User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

The Effects of Sunscreen on Marine Environments

Coastal travel accounts for 80% of all tourism worldwide, a number that continues to grow. The number of travelers to the Mediterranean Sea alone is expected to rise to 350 million individuals per year within the next 20 years.1 As the number of tourists visiting the world’s oceans increases, the rate of sunscreen unintentionally washed into these marine environments also rises. One study estimated that approximately one-quarter of the sunscreen applied to the skin is washed off over a 20-minute period spent in the water.2 Four of the most common sunscreen agents—benzophenone-3 (BP-3),

Benzophenone-3

4-Methylbenzylidene Camphor

Environmental concerns have also been raised about another common chemical UV filter: 4-MBC, or enzacamene. In laboratory studies, 4-MBC has been shown to cause oxidative stress to Tetrahymena thermophila, an aquatic protozoan, which results in inhibited growth. At higher concentrations, damage to the cellular membrane was seen as soon as 4 hours after exposure.6 In embryonic zebrafish, elevated 4-MBC levels were correlated to improper nerve and muscular development, resulting in developmental defects.7 Another study demonstrated that 4-MBC was toxic to Mytilus galloprovincialis, known as the Mediterranean mussel, and Paracentrotus lividus, a species of sea urchin.8 Although these studies utilized highly controlled laboratory settings, further studies are needed to examine the effects of 4-MBC on these species at environmentally relevant concentrations.

Physical Sunscreens

Physical sunscreens, as compared to the chemical filters referenced above, use either zinc or titanium to protect the skin from the sun’s rays. Nanoparticles, in particular, are preferred because they do not leave a white film on the skin.9 Both titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles have been found to inhibit the growth and photosynthesis of marine phytoplankton, the most abundant primary producers on Earth.10,11 These metal contaminants can be transferred to organisms of higher trophic levels, including zooplankton,12 and filter-feeding organisms, including marine abalone13 and the Mediterranean mussel.14 These nanoparticles have been shown to cause oxidative stress to these organisms, making them less fit to withstand environmental stressors. It is difficult to show their true impact, however, as it is challenging to accurately detect and quantify nanoparticle concentrations in vivo.15

Final Thoughts

- Marine problems: tourism & coastal development. World Wide Fund for Nature website. http://wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/blue_planet/problems/tourism/. Published 2017. Accessed November 14, 2017.

- Danovaro R, Bongiorni L, Corinaldesi C, et al. Sunscreens cause coral bleaching by promoting viral infections. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:441-447.

- Downs C, Kramarsky-Winter E, Segal R, et al. Toxicopathological effects of the sunscreen UV filter, oxybenzone (benzophenone-3), on coral planulae and cultured primary cells and its environmental contamination in Hawaii and the US Virgin Islands. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2016;70:265-288.

- Sánchez Rodríguez A, Rodrigo Sanz M, Betancort Rodríguez JR. Occurrence of eight UV filters in beaches of Gran Canaria (Canary Islands)[published online March 17, 2015]. Chemosphere. 2015;131:85-90.

- Bratkovics S, Sapozhnikova Y. Determination of seven commonly used organic UV filters in fresh and saline waters by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Analytical Methods. 2011;3:2943-2950.

- Gao L, Yuan T, Zhou C, et al. Effects of four commonly used UV filters on the growth, cell viability and oxidative stress responses of the Tetrahymena thermophila. Chemosphere. 2013;93:2507-2513.

- Li VW, Tsui MP, Chen X, et al. Effects of 4-methylbenzylidene camphor (4-MBC) on neuronal and muscular development in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos [published online February 18, 2016]. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23:8275-8285.

- Paredes E, Perez S, Rodil R, et al. Ecotoxicological evaluation of four UV filters using marine organisms from different trophic levels Isochrysis galbana, Mytilus galloprovincialis, Paracentrotus lividus, and Siriella armata. Chemosphere. 2014;104:44-50.

- Osterwalder U, Sohn M, Herzog B. Global state of sunscreens. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:62-80.

- Miller RJ, Bennett S, Keller AA, et al. TiO2 nanoparticles are phototoxic to marine phytoplankton. PloS One. 2012;7:E30321.

- Spisni E. Toxicity Assessment of Industrial- and Sunscreen-derived ZnO Nanoparticles [master’s thesis]. Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami Libraries Scholarly Repository; 2016. http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1625&context=oa_theses. Accessed November 10, 2017.

- Jarvis TA, Miller RJ, Lenihan HS, et al. Toxicity of ZnO nanoparticles to the copepod Acartia tonsa, exposed through a phytoplankton diet [published online April 15, 2013]. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2013;32:1264-1269.

- Zhu X, Zhou J, Cai Z. The toxicity and oxidative stress of TiO2 nanoparticles in marine abalone (Haliotis diversicolor supertexta). Mar Pollut Bull. 2011;63:334-338.

- Barmo C, Ciacci C, Canonico B, et al. In vivo effects of n-TiO2 on digestive gland and immune function of the marine bivalve Mytilus galloprovincialis. Aquatic Toxicol. 2013;132:9-18.

- Sánchez-Quiles D, Tovar-Sánchez A. Are sunscreens a new environmental risk associated with coastal tourism? Environ Int. 2015;83:158-170.

- Xu S, Kwa M, Agarwal A, et al. Sunscreen product performance and other determinants of consumer preferences. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:920-927.

- Vesper I. Hawaii seeks to ban ‘reef-unfriendly’ sunscreen. Nature. February 3, 2017. https://www.nature.com/news/hawaii-seeks-to-ban-reef-unfriendly-sunscreen-1.21332. Accessed November 16, 2017.

Coastal travel accounts for 80% of all tourism worldwide, a number that continues to grow. The number of travelers to the Mediterranean Sea alone is expected to rise to 350 million individuals per year within the next 20 years.1 As the number of tourists visiting the world’s oceans increases, the rate of sunscreen unintentionally washed into these marine environments also rises. One study estimated that approximately one-quarter of the sunscreen applied to the skin is washed off over a 20-minute period spent in the water.2 Four of the most common sunscreen agents—benzophenone-3 (BP-3),

Benzophenone-3

4-Methylbenzylidene Camphor

Environmental concerns have also been raised about another common chemical UV filter: 4-MBC, or enzacamene. In laboratory studies, 4-MBC has been shown to cause oxidative stress to Tetrahymena thermophila, an aquatic protozoan, which results in inhibited growth. At higher concentrations, damage to the cellular membrane was seen as soon as 4 hours after exposure.6 In embryonic zebrafish, elevated 4-MBC levels were correlated to improper nerve and muscular development, resulting in developmental defects.7 Another study demonstrated that 4-MBC was toxic to Mytilus galloprovincialis, known as the Mediterranean mussel, and Paracentrotus lividus, a species of sea urchin.8 Although these studies utilized highly controlled laboratory settings, further studies are needed to examine the effects of 4-MBC on these species at environmentally relevant concentrations.

Physical Sunscreens

Physical sunscreens, as compared to the chemical filters referenced above, use either zinc or titanium to protect the skin from the sun’s rays. Nanoparticles, in particular, are preferred because they do not leave a white film on the skin.9 Both titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles have been found to inhibit the growth and photosynthesis of marine phytoplankton, the most abundant primary producers on Earth.10,11 These metal contaminants can be transferred to organisms of higher trophic levels, including zooplankton,12 and filter-feeding organisms, including marine abalone13 and the Mediterranean mussel.14 These nanoparticles have been shown to cause oxidative stress to these organisms, making them less fit to withstand environmental stressors. It is difficult to show their true impact, however, as it is challenging to accurately detect and quantify nanoparticle concentrations in vivo.15

Final Thoughts

Coastal travel accounts for 80% of all tourism worldwide, a number that continues to grow. The number of travelers to the Mediterranean Sea alone is expected to rise to 350 million individuals per year within the next 20 years.1 As the number of tourists visiting the world’s oceans increases, the rate of sunscreen unintentionally washed into these marine environments also rises. One study estimated that approximately one-quarter of the sunscreen applied to the skin is washed off over a 20-minute period spent in the water.2 Four of the most common sunscreen agents—benzophenone-3 (BP-3),

Benzophenone-3

4-Methylbenzylidene Camphor

Environmental concerns have also been raised about another common chemical UV filter: 4-MBC, or enzacamene. In laboratory studies, 4-MBC has been shown to cause oxidative stress to Tetrahymena thermophila, an aquatic protozoan, which results in inhibited growth. At higher concentrations, damage to the cellular membrane was seen as soon as 4 hours after exposure.6 In embryonic zebrafish, elevated 4-MBC levels were correlated to improper nerve and muscular development, resulting in developmental defects.7 Another study demonstrated that 4-MBC was toxic to Mytilus galloprovincialis, known as the Mediterranean mussel, and Paracentrotus lividus, a species of sea urchin.8 Although these studies utilized highly controlled laboratory settings, further studies are needed to examine the effects of 4-MBC on these species at environmentally relevant concentrations.

Physical Sunscreens

Physical sunscreens, as compared to the chemical filters referenced above, use either zinc or titanium to protect the skin from the sun’s rays. Nanoparticles, in particular, are preferred because they do not leave a white film on the skin.9 Both titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles have been found to inhibit the growth and photosynthesis of marine phytoplankton, the most abundant primary producers on Earth.10,11 These metal contaminants can be transferred to organisms of higher trophic levels, including zooplankton,12 and filter-feeding organisms, including marine abalone13 and the Mediterranean mussel.14 These nanoparticles have been shown to cause oxidative stress to these organisms, making them less fit to withstand environmental stressors. It is difficult to show their true impact, however, as it is challenging to accurately detect and quantify nanoparticle concentrations in vivo.15

Final Thoughts

- Marine problems: tourism & coastal development. World Wide Fund for Nature website. http://wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/blue_planet/problems/tourism/. Published 2017. Accessed November 14, 2017.

- Danovaro R, Bongiorni L, Corinaldesi C, et al. Sunscreens cause coral bleaching by promoting viral infections. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:441-447.

- Downs C, Kramarsky-Winter E, Segal R, et al. Toxicopathological effects of the sunscreen UV filter, oxybenzone (benzophenone-3), on coral planulae and cultured primary cells and its environmental contamination in Hawaii and the US Virgin Islands. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2016;70:265-288.

- Sánchez Rodríguez A, Rodrigo Sanz M, Betancort Rodríguez JR. Occurrence of eight UV filters in beaches of Gran Canaria (Canary Islands)[published online March 17, 2015]. Chemosphere. 2015;131:85-90.

- Bratkovics S, Sapozhnikova Y. Determination of seven commonly used organic UV filters in fresh and saline waters by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Analytical Methods. 2011;3:2943-2950.

- Gao L, Yuan T, Zhou C, et al. Effects of four commonly used UV filters on the growth, cell viability and oxidative stress responses of the Tetrahymena thermophila. Chemosphere. 2013;93:2507-2513.

- Li VW, Tsui MP, Chen X, et al. Effects of 4-methylbenzylidene camphor (4-MBC) on neuronal and muscular development in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos [published online February 18, 2016]. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23:8275-8285.

- Paredes E, Perez S, Rodil R, et al. Ecotoxicological evaluation of four UV filters using marine organisms from different trophic levels Isochrysis galbana, Mytilus galloprovincialis, Paracentrotus lividus, and Siriella armata. Chemosphere. 2014;104:44-50.

- Osterwalder U, Sohn M, Herzog B. Global state of sunscreens. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:62-80.

- Miller RJ, Bennett S, Keller AA, et al. TiO2 nanoparticles are phototoxic to marine phytoplankton. PloS One. 2012;7:E30321.

- Spisni E. Toxicity Assessment of Industrial- and Sunscreen-derived ZnO Nanoparticles [master’s thesis]. Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami Libraries Scholarly Repository; 2016. http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1625&context=oa_theses. Accessed November 10, 2017.

- Jarvis TA, Miller RJ, Lenihan HS, et al. Toxicity of ZnO nanoparticles to the copepod Acartia tonsa, exposed through a phytoplankton diet [published online April 15, 2013]. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2013;32:1264-1269.

- Zhu X, Zhou J, Cai Z. The toxicity and oxidative stress of TiO2 nanoparticles in marine abalone (Haliotis diversicolor supertexta). Mar Pollut Bull. 2011;63:334-338.

- Barmo C, Ciacci C, Canonico B, et al. In vivo effects of n-TiO2 on digestive gland and immune function of the marine bivalve Mytilus galloprovincialis. Aquatic Toxicol. 2013;132:9-18.

- Sánchez-Quiles D, Tovar-Sánchez A. Are sunscreens a new environmental risk associated with coastal tourism? Environ Int. 2015;83:158-170.

- Xu S, Kwa M, Agarwal A, et al. Sunscreen product performance and other determinants of consumer preferences. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:920-927.

- Vesper I. Hawaii seeks to ban ‘reef-unfriendly’ sunscreen. Nature. February 3, 2017. https://www.nature.com/news/hawaii-seeks-to-ban-reef-unfriendly-sunscreen-1.21332. Accessed November 16, 2017.

- Marine problems: tourism & coastal development. World Wide Fund for Nature website. http://wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/blue_planet/problems/tourism/. Published 2017. Accessed November 14, 2017.

- Danovaro R, Bongiorni L, Corinaldesi C, et al. Sunscreens cause coral bleaching by promoting viral infections. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:441-447.

- Downs C, Kramarsky-Winter E, Segal R, et al. Toxicopathological effects of the sunscreen UV filter, oxybenzone (benzophenone-3), on coral planulae and cultured primary cells and its environmental contamination in Hawaii and the US Virgin Islands. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2016;70:265-288.

- Sánchez Rodríguez A, Rodrigo Sanz M, Betancort Rodríguez JR. Occurrence of eight UV filters in beaches of Gran Canaria (Canary Islands)[published online March 17, 2015]. Chemosphere. 2015;131:85-90.

- Bratkovics S, Sapozhnikova Y. Determination of seven commonly used organic UV filters in fresh and saline waters by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Analytical Methods. 2011;3:2943-2950.

- Gao L, Yuan T, Zhou C, et al. Effects of four commonly used UV filters on the growth, cell viability and oxidative stress responses of the Tetrahymena thermophila. Chemosphere. 2013;93:2507-2513.

- Li VW, Tsui MP, Chen X, et al. Effects of 4-methylbenzylidene camphor (4-MBC) on neuronal and muscular development in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos [published online February 18, 2016]. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23:8275-8285.

- Paredes E, Perez S, Rodil R, et al. Ecotoxicological evaluation of four UV filters using marine organisms from different trophic levels Isochrysis galbana, Mytilus galloprovincialis, Paracentrotus lividus, and Siriella armata. Chemosphere. 2014;104:44-50.

- Osterwalder U, Sohn M, Herzog B. Global state of sunscreens. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:62-80.

- Miller RJ, Bennett S, Keller AA, et al. TiO2 nanoparticles are phototoxic to marine phytoplankton. PloS One. 2012;7:E30321.

- Spisni E. Toxicity Assessment of Industrial- and Sunscreen-derived ZnO Nanoparticles [master’s thesis]. Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami Libraries Scholarly Repository; 2016. http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1625&context=oa_theses. Accessed November 10, 2017.

- Jarvis TA, Miller RJ, Lenihan HS, et al. Toxicity of ZnO nanoparticles to the copepod Acartia tonsa, exposed through a phytoplankton diet [published online April 15, 2013]. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2013;32:1264-1269.

- Zhu X, Zhou J, Cai Z. The toxicity and oxidative stress of TiO2 nanoparticles in marine abalone (Haliotis diversicolor supertexta). Mar Pollut Bull. 2011;63:334-338.

- Barmo C, Ciacci C, Canonico B, et al. In vivo effects of n-TiO2 on digestive gland and immune function of the marine bivalve Mytilus galloprovincialis. Aquatic Toxicol. 2013;132:9-18.

- Sánchez-Quiles D, Tovar-Sánchez A. Are sunscreens a new environmental risk associated with coastal tourism? Environ Int. 2015;83:158-170.

- Xu S, Kwa M, Agarwal A, et al. Sunscreen product performance and other determinants of consumer preferences. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:920-927.

- Vesper I. Hawaii seeks to ban ‘reef-unfriendly’ sunscreen. Nature. February 3, 2017. https://www.nature.com/news/hawaii-seeks-to-ban-reef-unfriendly-sunscreen-1.21332. Accessed November 16, 2017.

Cordlike Dermal Plaques and Nodules on the Neck and Hands

The Diagnosis: Fibroblastic Rheumatism

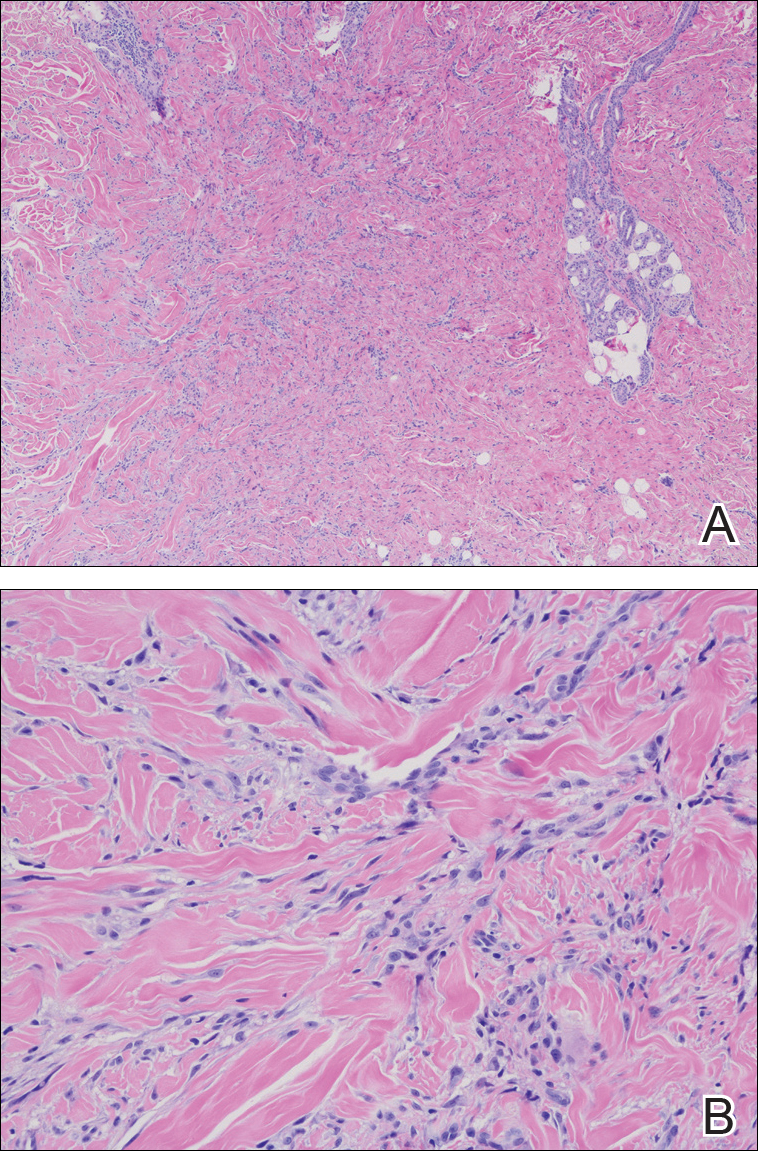

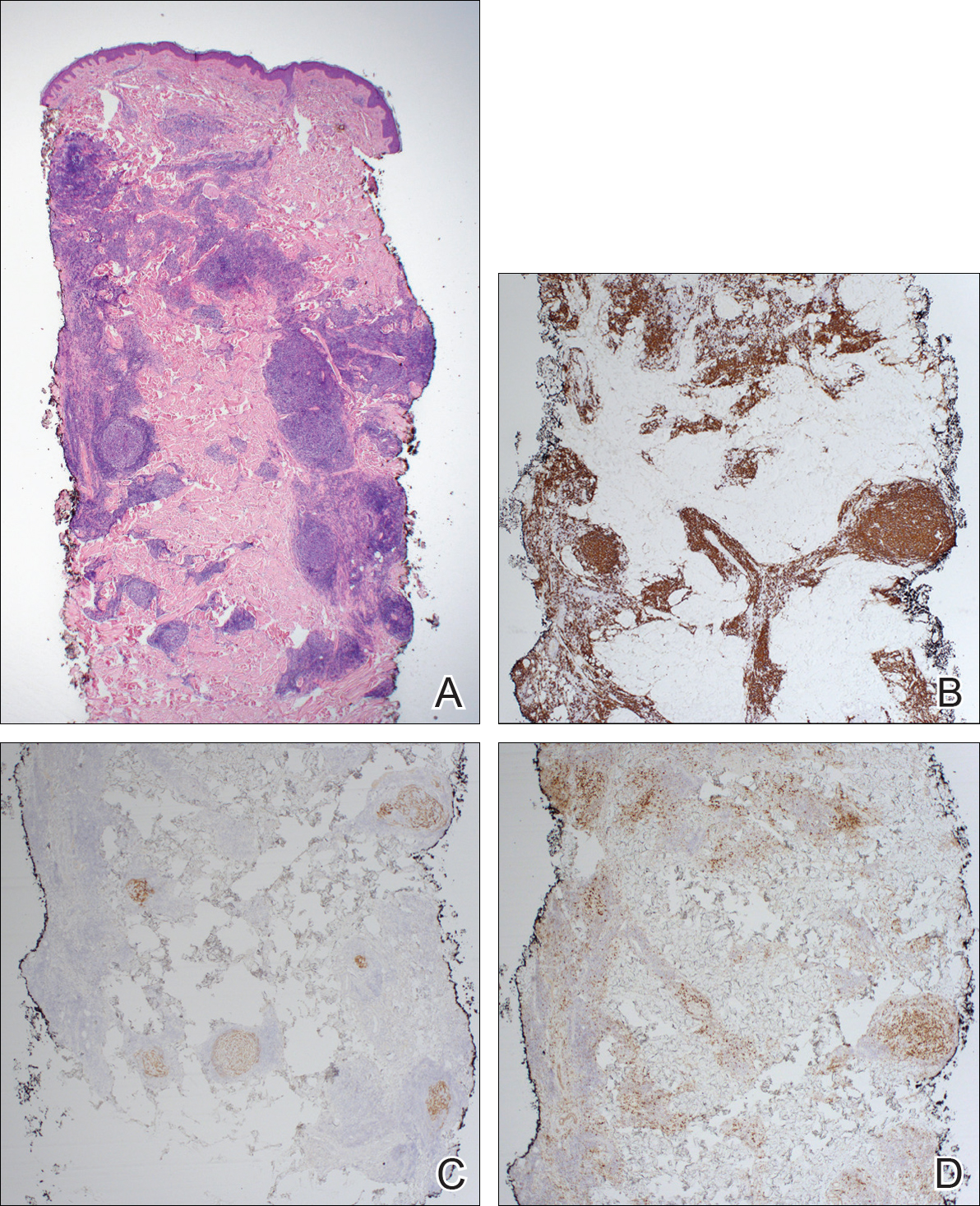

Routine histologic sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin demonstrated a noncircumscribed dermal proliferation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts with thickened collagen bundles (Figure, A and B). Focally fragmented elastin fibers were noted with Verhoeff elastic tissue stain. Alcian blue stain did not show increased dermal mucin. With the clinical presentation and histologic findings described, we diagnosed the patient with fibroblastic rheumatism (FR). To date, the patient's condition has stabilized overall with skin lesions fading and minimal to no joint pain. Current therapies include adalimumab, mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg 3 times daily, and low-dose prednisone.

Fibroblastic rheumatism is a rare arthropathy with cutaneous findings initially described by Chaouat et al1 in 1980. Age of onset varies, and the condition also has been observed in pediatric patients.2 Fibroblastic rheumatism is characterized by sudden onset of firm, flesh-colored, subcutaneous nodules on periungual and periarticular surfaces.2 Neck lesions rarely are described,2-4 and cordlike plaques previously have not been reported in FR. Typically, patients develop diffusely swollen fingers, palmar thickening, sclerodactyly, and contractures. The eruption may be accompanied by Raynaud phenomenon as well as a progressive symmetric erosive arthropathy.2,5

The clinical course in FR is variable. The cutaneous findings spontaneously may regress in months to years.3,4 However, polyarthropathy often is destructive and progresses to disability.3 Response to therapy has been unpredictable, and the following treatments have been tried, generally with poor efficacy: aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hydroxychloroquine, colchicine, methotrexate, prednisone, infliximab, D-penicillamine, interferon alfa, and intensive physical therapy.2-4,6 Histologic characteristics may include thickened collagen bundles along with a fibroblastic and myofibroblastic proliferation. Elastic fibers may be decreased or absent.2,3,5

Clinical and histologic features in FR may mimic other entities; thus, clinical pathological correlation is essential in determining the correct diagnosis. Considerations in the differential diagnoses include multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH), palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, and scleroderma.

In MRH, a symmetric erosive arthritis of mainly distal interphalangeal joints typically precedes the cutaneous disease. Occurrence of arthritis mutilans is reported in approximately half of patients.4 Cutaneous manifestations typically include the presence of coral bead-like papules and nodules over the dorsal aspect of the hands, face, and neck. Unlike FR, MRH has a concomitant autoimmune disease in up to 20% of cases and an associated malignancy in up to 31% of cases, with breast and ovarian carcinomas most common. On histology, MRH is characterized by a nodular infiltrate of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with eosinophilic ground-glass cytoplasm.4 No notable collagen changes or fibroblastic proliferations typically are present.

Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, usually associated with rheumatoid arthritis or connective tissue disease, classically presents as annular plaques and indurated linear bands over the trunk and extremities. However, its clinical presentation is quite variable and may include pink to violaceous urticarialike; livedoid-appearing; or nonspecific papules, plaques, or nodules. Histology in palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis shows a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate associated with interstitial histiocytes having a palisading arrangement around degenerated collagen.7 No fibroblastic proliferation typically is present.

Scleroderma can be distinguished based on additional clinical and laboratory findings as well as histology showing thickened collagen bundles without fibroblastic proliferation.2 The histologic findings also may suggest inclusion of dermatofibroma or a scar in the differential diagnosis, though the clinical presentation of these entities would not support these diagnoses.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient for granting permission to share this information. We also thank Sheng Chen, MD, PhD (Lake Success, New York), for his dermatopathological contributions to the case.

- Chaouat Y, Aron-Brunetiere R, Faures B, et al. Une nouvelle entité: le rhumatisme fibroblastique. a propos d'une observation [in French]. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. 1980;47:34-35.

- Jurado SA, Alvin GG, Selim MA, et al. Fibroblastic rheumatism: a report of 4 cases with potential therapeutic implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:959-965.

- Colonna L, Barbieri C, Di Lella G, et al. Fibroblastic rheumatism: a case without rheumatological symptoms. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:200-203.

- Trotta F, Colina M. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis and fibroblastic rheumatism. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26:543-557.

- Lee JM, Sundel RP, Liang MG. Fibroblastic rheumatism: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:532-535.

- Kluger N, Dumas-Tesici A, Hamel D, et al. Fibroblastic rheumatism: fibromatosis rather than non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:587-592.

- Stephenson SR, Campbell M, Dre GS, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis presenting in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis on adalimumab. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:644-648.

The Diagnosis: Fibroblastic Rheumatism

Routine histologic sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin demonstrated a noncircumscribed dermal proliferation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts with thickened collagen bundles (Figure, A and B). Focally fragmented elastin fibers were noted with Verhoeff elastic tissue stain. Alcian blue stain did not show increased dermal mucin. With the clinical presentation and histologic findings described, we diagnosed the patient with fibroblastic rheumatism (FR). To date, the patient's condition has stabilized overall with skin lesions fading and minimal to no joint pain. Current therapies include adalimumab, mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg 3 times daily, and low-dose prednisone.

Fibroblastic rheumatism is a rare arthropathy with cutaneous findings initially described by Chaouat et al1 in 1980. Age of onset varies, and the condition also has been observed in pediatric patients.2 Fibroblastic rheumatism is characterized by sudden onset of firm, flesh-colored, subcutaneous nodules on periungual and periarticular surfaces.2 Neck lesions rarely are described,2-4 and cordlike plaques previously have not been reported in FR. Typically, patients develop diffusely swollen fingers, palmar thickening, sclerodactyly, and contractures. The eruption may be accompanied by Raynaud phenomenon as well as a progressive symmetric erosive arthropathy.2,5

The clinical course in FR is variable. The cutaneous findings spontaneously may regress in months to years.3,4 However, polyarthropathy often is destructive and progresses to disability.3 Response to therapy has been unpredictable, and the following treatments have been tried, generally with poor efficacy: aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hydroxychloroquine, colchicine, methotrexate, prednisone, infliximab, D-penicillamine, interferon alfa, and intensive physical therapy.2-4,6 Histologic characteristics may include thickened collagen bundles along with a fibroblastic and myofibroblastic proliferation. Elastic fibers may be decreased or absent.2,3,5

Clinical and histologic features in FR may mimic other entities; thus, clinical pathological correlation is essential in determining the correct diagnosis. Considerations in the differential diagnoses include multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH), palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, and scleroderma.

In MRH, a symmetric erosive arthritis of mainly distal interphalangeal joints typically precedes the cutaneous disease. Occurrence of arthritis mutilans is reported in approximately half of patients.4 Cutaneous manifestations typically include the presence of coral bead-like papules and nodules over the dorsal aspect of the hands, face, and neck. Unlike FR, MRH has a concomitant autoimmune disease in up to 20% of cases and an associated malignancy in up to 31% of cases, with breast and ovarian carcinomas most common. On histology, MRH is characterized by a nodular infiltrate of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with eosinophilic ground-glass cytoplasm.4 No notable collagen changes or fibroblastic proliferations typically are present.

Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, usually associated with rheumatoid arthritis or connective tissue disease, classically presents as annular plaques and indurated linear bands over the trunk and extremities. However, its clinical presentation is quite variable and may include pink to violaceous urticarialike; livedoid-appearing; or nonspecific papules, plaques, or nodules. Histology in palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis shows a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate associated with interstitial histiocytes having a palisading arrangement around degenerated collagen.7 No fibroblastic proliferation typically is present.

Scleroderma can be distinguished based on additional clinical and laboratory findings as well as histology showing thickened collagen bundles without fibroblastic proliferation.2 The histologic findings also may suggest inclusion of dermatofibroma or a scar in the differential diagnosis, though the clinical presentation of these entities would not support these diagnoses.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient for granting permission to share this information. We also thank Sheng Chen, MD, PhD (Lake Success, New York), for his dermatopathological contributions to the case.

The Diagnosis: Fibroblastic Rheumatism

Routine histologic sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin demonstrated a noncircumscribed dermal proliferation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts with thickened collagen bundles (Figure, A and B). Focally fragmented elastin fibers were noted with Verhoeff elastic tissue stain. Alcian blue stain did not show increased dermal mucin. With the clinical presentation and histologic findings described, we diagnosed the patient with fibroblastic rheumatism (FR). To date, the patient's condition has stabilized overall with skin lesions fading and minimal to no joint pain. Current therapies include adalimumab, mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg 3 times daily, and low-dose prednisone.

Fibroblastic rheumatism is a rare arthropathy with cutaneous findings initially described by Chaouat et al1 in 1980. Age of onset varies, and the condition also has been observed in pediatric patients.2 Fibroblastic rheumatism is characterized by sudden onset of firm, flesh-colored, subcutaneous nodules on periungual and periarticular surfaces.2 Neck lesions rarely are described,2-4 and cordlike plaques previously have not been reported in FR. Typically, patients develop diffusely swollen fingers, palmar thickening, sclerodactyly, and contractures. The eruption may be accompanied by Raynaud phenomenon as well as a progressive symmetric erosive arthropathy.2,5

The clinical course in FR is variable. The cutaneous findings spontaneously may regress in months to years.3,4 However, polyarthropathy often is destructive and progresses to disability.3 Response to therapy has been unpredictable, and the following treatments have been tried, generally with poor efficacy: aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hydroxychloroquine, colchicine, methotrexate, prednisone, infliximab, D-penicillamine, interferon alfa, and intensive physical therapy.2-4,6 Histologic characteristics may include thickened collagen bundles along with a fibroblastic and myofibroblastic proliferation. Elastic fibers may be decreased or absent.2,3,5

Clinical and histologic features in FR may mimic other entities; thus, clinical pathological correlation is essential in determining the correct diagnosis. Considerations in the differential diagnoses include multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH), palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, and scleroderma.

In MRH, a symmetric erosive arthritis of mainly distal interphalangeal joints typically precedes the cutaneous disease. Occurrence of arthritis mutilans is reported in approximately half of patients.4 Cutaneous manifestations typically include the presence of coral bead-like papules and nodules over the dorsal aspect of the hands, face, and neck. Unlike FR, MRH has a concomitant autoimmune disease in up to 20% of cases and an associated malignancy in up to 31% of cases, with breast and ovarian carcinomas most common. On histology, MRH is characterized by a nodular infiltrate of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with eosinophilic ground-glass cytoplasm.4 No notable collagen changes or fibroblastic proliferations typically are present.

Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, usually associated with rheumatoid arthritis or connective tissue disease, classically presents as annular plaques and indurated linear bands over the trunk and extremities. However, its clinical presentation is quite variable and may include pink to violaceous urticarialike; livedoid-appearing; or nonspecific papules, plaques, or nodules. Histology in palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis shows a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate associated with interstitial histiocytes having a palisading arrangement around degenerated collagen.7 No fibroblastic proliferation typically is present.

Scleroderma can be distinguished based on additional clinical and laboratory findings as well as histology showing thickened collagen bundles without fibroblastic proliferation.2 The histologic findings also may suggest inclusion of dermatofibroma or a scar in the differential diagnosis, though the clinical presentation of these entities would not support these diagnoses.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient for granting permission to share this information. We also thank Sheng Chen, MD, PhD (Lake Success, New York), for his dermatopathological contributions to the case.

- Chaouat Y, Aron-Brunetiere R, Faures B, et al. Une nouvelle entité: le rhumatisme fibroblastique. a propos d'une observation [in French]. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. 1980;47:34-35.

- Jurado SA, Alvin GG, Selim MA, et al. Fibroblastic rheumatism: a report of 4 cases with potential therapeutic implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:959-965.

- Colonna L, Barbieri C, Di Lella G, et al. Fibroblastic rheumatism: a case without rheumatological symptoms. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:200-203.

- Trotta F, Colina M. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis and fibroblastic rheumatism. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26:543-557.

- Lee JM, Sundel RP, Liang MG. Fibroblastic rheumatism: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:532-535.

- Kluger N, Dumas-Tesici A, Hamel D, et al. Fibroblastic rheumatism: fibromatosis rather than non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:587-592.

- Stephenson SR, Campbell M, Dre GS, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis presenting in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis on adalimumab. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:644-648.

- Chaouat Y, Aron-Brunetiere R, Faures B, et al. Une nouvelle entité: le rhumatisme fibroblastique. a propos d'une observation [in French]. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. 1980;47:34-35.

- Jurado SA, Alvin GG, Selim MA, et al. Fibroblastic rheumatism: a report of 4 cases with potential therapeutic implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:959-965.

- Colonna L, Barbieri C, Di Lella G, et al. Fibroblastic rheumatism: a case without rheumatological symptoms. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:200-203.

- Trotta F, Colina M. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis and fibroblastic rheumatism. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26:543-557.

- Lee JM, Sundel RP, Liang MG. Fibroblastic rheumatism: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:532-535.

- Kluger N, Dumas-Tesici A, Hamel D, et al. Fibroblastic rheumatism: fibromatosis rather than non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:587-592.

- Stephenson SR, Campbell M, Dre GS, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis presenting in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis on adalimumab. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:644-648.

A 67-year-old man presented with asymptomatic plaques on the neck of 4 months' duration and nodules scattered over the hands, elbows, ears, and forehead of 3 years' duration. The eruption was associated with progressive thickening and contractures of the fingers, hand morning stiffness lasting less than 45 minutes, and Raynaud phenomenon. Physical examination revealed flesh-colored, firm, cordlike plaques on the neck bilaterally (top), with firm subcutaneous nodules on the helix and antihelix of the ears, forehead, elbows, and on the dorsal and ventral aspects of the hands (bottom). The largest nodules were approximately 5 cm. All fingers and first toes were thickened and firm with few contractile bands on the fingers. The patient had a persistently elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (80 mm/h)(reference range, 0-20 mm/h) and C-reactive protein level (3.27 mg/dL)(reference range, 0.00-0.40 mg/dL). Serologic workup was remarkable only for an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:80 (speckled). Plain radiographs confirmed an erosive arthropathy of the hands and feet. Erosions on the hands predominantly involved distal interphalangeal articulations, as well as, to a lesser extent, the proximal interphalangeal articulations, carpus, and the left distal radius. Erosive changes on the feet involved metatarsophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal articulations. Biopsies from the neck were performed for histopathologic correlation.

Indurated Plaque on the Eyebrow

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma

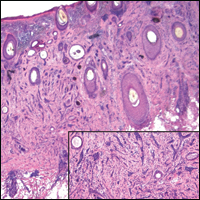

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC) is a rare, low-grade adnexal carcinoma consisting of both ductal and pilar differentiation.1 It typically presents in young to middle-aged adults as a flesh-colored or yellow indurated plaque on the upper lip, medial cheek, or chin. Histologically, MACs exhibit a biphasic pattern consisting of epithelial islands of cords and lumina creating tadpolelike ducts intermixed with basaloid nests (quiz image). Keratin horn cysts are common superficially. A dense red sclerotic stroma is seen interspersed between the ducts and epithelial islands creating a "paisley tie" appearance. The lesion displays an infiltrative pattern and can be deeply invasive, extending down to the fat and muscle (quiz image, inset). Perineural invasion is common. Atypia, when present, is minimal or mild and mitoses are rare. Although this tumor's histologic pattern appears aggressive in nature, it lacks immunohistochemical staining such as p53, Ki-67, bcl-2, and c-erbB-2 that correlate with malignant behavior.2 A common diagnostic pitfall is examination of a superficial biopsy in which an MAC may be mistakenly identified as another entity.

Syringomas are benign adnexal neoplasms with ductal differentiation.3 They are more common in women, especially those of Asian descent, and in patients with Down syndrome. They typically present as multiple small, firm, flesh-colored papules in the periorbital area or upper trunk. Histologically, syringomas also display comma-shaped tubules and ducts with a tadpolelike appearance and a dense red stroma creating a paisley tie-like pattern. Ductal cells have an abundant pink cytoplasm. Syringomas are well-circumscribed and more superficial than MACs without an infiltrative pattern. They lack mitotic activity or perineural invasion (Figure 1).

Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE) is a benign follicular neoplasm.4 It presents in adulthood with a female predominance. Clinically, it appears as a solitary flesh-colored to yellow annular plaque with raised borders and a depressed central area, often on the medial cheek. Histologically, DTEs are well-circumscribed with narrow branching cords lined with polygonal cells. A dense red stroma in combination with the epithelioid aggregates also creates the paisley tie-like pattern in this lesion. Retraction between collagen bundles within the stroma can be seen, helping distinguish this lesion from a morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which has retraction between the epithelium and stroma. Immunohistochemistry also can be a useful tool to help differentiate DTEs from morpheaform BCCs in that sparse cytokeratin 20-positive Merkel cells can be seen within the basaloid islands of DTE but not BCC.5 Also seen with DTEs are numerous keratin horn cysts that commonly are filled with dystrophic calcifications. Cellular atypia and mitoses are not seen (Figure 2). Compared to MACs, DTEs lack abundant ductal structures and also contain papillary mesenchymal bodies and a more fibroblast-rich stroma.

Morpheaform BCC is an aggressive subtype of BCC. It presents as a scarlike plaque that gradually expands. Thin infiltrating strands of basaloid cells are seen haphazardly throughout a pink sclerotic stroma. Tadpolelike basaloid islands and rarely horn cysts can be seen scattered superficially, creating the paisley tie-like pattern. This lesion is more infiltrating than a syringoma or a DTE, and perineural invasion is common. Retraction is uncommon, but when present, it is seen between the epithelial cords and adjacent stroma (Figure 3).

Trichoadenoma is another benign neoplasm of follicular differentiation.6 It typically presents as a dome-shaped papule or plaque on the head or neck. Histologically it displays numerous dilated cystic spaces that reflect its origin from isthmic and infundibular differentiation. There is no attachment to the overlying epidermis. It can be distinguished from MAC, DTE, and syringoma due to a lack of basaloid aggregates and only a small number of non-cyst-forming epithelial cells (Figure 4).

- Nickoloff BJ, Fleischmann HE, Carmel J. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: immunohistologic observations suggesting dual (pilar and eccrine) differentiation. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:290-294.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Corbett D, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study including markers of proliferation and apoptosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:464-471.

- Hashimoto K, Lever WF. Histogenesis of skin appendage tumors. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:356-369.

- Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Cancer. 1977;40:2979-2986.

- Hartschuh W, Schulz T. Merkel cells are integral constituents of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: an immunohistochemical and electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:413-421.

- Rahbari H, Mehregan A, Pinkus A. Trichoadenoma of Nikolowski. J Cutan Pathol. 1977;4:90-98.

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC) is a rare, low-grade adnexal carcinoma consisting of both ductal and pilar differentiation.1 It typically presents in young to middle-aged adults as a flesh-colored or yellow indurated plaque on the upper lip, medial cheek, or chin. Histologically, MACs exhibit a biphasic pattern consisting of epithelial islands of cords and lumina creating tadpolelike ducts intermixed with basaloid nests (quiz image). Keratin horn cysts are common superficially. A dense red sclerotic stroma is seen interspersed between the ducts and epithelial islands creating a "paisley tie" appearance. The lesion displays an infiltrative pattern and can be deeply invasive, extending down to the fat and muscle (quiz image, inset). Perineural invasion is common. Atypia, when present, is minimal or mild and mitoses are rare. Although this tumor's histologic pattern appears aggressive in nature, it lacks immunohistochemical staining such as p53, Ki-67, bcl-2, and c-erbB-2 that correlate with malignant behavior.2 A common diagnostic pitfall is examination of a superficial biopsy in which an MAC may be mistakenly identified as another entity.

Syringomas are benign adnexal neoplasms with ductal differentiation.3 They are more common in women, especially those of Asian descent, and in patients with Down syndrome. They typically present as multiple small, firm, flesh-colored papules in the periorbital area or upper trunk. Histologically, syringomas also display comma-shaped tubules and ducts with a tadpolelike appearance and a dense red stroma creating a paisley tie-like pattern. Ductal cells have an abundant pink cytoplasm. Syringomas are well-circumscribed and more superficial than MACs without an infiltrative pattern. They lack mitotic activity or perineural invasion (Figure 1).

Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE) is a benign follicular neoplasm.4 It presents in adulthood with a female predominance. Clinically, it appears as a solitary flesh-colored to yellow annular plaque with raised borders and a depressed central area, often on the medial cheek. Histologically, DTEs are well-circumscribed with narrow branching cords lined with polygonal cells. A dense red stroma in combination with the epithelioid aggregates also creates the paisley tie-like pattern in this lesion. Retraction between collagen bundles within the stroma can be seen, helping distinguish this lesion from a morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which has retraction between the epithelium and stroma. Immunohistochemistry also can be a useful tool to help differentiate DTEs from morpheaform BCCs in that sparse cytokeratin 20-positive Merkel cells can be seen within the basaloid islands of DTE but not BCC.5 Also seen with DTEs are numerous keratin horn cysts that commonly are filled with dystrophic calcifications. Cellular atypia and mitoses are not seen (Figure 2). Compared to MACs, DTEs lack abundant ductal structures and also contain papillary mesenchymal bodies and a more fibroblast-rich stroma.

Morpheaform BCC is an aggressive subtype of BCC. It presents as a scarlike plaque that gradually expands. Thin infiltrating strands of basaloid cells are seen haphazardly throughout a pink sclerotic stroma. Tadpolelike basaloid islands and rarely horn cysts can be seen scattered superficially, creating the paisley tie-like pattern. This lesion is more infiltrating than a syringoma or a DTE, and perineural invasion is common. Retraction is uncommon, but when present, it is seen between the epithelial cords and adjacent stroma (Figure 3).

Trichoadenoma is another benign neoplasm of follicular differentiation.6 It typically presents as a dome-shaped papule or plaque on the head or neck. Histologically it displays numerous dilated cystic spaces that reflect its origin from isthmic and infundibular differentiation. There is no attachment to the overlying epidermis. It can be distinguished from MAC, DTE, and syringoma due to a lack of basaloid aggregates and only a small number of non-cyst-forming epithelial cells (Figure 4).

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC) is a rare, low-grade adnexal carcinoma consisting of both ductal and pilar differentiation.1 It typically presents in young to middle-aged adults as a flesh-colored or yellow indurated plaque on the upper lip, medial cheek, or chin. Histologically, MACs exhibit a biphasic pattern consisting of epithelial islands of cords and lumina creating tadpolelike ducts intermixed with basaloid nests (quiz image). Keratin horn cysts are common superficially. A dense red sclerotic stroma is seen interspersed between the ducts and epithelial islands creating a "paisley tie" appearance. The lesion displays an infiltrative pattern and can be deeply invasive, extending down to the fat and muscle (quiz image, inset). Perineural invasion is common. Atypia, when present, is minimal or mild and mitoses are rare. Although this tumor's histologic pattern appears aggressive in nature, it lacks immunohistochemical staining such as p53, Ki-67, bcl-2, and c-erbB-2 that correlate with malignant behavior.2 A common diagnostic pitfall is examination of a superficial biopsy in which an MAC may be mistakenly identified as another entity.

Syringomas are benign adnexal neoplasms with ductal differentiation.3 They are more common in women, especially those of Asian descent, and in patients with Down syndrome. They typically present as multiple small, firm, flesh-colored papules in the periorbital area or upper trunk. Histologically, syringomas also display comma-shaped tubules and ducts with a tadpolelike appearance and a dense red stroma creating a paisley tie-like pattern. Ductal cells have an abundant pink cytoplasm. Syringomas are well-circumscribed and more superficial than MACs without an infiltrative pattern. They lack mitotic activity or perineural invasion (Figure 1).

Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE) is a benign follicular neoplasm.4 It presents in adulthood with a female predominance. Clinically, it appears as a solitary flesh-colored to yellow annular plaque with raised borders and a depressed central area, often on the medial cheek. Histologically, DTEs are well-circumscribed with narrow branching cords lined with polygonal cells. A dense red stroma in combination with the epithelioid aggregates also creates the paisley tie-like pattern in this lesion. Retraction between collagen bundles within the stroma can be seen, helping distinguish this lesion from a morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which has retraction between the epithelium and stroma. Immunohistochemistry also can be a useful tool to help differentiate DTEs from morpheaform BCCs in that sparse cytokeratin 20-positive Merkel cells can be seen within the basaloid islands of DTE but not BCC.5 Also seen with DTEs are numerous keratin horn cysts that commonly are filled with dystrophic calcifications. Cellular atypia and mitoses are not seen (Figure 2). Compared to MACs, DTEs lack abundant ductal structures and also contain papillary mesenchymal bodies and a more fibroblast-rich stroma.

Morpheaform BCC is an aggressive subtype of BCC. It presents as a scarlike plaque that gradually expands. Thin infiltrating strands of basaloid cells are seen haphazardly throughout a pink sclerotic stroma. Tadpolelike basaloid islands and rarely horn cysts can be seen scattered superficially, creating the paisley tie-like pattern. This lesion is more infiltrating than a syringoma or a DTE, and perineural invasion is common. Retraction is uncommon, but when present, it is seen between the epithelial cords and adjacent stroma (Figure 3).

Trichoadenoma is another benign neoplasm of follicular differentiation.6 It typically presents as a dome-shaped papule or plaque on the head or neck. Histologically it displays numerous dilated cystic spaces that reflect its origin from isthmic and infundibular differentiation. There is no attachment to the overlying epidermis. It can be distinguished from MAC, DTE, and syringoma due to a lack of basaloid aggregates and only a small number of non-cyst-forming epithelial cells (Figure 4).

- Nickoloff BJ, Fleischmann HE, Carmel J. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: immunohistologic observations suggesting dual (pilar and eccrine) differentiation. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:290-294.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Corbett D, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study including markers of proliferation and apoptosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:464-471.

- Hashimoto K, Lever WF. Histogenesis of skin appendage tumors. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:356-369.

- Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Cancer. 1977;40:2979-2986.

- Hartschuh W, Schulz T. Merkel cells are integral constituents of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: an immunohistochemical and electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:413-421.

- Rahbari H, Mehregan A, Pinkus A. Trichoadenoma of Nikolowski. J Cutan Pathol. 1977;4:90-98.

- Nickoloff BJ, Fleischmann HE, Carmel J. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: immunohistologic observations suggesting dual (pilar and eccrine) differentiation. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:290-294.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Corbett D, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study including markers of proliferation and apoptosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:464-471.

- Hashimoto K, Lever WF. Histogenesis of skin appendage tumors. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:356-369.

- Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Cancer. 1977;40:2979-2986.

- Hartschuh W, Schulz T. Merkel cells are integral constituents of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: an immunohistochemical and electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:413-421.

- Rahbari H, Mehregan A, Pinkus A. Trichoadenoma of Nikolowski. J Cutan Pathol. 1977;4:90-98.

A 52-year-old woman presented with an indurated plaque on the right lateral eyebrow that had been slowly enlarging over the last 4 months.

Over-the-counter Topical Musculoskeletal Pain Relievers Used With a Heat Source: A Dangerous Combination

To the Editor:

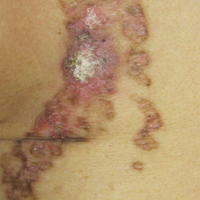

The combination of menthol and methyl salicylate found in a variety of over-the-counter (OTC) creams in conjunction with a heat source such as a heating pad used for musculoskeletal symptoms can be a dire combination due to increased systemic absorption with associated toxicity and localized effects ranging from contact dermatitis or irritation to burn or necrosis.1-6 We present a case of localized burn due a combination of topical methyl salicylate and heating pad use. We also discuss 2 commonly encountered side effects in the literature—localized burns and systemic toxicity associated with percutaneous absorption—and provide specific considerations related to the geriatric and pediatric populations.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of eczematous dermatitis and osteoarthritis with pain of the left shoulder presented to the dermatology clinic with painful skin-related changes on the left arm of 1 week’s duration. She was prescribed acetaminophen and ibuprofen. However, she self-medicated the left shoulder pain with 2 OTC products containing topical menthol and/or methyl salicylate in combination with a heating pad and likely fell asleep with this combination therapy applied. She noticed the burn the next morning. On examination, the left arm exhibited a geometric, irregularly shaped, erythematous, scaly plaque with a sharp transverse linear demarcation proximally and numerous erythematous linear scaly plaques oriented in an axial orientation with less-defined borders distally (Figure). The patient was diagnosed with burn secondary to combination of topical methyl salicylate and heating pad use. The patient was advised to discontinue the topical medication and to use caution with the heating pad in the future. She was prescribed pramoxine-hydrocortisone lotion to be applied to the affected area twice daily up to 5 days weekly until resolution. Subsequent evaluations revealed progressive improvement with only mild postinflammatory hyperpigmentation noted at 6 months after the burn.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released statements in 2012 regarding concern for burns related to use of OTC musculoskeletal pain relievers, with 43 cases of burns reported due to methyl salicylate and menthol from 2004 to 2010. Most of the second- and third-degree burns occurred following topical applications of products containing either menthol monotherapy or a combination of methyl salicylate and menthol.1,2 In 2006, the FDA had already ordered 5 firms to stop compounding topical pain relief formulations containing these ingredients, with concerns that it puts patients at increased risk because the compounded formulations had not received FDA approval.3 Despite package warnings, patients may not be aware of the concerning side effects and risks associated with use of OTC creams, especially in combination with occlusion or heating pad use. Our case highlights the importance of ongoing patient education and physician counseling when encountering patients with arthritis or musculoskeletal pain who may often try various OTC self-treatments for pain relief.7

In 2012, the FDA reports stated that the cases of mild to serious burns were associated with methyl salicylate and menthol usage, in some cases 24 hours after first usage. Typically, these effects occur when concentrations are more than either 3% menthol alone or a combination of more than 3% menthol and more than 10% methyl salicylate.1,2 In our case, the patient had been using 2 different OTC products that may have contained as much as 11% menthol and/or 30% methyl salicylate. Electronic resources are available that disclose safety instructions including not to occlude the site, not to use on wounds, and not to be used in conjunction with a heating pad.8,9 Skin breakdown and vasodilation are more likely to occur in a setting of heat and occlusion, which allows for more absorption and localized side effects.4,10 Localized reactions may range from contact dermatitis4 to muscle necrosis.5

The most noteworthy case of localized destruction described a 62-year-old man who had applied topical methyl salicylate and menthol to the forearms, calves, and thighs, then intermittently used a heating pad for 15 to 20 minutes (total duration).5 He subsequently developed erythema and numerous 7.62- to 10.16-cm bullae, which was thought to be consistent with contact dermatitis. Three days later, he was found to have full-thickness cutaneous, fascial, and muscle necrosis in a linear pattern. He was hospitalized for approximately 1 year and treated with extensive debridement and a skin graft. His serum creatinine level increased from 0.7 mg per 100 mL to 2.7 mg per 100 mL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL) with evidence of toxic nephrosis and persistent interstitial nephritis, demonstrating the severity of localized destruction that may result when combining these products with direct heat and potential subsequent systemic consequences of this combination.5

The systemic absorption of OTC formulations also has been studied. Morra et al10 studied 12 volunteers (6 women, 6 men) who applied either 5 g of methyl salicylate ointment 12.5% twice daily for 4 days to an area on the thigh (approximately equal to 567 mg salicylate) or trolamine cream 10% twice for 1 day. The participants underwent a break for 7 days and then switched to the alternate treatment. They found that 0.31 to 0.91 mg/L methyl salicylate was detected in the serum 1 hour after applying the ointment consisting of methyl salicylate, and 2 to 6 mg/L methyl salicylate was detected on day 4. Therapeutic serum salicylate levels are 150 to 300 mg/L. They found that approximately 22% of the methyl salicylate also was found in urine samples on day 4. Although these figures may appear small, this study was prompted when a 62-year-old man presented to the emergency department with symptoms of salicylate toxicity and a serum concentration of 518 mg/L from twice-daily use of an OTC formulation containing methyl salicylate over the course of multiple weeks.10 Additionally, those who have aspirin hypersensitivity should be cautious when using such products due to the risk for reported angioedema.4

Providers must exercise extreme caution while caring for geriatric patients, especially if patients are taking warfarin. The combined effects of warfarin and methyl salicylate have previously caused cutaneous purpura, gastrointestinal bleeding, and elevated international normalized ratio values.4,10 Older individuals also have increased skin fragility, allowing microtraumatic insult to easily develop. This fragility, along with an overall decreased intactness of the skin barrier, may lead to increased skin absorption. Furthermore, the addition of applying any heat source places the geriatric patient at greater risk for adverse events.10

In considering the limits of age, the pediatric population also has been studied regarding salicylate toxicity. Most commonly, oral ingestion has caused fatalities, as oil of wintergreen has been cited as extremely dangerous for children if swallowed; doses as small as a teaspoon (5 mL: 7000 mg salicylate) have resulted in fatalities.4,6 Although the consumption of a large amount of a cream- or ointment-based product is unlikely due to the consistency of the medication,6 the thought does merit consideration in the inquisitive toddler age group. For a 15-kg toddler, 150 mg/kg of aspirin or 2250 mg of aspirin, is considered the toxic level, which upon conversion to methyl salicylate levels using a 1.4 factor equates to 1607 mg of methyl salicylate to reach toxicity.6 If using a product with methyl salicylate 30% composition, 1 g of the product contains 300 mg of methyl salicylate; therefore if the toddler consumed approximately 5.3 g of the product (1607 mg methyl salicylate [toxic level] divided by 300 mg methyl salicylate per 1 g of product), he/she would reach toxic levels.6,11 To put this into perspective, a 2-oz tube contains 57 g (approximately 10 times the toxic dose) of the product.8 Thus, although there is less concern overall for consumption of cream- or ointment-based methyl salicylate, there still is potential for harm if a small child were to ingest such a product containing higher percentages of methyl salicylate.6

There also have been reports of pediatric toxicity related to percutaneous absorption, even leading to pediatric fatality.4,6 In particular, there was a case of a young boy hospitalized with ichthyosis who received escalating doses of percutaneous salicylate, which resulted in toxicity; when therapy was discontinued, he experienced full recovery.12 In 2007, a 17-year-old adolescent girl died from methyl salicylate toxicity after numerous applications of salicylate-containing products in conjunction with medicated pads.7

Although the FDA has drawn attention and encouraged caution with use of OTC topical musculoskeletal pain relievers, the importance of ensuring patients are fully aware of potential burns, permanent skin or muscle damage, and even death if used inappropriately cannot be overstated. The FDA consumer health information website has 2 patient-directed handouts2,3 that may be useful to post in patient waiting areas to increase overall understanding of the risks associated with OTC products containing methyl salicylate and menthol ingredients. Fortunately, our patient suffered only mild postinflammatory hyperpigmentation without substantial sustained consequences.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: rare cases of serious burns with the use of over-the-counter topical muscle and joint pain relievers. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm318858.htm. Published September 13, 2012. Updated February 11, 2016. Accessed October 31, 2017.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Topical pain relievers may cause burns. http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm318674.htm. Published September 13, 2012. Updated November 5, 2015. Accessed October 31, 2017.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Use caution with over-the-counter creams, ointments. http://www.fda.gov/forconsumers/consumerupdates/ucm049367.htm. Updated October 17, 2017. Accessed October 31, 2017.

- Chan TY. Potential dangers from topical preparations containing methyl salicylate. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1996;15:747-750.

- Heng MC. Local necrosis and interstitial nephritis due to topical methyl salicylate and menthol. Cutis. 1987;39:442-444.

- Davis JE. Are one or two dangerous? methyl salicylate exposure in toddlers. J Emerg Med. 2007;32:63-69.

- Associated Press. Sports cream warnings urged after teen’s death: track star’s overdose points to risks of popular muscle salve. NBC News. http://www.nbcnews.com/id/19208195. Updated June 13, 2007. Accessed October 31, 2017.

- Ultra Strength Bengay Cream. Bengay website. http://www.bengay.com/bengay-ultra-strength-cream. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- Tiger Balm Arthritis Rub. Tiger Balm website. http://www.tigerbalm.com/us/pages/tb_product?product_id=6. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- Morra P, Bartle WR, Walker SE, et al. Serum concentrations of salicylic acid following topically applied salicylate derivatives. Ann Pharmacother. 1996;9:935-940.

- US National Library of Medicine. Bengay Ultra Strength non greasy pain relieving- camphor (synthetic), menthol, and methyl salicylate cream. Daily Med website. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=5aa265f8-ab45-47b2-b5ab-d4df54daed01. Updated November 3, 2016. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- Aspinall JB, Goel KM. Salicylate poisoning in dermatological therapy. Br Med J. 1978;2:1373.

To the Editor:

The combination of menthol and methyl salicylate found in a variety of over-the-counter (OTC) creams in conjunction with a heat source such as a heating pad used for musculoskeletal symptoms can be a dire combination due to increased systemic absorption with associated toxicity and localized effects ranging from contact dermatitis or irritation to burn or necrosis.1-6 We present a case of localized burn due a combination of topical methyl salicylate and heating pad use. We also discuss 2 commonly encountered side effects in the literature—localized burns and systemic toxicity associated with percutaneous absorption—and provide specific considerations related to the geriatric and pediatric populations.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of eczematous dermatitis and osteoarthritis with pain of the left shoulder presented to the dermatology clinic with painful skin-related changes on the left arm of 1 week’s duration. She was prescribed acetaminophen and ibuprofen. However, she self-medicated the left shoulder pain with 2 OTC products containing topical menthol and/or methyl salicylate in combination with a heating pad and likely fell asleep with this combination therapy applied. She noticed the burn the next morning. On examination, the left arm exhibited a geometric, irregularly shaped, erythematous, scaly plaque with a sharp transverse linear demarcation proximally and numerous erythematous linear scaly plaques oriented in an axial orientation with less-defined borders distally (Figure). The patient was diagnosed with burn secondary to combination of topical methyl salicylate and heating pad use. The patient was advised to discontinue the topical medication and to use caution with the heating pad in the future. She was prescribed pramoxine-hydrocortisone lotion to be applied to the affected area twice daily up to 5 days weekly until resolution. Subsequent evaluations revealed progressive improvement with only mild postinflammatory hyperpigmentation noted at 6 months after the burn.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released statements in 2012 regarding concern for burns related to use of OTC musculoskeletal pain relievers, with 43 cases of burns reported due to methyl salicylate and menthol from 2004 to 2010. Most of the second- and third-degree burns occurred following topical applications of products containing either menthol monotherapy or a combination of methyl salicylate and menthol.1,2 In 2006, the FDA had already ordered 5 firms to stop compounding topical pain relief formulations containing these ingredients, with concerns that it puts patients at increased risk because the compounded formulations had not received FDA approval.3 Despite package warnings, patients may not be aware of the concerning side effects and risks associated with use of OTC creams, especially in combination with occlusion or heating pad use. Our case highlights the importance of ongoing patient education and physician counseling when encountering patients with arthritis or musculoskeletal pain who may often try various OTC self-treatments for pain relief.7

In 2012, the FDA reports stated that the cases of mild to serious burns were associated with methyl salicylate and menthol usage, in some cases 24 hours after first usage. Typically, these effects occur when concentrations are more than either 3% menthol alone or a combination of more than 3% menthol and more than 10% methyl salicylate.1,2 In our case, the patient had been using 2 different OTC products that may have contained as much as 11% menthol and/or 30% methyl salicylate. Electronic resources are available that disclose safety instructions including not to occlude the site, not to use on wounds, and not to be used in conjunction with a heating pad.8,9 Skin breakdown and vasodilation are more likely to occur in a setting of heat and occlusion, which allows for more absorption and localized side effects.4,10 Localized reactions may range from contact dermatitis4 to muscle necrosis.5

The most noteworthy case of localized destruction described a 62-year-old man who had applied topical methyl salicylate and menthol to the forearms, calves, and thighs, then intermittently used a heating pad for 15 to 20 minutes (total duration).5 He subsequently developed erythema and numerous 7.62- to 10.16-cm bullae, which was thought to be consistent with contact dermatitis. Three days later, he was found to have full-thickness cutaneous, fascial, and muscle necrosis in a linear pattern. He was hospitalized for approximately 1 year and treated with extensive debridement and a skin graft. His serum creatinine level increased from 0.7 mg per 100 mL to 2.7 mg per 100 mL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL) with evidence of toxic nephrosis and persistent interstitial nephritis, demonstrating the severity of localized destruction that may result when combining these products with direct heat and potential subsequent systemic consequences of this combination.5

The systemic absorption of OTC formulations also has been studied. Morra et al10 studied 12 volunteers (6 women, 6 men) who applied either 5 g of methyl salicylate ointment 12.5% twice daily for 4 days to an area on the thigh (approximately equal to 567 mg salicylate) or trolamine cream 10% twice for 1 day. The participants underwent a break for 7 days and then switched to the alternate treatment. They found that 0.31 to 0.91 mg/L methyl salicylate was detected in the serum 1 hour after applying the ointment consisting of methyl salicylate, and 2 to 6 mg/L methyl salicylate was detected on day 4. Therapeutic serum salicylate levels are 150 to 300 mg/L. They found that approximately 22% of the methyl salicylate also was found in urine samples on day 4. Although these figures may appear small, this study was prompted when a 62-year-old man presented to the emergency department with symptoms of salicylate toxicity and a serum concentration of 518 mg/L from twice-daily use of an OTC formulation containing methyl salicylate over the course of multiple weeks.10 Additionally, those who have aspirin hypersensitivity should be cautious when using such products due to the risk for reported angioedema.4

Providers must exercise extreme caution while caring for geriatric patients, especially if patients are taking warfarin. The combined effects of warfarin and methyl salicylate have previously caused cutaneous purpura, gastrointestinal bleeding, and elevated international normalized ratio values.4,10 Older individuals also have increased skin fragility, allowing microtraumatic insult to easily develop. This fragility, along with an overall decreased intactness of the skin barrier, may lead to increased skin absorption. Furthermore, the addition of applying any heat source places the geriatric patient at greater risk for adverse events.10

In considering the limits of age, the pediatric population also has been studied regarding salicylate toxicity. Most commonly, oral ingestion has caused fatalities, as oil of wintergreen has been cited as extremely dangerous for children if swallowed; doses as small as a teaspoon (5 mL: 7000 mg salicylate) have resulted in fatalities.4,6 Although the consumption of a large amount of a cream- or ointment-based product is unlikely due to the consistency of the medication,6 the thought does merit consideration in the inquisitive toddler age group. For a 15-kg toddler, 150 mg/kg of aspirin or 2250 mg of aspirin, is considered the toxic level, which upon conversion to methyl salicylate levels using a 1.4 factor equates to 1607 mg of methyl salicylate to reach toxicity.6 If using a product with methyl salicylate 30% composition, 1 g of the product contains 300 mg of methyl salicylate; therefore if the toddler consumed approximately 5.3 g of the product (1607 mg methyl salicylate [toxic level] divided by 300 mg methyl salicylate per 1 g of product), he/she would reach toxic levels.6,11 To put this into perspective, a 2-oz tube contains 57 g (approximately 10 times the toxic dose) of the product.8 Thus, although there is less concern overall for consumption of cream- or ointment-based methyl salicylate, there still is potential for harm if a small child were to ingest such a product containing higher percentages of methyl salicylate.6

There also have been reports of pediatric toxicity related to percutaneous absorption, even leading to pediatric fatality.4,6 In particular, there was a case of a young boy hospitalized with ichthyosis who received escalating doses of percutaneous salicylate, which resulted in toxicity; when therapy was discontinued, he experienced full recovery.12 In 2007, a 17-year-old adolescent girl died from methyl salicylate toxicity after numerous applications of salicylate-containing products in conjunction with medicated pads.7

Although the FDA has drawn attention and encouraged caution with use of OTC topical musculoskeletal pain relievers, the importance of ensuring patients are fully aware of potential burns, permanent skin or muscle damage, and even death if used inappropriately cannot be overstated. The FDA consumer health information website has 2 patient-directed handouts2,3 that may be useful to post in patient waiting areas to increase overall understanding of the risks associated with OTC products containing methyl salicylate and menthol ingredients. Fortunately, our patient suffered only mild postinflammatory hyperpigmentation without substantial sustained consequences.

To the Editor:

The combination of menthol and methyl salicylate found in a variety of over-the-counter (OTC) creams in conjunction with a heat source such as a heating pad used for musculoskeletal symptoms can be a dire combination due to increased systemic absorption with associated toxicity and localized effects ranging from contact dermatitis or irritation to burn or necrosis.1-6 We present a case of localized burn due a combination of topical methyl salicylate and heating pad use. We also discuss 2 commonly encountered side effects in the literature—localized burns and systemic toxicity associated with percutaneous absorption—and provide specific considerations related to the geriatric and pediatric populations.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of eczematous dermatitis and osteoarthritis with pain of the left shoulder presented to the dermatology clinic with painful skin-related changes on the left arm of 1 week’s duration. She was prescribed acetaminophen and ibuprofen. However, she self-medicated the left shoulder pain with 2 OTC products containing topical menthol and/or methyl salicylate in combination with a heating pad and likely fell asleep with this combination therapy applied. She noticed the burn the next morning. On examination, the left arm exhibited a geometric, irregularly shaped, erythematous, scaly plaque with a sharp transverse linear demarcation proximally and numerous erythematous linear scaly plaques oriented in an axial orientation with less-defined borders distally (Figure). The patient was diagnosed with burn secondary to combination of topical methyl salicylate and heating pad use. The patient was advised to discontinue the topical medication and to use caution with the heating pad in the future. She was prescribed pramoxine-hydrocortisone lotion to be applied to the affected area twice daily up to 5 days weekly until resolution. Subsequent evaluations revealed progressive improvement with only mild postinflammatory hyperpigmentation noted at 6 months after the burn.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released statements in 2012 regarding concern for burns related to use of OTC musculoskeletal pain relievers, with 43 cases of burns reported due to methyl salicylate and menthol from 2004 to 2010. Most of the second- and third-degree burns occurred following topical applications of products containing either menthol monotherapy or a combination of methyl salicylate and menthol.1,2 In 2006, the FDA had already ordered 5 firms to stop compounding topical pain relief formulations containing these ingredients, with concerns that it puts patients at increased risk because the compounded formulations had not received FDA approval.3 Despite package warnings, patients may not be aware of the concerning side effects and risks associated with use of OTC creams, especially in combination with occlusion or heating pad use. Our case highlights the importance of ongoing patient education and physician counseling when encountering patients with arthritis or musculoskeletal pain who may often try various OTC self-treatments for pain relief.7

In 2012, the FDA reports stated that the cases of mild to serious burns were associated with methyl salicylate and menthol usage, in some cases 24 hours after first usage. Typically, these effects occur when concentrations are more than either 3% menthol alone or a combination of more than 3% menthol and more than 10% methyl salicylate.1,2 In our case, the patient had been using 2 different OTC products that may have contained as much as 11% menthol and/or 30% methyl salicylate. Electronic resources are available that disclose safety instructions including not to occlude the site, not to use on wounds, and not to be used in conjunction with a heating pad.8,9 Skin breakdown and vasodilation are more likely to occur in a setting of heat and occlusion, which allows for more absorption and localized side effects.4,10 Localized reactions may range from contact dermatitis4 to muscle necrosis.5

The most noteworthy case of localized destruction described a 62-year-old man who had applied topical methyl salicylate and menthol to the forearms, calves, and thighs, then intermittently used a heating pad for 15 to 20 minutes (total duration).5 He subsequently developed erythema and numerous 7.62- to 10.16-cm bullae, which was thought to be consistent with contact dermatitis. Three days later, he was found to have full-thickness cutaneous, fascial, and muscle necrosis in a linear pattern. He was hospitalized for approximately 1 year and treated with extensive debridement and a skin graft. His serum creatinine level increased from 0.7 mg per 100 mL to 2.7 mg per 100 mL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL) with evidence of toxic nephrosis and persistent interstitial nephritis, demonstrating the severity of localized destruction that may result when combining these products with direct heat and potential subsequent systemic consequences of this combination.5