User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Cost of Diagnosing Psoriasis and Rosacea for Dermatologists Versus Primary Care Physicians

Growing incentives to control health care costs may cause accountable care organizations (ACOs) to reconsider how diseases are best managed. Few studies have examined the cost difference between primary care providers (PCPs) and specialists in managing the same disease. Limited data have suggested that management of some diseases by a PCP may be less costly compared to a specialist1,2; however, it is not clear if this finding extends to skin disease. This study sought to assess the cost of seeing a dermatologist versus a PCP for diagnosis of the common skin diseases psoriasis and rosacea.

Methods

Patient data were obtained from the Humana database, a large commercial data set for claims and reimbursed costs encompassing 18,162,539 patients covered between January 2007 and December 2014. Our study population consisted of 3,944,465 patients with claims that included International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), codes for dermatological diagnoses (680.0–709.9). We searched by ICD-9 code for US patients with primary diagnoses of psoriasis (696.1) and rosacea (695.3). We narrowed the search to include patients aged 30 to 64 years, as the diagnoses for these diseases are most common in patients older than 30 years. Patients who were older than 64 years were not included in the study, as most are covered by Medicare and therefore costs covered by Humana in this age group would not be as representative as in younger age groups. Total and average diagnosis-related costs per patient were compared between dermatologists and PCPs. Diagnosis-related costs encompassed physician reimbursement; laboratory and imaging costs, including skin biopsies; inpatient hospitalization cost; and any other charge that could be coded or billed by providers and reimbursed by the insurance company. To be eligible for reimbursement from Humana, dermatologists and PCPs must be registered with the insurer according to specialty board certification and practice credentialing, and they are reimbursed differently based on specialty. Drug costs, which would possibly skew the data toward providers using more expensive systemic medications (ie, dermatologists), were not included in this study, as the discussion is better reserved for long-term management of disease rather than diagnosis-related costs. All diagnoses of psoriasis were included in the study, which likely includes all severities of psoriasis, though we did not have the ability to further break down these diagnoses by severity.

Results

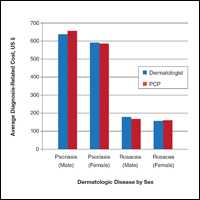

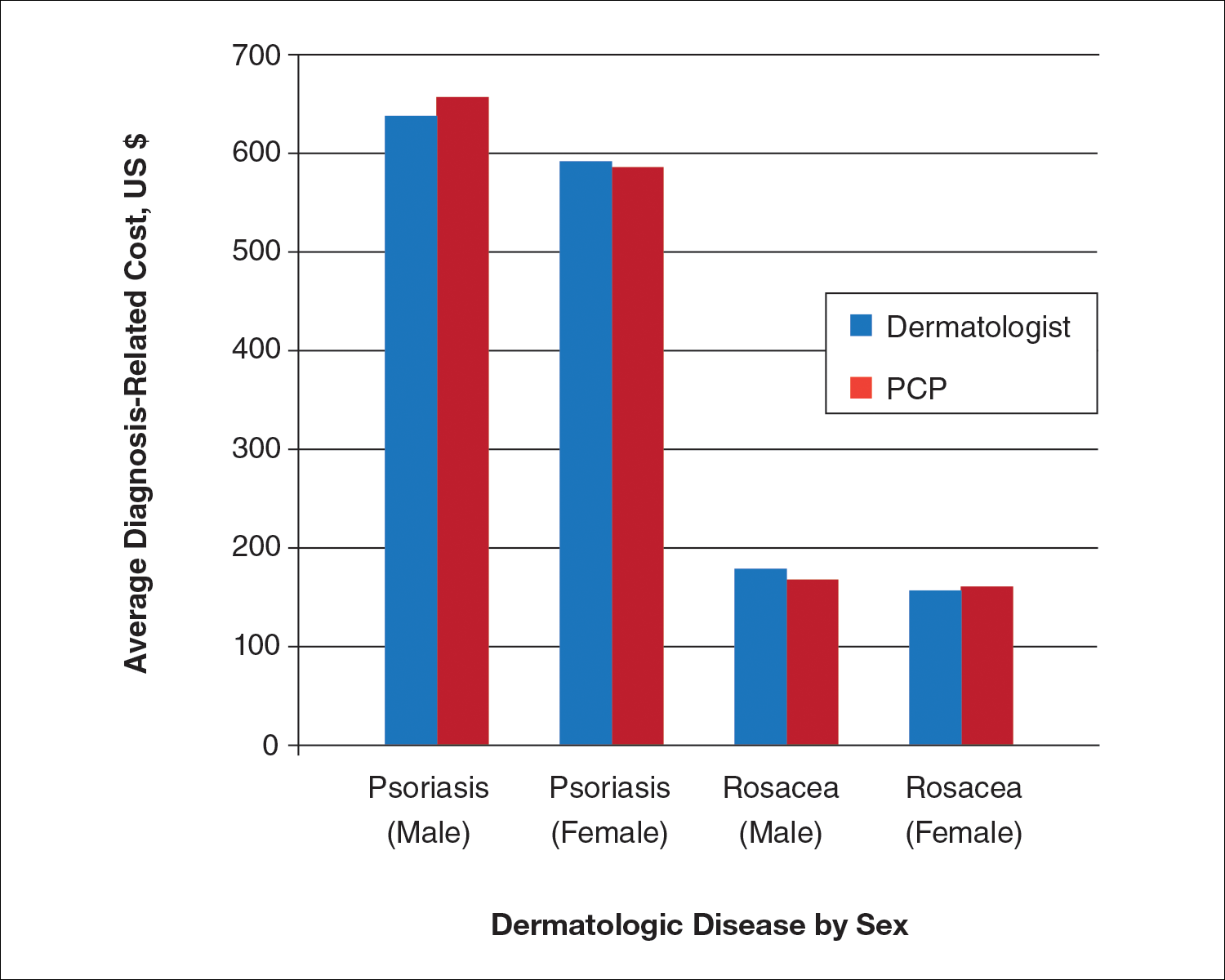

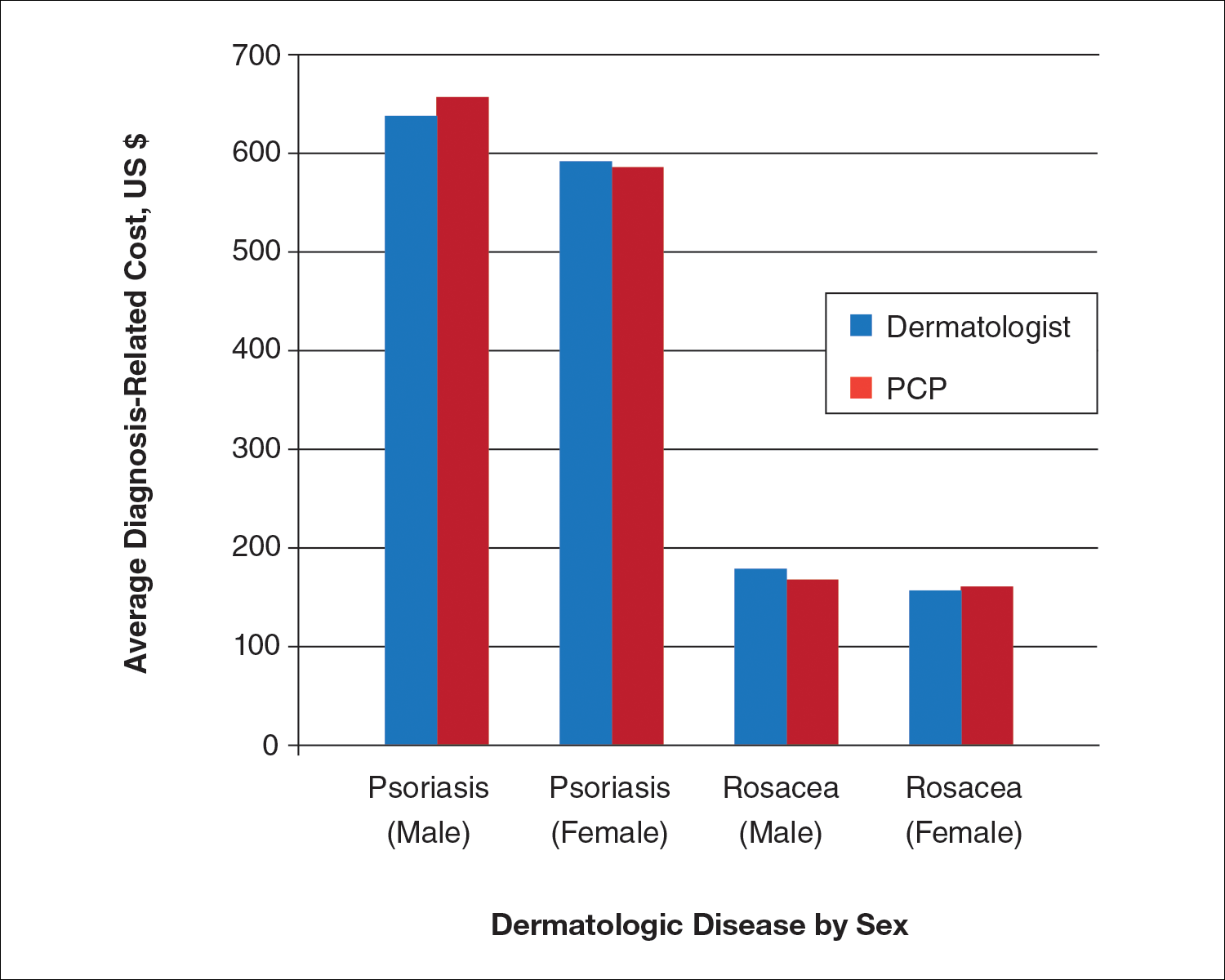

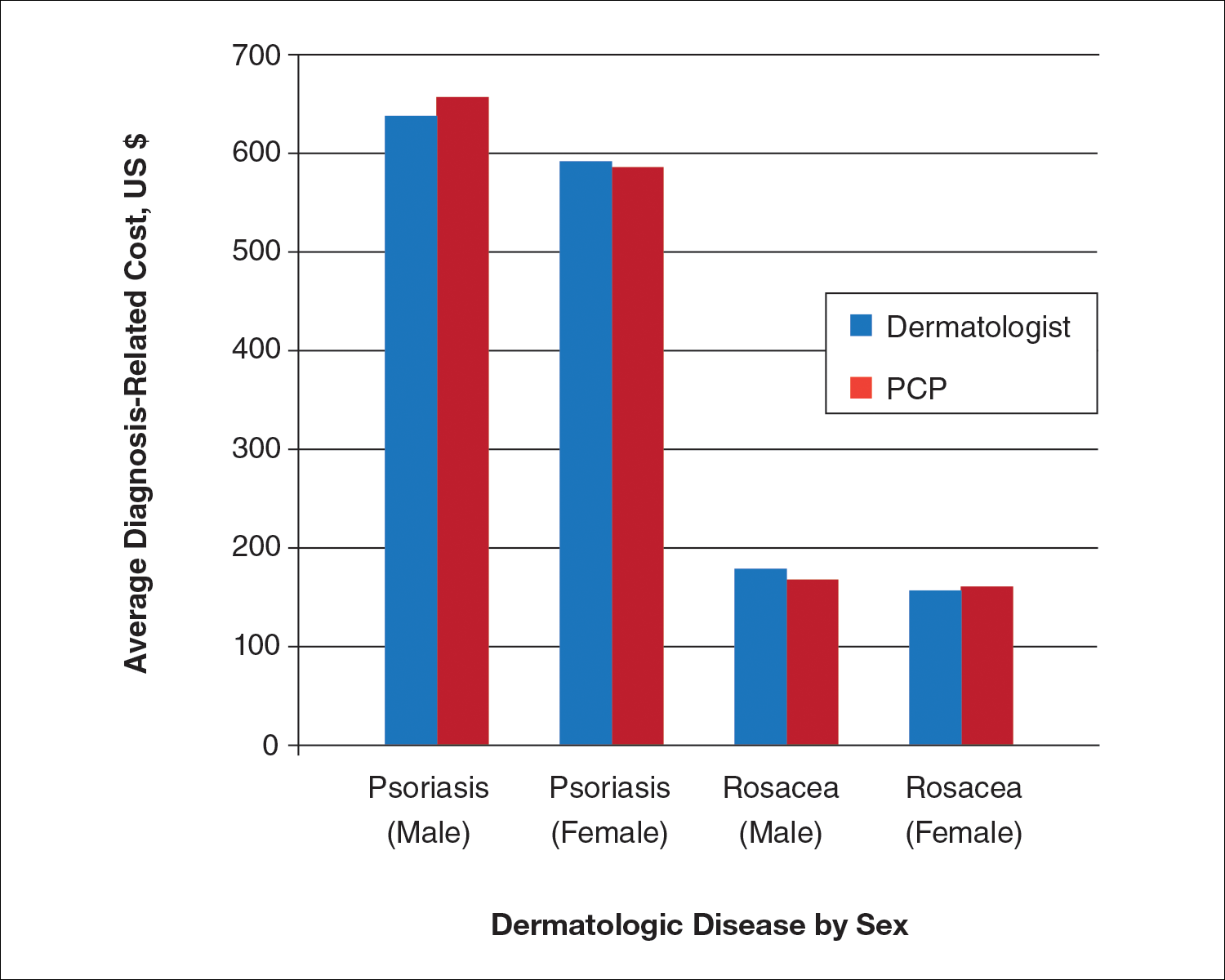

We identified 30,217 psoriasis patients and 37,561 rosacea patients. Of those patients with a primary diagnosis of psoriasis, 26,112 (86%) were seen by a dermatologist and 4105 (14%) were seen by a PCP (Table). Of those patients with a primary diagnosis of rosacea, 34,694 (92%) were seen by a dermatologist and 2867 (8%) were seen by a PCP (Table). There was little difference in the average diagnosis-related cost per patient for psoriasis in males (dermatologists, $638; PCPs, $657) versus females (dermatologists, $592; PCPs, $586) or between specialties (Figure). Findings were similar for rosacea in males (dermatologists, $179; PCPs, $168) versus females (dermatologists, $157; PCPs, $161). For these skin diseases, i

Comment

For the management of common skin disorders such as psoriasis and rosacea, there is little cost difference in seeing a dermatologist versus a PCP. Through extensive training and repeated exposure to many skin diseases, dermatologists are expected to be more comfortable in diagnosing and managing psoriasis and rosacea. Compared to PCPs, dermatologists have demonstrated increased diagnostic accuracy and efficiency when examining pigmented lesions and other dermatologic diseases in several studies.3-6 Although the current study shows that diagnosis-related costs for psoriasis and rosacea are essentially equal between dermatologists and PCPs, it actually may be less expensive for patients to see a dermatologist, as unnecessary tests, biopsies, or medications are more likely to be ordered/prescribed when there is less clinical diagnostic certainty.7,8 Additionally, seeing a PCP for diagnosis of a skin disease may be inefficient if subsequent referral to a dermatologist is needed, a common scenario that occurs when patients see a PCP for skin conditions.9

Our study had limitations, which is typical of a study using a claims database. We used ICD-9 codes recorded in patients’ medical claims to determine diagnosis of psoriasis and rosacea; therefore, our study and data are subject to coding errors. We could not assess the severity of disease, only the presence of disease. Further confirmation of diagnosis could have been made through searching for a second ICD-9 code in the patient’s history. Our data also are from a limited time period and may not represent costs from other time periods.

Conclusion

Given the lack of cost difference between both specialties, we conclude that ACOs should consider encouraging patients to seek care for dermatologic diseases by dermatologists who generally are more accurate and efficient skin diagnosticians, particularly if there is a shortage of PCPs within the ACO network.

- Wimo A, Religa D, Spångberg K, et al. Costs of diagnosing dementia: results from SveDem, the Swedish Dementia Registry. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28:1039-1044.

- Grunfeld E, Fitzpatrick R, Mant D, et al. Comparison of breast cancer patient satisfaction with follow-up in primary care versus specialist care: results from a randomized controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49:705-710.

- Chen SC, Pennie ML, Kolm P, et al. Diagnosing and managing cutaneous pigmented lesions: primary care physicians versus dermatologists. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:678-682.

- Federman D, Hogan D, Taylor JR, et al. A comparison of diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of patients with dermatologic disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:726-729.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, Young AC, et al. Time-efficiency of nondermatologists compared with dermatologists in the care of skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:194-199.

- Feldman SR, Peterson SR, Fleischer AB Jr. Dermatologists meet the primary care standard for first contact management of skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):182-186.

- Smith ES, Fleischer AB, Feldman SR. Nondermatologists are more likely than dermatologists to prescribe antifungal/corticosteroid products: an analysis of office visits for cutaneous fungal infections, 1990-1994. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:43-47.

- Shaffer MP, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB. Use of clotrimazole/betamethasone diproprionate by family physicians. Fam Med. 2000;32:561-565.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, Chen JG. The gatekeeper model is inefficient for the delivery of dermatologic services. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:426-432.

Growing incentives to control health care costs may cause accountable care organizations (ACOs) to reconsider how diseases are best managed. Few studies have examined the cost difference between primary care providers (PCPs) and specialists in managing the same disease. Limited data have suggested that management of some diseases by a PCP may be less costly compared to a specialist1,2; however, it is not clear if this finding extends to skin disease. This study sought to assess the cost of seeing a dermatologist versus a PCP for diagnosis of the common skin diseases psoriasis and rosacea.

Methods

Patient data were obtained from the Humana database, a large commercial data set for claims and reimbursed costs encompassing 18,162,539 patients covered between January 2007 and December 2014. Our study population consisted of 3,944,465 patients with claims that included International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), codes for dermatological diagnoses (680.0–709.9). We searched by ICD-9 code for US patients with primary diagnoses of psoriasis (696.1) and rosacea (695.3). We narrowed the search to include patients aged 30 to 64 years, as the diagnoses for these diseases are most common in patients older than 30 years. Patients who were older than 64 years were not included in the study, as most are covered by Medicare and therefore costs covered by Humana in this age group would not be as representative as in younger age groups. Total and average diagnosis-related costs per patient were compared between dermatologists and PCPs. Diagnosis-related costs encompassed physician reimbursement; laboratory and imaging costs, including skin biopsies; inpatient hospitalization cost; and any other charge that could be coded or billed by providers and reimbursed by the insurance company. To be eligible for reimbursement from Humana, dermatologists and PCPs must be registered with the insurer according to specialty board certification and practice credentialing, and they are reimbursed differently based on specialty. Drug costs, which would possibly skew the data toward providers using more expensive systemic medications (ie, dermatologists), were not included in this study, as the discussion is better reserved for long-term management of disease rather than diagnosis-related costs. All diagnoses of psoriasis were included in the study, which likely includes all severities of psoriasis, though we did not have the ability to further break down these diagnoses by severity.

Results

We identified 30,217 psoriasis patients and 37,561 rosacea patients. Of those patients with a primary diagnosis of psoriasis, 26,112 (86%) were seen by a dermatologist and 4105 (14%) were seen by a PCP (Table). Of those patients with a primary diagnosis of rosacea, 34,694 (92%) were seen by a dermatologist and 2867 (8%) were seen by a PCP (Table). There was little difference in the average diagnosis-related cost per patient for psoriasis in males (dermatologists, $638; PCPs, $657) versus females (dermatologists, $592; PCPs, $586) or between specialties (Figure). Findings were similar for rosacea in males (dermatologists, $179; PCPs, $168) versus females (dermatologists, $157; PCPs, $161). For these skin diseases, i

Comment

For the management of common skin disorders such as psoriasis and rosacea, there is little cost difference in seeing a dermatologist versus a PCP. Through extensive training and repeated exposure to many skin diseases, dermatologists are expected to be more comfortable in diagnosing and managing psoriasis and rosacea. Compared to PCPs, dermatologists have demonstrated increased diagnostic accuracy and efficiency when examining pigmented lesions and other dermatologic diseases in several studies.3-6 Although the current study shows that diagnosis-related costs for psoriasis and rosacea are essentially equal between dermatologists and PCPs, it actually may be less expensive for patients to see a dermatologist, as unnecessary tests, biopsies, or medications are more likely to be ordered/prescribed when there is less clinical diagnostic certainty.7,8 Additionally, seeing a PCP for diagnosis of a skin disease may be inefficient if subsequent referral to a dermatologist is needed, a common scenario that occurs when patients see a PCP for skin conditions.9

Our study had limitations, which is typical of a study using a claims database. We used ICD-9 codes recorded in patients’ medical claims to determine diagnosis of psoriasis and rosacea; therefore, our study and data are subject to coding errors. We could not assess the severity of disease, only the presence of disease. Further confirmation of diagnosis could have been made through searching for a second ICD-9 code in the patient’s history. Our data also are from a limited time period and may not represent costs from other time periods.

Conclusion

Given the lack of cost difference between both specialties, we conclude that ACOs should consider encouraging patients to seek care for dermatologic diseases by dermatologists who generally are more accurate and efficient skin diagnosticians, particularly if there is a shortage of PCPs within the ACO network.

Growing incentives to control health care costs may cause accountable care organizations (ACOs) to reconsider how diseases are best managed. Few studies have examined the cost difference between primary care providers (PCPs) and specialists in managing the same disease. Limited data have suggested that management of some diseases by a PCP may be less costly compared to a specialist1,2; however, it is not clear if this finding extends to skin disease. This study sought to assess the cost of seeing a dermatologist versus a PCP for diagnosis of the common skin diseases psoriasis and rosacea.

Methods

Patient data were obtained from the Humana database, a large commercial data set for claims and reimbursed costs encompassing 18,162,539 patients covered between January 2007 and December 2014. Our study population consisted of 3,944,465 patients with claims that included International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), codes for dermatological diagnoses (680.0–709.9). We searched by ICD-9 code for US patients with primary diagnoses of psoriasis (696.1) and rosacea (695.3). We narrowed the search to include patients aged 30 to 64 years, as the diagnoses for these diseases are most common in patients older than 30 years. Patients who were older than 64 years were not included in the study, as most are covered by Medicare and therefore costs covered by Humana in this age group would not be as representative as in younger age groups. Total and average diagnosis-related costs per patient were compared between dermatologists and PCPs. Diagnosis-related costs encompassed physician reimbursement; laboratory and imaging costs, including skin biopsies; inpatient hospitalization cost; and any other charge that could be coded or billed by providers and reimbursed by the insurance company. To be eligible for reimbursement from Humana, dermatologists and PCPs must be registered with the insurer according to specialty board certification and practice credentialing, and they are reimbursed differently based on specialty. Drug costs, which would possibly skew the data toward providers using more expensive systemic medications (ie, dermatologists), were not included in this study, as the discussion is better reserved for long-term management of disease rather than diagnosis-related costs. All diagnoses of psoriasis were included in the study, which likely includes all severities of psoriasis, though we did not have the ability to further break down these diagnoses by severity.

Results

We identified 30,217 psoriasis patients and 37,561 rosacea patients. Of those patients with a primary diagnosis of psoriasis, 26,112 (86%) were seen by a dermatologist and 4105 (14%) were seen by a PCP (Table). Of those patients with a primary diagnosis of rosacea, 34,694 (92%) were seen by a dermatologist and 2867 (8%) were seen by a PCP (Table). There was little difference in the average diagnosis-related cost per patient for psoriasis in males (dermatologists, $638; PCPs, $657) versus females (dermatologists, $592; PCPs, $586) or between specialties (Figure). Findings were similar for rosacea in males (dermatologists, $179; PCPs, $168) versus females (dermatologists, $157; PCPs, $161). For these skin diseases, i

Comment

For the management of common skin disorders such as psoriasis and rosacea, there is little cost difference in seeing a dermatologist versus a PCP. Through extensive training and repeated exposure to many skin diseases, dermatologists are expected to be more comfortable in diagnosing and managing psoriasis and rosacea. Compared to PCPs, dermatologists have demonstrated increased diagnostic accuracy and efficiency when examining pigmented lesions and other dermatologic diseases in several studies.3-6 Although the current study shows that diagnosis-related costs for psoriasis and rosacea are essentially equal between dermatologists and PCPs, it actually may be less expensive for patients to see a dermatologist, as unnecessary tests, biopsies, or medications are more likely to be ordered/prescribed when there is less clinical diagnostic certainty.7,8 Additionally, seeing a PCP for diagnosis of a skin disease may be inefficient if subsequent referral to a dermatologist is needed, a common scenario that occurs when patients see a PCP for skin conditions.9

Our study had limitations, which is typical of a study using a claims database. We used ICD-9 codes recorded in patients’ medical claims to determine diagnosis of psoriasis and rosacea; therefore, our study and data are subject to coding errors. We could not assess the severity of disease, only the presence of disease. Further confirmation of diagnosis could have been made through searching for a second ICD-9 code in the patient’s history. Our data also are from a limited time period and may not represent costs from other time periods.

Conclusion

Given the lack of cost difference between both specialties, we conclude that ACOs should consider encouraging patients to seek care for dermatologic diseases by dermatologists who generally are more accurate and efficient skin diagnosticians, particularly if there is a shortage of PCPs within the ACO network.

- Wimo A, Religa D, Spångberg K, et al. Costs of diagnosing dementia: results from SveDem, the Swedish Dementia Registry. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28:1039-1044.

- Grunfeld E, Fitzpatrick R, Mant D, et al. Comparison of breast cancer patient satisfaction with follow-up in primary care versus specialist care: results from a randomized controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49:705-710.

- Chen SC, Pennie ML, Kolm P, et al. Diagnosing and managing cutaneous pigmented lesions: primary care physicians versus dermatologists. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:678-682.

- Federman D, Hogan D, Taylor JR, et al. A comparison of diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of patients with dermatologic disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:726-729.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, Young AC, et al. Time-efficiency of nondermatologists compared with dermatologists in the care of skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:194-199.

- Feldman SR, Peterson SR, Fleischer AB Jr. Dermatologists meet the primary care standard for first contact management of skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):182-186.

- Smith ES, Fleischer AB, Feldman SR. Nondermatologists are more likely than dermatologists to prescribe antifungal/corticosteroid products: an analysis of office visits for cutaneous fungal infections, 1990-1994. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:43-47.

- Shaffer MP, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB. Use of clotrimazole/betamethasone diproprionate by family physicians. Fam Med. 2000;32:561-565.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, Chen JG. The gatekeeper model is inefficient for the delivery of dermatologic services. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:426-432.

- Wimo A, Religa D, Spångberg K, et al. Costs of diagnosing dementia: results from SveDem, the Swedish Dementia Registry. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28:1039-1044.

- Grunfeld E, Fitzpatrick R, Mant D, et al. Comparison of breast cancer patient satisfaction with follow-up in primary care versus specialist care: results from a randomized controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49:705-710.

- Chen SC, Pennie ML, Kolm P, et al. Diagnosing and managing cutaneous pigmented lesions: primary care physicians versus dermatologists. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:678-682.

- Federman D, Hogan D, Taylor JR, et al. A comparison of diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of patients with dermatologic disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:726-729.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, Young AC, et al. Time-efficiency of nondermatologists compared with dermatologists in the care of skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:194-199.

- Feldman SR, Peterson SR, Fleischer AB Jr. Dermatologists meet the primary care standard for first contact management of skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):182-186.

- Smith ES, Fleischer AB, Feldman SR. Nondermatologists are more likely than dermatologists to prescribe antifungal/corticosteroid products: an analysis of office visits for cutaneous fungal infections, 1990-1994. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:43-47.

- Shaffer MP, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB. Use of clotrimazole/betamethasone diproprionate by family physicians. Fam Med. 2000;32:561-565.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, Chen JG. The gatekeeper model is inefficient for the delivery of dermatologic services. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:426-432.

Practice Points

- Growing health care costs are causing accountable care organizations (ACOs) to reconsider how to best manage skin disease.

- There is little difference in average diagnosis-related cost between primary care physicians and dermatologists in diagnosing psoriasis or rosacea.

- With diagnosis costs essentially equal and increased dermatologist diagnostic accuracy, ACOs may encourage skin disease to be managed by dermatologists.

New Biologics in Psoriasis: An Update on IL-23 and IL-17 Inhibitors

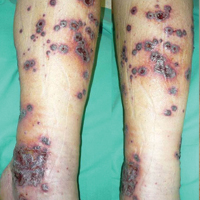

The role of current biologic therapies in psoriasis predicates on the pathogenic role of upregulated, immune-related mechanisms that result in the activation of myeloid dendritic cells, which release IL-17, IL-23, and other cytokines to activate T cells, including helper T cell TH17. Along with other immune cells, TH17 produces IL-17. This proinflammatory cascade results in keratinocyte proliferation, angiogenesis, and migration of immune cells toward psoriatic lesions.1 Thus, the newest classes of biologics target IL-12, IL-23, and IL-17 to disrupt this inflammatory cascade.

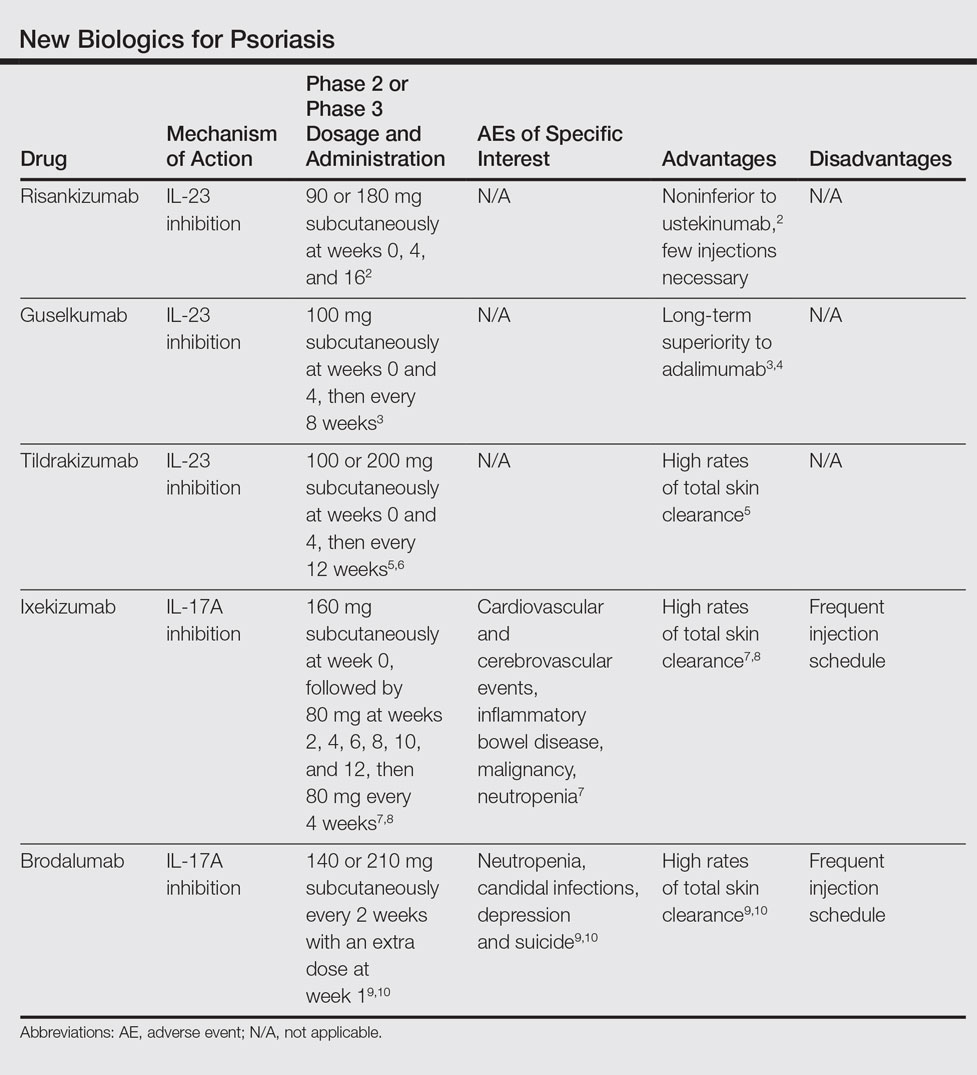

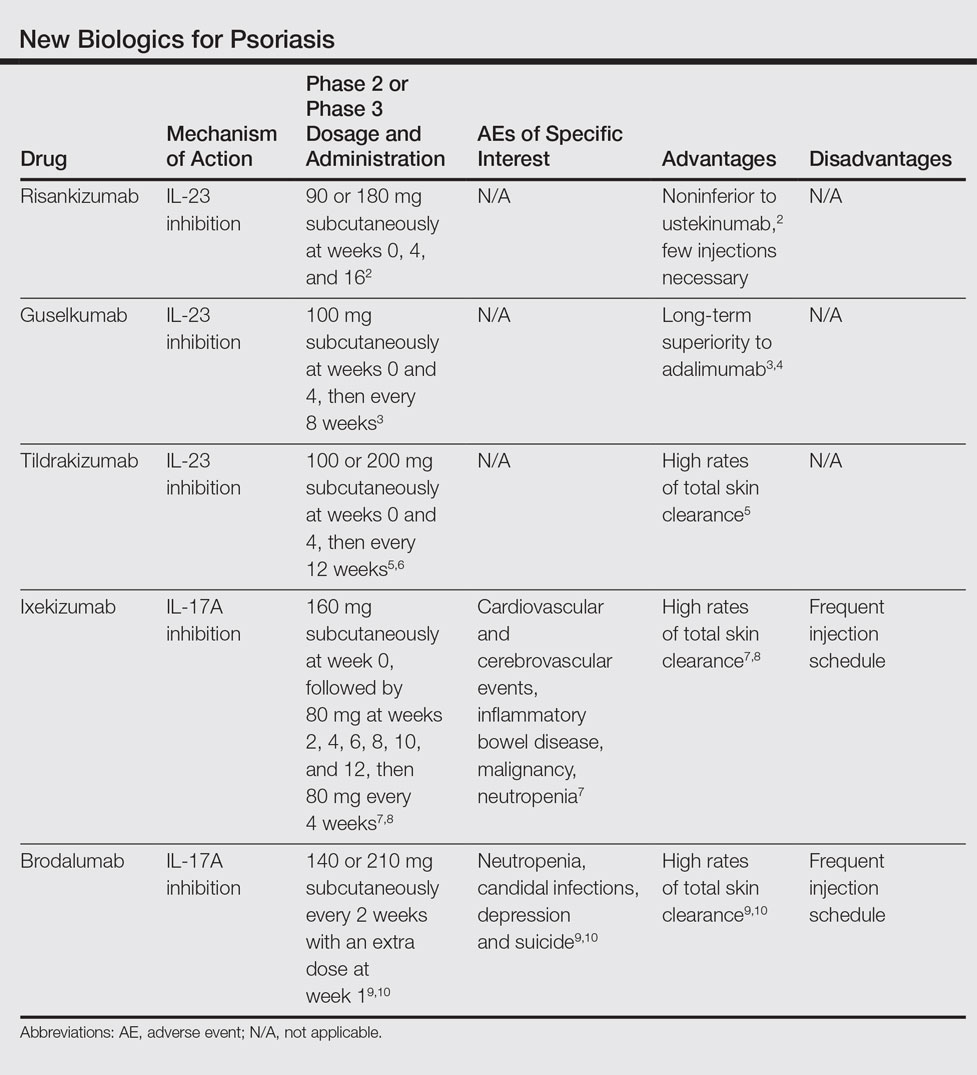

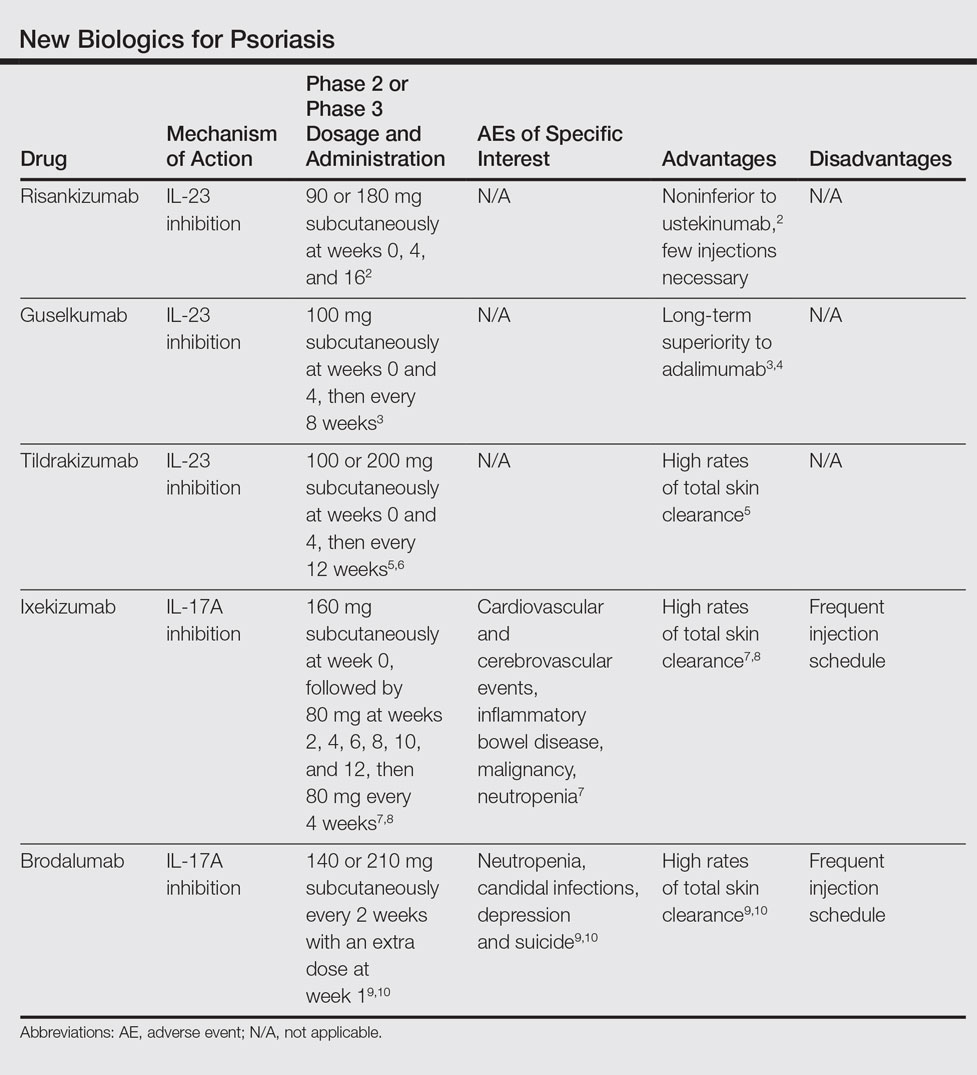

We provide an updated review of the most recent clinical efficacy and safety data on the newest IL-23 and IL-17 inhibitors in the pipeline or approved for psoriasis, including risankizumab, guselkumab, tildrakizumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab (Table). Ustekinumab and adalimumab, which have been previously approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), will be discussed here only as comparators.

IL-23 Inhibitors

Risankizumab

Risankizumab (formerly known as BI 655066)(Boehringer Ingelheim) is a selective human monoclonal antibody targeting the p19 subunit of IL-23 and currently is undergoing phase 3 trials for psoriasis. A proof-of-concept phase 1 study of 39 participants demonstrated efficacy after 12 weeks of treatment at varying subcutaneous and intravenous doses with placebo control.11 At week 12, 87% (27/31)(P<.001) of all risankizumab-treated participants achieved 75% reduction in psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score compared to 0% of 8 placebo-treated participants. Common adverse effects (AEs) occurred in 65% (20/31) of risankizumab-treated participants, including non–dose-dependent upper respiratory tract infections, nasopharyngitis, and headache. Serious adverse events (SAEs) that occurred were considered unrelated to the study medication.11

A phase 2 trial of 166 participants compared 3 dosing regimens of subcutaneous risankizumab (single 18-mg dose at week 0; single 90-mg dose at weeks 0, 4, and 16; or single 180-mg dose at weeks 0, 4, and 16) and ustekinumab (weight-based single 45- or 90-mg dose at weeks 0, 4, and 16), demonstrating noninferiority at higher doses of risankizumab.2 Preliminary primary end point results at week 12 showed PASI 90 in 32.6% (P=.4667), 73.2% (P=.0013), 81.0% (P<.0001), and 40.0% of the treatment groups, respectively. Participants in the 180-mg risankizumab group achieved PASI 90 eight weeks faster than those on ustekinumab, lasting more than 2 months longer. Adverse effects were similar across all treatment groups and SAEs were unrelated to the study medications.2

Guselkumab

Guselkumab (Janssen Biotech, Inc) is a selective human monoclonal antibody against the p19 subunit of IL-23. The 52-week phase 2 X-PLORE trial compared dose-ranging subcutaneous guselkumab (5 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks; 15 mg every 8 weeks; 50 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks; 100 mg every 8 weeks; or 200 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks), adalimumab (80-mg loading dose, followed by 40 mg at week 1, then every other week), and placebo in 293 randomized participants.4 At week 16, 34% (P=.002) of participants in the 5-mg guselkumab group, 61% (P<.001) in the 15-mg group, 79% (P<.001) in the 50-mg group, 86% (P<.001) in the 100-mg group, 83% (P<.001) in the 200-mg group, and 58% (P<.001) in the adalimumab group achieved physician global assessment (PGA) scores of 0 (clear) or 1 (minimal psoriasis) compared to 7% of the placebo group. Achievement of PASI 75 similarly favored the guselkumab (44% [P<.001]; 76% [no P value given]; 81% [P<.001]; 79% [P<.001]; and 81% [P<.001], respectively) and adalimumab treatment arms (70% [P<.001]) compared to 5% in the placebo group. In longer-term comparisons to week 40, participants in the 50-, 100-, and 200-mg guselkumab groups showed significantly greater remission of psoriatic lesions, measured by a PGA score of 0 or 1, than participants in the adalimumab group (71% [P=.05]; 77% [P=.005]; 81% [P=.01]; and 49%, respectively).4

Preliminary results from VOYAGE 1 (N=837), the first of several phase 3 trials, further demonstrate the superiority of guselkumab 100 mg at weeks 0 and 4 and then every 8 weeks over adalimumab (standard dosing) and placebo; at week 16, 73.3% (P<.001 for both comparisons) versus 49.7% and 2.9% of participants, respectively, achieved PASI 90, with sustained superiority of skin clearance in guselkumab-treated participants compared to adalimumab and placebo through week 48.3

Long-term safety data showed no dose dependence or trend from 0 to 16 weeks and 16 to 52 weeks of treatment regarding rates of AEs, SAEs, or serious infections.4 Between weeks 16 and 52, 48.9% of all guselkumab-treated participants exhibited AEs compared to 60.5% of adalimumab-treated participants and 51.3% of placebo participants. Overall infection rates also were lowest in the guselkumab group at 29.8% compared to 36.8% and 35.9%, respectively. Three participants treated with guselkumab had major cardiovascular events, including a fatal myocardial infarction. No cases of tuberculosis or serious opportunistic infections were reported.4

Tildrakizumab

Tildrakizumab (formerly known as MK-3222)(Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd) is a human monoclonal antibody also targeting the p19 subunit of IL-23. In a phase 2 study of 355 participants with chronic plaque psoriasis, participants received 5-, 25-, 100-, or 200-mg subcutaneous tildrakizumab or placebo at weeks 0 and 4 and then every 12 weeks for a total of 52 weeks.6 At week 16, PASI 75 results were 33.3%, 64.4%, 66.3%, 74.4%, and 4.4%, respectively (P<.001 for each comparison). Improvement began within the first month of treatment, with median times to PASI 75 of 57 days at 200-mg dosing and 84 days at 100-mg dosing. Of those participants achieving PASI 75 by drug discontinuation at week 52, 96% of the 100-mg group and 93% of the 200-mg group maintained PASI 75 through week 72, suggesting low relapse rates after treatment cessation.6

In October 2016, the efficacy results of 2 pivotal phase 3 trials (reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2) involving more than 1800 participants combined revealed PASI 90 achievement in an average of 54% of participants on tildrakizumab 100 mg and 59% of participants on tildrakizumab 200 mg at week 28.5 Achievement of PASI 100 occurred in 24% and 30% of participants at week 28, respectively. The second of these trials included an etanercept comparison group and demonstrated head-to-head superiority of 100 and 200 mg subcutaneous tildrakizumab at week 12 by end point measures.5

Treatment-related AEs occurred at rates of 25% in tildrakizumab-treated participants and 22% in placebo-treated participants, most frequently nasopharyngitis and headache.6 At least 1 AE occurred in 64% of tildrakizumab-treated participants without dose dependence compared to 69% of placebo-treated participants. Severe AEs thought to be drug treatment related were bacterial arthritis, lymphedema, melanoma, stroke, and epiglottitis.6

IL-17 Inhibitors

Ixekizumab

Ixekizumab (Eli Lilly and Company), a monoclonal inhibitor of IL-17A, is the most recently approved psoriasis biologic on the market and has been cleared for use in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Recommended dosing is 160 mg (given in two 80-mg subcutaneous injections via an autoinjector or prefilled syringe) at week 0, followed by an 80-mg injection at weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12, and then 80 mg every 4 weeks thereafter. The FDA approved ixekizumab in March 2016 following favorable results of several phase 3 trials: UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3.7,8

In UNCOVER-1, 1296 participants were randomized to 1 of 2 ixekizumab treatment arms—160 mg starting dose at week 0, 80 mg every 2 or 4 weeks thereafter—or placebo.7 At week 12, 89.1%, 82.6%, and 3.9% achieved PASI 75, respectively (P<.001 for both). Importantly, high numbers of participants also achieved PASI 90 (70.9% in the 2-week group and 64.6% in the 4-week group vs 0.5% in the placebo group [P<.001]) and PASI 100 (35.3% and 33.6% vs 0%, respectively [P<.001]), suggesting high rates of disease clearance.7

UNCOVER-2 (N=1224) and UNCOVER-3 (N=1346) investigated the same 2 dosing regimens of ixekizumab compared to etanercept 50 mg biweekly and placebo.8 At week 12, the percentage of participants achieving PASI 90 in UNCOVER-2 was 70.7%, 59.7%, 18.7%, and 0.6%, respectively, and 68.1%, 65.3%, 25.7%, and 3.1%, respectively, in UNCOVER-3 (P<.0001 for all comparisons to placebo and etanercept). At week 12, PASI 100 results also showed striking superiority, with 40.5%, 30.8%, 5.3%, and 0.6% of participants, respectively, in UNCOVER-2, and 37.7%, 35%, 7.3%, and 0%, respectively, in UNCOVER-3, achieving complete clearance of disease (P<.0001 for all comparisons to placebo and etanercept). Responses to ixekizumab were observed as early as weeks 1 and 2, while no participants in the etanercept and placebo treatment groups achieved comparative efficiency.8

In an extension of UNCOVER-3, efficacy increased from week 12 to week 60 according to PASI 90 (68%–73% in the 2-week group; 65%–72% in the 4-week group) and PASI 100 measures (38%–55% in the 2-week group; 35%–52% in the 4-week group).7

The most common AEs associated with ixekizumab treatment from weeks 0 to 12 occurred at higher rates in the 2-week and 4-week ixekizumab groups compared to placebo, including nasopharyngitis (9.5% and 9% vs 8.7%, respectively), upper respiratory tract infection (4.4% and 3.9% vs 3.5%, respectively), injection-site reaction (10% and 7.7% vs 1%, respectively), arthralgia (4.4% and 4.3% vs 2.9%, respectively), and headache (2.5% and 1.9% vs 2.1%, respectively). Infections, including candidal, oral, vulvovaginal, and cutaneous, occurred in 27% of the 2-week dosing group and 27.4% of the 4-week dosing group compared to 22.9% of the placebo group during weeks 0 to 12, with candidal infections in particular occurring more frequently in the active treatment groups and exhibiting dose dependence. Other AEs of special interest that occurred among all ixekizumab-treated participants (n=3736) from weeks 0 to 60 were cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (22 [0.6%]), inflammatory bowel disease (11 [0.3%]), non–skin cancer malignancy (14 [0.4%]), and nonmelanoma skin cancer (20 [0.5%]). Neutropenia occurred at higher rates in ixekizumab-treated participants (9.3% in the 2-week group and 8.6% in the 4-week group) compared to placebo (3.3%) and occurred in 11.5% of all ixekizumab participants over 60 weeks.7

Brodalumab

Brodalumab (Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc) is a human monoclonal antibody targeting the IL-17A receptor currently under review for FDA approval after undergoing phase 3 trials. The first of these trials, AMAGINE-1, showed efficacy of subcutaneous brodalumab (140 or 210 mg administered every 2 weeks with an extra dose at week 1) compared to placebo in 661 participants.9 At week 12, 60%, 83%, and 3%, respectively, achieved PASI 75; 43%, 70%, and 1%, respectively, achieved PASI 90; and 23%, 42%, and 1%, respectively, achieved PASI 100 (P<.001 for all respective comparisons to placebo). These effects were retained through 52 weeks of treatment. The median time to complete disease clearance in participants reaching PASI 100 was 12 weeks. Conversely, participants who were re-randomized to placebo after week 12 of brodalumab treatment relapsed within weeks to months.9

AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 further demonstrated the efficacy of brodalumab (140 or 210 mg every 2 weeks with extra dose at week 1) compared to ustekinumab (45 or 90 mg weight-based standard dosing) and placebo in 1831 participants, respectively.10 In AMAGINE-2, 49% of participants in the 140-mg group (P<.001 vs placebo), 70% in the 210-mg group (P<.001 vs placebo), 47% in the ustekinumab group, and 3% in the placebo group achieved PASI 90 at week 12. Similarly, in AMAGINE-3, 52% of participants in the 140-mg group (P<.001), 69% in the 210-mg group (P<.001), 48% in the ustekinumab group, and 2% in the placebo group achieved PASI 90. Impressively, complete clearance (PASI 100) at week 12 occurred in 26% of the 140-mg group (P<.001 vs placebo), 44% of the 210-mg group (P<.001 vs placebo), and 22% of the ustekinumab group compared to 2% of the placebo group in AMAGINE-2, with similar rates in AMAGINE-3. Brodalumab was significantly superior to ustekinumab at the 210-mg dose by PASI 90 measures (P<.001) in both studies and at the 140-mg dose by PASI 100 measures (P=.007) in AMAGINE-3 only.10

Common AEs were nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, and arthralgia, all occurring at grossly similar rates (49%–60%) across all experimental groups in AMAGINE-1, AMAGINE-2, and AMAGINE-3 during the first 12-week treatment period.9,10 Brodalumab treatment groups had high rates of specific interest AEs compared to ustekinumab and placebo groups, including neutropenia (0.8%, 1.1%, 0.3%, and 0%, respectively) and candidal infections (0.8%, 1.3%, 0.3%, and 0.3%, respectively). Induction phase (weeks 0–12) depression rates were concerning, with 6 cases each in AMAGINE-2 (4 [0.7%] in the 140-mg group, 2 [0.3%] in the 210-mg group) and AMAGINE-3 (4 [0.6%] in the 140-mg group, 2 [0.3%] in the 210-mg group). Cases of neutropenia were mild, were not associated with major infection, and were transient or reversible. Depression rates after 52 weeks of treatment were 1.7% (23/1567) of brodalumab participants in AMAGINE-2 and 1.8% (21/1613) in AMAGINE-3. Three participants, all on constant 210-mg dosing through week 52, attempted suicide with 1 completion10; however, because no other IL-17 inhibitors were associated with depression or suicide in other trials, it has been suggested that these cases were incidental and not treatment related.12 An FDA advisory panel recommended approval of brodalumab in July 2016 despite ongoing concerns of depression and suicide.13

Conclusion

The robust investigation into IL-23 and IL-17 inhibitors to treat plaque psoriasis has yielded promising results, including the unprecedented rates of PASI 100 achievement with these new biologics. Risankizumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab have demonstrated superior efficacy in trials compared to ustekinumab. Tildrakizumab has shown low disease relapse after drug cessation. Ixekizumab and brodalumab have shown high rates of total disease clearance. Thus far, safety findings for these pipeline biologics have been consistent with those of ustekinumab. With ixekizumab approved in 2016 and brodalumab under review, new options in biologic therapy will offer patients and clinicians greater choices in treating severe and recalcitrant psoriasis.

- Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:496-509.

- Papp K, Menter A, Sofen H, et al. Efficacy and safety of different dose regimens of a selective IL-23p19 inhibitor (BI 655066) compared with ustekinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis with and without psoriatic arthritis. Paper presented at: 2015 American College of Rheumatology/Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals Annual Meeting; November 6-11, 2015; San Francisco, CA.

- New phase 3 data show significant efficacy versus placebo and superiority of guselkumab versus Humira in treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis [press release]. Vienna, Austria; Janssen Research & Development, LLC: October 1, 2016.

- Gordon KB, Duffin KC, Bissonnette R, et al. A phase 2 trial of guselkumab versus adalimumab for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:136-144.

- Sun Pharma to announce late-breaking results for investigational IL-23p19 inhibitor, Tildrakizumab, achieves primary end point in both phase-3 studies in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [press release]. Mumbai, India; Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd: October 1, 2016.

- Papp K, Thaci D, Reich K, et al. Tildrakizumab (MK-3222), an anti-interleukin-23p19 monoclonal antibody, improves psoriasis in a phase IIb randomized placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:930-939.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al; UNCOVER-1 Study Group, UNCOVER-2 Study Group, UNCOVER-3 Study Group. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- Griffiths CE, Reich K, Lebwohl M, et al. Comparison of ixekizumab with etanercept or placebo in moderate-to-severe psoriasis (UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3): results from two phase 3 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;386:541-551.

- Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [published online June 23, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:273-286.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318-1328.

- Krueger JG, Ferris LK, Menter A, et al. Anti-IL-23A mAb BI 655066 for treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and biomarker results of a single-rising-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [published online March 1, 2015]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:116-124.e7.

- Chiricozzi A, Romanelli M, Saraceno R, et al. No meaningful association between suicidal behavior and the use of IL-17A-neutralizing or IL-17RA-blocking agents [published online August 31, 2016]. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:1653-1659.

- FDA advisory committee recommends approval of brodalumab for treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [news release]. Laval, Quebec: Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc; July 19, 2016.

The role of current biologic therapies in psoriasis predicates on the pathogenic role of upregulated, immune-related mechanisms that result in the activation of myeloid dendritic cells, which release IL-17, IL-23, and other cytokines to activate T cells, including helper T cell TH17. Along with other immune cells, TH17 produces IL-17. This proinflammatory cascade results in keratinocyte proliferation, angiogenesis, and migration of immune cells toward psoriatic lesions.1 Thus, the newest classes of biologics target IL-12, IL-23, and IL-17 to disrupt this inflammatory cascade.

We provide an updated review of the most recent clinical efficacy and safety data on the newest IL-23 and IL-17 inhibitors in the pipeline or approved for psoriasis, including risankizumab, guselkumab, tildrakizumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab (Table). Ustekinumab and adalimumab, which have been previously approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), will be discussed here only as comparators.

IL-23 Inhibitors

Risankizumab

Risankizumab (formerly known as BI 655066)(Boehringer Ingelheim) is a selective human monoclonal antibody targeting the p19 subunit of IL-23 and currently is undergoing phase 3 trials for psoriasis. A proof-of-concept phase 1 study of 39 participants demonstrated efficacy after 12 weeks of treatment at varying subcutaneous and intravenous doses with placebo control.11 At week 12, 87% (27/31)(P<.001) of all risankizumab-treated participants achieved 75% reduction in psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score compared to 0% of 8 placebo-treated participants. Common adverse effects (AEs) occurred in 65% (20/31) of risankizumab-treated participants, including non–dose-dependent upper respiratory tract infections, nasopharyngitis, and headache. Serious adverse events (SAEs) that occurred were considered unrelated to the study medication.11

A phase 2 trial of 166 participants compared 3 dosing regimens of subcutaneous risankizumab (single 18-mg dose at week 0; single 90-mg dose at weeks 0, 4, and 16; or single 180-mg dose at weeks 0, 4, and 16) and ustekinumab (weight-based single 45- or 90-mg dose at weeks 0, 4, and 16), demonstrating noninferiority at higher doses of risankizumab.2 Preliminary primary end point results at week 12 showed PASI 90 in 32.6% (P=.4667), 73.2% (P=.0013), 81.0% (P<.0001), and 40.0% of the treatment groups, respectively. Participants in the 180-mg risankizumab group achieved PASI 90 eight weeks faster than those on ustekinumab, lasting more than 2 months longer. Adverse effects were similar across all treatment groups and SAEs were unrelated to the study medications.2

Guselkumab

Guselkumab (Janssen Biotech, Inc) is a selective human monoclonal antibody against the p19 subunit of IL-23. The 52-week phase 2 X-PLORE trial compared dose-ranging subcutaneous guselkumab (5 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks; 15 mg every 8 weeks; 50 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks; 100 mg every 8 weeks; or 200 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks), adalimumab (80-mg loading dose, followed by 40 mg at week 1, then every other week), and placebo in 293 randomized participants.4 At week 16, 34% (P=.002) of participants in the 5-mg guselkumab group, 61% (P<.001) in the 15-mg group, 79% (P<.001) in the 50-mg group, 86% (P<.001) in the 100-mg group, 83% (P<.001) in the 200-mg group, and 58% (P<.001) in the adalimumab group achieved physician global assessment (PGA) scores of 0 (clear) or 1 (minimal psoriasis) compared to 7% of the placebo group. Achievement of PASI 75 similarly favored the guselkumab (44% [P<.001]; 76% [no P value given]; 81% [P<.001]; 79% [P<.001]; and 81% [P<.001], respectively) and adalimumab treatment arms (70% [P<.001]) compared to 5% in the placebo group. In longer-term comparisons to week 40, participants in the 50-, 100-, and 200-mg guselkumab groups showed significantly greater remission of psoriatic lesions, measured by a PGA score of 0 or 1, than participants in the adalimumab group (71% [P=.05]; 77% [P=.005]; 81% [P=.01]; and 49%, respectively).4

Preliminary results from VOYAGE 1 (N=837), the first of several phase 3 trials, further demonstrate the superiority of guselkumab 100 mg at weeks 0 and 4 and then every 8 weeks over adalimumab (standard dosing) and placebo; at week 16, 73.3% (P<.001 for both comparisons) versus 49.7% and 2.9% of participants, respectively, achieved PASI 90, with sustained superiority of skin clearance in guselkumab-treated participants compared to adalimumab and placebo through week 48.3

Long-term safety data showed no dose dependence or trend from 0 to 16 weeks and 16 to 52 weeks of treatment regarding rates of AEs, SAEs, or serious infections.4 Between weeks 16 and 52, 48.9% of all guselkumab-treated participants exhibited AEs compared to 60.5% of adalimumab-treated participants and 51.3% of placebo participants. Overall infection rates also were lowest in the guselkumab group at 29.8% compared to 36.8% and 35.9%, respectively. Three participants treated with guselkumab had major cardiovascular events, including a fatal myocardial infarction. No cases of tuberculosis or serious opportunistic infections were reported.4

Tildrakizumab

Tildrakizumab (formerly known as MK-3222)(Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd) is a human monoclonal antibody also targeting the p19 subunit of IL-23. In a phase 2 study of 355 participants with chronic plaque psoriasis, participants received 5-, 25-, 100-, or 200-mg subcutaneous tildrakizumab or placebo at weeks 0 and 4 and then every 12 weeks for a total of 52 weeks.6 At week 16, PASI 75 results were 33.3%, 64.4%, 66.3%, 74.4%, and 4.4%, respectively (P<.001 for each comparison). Improvement began within the first month of treatment, with median times to PASI 75 of 57 days at 200-mg dosing and 84 days at 100-mg dosing. Of those participants achieving PASI 75 by drug discontinuation at week 52, 96% of the 100-mg group and 93% of the 200-mg group maintained PASI 75 through week 72, suggesting low relapse rates after treatment cessation.6

In October 2016, the efficacy results of 2 pivotal phase 3 trials (reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2) involving more than 1800 participants combined revealed PASI 90 achievement in an average of 54% of participants on tildrakizumab 100 mg and 59% of participants on tildrakizumab 200 mg at week 28.5 Achievement of PASI 100 occurred in 24% and 30% of participants at week 28, respectively. The second of these trials included an etanercept comparison group and demonstrated head-to-head superiority of 100 and 200 mg subcutaneous tildrakizumab at week 12 by end point measures.5

Treatment-related AEs occurred at rates of 25% in tildrakizumab-treated participants and 22% in placebo-treated participants, most frequently nasopharyngitis and headache.6 At least 1 AE occurred in 64% of tildrakizumab-treated participants without dose dependence compared to 69% of placebo-treated participants. Severe AEs thought to be drug treatment related were bacterial arthritis, lymphedema, melanoma, stroke, and epiglottitis.6

IL-17 Inhibitors

Ixekizumab

Ixekizumab (Eli Lilly and Company), a monoclonal inhibitor of IL-17A, is the most recently approved psoriasis biologic on the market and has been cleared for use in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Recommended dosing is 160 mg (given in two 80-mg subcutaneous injections via an autoinjector or prefilled syringe) at week 0, followed by an 80-mg injection at weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12, and then 80 mg every 4 weeks thereafter. The FDA approved ixekizumab in March 2016 following favorable results of several phase 3 trials: UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3.7,8

In UNCOVER-1, 1296 participants were randomized to 1 of 2 ixekizumab treatment arms—160 mg starting dose at week 0, 80 mg every 2 or 4 weeks thereafter—or placebo.7 At week 12, 89.1%, 82.6%, and 3.9% achieved PASI 75, respectively (P<.001 for both). Importantly, high numbers of participants also achieved PASI 90 (70.9% in the 2-week group and 64.6% in the 4-week group vs 0.5% in the placebo group [P<.001]) and PASI 100 (35.3% and 33.6% vs 0%, respectively [P<.001]), suggesting high rates of disease clearance.7

UNCOVER-2 (N=1224) and UNCOVER-3 (N=1346) investigated the same 2 dosing regimens of ixekizumab compared to etanercept 50 mg biweekly and placebo.8 At week 12, the percentage of participants achieving PASI 90 in UNCOVER-2 was 70.7%, 59.7%, 18.7%, and 0.6%, respectively, and 68.1%, 65.3%, 25.7%, and 3.1%, respectively, in UNCOVER-3 (P<.0001 for all comparisons to placebo and etanercept). At week 12, PASI 100 results also showed striking superiority, with 40.5%, 30.8%, 5.3%, and 0.6% of participants, respectively, in UNCOVER-2, and 37.7%, 35%, 7.3%, and 0%, respectively, in UNCOVER-3, achieving complete clearance of disease (P<.0001 for all comparisons to placebo and etanercept). Responses to ixekizumab were observed as early as weeks 1 and 2, while no participants in the etanercept and placebo treatment groups achieved comparative efficiency.8

In an extension of UNCOVER-3, efficacy increased from week 12 to week 60 according to PASI 90 (68%–73% in the 2-week group; 65%–72% in the 4-week group) and PASI 100 measures (38%–55% in the 2-week group; 35%–52% in the 4-week group).7

The most common AEs associated with ixekizumab treatment from weeks 0 to 12 occurred at higher rates in the 2-week and 4-week ixekizumab groups compared to placebo, including nasopharyngitis (9.5% and 9% vs 8.7%, respectively), upper respiratory tract infection (4.4% and 3.9% vs 3.5%, respectively), injection-site reaction (10% and 7.7% vs 1%, respectively), arthralgia (4.4% and 4.3% vs 2.9%, respectively), and headache (2.5% and 1.9% vs 2.1%, respectively). Infections, including candidal, oral, vulvovaginal, and cutaneous, occurred in 27% of the 2-week dosing group and 27.4% of the 4-week dosing group compared to 22.9% of the placebo group during weeks 0 to 12, with candidal infections in particular occurring more frequently in the active treatment groups and exhibiting dose dependence. Other AEs of special interest that occurred among all ixekizumab-treated participants (n=3736) from weeks 0 to 60 were cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (22 [0.6%]), inflammatory bowel disease (11 [0.3%]), non–skin cancer malignancy (14 [0.4%]), and nonmelanoma skin cancer (20 [0.5%]). Neutropenia occurred at higher rates in ixekizumab-treated participants (9.3% in the 2-week group and 8.6% in the 4-week group) compared to placebo (3.3%) and occurred in 11.5% of all ixekizumab participants over 60 weeks.7

Brodalumab

Brodalumab (Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc) is a human monoclonal antibody targeting the IL-17A receptor currently under review for FDA approval after undergoing phase 3 trials. The first of these trials, AMAGINE-1, showed efficacy of subcutaneous brodalumab (140 or 210 mg administered every 2 weeks with an extra dose at week 1) compared to placebo in 661 participants.9 At week 12, 60%, 83%, and 3%, respectively, achieved PASI 75; 43%, 70%, and 1%, respectively, achieved PASI 90; and 23%, 42%, and 1%, respectively, achieved PASI 100 (P<.001 for all respective comparisons to placebo). These effects were retained through 52 weeks of treatment. The median time to complete disease clearance in participants reaching PASI 100 was 12 weeks. Conversely, participants who were re-randomized to placebo after week 12 of brodalumab treatment relapsed within weeks to months.9

AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 further demonstrated the efficacy of brodalumab (140 or 210 mg every 2 weeks with extra dose at week 1) compared to ustekinumab (45 or 90 mg weight-based standard dosing) and placebo in 1831 participants, respectively.10 In AMAGINE-2, 49% of participants in the 140-mg group (P<.001 vs placebo), 70% in the 210-mg group (P<.001 vs placebo), 47% in the ustekinumab group, and 3% in the placebo group achieved PASI 90 at week 12. Similarly, in AMAGINE-3, 52% of participants in the 140-mg group (P<.001), 69% in the 210-mg group (P<.001), 48% in the ustekinumab group, and 2% in the placebo group achieved PASI 90. Impressively, complete clearance (PASI 100) at week 12 occurred in 26% of the 140-mg group (P<.001 vs placebo), 44% of the 210-mg group (P<.001 vs placebo), and 22% of the ustekinumab group compared to 2% of the placebo group in AMAGINE-2, with similar rates in AMAGINE-3. Brodalumab was significantly superior to ustekinumab at the 210-mg dose by PASI 90 measures (P<.001) in both studies and at the 140-mg dose by PASI 100 measures (P=.007) in AMAGINE-3 only.10

Common AEs were nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, and arthralgia, all occurring at grossly similar rates (49%–60%) across all experimental groups in AMAGINE-1, AMAGINE-2, and AMAGINE-3 during the first 12-week treatment period.9,10 Brodalumab treatment groups had high rates of specific interest AEs compared to ustekinumab and placebo groups, including neutropenia (0.8%, 1.1%, 0.3%, and 0%, respectively) and candidal infections (0.8%, 1.3%, 0.3%, and 0.3%, respectively). Induction phase (weeks 0–12) depression rates were concerning, with 6 cases each in AMAGINE-2 (4 [0.7%] in the 140-mg group, 2 [0.3%] in the 210-mg group) and AMAGINE-3 (4 [0.6%] in the 140-mg group, 2 [0.3%] in the 210-mg group). Cases of neutropenia were mild, were not associated with major infection, and were transient or reversible. Depression rates after 52 weeks of treatment were 1.7% (23/1567) of brodalumab participants in AMAGINE-2 and 1.8% (21/1613) in AMAGINE-3. Three participants, all on constant 210-mg dosing through week 52, attempted suicide with 1 completion10; however, because no other IL-17 inhibitors were associated with depression or suicide in other trials, it has been suggested that these cases were incidental and not treatment related.12 An FDA advisory panel recommended approval of brodalumab in July 2016 despite ongoing concerns of depression and suicide.13

Conclusion

The robust investigation into IL-23 and IL-17 inhibitors to treat plaque psoriasis has yielded promising results, including the unprecedented rates of PASI 100 achievement with these new biologics. Risankizumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab have demonstrated superior efficacy in trials compared to ustekinumab. Tildrakizumab has shown low disease relapse after drug cessation. Ixekizumab and brodalumab have shown high rates of total disease clearance. Thus far, safety findings for these pipeline biologics have been consistent with those of ustekinumab. With ixekizumab approved in 2016 and brodalumab under review, new options in biologic therapy will offer patients and clinicians greater choices in treating severe and recalcitrant psoriasis.

The role of current biologic therapies in psoriasis predicates on the pathogenic role of upregulated, immune-related mechanisms that result in the activation of myeloid dendritic cells, which release IL-17, IL-23, and other cytokines to activate T cells, including helper T cell TH17. Along with other immune cells, TH17 produces IL-17. This proinflammatory cascade results in keratinocyte proliferation, angiogenesis, and migration of immune cells toward psoriatic lesions.1 Thus, the newest classes of biologics target IL-12, IL-23, and IL-17 to disrupt this inflammatory cascade.

We provide an updated review of the most recent clinical efficacy and safety data on the newest IL-23 and IL-17 inhibitors in the pipeline or approved for psoriasis, including risankizumab, guselkumab, tildrakizumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab (Table). Ustekinumab and adalimumab, which have been previously approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), will be discussed here only as comparators.

IL-23 Inhibitors

Risankizumab

Risankizumab (formerly known as BI 655066)(Boehringer Ingelheim) is a selective human monoclonal antibody targeting the p19 subunit of IL-23 and currently is undergoing phase 3 trials for psoriasis. A proof-of-concept phase 1 study of 39 participants demonstrated efficacy after 12 weeks of treatment at varying subcutaneous and intravenous doses with placebo control.11 At week 12, 87% (27/31)(P<.001) of all risankizumab-treated participants achieved 75% reduction in psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score compared to 0% of 8 placebo-treated participants. Common adverse effects (AEs) occurred in 65% (20/31) of risankizumab-treated participants, including non–dose-dependent upper respiratory tract infections, nasopharyngitis, and headache. Serious adverse events (SAEs) that occurred were considered unrelated to the study medication.11

A phase 2 trial of 166 participants compared 3 dosing regimens of subcutaneous risankizumab (single 18-mg dose at week 0; single 90-mg dose at weeks 0, 4, and 16; or single 180-mg dose at weeks 0, 4, and 16) and ustekinumab (weight-based single 45- or 90-mg dose at weeks 0, 4, and 16), demonstrating noninferiority at higher doses of risankizumab.2 Preliminary primary end point results at week 12 showed PASI 90 in 32.6% (P=.4667), 73.2% (P=.0013), 81.0% (P<.0001), and 40.0% of the treatment groups, respectively. Participants in the 180-mg risankizumab group achieved PASI 90 eight weeks faster than those on ustekinumab, lasting more than 2 months longer. Adverse effects were similar across all treatment groups and SAEs were unrelated to the study medications.2

Guselkumab

Guselkumab (Janssen Biotech, Inc) is a selective human monoclonal antibody against the p19 subunit of IL-23. The 52-week phase 2 X-PLORE trial compared dose-ranging subcutaneous guselkumab (5 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks; 15 mg every 8 weeks; 50 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks; 100 mg every 8 weeks; or 200 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks), adalimumab (80-mg loading dose, followed by 40 mg at week 1, then every other week), and placebo in 293 randomized participants.4 At week 16, 34% (P=.002) of participants in the 5-mg guselkumab group, 61% (P<.001) in the 15-mg group, 79% (P<.001) in the 50-mg group, 86% (P<.001) in the 100-mg group, 83% (P<.001) in the 200-mg group, and 58% (P<.001) in the adalimumab group achieved physician global assessment (PGA) scores of 0 (clear) or 1 (minimal psoriasis) compared to 7% of the placebo group. Achievement of PASI 75 similarly favored the guselkumab (44% [P<.001]; 76% [no P value given]; 81% [P<.001]; 79% [P<.001]; and 81% [P<.001], respectively) and adalimumab treatment arms (70% [P<.001]) compared to 5% in the placebo group. In longer-term comparisons to week 40, participants in the 50-, 100-, and 200-mg guselkumab groups showed significantly greater remission of psoriatic lesions, measured by a PGA score of 0 or 1, than participants in the adalimumab group (71% [P=.05]; 77% [P=.005]; 81% [P=.01]; and 49%, respectively).4

Preliminary results from VOYAGE 1 (N=837), the first of several phase 3 trials, further demonstrate the superiority of guselkumab 100 mg at weeks 0 and 4 and then every 8 weeks over adalimumab (standard dosing) and placebo; at week 16, 73.3% (P<.001 for both comparisons) versus 49.7% and 2.9% of participants, respectively, achieved PASI 90, with sustained superiority of skin clearance in guselkumab-treated participants compared to adalimumab and placebo through week 48.3

Long-term safety data showed no dose dependence or trend from 0 to 16 weeks and 16 to 52 weeks of treatment regarding rates of AEs, SAEs, or serious infections.4 Between weeks 16 and 52, 48.9% of all guselkumab-treated participants exhibited AEs compared to 60.5% of adalimumab-treated participants and 51.3% of placebo participants. Overall infection rates also were lowest in the guselkumab group at 29.8% compared to 36.8% and 35.9%, respectively. Three participants treated with guselkumab had major cardiovascular events, including a fatal myocardial infarction. No cases of tuberculosis or serious opportunistic infections were reported.4

Tildrakizumab

Tildrakizumab (formerly known as MK-3222)(Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd) is a human monoclonal antibody also targeting the p19 subunit of IL-23. In a phase 2 study of 355 participants with chronic plaque psoriasis, participants received 5-, 25-, 100-, or 200-mg subcutaneous tildrakizumab or placebo at weeks 0 and 4 and then every 12 weeks for a total of 52 weeks.6 At week 16, PASI 75 results were 33.3%, 64.4%, 66.3%, 74.4%, and 4.4%, respectively (P<.001 for each comparison). Improvement began within the first month of treatment, with median times to PASI 75 of 57 days at 200-mg dosing and 84 days at 100-mg dosing. Of those participants achieving PASI 75 by drug discontinuation at week 52, 96% of the 100-mg group and 93% of the 200-mg group maintained PASI 75 through week 72, suggesting low relapse rates after treatment cessation.6

In October 2016, the efficacy results of 2 pivotal phase 3 trials (reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2) involving more than 1800 participants combined revealed PASI 90 achievement in an average of 54% of participants on tildrakizumab 100 mg and 59% of participants on tildrakizumab 200 mg at week 28.5 Achievement of PASI 100 occurred in 24% and 30% of participants at week 28, respectively. The second of these trials included an etanercept comparison group and demonstrated head-to-head superiority of 100 and 200 mg subcutaneous tildrakizumab at week 12 by end point measures.5

Treatment-related AEs occurred at rates of 25% in tildrakizumab-treated participants and 22% in placebo-treated participants, most frequently nasopharyngitis and headache.6 At least 1 AE occurred in 64% of tildrakizumab-treated participants without dose dependence compared to 69% of placebo-treated participants. Severe AEs thought to be drug treatment related were bacterial arthritis, lymphedema, melanoma, stroke, and epiglottitis.6

IL-17 Inhibitors

Ixekizumab

Ixekizumab (Eli Lilly and Company), a monoclonal inhibitor of IL-17A, is the most recently approved psoriasis biologic on the market and has been cleared for use in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Recommended dosing is 160 mg (given in two 80-mg subcutaneous injections via an autoinjector or prefilled syringe) at week 0, followed by an 80-mg injection at weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12, and then 80 mg every 4 weeks thereafter. The FDA approved ixekizumab in March 2016 following favorable results of several phase 3 trials: UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3.7,8

In UNCOVER-1, 1296 participants were randomized to 1 of 2 ixekizumab treatment arms—160 mg starting dose at week 0, 80 mg every 2 or 4 weeks thereafter—or placebo.7 At week 12, 89.1%, 82.6%, and 3.9% achieved PASI 75, respectively (P<.001 for both). Importantly, high numbers of participants also achieved PASI 90 (70.9% in the 2-week group and 64.6% in the 4-week group vs 0.5% in the placebo group [P<.001]) and PASI 100 (35.3% and 33.6% vs 0%, respectively [P<.001]), suggesting high rates of disease clearance.7

UNCOVER-2 (N=1224) and UNCOVER-3 (N=1346) investigated the same 2 dosing regimens of ixekizumab compared to etanercept 50 mg biweekly and placebo.8 At week 12, the percentage of participants achieving PASI 90 in UNCOVER-2 was 70.7%, 59.7%, 18.7%, and 0.6%, respectively, and 68.1%, 65.3%, 25.7%, and 3.1%, respectively, in UNCOVER-3 (P<.0001 for all comparisons to placebo and etanercept). At week 12, PASI 100 results also showed striking superiority, with 40.5%, 30.8%, 5.3%, and 0.6% of participants, respectively, in UNCOVER-2, and 37.7%, 35%, 7.3%, and 0%, respectively, in UNCOVER-3, achieving complete clearance of disease (P<.0001 for all comparisons to placebo and etanercept). Responses to ixekizumab were observed as early as weeks 1 and 2, while no participants in the etanercept and placebo treatment groups achieved comparative efficiency.8

In an extension of UNCOVER-3, efficacy increased from week 12 to week 60 according to PASI 90 (68%–73% in the 2-week group; 65%–72% in the 4-week group) and PASI 100 measures (38%–55% in the 2-week group; 35%–52% in the 4-week group).7

The most common AEs associated with ixekizumab treatment from weeks 0 to 12 occurred at higher rates in the 2-week and 4-week ixekizumab groups compared to placebo, including nasopharyngitis (9.5% and 9% vs 8.7%, respectively), upper respiratory tract infection (4.4% and 3.9% vs 3.5%, respectively), injection-site reaction (10% and 7.7% vs 1%, respectively), arthralgia (4.4% and 4.3% vs 2.9%, respectively), and headache (2.5% and 1.9% vs 2.1%, respectively). Infections, including candidal, oral, vulvovaginal, and cutaneous, occurred in 27% of the 2-week dosing group and 27.4% of the 4-week dosing group compared to 22.9% of the placebo group during weeks 0 to 12, with candidal infections in particular occurring more frequently in the active treatment groups and exhibiting dose dependence. Other AEs of special interest that occurred among all ixekizumab-treated participants (n=3736) from weeks 0 to 60 were cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (22 [0.6%]), inflammatory bowel disease (11 [0.3%]), non–skin cancer malignancy (14 [0.4%]), and nonmelanoma skin cancer (20 [0.5%]). Neutropenia occurred at higher rates in ixekizumab-treated participants (9.3% in the 2-week group and 8.6% in the 4-week group) compared to placebo (3.3%) and occurred in 11.5% of all ixekizumab participants over 60 weeks.7

Brodalumab

Brodalumab (Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc) is a human monoclonal antibody targeting the IL-17A receptor currently under review for FDA approval after undergoing phase 3 trials. The first of these trials, AMAGINE-1, showed efficacy of subcutaneous brodalumab (140 or 210 mg administered every 2 weeks with an extra dose at week 1) compared to placebo in 661 participants.9 At week 12, 60%, 83%, and 3%, respectively, achieved PASI 75; 43%, 70%, and 1%, respectively, achieved PASI 90; and 23%, 42%, and 1%, respectively, achieved PASI 100 (P<.001 for all respective comparisons to placebo). These effects were retained through 52 weeks of treatment. The median time to complete disease clearance in participants reaching PASI 100 was 12 weeks. Conversely, participants who were re-randomized to placebo after week 12 of brodalumab treatment relapsed within weeks to months.9

AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 further demonstrated the efficacy of brodalumab (140 or 210 mg every 2 weeks with extra dose at week 1) compared to ustekinumab (45 or 90 mg weight-based standard dosing) and placebo in 1831 participants, respectively.10 In AMAGINE-2, 49% of participants in the 140-mg group (P<.001 vs placebo), 70% in the 210-mg group (P<.001 vs placebo), 47% in the ustekinumab group, and 3% in the placebo group achieved PASI 90 at week 12. Similarly, in AMAGINE-3, 52% of participants in the 140-mg group (P<.001), 69% in the 210-mg group (P<.001), 48% in the ustekinumab group, and 2% in the placebo group achieved PASI 90. Impressively, complete clearance (PASI 100) at week 12 occurred in 26% of the 140-mg group (P<.001 vs placebo), 44% of the 210-mg group (P<.001 vs placebo), and 22% of the ustekinumab group compared to 2% of the placebo group in AMAGINE-2, with similar rates in AMAGINE-3. Brodalumab was significantly superior to ustekinumab at the 210-mg dose by PASI 90 measures (P<.001) in both studies and at the 140-mg dose by PASI 100 measures (P=.007) in AMAGINE-3 only.10

Common AEs were nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, and arthralgia, all occurring at grossly similar rates (49%–60%) across all experimental groups in AMAGINE-1, AMAGINE-2, and AMAGINE-3 during the first 12-week treatment period.9,10 Brodalumab treatment groups had high rates of specific interest AEs compared to ustekinumab and placebo groups, including neutropenia (0.8%, 1.1%, 0.3%, and 0%, respectively) and candidal infections (0.8%, 1.3%, 0.3%, and 0.3%, respectively). Induction phase (weeks 0–12) depression rates were concerning, with 6 cases each in AMAGINE-2 (4 [0.7%] in the 140-mg group, 2 [0.3%] in the 210-mg group) and AMAGINE-3 (4 [0.6%] in the 140-mg group, 2 [0.3%] in the 210-mg group). Cases of neutropenia were mild, were not associated with major infection, and were transient or reversible. Depression rates after 52 weeks of treatment were 1.7% (23/1567) of brodalumab participants in AMAGINE-2 and 1.8% (21/1613) in AMAGINE-3. Three participants, all on constant 210-mg dosing through week 52, attempted suicide with 1 completion10; however, because no other IL-17 inhibitors were associated with depression or suicide in other trials, it has been suggested that these cases were incidental and not treatment related.12 An FDA advisory panel recommended approval of brodalumab in July 2016 despite ongoing concerns of depression and suicide.13

Conclusion

The robust investigation into IL-23 and IL-17 inhibitors to treat plaque psoriasis has yielded promising results, including the unprecedented rates of PASI 100 achievement with these new biologics. Risankizumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab have demonstrated superior efficacy in trials compared to ustekinumab. Tildrakizumab has shown low disease relapse after drug cessation. Ixekizumab and brodalumab have shown high rates of total disease clearance. Thus far, safety findings for these pipeline biologics have been consistent with those of ustekinumab. With ixekizumab approved in 2016 and brodalumab under review, new options in biologic therapy will offer patients and clinicians greater choices in treating severe and recalcitrant psoriasis.

- Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:496-509.

- Papp K, Menter A, Sofen H, et al. Efficacy and safety of different dose regimens of a selective IL-23p19 inhibitor (BI 655066) compared with ustekinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis with and without psoriatic arthritis. Paper presented at: 2015 American College of Rheumatology/Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals Annual Meeting; November 6-11, 2015; San Francisco, CA.

- New phase 3 data show significant efficacy versus placebo and superiority of guselkumab versus Humira in treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis [press release]. Vienna, Austria; Janssen Research & Development, LLC: October 1, 2016.

- Gordon KB, Duffin KC, Bissonnette R, et al. A phase 2 trial of guselkumab versus adalimumab for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:136-144.

- Sun Pharma to announce late-breaking results for investigational IL-23p19 inhibitor, Tildrakizumab, achieves primary end point in both phase-3 studies in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [press release]. Mumbai, India; Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd: October 1, 2016.

- Papp K, Thaci D, Reich K, et al. Tildrakizumab (MK-3222), an anti-interleukin-23p19 monoclonal antibody, improves psoriasis in a phase IIb randomized placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:930-939.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al; UNCOVER-1 Study Group, UNCOVER-2 Study Group, UNCOVER-3 Study Group. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- Griffiths CE, Reich K, Lebwohl M, et al. Comparison of ixekizumab with etanercept or placebo in moderate-to-severe psoriasis (UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3): results from two phase 3 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;386:541-551.

- Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [published online June 23, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:273-286.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318-1328.

- Krueger JG, Ferris LK, Menter A, et al. Anti-IL-23A mAb BI 655066 for treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and biomarker results of a single-rising-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [published online March 1, 2015]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:116-124.e7.

- Chiricozzi A, Romanelli M, Saraceno R, et al. No meaningful association between suicidal behavior and the use of IL-17A-neutralizing or IL-17RA-blocking agents [published online August 31, 2016]. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:1653-1659.

- FDA advisory committee recommends approval of brodalumab for treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [news release]. Laval, Quebec: Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc; July 19, 2016.

- Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:496-509.

- Papp K, Menter A, Sofen H, et al. Efficacy and safety of different dose regimens of a selective IL-23p19 inhibitor (BI 655066) compared with ustekinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis with and without psoriatic arthritis. Paper presented at: 2015 American College of Rheumatology/Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals Annual Meeting; November 6-11, 2015; San Francisco, CA.

- New phase 3 data show significant efficacy versus placebo and superiority of guselkumab versus Humira in treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis [press release]. Vienna, Austria; Janssen Research & Development, LLC: October 1, 2016.

- Gordon KB, Duffin KC, Bissonnette R, et al. A phase 2 trial of guselkumab versus adalimumab for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:136-144.

- Sun Pharma to announce late-breaking results for investigational IL-23p19 inhibitor, Tildrakizumab, achieves primary end point in both phase-3 studies in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [press release]. Mumbai, India; Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd: October 1, 2016.

- Papp K, Thaci D, Reich K, et al. Tildrakizumab (MK-3222), an anti-interleukin-23p19 monoclonal antibody, improves psoriasis in a phase IIb randomized placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:930-939.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al; UNCOVER-1 Study Group, UNCOVER-2 Study Group, UNCOVER-3 Study Group. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- Griffiths CE, Reich K, Lebwohl M, et al. Comparison of ixekizumab with etanercept or placebo in moderate-to-severe psoriasis (UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3): results from two phase 3 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;386:541-551.

- Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [published online June 23, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:273-286.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318-1328.

- Krueger JG, Ferris LK, Menter A, et al. Anti-IL-23A mAb BI 655066 for treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and biomarker results of a single-rising-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [published online March 1, 2015]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:116-124.e7.

- Chiricozzi A, Romanelli M, Saraceno R, et al. No meaningful association between suicidal behavior and the use of IL-17A-neutralizing or IL-17RA-blocking agents [published online August 31, 2016]. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:1653-1659.

- FDA advisory committee recommends approval of brodalumab for treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [news release]. Laval, Quebec: Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc; July 19, 2016.

Practice Points

- The newest biologics for treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis are IL-23 and IL-17 inhibitors with unprecedented efficacy of complete skin clearance compared to older biologics.

- Risankizumab, guselkumab, and tildrakizumab are new IL-23 inhibitors currently in phase 3 trials with promising early efficacy and safety results.

- Ixekizumab, which recently was approved, and brodalumab, which is pending US Food and Drug Administration review, are new IL-17 inhibitors that achieved total skin clearance in more than one-quarter of phase 3 participants after 12 weeks of treatment.

Coding Changes for 2017

All physicians will see changes in reimbursement in 2017. A new president with a new agenda makes for an interesting time ahead for health care in the United States. However, in this time of flux, there is one constant: the Final Rule, an informal term for the annual update on how the Medicare system will function and how much you will get paid for what you do.1 The document is 393 pages and outlines what is new in the Medicare system, with lots of supplements giving granular details about physician work, overhead, and supply and labor costs. In this column, I have taken the liberty of dissecting the Final Rule for you and to bring attention to its high and low points for dermatologists.

Changes in Relative Value Units

The conversion factor has gone up, meaning you will be paid a bit more this year for what you do; it is not enough to account for inflation or the increasing cost of unfunded mandates, but it is better than nothing. Although the conversion factor was $35.8043 in 2016, it increased by more than 0.2% on January 1, 2017, to $35.8887.1 How is this conversion factor calculated? We go up 0.5% due to MACRA (Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act), down 0.013% due to budget neutrality, down 0.07% due to multiple procedure payment reduction changes, and down another 0.18% due to the misvalued code target.1 The misvalued code target is related to targets established by statute for 2016 to 2018 and payment rates are reduced across the board if they are not met.

If payments suffer from reductions in work value, they may not happen all at once. If the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) reduce total relative value units (RVUs) by more than 20%, reductions will take place over at least 2 years with a single year drop maximum of 19%.1 Unfortunately, such limits do not apply to revised codes, which can take as big a hit as the CMS cares to make.

Changes to Global Periods