User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on Redness-Reducing Products

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on redness-reducing products. Consideration must be given to:

- Avène Antirougeurs FORT Relief Concentrate

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA

“This formula has medical-grade ruscus extract to support microcirculation and soothe skin reactivity and redness, as well as soothing Avène Thermal Spring Water.” — Jeannette Graf, MD, New York, New York

- Eucerin Redness Relief

Beiersdorf Inc

“Eucerin’s Redness Relief product line has worked well for some of my patients.” — Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Redness Solutions Daily Protective Base Broad Spectrum SPF 15

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

“This oil-free makeup primer has a sheer green tint that camouflages redness while also protecting from UV rays.” — Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments, cleansing devices, and men’s products will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please email your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on redness-reducing products. Consideration must be given to:

- Avène Antirougeurs FORT Relief Concentrate

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA

“This formula has medical-grade ruscus extract to support microcirculation and soothe skin reactivity and redness, as well as soothing Avène Thermal Spring Water.” — Jeannette Graf, MD, New York, New York

- Eucerin Redness Relief

Beiersdorf Inc

“Eucerin’s Redness Relief product line has worked well for some of my patients.” — Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Redness Solutions Daily Protective Base Broad Spectrum SPF 15

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

“This oil-free makeup primer has a sheer green tint that camouflages redness while also protecting from UV rays.” — Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments, cleansing devices, and men’s products will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please email your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on redness-reducing products. Consideration must be given to:

- Avène Antirougeurs FORT Relief Concentrate

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA

“This formula has medical-grade ruscus extract to support microcirculation and soothe skin reactivity and redness, as well as soothing Avène Thermal Spring Water.” — Jeannette Graf, MD, New York, New York

- Eucerin Redness Relief

Beiersdorf Inc

“Eucerin’s Redness Relief product line has worked well for some of my patients.” — Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Redness Solutions Daily Protective Base Broad Spectrum SPF 15

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

“This oil-free makeup primer has a sheer green tint that camouflages redness while also protecting from UV rays.” — Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments, cleansing devices, and men’s products will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please email your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

Product News: 07 2017

Glytone Sunscreen Lotion Broad Spectrum SPF 40

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA introduces Glytone Sunscreen Lotion Broad Spectrum SPF 40, a mineral-based formula for face and body with micronized zinc oxide, octinoxate, and octisalate. The lightweight formula is water resistant for up to 40 minutes and contains hyaluronic acid to nourish the skin and help boost natural moisture levels to visibly reduce the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles. For more information, visit www.glytone-usa.com.

proactivMD

The Proactiv Company launches the proactivMD Essentials System, a 3-step acne regimen that has been reformulated to include

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Glytone Sunscreen Lotion Broad Spectrum SPF 40

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA introduces Glytone Sunscreen Lotion Broad Spectrum SPF 40, a mineral-based formula for face and body with micronized zinc oxide, octinoxate, and octisalate. The lightweight formula is water resistant for up to 40 minutes and contains hyaluronic acid to nourish the skin and help boost natural moisture levels to visibly reduce the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles. For more information, visit www.glytone-usa.com.

proactivMD

The Proactiv Company launches the proactivMD Essentials System, a 3-step acne regimen that has been reformulated to include

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Glytone Sunscreen Lotion Broad Spectrum SPF 40

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA introduces Glytone Sunscreen Lotion Broad Spectrum SPF 40, a mineral-based formula for face and body with micronized zinc oxide, octinoxate, and octisalate. The lightweight formula is water resistant for up to 40 minutes and contains hyaluronic acid to nourish the skin and help boost natural moisture levels to visibly reduce the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles. For more information, visit www.glytone-usa.com.

proactivMD

The Proactiv Company launches the proactivMD Essentials System, a 3-step acne regimen that has been reformulated to include

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Hair and Scalp Disorders in Adult and Pediatric Patients With Skin of Color

One of the most common concerns among black patients is hair- and scalp-related disease. As increasing numbers of black patients opt to see dermatologists, it is imperative that all dermatologists be adequately trained to address the concerns of this patient population. When patients ask for help with common skin diseases of the hair and scalp, there are details that must be included in diagnosis, treatment, and hair care recommendations to reach goals for excellence in patient care. Herein, we provide must-know information to effectively approach this patient population.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

A study utilizing data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 1993 to 2009 revealed seborrheic dermatitis (SD) as the second most common diagnosis for black patients who visit a dermatologist.1 Prevalence data from a population of 1408 white, black, and Chinese patients from the United States and China revealed scalp flaking in 81% to 95% of black patients, 66% to 82% in white patients, and 30% to 42% in Chinese patients.2 Seborrheic dermatitis has a notable prevalence in black women and often is considered normal by patients. It can be exacerbated by infrequent shampooing (ranging from once per month or longer in between shampoos) and the inappropriate use of hair oils and pomades; it also has been associated with hair breakage, lichen simplex chronicus, and folliculitis. Seborrheic dermatitis must be distinguished from other disorders including sarcoidosis, psoriasis, discoid lupus erythematosus, tinea capitis, and lichen simplex chronicus.

Although there is a paucity of literature on the treatment of SD in black patients, components of treatment are similar to those recommended for other populations. Black women are advised to carefully utilize antidandruff shampoos containing zinc pyrithione, selenium sulfide, or tar to avoid hair shaft damage and dryness. Ketoconazole shampoo rarely is recommended and may be more appropriately used in men and boys, as hair fragility is less of a concern for them. The shampoo should be applied directly to the scalp rather than the hair shafts to minimize dryness, with no particular elongated contact time needed for these medicated shampoos to be effective. Because conditioners can wash off the active ingredients in therapeutic shampoos, antidandruff conditioners are recommended. Potent or ultrapotent topical corticosteroids applied to the scalp 3 to 4 times weekly initially will control the symptoms of itching as well as scaling, and mid-potency topical corticosteroid oil may be used at weekly intervals.

Hairline and facial involvement of SD often co-occurs, and low-potency topical steroids may be applied to the affected areas twice daily for 3 to 4 weeks, which may be repeated for flares. Topical calcineurin inhibitors or antifungal creams such as ketoconazole or econazole may then provide effective control. Encouraging patients to increase shampooing to once weekly or every 2 weeks and discontinue use of scalp pomades and oils also is recommended. Patients must know that an itchy scaly scalp represents a treatable disorder.

Acquired Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Hair fragility and breakage is common and multifactorial in black patients. Hair shaft breakage can occur on the vertex scalp in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), with random localized breakage due to scratching in SD. Heat, hair colorants, and chemical relaxers may result in diffuse damage and breakage.3 Sodium-, potassium-, and guanine hydroxide–containing chemical relaxers change the physical properties of the hair by rearranging disulfide bonds. They remove the monomolecular layer of fatty acids covalently bound to the cuticle that help prevent penetration of water into the hair shaft. Additionally, chemical relaxers weaken the hair shaft and decrease tensile strength.

Unlike hair relaxers, colorants are less likely to lead to catastrophic hair breakage after a single use and require frequent use, which leads to cumulative damage. Thermal straightening is another cause of hair-shaft weakening in black patients.4,5 Flat irons and curling irons can cause substantially more damage than blow-dryers due to the amount of heat generated. Flat irons may reach a high temperature of 230ºC (450ºF) as compared to 100°C (210°F) for a blow-dryer. Even the simple act of combing the hair can cause hair breakage, as demonstrated in African volunteers whose hair remained short in contrast to white and Asian volunteers, despite the fact that they had not cut their hair for 1 or more years.6,7 These volunteers had many hair strand knots that led to breakage during combing and hair grooming.6

There is no known prevalence data for acquired trichorrhexis nodosa, though a study of 30 white and black women demonstrated that broken hairs were significantly increased in black women (P=.0001).8 Another study by Hall et al9 of 103 black women showed that 55% of the women reported breakage of hair shafts with normal styling. Khumalo et al6 investigated hair shaft fragility and reported no trichothiodystrophy; the authors concluded that the cause of the hair fragility likely was physical trauma or an undiscovered structural abnormality. Franbourg et al10 examined the structure of hair fibers in white, Asian, and black patients and found no differences, but microfractures were only present in black patients and were determined to be the cause of hair breakage. These studies underscore the need for specific questioning of the patient on hair care including combing, washing, drying, and using products and chemicals.

The approach to the treatment of hair breakage involves correcting underlying abnormalities (eg, iron deficiency, hypothyroidism, nutritional deficiencies). Patients should “give their hair a rest” by discontinuing use of heat, colorants, and chemical relaxers. For patients who are unable to comply, advising them to stop these processes for 6 to 12 months will allow for repair of the hair shaft. To minimize damage from colorants, recommend semipermanent, demipermanent, or temporary dyes. Patients should be counseled to stop bleaching their hair or using permanent colorants. The use of heat protectant products on the hair before styling as well as layering moisturizing regimens starting with a moisturizing shampoo followed by a leave-in, dimethicone-containing conditioner marketed for dry damaged hair is suggested. Dimethicone thinly coats the hair shaft to restore hydrophobicity, smoothes cuticular scales, decreases frizz, and protects the hair from damage. Use of a 2-in-1 shampoo and conditioner containing anionic surfactants and wide-toothed, smooth (no jagged edges in the grooves) combs along with rare brushing are recommended. The hair may be worn in its natural state, but straightening with heat should be avoided. Air drying the hair can minimize breakage, but if thermal styling is necessary, patients should turn the temperature setting of the flat or curling iron down. Protective hair care practices may include placing a loosely sewn-in hair weave that will allow for good hair care, wearing loose braids, or using a wig. Serial trimming of the hair every 6 to 8 weeks is recommended. Improvement may take time, and patients should be advised of this timeline to prevent frustration.

Acne Keloidalis Nuchae

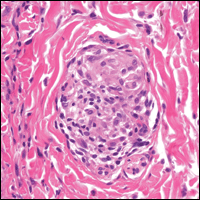

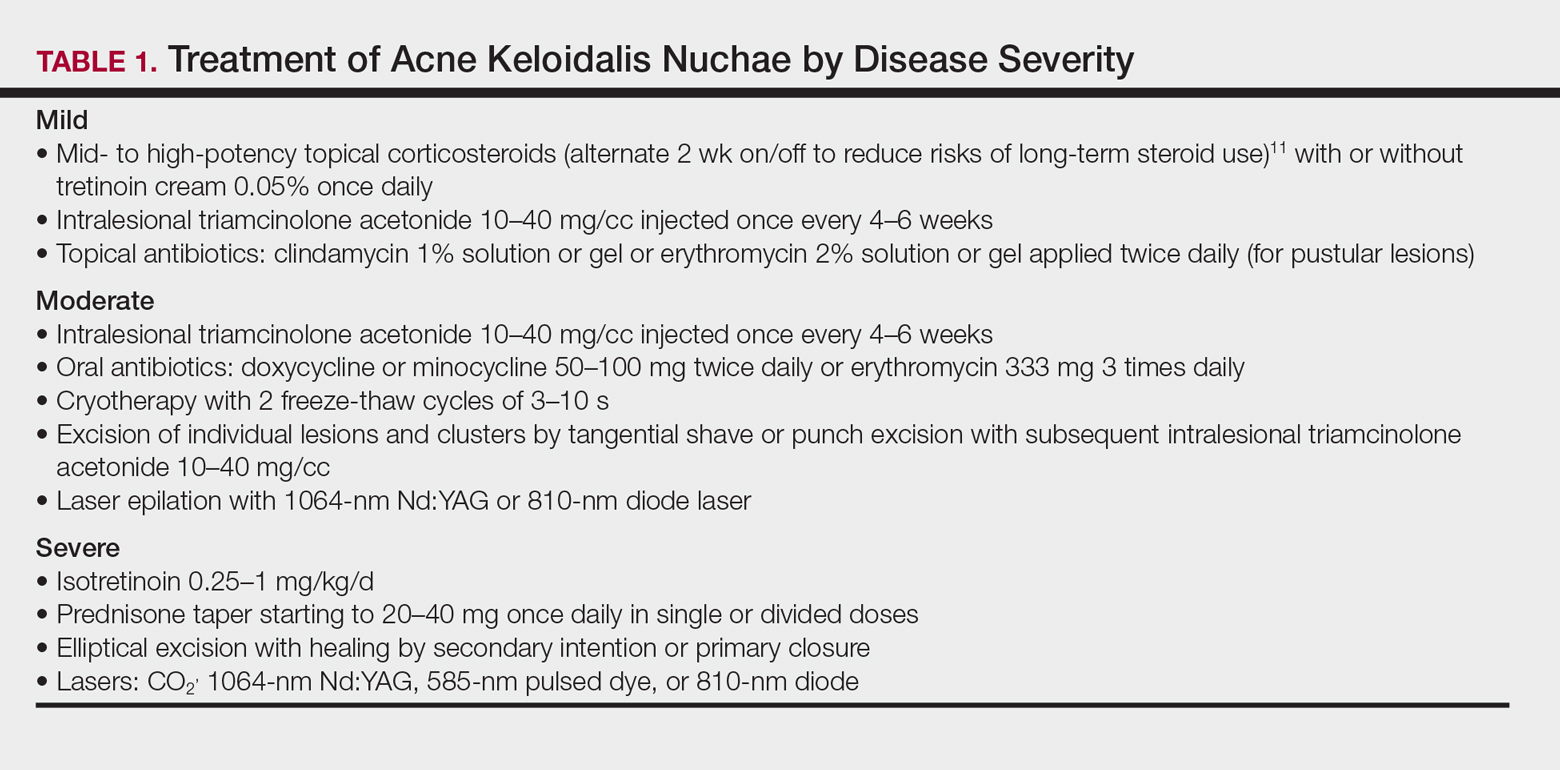

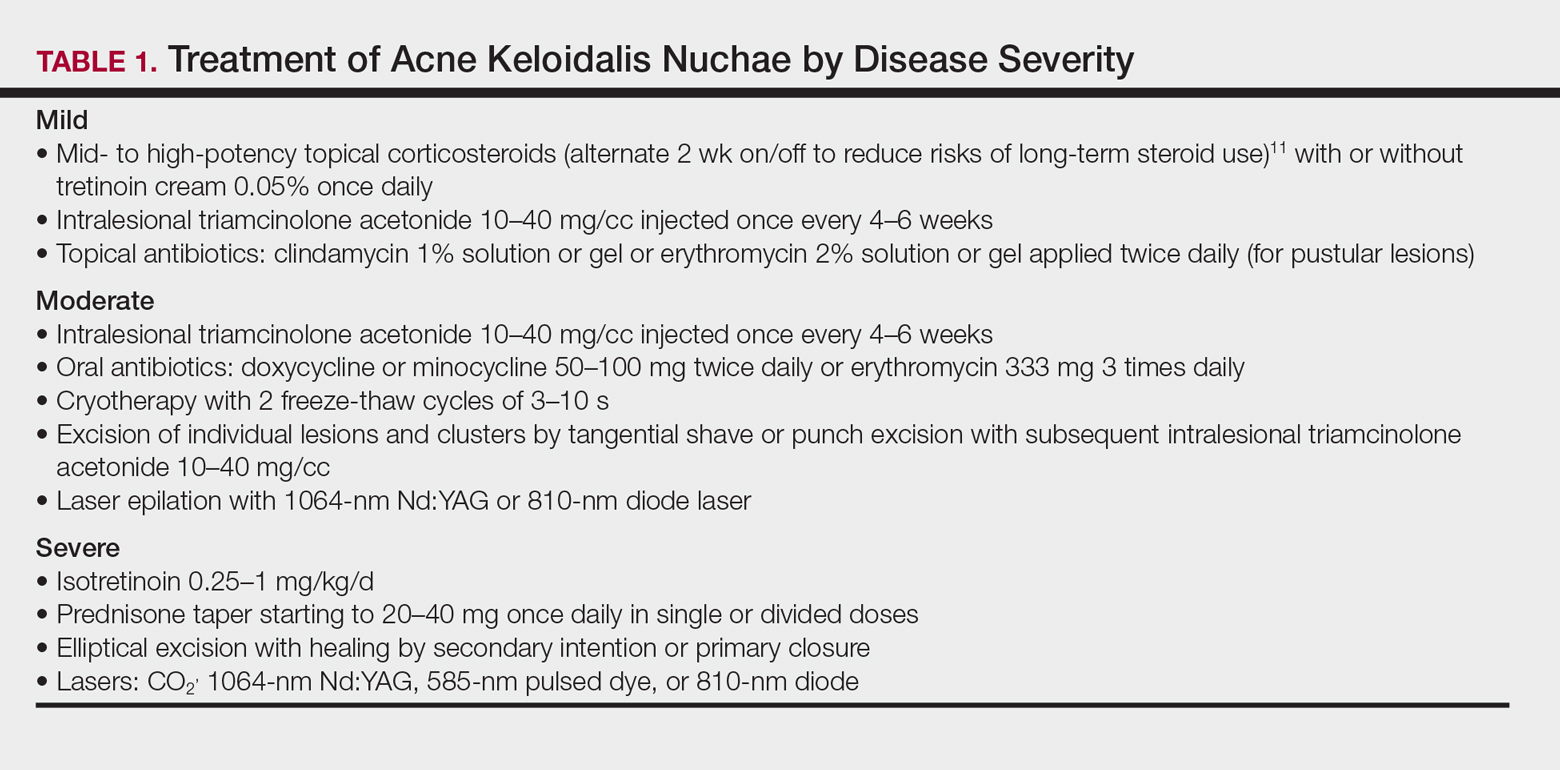

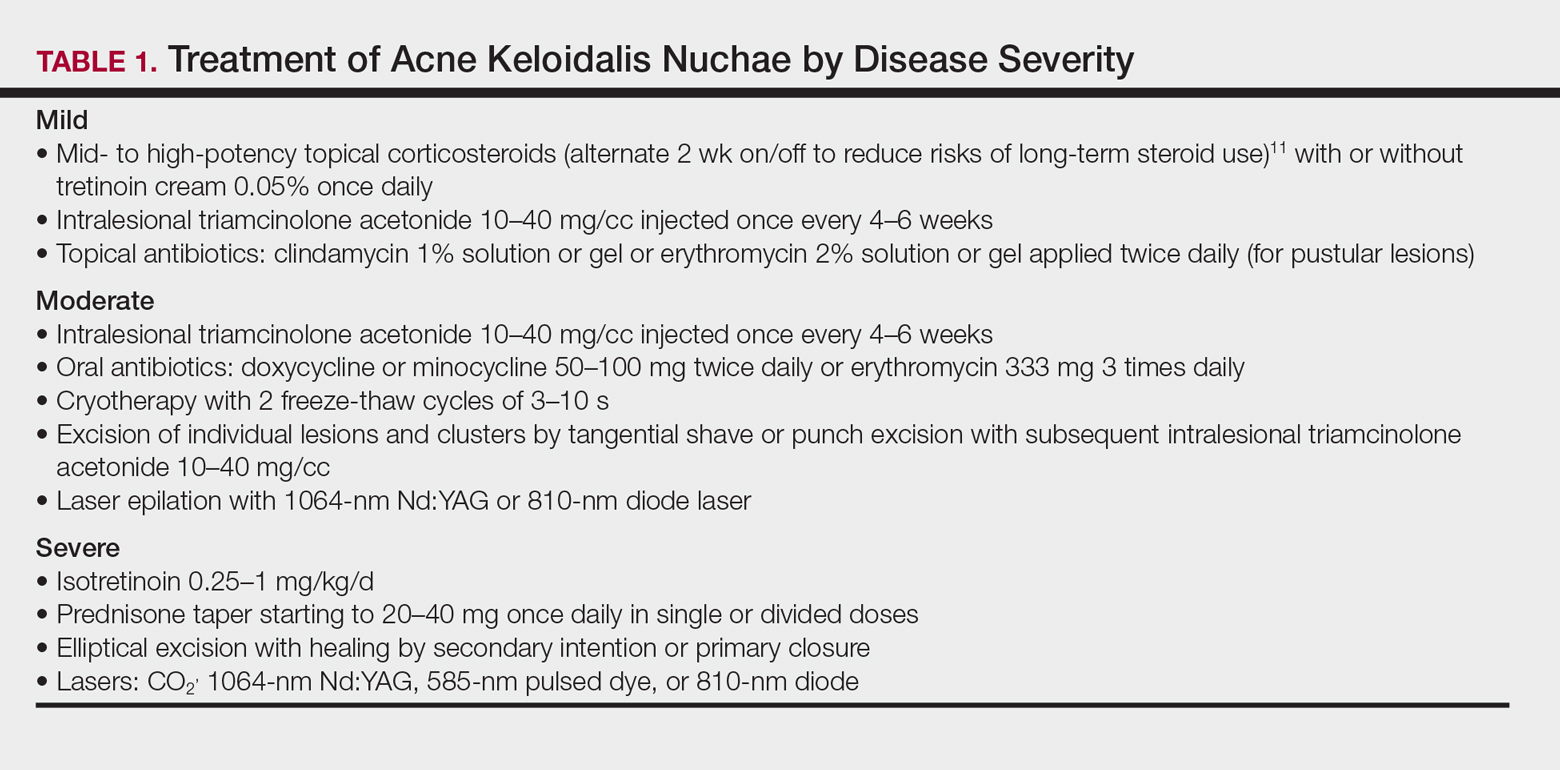

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) is characterized by papules and pustules located on the occipital scalp and/or the nape of the neck, which may result in keloidal papules and plaques. The etiology is unknown, but ingrown hairs, genetics, trauma, infection, inflammation, and androgen hormones have been proposed to play a role.11 Although AKN may occur in black women, it is primarily a disorder in black men. The diagnosis is made based primarily on clinical findings, and a history of short haircuts may support the diagnosis. Treatment is tailored to the severity of the disease (Table 1). Avoidance of short haircuts and irritation from shirt collars may be helpful. Patients should be advised that the condition is controllable but not curable.

Pseudofolliculitis Barbae

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) is characterized by papules and pustules in the beard region that may result in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, keloidal scar formation, and/or linear scarring. The coarse curled hairs characteristic of black men penetrate the follicle before exiting the skin and penetrate the skin after exiting the follicle, resulting in inflammation. Shaving methods and genetics also may contribute to the development of PFB. As with AKN, diagnosis is made clinically and does not require a skin biopsy. Important components of the patient’s history that should be obtained are hair removal practices and the use of over-the-counter products (eg, shave [pre and post] moisturizers, exfoliants, shaving creams or gels, keratin-softening agents containing α- or β-hydroxy acids). A bacterial culture may be appropriate if a notable pustular component is present. The patient should be advised to discontinue shaving if possible, which may require a physician’s letter explaining the necessity to the patient’s employer. Pseudofolliculitis barbae often can be prevented or lessened with the right hair removal strategy. Because there is not one optimal hair removal strategy that suits every patient, encourage the patient to experiment with different hair removal techniques, from depilatories to electric shavers, foil-guard razors, and multiple-blade razors. Preshave hydration and postshave moisturiza-tion also should be encouraged.12 Benzoyl peroxide–containing shave gels and cleansers, as well as moisturizers containing glycolic, salicylic, and phytic acids, may minimize ingrown hairs, papules, and inflammation.

Other useful topical agents include eflornithine hydrochloride to decrease hair growth, retinoids to soften hair fibers, mild topical steroids to reduce inflammation, and/or topical erythromycin or clindamycin if pustules are present.13 Oral antibiotics such as doxycycline, minocycline, or erythromycin can be added for more severe cases of inflammation or infection. Procedural interventions include laser hair removal to prevent PFB and intralesional triamcinolone 10 to 40 mg/cc every 4 to 6 weeks, with the total volume depending on the size and number of lesions.

Alopecia

Alopecia is the sixth most common diagnosis seen in black patients visiting a dermatologist.14 The physician’s response to the patient’s chief concern of hair loss is key to building a relationship of confidence and trust. Trivializing the concern or dismissing it will undermine the physician-patient relationship. A survey by Gathers and Mahan15 revealed that 68% of patients thought that physicians did not understand their hair.

Hair loss negatively impacts quality of life, and a study of 50 black South African women with alopecia demonstrated a notable disease burden. Factors with the highest impact were those related to self-image, relationships, and interactions with others.16

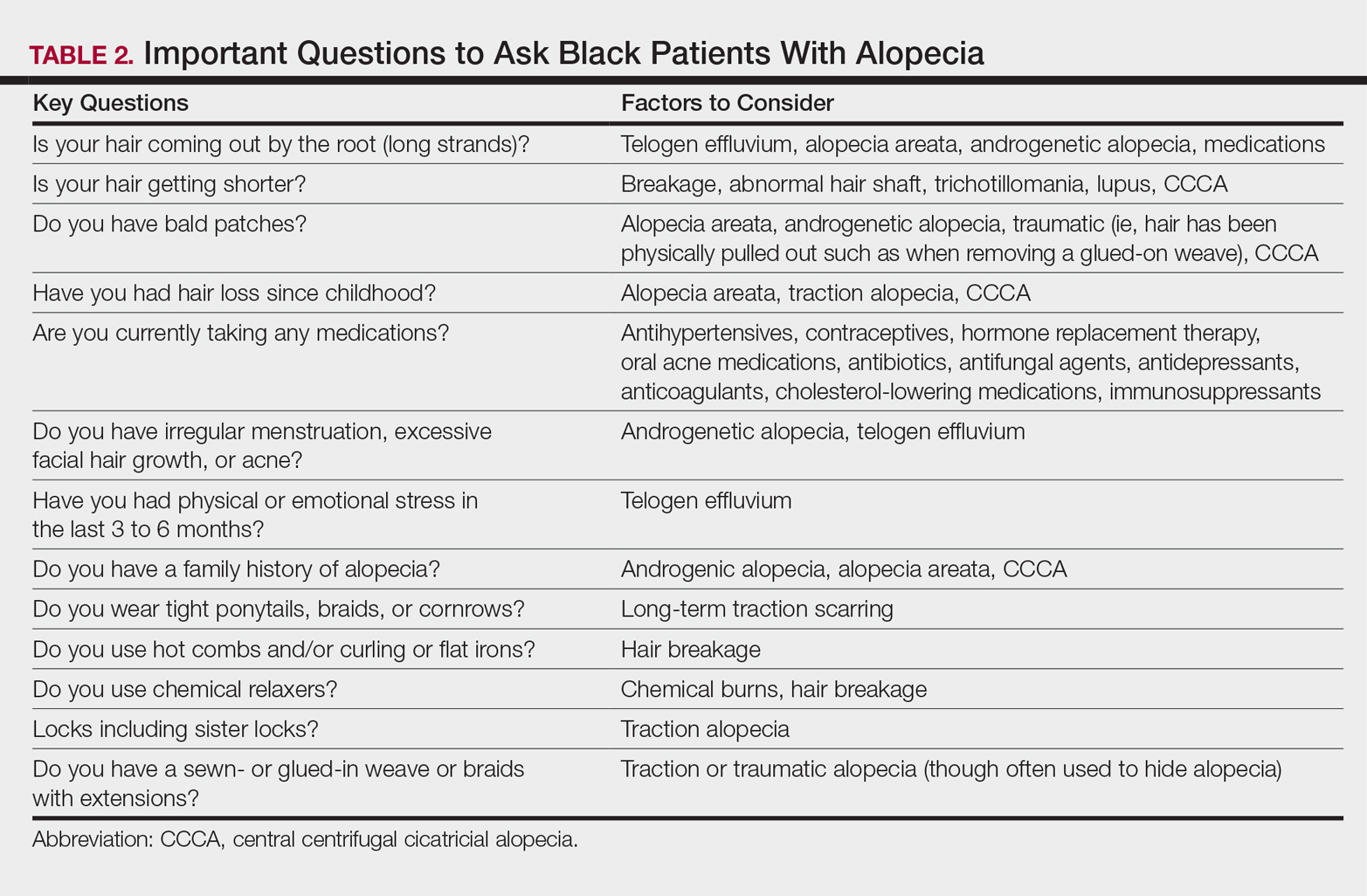

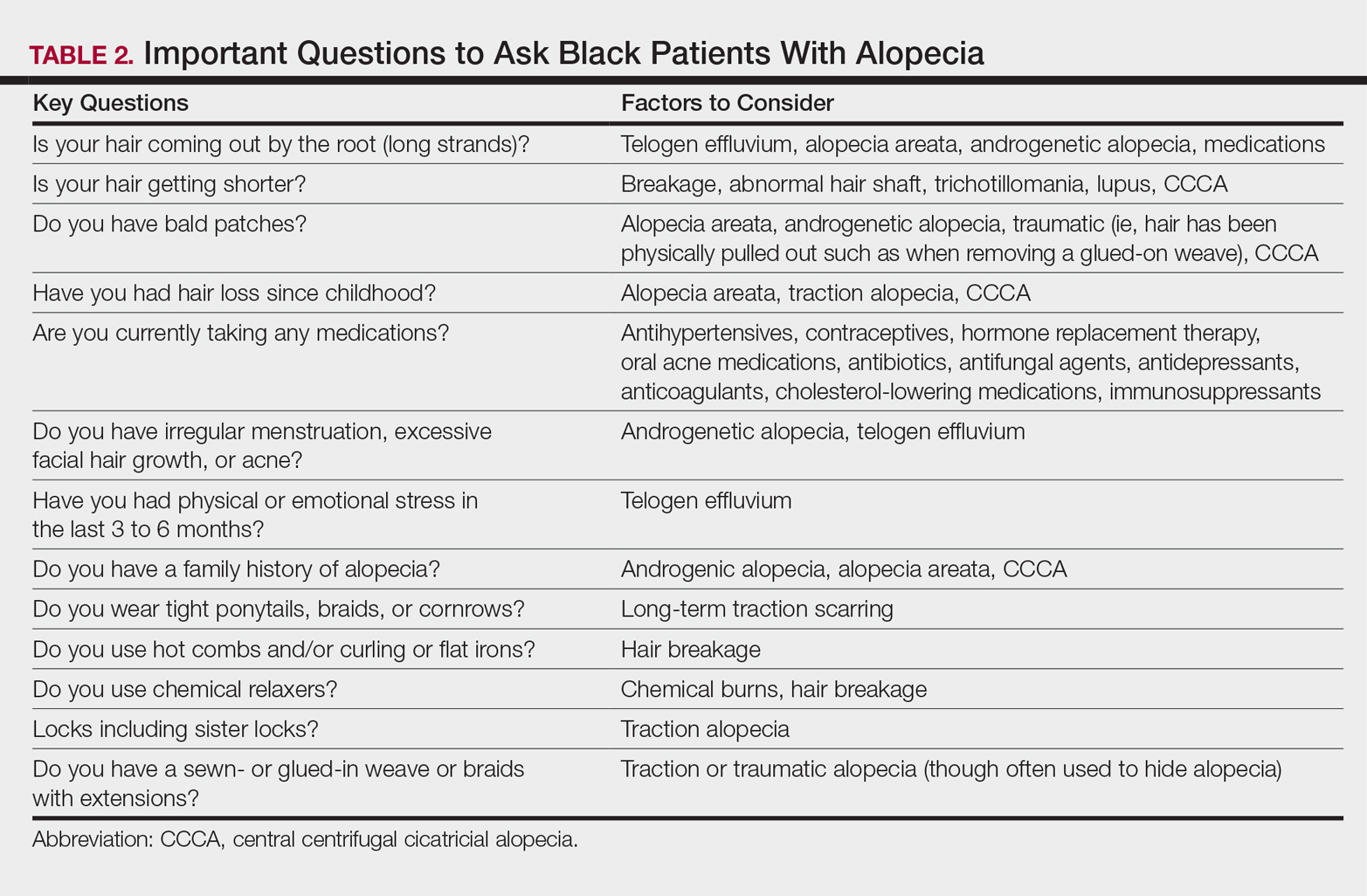

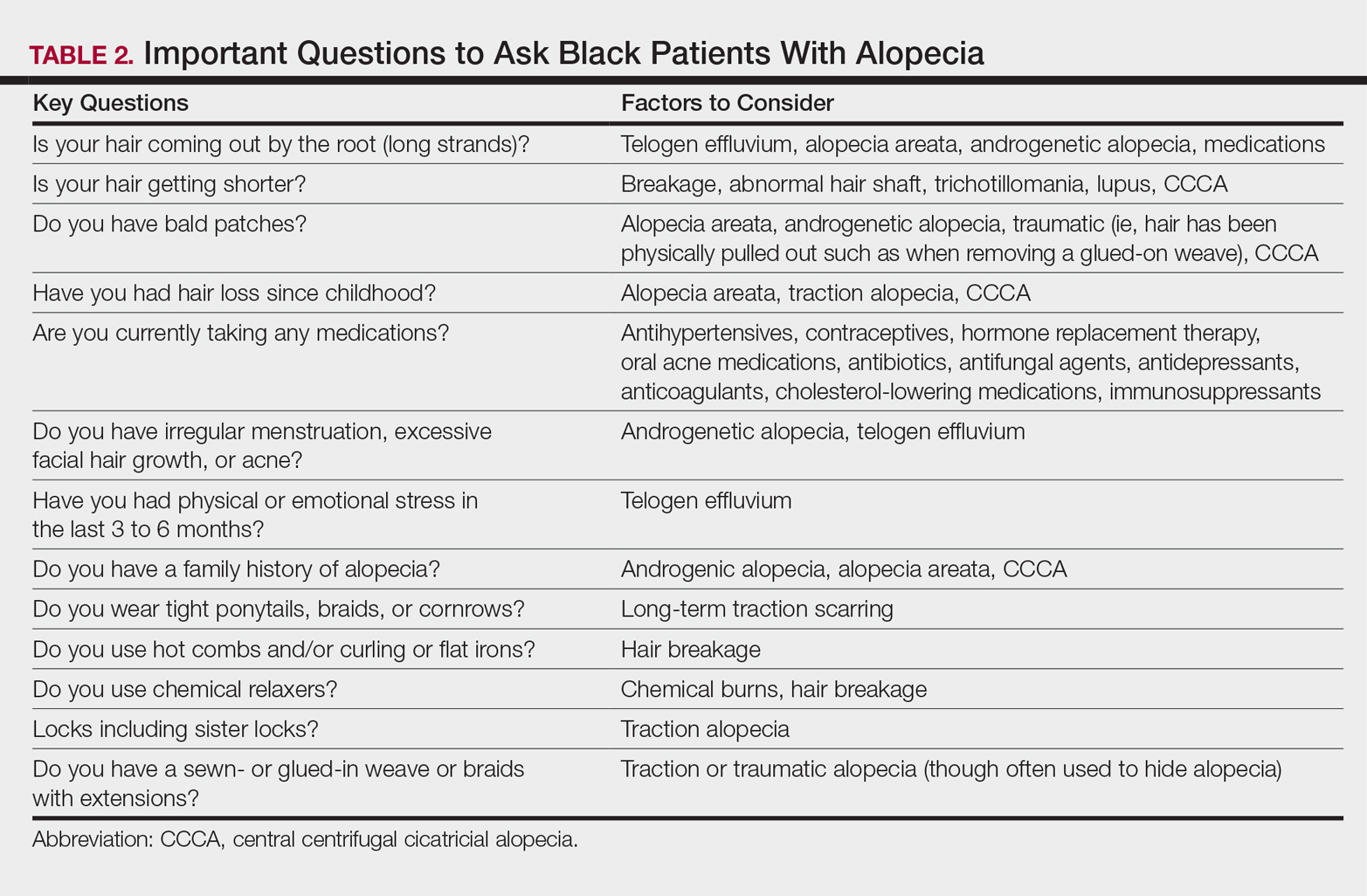

It is not unusual for black women to have multiple types of alopecia identified in one biopsy specimen. Wohltmann and Sperling17 demonstrated 2 or more different types of alopecia in more than 10% of biopsy specimens of alopecia, including CCCA, androgenetic alopecia, end-stage traction alopecia, telogen effluvium, and tinea capitis. A complete history, physical examination, and appropriate procedures (eg, hair pull test, dermatoscopic examination and scalp biopsy) likely will yield an accurate diagnosis. Table 2 highlights important questions that should be asked about the patient’s history.

Physical examination of the scalp including dermatoscopic examination and a hair pull test as well as an evaluation of other hair-bearing areas may suggest a diagnosis that can be confirmed with a scalp biopsy.18,19 Selection of a biopsy site at the periphery of the alopecic area that includes hair and consultation with a dermatopathologist familiar with features of CCCA, traction, and traumatic alopecia are important for making an accurate diagnosis.

Tinea Capitis in Black Pediatric Patients

Tinea capitis, a fungal infection of the scalp and hair, is one of the most common issues in children with skin of color. Clinical presentation may include widely distributed scaling, annular scaly plaques, annular patches of alopecia studded with black dots (broken hairs), and/or annular inflammatory plaques. Although scalp hyperkeratosis often is a hallmark of pediatric tinea capitis, it is not diagnostic. The differential diagnosis of pediatric scalp hyperkeratosis/scaling includes tinea capitis, SD, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and sebopsoriasis.20,21 Clues to accurate diagnosis of tinea capitis may be found by examination of the adult who combs the child’s hair, as erythematous annular scaly plaques representing tinea corporis may be observed on the forearms or thighs. Although the thighs are a seemingly unusual location, the frequent practice of the child sitting on the floor between the legs of the adult during hairstyling provides a point of contact for the transmission of tinea from the child’s scalp to the thighs or forearms of the adult. Once tinea capitis is clinically suspected, the diagnosis is confirmed by a fungal culture. Adequate sampling is obtained by clipping hairs in an area of scaling for submission and vigorously rubbing the area of black dots or hyperkeratosis with a cotton swab.

Hubbard22 shed light on the decision to treat tinea capitis empirically or await the culture results. One hundred consecutive children (98 were black) presented with the constellation of scalp alopecia, scaling, pruritus, and occipital lymphadenopathy. Sixty-eight of those children had positive fungal cultures, and of them, 60 had both occipital lymphadenopathy and scaling and 55 had both occipital lymphadenopathy and alopecia.22 Thus, occipital lymphadenopathy in conjunction with alopecia and/or scaling is predictive of tinea capitis in this population and suggests that the initiation of treatment prior to confirmative culture results is appropriate.

The mainstay of treatment for tinea capitis is griseofulvin, but it is often underdosed and not continued for an adequate period of time to ensure clearance of the infection. Griseofulvin microsize (125 mg/5 mL) at the dosage of 20 to 25 mg/kg once daily for 8 to 12 weeks is recommended instead of a lower-dosed 4- to 6-week course.23,24

Options for treating a child with residual disease include increasing and/or extending the griseofulvin dosage, encouraging ingestion of fatty foods to enhance absorption, dividing the dosage of griseofulvin from once daily to twice daily, changing therapy to oral terbinafine due to resistance to griseofulvin, examining siblings as a source of reinfection, and reviewing the positive fungal culture report to distinguish Trichophyton tonsurans versus Microsporum canis as the causative agent and adjust treatment accordingly. Although griseofulvin is the first-line treatment for M canis, terbinafine, which is approved for children 4 years and older for tineacapitis, is most efficacious for T tonsurans.25 Treatment with terbinafine is weight based and should extend for 2 to 4 weeksfor T tonsurans and 8 to 12 weeks for M canis.

Antifungal shampoos may help reduce household spread of tinea and decrease transmissible fungal spores, but they may cause hair dryness and breakage.26,27 Antifungal shampoos can be applied directly onto the scalp for a 5- to 10-minute contact time and rinsed, and then the hair should be shampooed with a moisturizing shampoo followed by a moisturizing conditioner. Hair conditioners may decrease household spread of tinea capitis and should be used by the patient and other members of the household.28 Infection control may be enhanced by advising parents to dispose of hair pomades and washing hair accessories, combs, and brushes in hot soapy water, preferably in the dishwasher.

Hair Growth

The inability of the hair of black children to grow long is a common concern for parents of toddlers and preschool-aged children. Although the hair does grow, it grows more slowly than hair in white children (0.259 vs 0.330 mm per day), and it is likely to break faster than it is growing in black versus white children (146.6 vs 13.13 total broken hairs).8 Reassurance that the hair is indeed growing and that the length will increase as the child matures is important. Avoidance of hairstyles that promote traction and use of hair extensions, as well as use of moisturizing shampoos and conditioners, may minimize breakage and support the growth of healthy hair.

Conclusion

Hair- and scalp-related disease in black adults and children is commonly encountered in dermatology practice. It is important to understand the intrinsic characteristics of facial and scalp hair as well as hair care practices in this patient population that differ from those of white and Asian populations, such as frequency of shampooing, products, and styling. Familiarity with these differences may aid in effective diagnosis, treatment, and hair care recommendations in patients with these conditions.

- Davis SA, Naarahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Hickman JG, Cardin C, Dawson TL, et al. Dandruff, part I: scalp disease prevalence in Caucasians, African Americans, and Chinese and the effects of shampoo frequency on scalp health. Poster presented at: 60th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; February 22-27, 2002; New Orleans, LA.

- Swee W, Klontz KC, Lambert LA. A nationwide outbreak of alopecia associated with the use of a hair-relaxing formulation. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1104-1108.

- Nicholson AG, Harland CC, Bull RH, et al. Chemically induced cosmetic alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:537-541.

- Detwiler SP, Carson JL, Woosley JT, et al. Bubble hair. case caused by an overheating hair dryer and reproducibility in normal hair with heat. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:54-60.

- Khumalo NP, Dawber RP, Ferguson DJ. Apparent fragility of African hair is unrelated to the cystine-rich protein distribution: a cytochemical electron microscopic study. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:311-314.

- Robbins C. Hair breakage during combing. I. pathways of breakage. J Cosmet Sci. 2006;57:233-243.

- Lewallen R, Francis S, Fisher B, et al. Hair care practices and structural evaluation of scalp and hair shaft parameter in African American and Caucasian women. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14:216-223.

- Hall RR, Francis S, Whitt-Glover M, et al. Hair care practices as a barrier to physical activity in African American women. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:310-314.

- Franbourg A, Hallegot P, Baltenneck F, et al. Current research on ethnic hair. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(6 suppl):S115-S119.

- Ogunbiyi A. Acne keloidalis nuchae: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:483-489.

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38(suppl 1):24-27.

- Kundu RV, Patterson S. Dermatologic conditions in skin of color: part II. disorders occurring predominately in skin of color. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:859-865.

- Davis SA, Naarahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African American women, hair care and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Dlova NC, Fabbrocini G, Lauro C, et al. Quality of life in South African black women with alopecia: a pilot study. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:875-881.

- Wohltmann WE, Sperling L. Histopathologic diagnosis of multifactorial alopecia. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:483-491.

- McDonald KA, Shelley AJ, Colantonio S, et al. Hair pull test: evidence-based update and revision of guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:472-477.

- Miteva M, Tosti A. Dermatoscopic features of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:443-444.

- Coley MK, Bhanusali DG, Silverberg JI, et al. Scalp hyperkeratosis and alopecia in children of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:511-516.

- Silverberg NB. Scalp hyperkeratosis in children with skin of color: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Cutis. 2015;95:199-204, 207.

- Hubbard TW. The predictive value of symptoms in diagnosing childhood tinea capitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1150-1153.

- Kakourou T, Uksal U; European Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Guidelines for the management of tinea capitis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:226-228.

- Sethi A, Antanya R. Systemic antifungal therapy for cutaneous infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:643-644.

- Gupta AK. Drummond-Main C. Meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials comparing particular doses of griseofulvin and terbinafine for the treatment of tinea capitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:1-6.

- Greer DL. Successful treatment of tinea capitis with 2% ketoconazole shampoo. Int J Dermatol 2000;39:302-304.

- Sharma V, Silverberg NB, Howard R, et al. Do hair care practices affect the acquisition of tinea capitis? a case-control study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:818-821.

- Greer DL. Successful treatment of tinea capitis with 2% ketoconazole shampoo. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:302-304.

One of the most common concerns among black patients is hair- and scalp-related disease. As increasing numbers of black patients opt to see dermatologists, it is imperative that all dermatologists be adequately trained to address the concerns of this patient population. When patients ask for help with common skin diseases of the hair and scalp, there are details that must be included in diagnosis, treatment, and hair care recommendations to reach goals for excellence in patient care. Herein, we provide must-know information to effectively approach this patient population.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

A study utilizing data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 1993 to 2009 revealed seborrheic dermatitis (SD) as the second most common diagnosis for black patients who visit a dermatologist.1 Prevalence data from a population of 1408 white, black, and Chinese patients from the United States and China revealed scalp flaking in 81% to 95% of black patients, 66% to 82% in white patients, and 30% to 42% in Chinese patients.2 Seborrheic dermatitis has a notable prevalence in black women and often is considered normal by patients. It can be exacerbated by infrequent shampooing (ranging from once per month or longer in between shampoos) and the inappropriate use of hair oils and pomades; it also has been associated with hair breakage, lichen simplex chronicus, and folliculitis. Seborrheic dermatitis must be distinguished from other disorders including sarcoidosis, psoriasis, discoid lupus erythematosus, tinea capitis, and lichen simplex chronicus.

Although there is a paucity of literature on the treatment of SD in black patients, components of treatment are similar to those recommended for other populations. Black women are advised to carefully utilize antidandruff shampoos containing zinc pyrithione, selenium sulfide, or tar to avoid hair shaft damage and dryness. Ketoconazole shampoo rarely is recommended and may be more appropriately used in men and boys, as hair fragility is less of a concern for them. The shampoo should be applied directly to the scalp rather than the hair shafts to minimize dryness, with no particular elongated contact time needed for these medicated shampoos to be effective. Because conditioners can wash off the active ingredients in therapeutic shampoos, antidandruff conditioners are recommended. Potent or ultrapotent topical corticosteroids applied to the scalp 3 to 4 times weekly initially will control the symptoms of itching as well as scaling, and mid-potency topical corticosteroid oil may be used at weekly intervals.

Hairline and facial involvement of SD often co-occurs, and low-potency topical steroids may be applied to the affected areas twice daily for 3 to 4 weeks, which may be repeated for flares. Topical calcineurin inhibitors or antifungal creams such as ketoconazole or econazole may then provide effective control. Encouraging patients to increase shampooing to once weekly or every 2 weeks and discontinue use of scalp pomades and oils also is recommended. Patients must know that an itchy scaly scalp represents a treatable disorder.

Acquired Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Hair fragility and breakage is common and multifactorial in black patients. Hair shaft breakage can occur on the vertex scalp in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), with random localized breakage due to scratching in SD. Heat, hair colorants, and chemical relaxers may result in diffuse damage and breakage.3 Sodium-, potassium-, and guanine hydroxide–containing chemical relaxers change the physical properties of the hair by rearranging disulfide bonds. They remove the monomolecular layer of fatty acids covalently bound to the cuticle that help prevent penetration of water into the hair shaft. Additionally, chemical relaxers weaken the hair shaft and decrease tensile strength.

Unlike hair relaxers, colorants are less likely to lead to catastrophic hair breakage after a single use and require frequent use, which leads to cumulative damage. Thermal straightening is another cause of hair-shaft weakening in black patients.4,5 Flat irons and curling irons can cause substantially more damage than blow-dryers due to the amount of heat generated. Flat irons may reach a high temperature of 230ºC (450ºF) as compared to 100°C (210°F) for a blow-dryer. Even the simple act of combing the hair can cause hair breakage, as demonstrated in African volunteers whose hair remained short in contrast to white and Asian volunteers, despite the fact that they had not cut their hair for 1 or more years.6,7 These volunteers had many hair strand knots that led to breakage during combing and hair grooming.6

There is no known prevalence data for acquired trichorrhexis nodosa, though a study of 30 white and black women demonstrated that broken hairs were significantly increased in black women (P=.0001).8 Another study by Hall et al9 of 103 black women showed that 55% of the women reported breakage of hair shafts with normal styling. Khumalo et al6 investigated hair shaft fragility and reported no trichothiodystrophy; the authors concluded that the cause of the hair fragility likely was physical trauma or an undiscovered structural abnormality. Franbourg et al10 examined the structure of hair fibers in white, Asian, and black patients and found no differences, but microfractures were only present in black patients and were determined to be the cause of hair breakage. These studies underscore the need for specific questioning of the patient on hair care including combing, washing, drying, and using products and chemicals.

The approach to the treatment of hair breakage involves correcting underlying abnormalities (eg, iron deficiency, hypothyroidism, nutritional deficiencies). Patients should “give their hair a rest” by discontinuing use of heat, colorants, and chemical relaxers. For patients who are unable to comply, advising them to stop these processes for 6 to 12 months will allow for repair of the hair shaft. To minimize damage from colorants, recommend semipermanent, demipermanent, or temporary dyes. Patients should be counseled to stop bleaching their hair or using permanent colorants. The use of heat protectant products on the hair before styling as well as layering moisturizing regimens starting with a moisturizing shampoo followed by a leave-in, dimethicone-containing conditioner marketed for dry damaged hair is suggested. Dimethicone thinly coats the hair shaft to restore hydrophobicity, smoothes cuticular scales, decreases frizz, and protects the hair from damage. Use of a 2-in-1 shampoo and conditioner containing anionic surfactants and wide-toothed, smooth (no jagged edges in the grooves) combs along with rare brushing are recommended. The hair may be worn in its natural state, but straightening with heat should be avoided. Air drying the hair can minimize breakage, but if thermal styling is necessary, patients should turn the temperature setting of the flat or curling iron down. Protective hair care practices may include placing a loosely sewn-in hair weave that will allow for good hair care, wearing loose braids, or using a wig. Serial trimming of the hair every 6 to 8 weeks is recommended. Improvement may take time, and patients should be advised of this timeline to prevent frustration.

Acne Keloidalis Nuchae

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) is characterized by papules and pustules located on the occipital scalp and/or the nape of the neck, which may result in keloidal papules and plaques. The etiology is unknown, but ingrown hairs, genetics, trauma, infection, inflammation, and androgen hormones have been proposed to play a role.11 Although AKN may occur in black women, it is primarily a disorder in black men. The diagnosis is made based primarily on clinical findings, and a history of short haircuts may support the diagnosis. Treatment is tailored to the severity of the disease (Table 1). Avoidance of short haircuts and irritation from shirt collars may be helpful. Patients should be advised that the condition is controllable but not curable.

Pseudofolliculitis Barbae

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) is characterized by papules and pustules in the beard region that may result in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, keloidal scar formation, and/or linear scarring. The coarse curled hairs characteristic of black men penetrate the follicle before exiting the skin and penetrate the skin after exiting the follicle, resulting in inflammation. Shaving methods and genetics also may contribute to the development of PFB. As with AKN, diagnosis is made clinically and does not require a skin biopsy. Important components of the patient’s history that should be obtained are hair removal practices and the use of over-the-counter products (eg, shave [pre and post] moisturizers, exfoliants, shaving creams or gels, keratin-softening agents containing α- or β-hydroxy acids). A bacterial culture may be appropriate if a notable pustular component is present. The patient should be advised to discontinue shaving if possible, which may require a physician’s letter explaining the necessity to the patient’s employer. Pseudofolliculitis barbae often can be prevented or lessened with the right hair removal strategy. Because there is not one optimal hair removal strategy that suits every patient, encourage the patient to experiment with different hair removal techniques, from depilatories to electric shavers, foil-guard razors, and multiple-blade razors. Preshave hydration and postshave moisturiza-tion also should be encouraged.12 Benzoyl peroxide–containing shave gels and cleansers, as well as moisturizers containing glycolic, salicylic, and phytic acids, may minimize ingrown hairs, papules, and inflammation.

Other useful topical agents include eflornithine hydrochloride to decrease hair growth, retinoids to soften hair fibers, mild topical steroids to reduce inflammation, and/or topical erythromycin or clindamycin if pustules are present.13 Oral antibiotics such as doxycycline, minocycline, or erythromycin can be added for more severe cases of inflammation or infection. Procedural interventions include laser hair removal to prevent PFB and intralesional triamcinolone 10 to 40 mg/cc every 4 to 6 weeks, with the total volume depending on the size and number of lesions.

Alopecia

Alopecia is the sixth most common diagnosis seen in black patients visiting a dermatologist.14 The physician’s response to the patient’s chief concern of hair loss is key to building a relationship of confidence and trust. Trivializing the concern or dismissing it will undermine the physician-patient relationship. A survey by Gathers and Mahan15 revealed that 68% of patients thought that physicians did not understand their hair.

Hair loss negatively impacts quality of life, and a study of 50 black South African women with alopecia demonstrated a notable disease burden. Factors with the highest impact were those related to self-image, relationships, and interactions with others.16

It is not unusual for black women to have multiple types of alopecia identified in one biopsy specimen. Wohltmann and Sperling17 demonstrated 2 or more different types of alopecia in more than 10% of biopsy specimens of alopecia, including CCCA, androgenetic alopecia, end-stage traction alopecia, telogen effluvium, and tinea capitis. A complete history, physical examination, and appropriate procedures (eg, hair pull test, dermatoscopic examination and scalp biopsy) likely will yield an accurate diagnosis. Table 2 highlights important questions that should be asked about the patient’s history.

Physical examination of the scalp including dermatoscopic examination and a hair pull test as well as an evaluation of other hair-bearing areas may suggest a diagnosis that can be confirmed with a scalp biopsy.18,19 Selection of a biopsy site at the periphery of the alopecic area that includes hair and consultation with a dermatopathologist familiar with features of CCCA, traction, and traumatic alopecia are important for making an accurate diagnosis.

Tinea Capitis in Black Pediatric Patients

Tinea capitis, a fungal infection of the scalp and hair, is one of the most common issues in children with skin of color. Clinical presentation may include widely distributed scaling, annular scaly plaques, annular patches of alopecia studded with black dots (broken hairs), and/or annular inflammatory plaques. Although scalp hyperkeratosis often is a hallmark of pediatric tinea capitis, it is not diagnostic. The differential diagnosis of pediatric scalp hyperkeratosis/scaling includes tinea capitis, SD, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and sebopsoriasis.20,21 Clues to accurate diagnosis of tinea capitis may be found by examination of the adult who combs the child’s hair, as erythematous annular scaly plaques representing tinea corporis may be observed on the forearms or thighs. Although the thighs are a seemingly unusual location, the frequent practice of the child sitting on the floor between the legs of the adult during hairstyling provides a point of contact for the transmission of tinea from the child’s scalp to the thighs or forearms of the adult. Once tinea capitis is clinically suspected, the diagnosis is confirmed by a fungal culture. Adequate sampling is obtained by clipping hairs in an area of scaling for submission and vigorously rubbing the area of black dots or hyperkeratosis with a cotton swab.

Hubbard22 shed light on the decision to treat tinea capitis empirically or await the culture results. One hundred consecutive children (98 were black) presented with the constellation of scalp alopecia, scaling, pruritus, and occipital lymphadenopathy. Sixty-eight of those children had positive fungal cultures, and of them, 60 had both occipital lymphadenopathy and scaling and 55 had both occipital lymphadenopathy and alopecia.22 Thus, occipital lymphadenopathy in conjunction with alopecia and/or scaling is predictive of tinea capitis in this population and suggests that the initiation of treatment prior to confirmative culture results is appropriate.

The mainstay of treatment for tinea capitis is griseofulvin, but it is often underdosed and not continued for an adequate period of time to ensure clearance of the infection. Griseofulvin microsize (125 mg/5 mL) at the dosage of 20 to 25 mg/kg once daily for 8 to 12 weeks is recommended instead of a lower-dosed 4- to 6-week course.23,24

Options for treating a child with residual disease include increasing and/or extending the griseofulvin dosage, encouraging ingestion of fatty foods to enhance absorption, dividing the dosage of griseofulvin from once daily to twice daily, changing therapy to oral terbinafine due to resistance to griseofulvin, examining siblings as a source of reinfection, and reviewing the positive fungal culture report to distinguish Trichophyton tonsurans versus Microsporum canis as the causative agent and adjust treatment accordingly. Although griseofulvin is the first-line treatment for M canis, terbinafine, which is approved for children 4 years and older for tineacapitis, is most efficacious for T tonsurans.25 Treatment with terbinafine is weight based and should extend for 2 to 4 weeksfor T tonsurans and 8 to 12 weeks for M canis.

Antifungal shampoos may help reduce household spread of tinea and decrease transmissible fungal spores, but they may cause hair dryness and breakage.26,27 Antifungal shampoos can be applied directly onto the scalp for a 5- to 10-minute contact time and rinsed, and then the hair should be shampooed with a moisturizing shampoo followed by a moisturizing conditioner. Hair conditioners may decrease household spread of tinea capitis and should be used by the patient and other members of the household.28 Infection control may be enhanced by advising parents to dispose of hair pomades and washing hair accessories, combs, and brushes in hot soapy water, preferably in the dishwasher.

Hair Growth

The inability of the hair of black children to grow long is a common concern for parents of toddlers and preschool-aged children. Although the hair does grow, it grows more slowly than hair in white children (0.259 vs 0.330 mm per day), and it is likely to break faster than it is growing in black versus white children (146.6 vs 13.13 total broken hairs).8 Reassurance that the hair is indeed growing and that the length will increase as the child matures is important. Avoidance of hairstyles that promote traction and use of hair extensions, as well as use of moisturizing shampoos and conditioners, may minimize breakage and support the growth of healthy hair.

Conclusion

Hair- and scalp-related disease in black adults and children is commonly encountered in dermatology practice. It is important to understand the intrinsic characteristics of facial and scalp hair as well as hair care practices in this patient population that differ from those of white and Asian populations, such as frequency of shampooing, products, and styling. Familiarity with these differences may aid in effective diagnosis, treatment, and hair care recommendations in patients with these conditions.

One of the most common concerns among black patients is hair- and scalp-related disease. As increasing numbers of black patients opt to see dermatologists, it is imperative that all dermatologists be adequately trained to address the concerns of this patient population. When patients ask for help with common skin diseases of the hair and scalp, there are details that must be included in diagnosis, treatment, and hair care recommendations to reach goals for excellence in patient care. Herein, we provide must-know information to effectively approach this patient population.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

A study utilizing data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 1993 to 2009 revealed seborrheic dermatitis (SD) as the second most common diagnosis for black patients who visit a dermatologist.1 Prevalence data from a population of 1408 white, black, and Chinese patients from the United States and China revealed scalp flaking in 81% to 95% of black patients, 66% to 82% in white patients, and 30% to 42% in Chinese patients.2 Seborrheic dermatitis has a notable prevalence in black women and often is considered normal by patients. It can be exacerbated by infrequent shampooing (ranging from once per month or longer in between shampoos) and the inappropriate use of hair oils and pomades; it also has been associated with hair breakage, lichen simplex chronicus, and folliculitis. Seborrheic dermatitis must be distinguished from other disorders including sarcoidosis, psoriasis, discoid lupus erythematosus, tinea capitis, and lichen simplex chronicus.

Although there is a paucity of literature on the treatment of SD in black patients, components of treatment are similar to those recommended for other populations. Black women are advised to carefully utilize antidandruff shampoos containing zinc pyrithione, selenium sulfide, or tar to avoid hair shaft damage and dryness. Ketoconazole shampoo rarely is recommended and may be more appropriately used in men and boys, as hair fragility is less of a concern for them. The shampoo should be applied directly to the scalp rather than the hair shafts to minimize dryness, with no particular elongated contact time needed for these medicated shampoos to be effective. Because conditioners can wash off the active ingredients in therapeutic shampoos, antidandruff conditioners are recommended. Potent or ultrapotent topical corticosteroids applied to the scalp 3 to 4 times weekly initially will control the symptoms of itching as well as scaling, and mid-potency topical corticosteroid oil may be used at weekly intervals.

Hairline and facial involvement of SD often co-occurs, and low-potency topical steroids may be applied to the affected areas twice daily for 3 to 4 weeks, which may be repeated for flares. Topical calcineurin inhibitors or antifungal creams such as ketoconazole or econazole may then provide effective control. Encouraging patients to increase shampooing to once weekly or every 2 weeks and discontinue use of scalp pomades and oils also is recommended. Patients must know that an itchy scaly scalp represents a treatable disorder.

Acquired Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Hair fragility and breakage is common and multifactorial in black patients. Hair shaft breakage can occur on the vertex scalp in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), with random localized breakage due to scratching in SD. Heat, hair colorants, and chemical relaxers may result in diffuse damage and breakage.3 Sodium-, potassium-, and guanine hydroxide–containing chemical relaxers change the physical properties of the hair by rearranging disulfide bonds. They remove the monomolecular layer of fatty acids covalently bound to the cuticle that help prevent penetration of water into the hair shaft. Additionally, chemical relaxers weaken the hair shaft and decrease tensile strength.

Unlike hair relaxers, colorants are less likely to lead to catastrophic hair breakage after a single use and require frequent use, which leads to cumulative damage. Thermal straightening is another cause of hair-shaft weakening in black patients.4,5 Flat irons and curling irons can cause substantially more damage than blow-dryers due to the amount of heat generated. Flat irons may reach a high temperature of 230ºC (450ºF) as compared to 100°C (210°F) for a blow-dryer. Even the simple act of combing the hair can cause hair breakage, as demonstrated in African volunteers whose hair remained short in contrast to white and Asian volunteers, despite the fact that they had not cut their hair for 1 or more years.6,7 These volunteers had many hair strand knots that led to breakage during combing and hair grooming.6

There is no known prevalence data for acquired trichorrhexis nodosa, though a study of 30 white and black women demonstrated that broken hairs were significantly increased in black women (P=.0001).8 Another study by Hall et al9 of 103 black women showed that 55% of the women reported breakage of hair shafts with normal styling. Khumalo et al6 investigated hair shaft fragility and reported no trichothiodystrophy; the authors concluded that the cause of the hair fragility likely was physical trauma or an undiscovered structural abnormality. Franbourg et al10 examined the structure of hair fibers in white, Asian, and black patients and found no differences, but microfractures were only present in black patients and were determined to be the cause of hair breakage. These studies underscore the need for specific questioning of the patient on hair care including combing, washing, drying, and using products and chemicals.

The approach to the treatment of hair breakage involves correcting underlying abnormalities (eg, iron deficiency, hypothyroidism, nutritional deficiencies). Patients should “give their hair a rest” by discontinuing use of heat, colorants, and chemical relaxers. For patients who are unable to comply, advising them to stop these processes for 6 to 12 months will allow for repair of the hair shaft. To minimize damage from colorants, recommend semipermanent, demipermanent, or temporary dyes. Patients should be counseled to stop bleaching their hair or using permanent colorants. The use of heat protectant products on the hair before styling as well as layering moisturizing regimens starting with a moisturizing shampoo followed by a leave-in, dimethicone-containing conditioner marketed for dry damaged hair is suggested. Dimethicone thinly coats the hair shaft to restore hydrophobicity, smoothes cuticular scales, decreases frizz, and protects the hair from damage. Use of a 2-in-1 shampoo and conditioner containing anionic surfactants and wide-toothed, smooth (no jagged edges in the grooves) combs along with rare brushing are recommended. The hair may be worn in its natural state, but straightening with heat should be avoided. Air drying the hair can minimize breakage, but if thermal styling is necessary, patients should turn the temperature setting of the flat or curling iron down. Protective hair care practices may include placing a loosely sewn-in hair weave that will allow for good hair care, wearing loose braids, or using a wig. Serial trimming of the hair every 6 to 8 weeks is recommended. Improvement may take time, and patients should be advised of this timeline to prevent frustration.

Acne Keloidalis Nuchae

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) is characterized by papules and pustules located on the occipital scalp and/or the nape of the neck, which may result in keloidal papules and plaques. The etiology is unknown, but ingrown hairs, genetics, trauma, infection, inflammation, and androgen hormones have been proposed to play a role.11 Although AKN may occur in black women, it is primarily a disorder in black men. The diagnosis is made based primarily on clinical findings, and a history of short haircuts may support the diagnosis. Treatment is tailored to the severity of the disease (Table 1). Avoidance of short haircuts and irritation from shirt collars may be helpful. Patients should be advised that the condition is controllable but not curable.

Pseudofolliculitis Barbae

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) is characterized by papules and pustules in the beard region that may result in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, keloidal scar formation, and/or linear scarring. The coarse curled hairs characteristic of black men penetrate the follicle before exiting the skin and penetrate the skin after exiting the follicle, resulting in inflammation. Shaving methods and genetics also may contribute to the development of PFB. As with AKN, diagnosis is made clinically and does not require a skin biopsy. Important components of the patient’s history that should be obtained are hair removal practices and the use of over-the-counter products (eg, shave [pre and post] moisturizers, exfoliants, shaving creams or gels, keratin-softening agents containing α- or β-hydroxy acids). A bacterial culture may be appropriate if a notable pustular component is present. The patient should be advised to discontinue shaving if possible, which may require a physician’s letter explaining the necessity to the patient’s employer. Pseudofolliculitis barbae often can be prevented or lessened with the right hair removal strategy. Because there is not one optimal hair removal strategy that suits every patient, encourage the patient to experiment with different hair removal techniques, from depilatories to electric shavers, foil-guard razors, and multiple-blade razors. Preshave hydration and postshave moisturiza-tion also should be encouraged.12 Benzoyl peroxide–containing shave gels and cleansers, as well as moisturizers containing glycolic, salicylic, and phytic acids, may minimize ingrown hairs, papules, and inflammation.

Other useful topical agents include eflornithine hydrochloride to decrease hair growth, retinoids to soften hair fibers, mild topical steroids to reduce inflammation, and/or topical erythromycin or clindamycin if pustules are present.13 Oral antibiotics such as doxycycline, minocycline, or erythromycin can be added for more severe cases of inflammation or infection. Procedural interventions include laser hair removal to prevent PFB and intralesional triamcinolone 10 to 40 mg/cc every 4 to 6 weeks, with the total volume depending on the size and number of lesions.

Alopecia

Alopecia is the sixth most common diagnosis seen in black patients visiting a dermatologist.14 The physician’s response to the patient’s chief concern of hair loss is key to building a relationship of confidence and trust. Trivializing the concern or dismissing it will undermine the physician-patient relationship. A survey by Gathers and Mahan15 revealed that 68% of patients thought that physicians did not understand their hair.

Hair loss negatively impacts quality of life, and a study of 50 black South African women with alopecia demonstrated a notable disease burden. Factors with the highest impact were those related to self-image, relationships, and interactions with others.16

It is not unusual for black women to have multiple types of alopecia identified in one biopsy specimen. Wohltmann and Sperling17 demonstrated 2 or more different types of alopecia in more than 10% of biopsy specimens of alopecia, including CCCA, androgenetic alopecia, end-stage traction alopecia, telogen effluvium, and tinea capitis. A complete history, physical examination, and appropriate procedures (eg, hair pull test, dermatoscopic examination and scalp biopsy) likely will yield an accurate diagnosis. Table 2 highlights important questions that should be asked about the patient’s history.

Physical examination of the scalp including dermatoscopic examination and a hair pull test as well as an evaluation of other hair-bearing areas may suggest a diagnosis that can be confirmed with a scalp biopsy.18,19 Selection of a biopsy site at the periphery of the alopecic area that includes hair and consultation with a dermatopathologist familiar with features of CCCA, traction, and traumatic alopecia are important for making an accurate diagnosis.

Tinea Capitis in Black Pediatric Patients

Tinea capitis, a fungal infection of the scalp and hair, is one of the most common issues in children with skin of color. Clinical presentation may include widely distributed scaling, annular scaly plaques, annular patches of alopecia studded with black dots (broken hairs), and/or annular inflammatory plaques. Although scalp hyperkeratosis often is a hallmark of pediatric tinea capitis, it is not diagnostic. The differential diagnosis of pediatric scalp hyperkeratosis/scaling includes tinea capitis, SD, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and sebopsoriasis.20,21 Clues to accurate diagnosis of tinea capitis may be found by examination of the adult who combs the child’s hair, as erythematous annular scaly plaques representing tinea corporis may be observed on the forearms or thighs. Although the thighs are a seemingly unusual location, the frequent practice of the child sitting on the floor between the legs of the adult during hairstyling provides a point of contact for the transmission of tinea from the child’s scalp to the thighs or forearms of the adult. Once tinea capitis is clinically suspected, the diagnosis is confirmed by a fungal culture. Adequate sampling is obtained by clipping hairs in an area of scaling for submission and vigorously rubbing the area of black dots or hyperkeratosis with a cotton swab.

Hubbard22 shed light on the decision to treat tinea capitis empirically or await the culture results. One hundred consecutive children (98 were black) presented with the constellation of scalp alopecia, scaling, pruritus, and occipital lymphadenopathy. Sixty-eight of those children had positive fungal cultures, and of them, 60 had both occipital lymphadenopathy and scaling and 55 had both occipital lymphadenopathy and alopecia.22 Thus, occipital lymphadenopathy in conjunction with alopecia and/or scaling is predictive of tinea capitis in this population and suggests that the initiation of treatment prior to confirmative culture results is appropriate.

The mainstay of treatment for tinea capitis is griseofulvin, but it is often underdosed and not continued for an adequate period of time to ensure clearance of the infection. Griseofulvin microsize (125 mg/5 mL) at the dosage of 20 to 25 mg/kg once daily for 8 to 12 weeks is recommended instead of a lower-dosed 4- to 6-week course.23,24

Options for treating a child with residual disease include increasing and/or extending the griseofulvin dosage, encouraging ingestion of fatty foods to enhance absorption, dividing the dosage of griseofulvin from once daily to twice daily, changing therapy to oral terbinafine due to resistance to griseofulvin, examining siblings as a source of reinfection, and reviewing the positive fungal culture report to distinguish Trichophyton tonsurans versus Microsporum canis as the causative agent and adjust treatment accordingly. Although griseofulvin is the first-line treatment for M canis, terbinafine, which is approved for children 4 years and older for tineacapitis, is most efficacious for T tonsurans.25 Treatment with terbinafine is weight based and should extend for 2 to 4 weeksfor T tonsurans and 8 to 12 weeks for M canis.

Antifungal shampoos may help reduce household spread of tinea and decrease transmissible fungal spores, but they may cause hair dryness and breakage.26,27 Antifungal shampoos can be applied directly onto the scalp for a 5- to 10-minute contact time and rinsed, and then the hair should be shampooed with a moisturizing shampoo followed by a moisturizing conditioner. Hair conditioners may decrease household spread of tinea capitis and should be used by the patient and other members of the household.28 Infection control may be enhanced by advising parents to dispose of hair pomades and washing hair accessories, combs, and brushes in hot soapy water, preferably in the dishwasher.

Hair Growth

The inability of the hair of black children to grow long is a common concern for parents of toddlers and preschool-aged children. Although the hair does grow, it grows more slowly than hair in white children (0.259 vs 0.330 mm per day), and it is likely to break faster than it is growing in black versus white children (146.6 vs 13.13 total broken hairs).8 Reassurance that the hair is indeed growing and that the length will increase as the child matures is important. Avoidance of hairstyles that promote traction and use of hair extensions, as well as use of moisturizing shampoos and conditioners, may minimize breakage and support the growth of healthy hair.

Conclusion

Hair- and scalp-related disease in black adults and children is commonly encountered in dermatology practice. It is important to understand the intrinsic characteristics of facial and scalp hair as well as hair care practices in this patient population that differ from those of white and Asian populations, such as frequency of shampooing, products, and styling. Familiarity with these differences may aid in effective diagnosis, treatment, and hair care recommendations in patients with these conditions.

- Davis SA, Naarahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Hickman JG, Cardin C, Dawson TL, et al. Dandruff, part I: scalp disease prevalence in Caucasians, African Americans, and Chinese and the effects of shampoo frequency on scalp health. Poster presented at: 60th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; February 22-27, 2002; New Orleans, LA.

- Swee W, Klontz KC, Lambert LA. A nationwide outbreak of alopecia associated with the use of a hair-relaxing formulation. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1104-1108.

- Nicholson AG, Harland CC, Bull RH, et al. Chemically induced cosmetic alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:537-541.

- Detwiler SP, Carson JL, Woosley JT, et al. Bubble hair. case caused by an overheating hair dryer and reproducibility in normal hair with heat. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:54-60.

- Khumalo NP, Dawber RP, Ferguson DJ. Apparent fragility of African hair is unrelated to the cystine-rich protein distribution: a cytochemical electron microscopic study. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:311-314.

- Robbins C. Hair breakage during combing. I. pathways of breakage. J Cosmet Sci. 2006;57:233-243.

- Lewallen R, Francis S, Fisher B, et al. Hair care practices and structural evaluation of scalp and hair shaft parameter in African American and Caucasian women. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14:216-223.

- Hall RR, Francis S, Whitt-Glover M, et al. Hair care practices as a barrier to physical activity in African American women. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:310-314.

- Franbourg A, Hallegot P, Baltenneck F, et al. Current research on ethnic hair. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(6 suppl):S115-S119.

- Ogunbiyi A. Acne keloidalis nuchae: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:483-489.

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38(suppl 1):24-27.

- Kundu RV, Patterson S. Dermatologic conditions in skin of color: part II. disorders occurring predominately in skin of color. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:859-865.

- Davis SA, Naarahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African American women, hair care and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Dlova NC, Fabbrocini G, Lauro C, et al. Quality of life in South African black women with alopecia: a pilot study. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:875-881.

- Wohltmann WE, Sperling L. Histopathologic diagnosis of multifactorial alopecia. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:483-491.

- McDonald KA, Shelley AJ, Colantonio S, et al. Hair pull test: evidence-based update and revision of guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:472-477.

- Miteva M, Tosti A. Dermatoscopic features of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:443-444.

- Coley MK, Bhanusali DG, Silverberg JI, et al. Scalp hyperkeratosis and alopecia in children of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:511-516.

- Silverberg NB. Scalp hyperkeratosis in children with skin of color: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Cutis. 2015;95:199-204, 207.

- Hubbard TW. The predictive value of symptoms in diagnosing childhood tinea capitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1150-1153.

- Kakourou T, Uksal U; European Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Guidelines for the management of tinea capitis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:226-228.

- Sethi A, Antanya R. Systemic antifungal therapy for cutaneous infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:643-644.

- Gupta AK. Drummond-Main C. Meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials comparing particular doses of griseofulvin and terbinafine for the treatment of tinea capitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:1-6.

- Greer DL. Successful treatment of tinea capitis with 2% ketoconazole shampoo. Int J Dermatol 2000;39:302-304.

- Sharma V, Silverberg NB, Howard R, et al. Do hair care practices affect the acquisition of tinea capitis? a case-control study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:818-821.

- Greer DL. Successful treatment of tinea capitis with 2% ketoconazole shampoo. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:302-304.

- Davis SA, Naarahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Hickman JG, Cardin C, Dawson TL, et al. Dandruff, part I: scalp disease prevalence in Caucasians, African Americans, and Chinese and the effects of shampoo frequency on scalp health. Poster presented at: 60th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; February 22-27, 2002; New Orleans, LA.

- Swee W, Klontz KC, Lambert LA. A nationwide outbreak of alopecia associated with the use of a hair-relaxing formulation. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1104-1108.

- Nicholson AG, Harland CC, Bull RH, et al. Chemically induced cosmetic alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:537-541.

- Detwiler SP, Carson JL, Woosley JT, et al. Bubble hair. case caused by an overheating hair dryer and reproducibility in normal hair with heat. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:54-60.

- Khumalo NP, Dawber RP, Ferguson DJ. Apparent fragility of African hair is unrelated to the cystine-rich protein distribution: a cytochemical electron microscopic study. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:311-314.

- Robbins C. Hair breakage during combing. I. pathways of breakage. J Cosmet Sci. 2006;57:233-243.

- Lewallen R, Francis S, Fisher B, et al. Hair care practices and structural evaluation of scalp and hair shaft parameter in African American and Caucasian women. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14:216-223.

- Hall RR, Francis S, Whitt-Glover M, et al. Hair care practices as a barrier to physical activity in African American women. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:310-314.

- Franbourg A, Hallegot P, Baltenneck F, et al. Current research on ethnic hair. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(6 suppl):S115-S119.

- Ogunbiyi A. Acne keloidalis nuchae: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:483-489.

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38(suppl 1):24-27.

- Kundu RV, Patterson S. Dermatologic conditions in skin of color: part II. disorders occurring predominately in skin of color. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:859-865.

- Davis SA, Naarahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African American women, hair care and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Dlova NC, Fabbrocini G, Lauro C, et al. Quality of life in South African black women with alopecia: a pilot study. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:875-881.

- Wohltmann WE, Sperling L. Histopathologic diagnosis of multifactorial alopecia. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:483-491.

- McDonald KA, Shelley AJ, Colantonio S, et al. Hair pull test: evidence-based update and revision of guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:472-477.

- Miteva M, Tosti A. Dermatoscopic features of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:443-444.

- Coley MK, Bhanusali DG, Silverberg JI, et al. Scalp hyperkeratosis and alopecia in children of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:511-516.

- Silverberg NB. Scalp hyperkeratosis in children with skin of color: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Cutis. 2015;95:199-204, 207.

- Hubbard TW. The predictive value of symptoms in diagnosing childhood tinea capitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1150-1153.

- Kakourou T, Uksal U; European Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Guidelines for the management of tinea capitis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:226-228.

- Sethi A, Antanya R. Systemic antifungal therapy for cutaneous infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:643-644.

- Gupta AK. Drummond-Main C. Meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials comparing particular doses of griseofulvin and terbinafine for the treatment of tinea capitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:1-6.

- Greer DL. Successful treatment of tinea capitis with 2% ketoconazole shampoo. Int J Dermatol 2000;39:302-304.

- Sharma V, Silverberg NB, Howard R, et al. Do hair care practices affect the acquisition of tinea capitis? a case-control study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:818-821.

- Greer DL. Successful treatment of tinea capitis with 2% ketoconazole shampoo. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:302-304.

Practice Points

- Instruct patients with acquired trichorrhexis nodosa to discontinue use of heat, colorants, and chemical relaxers on their hair.

- Create a contract with your seborrheic dermatitis patients to have them shampoo at least weekly or every 2 weeks.

- For children with treated tinea capitis that has not completely resolved, increase or extend the griseofulvin dosage, encourage ingestion of fatty foods to enhance absorption, and divide dosage of griseofulvin from once to twice daily.

- Selection of a biopsy site at the periphery of an alopecic area that includes hair and hair follicles and evaluation by a dermatopathologist familiar with the features of central centrifugal cicatricial, traction, and traumatic alopecias will ensure an accurate diagnosis of alopecia.

Management of Trauma and Burn Scars: The Dermatologist’s Role in Expanding Patient Access to Care

Hypertrophic scarring secondary to trauma, burns, and surgical interventions is a major source of morbidity worldwide and often is mechanically, aesthetically, and symptomatically debilitating. Modern advances in acute trauma care protocols have resulted in survival rates greater than 90% in both civilian and military populations.1,2 Patients with wounds that have historically proven fatal are now surviving and are confronted with the long-term sequelae of their injuries. With more than 52,000 service members injured in military engagements from 2001 to 2015 and 8.5 million civilians presenting annually with injury patterns at risk for hypertrophic scarring, it is paramount that we ensure access to safe and effective long-term scar care.2,3

At its simplest level, hypertrophic scarring is believed to result from a disequilibrium between collagen production and degradation. This failure to properly transition through the stages of wound healing results in bothersome symptoms, a disfigured appearance, and mechanical dysfunction of the skin (Figure, A). Decreased elasticity and extensibility, increased dermal thickness, and scar contractures impair patient range of motion and functional mobility. Those affected commonly experience varying degrees of pruritus and dysesthesia along the scar. Combined with aesthetic variations in pigmentation, erythema, texture, and thickness, hypertrophic scarring often leads to long-term psychosocial impairment and decreased health-related quality of life.4

Treatment Approach

Treatment of hypertrophic scars requires a multimodal approach due to the spectrum of associated concerns and the natural recalcitrance of the scar to therapy. Protocols should be tailored to the individual but generally begin with tissue-conserving surgical interventions followed by selective photothermolysis of the scar vasculature. Subsequently, deep and superficial ablative fractional laser (AFL) treatment and local pharmacotherapy also are employed. Treatment can be accomplished in the outpatient setting under local anesthesia in a serial fashion. In the authors’ experience, these therapies behave in a synergistic fashion, achieving outcomes that far exceed the sum of their parts, often obviating the need for scar excision in the majority of cases (Figure, B).

Tissue-Conserving Surgical Intervention

Z-plasty is an indispensable surgical tool due to its ability to lengthen scars and reduce wound tension. Treatment is easily customizable to the patient and can be performed using the individual or multiple Z-plasty techniques. Undermining and step-off correction while suturing allow the physician to lower raised scars, elevate depressed scars, and obscure scar presence by minimizing the straight lines that draw the eye to the scar. Z-plasties rely on the creation and transposition of 2 triangular flaps and permit a 75% increase in length along the desired tension vector. As such, Z-plasties decrease wound tension and facilitate scar maturation.

Selective Photothermolysis of the Vasculature

Although there are several devices available to treat vascular and immature hypertrophic scars, the majority of studies have been conducted with the 595-nm pulsed dye laser. By preferentially heating oxyhemoglobin within the dermal microvasculature, the pulsed dye laser irreparably injures the vascular endothelium. The subsequent tissue hypoxia and collagen fiber heating results in collagen fiber realignment, normalization of collagen subtypes, and neocollagenesis.5 Pulsed dye laser therapy most effectively reduces erythema and pruritus; however, improvements in scar volume, pliability, and elasticity also have been reported.5 When targeting the fine vasculature of the scar, thermal confinement is critical to prevent injury to the surrounding dermis. As such, pulse widths of 0.45 to 1.5 milliseconds are routinely utilized with a fluence just sufficient to elicit transient purpura lasting 3 to 5 seconds. Employing a spot size of 7 to 10 mm, typical fluences range from 4.5 to 6.5 J/cm2. Engagement of the dynamic cooling device reduces the risk for complications, allowing the patient to proceed to the next step in their therapy regimen: the AFL.

Ablative Fractional Laser