User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

A Rare Association in Down Syndrome: Milialike Idiopathic Calcinosis Cutis and Palpebral Syringoma

To the Editor:

Down syndrome (DS) is associated with rare dermatological disorders, and the prevalence of some common dermatoses is greater in patients with DS. We report a case of milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis (MICC) associated with syringomas in a patient with DS. We emphasize that MICC is one of the rare dermatoses associated with DS.

A 4-year-old girl with DS presented with a 4-mm, flesh-colored, regular-bordered, exophytic papular lesion on the left upper eyelid of 8 months' duration (Figure 1). It was clinically recognized as syringoma. On dermatologic examination of the patient, there also were 1- to 3-mm, round, whitish, painless, milialike papules on the dorsal surface of the hands and wrists (Figure 2). Some of these papules were surrounded by erythema. There was no sign of perforation. Her personal and family history were unremarkable.

Histopathologic examination of a biopsy from a milialike lesion on the hand showed a hyperkeratotic epidermis. In the dermis there was a roundish calcific nodule surrounded by a fibrovascular rim. The patient's guardians refused a biopsy from the lesion on the eyelid.

Laboratory tests including serum vitamin D, thyroid and parathyroid hormone, calcium, phosphorus, and urinary calcium levels, as well as renal function tests, were within reference range. On the basis of these clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with MICC and palpebral syringoma.

Many dermatoses associated with DS have been reported including elastosis perforans serpiginosa, alopecia areata, and syringomas.1-3 Sano et al4 first described MICC and syringomas in a patient with DS in 1978. Milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis is characterized by asymptomatic, millimetric, firm, round, whitish papules that are sometimes surrounded by erythema. These papules may show perforation leading to transepidermal elimination of calcium, similar to the transdermal elimination of elastic fibrils in elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Although MICC usually is described in acral sites of children with DS, it also is reported in adults without DS and on other parts of the body.5-7

The cause of MICC is unknown. One hypothesis of the development of MICC is an increase of the calcium content in the sweat leading to calcification of the acrosyringium.8 Milia are small keratin cysts that usually develop by occlusion of the hair follicle, sweat duct, or sebaceous duct. However, milia also can occur from occlusion of the eccrine ducts where syringomas originate.9 Therefore, syringomas can be seen in association with milia and calcium deposits.5,9-11

We believe that MICC in DS may be more common than usually recognized, as the lesions often are asymptomatic. It is important to differentiate MICC from other dermatological diseases such as molluscum contagiosum, verruca plana, milia, and inclusion cysts. Histopathology and dermoscopy could aid in the accurate diagnosis of MICC.

- Dourmishev A, Miteva L, Mitev V, et al. Cutaneous aspects of Down syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:420-424.

- Madan V, Williams J, Lear JT. Dermatological manifestations of Down's syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:623-629.

- Schepis C, Barone C, Siragusa M, et al. An updated survey on skin conditions in Down syndrome. Dermatology. 2002;205:234-238.

- Sano T, Tate S, Ishikawa C. A case of Down's syndrome associated with syringoma, milia, and subepidermal calcified nodule. Jpn J Dermatol. 1978;88:740.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Perforating milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis and periorbital syringomas in a girl with Down syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:258-260.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Milia like idiopathic calcinosis cutis: an unusual dermatosis associated with Down syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:143-146.

- Houtappel M, Leguit R, Sigurdsson V. Milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis in an adult without Down's syndrome. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2007;1:16-19.

- Eng AM, Mandrea E. Perforating calcinosis cutis presenting as milia. J Cutan Pathol. 1981;8:247-250.

- Wang KH, Chu JS, Lin YH, et al. Milium-like syringoma: a case study on histogenesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:336-340.

- Weiss E, Paez E, Greenberg AS, et al. Eruptive syringomas associated with milia. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:193-195.

- Kim SJ, Won YH, Chun IK. Subepidermal calcified nodules and syringoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1997;8:51-52.

To the Editor:

Down syndrome (DS) is associated with rare dermatological disorders, and the prevalence of some common dermatoses is greater in patients with DS. We report a case of milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis (MICC) associated with syringomas in a patient with DS. We emphasize that MICC is one of the rare dermatoses associated with DS.

A 4-year-old girl with DS presented with a 4-mm, flesh-colored, regular-bordered, exophytic papular lesion on the left upper eyelid of 8 months' duration (Figure 1). It was clinically recognized as syringoma. On dermatologic examination of the patient, there also were 1- to 3-mm, round, whitish, painless, milialike papules on the dorsal surface of the hands and wrists (Figure 2). Some of these papules were surrounded by erythema. There was no sign of perforation. Her personal and family history were unremarkable.

Histopathologic examination of a biopsy from a milialike lesion on the hand showed a hyperkeratotic epidermis. In the dermis there was a roundish calcific nodule surrounded by a fibrovascular rim. The patient's guardians refused a biopsy from the lesion on the eyelid.

Laboratory tests including serum vitamin D, thyroid and parathyroid hormone, calcium, phosphorus, and urinary calcium levels, as well as renal function tests, were within reference range. On the basis of these clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with MICC and palpebral syringoma.

Many dermatoses associated with DS have been reported including elastosis perforans serpiginosa, alopecia areata, and syringomas.1-3 Sano et al4 first described MICC and syringomas in a patient with DS in 1978. Milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis is characterized by asymptomatic, millimetric, firm, round, whitish papules that are sometimes surrounded by erythema. These papules may show perforation leading to transepidermal elimination of calcium, similar to the transdermal elimination of elastic fibrils in elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Although MICC usually is described in acral sites of children with DS, it also is reported in adults without DS and on other parts of the body.5-7

The cause of MICC is unknown. One hypothesis of the development of MICC is an increase of the calcium content in the sweat leading to calcification of the acrosyringium.8 Milia are small keratin cysts that usually develop by occlusion of the hair follicle, sweat duct, or sebaceous duct. However, milia also can occur from occlusion of the eccrine ducts where syringomas originate.9 Therefore, syringomas can be seen in association with milia and calcium deposits.5,9-11

We believe that MICC in DS may be more common than usually recognized, as the lesions often are asymptomatic. It is important to differentiate MICC from other dermatological diseases such as molluscum contagiosum, verruca plana, milia, and inclusion cysts. Histopathology and dermoscopy could aid in the accurate diagnosis of MICC.

To the Editor:

Down syndrome (DS) is associated with rare dermatological disorders, and the prevalence of some common dermatoses is greater in patients with DS. We report a case of milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis (MICC) associated with syringomas in a patient with DS. We emphasize that MICC is one of the rare dermatoses associated with DS.

A 4-year-old girl with DS presented with a 4-mm, flesh-colored, regular-bordered, exophytic papular lesion on the left upper eyelid of 8 months' duration (Figure 1). It was clinically recognized as syringoma. On dermatologic examination of the patient, there also were 1- to 3-mm, round, whitish, painless, milialike papules on the dorsal surface of the hands and wrists (Figure 2). Some of these papules were surrounded by erythema. There was no sign of perforation. Her personal and family history were unremarkable.

Histopathologic examination of a biopsy from a milialike lesion on the hand showed a hyperkeratotic epidermis. In the dermis there was a roundish calcific nodule surrounded by a fibrovascular rim. The patient's guardians refused a biopsy from the lesion on the eyelid.

Laboratory tests including serum vitamin D, thyroid and parathyroid hormone, calcium, phosphorus, and urinary calcium levels, as well as renal function tests, were within reference range. On the basis of these clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with MICC and palpebral syringoma.

Many dermatoses associated with DS have been reported including elastosis perforans serpiginosa, alopecia areata, and syringomas.1-3 Sano et al4 first described MICC and syringomas in a patient with DS in 1978. Milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis is characterized by asymptomatic, millimetric, firm, round, whitish papules that are sometimes surrounded by erythema. These papules may show perforation leading to transepidermal elimination of calcium, similar to the transdermal elimination of elastic fibrils in elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Although MICC usually is described in acral sites of children with DS, it also is reported in adults without DS and on other parts of the body.5-7

The cause of MICC is unknown. One hypothesis of the development of MICC is an increase of the calcium content in the sweat leading to calcification of the acrosyringium.8 Milia are small keratin cysts that usually develop by occlusion of the hair follicle, sweat duct, or sebaceous duct. However, milia also can occur from occlusion of the eccrine ducts where syringomas originate.9 Therefore, syringomas can be seen in association with milia and calcium deposits.5,9-11

We believe that MICC in DS may be more common than usually recognized, as the lesions often are asymptomatic. It is important to differentiate MICC from other dermatological diseases such as molluscum contagiosum, verruca plana, milia, and inclusion cysts. Histopathology and dermoscopy could aid in the accurate diagnosis of MICC.

- Dourmishev A, Miteva L, Mitev V, et al. Cutaneous aspects of Down syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:420-424.

- Madan V, Williams J, Lear JT. Dermatological manifestations of Down's syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:623-629.

- Schepis C, Barone C, Siragusa M, et al. An updated survey on skin conditions in Down syndrome. Dermatology. 2002;205:234-238.

- Sano T, Tate S, Ishikawa C. A case of Down's syndrome associated with syringoma, milia, and subepidermal calcified nodule. Jpn J Dermatol. 1978;88:740.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Perforating milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis and periorbital syringomas in a girl with Down syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:258-260.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Milia like idiopathic calcinosis cutis: an unusual dermatosis associated with Down syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:143-146.

- Houtappel M, Leguit R, Sigurdsson V. Milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis in an adult without Down's syndrome. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2007;1:16-19.

- Eng AM, Mandrea E. Perforating calcinosis cutis presenting as milia. J Cutan Pathol. 1981;8:247-250.

- Wang KH, Chu JS, Lin YH, et al. Milium-like syringoma: a case study on histogenesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:336-340.

- Weiss E, Paez E, Greenberg AS, et al. Eruptive syringomas associated with milia. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:193-195.

- Kim SJ, Won YH, Chun IK. Subepidermal calcified nodules and syringoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1997;8:51-52.

- Dourmishev A, Miteva L, Mitev V, et al. Cutaneous aspects of Down syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:420-424.

- Madan V, Williams J, Lear JT. Dermatological manifestations of Down's syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:623-629.

- Schepis C, Barone C, Siragusa M, et al. An updated survey on skin conditions in Down syndrome. Dermatology. 2002;205:234-238.

- Sano T, Tate S, Ishikawa C. A case of Down's syndrome associated with syringoma, milia, and subepidermal calcified nodule. Jpn J Dermatol. 1978;88:740.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Perforating milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis and periorbital syringomas in a girl with Down syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:258-260.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Milia like idiopathic calcinosis cutis: an unusual dermatosis associated with Down syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:143-146.

- Houtappel M, Leguit R, Sigurdsson V. Milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis in an adult without Down's syndrome. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2007;1:16-19.

- Eng AM, Mandrea E. Perforating calcinosis cutis presenting as milia. J Cutan Pathol. 1981;8:247-250.

- Wang KH, Chu JS, Lin YH, et al. Milium-like syringoma: a case study on histogenesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:336-340.

- Weiss E, Paez E, Greenberg AS, et al. Eruptive syringomas associated with milia. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:193-195.

- Kim SJ, Won YH, Chun IK. Subepidermal calcified nodules and syringoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1997;8:51-52.

Practice Points

- Down syndrome is associated with rare dermatological disorders and an increased prevalence of common dermatoses.

- It is important to differentiate milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis from other dermatological diseases using histopathology and dermoscopy.

Nominate a Patient or Colleague for a NORD Rare Impact Award

Do you have a patient or colleague who has demonstrated extraordinary commitment to advancing understanding of rare diseases or improving the lives of those affected by rare diseases? January 13th is the deadline to nominate individuals for NORD’s Rare Impact Awards. Nominations can be submitted through the NORD website.

NORD’s Rare Impact Awards ceremony will take place on May 18, 2017, in the amphitheater of the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center, the largest structure in Washington, DC, and the first and only federal building dedicated to both federal and private use. More than 500 distinguished guests are expected to attend. Registration will be available soon on the NORD website.

The Rare Impact Awards honor individuals and organizations for commitment to improving the lives of patients and families affected by rare diseases. Nominees may include patients, caregivers, clinicians, researchers, advocates, and others who in some way have contributed to the greater good of the community. Nominations are also being sought for organizations that have helped drive better understanding of rare diseases and/or improved care for those affected.

Do you have a patient or colleague who has demonstrated extraordinary commitment to advancing understanding of rare diseases or improving the lives of those affected by rare diseases? January 13th is the deadline to nominate individuals for NORD’s Rare Impact Awards. Nominations can be submitted through the NORD website.

NORD’s Rare Impact Awards ceremony will take place on May 18, 2017, in the amphitheater of the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center, the largest structure in Washington, DC, and the first and only federal building dedicated to both federal and private use. More than 500 distinguished guests are expected to attend. Registration will be available soon on the NORD website.

The Rare Impact Awards honor individuals and organizations for commitment to improving the lives of patients and families affected by rare diseases. Nominees may include patients, caregivers, clinicians, researchers, advocates, and others who in some way have contributed to the greater good of the community. Nominations are also being sought for organizations that have helped drive better understanding of rare diseases and/or improved care for those affected.

Do you have a patient or colleague who has demonstrated extraordinary commitment to advancing understanding of rare diseases or improving the lives of those affected by rare diseases? January 13th is the deadline to nominate individuals for NORD’s Rare Impact Awards. Nominations can be submitted through the NORD website.

NORD’s Rare Impact Awards ceremony will take place on May 18, 2017, in the amphitheater of the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center, the largest structure in Washington, DC, and the first and only federal building dedicated to both federal and private use. More than 500 distinguished guests are expected to attend. Registration will be available soon on the NORD website.

The Rare Impact Awards honor individuals and organizations for commitment to improving the lives of patients and families affected by rare diseases. Nominees may include patients, caregivers, clinicians, researchers, advocates, and others who in some way have contributed to the greater good of the community. Nominations are also being sought for organizations that have helped drive better understanding of rare diseases and/or improved care for those affected.

Transient Benign Neonatal Skin Findings

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on transient benign neonatal skin findings with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This fact sheet lists benign findings that can be seen in neonates and infants.

Practice Questions

1. The parents of a 2-month-old infant present with their child. They are worried because the infant has “acne” that is not going away. Friends told them to try gentle cleansers and they have avoided using lotions or cream on her face. However, the bumps will not go away. On examination she has papules and pustules. Comedones cannot be identified. What are your next steps?

a. adapalene cream 0.1% every night at bedtime

b. benzoyl peroxide cream 4%

c. benzoyl peroxide wash 2.5%

d. erythromycin gel 2%

e. ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily

2. While in the newborn nursery prior to discharge, the attending pediatrician notices a rash on a 2-day-old neonate who is otherwise completely healthy. The pediatrician consults a dermatologist for his/her opinion. The dermatologist sees erythematous macules with central pustules located predominately on the trunk and proximal extremities. A pustule is unroofed with a blade, the contents smeared on a glass slide, and a Giemsa stain is performed. What is the predominant cell type you would expect to see on histological examination?

a. eosinophils

b. Langerhans cells

c. lymphocytes

d. neutrophils

e. no cells are visualized

3. Shortly after delivery, the pediatricians notice that the baby has numerous hyperpigmented macules on the back. No other primary lesions are seen. The neonate is otherwise normal in appearance and nontoxic appearing. A dermatologist is consulted for a recommendation for further workup or potential biopsy. The dermatologist examines the newborn. He is a well-appearing black boy with skin that is otherwise intact. A few pustules on the back are present that have a collarette of scale. The dermatologist reviews the mother’s prenatal history and the review shows that she was screened for syphilis and had a negative screening test with no other history of infectious diseases. What is the most appropriate next step to confirm your suspicions?

a. do a swab of a pustule and send it for viral culture

b. have his blood drawn and check for signs of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection

c. perform a biopsy of a pustule

d. perform a Giemsa stain on a smear of the pustule

e. start treatment with permethrin

4. Which intraoral cysts occur on the alveolar ridge of a neonate?

a. Bohn nodule

b. branchial cleft cyst

c. Epstein pearls

d. median raphe cyst

e. palatal cysts of the newborn

5. Miliaria rubra is associated with inflammation of the sweat glands in what portion of the skin?

a. basement membrane zone

b. dermis

c. dermoepidermal junction

d. intraepidermal

e. subcutis

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. The parents of a 2-month-old infant present with their child. They are worried because the infant has “acne” that is not going away. Friends told them to try gentle cleansers and they have avoided using lotions or cream on her face. However, the bumps will not go away. On examination she has papules and pustules. Comedones cannot be identified. What are your next steps?

a. adapalene cream 0.1% every night at bedtime

b. benzoyl peroxide cream 4%

c. benzoyl peroxide wash 2.5%

d. erythromycin gel 2%

e. ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily

2. While in the newborn nursery prior to discharge, the attending pediatrician notices a rash on a 2-day-old neonate who is otherwise completely healthy. The pediatrician consults a dermatologist for his/her opinion. The dermatologist sees erythematous macules with central pustules located predominately on the trunk and proximal extremities. A pustule is unroofed with a blade, the contents smeared on a glass slide, and a Giemsa stain is performed. What is the predominant cell type you would expect to see on histological examination?

a. eosinophils

b. Langerhans cells

c. lymphocytes

d. neutrophils

e. no cells are visualized

3. Shortly after delivery, the pediatricians notice that the baby has numerous hyperpigmented macules on the back. No other primary lesions are seen. The neonate is otherwise normal in appearance and nontoxic appearing. A dermatologist is consulted for a recommendation for further workup or potential biopsy. The dermatologist examines the newborn. He is a well-appearing black boy with skin that is otherwise intact. A few pustules on the back are present that have a collarette of scale. The dermatologist reviews the mother’s prenatal history and the review shows that she was screened for syphilis and had a negative screening test with no other history of infectious diseases. What is the most appropriate next step to confirm your suspicions?

a. do a swab of a pustule and send it for viral culture

b. have his blood drawn and check for signs of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection

c. perform a biopsy of a pustule

d. perform a Giemsa stain on a smear of the pustule

e. start treatment with permethrin

4. Which intraoral cysts occur on the alveolar ridge of a neonate?

a. Bohn nodule

b. branchial cleft cyst

c. Epstein pearls

d. median raphe cyst

e. palatal cysts of the newborn

5. Miliaria rubra is associated with inflammation of the sweat glands in what portion of the skin?

a. basement membrane zone

b. dermis

c. dermoepidermal junction

d. intraepidermal

e. subcutis

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on transient benign neonatal skin findings with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This fact sheet lists benign findings that can be seen in neonates and infants.

Practice Questions

1. The parents of a 2-month-old infant present with their child. They are worried because the infant has “acne” that is not going away. Friends told them to try gentle cleansers and they have avoided using lotions or cream on her face. However, the bumps will not go away. On examination she has papules and pustules. Comedones cannot be identified. What are your next steps?

a. adapalene cream 0.1% every night at bedtime

b. benzoyl peroxide cream 4%

c. benzoyl peroxide wash 2.5%

d. erythromycin gel 2%

e. ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily

2. While in the newborn nursery prior to discharge, the attending pediatrician notices a rash on a 2-day-old neonate who is otherwise completely healthy. The pediatrician consults a dermatologist for his/her opinion. The dermatologist sees erythematous macules with central pustules located predominately on the trunk and proximal extremities. A pustule is unroofed with a blade, the contents smeared on a glass slide, and a Giemsa stain is performed. What is the predominant cell type you would expect to see on histological examination?

a. eosinophils

b. Langerhans cells

c. lymphocytes

d. neutrophils

e. no cells are visualized

3. Shortly after delivery, the pediatricians notice that the baby has numerous hyperpigmented macules on the back. No other primary lesions are seen. The neonate is otherwise normal in appearance and nontoxic appearing. A dermatologist is consulted for a recommendation for further workup or potential biopsy. The dermatologist examines the newborn. He is a well-appearing black boy with skin that is otherwise intact. A few pustules on the back are present that have a collarette of scale. The dermatologist reviews the mother’s prenatal history and the review shows that she was screened for syphilis and had a negative screening test with no other history of infectious diseases. What is the most appropriate next step to confirm your suspicions?

a. do a swab of a pustule and send it for viral culture

b. have his blood drawn and check for signs of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection

c. perform a biopsy of a pustule

d. perform a Giemsa stain on a smear of the pustule

e. start treatment with permethrin

4. Which intraoral cysts occur on the alveolar ridge of a neonate?

a. Bohn nodule

b. branchial cleft cyst

c. Epstein pearls

d. median raphe cyst

e. palatal cysts of the newborn

5. Miliaria rubra is associated with inflammation of the sweat glands in what portion of the skin?

a. basement membrane zone

b. dermis

c. dermoepidermal junction

d. intraepidermal

e. subcutis

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. The parents of a 2-month-old infant present with their child. They are worried because the infant has “acne” that is not going away. Friends told them to try gentle cleansers and they have avoided using lotions or cream on her face. However, the bumps will not go away. On examination she has papules and pustules. Comedones cannot be identified. What are your next steps?

a. adapalene cream 0.1% every night at bedtime

b. benzoyl peroxide cream 4%

c. benzoyl peroxide wash 2.5%

d. erythromycin gel 2%

e. ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily

2. While in the newborn nursery prior to discharge, the attending pediatrician notices a rash on a 2-day-old neonate who is otherwise completely healthy. The pediatrician consults a dermatologist for his/her opinion. The dermatologist sees erythematous macules with central pustules located predominately on the trunk and proximal extremities. A pustule is unroofed with a blade, the contents smeared on a glass slide, and a Giemsa stain is performed. What is the predominant cell type you would expect to see on histological examination?

a. eosinophils

b. Langerhans cells

c. lymphocytes

d. neutrophils

e. no cells are visualized

3. Shortly after delivery, the pediatricians notice that the baby has numerous hyperpigmented macules on the back. No other primary lesions are seen. The neonate is otherwise normal in appearance and nontoxic appearing. A dermatologist is consulted for a recommendation for further workup or potential biopsy. The dermatologist examines the newborn. He is a well-appearing black boy with skin that is otherwise intact. A few pustules on the back are present that have a collarette of scale. The dermatologist reviews the mother’s prenatal history and the review shows that she was screened for syphilis and had a negative screening test with no other history of infectious diseases. What is the most appropriate next step to confirm your suspicions?

a. do a swab of a pustule and send it for viral culture

b. have his blood drawn and check for signs of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection

c. perform a biopsy of a pustule

d. perform a Giemsa stain on a smear of the pustule

e. start treatment with permethrin

4. Which intraoral cysts occur on the alveolar ridge of a neonate?

a. Bohn nodule

b. branchial cleft cyst

c. Epstein pearls

d. median raphe cyst

e. palatal cysts of the newborn

5. Miliaria rubra is associated with inflammation of the sweat glands in what portion of the skin?

a. basement membrane zone

b. dermis

c. dermoepidermal junction

d. intraepidermal

e. subcutis

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on transient benign neonatal skin findings with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This fact sheet lists benign findings that can be seen in neonates and infants.

Practice Questions

1. The parents of a 2-month-old infant present with their child. They are worried because the infant has “acne” that is not going away. Friends told them to try gentle cleansers and they have avoided using lotions or cream on her face. However, the bumps will not go away. On examination she has papules and pustules. Comedones cannot be identified. What are your next steps?

a. adapalene cream 0.1% every night at bedtime

b. benzoyl peroxide cream 4%

c. benzoyl peroxide wash 2.5%

d. erythromycin gel 2%

e. ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily

2. While in the newborn nursery prior to discharge, the attending pediatrician notices a rash on a 2-day-old neonate who is otherwise completely healthy. The pediatrician consults a dermatologist for his/her opinion. The dermatologist sees erythematous macules with central pustules located predominately on the trunk and proximal extremities. A pustule is unroofed with a blade, the contents smeared on a glass slide, and a Giemsa stain is performed. What is the predominant cell type you would expect to see on histological examination?

a. eosinophils

b. Langerhans cells

c. lymphocytes

d. neutrophils

e. no cells are visualized

3. Shortly after delivery, the pediatricians notice that the baby has numerous hyperpigmented macules on the back. No other primary lesions are seen. The neonate is otherwise normal in appearance and nontoxic appearing. A dermatologist is consulted for a recommendation for further workup or potential biopsy. The dermatologist examines the newborn. He is a well-appearing black boy with skin that is otherwise intact. A few pustules on the back are present that have a collarette of scale. The dermatologist reviews the mother’s prenatal history and the review shows that she was screened for syphilis and had a negative screening test with no other history of infectious diseases. What is the most appropriate next step to confirm your suspicions?

a. do a swab of a pustule and send it for viral culture

b. have his blood drawn and check for signs of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection

c. perform a biopsy of a pustule

d. perform a Giemsa stain on a smear of the pustule

e. start treatment with permethrin

4. Which intraoral cysts occur on the alveolar ridge of a neonate?

a. Bohn nodule

b. branchial cleft cyst

c. Epstein pearls

d. median raphe cyst

e. palatal cysts of the newborn

5. Miliaria rubra is associated with inflammation of the sweat glands in what portion of the skin?

a. basement membrane zone

b. dermis

c. dermoepidermal junction

d. intraepidermal

e. subcutis

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. The parents of a 2-month-old infant present with their child. They are worried because the infant has “acne” that is not going away. Friends told them to try gentle cleansers and they have avoided using lotions or cream on her face. However, the bumps will not go away. On examination she has papules and pustules. Comedones cannot be identified. What are your next steps?

a. adapalene cream 0.1% every night at bedtime

b. benzoyl peroxide cream 4%

c. benzoyl peroxide wash 2.5%

d. erythromycin gel 2%

e. ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily

2. While in the newborn nursery prior to discharge, the attending pediatrician notices a rash on a 2-day-old neonate who is otherwise completely healthy. The pediatrician consults a dermatologist for his/her opinion. The dermatologist sees erythematous macules with central pustules located predominately on the trunk and proximal extremities. A pustule is unroofed with a blade, the contents smeared on a glass slide, and a Giemsa stain is performed. What is the predominant cell type you would expect to see on histological examination?

a. eosinophils

b. Langerhans cells

c. lymphocytes

d. neutrophils

e. no cells are visualized

3. Shortly after delivery, the pediatricians notice that the baby has numerous hyperpigmented macules on the back. No other primary lesions are seen. The neonate is otherwise normal in appearance and nontoxic appearing. A dermatologist is consulted for a recommendation for further workup or potential biopsy. The dermatologist examines the newborn. He is a well-appearing black boy with skin that is otherwise intact. A few pustules on the back are present that have a collarette of scale. The dermatologist reviews the mother’s prenatal history and the review shows that she was screened for syphilis and had a negative screening test with no other history of infectious diseases. What is the most appropriate next step to confirm your suspicions?

a. do a swab of a pustule and send it for viral culture

b. have his blood drawn and check for signs of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection

c. perform a biopsy of a pustule

d. perform a Giemsa stain on a smear of the pustule

e. start treatment with permethrin

4. Which intraoral cysts occur on the alveolar ridge of a neonate?

a. Bohn nodule

b. branchial cleft cyst

c. Epstein pearls

d. median raphe cyst

e. palatal cysts of the newborn

5. Miliaria rubra is associated with inflammation of the sweat glands in what portion of the skin?

a. basement membrane zone

b. dermis

c. dermoepidermal junction

d. intraepidermal

e. subcutis

Red-Blue Nodule on the Scalp

Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

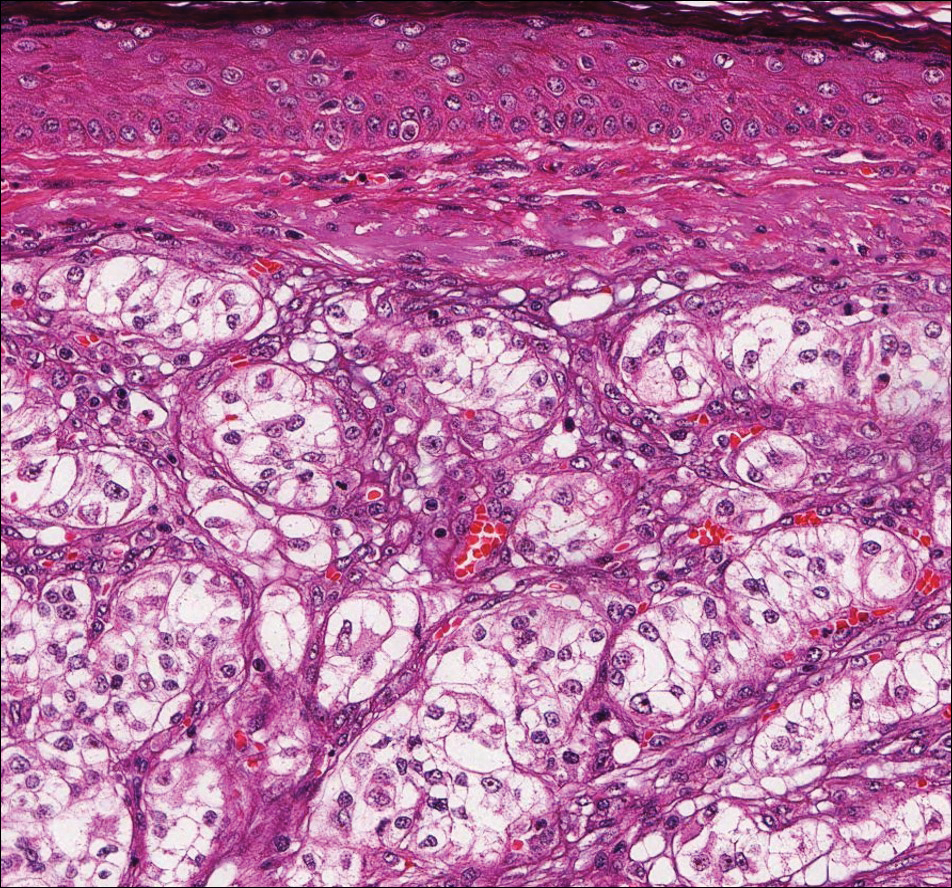

The differential diagnosis of cutaneous neoplasms with clear cells is broad. Clear cell features can be seen in primary tumors arising from the epidermis and cutaneous adnexa as well as in mesenchymal and melanocytic neoplasms. Furthermore, metastatic disease should be considered in the histologic differential diagnosis, as many visceral malignancies have clear cell features. This patient was subsequently found to have a large renal mass with metastasis to the lungs, spleen, and bone. The histologic findings support the diagnosis of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) to the skin.

Approximately 30% of patients with clear cell RCC present with metastatic disease with approximately 8% of those involving the skin.1,2 Cutaneous RCC metastases show a predilection for the head, especially the scalp. The clinical presentation is variable, but there often is a history of a rapidly growing brown, black, or purple nodule or plaque. A thorough review of the patient's history should be conducted if metastatic RCC is in the differential diagnosis, as it has been reported to occur up to 20 years after initial diagnosis.3

Histologically, clear cell RCC (quiz image) is composed of nests of tumor cells with clear cytoplasm and centrally located nuclei with prominent nucleoli. The clear cell features result from abundant cytoplasmic glycogen and lipid but may not be present in every case. One of the most important histologic features is the presence of delicate branching blood vessels (Figure 1). Numerous extravasated red blood cells also may be present. Positive immunohistochemical staining for PAX8, CD10, and RCC antigens support the diagnosis.4

Balloon cell nevi (Figure 2) most commonly occur on the head and neck in adolescents and young adults but clinically are indistinguishable from other banal nevi. The nevus cells are large with foamy to finely vacuolated cytoplasm and lack atypia. The clear cell change is the result of melanosome degeneration and may be extensive. The presence of melanin pigment, nests of typical nevus cells, and positive staining with MART-1 can help distinguish the tumor from xanthomas and RCC.5

Clear cell hidradenoma (Figure 3) is a well-circumscribed tumor of sweat gland origin that arises in the dermis. The architecture usually is solid, cystic, or a combination of both. The cytology is classically bland with poroid, squamoid, or clear cell morphology. Clear cells that are positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining predominate in up to one-third of cases. Carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen can be used to highlight the eosinophilic cuticles of ducts within solid areas.6

Sebaceous carcinoma (Figure 4) most frequently arises in a periorbital distribution, although extraocular lesions are known to occur. Histologically, there is a proliferation of both mature sebocytes and basaloid cells in the dermis, occasionally involving the epidermis. The mature sebocytes demonstrate clear cell features with foamy to vacuolated cytoplasm and large nuclei with scalloped borders. The clear cells may vary greatly in number and often are sparse in poorly differentiated tumors in which pleomorphic basaloid cells may predominate. The basaloid cells may resemble those of squamous or basal cell carcinoma, leading to a diagnostic dilemma in some cases. Special staining with Sudan black B and oil red O highlights the cytoplasmic lipid but must be performed on frozen section specimens. Although not entirely specific, immunohistochemical expression of epithelial membrane antigen, androgen receptor, and membranous vesicular adipophilin staining in sebaceous carcinoma can assist in the diagnosis.7

Cutaneous xanthomas (Figure 5) may arise in patients of any age and represent deposition of lipid-laden macrophages. Classification often is dependent on the clinical presentation; however, some subtypes demonstrate unique morphologic features (eg, verruciform xanthomas). Xanthomas classically arise in association with elevated serum lipids, but they also may occur in normolipemic patients. Individuals with Erdheim-Chester disease have an increased propensity to develop xanthelasma. Similarly, plane xanthomas have been associated with monoclonal gammopathy. Histologically, xanthomas are characterized by sheets of foamy macrophages within the dermis and subcutis. Positive immunohistochemical staining for CD68 highlighting the histiocytic nature of the cells and the absence of a delicate vascular network aid in the differentiation from RCC.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Calonje E, McKee PH. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Lin F, Prichard J. Handbook of Practical Immunohistochemistry: Frequently Asked Questions. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2015.

- McKee PH, Calonje E. Diagnostic Atlas of Melanocytic Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby/Elsevier; 2009.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Ansai S, Takeichi H, Arase S, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma: an immunohistochemical reappraisal. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:579-587.

Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

The differential diagnosis of cutaneous neoplasms with clear cells is broad. Clear cell features can be seen in primary tumors arising from the epidermis and cutaneous adnexa as well as in mesenchymal and melanocytic neoplasms. Furthermore, metastatic disease should be considered in the histologic differential diagnosis, as many visceral malignancies have clear cell features. This patient was subsequently found to have a large renal mass with metastasis to the lungs, spleen, and bone. The histologic findings support the diagnosis of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) to the skin.

Approximately 30% of patients with clear cell RCC present with metastatic disease with approximately 8% of those involving the skin.1,2 Cutaneous RCC metastases show a predilection for the head, especially the scalp. The clinical presentation is variable, but there often is a history of a rapidly growing brown, black, or purple nodule or plaque. A thorough review of the patient's history should be conducted if metastatic RCC is in the differential diagnosis, as it has been reported to occur up to 20 years after initial diagnosis.3

Histologically, clear cell RCC (quiz image) is composed of nests of tumor cells with clear cytoplasm and centrally located nuclei with prominent nucleoli. The clear cell features result from abundant cytoplasmic glycogen and lipid but may not be present in every case. One of the most important histologic features is the presence of delicate branching blood vessels (Figure 1). Numerous extravasated red blood cells also may be present. Positive immunohistochemical staining for PAX8, CD10, and RCC antigens support the diagnosis.4

Balloon cell nevi (Figure 2) most commonly occur on the head and neck in adolescents and young adults but clinically are indistinguishable from other banal nevi. The nevus cells are large with foamy to finely vacuolated cytoplasm and lack atypia. The clear cell change is the result of melanosome degeneration and may be extensive. The presence of melanin pigment, nests of typical nevus cells, and positive staining with MART-1 can help distinguish the tumor from xanthomas and RCC.5

Clear cell hidradenoma (Figure 3) is a well-circumscribed tumor of sweat gland origin that arises in the dermis. The architecture usually is solid, cystic, or a combination of both. The cytology is classically bland with poroid, squamoid, or clear cell morphology. Clear cells that are positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining predominate in up to one-third of cases. Carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen can be used to highlight the eosinophilic cuticles of ducts within solid areas.6

Sebaceous carcinoma (Figure 4) most frequently arises in a periorbital distribution, although extraocular lesions are known to occur. Histologically, there is a proliferation of both mature sebocytes and basaloid cells in the dermis, occasionally involving the epidermis. The mature sebocytes demonstrate clear cell features with foamy to vacuolated cytoplasm and large nuclei with scalloped borders. The clear cells may vary greatly in number and often are sparse in poorly differentiated tumors in which pleomorphic basaloid cells may predominate. The basaloid cells may resemble those of squamous or basal cell carcinoma, leading to a diagnostic dilemma in some cases. Special staining with Sudan black B and oil red O highlights the cytoplasmic lipid but must be performed on frozen section specimens. Although not entirely specific, immunohistochemical expression of epithelial membrane antigen, androgen receptor, and membranous vesicular adipophilin staining in sebaceous carcinoma can assist in the diagnosis.7

Cutaneous xanthomas (Figure 5) may arise in patients of any age and represent deposition of lipid-laden macrophages. Classification often is dependent on the clinical presentation; however, some subtypes demonstrate unique morphologic features (eg, verruciform xanthomas). Xanthomas classically arise in association with elevated serum lipids, but they also may occur in normolipemic patients. Individuals with Erdheim-Chester disease have an increased propensity to develop xanthelasma. Similarly, plane xanthomas have been associated with monoclonal gammopathy. Histologically, xanthomas are characterized by sheets of foamy macrophages within the dermis and subcutis. Positive immunohistochemical staining for CD68 highlighting the histiocytic nature of the cells and the absence of a delicate vascular network aid in the differentiation from RCC.

Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

The differential diagnosis of cutaneous neoplasms with clear cells is broad. Clear cell features can be seen in primary tumors arising from the epidermis and cutaneous adnexa as well as in mesenchymal and melanocytic neoplasms. Furthermore, metastatic disease should be considered in the histologic differential diagnosis, as many visceral malignancies have clear cell features. This patient was subsequently found to have a large renal mass with metastasis to the lungs, spleen, and bone. The histologic findings support the diagnosis of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) to the skin.

Approximately 30% of patients with clear cell RCC present with metastatic disease with approximately 8% of those involving the skin.1,2 Cutaneous RCC metastases show a predilection for the head, especially the scalp. The clinical presentation is variable, but there often is a history of a rapidly growing brown, black, or purple nodule or plaque. A thorough review of the patient's history should be conducted if metastatic RCC is in the differential diagnosis, as it has been reported to occur up to 20 years after initial diagnosis.3

Histologically, clear cell RCC (quiz image) is composed of nests of tumor cells with clear cytoplasm and centrally located nuclei with prominent nucleoli. The clear cell features result from abundant cytoplasmic glycogen and lipid but may not be present in every case. One of the most important histologic features is the presence of delicate branching blood vessels (Figure 1). Numerous extravasated red blood cells also may be present. Positive immunohistochemical staining for PAX8, CD10, and RCC antigens support the diagnosis.4

Balloon cell nevi (Figure 2) most commonly occur on the head and neck in adolescents and young adults but clinically are indistinguishable from other banal nevi. The nevus cells are large with foamy to finely vacuolated cytoplasm and lack atypia. The clear cell change is the result of melanosome degeneration and may be extensive. The presence of melanin pigment, nests of typical nevus cells, and positive staining with MART-1 can help distinguish the tumor from xanthomas and RCC.5

Clear cell hidradenoma (Figure 3) is a well-circumscribed tumor of sweat gland origin that arises in the dermis. The architecture usually is solid, cystic, or a combination of both. The cytology is classically bland with poroid, squamoid, or clear cell morphology. Clear cells that are positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining predominate in up to one-third of cases. Carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen can be used to highlight the eosinophilic cuticles of ducts within solid areas.6

Sebaceous carcinoma (Figure 4) most frequently arises in a periorbital distribution, although extraocular lesions are known to occur. Histologically, there is a proliferation of both mature sebocytes and basaloid cells in the dermis, occasionally involving the epidermis. The mature sebocytes demonstrate clear cell features with foamy to vacuolated cytoplasm and large nuclei with scalloped borders. The clear cells may vary greatly in number and often are sparse in poorly differentiated tumors in which pleomorphic basaloid cells may predominate. The basaloid cells may resemble those of squamous or basal cell carcinoma, leading to a diagnostic dilemma in some cases. Special staining with Sudan black B and oil red O highlights the cytoplasmic lipid but must be performed on frozen section specimens. Although not entirely specific, immunohistochemical expression of epithelial membrane antigen, androgen receptor, and membranous vesicular adipophilin staining in sebaceous carcinoma can assist in the diagnosis.7

Cutaneous xanthomas (Figure 5) may arise in patients of any age and represent deposition of lipid-laden macrophages. Classification often is dependent on the clinical presentation; however, some subtypes demonstrate unique morphologic features (eg, verruciform xanthomas). Xanthomas classically arise in association with elevated serum lipids, but they also may occur in normolipemic patients. Individuals with Erdheim-Chester disease have an increased propensity to develop xanthelasma. Similarly, plane xanthomas have been associated with monoclonal gammopathy. Histologically, xanthomas are characterized by sheets of foamy macrophages within the dermis and subcutis. Positive immunohistochemical staining for CD68 highlighting the histiocytic nature of the cells and the absence of a delicate vascular network aid in the differentiation from RCC.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Calonje E, McKee PH. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Lin F, Prichard J. Handbook of Practical Immunohistochemistry: Frequently Asked Questions. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2015.

- McKee PH, Calonje E. Diagnostic Atlas of Melanocytic Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby/Elsevier; 2009.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Ansai S, Takeichi H, Arase S, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma: an immunohistochemical reappraisal. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:579-587.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Calonje E, McKee PH. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Lin F, Prichard J. Handbook of Practical Immunohistochemistry: Frequently Asked Questions. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2015.

- McKee PH, Calonje E. Diagnostic Atlas of Melanocytic Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby/Elsevier; 2009.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Ansai S, Takeichi H, Arase S, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma: an immunohistochemical reappraisal. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:579-587.

A 59-year-old man presented with a 1.5×1.0-cm asymptomatic, smooth, red-blue nodule on the left parietal scalp. The nodule had been rapidly enlarging over the last 3 weeks. After resection, the cut surface was golden yellow and focally hemorrhagic.

Superficial Ulceration on the Vulva

Foscarnet-Induced Ulceration

Viral swabs were negative for herpes simplex virus. The diagnosis of foscarnet-induced ulceration was reached and the drug was discontinued. Symptomatic treatment with soap substitutes and lidocaine ointment was used.

Foscarnet is an antiviral agent used when resistance develops to first-line therapies.1 It is a pyrophosphate analogue that inhibits viral DNA polymerase, thereby preventing viral replication. It is used in treating cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus, which are resistant to first-line therapies, or patients who develop hematologic toxicity from antivirals. The main side effects of foscarnet include nephrotoxicity, alteration of calcium homeostasis, and malaise. Genital ulceration is a known side effect of therapy, though it is rare and more commonly seen in uncircumcised males. Approximately 94% of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine, which causes an irritant dermatitis that is more pronounced in males as the urine stays in the subpreputial area.1

Vulval ulceration2 and penile ulceration3 has been reported in AIDS patients treated with foscarnet. In these patients, the onset of ulceration is temporally related to foscarnet therapy, occurring at approximately day 7 to 24 of treatment and resolving after discontinuation of therapy.

- Wagstaff AJ, Bryson HM. Foscarnet. a reappraisal of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in immunocompromised patients with viral infections. Drugs. 1994;48:199-226.

- Lacey HB, Ness A, Mandal BK. Vulval ulceration associated with foscarnet. Genitourin Med. 1992;68:182.

- Moyle G, Barton S, Gazzard BG. Penile ulceration with foscarnet therapy. AIDS. 1993;7:140-141.

Foscarnet-Induced Ulceration

Viral swabs were negative for herpes simplex virus. The diagnosis of foscarnet-induced ulceration was reached and the drug was discontinued. Symptomatic treatment with soap substitutes and lidocaine ointment was used.

Foscarnet is an antiviral agent used when resistance develops to first-line therapies.1 It is a pyrophosphate analogue that inhibits viral DNA polymerase, thereby preventing viral replication. It is used in treating cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus, which are resistant to first-line therapies, or patients who develop hematologic toxicity from antivirals. The main side effects of foscarnet include nephrotoxicity, alteration of calcium homeostasis, and malaise. Genital ulceration is a known side effect of therapy, though it is rare and more commonly seen in uncircumcised males. Approximately 94% of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine, which causes an irritant dermatitis that is more pronounced in males as the urine stays in the subpreputial area.1

Vulval ulceration2 and penile ulceration3 has been reported in AIDS patients treated with foscarnet. In these patients, the onset of ulceration is temporally related to foscarnet therapy, occurring at approximately day 7 to 24 of treatment and resolving after discontinuation of therapy.

Foscarnet-Induced Ulceration

Viral swabs were negative for herpes simplex virus. The diagnosis of foscarnet-induced ulceration was reached and the drug was discontinued. Symptomatic treatment with soap substitutes and lidocaine ointment was used.

Foscarnet is an antiviral agent used when resistance develops to first-line therapies.1 It is a pyrophosphate analogue that inhibits viral DNA polymerase, thereby preventing viral replication. It is used in treating cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus, which are resistant to first-line therapies, or patients who develop hematologic toxicity from antivirals. The main side effects of foscarnet include nephrotoxicity, alteration of calcium homeostasis, and malaise. Genital ulceration is a known side effect of therapy, though it is rare and more commonly seen in uncircumcised males. Approximately 94% of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine, which causes an irritant dermatitis that is more pronounced in males as the urine stays in the subpreputial area.1

Vulval ulceration2 and penile ulceration3 has been reported in AIDS patients treated with foscarnet. In these patients, the onset of ulceration is temporally related to foscarnet therapy, occurring at approximately day 7 to 24 of treatment and resolving after discontinuation of therapy.

- Wagstaff AJ, Bryson HM. Foscarnet. a reappraisal of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in immunocompromised patients with viral infections. Drugs. 1994;48:199-226.

- Lacey HB, Ness A, Mandal BK. Vulval ulceration associated with foscarnet. Genitourin Med. 1992;68:182.

- Moyle G, Barton S, Gazzard BG. Penile ulceration with foscarnet therapy. AIDS. 1993;7:140-141.

- Wagstaff AJ, Bryson HM. Foscarnet. a reappraisal of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in immunocompromised patients with viral infections. Drugs. 1994;48:199-226.

- Lacey HB, Ness A, Mandal BK. Vulval ulceration associated with foscarnet. Genitourin Med. 1992;68:182.

- Moyle G, Barton S, Gazzard BG. Penile ulceration with foscarnet therapy. AIDS. 1993;7:140-141.

A 23-year-old woman who was immunosuppressed secondary to cyclophosphamide and prednisolone treatment of autoimmune panniculitis was admitted to intensive care with dyspnea. Cytomegalovirus and Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia were diagnosed on bronchoscopy and bronchial washings. Management with valganciclovir was started but worsened the patient's pancytopenia. She was started on intravenous foscarnet. After a week of therapy, the patient reported vulval soreness and painful micturition. On examination there was superficial ulceration of the labia minora. The affected area was symmetrical, and there was some extension into the vestibule. There were no vesicles or lesions on the cutaneous skin.

Shedding Light on Onychomadesis

Onychomadesis is an acute, noninflammatory, painless, proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix. It occurs due to an abrupt stoppage of nail production by matrix cells, producing temporary cessation of nail growth with or without subsequent complete shedding of nails.1-10 Onychomadesis has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations ranging from mild transverse ridges of the nail plate (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding.4,11 Onychomadesis may be related to systemic and dermatologic diseases, drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids), nail trauma, fever, or infection,5 and a connection between onychomadesis and hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) was first described by Clementz et al12 following outbreaks in Europe, Asia, and the United States.

Epidemiology

Onychomadesis has been observed in children of all ages including neonates. Neonatal onychomadesis is thought to be related to perinatal stressors and birth trauma, with possible exacerbation by superimposed candidiasis.10 Depending on the underlying cause, there may be involvement of a single nail or multiple nails. Nag et al1 noted that onychomadesis was most commonly observed in nails of the middle finger (73.7%), followed by the thumb (63.2%) and ring finger (52.6%). Fingernails are more commonly involved than toenails.1

Clementz et al12 first proposed the association between onychomadesis and HFMD in 2000. Patients with a history of HFMD were found to be 14 times more likely to develop onychomadesis (relative risk, 14; 95% confidence interval, 4.57-42.86).4 A common pathogen for HFMD is coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6),13,14 but the mechanism of onychomadesis in HFMD remains unclear.5,7,13 Outbreaks of HFMD have been reported in Spain, Finland, Japan, Thailand, the United States, Singapore, and China.15 During an outbreak of HFMD in Taiwan, the incidence of onychomadesis following CVA6 infection was 37% (48/130) compared to 5% (7/145) in cases with non-CVA6 causative strains.16 There also have been observed differences in the prevalence of onychomadesis by age: a 55% (18/33) occurrence rate was noted in the youngest age group (range, 9–23 months), 30% (8/27) in the middle age group (range, 24–32 months), and 4% (1/28) in the oldest age group (range, 33–42 months), with an average of 4 nails shed per case.17 A study in Spain also found a high occurrence of onychomadesis in a nursery setting, with 92% (11/12) of onychomadesis cases preceded by HFMD 2 months prior.18

Etiology

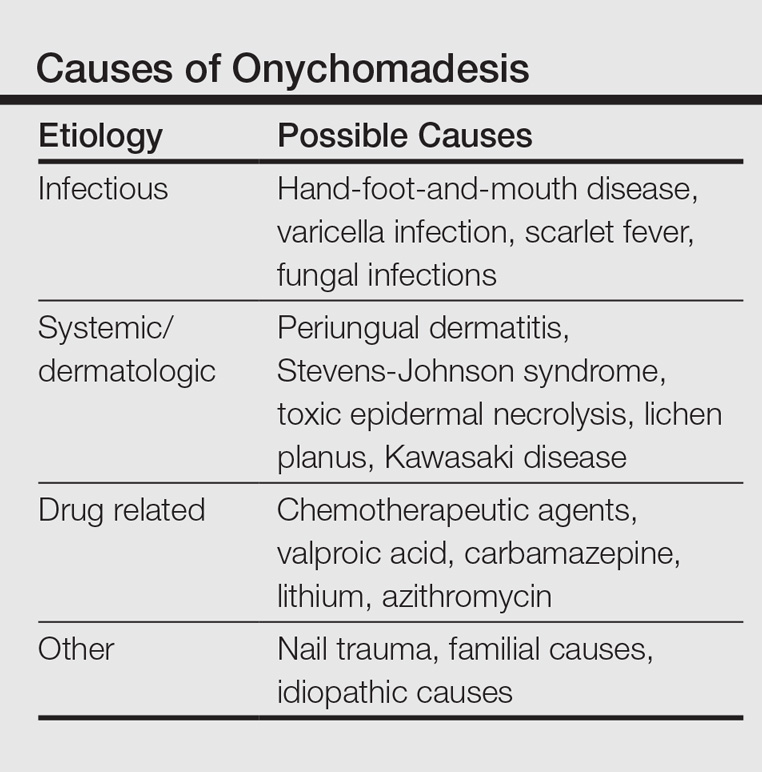

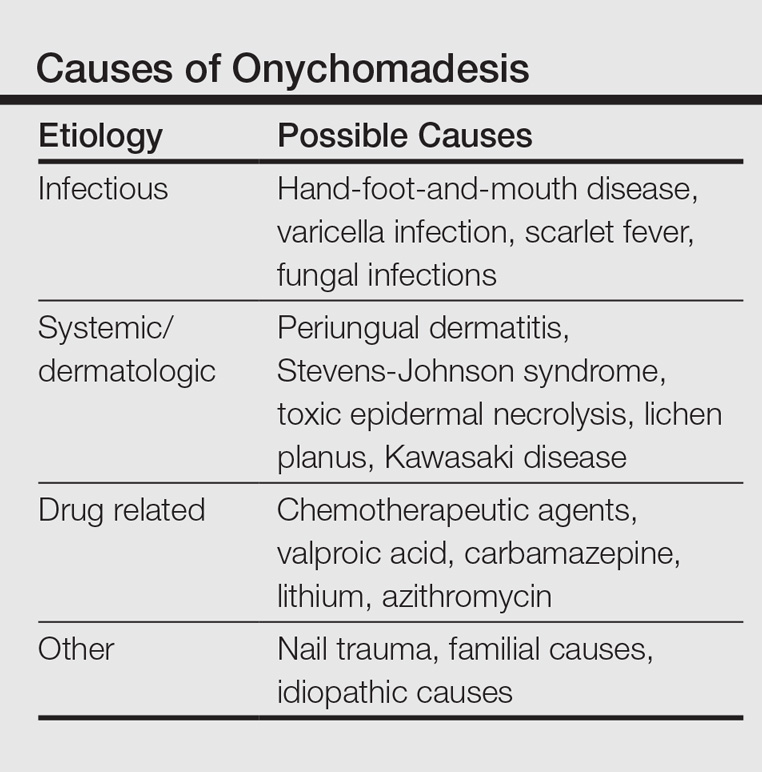

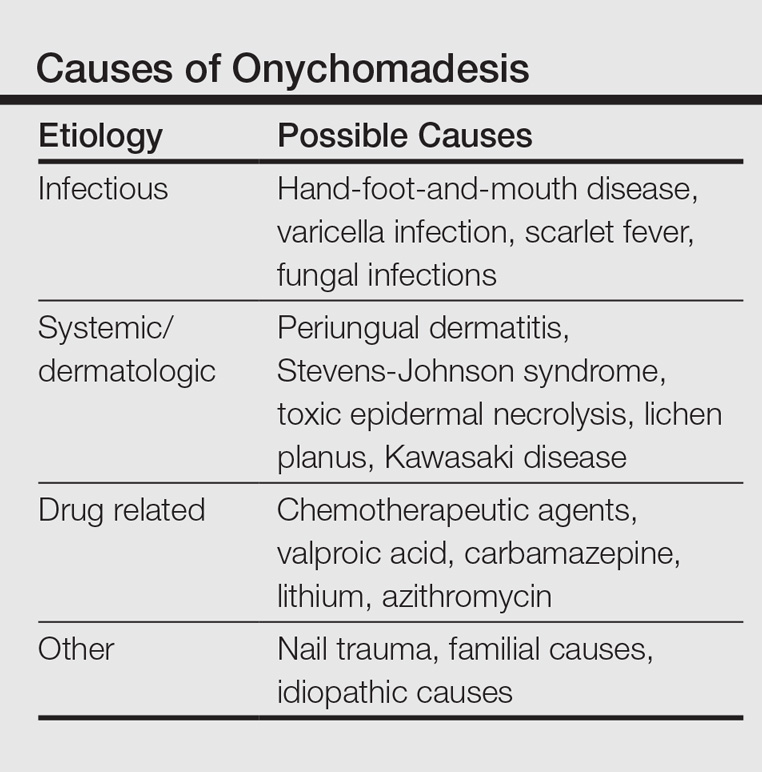

Local trauma to the nail bed is the most common cause of single-digit onychomadesis.4 Multiple-digit involvement suggests a systemic etiology such as fever, erythroderma, and Kawasaki disease; use of drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids); and viral infections such as HFMD and varicella at the infantile age (Table).5,9,19 Most drug-related nail changes are the outcome of acute toxicity to the proliferating nail matrix epithelium. If onychomadesis affects all nails at the same level, the patient’s history of medication use and other treatments taken 2 to 3 weeks prior to the appearance of the nail findings should be evaluated. Chemotherapeutic agents produce nail changes in a high proportion of patients, which often are related to drug dosage. These effects also are reproducible with re-administration of the drug.20 Onychomadesis also has been reported as a possible side effect of anticonvulsants such as valproic acid (VPA).21 One study evaluating the link between VPA and onychomadesis indicated that nail changes may be due to a disturbance of zinc metabolism.22 However, the pathomechanism of onychomadesis associated with VPA treatment remains unclear.21 Onychomadesis also has developed after an allergic drug reaction to oral penicillin V after treatment of a sore throat in a 23-month-old child.23

Nail involvement has been reported in 10% of cases of inflammatory conditions such as lichen planus21; however, it may be more common but underrecognized and underreported. Grover et al9 indicated that lichen planus–induced severe inflammation in the matrix of the nail unit leading to a temporary growth arrest was the possible mechanism leading to nail shedding. Prompt systemic and intramatricial steroid treatment of lichen planus is required to avoid potential scarring of the nail matrix and permanent damage.9

Onychomadesis also has been reported following varicella infection (chickenpox). Podder et al19 reported the case of a 7-year-old girl who had recovered from a varicella infection 5 weeks prior and presented with onychomadesis of the right index fingernail with all other fingernails and toenails appearing normal. Kocak and Koçak5 reported onychomadesis in 2 sisters with varicella infection. There are few reported cases, so it is still unclear whether varicella infection is an inciting factor.19

One of the most studied viral infections linked to onychomadesis is HFMD, which is a common viral infection that mostly affects children younger than 10 years.1 The precise mechanism of onychomadesis for these viral infection events remains unclear.7,10,13 Several theories have been delineated, including nail matrix arrest from fever occurring during HFMD.6 However, this cause is unlikely, as fevers are typically low grade and present only for a few hours.4,6,13 Direct inflammation spreading from skin lesions of HFMD around the nails or maceration associated with finger blisters could cause onychomadesis.1,5,7 Haneke24 hypothesized that nail shedding may be the consequence of vesicles localized in the periungual tissue, but studies have shown incidence without prior lesions on the fingers and no relationship between nail matrix arrest and severity of HFMD.5,6,13 Bettoli et al25 reported that inflammation secondary to viral infection around the nail matrix might be induced directly by viruses or indirectly by virus-specific immunocomplexes and consequent distal embolism. Osterback et al14 used reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction to detect CVA6 in fragmented nails from 2 children and 1 parent following an HFMD episode, suggesting that virus replication could damage the nail matrix, resulting in onychomadesis. Cabrerizo et al18 also suggested that virus replication directly damages the nail matrix based on the presence of CVA6 in shed nails. Because fingernails with onychomadesis are not always of the fingers affected by HFMD, an indirect effect of viral infection on the nail matrix is more plausible.8 Additional studies are needed to clarify the virus-associated mechanism of nail matrix arrest.6 Finally, frequent washing of hands15 resulting in maceration, Candida infection, and allergic contact dermatitis2 may be possible causes. It is unclear if onychomadesis following HFMD is related to viral replication, inflammation, or intensive hygienic measures, and further investigation is needed.2,15

Clinical Characteristics

The ventral floor is the site of the germinal matrix and is responsible for 90% of nail production. As a result, more of the nail plate substance is produced proximally, leading to a natural convex curvature from the proximal to distal nail.11 Beau lines are transverse ridging of the nail plates.6 Onychomadesis may be viewed as a more severe form of Beau lines, with complete separation and possible shedding of the nail plate (Figure).3,4 In both cases, an insult to the nail matrix is followed by recovery and production of the nail plate at the nail matrix.4 In Beau lines, slowing or disruption of cell growth from the proximal matrix results in a thinner nail plate, leading to transverse depressions. Onychomadesis has a similar pathophysiology but is associated with a complete halt in the nail plate production.3

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of onychomadesis is made clinically.3,10 Distinct nail changes can be detected by inspection and palpation of the nail plate,3,11 which allows for differentiation between Beau lines and complete nail shedding. Additionally, any signs of nail trauma need to be noted, as well as pain, swelling, or pruritus, as these symptoms also can guide in determining the etiology of the nail dystrophy. Ultrasonography can confirm the diagnosis, as the defect can be identified beneath the proximal nail fold.3,26 When it occurs after HFMD or varicella, onychomadesis tends to present in 28 to 40 days following infection.4,6,10 Physicians should consider underlying associations. A review of viral illnesses within 1 to 2 months prior to development of nail changes often will identify the causative disease.4 Each patient should be evaluated for recent nail trauma; medications; viral infection; and autoimmune, systemic, and inflammatory diseases.

Treatment

Onychomadesis typically is mild and self-limited.4,10 There is no specific treatment,10 but a conservative approach to management is recommended. Treatment of any underlying medical conditions or discontinuation of an offending medication may help to prevent recurrent onychomadesis.3 Supportive care along with protection of the nail bed by maintaining short nails and using adhesive bandages over the affected nails to avoid snagging the nail or ripping off the partially attached nails is recommended.4 In some cases, onychomadesis has been treated with topical application of urea cream 40% under occlusion27 or halcinonide cream 0.1% under occlusion for 5 to 6 days,28 but these treatments have not been universally effective.3 External use of basic fibroblast growth factor to stimulate new regrowth of the nail plate has been advocated.3 It is important to reassure patients that as long as the underlying causes are eliminated and the nail matrix has not been permanently scarred, the nails should grow back within 12 weeks or sooner in children. Thus, typically only reassurance and counseling of parents/guardians is required for onychomadesis in children.1,2 However, the nails may be dystrophic or fail to regrow if there is poor peripheral circulation or permanent nail matrix damage.

Conclusion

Fortunately, onychomadesis is self-limited. Physicians should look for underlying causes of onychomadesis, including a history of viral infections such as HFMD and varicella as well as systemic diseases and use of medications. As long as any underlying disorder or condition has been resolved, spontaneous regrowth of healthy nails usually but not always occurs within 12 weeks or sooner in children.

- Nag SS, Dutta A, Mandal RK. Delayed cutaneous findings of hand, foot, and mouth disease. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53:42-44.

- Tan ZH, Koh MJ. Nail shedding following hand, foot and mouth disease. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:665.

- Braswell MA, Daniel CR, Brodell RT. Beau lines, onychomadesis, and retronychia: a unifying hypothesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:849-855.

- Clark CM, Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM. What is your diagnosis? onychomadesis following hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Cutis. 2015;95:312, 319-320.

- Kocak AY, Koçak O. Onychomadesis in two sisters induced by varicella infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E108-E109.

- Shin JY, Cho BK, Park HJ. A clinical study of nail changes occurring secondary to hand-foot-mouth disease: onychomadesis and Beau’s lines. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:280-283.

- Shikuma E, Endo Y, Fujisawa A, et al. Onychomadesis developed only on the nails having cutaneous lesions of severe hand-foot-mouth disease. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:324193.

- Kim EJ, Park HS, Yoon HS, et al. Four cases of onychomadesis after hand-foot-mouth disease. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:777-778.

- Grover C, Vohra S. Onychomadesis with lichen planus: an under-recognized manifestation. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:420.

- Chu DH, Rubin AI. Diagnosis and management of nail disorders. In: Holland K, ed. The Pediatric Clinics of North America. Vol 61. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014:301-302.

- Kowalewski C, Schwartz RA. Components, growth, and composition of the nail. In: Demis D, ed. Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Scarfì F, Arunachalam M, Galeone M, et al. An uncommon onychomadesis in adults. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1392-1394.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Yan X, Zhang ZZ, Yang ZH, et al. Clinical and etiological characteristics of atypical hand-foot-and-mouth disease in children from Chongqing, China: a retrospective study [published online November 26, 2015]. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:802046.

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Cabrerizo M, De Miguel T, Armada A, et al. Onychomadesis after a hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreak in Spain, 2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1775-1778.

- Podder I, Das A, Gharami RC. Onychomadesis following varicella infection: is it a mere co-incidence? Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:626-627.

- Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M, Tosti A. Drug-induced nail abnormalities. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:31-37.

- Poretti A, Lips U, Belvedere M, et al. Onychomadesis: a rare side-effect of valproic acid medication? Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:749-750.

- Grech V, Vella C. Generalized onycholoysis associated with sodium valproate therapy. Eur Neurol. 1999;42:64-65.

- Shah RK, Uddin M, Fatunde OJ. Onychomadesis secondary to penicillin allergy in a child. J Pediatr. 2012;161:166.

- Haneke E. Onychomadesis and hand, foot and mouth disease—is there a connection? Euro Surveill. 2010;15(37).

- Bettoli V, Zauli S, Toni G, et al. Onychomadesis following hand, foot, and mouth disease: a case report from Italy and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:728-730.

- Wortsman X, Wortsman J, Guerrero R, et al. Anatomical changes in retronychia and onychomadesis detected using ultrasound. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1615-1620.

- Fleming CJ, Hunt MJ, Barnetson RS. Mycosis fungoides with onychomadesis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:1012-1013.

- Mishra D, Singh G, Pandey SS. Possible carbamazepine-induced reversible onychomadesis. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:460-461.

Onychomadesis is an acute, noninflammatory, painless, proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix. It occurs due to an abrupt stoppage of nail production by matrix cells, producing temporary cessation of nail growth with or without subsequent complete shedding of nails.1-10 Onychomadesis has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations ranging from mild transverse ridges of the nail plate (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding.4,11 Onychomadesis may be related to systemic and dermatologic diseases, drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids), nail trauma, fever, or infection,5 and a connection between onychomadesis and hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) was first described by Clementz et al12 following outbreaks in Europe, Asia, and the United States.

Epidemiology

Onychomadesis has been observed in children of all ages including neonates. Neonatal onychomadesis is thought to be related to perinatal stressors and birth trauma, with possible exacerbation by superimposed candidiasis.10 Depending on the underlying cause, there may be involvement of a single nail or multiple nails. Nag et al1 noted that onychomadesis was most commonly observed in nails of the middle finger (73.7%), followed by the thumb (63.2%) and ring finger (52.6%). Fingernails are more commonly involved than toenails.1

Clementz et al12 first proposed the association between onychomadesis and HFMD in 2000. Patients with a history of HFMD were found to be 14 times more likely to develop onychomadesis (relative risk, 14; 95% confidence interval, 4.57-42.86).4 A common pathogen for HFMD is coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6),13,14 but the mechanism of onychomadesis in HFMD remains unclear.5,7,13 Outbreaks of HFMD have been reported in Spain, Finland, Japan, Thailand, the United States, Singapore, and China.15 During an outbreak of HFMD in Taiwan, the incidence of onychomadesis following CVA6 infection was 37% (48/130) compared to 5% (7/145) in cases with non-CVA6 causative strains.16 There also have been observed differences in the prevalence of onychomadesis by age: a 55% (18/33) occurrence rate was noted in the youngest age group (range, 9–23 months), 30% (8/27) in the middle age group (range, 24–32 months), and 4% (1/28) in the oldest age group (range, 33–42 months), with an average of 4 nails shed per case.17 A study in Spain also found a high occurrence of onychomadesis in a nursery setting, with 92% (11/12) of onychomadesis cases preceded by HFMD 2 months prior.18

Etiology

Local trauma to the nail bed is the most common cause of single-digit onychomadesis.4 Multiple-digit involvement suggests a systemic etiology such as fever, erythroderma, and Kawasaki disease; use of drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids); and viral infections such as HFMD and varicella at the infantile age (Table).5,9,19 Most drug-related nail changes are the outcome of acute toxicity to the proliferating nail matrix epithelium. If onychomadesis affects all nails at the same level, the patient’s history of medication use and other treatments taken 2 to 3 weeks prior to the appearance of the nail findings should be evaluated. Chemotherapeutic agents produce nail changes in a high proportion of patients, which often are related to drug dosage. These effects also are reproducible with re-administration of the drug.20 Onychomadesis also has been reported as a possible side effect of anticonvulsants such as valproic acid (VPA).21 One study evaluating the link between VPA and onychomadesis indicated that nail changes may be due to a disturbance of zinc metabolism.22 However, the pathomechanism of onychomadesis associated with VPA treatment remains unclear.21 Onychomadesis also has developed after an allergic drug reaction to oral penicillin V after treatment of a sore throat in a 23-month-old child.23

Nail involvement has been reported in 10% of cases of inflammatory conditions such as lichen planus21; however, it may be more common but underrecognized and underreported. Grover et al9 indicated that lichen planus–induced severe inflammation in the matrix of the nail unit leading to a temporary growth arrest was the possible mechanism leading to nail shedding. Prompt systemic and intramatricial steroid treatment of lichen planus is required to avoid potential scarring of the nail matrix and permanent damage.9

Onychomadesis also has been reported following varicella infection (chickenpox). Podder et al19 reported the case of a 7-year-old girl who had recovered from a varicella infection 5 weeks prior and presented with onychomadesis of the right index fingernail with all other fingernails and toenails appearing normal. Kocak and Koçak5 reported onychomadesis in 2 sisters with varicella infection. There are few reported cases, so it is still unclear whether varicella infection is an inciting factor.19