User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Oral Biologics: The New Wave for Treating Psoriasis

Oral Biologics: The New Wave for Treating Psoriasis

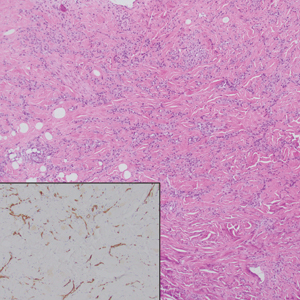

Biologic therapies have transformed the treatment of psoriasis. Current biologics approved for psoriasis include monoclonal antibodies targeting various pathways: tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept), the p40 subunit common to IL-12 and IL-23 (ustekinumab), the p19 subunit of IL-23 (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, risankizumab), IL-17A (secukinumab, ixekizumab), IL-17 receptor A (brodalumab), and dual IL-17A/IL-17F inhibition (bimekizumab). Recent research showed that risankizumab achieved the highest Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 90 scores in short- and long-term treatment periods (4 and 16 weeks, respectively) compared to other biologics, and IL-23 inhibitors demonstrated the lowest short- and long-term adverse event rates and the most favorable long-term risk-benefit profile compared to IL-17, IL-12/23, and TNF-α inhibitors.1

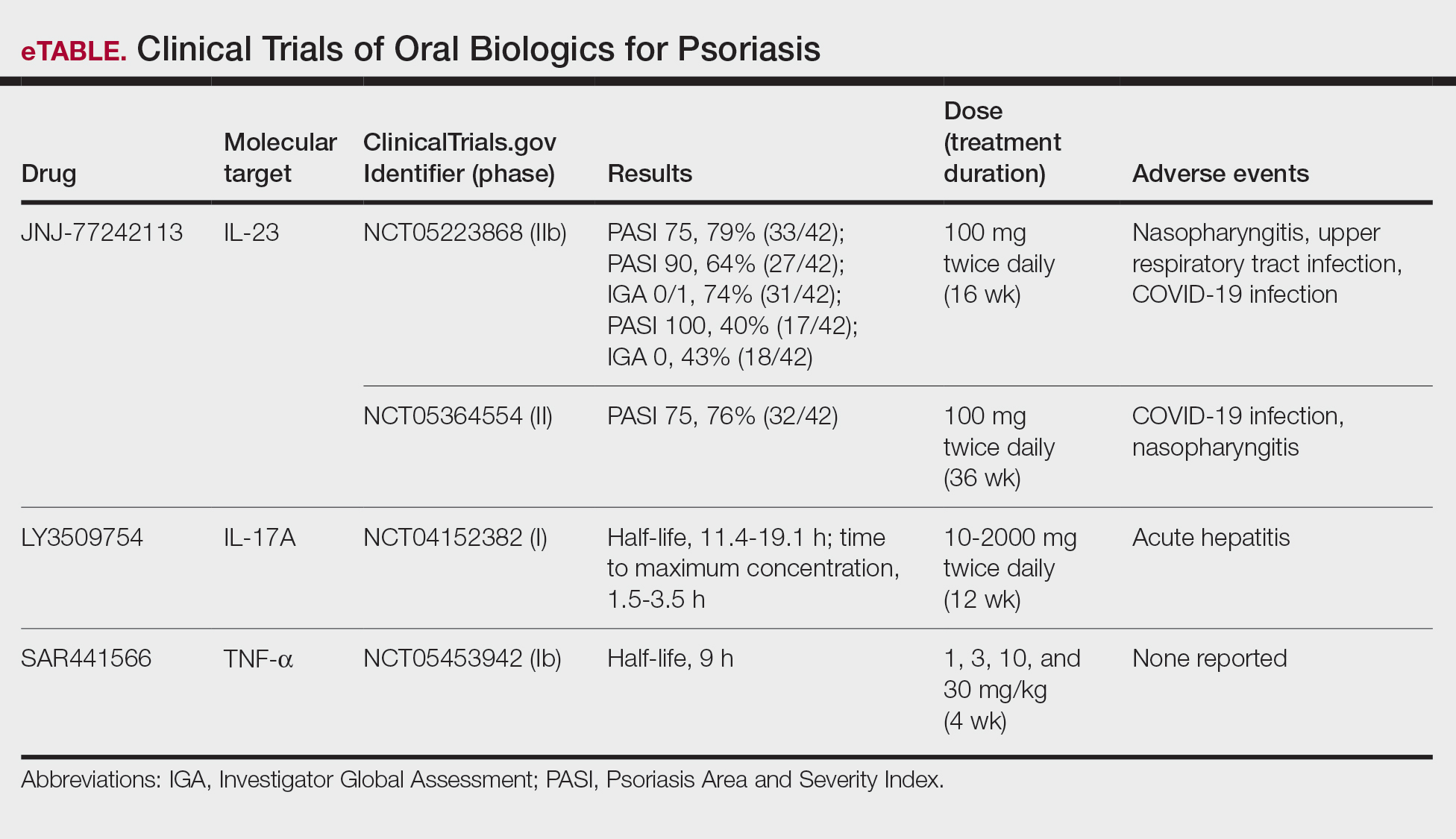

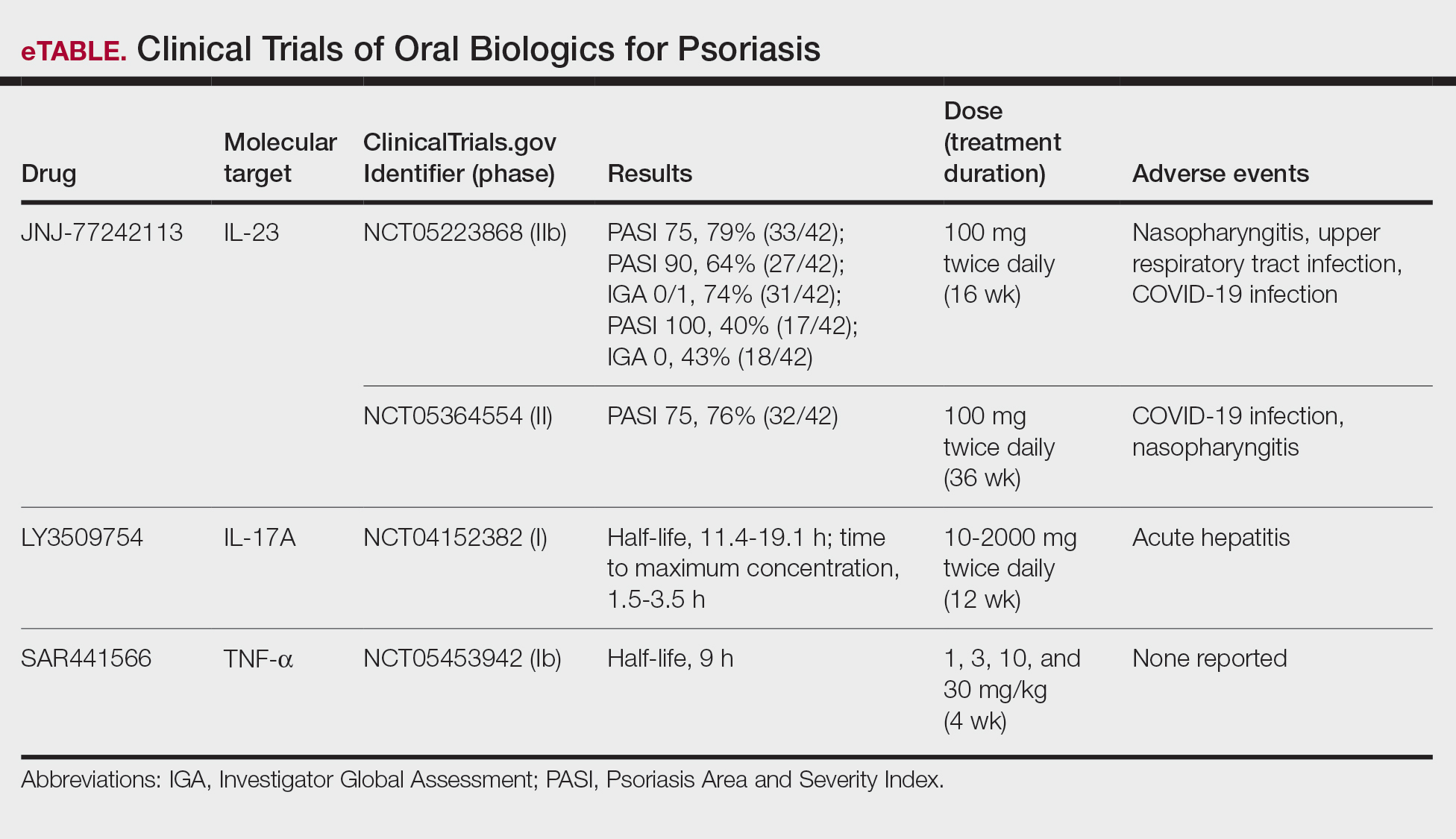

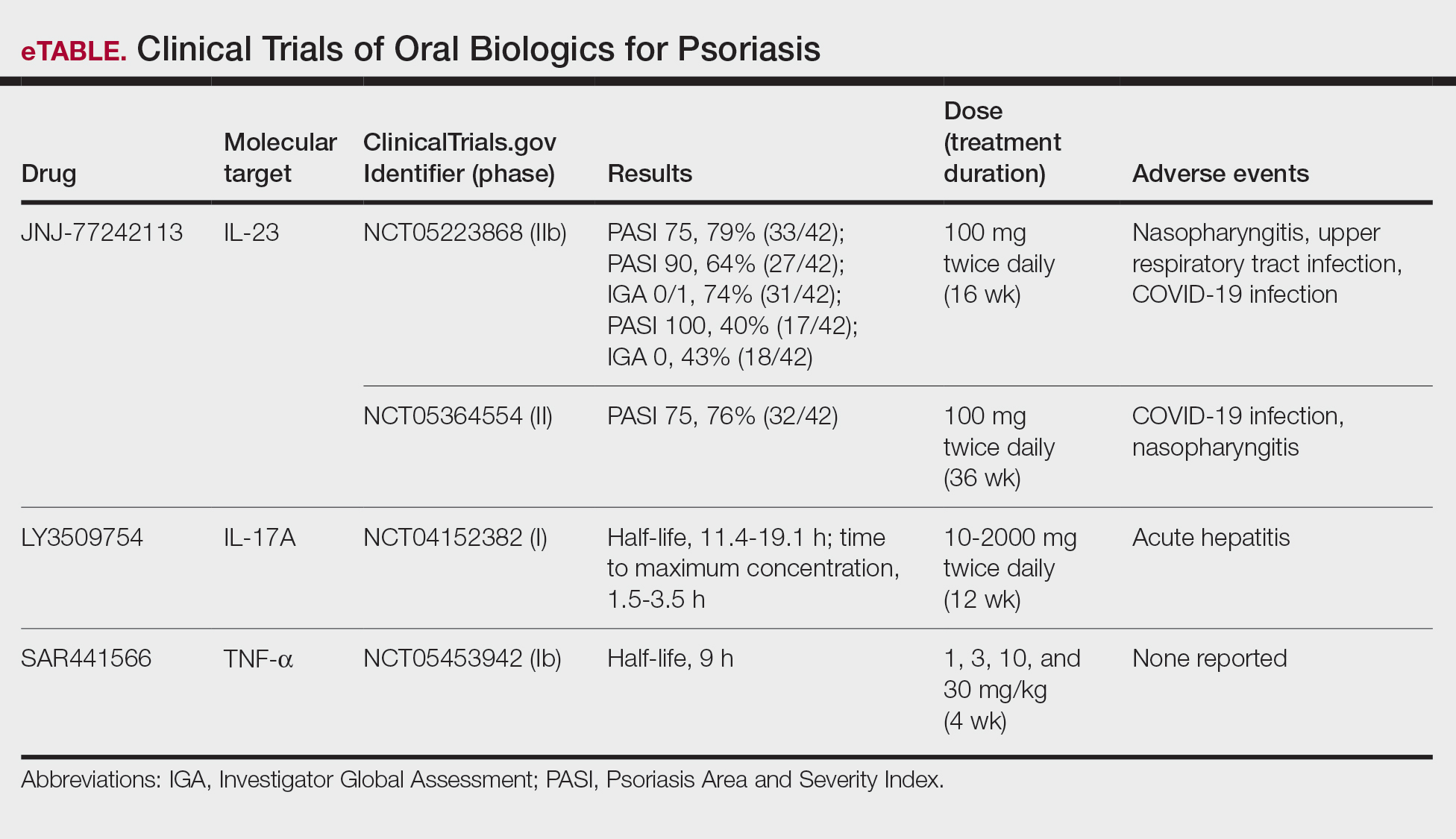

Although these monoclonal antibodies have revolutionized psoriasis treatment, they are large proteins that must be administered subcutaneously or via intravenous injection. Emerging biologics are smaller proteins administered orally via a tablet or pill. In clinical trials, oral biologics have demonstrated efficacy (eTable), suggesting that oral biologics may be the future for psoriasis treatment, as this noninvasive delivery method may help improve patient compliance with treatment.

A major inflammatory pathway in psoriasis, IL-23 has been an effective and safe drug target. The novel oral IL-23 inhibitor, JNJ-2113, was discovered in 2017 and currently is being compared to deucravacitinib in the phase III ICONIC-LEAD trial (ClinicalTrials. gov Identifier NCT06095115) in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.2,3 In the phase IIb FRONTIER 1 trial, treatment with either 3 once-daily (25 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg) and 2 twice-daily (25 mg, 100 mg) doses of JNJ-2113 led to significant improvements in PASI 75 response at 16 weeks compared to placebo (P<.001).4 In the phase IIb long-term extension FRONTIER 2 trial, JNJ-2113 maintained high rates of skin clearance through 52 weeks in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with the highest PASI 75 response observed in the 100-mg twice-daily group (32/42 [76.2%]).5 Responses were maintained through week 52 for all JNJ-2113 treatment groups for PASI 90 and PASI 100 endpoints. In addition to ICONIC-LEAD, JNJ-2113 is being evaluated in the phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial ICONIC-TOTAL (NCT06095102) in patients with special area psoriasis and ANTHEM-UC (NCT06049017) in patients with ulcerative colitis to evaluate its efficacy and safety. The most common adverse events associated with JNJ-77242113 were mild to moderate and included COVID-19 infection and nasopharyngitis.6 Higher rates of COVID-19 infection likely were due to immune compromise in the setting of the recent pandemic. Similar percentages of at least 1 adverse event were found in JNJ-77242113 and placebo groups (52%-58.6% and 51%-65.7%, respectively).4,5,7

An orally administered small-molecule inhibitor of IL-17A, LY3509754, may represent a convenient alternative to IL-17A–

The small potent molecule SAR441566 inhibits TNF-α by stabilizing an asymmetrical form of the soluble TNF trimer. As the asymmetrical trimer is the biologically active form of TNF-α, stabilization of the trimer compromises downstream signaling and inhibits the functions of TNF-α in vitro and in vivo. Recently, SAR441566 was found to be safe and well tolerated in healthy participants, showing efficacy in mild to moderate psoriasis in a phase Ib trial.9 A phase II trial of SAR441566 (NCT06073119) is being developed to create a more convenient orally bioavailable treatment option for patients with psoriasis compared to established biologic drugs targeting TNF-α.10

Few trials have focused on investigating the antipsoriatic effects of orally administered small molecules. Some of these small molecules can enter cells and inhibit the activation of T lymphocytes, leukocyte trafficking, leukotriene activity/production and angiogenesis, and promote apoptosis. Oral administration of small molecules is the future of effective and affordable psoriasis treatment, but safety and efficacy must first be assessed in clinical trials. JNJ-77242113 has shown a more promising safety profile, has recently undergone phase III trials, and may represent the newest wave for psoriasis treatment. While LY3509754 had a strong pharmacokinetics profile, it was poorly tolerated, and study participants' laboratory results suggested the drug to be hepatotoxic.8 SAR441566 has been shown to be safe and well tolerated in treating psoriasis, and phase II readouts are expected later in 2025. We can expect a new wave of psoriasis treatments with emerging oral therapies.

- Wride AM, Chen GF, Spaulding SL, et al. Biologics for psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 2024;42:339-355. doi:10.1016/j.det.2024.02.001

- New data shows JNJ-2113, the first and only investigational targeted oral peptide, maintained skin clearance in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis through one year. Johnson & Johnson website. March 9, 2024. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/new-data-shows-jnj-2113-the-first-and-only-investigational-targeted-oral-peptide-maintained-skin-clearance-in-moderate-to-severe-plaque-psoriasis-through-one-year

- Drakos A, Torres T, Vender R. Emerging oral therapies for the treatment of psoriasis: a review of pipeline agents. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16:111. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics16010111

- Bissonnette R. A phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose -ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate -to-severe plaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 1. Presented at: 25th World Congress of Dermatology; July 3, 2023; Suntec City, Singapore.

- Ferris L. S026. A phase 2b, long-term extension, dose-ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate-to-severeplaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 2. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; San Diego, California; March 8-12, 2024.

- Inc PT. Protagonist announces two new phase 3 ICONIC studies in psoriasis evaluating JNJ-2113 in head-to-head comparisons with deucravacitinib. ACCESSWIRE website. November 27, 2023. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.accesswire.com/810075/protagonist-announces-two-new-phase-3-iconic-studies-in-psoriasis-evaluating-jnj-2113-in-head-to-head-comparisons-with-deucravacitinib

- Bissonnette R, Pinter A, Ferris LK, et al. An oral interleukin-23-receptor antagonist peptide for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:510-521. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2308713

- Datta-Mannan A, Regev A, Coutant DE, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of an oral small molecule inhibitor of IL-17A (LY3509754): a phase I randomized placebo-controlled study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2024;115:1152-1161. doi:10.1002/cpt.3185

- Vugler A, O’Connell J, Nguyen MA, et al. An orally available small molecule that targets soluble TNF to deliver anti-TNF biologic-like efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1037983. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.1037983

- Sanofi pipeline transformation to accelerate growth driven by record number of potential blockbuster launches, paving the way to industry leadership in immunology. News release. Sanofi; New York: Sanofi; Dec 7, 2023. https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2023/2023-12-07-02-30-00-2792186

Biologic therapies have transformed the treatment of psoriasis. Current biologics approved for psoriasis include monoclonal antibodies targeting various pathways: tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept), the p40 subunit common to IL-12 and IL-23 (ustekinumab), the p19 subunit of IL-23 (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, risankizumab), IL-17A (secukinumab, ixekizumab), IL-17 receptor A (brodalumab), and dual IL-17A/IL-17F inhibition (bimekizumab). Recent research showed that risankizumab achieved the highest Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 90 scores in short- and long-term treatment periods (4 and 16 weeks, respectively) compared to other biologics, and IL-23 inhibitors demonstrated the lowest short- and long-term adverse event rates and the most favorable long-term risk-benefit profile compared to IL-17, IL-12/23, and TNF-α inhibitors.1

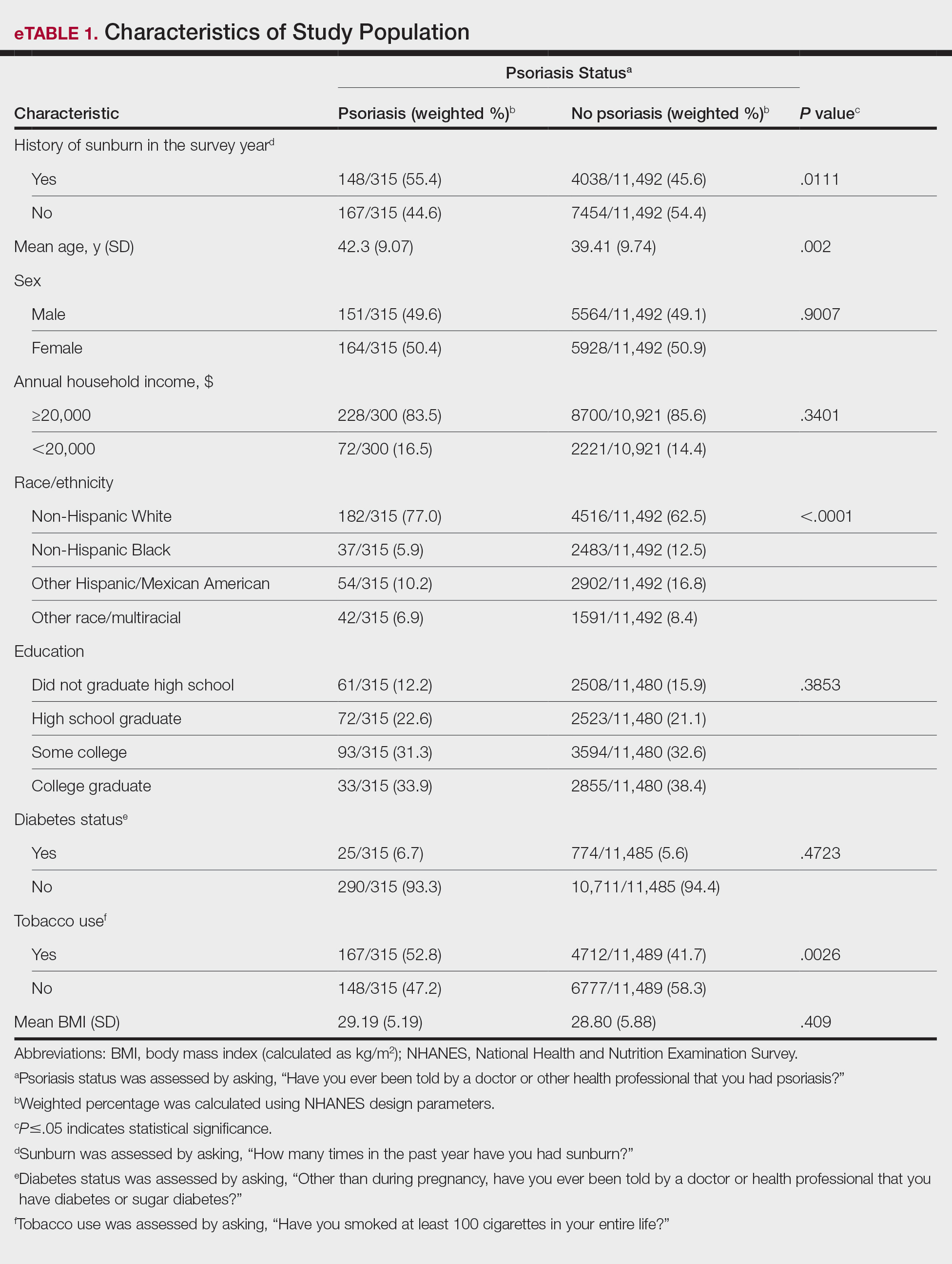

Although these monoclonal antibodies have revolutionized psoriasis treatment, they are large proteins that must be administered subcutaneously or via intravenous injection. Emerging biologics are smaller proteins administered orally via a tablet or pill. In clinical trials, oral biologics have demonstrated efficacy (eTable), suggesting that oral biologics may be the future for psoriasis treatment, as this noninvasive delivery method may help improve patient compliance with treatment.

A major inflammatory pathway in psoriasis, IL-23 has been an effective and safe drug target. The novel oral IL-23 inhibitor, JNJ-2113, was discovered in 2017 and currently is being compared to deucravacitinib in the phase III ICONIC-LEAD trial (ClinicalTrials. gov Identifier NCT06095115) in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.2,3 In the phase IIb FRONTIER 1 trial, treatment with either 3 once-daily (25 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg) and 2 twice-daily (25 mg, 100 mg) doses of JNJ-2113 led to significant improvements in PASI 75 response at 16 weeks compared to placebo (P<.001).4 In the phase IIb long-term extension FRONTIER 2 trial, JNJ-2113 maintained high rates of skin clearance through 52 weeks in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with the highest PASI 75 response observed in the 100-mg twice-daily group (32/42 [76.2%]).5 Responses were maintained through week 52 for all JNJ-2113 treatment groups for PASI 90 and PASI 100 endpoints. In addition to ICONIC-LEAD, JNJ-2113 is being evaluated in the phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial ICONIC-TOTAL (NCT06095102) in patients with special area psoriasis and ANTHEM-UC (NCT06049017) in patients with ulcerative colitis to evaluate its efficacy and safety. The most common adverse events associated with JNJ-77242113 were mild to moderate and included COVID-19 infection and nasopharyngitis.6 Higher rates of COVID-19 infection likely were due to immune compromise in the setting of the recent pandemic. Similar percentages of at least 1 adverse event were found in JNJ-77242113 and placebo groups (52%-58.6% and 51%-65.7%, respectively).4,5,7

An orally administered small-molecule inhibitor of IL-17A, LY3509754, may represent a convenient alternative to IL-17A–

The small potent molecule SAR441566 inhibits TNF-α by stabilizing an asymmetrical form of the soluble TNF trimer. As the asymmetrical trimer is the biologically active form of TNF-α, stabilization of the trimer compromises downstream signaling and inhibits the functions of TNF-α in vitro and in vivo. Recently, SAR441566 was found to be safe and well tolerated in healthy participants, showing efficacy in mild to moderate psoriasis in a phase Ib trial.9 A phase II trial of SAR441566 (NCT06073119) is being developed to create a more convenient orally bioavailable treatment option for patients with psoriasis compared to established biologic drugs targeting TNF-α.10

Few trials have focused on investigating the antipsoriatic effects of orally administered small molecules. Some of these small molecules can enter cells and inhibit the activation of T lymphocytes, leukocyte trafficking, leukotriene activity/production and angiogenesis, and promote apoptosis. Oral administration of small molecules is the future of effective and affordable psoriasis treatment, but safety and efficacy must first be assessed in clinical trials. JNJ-77242113 has shown a more promising safety profile, has recently undergone phase III trials, and may represent the newest wave for psoriasis treatment. While LY3509754 had a strong pharmacokinetics profile, it was poorly tolerated, and study participants' laboratory results suggested the drug to be hepatotoxic.8 SAR441566 has been shown to be safe and well tolerated in treating psoriasis, and phase II readouts are expected later in 2025. We can expect a new wave of psoriasis treatments with emerging oral therapies.

Biologic therapies have transformed the treatment of psoriasis. Current biologics approved for psoriasis include monoclonal antibodies targeting various pathways: tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept), the p40 subunit common to IL-12 and IL-23 (ustekinumab), the p19 subunit of IL-23 (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, risankizumab), IL-17A (secukinumab, ixekizumab), IL-17 receptor A (brodalumab), and dual IL-17A/IL-17F inhibition (bimekizumab). Recent research showed that risankizumab achieved the highest Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 90 scores in short- and long-term treatment periods (4 and 16 weeks, respectively) compared to other biologics, and IL-23 inhibitors demonstrated the lowest short- and long-term adverse event rates and the most favorable long-term risk-benefit profile compared to IL-17, IL-12/23, and TNF-α inhibitors.1

Although these monoclonal antibodies have revolutionized psoriasis treatment, they are large proteins that must be administered subcutaneously or via intravenous injection. Emerging biologics are smaller proteins administered orally via a tablet or pill. In clinical trials, oral biologics have demonstrated efficacy (eTable), suggesting that oral biologics may be the future for psoriasis treatment, as this noninvasive delivery method may help improve patient compliance with treatment.

A major inflammatory pathway in psoriasis, IL-23 has been an effective and safe drug target. The novel oral IL-23 inhibitor, JNJ-2113, was discovered in 2017 and currently is being compared to deucravacitinib in the phase III ICONIC-LEAD trial (ClinicalTrials. gov Identifier NCT06095115) in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.2,3 In the phase IIb FRONTIER 1 trial, treatment with either 3 once-daily (25 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg) and 2 twice-daily (25 mg, 100 mg) doses of JNJ-2113 led to significant improvements in PASI 75 response at 16 weeks compared to placebo (P<.001).4 In the phase IIb long-term extension FRONTIER 2 trial, JNJ-2113 maintained high rates of skin clearance through 52 weeks in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with the highest PASI 75 response observed in the 100-mg twice-daily group (32/42 [76.2%]).5 Responses were maintained through week 52 for all JNJ-2113 treatment groups for PASI 90 and PASI 100 endpoints. In addition to ICONIC-LEAD, JNJ-2113 is being evaluated in the phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial ICONIC-TOTAL (NCT06095102) in patients with special area psoriasis and ANTHEM-UC (NCT06049017) in patients with ulcerative colitis to evaluate its efficacy and safety. The most common adverse events associated with JNJ-77242113 were mild to moderate and included COVID-19 infection and nasopharyngitis.6 Higher rates of COVID-19 infection likely were due to immune compromise in the setting of the recent pandemic. Similar percentages of at least 1 adverse event were found in JNJ-77242113 and placebo groups (52%-58.6% and 51%-65.7%, respectively).4,5,7

An orally administered small-molecule inhibitor of IL-17A, LY3509754, may represent a convenient alternative to IL-17A–

The small potent molecule SAR441566 inhibits TNF-α by stabilizing an asymmetrical form of the soluble TNF trimer. As the asymmetrical trimer is the biologically active form of TNF-α, stabilization of the trimer compromises downstream signaling and inhibits the functions of TNF-α in vitro and in vivo. Recently, SAR441566 was found to be safe and well tolerated in healthy participants, showing efficacy in mild to moderate psoriasis in a phase Ib trial.9 A phase II trial of SAR441566 (NCT06073119) is being developed to create a more convenient orally bioavailable treatment option for patients with psoriasis compared to established biologic drugs targeting TNF-α.10

Few trials have focused on investigating the antipsoriatic effects of orally administered small molecules. Some of these small molecules can enter cells and inhibit the activation of T lymphocytes, leukocyte trafficking, leukotriene activity/production and angiogenesis, and promote apoptosis. Oral administration of small molecules is the future of effective and affordable psoriasis treatment, but safety and efficacy must first be assessed in clinical trials. JNJ-77242113 has shown a more promising safety profile, has recently undergone phase III trials, and may represent the newest wave for psoriasis treatment. While LY3509754 had a strong pharmacokinetics profile, it was poorly tolerated, and study participants' laboratory results suggested the drug to be hepatotoxic.8 SAR441566 has been shown to be safe and well tolerated in treating psoriasis, and phase II readouts are expected later in 2025. We can expect a new wave of psoriasis treatments with emerging oral therapies.

- Wride AM, Chen GF, Spaulding SL, et al. Biologics for psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 2024;42:339-355. doi:10.1016/j.det.2024.02.001

- New data shows JNJ-2113, the first and only investigational targeted oral peptide, maintained skin clearance in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis through one year. Johnson & Johnson website. March 9, 2024. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/new-data-shows-jnj-2113-the-first-and-only-investigational-targeted-oral-peptide-maintained-skin-clearance-in-moderate-to-severe-plaque-psoriasis-through-one-year

- Drakos A, Torres T, Vender R. Emerging oral therapies for the treatment of psoriasis: a review of pipeline agents. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16:111. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics16010111

- Bissonnette R. A phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose -ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate -to-severe plaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 1. Presented at: 25th World Congress of Dermatology; July 3, 2023; Suntec City, Singapore.

- Ferris L. S026. A phase 2b, long-term extension, dose-ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate-to-severeplaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 2. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; San Diego, California; March 8-12, 2024.

- Inc PT. Protagonist announces two new phase 3 ICONIC studies in psoriasis evaluating JNJ-2113 in head-to-head comparisons with deucravacitinib. ACCESSWIRE website. November 27, 2023. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.accesswire.com/810075/protagonist-announces-two-new-phase-3-iconic-studies-in-psoriasis-evaluating-jnj-2113-in-head-to-head-comparisons-with-deucravacitinib

- Bissonnette R, Pinter A, Ferris LK, et al. An oral interleukin-23-receptor antagonist peptide for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:510-521. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2308713

- Datta-Mannan A, Regev A, Coutant DE, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of an oral small molecule inhibitor of IL-17A (LY3509754): a phase I randomized placebo-controlled study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2024;115:1152-1161. doi:10.1002/cpt.3185

- Vugler A, O’Connell J, Nguyen MA, et al. An orally available small molecule that targets soluble TNF to deliver anti-TNF biologic-like efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1037983. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.1037983

- Sanofi pipeline transformation to accelerate growth driven by record number of potential blockbuster launches, paving the way to industry leadership in immunology. News release. Sanofi; New York: Sanofi; Dec 7, 2023. https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2023/2023-12-07-02-30-00-2792186

- Wride AM, Chen GF, Spaulding SL, et al. Biologics for psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 2024;42:339-355. doi:10.1016/j.det.2024.02.001

- New data shows JNJ-2113, the first and only investigational targeted oral peptide, maintained skin clearance in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis through one year. Johnson & Johnson website. March 9, 2024. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/new-data-shows-jnj-2113-the-first-and-only-investigational-targeted-oral-peptide-maintained-skin-clearance-in-moderate-to-severe-plaque-psoriasis-through-one-year

- Drakos A, Torres T, Vender R. Emerging oral therapies for the treatment of psoriasis: a review of pipeline agents. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16:111. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics16010111

- Bissonnette R. A phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose -ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate -to-severe plaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 1. Presented at: 25th World Congress of Dermatology; July 3, 2023; Suntec City, Singapore.

- Ferris L. S026. A phase 2b, long-term extension, dose-ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate-to-severeplaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 2. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; San Diego, California; March 8-12, 2024.

- Inc PT. Protagonist announces two new phase 3 ICONIC studies in psoriasis evaluating JNJ-2113 in head-to-head comparisons with deucravacitinib. ACCESSWIRE website. November 27, 2023. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.accesswire.com/810075/protagonist-announces-two-new-phase-3-iconic-studies-in-psoriasis-evaluating-jnj-2113-in-head-to-head-comparisons-with-deucravacitinib

- Bissonnette R, Pinter A, Ferris LK, et al. An oral interleukin-23-receptor antagonist peptide for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:510-521. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2308713

- Datta-Mannan A, Regev A, Coutant DE, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of an oral small molecule inhibitor of IL-17A (LY3509754): a phase I randomized placebo-controlled study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2024;115:1152-1161. doi:10.1002/cpt.3185

- Vugler A, O’Connell J, Nguyen MA, et al. An orally available small molecule that targets soluble TNF to deliver anti-TNF biologic-like efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1037983. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.1037983

- Sanofi pipeline transformation to accelerate growth driven by record number of potential blockbuster launches, paving the way to industry leadership in immunology. News release. Sanofi; New York: Sanofi; Dec 7, 2023. https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2023/2023-12-07-02-30-00-2792186

Oral Biologics: The New Wave for Treating Psoriasis

Oral Biologics: The New Wave for Treating Psoriasis

PRACTICE POINTS

- The biologics that currently are approved for psoriasis are expensive and must be administered via injection due to their large molecule size.

- Emerging small-molecule oral therapies for psoriasis are effective and affordable and may represent the future for psoriasis patients.

Legislative, Practice Management, and Coding Updates for 2025

Legislative, Practice Management, and Coding Updates for 2025

Health care costs continue to increase in 2025 while physician reimbursement continues to decrease. Of the $4.5 trillion spent on health care in 2022, only 20% was spent on physician and clinical services.1 Since 2001, practice expense has risen 47%, while the Consumer Price Index has risen 73%; adjusted for inflation, physician reimbursement has declined 30% since 2001.2

The formula for Medicare payments for physician services, calculated by multiplying the conversion factor (CF) by the relative value unit (RVU), was developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in 1992. The combination of the physician’s work, the practice’s expense, and the cost of professional liability insurance make up RVUs, which are aligned by geographic index adjustments.3 The 2024 CF was $32.75, compared to $32.00 in 1992. The proposed 2025 CF is $32.35, which is a 10% decrease since 2019 and a 2.8% decrease relative to the 2024 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS). The 2.8% cut is due to expiration of the 2.93% temporary payment increase for services provided by the Consolidated Appropriations Act 2024 and the supplemental relief provided from March 9, 2024, to December 31, 2024.4 If the CF had increased with inflation, it would have been $71.15 in 2024.4

Declining reimbursement rates for physician services undermine the ability of physician practices to keep their doors open in the face of increased operating costs. Faced with the widening gap between what Medicare pays for physician services and the cost of delivering value-based, quality care, physicians are urging Congress to pass a reform package to permanently strengthen Medicare.

Herein, an overview of key coding updates and changes, telehealth flexibilities, and a new dermatologyfocused Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Value Pathways is provided.

Update on the Medicare Economic Index Postponement

Developed in 1975, the Medicare Economic Index (MEI) is a measure of practice cost inflation. It is a yearly calculation that estimates the annual changes in physicians’ operating costs to determine appropriate Medicare physician payment updates.5 The MEI is composed of physician practice costs (eg, staff salaries, office space, malpractice insurance) and physician compensation (direct earnings by the physician). Both are used to calculate adjustments to Medicare physician payments to account for inflationary increases in health care costs. The MEI for 2025 is projected to increase by 3.5%, while physician payment continues to dwindle.5 This disparity between rising costs and declining physician payments will impact patient access to medical care. Physicians may choose to stop accepting Medicare and other health insurance, face the possibility of closing or selling their practices, or even decide to leave the profession.

The CMS has continued to delay implementation of the 2017 MEI cost weights (which currently are based on 2006 data5) for RVUs in the MPFS rate setting for 2025 pending completion of the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Practice Information Survey.6 The AMA contracted with an independent research company to conduct the survey, which will be used to update the MEI. Survey data will be shared with the CMS in early 2025.6

Future of Telehealth is Uncertain

On January 1, 2025, many telehealth flexibilities were set to expire; however, Congress passed an extension of the current telehealth policy flexibilities that have been in place since the COVID-19 pandemic through March 31, 2025.7 The CMS recognizes concerns about maintaining access to Medicare telehealth services once the statutory flexibilities expire; however, it maintains that it has limited statutory authority to extend these Medicare telehealth flexibilities.8 There will be originating site requirements and geographic location restrictions. Clinicians working in a federally qualified health center or a rural health clinic would not be affected.8

The CMS rejected adoption of 16 of 17 new Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (98000–98016) for telemedicine evaluation and management (E/M) services, rendering them nonreimbursable.8 Physicians should continue to use the standard E/M codes 99202 through 99215 for telehealth visits. The CMS only approved code 99016, which will replace Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code G2012, for brief virtual check-in encounters. The CMS specified that CPT codes 99441 through 99443, which describe telephone E/M services, have been removed and are no longer valid for billing. Asynchronous communication (eg, store-and-forward technology via an electronic health record portal) will continue to be reported using the online digital E/M service codes 99421, 99422, and 99423.8

Practitioners can use their enrolled practice location instead of their home address when providing telehealth services from home.8 Teaching physicians will continue to be allowed to have a virtual presence for purposes of billing for services involving residents in all teaching settings, but only when the service is furnished remotely (ie, the patient, resident, and teaching physician all are in separate locations). The use of real-time audio and video technology for direct supervision has been extended through December 31, 2025, allowing practitioners to be immediately available virtually. The CMS also plans to permanently allow virtual supervision for lower-risk services that typically do not require the billing practitioner’s physical presence or extensive direction (eg, diagnostic tests, behavioral health, dermatology, therapy).8

It is essential to verify the reimbursement policies and billing guidelines of individual payers, as some may adopt policies that differ from the AMA and CMS guidelines.

When to Use Modifiers -59 and -76

Modifiers -59 and -76 are used when billing for multiple procedures on the same day and can be confused. These modifiers help clarify situations in which procedures might appear redundant or improperly coded, reducing the risk for claim denials and ensuring compliance with coding guidelines. Use modifier -59 when a procedure or service is distinct or separate from other services performed on the same day (eg, cryosurgery of 4 actinic keratoses and a tangential biopsy of a nevus). Use modifier -76 when a physician performs the exact same procedure multiple times on the same patient on the same day (eg, removing 2 nevi on the face with the same excision code or performing multiple biopsies on different areas on the skin).9

What Are the Medical Team Conference CPT Codes?

Dermatologists frequently manage complex medical and surgical cases and actively participate in tumor boards and multidisciplinary teams conferences. It is essential to be familiar with the relevant CPT codes that can be used in these scenarios: CPT code 99366 can be used when the medical team conference occurs face-to-face with the patient present, and CPT code 99367 can be used for a medical team conference with an interdisciplinary group of health care professionals from different specialties, each of whom provides direct care to the patient.10 For CPT code 99367, the patient and/or family are not present during the meeting, which lasts a minimum of 30 minutes or more and requires participation by a physician. Current Procedural Terminology code 99368 can be used for participation in the medical team conference by a nonphysician qualified health care professional. The reporting participants need to document their participation in the medical team conference as well as their contributed information that explains the case and subsequent treatment recommendations.10

No more than 1 individual from the same specialty may report CPT codes 99366 through 99368 at the same encounter.10 Codes 99366 through 99368 should not be reported when participation in the medical team conference is part of a facility or contractually provided by the facility such as group therapy.10 The medical team conference starts at the beginning of the review of an individual patient and ends at the conclusion of the review for coding purposes. Time related to record-keeping or report generation does not need to be reported. The reporting participant needs to be present for the entire conference. The time reported is not limited to the time that the participant is communicating with other team members or the patient and/or their family/ caregiver(s). Time reported for medical team conferences may not be used in the determination for other services, such as care plan oversight (99374-99380), prolonged services (99358, 99359), psychotherapy, or any E/M service. When the patient is present for any part of the duration of the team conference, nonphysician qualified health care professionals (eg, speech-language pathologists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, social workers, dietitians) report the medical team conference face-to-face with code 99366.10

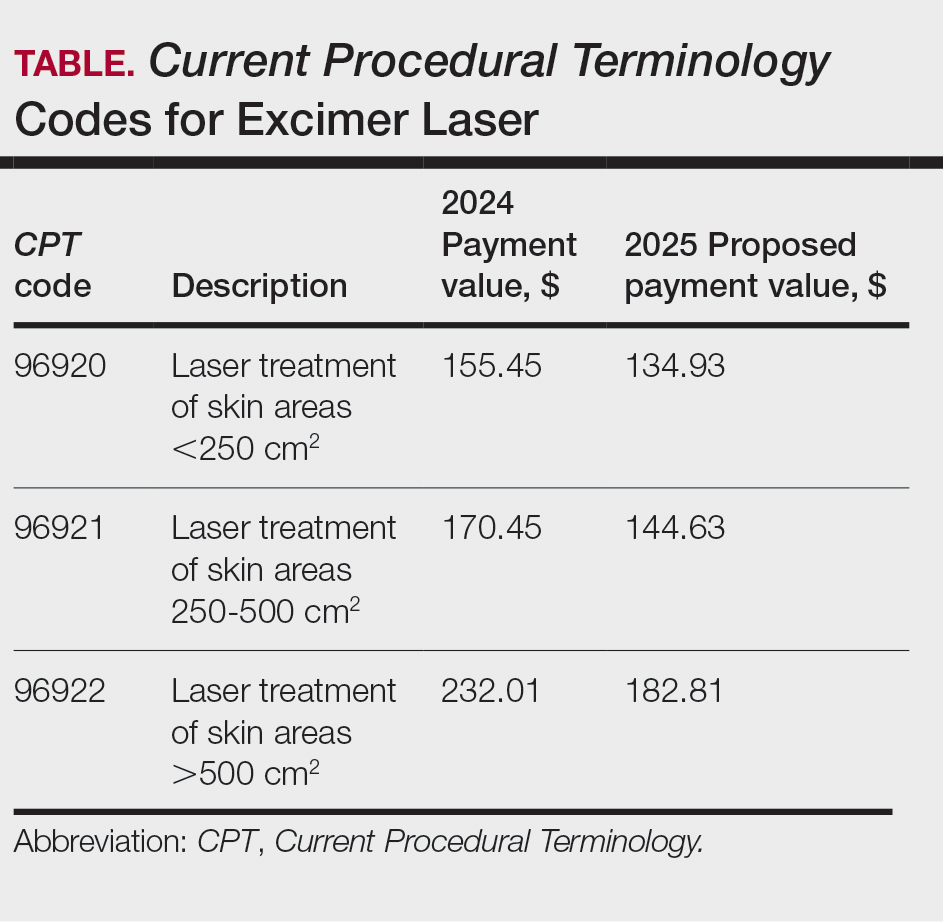

Update on Excimer Laser CPT Codes

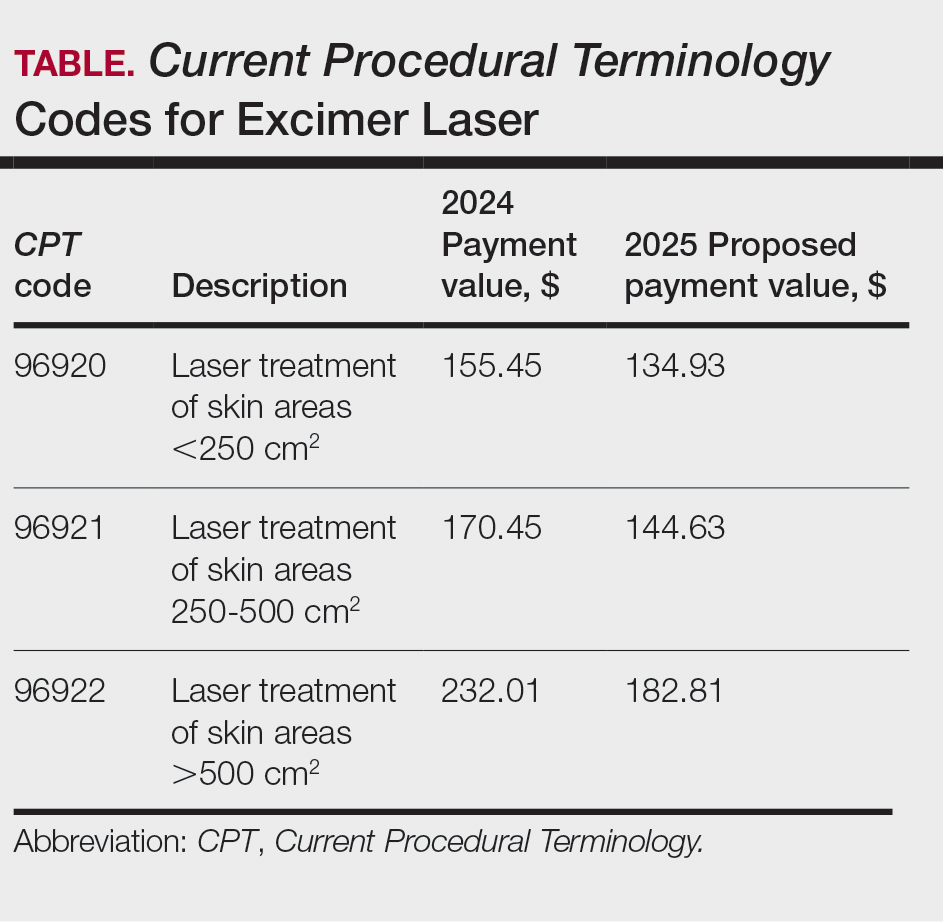

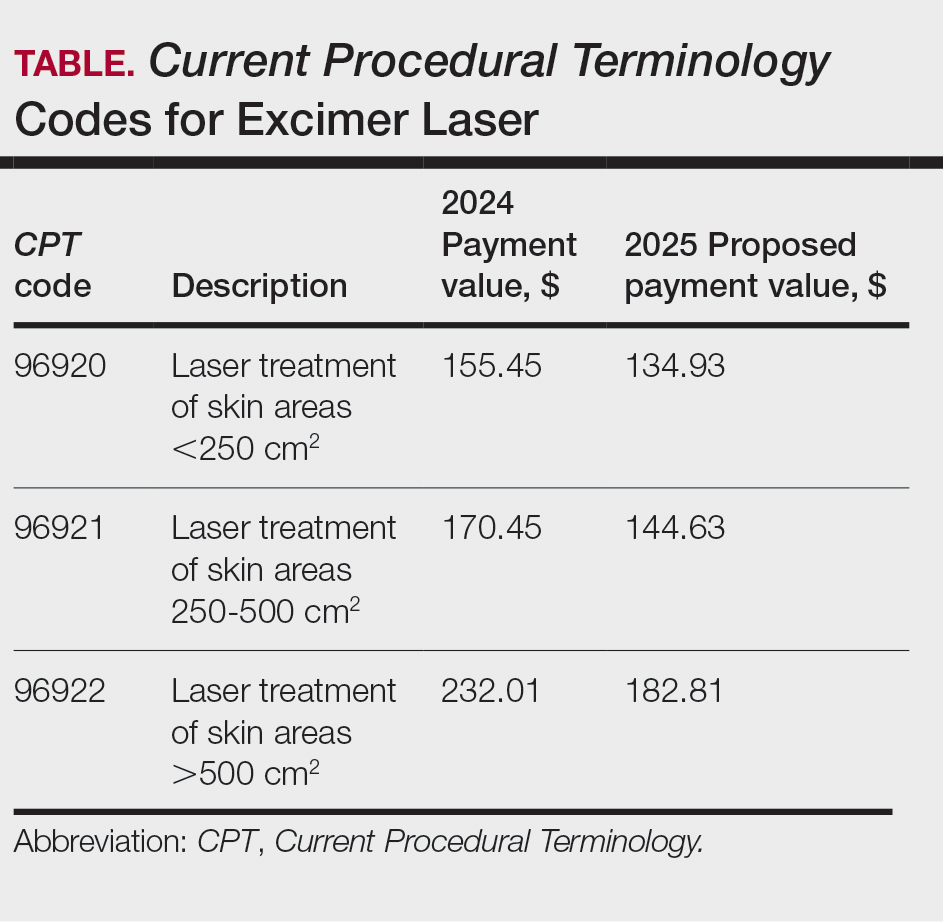

The CMS rejected values recommended for CPT codes (96920-96922) by the Relative Value Scale Update Committee, proposing lower work RVUs of 0.83, 0.90, and 1.15, respectively (Table).2,11 The CPT panel did not recognize the strength of the literature supporting the expanded use of the codes for conditions other than psoriasis. Report the use of excimer laser for treatment of vitiligo, atopic dermatitis, and alopecia areata using CPT code 96999 (unlisted special dermatological service or procedure).11

Update on the New G2211 Code

Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code G2211 is an add-on complexity code that can be reported with all outpatient E/M visits to better account for additional resources associated with primary care or similarly ongoing medical care related to a patient’s single serious condition or complex condition.12 It can be billed if the physician is serving as the continuing focal point for all the patient's health care service needs, acting as the central point of contact for the patient’s ongoing medical care, and managing all aspects of their health needs over time. It is not restricted based on specialty, but it is determined based on the nature of the physician-patient relationship.12

Code G2211 should not be used for the following scenarios: (1) care provided by a clinician with a discrete, routine, or time-limited relationship with the patient, such as a routine skin examination or an acute allergic contact dermatitis; (2) conditions in which comorbidities are not present or addressed; (3) when the billing clinician has not assumed responsibility for ongoing medical care with consistency and continuity over time; and (4) visits billed with modifier -25.12 In the 2025 MPFS, the CMS is proposing to allow payment of G2211 when the code is reported by the same practitioner on the same day as an annual wellness visit, vaccine administration, or any Medicare Part B preventive service furnished in the office or outpatient setting (ie, creating a limited exception to the prohibition of using this code with modifier -25).2

Documentation in the medical record must support reporting code G2211 and indicate a medically reasonable and necessary reason for the additional RVUs (0.33 and additional payment of $16.05).12

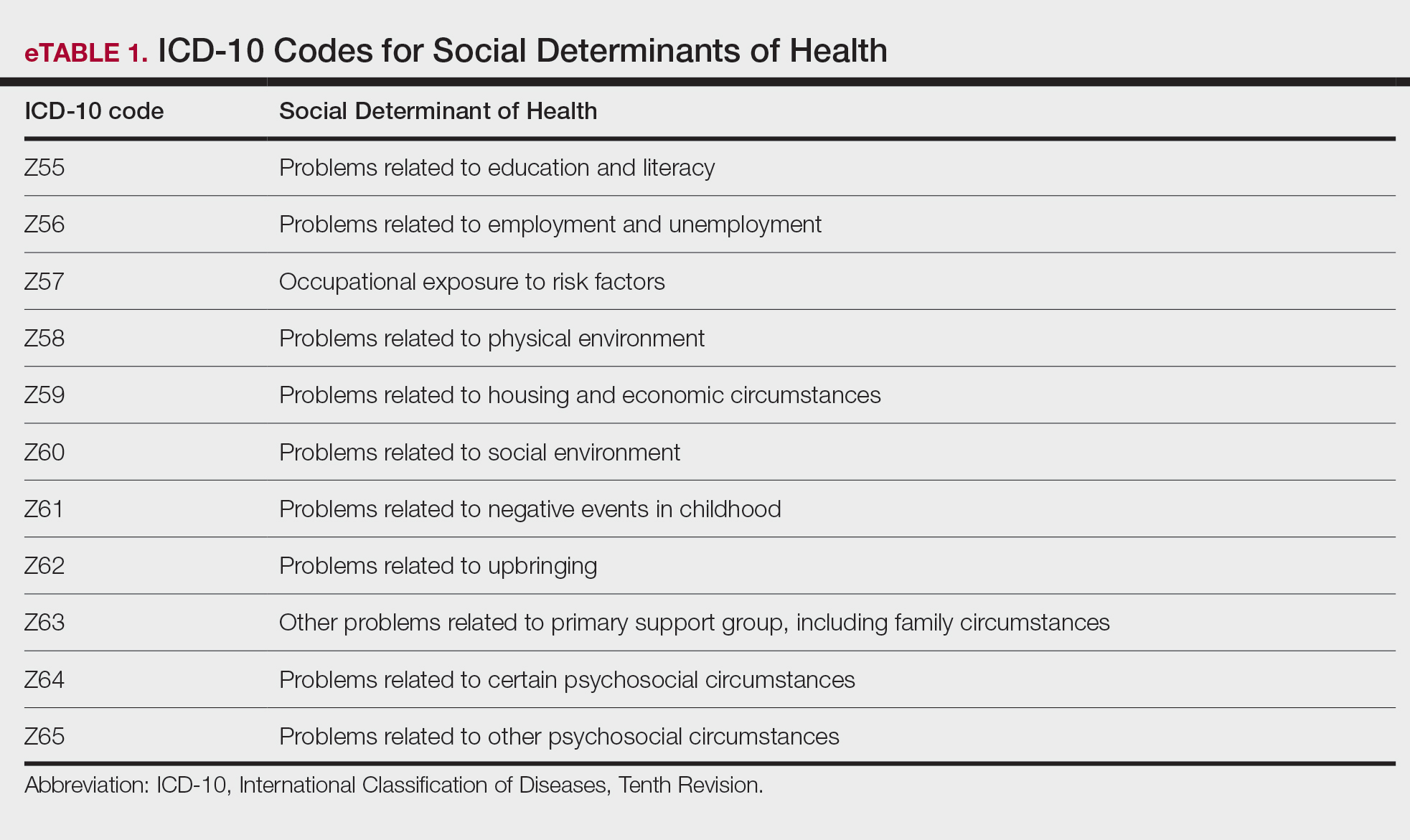

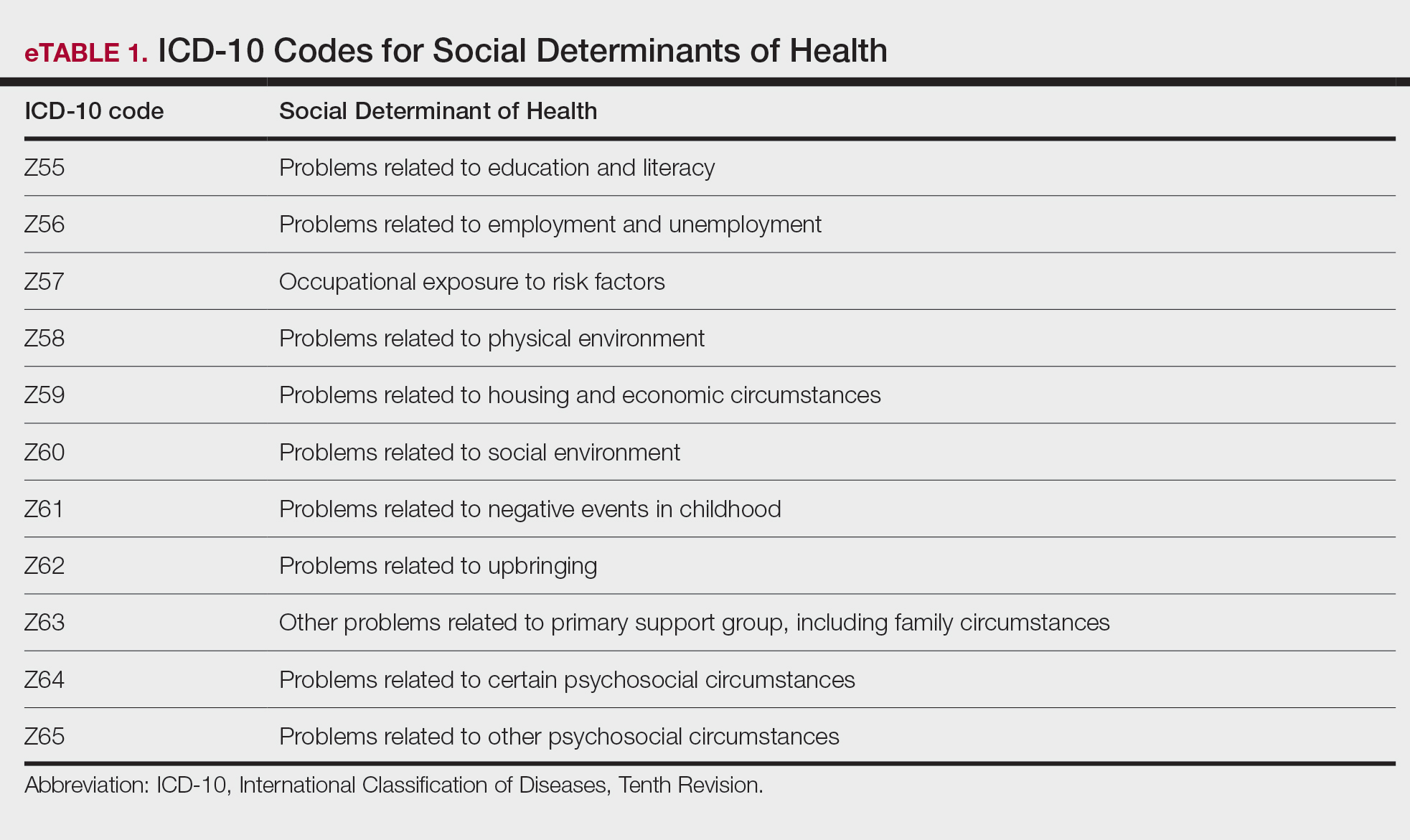

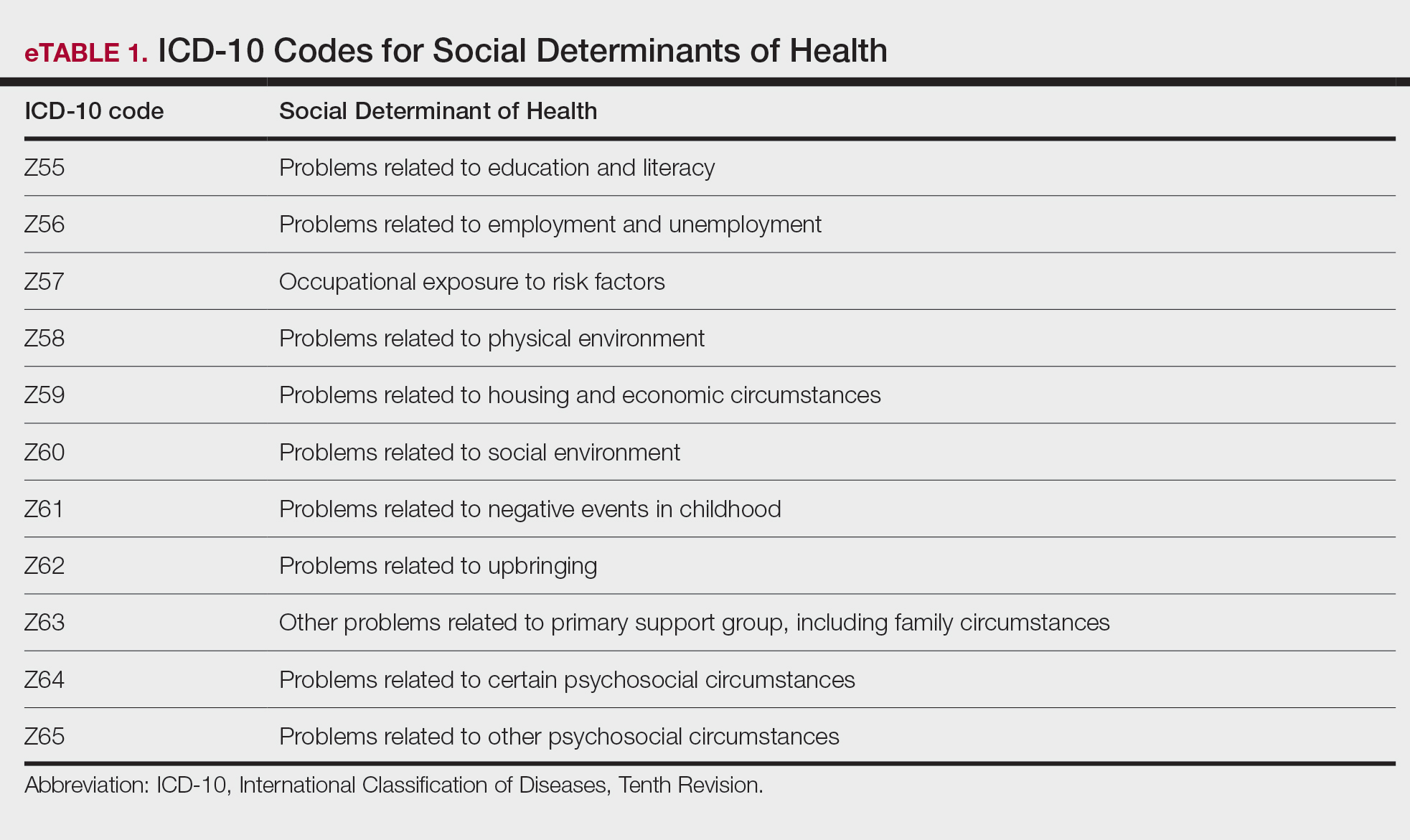

Underutilization of Z Codes for Social Determinants of Health

Barriers to documentation of social determinants of health (SDOH)–related International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Z codes (Z55-Z66)(eTable 1), include lack of clarity on who can document patients’ social needs, lack of systems and processes for documenting and coding SDOH, unfamiliarity with these Z codes, and a low prioritization of collecting these data.13 Documentation of a SDOH-related Z code relevant to a patient encounter is considered moderate risk and can have a major impact on a patient’s overall health, unmet social needs, and outcomes.13 If the other 2 medical decision-making elements (ie, number and complexity of problems addressed along with amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed) for the E/M visit also are moderate, then the encounter can be coded as level 4.13

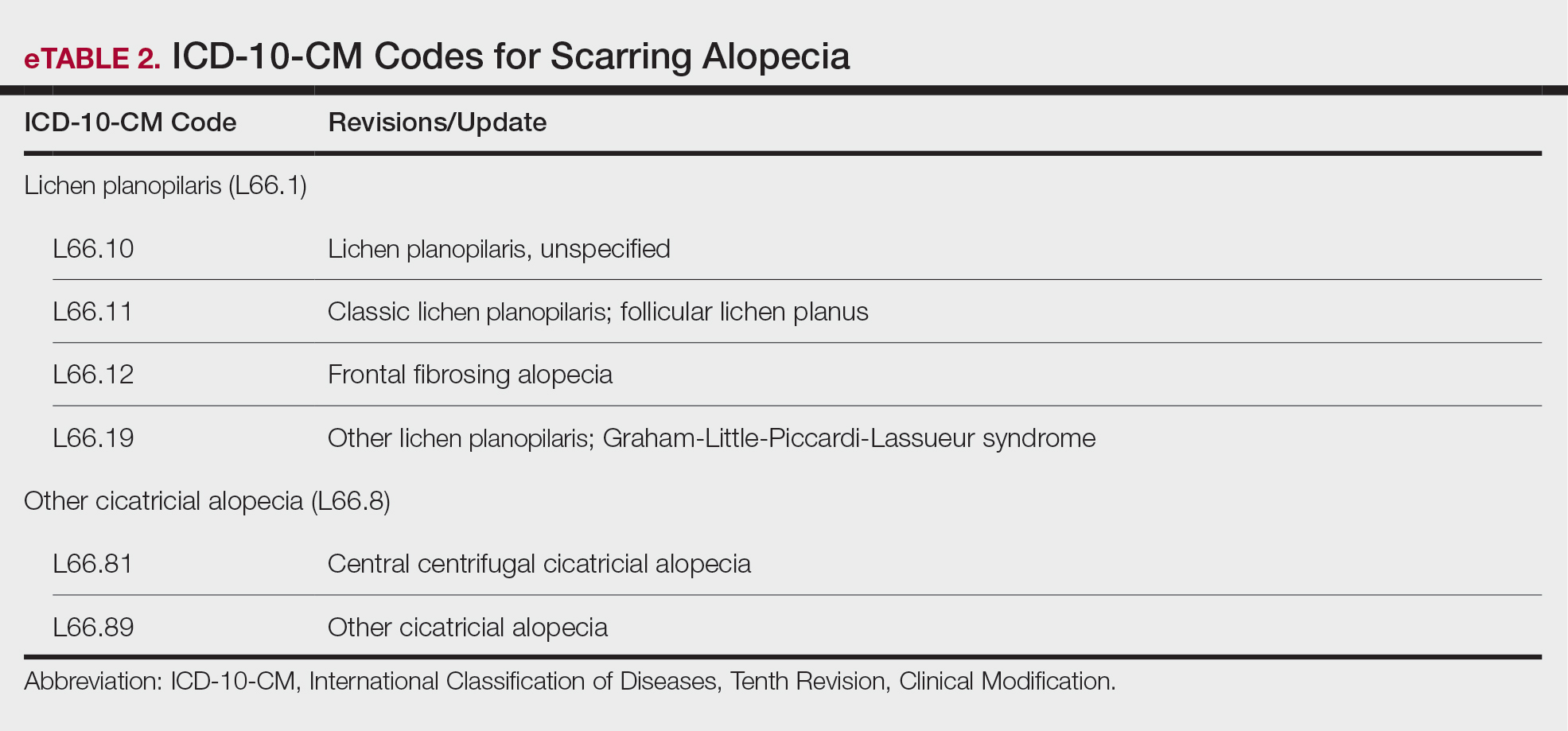

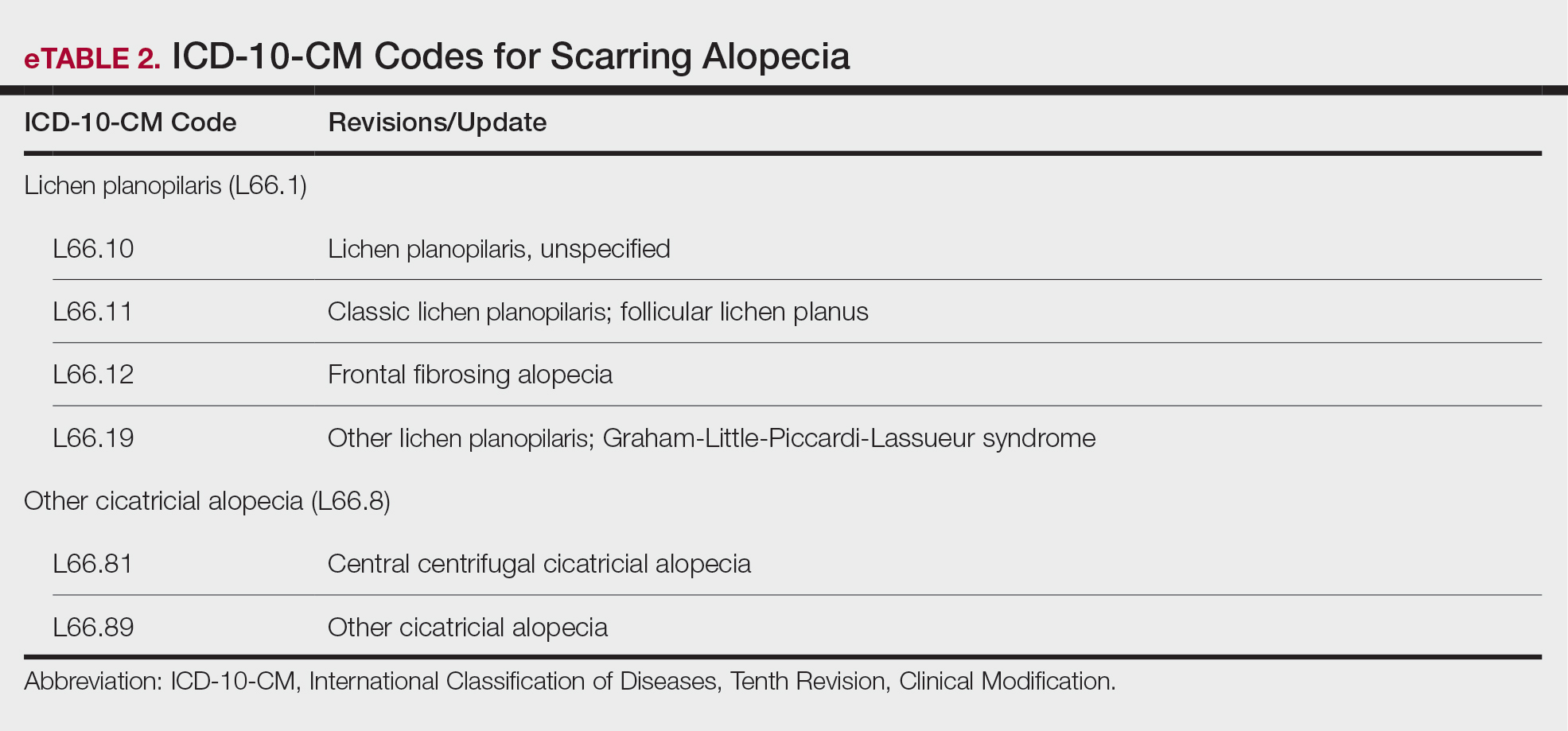

New Codes for Alopecia and Acne Surgery

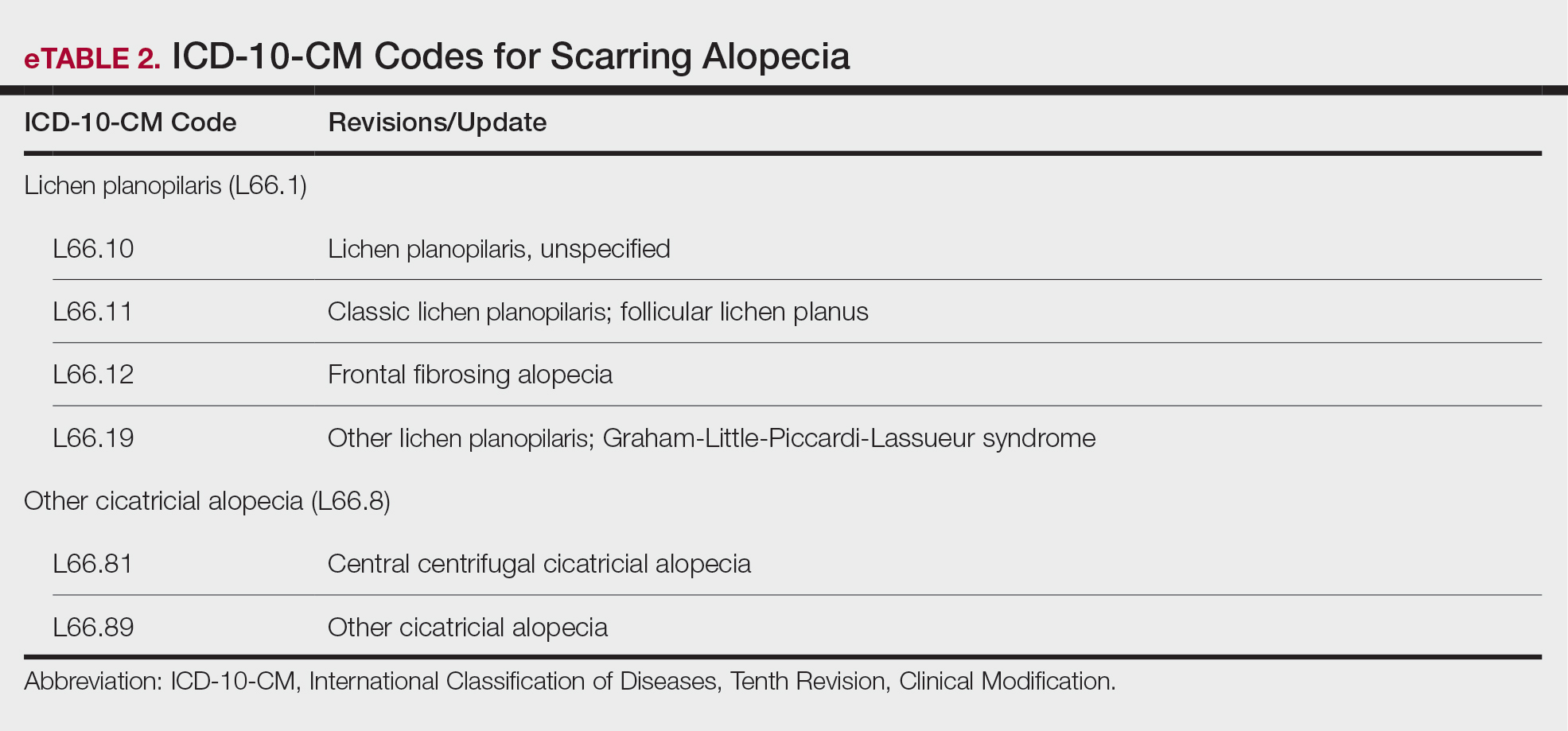

New International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification, codes for alopecia have been developed through collaboration of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Scarring Alopecia Foundation (eTable 2). Cutaneous extraction—previously coded as acne surgery (CPT code 10040)—will now be listed in the 2026 CPT coding manual as “extraction” (eg, marsupialization, opening of multiple milia, acne comedones, cysts, pustules).14

Quality Payment Program Update

The MIPS performance threshold will remain at 75 for the 2025 performance period, impacting the 2027 payment year.15 The MIPS Value Pathways will be available but optional in 2025, and the CMS plans to fully replace MIPS by 2029. The goal for the MVPs is to reduce the administrative burden of MIPS for physicians and their staff while simplifying reporting; however, there are several concerns. The MIPS Value Pathways build on the MIPS’s flawed processes; compare the cost for one condition to the quality of another; continue to be burdensome to physicians; have not demonstrated improved patient care; are a broad, one-size-fits-all model that could lead to inequity based on practice mix; and are not clinically relevant to physicians and patients.15

Beginning in 2025, dermatologists also will have access to a new high-priority quality measure—Melanoma: Tracking and Evaluation of Recurrence—and the Melanoma: Continuity of Care–Recall System measure (MIPS measure 137) will be removed starting in 2025.15

What Can Dermatologists Do?

With the fifth consecutive year of payment cuts, the cumulative reduction to physician payments has reached an untenable level, and physicians cannot continue to absorb the reductions, which impact access and ability to provide patient care. Members of the American Academy of Dermatology Association must urge members of Congress to stop the cuts and find a permanent solution to fix Medicare physician payment by asking their representatives to cosponsor the following bills in the US House of Representatives and Senate16:

- HR 10073—The Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act of 2024 would stop the 2.8% cut to the 2025 MPFS and provide a positive inflationary adjustment for physician practices equal to 50% of the 2025 MEI, which comes down to an increase of approximately 1.8%.17

- HR 2424—The Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act would provide an annual inflation update equal to the MEI for Medicare physician payments.18

- HR 6371—The Provider Reimbursement Stability Act would revise budget neutrality policies that contribute to eroding Medicare physician reimbursement.19

- S 4935—The Physician Fee Stabilization Act would increase the budget neutrality trigger from $20 million to $53 million.20

Advocacy is critically important: be engaged and get involved in grassroots efforts to protect access to health care, as these cuts do nothing to curb health care costs.

Final Thoughts

Congress has failed to address declining Medicare reimbursement rates, allowing cuts that jeopardize patient access to care as physicians close or sell their practices. It is important for dermatologists to attend the American Medical Association’s National Advocacy Conference in February 2025, which will feature an event on fixing Medicare. Dermatologists also can join prominent House members in urging Congress to reverse Medicare cuts and reform the physician payment system as well as write to their representatives and share how these cuts impact their practices and patients.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Office of the Actuary. National Health Statistics Group. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/nations-health-dollar-where-it-came-where-it-went.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY) 2025 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposed rule. July 10, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2025-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-proposed-rule

- RVS Update Committee (RUC). RBRVS overview. American Medical Association. Updated November 8, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/rvs-update-committee-ruc/rbrvs-overview

- American Medical Association. History of Medicare conversion charts. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/cf-history.pdf

- American Medical Association. Medicare basics series: the Medicare Economic Index. June 3, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/medicare-medicaid/medicare-basics-series-medicare-economic-index

- O’Reilly KB. Physician answers on this survey will shape future Medicare pay. American Medical Association. November 3, 2023. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/medicare-medicaid/physician-answers-survey-will-shape-future-medicare-pay

- Solis E. Stopgap spending bill extends telehealth flexibility, Medicare payment relief still awaits. American Academy of Family Physicians. December 3, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/fpm/blogs/gettingpaid/entry/2024-shutdown-averted.html

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY) 2025 Medicare physician fee schedule final rule. November 1, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2025-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-final-rulen

- Novitas Solutions. Other CPT modifiers. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/portal/MedicareJH/pagebyid?contentId=00144515

- Medical team conference, without direct (face-to-face) contact with patient and/or family CPT® code range 99367-99368. Codify by AAPC. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.aapc.com/codes/cpt-codes-range/99367-99368/

- McNichols FCM. Cracking the code. DermWorld. November 2023. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://digitaleditions.walsworth.com/publication/?i=806167&article_id=4666988

- McNichols FCM. Coding Consult. Derm World. Published April 2024. https://www.aad.org/dw/monthly/2024/may/dcc-hcpcs-add-on-code-g2211

- Venkatesh KP, Jothishankar B, Nambudiri VE. Incorporating social determinants of health into medical decision-making -implications for dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:367-368.

- McNichols FCM. Coding consult. DermWorld. October 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://digitaleditions.walsworth.com/publication/?i=832260&article_id=4863646

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality Payment Program. Dermatologic care MVP candidate. December 1, 2023. Updated December 15, 2023. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://qpp.cms.gov/resources/document/78e999ba-3690-4e02-9b35-6cc7c98d840b

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. AADA advocacy action center. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/take-action

- Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act of 2024, HR 10073, 118th Congress (NC 2024).

- Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act, HR 2424, 118th Congress (CA 2023).

- Provider Reimbursement Stability Act, HR 6371, 118th Congress (NC 2023).

- Physician Fee Stabilization Act. S 4935. 2023-2024 Session (AR 2024).

Health care costs continue to increase in 2025 while physician reimbursement continues to decrease. Of the $4.5 trillion spent on health care in 2022, only 20% was spent on physician and clinical services.1 Since 2001, practice expense has risen 47%, while the Consumer Price Index has risen 73%; adjusted for inflation, physician reimbursement has declined 30% since 2001.2

The formula for Medicare payments for physician services, calculated by multiplying the conversion factor (CF) by the relative value unit (RVU), was developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in 1992. The combination of the physician’s work, the practice’s expense, and the cost of professional liability insurance make up RVUs, which are aligned by geographic index adjustments.3 The 2024 CF was $32.75, compared to $32.00 in 1992. The proposed 2025 CF is $32.35, which is a 10% decrease since 2019 and a 2.8% decrease relative to the 2024 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS). The 2.8% cut is due to expiration of the 2.93% temporary payment increase for services provided by the Consolidated Appropriations Act 2024 and the supplemental relief provided from March 9, 2024, to December 31, 2024.4 If the CF had increased with inflation, it would have been $71.15 in 2024.4

Declining reimbursement rates for physician services undermine the ability of physician practices to keep their doors open in the face of increased operating costs. Faced with the widening gap between what Medicare pays for physician services and the cost of delivering value-based, quality care, physicians are urging Congress to pass a reform package to permanently strengthen Medicare.

Herein, an overview of key coding updates and changes, telehealth flexibilities, and a new dermatologyfocused Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Value Pathways is provided.

Update on the Medicare Economic Index Postponement

Developed in 1975, the Medicare Economic Index (MEI) is a measure of practice cost inflation. It is a yearly calculation that estimates the annual changes in physicians’ operating costs to determine appropriate Medicare physician payment updates.5 The MEI is composed of physician practice costs (eg, staff salaries, office space, malpractice insurance) and physician compensation (direct earnings by the physician). Both are used to calculate adjustments to Medicare physician payments to account for inflationary increases in health care costs. The MEI for 2025 is projected to increase by 3.5%, while physician payment continues to dwindle.5 This disparity between rising costs and declining physician payments will impact patient access to medical care. Physicians may choose to stop accepting Medicare and other health insurance, face the possibility of closing or selling their practices, or even decide to leave the profession.

The CMS has continued to delay implementation of the 2017 MEI cost weights (which currently are based on 2006 data5) for RVUs in the MPFS rate setting for 2025 pending completion of the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Practice Information Survey.6 The AMA contracted with an independent research company to conduct the survey, which will be used to update the MEI. Survey data will be shared with the CMS in early 2025.6

Future of Telehealth is Uncertain

On January 1, 2025, many telehealth flexibilities were set to expire; however, Congress passed an extension of the current telehealth policy flexibilities that have been in place since the COVID-19 pandemic through March 31, 2025.7 The CMS recognizes concerns about maintaining access to Medicare telehealth services once the statutory flexibilities expire; however, it maintains that it has limited statutory authority to extend these Medicare telehealth flexibilities.8 There will be originating site requirements and geographic location restrictions. Clinicians working in a federally qualified health center or a rural health clinic would not be affected.8

The CMS rejected adoption of 16 of 17 new Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (98000–98016) for telemedicine evaluation and management (E/M) services, rendering them nonreimbursable.8 Physicians should continue to use the standard E/M codes 99202 through 99215 for telehealth visits. The CMS only approved code 99016, which will replace Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code G2012, for brief virtual check-in encounters. The CMS specified that CPT codes 99441 through 99443, which describe telephone E/M services, have been removed and are no longer valid for billing. Asynchronous communication (eg, store-and-forward technology via an electronic health record portal) will continue to be reported using the online digital E/M service codes 99421, 99422, and 99423.8

Practitioners can use their enrolled practice location instead of their home address when providing telehealth services from home.8 Teaching physicians will continue to be allowed to have a virtual presence for purposes of billing for services involving residents in all teaching settings, but only when the service is furnished remotely (ie, the patient, resident, and teaching physician all are in separate locations). The use of real-time audio and video technology for direct supervision has been extended through December 31, 2025, allowing practitioners to be immediately available virtually. The CMS also plans to permanently allow virtual supervision for lower-risk services that typically do not require the billing practitioner’s physical presence or extensive direction (eg, diagnostic tests, behavioral health, dermatology, therapy).8

It is essential to verify the reimbursement policies and billing guidelines of individual payers, as some may adopt policies that differ from the AMA and CMS guidelines.

When to Use Modifiers -59 and -76

Modifiers -59 and -76 are used when billing for multiple procedures on the same day and can be confused. These modifiers help clarify situations in which procedures might appear redundant or improperly coded, reducing the risk for claim denials and ensuring compliance with coding guidelines. Use modifier -59 when a procedure or service is distinct or separate from other services performed on the same day (eg, cryosurgery of 4 actinic keratoses and a tangential biopsy of a nevus). Use modifier -76 when a physician performs the exact same procedure multiple times on the same patient on the same day (eg, removing 2 nevi on the face with the same excision code or performing multiple biopsies on different areas on the skin).9

What Are the Medical Team Conference CPT Codes?

Dermatologists frequently manage complex medical and surgical cases and actively participate in tumor boards and multidisciplinary teams conferences. It is essential to be familiar with the relevant CPT codes that can be used in these scenarios: CPT code 99366 can be used when the medical team conference occurs face-to-face with the patient present, and CPT code 99367 can be used for a medical team conference with an interdisciplinary group of health care professionals from different specialties, each of whom provides direct care to the patient.10 For CPT code 99367, the patient and/or family are not present during the meeting, which lasts a minimum of 30 minutes or more and requires participation by a physician. Current Procedural Terminology code 99368 can be used for participation in the medical team conference by a nonphysician qualified health care professional. The reporting participants need to document their participation in the medical team conference as well as their contributed information that explains the case and subsequent treatment recommendations.10

No more than 1 individual from the same specialty may report CPT codes 99366 through 99368 at the same encounter.10 Codes 99366 through 99368 should not be reported when participation in the medical team conference is part of a facility or contractually provided by the facility such as group therapy.10 The medical team conference starts at the beginning of the review of an individual patient and ends at the conclusion of the review for coding purposes. Time related to record-keeping or report generation does not need to be reported. The reporting participant needs to be present for the entire conference. The time reported is not limited to the time that the participant is communicating with other team members or the patient and/or their family/ caregiver(s). Time reported for medical team conferences may not be used in the determination for other services, such as care plan oversight (99374-99380), prolonged services (99358, 99359), psychotherapy, or any E/M service. When the patient is present for any part of the duration of the team conference, nonphysician qualified health care professionals (eg, speech-language pathologists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, social workers, dietitians) report the medical team conference face-to-face with code 99366.10

Update on Excimer Laser CPT Codes

The CMS rejected values recommended for CPT codes (96920-96922) by the Relative Value Scale Update Committee, proposing lower work RVUs of 0.83, 0.90, and 1.15, respectively (Table).2,11 The CPT panel did not recognize the strength of the literature supporting the expanded use of the codes for conditions other than psoriasis. Report the use of excimer laser for treatment of vitiligo, atopic dermatitis, and alopecia areata using CPT code 96999 (unlisted special dermatological service or procedure).11

Update on the New G2211 Code

Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code G2211 is an add-on complexity code that can be reported with all outpatient E/M visits to better account for additional resources associated with primary care or similarly ongoing medical care related to a patient’s single serious condition or complex condition.12 It can be billed if the physician is serving as the continuing focal point for all the patient's health care service needs, acting as the central point of contact for the patient’s ongoing medical care, and managing all aspects of their health needs over time. It is not restricted based on specialty, but it is determined based on the nature of the physician-patient relationship.12

Code G2211 should not be used for the following scenarios: (1) care provided by a clinician with a discrete, routine, or time-limited relationship with the patient, such as a routine skin examination or an acute allergic contact dermatitis; (2) conditions in which comorbidities are not present or addressed; (3) when the billing clinician has not assumed responsibility for ongoing medical care with consistency and continuity over time; and (4) visits billed with modifier -25.12 In the 2025 MPFS, the CMS is proposing to allow payment of G2211 when the code is reported by the same practitioner on the same day as an annual wellness visit, vaccine administration, or any Medicare Part B preventive service furnished in the office or outpatient setting (ie, creating a limited exception to the prohibition of using this code with modifier -25).2

Documentation in the medical record must support reporting code G2211 and indicate a medically reasonable and necessary reason for the additional RVUs (0.33 and additional payment of $16.05).12

Underutilization of Z Codes for Social Determinants of Health

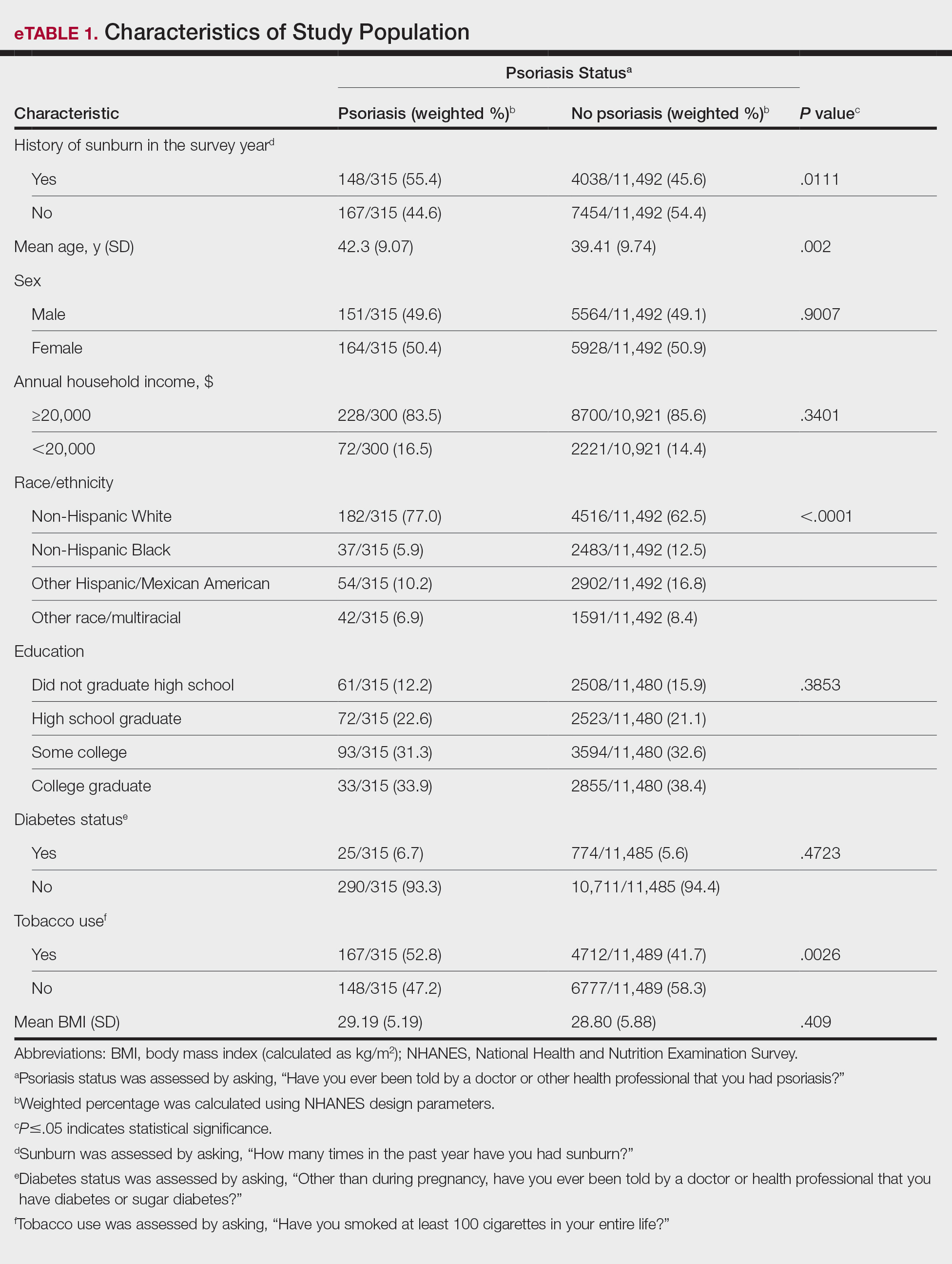

Barriers to documentation of social determinants of health (SDOH)–related International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Z codes (Z55-Z66)(eTable 1), include lack of clarity on who can document patients’ social needs, lack of systems and processes for documenting and coding SDOH, unfamiliarity with these Z codes, and a low prioritization of collecting these data.13 Documentation of a SDOH-related Z code relevant to a patient encounter is considered moderate risk and can have a major impact on a patient’s overall health, unmet social needs, and outcomes.13 If the other 2 medical decision-making elements (ie, number and complexity of problems addressed along with amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed) for the E/M visit also are moderate, then the encounter can be coded as level 4.13

New Codes for Alopecia and Acne Surgery

New International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification, codes for alopecia have been developed through collaboration of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Scarring Alopecia Foundation (eTable 2). Cutaneous extraction—previously coded as acne surgery (CPT code 10040)—will now be listed in the 2026 CPT coding manual as “extraction” (eg, marsupialization, opening of multiple milia, acne comedones, cysts, pustules).14

Quality Payment Program Update

The MIPS performance threshold will remain at 75 for the 2025 performance period, impacting the 2027 payment year.15 The MIPS Value Pathways will be available but optional in 2025, and the CMS plans to fully replace MIPS by 2029. The goal for the MVPs is to reduce the administrative burden of MIPS for physicians and their staff while simplifying reporting; however, there are several concerns. The MIPS Value Pathways build on the MIPS’s flawed processes; compare the cost for one condition to the quality of another; continue to be burdensome to physicians; have not demonstrated improved patient care; are a broad, one-size-fits-all model that could lead to inequity based on practice mix; and are not clinically relevant to physicians and patients.15

Beginning in 2025, dermatologists also will have access to a new high-priority quality measure—Melanoma: Tracking and Evaluation of Recurrence—and the Melanoma: Continuity of Care–Recall System measure (MIPS measure 137) will be removed starting in 2025.15

What Can Dermatologists Do?

With the fifth consecutive year of payment cuts, the cumulative reduction to physician payments has reached an untenable level, and physicians cannot continue to absorb the reductions, which impact access and ability to provide patient care. Members of the American Academy of Dermatology Association must urge members of Congress to stop the cuts and find a permanent solution to fix Medicare physician payment by asking their representatives to cosponsor the following bills in the US House of Representatives and Senate16:

- HR 10073—The Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act of 2024 would stop the 2.8% cut to the 2025 MPFS and provide a positive inflationary adjustment for physician practices equal to 50% of the 2025 MEI, which comes down to an increase of approximately 1.8%.17

- HR 2424—The Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act would provide an annual inflation update equal to the MEI for Medicare physician payments.18

- HR 6371—The Provider Reimbursement Stability Act would revise budget neutrality policies that contribute to eroding Medicare physician reimbursement.19

- S 4935—The Physician Fee Stabilization Act would increase the budget neutrality trigger from $20 million to $53 million.20

Advocacy is critically important: be engaged and get involved in grassroots efforts to protect access to health care, as these cuts do nothing to curb health care costs.

Final Thoughts

Congress has failed to address declining Medicare reimbursement rates, allowing cuts that jeopardize patient access to care as physicians close or sell their practices. It is important for dermatologists to attend the American Medical Association’s National Advocacy Conference in February 2025, which will feature an event on fixing Medicare. Dermatologists also can join prominent House members in urging Congress to reverse Medicare cuts and reform the physician payment system as well as write to their representatives and share how these cuts impact their practices and patients.

Health care costs continue to increase in 2025 while physician reimbursement continues to decrease. Of the $4.5 trillion spent on health care in 2022, only 20% was spent on physician and clinical services.1 Since 2001, practice expense has risen 47%, while the Consumer Price Index has risen 73%; adjusted for inflation, physician reimbursement has declined 30% since 2001.2

The formula for Medicare payments for physician services, calculated by multiplying the conversion factor (CF) by the relative value unit (RVU), was developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in 1992. The combination of the physician’s work, the practice’s expense, and the cost of professional liability insurance make up RVUs, which are aligned by geographic index adjustments.3 The 2024 CF was $32.75, compared to $32.00 in 1992. The proposed 2025 CF is $32.35, which is a 10% decrease since 2019 and a 2.8% decrease relative to the 2024 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS). The 2.8% cut is due to expiration of the 2.93% temporary payment increase for services provided by the Consolidated Appropriations Act 2024 and the supplemental relief provided from March 9, 2024, to December 31, 2024.4 If the CF had increased with inflation, it would have been $71.15 in 2024.4

Declining reimbursement rates for physician services undermine the ability of physician practices to keep their doors open in the face of increased operating costs. Faced with the widening gap between what Medicare pays for physician services and the cost of delivering value-based, quality care, physicians are urging Congress to pass a reform package to permanently strengthen Medicare.

Herein, an overview of key coding updates and changes, telehealth flexibilities, and a new dermatologyfocused Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Value Pathways is provided.

Update on the Medicare Economic Index Postponement

Developed in 1975, the Medicare Economic Index (MEI) is a measure of practice cost inflation. It is a yearly calculation that estimates the annual changes in physicians’ operating costs to determine appropriate Medicare physician payment updates.5 The MEI is composed of physician practice costs (eg, staff salaries, office space, malpractice insurance) and physician compensation (direct earnings by the physician). Both are used to calculate adjustments to Medicare physician payments to account for inflationary increases in health care costs. The MEI for 2025 is projected to increase by 3.5%, while physician payment continues to dwindle.5 This disparity between rising costs and declining physician payments will impact patient access to medical care. Physicians may choose to stop accepting Medicare and other health insurance, face the possibility of closing or selling their practices, or even decide to leave the profession.

The CMS has continued to delay implementation of the 2017 MEI cost weights (which currently are based on 2006 data5) for RVUs in the MPFS rate setting for 2025 pending completion of the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Practice Information Survey.6 The AMA contracted with an independent research company to conduct the survey, which will be used to update the MEI. Survey data will be shared with the CMS in early 2025.6

Future of Telehealth is Uncertain

On January 1, 2025, many telehealth flexibilities were set to expire; however, Congress passed an extension of the current telehealth policy flexibilities that have been in place since the COVID-19 pandemic through March 31, 2025.7 The CMS recognizes concerns about maintaining access to Medicare telehealth services once the statutory flexibilities expire; however, it maintains that it has limited statutory authority to extend these Medicare telehealth flexibilities.8 There will be originating site requirements and geographic location restrictions. Clinicians working in a federally qualified health center or a rural health clinic would not be affected.8

The CMS rejected adoption of 16 of 17 new Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (98000–98016) for telemedicine evaluation and management (E/M) services, rendering them nonreimbursable.8 Physicians should continue to use the standard E/M codes 99202 through 99215 for telehealth visits. The CMS only approved code 99016, which will replace Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code G2012, for brief virtual check-in encounters. The CMS specified that CPT codes 99441 through 99443, which describe telephone E/M services, have been removed and are no longer valid for billing. Asynchronous communication (eg, store-and-forward technology via an electronic health record portal) will continue to be reported using the online digital E/M service codes 99421, 99422, and 99423.8

Practitioners can use their enrolled practice location instead of their home address when providing telehealth services from home.8 Teaching physicians will continue to be allowed to have a virtual presence for purposes of billing for services involving residents in all teaching settings, but only when the service is furnished remotely (ie, the patient, resident, and teaching physician all are in separate locations). The use of real-time audio and video technology for direct supervision has been extended through December 31, 2025, allowing practitioners to be immediately available virtually. The CMS also plans to permanently allow virtual supervision for lower-risk services that typically do not require the billing practitioner’s physical presence or extensive direction (eg, diagnostic tests, behavioral health, dermatology, therapy).8

It is essential to verify the reimbursement policies and billing guidelines of individual payers, as some may adopt policies that differ from the AMA and CMS guidelines.

When to Use Modifiers -59 and -76

Modifiers -59 and -76 are used when billing for multiple procedures on the same day and can be confused. These modifiers help clarify situations in which procedures might appear redundant or improperly coded, reducing the risk for claim denials and ensuring compliance with coding guidelines. Use modifier -59 when a procedure or service is distinct or separate from other services performed on the same day (eg, cryosurgery of 4 actinic keratoses and a tangential biopsy of a nevus). Use modifier -76 when a physician performs the exact same procedure multiple times on the same patient on the same day (eg, removing 2 nevi on the face with the same excision code or performing multiple biopsies on different areas on the skin).9

What Are the Medical Team Conference CPT Codes?

Dermatologists frequently manage complex medical and surgical cases and actively participate in tumor boards and multidisciplinary teams conferences. It is essential to be familiar with the relevant CPT codes that can be used in these scenarios: CPT code 99366 can be used when the medical team conference occurs face-to-face with the patient present, and CPT code 99367 can be used for a medical team conference with an interdisciplinary group of health care professionals from different specialties, each of whom provides direct care to the patient.10 For CPT code 99367, the patient and/or family are not present during the meeting, which lasts a minimum of 30 minutes or more and requires participation by a physician. Current Procedural Terminology code 99368 can be used for participation in the medical team conference by a nonphysician qualified health care professional. The reporting participants need to document their participation in the medical team conference as well as their contributed information that explains the case and subsequent treatment recommendations.10

No more than 1 individual from the same specialty may report CPT codes 99366 through 99368 at the same encounter.10 Codes 99366 through 99368 should not be reported when participation in the medical team conference is part of a facility or contractually provided by the facility such as group therapy.10 The medical team conference starts at the beginning of the review of an individual patient and ends at the conclusion of the review for coding purposes. Time related to record-keeping or report generation does not need to be reported. The reporting participant needs to be present for the entire conference. The time reported is not limited to the time that the participant is communicating with other team members or the patient and/or their family/ caregiver(s). Time reported for medical team conferences may not be used in the determination for other services, such as care plan oversight (99374-99380), prolonged services (99358, 99359), psychotherapy, or any E/M service. When the patient is present for any part of the duration of the team conference, nonphysician qualified health care professionals (eg, speech-language pathologists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, social workers, dietitians) report the medical team conference face-to-face with code 99366.10

Update on Excimer Laser CPT Codes

The CMS rejected values recommended for CPT codes (96920-96922) by the Relative Value Scale Update Committee, proposing lower work RVUs of 0.83, 0.90, and 1.15, respectively (Table).2,11 The CPT panel did not recognize the strength of the literature supporting the expanded use of the codes for conditions other than psoriasis. Report the use of excimer laser for treatment of vitiligo, atopic dermatitis, and alopecia areata using CPT code 96999 (unlisted special dermatological service or procedure).11

Update on the New G2211 Code

Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code G2211 is an add-on complexity code that can be reported with all outpatient E/M visits to better account for additional resources associated with primary care or similarly ongoing medical care related to a patient’s single serious condition or complex condition.12 It can be billed if the physician is serving as the continuing focal point for all the patient's health care service needs, acting as the central point of contact for the patient’s ongoing medical care, and managing all aspects of their health needs over time. It is not restricted based on specialty, but it is determined based on the nature of the physician-patient relationship.12

Code G2211 should not be used for the following scenarios: (1) care provided by a clinician with a discrete, routine, or time-limited relationship with the patient, such as a routine skin examination or an acute allergic contact dermatitis; (2) conditions in which comorbidities are not present or addressed; (3) when the billing clinician has not assumed responsibility for ongoing medical care with consistency and continuity over time; and (4) visits billed with modifier -25.12 In the 2025 MPFS, the CMS is proposing to allow payment of G2211 when the code is reported by the same practitioner on the same day as an annual wellness visit, vaccine administration, or any Medicare Part B preventive service furnished in the office or outpatient setting (ie, creating a limited exception to the prohibition of using this code with modifier -25).2

Documentation in the medical record must support reporting code G2211 and indicate a medically reasonable and necessary reason for the additional RVUs (0.33 and additional payment of $16.05).12

Underutilization of Z Codes for Social Determinants of Health

Barriers to documentation of social determinants of health (SDOH)–related International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Z codes (Z55-Z66)(eTable 1), include lack of clarity on who can document patients’ social needs, lack of systems and processes for documenting and coding SDOH, unfamiliarity with these Z codes, and a low prioritization of collecting these data.13 Documentation of a SDOH-related Z code relevant to a patient encounter is considered moderate risk and can have a major impact on a patient’s overall health, unmet social needs, and outcomes.13 If the other 2 medical decision-making elements (ie, number and complexity of problems addressed along with amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed) for the E/M visit also are moderate, then the encounter can be coded as level 4.13

New Codes for Alopecia and Acne Surgery

New International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification, codes for alopecia have been developed through collaboration of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Scarring Alopecia Foundation (eTable 2). Cutaneous extraction—previously coded as acne surgery (CPT code 10040)—will now be listed in the 2026 CPT coding manual as “extraction” (eg, marsupialization, opening of multiple milia, acne comedones, cysts, pustules).14

Quality Payment Program Update

The MIPS performance threshold will remain at 75 for the 2025 performance period, impacting the 2027 payment year.15 The MIPS Value Pathways will be available but optional in 2025, and the CMS plans to fully replace MIPS by 2029. The goal for the MVPs is to reduce the administrative burden of MIPS for physicians and their staff while simplifying reporting; however, there are several concerns. The MIPS Value Pathways build on the MIPS’s flawed processes; compare the cost for one condition to the quality of another; continue to be burdensome to physicians; have not demonstrated improved patient care; are a broad, one-size-fits-all model that could lead to inequity based on practice mix; and are not clinically relevant to physicians and patients.15

Beginning in 2025, dermatologists also will have access to a new high-priority quality measure—Melanoma: Tracking and Evaluation of Recurrence—and the Melanoma: Continuity of Care–Recall System measure (MIPS measure 137) will be removed starting in 2025.15

What Can Dermatologists Do?

With the fifth consecutive year of payment cuts, the cumulative reduction to physician payments has reached an untenable level, and physicians cannot continue to absorb the reductions, which impact access and ability to provide patient care. Members of the American Academy of Dermatology Association must urge members of Congress to stop the cuts and find a permanent solution to fix Medicare physician payment by asking their representatives to cosponsor the following bills in the US House of Representatives and Senate16:

- HR 10073—The Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act of 2024 would stop the 2.8% cut to the 2025 MPFS and provide a positive inflationary adjustment for physician practices equal to 50% of the 2025 MEI, which comes down to an increase of approximately 1.8%.17

- HR 2424—The Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act would provide an annual inflation update equal to the MEI for Medicare physician payments.18

- HR 6371—The Provider Reimbursement Stability Act would revise budget neutrality policies that contribute to eroding Medicare physician reimbursement.19

- S 4935—The Physician Fee Stabilization Act would increase the budget neutrality trigger from $20 million to $53 million.20

Advocacy is critically important: be engaged and get involved in grassroots efforts to protect access to health care, as these cuts do nothing to curb health care costs.

Final Thoughts

Congress has failed to address declining Medicare reimbursement rates, allowing cuts that jeopardize patient access to care as physicians close or sell their practices. It is important for dermatologists to attend the American Medical Association’s National Advocacy Conference in February 2025, which will feature an event on fixing Medicare. Dermatologists also can join prominent House members in urging Congress to reverse Medicare cuts and reform the physician payment system as well as write to their representatives and share how these cuts impact their practices and patients.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Office of the Actuary. National Health Statistics Group. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/nations-health-dollar-where-it-came-where-it-went.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY) 2025 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposed rule. July 10, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2025-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-proposed-rule

- RVS Update Committee (RUC). RBRVS overview. American Medical Association. Updated November 8, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/rvs-update-committee-ruc/rbrvs-overview

- American Medical Association. History of Medicare conversion charts. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/cf-history.pdf

- American Medical Association. Medicare basics series: the Medicare Economic Index. June 3, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/medicare-medicaid/medicare-basics-series-medicare-economic-index

- O’Reilly KB. Physician answers on this survey will shape future Medicare pay. American Medical Association. November 3, 2023. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/medicare-medicaid/physician-answers-survey-will-shape-future-medicare-pay

- Solis E. Stopgap spending bill extends telehealth flexibility, Medicare payment relief still awaits. American Academy of Family Physicians. December 3, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/fpm/blogs/gettingpaid/entry/2024-shutdown-averted.html

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY) 2025 Medicare physician fee schedule final rule. November 1, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2025-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-final-rulen

- Novitas Solutions. Other CPT modifiers. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/portal/MedicareJH/pagebyid?contentId=00144515

- Medical team conference, without direct (face-to-face) contact with patient and/or family CPT® code range 99367-99368. Codify by AAPC. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.aapc.com/codes/cpt-codes-range/99367-99368/

- McNichols FCM. Cracking the code. DermWorld. November 2023. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://digitaleditions.walsworth.com/publication/?i=806167&article_id=4666988

- McNichols FCM. Coding Consult. Derm World. Published April 2024. https://www.aad.org/dw/monthly/2024/may/dcc-hcpcs-add-on-code-g2211

- Venkatesh KP, Jothishankar B, Nambudiri VE. Incorporating social determinants of health into medical decision-making -implications for dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:367-368.

- McNichols FCM. Coding consult. DermWorld. October 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://digitaleditions.walsworth.com/publication/?i=832260&article_id=4863646

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality Payment Program. Dermatologic care MVP candidate. December 1, 2023. Updated December 15, 2023. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://qpp.cms.gov/resources/document/78e999ba-3690-4e02-9b35-6cc7c98d840b

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. AADA advocacy action center. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/take-action

- Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act of 2024, HR 10073, 118th Congress (NC 2024).

- Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act, HR 2424, 118th Congress (CA 2023).

- Provider Reimbursement Stability Act, HR 6371, 118th Congress (NC 2023).

- Physician Fee Stabilization Act. S 4935. 2023-2024 Session (AR 2024).

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Office of the Actuary. National Health Statistics Group. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/nations-health-dollar-where-it-came-where-it-went.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY) 2025 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposed rule. July 10, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2025-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-proposed-rule

- RVS Update Committee (RUC). RBRVS overview. American Medical Association. Updated November 8, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/rvs-update-committee-ruc/rbrvs-overview