User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Hyaluronic Acid Gel Filler for Nipple Enhancement Following Breast Reconstruction

The most frequently used surgical techniques in nipple-areola complex (NAC) reconstruction involve the use of local tissue flaps and yield the fewest complications, though these techniques can be associated with up to a 75% loss in nipple projection over time.1 In a best-case scenario for both the surgeon and the patient, the NAC is preserved during mastectomy; however, even when the tissues are spared, an eventual loss of nipple projection is expected due to atrophy and contraction of the healing skin.2 Loss of nipple projection is the most common attribute that patients dislike regarding their NAC reconstruction results.Additional efforts made to restore the natural look and feel of the NAC provides undeniable benefit to the patient in the form of improved body image and psychosocial well-being.3

Augmentation with a grafted material can include cartilage or fat (autologous grafts), calcium hydroxylapatite or polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)(alloplastic grafts), and acellular dermal matrix or biologic collagen (allografts). Among these options, successive treatment with autologous fat has been shown to provide satisfactory projections over time with minimal complications.4 However, an additional consideration associated with graft augmentation is the need for an additional surgical site (autologous grafts) or the possibility that graft material may not be compatible with subsequent breast examination techniques. For example, calcium hydroxylapatite is a radiopaque material that may interfere with the interpretation of radiography and mammography.5

The use of injectable hyaluronic acid (HA) dermal fillers to enhance nipple projection represents a noninvasive procedure with immediate and adjustable results. A variety of dermal fillers that do not interfere with subsequent breast imaging needs have already been successfully used for nipple reconstruction including HA 60% plus acrylic hydrogel 40%, PMMA microspheres in a bovine collagen 3.5% gel, and poly-L-lactic acid.5-7

The results achieved with HA 60% plus acrylic hydrogel 40% were as much as a 2.5-mm mean increase in nipple projection after 12 months for 70 nipples reconstructed using a small wedge from the labia minora.5 In these treatments, an initial injection of 0.1 to 0.3 mL of filler into each nipple along with a 0.2-mL injection at the base of each nipple was made. Further optional treatments at 2 and 4 months after the initial injection were made using up to 0.3 mL additional volume depending on filler reabsorption.5 Results achieved with PMMA microspheres in a bovine collagen 3.5% gel included a 1.6-mm mean increase in nipple projection at 9 months versus baseline for 33 nipples in 23 patients, which involved up to 2 injections at baseline and again at 3 months.6 Treatment with poly-L-lactic acid provided a 2.3-mm mean increase in nipple projection for 12 patients after 1 year of treatment, which involved 0.5-mL injections every 4 weeks over a series of 4 treatments.7

This report describes the technique and cosmetic outcome using an injectable HA gel to postoperatively restore the 3-dimensional contour of the nipple following surgical breast reconstruction. This chemically cross-linked, stabilized HA gel suspended in phosphate-buffered saline at a pH of 7 and a concentration of 20 mg/mL with lidocaine 0.3% is indicated for mid to deep dermal implantation for the correction of moderate to severe facial wrinkles and folds, such as the nasolabial folds.8

Case Report

A 49-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer with a focal, high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ underwent a complete bilateral mastectomy. The sentinel lymph nodes were negative at the time of mastectomy. One year later, the patient elected to have breast and nipple-areola (flap) reconstruction. Following the reconstructive surgery, her nipples had become visibly atrophic and flat, and she was interested in cosmetic enhancement.

After informed consent had been obtained from the patient, a baseline measurement of each nipple was made while the patient was standing. Each nipple was then injected with up to 0.1 to 0.2 mL of HA gel filler using a 30-gauge needle inserted 2-mm deep (bilaterally) into each nipple. The patient tolerated the procedure well with no pain, bleeding, or bruising. Although HA gel filler contains lidocaine 0.3% and tricaine can further be used to ensure patient comfort, the nipple reconstruction surgery left the patient with little sensation in the treatment area. Rubbing alcohol was used to prepare the skin prior to the procedure, and fractionated coconut oil spray with a nonadherent dressing was used postprocedure.

Following the injection, an immediate increase of 1.6 and 1.5 mm in nipple projection in the right and left breasts, respectively, was achieved with HA gel. The nipple projection of the right breast was 1.7 mm before injection (Figure, A) and 3.3 mm immediately postinjection (Figure, C). The nipple projection of the left breast was 1.8 mm before injection (Figure, B) and 3.3 mm immediately postinjection (Figure, D).

Comment

With a single treatment consisting of 0.2 mL or less of filler volume, the HA gel used in this procedure provided an immediate mean increase in nipple projection of 1.5 mm. Although our assessment involved a single patient evaluated at baseline and immediately post-injection of HA filler only, it is reasonable to assume that subsequent reinjections would provide results comparable to other fillers. Although other fillers that are semipermanent (acrylic hydrogel) and nonbiodegradable (PMMA) make them more durable, these properties also make the augmentation less reversible in the case of overfilling. As with all dermal fillers, rare side effects associated with injection of HA gel filler could potentially include injection-site inflammation, extrusion of filler at the needle insertion site, minimal pain or discomfort during or after injections, bruising, swelling, or delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction. Ideally, HA gel is a soft transparent filler that is reversible with hyaluronidase, an advantage not shared by other filler materials.9

Conclusion

Nipple augmentation with HA gel is a simple noninvasive

- Sisti A, Grimaldi L, Tassinari J, et al. Nipple-areola complex reconstruction techniques: a literature review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:441-465.

- Murthy V, Chamberlain RS. Defining a place for nipple sparing mastectomy in modern breast care: an evidence based review. Breast J. 2013;19:571-581.

- Jabor MA, Shayani P, Collins DR Jr, et al. Nipple-areola reconstruction: satisfaction and clinical determinants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:457-463.

- Kaoutzanis C, Xin M, Ballard TN, et al. Autologous fat grafting after breast reconstruction in postmastectomy patients: complications, biopsy rates, and locoregional cancer recurrence rates. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76:270-275.

- Panettiere P, Marchetti L, Accorsi D. Filler injection enhances the projection of the reconstructed nipple: an original easy technique. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2005;29:287-294.

- McCarthy CM, Van Laeken N, Lennox P, et al. The efficacy of Artecoll injections for the augmentation of nipple projection in breast reconstruction. Eplasty. 2010;10:E7.

- Dessy LA, Troccola A, Ranno RL, et al. The use of Poly-lactic acid to improve projection of reconstructed nipple. Breast. 2011;20:220-224.

- Restylane L [package insert]. Fort Worth, TX: Galderma Laboratories, LP; 2016.

- Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:295-316.

The most frequently used surgical techniques in nipple-areola complex (NAC) reconstruction involve the use of local tissue flaps and yield the fewest complications, though these techniques can be associated with up to a 75% loss in nipple projection over time.1 In a best-case scenario for both the surgeon and the patient, the NAC is preserved during mastectomy; however, even when the tissues are spared, an eventual loss of nipple projection is expected due to atrophy and contraction of the healing skin.2 Loss of nipple projection is the most common attribute that patients dislike regarding their NAC reconstruction results.Additional efforts made to restore the natural look and feel of the NAC provides undeniable benefit to the patient in the form of improved body image and psychosocial well-being.3

Augmentation with a grafted material can include cartilage or fat (autologous grafts), calcium hydroxylapatite or polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)(alloplastic grafts), and acellular dermal matrix or biologic collagen (allografts). Among these options, successive treatment with autologous fat has been shown to provide satisfactory projections over time with minimal complications.4 However, an additional consideration associated with graft augmentation is the need for an additional surgical site (autologous grafts) or the possibility that graft material may not be compatible with subsequent breast examination techniques. For example, calcium hydroxylapatite is a radiopaque material that may interfere with the interpretation of radiography and mammography.5

The use of injectable hyaluronic acid (HA) dermal fillers to enhance nipple projection represents a noninvasive procedure with immediate and adjustable results. A variety of dermal fillers that do not interfere with subsequent breast imaging needs have already been successfully used for nipple reconstruction including HA 60% plus acrylic hydrogel 40%, PMMA microspheres in a bovine collagen 3.5% gel, and poly-L-lactic acid.5-7

The results achieved with HA 60% plus acrylic hydrogel 40% were as much as a 2.5-mm mean increase in nipple projection after 12 months for 70 nipples reconstructed using a small wedge from the labia minora.5 In these treatments, an initial injection of 0.1 to 0.3 mL of filler into each nipple along with a 0.2-mL injection at the base of each nipple was made. Further optional treatments at 2 and 4 months after the initial injection were made using up to 0.3 mL additional volume depending on filler reabsorption.5 Results achieved with PMMA microspheres in a bovine collagen 3.5% gel included a 1.6-mm mean increase in nipple projection at 9 months versus baseline for 33 nipples in 23 patients, which involved up to 2 injections at baseline and again at 3 months.6 Treatment with poly-L-lactic acid provided a 2.3-mm mean increase in nipple projection for 12 patients after 1 year of treatment, which involved 0.5-mL injections every 4 weeks over a series of 4 treatments.7

This report describes the technique and cosmetic outcome using an injectable HA gel to postoperatively restore the 3-dimensional contour of the nipple following surgical breast reconstruction. This chemically cross-linked, stabilized HA gel suspended in phosphate-buffered saline at a pH of 7 and a concentration of 20 mg/mL with lidocaine 0.3% is indicated for mid to deep dermal implantation for the correction of moderate to severe facial wrinkles and folds, such as the nasolabial folds.8

Case Report

A 49-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer with a focal, high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ underwent a complete bilateral mastectomy. The sentinel lymph nodes were negative at the time of mastectomy. One year later, the patient elected to have breast and nipple-areola (flap) reconstruction. Following the reconstructive surgery, her nipples had become visibly atrophic and flat, and she was interested in cosmetic enhancement.

After informed consent had been obtained from the patient, a baseline measurement of each nipple was made while the patient was standing. Each nipple was then injected with up to 0.1 to 0.2 mL of HA gel filler using a 30-gauge needle inserted 2-mm deep (bilaterally) into each nipple. The patient tolerated the procedure well with no pain, bleeding, or bruising. Although HA gel filler contains lidocaine 0.3% and tricaine can further be used to ensure patient comfort, the nipple reconstruction surgery left the patient with little sensation in the treatment area. Rubbing alcohol was used to prepare the skin prior to the procedure, and fractionated coconut oil spray with a nonadherent dressing was used postprocedure.

Following the injection, an immediate increase of 1.6 and 1.5 mm in nipple projection in the right and left breasts, respectively, was achieved with HA gel. The nipple projection of the right breast was 1.7 mm before injection (Figure, A) and 3.3 mm immediately postinjection (Figure, C). The nipple projection of the left breast was 1.8 mm before injection (Figure, B) and 3.3 mm immediately postinjection (Figure, D).

Comment

With a single treatment consisting of 0.2 mL or less of filler volume, the HA gel used in this procedure provided an immediate mean increase in nipple projection of 1.5 mm. Although our assessment involved a single patient evaluated at baseline and immediately post-injection of HA filler only, it is reasonable to assume that subsequent reinjections would provide results comparable to other fillers. Although other fillers that are semipermanent (acrylic hydrogel) and nonbiodegradable (PMMA) make them more durable, these properties also make the augmentation less reversible in the case of overfilling. As with all dermal fillers, rare side effects associated with injection of HA gel filler could potentially include injection-site inflammation, extrusion of filler at the needle insertion site, minimal pain or discomfort during or after injections, bruising, swelling, or delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction. Ideally, HA gel is a soft transparent filler that is reversible with hyaluronidase, an advantage not shared by other filler materials.9

Conclusion

Nipple augmentation with HA gel is a simple noninvasive

The most frequently used surgical techniques in nipple-areola complex (NAC) reconstruction involve the use of local tissue flaps and yield the fewest complications, though these techniques can be associated with up to a 75% loss in nipple projection over time.1 In a best-case scenario for both the surgeon and the patient, the NAC is preserved during mastectomy; however, even when the tissues are spared, an eventual loss of nipple projection is expected due to atrophy and contraction of the healing skin.2 Loss of nipple projection is the most common attribute that patients dislike regarding their NAC reconstruction results.Additional efforts made to restore the natural look and feel of the NAC provides undeniable benefit to the patient in the form of improved body image and psychosocial well-being.3

Augmentation with a grafted material can include cartilage or fat (autologous grafts), calcium hydroxylapatite or polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)(alloplastic grafts), and acellular dermal matrix or biologic collagen (allografts). Among these options, successive treatment with autologous fat has been shown to provide satisfactory projections over time with minimal complications.4 However, an additional consideration associated with graft augmentation is the need for an additional surgical site (autologous grafts) or the possibility that graft material may not be compatible with subsequent breast examination techniques. For example, calcium hydroxylapatite is a radiopaque material that may interfere with the interpretation of radiography and mammography.5

The use of injectable hyaluronic acid (HA) dermal fillers to enhance nipple projection represents a noninvasive procedure with immediate and adjustable results. A variety of dermal fillers that do not interfere with subsequent breast imaging needs have already been successfully used for nipple reconstruction including HA 60% plus acrylic hydrogel 40%, PMMA microspheres in a bovine collagen 3.5% gel, and poly-L-lactic acid.5-7

The results achieved with HA 60% plus acrylic hydrogel 40% were as much as a 2.5-mm mean increase in nipple projection after 12 months for 70 nipples reconstructed using a small wedge from the labia minora.5 In these treatments, an initial injection of 0.1 to 0.3 mL of filler into each nipple along with a 0.2-mL injection at the base of each nipple was made. Further optional treatments at 2 and 4 months after the initial injection were made using up to 0.3 mL additional volume depending on filler reabsorption.5 Results achieved with PMMA microspheres in a bovine collagen 3.5% gel included a 1.6-mm mean increase in nipple projection at 9 months versus baseline for 33 nipples in 23 patients, which involved up to 2 injections at baseline and again at 3 months.6 Treatment with poly-L-lactic acid provided a 2.3-mm mean increase in nipple projection for 12 patients after 1 year of treatment, which involved 0.5-mL injections every 4 weeks over a series of 4 treatments.7

This report describes the technique and cosmetic outcome using an injectable HA gel to postoperatively restore the 3-dimensional contour of the nipple following surgical breast reconstruction. This chemically cross-linked, stabilized HA gel suspended in phosphate-buffered saline at a pH of 7 and a concentration of 20 mg/mL with lidocaine 0.3% is indicated for mid to deep dermal implantation for the correction of moderate to severe facial wrinkles and folds, such as the nasolabial folds.8

Case Report

A 49-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer with a focal, high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ underwent a complete bilateral mastectomy. The sentinel lymph nodes were negative at the time of mastectomy. One year later, the patient elected to have breast and nipple-areola (flap) reconstruction. Following the reconstructive surgery, her nipples had become visibly atrophic and flat, and she was interested in cosmetic enhancement.

After informed consent had been obtained from the patient, a baseline measurement of each nipple was made while the patient was standing. Each nipple was then injected with up to 0.1 to 0.2 mL of HA gel filler using a 30-gauge needle inserted 2-mm deep (bilaterally) into each nipple. The patient tolerated the procedure well with no pain, bleeding, or bruising. Although HA gel filler contains lidocaine 0.3% and tricaine can further be used to ensure patient comfort, the nipple reconstruction surgery left the patient with little sensation in the treatment area. Rubbing alcohol was used to prepare the skin prior to the procedure, and fractionated coconut oil spray with a nonadherent dressing was used postprocedure.

Following the injection, an immediate increase of 1.6 and 1.5 mm in nipple projection in the right and left breasts, respectively, was achieved with HA gel. The nipple projection of the right breast was 1.7 mm before injection (Figure, A) and 3.3 mm immediately postinjection (Figure, C). The nipple projection of the left breast was 1.8 mm before injection (Figure, B) and 3.3 mm immediately postinjection (Figure, D).

Comment

With a single treatment consisting of 0.2 mL or less of filler volume, the HA gel used in this procedure provided an immediate mean increase in nipple projection of 1.5 mm. Although our assessment involved a single patient evaluated at baseline and immediately post-injection of HA filler only, it is reasonable to assume that subsequent reinjections would provide results comparable to other fillers. Although other fillers that are semipermanent (acrylic hydrogel) and nonbiodegradable (PMMA) make them more durable, these properties also make the augmentation less reversible in the case of overfilling. As with all dermal fillers, rare side effects associated with injection of HA gel filler could potentially include injection-site inflammation, extrusion of filler at the needle insertion site, minimal pain or discomfort during or after injections, bruising, swelling, or delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction. Ideally, HA gel is a soft transparent filler that is reversible with hyaluronidase, an advantage not shared by other filler materials.9

Conclusion

Nipple augmentation with HA gel is a simple noninvasive

- Sisti A, Grimaldi L, Tassinari J, et al. Nipple-areola complex reconstruction techniques: a literature review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:441-465.

- Murthy V, Chamberlain RS. Defining a place for nipple sparing mastectomy in modern breast care: an evidence based review. Breast J. 2013;19:571-581.

- Jabor MA, Shayani P, Collins DR Jr, et al. Nipple-areola reconstruction: satisfaction and clinical determinants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:457-463.

- Kaoutzanis C, Xin M, Ballard TN, et al. Autologous fat grafting after breast reconstruction in postmastectomy patients: complications, biopsy rates, and locoregional cancer recurrence rates. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76:270-275.

- Panettiere P, Marchetti L, Accorsi D. Filler injection enhances the projection of the reconstructed nipple: an original easy technique. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2005;29:287-294.

- McCarthy CM, Van Laeken N, Lennox P, et al. The efficacy of Artecoll injections for the augmentation of nipple projection in breast reconstruction. Eplasty. 2010;10:E7.

- Dessy LA, Troccola A, Ranno RL, et al. The use of Poly-lactic acid to improve projection of reconstructed nipple. Breast. 2011;20:220-224.

- Restylane L [package insert]. Fort Worth, TX: Galderma Laboratories, LP; 2016.

- Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:295-316.

- Sisti A, Grimaldi L, Tassinari J, et al. Nipple-areola complex reconstruction techniques: a literature review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:441-465.

- Murthy V, Chamberlain RS. Defining a place for nipple sparing mastectomy in modern breast care: an evidence based review. Breast J. 2013;19:571-581.

- Jabor MA, Shayani P, Collins DR Jr, et al. Nipple-areola reconstruction: satisfaction and clinical determinants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:457-463.

- Kaoutzanis C, Xin M, Ballard TN, et al. Autologous fat grafting after breast reconstruction in postmastectomy patients: complications, biopsy rates, and locoregional cancer recurrence rates. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76:270-275.

- Panettiere P, Marchetti L, Accorsi D. Filler injection enhances the projection of the reconstructed nipple: an original easy technique. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2005;29:287-294.

- McCarthy CM, Van Laeken N, Lennox P, et al. The efficacy of Artecoll injections for the augmentation of nipple projection in breast reconstruction. Eplasty. 2010;10:E7.

- Dessy LA, Troccola A, Ranno RL, et al. The use of Poly-lactic acid to improve projection of reconstructed nipple. Breast. 2011;20:220-224.

- Restylane L [package insert]. Fort Worth, TX: Galderma Laboratories, LP; 2016.

- Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:295-316.

Practice Points

- The use of injectable hyaluronic acid (HA) gel to restore 3-dimensional contour of the nipple following nipple-areola complex (NAC) reconstruction is a noninvasive procedure that contributes to patient well-being.

- The use of HA gel for NAC augmentation can be performed in an office setting and may eliminate the need for secondary reconstructive surgeries.

Aggressive Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Liver Transplant Recipient

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor derived from the nerve-associated Merkel cell touch receptors.1 It typically presents as a solitary, rapidly growing, red to violaceous, asymptomatic nodule, though ulcerated, acneform, and cystic lesions also have been described.2 Merkel cell carcinoma follows an aggressive clinical course with a tendency for rapid growth, local recurrence (26%–60% of cases), lymph node invasion, and distant metastases (18%–52% of cases).3

Several risk factors contribute to the development of MCC, including chronic immunosuppression, exposure to UV radiation, and infection with the Merkel cell polyomavirus. Immunosuppression has been shown to increase the risk for MCC and is associated with a worse prognosis independent of stage at diagnosis.4 Organ transplant recipients represent a subset of immunosuppressed patients who are at increased risk for the development of MCC. We report a case of metastatic MCC in a 67-year-old woman 6 years after liver transplantation.

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman presented to our clinic with 2 masses—1 on the left buttock and 1 on the left hip—of 4 months’ duration. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for autoimmune hepatitis requiring liver transplantation 6 years prior as well as hypertension and thyroid disorder. Her posttransplantation course was unremarkable, and she was maintained on chronic immunosuppression with tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. Six years after transplantation, the patient was observed to have a 4-cm, red-violaceous, painless, dome-shaped tumor on the left buttock (Figure 1). She also was noted to have pink-red papulonodules forming a painless 8-cm plaque on the left hip that was present for 2 weeks prior to presentation (Figure 1). Both lesions were subsequently biopsied.

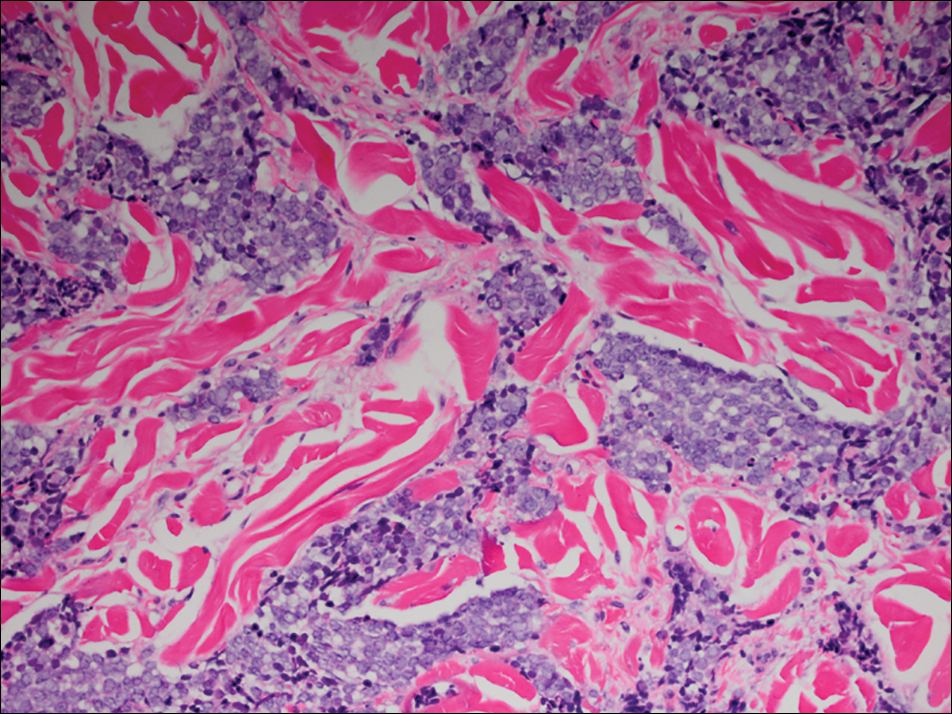

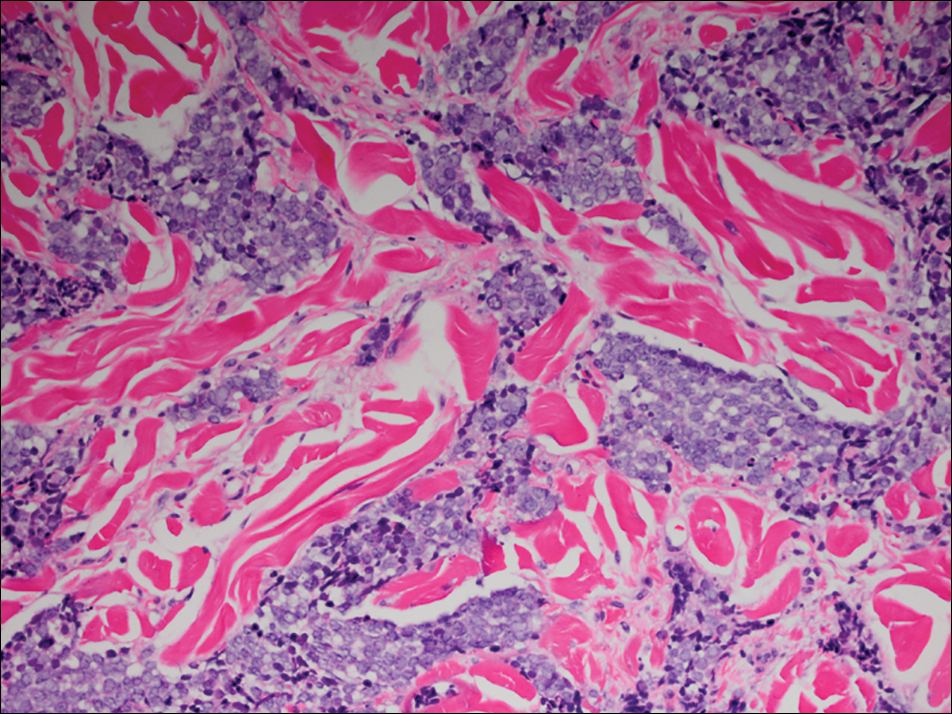

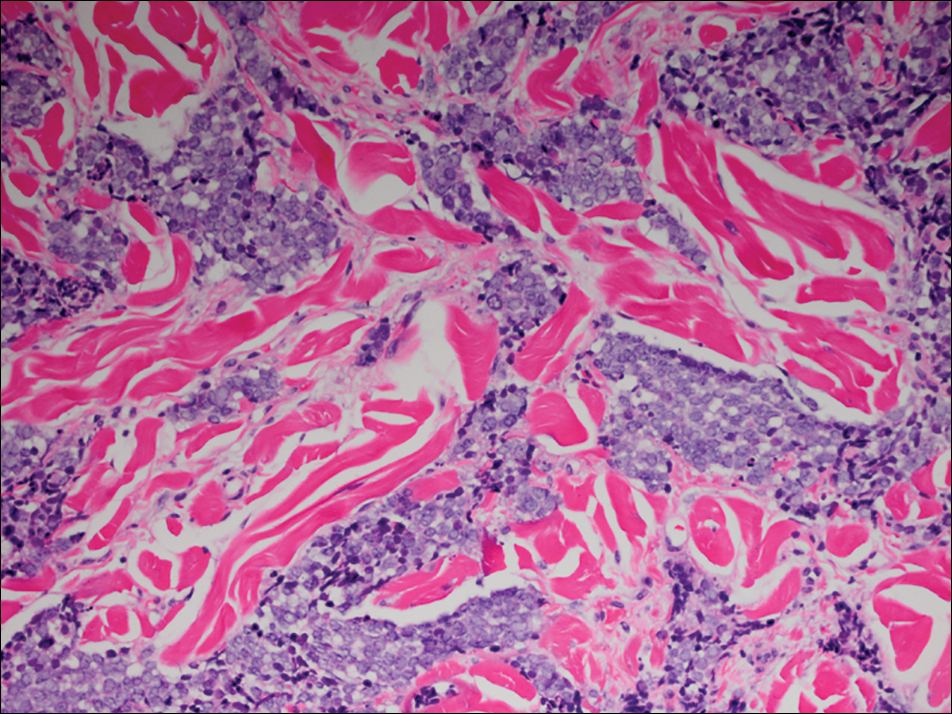

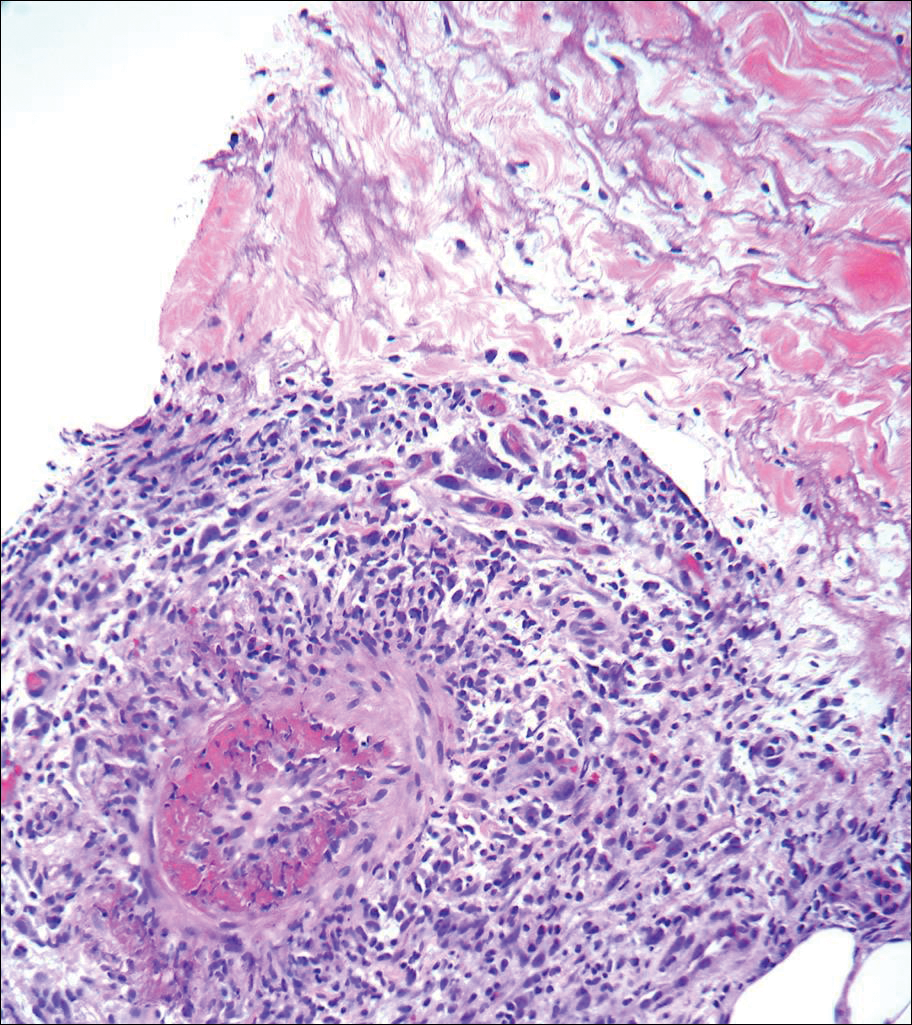

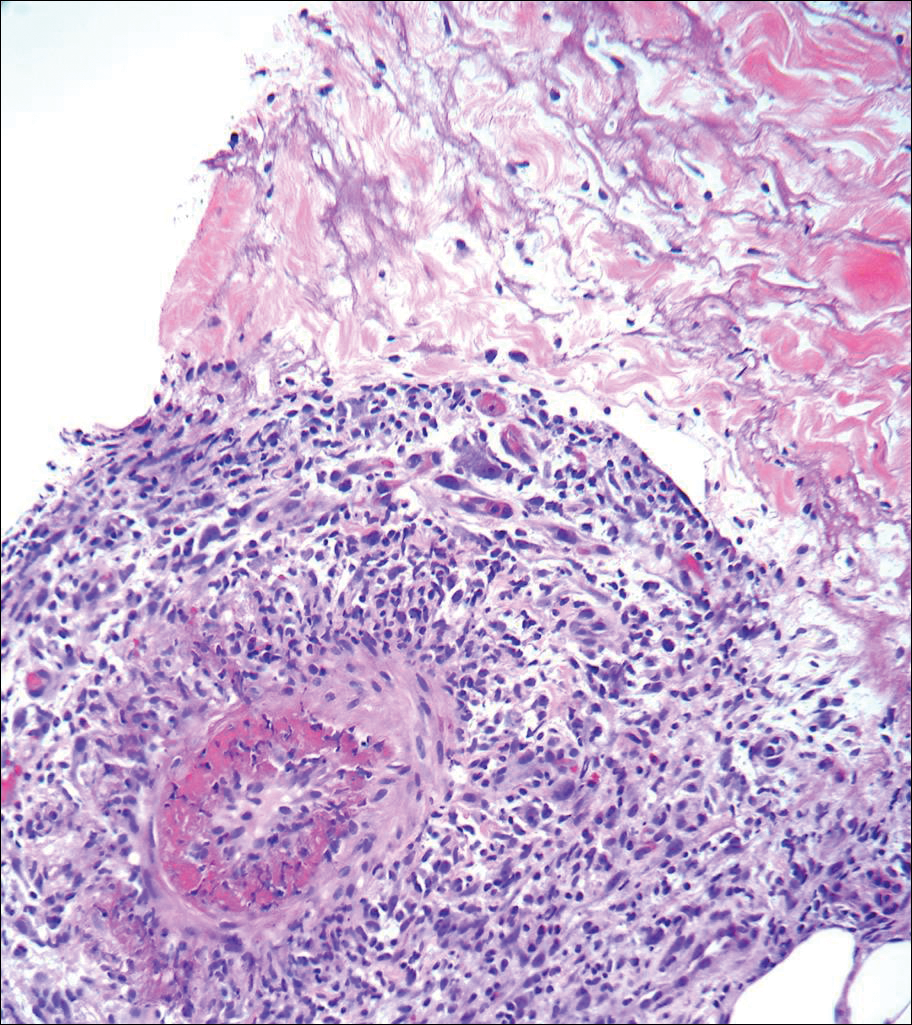

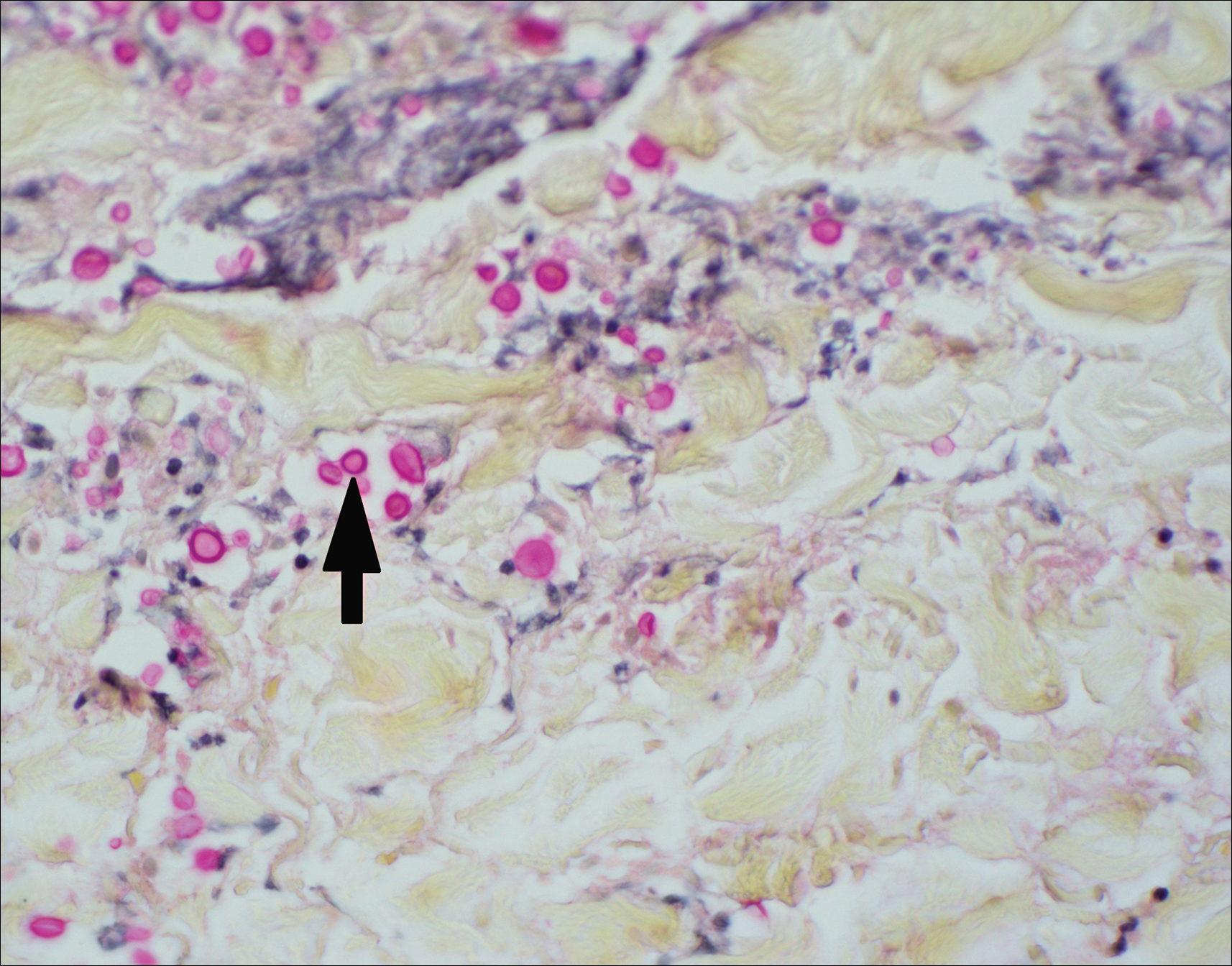

Microscopic examination of both lesions was consistent with the diagnosis of MCC. On histopathology, both samples exhibited a dense cellular dermis composed of atypical basophilic tumor cells with extension into superficial dilated lymphatic channels indicating lymphovascular invasion (Figure 2). Tumor cells were positive for the immunohistochemical markers pankeratin AE1/AE3, CAM 5.2, cytokeratin 20, synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and Merkel cell polyomavirus.

Total-body computed tomography and positron emission tomography revealed a hypermetabolic lobular density in the left gluteal region measuring 3.9×1.1 cm. The mass was associated with avid disease involving the left inguinal, bilateral iliac chain, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. The patient was determined to have stage IV MCC based on the presence of distant lymph node metastases. The mass on the left hip was identified as an in-transit metastasis from the primary tumor on the left buttock.

The patient was referred to surgical and medical oncology. The decision was made to start palliative chemotherapy without surgical intervention given the extent of metastases not amenable for resection. The patient was subsequently initiated on chemotherapy with etoposide and carboplatin. After one cycle of chemotherapy, both tumors initially decreased in size; however, 4 months later, despite multiple cycles of chemotherapy, the patient was noted to have growth of existing tumors and interval development of a new 7×5-cm erythematous plaque in the left groin (Figure 3A) and a 1.1×1.0-cm smooth nodule on the right upper back (Figure 3B), both also found to be consistent with distant skin metastases of MCC upon microscopic examination after biopsy. Despite chemotherapy, the patient’s tumor continued to spread and the patient died within 8 months of diagnosis.

Comment

Transplant recipients represent a well-described cohort of immunosuppressed patients prone to the development of MCC. Merkel cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients has been most frequently documented to occur after kidney transplantation and less frequently after heart and liver transplantations.5,6 However, the role of organ type and immunosuppressive regimen is not well characterized in the literature. Clarke et al7 investigated the risk for MCC in a large cohort of solid organ transplant recipients based on specific immunosuppression medications. They found a higher risk for MCC in patients who were maintained on cyclosporine, azathioprine, and mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) inhibitors rather than tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and corticosteroids. In comparison to combination tacrolimus–mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine-azathioprine was associated with an increased incidence of MCC; this risk rose remarkably in patients who resided in geographic locations with a higher average of UV exposure. The authors suggested that UV radiation and immunosuppression-induced DNA damage may be synergistic in the development of MCC.7

Merkel cell carcinoma most frequently occurs on sun-exposed sites, including the face, head, and neck (55%); upper and lower extremities (40%); and truncal regions (5%).8 However, case reports highlight MCC arising in atypical locations such as the buttocks and gluteal region in organ transplant recipients.7,9 In the general population, MCC predominantly arises in elderly patients (ie, >70 years), but it is more likely to present at an earlier age in transplant recipients.6,10 In a retrospective analysis of 41 solid organ transplant recipients, 12 were diagnosed before the age of 50 years.6 Data from the US Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients showed a median age at diagnosis of 62 years, with the highest incidence occurring 10 or more years after transplantation.7

Merkel cell carcinoma behaves aggressively and is the most common cause of skin cancer death after melanoma.11 Organ transplant recipients with MCC have a worse prognosis than MCC patients who are not transplant recipients. In a retrospective registry analysis of 45 de novo cases, Buell at al5 found a 60% mortality rate in transplant recipients, almost double the 33% mortality rate of the general population. Furthermore, Arron et al10 revealed substantially increased rates of disease progression and decreased rates of disease-specific and overall survival in solid organ transplant recipients on immunosuppression compared to immunocompetent controls. The most important factor for poor prognosis is the presence of lymph node invasion, which lowers survival rate.12

Conclusion

Merkel cell carcinoma following liver transplantation is not well described in the literature. We highlight a case of an aggressive MCC arising in a sun-protected site with rapid metastasis 6 years after liver transplantation. This case emphasizes the importance of surveillance for cutaneous malignancy in solid organ transplant recipients.

- Gould VE, Moll R, Moll I, et al. Neuroendocrine (Merkel) cells of the skin: hyperplasias, dysplasias, and neoplasms. Lab Invest. 1985;52:334-353.

- Ratner D, Nelson BR, Brown MD, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):143-156.

- Pectasides D, Pectasides M, Economopoulos T. Merkel cell cancer of the skin. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1489-1495.

- Paulson KG, Iyer JG, Blom A, et al. Systemic immune suppression predicts diminished Merkel cell carcinoma-specific survival independent of stage. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:642-646.

- Buell JF, Trofe J, Hanaway MJ, et al. Immunosuppression and Merkel cell cancer. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:1780-1781.

- Penn I, First MR. Merkel’s cell carcinoma in organ recipients: report of 41 cases. Transplantation. 1999;68:1717-1721.

- Clarke CA, Robbins HA, Tatalovich Z, et al. Risk of Merkel cell carcinoma after solid organ transplantation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107. pii:dju382. doi:10.1093/jnci/dju382.

- Rockville Merkel Cell Carcinoma Group. Merkel cell carcinoma: recent progress and current priorities on etiology, pathogenesis and clinical management [published online July 13, 2009]. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4021-4026.

- Krejčí K, Tichý T, Horák P, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the gluteal region with ipsilateral metastasis into the pancreatic graft of a patient after combined kidney-pancreas transplantation [published online September 20, 2010]. Onkologie. 2010;33:520-524.

- Arron ST, Canavan T, Yu SS. Organ transplant recipients with Merkel cell carcinoma have reduced progression-free, overall, and disease-specific survival independent of stage at presentation [published online July 1, 2014]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:684-690.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population-based study [published online July 23, 2009]. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:20-27.

- Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al. Treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2004;27:510-515.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor derived from the nerve-associated Merkel cell touch receptors.1 It typically presents as a solitary, rapidly growing, red to violaceous, asymptomatic nodule, though ulcerated, acneform, and cystic lesions also have been described.2 Merkel cell carcinoma follows an aggressive clinical course with a tendency for rapid growth, local recurrence (26%–60% of cases), lymph node invasion, and distant metastases (18%–52% of cases).3

Several risk factors contribute to the development of MCC, including chronic immunosuppression, exposure to UV radiation, and infection with the Merkel cell polyomavirus. Immunosuppression has been shown to increase the risk for MCC and is associated with a worse prognosis independent of stage at diagnosis.4 Organ transplant recipients represent a subset of immunosuppressed patients who are at increased risk for the development of MCC. We report a case of metastatic MCC in a 67-year-old woman 6 years after liver transplantation.

Case Report

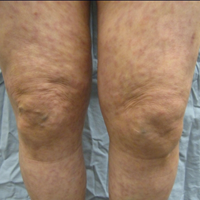

A 67-year-old woman presented to our clinic with 2 masses—1 on the left buttock and 1 on the left hip—of 4 months’ duration. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for autoimmune hepatitis requiring liver transplantation 6 years prior as well as hypertension and thyroid disorder. Her posttransplantation course was unremarkable, and she was maintained on chronic immunosuppression with tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. Six years after transplantation, the patient was observed to have a 4-cm, red-violaceous, painless, dome-shaped tumor on the left buttock (Figure 1). She also was noted to have pink-red papulonodules forming a painless 8-cm plaque on the left hip that was present for 2 weeks prior to presentation (Figure 1). Both lesions were subsequently biopsied.

Microscopic examination of both lesions was consistent with the diagnosis of MCC. On histopathology, both samples exhibited a dense cellular dermis composed of atypical basophilic tumor cells with extension into superficial dilated lymphatic channels indicating lymphovascular invasion (Figure 2). Tumor cells were positive for the immunohistochemical markers pankeratin AE1/AE3, CAM 5.2, cytokeratin 20, synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and Merkel cell polyomavirus.

Total-body computed tomography and positron emission tomography revealed a hypermetabolic lobular density in the left gluteal region measuring 3.9×1.1 cm. The mass was associated with avid disease involving the left inguinal, bilateral iliac chain, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. The patient was determined to have stage IV MCC based on the presence of distant lymph node metastases. The mass on the left hip was identified as an in-transit metastasis from the primary tumor on the left buttock.

The patient was referred to surgical and medical oncology. The decision was made to start palliative chemotherapy without surgical intervention given the extent of metastases not amenable for resection. The patient was subsequently initiated on chemotherapy with etoposide and carboplatin. After one cycle of chemotherapy, both tumors initially decreased in size; however, 4 months later, despite multiple cycles of chemotherapy, the patient was noted to have growth of existing tumors and interval development of a new 7×5-cm erythematous plaque in the left groin (Figure 3A) and a 1.1×1.0-cm smooth nodule on the right upper back (Figure 3B), both also found to be consistent with distant skin metastases of MCC upon microscopic examination after biopsy. Despite chemotherapy, the patient’s tumor continued to spread and the patient died within 8 months of diagnosis.

Comment

Transplant recipients represent a well-described cohort of immunosuppressed patients prone to the development of MCC. Merkel cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients has been most frequently documented to occur after kidney transplantation and less frequently after heart and liver transplantations.5,6 However, the role of organ type and immunosuppressive regimen is not well characterized in the literature. Clarke et al7 investigated the risk for MCC in a large cohort of solid organ transplant recipients based on specific immunosuppression medications. They found a higher risk for MCC in patients who were maintained on cyclosporine, azathioprine, and mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) inhibitors rather than tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and corticosteroids. In comparison to combination tacrolimus–mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine-azathioprine was associated with an increased incidence of MCC; this risk rose remarkably in patients who resided in geographic locations with a higher average of UV exposure. The authors suggested that UV radiation and immunosuppression-induced DNA damage may be synergistic in the development of MCC.7

Merkel cell carcinoma most frequently occurs on sun-exposed sites, including the face, head, and neck (55%); upper and lower extremities (40%); and truncal regions (5%).8 However, case reports highlight MCC arising in atypical locations such as the buttocks and gluteal region in organ transplant recipients.7,9 In the general population, MCC predominantly arises in elderly patients (ie, >70 years), but it is more likely to present at an earlier age in transplant recipients.6,10 In a retrospective analysis of 41 solid organ transplant recipients, 12 were diagnosed before the age of 50 years.6 Data from the US Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients showed a median age at diagnosis of 62 years, with the highest incidence occurring 10 or more years after transplantation.7

Merkel cell carcinoma behaves aggressively and is the most common cause of skin cancer death after melanoma.11 Organ transplant recipients with MCC have a worse prognosis than MCC patients who are not transplant recipients. In a retrospective registry analysis of 45 de novo cases, Buell at al5 found a 60% mortality rate in transplant recipients, almost double the 33% mortality rate of the general population. Furthermore, Arron et al10 revealed substantially increased rates of disease progression and decreased rates of disease-specific and overall survival in solid organ transplant recipients on immunosuppression compared to immunocompetent controls. The most important factor for poor prognosis is the presence of lymph node invasion, which lowers survival rate.12

Conclusion

Merkel cell carcinoma following liver transplantation is not well described in the literature. We highlight a case of an aggressive MCC arising in a sun-protected site with rapid metastasis 6 years after liver transplantation. This case emphasizes the importance of surveillance for cutaneous malignancy in solid organ transplant recipients.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor derived from the nerve-associated Merkel cell touch receptors.1 It typically presents as a solitary, rapidly growing, red to violaceous, asymptomatic nodule, though ulcerated, acneform, and cystic lesions also have been described.2 Merkel cell carcinoma follows an aggressive clinical course with a tendency for rapid growth, local recurrence (26%–60% of cases), lymph node invasion, and distant metastases (18%–52% of cases).3

Several risk factors contribute to the development of MCC, including chronic immunosuppression, exposure to UV radiation, and infection with the Merkel cell polyomavirus. Immunosuppression has been shown to increase the risk for MCC and is associated with a worse prognosis independent of stage at diagnosis.4 Organ transplant recipients represent a subset of immunosuppressed patients who are at increased risk for the development of MCC. We report a case of metastatic MCC in a 67-year-old woman 6 years after liver transplantation.

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman presented to our clinic with 2 masses—1 on the left buttock and 1 on the left hip—of 4 months’ duration. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for autoimmune hepatitis requiring liver transplantation 6 years prior as well as hypertension and thyroid disorder. Her posttransplantation course was unremarkable, and she was maintained on chronic immunosuppression with tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. Six years after transplantation, the patient was observed to have a 4-cm, red-violaceous, painless, dome-shaped tumor on the left buttock (Figure 1). She also was noted to have pink-red papulonodules forming a painless 8-cm plaque on the left hip that was present for 2 weeks prior to presentation (Figure 1). Both lesions were subsequently biopsied.

Microscopic examination of both lesions was consistent with the diagnosis of MCC. On histopathology, both samples exhibited a dense cellular dermis composed of atypical basophilic tumor cells with extension into superficial dilated lymphatic channels indicating lymphovascular invasion (Figure 2). Tumor cells were positive for the immunohistochemical markers pankeratin AE1/AE3, CAM 5.2, cytokeratin 20, synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and Merkel cell polyomavirus.

Total-body computed tomography and positron emission tomography revealed a hypermetabolic lobular density in the left gluteal region measuring 3.9×1.1 cm. The mass was associated with avid disease involving the left inguinal, bilateral iliac chain, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. The patient was determined to have stage IV MCC based on the presence of distant lymph node metastases. The mass on the left hip was identified as an in-transit metastasis from the primary tumor on the left buttock.

The patient was referred to surgical and medical oncology. The decision was made to start palliative chemotherapy without surgical intervention given the extent of metastases not amenable for resection. The patient was subsequently initiated on chemotherapy with etoposide and carboplatin. After one cycle of chemotherapy, both tumors initially decreased in size; however, 4 months later, despite multiple cycles of chemotherapy, the patient was noted to have growth of existing tumors and interval development of a new 7×5-cm erythematous plaque in the left groin (Figure 3A) and a 1.1×1.0-cm smooth nodule on the right upper back (Figure 3B), both also found to be consistent with distant skin metastases of MCC upon microscopic examination after biopsy. Despite chemotherapy, the patient’s tumor continued to spread and the patient died within 8 months of diagnosis.

Comment

Transplant recipients represent a well-described cohort of immunosuppressed patients prone to the development of MCC. Merkel cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients has been most frequently documented to occur after kidney transplantation and less frequently after heart and liver transplantations.5,6 However, the role of organ type and immunosuppressive regimen is not well characterized in the literature. Clarke et al7 investigated the risk for MCC in a large cohort of solid organ transplant recipients based on specific immunosuppression medications. They found a higher risk for MCC in patients who were maintained on cyclosporine, azathioprine, and mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) inhibitors rather than tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and corticosteroids. In comparison to combination tacrolimus–mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine-azathioprine was associated with an increased incidence of MCC; this risk rose remarkably in patients who resided in geographic locations with a higher average of UV exposure. The authors suggested that UV radiation and immunosuppression-induced DNA damage may be synergistic in the development of MCC.7

Merkel cell carcinoma most frequently occurs on sun-exposed sites, including the face, head, and neck (55%); upper and lower extremities (40%); and truncal regions (5%).8 However, case reports highlight MCC arising in atypical locations such as the buttocks and gluteal region in organ transplant recipients.7,9 In the general population, MCC predominantly arises in elderly patients (ie, >70 years), but it is more likely to present at an earlier age in transplant recipients.6,10 In a retrospective analysis of 41 solid organ transplant recipients, 12 were diagnosed before the age of 50 years.6 Data from the US Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients showed a median age at diagnosis of 62 years, with the highest incidence occurring 10 or more years after transplantation.7

Merkel cell carcinoma behaves aggressively and is the most common cause of skin cancer death after melanoma.11 Organ transplant recipients with MCC have a worse prognosis than MCC patients who are not transplant recipients. In a retrospective registry analysis of 45 de novo cases, Buell at al5 found a 60% mortality rate in transplant recipients, almost double the 33% mortality rate of the general population. Furthermore, Arron et al10 revealed substantially increased rates of disease progression and decreased rates of disease-specific and overall survival in solid organ transplant recipients on immunosuppression compared to immunocompetent controls. The most important factor for poor prognosis is the presence of lymph node invasion, which lowers survival rate.12

Conclusion

Merkel cell carcinoma following liver transplantation is not well described in the literature. We highlight a case of an aggressive MCC arising in a sun-protected site with rapid metastasis 6 years after liver transplantation. This case emphasizes the importance of surveillance for cutaneous malignancy in solid organ transplant recipients.

- Gould VE, Moll R, Moll I, et al. Neuroendocrine (Merkel) cells of the skin: hyperplasias, dysplasias, and neoplasms. Lab Invest. 1985;52:334-353.

- Ratner D, Nelson BR, Brown MD, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):143-156.

- Pectasides D, Pectasides M, Economopoulos T. Merkel cell cancer of the skin. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1489-1495.

- Paulson KG, Iyer JG, Blom A, et al. Systemic immune suppression predicts diminished Merkel cell carcinoma-specific survival independent of stage. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:642-646.

- Buell JF, Trofe J, Hanaway MJ, et al. Immunosuppression and Merkel cell cancer. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:1780-1781.

- Penn I, First MR. Merkel’s cell carcinoma in organ recipients: report of 41 cases. Transplantation. 1999;68:1717-1721.

- Clarke CA, Robbins HA, Tatalovich Z, et al. Risk of Merkel cell carcinoma after solid organ transplantation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107. pii:dju382. doi:10.1093/jnci/dju382.

- Rockville Merkel Cell Carcinoma Group. Merkel cell carcinoma: recent progress and current priorities on etiology, pathogenesis and clinical management [published online July 13, 2009]. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4021-4026.

- Krejčí K, Tichý T, Horák P, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the gluteal region with ipsilateral metastasis into the pancreatic graft of a patient after combined kidney-pancreas transplantation [published online September 20, 2010]. Onkologie. 2010;33:520-524.

- Arron ST, Canavan T, Yu SS. Organ transplant recipients with Merkel cell carcinoma have reduced progression-free, overall, and disease-specific survival independent of stage at presentation [published online July 1, 2014]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:684-690.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population-based study [published online July 23, 2009]. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:20-27.

- Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al. Treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2004;27:510-515.

- Gould VE, Moll R, Moll I, et al. Neuroendocrine (Merkel) cells of the skin: hyperplasias, dysplasias, and neoplasms. Lab Invest. 1985;52:334-353.

- Ratner D, Nelson BR, Brown MD, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):143-156.

- Pectasides D, Pectasides M, Economopoulos T. Merkel cell cancer of the skin. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1489-1495.

- Paulson KG, Iyer JG, Blom A, et al. Systemic immune suppression predicts diminished Merkel cell carcinoma-specific survival independent of stage. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:642-646.

- Buell JF, Trofe J, Hanaway MJ, et al. Immunosuppression and Merkel cell cancer. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:1780-1781.

- Penn I, First MR. Merkel’s cell carcinoma in organ recipients: report of 41 cases. Transplantation. 1999;68:1717-1721.

- Clarke CA, Robbins HA, Tatalovich Z, et al. Risk of Merkel cell carcinoma after solid organ transplantation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107. pii:dju382. doi:10.1093/jnci/dju382.

- Rockville Merkel Cell Carcinoma Group. Merkel cell carcinoma: recent progress and current priorities on etiology, pathogenesis and clinical management [published online July 13, 2009]. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4021-4026.

- Krejčí K, Tichý T, Horák P, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the gluteal region with ipsilateral metastasis into the pancreatic graft of a patient after combined kidney-pancreas transplantation [published online September 20, 2010]. Onkologie. 2010;33:520-524.

- Arron ST, Canavan T, Yu SS. Organ transplant recipients with Merkel cell carcinoma have reduced progression-free, overall, and disease-specific survival independent of stage at presentation [published online July 1, 2014]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:684-690.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population-based study [published online July 23, 2009]. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:20-27.

- Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al. Treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2004;27:510-515.

Practice Points

- Organ transplant recipients are at an increased risk for Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

- Early recognition and diagnosis of MCC is important to improve morbidity and mortality.

Annular Atrophic Lichen Planus Responds to Hydroxychloroquine and Acitretin

Annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP) is a rare variant of lichen planus that was first described by Friedman and Hashimoto1 in 1991. Clinically, it combines the configuration and morphological features of both annular and atrophic lichen planus. It is a rare entity. We report a case of AALP in a 69-year-old black man. The clinical and histopathological presentation depicted the defining features of this entity with a characteristic loss of elastic fibers corresponding to central atrophy of active lesions.

Case Report

A 69-year-old black man with a history of hepatitis C virus infection and hypothyroidism presented to the dermatology clinic with a pruritic rash on the trunk, extremities, groin, and scalp of 4 months' duration. He denied any new medications, recent illnesses, or sick contacts. Physical examination demonstrated well-demarcated violaceous papules and plaques on the trunk, extensor aspect of the forearms, and thighs involving 10% of the body surface area (Figure 1A). The lesions were annular with raised borders and central depigmented atrophic scarring (Figure 1B). The examination also revealed several large hypopigmented atrophic patches and plaques in the right inguinal region and on the dorsal aspect of the penile shaft and buttocks as well as a single atrophic plaque on the scalp. No oral lesions were seen. An initial punch biopsy was consistent with a nonspecific lichenoid dermatitis (Figure 2), and the patient was prescribed triamcinolone ointment 0.1% for the trunk and extremities and tacrolimus ointment 0.1% for the groin and genital region.

The patient continued to develop new annular atrophic skin lesions over the next several months. Repeat punch biopsies of lesional and uninvolved perilesional skin from the trunk were obtained for histopathologic confirmation and special staining. Lichenoid dermatitis again was noted on the lesional biopsy, and no notable histopathologic changes were observed on the perilesional biopsy. Verhoeff-van Gieson staining for elastic fibers was performed on both biopsies, which revealed destruction of elastic fibers in the central papillary dermis and upper reticular dermis of the lesional biopsy (Figure 3A). The elastic fibers on the perilesional biopsy were preserved (Figure 3B).

The clinical presentation and histopathological findings confirmed a diagnosis of AALP. The patient was prescribed a short taper of oral prednisone, which halted further disease progression. The patient was then started on pentoxifylline and continued on tacrolimus ointment 0.1% with minimal improvement in existing lesions. These medications were discontinued after 3 months. Hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily was administered, which initially resulted in some thinning of the plaques on the trunk; however, further progression of the disease was noted after 3 months. Acitretin 25 mg once daily was added to his treatment regimen. Marked thinning of active lesions, hyperpigmentation, and residual scarring was noted after 2 months of combined therapy with acitretin and hydroxychloroquine (Figure 4), with continued improvement appreciable several months later.

Comment

Lichen planus is a common pruritic inflammatory disease of the skin, mucous membranes, hair follicles, and nails with a highly variable clinical pattern and disease course that typically affects the adult population.2 There are many clinical variants of lichen planus, which all demonstrate lichenoid dermatitis on histology. Annular lichen planus is an uncommon variant most commonly seen in men with asymptomatic lesions involving the axillae and groin.2 Atrophic lichen planus is another variant demonstrating atrophic papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities.3 Annular atrophic lichen planus is the rarest variant of lichen planus, incorporating features of both annular and atrophic lichen planus.

The first case of AALP involved a 56-year-old black man with a 25-year history of annular atrophic papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities.1 The second case reported by Requena et al4 in 1994 described a 65-year-old woman with characteristic lesions on the right elbow and left knee. Lipsker et al5 reported a third case in a 41-year-old man with a history of Sneddon syndrome who had lesions typical for AALP for 20 years. In all of these cases, histopathologic examination revealed a lichenoid infiltrate with thinning of the epidermis and loss of elastic fibers in the center of the active lesions.

In more recent cases of AALP, the characteristic findings primarily occurred on the trunk and extremities.6-10 Treatment with topical corticosteroids failed in most cases and some patients noted moderate improvement with tacrolimus ointment 0.1%. Sugashima and Yamamoto11 reported a unique case in 2012 of a 32-year-old woman with AALP on the lower lip. She had notable improvement with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% after 6 months.11

All of the known cases of AALP to date have occurred in adults, both male and female, presenting with a limited number of annular plaques with slightly elevated borders and depressed atrophic centers.1,3-11 Disease duration of AALP has ranged from 2 months to 25 years.11 Histopathologic findings characteristically demonstrate a lichenoid dermatitis of the raised lesional border with a flattened epidermis, loss of rete ridges, and fibrosis of dermal papillae in the lesion center.7 The elastic fibers are destroyed in the papillary dermis of the lesion center, presumably due to elastolytic activity of inflammatory cells.1 Macrophages present in the lichenoid infiltrate of acute lesions release elastases contributing to this destruction.7 Furthermore, elastic fibers appear fragmented on electron microscopy.1

The clinical course of AALP has proven to be chronic in most cases and frequently is resistant to treatment with topical corticosteroids, retinoids, phototherapy, and immunosuppressive agents.3 Treatment administered early in the disease course may provide a more favorable outcome.11 Lesions characteristically heal with scarring and hyperpigmentation. Our case displayed more extensive involvement than has previously been reported. Our patient showed minimal improvement with topical therapy; however, he demonstrated thinning and regression of active lesions after 2 months of combined treatment with hydroxychloroquine and acitretin. Our use of oral pentoxifylline, hydroxychloroquine, and acitretin has not been previously reported in the other cases of AALP we reviewed. Acitretin is the only systemic agent for lichen planus that has achieved level A evidence, as it previously was shown to be highly effective in a placebo-controlled, double-blind study of 65 patients.12

Conclusion

Annular atrophic lichen planus is a known variant of lichen planus characterized by a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of active lesions. Treatment with topical corticosteroids and phototherapy frequently is ineffective. To our knowledge, there are no studies to date regarding the efficacy of systemic therapy in treatment of AALP. Hydroxychloroquine and acitretin may prove to be beneficial treatment options for resistant AALP. Additional alternative treatments continue to be explored. We encourage reporting additional cases of AALP to further characterize its clinical presentation and response to treatments.

- Friedman DB, Hashimoto K. Annular atrophic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:392-394.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Lichen planus and related conditions. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:213-215.

- Kim BS, Seo SH, Jang BS, et al. A case of annular atrophic lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:989-990.

- Requena L, Olivares M, Pique E, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Dermatology. 1994;189:95-98.

- Lipsker D, Piette JC, Laporte JL, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus and Sneddon's syndrome. Dermatology. 1997;105:402-403.

- Mseddi M, Bouassadi S, Marrakchi S, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Dermatology. 2003;207:208-209.

- Morales-Callaghan A Jr, Martinez G, Aragoneses H, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:906-908.

- Ponce-Olivera RM, Tirado-Sánchez A, Montes-de-Oca-Sánchez G, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:490-491.

- Kim JS, Kang MS, Sagong C, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus associated with hypertrophic lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:195-197.

- Li B, Li JH, Xiao T, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:842-843.

- Sugashima Y, Yamamoto T. Annular atrophic lichen planus of the lip. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:14.

- Manousaridis I, Manousaridis K, Peitsch WK, et al. Individualizing treatment and choice of medication in lichen planus: a step by step approach. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:981-991.

Annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP) is a rare variant of lichen planus that was first described by Friedman and Hashimoto1 in 1991. Clinically, it combines the configuration and morphological features of both annular and atrophic lichen planus. It is a rare entity. We report a case of AALP in a 69-year-old black man. The clinical and histopathological presentation depicted the defining features of this entity with a characteristic loss of elastic fibers corresponding to central atrophy of active lesions.

Case Report

A 69-year-old black man with a history of hepatitis C virus infection and hypothyroidism presented to the dermatology clinic with a pruritic rash on the trunk, extremities, groin, and scalp of 4 months' duration. He denied any new medications, recent illnesses, or sick contacts. Physical examination demonstrated well-demarcated violaceous papules and plaques on the trunk, extensor aspect of the forearms, and thighs involving 10% of the body surface area (Figure 1A). The lesions were annular with raised borders and central depigmented atrophic scarring (Figure 1B). The examination also revealed several large hypopigmented atrophic patches and plaques in the right inguinal region and on the dorsal aspect of the penile shaft and buttocks as well as a single atrophic plaque on the scalp. No oral lesions were seen. An initial punch biopsy was consistent with a nonspecific lichenoid dermatitis (Figure 2), and the patient was prescribed triamcinolone ointment 0.1% for the trunk and extremities and tacrolimus ointment 0.1% for the groin and genital region.

The patient continued to develop new annular atrophic skin lesions over the next several months. Repeat punch biopsies of lesional and uninvolved perilesional skin from the trunk were obtained for histopathologic confirmation and special staining. Lichenoid dermatitis again was noted on the lesional biopsy, and no notable histopathologic changes were observed on the perilesional biopsy. Verhoeff-van Gieson staining for elastic fibers was performed on both biopsies, which revealed destruction of elastic fibers in the central papillary dermis and upper reticular dermis of the lesional biopsy (Figure 3A). The elastic fibers on the perilesional biopsy were preserved (Figure 3B).

The clinical presentation and histopathological findings confirmed a diagnosis of AALP. The patient was prescribed a short taper of oral prednisone, which halted further disease progression. The patient was then started on pentoxifylline and continued on tacrolimus ointment 0.1% with minimal improvement in existing lesions. These medications were discontinued after 3 months. Hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily was administered, which initially resulted in some thinning of the plaques on the trunk; however, further progression of the disease was noted after 3 months. Acitretin 25 mg once daily was added to his treatment regimen. Marked thinning of active lesions, hyperpigmentation, and residual scarring was noted after 2 months of combined therapy with acitretin and hydroxychloroquine (Figure 4), with continued improvement appreciable several months later.

Comment

Lichen planus is a common pruritic inflammatory disease of the skin, mucous membranes, hair follicles, and nails with a highly variable clinical pattern and disease course that typically affects the adult population.2 There are many clinical variants of lichen planus, which all demonstrate lichenoid dermatitis on histology. Annular lichen planus is an uncommon variant most commonly seen in men with asymptomatic lesions involving the axillae and groin.2 Atrophic lichen planus is another variant demonstrating atrophic papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities.3 Annular atrophic lichen planus is the rarest variant of lichen planus, incorporating features of both annular and atrophic lichen planus.

The first case of AALP involved a 56-year-old black man with a 25-year history of annular atrophic papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities.1 The second case reported by Requena et al4 in 1994 described a 65-year-old woman with characteristic lesions on the right elbow and left knee. Lipsker et al5 reported a third case in a 41-year-old man with a history of Sneddon syndrome who had lesions typical for AALP for 20 years. In all of these cases, histopathologic examination revealed a lichenoid infiltrate with thinning of the epidermis and loss of elastic fibers in the center of the active lesions.

In more recent cases of AALP, the characteristic findings primarily occurred on the trunk and extremities.6-10 Treatment with topical corticosteroids failed in most cases and some patients noted moderate improvement with tacrolimus ointment 0.1%. Sugashima and Yamamoto11 reported a unique case in 2012 of a 32-year-old woman with AALP on the lower lip. She had notable improvement with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% after 6 months.11

All of the known cases of AALP to date have occurred in adults, both male and female, presenting with a limited number of annular plaques with slightly elevated borders and depressed atrophic centers.1,3-11 Disease duration of AALP has ranged from 2 months to 25 years.11 Histopathologic findings characteristically demonstrate a lichenoid dermatitis of the raised lesional border with a flattened epidermis, loss of rete ridges, and fibrosis of dermal papillae in the lesion center.7 The elastic fibers are destroyed in the papillary dermis of the lesion center, presumably due to elastolytic activity of inflammatory cells.1 Macrophages present in the lichenoid infiltrate of acute lesions release elastases contributing to this destruction.7 Furthermore, elastic fibers appear fragmented on electron microscopy.1

The clinical course of AALP has proven to be chronic in most cases and frequently is resistant to treatment with topical corticosteroids, retinoids, phototherapy, and immunosuppressive agents.3 Treatment administered early in the disease course may provide a more favorable outcome.11 Lesions characteristically heal with scarring and hyperpigmentation. Our case displayed more extensive involvement than has previously been reported. Our patient showed minimal improvement with topical therapy; however, he demonstrated thinning and regression of active lesions after 2 months of combined treatment with hydroxychloroquine and acitretin. Our use of oral pentoxifylline, hydroxychloroquine, and acitretin has not been previously reported in the other cases of AALP we reviewed. Acitretin is the only systemic agent for lichen planus that has achieved level A evidence, as it previously was shown to be highly effective in a placebo-controlled, double-blind study of 65 patients.12

Conclusion

Annular atrophic lichen planus is a known variant of lichen planus characterized by a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of active lesions. Treatment with topical corticosteroids and phototherapy frequently is ineffective. To our knowledge, there are no studies to date regarding the efficacy of systemic therapy in treatment of AALP. Hydroxychloroquine and acitretin may prove to be beneficial treatment options for resistant AALP. Additional alternative treatments continue to be explored. We encourage reporting additional cases of AALP to further characterize its clinical presentation and response to treatments.

Annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP) is a rare variant of lichen planus that was first described by Friedman and Hashimoto1 in 1991. Clinically, it combines the configuration and morphological features of both annular and atrophic lichen planus. It is a rare entity. We report a case of AALP in a 69-year-old black man. The clinical and histopathological presentation depicted the defining features of this entity with a characteristic loss of elastic fibers corresponding to central atrophy of active lesions.

Case Report

A 69-year-old black man with a history of hepatitis C virus infection and hypothyroidism presented to the dermatology clinic with a pruritic rash on the trunk, extremities, groin, and scalp of 4 months' duration. He denied any new medications, recent illnesses, or sick contacts. Physical examination demonstrated well-demarcated violaceous papules and plaques on the trunk, extensor aspect of the forearms, and thighs involving 10% of the body surface area (Figure 1A). The lesions were annular with raised borders and central depigmented atrophic scarring (Figure 1B). The examination also revealed several large hypopigmented atrophic patches and plaques in the right inguinal region and on the dorsal aspect of the penile shaft and buttocks as well as a single atrophic plaque on the scalp. No oral lesions were seen. An initial punch biopsy was consistent with a nonspecific lichenoid dermatitis (Figure 2), and the patient was prescribed triamcinolone ointment 0.1% for the trunk and extremities and tacrolimus ointment 0.1% for the groin and genital region.

The patient continued to develop new annular atrophic skin lesions over the next several months. Repeat punch biopsies of lesional and uninvolved perilesional skin from the trunk were obtained for histopathologic confirmation and special staining. Lichenoid dermatitis again was noted on the lesional biopsy, and no notable histopathologic changes were observed on the perilesional biopsy. Verhoeff-van Gieson staining for elastic fibers was performed on both biopsies, which revealed destruction of elastic fibers in the central papillary dermis and upper reticular dermis of the lesional biopsy (Figure 3A). The elastic fibers on the perilesional biopsy were preserved (Figure 3B).

The clinical presentation and histopathological findings confirmed a diagnosis of AALP. The patient was prescribed a short taper of oral prednisone, which halted further disease progression. The patient was then started on pentoxifylline and continued on tacrolimus ointment 0.1% with minimal improvement in existing lesions. These medications were discontinued after 3 months. Hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily was administered, which initially resulted in some thinning of the plaques on the trunk; however, further progression of the disease was noted after 3 months. Acitretin 25 mg once daily was added to his treatment regimen. Marked thinning of active lesions, hyperpigmentation, and residual scarring was noted after 2 months of combined therapy with acitretin and hydroxychloroquine (Figure 4), with continued improvement appreciable several months later.

Comment

Lichen planus is a common pruritic inflammatory disease of the skin, mucous membranes, hair follicles, and nails with a highly variable clinical pattern and disease course that typically affects the adult population.2 There are many clinical variants of lichen planus, which all demonstrate lichenoid dermatitis on histology. Annular lichen planus is an uncommon variant most commonly seen in men with asymptomatic lesions involving the axillae and groin.2 Atrophic lichen planus is another variant demonstrating atrophic papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities.3 Annular atrophic lichen planus is the rarest variant of lichen planus, incorporating features of both annular and atrophic lichen planus.

The first case of AALP involved a 56-year-old black man with a 25-year history of annular atrophic papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities.1 The second case reported by Requena et al4 in 1994 described a 65-year-old woman with characteristic lesions on the right elbow and left knee. Lipsker et al5 reported a third case in a 41-year-old man with a history of Sneddon syndrome who had lesions typical for AALP for 20 years. In all of these cases, histopathologic examination revealed a lichenoid infiltrate with thinning of the epidermis and loss of elastic fibers in the center of the active lesions.

In more recent cases of AALP, the characteristic findings primarily occurred on the trunk and extremities.6-10 Treatment with topical corticosteroids failed in most cases and some patients noted moderate improvement with tacrolimus ointment 0.1%. Sugashima and Yamamoto11 reported a unique case in 2012 of a 32-year-old woman with AALP on the lower lip. She had notable improvement with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% after 6 months.11

All of the known cases of AALP to date have occurred in adults, both male and female, presenting with a limited number of annular plaques with slightly elevated borders and depressed atrophic centers.1,3-11 Disease duration of AALP has ranged from 2 months to 25 years.11 Histopathologic findings characteristically demonstrate a lichenoid dermatitis of the raised lesional border with a flattened epidermis, loss of rete ridges, and fibrosis of dermal papillae in the lesion center.7 The elastic fibers are destroyed in the papillary dermis of the lesion center, presumably due to elastolytic activity of inflammatory cells.1 Macrophages present in the lichenoid infiltrate of acute lesions release elastases contributing to this destruction.7 Furthermore, elastic fibers appear fragmented on electron microscopy.1

The clinical course of AALP has proven to be chronic in most cases and frequently is resistant to treatment with topical corticosteroids, retinoids, phototherapy, and immunosuppressive agents.3 Treatment administered early in the disease course may provide a more favorable outcome.11 Lesions characteristically heal with scarring and hyperpigmentation. Our case displayed more extensive involvement than has previously been reported. Our patient showed minimal improvement with topical therapy; however, he demonstrated thinning and regression of active lesions after 2 months of combined treatment with hydroxychloroquine and acitretin. Our use of oral pentoxifylline, hydroxychloroquine, and acitretin has not been previously reported in the other cases of AALP we reviewed. Acitretin is the only systemic agent for lichen planus that has achieved level A evidence, as it previously was shown to be highly effective in a placebo-controlled, double-blind study of 65 patients.12

Conclusion

Annular atrophic lichen planus is a known variant of lichen planus characterized by a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of active lesions. Treatment with topical corticosteroids and phototherapy frequently is ineffective. To our knowledge, there are no studies to date regarding the efficacy of systemic therapy in treatment of AALP. Hydroxychloroquine and acitretin may prove to be beneficial treatment options for resistant AALP. Additional alternative treatments continue to be explored. We encourage reporting additional cases of AALP to further characterize its clinical presentation and response to treatments.

- Friedman DB, Hashimoto K. Annular atrophic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:392-394.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Lichen planus and related conditions. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:213-215.

- Kim BS, Seo SH, Jang BS, et al. A case of annular atrophic lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:989-990.

- Requena L, Olivares M, Pique E, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Dermatology. 1994;189:95-98.

- Lipsker D, Piette JC, Laporte JL, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus and Sneddon's syndrome. Dermatology. 1997;105:402-403.

- Mseddi M, Bouassadi S, Marrakchi S, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Dermatology. 2003;207:208-209.

- Morales-Callaghan A Jr, Martinez G, Aragoneses H, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:906-908.

- Ponce-Olivera RM, Tirado-Sánchez A, Montes-de-Oca-Sánchez G, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:490-491.

- Kim JS, Kang MS, Sagong C, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus associated with hypertrophic lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:195-197.

- Li B, Li JH, Xiao T, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:842-843.

- Sugashima Y, Yamamoto T. Annular atrophic lichen planus of the lip. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:14.

- Manousaridis I, Manousaridis K, Peitsch WK, et al. Individualizing treatment and choice of medication in lichen planus: a step by step approach. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:981-991.

- Friedman DB, Hashimoto K. Annular atrophic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:392-394.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Lichen planus and related conditions. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:213-215.

- Kim BS, Seo SH, Jang BS, et al. A case of annular atrophic lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:989-990.

- Requena L, Olivares M, Pique E, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Dermatology. 1994;189:95-98.

- Lipsker D, Piette JC, Laporte JL, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus and Sneddon's syndrome. Dermatology. 1997;105:402-403.

- Mseddi M, Bouassadi S, Marrakchi S, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Dermatology. 2003;207:208-209.

- Morales-Callaghan A Jr, Martinez G, Aragoneses H, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:906-908.

- Ponce-Olivera RM, Tirado-Sánchez A, Montes-de-Oca-Sánchez G, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:490-491.

- Kim JS, Kang MS, Sagong C, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus associated with hypertrophic lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:195-197.

- Li B, Li JH, Xiao T, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:842-843.

- Sugashima Y, Yamamoto T. Annular atrophic lichen planus of the lip. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:14.

- Manousaridis I, Manousaridis K, Peitsch WK, et al. Individualizing treatment and choice of medication in lichen planus: a step by step approach. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:981-991.

Asymptomatic Cutaneous Polyarteritis Nodosa: Treatment Options and Therapeutic Guidelines