User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Relapsing Polychondritis With Meningoencephalitis

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is an autoimmune disease affecting cartilaginous structures such as the ears, respiratory passages, joints, and cardiovascular system.1,2 In rare cases, the systemic effects of this autoimmune process can cause central nervous system (CNS) involvement such as meningoencephalitis (ME).3 In 2011, Wang et al4 described 4 cases of RP with ME and reviewed 24 cases from the literature. We present a case of a man with RP-associated ME that was responsive to steroid treatment. We also provide an updated review of the literature.

Case Report

A 44-year-old man developed gradually worsening bilateral ear pain, headaches, and seizures. He was briefly hospitalized and discharged with levetiracetam and quetiapine. However, his mental status continued to deteriorate and he was subsequently hospitalized 3 months later with confusion, hallucinations, and seizures.

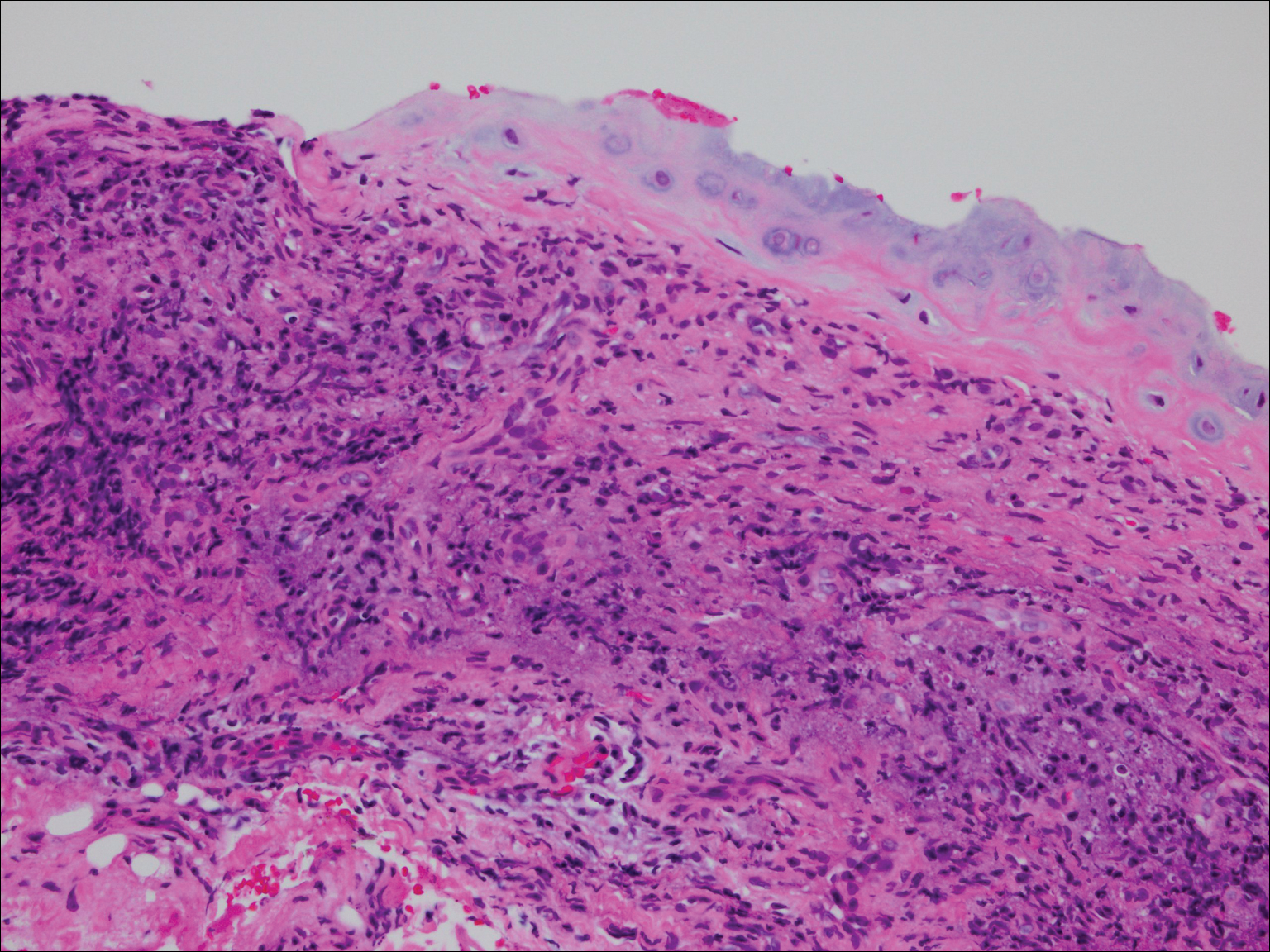

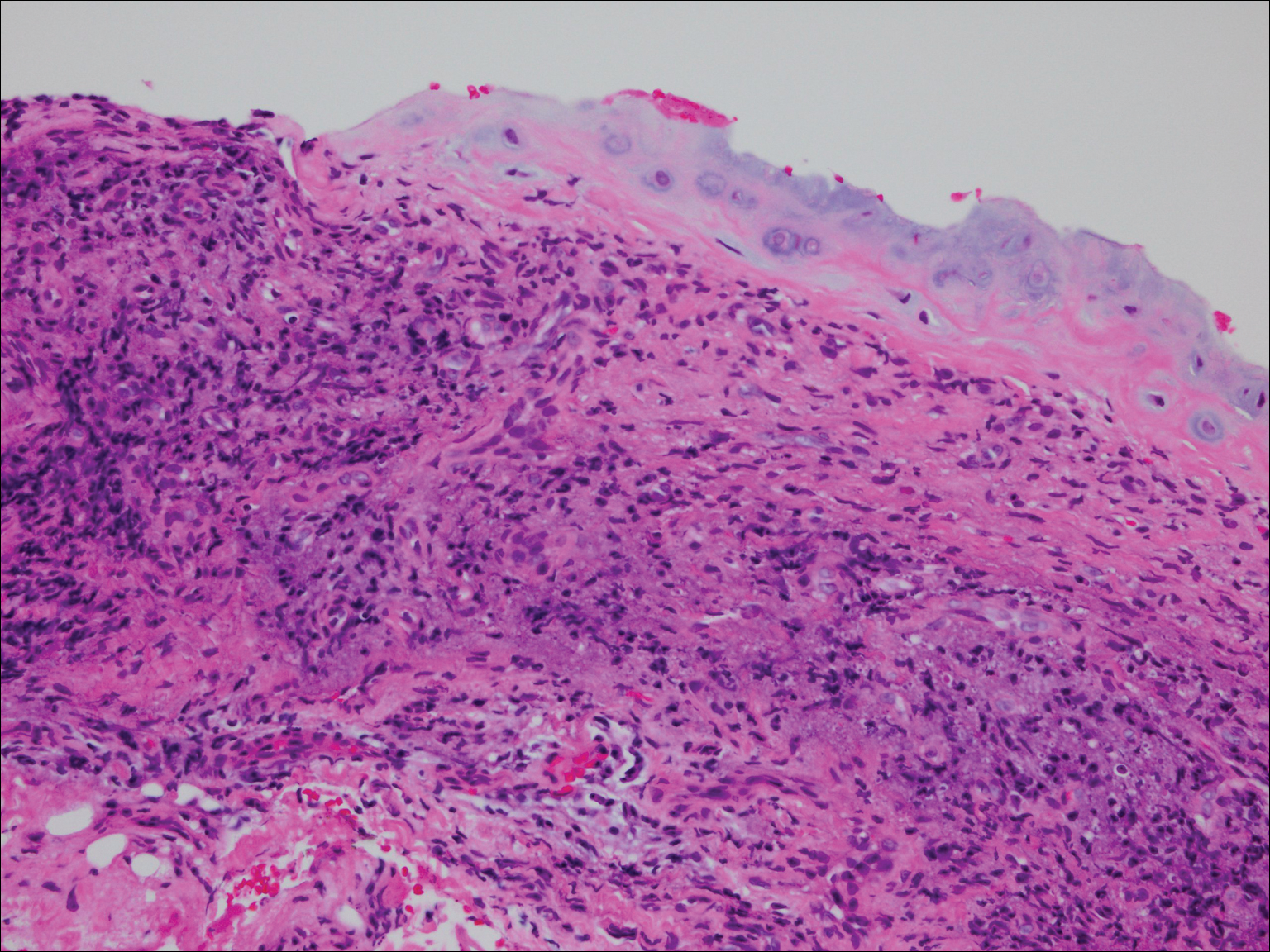

On physical examination the patient was disoriented and unable to form cohesive sentences. He had bilateral tenderness, erythema, and edema of the auricles, which notably spared the lobules (Figure 1). The conjunctivae were injected bilaterally, and joint involvement included bilateral knee tenderness and swelling. Neurologic examination revealed questionable meningeal signs but no motor or sensory deficits. An extensive laboratory workup for the etiology of his altered mental status was unremarkable, except for a mildly elevated white blood cell count in the cerebrospinal fluid with predominantly lymphocytes. No infectious etiologies were identified on laboratory testing, and rheumatologic markers were negative including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen A/Sjögren syndrome antigen B. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed nonspecific findings of bilateral T2 hyperdensities in the subcortical white matter; however, cerebral angiography revealed no evidence of vasculitis. A biopsy of the right antihelix revealed prominent perichondritis and a neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate with several lymphocytes and histiocytes (Figure 2). There was degeneration of the cartilaginous tissue with evidence of pyknotic nuclei, eosinophilia, and vacuolization of the chondrocytes. He was diagnosed with RP on the basis of clinical and histologic inflammation of the auricular cartilage, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation.

The patient was treated with high-dose immunosuppression with methylprednisolone (1000 mg intravenous once daily for 5 days) and cyclophosphamide (one dose at 500 mg/m2), which resulted in remarkable improvement in his mental status, auricular inflammation, and knee pain. After 31 days of hospitalization the patient was discharged with a course of oral prednisone (starting at 60 mg/d, then tapered over the following 2 months) and monthly cyclophosphamide infusions (5 months total; starting at 500 mg/m2, then uptitrated to goal of 1000 mg/m2). Maintenance suppression was achieved with azathioprine (starting at 50 mg daily, then uptitrated to 100 mg daily), which was continued without any evidence of relapsed disease through his last outpatient visit 1 year after the diagnosis.

Comment

Auricular inflammation is a hallmark of RP and is present in 83% to 95% of patients.1,3 The affected ears can appear erythematous to violaceous with tender edema of the auricle that spares the lobules where no cartilage is present. The inflammation can extend into the ear canal and cause hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo. Histologically, RP can present with a nonspecific leukocytoclastic vasculitis and inflammatory destruction of the cartilage. Therefore, diagnosis of RP is reliant mainly on clinical characteristics rather than pathologic findings. In 1976, McAdam et al5 established diagnostic criteria for RP based on the presence of common clinical manifestations (eg, auricular chondritis, seronegative inflammatory polyarthritis, nasal chondritis, ocular inflammation). Michet et al6 later proposed major and minor criteria to classify and diagnose RP based on clinical manifestations. Diagnosis of our patient was confirmed by the presence of auricular chondritis, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation. Diagnosing RP can be difficult because it has many systemic manifestations that can evoke a broad differential diagnosis. The time to diagnosis in our patient was 3 months, but the mean delay in diagnosis for patients with RP and ME is 2.9 years.4

The etiology of RP remains unclear, but current evidence supports an immune-mediated process directed toward proteins found in cartilage. Animal studies have suggested that RP may be driven by antibodies to matrillin 1 and type II collagen. There also may be a familial association with HLA-DR4 and genetic predisposition to autoimmune diseases in individuals affected by RP.1,3 The pathogenesis of CNS involvement in RP is thought to be due to a localized small vessel vasculitis.7,8 In our patient, however, cerebral angiography was negative for vasculitis, and thus our case may represent another mechanism for CNS involvement. There have been cases of encephalitis in RP caused by pathways other than CNS vasculitis. Kashihara et al9 reported a case of RP with encephalitis associated with antiglutamate receptor antibodies found in the cerebrospinal fluid and blood.

Treatment of RP has been based on pathophysiological considerations rather than empiric data due to its rarity. Relapsing polychondritis has been responsive to steroid treatment in reported cases as well as in our patient; however, in cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, infliximab may be effective for RP with ME.10 Further research regarding the treatment outcomes of RP with ME may be warranted.

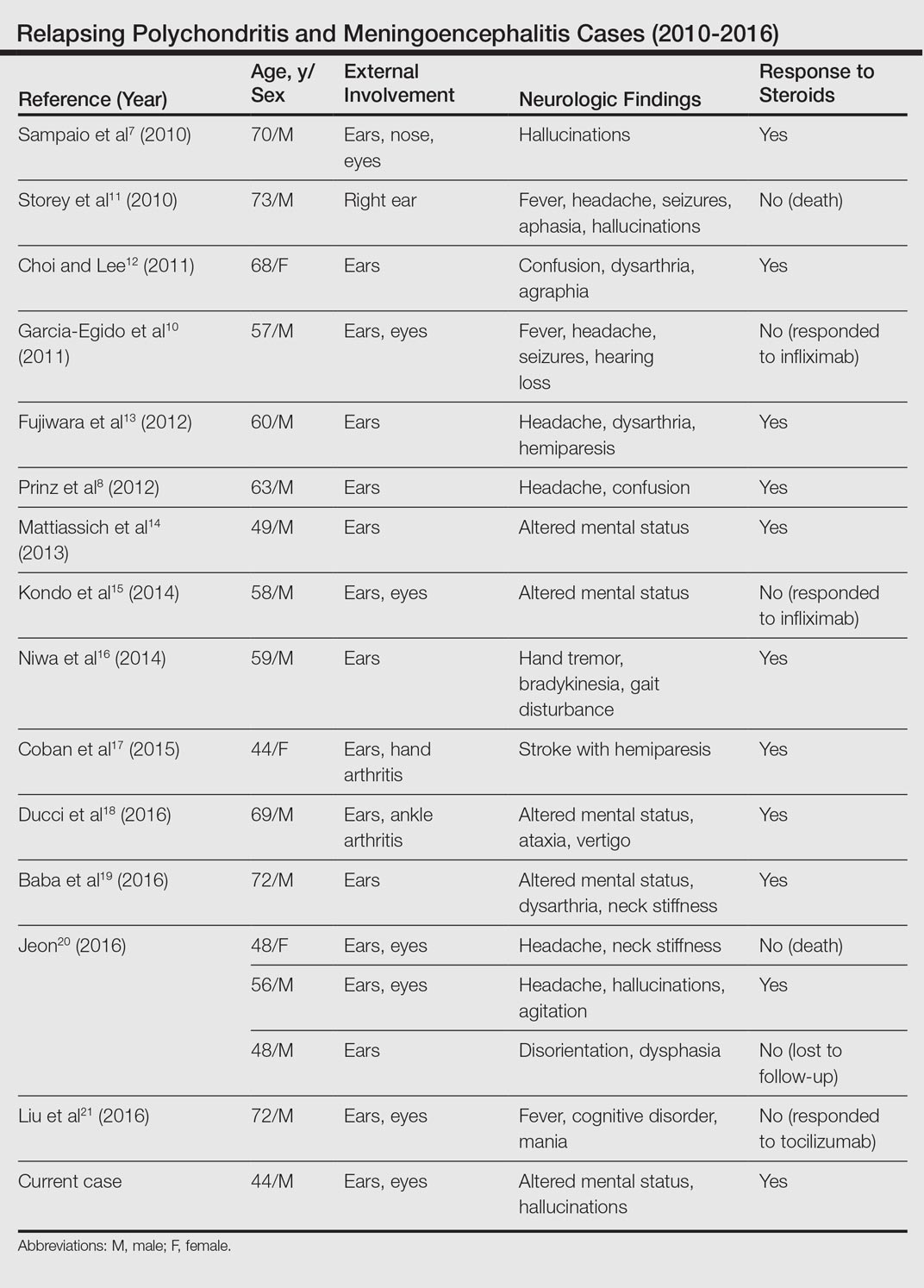

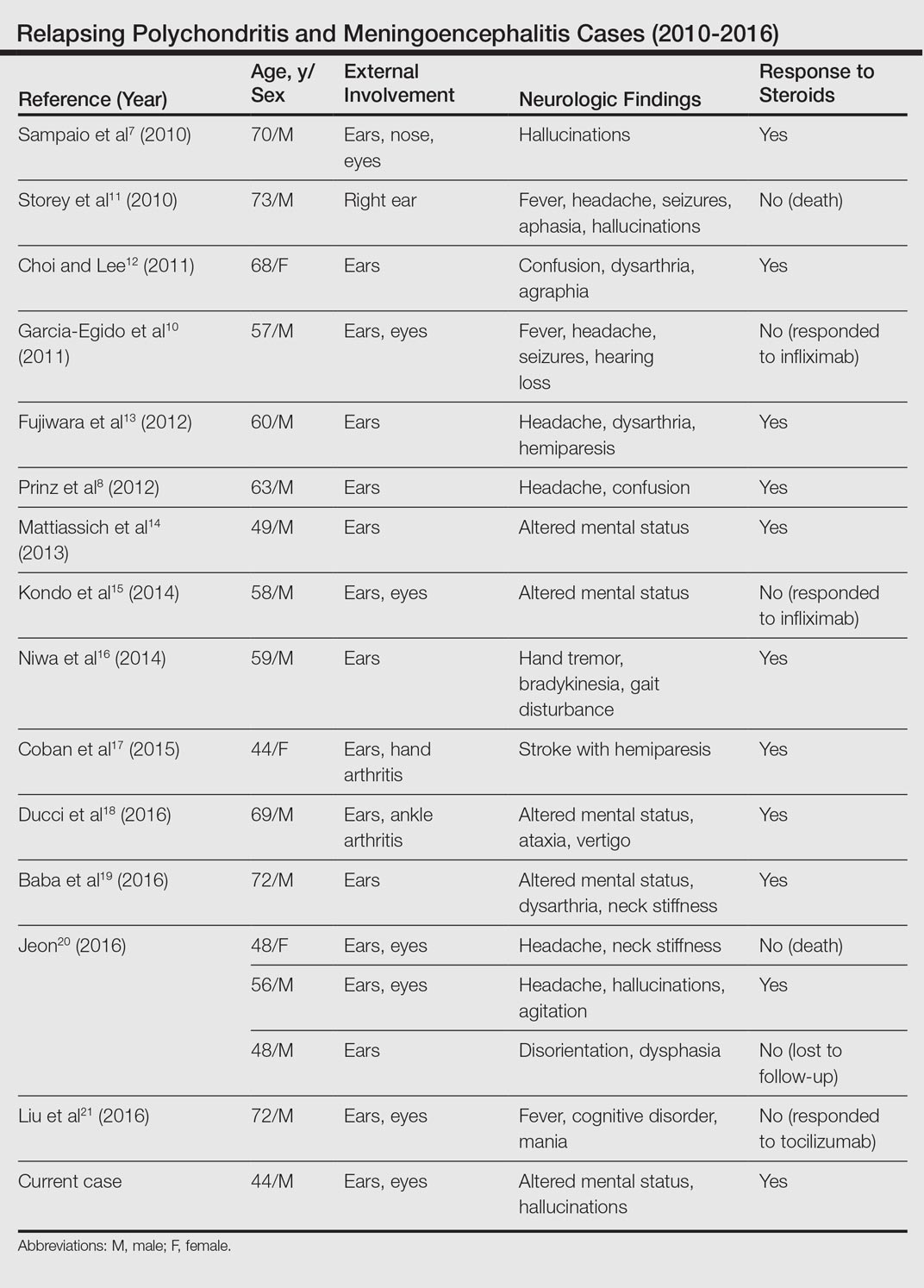

Although rare, additional cases of RP with ME have been reported (Table). Wang et al4 described a series of 28 patients with RP and ME from 1960 to 2010. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE that were published in the English-language literature from 2010 to 2016 was performed using the search terms relapsing polychondritis and nervous system. Including our patient, RP with ME was reported in 17 additional cases since Wang et al4 published their findings. These cases involved adults ranging in age from 44 to 73 years who were mainly men (14/17 [82%]). All of the patients presented with bilateral auricular chondritis, except for a case of unilateral ear involvement reported by Storey et al.11 Common neurologic manifestations included fever, headache, and altered mental status. Motor symptoms ranged from dysarthria and agraphia12 to hemiparesis.13 The mechanism of CNS involvement in RP was not identified in most cases; however, Mattiassich et al14 documented cerebral vasculitis in their patient, and Niwa et al16 found diffuse cerebral vasculitis on autopsy. Eleven of 17 (65%) cases responded to steroid treatment. Of the 6 cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, 2 patients died despite high-dose steroid treatment,11,20 2 responded to infliximab,10,15 1 responded to tocilizumab,21 and 1 was lost to follow-up after initial treatment failure.20

Conclusion

Although rare, RP should not be overlooked in the inpatient setting due to its potential for life-threatening systemic effects. Early diagnosis of this condition may be of benefit to this select population of patients, and further research regarding the prognosis, mechanisms, and treatment of RP may be necessary in the future.

- Arnaud L, Mathian A, Haroche J, et al. Pathogenesis of relapsing polychondritis: a 2013 update. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:90-95.

- Ostrowski RA, Takagishi T, Robinson J. Rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathies, and relapsing polychondritis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;119:449-461.

- Lahmer T, Treiber M, von Werder A, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: an autoimmune disease with many faces. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:540-546.

- Wang ZJ, Pu CQ, Wang ZJ, et al. Meningoencephalitis or meningitis in relapsing polychondritis: four case reports and a literature review. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:1608-1615.

- McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1976;55:193-215.

- Michet C, McKenna C, Luthra H, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: survival and predictive role of early disease manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:74-78.

- Sampaio L, Silva L, Mariz E, et al. CNS involvement in relapsing polychondritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:619-620.

- Prinz S, Dafotakis M, Schneider RK, et al. The red puffy ear sign—a clinical sign to diagnose a rare cause of meningoencephalitis. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2012;80:463-467.

- Kashihara K, Kawada S, Takahashi Y. Autoantibodies to glutamate receptor GluR2 in a patient with limic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;287:275-277.

- Garcia-Egido A, Gutierrez C, de la Fuente C, et al. Relapsing polychondritis-associated meningitis and encephalitis: response to infliximab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:1721-1723.

- Storey K, Matej R, Rusina R. Unusual association of seronegative, nonparaneoplastic limbic encephalitis and relapsing polychondritis in a patient with history of thymectomy for myasthemia: a case study. J Neurol. 2010;258:159-161.

- Choi HJ, Lee HJ. Relapsing polychondritis with encephalitis. J Clin Rheum. 2011;6:329-331.

- Fujiwara S, Zenke K, Iwata S, et al. Relapsing polychondritis presenting as encephalitis. No Shinkei Geka. 2012;40:247-253.

- Mattiassich G, Egger M, Semlitsch G, et al. Occurrence of relapsing polychondritis with a rising cANCA titre in a cANCA-positive systemic and cerebral vasculitis patient [published online February 5, 2013]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008717.

- Kondo T, Fukuta M, Takemoto A, et al. Limbic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis responded to infliximab and maintained its condition without recurrence after discontinuation: a case report and review of the literature. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2014;76:361-368.

- Niwa A, Okamoto Y, Kondo T, et al. Perivasculitic pancencephalitis with relapsing polychondritis: an autopsy case report and review of previous cases. Intern Med. 2014;53:1191-1195.

- Coban EK, Xanmemmedoy E, Colak M, et al. A rare complication of a rare disease; stroke due to relapsing polychondritis. Ideggyogy Sz. 2015;68:429-432.

- Ducci R, Germiniani F, Czecko L, et al. Relapsing polychondritis and lymphocytic meningitis with varied neurological symptoms [published online February 5, 2016]. Rev Bras Reumatol. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2015.09.005.

- Baba T, Kanno S, Shijo T, et al. Callosal disconnection syndrome associated with relapsing polychondritis. Intern Med. 2016;55:1191-1193.

- Jeon C. Relapsing polychondritis with central nervous system involvement: experience of three different cases in a single center. J Korean Med. 2016;31:1846-1850.

- Liu L, Liu S, Guan W, et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab for psychiatric symptoms associated with relapsing polychondritis: the first case report and review of the literature. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36:1185-1189.

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is an autoimmune disease affecting cartilaginous structures such as the ears, respiratory passages, joints, and cardiovascular system.1,2 In rare cases, the systemic effects of this autoimmune process can cause central nervous system (CNS) involvement such as meningoencephalitis (ME).3 In 2011, Wang et al4 described 4 cases of RP with ME and reviewed 24 cases from the literature. We present a case of a man with RP-associated ME that was responsive to steroid treatment. We also provide an updated review of the literature.

Case Report

A 44-year-old man developed gradually worsening bilateral ear pain, headaches, and seizures. He was briefly hospitalized and discharged with levetiracetam and quetiapine. However, his mental status continued to deteriorate and he was subsequently hospitalized 3 months later with confusion, hallucinations, and seizures.

On physical examination the patient was disoriented and unable to form cohesive sentences. He had bilateral tenderness, erythema, and edema of the auricles, which notably spared the lobules (Figure 1). The conjunctivae were injected bilaterally, and joint involvement included bilateral knee tenderness and swelling. Neurologic examination revealed questionable meningeal signs but no motor or sensory deficits. An extensive laboratory workup for the etiology of his altered mental status was unremarkable, except for a mildly elevated white blood cell count in the cerebrospinal fluid with predominantly lymphocytes. No infectious etiologies were identified on laboratory testing, and rheumatologic markers were negative including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen A/Sjögren syndrome antigen B. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed nonspecific findings of bilateral T2 hyperdensities in the subcortical white matter; however, cerebral angiography revealed no evidence of vasculitis. A biopsy of the right antihelix revealed prominent perichondritis and a neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate with several lymphocytes and histiocytes (Figure 2). There was degeneration of the cartilaginous tissue with evidence of pyknotic nuclei, eosinophilia, and vacuolization of the chondrocytes. He was diagnosed with RP on the basis of clinical and histologic inflammation of the auricular cartilage, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation.

The patient was treated with high-dose immunosuppression with methylprednisolone (1000 mg intravenous once daily for 5 days) and cyclophosphamide (one dose at 500 mg/m2), which resulted in remarkable improvement in his mental status, auricular inflammation, and knee pain. After 31 days of hospitalization the patient was discharged with a course of oral prednisone (starting at 60 mg/d, then tapered over the following 2 months) and monthly cyclophosphamide infusions (5 months total; starting at 500 mg/m2, then uptitrated to goal of 1000 mg/m2). Maintenance suppression was achieved with azathioprine (starting at 50 mg daily, then uptitrated to 100 mg daily), which was continued without any evidence of relapsed disease through his last outpatient visit 1 year after the diagnosis.

Comment

Auricular inflammation is a hallmark of RP and is present in 83% to 95% of patients.1,3 The affected ears can appear erythematous to violaceous with tender edema of the auricle that spares the lobules where no cartilage is present. The inflammation can extend into the ear canal and cause hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo. Histologically, RP can present with a nonspecific leukocytoclastic vasculitis and inflammatory destruction of the cartilage. Therefore, diagnosis of RP is reliant mainly on clinical characteristics rather than pathologic findings. In 1976, McAdam et al5 established diagnostic criteria for RP based on the presence of common clinical manifestations (eg, auricular chondritis, seronegative inflammatory polyarthritis, nasal chondritis, ocular inflammation). Michet et al6 later proposed major and minor criteria to classify and diagnose RP based on clinical manifestations. Diagnosis of our patient was confirmed by the presence of auricular chondritis, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation. Diagnosing RP can be difficult because it has many systemic manifestations that can evoke a broad differential diagnosis. The time to diagnosis in our patient was 3 months, but the mean delay in diagnosis for patients with RP and ME is 2.9 years.4

The etiology of RP remains unclear, but current evidence supports an immune-mediated process directed toward proteins found in cartilage. Animal studies have suggested that RP may be driven by antibodies to matrillin 1 and type II collagen. There also may be a familial association with HLA-DR4 and genetic predisposition to autoimmune diseases in individuals affected by RP.1,3 The pathogenesis of CNS involvement in RP is thought to be due to a localized small vessel vasculitis.7,8 In our patient, however, cerebral angiography was negative for vasculitis, and thus our case may represent another mechanism for CNS involvement. There have been cases of encephalitis in RP caused by pathways other than CNS vasculitis. Kashihara et al9 reported a case of RP with encephalitis associated with antiglutamate receptor antibodies found in the cerebrospinal fluid and blood.

Treatment of RP has been based on pathophysiological considerations rather than empiric data due to its rarity. Relapsing polychondritis has been responsive to steroid treatment in reported cases as well as in our patient; however, in cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, infliximab may be effective for RP with ME.10 Further research regarding the treatment outcomes of RP with ME may be warranted.

Although rare, additional cases of RP with ME have been reported (Table). Wang et al4 described a series of 28 patients with RP and ME from 1960 to 2010. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE that were published in the English-language literature from 2010 to 2016 was performed using the search terms relapsing polychondritis and nervous system. Including our patient, RP with ME was reported in 17 additional cases since Wang et al4 published their findings. These cases involved adults ranging in age from 44 to 73 years who were mainly men (14/17 [82%]). All of the patients presented with bilateral auricular chondritis, except for a case of unilateral ear involvement reported by Storey et al.11 Common neurologic manifestations included fever, headache, and altered mental status. Motor symptoms ranged from dysarthria and agraphia12 to hemiparesis.13 The mechanism of CNS involvement in RP was not identified in most cases; however, Mattiassich et al14 documented cerebral vasculitis in their patient, and Niwa et al16 found diffuse cerebral vasculitis on autopsy. Eleven of 17 (65%) cases responded to steroid treatment. Of the 6 cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, 2 patients died despite high-dose steroid treatment,11,20 2 responded to infliximab,10,15 1 responded to tocilizumab,21 and 1 was lost to follow-up after initial treatment failure.20

Conclusion

Although rare, RP should not be overlooked in the inpatient setting due to its potential for life-threatening systemic effects. Early diagnosis of this condition may be of benefit to this select population of patients, and further research regarding the prognosis, mechanisms, and treatment of RP may be necessary in the future.

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is an autoimmune disease affecting cartilaginous structures such as the ears, respiratory passages, joints, and cardiovascular system.1,2 In rare cases, the systemic effects of this autoimmune process can cause central nervous system (CNS) involvement such as meningoencephalitis (ME).3 In 2011, Wang et al4 described 4 cases of RP with ME and reviewed 24 cases from the literature. We present a case of a man with RP-associated ME that was responsive to steroid treatment. We also provide an updated review of the literature.

Case Report

A 44-year-old man developed gradually worsening bilateral ear pain, headaches, and seizures. He was briefly hospitalized and discharged with levetiracetam and quetiapine. However, his mental status continued to deteriorate and he was subsequently hospitalized 3 months later with confusion, hallucinations, and seizures.

On physical examination the patient was disoriented and unable to form cohesive sentences. He had bilateral tenderness, erythema, and edema of the auricles, which notably spared the lobules (Figure 1). The conjunctivae were injected bilaterally, and joint involvement included bilateral knee tenderness and swelling. Neurologic examination revealed questionable meningeal signs but no motor or sensory deficits. An extensive laboratory workup for the etiology of his altered mental status was unremarkable, except for a mildly elevated white blood cell count in the cerebrospinal fluid with predominantly lymphocytes. No infectious etiologies were identified on laboratory testing, and rheumatologic markers were negative including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen A/Sjögren syndrome antigen B. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed nonspecific findings of bilateral T2 hyperdensities in the subcortical white matter; however, cerebral angiography revealed no evidence of vasculitis. A biopsy of the right antihelix revealed prominent perichondritis and a neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate with several lymphocytes and histiocytes (Figure 2). There was degeneration of the cartilaginous tissue with evidence of pyknotic nuclei, eosinophilia, and vacuolization of the chondrocytes. He was diagnosed with RP on the basis of clinical and histologic inflammation of the auricular cartilage, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation.

The patient was treated with high-dose immunosuppression with methylprednisolone (1000 mg intravenous once daily for 5 days) and cyclophosphamide (one dose at 500 mg/m2), which resulted in remarkable improvement in his mental status, auricular inflammation, and knee pain. After 31 days of hospitalization the patient was discharged with a course of oral prednisone (starting at 60 mg/d, then tapered over the following 2 months) and monthly cyclophosphamide infusions (5 months total; starting at 500 mg/m2, then uptitrated to goal of 1000 mg/m2). Maintenance suppression was achieved with azathioprine (starting at 50 mg daily, then uptitrated to 100 mg daily), which was continued without any evidence of relapsed disease through his last outpatient visit 1 year after the diagnosis.

Comment

Auricular inflammation is a hallmark of RP and is present in 83% to 95% of patients.1,3 The affected ears can appear erythematous to violaceous with tender edema of the auricle that spares the lobules where no cartilage is present. The inflammation can extend into the ear canal and cause hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo. Histologically, RP can present with a nonspecific leukocytoclastic vasculitis and inflammatory destruction of the cartilage. Therefore, diagnosis of RP is reliant mainly on clinical characteristics rather than pathologic findings. In 1976, McAdam et al5 established diagnostic criteria for RP based on the presence of common clinical manifestations (eg, auricular chondritis, seronegative inflammatory polyarthritis, nasal chondritis, ocular inflammation). Michet et al6 later proposed major and minor criteria to classify and diagnose RP based on clinical manifestations. Diagnosis of our patient was confirmed by the presence of auricular chondritis, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation. Diagnosing RP can be difficult because it has many systemic manifestations that can evoke a broad differential diagnosis. The time to diagnosis in our patient was 3 months, but the mean delay in diagnosis for patients with RP and ME is 2.9 years.4

The etiology of RP remains unclear, but current evidence supports an immune-mediated process directed toward proteins found in cartilage. Animal studies have suggested that RP may be driven by antibodies to matrillin 1 and type II collagen. There also may be a familial association with HLA-DR4 and genetic predisposition to autoimmune diseases in individuals affected by RP.1,3 The pathogenesis of CNS involvement in RP is thought to be due to a localized small vessel vasculitis.7,8 In our patient, however, cerebral angiography was negative for vasculitis, and thus our case may represent another mechanism for CNS involvement. There have been cases of encephalitis in RP caused by pathways other than CNS vasculitis. Kashihara et al9 reported a case of RP with encephalitis associated with antiglutamate receptor antibodies found in the cerebrospinal fluid and blood.

Treatment of RP has been based on pathophysiological considerations rather than empiric data due to its rarity. Relapsing polychondritis has been responsive to steroid treatment in reported cases as well as in our patient; however, in cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, infliximab may be effective for RP with ME.10 Further research regarding the treatment outcomes of RP with ME may be warranted.

Although rare, additional cases of RP with ME have been reported (Table). Wang et al4 described a series of 28 patients with RP and ME from 1960 to 2010. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE that were published in the English-language literature from 2010 to 2016 was performed using the search terms relapsing polychondritis and nervous system. Including our patient, RP with ME was reported in 17 additional cases since Wang et al4 published their findings. These cases involved adults ranging in age from 44 to 73 years who were mainly men (14/17 [82%]). All of the patients presented with bilateral auricular chondritis, except for a case of unilateral ear involvement reported by Storey et al.11 Common neurologic manifestations included fever, headache, and altered mental status. Motor symptoms ranged from dysarthria and agraphia12 to hemiparesis.13 The mechanism of CNS involvement in RP was not identified in most cases; however, Mattiassich et al14 documented cerebral vasculitis in their patient, and Niwa et al16 found diffuse cerebral vasculitis on autopsy. Eleven of 17 (65%) cases responded to steroid treatment. Of the 6 cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, 2 patients died despite high-dose steroid treatment,11,20 2 responded to infliximab,10,15 1 responded to tocilizumab,21 and 1 was lost to follow-up after initial treatment failure.20

Conclusion

Although rare, RP should not be overlooked in the inpatient setting due to its potential for life-threatening systemic effects. Early diagnosis of this condition may be of benefit to this select population of patients, and further research regarding the prognosis, mechanisms, and treatment of RP may be necessary in the future.

- Arnaud L, Mathian A, Haroche J, et al. Pathogenesis of relapsing polychondritis: a 2013 update. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:90-95.

- Ostrowski RA, Takagishi T, Robinson J. Rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathies, and relapsing polychondritis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;119:449-461.

- Lahmer T, Treiber M, von Werder A, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: an autoimmune disease with many faces. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:540-546.

- Wang ZJ, Pu CQ, Wang ZJ, et al. Meningoencephalitis or meningitis in relapsing polychondritis: four case reports and a literature review. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:1608-1615.

- McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1976;55:193-215.

- Michet C, McKenna C, Luthra H, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: survival and predictive role of early disease manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:74-78.

- Sampaio L, Silva L, Mariz E, et al. CNS involvement in relapsing polychondritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:619-620.

- Prinz S, Dafotakis M, Schneider RK, et al. The red puffy ear sign—a clinical sign to diagnose a rare cause of meningoencephalitis. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2012;80:463-467.

- Kashihara K, Kawada S, Takahashi Y. Autoantibodies to glutamate receptor GluR2 in a patient with limic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;287:275-277.

- Garcia-Egido A, Gutierrez C, de la Fuente C, et al. Relapsing polychondritis-associated meningitis and encephalitis: response to infliximab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:1721-1723.

- Storey K, Matej R, Rusina R. Unusual association of seronegative, nonparaneoplastic limbic encephalitis and relapsing polychondritis in a patient with history of thymectomy for myasthemia: a case study. J Neurol. 2010;258:159-161.

- Choi HJ, Lee HJ. Relapsing polychondritis with encephalitis. J Clin Rheum. 2011;6:329-331.

- Fujiwara S, Zenke K, Iwata S, et al. Relapsing polychondritis presenting as encephalitis. No Shinkei Geka. 2012;40:247-253.

- Mattiassich G, Egger M, Semlitsch G, et al. Occurrence of relapsing polychondritis with a rising cANCA titre in a cANCA-positive systemic and cerebral vasculitis patient [published online February 5, 2013]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008717.

- Kondo T, Fukuta M, Takemoto A, et al. Limbic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis responded to infliximab and maintained its condition without recurrence after discontinuation: a case report and review of the literature. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2014;76:361-368.

- Niwa A, Okamoto Y, Kondo T, et al. Perivasculitic pancencephalitis with relapsing polychondritis: an autopsy case report and review of previous cases. Intern Med. 2014;53:1191-1195.

- Coban EK, Xanmemmedoy E, Colak M, et al. A rare complication of a rare disease; stroke due to relapsing polychondritis. Ideggyogy Sz. 2015;68:429-432.

- Ducci R, Germiniani F, Czecko L, et al. Relapsing polychondritis and lymphocytic meningitis with varied neurological symptoms [published online February 5, 2016]. Rev Bras Reumatol. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2015.09.005.

- Baba T, Kanno S, Shijo T, et al. Callosal disconnection syndrome associated with relapsing polychondritis. Intern Med. 2016;55:1191-1193.

- Jeon C. Relapsing polychondritis with central nervous system involvement: experience of three different cases in a single center. J Korean Med. 2016;31:1846-1850.

- Liu L, Liu S, Guan W, et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab for psychiatric symptoms associated with relapsing polychondritis: the first case report and review of the literature. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36:1185-1189.

- Arnaud L, Mathian A, Haroche J, et al. Pathogenesis of relapsing polychondritis: a 2013 update. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:90-95.

- Ostrowski RA, Takagishi T, Robinson J. Rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathies, and relapsing polychondritis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;119:449-461.

- Lahmer T, Treiber M, von Werder A, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: an autoimmune disease with many faces. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:540-546.

- Wang ZJ, Pu CQ, Wang ZJ, et al. Meningoencephalitis or meningitis in relapsing polychondritis: four case reports and a literature review. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:1608-1615.

- McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1976;55:193-215.

- Michet C, McKenna C, Luthra H, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: survival and predictive role of early disease manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:74-78.

- Sampaio L, Silva L, Mariz E, et al. CNS involvement in relapsing polychondritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:619-620.

- Prinz S, Dafotakis M, Schneider RK, et al. The red puffy ear sign—a clinical sign to diagnose a rare cause of meningoencephalitis. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2012;80:463-467.

- Kashihara K, Kawada S, Takahashi Y. Autoantibodies to glutamate receptor GluR2 in a patient with limic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;287:275-277.

- Garcia-Egido A, Gutierrez C, de la Fuente C, et al. Relapsing polychondritis-associated meningitis and encephalitis: response to infliximab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:1721-1723.

- Storey K, Matej R, Rusina R. Unusual association of seronegative, nonparaneoplastic limbic encephalitis and relapsing polychondritis in a patient with history of thymectomy for myasthemia: a case study. J Neurol. 2010;258:159-161.

- Choi HJ, Lee HJ. Relapsing polychondritis with encephalitis. J Clin Rheum. 2011;6:329-331.

- Fujiwara S, Zenke K, Iwata S, et al. Relapsing polychondritis presenting as encephalitis. No Shinkei Geka. 2012;40:247-253.

- Mattiassich G, Egger M, Semlitsch G, et al. Occurrence of relapsing polychondritis with a rising cANCA titre in a cANCA-positive systemic and cerebral vasculitis patient [published online February 5, 2013]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008717.

- Kondo T, Fukuta M, Takemoto A, et al. Limbic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis responded to infliximab and maintained its condition without recurrence after discontinuation: a case report and review of the literature. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2014;76:361-368.

- Niwa A, Okamoto Y, Kondo T, et al. Perivasculitic pancencephalitis with relapsing polychondritis: an autopsy case report and review of previous cases. Intern Med. 2014;53:1191-1195.

- Coban EK, Xanmemmedoy E, Colak M, et al. A rare complication of a rare disease; stroke due to relapsing polychondritis. Ideggyogy Sz. 2015;68:429-432.

- Ducci R, Germiniani F, Czecko L, et al. Relapsing polychondritis and lymphocytic meningitis with varied neurological symptoms [published online February 5, 2016]. Rev Bras Reumatol. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2015.09.005.

- Baba T, Kanno S, Shijo T, et al. Callosal disconnection syndrome associated with relapsing polychondritis. Intern Med. 2016;55:1191-1193.

- Jeon C. Relapsing polychondritis with central nervous system involvement: experience of three different cases in a single center. J Korean Med. 2016;31:1846-1850.

- Liu L, Liu S, Guan W, et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab for psychiatric symptoms associated with relapsing polychondritis: the first case report and review of the literature. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36:1185-1189.

Practice Points

- Meningoencephalitis (ME) is a potentially rare complication of relapsing polychondritis (RP).

- Treatment of ME due to RP can include high-dose steroids and biologics.

Clinicians Should Retain the Ability to Choose a Pathologist

As employers search for ways to reduce the cost of providing health care to their employees, there is a growing trend toward narrowed provider networks and exclusive laboratory contracts. In the case of clinical pathology, some of these choices make sense from the employer’s perspective. A complete blood cell count or comprehensive metabolic panel is done on a machine and the result is much the same regardless of the laboratory. So why not have all laboratory tests performed by the lowest bidder?

Laboratories vary in quality and anatomic pathology services are different from blood tests. Each slide must be interpreted by a physician and skill in the interpretation of skin specimens varies widely. Dermatopathology was one of the first subspecialties to be recognized within pathology, as it requires a high level of expertise. Clinicopathological correlation often is key to the accurate interpretation of a specimen. The stakes are high, and a delay in diagnosis of melanoma remains one of the most serious errors in medicine and one of the most common causes for litigation in dermatology.

The accurate interpretation of skin biopsy specimens becomes especially difficult when inadequate or misleading clinical information accompanies the specimen. A study of 589 biopsies submitted by primary care physicians and reported by general pathologists demonstrated a 6.5% error rate. False-negative errors were the most common, but false-positives also were observed.1 A study of pigmented lesions referred to the University of California, San Francisco, demonstrated a discordance rate of 14.3%.2 The degree of discordance would be expected to vary based on the range of diagnoses included in each study.

Board-certified dermatopathologists have varying areas of expertise and there is notable subjectivity in the interpretation of biopsy specimens. In the case of problematic pigmented lesions such as atypical Spitz nevi, there can be low interobserver agreement even among the experts in categorizing lesions as malignant versus nonmalignant (κ=0.30).3 The low concordance among expert dermatopathologists demonstrates that light microscopic features alone often are inadequate for diagnosis. Advanced studies, including immunohistochemical stains, can help to clarify the diagnosis. In the case of atypical Spitz tumors, the contribution of special stains to the final diagnosis is statistically similar to that of hematoxylin and eosin sections and age, suggesting that nothing alone is sufficiently reliable to establish a definitive diagnosis in every case.4 Although helpful, these studies are costly, and savings obtained by sending cases to the lowest bidder can evaporate quickly. Costs are higher when factoring in molecular studies, which can run upwards of $3000 per slide; the cost of litigation related to incorrect diagnoses; or the human costs of an incorrect diagnosis.

As a group, dermatopathologists are highly skilled in the interpretation of skin specimens, but challenging lesions are common in the routine practice of dermatopathology. A study of 1249 pigmented melanocytic lesions demonstrated substantial agreement among expert dermatopathologists for less problematic lesions, though agreement was greater for patients 40 years and older (κ=0.67) than for younger patients (κ=0.49). Agreement was lower for patients with atypical mole syndrome (κ=0.31).5 These discrepancies occur despite the fact that there is good interobserver reproducibility for grading of individual histological features such as asymmetry, circumscription, irregular confluent nests, single melanocytes predominating, absence of maturation, suprabasal melanocytes, symmetrical melanin, deep melanin, cytological atypia, mitoses, dermal lymphocytic infiltrate, and necrosis.6 These results indicate that accurate diagnoses cannot be reliably established simply by grading a list of histological features. Accurate diagnosis requires complex pattern recognition and integration of findings. Conflicting criteria often are present and an accurate interpretation requires considerable judgment as to which features are significant and which are not.

Separation of sebaceous adenoma, sebaceoma, and well-differentiated sebaceous carcinoma is another challenging area, and interobserver consensus can be as low as 11%,7 which suggests notable subjectivity in the criteria for diagnosis of nonmelanocytic tumors and emphasizes the importance of communication between the dermatopathologist and clinician when determining how to manage an ambiguous lesion. The interpretation of inflammatory skin diseases, alopecia, and lymphoid proliferations also can be problematic, and expert consultation often is required.

All dermatologists receive substantial training in dermatopathology, which puts them in an excellent position to interpret ambiguous findings in the context of the clinical presentation. Sometimes the dermatologist who has seen the clinical presentation can be in the best position to make the diagnosis. All clinicians must be wary of bias and an objective set of eyes often can be helpful. Communication is crucial to ensure appropriate care for each patient, and policies that restrict the choice of pathologist can be damaging.

- Trotter MJ, Bruecks AK. Interpretation of skin biopsies by general pathologists: diagnostic discrepancy rate measured by blinded review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1489-1492.

- Shoo BA, Sagebiel RW, Kashani-Sabet M. Discordance in the histopathologic diagnosis of melanoma at a melanoma referral center [published online March 19, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:751-756.

- Gerami P, Busam K, Cochran A, et al. Histomorphologic assessment and interobserver diagnostic reproducibility of atypical spitzoid melanocytic neoplasms with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:934-940.

- Puri PK, Ferringer TC, Tyler WB, et al. Statistical analysis of the concordance of immunohistochemical stains with the final diagnosis in spitzoid neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:72-77.

- Braun RP, Gutkowicz-Krusin D, Rabinovitz H, et al. Agreement of dermatopathologists in the evaluation of clinically difficult melanocytic lesions: how golden is the ‘gold standard’? Dermatology. 2012;224:51-58.

- Urso C, Rongioletti F, Innocenzi D, et al. Interobserver reproducibility of histological features in cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:1194-1198.

- Harvey NT, Budgeon CA, Leecy T, et al. Interobserver variability in the diagnosis of circumscribed sebaceous neoplasms of the skin. Pathology. 2013;45:581-586.

As employers search for ways to reduce the cost of providing health care to their employees, there is a growing trend toward narrowed provider networks and exclusive laboratory contracts. In the case of clinical pathology, some of these choices make sense from the employer’s perspective. A complete blood cell count or comprehensive metabolic panel is done on a machine and the result is much the same regardless of the laboratory. So why not have all laboratory tests performed by the lowest bidder?

Laboratories vary in quality and anatomic pathology services are different from blood tests. Each slide must be interpreted by a physician and skill in the interpretation of skin specimens varies widely. Dermatopathology was one of the first subspecialties to be recognized within pathology, as it requires a high level of expertise. Clinicopathological correlation often is key to the accurate interpretation of a specimen. The stakes are high, and a delay in diagnosis of melanoma remains one of the most serious errors in medicine and one of the most common causes for litigation in dermatology.

The accurate interpretation of skin biopsy specimens becomes especially difficult when inadequate or misleading clinical information accompanies the specimen. A study of 589 biopsies submitted by primary care physicians and reported by general pathologists demonstrated a 6.5% error rate. False-negative errors were the most common, but false-positives also were observed.1 A study of pigmented lesions referred to the University of California, San Francisco, demonstrated a discordance rate of 14.3%.2 The degree of discordance would be expected to vary based on the range of diagnoses included in each study.

Board-certified dermatopathologists have varying areas of expertise and there is notable subjectivity in the interpretation of biopsy specimens. In the case of problematic pigmented lesions such as atypical Spitz nevi, there can be low interobserver agreement even among the experts in categorizing lesions as malignant versus nonmalignant (κ=0.30).3 The low concordance among expert dermatopathologists demonstrates that light microscopic features alone often are inadequate for diagnosis. Advanced studies, including immunohistochemical stains, can help to clarify the diagnosis. In the case of atypical Spitz tumors, the contribution of special stains to the final diagnosis is statistically similar to that of hematoxylin and eosin sections and age, suggesting that nothing alone is sufficiently reliable to establish a definitive diagnosis in every case.4 Although helpful, these studies are costly, and savings obtained by sending cases to the lowest bidder can evaporate quickly. Costs are higher when factoring in molecular studies, which can run upwards of $3000 per slide; the cost of litigation related to incorrect diagnoses; or the human costs of an incorrect diagnosis.

As a group, dermatopathologists are highly skilled in the interpretation of skin specimens, but challenging lesions are common in the routine practice of dermatopathology. A study of 1249 pigmented melanocytic lesions demonstrated substantial agreement among expert dermatopathologists for less problematic lesions, though agreement was greater for patients 40 years and older (κ=0.67) than for younger patients (κ=0.49). Agreement was lower for patients with atypical mole syndrome (κ=0.31).5 These discrepancies occur despite the fact that there is good interobserver reproducibility for grading of individual histological features such as asymmetry, circumscription, irregular confluent nests, single melanocytes predominating, absence of maturation, suprabasal melanocytes, symmetrical melanin, deep melanin, cytological atypia, mitoses, dermal lymphocytic infiltrate, and necrosis.6 These results indicate that accurate diagnoses cannot be reliably established simply by grading a list of histological features. Accurate diagnosis requires complex pattern recognition and integration of findings. Conflicting criteria often are present and an accurate interpretation requires considerable judgment as to which features are significant and which are not.

Separation of sebaceous adenoma, sebaceoma, and well-differentiated sebaceous carcinoma is another challenging area, and interobserver consensus can be as low as 11%,7 which suggests notable subjectivity in the criteria for diagnosis of nonmelanocytic tumors and emphasizes the importance of communication between the dermatopathologist and clinician when determining how to manage an ambiguous lesion. The interpretation of inflammatory skin diseases, alopecia, and lymphoid proliferations also can be problematic, and expert consultation often is required.

All dermatologists receive substantial training in dermatopathology, which puts them in an excellent position to interpret ambiguous findings in the context of the clinical presentation. Sometimes the dermatologist who has seen the clinical presentation can be in the best position to make the diagnosis. All clinicians must be wary of bias and an objective set of eyes often can be helpful. Communication is crucial to ensure appropriate care for each patient, and policies that restrict the choice of pathologist can be damaging.

As employers search for ways to reduce the cost of providing health care to their employees, there is a growing trend toward narrowed provider networks and exclusive laboratory contracts. In the case of clinical pathology, some of these choices make sense from the employer’s perspective. A complete blood cell count or comprehensive metabolic panel is done on a machine and the result is much the same regardless of the laboratory. So why not have all laboratory tests performed by the lowest bidder?

Laboratories vary in quality and anatomic pathology services are different from blood tests. Each slide must be interpreted by a physician and skill in the interpretation of skin specimens varies widely. Dermatopathology was one of the first subspecialties to be recognized within pathology, as it requires a high level of expertise. Clinicopathological correlation often is key to the accurate interpretation of a specimen. The stakes are high, and a delay in diagnosis of melanoma remains one of the most serious errors in medicine and one of the most common causes for litigation in dermatology.

The accurate interpretation of skin biopsy specimens becomes especially difficult when inadequate or misleading clinical information accompanies the specimen. A study of 589 biopsies submitted by primary care physicians and reported by general pathologists demonstrated a 6.5% error rate. False-negative errors were the most common, but false-positives also were observed.1 A study of pigmented lesions referred to the University of California, San Francisco, demonstrated a discordance rate of 14.3%.2 The degree of discordance would be expected to vary based on the range of diagnoses included in each study.

Board-certified dermatopathologists have varying areas of expertise and there is notable subjectivity in the interpretation of biopsy specimens. In the case of problematic pigmented lesions such as atypical Spitz nevi, there can be low interobserver agreement even among the experts in categorizing lesions as malignant versus nonmalignant (κ=0.30).3 The low concordance among expert dermatopathologists demonstrates that light microscopic features alone often are inadequate for diagnosis. Advanced studies, including immunohistochemical stains, can help to clarify the diagnosis. In the case of atypical Spitz tumors, the contribution of special stains to the final diagnosis is statistically similar to that of hematoxylin and eosin sections and age, suggesting that nothing alone is sufficiently reliable to establish a definitive diagnosis in every case.4 Although helpful, these studies are costly, and savings obtained by sending cases to the lowest bidder can evaporate quickly. Costs are higher when factoring in molecular studies, which can run upwards of $3000 per slide; the cost of litigation related to incorrect diagnoses; or the human costs of an incorrect diagnosis.

As a group, dermatopathologists are highly skilled in the interpretation of skin specimens, but challenging lesions are common in the routine practice of dermatopathology. A study of 1249 pigmented melanocytic lesions demonstrated substantial agreement among expert dermatopathologists for less problematic lesions, though agreement was greater for patients 40 years and older (κ=0.67) than for younger patients (κ=0.49). Agreement was lower for patients with atypical mole syndrome (κ=0.31).5 These discrepancies occur despite the fact that there is good interobserver reproducibility for grading of individual histological features such as asymmetry, circumscription, irregular confluent nests, single melanocytes predominating, absence of maturation, suprabasal melanocytes, symmetrical melanin, deep melanin, cytological atypia, mitoses, dermal lymphocytic infiltrate, and necrosis.6 These results indicate that accurate diagnoses cannot be reliably established simply by grading a list of histological features. Accurate diagnosis requires complex pattern recognition and integration of findings. Conflicting criteria often are present and an accurate interpretation requires considerable judgment as to which features are significant and which are not.

Separation of sebaceous adenoma, sebaceoma, and well-differentiated sebaceous carcinoma is another challenging area, and interobserver consensus can be as low as 11%,7 which suggests notable subjectivity in the criteria for diagnosis of nonmelanocytic tumors and emphasizes the importance of communication between the dermatopathologist and clinician when determining how to manage an ambiguous lesion. The interpretation of inflammatory skin diseases, alopecia, and lymphoid proliferations also can be problematic, and expert consultation often is required.

All dermatologists receive substantial training in dermatopathology, which puts them in an excellent position to interpret ambiguous findings in the context of the clinical presentation. Sometimes the dermatologist who has seen the clinical presentation can be in the best position to make the diagnosis. All clinicians must be wary of bias and an objective set of eyes often can be helpful. Communication is crucial to ensure appropriate care for each patient, and policies that restrict the choice of pathologist can be damaging.

- Trotter MJ, Bruecks AK. Interpretation of skin biopsies by general pathologists: diagnostic discrepancy rate measured by blinded review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1489-1492.

- Shoo BA, Sagebiel RW, Kashani-Sabet M. Discordance in the histopathologic diagnosis of melanoma at a melanoma referral center [published online March 19, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:751-756.

- Gerami P, Busam K, Cochran A, et al. Histomorphologic assessment and interobserver diagnostic reproducibility of atypical spitzoid melanocytic neoplasms with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:934-940.

- Puri PK, Ferringer TC, Tyler WB, et al. Statistical analysis of the concordance of immunohistochemical stains with the final diagnosis in spitzoid neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:72-77.

- Braun RP, Gutkowicz-Krusin D, Rabinovitz H, et al. Agreement of dermatopathologists in the evaluation of clinically difficult melanocytic lesions: how golden is the ‘gold standard’? Dermatology. 2012;224:51-58.

- Urso C, Rongioletti F, Innocenzi D, et al. Interobserver reproducibility of histological features in cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:1194-1198.

- Harvey NT, Budgeon CA, Leecy T, et al. Interobserver variability in the diagnosis of circumscribed sebaceous neoplasms of the skin. Pathology. 2013;45:581-586.

- Trotter MJ, Bruecks AK. Interpretation of skin biopsies by general pathologists: diagnostic discrepancy rate measured by blinded review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1489-1492.

- Shoo BA, Sagebiel RW, Kashani-Sabet M. Discordance in the histopathologic diagnosis of melanoma at a melanoma referral center [published online March 19, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:751-756.

- Gerami P, Busam K, Cochran A, et al. Histomorphologic assessment and interobserver diagnostic reproducibility of atypical spitzoid melanocytic neoplasms with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:934-940.

- Puri PK, Ferringer TC, Tyler WB, et al. Statistical analysis of the concordance of immunohistochemical stains with the final diagnosis in spitzoid neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:72-77.

- Braun RP, Gutkowicz-Krusin D, Rabinovitz H, et al. Agreement of dermatopathologists in the evaluation of clinically difficult melanocytic lesions: how golden is the ‘gold standard’? Dermatology. 2012;224:51-58.

- Urso C, Rongioletti F, Innocenzi D, et al. Interobserver reproducibility of histological features in cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:1194-1198.

- Harvey NT, Budgeon CA, Leecy T, et al. Interobserver variability in the diagnosis of circumscribed sebaceous neoplasms of the skin. Pathology. 2013;45:581-586.

Papillary Transitional Cell Bladder Carcinoma and Systematized Epidermal Nevus Syndrome

Epidermal nevi can occur in isolation or in association with internal abnormalities. Epidermal nevus syndrome (ENS) is a heterogeneous group of neurocutaneous disorders characterized by mosaicism and epidermal nevi found in association with various systemic abnormalities.1-4 There are many possible associated systemic findings, including abnormalities of the central nervous, musculoskeletal, renal, and hematologic systems. Epidermal nevi have been associated with internal malignancies. We present the case of a patient with epidermal nevi associated with papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms transitional cell bladder carcinoma and epidermal nevus, there have only been 4 other cases of transitional cell bladder carcinoma and ENS reported in the literature,5-8 2 of which were reports of papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma.5,6

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a rash that had been present since 3 years of age. The emergency department consulted dermatology for evaluation of what was believed to be contact dermatitis; however, upon questioning the patient, it was revealed that the rash was chronic and persistent.

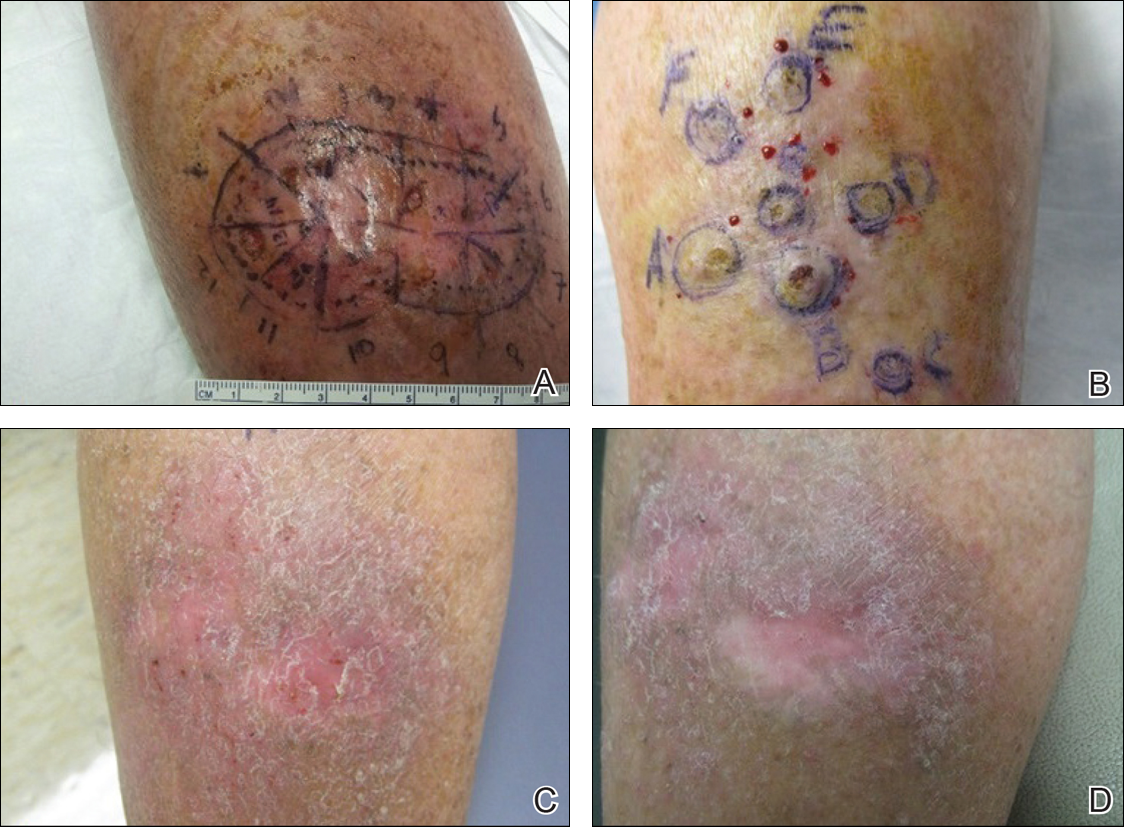

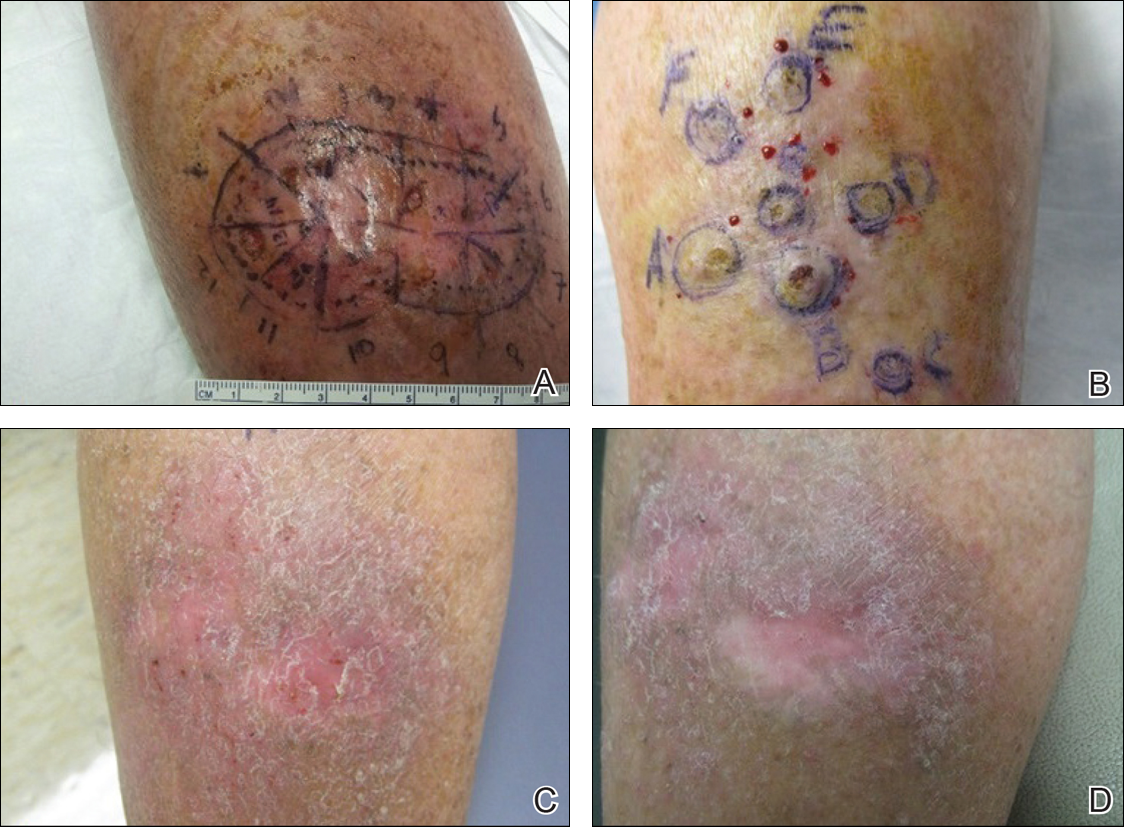

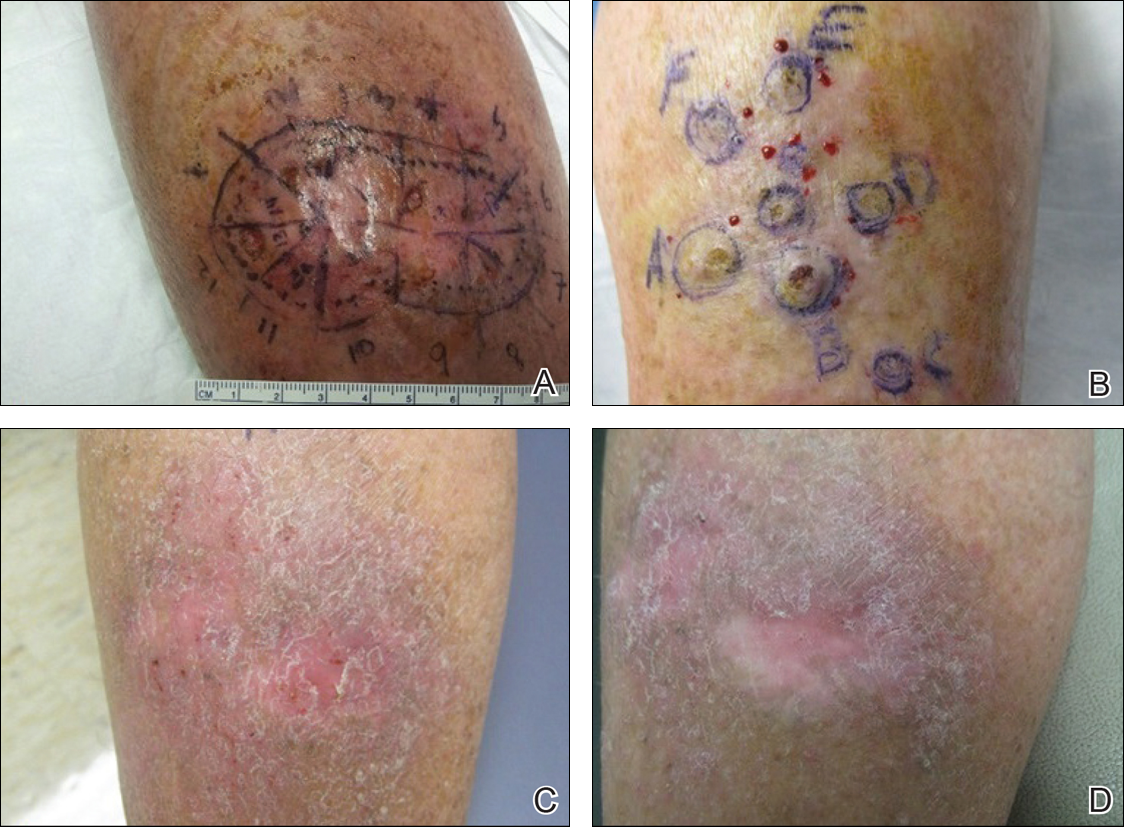

The rash was nonpruritic and was located on the face, hands (Figure 1), chest, buttocks, thighs, legs, and back (Figure 2). Although asymptomatic, the appearance of the skin caused the patient some emotional distress. As a child she had been evaluated by a dermatologist and a biopsy was performed, but she did not recall the results or have any records. She had been prescribed an oral medication by the dermatologist, but treatment was terminated early due to nausea. The skin lesions did not improve with the short course of treatment.

Eighteen months prior to presentation to our clinic, the patient was discovered to have hematuria on routine examination by her primary care physician. At that time, the patient underwent a workup for hematuria and a mass was discovered in the bladder via cystoscopy. A diagnosis of low-grade papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma was made, and she underwent a partial cystectomy. No radiation or chemotherapy was required. The remainder of her medical history was only remarkable for asthma, which was well controlled with albuterol. On examination, generalized, hyperpigmented, reticulated patches, macules, and hyperpigmented verrucous plaques were distributed along the Blaschko lines, sparing the face. No limb abnormalities or dental or nail abnormalities were noted. Examination of the axillary and cervical lymph nodes was unremarkable, and no neurological abnormalities were noted. A 3-mm punch biopsy of the mid upper back was performed. Histopathology revealed papillomatous, nonorganoid, nonepidermolytic hyperplasia of the epidermis with elongated rete ridges (Figure 3), which was diagnosed as a nonorganoid nonepidermolytic epidermal nevus.

Comment

Epidermal nevus syndrome is a group of disorders characterized by both local or systematized epidermal nevi and systemic findings. Solomon et al4 first coined the term epidermal nevus syndrome more than 40 years ago; however, since then there has been confusion about how to define ENS. Epidermal nevus syndrome has been considered an umbrella term that includes more specific syndromes involving epidermal nevi, such as Proteus syndrome and Schimmelpenning syndrome; conversely, it also has been considered a term for those who do not meet the criteria for more specific syndromes.1,9 Happle1 discussed that the genetic variations found in ENS warrant recognition. Simply put, ENS is a heterogeneous group of syndromes that are similar in that they involve epidermal nevi and internal abnormalities but are genetically distinct. The list of definitive ENSs, as suggested by Happle1 and others, will likely continue to grow.3,5

The exact pathomechanism of ENS is unknown, but the clinical presentation most likely represents a lethal disorder mitigated by mosaicism.2,9 Gene defects vary depending on the specific ENS. For instance, the phosphatase and tensin homolog gene, PTEN, mutations have been associated with type 2 segmental Cowden disease. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3, FGFR3, mutations have been linked to Garcia-Hafner-Happle syndrome.3FGFR3 mutations have been found in nonepidermolytic epidermal nevi, and some suggest that the majority of epidermal nevi exhibit mutations in FGFR3.5,10,11 On the other hand, other gene defects have not been elucidated, such as in Schimmelpenning syndrome.3

Clinically, ENS may involve nonepidermolytic verrucous nevi, sebaceous nevi, organoid nevi, linear Cowden nevi, and woolly hair nevi. Lesions may be flesh-colored, pink, yellow, or hyperpigmented plaques in a blaschkoid distribution and may be localized or systematized. Nevi typically are present at birth or develop within the first year of life.9,12,13 Other cutaneous findings may be noted apart from epidermal nevi, including melanocytic nevi, aplasia cutis congenita, and hemangiomas.13,14

Extracutaneous findings include central nervous system, skeletal, ocular, cardiac, and genitourinary defects, which are often observed in these patients.3,9,13,14 Central nervous system findings are seen in 50% to 70% of cases, with seizures and mental retardation among the most common.13-15 Genitourinary abnormalities associated with epidermal nevi, including horseshoe kidney, cystic kidney, duplicated collecting system, testicular and paratesticular tumors, and hypospadias have been documented in the literature.16 Our patient had a history of papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma, which is rare for a patient younger than 30 years. The overall median age of diagnosis of bladder cancer is 65 years, and it is more common in men than in women.17 Transitional cell carcinomas account for approximately 90% of all bladder cancers in the United States. Other common types of bladder cancer include squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma.16 Typically, transitional cell carcinoma is associated with smoking, exposure to aniline dyes, cyclophosphamide, and living in industrialized areas.16,17 Individuals who work with textiles, dyes, leather, tires, rubber, and/or petroleum; painters; truck drivers; drill press operators; and hairdressers are at an increased risk for development of bladder cancer.16

Interestingly, it has been shown in some studies that papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma frequently is associated with FGFR3 mutations, which may be the missing link in the rare finding of papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma and epidermal nevi.5,18,19 In addition, PTEN mutations also have been identified in low-grade papillary transitional cell carcinomas of the bladder, another gene linked to an ENS with type 2 segmental Cowden disease.3,20

Histopathologically, epidermal nevi have 10 different descriptions. Our patient had a nonorganoid nonepidermolytic epidermal nevus characterized by hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, papillomatosis, and elongated rete ridges. Focal acantholysis and epidermolytic hyperkeratosis also is seen in some epidermal nevi but was not seen in this case.9,21

Simple epidermal nevi occur in approximately 1 in 1000 newborns; however, when a child presents with multiple or systematized epidermal nevi, investigation should be undertaken for other possible associations.13,14 Of note, there have been several cases of squamous cell, verrucous, basal cell, and adnexal carcinomas arising in linear epidermal nevi.22-24

Epidermal nevi can be difficult to treat. Some patients are troubled by the appearance of these nevi, especially those with systematized disease. Unfortunately, for patients with multiple nevi or systematized disease, there are no consistently effective treatment options; however, there are case reports25,26 in the literature citing improvement or cure of epidermal nevi with full-thickness excision, continuous and pulsed CO2 laser, pulsed dye laser, and erbium-doped YAG laser.25 Other therapies that have been purported to help improve epidermal nevi are topical and oral retinoids, corticosteroids, topical 5-fluorouracil, anthralin, and podophyllin.26

Conclusion

Transitional cell bladder carcinoma is rare in patients in the third decade of life and younger. Given the age of our patient and her concomitant lack of risk factors, such as older age, history of smoking, and exposure to certain chemicals (eg, aniline dyes) and medications (eg, cyclophosphamide), it is more likely that the finding of papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma and ENS are related. A clear genetic link between ENS and transitional cell papillary bladder carcinoma has yet to be elucidated, but the FGFR3 gene is promising.

- Happle R. What is a nevus? a proposed definition of a common medical term. Dermatology. 1995;191:1-5.

- Gonzalez ME, Jabbari A, Tlougan BE, et al. Epidermal nevus. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:12.

- Happle R. The group of epidermal nevus syndromes. part I. well defined phenotypes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1-22.

- Solomon LM, Fretzin DF, Dewald RL. The epidermal nevus syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:273-285.

- Flosadottir E, Bjarnason B. A non-epidermolytic epidermal nevus of a soft, papillomatous type with transitional cell cancer of the bladder: a case report and review of non-cutaneous cancers associated with epidermal naevi. Acta Derm Venerol. 2008;88:173-175.

- Rosenthal D, Fretzin DF. Epidermal nevus syndrome: report of association with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:455-458.

- Garcia de Jalon A, Azua-Romea J, Trivez MA, et al. Epidermal naevus syndrome (Solomon’s syndrome) associated with bladder cancer in a 20-year-old female. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2004;38:85-87.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Epidermal nevus with transitional cell carcinomas of the urinary tract. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:856-858.

- Moss C. Mosacism and linear lesions. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby/Elsevier; 2012:943-962.

- Hafner C, van Oers JM, Vogt T, et al. Mosaicisim of activating FGFR3 mutations in human skin causes epidermal nevi. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2201-2207.

- Bygum A, Fagerberg CR, Clemmensen OJ, et al. Systemic epidermal nevus with involvement of the oral mucosa due to FGFR3 mutation. BMC Med Genet. 2011;12:79.

- Happle R. Linear Cowden nevus: a new distinct epidermal nevus. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:133-136.

- Vujevich JJ, Mancini AJ. The epidermal nevus syndromes: multisystem disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:957-961.

- Solomon L, Esterly N. Epidermal and other congenital organoid nevi. Curr Probl Pediatr. 1975;6:1-56.

- Grebe TA, Rimsa ME, Richter SF, et al. Further delineation of the epidermal nevus syndrome: two cases with new findings and literature review. Am J Med Genet. 1993;47:24-30.

- Lamm DL, Torti FM. Bladder cancer, 1996. Ca Cancer J Clin. 1996;46:93-112.

- Metts MC, Metts JC, Milito SJ, et al. Bladder cancer: a review of diagnosis and management. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92:285-294.

- Kimura T, Suzuki H, Ohashi T, et al. The incidence of thanatophoric dysplasia mutations in FGFR3 gene is higher in low-grade or superficial bladder carcinomas. Cancer. 2001;92:2555-2561.

- Cappellen D, DeOliveira C, Ricol D, et al. Frequent activating mutations of FGFR3 in human bladder and cervix carcinomas. Nat Genet. 1999;23:18-20.

- Knowles MA, Platt FM, Ross RL, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway activation in bladder cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:305-316.

- Luzar B, Calonje E, Bastian B. Tumors of the surface epithelium. In: Calonje JE, Breen T, McKee PH, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1076-1149.

- Masood Q, Narayan D. Squamous cell carcinoma in a linear epidermal nevus. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:693-694.

- Cramer SF, Mandel MA, Hauler R, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a linear epidermal nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:222-224.

- Affleck AG, Leach IJ, Varma S. Two squamous cell carcinomas arising in a linear epidermal nevus in a 28-year-old female. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:382-384.

- Alam M, Arndt KA. A method for pulsed carbon dioxide laser treatment of epidermal nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:554-556.

- Requena L, Requena C, Cockerell CJ. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby/Elsevier; 2012:1809-1810.

Epidermal nevi can occur in isolation or in association with internal abnormalities. Epidermal nevus syndrome (ENS) is a heterogeneous group of neurocutaneous disorders characterized by mosaicism and epidermal nevi found in association with various systemic abnormalities.1-4 There are many possible associated systemic findings, including abnormalities of the central nervous, musculoskeletal, renal, and hematologic systems. Epidermal nevi have been associated with internal malignancies. We present the case of a patient with epidermal nevi associated with papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms transitional cell bladder carcinoma and epidermal nevus, there have only been 4 other cases of transitional cell bladder carcinoma and ENS reported in the literature,5-8 2 of which were reports of papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma.5,6

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a rash that had been present since 3 years of age. The emergency department consulted dermatology for evaluation of what was believed to be contact dermatitis; however, upon questioning the patient, it was revealed that the rash was chronic and persistent.

The rash was nonpruritic and was located on the face, hands (Figure 1), chest, buttocks, thighs, legs, and back (Figure 2). Although asymptomatic, the appearance of the skin caused the patient some emotional distress. As a child she had been evaluated by a dermatologist and a biopsy was performed, but she did not recall the results or have any records. She had been prescribed an oral medication by the dermatologist, but treatment was terminated early due to nausea. The skin lesions did not improve with the short course of treatment.

Eighteen months prior to presentation to our clinic, the patient was discovered to have hematuria on routine examination by her primary care physician. At that time, the patient underwent a workup for hematuria and a mass was discovered in the bladder via cystoscopy. A diagnosis of low-grade papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma was made, and she underwent a partial cystectomy. No radiation or chemotherapy was required. The remainder of her medical history was only remarkable for asthma, which was well controlled with albuterol. On examination, generalized, hyperpigmented, reticulated patches, macules, and hyperpigmented verrucous plaques were distributed along the Blaschko lines, sparing the face. No limb abnormalities or dental or nail abnormalities were noted. Examination of the axillary and cervical lymph nodes was unremarkable, and no neurological abnormalities were noted. A 3-mm punch biopsy of the mid upper back was performed. Histopathology revealed papillomatous, nonorganoid, nonepidermolytic hyperplasia of the epidermis with elongated rete ridges (Figure 3), which was diagnosed as a nonorganoid nonepidermolytic epidermal nevus.

Comment

Epidermal nevus syndrome is a group of disorders characterized by both local or systematized epidermal nevi and systemic findings. Solomon et al4 first coined the term epidermal nevus syndrome more than 40 years ago; however, since then there has been confusion about how to define ENS. Epidermal nevus syndrome has been considered an umbrella term that includes more specific syndromes involving epidermal nevi, such as Proteus syndrome and Schimmelpenning syndrome; conversely, it also has been considered a term for those who do not meet the criteria for more specific syndromes.1,9 Happle1 discussed that the genetic variations found in ENS warrant recognition. Simply put, ENS is a heterogeneous group of syndromes that are similar in that they involve epidermal nevi and internal abnormalities but are genetically distinct. The list of definitive ENSs, as suggested by Happle1 and others, will likely continue to grow.3,5

The exact pathomechanism of ENS is unknown, but the clinical presentation most likely represents a lethal disorder mitigated by mosaicism.2,9 Gene defects vary depending on the specific ENS. For instance, the phosphatase and tensin homolog gene, PTEN, mutations have been associated with type 2 segmental Cowden disease. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3, FGFR3, mutations have been linked to Garcia-Hafner-Happle syndrome.3FGFR3 mutations have been found in nonepidermolytic epidermal nevi, and some suggest that the majority of epidermal nevi exhibit mutations in FGFR3.5,10,11 On the other hand, other gene defects have not been elucidated, such as in Schimmelpenning syndrome.3

Clinically, ENS may involve nonepidermolytic verrucous nevi, sebaceous nevi, organoid nevi, linear Cowden nevi, and woolly hair nevi. Lesions may be flesh-colored, pink, yellow, or hyperpigmented plaques in a blaschkoid distribution and may be localized or systematized. Nevi typically are present at birth or develop within the first year of life.9,12,13 Other cutaneous findings may be noted apart from epidermal nevi, including melanocytic nevi, aplasia cutis congenita, and hemangiomas.13,14

Extracutaneous findings include central nervous system, skeletal, ocular, cardiac, and genitourinary defects, which are often observed in these patients.3,9,13,14 Central nervous system findings are seen in 50% to 70% of cases, with seizures and mental retardation among the most common.13-15 Genitourinary abnormalities associated with epidermal nevi, including horseshoe kidney, cystic kidney, duplicated collecting system, testicular and paratesticular tumors, and hypospadias have been documented in the literature.16 Our patient had a history of papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma, which is rare for a patient younger than 30 years. The overall median age of diagnosis of bladder cancer is 65 years, and it is more common in men than in women.17 Transitional cell carcinomas account for approximately 90% of all bladder cancers in the United States. Other common types of bladder cancer include squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma.16 Typically, transitional cell carcinoma is associated with smoking, exposure to aniline dyes, cyclophosphamide, and living in industrialized areas.16,17 Individuals who work with textiles, dyes, leather, tires, rubber, and/or petroleum; painters; truck drivers; drill press operators; and hairdressers are at an increased risk for development of bladder cancer.16

Interestingly, it has been shown in some studies that papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma frequently is associated with FGFR3 mutations, which may be the missing link in the rare finding of papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma and epidermal nevi.5,18,19 In addition, PTEN mutations also have been identified in low-grade papillary transitional cell carcinomas of the bladder, another gene linked to an ENS with type 2 segmental Cowden disease.3,20

Histopathologically, epidermal nevi have 10 different descriptions. Our patient had a nonorganoid nonepidermolytic epidermal nevus characterized by hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, papillomatosis, and elongated rete ridges. Focal acantholysis and epidermolytic hyperkeratosis also is seen in some epidermal nevi but was not seen in this case.9,21

Simple epidermal nevi occur in approximately 1 in 1000 newborns; however, when a child presents with multiple or systematized epidermal nevi, investigation should be undertaken for other possible associations.13,14 Of note, there have been several cases of squamous cell, verrucous, basal cell, and adnexal carcinomas arising in linear epidermal nevi.22-24

Epidermal nevi can be difficult to treat. Some patients are troubled by the appearance of these nevi, especially those with systematized disease. Unfortunately, for patients with multiple nevi or systematized disease, there are no consistently effective treatment options; however, there are case reports25,26 in the literature citing improvement or cure of epidermal nevi with full-thickness excision, continuous and pulsed CO2 laser, pulsed dye laser, and erbium-doped YAG laser.25 Other therapies that have been purported to help improve epidermal nevi are topical and oral retinoids, corticosteroids, topical 5-fluorouracil, anthralin, and podophyllin.26

Conclusion

Transitional cell bladder carcinoma is rare in patients in the third decade of life and younger. Given the age of our patient and her concomitant lack of risk factors, such as older age, history of smoking, and exposure to certain chemicals (eg, aniline dyes) and medications (eg, cyclophosphamide), it is more likely that the finding of papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma and ENS are related. A clear genetic link between ENS and transitional cell papillary bladder carcinoma has yet to be elucidated, but the FGFR3 gene is promising.

Epidermal nevi can occur in isolation or in association with internal abnormalities. Epidermal nevus syndrome (ENS) is a heterogeneous group of neurocutaneous disorders characterized by mosaicism and epidermal nevi found in association with various systemic abnormalities.1-4 There are many possible associated systemic findings, including abnormalities of the central nervous, musculoskeletal, renal, and hematologic systems. Epidermal nevi have been associated with internal malignancies. We present the case of a patient with epidermal nevi associated with papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms transitional cell bladder carcinoma and epidermal nevus, there have only been 4 other cases of transitional cell bladder carcinoma and ENS reported in the literature,5-8 2 of which were reports of papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma.5,6

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a rash that had been present since 3 years of age. The emergency department consulted dermatology for evaluation of what was believed to be contact dermatitis; however, upon questioning the patient, it was revealed that the rash was chronic and persistent.

The rash was nonpruritic and was located on the face, hands (Figure 1), chest, buttocks, thighs, legs, and back (Figure 2). Although asymptomatic, the appearance of the skin caused the patient some emotional distress. As a child she had been evaluated by a dermatologist and a biopsy was performed, but she did not recall the results or have any records. She had been prescribed an oral medication by the dermatologist, but treatment was terminated early due to nausea. The skin lesions did not improve with the short course of treatment.