User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Recent Controversies in Pediatric Dermatology: The Usage of General Anesthesia in Young Children

Clinicians who have attempted to perform an in-office procedure on infants or young children will recognize the difficulties that arise from the developmental inability to cooperate with procedures.1 Potential problems mentioned in the literature include but are not limited to anxiety, which is identified in all age groups of patients undergoing dermatologic procedures2; limitation of pain control3; and poor outcomes due to movement by the patient.1 In one author’s experience (N.B.S.), anxious and scared children can potentially cause injury to themselves, parents/guardians, and health care professionals by flailing and kicking; children are flexible and can wriggle out of even fine grips, and some children, especially toddlers, can be strong.

The usage of topical anesthetics can only give superficial anesthesia. They can ostensibly reduce pain and are useful for anesthesia of curettage, but their use is limited in infants and young children by the minimal amount of drug that is safe for application, as risks of absorption include methemoglobinemia and seizure

General anesthesia seems to be the best alternative due to associated amnesia of the events occurring including pain; immobilization and ability to produce more accurate biopsy sampling; better immobilization leading to superior cosmetic results; and reduced risk to patients, parents/guardians, and health care professionals from a flailing child. In the field of pediatric dermatology, general anesthesia often is used for excision of larger lesions and cosmetic repairs. Operating room privileges are not always easy to obtain, but many pediatric dermatologists take advantage of outpatient surgical centers associated with their medical center. A retrospective review of 226 children receiving 681 procedures at a single institution documented low rates of complications.1

If it was that easy, most children would be anesthetized with general anesthesia. However, there are risks associated with general anesthesia. Parents/guardians often will do what they can to avoid risk and may therefore refuse general anesthesia, but it is not completely avoidable in complicated skin disease. Despite the risks, the benefit is present in a major anomaly correction such as a cleft palate in a 6-month-old but may not be there for the treatment of a wart. When procedures are nonessential or may be conducted without anesthesia, avoidance of general anesthesia is reasonable and a combination of topical and local infiltrative anesthesia can help. In the American Academy of Dermatology guidelines on in-office anesthesia, Kouba et al5 states: “Topical agents are recommended as a first-line method of anesthesia for the repair of dermal lacerations in children and for other minor dermatologic procedures, including curettage. For skin biopsy, excision, or other cases where topical agents alone are insufficient, adjunctive use of topical anesthesia to lessen the discomfort of infiltrative anesthetic should be considered.”

A new controversy recently has emerged concerning the potential risks of anesthesia on neurocognitive development in infants and young children. These concerns regardingthe labeling changes of anesthetic and sedation drugs by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December 2016 specifically focused on these risks in children younger than 3 years with prolonged (>3 hours) and repeated exposures; however, this kind of exposure is unlikely with standard pediatric dermatologic procedures.6-9

There is compelling evidence from animal studies that exposure to all anesthetic agents in clinical use induces neurotoxicity and long-term adverse neurobehavioral deficits; however, whether these findings are applicable in human infants is unknown.6-9 Most of the studies in humans showing adverse outcomes have been retrospective observational studies subject to multiple sources of bias. Two recent large clinical studies—the GAS (General Anaesthesia compared to Spinal anaesthesia) trial10 and the PANDA (Pediatric Anesthesia and Neurodevelopment Assessment) study11—have shown no evidence of abnormal neurocognitive effects with a single brief exposure before 3 years of age (PANDA) or during infancy (GAS) in otherwise-healthy children.10,11

It is important to note that the FDA labeling change warning specifically stated that “[c]onsistent with animal studies, recent human data suggest that a single, relatively short exposure to general anesthetic and sedation drugs in infants or toddlers is unlikely to have negative effects on behavior or learning.” Moreover, the FDA emphasized that “Surgeries or procedures in children younger than 3 years should not be delayed or avoided when medically necessary.”12 Taking these points into consideration, we should offer our patients in-office care when possible and postpone elective procedures when advisable but proceed when necessary for our patients’ physical and emotional health.

- Juern AM, Cassidy LD, Lyon VB. More evidence confirming the safety of general anesthesia in pediatric dermatologic surgery. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:355-360.

- Gerwels JW, Bezzant JL, Le Maire L, et al. Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate premedication in patients undergoing outpatient dermatologic procedures. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:823-826.

- D’Acunto C, Raone B, Neri I, et al. Outpatient pediatric dermatologic surgery: experience in 296 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:424-426.

- Gunter JB. Benefit and risks of local anesthetics in infants and children. Paediatr Drugs. 2002;4:649-672.

- Kouba DJ, LoPiccolo MC, Alam M, et al. Guidelines for the use of local anesthesia in office-based dermatologic surgery [published online March 4, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1201-1219.

- Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Hartman RE, Izumi Y, et al. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. J Neurosci. 2003;23:876-882.

- Brambrink AM, Evers AS, Avidan MS, et al. Isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis in the neonatal rhesus macaque brain. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:834-841.

- Raper J, Alvarado MC, Murphy KL, et al. Multiple anesthetic exposure in infant monkeys alters emotional reactivity to an acute stressor. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:1084-1092.

- Davidson AJ. Anesthesia and neurotoxicity to the developing brain: the clinical relevance. Paediatric Anaesthesia. 2011;21:716-721.

- Davidson AJ, Disma N, de Graaff JC, et al; GAS consortium. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years of age after general anaesthesia and awake-regional anaesthesia in infancy (GAS): an international multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:239-250.

- Sun LS, Li G, Miller TL, et al. Association between a single general anesthesia exposure before age 36 months and neurocognitive outcomes in later childhood. JAMA. 2016;315:2312-2320.

- General anesthetic and sedation drugs: drug safety communication—new warnings for young children and pregnant women. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch/safetyinformation/safetyalertsforhumanmedicalproducts/ucm533195.htm. Published December 14, 2016. Accessed July 25, 2017.

Clinicians who have attempted to perform an in-office procedure on infants or young children will recognize the difficulties that arise from the developmental inability to cooperate with procedures.1 Potential problems mentioned in the literature include but are not limited to anxiety, which is identified in all age groups of patients undergoing dermatologic procedures2; limitation of pain control3; and poor outcomes due to movement by the patient.1 In one author’s experience (N.B.S.), anxious and scared children can potentially cause injury to themselves, parents/guardians, and health care professionals by flailing and kicking; children are flexible and can wriggle out of even fine grips, and some children, especially toddlers, can be strong.

The usage of topical anesthetics can only give superficial anesthesia. They can ostensibly reduce pain and are useful for anesthesia of curettage, but their use is limited in infants and young children by the minimal amount of drug that is safe for application, as risks of absorption include methemoglobinemia and seizure

General anesthesia seems to be the best alternative due to associated amnesia of the events occurring including pain; immobilization and ability to produce more accurate biopsy sampling; better immobilization leading to superior cosmetic results; and reduced risk to patients, parents/guardians, and health care professionals from a flailing child. In the field of pediatric dermatology, general anesthesia often is used for excision of larger lesions and cosmetic repairs. Operating room privileges are not always easy to obtain, but many pediatric dermatologists take advantage of outpatient surgical centers associated with their medical center. A retrospective review of 226 children receiving 681 procedures at a single institution documented low rates of complications.1

If it was that easy, most children would be anesthetized with general anesthesia. However, there are risks associated with general anesthesia. Parents/guardians often will do what they can to avoid risk and may therefore refuse general anesthesia, but it is not completely avoidable in complicated skin disease. Despite the risks, the benefit is present in a major anomaly correction such as a cleft palate in a 6-month-old but may not be there for the treatment of a wart. When procedures are nonessential or may be conducted without anesthesia, avoidance of general anesthesia is reasonable and a combination of topical and local infiltrative anesthesia can help. In the American Academy of Dermatology guidelines on in-office anesthesia, Kouba et al5 states: “Topical agents are recommended as a first-line method of anesthesia for the repair of dermal lacerations in children and for other minor dermatologic procedures, including curettage. For skin biopsy, excision, or other cases where topical agents alone are insufficient, adjunctive use of topical anesthesia to lessen the discomfort of infiltrative anesthetic should be considered.”

A new controversy recently has emerged concerning the potential risks of anesthesia on neurocognitive development in infants and young children. These concerns regardingthe labeling changes of anesthetic and sedation drugs by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December 2016 specifically focused on these risks in children younger than 3 years with prolonged (>3 hours) and repeated exposures; however, this kind of exposure is unlikely with standard pediatric dermatologic procedures.6-9

There is compelling evidence from animal studies that exposure to all anesthetic agents in clinical use induces neurotoxicity and long-term adverse neurobehavioral deficits; however, whether these findings are applicable in human infants is unknown.6-9 Most of the studies in humans showing adverse outcomes have been retrospective observational studies subject to multiple sources of bias. Two recent large clinical studies—the GAS (General Anaesthesia compared to Spinal anaesthesia) trial10 and the PANDA (Pediatric Anesthesia and Neurodevelopment Assessment) study11—have shown no evidence of abnormal neurocognitive effects with a single brief exposure before 3 years of age (PANDA) or during infancy (GAS) in otherwise-healthy children.10,11

It is important to note that the FDA labeling change warning specifically stated that “[c]onsistent with animal studies, recent human data suggest that a single, relatively short exposure to general anesthetic and sedation drugs in infants or toddlers is unlikely to have negative effects on behavior or learning.” Moreover, the FDA emphasized that “Surgeries or procedures in children younger than 3 years should not be delayed or avoided when medically necessary.”12 Taking these points into consideration, we should offer our patients in-office care when possible and postpone elective procedures when advisable but proceed when necessary for our patients’ physical and emotional health.

Clinicians who have attempted to perform an in-office procedure on infants or young children will recognize the difficulties that arise from the developmental inability to cooperate with procedures.1 Potential problems mentioned in the literature include but are not limited to anxiety, which is identified in all age groups of patients undergoing dermatologic procedures2; limitation of pain control3; and poor outcomes due to movement by the patient.1 In one author’s experience (N.B.S.), anxious and scared children can potentially cause injury to themselves, parents/guardians, and health care professionals by flailing and kicking; children are flexible and can wriggle out of even fine grips, and some children, especially toddlers, can be strong.

The usage of topical anesthetics can only give superficial anesthesia. They can ostensibly reduce pain and are useful for anesthesia of curettage, but their use is limited in infants and young children by the minimal amount of drug that is safe for application, as risks of absorption include methemoglobinemia and seizure

General anesthesia seems to be the best alternative due to associated amnesia of the events occurring including pain; immobilization and ability to produce more accurate biopsy sampling; better immobilization leading to superior cosmetic results; and reduced risk to patients, parents/guardians, and health care professionals from a flailing child. In the field of pediatric dermatology, general anesthesia often is used for excision of larger lesions and cosmetic repairs. Operating room privileges are not always easy to obtain, but many pediatric dermatologists take advantage of outpatient surgical centers associated with their medical center. A retrospective review of 226 children receiving 681 procedures at a single institution documented low rates of complications.1

If it was that easy, most children would be anesthetized with general anesthesia. However, there are risks associated with general anesthesia. Parents/guardians often will do what they can to avoid risk and may therefore refuse general anesthesia, but it is not completely avoidable in complicated skin disease. Despite the risks, the benefit is present in a major anomaly correction such as a cleft palate in a 6-month-old but may not be there for the treatment of a wart. When procedures are nonessential or may be conducted without anesthesia, avoidance of general anesthesia is reasonable and a combination of topical and local infiltrative anesthesia can help. In the American Academy of Dermatology guidelines on in-office anesthesia, Kouba et al5 states: “Topical agents are recommended as a first-line method of anesthesia for the repair of dermal lacerations in children and for other minor dermatologic procedures, including curettage. For skin biopsy, excision, or other cases where topical agents alone are insufficient, adjunctive use of topical anesthesia to lessen the discomfort of infiltrative anesthetic should be considered.”

A new controversy recently has emerged concerning the potential risks of anesthesia on neurocognitive development in infants and young children. These concerns regardingthe labeling changes of anesthetic and sedation drugs by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December 2016 specifically focused on these risks in children younger than 3 years with prolonged (>3 hours) and repeated exposures; however, this kind of exposure is unlikely with standard pediatric dermatologic procedures.6-9

There is compelling evidence from animal studies that exposure to all anesthetic agents in clinical use induces neurotoxicity and long-term adverse neurobehavioral deficits; however, whether these findings are applicable in human infants is unknown.6-9 Most of the studies in humans showing adverse outcomes have been retrospective observational studies subject to multiple sources of bias. Two recent large clinical studies—the GAS (General Anaesthesia compared to Spinal anaesthesia) trial10 and the PANDA (Pediatric Anesthesia and Neurodevelopment Assessment) study11—have shown no evidence of abnormal neurocognitive effects with a single brief exposure before 3 years of age (PANDA) or during infancy (GAS) in otherwise-healthy children.10,11

It is important to note that the FDA labeling change warning specifically stated that “[c]onsistent with animal studies, recent human data suggest that a single, relatively short exposure to general anesthetic and sedation drugs in infants or toddlers is unlikely to have negative effects on behavior or learning.” Moreover, the FDA emphasized that “Surgeries or procedures in children younger than 3 years should not be delayed or avoided when medically necessary.”12 Taking these points into consideration, we should offer our patients in-office care when possible and postpone elective procedures when advisable but proceed when necessary for our patients’ physical and emotional health.

- Juern AM, Cassidy LD, Lyon VB. More evidence confirming the safety of general anesthesia in pediatric dermatologic surgery. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:355-360.

- Gerwels JW, Bezzant JL, Le Maire L, et al. Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate premedication in patients undergoing outpatient dermatologic procedures. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:823-826.

- D’Acunto C, Raone B, Neri I, et al. Outpatient pediatric dermatologic surgery: experience in 296 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:424-426.

- Gunter JB. Benefit and risks of local anesthetics in infants and children. Paediatr Drugs. 2002;4:649-672.

- Kouba DJ, LoPiccolo MC, Alam M, et al. Guidelines for the use of local anesthesia in office-based dermatologic surgery [published online March 4, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1201-1219.

- Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Hartman RE, Izumi Y, et al. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. J Neurosci. 2003;23:876-882.

- Brambrink AM, Evers AS, Avidan MS, et al. Isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis in the neonatal rhesus macaque brain. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:834-841.

- Raper J, Alvarado MC, Murphy KL, et al. Multiple anesthetic exposure in infant monkeys alters emotional reactivity to an acute stressor. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:1084-1092.

- Davidson AJ. Anesthesia and neurotoxicity to the developing brain: the clinical relevance. Paediatric Anaesthesia. 2011;21:716-721.

- Davidson AJ, Disma N, de Graaff JC, et al; GAS consortium. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years of age after general anaesthesia and awake-regional anaesthesia in infancy (GAS): an international multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:239-250.

- Sun LS, Li G, Miller TL, et al. Association between a single general anesthesia exposure before age 36 months and neurocognitive outcomes in later childhood. JAMA. 2016;315:2312-2320.

- General anesthetic and sedation drugs: drug safety communication—new warnings for young children and pregnant women. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch/safetyinformation/safetyalertsforhumanmedicalproducts/ucm533195.htm. Published December 14, 2016. Accessed July 25, 2017.

- Juern AM, Cassidy LD, Lyon VB. More evidence confirming the safety of general anesthesia in pediatric dermatologic surgery. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:355-360.

- Gerwels JW, Bezzant JL, Le Maire L, et al. Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate premedication in patients undergoing outpatient dermatologic procedures. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:823-826.

- D’Acunto C, Raone B, Neri I, et al. Outpatient pediatric dermatologic surgery: experience in 296 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:424-426.

- Gunter JB. Benefit and risks of local anesthetics in infants and children. Paediatr Drugs. 2002;4:649-672.

- Kouba DJ, LoPiccolo MC, Alam M, et al. Guidelines for the use of local anesthesia in office-based dermatologic surgery [published online March 4, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1201-1219.

- Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Hartman RE, Izumi Y, et al. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. J Neurosci. 2003;23:876-882.

- Brambrink AM, Evers AS, Avidan MS, et al. Isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis in the neonatal rhesus macaque brain. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:834-841.

- Raper J, Alvarado MC, Murphy KL, et al. Multiple anesthetic exposure in infant monkeys alters emotional reactivity to an acute stressor. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:1084-1092.

- Davidson AJ. Anesthesia and neurotoxicity to the developing brain: the clinical relevance. Paediatric Anaesthesia. 2011;21:716-721.

- Davidson AJ, Disma N, de Graaff JC, et al; GAS consortium. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years of age after general anaesthesia and awake-regional anaesthesia in infancy (GAS): an international multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:239-250.

- Sun LS, Li G, Miller TL, et al. Association between a single general anesthesia exposure before age 36 months and neurocognitive outcomes in later childhood. JAMA. 2016;315:2312-2320.

- General anesthetic and sedation drugs: drug safety communication—new warnings for young children and pregnant women. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch/safetyinformation/safetyalertsforhumanmedicalproducts/ucm533195.htm. Published December 14, 2016. Accessed July 25, 2017.

Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy: A Diagnostic Tool for Skin Malignancies

Skin cancer is diagnosed in approximately 5.4 million individuals annually in the United States, more than the total number of breast, lung, colon, and prostate cancers diagnosed per year.1 It is estimated that 1 in 5 Americans will develop skin cancer during their lifetime.2 The 2 most common forms of skin cancer are basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), accounting for 4 million and 1 million cases diagnosed each year, respectively.3 With the increasing incidence of these skin cancers, the use of noninvasive imaging tools for detection and diagnosis has grown.

Ex vivo confocal microscopy is a diagnostic imaging tool that can be used in real-time at the bedside to assess freshly excised tissue for malignancies. It images tissue samples with cellular resolution and within minutes of biopsy or excision. Ex vivo confocal microscopy is a versatile tool that can assist in the diagnosis and management of skin malignancies such as melanoma, BCC, and SCC.

Reflectance vs Fluorescence Mode

Excised lesions can be examined in reflectance or fluorescence mode in great detail but with slightly varying nuclear-to-dermis contrasts depending on the chromophore that is targeted. In reflectance mode (reflectance confocal microscopy [RCM]), melanin and keratin act as endogenous chromophores because of their high refractive index relative to water,4,5 which allows for the visualization of cellular structures of the skin at low power, as well as microscopic substructures such as melanosomes, cytoplasmic granules, and other cellular organelles at high power. Although an exogenous contrast agent is not required, acetic acid has the capability to highlight nuclei, enhancing the tumor cell-to-dermis contrast in RCM.6 Acetic acid is clinically used as a predictor for certain skin and mucosal membrane neoplasms that blanch when exposed to the solution. In the case of RCM, acetic acid increases the visibility of nuclei by inducing the compaction of chromatin. For the acetowhitening to be effective, the sample must be soaked in the solution for a specific amount of time, depending on the concentration.7 A concentration between 1% and 10% can be used, but the less concentrated the solution, the longer the time of soaking that is required to achieve sufficiently bright nuclei.6

The contrast with acetic acid, however, is quite weak when the tissue is imaged en face, or along the horizontal surface of the sample, due to the collagen in the dermal layer, which has a high reflectance index. This issue is rectified when using the confocal microscope in the fluorescence mode with an exogenous fluorescent dye as a nuclear stain. Fluorescence confocal microscopy (FCM), results in a stronger nuclear-to-dermal contrast because of the role of contrast agents.8 The 1000-fold increase in contrast between nuclei and dermis is the result of dye agents that preferentially bind to nuclear DNA, of which acridine orange is the most commonly used.5,8 Basal cell carcinoma and SCC tumor cells can be visualized with FCM because they appear hyperfluorescent when stained with acridine orange.9 The acridine orange–stained cells display bright nuclei, while the cytoplasm and collagen remains dark. A positive feature of acridine orange is that it does not alter the tissue sample during freezing or formalin fixation and thus has no effect on subsequent histopathology that may need to be performed on the sample.10

High-Resolution Images Aid in Diagnosis

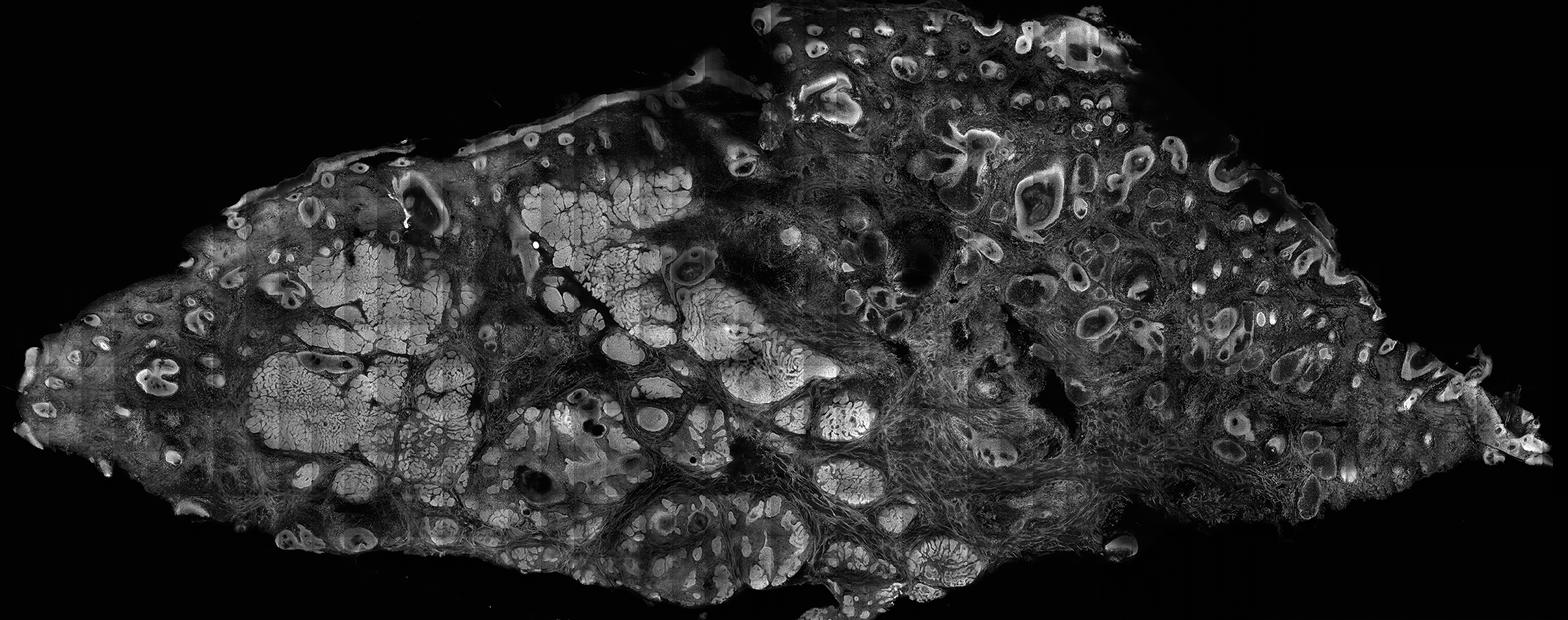

After it is harvested, the tissue sample is soaked in a contrast agent or dye, if needed, depending on the confocal mode to be used. The confocal microscope is then used to take a series of high-resolution individual en face images that are then stitched together to create a final mosaic image that can be up to 12×12 mm.6,11 With a 200-µm depth visibility, confocal microscopy can capture the cellular structures in the epidermis, dermis, and (if compressed enough) subcutaneous fat in just under 3 minutes.12

The images produced through confocal microscopy have an excellent correlation to frozen histological sections and can aid in the diagnosis of many epidermal and dermal malignancies including melanoma, BCC, and SCC. New criteria have been established to aid in the interpretation of the confocal images and identify some of the more common skin cancers.5,12,13 Basal cell carcinoma samples imaged through fluorescence and reflectance in low-power mode display the distinct nodular patterns with well-demarcated edges, as seen on classical histopathology. In the case of FCM, the cells that make up the tumor display hyperfluorescent areas consistent with nucleated cells that are stained with acridine orange. The main features that identify BCC on FCM images include nuclear pleomorphism and crowding, peripheral palisading, clefting of the basaloid islands, increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, and the presence of a modified dermis surrounding the mass known as the tumoral stroma5,12 (Figure).

In addition to fluorescence and a well-defined tumor silhouette, SCC under FCM displays keratin pearls composed of keratinized squames, nuclear pleomorphism, and fluorescent scales in the stratum corneum that are a result of keratin formation.5,13 The extent of differentiation of the SCC lesion also can be determined by assessing if the silhouette is well defined. A well-defined tumor silhouette is consistent with the diagnosis of a well-differentiated SCC, and vice versa.13 Ex vivo RCM also has been shown to be useful in diagnosing malignant melanomas, with melanin acting as an endogenous chromophore. Some of the features seen on imaging include a disarranged epithelium, hyperreflective roundish and dendritic pagetoid cells, and large hyperreflective polymorphic cells in the superficial chorion.14

Comparison to Conventional Histopathology

Ex vivo confocal microscopy in both the reflectance and fluorescence mode has been shown to perform well compared to conventional histopathology in the diagnosis of biopsy specimens. Ex vivo FCM has been shown to have an overall sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 99% in detecting residual BCC at the margins of excised tissue samples and in the fraction of the time it takes to attain similar results with frozen histopathology.9 Ex vivo RCM has been shown to have a higher prognostic capability, with 100% sensitivity and specificity in identifying BCC when scanning the tissue samples en face.15

Qualitatively, the images produced by RCM and FCM are similar to histopathology in overall architecture. Both techniques enhance the contrast between the epithelium and stroma and create images that can be examined in low as well as high resolution. A substantial difference between confocal microscopy and conventional hematoxylin and eosin–stained histopathology is that the confocal microscope produces images in gray scale. One way to alter the black-and-white images to resemble hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides is through the use of digital staining,16 which could boost clinical acceptance by physicians who are accustomed to the classical pink-purple appearance of pathology slides and could potentially limit the learning curve needed to read the confocal images.

Application in Mohs Micrographic Surgery

An important clinical application of ex vivo FCM imaging that has emerged is the detection of malignant cells at the excision margins during Mohs micrographic surgery. The use of confocal microscopy has the potential to save time by eliminating the need for tissue fixation while still providing good diagnostic accuracy. Implementing FCM as an imaging tool to guide surgical excisions could provide rapid diagnosis of the tissue, expediting excisions and reconstruction or the Mohs procedure while eliminating patient wait time and the need for frozen histopathology. Ex vivo RCM also has been used to establish laser parameters for CO2 laser ablation of superficial and early nodular BCC lesions.17 Other potential uses for ex vivo RCM/FCM could include rapid evaluation of tissue during operating room procedures where rapid frozen sections are currently utilized.

Combining In Vivo and Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy

Many of the diagnostic guidelines created with the use of ex vivo confocal microscopy have been applied to in vivo use, and therefore the use of both modalities is appealing. In vivo confocal microscopy is a noninvasive technique that has been used to map margins of skin tumors such as BCC and lentigo maligna at the bedside.5 It also has been shown to help plan both surgical and nonsurgical treatment modalities and reconstruction before the tumor is excised.18 This technique also can help the patient understand the extent of the excision and any subsequent reconstruction that may be needed.

Limitations

Ex vivo confocal microscopy used as a diagnostic tool does have some limitations. Its novelty may require surgeons and pathologists to be trained to interpret the images properly and correlate them to conventional diagnostic guidelines. The imaging also is limited to a depth of approximately 200 µm; however, the sample may be flipped so that the underside can be imaged as well, which increases the depth to approximately 400 µm. The tissue being imaged must be fixed flat, which may alter its shape. Complex tissue samples may be difficult to flatten out completely and therefore may be difficult to image. A special mount may be required for the sample to be fixed in a proper position for imaging.6

Final Thoughts

Despite some of these limitations, the need for rapid bedside tissue diagnosis makes ex vivo confocal microscopy an attractive device that can be used as an additional diagnostic tool to histopathology and also has been tested in other disciplines, such as breast cancer pathology. In the future, both in vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy may be utilized to diagnose cutaneous malignancies, guide surgical excisions, and detect lesion progression, and it may become a basis for rapid diagnosis and detection.19

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016 [published online January 7, 2016]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30.

- Robinson JK. Sun exposure, sun protection, and vitamin D. JAMA. 2005;294:1541-1543.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Welzel J, Kästle R, Sattler EC. Fluorescence (multiwave) confocal microscopy. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:527-533.

- Longo C, Ragazzi M, Rajadhyaksha M, et al. In vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy for dermatologic and Mohs surgeons. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:497-504.

- Patel YG, Nehal KS, Aranda I, et al. Confocal reflectance mosaicing of basal cell carcinomas in Mohs surgical skin excisions. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:034027.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Gonzalez S, Zavislan JM. Detectability of contrast agents for confocal reflectance imaging of skin and microcirculation. J Biomed Opt. 2004;9:323-331.

- Karen JK, Gareau DS, Dusza SW, et al. Detection of basal cell carcinomas in Mohs excisions with fluorescence confocal mosaicing microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:1242-1250.

- Bennàssar A, Vilata A, Puig S, et al. Ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy for fast evaluation of tumour margins during Mohs surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:360-365.

- Gareau DS, Li Y, Huang B, et al. Confocal mosaicing microscopy in Mohs skin excisions: feasibility of rapid surgical pathology. J Biomed Opt. 2008;13:054001.

- Bini J, Spain J, Nehal K, et al. Confocal mosaicing microscopy of human skin ex vivo: spectral analysis for digital staining to simulate histology-like appearance. J Biomed Opt. 2011;16:076008.

- Bennàssar A, Carrera C, Puig S, et al. Fast evaluation of 69 basal cell carcinomas with ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy: criteria description, histopathological correlation, and interobserver agreement. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:839-847.

- Longo C, Ragazzi M, Gardini S, et al. Ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy in conjunction with Mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:321-322.

- Cinotti E, Haouas M, Grivet D, et al. In vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy for the management of a melanoma of the eyelid margin. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1437-1440.

- , , , ‘En face’ ex vivo reflectance confocal microscopy to help the surgery of basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid [published online December 19, 2016]. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. doi:10.1111/ceo.12904.

- Gareau DS, Jeon H, Nehal KS, et al. Rapid screening of cancer margins in tissue with multimodal confocal microscopy. J Surg Res. 2012;178:533-538.

- Sierra H, Damanpour S, Hibler B, et al. Confocal imaging of carbon dioxide laser-ablated basal cell carcinomas: an ex-vivo study on the uptake of contrast agent and ablation parameters [published online September 22, 2015]. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:133-139.

- Hibler BP, Yélamos O, Cordova M, et al. Handheld reflectance confocal microscopy to aid in the management of complex facial lentigo maligna. Cutis. 2017;99:346-352.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Marghoob A, Rossi A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy of skin in vivo: from bench to bedside. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:7-19.

Skin cancer is diagnosed in approximately 5.4 million individuals annually in the United States, more than the total number of breast, lung, colon, and prostate cancers diagnosed per year.1 It is estimated that 1 in 5 Americans will develop skin cancer during their lifetime.2 The 2 most common forms of skin cancer are basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), accounting for 4 million and 1 million cases diagnosed each year, respectively.3 With the increasing incidence of these skin cancers, the use of noninvasive imaging tools for detection and diagnosis has grown.

Ex vivo confocal microscopy is a diagnostic imaging tool that can be used in real-time at the bedside to assess freshly excised tissue for malignancies. It images tissue samples with cellular resolution and within minutes of biopsy or excision. Ex vivo confocal microscopy is a versatile tool that can assist in the diagnosis and management of skin malignancies such as melanoma, BCC, and SCC.

Reflectance vs Fluorescence Mode

Excised lesions can be examined in reflectance or fluorescence mode in great detail but with slightly varying nuclear-to-dermis contrasts depending on the chromophore that is targeted. In reflectance mode (reflectance confocal microscopy [RCM]), melanin and keratin act as endogenous chromophores because of their high refractive index relative to water,4,5 which allows for the visualization of cellular structures of the skin at low power, as well as microscopic substructures such as melanosomes, cytoplasmic granules, and other cellular organelles at high power. Although an exogenous contrast agent is not required, acetic acid has the capability to highlight nuclei, enhancing the tumor cell-to-dermis contrast in RCM.6 Acetic acid is clinically used as a predictor for certain skin and mucosal membrane neoplasms that blanch when exposed to the solution. In the case of RCM, acetic acid increases the visibility of nuclei by inducing the compaction of chromatin. For the acetowhitening to be effective, the sample must be soaked in the solution for a specific amount of time, depending on the concentration.7 A concentration between 1% and 10% can be used, but the less concentrated the solution, the longer the time of soaking that is required to achieve sufficiently bright nuclei.6

The contrast with acetic acid, however, is quite weak when the tissue is imaged en face, or along the horizontal surface of the sample, due to the collagen in the dermal layer, which has a high reflectance index. This issue is rectified when using the confocal microscope in the fluorescence mode with an exogenous fluorescent dye as a nuclear stain. Fluorescence confocal microscopy (FCM), results in a stronger nuclear-to-dermal contrast because of the role of contrast agents.8 The 1000-fold increase in contrast between nuclei and dermis is the result of dye agents that preferentially bind to nuclear DNA, of which acridine orange is the most commonly used.5,8 Basal cell carcinoma and SCC tumor cells can be visualized with FCM because they appear hyperfluorescent when stained with acridine orange.9 The acridine orange–stained cells display bright nuclei, while the cytoplasm and collagen remains dark. A positive feature of acridine orange is that it does not alter the tissue sample during freezing or formalin fixation and thus has no effect on subsequent histopathology that may need to be performed on the sample.10

High-Resolution Images Aid in Diagnosis

After it is harvested, the tissue sample is soaked in a contrast agent or dye, if needed, depending on the confocal mode to be used. The confocal microscope is then used to take a series of high-resolution individual en face images that are then stitched together to create a final mosaic image that can be up to 12×12 mm.6,11 With a 200-µm depth visibility, confocal microscopy can capture the cellular structures in the epidermis, dermis, and (if compressed enough) subcutaneous fat in just under 3 minutes.12

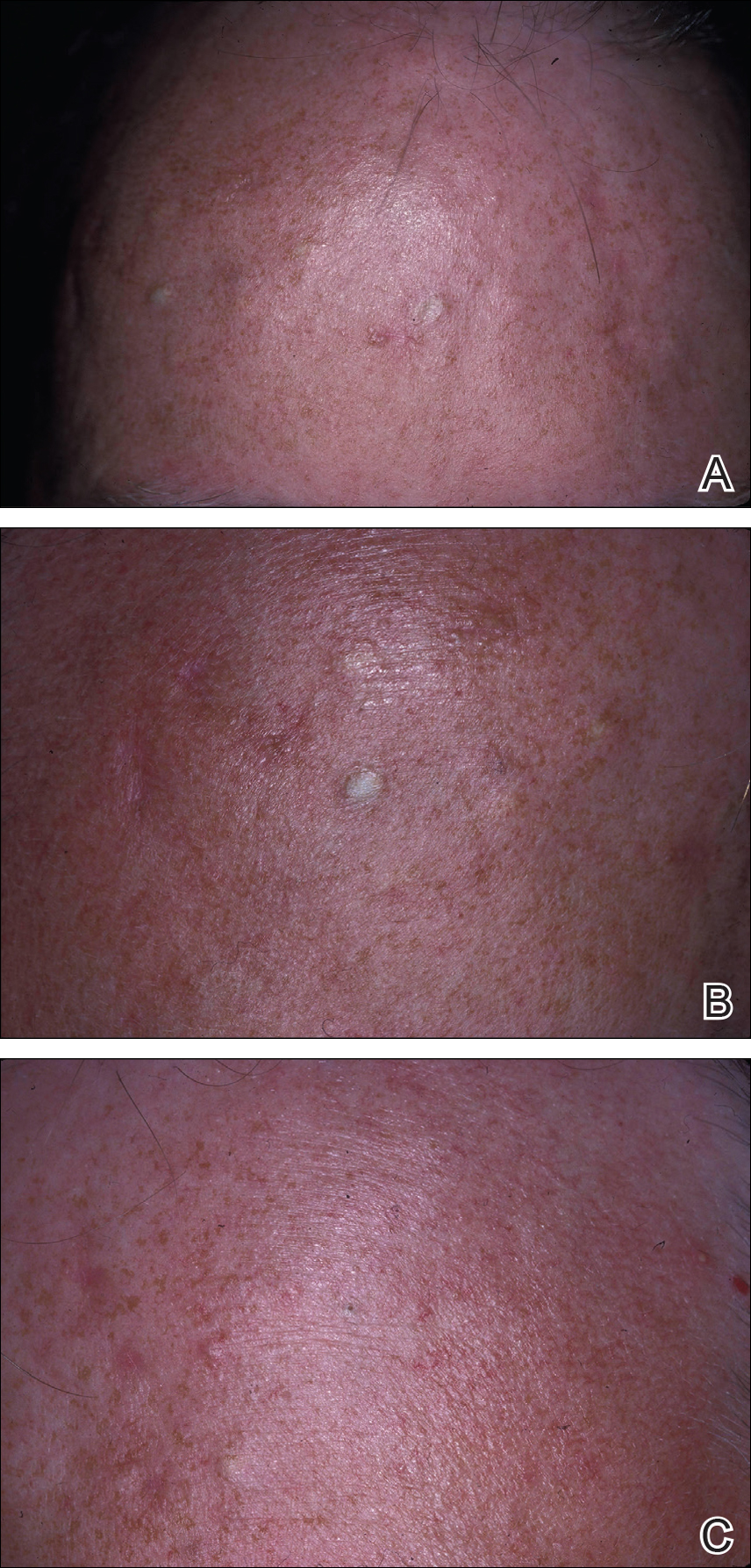

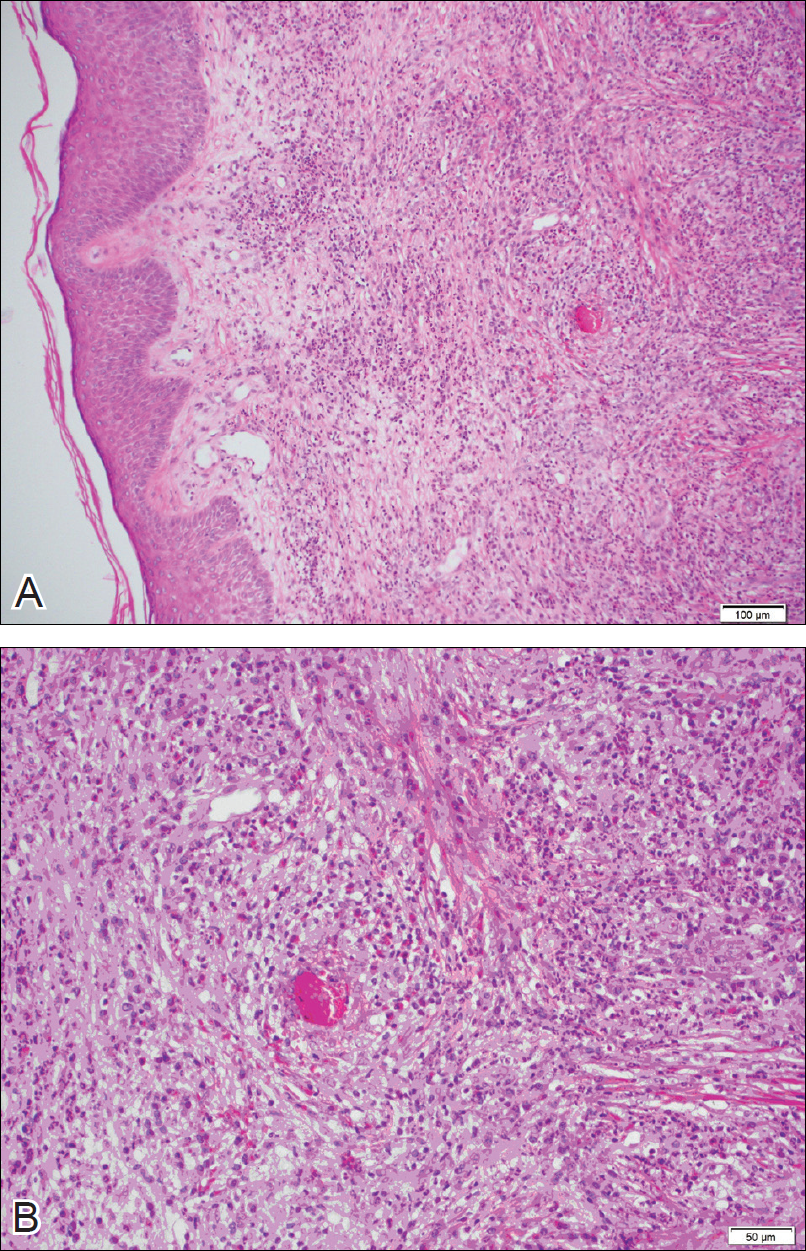

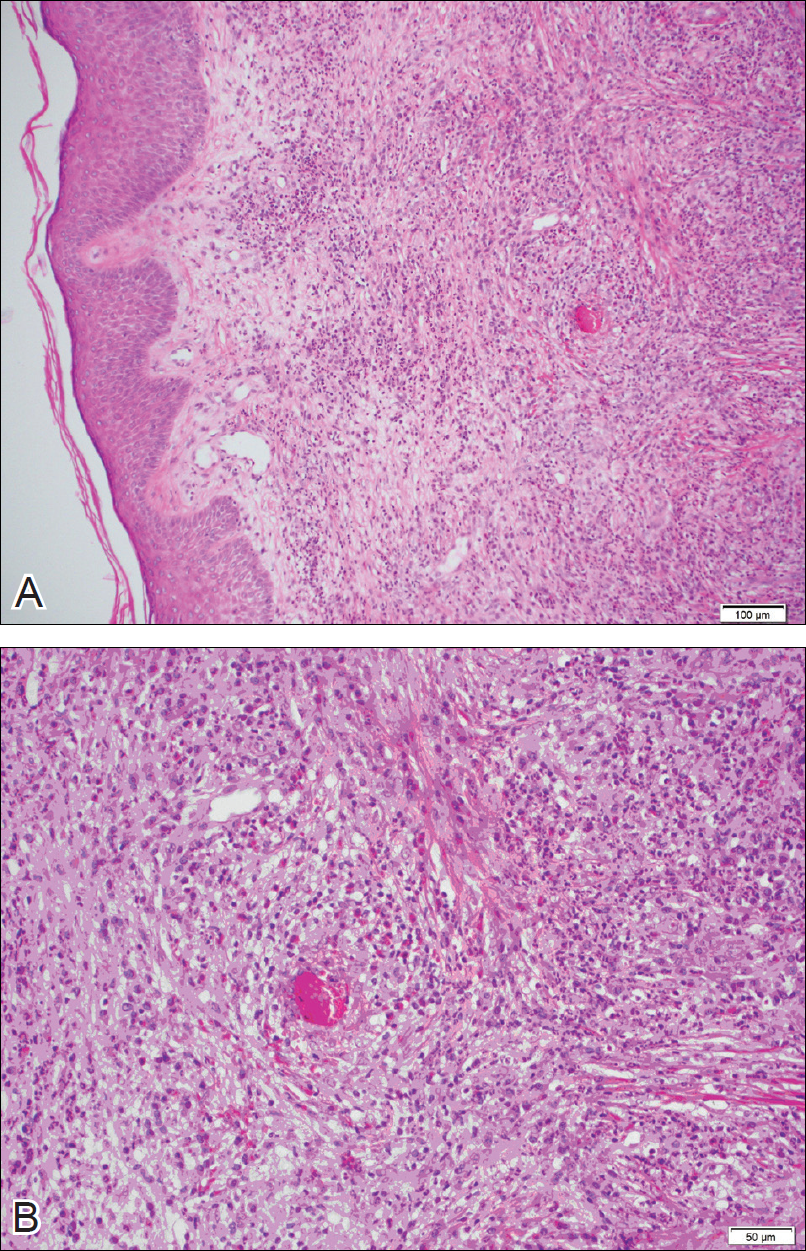

The images produced through confocal microscopy have an excellent correlation to frozen histological sections and can aid in the diagnosis of many epidermal and dermal malignancies including melanoma, BCC, and SCC. New criteria have been established to aid in the interpretation of the confocal images and identify some of the more common skin cancers.5,12,13 Basal cell carcinoma samples imaged through fluorescence and reflectance in low-power mode display the distinct nodular patterns with well-demarcated edges, as seen on classical histopathology. In the case of FCM, the cells that make up the tumor display hyperfluorescent areas consistent with nucleated cells that are stained with acridine orange. The main features that identify BCC on FCM images include nuclear pleomorphism and crowding, peripheral palisading, clefting of the basaloid islands, increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, and the presence of a modified dermis surrounding the mass known as the tumoral stroma5,12 (Figure).

In addition to fluorescence and a well-defined tumor silhouette, SCC under FCM displays keratin pearls composed of keratinized squames, nuclear pleomorphism, and fluorescent scales in the stratum corneum that are a result of keratin formation.5,13 The extent of differentiation of the SCC lesion also can be determined by assessing if the silhouette is well defined. A well-defined tumor silhouette is consistent with the diagnosis of a well-differentiated SCC, and vice versa.13 Ex vivo RCM also has been shown to be useful in diagnosing malignant melanomas, with melanin acting as an endogenous chromophore. Some of the features seen on imaging include a disarranged epithelium, hyperreflective roundish and dendritic pagetoid cells, and large hyperreflective polymorphic cells in the superficial chorion.14

Comparison to Conventional Histopathology

Ex vivo confocal microscopy in both the reflectance and fluorescence mode has been shown to perform well compared to conventional histopathology in the diagnosis of biopsy specimens. Ex vivo FCM has been shown to have an overall sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 99% in detecting residual BCC at the margins of excised tissue samples and in the fraction of the time it takes to attain similar results with frozen histopathology.9 Ex vivo RCM has been shown to have a higher prognostic capability, with 100% sensitivity and specificity in identifying BCC when scanning the tissue samples en face.15

Qualitatively, the images produced by RCM and FCM are similar to histopathology in overall architecture. Both techniques enhance the contrast between the epithelium and stroma and create images that can be examined in low as well as high resolution. A substantial difference between confocal microscopy and conventional hematoxylin and eosin–stained histopathology is that the confocal microscope produces images in gray scale. One way to alter the black-and-white images to resemble hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides is through the use of digital staining,16 which could boost clinical acceptance by physicians who are accustomed to the classical pink-purple appearance of pathology slides and could potentially limit the learning curve needed to read the confocal images.

Application in Mohs Micrographic Surgery

An important clinical application of ex vivo FCM imaging that has emerged is the detection of malignant cells at the excision margins during Mohs micrographic surgery. The use of confocal microscopy has the potential to save time by eliminating the need for tissue fixation while still providing good diagnostic accuracy. Implementing FCM as an imaging tool to guide surgical excisions could provide rapid diagnosis of the tissue, expediting excisions and reconstruction or the Mohs procedure while eliminating patient wait time and the need for frozen histopathology. Ex vivo RCM also has been used to establish laser parameters for CO2 laser ablation of superficial and early nodular BCC lesions.17 Other potential uses for ex vivo RCM/FCM could include rapid evaluation of tissue during operating room procedures where rapid frozen sections are currently utilized.

Combining In Vivo and Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy

Many of the diagnostic guidelines created with the use of ex vivo confocal microscopy have been applied to in vivo use, and therefore the use of both modalities is appealing. In vivo confocal microscopy is a noninvasive technique that has been used to map margins of skin tumors such as BCC and lentigo maligna at the bedside.5 It also has been shown to help plan both surgical and nonsurgical treatment modalities and reconstruction before the tumor is excised.18 This technique also can help the patient understand the extent of the excision and any subsequent reconstruction that may be needed.

Limitations

Ex vivo confocal microscopy used as a diagnostic tool does have some limitations. Its novelty may require surgeons and pathologists to be trained to interpret the images properly and correlate them to conventional diagnostic guidelines. The imaging also is limited to a depth of approximately 200 µm; however, the sample may be flipped so that the underside can be imaged as well, which increases the depth to approximately 400 µm. The tissue being imaged must be fixed flat, which may alter its shape. Complex tissue samples may be difficult to flatten out completely and therefore may be difficult to image. A special mount may be required for the sample to be fixed in a proper position for imaging.6

Final Thoughts

Despite some of these limitations, the need for rapid bedside tissue diagnosis makes ex vivo confocal microscopy an attractive device that can be used as an additional diagnostic tool to histopathology and also has been tested in other disciplines, such as breast cancer pathology. In the future, both in vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy may be utilized to diagnose cutaneous malignancies, guide surgical excisions, and detect lesion progression, and it may become a basis for rapid diagnosis and detection.19

Skin cancer is diagnosed in approximately 5.4 million individuals annually in the United States, more than the total number of breast, lung, colon, and prostate cancers diagnosed per year.1 It is estimated that 1 in 5 Americans will develop skin cancer during their lifetime.2 The 2 most common forms of skin cancer are basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), accounting for 4 million and 1 million cases diagnosed each year, respectively.3 With the increasing incidence of these skin cancers, the use of noninvasive imaging tools for detection and diagnosis has grown.

Ex vivo confocal microscopy is a diagnostic imaging tool that can be used in real-time at the bedside to assess freshly excised tissue for malignancies. It images tissue samples with cellular resolution and within minutes of biopsy or excision. Ex vivo confocal microscopy is a versatile tool that can assist in the diagnosis and management of skin malignancies such as melanoma, BCC, and SCC.

Reflectance vs Fluorescence Mode

Excised lesions can be examined in reflectance or fluorescence mode in great detail but with slightly varying nuclear-to-dermis contrasts depending on the chromophore that is targeted. In reflectance mode (reflectance confocal microscopy [RCM]), melanin and keratin act as endogenous chromophores because of their high refractive index relative to water,4,5 which allows for the visualization of cellular structures of the skin at low power, as well as microscopic substructures such as melanosomes, cytoplasmic granules, and other cellular organelles at high power. Although an exogenous contrast agent is not required, acetic acid has the capability to highlight nuclei, enhancing the tumor cell-to-dermis contrast in RCM.6 Acetic acid is clinically used as a predictor for certain skin and mucosal membrane neoplasms that blanch when exposed to the solution. In the case of RCM, acetic acid increases the visibility of nuclei by inducing the compaction of chromatin. For the acetowhitening to be effective, the sample must be soaked in the solution for a specific amount of time, depending on the concentration.7 A concentration between 1% and 10% can be used, but the less concentrated the solution, the longer the time of soaking that is required to achieve sufficiently bright nuclei.6

The contrast with acetic acid, however, is quite weak when the tissue is imaged en face, or along the horizontal surface of the sample, due to the collagen in the dermal layer, which has a high reflectance index. This issue is rectified when using the confocal microscope in the fluorescence mode with an exogenous fluorescent dye as a nuclear stain. Fluorescence confocal microscopy (FCM), results in a stronger nuclear-to-dermal contrast because of the role of contrast agents.8 The 1000-fold increase in contrast between nuclei and dermis is the result of dye agents that preferentially bind to nuclear DNA, of which acridine orange is the most commonly used.5,8 Basal cell carcinoma and SCC tumor cells can be visualized with FCM because they appear hyperfluorescent when stained with acridine orange.9 The acridine orange–stained cells display bright nuclei, while the cytoplasm and collagen remains dark. A positive feature of acridine orange is that it does not alter the tissue sample during freezing or formalin fixation and thus has no effect on subsequent histopathology that may need to be performed on the sample.10

High-Resolution Images Aid in Diagnosis

After it is harvested, the tissue sample is soaked in a contrast agent or dye, if needed, depending on the confocal mode to be used. The confocal microscope is then used to take a series of high-resolution individual en face images that are then stitched together to create a final mosaic image that can be up to 12×12 mm.6,11 With a 200-µm depth visibility, confocal microscopy can capture the cellular structures in the epidermis, dermis, and (if compressed enough) subcutaneous fat in just under 3 minutes.12

The images produced through confocal microscopy have an excellent correlation to frozen histological sections and can aid in the diagnosis of many epidermal and dermal malignancies including melanoma, BCC, and SCC. New criteria have been established to aid in the interpretation of the confocal images and identify some of the more common skin cancers.5,12,13 Basal cell carcinoma samples imaged through fluorescence and reflectance in low-power mode display the distinct nodular patterns with well-demarcated edges, as seen on classical histopathology. In the case of FCM, the cells that make up the tumor display hyperfluorescent areas consistent with nucleated cells that are stained with acridine orange. The main features that identify BCC on FCM images include nuclear pleomorphism and crowding, peripheral palisading, clefting of the basaloid islands, increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, and the presence of a modified dermis surrounding the mass known as the tumoral stroma5,12 (Figure).

In addition to fluorescence and a well-defined tumor silhouette, SCC under FCM displays keratin pearls composed of keratinized squames, nuclear pleomorphism, and fluorescent scales in the stratum corneum that are a result of keratin formation.5,13 The extent of differentiation of the SCC lesion also can be determined by assessing if the silhouette is well defined. A well-defined tumor silhouette is consistent with the diagnosis of a well-differentiated SCC, and vice versa.13 Ex vivo RCM also has been shown to be useful in diagnosing malignant melanomas, with melanin acting as an endogenous chromophore. Some of the features seen on imaging include a disarranged epithelium, hyperreflective roundish and dendritic pagetoid cells, and large hyperreflective polymorphic cells in the superficial chorion.14

Comparison to Conventional Histopathology

Ex vivo confocal microscopy in both the reflectance and fluorescence mode has been shown to perform well compared to conventional histopathology in the diagnosis of biopsy specimens. Ex vivo FCM has been shown to have an overall sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 99% in detecting residual BCC at the margins of excised tissue samples and in the fraction of the time it takes to attain similar results with frozen histopathology.9 Ex vivo RCM has been shown to have a higher prognostic capability, with 100% sensitivity and specificity in identifying BCC when scanning the tissue samples en face.15

Qualitatively, the images produced by RCM and FCM are similar to histopathology in overall architecture. Both techniques enhance the contrast between the epithelium and stroma and create images that can be examined in low as well as high resolution. A substantial difference between confocal microscopy and conventional hematoxylin and eosin–stained histopathology is that the confocal microscope produces images in gray scale. One way to alter the black-and-white images to resemble hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides is through the use of digital staining,16 which could boost clinical acceptance by physicians who are accustomed to the classical pink-purple appearance of pathology slides and could potentially limit the learning curve needed to read the confocal images.

Application in Mohs Micrographic Surgery

An important clinical application of ex vivo FCM imaging that has emerged is the detection of malignant cells at the excision margins during Mohs micrographic surgery. The use of confocal microscopy has the potential to save time by eliminating the need for tissue fixation while still providing good diagnostic accuracy. Implementing FCM as an imaging tool to guide surgical excisions could provide rapid diagnosis of the tissue, expediting excisions and reconstruction or the Mohs procedure while eliminating patient wait time and the need for frozen histopathology. Ex vivo RCM also has been used to establish laser parameters for CO2 laser ablation of superficial and early nodular BCC lesions.17 Other potential uses for ex vivo RCM/FCM could include rapid evaluation of tissue during operating room procedures where rapid frozen sections are currently utilized.

Combining In Vivo and Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy

Many of the diagnostic guidelines created with the use of ex vivo confocal microscopy have been applied to in vivo use, and therefore the use of both modalities is appealing. In vivo confocal microscopy is a noninvasive technique that has been used to map margins of skin tumors such as BCC and lentigo maligna at the bedside.5 It also has been shown to help plan both surgical and nonsurgical treatment modalities and reconstruction before the tumor is excised.18 This technique also can help the patient understand the extent of the excision and any subsequent reconstruction that may be needed.

Limitations

Ex vivo confocal microscopy used as a diagnostic tool does have some limitations. Its novelty may require surgeons and pathologists to be trained to interpret the images properly and correlate them to conventional diagnostic guidelines. The imaging also is limited to a depth of approximately 200 µm; however, the sample may be flipped so that the underside can be imaged as well, which increases the depth to approximately 400 µm. The tissue being imaged must be fixed flat, which may alter its shape. Complex tissue samples may be difficult to flatten out completely and therefore may be difficult to image. A special mount may be required for the sample to be fixed in a proper position for imaging.6

Final Thoughts

Despite some of these limitations, the need for rapid bedside tissue diagnosis makes ex vivo confocal microscopy an attractive device that can be used as an additional diagnostic tool to histopathology and also has been tested in other disciplines, such as breast cancer pathology. In the future, both in vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy may be utilized to diagnose cutaneous malignancies, guide surgical excisions, and detect lesion progression, and it may become a basis for rapid diagnosis and detection.19

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016 [published online January 7, 2016]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30.

- Robinson JK. Sun exposure, sun protection, and vitamin D. JAMA. 2005;294:1541-1543.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Welzel J, Kästle R, Sattler EC. Fluorescence (multiwave) confocal microscopy. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:527-533.

- Longo C, Ragazzi M, Rajadhyaksha M, et al. In vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy for dermatologic and Mohs surgeons. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:497-504.

- Patel YG, Nehal KS, Aranda I, et al. Confocal reflectance mosaicing of basal cell carcinomas in Mohs surgical skin excisions. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:034027.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Gonzalez S, Zavislan JM. Detectability of contrast agents for confocal reflectance imaging of skin and microcirculation. J Biomed Opt. 2004;9:323-331.

- Karen JK, Gareau DS, Dusza SW, et al. Detection of basal cell carcinomas in Mohs excisions with fluorescence confocal mosaicing microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:1242-1250.

- Bennàssar A, Vilata A, Puig S, et al. Ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy for fast evaluation of tumour margins during Mohs surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:360-365.

- Gareau DS, Li Y, Huang B, et al. Confocal mosaicing microscopy in Mohs skin excisions: feasibility of rapid surgical pathology. J Biomed Opt. 2008;13:054001.

- Bini J, Spain J, Nehal K, et al. Confocal mosaicing microscopy of human skin ex vivo: spectral analysis for digital staining to simulate histology-like appearance. J Biomed Opt. 2011;16:076008.

- Bennàssar A, Carrera C, Puig S, et al. Fast evaluation of 69 basal cell carcinomas with ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy: criteria description, histopathological correlation, and interobserver agreement. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:839-847.

- Longo C, Ragazzi M, Gardini S, et al. Ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy in conjunction with Mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:321-322.

- Cinotti E, Haouas M, Grivet D, et al. In vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy for the management of a melanoma of the eyelid margin. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1437-1440.

- , , , ‘En face’ ex vivo reflectance confocal microscopy to help the surgery of basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid [published online December 19, 2016]. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. doi:10.1111/ceo.12904.

- Gareau DS, Jeon H, Nehal KS, et al. Rapid screening of cancer margins in tissue with multimodal confocal microscopy. J Surg Res. 2012;178:533-538.

- Sierra H, Damanpour S, Hibler B, et al. Confocal imaging of carbon dioxide laser-ablated basal cell carcinomas: an ex-vivo study on the uptake of contrast agent and ablation parameters [published online September 22, 2015]. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:133-139.

- Hibler BP, Yélamos O, Cordova M, et al. Handheld reflectance confocal microscopy to aid in the management of complex facial lentigo maligna. Cutis. 2017;99:346-352.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Marghoob A, Rossi A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy of skin in vivo: from bench to bedside. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:7-19.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016 [published online January 7, 2016]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30.

- Robinson JK. Sun exposure, sun protection, and vitamin D. JAMA. 2005;294:1541-1543.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Welzel J, Kästle R, Sattler EC. Fluorescence (multiwave) confocal microscopy. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:527-533.

- Longo C, Ragazzi M, Rajadhyaksha M, et al. In vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy for dermatologic and Mohs surgeons. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:497-504.

- Patel YG, Nehal KS, Aranda I, et al. Confocal reflectance mosaicing of basal cell carcinomas in Mohs surgical skin excisions. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:034027.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Gonzalez S, Zavislan JM. Detectability of contrast agents for confocal reflectance imaging of skin and microcirculation. J Biomed Opt. 2004;9:323-331.

- Karen JK, Gareau DS, Dusza SW, et al. Detection of basal cell carcinomas in Mohs excisions with fluorescence confocal mosaicing microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:1242-1250.

- Bennàssar A, Vilata A, Puig S, et al. Ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy for fast evaluation of tumour margins during Mohs surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:360-365.

- Gareau DS, Li Y, Huang B, et al. Confocal mosaicing microscopy in Mohs skin excisions: feasibility of rapid surgical pathology. J Biomed Opt. 2008;13:054001.

- Bini J, Spain J, Nehal K, et al. Confocal mosaicing microscopy of human skin ex vivo: spectral analysis for digital staining to simulate histology-like appearance. J Biomed Opt. 2011;16:076008.

- Bennàssar A, Carrera C, Puig S, et al. Fast evaluation of 69 basal cell carcinomas with ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy: criteria description, histopathological correlation, and interobserver agreement. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:839-847.

- Longo C, Ragazzi M, Gardini S, et al. Ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy in conjunction with Mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:321-322.

- Cinotti E, Haouas M, Grivet D, et al. In vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy for the management of a melanoma of the eyelid margin. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1437-1440.

- , , , ‘En face’ ex vivo reflectance confocal microscopy to help the surgery of basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid [published online December 19, 2016]. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. doi:10.1111/ceo.12904.

- Gareau DS, Jeon H, Nehal KS, et al. Rapid screening of cancer margins in tissue with multimodal confocal microscopy. J Surg Res. 2012;178:533-538.

- Sierra H, Damanpour S, Hibler B, et al. Confocal imaging of carbon dioxide laser-ablated basal cell carcinomas: an ex-vivo study on the uptake of contrast agent and ablation parameters [published online September 22, 2015]. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:133-139.

- Hibler BP, Yélamos O, Cordova M, et al. Handheld reflectance confocal microscopy to aid in the management of complex facial lentigo maligna. Cutis. 2017;99:346-352.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Marghoob A, Rossi A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy of skin in vivo: from bench to bedside. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:7-19.

Practice Points

- Confocal microscopy is an imaging tool that can be used both in vivo and ex vivo to aid in the diagnosis and management of cutaneous neoplasms, including melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma, as well as inflammatory dermatoses.

- Ex vivo confocal microscopy can be used in both reflectance and fluorescent modes to render diagnosis in excised tissue or check surgical margins.

- Both in vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy produces images with cellular resolution with a main limitation being depth of imaging.

Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy in Clinical Practice: Report From the AAD Meeting

Topical Timolol May Improve Overall Scar Cosmesis in Acute Surgical Wounds

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist indicated for treating glaucoma, heart attacks, hypertension, and migraine headaches. It is made in both an oral and ophthalmic form. In dermatology, the beta-blocker propranolol is approved for the treatment of infantile hemangiomas (IHs). The exact mechanism of action of beta-blockers for the treatment of IHs is not yet completely understood, but it is postulated that they inhibit growth by at least 4 distinct mechanisms: (1) vasoconstriction, (2) inhibition of angiogenesis or vasculogenesis, (3) induction of apoptosis, and (4) recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells to the site of the hemangioma.1

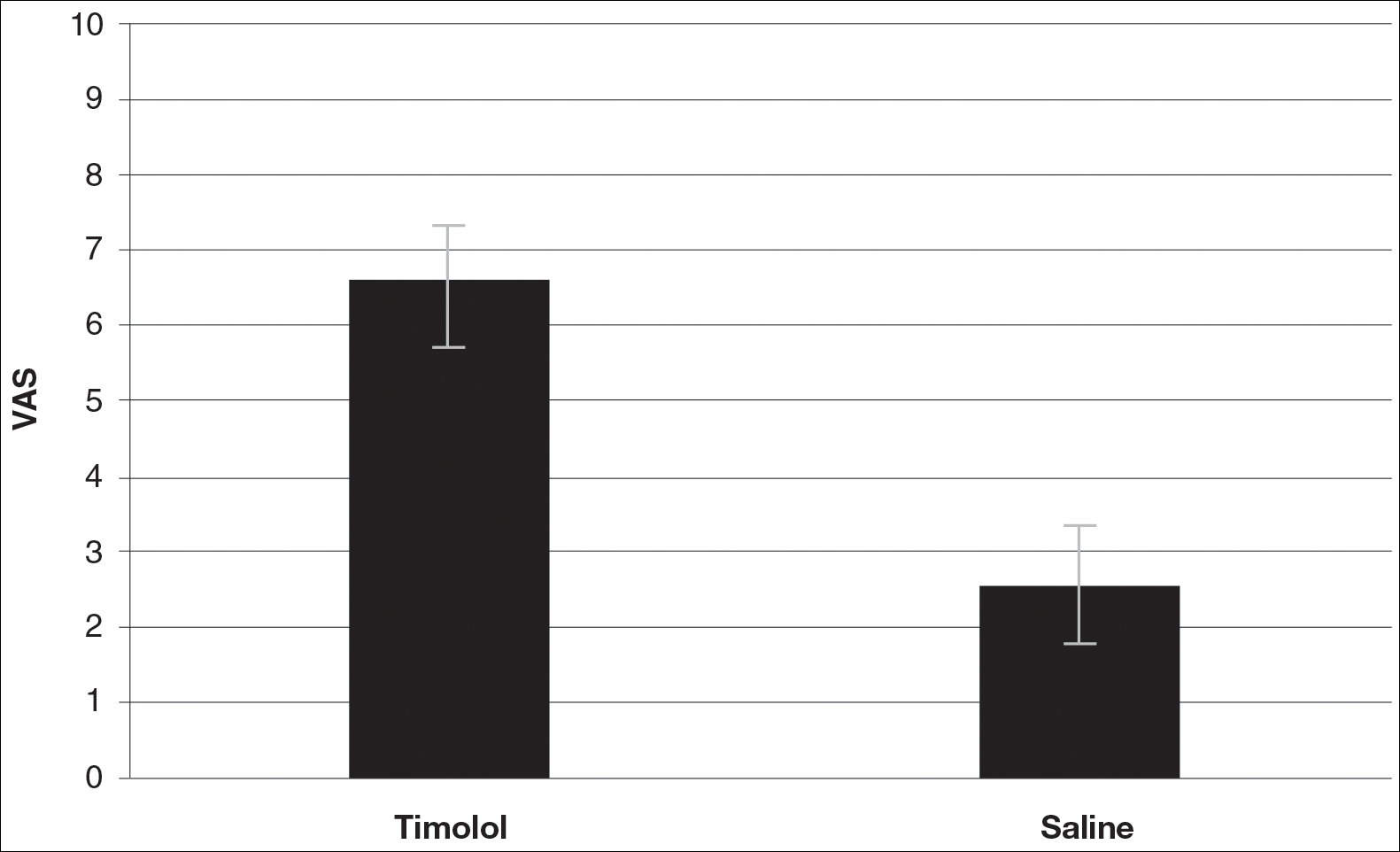

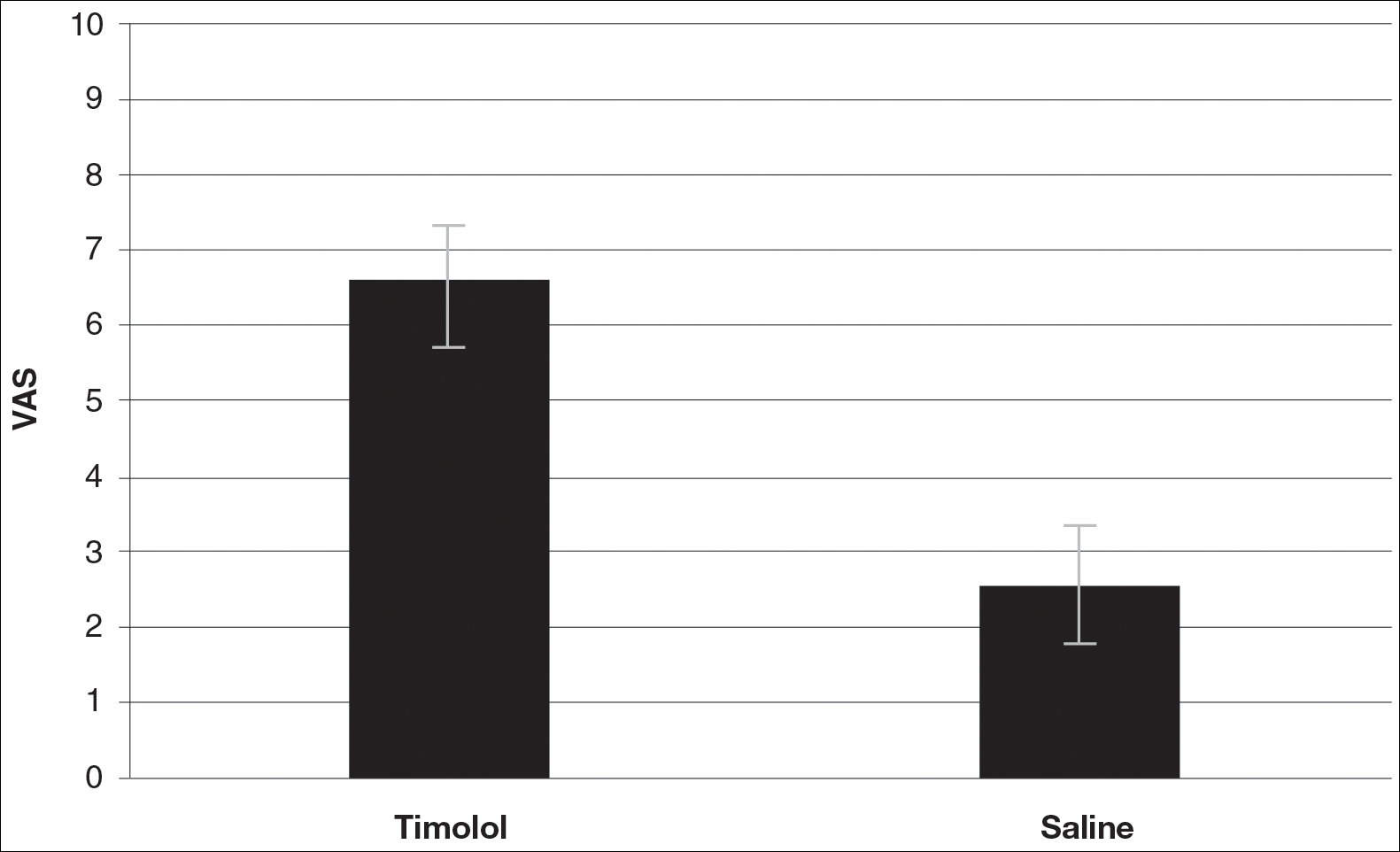

Scar cosmesis can be calculated using the visual analog scale (VAS), which is a subjective scar assessment scored from poor to excellent. The multidimensional VAS is a photograph-based scale derived from evaluating standardized digital photographs in 4 dimensions—pigmentation, vascularity, acceptability, and observer comfort—plus contour. It uses the sum of the individual scores to obtain a single overall score ranging from excellent to poor.2 In this study, we sought to determine if the use of topical timolol after excision or Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers improved the overall cosmesis of the scar.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Roger Williams Medical Center (Providence, Rhode Island). Eligibility criteria included patients who required excision or MMS for their nonmelanoma skin cancer located below the patella and those who agreed to allow their wounds to heal by secondary intention when given options for closure of their wounds. Patients were randomized to either the timolol (study medication) group or the saline (placebo) group. The initial defects were measured and photographed. Patients were educated on how to apply the study medication. All patients were prescribed 40 mm Hg compression stockings to wear following application of the study medication. Patients were asked to return at 1 and 5 weeks postsurgery and then every 1 to 2 weeks for wound assessment and measurement until their wounds had healed or at 13 weeks, depending on which came first. A healed wound was defined as having no exudate, exhibiting complete reepithelialization, and being stable for 1 week.

Healed wounds were assessed by a blinded outside dermatologist who examined photographs of the wounds and then completed the VAS for each participant’s scar.

Results

A total of 9 participants were enrolled in the study. Three participants were lost to follow-up; 6 completed the study (4 females, 2 males). The mean age was 70 years (age range, 46–89 years). The average wound size was 2×2 cm with a depth of 1 mm. Three participants were in the active medication group and 3 were in the control group.

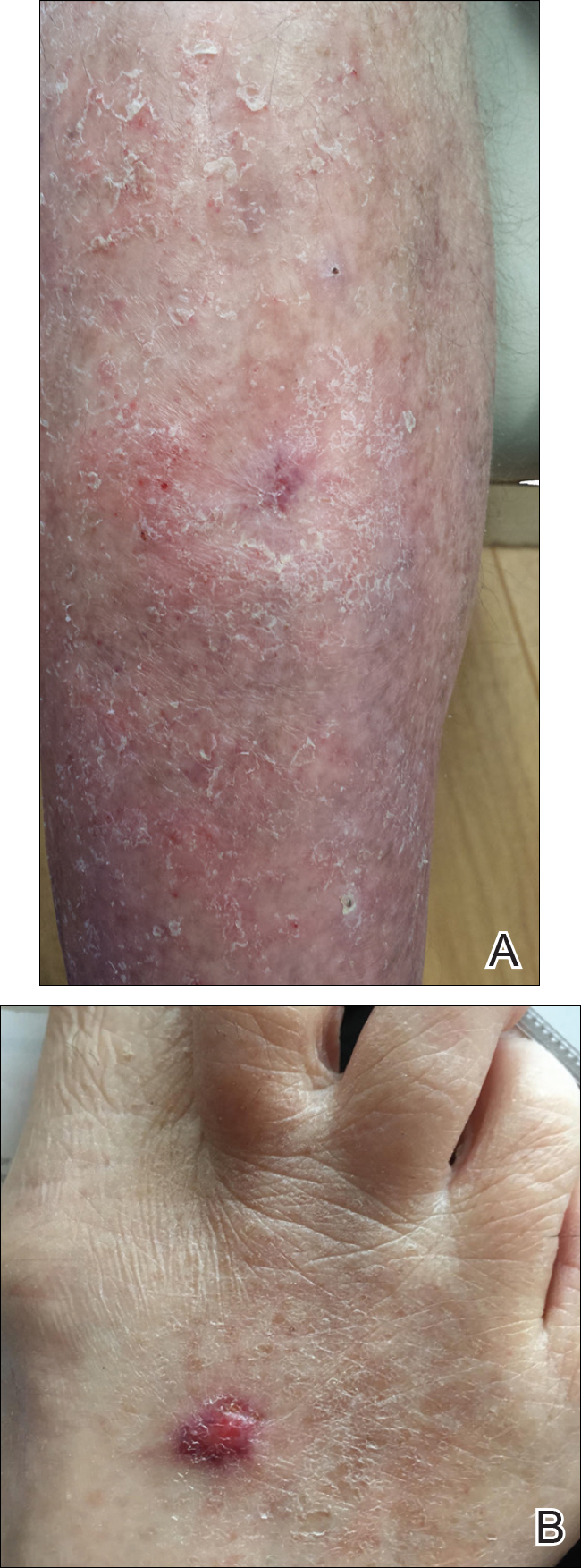

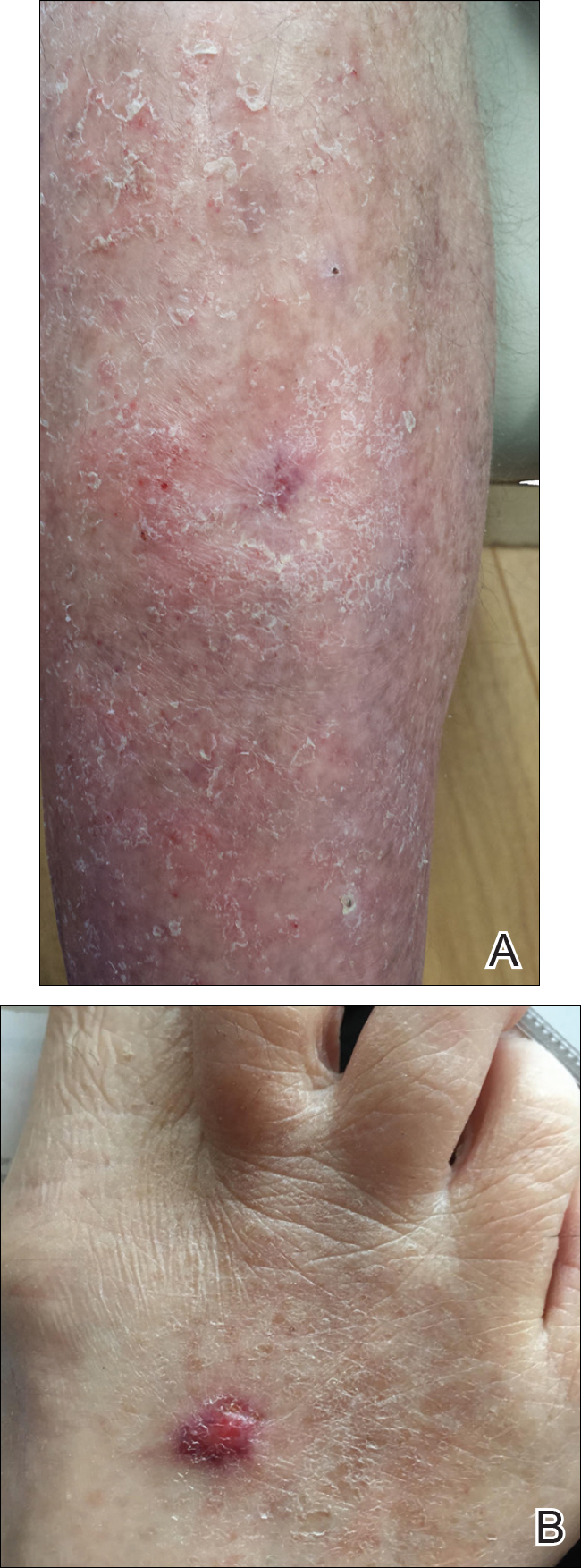

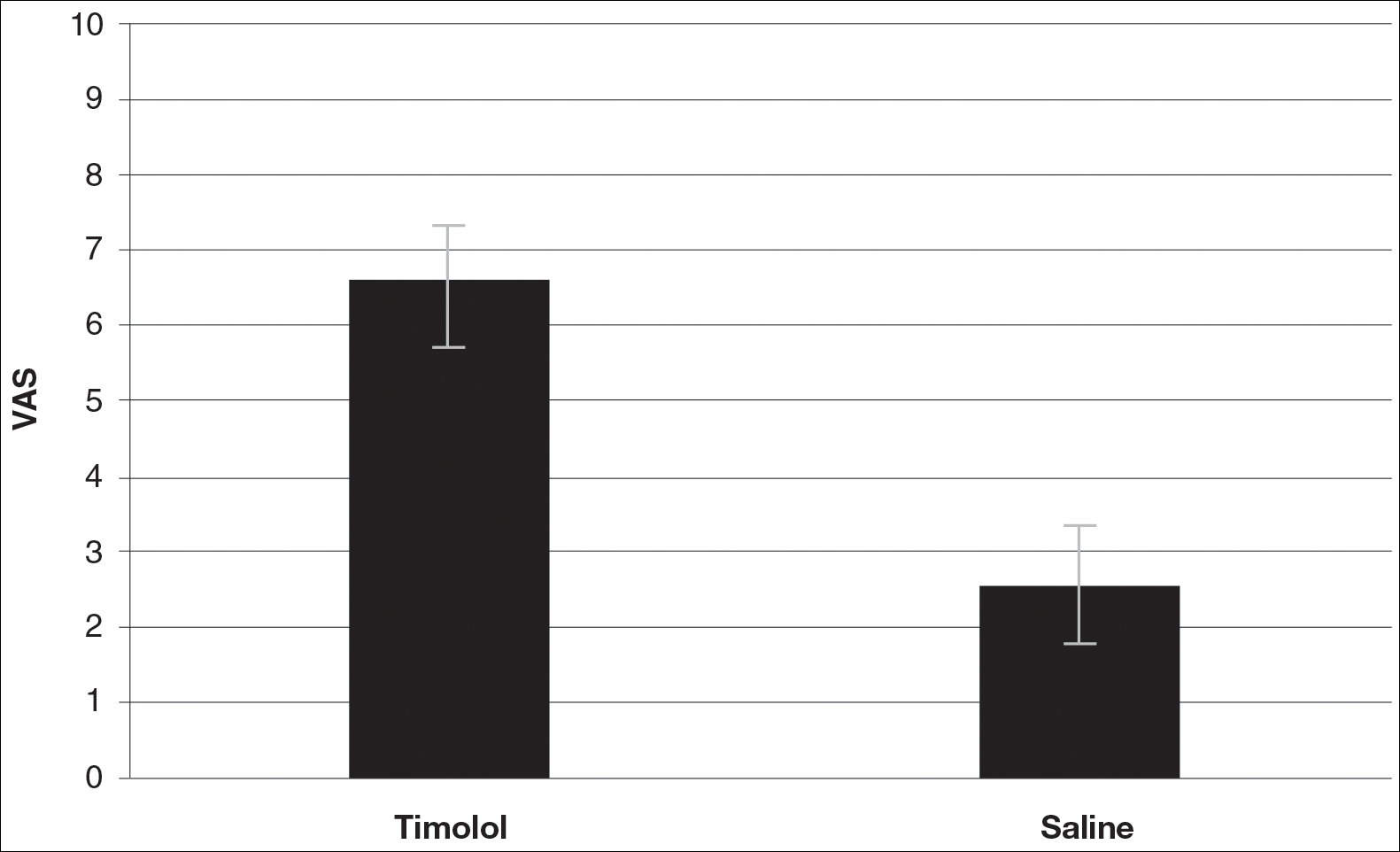

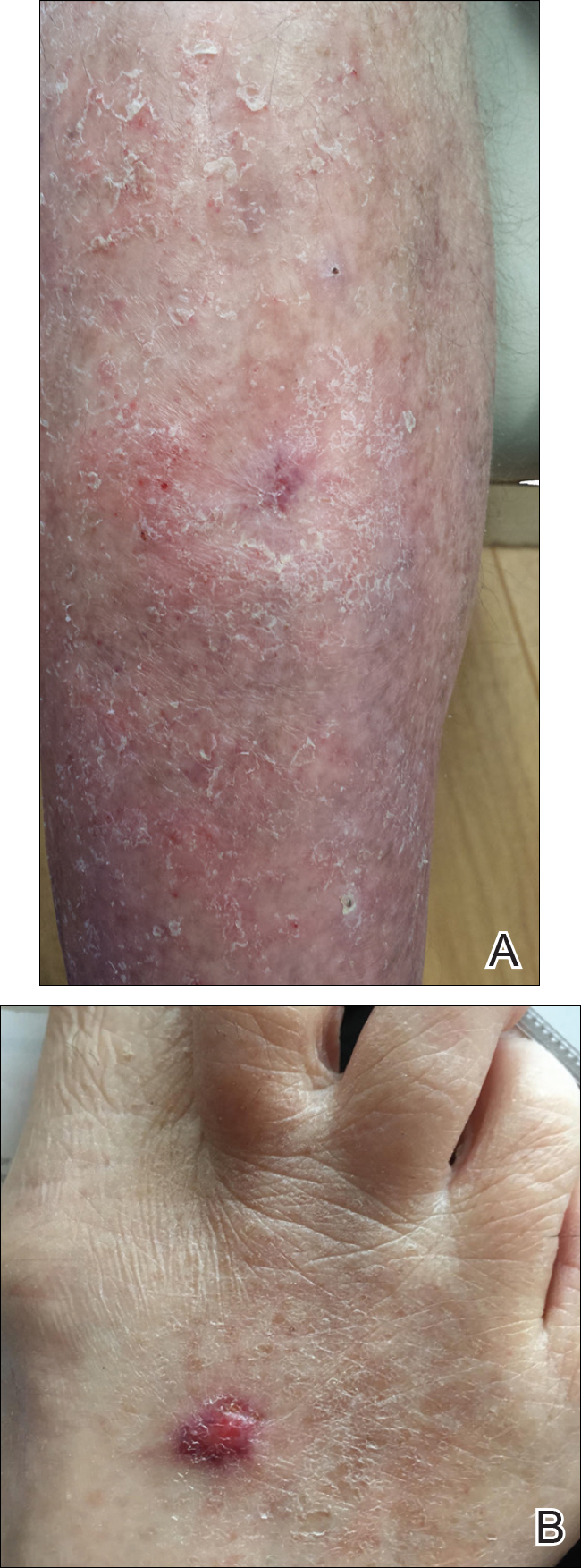

A VAS was completed for each participant’s scar by an outside blinded dermatologist. Based on the VAS, wounds treated with timolol resulted in more cosmetically favorable scars (scored higher on the VAS) compared to control (mean [SD]: 6.5±0.9 vs 2.5±0.7; P<0.05). See Figures 1 and 2 for representative results.

Comment

Dermatologists create acute wounds in patients on a daily basis. Ensuring that patients achieve the most desirable cosmetic outcome is a primary goal for dermatologists and an important component of patient satisfaction. A number of studies have examined patient satisfaction following MMS.3,4 Patient satisfaction is an especially important outcome measure in dermatology, as dermatologic diseases affect cosmetic appearance and are related to quality of life.3,4

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist that is used in dermatology to treat IHs. In this preliminary study, the authors sought to determine if topical timolol applied to acute wounds following surgical removal of nonmelanoma skin cancers could improve the overall cosmetic outcome of acute surgical scars. The results showed that compared to control, topical timolol resulted in a more cosmetically favorable scar. The results are preliminary, and it would be of future interest to further study the effects of topical timolol on acute surgical wounds from a wound-healing standpoint as well as to further test its effects on the cosmesis of these wounds.

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, et al. β-Adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors [published online June 29, 2012]. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1446-1451.

- Fearmonti R, Bond J, Erdmann D, et al. A review of scar scales and scar measuring devices. Eplasty. 2010;10:e43.

- Asgari MM, Warton EM, Neugebauer R, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with Mohs surgery: analysis of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative factors in a prospective cohort. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1387-1394.

- Asgari MM, Bertenthal D, Sen S, et al. Patient satisfaction after treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1041-1049.

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist indicated for treating glaucoma, heart attacks, hypertension, and migraine headaches. It is made in both an oral and ophthalmic form. In dermatology, the beta-blocker propranolol is approved for the treatment of infantile hemangiomas (IHs). The exact mechanism of action of beta-blockers for the treatment of IHs is not yet completely understood, but it is postulated that they inhibit growth by at least 4 distinct mechanisms: (1) vasoconstriction, (2) inhibition of angiogenesis or vasculogenesis, (3) induction of apoptosis, and (4) recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells to the site of the hemangioma.1

Scar cosmesis can be calculated using the visual analog scale (VAS), which is a subjective scar assessment scored from poor to excellent. The multidimensional VAS is a photograph-based scale derived from evaluating standardized digital photographs in 4 dimensions—pigmentation, vascularity, acceptability, and observer comfort—plus contour. It uses the sum of the individual scores to obtain a single overall score ranging from excellent to poor.2 In this study, we sought to determine if the use of topical timolol after excision or Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers improved the overall cosmesis of the scar.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Roger Williams Medical Center (Providence, Rhode Island). Eligibility criteria included patients who required excision or MMS for their nonmelanoma skin cancer located below the patella and those who agreed to allow their wounds to heal by secondary intention when given options for closure of their wounds. Patients were randomized to either the timolol (study medication) group or the saline (placebo) group. The initial defects were measured and photographed. Patients were educated on how to apply the study medication. All patients were prescribed 40 mm Hg compression stockings to wear following application of the study medication. Patients were asked to return at 1 and 5 weeks postsurgery and then every 1 to 2 weeks for wound assessment and measurement until their wounds had healed or at 13 weeks, depending on which came first. A healed wound was defined as having no exudate, exhibiting complete reepithelialization, and being stable for 1 week.

Healed wounds were assessed by a blinded outside dermatologist who examined photographs of the wounds and then completed the VAS for each participant’s scar.

Results

A total of 9 participants were enrolled in the study. Three participants were lost to follow-up; 6 completed the study (4 females, 2 males). The mean age was 70 years (age range, 46–89 years). The average wound size was 2×2 cm with a depth of 1 mm. Three participants were in the active medication group and 3 were in the control group.

A VAS was completed for each participant’s scar by an outside blinded dermatologist. Based on the VAS, wounds treated with timolol resulted in more cosmetically favorable scars (scored higher on the VAS) compared to control (mean [SD]: 6.5±0.9 vs 2.5±0.7; P<0.05). See Figures 1 and 2 for representative results.

Comment

Dermatologists create acute wounds in patients on a daily basis. Ensuring that patients achieve the most desirable cosmetic outcome is a primary goal for dermatologists and an important component of patient satisfaction. A number of studies have examined patient satisfaction following MMS.3,4 Patient satisfaction is an especially important outcome measure in dermatology, as dermatologic diseases affect cosmetic appearance and are related to quality of life.3,4

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist that is used in dermatology to treat IHs. In this preliminary study, the authors sought to determine if topical timolol applied to acute wounds following surgical removal of nonmelanoma skin cancers could improve the overall cosmetic outcome of acute surgical scars. The results showed that compared to control, topical timolol resulted in a more cosmetically favorable scar. The results are preliminary, and it would be of future interest to further study the effects of topical timolol on acute surgical wounds from a wound-healing standpoint as well as to further test its effects on the cosmesis of these wounds.

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist indicated for treating glaucoma, heart attacks, hypertension, and migraine headaches. It is made in both an oral and ophthalmic form. In dermatology, the beta-blocker propranolol is approved for the treatment of infantile hemangiomas (IHs). The exact mechanism of action of beta-blockers for the treatment of IHs is not yet completely understood, but it is postulated that they inhibit growth by at least 4 distinct mechanisms: (1) vasoconstriction, (2) inhibition of angiogenesis or vasculogenesis, (3) induction of apoptosis, and (4) recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells to the site of the hemangioma.1

Scar cosmesis can be calculated using the visual analog scale (VAS), which is a subjective scar assessment scored from poor to excellent. The multidimensional VAS is a photograph-based scale derived from evaluating standardized digital photographs in 4 dimensions—pigmentation, vascularity, acceptability, and observer comfort—plus contour. It uses the sum of the individual scores to obtain a single overall score ranging from excellent to poor.2 In this study, we sought to determine if the use of topical timolol after excision or Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers improved the overall cosmesis of the scar.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Roger Williams Medical Center (Providence, Rhode Island). Eligibility criteria included patients who required excision or MMS for their nonmelanoma skin cancer located below the patella and those who agreed to allow their wounds to heal by secondary intention when given options for closure of their wounds. Patients were randomized to either the timolol (study medication) group or the saline (placebo) group. The initial defects were measured and photographed. Patients were educated on how to apply the study medication. All patients were prescribed 40 mm Hg compression stockings to wear following application of the study medication. Patients were asked to return at 1 and 5 weeks postsurgery and then every 1 to 2 weeks for wound assessment and measurement until their wounds had healed or at 13 weeks, depending on which came first. A healed wound was defined as having no exudate, exhibiting complete reepithelialization, and being stable for 1 week.

Healed wounds were assessed by a blinded outside dermatologist who examined photographs of the wounds and then completed the VAS for each participant’s scar.

Results

A total of 9 participants were enrolled in the study. Three participants were lost to follow-up; 6 completed the study (4 females, 2 males). The mean age was 70 years (age range, 46–89 years). The average wound size was 2×2 cm with a depth of 1 mm. Three participants were in the active medication group and 3 were in the control group.

A VAS was completed for each participant’s scar by an outside blinded dermatologist. Based on the VAS, wounds treated with timolol resulted in more cosmetically favorable scars (scored higher on the VAS) compared to control (mean [SD]: 6.5±0.9 vs 2.5±0.7; P<0.05). See Figures 1 and 2 for representative results.

Comment

Dermatologists create acute wounds in patients on a daily basis. Ensuring that patients achieve the most desirable cosmetic outcome is a primary goal for dermatologists and an important component of patient satisfaction. A number of studies have examined patient satisfaction following MMS.3,4 Patient satisfaction is an especially important outcome measure in dermatology, as dermatologic diseases affect cosmetic appearance and are related to quality of life.3,4

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist that is used in dermatology to treat IHs. In this preliminary study, the authors sought to determine if topical timolol applied to acute wounds following surgical removal of nonmelanoma skin cancers could improve the overall cosmetic outcome of acute surgical scars. The results showed that compared to control, topical timolol resulted in a more cosmetically favorable scar. The results are preliminary, and it would be of future interest to further study the effects of topical timolol on acute surgical wounds from a wound-healing standpoint as well as to further test its effects on the cosmesis of these wounds.

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, et al. β-Adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors [published online June 29, 2012]. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1446-1451.

- Fearmonti R, Bond J, Erdmann D, et al. A review of scar scales and scar measuring devices. Eplasty. 2010;10:e43.

- Asgari MM, Warton EM, Neugebauer R, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with Mohs surgery: analysis of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative factors in a prospective cohort. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1387-1394.

- Asgari MM, Bertenthal D, Sen S, et al. Patient satisfaction after treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1041-1049.

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, et al. β-Adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors [published online June 29, 2012]. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1446-1451.

- Fearmonti R, Bond J, Erdmann D, et al. A review of scar scales and scar measuring devices. Eplasty. 2010;10:e43.

- Asgari MM, Warton EM, Neugebauer R, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with Mohs surgery: analysis of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative factors in a prospective cohort. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1387-1394.

- Asgari MM, Bertenthal D, Sen S, et al. Patient satisfaction after treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1041-1049.