User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Erratum

Due to a submission error, the article “A Boxed Warning for Inadequate Psoriasis Treatment” (Cutis. 2016;98:206-207) did not contain the complete author disclosure information. The corrected disclosure statement appears below:

Ms. Kagha and Ms. Anderson report no conflict of interest. Dr. Blauvelt has served as a clinical study investigator and scientific adviser for AbbVie Inc; Amgen, Inc; Boehringer Ingelheim; Celgene Corporation; Dermira Inc; Eli Lilly and Company; Genentech, Inc; GlaxoSmithKline; Janssen Biotech, Inc; Merck & Co; Novartis; Pfizer Inc; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Sandoz, a Novartis Division; Sanofi; Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd; UCB; and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc, as well as a paid speaker for Eli Lilly and Company. Dr. Leonardi has served as an advisory board member and consultant for AbbVie Inc; Amgen, Inc; Boehringer Ingelheim; Dermira Inc; Eli Lilly and Company; Janssen Biotech, Inc; LEO Pharma; Pfizer Inc; Sandoz, a Novartis Division; UCB; and Vitae Pharmaceuticals. He also has been an investigator for AbbVie Inc; Actavis Pharma, Inc; Amgen, Inc; Boehringer Ingelheim; Celgene Corporation; Coherus BioSciences; Corrona, LLC; Dermira Inc; Eli Lilly and Company; Galderma Laboratories, LP; Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Inc; Janssen Biotech, Inc; LEO Pharma; Merck & Co; Novartis; Pfizer Inc; Sandoz, a Novartis Division; Stiefel, a GSK company; and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Dr. Leonardi also has been on the speaker’s bureau for AbbVie Inc; Celgene Corporation; Eli Lilly and Company; and Novartis. Dr. Feldman is a consultant, researcher, and/or speaker for AbbVie Inc; Amgen, Inc; Baxter; Boehringer Ingelheim; Celgene Corporation; Janssen Biotech, Inc; Merck & Co; Mylan; Novartis; Pfizer Inc; and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc.

The staff of Cutis® makes every possible effort to ensure accuracy in its articles and apologizes for the mistake.

Due to a submission error, the article “A Boxed Warning for Inadequate Psoriasis Treatment” (Cutis. 2016;98:206-207) did not contain the complete author disclosure information. The corrected disclosure statement appears below:

Ms. Kagha and Ms. Anderson report no conflict of interest. Dr. Blauvelt has served as a clinical study investigator and scientific adviser for AbbVie Inc; Amgen, Inc; Boehringer Ingelheim; Celgene Corporation; Dermira Inc; Eli Lilly and Company; Genentech, Inc; GlaxoSmithKline; Janssen Biotech, Inc; Merck & Co; Novartis; Pfizer Inc; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Sandoz, a Novartis Division; Sanofi; Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd; UCB; and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc, as well as a paid speaker for Eli Lilly and Company. Dr. Leonardi has served as an advisory board member and consultant for AbbVie Inc; Amgen, Inc; Boehringer Ingelheim; Dermira Inc; Eli Lilly and Company; Janssen Biotech, Inc; LEO Pharma; Pfizer Inc; Sandoz, a Novartis Division; UCB; and Vitae Pharmaceuticals. He also has been an investigator for AbbVie Inc; Actavis Pharma, Inc; Amgen, Inc; Boehringer Ingelheim; Celgene Corporation; Coherus BioSciences; Corrona, LLC; Dermira Inc; Eli Lilly and Company; Galderma Laboratories, LP; Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Inc; Janssen Biotech, Inc; LEO Pharma; Merck & Co; Novartis; Pfizer Inc; Sandoz, a Novartis Division; Stiefel, a GSK company; and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Dr. Leonardi also has been on the speaker’s bureau for AbbVie Inc; Celgene Corporation; Eli Lilly and Company; and Novartis. Dr. Feldman is a consultant, researcher, and/or speaker for AbbVie Inc; Amgen, Inc; Baxter; Boehringer Ingelheim; Celgene Corporation; Janssen Biotech, Inc; Merck & Co; Mylan; Novartis; Pfizer Inc; and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc.

The staff of Cutis® makes every possible effort to ensure accuracy in its articles and apologizes for the mistake.

Due to a submission error, the article “A Boxed Warning for Inadequate Psoriasis Treatment” (Cutis. 2016;98:206-207) did not contain the complete author disclosure information. The corrected disclosure statement appears below:

Ms. Kagha and Ms. Anderson report no conflict of interest. Dr. Blauvelt has served as a clinical study investigator and scientific adviser for AbbVie Inc; Amgen, Inc; Boehringer Ingelheim; Celgene Corporation; Dermira Inc; Eli Lilly and Company; Genentech, Inc; GlaxoSmithKline; Janssen Biotech, Inc; Merck & Co; Novartis; Pfizer Inc; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Sandoz, a Novartis Division; Sanofi; Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd; UCB; and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc, as well as a paid speaker for Eli Lilly and Company. Dr. Leonardi has served as an advisory board member and consultant for AbbVie Inc; Amgen, Inc; Boehringer Ingelheim; Dermira Inc; Eli Lilly and Company; Janssen Biotech, Inc; LEO Pharma; Pfizer Inc; Sandoz, a Novartis Division; UCB; and Vitae Pharmaceuticals. He also has been an investigator for AbbVie Inc; Actavis Pharma, Inc; Amgen, Inc; Boehringer Ingelheim; Celgene Corporation; Coherus BioSciences; Corrona, LLC; Dermira Inc; Eli Lilly and Company; Galderma Laboratories, LP; Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Inc; Janssen Biotech, Inc; LEO Pharma; Merck & Co; Novartis; Pfizer Inc; Sandoz, a Novartis Division; Stiefel, a GSK company; and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Dr. Leonardi also has been on the speaker’s bureau for AbbVie Inc; Celgene Corporation; Eli Lilly and Company; and Novartis. Dr. Feldman is a consultant, researcher, and/or speaker for AbbVie Inc; Amgen, Inc; Baxter; Boehringer Ingelheim; Celgene Corporation; Janssen Biotech, Inc; Merck & Co; Mylan; Novartis; Pfizer Inc; and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc.

The staff of Cutis® makes every possible effort to ensure accuracy in its articles and apologizes for the mistake.

Renewal in Cosmetic Dermatology

It is an exciting time for dermatologists. In the 16 years that I have been in practice our knowledge of disease pathogenesis has increased and has shaped treatments that can now offer life-changing improvement for patients with extensive dermatologic disease. The everyday practice of cosmetic dermatology also has advanced. Sixteen years ago the only cosmetic options we had for our patients were bovine or human collagen injections, traditional CO2 laser resurfacing, and the older generations of pulsed dye lasers. Neuromodulators were just being introduced. We quickly learned the limitations and complications associated with these modalities. Collagen injections were directed at fine perioral lines and lasted 3 to 4 months. The worst complication would be a bruise or an allergic reaction to the bovine collagen. If we really needed to restore volume beyond the perioral regions, our only option was autologous fat transfer. CO2 laser resurfacing was used to firm skin, erase deep wrinkles, and improve sun damage, but its use was limited to older, fair-skinned individuals due to the inherent risk for hypopigmentation and depigmentation. Pulsed dye lasers similarly had no means of cooling the skin, thus they were limited to lighter-skinned individuals and had notable risk for blisters, burns, and hypopigmentation. Since then, our understanding of skin healing, laser-tissue interaction, and facial aging has driven the field to new heights of technological advances and safety. Just as I tell my patients and residents, there is no better time to be in this field than at this moment. Dermatologists have driven the advances behind many of the technologies that are now in widespread use among physicians in a variety of specialties.

Our understanding of facial aging has evolved to include the complex interplay of skeletal change, fat atrophy, and skin aging, which must all be considered when improving a patient’s appearance. Fillers have evolved in physical characteristics to give us the ability to choose between lift, spread, neocollagenesis, or water absorption. Thus, we can select the proper filler for the specific anatomic area we are rejuvenating.

Our understanding of photoaging and laser-tissue physics has allowed for the development of a newer generation of lasers ranging from fractionated lasers to noninvasive modalities that can safely be used in a variety of ethnic skin types to address acne scars, wrinkles, and inflammatory processes such as acne and rosacea. Similarly, the desire to tighten redundant skin has continued to drive ultrasound and radiofrequency technology and sparked growth in a newer field of cryolipolysis and chemical lipolysis agents.

Our dialogue with patients also has evolved to include the 4 R’s of antiaging: resurfacing the skin (eg, lasers, peels), refilling the lost volume (eg, fillers, fat), redraping the excess skin (eg, radiofrequency, ultrasound, laser, surgery), and relaxing dynamic lines (eg, neuromodulators). I propose an additional R: renewal! We must focus on the need for constant renewal so that patients maintain the results we have achieved. I apply the analogy of exercising to get into shape. One must go to the gym regularly to get to the desired level of fitness, but you do not stop exercising, otherwise you will quickly relapse to your former lack of fitness. Similarly, patients should receive the appropriate treatments to bring them to the desired level of rejuvenation, but then some form of constant renewal process is needed to maintain them at that level. Without the stimulation of the skin, the aging process continues and the cycle begins all over again.

In my practice, renewal is achieved by driving the skin to maintain the glow and smoothness that enhances the results of the fillers, neuromodulators, lasers, and peels that we have used. The skin is the first thing people notice. Without the glow, the patient will look good but not great. I tell patients that this part of the process is their responsibility. They must adhere to the skin care regimen specifically designed to address their needs. By incorporating the patient in the rejuvenation process, he/she is empowered to take control over the aging process and has grown more confident in you as a physician.

These are exciting times and there is still so much in the pipeline. By continually learning, reading, and attending workshops and meetings, you can make sure our specialty continue to be the leader in the antiaging field.

It is an exciting time for dermatologists. In the 16 years that I have been in practice our knowledge of disease pathogenesis has increased and has shaped treatments that can now offer life-changing improvement for patients with extensive dermatologic disease. The everyday practice of cosmetic dermatology also has advanced. Sixteen years ago the only cosmetic options we had for our patients were bovine or human collagen injections, traditional CO2 laser resurfacing, and the older generations of pulsed dye lasers. Neuromodulators were just being introduced. We quickly learned the limitations and complications associated with these modalities. Collagen injections were directed at fine perioral lines and lasted 3 to 4 months. The worst complication would be a bruise or an allergic reaction to the bovine collagen. If we really needed to restore volume beyond the perioral regions, our only option was autologous fat transfer. CO2 laser resurfacing was used to firm skin, erase deep wrinkles, and improve sun damage, but its use was limited to older, fair-skinned individuals due to the inherent risk for hypopigmentation and depigmentation. Pulsed dye lasers similarly had no means of cooling the skin, thus they were limited to lighter-skinned individuals and had notable risk for blisters, burns, and hypopigmentation. Since then, our understanding of skin healing, laser-tissue interaction, and facial aging has driven the field to new heights of technological advances and safety. Just as I tell my patients and residents, there is no better time to be in this field than at this moment. Dermatologists have driven the advances behind many of the technologies that are now in widespread use among physicians in a variety of specialties.

Our understanding of facial aging has evolved to include the complex interplay of skeletal change, fat atrophy, and skin aging, which must all be considered when improving a patient’s appearance. Fillers have evolved in physical characteristics to give us the ability to choose between lift, spread, neocollagenesis, or water absorption. Thus, we can select the proper filler for the specific anatomic area we are rejuvenating.

Our understanding of photoaging and laser-tissue physics has allowed for the development of a newer generation of lasers ranging from fractionated lasers to noninvasive modalities that can safely be used in a variety of ethnic skin types to address acne scars, wrinkles, and inflammatory processes such as acne and rosacea. Similarly, the desire to tighten redundant skin has continued to drive ultrasound and radiofrequency technology and sparked growth in a newer field of cryolipolysis and chemical lipolysis agents.

Our dialogue with patients also has evolved to include the 4 R’s of antiaging: resurfacing the skin (eg, lasers, peels), refilling the lost volume (eg, fillers, fat), redraping the excess skin (eg, radiofrequency, ultrasound, laser, surgery), and relaxing dynamic lines (eg, neuromodulators). I propose an additional R: renewal! We must focus on the need for constant renewal so that patients maintain the results we have achieved. I apply the analogy of exercising to get into shape. One must go to the gym regularly to get to the desired level of fitness, but you do not stop exercising, otherwise you will quickly relapse to your former lack of fitness. Similarly, patients should receive the appropriate treatments to bring them to the desired level of rejuvenation, but then some form of constant renewal process is needed to maintain them at that level. Without the stimulation of the skin, the aging process continues and the cycle begins all over again.

In my practice, renewal is achieved by driving the skin to maintain the glow and smoothness that enhances the results of the fillers, neuromodulators, lasers, and peels that we have used. The skin is the first thing people notice. Without the glow, the patient will look good but not great. I tell patients that this part of the process is their responsibility. They must adhere to the skin care regimen specifically designed to address their needs. By incorporating the patient in the rejuvenation process, he/she is empowered to take control over the aging process and has grown more confident in you as a physician.

These are exciting times and there is still so much in the pipeline. By continually learning, reading, and attending workshops and meetings, you can make sure our specialty continue to be the leader in the antiaging field.

It is an exciting time for dermatologists. In the 16 years that I have been in practice our knowledge of disease pathogenesis has increased and has shaped treatments that can now offer life-changing improvement for patients with extensive dermatologic disease. The everyday practice of cosmetic dermatology also has advanced. Sixteen years ago the only cosmetic options we had for our patients were bovine or human collagen injections, traditional CO2 laser resurfacing, and the older generations of pulsed dye lasers. Neuromodulators were just being introduced. We quickly learned the limitations and complications associated with these modalities. Collagen injections were directed at fine perioral lines and lasted 3 to 4 months. The worst complication would be a bruise or an allergic reaction to the bovine collagen. If we really needed to restore volume beyond the perioral regions, our only option was autologous fat transfer. CO2 laser resurfacing was used to firm skin, erase deep wrinkles, and improve sun damage, but its use was limited to older, fair-skinned individuals due to the inherent risk for hypopigmentation and depigmentation. Pulsed dye lasers similarly had no means of cooling the skin, thus they were limited to lighter-skinned individuals and had notable risk for blisters, burns, and hypopigmentation. Since then, our understanding of skin healing, laser-tissue interaction, and facial aging has driven the field to new heights of technological advances and safety. Just as I tell my patients and residents, there is no better time to be in this field than at this moment. Dermatologists have driven the advances behind many of the technologies that are now in widespread use among physicians in a variety of specialties.

Our understanding of facial aging has evolved to include the complex interplay of skeletal change, fat atrophy, and skin aging, which must all be considered when improving a patient’s appearance. Fillers have evolved in physical characteristics to give us the ability to choose between lift, spread, neocollagenesis, or water absorption. Thus, we can select the proper filler for the specific anatomic area we are rejuvenating.

Our understanding of photoaging and laser-tissue physics has allowed for the development of a newer generation of lasers ranging from fractionated lasers to noninvasive modalities that can safely be used in a variety of ethnic skin types to address acne scars, wrinkles, and inflammatory processes such as acne and rosacea. Similarly, the desire to tighten redundant skin has continued to drive ultrasound and radiofrequency technology and sparked growth in a newer field of cryolipolysis and chemical lipolysis agents.

Our dialogue with patients also has evolved to include the 4 R’s of antiaging: resurfacing the skin (eg, lasers, peels), refilling the lost volume (eg, fillers, fat), redraping the excess skin (eg, radiofrequency, ultrasound, laser, surgery), and relaxing dynamic lines (eg, neuromodulators). I propose an additional R: renewal! We must focus on the need for constant renewal so that patients maintain the results we have achieved. I apply the analogy of exercising to get into shape. One must go to the gym regularly to get to the desired level of fitness, but you do not stop exercising, otherwise you will quickly relapse to your former lack of fitness. Similarly, patients should receive the appropriate treatments to bring them to the desired level of rejuvenation, but then some form of constant renewal process is needed to maintain them at that level. Without the stimulation of the skin, the aging process continues and the cycle begins all over again.

In my practice, renewal is achieved by driving the skin to maintain the glow and smoothness that enhances the results of the fillers, neuromodulators, lasers, and peels that we have used. The skin is the first thing people notice. Without the glow, the patient will look good but not great. I tell patients that this part of the process is their responsibility. They must adhere to the skin care regimen specifically designed to address their needs. By incorporating the patient in the rejuvenation process, he/she is empowered to take control over the aging process and has grown more confident in you as a physician.

These are exciting times and there is still so much in the pipeline. By continually learning, reading, and attending workshops and meetings, you can make sure our specialty continue to be the leader in the antiaging field.

How to Increase Patient Adherence to Therapy

How do we increase patient adherence to therapy? This question fascinates me. As dermatologists, we will see thousands of patients over the course of our careers, most with treatable conditions that will improve with therapy and others with chronic or genetic conditions that will at least be made more tolerable with therapy. Only 50% of patients with a chronic condition are adherent to therapy.1 Why some patients adhere to treatment and others do not can be difficult to understand. The emotional makeup, culture, family background, socioeconomic status, and motivation of each person is unique, which leads to complexity. This column is not meant to answer a question that is both complex and broad; rather, it is meant to survey and summarize the literature on this topic.

Education

Health literacy is defined as cognitive and social skills that determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand, and use information in ways that promote and maintain good health.2 Greater health literacy leads to improved compliance and health outcomes.3,4 When we take the time to educate patients about their condition, it improves health literacy, treatment compliance, and patient safety and satisfaction, factors that ultimately are linked to better health outcomes.3-8

There are many practical ways of educating patients. Interestingly, one meta-analysis found that no single strategy is more effective than another.6 This analysis found that "[c]omprehensive interventions combining cognitive, behavioral, and affective components were more effective than single-focus interventions."6 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website is an excellent source of information on how to educate patients and increase patient treatment compliance.2 The CDC website offers a free tool kit on how to design educational information to your target audience, resources for children, a database of health-related educational images, an electronic textbook on teaching patients with low literacy skills, a summary of evidence-based ideas on how to improve patient adherence to medications used long-term, and more.2

Facilitating Adherence

The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes 5 dimensions of patient adherence: health system, socioeconomic, condition-related, therapy-related, and patient-related factors.9 Becker and Maiman5 summarized it eloquently when they wrote that we must take "clinically appropriate steps to reduce the cost, complexity, duration, and amount of behavioral change required by the regimen and increasing the regimen's convenience through 'tailoring' and other approaches." It is a broad ultimatum that will require creativity and persistence on the part of the dermatology community.

Some common patient-related factors associated with nonadherence to treatment are lack of information and skills as they pertain to self-management, difficulty with motivation and self-efficacy, and lack of support for behavioral changes.9 It is interesting that low socioeconomic status has not been consistently shown to portend low treatment adherence. It has been shown that children, especially adolescents, and elderly patients tend to be the least adherent.9-11

Dermatologists Take Action

As dermatologists, the WHO encourages us (physicians) to promote optimism, provide enthusiasm, and encourage maintenance of healthy behaviors.9 Comprehensive interventions that have had a positive impact on patient adherence to therapy for diseases such as diabetes mellitus, asthma, and hypertension may serve as motivating examples.9 Some specific dermatologic conditions that will benefit from increased patient adherence include acne, vesiculobullous disease, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis. We can lend support to efforts to reduce the cost of dermatologic medications and be aware of the populations most at risk for low adherence to treatment.9-12

Final Thoughts

As we work to increase patient adherence to therapy in dermatology, we will help improve health literacy, patient safety, and patient satisfaction. These factors are ultimately linked to better health outcomes. The CDC and WHO websites are excellent sources of information on practical methods for doing so.2,9

- Haynes RB, McDonald H, Garg AX, et al. Interventions for helping patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002:CD000011.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health literacy. http://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/index.html. Updated January 13, 2016. Accessed September 23, 2016.

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:97-107.

- Pignone MP, DeWalt DA. Literacy and health outcomes: is adherence the missing link? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:896-897.

- Becker MH, Maiman LA. Strategies for enhancing patient compliance. J Community Health. 1980;6:113-135.

- Roter DL, Hall JA, Merisca R, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to improve patient compliance: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 1998;36:1138-1161.

- Renzi C, Abeni D, Picardi A, et al. Factors associated with patient satisfaction with care among dermatological outpatients. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:617-623.

- Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423-1433.

- World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf. Posted 2003. Accessed September 23, 2016.

- Lee IA, Maibach HI. Pharmionics in dermatology: a review of topical medication adherence. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:231-236.

- Burkhart P, Dunbar-Jacob J. Adherence research in the pediatric and adolescent populations: a decade in review. In: Hayman L, Mahon M, Turner R, eds. Chronic Illness in Children: An Evidence-Based Approach. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2002:199-229.

- Rosenberg ME, Rosenberg SP. Changes in retail prices of prescription dermatologic drugs from 2009 to 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:158-163.

How do we increase patient adherence to therapy? This question fascinates me. As dermatologists, we will see thousands of patients over the course of our careers, most with treatable conditions that will improve with therapy and others with chronic or genetic conditions that will at least be made more tolerable with therapy. Only 50% of patients with a chronic condition are adherent to therapy.1 Why some patients adhere to treatment and others do not can be difficult to understand. The emotional makeup, culture, family background, socioeconomic status, and motivation of each person is unique, which leads to complexity. This column is not meant to answer a question that is both complex and broad; rather, it is meant to survey and summarize the literature on this topic.

Education

Health literacy is defined as cognitive and social skills that determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand, and use information in ways that promote and maintain good health.2 Greater health literacy leads to improved compliance and health outcomes.3,4 When we take the time to educate patients about their condition, it improves health literacy, treatment compliance, and patient safety and satisfaction, factors that ultimately are linked to better health outcomes.3-8

There are many practical ways of educating patients. Interestingly, one meta-analysis found that no single strategy is more effective than another.6 This analysis found that "[c]omprehensive interventions combining cognitive, behavioral, and affective components were more effective than single-focus interventions."6 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website is an excellent source of information on how to educate patients and increase patient treatment compliance.2 The CDC website offers a free tool kit on how to design educational information to your target audience, resources for children, a database of health-related educational images, an electronic textbook on teaching patients with low literacy skills, a summary of evidence-based ideas on how to improve patient adherence to medications used long-term, and more.2

Facilitating Adherence

The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes 5 dimensions of patient adherence: health system, socioeconomic, condition-related, therapy-related, and patient-related factors.9 Becker and Maiman5 summarized it eloquently when they wrote that we must take "clinically appropriate steps to reduce the cost, complexity, duration, and amount of behavioral change required by the regimen and increasing the regimen's convenience through 'tailoring' and other approaches." It is a broad ultimatum that will require creativity and persistence on the part of the dermatology community.

Some common patient-related factors associated with nonadherence to treatment are lack of information and skills as they pertain to self-management, difficulty with motivation and self-efficacy, and lack of support for behavioral changes.9 It is interesting that low socioeconomic status has not been consistently shown to portend low treatment adherence. It has been shown that children, especially adolescents, and elderly patients tend to be the least adherent.9-11

Dermatologists Take Action

As dermatologists, the WHO encourages us (physicians) to promote optimism, provide enthusiasm, and encourage maintenance of healthy behaviors.9 Comprehensive interventions that have had a positive impact on patient adherence to therapy for diseases such as diabetes mellitus, asthma, and hypertension may serve as motivating examples.9 Some specific dermatologic conditions that will benefit from increased patient adherence include acne, vesiculobullous disease, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis. We can lend support to efforts to reduce the cost of dermatologic medications and be aware of the populations most at risk for low adherence to treatment.9-12

Final Thoughts

As we work to increase patient adherence to therapy in dermatology, we will help improve health literacy, patient safety, and patient satisfaction. These factors are ultimately linked to better health outcomes. The CDC and WHO websites are excellent sources of information on practical methods for doing so.2,9

How do we increase patient adherence to therapy? This question fascinates me. As dermatologists, we will see thousands of patients over the course of our careers, most with treatable conditions that will improve with therapy and others with chronic or genetic conditions that will at least be made more tolerable with therapy. Only 50% of patients with a chronic condition are adherent to therapy.1 Why some patients adhere to treatment and others do not can be difficult to understand. The emotional makeup, culture, family background, socioeconomic status, and motivation of each person is unique, which leads to complexity. This column is not meant to answer a question that is both complex and broad; rather, it is meant to survey and summarize the literature on this topic.

Education

Health literacy is defined as cognitive and social skills that determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand, and use information in ways that promote and maintain good health.2 Greater health literacy leads to improved compliance and health outcomes.3,4 When we take the time to educate patients about their condition, it improves health literacy, treatment compliance, and patient safety and satisfaction, factors that ultimately are linked to better health outcomes.3-8

There are many practical ways of educating patients. Interestingly, one meta-analysis found that no single strategy is more effective than another.6 This analysis found that "[c]omprehensive interventions combining cognitive, behavioral, and affective components were more effective than single-focus interventions."6 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website is an excellent source of information on how to educate patients and increase patient treatment compliance.2 The CDC website offers a free tool kit on how to design educational information to your target audience, resources for children, a database of health-related educational images, an electronic textbook on teaching patients with low literacy skills, a summary of evidence-based ideas on how to improve patient adherence to medications used long-term, and more.2

Facilitating Adherence

The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes 5 dimensions of patient adherence: health system, socioeconomic, condition-related, therapy-related, and patient-related factors.9 Becker and Maiman5 summarized it eloquently when they wrote that we must take "clinically appropriate steps to reduce the cost, complexity, duration, and amount of behavioral change required by the regimen and increasing the regimen's convenience through 'tailoring' and other approaches." It is a broad ultimatum that will require creativity and persistence on the part of the dermatology community.

Some common patient-related factors associated with nonadherence to treatment are lack of information and skills as they pertain to self-management, difficulty with motivation and self-efficacy, and lack of support for behavioral changes.9 It is interesting that low socioeconomic status has not been consistently shown to portend low treatment adherence. It has been shown that children, especially adolescents, and elderly patients tend to be the least adherent.9-11

Dermatologists Take Action

As dermatologists, the WHO encourages us (physicians) to promote optimism, provide enthusiasm, and encourage maintenance of healthy behaviors.9 Comprehensive interventions that have had a positive impact on patient adherence to therapy for diseases such as diabetes mellitus, asthma, and hypertension may serve as motivating examples.9 Some specific dermatologic conditions that will benefit from increased patient adherence include acne, vesiculobullous disease, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis. We can lend support to efforts to reduce the cost of dermatologic medications and be aware of the populations most at risk for low adherence to treatment.9-12

Final Thoughts

As we work to increase patient adherence to therapy in dermatology, we will help improve health literacy, patient safety, and patient satisfaction. These factors are ultimately linked to better health outcomes. The CDC and WHO websites are excellent sources of information on practical methods for doing so.2,9

- Haynes RB, McDonald H, Garg AX, et al. Interventions for helping patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002:CD000011.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health literacy. http://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/index.html. Updated January 13, 2016. Accessed September 23, 2016.

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:97-107.

- Pignone MP, DeWalt DA. Literacy and health outcomes: is adherence the missing link? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:896-897.

- Becker MH, Maiman LA. Strategies for enhancing patient compliance. J Community Health. 1980;6:113-135.

- Roter DL, Hall JA, Merisca R, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to improve patient compliance: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 1998;36:1138-1161.

- Renzi C, Abeni D, Picardi A, et al. Factors associated with patient satisfaction with care among dermatological outpatients. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:617-623.

- Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423-1433.

- World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf. Posted 2003. Accessed September 23, 2016.

- Lee IA, Maibach HI. Pharmionics in dermatology: a review of topical medication adherence. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:231-236.

- Burkhart P, Dunbar-Jacob J. Adherence research in the pediatric and adolescent populations: a decade in review. In: Hayman L, Mahon M, Turner R, eds. Chronic Illness in Children: An Evidence-Based Approach. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2002:199-229.

- Rosenberg ME, Rosenberg SP. Changes in retail prices of prescription dermatologic drugs from 2009 to 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:158-163.

- Haynes RB, McDonald H, Garg AX, et al. Interventions for helping patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002:CD000011.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health literacy. http://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/index.html. Updated January 13, 2016. Accessed September 23, 2016.

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:97-107.

- Pignone MP, DeWalt DA. Literacy and health outcomes: is adherence the missing link? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:896-897.

- Becker MH, Maiman LA. Strategies for enhancing patient compliance. J Community Health. 1980;6:113-135.

- Roter DL, Hall JA, Merisca R, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to improve patient compliance: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 1998;36:1138-1161.

- Renzi C, Abeni D, Picardi A, et al. Factors associated with patient satisfaction with care among dermatological outpatients. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:617-623.

- Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423-1433.

- World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf. Posted 2003. Accessed September 23, 2016.

- Lee IA, Maibach HI. Pharmionics in dermatology: a review of topical medication adherence. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:231-236.

- Burkhart P, Dunbar-Jacob J. Adherence research in the pediatric and adolescent populations: a decade in review. In: Hayman L, Mahon M, Turner R, eds. Chronic Illness in Children: An Evidence-Based Approach. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2002:199-229.

- Rosenberg ME, Rosenberg SP. Changes in retail prices of prescription dermatologic drugs from 2009 to 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:158-163.

Chemical Peels

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on Chemical Peels with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This fact sheet will review the use of chemical peels for dermatologic indications.

Practice Questions

1. Which peel requires neutralization?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

2. Which peel contains resorcinol?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

3. Which peel would be the best treatment of severe actinic photodamage?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

4. Which peel would not be indicated for treatment of melasma in a patient with Fitzpatrick skin type IV?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

5. Which peel is a β-hydroxy acid?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. Which peel requires neutralization?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

2. Which peel contains resorcinol?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

3. Which peel would be the best treatment of severe actinic photodamage?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

4. Which peel would not be indicated for treatment of melasma in a patient with Fitzpatrick skin type IV?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

5. Which peel is a β-hydroxy acid?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on Chemical Peels with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This fact sheet will review the use of chemical peels for dermatologic indications.

Practice Questions

1. Which peel requires neutralization?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

2. Which peel contains resorcinol?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

3. Which peel would be the best treatment of severe actinic photodamage?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

4. Which peel would not be indicated for treatment of melasma in a patient with Fitzpatrick skin type IV?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

5. Which peel is a β-hydroxy acid?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. Which peel requires neutralization?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

2. Which peel contains resorcinol?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

3. Which peel would be the best treatment of severe actinic photodamage?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

4. Which peel would not be indicated for treatment of melasma in a patient with Fitzpatrick skin type IV?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

5. Which peel is a β-hydroxy acid?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on Chemical Peels with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This fact sheet will review the use of chemical peels for dermatologic indications.

Practice Questions

1. Which peel requires neutralization?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

2. Which peel contains resorcinol?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

3. Which peel would be the best treatment of severe actinic photodamage?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

4. Which peel would not be indicated for treatment of melasma in a patient with Fitzpatrick skin type IV?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

5. Which peel is a β-hydroxy acid?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. Which peel requires neutralization?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

2. Which peel contains resorcinol?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

3. Which peel would be the best treatment of severe actinic photodamage?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

4. Which peel would not be indicated for treatment of melasma in a patient with Fitzpatrick skin type IV?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

5. Which peel is a β-hydroxy acid?

a. Baker-Gordon

b. glycolic acid

c. Jessner

d. salicylic acid

e. trichloroacetic acid

Lip Augmentation With Juvéderm Ultra XC

Evaluating the Malignant Potential of Nevus Spilus

Abnormal Wound Healing Related to High-Dose Systemic Corticosteroid Therapy in a Patient With Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Benign Hypermobility Type

The process of wound healing has been well characterized. Immediately following injury, neutrophils arrive at the site in response to chemotactic factors produced by the coagulation cascade. Monocytes follow 24 to 36 hours later; transform into macrophages; and begin to phagocytose tissue debris, organisms, and any remaining neutrophils. In turn, macrophages release chemotactic factors such as basic fibroblast growth factor to attract fibroblasts to the wound, which then begin the process of synthesizing collagen and ground substance. Fibroblasts then take over as the dominant cell type, with collagen synthesis continuing for approximately 6 weeks. Keratinocytes and endothelial cells also proliferate during this time. After approximately 6 weeks, collagen remodeling begins. Tensile strength of the wound may continue to increase up to one year after the injury.1,2

Corticosteroids inhibit wound healing in several ways. Notably, they decrease the number of circulating monocytes, leading to fewer macrophages in the tissue at the site of injury, which then leads to impaired phagocytosis and reduced release of chemotactic factors that attract fibroblasts. Additionally, corticosteroids can inhibit collagen synthesis and remodeling, leading to delayed wound healing and decreased tensile strength of the wound as well as impacting capillary proliferation.3

The subtypes of EDS were reclassified in 1998 by Beighton et al,4 and the benign hypermobility type (EDS-BHT)(formerly type III) is considered the least severe. There is some controversy as to whether this subtype constitutes a separate diagnosis from the benign familial joint hypermobility syndrome. It is characterized by hypermobility of the joints (objectively measured with the Beighton scale) and mild hyperextensibility of the skin, and patients often have a history of joint subluxations and dislocations with resultant degenerative joint disease and chronic pain. Manifestations of fragile skin and soft tissue (eg, abnormal wound healing or scarring; spontaneous tearing of the skin, ligaments, tendons, or organs) are notably absent from the findings in this syndrome.5 The genetic basis for EDS is unknown in the majority of patients, although a deficiency in tenascin X (secondary to defects in the tenascin XB gene [TNXB]) has been identified in a small subset (<5%) of patients, leading to elastic fiber abnormalities, reduced collagen deposition, and impaired cross-linking of collagen.6,7 Inheritance usually is autosomal dominant but also can be autosomal recessive. In contrast, the classic type of EDS (formerly types I and II) is associated with atrophic scarring and tissue fragility, in addition to joint hypermobility and skin hyperextensibility. Type V collagen mutations are found in more than half of patients with this disorder.8

We present the case of a patient with EDS-BHT who developed large nonhealing cutaneous ulcerations with initiation of high-dose systemic corticosteroids for treatment of dermatomyositis. This case provides a dramatic illustration of the effects of the use of chronic systemic corticosteroids on skin fragility and wound healing in patients with an underlying inherited defect in collagen or connective tissue.

Case Report

A 23-year-old man with an unremarkable medical history was admitted to our inpatient cardiology service with palpitations attributable to new-onset atrial fibrillation. Dermatology was consulted to evaluate a rash of approximately 4 months’ duration that started on the dorsal aspect of the hands, then progressed to involve the extensor elbows and knees. The rash also was associated with fatigue, arthralgia, and proximal muscle weakness. A taper of prednisone that was prescribed approximately 2 months prior to admission by a rheumatologist for presumed dermatomyositis improved his symptoms, but they recurred with discontinuation of the medication.

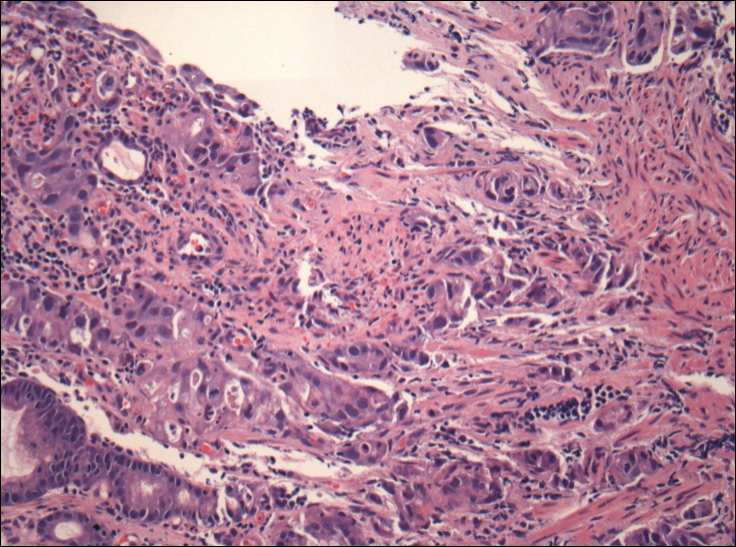

Physical examination revealed reddish, violaceous and hyperpigmented patches on the dorsal aspect of the hands and digits and the extensor aspect of the knees and elbows. A skin biopsy from the right elbow showed a mild interface reaction and nonspecific direct immunofluorescence, consistent with a diagnosis of dermatomyositis. Autoimmune serologies were negative, including antinuclear, anti–Jo-1, anti–Mi-2, anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen A, anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anti-Smith, and antiribonucleoprotein antibodies. Creatine kinase and rheumatoid factor levels were within reference range. Electromyogram was supportive of the diagnosis of dermatomyositis, showing an irritable myopathy. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed an acute inflammatory process of the myocardium, and a transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a depressed left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% to 40% (reference range, 55%–70%). His cardiac disease also was attributed to dermatomyositis, and he was managed by cardiology with anangiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and antiarrhythmic therapy. Rheumatology was consulted and prednisone 60 mg once daily was started, with the patient reporting improvement in his muscle weakness and the rash.

Interestingly, the patient also noted a history of joint hypermobility, and a genetics consultation was obtained during the current hospitalization. He denied a history of abnormal scarring or skin problems, but he did note dislocation of the patella on 2 occasions and an umbilical hernia repair at 3 years of age. A paternal uncle had a history of similar joint hypermobility. His Beighton score was noted to be 8/8 (bending at the waist was unable to be tested due to recent lumbar puncture obtained during this hospitalization). The patient was diagnosed with EDS-BHT, and no further workup was recommended.

Subsequent to his hospitalization for several days, the patient’s prednisone was slowly tapered down from 60 mg once daily to 12.5 mg once daily, and azathioprine was started and titrated up to 150 mg once daily. Approximately 6 months after his initial hospitalization, he was readmitted due to increased pain of the right knee with concern for osteomyelitis. Dermatology was again consulted, and at this time, the patient reported a 4-month history of nonhealing ulcers to the knees and elbows (Figure 1). He stated that the ulcers were initially about the size of a pencil eraser and had started approximately 2 months after the prednisone was started, with subsequent slow enlargement. He noted a stinging sensation with enlargement of the ulcers, but otherwise they were not painful. He denied major trauma to the areas. He noted that his prior rash from the dermatomyositis seemed to have resolved, along with his muscle weakness, and he reported weight gain and improvement in his energy levels. Physical examination at this time revealed several stigmata of chronic systemic corticosteroids, including fatty deposits in the face (moon facies) and between the shoulders (buffalo hump), facial acne, and numerous erythematous striae on the trunk and proximal extremities (Figure 2). Multiple noninflammatory ulcers with punched-out borders ranging in size from 0.5 to 6 cm were seen at sites overlying bony prominences, including the bilateral extensor elbows and knees and the right plantar foot. Similar ulcers were noted on the trunk within the striae. Some of the ulcers were covered with a thick hyperkeratotic crust. A biopsy from the edge of an ulcer on the right side of the flank showed only dermal fibrosis. Workup by orthopedic surgery was felt to be inconsistent with osteomyelitis, and plastic surgery was consulted to consider surgical options for repair. Consequently, the patient was taken to the operating room for primary closure of the ulcers to the bilateral knees and right elbow. He has been followed closely by plastic surgery, with the use of joint immobilization to promote wound healing.

Comment

This case represents a dramatic illustration of the effects of chronic systemic corticosteroids on skin fragility and wound healing in a patient with an underlying genetic defect in the connective tissue. The ulcers were all located within striae or overlying bony prominences where the skin was subjected to increased tension; however, the patient reported no problems with wound healing or scarring at these sites prior to the initiation of corticosteroids, suggesting that the addition of this medication was disruptive to the cutaneous wound healing mechanisms. This case is unique because abnormal wound healing in an EDS patient was so clearly linked to the initiation of systemic steroids.

The exact pathogenesis of the patient’s ulcers is unclear. The diagnosis of EDS was primarily clinical, and without genetic testing, we cannot state with certainty the underlying molecular problem in this patient. Although tenascin X deficiency has been found in a few patients, a genetic defect remains uncharacterized in most patients with EDS-BHT, and in most situations, EDS-BHT remains a clinical diagnosis. In 2001, Schalkwijk et al9 first described the association of tenascin X deficiency and EDS in 5 patients, and they noted delayed wound healing in 1 patient who had received systemic corticosteroids for congenital adrenal hyperplasia. The authors remarked that it was not clear whether the abnormality was linked to the patient’s EDS or to his treatment with systemic corticosteroids.9 Furthermore, it is possible that our patient in fact has a milder variant of classic type EDS and that the manifestations of tissue fragility remained subclinical until the addition of systemic corticosteroids. It also is interesting to note that muscle weakness can be a symptom of EDS, both classic and BHT of EDS, but our patient’s muscle weakness improved with immunosuppression, supporting an underlying autoimmune disease as the cause for it.10 Skin ulcerations have been reported as a rare manifestation of dermatomyositis, but it is remarkable that his ulcers progressed as his other dermatomyositis symptoms improved with therapy, suggesting that his autoimmune disease was not the underlying cause for the ulcers.11-13 This case points to the need to thoughtfully consider the adverse effects of corticosteroids on wound healing in patients with an inherited disorder of collagen or connective tissue such as EDS.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

- Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, et al. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314-321.

- Poetker DM, Reh DD. A comprehensive review of the adverse effects of systemic corticosteroids. Otolaryng Clin N Am. 2010;43:753-768.

- Beighton P, De Paepe A, Steinmann B, et al. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: revised nosology, Villefranche, 1997. Ehlers-Danlos National Foundation (USA) and Ehlers-Danlos Support Group (UK). Am J Med Genet. 1998;77:31-37.

- Levy HP. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, es. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1279/. Accessed August 5, 2015.

- Zweers MC, Bristow J, Steijlen PM, et al. Haploinsufficiency of TNXB is associated with hypermobility type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:214-217.

- Brellier F, Tucker RP, Chiquet-Ehrismann R. Tenascins and their implications in diseases and tissue mechanics. Scand J Med Sci Spor. 2009;19:511-519.

- Malfait F, Wenstrup R, De Paepe A. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, classic type. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle,WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1244/. Accessed August 5, 2015.

- Schalkwijk J, Zweers MC, Steijlen PM, et al. A recessive form of the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome caused by tenascin X deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1167-1175.

- Voermans NC, Alfen NV, Pillen S, et al. Neuromuscular involvement in various types of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:687-697.

- Scheinfeld NS. Ulcerative paraneoplastic dermatomyositis secondary to metastatic breast cancer. Skinmed. 2006;5:94-96.

- Tomb R, Stephan F. Perforating skin ulcers occurring in an adult with dermatomyositis [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venerol. 2002;129:1383-1385.

- Yosipovitch G, Feinmesser M, David M. Adult dermatomyositis with livedo reticularis and multiple skin ulcers. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 1998;11:48-50.

The process of wound healing has been well characterized. Immediately following injury, neutrophils arrive at the site in response to chemotactic factors produced by the coagulation cascade. Monocytes follow 24 to 36 hours later; transform into macrophages; and begin to phagocytose tissue debris, organisms, and any remaining neutrophils. In turn, macrophages release chemotactic factors such as basic fibroblast growth factor to attract fibroblasts to the wound, which then begin the process of synthesizing collagen and ground substance. Fibroblasts then take over as the dominant cell type, with collagen synthesis continuing for approximately 6 weeks. Keratinocytes and endothelial cells also proliferate during this time. After approximately 6 weeks, collagen remodeling begins. Tensile strength of the wound may continue to increase up to one year after the injury.1,2

Corticosteroids inhibit wound healing in several ways. Notably, they decrease the number of circulating monocytes, leading to fewer macrophages in the tissue at the site of injury, which then leads to impaired phagocytosis and reduced release of chemotactic factors that attract fibroblasts. Additionally, corticosteroids can inhibit collagen synthesis and remodeling, leading to delayed wound healing and decreased tensile strength of the wound as well as impacting capillary proliferation.3

The subtypes of EDS were reclassified in 1998 by Beighton et al,4 and the benign hypermobility type (EDS-BHT)(formerly type III) is considered the least severe. There is some controversy as to whether this subtype constitutes a separate diagnosis from the benign familial joint hypermobility syndrome. It is characterized by hypermobility of the joints (objectively measured with the Beighton scale) and mild hyperextensibility of the skin, and patients often have a history of joint subluxations and dislocations with resultant degenerative joint disease and chronic pain. Manifestations of fragile skin and soft tissue (eg, abnormal wound healing or scarring; spontaneous tearing of the skin, ligaments, tendons, or organs) are notably absent from the findings in this syndrome.5 The genetic basis for EDS is unknown in the majority of patients, although a deficiency in tenascin X (secondary to defects in the tenascin XB gene [TNXB]) has been identified in a small subset (<5%) of patients, leading to elastic fiber abnormalities, reduced collagen deposition, and impaired cross-linking of collagen.6,7 Inheritance usually is autosomal dominant but also can be autosomal recessive. In contrast, the classic type of EDS (formerly types I and II) is associated with atrophic scarring and tissue fragility, in addition to joint hypermobility and skin hyperextensibility. Type V collagen mutations are found in more than half of patients with this disorder.8

We present the case of a patient with EDS-BHT who developed large nonhealing cutaneous ulcerations with initiation of high-dose systemic corticosteroids for treatment of dermatomyositis. This case provides a dramatic illustration of the effects of the use of chronic systemic corticosteroids on skin fragility and wound healing in patients with an underlying inherited defect in collagen or connective tissue.

Case Report

A 23-year-old man with an unremarkable medical history was admitted to our inpatient cardiology service with palpitations attributable to new-onset atrial fibrillation. Dermatology was consulted to evaluate a rash of approximately 4 months’ duration that started on the dorsal aspect of the hands, then progressed to involve the extensor elbows and knees. The rash also was associated with fatigue, arthralgia, and proximal muscle weakness. A taper of prednisone that was prescribed approximately 2 months prior to admission by a rheumatologist for presumed dermatomyositis improved his symptoms, but they recurred with discontinuation of the medication.

Physical examination revealed reddish, violaceous and hyperpigmented patches on the dorsal aspect of the hands and digits and the extensor aspect of the knees and elbows. A skin biopsy from the right elbow showed a mild interface reaction and nonspecific direct immunofluorescence, consistent with a diagnosis of dermatomyositis. Autoimmune serologies were negative, including antinuclear, anti–Jo-1, anti–Mi-2, anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen A, anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anti-Smith, and antiribonucleoprotein antibodies. Creatine kinase and rheumatoid factor levels were within reference range. Electromyogram was supportive of the diagnosis of dermatomyositis, showing an irritable myopathy. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed an acute inflammatory process of the myocardium, and a transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a depressed left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% to 40% (reference range, 55%–70%). His cardiac disease also was attributed to dermatomyositis, and he was managed by cardiology with anangiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and antiarrhythmic therapy. Rheumatology was consulted and prednisone 60 mg once daily was started, with the patient reporting improvement in his muscle weakness and the rash.

Interestingly, the patient also noted a history of joint hypermobility, and a genetics consultation was obtained during the current hospitalization. He denied a history of abnormal scarring or skin problems, but he did note dislocation of the patella on 2 occasions and an umbilical hernia repair at 3 years of age. A paternal uncle had a history of similar joint hypermobility. His Beighton score was noted to be 8/8 (bending at the waist was unable to be tested due to recent lumbar puncture obtained during this hospitalization). The patient was diagnosed with EDS-BHT, and no further workup was recommended.

Subsequent to his hospitalization for several days, the patient’s prednisone was slowly tapered down from 60 mg once daily to 12.5 mg once daily, and azathioprine was started and titrated up to 150 mg once daily. Approximately 6 months after his initial hospitalization, he was readmitted due to increased pain of the right knee with concern for osteomyelitis. Dermatology was again consulted, and at this time, the patient reported a 4-month history of nonhealing ulcers to the knees and elbows (Figure 1). He stated that the ulcers were initially about the size of a pencil eraser and had started approximately 2 months after the prednisone was started, with subsequent slow enlargement. He noted a stinging sensation with enlargement of the ulcers, but otherwise they were not painful. He denied major trauma to the areas. He noted that his prior rash from the dermatomyositis seemed to have resolved, along with his muscle weakness, and he reported weight gain and improvement in his energy levels. Physical examination at this time revealed several stigmata of chronic systemic corticosteroids, including fatty deposits in the face (moon facies) and between the shoulders (buffalo hump), facial acne, and numerous erythematous striae on the trunk and proximal extremities (Figure 2). Multiple noninflammatory ulcers with punched-out borders ranging in size from 0.5 to 6 cm were seen at sites overlying bony prominences, including the bilateral extensor elbows and knees and the right plantar foot. Similar ulcers were noted on the trunk within the striae. Some of the ulcers were covered with a thick hyperkeratotic crust. A biopsy from the edge of an ulcer on the right side of the flank showed only dermal fibrosis. Workup by orthopedic surgery was felt to be inconsistent with osteomyelitis, and plastic surgery was consulted to consider surgical options for repair. Consequently, the patient was taken to the operating room for primary closure of the ulcers to the bilateral knees and right elbow. He has been followed closely by plastic surgery, with the use of joint immobilization to promote wound healing.

Comment

This case represents a dramatic illustration of the effects of chronic systemic corticosteroids on skin fragility and wound healing in a patient with an underlying genetic defect in the connective tissue. The ulcers were all located within striae or overlying bony prominences where the skin was subjected to increased tension; however, the patient reported no problems with wound healing or scarring at these sites prior to the initiation of corticosteroids, suggesting that the addition of this medication was disruptive to the cutaneous wound healing mechanisms. This case is unique because abnormal wound healing in an EDS patient was so clearly linked to the initiation of systemic steroids.

The exact pathogenesis of the patient’s ulcers is unclear. The diagnosis of EDS was primarily clinical, and without genetic testing, we cannot state with certainty the underlying molecular problem in this patient. Although tenascin X deficiency has been found in a few patients, a genetic defect remains uncharacterized in most patients with EDS-BHT, and in most situations, EDS-BHT remains a clinical diagnosis. In 2001, Schalkwijk et al9 first described the association of tenascin X deficiency and EDS in 5 patients, and they noted delayed wound healing in 1 patient who had received systemic corticosteroids for congenital adrenal hyperplasia. The authors remarked that it was not clear whether the abnormality was linked to the patient’s EDS or to his treatment with systemic corticosteroids.9 Furthermore, it is possible that our patient in fact has a milder variant of classic type EDS and that the manifestations of tissue fragility remained subclinical until the addition of systemic corticosteroids. It also is interesting to note that muscle weakness can be a symptom of EDS, both classic and BHT of EDS, but our patient’s muscle weakness improved with immunosuppression, supporting an underlying autoimmune disease as the cause for it.10 Skin ulcerations have been reported as a rare manifestation of dermatomyositis, but it is remarkable that his ulcers progressed as his other dermatomyositis symptoms improved with therapy, suggesting that his autoimmune disease was not the underlying cause for the ulcers.11-13 This case points to the need to thoughtfully consider the adverse effects of corticosteroids on wound healing in patients with an inherited disorder of collagen or connective tissue such as EDS.

The process of wound healing has been well characterized. Immediately following injury, neutrophils arrive at the site in response to chemotactic factors produced by the coagulation cascade. Monocytes follow 24 to 36 hours later; transform into macrophages; and begin to phagocytose tissue debris, organisms, and any remaining neutrophils. In turn, macrophages release chemotactic factors such as basic fibroblast growth factor to attract fibroblasts to the wound, which then begin the process of synthesizing collagen and ground substance. Fibroblasts then take over as the dominant cell type, with collagen synthesis continuing for approximately 6 weeks. Keratinocytes and endothelial cells also proliferate during this time. After approximately 6 weeks, collagen remodeling begins. Tensile strength of the wound may continue to increase up to one year after the injury.1,2

Corticosteroids inhibit wound healing in several ways. Notably, they decrease the number of circulating monocytes, leading to fewer macrophages in the tissue at the site of injury, which then leads to impaired phagocytosis and reduced release of chemotactic factors that attract fibroblasts. Additionally, corticosteroids can inhibit collagen synthesis and remodeling, leading to delayed wound healing and decreased tensile strength of the wound as well as impacting capillary proliferation.3

The subtypes of EDS were reclassified in 1998 by Beighton et al,4 and the benign hypermobility type (EDS-BHT)(formerly type III) is considered the least severe. There is some controversy as to whether this subtype constitutes a separate diagnosis from the benign familial joint hypermobility syndrome. It is characterized by hypermobility of the joints (objectively measured with the Beighton scale) and mild hyperextensibility of the skin, and patients often have a history of joint subluxations and dislocations with resultant degenerative joint disease and chronic pain. Manifestations of fragile skin and soft tissue (eg, abnormal wound healing or scarring; spontaneous tearing of the skin, ligaments, tendons, or organs) are notably absent from the findings in this syndrome.5 The genetic basis for EDS is unknown in the majority of patients, although a deficiency in tenascin X (secondary to defects in the tenascin XB gene [TNXB]) has been identified in a small subset (<5%) of patients, leading to elastic fiber abnormalities, reduced collagen deposition, and impaired cross-linking of collagen.6,7 Inheritance usually is autosomal dominant but also can be autosomal recessive. In contrast, the classic type of EDS (formerly types I and II) is associated with atrophic scarring and tissue fragility, in addition to joint hypermobility and skin hyperextensibility. Type V collagen mutations are found in more than half of patients with this disorder.8

We present the case of a patient with EDS-BHT who developed large nonhealing cutaneous ulcerations with initiation of high-dose systemic corticosteroids for treatment of dermatomyositis. This case provides a dramatic illustration of the effects of the use of chronic systemic corticosteroids on skin fragility and wound healing in patients with an underlying inherited defect in collagen or connective tissue.

Case Report

A 23-year-old man with an unremarkable medical history was admitted to our inpatient cardiology service with palpitations attributable to new-onset atrial fibrillation. Dermatology was consulted to evaluate a rash of approximately 4 months’ duration that started on the dorsal aspect of the hands, then progressed to involve the extensor elbows and knees. The rash also was associated with fatigue, arthralgia, and proximal muscle weakness. A taper of prednisone that was prescribed approximately 2 months prior to admission by a rheumatologist for presumed dermatomyositis improved his symptoms, but they recurred with discontinuation of the medication.

Physical examination revealed reddish, violaceous and hyperpigmented patches on the dorsal aspect of the hands and digits and the extensor aspect of the knees and elbows. A skin biopsy from the right elbow showed a mild interface reaction and nonspecific direct immunofluorescence, consistent with a diagnosis of dermatomyositis. Autoimmune serologies were negative, including antinuclear, anti–Jo-1, anti–Mi-2, anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen A, anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anti-Smith, and antiribonucleoprotein antibodies. Creatine kinase and rheumatoid factor levels were within reference range. Electromyogram was supportive of the diagnosis of dermatomyositis, showing an irritable myopathy. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed an acute inflammatory process of the myocardium, and a transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a depressed left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% to 40% (reference range, 55%–70%). His cardiac disease also was attributed to dermatomyositis, and he was managed by cardiology with anangiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and antiarrhythmic therapy. Rheumatology was consulted and prednisone 60 mg once daily was started, with the patient reporting improvement in his muscle weakness and the rash.

Interestingly, the patient also noted a history of joint hypermobility, and a genetics consultation was obtained during the current hospitalization. He denied a history of abnormal scarring or skin problems, but he did note dislocation of the patella on 2 occasions and an umbilical hernia repair at 3 years of age. A paternal uncle had a history of similar joint hypermobility. His Beighton score was noted to be 8/8 (bending at the waist was unable to be tested due to recent lumbar puncture obtained during this hospitalization). The patient was diagnosed with EDS-BHT, and no further workup was recommended.

Subsequent to his hospitalization for several days, the patient’s prednisone was slowly tapered down from 60 mg once daily to 12.5 mg once daily, and azathioprine was started and titrated up to 150 mg once daily. Approximately 6 months after his initial hospitalization, he was readmitted due to increased pain of the right knee with concern for osteomyelitis. Dermatology was again consulted, and at this time, the patient reported a 4-month history of nonhealing ulcers to the knees and elbows (Figure 1). He stated that the ulcers were initially about the size of a pencil eraser and had started approximately 2 months after the prednisone was started, with subsequent slow enlargement. He noted a stinging sensation with enlargement of the ulcers, but otherwise they were not painful. He denied major trauma to the areas. He noted that his prior rash from the dermatomyositis seemed to have resolved, along with his muscle weakness, and he reported weight gain and improvement in his energy levels. Physical examination at this time revealed several stigmata of chronic systemic corticosteroids, including fatty deposits in the face (moon facies) and between the shoulders (buffalo hump), facial acne, and numerous erythematous striae on the trunk and proximal extremities (Figure 2). Multiple noninflammatory ulcers with punched-out borders ranging in size from 0.5 to 6 cm were seen at sites overlying bony prominences, including the bilateral extensor elbows and knees and the right plantar foot. Similar ulcers were noted on the trunk within the striae. Some of the ulcers were covered with a thick hyperkeratotic crust. A biopsy from the edge of an ulcer on the right side of the flank showed only dermal fibrosis. Workup by orthopedic surgery was felt to be inconsistent with osteomyelitis, and plastic surgery was consulted to consider surgical options for repair. Consequently, the patient was taken to the operating room for primary closure of the ulcers to the bilateral knees and right elbow. He has been followed closely by plastic surgery, with the use of joint immobilization to promote wound healing.

Comment

This case represents a dramatic illustration of the effects of chronic systemic corticosteroids on skin fragility and wound healing in a patient with an underlying genetic defect in the connective tissue. The ulcers were all located within striae or overlying bony prominences where the skin was subjected to increased tension; however, the patient reported no problems with wound healing or scarring at these sites prior to the initiation of corticosteroids, suggesting that the addition of this medication was disruptive to the cutaneous wound healing mechanisms. This case is unique because abnormal wound healing in an EDS patient was so clearly linked to the initiation of systemic steroids.

The exact pathogenesis of the patient’s ulcers is unclear. The diagnosis of EDS was primarily clinical, and without genetic testing, we cannot state with certainty the underlying molecular problem in this patient. Although tenascin X deficiency has been found in a few patients, a genetic defect remains uncharacterized in most patients with EDS-BHT, and in most situations, EDS-BHT remains a clinical diagnosis. In 2001, Schalkwijk et al9 first described the association of tenascin X deficiency and EDS in 5 patients, and they noted delayed wound healing in 1 patient who had received systemic corticosteroids for congenital adrenal hyperplasia. The authors remarked that it was not clear whether the abnormality was linked to the patient’s EDS or to his treatment with systemic corticosteroids.9 Furthermore, it is possible that our patient in fact has a milder variant of classic type EDS and that the manifestations of tissue fragility remained subclinical until the addition of systemic corticosteroids. It also is interesting to note that muscle weakness can be a symptom of EDS, both classic and BHT of EDS, but our patient’s muscle weakness improved with immunosuppression, supporting an underlying autoimmune disease as the cause for it.10 Skin ulcerations have been reported as a rare manifestation of dermatomyositis, but it is remarkable that his ulcers progressed as his other dermatomyositis symptoms improved with therapy, suggesting that his autoimmune disease was not the underlying cause for the ulcers.11-13 This case points to the need to thoughtfully consider the adverse effects of corticosteroids on wound healing in patients with an inherited disorder of collagen or connective tissue such as EDS.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

- Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, et al. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314-321.

- Poetker DM, Reh DD. A comprehensive review of the adverse effects of systemic corticosteroids. Otolaryng Clin N Am. 2010;43:753-768.