User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Erratum

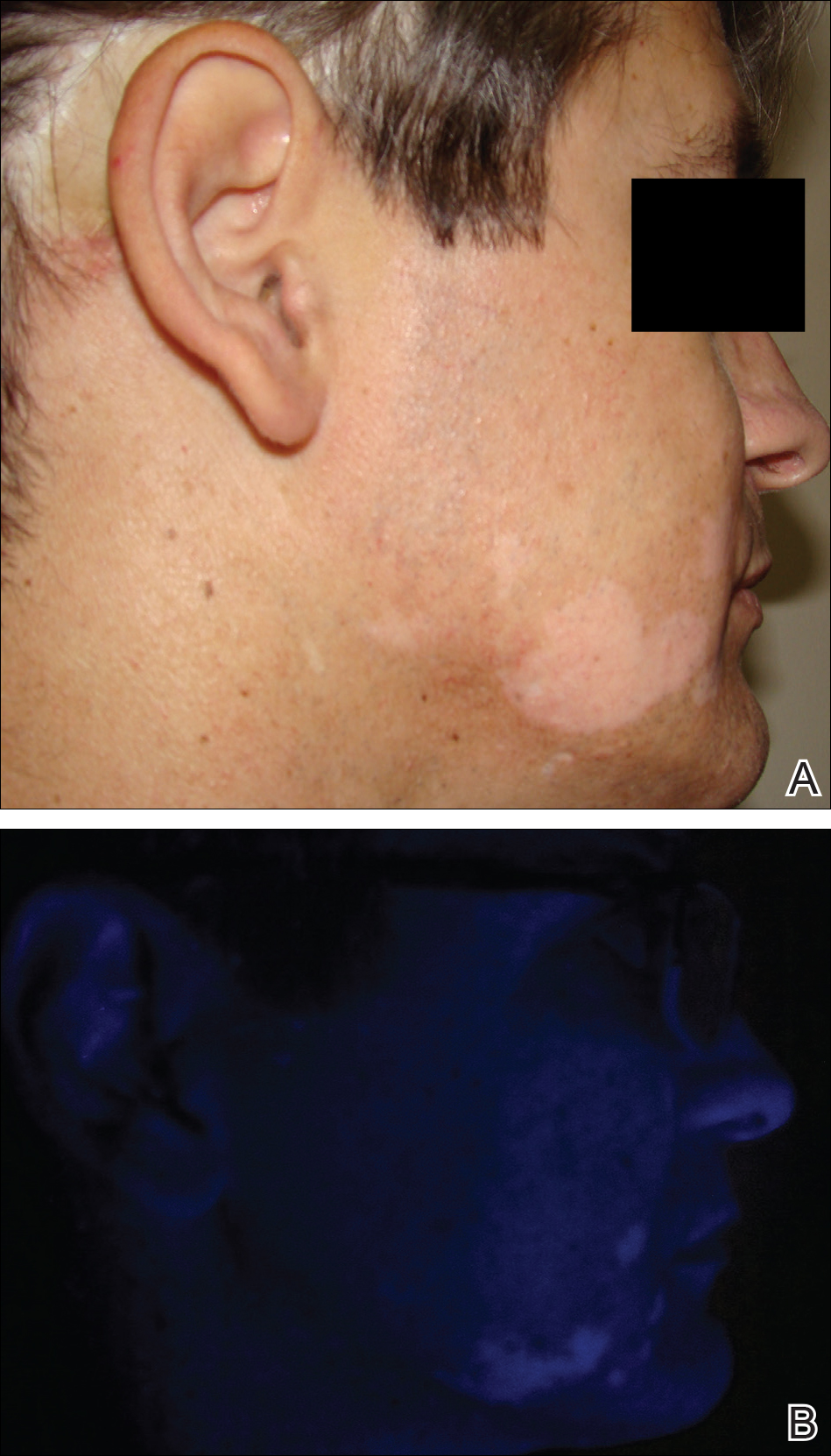

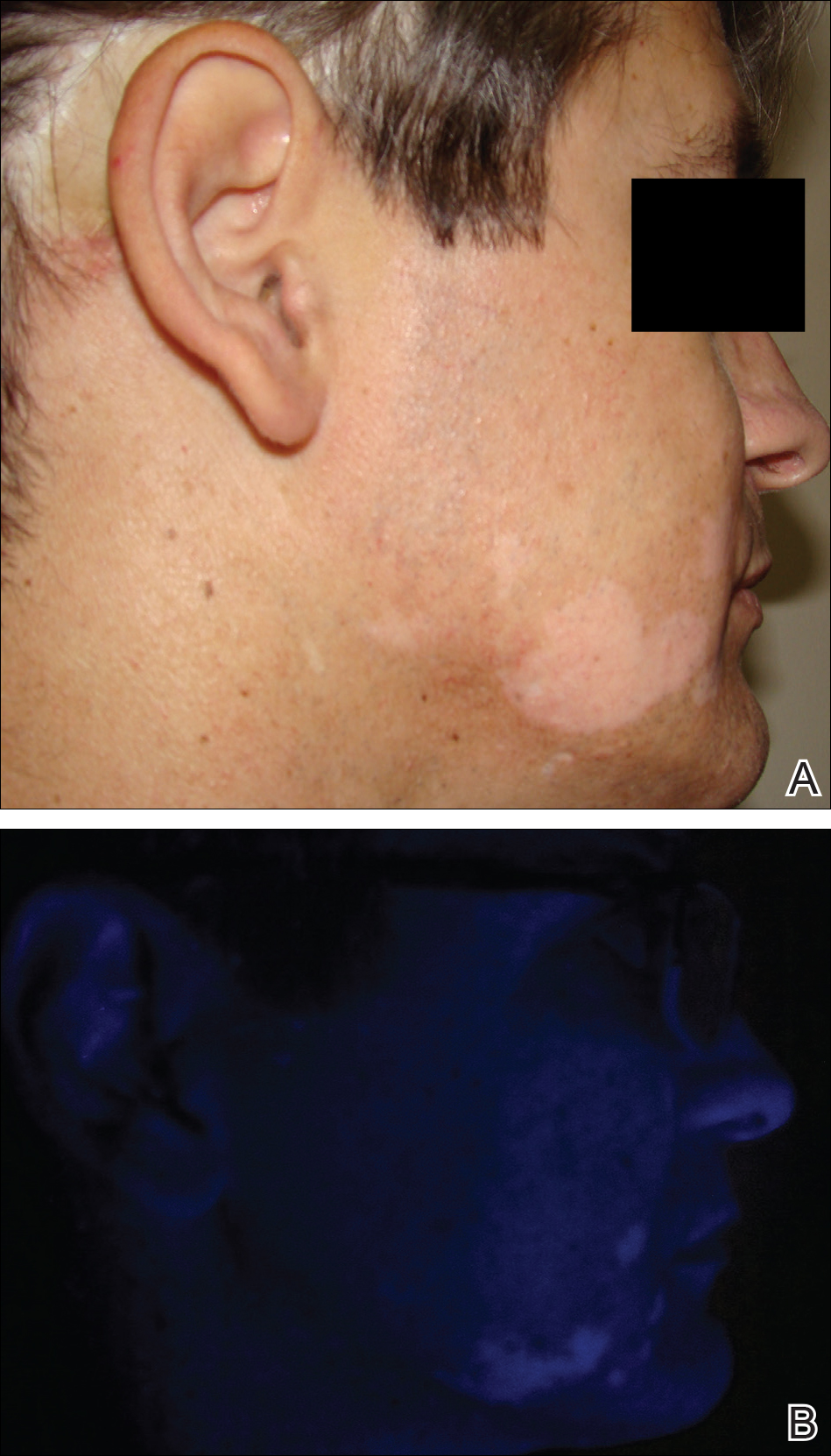

The article "Handheld Reflectance Confocal Microscopy to Aid in the Management of Complex Facial Lentigo Maligna" (Cutis. 2017;99:346-352) contained an error in the author affiliations. The affiliations should have read:

All from the Dermatology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York. Dr. Yélamos also is from the Dermatology Department, Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, Spain. Dr. Rossi also is from the Department of Dermatology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

The staff of Cutis® makes every possible effort to ensure accuracy in its articles and apologizes for the mistake.

The article "Handheld Reflectance Confocal Microscopy to Aid in the Management of Complex Facial Lentigo Maligna" (Cutis. 2017;99:346-352) contained an error in the author affiliations. The affiliations should have read:

All from the Dermatology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York. Dr. Yélamos also is from the Dermatology Department, Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, Spain. Dr. Rossi also is from the Department of Dermatology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

The staff of Cutis® makes every possible effort to ensure accuracy in its articles and apologizes for the mistake.

The article "Handheld Reflectance Confocal Microscopy to Aid in the Management of Complex Facial Lentigo Maligna" (Cutis. 2017;99:346-352) contained an error in the author affiliations. The affiliations should have read:

All from the Dermatology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York. Dr. Yélamos also is from the Dermatology Department, Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, Spain. Dr. Rossi also is from the Department of Dermatology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

The staff of Cutis® makes every possible effort to ensure accuracy in its articles and apologizes for the mistake.

Purpuric Lesions of the Scalp, Axillae, and Groin of an Infant

The Diagnosis: Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

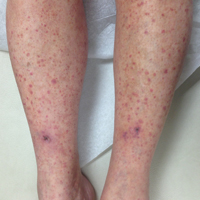

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a clonal proliferative disorder of Langerhans cells that can affect any organ, most commonly the skin and bones. It typically develops in children aged 1 to 3 years, with a male to female ratio of 2 to 1.1 Skin manifestations include purpuric papules, pustules, vesicles, erosions, and fissuring distributed predominantly on the scalp and flexural sites. Mucosal sites, particularly the oral mucosa, may be involved and usually present as erosions associated with underlying bone lesions.1 Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of recalcitrant diaper dermatitis in an infant, especially when there is purpura and erosions, as seen in our patient. Common conditions in infants such as cutaneous candidiasis (intense erythema with superficial erosions, peripheral scale and satellite pustules on flexural areas, potassium hydroxide microscopy revealing yeast forms and pseudohyphae) and seborrheic dermatitis (well-defined pink to red, moist, and often scaly patches favoring the folds) may be distinguished clinically from Hailey-Hailey disease (malodorous plaques with fissures and erosions favoring the folds), which is rare in infancy, and acrodermatitis enteropathica (erythema and erosions with scale-crust and desquamation on periorificial, acral, and intertriginous skin).

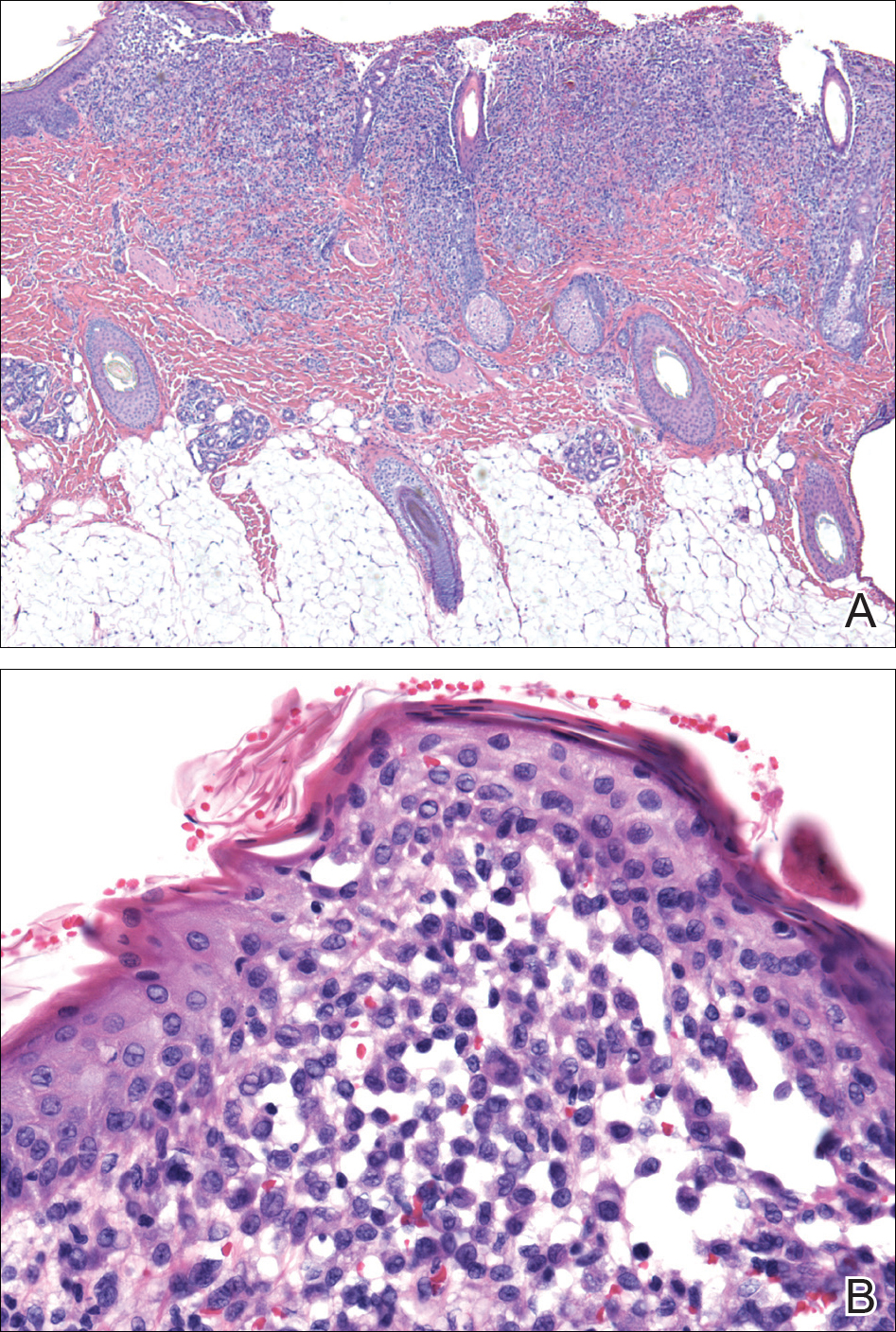

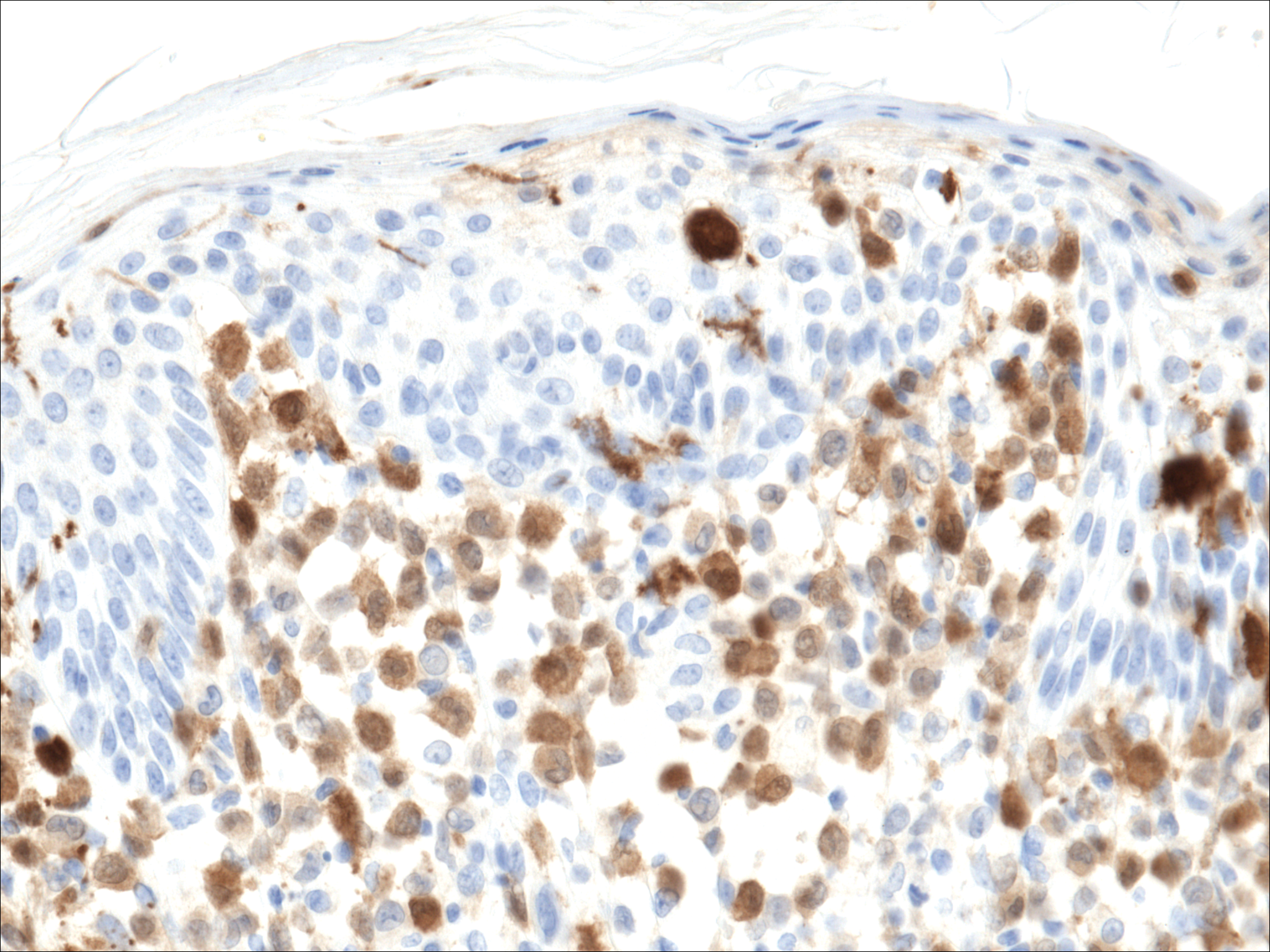

Histopathologic evaluation is instrumental in diagnosing the skin lesions of LCH. Further evaluation for systemic involvement is necessary once the diagnosis is made. Skin biopsy of the scalp and right inguinal fold revealed a wedge-shaped infiltrate of histiocytes with slightly folded nuclear contours in our patient (Figure 1). CD1a (Figure 2) and S-100 stains were markedly positive, which is characteristic of LCH. Complete blood cell count, renal function, liver function, urinalysis, and flow cytometry results were within reference range. A skeletal survey and echocardiogram were unremarkable; however, mild hepatosplenomegaly was noted on abdominal ultrasonography.

Treatment of LCH varies based on the extent of organ involvement. For isolated cutaneous disease, topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, phototherapy, and thalidomide may be employed.2 Multisystem disease requires chemotherapeutic agents including vinblastine and prednisone.2,3 Because more than half of patients with LCH have oncogenic BRAF V600E mutations,4 vemurafenib may have a therapeutic role in treatment. Rare case reports have documented disease response in patients with LCH and Erdheim-Chester disease.5,6

Prognosis varies based on age and extent of systemic involvement. Children younger than 2 years with multiorgan involvement have a poor prognosis (35%-55% mortality rate) compared to older children without hematopoietic, hepatosplenic, or lung involvement (100% survival rate). Additionally, response to treatment affects prognosis, as there is a 66% mortality rate in those who do not respond to treatment after 6 weeks.3 Long-term sequelae of LCH include endocrine dysfunction (ie, diabetes insipidus, growth hormone deficiencies), hearing impairment, orthopedic impairment, and neuropsychological disease; thus, multidisciplinary care often is neccessary.7

Given the multisystem involvement in our patient, he was treated with vinblastine, 6-mercaptopurine, and prednisolone with only partial and transient disease response. He was then treated with clofarabine with dramatic resolution of the mediastinal mass on follow-up positron emission tomography. The cutaneous lesions persisted and were managed with topical corticosteroids.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years [published online October 25, 2012]. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184.

- Gadner H, Grois N, Arico M, et al; Histiocyte Society. A randomized trial of treatment for multisystem Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2001;138:728-734.

- Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923.

- Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Emile JF, et al. Dramatic efficacy of vemurafenib in both multisystemic and refractory Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring the BRAF V600E mutation. Blood. 2013;121:1495-1500.

- Charles J, Beani JC, Fiandrino G, et al. Major response to vemurafenib in patient with severe cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring BRAF V600E mutation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E97-E99.

- Martin A, Macmillan S, Murphy D, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: 23 years' paediatric experience highlights severe long-term sequelae. Scott Med J. 2014;59:149-157.

The Diagnosis: Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a clonal proliferative disorder of Langerhans cells that can affect any organ, most commonly the skin and bones. It typically develops in children aged 1 to 3 years, with a male to female ratio of 2 to 1.1 Skin manifestations include purpuric papules, pustules, vesicles, erosions, and fissuring distributed predominantly on the scalp and flexural sites. Mucosal sites, particularly the oral mucosa, may be involved and usually present as erosions associated with underlying bone lesions.1 Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of recalcitrant diaper dermatitis in an infant, especially when there is purpura and erosions, as seen in our patient. Common conditions in infants such as cutaneous candidiasis (intense erythema with superficial erosions, peripheral scale and satellite pustules on flexural areas, potassium hydroxide microscopy revealing yeast forms and pseudohyphae) and seborrheic dermatitis (well-defined pink to red, moist, and often scaly patches favoring the folds) may be distinguished clinically from Hailey-Hailey disease (malodorous plaques with fissures and erosions favoring the folds), which is rare in infancy, and acrodermatitis enteropathica (erythema and erosions with scale-crust and desquamation on periorificial, acral, and intertriginous skin).

Histopathologic evaluation is instrumental in diagnosing the skin lesions of LCH. Further evaluation for systemic involvement is necessary once the diagnosis is made. Skin biopsy of the scalp and right inguinal fold revealed a wedge-shaped infiltrate of histiocytes with slightly folded nuclear contours in our patient (Figure 1). CD1a (Figure 2) and S-100 stains were markedly positive, which is characteristic of LCH. Complete blood cell count, renal function, liver function, urinalysis, and flow cytometry results were within reference range. A skeletal survey and echocardiogram were unremarkable; however, mild hepatosplenomegaly was noted on abdominal ultrasonography.

Treatment of LCH varies based on the extent of organ involvement. For isolated cutaneous disease, topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, phototherapy, and thalidomide may be employed.2 Multisystem disease requires chemotherapeutic agents including vinblastine and prednisone.2,3 Because more than half of patients with LCH have oncogenic BRAF V600E mutations,4 vemurafenib may have a therapeutic role in treatment. Rare case reports have documented disease response in patients with LCH and Erdheim-Chester disease.5,6

Prognosis varies based on age and extent of systemic involvement. Children younger than 2 years with multiorgan involvement have a poor prognosis (35%-55% mortality rate) compared to older children without hematopoietic, hepatosplenic, or lung involvement (100% survival rate). Additionally, response to treatment affects prognosis, as there is a 66% mortality rate in those who do not respond to treatment after 6 weeks.3 Long-term sequelae of LCH include endocrine dysfunction (ie, diabetes insipidus, growth hormone deficiencies), hearing impairment, orthopedic impairment, and neuropsychological disease; thus, multidisciplinary care often is neccessary.7

Given the multisystem involvement in our patient, he was treated with vinblastine, 6-mercaptopurine, and prednisolone with only partial and transient disease response. He was then treated with clofarabine with dramatic resolution of the mediastinal mass on follow-up positron emission tomography. The cutaneous lesions persisted and were managed with topical corticosteroids.

The Diagnosis: Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a clonal proliferative disorder of Langerhans cells that can affect any organ, most commonly the skin and bones. It typically develops in children aged 1 to 3 years, with a male to female ratio of 2 to 1.1 Skin manifestations include purpuric papules, pustules, vesicles, erosions, and fissuring distributed predominantly on the scalp and flexural sites. Mucosal sites, particularly the oral mucosa, may be involved and usually present as erosions associated with underlying bone lesions.1 Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of recalcitrant diaper dermatitis in an infant, especially when there is purpura and erosions, as seen in our patient. Common conditions in infants such as cutaneous candidiasis (intense erythema with superficial erosions, peripheral scale and satellite pustules on flexural areas, potassium hydroxide microscopy revealing yeast forms and pseudohyphae) and seborrheic dermatitis (well-defined pink to red, moist, and often scaly patches favoring the folds) may be distinguished clinically from Hailey-Hailey disease (malodorous plaques with fissures and erosions favoring the folds), which is rare in infancy, and acrodermatitis enteropathica (erythema and erosions with scale-crust and desquamation on periorificial, acral, and intertriginous skin).

Histopathologic evaluation is instrumental in diagnosing the skin lesions of LCH. Further evaluation for systemic involvement is necessary once the diagnosis is made. Skin biopsy of the scalp and right inguinal fold revealed a wedge-shaped infiltrate of histiocytes with slightly folded nuclear contours in our patient (Figure 1). CD1a (Figure 2) and S-100 stains were markedly positive, which is characteristic of LCH. Complete blood cell count, renal function, liver function, urinalysis, and flow cytometry results were within reference range. A skeletal survey and echocardiogram were unremarkable; however, mild hepatosplenomegaly was noted on abdominal ultrasonography.

Treatment of LCH varies based on the extent of organ involvement. For isolated cutaneous disease, topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, phototherapy, and thalidomide may be employed.2 Multisystem disease requires chemotherapeutic agents including vinblastine and prednisone.2,3 Because more than half of patients with LCH have oncogenic BRAF V600E mutations,4 vemurafenib may have a therapeutic role in treatment. Rare case reports have documented disease response in patients with LCH and Erdheim-Chester disease.5,6

Prognosis varies based on age and extent of systemic involvement. Children younger than 2 years with multiorgan involvement have a poor prognosis (35%-55% mortality rate) compared to older children without hematopoietic, hepatosplenic, or lung involvement (100% survival rate). Additionally, response to treatment affects prognosis, as there is a 66% mortality rate in those who do not respond to treatment after 6 weeks.3 Long-term sequelae of LCH include endocrine dysfunction (ie, diabetes insipidus, growth hormone deficiencies), hearing impairment, orthopedic impairment, and neuropsychological disease; thus, multidisciplinary care often is neccessary.7

Given the multisystem involvement in our patient, he was treated with vinblastine, 6-mercaptopurine, and prednisolone with only partial and transient disease response. He was then treated with clofarabine with dramatic resolution of the mediastinal mass on follow-up positron emission tomography. The cutaneous lesions persisted and were managed with topical corticosteroids.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years [published online October 25, 2012]. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184.

- Gadner H, Grois N, Arico M, et al; Histiocyte Society. A randomized trial of treatment for multisystem Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2001;138:728-734.

- Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923.

- Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Emile JF, et al. Dramatic efficacy of vemurafenib in both multisystemic and refractory Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring the BRAF V600E mutation. Blood. 2013;121:1495-1500.

- Charles J, Beani JC, Fiandrino G, et al. Major response to vemurafenib in patient with severe cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring BRAF V600E mutation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E97-E99.

- Martin A, Macmillan S, Murphy D, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: 23 years' paediatric experience highlights severe long-term sequelae. Scott Med J. 2014;59:149-157.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years [published online October 25, 2012]. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184.

- Gadner H, Grois N, Arico M, et al; Histiocyte Society. A randomized trial of treatment for multisystem Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2001;138:728-734.

- Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923.

- Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Emile JF, et al. Dramatic efficacy of vemurafenib in both multisystemic and refractory Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring the BRAF V600E mutation. Blood. 2013;121:1495-1500.

- Charles J, Beani JC, Fiandrino G, et al. Major response to vemurafenib in patient with severe cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring BRAF V600E mutation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E97-E99.

- Martin A, Macmillan S, Murphy D, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: 23 years' paediatric experience highlights severe long-term sequelae. Scott Med J. 2014;59:149-157.

A 7-month-old boy admitted to the hospital with new-onset respiratory stridor was found to have a rash of the scalp, axillae, and groin of 1 month's duration that was unresponsive to treatment with mineral oil. Bronchoscopy revealed tracheal compression, and urgent magnetic resonance imaging of the chest demonstrated an anterior mediastinal mass. Prior to presentation, the patient was otherwise healthy with normal growth and development. On physical examination, scattered red-brown and purpuric papules with hemorrhagic crust were noted on the scalp. There were well-defined pink erosive patches and purpuric papules in the inguinal folds bilaterally and similar erosive patches in the axillae. Numerous punched out ulcerations were noted on the lower gingiva. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy. The hands, feet, penis, scrotum, and perianal area were spared. Biopsies of the skin and mediastinal mass were performed.

Local Anesthetics in Cosmetic Dermatology

Local anesthesia is a central component of successful interventions in cosmetic dermatology. The number of anesthetic medications and administration techniques has grown in recent years as outpatient cosmetic procedures continue to expand. Pain is a common barrier to cosmetic procedures, and alleviating the fear of painful interventions is critical to patient satisfaction and future visits. To accommodate a multitude of cosmetic interventions, it is important for clinicians to be well versed in applications of topical and regional anesthesia. In this article, we review pain management strategies for use in cosmetic practice.

Local Anesthetics

The sensation of pain is carried to the central nervous system by unmyelinated C nerve fibers. Local anesthetics (LAs) act by blocking fast voltage-gated sodium channels in the cell membrane of the nerve, thereby inhibiting downstream propagation of an action potential and the transmission of painful stimuli.1 The chemical structure of LAs is fundamental to their mechanism of action and metabolism. Local anesthetics contain a lipophilic aromatic group, an intermediate chain, and a hydrophilic amine group. Broadly, agents are classified as amides or esters depending on the chemical group attached to the intermediate chain.2 Amides (eg, lidocaine, bupivacaine, articaine, mepivacaine, prilocaine, levobupivacaine) are metabolized by the hepatic system; esters (eg, procaine, proparacaine, benzocaine, chlorprocaine, tetracaine, cocaine) are metabolized by plasma cholinesterase, which produces para-aminobenzoic acid, a potentially dangerous metabolite that has been implicated in allergic reactions.3

Lidocaine is the most prevalent LA used in dermatology practices. Importantly, lidocaine is a class IB antiarrhythmic agent used in cardiology to treat ventricular arrhythmias.4 As an anesthetic, a maximum dose of 4.5 mg/kg can be administered, increasing to 7.0 mg/kg when mixed with epinephrine; with higher doses, there is a risk for central nervous system and cardiovascular toxicity.5 Initial symptoms of lidocaine toxicity include dizziness, tinnitus, circumoral paresthesia, blurred vision, and a metallic taste in the mouth.6 Systemic absorption of topical anesthetics is heightened across mucosal membranes, and care should be taken when applying over large surface areas.

Allergic reactions to LAs may be local or less frequently systemic. It is important to note that LAs tend to show cross-reactivity within their class rather than across different classes.7 Reactions can be classified as type I or type IV. Type I (IgE-mediated) reactions evolve in minutes to hours, affecting the skin and possibly leading to respiratory and circulatory collapse. Delayed reactions to LAs have increased in recent years, with type IV contact allergy most frequently found in connection with benzocaine and lidocaine.8

Topical Anesthesia

Topical anesthetics are effective and easy to use and are particularly valuable in patients with needle phobia. In certain cases, these medications may be applied by the patient prior to arrival, thereby reducing visit time. Topical agents act on nerve fibers running through the dermis; therefore, efficacy is dependent on successful penetration through the stratum corneum and viable epidermis. To enhance absorption, agents may be applied under an occlusive dressing.

Topical anesthetics are most commonly used for injectable fillers, ablative and nonablative laser resurfacing, laser hair removal, and tattoo removal. The eutectic mixture of 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine as well as topical 4% or 5% lidocaine are the most commonly used US Food and Drug Administration–approved products for topical anesthesia. In addition, several compounded pharmacy products are available.

After 60 minutes of application of the eutectic mixture of 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine, a 3-mm depth of analgesia is reached, and after 120 minutes, a 4.5-mm depth is reached.9 It elicits a biphasic vascular response of vasoconstriction and blanching followed by vasodilation and erythema.10 Most adverse events are mild and transient, but allergic contact dermatitis and contact urticaria have been reported.11-13 In older children and adults, the maximum application area is 200 cm2, with a maximum dose of 20 g used for no longer than 4 hours.

The 4% or 5% lidocaine cream uses a liposomal delivery system, which is designed to improve cutaneous penetration and has been shown to provide longer durations of anesthesia than nonliposomal lidocaine preparations.14 Application should be performed 30 to 60 minutes prior to a procedure. In a study comparing the eutectic mixture of 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine versus lidocaine cream 5% for pain control during laser hair removal with a 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser, no significant differences were found.15 The maximum application area is 100 cm2 in children weighing less than 20 kg. A study of healthy adults demonstrated safety with the use of 30 to 60 g of occluded liposomal lidocaine cream 4%.16

In addition to US Food and Drug Administration–approved products, several compounded pharmacy products are available for topical anesthesia. These formulations include benzocaine-lidocaine-tetracaine gel, tetracaine-adrenaline-cocaine solution, and lidocaine-epinephrine-tetracaine solution. A triple-anesthetic gel, benzocaine-lidocaine-tetracaine is widely used in cosmetic practice. The product has been shown to provide adequate anesthesia for laser resurfacing after 20 minutes without occlusion.17 Of note, compounded anesthetics lack standardization, and different pharmacies may follow their own individual protocols.

Regional Anesthesia

Regional nerve blockade is a useful option for more widespread or complex interventions. Using regional nerve blockade, effective analgesia can be delivered to a target area while avoiding the toxicity and pain associated with numerous anesthetic infiltrations. In addition, there is no distortion of the tissue architecture, allowing for improved visual evaluation during the procedure. Recently, hyaluronic acid fillers have been compounded with lidocaine as a means of reducing procedural pain.

Blocks for Dermal Fillers

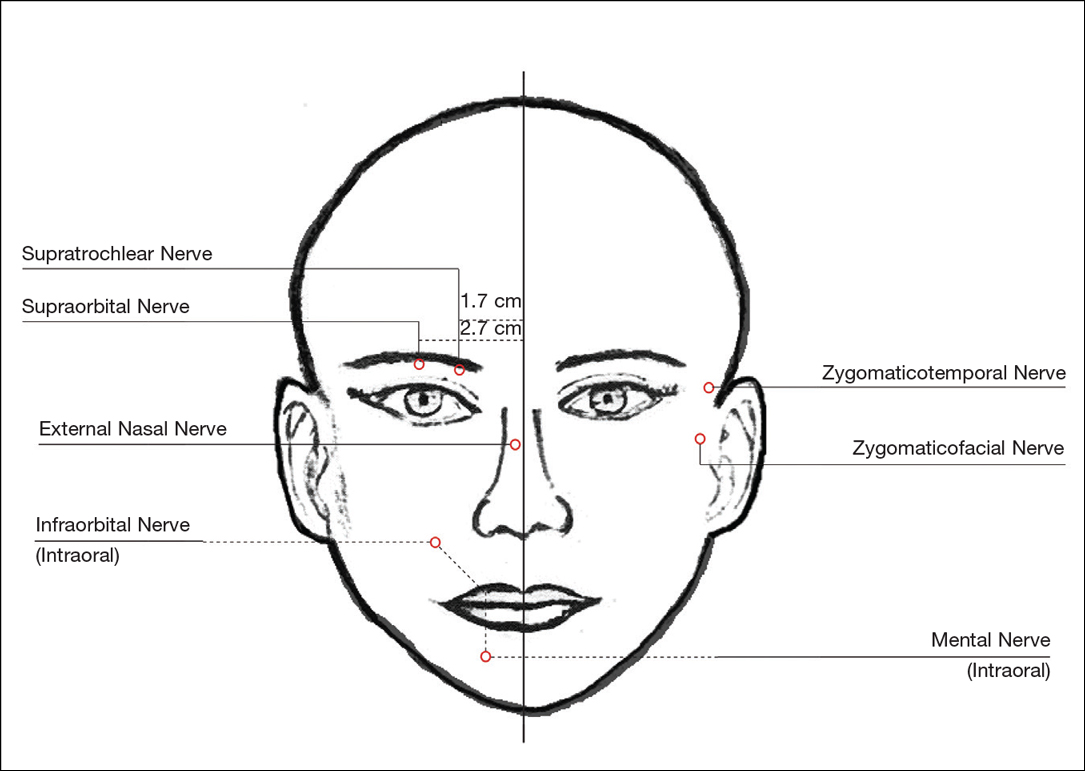

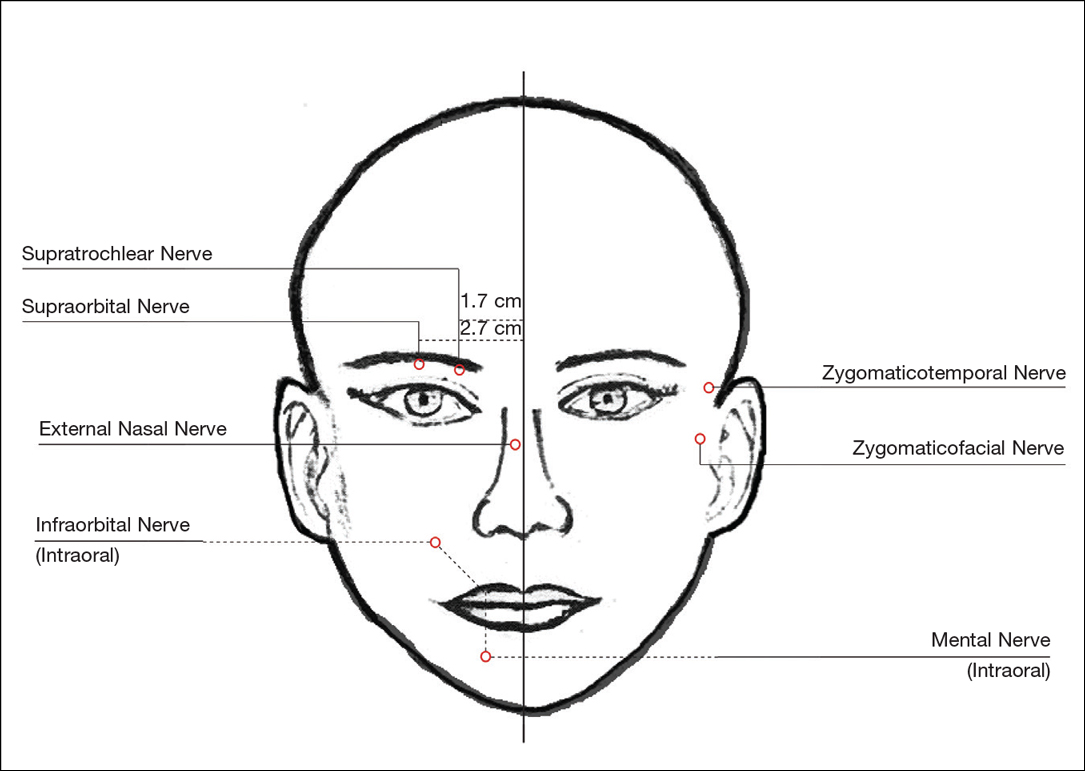

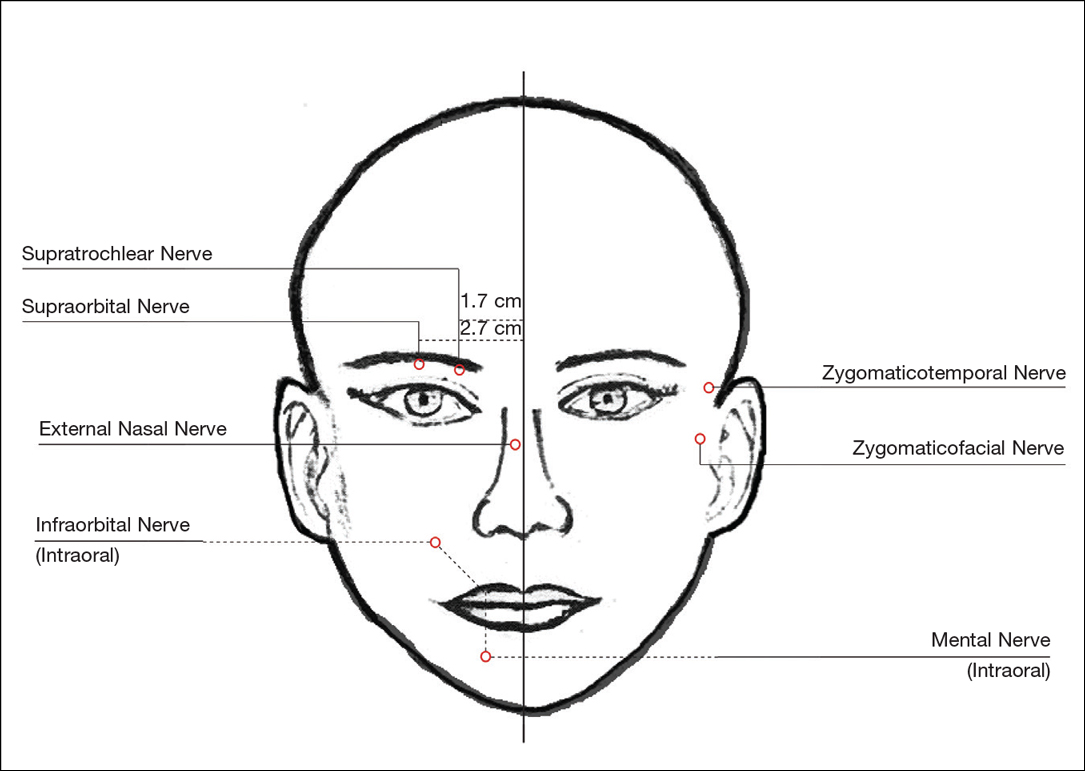

Forehead

For dermal filler injections of the glabellar and frontalis lines, anesthesia of the forehead may be desired. The supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves supply this area. The supraorbital nerve can be injected at the supraorbital notch, which is measured roughly 2.7 cm from the glabella. The orbital rim should be palpated with the nondominant hand, and 1 to 2 mL of anesthetic should be injected just below the rim (Figure 1). The supratrochlear nerve is located roughly 1.7 cm from the midline and can be similarly injected under the orbital rim with 1 to 2 mL of anesthetic (Figure 1).

Lateral Temple Region

Anesthesia of the zygomaticotemporal nerve can be used to reduce pain from dermal filler injections of the lateral canthal and temporal areas. The nerve is identified by first palpating the zygomaticofrontal suture. A long needle is then inserted posteriorly, immediately behind the concave surface of the lateral orbital rim, and 1 to 2 mL of anesthetic is injected (Figure 1).

Malar Region

Blockade of the zygomaticofacial nerve is commonly performed in conjunction with the zygomaticotemporal nerve and provides anesthesia to the malar region for cheek augmentation procedures. To identify the target area, the junction of the lateral and inferior orbital rim should be palpated. With the needle placed just lateral to this point, 1 to 2 mL of anesthetic is injected (Figure 1).

Blocks for Perioral Fillers

Upper Lips/Nasolabial Folds

Bilateral blockade of the infraorbital nerves provides anesthesia to the upper lip and nasolabial folds prior to filler injections. The infraorbital nerve can be targeted via an intraoral route where it exits the maxilla at the infraorbital foramen. The nerve is anesthetized by palpating the infraorbital ridge and injecting 3 to 5 mL of anesthetic roughly 1 cm below this point on the vertical axis of the midpupillary line (Figure 1). The external nasal nerve, thought to be a branch of cranial nerve V, also may be targeted if there is inadequate anesthesia from the infraorbital block. This nerve is reached by injecting at the osseocartilaginous junction of the nasal bones (Figure 1).

Lower Lips

Blockade of the mental nerve provides anesthesia to the lower lips for augmentation procedures. The mental nerve can be targeted on each side at the mental foramen, which is located below the root of the lower second premolar. Aiming roughly 1 cm below the gumline, 3 to 5 mL of anesthetic is injected intraorally (Figure 1). A transcutaneous approach toward the same target also is possible, though this technique risks visible bruising. Alternatively, the upper or lower lips can be anesthetized using 4 to 5 submucosal injections at evenly spaced intervals between the canine teeth.18

Blocks for Palmoplantar Hyperhidrosis

The treatment of palmoplantar hyperhidrosis benefits from regional blocks. Botulinum toxin has been well established as an effective therapy for the condition.19-21 Given the sensitivity of palmoplantar sites, it is valuable to achieve effective analgesia of the region prior to dermal injections of botulinum toxin.

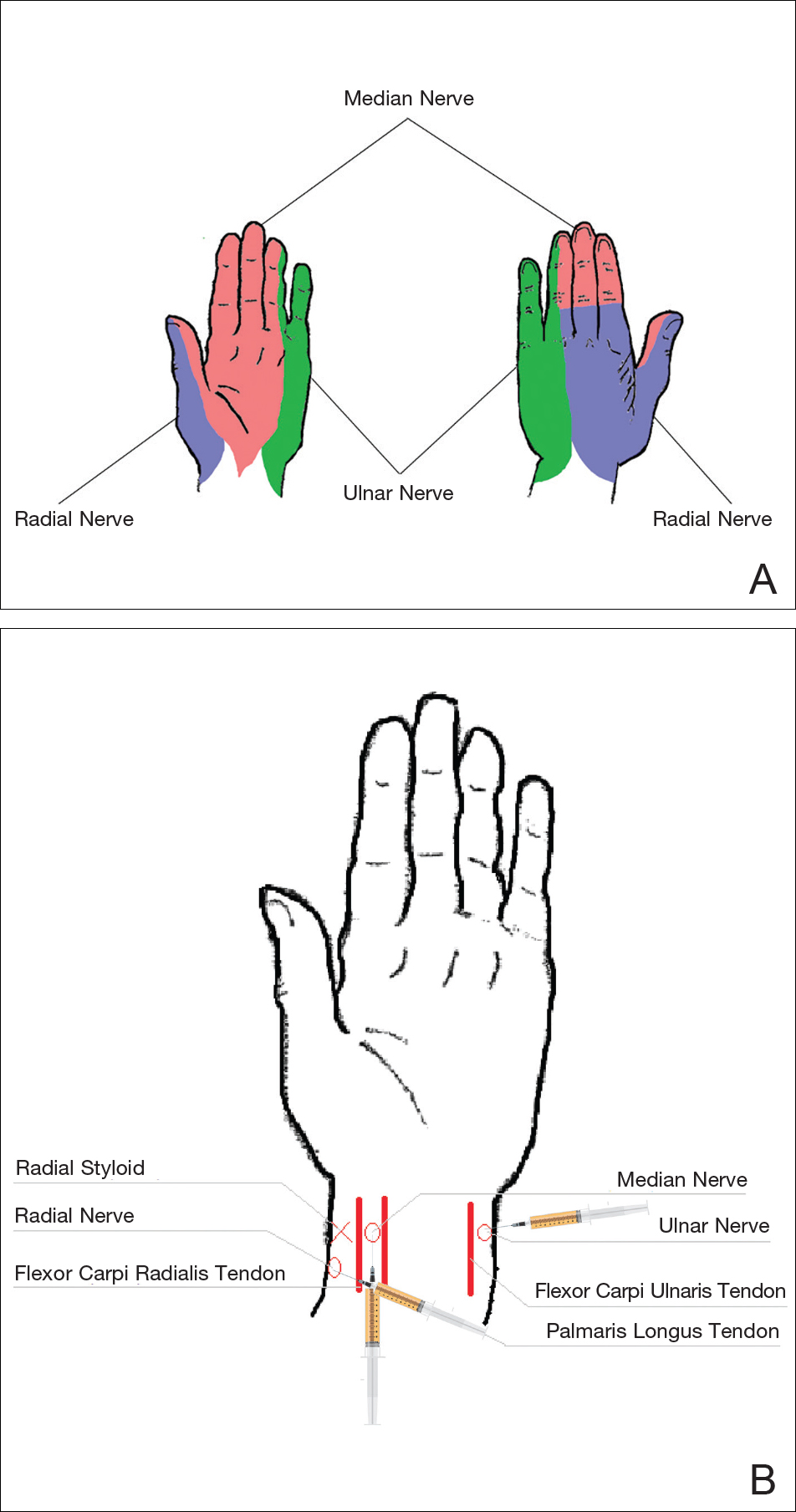

Wrists

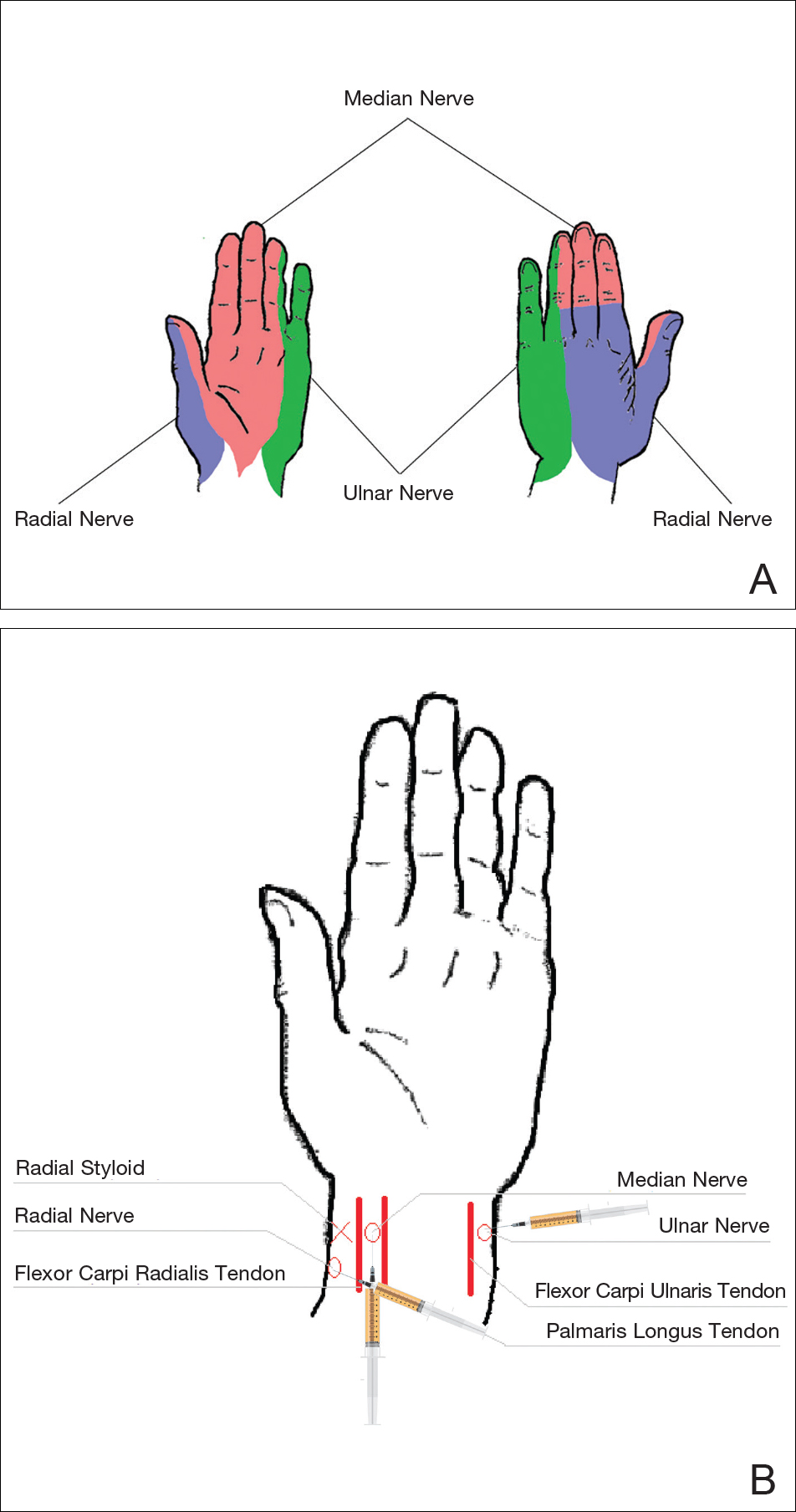

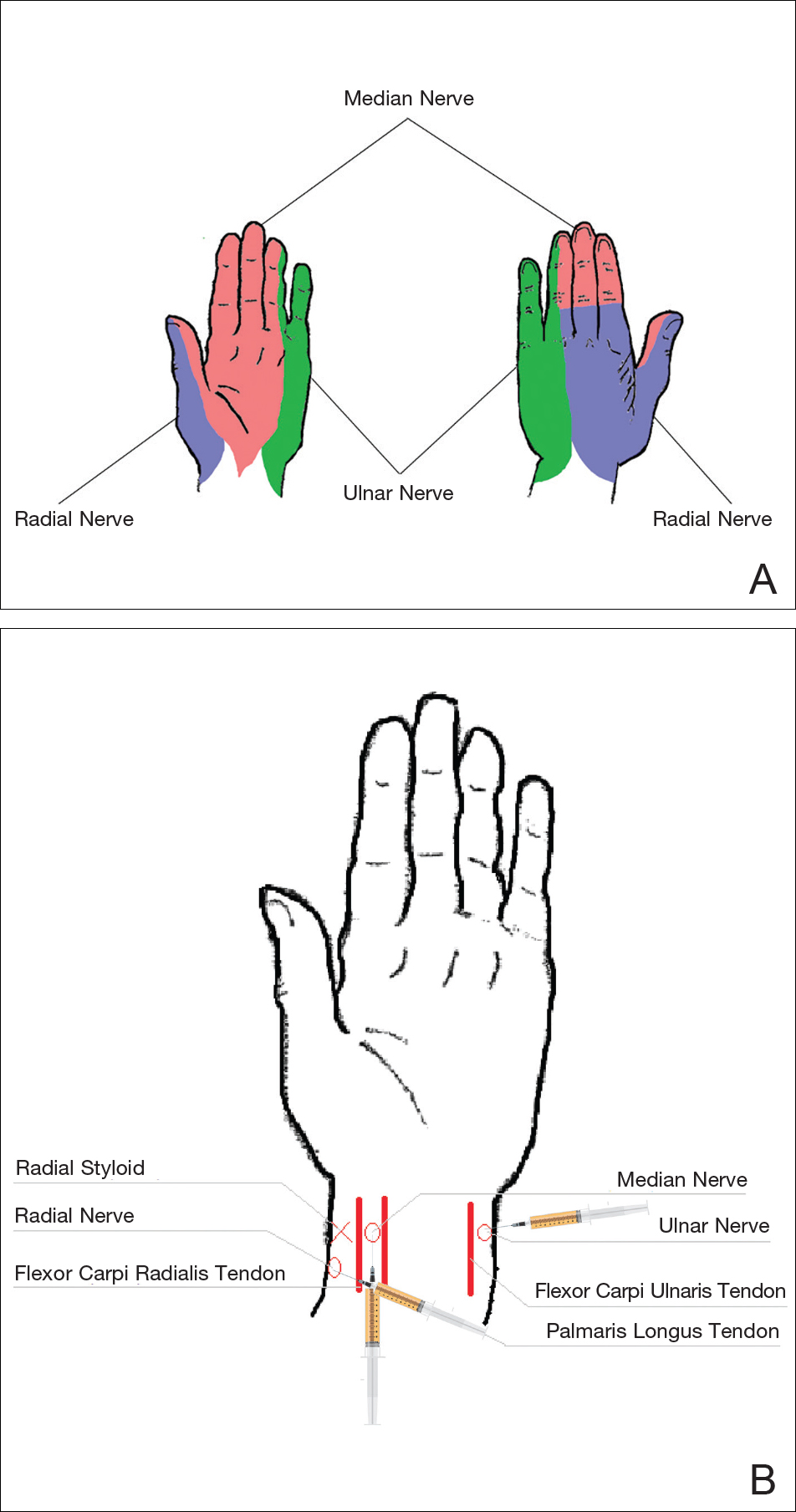

Sensory innervation of the palm is provided by the median, ulnar, and radial nerves (Figure 2A).

The ulnar nerve is anesthetized between the ulnar artery and the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle. The artery is identified by palpation, and special care should be taken to avoid intra-arterial injection. The needle is directed toward the radial styloid, and 3 to 5 mL of anesthetic is injected roughly 1 cm proximal to the wrist crease (Figure 2B).

Anesthesia of the radial nerve can be considered a field block given the numerous small branches that supply the hand. These branches are reached by injecting anesthetic roughly 2 to 3 cm proximal to the radial styloid with the needle aimed medially and extending the injection dorsally (Figure 2B). A total of 4 to 6 mL of anesthetic is used.

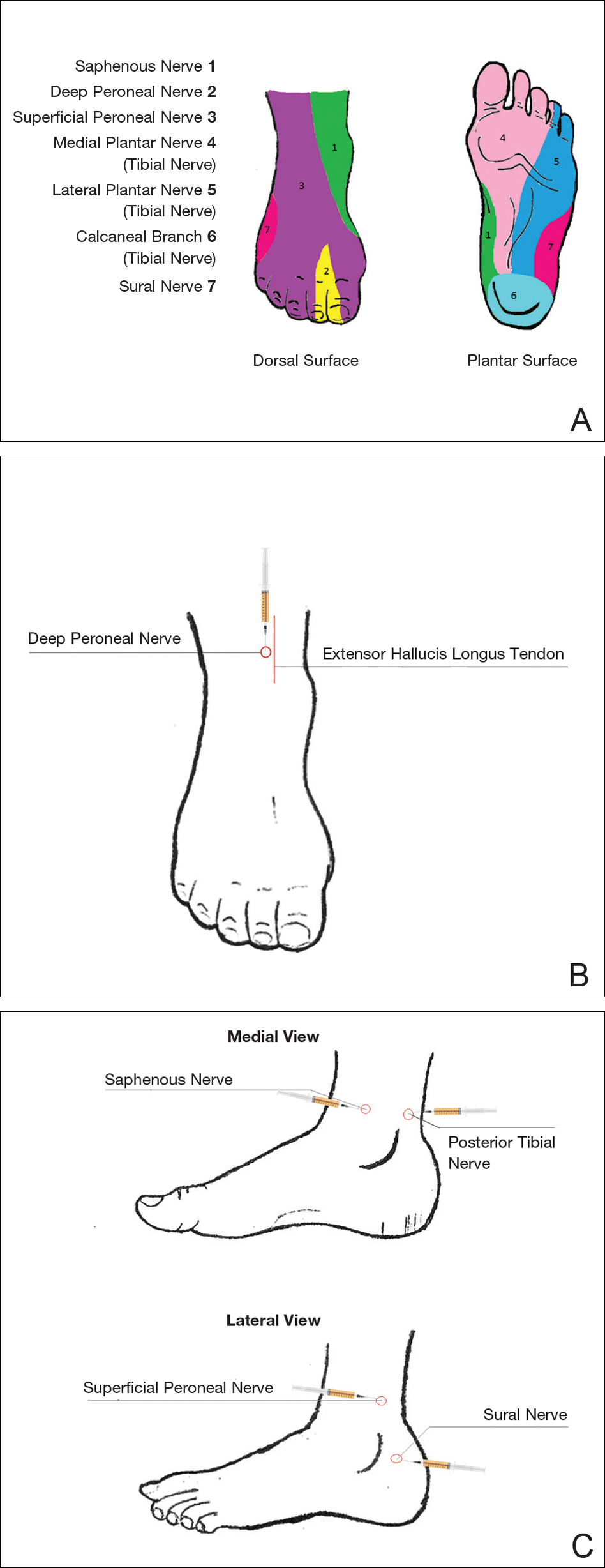

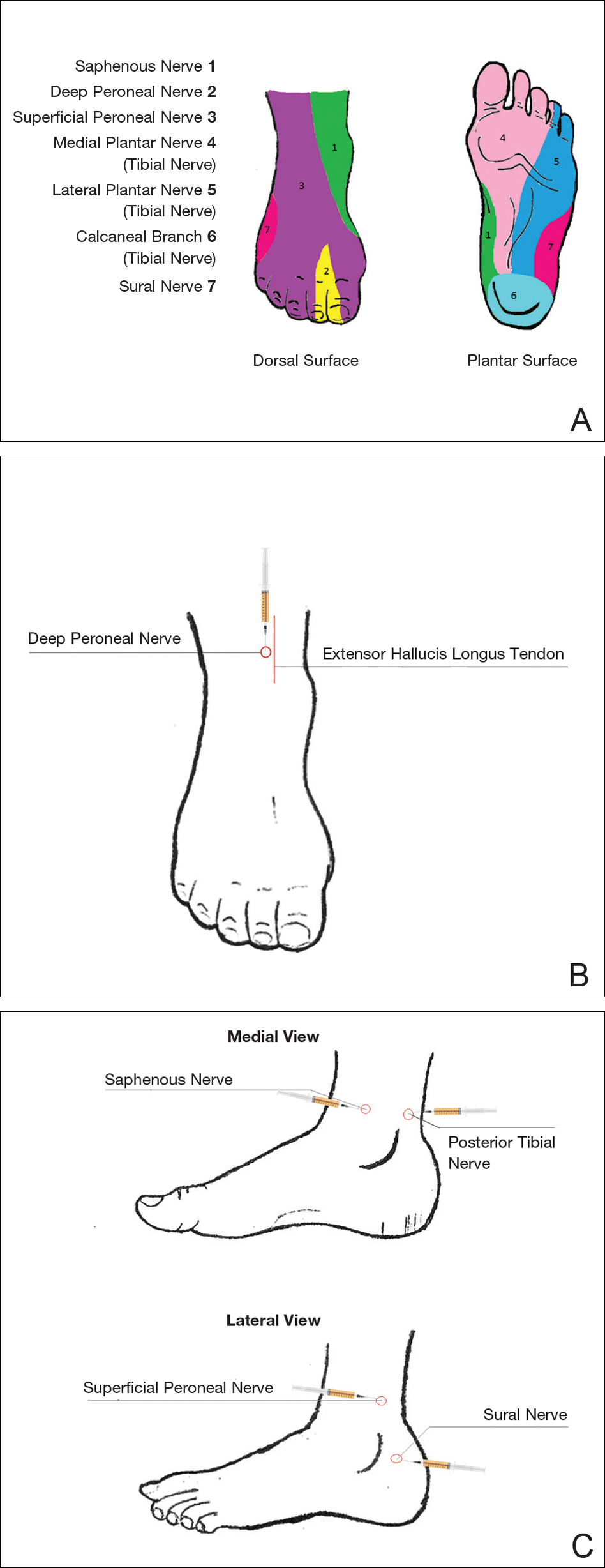

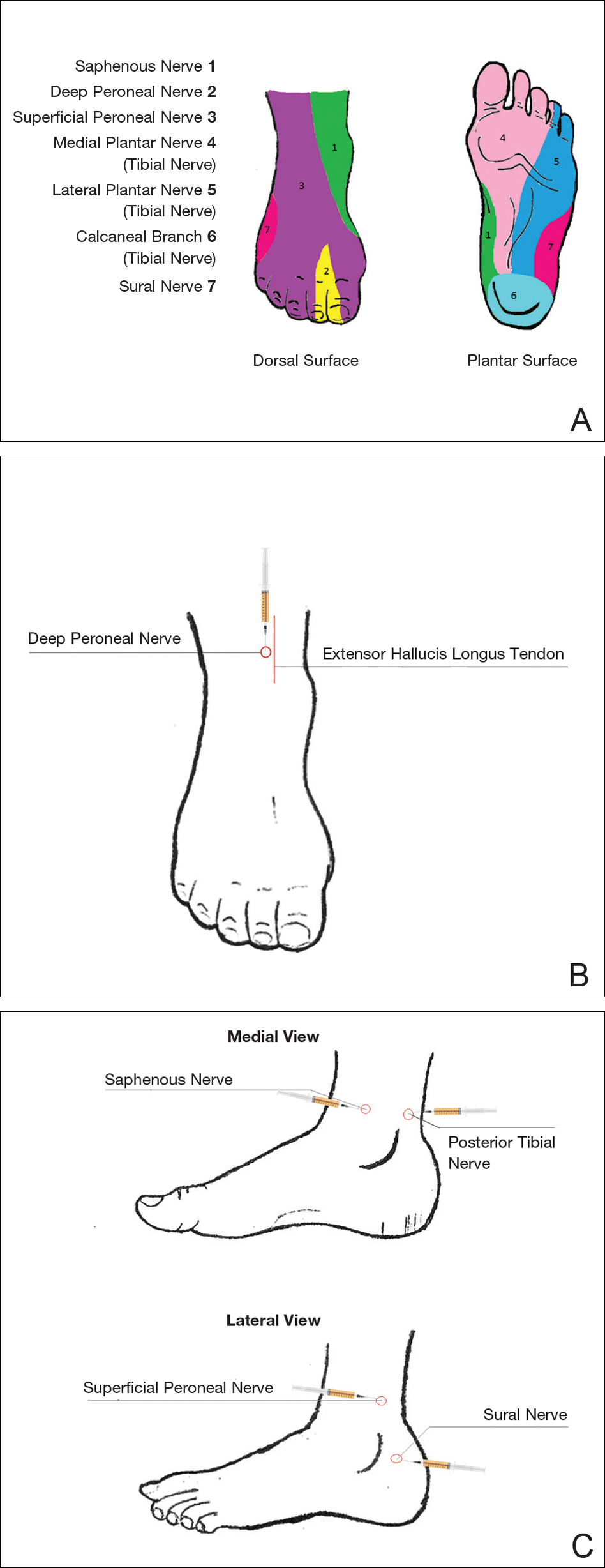

Ankles

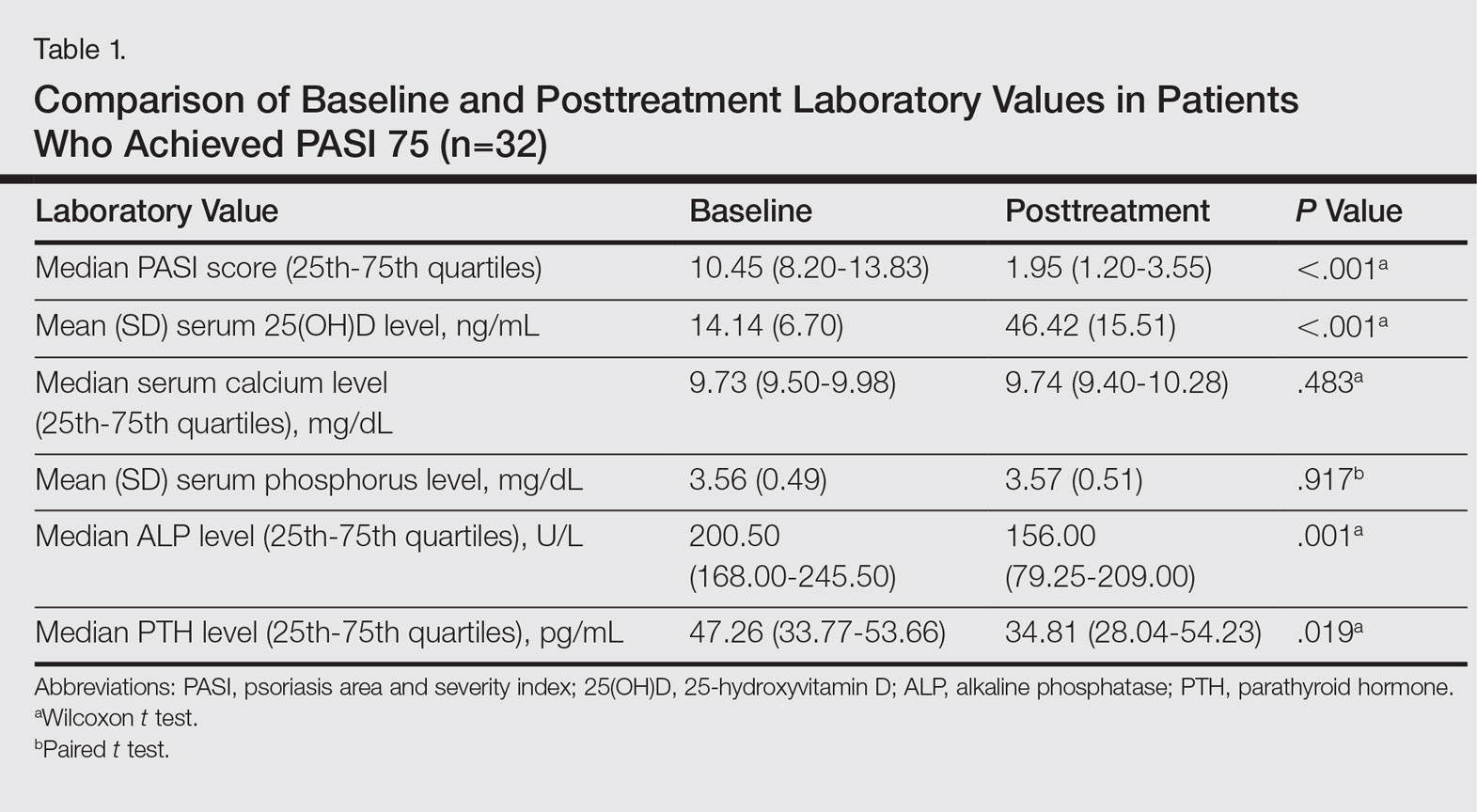

An ankle block provides anesthesia to the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the foot.22 The region is supplied by the superficial peroneal nerve, deep peroneal nerve, sural nerve, saphenous nerve, and branches of the posterior tibial nerve (Figure 3A).

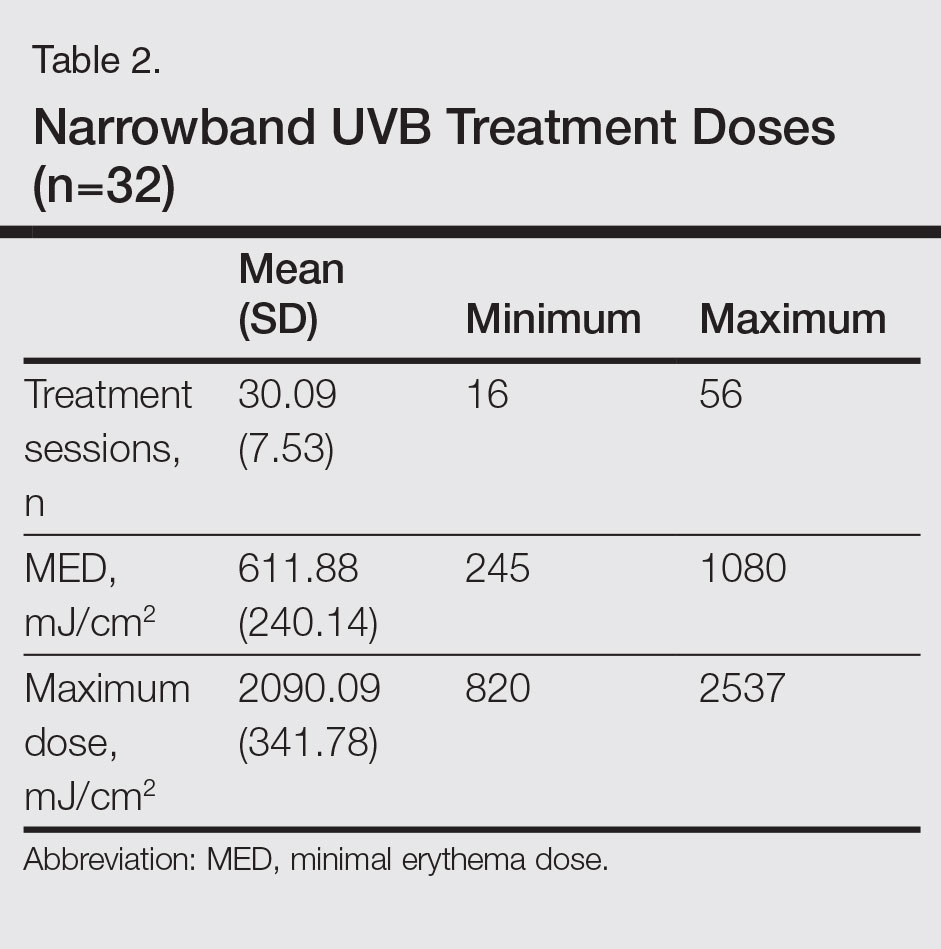

To anesthetize the deep peroneal nerve, the extensor hallucis longus tendon is first identified on the anterior surface of the ankle through dorsiflexion of the toes; the dorsalis pedis artery runs in close proximity. The injection should be placed lateral to the tendon and artery (Figure 3B). The needle should be inserted until bone is reached, withdrawn slightly, and then 3 to 5 mL of anesthetic should be injected. To block the saphenous nerve, the needle can then be directed superficially toward the medial malleolus, and 3 to 5 mL should be injected in a subcutaneous wheal (Figure 3C). To block the superficial peroneal nerve, the needle should then be directed toward the lateral malleolus, and 3 to 5 mL should be injected in a subcutaneous wheal (Figure 3C).

The posterior tibial nerve is located posterior to the medial malleolus. The dorsalis pedis artery can be palpated near this location. The needle should be inserted posterior to the artery, extending until bone is reached (Figure 3C). The needle is then withdrawn slightly, and 3 to 5 mL of anesthetic is injected. Finally, the sural nerve is anesthetized between the Achilles tendon and the lateral malleolus, using 5 mL of anesthetic to raise a subcutaneous wheal (Figure 3C).

Conclusion

Proper pain management is integral to ensuring a positive experience for cosmetic patients. Enhanced knowledge of local anesthetic techniques allows the clinician to provide for a variety of procedural indications and patient preferences. As anesthetic strategies are continually evolving, it is important for practitioners to remain informed of these developments.

- Scholz A. Mechanisms of (local) anaesthetics on voltage-gated sodium and other ion channels. Br J Anaesth. 2002;89:52-61.

- Auletta MJ. Local anesthesia for dermatologic surgery. Semin Dermatol. 1994;13:35-42.

- Park KK, Sharon VR. A review of local anesthetics: minimizing risk and side effects in cutaneous surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:173-187.

- Reiz S, Nath S. Cardiotoxicity of local anaesthetic agents. Br J Anaesth. 1986;58:736-746.

- Klein JA, Kassarjdian N. Lidocaine toxicity with tumescent liposuction. a case report of probable drug interactions. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:1169-1174.

- Minkis K, Whittington A, Alam M. Dermatologic surgery emergencies: complications caused by systemic reactions, high-energy systems, and trauma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:265-284.

- Morais-Almeida M, Gaspar A, Marinho S, et al. Allergy to local anesthetics of the amide group with tolerance to procaine. Allergy. 2003;58:827-828.

- To D, Kossintseva I, de Gannes G. Lidocaine contact allergy is becoming more prevalent. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1367-1372.

- Wahlgren CF, Quiding H. Depth of cutaneous analgesia after application of a eutectic mixture of the local anesthetics lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA cream). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:584-588.

- Bjerring P, Andersen PH, Arendt-Nielsen L. Vascular response of human skin after analgesia with EMLA cream. Br J Anaesth. 1989;63:655-660.

- Ismail F, Goldsmith PC. EMLA cream-induced allergic contact dermatitis in a child with thalassaemia major. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;52:111.

- Thakur BK, Murali MR. EMLA cream-induced allergic contact dermatitis: a role for prilocaine as an immunogen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;95:776-778.

- Waton J, Boulanger A, Trechot PH, et al. Contact urticaria from EMLA cream. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:284-287.

- Bucalo BD, Mirikitani EJ, Moy RL. Comparison of skin anesthetic effect of liposomal lidocaine, nonliposomal lidocaine, and EMLA using 30-minute application time. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:537-541.

- Guardiano RA, Norwood CW. Direct comparison of EMLA versus lidocaine for pain control in Nd:YAG 1,064 nm laser hair removal. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:396-398.

- Nestor MS. Safety of occluded 4% liposomal lidocaine cream. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:618-620.

- Oni G, Rasko Y, Kenkel J. Topical lidocaine enhanced by laser pretreatment: a safe and effective method of analgesia for facial rejuvenation. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:854-861.

- Niamtu J 3rd. Simple technique for lip and nasolabial fold anesthesia for injectable fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1330-1332.

- Naumann M, Flachenecker P, Brocker EB, et al. Botulinum toxin for palmar hyperhidrosis. Lancet. 1997;349:252.

- Naumann M, Hofmann U, Bergmann I, et al. Focal hyperhidrosis: effective treatment with intracutaneous botulinum toxin. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:301-304.

- Shelley WB, Talanin NY, Shelley ED. Botulinum toxin therapy for palmar hyperhidrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(2, pt 1):227-229.

- Davies T, Karanovic S, Shergill B. Essential regional nerve blocks for the dermatologist: part 2. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:861-867.

Local anesthesia is a central component of successful interventions in cosmetic dermatology. The number of anesthetic medications and administration techniques has grown in recent years as outpatient cosmetic procedures continue to expand. Pain is a common barrier to cosmetic procedures, and alleviating the fear of painful interventions is critical to patient satisfaction and future visits. To accommodate a multitude of cosmetic interventions, it is important for clinicians to be well versed in applications of topical and regional anesthesia. In this article, we review pain management strategies for use in cosmetic practice.

Local Anesthetics

The sensation of pain is carried to the central nervous system by unmyelinated C nerve fibers. Local anesthetics (LAs) act by blocking fast voltage-gated sodium channels in the cell membrane of the nerve, thereby inhibiting downstream propagation of an action potential and the transmission of painful stimuli.1 The chemical structure of LAs is fundamental to their mechanism of action and metabolism. Local anesthetics contain a lipophilic aromatic group, an intermediate chain, and a hydrophilic amine group. Broadly, agents are classified as amides or esters depending on the chemical group attached to the intermediate chain.2 Amides (eg, lidocaine, bupivacaine, articaine, mepivacaine, prilocaine, levobupivacaine) are metabolized by the hepatic system; esters (eg, procaine, proparacaine, benzocaine, chlorprocaine, tetracaine, cocaine) are metabolized by plasma cholinesterase, which produces para-aminobenzoic acid, a potentially dangerous metabolite that has been implicated in allergic reactions.3

Lidocaine is the most prevalent LA used in dermatology practices. Importantly, lidocaine is a class IB antiarrhythmic agent used in cardiology to treat ventricular arrhythmias.4 As an anesthetic, a maximum dose of 4.5 mg/kg can be administered, increasing to 7.0 mg/kg when mixed with epinephrine; with higher doses, there is a risk for central nervous system and cardiovascular toxicity.5 Initial symptoms of lidocaine toxicity include dizziness, tinnitus, circumoral paresthesia, blurred vision, and a metallic taste in the mouth.6 Systemic absorption of topical anesthetics is heightened across mucosal membranes, and care should be taken when applying over large surface areas.

Allergic reactions to LAs may be local or less frequently systemic. It is important to note that LAs tend to show cross-reactivity within their class rather than across different classes.7 Reactions can be classified as type I or type IV. Type I (IgE-mediated) reactions evolve in minutes to hours, affecting the skin and possibly leading to respiratory and circulatory collapse. Delayed reactions to LAs have increased in recent years, with type IV contact allergy most frequently found in connection with benzocaine and lidocaine.8

Topical Anesthesia

Topical anesthetics are effective and easy to use and are particularly valuable in patients with needle phobia. In certain cases, these medications may be applied by the patient prior to arrival, thereby reducing visit time. Topical agents act on nerve fibers running through the dermis; therefore, efficacy is dependent on successful penetration through the stratum corneum and viable epidermis. To enhance absorption, agents may be applied under an occlusive dressing.

Topical anesthetics are most commonly used for injectable fillers, ablative and nonablative laser resurfacing, laser hair removal, and tattoo removal. The eutectic mixture of 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine as well as topical 4% or 5% lidocaine are the most commonly used US Food and Drug Administration–approved products for topical anesthesia. In addition, several compounded pharmacy products are available.

After 60 minutes of application of the eutectic mixture of 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine, a 3-mm depth of analgesia is reached, and after 120 minutes, a 4.5-mm depth is reached.9 It elicits a biphasic vascular response of vasoconstriction and blanching followed by vasodilation and erythema.10 Most adverse events are mild and transient, but allergic contact dermatitis and contact urticaria have been reported.11-13 In older children and adults, the maximum application area is 200 cm2, with a maximum dose of 20 g used for no longer than 4 hours.

The 4% or 5% lidocaine cream uses a liposomal delivery system, which is designed to improve cutaneous penetration and has been shown to provide longer durations of anesthesia than nonliposomal lidocaine preparations.14 Application should be performed 30 to 60 minutes prior to a procedure. In a study comparing the eutectic mixture of 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine versus lidocaine cream 5% for pain control during laser hair removal with a 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser, no significant differences were found.15 The maximum application area is 100 cm2 in children weighing less than 20 kg. A study of healthy adults demonstrated safety with the use of 30 to 60 g of occluded liposomal lidocaine cream 4%.16

In addition to US Food and Drug Administration–approved products, several compounded pharmacy products are available for topical anesthesia. These formulations include benzocaine-lidocaine-tetracaine gel, tetracaine-adrenaline-cocaine solution, and lidocaine-epinephrine-tetracaine solution. A triple-anesthetic gel, benzocaine-lidocaine-tetracaine is widely used in cosmetic practice. The product has been shown to provide adequate anesthesia for laser resurfacing after 20 minutes without occlusion.17 Of note, compounded anesthetics lack standardization, and different pharmacies may follow their own individual protocols.

Regional Anesthesia

Regional nerve blockade is a useful option for more widespread or complex interventions. Using regional nerve blockade, effective analgesia can be delivered to a target area while avoiding the toxicity and pain associated with numerous anesthetic infiltrations. In addition, there is no distortion of the tissue architecture, allowing for improved visual evaluation during the procedure. Recently, hyaluronic acid fillers have been compounded with lidocaine as a means of reducing procedural pain.

Blocks for Dermal Fillers

Forehead

For dermal filler injections of the glabellar and frontalis lines, anesthesia of the forehead may be desired. The supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves supply this area. The supraorbital nerve can be injected at the supraorbital notch, which is measured roughly 2.7 cm from the glabella. The orbital rim should be palpated with the nondominant hand, and 1 to 2 mL of anesthetic should be injected just below the rim (Figure 1). The supratrochlear nerve is located roughly 1.7 cm from the midline and can be similarly injected under the orbital rim with 1 to 2 mL of anesthetic (Figure 1).

Lateral Temple Region

Anesthesia of the zygomaticotemporal nerve can be used to reduce pain from dermal filler injections of the lateral canthal and temporal areas. The nerve is identified by first palpating the zygomaticofrontal suture. A long needle is then inserted posteriorly, immediately behind the concave surface of the lateral orbital rim, and 1 to 2 mL of anesthetic is injected (Figure 1).

Malar Region

Blockade of the zygomaticofacial nerve is commonly performed in conjunction with the zygomaticotemporal nerve and provides anesthesia to the malar region for cheek augmentation procedures. To identify the target area, the junction of the lateral and inferior orbital rim should be palpated. With the needle placed just lateral to this point, 1 to 2 mL of anesthetic is injected (Figure 1).

Blocks for Perioral Fillers

Upper Lips/Nasolabial Folds

Bilateral blockade of the infraorbital nerves provides anesthesia to the upper lip and nasolabial folds prior to filler injections. The infraorbital nerve can be targeted via an intraoral route where it exits the maxilla at the infraorbital foramen. The nerve is anesthetized by palpating the infraorbital ridge and injecting 3 to 5 mL of anesthetic roughly 1 cm below this point on the vertical axis of the midpupillary line (Figure 1). The external nasal nerve, thought to be a branch of cranial nerve V, also may be targeted if there is inadequate anesthesia from the infraorbital block. This nerve is reached by injecting at the osseocartilaginous junction of the nasal bones (Figure 1).

Lower Lips

Blockade of the mental nerve provides anesthesia to the lower lips for augmentation procedures. The mental nerve can be targeted on each side at the mental foramen, which is located below the root of the lower second premolar. Aiming roughly 1 cm below the gumline, 3 to 5 mL of anesthetic is injected intraorally (Figure 1). A transcutaneous approach toward the same target also is possible, though this technique risks visible bruising. Alternatively, the upper or lower lips can be anesthetized using 4 to 5 submucosal injections at evenly spaced intervals between the canine teeth.18

Blocks for Palmoplantar Hyperhidrosis

The treatment of palmoplantar hyperhidrosis benefits from regional blocks. Botulinum toxin has been well established as an effective therapy for the condition.19-21 Given the sensitivity of palmoplantar sites, it is valuable to achieve effective analgesia of the region prior to dermal injections of botulinum toxin.

Wrists

Sensory innervation of the palm is provided by the median, ulnar, and radial nerves (Figure 2A).

The ulnar nerve is anesthetized between the ulnar artery and the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle. The artery is identified by palpation, and special care should be taken to avoid intra-arterial injection. The needle is directed toward the radial styloid, and 3 to 5 mL of anesthetic is injected roughly 1 cm proximal to the wrist crease (Figure 2B).

Anesthesia of the radial nerve can be considered a field block given the numerous small branches that supply the hand. These branches are reached by injecting anesthetic roughly 2 to 3 cm proximal to the radial styloid with the needle aimed medially and extending the injection dorsally (Figure 2B). A total of 4 to 6 mL of anesthetic is used.

Ankles

An ankle block provides anesthesia to the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the foot.22 The region is supplied by the superficial peroneal nerve, deep peroneal nerve, sural nerve, saphenous nerve, and branches of the posterior tibial nerve (Figure 3A).

To anesthetize the deep peroneal nerve, the extensor hallucis longus tendon is first identified on the anterior surface of the ankle through dorsiflexion of the toes; the dorsalis pedis artery runs in close proximity. The injection should be placed lateral to the tendon and artery (Figure 3B). The needle should be inserted until bone is reached, withdrawn slightly, and then 3 to 5 mL of anesthetic should be injected. To block the saphenous nerve, the needle can then be directed superficially toward the medial malleolus, and 3 to 5 mL should be injected in a subcutaneous wheal (Figure 3C). To block the superficial peroneal nerve, the needle should then be directed toward the lateral malleolus, and 3 to 5 mL should be injected in a subcutaneous wheal (Figure 3C).

The posterior tibial nerve is located posterior to the medial malleolus. The dorsalis pedis artery can be palpated near this location. The needle should be inserted posterior to the artery, extending until bone is reached (Figure 3C). The needle is then withdrawn slightly, and 3 to 5 mL of anesthetic is injected. Finally, the sural nerve is anesthetized between the Achilles tendon and the lateral malleolus, using 5 mL of anesthetic to raise a subcutaneous wheal (Figure 3C).

Conclusion

Proper pain management is integral to ensuring a positive experience for cosmetic patients. Enhanced knowledge of local anesthetic techniques allows the clinician to provide for a variety of procedural indications and patient preferences. As anesthetic strategies are continually evolving, it is important for practitioners to remain informed of these developments.

Local anesthesia is a central component of successful interventions in cosmetic dermatology. The number of anesthetic medications and administration techniques has grown in recent years as outpatient cosmetic procedures continue to expand. Pain is a common barrier to cosmetic procedures, and alleviating the fear of painful interventions is critical to patient satisfaction and future visits. To accommodate a multitude of cosmetic interventions, it is important for clinicians to be well versed in applications of topical and regional anesthesia. In this article, we review pain management strategies for use in cosmetic practice.

Local Anesthetics

The sensation of pain is carried to the central nervous system by unmyelinated C nerve fibers. Local anesthetics (LAs) act by blocking fast voltage-gated sodium channels in the cell membrane of the nerve, thereby inhibiting downstream propagation of an action potential and the transmission of painful stimuli.1 The chemical structure of LAs is fundamental to their mechanism of action and metabolism. Local anesthetics contain a lipophilic aromatic group, an intermediate chain, and a hydrophilic amine group. Broadly, agents are classified as amides or esters depending on the chemical group attached to the intermediate chain.2 Amides (eg, lidocaine, bupivacaine, articaine, mepivacaine, prilocaine, levobupivacaine) are metabolized by the hepatic system; esters (eg, procaine, proparacaine, benzocaine, chlorprocaine, tetracaine, cocaine) are metabolized by plasma cholinesterase, which produces para-aminobenzoic acid, a potentially dangerous metabolite that has been implicated in allergic reactions.3

Lidocaine is the most prevalent LA used in dermatology practices. Importantly, lidocaine is a class IB antiarrhythmic agent used in cardiology to treat ventricular arrhythmias.4 As an anesthetic, a maximum dose of 4.5 mg/kg can be administered, increasing to 7.0 mg/kg when mixed with epinephrine; with higher doses, there is a risk for central nervous system and cardiovascular toxicity.5 Initial symptoms of lidocaine toxicity include dizziness, tinnitus, circumoral paresthesia, blurred vision, and a metallic taste in the mouth.6 Systemic absorption of topical anesthetics is heightened across mucosal membranes, and care should be taken when applying over large surface areas.

Allergic reactions to LAs may be local or less frequently systemic. It is important to note that LAs tend to show cross-reactivity within their class rather than across different classes.7 Reactions can be classified as type I or type IV. Type I (IgE-mediated) reactions evolve in minutes to hours, affecting the skin and possibly leading to respiratory and circulatory collapse. Delayed reactions to LAs have increased in recent years, with type IV contact allergy most frequently found in connection with benzocaine and lidocaine.8

Topical Anesthesia

Topical anesthetics are effective and easy to use and are particularly valuable in patients with needle phobia. In certain cases, these medications may be applied by the patient prior to arrival, thereby reducing visit time. Topical agents act on nerve fibers running through the dermis; therefore, efficacy is dependent on successful penetration through the stratum corneum and viable epidermis. To enhance absorption, agents may be applied under an occlusive dressing.

Topical anesthetics are most commonly used for injectable fillers, ablative and nonablative laser resurfacing, laser hair removal, and tattoo removal. The eutectic mixture of 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine as well as topical 4% or 5% lidocaine are the most commonly used US Food and Drug Administration–approved products for topical anesthesia. In addition, several compounded pharmacy products are available.

After 60 minutes of application of the eutectic mixture of 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine, a 3-mm depth of analgesia is reached, and after 120 minutes, a 4.5-mm depth is reached.9 It elicits a biphasic vascular response of vasoconstriction and blanching followed by vasodilation and erythema.10 Most adverse events are mild and transient, but allergic contact dermatitis and contact urticaria have been reported.11-13 In older children and adults, the maximum application area is 200 cm2, with a maximum dose of 20 g used for no longer than 4 hours.

The 4% or 5% lidocaine cream uses a liposomal delivery system, which is designed to improve cutaneous penetration and has been shown to provide longer durations of anesthesia than nonliposomal lidocaine preparations.14 Application should be performed 30 to 60 minutes prior to a procedure. In a study comparing the eutectic mixture of 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine versus lidocaine cream 5% for pain control during laser hair removal with a 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser, no significant differences were found.15 The maximum application area is 100 cm2 in children weighing less than 20 kg. A study of healthy adults demonstrated safety with the use of 30 to 60 g of occluded liposomal lidocaine cream 4%.16

In addition to US Food and Drug Administration–approved products, several compounded pharmacy products are available for topical anesthesia. These formulations include benzocaine-lidocaine-tetracaine gel, tetracaine-adrenaline-cocaine solution, and lidocaine-epinephrine-tetracaine solution. A triple-anesthetic gel, benzocaine-lidocaine-tetracaine is widely used in cosmetic practice. The product has been shown to provide adequate anesthesia for laser resurfacing after 20 minutes without occlusion.17 Of note, compounded anesthetics lack standardization, and different pharmacies may follow their own individual protocols.

Regional Anesthesia

Regional nerve blockade is a useful option for more widespread or complex interventions. Using regional nerve blockade, effective analgesia can be delivered to a target area while avoiding the toxicity and pain associated with numerous anesthetic infiltrations. In addition, there is no distortion of the tissue architecture, allowing for improved visual evaluation during the procedure. Recently, hyaluronic acid fillers have been compounded with lidocaine as a means of reducing procedural pain.

Blocks for Dermal Fillers

Forehead

For dermal filler injections of the glabellar and frontalis lines, anesthesia of the forehead may be desired. The supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves supply this area. The supraorbital nerve can be injected at the supraorbital notch, which is measured roughly 2.7 cm from the glabella. The orbital rim should be palpated with the nondominant hand, and 1 to 2 mL of anesthetic should be injected just below the rim (Figure 1). The supratrochlear nerve is located roughly 1.7 cm from the midline and can be similarly injected under the orbital rim with 1 to 2 mL of anesthetic (Figure 1).

Lateral Temple Region

Anesthesia of the zygomaticotemporal nerve can be used to reduce pain from dermal filler injections of the lateral canthal and temporal areas. The nerve is identified by first palpating the zygomaticofrontal suture. A long needle is then inserted posteriorly, immediately behind the concave surface of the lateral orbital rim, and 1 to 2 mL of anesthetic is injected (Figure 1).

Malar Region

Blockade of the zygomaticofacial nerve is commonly performed in conjunction with the zygomaticotemporal nerve and provides anesthesia to the malar region for cheek augmentation procedures. To identify the target area, the junction of the lateral and inferior orbital rim should be palpated. With the needle placed just lateral to this point, 1 to 2 mL of anesthetic is injected (Figure 1).

Blocks for Perioral Fillers

Upper Lips/Nasolabial Folds

Bilateral blockade of the infraorbital nerves provides anesthesia to the upper lip and nasolabial folds prior to filler injections. The infraorbital nerve can be targeted via an intraoral route where it exits the maxilla at the infraorbital foramen. The nerve is anesthetized by palpating the infraorbital ridge and injecting 3 to 5 mL of anesthetic roughly 1 cm below this point on the vertical axis of the midpupillary line (Figure 1). The external nasal nerve, thought to be a branch of cranial nerve V, also may be targeted if there is inadequate anesthesia from the infraorbital block. This nerve is reached by injecting at the osseocartilaginous junction of the nasal bones (Figure 1).

Lower Lips

Blockade of the mental nerve provides anesthesia to the lower lips for augmentation procedures. The mental nerve can be targeted on each side at the mental foramen, which is located below the root of the lower second premolar. Aiming roughly 1 cm below the gumline, 3 to 5 mL of anesthetic is injected intraorally (Figure 1). A transcutaneous approach toward the same target also is possible, though this technique risks visible bruising. Alternatively, the upper or lower lips can be anesthetized using 4 to 5 submucosal injections at evenly spaced intervals between the canine teeth.18

Blocks for Palmoplantar Hyperhidrosis

The treatment of palmoplantar hyperhidrosis benefits from regional blocks. Botulinum toxin has been well established as an effective therapy for the condition.19-21 Given the sensitivity of palmoplantar sites, it is valuable to achieve effective analgesia of the region prior to dermal injections of botulinum toxin.

Wrists

Sensory innervation of the palm is provided by the median, ulnar, and radial nerves (Figure 2A).

The ulnar nerve is anesthetized between the ulnar artery and the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle. The artery is identified by palpation, and special care should be taken to avoid intra-arterial injection. The needle is directed toward the radial styloid, and 3 to 5 mL of anesthetic is injected roughly 1 cm proximal to the wrist crease (Figure 2B).

Anesthesia of the radial nerve can be considered a field block given the numerous small branches that supply the hand. These branches are reached by injecting anesthetic roughly 2 to 3 cm proximal to the radial styloid with the needle aimed medially and extending the injection dorsally (Figure 2B). A total of 4 to 6 mL of anesthetic is used.

Ankles

An ankle block provides anesthesia to the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the foot.22 The region is supplied by the superficial peroneal nerve, deep peroneal nerve, sural nerve, saphenous nerve, and branches of the posterior tibial nerve (Figure 3A).

To anesthetize the deep peroneal nerve, the extensor hallucis longus tendon is first identified on the anterior surface of the ankle through dorsiflexion of the toes; the dorsalis pedis artery runs in close proximity. The injection should be placed lateral to the tendon and artery (Figure 3B). The needle should be inserted until bone is reached, withdrawn slightly, and then 3 to 5 mL of anesthetic should be injected. To block the saphenous nerve, the needle can then be directed superficially toward the medial malleolus, and 3 to 5 mL should be injected in a subcutaneous wheal (Figure 3C). To block the superficial peroneal nerve, the needle should then be directed toward the lateral malleolus, and 3 to 5 mL should be injected in a subcutaneous wheal (Figure 3C).

The posterior tibial nerve is located posterior to the medial malleolus. The dorsalis pedis artery can be palpated near this location. The needle should be inserted posterior to the artery, extending until bone is reached (Figure 3C). The needle is then withdrawn slightly, and 3 to 5 mL of anesthetic is injected. Finally, the sural nerve is anesthetized between the Achilles tendon and the lateral malleolus, using 5 mL of anesthetic to raise a subcutaneous wheal (Figure 3C).

Conclusion

Proper pain management is integral to ensuring a positive experience for cosmetic patients. Enhanced knowledge of local anesthetic techniques allows the clinician to provide for a variety of procedural indications and patient preferences. As anesthetic strategies are continually evolving, it is important for practitioners to remain informed of these developments.

- Scholz A. Mechanisms of (local) anaesthetics on voltage-gated sodium and other ion channels. Br J Anaesth. 2002;89:52-61.

- Auletta MJ. Local anesthesia for dermatologic surgery. Semin Dermatol. 1994;13:35-42.

- Park KK, Sharon VR. A review of local anesthetics: minimizing risk and side effects in cutaneous surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:173-187.

- Reiz S, Nath S. Cardiotoxicity of local anaesthetic agents. Br J Anaesth. 1986;58:736-746.

- Klein JA, Kassarjdian N. Lidocaine toxicity with tumescent liposuction. a case report of probable drug interactions. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:1169-1174.

- Minkis K, Whittington A, Alam M. Dermatologic surgery emergencies: complications caused by systemic reactions, high-energy systems, and trauma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:265-284.

- Morais-Almeida M, Gaspar A, Marinho S, et al. Allergy to local anesthetics of the amide group with tolerance to procaine. Allergy. 2003;58:827-828.

- To D, Kossintseva I, de Gannes G. Lidocaine contact allergy is becoming more prevalent. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1367-1372.

- Wahlgren CF, Quiding H. Depth of cutaneous analgesia after application of a eutectic mixture of the local anesthetics lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA cream). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:584-588.

- Bjerring P, Andersen PH, Arendt-Nielsen L. Vascular response of human skin after analgesia with EMLA cream. Br J Anaesth. 1989;63:655-660.

- Ismail F, Goldsmith PC. EMLA cream-induced allergic contact dermatitis in a child with thalassaemia major. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;52:111.

- Thakur BK, Murali MR. EMLA cream-induced allergic contact dermatitis: a role for prilocaine as an immunogen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;95:776-778.

- Waton J, Boulanger A, Trechot PH, et al. Contact urticaria from EMLA cream. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:284-287.

- Bucalo BD, Mirikitani EJ, Moy RL. Comparison of skin anesthetic effect of liposomal lidocaine, nonliposomal lidocaine, and EMLA using 30-minute application time. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:537-541.

- Guardiano RA, Norwood CW. Direct comparison of EMLA versus lidocaine for pain control in Nd:YAG 1,064 nm laser hair removal. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:396-398.

- Nestor MS. Safety of occluded 4% liposomal lidocaine cream. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:618-620.

- Oni G, Rasko Y, Kenkel J. Topical lidocaine enhanced by laser pretreatment: a safe and effective method of analgesia for facial rejuvenation. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:854-861.

- Niamtu J 3rd. Simple technique for lip and nasolabial fold anesthesia for injectable fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1330-1332.

- Naumann M, Flachenecker P, Brocker EB, et al. Botulinum toxin for palmar hyperhidrosis. Lancet. 1997;349:252.

- Naumann M, Hofmann U, Bergmann I, et al. Focal hyperhidrosis: effective treatment with intracutaneous botulinum toxin. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:301-304.

- Shelley WB, Talanin NY, Shelley ED. Botulinum toxin therapy for palmar hyperhidrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(2, pt 1):227-229.

- Davies T, Karanovic S, Shergill B. Essential regional nerve blocks for the dermatologist: part 2. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:861-867.

- Scholz A. Mechanisms of (local) anaesthetics on voltage-gated sodium and other ion channels. Br J Anaesth. 2002;89:52-61.

- Auletta MJ. Local anesthesia for dermatologic surgery. Semin Dermatol. 1994;13:35-42.

- Park KK, Sharon VR. A review of local anesthetics: minimizing risk and side effects in cutaneous surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:173-187.

- Reiz S, Nath S. Cardiotoxicity of local anaesthetic agents. Br J Anaesth. 1986;58:736-746.

- Klein JA, Kassarjdian N. Lidocaine toxicity with tumescent liposuction. a case report of probable drug interactions. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:1169-1174.

- Minkis K, Whittington A, Alam M. Dermatologic surgery emergencies: complications caused by systemic reactions, high-energy systems, and trauma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:265-284.

- Morais-Almeida M, Gaspar A, Marinho S, et al. Allergy to local anesthetics of the amide group with tolerance to procaine. Allergy. 2003;58:827-828.

- To D, Kossintseva I, de Gannes G. Lidocaine contact allergy is becoming more prevalent. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1367-1372.

- Wahlgren CF, Quiding H. Depth of cutaneous analgesia after application of a eutectic mixture of the local anesthetics lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA cream). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:584-588.

- Bjerring P, Andersen PH, Arendt-Nielsen L. Vascular response of human skin after analgesia with EMLA cream. Br J Anaesth. 1989;63:655-660.

- Ismail F, Goldsmith PC. EMLA cream-induced allergic contact dermatitis in a child with thalassaemia major. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;52:111.

- Thakur BK, Murali MR. EMLA cream-induced allergic contact dermatitis: a role for prilocaine as an immunogen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;95:776-778.

- Waton J, Boulanger A, Trechot PH, et al. Contact urticaria from EMLA cream. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:284-287.

- Bucalo BD, Mirikitani EJ, Moy RL. Comparison of skin anesthetic effect of liposomal lidocaine, nonliposomal lidocaine, and EMLA using 30-minute application time. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:537-541.

- Guardiano RA, Norwood CW. Direct comparison of EMLA versus lidocaine for pain control in Nd:YAG 1,064 nm laser hair removal. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:396-398.

- Nestor MS. Safety of occluded 4% liposomal lidocaine cream. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:618-620.

- Oni G, Rasko Y, Kenkel J. Topical lidocaine enhanced by laser pretreatment: a safe and effective method of analgesia for facial rejuvenation. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:854-861.

- Niamtu J 3rd. Simple technique for lip and nasolabial fold anesthesia for injectable fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1330-1332.

- Naumann M, Flachenecker P, Brocker EB, et al. Botulinum toxin for palmar hyperhidrosis. Lancet. 1997;349:252.

- Naumann M, Hofmann U, Bergmann I, et al. Focal hyperhidrosis: effective treatment with intracutaneous botulinum toxin. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:301-304.

- Shelley WB, Talanin NY, Shelley ED. Botulinum toxin therapy for palmar hyperhidrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(2, pt 1):227-229.

- Davies T, Karanovic S, Shergill B. Essential regional nerve blocks for the dermatologist: part 2. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:861-867.

Practice Points

- The proper delivery of local anesthesia is integral to successful cosmetic interventions.

- Regional nerve blocks can provide effective analgesia while reducing the number of injections and preserving the architecture of the cosmetic field.

Product News: 06 2017

Avène Complexion Correcting Shield SPF 50+

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA adds the Avène Complexion Correcting Shield SPF 50+ mineral sunscreen to its physician-dispensed sun care line. This tinted moisturizer, available in 3 shades, provides 24-hour hydration and an effective antioxidant defense against sun-induced free radicals. Avène Complexion Correcting Shield provides an instant blurring effect to camouflage skin imperfections such as large pores, uneven skin tone, redness, fine lines, and wrinkles. For more information, visit www.aveneusa.com.

Coppertone Clearly Sheer Whipped Sunscreen

Bayer introduces Coppertone Clearly Sheer Whipped Sunscreen, a rich and creamy formula available in sun protection factor 30 and 50. Coppertone Clearly Sheer Whipped Sunscreen absorbs quickly to leave skin feeling soft and smooth. It offers broad-spectrum UVA/UVB protection and is water resistant for up to 80 minutes.For more information, visit www.coppertone.com.

DerMend Mature Skin Solutions

Ferndale Healthcare launches DerMend Mature Skin Solutions, an over-the-counter line consisting of 3 products specifically designed for patients aged 50 years and older. The Fragile Skin Moisturizing Formula rejuvenates thin and fragile skin with hyaluronic acid, retinol, glycolic acid, niacinaminde, and 5 ceramides. The Moisturizing Anti-Itch Lotion is steroid free and contains

Jan Marini Sunscreens

Jan Marini Skin Research, Inc, introduces Antioxidant Daily Face Protectant SPF 33 and Marini Physical Protectant SPF 45, both providing broad-spectrum UVA/UVB protection. Antioxidant Daily Face Protectant provides oil control and advanced hydration for daily use to reduce and address damage caused by sun exposure. Marini Physical Protectant utilizes purely physical filters to decrease the risk of premature skin aging and features a universal tint with a sheer matte finish. For more information, visit www.janmarini.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Avène Complexion Correcting Shield SPF 50+

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA adds the Avène Complexion Correcting Shield SPF 50+ mineral sunscreen to its physician-dispensed sun care line. This tinted moisturizer, available in 3 shades, provides 24-hour hydration and an effective antioxidant defense against sun-induced free radicals. Avène Complexion Correcting Shield provides an instant blurring effect to camouflage skin imperfections such as large pores, uneven skin tone, redness, fine lines, and wrinkles. For more information, visit www.aveneusa.com.

Coppertone Clearly Sheer Whipped Sunscreen

Bayer introduces Coppertone Clearly Sheer Whipped Sunscreen, a rich and creamy formula available in sun protection factor 30 and 50. Coppertone Clearly Sheer Whipped Sunscreen absorbs quickly to leave skin feeling soft and smooth. It offers broad-spectrum UVA/UVB protection and is water resistant for up to 80 minutes.For more information, visit www.coppertone.com.

DerMend Mature Skin Solutions

Ferndale Healthcare launches DerMend Mature Skin Solutions, an over-the-counter line consisting of 3 products specifically designed for patients aged 50 years and older. The Fragile Skin Moisturizing Formula rejuvenates thin and fragile skin with hyaluronic acid, retinol, glycolic acid, niacinaminde, and 5 ceramides. The Moisturizing Anti-Itch Lotion is steroid free and contains

Jan Marini Sunscreens

Jan Marini Skin Research, Inc, introduces Antioxidant Daily Face Protectant SPF 33 and Marini Physical Protectant SPF 45, both providing broad-spectrum UVA/UVB protection. Antioxidant Daily Face Protectant provides oil control and advanced hydration for daily use to reduce and address damage caused by sun exposure. Marini Physical Protectant utilizes purely physical filters to decrease the risk of premature skin aging and features a universal tint with a sheer matte finish. For more information, visit www.janmarini.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Avène Complexion Correcting Shield SPF 50+

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA adds the Avène Complexion Correcting Shield SPF 50+ mineral sunscreen to its physician-dispensed sun care line. This tinted moisturizer, available in 3 shades, provides 24-hour hydration and an effective antioxidant defense against sun-induced free radicals. Avène Complexion Correcting Shield provides an instant blurring effect to camouflage skin imperfections such as large pores, uneven skin tone, redness, fine lines, and wrinkles. For more information, visit www.aveneusa.com.

Coppertone Clearly Sheer Whipped Sunscreen

Bayer introduces Coppertone Clearly Sheer Whipped Sunscreen, a rich and creamy formula available in sun protection factor 30 and 50. Coppertone Clearly Sheer Whipped Sunscreen absorbs quickly to leave skin feeling soft and smooth. It offers broad-spectrum UVA/UVB protection and is water resistant for up to 80 minutes.For more information, visit www.coppertone.com.

DerMend Mature Skin Solutions

Ferndale Healthcare launches DerMend Mature Skin Solutions, an over-the-counter line consisting of 3 products specifically designed for patients aged 50 years and older. The Fragile Skin Moisturizing Formula rejuvenates thin and fragile skin with hyaluronic acid, retinol, glycolic acid, niacinaminde, and 5 ceramides. The Moisturizing Anti-Itch Lotion is steroid free and contains

Jan Marini Sunscreens

Jan Marini Skin Research, Inc, introduces Antioxidant Daily Face Protectant SPF 33 and Marini Physical Protectant SPF 45, both providing broad-spectrum UVA/UVB protection. Antioxidant Daily Face Protectant provides oil control and advanced hydration for daily use to reduce and address damage caused by sun exposure. Marini Physical Protectant utilizes purely physical filters to decrease the risk of premature skin aging and features a universal tint with a sheer matte finish. For more information, visit www.janmarini.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

What’s Eating You? Chiggers

Identifying Characteristics and Disease Transmission

Chiggers belong to the Trombiculidae family of mites and also are referred to as harvest mites, harvest bugs, harvest lice, mower’s mites, and redbugs.1 The term chigger specifically describes the larval stage of this mite’s life cycle, as it is the only stage responsible for chigger bites. The nymph and adult phases feed on vegetable matter. Trombiculid mites are most often found in forests, grassy areas, gardens, and moist areas of soil near bodies of water. Trombicula alfreddugesi is the most common species in the United States, and these mites mainly live in the southeastern and south central regions of the country. Conversely, Trombicula autumnalis is most predominant in Western Europe and East Asia.1

The life cycle of the mite includes the egg, larval, nymphal, and adult stages.2 Due to their need for air humidity greater than 80%, mites lay their eggs on low leaves, blades of grass, or on the ground. They spend most of their lives on vegetation no more than 30 cm above ground level.3 Eggs remain dormant for approximately 6 days until the hatching of the prelarvae, which have 6 legs and are nonfeeding. It takes another 6 days for the prelarvae to mature into larvae. Measuring 0.15 to 0.3 mm in length, mite larvae are a mere fraction of the size of adult mites, which generally are 1 to 2 mm in length, and are bright red or brown-red in color (Figure 1).

The biting larvae have many acceptable hosts including turtles, toads, birds, small mammals, and humans, which act as accidental hosts. Larvae remain on vegetation waiting for a suitable host to pass by so they may attach to its skin and remain there for several days. In the exploration for an ideal area to begin feeding (eg, thin epidermis,4 localized increased air humidity5), larvae can travel extensively on the skin; however, they often are stopped by tight-fitting sections of clothing (eg, waistbands), so bites are mostly found in clusters. To feed, mite larvae latch onto the skin using chelicerae, jawlike appendages found in the front of the mouth in arachnids.6 They then inject digestive enzymes that liquefy epidermal cells on direct contact, which results in the formation of a stylostome from which the mites may suck up lymph fluid and broken down tissue.7 Although the actual initial bite is painless, this feeding process leads to the localized inflammation and irritation noticed by infested patients.8

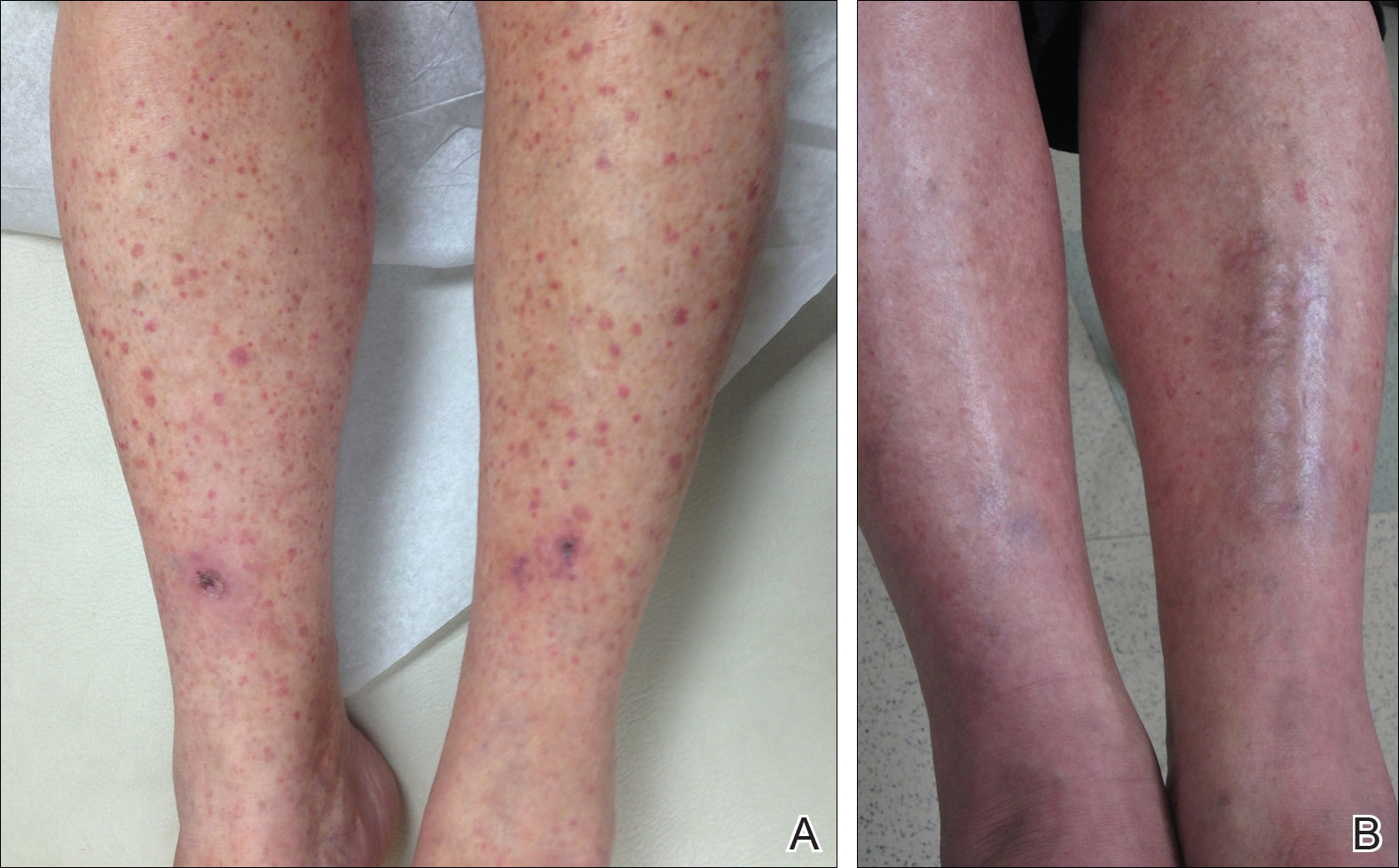

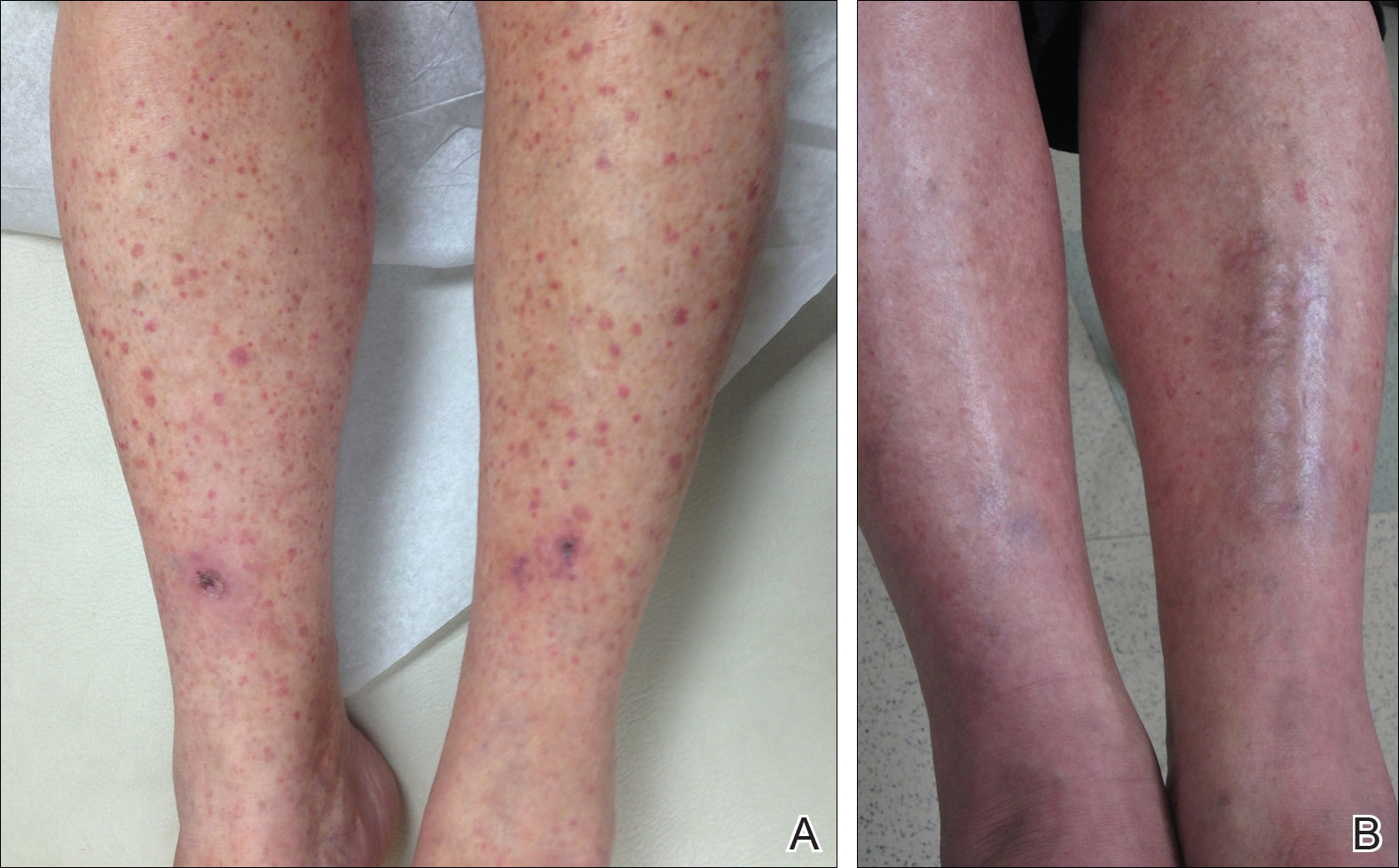

The classic clinical presentation includes severe pruritus and cutaneous swelling as well as erythema caused by the combination of several factors, such as enzyme-induced cellular mechanical damage, human immune response, and sometimes a superimposed bacterial infection. Papules and papulovesicles appear in groups, most commonly affecting the legs and waistline (Figure 2).9 Itching generally occurs within hours of larval latching and subsides within 72 hours. Cutaneous lesions typically take 1 to 2 weeks to heal. In some rare cases, patients may react with urticarial, bullous, or morbilliform eruptions, and the inflammation and pruritus can last for weeks.6 Summer penile syndrome has been noted in boys who display a local hypersensitivity to chigger bites.10 This syndrome represents a triad of penile swelling, dysuria, and pruritus, which lasts for a few days to a few weeks.

Disease Management

Because the lesions are self-healing, treatment is focused on symptomatic relief of itching by means of topical antipruritics (eg, camphor and menthol, pramoxine lotion) or oral antihistamines (eg, diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine). Potent topical corticosteroids may be used to alleviate inflammation and pruritus, especially when occluded under plastic wrap to increase absorption. In severe cases, an intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (2.5–5 mg/mL) injection may be required.9 The best practice, however, is to take preventative measures to avoid becoming a host for the mites. Patients should take special care when traveling in infested areas by completely covering their skin, tucking pant cuffs into their socks, and applying products containing DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide or N,N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide) to the skin and clothing. The odds of prevention are increased even further when clothing also is treated with permethrin.11

In parts of Asia and Australia, these mites may transmit Orientia tsutsugamushi, the organism responsible for scrub typhus, through their saliva during a bite.12 Scrub typhus is associated with an eschar, as well as fever, intense headache, and diffuse myalgia. It responds well to treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily.13 Studies investigating genetic material found in trombiculid mites across the globe have detected Ehrlichia-specific DNA in Spain,14Borrelia-specific DNA in the Czech Republic,15,16 and Hantavirus-specific RNA in Texas.17 There is evidence that the mites play a role in maintenance of zoonotic reservoirs, while humans are infected via ingestion or inhalation of infectious rodent extreta.18

- McClain D, Dana AN, Goldenberg G. Mite infestations. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:327-346.

- Lane RP, Crosskey RW. Medical Insects and Arachnids. London, England: Chapman & Hall; 1993.

- Gasser R, Wyniger R. Distribution and control of Trombiculidae with special reference to Trombicula autumnalis [article in German]. Acta Trop. 1955;12:308-326.

- Jones BM. The penetration of the host tissue by the harvest mite, Trombicula autumnalis Shaw. Parasitology. 1950;40:247-260.

- Farkas J. Concerning the predilected localisation of the manifestations of trombidiosis. predilected localisation and its relation to the ways of invasion [article in German]. Dermatol Monatsschr. 1979;165:858-861.

- Jones JG. Chiggers. Am Fam Physician. 1987;36:149-152.

- Shatrov AB. Stylostome formation in trombiculid mites (Acariformes: Trombiculidae). Exp Appl Acarol. 2009;49:261-280.

- Potts J. Eradication of ectoparasites in children. how to treat infestations of lice, scabies, and chiggers. Postgrad Med. 2001;110:57-59, 63-64.

- Elston DM. Arthropods and infestations. Infectious Diseases of the Skin. Boca Raton, FL; CRC Press; 2009:112-116.

- Smith GA, Sharma V, Knapp JF, et al. The summer penile syndrome: seasonal acute hypersensitivity reaction caused by chigger bites on the penis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1998;14:116-118.

- Young GD, Evans S. Safety of DEET and permethrin in the prevention of arthropod attack. Military Med. 1998;163:324-330.

- Watt G, Parola P. Scrub typhus and tropical rickettsioses. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16:429-436.

- Panpanich R, Garner P. Antibiotics for treating scrub typhus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD002150.

- Fernández-Soto P, Pérez-Sánchez R, Encinas-Grandes A. Molecular detection of Ehrlichia phagocytophila genogroup organisms in larvae of Neotrombicula autumnalis (Acari: Trombiculidae) captured in Spain. J Parasitol. 2001;87:1482-1483.

- Literak I, Stekolnikov AA, Sychra O, et al. Larvae of chigger mites Neotrombicula spp. (Acari: Trombiculidae) exhibited Borrelia but no Anaplasma infections: a field study including birds from the Czech Carpathians as hosts of chiggers. Exp Appl Acarol. 2008;44:307-314.