 4% to 8% every year in the United States.1

BCC most often affects sun-damaged areas—especially on the head and neck—and frequently causes significant tissue damage. It is, however, associated with a low risk of metastasis and mortality.

BCCs may appear as a pink, brown, blue, or white papule or macule. The surface is frequently shiny or pearly in appearance with a rolled border. Dilated, angulated, tree-branch like vessels termed “arborizing vessels” are common. Infiltrative BCC subtypes may look like melted candlewax and extend beyond the area that is clinically apparent.

Partial shave biopsies of a lesion can confirm the diagnosis. A punch biopsy can make it easier to evaluate flat (or even sunken) lesions.

The patient described here was treated with electrodessication and curettage (EDC)—a fast, economical, and effective treatment for the low-risk subtypes of superficial or nodular BCCs on the trunk or extremities. EDC should be avoided with higher risk subtypes of micronodular and infiltrative BCC. With these subtypes, excision (with 4- to 6-mm margins) or Mohs microsurgery is recommended.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. References

1. Kim DP, Kus KJB, Ruiz E. Basal cell carcinoma review. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:13-24. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.09.004

2. Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;21:170-177, 206.

1. Kim DP, Kus KJB, Ruiz E. Basal cell carcinoma review. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:13-24. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.09.004

2. Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;21:170-177, 206.

Florida medical boards ban transgender care for minors

Florida’s two main medical bodies have voted to stop gender-affirming treatment of children, including the use of puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgery, other than in minors who are already receiving such care.

The move, which is unprecedented, makes Florida one of several U.S. states to restrict gender-affirming care for adolescents, but the first to do so via an administrative process, through the actions of its Board of Medicine and Board of Osteopathic Medicine.

“I appreciate the integrity of the Boards for ruling in the best interest of children in Florida despite facing tremendous pressure to permit these unproven and risky treatments,” Florida Surgeon General Joseph Ladapo, MD, PhD, said in a statement.

In a statement, The Endocrine Society criticizes the decision as “blatantly discriminatory” and not based on medical evidence.

During a meeting on Oct. 28 that involved testimonies from doctors, parents of transgender children, detransitioners, and patients, board members referred to similar changes in Europe, where some countries have pushed psychotherapy instead of surgery or hormone treatment.

Then, on Nov. 4, the boards each set slightly different instructions, with the Board of Osteopathic Medicine voting to restrict care for new patients but allowing an exception for children enrolled in clinical studies, which “must include long-term longitudinal assessments of the patients’ physiologic and psychologic outcomes,” according to the Florida Department of Health.

The Board of Medicine did not allow the latter.

The proposed rules are open to public comment before finalization.

Arkansas was the first state to enact such a ban on gender-affirming care, with Republican lawmakers in 2021 overriding GOP Gov. Asa Hutchinson’s veto of the legislation. Alabama Republicans in 2022 approved legislation to outlaw gender-affirming medications for transgender youths. Both laws have been paused amid unfolding legal battles, according to Associated Press.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, a Republican, signed a bill in October that bars federal funds earmarked for the University of Oklahoma Medical Center from being used for gender reassignment treatments for minors. Gov. Stitt also called for the legislature to ban some of those gender reassignment treatments statewide when it returns in February.

Top Tennessee Republicans also have vowed to push for strict antitransgender policies. The state already bans doctors from providing gender-confirming hormone treatment to prepubescent minors. To date, no one has legally challenged the law as medical experts maintain no doctor in Tennessee does so.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Florida’s two main medical bodies have voted to stop gender-affirming treatment of children, including the use of puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgery, other than in minors who are already receiving such care.

The move, which is unprecedented, makes Florida one of several U.S. states to restrict gender-affirming care for adolescents, but the first to do so via an administrative process, through the actions of its Board of Medicine and Board of Osteopathic Medicine.

“I appreciate the integrity of the Boards for ruling in the best interest of children in Florida despite facing tremendous pressure to permit these unproven and risky treatments,” Florida Surgeon General Joseph Ladapo, MD, PhD, said in a statement.

In a statement, The Endocrine Society criticizes the decision as “blatantly discriminatory” and not based on medical evidence.

During a meeting on Oct. 28 that involved testimonies from doctors, parents of transgender children, detransitioners, and patients, board members referred to similar changes in Europe, where some countries have pushed psychotherapy instead of surgery or hormone treatment.

Then, on Nov. 4, the boards each set slightly different instructions, with the Board of Osteopathic Medicine voting to restrict care for new patients but allowing an exception for children enrolled in clinical studies, which “must include long-term longitudinal assessments of the patients’ physiologic and psychologic outcomes,” according to the Florida Department of Health.

The Board of Medicine did not allow the latter.

The proposed rules are open to public comment before finalization.

Arkansas was the first state to enact such a ban on gender-affirming care, with Republican lawmakers in 2021 overriding GOP Gov. Asa Hutchinson’s veto of the legislation. Alabama Republicans in 2022 approved legislation to outlaw gender-affirming medications for transgender youths. Both laws have been paused amid unfolding legal battles, according to Associated Press.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, a Republican, signed a bill in October that bars federal funds earmarked for the University of Oklahoma Medical Center from being used for gender reassignment treatments for minors. Gov. Stitt also called for the legislature to ban some of those gender reassignment treatments statewide when it returns in February.

Top Tennessee Republicans also have vowed to push for strict antitransgender policies. The state already bans doctors from providing gender-confirming hormone treatment to prepubescent minors. To date, no one has legally challenged the law as medical experts maintain no doctor in Tennessee does so.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Florida’s two main medical bodies have voted to stop gender-affirming treatment of children, including the use of puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgery, other than in minors who are already receiving such care.

The move, which is unprecedented, makes Florida one of several U.S. states to restrict gender-affirming care for adolescents, but the first to do so via an administrative process, through the actions of its Board of Medicine and Board of Osteopathic Medicine.

“I appreciate the integrity of the Boards for ruling in the best interest of children in Florida despite facing tremendous pressure to permit these unproven and risky treatments,” Florida Surgeon General Joseph Ladapo, MD, PhD, said in a statement.

In a statement, The Endocrine Society criticizes the decision as “blatantly discriminatory” and not based on medical evidence.

During a meeting on Oct. 28 that involved testimonies from doctors, parents of transgender children, detransitioners, and patients, board members referred to similar changes in Europe, where some countries have pushed psychotherapy instead of surgery or hormone treatment.

Then, on Nov. 4, the boards each set slightly different instructions, with the Board of Osteopathic Medicine voting to restrict care for new patients but allowing an exception for children enrolled in clinical studies, which “must include long-term longitudinal assessments of the patients’ physiologic and psychologic outcomes,” according to the Florida Department of Health.

The Board of Medicine did not allow the latter.

The proposed rules are open to public comment before finalization.

Arkansas was the first state to enact such a ban on gender-affirming care, with Republican lawmakers in 2021 overriding GOP Gov. Asa Hutchinson’s veto of the legislation. Alabama Republicans in 2022 approved legislation to outlaw gender-affirming medications for transgender youths. Both laws have been paused amid unfolding legal battles, according to Associated Press.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, a Republican, signed a bill in October that bars federal funds earmarked for the University of Oklahoma Medical Center from being used for gender reassignment treatments for minors. Gov. Stitt also called for the legislature to ban some of those gender reassignment treatments statewide when it returns in February.

Top Tennessee Republicans also have vowed to push for strict antitransgender policies. The state already bans doctors from providing gender-confirming hormone treatment to prepubescent minors. To date, no one has legally challenged the law as medical experts maintain no doctor in Tennessee does so.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Study finds high rate of psychiatric burden in cosmetic dermatology patients

results from a large retrospective analysis showed.

“As the rate of cosmetic procedures continues to increase, it is crucial that physicians understand that many patients with a psychiatric disorder require clear communication and appropriate consultation visits,” lead study author Patricia Richey, MD, told this news organization.

While studies have displayed links between the desire for a cosmetic procedure and psychiatric stressors and disorders – most commonly mood disorders, personality disorders, body dysmorphic disorder, and addiction-like behavior – the scarce literature on the subject mostly comes from the realm of plastic surgery.

“The relationship between psychiatric disease and the motivation for dermatologic cosmetic procedures has never been fully elucidated,” said Dr. Richey, who practices Mohs surgery and cosmetic dermatology in Washington, D.C., and conducts research for the Wellman Center for Photomedicine and the Dermatology Laser and Cosmetic Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “A possible association between psychiatric disorder and the motivation for cosmetic procedures is critical to understand given increasing procedure rates and the need for clear communication and appropriate consultation visits with these patients.”

For the retrospective cohort study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Richey; Mathew Avram, MD, JD, director of the Dermatology Laser and Cosmetic Center at MGH; and Ryan W. Chapin, PharmD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, reviewed the medical records of 1,000 patients from a cosmetic dermatology clinic and 1,000 patients from a medical dermatology clinic, both at MGH. Those who crossed over between the two clinics were excluded from the analysis.

Patients in the cosmetic group were significantly younger than those in the medical group (a mean of 48 vs. 56 years, respectively; P < .0001), and there was a higher percentage of women than men in both groups (78.5% vs. 21.5% in the cosmetic group and 61.4% vs. 38.6% in the medical group; P < .00001).

The researchers found that 49% of patients in the cosmetic group had been diagnosed with at least one psychiatric disorder, compared with 33% in the medical group (P < .00001), most commonly anxiety, depression, ADHD, and insomnia. In addition, 39 patients in the cosmetic group had 2 or more psychiatric disorders, compared with 22 of those in the medical group.

Similarly, 44% of patients in the cosmetic group were on a psychiatric medication, compared with 28% in the medical group (P < .00001). The average number of medications among those on more than one psychiatric medication was 1.67 among those in the cosmetic dermatology group versus 1.48 among those in the medical dermatology group (P = .020).

By drug class, a higher percentage of patients in the cosmetic group, compared with those in the medical group, were taking antidepressants (33% vs. 21%, respectively; P < .00001), anxiolytics (26% vs. 13%; P < .00001), mood stabilizers (2.80% vs. 1.10%; P = .006), and stimulants (15.2% vs. 7.20%; P < .00001). The proportion of those taking antipsychotics was essentially even in the two groups (2.50% vs. 2.70%; P = .779).

Dr. Richey and colleagues also observed that patients in the cosmetic group had significantly higher rates of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and ADHD than those in the medical group. “This finding did not particularly surprise me,” she said, since she and her colleagues recently published a study on the association of stimulant use with psychocutaneous disease.

“Stimulants are used to treat ADHD and are also known to trigger OCD-like symptoms,” she said. “I was surprised that no patients had been diagnosed with body dysmorphic disorder, but we know that with increased patient access to medical records, physicians are often cautious in their documentation.”

She added that the overall results of the new study underscore the importance of consultation visits with cosmetic patients, including obtaining a full medication list and accurate medical history, if possible. “One could also consider well-studied screening tools mostly from the mood disorder realm, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire–2,” Dr. Richey said. “Much can be gained from simply talking to the patient and trying to understand him/her and underlying motivations prior to performing a procedure.”

Evan Rieder, MD, a New York City–based dermatologist and psychiatrist who was asked to comment on the study, characterized the analysis as demonstrating what medical and cosmetic dermatologists have been seeing in their practices for years. “While this study is limited by its single-center retrospective nature in an academic center that may not be representative of the general population, it does demonstrate a high burden of psychopathology and psychopharmacologic treatments in aesthetic patients,” Dr. Rieder said in an interview.

“While psychiatric illness is not a contraindication to cosmetic treatment, a high percentage of patients with ADHD, OCD, and likely [body dysmorphic disorder] in cosmetic dermatology practices should give us pause.” The nature of these diseases may indicate that some people are seeking aesthetic treatments for reasons yet to be elucidated, he added.

“It certainly indicates that dermatologists should be equipped to screen for, identify, and provide such patients with the appropriate resources for psychological treatment, regardless if they are deemed appropriate candidates for cosmetic intervention,” he said.

In an interview, Pooja Sodha, MD, director of the Center for Laser and Cosmetic Dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, noted that previous studies have demonstrated the interplay between mood disorders and dermatologic conditions for years, namely in acne, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and immune mediated disorders.

“In these conditions, the psychiatric stressors can worsen the skin condition and impede treatment,” Dr. Sodha said. “This study is an important segue into further elucidating our cosmetic patient population, and we should try to ask the next important question: how do we as physicians build a better rapport with these patients, understand their motivations for care, and effectively guide the patient through the consultation process to realistically address their concerns? It might help us both.”

Neither the researchers nor Dr. Sodha reported having financial disclosures. Dr. Rieder disclosed that he is a consultant for Allergan, Almirall, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dr. Brandt, L’Oreal, Procter & Gamble, and Unilever.

results from a large retrospective analysis showed.

“As the rate of cosmetic procedures continues to increase, it is crucial that physicians understand that many patients with a psychiatric disorder require clear communication and appropriate consultation visits,” lead study author Patricia Richey, MD, told this news organization.

While studies have displayed links between the desire for a cosmetic procedure and psychiatric stressors and disorders – most commonly mood disorders, personality disorders, body dysmorphic disorder, and addiction-like behavior – the scarce literature on the subject mostly comes from the realm of plastic surgery.

“The relationship between psychiatric disease and the motivation for dermatologic cosmetic procedures has never been fully elucidated,” said Dr. Richey, who practices Mohs surgery and cosmetic dermatology in Washington, D.C., and conducts research for the Wellman Center for Photomedicine and the Dermatology Laser and Cosmetic Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “A possible association between psychiatric disorder and the motivation for cosmetic procedures is critical to understand given increasing procedure rates and the need for clear communication and appropriate consultation visits with these patients.”

For the retrospective cohort study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Richey; Mathew Avram, MD, JD, director of the Dermatology Laser and Cosmetic Center at MGH; and Ryan W. Chapin, PharmD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, reviewed the medical records of 1,000 patients from a cosmetic dermatology clinic and 1,000 patients from a medical dermatology clinic, both at MGH. Those who crossed over between the two clinics were excluded from the analysis.

Patients in the cosmetic group were significantly younger than those in the medical group (a mean of 48 vs. 56 years, respectively; P < .0001), and there was a higher percentage of women than men in both groups (78.5% vs. 21.5% in the cosmetic group and 61.4% vs. 38.6% in the medical group; P < .00001).

The researchers found that 49% of patients in the cosmetic group had been diagnosed with at least one psychiatric disorder, compared with 33% in the medical group (P < .00001), most commonly anxiety, depression, ADHD, and insomnia. In addition, 39 patients in the cosmetic group had 2 or more psychiatric disorders, compared with 22 of those in the medical group.

Similarly, 44% of patients in the cosmetic group were on a psychiatric medication, compared with 28% in the medical group (P < .00001). The average number of medications among those on more than one psychiatric medication was 1.67 among those in the cosmetic dermatology group versus 1.48 among those in the medical dermatology group (P = .020).

By drug class, a higher percentage of patients in the cosmetic group, compared with those in the medical group, were taking antidepressants (33% vs. 21%, respectively; P < .00001), anxiolytics (26% vs. 13%; P < .00001), mood stabilizers (2.80% vs. 1.10%; P = .006), and stimulants (15.2% vs. 7.20%; P < .00001). The proportion of those taking antipsychotics was essentially even in the two groups (2.50% vs. 2.70%; P = .779).

Dr. Richey and colleagues also observed that patients in the cosmetic group had significantly higher rates of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and ADHD than those in the medical group. “This finding did not particularly surprise me,” she said, since she and her colleagues recently published a study on the association of stimulant use with psychocutaneous disease.

“Stimulants are used to treat ADHD and are also known to trigger OCD-like symptoms,” she said. “I was surprised that no patients had been diagnosed with body dysmorphic disorder, but we know that with increased patient access to medical records, physicians are often cautious in their documentation.”

She added that the overall results of the new study underscore the importance of consultation visits with cosmetic patients, including obtaining a full medication list and accurate medical history, if possible. “One could also consider well-studied screening tools mostly from the mood disorder realm, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire–2,” Dr. Richey said. “Much can be gained from simply talking to the patient and trying to understand him/her and underlying motivations prior to performing a procedure.”

Evan Rieder, MD, a New York City–based dermatologist and psychiatrist who was asked to comment on the study, characterized the analysis as demonstrating what medical and cosmetic dermatologists have been seeing in their practices for years. “While this study is limited by its single-center retrospective nature in an academic center that may not be representative of the general population, it does demonstrate a high burden of psychopathology and psychopharmacologic treatments in aesthetic patients,” Dr. Rieder said in an interview.

“While psychiatric illness is not a contraindication to cosmetic treatment, a high percentage of patients with ADHD, OCD, and likely [body dysmorphic disorder] in cosmetic dermatology practices should give us pause.” The nature of these diseases may indicate that some people are seeking aesthetic treatments for reasons yet to be elucidated, he added.

“It certainly indicates that dermatologists should be equipped to screen for, identify, and provide such patients with the appropriate resources for psychological treatment, regardless if they are deemed appropriate candidates for cosmetic intervention,” he said.

In an interview, Pooja Sodha, MD, director of the Center for Laser and Cosmetic Dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, noted that previous studies have demonstrated the interplay between mood disorders and dermatologic conditions for years, namely in acne, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and immune mediated disorders.

“In these conditions, the psychiatric stressors can worsen the skin condition and impede treatment,” Dr. Sodha said. “This study is an important segue into further elucidating our cosmetic patient population, and we should try to ask the next important question: how do we as physicians build a better rapport with these patients, understand their motivations for care, and effectively guide the patient through the consultation process to realistically address their concerns? It might help us both.”

Neither the researchers nor Dr. Sodha reported having financial disclosures. Dr. Rieder disclosed that he is a consultant for Allergan, Almirall, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dr. Brandt, L’Oreal, Procter & Gamble, and Unilever.

results from a large retrospective analysis showed.

“As the rate of cosmetic procedures continues to increase, it is crucial that physicians understand that many patients with a psychiatric disorder require clear communication and appropriate consultation visits,” lead study author Patricia Richey, MD, told this news organization.

While studies have displayed links between the desire for a cosmetic procedure and psychiatric stressors and disorders – most commonly mood disorders, personality disorders, body dysmorphic disorder, and addiction-like behavior – the scarce literature on the subject mostly comes from the realm of plastic surgery.

“The relationship between psychiatric disease and the motivation for dermatologic cosmetic procedures has never been fully elucidated,” said Dr. Richey, who practices Mohs surgery and cosmetic dermatology in Washington, D.C., and conducts research for the Wellman Center for Photomedicine and the Dermatology Laser and Cosmetic Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “A possible association between psychiatric disorder and the motivation for cosmetic procedures is critical to understand given increasing procedure rates and the need for clear communication and appropriate consultation visits with these patients.”

For the retrospective cohort study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Richey; Mathew Avram, MD, JD, director of the Dermatology Laser and Cosmetic Center at MGH; and Ryan W. Chapin, PharmD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, reviewed the medical records of 1,000 patients from a cosmetic dermatology clinic and 1,000 patients from a medical dermatology clinic, both at MGH. Those who crossed over between the two clinics were excluded from the analysis.

Patients in the cosmetic group were significantly younger than those in the medical group (a mean of 48 vs. 56 years, respectively; P < .0001), and there was a higher percentage of women than men in both groups (78.5% vs. 21.5% in the cosmetic group and 61.4% vs. 38.6% in the medical group; P < .00001).

The researchers found that 49% of patients in the cosmetic group had been diagnosed with at least one psychiatric disorder, compared with 33% in the medical group (P < .00001), most commonly anxiety, depression, ADHD, and insomnia. In addition, 39 patients in the cosmetic group had 2 or more psychiatric disorders, compared with 22 of those in the medical group.

Similarly, 44% of patients in the cosmetic group were on a psychiatric medication, compared with 28% in the medical group (P < .00001). The average number of medications among those on more than one psychiatric medication was 1.67 among those in the cosmetic dermatology group versus 1.48 among those in the medical dermatology group (P = .020).

By drug class, a higher percentage of patients in the cosmetic group, compared with those in the medical group, were taking antidepressants (33% vs. 21%, respectively; P < .00001), anxiolytics (26% vs. 13%; P < .00001), mood stabilizers (2.80% vs. 1.10%; P = .006), and stimulants (15.2% vs. 7.20%; P < .00001). The proportion of those taking antipsychotics was essentially even in the two groups (2.50% vs. 2.70%; P = .779).

Dr. Richey and colleagues also observed that patients in the cosmetic group had significantly higher rates of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and ADHD than those in the medical group. “This finding did not particularly surprise me,” she said, since she and her colleagues recently published a study on the association of stimulant use with psychocutaneous disease.

“Stimulants are used to treat ADHD and are also known to trigger OCD-like symptoms,” she said. “I was surprised that no patients had been diagnosed with body dysmorphic disorder, but we know that with increased patient access to medical records, physicians are often cautious in their documentation.”

She added that the overall results of the new study underscore the importance of consultation visits with cosmetic patients, including obtaining a full medication list and accurate medical history, if possible. “One could also consider well-studied screening tools mostly from the mood disorder realm, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire–2,” Dr. Richey said. “Much can be gained from simply talking to the patient and trying to understand him/her and underlying motivations prior to performing a procedure.”

Evan Rieder, MD, a New York City–based dermatologist and psychiatrist who was asked to comment on the study, characterized the analysis as demonstrating what medical and cosmetic dermatologists have been seeing in their practices for years. “While this study is limited by its single-center retrospective nature in an academic center that may not be representative of the general population, it does demonstrate a high burden of psychopathology and psychopharmacologic treatments in aesthetic patients,” Dr. Rieder said in an interview.

“While psychiatric illness is not a contraindication to cosmetic treatment, a high percentage of patients with ADHD, OCD, and likely [body dysmorphic disorder] in cosmetic dermatology practices should give us pause.” The nature of these diseases may indicate that some people are seeking aesthetic treatments for reasons yet to be elucidated, he added.

“It certainly indicates that dermatologists should be equipped to screen for, identify, and provide such patients with the appropriate resources for psychological treatment, regardless if they are deemed appropriate candidates for cosmetic intervention,” he said.

In an interview, Pooja Sodha, MD, director of the Center for Laser and Cosmetic Dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, noted that previous studies have demonstrated the interplay between mood disorders and dermatologic conditions for years, namely in acne, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and immune mediated disorders.

“In these conditions, the psychiatric stressors can worsen the skin condition and impede treatment,” Dr. Sodha said. “This study is an important segue into further elucidating our cosmetic patient population, and we should try to ask the next important question: how do we as physicians build a better rapport with these patients, understand their motivations for care, and effectively guide the patient through the consultation process to realistically address their concerns? It might help us both.”

Neither the researchers nor Dr. Sodha reported having financial disclosures. Dr. Rieder disclosed that he is a consultant for Allergan, Almirall, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dr. Brandt, L’Oreal, Procter & Gamble, and Unilever.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Living donor liver transplants on rise for most urgent need

Living donor liver transplants (LDLT) for recipients with the most urgent need for a liver transplant in the next 3 months – a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score of 25 or higher – have become more frequent during the past decade, according to new findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Among LDLT recipients, researchers found comparable patient and graft survival at low and high MELD scores. But among patients with high MELD scores, researchers found lower adjusted graft survival and a higher transplant rate among those with living donors, compared with recipients of deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT).

The findings suggest certain advantages of LDLT over DDLT may be lost in the high-MELD setting in terms of graft survival, said Benjamin Rosenthal, MD, an internal medicine resident focused on transplant hepatology at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Historically, in the United States especially, living donor liver transplantation has been offered to patients with low or moderate MELD,” he said. “The outcomes of LDLT at high MELD are currently unknown.”

Previous data from the Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Cohort Study (A2ALL) found that LDLT offered a survival benefit versus remaining on the wait list, independent of MELD score, he said. A recent study also has demonstrated a survival benefit across MELD scores of 11-26, but findings for MELD scores of 25 and higher have been mixed.

Trends and outcomes in LDLT at high MELD scores

Dr. Rosenthal and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of adult LDLT recipients from 2010 to 2021 using data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), the U.S. donation and transplantation system.

In baseline characteristics among LDLT transplant recipients, there weren’t significant differences in age, sex, race, and ethnicity for MELD scores below 25 or at 25 and higher. There also weren’t significant differences in donor age, relationship, use of nondirected grafts, or percentage of right and left lobe donors for LDLT recipients. However, recipients with high MELD scores had more nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (29.5% versus 24.6%) and alcohol-assisted cirrhosis (21.6% versus 14.3%).

The research team evaluated graft survival among LDLT recipients by MELD below 25 and at 25 or higher. They also compared posttransplant patient and graft survival between LDLT and DDLT recipients with a MELD of 25 or higher. They excluded transplant candidates on the wait list for Status 1/1A, redo transplant, or multiorgan transplant.

Among the 3,590 patients who had LDLT between 2010 and 2021, 342 patients (9.5%) had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant. There was some progression during the waiting period, Dr. Rosenthal noted, with a median listing MELD score of 19 among those who had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant and 21 among those who had a MELD of 30 or higher at transplant.

For LDLT recipients with MELD scores above or below 25, researchers found no significant differences in adjusted patient survival or adjusted graft survival.

Then the team compared outcomes of LDLT and DDLT in high-MELD recipients. Among the 67,279-patient DDLT comparator group, 27,552 patients (41%) had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant.

In terms of LDLT versus DDLT, unadjusted and adjusted patient survival were no different for patients with MELD of 25 or higher. In addition, unadjusted graft survival was no different.

However, adjusted graft survival was worse for LDLT recipients with high MELD scores. In addition, the retransplant rate was higher in LDLT recipients, at 5.7% versus 2.4%.

The reason why graft survival may be worse remains unclear, Dr. Rosenthal said. One hypothesis is that a low graft-to-recipient weight ratio in LDLT can cause small-for-size syndrome. However, these ratios were not available from OPTN.

“Further studies should be done to see what the benefit is, with graft-to-recipient weight ratios included,” he said. “The differences between DDLT and LDLT in this setting should be further explored as well.”

The research team also described temporal and transplant center trends for LDLT by MELD group. For temporal trends, they expanded the study period from 2002-2021.

The found a marked U.S. increase in the percentage of LDLT with a MELD of 25 or higher, particularly in the last decade and especially in the last 5 years. But the percentage of LDLT with high MELD remains lower than 15%, even in recent years, Dr. Rosenthal noted.

Across transplant centers, there was a trend toward centers with increasing LDLT volume having a greater proportion of LDLT recipients with a MELD of 25 or higher. At the 19.6% of centers performing 10 or fewer LDLT during the study period, none of the LDLT recipients had a MELD of 25 or higher, Dr. Rosenthal said.

The authors didn’t report a funding source. The authors declared no relevant disclosures.

Living donor liver transplants (LDLT) for recipients with the most urgent need for a liver transplant in the next 3 months – a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score of 25 or higher – have become more frequent during the past decade, according to new findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Among LDLT recipients, researchers found comparable patient and graft survival at low and high MELD scores. But among patients with high MELD scores, researchers found lower adjusted graft survival and a higher transplant rate among those with living donors, compared with recipients of deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT).

The findings suggest certain advantages of LDLT over DDLT may be lost in the high-MELD setting in terms of graft survival, said Benjamin Rosenthal, MD, an internal medicine resident focused on transplant hepatology at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Historically, in the United States especially, living donor liver transplantation has been offered to patients with low or moderate MELD,” he said. “The outcomes of LDLT at high MELD are currently unknown.”

Previous data from the Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Cohort Study (A2ALL) found that LDLT offered a survival benefit versus remaining on the wait list, independent of MELD score, he said. A recent study also has demonstrated a survival benefit across MELD scores of 11-26, but findings for MELD scores of 25 and higher have been mixed.

Trends and outcomes in LDLT at high MELD scores

Dr. Rosenthal and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of adult LDLT recipients from 2010 to 2021 using data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), the U.S. donation and transplantation system.

In baseline characteristics among LDLT transplant recipients, there weren’t significant differences in age, sex, race, and ethnicity for MELD scores below 25 or at 25 and higher. There also weren’t significant differences in donor age, relationship, use of nondirected grafts, or percentage of right and left lobe donors for LDLT recipients. However, recipients with high MELD scores had more nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (29.5% versus 24.6%) and alcohol-assisted cirrhosis (21.6% versus 14.3%).

The research team evaluated graft survival among LDLT recipients by MELD below 25 and at 25 or higher. They also compared posttransplant patient and graft survival between LDLT and DDLT recipients with a MELD of 25 or higher. They excluded transplant candidates on the wait list for Status 1/1A, redo transplant, or multiorgan transplant.

Among the 3,590 patients who had LDLT between 2010 and 2021, 342 patients (9.5%) had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant. There was some progression during the waiting period, Dr. Rosenthal noted, with a median listing MELD score of 19 among those who had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant and 21 among those who had a MELD of 30 or higher at transplant.

For LDLT recipients with MELD scores above or below 25, researchers found no significant differences in adjusted patient survival or adjusted graft survival.

Then the team compared outcomes of LDLT and DDLT in high-MELD recipients. Among the 67,279-patient DDLT comparator group, 27,552 patients (41%) had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant.

In terms of LDLT versus DDLT, unadjusted and adjusted patient survival were no different for patients with MELD of 25 or higher. In addition, unadjusted graft survival was no different.

However, adjusted graft survival was worse for LDLT recipients with high MELD scores. In addition, the retransplant rate was higher in LDLT recipients, at 5.7% versus 2.4%.

The reason why graft survival may be worse remains unclear, Dr. Rosenthal said. One hypothesis is that a low graft-to-recipient weight ratio in LDLT can cause small-for-size syndrome. However, these ratios were not available from OPTN.

“Further studies should be done to see what the benefit is, with graft-to-recipient weight ratios included,” he said. “The differences between DDLT and LDLT in this setting should be further explored as well.”

The research team also described temporal and transplant center trends for LDLT by MELD group. For temporal trends, they expanded the study period from 2002-2021.

The found a marked U.S. increase in the percentage of LDLT with a MELD of 25 or higher, particularly in the last decade and especially in the last 5 years. But the percentage of LDLT with high MELD remains lower than 15%, even in recent years, Dr. Rosenthal noted.

Across transplant centers, there was a trend toward centers with increasing LDLT volume having a greater proportion of LDLT recipients with a MELD of 25 or higher. At the 19.6% of centers performing 10 or fewer LDLT during the study period, none of the LDLT recipients had a MELD of 25 or higher, Dr. Rosenthal said.

The authors didn’t report a funding source. The authors declared no relevant disclosures.

Living donor liver transplants (LDLT) for recipients with the most urgent need for a liver transplant in the next 3 months – a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score of 25 or higher – have become more frequent during the past decade, according to new findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Among LDLT recipients, researchers found comparable patient and graft survival at low and high MELD scores. But among patients with high MELD scores, researchers found lower adjusted graft survival and a higher transplant rate among those with living donors, compared with recipients of deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT).

The findings suggest certain advantages of LDLT over DDLT may be lost in the high-MELD setting in terms of graft survival, said Benjamin Rosenthal, MD, an internal medicine resident focused on transplant hepatology at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Historically, in the United States especially, living donor liver transplantation has been offered to patients with low or moderate MELD,” he said. “The outcomes of LDLT at high MELD are currently unknown.”

Previous data from the Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Cohort Study (A2ALL) found that LDLT offered a survival benefit versus remaining on the wait list, independent of MELD score, he said. A recent study also has demonstrated a survival benefit across MELD scores of 11-26, but findings for MELD scores of 25 and higher have been mixed.

Trends and outcomes in LDLT at high MELD scores

Dr. Rosenthal and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of adult LDLT recipients from 2010 to 2021 using data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), the U.S. donation and transplantation system.

In baseline characteristics among LDLT transplant recipients, there weren’t significant differences in age, sex, race, and ethnicity for MELD scores below 25 or at 25 and higher. There also weren’t significant differences in donor age, relationship, use of nondirected grafts, or percentage of right and left lobe donors for LDLT recipients. However, recipients with high MELD scores had more nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (29.5% versus 24.6%) and alcohol-assisted cirrhosis (21.6% versus 14.3%).

The research team evaluated graft survival among LDLT recipients by MELD below 25 and at 25 or higher. They also compared posttransplant patient and graft survival between LDLT and DDLT recipients with a MELD of 25 or higher. They excluded transplant candidates on the wait list for Status 1/1A, redo transplant, or multiorgan transplant.

Among the 3,590 patients who had LDLT between 2010 and 2021, 342 patients (9.5%) had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant. There was some progression during the waiting period, Dr. Rosenthal noted, with a median listing MELD score of 19 among those who had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant and 21 among those who had a MELD of 30 or higher at transplant.

For LDLT recipients with MELD scores above or below 25, researchers found no significant differences in adjusted patient survival or adjusted graft survival.

Then the team compared outcomes of LDLT and DDLT in high-MELD recipients. Among the 67,279-patient DDLT comparator group, 27,552 patients (41%) had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant.

In terms of LDLT versus DDLT, unadjusted and adjusted patient survival were no different for patients with MELD of 25 or higher. In addition, unadjusted graft survival was no different.

However, adjusted graft survival was worse for LDLT recipients with high MELD scores. In addition, the retransplant rate was higher in LDLT recipients, at 5.7% versus 2.4%.

The reason why graft survival may be worse remains unclear, Dr. Rosenthal said. One hypothesis is that a low graft-to-recipient weight ratio in LDLT can cause small-for-size syndrome. However, these ratios were not available from OPTN.

“Further studies should be done to see what the benefit is, with graft-to-recipient weight ratios included,” he said. “The differences between DDLT and LDLT in this setting should be further explored as well.”

The research team also described temporal and transplant center trends for LDLT by MELD group. For temporal trends, they expanded the study period from 2002-2021.

The found a marked U.S. increase in the percentage of LDLT with a MELD of 25 or higher, particularly in the last decade and especially in the last 5 years. But the percentage of LDLT with high MELD remains lower than 15%, even in recent years, Dr. Rosenthal noted.

Across transplant centers, there was a trend toward centers with increasing LDLT volume having a greater proportion of LDLT recipients with a MELD of 25 or higher. At the 19.6% of centers performing 10 or fewer LDLT during the study period, none of the LDLT recipients had a MELD of 25 or higher, Dr. Rosenthal said.

The authors didn’t report a funding source. The authors declared no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE LIVER MEETING

Have you heard the one about the emergency dept. that called 911?

Who watches the ED staff?

We heard a really great joke recently, one we simply have to share.

A man in Seattle went to a therapist. “I’m depressed,” he says. “Depressed, overworked, and lonely.”

“Oh dear, that sounds quite serious,” the therapist replies. “Tell me all about it.”

“Life just seems so harsh and cruel,” the man explains. “The pandemic has caused 300,000 health care workers across the country to leave the industry.”

“Such as the doctor typically filling this role in the joke,” the therapist, who is not licensed to prescribe medicine, nods.

“Exactly! And with so many respiratory viruses circulating and COVID still hanging around, emergency departments all over the country are facing massive backups. People are waiting outside the hospital for hours, hoping a bed will open up. Things got so bad at a hospital near Seattle in October that a nurse called 911 on her own ED. Told the 911 operator to send the fire department to help out, since they were ‘drowning’ and ‘in dire straits.’ They had 45 patients waiting and only five nurses to take care of them.”

“That is quite serious,” the therapist says, scribbling down unseen notes.

“The fire chief did send a crew out, and they cleaned rooms, changed beds, and took vitals for 90 minutes until the crisis passed,” the man says. “But it’s only a matter of time before it happens again. The hospital president said they have 300 open positions, and literally no one has applied to work in the emergency department. Not one person.”

“And how does all this make you feel?” the therapist asks.

“I feel all alone,” the man says. “This world feels so threatening, like no one cares, and I have no idea what will come next. It’s so vague and uncertain.”

“Ah, I think I have a solution for you,” the therapist says. “Go to the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center in Silverdale, near Seattle. They’ll get your bad mood all settled, and they’ll prescribe you the medicine you need to relax.”

The man bursts into tears. “You don’t understand,” he says. “I am the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center.”

Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains.

Myth buster: Supplements for cholesterol lowering

When it comes to that nasty low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, some people swear by supplements over statins as a holistic approach. Well, we’re busting the myth that those heart-healthy supplements are even effective in comparison.

Which supplements are we talking about? These six are always on sale at the pharmacy: fish oil, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, plant sterols, and red yeast rice.

In a study presented at the recent American Heart Association scientific sessions, researchers compared these supplements’ effectiveness in lowering LDL cholesterol with low-dose rosuvastatin or placebo among 199 adults aged 40-75 years who didn’t have a personal history of cardiovascular disease.

Participants who took the statin for 28 days had an average of 24% decrease in total cholesterol and a 38% reduction in LDL cholesterol, while 28 days’ worth of the supplements did no better than the placebo in either measure. Compared with placebo, the plant sterols supplement notably lowered HDL cholesterol and the garlic supplement notably increased LDL cholesterol.

Even though there are other studies showing the validity of plant sterols and red yeast rice to lower LDL cholesterol, author Luke J. Laffin, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic noted that this study shows how supplement results can vary and that more research is needed to see the effect they truly have on cholesterol over time.

So, should you stop taking or recommending supplements for heart health or healthy cholesterol levels? Well, we’re not going to come to your house and raid your medicine cabinet, but the authors of this study are definitely not saying that you should rely on them.

Consider this myth mostly busted.

COVID dept. of unintended consequences, part 2

The surveillance testing programs conducted in the first year of the pandemic were, in theory, meant to keep everyone safer. Someone, apparently, forgot to explain that to the students of the University of Wyoming and the University of Idaho.

We’re all familiar with the drill: Students at the two schools had to undergo frequent COVID screening to keep the virus from spreading, thereby making everyone safer. Duck your head now, because here comes the unintended consequence.

The students who didn’t get COVID eventually, and perhaps not so surprisingly, “perceived that the mandatory testing policy decreased their risk of contracting COVID-19, and … this perception led to higher participation in COVID-risky events,” Chian Jones Ritten, PhD, and associates said in PNAS Nexus.

They surveyed 757 students from the Univ. of Washington and 517 from the Univ. of Idaho and found that those who were tested more frequently perceived that they were less likely to contract the virus. Those respondents also more frequently attended indoor gatherings, both small and large, and spent more time in restaurants and bars.

The investigators did not mince words: “From a public health standpoint, such behavior is problematic.”

Current parents/participants in the workforce might have other ideas about an appropriate response to COVID.

At this point, we probably should mention that appropriation is the second-most sincere form of flattery.

Who watches the ED staff?

We heard a really great joke recently, one we simply have to share.

A man in Seattle went to a therapist. “I’m depressed,” he says. “Depressed, overworked, and lonely.”

“Oh dear, that sounds quite serious,” the therapist replies. “Tell me all about it.”

“Life just seems so harsh and cruel,” the man explains. “The pandemic has caused 300,000 health care workers across the country to leave the industry.”

“Such as the doctor typically filling this role in the joke,” the therapist, who is not licensed to prescribe medicine, nods.

“Exactly! And with so many respiratory viruses circulating and COVID still hanging around, emergency departments all over the country are facing massive backups. People are waiting outside the hospital for hours, hoping a bed will open up. Things got so bad at a hospital near Seattle in October that a nurse called 911 on her own ED. Told the 911 operator to send the fire department to help out, since they were ‘drowning’ and ‘in dire straits.’ They had 45 patients waiting and only five nurses to take care of them.”

“That is quite serious,” the therapist says, scribbling down unseen notes.

“The fire chief did send a crew out, and they cleaned rooms, changed beds, and took vitals for 90 minutes until the crisis passed,” the man says. “But it’s only a matter of time before it happens again. The hospital president said they have 300 open positions, and literally no one has applied to work in the emergency department. Not one person.”

“And how does all this make you feel?” the therapist asks.

“I feel all alone,” the man says. “This world feels so threatening, like no one cares, and I have no idea what will come next. It’s so vague and uncertain.”

“Ah, I think I have a solution for you,” the therapist says. “Go to the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center in Silverdale, near Seattle. They’ll get your bad mood all settled, and they’ll prescribe you the medicine you need to relax.”

The man bursts into tears. “You don’t understand,” he says. “I am the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center.”

Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains.

Myth buster: Supplements for cholesterol lowering

When it comes to that nasty low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, some people swear by supplements over statins as a holistic approach. Well, we’re busting the myth that those heart-healthy supplements are even effective in comparison.

Which supplements are we talking about? These six are always on sale at the pharmacy: fish oil, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, plant sterols, and red yeast rice.

In a study presented at the recent American Heart Association scientific sessions, researchers compared these supplements’ effectiveness in lowering LDL cholesterol with low-dose rosuvastatin or placebo among 199 adults aged 40-75 years who didn’t have a personal history of cardiovascular disease.

Participants who took the statin for 28 days had an average of 24% decrease in total cholesterol and a 38% reduction in LDL cholesterol, while 28 days’ worth of the supplements did no better than the placebo in either measure. Compared with placebo, the plant sterols supplement notably lowered HDL cholesterol and the garlic supplement notably increased LDL cholesterol.

Even though there are other studies showing the validity of plant sterols and red yeast rice to lower LDL cholesterol, author Luke J. Laffin, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic noted that this study shows how supplement results can vary and that more research is needed to see the effect they truly have on cholesterol over time.

So, should you stop taking or recommending supplements for heart health or healthy cholesterol levels? Well, we’re not going to come to your house and raid your medicine cabinet, but the authors of this study are definitely not saying that you should rely on them.

Consider this myth mostly busted.

COVID dept. of unintended consequences, part 2

The surveillance testing programs conducted in the first year of the pandemic were, in theory, meant to keep everyone safer. Someone, apparently, forgot to explain that to the students of the University of Wyoming and the University of Idaho.

We’re all familiar with the drill: Students at the two schools had to undergo frequent COVID screening to keep the virus from spreading, thereby making everyone safer. Duck your head now, because here comes the unintended consequence.

The students who didn’t get COVID eventually, and perhaps not so surprisingly, “perceived that the mandatory testing policy decreased their risk of contracting COVID-19, and … this perception led to higher participation in COVID-risky events,” Chian Jones Ritten, PhD, and associates said in PNAS Nexus.

They surveyed 757 students from the Univ. of Washington and 517 from the Univ. of Idaho and found that those who were tested more frequently perceived that they were less likely to contract the virus. Those respondents also more frequently attended indoor gatherings, both small and large, and spent more time in restaurants and bars.

The investigators did not mince words: “From a public health standpoint, such behavior is problematic.”

Current parents/participants in the workforce might have other ideas about an appropriate response to COVID.

At this point, we probably should mention that appropriation is the second-most sincere form of flattery.

Who watches the ED staff?

We heard a really great joke recently, one we simply have to share.

A man in Seattle went to a therapist. “I’m depressed,” he says. “Depressed, overworked, and lonely.”

“Oh dear, that sounds quite serious,” the therapist replies. “Tell me all about it.”

“Life just seems so harsh and cruel,” the man explains. “The pandemic has caused 300,000 health care workers across the country to leave the industry.”

“Such as the doctor typically filling this role in the joke,” the therapist, who is not licensed to prescribe medicine, nods.

“Exactly! And with so many respiratory viruses circulating and COVID still hanging around, emergency departments all over the country are facing massive backups. People are waiting outside the hospital for hours, hoping a bed will open up. Things got so bad at a hospital near Seattle in October that a nurse called 911 on her own ED. Told the 911 operator to send the fire department to help out, since they were ‘drowning’ and ‘in dire straits.’ They had 45 patients waiting and only five nurses to take care of them.”

“That is quite serious,” the therapist says, scribbling down unseen notes.

“The fire chief did send a crew out, and they cleaned rooms, changed beds, and took vitals for 90 minutes until the crisis passed,” the man says. “But it’s only a matter of time before it happens again. The hospital president said they have 300 open positions, and literally no one has applied to work in the emergency department. Not one person.”

“And how does all this make you feel?” the therapist asks.

“I feel all alone,” the man says. “This world feels so threatening, like no one cares, and I have no idea what will come next. It’s so vague and uncertain.”

“Ah, I think I have a solution for you,” the therapist says. “Go to the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center in Silverdale, near Seattle. They’ll get your bad mood all settled, and they’ll prescribe you the medicine you need to relax.”

The man bursts into tears. “You don’t understand,” he says. “I am the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center.”

Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains.

Myth buster: Supplements for cholesterol lowering

When it comes to that nasty low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, some people swear by supplements over statins as a holistic approach. Well, we’re busting the myth that those heart-healthy supplements are even effective in comparison.

Which supplements are we talking about? These six are always on sale at the pharmacy: fish oil, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, plant sterols, and red yeast rice.

In a study presented at the recent American Heart Association scientific sessions, researchers compared these supplements’ effectiveness in lowering LDL cholesterol with low-dose rosuvastatin or placebo among 199 adults aged 40-75 years who didn’t have a personal history of cardiovascular disease.

Participants who took the statin for 28 days had an average of 24% decrease in total cholesterol and a 38% reduction in LDL cholesterol, while 28 days’ worth of the supplements did no better than the placebo in either measure. Compared with placebo, the plant sterols supplement notably lowered HDL cholesterol and the garlic supplement notably increased LDL cholesterol.

Even though there are other studies showing the validity of plant sterols and red yeast rice to lower LDL cholesterol, author Luke J. Laffin, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic noted that this study shows how supplement results can vary and that more research is needed to see the effect they truly have on cholesterol over time.

So, should you stop taking or recommending supplements for heart health or healthy cholesterol levels? Well, we’re not going to come to your house and raid your medicine cabinet, but the authors of this study are definitely not saying that you should rely on them.

Consider this myth mostly busted.

COVID dept. of unintended consequences, part 2

The surveillance testing programs conducted in the first year of the pandemic were, in theory, meant to keep everyone safer. Someone, apparently, forgot to explain that to the students of the University of Wyoming and the University of Idaho.

We’re all familiar with the drill: Students at the two schools had to undergo frequent COVID screening to keep the virus from spreading, thereby making everyone safer. Duck your head now, because here comes the unintended consequence.

The students who didn’t get COVID eventually, and perhaps not so surprisingly, “perceived that the mandatory testing policy decreased their risk of contracting COVID-19, and … this perception led to higher participation in COVID-risky events,” Chian Jones Ritten, PhD, and associates said in PNAS Nexus.

They surveyed 757 students from the Univ. of Washington and 517 from the Univ. of Idaho and found that those who were tested more frequently perceived that they were less likely to contract the virus. Those respondents also more frequently attended indoor gatherings, both small and large, and spent more time in restaurants and bars.

The investigators did not mince words: “From a public health standpoint, such behavior is problematic.”

Current parents/participants in the workforce might have other ideas about an appropriate response to COVID.

At this point, we probably should mention that appropriation is the second-most sincere form of flattery.

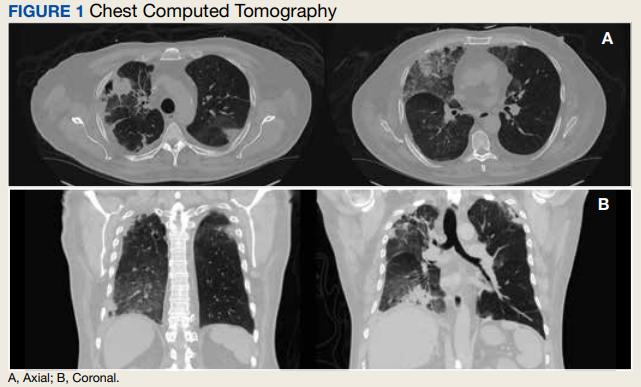

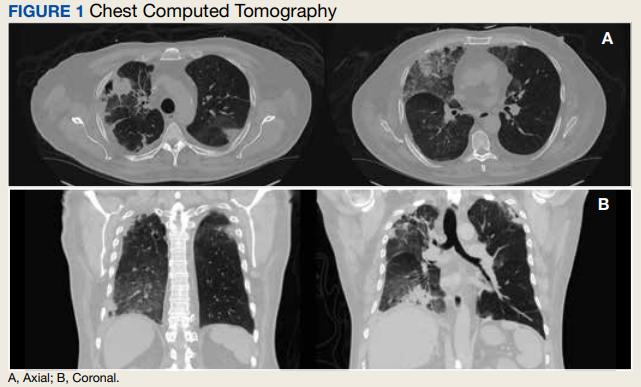

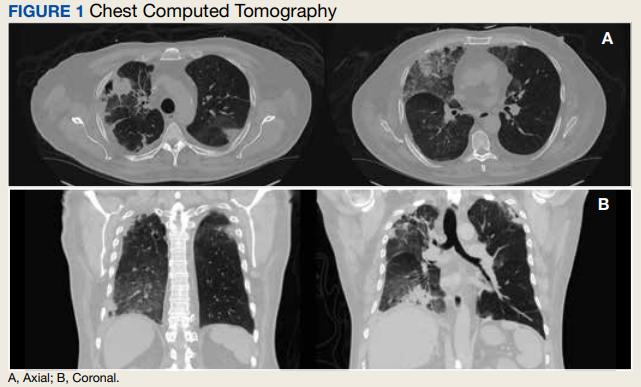

A Patient Presenting With Shortness of Breath, Fever, and Eosinophilia

A 70-year-old veteran with a history notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, complicated by peripheral neuropathy and bilateral foot ulceration, and previous pulmonary tuberculosis (treated in June 2013) presented to an outside medical facility with bilateral worsening foot pain, swelling, and drainage of preexisting ulcers. He received a diagnosis of bilateral fifth toe osteomyelitis and was discharged with a 6-week course of IV daptomycin 600 mg (8 mg/kg) and ertapenem 1 g/d. At discharge, the patient was in stable condition. Follow-up was done by our outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) team, which consists of an infectious disease pharmacist and the physician director of antimicrobial stewardship who monitor veterans receiving outpatient IV antibiotic therapy.1

Three weeks later as part of the regular OPAT surveillance, the patient reported via telephone that his foot osteomyelitis was stable, but he had a 101 °F fever and a new cough. He was instructed to come to the emergency department (ED) immediately. On arrival,

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

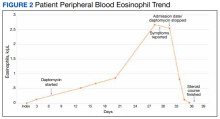

In the ED, the patient was given a provisional diagnosis of multifocal bacterial pneumonia and was admitted to the hospital for further management. His outpatient regimen of IV daptomycin and ertapenem was adjusted to IV vancomycin and meropenem. The infectious disease service was consulted within 24 hours of admission, and based on the new onset chest infiltrates, therapy with daptomycin and notable peripheral blood eosinophilia, a presumptive diagnosis of daptomycin-related acute eosinophilic pneumonia was made. A medication list review yielded no other potential etiologic agents for drug-related eosinophilia, and the patient did not have any remote or recent pertinent travel history concerning for parasitic disease.

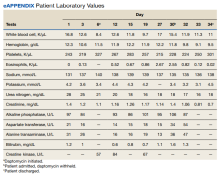

The patient was treated with oral prednisone 40 mg (0.5 mg/kg) daily and the daptomycin was not restarted. Within 24 hours, the patient’s fevers, oxygen requirements, and cough subsided. Laboratory values

Discussion

Daptomycin is a commonly used cyclic lipopeptide IV antibiotic with broad activity against gram-positive organisms, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE). Daptomycin has emerged as a convenient alternative for infections typically treated with IV vancomycin: shorter infusion time (2-30 minutes vs 60-180 minutes), daily administration, and less need for dose adjustments. A recent survey reported higher satisfaction and less disruption in patients receiving daptomycin compared with vancomycin.2 The main daptomycin-specific adverse effect (AE) that warrants close monitoring is elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels and skeletal muscle breakdown (reversible after holding medication).3 Other rarely reported AEs include drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), acute eosinophilic pneumonitis, hepatitis, and peripheral neuropathy.4-6 Consequently, weekly monitoring for this drug should include symptom inquiry for cough and muscle pain, and laboratory testing with CBC with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and CK.

Daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia has been described in several case reports and in a recent study, the frequency of this event was almost 5% in those receiving long-term daptomycin therapy.7 The most common symptoms include dyspnea, fever, infiltrates/opacities on chest imaging, and peripheral eosinophilia. It is theorized that the chemical structure of daptomycin causes immune-mediated pulmonary epithelial cell injury with eosinophils, resulting in increased peripheral eosinophilia.3 Risk factors that have been identified for daptomycin-induced eosinophilia include age > 70 years; the presence of comorbidities of heart and pulmonary disease; duration of daptomycin beyond 2 weeks; and cumulative doses over 10 g. Average onset of illness from initiation of daptomycin has been reported to be about 3 weeks.7,8 The diagnosis of daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonitis is made on several criteria per the FDA. These include exposure to daptomycin, fever, dyspnea with oxygen requirement, new infiltrates on imaging, bronchoalveolar lavage with > 25% eosinophils, and last, clinical improvement on removal of the drug.9 However, as bronchoscopy is an invasive diagnostic modality, it is not always performed or necessary as seen in this case. Furthermore, not all patients will have peripheral eosinophilia, with only 77% of patients having that finding in a systematic review.10 Taken together, the overall true incidence of daptomycin-induced eosinophilia may be underestimated. Treatment involves discontinuation of the daptomycin and initiation of steroids. In a review of 35 cases, the majority did receive systemic steroids, usually 60 to 125 mg of IV methylprednisolone every 6 hours, which was converted to oral steroids and tapered over 2 to 6 weeks.10 However, all patients including those who did not receive steroids had symptom improvement or complete resolution, highlighting that prompt discontinuation of daptomycin is the most crucial intervention.

Conclusions

As home IV antibiotic therapy becomes increasingly used to facilitate shorter lengths of stay in hospitals and enable more patients to receive their infectious disease care at home, the general practitioner must be aware of the potential AEs of commonly used IV antibiotics. While acute cutaneous reactions and disturbances in renal and liver function are commonly recognized entities of adverse drug reactions, symptoms of fever and cough are more likely to be interpreted as acute viral or bacterial respiratory infections. A high index of clinical suspicion is needed for eosinophilic pneumonitis secondary to daptomycin. A simple and readily available test, such as a CBC with differential may facilitate the identification of this potentially serious AE, allowing prompt discontinuation of the drug.

1. Kent M, Kouma M, Jodlowski T, Cutrell JB. 755. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy program evaluation within a large Veterans Affairs healthcare system. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(suppl 2):S337. Published 2019 Oct 23. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz360.823

2. Wu KH, Sakoulas G, Geriak M. Vancomycin or daptomycin for outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy: does it make a difference in patient satisfaction? Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(8):ofab418. Published 2021 Aug 30. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab418

3. Gonzalez-Ruiz A, Seaton RA, Hamed K. Daptomycin: an evidence-based review of its role in the treatment of gram-positive infections. Infect Drug Resist. 2016;9:47-58. Published 2016 Apr 15. doi:10.2147/IDR.S99046

4. Sharifzadeh S, Mohammadpour AH, Tavanaee A, Elyasi S. Antibacterial antibiotic-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome: a literature review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;77(3):275-289. doi:10.1007/s00228-020-03005-9

5. Mo Y, Nehring F, Jung AH, Housman ST. Possible hepatotoxicity associated with daptomycin: a case report and literature review. J Pharm Pract. 2016;29(3):253-256. doi:10.1177/0897190015625403

6. Villaverde Piñeiro L, Rabuñal Rey R, García Sabina A, Monte Secades R, García Pais MJ. Paralysis of the external popliteal sciatic nerve associated with daptomycin administration. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2018;43(4):578-580. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12666

7. Soldevila-Boixader L, Villanueva B, Ulldemolins M, et al. Risk factors of daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia in a population with osteoarticular infection. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(4):446. Published 2021 Apr 16. doi:10.3390/antibiotics10040446

8. Kumar S, Acosta-Sanchez I, Rajagopalan N. Daptomycin-induced acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Cureus. 2018;10(6):e2899. Published 2018 Jun 30. doi:10.7759/cureus.2899

9. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Eosinophilic pneumonia associated with the use of cubicin. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Updated August 3, 2017. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/fda-drug-safety-communication-eosinophilic-pneumonia-associated-use-cubicin-daptomycin

10. Uppal P, LaPlante KL, Gaitanis MM, Jankowich MD, Ward KE. Daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia—a systematic review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2016;5:55. Published 2016 Dec 12. doi:10.1186/s13756-016-0158-8

A 70-year-old veteran with a history notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, complicated by peripheral neuropathy and bilateral foot ulceration, and previous pulmonary tuberculosis (treated in June 2013) presented to an outside medical facility with bilateral worsening foot pain, swelling, and drainage of preexisting ulcers. He received a diagnosis of bilateral fifth toe osteomyelitis and was discharged with a 6-week course of IV daptomycin 600 mg (8 mg/kg) and ertapenem 1 g/d. At discharge, the patient was in stable condition. Follow-up was done by our outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) team, which consists of an infectious disease pharmacist and the physician director of antimicrobial stewardship who monitor veterans receiving outpatient IV antibiotic therapy.1

Three weeks later as part of the regular OPAT surveillance, the patient reported via telephone that his foot osteomyelitis was stable, but he had a 101 °F fever and a new cough. He was instructed to come to the emergency department (ED) immediately. On arrival,

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

In the ED, the patient was given a provisional diagnosis of multifocal bacterial pneumonia and was admitted to the hospital for further management. His outpatient regimen of IV daptomycin and ertapenem was adjusted to IV vancomycin and meropenem. The infectious disease service was consulted within 24 hours of admission, and based on the new onset chest infiltrates, therapy with daptomycin and notable peripheral blood eosinophilia, a presumptive diagnosis of daptomycin-related acute eosinophilic pneumonia was made. A medication list review yielded no other potential etiologic agents for drug-related eosinophilia, and the patient did not have any remote or recent pertinent travel history concerning for parasitic disease.

The patient was treated with oral prednisone 40 mg (0.5 mg/kg) daily and the daptomycin was not restarted. Within 24 hours, the patient’s fevers, oxygen requirements, and cough subsided. Laboratory values

Discussion

Daptomycin is a commonly used cyclic lipopeptide IV antibiotic with broad activity against gram-positive organisms, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE). Daptomycin has emerged as a convenient alternative for infections typically treated with IV vancomycin: shorter infusion time (2-30 minutes vs 60-180 minutes), daily administration, and less need for dose adjustments. A recent survey reported higher satisfaction and less disruption in patients receiving daptomycin compared with vancomycin.2 The main daptomycin-specific adverse effect (AE) that warrants close monitoring is elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels and skeletal muscle breakdown (reversible after holding medication).3 Other rarely reported AEs include drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), acute eosinophilic pneumonitis, hepatitis, and peripheral neuropathy.4-6 Consequently, weekly monitoring for this drug should include symptom inquiry for cough and muscle pain, and laboratory testing with CBC with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and CK.