User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Videodermoscopy as a Novel Tool for Dermatologic Education

Dermoscopy, or the noninvasive in vivo examination of the epidermis and superficial dermis using magnification, facilitates the diagnosis of pigmented and nonpigmented skin lesions.1 Despite the benefit of dermoscopy in making early and accurate diagnoses of potentially life-limiting skin cancers, only 48% of dermatologists in the United States use dermoscopy in their practices.2 The most commonly cited reason for not using dermoscopy is lack of training.

Although the use of dermoscopy is associated with younger age and more recent graduation from residency compared to nonusers, dermatology resident physicians continue to receive limited training in dermoscopy.2 In a survey of 139 dermatology chief residents, 48% were not satisfied with the dermoscopy training that they had received during residency. Residents who received bedside instruction in dermoscopy reported greater satisfaction with their dermoscopy training compared to those who did not receive bedside instruction.3 This article provides a brief comparison of standard dermoscopy versus videodermoscopy for the instruction of trainees on common dermatologic diagnoses.

Bedside Dermoscopy

Standard optical dermatoscopes used for patient care and educational purposes typically incorporate 10-fold magnification and permit examination by a single viewer through a lens. With standard dermatoscopes, bedside dermoscopy instruction consists of the independent sequential viewing of skin lesions by instructors and trainees. Trainees must independently search for dermoscopic features noted by the instructor, which may be difficult for novice users. Simultaneous viewing of lesions would allow instructors to clearly indicate in real time pertinent dermoscopic features to their trainees.

Videodermatoscopes facilitate the simultaneous examination of cutaneous lesions by projecting the dermoscopic image onto a digital screen. Furthermore, these devices can incorporate magnifications of up to 200-fold or greater. In recent years, research pertaining to videodermoscopy has focused on the high magnification capabilities of these devices, specifically dermoscopic features that are visualized at magnifications greater than 10-fold, including the light brown nests of basal cell carcinomas that are seen at 50- to 70-fold magnification, twisted red capillary loops seen in active scalp psoriasis at 50-fold magnification, and longitudinal white indentations seen on nail plates affected by onychomycosis at 20-fold magnification.4-6 The potential value of videodermoscopy in medical education lies not only in the high magnification potential, which may make subtle dermoscopic findings more apparent to novice dermoscopists, but also in the ability to facilitate simultaneous dermoscopic examinations by instructors and trainees.

Educational Applications for Videodermoscopy

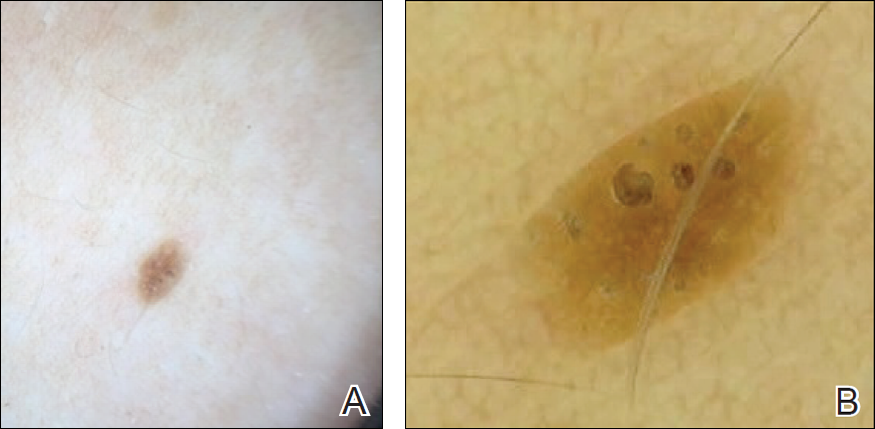

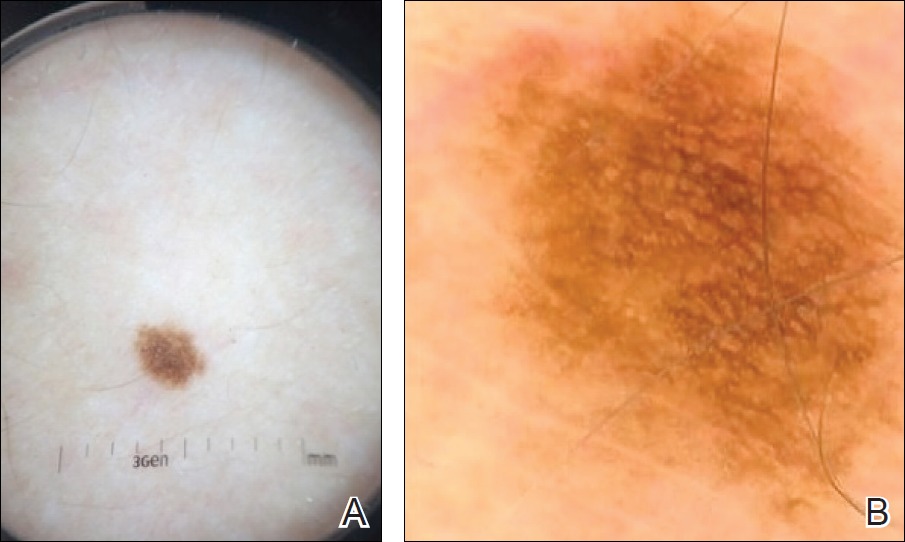

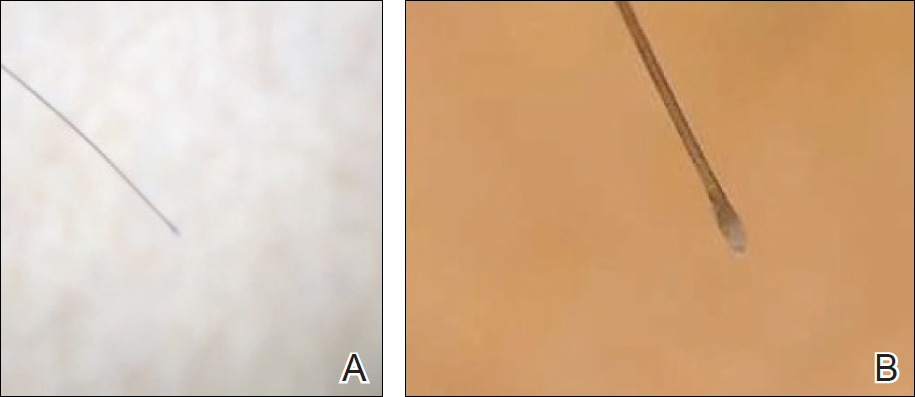

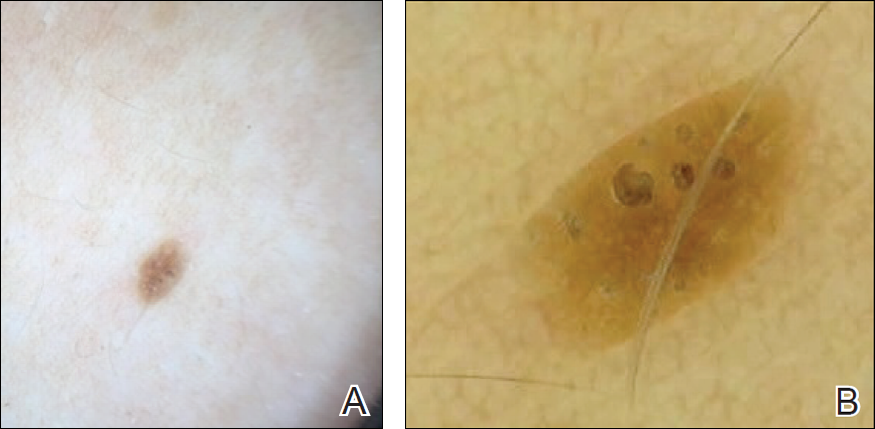

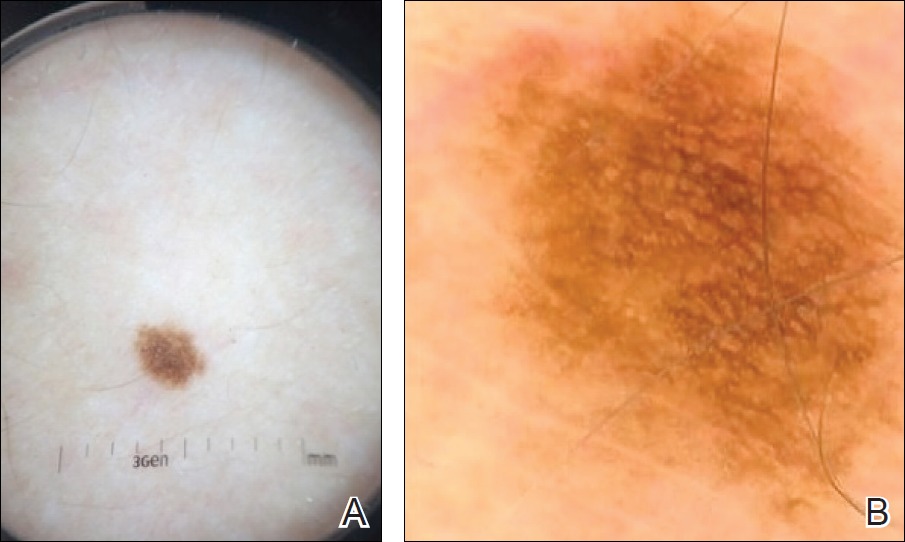

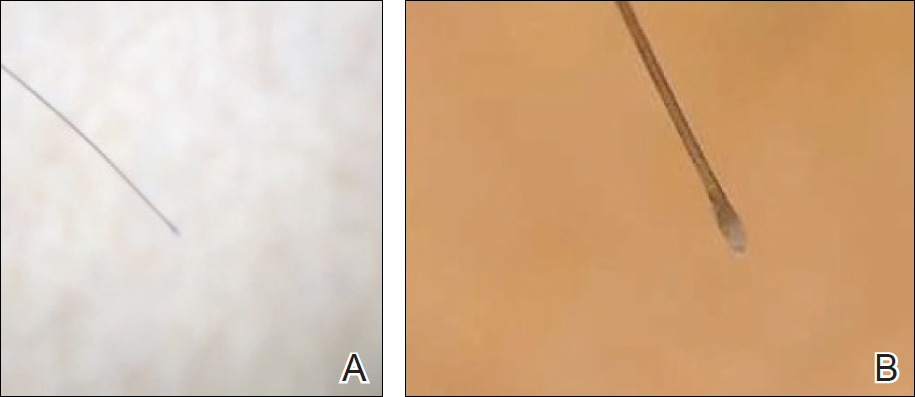

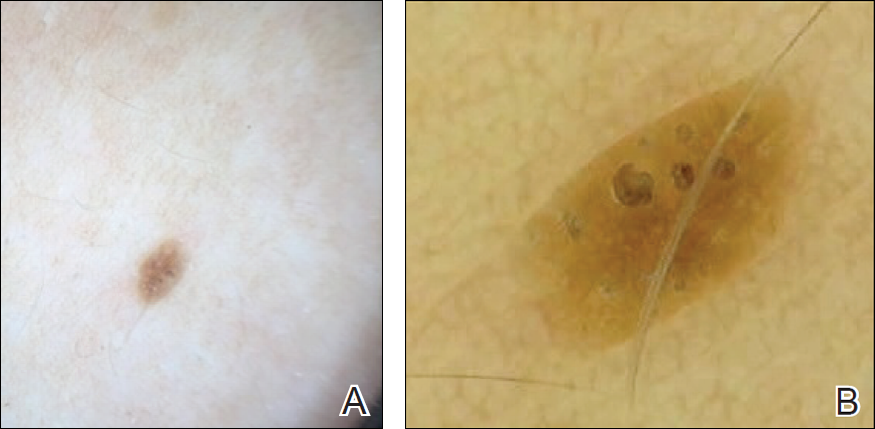

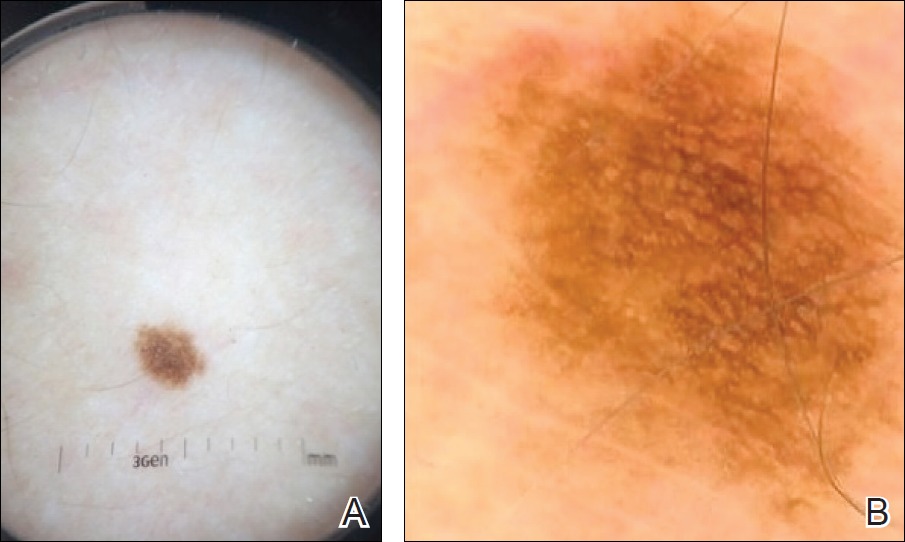

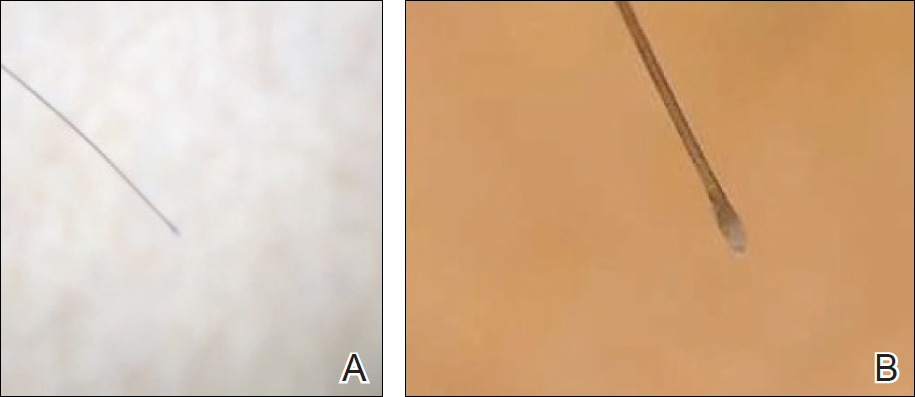

To illustrate the educational potential of videodermoscopy, images taken with a standard dermatoscope at 10-fold magnification are presented with videodermoscopic images taken at magnifications ranging from 60- to 185-fold (Figures 1–3). These examples demonstrate the potential for videodermoscopy to facilitate the visualization of subtle dermoscopic features by novice dermoscopists, relating to both the enhanced magnification potential and the potential for simultaneous rather than sequential examination.

Final Thoughts

High-magnification videodermoscopy may be a useful tool to further dermoscopic education. Videodermatoscopes vary in functionality and cost but are available at price points comparable to those of standard optical dermatoscopes. Owners of standard dermatoscopes can approximate some of the benefits of a digital videodermatoscope by using the standard dermatoscope in conjunction with a camera, including those integrated into mobile phones and tablets. By attaching the standard dermatoscope to a camera with a digital display, the digital zoom of the camera can be used to magnify the standard dermoscopic image, enhancing the ability of novice dermoscopists to visualize subtle findings. By presenting this magnified image on a digital display, dermoscopy instructors and trainees would be able to simultaneously view dermoscopic images of lesions, sometimes with magnifications comparable to videodermatoscopes.

In the setting of a dermatology residency program, videodermoscopy can be incorporated into bedside teaching with experienced dermoscopists and for the live presentation of dermoscopic features at departmental grand rounds. By facilitating the simultaneous, high-magnification and live viewing of skin lesions by dermoscopy instructors and trainees, digital videodermoscopy has the potential to address an area of weakness in dermatologic training.

- Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

- Engasser HC, Warshaw EM. Dermatoscopy use by US dermatologists: a cross-sectional survey [published online July 8, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:412-419, 419.e1-419.e2.

- Wu TP, Newlove T, Smith L, et al. The importance of dedicated dermoscopy training during residency: a survey of US dermatology chief residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1000-1005.

- Seidenari S, Bellucci C, Bassoli S, et al. High magnification digital dermoscopy of basal cell carcinoma: a single-centre study on 400 cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:677-682.

- Ross EK, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Videodermoscopy in the evaluation of hair and scalp disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:799-806.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

Dermoscopy, or the noninvasive in vivo examination of the epidermis and superficial dermis using magnification, facilitates the diagnosis of pigmented and nonpigmented skin lesions.1 Despite the benefit of dermoscopy in making early and accurate diagnoses of potentially life-limiting skin cancers, only 48% of dermatologists in the United States use dermoscopy in their practices.2 The most commonly cited reason for not using dermoscopy is lack of training.

Although the use of dermoscopy is associated with younger age and more recent graduation from residency compared to nonusers, dermatology resident physicians continue to receive limited training in dermoscopy.2 In a survey of 139 dermatology chief residents, 48% were not satisfied with the dermoscopy training that they had received during residency. Residents who received bedside instruction in dermoscopy reported greater satisfaction with their dermoscopy training compared to those who did not receive bedside instruction.3 This article provides a brief comparison of standard dermoscopy versus videodermoscopy for the instruction of trainees on common dermatologic diagnoses.

Bedside Dermoscopy

Standard optical dermatoscopes used for patient care and educational purposes typically incorporate 10-fold magnification and permit examination by a single viewer through a lens. With standard dermatoscopes, bedside dermoscopy instruction consists of the independent sequential viewing of skin lesions by instructors and trainees. Trainees must independently search for dermoscopic features noted by the instructor, which may be difficult for novice users. Simultaneous viewing of lesions would allow instructors to clearly indicate in real time pertinent dermoscopic features to their trainees.

Videodermatoscopes facilitate the simultaneous examination of cutaneous lesions by projecting the dermoscopic image onto a digital screen. Furthermore, these devices can incorporate magnifications of up to 200-fold or greater. In recent years, research pertaining to videodermoscopy has focused on the high magnification capabilities of these devices, specifically dermoscopic features that are visualized at magnifications greater than 10-fold, including the light brown nests of basal cell carcinomas that are seen at 50- to 70-fold magnification, twisted red capillary loops seen in active scalp psoriasis at 50-fold magnification, and longitudinal white indentations seen on nail plates affected by onychomycosis at 20-fold magnification.4-6 The potential value of videodermoscopy in medical education lies not only in the high magnification potential, which may make subtle dermoscopic findings more apparent to novice dermoscopists, but also in the ability to facilitate simultaneous dermoscopic examinations by instructors and trainees.

Educational Applications for Videodermoscopy

To illustrate the educational potential of videodermoscopy, images taken with a standard dermatoscope at 10-fold magnification are presented with videodermoscopic images taken at magnifications ranging from 60- to 185-fold (Figures 1–3). These examples demonstrate the potential for videodermoscopy to facilitate the visualization of subtle dermoscopic features by novice dermoscopists, relating to both the enhanced magnification potential and the potential for simultaneous rather than sequential examination.

Final Thoughts

High-magnification videodermoscopy may be a useful tool to further dermoscopic education. Videodermatoscopes vary in functionality and cost but are available at price points comparable to those of standard optical dermatoscopes. Owners of standard dermatoscopes can approximate some of the benefits of a digital videodermatoscope by using the standard dermatoscope in conjunction with a camera, including those integrated into mobile phones and tablets. By attaching the standard dermatoscope to a camera with a digital display, the digital zoom of the camera can be used to magnify the standard dermoscopic image, enhancing the ability of novice dermoscopists to visualize subtle findings. By presenting this magnified image on a digital display, dermoscopy instructors and trainees would be able to simultaneously view dermoscopic images of lesions, sometimes with magnifications comparable to videodermatoscopes.

In the setting of a dermatology residency program, videodermoscopy can be incorporated into bedside teaching with experienced dermoscopists and for the live presentation of dermoscopic features at departmental grand rounds. By facilitating the simultaneous, high-magnification and live viewing of skin lesions by dermoscopy instructors and trainees, digital videodermoscopy has the potential to address an area of weakness in dermatologic training.

Dermoscopy, or the noninvasive in vivo examination of the epidermis and superficial dermis using magnification, facilitates the diagnosis of pigmented and nonpigmented skin lesions.1 Despite the benefit of dermoscopy in making early and accurate diagnoses of potentially life-limiting skin cancers, only 48% of dermatologists in the United States use dermoscopy in their practices.2 The most commonly cited reason for not using dermoscopy is lack of training.

Although the use of dermoscopy is associated with younger age and more recent graduation from residency compared to nonusers, dermatology resident physicians continue to receive limited training in dermoscopy.2 In a survey of 139 dermatology chief residents, 48% were not satisfied with the dermoscopy training that they had received during residency. Residents who received bedside instruction in dermoscopy reported greater satisfaction with their dermoscopy training compared to those who did not receive bedside instruction.3 This article provides a brief comparison of standard dermoscopy versus videodermoscopy for the instruction of trainees on common dermatologic diagnoses.

Bedside Dermoscopy

Standard optical dermatoscopes used for patient care and educational purposes typically incorporate 10-fold magnification and permit examination by a single viewer through a lens. With standard dermatoscopes, bedside dermoscopy instruction consists of the independent sequential viewing of skin lesions by instructors and trainees. Trainees must independently search for dermoscopic features noted by the instructor, which may be difficult for novice users. Simultaneous viewing of lesions would allow instructors to clearly indicate in real time pertinent dermoscopic features to their trainees.

Videodermatoscopes facilitate the simultaneous examination of cutaneous lesions by projecting the dermoscopic image onto a digital screen. Furthermore, these devices can incorporate magnifications of up to 200-fold or greater. In recent years, research pertaining to videodermoscopy has focused on the high magnification capabilities of these devices, specifically dermoscopic features that are visualized at magnifications greater than 10-fold, including the light brown nests of basal cell carcinomas that are seen at 50- to 70-fold magnification, twisted red capillary loops seen in active scalp psoriasis at 50-fold magnification, and longitudinal white indentations seen on nail plates affected by onychomycosis at 20-fold magnification.4-6 The potential value of videodermoscopy in medical education lies not only in the high magnification potential, which may make subtle dermoscopic findings more apparent to novice dermoscopists, but also in the ability to facilitate simultaneous dermoscopic examinations by instructors and trainees.

Educational Applications for Videodermoscopy

To illustrate the educational potential of videodermoscopy, images taken with a standard dermatoscope at 10-fold magnification are presented with videodermoscopic images taken at magnifications ranging from 60- to 185-fold (Figures 1–3). These examples demonstrate the potential for videodermoscopy to facilitate the visualization of subtle dermoscopic features by novice dermoscopists, relating to both the enhanced magnification potential and the potential for simultaneous rather than sequential examination.

Final Thoughts

High-magnification videodermoscopy may be a useful tool to further dermoscopic education. Videodermatoscopes vary in functionality and cost but are available at price points comparable to those of standard optical dermatoscopes. Owners of standard dermatoscopes can approximate some of the benefits of a digital videodermatoscope by using the standard dermatoscope in conjunction with a camera, including those integrated into mobile phones and tablets. By attaching the standard dermatoscope to a camera with a digital display, the digital zoom of the camera can be used to magnify the standard dermoscopic image, enhancing the ability of novice dermoscopists to visualize subtle findings. By presenting this magnified image on a digital display, dermoscopy instructors and trainees would be able to simultaneously view dermoscopic images of lesions, sometimes with magnifications comparable to videodermatoscopes.

In the setting of a dermatology residency program, videodermoscopy can be incorporated into bedside teaching with experienced dermoscopists and for the live presentation of dermoscopic features at departmental grand rounds. By facilitating the simultaneous, high-magnification and live viewing of skin lesions by dermoscopy instructors and trainees, digital videodermoscopy has the potential to address an area of weakness in dermatologic training.

- Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

- Engasser HC, Warshaw EM. Dermatoscopy use by US dermatologists: a cross-sectional survey [published online July 8, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:412-419, 419.e1-419.e2.

- Wu TP, Newlove T, Smith L, et al. The importance of dedicated dermoscopy training during residency: a survey of US dermatology chief residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1000-1005.

- Seidenari S, Bellucci C, Bassoli S, et al. High magnification digital dermoscopy of basal cell carcinoma: a single-centre study on 400 cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:677-682.

- Ross EK, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Videodermoscopy in the evaluation of hair and scalp disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:799-806.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

- Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

- Engasser HC, Warshaw EM. Dermatoscopy use by US dermatologists: a cross-sectional survey [published online July 8, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:412-419, 419.e1-419.e2.

- Wu TP, Newlove T, Smith L, et al. The importance of dedicated dermoscopy training during residency: a survey of US dermatology chief residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1000-1005.

- Seidenari S, Bellucci C, Bassoli S, et al. High magnification digital dermoscopy of basal cell carcinoma: a single-centre study on 400 cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:677-682.

- Ross EK, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Videodermoscopy in the evaluation of hair and scalp disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:799-806.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

Resident Pearl

- Bedside dermoscopy training can be enhanced through the use of videodermoscopy, which permits simultaneous, high-magnification viewing.

Bullous Lesions in a Neonate

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

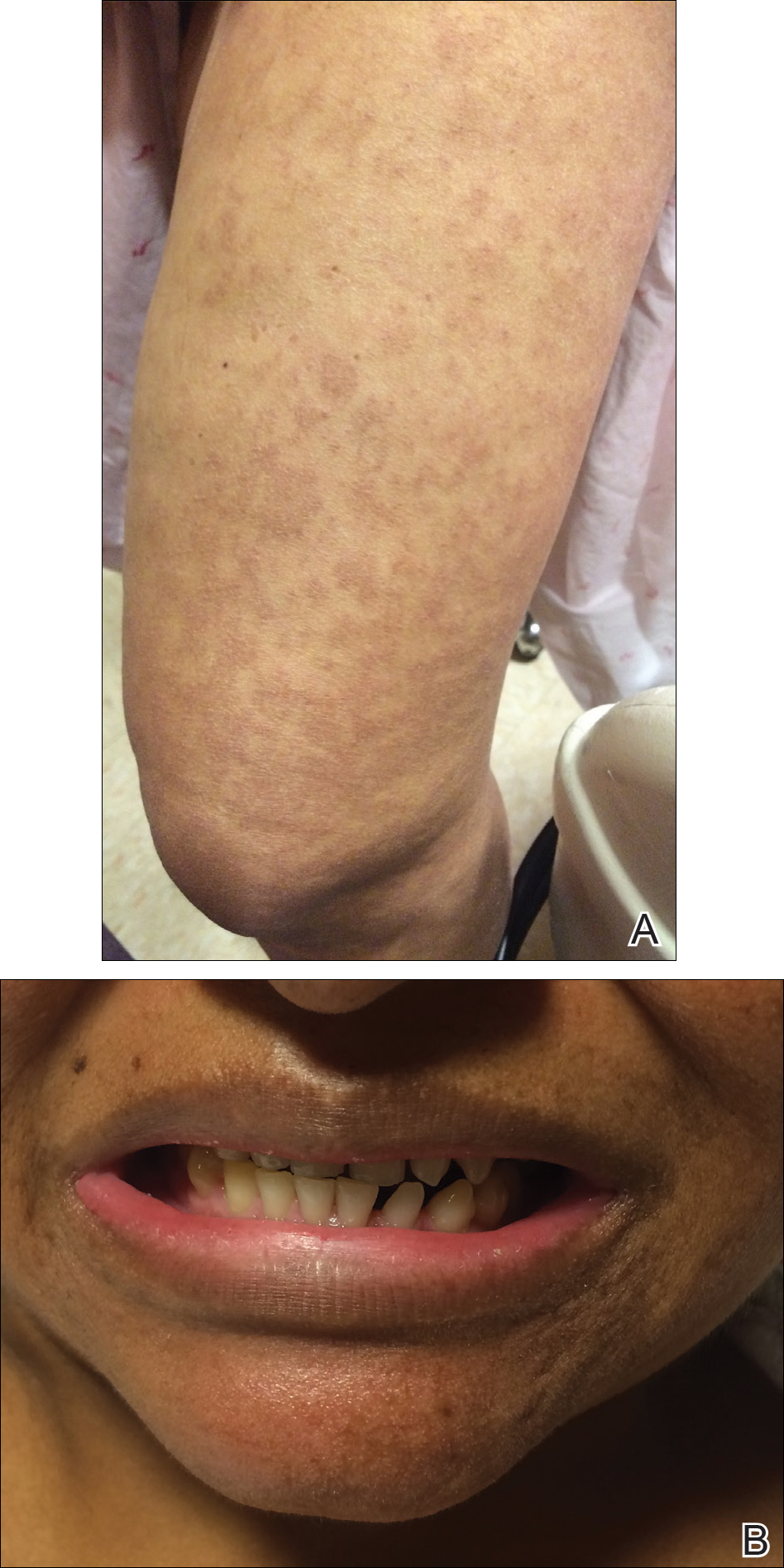

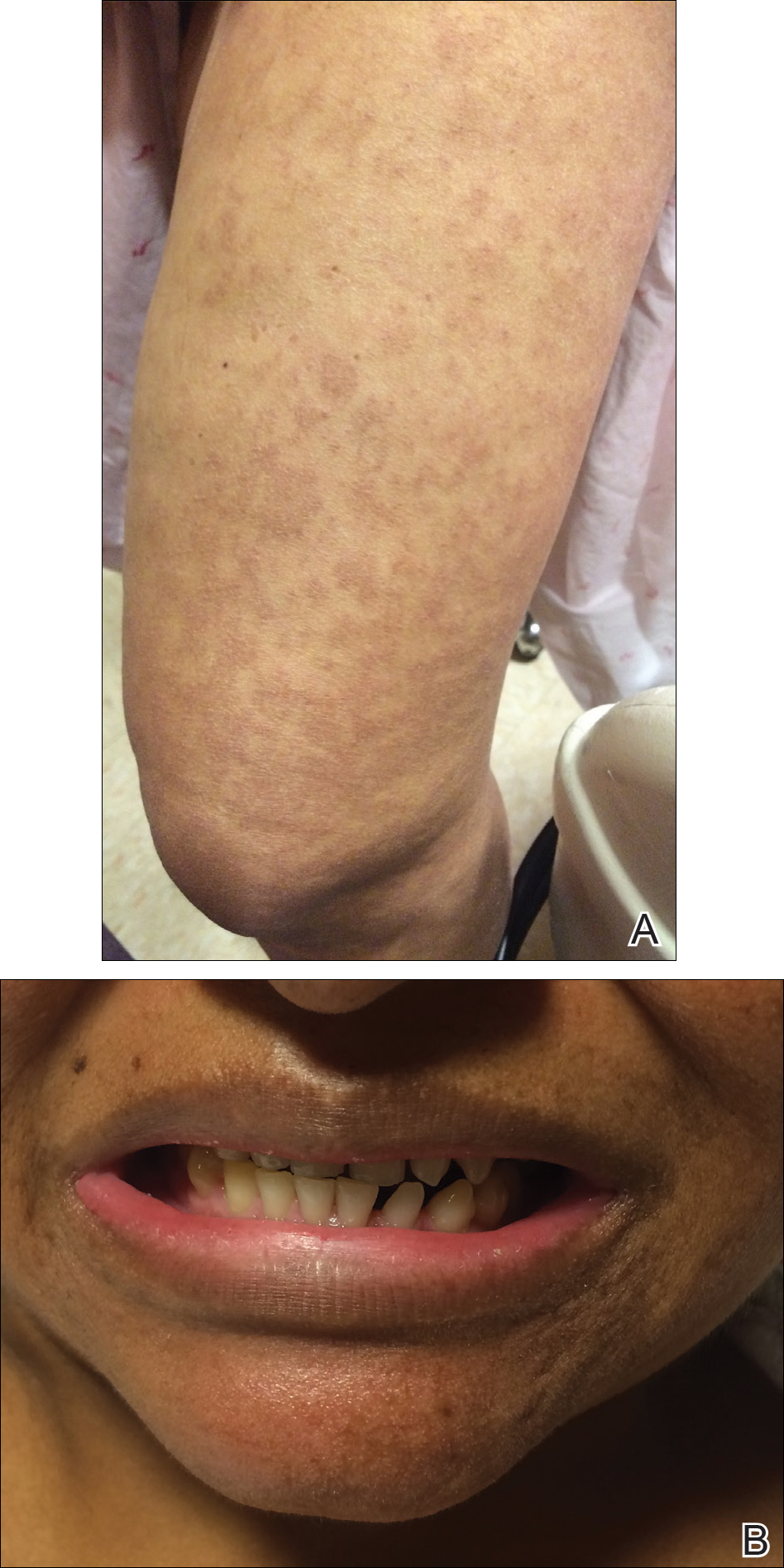

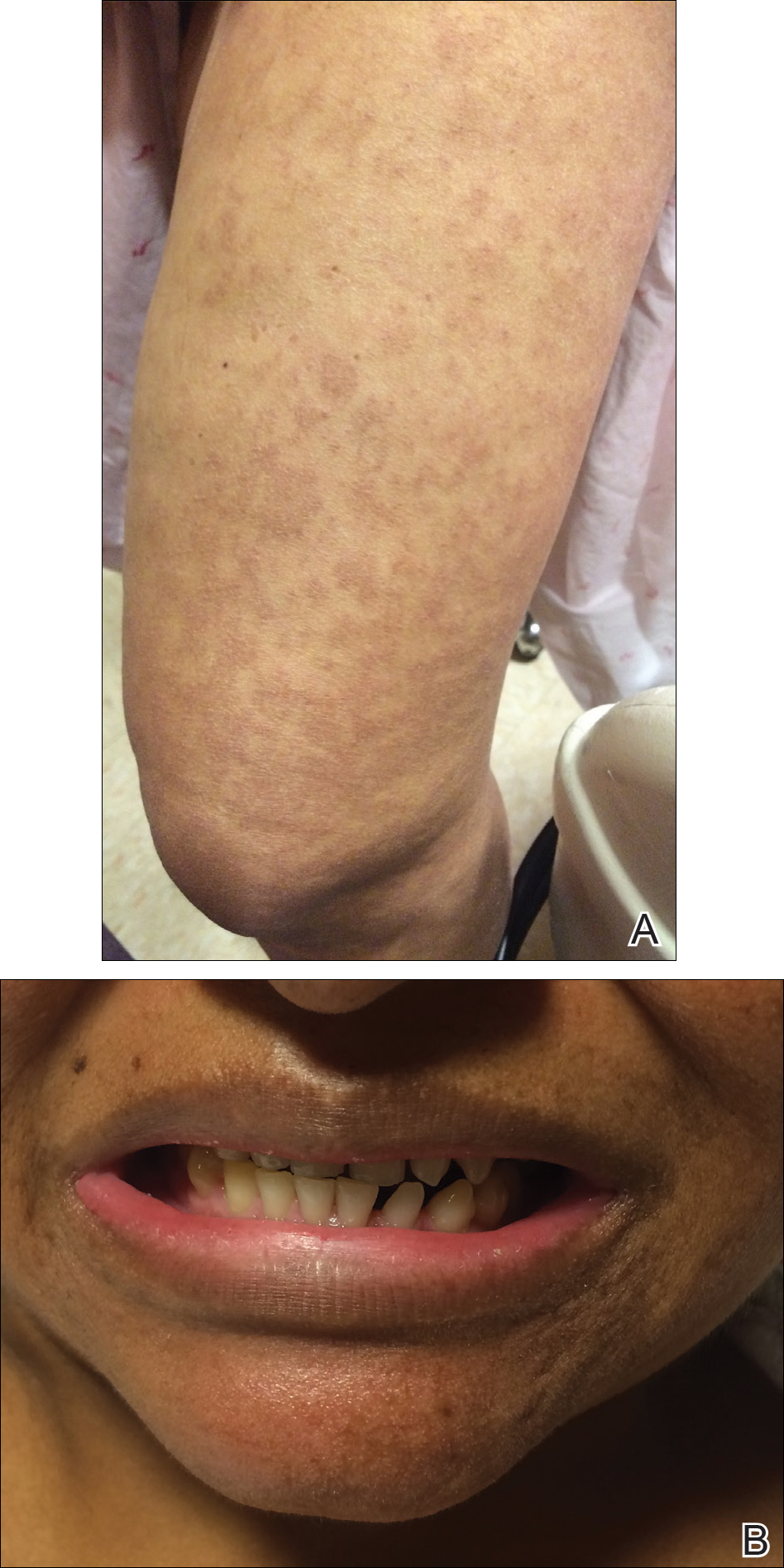

The infant's mother was noted to have diffuse hypopigmented patches over the trunk, arms, and legs (present since adolescence) with whorled cicatricial alopecia of the vertex scalp and peg-shaped teeth (Figure). Together, these findings suggested incontinentia pigmenti (IP), which the mother revealed she had been diagnosed with in childhood. The infant's characteristic lesions in the setting of her mother's diagnosed genodermatosis confirmed the diagnosis of IP.

Incontinentia pigmenti is an X-linked dominant disorder that presents with many classic dermatologic, dental, neurologic, and ophthalmologic findings. The causative mutation occurs in IKBKG/NEMO (inhibitor of κ polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase γ/nuclear factor-κB essential modulator) gene on Xq28, disabling the resultant protein that normally protects cells from tumor necrosis factor family-induced apoptosis.1 Incontinentia pigmenti usually is lethal in males and causes an unbalanced X-inactivation in surviving female IP patients. Occurring at a rate of 1.2 per 100,000 births,2 IP typically presents in female infants with skin lesions patterned along Blaschko lines that evolve in 4 stages over a lifetime.3 Stage I, presenting in the neonatal period, manifests as vesiculobullous eruptions on the limbs and scalp. Stages II to IV vary in duration from months to years and are comprised of a verrucous stage, a hyperpigmented stage, and a hypopigmented stage, respectively.3 All stages of IP can overlap and coexist.

The vesiculobullous findings in infants with IP may be mistakenly attributed to other diseases with prominent vesicular or bullous components including herpes simplex virus, epidermolysis bullosa, and infantile acropustulosis. With neonatal herpes simplex virus infection, vesicular skin or mucocutaneous lesions occur 9 to 11 days after birth and can be confirmed by specimen culture or qualitative polymerase chain reaction, while stage I of IP appears within the first 6 to 8 weeks of life and can be present at birth.4 The hallmark of epidermolysis bullosa, caused by mutations in keratins 5 and 14, is blistering erosions of the skin in response to frictional stress,1 thus these lesions do not follow Blaschko lines. Infantile acropustulosis, a nonheritable vesiculopustular eruption of the hands and feet, rarely occurs in the immediate newborn period; it most often appears in the 3- to 6-month age range with recurrent eruptions at 3- to 4-week intervals.5 Focal dermal hypoplasia is another X-linked dominant disorder with blaschkolinear findings at birth that presents with pink or red, angular, atrophic macules, in contrast to the bullous lesions of IP.6

Incontinentia pigmenti may encompass a wide range of systemic symptoms in addition to the classic dermatologic findings. Notably, central nervous system defects are concurrent in up to 40% of IP cases, with seizures, mental retardation, and spastic paresis being the most common sequelae.7 Teeth defects, seen in 35% of patients, include delayed primary dentition and peg-shaped teeth. Many patients will experience ophthalmologic defects including vision problems (16%) and retinopathy (15%).7

The cutaneous eruptions of IP may be treated with topical corticosteroids or topical tacrolimus, and vesicles should be left intact and monitored for signs of infection.8,9 Seizures, if present, should be treated with anticonvulsants, and regular neuropsychiatric monitoring and physical rehabilitation may be warranted. Patients should be regularly monitored for retinopathy beginning at the time of diagnosis. Retinal fibrovascular proliferation is treated with xenon laser photocoagulation to reduce the high risk for retinal detachment in this population.10,11 Older and younger at-risk relatives must be evaluated by genetic testing or thorough physical examination to clarify their disease status and determine the need for additional genetic counseling.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Prevalence and incidence of rare diseases: bibliographic data. Orphanet Report Series, Rare Diseases collection. http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/cahiers/docs/GB/Prevalence_of_rare_diseases_by_alphabetical_list.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed July 13, 2017.

- Scheuerle AE, Ursini MV. Incontinentia pigmenti. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1472/. Accessed July 25, 2017.

- James SH, Kimberlin DW. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:391-400.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, Mathes E, et al, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2015.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Fusco F, Paciolla M, Conte MI, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: report on data from 2000 to 2013. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:93.

- Jessup CJ, Morgan SC, Cohen LM, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: treatment of IP with topical tacrolimus. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:944-946.

- Kaya TI, Tursen U, Ikizoglu G. Therapeutic use of topical corticosteroids in the vesiculobullous lesions of incontinentia pigmenti [published online June 1, 2009]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E611-E613.

- Nguyen JK, Brady-Mccreery KM. Laser photocoagulation in preproliferative retinopathy of incontinentia pigmenti. J AAPOS. 2001;5:258-259.

- Chen CJ, Han IC, Tian J, et al. Extended follow-up of treated and untreated retinopathy in incontinentia pigmenti: analysis of peripheral vascular changes and incidence of retinal detachment. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:542-548.

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The infant's mother was noted to have diffuse hypopigmented patches over the trunk, arms, and legs (present since adolescence) with whorled cicatricial alopecia of the vertex scalp and peg-shaped teeth (Figure). Together, these findings suggested incontinentia pigmenti (IP), which the mother revealed she had been diagnosed with in childhood. The infant's characteristic lesions in the setting of her mother's diagnosed genodermatosis confirmed the diagnosis of IP.

Incontinentia pigmenti is an X-linked dominant disorder that presents with many classic dermatologic, dental, neurologic, and ophthalmologic findings. The causative mutation occurs in IKBKG/NEMO (inhibitor of κ polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase γ/nuclear factor-κB essential modulator) gene on Xq28, disabling the resultant protein that normally protects cells from tumor necrosis factor family-induced apoptosis.1 Incontinentia pigmenti usually is lethal in males and causes an unbalanced X-inactivation in surviving female IP patients. Occurring at a rate of 1.2 per 100,000 births,2 IP typically presents in female infants with skin lesions patterned along Blaschko lines that evolve in 4 stages over a lifetime.3 Stage I, presenting in the neonatal period, manifests as vesiculobullous eruptions on the limbs and scalp. Stages II to IV vary in duration from months to years and are comprised of a verrucous stage, a hyperpigmented stage, and a hypopigmented stage, respectively.3 All stages of IP can overlap and coexist.

The vesiculobullous findings in infants with IP may be mistakenly attributed to other diseases with prominent vesicular or bullous components including herpes simplex virus, epidermolysis bullosa, and infantile acropustulosis. With neonatal herpes simplex virus infection, vesicular skin or mucocutaneous lesions occur 9 to 11 days after birth and can be confirmed by specimen culture or qualitative polymerase chain reaction, while stage I of IP appears within the first 6 to 8 weeks of life and can be present at birth.4 The hallmark of epidermolysis bullosa, caused by mutations in keratins 5 and 14, is blistering erosions of the skin in response to frictional stress,1 thus these lesions do not follow Blaschko lines. Infantile acropustulosis, a nonheritable vesiculopustular eruption of the hands and feet, rarely occurs in the immediate newborn period; it most often appears in the 3- to 6-month age range with recurrent eruptions at 3- to 4-week intervals.5 Focal dermal hypoplasia is another X-linked dominant disorder with blaschkolinear findings at birth that presents with pink or red, angular, atrophic macules, in contrast to the bullous lesions of IP.6

Incontinentia pigmenti may encompass a wide range of systemic symptoms in addition to the classic dermatologic findings. Notably, central nervous system defects are concurrent in up to 40% of IP cases, with seizures, mental retardation, and spastic paresis being the most common sequelae.7 Teeth defects, seen in 35% of patients, include delayed primary dentition and peg-shaped teeth. Many patients will experience ophthalmologic defects including vision problems (16%) and retinopathy (15%).7

The cutaneous eruptions of IP may be treated with topical corticosteroids or topical tacrolimus, and vesicles should be left intact and monitored for signs of infection.8,9 Seizures, if present, should be treated with anticonvulsants, and regular neuropsychiatric monitoring and physical rehabilitation may be warranted. Patients should be regularly monitored for retinopathy beginning at the time of diagnosis. Retinal fibrovascular proliferation is treated with xenon laser photocoagulation to reduce the high risk for retinal detachment in this population.10,11 Older and younger at-risk relatives must be evaluated by genetic testing or thorough physical examination to clarify their disease status and determine the need for additional genetic counseling.

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The infant's mother was noted to have diffuse hypopigmented patches over the trunk, arms, and legs (present since adolescence) with whorled cicatricial alopecia of the vertex scalp and peg-shaped teeth (Figure). Together, these findings suggested incontinentia pigmenti (IP), which the mother revealed she had been diagnosed with in childhood. The infant's characteristic lesions in the setting of her mother's diagnosed genodermatosis confirmed the diagnosis of IP.

Incontinentia pigmenti is an X-linked dominant disorder that presents with many classic dermatologic, dental, neurologic, and ophthalmologic findings. The causative mutation occurs in IKBKG/NEMO (inhibitor of κ polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase γ/nuclear factor-κB essential modulator) gene on Xq28, disabling the resultant protein that normally protects cells from tumor necrosis factor family-induced apoptosis.1 Incontinentia pigmenti usually is lethal in males and causes an unbalanced X-inactivation in surviving female IP patients. Occurring at a rate of 1.2 per 100,000 births,2 IP typically presents in female infants with skin lesions patterned along Blaschko lines that evolve in 4 stages over a lifetime.3 Stage I, presenting in the neonatal period, manifests as vesiculobullous eruptions on the limbs and scalp. Stages II to IV vary in duration from months to years and are comprised of a verrucous stage, a hyperpigmented stage, and a hypopigmented stage, respectively.3 All stages of IP can overlap and coexist.

The vesiculobullous findings in infants with IP may be mistakenly attributed to other diseases with prominent vesicular or bullous components including herpes simplex virus, epidermolysis bullosa, and infantile acropustulosis. With neonatal herpes simplex virus infection, vesicular skin or mucocutaneous lesions occur 9 to 11 days after birth and can be confirmed by specimen culture or qualitative polymerase chain reaction, while stage I of IP appears within the first 6 to 8 weeks of life and can be present at birth.4 The hallmark of epidermolysis bullosa, caused by mutations in keratins 5 and 14, is blistering erosions of the skin in response to frictional stress,1 thus these lesions do not follow Blaschko lines. Infantile acropustulosis, a nonheritable vesiculopustular eruption of the hands and feet, rarely occurs in the immediate newborn period; it most often appears in the 3- to 6-month age range with recurrent eruptions at 3- to 4-week intervals.5 Focal dermal hypoplasia is another X-linked dominant disorder with blaschkolinear findings at birth that presents with pink or red, angular, atrophic macules, in contrast to the bullous lesions of IP.6

Incontinentia pigmenti may encompass a wide range of systemic symptoms in addition to the classic dermatologic findings. Notably, central nervous system defects are concurrent in up to 40% of IP cases, with seizures, mental retardation, and spastic paresis being the most common sequelae.7 Teeth defects, seen in 35% of patients, include delayed primary dentition and peg-shaped teeth. Many patients will experience ophthalmologic defects including vision problems (16%) and retinopathy (15%).7

The cutaneous eruptions of IP may be treated with topical corticosteroids or topical tacrolimus, and vesicles should be left intact and monitored for signs of infection.8,9 Seizures, if present, should be treated with anticonvulsants, and regular neuropsychiatric monitoring and physical rehabilitation may be warranted. Patients should be regularly monitored for retinopathy beginning at the time of diagnosis. Retinal fibrovascular proliferation is treated with xenon laser photocoagulation to reduce the high risk for retinal detachment in this population.10,11 Older and younger at-risk relatives must be evaluated by genetic testing or thorough physical examination to clarify their disease status and determine the need for additional genetic counseling.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Prevalence and incidence of rare diseases: bibliographic data. Orphanet Report Series, Rare Diseases collection. http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/cahiers/docs/GB/Prevalence_of_rare_diseases_by_alphabetical_list.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed July 13, 2017.

- Scheuerle AE, Ursini MV. Incontinentia pigmenti. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1472/. Accessed July 25, 2017.

- James SH, Kimberlin DW. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:391-400.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, Mathes E, et al, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2015.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Fusco F, Paciolla M, Conte MI, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: report on data from 2000 to 2013. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:93.

- Jessup CJ, Morgan SC, Cohen LM, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: treatment of IP with topical tacrolimus. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:944-946.

- Kaya TI, Tursen U, Ikizoglu G. Therapeutic use of topical corticosteroids in the vesiculobullous lesions of incontinentia pigmenti [published online June 1, 2009]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E611-E613.

- Nguyen JK, Brady-Mccreery KM. Laser photocoagulation in preproliferative retinopathy of incontinentia pigmenti. J AAPOS. 2001;5:258-259.

- Chen CJ, Han IC, Tian J, et al. Extended follow-up of treated and untreated retinopathy in incontinentia pigmenti: analysis of peripheral vascular changes and incidence of retinal detachment. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:542-548.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Prevalence and incidence of rare diseases: bibliographic data. Orphanet Report Series, Rare Diseases collection. http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/cahiers/docs/GB/Prevalence_of_rare_diseases_by_alphabetical_list.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed July 13, 2017.

- Scheuerle AE, Ursini MV. Incontinentia pigmenti. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1472/. Accessed July 25, 2017.

- James SH, Kimberlin DW. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:391-400.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, Mathes E, et al, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2015.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Fusco F, Paciolla M, Conte MI, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: report on data from 2000 to 2013. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:93.

- Jessup CJ, Morgan SC, Cohen LM, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: treatment of IP with topical tacrolimus. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:944-946.

- Kaya TI, Tursen U, Ikizoglu G. Therapeutic use of topical corticosteroids in the vesiculobullous lesions of incontinentia pigmenti [published online June 1, 2009]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E611-E613.

- Nguyen JK, Brady-Mccreery KM. Laser photocoagulation in preproliferative retinopathy of incontinentia pigmenti. J AAPOS. 2001;5:258-259.

- Chen CJ, Han IC, Tian J, et al. Extended follow-up of treated and untreated retinopathy in incontinentia pigmenti: analysis of peripheral vascular changes and incidence of retinal detachment. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:542-548.

A 1-day-old Hispanic female infant was born via uncomplicated vaginal delivery at 41 weeks' gestation after a normal pregnancy. Linear plaques containing multiple ruptured vesicles and bullae following Blaschko lines were noted on the right medial thigh and anterior arm. The infant was afebrile and generally well-appearing.

Pediatric Pearls From the AAD Annual Meeting

This article exhibits key pediatric dermatology pearls garnered at the 2017 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) in Orlando, Florida (March 3–7, 2017). Highlights from both the Society for Pediatric Dermatology pre-AAD meeting (March 2, 2017) and the AAD general meeting sessions are included. This discussion is intended to help maximize care of our pediatric patients in dermatology and present high-yield take-home points from the AAD that can be readily transferred to our patient care.

“New Tools for Your Therapeutic Toolbox” by Erin Mathes, MD (University of California, San Francisco)

During this lecture at the Society for Pediatric Dermatology meeting, Dr. Mathes discussed a randomized controlled trial that took place in 2014 in both the United States and the United Kingdom to assess skin barrier enhancement to reduce the incidence of atopic dermatitis (AD) in 124 high-risk infants.1 The high-risk infants had either a parent or sibling with physician-diagnosed AD, asthma, or rhinitis, or a first-degree relative with an aforementioned condition. Full-body emollient therapy was applied at least once daily within 3 weeks of birth for 6 months, while the control arm did not use emollient. Parents were allowed to choose from the following emollients: sunflower seed oil, moisturizing cream, or ointment. The primary outcome was the incidence of AD at 6 months. The authors found a 43% incidence of AD in the control group compared to 22% in the emollient group, amounting to a relative risk reduction of approximately 50%.1

Emollients in AD are hypothesized to help through the enhanced barrier function and decreased penetration of irritant substances and allergens. This study is vital given the ease of use of emollients and the foreseeable substantial impact on reduced health care costs associated with the decreased incidence of AD.

Take-Home Point

Full-body emollient therapy within 3 weeks of birth may reduce the incidence of AD in high-risk infants.

Dr. Mathes also discussed the novel topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor crisaborole and its emerging role in AD. She reviewed the results of a large phase 3 trial of crisaborole therapy for patients aged 2 years or older with mild to moderate AD.2 Crisaborole ointment was applied twice daily for 28 days. The primary outcome measured was an investigator static global assessment score of clear or almost clear, which is a score for AD based on the degree of erythema, presence of oozing and crusting, and presence of induration or papulation. Overall, 32.8% of patients treated with crisaborole achieved success compared to 25.4% of vehicle-treated patients. The control patients were still given a vehicle to apply, which can function as therapy to help repair the barrier of AD and thus theoretically reduced the percentage gap between patients who met success with and without crisaborole therapy. Furthermore, only 4% of patients reported adverse effects such as burning and stinging with application of crisaborole in contrast to topical calcineurin inhibitors, which can elicit symptoms up to 50% of the time.2 In summary, this lecture reviewed the first new topical treatment for AD in 15 years.

Take-Home Point

Crisaborole ointment is a novel topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor approved for mild to moderate AD in patients 2 years of age and older.

“The Truth About Pediatric Contact Dermatitis” by Sharon Jacob, MD (Loma Linda University, California)

In this session, Dr. Jacob discussed how she approaches pediatric patients with suspected contact dermatitis and elaborated on the common allergens unique to this patient population. Furthermore, she explained the substantial role of nickel in pediatric contact dermatitis, citing a study performed in Denmark and the United States, which tested 212 toys for nickel using the dimethylglyoxime test and found that 34.4% of toys did in fact release nickel.3 Additional studies have shown that nickel released from children’s toys is deposited on the skin, even with short contact times such as 30 minutes on one or more occasions within 2 weeks.3,4 She is currently evaluating the presence of nickel in locales frequented by children such as schools, libraries, and supermarkets. Interestingly, she anecdotally found that a pediatric eczematous eruption in a spiralized distribution of the legs can be attributed to the presence of nickel in school chairs, and the morphology is secondary to children wrapping their legs around the chairs. In conclusion, she reiterated that nickel continues to be the top allergen among pediatric patients, and states that additional allergens for patch testing in this population are unique to their adult counterparts.

Take-Home Point

Nickel is an ubiquitous allergen for pediatric contact dermatitis; additionally, the list of allergens for patch testing should be tailored to this patient population.

“When to Image, When to Sedate” by Annette Wagner, MD (Northwestern Medicine, Chicago, Illinois)

This lecture was a 3-part discussion on the safety of general anesthesia in children, when to image children, and when sedation may be worth the risk. Dr. Wagner shared her pearls for when children younger than 3 years may benefit from dermatologic procedures that involve general anesthesia. Large congenital lesions of the scalp or face that require tissue expansion or multiple stages may be best performed at a younger age due to the flexibility of the infant scalp, providing the best outcome. Additional considerations include a questionable malignant diagnosis in which a punch biopsy is not enough, rapidly growing facial lesions, Spitz nevi of the face, congenital lesions with no available therapy, and nonhealing refractory lesions causing severe pain. The general rule proposed was intervention for single procedures lasting less than 1 hour that otherwise would result in a worse outcome if postponed. Finally, she concluded to always advocate for your patient, to wait if the outcome will be the same regardless of timing, and to be frank about not knowing the risks of general anesthesia in this population. The resource, SmartTots (http://smarttots.org) provides current consensus statements and ongoing research on the use and safety of general anesthesia in children.

Take-Home Point

General sedation may be considered for short pediatric procedures that will result in a worse outcome if postponed.

“Highlights From the Pediatric Literature” by Katherine Marks, DO (Geisinger, Danville and Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania)

Dr. Marks discussed numerous emerging pediatric dermatology articles. One article looked at 40 infants with proliferating infantile hemangiomas (IHs) who had timolol gel 0.5% applied twice daily.5 The primary outcomes were the urinary excretion and serum levels of timolol as well as the clinical response to therapy measured by a visual analog scale at monthly visits. A urinalysis collected 3 to 4 hours after timolol application was found to be positive in 83% (20/24) of the tested patients; the first 3 positive infants were then sent to have their serum timolol levels drawn and also were found to be positive, though substantially small levels (median, 0.16 ng/mL). The 3 patients tested had small IHs on the face with no ulceration. None of these patients experienced adverse effects and all of the IHs significantly (P<.001) improved with therapy. The authors stated that even though the absorption was minimal, it is wise to be cognizant about the use of timolol in certain patient demographics such as preterm or young infants with large ulcerating IHs.5

Take-Home Point

Systemic absorption with topical timolol occurs, albeit substantially small; be judicious about giving this medication in select patient populations with ulcerated hemangiomas.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks the presenters for their review and contributions to this article.

- Simpson EL, Chalmers JR, Hanifin JM, et al. Emollient enhancement of the skin barrier from birth offers effective atopic dermatitis prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:818-823.

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor for the topical treatment of AD in children and adults [published online July 11, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:494-503.

- Jensen P, Hamann D, Hamann CR, et al. Nickel and cobalt release from children’s toys purchased in Denmark and the United States. Dermatitis. 2014;25:356-365.

- Overgaard LE, Engebretsen KA, Jensen P, et al. Nickel released from children’s toys is deposited on the skin. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;74:380-381.

- Weibel L, Barysch MJ, Scheer HS, et al. Topical timolol for infantile hemangiomas: evidence for efficacy and degree of systemic absorption [published online February 3, 2016]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:184-190.

This article exhibits key pediatric dermatology pearls garnered at the 2017 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) in Orlando, Florida (March 3–7, 2017). Highlights from both the Society for Pediatric Dermatology pre-AAD meeting (March 2, 2017) and the AAD general meeting sessions are included. This discussion is intended to help maximize care of our pediatric patients in dermatology and present high-yield take-home points from the AAD that can be readily transferred to our patient care.

“New Tools for Your Therapeutic Toolbox” by Erin Mathes, MD (University of California, San Francisco)

During this lecture at the Society for Pediatric Dermatology meeting, Dr. Mathes discussed a randomized controlled trial that took place in 2014 in both the United States and the United Kingdom to assess skin barrier enhancement to reduce the incidence of atopic dermatitis (AD) in 124 high-risk infants.1 The high-risk infants had either a parent or sibling with physician-diagnosed AD, asthma, or rhinitis, or a first-degree relative with an aforementioned condition. Full-body emollient therapy was applied at least once daily within 3 weeks of birth for 6 months, while the control arm did not use emollient. Parents were allowed to choose from the following emollients: sunflower seed oil, moisturizing cream, or ointment. The primary outcome was the incidence of AD at 6 months. The authors found a 43% incidence of AD in the control group compared to 22% in the emollient group, amounting to a relative risk reduction of approximately 50%.1

Emollients in AD are hypothesized to help through the enhanced barrier function and decreased penetration of irritant substances and allergens. This study is vital given the ease of use of emollients and the foreseeable substantial impact on reduced health care costs associated with the decreased incidence of AD.

Take-Home Point

Full-body emollient therapy within 3 weeks of birth may reduce the incidence of AD in high-risk infants.

Dr. Mathes also discussed the novel topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor crisaborole and its emerging role in AD. She reviewed the results of a large phase 3 trial of crisaborole therapy for patients aged 2 years or older with mild to moderate AD.2 Crisaborole ointment was applied twice daily for 28 days. The primary outcome measured was an investigator static global assessment score of clear or almost clear, which is a score for AD based on the degree of erythema, presence of oozing and crusting, and presence of induration or papulation. Overall, 32.8% of patients treated with crisaborole achieved success compared to 25.4% of vehicle-treated patients. The control patients were still given a vehicle to apply, which can function as therapy to help repair the barrier of AD and thus theoretically reduced the percentage gap between patients who met success with and without crisaborole therapy. Furthermore, only 4% of patients reported adverse effects such as burning and stinging with application of crisaborole in contrast to topical calcineurin inhibitors, which can elicit symptoms up to 50% of the time.2 In summary, this lecture reviewed the first new topical treatment for AD in 15 years.

Take-Home Point

Crisaborole ointment is a novel topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor approved for mild to moderate AD in patients 2 years of age and older.

“The Truth About Pediatric Contact Dermatitis” by Sharon Jacob, MD (Loma Linda University, California)

In this session, Dr. Jacob discussed how she approaches pediatric patients with suspected contact dermatitis and elaborated on the common allergens unique to this patient population. Furthermore, she explained the substantial role of nickel in pediatric contact dermatitis, citing a study performed in Denmark and the United States, which tested 212 toys for nickel using the dimethylglyoxime test and found that 34.4% of toys did in fact release nickel.3 Additional studies have shown that nickel released from children’s toys is deposited on the skin, even with short contact times such as 30 minutes on one or more occasions within 2 weeks.3,4 She is currently evaluating the presence of nickel in locales frequented by children such as schools, libraries, and supermarkets. Interestingly, she anecdotally found that a pediatric eczematous eruption in a spiralized distribution of the legs can be attributed to the presence of nickel in school chairs, and the morphology is secondary to children wrapping their legs around the chairs. In conclusion, she reiterated that nickel continues to be the top allergen among pediatric patients, and states that additional allergens for patch testing in this population are unique to their adult counterparts.

Take-Home Point

Nickel is an ubiquitous allergen for pediatric contact dermatitis; additionally, the list of allergens for patch testing should be tailored to this patient population.

“When to Image, When to Sedate” by Annette Wagner, MD (Northwestern Medicine, Chicago, Illinois)

This lecture was a 3-part discussion on the safety of general anesthesia in children, when to image children, and when sedation may be worth the risk. Dr. Wagner shared her pearls for when children younger than 3 years may benefit from dermatologic procedures that involve general anesthesia. Large congenital lesions of the scalp or face that require tissue expansion or multiple stages may be best performed at a younger age due to the flexibility of the infant scalp, providing the best outcome. Additional considerations include a questionable malignant diagnosis in which a punch biopsy is not enough, rapidly growing facial lesions, Spitz nevi of the face, congenital lesions with no available therapy, and nonhealing refractory lesions causing severe pain. The general rule proposed was intervention for single procedures lasting less than 1 hour that otherwise would result in a worse outcome if postponed. Finally, she concluded to always advocate for your patient, to wait if the outcome will be the same regardless of timing, and to be frank about not knowing the risks of general anesthesia in this population. The resource, SmartTots (http://smarttots.org) provides current consensus statements and ongoing research on the use and safety of general anesthesia in children.

Take-Home Point

General sedation may be considered for short pediatric procedures that will result in a worse outcome if postponed.

“Highlights From the Pediatric Literature” by Katherine Marks, DO (Geisinger, Danville and Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania)

Dr. Marks discussed numerous emerging pediatric dermatology articles. One article looked at 40 infants with proliferating infantile hemangiomas (IHs) who had timolol gel 0.5% applied twice daily.5 The primary outcomes were the urinary excretion and serum levels of timolol as well as the clinical response to therapy measured by a visual analog scale at monthly visits. A urinalysis collected 3 to 4 hours after timolol application was found to be positive in 83% (20/24) of the tested patients; the first 3 positive infants were then sent to have their serum timolol levels drawn and also were found to be positive, though substantially small levels (median, 0.16 ng/mL). The 3 patients tested had small IHs on the face with no ulceration. None of these patients experienced adverse effects and all of the IHs significantly (P<.001) improved with therapy. The authors stated that even though the absorption was minimal, it is wise to be cognizant about the use of timolol in certain patient demographics such as preterm or young infants with large ulcerating IHs.5

Take-Home Point

Systemic absorption with topical timolol occurs, albeit substantially small; be judicious about giving this medication in select patient populations with ulcerated hemangiomas.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks the presenters for their review and contributions to this article.

This article exhibits key pediatric dermatology pearls garnered at the 2017 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) in Orlando, Florida (March 3–7, 2017). Highlights from both the Society for Pediatric Dermatology pre-AAD meeting (March 2, 2017) and the AAD general meeting sessions are included. This discussion is intended to help maximize care of our pediatric patients in dermatology and present high-yield take-home points from the AAD that can be readily transferred to our patient care.

“New Tools for Your Therapeutic Toolbox” by Erin Mathes, MD (University of California, San Francisco)

During this lecture at the Society for Pediatric Dermatology meeting, Dr. Mathes discussed a randomized controlled trial that took place in 2014 in both the United States and the United Kingdom to assess skin barrier enhancement to reduce the incidence of atopic dermatitis (AD) in 124 high-risk infants.1 The high-risk infants had either a parent or sibling with physician-diagnosed AD, asthma, or rhinitis, or a first-degree relative with an aforementioned condition. Full-body emollient therapy was applied at least once daily within 3 weeks of birth for 6 months, while the control arm did not use emollient. Parents were allowed to choose from the following emollients: sunflower seed oil, moisturizing cream, or ointment. The primary outcome was the incidence of AD at 6 months. The authors found a 43% incidence of AD in the control group compared to 22% in the emollient group, amounting to a relative risk reduction of approximately 50%.1

Emollients in AD are hypothesized to help through the enhanced barrier function and decreased penetration of irritant substances and allergens. This study is vital given the ease of use of emollients and the foreseeable substantial impact on reduced health care costs associated with the decreased incidence of AD.

Take-Home Point

Full-body emollient therapy within 3 weeks of birth may reduce the incidence of AD in high-risk infants.

Dr. Mathes also discussed the novel topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor crisaborole and its emerging role in AD. She reviewed the results of a large phase 3 trial of crisaborole therapy for patients aged 2 years or older with mild to moderate AD.2 Crisaborole ointment was applied twice daily for 28 days. The primary outcome measured was an investigator static global assessment score of clear or almost clear, which is a score for AD based on the degree of erythema, presence of oozing and crusting, and presence of induration or papulation. Overall, 32.8% of patients treated with crisaborole achieved success compared to 25.4% of vehicle-treated patients. The control patients were still given a vehicle to apply, which can function as therapy to help repair the barrier of AD and thus theoretically reduced the percentage gap between patients who met success with and without crisaborole therapy. Furthermore, only 4% of patients reported adverse effects such as burning and stinging with application of crisaborole in contrast to topical calcineurin inhibitors, which can elicit symptoms up to 50% of the time.2 In summary, this lecture reviewed the first new topical treatment for AD in 15 years.

Take-Home Point

Crisaborole ointment is a novel topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor approved for mild to moderate AD in patients 2 years of age and older.

“The Truth About Pediatric Contact Dermatitis” by Sharon Jacob, MD (Loma Linda University, California)

In this session, Dr. Jacob discussed how she approaches pediatric patients with suspected contact dermatitis and elaborated on the common allergens unique to this patient population. Furthermore, she explained the substantial role of nickel in pediatric contact dermatitis, citing a study performed in Denmark and the United States, which tested 212 toys for nickel using the dimethylglyoxime test and found that 34.4% of toys did in fact release nickel.3 Additional studies have shown that nickel released from children’s toys is deposited on the skin, even with short contact times such as 30 minutes on one or more occasions within 2 weeks.3,4 She is currently evaluating the presence of nickel in locales frequented by children such as schools, libraries, and supermarkets. Interestingly, she anecdotally found that a pediatric eczematous eruption in a spiralized distribution of the legs can be attributed to the presence of nickel in school chairs, and the morphology is secondary to children wrapping their legs around the chairs. In conclusion, she reiterated that nickel continues to be the top allergen among pediatric patients, and states that additional allergens for patch testing in this population are unique to their adult counterparts.

Take-Home Point

Nickel is an ubiquitous allergen for pediatric contact dermatitis; additionally, the list of allergens for patch testing should be tailored to this patient population.

“When to Image, When to Sedate” by Annette Wagner, MD (Northwestern Medicine, Chicago, Illinois)

This lecture was a 3-part discussion on the safety of general anesthesia in children, when to image children, and when sedation may be worth the risk. Dr. Wagner shared her pearls for when children younger than 3 years may benefit from dermatologic procedures that involve general anesthesia. Large congenital lesions of the scalp or face that require tissue expansion or multiple stages may be best performed at a younger age due to the flexibility of the infant scalp, providing the best outcome. Additional considerations include a questionable malignant diagnosis in which a punch biopsy is not enough, rapidly growing facial lesions, Spitz nevi of the face, congenital lesions with no available therapy, and nonhealing refractory lesions causing severe pain. The general rule proposed was intervention for single procedures lasting less than 1 hour that otherwise would result in a worse outcome if postponed. Finally, she concluded to always advocate for your patient, to wait if the outcome will be the same regardless of timing, and to be frank about not knowing the risks of general anesthesia in this population. The resource, SmartTots (http://smarttots.org) provides current consensus statements and ongoing research on the use and safety of general anesthesia in children.

Take-Home Point

General sedation may be considered for short pediatric procedures that will result in a worse outcome if postponed.

“Highlights From the Pediatric Literature” by Katherine Marks, DO (Geisinger, Danville and Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania)

Dr. Marks discussed numerous emerging pediatric dermatology articles. One article looked at 40 infants with proliferating infantile hemangiomas (IHs) who had timolol gel 0.5% applied twice daily.5 The primary outcomes were the urinary excretion and serum levels of timolol as well as the clinical response to therapy measured by a visual analog scale at monthly visits. A urinalysis collected 3 to 4 hours after timolol application was found to be positive in 83% (20/24) of the tested patients; the first 3 positive infants were then sent to have their serum timolol levels drawn and also were found to be positive, though substantially small levels (median, 0.16 ng/mL). The 3 patients tested had small IHs on the face with no ulceration. None of these patients experienced adverse effects and all of the IHs significantly (P<.001) improved with therapy. The authors stated that even though the absorption was minimal, it is wise to be cognizant about the use of timolol in certain patient demographics such as preterm or young infants with large ulcerating IHs.5

Take-Home Point

Systemic absorption with topical timolol occurs, albeit substantially small; be judicious about giving this medication in select patient populations with ulcerated hemangiomas.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks the presenters for their review and contributions to this article.

- Simpson EL, Chalmers JR, Hanifin JM, et al. Emollient enhancement of the skin barrier from birth offers effective atopic dermatitis prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:818-823.

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor for the topical treatment of AD in children and adults [published online July 11, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:494-503.

- Jensen P, Hamann D, Hamann CR, et al. Nickel and cobalt release from children’s toys purchased in Denmark and the United States. Dermatitis. 2014;25:356-365.

- Overgaard LE, Engebretsen KA, Jensen P, et al. Nickel released from children’s toys is deposited on the skin. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;74:380-381.

- Weibel L, Barysch MJ, Scheer HS, et al. Topical timolol for infantile hemangiomas: evidence for efficacy and degree of systemic absorption [published online February 3, 2016]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:184-190.

- Simpson EL, Chalmers JR, Hanifin JM, et al. Emollient enhancement of the skin barrier from birth offers effective atopic dermatitis prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:818-823.

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor for the topical treatment of AD in children and adults [published online July 11, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:494-503.

- Jensen P, Hamann D, Hamann CR, et al. Nickel and cobalt release from children’s toys purchased in Denmark and the United States. Dermatitis. 2014;25:356-365.

- Overgaard LE, Engebretsen KA, Jensen P, et al. Nickel released from children’s toys is deposited on the skin. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;74:380-381.

- Weibel L, Barysch MJ, Scheer HS, et al. Topical timolol for infantile hemangiomas: evidence for efficacy and degree of systemic absorption [published online February 3, 2016]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:184-190.

Avoiding Disasters With Injectables: Tips From Charlene Lam at the Summer AAD

Preventing complications from fillers and managing sharps injury are important areas for dermatologists who practice cosmetic procedures. Charlene C. Lam, MD, MPH, Penn State Hershey Dermatology, Pennsylvania, provided tips in the presentation, “Preventing Disasters in Your Practice,” at the Summer Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

There are a number of potential complications of fillers, and one of the most serious is blindness. Dr. Lam reported that autologous fat is most often associated with blindness; however, hyaluronic acid, collagen, poly-L-lactic acid, and calcium hydroxylapatite also have been associated. An understanding of facial anatomy is important. (Dr. Julie Woodward reviews the anatomy surrounding the eyes in a November 2016 Cutis article.) If your patient is experiencing vision changes, call ophthalmology immediately. “There is a 90-minute window to start treatment,” said Dr. Lam. “No treatment has been found consistently successful. Theoretically, the use of a retrobulbar injection of 300 to 600 U of hyaluronidase could potentially save the patient’s vision in the setting of hyaluronic acid filler use, though this strategy has not been attempted.

To prevent necrosis, Dr. Lam recommended obtaining a patient history of cosmetic procedures and prior surgical procedures that may alter underlying anatomy, using reversible fillers such as those formulated with hyaluronic acid, using cannulas and smaller-gauge needles, injecting small amounts under low pressure slowly, and keep moving so that you are not depositing a large amount of filler in one area. If you see blanching, Dr. Lam advised to stop; apply warm compresses for 10 minutes every 1 to 2 hours; use vigorous massage; and consider hyaluronidase and nitroglycerin paste 2%, aspirin, and/or prednisone.

In all instances, Dr. Lam recommends having a safety kit that is easily accessible with printed directions of how to handle complications. “I like to have all contact numbers of specialists available, hyaluronidase, aspirin, and nitroglycerin paste 2%,” said Dr. Lam. “These complications occur so rarely that when they do occur, you want to be prepared.”

Dr. Lam polled those in attendance at the session and learned that 91% had a sharps (ie, needlestick) injury. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates approximately 385,000 sharps injuries annually among hospital-based health care personnel. This number actually may be an underestimate, as many instances go unreported. Nearly half of the injuries associated with hollow-bore needles is related to disposal. “Injuries could be prevented with a safe way to protect the needle after its use,” Dr. Lam said. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends using devices with safety features engineered to prevent sharps injuries.

However, if a health care provider gets stuck, first wash the area with soap and water, and then have a plan in place for medical care. He/she and the patient should be tested for hepatitis B and C viruses as well as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The risk for hepatitis B infection is greatest (6%–30%); the risk for hepatitis C virus is approximately 2% and the risk for HIV is 0.3%. “It is so important to create a positive culture of reporting that makes it acceptable for all members of the team to report a sharps injury,” said Dr. Lam. “Postexposure prophylaxis is available for HIV and it is critical to start as soon as possible.”

Preventing complications from fillers and managing sharps injury are important areas for dermatologists who practice cosmetic procedures. Charlene C. Lam, MD, MPH, Penn State Hershey Dermatology, Pennsylvania, provided tips in the presentation, “Preventing Disasters in Your Practice,” at the Summer Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

There are a number of potential complications of fillers, and one of the most serious is blindness. Dr. Lam reported that autologous fat is most often associated with blindness; however, hyaluronic acid, collagen, poly-L-lactic acid, and calcium hydroxylapatite also have been associated. An understanding of facial anatomy is important. (Dr. Julie Woodward reviews the anatomy surrounding the eyes in a November 2016 Cutis article.) If your patient is experiencing vision changes, call ophthalmology immediately. “There is a 90-minute window to start treatment,” said Dr. Lam. “No treatment has been found consistently successful. Theoretically, the use of a retrobulbar injection of 300 to 600 U of hyaluronidase could potentially save the patient’s vision in the setting of hyaluronic acid filler use, though this strategy has not been attempted.

To prevent necrosis, Dr. Lam recommended obtaining a patient history of cosmetic procedures and prior surgical procedures that may alter underlying anatomy, using reversible fillers such as those formulated with hyaluronic acid, using cannulas and smaller-gauge needles, injecting small amounts under low pressure slowly, and keep moving so that you are not depositing a large amount of filler in one area. If you see blanching, Dr. Lam advised to stop; apply warm compresses for 10 minutes every 1 to 2 hours; use vigorous massage; and consider hyaluronidase and nitroglycerin paste 2%, aspirin, and/or prednisone.

In all instances, Dr. Lam recommends having a safety kit that is easily accessible with printed directions of how to handle complications. “I like to have all contact numbers of specialists available, hyaluronidase, aspirin, and nitroglycerin paste 2%,” said Dr. Lam. “These complications occur so rarely that when they do occur, you want to be prepared.”

Dr. Lam polled those in attendance at the session and learned that 91% had a sharps (ie, needlestick) injury. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates approximately 385,000 sharps injuries annually among hospital-based health care personnel. This number actually may be an underestimate, as many instances go unreported. Nearly half of the injuries associated with hollow-bore needles is related to disposal. “Injuries could be prevented with a safe way to protect the needle after its use,” Dr. Lam said. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends using devices with safety features engineered to prevent sharps injuries.

However, if a health care provider gets stuck, first wash the area with soap and water, and then have a plan in place for medical care. He/she and the patient should be tested for hepatitis B and C viruses as well as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The risk for hepatitis B infection is greatest (6%–30%); the risk for hepatitis C virus is approximately 2% and the risk for HIV is 0.3%. “It is so important to create a positive culture of reporting that makes it acceptable for all members of the team to report a sharps injury,” said Dr. Lam. “Postexposure prophylaxis is available for HIV and it is critical to start as soon as possible.”

Preventing complications from fillers and managing sharps injury are important areas for dermatologists who practice cosmetic procedures. Charlene C. Lam, MD, MPH, Penn State Hershey Dermatology, Pennsylvania, provided tips in the presentation, “Preventing Disasters in Your Practice,” at the Summer Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

There are a number of potential complications of fillers, and one of the most serious is blindness. Dr. Lam reported that autologous fat is most often associated with blindness; however, hyaluronic acid, collagen, poly-L-lactic acid, and calcium hydroxylapatite also have been associated. An understanding of facial anatomy is important. (Dr. Julie Woodward reviews the anatomy surrounding the eyes in a November 2016 Cutis article.) If your patient is experiencing vision changes, call ophthalmology immediately. “There is a 90-minute window to start treatment,” said Dr. Lam. “No treatment has been found consistently successful. Theoretically, the use of a retrobulbar injection of 300 to 600 U of hyaluronidase could potentially save the patient’s vision in the setting of hyaluronic acid filler use, though this strategy has not been attempted.

To prevent necrosis, Dr. Lam recommended obtaining a patient history of cosmetic procedures and prior surgical procedures that may alter underlying anatomy, using reversible fillers such as those formulated with hyaluronic acid, using cannulas and smaller-gauge needles, injecting small amounts under low pressure slowly, and keep moving so that you are not depositing a large amount of filler in one area. If you see blanching, Dr. Lam advised to stop; apply warm compresses for 10 minutes every 1 to 2 hours; use vigorous massage; and consider hyaluronidase and nitroglycerin paste 2%, aspirin, and/or prednisone.

In all instances, Dr. Lam recommends having a safety kit that is easily accessible with printed directions of how to handle complications. “I like to have all contact numbers of specialists available, hyaluronidase, aspirin, and nitroglycerin paste 2%,” said Dr. Lam. “These complications occur so rarely that when they do occur, you want to be prepared.”

Dr. Lam polled those in attendance at the session and learned that 91% had a sharps (ie, needlestick) injury. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates approximately 385,000 sharps injuries annually among hospital-based health care personnel. This number actually may be an underestimate, as many instances go unreported. Nearly half of the injuries associated with hollow-bore needles is related to disposal. “Injuries could be prevented with a safe way to protect the needle after its use,” Dr. Lam said. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends using devices with safety features engineered to prevent sharps injuries.

However, if a health care provider gets stuck, first wash the area with soap and water, and then have a plan in place for medical care. He/she and the patient should be tested for hepatitis B and C viruses as well as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The risk for hepatitis B infection is greatest (6%–30%); the risk for hepatitis C virus is approximately 2% and the risk for HIV is 0.3%. “It is so important to create a positive culture of reporting that makes it acceptable for all members of the team to report a sharps injury,” said Dr. Lam. “Postexposure prophylaxis is available for HIV and it is critical to start as soon as possible.”

Birth Control Pills for Acne: Tips From Julie Harper at the Summer AAD

Acne treatment options now extend beyond antibiotics, and hormonal therapy, particularly birth control pills (BCPs), may provide clearance of acne in women who may not respond to other therapies. "Challenge [yourselves] to learn how to safely use BCPs," said Dr. Julie Harper, Clinical Associate Professor of Dermatology at the University of Alabama in Birmingham, in the presentation, "Use of Hormonal Therapy for Acne," at the Summer Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. The use of BCPs for acne has a strength-of-recommendation grade of A (consistent, good-quality patient-oriented evidence).

According to Dr. Harper, all combination BCPs should work for acne, except progestin-only BCPs, which will make acne worse. Currently, there are 4 BCPs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for acne: norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol (Ortho Tri-Cyclen); norethindrone acetate-ethinyl estradiol (Estrostep Fe); drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol (Yaz); and drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol-levomefolate calcium (Beyaz). Birth control pills are known to carry risks for venous thromboembolism (VTE), stroke, hypertension, and myocardial infarction; however, they are generally well tolerated in acne patients. "The risk of venous thromboembolism in women who take BCPs is doubled or tripled compared to women who do not take these pills. This sounds scary until you put it into context," said Dr. Harper. She explains the risks to patients using the following 3-6-9-12 model: A woman's baseline risk of having a VTE if she is not on a BCP is approximately 3 in 10,000 women in one year. When she takes a BCP, her risk doubles to 6 per 10,000 women in one year. If she takes a BCP that contains drospirenone, her risk is 9 per 10,000 women in one year. If she gets pregnant, her risk is 12 per 10,000 women in one year.

Dermatologists may be apprehensive to prescribe BCPs, but Dr. Harper provided several important tips on managing patient expectations and monitoring patients. Dr. Harper emphasized that BCPs should be used patiently for acne. "It frequently takes at least 3 cycles of BCPs to see a meaningful change in acne reduction," she advised. She recommended obtaining a thorough medical history and blood pressure measurement prior to prescribing BCPs. However, a Papanicolaou test and bimanual pelvic examination are no longer deemed mandatory prior to initiating a BCP, according to the World Health Organization and the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. "While these exams may help to detect cervical cancer and other pelvic diseases, BCPs help to prevent unwanted pregnancies and the risks that accompany those pregnancies," said Dr. Harper. "Remember that BCPs reduce the risk of ovarian, uterine and colorectal cancer and also lessen ovarian cysts and pelvic inflammatory disease." Dermatologists also should inform patients that rifampin and griseofulvin, both anti-infectives, will interact with BCPs, lessening their effectiveness.

A March 2017 study published in Cutis (2017;99:195-201) of US dermatologists' knowledge, comfort, and prescribing practices (N=116) revealed that most dermatologists (95.4%) believe BCPs effectively treat acne; however, only 54% reported prescribing them. The American Academy of Dermatology's guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris published in February 2016 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973) stated that "estrogen-containing combined oral contraceptives are effective and recommended in the treatment of inflammatory acne in females."

Overall, Dr. Harper's take-home message was that dermatologists should not be afraid to prescribe BCPs, even in teenaged girls (following the onset of menarche). "Birth control pills can be used in younger patients but it is not my first line of treatment," said Dr. Harper. "It is recommended that BCPs not be prescribed for acne until 2 years after the young woman has achieved menarche. When considering whether or not to use a BCP in the early teenage years, keep in mind that these are not short-term treatments. If a BCP does help acne, it will likely need to be maintained for many years." When discussing this treatment in front of parents/guardians, consider referring to it as hormonal therapy and use the term birth control pills only initially.