User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Primary Mucinous Carcinoma of the Eyelid Treated With Mohs Micrographic Surgery

To the Editor:

Primary mucinous carcinoma (PMC) is an exceedingly rare adnexal tumor with an incidence of 0.07 cases per million individuals.1,2 First described by Lennox et al3 in 1952, this entity often presents as slow-growing, solitary nodules that often are soft on palpation but may have an indurated quality and range in color from reddish blue to flesh colored to white.4 Primary mucinous carcinoma most commonly is found on the eyelid (38%) but may affect other sites on the face (20.3%), scalp (16%), and axilla (10%).5 Historically, it has been thought to be more common among men; however, a 2005 large case series by Kazakov et al5 found that women were twice as likely to be affected. Primary mucinous carcinoma most frequently is diagnosed in the fifth through seventh decades of life, with a median age at onset of 63 years.6,7 Because of its rarity, PMC is most frequently confused clinically with basal cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, apocrine hidrocystoma, epidermoid cyst, Kaposi sarcoma, neuroma, lacrimal sac tumor, squamous cell carcinoma, granulomatous tumors, and metastatic adenocarcinoma.1,8-10

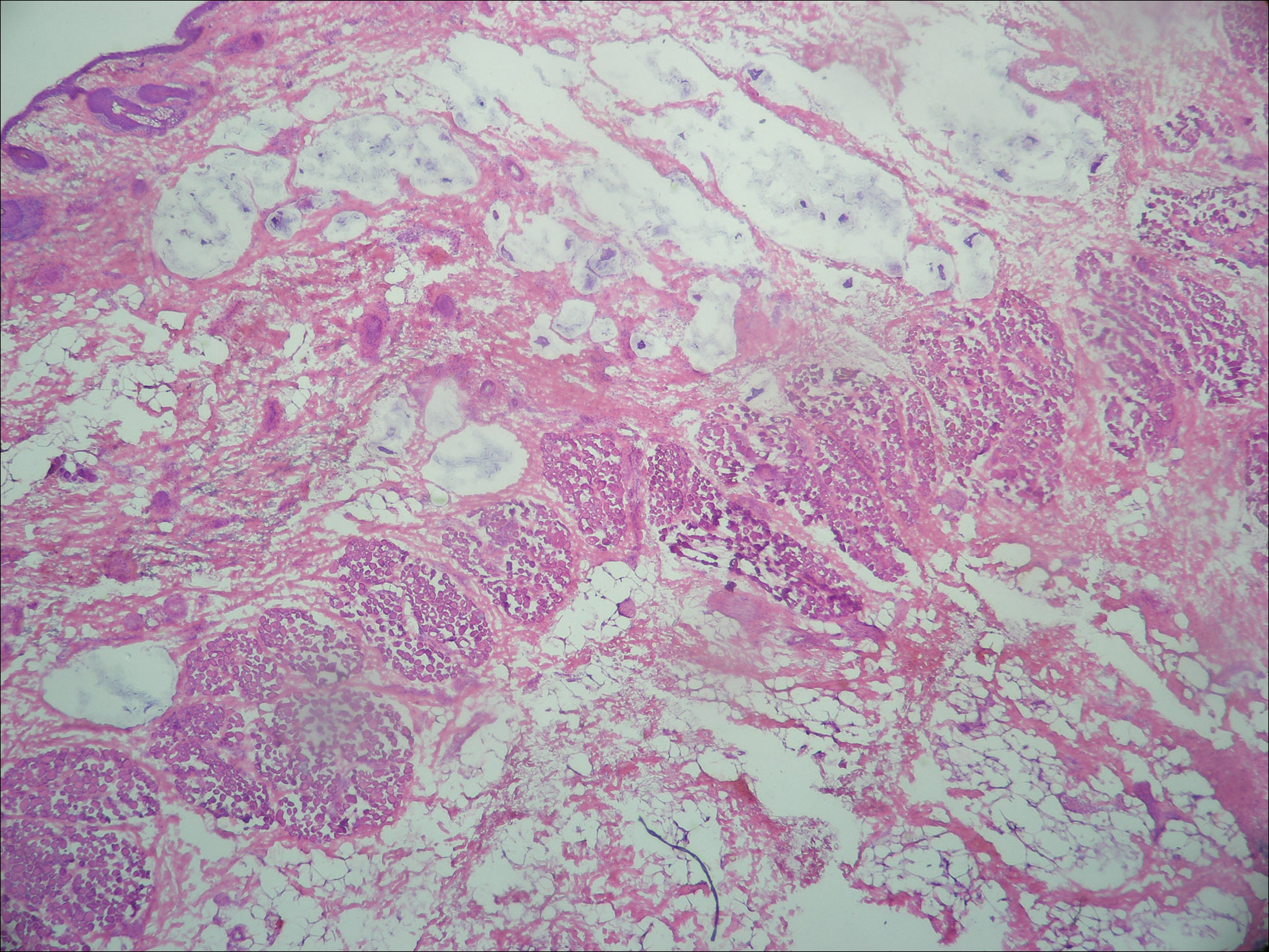

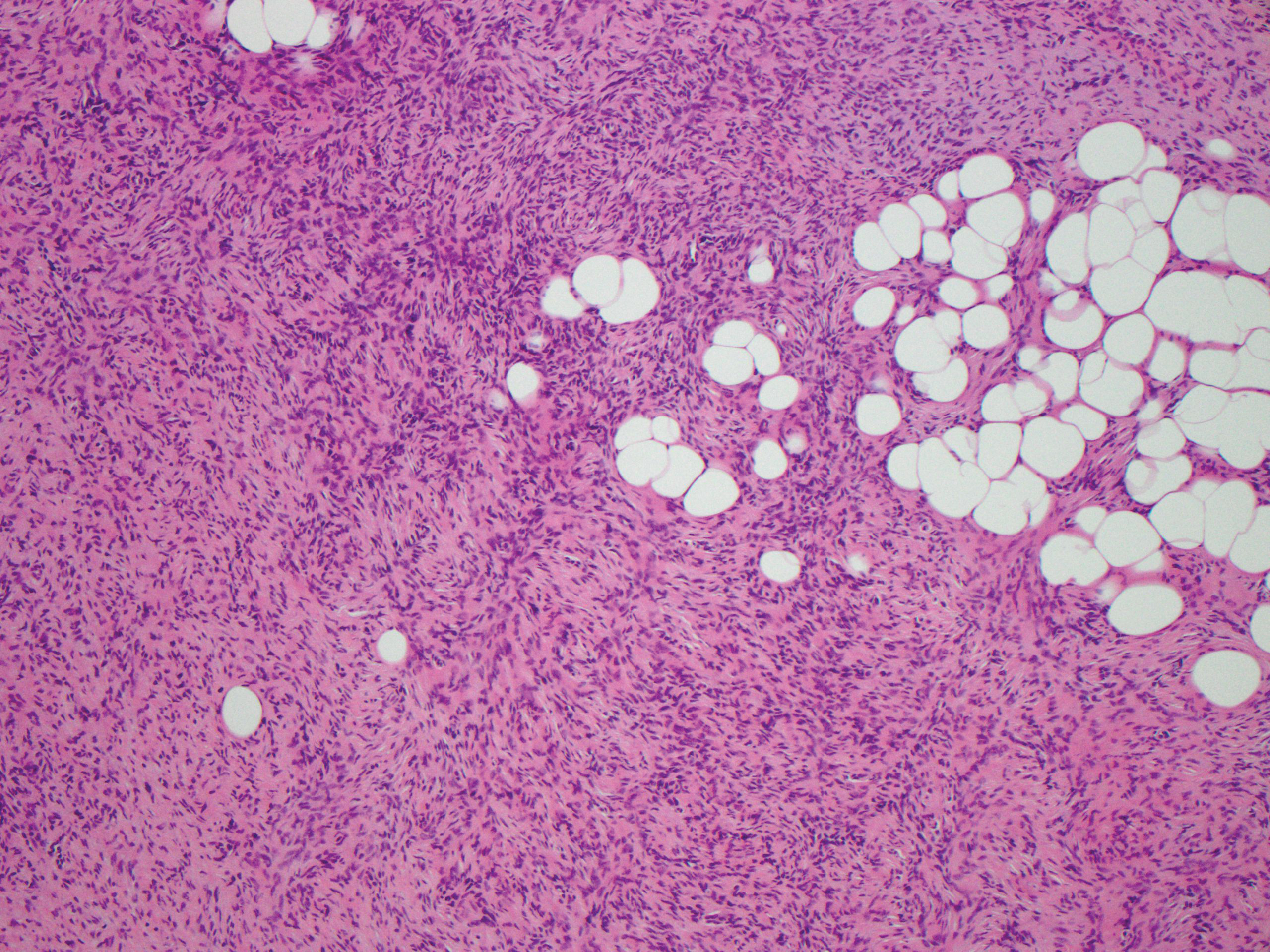

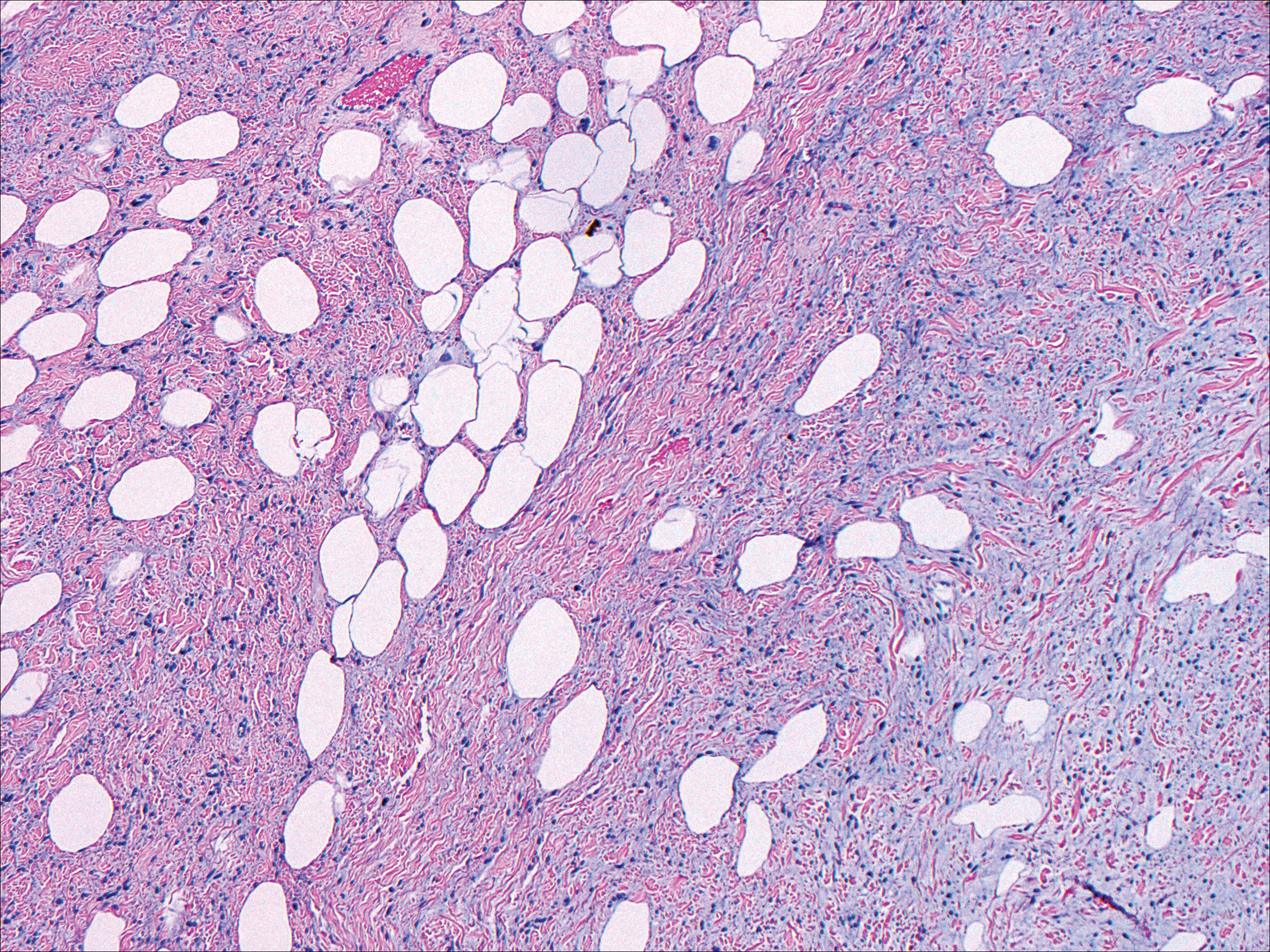

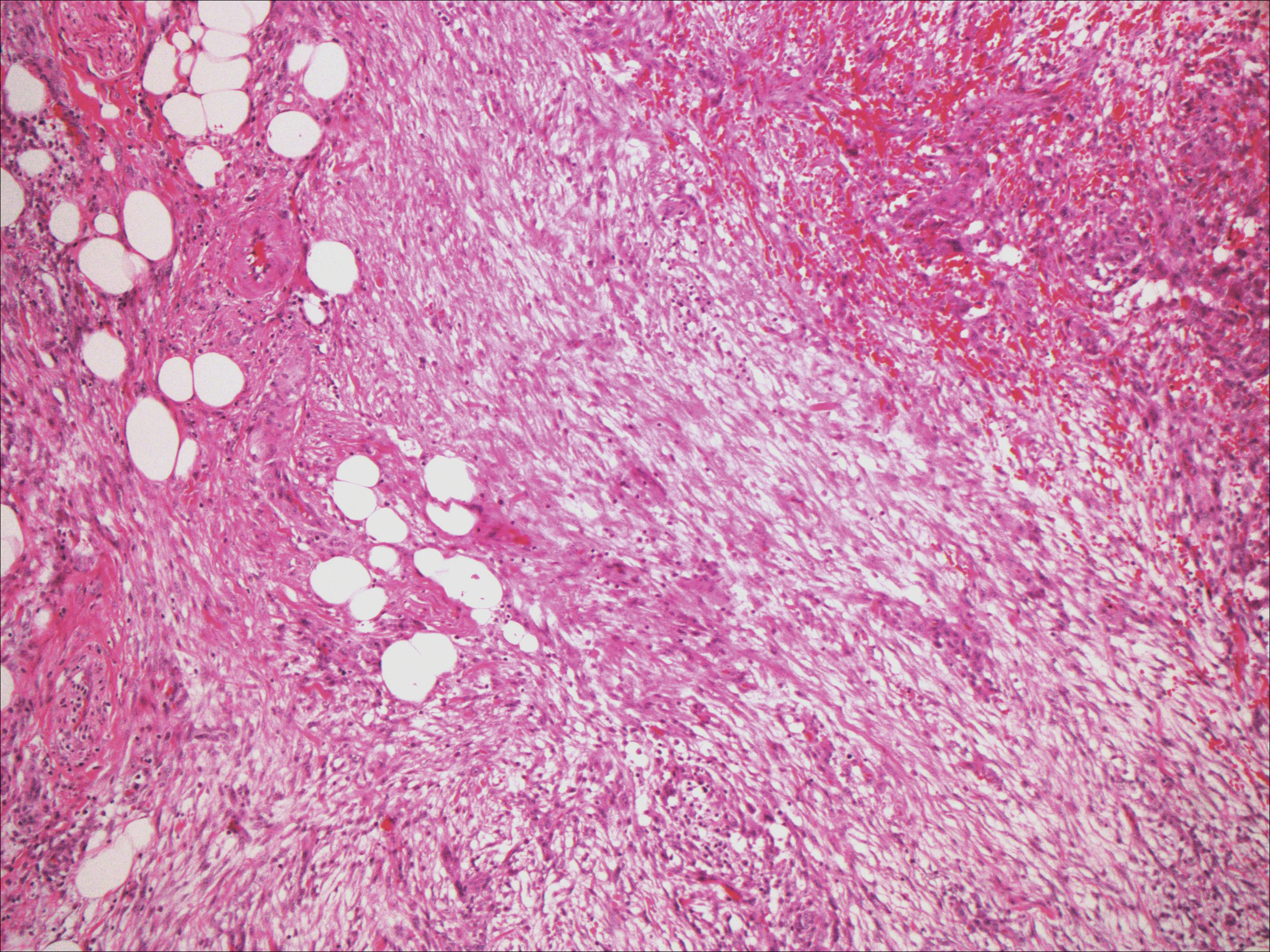

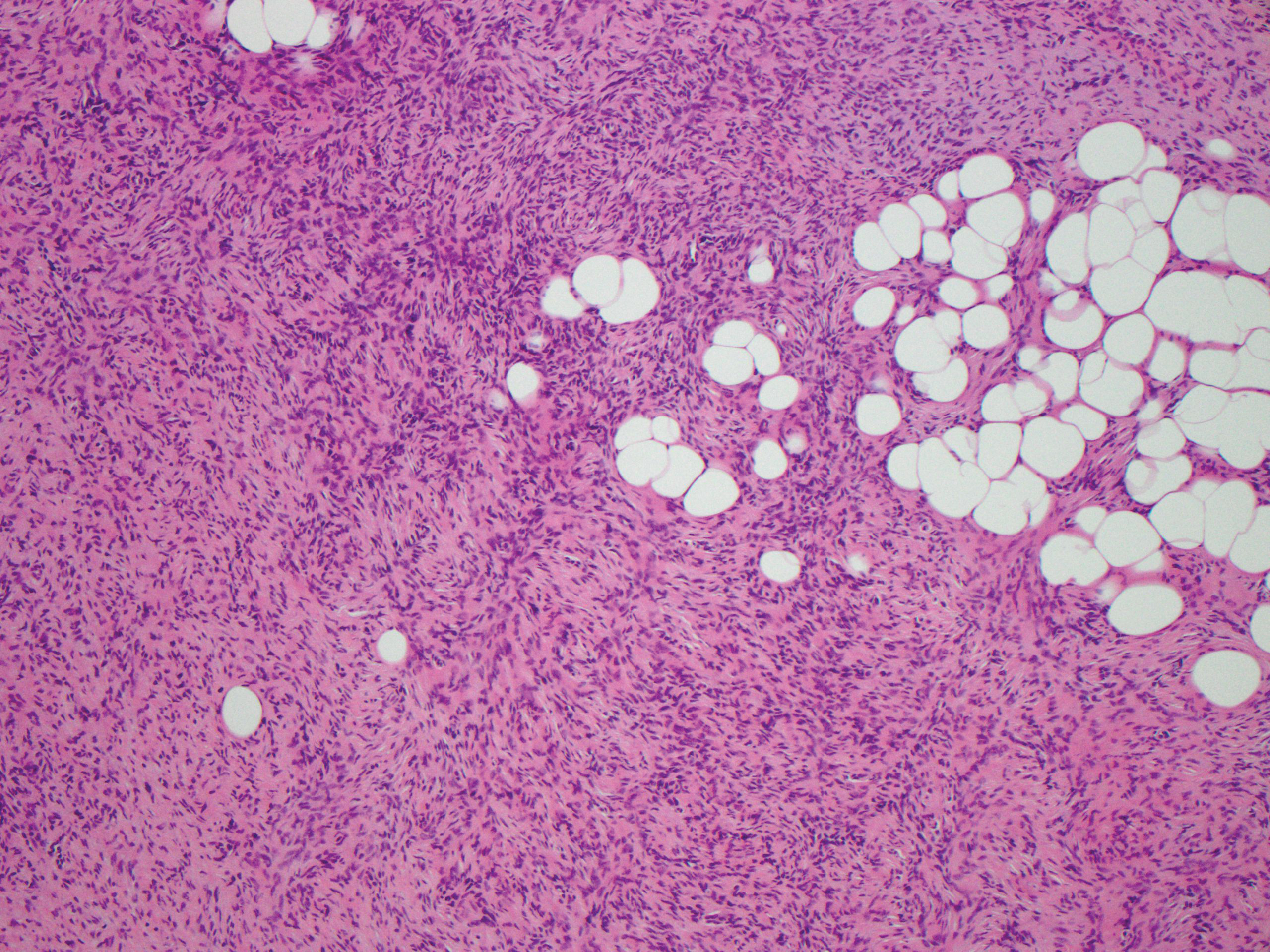

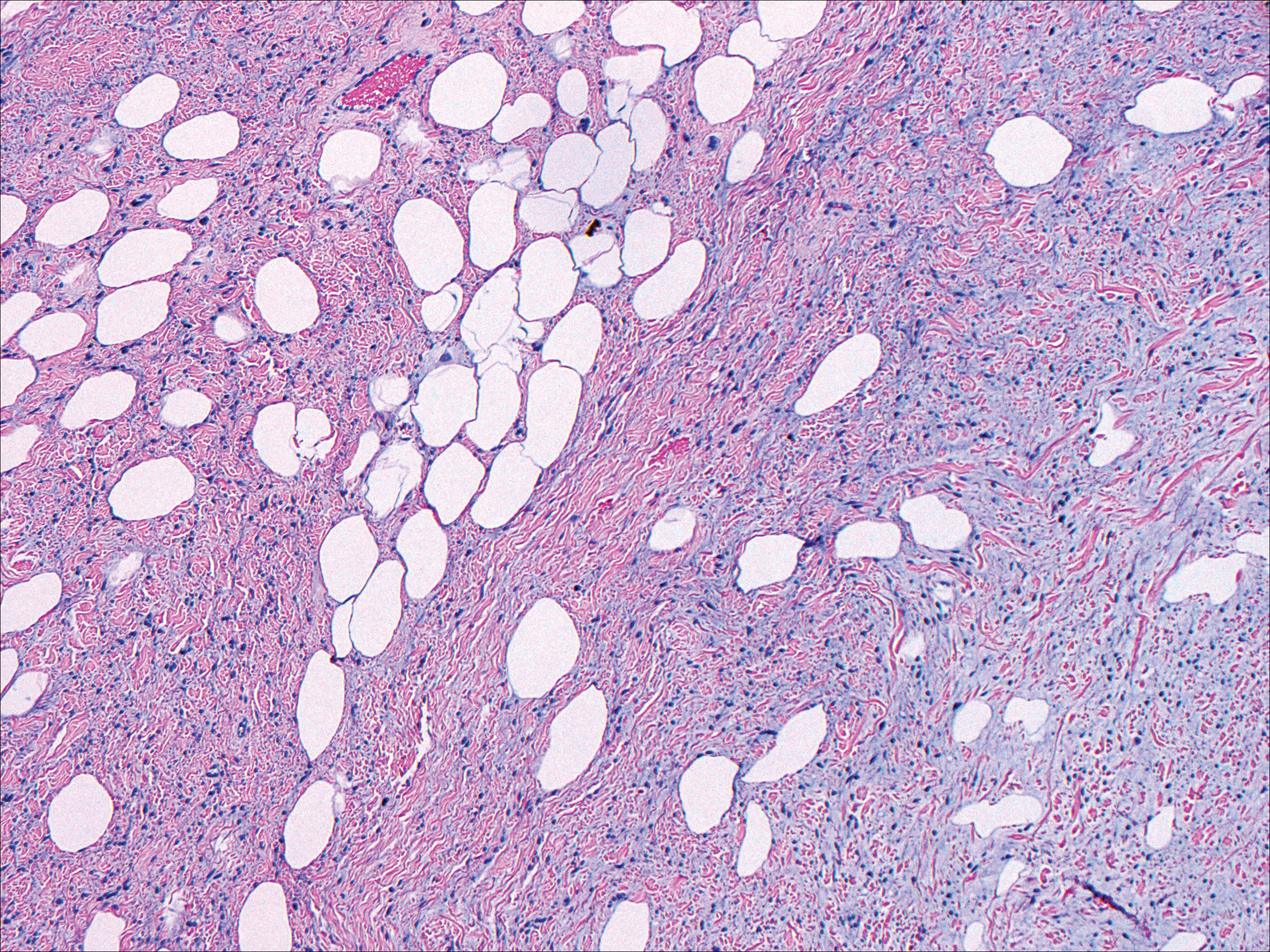

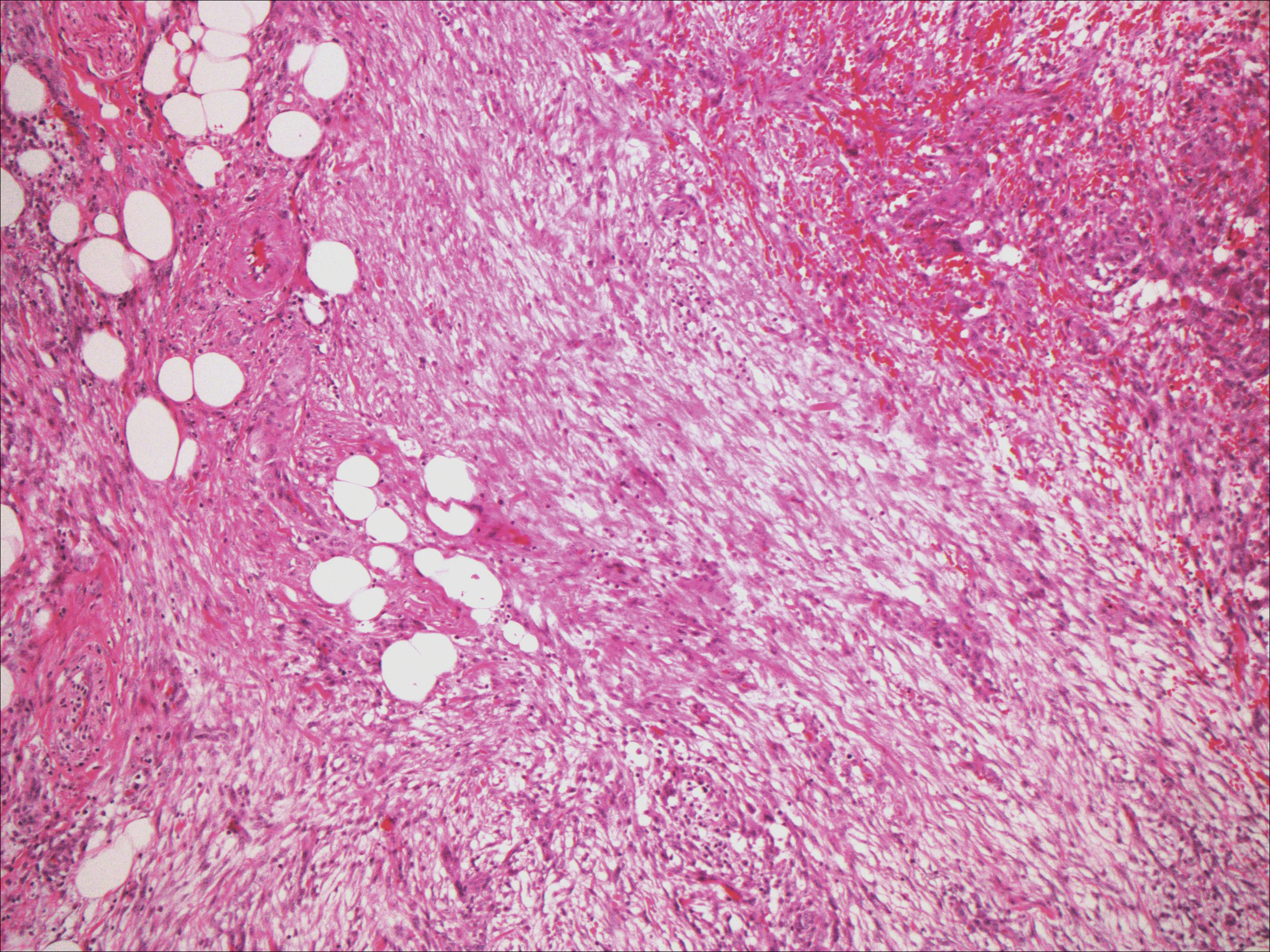

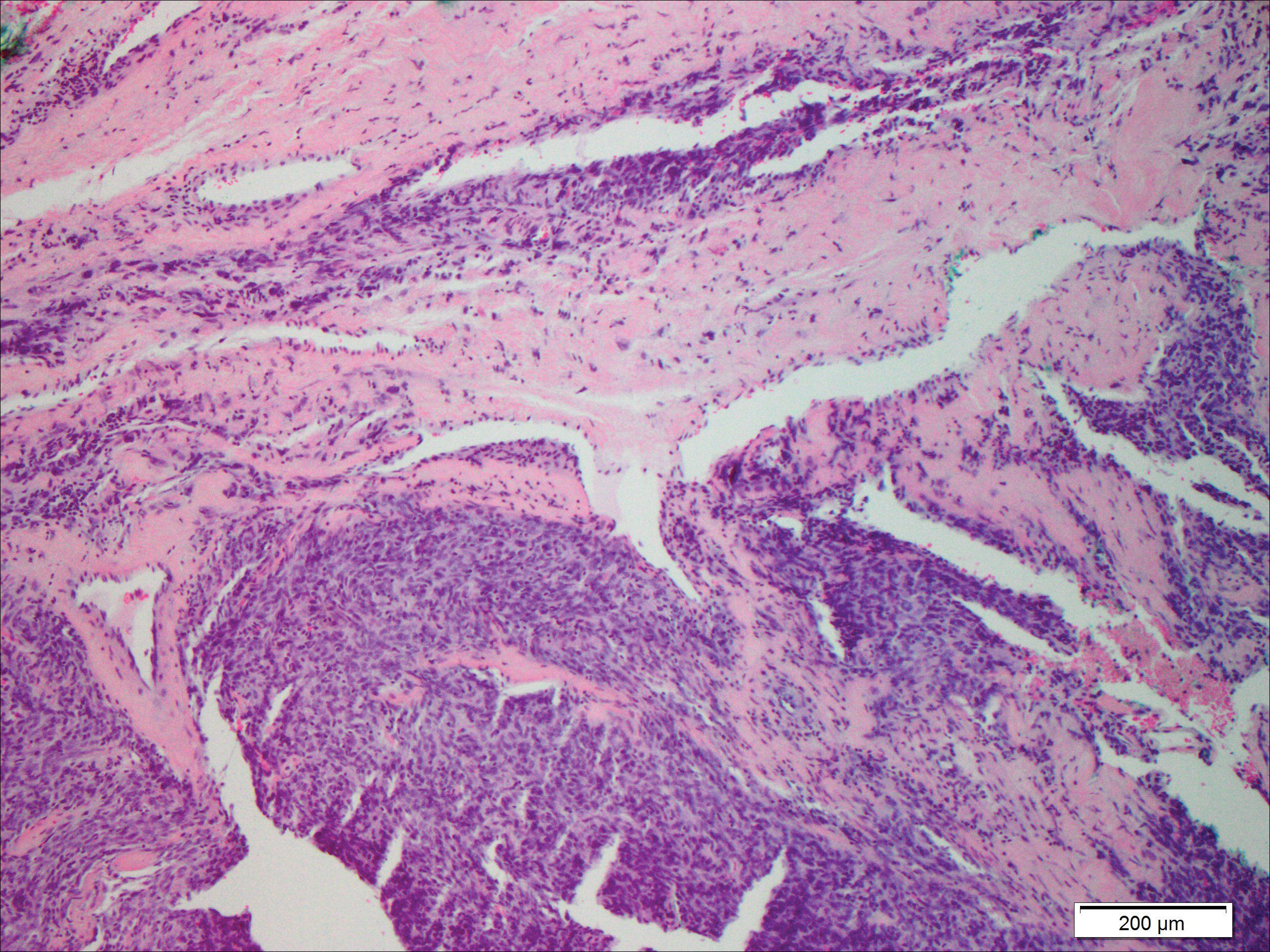

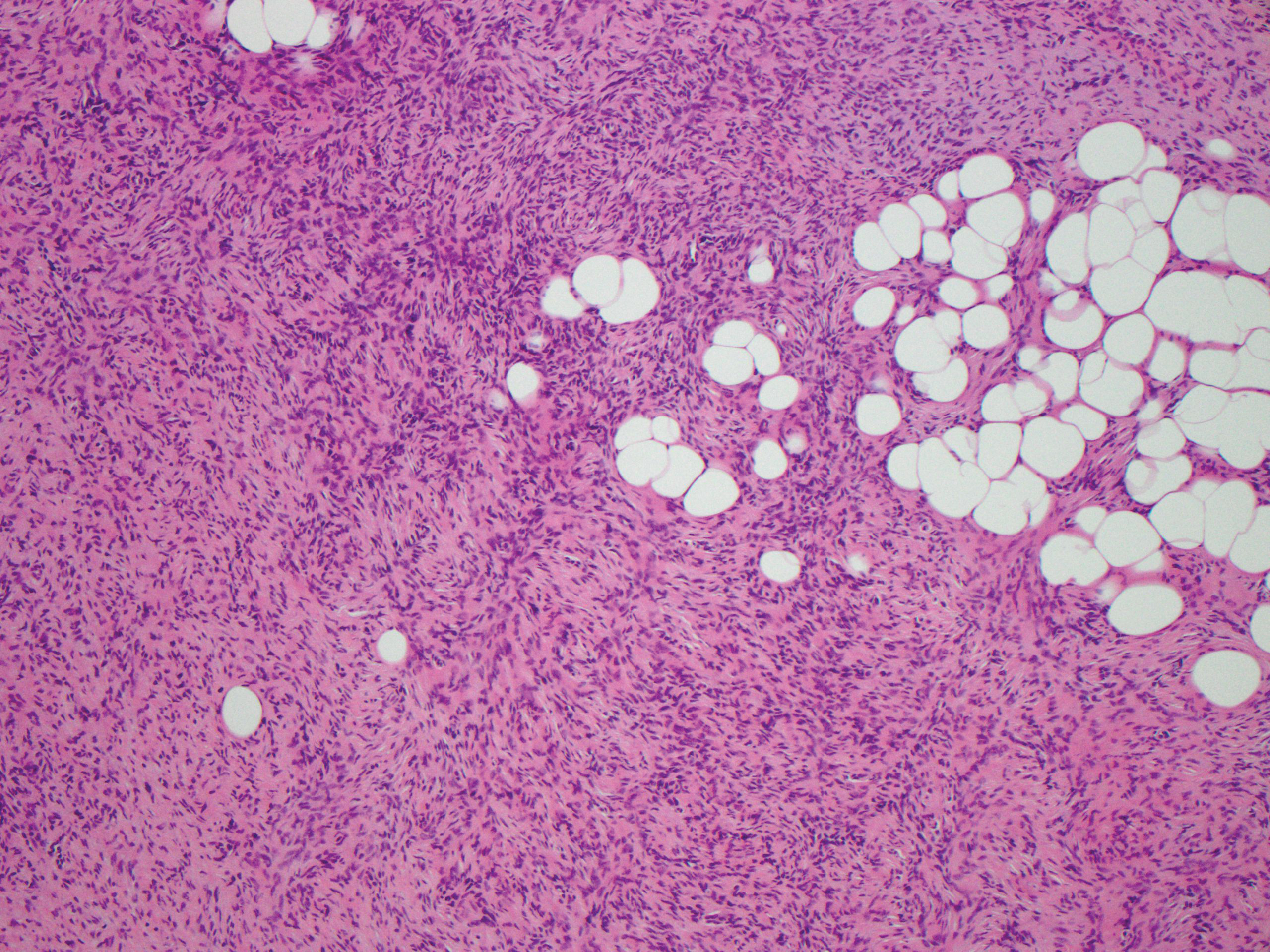

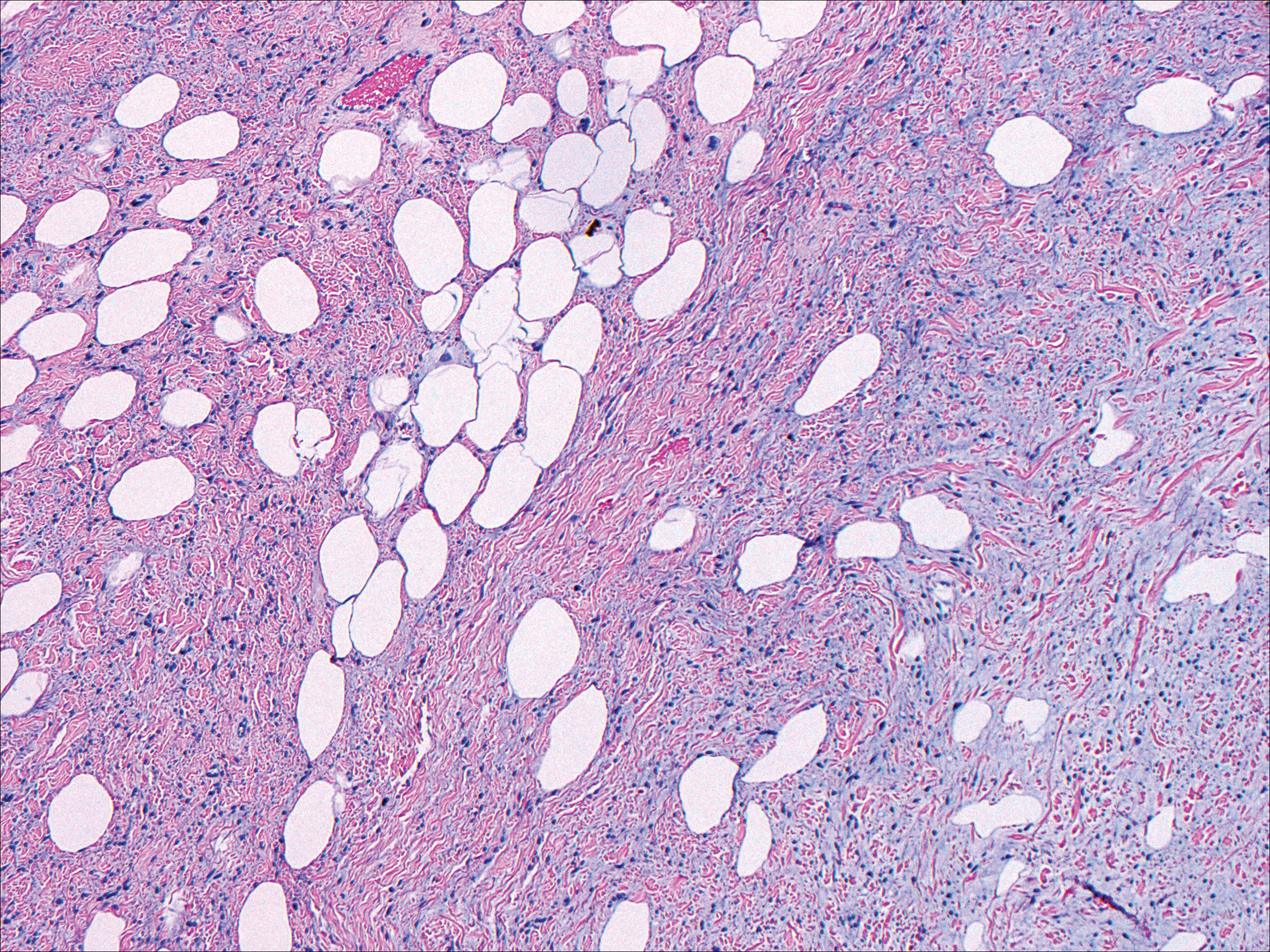

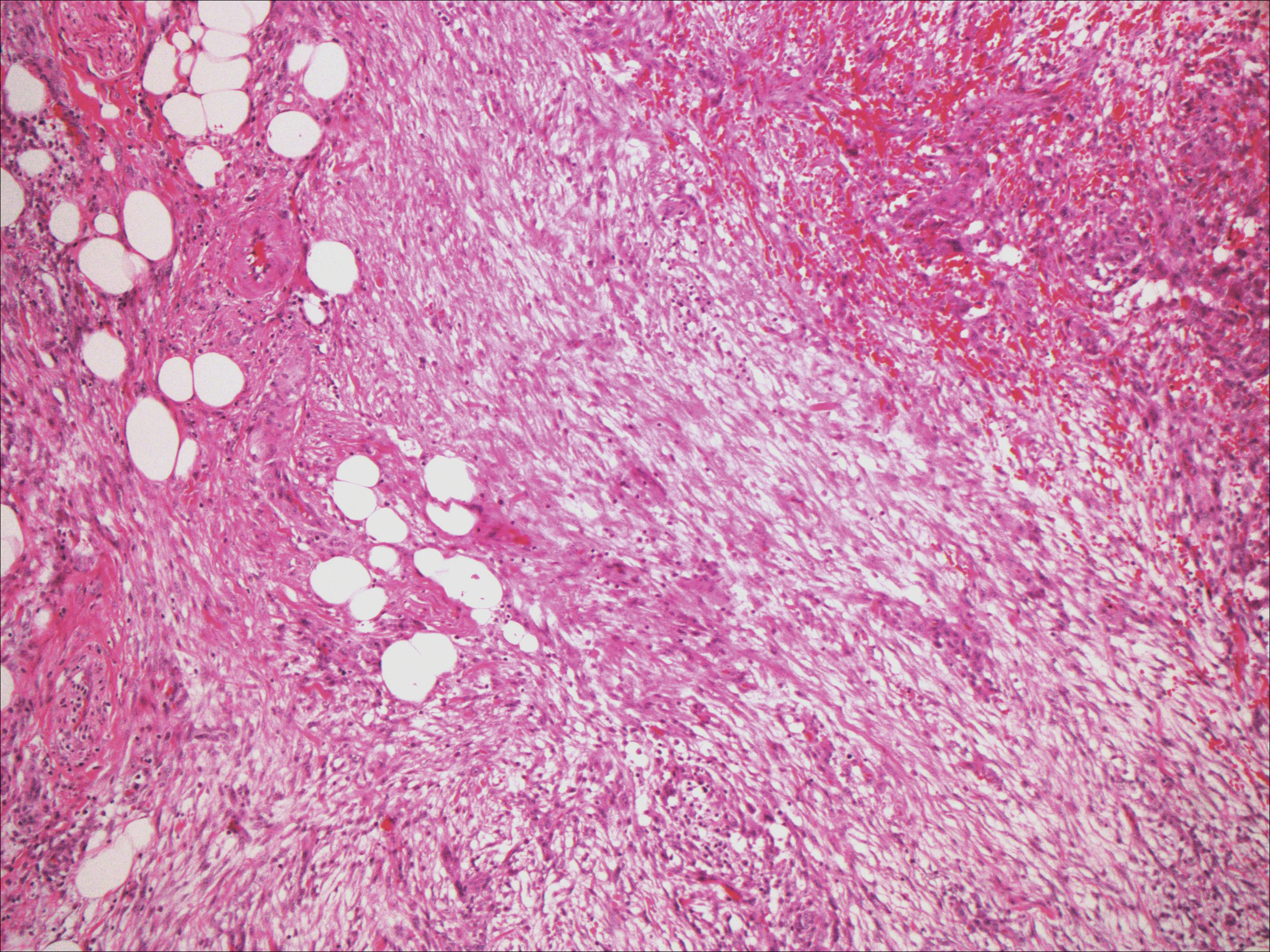

Primary mucinous carcinoma is thought to be derived from sweat glands, and select features such as decapitation secretion are more suggestive of apocrine than eccrine differentiation.5,8 On histopathology, PMC classically is described as nests of epithelial cells floating in lakes of extracellular mucin, primarily in the dermis and subcutis. The nests are composed of basaloid cells in solid to cribriform arrangements, usually with a low mitotic count and little nuclear atypia. These nests are suspended within periodic acid–Schiff positive mucinous pools partitioned by delicate fibrous septa. The mucin produced by PMC is sialomucin, and as such it is hyaluronidase resistant and sialidase labile.6 At least 1 report has been made of the presence of psammoma bodies in PMC.11

The neoplasm is characterized by an indolent course with frequent recurrence but rare metastasis.5,12 Treatment is primarily surgical, with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) offering improved tissue conservation and reduced recurrence rates.12 The diagnostic challenge lies in distinguishing PMC from a variety of metastatic mucinous internal malignancies that portend a notably greater morbidity and mortality to the patient. We describe a case of PMC, discuss the differentiation of PMC from metastatic mucinous carcinoma, and review the literature regarding treatment of this rare neoplasm.

A 65-year-old white woman was referred to our tertiary-care dermatologic surgery clinic for treatment of an incompletely excised mucinous carcinoma of the right lateral canthus (Figure 1). The clinically evident scar measured 0.5×0.5 cm. Although difficult to appreciate in Figure 1, a slight textural change of the surrounding skin, including the upper and lower eyelid, was apparent. Prior to her arrival to our clinic, the referring physician had completed a thorough review of systems and physical examination, which did not suggest an underlying malignancy. Computed tomography of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed a mass in the thyroid that was removed and found to be benign. The patient’s cutaneous lesion was therefore considered to be a PMC of the skin.

Given the prior incomplete excision of the lesion and its periocular location, we treated the patient with MMS. After 6 surgical stages, we continued to see evidence of the neoplasm as it tracked medially along the orbicularis oculi muscle (Figure 2). Due to the patient’s physical and emotional exhaustion at this point, we discontinued MMS and referred her to a colleague in plastic surgery for further excision of the remaining focus of positivity as well as repair. The final Mohs defect measured 4.2×4.0 cm (Figure 3). Approximately 2.3×1.0 cm of tissue in the area of remaining tumor was excised by plastic surgery, and the defect was repaired with a cervicofacial advancement flap closure of the right cheek and lower eyelid and full-thickness skin graft of the left upper eyelid. Histopathologic investigation found the additional tissue resected to be free of residual tumor.

To diagnose a patient with PMC, one must first rule out cutaneous metastasis of various internal malignancies that may appear similar on histopathology. A full clinical investigation consisting of a thorough history, physical examination, and appropriate radiographic imaging is required. Cutaneous metastases most commonly arise from the breast or gastrointestinal tract (GIT) but also can originate from the prostate, lungs, ovaries, pancreas, and kidneys.5 Histologically, PMC may be identical to metastatic adenocarcinoma.13 Location on the body may be a clue to a lesion’s origin, as metastases from a mucinous adenocarcinoma of the breast typically occur on the chest, breast, or axilla,5 whereas PMC primarily is found on the head and neck.

Certain histopathologic features may be suggestive of either a primary or metastatic etiology. Lesions arising in the skin may reveal an in situ component representing ductal hyperplasia, atypical ductal hyperplasia, or ductal carcinoma in situ. Identification of an in situ component defines a cutaneous primary neoplasm, but its absence does not exclude PMC.5 Additionally, metastatic lesions from the GIT typically have greater pleomorphism and “dirty” necrosis defined as eosinophilic foci containing nuclear debris.5

The expression pattern of cytokeratins (CKs) also can be suggestive. Primary mucinous carcinoma and metastatic breast adenocarcinoma are both CK7+ and CK20−. By contrast, mucinous adenocarcinoma of the GIT stains CK20+ and CK7−.14 Another marker that stains PMC is CK5 and CK6, though infrequently present. Levy et al15 reported positive staining for CK5 and CK6 in only 1 of 5 PMC cases. Positive staining for CK5 and CK6 has not been reported in any metastatic mucinous carcinoma.

The role of p63 immunostaining in the setting of mucinous carcinoma is controversial.16-18 Some practi-tioners have reported using p63 immunostaining to assist in establishing the diagnosis of PMC but only after performing a clinical workup to search for any primary sites of mucinous carcinoma in other organs.11 Other studies, however, have found select metastatic lesions from the breast17,18 and GIT18 to stain positively with p63. It is important to remember that these clinical and pathologic features are only suggestive of the primary etiology and are not replacement for a full clinical investigation.

Primary mucinous carcinoma is considered an indolent tumor with the majority of patient morbidity attributable to local recurrence and regional metastasis. Although uncommon, regional and distant metastasis rates have been reported to be 11% and 3%, respectively.19 Direct lymphatic invasion has been reported and indicates a more aggressive tumor with shorter recurrence-free intervals and predicts nodal metastases. Paradela et al20 recommended the use of D2-40, a monoclonal antibody and specific marker for lymphatic endothelium, to detect lymphatic invasion, particularly in node-negative primary tumors.

In one case of PMC on the jaw of a 39-year-old Japanese man, no recurrence or metastases were discovered until the 11th year of follow-up. At that time, he was found to have lung and bone metastases and died after 3 years.21 Other investigators report death occurring 4 to 24 months following diagnosis of distant metastases.7,22 Direct extension of the tumor into skeletal muscle, periosteum, bone, and dura also has been documented.7

Treatment principally is surgical, with PMC known to be resistant to both chemotherapy and radiation therapy.19,22 The recommended margins for simple excision range from 1 to 2 cm, but this method of treatment yields recurrence rates upward of 30% to 40%, especially for lesions located on the eyelid.12,13 First utilized in PMC of the eyelid to conserve tissue, MMS is rapidly becoming the treatment of choice because of its notably improved recurrence rate. A case series of 4 PMCs of the eyelid treated via MMS or frozen section control found the recurrence rate to be 7%.23 Another report of 2 cases of PMC treated by MMS reported no recurrence after 42 and 26 months.13 Ortiz et al7 reported an additional case of a patient treated by MMS that was recurrence free for 30 months at the time of publication. Further investigation is required to definitively recommend MMS on the basis of improved recurrence rate but should now be considered standard of care in recurrent, sizeable, or eyelid PMC.

Despite its ascension as treatment of choice in many cases of PMC, MMS is not without its risk of metastasis and recurrence. Tam et al24 reported a case of PMC with multiple recurrences and metastases following 3 simple excisions and 2 excisions via MMS. Although the lesion’s previously recurrent nature increased the likelihood of failure of MMS, this case demonstrates that all patients should be followed periodically after the treatment of PMC.

We presented a case of PMC in which standard surgical margins would have been insufficient to clear the lesion. Mohs micrographic surgery was used to remove the majority of the tumor. As is common in PMC, the lesion was indolent and periocular in location. It also was incompletely excised due to notable subclinical extension, which is common for PMC. The distinction of PMC from metastatic mucinous carcinoma is paramount but sometimes difficult. Randomized controlled trials are lacking with regards to preferred method of treatment, but MMS has shown benefit and should be considered for recurrent lesions and lesions in cosmetically sensitive areas.

- Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrom K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-245.

- Martinez SR, Young SE. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a review. Int J Oncol. 2005;2:432-437.

- Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-880.

- Marra DE, Schanbacher CF, Torres A. Mohs micrographic surgery of primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma using immunohistochemistry for margin control. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:799-802.

- Kazakov DV, Suster S, LeBoit PE, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin, primary, and secondary: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum of primary cutaneous forms: homologies with mucinous lesions in the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:764-782.

- Mendoza S, Helwig EB. Mucinous (adenocystic) carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:68-78.

- Ortiz KJ, Gaughan MD, Bang RH, et al. A case of primary mucinous carcinoma of the scalp treated with Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:751-754.

- Bellezza G, Sidoni A, Bucciarelli E. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:166-170.

- Teng P, Muir J. Small primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma mimicking an early basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:3.

- Terada T, Sato Y, Furukawa K, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma initially diagnosed as metastatic adenocarcinoma. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2004;203:345-348.

- Kalebi A, Hale M. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: usefulness of p63 in excluding metastasis and first report of psammoma bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:510.

- Cabell CE, Helm KF, Sakol PJ, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma in a 54-year-old man. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:941-943.

- Cecchi R, Rapicano V. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: report of two cases treated with Mohs’ micrographic surgery. Australas J Dermatol. 2006;47:192-194.

- Eckert F, Schmid U, Hardmeier T, et al. Cytokeratin expression in mucinous sweat gland carcinomas: an immunohistochemical analysis of four cases. Histopathology. 1992;21:161-165.

- Levy G, Finkelstein A, McNiff JM. Immunohistochemical techniques to compare primary vs. metastatic mucinous carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:411-415.

- Ivan D, Hafeez Diwan A, Prieto VG. Expression of p63 in primary cutaneous adnexal neoplasms and adenocarcinoma metastatic to the skin. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:137-142.

- Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Expression of p63 in cutaneous metastases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:753-758.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613-620.

- Snow SN, Reizner GT. Mucinous eccrine carcinoma of the eyelid. Cancer. 1992;70:2099-2104.

- Paradela S, Castiñeiras I, Cuevas J, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin: evaluation of lymphatic invasion with D2-40. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:504-508.

- Miyasaka M, Tanaka R, Hirabayashi K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a case of metastasis after 10 years of disease-free interval. Eur J Plast Surg. 2009;32:189-193.

- Yeung KY, Stinson JC. Mucinous (adenocystic) carcinoma of sweat glands with widespread metastasis. case report with ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1977;39:2556-2562.

- Papalas JA, Proia AD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases and an update on recurrence rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1160-1165.

- Tam CC, Dare DM, DiGiovanni JJ, et al. Recurrent and metastatic primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma after excision and Mohs micrographic surgery. Cutis. 2011;87:245-248.

To the Editor:

Primary mucinous carcinoma (PMC) is an exceedingly rare adnexal tumor with an incidence of 0.07 cases per million individuals.1,2 First described by Lennox et al3 in 1952, this entity often presents as slow-growing, solitary nodules that often are soft on palpation but may have an indurated quality and range in color from reddish blue to flesh colored to white.4 Primary mucinous carcinoma most commonly is found on the eyelid (38%) but may affect other sites on the face (20.3%), scalp (16%), and axilla (10%).5 Historically, it has been thought to be more common among men; however, a 2005 large case series by Kazakov et al5 found that women were twice as likely to be affected. Primary mucinous carcinoma most frequently is diagnosed in the fifth through seventh decades of life, with a median age at onset of 63 years.6,7 Because of its rarity, PMC is most frequently confused clinically with basal cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, apocrine hidrocystoma, epidermoid cyst, Kaposi sarcoma, neuroma, lacrimal sac tumor, squamous cell carcinoma, granulomatous tumors, and metastatic adenocarcinoma.1,8-10

Primary mucinous carcinoma is thought to be derived from sweat glands, and select features such as decapitation secretion are more suggestive of apocrine than eccrine differentiation.5,8 On histopathology, PMC classically is described as nests of epithelial cells floating in lakes of extracellular mucin, primarily in the dermis and subcutis. The nests are composed of basaloid cells in solid to cribriform arrangements, usually with a low mitotic count and little nuclear atypia. These nests are suspended within periodic acid–Schiff positive mucinous pools partitioned by delicate fibrous septa. The mucin produced by PMC is sialomucin, and as such it is hyaluronidase resistant and sialidase labile.6 At least 1 report has been made of the presence of psammoma bodies in PMC.11

The neoplasm is characterized by an indolent course with frequent recurrence but rare metastasis.5,12 Treatment is primarily surgical, with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) offering improved tissue conservation and reduced recurrence rates.12 The diagnostic challenge lies in distinguishing PMC from a variety of metastatic mucinous internal malignancies that portend a notably greater morbidity and mortality to the patient. We describe a case of PMC, discuss the differentiation of PMC from metastatic mucinous carcinoma, and review the literature regarding treatment of this rare neoplasm.

A 65-year-old white woman was referred to our tertiary-care dermatologic surgery clinic for treatment of an incompletely excised mucinous carcinoma of the right lateral canthus (Figure 1). The clinically evident scar measured 0.5×0.5 cm. Although difficult to appreciate in Figure 1, a slight textural change of the surrounding skin, including the upper and lower eyelid, was apparent. Prior to her arrival to our clinic, the referring physician had completed a thorough review of systems and physical examination, which did not suggest an underlying malignancy. Computed tomography of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed a mass in the thyroid that was removed and found to be benign. The patient’s cutaneous lesion was therefore considered to be a PMC of the skin.

Given the prior incomplete excision of the lesion and its periocular location, we treated the patient with MMS. After 6 surgical stages, we continued to see evidence of the neoplasm as it tracked medially along the orbicularis oculi muscle (Figure 2). Due to the patient’s physical and emotional exhaustion at this point, we discontinued MMS and referred her to a colleague in plastic surgery for further excision of the remaining focus of positivity as well as repair. The final Mohs defect measured 4.2×4.0 cm (Figure 3). Approximately 2.3×1.0 cm of tissue in the area of remaining tumor was excised by plastic surgery, and the defect was repaired with a cervicofacial advancement flap closure of the right cheek and lower eyelid and full-thickness skin graft of the left upper eyelid. Histopathologic investigation found the additional tissue resected to be free of residual tumor.

To diagnose a patient with PMC, one must first rule out cutaneous metastasis of various internal malignancies that may appear similar on histopathology. A full clinical investigation consisting of a thorough history, physical examination, and appropriate radiographic imaging is required. Cutaneous metastases most commonly arise from the breast or gastrointestinal tract (GIT) but also can originate from the prostate, lungs, ovaries, pancreas, and kidneys.5 Histologically, PMC may be identical to metastatic adenocarcinoma.13 Location on the body may be a clue to a lesion’s origin, as metastases from a mucinous adenocarcinoma of the breast typically occur on the chest, breast, or axilla,5 whereas PMC primarily is found on the head and neck.

Certain histopathologic features may be suggestive of either a primary or metastatic etiology. Lesions arising in the skin may reveal an in situ component representing ductal hyperplasia, atypical ductal hyperplasia, or ductal carcinoma in situ. Identification of an in situ component defines a cutaneous primary neoplasm, but its absence does not exclude PMC.5 Additionally, metastatic lesions from the GIT typically have greater pleomorphism and “dirty” necrosis defined as eosinophilic foci containing nuclear debris.5

The expression pattern of cytokeratins (CKs) also can be suggestive. Primary mucinous carcinoma and metastatic breast adenocarcinoma are both CK7+ and CK20−. By contrast, mucinous adenocarcinoma of the GIT stains CK20+ and CK7−.14 Another marker that stains PMC is CK5 and CK6, though infrequently present. Levy et al15 reported positive staining for CK5 and CK6 in only 1 of 5 PMC cases. Positive staining for CK5 and CK6 has not been reported in any metastatic mucinous carcinoma.

The role of p63 immunostaining in the setting of mucinous carcinoma is controversial.16-18 Some practi-tioners have reported using p63 immunostaining to assist in establishing the diagnosis of PMC but only after performing a clinical workup to search for any primary sites of mucinous carcinoma in other organs.11 Other studies, however, have found select metastatic lesions from the breast17,18 and GIT18 to stain positively with p63. It is important to remember that these clinical and pathologic features are only suggestive of the primary etiology and are not replacement for a full clinical investigation.

Primary mucinous carcinoma is considered an indolent tumor with the majority of patient morbidity attributable to local recurrence and regional metastasis. Although uncommon, regional and distant metastasis rates have been reported to be 11% and 3%, respectively.19 Direct lymphatic invasion has been reported and indicates a more aggressive tumor with shorter recurrence-free intervals and predicts nodal metastases. Paradela et al20 recommended the use of D2-40, a monoclonal antibody and specific marker for lymphatic endothelium, to detect lymphatic invasion, particularly in node-negative primary tumors.

In one case of PMC on the jaw of a 39-year-old Japanese man, no recurrence or metastases were discovered until the 11th year of follow-up. At that time, he was found to have lung and bone metastases and died after 3 years.21 Other investigators report death occurring 4 to 24 months following diagnosis of distant metastases.7,22 Direct extension of the tumor into skeletal muscle, periosteum, bone, and dura also has been documented.7

Treatment principally is surgical, with PMC known to be resistant to both chemotherapy and radiation therapy.19,22 The recommended margins for simple excision range from 1 to 2 cm, but this method of treatment yields recurrence rates upward of 30% to 40%, especially for lesions located on the eyelid.12,13 First utilized in PMC of the eyelid to conserve tissue, MMS is rapidly becoming the treatment of choice because of its notably improved recurrence rate. A case series of 4 PMCs of the eyelid treated via MMS or frozen section control found the recurrence rate to be 7%.23 Another report of 2 cases of PMC treated by MMS reported no recurrence after 42 and 26 months.13 Ortiz et al7 reported an additional case of a patient treated by MMS that was recurrence free for 30 months at the time of publication. Further investigation is required to definitively recommend MMS on the basis of improved recurrence rate but should now be considered standard of care in recurrent, sizeable, or eyelid PMC.

Despite its ascension as treatment of choice in many cases of PMC, MMS is not without its risk of metastasis and recurrence. Tam et al24 reported a case of PMC with multiple recurrences and metastases following 3 simple excisions and 2 excisions via MMS. Although the lesion’s previously recurrent nature increased the likelihood of failure of MMS, this case demonstrates that all patients should be followed periodically after the treatment of PMC.

We presented a case of PMC in which standard surgical margins would have been insufficient to clear the lesion. Mohs micrographic surgery was used to remove the majority of the tumor. As is common in PMC, the lesion was indolent and periocular in location. It also was incompletely excised due to notable subclinical extension, which is common for PMC. The distinction of PMC from metastatic mucinous carcinoma is paramount but sometimes difficult. Randomized controlled trials are lacking with regards to preferred method of treatment, but MMS has shown benefit and should be considered for recurrent lesions and lesions in cosmetically sensitive areas.

To the Editor:

Primary mucinous carcinoma (PMC) is an exceedingly rare adnexal tumor with an incidence of 0.07 cases per million individuals.1,2 First described by Lennox et al3 in 1952, this entity often presents as slow-growing, solitary nodules that often are soft on palpation but may have an indurated quality and range in color from reddish blue to flesh colored to white.4 Primary mucinous carcinoma most commonly is found on the eyelid (38%) but may affect other sites on the face (20.3%), scalp (16%), and axilla (10%).5 Historically, it has been thought to be more common among men; however, a 2005 large case series by Kazakov et al5 found that women were twice as likely to be affected. Primary mucinous carcinoma most frequently is diagnosed in the fifth through seventh decades of life, with a median age at onset of 63 years.6,7 Because of its rarity, PMC is most frequently confused clinically with basal cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, apocrine hidrocystoma, epidermoid cyst, Kaposi sarcoma, neuroma, lacrimal sac tumor, squamous cell carcinoma, granulomatous tumors, and metastatic adenocarcinoma.1,8-10

Primary mucinous carcinoma is thought to be derived from sweat glands, and select features such as decapitation secretion are more suggestive of apocrine than eccrine differentiation.5,8 On histopathology, PMC classically is described as nests of epithelial cells floating in lakes of extracellular mucin, primarily in the dermis and subcutis. The nests are composed of basaloid cells in solid to cribriform arrangements, usually with a low mitotic count and little nuclear atypia. These nests are suspended within periodic acid–Schiff positive mucinous pools partitioned by delicate fibrous septa. The mucin produced by PMC is sialomucin, and as such it is hyaluronidase resistant and sialidase labile.6 At least 1 report has been made of the presence of psammoma bodies in PMC.11

The neoplasm is characterized by an indolent course with frequent recurrence but rare metastasis.5,12 Treatment is primarily surgical, with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) offering improved tissue conservation and reduced recurrence rates.12 The diagnostic challenge lies in distinguishing PMC from a variety of metastatic mucinous internal malignancies that portend a notably greater morbidity and mortality to the patient. We describe a case of PMC, discuss the differentiation of PMC from metastatic mucinous carcinoma, and review the literature regarding treatment of this rare neoplasm.

A 65-year-old white woman was referred to our tertiary-care dermatologic surgery clinic for treatment of an incompletely excised mucinous carcinoma of the right lateral canthus (Figure 1). The clinically evident scar measured 0.5×0.5 cm. Although difficult to appreciate in Figure 1, a slight textural change of the surrounding skin, including the upper and lower eyelid, was apparent. Prior to her arrival to our clinic, the referring physician had completed a thorough review of systems and physical examination, which did not suggest an underlying malignancy. Computed tomography of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed a mass in the thyroid that was removed and found to be benign. The patient’s cutaneous lesion was therefore considered to be a PMC of the skin.

Given the prior incomplete excision of the lesion and its periocular location, we treated the patient with MMS. After 6 surgical stages, we continued to see evidence of the neoplasm as it tracked medially along the orbicularis oculi muscle (Figure 2). Due to the patient’s physical and emotional exhaustion at this point, we discontinued MMS and referred her to a colleague in plastic surgery for further excision of the remaining focus of positivity as well as repair. The final Mohs defect measured 4.2×4.0 cm (Figure 3). Approximately 2.3×1.0 cm of tissue in the area of remaining tumor was excised by plastic surgery, and the defect was repaired with a cervicofacial advancement flap closure of the right cheek and lower eyelid and full-thickness skin graft of the left upper eyelid. Histopathologic investigation found the additional tissue resected to be free of residual tumor.

To diagnose a patient with PMC, one must first rule out cutaneous metastasis of various internal malignancies that may appear similar on histopathology. A full clinical investigation consisting of a thorough history, physical examination, and appropriate radiographic imaging is required. Cutaneous metastases most commonly arise from the breast or gastrointestinal tract (GIT) but also can originate from the prostate, lungs, ovaries, pancreas, and kidneys.5 Histologically, PMC may be identical to metastatic adenocarcinoma.13 Location on the body may be a clue to a lesion’s origin, as metastases from a mucinous adenocarcinoma of the breast typically occur on the chest, breast, or axilla,5 whereas PMC primarily is found on the head and neck.

Certain histopathologic features may be suggestive of either a primary or metastatic etiology. Lesions arising in the skin may reveal an in situ component representing ductal hyperplasia, atypical ductal hyperplasia, or ductal carcinoma in situ. Identification of an in situ component defines a cutaneous primary neoplasm, but its absence does not exclude PMC.5 Additionally, metastatic lesions from the GIT typically have greater pleomorphism and “dirty” necrosis defined as eosinophilic foci containing nuclear debris.5

The expression pattern of cytokeratins (CKs) also can be suggestive. Primary mucinous carcinoma and metastatic breast adenocarcinoma are both CK7+ and CK20−. By contrast, mucinous adenocarcinoma of the GIT stains CK20+ and CK7−.14 Another marker that stains PMC is CK5 and CK6, though infrequently present. Levy et al15 reported positive staining for CK5 and CK6 in only 1 of 5 PMC cases. Positive staining for CK5 and CK6 has not been reported in any metastatic mucinous carcinoma.

The role of p63 immunostaining in the setting of mucinous carcinoma is controversial.16-18 Some practi-tioners have reported using p63 immunostaining to assist in establishing the diagnosis of PMC but only after performing a clinical workup to search for any primary sites of mucinous carcinoma in other organs.11 Other studies, however, have found select metastatic lesions from the breast17,18 and GIT18 to stain positively with p63. It is important to remember that these clinical and pathologic features are only suggestive of the primary etiology and are not replacement for a full clinical investigation.

Primary mucinous carcinoma is considered an indolent tumor with the majority of patient morbidity attributable to local recurrence and regional metastasis. Although uncommon, regional and distant metastasis rates have been reported to be 11% and 3%, respectively.19 Direct lymphatic invasion has been reported and indicates a more aggressive tumor with shorter recurrence-free intervals and predicts nodal metastases. Paradela et al20 recommended the use of D2-40, a monoclonal antibody and specific marker for lymphatic endothelium, to detect lymphatic invasion, particularly in node-negative primary tumors.

In one case of PMC on the jaw of a 39-year-old Japanese man, no recurrence or metastases were discovered until the 11th year of follow-up. At that time, he was found to have lung and bone metastases and died after 3 years.21 Other investigators report death occurring 4 to 24 months following diagnosis of distant metastases.7,22 Direct extension of the tumor into skeletal muscle, periosteum, bone, and dura also has been documented.7

Treatment principally is surgical, with PMC known to be resistant to both chemotherapy and radiation therapy.19,22 The recommended margins for simple excision range from 1 to 2 cm, but this method of treatment yields recurrence rates upward of 30% to 40%, especially for lesions located on the eyelid.12,13 First utilized in PMC of the eyelid to conserve tissue, MMS is rapidly becoming the treatment of choice because of its notably improved recurrence rate. A case series of 4 PMCs of the eyelid treated via MMS or frozen section control found the recurrence rate to be 7%.23 Another report of 2 cases of PMC treated by MMS reported no recurrence after 42 and 26 months.13 Ortiz et al7 reported an additional case of a patient treated by MMS that was recurrence free for 30 months at the time of publication. Further investigation is required to definitively recommend MMS on the basis of improved recurrence rate but should now be considered standard of care in recurrent, sizeable, or eyelid PMC.

Despite its ascension as treatment of choice in many cases of PMC, MMS is not without its risk of metastasis and recurrence. Tam et al24 reported a case of PMC with multiple recurrences and metastases following 3 simple excisions and 2 excisions via MMS. Although the lesion’s previously recurrent nature increased the likelihood of failure of MMS, this case demonstrates that all patients should be followed periodically after the treatment of PMC.

We presented a case of PMC in which standard surgical margins would have been insufficient to clear the lesion. Mohs micrographic surgery was used to remove the majority of the tumor. As is common in PMC, the lesion was indolent and periocular in location. It also was incompletely excised due to notable subclinical extension, which is common for PMC. The distinction of PMC from metastatic mucinous carcinoma is paramount but sometimes difficult. Randomized controlled trials are lacking with regards to preferred method of treatment, but MMS has shown benefit and should be considered for recurrent lesions and lesions in cosmetically sensitive areas.

- Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrom K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-245.

- Martinez SR, Young SE. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a review. Int J Oncol. 2005;2:432-437.

- Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-880.

- Marra DE, Schanbacher CF, Torres A. Mohs micrographic surgery of primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma using immunohistochemistry for margin control. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:799-802.

- Kazakov DV, Suster S, LeBoit PE, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin, primary, and secondary: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum of primary cutaneous forms: homologies with mucinous lesions in the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:764-782.

- Mendoza S, Helwig EB. Mucinous (adenocystic) carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:68-78.

- Ortiz KJ, Gaughan MD, Bang RH, et al. A case of primary mucinous carcinoma of the scalp treated with Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:751-754.

- Bellezza G, Sidoni A, Bucciarelli E. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:166-170.

- Teng P, Muir J. Small primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma mimicking an early basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:3.

- Terada T, Sato Y, Furukawa K, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma initially diagnosed as metastatic adenocarcinoma. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2004;203:345-348.

- Kalebi A, Hale M. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: usefulness of p63 in excluding metastasis and first report of psammoma bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:510.

- Cabell CE, Helm KF, Sakol PJ, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma in a 54-year-old man. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:941-943.

- Cecchi R, Rapicano V. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: report of two cases treated with Mohs’ micrographic surgery. Australas J Dermatol. 2006;47:192-194.

- Eckert F, Schmid U, Hardmeier T, et al. Cytokeratin expression in mucinous sweat gland carcinomas: an immunohistochemical analysis of four cases. Histopathology. 1992;21:161-165.

- Levy G, Finkelstein A, McNiff JM. Immunohistochemical techniques to compare primary vs. metastatic mucinous carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:411-415.

- Ivan D, Hafeez Diwan A, Prieto VG. Expression of p63 in primary cutaneous adnexal neoplasms and adenocarcinoma metastatic to the skin. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:137-142.

- Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Expression of p63 in cutaneous metastases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:753-758.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613-620.

- Snow SN, Reizner GT. Mucinous eccrine carcinoma of the eyelid. Cancer. 1992;70:2099-2104.

- Paradela S, Castiñeiras I, Cuevas J, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin: evaluation of lymphatic invasion with D2-40. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:504-508.

- Miyasaka M, Tanaka R, Hirabayashi K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a case of metastasis after 10 years of disease-free interval. Eur J Plast Surg. 2009;32:189-193.

- Yeung KY, Stinson JC. Mucinous (adenocystic) carcinoma of sweat glands with widespread metastasis. case report with ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1977;39:2556-2562.

- Papalas JA, Proia AD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases and an update on recurrence rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1160-1165.

- Tam CC, Dare DM, DiGiovanni JJ, et al. Recurrent and metastatic primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma after excision and Mohs micrographic surgery. Cutis. 2011;87:245-248.

- Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrom K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-245.

- Martinez SR, Young SE. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a review. Int J Oncol. 2005;2:432-437.

- Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-880.

- Marra DE, Schanbacher CF, Torres A. Mohs micrographic surgery of primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma using immunohistochemistry for margin control. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:799-802.

- Kazakov DV, Suster S, LeBoit PE, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin, primary, and secondary: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum of primary cutaneous forms: homologies with mucinous lesions in the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:764-782.

- Mendoza S, Helwig EB. Mucinous (adenocystic) carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:68-78.

- Ortiz KJ, Gaughan MD, Bang RH, et al. A case of primary mucinous carcinoma of the scalp treated with Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:751-754.

- Bellezza G, Sidoni A, Bucciarelli E. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:166-170.

- Teng P, Muir J. Small primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma mimicking an early basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:3.

- Terada T, Sato Y, Furukawa K, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma initially diagnosed as metastatic adenocarcinoma. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2004;203:345-348.

- Kalebi A, Hale M. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: usefulness of p63 in excluding metastasis and first report of psammoma bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:510.

- Cabell CE, Helm KF, Sakol PJ, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma in a 54-year-old man. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:941-943.

- Cecchi R, Rapicano V. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: report of two cases treated with Mohs’ micrographic surgery. Australas J Dermatol. 2006;47:192-194.

- Eckert F, Schmid U, Hardmeier T, et al. Cytokeratin expression in mucinous sweat gland carcinomas: an immunohistochemical analysis of four cases. Histopathology. 1992;21:161-165.

- Levy G, Finkelstein A, McNiff JM. Immunohistochemical techniques to compare primary vs. metastatic mucinous carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:411-415.

- Ivan D, Hafeez Diwan A, Prieto VG. Expression of p63 in primary cutaneous adnexal neoplasms and adenocarcinoma metastatic to the skin. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:137-142.

- Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Expression of p63 in cutaneous metastases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:753-758.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613-620.

- Snow SN, Reizner GT. Mucinous eccrine carcinoma of the eyelid. Cancer. 1992;70:2099-2104.

- Paradela S, Castiñeiras I, Cuevas J, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin: evaluation of lymphatic invasion with D2-40. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:504-508.

- Miyasaka M, Tanaka R, Hirabayashi K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a case of metastasis after 10 years of disease-free interval. Eur J Plast Surg. 2009;32:189-193.

- Yeung KY, Stinson JC. Mucinous (adenocystic) carcinoma of sweat glands with widespread metastasis. case report with ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1977;39:2556-2562.

- Papalas JA, Proia AD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases and an update on recurrence rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1160-1165.

- Tam CC, Dare DM, DiGiovanni JJ, et al. Recurrent and metastatic primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma after excision and Mohs micrographic surgery. Cutis. 2011;87:245-248.

Practice Points

- Primary mucinous carcinoma (PMC) of the skin is a rare adnexal tumor.

- Prior to treatment, the diagnostic importance lies in distinguishing PMC from metastatic mucinous malignancies, which portend a poorer prognosis.

- Treatment primarily is surgical, with Mohs micrographic surgery offering improved tissue conservation and reduced recurrence rates.

Acrodermatitis Enteropathica in a Patient With Short Bowel Syndrome

To the Editor:

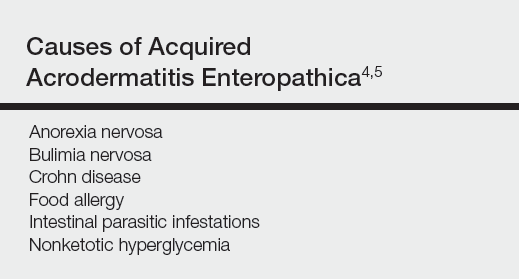

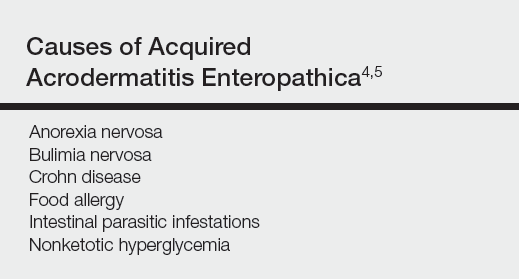

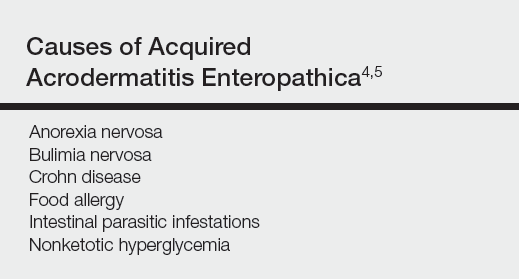

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is an inherited defect in zinc absorption that leads to hypozincemia. Its clinical presentation can vary based on serum zinc level and ranges from periorificial erosive dermatitis to psoriasiform dermatitis.1 Recognition of the cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency can lead to early intervention with zinc supplementation and prevention of long-term morbidity and even mortality. In our case, the coexistence of a bullous acral dermatosis with the additional feature of extensor digital dermatitis with fissuring suggests a diagnosis of AE and can alert the astute clinician to the need for testing of serum zinc levels and/or treatment with zinc supplementation. Causes of acquired zinc deficiency that have been reported in the literature include eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, Crohn disease, food allergy, intestinal parasitic infestations, and an inborn error of metabolism known as nonketotic hyperglycemia (Table).2-4

RELATED ARTICLE: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Secondary to Alcoholism

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and short bowel syndrome due to multiple small bowel obstructions with subsequent bowel resections who was on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented with bullae on the hands, shins, and feet. The patient initially noticed small erythematous macules on the hands and feet months prior to presentation. Three weeks prior to presentation, bullae started to form on the hands, mostly between the web spaces; dorsal aspects of the feet; and anterior aspects of the shins. The patient denied any oral ulcers. One day prior to presentation the patient was seen at an outside hospital and was started on prednisone 5 mg daily, oral clindamycin, mupirocin ointment, and nystatin-triamcinolone cream. These medications failed to improve her condition. On review of systems, the patient denied any fever, chills, eye pain, or dysuria.

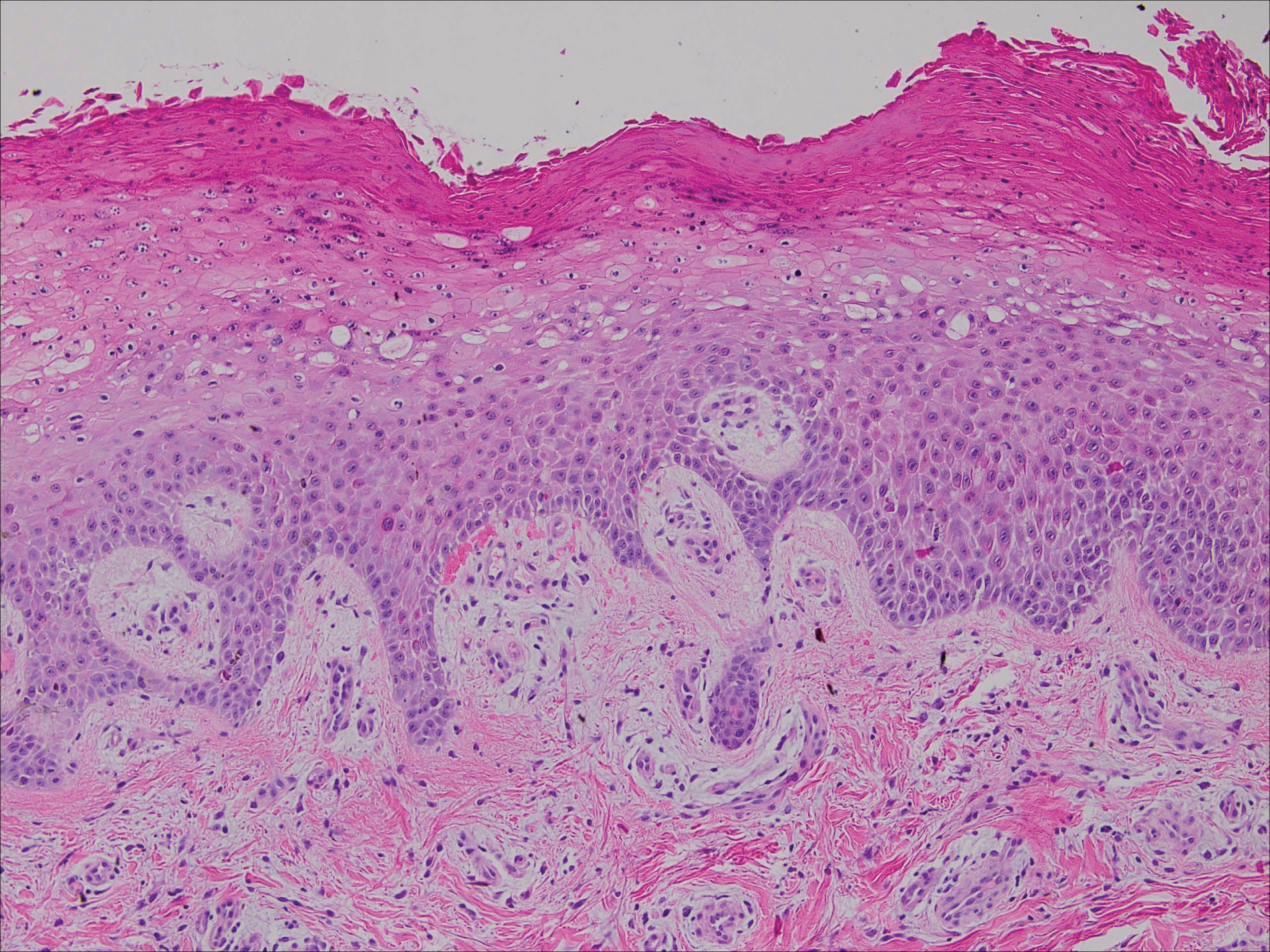

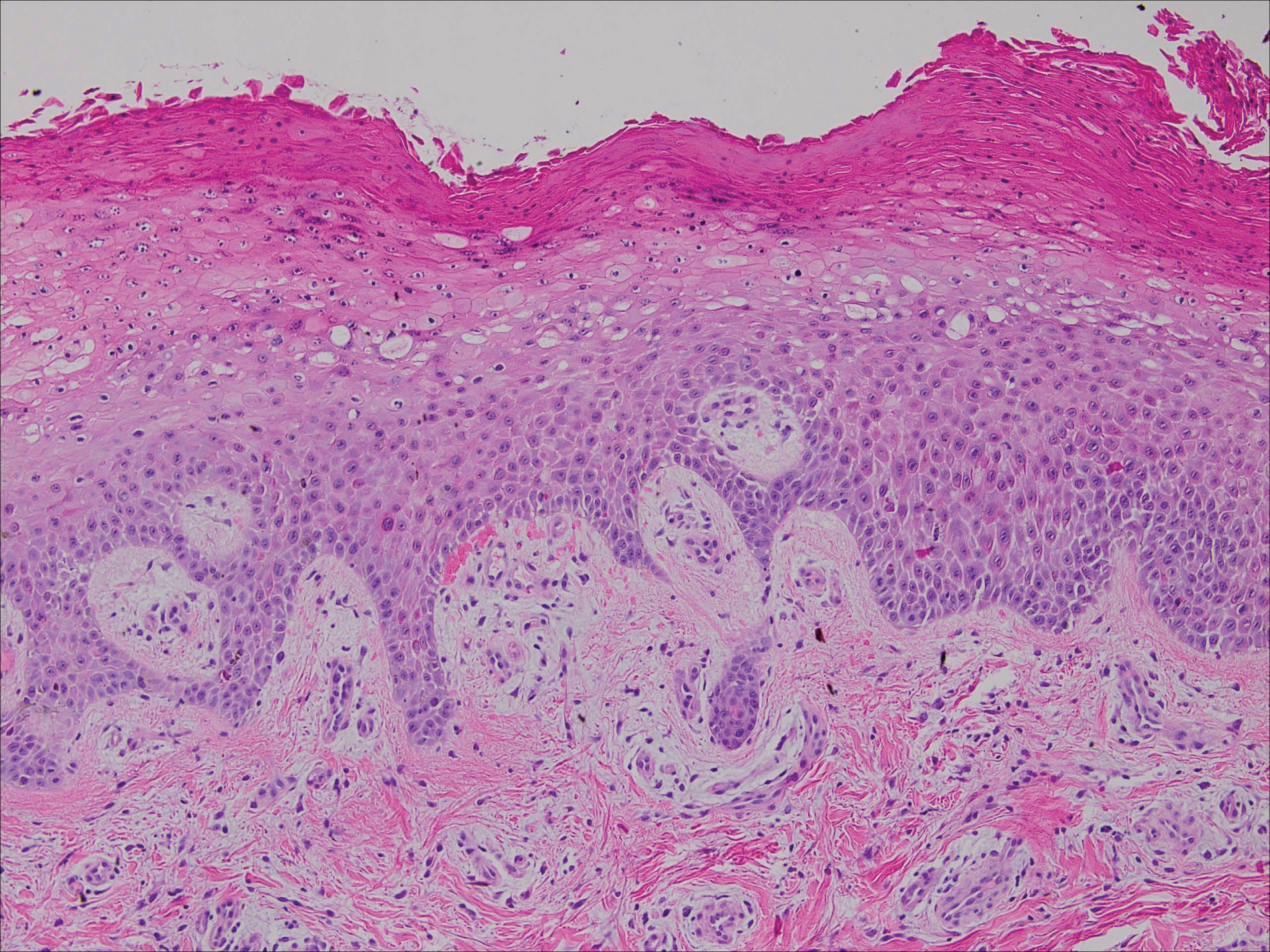

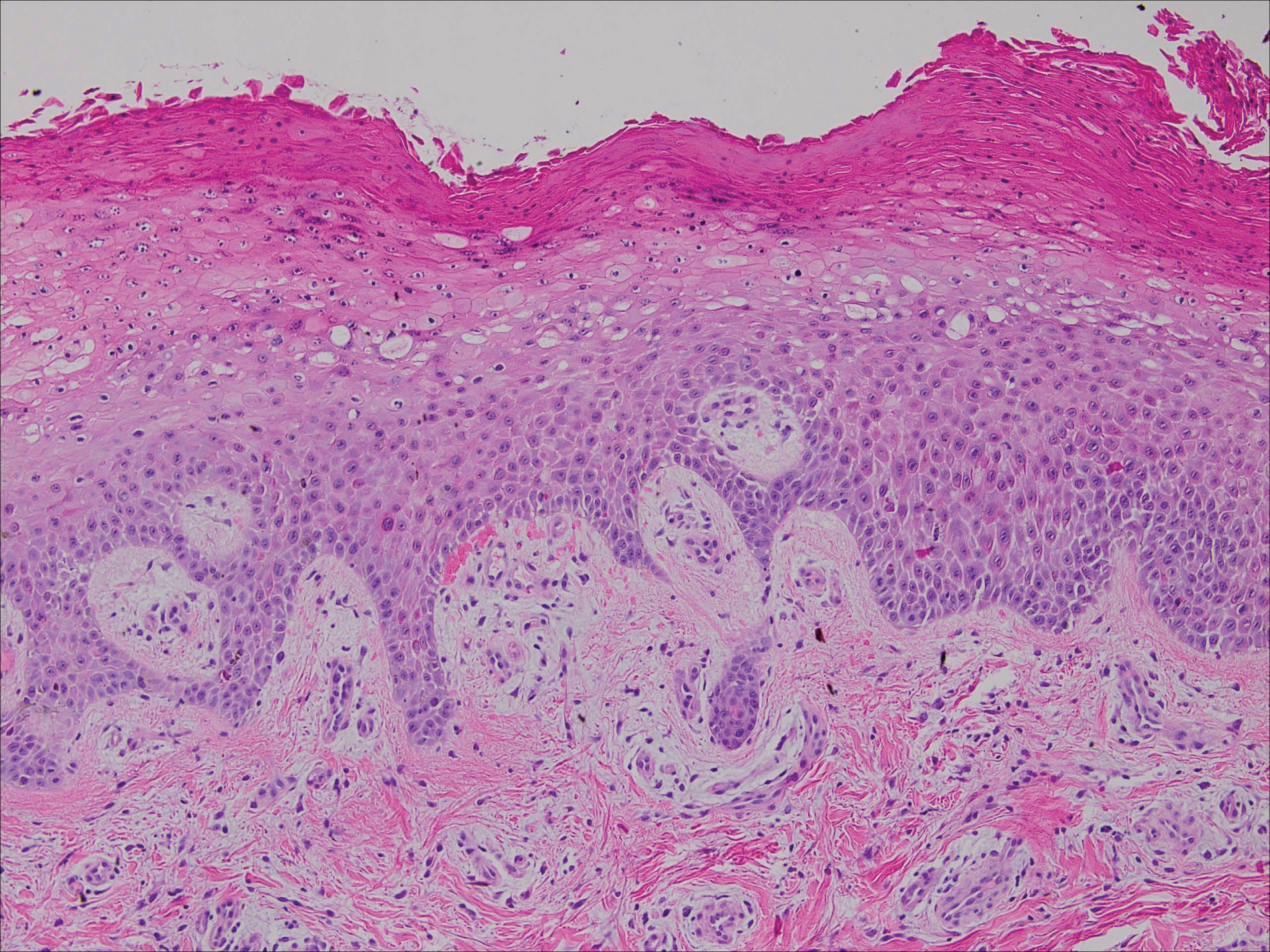

Upon initial presentation the patient appeared weak and fatigued, though vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed multiple flaccid bullae in the web spaces of the hands and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral wrists. She also had violaceous patches in the extensor creases of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints, which were strikingly symmetric (Figure 1). Prominent flaccid bullae and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts also were present on the bilateral shins and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 2). No oral ulcers were present. A punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the left foot revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with prominent ballooning degeneration and hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis (Figure 3); a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms.

Given the biopsy results and clinical presentation, a nutritional deficiency was suspected and serum levels of zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3 were assessed. Vitamins B1, B2

Zinc is an essential trace element and can be found in high concentration in foods such as shellfish, green vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.6 The majority of zinc is absorbed in the jejunum; as such, many cases of acquired zinc deficiency leading to AE are dueto disorders that affect the small intestine.2 Conditions that may lead to poor gastrointestinal zinc absorption include alcoholism, eating disorders, TPN, burns, surgery, and malignancies.2,7

Diagnosis typically is made based on characteristic clinical features, biopsy results, and a measurement of the serum zinc concentration. Although a low serum zinc level supports the diagnosis, serum zinc concentration is not a reliable indicator of body zinc stores and a normal serum zinc concentration does not rule out AE. The gold standard for diagnosis is the resolution of lesions after zinc supplementation.1 Notably, because the production of alkaline phosphatase is dependent on zinc, levels of this enzyme also may be low in cases of AE,6 as in our patient.

The clinical manifestations of AE can vary greatly; patients may initially present with eczematous pink scaly plaques, which may subsequently become vesicular, bullous, pustular, or desquamative. The lesions may develop over the arms and legs as well as the anogenital and periorificial areas.5 Other notable manifestations that may present early in the course of AE include angular cheilitis followed by paronychia. In patients who are not promptly treated, long-term zinc deficiency may lead to growth delay, mental slowing, poor wound healing, anemia, and anorexia.5 Of note, deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids may appear clinically similar to AE.2

Zinc replacement is the treatment of choice for patients with AE due to dietary deficiency, and replacement therapy should begin with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily of elemental zinc.5 Response to acquired AE with zinc supplementation often is rapid. Lesions tend to resolve within days to weeks depending on the degree of deficiency.2

Although AE is an uncommon dermatosis in the United States, it is an important diagnosis to make because its clinical features are fairly specific and early zinc supplementation allows for full resolution of the disease without permanent sequelae. The diagnosis of AE should be strongly considered when features of an acral bullous dermatosis are combined with a fissured dermatitis of extensor joints of the hands or elbows. It is particularly important to recognize that alcoholics, burn victims, postsurgical patients, and those with malignancies and eating disorders are at an increased risk for developing this nutritional deficiency.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal AK, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Suchithra N, Sreejith P, Pappachan JM, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:20.

- Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207-220.

- Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, et al. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:235-239.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism [published online October 30, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Cheshire H, Stather P, Vorster J. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency in a patient with pre-existing Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;3:41-43.

- Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:165-173.

To the Editor:

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is an inherited defect in zinc absorption that leads to hypozincemia. Its clinical presentation can vary based on serum zinc level and ranges from periorificial erosive dermatitis to psoriasiform dermatitis.1 Recognition of the cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency can lead to early intervention with zinc supplementation and prevention of long-term morbidity and even mortality. In our case, the coexistence of a bullous acral dermatosis with the additional feature of extensor digital dermatitis with fissuring suggests a diagnosis of AE and can alert the astute clinician to the need for testing of serum zinc levels and/or treatment with zinc supplementation. Causes of acquired zinc deficiency that have been reported in the literature include eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, Crohn disease, food allergy, intestinal parasitic infestations, and an inborn error of metabolism known as nonketotic hyperglycemia (Table).2-4

RELATED ARTICLE: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Secondary to Alcoholism

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and short bowel syndrome due to multiple small bowel obstructions with subsequent bowel resections who was on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented with bullae on the hands, shins, and feet. The patient initially noticed small erythematous macules on the hands and feet months prior to presentation. Three weeks prior to presentation, bullae started to form on the hands, mostly between the web spaces; dorsal aspects of the feet; and anterior aspects of the shins. The patient denied any oral ulcers. One day prior to presentation the patient was seen at an outside hospital and was started on prednisone 5 mg daily, oral clindamycin, mupirocin ointment, and nystatin-triamcinolone cream. These medications failed to improve her condition. On review of systems, the patient denied any fever, chills, eye pain, or dysuria.

Upon initial presentation the patient appeared weak and fatigued, though vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed multiple flaccid bullae in the web spaces of the hands and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral wrists. She also had violaceous patches in the extensor creases of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints, which were strikingly symmetric (Figure 1). Prominent flaccid bullae and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts also were present on the bilateral shins and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 2). No oral ulcers were present. A punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the left foot revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with prominent ballooning degeneration and hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis (Figure 3); a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms.

Given the biopsy results and clinical presentation, a nutritional deficiency was suspected and serum levels of zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3 were assessed. Vitamins B1, B2

Zinc is an essential trace element and can be found in high concentration in foods such as shellfish, green vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.6 The majority of zinc is absorbed in the jejunum; as such, many cases of acquired zinc deficiency leading to AE are dueto disorders that affect the small intestine.2 Conditions that may lead to poor gastrointestinal zinc absorption include alcoholism, eating disorders, TPN, burns, surgery, and malignancies.2,7

Diagnosis typically is made based on characteristic clinical features, biopsy results, and a measurement of the serum zinc concentration. Although a low serum zinc level supports the diagnosis, serum zinc concentration is not a reliable indicator of body zinc stores and a normal serum zinc concentration does not rule out AE. The gold standard for diagnosis is the resolution of lesions after zinc supplementation.1 Notably, because the production of alkaline phosphatase is dependent on zinc, levels of this enzyme also may be low in cases of AE,6 as in our patient.

The clinical manifestations of AE can vary greatly; patients may initially present with eczematous pink scaly plaques, which may subsequently become vesicular, bullous, pustular, or desquamative. The lesions may develop over the arms and legs as well as the anogenital and periorificial areas.5 Other notable manifestations that may present early in the course of AE include angular cheilitis followed by paronychia. In patients who are not promptly treated, long-term zinc deficiency may lead to growth delay, mental slowing, poor wound healing, anemia, and anorexia.5 Of note, deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids may appear clinically similar to AE.2

Zinc replacement is the treatment of choice for patients with AE due to dietary deficiency, and replacement therapy should begin with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily of elemental zinc.5 Response to acquired AE with zinc supplementation often is rapid. Lesions tend to resolve within days to weeks depending on the degree of deficiency.2

Although AE is an uncommon dermatosis in the United States, it is an important diagnosis to make because its clinical features are fairly specific and early zinc supplementation allows for full resolution of the disease without permanent sequelae. The diagnosis of AE should be strongly considered when features of an acral bullous dermatosis are combined with a fissured dermatitis of extensor joints of the hands or elbows. It is particularly important to recognize that alcoholics, burn victims, postsurgical patients, and those with malignancies and eating disorders are at an increased risk for developing this nutritional deficiency.

To the Editor:

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is an inherited defect in zinc absorption that leads to hypozincemia. Its clinical presentation can vary based on serum zinc level and ranges from periorificial erosive dermatitis to psoriasiform dermatitis.1 Recognition of the cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency can lead to early intervention with zinc supplementation and prevention of long-term morbidity and even mortality. In our case, the coexistence of a bullous acral dermatosis with the additional feature of extensor digital dermatitis with fissuring suggests a diagnosis of AE and can alert the astute clinician to the need for testing of serum zinc levels and/or treatment with zinc supplementation. Causes of acquired zinc deficiency that have been reported in the literature include eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, Crohn disease, food allergy, intestinal parasitic infestations, and an inborn error of metabolism known as nonketotic hyperglycemia (Table).2-4

RELATED ARTICLE: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Secondary to Alcoholism

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and short bowel syndrome due to multiple small bowel obstructions with subsequent bowel resections who was on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented with bullae on the hands, shins, and feet. The patient initially noticed small erythematous macules on the hands and feet months prior to presentation. Three weeks prior to presentation, bullae started to form on the hands, mostly between the web spaces; dorsal aspects of the feet; and anterior aspects of the shins. The patient denied any oral ulcers. One day prior to presentation the patient was seen at an outside hospital and was started on prednisone 5 mg daily, oral clindamycin, mupirocin ointment, and nystatin-triamcinolone cream. These medications failed to improve her condition. On review of systems, the patient denied any fever, chills, eye pain, or dysuria.

Upon initial presentation the patient appeared weak and fatigued, though vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed multiple flaccid bullae in the web spaces of the hands and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral wrists. She also had violaceous patches in the extensor creases of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints, which were strikingly symmetric (Figure 1). Prominent flaccid bullae and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts also were present on the bilateral shins and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 2). No oral ulcers were present. A punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the left foot revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with prominent ballooning degeneration and hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis (Figure 3); a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms.

Given the biopsy results and clinical presentation, a nutritional deficiency was suspected and serum levels of zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3 were assessed. Vitamins B1, B2

Zinc is an essential trace element and can be found in high concentration in foods such as shellfish, green vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.6 The majority of zinc is absorbed in the jejunum; as such, many cases of acquired zinc deficiency leading to AE are dueto disorders that affect the small intestine.2 Conditions that may lead to poor gastrointestinal zinc absorption include alcoholism, eating disorders, TPN, burns, surgery, and malignancies.2,7

Diagnosis typically is made based on characteristic clinical features, biopsy results, and a measurement of the serum zinc concentration. Although a low serum zinc level supports the diagnosis, serum zinc concentration is not a reliable indicator of body zinc stores and a normal serum zinc concentration does not rule out AE. The gold standard for diagnosis is the resolution of lesions after zinc supplementation.1 Notably, because the production of alkaline phosphatase is dependent on zinc, levels of this enzyme also may be low in cases of AE,6 as in our patient.

The clinical manifestations of AE can vary greatly; patients may initially present with eczematous pink scaly plaques, which may subsequently become vesicular, bullous, pustular, or desquamative. The lesions may develop over the arms and legs as well as the anogenital and periorificial areas.5 Other notable manifestations that may present early in the course of AE include angular cheilitis followed by paronychia. In patients who are not promptly treated, long-term zinc deficiency may lead to growth delay, mental slowing, poor wound healing, anemia, and anorexia.5 Of note, deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids may appear clinically similar to AE.2

Zinc replacement is the treatment of choice for patients with AE due to dietary deficiency, and replacement therapy should begin with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily of elemental zinc.5 Response to acquired AE with zinc supplementation often is rapid. Lesions tend to resolve within days to weeks depending on the degree of deficiency.2

Although AE is an uncommon dermatosis in the United States, it is an important diagnosis to make because its clinical features are fairly specific and early zinc supplementation allows for full resolution of the disease without permanent sequelae. The diagnosis of AE should be strongly considered when features of an acral bullous dermatosis are combined with a fissured dermatitis of extensor joints of the hands or elbows. It is particularly important to recognize that alcoholics, burn victims, postsurgical patients, and those with malignancies and eating disorders are at an increased risk for developing this nutritional deficiency.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal AK, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Suchithra N, Sreejith P, Pappachan JM, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:20.

- Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207-220.

- Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, et al. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:235-239.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism [published online October 30, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Cheshire H, Stather P, Vorster J. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency in a patient with pre-existing Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;3:41-43.

- Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:165-173.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal AK, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Suchithra N, Sreejith P, Pappachan JM, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:20.

- Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207-220.

- Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, et al. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:235-239.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism [published online October 30, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Cheshire H, Stather P, Vorster J. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency in a patient with pre-existing Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;3:41-43.

- Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:165-173.

Practice Points

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica can be a manifestation of zinc deficiency.

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica should be considered in patients with poor intestinal absorption of nutrients.

A Peek at Our November 2017 Issue

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Red Scaly Rash Following Tattoo Application

The Diagnosis: Isomorphic Psoriasis

Tattooing has become an increasingly popular trend among young people. Currently, there are no guidelines in the United States regulating the production of tattoo ink and pigments.1 Henna tattooing, a form of temporary skin painting, also has risks of allergic contact dermatitis from paraphenylenediamine dye.2 Complications following tattoo application include an allergic contact dermatitis to tattoo pigments, infection, granulomatous and lichenoid reactions, and skin disease localized to the tattooed area.3

Localized dermatosis arising in a traumatized area, or the Koebner phenomenon, was first described by Heinrich Koebner in 1877.4 He described the formation of psoriasiform lesions at the site of cutaneous trauma.5 These isomorphic lesions can occur in 25% of patients with psoriasis after trauma to the skin such as tattooing.6 Other dermatologic diseases that can present as an isomorphic response to tattooing include lichen planus, Darier disease, vitiligo, and autoimmune bullous disease.3,5,6

Various causes of trauma such as burns, insect bites, physical trauma, and needle trauma have been shown to produce new psoriatic lesions.6 The time period from trauma to formation of psoriasiform lesions usually ranges from 10 to 20 days; however, an initial reaction can occur as early as 3 days or as long as 2 years after trauma.4 Although the pathophysiology of the isomorphic response is not well known, it has been shown that nerve growth factor has a role. Raychaudhuri et al7 demonstrated the upregulation of nerve growth factor in the development of a psoriatic lesion, influencing keratinocyte proliferation, angiogenesis, and T-cell activation.

Physical trauma such as tattooing has been shown to cause an isomorphic response in psoriasis. We describe a case of isomorphic psoriasis in a patient after tattoo application. Our patient had a several-month history of well-controlled psoriasis prior to obtaining the new tattoo. Several days after receiving the tattoo, the patient reported an increase in psoriatic lesions, including at the site of the tattoo. The trauma causing the isomorphic response could have been either a response to the tattoo pigment or needle injury to the skin.6

Psoriasis and isomorphic lesions can be treated with topical corticosteroids as well as systemic and biologic agents. Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream with good response.8

- Haugh IM, Laumann SL, Laumann AE. Regulation of tattoo ink production and the tattoo business in the US. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:248-252.

- Marcoux D, Couture-Trudel PM, Rboulet-Delmas G, et al. Sensitization to paraphenylenediame from a streetside temporary tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:498-502.

- Bassi A, Campolmi P, Cannarozzo G, et al. Tattoo-associated skin reaction: the importance of an early diagnosis and proper treatment [published online July 23, 2014]. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:354608.

- Weiss G, Shemer A, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon: review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:241-248.

- Sagi L, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:231-236.

- Orzan OA, Popa LG, Vexler ES, et al. Tattoo-induced psoriasis. J Med Life. 2014;7:65-68.

- Raychaudhuri SP, Jiang WY, Raychaudhuri SK. Revisiting the Koebner phenomenon: role of NGF and its receptor system in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:961-971.

- Gottlieb AB. Therapeutic options in the treatment of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(1 suppl 1):S3-S16.

The Diagnosis: Isomorphic Psoriasis

Tattooing has become an increasingly popular trend among young people. Currently, there are no guidelines in the United States regulating the production of tattoo ink and pigments.1 Henna tattooing, a form of temporary skin painting, also has risks of allergic contact dermatitis from paraphenylenediamine dye.2 Complications following tattoo application include an allergic contact dermatitis to tattoo pigments, infection, granulomatous and lichenoid reactions, and skin disease localized to the tattooed area.3

Localized dermatosis arising in a traumatized area, or the Koebner phenomenon, was first described by Heinrich Koebner in 1877.4 He described the formation of psoriasiform lesions at the site of cutaneous trauma.5 These isomorphic lesions can occur in 25% of patients with psoriasis after trauma to the skin such as tattooing.6 Other dermatologic diseases that can present as an isomorphic response to tattooing include lichen planus, Darier disease, vitiligo, and autoimmune bullous disease.3,5,6

Various causes of trauma such as burns, insect bites, physical trauma, and needle trauma have been shown to produce new psoriatic lesions.6 The time period from trauma to formation of psoriasiform lesions usually ranges from 10 to 20 days; however, an initial reaction can occur as early as 3 days or as long as 2 years after trauma.4 Although the pathophysiology of the isomorphic response is not well known, it has been shown that nerve growth factor has a role. Raychaudhuri et al7 demonstrated the upregulation of nerve growth factor in the development of a psoriatic lesion, influencing keratinocyte proliferation, angiogenesis, and T-cell activation.

Physical trauma such as tattooing has been shown to cause an isomorphic response in psoriasis. We describe a case of isomorphic psoriasis in a patient after tattoo application. Our patient had a several-month history of well-controlled psoriasis prior to obtaining the new tattoo. Several days after receiving the tattoo, the patient reported an increase in psoriatic lesions, including at the site of the tattoo. The trauma causing the isomorphic response could have been either a response to the tattoo pigment or needle injury to the skin.6

Psoriasis and isomorphic lesions can be treated with topical corticosteroids as well as systemic and biologic agents. Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream with good response.8

The Diagnosis: Isomorphic Psoriasis

Tattooing has become an increasingly popular trend among young people. Currently, there are no guidelines in the United States regulating the production of tattoo ink and pigments.1 Henna tattooing, a form of temporary skin painting, also has risks of allergic contact dermatitis from paraphenylenediamine dye.2 Complications following tattoo application include an allergic contact dermatitis to tattoo pigments, infection, granulomatous and lichenoid reactions, and skin disease localized to the tattooed area.3

Localized dermatosis arising in a traumatized area, or the Koebner phenomenon, was first described by Heinrich Koebner in 1877.4 He described the formation of psoriasiform lesions at the site of cutaneous trauma.5 These isomorphic lesions can occur in 25% of patients with psoriasis after trauma to the skin such as tattooing.6 Other dermatologic diseases that can present as an isomorphic response to tattooing include lichen planus, Darier disease, vitiligo, and autoimmune bullous disease.3,5,6

Various causes of trauma such as burns, insect bites, physical trauma, and needle trauma have been shown to produce new psoriatic lesions.6 The time period from trauma to formation of psoriasiform lesions usually ranges from 10 to 20 days; however, an initial reaction can occur as early as 3 days or as long as 2 years after trauma.4 Although the pathophysiology of the isomorphic response is not well known, it has been shown that nerve growth factor has a role. Raychaudhuri et al7 demonstrated the upregulation of nerve growth factor in the development of a psoriatic lesion, influencing keratinocyte proliferation, angiogenesis, and T-cell activation.

Physical trauma such as tattooing has been shown to cause an isomorphic response in psoriasis. We describe a case of isomorphic psoriasis in a patient after tattoo application. Our patient had a several-month history of well-controlled psoriasis prior to obtaining the new tattoo. Several days after receiving the tattoo, the patient reported an increase in psoriatic lesions, including at the site of the tattoo. The trauma causing the isomorphic response could have been either a response to the tattoo pigment or needle injury to the skin.6

Psoriasis and isomorphic lesions can be treated with topical corticosteroids as well as systemic and biologic agents. Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream with good response.8

- Haugh IM, Laumann SL, Laumann AE. Regulation of tattoo ink production and the tattoo business in the US. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:248-252.

- Marcoux D, Couture-Trudel PM, Rboulet-Delmas G, et al. Sensitization to paraphenylenediame from a streetside temporary tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:498-502.

- Bassi A, Campolmi P, Cannarozzo G, et al. Tattoo-associated skin reaction: the importance of an early diagnosis and proper treatment [published online July 23, 2014]. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:354608.

- Weiss G, Shemer A, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon: review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:241-248.

- Sagi L, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:231-236.

- Orzan OA, Popa LG, Vexler ES, et al. Tattoo-induced psoriasis. J Med Life. 2014;7:65-68.

- Raychaudhuri SP, Jiang WY, Raychaudhuri SK. Revisiting the Koebner phenomenon: role of NGF and its receptor system in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:961-971.

- Gottlieb AB. Therapeutic options in the treatment of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(1 suppl 1):S3-S16.

- Haugh IM, Laumann SL, Laumann AE. Regulation of tattoo ink production and the tattoo business in the US. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:248-252.

- Marcoux D, Couture-Trudel PM, Rboulet-Delmas G, et al. Sensitization to paraphenylenediame from a streetside temporary tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:498-502.

- Bassi A, Campolmi P, Cannarozzo G, et al. Tattoo-associated skin reaction: the importance of an early diagnosis and proper treatment [published online July 23, 2014]. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:354608.

- Weiss G, Shemer A, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon: review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:241-248.

- Sagi L, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:231-236.

- Orzan OA, Popa LG, Vexler ES, et al. Tattoo-induced psoriasis. J Med Life. 2014;7:65-68.

- Raychaudhuri SP, Jiang WY, Raychaudhuri SK. Revisiting the Koebner phenomenon: role of NGF and its receptor system in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:961-971.

- Gottlieb AB. Therapeutic options in the treatment of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(1 suppl 1):S3-S16.

A 26-year-old man presented with a mildly pruritic red scaly rash on the right arm of 3 weeks' duration. He reported having a tattoo placed on previously normal skin on the right lateral arm prior to the development of the rash. Two weeks after receiving the tattoo, he developed scaling and redness of the skin involved in the tattoo. He also had similar papules and plaques over the rest of his body. Physical examination showed well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly papules and plaques following the design of a black-pigmented tattoo on the lateral aspect of the right arm. There also were similar erythematous scaly plaques scattered over both arms and the trunk. He denied any pain or blister formation of the involved areas.

Solitary Tender Nodule on the Back

The Diagnosis: Solitary Fibrous Tumor

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs), as first described by Klemperer and Rabin1 in 1931, are relatively uncommon mesenchymal neoplasms that occur primarily in the pleura. This lesion is now known to affect many other extrathoracic sites, such as the liver, kidney, adrenal glands, thyroid, central nervous system, and soft tissue, with rare examples originating from the skin.2 Okamura et al3 reported the first known case of cutaneous SFT in 1997, with most of the literature limited to case reports. Erdag et al2 described one of the largest case series of primary cutaneous SFTs. These lesions can occur across a wide age range but tend to primarily affect middle-aged adults. Solitary fibrous tumors have been known to have no sex predilection; however, Erdag et al2 found a male predominance with a male to female ratio of 4 to 1.

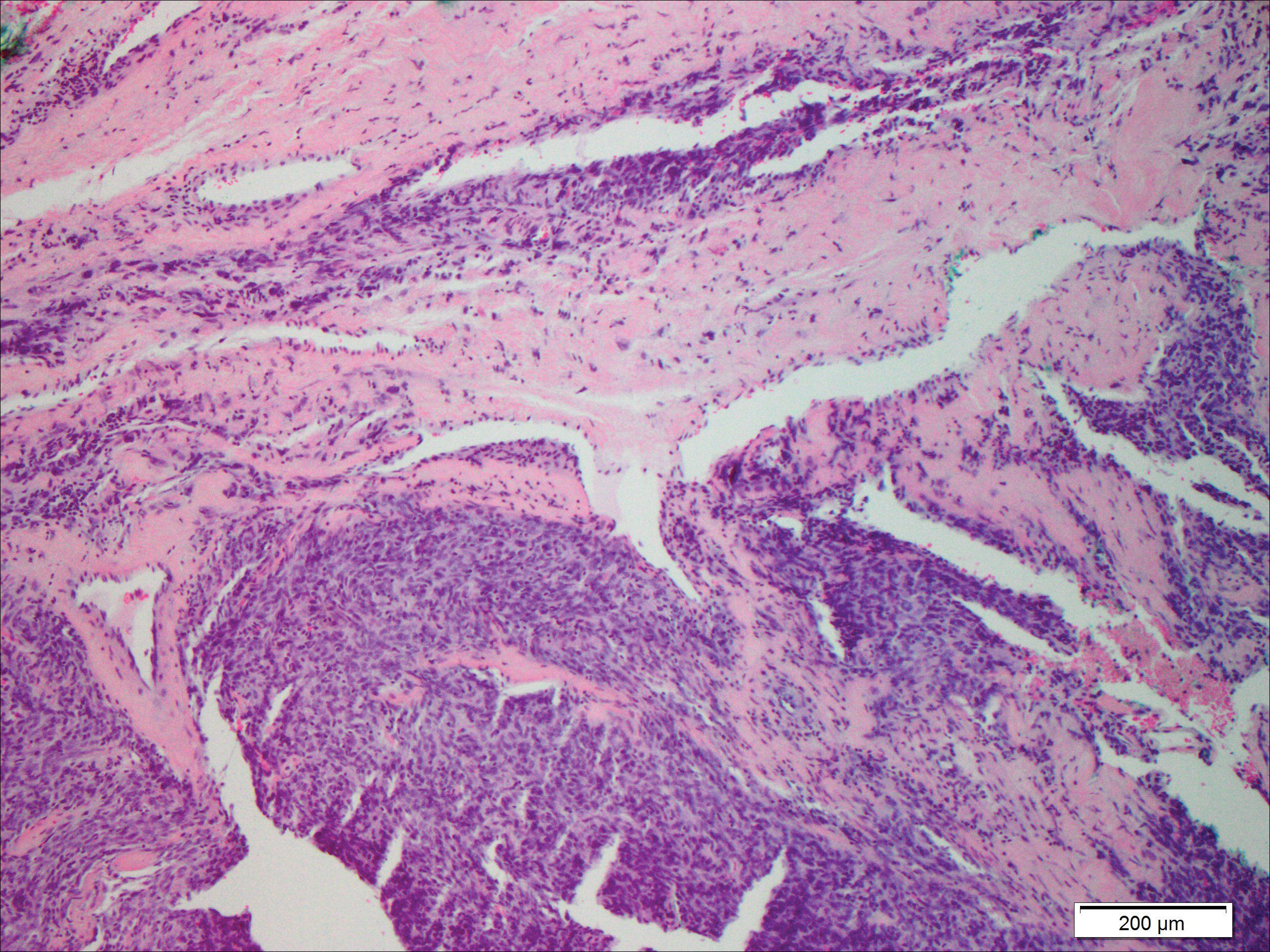

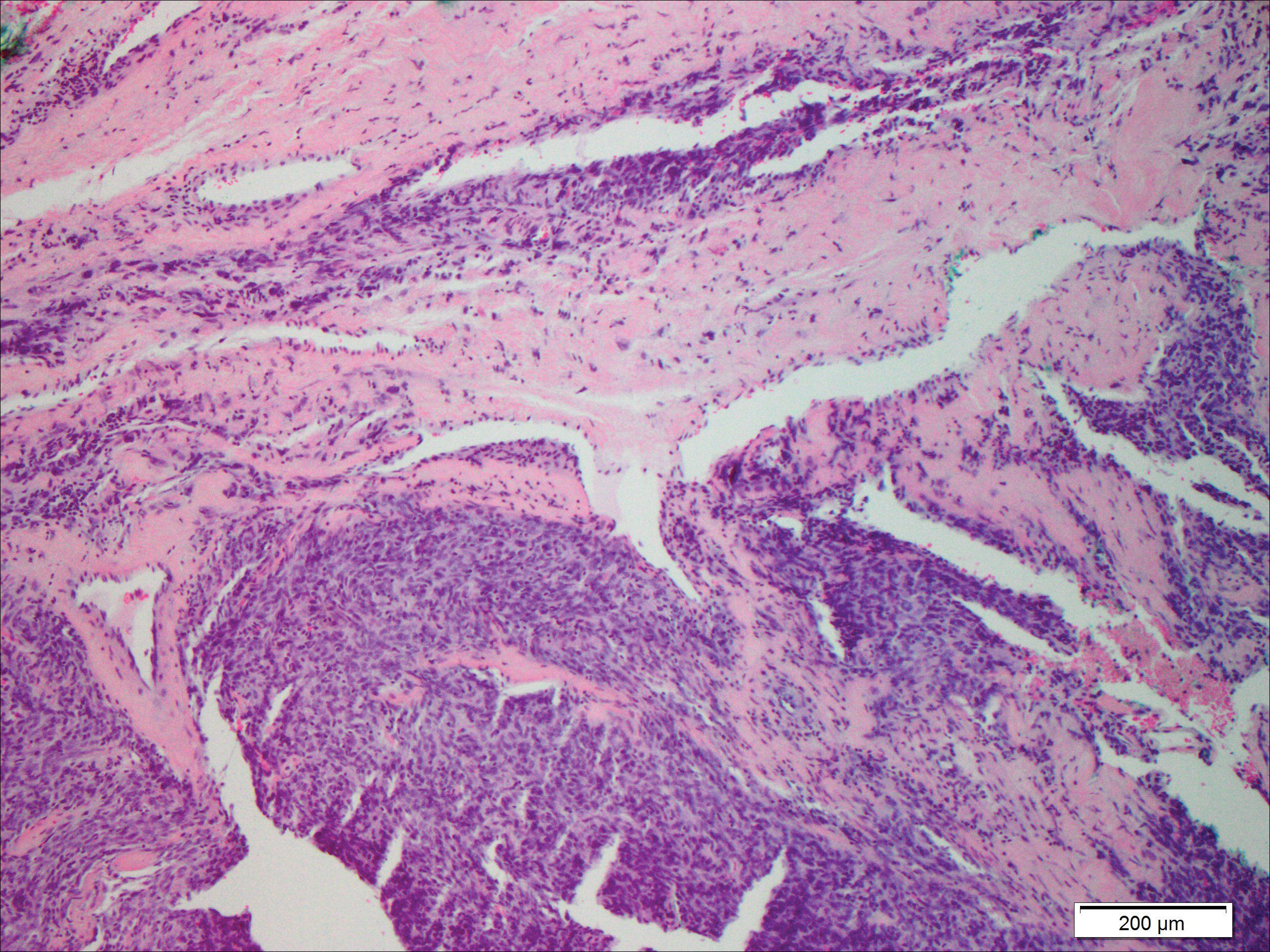

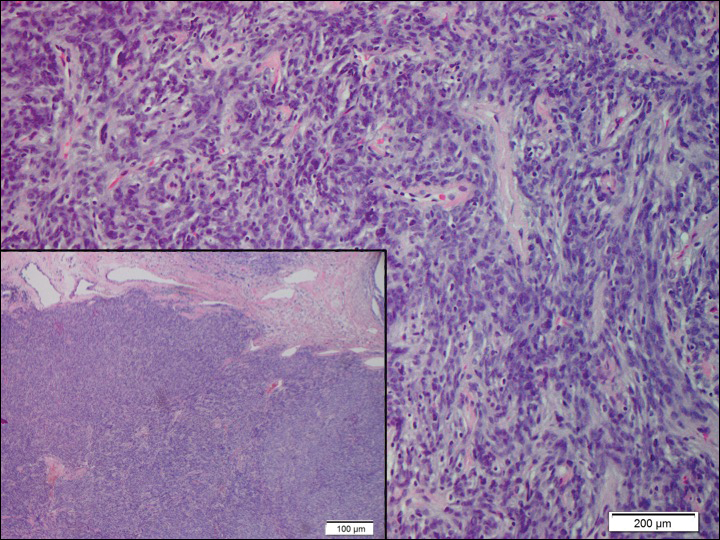

Histopathologically, a cutaneous SFT is known to appear as a well-circumscribed nodular spindle cell proliferation arranged in interlacing fascicles with an abundant hyalinized collagen stroma (quiz image). Alternating hypocellular and hypercellular areas can be seen. Supporting vasculature often is relatively prominent, represented by angulated and branching staghorn blood vessels (Figure 1).2 A common histopathologic finding of SFTs is a patternless pattern, which suggests that the tumor can have a variety of morphologic appearances (eg, storiform, fascicular, neural, herringbone growth patterns), making histologic diagnosis difficult (quiz image).4 Therefore, immunohistochemistry plays a large role in the diagnosis of this tumor. The most important positive markers include CD34, CD99, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6).5 Nuclear STAT6 staining is an immunomarker for NGFI-A binding protein 2 (NAB2)-STAT6 gene fusion, which is specific for SFT.5,6 Vivero et al7 also reported glutamate receptor, inotropic, AMPA 2 (GRIA2) as a useful immunostain in SFT, though it is also expressed in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). In this case, the clinical and histopathologic findings best supported a diagnosis of SFT. Some consider hemangiopericytomas to be examples of SFTs; however, true hemangiopericytomas lack the thick hyalinized collagen and hypercellular areas seen in SFT.

A cellular dermatofibroma generally presents as a single round, reddish brown papule or nodule approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter that is firm to palpation with a central depression or dimple created over the lesion from the lateral pressure. Cellular dermatofibromas mostly occur in middle-aged adults, with the most common locations on the legs and on the sides of the trunk. They are thought to arise after injuries to the skin. On histopathologic examination, cellular dermatofibromas typically exhibit a proliferation of fibrohistiocytic cells with collagen trapping, often at the periphery of the tumor (Figure 2). Although cellular dermatofibromas appear clinically different than SFTs, they often mimic SFTs histopathologically. Immunostaining also can be helpful in differentiating cellular dermatofibromas in which cells stain positive for factor XIIIa. CD34 staining is negative.