User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Lichen Planus Pemphigoides Treated With Ustekinumab

Case Report

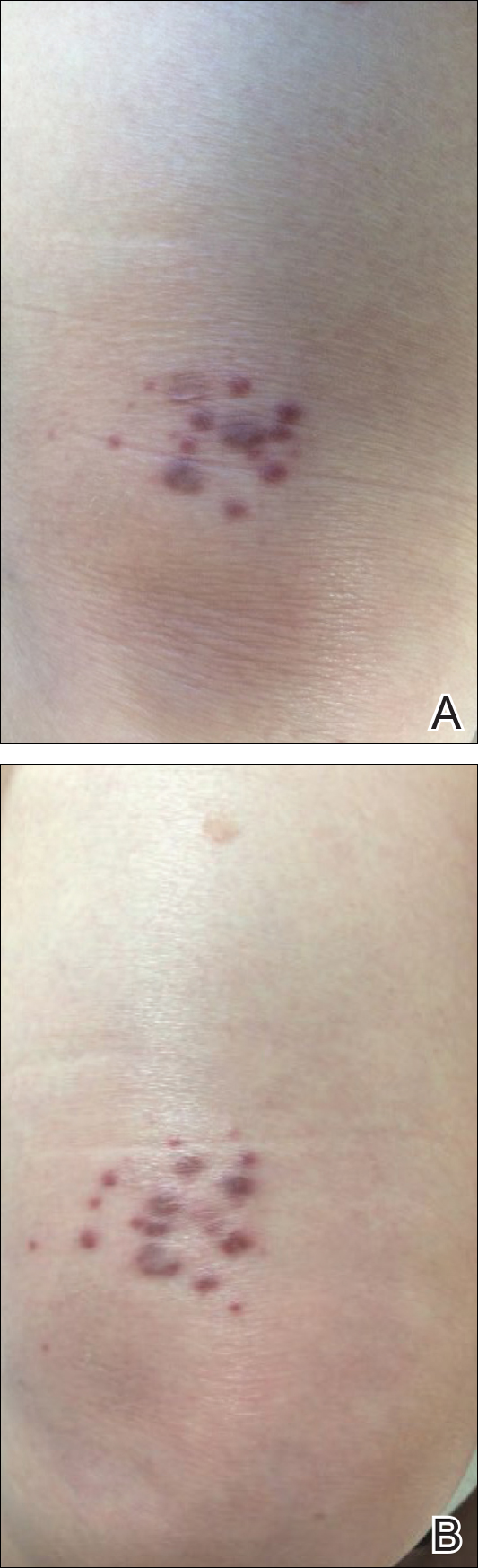

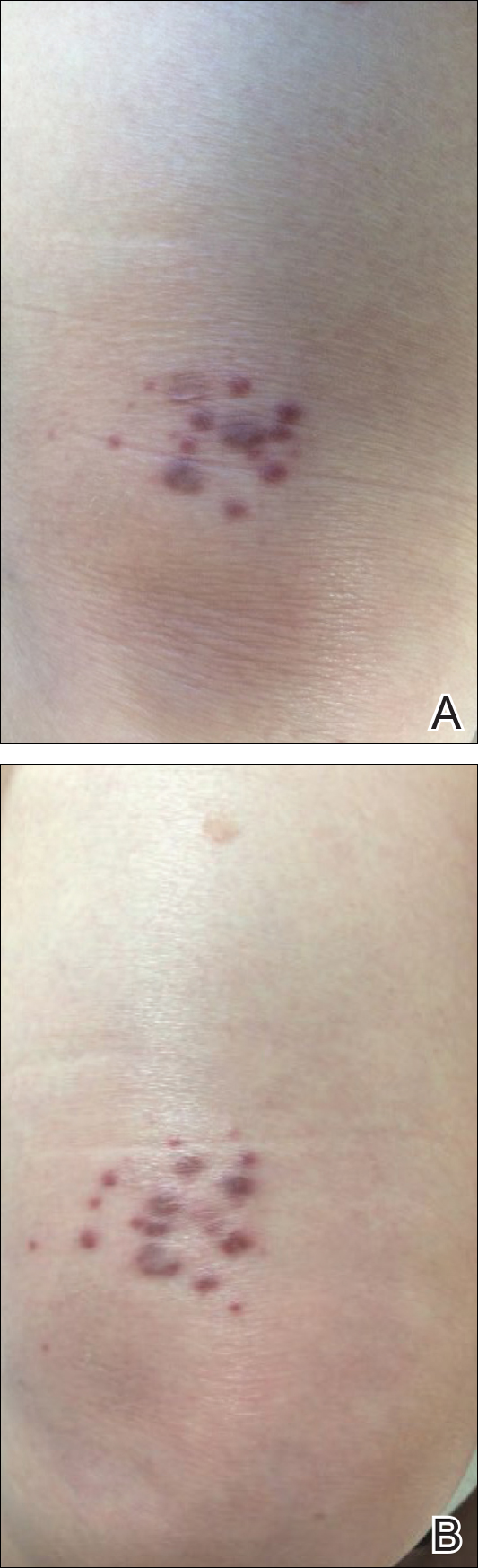

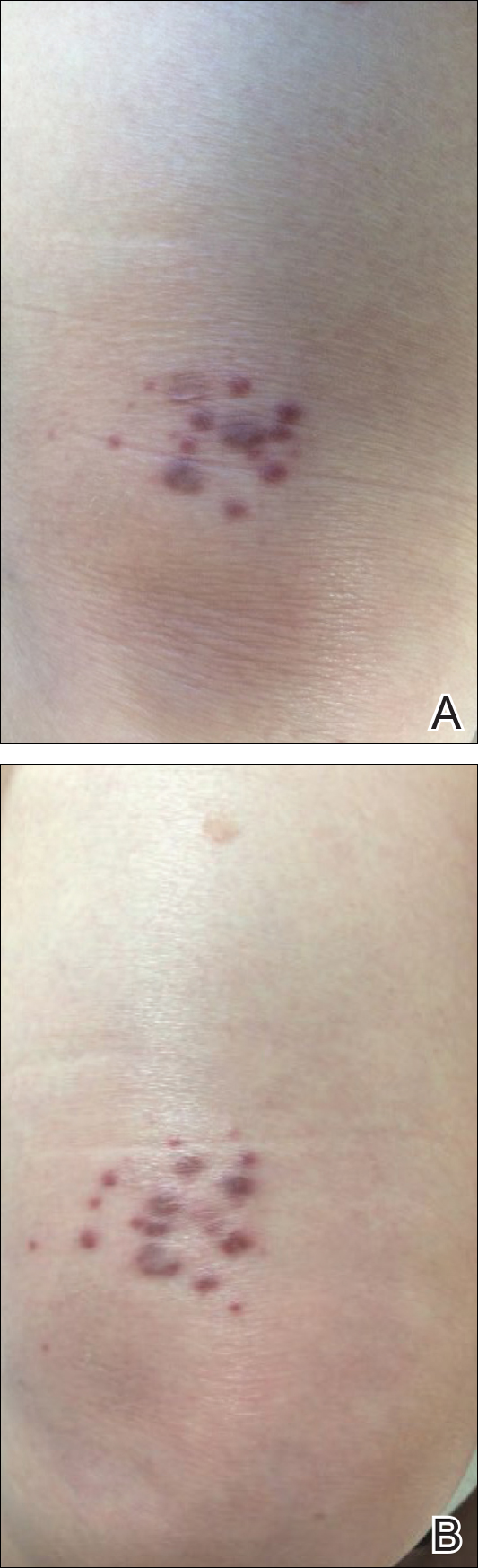

A 71-year-old woman presented with pink to violaceous, flat-topped, polygonal papules consistent with lichen planus (LP) on the volar wrists, extensor elbows, and bilateral lower legs of 3 years’ duration. She also had erythematous, violaceous, infiltrated plaques with microvesiculation on the bilateral thighs of several months’ duration (Figure 1). She reported pruritus, burning, and discomfort. Her medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and asthma with no history of skin rashes. A complete physical examination was performed. Age-appropriate screening for malignancy was negative. Hepatitis B and C antibody serologies were negative. Her medications at the time included risedronate and atenolol, which she had been taking for several years.

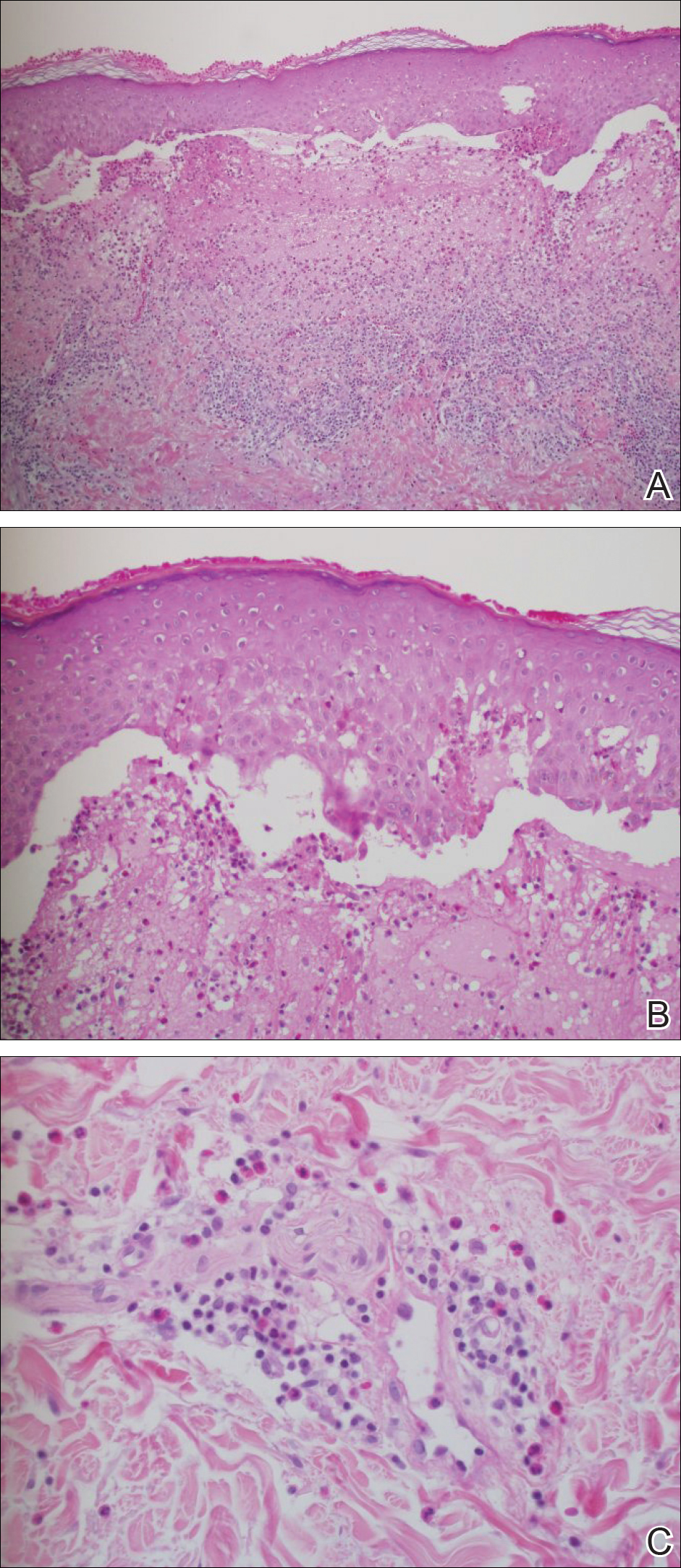

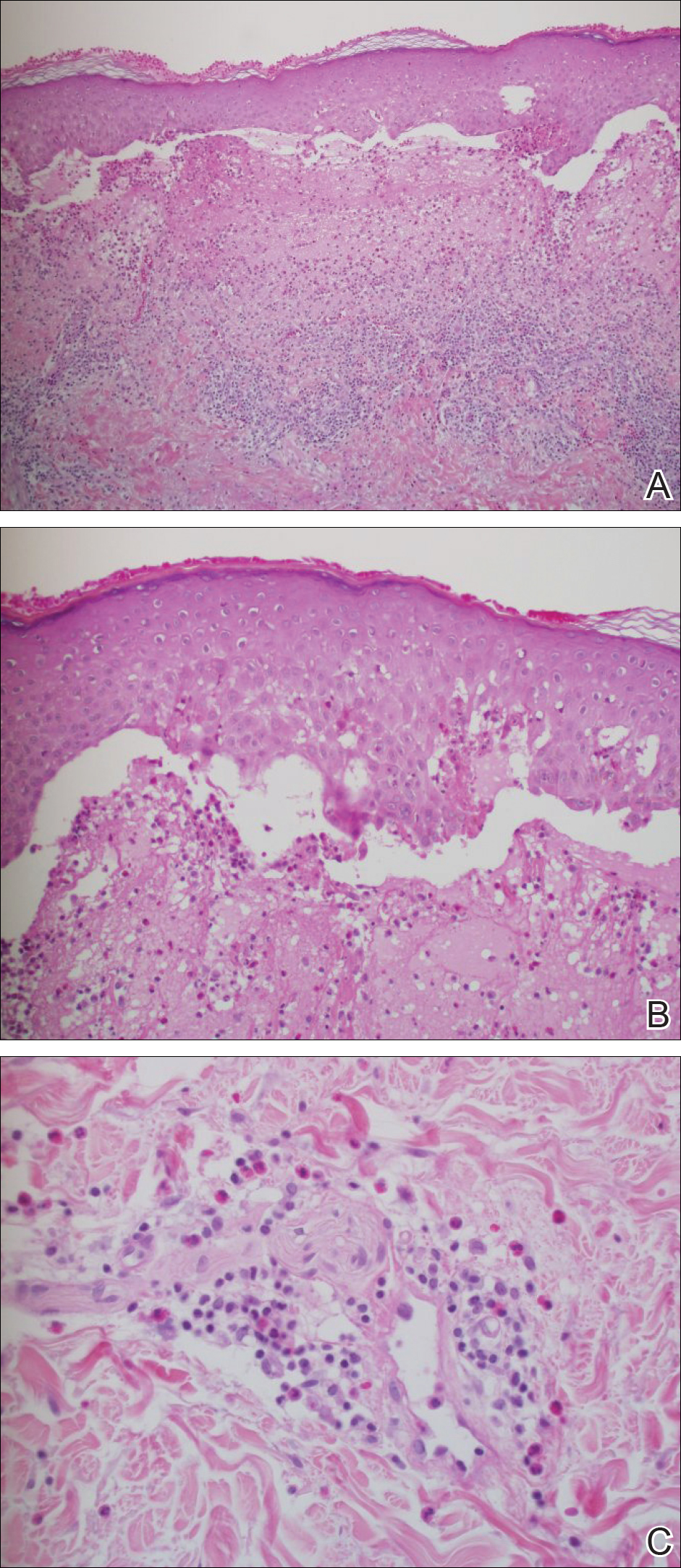

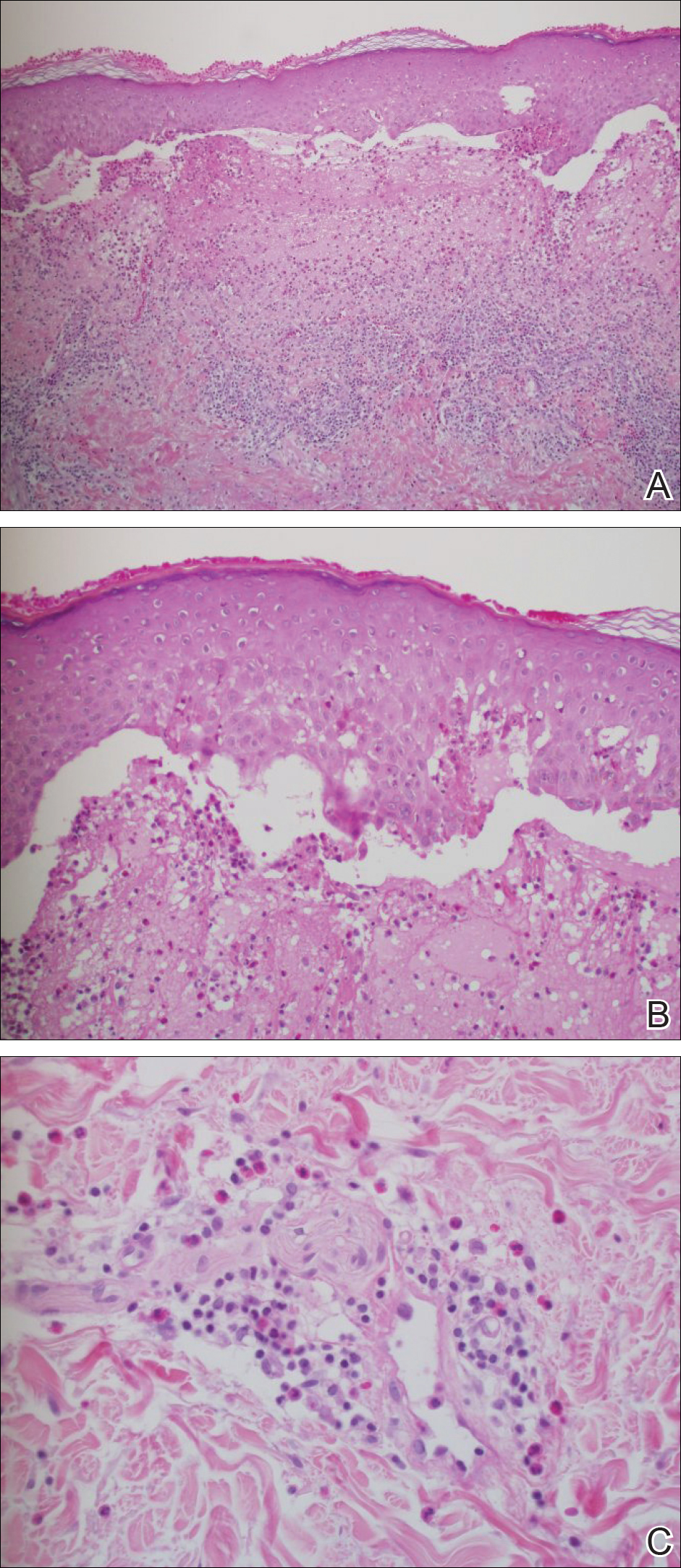

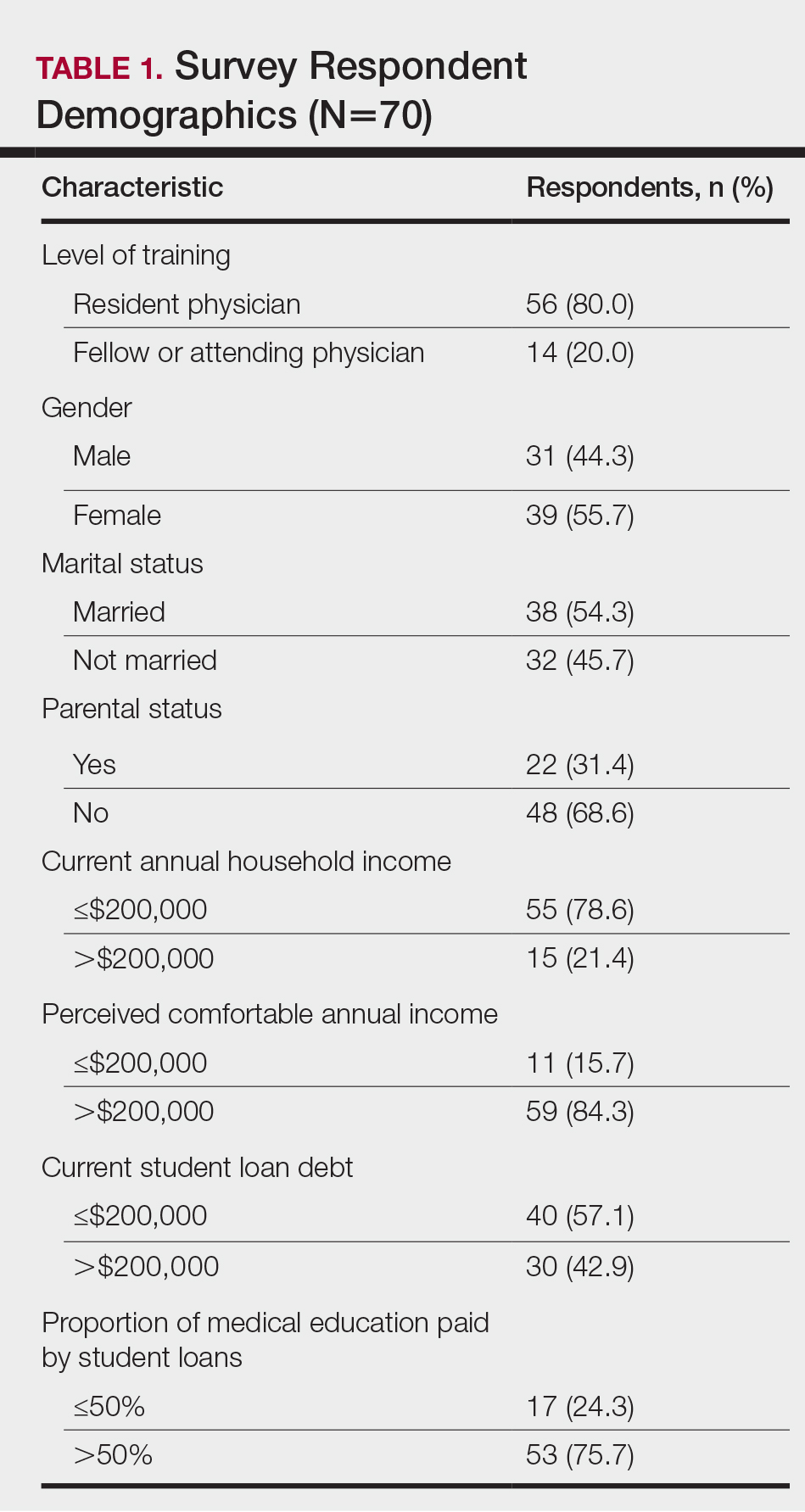

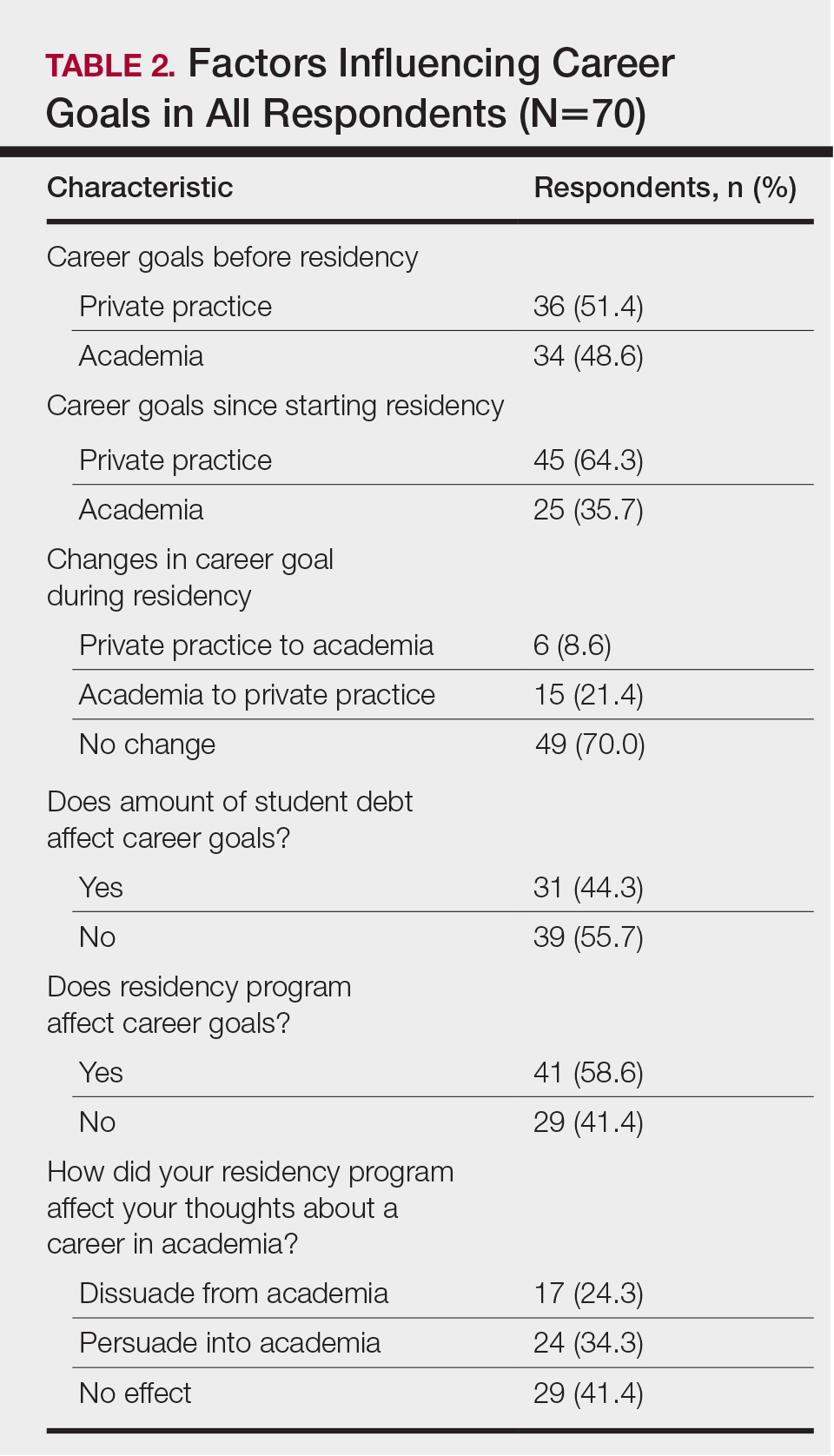

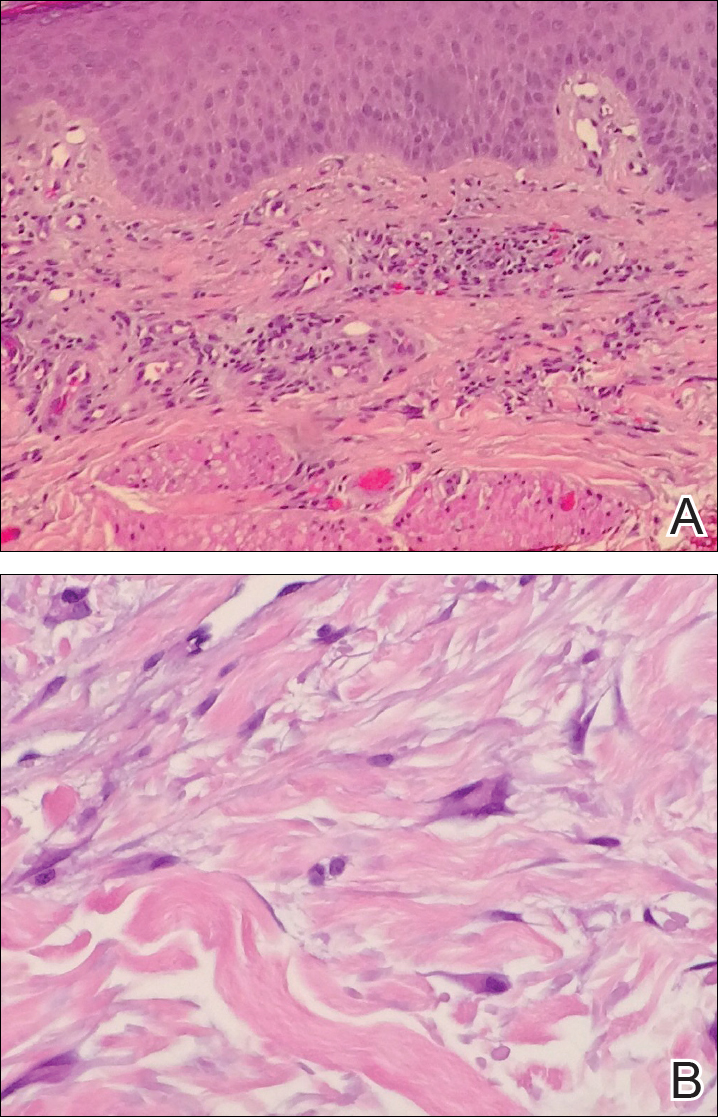

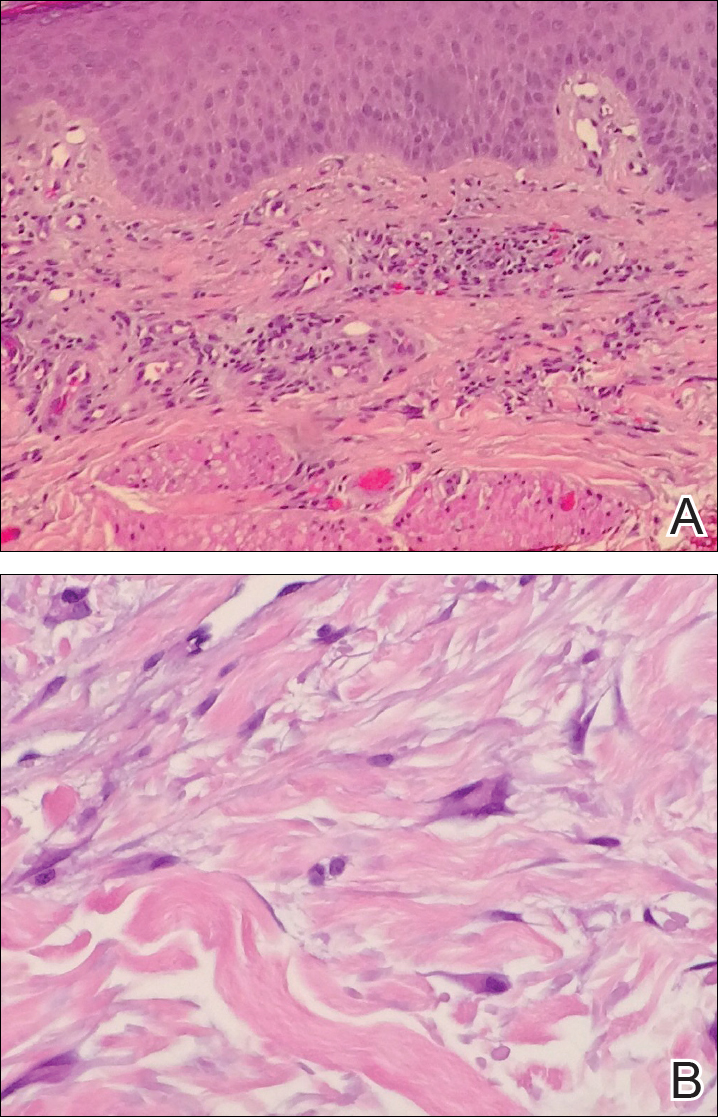

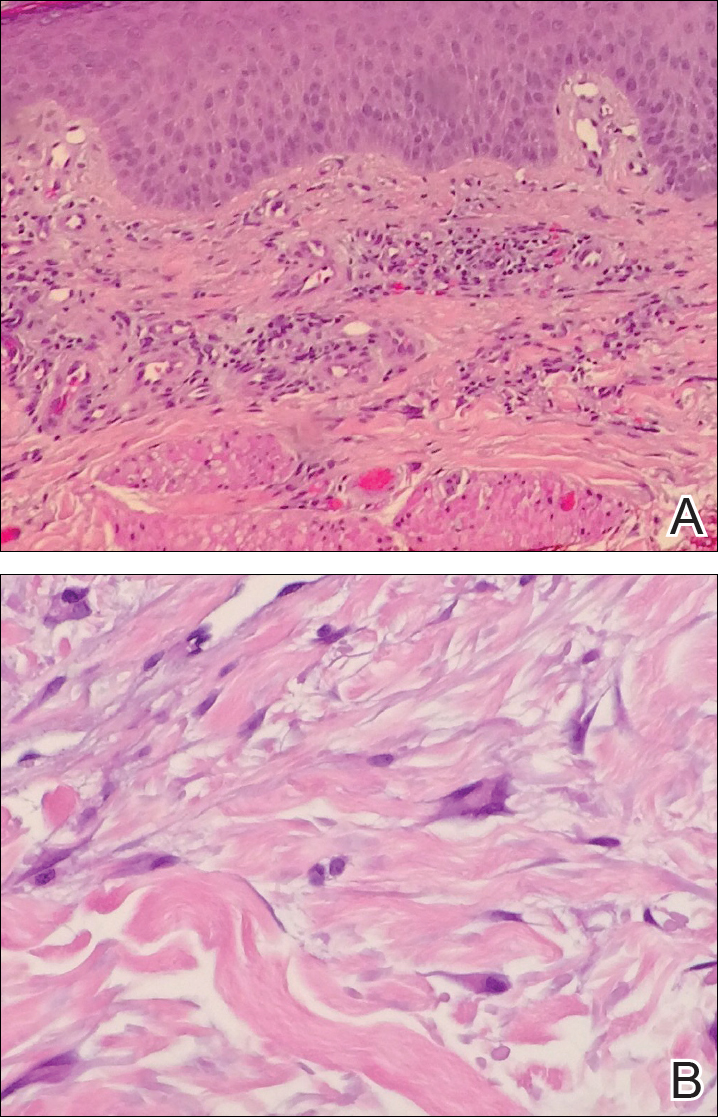

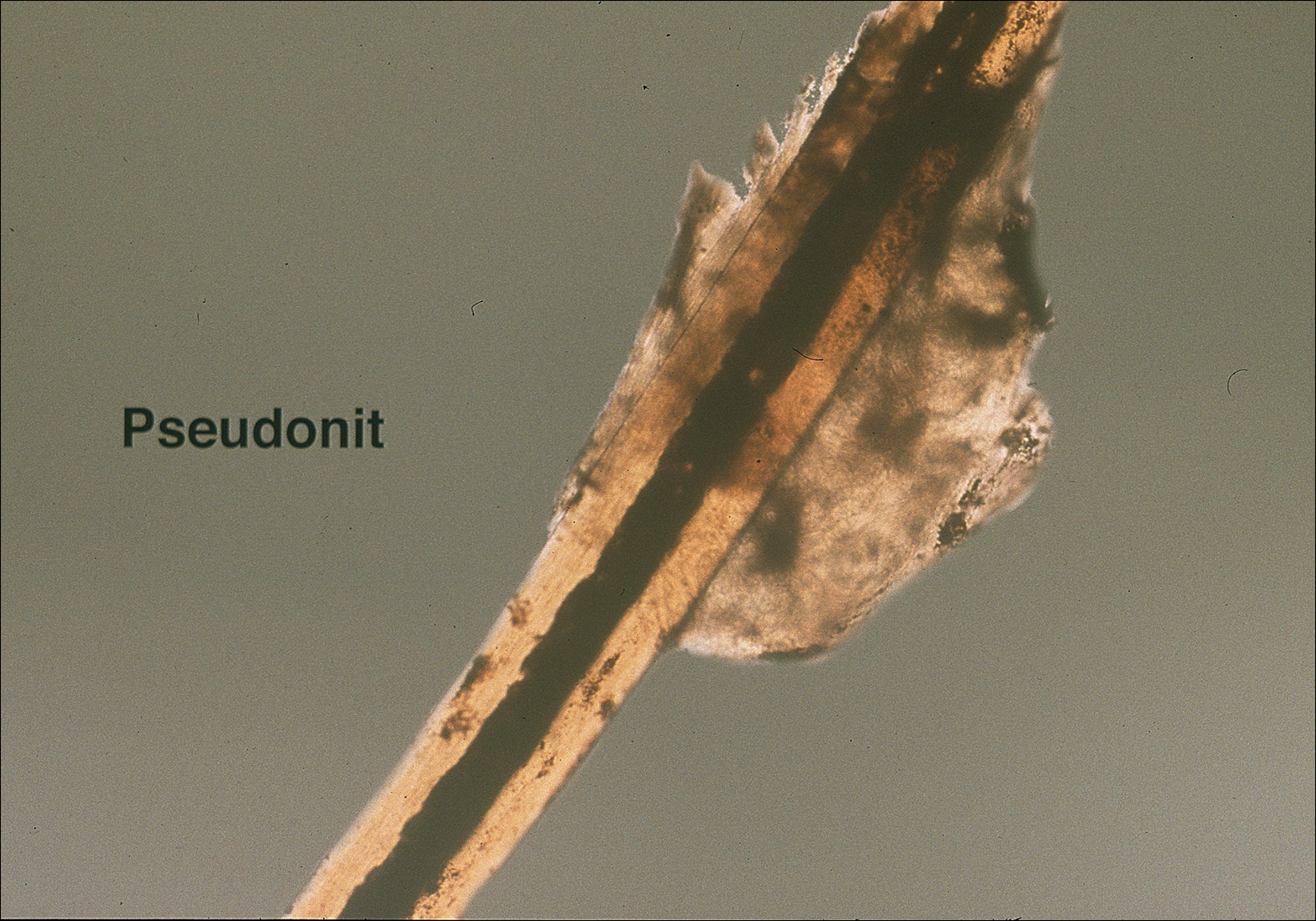

Punch biopsies from perilesional skin were submitted for hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence (DIF). Histopathology showed a subepidermal blistering disease with tissue eosinophilia consistent with lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP)(Figure 2); direct immunofluorescence was positive for IgG, C3, and type IV collagen at the dermoepidermal junction. Serum BP180 was positive at 51 U/mL (reference range, <14 U/mL) and BP230 was negative. She was then started on tetracycline (500 mg twice daily), nicotinamide (500 mg twice daily), prednisone (5 mg daily), and dapsone (100 mg daily).

After 3 months without improvement, tetracycline and nicotinamide were discontinued, prednisone was increased to 10 mg daily, and dapsone was continued. A repeat biopsy was taken from a new area of involvement on the left lower leg, which revealed a psoriasiform dermatitis with interface changes. The DIF was positive for IgG and C3 along the basement membrane. A serum indirect immunofluorescence for BP180 also was positive.

The patient developed mild hemolytic anemia on dapsone; the medication was eventually discontinued. Subsequent treatments included adequate trials of azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and hydroxychloroquine. Azathioprine (150 mg daily) and hydroxychloroquine (400 mg daily) treatment failed. She initially improved on mycophenolate mofetil (500 mg in the morning and 1000 mg in the evening) with flattening of the papules on the arms and legs and decreased erythema. However, mycophenolate mofetil eventually lost its efficacy and was discontinued.

Because several medications failed (ie, tetracycline, nicotinamide, prednisone, dapsone, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, hydroxychloroquine), she was started on ustekinumab (45 mg) initial loading dose by subcutaneous injection (patient’s weight, 63 kg). At 4 weeks, the patient was given the second subcutaneous injection of ustekinumab (45 mg). She experienced marked improvement with no new lesions. The prior lesions also had decreased in size and were only slightly pink. The prednisone dose was tapered to 5 mg daily.

She had near-complete resolution of the skin lesions 12 weeks after the second dose of ustekinumab. Since then, she has had some recrudescence of the papulosquamous lesions but no vesicles or bullae. With the exception of occasional scattered pink papules on the forearms, her condition greatly improved on ustekinumab. She is no longer taking any of the other medications with the exception of prednisone (down to 1 mg daily) with a plan to gradually taper completely off of it.

Comment

Clinical Presentation

Lichen planus pemphigoides is a rare autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease with few cases reported in the literature. It is considered a clinical variation of bullous pemphigoid (BP) or a coexistence of LP and BP.1,2 It is characterized by bullous lesions developing on LP papules as well as on clinically uninvolved areas of the skin. It has been reported that LPP is provoked by several medications including cinnarizine, captopril, ramipril, simvastatin, psoralen plus UVA, and antituberculous medications (eg, isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide).1 Risedronate or atenolol have not been reported to cause LPP, LP, or BP; however, according to Litt,3 a lichenoid drug eruption has been associated with atenolol. Furthermore, some cases of LPP demonstrate overlapping characteristics with paraneoplastic pemphigus and have been associated with internal malignancy. Hamada et al4 described a case of LPP coupled with colon adenocarcinoma and numerous keratoacanthomas. The earliest depiction of the coexistence of a case of mainstream LP complicated by an extensive bullous eruption was by Kaposi5 in 1892. He coined the term lichen ruber pemphigoides.5

Compared to BP, LPP is believed to affect a younger age group and have a less serious clinical course. The mean age of onset of LPP is in the third to fourth decades of life, while BP typically presents in the sixth decade. When comparing the location of bullae in LPP versus BP, the lesions of LPP tend to occur on the limbs, while BP tends to occur on the trunk.6

Clinically, LPP is distinguished by the existence of bullous lesions developing atop of the lesions of LP as well as on normal skin, with the latter being more commonplace. A classic example of LPP is characterized by an initial episode of traditional LP lesions often having severe pruritus, with or without patches of erythema, with the sudden eruption of tense bullae. These bullae commonly appear on the extremities and can appear over the normal skin, erythematous patches, or preexisting papules.7 In the atypical clinical presentations of this dubious skin condition, the bullae may only be seen on the lesions of LP.8 There also could be a lichenoid erythrodermic manifestation of a bullous eruption.9

Oral lesions of LPP have been described but had not been studied immunopathologically until Allen et al10 portrayed a 59-year-old man with cutaneous and oral lesions of LPP. They performed biopsies on the oral lesions and examined them by routine light microscopy and immunofluorescent techniques. The fine keratotic striae on the anterior buccal mucosal lesions were clinically consistent with oral LP. Perilesional tissue in conjunction with ulceration of the posterior buccal mucosa demonstrated histologic and immunopathologic alterations consistent with BP.10

Histopathology

Histopathologically, the lesions of LP show a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, colloid bodies in the dermis, irregular acanthosis with saw-toothed rete ridges, orthokeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, and liquefaction degeneration of the basal layer. Direct immunofluorescence shows mainly IgM and C3 deposited on colloid bodies, fibrin, and fibrinogen.11 The histopathology of the bullous lesion of LPP depicts a subepidermal bulla with variable diffuse or sparse lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and frequent eosinophils with or without neutrophils in the upper dermis. The existence of C3 alone or with IgG along the dermoepidermal junction gives confirmation on DIF.7

Autoantibodies

The expression of IgG autoantibodies directed against the basement membrane zone distinguishes LPP from bullous LP.2 IgG autoantibodies to either one or both the 230-kDa and 180-kDa BP (type XVII collagen) antigens has been demonstrated with LPP.4,12-14 Hamada et al4 described a histologic pattern more consistent with paraneoplastic pemphigus. It has been suggested that injury to the basal cells in LP or damage due to other courses of therapy such as psoralen plus UVA unveil suppressed antigenic determinants or produce new antigens, leading to antibody development and production of BP.12,15

Zillikens et al2 performed a study to identify the target antigen of LPP autoantibodies. They used sera from patients with LPP (n=4) and stained the epidermal side of salt-split human skin in a configuration identical to BP sera. In BP, the autoimmune response is directed against BP180, a hemidesmosomal transmembrane collagenous glycoprotein. They demonstrated that sera from BP patients largely reacted with a set of 4 epitopes (MCW-0 through MCW-3) grouped within a 45 amino acid stretch of the major noncollagenous extracellular domain (NC16A) of BP180. By immunoblotting and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, LPP sera also were compellingly reactive with recombinant BP180 NC16A. Lichen planus pemphigoides epitopes were additionally mapped using a series of overlapping recombinant segments of the NC16A domain. The authors demonstrated that all LPP sera reacted with amino acids 46 through 59 of domain NC16A, a protein portion that was previously shown to be unreactive with BP sera. In addition, they showed that 2 LPP sera reacted with the immunodominant antigenic region related to BP. Furthermore, they identified a unique epitope within the BP180 NC16A domain—MCW-4—which was distinctively recognized by sera from patients with LPP.2

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of both LP and BP has been linked to multiple cytokines that induce apoptosis in basal keratinocytes. Implicated cytokines include IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8, as well as other apoptosis-related molecules, such as Fas/Apo-1 and Bcl-2 in LP.16-18 Soluble E-selectin, vascular endothelial growth factor, IL-1β, IL-8, IL-5, transforming growth factor β1, and TNF-α were found to be elevated in either blister fluid or sera of BP patients.15-17

Management

Lichen planus pemphigoides usually responds well to traditional therapies, with systemic steroids being the most efficacious treatment of extensive disease.12,13 Other options include tetracycline and nicotinamide, isotretinoin, dapsone, and immunosuppressive drugs such as systemic cortico-steroids.12 Demirçay et al12 described a patient with skin lesions that rapidly cleared after the administration of oral methylprednisolone (48 mg/d) and oral dapsone (100 mg/d). The methylprednisolone and dapsone were withdrawn after 12 and 16 weeks, respectively. There was no recurrence during the 1-year follow-up period.12 et al19 described a patient who was treated with pulsed intravenous corticosteroids and continued to develop new papular and vesicular skin lesions. However, when oral acitretin was added to the patient’s regimen, the skin lesions cleared.19 There are several case reports of the successful use of hydroxychloroquine in LP.20,21

Cutaneous, nail, and oral LP also can be treated with TNF-α inhibitors (eg, adalimumab, etanercept) with resolution of lesions.22-25 However, we have not been able to find any reports of treating LPP with biologic medications in a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms lichen planus pemphigoides and biologic treatments/therapies. Given the fact that TNF-α and other inflammatory cytokines are involved in the pathogenesis of BP and LP, it is feasible that they also may be involved in the pathogenesis of LPP.

In our patient with cutaneous LPP, we chose to use ustekinumab instead of a primary TNF-α inhibitor because ustekinumab indirectly blocks TNF-α, as well as other proinflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22, which also could have played a role in the patient’s disease. Our goal was to use ustekinumab as a potential corticosteroid-sparing agent. Ustekinumab greatly improved her skin condition and allowed us to discontinue other medications.

- Harting MS, Hsu S. Lichen planus pemphigoides: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:10.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaro JM, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Litt J. Litt’s Drug Eruptions and Reactions Manual. 18th Ed. London, England: Informa Healthcare; 2011.

- Hamada T, Fujimoto W, Okazaki F, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides and multiple keratoacanthomas associated with colon adenocarcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:252-254.

- Kaposi M. Lichen ruber pemphigoides. Arch Derm Syph. 1892;343-346.

- Swale VJ, Black MM, Bhogal BS. Lichen planus pemphigoides: two case reports. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:132-135.

- Okochi H, Nashiro K, Tsuchida T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: case reports and results of immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:626-631.

- Mendiratta V, Asati DP, Koranne RV. Lichen planus pemphigoides in an Indian female. Indian J Dermatol. 2005;50:224-226.

- Joly P, Tanasescu S, Wolkenstein P, et al. Lichenoid erythrodermic bullous pemphigoid of the African patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:691-697.

- Allen , , R. Lichen planus pemphigoides: report of a case with oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:184-188.

- Rapini RP. Practical Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2005.

- Demirçay Z, Baykal C, Demirkesen C. Lichen planus pemphigoides: report of two cases. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:757-759.

- Sakuma-Oyama Y, Powell AM, Albert S, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides evolving into pemphigoid nodularis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;28:613-616.

- Hsu S, Ghohestani RF, Uitto J. Lichen planus pemphigoides with IgG autoantibodies to the 180kd bullous pemphigoid antigen (type XVII collagen). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:136-141.

- Kuramoto N, Kishimoto S, Shibagaki R, et al. PUVA-induced lichen planus pemphigoides. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:509-512.

- Ameglio F, D’Auria L, Cordiali-Fei P, et al. Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris: correlated behaviour of serum VEGF, sE-selectin and TNF-alpha levels. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 1997;11:148-153.

- Ameglio F, D’auria L, Bonifati C, et al. Cytokine pattern in blister fluid and serum of patients with bullous pemphigoid: relationships with disease intensity. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:611-614.

- D’Auria L, Mussi A, Bonifati C, et al. Increased serum IL-6, TNF-alpha and IL-10 levels in patients with bullous pemphigoid: relationships with disease activity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;12:11-15.

- , ,, . Treatment of lichen planus pemphigoides with acitretin and pulsed corticosteroids. Hautarzt. 2003;54:268-273.

- Eisen D. Hydroxychloroquine sulfate (Plaquenil) improves oral lichen planus: an open trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:609-612.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2011.

- Holló P, Szakonyi J, Kiss D, et al. Successful treatment of lichen planus with adalimumab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:385-386.

- Yarom N. Etanercept for the management of oral lichen planus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:121.

- Chao TJ. Adalimumab in the management of cutaneous and oral lichen planus. Cutis. 2009;84:325-328.

- Irla N, Schneiter T, Haneke E, et al. Nail lichen planus: successful treatment with etanercept. Case Rep Dermatol. 2010;2:173-176.

Case Report

A 71-year-old woman presented with pink to violaceous, flat-topped, polygonal papules consistent with lichen planus (LP) on the volar wrists, extensor elbows, and bilateral lower legs of 3 years’ duration. She also had erythematous, violaceous, infiltrated plaques with microvesiculation on the bilateral thighs of several months’ duration (Figure 1). She reported pruritus, burning, and discomfort. Her medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and asthma with no history of skin rashes. A complete physical examination was performed. Age-appropriate screening for malignancy was negative. Hepatitis B and C antibody serologies were negative. Her medications at the time included risedronate and atenolol, which she had been taking for several years.

Punch biopsies from perilesional skin were submitted for hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence (DIF). Histopathology showed a subepidermal blistering disease with tissue eosinophilia consistent with lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP)(Figure 2); direct immunofluorescence was positive for IgG, C3, and type IV collagen at the dermoepidermal junction. Serum BP180 was positive at 51 U/mL (reference range, <14 U/mL) and BP230 was negative. She was then started on tetracycline (500 mg twice daily), nicotinamide (500 mg twice daily), prednisone (5 mg daily), and dapsone (100 mg daily).

After 3 months without improvement, tetracycline and nicotinamide were discontinued, prednisone was increased to 10 mg daily, and dapsone was continued. A repeat biopsy was taken from a new area of involvement on the left lower leg, which revealed a psoriasiform dermatitis with interface changes. The DIF was positive for IgG and C3 along the basement membrane. A serum indirect immunofluorescence for BP180 also was positive.

The patient developed mild hemolytic anemia on dapsone; the medication was eventually discontinued. Subsequent treatments included adequate trials of azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and hydroxychloroquine. Azathioprine (150 mg daily) and hydroxychloroquine (400 mg daily) treatment failed. She initially improved on mycophenolate mofetil (500 mg in the morning and 1000 mg in the evening) with flattening of the papules on the arms and legs and decreased erythema. However, mycophenolate mofetil eventually lost its efficacy and was discontinued.

Because several medications failed (ie, tetracycline, nicotinamide, prednisone, dapsone, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, hydroxychloroquine), she was started on ustekinumab (45 mg) initial loading dose by subcutaneous injection (patient’s weight, 63 kg). At 4 weeks, the patient was given the second subcutaneous injection of ustekinumab (45 mg). She experienced marked improvement with no new lesions. The prior lesions also had decreased in size and were only slightly pink. The prednisone dose was tapered to 5 mg daily.

She had near-complete resolution of the skin lesions 12 weeks after the second dose of ustekinumab. Since then, she has had some recrudescence of the papulosquamous lesions but no vesicles or bullae. With the exception of occasional scattered pink papules on the forearms, her condition greatly improved on ustekinumab. She is no longer taking any of the other medications with the exception of prednisone (down to 1 mg daily) with a plan to gradually taper completely off of it.

Comment

Clinical Presentation

Lichen planus pemphigoides is a rare autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease with few cases reported in the literature. It is considered a clinical variation of bullous pemphigoid (BP) or a coexistence of LP and BP.1,2 It is characterized by bullous lesions developing on LP papules as well as on clinically uninvolved areas of the skin. It has been reported that LPP is provoked by several medications including cinnarizine, captopril, ramipril, simvastatin, psoralen plus UVA, and antituberculous medications (eg, isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide).1 Risedronate or atenolol have not been reported to cause LPP, LP, or BP; however, according to Litt,3 a lichenoid drug eruption has been associated with atenolol. Furthermore, some cases of LPP demonstrate overlapping characteristics with paraneoplastic pemphigus and have been associated with internal malignancy. Hamada et al4 described a case of LPP coupled with colon adenocarcinoma and numerous keratoacanthomas. The earliest depiction of the coexistence of a case of mainstream LP complicated by an extensive bullous eruption was by Kaposi5 in 1892. He coined the term lichen ruber pemphigoides.5

Compared to BP, LPP is believed to affect a younger age group and have a less serious clinical course. The mean age of onset of LPP is in the third to fourth decades of life, while BP typically presents in the sixth decade. When comparing the location of bullae in LPP versus BP, the lesions of LPP tend to occur on the limbs, while BP tends to occur on the trunk.6

Clinically, LPP is distinguished by the existence of bullous lesions developing atop of the lesions of LP as well as on normal skin, with the latter being more commonplace. A classic example of LPP is characterized by an initial episode of traditional LP lesions often having severe pruritus, with or without patches of erythema, with the sudden eruption of tense bullae. These bullae commonly appear on the extremities and can appear over the normal skin, erythematous patches, or preexisting papules.7 In the atypical clinical presentations of this dubious skin condition, the bullae may only be seen on the lesions of LP.8 There also could be a lichenoid erythrodermic manifestation of a bullous eruption.9

Oral lesions of LPP have been described but had not been studied immunopathologically until Allen et al10 portrayed a 59-year-old man with cutaneous and oral lesions of LPP. They performed biopsies on the oral lesions and examined them by routine light microscopy and immunofluorescent techniques. The fine keratotic striae on the anterior buccal mucosal lesions were clinically consistent with oral LP. Perilesional tissue in conjunction with ulceration of the posterior buccal mucosa demonstrated histologic and immunopathologic alterations consistent with BP.10

Histopathology

Histopathologically, the lesions of LP show a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, colloid bodies in the dermis, irregular acanthosis with saw-toothed rete ridges, orthokeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, and liquefaction degeneration of the basal layer. Direct immunofluorescence shows mainly IgM and C3 deposited on colloid bodies, fibrin, and fibrinogen.11 The histopathology of the bullous lesion of LPP depicts a subepidermal bulla with variable diffuse or sparse lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and frequent eosinophils with or without neutrophils in the upper dermis. The existence of C3 alone or with IgG along the dermoepidermal junction gives confirmation on DIF.7

Autoantibodies

The expression of IgG autoantibodies directed against the basement membrane zone distinguishes LPP from bullous LP.2 IgG autoantibodies to either one or both the 230-kDa and 180-kDa BP (type XVII collagen) antigens has been demonstrated with LPP.4,12-14 Hamada et al4 described a histologic pattern more consistent with paraneoplastic pemphigus. It has been suggested that injury to the basal cells in LP or damage due to other courses of therapy such as psoralen plus UVA unveil suppressed antigenic determinants or produce new antigens, leading to antibody development and production of BP.12,15

Zillikens et al2 performed a study to identify the target antigen of LPP autoantibodies. They used sera from patients with LPP (n=4) and stained the epidermal side of salt-split human skin in a configuration identical to BP sera. In BP, the autoimmune response is directed against BP180, a hemidesmosomal transmembrane collagenous glycoprotein. They demonstrated that sera from BP patients largely reacted with a set of 4 epitopes (MCW-0 through MCW-3) grouped within a 45 amino acid stretch of the major noncollagenous extracellular domain (NC16A) of BP180. By immunoblotting and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, LPP sera also were compellingly reactive with recombinant BP180 NC16A. Lichen planus pemphigoides epitopes were additionally mapped using a series of overlapping recombinant segments of the NC16A domain. The authors demonstrated that all LPP sera reacted with amino acids 46 through 59 of domain NC16A, a protein portion that was previously shown to be unreactive with BP sera. In addition, they showed that 2 LPP sera reacted with the immunodominant antigenic region related to BP. Furthermore, they identified a unique epitope within the BP180 NC16A domain—MCW-4—which was distinctively recognized by sera from patients with LPP.2

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of both LP and BP has been linked to multiple cytokines that induce apoptosis in basal keratinocytes. Implicated cytokines include IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8, as well as other apoptosis-related molecules, such as Fas/Apo-1 and Bcl-2 in LP.16-18 Soluble E-selectin, vascular endothelial growth factor, IL-1β, IL-8, IL-5, transforming growth factor β1, and TNF-α were found to be elevated in either blister fluid or sera of BP patients.15-17

Management

Lichen planus pemphigoides usually responds well to traditional therapies, with systemic steroids being the most efficacious treatment of extensive disease.12,13 Other options include tetracycline and nicotinamide, isotretinoin, dapsone, and immunosuppressive drugs such as systemic cortico-steroids.12 Demirçay et al12 described a patient with skin lesions that rapidly cleared after the administration of oral methylprednisolone (48 mg/d) and oral dapsone (100 mg/d). The methylprednisolone and dapsone were withdrawn after 12 and 16 weeks, respectively. There was no recurrence during the 1-year follow-up period.12 et al19 described a patient who was treated with pulsed intravenous corticosteroids and continued to develop new papular and vesicular skin lesions. However, when oral acitretin was added to the patient’s regimen, the skin lesions cleared.19 There are several case reports of the successful use of hydroxychloroquine in LP.20,21

Cutaneous, nail, and oral LP also can be treated with TNF-α inhibitors (eg, adalimumab, etanercept) with resolution of lesions.22-25 However, we have not been able to find any reports of treating LPP with biologic medications in a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms lichen planus pemphigoides and biologic treatments/therapies. Given the fact that TNF-α and other inflammatory cytokines are involved in the pathogenesis of BP and LP, it is feasible that they also may be involved in the pathogenesis of LPP.

In our patient with cutaneous LPP, we chose to use ustekinumab instead of a primary TNF-α inhibitor because ustekinumab indirectly blocks TNF-α, as well as other proinflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22, which also could have played a role in the patient’s disease. Our goal was to use ustekinumab as a potential corticosteroid-sparing agent. Ustekinumab greatly improved her skin condition and allowed us to discontinue other medications.

Case Report

A 71-year-old woman presented with pink to violaceous, flat-topped, polygonal papules consistent with lichen planus (LP) on the volar wrists, extensor elbows, and bilateral lower legs of 3 years’ duration. She also had erythematous, violaceous, infiltrated plaques with microvesiculation on the bilateral thighs of several months’ duration (Figure 1). She reported pruritus, burning, and discomfort. Her medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and asthma with no history of skin rashes. A complete physical examination was performed. Age-appropriate screening for malignancy was negative. Hepatitis B and C antibody serologies were negative. Her medications at the time included risedronate and atenolol, which she had been taking for several years.

Punch biopsies from perilesional skin were submitted for hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence (DIF). Histopathology showed a subepidermal blistering disease with tissue eosinophilia consistent with lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP)(Figure 2); direct immunofluorescence was positive for IgG, C3, and type IV collagen at the dermoepidermal junction. Serum BP180 was positive at 51 U/mL (reference range, <14 U/mL) and BP230 was negative. She was then started on tetracycline (500 mg twice daily), nicotinamide (500 mg twice daily), prednisone (5 mg daily), and dapsone (100 mg daily).

After 3 months without improvement, tetracycline and nicotinamide were discontinued, prednisone was increased to 10 mg daily, and dapsone was continued. A repeat biopsy was taken from a new area of involvement on the left lower leg, which revealed a psoriasiform dermatitis with interface changes. The DIF was positive for IgG and C3 along the basement membrane. A serum indirect immunofluorescence for BP180 also was positive.

The patient developed mild hemolytic anemia on dapsone; the medication was eventually discontinued. Subsequent treatments included adequate trials of azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and hydroxychloroquine. Azathioprine (150 mg daily) and hydroxychloroquine (400 mg daily) treatment failed. She initially improved on mycophenolate mofetil (500 mg in the morning and 1000 mg in the evening) with flattening of the papules on the arms and legs and decreased erythema. However, mycophenolate mofetil eventually lost its efficacy and was discontinued.

Because several medications failed (ie, tetracycline, nicotinamide, prednisone, dapsone, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, hydroxychloroquine), she was started on ustekinumab (45 mg) initial loading dose by subcutaneous injection (patient’s weight, 63 kg). At 4 weeks, the patient was given the second subcutaneous injection of ustekinumab (45 mg). She experienced marked improvement with no new lesions. The prior lesions also had decreased in size and were only slightly pink. The prednisone dose was tapered to 5 mg daily.

She had near-complete resolution of the skin lesions 12 weeks after the second dose of ustekinumab. Since then, she has had some recrudescence of the papulosquamous lesions but no vesicles or bullae. With the exception of occasional scattered pink papules on the forearms, her condition greatly improved on ustekinumab. She is no longer taking any of the other medications with the exception of prednisone (down to 1 mg daily) with a plan to gradually taper completely off of it.

Comment

Clinical Presentation

Lichen planus pemphigoides is a rare autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease with few cases reported in the literature. It is considered a clinical variation of bullous pemphigoid (BP) or a coexistence of LP and BP.1,2 It is characterized by bullous lesions developing on LP papules as well as on clinically uninvolved areas of the skin. It has been reported that LPP is provoked by several medications including cinnarizine, captopril, ramipril, simvastatin, psoralen plus UVA, and antituberculous medications (eg, isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide).1 Risedronate or atenolol have not been reported to cause LPP, LP, or BP; however, according to Litt,3 a lichenoid drug eruption has been associated with atenolol. Furthermore, some cases of LPP demonstrate overlapping characteristics with paraneoplastic pemphigus and have been associated with internal malignancy. Hamada et al4 described a case of LPP coupled with colon adenocarcinoma and numerous keratoacanthomas. The earliest depiction of the coexistence of a case of mainstream LP complicated by an extensive bullous eruption was by Kaposi5 in 1892. He coined the term lichen ruber pemphigoides.5

Compared to BP, LPP is believed to affect a younger age group and have a less serious clinical course. The mean age of onset of LPP is in the third to fourth decades of life, while BP typically presents in the sixth decade. When comparing the location of bullae in LPP versus BP, the lesions of LPP tend to occur on the limbs, while BP tends to occur on the trunk.6

Clinically, LPP is distinguished by the existence of bullous lesions developing atop of the lesions of LP as well as on normal skin, with the latter being more commonplace. A classic example of LPP is characterized by an initial episode of traditional LP lesions often having severe pruritus, with or without patches of erythema, with the sudden eruption of tense bullae. These bullae commonly appear on the extremities and can appear over the normal skin, erythematous patches, or preexisting papules.7 In the atypical clinical presentations of this dubious skin condition, the bullae may only be seen on the lesions of LP.8 There also could be a lichenoid erythrodermic manifestation of a bullous eruption.9

Oral lesions of LPP have been described but had not been studied immunopathologically until Allen et al10 portrayed a 59-year-old man with cutaneous and oral lesions of LPP. They performed biopsies on the oral lesions and examined them by routine light microscopy and immunofluorescent techniques. The fine keratotic striae on the anterior buccal mucosal lesions were clinically consistent with oral LP. Perilesional tissue in conjunction with ulceration of the posterior buccal mucosa demonstrated histologic and immunopathologic alterations consistent with BP.10

Histopathology

Histopathologically, the lesions of LP show a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, colloid bodies in the dermis, irregular acanthosis with saw-toothed rete ridges, orthokeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, and liquefaction degeneration of the basal layer. Direct immunofluorescence shows mainly IgM and C3 deposited on colloid bodies, fibrin, and fibrinogen.11 The histopathology of the bullous lesion of LPP depicts a subepidermal bulla with variable diffuse or sparse lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and frequent eosinophils with or without neutrophils in the upper dermis. The existence of C3 alone or with IgG along the dermoepidermal junction gives confirmation on DIF.7

Autoantibodies

The expression of IgG autoantibodies directed against the basement membrane zone distinguishes LPP from bullous LP.2 IgG autoantibodies to either one or both the 230-kDa and 180-kDa BP (type XVII collagen) antigens has been demonstrated with LPP.4,12-14 Hamada et al4 described a histologic pattern more consistent with paraneoplastic pemphigus. It has been suggested that injury to the basal cells in LP or damage due to other courses of therapy such as psoralen plus UVA unveil suppressed antigenic determinants or produce new antigens, leading to antibody development and production of BP.12,15

Zillikens et al2 performed a study to identify the target antigen of LPP autoantibodies. They used sera from patients with LPP (n=4) and stained the epidermal side of salt-split human skin in a configuration identical to BP sera. In BP, the autoimmune response is directed against BP180, a hemidesmosomal transmembrane collagenous glycoprotein. They demonstrated that sera from BP patients largely reacted with a set of 4 epitopes (MCW-0 through MCW-3) grouped within a 45 amino acid stretch of the major noncollagenous extracellular domain (NC16A) of BP180. By immunoblotting and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, LPP sera also were compellingly reactive with recombinant BP180 NC16A. Lichen planus pemphigoides epitopes were additionally mapped using a series of overlapping recombinant segments of the NC16A domain. The authors demonstrated that all LPP sera reacted with amino acids 46 through 59 of domain NC16A, a protein portion that was previously shown to be unreactive with BP sera. In addition, they showed that 2 LPP sera reacted with the immunodominant antigenic region related to BP. Furthermore, they identified a unique epitope within the BP180 NC16A domain—MCW-4—which was distinctively recognized by sera from patients with LPP.2

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of both LP and BP has been linked to multiple cytokines that induce apoptosis in basal keratinocytes. Implicated cytokines include IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8, as well as other apoptosis-related molecules, such as Fas/Apo-1 and Bcl-2 in LP.16-18 Soluble E-selectin, vascular endothelial growth factor, IL-1β, IL-8, IL-5, transforming growth factor β1, and TNF-α were found to be elevated in either blister fluid or sera of BP patients.15-17

Management

Lichen planus pemphigoides usually responds well to traditional therapies, with systemic steroids being the most efficacious treatment of extensive disease.12,13 Other options include tetracycline and nicotinamide, isotretinoin, dapsone, and immunosuppressive drugs such as systemic cortico-steroids.12 Demirçay et al12 described a patient with skin lesions that rapidly cleared after the administration of oral methylprednisolone (48 mg/d) and oral dapsone (100 mg/d). The methylprednisolone and dapsone were withdrawn after 12 and 16 weeks, respectively. There was no recurrence during the 1-year follow-up period.12 et al19 described a patient who was treated with pulsed intravenous corticosteroids and continued to develop new papular and vesicular skin lesions. However, when oral acitretin was added to the patient’s regimen, the skin lesions cleared.19 There are several case reports of the successful use of hydroxychloroquine in LP.20,21

Cutaneous, nail, and oral LP also can be treated with TNF-α inhibitors (eg, adalimumab, etanercept) with resolution of lesions.22-25 However, we have not been able to find any reports of treating LPP with biologic medications in a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms lichen planus pemphigoides and biologic treatments/therapies. Given the fact that TNF-α and other inflammatory cytokines are involved in the pathogenesis of BP and LP, it is feasible that they also may be involved in the pathogenesis of LPP.

In our patient with cutaneous LPP, we chose to use ustekinumab instead of a primary TNF-α inhibitor because ustekinumab indirectly blocks TNF-α, as well as other proinflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22, which also could have played a role in the patient’s disease. Our goal was to use ustekinumab as a potential corticosteroid-sparing agent. Ustekinumab greatly improved her skin condition and allowed us to discontinue other medications.

- Harting MS, Hsu S. Lichen planus pemphigoides: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:10.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaro JM, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Litt J. Litt’s Drug Eruptions and Reactions Manual. 18th Ed. London, England: Informa Healthcare; 2011.

- Hamada T, Fujimoto W, Okazaki F, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides and multiple keratoacanthomas associated with colon adenocarcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:252-254.

- Kaposi M. Lichen ruber pemphigoides. Arch Derm Syph. 1892;343-346.

- Swale VJ, Black MM, Bhogal BS. Lichen planus pemphigoides: two case reports. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:132-135.

- Okochi H, Nashiro K, Tsuchida T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: case reports and results of immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:626-631.

- Mendiratta V, Asati DP, Koranne RV. Lichen planus pemphigoides in an Indian female. Indian J Dermatol. 2005;50:224-226.

- Joly P, Tanasescu S, Wolkenstein P, et al. Lichenoid erythrodermic bullous pemphigoid of the African patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:691-697.

- Allen , , R. Lichen planus pemphigoides: report of a case with oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:184-188.

- Rapini RP. Practical Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2005.

- Demirçay Z, Baykal C, Demirkesen C. Lichen planus pemphigoides: report of two cases. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:757-759.

- Sakuma-Oyama Y, Powell AM, Albert S, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides evolving into pemphigoid nodularis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;28:613-616.

- Hsu S, Ghohestani RF, Uitto J. Lichen planus pemphigoides with IgG autoantibodies to the 180kd bullous pemphigoid antigen (type XVII collagen). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:136-141.

- Kuramoto N, Kishimoto S, Shibagaki R, et al. PUVA-induced lichen planus pemphigoides. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:509-512.

- Ameglio F, D’Auria L, Cordiali-Fei P, et al. Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris: correlated behaviour of serum VEGF, sE-selectin and TNF-alpha levels. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 1997;11:148-153.

- Ameglio F, D’auria L, Bonifati C, et al. Cytokine pattern in blister fluid and serum of patients with bullous pemphigoid: relationships with disease intensity. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:611-614.

- D’Auria L, Mussi A, Bonifati C, et al. Increased serum IL-6, TNF-alpha and IL-10 levels in patients with bullous pemphigoid: relationships with disease activity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;12:11-15.

- , ,, . Treatment of lichen planus pemphigoides with acitretin and pulsed corticosteroids. Hautarzt. 2003;54:268-273.

- Eisen D. Hydroxychloroquine sulfate (Plaquenil) improves oral lichen planus: an open trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:609-612.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2011.

- Holló P, Szakonyi J, Kiss D, et al. Successful treatment of lichen planus with adalimumab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:385-386.

- Yarom N. Etanercept for the management of oral lichen planus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:121.

- Chao TJ. Adalimumab in the management of cutaneous and oral lichen planus. Cutis. 2009;84:325-328.

- Irla N, Schneiter T, Haneke E, et al. Nail lichen planus: successful treatment with etanercept. Case Rep Dermatol. 2010;2:173-176.

- Harting MS, Hsu S. Lichen planus pemphigoides: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:10.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaro JM, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Litt J. Litt’s Drug Eruptions and Reactions Manual. 18th Ed. London, England: Informa Healthcare; 2011.

- Hamada T, Fujimoto W, Okazaki F, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides and multiple keratoacanthomas associated with colon adenocarcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:252-254.

- Kaposi M. Lichen ruber pemphigoides. Arch Derm Syph. 1892;343-346.

- Swale VJ, Black MM, Bhogal BS. Lichen planus pemphigoides: two case reports. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:132-135.

- Okochi H, Nashiro K, Tsuchida T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: case reports and results of immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:626-631.

- Mendiratta V, Asati DP, Koranne RV. Lichen planus pemphigoides in an Indian female. Indian J Dermatol. 2005;50:224-226.

- Joly P, Tanasescu S, Wolkenstein P, et al. Lichenoid erythrodermic bullous pemphigoid of the African patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:691-697.

- Allen , , R. Lichen planus pemphigoides: report of a case with oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:184-188.

- Rapini RP. Practical Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2005.

- Demirçay Z, Baykal C, Demirkesen C. Lichen planus pemphigoides: report of two cases. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:757-759.

- Sakuma-Oyama Y, Powell AM, Albert S, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides evolving into pemphigoid nodularis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;28:613-616.

- Hsu S, Ghohestani RF, Uitto J. Lichen planus pemphigoides with IgG autoantibodies to the 180kd bullous pemphigoid antigen (type XVII collagen). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:136-141.

- Kuramoto N, Kishimoto S, Shibagaki R, et al. PUVA-induced lichen planus pemphigoides. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:509-512.

- Ameglio F, D’Auria L, Cordiali-Fei P, et al. Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris: correlated behaviour of serum VEGF, sE-selectin and TNF-alpha levels. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 1997;11:148-153.

- Ameglio F, D’auria L, Bonifati C, et al. Cytokine pattern in blister fluid and serum of patients with bullous pemphigoid: relationships with disease intensity. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:611-614.

- D’Auria L, Mussi A, Bonifati C, et al. Increased serum IL-6, TNF-alpha and IL-10 levels in patients with bullous pemphigoid: relationships with disease activity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;12:11-15.

- , ,, . Treatment of lichen planus pemphigoides with acitretin and pulsed corticosteroids. Hautarzt. 2003;54:268-273.

- Eisen D. Hydroxychloroquine sulfate (Plaquenil) improves oral lichen planus: an open trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:609-612.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2011.

- Holló P, Szakonyi J, Kiss D, et al. Successful treatment of lichen planus with adalimumab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:385-386.

- Yarom N. Etanercept for the management of oral lichen planus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:121.

- Chao TJ. Adalimumab in the management of cutaneous and oral lichen planus. Cutis. 2009;84:325-328.

- Irla N, Schneiter T, Haneke E, et al. Nail lichen planus: successful treatment with etanercept. Case Rep Dermatol. 2010;2:173-176.

- Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease with few cases reported in the literature.

- Because tumor necrosis factor 11α (TNF-11α) and other inflammatory cytokines are involved in the pathogenesis of bullous pemphigoid and lichen planus, it is feasible that they also may be involved in the pathogenesis of LPP.

- Ustekinumab may be used to treat LPP as a potential corticosteroid-sparing agent because it indirectly blocks TNF-α, as well as other proinflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22.

Student Loan Burden and Its Impact on Career Decisions in Dermatology

Dermatology departments in the United States have been facing challenges in recruiting and retaining dermatologists for academic positions. Accordingly, a survey study reported that academic dermatologists were more likely than those in private practice to state that their institutions were recruiting new associates.1 Several factors could explain this phenomenon. Salary differences between jobs in academic and nonacademic settings may contribute to difficulty in recruiting dermatologists into academia, which is exacerbated by a theoretical shortage of dermatologists, leading to graduates who receive and accept private practice job offers.1,2 Furthermore, a large survey study reported that challenges unique to academic dermatologists include longer patient wait times in addition to responsibilities such as research, hospital consultations, medical writing, and teaching. These patterns raise concerns for the future of teaching institutions because academic dermatologists not only train future physicians but also conduct clinical and basic science research necessary to advance the field and improve patient care.2 Thus, it is important to evaluate the factors that affect career decisions in dermatology and to determine if these factors can be addressed. We hypothesized that student loan burden influences career plans in dermatology and that physicians are not fully educated on loan repayment options. The aims of this preliminary study were to explore the influence of student loan burden on career plans in dermatology and to determine if the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program could potentially encourage more dermatologists to consider academic careers.

Methods

The study aimed to investigate the factors that influence career decisions in dermatology and to assess attitudes toward the PSLF program as an option for student loan repayment. The target population included dermatology residents and attending physicians in the United States. Survey questions were adapted from a previously published study3 and were modified based on feedback from reviewers in the University of California (UC) Irvine department of dermatology. The survey was voluntary and did not collect identifying information. This study was granted exemption from oversight by the UC Irvine institutional review board.

Recruitment materials informed potential participants of the nature of the study and provided a hyperlink to the electronic survey. The UC Irvine department of dermatology emailed US dermatology residency program coordinators, requesting that they forward this study to residents and attending physicians in their programs.

Results

Demographics

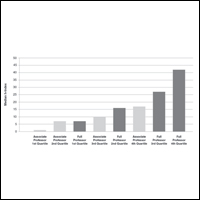

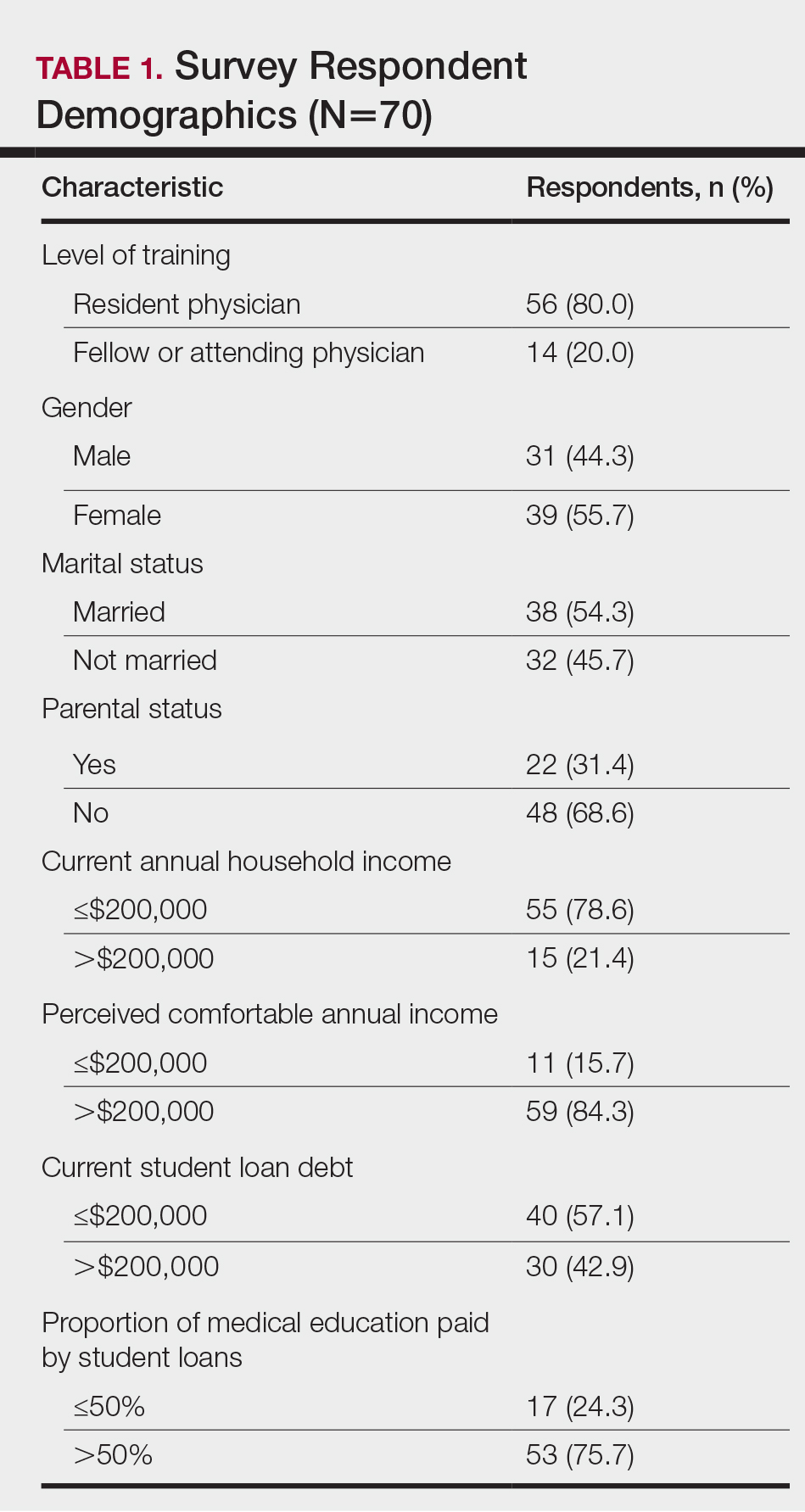

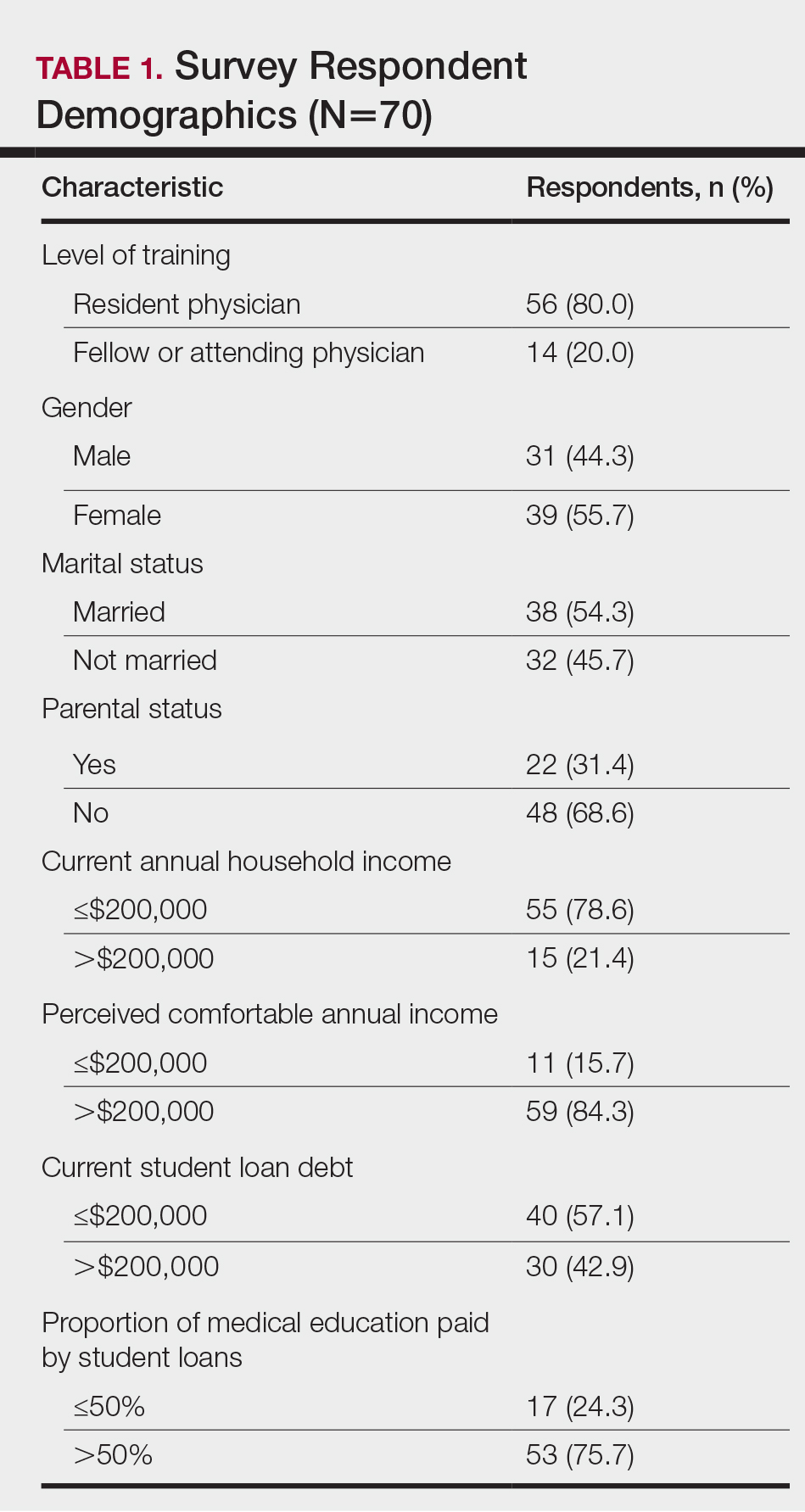

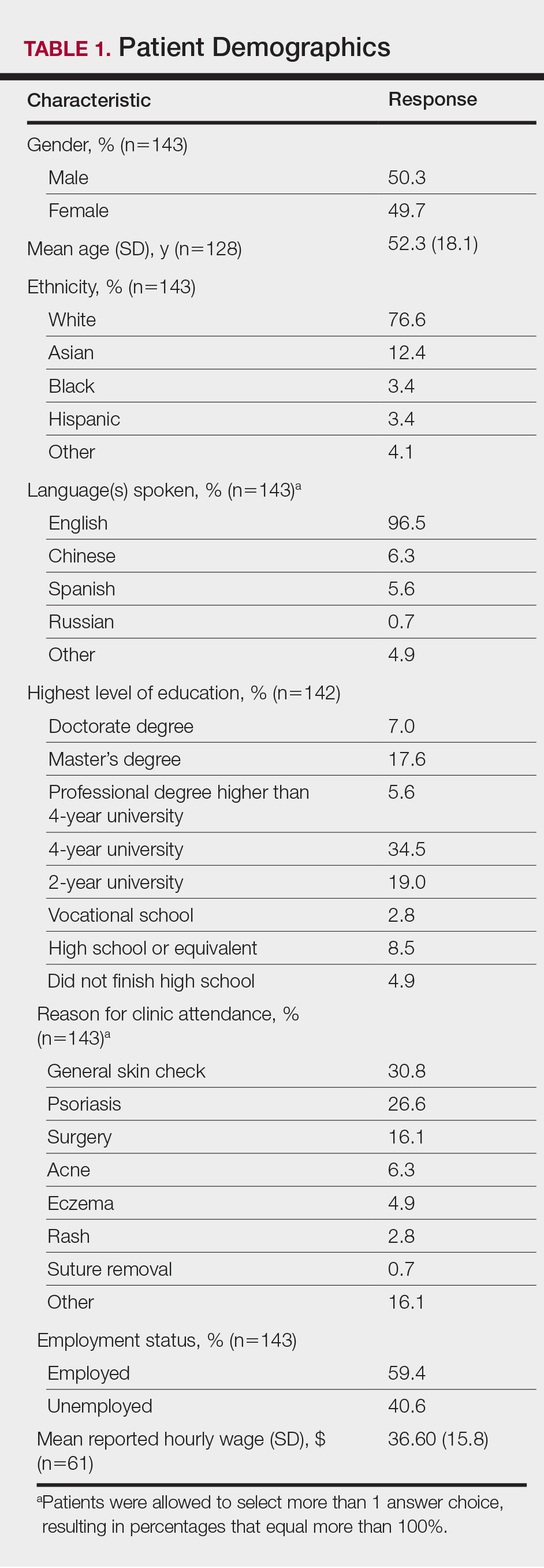

The survey had 70 respondents including residents (56 [80.0%]) and attending physicians (14 [20.0%]). The mean age (SD) of the respondents was 32.4 (6.1) years, with 31 (44.3%) men and 39 (55.7%) women. The majority were married (38 [54.3%]) and did not have children (48 [68.6%]). Most respondents reported an annual household income of $200,000 or less (55 [78.6%]) and perceived a comfortable annual household income as greater than $200,000 (59 [84.3%])(Table 1).

Financing Medical Education

Most respondents currently had $200,000 or less in student loan debt (40 [57.1%]) and financed more than half of their medical education with student loans (53 [75.7%]). A large majority (61 [87.1%]) indicated that some portion of their medical education was funded by student loans.

Career Goals in Dermatology and the Influence of Student Loans

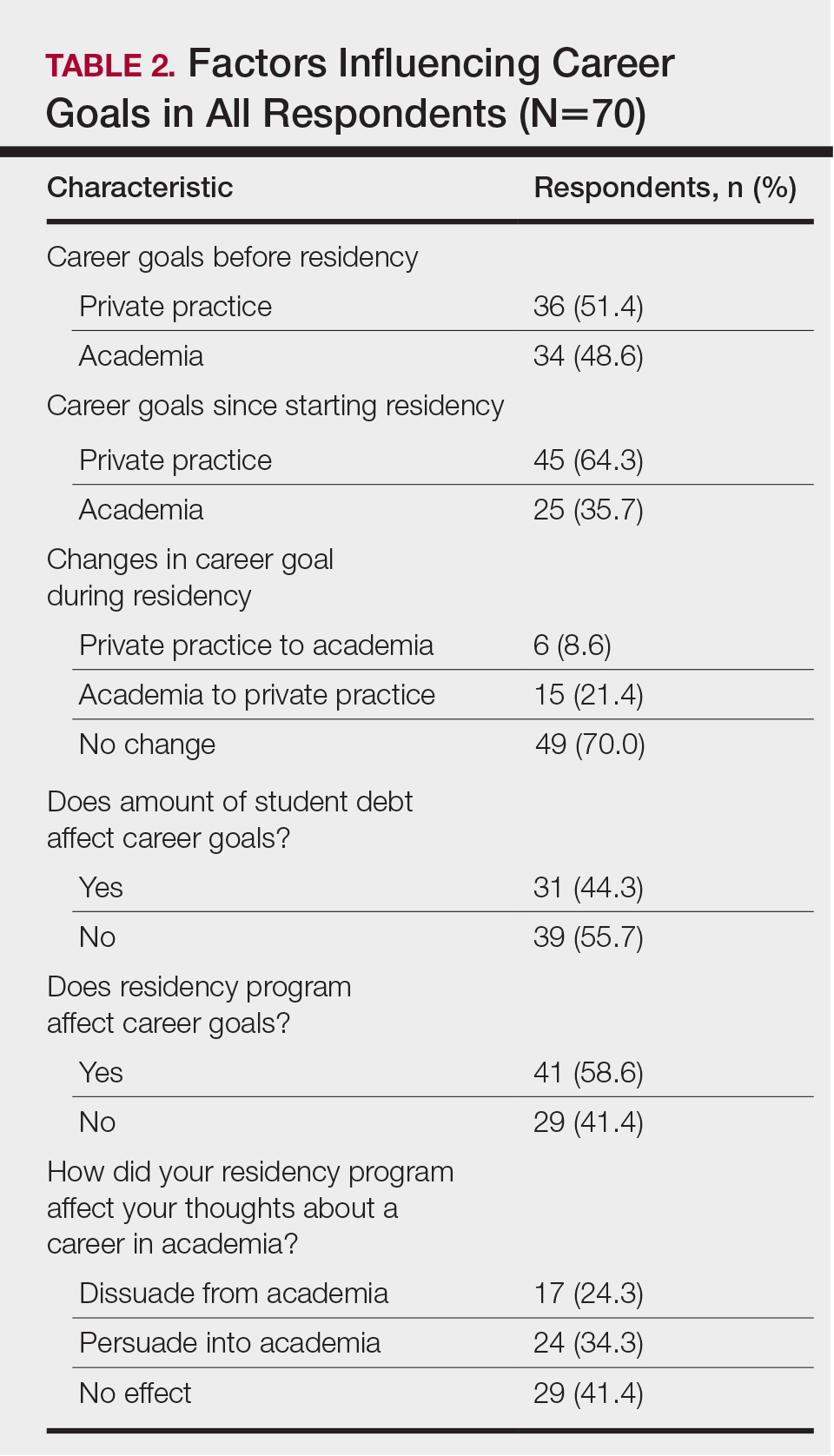

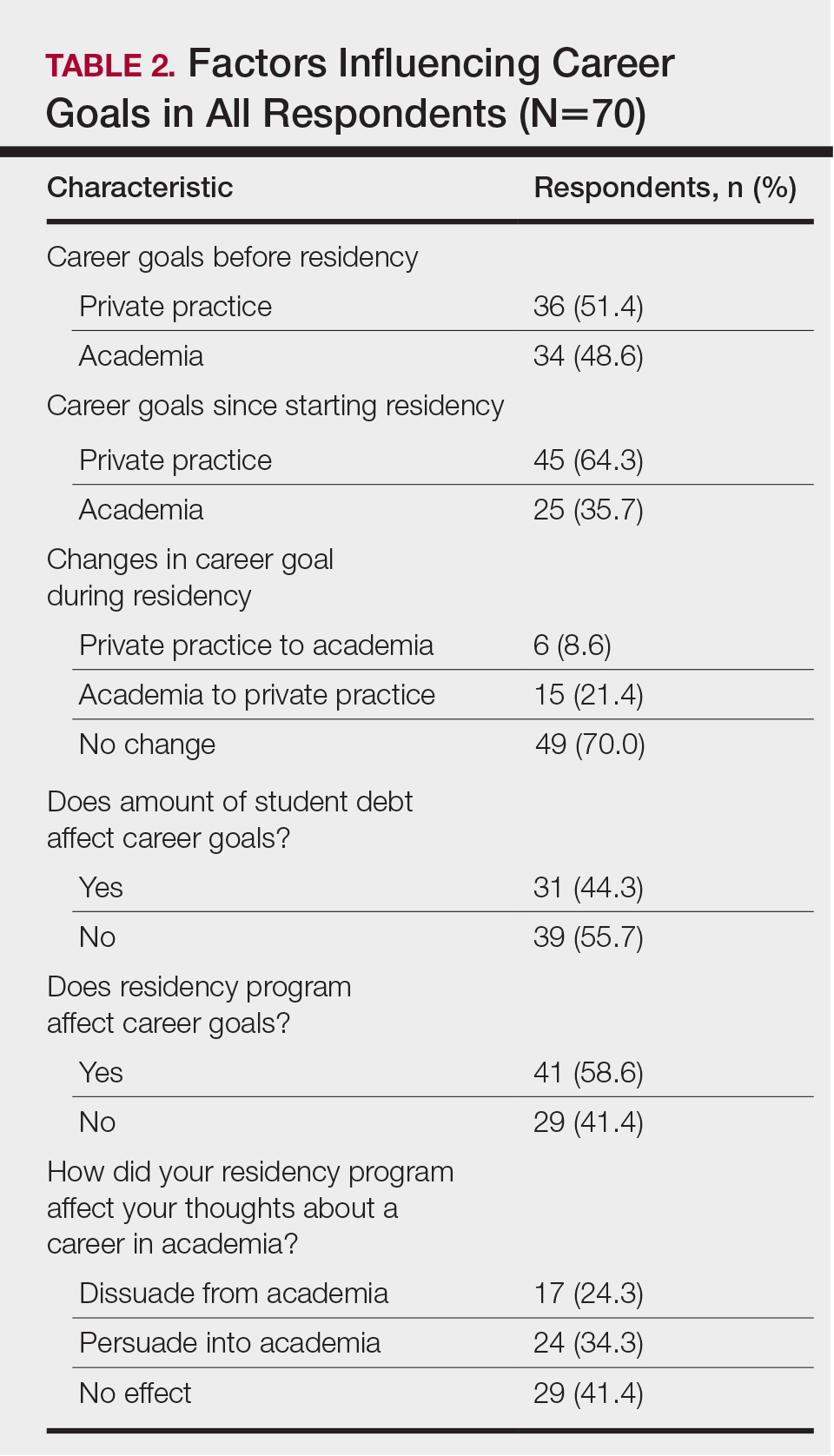

Respondents were asked to specify their career plans before versus after starting dermatology residency training (ie, current career plan). Prior to starting residency, 36 (51.4%) and 34 (48.6%) respondents indicated they were interested in private practice and academia, respectively. After starting residency, the number of respondents interested in private practice increased to 45 (64.3%), and the number of respondents interested in academia decreased to 25 (35.7%). Fifteen (21.4%) respondents changed career trajectories from academia to private practice, 6 (8.6%) changed from private practice to academia, and 49 (70.0%) did not change career goals.

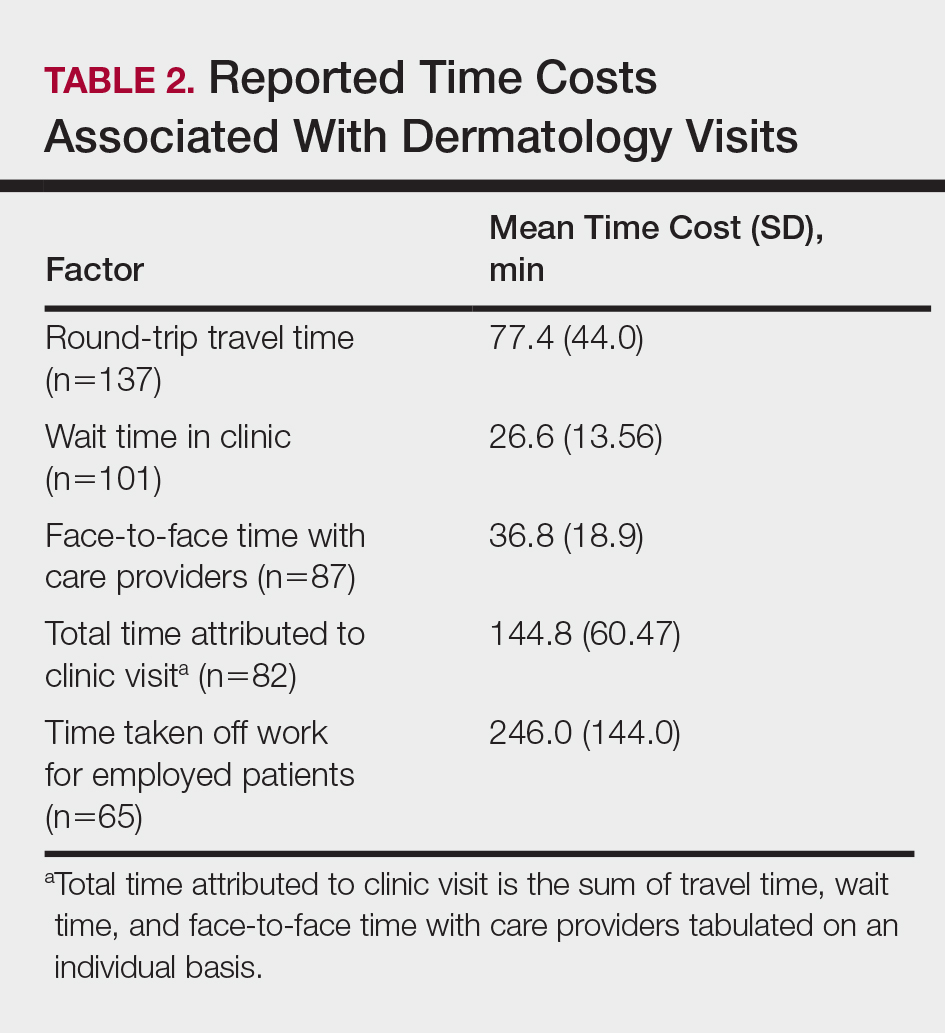

The majority of respondents (39 [55.7%]) indicated that the amount of their student loan debt did not influence their career goals (Table 2); however, those with more than $200,000 in debt were more likely to state that student loans impacted their career goals compared to those with $200,000 or less in debt (70.0% [21/30] vs 25.0% [10/40]; P<.001).

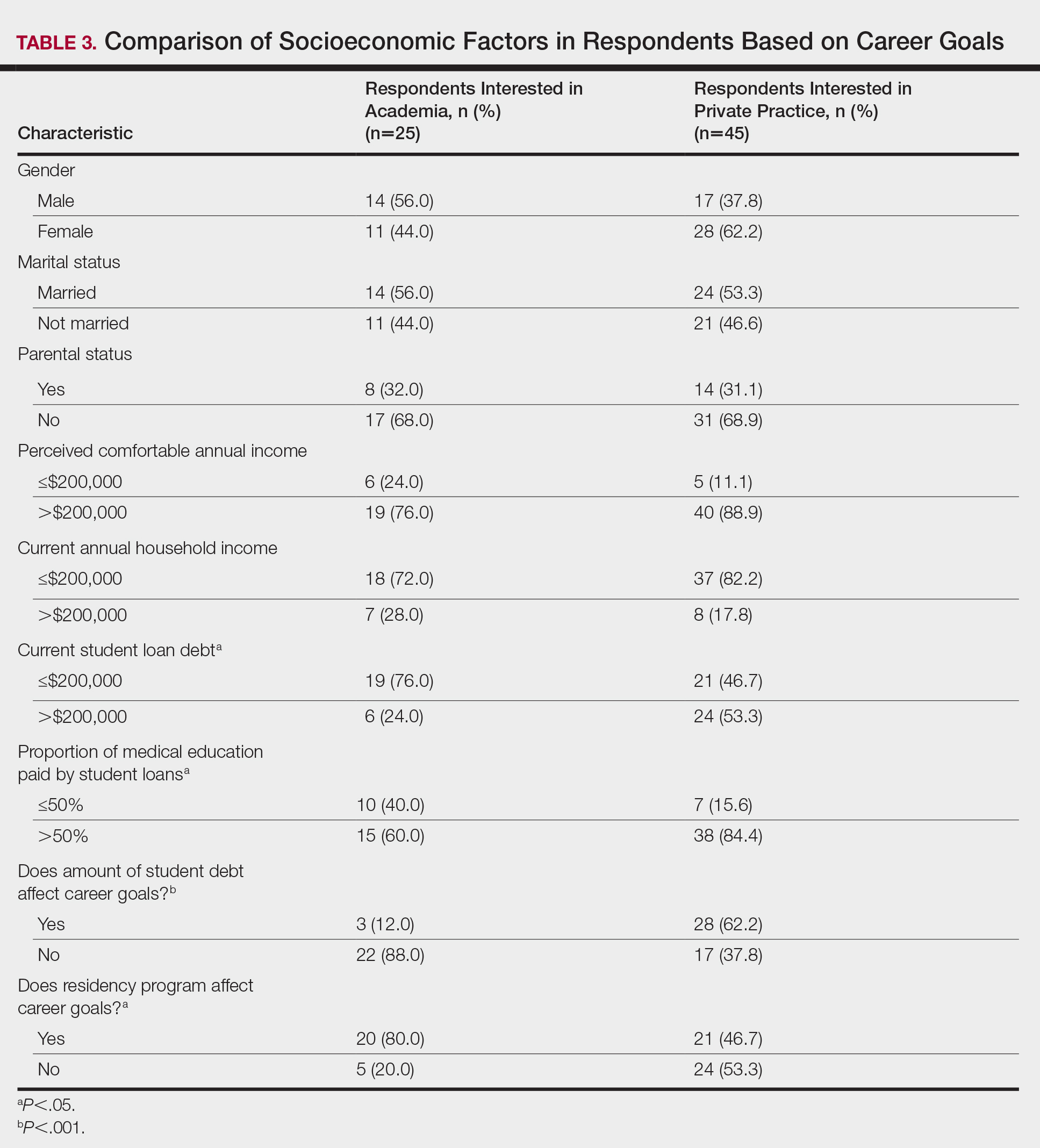

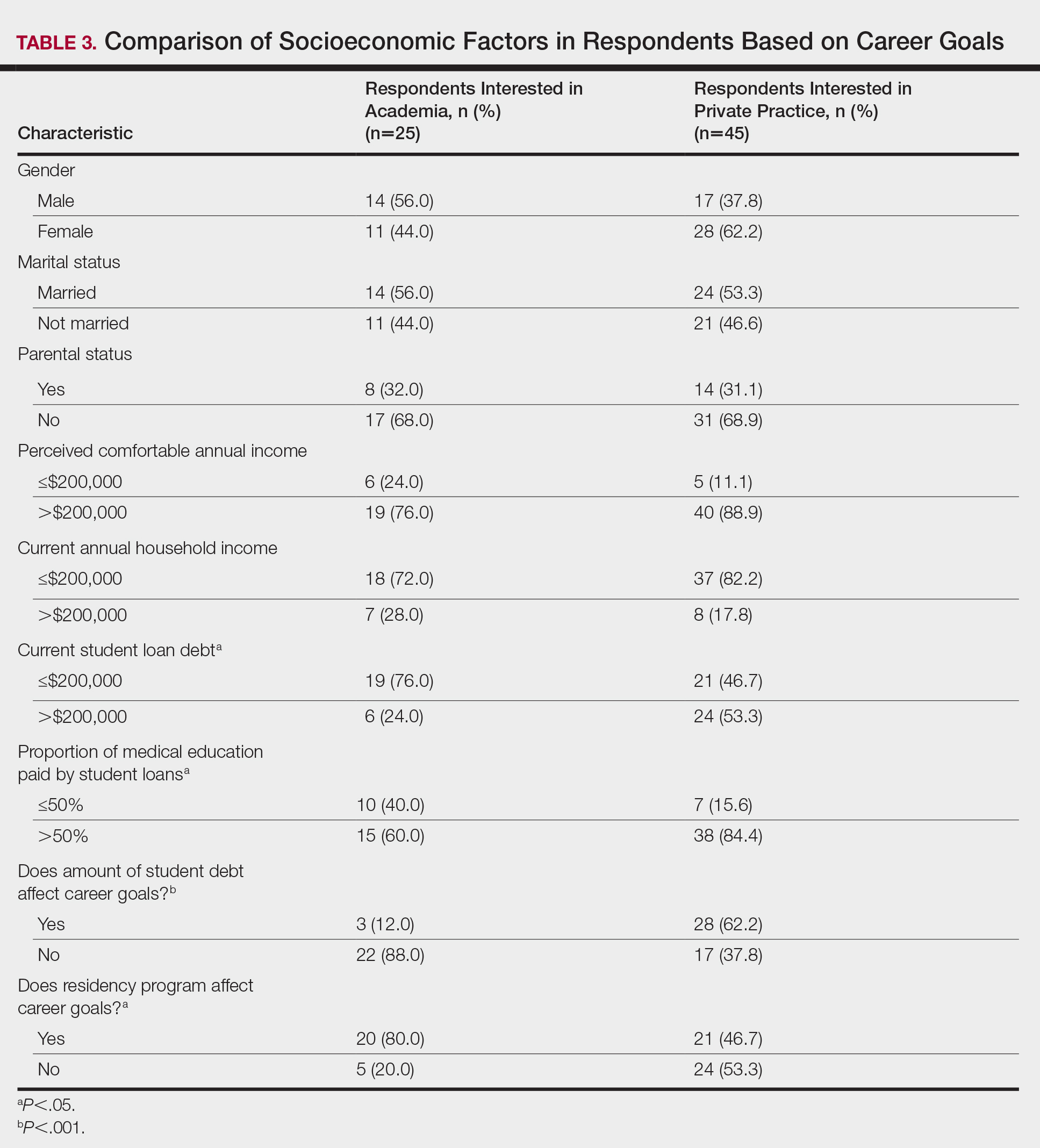

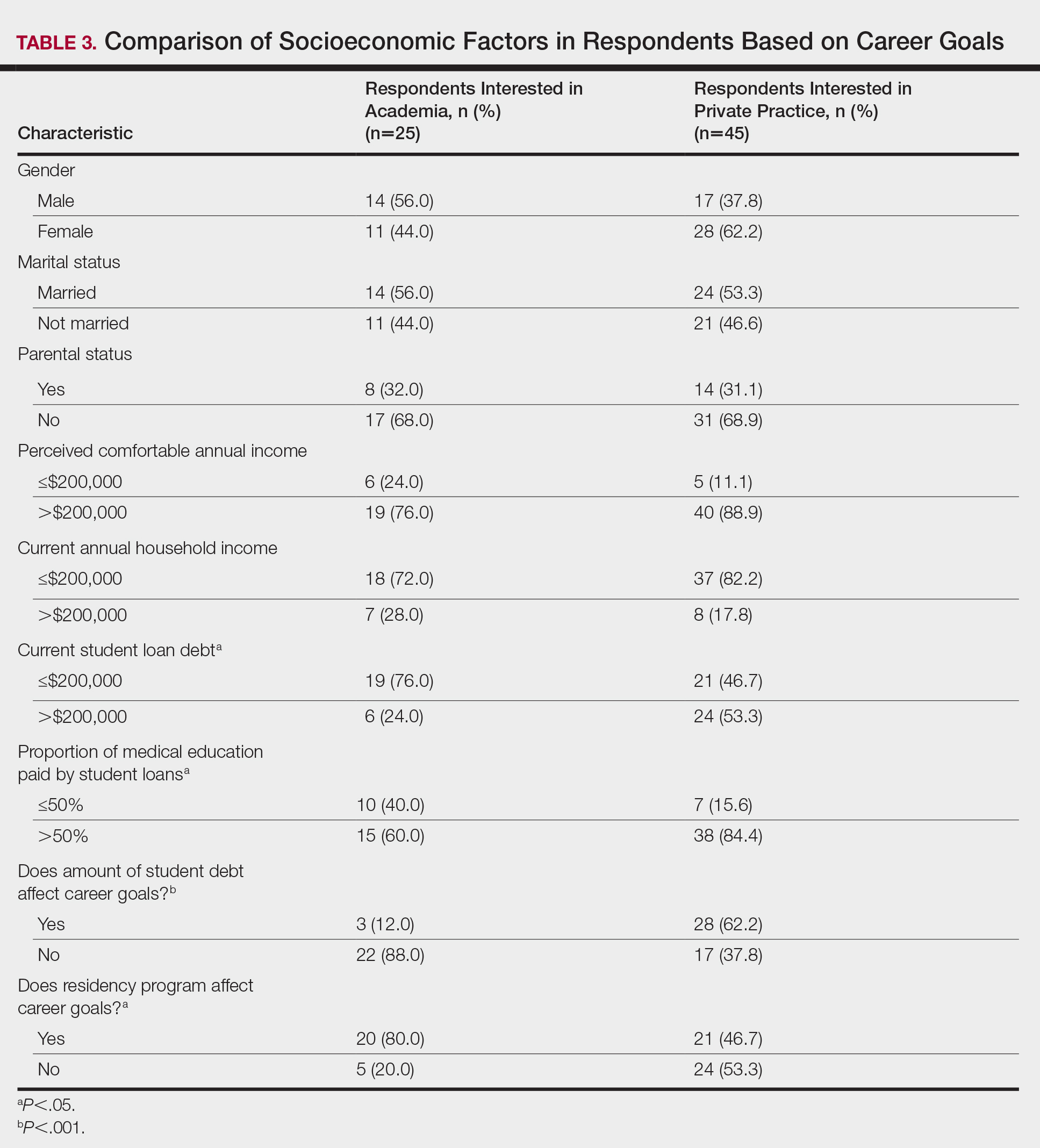

Comparison of Respondents Interested in Careers in Academia vs Private Practice

There were differences in financial circumstances between respondents interested in academia versus those interested in private practice. Compared to respondents interested in academia, those interested in private practice were more likely to have more than $200,000 in student loan debt (24 [53.3%] vs 6 [24.0%]; P<.05), have more than half of their education paid with student loans (38 [84.4%] vs 15 [60.0%]; P<.05), and state that student debt affected their career goals (28 [62.2%] vs 3 [12.0%]; P<.001)(Table 3). Demographic characteristics including gender, marital status, parental status, and current annual household income were not associated with a specific career goal.

Subgroup analysis was performed on respondents who were initially interested in academic careers but subsequently decided to pursue private practice (n=15).

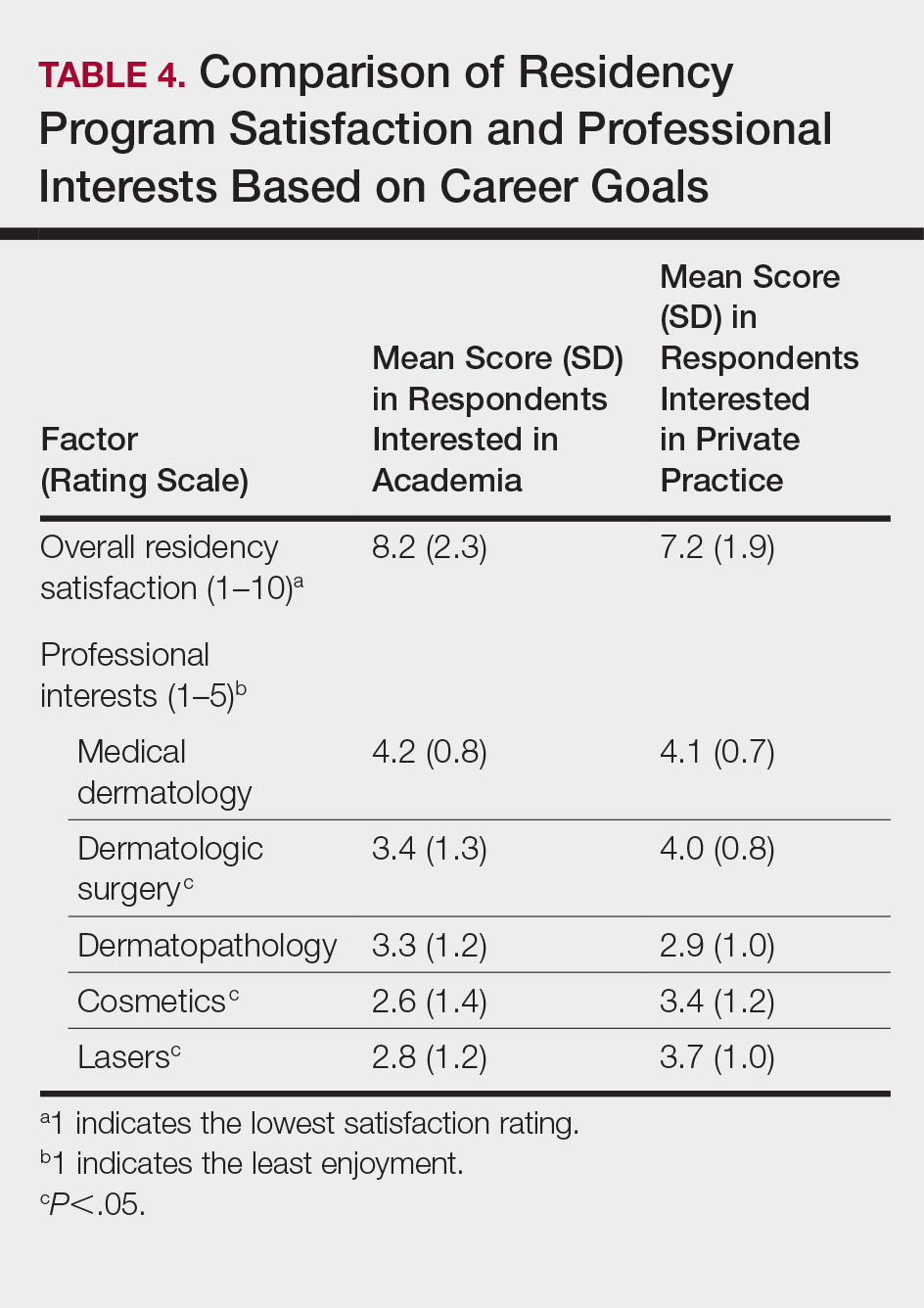

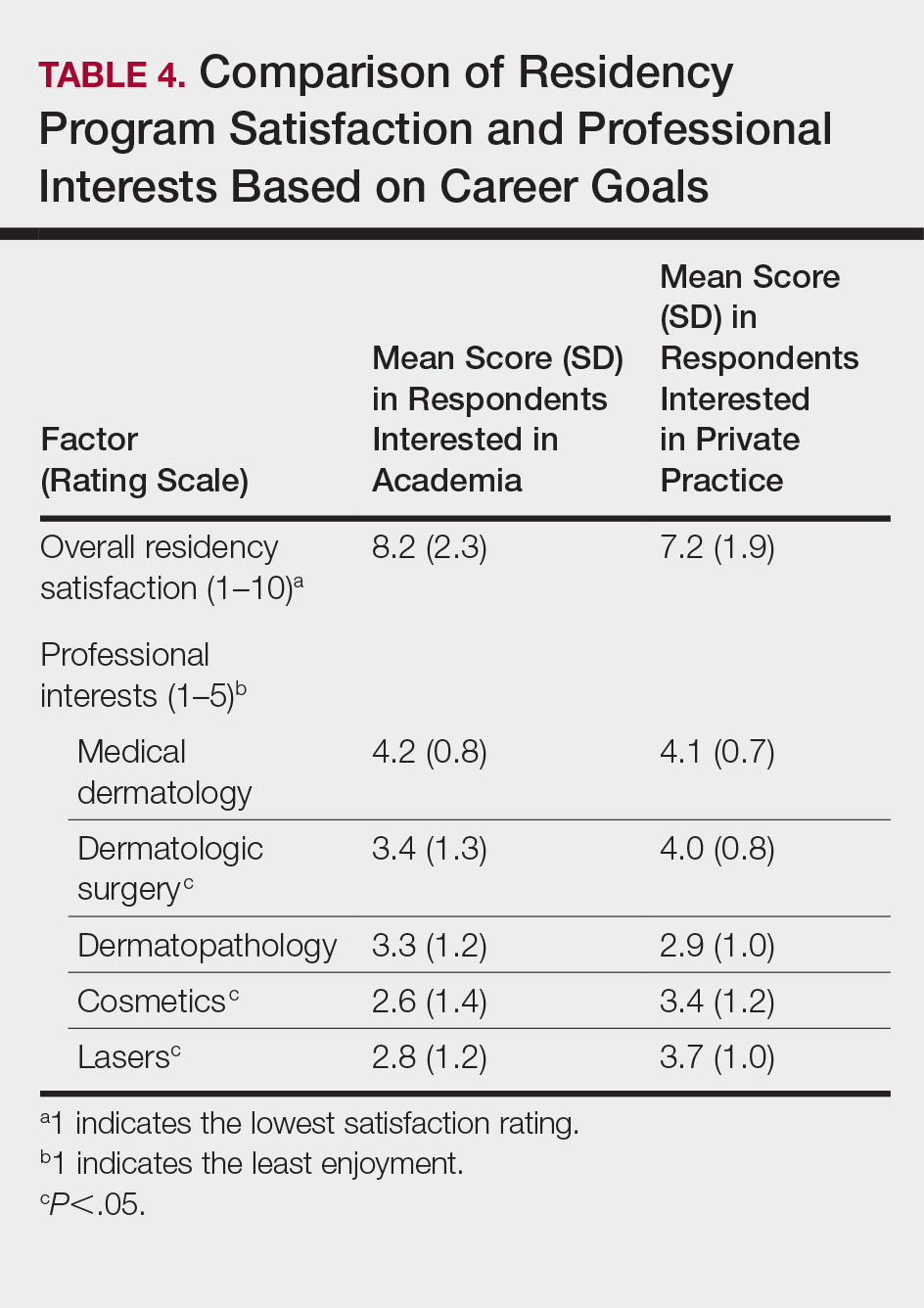

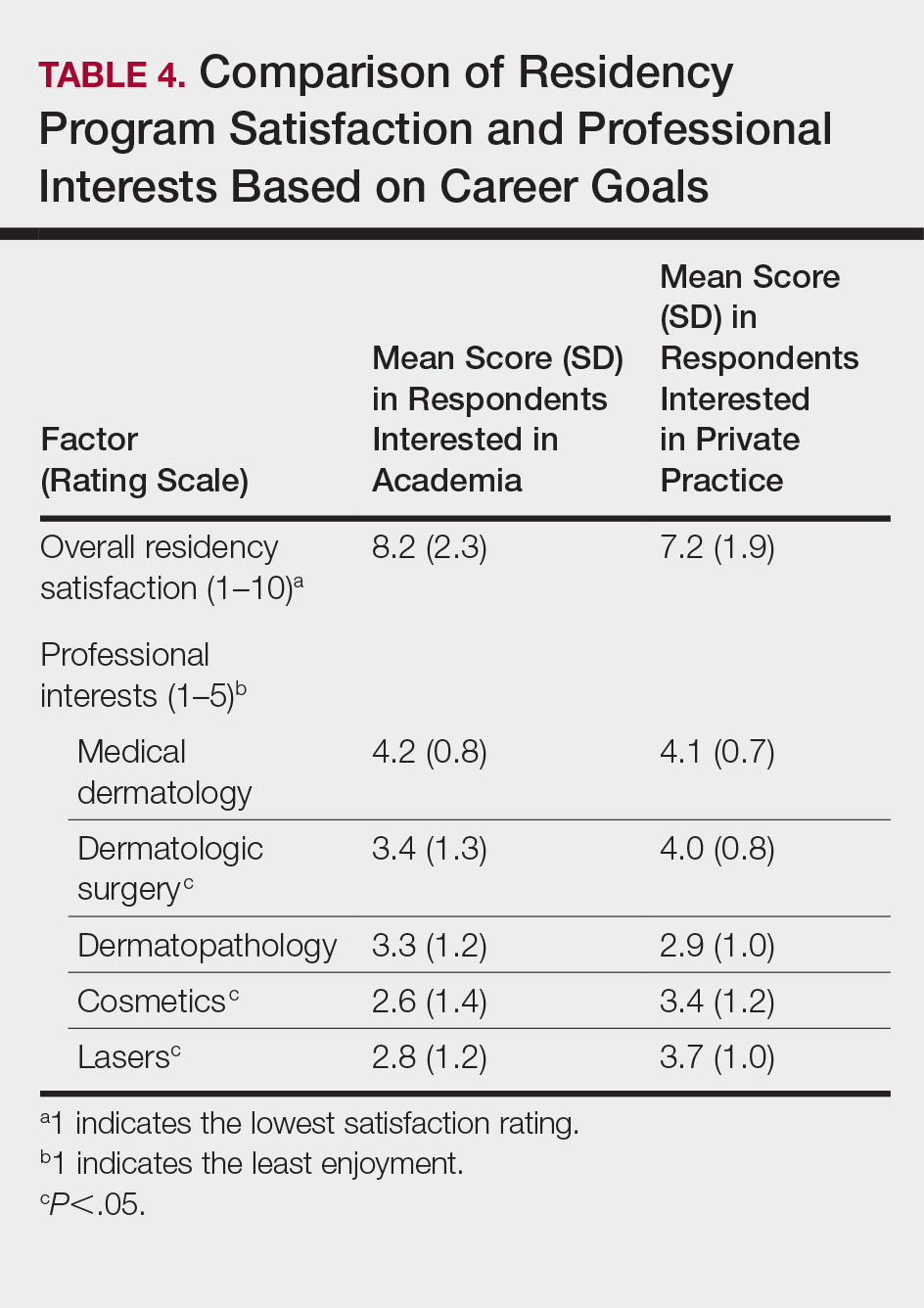

Residency program experience also may influence career trajectory. The majority (n=41 [58.6%]) of respondents indicated that their residency program experience affected their dermatology career goals. Of those, 41.7% and 58.5% stated that their residency program experiences dissuaded and persuaded them into academic positions, respectively. Those interested in academic dermatology were more likely to state that their residency program experience influenced their career goals (80.0% [20/25] vs 46.7% [21/45]; P<.05). Furthermore, those interested in academic positions responded with higher overall residency program satisfaction ratings on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 indicated the lowest satisfaction) than those interested in private practice, but the difference was not significant (mean [SD] score, 8.2 [2.3] vs 7.2 [1.9]; P=.07).

Respondents were asked to rate their interest in the following dermatology-related professional interests on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 indicated the least enjoyment): medical dermatology, dermatologic surgery, dermatopathology, cosmetics, and lasers. Those interested in private practice versus those interested in academic dermatology found more enjoyment in dermatologic surgery (mean [SD] score, 4.0 [0.8] vs 3.4 [1.3]; P<.05), cosmetics (3.4 [1.2] vs 2.6 [1.4]; P<.05), and lasers (3.7 [1.0] vs 2.8 [1.2]; P<.05)(Table 4).

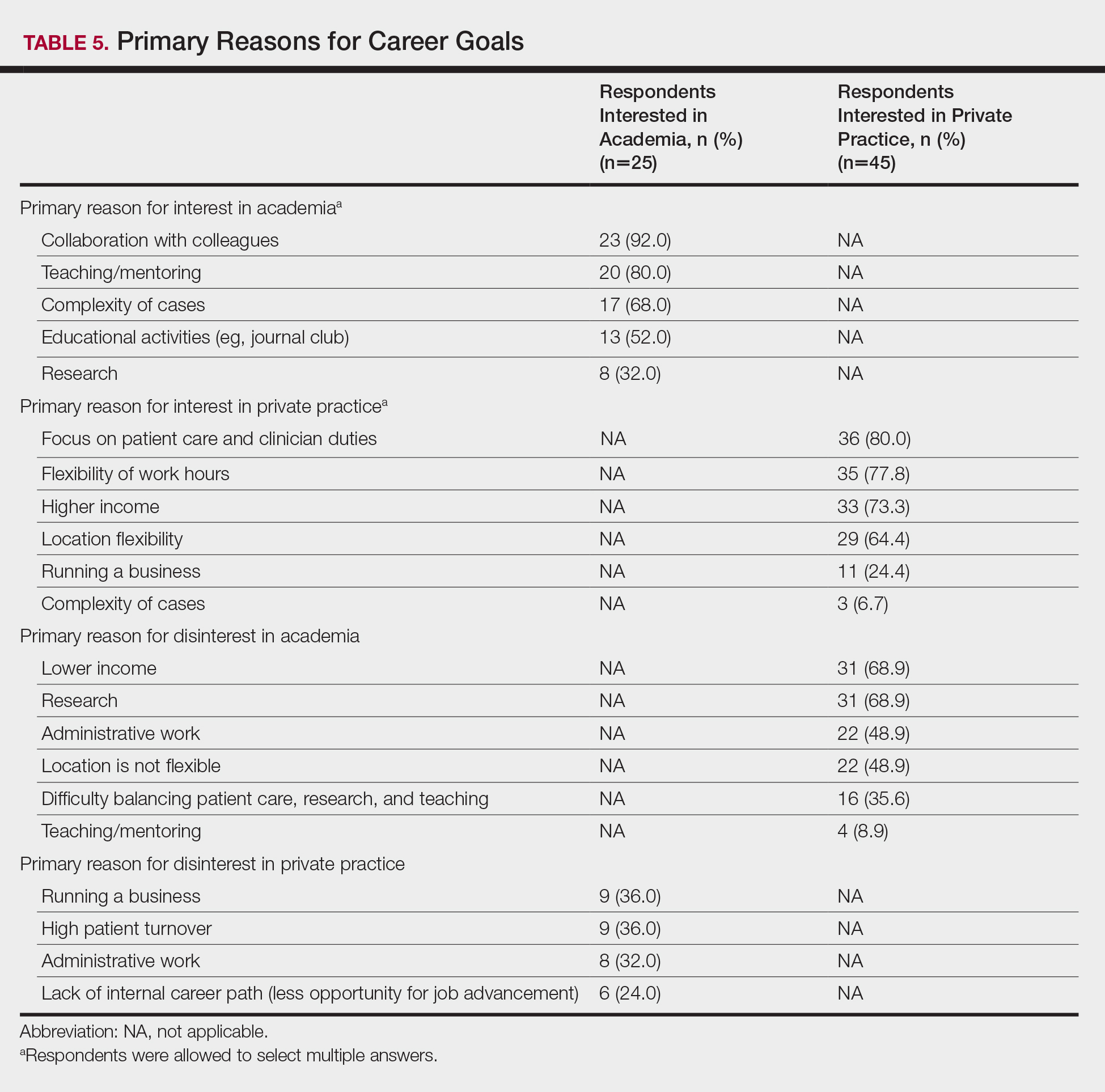

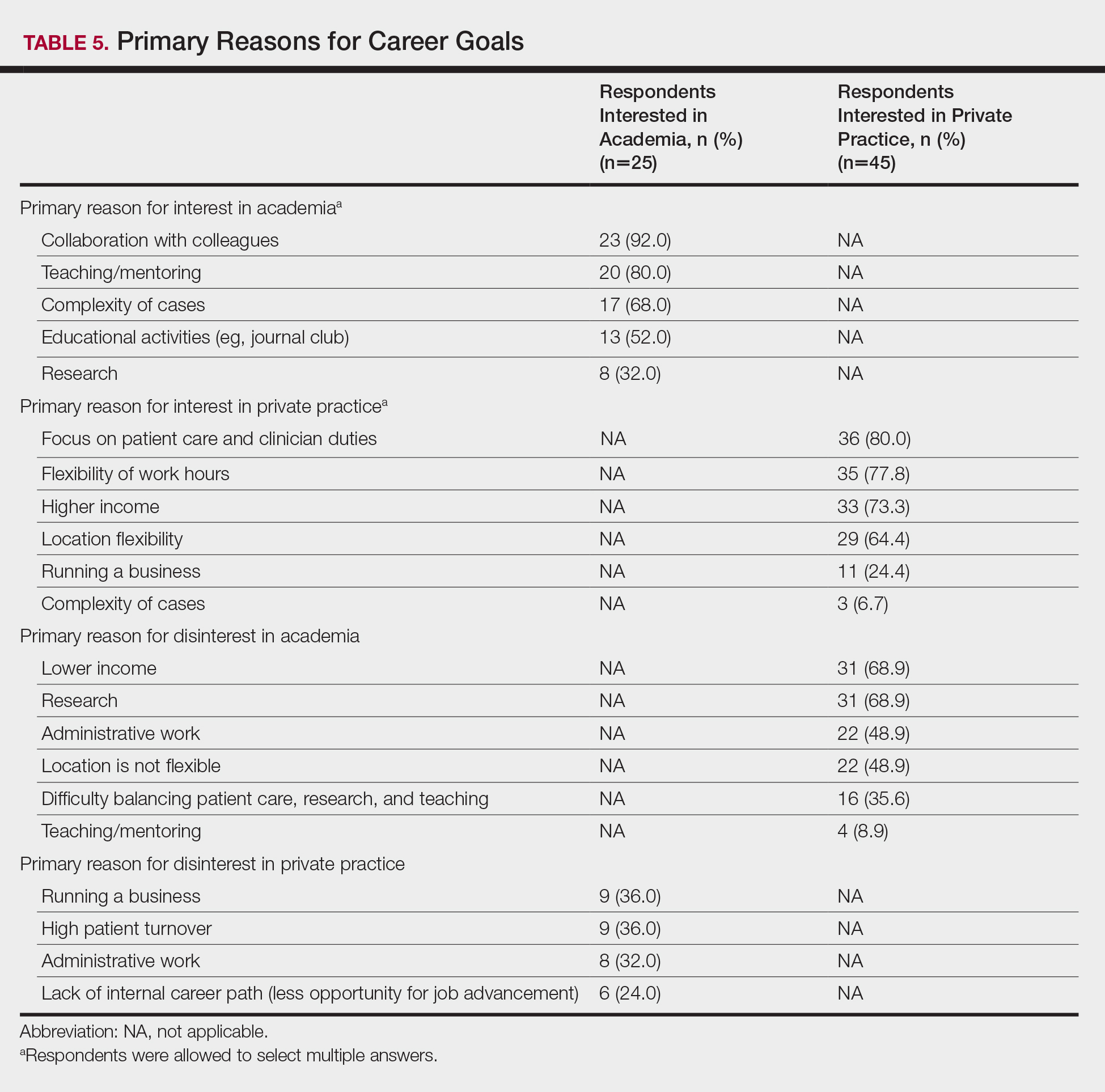

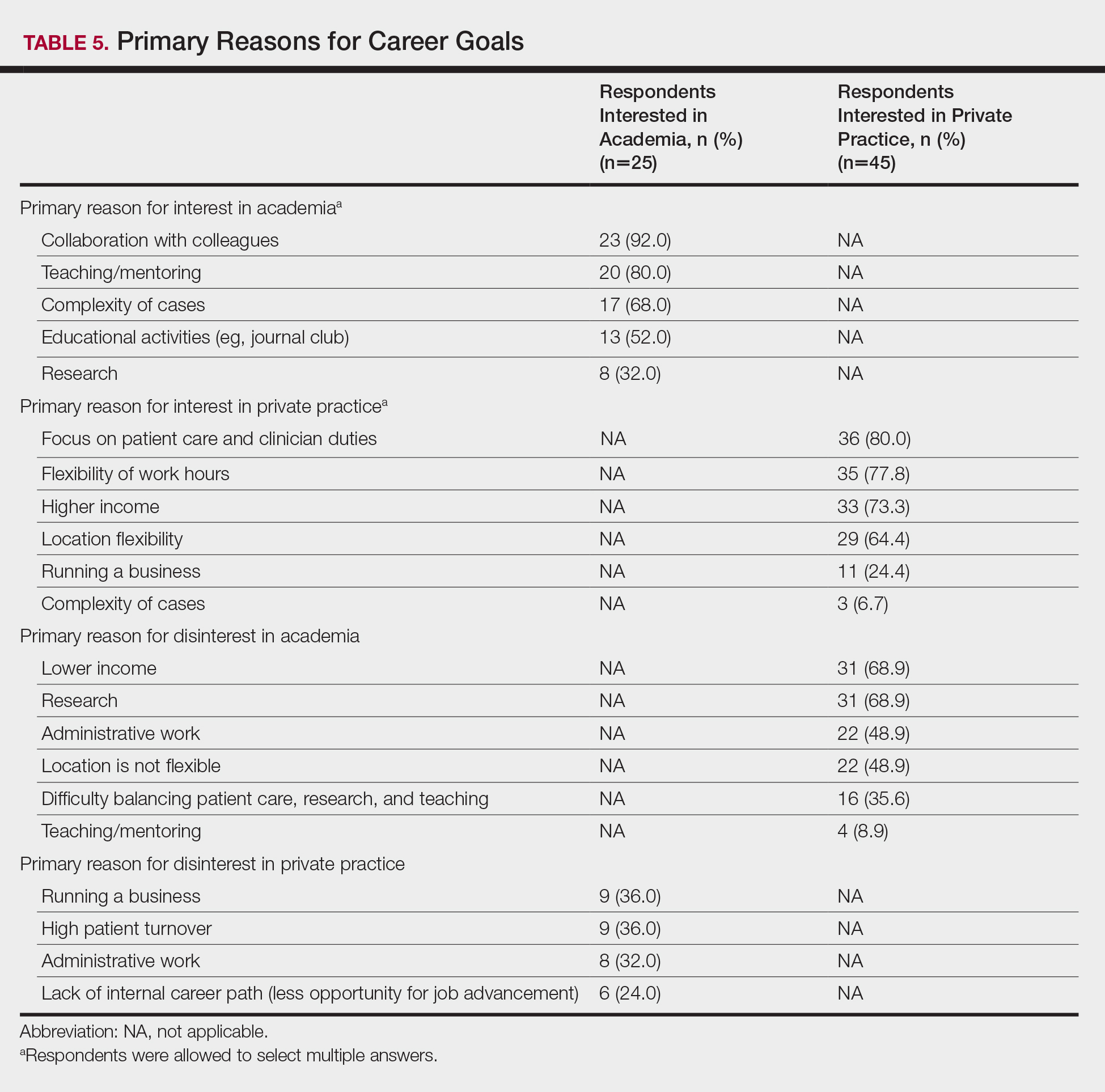

Respondents also were asked to select primary motivating factors for their career goals (ie, academia or private practice) and to indicate reasons for not choosing the alternative. The majority of those pursuing academia were motivated by opportunities to collaborate with colleagues (23 [92.0%]), teach and mentor (20 [80%]), and manage complex cases (17 [68.0%]). Most of the respondents who were pursing private practice were motivated by focus on patient care and clinician duties (36 [80.0%]), flexible work hours (35 [77.8%]), higher income (33 [73.3%]), and location flexibility (29 [64.4%]). Among those interested in academic dermatology, the top factors for disinterest in private practice were running a business (9 [36.0%]) and high patient turnover (9 [36.0%]). Most of those interested in private practice indicated that they were not interested in an academic position because of lower income (31 [68.9%]) and research duties (31 [68.9%])(Table 5).

Awareness of and Attitudes Toward the PSLF Program

The majority of respondents were aware of PSLF (53 [75.7%]); however, only 1 respondent endorsed current plans to use PSLF for loan repayment. Respondents were asked how likely they would be to pursue an academic position if given the option to have their student loans forgiven by the PSLF program. Overall, 44.6% (n=25) of respondents indicated that this option would have no effect or would unlikely convince them to pursue an academic position, and 55.4% (n=31) of respondents indicated that they were somewhat likely, likely, or very likely to pursue academia if PSLF was an option. Of those who stated that they would consider enrolling in PSLF, 64.5% (20/31) of individuals were pursuing careers in private practice. Neither current student loan burden nor career goal was associated with likelihood of enrolling in the PSLF.

Comment

In 2015, 76% of medical school graduates in the United States accrued educational debt, with an average of $189,165, a number that has continued to increase over the years.4 In addition to the increasing cost of medical education, higher interest rates on federal student loans contribute to debt burden. Over the last 2 decades, some research has posited that debt may influence medical specialty selection, with most studies focusing on primary care.5-9 However, there is limited information on the effect of student loan debt on career decisions within dermatology.

The results of our study suggest that financial factors including income and amount of educational debt may influence career decisions in dermatology. There is a known income gap between academic and nonacademic settings.

The PSLF can potentially address this issue and be used as a recruiting tool for dermatology positions in academia. Under PSLF, borrowers can have the remainder of their loan balances forgiven after making 120 monthly payments while employed full time by public service employers, including some academic medical institutions. In our study, a large majority of respondents indicated that they are aware of the PSLF, and more than half said they would consider pursuing positions in academia if their loans could be forgiven through the program; however, when asked about plans for loan repayment, only 1 respondent endorsed current plans to enroll in PSLF. Thus, despite high interest in PSLF among the survey respondents, few had actual plans to use the service, suggesting that perhaps dermatologists are not provided enough information about PSLF to motivate enrollment. In the same way, almost a quarter of respondents were not familiar with the PSLF as a repayment option, further signifying that distribution of information about financial planning may be inadequate. If student loan burden is a notable factor in career decisions in dermatology, it is important that academic institutions provide sufficient information about repayment to encourage informed decisions. As such, it is possible that educating physicians about options such as PSLF can potentially recruit more dermatologists to academic positions.

Aside from financial reasons, residency program experience and differences in practices in academic and nonacademic settings may impact career trajectories. The majority of respondents stated their residency program experience influenced their career decisions; however, the majority of respondents did not change their minds about career goals since starting residency, suggesting that residency program experience may reinforce but not necessarily alter these choices. Interests in specific focuses within dermatology also may influence career decisions. This study suggests that those pursuing private practice positions are more interested in dermatologic surgery, lasers, and cosmetics.

In this study, we did not find an association between gender and career plans in dermatology. In 2013, more than 60% of dermatology resident physicians were female.12 However, a recent study suggested that women face challenges in academic dermatology, including a downtrend in the number of female investigators with grants from the National Institutes of Health.13

This preliminary study has several limitations. First, the small sample size limited generalizability to all dermatologists. Second, responder bias was possible, as those who have stronger opinions about this topic may have been more inclined to participate in this voluntary survey. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further explore the factors that influence career decisions within dermatology and to determine if there are additional means to increase recruitment into academia.

Conclusion

It is recognized that there are challenges in recruiting dermatologists into academic positions. This study suggests that student loan burden influences career decisions in dermatology. Dermatologists may not be fully educated on options for student loan repayment. With increased awareness, the PSLF can potentially be used as a recruitment tool for positions in academic dermatology.

- Resneck JS Jr, Kimball AB. The dermatology workforce shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:50-54.

- Resneck JS Jr, Tierney EP, Kimball AB. Challenges facing academic dermatology: survey data on the faculty workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:211-216.

- Lanzon J, Edwards SP, Inglehart MR. Choosing academia versus private practice: factors affecting oral maxillofacial surgery residents’ career choices. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:1751-1761.

- AAMC Medical Student Education: Debt, Costs, and Loan Repayment Fact Card. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/2016_Debt_Fact_Card.pdf. Published October 2016. Accessed November 18, 2017.

- Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CH. The impact of U.S. medical students’ debt on their choice of primary care careers: an analysis of data from the 2002 medical school graduation questionnaire. Acad Med. 2005;80:815-819.

- Woodworth PA, Chang FC, Helmer SD. Debt and other influences on career choices among surgical and primary care residents in a community-based hospital system. Am J Surg. 2000;180:570-575; discussion 575-576.

- Phillips RL Jr, Dodoo MS, Petterson S, et al. Specialty and geographic distribution of the physician workforce: what influences medical student and resident choices? Robert Graham Center website. http://www.graham-center.org/dam/rgc/documents/publications-reports/monographs-books/Specialty-geography-compressed.pdf. Published March 2, 2009. Accessed November 17, 2017.

- Rosenthal MP, Marquette PA, Diamond JJ. Trends along the debt-income axis: implications for medical students’ selections of family practice careers. Acad Med. 1996;71:675-677.

- McDonald FS, West CP, Popkave C, et al. Educational debt and reported career plans among internal medicine residents. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:416-420.

- Careers in Medicine. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/cim/specialty/exploreoptions/list/us/336836/dermatology.html. Accessed November 18, 2017.

- Youngclaus JA, Koehler PA, Kotlikoff LJ, et al. Can medical students afford to choose primary care? an economic analysis of physician education debt repayment. Acad Med. 2013;88:16-25.

- Physician specialty data book 2014. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Physician Specialty Databook 2014.pdf. Published November 2014. Updated June 3, 2015. Accessed November 17, 2017.

- Cheng MY, Sukhov A, Sultani H, et al. Trends in National Institutes of Health funding of principal investigators in dermatology research by academic degree and sex. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:883-888.

Dermatology departments in the United States have been facing challenges in recruiting and retaining dermatologists for academic positions. Accordingly, a survey study reported that academic dermatologists were more likely than those in private practice to state that their institutions were recruiting new associates.1 Several factors could explain this phenomenon. Salary differences between jobs in academic and nonacademic settings may contribute to difficulty in recruiting dermatologists into academia, which is exacerbated by a theoretical shortage of dermatologists, leading to graduates who receive and accept private practice job offers.1,2 Furthermore, a large survey study reported that challenges unique to academic dermatologists include longer patient wait times in addition to responsibilities such as research, hospital consultations, medical writing, and teaching. These patterns raise concerns for the future of teaching institutions because academic dermatologists not only train future physicians but also conduct clinical and basic science research necessary to advance the field and improve patient care.2 Thus, it is important to evaluate the factors that affect career decisions in dermatology and to determine if these factors can be addressed. We hypothesized that student loan burden influences career plans in dermatology and that physicians are not fully educated on loan repayment options. The aims of this preliminary study were to explore the influence of student loan burden on career plans in dermatology and to determine if the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program could potentially encourage more dermatologists to consider academic careers.

Methods

The study aimed to investigate the factors that influence career decisions in dermatology and to assess attitudes toward the PSLF program as an option for student loan repayment. The target population included dermatology residents and attending physicians in the United States. Survey questions were adapted from a previously published study3 and were modified based on feedback from reviewers in the University of California (UC) Irvine department of dermatology. The survey was voluntary and did not collect identifying information. This study was granted exemption from oversight by the UC Irvine institutional review board.

Recruitment materials informed potential participants of the nature of the study and provided a hyperlink to the electronic survey. The UC Irvine department of dermatology emailed US dermatology residency program coordinators, requesting that they forward this study to residents and attending physicians in their programs.

Results

Demographics

The survey had 70 respondents including residents (56 [80.0%]) and attending physicians (14 [20.0%]). The mean age (SD) of the respondents was 32.4 (6.1) years, with 31 (44.3%) men and 39 (55.7%) women. The majority were married (38 [54.3%]) and did not have children (48 [68.6%]). Most respondents reported an annual household income of $200,000 or less (55 [78.6%]) and perceived a comfortable annual household income as greater than $200,000 (59 [84.3%])(Table 1).

Financing Medical Education

Most respondents currently had $200,000 or less in student loan debt (40 [57.1%]) and financed more than half of their medical education with student loans (53 [75.7%]). A large majority (61 [87.1%]) indicated that some portion of their medical education was funded by student loans.

Career Goals in Dermatology and the Influence of Student Loans

Respondents were asked to specify their career plans before versus after starting dermatology residency training (ie, current career plan). Prior to starting residency, 36 (51.4%) and 34 (48.6%) respondents indicated they were interested in private practice and academia, respectively. After starting residency, the number of respondents interested in private practice increased to 45 (64.3%), and the number of respondents interested in academia decreased to 25 (35.7%). Fifteen (21.4%) respondents changed career trajectories from academia to private practice, 6 (8.6%) changed from private practice to academia, and 49 (70.0%) did not change career goals.

The majority of respondents (39 [55.7%]) indicated that the amount of their student loan debt did not influence their career goals (Table 2); however, those with more than $200,000 in debt were more likely to state that student loans impacted their career goals compared to those with $200,000 or less in debt (70.0% [21/30] vs 25.0% [10/40]; P<.001).

Comparison of Respondents Interested in Careers in Academia vs Private Practice

There were differences in financial circumstances between respondents interested in academia versus those interested in private practice. Compared to respondents interested in academia, those interested in private practice were more likely to have more than $200,000 in student loan debt (24 [53.3%] vs 6 [24.0%]; P<.05), have more than half of their education paid with student loans (38 [84.4%] vs 15 [60.0%]; P<.05), and state that student debt affected their career goals (28 [62.2%] vs 3 [12.0%]; P<.001)(Table 3). Demographic characteristics including gender, marital status, parental status, and current annual household income were not associated with a specific career goal.

Subgroup analysis was performed on respondents who were initially interested in academic careers but subsequently decided to pursue private practice (n=15).

Residency program experience also may influence career trajectory. The majority (n=41 [58.6%]) of respondents indicated that their residency program experience affected their dermatology career goals. Of those, 41.7% and 58.5% stated that their residency program experiences dissuaded and persuaded them into academic positions, respectively. Those interested in academic dermatology were more likely to state that their residency program experience influenced their career goals (80.0% [20/25] vs 46.7% [21/45]; P<.05). Furthermore, those interested in academic positions responded with higher overall residency program satisfaction ratings on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 indicated the lowest satisfaction) than those interested in private practice, but the difference was not significant (mean [SD] score, 8.2 [2.3] vs 7.2 [1.9]; P=.07).

Respondents were asked to rate their interest in the following dermatology-related professional interests on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 indicated the least enjoyment): medical dermatology, dermatologic surgery, dermatopathology, cosmetics, and lasers. Those interested in private practice versus those interested in academic dermatology found more enjoyment in dermatologic surgery (mean [SD] score, 4.0 [0.8] vs 3.4 [1.3]; P<.05), cosmetics (3.4 [1.2] vs 2.6 [1.4]; P<.05), and lasers (3.7 [1.0] vs 2.8 [1.2]; P<.05)(Table 4).

Respondents also were asked to select primary motivating factors for their career goals (ie, academia or private practice) and to indicate reasons for not choosing the alternative. The majority of those pursuing academia were motivated by opportunities to collaborate with colleagues (23 [92.0%]), teach and mentor (20 [80%]), and manage complex cases (17 [68.0%]). Most of the respondents who were pursing private practice were motivated by focus on patient care and clinician duties (36 [80.0%]), flexible work hours (35 [77.8%]), higher income (33 [73.3%]), and location flexibility (29 [64.4%]). Among those interested in academic dermatology, the top factors for disinterest in private practice were running a business (9 [36.0%]) and high patient turnover (9 [36.0%]). Most of those interested in private practice indicated that they were not interested in an academic position because of lower income (31 [68.9%]) and research duties (31 [68.9%])(Table 5).

Awareness of and Attitudes Toward the PSLF Program

The majority of respondents were aware of PSLF (53 [75.7%]); however, only 1 respondent endorsed current plans to use PSLF for loan repayment. Respondents were asked how likely they would be to pursue an academic position if given the option to have their student loans forgiven by the PSLF program. Overall, 44.6% (n=25) of respondents indicated that this option would have no effect or would unlikely convince them to pursue an academic position, and 55.4% (n=31) of respondents indicated that they were somewhat likely, likely, or very likely to pursue academia if PSLF was an option. Of those who stated that they would consider enrolling in PSLF, 64.5% (20/31) of individuals were pursuing careers in private practice. Neither current student loan burden nor career goal was associated with likelihood of enrolling in the PSLF.

Comment

In 2015, 76% of medical school graduates in the United States accrued educational debt, with an average of $189,165, a number that has continued to increase over the years.4 In addition to the increasing cost of medical education, higher interest rates on federal student loans contribute to debt burden. Over the last 2 decades, some research has posited that debt may influence medical specialty selection, with most studies focusing on primary care.5-9 However, there is limited information on the effect of student loan debt on career decisions within dermatology.

The results of our study suggest that financial factors including income and amount of educational debt may influence career decisions in dermatology. There is a known income gap between academic and nonacademic settings.

The PSLF can potentially address this issue and be used as a recruiting tool for dermatology positions in academia. Under PSLF, borrowers can have the remainder of their loan balances forgiven after making 120 monthly payments while employed full time by public service employers, including some academic medical institutions. In our study, a large majority of respondents indicated that they are aware of the PSLF, and more than half said they would consider pursuing positions in academia if their loans could be forgiven through the program; however, when asked about plans for loan repayment, only 1 respondent endorsed current plans to enroll in PSLF. Thus, despite high interest in PSLF among the survey respondents, few had actual plans to use the service, suggesting that perhaps dermatologists are not provided enough information about PSLF to motivate enrollment. In the same way, almost a quarter of respondents were not familiar with the PSLF as a repayment option, further signifying that distribution of information about financial planning may be inadequate. If student loan burden is a notable factor in career decisions in dermatology, it is important that academic institutions provide sufficient information about repayment to encourage informed decisions. As such, it is possible that educating physicians about options such as PSLF can potentially recruit more dermatologists to academic positions.

Aside from financial reasons, residency program experience and differences in practices in academic and nonacademic settings may impact career trajectories. The majority of respondents stated their residency program experience influenced their career decisions; however, the majority of respondents did not change their minds about career goals since starting residency, suggesting that residency program experience may reinforce but not necessarily alter these choices. Interests in specific focuses within dermatology also may influence career decisions. This study suggests that those pursuing private practice positions are more interested in dermatologic surgery, lasers, and cosmetics.

In this study, we did not find an association between gender and career plans in dermatology. In 2013, more than 60% of dermatology resident physicians were female.12 However, a recent study suggested that women face challenges in academic dermatology, including a downtrend in the number of female investigators with grants from the National Institutes of Health.13

This preliminary study has several limitations. First, the small sample size limited generalizability to all dermatologists. Second, responder bias was possible, as those who have stronger opinions about this topic may have been more inclined to participate in this voluntary survey. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further explore the factors that influence career decisions within dermatology and to determine if there are additional means to increase recruitment into academia.

Conclusion

It is recognized that there are challenges in recruiting dermatologists into academic positions. This study suggests that student loan burden influences career decisions in dermatology. Dermatologists may not be fully educated on options for student loan repayment. With increased awareness, the PSLF can potentially be used as a recruitment tool for positions in academic dermatology.

Dermatology departments in the United States have been facing challenges in recruiting and retaining dermatologists for academic positions. Accordingly, a survey study reported that academic dermatologists were more likely than those in private practice to state that their institutions were recruiting new associates.1 Several factors could explain this phenomenon. Salary differences between jobs in academic and nonacademic settings may contribute to difficulty in recruiting dermatologists into academia, which is exacerbated by a theoretical shortage of dermatologists, leading to graduates who receive and accept private practice job offers.1,2 Furthermore, a large survey study reported that challenges unique to academic dermatologists include longer patient wait times in addition to responsibilities such as research, hospital consultations, medical writing, and teaching. These patterns raise concerns for the future of teaching institutions because academic dermatologists not only train future physicians but also conduct clinical and basic science research necessary to advance the field and improve patient care.2 Thus, it is important to evaluate the factors that affect career decisions in dermatology and to determine if these factors can be addressed. We hypothesized that student loan burden influences career plans in dermatology and that physicians are not fully educated on loan repayment options. The aims of this preliminary study were to explore the influence of student loan burden on career plans in dermatology and to determine if the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program could potentially encourage more dermatologists to consider academic careers.

Methods

The study aimed to investigate the factors that influence career decisions in dermatology and to assess attitudes toward the PSLF program as an option for student loan repayment. The target population included dermatology residents and attending physicians in the United States. Survey questions were adapted from a previously published study3 and were modified based on feedback from reviewers in the University of California (UC) Irvine department of dermatology. The survey was voluntary and did not collect identifying information. This study was granted exemption from oversight by the UC Irvine institutional review board.

Recruitment materials informed potential participants of the nature of the study and provided a hyperlink to the electronic survey. The UC Irvine department of dermatology emailed US dermatology residency program coordinators, requesting that they forward this study to residents and attending physicians in their programs.

Results

Demographics

The survey had 70 respondents including residents (56 [80.0%]) and attending physicians (14 [20.0%]). The mean age (SD) of the respondents was 32.4 (6.1) years, with 31 (44.3%) men and 39 (55.7%) women. The majority were married (38 [54.3%]) and did not have children (48 [68.6%]). Most respondents reported an annual household income of $200,000 or less (55 [78.6%]) and perceived a comfortable annual household income as greater than $200,000 (59 [84.3%])(Table 1).

Financing Medical Education

Most respondents currently had $200,000 or less in student loan debt (40 [57.1%]) and financed more than half of their medical education with student loans (53 [75.7%]). A large majority (61 [87.1%]) indicated that some portion of their medical education was funded by student loans.

Career Goals in Dermatology and the Influence of Student Loans