User login

Defining six asthma subtypes may promote personalized treatment

Six subtypes of asthma that may facilitate personalized treatment were identified and confirmed in a large database review of approximately 50,000 patients, according to a recent study.

Previous studies of asthma subtypes have involved age of disease onset, the presence of allergies, and level of eosinophilic inflammation, and have been limited by factors including small sample size and lack of formal validation, Elsie M.F. Horne, MD, of the Asthma UK Centre for Applied Research, Edinburgh, and colleagues wrote.

In a study published in the International Journal of Medical Informatics, the researchers used data from two databases in the United Kingdom: the Optimum Patient Care Research Database (OPCRD) and the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage Database (SAIL). Each dataset included 50,000 randomly selected nonoverlapping adult asthma patients.

The researchers identified 45 categorical features from primary care electronic health records. The features included those directly linked to asthma, such as medications; and features indirectly linked to asthma, such as comorbidities.

The subtypes were defined by the clinically applicable features of level of inhaled corticosteroid use, level of health care use, and the presence of comorbidities, using multiple correspondence analysis and k-means cluster analysis.

The six asthma subtypes were identified in the OPCRD study population as follows: low inhaled corticosteroid use and low health care utilization (30%); low to medium ICS use (36%); low to medium ICS use and comorbidities (12%); varied ICS use and comorbid chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (4%); high ICS use (10%); and very high ICS use (7%).

The researchers replicated the subtypes with 91%-92% accuracy in an internal dataset and 84%-86% accuracy in an external dataset. “These subtypes generalized well at two future time points, and in an additional EHR database from a different U.K. nation (the SAIL Databank),” they wrote in their discussion.

The findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design, the possible inclusion of people without asthma because of the cohort selection criteria, and the possible biases associated with the use of EHRs; however, the results were strengthened by the large dataset and the additional validations, the researchers noted.

“Using these subtypes to summarize asthma populations could help with management and resource planning at the practice level, and could be useful for understanding regional differences in the asthma population,” they noted. For example, key clinical implications for individuals in a low health care utilization subtype could include being flagged for barriers to care and misdiagnoses, while those in a high health care utilization subtype could be considered for reassessment of medication and other options.

The study received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Horne had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Six subtypes of asthma that may facilitate personalized treatment were identified and confirmed in a large database review of approximately 50,000 patients, according to a recent study.

Previous studies of asthma subtypes have involved age of disease onset, the presence of allergies, and level of eosinophilic inflammation, and have been limited by factors including small sample size and lack of formal validation, Elsie M.F. Horne, MD, of the Asthma UK Centre for Applied Research, Edinburgh, and colleagues wrote.

In a study published in the International Journal of Medical Informatics, the researchers used data from two databases in the United Kingdom: the Optimum Patient Care Research Database (OPCRD) and the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage Database (SAIL). Each dataset included 50,000 randomly selected nonoverlapping adult asthma patients.

The researchers identified 45 categorical features from primary care electronic health records. The features included those directly linked to asthma, such as medications; and features indirectly linked to asthma, such as comorbidities.

The subtypes were defined by the clinically applicable features of level of inhaled corticosteroid use, level of health care use, and the presence of comorbidities, using multiple correspondence analysis and k-means cluster analysis.

The six asthma subtypes were identified in the OPCRD study population as follows: low inhaled corticosteroid use and low health care utilization (30%); low to medium ICS use (36%); low to medium ICS use and comorbidities (12%); varied ICS use and comorbid chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (4%); high ICS use (10%); and very high ICS use (7%).

The researchers replicated the subtypes with 91%-92% accuracy in an internal dataset and 84%-86% accuracy in an external dataset. “These subtypes generalized well at two future time points, and in an additional EHR database from a different U.K. nation (the SAIL Databank),” they wrote in their discussion.

The findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design, the possible inclusion of people without asthma because of the cohort selection criteria, and the possible biases associated with the use of EHRs; however, the results were strengthened by the large dataset and the additional validations, the researchers noted.

“Using these subtypes to summarize asthma populations could help with management and resource planning at the practice level, and could be useful for understanding regional differences in the asthma population,” they noted. For example, key clinical implications for individuals in a low health care utilization subtype could include being flagged for barriers to care and misdiagnoses, while those in a high health care utilization subtype could be considered for reassessment of medication and other options.

The study received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Horne had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Six subtypes of asthma that may facilitate personalized treatment were identified and confirmed in a large database review of approximately 50,000 patients, according to a recent study.

Previous studies of asthma subtypes have involved age of disease onset, the presence of allergies, and level of eosinophilic inflammation, and have been limited by factors including small sample size and lack of formal validation, Elsie M.F. Horne, MD, of the Asthma UK Centre for Applied Research, Edinburgh, and colleagues wrote.

In a study published in the International Journal of Medical Informatics, the researchers used data from two databases in the United Kingdom: the Optimum Patient Care Research Database (OPCRD) and the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage Database (SAIL). Each dataset included 50,000 randomly selected nonoverlapping adult asthma patients.

The researchers identified 45 categorical features from primary care electronic health records. The features included those directly linked to asthma, such as medications; and features indirectly linked to asthma, such as comorbidities.

The subtypes were defined by the clinically applicable features of level of inhaled corticosteroid use, level of health care use, and the presence of comorbidities, using multiple correspondence analysis and k-means cluster analysis.

The six asthma subtypes were identified in the OPCRD study population as follows: low inhaled corticosteroid use and low health care utilization (30%); low to medium ICS use (36%); low to medium ICS use and comorbidities (12%); varied ICS use and comorbid chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (4%); high ICS use (10%); and very high ICS use (7%).

The researchers replicated the subtypes with 91%-92% accuracy in an internal dataset and 84%-86% accuracy in an external dataset. “These subtypes generalized well at two future time points, and in an additional EHR database from a different U.K. nation (the SAIL Databank),” they wrote in their discussion.

The findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design, the possible inclusion of people without asthma because of the cohort selection criteria, and the possible biases associated with the use of EHRs; however, the results were strengthened by the large dataset and the additional validations, the researchers noted.

“Using these subtypes to summarize asthma populations could help with management and resource planning at the practice level, and could be useful for understanding regional differences in the asthma population,” they noted. For example, key clinical implications for individuals in a low health care utilization subtype could include being flagged for barriers to care and misdiagnoses, while those in a high health care utilization subtype could be considered for reassessment of medication and other options.

The study received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Horne had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MEDICAL INFORMATICS

CHEST President shares inside look at priorities, plans for 2023

Attendees at the CHEST 2022 Opening Session on October 16 got a sneak peek into plans and priorities for CHEST President Doreen J. Addrizzo-Harris, MD, FCCP, in 2023 – and some insights into her own path to the role.

A longtime leader at CHEST, she shared how members’ pandemic response reminded her of the great impact the organization can have. In March 2020, Dr. Addrizzo-Harris was overseeing ICU staffing at NYU Langone Health’s Bellevue Hospital Center and organizing dozens of volunteer physicians to help meet the pandemic care burden.

“I knew all too quickly that we wouldn’t have enough intensivists,” said Dr. Addrizzo-Harris. “It was a quick call very late one night, probably around 1 am, that I made to CHEST CEO, Bob Musacchio, that helped materialize a monumental effort ... many of these physicians were CHEST members themselves. They were fearless and unselfish, and they came to help us in our time of need.”

She saw this same spirit of dedication and drive in CHEST’s leadership and staff, she said – one she will continue and expand upon during her presidency.

“I’ve watched our last three presidents lead by great example ... with innovation and nimbleness, in a time when we were so isolated from each other and so tired from the long hours that we worked each day,” she said. “They, along with the Board of Regents, the CEO, and our phenomenal staff, were able to keep CHEST amazingly alive and vibrant and more connected than ever. They are truly inspiring. For 2023, I hope to take this incredible energy to the next level.”

As CHEST president, Dr. in the United States and advancing international outreach initiatives launched by CHEST Past President David Schulman, MD, MPH, FCCP. This also includes supporting and building upon CHEST’s ongoing commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives to encourage greater representation in the field and improve patient care.

“Whether it’s through supporting our clinical research grants, expanding patient education and advocacy, or programs like the First 5 Minutes™ and the Harold Amos scholarship program, we want to train our leaders for the future,” she said.

Revisit the September issue of CHEST Physician, and watch future issues to learn more about Dr. Addrizzo-Harris and her plans for the presidency.

Attendees at the CHEST 2022 Opening Session on October 16 got a sneak peek into plans and priorities for CHEST President Doreen J. Addrizzo-Harris, MD, FCCP, in 2023 – and some insights into her own path to the role.

A longtime leader at CHEST, she shared how members’ pandemic response reminded her of the great impact the organization can have. In March 2020, Dr. Addrizzo-Harris was overseeing ICU staffing at NYU Langone Health’s Bellevue Hospital Center and organizing dozens of volunteer physicians to help meet the pandemic care burden.

“I knew all too quickly that we wouldn’t have enough intensivists,” said Dr. Addrizzo-Harris. “It was a quick call very late one night, probably around 1 am, that I made to CHEST CEO, Bob Musacchio, that helped materialize a monumental effort ... many of these physicians were CHEST members themselves. They were fearless and unselfish, and they came to help us in our time of need.”

She saw this same spirit of dedication and drive in CHEST’s leadership and staff, she said – one she will continue and expand upon during her presidency.

“I’ve watched our last three presidents lead by great example ... with innovation and nimbleness, in a time when we were so isolated from each other and so tired from the long hours that we worked each day,” she said. “They, along with the Board of Regents, the CEO, and our phenomenal staff, were able to keep CHEST amazingly alive and vibrant and more connected than ever. They are truly inspiring. For 2023, I hope to take this incredible energy to the next level.”

As CHEST president, Dr. in the United States and advancing international outreach initiatives launched by CHEST Past President David Schulman, MD, MPH, FCCP. This also includes supporting and building upon CHEST’s ongoing commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives to encourage greater representation in the field and improve patient care.

“Whether it’s through supporting our clinical research grants, expanding patient education and advocacy, or programs like the First 5 Minutes™ and the Harold Amos scholarship program, we want to train our leaders for the future,” she said.

Revisit the September issue of CHEST Physician, and watch future issues to learn more about Dr. Addrizzo-Harris and her plans for the presidency.

Attendees at the CHEST 2022 Opening Session on October 16 got a sneak peek into plans and priorities for CHEST President Doreen J. Addrizzo-Harris, MD, FCCP, in 2023 – and some insights into her own path to the role.

A longtime leader at CHEST, she shared how members’ pandemic response reminded her of the great impact the organization can have. In March 2020, Dr. Addrizzo-Harris was overseeing ICU staffing at NYU Langone Health’s Bellevue Hospital Center and organizing dozens of volunteer physicians to help meet the pandemic care burden.

“I knew all too quickly that we wouldn’t have enough intensivists,” said Dr. Addrizzo-Harris. “It was a quick call very late one night, probably around 1 am, that I made to CHEST CEO, Bob Musacchio, that helped materialize a monumental effort ... many of these physicians were CHEST members themselves. They were fearless and unselfish, and they came to help us in our time of need.”

She saw this same spirit of dedication and drive in CHEST’s leadership and staff, she said – one she will continue and expand upon during her presidency.

“I’ve watched our last three presidents lead by great example ... with innovation and nimbleness, in a time when we were so isolated from each other and so tired from the long hours that we worked each day,” she said. “They, along with the Board of Regents, the CEO, and our phenomenal staff, were able to keep CHEST amazingly alive and vibrant and more connected than ever. They are truly inspiring. For 2023, I hope to take this incredible energy to the next level.”

As CHEST president, Dr. in the United States and advancing international outreach initiatives launched by CHEST Past President David Schulman, MD, MPH, FCCP. This also includes supporting and building upon CHEST’s ongoing commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives to encourage greater representation in the field and improve patient care.

“Whether it’s through supporting our clinical research grants, expanding patient education and advocacy, or programs like the First 5 Minutes™ and the Harold Amos scholarship program, we want to train our leaders for the future,” she said.

Revisit the September issue of CHEST Physician, and watch future issues to learn more about Dr. Addrizzo-Harris and her plans for the presidency.

Genomics data reveal promising PSC therapeutic target

, according to a study published in Gastro Hep Advances.

PSC is very rare, with an incidence of 0-1.3 cases per 100,000 people per year. Because up to 80% of patients with PSC also have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a link along the gut-liver axis is suspected. So far, scientists have not understood the causes of PSC, the main complications of which include biliary cirrhosis, bacterial cholangitis, and cholangiocarcinoma.

No treatment is currently available for PSC, but the findings of this genomics study suggest several targets that may be worth pursuing, particularly the gene NR0B2.

“The therapeutic targeting of NR0B2 may potentiate that of FXR [farnesoid X receptor] and enable action on early events of the disease and prevent its progression,” wrote Christophe Desterke, PhD, of the Paul-Brousse Hospital, the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research, and the University of Paris-Saclay in Villejuif, France, and his associates.

The researchers used an algorithmic tool to mine the MEDLINE/PubMed/NCBI database using the three key symptoms of PSC – biliary fibrosis, biliary inflammation, and biliary stasis – as their keywords. This approach allowed them to discover the genes and potential pathways related to PSC in published research text or in clinical, animal, and cellular models.

The researchers initially found 525 genes linked to PSC and then compared them to RNA data from liver biopsies taken from patients with liver disease from various causes. This process led to a ranking of the 10 best markers of PSC, based on the data-mining method and the genes’ association with one or more of the three PSC symptoms.

At the top of the list is NR1H4, also called FXR, which ranks most highly with biliary fibrosis and biliary stasis. NR1H4 is already a clear target for cholestatic and fatty liver diseases, the authors noted. The other genes, in descending order of relevance, are: ABCB4, ABCB11, TGFB1, IFNL3, PNPLA3, IL6, TLR4, GPBAR1, and IL17A. In addition, complications of PSC were significantly associated with upregulation of TNFRS12A, SOX9, ANXA2, MMP7, and LCN2.

Separately, investigation of the 525 initially identified genes in mouse models of PSC revealed that NR0B2 is also a key player in the pathogenesis of PSC.

"NR0B2 was upregulated in PSC livers independent of gender, age, and body mass index,” the authors reported. “Importantly, it was not dependent on the severity of PSC in the prognostic cohort, suggesting that this may be an early event during the disease.”

The researchers also found a possible pathway explaining the autoimmunity of PSC – the involvement of CD274, also known as the PDL1 immune checkpoint. The authors noted that the PDL1 inhibitor pembrolizumab has previously been reported as a cause of sclerosing cholangitis.

Further, the researchers discovered overexpression of FOXP3 in the livers of patients with PSC. Because FOXP3 determines what T-cell subtypes look like, the finding suggests that an “imbalance between Foxp3þ regulatory T cells and Th17 cells may be involved in IBD and PSC,” they wrote.

Also of note was the overexpression of SOX9 in the livers of patients with PSC whose profiles suggested the worst clinical prognoses.

Finally, the researchers identified three genes as potentially involved in development of cholangiocarcinoma: GSTA3, ID2 (which is overexpressed in biliary tract cancer), and especially TMEM45A, a protein in cells’ Golgi apparatus that is already known to be involved in the development of several other cancers.

The research was funded by the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a bile duct disease with few therapeutic options other than liver transplant, and thus its prognosis remains grim. Additionally, the factors that cause the disease are not well understood. Identifying the pathways and genes involved in PSC pathogenesis could help in the development of potential therapeutic targets.

In this report Desterke et al. mined public data sets to identify and define a PSC-specific network. Of the top genes in this list, NR0B2 stood out as a potential player in pathogenesis because of its involvement in regulating bile acid metabolism. The authors showed that upregulation of NR0B2 occurs early in the disease process and in patient tissues is independent of variables such as gender and sex. Interestingly, the authors showed that this upregulation occurs primarily in cholangiocytes, the cells lining the bile duct. Higher expression of NR0B2 results in reprogramming that alters the metabolic function of these cells and predisposes them to malignancy.

This study, which is the first to look at omics data for PSC, highlights the involvement of genes and pathways that were previously unrecognized in disease pathogenesis. By using data derived from human PSC liver biopsies and animal models of PSC, the authors were able to validate their findings across species, which strengthened their conclusions. This approach also showed that NR0B2 deregulation occurs primarily in cholangiocytes, suggesting that future therapies should be targeted to this cell type. These important findings will improve our understanding of this rare but clinically significant disease.

Kari Nejak-Bowen, PhD, MBA, is associate professor, department of pathology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. She has no relevant conflicts of interest.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a bile duct disease with few therapeutic options other than liver transplant, and thus its prognosis remains grim. Additionally, the factors that cause the disease are not well understood. Identifying the pathways and genes involved in PSC pathogenesis could help in the development of potential therapeutic targets.

In this report Desterke et al. mined public data sets to identify and define a PSC-specific network. Of the top genes in this list, NR0B2 stood out as a potential player in pathogenesis because of its involvement in regulating bile acid metabolism. The authors showed that upregulation of NR0B2 occurs early in the disease process and in patient tissues is independent of variables such as gender and sex. Interestingly, the authors showed that this upregulation occurs primarily in cholangiocytes, the cells lining the bile duct. Higher expression of NR0B2 results in reprogramming that alters the metabolic function of these cells and predisposes them to malignancy.

This study, which is the first to look at omics data for PSC, highlights the involvement of genes and pathways that were previously unrecognized in disease pathogenesis. By using data derived from human PSC liver biopsies and animal models of PSC, the authors were able to validate their findings across species, which strengthened their conclusions. This approach also showed that NR0B2 deregulation occurs primarily in cholangiocytes, suggesting that future therapies should be targeted to this cell type. These important findings will improve our understanding of this rare but clinically significant disease.

Kari Nejak-Bowen, PhD, MBA, is associate professor, department of pathology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. She has no relevant conflicts of interest.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a bile duct disease with few therapeutic options other than liver transplant, and thus its prognosis remains grim. Additionally, the factors that cause the disease are not well understood. Identifying the pathways and genes involved in PSC pathogenesis could help in the development of potential therapeutic targets.

In this report Desterke et al. mined public data sets to identify and define a PSC-specific network. Of the top genes in this list, NR0B2 stood out as a potential player in pathogenesis because of its involvement in regulating bile acid metabolism. The authors showed that upregulation of NR0B2 occurs early in the disease process and in patient tissues is independent of variables such as gender and sex. Interestingly, the authors showed that this upregulation occurs primarily in cholangiocytes, the cells lining the bile duct. Higher expression of NR0B2 results in reprogramming that alters the metabolic function of these cells and predisposes them to malignancy.

This study, which is the first to look at omics data for PSC, highlights the involvement of genes and pathways that were previously unrecognized in disease pathogenesis. By using data derived from human PSC liver biopsies and animal models of PSC, the authors were able to validate their findings across species, which strengthened their conclusions. This approach also showed that NR0B2 deregulation occurs primarily in cholangiocytes, suggesting that future therapies should be targeted to this cell type. These important findings will improve our understanding of this rare but clinically significant disease.

Kari Nejak-Bowen, PhD, MBA, is associate professor, department of pathology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. She has no relevant conflicts of interest.

, according to a study published in Gastro Hep Advances.

PSC is very rare, with an incidence of 0-1.3 cases per 100,000 people per year. Because up to 80% of patients with PSC also have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a link along the gut-liver axis is suspected. So far, scientists have not understood the causes of PSC, the main complications of which include biliary cirrhosis, bacterial cholangitis, and cholangiocarcinoma.

No treatment is currently available for PSC, but the findings of this genomics study suggest several targets that may be worth pursuing, particularly the gene NR0B2.

“The therapeutic targeting of NR0B2 may potentiate that of FXR [farnesoid X receptor] and enable action on early events of the disease and prevent its progression,” wrote Christophe Desterke, PhD, of the Paul-Brousse Hospital, the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research, and the University of Paris-Saclay in Villejuif, France, and his associates.

The researchers used an algorithmic tool to mine the MEDLINE/PubMed/NCBI database using the three key symptoms of PSC – biliary fibrosis, biliary inflammation, and biliary stasis – as their keywords. This approach allowed them to discover the genes and potential pathways related to PSC in published research text or in clinical, animal, and cellular models.

The researchers initially found 525 genes linked to PSC and then compared them to RNA data from liver biopsies taken from patients with liver disease from various causes. This process led to a ranking of the 10 best markers of PSC, based on the data-mining method and the genes’ association with one or more of the three PSC symptoms.

At the top of the list is NR1H4, also called FXR, which ranks most highly with biliary fibrosis and biliary stasis. NR1H4 is already a clear target for cholestatic and fatty liver diseases, the authors noted. The other genes, in descending order of relevance, are: ABCB4, ABCB11, TGFB1, IFNL3, PNPLA3, IL6, TLR4, GPBAR1, and IL17A. In addition, complications of PSC were significantly associated with upregulation of TNFRS12A, SOX9, ANXA2, MMP7, and LCN2.

Separately, investigation of the 525 initially identified genes in mouse models of PSC revealed that NR0B2 is also a key player in the pathogenesis of PSC.

"NR0B2 was upregulated in PSC livers independent of gender, age, and body mass index,” the authors reported. “Importantly, it was not dependent on the severity of PSC in the prognostic cohort, suggesting that this may be an early event during the disease.”

The researchers also found a possible pathway explaining the autoimmunity of PSC – the involvement of CD274, also known as the PDL1 immune checkpoint. The authors noted that the PDL1 inhibitor pembrolizumab has previously been reported as a cause of sclerosing cholangitis.

Further, the researchers discovered overexpression of FOXP3 in the livers of patients with PSC. Because FOXP3 determines what T-cell subtypes look like, the finding suggests that an “imbalance between Foxp3þ regulatory T cells and Th17 cells may be involved in IBD and PSC,” they wrote.

Also of note was the overexpression of SOX9 in the livers of patients with PSC whose profiles suggested the worst clinical prognoses.

Finally, the researchers identified three genes as potentially involved in development of cholangiocarcinoma: GSTA3, ID2 (which is overexpressed in biliary tract cancer), and especially TMEM45A, a protein in cells’ Golgi apparatus that is already known to be involved in the development of several other cancers.

The research was funded by the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

, according to a study published in Gastro Hep Advances.

PSC is very rare, with an incidence of 0-1.3 cases per 100,000 people per year. Because up to 80% of patients with PSC also have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a link along the gut-liver axis is suspected. So far, scientists have not understood the causes of PSC, the main complications of which include biliary cirrhosis, bacterial cholangitis, and cholangiocarcinoma.

No treatment is currently available for PSC, but the findings of this genomics study suggest several targets that may be worth pursuing, particularly the gene NR0B2.

“The therapeutic targeting of NR0B2 may potentiate that of FXR [farnesoid X receptor] and enable action on early events of the disease and prevent its progression,” wrote Christophe Desterke, PhD, of the Paul-Brousse Hospital, the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research, and the University of Paris-Saclay in Villejuif, France, and his associates.

The researchers used an algorithmic tool to mine the MEDLINE/PubMed/NCBI database using the three key symptoms of PSC – biliary fibrosis, biliary inflammation, and biliary stasis – as their keywords. This approach allowed them to discover the genes and potential pathways related to PSC in published research text or in clinical, animal, and cellular models.

The researchers initially found 525 genes linked to PSC and then compared them to RNA data from liver biopsies taken from patients with liver disease from various causes. This process led to a ranking of the 10 best markers of PSC, based on the data-mining method and the genes’ association with one or more of the three PSC symptoms.

At the top of the list is NR1H4, also called FXR, which ranks most highly with biliary fibrosis and biliary stasis. NR1H4 is already a clear target for cholestatic and fatty liver diseases, the authors noted. The other genes, in descending order of relevance, are: ABCB4, ABCB11, TGFB1, IFNL3, PNPLA3, IL6, TLR4, GPBAR1, and IL17A. In addition, complications of PSC were significantly associated with upregulation of TNFRS12A, SOX9, ANXA2, MMP7, and LCN2.

Separately, investigation of the 525 initially identified genes in mouse models of PSC revealed that NR0B2 is also a key player in the pathogenesis of PSC.

"NR0B2 was upregulated in PSC livers independent of gender, age, and body mass index,” the authors reported. “Importantly, it was not dependent on the severity of PSC in the prognostic cohort, suggesting that this may be an early event during the disease.”

The researchers also found a possible pathway explaining the autoimmunity of PSC – the involvement of CD274, also known as the PDL1 immune checkpoint. The authors noted that the PDL1 inhibitor pembrolizumab has previously been reported as a cause of sclerosing cholangitis.

Further, the researchers discovered overexpression of FOXP3 in the livers of patients with PSC. Because FOXP3 determines what T-cell subtypes look like, the finding suggests that an “imbalance between Foxp3þ regulatory T cells and Th17 cells may be involved in IBD and PSC,” they wrote.

Also of note was the overexpression of SOX9 in the livers of patients with PSC whose profiles suggested the worst clinical prognoses.

Finally, the researchers identified three genes as potentially involved in development of cholangiocarcinoma: GSTA3, ID2 (which is overexpressed in biliary tract cancer), and especially TMEM45A, a protein in cells’ Golgi apparatus that is already known to be involved in the development of several other cancers.

The research was funded by the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM GASTRO HEP ADVANCES

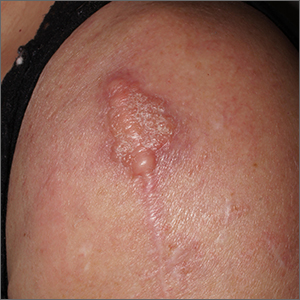

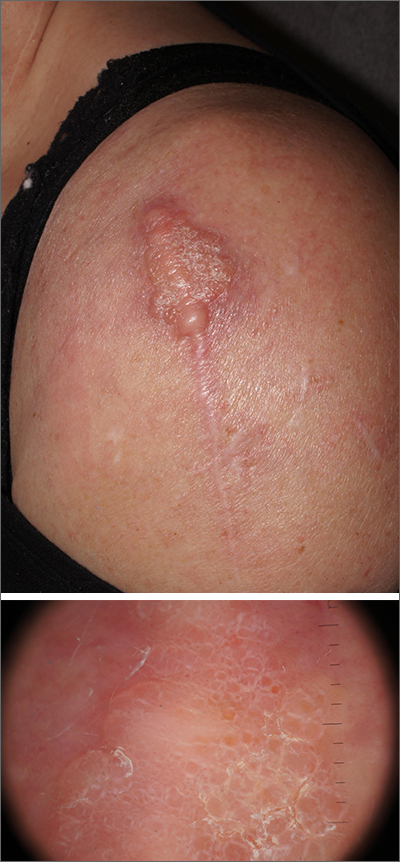

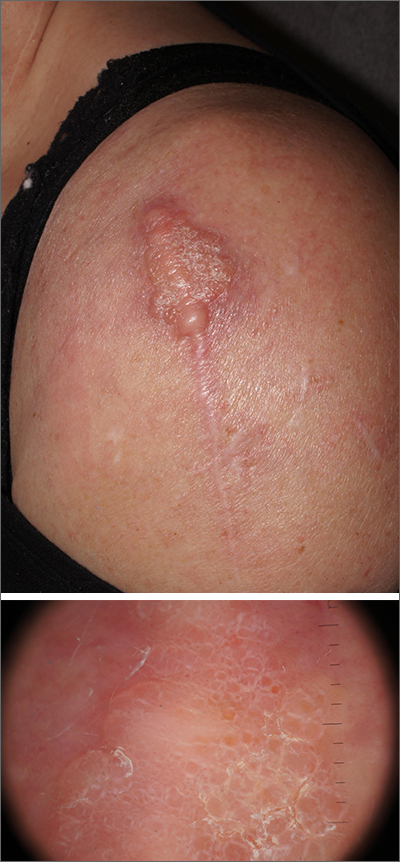

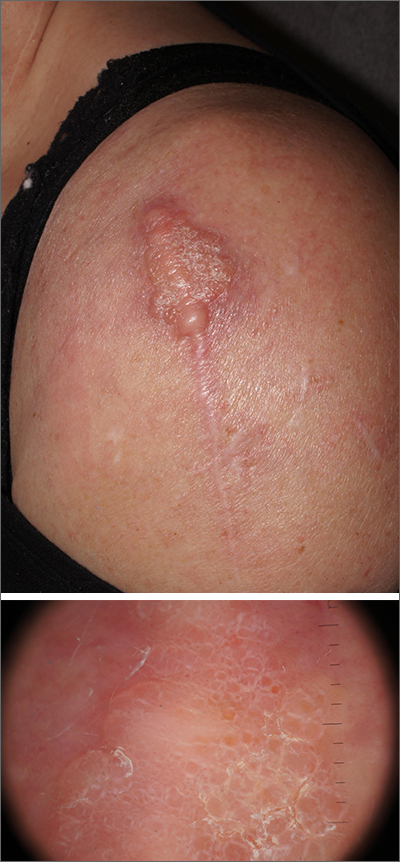

Scar overgrowth

Dermatopathology was consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous myxoma (CM). There are very few dermoscopic descriptions of CM in the literature, so diagnostic features are not established. However, the absence of more diagnostic features of basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) increases the likelihood of a rare diagnosis, such as CM.

CMs are rare benign neoplasms that manifest most commonly in young adults as small (< 1 cm) flesh-colored to blue papules on the head, neck, and trunk. The size of this particular CM was an outlier. CMs may be associated with Carney Complex (CNC), a rare inherited syndrome that has been linked to multiple endocrine neoplasias—namely, pituitary adenomas, testicular Sertoli cell tumors, thyroid tumors, and cardiac atrial myxomas.1 Additionally, in CNC, lentigines and multiple blue nevi develop on the skin and mucosal surfaces.

The differential diagnosis for a large, pink to flesh-colored nodule of this size includes benign histiocytoma, SCC, CM, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Benign histiocytomas and SCCs are much more common than CM. Clinical features only hint at the correct diagnosis, which must be made histologically.

Patients with CMs benefit from ongoing dermatology surveillance to monitor for the development of atypical nevi or new CMs. In this case, a wide excision with generous margins was planned with plastic surgery. (CMs have been reported to recur after surgery, which is why wide margins are essential.)

Additionally, 2 factors prompted an echocardiogram: the association between CMs and possible cardiac tumors and the patient’s need to undergo future orthopedic surgery under general anesthesia. No cardiac tumors were visible on echocardiogram. Thyroid imaging and genetic evaluation were planned but not completed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Zou Y, Billings SD. Myxoid cutaneous tumors: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:903-18. doi: 10.1111/cup.12749.

Dermatopathology was consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous myxoma (CM). There are very few dermoscopic descriptions of CM in the literature, so diagnostic features are not established. However, the absence of more diagnostic features of basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) increases the likelihood of a rare diagnosis, such as CM.

CMs are rare benign neoplasms that manifest most commonly in young adults as small (< 1 cm) flesh-colored to blue papules on the head, neck, and trunk. The size of this particular CM was an outlier. CMs may be associated with Carney Complex (CNC), a rare inherited syndrome that has been linked to multiple endocrine neoplasias—namely, pituitary adenomas, testicular Sertoli cell tumors, thyroid tumors, and cardiac atrial myxomas.1 Additionally, in CNC, lentigines and multiple blue nevi develop on the skin and mucosal surfaces.

The differential diagnosis for a large, pink to flesh-colored nodule of this size includes benign histiocytoma, SCC, CM, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Benign histiocytomas and SCCs are much more common than CM. Clinical features only hint at the correct diagnosis, which must be made histologically.

Patients with CMs benefit from ongoing dermatology surveillance to monitor for the development of atypical nevi or new CMs. In this case, a wide excision with generous margins was planned with plastic surgery. (CMs have been reported to recur after surgery, which is why wide margins are essential.)

Additionally, 2 factors prompted an echocardiogram: the association between CMs and possible cardiac tumors and the patient’s need to undergo future orthopedic surgery under general anesthesia. No cardiac tumors were visible on echocardiogram. Thyroid imaging and genetic evaluation were planned but not completed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Dermatopathology was consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous myxoma (CM). There are very few dermoscopic descriptions of CM in the literature, so diagnostic features are not established. However, the absence of more diagnostic features of basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) increases the likelihood of a rare diagnosis, such as CM.

CMs are rare benign neoplasms that manifest most commonly in young adults as small (< 1 cm) flesh-colored to blue papules on the head, neck, and trunk. The size of this particular CM was an outlier. CMs may be associated with Carney Complex (CNC), a rare inherited syndrome that has been linked to multiple endocrine neoplasias—namely, pituitary adenomas, testicular Sertoli cell tumors, thyroid tumors, and cardiac atrial myxomas.1 Additionally, in CNC, lentigines and multiple blue nevi develop on the skin and mucosal surfaces.

The differential diagnosis for a large, pink to flesh-colored nodule of this size includes benign histiocytoma, SCC, CM, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Benign histiocytomas and SCCs are much more common than CM. Clinical features only hint at the correct diagnosis, which must be made histologically.

Patients with CMs benefit from ongoing dermatology surveillance to monitor for the development of atypical nevi or new CMs. In this case, a wide excision with generous margins was planned with plastic surgery. (CMs have been reported to recur after surgery, which is why wide margins are essential.)

Additionally, 2 factors prompted an echocardiogram: the association between CMs and possible cardiac tumors and the patient’s need to undergo future orthopedic surgery under general anesthesia. No cardiac tumors were visible on echocardiogram. Thyroid imaging and genetic evaluation were planned but not completed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Zou Y, Billings SD. Myxoid cutaneous tumors: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:903-18. doi: 10.1111/cup.12749.

1. Zou Y, Billings SD. Myxoid cutaneous tumors: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:903-18. doi: 10.1111/cup.12749.

CHEST 2022 award winners More award winners

Each year,

MASTER FELLOW AWARD

Gerard A. Silvestri, MD, MS, Master FCCP

DISTINGUISHED SERVICE AWARD

Aneesa M. Das, MD, FCCP

COLLEGE MEDALIST AWARD

William R. Auger, MD, FCCP

ALFRED SOFFER AWARD FOR EDITORIAL EXCELLENCE

Todd W. Rice, MD, FCCP

EARLY CAREER CLINICIAN EDUCATOR AWARD

Mauricio Danckers, MD, FCCP

MASTER CLINICIAN EDUCATOR AWARD

Neil R. MacIntyre, MD, FCCP

PRESIDENTIAL CITATION

CHEST Staff

EDWARD C. ROSENOW III, MD, MASTER FCCP/MASTER TEACHER ENDOWED HONOR LECTURE

Alexander S. Niven, MD, FCCP

THOMAS L. PETTY, MD, MASTER FCCP MEMORIAL LECTURE

Sandra G. Adams, MD, FCCP

2021 DISTINGUISHED SCIENTIST HONOR LECTURE IN CARDIOPULMONARY PHYSIOLOGY

Kenneth I. Berger, MD, FCCP

PRESIDENTIAL HONOR LECTURE

Jack D. Buckley, MD, MPH, FCCP

PASQUALE CIAGLIA MEMORIAL LECTURE IN INTERVENTIONAL MEDICINE

Nicholas J. Pastis, MD, FCCP

ROGER C. BONE MEMORIAL LECTURE IN CRITICAL CARE

E. Wesley Ely, MD, MPH, FCCP

MURRAY KORNFELD MEMORIAL FOUNDERS AWARD

Marin H. Kollef, MD, FCCP

OM P. SHARMA, MD, MASTER FCCP MEMORIAL LECTURE

Daniel A. Culver, DO, FCCP

RICHARD S. IRWIN, MD, MASTER FCCP HONOR LECTURE

Nneka O. Sederstrom, PhD, MS, MA, FCCP

2022 DISTINGUISHED SCIENTIST HONOR LECTURE IN CARDIOPULMONARY PHYSIOLOGY

Martin J. Tobin, MBBCh, FCCP

MARK J. ROSEN, MD, MASTER FCCP ENDOWED MEMORIAL LECTURE

Stephanie M. Levine, MD, FCCP

MARGARET PFROMMER ENDOWED MEMORIAL LECTURE IN HOME-BASED MECHANICAL VENTILATION

Lisa Wolfe, MD, FCCP

CHEST CHALLENGE FINALISTS

1st Place – Mayo Clinic

Amjad Kanj, MD

Paige Marty, MD

Zhenmei Zhang, MD

Program Director: Darlene Nelson, MD, FCCP

2nd Place – Brooke Army Medical Center

Joshua Boster, MD

Tyler Campbell, DO

Daniel Foster, MD

Program Director: Robert Walter, MD, PhD

3rd Place – NewYork-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist

Albina Guri, DO

Jahrul Islam, MD

Sylvana Salama, MD

Program Director: Anthony Saleh, MD, FCCP

Please Note: Award winners from the following categories will be listed in the February issue of CHEST Physician.

CHEST Foundation Grant Awards

Scientific Abstract Awards

Alfred Soffer Research Award Winners

Young Investigator Award Winners

Abstract Rapid Fire Winners

Case Report Session Winners

Case Report Rapid Fire Winners

Each year,

MASTER FELLOW AWARD

Gerard A. Silvestri, MD, MS, Master FCCP

DISTINGUISHED SERVICE AWARD

Aneesa M. Das, MD, FCCP

COLLEGE MEDALIST AWARD

William R. Auger, MD, FCCP

ALFRED SOFFER AWARD FOR EDITORIAL EXCELLENCE

Todd W. Rice, MD, FCCP

EARLY CAREER CLINICIAN EDUCATOR AWARD

Mauricio Danckers, MD, FCCP

MASTER CLINICIAN EDUCATOR AWARD

Neil R. MacIntyre, MD, FCCP

PRESIDENTIAL CITATION

CHEST Staff

EDWARD C. ROSENOW III, MD, MASTER FCCP/MASTER TEACHER ENDOWED HONOR LECTURE

Alexander S. Niven, MD, FCCP

THOMAS L. PETTY, MD, MASTER FCCP MEMORIAL LECTURE

Sandra G. Adams, MD, FCCP

2021 DISTINGUISHED SCIENTIST HONOR LECTURE IN CARDIOPULMONARY PHYSIOLOGY

Kenneth I. Berger, MD, FCCP

PRESIDENTIAL HONOR LECTURE

Jack D. Buckley, MD, MPH, FCCP

PASQUALE CIAGLIA MEMORIAL LECTURE IN INTERVENTIONAL MEDICINE

Nicholas J. Pastis, MD, FCCP

ROGER C. BONE MEMORIAL LECTURE IN CRITICAL CARE

E. Wesley Ely, MD, MPH, FCCP

MURRAY KORNFELD MEMORIAL FOUNDERS AWARD

Marin H. Kollef, MD, FCCP

OM P. SHARMA, MD, MASTER FCCP MEMORIAL LECTURE

Daniel A. Culver, DO, FCCP

RICHARD S. IRWIN, MD, MASTER FCCP HONOR LECTURE

Nneka O. Sederstrom, PhD, MS, MA, FCCP

2022 DISTINGUISHED SCIENTIST HONOR LECTURE IN CARDIOPULMONARY PHYSIOLOGY

Martin J. Tobin, MBBCh, FCCP

MARK J. ROSEN, MD, MASTER FCCP ENDOWED MEMORIAL LECTURE

Stephanie M. Levine, MD, FCCP

MARGARET PFROMMER ENDOWED MEMORIAL LECTURE IN HOME-BASED MECHANICAL VENTILATION

Lisa Wolfe, MD, FCCP

CHEST CHALLENGE FINALISTS

1st Place – Mayo Clinic

Amjad Kanj, MD

Paige Marty, MD

Zhenmei Zhang, MD

Program Director: Darlene Nelson, MD, FCCP

2nd Place – Brooke Army Medical Center

Joshua Boster, MD

Tyler Campbell, DO

Daniel Foster, MD

Program Director: Robert Walter, MD, PhD

3rd Place – NewYork-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist

Albina Guri, DO

Jahrul Islam, MD

Sylvana Salama, MD

Program Director: Anthony Saleh, MD, FCCP

Please Note: Award winners from the following categories will be listed in the February issue of CHEST Physician.

CHEST Foundation Grant Awards

Scientific Abstract Awards

Alfred Soffer Research Award Winners

Young Investigator Award Winners

Abstract Rapid Fire Winners

Case Report Session Winners

Case Report Rapid Fire Winners

Each year,

MASTER FELLOW AWARD

Gerard A. Silvestri, MD, MS, Master FCCP

DISTINGUISHED SERVICE AWARD

Aneesa M. Das, MD, FCCP

COLLEGE MEDALIST AWARD

William R. Auger, MD, FCCP

ALFRED SOFFER AWARD FOR EDITORIAL EXCELLENCE

Todd W. Rice, MD, FCCP

EARLY CAREER CLINICIAN EDUCATOR AWARD

Mauricio Danckers, MD, FCCP

MASTER CLINICIAN EDUCATOR AWARD

Neil R. MacIntyre, MD, FCCP

PRESIDENTIAL CITATION

CHEST Staff

EDWARD C. ROSENOW III, MD, MASTER FCCP/MASTER TEACHER ENDOWED HONOR LECTURE

Alexander S. Niven, MD, FCCP

THOMAS L. PETTY, MD, MASTER FCCP MEMORIAL LECTURE

Sandra G. Adams, MD, FCCP

2021 DISTINGUISHED SCIENTIST HONOR LECTURE IN CARDIOPULMONARY PHYSIOLOGY

Kenneth I. Berger, MD, FCCP

PRESIDENTIAL HONOR LECTURE

Jack D. Buckley, MD, MPH, FCCP

PASQUALE CIAGLIA MEMORIAL LECTURE IN INTERVENTIONAL MEDICINE

Nicholas J. Pastis, MD, FCCP

ROGER C. BONE MEMORIAL LECTURE IN CRITICAL CARE

E. Wesley Ely, MD, MPH, FCCP

MURRAY KORNFELD MEMORIAL FOUNDERS AWARD

Marin H. Kollef, MD, FCCP

OM P. SHARMA, MD, MASTER FCCP MEMORIAL LECTURE

Daniel A. Culver, DO, FCCP

RICHARD S. IRWIN, MD, MASTER FCCP HONOR LECTURE

Nneka O. Sederstrom, PhD, MS, MA, FCCP

2022 DISTINGUISHED SCIENTIST HONOR LECTURE IN CARDIOPULMONARY PHYSIOLOGY

Martin J. Tobin, MBBCh, FCCP

MARK J. ROSEN, MD, MASTER FCCP ENDOWED MEMORIAL LECTURE

Stephanie M. Levine, MD, FCCP

MARGARET PFROMMER ENDOWED MEMORIAL LECTURE IN HOME-BASED MECHANICAL VENTILATION

Lisa Wolfe, MD, FCCP

CHEST CHALLENGE FINALISTS

1st Place – Mayo Clinic

Amjad Kanj, MD

Paige Marty, MD

Zhenmei Zhang, MD

Program Director: Darlene Nelson, MD, FCCP

2nd Place – Brooke Army Medical Center

Joshua Boster, MD

Tyler Campbell, DO

Daniel Foster, MD

Program Director: Robert Walter, MD, PhD

3rd Place – NewYork-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist

Albina Guri, DO

Jahrul Islam, MD

Sylvana Salama, MD

Program Director: Anthony Saleh, MD, FCCP

Please Note: Award winners from the following categories will be listed in the February issue of CHEST Physician.

CHEST Foundation Grant Awards

Scientific Abstract Awards

Alfred Soffer Research Award Winners

Young Investigator Award Winners

Abstract Rapid Fire Winners

Case Report Session Winners

Case Report Rapid Fire Winners

New osteoporosis guideline says start with a bisphosphonate

This is the first update for 5 years since the previous guidance was published in 2017.

It strongly recommends initial therapy with bisphosphonates for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, as well as men with osteoporosis, among other recommendations.

However, the author of an accompanying editorial, Susan M. Ott, MD, says: “The decision to start a bisphosphonate is actually not that easy.”

She also queries some of the other recommendations in the guidance.

Her editorial, along with the guideline by Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MPH, and colleagues, and systematic review by Chelsea Ayers, MPH, and colleagues, were published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Ryan D. Mire, MD, MACP, president of the ACP, gave a brief overview of the new guidance in a video.

Systematic review

The ACP commissioned a review of the evidence because it says new data have emerged on the efficacy of newer medications for osteoporosis and low bone mass, as well as treatment comparisons, and treatment in men.

The review authors identified 34 randomized controlled trials (in 100 publications) and 36 observational studies, which evaluated the following pharmacologic interventions:

- Antiresorptive drugs: four bisphosphonates (alendronate, ibandronate, risedronate, zoledronate) and a RANK ligand inhibitor (denosumab).

- Anabolic drugs: an analog of human parathyroid hormone (PTH)–related protein (abaloparatide), recombinant human PTH (teriparatide), and a sclerostin inhibitor (romosozumab).

- Estrogen agonists: selective estrogen receptor modulators (bazedoxifene, raloxifene).

The authors focused on effectiveness and harms of active drugs compared with placebo or bisphosphonates.

Major changes from 2017 guidelines, some questions

“Though there are many nuanced changes in this [2023 guideline] version, perhaps the major change is the explicit hierarchy of pharmacologic recommendations: bisphosphonates first, then denosumab,” Thomas G. Cooney, MD, senior author of the clinical guideline, explained in an interview.

“Bisphosphonates had the most favorable balance among benefits, harms, patient values and preferences, and cost among the examined drugs in postmenopausal females with primary osteoporosis,” Dr. Cooney, professor of medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, noted, as is stated in the guideline.

“Denosumab also had a favorable long-term net benefit, but bisphosphonates are much cheaper than other pharmacologic treatments and available in generic formulations,” the document states.

The new guideline suggests use of denosumab as second-line pharmacotherapy in adults who have contraindications to or experience adverse effects with bisphosphonates.

The choice among bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid) would be based on a patient-centered discussion between physician and patient, addressing costs (often related to insurance), delivery-mode preferences (oral versus intravenous), and “values,” which includes the patient’s priorities, concerns, and expectations regarding their health care, Dr. Cooney explained.

Another update in the new guideline is, “We also clarify the specific, albeit more limited, role of sclerostin inhibitors and recombinant PTH ‘to reduce the risk of fractures only in females with primary osteoporosis with very high-risk of fracture’,” Dr. Cooney noted.

In addition, the guideline now states, “treatment to reduce the risk of fractures in males rather than limiting it to ‘vertebral fracture’ in men,” as in the 2017 guideline.

It also explicitly includes denosumab as second-line therapy for men, Dr. Cooney noted, but as in 2017, the strength of evidence in men remains low.

“Finally, we also clarified that in females over the age of 65 with low bone mass or osteopenia that an individualized approach be taken to treatment (similar to last guideline), but if treatment is initiated, that a bisphosphonate be used (new content),” he said.

The use of estrogen, treatment duration, drug discontinuation, and serial bone mineral density monitoring were not addressed in this guideline, but will likely be evaluated within 2 to 3 years.

‘Osteoporosis treatment: Not easy’ – editorial

In her editorial, Dr. Ott writes: “The data about bisphosphonates may seem overwhelmingly positive, leading to strong recommendations for their use to treat osteoporosis, but the decision to start a bisphosphonate is actually not that easy.”

“A strong recommendation should be given only when future studies are unlikely to change it,” continues Dr. Ott, professor of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle.

“Yet, data already suggest that, in patients with serious osteoporosis, treatment should start with anabolic medications because previous treatment with either bisphosphonates or denosumab will prevent the anabolic response of newer medications.”

“Starting with bisphosphonate will change the bone so it will not respond to the newer medicines, and then a patient will lose the chance for getting the best improvement,” Dr. Ott clarified in an email to this news organization.

But, in fact, the new guidance does suggest that, to reduce the risk of fractures in females with primary osteoporosis at very high risk of fracture, one should consider use of the sclerostin inhibitor romosozumab (moderate-certainty evidence) or recombinant human parathyroid hormone (teriparatide) (low-certainty evidence) followed by a bisphosphonate (conditional recommendation).

Dr. Ott said: “If the [fracture] risk is high, then we should start with an anabolic medication for 1-2 years. If the risk is medium, then use a bisphosphonate for up to 5 years, and then stop and monitor the patient for signs that the medicine is wearing off,” based on blood and urine tests.

‘We need medicines that will stop bone aging’

Osteopenia is defined by an arbitrary bone density measurement, Dr. Ott explained. “About half of women over 65 will have osteopenia, and by age 85 there are hardly any ‘normal’ women left.”

“We need medicines that will stop bone aging, which might sound impossible, but we should still try,” she continued.

“In the meantime, while waiting on new discoveries,” Dr. Ott said, “I would not use bisphosphonates in patients who did not already have a fracture or whose bone density T-score was better than –2.5 because, in the major study, alendronate did not prevent fractures in this group.”

Many people are worried about bisphosphonates because of problems with the jaw or femur. These are real, but they are very rare during the first 5 years of treatment, Dr. Ott noted. Then the risk starts to rise, up to more than 1 in 1,000 after 8 years. So people can get the benefits of these drugs with very low risk for 5 years.

“An immediate [guideline] update is necessary to address the severity of bone loss and the high risk for vertebral fractures after discontinuation of denosumab,” Dr. Ott urged.

“I don’t agree with using denosumab for osteoporosis as a second-line treatment,” she said. “I would use it only in patients who have cancer or unusually high bone resorption. You have to get a dose strictly every 6 months, and if you need to stop, it is recommended to treat with bisphosphonates. Denosumab is a poor choice for somebody who does not want to take a bisphosphonate. Many patients and even too many doctors do not realize how serious it can be to skip a dose.”

“I also think that men could be treated with anabolic medications,” Dr. Ott said. “Clinical trials show they respond the same as women. Many men have osteoporosis as a consequence of low testosterone, and then they can usually be treated with testosterone. Osteoporosis in men is a serious problem that is too often ignored – almost reverse discrimination.”

It is also unfortunate that the review and recommendations do not address estrogen, one of the most effective medications to prevent osteoporotic fractures, according to Dr. Ott.

Clinical considerations in addition to drug types

The new guideline also advises:

- Clinicians treating adults with osteoporosis should encourage adherence to recommended treatments and healthy lifestyle habits, including exercise, and counseling to evaluate and prevent falls.

- All adults with osteopenia or osteoporosis should have adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, as part of fracture prevention.

- Clinicians should assess baseline fracture risk based on bone density, fracture history, fracture risk factors, and response to prior osteoporosis treatments.

- Current evidence suggests that more than 3-5 years of bisphosphonate therapy reduces risk for new vertebral but not other fractures; however, it also increases risk for long-term harms. Therefore, clinicians should consider stopping bisphosphonate treatment after 5 years unless the patient has a strong indication for treatment continuation.

- The decision for a bisphosphonate holiday (temporary discontinuation) and its duration should be based on baseline fracture risk, medication half-life in bone, and benefits and harms.

- Women treated with an anabolic agent who discontinue it should be offered an antiresorptive agent to preserve gains and because of serious risk for rebound and multiple vertebral fractures.

- Adults older than 65 years with osteoporosis may be at increased risk for falls or other adverse events because of drug interactions.

- Transgender persons have variable risk for low bone mass.

The review and guideline were funded by the ACP. Dr. Ott has reported no relevant disclosures. Relevant financial disclosures for other authors are listed with the guideline and review.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This is the first update for 5 years since the previous guidance was published in 2017.

It strongly recommends initial therapy with bisphosphonates for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, as well as men with osteoporosis, among other recommendations.

However, the author of an accompanying editorial, Susan M. Ott, MD, says: “The decision to start a bisphosphonate is actually not that easy.”

She also queries some of the other recommendations in the guidance.

Her editorial, along with the guideline by Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MPH, and colleagues, and systematic review by Chelsea Ayers, MPH, and colleagues, were published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Ryan D. Mire, MD, MACP, president of the ACP, gave a brief overview of the new guidance in a video.

Systematic review

The ACP commissioned a review of the evidence because it says new data have emerged on the efficacy of newer medications for osteoporosis and low bone mass, as well as treatment comparisons, and treatment in men.

The review authors identified 34 randomized controlled trials (in 100 publications) and 36 observational studies, which evaluated the following pharmacologic interventions:

- Antiresorptive drugs: four bisphosphonates (alendronate, ibandronate, risedronate, zoledronate) and a RANK ligand inhibitor (denosumab).

- Anabolic drugs: an analog of human parathyroid hormone (PTH)–related protein (abaloparatide), recombinant human PTH (teriparatide), and a sclerostin inhibitor (romosozumab).

- Estrogen agonists: selective estrogen receptor modulators (bazedoxifene, raloxifene).

The authors focused on effectiveness and harms of active drugs compared with placebo or bisphosphonates.

Major changes from 2017 guidelines, some questions

“Though there are many nuanced changes in this [2023 guideline] version, perhaps the major change is the explicit hierarchy of pharmacologic recommendations: bisphosphonates first, then denosumab,” Thomas G. Cooney, MD, senior author of the clinical guideline, explained in an interview.

“Bisphosphonates had the most favorable balance among benefits, harms, patient values and preferences, and cost among the examined drugs in postmenopausal females with primary osteoporosis,” Dr. Cooney, professor of medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, noted, as is stated in the guideline.

“Denosumab also had a favorable long-term net benefit, but bisphosphonates are much cheaper than other pharmacologic treatments and available in generic formulations,” the document states.

The new guideline suggests use of denosumab as second-line pharmacotherapy in adults who have contraindications to or experience adverse effects with bisphosphonates.

The choice among bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid) would be based on a patient-centered discussion between physician and patient, addressing costs (often related to insurance), delivery-mode preferences (oral versus intravenous), and “values,” which includes the patient’s priorities, concerns, and expectations regarding their health care, Dr. Cooney explained.

Another update in the new guideline is, “We also clarify the specific, albeit more limited, role of sclerostin inhibitors and recombinant PTH ‘to reduce the risk of fractures only in females with primary osteoporosis with very high-risk of fracture’,” Dr. Cooney noted.

In addition, the guideline now states, “treatment to reduce the risk of fractures in males rather than limiting it to ‘vertebral fracture’ in men,” as in the 2017 guideline.

It also explicitly includes denosumab as second-line therapy for men, Dr. Cooney noted, but as in 2017, the strength of evidence in men remains low.

“Finally, we also clarified that in females over the age of 65 with low bone mass or osteopenia that an individualized approach be taken to treatment (similar to last guideline), but if treatment is initiated, that a bisphosphonate be used (new content),” he said.

The use of estrogen, treatment duration, drug discontinuation, and serial bone mineral density monitoring were not addressed in this guideline, but will likely be evaluated within 2 to 3 years.

‘Osteoporosis treatment: Not easy’ – editorial

In her editorial, Dr. Ott writes: “The data about bisphosphonates may seem overwhelmingly positive, leading to strong recommendations for their use to treat osteoporosis, but the decision to start a bisphosphonate is actually not that easy.”

“A strong recommendation should be given only when future studies are unlikely to change it,” continues Dr. Ott, professor of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle.

“Yet, data already suggest that, in patients with serious osteoporosis, treatment should start with anabolic medications because previous treatment with either bisphosphonates or denosumab will prevent the anabolic response of newer medications.”

“Starting with bisphosphonate will change the bone so it will not respond to the newer medicines, and then a patient will lose the chance for getting the best improvement,” Dr. Ott clarified in an email to this news organization.

But, in fact, the new guidance does suggest that, to reduce the risk of fractures in females with primary osteoporosis at very high risk of fracture, one should consider use of the sclerostin inhibitor romosozumab (moderate-certainty evidence) or recombinant human parathyroid hormone (teriparatide) (low-certainty evidence) followed by a bisphosphonate (conditional recommendation).

Dr. Ott said: “If the [fracture] risk is high, then we should start with an anabolic medication for 1-2 years. If the risk is medium, then use a bisphosphonate for up to 5 years, and then stop and monitor the patient for signs that the medicine is wearing off,” based on blood and urine tests.

‘We need medicines that will stop bone aging’

Osteopenia is defined by an arbitrary bone density measurement, Dr. Ott explained. “About half of women over 65 will have osteopenia, and by age 85 there are hardly any ‘normal’ women left.”

“We need medicines that will stop bone aging, which might sound impossible, but we should still try,” she continued.

“In the meantime, while waiting on new discoveries,” Dr. Ott said, “I would not use bisphosphonates in patients who did not already have a fracture or whose bone density T-score was better than –2.5 because, in the major study, alendronate did not prevent fractures in this group.”

Many people are worried about bisphosphonates because of problems with the jaw or femur. These are real, but they are very rare during the first 5 years of treatment, Dr. Ott noted. Then the risk starts to rise, up to more than 1 in 1,000 after 8 years. So people can get the benefits of these drugs with very low risk for 5 years.

“An immediate [guideline] update is necessary to address the severity of bone loss and the high risk for vertebral fractures after discontinuation of denosumab,” Dr. Ott urged.

“I don’t agree with using denosumab for osteoporosis as a second-line treatment,” she said. “I would use it only in patients who have cancer or unusually high bone resorption. You have to get a dose strictly every 6 months, and if you need to stop, it is recommended to treat with bisphosphonates. Denosumab is a poor choice for somebody who does not want to take a bisphosphonate. Many patients and even too many doctors do not realize how serious it can be to skip a dose.”

“I also think that men could be treated with anabolic medications,” Dr. Ott said. “Clinical trials show they respond the same as women. Many men have osteoporosis as a consequence of low testosterone, and then they can usually be treated with testosterone. Osteoporosis in men is a serious problem that is too often ignored – almost reverse discrimination.”

It is also unfortunate that the review and recommendations do not address estrogen, one of the most effective medications to prevent osteoporotic fractures, according to Dr. Ott.

Clinical considerations in addition to drug types

The new guideline also advises:

- Clinicians treating adults with osteoporosis should encourage adherence to recommended treatments and healthy lifestyle habits, including exercise, and counseling to evaluate and prevent falls.

- All adults with osteopenia or osteoporosis should have adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, as part of fracture prevention.

- Clinicians should assess baseline fracture risk based on bone density, fracture history, fracture risk factors, and response to prior osteoporosis treatments.

- Current evidence suggests that more than 3-5 years of bisphosphonate therapy reduces risk for new vertebral but not other fractures; however, it also increases risk for long-term harms. Therefore, clinicians should consider stopping bisphosphonate treatment after 5 years unless the patient has a strong indication for treatment continuation.

- The decision for a bisphosphonate holiday (temporary discontinuation) and its duration should be based on baseline fracture risk, medication half-life in bone, and benefits and harms.

- Women treated with an anabolic agent who discontinue it should be offered an antiresorptive agent to preserve gains and because of serious risk for rebound and multiple vertebral fractures.

- Adults older than 65 years with osteoporosis may be at increased risk for falls or other adverse events because of drug interactions.

- Transgender persons have variable risk for low bone mass.

The review and guideline were funded by the ACP. Dr. Ott has reported no relevant disclosures. Relevant financial disclosures for other authors are listed with the guideline and review.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This is the first update for 5 years since the previous guidance was published in 2017.

It strongly recommends initial therapy with bisphosphonates for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, as well as men with osteoporosis, among other recommendations.

However, the author of an accompanying editorial, Susan M. Ott, MD, says: “The decision to start a bisphosphonate is actually not that easy.”

She also queries some of the other recommendations in the guidance.

Her editorial, along with the guideline by Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MPH, and colleagues, and systematic review by Chelsea Ayers, MPH, and colleagues, were published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Ryan D. Mire, MD, MACP, president of the ACP, gave a brief overview of the new guidance in a video.

Systematic review

The ACP commissioned a review of the evidence because it says new data have emerged on the efficacy of newer medications for osteoporosis and low bone mass, as well as treatment comparisons, and treatment in men.

The review authors identified 34 randomized controlled trials (in 100 publications) and 36 observational studies, which evaluated the following pharmacologic interventions:

- Antiresorptive drugs: four bisphosphonates (alendronate, ibandronate, risedronate, zoledronate) and a RANK ligand inhibitor (denosumab).

- Anabolic drugs: an analog of human parathyroid hormone (PTH)–related protein (abaloparatide), recombinant human PTH (teriparatide), and a sclerostin inhibitor (romosozumab).

- Estrogen agonists: selective estrogen receptor modulators (bazedoxifene, raloxifene).

The authors focused on effectiveness and harms of active drugs compared with placebo or bisphosphonates.

Major changes from 2017 guidelines, some questions

“Though there are many nuanced changes in this [2023 guideline] version, perhaps the major change is the explicit hierarchy of pharmacologic recommendations: bisphosphonates first, then denosumab,” Thomas G. Cooney, MD, senior author of the clinical guideline, explained in an interview.

“Bisphosphonates had the most favorable balance among benefits, harms, patient values and preferences, and cost among the examined drugs in postmenopausal females with primary osteoporosis,” Dr. Cooney, professor of medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, noted, as is stated in the guideline.

“Denosumab also had a favorable long-term net benefit, but bisphosphonates are much cheaper than other pharmacologic treatments and available in generic formulations,” the document states.

The new guideline suggests use of denosumab as second-line pharmacotherapy in adults who have contraindications to or experience adverse effects with bisphosphonates.

The choice among bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid) would be based on a patient-centered discussion between physician and patient, addressing costs (often related to insurance), delivery-mode preferences (oral versus intravenous), and “values,” which includes the patient’s priorities, concerns, and expectations regarding their health care, Dr. Cooney explained.

Another update in the new guideline is, “We also clarify the specific, albeit more limited, role of sclerostin inhibitors and recombinant PTH ‘to reduce the risk of fractures only in females with primary osteoporosis with very high-risk of fracture’,” Dr. Cooney noted.

In addition, the guideline now states, “treatment to reduce the risk of fractures in males rather than limiting it to ‘vertebral fracture’ in men,” as in the 2017 guideline.

It also explicitly includes denosumab as second-line therapy for men, Dr. Cooney noted, but as in 2017, the strength of evidence in men remains low.

“Finally, we also clarified that in females over the age of 65 with low bone mass or osteopenia that an individualized approach be taken to treatment (similar to last guideline), but if treatment is initiated, that a bisphosphonate be used (new content),” he said.

The use of estrogen, treatment duration, drug discontinuation, and serial bone mineral density monitoring were not addressed in this guideline, but will likely be evaluated within 2 to 3 years.

‘Osteoporosis treatment: Not easy’ – editorial

In her editorial, Dr. Ott writes: “The data about bisphosphonates may seem overwhelmingly positive, leading to strong recommendations for their use to treat osteoporosis, but the decision to start a bisphosphonate is actually not that easy.”

“A strong recommendation should be given only when future studies are unlikely to change it,” continues Dr. Ott, professor of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle.

“Yet, data already suggest that, in patients with serious osteoporosis, treatment should start with anabolic medications because previous treatment with either bisphosphonates or denosumab will prevent the anabolic response of newer medications.”

“Starting with bisphosphonate will change the bone so it will not respond to the newer medicines, and then a patient will lose the chance for getting the best improvement,” Dr. Ott clarified in an email to this news organization.

But, in fact, the new guidance does suggest that, to reduce the risk of fractures in females with primary osteoporosis at very high risk of fracture, one should consider use of the sclerostin inhibitor romosozumab (moderate-certainty evidence) or recombinant human parathyroid hormone (teriparatide) (low-certainty evidence) followed by a bisphosphonate (conditional recommendation).

Dr. Ott said: “If the [fracture] risk is high, then we should start with an anabolic medication for 1-2 years. If the risk is medium, then use a bisphosphonate for up to 5 years, and then stop and monitor the patient for signs that the medicine is wearing off,” based on blood and urine tests.

‘We need medicines that will stop bone aging’

Osteopenia is defined by an arbitrary bone density measurement, Dr. Ott explained. “About half of women over 65 will have osteopenia, and by age 85 there are hardly any ‘normal’ women left.”

“We need medicines that will stop bone aging, which might sound impossible, but we should still try,” she continued.

“In the meantime, while waiting on new discoveries,” Dr. Ott said, “I would not use bisphosphonates in patients who did not already have a fracture or whose bone density T-score was better than –2.5 because, in the major study, alendronate did not prevent fractures in this group.”

Many people are worried about bisphosphonates because of problems with the jaw or femur. These are real, but they are very rare during the first 5 years of treatment, Dr. Ott noted. Then the risk starts to rise, up to more than 1 in 1,000 after 8 years. So people can get the benefits of these drugs with very low risk for 5 years.

“An immediate [guideline] update is necessary to address the severity of bone loss and the high risk for vertebral fractures after discontinuation of denosumab,” Dr. Ott urged.

“I don’t agree with using denosumab for osteoporosis as a second-line treatment,” she said. “I would use it only in patients who have cancer or unusually high bone resorption. You have to get a dose strictly every 6 months, and if you need to stop, it is recommended to treat with bisphosphonates. Denosumab is a poor choice for somebody who does not want to take a bisphosphonate. Many patients and even too many doctors do not realize how serious it can be to skip a dose.”

“I also think that men could be treated with anabolic medications,” Dr. Ott said. “Clinical trials show they respond the same as women. Many men have osteoporosis as a consequence of low testosterone, and then they can usually be treated with testosterone. Osteoporosis in men is a serious problem that is too often ignored – almost reverse discrimination.”

It is also unfortunate that the review and recommendations do not address estrogen, one of the most effective medications to prevent osteoporotic fractures, according to Dr. Ott.

Clinical considerations in addition to drug types

The new guideline also advises:

- Clinicians treating adults with osteoporosis should encourage adherence to recommended treatments and healthy lifestyle habits, including exercise, and counseling to evaluate and prevent falls.

- All adults with osteopenia or osteoporosis should have adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, as part of fracture prevention.

- Clinicians should assess baseline fracture risk based on bone density, fracture history, fracture risk factors, and response to prior osteoporosis treatments.

- Current evidence suggests that more than 3-5 years of bisphosphonate therapy reduces risk for new vertebral but not other fractures; however, it also increases risk for long-term harms. Therefore, clinicians should consider stopping bisphosphonate treatment after 5 years unless the patient has a strong indication for treatment continuation.

- The decision for a bisphosphonate holiday (temporary discontinuation) and its duration should be based on baseline fracture risk, medication half-life in bone, and benefits and harms.

- Women treated with an anabolic agent who discontinue it should be offered an antiresorptive agent to preserve gains and because of serious risk for rebound and multiple vertebral fractures.

- Adults older than 65 years with osteoporosis may be at increased risk for falls or other adverse events because of drug interactions.

- Transgender persons have variable risk for low bone mass.

The review and guideline were funded by the ACP. Dr. Ott has reported no relevant disclosures. Relevant financial disclosures for other authors are listed with the guideline and review.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Surgeon’s license suspension spotlights hazards, ethics of live-streaming surgeries

potentially endangering patients. The surgeon has a large social media following.

In November, the State Medical Board of Ohio temporarily suspended the license of Katherine Roxanne Grawe, MD, who practices in the wealthy Columbus suburb of Powell.

Among other accusations of misconduct, the board stated that “during some videos/live-streams you engage in dialogue to respond to viewers’ online questions while the surgical procedure remains actively ongoing.”

One patient needed emergency treatment following liposuction and was diagnosed with a perforated bowel and serious bacterial infection.

“Despite liposuction being a blind surgery that requires awareness of the tip of the cannula to avoid injury, your attention to the camera meant at those moments you were not looking at the patient or palpating the location of the tip of the cannula,” the medical board said.

Neither Dr. Grawe nor her attorney responded to requests for comment.

Dr. Grawe, known as “Dr. Roxy,” has a popular TikTok account – now set to private – with 841,600 followers and 14.6 million likes. She has another 123,000 followers on her Instagram account, also now private.

The Columbus Dispatch reported that Dr. Grawe had previously been warned to protect patient privacy on social media. The board has yet to make a final decision regarding her license.

According to Columbus TV station WSYX, she said in a TikTok video, “We show our surgeries every single day on Snapchat. Patients get to decide if they want to be part of it. And if you do, you can watch your own surgery.”

The TV station quoted former patients who described surgical complications. One said: “I went to her because, I thought, from all of her social media that she uplifted women. That she helped women empower themselves. But she didn’t.”

Dallas plastic surgeon Rod J. Rohrich, MD, who has written about social-media best practices and has 430,000 followers on Instagram, said in an interview that many surgeons have been reprimanded by state medical boards for being distracted by social media during procedures.

“It is best not to do live-streaming unless it is an educational event to demonstrate techniques and technology with full informed consent of the patient. It should be a very well-rehearsed event for education,” he said.

Nurses also have been disciplined for inappropriate posts on social media. In December 2022, an Atlanta hospital announced that four nurses were no longer on the job after they appeared in a TikTok video in scrubs and revealed their “icks” regarding obstetric care.

“My ick is when you ask me how much the baby weighs,” one worker said in the video, “and it’s still ... in your hands.”