User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Alpha-1 Foundation Announces Funding Opportunities

The Alpha-1 Foundation has announced its funding opportunities in its 2017-2018 grants cycle. In-cycle Letters of Intent are due by September 22, 2017, and may be submitted online.

The Alpha-1 Foundation has announced its funding opportunities in its 2017-2018 grants cycle. In-cycle Letters of Intent are due by September 22, 2017, and may be submitted online.

The Alpha-1 Foundation has announced its funding opportunities in its 2017-2018 grants cycle. In-cycle Letters of Intent are due by September 22, 2017, and may be submitted online.

NORD Welcomes All Things Kabuki as New Member

All Things Kabuki, an organization providing awareness, education, and support on behalf of those affected by Kabuki syndrome, is NORD’s newest member organization. Read NORD’s Rare Disease Database report on Kabuki syndrome.

All Things Kabuki, an organization providing awareness, education, and support on behalf of those affected by Kabuki syndrome, is NORD’s newest member organization. Read NORD’s Rare Disease Database report on Kabuki syndrome.

All Things Kabuki, an organization providing awareness, education, and support on behalf of those affected by Kabuki syndrome, is NORD’s newest member organization. Read NORD’s Rare Disease Database report on Kabuki syndrome.

Columbia Neurosurgery Article Highlights Medical Expert’s Support for NORD Patient Information

An article on the Columbia University Medical Center website describes how neurosurgeon Jeffrey Bruce, MD, helped NORD develop a report for patient/family education on anaplastic astrocytoma. Dr. Bruce is one of many rare disease medical experts who volunteer their time and expertise to help NORD provide information on rare conditions for patients and their families.

An article on the Columbia University Medical Center website describes how neurosurgeon Jeffrey Bruce, MD, helped NORD develop a report for patient/family education on anaplastic astrocytoma. Dr. Bruce is one of many rare disease medical experts who volunteer their time and expertise to help NORD provide information on rare conditions for patients and their families.

An article on the Columbia University Medical Center website describes how neurosurgeon Jeffrey Bruce, MD, helped NORD develop a report for patient/family education on anaplastic astrocytoma. Dr. Bruce is one of many rare disease medical experts who volunteer their time and expertise to help NORD provide information on rare conditions for patients and their families.

FDA Launches Expanded Access Navigator

Patients with serious or immediately life-threatening diseases or conditions who have no comparable or satisfactory alternative therapy and who seek access to potentially life-saving investigational drugs can use the FDA’s new Expanded Access Navigator to guide them through the process. The Navigator was a team effort led by the Reagan-Udall Foundation in collaboration with patient advocacy groups, the pharmaceutical industry, the FDA, and others in the Federal government.

Patients with serious or immediately life-threatening diseases or conditions who have no comparable or satisfactory alternative therapy and who seek access to potentially life-saving investigational drugs can use the FDA’s new Expanded Access Navigator to guide them through the process. The Navigator was a team effort led by the Reagan-Udall Foundation in collaboration with patient advocacy groups, the pharmaceutical industry, the FDA, and others in the Federal government.

Patients with serious or immediately life-threatening diseases or conditions who have no comparable or satisfactory alternative therapy and who seek access to potentially life-saving investigational drugs can use the FDA’s new Expanded Access Navigator to guide them through the process. The Navigator was a team effort led by the Reagan-Udall Foundation in collaboration with patient advocacy groups, the pharmaceutical industry, the FDA, and others in the Federal government.

Examining the Role of Caregivers at NINR Caregiving Summit

Mary Dunkle, NORD Vice President of Educational Initiatives, will speak on a panel discussing the role and needs of caregivers at “The Science of Caregiving: Bringing Voices Together” to be hosted by the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) on August 7-8, 2017, in Bethesda, Maryland. This conference is open to all and will also be livestreamed and archived for on-demand viewing.

Mary Dunkle, NORD Vice President of Educational Initiatives, will speak on a panel discussing the role and needs of caregivers at “The Science of Caregiving: Bringing Voices Together” to be hosted by the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) on August 7-8, 2017, in Bethesda, Maryland. This conference is open to all and will also be livestreamed and archived for on-demand viewing.

Mary Dunkle, NORD Vice President of Educational Initiatives, will speak on a panel discussing the role and needs of caregivers at “The Science of Caregiving: Bringing Voices Together” to be hosted by the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) on August 7-8, 2017, in Bethesda, Maryland. This conference is open to all and will also be livestreamed and archived for on-demand viewing.

FDA Commissioner to Present Keynote Address at NORD Summit

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, will present the keynote address in the opening session of the 2017 NORD Summit. Dr. Gottlieb, who was sworn in as FDA Commissioner in May 2017, previously served as FDA’s Deputy Commissioner for Medical and Scientific Affairs. Before that, he was Senior Adviser to the FDA Commissioner.

Mike Porath, award-winning journalist and founder/CEO of The Mighty, will present the patient keynote. He has held writing, editing, and executive positions at ABC News, NBC News, the New York Times, and AOL. Mr. Porath is the father of a child with Dup15q syndrome and sits on the board of Dup15q Alliance.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, will present the keynote address in the opening session of the 2017 NORD Summit. Dr. Gottlieb, who was sworn in as FDA Commissioner in May 2017, previously served as FDA’s Deputy Commissioner for Medical and Scientific Affairs. Before that, he was Senior Adviser to the FDA Commissioner.

Mike Porath, award-winning journalist and founder/CEO of The Mighty, will present the patient keynote. He has held writing, editing, and executive positions at ABC News, NBC News, the New York Times, and AOL. Mr. Porath is the father of a child with Dup15q syndrome and sits on the board of Dup15q Alliance.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, will present the keynote address in the opening session of the 2017 NORD Summit. Dr. Gottlieb, who was sworn in as FDA Commissioner in May 2017, previously served as FDA’s Deputy Commissioner for Medical and Scientific Affairs. Before that, he was Senior Adviser to the FDA Commissioner.

Mike Porath, award-winning journalist and founder/CEO of The Mighty, will present the patient keynote. He has held writing, editing, and executive positions at ABC News, NBC News, the New York Times, and AOL. Mr. Porath is the father of a child with Dup15q syndrome and sits on the board of Dup15q Alliance.

Preview Agenda for NORD’s 2017 Rare Diseases and Orphan Products

Promoting Earlier Diagnosis, the Power of Data Sharing, Next-Generation Treatments, and Advancing Clinical Trials will be among the topics discussed at the 2017 NORD Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit, to be held on October 16-17, 2017, in Washington DC. The program is open to all and will feature more than 80 expert speakers. Learn more and download the agenda.

Register by August 25 for Early-Bird Pricing

Online registration is now open for the NORD Summit. Register by August 25 to save up to $400. The NORD Summit will take place October 16-17 at the Marriott Wardman Park Hotel in Washington DC.

Submit a Poster Abstract or Become an Exhibitor or Sponsor

August 18 is the deadline to submit abstracts for the Summit Poster Session. The overall poster theme is “Life-Transforming Treatments.” In addition, there are opportunities to exhibit at the Summit or become a sponsor. Exhibiting and sponsorship inquiries may be sent to [email protected].

Promoting Earlier Diagnosis, the Power of Data Sharing, Next-Generation Treatments, and Advancing Clinical Trials will be among the topics discussed at the 2017 NORD Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit, to be held on October 16-17, 2017, in Washington DC. The program is open to all and will feature more than 80 expert speakers. Learn more and download the agenda.

Register by August 25 for Early-Bird Pricing

Online registration is now open for the NORD Summit. Register by August 25 to save up to $400. The NORD Summit will take place October 16-17 at the Marriott Wardman Park Hotel in Washington DC.

Submit a Poster Abstract or Become an Exhibitor or Sponsor

August 18 is the deadline to submit abstracts for the Summit Poster Session. The overall poster theme is “Life-Transforming Treatments.” In addition, there are opportunities to exhibit at the Summit or become a sponsor. Exhibiting and sponsorship inquiries may be sent to [email protected].

Promoting Earlier Diagnosis, the Power of Data Sharing, Next-Generation Treatments, and Advancing Clinical Trials will be among the topics discussed at the 2017 NORD Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit, to be held on October 16-17, 2017, in Washington DC. The program is open to all and will feature more than 80 expert speakers. Learn more and download the agenda.

Register by August 25 for Early-Bird Pricing

Online registration is now open for the NORD Summit. Register by August 25 to save up to $400. The NORD Summit will take place October 16-17 at the Marriott Wardman Park Hotel in Washington DC.

Submit a Poster Abstract or Become an Exhibitor or Sponsor

August 18 is the deadline to submit abstracts for the Summit Poster Session. The overall poster theme is “Life-Transforming Treatments.” In addition, there are opportunities to exhibit at the Summit or become a sponsor. Exhibiting and sponsorship inquiries may be sent to [email protected].

Paraneoplastic Acrokeratosis Bazex Syndrome: Unusual Association With In Situ Follicular Lymphoma and Response to Acitretin

To the Editor:

Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis (PA), also known as Bazex syndrome, is a rare paraneoplastic dermatosis first described in 1965 by Bazex et al.1 This entity is clinically characterized by dusky erythematous to violaceous keratoderma of the acral sites and commonly affects men older than 40 years. In most reported cases, there has been an underlying primary malignant neoplasm of the upper aerodigestive tract2; however, some other associated malignancies also have been reported. Skin changes tend to occur before the diagnosis of the associated tumor in 67% of cases. The cutaneous lesions usually resolve after successful treatment of the tumor and relapse in case of recurrence of the malignancy.3

A 53-year-old woman who was a smoker with no relevant medical background was referred to the dermatology department with an itching psoriasiform dermatitis on the palms and soles of 2 months' duration. There were no signs of systemic disease. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated, dusky red, thick, scaly plaques on the soles with sparing of the insteps (Figure, A). Scattered symmetric hyperkeratotic plaques were present on the palms (Figure, B). We also detected onychodystrophy on the hands. Other dermatologic findings were normal. Histologic examination of a biopsy specimen of the left sole showed hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, acanthosis, hypergranulosis, and a predominantly perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.

With the diagnostic suspicion of PA, blood tests, chest radiograph, and colonoscopy were performed without revealing abnormalities. Positron emission tomography and computed tomography also was performed, showing cervical, mesenteric, retroperitoneal, and inguinal adenopathies. Histologic examination of both inguinal adenectomy and cervical lymph node biopsy revealed Bcl-2-positive in situ follicular lymphoma (ISFL). Examination of an iliac crest marrow aspirate showed minimal involvement of lymphoma (10%). Follow-up imaging performed 4 months after diagnosis showed no changes. The patient was diagnosed with a low-grade chronic lymphoproliferative disorder with histologic findings consistent with ISFL presenting with small disperse adenopathies and minimal bone marrow involvement. The hematology department opted for a wait-and-see approach with 6-month follow-up imaging.

The skin lesions were first treated with salicylic acid cream 10%, psoralen plus UVA therapy, and methotrexate 20 mg weekly for 2 months without remission. Replacing the other therapies, we initiated acitretin 25 mg daily, achieving sustained remission after 6 months of treatment, and then continued with a scaled dose reduction. The patient remained lesion free 1 year after starting the treatment, with a daily dose of 10 mg of acitretin.

Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis has been traditionally described as a paraneoplastic entity mainly associated with primary squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the upper aerodigestive tract or a metastatic SCC of the cervical lymph nodes with an unknown origin.4,5 However, uncommon associations such as adenocarcinoma of the prostate, lung, esophagus, stomach, and colon; transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder; small cell carcinoma of the lung; cutaneous SCC; breast cancer; metastatic thymic carcinoma; metastatic neuroendocrine tumor; bronchial carcinoid tumor; SCC of the vulvar region; simultaneous multiple genitourinary tumors; and liposarcoma also have been described.6 Regarding the association with lymphoma, PA has been reported with peripheral T-cell lymphoma7 and Hodgkin disease8; however, ISFL underlying PA is rare.

Follicular lymphoma is the second most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Western countries and comprises approximately 20% of all lymphomas.9 It is slightly more prevalent in females, and the majority of patients present with advanced-stage disease. Generally considered to be an incurable disease, a watchful-waiting approach of conservative management has been advocated in most cases, deferring treatment until symptoms appear.9

Histology of PA is nonspecific, as in our case. However, it facilitates a differential diagnosis of major dermatoses including psoriasis vulgaris, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and lupus erythematosus.

Paraneoplastic palmoplantar keratoderma also is characteristic of Howel-Evans syndrome, which is a rare inherited condition associated with esophageal cancer. In contrast to our case, palmoplantar keratoderma in these patients usually begins around 10 years of age, is caused by a mutation in the RHBDF2 gene, and is inherited in an autosomal pattern.10

The diagnosis in our case was supported by a typical clinical picture, nonspecific histology, and the concurrent finding of the underlying lymphoma. Treatment of PA must focus on the removal of the underlying malignancy, which implies the remission of the cutaneous lesions. Taking into account that a recurrence of the primary tumor leads to a relapse of skin manifestations while distant metastases do not cause a reappearance of PA, it could be suggested that pathogenetically relevant factors are produced by the primary tumor and by lymph node metastases but not by metastases elsewhere.

In this case, due to the wait-and-see approach, a specific treatment for the skin lesions was established. Although management of the skin itself generally is ineffective, there are isolated reports of response after corticosteroids, antibiotics, antimycotics, keratolytic measures, or psoralen plus UVA therapy.6 Wishart11 used etretinate to achieve an improvement of PA. We also achieved good response with acitretin. Retinoids are known to have antineoplastic activity, which may have been helpful in both the patient we presented and the one reported by Wishart.11 In summary, we propose adding ISFL to the expanding list of malignant neoplasms associated with PA, noting the response of skin lesions after acitretin.

- Bazex A, Salvador R, Dupré A, et al. Syndrome paranéoplasique à type d'hyperkératose des extremités. Guérison après le traitement de l'épithelioma laryngé. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1965;72:182.

- Bazex A, Griffiths A. Acrokeratosis paraneoplasticae--a new cutaneous marker of malignancy. Br J Dermatol. 1980;103:301-306.

- Bolognia JL. Bazex syndrome: acrokeratosis paraneoplastica. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:84-89.

- Witkowski JA, Parish LC. Bazex's syndrome. Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis. JAMA. 1982;248:2883-2884.

- Bolognia JL. Bazex's syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:37-42.

- Sator PG, Breier F, Gschnait F. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex's syndrome): association with liposarcoma [published online August 28, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:1103-1105.

- Lin YC, Chu CY, Chiu HC. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica Bazex's syndrome: unusual association with a peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:440-441.

- Lucker GP, Steijlen PM. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex syndrome) occurring with acquired ichthyosis in Hodgkin's disease. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:322-325.

- Jegalian AG, Eberle FC, Pack SD, et al. Follicular lymphoma in situ: clinical implications and comparisons with partial involvement by follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:2976-2984.

- Sroa N, Witman P. Howel-Evans syndrome: a variant of ectodermal dysplasia. Cutis. 2010;85:183-185.

- Wishart JM. Bazex paraneoplastic acrokeratosis: a case report and response to Tigason. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:595-599.

To the Editor:

Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis (PA), also known as Bazex syndrome, is a rare paraneoplastic dermatosis first described in 1965 by Bazex et al.1 This entity is clinically characterized by dusky erythematous to violaceous keratoderma of the acral sites and commonly affects men older than 40 years. In most reported cases, there has been an underlying primary malignant neoplasm of the upper aerodigestive tract2; however, some other associated malignancies also have been reported. Skin changes tend to occur before the diagnosis of the associated tumor in 67% of cases. The cutaneous lesions usually resolve after successful treatment of the tumor and relapse in case of recurrence of the malignancy.3

A 53-year-old woman who was a smoker with no relevant medical background was referred to the dermatology department with an itching psoriasiform dermatitis on the palms and soles of 2 months' duration. There were no signs of systemic disease. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated, dusky red, thick, scaly plaques on the soles with sparing of the insteps (Figure, A). Scattered symmetric hyperkeratotic plaques were present on the palms (Figure, B). We also detected onychodystrophy on the hands. Other dermatologic findings were normal. Histologic examination of a biopsy specimen of the left sole showed hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, acanthosis, hypergranulosis, and a predominantly perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.

With the diagnostic suspicion of PA, blood tests, chest radiograph, and colonoscopy were performed without revealing abnormalities. Positron emission tomography and computed tomography also was performed, showing cervical, mesenteric, retroperitoneal, and inguinal adenopathies. Histologic examination of both inguinal adenectomy and cervical lymph node biopsy revealed Bcl-2-positive in situ follicular lymphoma (ISFL). Examination of an iliac crest marrow aspirate showed minimal involvement of lymphoma (10%). Follow-up imaging performed 4 months after diagnosis showed no changes. The patient was diagnosed with a low-grade chronic lymphoproliferative disorder with histologic findings consistent with ISFL presenting with small disperse adenopathies and minimal bone marrow involvement. The hematology department opted for a wait-and-see approach with 6-month follow-up imaging.

The skin lesions were first treated with salicylic acid cream 10%, psoralen plus UVA therapy, and methotrexate 20 mg weekly for 2 months without remission. Replacing the other therapies, we initiated acitretin 25 mg daily, achieving sustained remission after 6 months of treatment, and then continued with a scaled dose reduction. The patient remained lesion free 1 year after starting the treatment, with a daily dose of 10 mg of acitretin.

Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis has been traditionally described as a paraneoplastic entity mainly associated with primary squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the upper aerodigestive tract or a metastatic SCC of the cervical lymph nodes with an unknown origin.4,5 However, uncommon associations such as adenocarcinoma of the prostate, lung, esophagus, stomach, and colon; transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder; small cell carcinoma of the lung; cutaneous SCC; breast cancer; metastatic thymic carcinoma; metastatic neuroendocrine tumor; bronchial carcinoid tumor; SCC of the vulvar region; simultaneous multiple genitourinary tumors; and liposarcoma also have been described.6 Regarding the association with lymphoma, PA has been reported with peripheral T-cell lymphoma7 and Hodgkin disease8; however, ISFL underlying PA is rare.

Follicular lymphoma is the second most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Western countries and comprises approximately 20% of all lymphomas.9 It is slightly more prevalent in females, and the majority of patients present with advanced-stage disease. Generally considered to be an incurable disease, a watchful-waiting approach of conservative management has been advocated in most cases, deferring treatment until symptoms appear.9

Histology of PA is nonspecific, as in our case. However, it facilitates a differential diagnosis of major dermatoses including psoriasis vulgaris, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and lupus erythematosus.

Paraneoplastic palmoplantar keratoderma also is characteristic of Howel-Evans syndrome, which is a rare inherited condition associated with esophageal cancer. In contrast to our case, palmoplantar keratoderma in these patients usually begins around 10 years of age, is caused by a mutation in the RHBDF2 gene, and is inherited in an autosomal pattern.10

The diagnosis in our case was supported by a typical clinical picture, nonspecific histology, and the concurrent finding of the underlying lymphoma. Treatment of PA must focus on the removal of the underlying malignancy, which implies the remission of the cutaneous lesions. Taking into account that a recurrence of the primary tumor leads to a relapse of skin manifestations while distant metastases do not cause a reappearance of PA, it could be suggested that pathogenetically relevant factors are produced by the primary tumor and by lymph node metastases but not by metastases elsewhere.

In this case, due to the wait-and-see approach, a specific treatment for the skin lesions was established. Although management of the skin itself generally is ineffective, there are isolated reports of response after corticosteroids, antibiotics, antimycotics, keratolytic measures, or psoralen plus UVA therapy.6 Wishart11 used etretinate to achieve an improvement of PA. We also achieved good response with acitretin. Retinoids are known to have antineoplastic activity, which may have been helpful in both the patient we presented and the one reported by Wishart.11 In summary, we propose adding ISFL to the expanding list of malignant neoplasms associated with PA, noting the response of skin lesions after acitretin.

To the Editor:

Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis (PA), also known as Bazex syndrome, is a rare paraneoplastic dermatosis first described in 1965 by Bazex et al.1 This entity is clinically characterized by dusky erythematous to violaceous keratoderma of the acral sites and commonly affects men older than 40 years. In most reported cases, there has been an underlying primary malignant neoplasm of the upper aerodigestive tract2; however, some other associated malignancies also have been reported. Skin changes tend to occur before the diagnosis of the associated tumor in 67% of cases. The cutaneous lesions usually resolve after successful treatment of the tumor and relapse in case of recurrence of the malignancy.3

A 53-year-old woman who was a smoker with no relevant medical background was referred to the dermatology department with an itching psoriasiform dermatitis on the palms and soles of 2 months' duration. There were no signs of systemic disease. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated, dusky red, thick, scaly plaques on the soles with sparing of the insteps (Figure, A). Scattered symmetric hyperkeratotic plaques were present on the palms (Figure, B). We also detected onychodystrophy on the hands. Other dermatologic findings were normal. Histologic examination of a biopsy specimen of the left sole showed hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, acanthosis, hypergranulosis, and a predominantly perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.

With the diagnostic suspicion of PA, blood tests, chest radiograph, and colonoscopy were performed without revealing abnormalities. Positron emission tomography and computed tomography also was performed, showing cervical, mesenteric, retroperitoneal, and inguinal adenopathies. Histologic examination of both inguinal adenectomy and cervical lymph node biopsy revealed Bcl-2-positive in situ follicular lymphoma (ISFL). Examination of an iliac crest marrow aspirate showed minimal involvement of lymphoma (10%). Follow-up imaging performed 4 months after diagnosis showed no changes. The patient was diagnosed with a low-grade chronic lymphoproliferative disorder with histologic findings consistent with ISFL presenting with small disperse adenopathies and minimal bone marrow involvement. The hematology department opted for a wait-and-see approach with 6-month follow-up imaging.

The skin lesions were first treated with salicylic acid cream 10%, psoralen plus UVA therapy, and methotrexate 20 mg weekly for 2 months without remission. Replacing the other therapies, we initiated acitretin 25 mg daily, achieving sustained remission after 6 months of treatment, and then continued with a scaled dose reduction. The patient remained lesion free 1 year after starting the treatment, with a daily dose of 10 mg of acitretin.

Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis has been traditionally described as a paraneoplastic entity mainly associated with primary squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the upper aerodigestive tract or a metastatic SCC of the cervical lymph nodes with an unknown origin.4,5 However, uncommon associations such as adenocarcinoma of the prostate, lung, esophagus, stomach, and colon; transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder; small cell carcinoma of the lung; cutaneous SCC; breast cancer; metastatic thymic carcinoma; metastatic neuroendocrine tumor; bronchial carcinoid tumor; SCC of the vulvar region; simultaneous multiple genitourinary tumors; and liposarcoma also have been described.6 Regarding the association with lymphoma, PA has been reported with peripheral T-cell lymphoma7 and Hodgkin disease8; however, ISFL underlying PA is rare.

Follicular lymphoma is the second most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Western countries and comprises approximately 20% of all lymphomas.9 It is slightly more prevalent in females, and the majority of patients present with advanced-stage disease. Generally considered to be an incurable disease, a watchful-waiting approach of conservative management has been advocated in most cases, deferring treatment until symptoms appear.9

Histology of PA is nonspecific, as in our case. However, it facilitates a differential diagnosis of major dermatoses including psoriasis vulgaris, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and lupus erythematosus.

Paraneoplastic palmoplantar keratoderma also is characteristic of Howel-Evans syndrome, which is a rare inherited condition associated with esophageal cancer. In contrast to our case, palmoplantar keratoderma in these patients usually begins around 10 years of age, is caused by a mutation in the RHBDF2 gene, and is inherited in an autosomal pattern.10

The diagnosis in our case was supported by a typical clinical picture, nonspecific histology, and the concurrent finding of the underlying lymphoma. Treatment of PA must focus on the removal of the underlying malignancy, which implies the remission of the cutaneous lesions. Taking into account that a recurrence of the primary tumor leads to a relapse of skin manifestations while distant metastases do not cause a reappearance of PA, it could be suggested that pathogenetically relevant factors are produced by the primary tumor and by lymph node metastases but not by metastases elsewhere.

In this case, due to the wait-and-see approach, a specific treatment for the skin lesions was established. Although management of the skin itself generally is ineffective, there are isolated reports of response after corticosteroids, antibiotics, antimycotics, keratolytic measures, or psoralen plus UVA therapy.6 Wishart11 used etretinate to achieve an improvement of PA. We also achieved good response with acitretin. Retinoids are known to have antineoplastic activity, which may have been helpful in both the patient we presented and the one reported by Wishart.11 In summary, we propose adding ISFL to the expanding list of malignant neoplasms associated with PA, noting the response of skin lesions after acitretin.

- Bazex A, Salvador R, Dupré A, et al. Syndrome paranéoplasique à type d'hyperkératose des extremités. Guérison après le traitement de l'épithelioma laryngé. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1965;72:182.

- Bazex A, Griffiths A. Acrokeratosis paraneoplasticae--a new cutaneous marker of malignancy. Br J Dermatol. 1980;103:301-306.

- Bolognia JL. Bazex syndrome: acrokeratosis paraneoplastica. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:84-89.

- Witkowski JA, Parish LC. Bazex's syndrome. Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis. JAMA. 1982;248:2883-2884.

- Bolognia JL. Bazex's syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:37-42.

- Sator PG, Breier F, Gschnait F. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex's syndrome): association with liposarcoma [published online August 28, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:1103-1105.

- Lin YC, Chu CY, Chiu HC. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica Bazex's syndrome: unusual association with a peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:440-441.

- Lucker GP, Steijlen PM. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex syndrome) occurring with acquired ichthyosis in Hodgkin's disease. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:322-325.

- Jegalian AG, Eberle FC, Pack SD, et al. Follicular lymphoma in situ: clinical implications and comparisons with partial involvement by follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:2976-2984.

- Sroa N, Witman P. Howel-Evans syndrome: a variant of ectodermal dysplasia. Cutis. 2010;85:183-185.

- Wishart JM. Bazex paraneoplastic acrokeratosis: a case report and response to Tigason. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:595-599.

- Bazex A, Salvador R, Dupré A, et al. Syndrome paranéoplasique à type d'hyperkératose des extremités. Guérison après le traitement de l'épithelioma laryngé. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1965;72:182.

- Bazex A, Griffiths A. Acrokeratosis paraneoplasticae--a new cutaneous marker of malignancy. Br J Dermatol. 1980;103:301-306.

- Bolognia JL. Bazex syndrome: acrokeratosis paraneoplastica. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:84-89.

- Witkowski JA, Parish LC. Bazex's syndrome. Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis. JAMA. 1982;248:2883-2884.

- Bolognia JL. Bazex's syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:37-42.

- Sator PG, Breier F, Gschnait F. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex's syndrome): association with liposarcoma [published online August 28, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:1103-1105.

- Lin YC, Chu CY, Chiu HC. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica Bazex's syndrome: unusual association with a peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:440-441.

- Lucker GP, Steijlen PM. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex syndrome) occurring with acquired ichthyosis in Hodgkin's disease. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:322-325.

- Jegalian AG, Eberle FC, Pack SD, et al. Follicular lymphoma in situ: clinical implications and comparisons with partial involvement by follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:2976-2984.

- Sroa N, Witman P. Howel-Evans syndrome: a variant of ectodermal dysplasia. Cutis. 2010;85:183-185.

- Wishart JM. Bazex paraneoplastic acrokeratosis: a case report and response to Tigason. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:595-599.

Practice Points

- Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis may mimic palmo-plantar acrokeratosis in both clinical presentation and treatment.

- Uncommon associations of paraneoplastic acrokeratosis with different types of lymphoma have been described.

Solitary Nodule With White Hairs

The Diagnosis: Trichofolliculoma

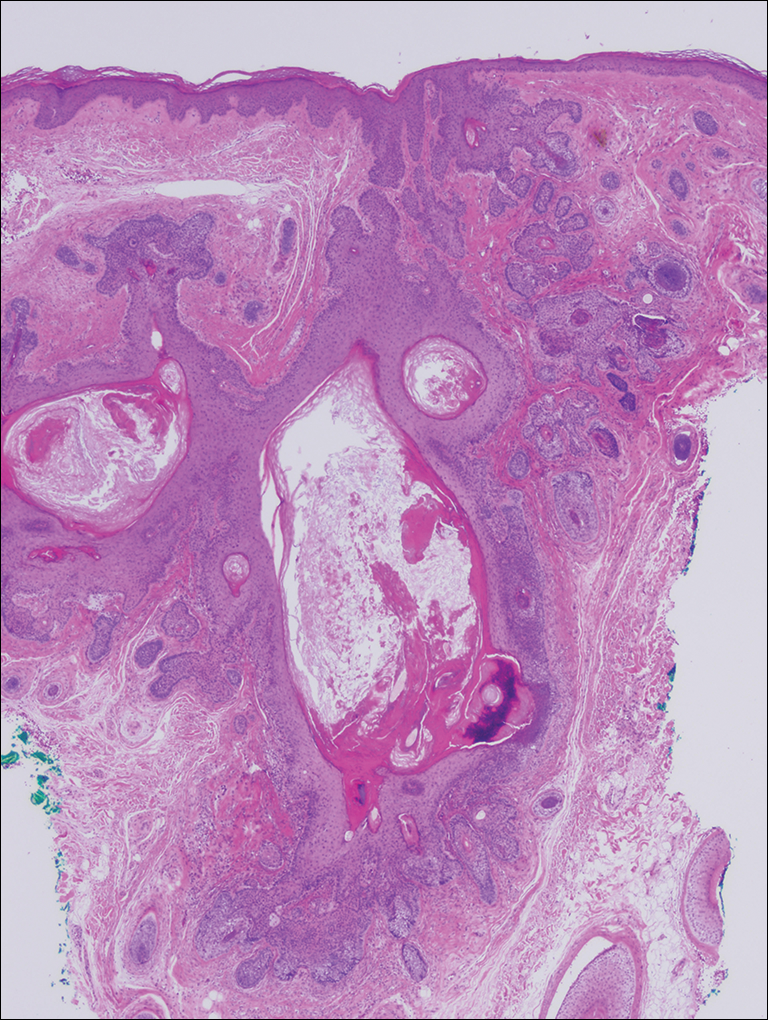

Microscopic examination revealed a dilated cystic follicle that communicated with the skin surface (Figure). The follicle was lined with squamous epithelium and surrounded by numerous secondary follicles, many of which contained a hair shaft. A diagnosis of trichofolliculoma was made.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of a flesh-colored papule on the scalp with prominent follicle includes dilated pore of Winer, epidermoid cyst, pilar sheath acanthoma, and trichoepithelioma.1,2 Multiple hair shafts present in a single follicle may be seen in pili multigemini, tufted folliculitis, trichostasis spinulosa, and trichofolliculoma. On histopathologic examination, a dilated central follicle surrounded with smaller secondary follicles was identified, consistent with trichofolliculoma.

Trichofolliculoma is a rare follicular hamartoma typically occurring on the face, scalp, or trunk as a solitary papule or nodule due to the proliferation of abnormal hair follicle stem cells.3,4 It may present as a flesh-colored nodule with a central pore that may drain sebum or contain white vellus hairs. Trichofolliculoma is considered a benign entity, despite one case report of malignant transformation.5 Biopsy is diagnostic and no further treatment is needed. Recurrence rarely occurs at the primary site after surgical excision, which may be performed for cosmetic purposes or to alleviate functional impairment.

- Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Barma KD. Perifollicular nodule on the face of a young man. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:531-533.

- Gokalp H, Gurer MA, Alan S. Trichofolliculoma: a rare variant of hair follicle hamartoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19264.

- Choi CM, Lew BL, Sim WY. Multiple trichofolliculomas on unusual sites: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:87-89.

- Misago N, Kimura T, Toda S, et al. A revaluation of trichofolliculoma: the histopathological and immunohistochemical features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:35-43.

- Stem JB, Stout DA. Trichofolliculoma showing perineural invasion. trichofolliculocarcinoma? Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1003-1004.

The Diagnosis: Trichofolliculoma

Microscopic examination revealed a dilated cystic follicle that communicated with the skin surface (Figure). The follicle was lined with squamous epithelium and surrounded by numerous secondary follicles, many of which contained a hair shaft. A diagnosis of trichofolliculoma was made.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of a flesh-colored papule on the scalp with prominent follicle includes dilated pore of Winer, epidermoid cyst, pilar sheath acanthoma, and trichoepithelioma.1,2 Multiple hair shafts present in a single follicle may be seen in pili multigemini, tufted folliculitis, trichostasis spinulosa, and trichofolliculoma. On histopathologic examination, a dilated central follicle surrounded with smaller secondary follicles was identified, consistent with trichofolliculoma.

Trichofolliculoma is a rare follicular hamartoma typically occurring on the face, scalp, or trunk as a solitary papule or nodule due to the proliferation of abnormal hair follicle stem cells.3,4 It may present as a flesh-colored nodule with a central pore that may drain sebum or contain white vellus hairs. Trichofolliculoma is considered a benign entity, despite one case report of malignant transformation.5 Biopsy is diagnostic and no further treatment is needed. Recurrence rarely occurs at the primary site after surgical excision, which may be performed for cosmetic purposes or to alleviate functional impairment.

The Diagnosis: Trichofolliculoma

Microscopic examination revealed a dilated cystic follicle that communicated with the skin surface (Figure). The follicle was lined with squamous epithelium and surrounded by numerous secondary follicles, many of which contained a hair shaft. A diagnosis of trichofolliculoma was made.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of a flesh-colored papule on the scalp with prominent follicle includes dilated pore of Winer, epidermoid cyst, pilar sheath acanthoma, and trichoepithelioma.1,2 Multiple hair shafts present in a single follicle may be seen in pili multigemini, tufted folliculitis, trichostasis spinulosa, and trichofolliculoma. On histopathologic examination, a dilated central follicle surrounded with smaller secondary follicles was identified, consistent with trichofolliculoma.

Trichofolliculoma is a rare follicular hamartoma typically occurring on the face, scalp, or trunk as a solitary papule or nodule due to the proliferation of abnormal hair follicle stem cells.3,4 It may present as a flesh-colored nodule with a central pore that may drain sebum or contain white vellus hairs. Trichofolliculoma is considered a benign entity, despite one case report of malignant transformation.5 Biopsy is diagnostic and no further treatment is needed. Recurrence rarely occurs at the primary site after surgical excision, which may be performed for cosmetic purposes or to alleviate functional impairment.

- Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Barma KD. Perifollicular nodule on the face of a young man. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:531-533.

- Gokalp H, Gurer MA, Alan S. Trichofolliculoma: a rare variant of hair follicle hamartoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19264.

- Choi CM, Lew BL, Sim WY. Multiple trichofolliculomas on unusual sites: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:87-89.

- Misago N, Kimura T, Toda S, et al. A revaluation of trichofolliculoma: the histopathological and immunohistochemical features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:35-43.

- Stem JB, Stout DA. Trichofolliculoma showing perineural invasion. trichofolliculocarcinoma? Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1003-1004.

- Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Barma KD. Perifollicular nodule on the face of a young man. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:531-533.

- Gokalp H, Gurer MA, Alan S. Trichofolliculoma: a rare variant of hair follicle hamartoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19264.

- Choi CM, Lew BL, Sim WY. Multiple trichofolliculomas on unusual sites: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:87-89.

- Misago N, Kimura T, Toda S, et al. A revaluation of trichofolliculoma: the histopathological and immunohistochemical features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:35-43.

- Stem JB, Stout DA. Trichofolliculoma showing perineural invasion. trichofolliculocarcinoma? Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1003-1004.

A 72-year-old man presented with a new asymptomatic 0.7-cm flesh-colored papule with a central tuft of white hairs on the posterior scalp. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. Biopsy for histopathologic examination was performed to confirm diagnosis.

Pruritic Eruption on the Chest

The Diagnosis: Grover Disease

Grover disease (also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis) was first described by Ralph W. Grover in 1970 as an idiopathic, acquired, monomorphous, papulovesicular eruption. Although originally characterized by solely transient acantholytic dermatosis, over time the term Grover disease has been expanded to include persistent acantholytic dermatoses. Grover disease chiefly affects white adults older than 40 years and is more prevalent in males than females. Cases generally are self-limited but correlate with age, as older adults are more likely to have prolonged eruptions.1

Grover disease typically erupts with discrete, erythematous, edematous, acneform, red-brown or flesh-colored papules, papulovesicles, or keratotic papules that primarily are seen on the trunk and anterior portion of the chest. As the rash spreads, it can erupt on the neck and thighs. The etiology of Grover disease is unknown, but many factors have been associated with the condition in a limited number of patients, including exposure to UV radiation, excessive heat or sweating, use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and recombinant human IL-4, and infection with Malassezia furfur and Demodex folliculorum.1 Grover disease also has been associated with other conditions such as asteatotic eczema, allergic contact dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis.2

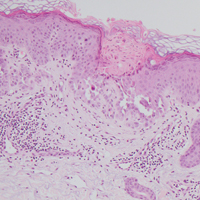

Histologically, Grover disease (Figure 1) is an acantholytic process that can exhibit dyskeratosis (corps ronds and grains). Foci often are small and multiple foci are seen on shave biopsy. There also may be spongiotic changes when associated with an eczematous element. A perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils usually is seen.3 Basket weave keratin may be seen; however, as the lesions cause pruritus, erosions and ulcerations often are present.4

Grover disease has multiple histologic variants that may resemble Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and spongiotic dermatitis and can present in combination.5

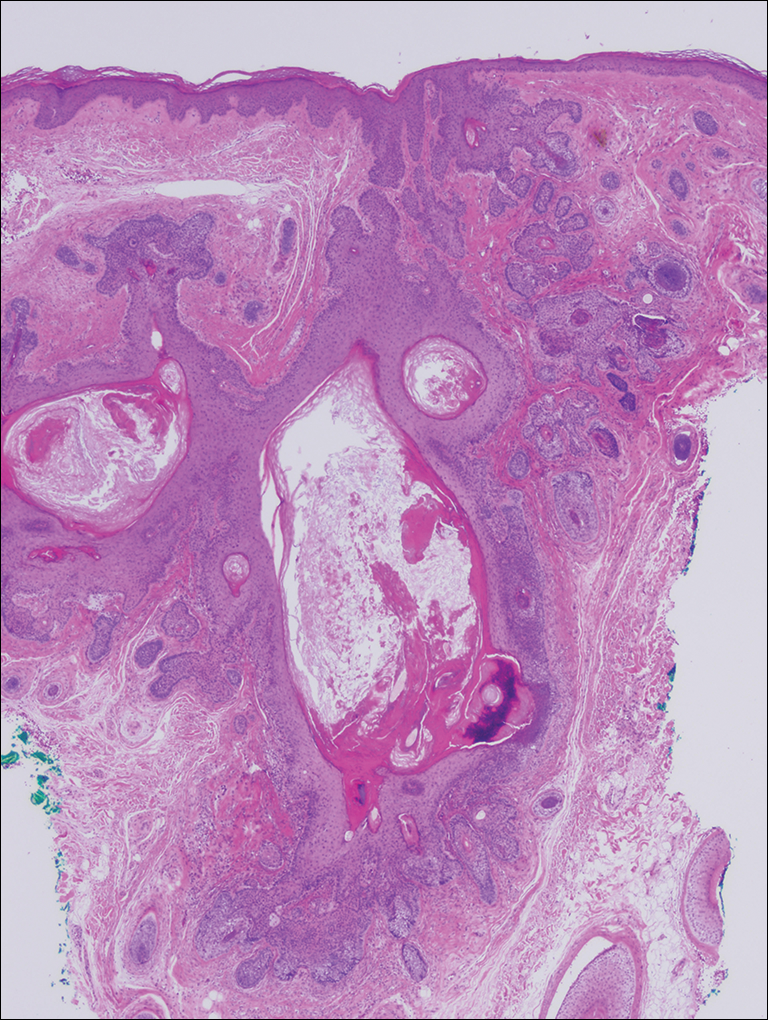

The variant of Grover disease that has a Darier-like pattern is difficult to distinguish from Darier disease, an autosomal-dominant-inherited disorder classified by small papules that emerge in seborrheic areas during childhood and adolescence. Histologically, Darier disease (Figure 2) shows broad areas of dyskeratosis and acantholysis that lead to suprabasal cleavage. Follicular extension may be present. In addition, there often is prominent vertical parakeratosis in Darier disease.6 Histologic features that favor Darier disease over the Darier-like variant of Grover disease include a broad focus of acanthotic dyskeratosis with follicular extension; the presence of a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum; and a lack of spongiosis and eosinophils, which are notably absent in Darier disease but may be present in Grover disease.4

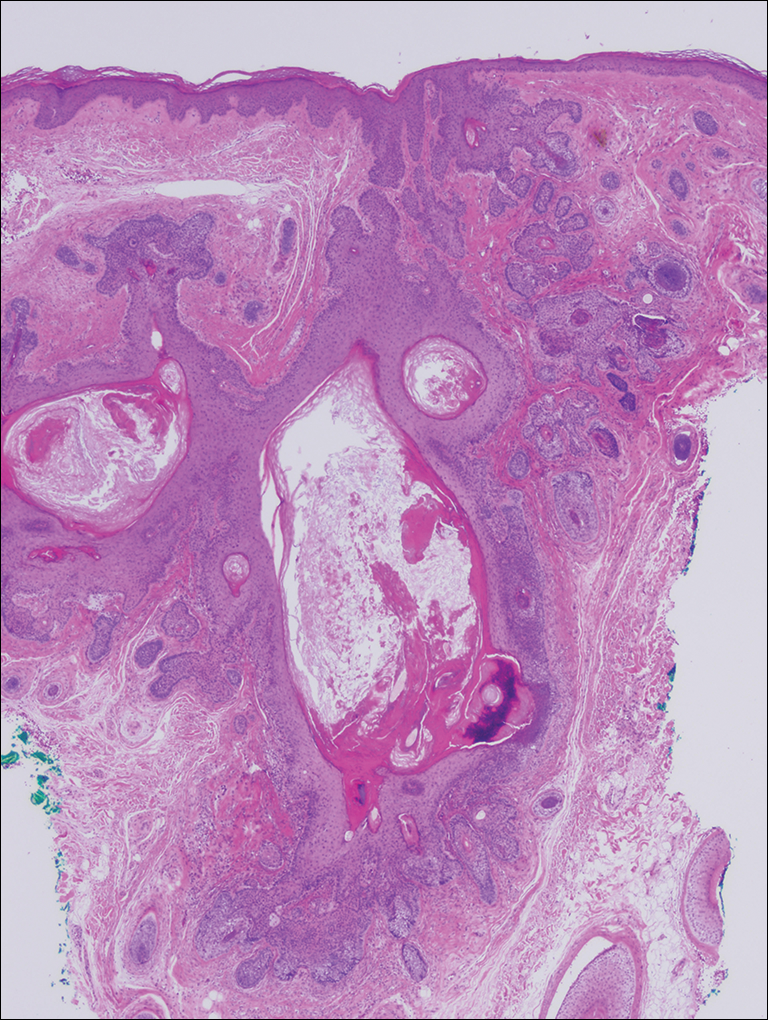

Another variant of Grover disease has a Hailey-Hailey-like pattern, which is characterized by Hailey-Hailey disease's dilapidated brick wall appearance or the diffuse suprabasal acantholysis of all epidermal layers without notable dyskeratosis.4 Hailey-Hailey disease, also known as familial benign pemphigus, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that presents with erythematous vesicular plaques in flexural areas. The plaques progress to flaccid bullae with rupture and crusting and spread peripherally.7 Pathology shows suprabasilar clefts and numerous acantholytic cells (Figure 3). Dyskeratotic keratinocytes are rare with infrequent corps ronds and rare grains. The epidermis also is less hyperplastic in Grover disease than in Hailey-Hailey disease.1

Grover disease also may present histologically with a pemphiguslike pattern, mimicking pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus vulgaris; however, direct immunofluorescence studies are negative in Grover disease.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune disorder caused by autoantibodies to desmoglein 1, which are present on the surfaces of keratinocytes, and is characterized by scaly crusts and blisters.8 Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus (Figure 4) shows a superficial epidermal blistering process. The acantholysis may be subtle and is commonly localized to the stratum granulosum, extending into the stratum corneum. Complete loss of the stratum corneum can be seen, resulting in only scattered acantholytic cells. Spongiosis also may be seen. The dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate that often contains eosinophils. Pemphigus foliaceus is confirmed by direct immunofluorescence.9

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune blistering disorder that is characterized by IgG autoantibodies to desmoglein 3, a component of desmosomes that are involved in keratinocyte-to-keratinocyte adhesion. Clinically, patients present with flaccid fragile blisters on the skin and mucous membranes that rupture easily, leading to painful erosions.10 Intraepidermal blisters are seen histologically (Figure 5) with the loss of cohesion (acantholysis) seen classically in the lower portions of the epidermis where desmoglein 3 is most prominent. When only the basal layer remains, the histology has been likened to a tombstone row.11 Extension of the blister along the adnexa is common. The underlying dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate with eosinophils. Early lesions may show only eosinophilic spongiosis. Direct immunofluorescence studies show IgG and C3 in an intercellular pattern that resembles a fish net or chicken wire.4,11

The spongioticlike pattern of Grover disease is marked by epidermal edema with separation of the keratinocytes and the revelation of their intracellular bridges,4 which manifests as vesiculation in the stratum corneum or upper layers of the epidermis.12

Grover disease is self-limited and may spontaneously resolve; however, the disease may be responsive to topical and systemic steroids. Additionally, avoidance of aggravating factors such as sunlight, heat, and sweating can improve symptoms.2

- Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover's disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5, pt 1):653-666; quiz 667-670.

- Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover's disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:83-86.

- Davis MD, Dinneen AM, Landa N, et al. Grover's disease: clinicopathologic review of 72 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:229-234.

- Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1490-1494.

- Chalet M, Grover R, Ackerman AB. Transient acantholytic dermatosis: a reevaluation. Arch Dermatol. 1977;133:431-435.

- Takagi A, Kamijo M, Ikeda S. Darier disease. J Dermatol. 2016;43:275-279.

- Engin B, Kutlubay Z, Celik U, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease: a fold (intertriginous) dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:452-455.

- de Sena Nogueira Maehara L, Huizinga J, Jonkman MF. Rituximab therapy in pemphigus foliaceus: report of 12 cases and review of recent literature [published online March 31, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1420-1423.

- James KA, Culton DA, Diaz LA. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus foliaceus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:405-412.

- Black M, Mignogna MD, Scully C. Number II. pemphigus vulgaris. Oral Dis. 2005;11:119-130.

- Madke B, Doshi B, Khopkar U, et al. Appearances in dermatopathology: the diagnostic and the deceptive. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79:338-348.

- Motaparthi K. Pseudoherpetic transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease): case series and review of the literature [published online February 16, 2017]. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:486-489.

The Diagnosis: Grover Disease

Grover disease (also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis) was first described by Ralph W. Grover in 1970 as an idiopathic, acquired, monomorphous, papulovesicular eruption. Although originally characterized by solely transient acantholytic dermatosis, over time the term Grover disease has been expanded to include persistent acantholytic dermatoses. Grover disease chiefly affects white adults older than 40 years and is more prevalent in males than females. Cases generally are self-limited but correlate with age, as older adults are more likely to have prolonged eruptions.1

Grover disease typically erupts with discrete, erythematous, edematous, acneform, red-brown or flesh-colored papules, papulovesicles, or keratotic papules that primarily are seen on the trunk and anterior portion of the chest. As the rash spreads, it can erupt on the neck and thighs. The etiology of Grover disease is unknown, but many factors have been associated with the condition in a limited number of patients, including exposure to UV radiation, excessive heat or sweating, use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and recombinant human IL-4, and infection with Malassezia furfur and Demodex folliculorum.1 Grover disease also has been associated with other conditions such as asteatotic eczema, allergic contact dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis.2

Histologically, Grover disease (Figure 1) is an acantholytic process that can exhibit dyskeratosis (corps ronds and grains). Foci often are small and multiple foci are seen on shave biopsy. There also may be spongiotic changes when associated with an eczematous element. A perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils usually is seen.3 Basket weave keratin may be seen; however, as the lesions cause pruritus, erosions and ulcerations often are present.4

Grover disease has multiple histologic variants that may resemble Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and spongiotic dermatitis and can present in combination.5

The variant of Grover disease that has a Darier-like pattern is difficult to distinguish from Darier disease, an autosomal-dominant-inherited disorder classified by small papules that emerge in seborrheic areas during childhood and adolescence. Histologically, Darier disease (Figure 2) shows broad areas of dyskeratosis and acantholysis that lead to suprabasal cleavage. Follicular extension may be present. In addition, there often is prominent vertical parakeratosis in Darier disease.6 Histologic features that favor Darier disease over the Darier-like variant of Grover disease include a broad focus of acanthotic dyskeratosis with follicular extension; the presence of a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum; and a lack of spongiosis and eosinophils, which are notably absent in Darier disease but may be present in Grover disease.4

Another variant of Grover disease has a Hailey-Hailey-like pattern, which is characterized by Hailey-Hailey disease's dilapidated brick wall appearance or the diffuse suprabasal acantholysis of all epidermal layers without notable dyskeratosis.4 Hailey-Hailey disease, also known as familial benign pemphigus, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that presents with erythematous vesicular plaques in flexural areas. The plaques progress to flaccid bullae with rupture and crusting and spread peripherally.7 Pathology shows suprabasilar clefts and numerous acantholytic cells (Figure 3). Dyskeratotic keratinocytes are rare with infrequent corps ronds and rare grains. The epidermis also is less hyperplastic in Grover disease than in Hailey-Hailey disease.1

Grover disease also may present histologically with a pemphiguslike pattern, mimicking pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus vulgaris; however, direct immunofluorescence studies are negative in Grover disease.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune disorder caused by autoantibodies to desmoglein 1, which are present on the surfaces of keratinocytes, and is characterized by scaly crusts and blisters.8 Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus (Figure 4) shows a superficial epidermal blistering process. The acantholysis may be subtle and is commonly localized to the stratum granulosum, extending into the stratum corneum. Complete loss of the stratum corneum can be seen, resulting in only scattered acantholytic cells. Spongiosis also may be seen. The dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate that often contains eosinophils. Pemphigus foliaceus is confirmed by direct immunofluorescence.9

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune blistering disorder that is characterized by IgG autoantibodies to desmoglein 3, a component of desmosomes that are involved in keratinocyte-to-keratinocyte adhesion. Clinically, patients present with flaccid fragile blisters on the skin and mucous membranes that rupture easily, leading to painful erosions.10 Intraepidermal blisters are seen histologically (Figure 5) with the loss of cohesion (acantholysis) seen classically in the lower portions of the epidermis where desmoglein 3 is most prominent. When only the basal layer remains, the histology has been likened to a tombstone row.11 Extension of the blister along the adnexa is common. The underlying dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate with eosinophils. Early lesions may show only eosinophilic spongiosis. Direct immunofluorescence studies show IgG and C3 in an intercellular pattern that resembles a fish net or chicken wire.4,11

The spongioticlike pattern of Grover disease is marked by epidermal edema with separation of the keratinocytes and the revelation of their intracellular bridges,4 which manifests as vesiculation in the stratum corneum or upper layers of the epidermis.12

Grover disease is self-limited and may spontaneously resolve; however, the disease may be responsive to topical and systemic steroids. Additionally, avoidance of aggravating factors such as sunlight, heat, and sweating can improve symptoms.2

The Diagnosis: Grover Disease

Grover disease (also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis) was first described by Ralph W. Grover in 1970 as an idiopathic, acquired, monomorphous, papulovesicular eruption. Although originally characterized by solely transient acantholytic dermatosis, over time the term Grover disease has been expanded to include persistent acantholytic dermatoses. Grover disease chiefly affects white adults older than 40 years and is more prevalent in males than females. Cases generally are self-limited but correlate with age, as older adults are more likely to have prolonged eruptions.1

Grover disease typically erupts with discrete, erythematous, edematous, acneform, red-brown or flesh-colored papules, papulovesicles, or keratotic papules that primarily are seen on the trunk and anterior portion of the chest. As the rash spreads, it can erupt on the neck and thighs. The etiology of Grover disease is unknown, but many factors have been associated with the condition in a limited number of patients, including exposure to UV radiation, excessive heat or sweating, use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and recombinant human IL-4, and infection with Malassezia furfur and Demodex folliculorum.1 Grover disease also has been associated with other conditions such as asteatotic eczema, allergic contact dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis.2

Histologically, Grover disease (Figure 1) is an acantholytic process that can exhibit dyskeratosis (corps ronds and grains). Foci often are small and multiple foci are seen on shave biopsy. There also may be spongiotic changes when associated with an eczematous element. A perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils usually is seen.3 Basket weave keratin may be seen; however, as the lesions cause pruritus, erosions and ulcerations often are present.4

Grover disease has multiple histologic variants that may resemble Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and spongiotic dermatitis and can present in combination.5

The variant of Grover disease that has a Darier-like pattern is difficult to distinguish from Darier disease, an autosomal-dominant-inherited disorder classified by small papules that emerge in seborrheic areas during childhood and adolescence. Histologically, Darier disease (Figure 2) shows broad areas of dyskeratosis and acantholysis that lead to suprabasal cleavage. Follicular extension may be present. In addition, there often is prominent vertical parakeratosis in Darier disease.6 Histologic features that favor Darier disease over the Darier-like variant of Grover disease include a broad focus of acanthotic dyskeratosis with follicular extension; the presence of a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum; and a lack of spongiosis and eosinophils, which are notably absent in Darier disease but may be present in Grover disease.4

Another variant of Grover disease has a Hailey-Hailey-like pattern, which is characterized by Hailey-Hailey disease's dilapidated brick wall appearance or the diffuse suprabasal acantholysis of all epidermal layers without notable dyskeratosis.4 Hailey-Hailey disease, also known as familial benign pemphigus, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that presents with erythematous vesicular plaques in flexural areas. The plaques progress to flaccid bullae with rupture and crusting and spread peripherally.7 Pathology shows suprabasilar clefts and numerous acantholytic cells (Figure 3). Dyskeratotic keratinocytes are rare with infrequent corps ronds and rare grains. The epidermis also is less hyperplastic in Grover disease than in Hailey-Hailey disease.1

Grover disease also may present histologically with a pemphiguslike pattern, mimicking pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus vulgaris; however, direct immunofluorescence studies are negative in Grover disease.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune disorder caused by autoantibodies to desmoglein 1, which are present on the surfaces of keratinocytes, and is characterized by scaly crusts and blisters.8 Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus (Figure 4) shows a superficial epidermal blistering process. The acantholysis may be subtle and is commonly localized to the stratum granulosum, extending into the stratum corneum. Complete loss of the stratum corneum can be seen, resulting in only scattered acantholytic cells. Spongiosis also may be seen. The dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate that often contains eosinophils. Pemphigus foliaceus is confirmed by direct immunofluorescence.9

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune blistering disorder that is characterized by IgG autoantibodies to desmoglein 3, a component of desmosomes that are involved in keratinocyte-to-keratinocyte adhesion. Clinically, patients present with flaccid fragile blisters on the skin and mucous membranes that rupture easily, leading to painful erosions.10 Intraepidermal blisters are seen histologically (Figure 5) with the loss of cohesion (acantholysis) seen classically in the lower portions of the epidermis where desmoglein 3 is most prominent. When only the basal layer remains, the histology has been likened to a tombstone row.11 Extension of the blister along the adnexa is common. The underlying dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate with eosinophils. Early lesions may show only eosinophilic spongiosis. Direct immunofluorescence studies show IgG and C3 in an intercellular pattern that resembles a fish net or chicken wire.4,11

The spongioticlike pattern of Grover disease is marked by epidermal edema with separation of the keratinocytes and the revelation of their intracellular bridges,4 which manifests as vesiculation in the stratum corneum or upper layers of the epidermis.12

Grover disease is self-limited and may spontaneously resolve; however, the disease may be responsive to topical and systemic steroids. Additionally, avoidance of aggravating factors such as sunlight, heat, and sweating can improve symptoms.2

- Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover's disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5, pt 1):653-666; quiz 667-670.

- Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover's disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:83-86.

- Davis MD, Dinneen AM, Landa N, et al. Grover's disease: clinicopathologic review of 72 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:229-234.

- Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1490-1494.

- Chalet M, Grover R, Ackerman AB. Transient acantholytic dermatosis: a reevaluation. Arch Dermatol. 1977;133:431-435.

- Takagi A, Kamijo M, Ikeda S. Darier disease. J Dermatol. 2016;43:275-279.

- Engin B, Kutlubay Z, Celik U, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease: a fold (intertriginous) dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:452-455.

- de Sena Nogueira Maehara L, Huizinga J, Jonkman MF. Rituximab therapy in pemphigus foliaceus: report of 12 cases and review of recent literature [published online March 31, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1420-1423.

- James KA, Culton DA, Diaz LA. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus foliaceus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:405-412.

- Black M, Mignogna MD, Scully C. Number II. pemphigus vulgaris. Oral Dis. 2005;11:119-130.

- Madke B, Doshi B, Khopkar U, et al. Appearances in dermatopathology: the diagnostic and the deceptive. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79:338-348.

- Motaparthi K. Pseudoherpetic transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease): case series and review of the literature [published online February 16, 2017]. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:486-489.

- Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover's disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5, pt 1):653-666; quiz 667-670.

- Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover's disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:83-86.

- Davis MD, Dinneen AM, Landa N, et al. Grover's disease: clinicopathologic review of 72 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:229-234.

- Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1490-1494.

- Chalet M, Grover R, Ackerman AB. Transient acantholytic dermatosis: a reevaluation. Arch Dermatol. 1977;133:431-435.

- Takagi A, Kamijo M, Ikeda S. Darier disease. J Dermatol. 2016;43:275-279.

- Engin B, Kutlubay Z, Celik U, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease: a fold (intertriginous) dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:452-455.

- de Sena Nogueira Maehara L, Huizinga J, Jonkman MF. Rituximab therapy in pemphigus foliaceus: report of 12 cases and review of recent literature [published online March 31, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1420-1423.

- James KA, Culton DA, Diaz LA. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus foliaceus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:405-412.

- Black M, Mignogna MD, Scully C. Number II. pemphigus vulgaris. Oral Dis. 2005;11:119-130.

- Madke B, Doshi B, Khopkar U, et al. Appearances in dermatopathology: the diagnostic and the deceptive. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79:338-348.

- Motaparthi K. Pseudoherpetic transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease): case series and review of the literature [published online February 16, 2017]. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:486-489.

A 55-year-old man presented with small, erythematous, nonfollicular, pruritic papules on the mid chest.