User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

NORD to Partner Again With Hole in the Wall Gang Camp

NORD is proud to once again partner with the Hole in the Wall Gang Camp on a rare disease summer family camp in Connecticut. The camp provides a special opportunity for children and families affected by rare diseases to join together for a weekend of pure fun—free of charge. The camp is open to 25 families who are located in the Northeast, and it will take place June 1 to 4 in Ashford, Connecticut. Apply here.

NORD is proud to once again partner with the Hole in the Wall Gang Camp on a rare disease summer family camp in Connecticut. The camp provides a special opportunity for children and families affected by rare diseases to join together for a weekend of pure fun—free of charge. The camp is open to 25 families who are located in the Northeast, and it will take place June 1 to 4 in Ashford, Connecticut. Apply here.

NORD is proud to once again partner with the Hole in the Wall Gang Camp on a rare disease summer family camp in Connecticut. The camp provides a special opportunity for children and families affected by rare diseases to join together for a weekend of pure fun—free of charge. The camp is open to 25 families who are located in the Northeast, and it will take place June 1 to 4 in Ashford, Connecticut. Apply here.

Rare Disease Day 2017 Will Highlight Research Theme

On February 28th, medical professionals, patients, and advocates will observe Rare Disease Day in more than 90 nations worldwide. This awareness day was established in 2008 to promote education regarding rare diseases. As the national sponsor of Rare Disease Day in the US, NORD hosts the official website at www.rarediseaseday.us.

The theme for 2017 is Research and, in particular, the importance of research on rare diseases. This theme will be observed in all participating nations.

NORD provides tools and resources for those hosting events at academic centers and hospitals. Download this presentation for other suggestions regarding how to get involved. NORD will be co-hosting a tweetchat with ABC News and Dr. Richard Besser on Rare Disease Day. Details on this and other activities will be available on the Rare Disease Day US website.

On February 28th, medical professionals, patients, and advocates will observe Rare Disease Day in more than 90 nations worldwide. This awareness day was established in 2008 to promote education regarding rare diseases. As the national sponsor of Rare Disease Day in the US, NORD hosts the official website at www.rarediseaseday.us.

The theme for 2017 is Research and, in particular, the importance of research on rare diseases. This theme will be observed in all participating nations.

NORD provides tools and resources for those hosting events at academic centers and hospitals. Download this presentation for other suggestions regarding how to get involved. NORD will be co-hosting a tweetchat with ABC News and Dr. Richard Besser on Rare Disease Day. Details on this and other activities will be available on the Rare Disease Day US website.

On February 28th, medical professionals, patients, and advocates will observe Rare Disease Day in more than 90 nations worldwide. This awareness day was established in 2008 to promote education regarding rare diseases. As the national sponsor of Rare Disease Day in the US, NORD hosts the official website at www.rarediseaseday.us.

The theme for 2017 is Research and, in particular, the importance of research on rare diseases. This theme will be observed in all participating nations.

NORD provides tools and resources for those hosting events at academic centers and hospitals. Download this presentation for other suggestions regarding how to get involved. NORD will be co-hosting a tweetchat with ABC News and Dr. Richard Besser on Rare Disease Day. Details on this and other activities will be available on the Rare Disease Day US website.

NORD Seeks Input Regarding Patient Protections and ACA

As the new administration and Congress consider replacing the Affordable Care Act with a new system, NORD is seeking input from patients and health care providers for its advocacy on behalf of rare disease patients. Patients or providers who have experiences or concerns to share regarding pre-existing conditions, annual or lifetime insurance caps, high-risk pools, or other topics may share their experiences with NORD.

As the new administration and Congress consider replacing the Affordable Care Act with a new system, NORD is seeking input from patients and health care providers for its advocacy on behalf of rare disease patients. Patients or providers who have experiences or concerns to share regarding pre-existing conditions, annual or lifetime insurance caps, high-risk pools, or other topics may share their experiences with NORD.

As the new administration and Congress consider replacing the Affordable Care Act with a new system, NORD is seeking input from patients and health care providers for its advocacy on behalf of rare disease patients. Patients or providers who have experiences or concerns to share regarding pre-existing conditions, annual or lifetime insurance caps, high-risk pools, or other topics may share their experiences with NORD.

Pediatric Nail Diseases: Clinical Pearls

Our dermatology department recently sponsored a pediatric dermatology lecture series for the pediatric residency program. Within this series, Antonella Tosti, MD, a professor at the University of Miami Health System, Florida, and a renowned expert in nail disorders and allergic contact dermatitis, presented her clinical expertise on the presentation and management of common pediatric nail diseases. This article highlights pearls from her unique and enlightening lecture.

Pearl: Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is a recognized trigger for onychomadesis

An arrest in nail matrix activity is responsible for onychomadesis, or shedding of the nail. Its presentation in children can be further divided based upon the degree of involvement. If a few nails are affected, trauma should be implicated. In contrast, if all nails are involved, a systemic etiology should be suspected. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) has been recognized as a trigger for onychomadesis in school-aged children. Onychomadesis presents with characteristic proximal nail detachment (Figure 1). The association of HFMD with onychomadesis and Beau lines was first reported in 2000. Five patients who resided within close proximity and shared a physician-diagnosed case of HFMD presented with representative nail findings 4 weeks after illness.1 Hypotheses for these changes include viral-induced nail pathology, inflammation from cutaneous lesions of HFMD, and systemic effects from the disease.2 Given the prevalence of HFMD and benign outcome, clinicians should be cognizant of this unique cutaneous manifestation.

Pearl: Management of pediatric melanonychia can take a wait-and-see approach

Melanonychia is the presence of a longitudinal brown-black band extending from the proximal nail fold. The cause of melanonychia can be due to either activation or hyperplasia. Activation is the less common etiology in children; however, if present, activation can be due to Laugier-Hunziker syndrome or trauma such as onychotillomania. Melanonychia in children usually is the result of hyperplasia of melanocytes and can manifest as a lentigo, nevus, or more rarely melanoma. Nail matrix nevi are typically exhibited on the fingernails, particularly the thumb, and frequently are junctional nevi (Figure 2). Spontaneous fading of nevi is expected with time due to decreased melanin production. Therapeutic options for melanonychia include regular clinical monitoring, biopsy, or excision. Dr. Tosti explained that one must be wary when pursuing a biopsy, as it can result in a false-negative finding due to missed pathology. If clinically indicated, a shave biopsy of the nail matrix can be performed to best analyze the lesion. She noted that if more than 3 mm of the matrix is removed, a resultant scar will ensue. Conservative management is recommended given the indolent clinical behavior of the majority of cases of melanonychia in children.3

Pearl: Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds can be treated with tape

Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds is relatively common in children and normally improves with age. Koilonychia may also occur simultaneously and can be viewed as a physiologic process in this age group. The etiology of the underlying disorder is due to anomalous periungual soft-tissue changes of the bilateral halluces; the resulting overgrowth can partially cover the nail plate. Although usually a self-limiting condition, the changes can cause inflammation and discomfort due to an ingrown nail.4 Dr. Tosti advised that by simply taping and retracting the bilateral overgrowth, the condition can be more readily resolved. This simple treatment can be demonstrated in the office and subsequently performed at home.

Pearl: Onychomycosis is uncommon in children

Onychomycosis occurs in less than 1% of children.5 Several factors are responsible for this decreased prevalence. More rapid nail growth and smaller nail surface area decreases the ability of the fungi to penetrate the nail plate.6 Furthermore, children have a diminished rate of tinea pedis, leading to less neighboring infection. When onychomycosis does affect this patient population, it commonly presents as distal subungual onychomycosis and favors the fingernails over the toenails. Treatment options usually parallel those of the adult population; however, all medications for children are considered off-label use by the US Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Tosti explained that oral granules of terbinafine can be sprinkled on food to help with pediatric ingestion. Topical therapies should also be considered; children usually respond better than their adult counterparts due to their thinner nails, which grant enhanced drug delivery and penetration.6

Pearl: Acute paronychia can be due to nail-biting and sucking

Acute paronychia is inflammation of the proximal nail fold. In children, it frequently is a result of mixed flora induced by nail-biting and sucking. Management involves culturing the affected lesions and is effectively treated with warm soaks alone. Dr. Tosti highlighted that Candida in the subungual space is a common colonizer and is typically self-limiting in nature if isolated. Candida can be cultured more readily in premature infants, immunosuppressed patients, and those with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis can exhibit periungual inflammation involving several digits. The differential can include nail psoriasis, as both can demonstrate dystrophic changes. The differential for localized paronychia includes herpetic whitlow and can manifest as vesicles under the proximal nail fold.

Final Thoughts

These clinical pearls are shared to help deliver utmost care to our pediatric patients presenting with nail pathology. For example, a child exhibiting melanonychia can cause alarm due to the possibility of underlying melanoma; given the rarity of neoplasia in these patients, a conservative approach is favored to help avoid unnecessary biopsies and subsequent scarring. Similarly, it is important to be aware of the common colonizers of the subungual area, particularly Candida, to avoid unessential medications with potential side effects. The examples demonstrated help shed light on the management of pediatric nail diseases.

Acknowledgment

This article is possible thanks to the help of Antonella Tosti, MD (Miami, Florida), who contributed her time and expertise at the University of Miami Pediatric Grand Rounds to expand the foundation and knowledge of pediatric nail diseases.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Yuksel S, Evrengul H, Ozhan B, et al. Onychomadesis-a late complication of hand-foot-mouth disease [published online May 2, 2016]. J Pediatr. 2016;174:274.

- Cooper C, Arva NC, Lee C, et al. A clinical, histopathologic, and outcome study of melanonychia striata in childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:773-779.

- Piraccini BM, Parente GL, Varotti E, et al. Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds of the hallux: clinical features and follow-up of seven cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:348-351.

- Totri CR, Feldstein S, Admani S, et al. Epidemiologic analysis of onychomycosis in the San Diego pediatric population [published online October 4, 2016]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:46-49.

- Feldstein S, Totri C, Friedlander SF. Antifungal therapy for onychomycosis in children. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:333-339.

Our dermatology department recently sponsored a pediatric dermatology lecture series for the pediatric residency program. Within this series, Antonella Tosti, MD, a professor at the University of Miami Health System, Florida, and a renowned expert in nail disorders and allergic contact dermatitis, presented her clinical expertise on the presentation and management of common pediatric nail diseases. This article highlights pearls from her unique and enlightening lecture.

Pearl: Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is a recognized trigger for onychomadesis

An arrest in nail matrix activity is responsible for onychomadesis, or shedding of the nail. Its presentation in children can be further divided based upon the degree of involvement. If a few nails are affected, trauma should be implicated. In contrast, if all nails are involved, a systemic etiology should be suspected. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) has been recognized as a trigger for onychomadesis in school-aged children. Onychomadesis presents with characteristic proximal nail detachment (Figure 1). The association of HFMD with onychomadesis and Beau lines was first reported in 2000. Five patients who resided within close proximity and shared a physician-diagnosed case of HFMD presented with representative nail findings 4 weeks after illness.1 Hypotheses for these changes include viral-induced nail pathology, inflammation from cutaneous lesions of HFMD, and systemic effects from the disease.2 Given the prevalence of HFMD and benign outcome, clinicians should be cognizant of this unique cutaneous manifestation.

Pearl: Management of pediatric melanonychia can take a wait-and-see approach

Melanonychia is the presence of a longitudinal brown-black band extending from the proximal nail fold. The cause of melanonychia can be due to either activation or hyperplasia. Activation is the less common etiology in children; however, if present, activation can be due to Laugier-Hunziker syndrome or trauma such as onychotillomania. Melanonychia in children usually is the result of hyperplasia of melanocytes and can manifest as a lentigo, nevus, or more rarely melanoma. Nail matrix nevi are typically exhibited on the fingernails, particularly the thumb, and frequently are junctional nevi (Figure 2). Spontaneous fading of nevi is expected with time due to decreased melanin production. Therapeutic options for melanonychia include regular clinical monitoring, biopsy, or excision. Dr. Tosti explained that one must be wary when pursuing a biopsy, as it can result in a false-negative finding due to missed pathology. If clinically indicated, a shave biopsy of the nail matrix can be performed to best analyze the lesion. She noted that if more than 3 mm of the matrix is removed, a resultant scar will ensue. Conservative management is recommended given the indolent clinical behavior of the majority of cases of melanonychia in children.3

Pearl: Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds can be treated with tape

Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds is relatively common in children and normally improves with age. Koilonychia may also occur simultaneously and can be viewed as a physiologic process in this age group. The etiology of the underlying disorder is due to anomalous periungual soft-tissue changes of the bilateral halluces; the resulting overgrowth can partially cover the nail plate. Although usually a self-limiting condition, the changes can cause inflammation and discomfort due to an ingrown nail.4 Dr. Tosti advised that by simply taping and retracting the bilateral overgrowth, the condition can be more readily resolved. This simple treatment can be demonstrated in the office and subsequently performed at home.

Pearl: Onychomycosis is uncommon in children

Onychomycosis occurs in less than 1% of children.5 Several factors are responsible for this decreased prevalence. More rapid nail growth and smaller nail surface area decreases the ability of the fungi to penetrate the nail plate.6 Furthermore, children have a diminished rate of tinea pedis, leading to less neighboring infection. When onychomycosis does affect this patient population, it commonly presents as distal subungual onychomycosis and favors the fingernails over the toenails. Treatment options usually parallel those of the adult population; however, all medications for children are considered off-label use by the US Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Tosti explained that oral granules of terbinafine can be sprinkled on food to help with pediatric ingestion. Topical therapies should also be considered; children usually respond better than their adult counterparts due to their thinner nails, which grant enhanced drug delivery and penetration.6

Pearl: Acute paronychia can be due to nail-biting and sucking

Acute paronychia is inflammation of the proximal nail fold. In children, it frequently is a result of mixed flora induced by nail-biting and sucking. Management involves culturing the affected lesions and is effectively treated with warm soaks alone. Dr. Tosti highlighted that Candida in the subungual space is a common colonizer and is typically self-limiting in nature if isolated. Candida can be cultured more readily in premature infants, immunosuppressed patients, and those with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis can exhibit periungual inflammation involving several digits. The differential can include nail psoriasis, as both can demonstrate dystrophic changes. The differential for localized paronychia includes herpetic whitlow and can manifest as vesicles under the proximal nail fold.

Final Thoughts

These clinical pearls are shared to help deliver utmost care to our pediatric patients presenting with nail pathology. For example, a child exhibiting melanonychia can cause alarm due to the possibility of underlying melanoma; given the rarity of neoplasia in these patients, a conservative approach is favored to help avoid unnecessary biopsies and subsequent scarring. Similarly, it is important to be aware of the common colonizers of the subungual area, particularly Candida, to avoid unessential medications with potential side effects. The examples demonstrated help shed light on the management of pediatric nail diseases.

Acknowledgment

This article is possible thanks to the help of Antonella Tosti, MD (Miami, Florida), who contributed her time and expertise at the University of Miami Pediatric Grand Rounds to expand the foundation and knowledge of pediatric nail diseases.

Our dermatology department recently sponsored a pediatric dermatology lecture series for the pediatric residency program. Within this series, Antonella Tosti, MD, a professor at the University of Miami Health System, Florida, and a renowned expert in nail disorders and allergic contact dermatitis, presented her clinical expertise on the presentation and management of common pediatric nail diseases. This article highlights pearls from her unique and enlightening lecture.

Pearl: Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is a recognized trigger for onychomadesis

An arrest in nail matrix activity is responsible for onychomadesis, or shedding of the nail. Its presentation in children can be further divided based upon the degree of involvement. If a few nails are affected, trauma should be implicated. In contrast, if all nails are involved, a systemic etiology should be suspected. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) has been recognized as a trigger for onychomadesis in school-aged children. Onychomadesis presents with characteristic proximal nail detachment (Figure 1). The association of HFMD with onychomadesis and Beau lines was first reported in 2000. Five patients who resided within close proximity and shared a physician-diagnosed case of HFMD presented with representative nail findings 4 weeks after illness.1 Hypotheses for these changes include viral-induced nail pathology, inflammation from cutaneous lesions of HFMD, and systemic effects from the disease.2 Given the prevalence of HFMD and benign outcome, clinicians should be cognizant of this unique cutaneous manifestation.

Pearl: Management of pediatric melanonychia can take a wait-and-see approach

Melanonychia is the presence of a longitudinal brown-black band extending from the proximal nail fold. The cause of melanonychia can be due to either activation or hyperplasia. Activation is the less common etiology in children; however, if present, activation can be due to Laugier-Hunziker syndrome or trauma such as onychotillomania. Melanonychia in children usually is the result of hyperplasia of melanocytes and can manifest as a lentigo, nevus, or more rarely melanoma. Nail matrix nevi are typically exhibited on the fingernails, particularly the thumb, and frequently are junctional nevi (Figure 2). Spontaneous fading of nevi is expected with time due to decreased melanin production. Therapeutic options for melanonychia include regular clinical monitoring, biopsy, or excision. Dr. Tosti explained that one must be wary when pursuing a biopsy, as it can result in a false-negative finding due to missed pathology. If clinically indicated, a shave biopsy of the nail matrix can be performed to best analyze the lesion. She noted that if more than 3 mm of the matrix is removed, a resultant scar will ensue. Conservative management is recommended given the indolent clinical behavior of the majority of cases of melanonychia in children.3

Pearl: Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds can be treated with tape

Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds is relatively common in children and normally improves with age. Koilonychia may also occur simultaneously and can be viewed as a physiologic process in this age group. The etiology of the underlying disorder is due to anomalous periungual soft-tissue changes of the bilateral halluces; the resulting overgrowth can partially cover the nail plate. Although usually a self-limiting condition, the changes can cause inflammation and discomfort due to an ingrown nail.4 Dr. Tosti advised that by simply taping and retracting the bilateral overgrowth, the condition can be more readily resolved. This simple treatment can be demonstrated in the office and subsequently performed at home.

Pearl: Onychomycosis is uncommon in children

Onychomycosis occurs in less than 1% of children.5 Several factors are responsible for this decreased prevalence. More rapid nail growth and smaller nail surface area decreases the ability of the fungi to penetrate the nail plate.6 Furthermore, children have a diminished rate of tinea pedis, leading to less neighboring infection. When onychomycosis does affect this patient population, it commonly presents as distal subungual onychomycosis and favors the fingernails over the toenails. Treatment options usually parallel those of the adult population; however, all medications for children are considered off-label use by the US Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Tosti explained that oral granules of terbinafine can be sprinkled on food to help with pediatric ingestion. Topical therapies should also be considered; children usually respond better than their adult counterparts due to their thinner nails, which grant enhanced drug delivery and penetration.6

Pearl: Acute paronychia can be due to nail-biting and sucking

Acute paronychia is inflammation of the proximal nail fold. In children, it frequently is a result of mixed flora induced by nail-biting and sucking. Management involves culturing the affected lesions and is effectively treated with warm soaks alone. Dr. Tosti highlighted that Candida in the subungual space is a common colonizer and is typically self-limiting in nature if isolated. Candida can be cultured more readily in premature infants, immunosuppressed patients, and those with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis can exhibit periungual inflammation involving several digits. The differential can include nail psoriasis, as both can demonstrate dystrophic changes. The differential for localized paronychia includes herpetic whitlow and can manifest as vesicles under the proximal nail fold.

Final Thoughts

These clinical pearls are shared to help deliver utmost care to our pediatric patients presenting with nail pathology. For example, a child exhibiting melanonychia can cause alarm due to the possibility of underlying melanoma; given the rarity of neoplasia in these patients, a conservative approach is favored to help avoid unnecessary biopsies and subsequent scarring. Similarly, it is important to be aware of the common colonizers of the subungual area, particularly Candida, to avoid unessential medications with potential side effects. The examples demonstrated help shed light on the management of pediatric nail diseases.

Acknowledgment

This article is possible thanks to the help of Antonella Tosti, MD (Miami, Florida), who contributed her time and expertise at the University of Miami Pediatric Grand Rounds to expand the foundation and knowledge of pediatric nail diseases.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Yuksel S, Evrengul H, Ozhan B, et al. Onychomadesis-a late complication of hand-foot-mouth disease [published online May 2, 2016]. J Pediatr. 2016;174:274.

- Cooper C, Arva NC, Lee C, et al. A clinical, histopathologic, and outcome study of melanonychia striata in childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:773-779.

- Piraccini BM, Parente GL, Varotti E, et al. Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds of the hallux: clinical features and follow-up of seven cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:348-351.

- Totri CR, Feldstein S, Admani S, et al. Epidemiologic analysis of onychomycosis in the San Diego pediatric population [published online October 4, 2016]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:46-49.

- Feldstein S, Totri C, Friedlander SF. Antifungal therapy for onychomycosis in children. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:333-339.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Yuksel S, Evrengul H, Ozhan B, et al. Onychomadesis-a late complication of hand-foot-mouth disease [published online May 2, 2016]. J Pediatr. 2016;174:274.

- Cooper C, Arva NC, Lee C, et al. A clinical, histopathologic, and outcome study of melanonychia striata in childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:773-779.

- Piraccini BM, Parente GL, Varotti E, et al. Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds of the hallux: clinical features and follow-up of seven cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:348-351.

- Totri CR, Feldstein S, Admani S, et al. Epidemiologic analysis of onychomycosis in the San Diego pediatric population [published online October 4, 2016]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:46-49.

- Feldstein S, Totri C, Friedlander SF. Antifungal therapy for onychomycosis in children. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:333-339.

Actinomycetoma: An Update on Diagnosis and Treatment

Mycetoma is a subcutaneous disease that can be caused by aerobic bacteria (actinomycetoma) or fungi (eumycetoma). Diagnosis is based on clinical manifestations, including swelling and deformity of affected areas, as well as the presence of granulation tissue, scars, abscesses, sinus tracts, and a purulent exudate that contains the microorganisms.

The worldwide proportion of mycetomas is 60% actinomycetomas and 40% eumycetomas.1 The disease is endemic in tropical, subtropical, and temperate regions, predominating between latitudes 30°N and 15°S. Most cases occur in Africa, especially Sudan, Mauritania, and Senegal; India; Yemen; and Pakistan. In the Americas, the countries with the most reported cases are Mexico and Venezuela.1

Although mycetoma is rare in developed countries, migration of patients from endemic areas makes knowledge of this condition crucial for dermatologists worldwide. We present a review of the current concepts in the epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of actinomycetoma.

Epidemiology

Actinomycetoma is more common in Latin America, with Mexico having the highest incidence. At last count, there were 2631 cases reported in Mexico.2 The majority of cases of mycetoma in Mexico are actinomycetoma (98%), including Nocardia (86%) and Actinomadura madurae (10%). Eumycetoma is rare in Mexico, constituting only 2% of cases.2 Worldwide, men are affected more commonly than women, which is thought to be related to a higher occupational risk during agricultural labor.

Clinical Features

Mycetoma can affect the skin, subcutaneous tissue, bones, and occasionally the internal organs. It is characterized by swelling, deformation of the affected area, and fistulae that drain serosanguineous or purulent exudates.

In Mexico, 60% of cases of mycetoma affect the lower extremities; the feet are the most commonly affected area, followed by the trunk (back and chest), arms, forearms, legs, knees, and thighs.1 Other sites include the hands, shoulders, and abdominal wall. The head and neck area are seldom affected.3 Mycetoma lesions grow and disseminate locally. Bone lesions are possible depending on the osteophilic affinity of the etiological agent and on the interactions between the fungus and the host’s immune system. In severe advanced cases of mycetoma, the lesions may involve tendons and nerves. Dissemination via blood or lymphatics is extremely rare.4

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of actinomycetoma is suspected based on clinical features and confirmed by direct examination of exudates with Lugol iodine or saline solution. On direct microscopy, actinomycetes are recognized by the production of filaments with a width of 0.5 to 1 μm. On hematoxylin and eosin stain, the small grains of Nocardia appear eosinophilic with a blue center and pink filaments. On Gram stain, actinomycetoma grains show positive branching filaments. Culture of grains recovered from aspirated material or biopsy specimens provides specific etiologic diagnosis. Cultures should be held for at least 4 weeks. Additionally, there are some enzymatic, molecular, and serologic tests available for diagnosis.5-7 Serologic diagnosis is available in a few centers in Mexico and can be helpful in some cases for diagnosis or follow-up during treatment. Antibodies can be determined via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, Western blot analysis, immunodiffusion, or counterimmunoelectrophoresis.8

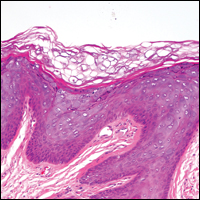

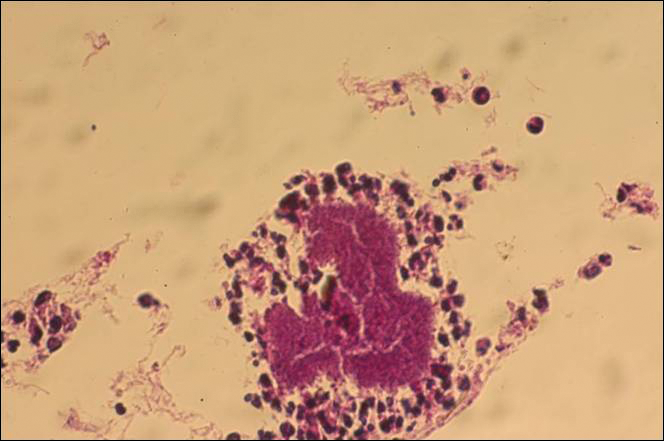

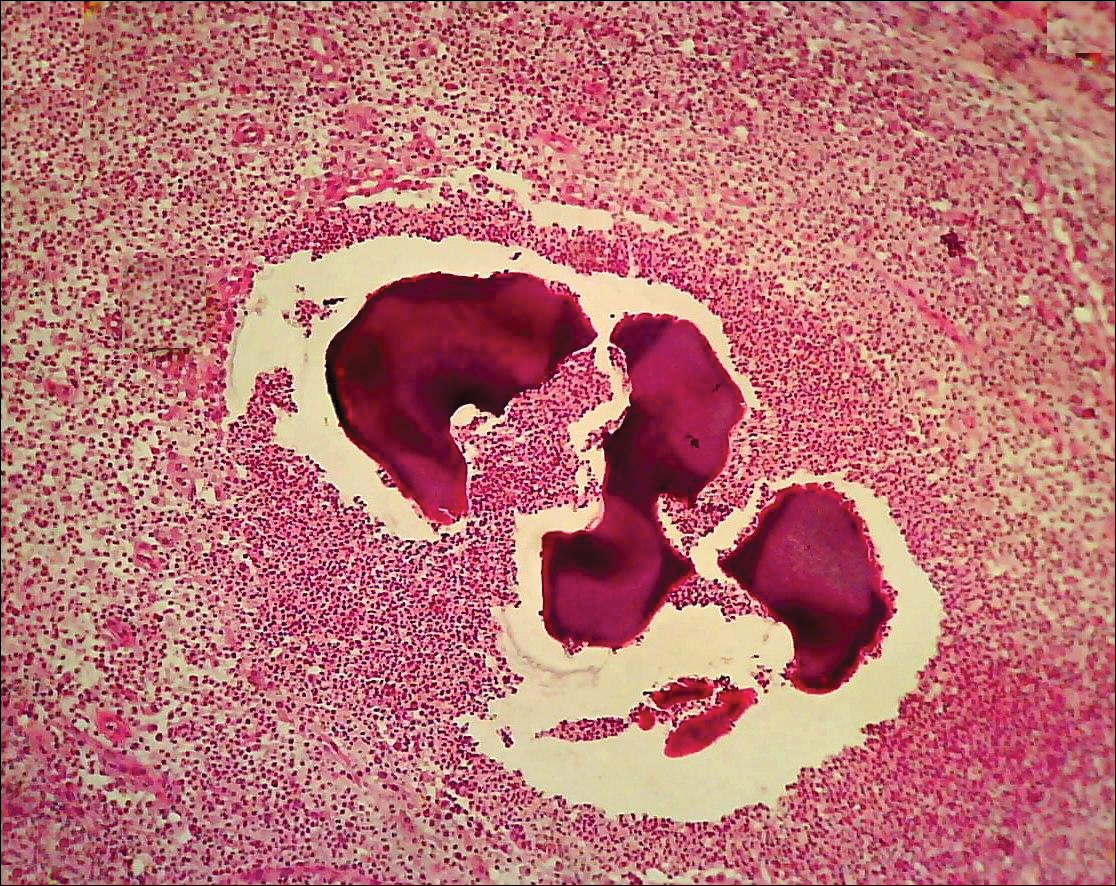

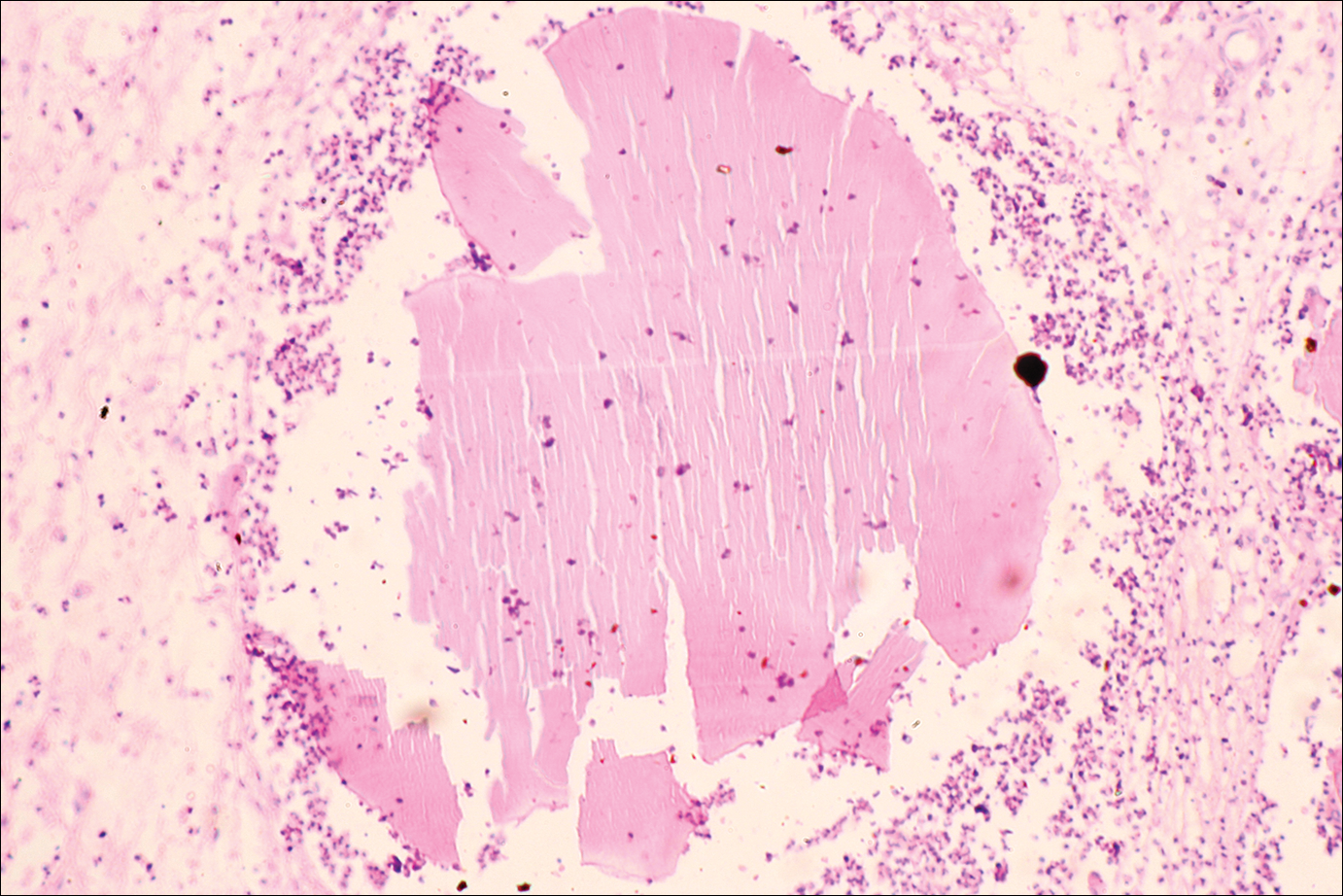

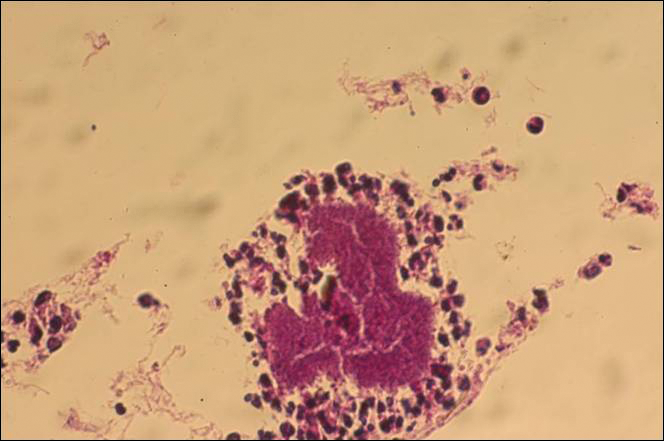

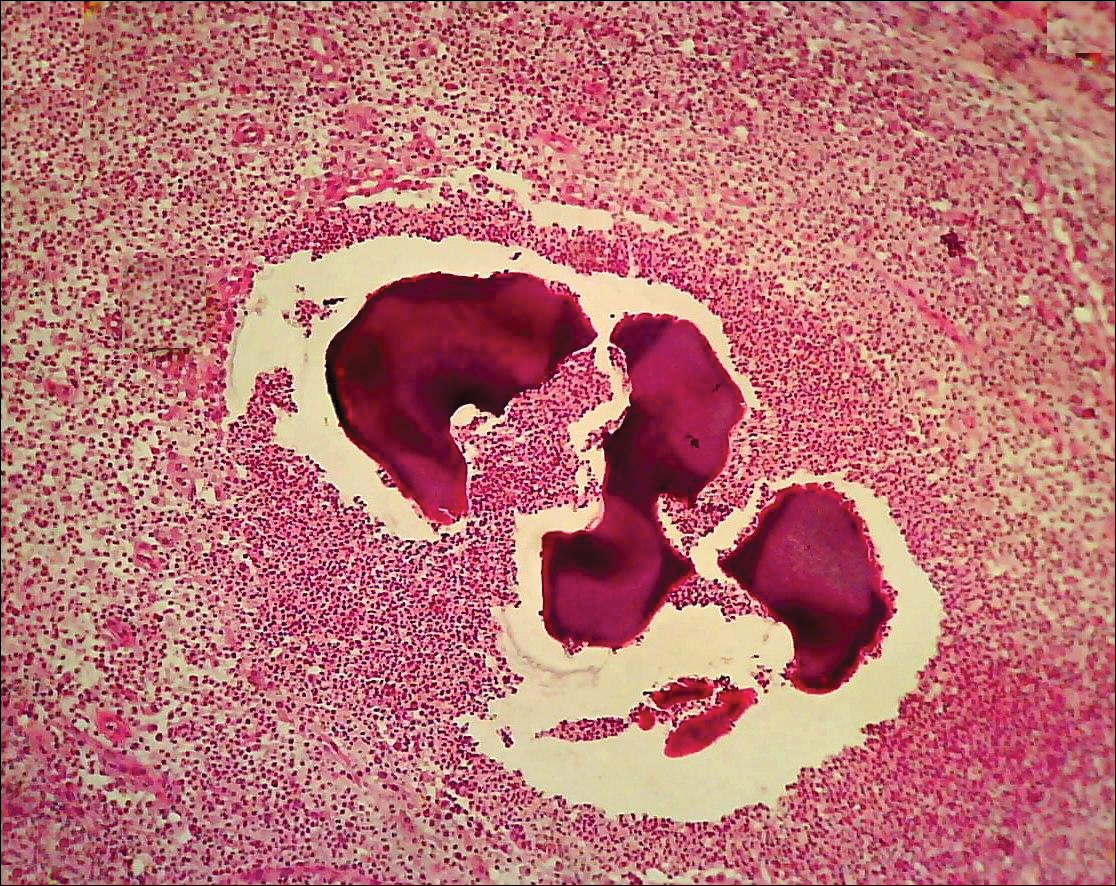

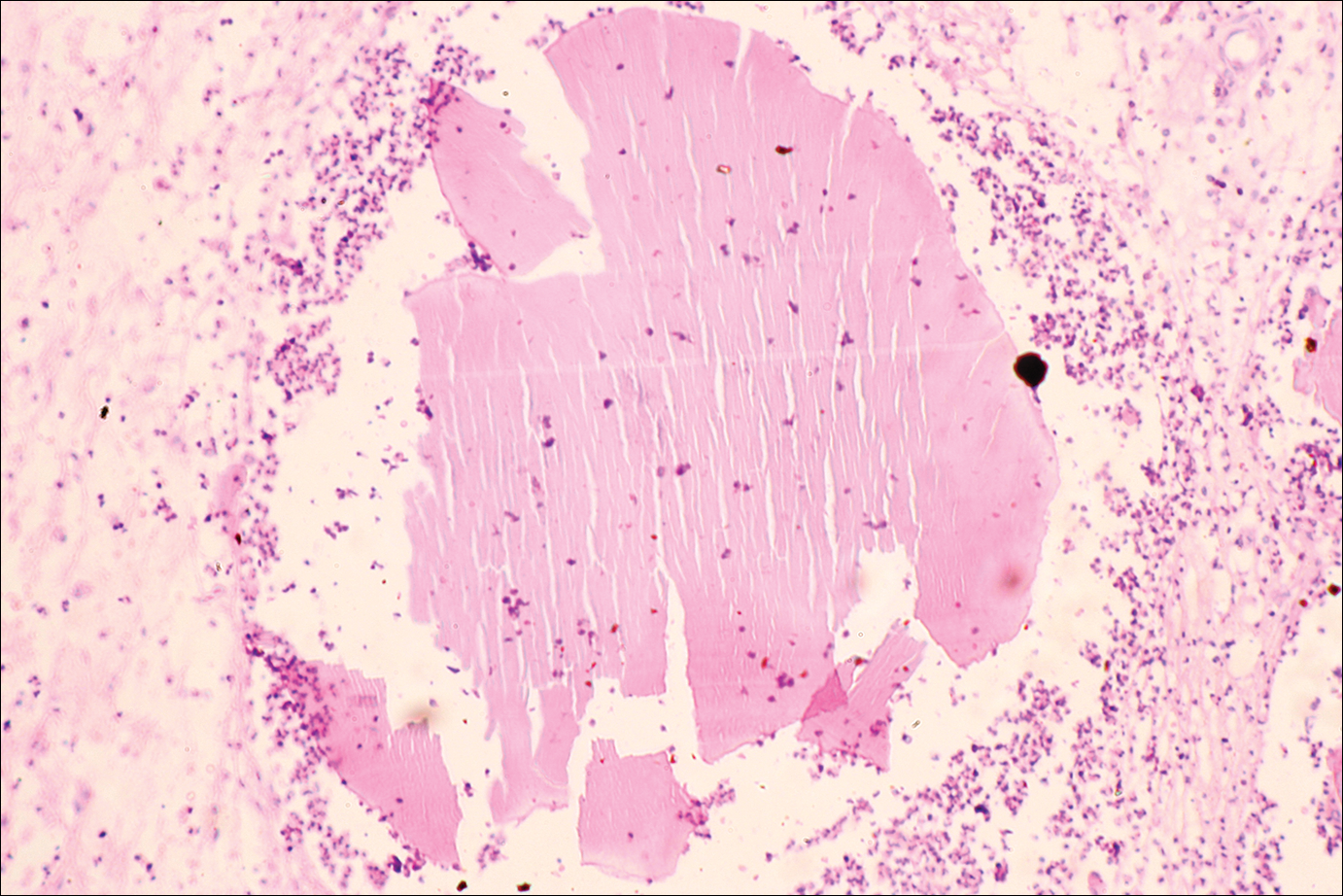

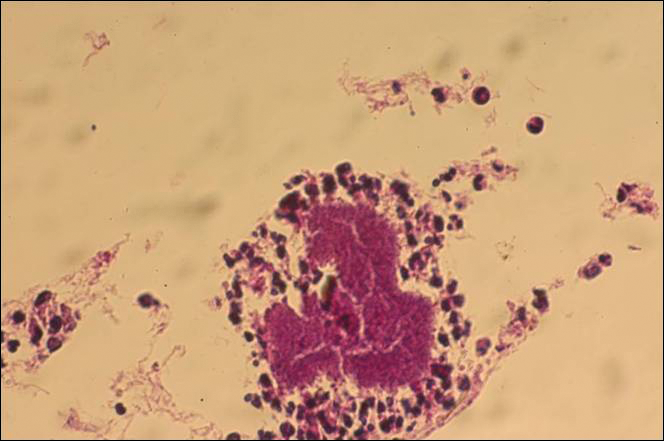

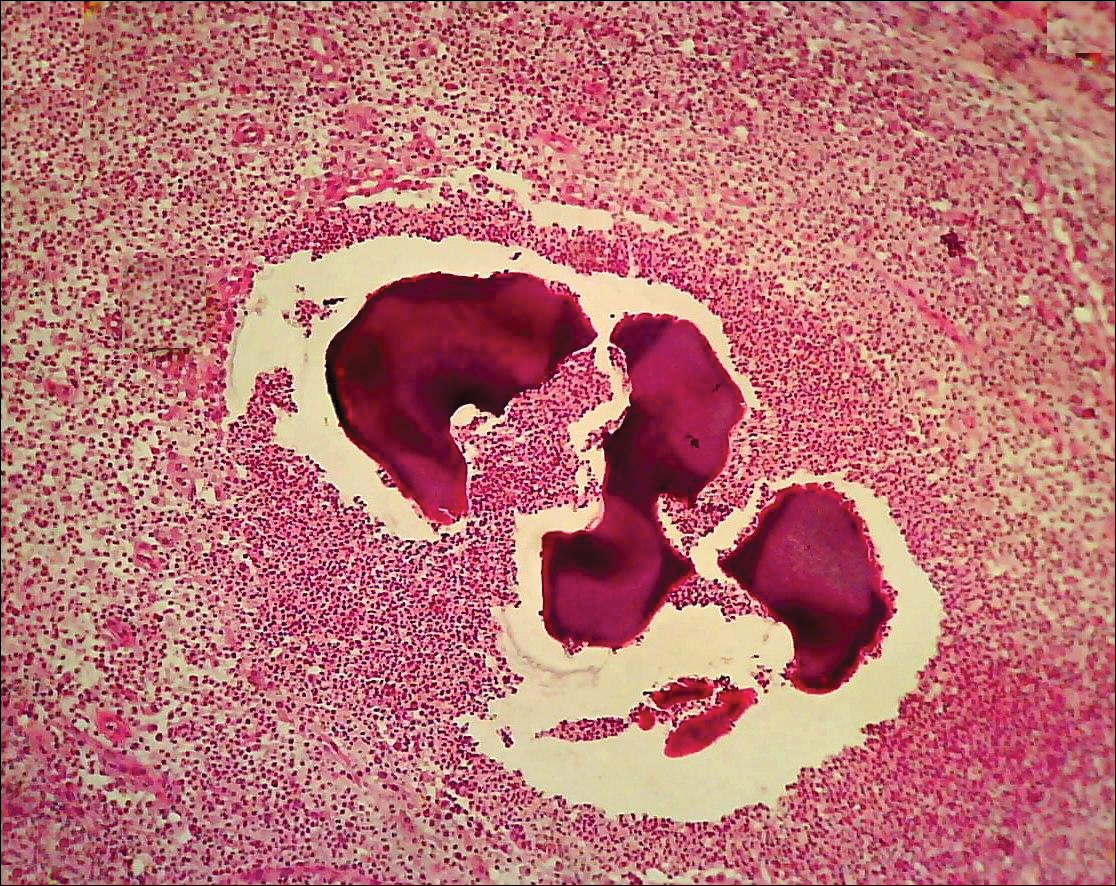

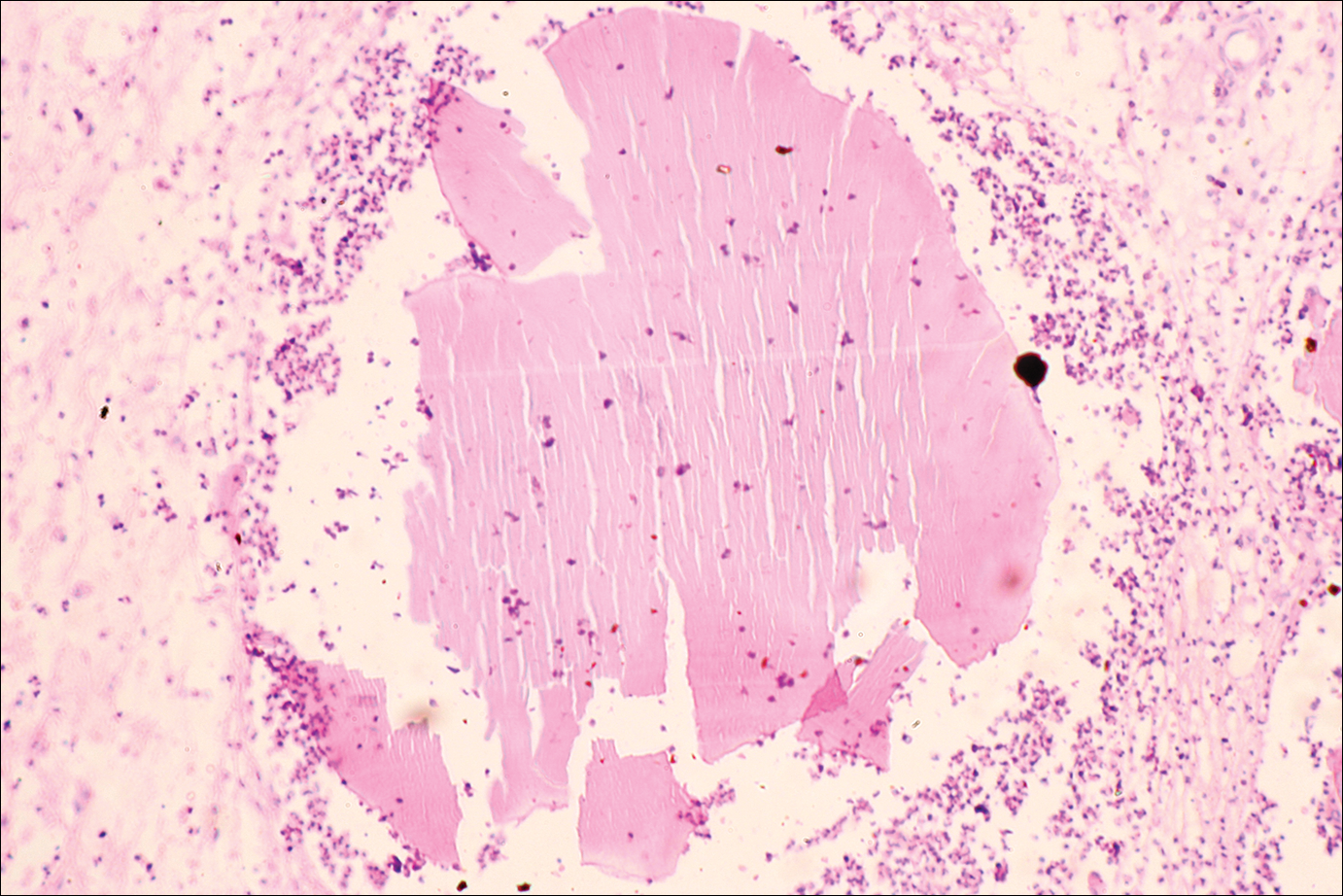

The causative agents of actinomycetoma can be isolated in Sabouraud dextrose agar. Deep wedge biopsies (or puncture aspiration) are useful in observing the diagnostic grains, which can be identified adequately with Gram stain. Grains usually are surrounded and/or infiltrated by neutrophils. The size, form, and color of grains can identify the causative agent.1 The granules of Nocardia are small (80–130 mm) and reniform or wormlike, with club structures in their periphery (Figure 1). Actinomadura madurae is characterized by large, white-yellow granules that can be seen with the naked eye (1–3 mm). On microscopic examination with hematoxylin and eosin stain, these grains are purple and exhibit peripheral pink pseudofilaments (Figure 2).2 The grains of Actinomadura pelletieri are large (1–3 mm) and red or violaceous. They fragment or break easily, giving the appearance of a broken dish (Figure 3). Streptomyces somaliensis forms round grains approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter. These grains stain poorly and are extremely hard. Cutting the grains during processing results in striation, giving them the appearance of a potato chip (Figure 4).2

Treatment of Actinomycetoma

Precise identification of the etiologic agent is essential to provide effective treatment of actinomycetoma. Without treatment, or in resistant cases, progressive osseous and visceral involvement is inevitable.9 Actinomycetoma without osseous involvement usually responds well to medical treatment.

The treatment of choice for actinomycetoma involving Nocardia brasiliensis is a combination of dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years.10 Other treatments have included the following: (1) amikacin 15 mg/kg or 500 mg intramuscularly twice daily for 3 weeks plus dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily plus TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg daily for 2 to 3 years (amikacin, however, is expensive and potentially toxic [nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity] and therefore is used only in resistant cases); (2) dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily or TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg daily for 2 to 3 years plus intramuscular kanamycin 15 mg/kg once daily for 2 weeks at the beginning of treatment, alternating with rest periods to reduce the risk for nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity10; (3) dapsone 1.5 mg/kg orally twice daily plus phosphomycin 500 mg once daily; (4) dapsone 1.5 mg/kg orally twice daily plus streptomycin 1 g once daily (14 mg/kg/d) for 1 month, then the same dose every other day for 1 to 2 months monitoring for ototoxicity; and (5) TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years or rifampicin (15–20 mg/kg/d) plus streptomycin 1 g once daily (14 mg/kg/d) for 1 month at the beginning of treatment, then the same dose every other day for 2 to 3 months until a total dose of 60 g is administered, monitoring for ototoxicity.11 Audiometric tests and creatinine levels must be performed every 5 weeks during the treatment to monitor toxicity.10

The best results for infections with A pelletieri, A madurae, and S somaliensis have been with streptomycin (1 g once daily in adults; 20 mg/kg once daily in children) until a total dose of 50 g is reached in combination with TMP-SMX or dapsone12 (Figure 5). Alternatives for A madurae infections include streptomycin plus oral clofazimine (100 mg once daily), oral rifampicin (300 mg twice daily), oral tetracycline (1 g once daily), oral isoniazid (300–600 mg once daily), or oral minocycline (100 mg twice daily; also effective for A pelletieri).

More recently, other drugs have been used such as carbapenems (eg, imipenem, meropenem), which have wide-spectrum efficacy and are resistant to β-lactamases. Patients should be hospitalized to receive intravenous therapy with imipenem.2 Carbapenems are effective against gram-positive and gram-negative as well as Nocardia species.13,14 Mycetoma that is resistant, severe, or has visceral involvement can be treated with a combination of amikacin and imipenem.15,16 Meropenem is a similar drug that is available as an oral formulation. Both imipenem and meropenem are recommended in cases with bone involvement.17,18 Alternatives for resistant cases include amoxicillin–clavulanic acid 500/125 mg orally 3 times daily for 3 to 6 months or intravenous cefotaxime 1 g every 8 hours plus intramuscular amikacin 500 mg twice daily plus oral levamisole 300 mg once weekly for 4 weeks.19-23

For resistant cases associated with Nocardia species, clindamycin plus quinolones (eg, ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, garenoxacin) at a dose of 25 mg/kg once daily for at least 3 months has been suggested in in vivo studies.23

Overall, the cure rate for actinomycetoma treated with any of the prior therapies ranges from 60% to 90%. Treatment must be modified or stopped if there is clinical or laboratory evidence of drug toxicity.13,24 Surgical treatment of actinomycetoma is contraindicated, as it may cause hematogenous dissemination.

Prognosis

Actinomycetomas of a few months’ duration and without bone involvement respond well to therapy. If no therapy is provided or if there is resistance, the functional and cosmetic prognosis is poor, mainly for the feet. There is a risk for spine involvement with mycetoma on the back and posterior head. Thoracic lesions may penetrate into the lungs. The muscular fascia impedes the penetration of abdominal lesions, but the inguinal canals can offer a path for intra-abdominal dissemination.4 Advanced cases lead to a poor general condition of patients, difficulty in using affected extremities, and in extreme cases even death.

The criteria used to guide the discontinuation of initial therapy for any mycetoma include a decrease in the volume of the lesion, closure of fistulae, 3 consecutive negative monthly cultures, imaging studies showing bone regeneration, lack of echoes and cavities on echography, and absence of grains on examination of fine-needle aspirates.11 After the initial treatment protocol is finished, most experts recommend continuing treatment with dapsone 100 to 300 mg once daily for several years to prevent recurrence.12

Prevention

Mycetoma is a disease associated with poverty. It could be prevented by improving living conditions and by regular use of shoes in rural populations.2

Conclusion

Mycetoma is a chronic infection that develops after traumatic inoculation of the skin with either true fungi or aerobic actinomycetes. The resultant infections are known as eumycetoma or actinomycetoma, respectively. The etiologic agents can be found in the so-called grains. Black grains suggest a fungal infection, minute white grains suggest Nocardia, and red grains are due to A pelletieri. Larger white grains or yellow-white grains may be fungal or actinomycotic in origin.

Specific diagnosis requires direct examination, culture, and biopsy. The treatment of choice for actinomycetoma by N brasiliensis is a combination of dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily and TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years. Other effective treatments include aminoglycosides (eg, amikacine, streptomycin) and quinolones. More recently, some other agents have been used such as carbapenems and natural products of Streptomyces cattleya (imipenem), which have wide-spectrum efficacy and are resistant to β-lactamases.

- Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Welsh E, et al. Actinomycetoma and advances in its treatment. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:372-381.

- Arenas R. Micología Medica Ilustrada. 4th ed. Mexico City, Mexico: McGraw-Hill Interamericana; 2011:125-146.

- McGinnis MR. Mycetoma. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:97-104.

- Fahal AH. Mycetoma: Clinico-pathological Monograph. Khartoum, Sudan: University of Khartoum Press; 2006:20-23, 81-82.

- Estrada-Chavez GE, Vega-Memije ME, Arenas R, et al. Eumycotic mycetoma caused by Madurella mycetomatis successfully treated with antifungals, surgery, and topical negative pressure therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:401-403.

- Chávez G, Arenas R, Pérez-Polito A, et al. Eumycetic mycetoma due to Madurella mycetomatis. report of six cases. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1998;15:90-93.

- Vasquez del Mercado E, Arenas R, Moreno G. Sequelae and long-term consequences of systemic and subcutaneous mycoses. In: Fratamico PM, Smith JL, Brogden KA, eds. Sequelae and Long-term Consequences of Infectious Diseases. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2009:415-420.

- Mancini N, Ossi CM, Perotti M, et al. Molecular mycological diagnosis and correct antimycotic treatments. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3584-3585.

- Arenas R, Lavalle P. Micetoma (madura foot). In: Arenas R, Estrada R, eds. Tropical Dermatology. Austin, TX: Landes Bioscience; 2001:51-61.

- Welsh O, Sauceda E, González J, et al. Amikacin alone and in combination with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of actinomycotic mycetoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:443-448.

- Fahal AH. Mycetoma: clinico-pathological monograph. In: Fahal AH. Evidence Based Guidelines for the Management of Mycetoma Patients. Khartoum, Sudan: University of Khartoum Press; 2002:5-15.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodríguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Valle ACF, Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L. Subcutaneous mycoses—mycetoma. In: Tyring SK, Lupi O, Hengge UR, eds. Tropical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2006:197-200.

- Fuentes A, Arenas R, Reyes M, et al. Actinomicetoma por Nocardia sp. Informe de cinco casos tratados con imipenem solo o combinado con amikacina. Gac Med Mex. 2006;142:247-252.

- Gombert ME, Aulicino TM, DuBouchet L, et al. Therapy of experimental cerebral nocardiosis with imipenem, amikacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and minocylina. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:270-273.

- Calandra GB, Ricci FM, Wang C, et al. Safety and tolerance comparison of imipenem-cilastatin to cephalotin and cefazolin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1983;12:125-131.

- Ameen M, Arenas R, Vasquez del Mercado E, et al. Efficacy of imipenem therapy for Nocardia actinomycetomas refractory to sulfonamides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:239-246.

- Ameen M, Vargas F, Vasquez del Mercado E, et al. Successful treatment of Nocardia actinomycetoma with meropenem and amikacin combination therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:443-445.

- Ameen M, Arenas R. Emerging therapeutic regimes for the management of mycetomas. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:2077-2085.

- Vera-Cabrera L, Daw-Garza A, Said-Fernández S, et al. Therapeutic effect of a novel oxazolidinone, DA-7867 in BALB/c mice infected with Nocardia brasiliensis. PloS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e289.

- Gómez A, Saúl A, Bonifaz A. Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid in the treatment of actinomicetoma. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:218-220.

- Méndez-Tovar L, Serrano-Jaen L, Almeida-Arvizu VM. Cefotaxima mas amikacina asociadas a inmunomodulación en el tratamiento de actinomicetoma resistente a tratamiento convencional. Gac Med Mex. 1999;135:517-521.

- Chacon-Moreno BE, Welsh O, Cavazos-Rocha N, et al. Efficacy of ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin against Nocardia brasiliensis in vitro in an experimental model of actinomycetoma in BALB/c mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:295-297.

- Welsh O. Treatment of actinomycetoma. Arch Med Res. 1993;24:413-415.

Mycetoma is a subcutaneous disease that can be caused by aerobic bacteria (actinomycetoma) or fungi (eumycetoma). Diagnosis is based on clinical manifestations, including swelling and deformity of affected areas, as well as the presence of granulation tissue, scars, abscesses, sinus tracts, and a purulent exudate that contains the microorganisms.

The worldwide proportion of mycetomas is 60% actinomycetomas and 40% eumycetomas.1 The disease is endemic in tropical, subtropical, and temperate regions, predominating between latitudes 30°N and 15°S. Most cases occur in Africa, especially Sudan, Mauritania, and Senegal; India; Yemen; and Pakistan. In the Americas, the countries with the most reported cases are Mexico and Venezuela.1

Although mycetoma is rare in developed countries, migration of patients from endemic areas makes knowledge of this condition crucial for dermatologists worldwide. We present a review of the current concepts in the epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of actinomycetoma.

Epidemiology

Actinomycetoma is more common in Latin America, with Mexico having the highest incidence. At last count, there were 2631 cases reported in Mexico.2 The majority of cases of mycetoma in Mexico are actinomycetoma (98%), including Nocardia (86%) and Actinomadura madurae (10%). Eumycetoma is rare in Mexico, constituting only 2% of cases.2 Worldwide, men are affected more commonly than women, which is thought to be related to a higher occupational risk during agricultural labor.

Clinical Features

Mycetoma can affect the skin, subcutaneous tissue, bones, and occasionally the internal organs. It is characterized by swelling, deformation of the affected area, and fistulae that drain serosanguineous or purulent exudates.

In Mexico, 60% of cases of mycetoma affect the lower extremities; the feet are the most commonly affected area, followed by the trunk (back and chest), arms, forearms, legs, knees, and thighs.1 Other sites include the hands, shoulders, and abdominal wall. The head and neck area are seldom affected.3 Mycetoma lesions grow and disseminate locally. Bone lesions are possible depending on the osteophilic affinity of the etiological agent and on the interactions between the fungus and the host’s immune system. In severe advanced cases of mycetoma, the lesions may involve tendons and nerves. Dissemination via blood or lymphatics is extremely rare.4

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of actinomycetoma is suspected based on clinical features and confirmed by direct examination of exudates with Lugol iodine or saline solution. On direct microscopy, actinomycetes are recognized by the production of filaments with a width of 0.5 to 1 μm. On hematoxylin and eosin stain, the small grains of Nocardia appear eosinophilic with a blue center and pink filaments. On Gram stain, actinomycetoma grains show positive branching filaments. Culture of grains recovered from aspirated material or biopsy specimens provides specific etiologic diagnosis. Cultures should be held for at least 4 weeks. Additionally, there are some enzymatic, molecular, and serologic tests available for diagnosis.5-7 Serologic diagnosis is available in a few centers in Mexico and can be helpful in some cases for diagnosis or follow-up during treatment. Antibodies can be determined via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, Western blot analysis, immunodiffusion, or counterimmunoelectrophoresis.8

The causative agents of actinomycetoma can be isolated in Sabouraud dextrose agar. Deep wedge biopsies (or puncture aspiration) are useful in observing the diagnostic grains, which can be identified adequately with Gram stain. Grains usually are surrounded and/or infiltrated by neutrophils. The size, form, and color of grains can identify the causative agent.1 The granules of Nocardia are small (80–130 mm) and reniform or wormlike, with club structures in their periphery (Figure 1). Actinomadura madurae is characterized by large, white-yellow granules that can be seen with the naked eye (1–3 mm). On microscopic examination with hematoxylin and eosin stain, these grains are purple and exhibit peripheral pink pseudofilaments (Figure 2).2 The grains of Actinomadura pelletieri are large (1–3 mm) and red or violaceous. They fragment or break easily, giving the appearance of a broken dish (Figure 3). Streptomyces somaliensis forms round grains approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter. These grains stain poorly and are extremely hard. Cutting the grains during processing results in striation, giving them the appearance of a potato chip (Figure 4).2

Treatment of Actinomycetoma

Precise identification of the etiologic agent is essential to provide effective treatment of actinomycetoma. Without treatment, or in resistant cases, progressive osseous and visceral involvement is inevitable.9 Actinomycetoma without osseous involvement usually responds well to medical treatment.

The treatment of choice for actinomycetoma involving Nocardia brasiliensis is a combination of dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years.10 Other treatments have included the following: (1) amikacin 15 mg/kg or 500 mg intramuscularly twice daily for 3 weeks plus dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily plus TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg daily for 2 to 3 years (amikacin, however, is expensive and potentially toxic [nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity] and therefore is used only in resistant cases); (2) dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily or TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg daily for 2 to 3 years plus intramuscular kanamycin 15 mg/kg once daily for 2 weeks at the beginning of treatment, alternating with rest periods to reduce the risk for nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity10; (3) dapsone 1.5 mg/kg orally twice daily plus phosphomycin 500 mg once daily; (4) dapsone 1.5 mg/kg orally twice daily plus streptomycin 1 g once daily (14 mg/kg/d) for 1 month, then the same dose every other day for 1 to 2 months monitoring for ototoxicity; and (5) TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years or rifampicin (15–20 mg/kg/d) plus streptomycin 1 g once daily (14 mg/kg/d) for 1 month at the beginning of treatment, then the same dose every other day for 2 to 3 months until a total dose of 60 g is administered, monitoring for ototoxicity.11 Audiometric tests and creatinine levels must be performed every 5 weeks during the treatment to monitor toxicity.10

The best results for infections with A pelletieri, A madurae, and S somaliensis have been with streptomycin (1 g once daily in adults; 20 mg/kg once daily in children) until a total dose of 50 g is reached in combination with TMP-SMX or dapsone12 (Figure 5). Alternatives for A madurae infections include streptomycin plus oral clofazimine (100 mg once daily), oral rifampicin (300 mg twice daily), oral tetracycline (1 g once daily), oral isoniazid (300–600 mg once daily), or oral minocycline (100 mg twice daily; also effective for A pelletieri).

More recently, other drugs have been used such as carbapenems (eg, imipenem, meropenem), which have wide-spectrum efficacy and are resistant to β-lactamases. Patients should be hospitalized to receive intravenous therapy with imipenem.2 Carbapenems are effective against gram-positive and gram-negative as well as Nocardia species.13,14 Mycetoma that is resistant, severe, or has visceral involvement can be treated with a combination of amikacin and imipenem.15,16 Meropenem is a similar drug that is available as an oral formulation. Both imipenem and meropenem are recommended in cases with bone involvement.17,18 Alternatives for resistant cases include amoxicillin–clavulanic acid 500/125 mg orally 3 times daily for 3 to 6 months or intravenous cefotaxime 1 g every 8 hours plus intramuscular amikacin 500 mg twice daily plus oral levamisole 300 mg once weekly for 4 weeks.19-23

For resistant cases associated with Nocardia species, clindamycin plus quinolones (eg, ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, garenoxacin) at a dose of 25 mg/kg once daily for at least 3 months has been suggested in in vivo studies.23

Overall, the cure rate for actinomycetoma treated with any of the prior therapies ranges from 60% to 90%. Treatment must be modified or stopped if there is clinical or laboratory evidence of drug toxicity.13,24 Surgical treatment of actinomycetoma is contraindicated, as it may cause hematogenous dissemination.

Prognosis

Actinomycetomas of a few months’ duration and without bone involvement respond well to therapy. If no therapy is provided or if there is resistance, the functional and cosmetic prognosis is poor, mainly for the feet. There is a risk for spine involvement with mycetoma on the back and posterior head. Thoracic lesions may penetrate into the lungs. The muscular fascia impedes the penetration of abdominal lesions, but the inguinal canals can offer a path for intra-abdominal dissemination.4 Advanced cases lead to a poor general condition of patients, difficulty in using affected extremities, and in extreme cases even death.

The criteria used to guide the discontinuation of initial therapy for any mycetoma include a decrease in the volume of the lesion, closure of fistulae, 3 consecutive negative monthly cultures, imaging studies showing bone regeneration, lack of echoes and cavities on echography, and absence of grains on examination of fine-needle aspirates.11 After the initial treatment protocol is finished, most experts recommend continuing treatment with dapsone 100 to 300 mg once daily for several years to prevent recurrence.12

Prevention

Mycetoma is a disease associated with poverty. It could be prevented by improving living conditions and by regular use of shoes in rural populations.2

Conclusion

Mycetoma is a chronic infection that develops after traumatic inoculation of the skin with either true fungi or aerobic actinomycetes. The resultant infections are known as eumycetoma or actinomycetoma, respectively. The etiologic agents can be found in the so-called grains. Black grains suggest a fungal infection, minute white grains suggest Nocardia, and red grains are due to A pelletieri. Larger white grains or yellow-white grains may be fungal or actinomycotic in origin.

Specific diagnosis requires direct examination, culture, and biopsy. The treatment of choice for actinomycetoma by N brasiliensis is a combination of dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily and TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years. Other effective treatments include aminoglycosides (eg, amikacine, streptomycin) and quinolones. More recently, some other agents have been used such as carbapenems and natural products of Streptomyces cattleya (imipenem), which have wide-spectrum efficacy and are resistant to β-lactamases.

Mycetoma is a subcutaneous disease that can be caused by aerobic bacteria (actinomycetoma) or fungi (eumycetoma). Diagnosis is based on clinical manifestations, including swelling and deformity of affected areas, as well as the presence of granulation tissue, scars, abscesses, sinus tracts, and a purulent exudate that contains the microorganisms.

The worldwide proportion of mycetomas is 60% actinomycetomas and 40% eumycetomas.1 The disease is endemic in tropical, subtropical, and temperate regions, predominating between latitudes 30°N and 15°S. Most cases occur in Africa, especially Sudan, Mauritania, and Senegal; India; Yemen; and Pakistan. In the Americas, the countries with the most reported cases are Mexico and Venezuela.1

Although mycetoma is rare in developed countries, migration of patients from endemic areas makes knowledge of this condition crucial for dermatologists worldwide. We present a review of the current concepts in the epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of actinomycetoma.

Epidemiology

Actinomycetoma is more common in Latin America, with Mexico having the highest incidence. At last count, there were 2631 cases reported in Mexico.2 The majority of cases of mycetoma in Mexico are actinomycetoma (98%), including Nocardia (86%) and Actinomadura madurae (10%). Eumycetoma is rare in Mexico, constituting only 2% of cases.2 Worldwide, men are affected more commonly than women, which is thought to be related to a higher occupational risk during agricultural labor.

Clinical Features

Mycetoma can affect the skin, subcutaneous tissue, bones, and occasionally the internal organs. It is characterized by swelling, deformation of the affected area, and fistulae that drain serosanguineous or purulent exudates.

In Mexico, 60% of cases of mycetoma affect the lower extremities; the feet are the most commonly affected area, followed by the trunk (back and chest), arms, forearms, legs, knees, and thighs.1 Other sites include the hands, shoulders, and abdominal wall. The head and neck area are seldom affected.3 Mycetoma lesions grow and disseminate locally. Bone lesions are possible depending on the osteophilic affinity of the etiological agent and on the interactions between the fungus and the host’s immune system. In severe advanced cases of mycetoma, the lesions may involve tendons and nerves. Dissemination via blood or lymphatics is extremely rare.4

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of actinomycetoma is suspected based on clinical features and confirmed by direct examination of exudates with Lugol iodine or saline solution. On direct microscopy, actinomycetes are recognized by the production of filaments with a width of 0.5 to 1 μm. On hematoxylin and eosin stain, the small grains of Nocardia appear eosinophilic with a blue center and pink filaments. On Gram stain, actinomycetoma grains show positive branching filaments. Culture of grains recovered from aspirated material or biopsy specimens provides specific etiologic diagnosis. Cultures should be held for at least 4 weeks. Additionally, there are some enzymatic, molecular, and serologic tests available for diagnosis.5-7 Serologic diagnosis is available in a few centers in Mexico and can be helpful in some cases for diagnosis or follow-up during treatment. Antibodies can be determined via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, Western blot analysis, immunodiffusion, or counterimmunoelectrophoresis.8

The causative agents of actinomycetoma can be isolated in Sabouraud dextrose agar. Deep wedge biopsies (or puncture aspiration) are useful in observing the diagnostic grains, which can be identified adequately with Gram stain. Grains usually are surrounded and/or infiltrated by neutrophils. The size, form, and color of grains can identify the causative agent.1 The granules of Nocardia are small (80–130 mm) and reniform or wormlike, with club structures in their periphery (Figure 1). Actinomadura madurae is characterized by large, white-yellow granules that can be seen with the naked eye (1–3 mm). On microscopic examination with hematoxylin and eosin stain, these grains are purple and exhibit peripheral pink pseudofilaments (Figure 2).2 The grains of Actinomadura pelletieri are large (1–3 mm) and red or violaceous. They fragment or break easily, giving the appearance of a broken dish (Figure 3). Streptomyces somaliensis forms round grains approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter. These grains stain poorly and are extremely hard. Cutting the grains during processing results in striation, giving them the appearance of a potato chip (Figure 4).2

Treatment of Actinomycetoma

Precise identification of the etiologic agent is essential to provide effective treatment of actinomycetoma. Without treatment, or in resistant cases, progressive osseous and visceral involvement is inevitable.9 Actinomycetoma without osseous involvement usually responds well to medical treatment.

The treatment of choice for actinomycetoma involving Nocardia brasiliensis is a combination of dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years.10 Other treatments have included the following: (1) amikacin 15 mg/kg or 500 mg intramuscularly twice daily for 3 weeks plus dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily plus TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg daily for 2 to 3 years (amikacin, however, is expensive and potentially toxic [nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity] and therefore is used only in resistant cases); (2) dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily or TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg daily for 2 to 3 years plus intramuscular kanamycin 15 mg/kg once daily for 2 weeks at the beginning of treatment, alternating with rest periods to reduce the risk for nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity10; (3) dapsone 1.5 mg/kg orally twice daily plus phosphomycin 500 mg once daily; (4) dapsone 1.5 mg/kg orally twice daily plus streptomycin 1 g once daily (14 mg/kg/d) for 1 month, then the same dose every other day for 1 to 2 months monitoring for ototoxicity; and (5) TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years or rifampicin (15–20 mg/kg/d) plus streptomycin 1 g once daily (14 mg/kg/d) for 1 month at the beginning of treatment, then the same dose every other day for 2 to 3 months until a total dose of 60 g is administered, monitoring for ototoxicity.11 Audiometric tests and creatinine levels must be performed every 5 weeks during the treatment to monitor toxicity.10

The best results for infections with A pelletieri, A madurae, and S somaliensis have been with streptomycin (1 g once daily in adults; 20 mg/kg once daily in children) until a total dose of 50 g is reached in combination with TMP-SMX or dapsone12 (Figure 5). Alternatives for A madurae infections include streptomycin plus oral clofazimine (100 mg once daily), oral rifampicin (300 mg twice daily), oral tetracycline (1 g once daily), oral isoniazid (300–600 mg once daily), or oral minocycline (100 mg twice daily; also effective for A pelletieri).

More recently, other drugs have been used such as carbapenems (eg, imipenem, meropenem), which have wide-spectrum efficacy and are resistant to β-lactamases. Patients should be hospitalized to receive intravenous therapy with imipenem.2 Carbapenems are effective against gram-positive and gram-negative as well as Nocardia species.13,14 Mycetoma that is resistant, severe, or has visceral involvement can be treated with a combination of amikacin and imipenem.15,16 Meropenem is a similar drug that is available as an oral formulation. Both imipenem and meropenem are recommended in cases with bone involvement.17,18 Alternatives for resistant cases include amoxicillin–clavulanic acid 500/125 mg orally 3 times daily for 3 to 6 months or intravenous cefotaxime 1 g every 8 hours plus intramuscular amikacin 500 mg twice daily plus oral levamisole 300 mg once weekly for 4 weeks.19-23

For resistant cases associated with Nocardia species, clindamycin plus quinolones (eg, ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, garenoxacin) at a dose of 25 mg/kg once daily for at least 3 months has been suggested in in vivo studies.23

Overall, the cure rate for actinomycetoma treated with any of the prior therapies ranges from 60% to 90%. Treatment must be modified or stopped if there is clinical or laboratory evidence of drug toxicity.13,24 Surgical treatment of actinomycetoma is contraindicated, as it may cause hematogenous dissemination.

Prognosis

Actinomycetomas of a few months’ duration and without bone involvement respond well to therapy. If no therapy is provided or if there is resistance, the functional and cosmetic prognosis is poor, mainly for the feet. There is a risk for spine involvement with mycetoma on the back and posterior head. Thoracic lesions may penetrate into the lungs. The muscular fascia impedes the penetration of abdominal lesions, but the inguinal canals can offer a path for intra-abdominal dissemination.4 Advanced cases lead to a poor general condition of patients, difficulty in using affected extremities, and in extreme cases even death.

The criteria used to guide the discontinuation of initial therapy for any mycetoma include a decrease in the volume of the lesion, closure of fistulae, 3 consecutive negative monthly cultures, imaging studies showing bone regeneration, lack of echoes and cavities on echography, and absence of grains on examination of fine-needle aspirates.11 After the initial treatment protocol is finished, most experts recommend continuing treatment with dapsone 100 to 300 mg once daily for several years to prevent recurrence.12

Prevention

Mycetoma is a disease associated with poverty. It could be prevented by improving living conditions and by regular use of shoes in rural populations.2

Conclusion

Mycetoma is a chronic infection that develops after traumatic inoculation of the skin with either true fungi or aerobic actinomycetes. The resultant infections are known as eumycetoma or actinomycetoma, respectively. The etiologic agents can be found in the so-called grains. Black grains suggest a fungal infection, minute white grains suggest Nocardia, and red grains are due to A pelletieri. Larger white grains or yellow-white grains may be fungal or actinomycotic in origin.

Specific diagnosis requires direct examination, culture, and biopsy. The treatment of choice for actinomycetoma by N brasiliensis is a combination of dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily and TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years. Other effective treatments include aminoglycosides (eg, amikacine, streptomycin) and quinolones. More recently, some other agents have been used such as carbapenems and natural products of Streptomyces cattleya (imipenem), which have wide-spectrum efficacy and are resistant to β-lactamases.

- Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Welsh E, et al. Actinomycetoma and advances in its treatment. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:372-381.

- Arenas R. Micología Medica Ilustrada. 4th ed. Mexico City, Mexico: McGraw-Hill Interamericana; 2011:125-146.

- McGinnis MR. Mycetoma. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:97-104.

- Fahal AH. Mycetoma: Clinico-pathological Monograph. Khartoum, Sudan: University of Khartoum Press; 2006:20-23, 81-82.

- Estrada-Chavez GE, Vega-Memije ME, Arenas R, et al. Eumycotic mycetoma caused by Madurella mycetomatis successfully treated with antifungals, surgery, and topical negative pressure therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:401-403.

- Chávez G, Arenas R, Pérez-Polito A, et al. Eumycetic mycetoma due to Madurella mycetomatis. report of six cases. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1998;15:90-93.

- Vasquez del Mercado E, Arenas R, Moreno G. Sequelae and long-term consequences of systemic and subcutaneous mycoses. In: Fratamico PM, Smith JL, Brogden KA, eds. Sequelae and Long-term Consequences of Infectious Diseases. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2009:415-420.

- Mancini N, Ossi CM, Perotti M, et al. Molecular mycological diagnosis and correct antimycotic treatments. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3584-3585.

- Arenas R, Lavalle P. Micetoma (madura foot). In: Arenas R, Estrada R, eds. Tropical Dermatology. Austin, TX: Landes Bioscience; 2001:51-61.

- Welsh O, Sauceda E, González J, et al. Amikacin alone and in combination with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of actinomycotic mycetoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:443-448.

- Fahal AH. Mycetoma: clinico-pathological monograph. In: Fahal AH. Evidence Based Guidelines for the Management of Mycetoma Patients. Khartoum, Sudan: University of Khartoum Press; 2002:5-15.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodríguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Valle ACF, Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L. Subcutaneous mycoses—mycetoma. In: Tyring SK, Lupi O, Hengge UR, eds. Tropical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2006:197-200.

- Fuentes A, Arenas R, Reyes M, et al. Actinomicetoma por Nocardia sp. Informe de cinco casos tratados con imipenem solo o combinado con amikacina. Gac Med Mex. 2006;142:247-252.

- Gombert ME, Aulicino TM, DuBouchet L, et al. Therapy of experimental cerebral nocardiosis with imipenem, amikacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and minocylina. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:270-273.

- Calandra GB, Ricci FM, Wang C, et al. Safety and tolerance comparison of imipenem-cilastatin to cephalotin and cefazolin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1983;12:125-131.

- Ameen M, Arenas R, Vasquez del Mercado E, et al. Efficacy of imipenem therapy for Nocardia actinomycetomas refractory to sulfonamides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:239-246.

- Ameen M, Vargas F, Vasquez del Mercado E, et al. Successful treatment of Nocardia actinomycetoma with meropenem and amikacin combination therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:443-445.

- Ameen M, Arenas R. Emerging therapeutic regimes for the management of mycetomas. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:2077-2085.

- Vera-Cabrera L, Daw-Garza A, Said-Fernández S, et al. Therapeutic effect of a novel oxazolidinone, DA-7867 in BALB/c mice infected with Nocardia brasiliensis. PloS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e289.

- Gómez A, Saúl A, Bonifaz A. Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid in the treatment of actinomicetoma. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:218-220.

- Méndez-Tovar L, Serrano-Jaen L, Almeida-Arvizu VM. Cefotaxima mas amikacina asociadas a inmunomodulación en el tratamiento de actinomicetoma resistente a tratamiento convencional. Gac Med Mex. 1999;135:517-521.

- Chacon-Moreno BE, Welsh O, Cavazos-Rocha N, et al. Efficacy of ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin against Nocardia brasiliensis in vitro in an experimental model of actinomycetoma in BALB/c mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:295-297.

- Welsh O. Treatment of actinomycetoma. Arch Med Res. 1993;24:413-415.

- Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Welsh E, et al. Actinomycetoma and advances in its treatment. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:372-381.

- Arenas R. Micología Medica Ilustrada. 4th ed. Mexico City, Mexico: McGraw-Hill Interamericana; 2011:125-146.

- McGinnis MR. Mycetoma. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:97-104.

- Fahal AH. Mycetoma: Clinico-pathological Monograph. Khartoum, Sudan: University of Khartoum Press; 2006:20-23, 81-82.

- Estrada-Chavez GE, Vega-Memije ME, Arenas R, et al. Eumycotic mycetoma caused by Madurella mycetomatis successfully treated with antifungals, surgery, and topical negative pressure therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:401-403.

- Chávez G, Arenas R, Pérez-Polito A, et al. Eumycetic mycetoma due to Madurella mycetomatis. report of six cases. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1998;15:90-93.

- Vasquez del Mercado E, Arenas R, Moreno G. Sequelae and long-term consequences of systemic and subcutaneous mycoses. In: Fratamico PM, Smith JL, Brogden KA, eds. Sequelae and Long-term Consequences of Infectious Diseases. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2009:415-420.

- Mancini N, Ossi CM, Perotti M, et al. Molecular mycological diagnosis and correct antimycotic treatments. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3584-3585.

- Arenas R, Lavalle P. Micetoma (madura foot). In: Arenas R, Estrada R, eds. Tropical Dermatology. Austin, TX: Landes Bioscience; 2001:51-61.

- Welsh O, Sauceda E, González J, et al. Amikacin alone and in combination with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of actinomycotic mycetoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:443-448.

- Fahal AH. Mycetoma: clinico-pathological monograph. In: Fahal AH. Evidence Based Guidelines for the Management of Mycetoma Patients. Khartoum, Sudan: University of Khartoum Press; 2002:5-15.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodríguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Valle ACF, Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L. Subcutaneous mycoses—mycetoma. In: Tyring SK, Lupi O, Hengge UR, eds. Tropical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2006:197-200.

- Fuentes A, Arenas R, Reyes M, et al. Actinomicetoma por Nocardia sp. Informe de cinco casos tratados con imipenem solo o combinado con amikacina. Gac Med Mex. 2006;142:247-252.

- Gombert ME, Aulicino TM, DuBouchet L, et al. Therapy of experimental cerebral nocardiosis with imipenem, amikacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and minocylina. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:270-273.

- Calandra GB, Ricci FM, Wang C, et al. Safety and tolerance comparison of imipenem-cilastatin to cephalotin and cefazolin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1983;12:125-131.

- Ameen M, Arenas R, Vasquez del Mercado E, et al. Efficacy of imipenem therapy for Nocardia actinomycetomas refractory to sulfonamides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:239-246.

- Ameen M, Vargas F, Vasquez del Mercado E, et al. Successful treatment of Nocardia actinomycetoma with meropenem and amikacin combination therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:443-445.

- Ameen M, Arenas R. Emerging therapeutic regimes for the management of mycetomas. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:2077-2085.

- Vera-Cabrera L, Daw-Garza A, Said-Fernández S, et al. Therapeutic effect of a novel oxazolidinone, DA-7867 in BALB/c mice infected with Nocardia brasiliensis. PloS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e289.

- Gómez A, Saúl A, Bonifaz A. Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid in the treatment of actinomicetoma. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:218-220.

- Méndez-Tovar L, Serrano-Jaen L, Almeida-Arvizu VM. Cefotaxima mas amikacina asociadas a inmunomodulación en el tratamiento de actinomicetoma resistente a tratamiento convencional. Gac Med Mex. 1999;135:517-521.

- Chacon-Moreno BE, Welsh O, Cavazos-Rocha N, et al. Efficacy of ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin against Nocardia brasiliensis in vitro in an experimental model of actinomycetoma in BALB/c mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:295-297.

- Welsh O. Treatment of actinomycetoma. Arch Med Res. 1993;24:413-415.

Practice Points

- Diagnosis of actinomycetoma is based on clinical manifestations including increased swelling and deformity of affected areas, presence of granulation tissue, scars, abscesses, sinus tracts, and a purulent exudate containing microorganisms.

- The feet are the most commonly affected location, followed by the trunk (back and chest), arms, forearms, legs, knees, and thighs.

- Specific diagnosis of actinomycetoma requires clinical examination as well as direct examination of culture and biopsy results.

- Overall, the cure rate for actinomycetoma ranges from 60% to 90%.

Verrucous Carcinoma of the Buccal Mucosa With Extension to the Cheek

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is an uncommon type of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and was first described by Ackerman1 in 1948. Rock and Fisher2 called this condition oral florid papillomatosis. The distinctive features of this tumor are low-grade malignancy, slow growth, local invasiveness, and rarely intraoral and extraoral metastasis. Extraorally, it can occur in any part of the body,3 a common site being the anogenital region. Depending on the area of occurrence, the condition also is known as Buschke-Lowenstein tumor4 or giant condyloma acuminatum (anogenital region) and carcinoma cuniculatum5 (plantar region). The exact etiology of the condition is unknown, though it is associated with human papillomavirus infection, traumatic scars, chronic infection, tobacco, and chemical carcinogens.3 We report a rare case of verrucous carcinoma originating from the buccal mucosa that subsequently spread to involve the lip and cheek as a large cauliflowerlike growth, which is an unusual presentation.

A 65-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a painless growth inside the left side of the oral cavity that had developed 5 years prior as a growth on the left buccal mucosa. The lesion gradually increased in size to involve the left oral commissure including the upper and lower lips and the skin of the left cheek; it extended beyond the nasolabial fold in a cauliflowerlike pattern. The lesion was insidious in onset and was not associated with pain, itching, or bleeding. The patient chewed tobacco for the last 40 years, with no similar lesions on any part of the body. On physical examination a warty papilliform lesion was seen on the left buccal mucosa with extension to 2 cm of the upper and lower lip on the left side including the left oral commissure and the skin of the left cheek beyond the nasolabial fold where it appeared as a cauliflowerlike growth measuring 4×5 cm in size (Figure 1). No notable lymphadenopathy was present.

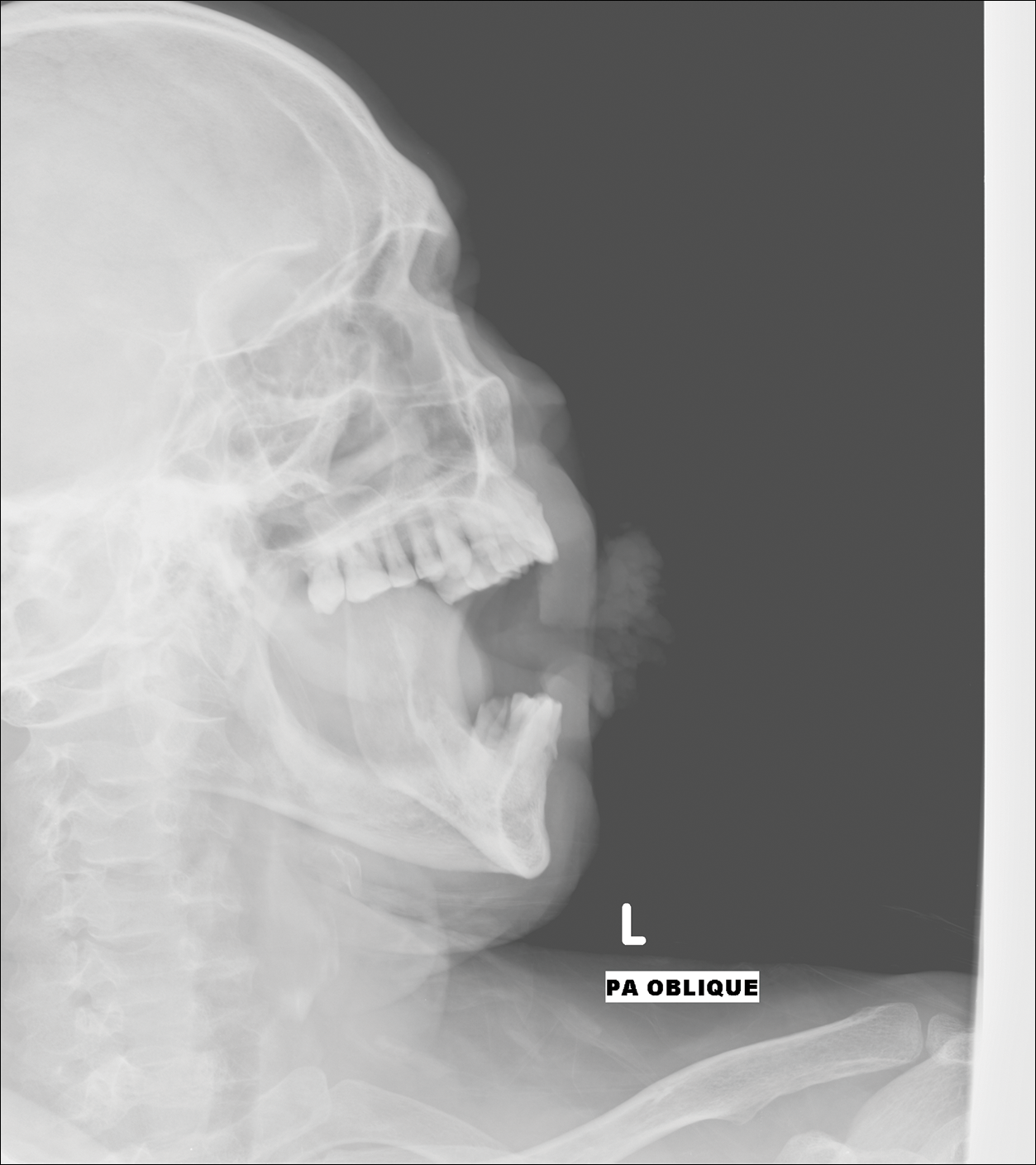

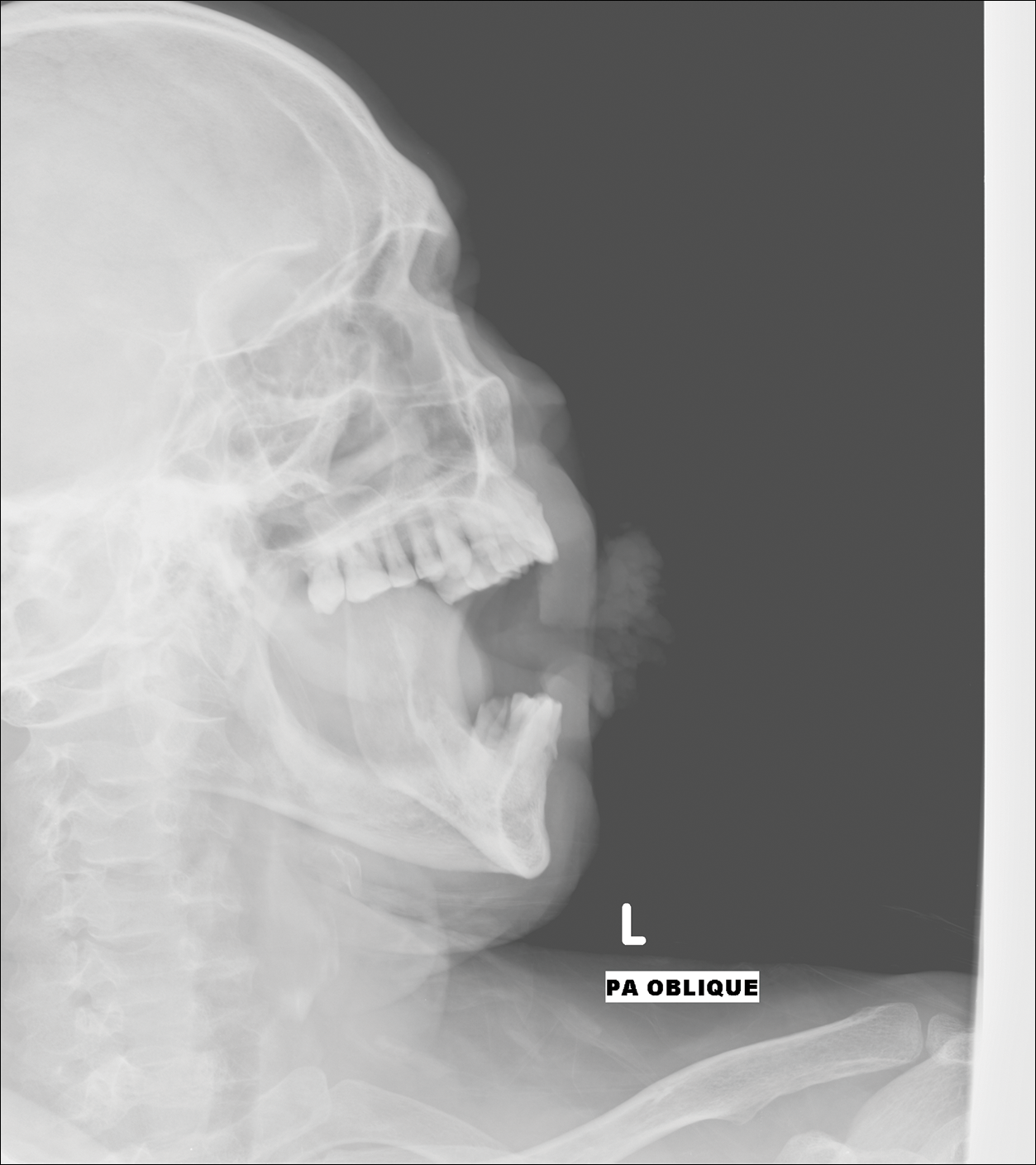

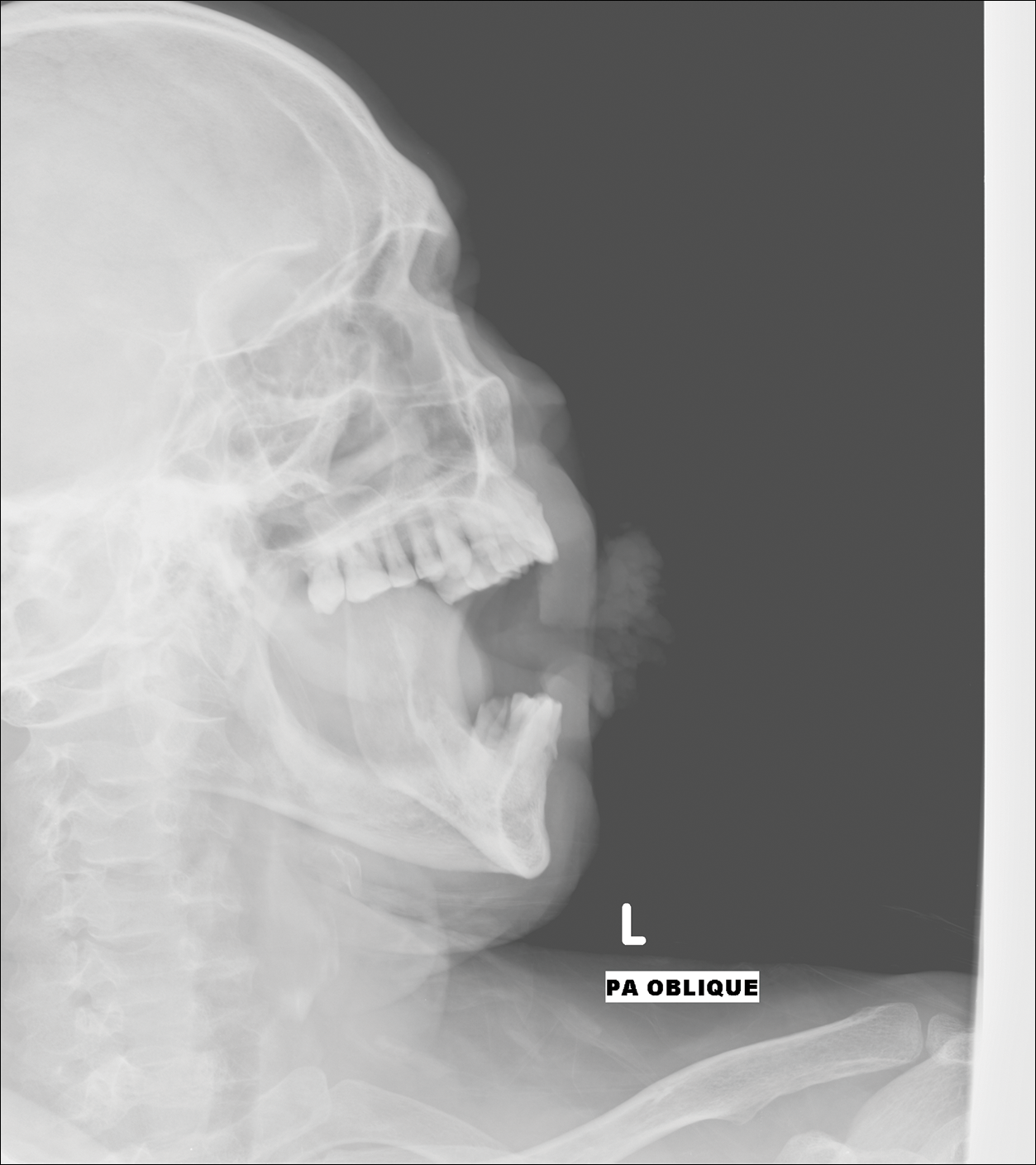

Digital radiographs of the skull (posteroanterior oblique view)(Figure 2) and mandible (left oblique view) showed a lobulated soft-tissue density lesion overlying the left half of the mandible (near the mandibular angle) with involvement of both the upper and lower lips on the left side. However, no obvious underlying bony erosion was noted.

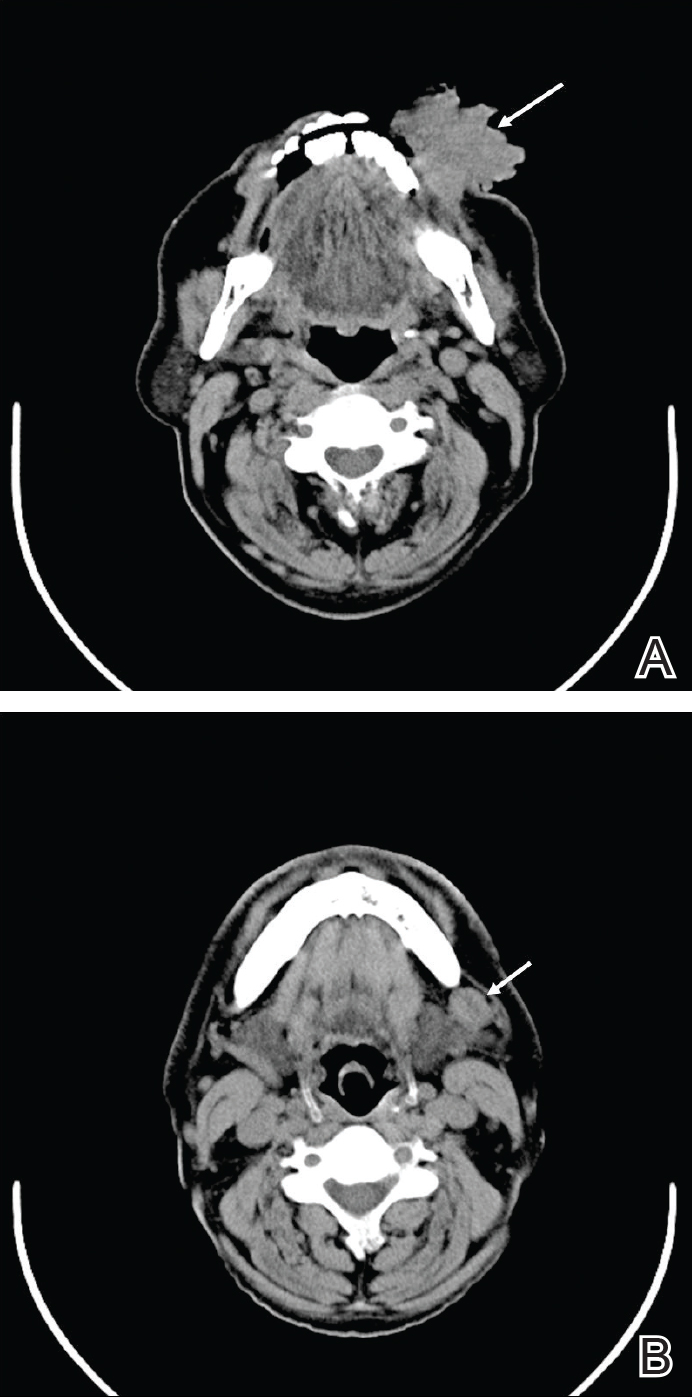

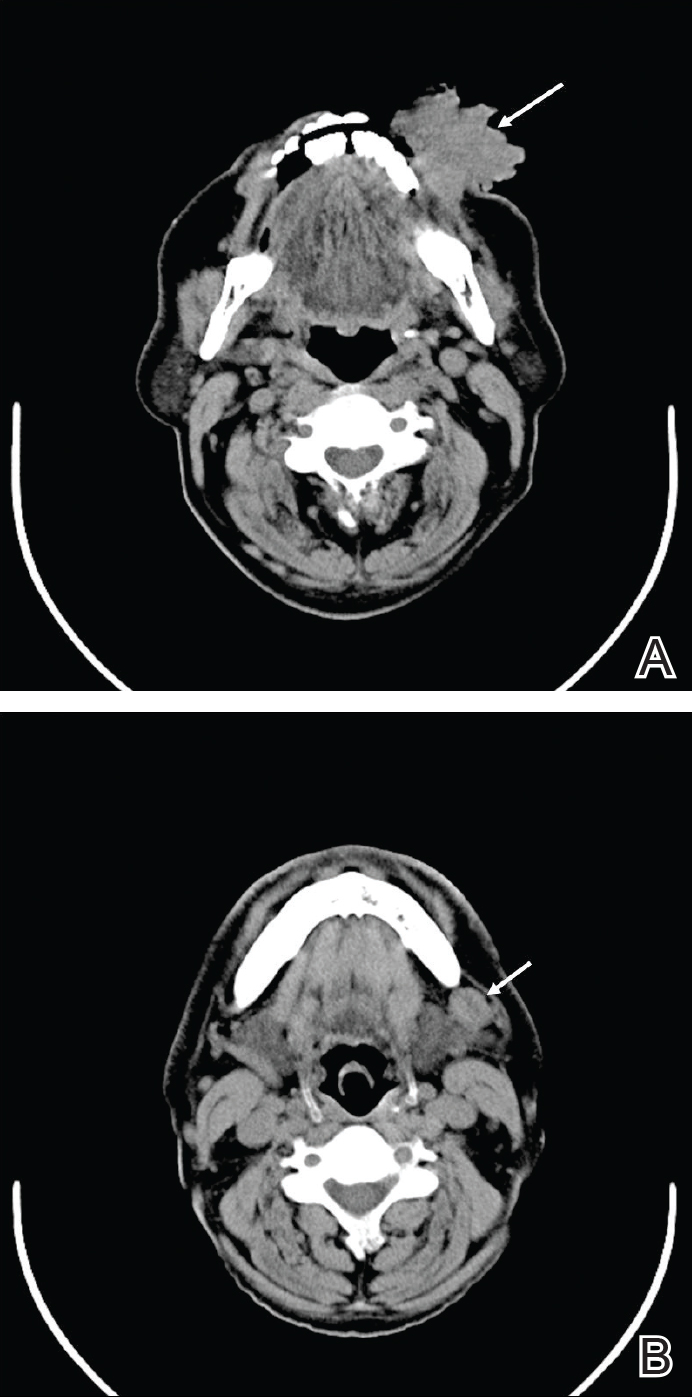

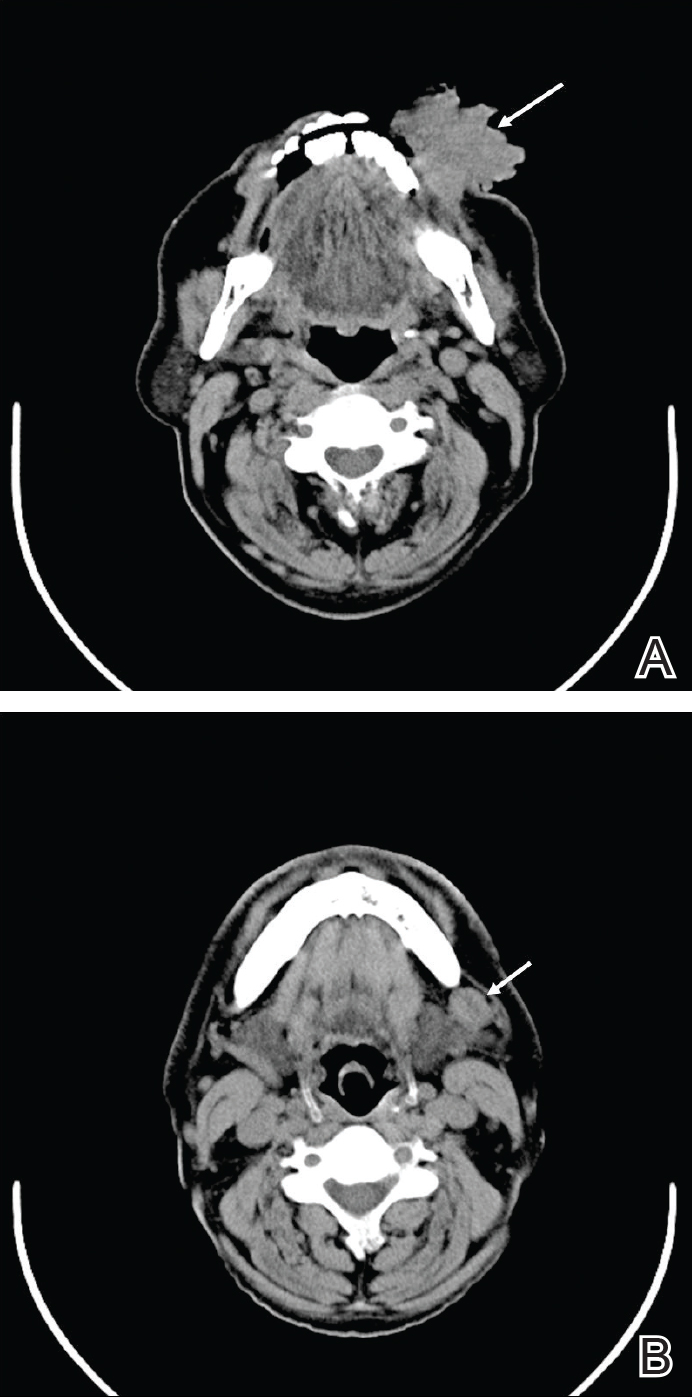

Computed tomography revealed a large soft-tissue mass (41.3×35.3 mm)(Figure 3A) involving the left buccal mucosa with extension into overlying muscle, subcutaneous tissue, and skin. Externally, the lesion was exophytic, irregular, and polypoidal with surface ulceration. Medially, the lesion involved the left oral commissure and parts of the adjoining upper and lower lips. No underlying bony erosion was seen. An enlarged lymph node measuring 20×15 mm was noted in the left upper deep cervical group in the submandibular region (Figure 3B).

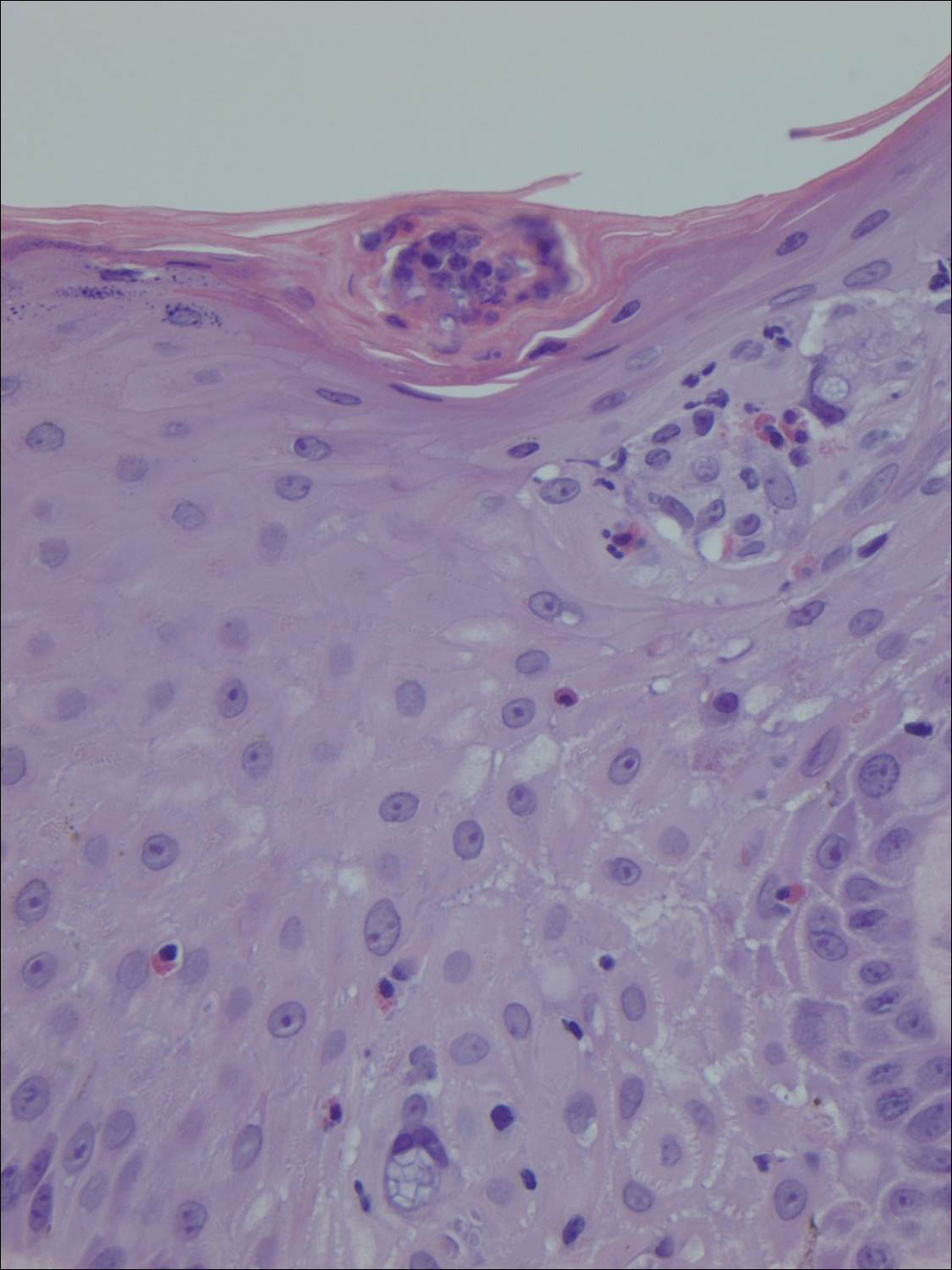

Our clinical differential diagnosis included verrucous carcinoma and hypertrophic variety of lupus vulgaris. A 1×2-cm diagnostic incisional biopsy was performed from the cauliflowerlike growth and ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration was done from the lymph node. Histopathology revealed a hyperplastic stratified squamous epithelium with upward extension of verrucous projections, which was largely superficial to the adjacent epithelium (Figure 4A). In addition to the surface verrucous projections, there was lesion extension into the subepithelial zone in the form of round club-shaped protrusions (Figure 4B). There was no loss of polarity in these downward proliferations. No horn pearl formation was present. Fine-needle aspiration revealed reactive lymphadenitis.

The final diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma was made and the patient was referred to the oncosurgery department for further management.

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, low-grade, well-differentiated SCC of the skin or mucosa presenting with a verrucoid or cauliflowerlike appearance. It shows locally aggressive behavior and has low metastatic potential,6 a low degree of dysplasia, and a good prognosis. Because it is a tumor with predominantly horizontal growth, it tends to erode more than infiltrate. It does not present with remote metastasis.7 It has been known by several different names, usually related to anatomic sites (eg, Ackerman tumor, oral florid papillomatosis, carcinoma cuniculatum).