User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Muckle-Wells Syndrome in the Setting of Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome

Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS) was first described in 1962 and is part of a broad category of hereditary periodic fever syndromes that include the autoinflammatory syndromes and the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPSs). Unlike autoimmune diseases, autoinflammatory syndromes are not associated with antigen-specific T-cell responses or high titers of autoantibodies but are related to disorders of the innate immune system. Basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS), or Gorlin syndrome, is a rare genodermatosis inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion that is characterized by a broad range of anomalies. Most notable is the early and strong predisposition to develop several to hundreds of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs). Classic clinical features of MWS and a thorough history and physical examination can assist in the diagnosis of this rare entity.

Case Report

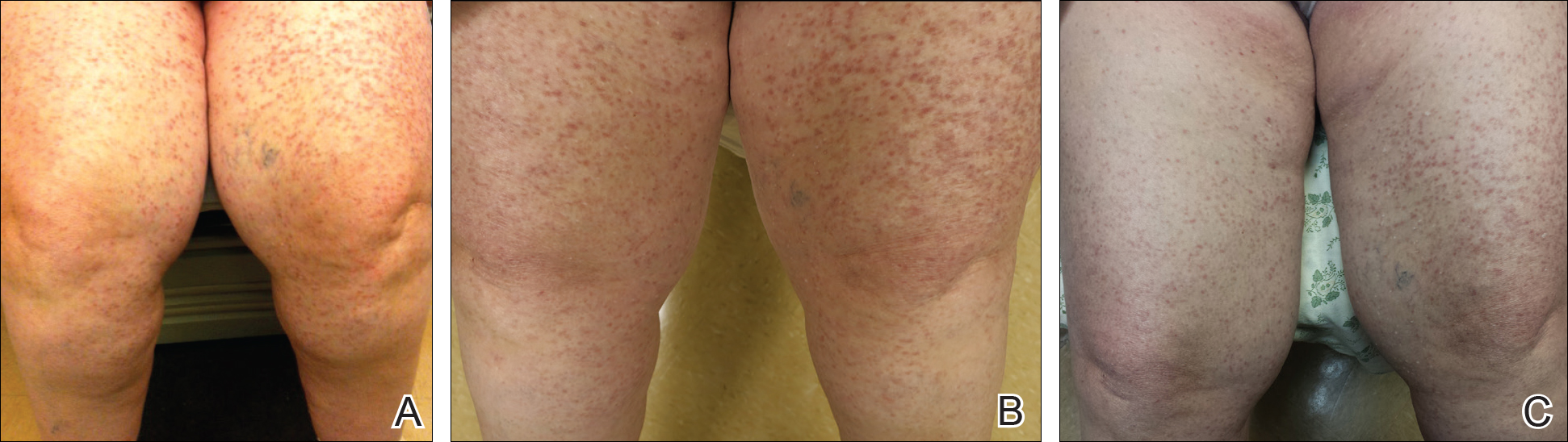

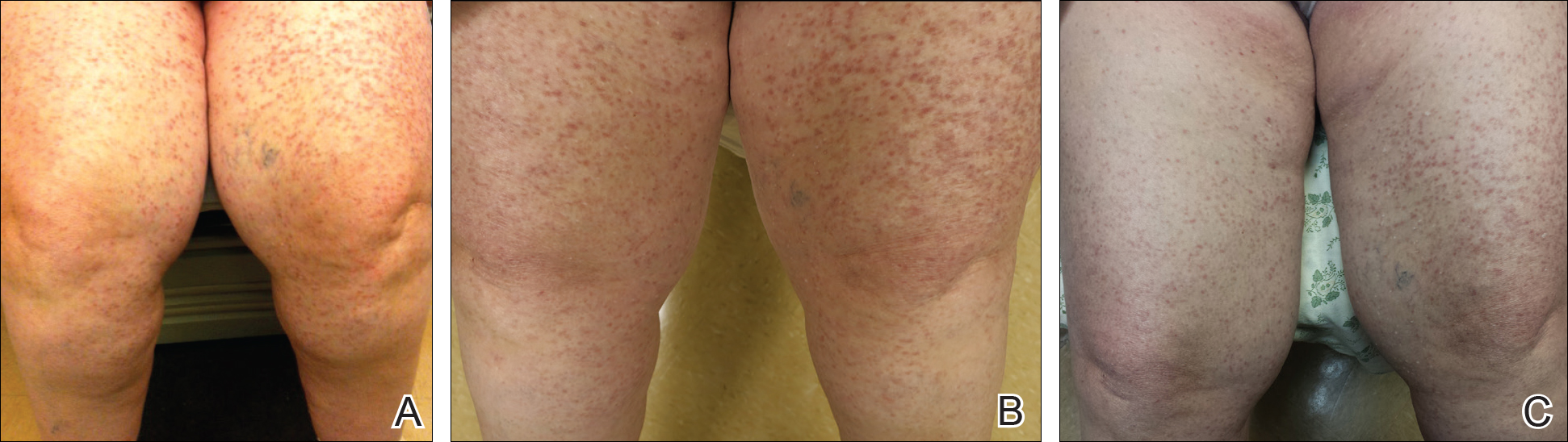

A 35-year-old woman with a history of BCNS, which had been diagnosed at 24 years of age based on the presence of more than 2 BCCs and a family history of BCNS in her mother, presented with intermittent pruritic urticaria on the chest and back, episodic fevers, associated joint pain and swelling that worsened several hours after exercise, headache, conjunctivitis, blurred vision, and severe debilitating fatigue that had been present since childhood. The symptoms had progressively worsened with age and symptom-free intervals became shorter. She was diagnosed by her rheumatologist with biopsy-proven MWS and a positive NLRP3 (NLR family pyrin domain containing 3) gene mutation at 29 years of age. She was treated unsuccessfully with prednisone and antihistamines and entered a trial with anakinra. She showed improvement for 2 weeks but developed severe swelling and erythema at the injection sites at week 3, along with large leathery patches on the legs and difficulty ambulating.

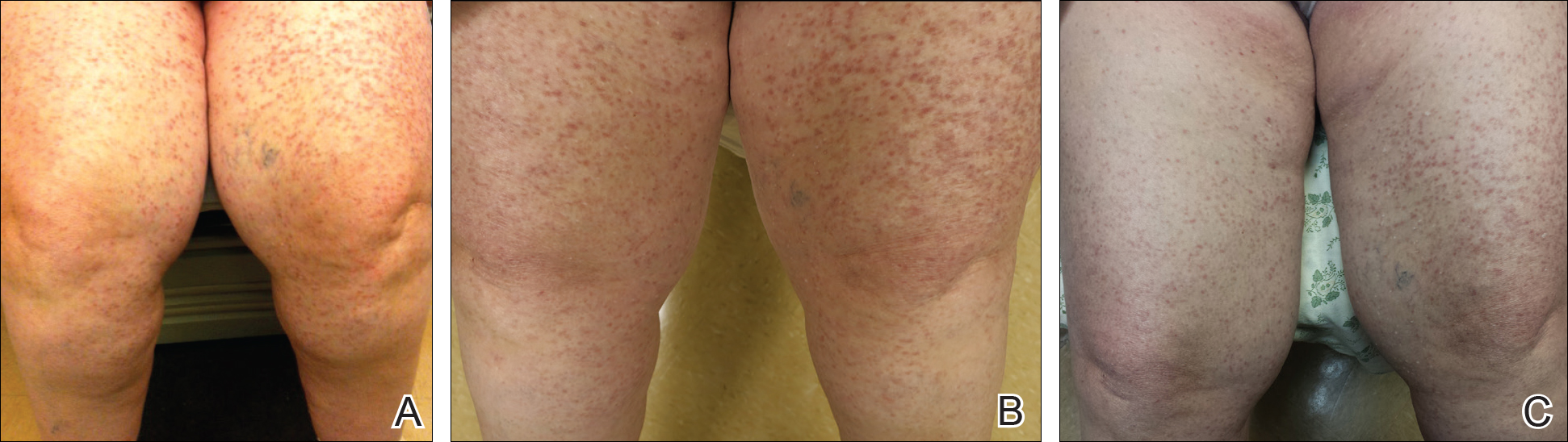

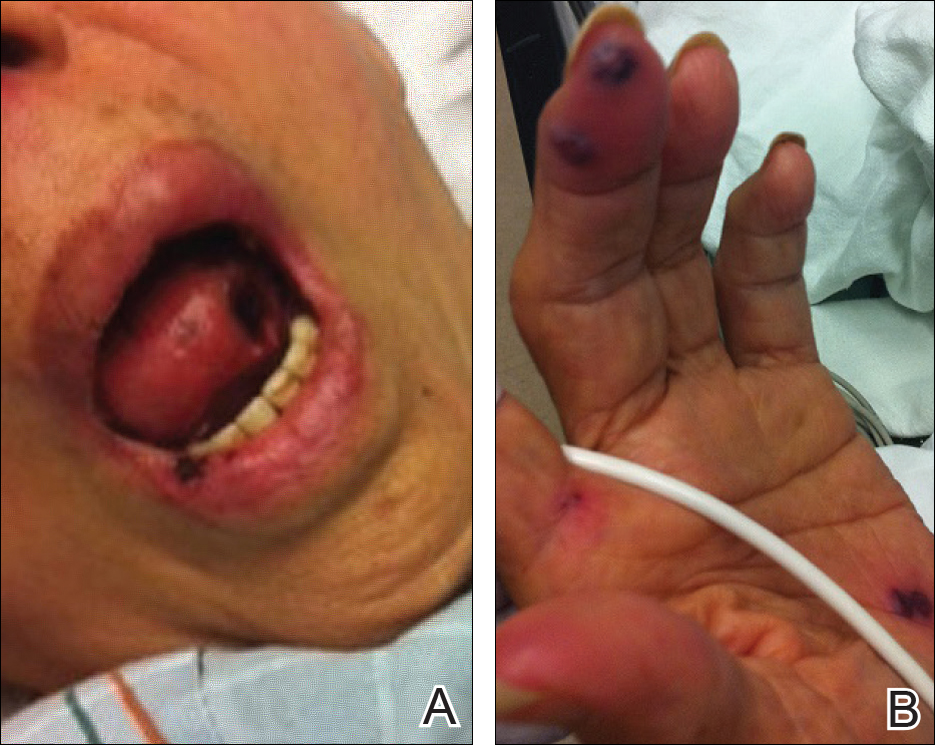

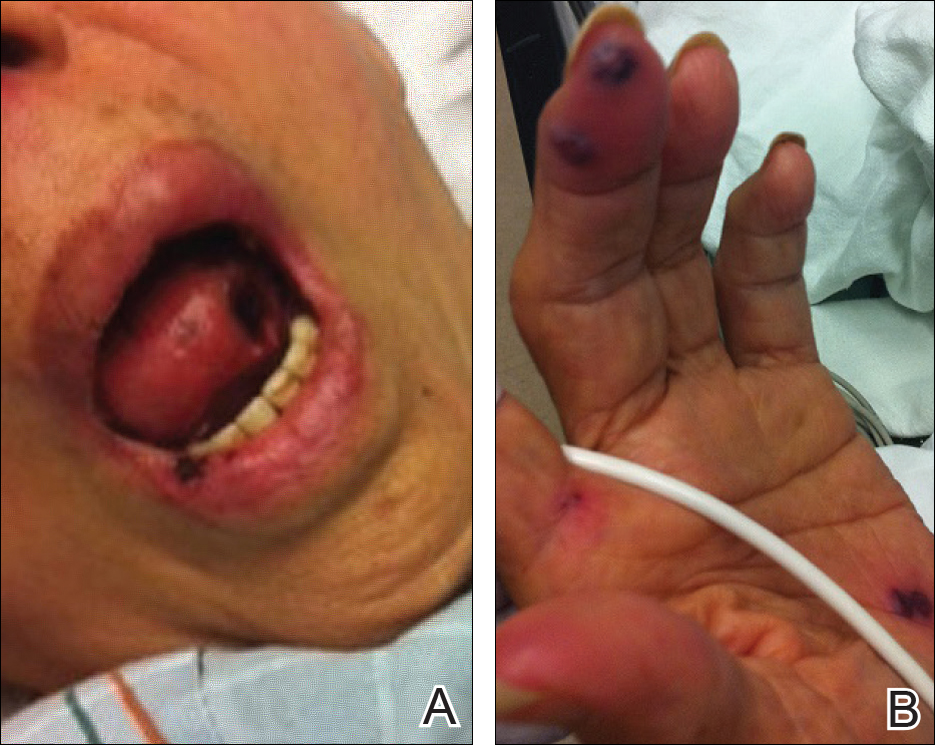

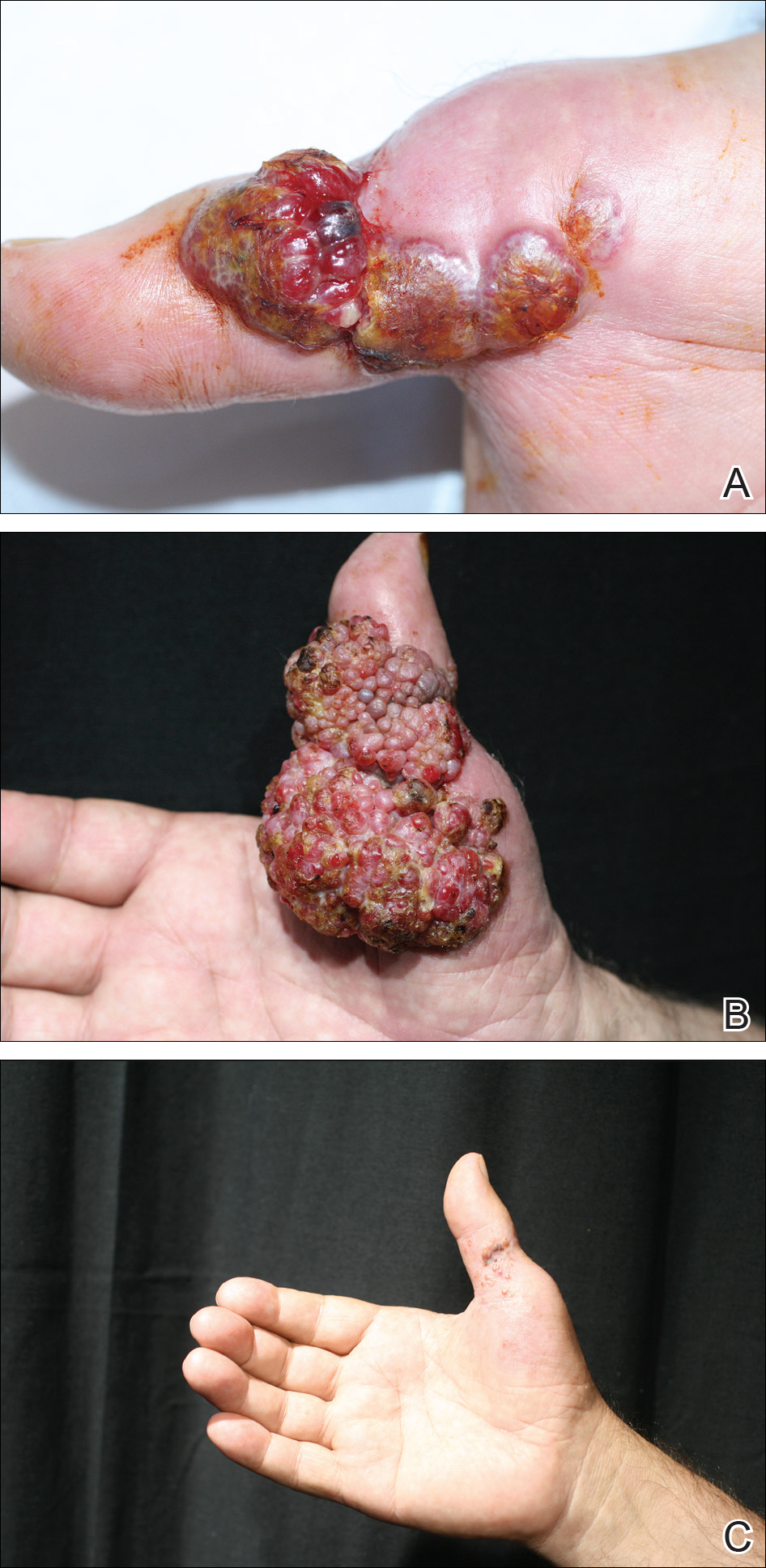

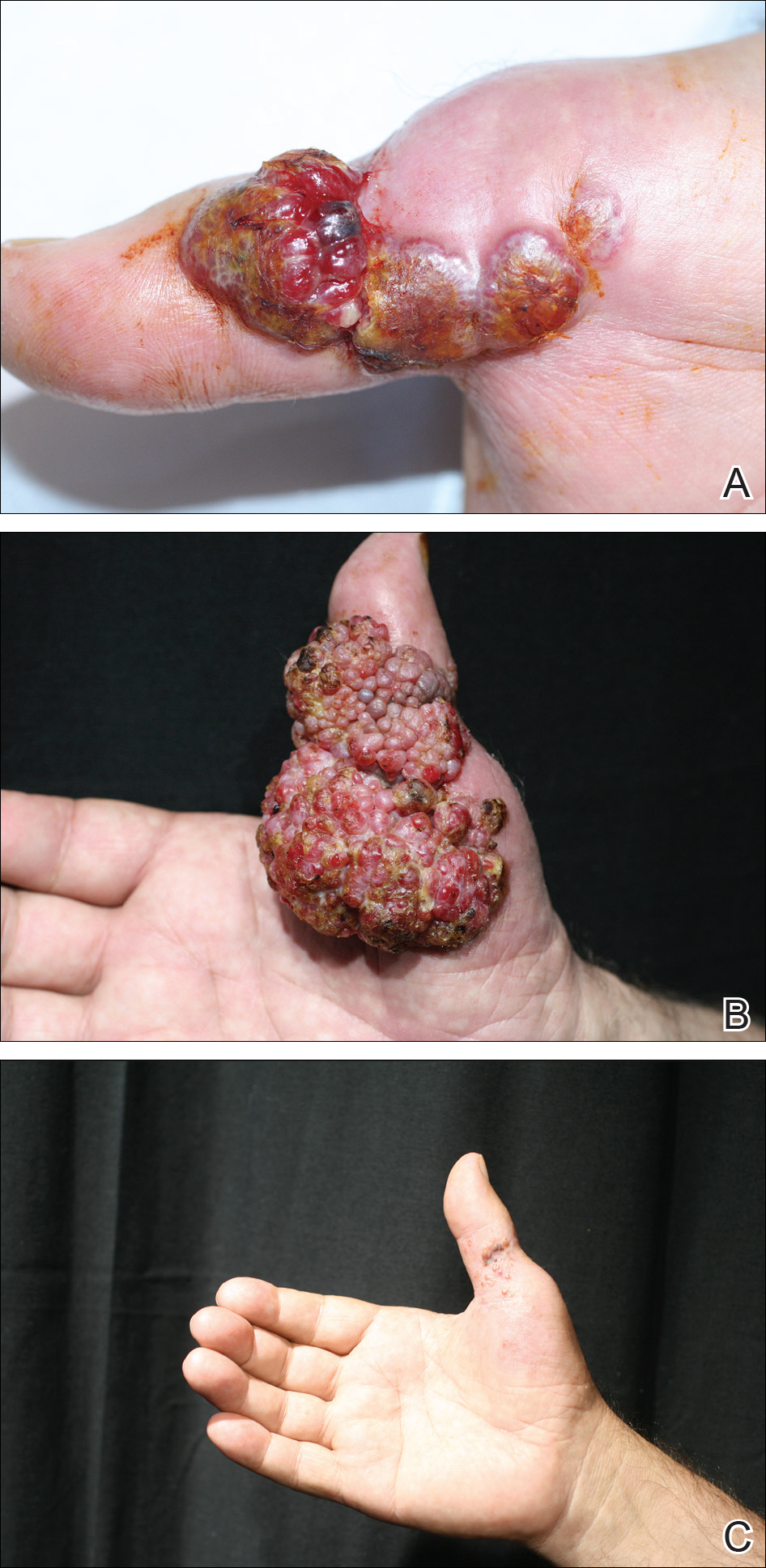

The patient subsequently underwent excision of her BCCs and reported each site became erythematous, edematous, warm, and painful 6 hours after excision, which lasted for hours to days (Figures 1–3). After the first excision on the right forearm, she was seen in the emergency department, started on intravenous antibiotics and prednisone, and kept overnight in the hospital. She was discharged the following day and the edema in the right forearm subsided over several days. Bacterial culture and laboratory evaluation for infection were negative after the first excision on the right forearm. Because of the symptoms she experienced following this excision, she was referred to the plastic surgery department for excision followed by postoperative monitoring in the hospital. The patient continued to undergo excisions for BCCs and developed more severe symptoms including erythema, edema, warmth, and tenderness at the surrounding sites. Once again, the excision sites were cultured and laboratory work to rule out infection was ordered with a negative result. After several excisions and subsequent clinical findings, the patients’ symptoms were deemed consistent with MWS and not a result of infectious etiology. A diagnosis of MWS and BCNS with exacerbation of MWS with surgical procedures was made.

The patient has continued therapy with rilonacept for MWS, which is managed by her rheumatologist. She has tolerated rilonacept without adverse effects and has experienced a reduction in symptoms that has enhanced her quality of life and allows for further treatment of her BCNS. Her dermatologist (J.W.L.) has been treating her BCCs with vismodegib, but treatment has been sporadic due to muscle cramping after 7 days of therapy. She reported subjective improvement to her dermatologist and has tried alternating 7 days on and 7 days off vismodegib. The muscle cramping still has limited her treatment with this regimen, and she is currently on a trial of 3 days on, 4 days off per week.

Comment

Classification and Clinical Presentation

The hereditary periodic fever syndromes include the autoinflammatory syndromes and the CAPSs. The autoinflammatory syndromes include familial Mediterranean fever, hyperimmunoglobulinemia D with periodic fever syndrome, and tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic syndrome. The CAPSs are similar but distinct and include familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome, neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (also known as chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous and articular syndrome, or cutaneous articular syndrome) and MWS.1,2

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes are rare inherited diseases that result from mutations in the NLRP3 gene. There is a gain-of-function mutation on the NLRP3 gene located on the long arm of chromosome 1 at position 44, which codes for cryopyrin. An NLRP3 gene mutation causes cryopyrin to become hyperactive, leading to the formation of an inflammasome, which is a group of cryopyrin molecules. Inflammasomes, along with other proteins, activate caspase 1 to produce excess IL-1β, leading to persistent inflammatory symptoms.3 IL-1β is one of the key mediators of the body’s response to microbial invasion, inflammation, immunologic reactions, and tissue injury. It affects a large range of cells and organs. Although IL-1β production is critical for the control of pathogenic infections, excessive cytokine production is harmful to the host and can even be fatal.3,4

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes encompass a disease continuum. The 3 distinct entities share many overlapping features as well as unique and distinguishing characteristics. Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome is the mildest phenotype and is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. It is characterized by a chronic urticarial eruption that starts early in infancy or childhood. The distribution of the cutaneous eruption is widespread and favors the arms and legs over the face and trunk. A low-grade fever often is seen along with musculoskeletal concerns of arthralgia and pain. Other commonly reported symptoms include conjunctivitis, myalgia, fatigue, and headache. Neurologic symptoms can include headaches. Symptoms usually begin 1 to 2 hours after cold exposure and last less than 24 hours.5-8

Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease is the most severe phenotype and occurs sporadically. Continuous symptoms and flares are characteristic and the length of the flare can vary from minutes to days. The cutaneous eruption favors the face, trunk, arms, and legs, and varies in intensity, beginning in infancy or childhood. Fever may be intermittent, mild, or absent. Rheumatologic manifestations include arthralgia and swelling, with approximately one-third of patients experiencing severe disabling arthropathy that causes gross joint deformity. Ocular findings include conjunctivitis, uveitis, papilledema, and even blindness. Neurologic sequelae include headaches, sensorineural hearing loss, and aseptic meningitis. Amyloidosis has been seen as a late complication.5,8

Muckle-Wells syndrome is a rare hereditary inflammatory disorder. It has no ethnic predisposition and is mostly inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Classically, the condition is characterized by recurrent urticaria beginning at birth with intermittent episodic fever and malaise. The eruption has a predilection for the face, trunk, arms, and legs, which is similar to neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease. Associated myalgia and arthralgia are common as well as ocular findings of conjunctivitis and episcleritis. Neurologic manifestations include headache and progressive sensorineural hearing loss in 60% to 70% of patients.6 Abdominal pain may be seen along with rare serositis in MWS but is rare in the other CAPSs. Amyloidosis caused by chronic inflammation is the most serious complication of MWS and is seen in approximately one-third of patients, manifesting as proteinuria followed by renal impairment. Symptoms of MWS may occur daily but vary individually, are broad in intensity and duration, and can last 1 to 2 days before resolving spontaneously. The symptoms can result from metabolic stressors including cold, stress, and exercise, as well as microbial pathogens. Leukocytosis and increased acute-phase reactants are observed during episodes of inflammation.4,6,8

Histopathology

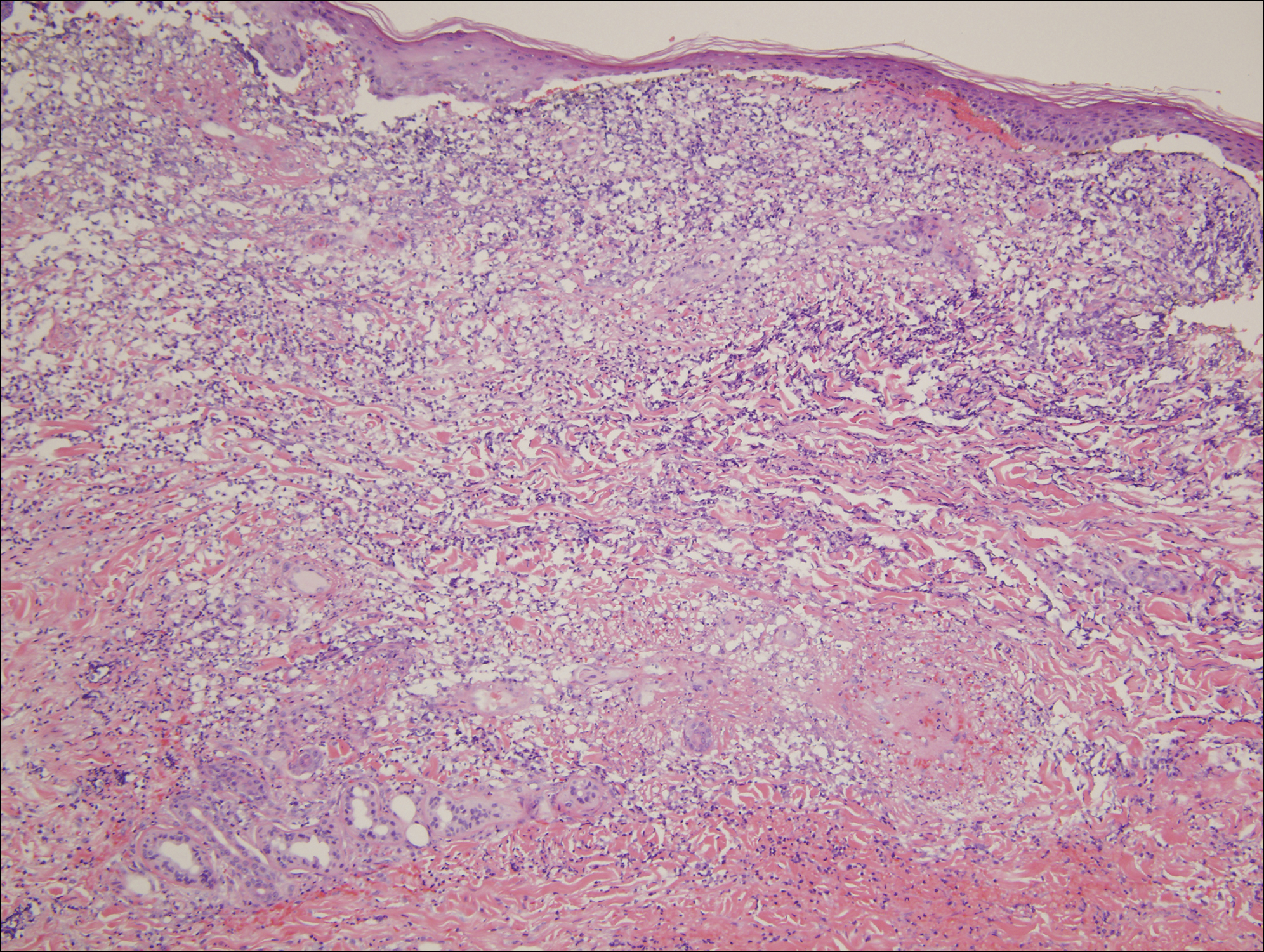

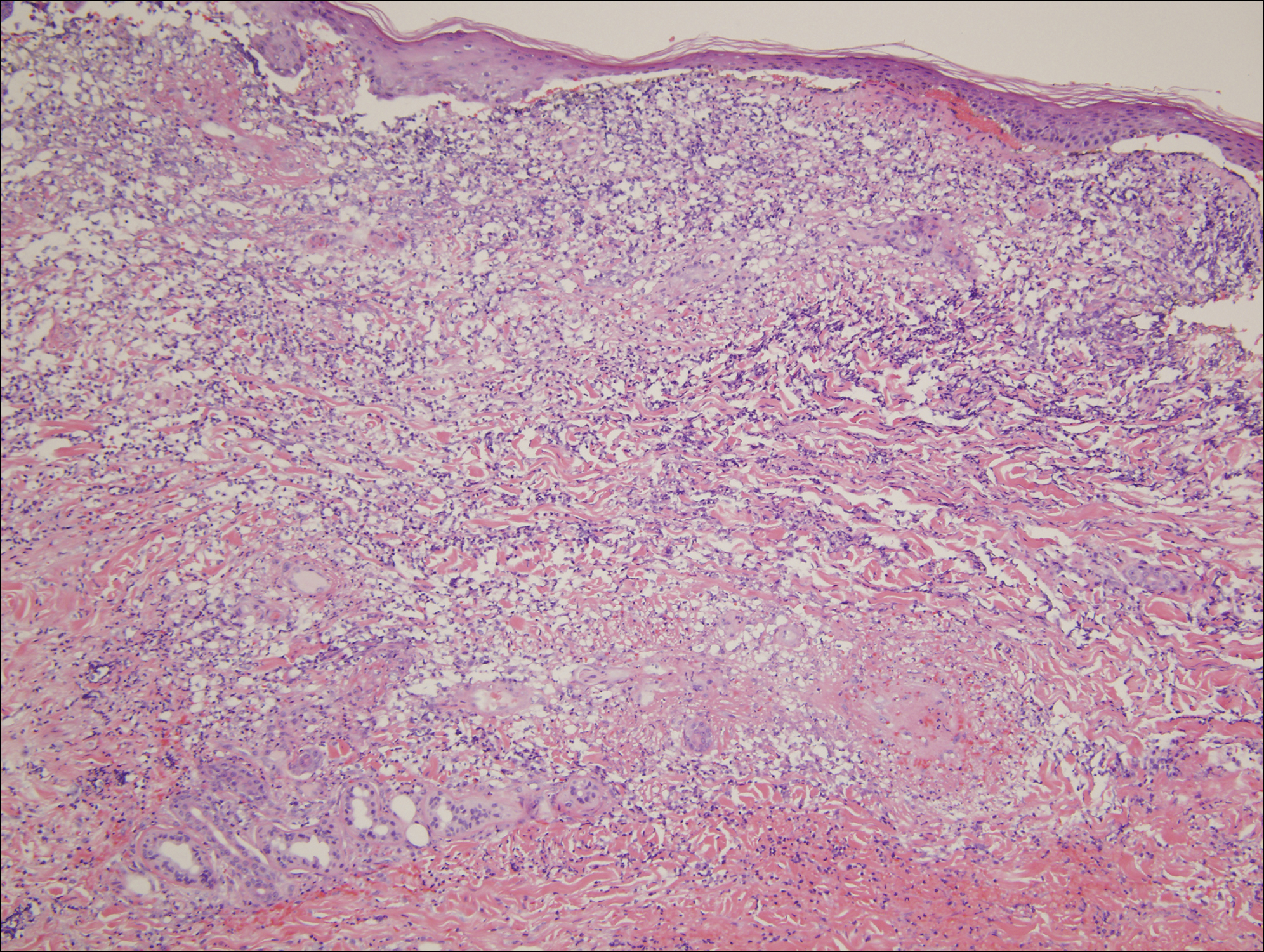

Mild phenotypic variability exists between individuals, and many of the symptoms overlap in CAPSs. Although CAPSs display several distinguishing clinical characteristics, interestingly they share the same histopathological features regardless of the syndrome. The typical histopathological finding is a dermal neutrophilic infiltrate that tends to be perivascular and also may be perieccrine. Vasodilation and dermal edema also may be seen. These histopathological findings contrast with the typical lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltrate seen in classic urticaria. Similar histopathologic findings have been seen in other neutrophilic urticarial dermatoses such as Schnitzler syndrome.4,6

Differential

The differential diagnoses for CAPSs include Schnitzler syndrome, cold urticaria, systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis/adult-onset Still disease, and deficiency in IL-1ra. It is important to consider these differential diagnoses for management and treatment options.

Management

The discovery of the NLRP3 gene mutation as well as an understanding of IL-1 biology has led to targeted therapy for these syndromes. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes are mediated by IL-1β with an in vivo rate 5 times higher than in healthy patients.4 The blockade of IL-1β results in complete resolution of symptoms.

In the last several years, anakinra, rilonacept, and canakinumab have shown efficacy in targeting IL-1β as receptor antagonists. Anakinra is a short-acting recombinant IL-1ra with a half-life of 4 to 6 hours. This short half-life requires daily injections and the most common adverse events included injection-site reaction and upper respiratory tract infection.2,4 Rilonacept is a dimeric fusion protein that contains binding regions for the type 1 receptor and the IL-1 receptor accessory protein and is fused to the fragment, crystallizable (Fc) portion of human IgG1. Rilonacept is long acting with a circulating half-life of 8.6 days and offers patients ease of dosing with weekly subcutaneous injections. Rilonacept generally is well tolerated, with the most frequent adverse effects being injection-site reaction, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, arthralgia, and diarrhea.2,7

The newest of the treatments for patients with CAPS is canakinumab. It is a fully human IL-1β monoclonal antibody that is specific for IL-1β and not other members of the IL-1 family. It has a mean half-life of 26 days and is dosed subcutaneously once every 8 weeks. The most common adverse effects include nasopharyngitis, rhinitis, nausea, diarrhea, and vertigo.4 In one study, most patients did not report injection-site reactions.7 Studies also are underway on VX-765, a caspace-1 targeted therapy that acts upstream in the IL-1β pathway. Treatment with anakinra, rilonacept, and canakinumab generally offers rapid and sustained remission in the majority of MWS patients and helps prevent the development of systemic amyloidosis and lessens the potential for end organ damage.2,7

MWS and BCNS

Our patient had an unusual presentation of MWS complicated by BCNS, another rare autosomal-dominant inherited genodermatosis. In an extensive review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms Muckle-Wells syndrome and basal cell nevus syndrome, no association was identified between MWS and BCNS. Basal cell nevus syndrome is linked to PTCH1 (patched 1) gene mutation with an incidence of 1:150,000 in the United States and Europe and is characterized by a broad range of anomalies including skeletal abnormalities, ectopic calcification, odontogenic keratocysts, facial dysmorphism with macrocephaly, palmoplantar pits, and numerous tumors. Most notable is the early and strong predisposition to develop several to hundreds of BCCs.9

Conclusion

Muckle-Wells syndrome may go undiagnosed for many years or may be misdiagnosed as refractory urticaria, as in our patient. It is important to include periodic fever syndromes in the differential diagnosis of refractory urticaria with episodic fever to diagnose these cases of MWS earlier.

- Kagami S, Saeki H, Kuwano Y, et al. A probable case of Muckle-Wells syndrome. J Dermatol. 2006;2:118-121.

- Kanazawa N, Furukawa F. Autoinflammatory syndromes with a dermatological perspective. J Dermatol. 2007;34:601-618.

- Martinon F, Tschopp J. Inflammatory caspases: linking an intracellular innate immune system to autoinflammatory diseases. Cell. 2004;117:561-574.

- Mueller SM, Itin P, Haeusermann P. Muckle-Wells syndrome effectively treated with canakinumab: is the recommended dosing schedule mandatory? Dermatology. 2011;223:113-118.

- Neven B, Prieur A, Quartier dit Maire P. Cryopyrinopathies: update on pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:481-489.

- Newell L, August S, Foria V, et al. Lifelong urticaria and multiple unexplained systemic symptoms. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:431-433.

- Yu JR, Kieron KS. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome: an update on diagnosis and treatment response. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:12-20.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Barcelona, Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008. 9. Göppner D, Leverkus M. Basal cell carcinoma: from the molecular understanding of the pathogenesis to targeted therapy of progressive disease. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:650258.

Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS) was first described in 1962 and is part of a broad category of hereditary periodic fever syndromes that include the autoinflammatory syndromes and the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPSs). Unlike autoimmune diseases, autoinflammatory syndromes are not associated with antigen-specific T-cell responses or high titers of autoantibodies but are related to disorders of the innate immune system. Basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS), or Gorlin syndrome, is a rare genodermatosis inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion that is characterized by a broad range of anomalies. Most notable is the early and strong predisposition to develop several to hundreds of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs). Classic clinical features of MWS and a thorough history and physical examination can assist in the diagnosis of this rare entity.

Case Report

A 35-year-old woman with a history of BCNS, which had been diagnosed at 24 years of age based on the presence of more than 2 BCCs and a family history of BCNS in her mother, presented with intermittent pruritic urticaria on the chest and back, episodic fevers, associated joint pain and swelling that worsened several hours after exercise, headache, conjunctivitis, blurred vision, and severe debilitating fatigue that had been present since childhood. The symptoms had progressively worsened with age and symptom-free intervals became shorter. She was diagnosed by her rheumatologist with biopsy-proven MWS and a positive NLRP3 (NLR family pyrin domain containing 3) gene mutation at 29 years of age. She was treated unsuccessfully with prednisone and antihistamines and entered a trial with anakinra. She showed improvement for 2 weeks but developed severe swelling and erythema at the injection sites at week 3, along with large leathery patches on the legs and difficulty ambulating.

The patient subsequently underwent excision of her BCCs and reported each site became erythematous, edematous, warm, and painful 6 hours after excision, which lasted for hours to days (Figures 1–3). After the first excision on the right forearm, she was seen in the emergency department, started on intravenous antibiotics and prednisone, and kept overnight in the hospital. She was discharged the following day and the edema in the right forearm subsided over several days. Bacterial culture and laboratory evaluation for infection were negative after the first excision on the right forearm. Because of the symptoms she experienced following this excision, she was referred to the plastic surgery department for excision followed by postoperative monitoring in the hospital. The patient continued to undergo excisions for BCCs and developed more severe symptoms including erythema, edema, warmth, and tenderness at the surrounding sites. Once again, the excision sites were cultured and laboratory work to rule out infection was ordered with a negative result. After several excisions and subsequent clinical findings, the patients’ symptoms were deemed consistent with MWS and not a result of infectious etiology. A diagnosis of MWS and BCNS with exacerbation of MWS with surgical procedures was made.

The patient has continued therapy with rilonacept for MWS, which is managed by her rheumatologist. She has tolerated rilonacept without adverse effects and has experienced a reduction in symptoms that has enhanced her quality of life and allows for further treatment of her BCNS. Her dermatologist (J.W.L.) has been treating her BCCs with vismodegib, but treatment has been sporadic due to muscle cramping after 7 days of therapy. She reported subjective improvement to her dermatologist and has tried alternating 7 days on and 7 days off vismodegib. The muscle cramping still has limited her treatment with this regimen, and she is currently on a trial of 3 days on, 4 days off per week.

Comment

Classification and Clinical Presentation

The hereditary periodic fever syndromes include the autoinflammatory syndromes and the CAPSs. The autoinflammatory syndromes include familial Mediterranean fever, hyperimmunoglobulinemia D with periodic fever syndrome, and tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic syndrome. The CAPSs are similar but distinct and include familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome, neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (also known as chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous and articular syndrome, or cutaneous articular syndrome) and MWS.1,2

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes are rare inherited diseases that result from mutations in the NLRP3 gene. There is a gain-of-function mutation on the NLRP3 gene located on the long arm of chromosome 1 at position 44, which codes for cryopyrin. An NLRP3 gene mutation causes cryopyrin to become hyperactive, leading to the formation of an inflammasome, which is a group of cryopyrin molecules. Inflammasomes, along with other proteins, activate caspase 1 to produce excess IL-1β, leading to persistent inflammatory symptoms.3 IL-1β is one of the key mediators of the body’s response to microbial invasion, inflammation, immunologic reactions, and tissue injury. It affects a large range of cells and organs. Although IL-1β production is critical for the control of pathogenic infections, excessive cytokine production is harmful to the host and can even be fatal.3,4

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes encompass a disease continuum. The 3 distinct entities share many overlapping features as well as unique and distinguishing characteristics. Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome is the mildest phenotype and is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. It is characterized by a chronic urticarial eruption that starts early in infancy or childhood. The distribution of the cutaneous eruption is widespread and favors the arms and legs over the face and trunk. A low-grade fever often is seen along with musculoskeletal concerns of arthralgia and pain. Other commonly reported symptoms include conjunctivitis, myalgia, fatigue, and headache. Neurologic symptoms can include headaches. Symptoms usually begin 1 to 2 hours after cold exposure and last less than 24 hours.5-8

Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease is the most severe phenotype and occurs sporadically. Continuous symptoms and flares are characteristic and the length of the flare can vary from minutes to days. The cutaneous eruption favors the face, trunk, arms, and legs, and varies in intensity, beginning in infancy or childhood. Fever may be intermittent, mild, or absent. Rheumatologic manifestations include arthralgia and swelling, with approximately one-third of patients experiencing severe disabling arthropathy that causes gross joint deformity. Ocular findings include conjunctivitis, uveitis, papilledema, and even blindness. Neurologic sequelae include headaches, sensorineural hearing loss, and aseptic meningitis. Amyloidosis has been seen as a late complication.5,8

Muckle-Wells syndrome is a rare hereditary inflammatory disorder. It has no ethnic predisposition and is mostly inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Classically, the condition is characterized by recurrent urticaria beginning at birth with intermittent episodic fever and malaise. The eruption has a predilection for the face, trunk, arms, and legs, which is similar to neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease. Associated myalgia and arthralgia are common as well as ocular findings of conjunctivitis and episcleritis. Neurologic manifestations include headache and progressive sensorineural hearing loss in 60% to 70% of patients.6 Abdominal pain may be seen along with rare serositis in MWS but is rare in the other CAPSs. Amyloidosis caused by chronic inflammation is the most serious complication of MWS and is seen in approximately one-third of patients, manifesting as proteinuria followed by renal impairment. Symptoms of MWS may occur daily but vary individually, are broad in intensity and duration, and can last 1 to 2 days before resolving spontaneously. The symptoms can result from metabolic stressors including cold, stress, and exercise, as well as microbial pathogens. Leukocytosis and increased acute-phase reactants are observed during episodes of inflammation.4,6,8

Histopathology

Mild phenotypic variability exists between individuals, and many of the symptoms overlap in CAPSs. Although CAPSs display several distinguishing clinical characteristics, interestingly they share the same histopathological features regardless of the syndrome. The typical histopathological finding is a dermal neutrophilic infiltrate that tends to be perivascular and also may be perieccrine. Vasodilation and dermal edema also may be seen. These histopathological findings contrast with the typical lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltrate seen in classic urticaria. Similar histopathologic findings have been seen in other neutrophilic urticarial dermatoses such as Schnitzler syndrome.4,6

Differential

The differential diagnoses for CAPSs include Schnitzler syndrome, cold urticaria, systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis/adult-onset Still disease, and deficiency in IL-1ra. It is important to consider these differential diagnoses for management and treatment options.

Management

The discovery of the NLRP3 gene mutation as well as an understanding of IL-1 biology has led to targeted therapy for these syndromes. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes are mediated by IL-1β with an in vivo rate 5 times higher than in healthy patients.4 The blockade of IL-1β results in complete resolution of symptoms.

In the last several years, anakinra, rilonacept, and canakinumab have shown efficacy in targeting IL-1β as receptor antagonists. Anakinra is a short-acting recombinant IL-1ra with a half-life of 4 to 6 hours. This short half-life requires daily injections and the most common adverse events included injection-site reaction and upper respiratory tract infection.2,4 Rilonacept is a dimeric fusion protein that contains binding regions for the type 1 receptor and the IL-1 receptor accessory protein and is fused to the fragment, crystallizable (Fc) portion of human IgG1. Rilonacept is long acting with a circulating half-life of 8.6 days and offers patients ease of dosing with weekly subcutaneous injections. Rilonacept generally is well tolerated, with the most frequent adverse effects being injection-site reaction, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, arthralgia, and diarrhea.2,7

The newest of the treatments for patients with CAPS is canakinumab. It is a fully human IL-1β monoclonal antibody that is specific for IL-1β and not other members of the IL-1 family. It has a mean half-life of 26 days and is dosed subcutaneously once every 8 weeks. The most common adverse effects include nasopharyngitis, rhinitis, nausea, diarrhea, and vertigo.4 In one study, most patients did not report injection-site reactions.7 Studies also are underway on VX-765, a caspace-1 targeted therapy that acts upstream in the IL-1β pathway. Treatment with anakinra, rilonacept, and canakinumab generally offers rapid and sustained remission in the majority of MWS patients and helps prevent the development of systemic amyloidosis and lessens the potential for end organ damage.2,7

MWS and BCNS

Our patient had an unusual presentation of MWS complicated by BCNS, another rare autosomal-dominant inherited genodermatosis. In an extensive review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms Muckle-Wells syndrome and basal cell nevus syndrome, no association was identified between MWS and BCNS. Basal cell nevus syndrome is linked to PTCH1 (patched 1) gene mutation with an incidence of 1:150,000 in the United States and Europe and is characterized by a broad range of anomalies including skeletal abnormalities, ectopic calcification, odontogenic keratocysts, facial dysmorphism with macrocephaly, palmoplantar pits, and numerous tumors. Most notable is the early and strong predisposition to develop several to hundreds of BCCs.9

Conclusion

Muckle-Wells syndrome may go undiagnosed for many years or may be misdiagnosed as refractory urticaria, as in our patient. It is important to include periodic fever syndromes in the differential diagnosis of refractory urticaria with episodic fever to diagnose these cases of MWS earlier.

Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS) was first described in 1962 and is part of a broad category of hereditary periodic fever syndromes that include the autoinflammatory syndromes and the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPSs). Unlike autoimmune diseases, autoinflammatory syndromes are not associated with antigen-specific T-cell responses or high titers of autoantibodies but are related to disorders of the innate immune system. Basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS), or Gorlin syndrome, is a rare genodermatosis inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion that is characterized by a broad range of anomalies. Most notable is the early and strong predisposition to develop several to hundreds of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs). Classic clinical features of MWS and a thorough history and physical examination can assist in the diagnosis of this rare entity.

Case Report

A 35-year-old woman with a history of BCNS, which had been diagnosed at 24 years of age based on the presence of more than 2 BCCs and a family history of BCNS in her mother, presented with intermittent pruritic urticaria on the chest and back, episodic fevers, associated joint pain and swelling that worsened several hours after exercise, headache, conjunctivitis, blurred vision, and severe debilitating fatigue that had been present since childhood. The symptoms had progressively worsened with age and symptom-free intervals became shorter. She was diagnosed by her rheumatologist with biopsy-proven MWS and a positive NLRP3 (NLR family pyrin domain containing 3) gene mutation at 29 years of age. She was treated unsuccessfully with prednisone and antihistamines and entered a trial with anakinra. She showed improvement for 2 weeks but developed severe swelling and erythema at the injection sites at week 3, along with large leathery patches on the legs and difficulty ambulating.

The patient subsequently underwent excision of her BCCs and reported each site became erythematous, edematous, warm, and painful 6 hours after excision, which lasted for hours to days (Figures 1–3). After the first excision on the right forearm, she was seen in the emergency department, started on intravenous antibiotics and prednisone, and kept overnight in the hospital. She was discharged the following day and the edema in the right forearm subsided over several days. Bacterial culture and laboratory evaluation for infection were negative after the first excision on the right forearm. Because of the symptoms she experienced following this excision, she was referred to the plastic surgery department for excision followed by postoperative monitoring in the hospital. The patient continued to undergo excisions for BCCs and developed more severe symptoms including erythema, edema, warmth, and tenderness at the surrounding sites. Once again, the excision sites were cultured and laboratory work to rule out infection was ordered with a negative result. After several excisions and subsequent clinical findings, the patients’ symptoms were deemed consistent with MWS and not a result of infectious etiology. A diagnosis of MWS and BCNS with exacerbation of MWS with surgical procedures was made.

The patient has continued therapy with rilonacept for MWS, which is managed by her rheumatologist. She has tolerated rilonacept without adverse effects and has experienced a reduction in symptoms that has enhanced her quality of life and allows for further treatment of her BCNS. Her dermatologist (J.W.L.) has been treating her BCCs with vismodegib, but treatment has been sporadic due to muscle cramping after 7 days of therapy. She reported subjective improvement to her dermatologist and has tried alternating 7 days on and 7 days off vismodegib. The muscle cramping still has limited her treatment with this regimen, and she is currently on a trial of 3 days on, 4 days off per week.

Comment

Classification and Clinical Presentation

The hereditary periodic fever syndromes include the autoinflammatory syndromes and the CAPSs. The autoinflammatory syndromes include familial Mediterranean fever, hyperimmunoglobulinemia D with periodic fever syndrome, and tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic syndrome. The CAPSs are similar but distinct and include familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome, neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (also known as chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous and articular syndrome, or cutaneous articular syndrome) and MWS.1,2

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes are rare inherited diseases that result from mutations in the NLRP3 gene. There is a gain-of-function mutation on the NLRP3 gene located on the long arm of chromosome 1 at position 44, which codes for cryopyrin. An NLRP3 gene mutation causes cryopyrin to become hyperactive, leading to the formation of an inflammasome, which is a group of cryopyrin molecules. Inflammasomes, along with other proteins, activate caspase 1 to produce excess IL-1β, leading to persistent inflammatory symptoms.3 IL-1β is one of the key mediators of the body’s response to microbial invasion, inflammation, immunologic reactions, and tissue injury. It affects a large range of cells and organs. Although IL-1β production is critical for the control of pathogenic infections, excessive cytokine production is harmful to the host and can even be fatal.3,4

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes encompass a disease continuum. The 3 distinct entities share many overlapping features as well as unique and distinguishing characteristics. Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome is the mildest phenotype and is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. It is characterized by a chronic urticarial eruption that starts early in infancy or childhood. The distribution of the cutaneous eruption is widespread and favors the arms and legs over the face and trunk. A low-grade fever often is seen along with musculoskeletal concerns of arthralgia and pain. Other commonly reported symptoms include conjunctivitis, myalgia, fatigue, and headache. Neurologic symptoms can include headaches. Symptoms usually begin 1 to 2 hours after cold exposure and last less than 24 hours.5-8

Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease is the most severe phenotype and occurs sporadically. Continuous symptoms and flares are characteristic and the length of the flare can vary from minutes to days. The cutaneous eruption favors the face, trunk, arms, and legs, and varies in intensity, beginning in infancy or childhood. Fever may be intermittent, mild, or absent. Rheumatologic manifestations include arthralgia and swelling, with approximately one-third of patients experiencing severe disabling arthropathy that causes gross joint deformity. Ocular findings include conjunctivitis, uveitis, papilledema, and even blindness. Neurologic sequelae include headaches, sensorineural hearing loss, and aseptic meningitis. Amyloidosis has been seen as a late complication.5,8

Muckle-Wells syndrome is a rare hereditary inflammatory disorder. It has no ethnic predisposition and is mostly inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Classically, the condition is characterized by recurrent urticaria beginning at birth with intermittent episodic fever and malaise. The eruption has a predilection for the face, trunk, arms, and legs, which is similar to neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease. Associated myalgia and arthralgia are common as well as ocular findings of conjunctivitis and episcleritis. Neurologic manifestations include headache and progressive sensorineural hearing loss in 60% to 70% of patients.6 Abdominal pain may be seen along with rare serositis in MWS but is rare in the other CAPSs. Amyloidosis caused by chronic inflammation is the most serious complication of MWS and is seen in approximately one-third of patients, manifesting as proteinuria followed by renal impairment. Symptoms of MWS may occur daily but vary individually, are broad in intensity and duration, and can last 1 to 2 days before resolving spontaneously. The symptoms can result from metabolic stressors including cold, stress, and exercise, as well as microbial pathogens. Leukocytosis and increased acute-phase reactants are observed during episodes of inflammation.4,6,8

Histopathology

Mild phenotypic variability exists between individuals, and many of the symptoms overlap in CAPSs. Although CAPSs display several distinguishing clinical characteristics, interestingly they share the same histopathological features regardless of the syndrome. The typical histopathological finding is a dermal neutrophilic infiltrate that tends to be perivascular and also may be perieccrine. Vasodilation and dermal edema also may be seen. These histopathological findings contrast with the typical lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltrate seen in classic urticaria. Similar histopathologic findings have been seen in other neutrophilic urticarial dermatoses such as Schnitzler syndrome.4,6

Differential

The differential diagnoses for CAPSs include Schnitzler syndrome, cold urticaria, systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis/adult-onset Still disease, and deficiency in IL-1ra. It is important to consider these differential diagnoses for management and treatment options.

Management

The discovery of the NLRP3 gene mutation as well as an understanding of IL-1 biology has led to targeted therapy for these syndromes. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes are mediated by IL-1β with an in vivo rate 5 times higher than in healthy patients.4 The blockade of IL-1β results in complete resolution of symptoms.

In the last several years, anakinra, rilonacept, and canakinumab have shown efficacy in targeting IL-1β as receptor antagonists. Anakinra is a short-acting recombinant IL-1ra with a half-life of 4 to 6 hours. This short half-life requires daily injections and the most common adverse events included injection-site reaction and upper respiratory tract infection.2,4 Rilonacept is a dimeric fusion protein that contains binding regions for the type 1 receptor and the IL-1 receptor accessory protein and is fused to the fragment, crystallizable (Fc) portion of human IgG1. Rilonacept is long acting with a circulating half-life of 8.6 days and offers patients ease of dosing with weekly subcutaneous injections. Rilonacept generally is well tolerated, with the most frequent adverse effects being injection-site reaction, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, arthralgia, and diarrhea.2,7

The newest of the treatments for patients with CAPS is canakinumab. It is a fully human IL-1β monoclonal antibody that is specific for IL-1β and not other members of the IL-1 family. It has a mean half-life of 26 days and is dosed subcutaneously once every 8 weeks. The most common adverse effects include nasopharyngitis, rhinitis, nausea, diarrhea, and vertigo.4 In one study, most patients did not report injection-site reactions.7 Studies also are underway on VX-765, a caspace-1 targeted therapy that acts upstream in the IL-1β pathway. Treatment with anakinra, rilonacept, and canakinumab generally offers rapid and sustained remission in the majority of MWS patients and helps prevent the development of systemic amyloidosis and lessens the potential for end organ damage.2,7

MWS and BCNS

Our patient had an unusual presentation of MWS complicated by BCNS, another rare autosomal-dominant inherited genodermatosis. In an extensive review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms Muckle-Wells syndrome and basal cell nevus syndrome, no association was identified between MWS and BCNS. Basal cell nevus syndrome is linked to PTCH1 (patched 1) gene mutation with an incidence of 1:150,000 in the United States and Europe and is characterized by a broad range of anomalies including skeletal abnormalities, ectopic calcification, odontogenic keratocysts, facial dysmorphism with macrocephaly, palmoplantar pits, and numerous tumors. Most notable is the early and strong predisposition to develop several to hundreds of BCCs.9

Conclusion

Muckle-Wells syndrome may go undiagnosed for many years or may be misdiagnosed as refractory urticaria, as in our patient. It is important to include periodic fever syndromes in the differential diagnosis of refractory urticaria with episodic fever to diagnose these cases of MWS earlier.

- Kagami S, Saeki H, Kuwano Y, et al. A probable case of Muckle-Wells syndrome. J Dermatol. 2006;2:118-121.

- Kanazawa N, Furukawa F. Autoinflammatory syndromes with a dermatological perspective. J Dermatol. 2007;34:601-618.

- Martinon F, Tschopp J. Inflammatory caspases: linking an intracellular innate immune system to autoinflammatory diseases. Cell. 2004;117:561-574.

- Mueller SM, Itin P, Haeusermann P. Muckle-Wells syndrome effectively treated with canakinumab: is the recommended dosing schedule mandatory? Dermatology. 2011;223:113-118.

- Neven B, Prieur A, Quartier dit Maire P. Cryopyrinopathies: update on pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:481-489.

- Newell L, August S, Foria V, et al. Lifelong urticaria and multiple unexplained systemic symptoms. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:431-433.

- Yu JR, Kieron KS. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome: an update on diagnosis and treatment response. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:12-20.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Barcelona, Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008. 9. Göppner D, Leverkus M. Basal cell carcinoma: from the molecular understanding of the pathogenesis to targeted therapy of progressive disease. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:650258.

- Kagami S, Saeki H, Kuwano Y, et al. A probable case of Muckle-Wells syndrome. J Dermatol. 2006;2:118-121.

- Kanazawa N, Furukawa F. Autoinflammatory syndromes with a dermatological perspective. J Dermatol. 2007;34:601-618.

- Martinon F, Tschopp J. Inflammatory caspases: linking an intracellular innate immune system to autoinflammatory diseases. Cell. 2004;117:561-574.

- Mueller SM, Itin P, Haeusermann P. Muckle-Wells syndrome effectively treated with canakinumab: is the recommended dosing schedule mandatory? Dermatology. 2011;223:113-118.

- Neven B, Prieur A, Quartier dit Maire P. Cryopyrinopathies: update on pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:481-489.

- Newell L, August S, Foria V, et al. Lifelong urticaria and multiple unexplained systemic symptoms. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:431-433.

- Yu JR, Kieron KS. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome: an update on diagnosis and treatment response. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:12-20.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Barcelona, Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008. 9. Göppner D, Leverkus M. Basal cell carcinoma: from the molecular understanding of the pathogenesis to targeted therapy of progressive disease. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:650258.

Practice Points

- An urticarial rash occurring in childhood with symptoms of fever, joint pain, and swelling along with visual symptoms should prompt consideration of a cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome.

- Histopathology shows a dermal neutrophilic infiltrate that tends to be perivascular and also may be perieccrine. This atypical urticaria contrasts with the typical lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltrate seen in classic urticaria.

Magnification for the Dermatologic Surgeon

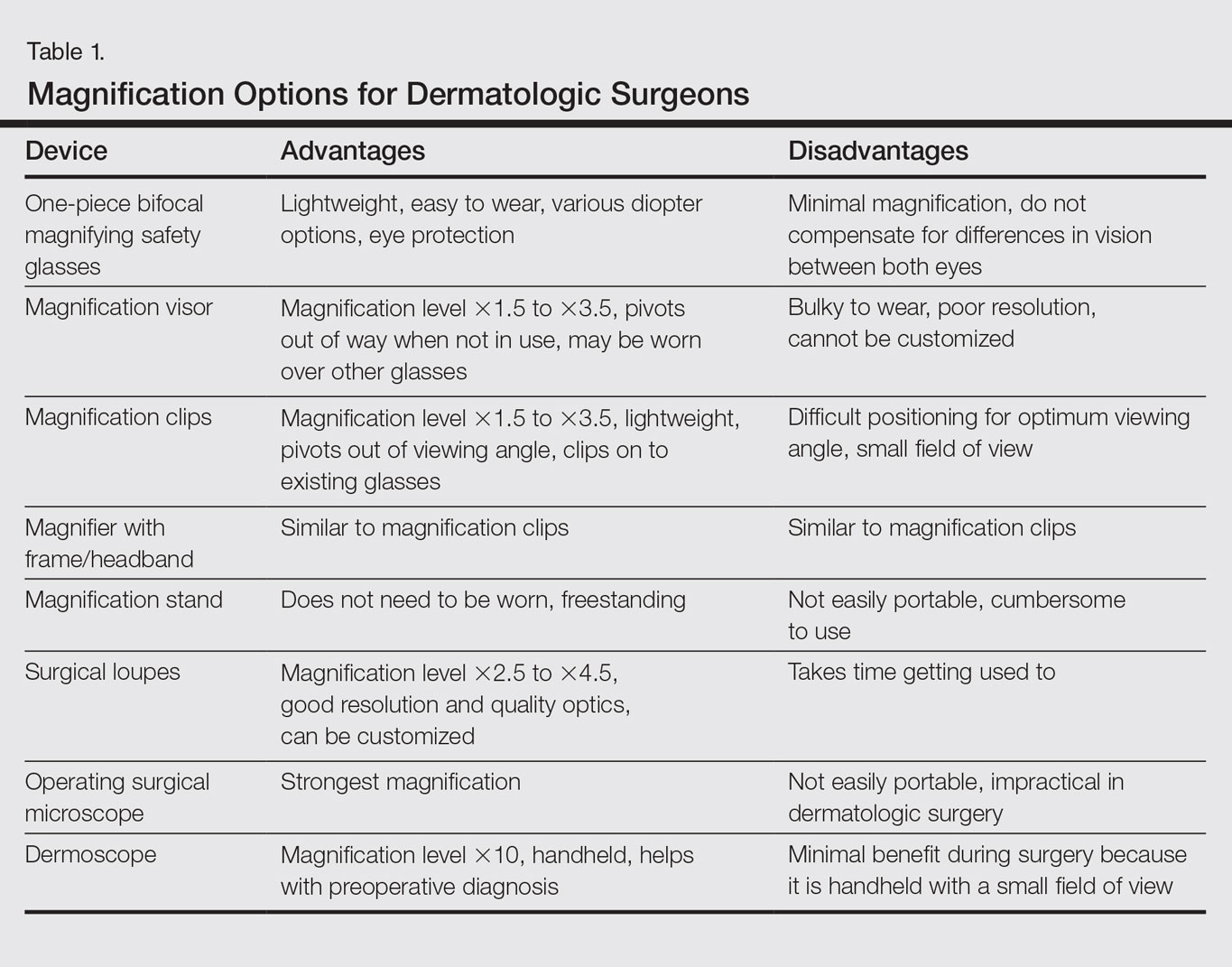

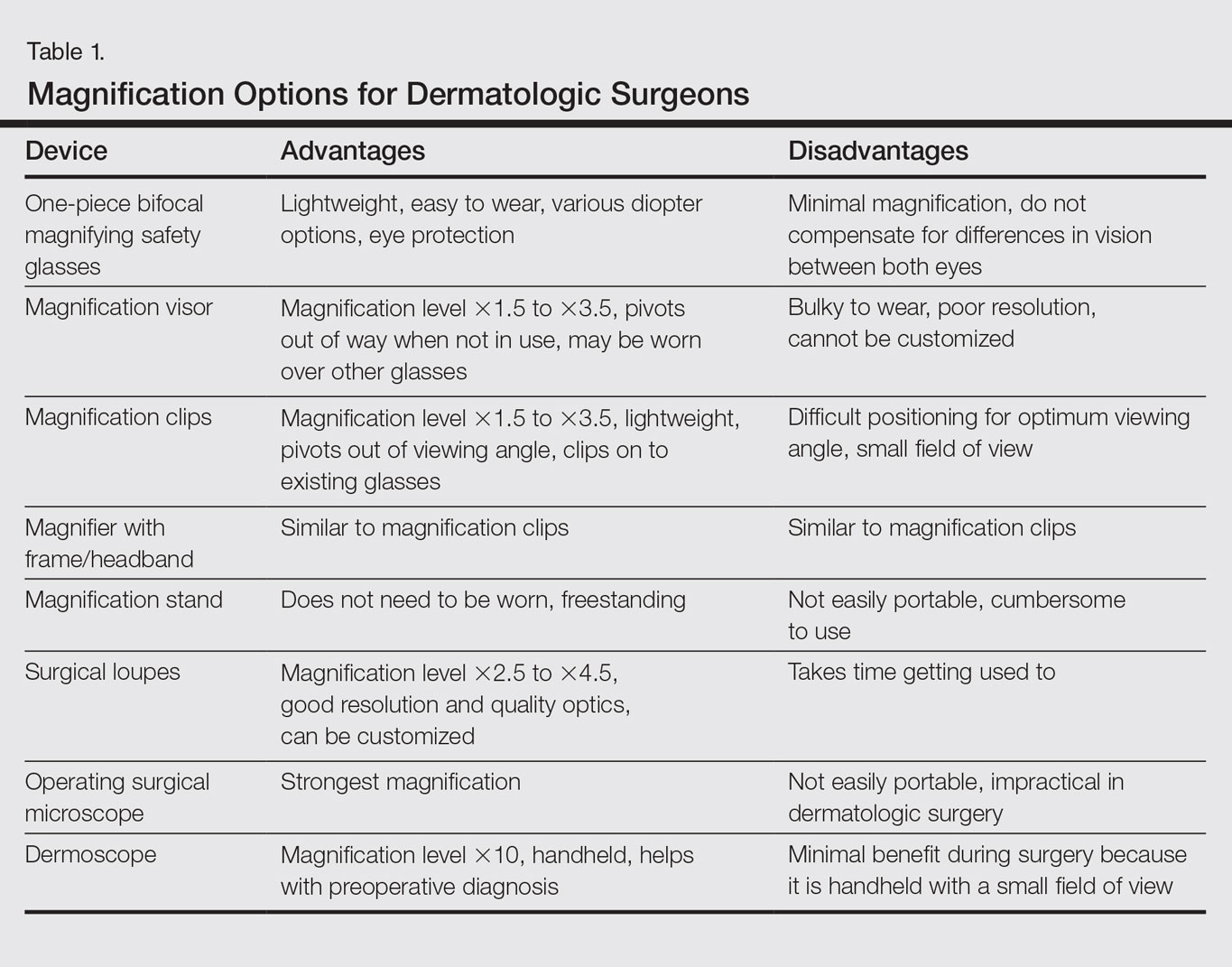

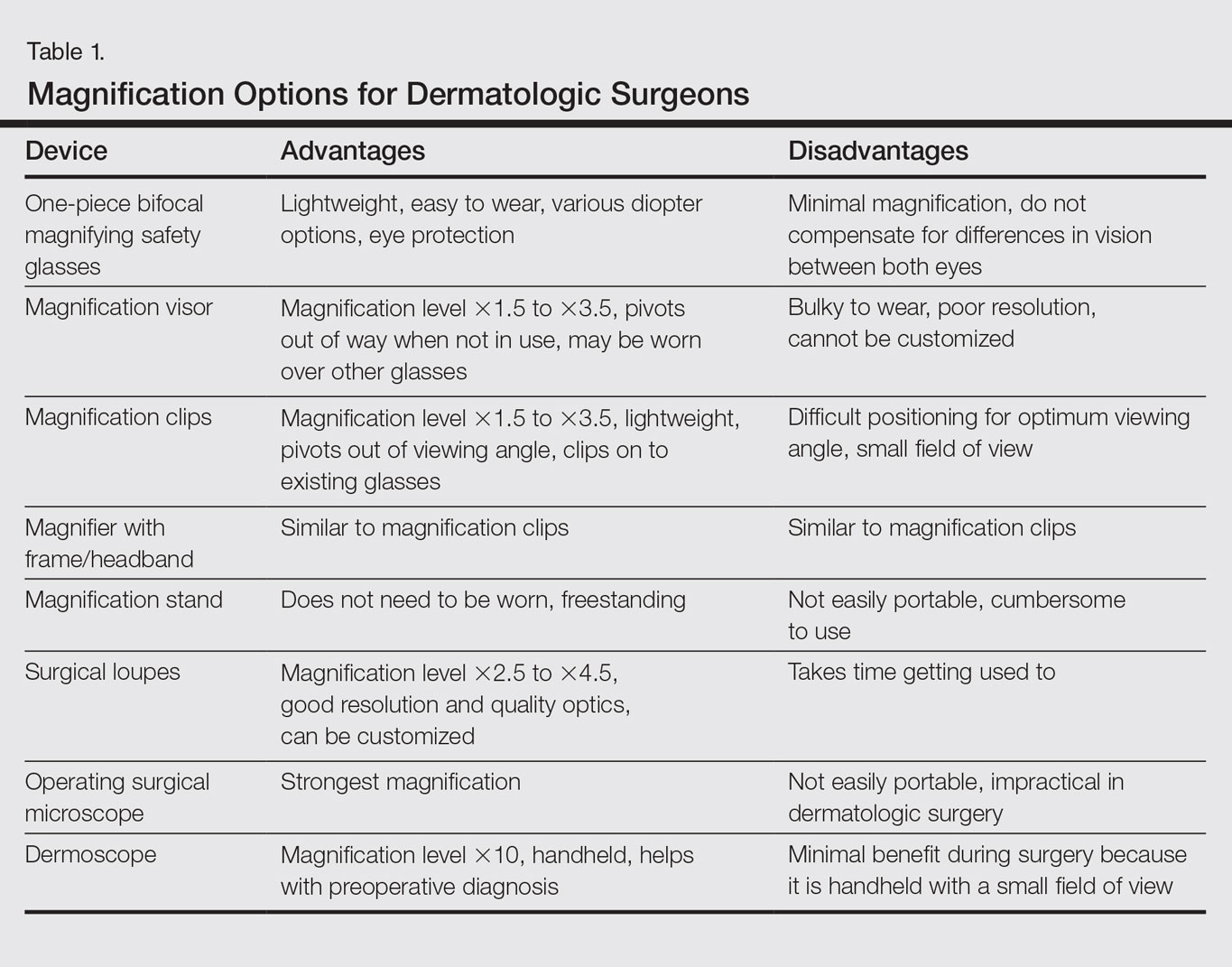

Dermatologic surgeons are susceptible to work-related ailments given the nature of their working posture, the most common of which are pain and stiffness in the neck, shoulders, and lower back, as well as headaches.1,2 Awkward posture and positioning, for the sake of getting a better view of the task at hand, puts the surgeon in ergonomically disagreeable positions. Because the prime working years for a dermatologic surgeon tend to coincide with the age of presbyopia onset, magnification may help reduce and thwart musculoskeletal problems and eye strain. Indeed, a multitude of surgical specialties and dentists use intraoperative magnification.3 Knowledge and use of available magnification options can be a key addition to the dermatologic surgeon’s armamentarium. We discuss the need for magnification and review magnification devices that are readily available to the dermatologic surgeon. Table 1 presents a summary of all magnification options discussed.

Need for Magnification

Presbyopia is a condition of aging in which one loses the ability to accommodate and focus at near distances. The estimated prevalence of presbyopia in North America is 83%, typically with onset by 45 years of age.4 Individuals with presbyopia often hold objects farther away from their eyes to bring them into focus, causing eye strain, headaches, and musculoskeletal injury.

Use of intraoperative magnification allows for enhanced visualization of fine anatomic details and precise suture placement for the surgeon with or without presbyopia. Higher magnification produces a larger image; however, it also reduces field of view and depth of field (ie, the amount of depth that stays in focus without repositioning). The resolution and quality of the image are dependent on the optical properties of the lens system. The ideal optic system is surgeon dependent and involves a combination of magnification level that will not result in dramatic loss of view and depth of field, while maintaining crispness and quality of image.

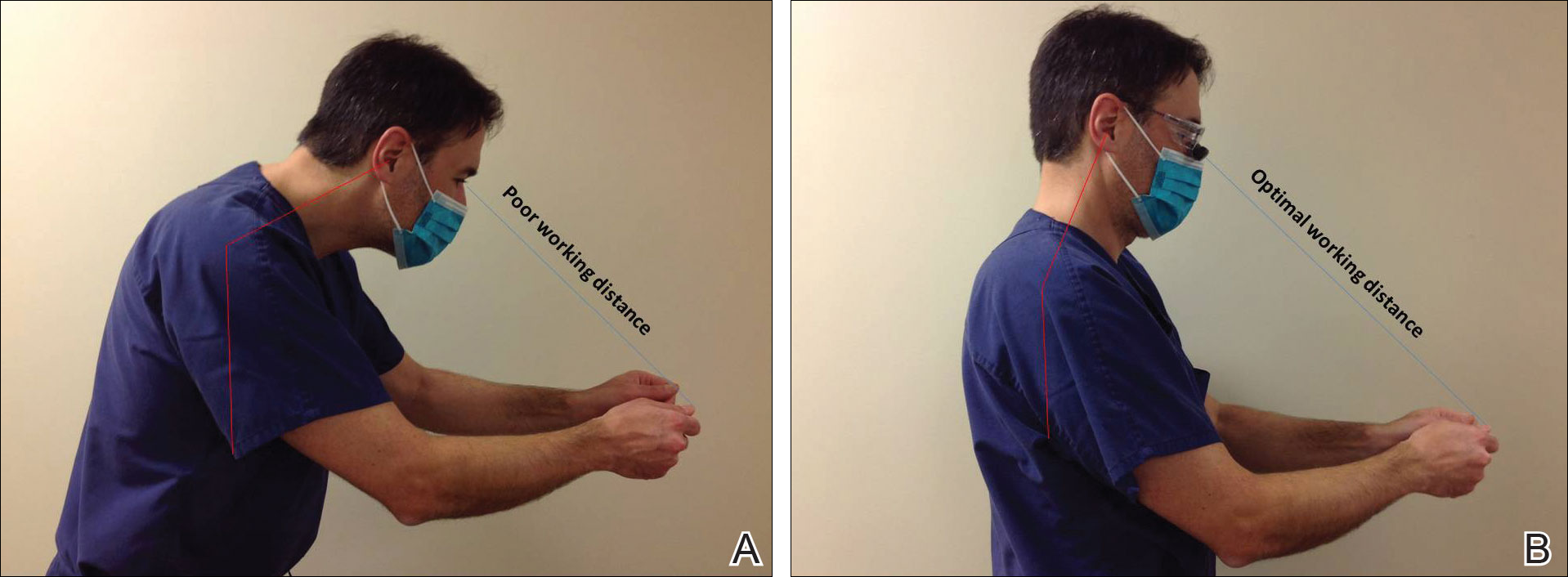

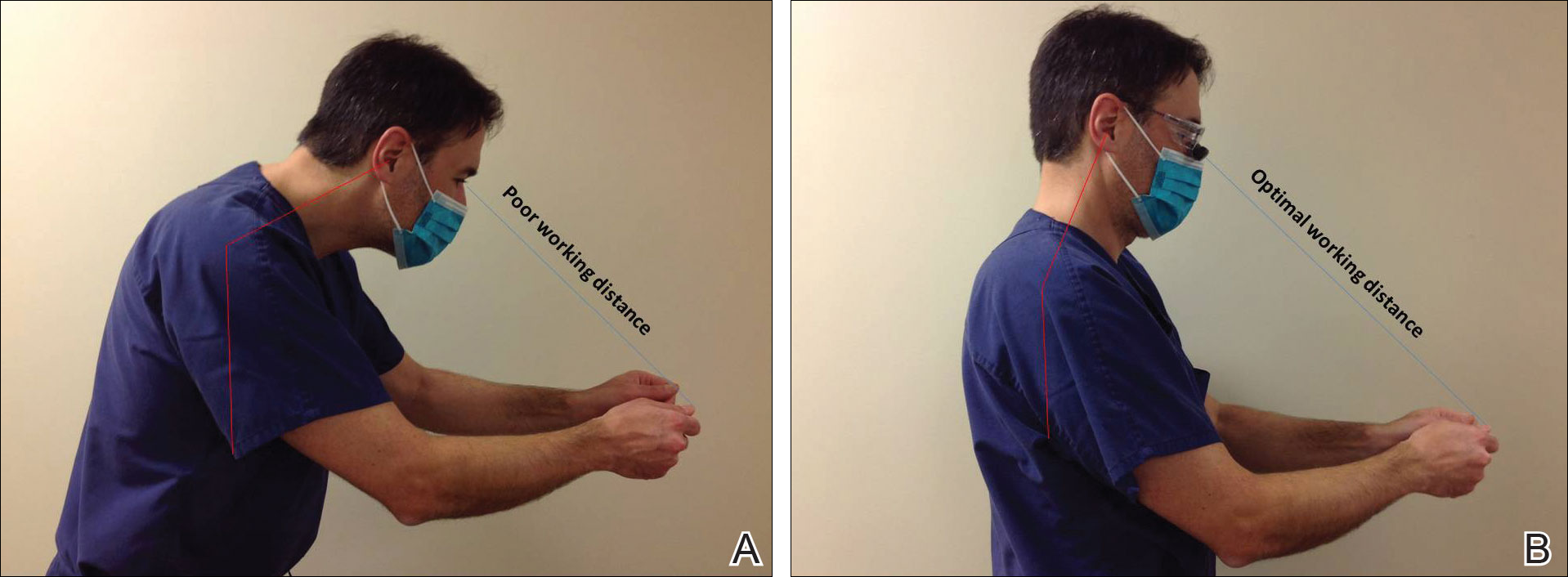

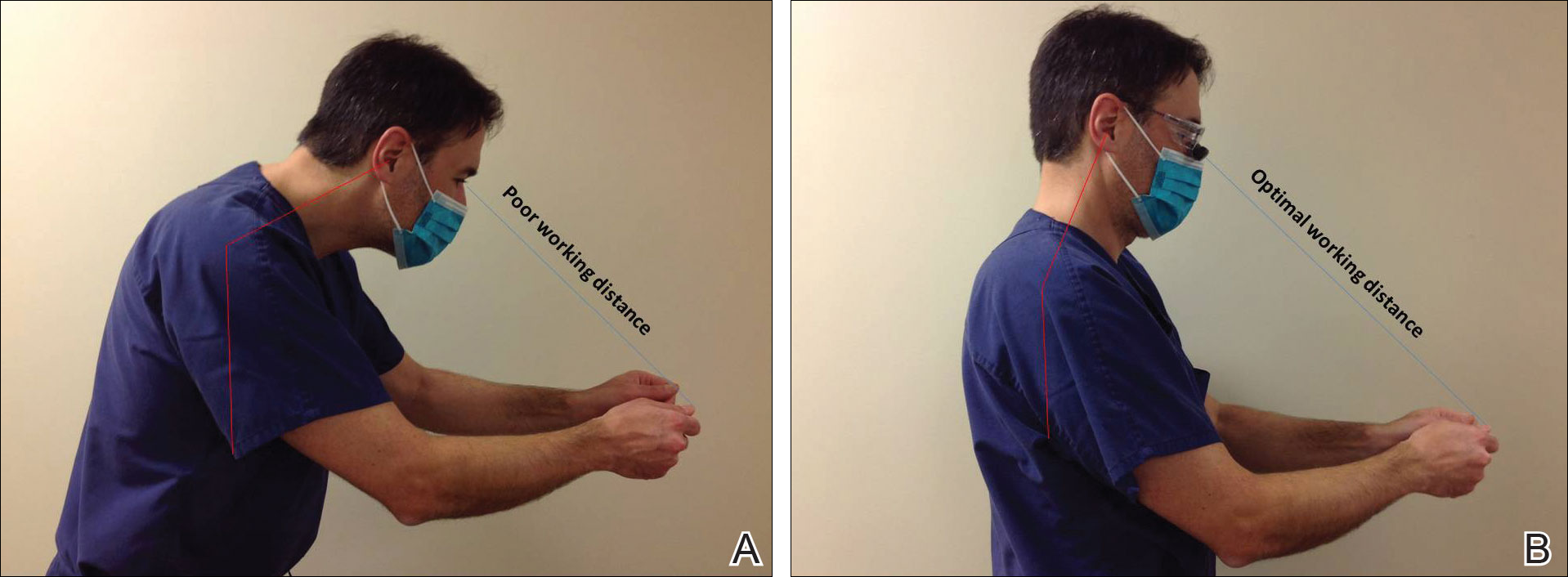

Intraoperative magnification yields ergonomic benefits by promoting a safer neck flexion angle by increasing the working distance to a more ideal position (Figure). In doing so, it improves posture and minimizes eye and musculoskeletal strain secondary to awkward positioning and presbyopia.1,5 Stationary working position and neck flexion and rotation with precise and repetitive tasks are risk factors for strain and injuries that dermatologic surgeons often encounter.1 Magnification devices are tools that the dermatologic surgeon can utilize for a more ergonomically sound practice. Indeed, magnification has been shown to improve posture in the dental literature, a specialty with similar occupational risk factors to dermatologic surgery.6-8 Ergonomic practice reduces occupational injuries and improves work quality and productivity, thereby having a favorable effect on both the patient and the physician.

Improved Outcomes With Magnification

There are many examples of improved surgical quality and outcomes with magnification in other specialties. Hart and Hall5 illustrated the advantage of magnification in laceration repairs in the emergency department. In one study, increased magnification resulted in a substantial decrease in positive surgical margin rates in open radical retropubic prostatectomy.9 Schoeffl et al10 demonstrated that the microsurgical success of fine surgical procedures was directly related to optical magnification strength when comparing the unaided eye, surgical loupes, and the operating microscope. The dental literature also has numerous examples of magnification producing improved quality dentistry.11-13 Although magnification is not a novel concept to dermatologic surgery, little has been written about its use in the dermatologic surgery literature.

Magnification Options

One-Piece Bifocal Magnifying Safety Glasses

Bifocal magnifying safety glasses are polycarbonate safety glasses made with lenses in which the lower half is a magnifying lens. They are available in +1.5, +2.0, +2.5, and +3.0 diopter strengths. The total magnification power is calculated as follows: (diopter/4) + 1. The glasses are lightweight, easy to wear, inexpensive, and protect the eyes; however, they provide minimal magnification and do not compensate for differences in vision between both eyes.

Magnification Visor

The magnification visor is a headband visor with magnification lenses. It comes in various levels of magnification ranging from ×1.5 to ×3.5. It can be worn over prescription or safety glasses, may be pivoted out of the way when not in use, and is inexpensive. Conversely, it may be bulky to wear, cannot be customized, and does not offer the best resolution.

Magnification Clips

Magnification clips are hard-coated magnifying lens plates that fasten to eyeglass frames and range in level of magnification from ×1.5 to ×3.5. They can be pivoted out of the viewing angle, are lightweight, and are inexpensive; however, positioning may be difficult for ideal working distance and viewing angle.

Magnifier With Frame/Headband

The magnifier with frame is similar to magnification clips, but the magnification lens plate comes with a frame. It can be used with or without glasses and comes in magnification levels of ×1.5 to ×3.5. It is light, inexpensive, and may be pivoted out of sight, but similar to magnification clips, positioning for the right viewing angle and working distance may be difficult.

The magnifier with headband is essentially the same as the magnifier with frame. The only difference is the magnification plate is attached to a headband as opposed to a frame. It has similar benefits and limitations as the magnifier with frame.

Magnification Stand

The magnification stand comes as a large magnification lens with a flexible arm attached to a stand. It is a basic magnification tool and does not need to be worn; however, the stand is not easily portable and may be cumbersome to use.

Surgical Loupes

Surgical loupes are a robust magnification choice and the mainstay in magnification for the dermatologic surgeon. Loupes have proven to have comparable results in some procedures to the powerful operating surgical microscope.14-17 Factors to consider with loupes include brand, design, lens, magnification, resolution, optimal working distance, field depth, and declination angle.18

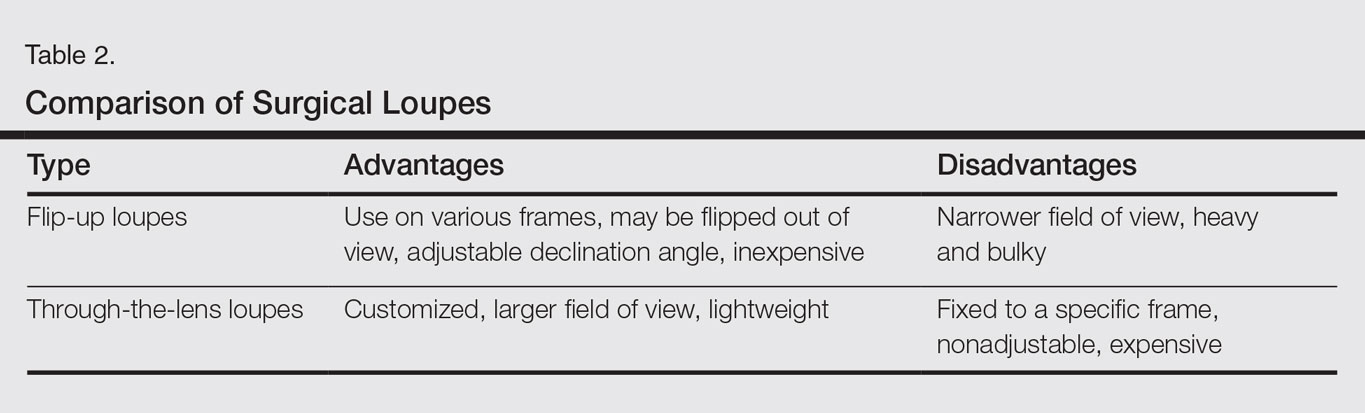

The 2 surgical loupe designs—flip-up loupes and through-the-lens loupes—differ in the mounting of the optic lenses on safety glasses. Flip-up loupes have the optics mounted to the bridge of the frame, whereas through-the-lens loupes are fixed in the lenses.

There are 3 different optical systems for surgical loupe magnification: simple, compound, and prismatic. Simple lenses consist of one pair of positive meniscus lenses similar to reading glasses. Compound lenses are made of 2 magnification lenses. Prismatic lenses magnify using a prism that folds and lengthens the light path.19,20

Loupes range in magnification level from ×2.5 to ×4.5. Compared to other magnification modalities, they can be customized and offer better resolution with quality magnification. Additionally, loupes can be fitted with a light source; however, they are expensive and surgeons need time to get used to the increased magnification as well as wearing the loupes.

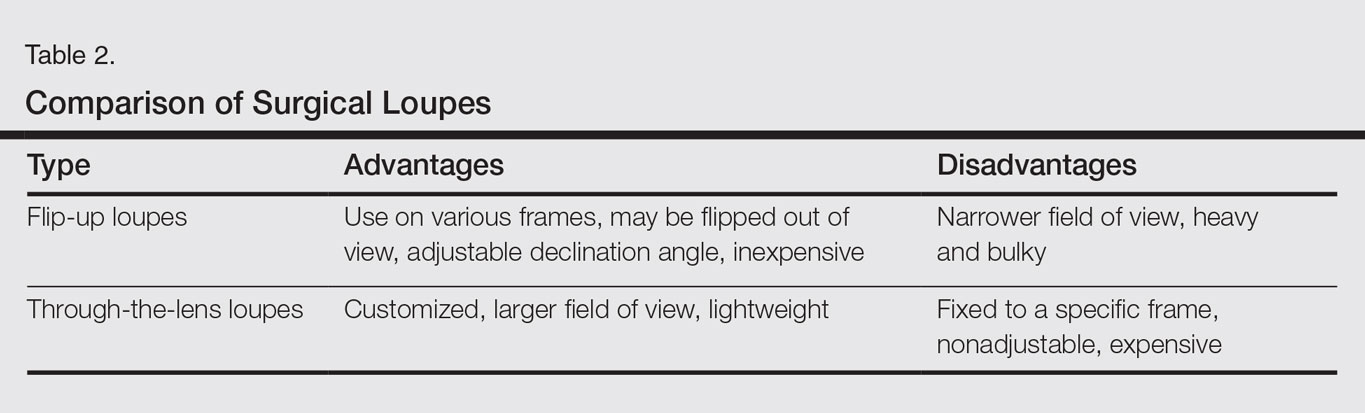

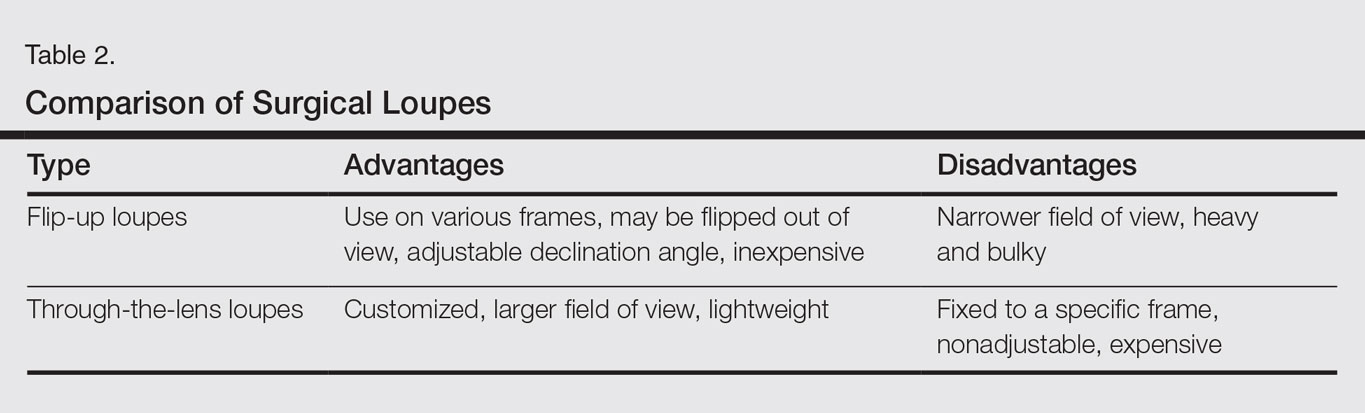

There are advantages and disadvantages to the different loupe designs (Table 2). Flip-up loupes are more versatile, allowing for use on various safety glasses. They can be flipped out of view, and the declination angle may be altered; however, flip-up loupes have a narrower field of view and are heavier and bulkier than through-the-lens loupes. Through-the-lens loupes are lighter and have a larger field of view, as the optics are closer to the eye. They are customized to the declination angle and working distance of the surgeon. Conversely, through-the-lens loupes are more expensive and cannot be adjusted or moved from the line of vision.

Operating Surgical Microscope

The operating surgical microscope is not practical in the dermatologic surgeon’s practice. It is expensive and provides unnecessarily powerful magnification for dermatologic surgery. This tool usually is used in the operating room for suturing nerves and vessels with sutures sized 8-0 and smaller. Most skin procedures require size 6-0 and larger sutures.

Dermoscope

Dermoscopy, also known as epiluminescence microscopy, is a technique utilizing a handheld device made up of polarized light and a ×10 magnifying lens to evaluate skin lesions. In skilled hands, dermoscopy allows for the examination of characteristic patterns and morphologic features of skin lesions to enhance the clinician’s diagnostic accuracy.21 It may aid the dermatologic surgeon in identifying the surgical margins of difficult-to-define skin cancers. It is small and mobile; however, it has minimal benefit to the dermatologic surgeon during surgery because it is handheld and has a small field of view.

Conclusion

Good ergonomic practices facilitate a healthier and prolonged career for the dermatologic surgeon. When used properly, magnification devices can be a beneficial adjunct to the dermatologic surgeon by promoting better posture, preventing eyestrain, and providing enhanced visualization of the operating field and instruments. Use of magnification devices has been demonstrated to improve patient outcomes in other specialties. There are opportunities for further research specific to magnification improving dermatologic surgery outcomes given the high level of precision and accuracy needed for Mohs micrographic surgery, wound reconstruction, nail surgery, and hair transplantation.

- Liang CA, Levine VJ, Dusza SW, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders and ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: a survey of Mohs surgeons in 2010. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:240-248.

- Esser AC, Koshy JG, Randle HW. Ergonomics in office-based surgery: a survey-guided observational study. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1304-1313; discussion, 1313-1314.

- Jarrett PM. Intraoperative magnification: who uses it? Microsurgery. 2004;24:420-422.

- Holden BA, Fricke TR, Ho SM, et al. Global vision impairment due to uncorrected presbyopia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1731-1739.

- Hart RG, Hall J. The value of loupe magnification: an underused tool in emergency medicine. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:704-707.

- Branson BG, Bray KK, Gadbury-Amyot C, et al. Effect of magnification lenses on student operator posture. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:384-389.

- Maillet JP, Millar AM, Burke JM, et al. Effect of magnification loupes on dental hygiene student posture. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:33-44.

- Branson BG, Black MA, Simmer-Beck M. Changes in posture: a case study of a dental hygienist’s use of magnification loupes. Work. 2010;35:467-476.

- Magera JS Jr, Inman BA, Slezak JM, et al. Increased optical magnification from 2.5× to 4.3× with technical modification lowers the positive margin rate in open radical retropubic prostatectomy [published online November 13, 2007].J Urol. 2008;179:130-135.

- Schoeffl H, Lazzeri D, Schnelzer R, et al. Optical magnification should be mandatory for microsurgery: scientific basis and clinical data contributing to quality assurance. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:104-108.

- Taschieri S, Del Fabbro M, Testori T, et al. Endodontic surgery using 2 different magnification devices: preliminary results of a randomized controlled study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:235-242.

- Christensen GJ. Magnification in dentistry: useful tool or another gimmick? J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1647-1650.

- Syme SE, Fried JL, Strassler HE. Enhanced visualization using magnification systems. J Dent Hyg. 1997;71:202-206.

- Pieptu D, Luchian S. Loupes-only microsurgery. Microsurgery. 2003;23:181-188.

- Shenaq SM, Klebuc MJ, Vargo D. Free-tissue transfer with the aid of loupe magnification: experience with 251 procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:261-269.

- Serletti JM, Deuber MA, Guidera PM, et al. Comparison of the operating microscope and loupes for free microvascular tissue transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:270-276.

- Ross DA, Ariyan S, Restifo R, et al. Use of the operating microscope and loupes for head and neck free microvascular tissue transfer: a retrospective comparison. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:189-193.

- Mungadi IA. Refinement on surgical technique: role of magnification. J Surg Tech Case Rep. 2010;2:1-2.

- Stanbury SJ, Elfar J. The use of surgical loupes in microsurgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:154-156.

- Baker JM, Meals RA. A practical guide to surgical loupes. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22:967-974.

- Campos-do-Carmo G, Ramos-e-Silva M. Dermoscopy: basic concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:712-719.

Dermatologic surgeons are susceptible to work-related ailments given the nature of their working posture, the most common of which are pain and stiffness in the neck, shoulders, and lower back, as well as headaches.1,2 Awkward posture and positioning, for the sake of getting a better view of the task at hand, puts the surgeon in ergonomically disagreeable positions. Because the prime working years for a dermatologic surgeon tend to coincide with the age of presbyopia onset, magnification may help reduce and thwart musculoskeletal problems and eye strain. Indeed, a multitude of surgical specialties and dentists use intraoperative magnification.3 Knowledge and use of available magnification options can be a key addition to the dermatologic surgeon’s armamentarium. We discuss the need for magnification and review magnification devices that are readily available to the dermatologic surgeon. Table 1 presents a summary of all magnification options discussed.

Need for Magnification

Presbyopia is a condition of aging in which one loses the ability to accommodate and focus at near distances. The estimated prevalence of presbyopia in North America is 83%, typically with onset by 45 years of age.4 Individuals with presbyopia often hold objects farther away from their eyes to bring them into focus, causing eye strain, headaches, and musculoskeletal injury.

Use of intraoperative magnification allows for enhanced visualization of fine anatomic details and precise suture placement for the surgeon with or without presbyopia. Higher magnification produces a larger image; however, it also reduces field of view and depth of field (ie, the amount of depth that stays in focus without repositioning). The resolution and quality of the image are dependent on the optical properties of the lens system. The ideal optic system is surgeon dependent and involves a combination of magnification level that will not result in dramatic loss of view and depth of field, while maintaining crispness and quality of image.

Intraoperative magnification yields ergonomic benefits by promoting a safer neck flexion angle by increasing the working distance to a more ideal position (Figure). In doing so, it improves posture and minimizes eye and musculoskeletal strain secondary to awkward positioning and presbyopia.1,5 Stationary working position and neck flexion and rotation with precise and repetitive tasks are risk factors for strain and injuries that dermatologic surgeons often encounter.1 Magnification devices are tools that the dermatologic surgeon can utilize for a more ergonomically sound practice. Indeed, magnification has been shown to improve posture in the dental literature, a specialty with similar occupational risk factors to dermatologic surgery.6-8 Ergonomic practice reduces occupational injuries and improves work quality and productivity, thereby having a favorable effect on both the patient and the physician.

Improved Outcomes With Magnification

There are many examples of improved surgical quality and outcomes with magnification in other specialties. Hart and Hall5 illustrated the advantage of magnification in laceration repairs in the emergency department. In one study, increased magnification resulted in a substantial decrease in positive surgical margin rates in open radical retropubic prostatectomy.9 Schoeffl et al10 demonstrated that the microsurgical success of fine surgical procedures was directly related to optical magnification strength when comparing the unaided eye, surgical loupes, and the operating microscope. The dental literature also has numerous examples of magnification producing improved quality dentistry.11-13 Although magnification is not a novel concept to dermatologic surgery, little has been written about its use in the dermatologic surgery literature.

Magnification Options

One-Piece Bifocal Magnifying Safety Glasses

Bifocal magnifying safety glasses are polycarbonate safety glasses made with lenses in which the lower half is a magnifying lens. They are available in +1.5, +2.0, +2.5, and +3.0 diopter strengths. The total magnification power is calculated as follows: (diopter/4) + 1. The glasses are lightweight, easy to wear, inexpensive, and protect the eyes; however, they provide minimal magnification and do not compensate for differences in vision between both eyes.

Magnification Visor

The magnification visor is a headband visor with magnification lenses. It comes in various levels of magnification ranging from ×1.5 to ×3.5. It can be worn over prescription or safety glasses, may be pivoted out of the way when not in use, and is inexpensive. Conversely, it may be bulky to wear, cannot be customized, and does not offer the best resolution.

Magnification Clips

Magnification clips are hard-coated magnifying lens plates that fasten to eyeglass frames and range in level of magnification from ×1.5 to ×3.5. They can be pivoted out of the viewing angle, are lightweight, and are inexpensive; however, positioning may be difficult for ideal working distance and viewing angle.

Magnifier With Frame/Headband

The magnifier with frame is similar to magnification clips, but the magnification lens plate comes with a frame. It can be used with or without glasses and comes in magnification levels of ×1.5 to ×3.5. It is light, inexpensive, and may be pivoted out of sight, but similar to magnification clips, positioning for the right viewing angle and working distance may be difficult.

The magnifier with headband is essentially the same as the magnifier with frame. The only difference is the magnification plate is attached to a headband as opposed to a frame. It has similar benefits and limitations as the magnifier with frame.

Magnification Stand

The magnification stand comes as a large magnification lens with a flexible arm attached to a stand. It is a basic magnification tool and does not need to be worn; however, the stand is not easily portable and may be cumbersome to use.

Surgical Loupes

Surgical loupes are a robust magnification choice and the mainstay in magnification for the dermatologic surgeon. Loupes have proven to have comparable results in some procedures to the powerful operating surgical microscope.14-17 Factors to consider with loupes include brand, design, lens, magnification, resolution, optimal working distance, field depth, and declination angle.18

The 2 surgical loupe designs—flip-up loupes and through-the-lens loupes—differ in the mounting of the optic lenses on safety glasses. Flip-up loupes have the optics mounted to the bridge of the frame, whereas through-the-lens loupes are fixed in the lenses.

There are 3 different optical systems for surgical loupe magnification: simple, compound, and prismatic. Simple lenses consist of one pair of positive meniscus lenses similar to reading glasses. Compound lenses are made of 2 magnification lenses. Prismatic lenses magnify using a prism that folds and lengthens the light path.19,20

Loupes range in magnification level from ×2.5 to ×4.5. Compared to other magnification modalities, they can be customized and offer better resolution with quality magnification. Additionally, loupes can be fitted with a light source; however, they are expensive and surgeons need time to get used to the increased magnification as well as wearing the loupes.

There are advantages and disadvantages to the different loupe designs (Table 2). Flip-up loupes are more versatile, allowing for use on various safety glasses. They can be flipped out of view, and the declination angle may be altered; however, flip-up loupes have a narrower field of view and are heavier and bulkier than through-the-lens loupes. Through-the-lens loupes are lighter and have a larger field of view, as the optics are closer to the eye. They are customized to the declination angle and working distance of the surgeon. Conversely, through-the-lens loupes are more expensive and cannot be adjusted or moved from the line of vision.

Operating Surgical Microscope

The operating surgical microscope is not practical in the dermatologic surgeon’s practice. It is expensive and provides unnecessarily powerful magnification for dermatologic surgery. This tool usually is used in the operating room for suturing nerves and vessels with sutures sized 8-0 and smaller. Most skin procedures require size 6-0 and larger sutures.

Dermoscope

Dermoscopy, also known as epiluminescence microscopy, is a technique utilizing a handheld device made up of polarized light and a ×10 magnifying lens to evaluate skin lesions. In skilled hands, dermoscopy allows for the examination of characteristic patterns and morphologic features of skin lesions to enhance the clinician’s diagnostic accuracy.21 It may aid the dermatologic surgeon in identifying the surgical margins of difficult-to-define skin cancers. It is small and mobile; however, it has minimal benefit to the dermatologic surgeon during surgery because it is handheld and has a small field of view.

Conclusion

Good ergonomic practices facilitate a healthier and prolonged career for the dermatologic surgeon. When used properly, magnification devices can be a beneficial adjunct to the dermatologic surgeon by promoting better posture, preventing eyestrain, and providing enhanced visualization of the operating field and instruments. Use of magnification devices has been demonstrated to improve patient outcomes in other specialties. There are opportunities for further research specific to magnification improving dermatologic surgery outcomes given the high level of precision and accuracy needed for Mohs micrographic surgery, wound reconstruction, nail surgery, and hair transplantation.

Dermatologic surgeons are susceptible to work-related ailments given the nature of their working posture, the most common of which are pain and stiffness in the neck, shoulders, and lower back, as well as headaches.1,2 Awkward posture and positioning, for the sake of getting a better view of the task at hand, puts the surgeon in ergonomically disagreeable positions. Because the prime working years for a dermatologic surgeon tend to coincide with the age of presbyopia onset, magnification may help reduce and thwart musculoskeletal problems and eye strain. Indeed, a multitude of surgical specialties and dentists use intraoperative magnification.3 Knowledge and use of available magnification options can be a key addition to the dermatologic surgeon’s armamentarium. We discuss the need for magnification and review magnification devices that are readily available to the dermatologic surgeon. Table 1 presents a summary of all magnification options discussed.

Need for Magnification

Presbyopia is a condition of aging in which one loses the ability to accommodate and focus at near distances. The estimated prevalence of presbyopia in North America is 83%, typically with onset by 45 years of age.4 Individuals with presbyopia often hold objects farther away from their eyes to bring them into focus, causing eye strain, headaches, and musculoskeletal injury.

Use of intraoperative magnification allows for enhanced visualization of fine anatomic details and precise suture placement for the surgeon with or without presbyopia. Higher magnification produces a larger image; however, it also reduces field of view and depth of field (ie, the amount of depth that stays in focus without repositioning). The resolution and quality of the image are dependent on the optical properties of the lens system. The ideal optic system is surgeon dependent and involves a combination of magnification level that will not result in dramatic loss of view and depth of field, while maintaining crispness and quality of image.

Intraoperative magnification yields ergonomic benefits by promoting a safer neck flexion angle by increasing the working distance to a more ideal position (Figure). In doing so, it improves posture and minimizes eye and musculoskeletal strain secondary to awkward positioning and presbyopia.1,5 Stationary working position and neck flexion and rotation with precise and repetitive tasks are risk factors for strain and injuries that dermatologic surgeons often encounter.1 Magnification devices are tools that the dermatologic surgeon can utilize for a more ergonomically sound practice. Indeed, magnification has been shown to improve posture in the dental literature, a specialty with similar occupational risk factors to dermatologic surgery.6-8 Ergonomic practice reduces occupational injuries and improves work quality and productivity, thereby having a favorable effect on both the patient and the physician.

Improved Outcomes With Magnification

There are many examples of improved surgical quality and outcomes with magnification in other specialties. Hart and Hall5 illustrated the advantage of magnification in laceration repairs in the emergency department. In one study, increased magnification resulted in a substantial decrease in positive surgical margin rates in open radical retropubic prostatectomy.9 Schoeffl et al10 demonstrated that the microsurgical success of fine surgical procedures was directly related to optical magnification strength when comparing the unaided eye, surgical loupes, and the operating microscope. The dental literature also has numerous examples of magnification producing improved quality dentistry.11-13 Although magnification is not a novel concept to dermatologic surgery, little has been written about its use in the dermatologic surgery literature.

Magnification Options

One-Piece Bifocal Magnifying Safety Glasses

Bifocal magnifying safety glasses are polycarbonate safety glasses made with lenses in which the lower half is a magnifying lens. They are available in +1.5, +2.0, +2.5, and +3.0 diopter strengths. The total magnification power is calculated as follows: (diopter/4) + 1. The glasses are lightweight, easy to wear, inexpensive, and protect the eyes; however, they provide minimal magnification and do not compensate for differences in vision between both eyes.

Magnification Visor

The magnification visor is a headband visor with magnification lenses. It comes in various levels of magnification ranging from ×1.5 to ×3.5. It can be worn over prescription or safety glasses, may be pivoted out of the way when not in use, and is inexpensive. Conversely, it may be bulky to wear, cannot be customized, and does not offer the best resolution.

Magnification Clips

Magnification clips are hard-coated magnifying lens plates that fasten to eyeglass frames and range in level of magnification from ×1.5 to ×3.5. They can be pivoted out of the viewing angle, are lightweight, and are inexpensive; however, positioning may be difficult for ideal working distance and viewing angle.

Magnifier With Frame/Headband

The magnifier with frame is similar to magnification clips, but the magnification lens plate comes with a frame. It can be used with or without glasses and comes in magnification levels of ×1.5 to ×3.5. It is light, inexpensive, and may be pivoted out of sight, but similar to magnification clips, positioning for the right viewing angle and working distance may be difficult.

The magnifier with headband is essentially the same as the magnifier with frame. The only difference is the magnification plate is attached to a headband as opposed to a frame. It has similar benefits and limitations as the magnifier with frame.

Magnification Stand

The magnification stand comes as a large magnification lens with a flexible arm attached to a stand. It is a basic magnification tool and does not need to be worn; however, the stand is not easily portable and may be cumbersome to use.

Surgical Loupes

Surgical loupes are a robust magnification choice and the mainstay in magnification for the dermatologic surgeon. Loupes have proven to have comparable results in some procedures to the powerful operating surgical microscope.14-17 Factors to consider with loupes include brand, design, lens, magnification, resolution, optimal working distance, field depth, and declination angle.18

The 2 surgical loupe designs—flip-up loupes and through-the-lens loupes—differ in the mounting of the optic lenses on safety glasses. Flip-up loupes have the optics mounted to the bridge of the frame, whereas through-the-lens loupes are fixed in the lenses.

There are 3 different optical systems for surgical loupe magnification: simple, compound, and prismatic. Simple lenses consist of one pair of positive meniscus lenses similar to reading glasses. Compound lenses are made of 2 magnification lenses. Prismatic lenses magnify using a prism that folds and lengthens the light path.19,20

Loupes range in magnification level from ×2.5 to ×4.5. Compared to other magnification modalities, they can be customized and offer better resolution with quality magnification. Additionally, loupes can be fitted with a light source; however, they are expensive and surgeons need time to get used to the increased magnification as well as wearing the loupes.

There are advantages and disadvantages to the different loupe designs (Table 2). Flip-up loupes are more versatile, allowing for use on various safety glasses. They can be flipped out of view, and the declination angle may be altered; however, flip-up loupes have a narrower field of view and are heavier and bulkier than through-the-lens loupes. Through-the-lens loupes are lighter and have a larger field of view, as the optics are closer to the eye. They are customized to the declination angle and working distance of the surgeon. Conversely, through-the-lens loupes are more expensive and cannot be adjusted or moved from the line of vision.

Operating Surgical Microscope

The operating surgical microscope is not practical in the dermatologic surgeon’s practice. It is expensive and provides unnecessarily powerful magnification for dermatologic surgery. This tool usually is used in the operating room for suturing nerves and vessels with sutures sized 8-0 and smaller. Most skin procedures require size 6-0 and larger sutures.

Dermoscope

Dermoscopy, also known as epiluminescence microscopy, is a technique utilizing a handheld device made up of polarized light and a ×10 magnifying lens to evaluate skin lesions. In skilled hands, dermoscopy allows for the examination of characteristic patterns and morphologic features of skin lesions to enhance the clinician’s diagnostic accuracy.21 It may aid the dermatologic surgeon in identifying the surgical margins of difficult-to-define skin cancers. It is small and mobile; however, it has minimal benefit to the dermatologic surgeon during surgery because it is handheld and has a small field of view.

Conclusion

Good ergonomic practices facilitate a healthier and prolonged career for the dermatologic surgeon. When used properly, magnification devices can be a beneficial adjunct to the dermatologic surgeon by promoting better posture, preventing eyestrain, and providing enhanced visualization of the operating field and instruments. Use of magnification devices has been demonstrated to improve patient outcomes in other specialties. There are opportunities for further research specific to magnification improving dermatologic surgery outcomes given the high level of precision and accuracy needed for Mohs micrographic surgery, wound reconstruction, nail surgery, and hair transplantation.

- Liang CA, Levine VJ, Dusza SW, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders and ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: a survey of Mohs surgeons in 2010. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:240-248.

- Esser AC, Koshy JG, Randle HW. Ergonomics in office-based surgery: a survey-guided observational study. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1304-1313; discussion, 1313-1314.

- Jarrett PM. Intraoperative magnification: who uses it? Microsurgery. 2004;24:420-422.

- Holden BA, Fricke TR, Ho SM, et al. Global vision impairment due to uncorrected presbyopia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1731-1739.

- Hart RG, Hall J. The value of loupe magnification: an underused tool in emergency medicine. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:704-707.

- Branson BG, Bray KK, Gadbury-Amyot C, et al. Effect of magnification lenses on student operator posture. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:384-389.

- Maillet JP, Millar AM, Burke JM, et al. Effect of magnification loupes on dental hygiene student posture. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:33-44.

- Branson BG, Black MA, Simmer-Beck M. Changes in posture: a case study of a dental hygienist’s use of magnification loupes. Work. 2010;35:467-476.

- Magera JS Jr, Inman BA, Slezak JM, et al. Increased optical magnification from 2.5× to 4.3× with technical modification lowers the positive margin rate in open radical retropubic prostatectomy [published online November 13, 2007].J Urol. 2008;179:130-135.

- Schoeffl H, Lazzeri D, Schnelzer R, et al. Optical magnification should be mandatory for microsurgery: scientific basis and clinical data contributing to quality assurance. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:104-108.

- Taschieri S, Del Fabbro M, Testori T, et al. Endodontic surgery using 2 different magnification devices: preliminary results of a randomized controlled study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:235-242.

- Christensen GJ. Magnification in dentistry: useful tool or another gimmick? J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1647-1650.

- Syme SE, Fried JL, Strassler HE. Enhanced visualization using magnification systems. J Dent Hyg. 1997;71:202-206.

- Pieptu D, Luchian S. Loupes-only microsurgery. Microsurgery. 2003;23:181-188.

- Shenaq SM, Klebuc MJ, Vargo D. Free-tissue transfer with the aid of loupe magnification: experience with 251 procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:261-269.

- Serletti JM, Deuber MA, Guidera PM, et al. Comparison of the operating microscope and loupes for free microvascular tissue transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:270-276.

- Ross DA, Ariyan S, Restifo R, et al. Use of the operating microscope and loupes for head and neck free microvascular tissue transfer: a retrospective comparison. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:189-193.

- Mungadi IA. Refinement on surgical technique: role of magnification. J Surg Tech Case Rep. 2010;2:1-2.

- Stanbury SJ, Elfar J. The use of surgical loupes in microsurgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:154-156.

- Baker JM, Meals RA. A practical guide to surgical loupes. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22:967-974.

- Campos-do-Carmo G, Ramos-e-Silva M. Dermoscopy: basic concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:712-719.

- Liang CA, Levine VJ, Dusza SW, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders and ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: a survey of Mohs surgeons in 2010. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:240-248.

- Esser AC, Koshy JG, Randle HW. Ergonomics in office-based surgery: a survey-guided observational study. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1304-1313; discussion, 1313-1314.

- Jarrett PM. Intraoperative magnification: who uses it? Microsurgery. 2004;24:420-422.

- Holden BA, Fricke TR, Ho SM, et al. Global vision impairment due to uncorrected presbyopia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1731-1739.

- Hart RG, Hall J. The value of loupe magnification: an underused tool in emergency medicine. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:704-707.