User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Multiple Primary Atypical Vascular Lesions Occurring in the Same Breast

Atypical vascular lesions (AVLs) of the breast are rare cutaneous vascular proliferations that present as erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored papules, patches, or plaques in women who have undergone radiation treatment for breast carcinoma.1,2 These lesions most commonly develop in the irradiated area within 3 to 6 years following radiation treatment.3

Various terms have been used to describe AVLs in the literature, including atypical hemangiomas, benign lymphangiomatous papules, benign lymphangioendotheliomas, lymphangioma circumscriptum, and acquired progressive lymphangiomas, suggesting benign behavior.4-10 However, their identity as benign lesions has been a source of controversy, with some investigators proposing that AVLs may be a precursor lesion to postirradiation angiosarcoma.2 Research has addressed if there are markers that can predict AVL types that are more likely to develop into angiosarcomas.1 Although most clinicians treat AVLs with complete excision, there currently are no specific guidelines to direct this practice.

We report the case of a patient with a history of 1 AVL that was excised who developed 3 additional AVLs in the same breast over the course of 15 months.

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman with a history of obesity, hypertension, and infiltrating ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast (grade 2, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive) underwent a right breast lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node dissection. Three months later, she underwent re-excision for positive margins and started adjuvant hormonal therapy with tamoxifen. One month later, she began external beam radiation therapy and received a total dose of 6040 cGy over the course of 9 weeks (34 total treatments).

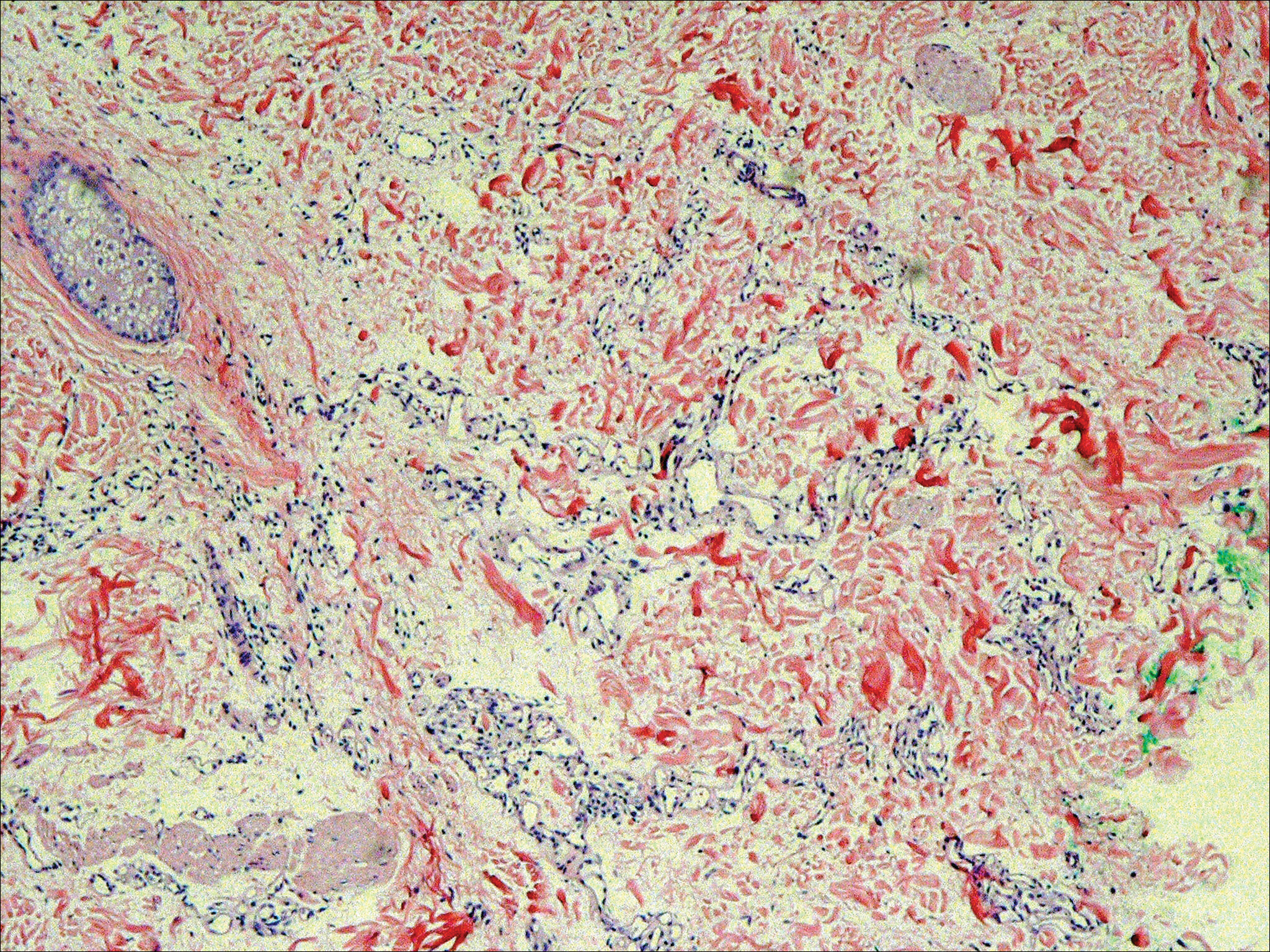

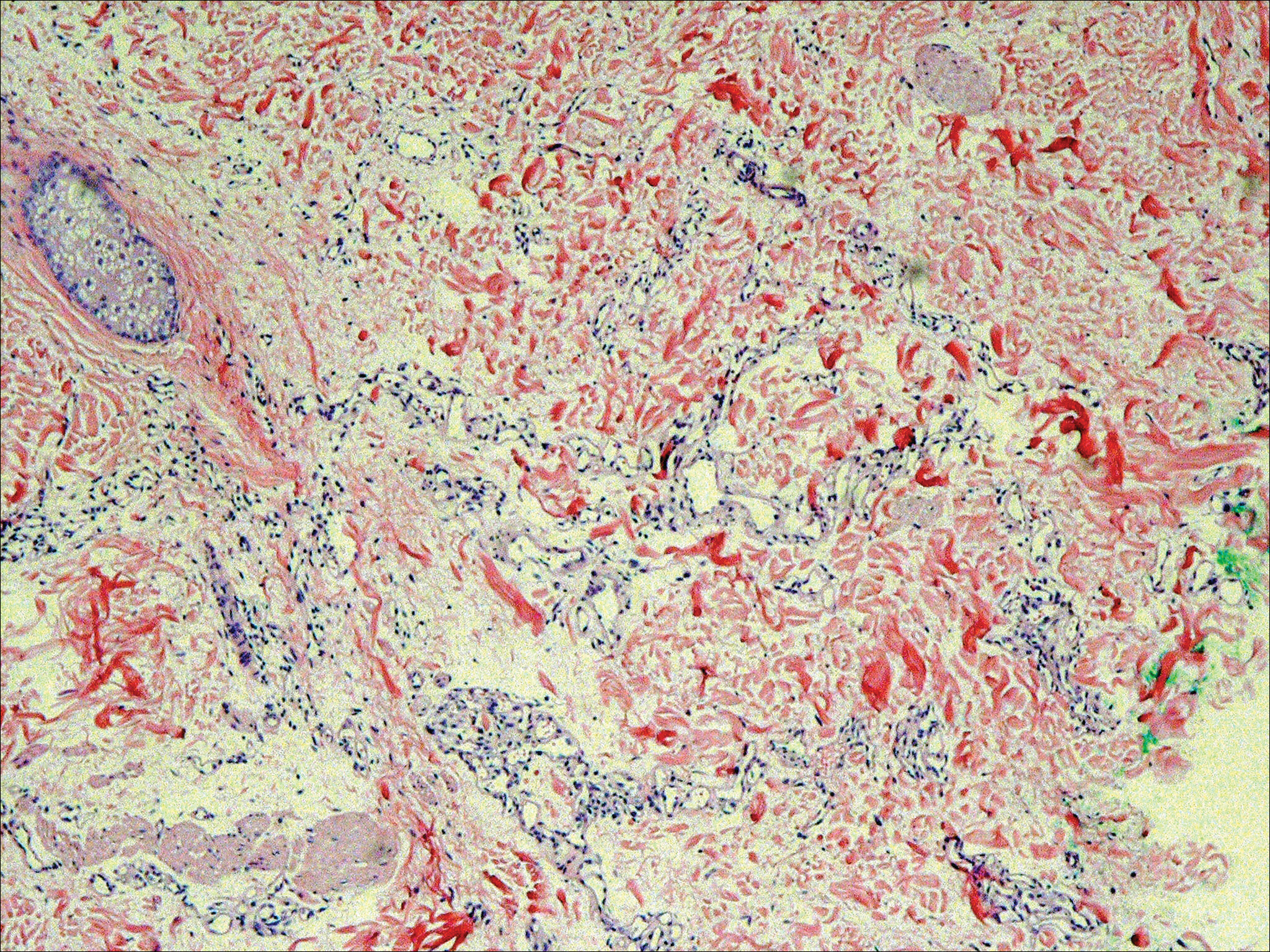

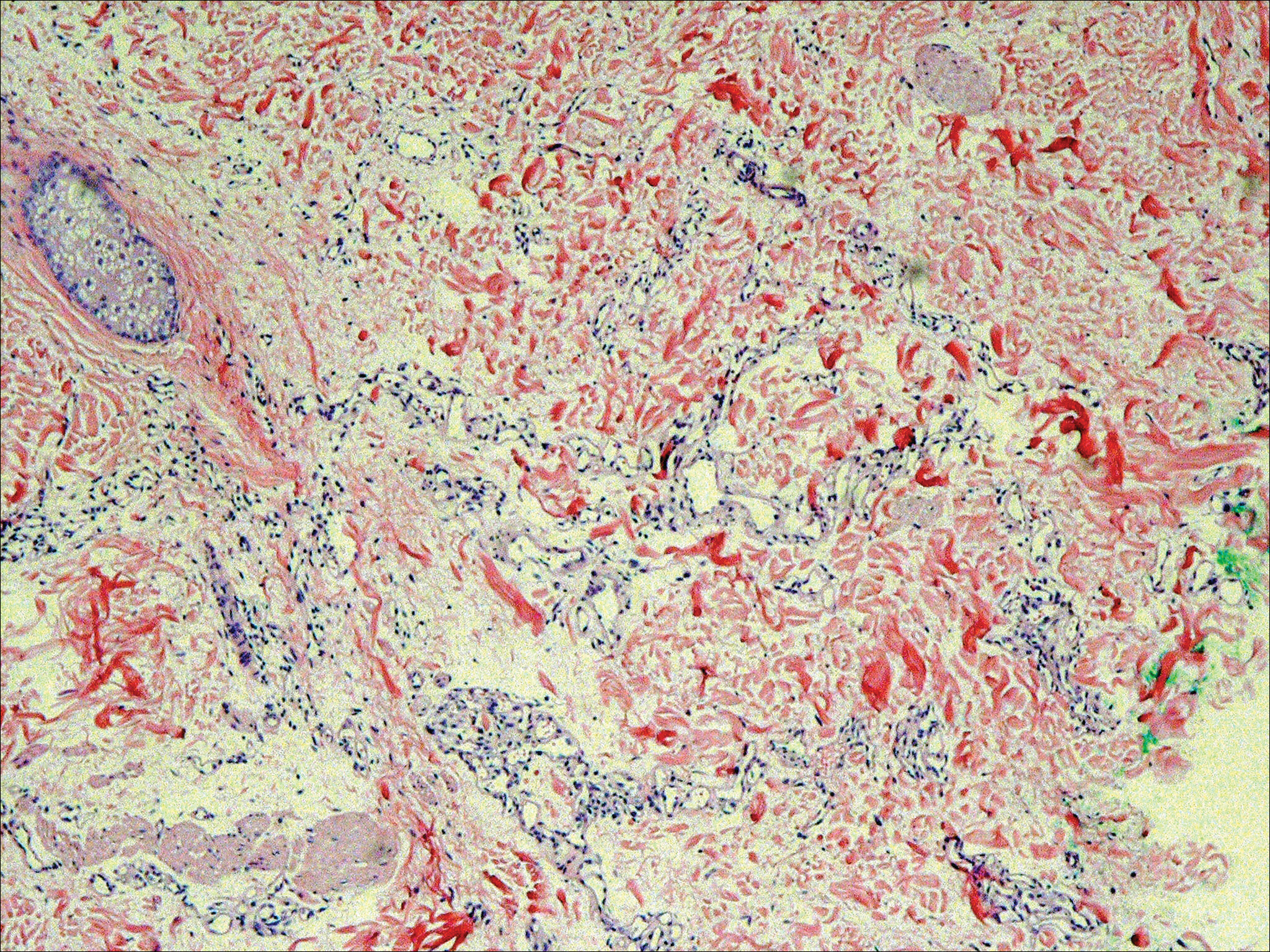

The patient presented to an outside dermatology clinic 2 years after completing external beam radiation therapy for evaluation of a new pink nodule on the right mid breast. The nodule was biopsied and discovered to be an AVL. Pathology showed an anastomosing proliferation of thin-walled vascular channels mainly located in the superficial dermis with notable endothelial nuclear atypia and hyperchromasia. There were several tiny foci with the beginnings of multilayering with prominent endothelial atypia (Figure 1). She underwent complete excision for this AVL with negative margins.

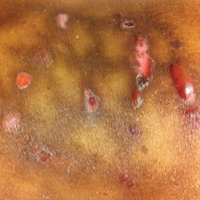

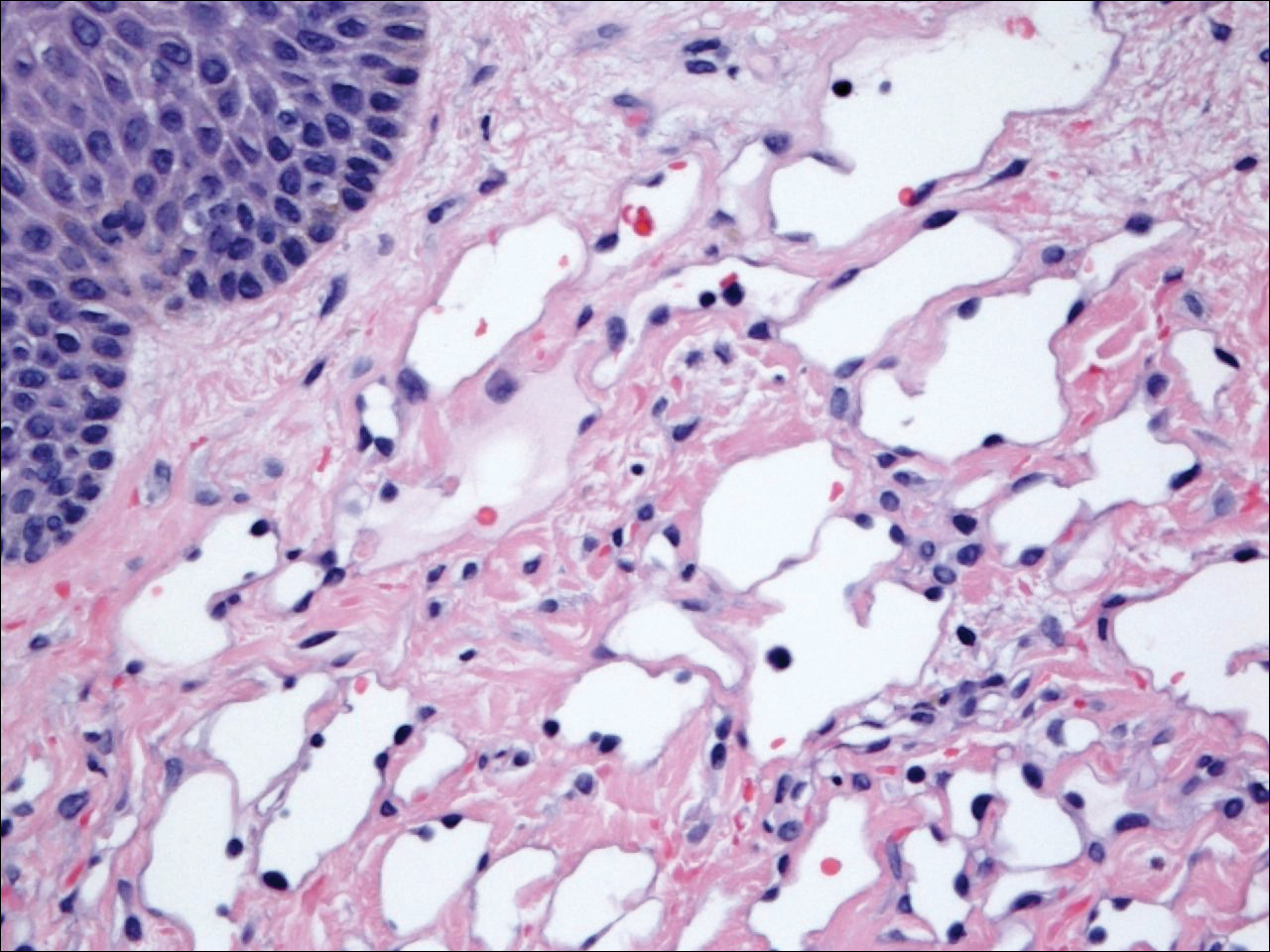

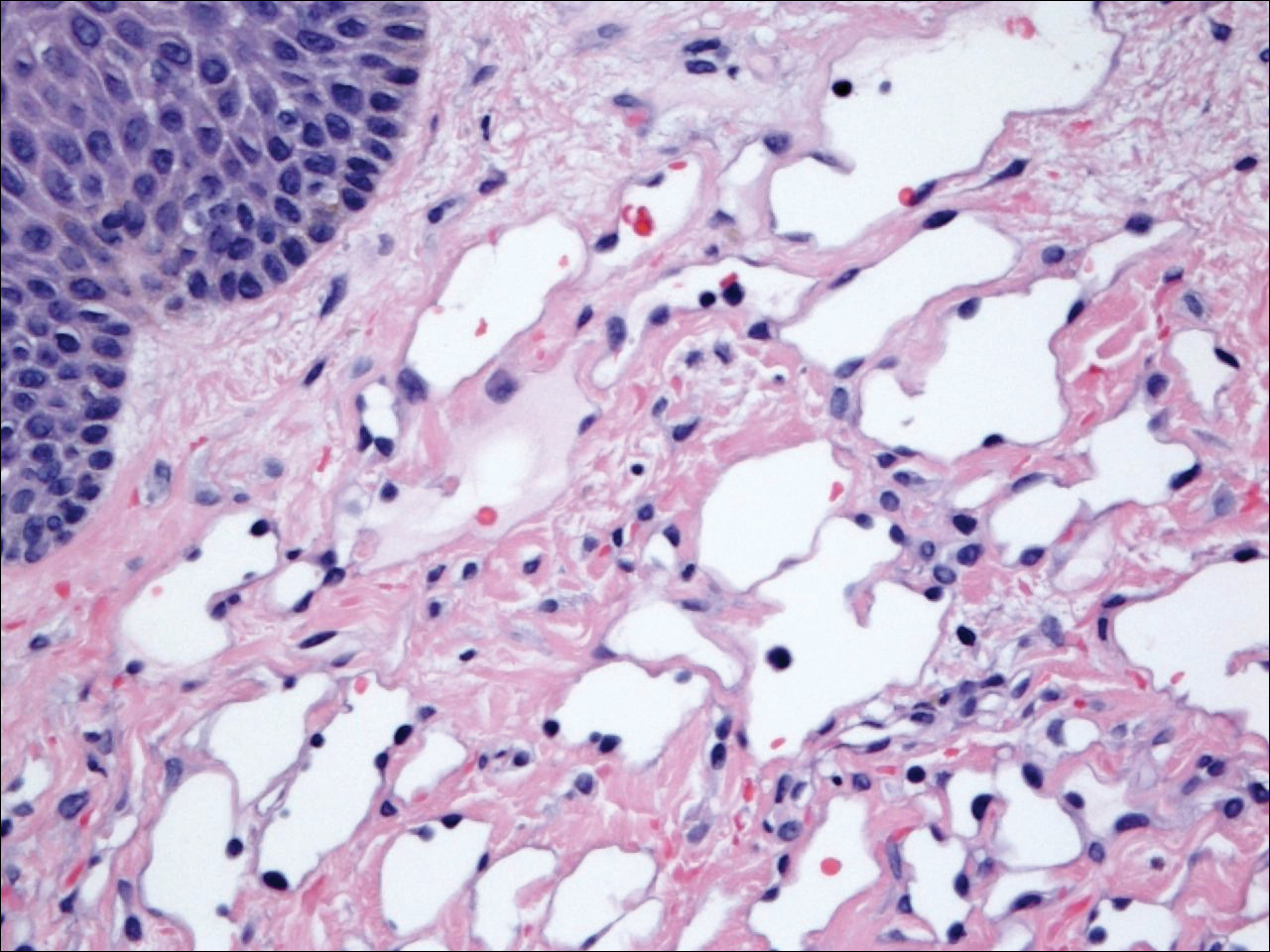

Six months after the initial AVL diagnosis, she presented to our dermatology clinic with another asymptomatic red bump on the right breast. On physical examination, a 4-mm firm, erythematous, well-circumscribed papule was noted on the medial aspect of the right breast along with a similar-appearing 4-mm papule on the right lateral aspect of the right breast (Figure 2). The patient was unsure of the duration of the second lesion but felt that it had been present at least as long as the other lesion. Both lesions clinically resembled typical capillary hemangiomas. A 6-mm punch biopsy of the right medial breast was performed and revealed enlarged vessels and capillaries in the upper dermis lined by endothelial cells with focal prominent nuclei without necrosis, overt atypia, mitosis, or tufting (Figure 3). Immunostaining was positive for CD34, factor VIII antigen, podoplanin (D2-40), and CD31, and negative for cytokeratin 7 and pankeratin. This staining was compatible with a lymphatic-type AVL.1 A diagnosis of AVL was made and complete excision with clear margins was performed. At the time of this excision, a biopsy of the right lateral breast was performed revealing thin-walled, dilated vascular channels in the superficial dermis with architecturally atypical angulated outlines, mild endothelial nuclear atypia, and hyperchromasia without endothelial multilayering. Clear margins were noted on the biopsy, but the patient subsequently declined re-excision of this third AVL.

During a subsequent follow-up visit 9 months later, the patient was noted to have a 2-mm red, vascular-appearing papule on the right upper medial breast (Figure 2). A 6-mm biopsy was performed and revealed thin-walled vascular channels in the superficial dermis with endothelial nuclear atypia consistent with an AVL.

Comment

Fineberg and Rosen8 were the first to describe AVLs in their 1994 study of 4 women with cutaneous vascular proliferations that developed after radiation and chemotherapy for breast cancer. They concluded that these AVLs were benign lesions distinct from angiosarcomas.8 However, further research has challenged the benign nature of AVLs. In 2005, Brenn and Fletcher2 studied 42 women diagnosed with either angiosarcoma or atypical radiation-associated cutaneous vascular lesions. They suggested that AVLs resided on the same spectrum as angiosarcomas and that AVLs may be precursor lesions to angiosarcomas.2 Furthermore, Hildebrandt et al11 in 2001 and Di Tommaso and Fabbri12 in 2003 published case reports of individual patients who developed an angiosarcoma from a preexisting AVL.

The controversy continued when Patton et al1 published a study in 2008 in which 32 cases of AVLs were reviewed. In this study, 2 histologic types of AVLs were described: vascular type and lymphatic type. Vascular-type AVLs are characterized by irregularly dispersed, pericyte-invested, capillary-sized vessels within the papillary or reticular dermis that often are associated with extravasated erythrocytes or hemosiderin. On the other hand, lymphatic-type AVLs display thin-walled, variably anastomosing, lymphatic vessels lined by attenuated or slightly protuberant endothelial cells. These subtypes have been suggested based on the antigens known to be present in certain tissues, specifically vascular and lymphatic tissue. Despite these seemingly distinct histologies, 6 lesions classified as vascular type displayed some histologic overlap with the lymphatic-type AVLs. The authors concluded that the vascular type showed greater potential to develop into an angiosarcoma based on the degree of endothelial atypia.1

In 2011, Santi et al13 found that both AVLs and angiosarcomas share inactivation mutations in the tumor suppressor gene TP53, providing further evidence to suggest that AVLs may be precursors to angiosarcomas.

Although the malignant potential of AVLs remains questionable, research has shown that they do have a propensity to recur.3 In 2007, Gengler et al3 determined that 20% of patients with AVLs experienced recurrence after a biopsy or excision with varying margins; however, the group stated that these new vascular lesions might not be recurrences but rather entirely new lesions in the same irradiated field (field-effect phenomenon). Several other studies demonstrated that more than 30% of patients with 1 AVL developed more lesions within the same irradiated area.3,14-16 Despite the high rate of recurrence documented in the literature, only 5 of more than 100 diagnosed AVLs have progressed to angiosarcoma.1,3

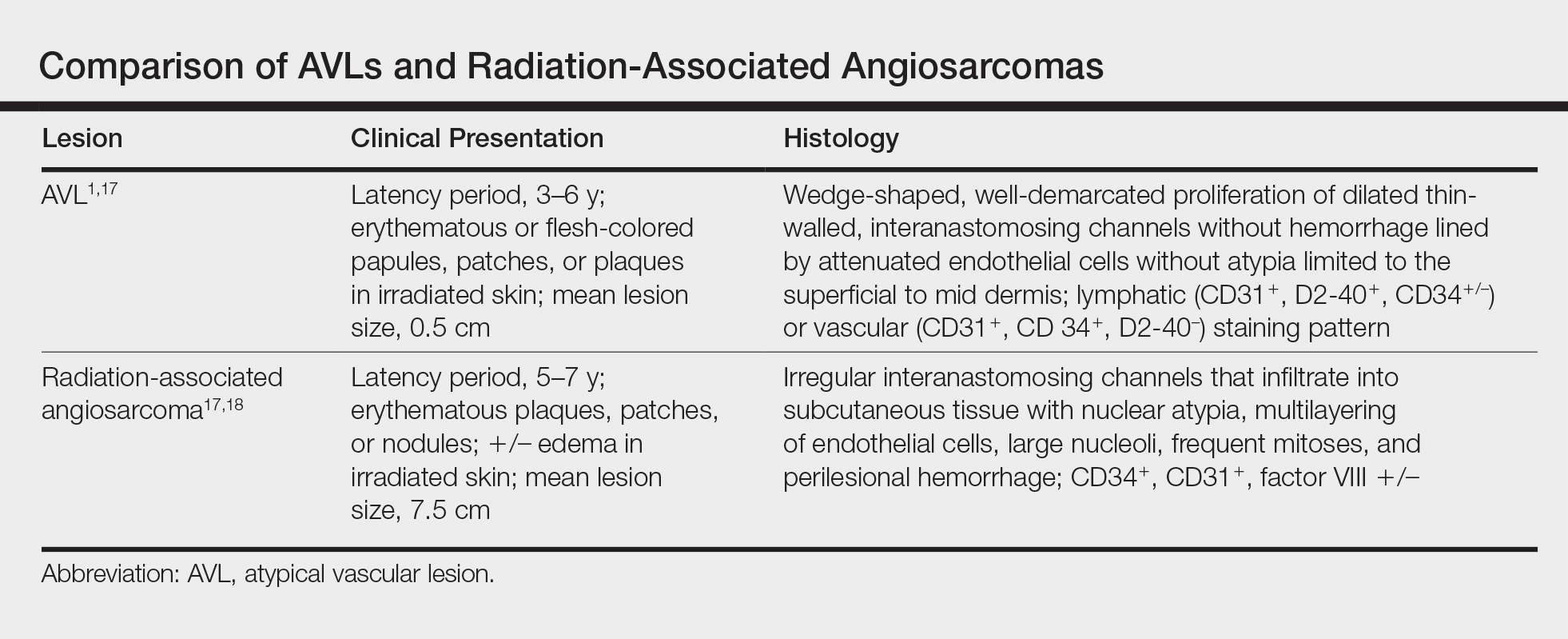

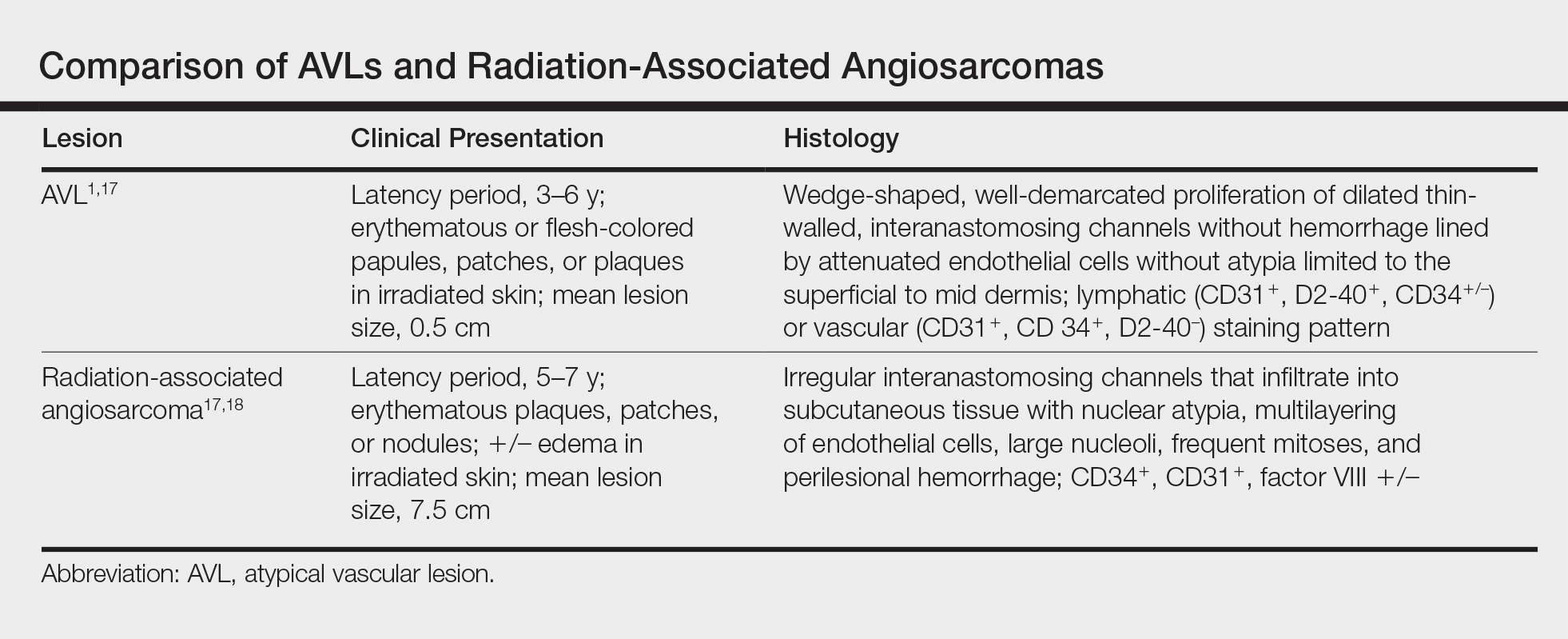

Many differences can be noted when comparing the histology of AVLs versus angiosarcomas, though some are subtle (Table). Angiosarcomas display poorly circumscribed vascular infiltration into the subcutaneous tissue, multilayering of endothelial cells, prominent nucleoli, hemorrhage, mitoses, and notable aytpia. Atypical vascular lesions lack these features and tend to be wedge shaped and display chronic inflammation.8,15,17-19 Atypical vascular lesions show superficial localized growth without destruction of adjacent adnexa, display dilated vascular spaces, and exhibit large endothelial cells.5,6,8,14,15,19,20 However, there is overlap between AVLs and angiosarcomas that can make diagnosis difficult.2,14,16,17,19 Areas within or just outside of an angiosarcoma, especially in well-differentiated angiosarcomas, can appear histologically identical to AVLs, and multiple biopsies may be required for diagnosis.17,19,21

Conclusion

More research is needed in the arenas of classification, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up recommendations for AVLs. In particular, more specific histologic markers may be needed to identify those AVLs that may progress to angiosarcomas. Although most AVLs are treated with excision, a consensus needs to be reached on adequate surgical margins. Lastly, due to the tendency of AVLs to recur coupled with their unknown malignant potential, recommendations are needed for consistent follow-up examinations.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A, et al. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process; a study from the French sarcoma group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Hoda SA, Cranor ML, Rosen PP. Hemangiomas of the breast with atypical histological features: further analysis of histological subtypes confirming their benign character. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:553-560.

- Wagamon K, Ranchoff RE, Rosenberg AS, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:912-913.

- Diaz-Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin following radiotherapy: a report of five new cases and review of the literature. Histopathology. 1999;35:319-327.

- Martín-González T, Sanz-Trelles A, Del Boz J, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules and plaques after radiotherapy [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:84-86.

- Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:757-763.

- Guillou L, Fletcher CD. Benign lymphangioendothelioma (acquired progressive lymphangioma): a lesion not to be confused with well-differentiated angiosarcoma and patch stage Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1047-1057.

- Rosso R, Gianelli U, Carnevali L. Acquired progressive lymphangioma of the skin following radiotherapy for breast carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:164-167.

- Hildebrandt G, Mittag M, Gutz U, et al. Cutaneous breast angiosarcoma after conservative treatment of breast cancer. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:580-583.

- Di Tommaso L, Fabbri A. Cutaneous angiosarcoma arising after radiotherapy treatment of a breast carcinoma: description of a case and review of the literature [in Italian]. Pathologica. 2003;95:196-202.

- Santi R, Cetica V, Franchi A, et al. Tumour suppressor gene TP53 mutations in atypical vascular lesions of breast skin following radiotherapy. Histopathology. 2011;58:455-466.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Mentzel T, et al. Benign vascular proliferations in irradiated skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:328-337.

- Brodie C, Provenzano E. Vascular proliferations of the breast. Histopathology. 2008;52:30-44.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Postradiation vascular proliferations: an increasing problem. Histopathology. 2006;48:106-114.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Kardum-Skelin I, Jelić-Puskarić B, Pazur M, et al. A case report of breast angiosarcoma. Coll Antropol. 2010;34:645-648.

- Mattoch IW, Robbins JB, Kempson RL, et al. Post-radiotherapy vascular proliferations in mammary skin: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:126-133.

- Bodet D, Rodríguez-Cano L, Bartralot R, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin associated with ovarian fibroma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2 suppl):S41-S44.

- Losch A, Chilek KD, Zirwas MJ. Post-radiation atypical vascular proliferation mimicking angiosarcoma eight months following breast-conserving therapy for breast carcinoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:47-48.

Atypical vascular lesions (AVLs) of the breast are rare cutaneous vascular proliferations that present as erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored papules, patches, or plaques in women who have undergone radiation treatment for breast carcinoma.1,2 These lesions most commonly develop in the irradiated area within 3 to 6 years following radiation treatment.3

Various terms have been used to describe AVLs in the literature, including atypical hemangiomas, benign lymphangiomatous papules, benign lymphangioendotheliomas, lymphangioma circumscriptum, and acquired progressive lymphangiomas, suggesting benign behavior.4-10 However, their identity as benign lesions has been a source of controversy, with some investigators proposing that AVLs may be a precursor lesion to postirradiation angiosarcoma.2 Research has addressed if there are markers that can predict AVL types that are more likely to develop into angiosarcomas.1 Although most clinicians treat AVLs with complete excision, there currently are no specific guidelines to direct this practice.

We report the case of a patient with a history of 1 AVL that was excised who developed 3 additional AVLs in the same breast over the course of 15 months.

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman with a history of obesity, hypertension, and infiltrating ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast (grade 2, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive) underwent a right breast lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node dissection. Three months later, she underwent re-excision for positive margins and started adjuvant hormonal therapy with tamoxifen. One month later, she began external beam radiation therapy and received a total dose of 6040 cGy over the course of 9 weeks (34 total treatments).

The patient presented to an outside dermatology clinic 2 years after completing external beam radiation therapy for evaluation of a new pink nodule on the right mid breast. The nodule was biopsied and discovered to be an AVL. Pathology showed an anastomosing proliferation of thin-walled vascular channels mainly located in the superficial dermis with notable endothelial nuclear atypia and hyperchromasia. There were several tiny foci with the beginnings of multilayering with prominent endothelial atypia (Figure 1). She underwent complete excision for this AVL with negative margins.

Six months after the initial AVL diagnosis, she presented to our dermatology clinic with another asymptomatic red bump on the right breast. On physical examination, a 4-mm firm, erythematous, well-circumscribed papule was noted on the medial aspect of the right breast along with a similar-appearing 4-mm papule on the right lateral aspect of the right breast (Figure 2). The patient was unsure of the duration of the second lesion but felt that it had been present at least as long as the other lesion. Both lesions clinically resembled typical capillary hemangiomas. A 6-mm punch biopsy of the right medial breast was performed and revealed enlarged vessels and capillaries in the upper dermis lined by endothelial cells with focal prominent nuclei without necrosis, overt atypia, mitosis, or tufting (Figure 3). Immunostaining was positive for CD34, factor VIII antigen, podoplanin (D2-40), and CD31, and negative for cytokeratin 7 and pankeratin. This staining was compatible with a lymphatic-type AVL.1 A diagnosis of AVL was made and complete excision with clear margins was performed. At the time of this excision, a biopsy of the right lateral breast was performed revealing thin-walled, dilated vascular channels in the superficial dermis with architecturally atypical angulated outlines, mild endothelial nuclear atypia, and hyperchromasia without endothelial multilayering. Clear margins were noted on the biopsy, but the patient subsequently declined re-excision of this third AVL.

During a subsequent follow-up visit 9 months later, the patient was noted to have a 2-mm red, vascular-appearing papule on the right upper medial breast (Figure 2). A 6-mm biopsy was performed and revealed thin-walled vascular channels in the superficial dermis with endothelial nuclear atypia consistent with an AVL.

Comment

Fineberg and Rosen8 were the first to describe AVLs in their 1994 study of 4 women with cutaneous vascular proliferations that developed after radiation and chemotherapy for breast cancer. They concluded that these AVLs were benign lesions distinct from angiosarcomas.8 However, further research has challenged the benign nature of AVLs. In 2005, Brenn and Fletcher2 studied 42 women diagnosed with either angiosarcoma or atypical radiation-associated cutaneous vascular lesions. They suggested that AVLs resided on the same spectrum as angiosarcomas and that AVLs may be precursor lesions to angiosarcomas.2 Furthermore, Hildebrandt et al11 in 2001 and Di Tommaso and Fabbri12 in 2003 published case reports of individual patients who developed an angiosarcoma from a preexisting AVL.

The controversy continued when Patton et al1 published a study in 2008 in which 32 cases of AVLs were reviewed. In this study, 2 histologic types of AVLs were described: vascular type and lymphatic type. Vascular-type AVLs are characterized by irregularly dispersed, pericyte-invested, capillary-sized vessels within the papillary or reticular dermis that often are associated with extravasated erythrocytes or hemosiderin. On the other hand, lymphatic-type AVLs display thin-walled, variably anastomosing, lymphatic vessels lined by attenuated or slightly protuberant endothelial cells. These subtypes have been suggested based on the antigens known to be present in certain tissues, specifically vascular and lymphatic tissue. Despite these seemingly distinct histologies, 6 lesions classified as vascular type displayed some histologic overlap with the lymphatic-type AVLs. The authors concluded that the vascular type showed greater potential to develop into an angiosarcoma based on the degree of endothelial atypia.1

In 2011, Santi et al13 found that both AVLs and angiosarcomas share inactivation mutations in the tumor suppressor gene TP53, providing further evidence to suggest that AVLs may be precursors to angiosarcomas.

Although the malignant potential of AVLs remains questionable, research has shown that they do have a propensity to recur.3 In 2007, Gengler et al3 determined that 20% of patients with AVLs experienced recurrence after a biopsy or excision with varying margins; however, the group stated that these new vascular lesions might not be recurrences but rather entirely new lesions in the same irradiated field (field-effect phenomenon). Several other studies demonstrated that more than 30% of patients with 1 AVL developed more lesions within the same irradiated area.3,14-16 Despite the high rate of recurrence documented in the literature, only 5 of more than 100 diagnosed AVLs have progressed to angiosarcoma.1,3

Many differences can be noted when comparing the histology of AVLs versus angiosarcomas, though some are subtle (Table). Angiosarcomas display poorly circumscribed vascular infiltration into the subcutaneous tissue, multilayering of endothelial cells, prominent nucleoli, hemorrhage, mitoses, and notable aytpia. Atypical vascular lesions lack these features and tend to be wedge shaped and display chronic inflammation.8,15,17-19 Atypical vascular lesions show superficial localized growth without destruction of adjacent adnexa, display dilated vascular spaces, and exhibit large endothelial cells.5,6,8,14,15,19,20 However, there is overlap between AVLs and angiosarcomas that can make diagnosis difficult.2,14,16,17,19 Areas within or just outside of an angiosarcoma, especially in well-differentiated angiosarcomas, can appear histologically identical to AVLs, and multiple biopsies may be required for diagnosis.17,19,21

Conclusion

More research is needed in the arenas of classification, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up recommendations for AVLs. In particular, more specific histologic markers may be needed to identify those AVLs that may progress to angiosarcomas. Although most AVLs are treated with excision, a consensus needs to be reached on adequate surgical margins. Lastly, due to the tendency of AVLs to recur coupled with their unknown malignant potential, recommendations are needed for consistent follow-up examinations.

Atypical vascular lesions (AVLs) of the breast are rare cutaneous vascular proliferations that present as erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored papules, patches, or plaques in women who have undergone radiation treatment for breast carcinoma.1,2 These lesions most commonly develop in the irradiated area within 3 to 6 years following radiation treatment.3

Various terms have been used to describe AVLs in the literature, including atypical hemangiomas, benign lymphangiomatous papules, benign lymphangioendotheliomas, lymphangioma circumscriptum, and acquired progressive lymphangiomas, suggesting benign behavior.4-10 However, their identity as benign lesions has been a source of controversy, with some investigators proposing that AVLs may be a precursor lesion to postirradiation angiosarcoma.2 Research has addressed if there are markers that can predict AVL types that are more likely to develop into angiosarcomas.1 Although most clinicians treat AVLs with complete excision, there currently are no specific guidelines to direct this practice.

We report the case of a patient with a history of 1 AVL that was excised who developed 3 additional AVLs in the same breast over the course of 15 months.

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman with a history of obesity, hypertension, and infiltrating ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast (grade 2, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive) underwent a right breast lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node dissection. Three months later, she underwent re-excision for positive margins and started adjuvant hormonal therapy with tamoxifen. One month later, she began external beam radiation therapy and received a total dose of 6040 cGy over the course of 9 weeks (34 total treatments).

The patient presented to an outside dermatology clinic 2 years after completing external beam radiation therapy for evaluation of a new pink nodule on the right mid breast. The nodule was biopsied and discovered to be an AVL. Pathology showed an anastomosing proliferation of thin-walled vascular channels mainly located in the superficial dermis with notable endothelial nuclear atypia and hyperchromasia. There were several tiny foci with the beginnings of multilayering with prominent endothelial atypia (Figure 1). She underwent complete excision for this AVL with negative margins.

Six months after the initial AVL diagnosis, she presented to our dermatology clinic with another asymptomatic red bump on the right breast. On physical examination, a 4-mm firm, erythematous, well-circumscribed papule was noted on the medial aspect of the right breast along with a similar-appearing 4-mm papule on the right lateral aspect of the right breast (Figure 2). The patient was unsure of the duration of the second lesion but felt that it had been present at least as long as the other lesion. Both lesions clinically resembled typical capillary hemangiomas. A 6-mm punch biopsy of the right medial breast was performed and revealed enlarged vessels and capillaries in the upper dermis lined by endothelial cells with focal prominent nuclei without necrosis, overt atypia, mitosis, or tufting (Figure 3). Immunostaining was positive for CD34, factor VIII antigen, podoplanin (D2-40), and CD31, and negative for cytokeratin 7 and pankeratin. This staining was compatible with a lymphatic-type AVL.1 A diagnosis of AVL was made and complete excision with clear margins was performed. At the time of this excision, a biopsy of the right lateral breast was performed revealing thin-walled, dilated vascular channels in the superficial dermis with architecturally atypical angulated outlines, mild endothelial nuclear atypia, and hyperchromasia without endothelial multilayering. Clear margins were noted on the biopsy, but the patient subsequently declined re-excision of this third AVL.

During a subsequent follow-up visit 9 months later, the patient was noted to have a 2-mm red, vascular-appearing papule on the right upper medial breast (Figure 2). A 6-mm biopsy was performed and revealed thin-walled vascular channels in the superficial dermis with endothelial nuclear atypia consistent with an AVL.

Comment

Fineberg and Rosen8 were the first to describe AVLs in their 1994 study of 4 women with cutaneous vascular proliferations that developed after radiation and chemotherapy for breast cancer. They concluded that these AVLs were benign lesions distinct from angiosarcomas.8 However, further research has challenged the benign nature of AVLs. In 2005, Brenn and Fletcher2 studied 42 women diagnosed with either angiosarcoma or atypical radiation-associated cutaneous vascular lesions. They suggested that AVLs resided on the same spectrum as angiosarcomas and that AVLs may be precursor lesions to angiosarcomas.2 Furthermore, Hildebrandt et al11 in 2001 and Di Tommaso and Fabbri12 in 2003 published case reports of individual patients who developed an angiosarcoma from a preexisting AVL.

The controversy continued when Patton et al1 published a study in 2008 in which 32 cases of AVLs were reviewed. In this study, 2 histologic types of AVLs were described: vascular type and lymphatic type. Vascular-type AVLs are characterized by irregularly dispersed, pericyte-invested, capillary-sized vessels within the papillary or reticular dermis that often are associated with extravasated erythrocytes or hemosiderin. On the other hand, lymphatic-type AVLs display thin-walled, variably anastomosing, lymphatic vessels lined by attenuated or slightly protuberant endothelial cells. These subtypes have been suggested based on the antigens known to be present in certain tissues, specifically vascular and lymphatic tissue. Despite these seemingly distinct histologies, 6 lesions classified as vascular type displayed some histologic overlap with the lymphatic-type AVLs. The authors concluded that the vascular type showed greater potential to develop into an angiosarcoma based on the degree of endothelial atypia.1

In 2011, Santi et al13 found that both AVLs and angiosarcomas share inactivation mutations in the tumor suppressor gene TP53, providing further evidence to suggest that AVLs may be precursors to angiosarcomas.

Although the malignant potential of AVLs remains questionable, research has shown that they do have a propensity to recur.3 In 2007, Gengler et al3 determined that 20% of patients with AVLs experienced recurrence after a biopsy or excision with varying margins; however, the group stated that these new vascular lesions might not be recurrences but rather entirely new lesions in the same irradiated field (field-effect phenomenon). Several other studies demonstrated that more than 30% of patients with 1 AVL developed more lesions within the same irradiated area.3,14-16 Despite the high rate of recurrence documented in the literature, only 5 of more than 100 diagnosed AVLs have progressed to angiosarcoma.1,3

Many differences can be noted when comparing the histology of AVLs versus angiosarcomas, though some are subtle (Table). Angiosarcomas display poorly circumscribed vascular infiltration into the subcutaneous tissue, multilayering of endothelial cells, prominent nucleoli, hemorrhage, mitoses, and notable aytpia. Atypical vascular lesions lack these features and tend to be wedge shaped and display chronic inflammation.8,15,17-19 Atypical vascular lesions show superficial localized growth without destruction of adjacent adnexa, display dilated vascular spaces, and exhibit large endothelial cells.5,6,8,14,15,19,20 However, there is overlap between AVLs and angiosarcomas that can make diagnosis difficult.2,14,16,17,19 Areas within or just outside of an angiosarcoma, especially in well-differentiated angiosarcomas, can appear histologically identical to AVLs, and multiple biopsies may be required for diagnosis.17,19,21

Conclusion

More research is needed in the arenas of classification, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up recommendations for AVLs. In particular, more specific histologic markers may be needed to identify those AVLs that may progress to angiosarcomas. Although most AVLs are treated with excision, a consensus needs to be reached on adequate surgical margins. Lastly, due to the tendency of AVLs to recur coupled with their unknown malignant potential, recommendations are needed for consistent follow-up examinations.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A, et al. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process; a study from the French sarcoma group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Hoda SA, Cranor ML, Rosen PP. Hemangiomas of the breast with atypical histological features: further analysis of histological subtypes confirming their benign character. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:553-560.

- Wagamon K, Ranchoff RE, Rosenberg AS, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:912-913.

- Diaz-Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin following radiotherapy: a report of five new cases and review of the literature. Histopathology. 1999;35:319-327.

- Martín-González T, Sanz-Trelles A, Del Boz J, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules and plaques after radiotherapy [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:84-86.

- Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:757-763.

- Guillou L, Fletcher CD. Benign lymphangioendothelioma (acquired progressive lymphangioma): a lesion not to be confused with well-differentiated angiosarcoma and patch stage Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1047-1057.

- Rosso R, Gianelli U, Carnevali L. Acquired progressive lymphangioma of the skin following radiotherapy for breast carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:164-167.

- Hildebrandt G, Mittag M, Gutz U, et al. Cutaneous breast angiosarcoma after conservative treatment of breast cancer. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:580-583.

- Di Tommaso L, Fabbri A. Cutaneous angiosarcoma arising after radiotherapy treatment of a breast carcinoma: description of a case and review of the literature [in Italian]. Pathologica. 2003;95:196-202.

- Santi R, Cetica V, Franchi A, et al. Tumour suppressor gene TP53 mutations in atypical vascular lesions of breast skin following radiotherapy. Histopathology. 2011;58:455-466.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Mentzel T, et al. Benign vascular proliferations in irradiated skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:328-337.

- Brodie C, Provenzano E. Vascular proliferations of the breast. Histopathology. 2008;52:30-44.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Postradiation vascular proliferations: an increasing problem. Histopathology. 2006;48:106-114.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Kardum-Skelin I, Jelić-Puskarić B, Pazur M, et al. A case report of breast angiosarcoma. Coll Antropol. 2010;34:645-648.

- Mattoch IW, Robbins JB, Kempson RL, et al. Post-radiotherapy vascular proliferations in mammary skin: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:126-133.

- Bodet D, Rodríguez-Cano L, Bartralot R, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin associated with ovarian fibroma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2 suppl):S41-S44.

- Losch A, Chilek KD, Zirwas MJ. Post-radiation atypical vascular proliferation mimicking angiosarcoma eight months following breast-conserving therapy for breast carcinoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:47-48.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A, et al. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process; a study from the French sarcoma group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Hoda SA, Cranor ML, Rosen PP. Hemangiomas of the breast with atypical histological features: further analysis of histological subtypes confirming their benign character. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:553-560.

- Wagamon K, Ranchoff RE, Rosenberg AS, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:912-913.

- Diaz-Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin following radiotherapy: a report of five new cases and review of the literature. Histopathology. 1999;35:319-327.

- Martín-González T, Sanz-Trelles A, Del Boz J, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules and plaques after radiotherapy [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:84-86.

- Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:757-763.

- Guillou L, Fletcher CD. Benign lymphangioendothelioma (acquired progressive lymphangioma): a lesion not to be confused with well-differentiated angiosarcoma and patch stage Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1047-1057.

- Rosso R, Gianelli U, Carnevali L. Acquired progressive lymphangioma of the skin following radiotherapy for breast carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:164-167.

- Hildebrandt G, Mittag M, Gutz U, et al. Cutaneous breast angiosarcoma after conservative treatment of breast cancer. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:580-583.

- Di Tommaso L, Fabbri A. Cutaneous angiosarcoma arising after radiotherapy treatment of a breast carcinoma: description of a case and review of the literature [in Italian]. Pathologica. 2003;95:196-202.

- Santi R, Cetica V, Franchi A, et al. Tumour suppressor gene TP53 mutations in atypical vascular lesions of breast skin following radiotherapy. Histopathology. 2011;58:455-466.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Mentzel T, et al. Benign vascular proliferations in irradiated skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:328-337.

- Brodie C, Provenzano E. Vascular proliferations of the breast. Histopathology. 2008;52:30-44.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Postradiation vascular proliferations: an increasing problem. Histopathology. 2006;48:106-114.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Kardum-Skelin I, Jelić-Puskarić B, Pazur M, et al. A case report of breast angiosarcoma. Coll Antropol. 2010;34:645-648.

- Mattoch IW, Robbins JB, Kempson RL, et al. Post-radiotherapy vascular proliferations in mammary skin: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:126-133.

- Bodet D, Rodríguez-Cano L, Bartralot R, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin associated with ovarian fibroma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2 suppl):S41-S44.

- Losch A, Chilek KD, Zirwas MJ. Post-radiation atypical vascular proliferation mimicking angiosarcoma eight months following breast-conserving therapy for breast carcinoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:47-48.

Practice Points

- Atypical vascular lesions (AVLs) of the breast can appear an average of 5 years following radiation therapy.

- Although the malignant potential of AVLs remains debatable, excision generally is recommended, as lesions tend to recur.

Vestibular Disorders Association Celebrates Balance Awareness Week

Vestibular (inner ear and brain) disorders affect patients physically, mentally, and emotionally, causing chronic dizziness, vertigo, imbalance, tinnitus, depression, and anxiety. To promote awareness of these invisible conditions, the Vestibular Disorders Association celebrates Balance Awareness Week on September 18-24, 2017. Visit the website for more information.

Vestibular (inner ear and brain) disorders affect patients physically, mentally, and emotionally, causing chronic dizziness, vertigo, imbalance, tinnitus, depression, and anxiety. To promote awareness of these invisible conditions, the Vestibular Disorders Association celebrates Balance Awareness Week on September 18-24, 2017. Visit the website for more information.

Vestibular (inner ear and brain) disorders affect patients physically, mentally, and emotionally, causing chronic dizziness, vertigo, imbalance, tinnitus, depression, and anxiety. To promote awareness of these invisible conditions, the Vestibular Disorders Association celebrates Balance Awareness Week on September 18-24, 2017. Visit the website for more information.

Spinal CSF Leak Foundation and Cedars-Sinai Plan Intracranial Hypotension Symposium

A full-day multidisciplinary symposium on intracranial hypotension secondary to spinal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak will bring together top clinicians and researchers to share the latest advances in diagnostics and treatments for this under-diagnosed but treatable secondary headache disorder. This event will take place Saturday, Oct. 14, 2017, in Santa Monica, California.

A full-day multidisciplinary symposium on intracranial hypotension secondary to spinal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak will bring together top clinicians and researchers to share the latest advances in diagnostics and treatments for this under-diagnosed but treatable secondary headache disorder. This event will take place Saturday, Oct. 14, 2017, in Santa Monica, California.

A full-day multidisciplinary symposium on intracranial hypotension secondary to spinal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak will bring together top clinicians and researchers to share the latest advances in diagnostics and treatments for this under-diagnosed but treatable secondary headache disorder. This event will take place Saturday, Oct. 14, 2017, in Santa Monica, California.

Neuroendocrine Tumor Research Foundation Issues Request for Proposals

The Neuroendocrine Tumor Research Foundation (NETRF) has issued an invitation for Letters of Intent for 2017 research grants. Proposals are being sought with the potential to transform understanding of neuroendocrine tumors and/or lead to improved treatments and diagnostics for patients. Letters of Intent may focus on any type of neuroendocrine tumor and may be for basic, translational, or clinical research.

The Neuroendocrine Tumor Research Foundation (NETRF) has issued an invitation for Letters of Intent for 2017 research grants. Proposals are being sought with the potential to transform understanding of neuroendocrine tumors and/or lead to improved treatments and diagnostics for patients. Letters of Intent may focus on any type of neuroendocrine tumor and may be for basic, translational, or clinical research.

The Neuroendocrine Tumor Research Foundation (NETRF) has issued an invitation for Letters of Intent for 2017 research grants. Proposals are being sought with the potential to transform understanding of neuroendocrine tumors and/or lead to improved treatments and diagnostics for patients. Letters of Intent may focus on any type of neuroendocrine tumor and may be for basic, translational, or clinical research.

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on Men’s Products

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on men’s products. Consideration must be given to:

- bareMinerals SPF 30 Natural Sunscreen

Bare Escentuals Beauty, Inc

“I recommend this product to my male patients when they are not wearing a hat. It protects the scalp from UV damage without a heavy greasy finish.”—Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

- Ducray Alopexy 5% For Men

Pierre Fabre Laboratories

“This dermatologist-dispensed product for men addresses chronic hair loss as well as thinning hair. It contains an optimal level of minoxidil 5% in an elegant unscented formulation and is designed to spray on smoothly and evenly.”—Jeannette Graf, MD, Great Neck, New York

- Facial Fuel Energizing Scrub

Kiehl’s

“This product is great for oily skin and enlarged pores. The particles in the product allow one to get a deep-clean feeling.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Physical Matte UV Defense SPF 50

SkinCeuticals

“For men I like to keep things simple. I recommend what I use with the single most important thing being daily sun protection. SkinCeuticals Physical Matte UV Defense SPF 50 is my favorite and I use it after I shave. It goes on smoothly and has a natural tint along with a high SPF.”—Jerome Potozkin, MD, Danville, California

- Ultimate Brushless Shave Cream

Kiehl’s

“I recommend this product for men with frequent irritation from shaving. This cream-based product helps to provide a close shave without as much irritation from other gel-based products. A small amount goes a long way!”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments and cleansing devices will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please email your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on men’s products. Consideration must be given to:

- bareMinerals SPF 30 Natural Sunscreen

Bare Escentuals Beauty, Inc

“I recommend this product to my male patients when they are not wearing a hat. It protects the scalp from UV damage without a heavy greasy finish.”—Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

- Ducray Alopexy 5% For Men

Pierre Fabre Laboratories

“This dermatologist-dispensed product for men addresses chronic hair loss as well as thinning hair. It contains an optimal level of minoxidil 5% in an elegant unscented formulation and is designed to spray on smoothly and evenly.”—Jeannette Graf, MD, Great Neck, New York

- Facial Fuel Energizing Scrub

Kiehl’s

“This product is great for oily skin and enlarged pores. The particles in the product allow one to get a deep-clean feeling.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Physical Matte UV Defense SPF 50

SkinCeuticals

“For men I like to keep things simple. I recommend what I use with the single most important thing being daily sun protection. SkinCeuticals Physical Matte UV Defense SPF 50 is my favorite and I use it after I shave. It goes on smoothly and has a natural tint along with a high SPF.”—Jerome Potozkin, MD, Danville, California

- Ultimate Brushless Shave Cream

Kiehl’s

“I recommend this product for men with frequent irritation from shaving. This cream-based product helps to provide a close shave without as much irritation from other gel-based products. A small amount goes a long way!”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments and cleansing devices will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please email your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on men’s products. Consideration must be given to:

- bareMinerals SPF 30 Natural Sunscreen

Bare Escentuals Beauty, Inc

“I recommend this product to my male patients when they are not wearing a hat. It protects the scalp from UV damage without a heavy greasy finish.”—Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

- Ducray Alopexy 5% For Men

Pierre Fabre Laboratories

“This dermatologist-dispensed product for men addresses chronic hair loss as well as thinning hair. It contains an optimal level of minoxidil 5% in an elegant unscented formulation and is designed to spray on smoothly and evenly.”—Jeannette Graf, MD, Great Neck, New York

- Facial Fuel Energizing Scrub

Kiehl’s

“This product is great for oily skin and enlarged pores. The particles in the product allow one to get a deep-clean feeling.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Physical Matte UV Defense SPF 50

SkinCeuticals

“For men I like to keep things simple. I recommend what I use with the single most important thing being daily sun protection. SkinCeuticals Physical Matte UV Defense SPF 50 is my favorite and I use it after I shave. It goes on smoothly and has a natural tint along with a high SPF.”—Jerome Potozkin, MD, Danville, California

- Ultimate Brushless Shave Cream

Kiehl’s

“I recommend this product for men with frequent irritation from shaving. This cream-based product helps to provide a close shave without as much irritation from other gel-based products. A small amount goes a long way!”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments and cleansing devices will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please email your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

MSA Coalition Plans Patient/Family Conference

The Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) Coalition Patient/Family Conference will take place October 13-14, 2017, in Nashville.

The Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) Coalition Patient/Family Conference will take place October 13-14, 2017, in Nashville.

The Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) Coalition Patient/Family Conference will take place October 13-14, 2017, in Nashville.

Hyper IgM Foundation Publishes Blog

The Hyper IgM Foundation recently published a blog promoting better understanding of Hyper IgM syndrome, a rare, genetic, immunodeficiency disorder. In particular, they are seeking to provide information for patients and families going through stem cell transplantation.

The Hyper IgM Foundation recently published a blog promoting better understanding of Hyper IgM syndrome, a rare, genetic, immunodeficiency disorder. In particular, they are seeking to provide information for patients and families going through stem cell transplantation.

The Hyper IgM Foundation recently published a blog promoting better understanding of Hyper IgM syndrome, a rare, genetic, immunodeficiency disorder. In particular, they are seeking to provide information for patients and families going through stem cell transplantation.

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome Secondary to Isolated Albuterol Use

To the Editor:

A 22-year-old obese man with untreated mild asthma diagnosed in childhood presented to the emergency department with cheilitis (Figure 1); conjunctivitis; and painful desquamation of the oral mucosa, penis (Figure 2), and perirectal area (Figure 3). Physical examination was notable for palpebral conjunctiva; mucosal involvement with stomatitis (Figure 1B); and isolated 0.5- to 2-cm erosions and ulcerations with positive Nikolsky sign of the scrotum (Figure 2), trunk, back, and arms and legs. Some areas had evidence of hemorrhagic crust, flaccid bullae, and denudation. Few scant targetoid lesions and dusky red macules on the trunk, face, palms, and soles also were present.

One week prior to presentation he had an episode of diarrhea and dyspnea with symptoms of mild heat stroke after working outdoors, and he self-treated with ibuprofen, which he had taken intermittently for years. He was subsequently seen at an outpatient clinic and was prescribed an albuterol inhaler for previously untreated childhood asthma. The patient stated that he inhaled 2 puffs every 6 hours for a total of 3 treatments. Shortly after the last dose, he noticed a tingling sensation of the oral mucosa that developed into a painful 2-cm bullous ulcer. Over the next 3 days, he developed several more oral ulcers and erosions. Three days before admission he developed dysuria and tense bullae at the glans penis. After admission, he developed cheilitis, conjunctivitis, dysuria, odynophagia, and dysphagia to solids. One day after admission, the patient had the onset of systemic symptoms, including cough with worsening dyspnea, fever, chills, hemoptysis, epistaxis, nausea, diarrhea, loss of appetite, joint pain, and myalgia. Review of systems was otherwise negative. A radiograph was performed at admission and was notable for mild atelectasis but was otherwise normal. The chest radiograph was negative for signs of perihilar lymphadenopathy, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, or lobar infiltrates suggestive of bacterial pneumonia. It also did not show signs of patchy opacities or air bronchograms suggestive of an interstitial pneumonia. On admission, he was started on acyclovir, fluconazole, methylprednisolone, nystatin, pantoprazole, acetaminophen, topical bacitracin, oxycodone, and topical silver nitrate.

At the time of admission our patient was afebrile with a normal heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. However, he was hypoxic, with a pulse oximetry of 86% on room air and 94% on 40% fraction of inspired oxygen. Complete blood cell count, electrolytes, and liver function tests were all within reference range. Urinalysis revealed evidence of scant red blood cells without pyuria, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and creatine kinase level were both elevated. Two blood cultures; sputum cultures; and polymerase chain reaction for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, herpes simplex virus, varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus were negative. Human immunodeficiency virus panel, antinuclear antibody screen, and hepatitis B and C panels were all negative. Four punch biopsies were obtained showing full-thickness epidermal necrosis with neutrophils, few dyskeratotic cells, and sparse inflammatory infiltrate compatible with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS).

After hospital admission, the patient’s mucosal desquamation progressively improved. By day 3, he required minimal supplemental oxygen with resolution of bowel symptoms and improved mucosal and skin findings. He was discharged on day 4 with supplemental oxygen and a 7-day course of prednisone, fluconazole, liquid oxycodone, pantoprazole, and acetaminophen. He showed continued improvement at a follow-up outpatient visit 2 days following discharge.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome is a rare severe drug reaction characterized by high fevers, mucosal erosions, tenderness, and skin detachment approximately 1 to 3 weeks after an inciting event.1,2 Although SJS has been linked to infections and less commonly to immunizations, in more than 80% of cases, SJS is strongly associated with a recent medication change.3 The classes of drugs that have been implicated in SJS most commonly include antibiotics, anticonvulsants, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.4 Stevens-Johnson syndrome from drug reactions is not uncommon; however, SJS secondary to isolated albuterol use is rare.

Although it is presumed that albuterol was the key inciting factor in our patient’s case of SJS, it also is recognized that mucosal SJS can be associated with M pneumoniae infection. For this reason, we performed polymerase chain reaction for M pneumoniae as well as a chest radiograph to rule out this possibility. In addition, our patient had denied prolonged respiratory symptoms suggestive of a mycoplasma pneumonia infection, such as a prodrome of cough, myalgia, headache, sore throat, or fever. A report of 8 patients with documented SJS and M pneumoniae as well as a review of the literature also demonstrated a mean of 10 days of prodromal symptoms prior to the onset of mucosal lesions and/or a rash.5 However, mucosal SJS associated with mycoplasma pneumonia is an important clinical entity that should not be forgotten during the workup of a young patient with mucosal lesions or rash suggestive of SJS.

The exact etiology and mechanism of drug-induced SJS is not well understood at this time; however, evidence suggests that SJS is strongly linked to the host’s inability to detoxify drug metabolites.6,7 It has been postulated that SJS occurs secondary to a cell-mediated immune response, which activates cytotoxic T lymphocytes and subsequently results in keratinocyte apoptosis. Keratinocyte apoptosis occurs via the CD95-CD95 death receptor and soluble or membrane-bound ligand interaction.3,8,9 Stevens-Johnson syndrome is thought to occur from an interaction involving an HLA antigen–restricted presentation of drug metabolites to cytotoxic T cells, which can be further supported by evidence of strong genetic associations with HLA antigen alleles B15.02 and B58.01 in the cases of carbamazepine- and allopurinol-induced SJS, respectively.6,7 However, the genetic associations of specific HLA antigen alleles and polymorphisms with SJS and other cutaneous reactions is thought to be drug specific and HLA antigen subtype specific.7 Therefore, it is difficult to determine or correlate the clinical outcomes and manifestations of drug reactions in individualized patients. The precise mechanism of antigenicity of albuterol in initiating this cascade has not yet been determined. However, these investigations provide strong evidence for a correlation between specific HLA antigen haplotypes and occurrence of drug antigenicity resulting in SJS and other cutaneous reactions in susceptible patient populations.

Although the specific molecular pathway and etiology of SJS is not well delineated, pathology in combination with clinical correlation allows for diagnosis. Early-stage biopsies in SJS typically show apoptotic keratinocytes throughout the epidermis. Late-stage biopsies exhibit subepidermal blisters and full-thickness epidermal necrosis.1 Histopathology was performed on 4-mm punch biopsies of the chest and back and demonstrated full-thickness epidermal necrosis with neutrophils and a few dyskeratotic cells, likely representing a late stage of epidermal involvement. Given the predominance of neutrophils, other diagnostic considerations based solely on the biopsy results included contact dermatitis or phototoxic dermatitis. The remaining inflammatory infiltrate was sparse. Immunofluorescence was pan-negative.

This report illustrates a rare case of SJS from isolated albuterol use. This adverse drug reaction has not been well reported in the literature and may be an important consideration in the management of a patient with asthma.

- Stern RS. Clinical practice. exanthematous drug eruptions. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2492-2501.

- Tartarone A, Lerose R. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: what do we know? Ther Drug Monit. 2010;32:669-672.

- Ferrandiz-Pulido C, Garcia-Patos V. A review of causes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:998-1003.

- Mockenhaupt M, Viboud C, Dunant A, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: assessment of medication risks with emphasis on recently marketed drugs. the EuroSCAR-study. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:35-44.

- Levy M, Shear NH. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. report of eight cases and review of the literature. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1991;30:42-49.

- Chung WH, Hung SI. Genetic markers and danger signals in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis [published online October 25, 2010]. Allergol Int. 2010;59:325-332.

- Chung WH, Hung SI. Recent advances in the genetics and immunology of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrosis. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;66:190-196.

- Bharadwaj M, Illing P, Theodossis A, et al. Drug hypersensitivity and human leukocyte antigens of the major histocompatibility complex. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:401-431.

- Chessman D, Kostenko L, Lethborg T, et al. Human leukocyte antigen class I-restricted activation of CD8+ T cells provides the immunogenetic basis of a systemic drug hypersensitivity. Immunity. 2008;28:822-832.

To the Editor:

A 22-year-old obese man with untreated mild asthma diagnosed in childhood presented to the emergency department with cheilitis (Figure 1); conjunctivitis; and painful desquamation of the oral mucosa, penis (Figure 2), and perirectal area (Figure 3). Physical examination was notable for palpebral conjunctiva; mucosal involvement with stomatitis (Figure 1B); and isolated 0.5- to 2-cm erosions and ulcerations with positive Nikolsky sign of the scrotum (Figure 2), trunk, back, and arms and legs. Some areas had evidence of hemorrhagic crust, flaccid bullae, and denudation. Few scant targetoid lesions and dusky red macules on the trunk, face, palms, and soles also were present.

One week prior to presentation he had an episode of diarrhea and dyspnea with symptoms of mild heat stroke after working outdoors, and he self-treated with ibuprofen, which he had taken intermittently for years. He was subsequently seen at an outpatient clinic and was prescribed an albuterol inhaler for previously untreated childhood asthma. The patient stated that he inhaled 2 puffs every 6 hours for a total of 3 treatments. Shortly after the last dose, he noticed a tingling sensation of the oral mucosa that developed into a painful 2-cm bullous ulcer. Over the next 3 days, he developed several more oral ulcers and erosions. Three days before admission he developed dysuria and tense bullae at the glans penis. After admission, he developed cheilitis, conjunctivitis, dysuria, odynophagia, and dysphagia to solids. One day after admission, the patient had the onset of systemic symptoms, including cough with worsening dyspnea, fever, chills, hemoptysis, epistaxis, nausea, diarrhea, loss of appetite, joint pain, and myalgia. Review of systems was otherwise negative. A radiograph was performed at admission and was notable for mild atelectasis but was otherwise normal. The chest radiograph was negative for signs of perihilar lymphadenopathy, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, or lobar infiltrates suggestive of bacterial pneumonia. It also did not show signs of patchy opacities or air bronchograms suggestive of an interstitial pneumonia. On admission, he was started on acyclovir, fluconazole, methylprednisolone, nystatin, pantoprazole, acetaminophen, topical bacitracin, oxycodone, and topical silver nitrate.

At the time of admission our patient was afebrile with a normal heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. However, he was hypoxic, with a pulse oximetry of 86% on room air and 94% on 40% fraction of inspired oxygen. Complete blood cell count, electrolytes, and liver function tests were all within reference range. Urinalysis revealed evidence of scant red blood cells without pyuria, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and creatine kinase level were both elevated. Two blood cultures; sputum cultures; and polymerase chain reaction for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, herpes simplex virus, varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus were negative. Human immunodeficiency virus panel, antinuclear antibody screen, and hepatitis B and C panels were all negative. Four punch biopsies were obtained showing full-thickness epidermal necrosis with neutrophils, few dyskeratotic cells, and sparse inflammatory infiltrate compatible with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS).

After hospital admission, the patient’s mucosal desquamation progressively improved. By day 3, he required minimal supplemental oxygen with resolution of bowel symptoms and improved mucosal and skin findings. He was discharged on day 4 with supplemental oxygen and a 7-day course of prednisone, fluconazole, liquid oxycodone, pantoprazole, and acetaminophen. He showed continued improvement at a follow-up outpatient visit 2 days following discharge.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome is a rare severe drug reaction characterized by high fevers, mucosal erosions, tenderness, and skin detachment approximately 1 to 3 weeks after an inciting event.1,2 Although SJS has been linked to infections and less commonly to immunizations, in more than 80% of cases, SJS is strongly associated with a recent medication change.3 The classes of drugs that have been implicated in SJS most commonly include antibiotics, anticonvulsants, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.4 Stevens-Johnson syndrome from drug reactions is not uncommon; however, SJS secondary to isolated albuterol use is rare.

Although it is presumed that albuterol was the key inciting factor in our patient’s case of SJS, it also is recognized that mucosal SJS can be associated with M pneumoniae infection. For this reason, we performed polymerase chain reaction for M pneumoniae as well as a chest radiograph to rule out this possibility. In addition, our patient had denied prolonged respiratory symptoms suggestive of a mycoplasma pneumonia infection, such as a prodrome of cough, myalgia, headache, sore throat, or fever. A report of 8 patients with documented SJS and M pneumoniae as well as a review of the literature also demonstrated a mean of 10 days of prodromal symptoms prior to the onset of mucosal lesions and/or a rash.5 However, mucosal SJS associated with mycoplasma pneumonia is an important clinical entity that should not be forgotten during the workup of a young patient with mucosal lesions or rash suggestive of SJS.

The exact etiology and mechanism of drug-induced SJS is not well understood at this time; however, evidence suggests that SJS is strongly linked to the host’s inability to detoxify drug metabolites.6,7 It has been postulated that SJS occurs secondary to a cell-mediated immune response, which activates cytotoxic T lymphocytes and subsequently results in keratinocyte apoptosis. Keratinocyte apoptosis occurs via the CD95-CD95 death receptor and soluble or membrane-bound ligand interaction.3,8,9 Stevens-Johnson syndrome is thought to occur from an interaction involving an HLA antigen–restricted presentation of drug metabolites to cytotoxic T cells, which can be further supported by evidence of strong genetic associations with HLA antigen alleles B15.02 and B58.01 in the cases of carbamazepine- and allopurinol-induced SJS, respectively.6,7 However, the genetic associations of specific HLA antigen alleles and polymorphisms with SJS and other cutaneous reactions is thought to be drug specific and HLA antigen subtype specific.7 Therefore, it is difficult to determine or correlate the clinical outcomes and manifestations of drug reactions in individualized patients. The precise mechanism of antigenicity of albuterol in initiating this cascade has not yet been determined. However, these investigations provide strong evidence for a correlation between specific HLA antigen haplotypes and occurrence of drug antigenicity resulting in SJS and other cutaneous reactions in susceptible patient populations.

Although the specific molecular pathway and etiology of SJS is not well delineated, pathology in combination with clinical correlation allows for diagnosis. Early-stage biopsies in SJS typically show apoptotic keratinocytes throughout the epidermis. Late-stage biopsies exhibit subepidermal blisters and full-thickness epidermal necrosis.1 Histopathology was performed on 4-mm punch biopsies of the chest and back and demonstrated full-thickness epidermal necrosis with neutrophils and a few dyskeratotic cells, likely representing a late stage of epidermal involvement. Given the predominance of neutrophils, other diagnostic considerations based solely on the biopsy results included contact dermatitis or phototoxic dermatitis. The remaining inflammatory infiltrate was sparse. Immunofluorescence was pan-negative.

This report illustrates a rare case of SJS from isolated albuterol use. This adverse drug reaction has not been well reported in the literature and may be an important consideration in the management of a patient with asthma.

To the Editor:

A 22-year-old obese man with untreated mild asthma diagnosed in childhood presented to the emergency department with cheilitis (Figure 1); conjunctivitis; and painful desquamation of the oral mucosa, penis (Figure 2), and perirectal area (Figure 3). Physical examination was notable for palpebral conjunctiva; mucosal involvement with stomatitis (Figure 1B); and isolated 0.5- to 2-cm erosions and ulcerations with positive Nikolsky sign of the scrotum (Figure 2), trunk, back, and arms and legs. Some areas had evidence of hemorrhagic crust, flaccid bullae, and denudation. Few scant targetoid lesions and dusky red macules on the trunk, face, palms, and soles also were present.

One week prior to presentation he had an episode of diarrhea and dyspnea with symptoms of mild heat stroke after working outdoors, and he self-treated with ibuprofen, which he had taken intermittently for years. He was subsequently seen at an outpatient clinic and was prescribed an albuterol inhaler for previously untreated childhood asthma. The patient stated that he inhaled 2 puffs every 6 hours for a total of 3 treatments. Shortly after the last dose, he noticed a tingling sensation of the oral mucosa that developed into a painful 2-cm bullous ulcer. Over the next 3 days, he developed several more oral ulcers and erosions. Three days before admission he developed dysuria and tense bullae at the glans penis. After admission, he developed cheilitis, conjunctivitis, dysuria, odynophagia, and dysphagia to solids. One day after admission, the patient had the onset of systemic symptoms, including cough with worsening dyspnea, fever, chills, hemoptysis, epistaxis, nausea, diarrhea, loss of appetite, joint pain, and myalgia. Review of systems was otherwise negative. A radiograph was performed at admission and was notable for mild atelectasis but was otherwise normal. The chest radiograph was negative for signs of perihilar lymphadenopathy, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, or lobar infiltrates suggestive of bacterial pneumonia. It also did not show signs of patchy opacities or air bronchograms suggestive of an interstitial pneumonia. On admission, he was started on acyclovir, fluconazole, methylprednisolone, nystatin, pantoprazole, acetaminophen, topical bacitracin, oxycodone, and topical silver nitrate.

At the time of admission our patient was afebrile with a normal heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. However, he was hypoxic, with a pulse oximetry of 86% on room air and 94% on 40% fraction of inspired oxygen. Complete blood cell count, electrolytes, and liver function tests were all within reference range. Urinalysis revealed evidence of scant red blood cells without pyuria, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and creatine kinase level were both elevated. Two blood cultures; sputum cultures; and polymerase chain reaction for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, herpes simplex virus, varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus were negative. Human immunodeficiency virus panel, antinuclear antibody screen, and hepatitis B and C panels were all negative. Four punch biopsies were obtained showing full-thickness epidermal necrosis with neutrophils, few dyskeratotic cells, and sparse inflammatory infiltrate compatible with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS).

After hospital admission, the patient’s mucosal desquamation progressively improved. By day 3, he required minimal supplemental oxygen with resolution of bowel symptoms and improved mucosal and skin findings. He was discharged on day 4 with supplemental oxygen and a 7-day course of prednisone, fluconazole, liquid oxycodone, pantoprazole, and acetaminophen. He showed continued improvement at a follow-up outpatient visit 2 days following discharge.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome is a rare severe drug reaction characterized by high fevers, mucosal erosions, tenderness, and skin detachment approximately 1 to 3 weeks after an inciting event.1,2 Although SJS has been linked to infections and less commonly to immunizations, in more than 80% of cases, SJS is strongly associated with a recent medication change.3 The classes of drugs that have been implicated in SJS most commonly include antibiotics, anticonvulsants, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.4 Stevens-Johnson syndrome from drug reactions is not uncommon; however, SJS secondary to isolated albuterol use is rare.

Although it is presumed that albuterol was the key inciting factor in our patient’s case of SJS, it also is recognized that mucosal SJS can be associated with M pneumoniae infection. For this reason, we performed polymerase chain reaction for M pneumoniae as well as a chest radiograph to rule out this possibility. In addition, our patient had denied prolonged respiratory symptoms suggestive of a mycoplasma pneumonia infection, such as a prodrome of cough, myalgia, headache, sore throat, or fever. A report of 8 patients with documented SJS and M pneumoniae as well as a review of the literature also demonstrated a mean of 10 days of prodromal symptoms prior to the onset of mucosal lesions and/or a rash.5 However, mucosal SJS associated with mycoplasma pneumonia is an important clinical entity that should not be forgotten during the workup of a young patient with mucosal lesions or rash suggestive of SJS.

The exact etiology and mechanism of drug-induced SJS is not well understood at this time; however, evidence suggests that SJS is strongly linked to the host’s inability to detoxify drug metabolites.6,7 It has been postulated that SJS occurs secondary to a cell-mediated immune response, which activates cytotoxic T lymphocytes and subsequently results in keratinocyte apoptosis. Keratinocyte apoptosis occurs via the CD95-CD95 death receptor and soluble or membrane-bound ligand interaction.3,8,9 Stevens-Johnson syndrome is thought to occur from an interaction involving an HLA antigen–restricted presentation of drug metabolites to cytotoxic T cells, which can be further supported by evidence of strong genetic associations with HLA antigen alleles B15.02 and B58.01 in the cases of carbamazepine- and allopurinol-induced SJS, respectively.6,7 However, the genetic associations of specific HLA antigen alleles and polymorphisms with SJS and other cutaneous reactions is thought to be drug specific and HLA antigen subtype specific.7 Therefore, it is difficult to determine or correlate the clinical outcomes and manifestations of drug reactions in individualized patients. The precise mechanism of antigenicity of albuterol in initiating this cascade has not yet been determined. However, these investigations provide strong evidence for a correlation between specific HLA antigen haplotypes and occurrence of drug antigenicity resulting in SJS and other cutaneous reactions in susceptible patient populations.

Although the specific molecular pathway and etiology of SJS is not well delineated, pathology in combination with clinical correlation allows for diagnosis. Early-stage biopsies in SJS typically show apoptotic keratinocytes throughout the epidermis. Late-stage biopsies exhibit subepidermal blisters and full-thickness epidermal necrosis.1 Histopathology was performed on 4-mm punch biopsies of the chest and back and demonstrated full-thickness epidermal necrosis with neutrophils and a few dyskeratotic cells, likely representing a late stage of epidermal involvement. Given the predominance of neutrophils, other diagnostic considerations based solely on the biopsy results included contact dermatitis or phototoxic dermatitis. The remaining inflammatory infiltrate was sparse. Immunofluorescence was pan-negative.

This report illustrates a rare case of SJS from isolated albuterol use. This adverse drug reaction has not been well reported in the literature and may be an important consideration in the management of a patient with asthma.

- Stern RS. Clinical practice. exanthematous drug eruptions. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2492-2501.

- Tartarone A, Lerose R. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: what do we know? Ther Drug Monit. 2010;32:669-672.

- Ferrandiz-Pulido C, Garcia-Patos V. A review of causes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:998-1003.

- Mockenhaupt M, Viboud C, Dunant A, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: assessment of medication risks with emphasis on recently marketed drugs. the EuroSCAR-study. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:35-44.

- Levy M, Shear NH. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. report of eight cases and review of the literature. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1991;30:42-49.

- Chung WH, Hung SI. Genetic markers and danger signals in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis [published online October 25, 2010]. Allergol Int. 2010;59:325-332.

- Chung WH, Hung SI. Recent advances in the genetics and immunology of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrosis. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;66:190-196.

- Bharadwaj M, Illing P, Theodossis A, et al. Drug hypersensitivity and human leukocyte antigens of the major histocompatibility complex. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:401-431.

- Chessman D, Kostenko L, Lethborg T, et al. Human leukocyte antigen class I-restricted activation of CD8+ T cells provides the immunogenetic basis of a systemic drug hypersensitivity. Immunity. 2008;28:822-832.

- Stern RS. Clinical practice. exanthematous drug eruptions. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2492-2501.

- Tartarone A, Lerose R. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: what do we know? Ther Drug Monit. 2010;32:669-672.

- Ferrandiz-Pulido C, Garcia-Patos V. A review of causes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:998-1003.

- Mockenhaupt M, Viboud C, Dunant A, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: assessment of medication risks with emphasis on recently marketed drugs. the EuroSCAR-study. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:35-44.

- Levy M, Shear NH. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. report of eight cases and review of the literature. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1991;30:42-49.

- Chung WH, Hung SI. Genetic markers and danger signals in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis [published online October 25, 2010]. Allergol Int. 2010;59:325-332.

- Chung WH, Hung SI. Recent advances in the genetics and immunology of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrosis. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;66:190-196.

- Bharadwaj M, Illing P, Theodossis A, et al. Drug hypersensitivity and human leukocyte antigens of the major histocompatibility complex. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:401-431.

- Chessman D, Kostenko L, Lethborg T, et al. Human leukocyte antigen class I-restricted activation of CD8+ T cells provides the immunogenetic basis of a systemic drug hypersensitivity. Immunity. 2008;28:822-832.

Practice Points

- Think of Stevens-Johnson syndrome when new skin lesions are seen after any new medication is started.

- Perform a full-body examination to assess the extent of skin eruptions.

- When a medication is atypical for skin eruption, it becomes necessary to assess for other systemic causes and confirm pathologic results on skin biopsy.

Space Heater–Induced Bullous Erythema Ab Igne

To the Editor: