User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

To the Editor:

A 41-year-old man presented with a slowly enlarging, tender, firm lesion on the left hallux of approximately 5 months' duration that initially appeared to be a blister. He reported no history of keloids or trauma to the left foot. On examination, a 3.5-cm, flesh-colored, pedunculated, firm nodule was present on the lateral aspect of the left great hallux (Figure 1). No lymphadenopathy was found. The lesion was diagnosed at that time as a keloid and treated with intralesional steroids without response. The patient was lost to follow-up, and after 5 months he presented again with pain and drainage from the lesion. Acute drainage resolved after antibiotic therapy. A shave biopsy was performed, which revealed findings consistent with a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). A chest radiograph was unremarkable. Re-excision was performed with negative margins on frozen section but with positive peripheral and deep margins on permanent sections. The patient subsequently underwent amputation of the left great toe and was lost to follow-up after the initial postoperative period.

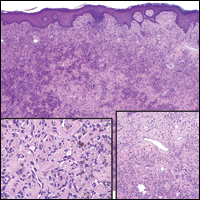

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a polypoid spindle cell tumor that filled the dermis and invaded into the subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figure 2). The spindle cells had tapered nuclei in a honeycomb arrangement with only mild nuclear pleomorphism arranged in fascicles with a herringbone formation. Areas showed a myxoid stroma with abundant mucin (Figure 3). Immunostaining demonstrated cells strongly positive for CD34 and negative for MART (melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells), S-100, and smooth muscle actin immunostains.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a sarcoma that is locally aggressive and tends to recur after surgical excision, though rare cases of metastasis involving the lungs have been reported.12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually affects young to middle-aged adults. Acral DFSP is rare in adults, with tumors most commonly occurring on the trunk (50%-60%), proximal extremities (20%-30%), or the head and neck (10%-15%).1,2 A higher rate of acral DFSP has been found in children, which may be due to the increased rate of extremity trauma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans commonly presents as an asymptomatic, slowly growing, indurated plaque that may be flesh colored or hyperpigmented, followed by development of erythematous firm nodules of up to several centimeters.1,3 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans may be associated with a purulent exudate or ulceration, and pain may develop as the lesion grows.

Histopathologic evaluation shows an early plaque stage characterized by low cellularity, minimal nuclear atypia, and rare mitotic figures.4 In the nodular stage, the spindle cells are arranged as short fascicles in a storiform arrangement and infiltrate the subcutaneous tissue in a honeycomb pattern with hyperchromatic nuclei and mitotic figures. The nodules may develop myxomatous areas as well as less-differentiated foci with intersecting fascicles in a herringbone pattern. Anti-CD34 antibody immunostaining demonstrates strongly positive spindle cells, while DFSP is negative for stromelysin 3, factor XIIIa, and D2-40, which can help to differentiate DFSP from dermatofibroma.5 The myxoid subtype of DFSP does not differ clinically or prognostically from conventional DFSP, though its recognition can be of use in differentiating other myxoid tumors. Myxoid DFSP is nearly always positive for CD34 and negative for the neural marker S-100 protein.6

Some reports have demonstrated that Mohs micrographic surgery is superior to wide local excision in treatment of DFSP, as it results in fewer local recurrences and metastases.7,8 Because of cytogenic abnormalities such as a reciprocal chromosomal (17;22) translocation or supernumerary ring chromosome derived from t(17;22) that place the PDGFB gene under the control of COL1A1 promoter, imatinib mesylate has been tested in DFSP and resulted in dramatic responses in both adults and children.9,10 Suggested uses of imatinib include metastatic disease and locally invasive disease not suitable for surgical excision as well as a method to debulk tumors prior to resection.11

- Gloster HM Jr. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3, pt 1):355-374; quiz 375-376.

- Do AN, Goleno K, Geisse JK. Mohs micrographic surgery and partial amputation preserving function and aesthetics in digits: case reports of invasive melanoma and digital dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1516-1521.

- Taylor HB, Helwig EB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a study of 115 cases. Cancer. 1962;15:717-725.

- Kamino H, Reddy VB, Pui J. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2012:1961-1977.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Monteagudo C, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a comprehensive review and update of diagnosis and management. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2013;30:13-28.

- Paradisi A, Abeni D, Rusciani A, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: wide local excision vs. Mohs micrographic surgery. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:728-736.

- Foroozan M, Sei JF, Amini M, et al. Efficacy of Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1055-1063.

- Patel KU, Szaebo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- McArthur GA, Demetri GD, van Oosterom A, et al. Molecular and clinical analysis of locally advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans treated with imatinib: Imatinib Target Exploration Consortium Study B2225. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:866-873.

- Rutkowski P, Van Glabbeke M, Rankin CJ, et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue/Bone Sarcoma Group, Southwest Oncology Group. Imatinib mesylate in advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: pooled analysis of two phase II clinical trials [published online March 1, 2010]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1772-1779.

- Mentzel T, Beham A, Katenkamp D, et al. Fibrosarcomatous ("high-grade") dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of a series of 41 cases with emphasis on prognostic significance. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:576-587.

To the Editor:

A 41-year-old man presented with a slowly enlarging, tender, firm lesion on the left hallux of approximately 5 months' duration that initially appeared to be a blister. He reported no history of keloids or trauma to the left foot. On examination, a 3.5-cm, flesh-colored, pedunculated, firm nodule was present on the lateral aspect of the left great hallux (Figure 1). No lymphadenopathy was found. The lesion was diagnosed at that time as a keloid and treated with intralesional steroids without response. The patient was lost to follow-up, and after 5 months he presented again with pain and drainage from the lesion. Acute drainage resolved after antibiotic therapy. A shave biopsy was performed, which revealed findings consistent with a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). A chest radiograph was unremarkable. Re-excision was performed with negative margins on frozen section but with positive peripheral and deep margins on permanent sections. The patient subsequently underwent amputation of the left great toe and was lost to follow-up after the initial postoperative period.

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a polypoid spindle cell tumor that filled the dermis and invaded into the subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figure 2). The spindle cells had tapered nuclei in a honeycomb arrangement with only mild nuclear pleomorphism arranged in fascicles with a herringbone formation. Areas showed a myxoid stroma with abundant mucin (Figure 3). Immunostaining demonstrated cells strongly positive for CD34 and negative for MART (melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells), S-100, and smooth muscle actin immunostains.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a sarcoma that is locally aggressive and tends to recur after surgical excision, though rare cases of metastasis involving the lungs have been reported.12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually affects young to middle-aged adults. Acral DFSP is rare in adults, with tumors most commonly occurring on the trunk (50%-60%), proximal extremities (20%-30%), or the head and neck (10%-15%).1,2 A higher rate of acral DFSP has been found in children, which may be due to the increased rate of extremity trauma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans commonly presents as an asymptomatic, slowly growing, indurated plaque that may be flesh colored or hyperpigmented, followed by development of erythematous firm nodules of up to several centimeters.1,3 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans may be associated with a purulent exudate or ulceration, and pain may develop as the lesion grows.

Histopathologic evaluation shows an early plaque stage characterized by low cellularity, minimal nuclear atypia, and rare mitotic figures.4 In the nodular stage, the spindle cells are arranged as short fascicles in a storiform arrangement and infiltrate the subcutaneous tissue in a honeycomb pattern with hyperchromatic nuclei and mitotic figures. The nodules may develop myxomatous areas as well as less-differentiated foci with intersecting fascicles in a herringbone pattern. Anti-CD34 antibody immunostaining demonstrates strongly positive spindle cells, while DFSP is negative for stromelysin 3, factor XIIIa, and D2-40, which can help to differentiate DFSP from dermatofibroma.5 The myxoid subtype of DFSP does not differ clinically or prognostically from conventional DFSP, though its recognition can be of use in differentiating other myxoid tumors. Myxoid DFSP is nearly always positive for CD34 and negative for the neural marker S-100 protein.6

Some reports have demonstrated that Mohs micrographic surgery is superior to wide local excision in treatment of DFSP, as it results in fewer local recurrences and metastases.7,8 Because of cytogenic abnormalities such as a reciprocal chromosomal (17;22) translocation or supernumerary ring chromosome derived from t(17;22) that place the PDGFB gene under the control of COL1A1 promoter, imatinib mesylate has been tested in DFSP and resulted in dramatic responses in both adults and children.9,10 Suggested uses of imatinib include metastatic disease and locally invasive disease not suitable for surgical excision as well as a method to debulk tumors prior to resection.11

To the Editor:

A 41-year-old man presented with a slowly enlarging, tender, firm lesion on the left hallux of approximately 5 months' duration that initially appeared to be a blister. He reported no history of keloids or trauma to the left foot. On examination, a 3.5-cm, flesh-colored, pedunculated, firm nodule was present on the lateral aspect of the left great hallux (Figure 1). No lymphadenopathy was found. The lesion was diagnosed at that time as a keloid and treated with intralesional steroids without response. The patient was lost to follow-up, and after 5 months he presented again with pain and drainage from the lesion. Acute drainage resolved after antibiotic therapy. A shave biopsy was performed, which revealed findings consistent with a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). A chest radiograph was unremarkable. Re-excision was performed with negative margins on frozen section but with positive peripheral and deep margins on permanent sections. The patient subsequently underwent amputation of the left great toe and was lost to follow-up after the initial postoperative period.

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a polypoid spindle cell tumor that filled the dermis and invaded into the subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figure 2). The spindle cells had tapered nuclei in a honeycomb arrangement with only mild nuclear pleomorphism arranged in fascicles with a herringbone formation. Areas showed a myxoid stroma with abundant mucin (Figure 3). Immunostaining demonstrated cells strongly positive for CD34 and negative for MART (melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells), S-100, and smooth muscle actin immunostains.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a sarcoma that is locally aggressive and tends to recur after surgical excision, though rare cases of metastasis involving the lungs have been reported.12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually affects young to middle-aged adults. Acral DFSP is rare in adults, with tumors most commonly occurring on the trunk (50%-60%), proximal extremities (20%-30%), or the head and neck (10%-15%).1,2 A higher rate of acral DFSP has been found in children, which may be due to the increased rate of extremity trauma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans commonly presents as an asymptomatic, slowly growing, indurated plaque that may be flesh colored or hyperpigmented, followed by development of erythematous firm nodules of up to several centimeters.1,3 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans may be associated with a purulent exudate or ulceration, and pain may develop as the lesion grows.

Histopathologic evaluation shows an early plaque stage characterized by low cellularity, minimal nuclear atypia, and rare mitotic figures.4 In the nodular stage, the spindle cells are arranged as short fascicles in a storiform arrangement and infiltrate the subcutaneous tissue in a honeycomb pattern with hyperchromatic nuclei and mitotic figures. The nodules may develop myxomatous areas as well as less-differentiated foci with intersecting fascicles in a herringbone pattern. Anti-CD34 antibody immunostaining demonstrates strongly positive spindle cells, while DFSP is negative for stromelysin 3, factor XIIIa, and D2-40, which can help to differentiate DFSP from dermatofibroma.5 The myxoid subtype of DFSP does not differ clinically or prognostically from conventional DFSP, though its recognition can be of use in differentiating other myxoid tumors. Myxoid DFSP is nearly always positive for CD34 and negative for the neural marker S-100 protein.6

Some reports have demonstrated that Mohs micrographic surgery is superior to wide local excision in treatment of DFSP, as it results in fewer local recurrences and metastases.7,8 Because of cytogenic abnormalities such as a reciprocal chromosomal (17;22) translocation or supernumerary ring chromosome derived from t(17;22) that place the PDGFB gene under the control of COL1A1 promoter, imatinib mesylate has been tested in DFSP and resulted in dramatic responses in both adults and children.9,10 Suggested uses of imatinib include metastatic disease and locally invasive disease not suitable for surgical excision as well as a method to debulk tumors prior to resection.11

- Gloster HM Jr. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3, pt 1):355-374; quiz 375-376.

- Do AN, Goleno K, Geisse JK. Mohs micrographic surgery and partial amputation preserving function and aesthetics in digits: case reports of invasive melanoma and digital dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1516-1521.

- Taylor HB, Helwig EB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a study of 115 cases. Cancer. 1962;15:717-725.

- Kamino H, Reddy VB, Pui J. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2012:1961-1977.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Monteagudo C, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a comprehensive review and update of diagnosis and management. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2013;30:13-28.

- Paradisi A, Abeni D, Rusciani A, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: wide local excision vs. Mohs micrographic surgery. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:728-736.

- Foroozan M, Sei JF, Amini M, et al. Efficacy of Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1055-1063.

- Patel KU, Szaebo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- McArthur GA, Demetri GD, van Oosterom A, et al. Molecular and clinical analysis of locally advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans treated with imatinib: Imatinib Target Exploration Consortium Study B2225. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:866-873.

- Rutkowski P, Van Glabbeke M, Rankin CJ, et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue/Bone Sarcoma Group, Southwest Oncology Group. Imatinib mesylate in advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: pooled analysis of two phase II clinical trials [published online March 1, 2010]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1772-1779.

- Mentzel T, Beham A, Katenkamp D, et al. Fibrosarcomatous ("high-grade") dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of a series of 41 cases with emphasis on prognostic significance. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:576-587.

- Gloster HM Jr. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3, pt 1):355-374; quiz 375-376.

- Do AN, Goleno K, Geisse JK. Mohs micrographic surgery and partial amputation preserving function and aesthetics in digits: case reports of invasive melanoma and digital dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1516-1521.

- Taylor HB, Helwig EB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a study of 115 cases. Cancer. 1962;15:717-725.

- Kamino H, Reddy VB, Pui J. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2012:1961-1977.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Monteagudo C, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a comprehensive review and update of diagnosis and management. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2013;30:13-28.

- Paradisi A, Abeni D, Rusciani A, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: wide local excision vs. Mohs micrographic surgery. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:728-736.

- Foroozan M, Sei JF, Amini M, et al. Efficacy of Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1055-1063.

- Patel KU, Szaebo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- McArthur GA, Demetri GD, van Oosterom A, et al. Molecular and clinical analysis of locally advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans treated with imatinib: Imatinib Target Exploration Consortium Study B2225. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:866-873.

- Rutkowski P, Van Glabbeke M, Rankin CJ, et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue/Bone Sarcoma Group, Southwest Oncology Group. Imatinib mesylate in advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: pooled analysis of two phase II clinical trials [published online March 1, 2010]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1772-1779.

- Mentzel T, Beham A, Katenkamp D, et al. Fibrosarcomatous ("high-grade") dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of a series of 41 cases with emphasis on prognostic significance. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:576-587.

Practice Points

- Consider dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans for a keloidlike enlarging lesion when there is no history of trauma or prior keloid formation.

- Treatments such as Mohs micrographic surgery or oral imatinib mesylate can provide lower recurrence rates in appropriate patients as stand-alone or adjuvant therapy.

Temporal Triangular Alopecia Acquired in Adulthood

To the Editor:

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA), a condition first described by Sabouraud1 in 1905, is a circumscribed nonscarring form of alopecia. Also referred to as congenital triangular alopecia, TTA presents as a triangular or lancet-shaped area of hair loss involving the frontotemporal hairline. Temporal triangular alopecia is characterized histologically by a normal number of miniaturized hair follicles without notable inflammation.2 Although the majority of cases arise between birth and 9 years of age,3,4 rare cases of adult-onset TTA also have been reported.5,6 Adult-onset cases can cause notable diagnostic confusion and inappropriate treatment, as reported in our patient.

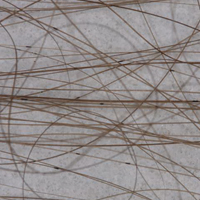

A 25-year-old woman with a history of Hashimoto thyroiditis presented with hair loss affecting the right temporal scalp of 3 years' duration that was first noticed by her husband. The lesion was an asymptomatic, 6×8-cm, roughly lancet-shaped patch of alopecia located on the right temporal scalp, bordering on the frontal hairline (Figure 1). Centrally, the patch appeared almost hairless with a few retained terminal hairs. The frontal hairline was thinned but still present. There was no scaling or erythema, and fine vellus hairs and a few isolated terminal hairs covered the area. The corresponding skin on the contralateral temporal scalp showed normal hair density. The patient insisted that she had normal hair at the affected area until 22 years of age, and she denied a history of trauma or tight hairstyles. Initially diagnosed with alopecia areata by her primary care provider, the patient was treated with topical corticosteroids for 6 months without benefit. She was subsequently referred to a dermatologist who again offered a diagnosis of alopecia areata and treated the lesions with 2 intralesional corticosteroid injections without benefit. No biopsies of the affected area were performed, and the patient was given a trial of topical minoxidil.

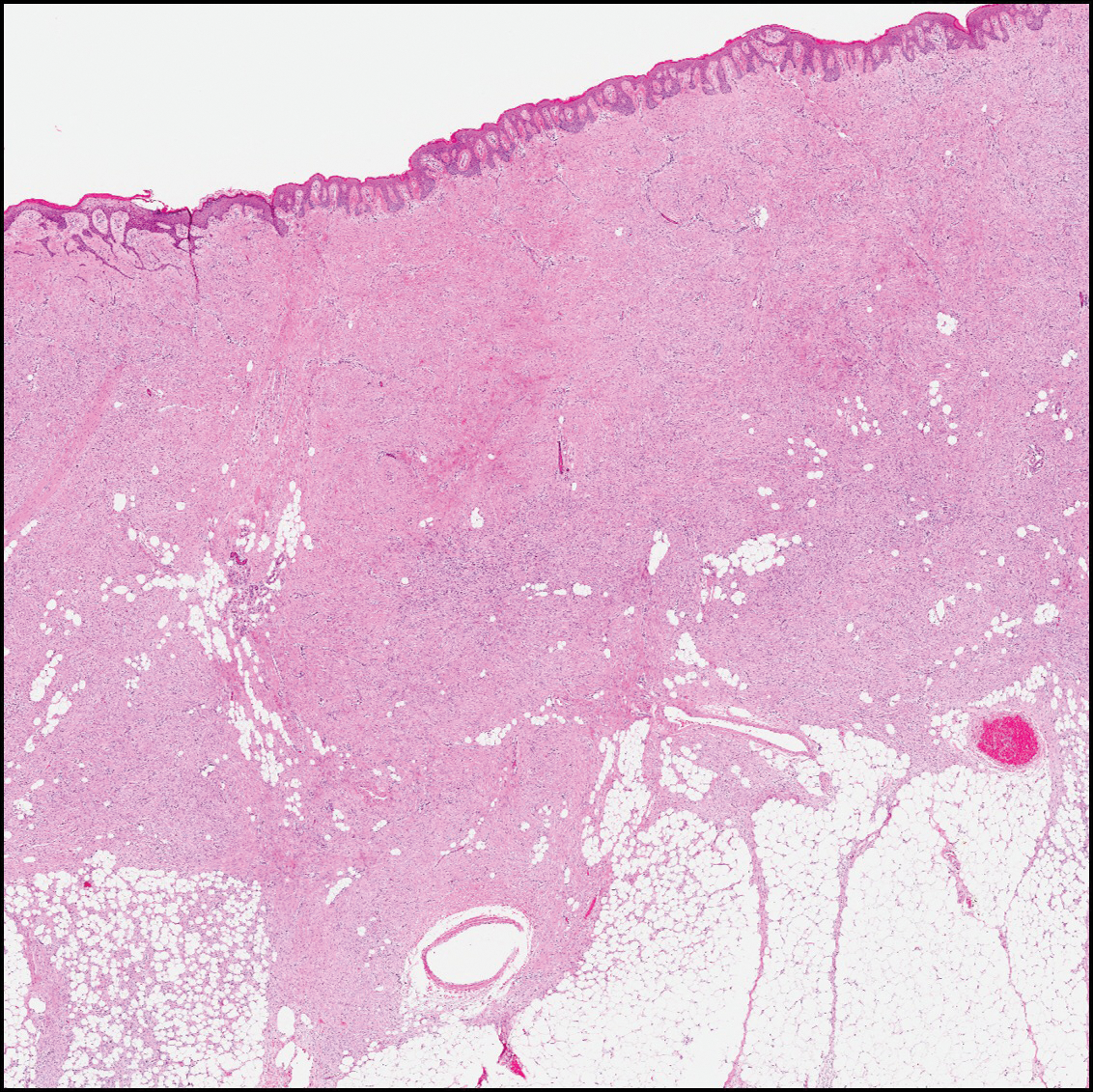

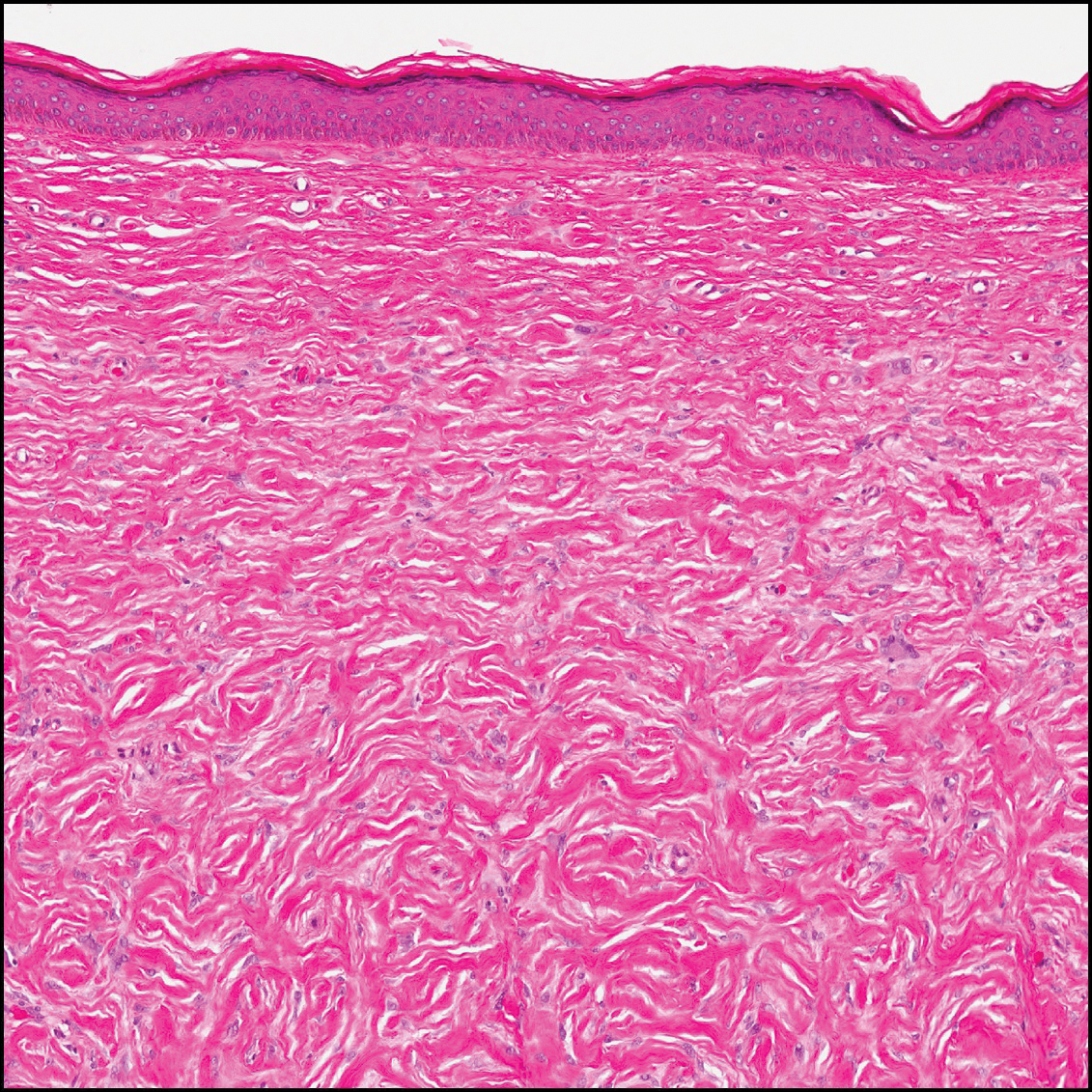

The patient consulted a new primary care provider and was diagnosed with scarring alopecia. She was referred to our dermatology department for further treatment. An initial biopsy at the edge of the affected area was interpreted as normal, but after failing additional intralesional corticosteroid injections, she was referred to our hair clinic where another biopsy was performed in the central portion of the lesion. A 4-mm diameter punch biopsy specimen revealed a normal epidermis and dermis; however, in the lower dermis only a single terminal follicle was seen (Figure 2). Sections through the upper dermis (Figure 3) showed that the total number of hairs was normal or nearly normal with at least 22 follicles, but most were vellus and indeterminate hairs with only a single terminal hair. The dermal architecture was otherwise normal. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of TTA was made. Subsequent to the diagnosis, the patient did not pursue any additional treatment options and preferred to style her hair so that the area of TTA remained covered.

The differential diagnosis in adults presenting with a patch of localized alopecia includes alopecia areata, trichotillomania, pressure-induced alopecia, traction alopecia, lichen planopilaris, discoid lupus erythematosus, and rarely TTA. Temporal triangular alopecia is a fairly common, if underreported, nonscarring form of alopecia that mainly affects young children. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms temporal triangular alopecia or congenital triangular alopecia or triangular alopecia documented only 76 cases of TTA including our own, with the majority of patients diagnosed before 9 years of age. Only 2 cases of adult-onset TTA have been reported,5,6 possibly leading to misdiagnosis of adult patients who present with similar areas of hair loss. As with some prior cases of TTA,5,7 our patient was misdiagnosed with alopecia areata and scarring alopecia, both treated unsuccessfully before a diagnosis of TTA was considered. Clues to the diagnosis included the location, the lack of change in size and shape, the lack of response to intralesional corticosteroids, and the presence of numerous vellus hairs on the surface. A biopsy of the visibly hairless zone was confirmatory. The normal or nearly normal number of miniaturized hairs in specimens of TTA suggest that topical minoxidil therapy (eg, 5% solution twice daily for at least 6 months) might be useful, but the authors have tried it on a few other patients with clinically typical TTA without discernible benefit. When lesions are small, excision provides a fast and permanent solution to the problem, albeit with the usual risks of minor surgery.

- Sabouraud RJA. Manuel Élémentaire de Dermatologie Topographique Régionale. Paris, France: Masson & Cie; 1905:197.

- Trakimas C, Sperling LC, Skelton HG 3rd, et al. Clinical and histologic findings in temporal triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:205-209.

- Yamazaki M, Irisawa R, Tsuboi R. Temporal triangular alopecia and a review of 52 past cases. J Dermatol. 2010;37:360-362.

- Sarifakioglu E, Yilmaz AE, Gorpelioglu C, et al. Prevalence of scalp disorders and hair loss in children. Cutis. 2012;90:225-229.

- Trakimas CA, Sperling LC. Temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:842-844.

- Akan IM, Yildirim S, Avci G, et al. Bilateral temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1616-1617.

- Gupta LK, Khare AK, Garg A, et al. Congenital triangular alopecia--a close mimicker of alopecia areata. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:40-41.

To the Editor:

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA), a condition first described by Sabouraud1 in 1905, is a circumscribed nonscarring form of alopecia. Also referred to as congenital triangular alopecia, TTA presents as a triangular or lancet-shaped area of hair loss involving the frontotemporal hairline. Temporal triangular alopecia is characterized histologically by a normal number of miniaturized hair follicles without notable inflammation.2 Although the majority of cases arise between birth and 9 years of age,3,4 rare cases of adult-onset TTA also have been reported.5,6 Adult-onset cases can cause notable diagnostic confusion and inappropriate treatment, as reported in our patient.

A 25-year-old woman with a history of Hashimoto thyroiditis presented with hair loss affecting the right temporal scalp of 3 years' duration that was first noticed by her husband. The lesion was an asymptomatic, 6×8-cm, roughly lancet-shaped patch of alopecia located on the right temporal scalp, bordering on the frontal hairline (Figure 1). Centrally, the patch appeared almost hairless with a few retained terminal hairs. The frontal hairline was thinned but still present. There was no scaling or erythema, and fine vellus hairs and a few isolated terminal hairs covered the area. The corresponding skin on the contralateral temporal scalp showed normal hair density. The patient insisted that she had normal hair at the affected area until 22 years of age, and she denied a history of trauma or tight hairstyles. Initially diagnosed with alopecia areata by her primary care provider, the patient was treated with topical corticosteroids for 6 months without benefit. She was subsequently referred to a dermatologist who again offered a diagnosis of alopecia areata and treated the lesions with 2 intralesional corticosteroid injections without benefit. No biopsies of the affected area were performed, and the patient was given a trial of topical minoxidil.

The patient consulted a new primary care provider and was diagnosed with scarring alopecia. She was referred to our dermatology department for further treatment. An initial biopsy at the edge of the affected area was interpreted as normal, but after failing additional intralesional corticosteroid injections, she was referred to our hair clinic where another biopsy was performed in the central portion of the lesion. A 4-mm diameter punch biopsy specimen revealed a normal epidermis and dermis; however, in the lower dermis only a single terminal follicle was seen (Figure 2). Sections through the upper dermis (Figure 3) showed that the total number of hairs was normal or nearly normal with at least 22 follicles, but most were vellus and indeterminate hairs with only a single terminal hair. The dermal architecture was otherwise normal. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of TTA was made. Subsequent to the diagnosis, the patient did not pursue any additional treatment options and preferred to style her hair so that the area of TTA remained covered.

The differential diagnosis in adults presenting with a patch of localized alopecia includes alopecia areata, trichotillomania, pressure-induced alopecia, traction alopecia, lichen planopilaris, discoid lupus erythematosus, and rarely TTA. Temporal triangular alopecia is a fairly common, if underreported, nonscarring form of alopecia that mainly affects young children. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms temporal triangular alopecia or congenital triangular alopecia or triangular alopecia documented only 76 cases of TTA including our own, with the majority of patients diagnosed before 9 years of age. Only 2 cases of adult-onset TTA have been reported,5,6 possibly leading to misdiagnosis of adult patients who present with similar areas of hair loss. As with some prior cases of TTA,5,7 our patient was misdiagnosed with alopecia areata and scarring alopecia, both treated unsuccessfully before a diagnosis of TTA was considered. Clues to the diagnosis included the location, the lack of change in size and shape, the lack of response to intralesional corticosteroids, and the presence of numerous vellus hairs on the surface. A biopsy of the visibly hairless zone was confirmatory. The normal or nearly normal number of miniaturized hairs in specimens of TTA suggest that topical minoxidil therapy (eg, 5% solution twice daily for at least 6 months) might be useful, but the authors have tried it on a few other patients with clinically typical TTA without discernible benefit. When lesions are small, excision provides a fast and permanent solution to the problem, albeit with the usual risks of minor surgery.

To the Editor:

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA), a condition first described by Sabouraud1 in 1905, is a circumscribed nonscarring form of alopecia. Also referred to as congenital triangular alopecia, TTA presents as a triangular or lancet-shaped area of hair loss involving the frontotemporal hairline. Temporal triangular alopecia is characterized histologically by a normal number of miniaturized hair follicles without notable inflammation.2 Although the majority of cases arise between birth and 9 years of age,3,4 rare cases of adult-onset TTA also have been reported.5,6 Adult-onset cases can cause notable diagnostic confusion and inappropriate treatment, as reported in our patient.

A 25-year-old woman with a history of Hashimoto thyroiditis presented with hair loss affecting the right temporal scalp of 3 years' duration that was first noticed by her husband. The lesion was an asymptomatic, 6×8-cm, roughly lancet-shaped patch of alopecia located on the right temporal scalp, bordering on the frontal hairline (Figure 1). Centrally, the patch appeared almost hairless with a few retained terminal hairs. The frontal hairline was thinned but still present. There was no scaling or erythema, and fine vellus hairs and a few isolated terminal hairs covered the area. The corresponding skin on the contralateral temporal scalp showed normal hair density. The patient insisted that she had normal hair at the affected area until 22 years of age, and she denied a history of trauma or tight hairstyles. Initially diagnosed with alopecia areata by her primary care provider, the patient was treated with topical corticosteroids for 6 months without benefit. She was subsequently referred to a dermatologist who again offered a diagnosis of alopecia areata and treated the lesions with 2 intralesional corticosteroid injections without benefit. No biopsies of the affected area were performed, and the patient was given a trial of topical minoxidil.

The patient consulted a new primary care provider and was diagnosed with scarring alopecia. She was referred to our dermatology department for further treatment. An initial biopsy at the edge of the affected area was interpreted as normal, but after failing additional intralesional corticosteroid injections, she was referred to our hair clinic where another biopsy was performed in the central portion of the lesion. A 4-mm diameter punch biopsy specimen revealed a normal epidermis and dermis; however, in the lower dermis only a single terminal follicle was seen (Figure 2). Sections through the upper dermis (Figure 3) showed that the total number of hairs was normal or nearly normal with at least 22 follicles, but most were vellus and indeterminate hairs with only a single terminal hair. The dermal architecture was otherwise normal. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of TTA was made. Subsequent to the diagnosis, the patient did not pursue any additional treatment options and preferred to style her hair so that the area of TTA remained covered.

The differential diagnosis in adults presenting with a patch of localized alopecia includes alopecia areata, trichotillomania, pressure-induced alopecia, traction alopecia, lichen planopilaris, discoid lupus erythematosus, and rarely TTA. Temporal triangular alopecia is a fairly common, if underreported, nonscarring form of alopecia that mainly affects young children. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms temporal triangular alopecia or congenital triangular alopecia or triangular alopecia documented only 76 cases of TTA including our own, with the majority of patients diagnosed before 9 years of age. Only 2 cases of adult-onset TTA have been reported,5,6 possibly leading to misdiagnosis of adult patients who present with similar areas of hair loss. As with some prior cases of TTA,5,7 our patient was misdiagnosed with alopecia areata and scarring alopecia, both treated unsuccessfully before a diagnosis of TTA was considered. Clues to the diagnosis included the location, the lack of change in size and shape, the lack of response to intralesional corticosteroids, and the presence of numerous vellus hairs on the surface. A biopsy of the visibly hairless zone was confirmatory. The normal or nearly normal number of miniaturized hairs in specimens of TTA suggest that topical minoxidil therapy (eg, 5% solution twice daily for at least 6 months) might be useful, but the authors have tried it on a few other patients with clinically typical TTA without discernible benefit. When lesions are small, excision provides a fast and permanent solution to the problem, albeit with the usual risks of minor surgery.

- Sabouraud RJA. Manuel Élémentaire de Dermatologie Topographique Régionale. Paris, France: Masson & Cie; 1905:197.

- Trakimas C, Sperling LC, Skelton HG 3rd, et al. Clinical and histologic findings in temporal triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:205-209.

- Yamazaki M, Irisawa R, Tsuboi R. Temporal triangular alopecia and a review of 52 past cases. J Dermatol. 2010;37:360-362.

- Sarifakioglu E, Yilmaz AE, Gorpelioglu C, et al. Prevalence of scalp disorders and hair loss in children. Cutis. 2012;90:225-229.

- Trakimas CA, Sperling LC. Temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:842-844.

- Akan IM, Yildirim S, Avci G, et al. Bilateral temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1616-1617.

- Gupta LK, Khare AK, Garg A, et al. Congenital triangular alopecia--a close mimicker of alopecia areata. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:40-41.

- Sabouraud RJA. Manuel Élémentaire de Dermatologie Topographique Régionale. Paris, France: Masson & Cie; 1905:197.

- Trakimas C, Sperling LC, Skelton HG 3rd, et al. Clinical and histologic findings in temporal triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:205-209.

- Yamazaki M, Irisawa R, Tsuboi R. Temporal triangular alopecia and a review of 52 past cases. J Dermatol. 2010;37:360-362.

- Sarifakioglu E, Yilmaz AE, Gorpelioglu C, et al. Prevalence of scalp disorders and hair loss in children. Cutis. 2012;90:225-229.

- Trakimas CA, Sperling LC. Temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:842-844.

- Akan IM, Yildirim S, Avci G, et al. Bilateral temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1616-1617.

- Gupta LK, Khare AK, Garg A, et al. Congenital triangular alopecia--a close mimicker of alopecia areata. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:40-41.

Practice Points

- Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA) in adults often is confused with alopecia areata.

- An acquired, persistent, unchanging, circumscribed hairless spot in an adult that does not respond to intralesional corticosteroids may represent TTA.

- Hair miniaturization without peribulbar inflammation is consistent with a diagnosis of TTA.

Eroded Plaque on the Lower Lip

The Diagnosis: Squamous Cell Carcinoma

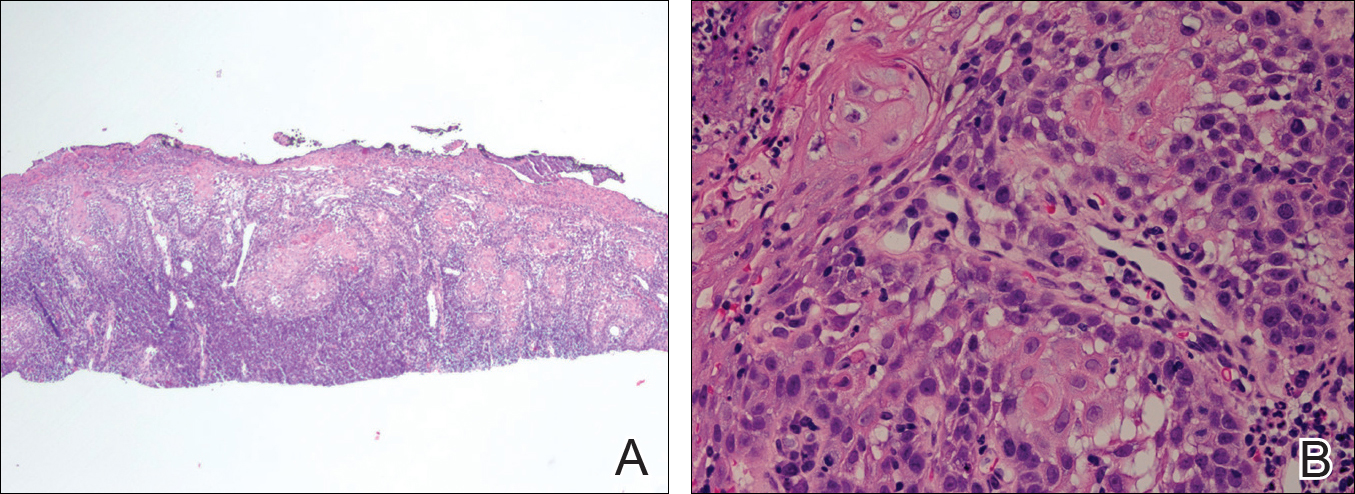

The initial clinical presentation suggested a diagnosis of herpes simplex labialis. The patient reported no response to topical acyclovir, and because the plaque persisted, a biopsy was performed. Pathology demonstrated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) that was moderately well differentiated and invasive (Figure).

Approximately 38% of all oral SCCs in the United States occur on the lower lip and typically are solar-related cancers developing within the epidermis.1 Oral lesions initially may be asymptomatic and may not be of concern to the patient; however, it is important to recognize SCC early, as invasive lesions have the potential to metastasize. Some factors that increase the chance for the development of metastases include tumor size larger than 2 cm; location on the ear, lip, or other sites on the head and neck; and history of prior unsuccessful treatment.2 Any solitary ulcer, lump, wound, or lesion that will not heal and persists for more than 3 weeks should be regarded as cancer until proven otherwise. Although few oral SCCs are detected by clinicians at an early stage, diagnostic aids such as vital staining and molecular markers in tissues and saliva may be implemented.3 Toluidine blue is a simple, fast, and inexpensive technique that stains the nuclear material of malignant lesions, but not normal mucosa, and may be a worthwhile diagnostic adjunct to clinical inspection.4

Our patient presented with a lesion that clinically looked herpetic, though he reported no prodromal signs of tingling, burning, or pain before the occurrence of the lesion. Due to the persistence of the lesion and lack of response to treatment, a biopsy was indicated. The differential diagnoses include aphthous ulcers, which may occasionally extend on to the vermilion border of the lip and exhibit nondiagnostic histology.5 Bullous oral lichen planus is the least common variant of oral lichen planus, is unlikely to present as a solitary lesion, and is rarely seen on the lips. Histologically, the lesion demonstrated lichenoid inflammation.6 Solitary keratoacanthoma, though histologically similar to SCC, typically presents as a rapidly growing crateriform nodule without erosion or ulceration.7 The differential diagnoses are summarized in the Table.

The patient underwent wide excision with repair by mucosal advancement flap. He continues to be regularly seen in the clinic for monitoring of other skin cancers and is doing well. Clinicians encountering any wound or ulcer that does not show signs of healing should be wary of underlying malignancy and be prompted to perform a biopsy.

- Fehrenbach MJ. Extraoral and intraoral clinical assessment. In: Darby ML, Walsh MM, eds. Dental Hygiene: Theory and Practice. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2014:214-233.

- Hawrot A, Alam M, Ratner D. Squamous cell carcinoma. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2003;15:91-133.

- Scully C, Bagan J. Oral squamous cell carcinoma overview. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:301-308.

- Chhabra N, Chhabra S, Sapra N. Diagnostic modalities for squamous cell carcinoma: an extensive review of literature considering toluidine blue as a useful adjunct. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;14:188-200.

- Porter SR, Scully C, Pedersen A. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;9:1499-1505.

- Bricker SL. Oral lichen planus: a review. Semin Dermatol. 1994;13:87-90.

- Cabrijan L, Lipozencic´ J, Batinac T, et al. Differences between keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma using TGF-alpha. Coll Antropol. 2013;37:147-150.

- Douglas GD, Couch RB. A prospective study of chronic herpes simplex virus infection and recurrent herpes labialis in humans. J Immunol. 1970;104:289-295.

- Alam M, Ratner D. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:976-983.

- van Tuyll van Serooskerken AM, van Marion AM, de Zwart-Storm E, et al. Lichen planus with bullous manifestation on the lip. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(suppl 3):25-26.

- Messadi DV, Younai F. Apthous ulcers. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:281-290.

- Ko CJ. Keratoacanthoma: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:254-261.

The Diagnosis: Squamous Cell Carcinoma

The initial clinical presentation suggested a diagnosis of herpes simplex labialis. The patient reported no response to topical acyclovir, and because the plaque persisted, a biopsy was performed. Pathology demonstrated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) that was moderately well differentiated and invasive (Figure).

Approximately 38% of all oral SCCs in the United States occur on the lower lip and typically are solar-related cancers developing within the epidermis.1 Oral lesions initially may be asymptomatic and may not be of concern to the patient; however, it is important to recognize SCC early, as invasive lesions have the potential to metastasize. Some factors that increase the chance for the development of metastases include tumor size larger than 2 cm; location on the ear, lip, or other sites on the head and neck; and history of prior unsuccessful treatment.2 Any solitary ulcer, lump, wound, or lesion that will not heal and persists for more than 3 weeks should be regarded as cancer until proven otherwise. Although few oral SCCs are detected by clinicians at an early stage, diagnostic aids such as vital staining and molecular markers in tissues and saliva may be implemented.3 Toluidine blue is a simple, fast, and inexpensive technique that stains the nuclear material of malignant lesions, but not normal mucosa, and may be a worthwhile diagnostic adjunct to clinical inspection.4

Our patient presented with a lesion that clinically looked herpetic, though he reported no prodromal signs of tingling, burning, or pain before the occurrence of the lesion. Due to the persistence of the lesion and lack of response to treatment, a biopsy was indicated. The differential diagnoses include aphthous ulcers, which may occasionally extend on to the vermilion border of the lip and exhibit nondiagnostic histology.5 Bullous oral lichen planus is the least common variant of oral lichen planus, is unlikely to present as a solitary lesion, and is rarely seen on the lips. Histologically, the lesion demonstrated lichenoid inflammation.6 Solitary keratoacanthoma, though histologically similar to SCC, typically presents as a rapidly growing crateriform nodule without erosion or ulceration.7 The differential diagnoses are summarized in the Table.

The patient underwent wide excision with repair by mucosal advancement flap. He continues to be regularly seen in the clinic for monitoring of other skin cancers and is doing well. Clinicians encountering any wound or ulcer that does not show signs of healing should be wary of underlying malignancy and be prompted to perform a biopsy.

The Diagnosis: Squamous Cell Carcinoma

The initial clinical presentation suggested a diagnosis of herpes simplex labialis. The patient reported no response to topical acyclovir, and because the plaque persisted, a biopsy was performed. Pathology demonstrated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) that was moderately well differentiated and invasive (Figure).

Approximately 38% of all oral SCCs in the United States occur on the lower lip and typically are solar-related cancers developing within the epidermis.1 Oral lesions initially may be asymptomatic and may not be of concern to the patient; however, it is important to recognize SCC early, as invasive lesions have the potential to metastasize. Some factors that increase the chance for the development of metastases include tumor size larger than 2 cm; location on the ear, lip, or other sites on the head and neck; and history of prior unsuccessful treatment.2 Any solitary ulcer, lump, wound, or lesion that will not heal and persists for more than 3 weeks should be regarded as cancer until proven otherwise. Although few oral SCCs are detected by clinicians at an early stage, diagnostic aids such as vital staining and molecular markers in tissues and saliva may be implemented.3 Toluidine blue is a simple, fast, and inexpensive technique that stains the nuclear material of malignant lesions, but not normal mucosa, and may be a worthwhile diagnostic adjunct to clinical inspection.4

Our patient presented with a lesion that clinically looked herpetic, though he reported no prodromal signs of tingling, burning, or pain before the occurrence of the lesion. Due to the persistence of the lesion and lack of response to treatment, a biopsy was indicated. The differential diagnoses include aphthous ulcers, which may occasionally extend on to the vermilion border of the lip and exhibit nondiagnostic histology.5 Bullous oral lichen planus is the least common variant of oral lichen planus, is unlikely to present as a solitary lesion, and is rarely seen on the lips. Histologically, the lesion demonstrated lichenoid inflammation.6 Solitary keratoacanthoma, though histologically similar to SCC, typically presents as a rapidly growing crateriform nodule without erosion or ulceration.7 The differential diagnoses are summarized in the Table.

The patient underwent wide excision with repair by mucosal advancement flap. He continues to be regularly seen in the clinic for monitoring of other skin cancers and is doing well. Clinicians encountering any wound or ulcer that does not show signs of healing should be wary of underlying malignancy and be prompted to perform a biopsy.

- Fehrenbach MJ. Extraoral and intraoral clinical assessment. In: Darby ML, Walsh MM, eds. Dental Hygiene: Theory and Practice. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2014:214-233.

- Hawrot A, Alam M, Ratner D. Squamous cell carcinoma. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2003;15:91-133.

- Scully C, Bagan J. Oral squamous cell carcinoma overview. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:301-308.

- Chhabra N, Chhabra S, Sapra N. Diagnostic modalities for squamous cell carcinoma: an extensive review of literature considering toluidine blue as a useful adjunct. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;14:188-200.

- Porter SR, Scully C, Pedersen A. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;9:1499-1505.

- Bricker SL. Oral lichen planus: a review. Semin Dermatol. 1994;13:87-90.

- Cabrijan L, Lipozencic´ J, Batinac T, et al. Differences between keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma using TGF-alpha. Coll Antropol. 2013;37:147-150.

- Douglas GD, Couch RB. A prospective study of chronic herpes simplex virus infection and recurrent herpes labialis in humans. J Immunol. 1970;104:289-295.

- Alam M, Ratner D. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:976-983.

- van Tuyll van Serooskerken AM, van Marion AM, de Zwart-Storm E, et al. Lichen planus with bullous manifestation on the lip. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(suppl 3):25-26.

- Messadi DV, Younai F. Apthous ulcers. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:281-290.

- Ko CJ. Keratoacanthoma: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:254-261.

- Fehrenbach MJ. Extraoral and intraoral clinical assessment. In: Darby ML, Walsh MM, eds. Dental Hygiene: Theory and Practice. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2014:214-233.

- Hawrot A, Alam M, Ratner D. Squamous cell carcinoma. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2003;15:91-133.

- Scully C, Bagan J. Oral squamous cell carcinoma overview. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:301-308.

- Chhabra N, Chhabra S, Sapra N. Diagnostic modalities for squamous cell carcinoma: an extensive review of literature considering toluidine blue as a useful adjunct. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;14:188-200.

- Porter SR, Scully C, Pedersen A. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;9:1499-1505.

- Bricker SL. Oral lichen planus: a review. Semin Dermatol. 1994;13:87-90.

- Cabrijan L, Lipozencic´ J, Batinac T, et al. Differences between keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma using TGF-alpha. Coll Antropol. 2013;37:147-150.

- Douglas GD, Couch RB. A prospective study of chronic herpes simplex virus infection and recurrent herpes labialis in humans. J Immunol. 1970;104:289-295.

- Alam M, Ratner D. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:976-983.

- van Tuyll van Serooskerken AM, van Marion AM, de Zwart-Storm E, et al. Lichen planus with bullous manifestation on the lip. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(suppl 3):25-26.

- Messadi DV, Younai F. Apthous ulcers. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:281-290.

- Ko CJ. Keratoacanthoma: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:254-261.

An 83-year-old man presented with a new-onset 1.2-cm eroded plaque on the vermilion border of the right lower lip that reportedly developed 2 weeks prior and was increasing in size. The plaque was moist and was composed of confluent glistening papules. Medical history was notable for the presence of both basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas.

Large Hyperpigmented Nodule on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibroma

Dermatofibroma (DF) is a commonly encountered lesion. Although usually a straightforward clinical diagnosis, histopathological diagnosis is sometimes required. Conventional histologic findings of DF are hyperkeratosis, induction of the epidermis with acanthosis, and basal layer hyperpigmentation.1,2 Within the dermis there usually is proliferation of fibroblasts, histiocytes, and blood vessels that sometimes spares the overlying papillary dermis. Nomenclature of specific variants may be assigned based on the predominant component (eg, nodular subepidermal fibrosis, histiocytoma, sclerosing hemangioma) or histologic findings (eg, fibrocollagenous, sclerotic, cellular, histiocytic, lipidized, angiomatous, aneurysmal, clear cell, monster cell, myxoid, keloidal, palisading, osteoclastic, epithelioid).3-5 Of the histologic variants, fibrocollagenous is most common, but knowledge of other variants is important for accurate diagnosis, especially to exclude malignancy.

The sclerosing hemangioma variant of DF may pre-sent a diagnostic dilemma. In addition to typical features of DF, pseudovascular spaces, abundant hemosiderin, and reactive-appearing spindled cells are histologically demonstrated. The marked sclerosis and pigment deposition may mimic a blue nevus, and the dilated pseudovascular spaces may be reminiscent of a vascular neoplasm such as angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma. However, the presence of characteristic features such as peripheral collagen trapping and overlying epidermal hyperplasia provide important clues for correct diagnosis.

Angiosarcomas (Figure 1) are malignant neoplasms with vascular differentiation. Cutaneous angiosarcomas present as purple plaques or nodules on the head and/or neck in elderly individuals as well as in patients with chronic lymphedema or prior radiation exposure.6-9 They are aggressive neoplasms with high rates of recurrence and metastases. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of anastomosing vascular channels lined by atypical endothelial cells with a multilayered appearance. There is frequent red blood cell extravasation, and substantial hemosiderin deposition may be noted in long-standing lesions. Neoplastic cells are positive for vascular markers (CD34, CD31, ETS-related gene transcription factor). Notably, cases associated with radiation exposure and chronic lymphedema are positive for MYC.10

Blue nevi (Figure 2) are benign melanocytic tumors that occur most frequently in children but may pre-sent in any age group. Clinical presentation is a blue to black, slightly raised papule that may be found on any site of the body. Biopsy typically shows a wedge-shaped infiltrate of spindled melanocytes with elongated dendritic processes in a sclerotic collagenous stroma. There frequently is a striking population of heavily pigmented melanophages. The melanocytes are positive for melanoma antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1)/melan-A, S-100, and transcription factor SOX-10. In contrast to other benign nevi, human melanoma black-45 will be positive in the dermal component.

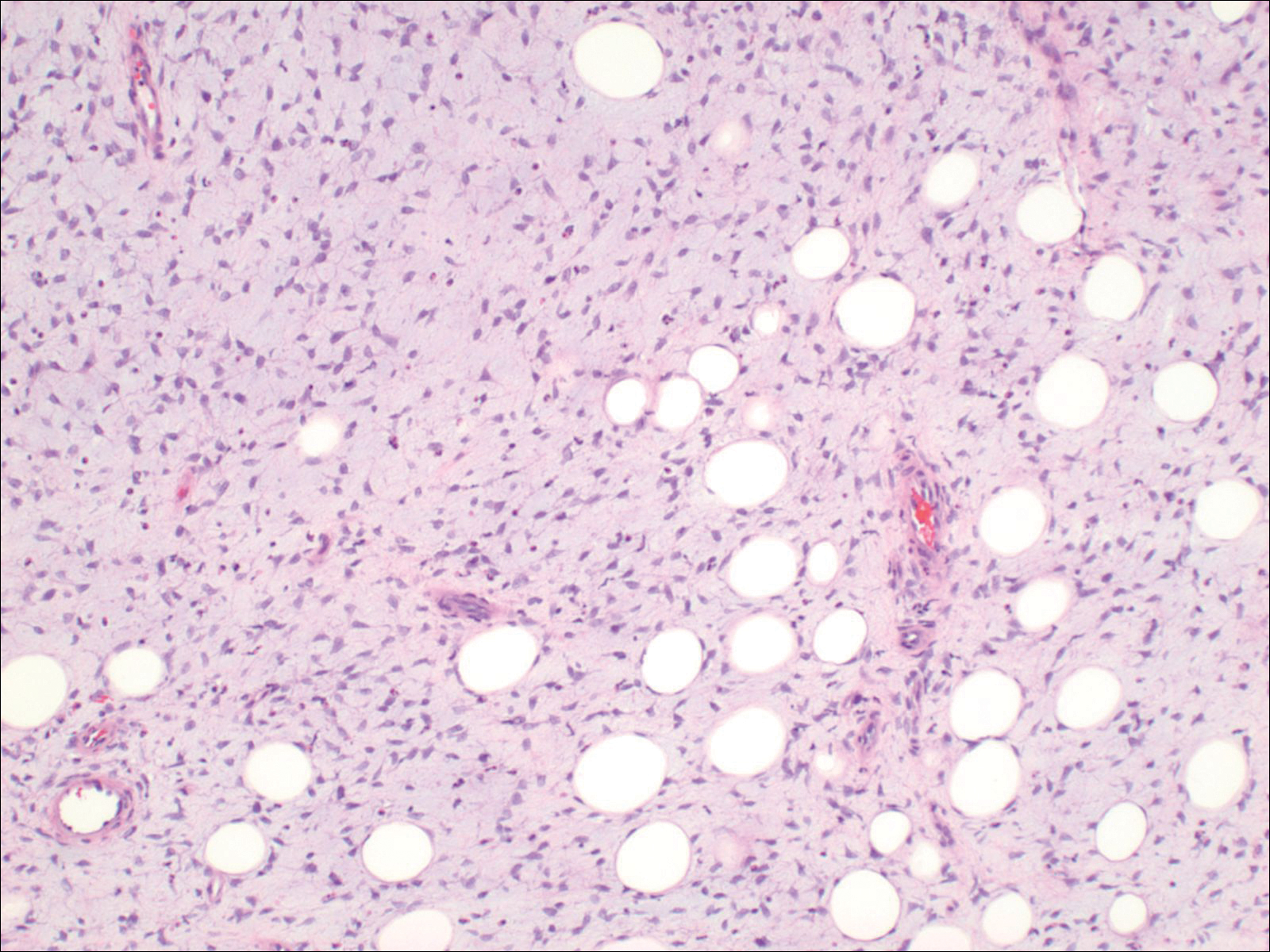

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (Figure 3) is a dermal-based tumor of intermediate malignant potential with a high rate of local recurrence and potential for sarcomatous transformation. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans most commonly presents in young adults as firm, pink to brown plaques and can occur on any site of the body. Histologically, they show a dermal proliferation of spindled cells that infiltrate in a storiform fashion into the subcutaneous adipose tissue,11 which imparts a honeycomb or Swiss cheese pattern. The tumor characteristically demonstrates positive staining for CD34. Loss of CD34 staining, increased mitoses, nuclear atypia, and fascicular growth are features suggestive of sarcomatous transformation.11,12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is associated with chromosomal abnormalities of chromosomes 17 and 22, resulting in COL1A1 (collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain) and PDGF-β (platelet-derived growth factor subunit B) gene fusion.13

Sclerotic fibromas (also known as storiform collagenomas)(Figure 4) may represent regressed DFs and are frequently associated with prior trauma to the affected area.14,15 They usually appear as flesh-colored papules or nodules on the face and trunk. The presence of multiple sclerotic fibromas is associated with Cowden syndrome.16,17 Histologically, the lesions present as well-demarcated, nonencapsulated, dermal nodules composed of a storiform or whorled arrangement of collagen with spindled fibroblasts. The sclerotic collagen bundles often are separated by small clefts imparting a plywoodlike pattern.16

The differential diagnosis for DF expands once atypical clinical and histopathological findings are present. In this case, the nodule was much larger and darker than the usual appearance of DF (3-10 mm).2,4 Given the lesion's nodularity, the clinical dimple sign on lateral compression could not be seen. On biopsy, the predominance of blood vessels and sclerosis further complicated the diagnostic picture. In unusual cases such as this one, correlation of clinical history, histology, and immunophenotype is ever important.

- Zeidi M, North JP. Sebaceous induction in dermatofibroma: a common feature of dermatofibromas on the shoulder. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:400-405.

- Şenel E, Yuyucu Karabulut Y, Doğruer S¸enel S. Clinical, histopathological, dermatoscopic and digital microscopic features of dermatofibroma: a retrospective analysis of 200 lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1958-1966.

- Vilanova JR, Flint A. The morphological variations of fibrous histiocytomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1974;1:155-164.

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JH, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma)[published online May 27, 2011]. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Alves JVP, Matos DM, Barreiros HF, et al. Variants of dermatofibroma--a histopathological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:472-477.

- Rosai J, Sumner HW, Major MC, et al. Angiosarcoma of the skin: a clinicopathologic and fine structural study. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:83-109.

- Haustein UF. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:851-856.

- Stewart FW, Treves N. Lymphangiosarcoma in postmastectomy lymphedema: a report of six cases in elephantiasis chirurgica. Cancer. 1948;1:64-81.

- Goette DK, Detlefs RL. Postirradiation angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(5 pt 2):922-926.

- Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:34-39.

- Voth H, Landsberg J, Hinz T, et al. Management of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with fibrosarcomatous transformation: an evidence-based review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1385-1391.

- Goldblum JR. CD34 positivity in fibrosarcomas which arise in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:238-241.

- Patel KU, Szabo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- Sohn IB, Hwang SM, Lee SH, et al. Dermatofibroma with sclerotic areas resembling a sclerotic fibroma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:44-47.

- Pujol RM, de Castro F, Schroeter AL, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a sclerotic dermatofibroma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:620-624.

- Requena L, Gutiérrez J, Sánchez Yus E. Multiple sclerotic fibromas of the skin: a cutaneous marker of Cowden's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:346-351.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibroma

Dermatofibroma (DF) is a commonly encountered lesion. Although usually a straightforward clinical diagnosis, histopathological diagnosis is sometimes required. Conventional histologic findings of DF are hyperkeratosis, induction of the epidermis with acanthosis, and basal layer hyperpigmentation.1,2 Within the dermis there usually is proliferation of fibroblasts, histiocytes, and blood vessels that sometimes spares the overlying papillary dermis. Nomenclature of specific variants may be assigned based on the predominant component (eg, nodular subepidermal fibrosis, histiocytoma, sclerosing hemangioma) or histologic findings (eg, fibrocollagenous, sclerotic, cellular, histiocytic, lipidized, angiomatous, aneurysmal, clear cell, monster cell, myxoid, keloidal, palisading, osteoclastic, epithelioid).3-5 Of the histologic variants, fibrocollagenous is most common, but knowledge of other variants is important for accurate diagnosis, especially to exclude malignancy.

The sclerosing hemangioma variant of DF may pre-sent a diagnostic dilemma. In addition to typical features of DF, pseudovascular spaces, abundant hemosiderin, and reactive-appearing spindled cells are histologically demonstrated. The marked sclerosis and pigment deposition may mimic a blue nevus, and the dilated pseudovascular spaces may be reminiscent of a vascular neoplasm such as angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma. However, the presence of characteristic features such as peripheral collagen trapping and overlying epidermal hyperplasia provide important clues for correct diagnosis.

Angiosarcomas (Figure 1) are malignant neoplasms with vascular differentiation. Cutaneous angiosarcomas present as purple plaques or nodules on the head and/or neck in elderly individuals as well as in patients with chronic lymphedema or prior radiation exposure.6-9 They are aggressive neoplasms with high rates of recurrence and metastases. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of anastomosing vascular channels lined by atypical endothelial cells with a multilayered appearance. There is frequent red blood cell extravasation, and substantial hemosiderin deposition may be noted in long-standing lesions. Neoplastic cells are positive for vascular markers (CD34, CD31, ETS-related gene transcription factor). Notably, cases associated with radiation exposure and chronic lymphedema are positive for MYC.10

Blue nevi (Figure 2) are benign melanocytic tumors that occur most frequently in children but may pre-sent in any age group. Clinical presentation is a blue to black, slightly raised papule that may be found on any site of the body. Biopsy typically shows a wedge-shaped infiltrate of spindled melanocytes with elongated dendritic processes in a sclerotic collagenous stroma. There frequently is a striking population of heavily pigmented melanophages. The melanocytes are positive for melanoma antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1)/melan-A, S-100, and transcription factor SOX-10. In contrast to other benign nevi, human melanoma black-45 will be positive in the dermal component.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (Figure 3) is a dermal-based tumor of intermediate malignant potential with a high rate of local recurrence and potential for sarcomatous transformation. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans most commonly presents in young adults as firm, pink to brown plaques and can occur on any site of the body. Histologically, they show a dermal proliferation of spindled cells that infiltrate in a storiform fashion into the subcutaneous adipose tissue,11 which imparts a honeycomb or Swiss cheese pattern. The tumor characteristically demonstrates positive staining for CD34. Loss of CD34 staining, increased mitoses, nuclear atypia, and fascicular growth are features suggestive of sarcomatous transformation.11,12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is associated with chromosomal abnormalities of chromosomes 17 and 22, resulting in COL1A1 (collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain) and PDGF-β (platelet-derived growth factor subunit B) gene fusion.13

Sclerotic fibromas (also known as storiform collagenomas)(Figure 4) may represent regressed DFs and are frequently associated with prior trauma to the affected area.14,15 They usually appear as flesh-colored papules or nodules on the face and trunk. The presence of multiple sclerotic fibromas is associated with Cowden syndrome.16,17 Histologically, the lesions present as well-demarcated, nonencapsulated, dermal nodules composed of a storiform or whorled arrangement of collagen with spindled fibroblasts. The sclerotic collagen bundles often are separated by small clefts imparting a plywoodlike pattern.16

The differential diagnosis for DF expands once atypical clinical and histopathological findings are present. In this case, the nodule was much larger and darker than the usual appearance of DF (3-10 mm).2,4 Given the lesion's nodularity, the clinical dimple sign on lateral compression could not be seen. On biopsy, the predominance of blood vessels and sclerosis further complicated the diagnostic picture. In unusual cases such as this one, correlation of clinical history, histology, and immunophenotype is ever important.

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibroma

Dermatofibroma (DF) is a commonly encountered lesion. Although usually a straightforward clinical diagnosis, histopathological diagnosis is sometimes required. Conventional histologic findings of DF are hyperkeratosis, induction of the epidermis with acanthosis, and basal layer hyperpigmentation.1,2 Within the dermis there usually is proliferation of fibroblasts, histiocytes, and blood vessels that sometimes spares the overlying papillary dermis. Nomenclature of specific variants may be assigned based on the predominant component (eg, nodular subepidermal fibrosis, histiocytoma, sclerosing hemangioma) or histologic findings (eg, fibrocollagenous, sclerotic, cellular, histiocytic, lipidized, angiomatous, aneurysmal, clear cell, monster cell, myxoid, keloidal, palisading, osteoclastic, epithelioid).3-5 Of the histologic variants, fibrocollagenous is most common, but knowledge of other variants is important for accurate diagnosis, especially to exclude malignancy.

The sclerosing hemangioma variant of DF may pre-sent a diagnostic dilemma. In addition to typical features of DF, pseudovascular spaces, abundant hemosiderin, and reactive-appearing spindled cells are histologically demonstrated. The marked sclerosis and pigment deposition may mimic a blue nevus, and the dilated pseudovascular spaces may be reminiscent of a vascular neoplasm such as angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma. However, the presence of characteristic features such as peripheral collagen trapping and overlying epidermal hyperplasia provide important clues for correct diagnosis.

Angiosarcomas (Figure 1) are malignant neoplasms with vascular differentiation. Cutaneous angiosarcomas present as purple plaques or nodules on the head and/or neck in elderly individuals as well as in patients with chronic lymphedema or prior radiation exposure.6-9 They are aggressive neoplasms with high rates of recurrence and metastases. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of anastomosing vascular channels lined by atypical endothelial cells with a multilayered appearance. There is frequent red blood cell extravasation, and substantial hemosiderin deposition may be noted in long-standing lesions. Neoplastic cells are positive for vascular markers (CD34, CD31, ETS-related gene transcription factor). Notably, cases associated with radiation exposure and chronic lymphedema are positive for MYC.10

Blue nevi (Figure 2) are benign melanocytic tumors that occur most frequently in children but may pre-sent in any age group. Clinical presentation is a blue to black, slightly raised papule that may be found on any site of the body. Biopsy typically shows a wedge-shaped infiltrate of spindled melanocytes with elongated dendritic processes in a sclerotic collagenous stroma. There frequently is a striking population of heavily pigmented melanophages. The melanocytes are positive for melanoma antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1)/melan-A, S-100, and transcription factor SOX-10. In contrast to other benign nevi, human melanoma black-45 will be positive in the dermal component.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (Figure 3) is a dermal-based tumor of intermediate malignant potential with a high rate of local recurrence and potential for sarcomatous transformation. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans most commonly presents in young adults as firm, pink to brown plaques and can occur on any site of the body. Histologically, they show a dermal proliferation of spindled cells that infiltrate in a storiform fashion into the subcutaneous adipose tissue,11 which imparts a honeycomb or Swiss cheese pattern. The tumor characteristically demonstrates positive staining for CD34. Loss of CD34 staining, increased mitoses, nuclear atypia, and fascicular growth are features suggestive of sarcomatous transformation.11,12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is associated with chromosomal abnormalities of chromosomes 17 and 22, resulting in COL1A1 (collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain) and PDGF-β (platelet-derived growth factor subunit B) gene fusion.13

Sclerotic fibromas (also known as storiform collagenomas)(Figure 4) may represent regressed DFs and are frequently associated with prior trauma to the affected area.14,15 They usually appear as flesh-colored papules or nodules on the face and trunk. The presence of multiple sclerotic fibromas is associated with Cowden syndrome.16,17 Histologically, the lesions present as well-demarcated, nonencapsulated, dermal nodules composed of a storiform or whorled arrangement of collagen with spindled fibroblasts. The sclerotic collagen bundles often are separated by small clefts imparting a plywoodlike pattern.16

The differential diagnosis for DF expands once atypical clinical and histopathological findings are present. In this case, the nodule was much larger and darker than the usual appearance of DF (3-10 mm).2,4 Given the lesion's nodularity, the clinical dimple sign on lateral compression could not be seen. On biopsy, the predominance of blood vessels and sclerosis further complicated the diagnostic picture. In unusual cases such as this one, correlation of clinical history, histology, and immunophenotype is ever important.

- Zeidi M, North JP. Sebaceous induction in dermatofibroma: a common feature of dermatofibromas on the shoulder. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:400-405.

- Şenel E, Yuyucu Karabulut Y, Doğruer S¸enel S. Clinical, histopathological, dermatoscopic and digital microscopic features of dermatofibroma: a retrospective analysis of 200 lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1958-1966.

- Vilanova JR, Flint A. The morphological variations of fibrous histiocytomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1974;1:155-164.

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JH, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma)[published online May 27, 2011]. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Alves JVP, Matos DM, Barreiros HF, et al. Variants of dermatofibroma--a histopathological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:472-477.

- Rosai J, Sumner HW, Major MC, et al. Angiosarcoma of the skin: a clinicopathologic and fine structural study. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:83-109.

- Haustein UF. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:851-856.

- Stewart FW, Treves N. Lymphangiosarcoma in postmastectomy lymphedema: a report of six cases in elephantiasis chirurgica. Cancer. 1948;1:64-81.

- Goette DK, Detlefs RL. Postirradiation angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(5 pt 2):922-926.

- Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:34-39.

- Voth H, Landsberg J, Hinz T, et al. Management of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with fibrosarcomatous transformation: an evidence-based review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1385-1391.

- Goldblum JR. CD34 positivity in fibrosarcomas which arise in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:238-241.

- Patel KU, Szabo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- Sohn IB, Hwang SM, Lee SH, et al. Dermatofibroma with sclerotic areas resembling a sclerotic fibroma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:44-47.

- Pujol RM, de Castro F, Schroeter AL, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a sclerotic dermatofibroma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:620-624.

- Requena L, Gutiérrez J, Sánchez Yus E. Multiple sclerotic fibromas of the skin: a cutaneous marker of Cowden's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:346-351.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Zeidi M, North JP. Sebaceous induction in dermatofibroma: a common feature of dermatofibromas on the shoulder. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:400-405.

- Şenel E, Yuyucu Karabulut Y, Doğruer S¸enel S. Clinical, histopathological, dermatoscopic and digital microscopic features of dermatofibroma: a retrospective analysis of 200 lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1958-1966.

- Vilanova JR, Flint A. The morphological variations of fibrous histiocytomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1974;1:155-164.

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JH, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma)[published online May 27, 2011]. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Alves JVP, Matos DM, Barreiros HF, et al. Variants of dermatofibroma--a histopathological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:472-477.

- Rosai J, Sumner HW, Major MC, et al. Angiosarcoma of the skin: a clinicopathologic and fine structural study. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:83-109.

- Haustein UF. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:851-856.

- Stewart FW, Treves N. Lymphangiosarcoma in postmastectomy lymphedema: a report of six cases in elephantiasis chirurgica. Cancer. 1948;1:64-81.

- Goette DK, Detlefs RL. Postirradiation angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(5 pt 2):922-926.

- Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:34-39.

- Voth H, Landsberg J, Hinz T, et al. Management of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with fibrosarcomatous transformation: an evidence-based review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1385-1391.

- Goldblum JR. CD34 positivity in fibrosarcomas which arise in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:238-241.

- Patel KU, Szabo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- Sohn IB, Hwang SM, Lee SH, et al. Dermatofibroma with sclerotic areas resembling a sclerotic fibroma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:44-47.

- Pujol RM, de Castro F, Schroeter AL, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a sclerotic dermatofibroma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:620-624.

- Requena L, Gutiérrez J, Sánchez Yus E. Multiple sclerotic fibromas of the skin: a cutaneous marker of Cowden's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:346-351.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

A 61-year-old woman presented with a 2.5-cm hyperpigmented exophytic nodule on the anterior aspect of the left shin of approximately 2 years' duration. The patient initially noticed a small lesion following a bee sting, but it subsequently grew over the ensuing 2 years. A shave biopsy was obtained.

Black Adherence Nodules on the Scalp Hair Shaft

The Diagnosis: Piedra

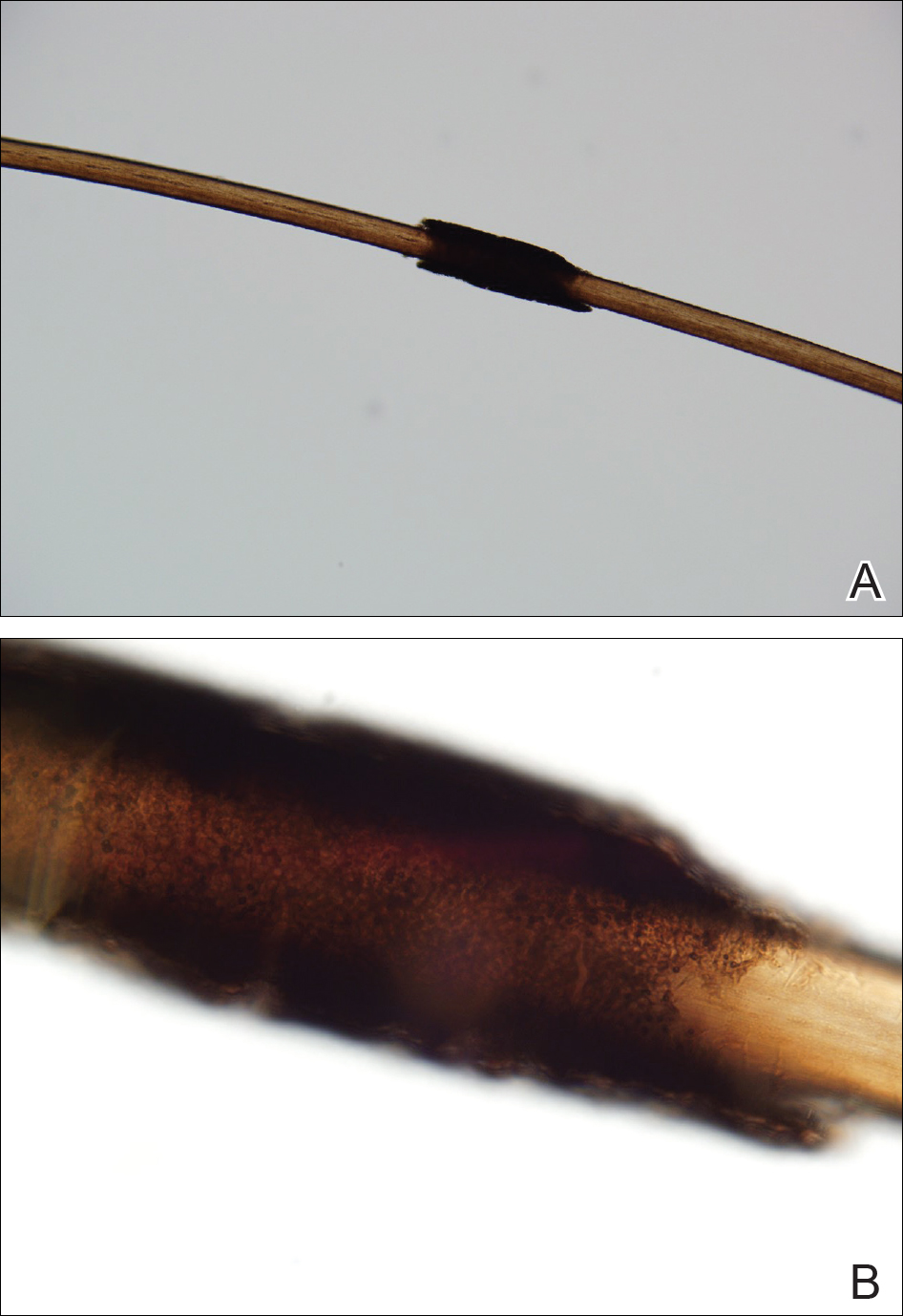

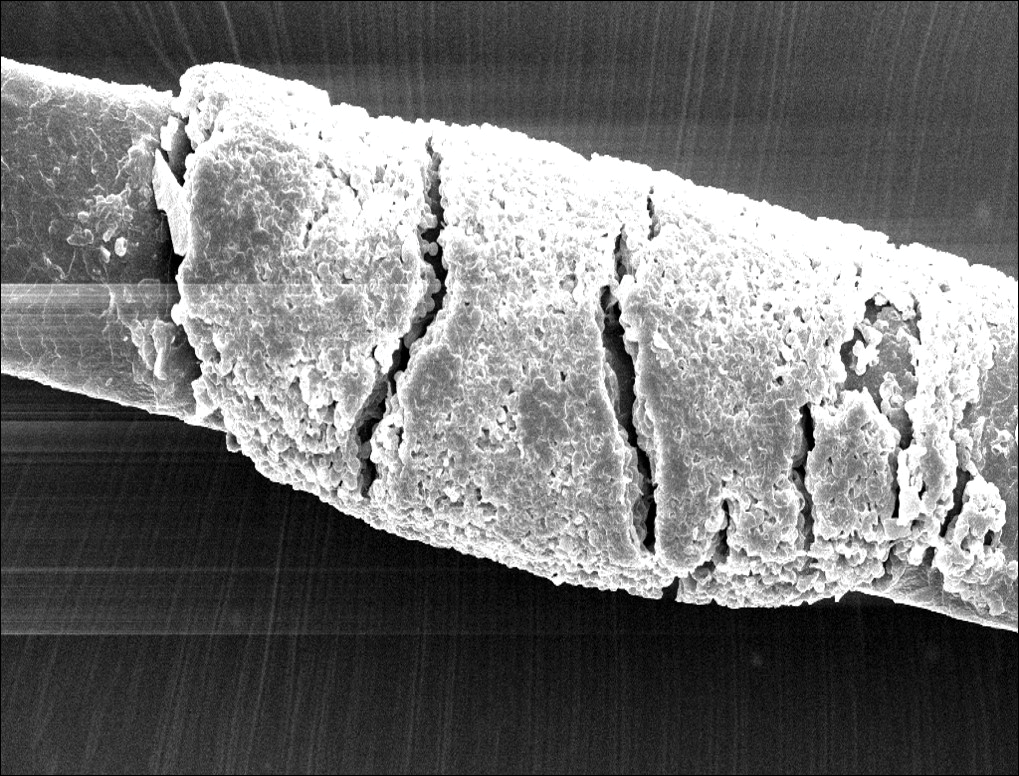

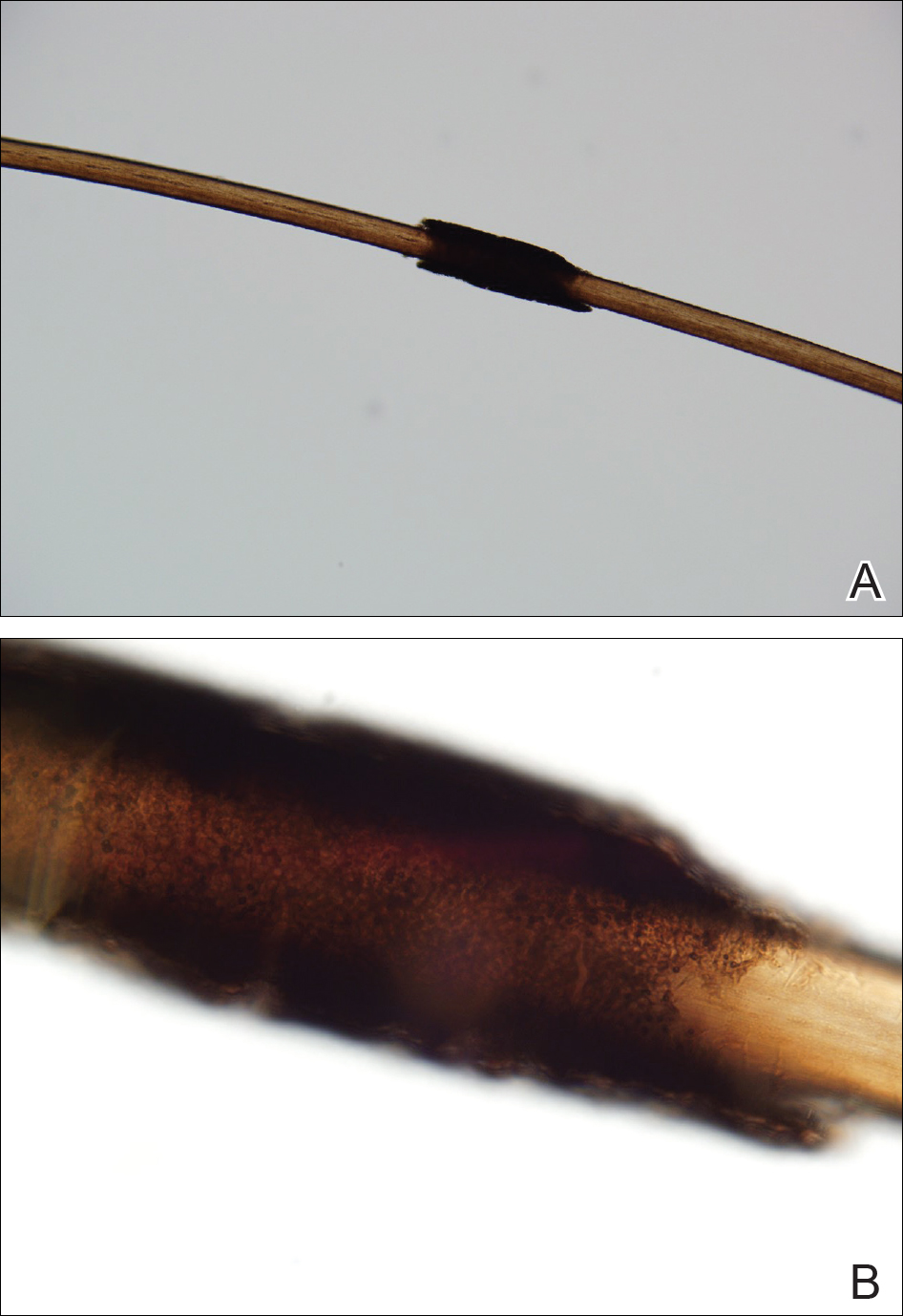

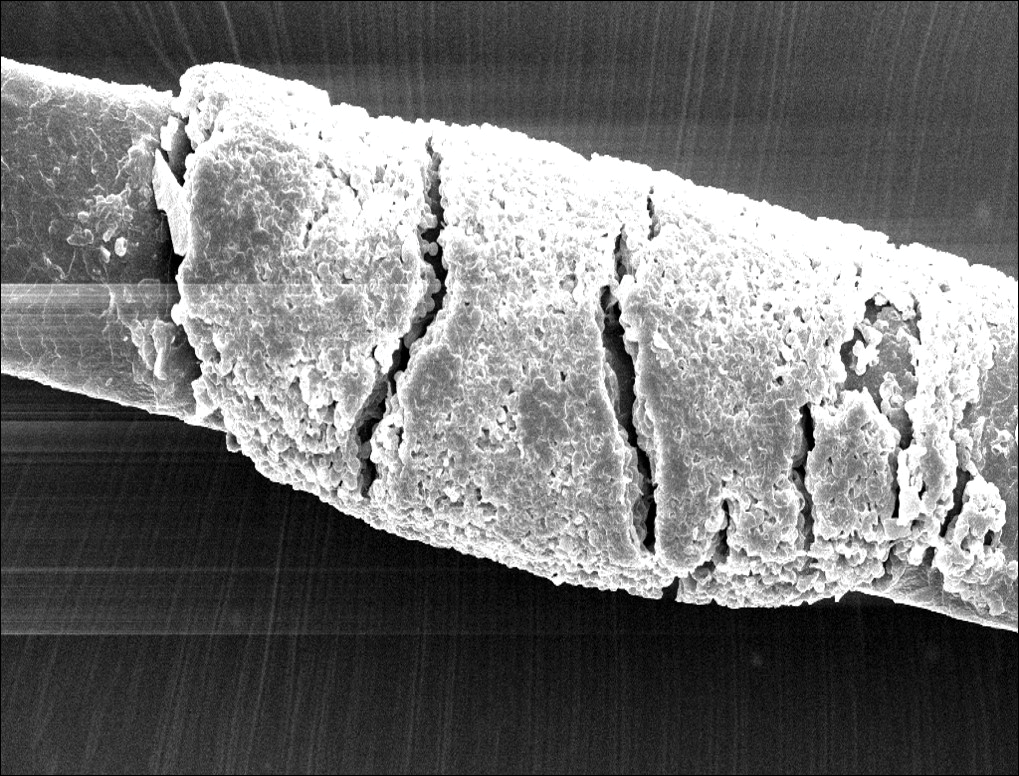

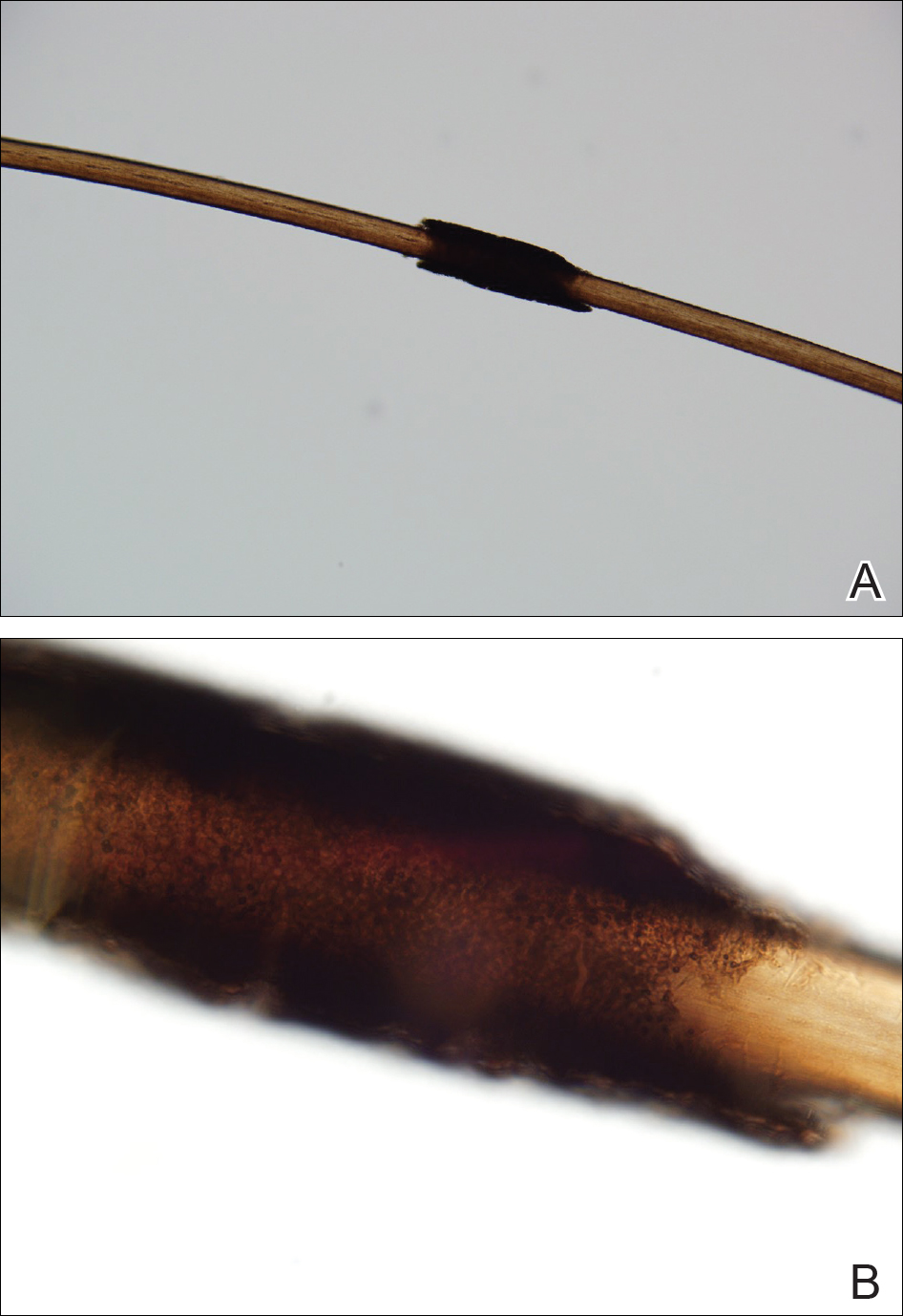

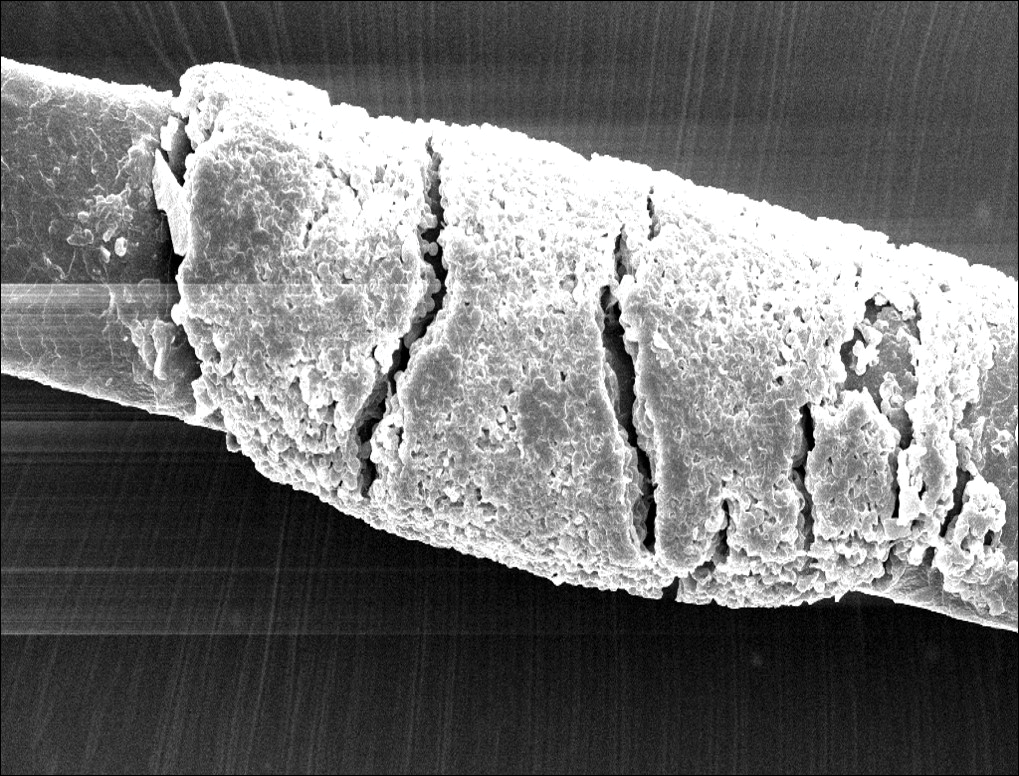

Microscopic examination of the hair shafts revealed brown to black, firmly adherent concretions (Figure 1). Scanning electron microscopy of the nodules was performed, which allowed for greater definition of the constituent hyphae and arthrospores (Figure 2).

Fungal cultures grew Trichosporon inkin along with other dematiaceous molds. The patient initially was treated with a combination of ketoconazole shampoo and weekly application of topical terbinafine. She trimmed 15.2 cm of the hair of her own volition. At 2-month follow-up the nodules were still present, though smaller and less numerous. Repeat cultures were obtained, which again grew T inkin. She then began taking oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 6 weeks.

This case of piedra is unique in that our patient presented with black nodules clinically, but cultures grew only the causative agent of white piedra, T inkin. A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms black piedra, white piedra, or piedra, and mixed infection or coinfection yielded one other similar case.1 Kanitakis et al1 speculated that perhaps there was coinfection of black and white piedra and that Piedraia hortae, the causative agent of black piedra, was unable to flourish in culture facing competition from other fungi. This scenario also could apply to our patient. However, the original culture taken from our patient also grew other dematiaceous molds including Cladosporium and Exophiala species. It also is possible that these other fungi could have contributed pigment to the nodules, giving it the appearance of black piedra when only T inkin was present as the true pathogen.