User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Cutaneous Myoepithelial Carcinoma With Disseminated Metastases

Cutaneous myoepithelial tumors are rare neoplasms but are being increasingly recognized and reported in the literature.1-7 Myoepithelial tumors are related to benign mixed tumors of the skin but lack the epithelial ductules that are present in mixed tumors. Cutaneous myoepithelial tumors may show a variety of architectural, cytological, and stromal features. Their immunophenotype usually is characterized by coexpression of an epithelial marker (eg, keratin, epithelial membrane antigen [EMA]) and S-100 protein; they also may express a variety of other myoepithelial markers, including keratins, smooth muscle actin, calponin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, p63, and desmin.7 EWS RNA binding protein 1 (EWSR1) and pleomorphic adenoma gene 1 (PLAG1) gene rearrangement has been detected in subsets of these tumors on in situ hybridization.8-10

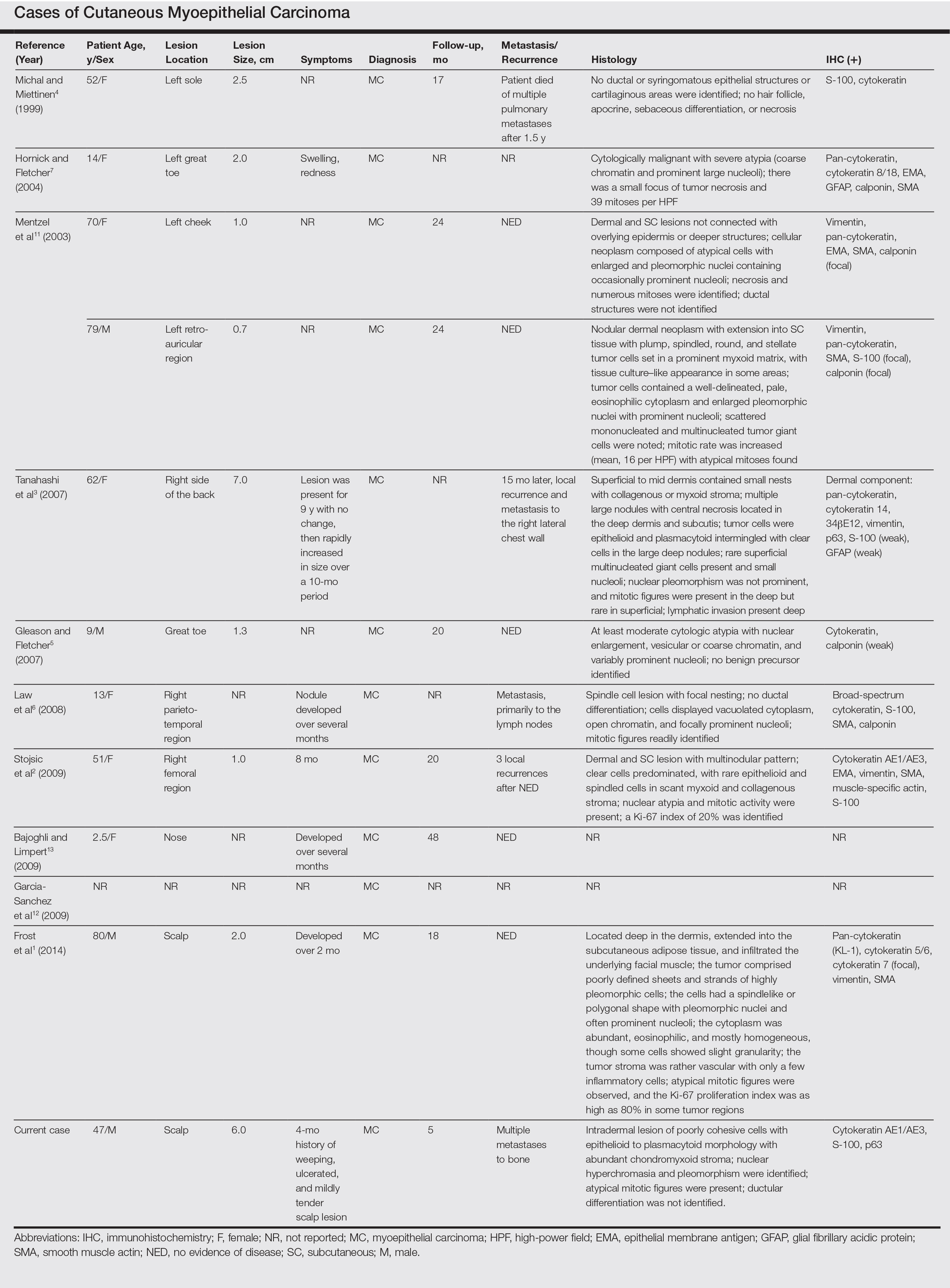

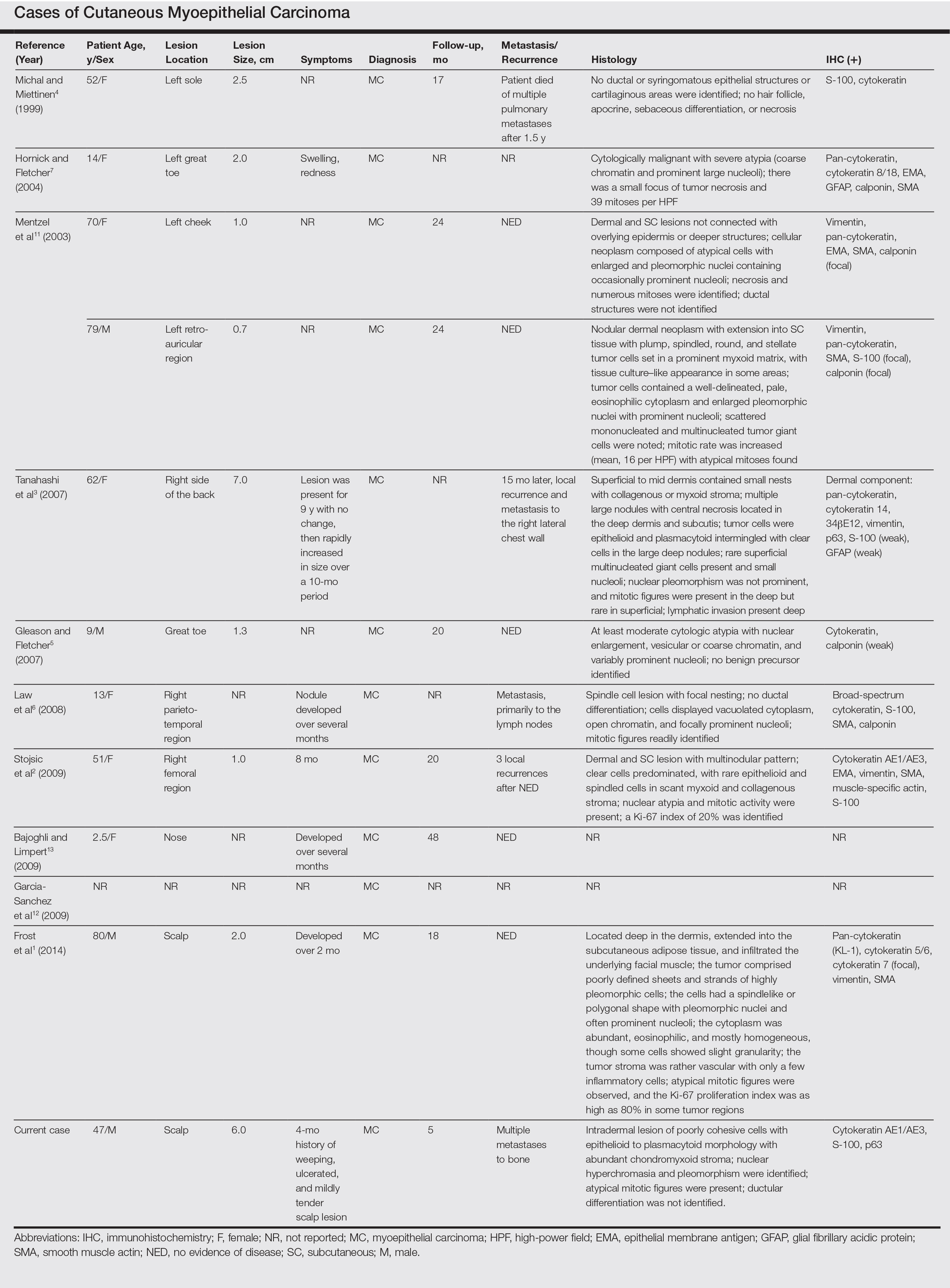

Malignant myoepithelial tumors of the skin, also referred to as cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas, are exceedingly rare. Including the current case, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE and Google Scholar using the terms myoepithelial carcinoma and cutaneous revealed 12 cases that have been reported in the literature (Table).1-7,11-13 These tumors often occur in the head and neck areas and the lower extremities and display a bimodal age distribution, generally occurring in patients younger than 21 years and older than 50 years of age; they also show a slight female predominance. Available follow-up data from the literature have shown local recurrence or metastasis in 3 cases3,4,6; however, in one case the metastatic focus was not histologically identified.4 Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma presenting with metastatic disease further limits treatment options. Here, we describe a case of metastatic cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma in a 47-year-old man, a rare example of cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma with histologically documented metastatic disease at the initial presentation.

Case Report

A 47-year-old man who underwent a renal transplant 19 years prior presented with a weeping, ulcerated, mildly tender lesion on the scalp of 4 months’ duration with neck and back pain of 3 months’ duration. Physical examination demonstrated a 6-cm area of ulceration on the anterior crown of the scalp with adjacent enlarged keratoacanthomalike craters and satellite nodules (Figure 1). He was previously diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp at an outside institution 4 years prior and was treated with radiation therapy. The prior scalp biopsy for BCC diagnosis was unavailable for review. The patient had a history of chronic eczematous dermatitis in the waistband area that had been present for 19 years and another BCC with nodular and infiltrative patterns on the left helix. Of note, he also had been taking long-term immunosuppressant medications (ie, cyclosporine, azathioprine) for maintenance following the renal transplant.

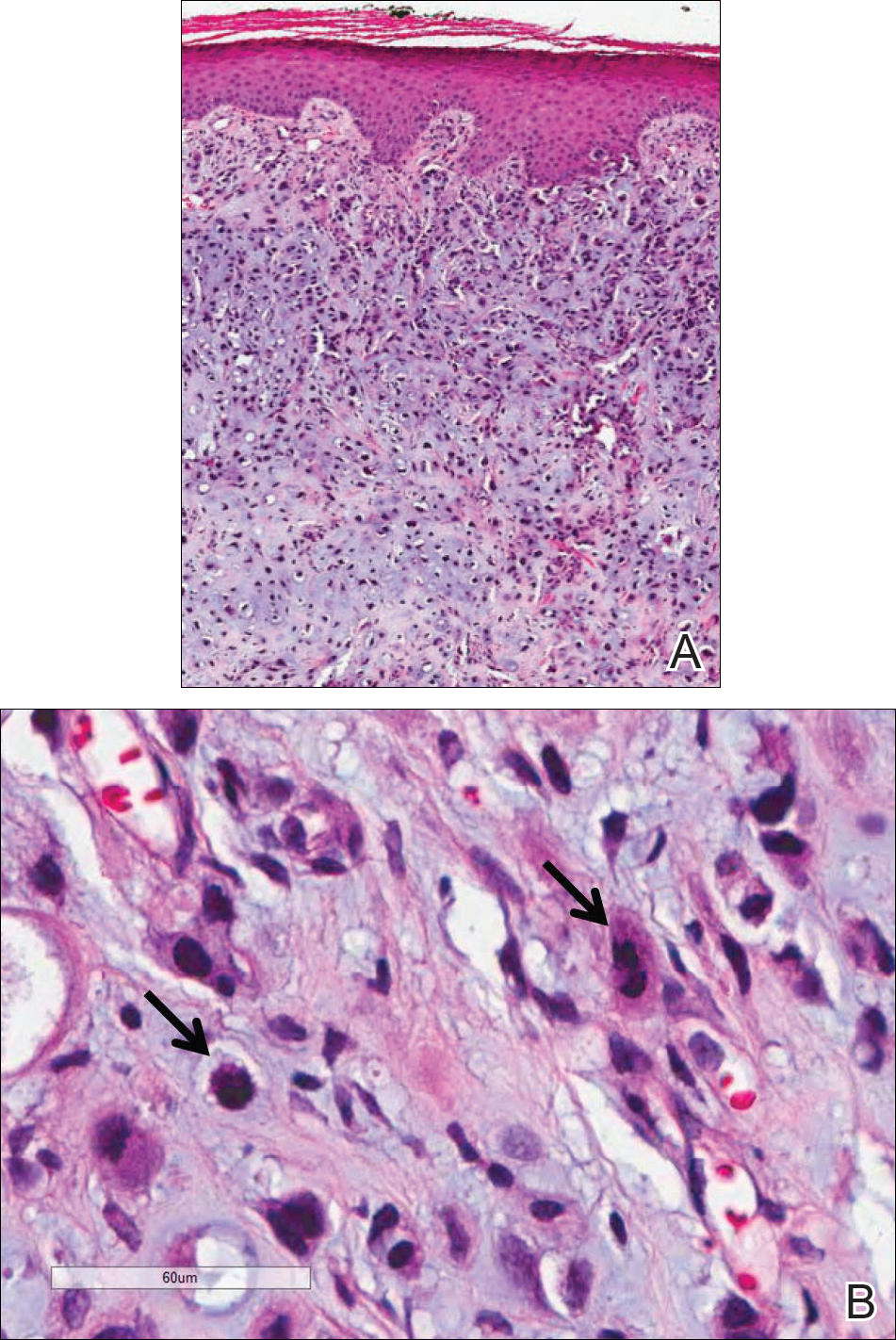

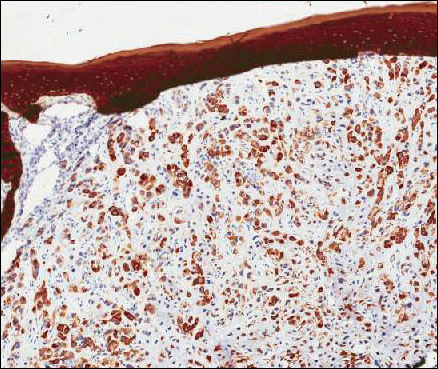

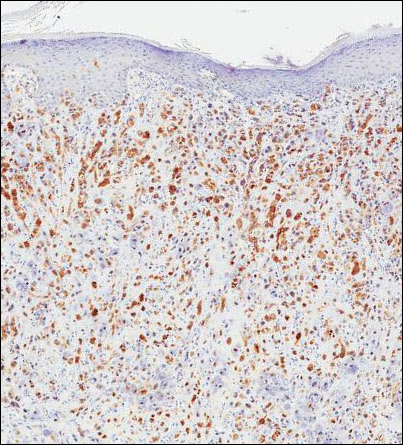

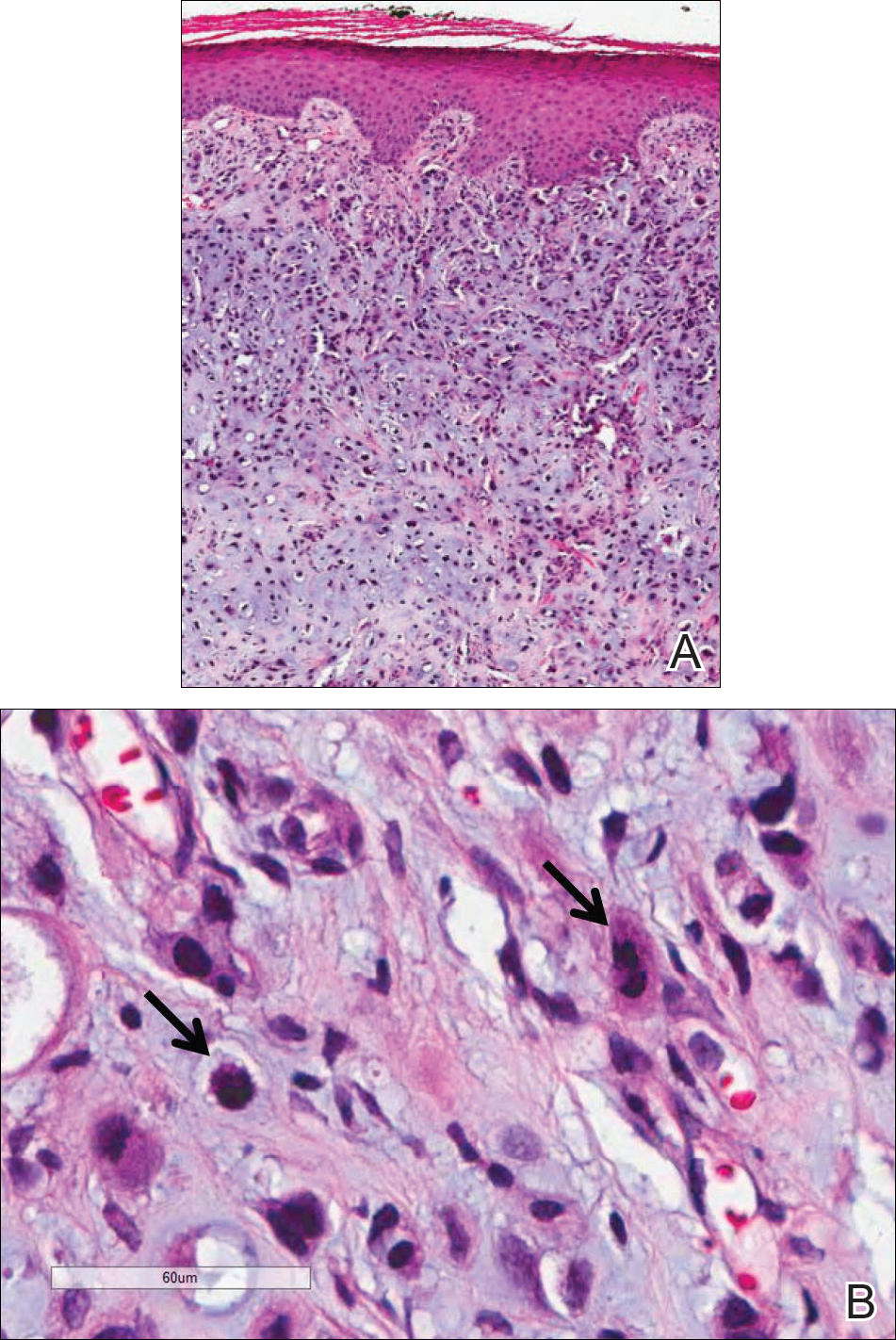

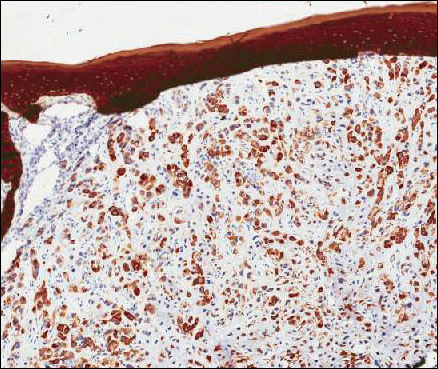

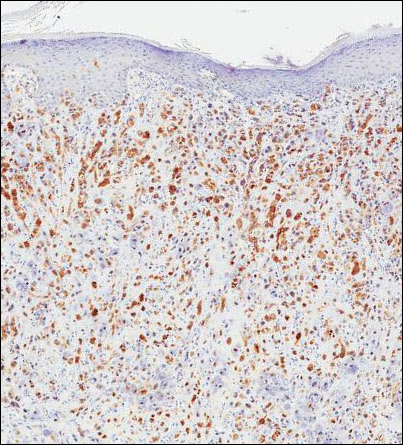

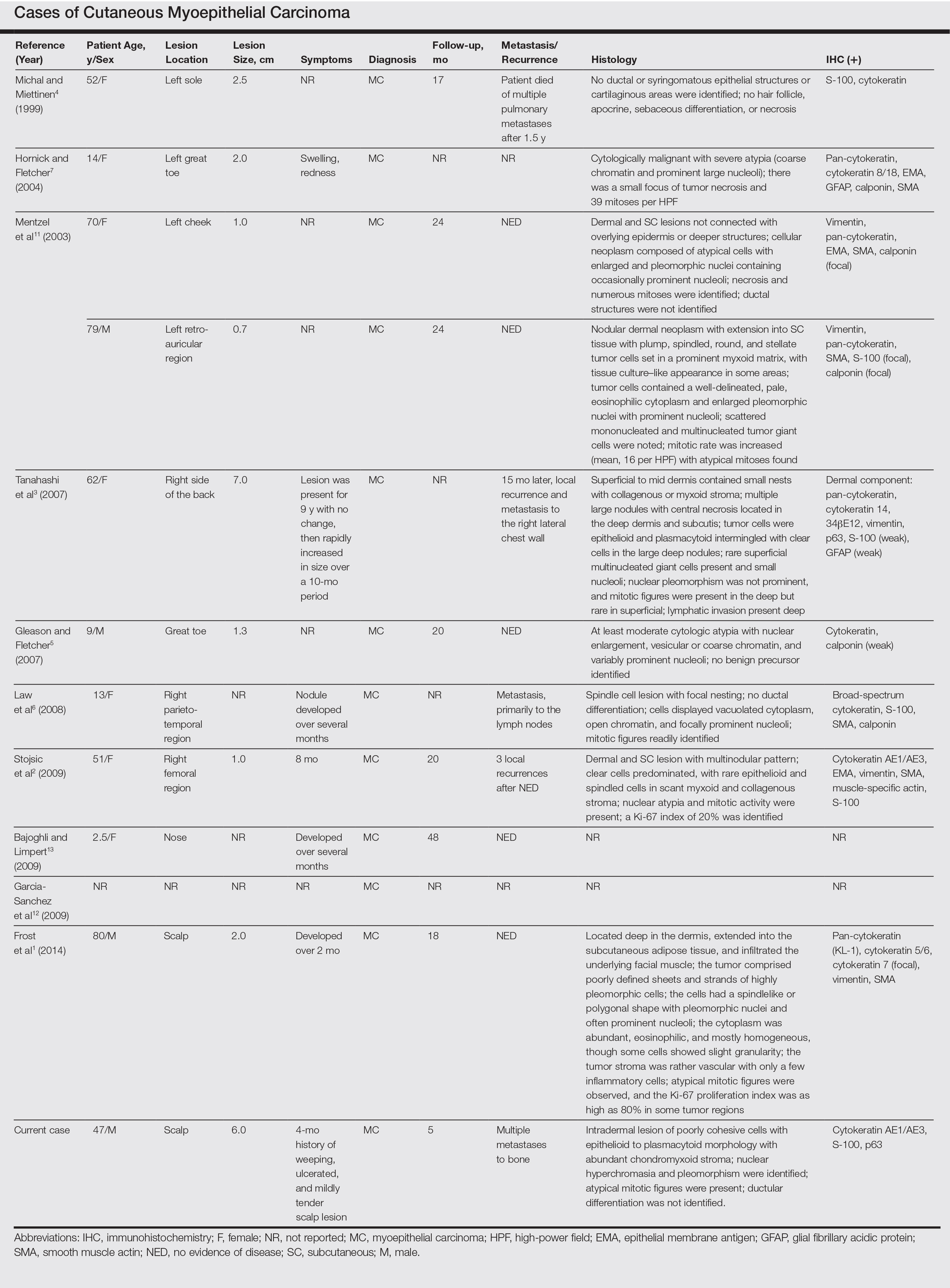

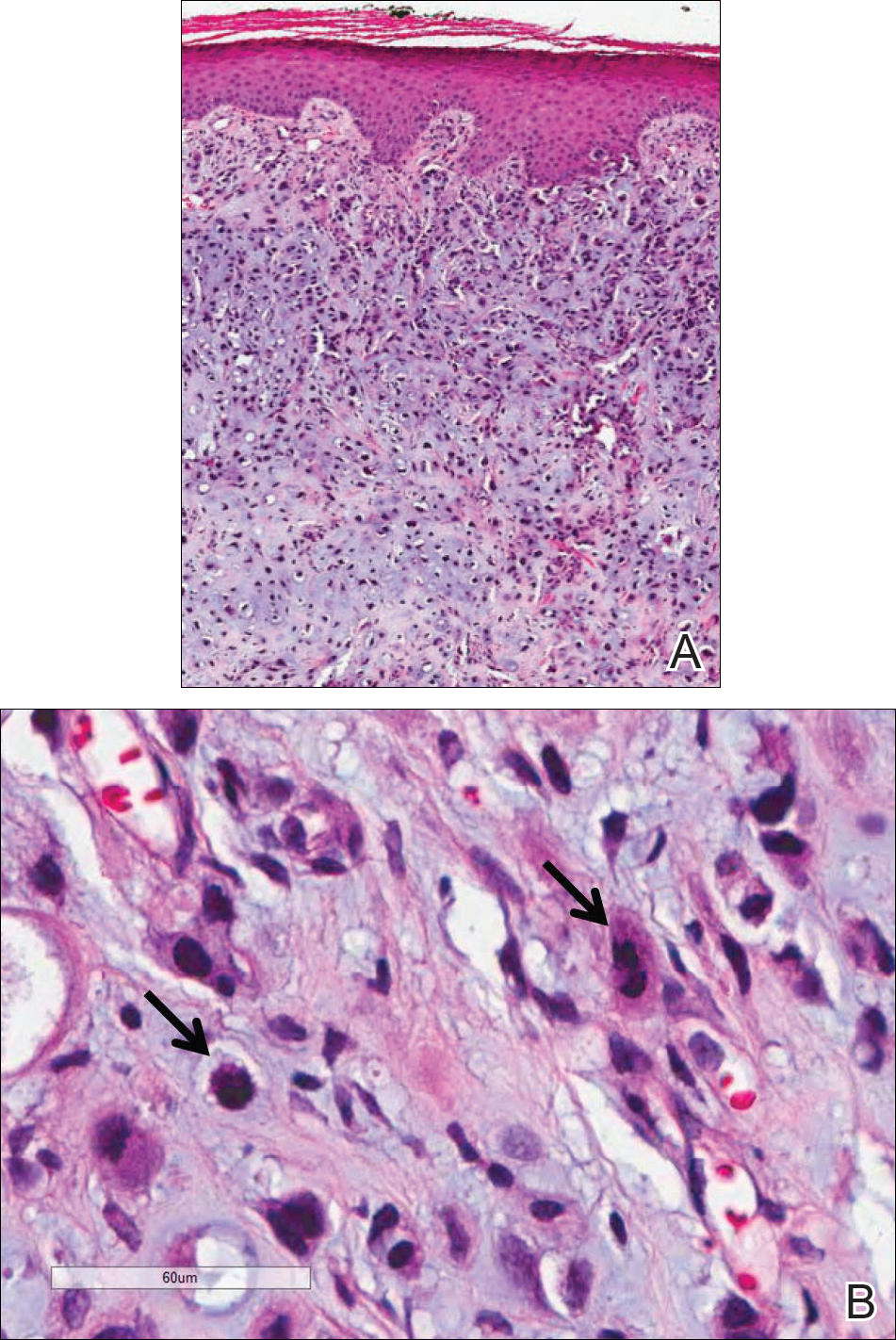

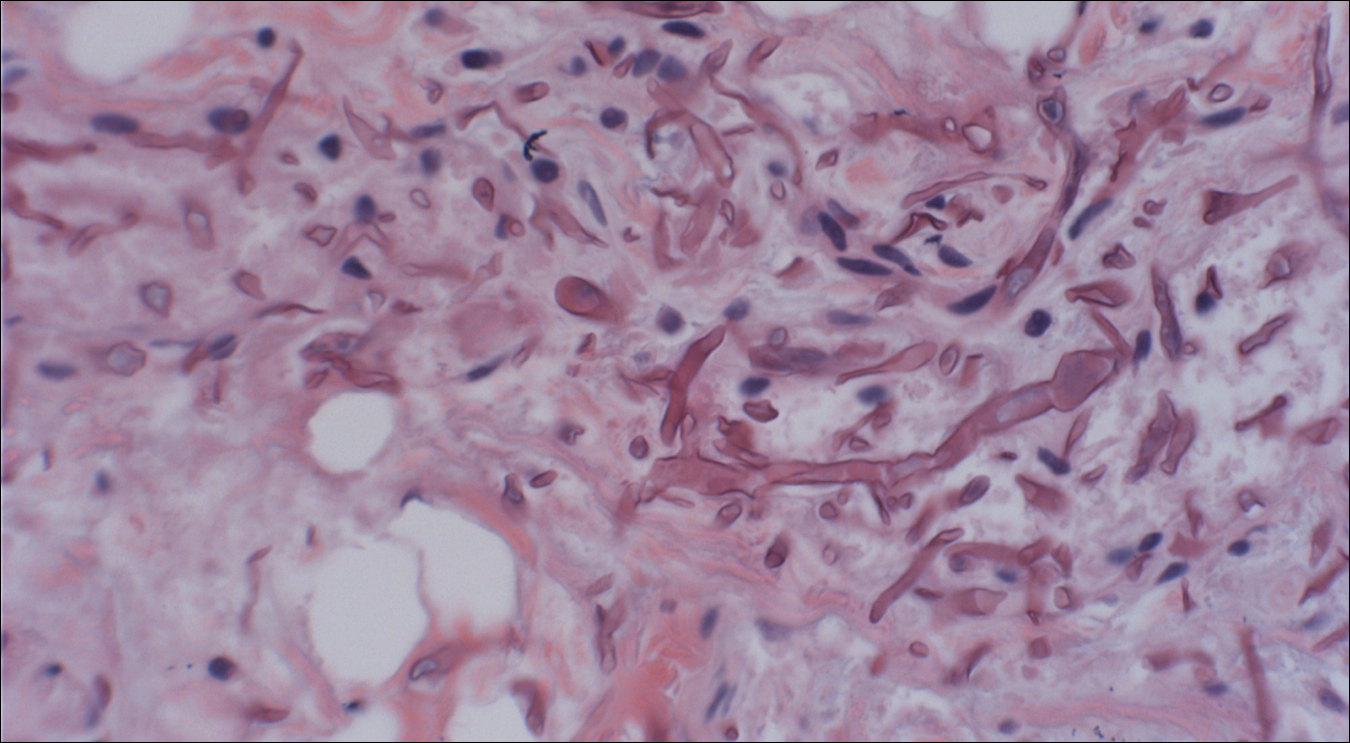

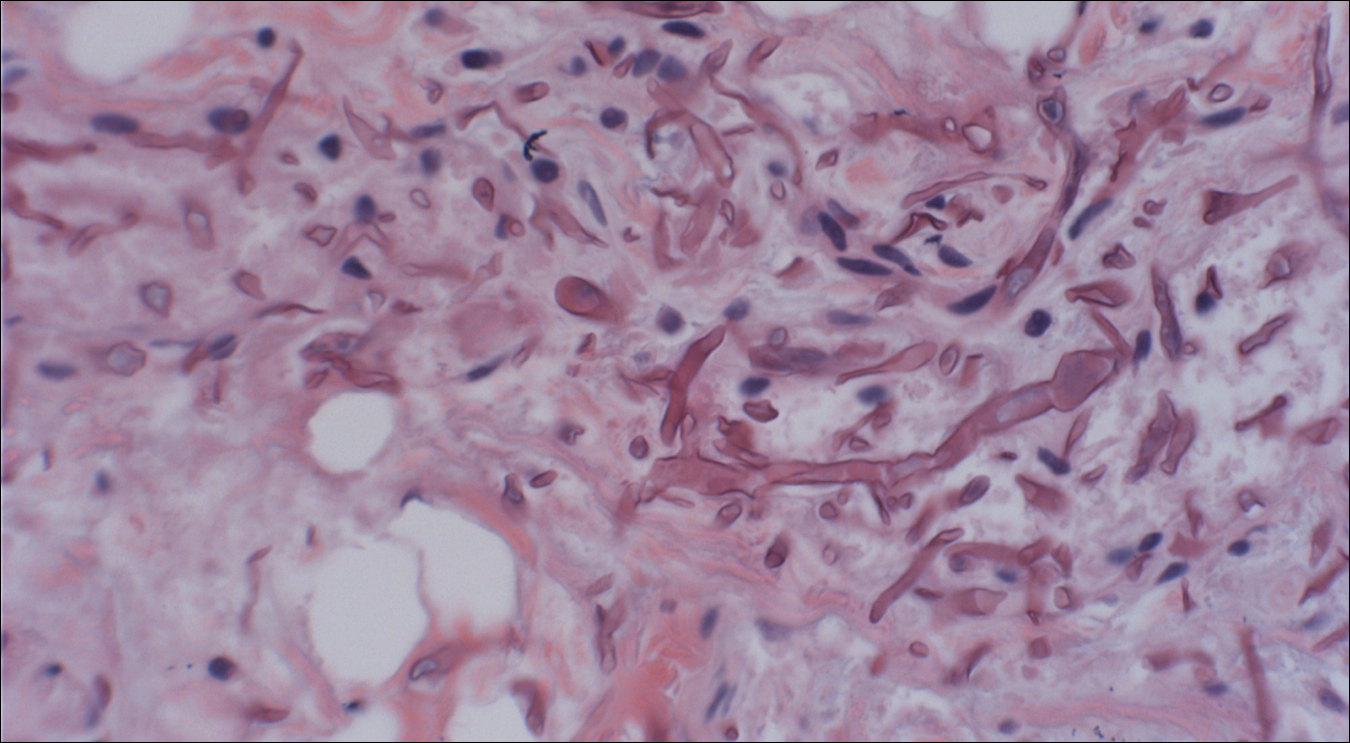

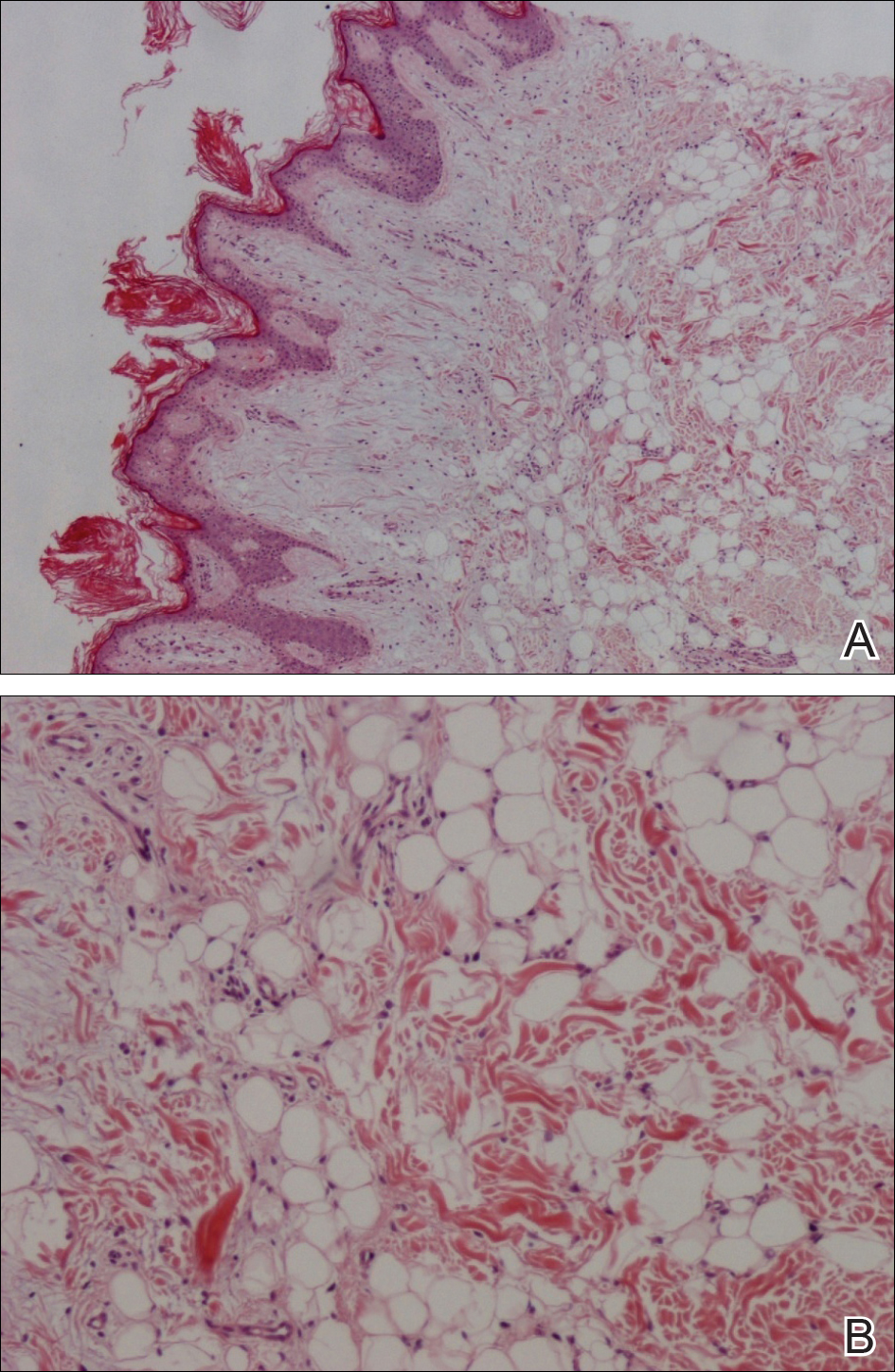

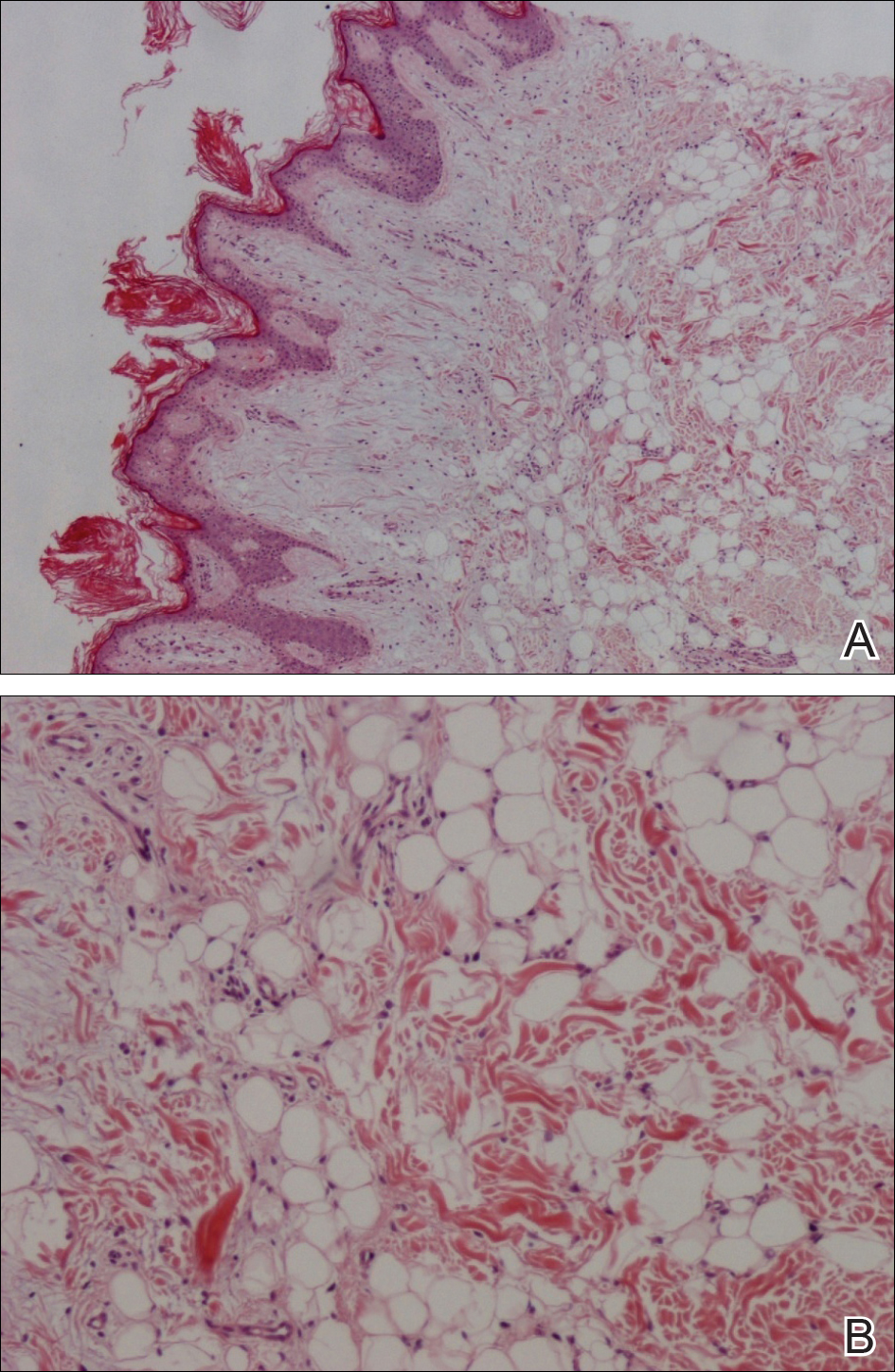

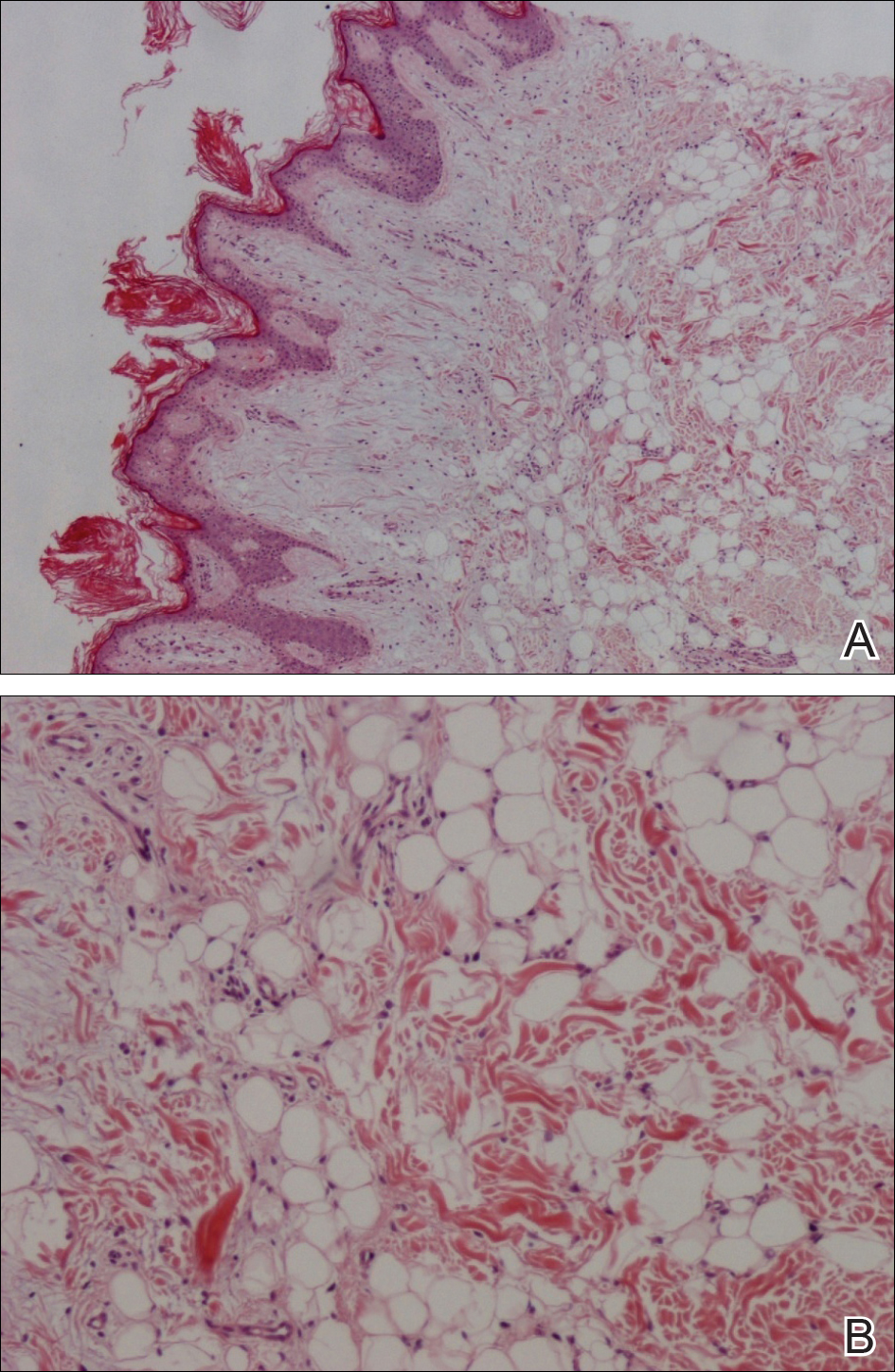

Because of the extensive ulceration of the primary lesion, a shave biopsy of the scalp was performed on an adjacent satellite nodule. Histopathologic findings showed an intradermal neoplasm characterized by poorly cohesive cells exhibiting epithelioid to plasmacytoid morphologic features surrounded by abundant chondromyxoid stroma. Ductular differentiation was not identified (Figure 2A). The neoplastic cells displayed hyperchromatic nuclei with marked nuclear pleomorphism and atypical mitotic figures (Figure 2B). On immunohistochemistry the tumor cells stained positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (Figure 3), S-100 protein (Figure 4), and p63, and were negative for calponin, desmin, melan-A, cytokeratin 7, and brachyury (Figure 5).

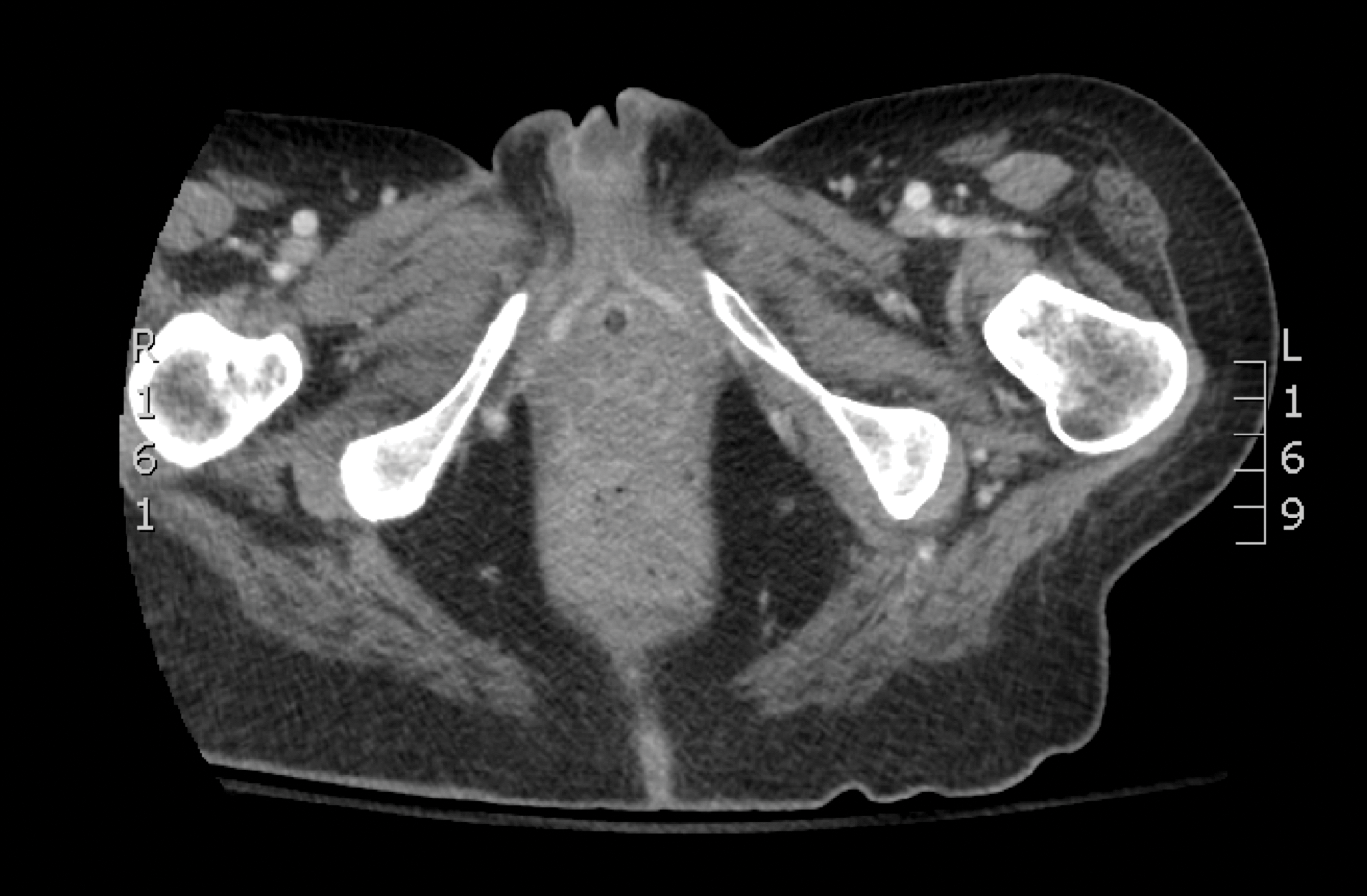

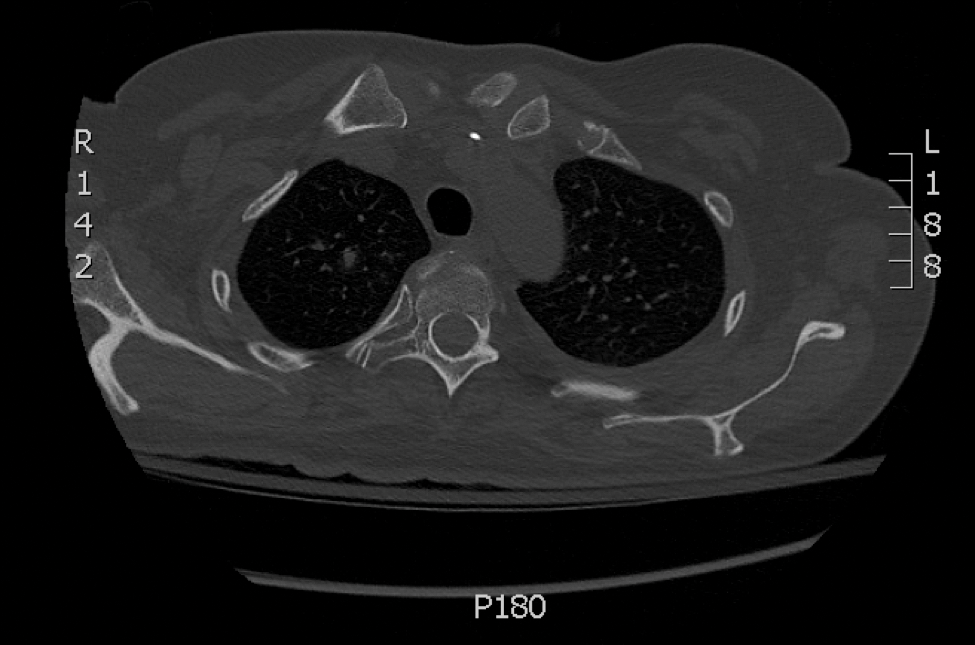

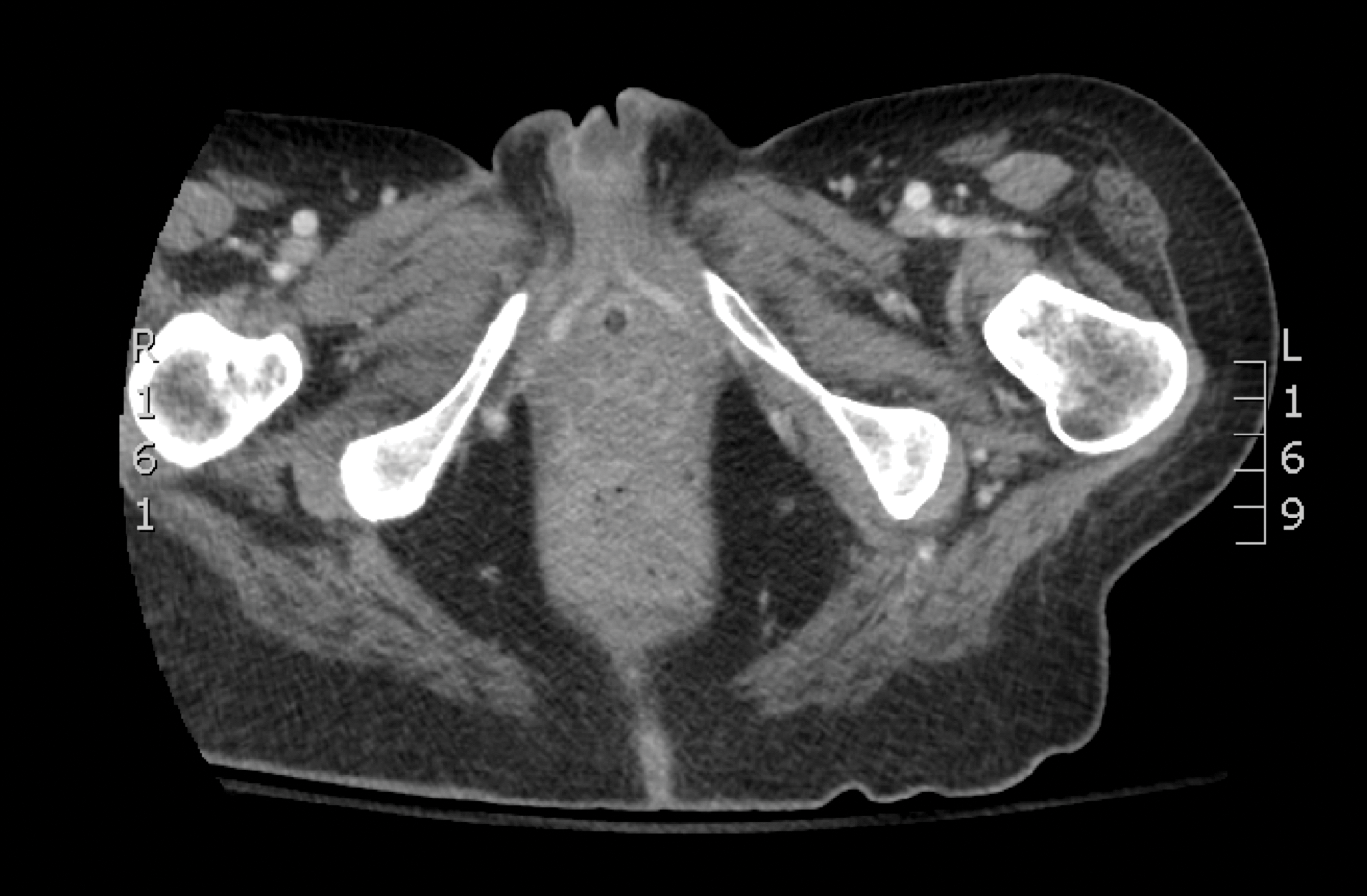

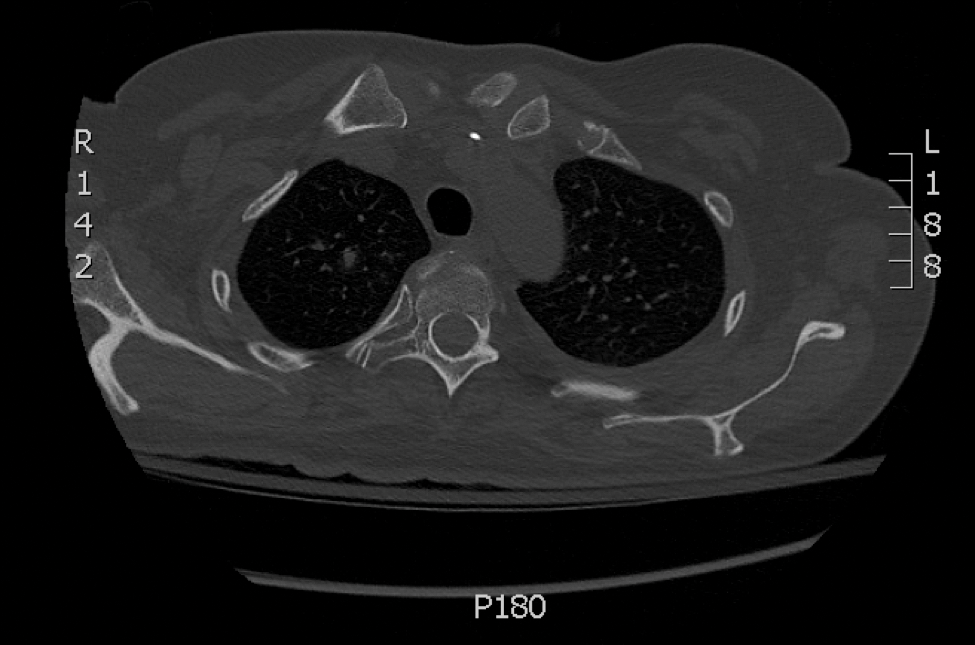

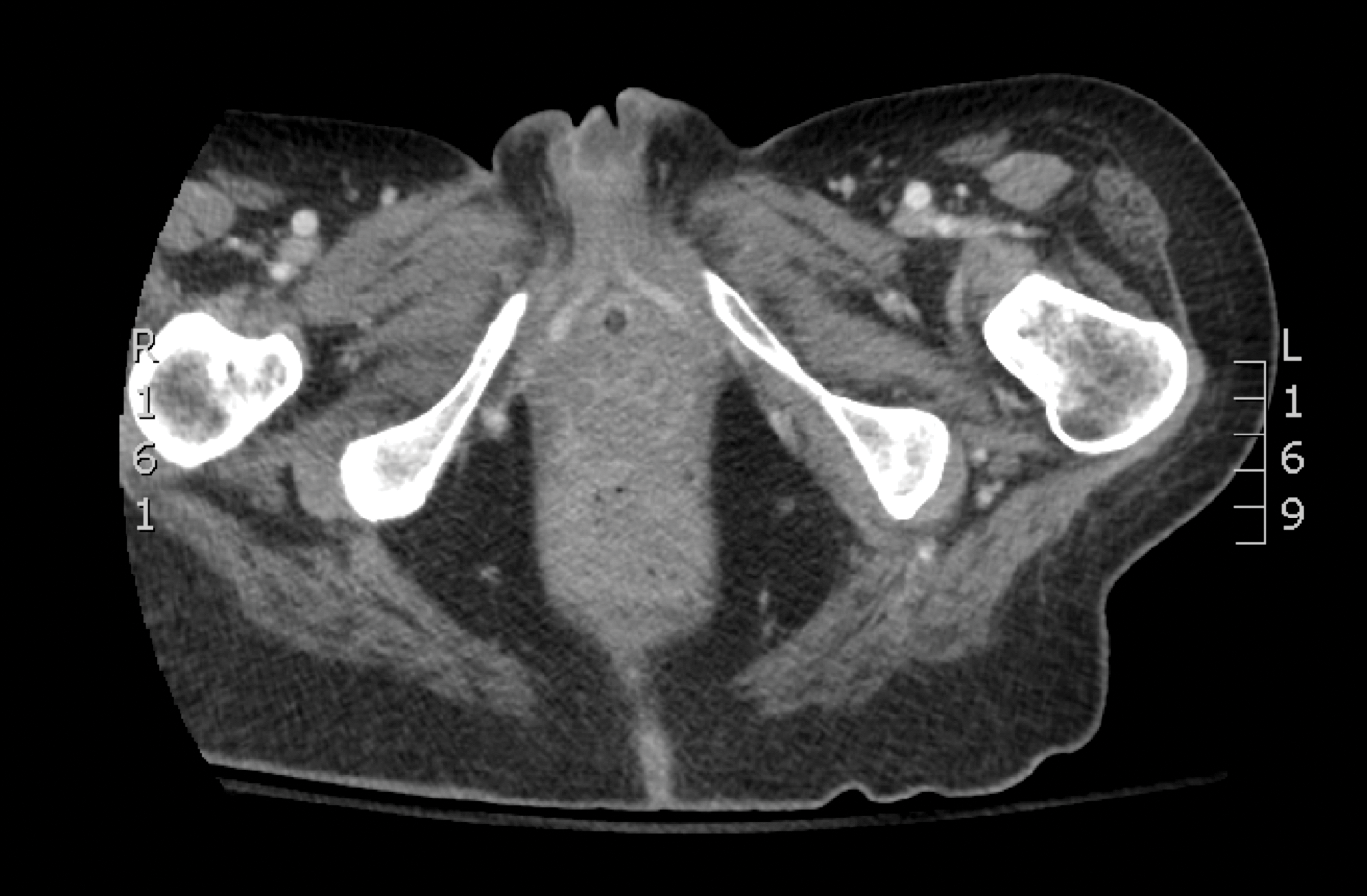

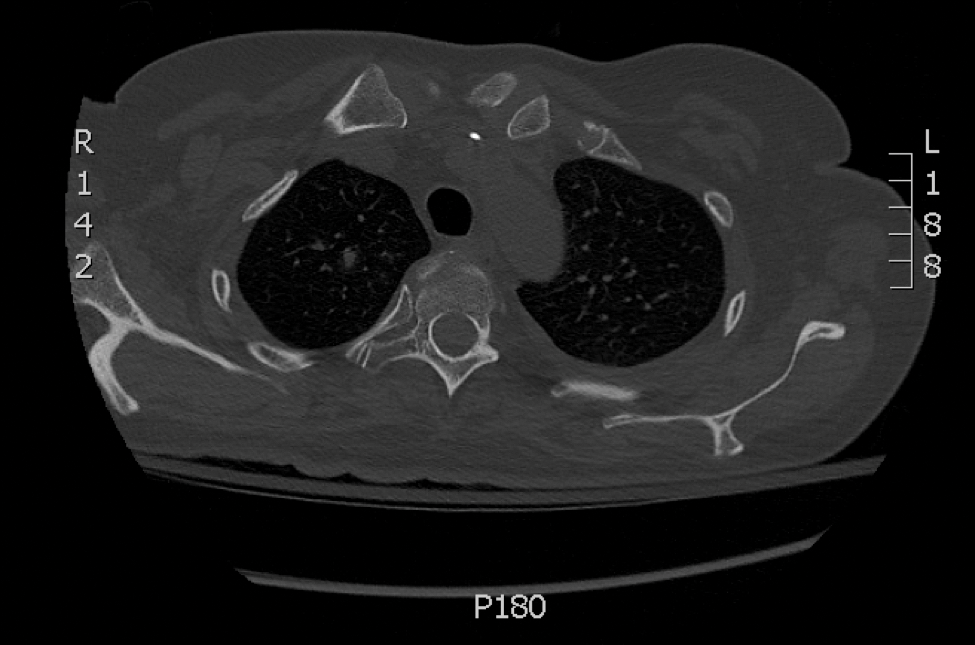

Radiographic imaging was performed due to the patient’s history of neck and back pain. Magnetic resonance imaging showed innumerable slightly expansile, T1-hypointense, T2-hyperintense, and robustly enhancing lesions involving the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spine, as well as the thoracic ribs and bilateral iliac bones. There was no evidence of soft tissue tumor around the bone lesions. Ventral cervical spinal cord compression was detected at the C4 vertebra, causing a symptomatic radiculopathy; however, due to widely metastatic disease, the patient was not considered appropriate for neurosurgical intervention of the compression. Computerized tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not identify any visceral source of malignancy, though multiple bilaterally enlarged cervical lymph nodes were identified on magnetic resonance imaging.

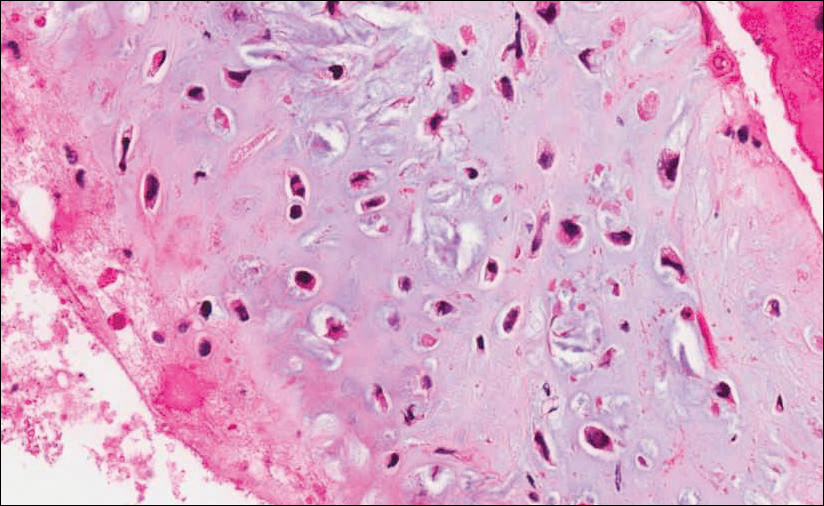

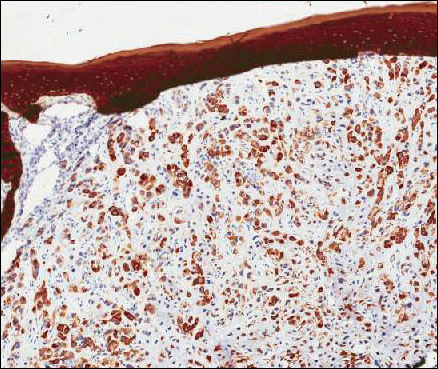

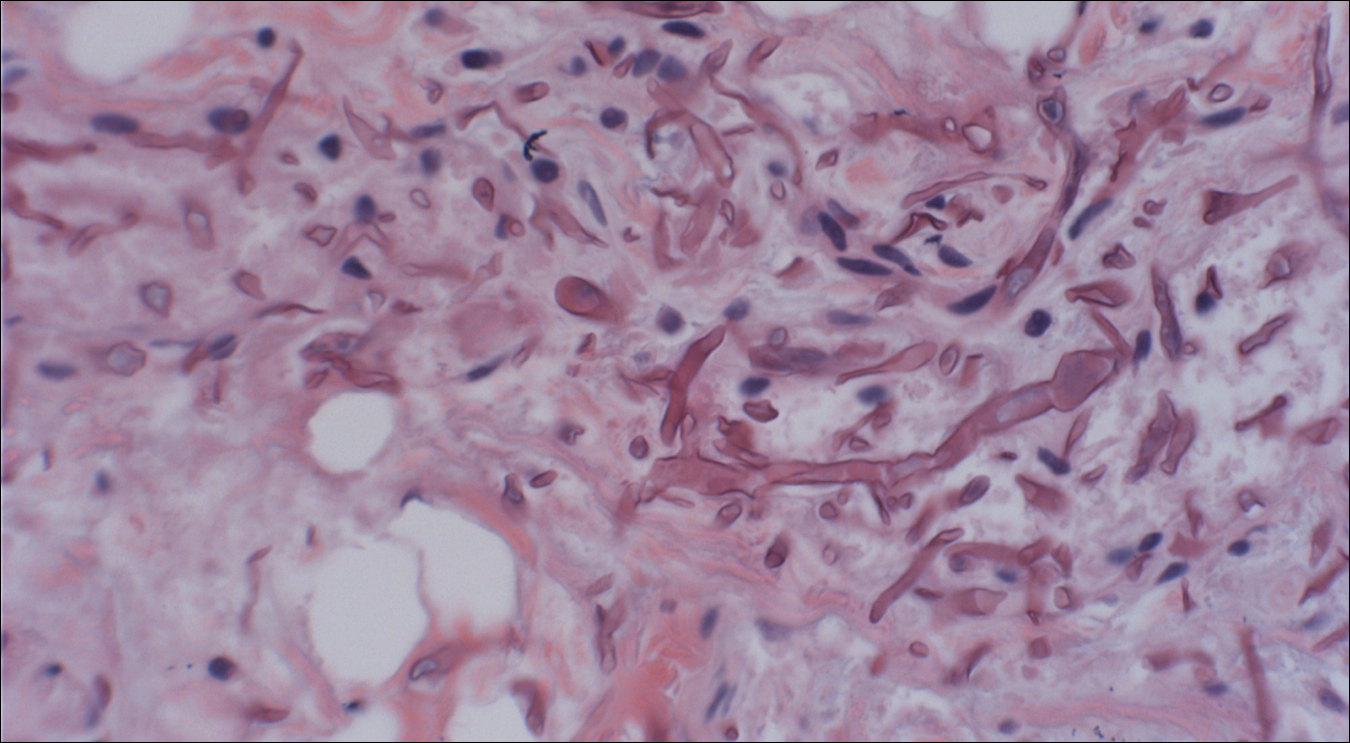

Fine needle aspiration of a left iliac bone lesion demonstrated neoplastic cells and chondromyxoid stroma essentially identical to the features shown in the skin biopsy (Figure 6). Given the morphologic features of the tumor and coexpression of cytokeratin and S-100 protein, the findings were interpreted as primary cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma with disseminated metastatic lesions. The patient began treatment with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy. To combat the symptomatic bone pain and upper extremity radiculopathy, palliative radiation was administered to the cervical spine, lumbar spine, and right sacrum (30 Gy to each site in 10 fractions at 3 Gy per fraction). Despite the attempted chemotherapy and radiation, the patient continued to decline, and after 2 months, he elected to pursue palliative care. The patient died after 3 months in palliative care (5 months after the initial presentation).

Comment

Myoepithelial cells normally surround ducts in secretory organs, such as the breasts, salivary glands, and cutaneous sweat glands. Myoepithelial neoplasms are well recognized in the salivary glands14,15; however, myoepithelial neoplasms also can arise in other sites, including the soft tissue4,5,16-18 and skin.1-3,7,11,19,20 Myoepithelioma of soft tissue was first described by Burke et al21 in 1995 and later described in the skin by Fernandez-Figueras et al22 in 1998. Since then, diagnostic criteria for cutaneous myoepithelial neoplasms have evolved, suggesting a spectrum of disease rather than a single distinct entity.11 Most often, cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas arise as soft nodular lesions in the head and neck areas or extremities of adults. The nodules typically are nontender and range in size from 0.5 to 18.0 cm. Our review of the literature revealed 11 additional cases of cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas have been reported, ranging in size from 0.7 to 7.0 cm (Table). In our case, the main lesion was 6 cm, mildly tender, ulcerated, and accompanied by satellite nodules.

Histologically, cutaneous myoepithelial tumors typically are well-defined, dermal-based nodules with no connection to the overlying epidermis. Similar to myoepithelial tumors of other sites, they can be diagnostically challenging due to the heterogeneity of both their architectural and cytological features. The presence of a chondromyxoid or hyalinized stroma is common but not always present. Neoplastic myoepithelial cells can exhibit spindled, epithelioid, plasmacytoid, or clear cell morphologic features and show growth patterns in clusters, cords, glands, or sheets. Focal epithelial cells can be present. Although benign myoepithelial neoplasms with overt ductal differentiation are consistent with cutaneous mixed tumors (chondroid syringomas), those without ducts are characterized as myoepitheliomas. It is uncertain if cases with only focal ductal differentiation should be classified as mixed tumors or as myoepitheliomas. Malignant myoepithelial tumors show infiltrative borders, nuclear pleomorphism, coarse nuclear chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and increased mitotic activity. A 2003 study by Hornick and Fletcher16 found that cytologic atypia was the primary predictor of malignant behavior for myoepithelial neoplasms of the soft tissue.

Despite a wide variety of expression patterns, immunohistochemistry is critical in demonstrating myoepithelial differentiation and establishing a diagnosis of a myoepithelial neoplasm. Most cases display coexpression of epithelial markers, including keratins and/or EMA as well as S-100 protein. Myogenic markers also may be variably expressed; however, the absence of myogenic markers does not exclude the diagnosis of a myoepithelial tumor. Commonly expressed epithelial markers are cytokeratin AE1/AE3, cytokeratin 8/18, and EMA, while commonly expressed myogenic markers include muscle specific actin and smooth muscle actin.5,7,11,19 Myoepithelial tumors also may express calponin, p63, and glial fibrillary acidic protein.16

Molecular studies also can aid in the diagnosis of myoepithelial tumors. A study by Antonescu et al8 demonstrated EWSR1 gene rearrangement in 45% (30/66) of extrasalivary myoepithelial tumors and the absence of EWSR1 gene rearrangement in salivary gland myoepithelial tumors. The authors also showed that EWSR1-negative tumors were more likely to be superficially located, display ductal differentiation, and possess a benign clinical course.8 In another study, Bahrami et al23 suggested that a subset of mixed tumors, specifically those with tubuloductal differentiation, are genetically linked to salivary gland pleomorphic adenomas, which was achieved by the coexpression of the PLAG1 protein and PLAG1 gene rearrangement on immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), respectively. Of the 19 cases evaluated, 11 (58%) expressed nuclear staining for PLAG1 immunohistochemistry; 8 of those 11 showed positive gene rearrangement for PLAG1 using FISH. These findings raise the possibility that cutaneous mixed tumors may be more closely related to those of the salivary glands, while deep myoepithelial tumors that lack ductal differentiation may represent a distinct group. Similar to the study by Antonescu et al,8 Flucke et al10 investigated EWSR1 gene rearrangement but limited their sample to cutaneous tumors, including myoepitheliomas, mixed tumors, and myoepithelial carcinoma. The authors found that 44% of cases (7/16) expressed EWSR1; this expression suggests that cutaneous myoepithelial tumors may have a genetic relationship to their soft tissue, bone, and visceral counterparts.10

Myoepithelial tumors display a broad spectrum of morphologic features; however, one of the most common growth patterns is that of oval to round cells forming cords and chains in a chondromyxoid stroma. As such, the histopathologic differential diagnosis for myoepithelial tumors includes other epithelioid or round-cell neoplasms with similar growth patterns including extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (EMC), ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts, and extra-axial soft tissue chordoma. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma bears the closest similarity to myoepithelial tumors both histologically and by ancillary studies. It typically possesses cords or chains of small round tumor cells set in a chondromyxoid or myxoid background. In contrast to myoepithelial tumors, which typically have more abundant cytoplasm and can show at least focal areas of spindle cell growth, the cells of EMC are more uniform, small, round cells with relatively scant cytoplasm. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcomas lack the typical myoepithelial coexpression of cytokeratin and S-100 protein, with a minority of EMCs expressing S-100 protein but rarely cytokeratin. Most cases of EMC possess a balanced t(9;22) translocation involving the EWSR1 gene,24 a finding that could lead to confusion with soft tissue myoepithelial tumors, which also may show EWSR1 rearrangement on FISH. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts is also composed of round cells arranged in cords in a myxoid or fibrous stroma; the majority of cases also display a peripheral rim of mature bone, a feature that is not typically seen in myoepithelial tumors. Similar to myoepithelial tumors, ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts often is positive for S-100 protein; however, it rarely is positive for cytokeratins. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts has been shown to have a rearrangement of the PHD finger protein 1 (PHF1) gene in approximately half of cases, a molecular finding that has not been reported for myoepithelial tumors.25 Finally, extra-axial soft tissue chordomas, though quite rare, may possess striking similarities to myoepithelial tumors both histopathologically and immunohistochemically. Chordomas are composed of epithelioid cells arranged in nests, nodules, and chains with a variably myxoid background. A variable amount of cells with bubbly cytoplasm (known as physaliphorous cells) can be seen. High mitotic activity is not a characteristic feature in chordomas. They classically coexpress cytokeratins and S-100 protein, similar to myoepithelial tumors.

Because cutaneous myoepithelial tumors are relatively rare, a well-defined standard of care for treatment is lacking. Surgical excision is the primary treatment method in most reported cases in the literature.17,19 Miller et al29 reported the successful treatment of recurrent cutaneous myoepitheliomas with Mohs micrographic surgery. Chemotherapy may be useful in the setting of metastatic myoepithelial carcinomas in adults, but reported results are inconsistent.30,31 Radiation treatment of recurrent or metastatic disease has not been shown to be effective. A study of children treated with surgical resection and chemotherapy using ifosfamide, cisplatin, and etoposide followed by radiation therapy showed positive results.32

Our case highlights several challenges that may arise in establishing a diagnosis of cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma with disseminated metastases. The diagnostic difficulty in our case was compounded by the advanced nature of the lesion at the time of presentation. Given the rarity of metastatic cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas and the lack of a prior primary diagnosis of a malignant myoepithelioma, the index of suspicion for this entity was not high. A report of myoepithelial carcinoma of the parotid gland metastatic to the skin has been reported,33 but in the absence of salivary gland involvement or other visceral lesions, metastasis from any source other than our patient’s cutaneous scalp lesion is unlikely. The histopathologic features in combination with the characteristic immunophenotype, unique clinical setting, and radiographic findings were essential to arriving at the correct diagnosis. Unlike previously reported metastatic lesions, our case is unique in that metastatic lesions were identified at the time of initial clinical presentation.

Conclusion

Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas are exceedingly rare tumors with a wide range of histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings. In challenging cases, studies for EWSR1 or PLAG1 gene rearrangement can be helpful. Furthermore, this case illustrates the potential for widespread dissemination of myoepithelial carcinomas requiring clinical evaluation and imaging studies to exclude metastatic lesions.

- Frost MW, Steiniche T, Damsgaard TE, et al. Primary cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. APMIS. 2014;122:369-379.

- Stojsic Z, Brasanac D, Boricic I, et al. Clear cell myoepithelial carcinoma of the skin. a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:680-683.

- Tanahashi J, Kashima K, Daa T, et al. A case of cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:648-653.

- Michal M, Miettinen M. Myoepitheliomas of the skin and soft tissues. report of 12 cases. Virchows Arch. 1999;434:393-400.

- Gleason BC, Fletcher CD. Myoepithelial carcinoma of soft tissue in children: an aggressive neoplasm analyzed in a series of 29 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1813-1824.

- Law RM, Viglione MP, Barrett TL. Metastatic myoepithelial carcinoma in a child. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:779-781.

- Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Cutaneous myoepithelioma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 14 cases. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:14-24.

- Antonescu CR, Zhang L, Chang NE, et al. EWSR1-POU5F1 fusion in soft tissue myoepithelial tumors. a molecular analysis of sixty-six cases, including soft tissue, bone, and visceral lesions, showing common involvement of the EWSR1 gene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:1114-1124.

- Antonescu CR, Zhang L, Shao SY, et al. Frequent PLAG1 gene rearrangements in skin and soft tissue myoepithelioma with ductal differentiation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;52:675-682.

- Flucke U, Palmedo G, Blankenhorn N, et al. EWSR1 gene rearrangement occurs in a subset of cutaneous myoepithelial tumors: a study of 18 cases. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1444-1450.

- Mentzel T, Requena L, Kaddu S, et al. Cutaneous myoepithelial neoplasms: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 20 cases suggesting a continuous spectrum ranging from benign mixed tumor of the skin to cutaneous myoepithelioma and myoepithelial carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:294-302.

- Garcia-Sanchez S, Elices M, Nieto S. Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma (malignant myoepithelial tumor of skin). Virchows Archiv. 2009;455(suppl 1):1-482.

- Bajoghli A, Limpert J. Treatment of cutaneous malignant myoepithelioma on the nasal ala using Mohs micrographic surgery in a two and a half year old child. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:S44.

- Prasad AR, Savera AT, Gown AM, et al. The myoepithelial immunophenotype in 135 benign and malignant salivary gland tumors other than pleomorphic adenoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:801-806.

- Savera AT, Sloman A, Huvos AG, et al. Myoepithelial carcinoma of the salivary glands. a clinicopathologic study of 25 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:761-774.

- Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Myoepithelial tumors of soft tissue: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 101 cases with evaluation of prognostic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1183-1196.

- Kilpatrick SE, Hitchcock MG, Kraus MD, et al. Mixed tumors and myoepitheliomas of soft tissue: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases with a unifying concept. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:13-22.

- Neto AG, Pineda-Daboin K, Luna MA. Myoepithelioma of the soft tissue of the head and neck: a case report and review of the literature. Head Neck. 2004;26:470-473.

- Kutzner H, Mentzel T, Kaddu S, et al. Cutaneous myoepithelioma: an under-recognized cutaneous neoplasm composed of myoepithelial cells. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:348-355.

- Dix BT, Hentges MJ, Saltrick KR, et al. Cutaneous myoepithelioma in the foot: case report. Foot Ankle Spec. 2013;6:239-241.

- Burke T, Sahin A, Johnson DE, et al. Myoepithelioma of the retroperitoneum. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1995;19:269-274.

- Fernandez-Figueras MT, Puig L, Trias I, et al. Benign myoepithelioma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:208-212.

- Bahrami A, Dalton JD, Krane JF, et al. A subset of cutaneous and soft tissue mixed tumors are genetically linked to their salivary gland counterpart. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:140-148.

- Panagopoulos I, Mertens F, Isaksson M, et al. Molecular genetic characterization of the EWS/CHN and RBP56/CHN fusion genes in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;35:340-352.

- Graham RP, Weiss SW, Sukov WR, et al. PHF1 rearrangements in ossifying fibromyxoid tumors of soft parts: a fluorescence in situ hybridization study of 41 cases with emphasis on the malignant variant. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1751-1755.

- Dabska M. Parachordoma: a new clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1977;40:1586-1592.

- Fletcher CDM, Mertens F, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2002.

- Lauer SR, Edgar MA, Gardner JM, et al. Soft tissue chordomas: a clinicopathologic analysis of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:719-726.

- Miller TD, McCalmont T, Tope WD. Recurrent cutaneous myoepithelioma treated using Mohs micrographic surgery: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:139-143.

- Gleason BC, Fletcher CD. Myoepithelial carcinoma of soft tissue in children: an aggressive neoplasm analyzed in a series of 29 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1813-1824.

- Noronha V, Cooper DL, Higgins SA, et al. Metastatic myoepithelial carcinoma of the vulva treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:270-271.

- Bisogno G, Tagarelli A, Schiavetti A, et al. Myoepithelial carcinoma treatment in children: a report from the TREP project. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:643-646.

- He DQ, Hua CG, Tang XF, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from a parotid myoepithelial carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1138-1143.

Cutaneous myoepithelial tumors are rare neoplasms but are being increasingly recognized and reported in the literature.1-7 Myoepithelial tumors are related to benign mixed tumors of the skin but lack the epithelial ductules that are present in mixed tumors. Cutaneous myoepithelial tumors may show a variety of architectural, cytological, and stromal features. Their immunophenotype usually is characterized by coexpression of an epithelial marker (eg, keratin, epithelial membrane antigen [EMA]) and S-100 protein; they also may express a variety of other myoepithelial markers, including keratins, smooth muscle actin, calponin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, p63, and desmin.7 EWS RNA binding protein 1 (EWSR1) and pleomorphic adenoma gene 1 (PLAG1) gene rearrangement has been detected in subsets of these tumors on in situ hybridization.8-10

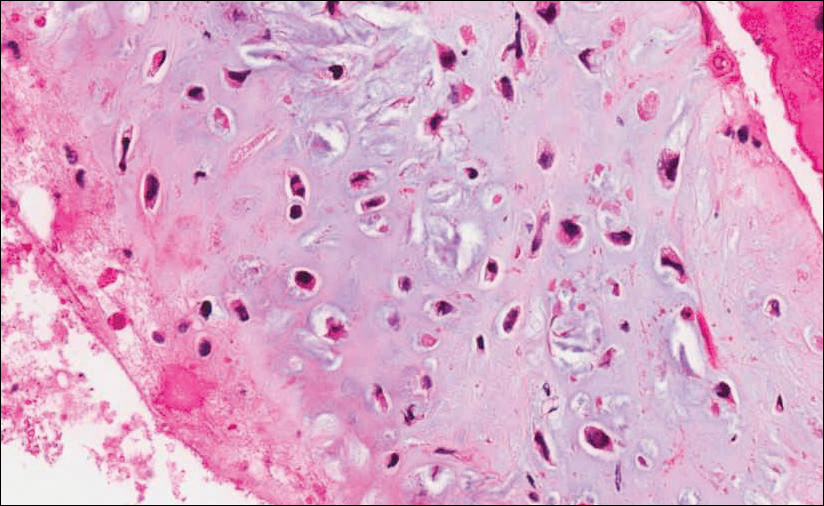

Malignant myoepithelial tumors of the skin, also referred to as cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas, are exceedingly rare. Including the current case, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE and Google Scholar using the terms myoepithelial carcinoma and cutaneous revealed 12 cases that have been reported in the literature (Table).1-7,11-13 These tumors often occur in the head and neck areas and the lower extremities and display a bimodal age distribution, generally occurring in patients younger than 21 years and older than 50 years of age; they also show a slight female predominance. Available follow-up data from the literature have shown local recurrence or metastasis in 3 cases3,4,6; however, in one case the metastatic focus was not histologically identified.4 Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma presenting with metastatic disease further limits treatment options. Here, we describe a case of metastatic cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma in a 47-year-old man, a rare example of cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma with histologically documented metastatic disease at the initial presentation.

Case Report

A 47-year-old man who underwent a renal transplant 19 years prior presented with a weeping, ulcerated, mildly tender lesion on the scalp of 4 months’ duration with neck and back pain of 3 months’ duration. Physical examination demonstrated a 6-cm area of ulceration on the anterior crown of the scalp with adjacent enlarged keratoacanthomalike craters and satellite nodules (Figure 1). He was previously diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp at an outside institution 4 years prior and was treated with radiation therapy. The prior scalp biopsy for BCC diagnosis was unavailable for review. The patient had a history of chronic eczematous dermatitis in the waistband area that had been present for 19 years and another BCC with nodular and infiltrative patterns on the left helix. Of note, he also had been taking long-term immunosuppressant medications (ie, cyclosporine, azathioprine) for maintenance following the renal transplant.

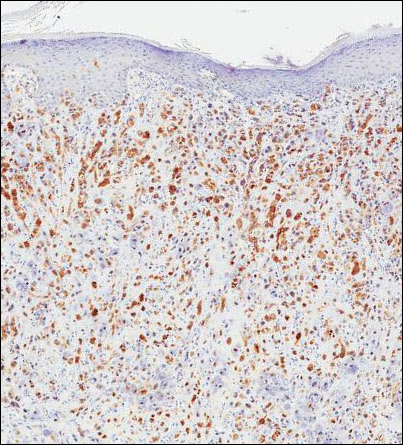

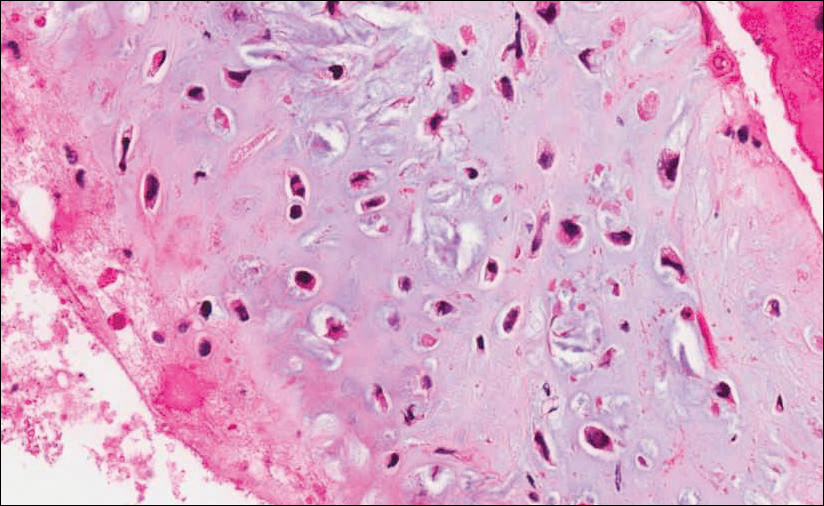

Because of the extensive ulceration of the primary lesion, a shave biopsy of the scalp was performed on an adjacent satellite nodule. Histopathologic findings showed an intradermal neoplasm characterized by poorly cohesive cells exhibiting epithelioid to plasmacytoid morphologic features surrounded by abundant chondromyxoid stroma. Ductular differentiation was not identified (Figure 2A). The neoplastic cells displayed hyperchromatic nuclei with marked nuclear pleomorphism and atypical mitotic figures (Figure 2B). On immunohistochemistry the tumor cells stained positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (Figure 3), S-100 protein (Figure 4), and p63, and were negative for calponin, desmin, melan-A, cytokeratin 7, and brachyury (Figure 5).

Radiographic imaging was performed due to the patient’s history of neck and back pain. Magnetic resonance imaging showed innumerable slightly expansile, T1-hypointense, T2-hyperintense, and robustly enhancing lesions involving the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spine, as well as the thoracic ribs and bilateral iliac bones. There was no evidence of soft tissue tumor around the bone lesions. Ventral cervical spinal cord compression was detected at the C4 vertebra, causing a symptomatic radiculopathy; however, due to widely metastatic disease, the patient was not considered appropriate for neurosurgical intervention of the compression. Computerized tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not identify any visceral source of malignancy, though multiple bilaterally enlarged cervical lymph nodes were identified on magnetic resonance imaging.

Fine needle aspiration of a left iliac bone lesion demonstrated neoplastic cells and chondromyxoid stroma essentially identical to the features shown in the skin biopsy (Figure 6). Given the morphologic features of the tumor and coexpression of cytokeratin and S-100 protein, the findings were interpreted as primary cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma with disseminated metastatic lesions. The patient began treatment with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy. To combat the symptomatic bone pain and upper extremity radiculopathy, palliative radiation was administered to the cervical spine, lumbar spine, and right sacrum (30 Gy to each site in 10 fractions at 3 Gy per fraction). Despite the attempted chemotherapy and radiation, the patient continued to decline, and after 2 months, he elected to pursue palliative care. The patient died after 3 months in palliative care (5 months after the initial presentation).

Comment

Myoepithelial cells normally surround ducts in secretory organs, such as the breasts, salivary glands, and cutaneous sweat glands. Myoepithelial neoplasms are well recognized in the salivary glands14,15; however, myoepithelial neoplasms also can arise in other sites, including the soft tissue4,5,16-18 and skin.1-3,7,11,19,20 Myoepithelioma of soft tissue was first described by Burke et al21 in 1995 and later described in the skin by Fernandez-Figueras et al22 in 1998. Since then, diagnostic criteria for cutaneous myoepithelial neoplasms have evolved, suggesting a spectrum of disease rather than a single distinct entity.11 Most often, cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas arise as soft nodular lesions in the head and neck areas or extremities of adults. The nodules typically are nontender and range in size from 0.5 to 18.0 cm. Our review of the literature revealed 11 additional cases of cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas have been reported, ranging in size from 0.7 to 7.0 cm (Table). In our case, the main lesion was 6 cm, mildly tender, ulcerated, and accompanied by satellite nodules.

Histologically, cutaneous myoepithelial tumors typically are well-defined, dermal-based nodules with no connection to the overlying epidermis. Similar to myoepithelial tumors of other sites, they can be diagnostically challenging due to the heterogeneity of both their architectural and cytological features. The presence of a chondromyxoid or hyalinized stroma is common but not always present. Neoplastic myoepithelial cells can exhibit spindled, epithelioid, plasmacytoid, or clear cell morphologic features and show growth patterns in clusters, cords, glands, or sheets. Focal epithelial cells can be present. Although benign myoepithelial neoplasms with overt ductal differentiation are consistent with cutaneous mixed tumors (chondroid syringomas), those without ducts are characterized as myoepitheliomas. It is uncertain if cases with only focal ductal differentiation should be classified as mixed tumors or as myoepitheliomas. Malignant myoepithelial tumors show infiltrative borders, nuclear pleomorphism, coarse nuclear chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and increased mitotic activity. A 2003 study by Hornick and Fletcher16 found that cytologic atypia was the primary predictor of malignant behavior for myoepithelial neoplasms of the soft tissue.

Despite a wide variety of expression patterns, immunohistochemistry is critical in demonstrating myoepithelial differentiation and establishing a diagnosis of a myoepithelial neoplasm. Most cases display coexpression of epithelial markers, including keratins and/or EMA as well as S-100 protein. Myogenic markers also may be variably expressed; however, the absence of myogenic markers does not exclude the diagnosis of a myoepithelial tumor. Commonly expressed epithelial markers are cytokeratin AE1/AE3, cytokeratin 8/18, and EMA, while commonly expressed myogenic markers include muscle specific actin and smooth muscle actin.5,7,11,19 Myoepithelial tumors also may express calponin, p63, and glial fibrillary acidic protein.16

Molecular studies also can aid in the diagnosis of myoepithelial tumors. A study by Antonescu et al8 demonstrated EWSR1 gene rearrangement in 45% (30/66) of extrasalivary myoepithelial tumors and the absence of EWSR1 gene rearrangement in salivary gland myoepithelial tumors. The authors also showed that EWSR1-negative tumors were more likely to be superficially located, display ductal differentiation, and possess a benign clinical course.8 In another study, Bahrami et al23 suggested that a subset of mixed tumors, specifically those with tubuloductal differentiation, are genetically linked to salivary gland pleomorphic adenomas, which was achieved by the coexpression of the PLAG1 protein and PLAG1 gene rearrangement on immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), respectively. Of the 19 cases evaluated, 11 (58%) expressed nuclear staining for PLAG1 immunohistochemistry; 8 of those 11 showed positive gene rearrangement for PLAG1 using FISH. These findings raise the possibility that cutaneous mixed tumors may be more closely related to those of the salivary glands, while deep myoepithelial tumors that lack ductal differentiation may represent a distinct group. Similar to the study by Antonescu et al,8 Flucke et al10 investigated EWSR1 gene rearrangement but limited their sample to cutaneous tumors, including myoepitheliomas, mixed tumors, and myoepithelial carcinoma. The authors found that 44% of cases (7/16) expressed EWSR1; this expression suggests that cutaneous myoepithelial tumors may have a genetic relationship to their soft tissue, bone, and visceral counterparts.10

Myoepithelial tumors display a broad spectrum of morphologic features; however, one of the most common growth patterns is that of oval to round cells forming cords and chains in a chondromyxoid stroma. As such, the histopathologic differential diagnosis for myoepithelial tumors includes other epithelioid or round-cell neoplasms with similar growth patterns including extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (EMC), ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts, and extra-axial soft tissue chordoma. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma bears the closest similarity to myoepithelial tumors both histologically and by ancillary studies. It typically possesses cords or chains of small round tumor cells set in a chondromyxoid or myxoid background. In contrast to myoepithelial tumors, which typically have more abundant cytoplasm and can show at least focal areas of spindle cell growth, the cells of EMC are more uniform, small, round cells with relatively scant cytoplasm. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcomas lack the typical myoepithelial coexpression of cytokeratin and S-100 protein, with a minority of EMCs expressing S-100 protein but rarely cytokeratin. Most cases of EMC possess a balanced t(9;22) translocation involving the EWSR1 gene,24 a finding that could lead to confusion with soft tissue myoepithelial tumors, which also may show EWSR1 rearrangement on FISH. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts is also composed of round cells arranged in cords in a myxoid or fibrous stroma; the majority of cases also display a peripheral rim of mature bone, a feature that is not typically seen in myoepithelial tumors. Similar to myoepithelial tumors, ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts often is positive for S-100 protein; however, it rarely is positive for cytokeratins. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts has been shown to have a rearrangement of the PHD finger protein 1 (PHF1) gene in approximately half of cases, a molecular finding that has not been reported for myoepithelial tumors.25 Finally, extra-axial soft tissue chordomas, though quite rare, may possess striking similarities to myoepithelial tumors both histopathologically and immunohistochemically. Chordomas are composed of epithelioid cells arranged in nests, nodules, and chains with a variably myxoid background. A variable amount of cells with bubbly cytoplasm (known as physaliphorous cells) can be seen. High mitotic activity is not a characteristic feature in chordomas. They classically coexpress cytokeratins and S-100 protein, similar to myoepithelial tumors.

Because cutaneous myoepithelial tumors are relatively rare, a well-defined standard of care for treatment is lacking. Surgical excision is the primary treatment method in most reported cases in the literature.17,19 Miller et al29 reported the successful treatment of recurrent cutaneous myoepitheliomas with Mohs micrographic surgery. Chemotherapy may be useful in the setting of metastatic myoepithelial carcinomas in adults, but reported results are inconsistent.30,31 Radiation treatment of recurrent or metastatic disease has not been shown to be effective. A study of children treated with surgical resection and chemotherapy using ifosfamide, cisplatin, and etoposide followed by radiation therapy showed positive results.32

Our case highlights several challenges that may arise in establishing a diagnosis of cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma with disseminated metastases. The diagnostic difficulty in our case was compounded by the advanced nature of the lesion at the time of presentation. Given the rarity of metastatic cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas and the lack of a prior primary diagnosis of a malignant myoepithelioma, the index of suspicion for this entity was not high. A report of myoepithelial carcinoma of the parotid gland metastatic to the skin has been reported,33 but in the absence of salivary gland involvement or other visceral lesions, metastasis from any source other than our patient’s cutaneous scalp lesion is unlikely. The histopathologic features in combination with the characteristic immunophenotype, unique clinical setting, and radiographic findings were essential to arriving at the correct diagnosis. Unlike previously reported metastatic lesions, our case is unique in that metastatic lesions were identified at the time of initial clinical presentation.

Conclusion

Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas are exceedingly rare tumors with a wide range of histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings. In challenging cases, studies for EWSR1 or PLAG1 gene rearrangement can be helpful. Furthermore, this case illustrates the potential for widespread dissemination of myoepithelial carcinomas requiring clinical evaluation and imaging studies to exclude metastatic lesions.

Cutaneous myoepithelial tumors are rare neoplasms but are being increasingly recognized and reported in the literature.1-7 Myoepithelial tumors are related to benign mixed tumors of the skin but lack the epithelial ductules that are present in mixed tumors. Cutaneous myoepithelial tumors may show a variety of architectural, cytological, and stromal features. Their immunophenotype usually is characterized by coexpression of an epithelial marker (eg, keratin, epithelial membrane antigen [EMA]) and S-100 protein; they also may express a variety of other myoepithelial markers, including keratins, smooth muscle actin, calponin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, p63, and desmin.7 EWS RNA binding protein 1 (EWSR1) and pleomorphic adenoma gene 1 (PLAG1) gene rearrangement has been detected in subsets of these tumors on in situ hybridization.8-10

Malignant myoepithelial tumors of the skin, also referred to as cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas, are exceedingly rare. Including the current case, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE and Google Scholar using the terms myoepithelial carcinoma and cutaneous revealed 12 cases that have been reported in the literature (Table).1-7,11-13 These tumors often occur in the head and neck areas and the lower extremities and display a bimodal age distribution, generally occurring in patients younger than 21 years and older than 50 years of age; they also show a slight female predominance. Available follow-up data from the literature have shown local recurrence or metastasis in 3 cases3,4,6; however, in one case the metastatic focus was not histologically identified.4 Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma presenting with metastatic disease further limits treatment options. Here, we describe a case of metastatic cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma in a 47-year-old man, a rare example of cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma with histologically documented metastatic disease at the initial presentation.

Case Report

A 47-year-old man who underwent a renal transplant 19 years prior presented with a weeping, ulcerated, mildly tender lesion on the scalp of 4 months’ duration with neck and back pain of 3 months’ duration. Physical examination demonstrated a 6-cm area of ulceration on the anterior crown of the scalp with adjacent enlarged keratoacanthomalike craters and satellite nodules (Figure 1). He was previously diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp at an outside institution 4 years prior and was treated with radiation therapy. The prior scalp biopsy for BCC diagnosis was unavailable for review. The patient had a history of chronic eczematous dermatitis in the waistband area that had been present for 19 years and another BCC with nodular and infiltrative patterns on the left helix. Of note, he also had been taking long-term immunosuppressant medications (ie, cyclosporine, azathioprine) for maintenance following the renal transplant.

Because of the extensive ulceration of the primary lesion, a shave biopsy of the scalp was performed on an adjacent satellite nodule. Histopathologic findings showed an intradermal neoplasm characterized by poorly cohesive cells exhibiting epithelioid to plasmacytoid morphologic features surrounded by abundant chondromyxoid stroma. Ductular differentiation was not identified (Figure 2A). The neoplastic cells displayed hyperchromatic nuclei with marked nuclear pleomorphism and atypical mitotic figures (Figure 2B). On immunohistochemistry the tumor cells stained positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (Figure 3), S-100 protein (Figure 4), and p63, and were negative for calponin, desmin, melan-A, cytokeratin 7, and brachyury (Figure 5).

Radiographic imaging was performed due to the patient’s history of neck and back pain. Magnetic resonance imaging showed innumerable slightly expansile, T1-hypointense, T2-hyperintense, and robustly enhancing lesions involving the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spine, as well as the thoracic ribs and bilateral iliac bones. There was no evidence of soft tissue tumor around the bone lesions. Ventral cervical spinal cord compression was detected at the C4 vertebra, causing a symptomatic radiculopathy; however, due to widely metastatic disease, the patient was not considered appropriate for neurosurgical intervention of the compression. Computerized tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not identify any visceral source of malignancy, though multiple bilaterally enlarged cervical lymph nodes were identified on magnetic resonance imaging.

Fine needle aspiration of a left iliac bone lesion demonstrated neoplastic cells and chondromyxoid stroma essentially identical to the features shown in the skin biopsy (Figure 6). Given the morphologic features of the tumor and coexpression of cytokeratin and S-100 protein, the findings were interpreted as primary cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma with disseminated metastatic lesions. The patient began treatment with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy. To combat the symptomatic bone pain and upper extremity radiculopathy, palliative radiation was administered to the cervical spine, lumbar spine, and right sacrum (30 Gy to each site in 10 fractions at 3 Gy per fraction). Despite the attempted chemotherapy and radiation, the patient continued to decline, and after 2 months, he elected to pursue palliative care. The patient died after 3 months in palliative care (5 months after the initial presentation).

Comment

Myoepithelial cells normally surround ducts in secretory organs, such as the breasts, salivary glands, and cutaneous sweat glands. Myoepithelial neoplasms are well recognized in the salivary glands14,15; however, myoepithelial neoplasms also can arise in other sites, including the soft tissue4,5,16-18 and skin.1-3,7,11,19,20 Myoepithelioma of soft tissue was first described by Burke et al21 in 1995 and later described in the skin by Fernandez-Figueras et al22 in 1998. Since then, diagnostic criteria for cutaneous myoepithelial neoplasms have evolved, suggesting a spectrum of disease rather than a single distinct entity.11 Most often, cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas arise as soft nodular lesions in the head and neck areas or extremities of adults. The nodules typically are nontender and range in size from 0.5 to 18.0 cm. Our review of the literature revealed 11 additional cases of cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas have been reported, ranging in size from 0.7 to 7.0 cm (Table). In our case, the main lesion was 6 cm, mildly tender, ulcerated, and accompanied by satellite nodules.

Histologically, cutaneous myoepithelial tumors typically are well-defined, dermal-based nodules with no connection to the overlying epidermis. Similar to myoepithelial tumors of other sites, they can be diagnostically challenging due to the heterogeneity of both their architectural and cytological features. The presence of a chondromyxoid or hyalinized stroma is common but not always present. Neoplastic myoepithelial cells can exhibit spindled, epithelioid, plasmacytoid, or clear cell morphologic features and show growth patterns in clusters, cords, glands, or sheets. Focal epithelial cells can be present. Although benign myoepithelial neoplasms with overt ductal differentiation are consistent with cutaneous mixed tumors (chondroid syringomas), those without ducts are characterized as myoepitheliomas. It is uncertain if cases with only focal ductal differentiation should be classified as mixed tumors or as myoepitheliomas. Malignant myoepithelial tumors show infiltrative borders, nuclear pleomorphism, coarse nuclear chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and increased mitotic activity. A 2003 study by Hornick and Fletcher16 found that cytologic atypia was the primary predictor of malignant behavior for myoepithelial neoplasms of the soft tissue.

Despite a wide variety of expression patterns, immunohistochemistry is critical in demonstrating myoepithelial differentiation and establishing a diagnosis of a myoepithelial neoplasm. Most cases display coexpression of epithelial markers, including keratins and/or EMA as well as S-100 protein. Myogenic markers also may be variably expressed; however, the absence of myogenic markers does not exclude the diagnosis of a myoepithelial tumor. Commonly expressed epithelial markers are cytokeratin AE1/AE3, cytokeratin 8/18, and EMA, while commonly expressed myogenic markers include muscle specific actin and smooth muscle actin.5,7,11,19 Myoepithelial tumors also may express calponin, p63, and glial fibrillary acidic protein.16

Molecular studies also can aid in the diagnosis of myoepithelial tumors. A study by Antonescu et al8 demonstrated EWSR1 gene rearrangement in 45% (30/66) of extrasalivary myoepithelial tumors and the absence of EWSR1 gene rearrangement in salivary gland myoepithelial tumors. The authors also showed that EWSR1-negative tumors were more likely to be superficially located, display ductal differentiation, and possess a benign clinical course.8 In another study, Bahrami et al23 suggested that a subset of mixed tumors, specifically those with tubuloductal differentiation, are genetically linked to salivary gland pleomorphic adenomas, which was achieved by the coexpression of the PLAG1 protein and PLAG1 gene rearrangement on immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), respectively. Of the 19 cases evaluated, 11 (58%) expressed nuclear staining for PLAG1 immunohistochemistry; 8 of those 11 showed positive gene rearrangement for PLAG1 using FISH. These findings raise the possibility that cutaneous mixed tumors may be more closely related to those of the salivary glands, while deep myoepithelial tumors that lack ductal differentiation may represent a distinct group. Similar to the study by Antonescu et al,8 Flucke et al10 investigated EWSR1 gene rearrangement but limited their sample to cutaneous tumors, including myoepitheliomas, mixed tumors, and myoepithelial carcinoma. The authors found that 44% of cases (7/16) expressed EWSR1; this expression suggests that cutaneous myoepithelial tumors may have a genetic relationship to their soft tissue, bone, and visceral counterparts.10

Myoepithelial tumors display a broad spectrum of morphologic features; however, one of the most common growth patterns is that of oval to round cells forming cords and chains in a chondromyxoid stroma. As such, the histopathologic differential diagnosis for myoepithelial tumors includes other epithelioid or round-cell neoplasms with similar growth patterns including extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (EMC), ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts, and extra-axial soft tissue chordoma. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma bears the closest similarity to myoepithelial tumors both histologically and by ancillary studies. It typically possesses cords or chains of small round tumor cells set in a chondromyxoid or myxoid background. In contrast to myoepithelial tumors, which typically have more abundant cytoplasm and can show at least focal areas of spindle cell growth, the cells of EMC are more uniform, small, round cells with relatively scant cytoplasm. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcomas lack the typical myoepithelial coexpression of cytokeratin and S-100 protein, with a minority of EMCs expressing S-100 protein but rarely cytokeratin. Most cases of EMC possess a balanced t(9;22) translocation involving the EWSR1 gene,24 a finding that could lead to confusion with soft tissue myoepithelial tumors, which also may show EWSR1 rearrangement on FISH. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts is also composed of round cells arranged in cords in a myxoid or fibrous stroma; the majority of cases also display a peripheral rim of mature bone, a feature that is not typically seen in myoepithelial tumors. Similar to myoepithelial tumors, ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts often is positive for S-100 protein; however, it rarely is positive for cytokeratins. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts has been shown to have a rearrangement of the PHD finger protein 1 (PHF1) gene in approximately half of cases, a molecular finding that has not been reported for myoepithelial tumors.25 Finally, extra-axial soft tissue chordomas, though quite rare, may possess striking similarities to myoepithelial tumors both histopathologically and immunohistochemically. Chordomas are composed of epithelioid cells arranged in nests, nodules, and chains with a variably myxoid background. A variable amount of cells with bubbly cytoplasm (known as physaliphorous cells) can be seen. High mitotic activity is not a characteristic feature in chordomas. They classically coexpress cytokeratins and S-100 protein, similar to myoepithelial tumors.

Because cutaneous myoepithelial tumors are relatively rare, a well-defined standard of care for treatment is lacking. Surgical excision is the primary treatment method in most reported cases in the literature.17,19 Miller et al29 reported the successful treatment of recurrent cutaneous myoepitheliomas with Mohs micrographic surgery. Chemotherapy may be useful in the setting of metastatic myoepithelial carcinomas in adults, but reported results are inconsistent.30,31 Radiation treatment of recurrent or metastatic disease has not been shown to be effective. A study of children treated with surgical resection and chemotherapy using ifosfamide, cisplatin, and etoposide followed by radiation therapy showed positive results.32

Our case highlights several challenges that may arise in establishing a diagnosis of cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma with disseminated metastases. The diagnostic difficulty in our case was compounded by the advanced nature of the lesion at the time of presentation. Given the rarity of metastatic cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas and the lack of a prior primary diagnosis of a malignant myoepithelioma, the index of suspicion for this entity was not high. A report of myoepithelial carcinoma of the parotid gland metastatic to the skin has been reported,33 but in the absence of salivary gland involvement or other visceral lesions, metastasis from any source other than our patient’s cutaneous scalp lesion is unlikely. The histopathologic features in combination with the characteristic immunophenotype, unique clinical setting, and radiographic findings were essential to arriving at the correct diagnosis. Unlike previously reported metastatic lesions, our case is unique in that metastatic lesions were identified at the time of initial clinical presentation.

Conclusion

Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas are exceedingly rare tumors with a wide range of histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings. In challenging cases, studies for EWSR1 or PLAG1 gene rearrangement can be helpful. Furthermore, this case illustrates the potential for widespread dissemination of myoepithelial carcinomas requiring clinical evaluation and imaging studies to exclude metastatic lesions.

- Frost MW, Steiniche T, Damsgaard TE, et al. Primary cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. APMIS. 2014;122:369-379.

- Stojsic Z, Brasanac D, Boricic I, et al. Clear cell myoepithelial carcinoma of the skin. a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:680-683.

- Tanahashi J, Kashima K, Daa T, et al. A case of cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:648-653.

- Michal M, Miettinen M. Myoepitheliomas of the skin and soft tissues. report of 12 cases. Virchows Arch. 1999;434:393-400.

- Gleason BC, Fletcher CD. Myoepithelial carcinoma of soft tissue in children: an aggressive neoplasm analyzed in a series of 29 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1813-1824.

- Law RM, Viglione MP, Barrett TL. Metastatic myoepithelial carcinoma in a child. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:779-781.

- Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Cutaneous myoepithelioma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 14 cases. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:14-24.

- Antonescu CR, Zhang L, Chang NE, et al. EWSR1-POU5F1 fusion in soft tissue myoepithelial tumors. a molecular analysis of sixty-six cases, including soft tissue, bone, and visceral lesions, showing common involvement of the EWSR1 gene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:1114-1124.

- Antonescu CR, Zhang L, Shao SY, et al. Frequent PLAG1 gene rearrangements in skin and soft tissue myoepithelioma with ductal differentiation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;52:675-682.

- Flucke U, Palmedo G, Blankenhorn N, et al. EWSR1 gene rearrangement occurs in a subset of cutaneous myoepithelial tumors: a study of 18 cases. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1444-1450.

- Mentzel T, Requena L, Kaddu S, et al. Cutaneous myoepithelial neoplasms: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 20 cases suggesting a continuous spectrum ranging from benign mixed tumor of the skin to cutaneous myoepithelioma and myoepithelial carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:294-302.

- Garcia-Sanchez S, Elices M, Nieto S. Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma (malignant myoepithelial tumor of skin). Virchows Archiv. 2009;455(suppl 1):1-482.

- Bajoghli A, Limpert J. Treatment of cutaneous malignant myoepithelioma on the nasal ala using Mohs micrographic surgery in a two and a half year old child. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:S44.

- Prasad AR, Savera AT, Gown AM, et al. The myoepithelial immunophenotype in 135 benign and malignant salivary gland tumors other than pleomorphic adenoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:801-806.

- Savera AT, Sloman A, Huvos AG, et al. Myoepithelial carcinoma of the salivary glands. a clinicopathologic study of 25 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:761-774.

- Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Myoepithelial tumors of soft tissue: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 101 cases with evaluation of prognostic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1183-1196.

- Kilpatrick SE, Hitchcock MG, Kraus MD, et al. Mixed tumors and myoepitheliomas of soft tissue: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases with a unifying concept. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:13-22.

- Neto AG, Pineda-Daboin K, Luna MA. Myoepithelioma of the soft tissue of the head and neck: a case report and review of the literature. Head Neck. 2004;26:470-473.

- Kutzner H, Mentzel T, Kaddu S, et al. Cutaneous myoepithelioma: an under-recognized cutaneous neoplasm composed of myoepithelial cells. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:348-355.

- Dix BT, Hentges MJ, Saltrick KR, et al. Cutaneous myoepithelioma in the foot: case report. Foot Ankle Spec. 2013;6:239-241.

- Burke T, Sahin A, Johnson DE, et al. Myoepithelioma of the retroperitoneum. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1995;19:269-274.

- Fernandez-Figueras MT, Puig L, Trias I, et al. Benign myoepithelioma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:208-212.

- Bahrami A, Dalton JD, Krane JF, et al. A subset of cutaneous and soft tissue mixed tumors are genetically linked to their salivary gland counterpart. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:140-148.

- Panagopoulos I, Mertens F, Isaksson M, et al. Molecular genetic characterization of the EWS/CHN and RBP56/CHN fusion genes in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;35:340-352.

- Graham RP, Weiss SW, Sukov WR, et al. PHF1 rearrangements in ossifying fibromyxoid tumors of soft parts: a fluorescence in situ hybridization study of 41 cases with emphasis on the malignant variant. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1751-1755.

- Dabska M. Parachordoma: a new clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1977;40:1586-1592.

- Fletcher CDM, Mertens F, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2002.

- Lauer SR, Edgar MA, Gardner JM, et al. Soft tissue chordomas: a clinicopathologic analysis of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:719-726.

- Miller TD, McCalmont T, Tope WD. Recurrent cutaneous myoepithelioma treated using Mohs micrographic surgery: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:139-143.

- Gleason BC, Fletcher CD. Myoepithelial carcinoma of soft tissue in children: an aggressive neoplasm analyzed in a series of 29 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1813-1824.

- Noronha V, Cooper DL, Higgins SA, et al. Metastatic myoepithelial carcinoma of the vulva treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:270-271.

- Bisogno G, Tagarelli A, Schiavetti A, et al. Myoepithelial carcinoma treatment in children: a report from the TREP project. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:643-646.

- He DQ, Hua CG, Tang XF, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from a parotid myoepithelial carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1138-1143.

- Frost MW, Steiniche T, Damsgaard TE, et al. Primary cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. APMIS. 2014;122:369-379.

- Stojsic Z, Brasanac D, Boricic I, et al. Clear cell myoepithelial carcinoma of the skin. a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:680-683.

- Tanahashi J, Kashima K, Daa T, et al. A case of cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:648-653.

- Michal M, Miettinen M. Myoepitheliomas of the skin and soft tissues. report of 12 cases. Virchows Arch. 1999;434:393-400.

- Gleason BC, Fletcher CD. Myoepithelial carcinoma of soft tissue in children: an aggressive neoplasm analyzed in a series of 29 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1813-1824.

- Law RM, Viglione MP, Barrett TL. Metastatic myoepithelial carcinoma in a child. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:779-781.

- Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Cutaneous myoepithelioma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 14 cases. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:14-24.

- Antonescu CR, Zhang L, Chang NE, et al. EWSR1-POU5F1 fusion in soft tissue myoepithelial tumors. a molecular analysis of sixty-six cases, including soft tissue, bone, and visceral lesions, showing common involvement of the EWSR1 gene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:1114-1124.

- Antonescu CR, Zhang L, Shao SY, et al. Frequent PLAG1 gene rearrangements in skin and soft tissue myoepithelioma with ductal differentiation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;52:675-682.

- Flucke U, Palmedo G, Blankenhorn N, et al. EWSR1 gene rearrangement occurs in a subset of cutaneous myoepithelial tumors: a study of 18 cases. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1444-1450.

- Mentzel T, Requena L, Kaddu S, et al. Cutaneous myoepithelial neoplasms: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 20 cases suggesting a continuous spectrum ranging from benign mixed tumor of the skin to cutaneous myoepithelioma and myoepithelial carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:294-302.

- Garcia-Sanchez S, Elices M, Nieto S. Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma (malignant myoepithelial tumor of skin). Virchows Archiv. 2009;455(suppl 1):1-482.

- Bajoghli A, Limpert J. Treatment of cutaneous malignant myoepithelioma on the nasal ala using Mohs micrographic surgery in a two and a half year old child. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:S44.

- Prasad AR, Savera AT, Gown AM, et al. The myoepithelial immunophenotype in 135 benign and malignant salivary gland tumors other than pleomorphic adenoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:801-806.

- Savera AT, Sloman A, Huvos AG, et al. Myoepithelial carcinoma of the salivary glands. a clinicopathologic study of 25 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:761-774.

- Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Myoepithelial tumors of soft tissue: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 101 cases with evaluation of prognostic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1183-1196.

- Kilpatrick SE, Hitchcock MG, Kraus MD, et al. Mixed tumors and myoepitheliomas of soft tissue: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases with a unifying concept. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:13-22.

- Neto AG, Pineda-Daboin K, Luna MA. Myoepithelioma of the soft tissue of the head and neck: a case report and review of the literature. Head Neck. 2004;26:470-473.

- Kutzner H, Mentzel T, Kaddu S, et al. Cutaneous myoepithelioma: an under-recognized cutaneous neoplasm composed of myoepithelial cells. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:348-355.

- Dix BT, Hentges MJ, Saltrick KR, et al. Cutaneous myoepithelioma in the foot: case report. Foot Ankle Spec. 2013;6:239-241.

- Burke T, Sahin A, Johnson DE, et al. Myoepithelioma of the retroperitoneum. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1995;19:269-274.

- Fernandez-Figueras MT, Puig L, Trias I, et al. Benign myoepithelioma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:208-212.

- Bahrami A, Dalton JD, Krane JF, et al. A subset of cutaneous and soft tissue mixed tumors are genetically linked to their salivary gland counterpart. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:140-148.

- Panagopoulos I, Mertens F, Isaksson M, et al. Molecular genetic characterization of the EWS/CHN and RBP56/CHN fusion genes in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;35:340-352.

- Graham RP, Weiss SW, Sukov WR, et al. PHF1 rearrangements in ossifying fibromyxoid tumors of soft parts: a fluorescence in situ hybridization study of 41 cases with emphasis on the malignant variant. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1751-1755.

- Dabska M. Parachordoma: a new clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1977;40:1586-1592.

- Fletcher CDM, Mertens F, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2002.

- Lauer SR, Edgar MA, Gardner JM, et al. Soft tissue chordomas: a clinicopathologic analysis of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:719-726.

- Miller TD, McCalmont T, Tope WD. Recurrent cutaneous myoepithelioma treated using Mohs micrographic surgery: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:139-143.

- Gleason BC, Fletcher CD. Myoepithelial carcinoma of soft tissue in children: an aggressive neoplasm analyzed in a series of 29 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1813-1824.

- Noronha V, Cooper DL, Higgins SA, et al. Metastatic myoepithelial carcinoma of the vulva treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:270-271.

- Bisogno G, Tagarelli A, Schiavetti A, et al. Myoepithelial carcinoma treatment in children: a report from the TREP project. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:643-646.

- He DQ, Hua CG, Tang XF, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from a parotid myoepithelial carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1138-1143.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma is a rare malignant adnexal neoplasm with metastatic potential that can present in the skin.

- Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma is a tumor that can occasionally show EWSR1 gene rearrangement.

- Excision with negative margins and close follow-up is recommended for cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma.

Completeness of Facial Self-application of Sunscreen in Cosmetic Surgery Patients

UV radiation from sun exposure is a risk factor for most types of skin cancer.1 Despite comprising only 1% of the body's surface area, the periocular region is the location of approximately 5% to 10% of skin cancers described in one US study.2 The efficacy of sunscreen in preventing skin cancer is widely accepted, and the American Academy of Dermatology recommends application of broad-spectrum UVA/UVB sunscreen with a sun protection factor of 30 or higher to help prevent skin cancer.3-5

RELATED ARTICLE: Sun Protection for Infants: Parent Behaviors and Beliefs

Reducing the risk of skin cancer from sun exposure relies on many factors, including completeness of application. A number of studies have demonstrated incomplete sunscreen application on the hairline, ears, neck, and dorsal feet.6-8 The purpose of this study was to assess the completeness of facial sunscreen self-application in oculofacial surgery patients using UV photography.

Methods

This single-site, cross-sectional, qualitative study assessed the completeness of facial sunscreen self-application among patients from a single surgeon's (J.A.W.) cosmetic and tertiary-care oculofacial surgery practice at the Duke Eye Center (Durham, North Carolina) between March 2016 and May 2016. Approval from the Duke University institutional review board was obtained, and the research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Informed consent was obtained from all patients, and patients could elect to provide specific written consent for publication of photographs in scientific presentations and publications. Patients younger than 18 years of age; those with known sensitivity to sunscreen or its ingredients; and those with an active lesion, rash, or open wound were excluded from the study.

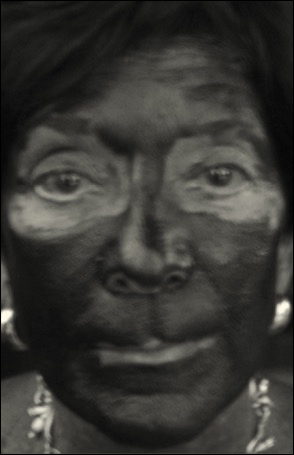

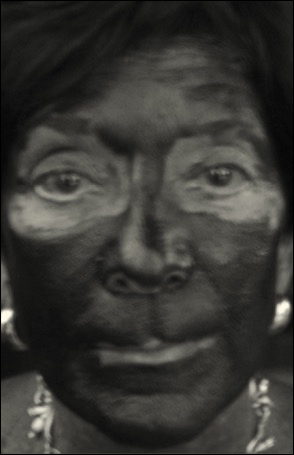

After obtaining informed consent, patients were photographed using a camera with a UV lens in natural outdoor lighting, first without sunscreen and again after self-application of a sunscreen of their choosing using their routine application technique. Completeness of sunscreen application was graded independently by 3 oculofacial surgeons (N.A.L., J.L., J.A.W.) as complete, partial, none, or cannot determine for 15 facial regions. The majority response was used for analysis.

Results

Forty-four patients were enrolled in the study. Six patients were disqualified due to use of mineral-based formulations (zinc oxide and/or titanium dioxide), as these sunscreens could not be visualized using UV photography. The age range of the remaining 38 patients was 28 to 74 years; 26% (10/38) were men and 74% (28/38) were women.

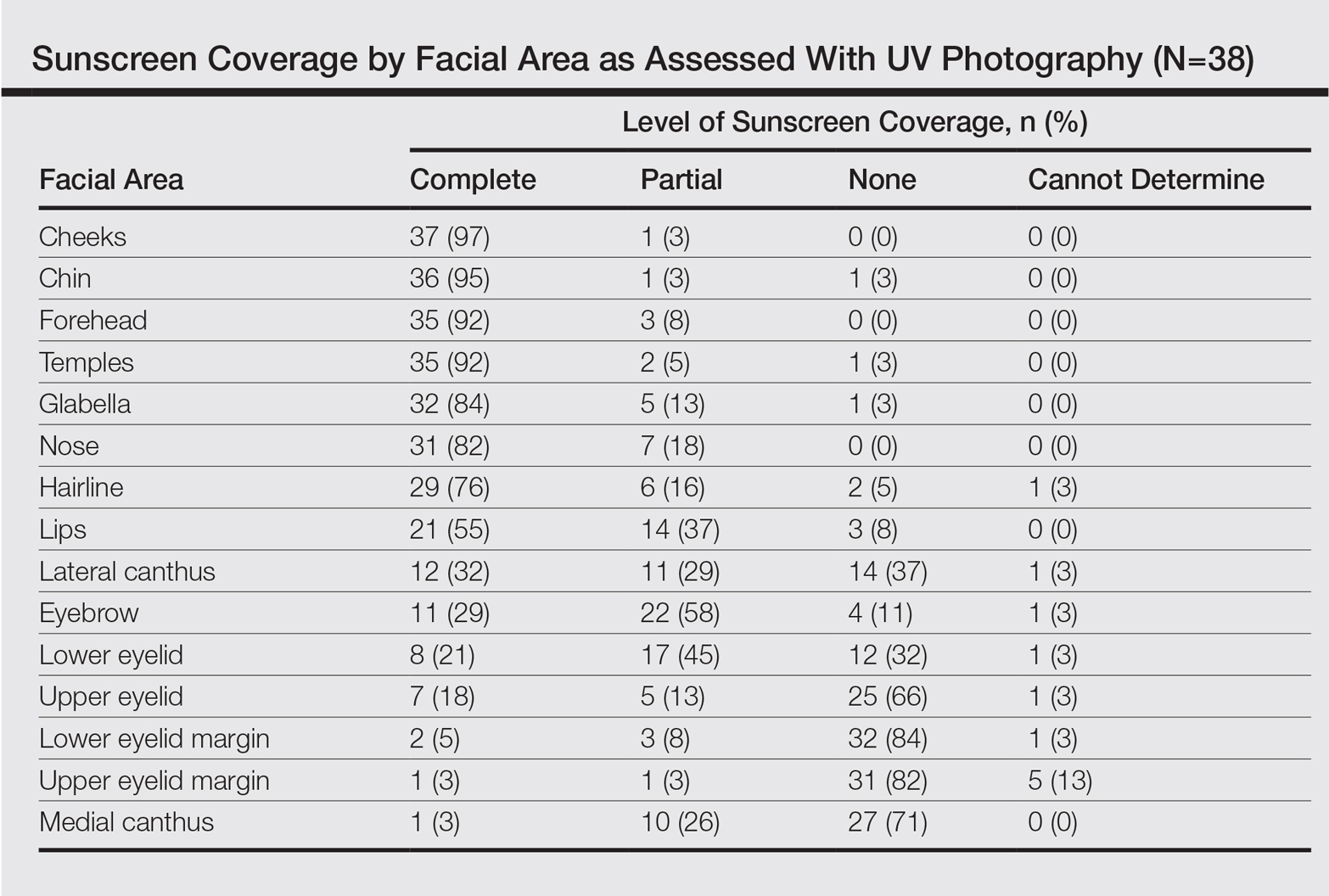

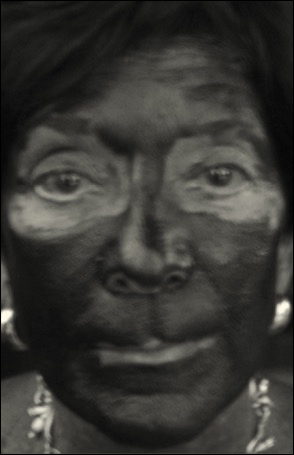

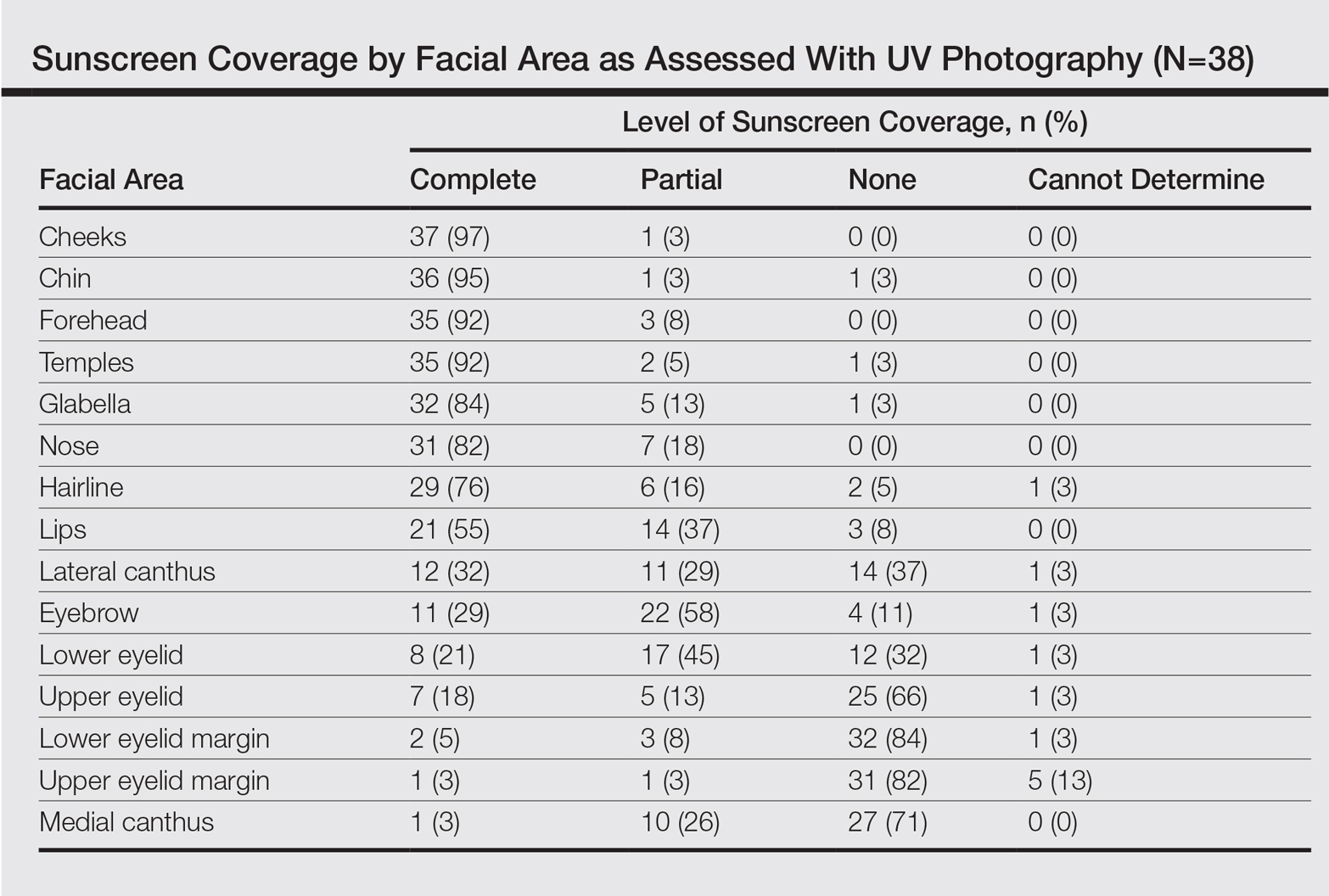

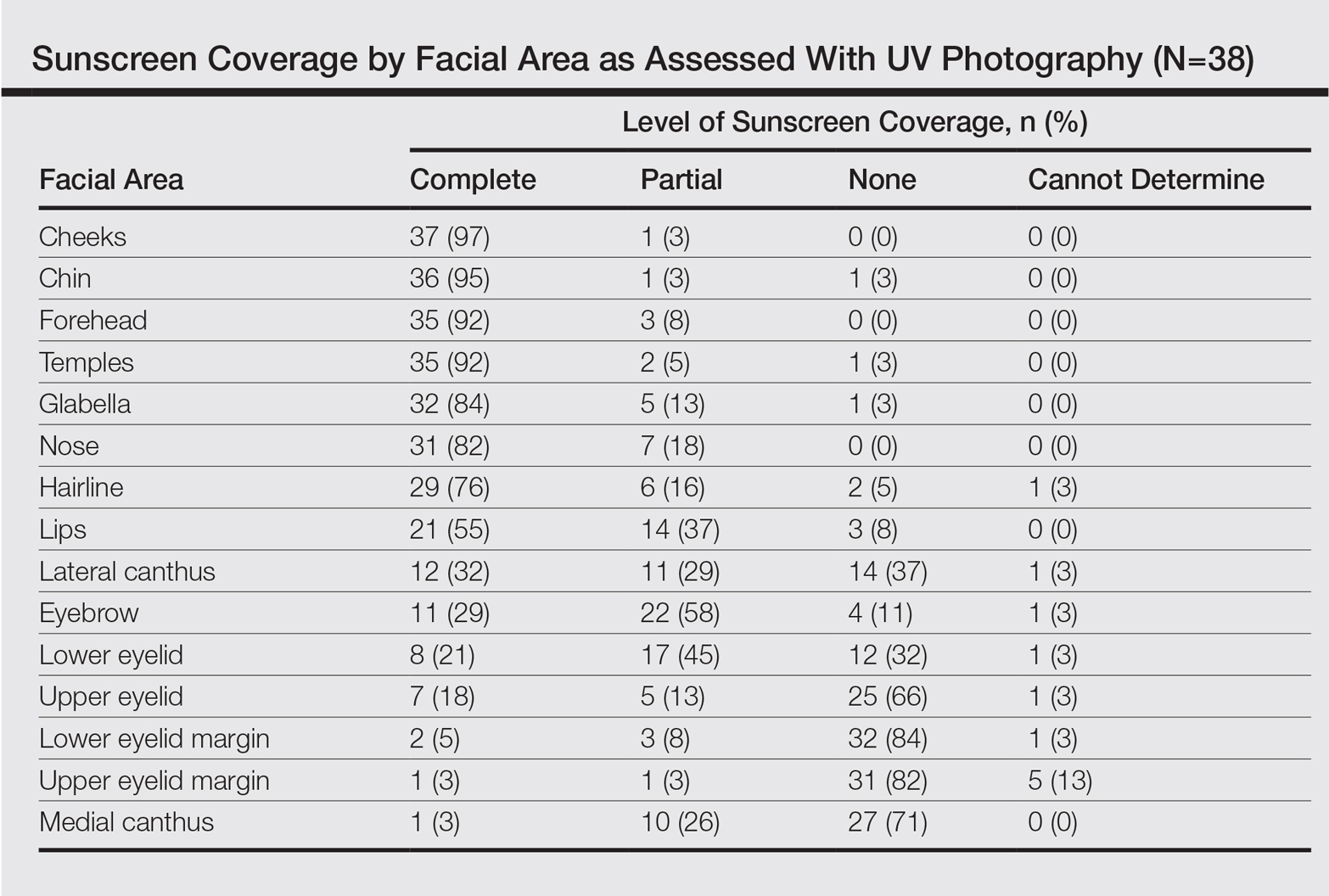

Complete sunscreen application was most frequently performed on the cheeks (97% [37/38]), chin (95% [36/38]), forehead (92% [35/38]), and temples (92% [35/38]). Complete absence of sunscreen coverage was most common on the lower eyelid margin (84% [32/38]), upper eyelid margin (82% [31/38]), medial canthus (71% 27/38]), and upper eyelid (66% [25/38])(Table)(Figure).

Comment

UV radiation-related skin cancers frequently occur in the periocular area, presumably because it is a frequent site of UV exposure. Clothing, sunglasses, and hats can be used to aid in protection from UV radiation, but these products are only regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration if the product claims to prevent skin cancer. Sunscreen is a proven method of protection from UV radiation and the prevention of skin cancer but must be properly applied for it to be effective.1,2,5,6 Incomplete sunscreen application has been demonstrated in numerous studies. Lademann et al7 studied sunscreen application among 60 beachgoers in Germany and found they typically missed the hairline, ears, and dorsal feet. In a study of 10 women with photosensitivity in England who were asked to apply sunscreen in their routine manner, Azurdia et al6 found the posterior neck, lateral neck, temples, and ears, respectively, were the most frequently missed sites. Yang et al8 assessed sunscreen application in 39 dermatologists and 41 photosensitive patients in China and found the neck, ears, dorsal hands, hairline, temples, and perioral region, respectively, were most commonly left unprotected.

Our study investigated detailed facial self-application of sunscreen and found excellent coverage of the larger facial units such as the forehead, cheeks, chin, and temples. The brow, medial canthus, lateral canthus, and upper and lower eyelids and eyelid margins were infrequently protected with sunscreen during routine application. Our opinion is that patients are unaware that eyelid sunscreen application is important. They may be afraid that the products will sting or cause damage if they get in the eyes. Although some products do sting if they get into the eyes, there is no evidence that sunscreens cause injury to the eyes. The US Food and Drug Administration does not have clear guidelines about applying sunscreens in the periocular area, but in general, mineral blocks are recommended because they have less chance of irritation. Several companies make such products that are designed to be applied to the eyelids.

Limitations of our study included a small sample size and a majority female demographic, which may have affected the results, as women generally are more familiar with the application of lotions to the face. Additionally, the patients were recruited from a tertiary-care clinic and may have had periocular malignancy or may have previously received counseling on the importance of sunscreen use.

Conclusion

Cancer reconstruction of the periocular area is challenging, and even in the best of hands, a patient's quality of life may be negatively affected by postreconstructive appearance or suboptimal function, resulting in ocular exposure. The authors recommend counseling patients on the importance of good sun protection habits, including daily application of sunscreen to the face and periocular region to prevent malignancy in these delicate areas.

- Olsen CM, Wilson LF, Green AC, et al. Cancers inAustralia attributable to exposure to solar ultraviolet radiation and prevented by regular sunscreen use. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2015;39:471-476.

- Cook BE Jr, Bartley GB. Epidemiologic characteristics and clinical course of patients with malignant eyelid tumors in an incidence cohort in an incidence cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:746-750.

- van de Pols JC, Williams GM, Pandeye N, et al. Prolonged prevention of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin by regular sunscreen use. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Preven. 2006;15:2546-2548.

- Skin Cancer Foundation. Basal cell carcinoma prevention guidelines. http://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/basal-cell-carcinoma/bcc-prevention-guidelines. Accessed May 24, 2017.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Basal cell carcinoma: tips for managing. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/skin-cancer/basal-cell-carcinoma#tips. Accessed May 24, 2017.

- Azurdia RM, Pagliaro JA, Diffey BL, et al. Sunscreen application by photosensitive patients is inadequate for protection. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:255-258.

- Lademann J, Schanzer S, Richter H, et al. Sunscreen application at the beach. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2004;3:62-68.

- Yang HP, Chen K, Chang BZ, et al. A study of the way in which dermatologists and photosensitive patients apply sunscreen in China. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2009;25:245-249.

UV radiation from sun exposure is a risk factor for most types of skin cancer.1 Despite comprising only 1% of the body's surface area, the periocular region is the location of approximately 5% to 10% of skin cancers described in one US study.2 The efficacy of sunscreen in preventing skin cancer is widely accepted, and the American Academy of Dermatology recommends application of broad-spectrum UVA/UVB sunscreen with a sun protection factor of 30 or higher to help prevent skin cancer.3-5

RELATED ARTICLE: Sun Protection for Infants: Parent Behaviors and Beliefs

Reducing the risk of skin cancer from sun exposure relies on many factors, including completeness of application. A number of studies have demonstrated incomplete sunscreen application on the hairline, ears, neck, and dorsal feet.6-8 The purpose of this study was to assess the completeness of facial sunscreen self-application in oculofacial surgery patients using UV photography.

Methods

This single-site, cross-sectional, qualitative study assessed the completeness of facial sunscreen self-application among patients from a single surgeon's (J.A.W.) cosmetic and tertiary-care oculofacial surgery practice at the Duke Eye Center (Durham, North Carolina) between March 2016 and May 2016. Approval from the Duke University institutional review board was obtained, and the research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Informed consent was obtained from all patients, and patients could elect to provide specific written consent for publication of photographs in scientific presentations and publications. Patients younger than 18 years of age; those with known sensitivity to sunscreen or its ingredients; and those with an active lesion, rash, or open wound were excluded from the study.

After obtaining informed consent, patients were photographed using a camera with a UV lens in natural outdoor lighting, first without sunscreen and again after self-application of a sunscreen of their choosing using their routine application technique. Completeness of sunscreen application was graded independently by 3 oculofacial surgeons (N.A.L., J.L., J.A.W.) as complete, partial, none, or cannot determine for 15 facial regions. The majority response was used for analysis.

Results

Forty-four patients were enrolled in the study. Six patients were disqualified due to use of mineral-based formulations (zinc oxide and/or titanium dioxide), as these sunscreens could not be visualized using UV photography. The age range of the remaining 38 patients was 28 to 74 years; 26% (10/38) were men and 74% (28/38) were women.

Complete sunscreen application was most frequently performed on the cheeks (97% [37/38]), chin (95% [36/38]), forehead (92% [35/38]), and temples (92% [35/38]). Complete absence of sunscreen coverage was most common on the lower eyelid margin (84% [32/38]), upper eyelid margin (82% [31/38]), medial canthus (71% 27/38]), and upper eyelid (66% [25/38])(Table)(Figure).

Comment

UV radiation-related skin cancers frequently occur in the periocular area, presumably because it is a frequent site of UV exposure. Clothing, sunglasses, and hats can be used to aid in protection from UV radiation, but these products are only regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration if the product claims to prevent skin cancer. Sunscreen is a proven method of protection from UV radiation and the prevention of skin cancer but must be properly applied for it to be effective.1,2,5,6 Incomplete sunscreen application has been demonstrated in numerous studies. Lademann et al7 studied sunscreen application among 60 beachgoers in Germany and found they typically missed the hairline, ears, and dorsal feet. In a study of 10 women with photosensitivity in England who were asked to apply sunscreen in their routine manner, Azurdia et al6 found the posterior neck, lateral neck, temples, and ears, respectively, were the most frequently missed sites. Yang et al8 assessed sunscreen application in 39 dermatologists and 41 photosensitive patients in China and found the neck, ears, dorsal hands, hairline, temples, and perioral region, respectively, were most commonly left unprotected.

Our study investigated detailed facial self-application of sunscreen and found excellent coverage of the larger facial units such as the forehead, cheeks, chin, and temples. The brow, medial canthus, lateral canthus, and upper and lower eyelids and eyelid margins were infrequently protected with sunscreen during routine application. Our opinion is that patients are unaware that eyelid sunscreen application is important. They may be afraid that the products will sting or cause damage if they get in the eyes. Although some products do sting if they get into the eyes, there is no evidence that sunscreens cause injury to the eyes. The US Food and Drug Administration does not have clear guidelines about applying sunscreens in the periocular area, but in general, mineral blocks are recommended because they have less chance of irritation. Several companies make such products that are designed to be applied to the eyelids.

Limitations of our study included a small sample size and a majority female demographic, which may have affected the results, as women generally are more familiar with the application of lotions to the face. Additionally, the patients were recruited from a tertiary-care clinic and may have had periocular malignancy or may have previously received counseling on the importance of sunscreen use.

Conclusion

Cancer reconstruction of the periocular area is challenging, and even in the best of hands, a patient's quality of life may be negatively affected by postreconstructive appearance or suboptimal function, resulting in ocular exposure. The authors recommend counseling patients on the importance of good sun protection habits, including daily application of sunscreen to the face and periocular region to prevent malignancy in these delicate areas.

UV radiation from sun exposure is a risk factor for most types of skin cancer.1 Despite comprising only 1% of the body's surface area, the periocular region is the location of approximately 5% to 10% of skin cancers described in one US study.2 The efficacy of sunscreen in preventing skin cancer is widely accepted, and the American Academy of Dermatology recommends application of broad-spectrum UVA/UVB sunscreen with a sun protection factor of 30 or higher to help prevent skin cancer.3-5

RELATED ARTICLE: Sun Protection for Infants: Parent Behaviors and Beliefs

Reducing the risk of skin cancer from sun exposure relies on many factors, including completeness of application. A number of studies have demonstrated incomplete sunscreen application on the hairline, ears, neck, and dorsal feet.6-8 The purpose of this study was to assess the completeness of facial sunscreen self-application in oculofacial surgery patients using UV photography.

Methods