User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on Skin-Lightening Agents

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on skin-lightening agents. Consideration must be given to:

- Even Better Clinical Dark Spot Corrector

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Lytera Skin Brightening Complex

SkinMedica, an Allergan compan

“It contains vitamin C, niacinamide, retinol, and licorice root extract to help lighten the skin and improve texture without hydroquinone.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Meladerm

Civant Skin Care

“This is an excellent hydroquinone-free cream for treating postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and melasma. It contains a combination of ingredients known to inhibit various steps along the melanogenesis pathway, such as retinyl palmitate, licorice extract, and arbutin, as well as lactic, kojic, and ascorbic acids.”—Cherise M. Levi, DO, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Cleansing devices, dry shampoos, athlete’s foot treatments, and face scrubs will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

[polldaddy:9711250]

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on skin-lightening agents. Consideration must be given to:

- Even Better Clinical Dark Spot Corrector

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Lytera Skin Brightening Complex

SkinMedica, an Allergan compan

“It contains vitamin C, niacinamide, retinol, and licorice root extract to help lighten the skin and improve texture without hydroquinone.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Meladerm

Civant Skin Care

“This is an excellent hydroquinone-free cream for treating postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and melasma. It contains a combination of ingredients known to inhibit various steps along the melanogenesis pathway, such as retinyl palmitate, licorice extract, and arbutin, as well as lactic, kojic, and ascorbic acids.”—Cherise M. Levi, DO, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Cleansing devices, dry shampoos, athlete’s foot treatments, and face scrubs will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

[polldaddy:9711250]

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on skin-lightening agents. Consideration must be given to:

- Even Better Clinical Dark Spot Corrector

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Lytera Skin Brightening Complex

SkinMedica, an Allergan compan

“It contains vitamin C, niacinamide, retinol, and licorice root extract to help lighten the skin and improve texture without hydroquinone.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Meladerm

Civant Skin Care

“This is an excellent hydroquinone-free cream for treating postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and melasma. It contains a combination of ingredients known to inhibit various steps along the melanogenesis pathway, such as retinyl palmitate, licorice extract, and arbutin, as well as lactic, kojic, and ascorbic acids.”—Cherise M. Levi, DO, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Cleansing devices, dry shampoos, athlete’s foot treatments, and face scrubs will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

[polldaddy:9711250]

Debunking Psoriasis Myths: Do Systemic Steroids Used in Psoriasis Patients Cause Pustular Psoriasis?

Myth: Systemic steroids cause pustular psoriasis

The advent of biologic therapy for psoriasis has changed the landscape of treatments offered to patients. Nevertheless, systemic therapies still play an important role, according to the American Academy of Dermatology psoriasis treatment guidelines, due to their oral route of administration and low cost compared to biologics. They are options for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis that is unresponsive to topical therapies or phototherapy. However, many dermatologists feel that it is inappropriate to prescribe oral steroids to psoriasis patients due to the risk for steroid-induced conversion to pustular psoriasis, the long-term side effects of steroids, and deterioration of psoriasis after withdrawal of steroids.

Pustular psoriasis appears clinically as white pustules (blisters of noninfectious pus) surrounded by red skin. The pus consists of white blood cells. There are a number of triggers in addition to systemic steroids, such as internal medications, irritating topical agents, overexposure to UV light, and pregnancy. Stopping an oral steroid abruptly can cause serious disease flares, fatigue, and joint pain.

Westphal et al described the case of a 70-year-old woman with palmoplantar psoriasis who was diagnosed with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis that was treated with corticotherapy by injection and then oral prednisone. She experienced improvement, but her symptoms worsened when she was in the process of reducing the prednisone dose. The dose was increased again, and the same worsening of symptoms was experienced when the dose was reduced. After completely abandoning oral steroid therapy, she developed a severe case of generalized pustular psoriasis that was treated with acitretin. This case illustrates the dangerous consequences of abruptly discontinuing oral steroids.

However, dermatologists may be using oral steroids for psoriasis more often than treatment guidelines suggest. In 2014, Al-Dabagh et al evaluated how frequently systemic corticosteroids are prescribed for psoriasis in the United States. The researchers reported, "Despite the absence or discouragement of systemic corticosteroids in psoriasis management guidelines, systemic corticosteroids are among the most common systemic treatments used for psoriasis." They found that systemic corticosteroids were prescribed at 650,000 of 21,020,000 psoriasis visits, of which 93% were visits to dermatologists. Prednisone was the most commonly prescribed systemic corticosteroid, followed by methylprednisolone and dexamethasone. To prevent rebound flares, systemic corticosteroids were prescribed with a topical corticosteroid in 45% of the visits in patients with psoriasis as the sole diagnosis. They concluded, "The striking contrast between the guidelines for psoriasis management and actual practice suggests that there is an acute need to better understand the use of systemic corticosteroids for psoriasis."

The benefits of systemic corticosteroids versus the frequency of adverse reactions should be weighed by dermatologists and patients to make evidence-based decisions about treatment. Patients should take oral steroids exactly as prescribed by physicians.

References

Al-Dabagh A, Al-Dabagh R, Davis SA, et al. Systemic corticosteroids are frequently prescribed for psoriasis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:195-199.

Delzell E. What you need to know about steroids. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/advance/what-you-need-to-know-about-steroids. Published September 2, 2015. Accessed January 13, 2017.

Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 4. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with traditional systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:451-485.

Pustular psoriasis. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/types/pustular. Accessed January 13, 2017.

Westphal DC, Schettini APM, de Souza PP, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis induced by systemic steroid dose reduction. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:664-666.

Expert Commentaries on next page

Expert Commentaries

When I was a resident, I was trained not to use systemic steroids in psoriasis patients for the reasons noted above, and I have faithfully followed these instructions 9 years into practice. However, I see many patients with severe psoriasis who are given systemic steroids by other physicians (ie, rheumatologists for psoriatic arthritis, pulmonologists for asthma). I often tell patients afterwards of the dangers of systemic steroids and to have them tell their other doctors to be cautious when giving another course of systemic steroids. However, I have yet to see a generalized pustular psoriasis outbreak or flare in psoriasis vulgaris after a course of systemic steroids. While I do not recommend systemic steroids for psoriasis patients since we have so many other systemic agents, I wonder if the risks that we were all trained about are really that high.

—Jashin J. Wu, MD (Los Angeles, California)

How bad is it to give patients with psoriasis systemic steroids? Are psoriasis patients treated with systemic steroids likely to get a pustular flare? Are patients with psoriasis who suddenly stop their corticosteroids more likely to get a pustular flare than psoriasis patients who suddenly stop other systemic psoriasis treatments? I don't have the answers to these questions. My sense is that we have a lot of dogma and strong opinions but very little hard evidence to answer these questions.

I don't typically prescribe systemic steroids to psoriasis patients, but systemic steroids are widely used. Sometimes there are problems. I have seen patients who received systemic steroids for psoriasis and who went on to have a pustular flare, but it's possible the systemic steroid was given because those patients were headed toward the pustular flare already.

I once had a psoriasis patient who came to see me with a suddenly inflamed tender joint. Not knowing what to do, I called a rheumatologist to see the patient. The rheumatologist, too busy to work the patient in, told me to give the patient a 2-week prednisone taper. I did, and nothing untoward happened with the psoriasis. This one anecdote doesn't give me much confidence that systemic steroids are safe for psoriasis patients.

Clearly, long-term steroids cause a host of problems (eg, osteoporosis, diabetes). But I'm not sure that the dogma that systemic steroids should be avoided in patients with psoriasis is well supported. Systemic steroids are being widely used, and I don't see an epidemic of pustular flares.

Is it a mistake to give systemic steroids to psoriasis patients? I just don't know.

—Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)

Myth: Systemic steroids cause pustular psoriasis

The advent of biologic therapy for psoriasis has changed the landscape of treatments offered to patients. Nevertheless, systemic therapies still play an important role, according to the American Academy of Dermatology psoriasis treatment guidelines, due to their oral route of administration and low cost compared to biologics. They are options for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis that is unresponsive to topical therapies or phototherapy. However, many dermatologists feel that it is inappropriate to prescribe oral steroids to psoriasis patients due to the risk for steroid-induced conversion to pustular psoriasis, the long-term side effects of steroids, and deterioration of psoriasis after withdrawal of steroids.

Pustular psoriasis appears clinically as white pustules (blisters of noninfectious pus) surrounded by red skin. The pus consists of white blood cells. There are a number of triggers in addition to systemic steroids, such as internal medications, irritating topical agents, overexposure to UV light, and pregnancy. Stopping an oral steroid abruptly can cause serious disease flares, fatigue, and joint pain.

Westphal et al described the case of a 70-year-old woman with palmoplantar psoriasis who was diagnosed with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis that was treated with corticotherapy by injection and then oral prednisone. She experienced improvement, but her symptoms worsened when she was in the process of reducing the prednisone dose. The dose was increased again, and the same worsening of symptoms was experienced when the dose was reduced. After completely abandoning oral steroid therapy, she developed a severe case of generalized pustular psoriasis that was treated with acitretin. This case illustrates the dangerous consequences of abruptly discontinuing oral steroids.

However, dermatologists may be using oral steroids for psoriasis more often than treatment guidelines suggest. In 2014, Al-Dabagh et al evaluated how frequently systemic corticosteroids are prescribed for psoriasis in the United States. The researchers reported, "Despite the absence or discouragement of systemic corticosteroids in psoriasis management guidelines, systemic corticosteroids are among the most common systemic treatments used for psoriasis." They found that systemic corticosteroids were prescribed at 650,000 of 21,020,000 psoriasis visits, of which 93% were visits to dermatologists. Prednisone was the most commonly prescribed systemic corticosteroid, followed by methylprednisolone and dexamethasone. To prevent rebound flares, systemic corticosteroids were prescribed with a topical corticosteroid in 45% of the visits in patients with psoriasis as the sole diagnosis. They concluded, "The striking contrast between the guidelines for psoriasis management and actual practice suggests that there is an acute need to better understand the use of systemic corticosteroids for psoriasis."

The benefits of systemic corticosteroids versus the frequency of adverse reactions should be weighed by dermatologists and patients to make evidence-based decisions about treatment. Patients should take oral steroids exactly as prescribed by physicians.

References

Al-Dabagh A, Al-Dabagh R, Davis SA, et al. Systemic corticosteroids are frequently prescribed for psoriasis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:195-199.

Delzell E. What you need to know about steroids. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/advance/what-you-need-to-know-about-steroids. Published September 2, 2015. Accessed January 13, 2017.

Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 4. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with traditional systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:451-485.

Pustular psoriasis. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/types/pustular. Accessed January 13, 2017.

Westphal DC, Schettini APM, de Souza PP, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis induced by systemic steroid dose reduction. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:664-666.

Expert Commentaries on next page

Expert Commentaries

When I was a resident, I was trained not to use systemic steroids in psoriasis patients for the reasons noted above, and I have faithfully followed these instructions 9 years into practice. However, I see many patients with severe psoriasis who are given systemic steroids by other physicians (ie, rheumatologists for psoriatic arthritis, pulmonologists for asthma). I often tell patients afterwards of the dangers of systemic steroids and to have them tell their other doctors to be cautious when giving another course of systemic steroids. However, I have yet to see a generalized pustular psoriasis outbreak or flare in psoriasis vulgaris after a course of systemic steroids. While I do not recommend systemic steroids for psoriasis patients since we have so many other systemic agents, I wonder if the risks that we were all trained about are really that high.

—Jashin J. Wu, MD (Los Angeles, California)

How bad is it to give patients with psoriasis systemic steroids? Are psoriasis patients treated with systemic steroids likely to get a pustular flare? Are patients with psoriasis who suddenly stop their corticosteroids more likely to get a pustular flare than psoriasis patients who suddenly stop other systemic psoriasis treatments? I don't have the answers to these questions. My sense is that we have a lot of dogma and strong opinions but very little hard evidence to answer these questions.

I don't typically prescribe systemic steroids to psoriasis patients, but systemic steroids are widely used. Sometimes there are problems. I have seen patients who received systemic steroids for psoriasis and who went on to have a pustular flare, but it's possible the systemic steroid was given because those patients were headed toward the pustular flare already.

I once had a psoriasis patient who came to see me with a suddenly inflamed tender joint. Not knowing what to do, I called a rheumatologist to see the patient. The rheumatologist, too busy to work the patient in, told me to give the patient a 2-week prednisone taper. I did, and nothing untoward happened with the psoriasis. This one anecdote doesn't give me much confidence that systemic steroids are safe for psoriasis patients.

Clearly, long-term steroids cause a host of problems (eg, osteoporosis, diabetes). But I'm not sure that the dogma that systemic steroids should be avoided in patients with psoriasis is well supported. Systemic steroids are being widely used, and I don't see an epidemic of pustular flares.

Is it a mistake to give systemic steroids to psoriasis patients? I just don't know.

—Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)

Myth: Systemic steroids cause pustular psoriasis

The advent of biologic therapy for psoriasis has changed the landscape of treatments offered to patients. Nevertheless, systemic therapies still play an important role, according to the American Academy of Dermatology psoriasis treatment guidelines, due to their oral route of administration and low cost compared to biologics. They are options for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis that is unresponsive to topical therapies or phototherapy. However, many dermatologists feel that it is inappropriate to prescribe oral steroids to psoriasis patients due to the risk for steroid-induced conversion to pustular psoriasis, the long-term side effects of steroids, and deterioration of psoriasis after withdrawal of steroids.

Pustular psoriasis appears clinically as white pustules (blisters of noninfectious pus) surrounded by red skin. The pus consists of white blood cells. There are a number of triggers in addition to systemic steroids, such as internal medications, irritating topical agents, overexposure to UV light, and pregnancy. Stopping an oral steroid abruptly can cause serious disease flares, fatigue, and joint pain.

Westphal et al described the case of a 70-year-old woman with palmoplantar psoriasis who was diagnosed with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis that was treated with corticotherapy by injection and then oral prednisone. She experienced improvement, but her symptoms worsened when she was in the process of reducing the prednisone dose. The dose was increased again, and the same worsening of symptoms was experienced when the dose was reduced. After completely abandoning oral steroid therapy, she developed a severe case of generalized pustular psoriasis that was treated with acitretin. This case illustrates the dangerous consequences of abruptly discontinuing oral steroids.

However, dermatologists may be using oral steroids for psoriasis more often than treatment guidelines suggest. In 2014, Al-Dabagh et al evaluated how frequently systemic corticosteroids are prescribed for psoriasis in the United States. The researchers reported, "Despite the absence or discouragement of systemic corticosteroids in psoriasis management guidelines, systemic corticosteroids are among the most common systemic treatments used for psoriasis." They found that systemic corticosteroids were prescribed at 650,000 of 21,020,000 psoriasis visits, of which 93% were visits to dermatologists. Prednisone was the most commonly prescribed systemic corticosteroid, followed by methylprednisolone and dexamethasone. To prevent rebound flares, systemic corticosteroids were prescribed with a topical corticosteroid in 45% of the visits in patients with psoriasis as the sole diagnosis. They concluded, "The striking contrast between the guidelines for psoriasis management and actual practice suggests that there is an acute need to better understand the use of systemic corticosteroids for psoriasis."

The benefits of systemic corticosteroids versus the frequency of adverse reactions should be weighed by dermatologists and patients to make evidence-based decisions about treatment. Patients should take oral steroids exactly as prescribed by physicians.

References

Al-Dabagh A, Al-Dabagh R, Davis SA, et al. Systemic corticosteroids are frequently prescribed for psoriasis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:195-199.

Delzell E. What you need to know about steroids. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/advance/what-you-need-to-know-about-steroids. Published September 2, 2015. Accessed January 13, 2017.

Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 4. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with traditional systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:451-485.

Pustular psoriasis. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/types/pustular. Accessed January 13, 2017.

Westphal DC, Schettini APM, de Souza PP, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis induced by systemic steroid dose reduction. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:664-666.

Expert Commentaries on next page

Expert Commentaries

When I was a resident, I was trained not to use systemic steroids in psoriasis patients for the reasons noted above, and I have faithfully followed these instructions 9 years into practice. However, I see many patients with severe psoriasis who are given systemic steroids by other physicians (ie, rheumatologists for psoriatic arthritis, pulmonologists for asthma). I often tell patients afterwards of the dangers of systemic steroids and to have them tell their other doctors to be cautious when giving another course of systemic steroids. However, I have yet to see a generalized pustular psoriasis outbreak or flare in psoriasis vulgaris after a course of systemic steroids. While I do not recommend systemic steroids for psoriasis patients since we have so many other systemic agents, I wonder if the risks that we were all trained about are really that high.

—Jashin J. Wu, MD (Los Angeles, California)

How bad is it to give patients with psoriasis systemic steroids? Are psoriasis patients treated with systemic steroids likely to get a pustular flare? Are patients with psoriasis who suddenly stop their corticosteroids more likely to get a pustular flare than psoriasis patients who suddenly stop other systemic psoriasis treatments? I don't have the answers to these questions. My sense is that we have a lot of dogma and strong opinions but very little hard evidence to answer these questions.

I don't typically prescribe systemic steroids to psoriasis patients, but systemic steroids are widely used. Sometimes there are problems. I have seen patients who received systemic steroids for psoriasis and who went on to have a pustular flare, but it's possible the systemic steroid was given because those patients were headed toward the pustular flare already.

I once had a psoriasis patient who came to see me with a suddenly inflamed tender joint. Not knowing what to do, I called a rheumatologist to see the patient. The rheumatologist, too busy to work the patient in, told me to give the patient a 2-week prednisone taper. I did, and nothing untoward happened with the psoriasis. This one anecdote doesn't give me much confidence that systemic steroids are safe for psoriasis patients.

Clearly, long-term steroids cause a host of problems (eg, osteoporosis, diabetes). But I'm not sure that the dogma that systemic steroids should be avoided in patients with psoriasis is well supported. Systemic steroids are being widely used, and I don't see an epidemic of pustular flares.

Is it a mistake to give systemic steroids to psoriasis patients? I just don't know.

—Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)

Telmisartan-Induced Lichen Planus Eruption Manifested on Vitiliginous Skin

To the Editor:

A 39-year-old man with a history of hypertension and vitiligo presented with a rapid-onset, generalized, pruritic rash covering the body of 4 weeks’ duration. He reported that the rash progressively worsened after developing mild sunburn. The patient stated that the rash was extremely pruritic with a burning sensation and was tender to touch. He was treated with betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% by an outside physician and an over-the-counter anti-itch lotion with no notable improvement. His only medication was telmisartan-hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) for hypertension. He denied any drug allergies.

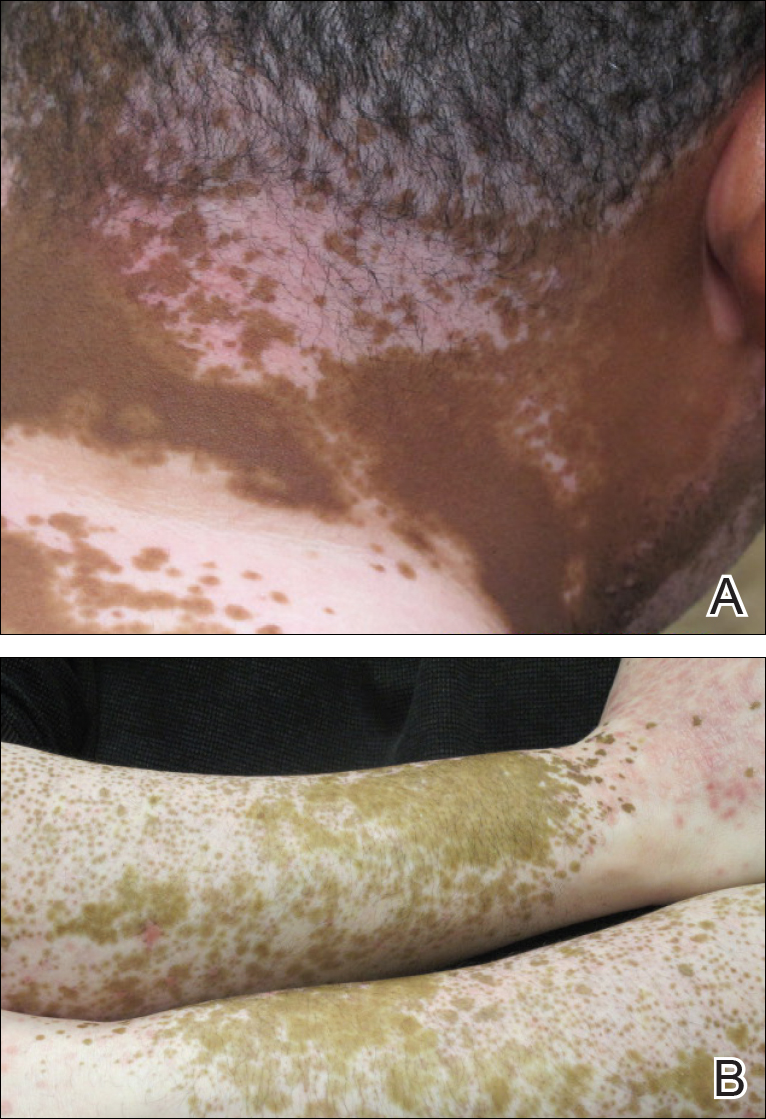

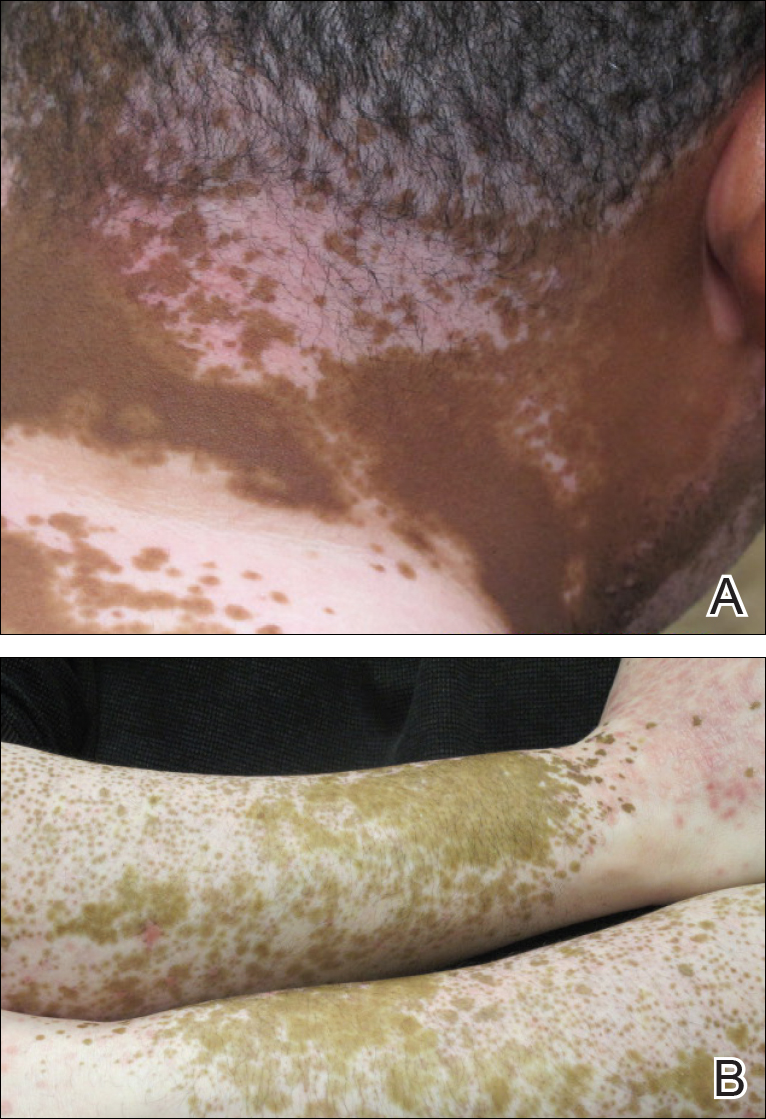

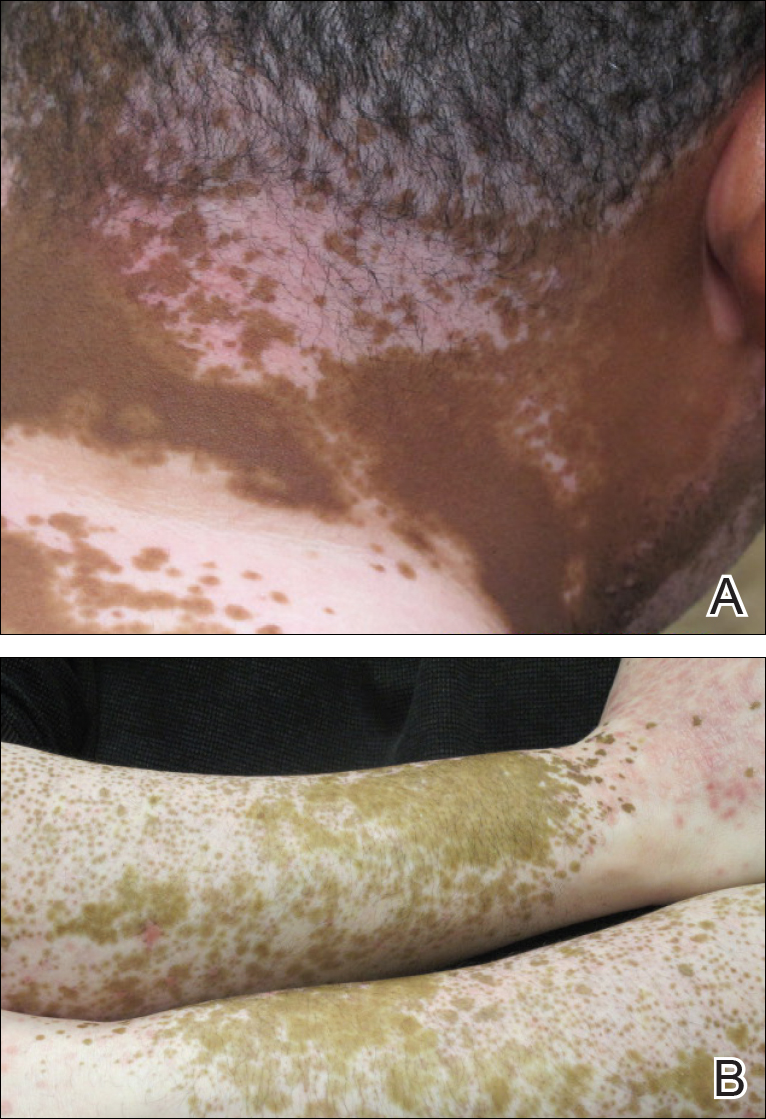

Physical examination revealed multiple discrete and coalescent planar erythematous papules and plaques involving only the depigmented vitiliginous skin of the forehead, eyelids, and nape of the neck (Figure 1A), and confluent on the lateral aspect of the bilateral forearms (Figure 1B), dorsal aspect of the right hand, and bilateral dorsi of the feet. Wickham striae were noted on the lips (Figure 1C). A clinical diagnosis of lichen planus (LP) was made. The patient initially was prescribed halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily. He reported notable relief of pruritus with reduction of overall symptoms and new lesion formation.

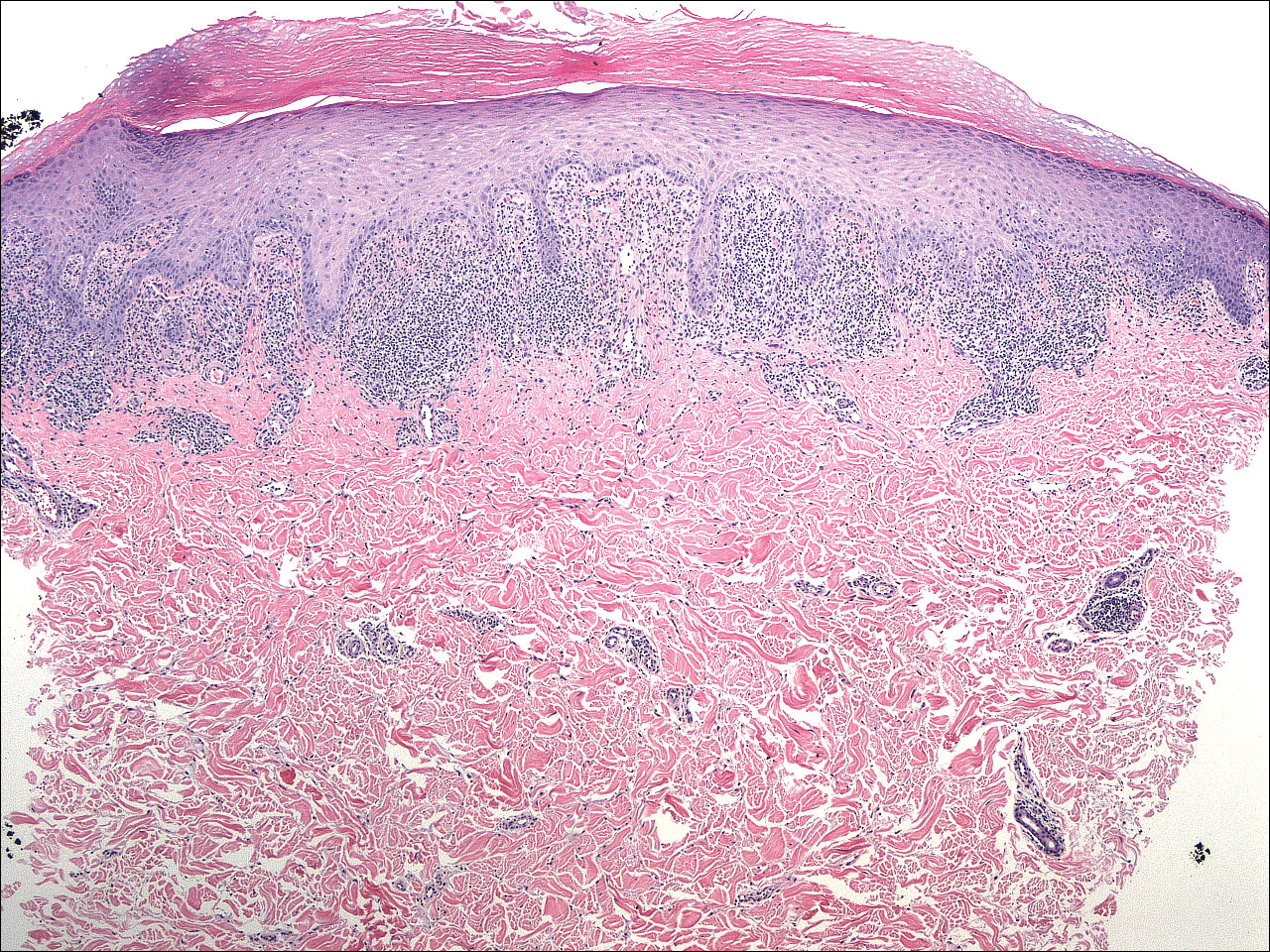

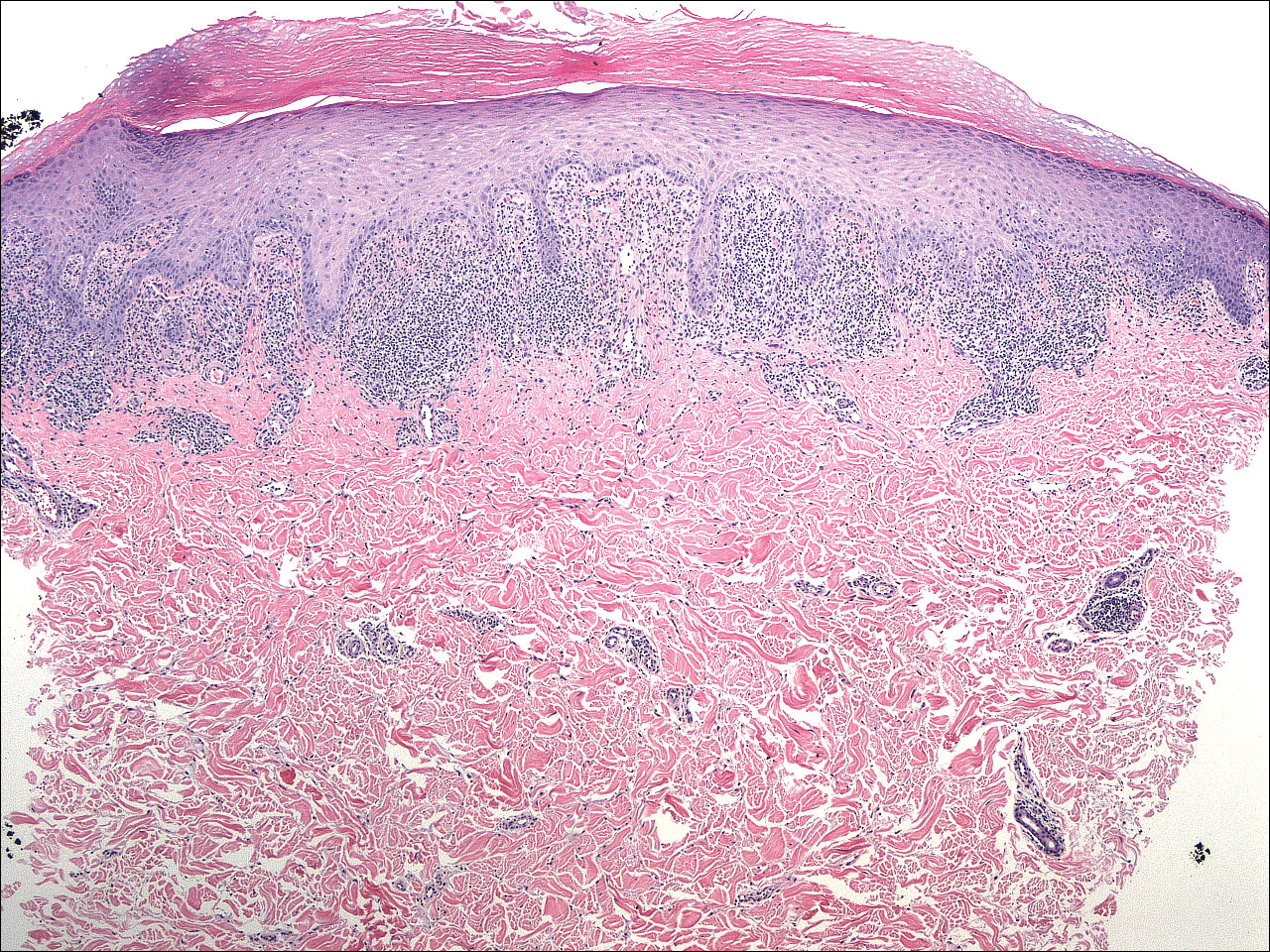

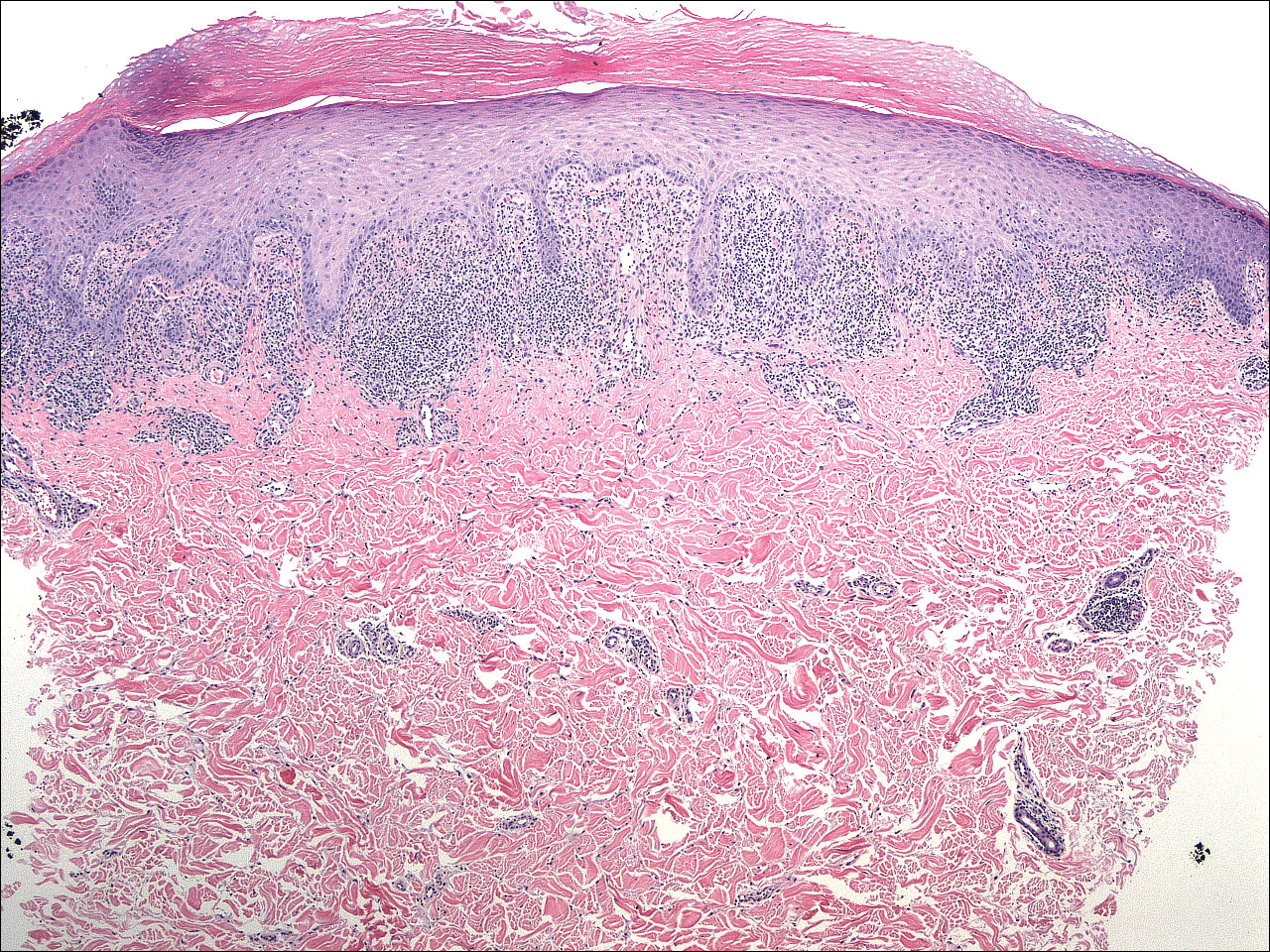

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed on the left forearm. Histopathology revealed LP. Microscopic examination of the hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen revealed a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that extended across the papillary dermis, focally obscuring the dermoepidermal junction where there were vacuolar changes and colloid bodies. The epidermis showed sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped foci of hypergranulosis, and compact hyperkeratosis (Figure 2).

On further questioning during follow-up, the patient revealed that his hypertensive medication was changed from HCTZ, which he had been taking for the last 8 years, to the combination antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ before the onset of the skin eruption. Due to the temporal relationship between the new medication and onset of the eruption, the clinical impression was highly suspicious for drug-induced eruptive LP with Köbner phenomenon caused by the recent sunburn. Systemic workup for underlying causes of LP was negative. Laboratory tests revealed normal complete blood cell counts. The hepatitis panel included hepatitis A antibodies; hepatitis B surface, e antigen, and core antibodies; hepatitis B surface antigen and e antibodies; hepatitis C antibodies; and antinuclear antibodies, which were all negative.

The patient continued to develop new pruritic papules clinically consistent with LP. He was instructed to return to his primary care physician to change the telmisartan-HCTZ to a different class of antihypertensive medication. His medication was changed to atenolol. The patient also was instructed to continue the halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily to the affected areas.

The patient returned for a follow-up visit 1 month later and reported notable improvement in pruritus and near-complete resolution of the LP after discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ. He also noted some degree of perifollicular repigmentation of the vitiliginous skin that had been unresponsive to prior therapy (Figure 3).

Lichen planus is a pruritic and inflammatory papulosquamous skin condition that presents as scaly, flat-topped, violaceous, polygonal-shaped papules commonly involving the flexor surface of the arms and legs, oral mucosa, scalp, nails, and genitalia. Clinically, LP can present in various forms including actinic, annular, atrophic, erosive, follicular, hypertrophic, linear, pigmented, and vesicular/bullous types. Koebnerization is common, especially in the linear form of LP. There are no specific laboratory findings or serologic markers seen in LP.

The exact cause of LP remains unknown. Clinical observations and anecdotal evidence have directed the cell-mediated immune response to insulting agents such as medications or contact allergy to metals triggering an abnormal cellular immune response. Various viral agents have been reported including hepatitis C virus, human herpesvirus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus.1-5 Other factors such as seasonal change and the environment may contribute to the development of LP and an increase in the incidence of LP eruption has been observed from January to July throughout the United States.6 Lichen planus also has been associated with other altered immune-related disease such as ulcerative colitis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, dermatomyositis, morphea, lichen sclerosis, and myasthenia gravis.7 Increased levels of emotional stress, particularly related to family members, often is related to the onset or aggravation of symptoms.8,9

Many drug-related LP-like and lichenoid eruptions have been reported with antihypertensive drugs, antimalarial drugs, diuretics, antidepressants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimicrobial drugs, and metals. In particular, medications such as captopril, enalapril, labetalol, propranolol, chlorothiazide, HCTZ, methyldopa, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, quinacrine, gold salts, penicillamine, and quinidine commonly are reported to induce lichenoid drug eruption.10

Several inflammatory papulosquamous skin conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis before confirming the diagnosis of LP. It is important to rule out lupus erythematosus, especially if the oral mucosa and scalp are involved. In addition, erosive paraneoplastic pemphigus involving primarily the oral mucosa can resemble oral LP. Nail diseases such as psoriasis, onychomycosis, and alopecia areata should be considered as the differential diagnosis of nail disease. Genital involvement also can be seen in psoriasis and lichen sclerosus.

Treatment of LP is mainly symptomatic because of the benign nature of the disease and the high spontaneous remission rate with varying amount of time. If drugs, dental/metal implants, or underlying viral infections are the identifiable triggering factors of LP, the offending agents should be discontinued or removed. Additionally, topical or systemic treatments can be given depending on the severity of the disease, focusing mainly on symptomatic relief as well as the balance of risks and benefits associated with treatment.

Treatment options include topical and intralesional corticosteroids. Systemic medications such as oral corticosteroids and/or acitretin commonly are used in acute, severe, and disseminated cases, though treatment duration varies depending on the clinical response. Other systemic agents used to treat LP include griseofulvin, metronidazole, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil.

Phototherapy is considered an alternative therapy, especially for recalcitrant LP. UVA1 and narrowband UVB (wavelength, 311 nm) have been reported to effectively treat long-standing and therapy-resistant LP.11 In addition, a small study used the excimer laser (wavelength, 308 nm), which is well tolerated by patients, to treat focal recalcitrant oral lesions with excellent results.12 Photochemotherapy has been used with notable improvement, but the potential of carcinogenicity, especially in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I and II, has limited its use.13

Our patient developed an unusual extensive LP eruption involving only vitiliginous skin shortly after initiation of the combined antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ, an angiotensin receptor blocker with a thiazide diuretic. Telmisartan and other angiotensin receptor blockers have not been reported to trigger LP; HCTZ is listed as one of the common drugs causing photosensitivity and LP.14,15 Although it is possible that our patient exhibited a delayed lichenoid drug eruption from the HCTZ, it is noteworthy that he did not experience a single episode of LP during his 8-year history of taking HCTZ. Instead, he developed the LP eruption shortly after the addition of telmisartan to his HCTZ antihypertensive regimen. The temporal relationship led us to direct the patient to the prescribing physician to discontinue telmisartan-HCTZ. After changing his antihypertensive medication to atenolol, the patient presented with improvement within the first month and near-complete resolution 2 months after the discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ.

Our patient’s LP lesions only manifested on the skin affected by vitiligo, sparing the normal-pigmented skin. Studies have demonstrated an increased ratio of CD8+ T cells to CD4+ T cells as well as increased intercellular adhesion molecule 1 at the dermal level.10,16 Both vitiligo and LP share some common histopathologic features including highly populated CD8+ T cells and intercellular adhesion molecule 1. In our case, LP was triggered on the vitiliginous skin by telmisartan. Vitiligo in combination with trauma induced by sunburn may represent the trigger that altered the cellular immune response and created the telmisartan-induced LP. As a result, the LP eruption was confined to the vitiliginous skin lesions.

Perifollicular repigmentation was observed in our patient after the LP lesions resolved; the patient’s vitiligo was unresponsive to prior treatment. The inflammatory process occurring in LP may exert and interfere in the underlying autoimmune cytotoxic effect toward the melanocytes and the melanin synthesis. It may be of interest to find out if the inflammatory response of LP has a positive influence on the effect of melanogenesis pathways or on the underlying autoimmune-related inflammatory process in vitiligo. Further studies are needed to investigate the role of immunotherapy targeting specific inflammatory pathways and the impact on the repigmentation in vitiligo.

Acknowledgment—Special thanks to Paul Chu, MD (Port Chester, New York).

- Pilli M, Zerbini A, Vescovi P, et al. Oral lichen planus pathogenesis: a role for the HCV-specific cellular immune response. Hepatology. 2002;36:1446-1452.

- De Vries HJ, van Marle J, Teunissen MB, et al. Lichen planus is associated with human herpesvirus type 7 replication and infiltration of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:361-364.

- De Vries HJ, Teunissen MB, Zorgdrager F, et al. Lichen planus remission is associated with a decrease of human herpes virus type 7 protein expression in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;299:213-219.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Escalonilla P, et al. Cutaneous reactions at sites of herpes zoster scars: an expanded spectrum. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:161-168.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Lichen planus occurring after hepatitis B vaccination: a new case. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:614-615.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Sadr-Ashkevari S. Familial actinic lichen planus: case reports in two brothers. Arch Int Med. 2001;4:204-206.

- Manolache L, Seceleanu-Petrescu D, Benea V. Lichen planus patients and stressful events. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:437-441.

- Mahood JM. Familial lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:292-294.

- Shimizu M, Higaki Y, Higaki M, et al. The role of granzyme B-expressing CD8-positive T cells in apoptosis of keratinocytes in lichen planus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1997;289:527-532.

- Bécherel PA, Bussel A, Chosidow O, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for chronic erosive lichen planus. Lancet. 1998;351:805.

- Trehan M, Taylar CR. Low-dose excimer 308-nm laser for the treatment of oral lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:415-420.

- Wackernagel A, Legat FJ, Hofer A, et al. Psoralen plus UVA vs. UVB-311 nm for the treatment of lichen planus. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007;23:15-19.

- Fellner MJ. Lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 1980;19:71-75.

- Moore DE. Drug-induced cutaneous photosensitivity: incidence, mechanism, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2002;25:345-372.

- Ongenae K, Van Geel N, Naeyaert JM. Evidence for an autoimmune pathogenesis of vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:90-100.

To the Editor:

A 39-year-old man with a history of hypertension and vitiligo presented with a rapid-onset, generalized, pruritic rash covering the body of 4 weeks’ duration. He reported that the rash progressively worsened after developing mild sunburn. The patient stated that the rash was extremely pruritic with a burning sensation and was tender to touch. He was treated with betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% by an outside physician and an over-the-counter anti-itch lotion with no notable improvement. His only medication was telmisartan-hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) for hypertension. He denied any drug allergies.

Physical examination revealed multiple discrete and coalescent planar erythematous papules and plaques involving only the depigmented vitiliginous skin of the forehead, eyelids, and nape of the neck (Figure 1A), and confluent on the lateral aspect of the bilateral forearms (Figure 1B), dorsal aspect of the right hand, and bilateral dorsi of the feet. Wickham striae were noted on the lips (Figure 1C). A clinical diagnosis of lichen planus (LP) was made. The patient initially was prescribed halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily. He reported notable relief of pruritus with reduction of overall symptoms and new lesion formation.

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed on the left forearm. Histopathology revealed LP. Microscopic examination of the hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen revealed a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that extended across the papillary dermis, focally obscuring the dermoepidermal junction where there were vacuolar changes and colloid bodies. The epidermis showed sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped foci of hypergranulosis, and compact hyperkeratosis (Figure 2).

On further questioning during follow-up, the patient revealed that his hypertensive medication was changed from HCTZ, which he had been taking for the last 8 years, to the combination antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ before the onset of the skin eruption. Due to the temporal relationship between the new medication and onset of the eruption, the clinical impression was highly suspicious for drug-induced eruptive LP with Köbner phenomenon caused by the recent sunburn. Systemic workup for underlying causes of LP was negative. Laboratory tests revealed normal complete blood cell counts. The hepatitis panel included hepatitis A antibodies; hepatitis B surface, e antigen, and core antibodies; hepatitis B surface antigen and e antibodies; hepatitis C antibodies; and antinuclear antibodies, which were all negative.

The patient continued to develop new pruritic papules clinically consistent with LP. He was instructed to return to his primary care physician to change the telmisartan-HCTZ to a different class of antihypertensive medication. His medication was changed to atenolol. The patient also was instructed to continue the halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily to the affected areas.

The patient returned for a follow-up visit 1 month later and reported notable improvement in pruritus and near-complete resolution of the LP after discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ. He also noted some degree of perifollicular repigmentation of the vitiliginous skin that had been unresponsive to prior therapy (Figure 3).

Lichen planus is a pruritic and inflammatory papulosquamous skin condition that presents as scaly, flat-topped, violaceous, polygonal-shaped papules commonly involving the flexor surface of the arms and legs, oral mucosa, scalp, nails, and genitalia. Clinically, LP can present in various forms including actinic, annular, atrophic, erosive, follicular, hypertrophic, linear, pigmented, and vesicular/bullous types. Koebnerization is common, especially in the linear form of LP. There are no specific laboratory findings or serologic markers seen in LP.

The exact cause of LP remains unknown. Clinical observations and anecdotal evidence have directed the cell-mediated immune response to insulting agents such as medications or contact allergy to metals triggering an abnormal cellular immune response. Various viral agents have been reported including hepatitis C virus, human herpesvirus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus.1-5 Other factors such as seasonal change and the environment may contribute to the development of LP and an increase in the incidence of LP eruption has been observed from January to July throughout the United States.6 Lichen planus also has been associated with other altered immune-related disease such as ulcerative colitis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, dermatomyositis, morphea, lichen sclerosis, and myasthenia gravis.7 Increased levels of emotional stress, particularly related to family members, often is related to the onset or aggravation of symptoms.8,9

Many drug-related LP-like and lichenoid eruptions have been reported with antihypertensive drugs, antimalarial drugs, diuretics, antidepressants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimicrobial drugs, and metals. In particular, medications such as captopril, enalapril, labetalol, propranolol, chlorothiazide, HCTZ, methyldopa, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, quinacrine, gold salts, penicillamine, and quinidine commonly are reported to induce lichenoid drug eruption.10

Several inflammatory papulosquamous skin conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis before confirming the diagnosis of LP. It is important to rule out lupus erythematosus, especially if the oral mucosa and scalp are involved. In addition, erosive paraneoplastic pemphigus involving primarily the oral mucosa can resemble oral LP. Nail diseases such as psoriasis, onychomycosis, and alopecia areata should be considered as the differential diagnosis of nail disease. Genital involvement also can be seen in psoriasis and lichen sclerosus.

Treatment of LP is mainly symptomatic because of the benign nature of the disease and the high spontaneous remission rate with varying amount of time. If drugs, dental/metal implants, or underlying viral infections are the identifiable triggering factors of LP, the offending agents should be discontinued or removed. Additionally, topical or systemic treatments can be given depending on the severity of the disease, focusing mainly on symptomatic relief as well as the balance of risks and benefits associated with treatment.

Treatment options include topical and intralesional corticosteroids. Systemic medications such as oral corticosteroids and/or acitretin commonly are used in acute, severe, and disseminated cases, though treatment duration varies depending on the clinical response. Other systemic agents used to treat LP include griseofulvin, metronidazole, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil.

Phototherapy is considered an alternative therapy, especially for recalcitrant LP. UVA1 and narrowband UVB (wavelength, 311 nm) have been reported to effectively treat long-standing and therapy-resistant LP.11 In addition, a small study used the excimer laser (wavelength, 308 nm), which is well tolerated by patients, to treat focal recalcitrant oral lesions with excellent results.12 Photochemotherapy has been used with notable improvement, but the potential of carcinogenicity, especially in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I and II, has limited its use.13

Our patient developed an unusual extensive LP eruption involving only vitiliginous skin shortly after initiation of the combined antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ, an angiotensin receptor blocker with a thiazide diuretic. Telmisartan and other angiotensin receptor blockers have not been reported to trigger LP; HCTZ is listed as one of the common drugs causing photosensitivity and LP.14,15 Although it is possible that our patient exhibited a delayed lichenoid drug eruption from the HCTZ, it is noteworthy that he did not experience a single episode of LP during his 8-year history of taking HCTZ. Instead, he developed the LP eruption shortly after the addition of telmisartan to his HCTZ antihypertensive regimen. The temporal relationship led us to direct the patient to the prescribing physician to discontinue telmisartan-HCTZ. After changing his antihypertensive medication to atenolol, the patient presented with improvement within the first month and near-complete resolution 2 months after the discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ.

Our patient’s LP lesions only manifested on the skin affected by vitiligo, sparing the normal-pigmented skin. Studies have demonstrated an increased ratio of CD8+ T cells to CD4+ T cells as well as increased intercellular adhesion molecule 1 at the dermal level.10,16 Both vitiligo and LP share some common histopathologic features including highly populated CD8+ T cells and intercellular adhesion molecule 1. In our case, LP was triggered on the vitiliginous skin by telmisartan. Vitiligo in combination with trauma induced by sunburn may represent the trigger that altered the cellular immune response and created the telmisartan-induced LP. As a result, the LP eruption was confined to the vitiliginous skin lesions.

Perifollicular repigmentation was observed in our patient after the LP lesions resolved; the patient’s vitiligo was unresponsive to prior treatment. The inflammatory process occurring in LP may exert and interfere in the underlying autoimmune cytotoxic effect toward the melanocytes and the melanin synthesis. It may be of interest to find out if the inflammatory response of LP has a positive influence on the effect of melanogenesis pathways or on the underlying autoimmune-related inflammatory process in vitiligo. Further studies are needed to investigate the role of immunotherapy targeting specific inflammatory pathways and the impact on the repigmentation in vitiligo.

Acknowledgment—Special thanks to Paul Chu, MD (Port Chester, New York).

To the Editor:

A 39-year-old man with a history of hypertension and vitiligo presented with a rapid-onset, generalized, pruritic rash covering the body of 4 weeks’ duration. He reported that the rash progressively worsened after developing mild sunburn. The patient stated that the rash was extremely pruritic with a burning sensation and was tender to touch. He was treated with betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% by an outside physician and an over-the-counter anti-itch lotion with no notable improvement. His only medication was telmisartan-hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) for hypertension. He denied any drug allergies.

Physical examination revealed multiple discrete and coalescent planar erythematous papules and plaques involving only the depigmented vitiliginous skin of the forehead, eyelids, and nape of the neck (Figure 1A), and confluent on the lateral aspect of the bilateral forearms (Figure 1B), dorsal aspect of the right hand, and bilateral dorsi of the feet. Wickham striae were noted on the lips (Figure 1C). A clinical diagnosis of lichen planus (LP) was made. The patient initially was prescribed halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily. He reported notable relief of pruritus with reduction of overall symptoms and new lesion formation.

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed on the left forearm. Histopathology revealed LP. Microscopic examination of the hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen revealed a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that extended across the papillary dermis, focally obscuring the dermoepidermal junction where there were vacuolar changes and colloid bodies. The epidermis showed sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped foci of hypergranulosis, and compact hyperkeratosis (Figure 2).

On further questioning during follow-up, the patient revealed that his hypertensive medication was changed from HCTZ, which he had been taking for the last 8 years, to the combination antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ before the onset of the skin eruption. Due to the temporal relationship between the new medication and onset of the eruption, the clinical impression was highly suspicious for drug-induced eruptive LP with Köbner phenomenon caused by the recent sunburn. Systemic workup for underlying causes of LP was negative. Laboratory tests revealed normal complete blood cell counts. The hepatitis panel included hepatitis A antibodies; hepatitis B surface, e antigen, and core antibodies; hepatitis B surface antigen and e antibodies; hepatitis C antibodies; and antinuclear antibodies, which were all negative.

The patient continued to develop new pruritic papules clinically consistent with LP. He was instructed to return to his primary care physician to change the telmisartan-HCTZ to a different class of antihypertensive medication. His medication was changed to atenolol. The patient also was instructed to continue the halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily to the affected areas.

The patient returned for a follow-up visit 1 month later and reported notable improvement in pruritus and near-complete resolution of the LP after discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ. He also noted some degree of perifollicular repigmentation of the vitiliginous skin that had been unresponsive to prior therapy (Figure 3).

Lichen planus is a pruritic and inflammatory papulosquamous skin condition that presents as scaly, flat-topped, violaceous, polygonal-shaped papules commonly involving the flexor surface of the arms and legs, oral mucosa, scalp, nails, and genitalia. Clinically, LP can present in various forms including actinic, annular, atrophic, erosive, follicular, hypertrophic, linear, pigmented, and vesicular/bullous types. Koebnerization is common, especially in the linear form of LP. There are no specific laboratory findings or serologic markers seen in LP.

The exact cause of LP remains unknown. Clinical observations and anecdotal evidence have directed the cell-mediated immune response to insulting agents such as medications or contact allergy to metals triggering an abnormal cellular immune response. Various viral agents have been reported including hepatitis C virus, human herpesvirus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus.1-5 Other factors such as seasonal change and the environment may contribute to the development of LP and an increase in the incidence of LP eruption has been observed from January to July throughout the United States.6 Lichen planus also has been associated with other altered immune-related disease such as ulcerative colitis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, dermatomyositis, morphea, lichen sclerosis, and myasthenia gravis.7 Increased levels of emotional stress, particularly related to family members, often is related to the onset or aggravation of symptoms.8,9

Many drug-related LP-like and lichenoid eruptions have been reported with antihypertensive drugs, antimalarial drugs, diuretics, antidepressants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimicrobial drugs, and metals. In particular, medications such as captopril, enalapril, labetalol, propranolol, chlorothiazide, HCTZ, methyldopa, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, quinacrine, gold salts, penicillamine, and quinidine commonly are reported to induce lichenoid drug eruption.10

Several inflammatory papulosquamous skin conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis before confirming the diagnosis of LP. It is important to rule out lupus erythematosus, especially if the oral mucosa and scalp are involved. In addition, erosive paraneoplastic pemphigus involving primarily the oral mucosa can resemble oral LP. Nail diseases such as psoriasis, onychomycosis, and alopecia areata should be considered as the differential diagnosis of nail disease. Genital involvement also can be seen in psoriasis and lichen sclerosus.

Treatment of LP is mainly symptomatic because of the benign nature of the disease and the high spontaneous remission rate with varying amount of time. If drugs, dental/metal implants, or underlying viral infections are the identifiable triggering factors of LP, the offending agents should be discontinued or removed. Additionally, topical or systemic treatments can be given depending on the severity of the disease, focusing mainly on symptomatic relief as well as the balance of risks and benefits associated with treatment.

Treatment options include topical and intralesional corticosteroids. Systemic medications such as oral corticosteroids and/or acitretin commonly are used in acute, severe, and disseminated cases, though treatment duration varies depending on the clinical response. Other systemic agents used to treat LP include griseofulvin, metronidazole, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil.

Phototherapy is considered an alternative therapy, especially for recalcitrant LP. UVA1 and narrowband UVB (wavelength, 311 nm) have been reported to effectively treat long-standing and therapy-resistant LP.11 In addition, a small study used the excimer laser (wavelength, 308 nm), which is well tolerated by patients, to treat focal recalcitrant oral lesions with excellent results.12 Photochemotherapy has been used with notable improvement, but the potential of carcinogenicity, especially in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I and II, has limited its use.13

Our patient developed an unusual extensive LP eruption involving only vitiliginous skin shortly after initiation of the combined antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ, an angiotensin receptor blocker with a thiazide diuretic. Telmisartan and other angiotensin receptor blockers have not been reported to trigger LP; HCTZ is listed as one of the common drugs causing photosensitivity and LP.14,15 Although it is possible that our patient exhibited a delayed lichenoid drug eruption from the HCTZ, it is noteworthy that he did not experience a single episode of LP during his 8-year history of taking HCTZ. Instead, he developed the LP eruption shortly after the addition of telmisartan to his HCTZ antihypertensive regimen. The temporal relationship led us to direct the patient to the prescribing physician to discontinue telmisartan-HCTZ. After changing his antihypertensive medication to atenolol, the patient presented with improvement within the first month and near-complete resolution 2 months after the discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ.

Our patient’s LP lesions only manifested on the skin affected by vitiligo, sparing the normal-pigmented skin. Studies have demonstrated an increased ratio of CD8+ T cells to CD4+ T cells as well as increased intercellular adhesion molecule 1 at the dermal level.10,16 Both vitiligo and LP share some common histopathologic features including highly populated CD8+ T cells and intercellular adhesion molecule 1. In our case, LP was triggered on the vitiliginous skin by telmisartan. Vitiligo in combination with trauma induced by sunburn may represent the trigger that altered the cellular immune response and created the telmisartan-induced LP. As a result, the LP eruption was confined to the vitiliginous skin lesions.

Perifollicular repigmentation was observed in our patient after the LP lesions resolved; the patient’s vitiligo was unresponsive to prior treatment. The inflammatory process occurring in LP may exert and interfere in the underlying autoimmune cytotoxic effect toward the melanocytes and the melanin synthesis. It may be of interest to find out if the inflammatory response of LP has a positive influence on the effect of melanogenesis pathways or on the underlying autoimmune-related inflammatory process in vitiligo. Further studies are needed to investigate the role of immunotherapy targeting specific inflammatory pathways and the impact on the repigmentation in vitiligo.

Acknowledgment—Special thanks to Paul Chu, MD (Port Chester, New York).

- Pilli M, Zerbini A, Vescovi P, et al. Oral lichen planus pathogenesis: a role for the HCV-specific cellular immune response. Hepatology. 2002;36:1446-1452.

- De Vries HJ, van Marle J, Teunissen MB, et al. Lichen planus is associated with human herpesvirus type 7 replication and infiltration of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:361-364.

- De Vries HJ, Teunissen MB, Zorgdrager F, et al. Lichen planus remission is associated with a decrease of human herpes virus type 7 protein expression in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;299:213-219.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Escalonilla P, et al. Cutaneous reactions at sites of herpes zoster scars: an expanded spectrum. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:161-168.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Lichen planus occurring after hepatitis B vaccination: a new case. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:614-615.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Sadr-Ashkevari S. Familial actinic lichen planus: case reports in two brothers. Arch Int Med. 2001;4:204-206.

- Manolache L, Seceleanu-Petrescu D, Benea V. Lichen planus patients and stressful events. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:437-441.

- Mahood JM. Familial lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:292-294.

- Shimizu M, Higaki Y, Higaki M, et al. The role of granzyme B-expressing CD8-positive T cells in apoptosis of keratinocytes in lichen planus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1997;289:527-532.

- Bécherel PA, Bussel A, Chosidow O, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for chronic erosive lichen planus. Lancet. 1998;351:805.

- Trehan M, Taylar CR. Low-dose excimer 308-nm laser for the treatment of oral lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:415-420.

- Wackernagel A, Legat FJ, Hofer A, et al. Psoralen plus UVA vs. UVB-311 nm for the treatment of lichen planus. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007;23:15-19.

- Fellner MJ. Lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 1980;19:71-75.

- Moore DE. Drug-induced cutaneous photosensitivity: incidence, mechanism, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2002;25:345-372.

- Ongenae K, Van Geel N, Naeyaert JM. Evidence for an autoimmune pathogenesis of vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:90-100.

- Pilli M, Zerbini A, Vescovi P, et al. Oral lichen planus pathogenesis: a role for the HCV-specific cellular immune response. Hepatology. 2002;36:1446-1452.

- De Vries HJ, van Marle J, Teunissen MB, et al. Lichen planus is associated with human herpesvirus type 7 replication and infiltration of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:361-364.

- De Vries HJ, Teunissen MB, Zorgdrager F, et al. Lichen planus remission is associated with a decrease of human herpes virus type 7 protein expression in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;299:213-219.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Escalonilla P, et al. Cutaneous reactions at sites of herpes zoster scars: an expanded spectrum. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:161-168.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Lichen planus occurring after hepatitis B vaccination: a new case. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:614-615.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Sadr-Ashkevari S. Familial actinic lichen planus: case reports in two brothers. Arch Int Med. 2001;4:204-206.

- Manolache L, Seceleanu-Petrescu D, Benea V. Lichen planus patients and stressful events. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:437-441.

- Mahood JM. Familial lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:292-294.

- Shimizu M, Higaki Y, Higaki M, et al. The role of granzyme B-expressing CD8-positive T cells in apoptosis of keratinocytes in lichen planus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1997;289:527-532.

- Bécherel PA, Bussel A, Chosidow O, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for chronic erosive lichen planus. Lancet. 1998;351:805.

- Trehan M, Taylar CR. Low-dose excimer 308-nm laser for the treatment of oral lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:415-420.

- Wackernagel A, Legat FJ, Hofer A, et al. Psoralen plus UVA vs. UVB-311 nm for the treatment of lichen planus. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007;23:15-19.

- Fellner MJ. Lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 1980;19:71-75.

- Moore DE. Drug-induced cutaneous photosensitivity: incidence, mechanism, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2002;25:345-372.

- Ongenae K, Van Geel N, Naeyaert JM. Evidence for an autoimmune pathogenesis of vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:90-100.

Practice Points

- Lichen planus (LP) is a T-cell–mediated autoimmune disease that affects the skin and often the mucosa, nails, and scalp.

- The etiology of LP is unknown. It can be induced by a variety of medications and may spread through the isomorphic phenomenon.

- Immune factors play a role in the development of LP, drug-induced LP, and vitiligo.

Bilateral Symmetric Onycholysis of Distal Fingernails

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

An allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to acrylates was suspected and 4 patches were applied to the forearm (the North American Standard Series of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group). The patches were 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (2-HEMA) 2.0% permissible exposure limit (peL), ethyl acrylate 0.1% peL, tosylamide formaldehyde resin 10.0% peL, and methyl methacrylate 2.0% peL. A reading at 72 hours was performed and showed a positive reaction to hydroxyethyl methacrylate, ethyl acrylate, and methyl methacrylate, and a negative patch test to tosylamide formaldehyde resin (nail polish)(Figure). The patient was diagnosed with an allergic contact hypersensitivity to the aforementioned acrylates and instructed to avoid artificial nails and acrylate glues. She also was started on oral biotin supplements. On 6-month follow-up the patient had regrowth of all 10 fingernails without brittleness or splitting. She was able to use nail polishes but avoided all acrylic artificial nails and acrylate-containing personal care products.

Acrylate Allergy and Artificial Nails

Acrylates are plastic materials formed by polymerization of acrylic or methacrylic acid monomers and have been cited as a major cause of occupational and nonoccupational contact dermatitis. Contact dermatitis to acrylates in artificial nails was first reported in the 1950s.1,2 Products containing 100% methyl methacrylate monomers in acrylic nails were banned by the US Food and Drug Administration in the early 1970s after receiving a number of complaints.3 However, no regulation prohibits the use of methyl methacrylate monomer in cosmetic products, and various methacrylate and acrylate monomers remain widely used.4 With a growing popularity in artificial nails, it is expected the number of sensitized persons will increase.

Acrylate allergy from sculptured nails concern self-curing resins made from a polymer powder and a liquid monomer solution. Advantages of new UV-cured products include the lack of unpleasant smell and simplified modeling. They also do not require an irritant, such as methacrylic acid, as a bonding agent. Instead, 2-HEMA and 2-hydroxypropyl methacrylate are added. These photobonded nails colloquially are called gel nails (acid free) as opposed to acrylic nails (using methacrylic acid as a primer). It is important to note that the esters of acrylic acid but not the acid itself sensitize patients, and sensitization is not caused by the uncured gel or the monomer solution but by the remaining monomers in the cured plastic nail and the dust filings that are produced during the finishing process.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms of an ACD to nail acrylates include pruritus and fingertip dermatitis along with nail plate dystrophy. There may be pruritus at the nail base, with subsequent dryness, thickening, and onycholysis. The brittle nails may become split, discolored, and develop paronychia. Inadvertent contact with glue monomers or other acrylate-containing substances may cause eczematous lesions at distant sites. Avoidance of the allergen often results in complete restoration of the normal nail and fingertip within months.

Sensitization

Acrylates and methacrylates are ubiquitous materials used for both industrial and commercial applications. Due to their widespread industrial use, contact allergies to acrylates including 2-HEMA, 2-hydroxypropyl methacrylate, and triethyleneglycol diacrylate (TREGDA) are common. Cross-reaction of these compounds has been observed and is postulated to be due to reaction of the (meth)acrylate carboxyethyl group with the receptors of antigen-presenting cells.5 As a result, an individual with an acrylate allergy sensitized to one allergen often is allergic to its similar compounds and cross-reactors and must avoid the assortment of compounds containing these ingredients, which is important for individuals with occupational sensitization to a particular acrylate who is subsequently susceptible to other acrylate-containing compounds triggering allergic reactions when reexposure occurs in different settings.

Allergens and Occupational Exposure

Acrylates in cosmetic nail products are a source of ACD for not only the customer but also the manicurist.6 The most frequently cited sources of ACD in beauticians are acrylate chemicals.7 However, acrylate compounds are an occupational hazard for a number of other specialists, including dentists and dental technicians, histology technicians, and individuals in the printing industry.8,9 Other individuals may be sensitized to acrylates through their inclusion in adhesives, dental bonding agents, hearing aids, electrocardiogram electrodes, artificial bone cement, and a myriad of other medical and nonmedical applications.4,10-12 For workers who cannot avoid occupational exposure to these allergens, polyvinyl alcohol and multilayer laminate gloves are recommended, as natural rubber latex gloves do not always provide adequate protection from many of these agents.10

Testing for Suspected Acrylate Allergy

Cross-reactivity among acrylates is widely considered in the literature but remains enigmatic and is an important consideration with regard to routine patch test screening.13 In the case of an acrylate allergy to nail products, using 2-HEMA and ethylene glycol dimethacrylate is effective in detecting sensitization by photobonded nails and in patients sensitized by powder liquid products.14 One study showed a patch test panel including 2-HEMA, ethylene glycol dimethacrylate, and TREGDA was effective in identifying the majority of individuals with an allergy to acrylates in nail products and nail technicians.15 Another study has shown the most commonly positive testing allergens to be HEMA, ethyl acrylate, and methyl methacrylate.16 If one is patch testing only one chemical, it appears 2-HEMA is preferred.17 However, broader panels of screening allergens are necessary to achieve an accurate diagnosis. Furthermore, different panels of test allergens have been shown to vary in their ability to detect an acrylate allergy in different occupational exposures.12

The time to patch test read also is important. A standard read at 72 hours is warranted; however, one study showed if only one read at day 3 was done without a subsequent day 7 read, then 25% of TREGDA and 50% of 2-HEMA allergies would have been missed in patients with occupational acrylate allergy.15 Other studies have reported late-appearing and long-lasting test reactions when testing for an acrylate allergy.18,19 Clinicians should be cognizant that an acrylate allergy may be present even if initial screening is negative but the history and clinical picture are suggestive.

- Canizares O. Contact dermatitis due to the acrylic materials used in artificial nails. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:141-143.

- Fisher AA, Franks A, Glick H. Allergic sensitization of the skin and nails to acrylic plastic nails. J Allergy. 1957;28:84-88.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Nail care products. http://www.fda.gov/Cosmetics/ProductsIngredients/Products/ucm127068.htm. Updated October 26, 2016. Accessed December 27, 2016.

- Haughton AM, Belsito DV. Acrylate allergy induced by acrylic nails resulting in prosthesis failure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S123-S124.

- Kanerva L. Cross-reactions of multifunctional methacrylates and acrylates. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001;59:320-329.

- Tammaro A, Narcisi A, Abruzzese C, et al. Fingertip dermatitis: occupational acrylate cross reaction. Allergol Int. 2014;63:609-610.

- Kwok C, Money A, Carder M, et al. Cases of occupational dermatitis and asthma in beauticians that were reported to The Health and Occupation Research (THOR) network from 1996 to 2011. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:590-595.

- Aalto-Korte K, Alanko K, Kuuliala O, et al. Methacrylate and acrylate allergy in dental personnel. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:324-330.

- Molina L, Amado A, Mattei PL 4th, et al. Contact dermatitis from acrylics in a histology laboratory assistant. Dermatitis. 2009;20:E11-E12.

- Prasad Hunasehally RY, Hughes TM, Stone NM. Atypical pattern of (meth)acrylate allergic contact dermatitis in dental professionals. Br Dent J. 2012;213:223-224.

- Stingeni L, Cerulli E, Spalletti A, et al. The role of acrylic acid impurity as a sensitizing component in electrocardiogram electrodes [published online January 27, 2015]. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73:44-48.

- Sasseville D. Acrylates in contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2012;23:6-16.

- Fisher AA. Cross reactions between methyl methacrylate monomer and acrylic monomers presently used in acrylic nail preparations. Contact Dermatitis. 1980;6:345-347.

- Hemmer W, Focke M, Wantke F, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to artificial fingernails prepared from UV light-cured acrylates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3, pt 1):377-380.

- Teik-Jin Goon A, Bruze M, Zimerson E, et al. Contact allergy to acrylates/methacrylates in the acrylate and nail acrylics series in southern Sweden: simultaneous positive patch test reaction patterns and possible screening allergens. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:21-27.

- Drucker AM, Pratt MD. Acrylate contact allergy: patient characteristics and evaluation of screening allergens. Dermatitis. 2011;22:98-101.

- Ramos L, Cabral R, Goncalo M. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by acrylates and methacrylates--a 7-year study. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:102-107.

- Goon AT, Isaksson M, Zimerson E, et al. Contact allergy to (meth)acrylates in the dental series in southern Sweden: simultaneous positive patch test reaction patterns and possible screening allergens. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:219-226.

- Isaksson M, Lindberg M, Sundberg K, et al. The development and course of patch-test reactions to 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate and ethyleneglycol dimethacrylate. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53:292-297.

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

An allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to acrylates was suspected and 4 patches were applied to the forearm (the North American Standard Series of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group). The patches were 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (2-HEMA) 2.0% permissible exposure limit (peL), ethyl acrylate 0.1% peL, tosylamide formaldehyde resin 10.0% peL, and methyl methacrylate 2.0% peL. A reading at 72 hours was performed and showed a positive reaction to hydroxyethyl methacrylate, ethyl acrylate, and methyl methacrylate, and a negative patch test to tosylamide formaldehyde resin (nail polish)(Figure). The patient was diagnosed with an allergic contact hypersensitivity to the aforementioned acrylates and instructed to avoid artificial nails and acrylate glues. She also was started on oral biotin supplements. On 6-month follow-up the patient had regrowth of all 10 fingernails without brittleness or splitting. She was able to use nail polishes but avoided all acrylic artificial nails and acrylate-containing personal care products.

Acrylate Allergy and Artificial Nails

Acrylates are plastic materials formed by polymerization of acrylic or methacrylic acid monomers and have been cited as a major cause of occupational and nonoccupational contact dermatitis. Contact dermatitis to acrylates in artificial nails was first reported in the 1950s.1,2 Products containing 100% methyl methacrylate monomers in acrylic nails were banned by the US Food and Drug Administration in the early 1970s after receiving a number of complaints.3 However, no regulation prohibits the use of methyl methacrylate monomer in cosmetic products, and various methacrylate and acrylate monomers remain widely used.4 With a growing popularity in artificial nails, it is expected the number of sensitized persons will increase.

Acrylate allergy from sculptured nails concern self-curing resins made from a polymer powder and a liquid monomer solution. Advantages of new UV-cured products include the lack of unpleasant smell and simplified modeling. They also do not require an irritant, such as methacrylic acid, as a bonding agent. Instead, 2-HEMA and 2-hydroxypropyl methacrylate are added. These photobonded nails colloquially are called gel nails (acid free) as opposed to acrylic nails (using methacrylic acid as a primer). It is important to note that the esters of acrylic acid but not the acid itself sensitize patients, and sensitization is not caused by the uncured gel or the monomer solution but by the remaining monomers in the cured plastic nail and the dust filings that are produced during the finishing process.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms of an ACD to nail acrylates include pruritus and fingertip dermatitis along with nail plate dystrophy. There may be pruritus at the nail base, with subsequent dryness, thickening, and onycholysis. The brittle nails may become split, discolored, and develop paronychia. Inadvertent contact with glue monomers or other acrylate-containing substances may cause eczematous lesions at distant sites. Avoidance of the allergen often results in complete restoration of the normal nail and fingertip within months.

Sensitization

Acrylates and methacrylates are ubiquitous materials used for both industrial and commercial applications. Due to their widespread industrial use, contact allergies to acrylates including 2-HEMA, 2-hydroxypropyl methacrylate, and triethyleneglycol diacrylate (TREGDA) are common. Cross-reaction of these compounds has been observed and is postulated to be due to reaction of the (meth)acrylate carboxyethyl group with the receptors of antigen-presenting cells.5 As a result, an individual with an acrylate allergy sensitized to one allergen often is allergic to its similar compounds and cross-reactors and must avoid the assortment of compounds containing these ingredients, which is important for individuals with occupational sensitization to a particular acrylate who is subsequently susceptible to other acrylate-containing compounds triggering allergic reactions when reexposure occurs in different settings.

Allergens and Occupational Exposure

Acrylates in cosmetic nail products are a source of ACD for not only the customer but also the manicurist.6 The most frequently cited sources of ACD in beauticians are acrylate chemicals.7 However, acrylate compounds are an occupational hazard for a number of other specialists, including dentists and dental technicians, histology technicians, and individuals in the printing industry.8,9 Other individuals may be sensitized to acrylates through their inclusion in adhesives, dental bonding agents, hearing aids, electrocardiogram electrodes, artificial bone cement, and a myriad of other medical and nonmedical applications.4,10-12 For workers who cannot avoid occupational exposure to these allergens, polyvinyl alcohol and multilayer laminate gloves are recommended, as natural rubber latex gloves do not always provide adequate protection from many of these agents.10