User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

A Case of Leprosy in Central Florida

Case Report

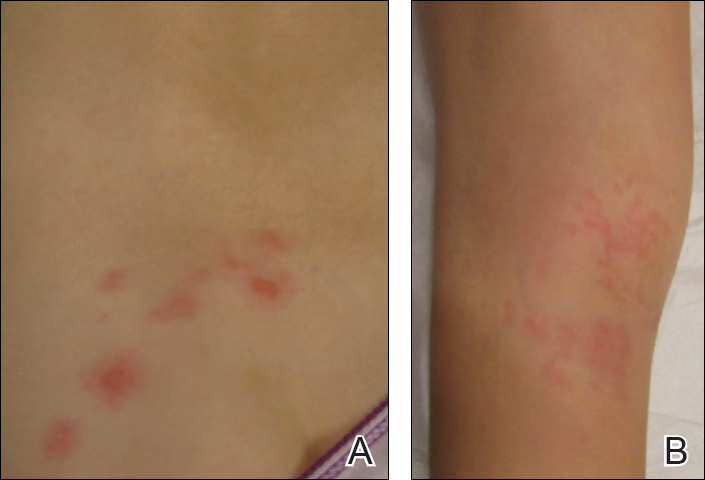

A 65-year-old man presented with multiple anesthetic, annular, erythematous, scaly plaques with a raised border of 6 weeks’ duration that were unresponsive to topical steroid therapy. Four plaques were noted on the lower back ranging from 2 to 4 cm in diameter as well as a fifth plaque on the anterior portion of the right ankle that was approximately 6×6 cm. He denied fever, malaise, muscle weakness, changes in vision, or sensory deficits outside of the lesions themselves. The patient also denied any recent travel to endemic areas or exposure to armadillos.

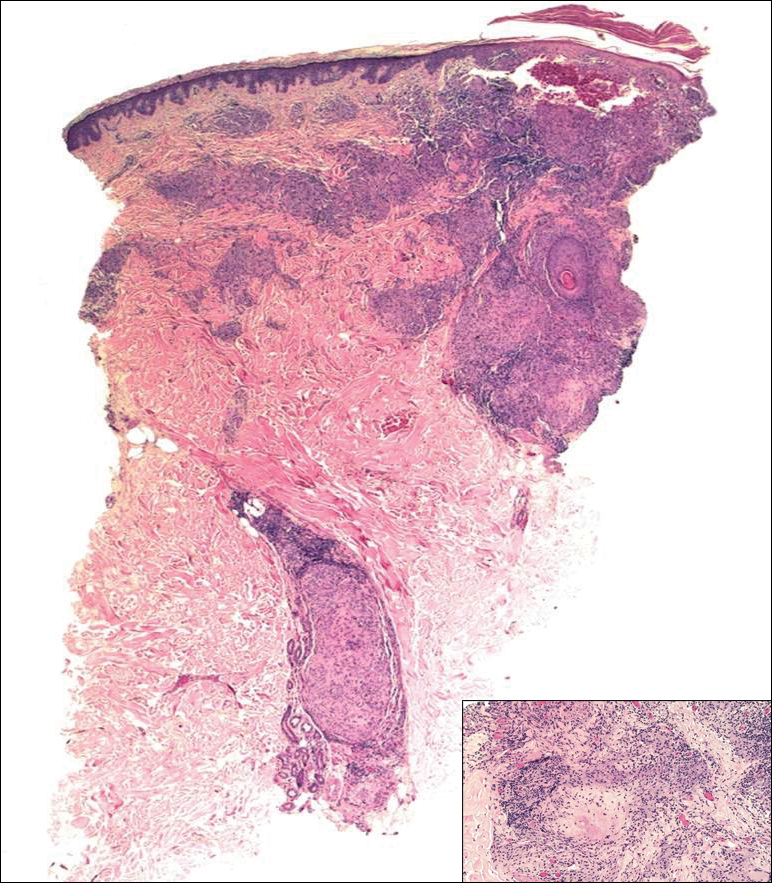

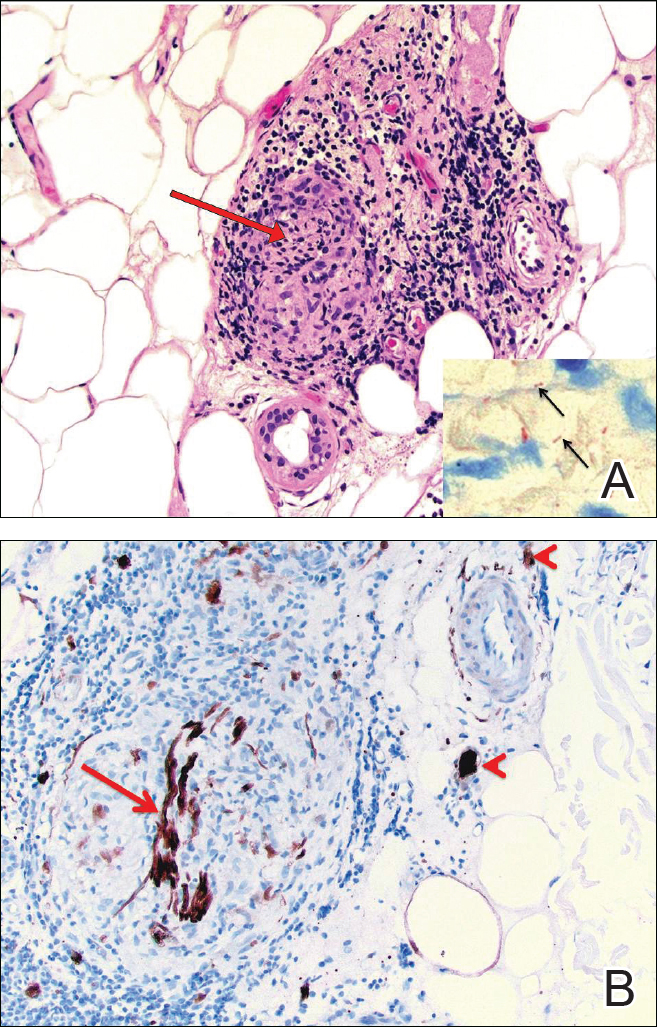

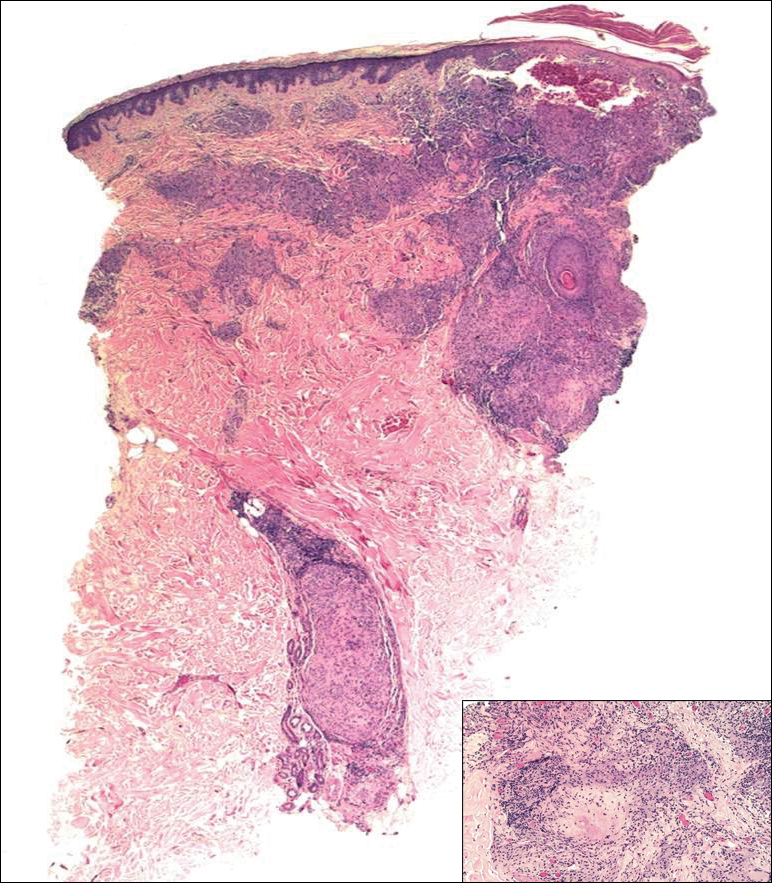

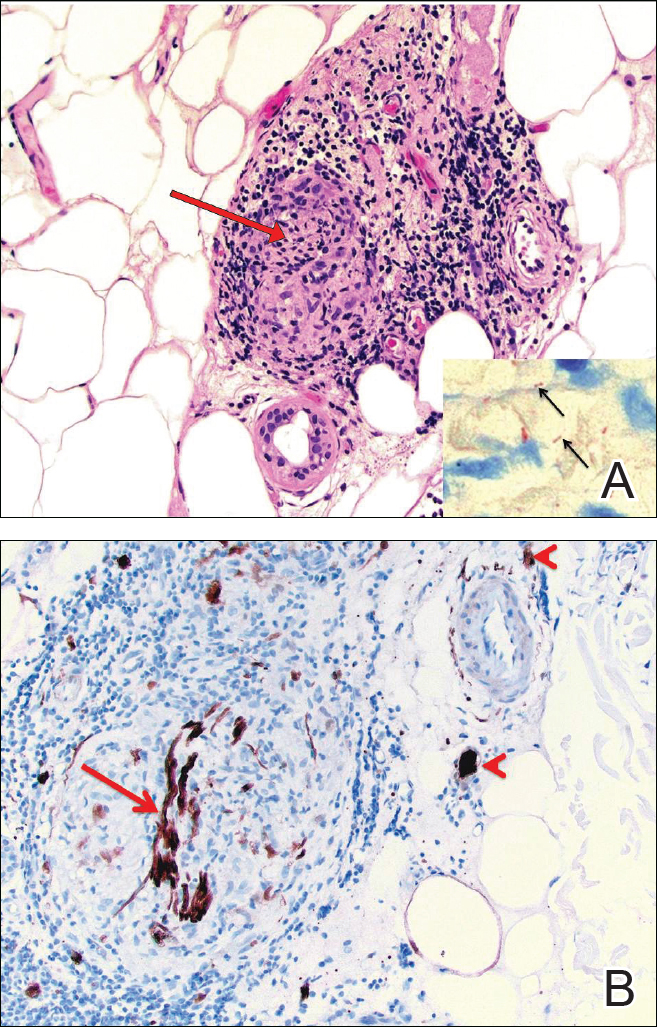

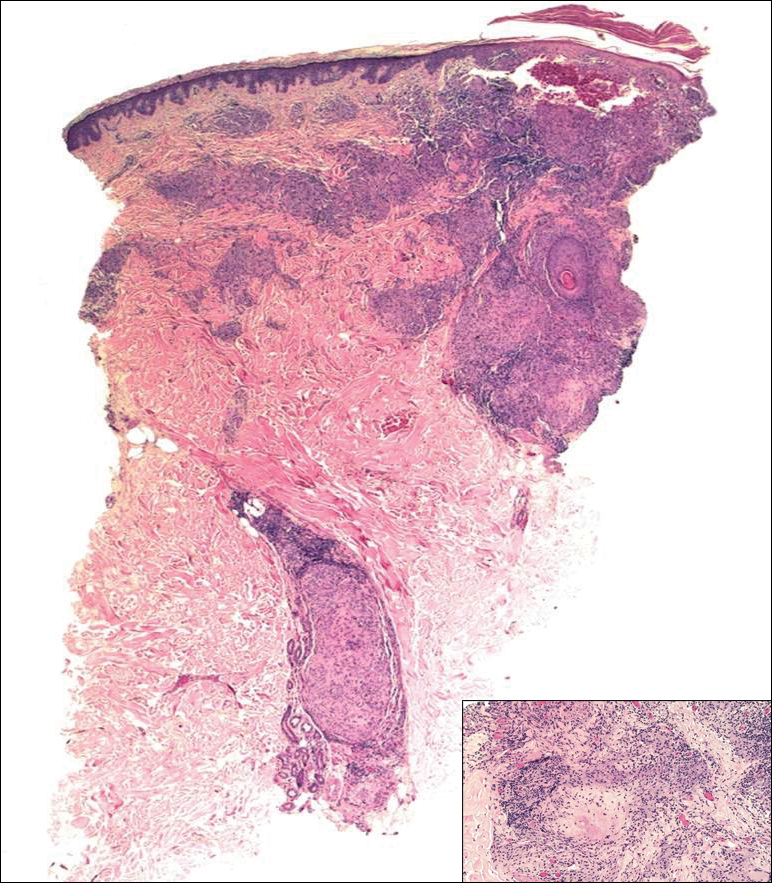

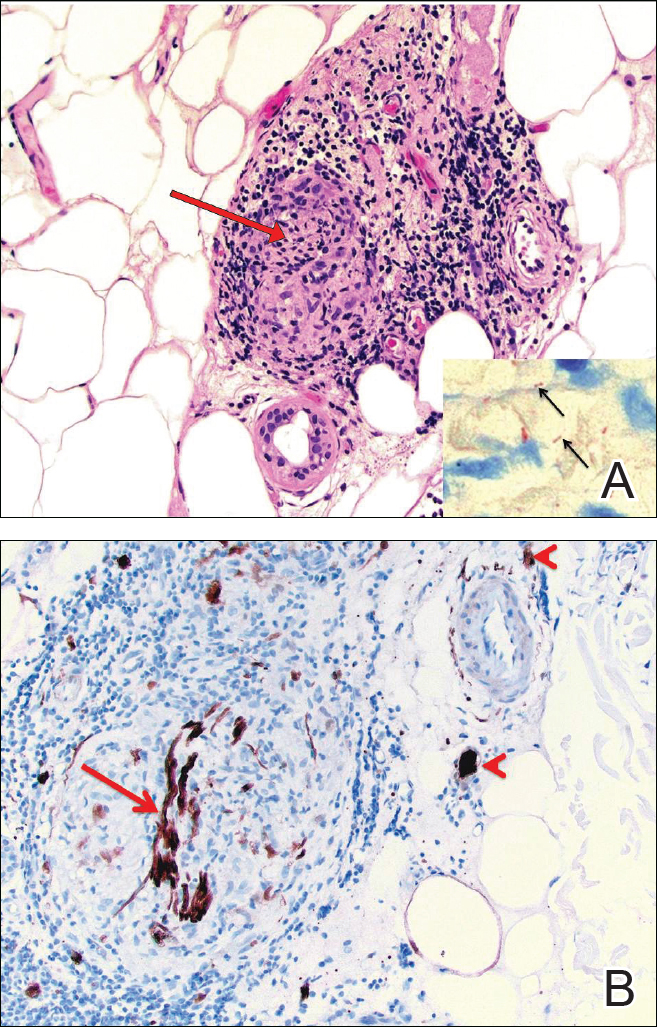

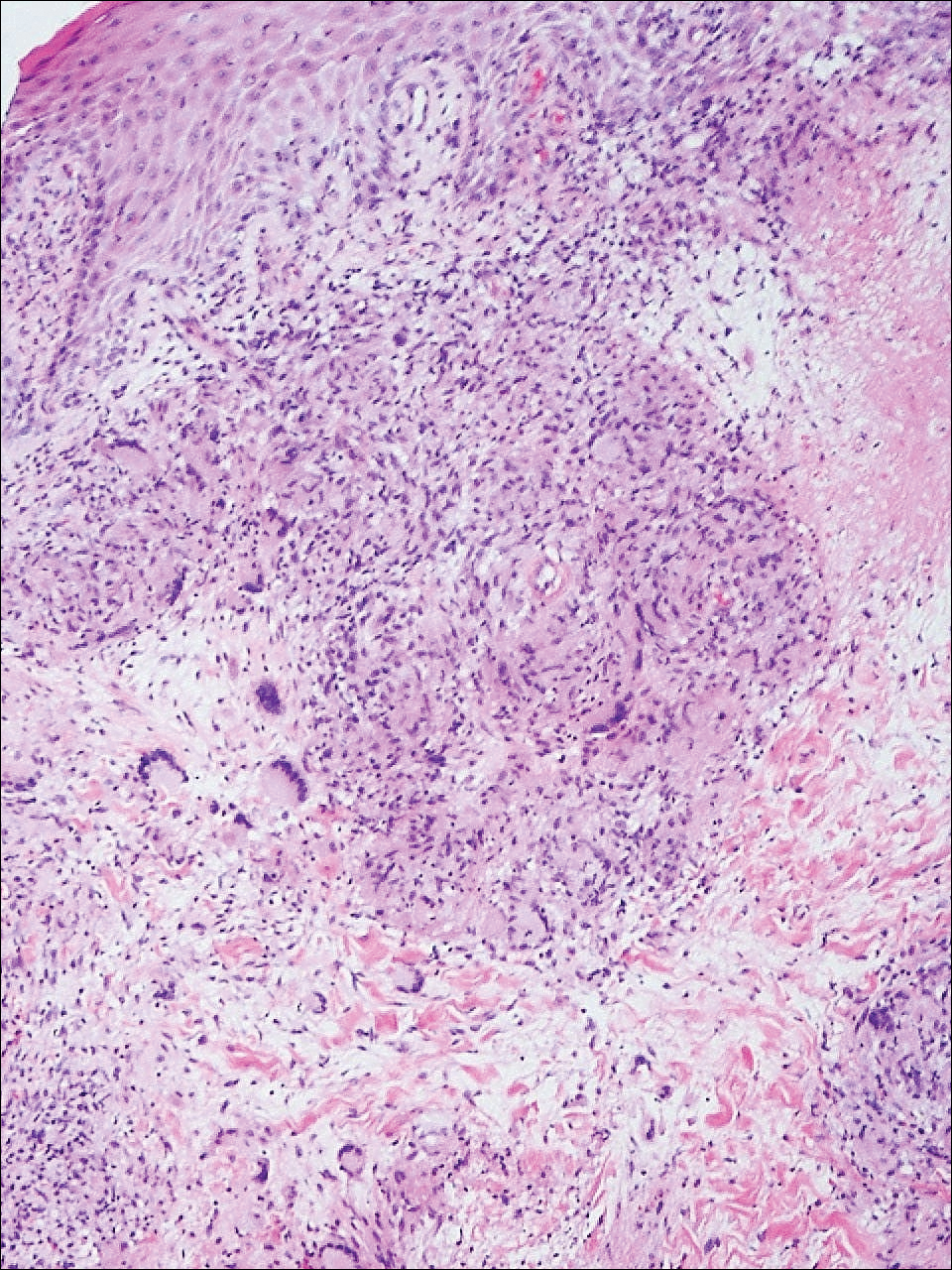

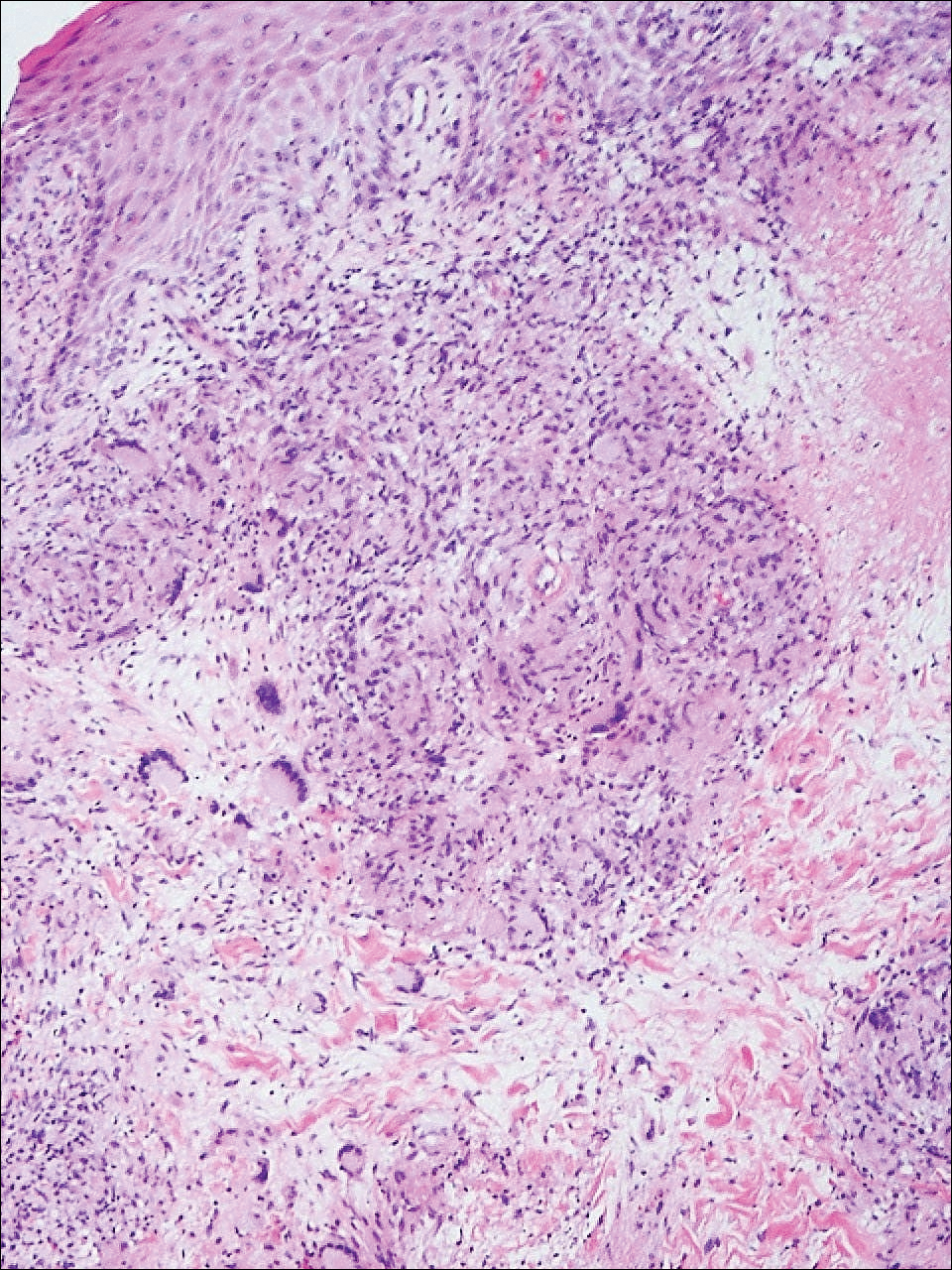

Biopsies were taken from lesions on the lumbar back and anterior aspect of the right ankle (Figure 1A). Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a granulomatous infiltrate spreading along neurovascular structures (Figure 2). Granulomas also were identified in the dermal interstitium exhibiting partial necrosis (Figure 2 inset). Conspicuous distension of lymphovascular and perineural areas also was noted. Immunohistochemical studies with S-100 and neurofilament stains allowed insight into the pathomechanism of the clinically observed anesthesia, as nerve fibers were identified showing different stages of damage elicited by the granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Fite staining was positive for occasional bacilli within histiocytes (Figure 3A inset). Despite the clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical evidence, the patient had no known exposure to leprosy; consequently, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay was ordered for confirmation of the diagnosis. Surprisingly, the PCR was positive for Mycobacterium leprae DNA. These findings were consistent with borderline tuberculoid leprosy.

The case was reported to the National Hansen’s Disease Program (Baton Rouge, Louisiana). The patient was started on rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 6 months. The lesions exhibited marked improvement after completion of therapy (Figure 1B).

Comment

Disease Transmission

Hansen disease, also known as leprosy, is a chronic granulomatous infectious disease that is caused by M leprae, an obligate intracellular bacillus aerobe.1 The mechanism of spread of M leprae is not clear. It is thought to be transmitted via respiratory droplets, though it may occur through injured skin.2 Studies have suggested that in addition to humans, nine-banded armadillos are a source of infection.2,3 Exposure to infected individuals, particularly multibacillary patients, increases the likelihood of contracting leprosy.2

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 81 cases of Hansen disease were diagnosed in the United States in 2013,4 compared to 178 cases registered in 2015.5 Cases from Hawaii, Texas, California, Louisiana, New York, and Florida made up 72% (129/178) of the reported cases. There was an increase from 34 cases to 49 cases in Florida from 2014 to 2015.5 The spread of leprosy throughout Florida may be from the merge of 2 armadillo populations, an M leprae–infected population migrating east from Texas and one from south central Florida that historically had not been infected with M leprae until recently.3,6 Our patient did not have any known exposures to armadillos.

Classification and Presentation

The clinical presentation of Hansen disease is widely variable, as it can present at any point along a spectrum ranging from tuberculoid leprosy to lepromatous leprosy with borderline conditions in between, according to the Ridley-Jopling critera.7 The World Health Organization also classifies leprosy based on the number of acid-fast bacilli seen in a skin smear as either paucibacillary or multibacillary.2 The paucibacillary classification correlates with tuberculoid, borderline tuberculoid, and indeterminate leprosy, and multibacillary correlates with borderline lepromatous and lepromatous leprosy. Paucibacillary leprosy usually presents with a less dramatic clinical picture than multibacillary leprosy. The clinical presentation is dependent on the magnitude of immune response to M leprae.2

Paucibacillary infection occurs when the body generates a strong cell-mediated immune response against the bacteria,8 which causes the activation and proliferation of CD4 and CD8 T cells, limiting the spread of the mycobacterium. Subsequently, the patient typically presents with a mild clinical picture with few skin lesions and limited nerve involvement.8 The skin lesions are papules or plaques with raised borders that are usually hypopigmented on dark skin and erythematous on light skin. Nerve involvement in paucibacillary forms of leprosy include sensory impairment and anhidrosis within the lesions. Nerve enlargement usually affects superficial nerves, with the posterior tibial nerve being most commonly affected.

Multibacillary leprosy presents with systemic involvement due to a weak cell-mediated immune response. Patients generally present with diffuse, poorly defined nodules; greater nerve impairment; and other systemic symptoms such as blindness, swelling of the fingers and toes, and testicular atrophy (in men). Additionally, enlargement of the earlobes and widening of the nasal bridge may contribute to the appearance of leonine facies. Nerve impairment in multibacillary forms of leprosy may be more severe, including more diffuse sensory involvement (eg, stocking glove–pattern neuropathy, nerve-trunk palsies), which ultimately may lead to foot drop, claw toe, and lagophthalmos.8

In addition to the clinical presentation, the histology of the paucibacillary and multibacillary types differ. Multibacillary leprosy shows diffuse histiocytes without granulomas and multiple bacilli seen on Fite staining.8 In the paucibacillary form, there are well-formed granulomas with Langerhans giant cells and a perineural lymphocytic infiltrate seen on hematoxylin and eosin staining with rare acid-fast bacilli seen on Fite staining.

To diagnose leprosy, at least one of the following 3 clinical signs must be present: (1) a hypopigmented or erythematous lesion with loss of sensation, (2) thickened peripheral nerve, or (3) acid-fast bacilli on slit-skin smear.2

Management

The World Health Organization guidelines involve multidrug therapy over an extended period of time.2 For adults, the paucibacillary regimen includes rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 6 months. The adult regimen for multibacillary leprosy includes clofazimine 300 mg once monthly and 50 mg once daily, in addition to rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 12 months. If classification cannot be determined, it is recommended the patient be treated for multibacillary disease.2

Reversal Reactions

During the course of the disease, patients may upgrade (to a less severe form) or downgrade (to a more severe form) between the tuberculoid, borderline, and lepromatous forms.8 The patient’s clinical picture also may change with complications of leprosy, which include type 1 and type 2 reactions. Type 1 reaction is a reversal reaction seen in 15% to 30% of patients at risk, usually those with borderline forms of leprosy.9 Reversal reactions usually manifest as erythema and edema of current skin lesions, formation of new tumid lesions, and tenderness of peripheral nerves with loss of nerve function.8 Treatment of reversal reactions involves systemic corticosteroids.10 Type 2 reaction is classified as erythema nodosum leprosum. It presents within the first 2 years of treatment in approximately 20% of lepromatous patients and approximately 10% of borderline lepromatous patients but is rare in paucibacillary infections.11 It presents with fever and crops of pink nodules and may include iritis, neuritis, lymphadenitis, orchitis, dactylitis, arthritis, and proteinuria.8 Treatment options for erythema nodosum leprosum include corticosteroids, clofazimine, and thalidomide.12,13

Conclusion

Hansen disease is a rare condition in the United States. This case is unique because, to our knowledge, it is the first known PCR-confirmed case of Hansen disease in Okeechobee County, Florida. Additionally, the patient had no known exposure to M leprae. Exposure is increasing due to the increased geographical range of infected armadillos. Infection rates also may rise due to travel to endemic countries. Initially lesions may appear as innocuous erythematous plaques. When they do not respond to standard therapy, infectious agents such as M leprae should be part of the differential diagnosis. Because hematoxylin and eosin staining does not always yield results, if clinical suspicion is present, PCR should be performed. If a patient meets the clinical and histological diagnosis, the case should be reported to the National Hansen’s Disease Program.

After completion of treatment, our patient has shown excellent results. He has not yet demonstrated a reversal reaction; however, he may still be at risk, as it most commonly presents 2 months after starting treatment but can present years after treatment has been initiated.8 Cutaneous leprosy must be considered in the differential diagnosis for steroid-nonresponsive skin lesions, particularly in states such as Florida with a documented increase in incidence.

Acknowledgment

We thank Sharon Barrineau, ARNP (Okeechobee, Florida), for her acumen, contributions, and support on this case.

- Britton WJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Lancet. 2004;363:1209-1219.

- World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy, 8th Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Truman RW, Singh P, Sharma R, et al. Probable zoonotic leprosy in the southern United States. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1626-1633.

- Adams DA, Fullerton K, Jajosky R, et al; Division of Notifiable Diseases and Healthcare Information, Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, CDC. Summary of notifiable diseases—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;62:1-122.

- A summary of Hansen’s disease in the United States—2015. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Hansen’s Disease Program. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hansensdisease/pdfs/hansens2015report.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2017.

- Loughry WJ, Truman RW, McDonough CM, et al. Is leprosy spreading among nine-banded armadillos in the southeastern United States? J Wildl Dis. 2009;45:144-152.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity: a five group system. Int J Lepr. 1966;34:225-273.

- Lee DJ, Rea TH, Modlin RL. Leprosy. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Scollard DM, Adams LB, Gillis TP, et al. The continuing challenges of leprosy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:338-381.

- Britton WJ. The management of leprosy reversal reactions. Lepr Rev. 1998;69:225-234.

- Manandhar R, LeMaster JW, Roche PW. Risk factors for erythema nodosum leprosum. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1999;67:270-278.

- Lockwood DN. The management of erythema nodosum leprosum: current and future options. Lepr Rev. 1996;67:253-259.

- Jakeman P, Smith WC. Thalidomide in leprosy reaction. Lancet. 1994;343:432-433.

Case Report

A 65-year-old man presented with multiple anesthetic, annular, erythematous, scaly plaques with a raised border of 6 weeks’ duration that were unresponsive to topical steroid therapy. Four plaques were noted on the lower back ranging from 2 to 4 cm in diameter as well as a fifth plaque on the anterior portion of the right ankle that was approximately 6×6 cm. He denied fever, malaise, muscle weakness, changes in vision, or sensory deficits outside of the lesions themselves. The patient also denied any recent travel to endemic areas or exposure to armadillos.

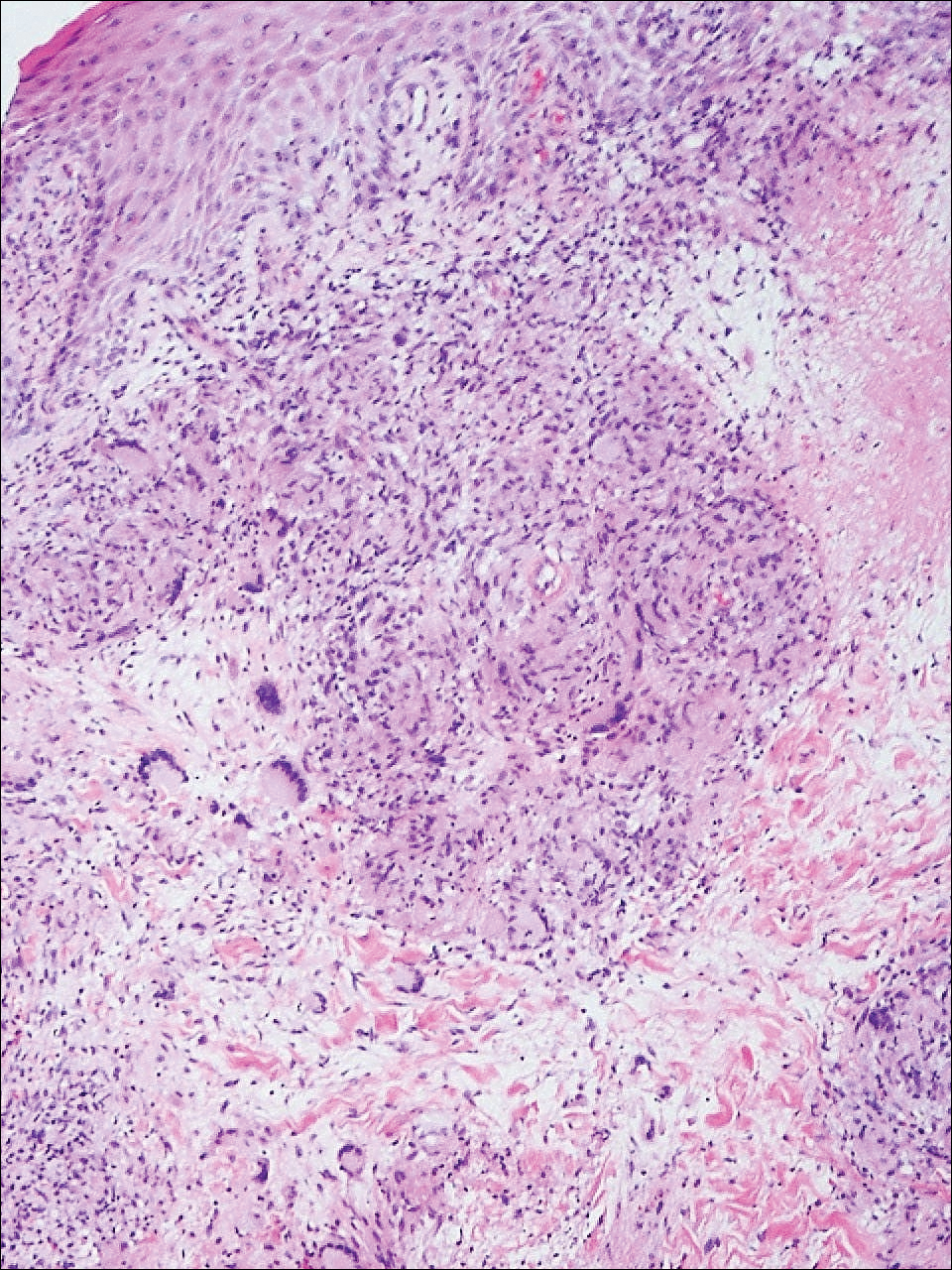

Biopsies were taken from lesions on the lumbar back and anterior aspect of the right ankle (Figure 1A). Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a granulomatous infiltrate spreading along neurovascular structures (Figure 2). Granulomas also were identified in the dermal interstitium exhibiting partial necrosis (Figure 2 inset). Conspicuous distension of lymphovascular and perineural areas also was noted. Immunohistochemical studies with S-100 and neurofilament stains allowed insight into the pathomechanism of the clinically observed anesthesia, as nerve fibers were identified showing different stages of damage elicited by the granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Fite staining was positive for occasional bacilli within histiocytes (Figure 3A inset). Despite the clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical evidence, the patient had no known exposure to leprosy; consequently, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay was ordered for confirmation of the diagnosis. Surprisingly, the PCR was positive for Mycobacterium leprae DNA. These findings were consistent with borderline tuberculoid leprosy.

The case was reported to the National Hansen’s Disease Program (Baton Rouge, Louisiana). The patient was started on rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 6 months. The lesions exhibited marked improvement after completion of therapy (Figure 1B).

Comment

Disease Transmission

Hansen disease, also known as leprosy, is a chronic granulomatous infectious disease that is caused by M leprae, an obligate intracellular bacillus aerobe.1 The mechanism of spread of M leprae is not clear. It is thought to be transmitted via respiratory droplets, though it may occur through injured skin.2 Studies have suggested that in addition to humans, nine-banded armadillos are a source of infection.2,3 Exposure to infected individuals, particularly multibacillary patients, increases the likelihood of contracting leprosy.2

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 81 cases of Hansen disease were diagnosed in the United States in 2013,4 compared to 178 cases registered in 2015.5 Cases from Hawaii, Texas, California, Louisiana, New York, and Florida made up 72% (129/178) of the reported cases. There was an increase from 34 cases to 49 cases in Florida from 2014 to 2015.5 The spread of leprosy throughout Florida may be from the merge of 2 armadillo populations, an M leprae–infected population migrating east from Texas and one from south central Florida that historically had not been infected with M leprae until recently.3,6 Our patient did not have any known exposures to armadillos.

Classification and Presentation

The clinical presentation of Hansen disease is widely variable, as it can present at any point along a spectrum ranging from tuberculoid leprosy to lepromatous leprosy with borderline conditions in between, according to the Ridley-Jopling critera.7 The World Health Organization also classifies leprosy based on the number of acid-fast bacilli seen in a skin smear as either paucibacillary or multibacillary.2 The paucibacillary classification correlates with tuberculoid, borderline tuberculoid, and indeterminate leprosy, and multibacillary correlates with borderline lepromatous and lepromatous leprosy. Paucibacillary leprosy usually presents with a less dramatic clinical picture than multibacillary leprosy. The clinical presentation is dependent on the magnitude of immune response to M leprae.2

Paucibacillary infection occurs when the body generates a strong cell-mediated immune response against the bacteria,8 which causes the activation and proliferation of CD4 and CD8 T cells, limiting the spread of the mycobacterium. Subsequently, the patient typically presents with a mild clinical picture with few skin lesions and limited nerve involvement.8 The skin lesions are papules or plaques with raised borders that are usually hypopigmented on dark skin and erythematous on light skin. Nerve involvement in paucibacillary forms of leprosy include sensory impairment and anhidrosis within the lesions. Nerve enlargement usually affects superficial nerves, with the posterior tibial nerve being most commonly affected.

Multibacillary leprosy presents with systemic involvement due to a weak cell-mediated immune response. Patients generally present with diffuse, poorly defined nodules; greater nerve impairment; and other systemic symptoms such as blindness, swelling of the fingers and toes, and testicular atrophy (in men). Additionally, enlargement of the earlobes and widening of the nasal bridge may contribute to the appearance of leonine facies. Nerve impairment in multibacillary forms of leprosy may be more severe, including more diffuse sensory involvement (eg, stocking glove–pattern neuropathy, nerve-trunk palsies), which ultimately may lead to foot drop, claw toe, and lagophthalmos.8

In addition to the clinical presentation, the histology of the paucibacillary and multibacillary types differ. Multibacillary leprosy shows diffuse histiocytes without granulomas and multiple bacilli seen on Fite staining.8 In the paucibacillary form, there are well-formed granulomas with Langerhans giant cells and a perineural lymphocytic infiltrate seen on hematoxylin and eosin staining with rare acid-fast bacilli seen on Fite staining.

To diagnose leprosy, at least one of the following 3 clinical signs must be present: (1) a hypopigmented or erythematous lesion with loss of sensation, (2) thickened peripheral nerve, or (3) acid-fast bacilli on slit-skin smear.2

Management

The World Health Organization guidelines involve multidrug therapy over an extended period of time.2 For adults, the paucibacillary regimen includes rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 6 months. The adult regimen for multibacillary leprosy includes clofazimine 300 mg once monthly and 50 mg once daily, in addition to rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 12 months. If classification cannot be determined, it is recommended the patient be treated for multibacillary disease.2

Reversal Reactions

During the course of the disease, patients may upgrade (to a less severe form) or downgrade (to a more severe form) between the tuberculoid, borderline, and lepromatous forms.8 The patient’s clinical picture also may change with complications of leprosy, which include type 1 and type 2 reactions. Type 1 reaction is a reversal reaction seen in 15% to 30% of patients at risk, usually those with borderline forms of leprosy.9 Reversal reactions usually manifest as erythema and edema of current skin lesions, formation of new tumid lesions, and tenderness of peripheral nerves with loss of nerve function.8 Treatment of reversal reactions involves systemic corticosteroids.10 Type 2 reaction is classified as erythema nodosum leprosum. It presents within the first 2 years of treatment in approximately 20% of lepromatous patients and approximately 10% of borderline lepromatous patients but is rare in paucibacillary infections.11 It presents with fever and crops of pink nodules and may include iritis, neuritis, lymphadenitis, orchitis, dactylitis, arthritis, and proteinuria.8 Treatment options for erythema nodosum leprosum include corticosteroids, clofazimine, and thalidomide.12,13

Conclusion

Hansen disease is a rare condition in the United States. This case is unique because, to our knowledge, it is the first known PCR-confirmed case of Hansen disease in Okeechobee County, Florida. Additionally, the patient had no known exposure to M leprae. Exposure is increasing due to the increased geographical range of infected armadillos. Infection rates also may rise due to travel to endemic countries. Initially lesions may appear as innocuous erythematous plaques. When they do not respond to standard therapy, infectious agents such as M leprae should be part of the differential diagnosis. Because hematoxylin and eosin staining does not always yield results, if clinical suspicion is present, PCR should be performed. If a patient meets the clinical and histological diagnosis, the case should be reported to the National Hansen’s Disease Program.

After completion of treatment, our patient has shown excellent results. He has not yet demonstrated a reversal reaction; however, he may still be at risk, as it most commonly presents 2 months after starting treatment but can present years after treatment has been initiated.8 Cutaneous leprosy must be considered in the differential diagnosis for steroid-nonresponsive skin lesions, particularly in states such as Florida with a documented increase in incidence.

Acknowledgment

We thank Sharon Barrineau, ARNP (Okeechobee, Florida), for her acumen, contributions, and support on this case.

Case Report

A 65-year-old man presented with multiple anesthetic, annular, erythematous, scaly plaques with a raised border of 6 weeks’ duration that were unresponsive to topical steroid therapy. Four plaques were noted on the lower back ranging from 2 to 4 cm in diameter as well as a fifth plaque on the anterior portion of the right ankle that was approximately 6×6 cm. He denied fever, malaise, muscle weakness, changes in vision, or sensory deficits outside of the lesions themselves. The patient also denied any recent travel to endemic areas or exposure to armadillos.

Biopsies were taken from lesions on the lumbar back and anterior aspect of the right ankle (Figure 1A). Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a granulomatous infiltrate spreading along neurovascular structures (Figure 2). Granulomas also were identified in the dermal interstitium exhibiting partial necrosis (Figure 2 inset). Conspicuous distension of lymphovascular and perineural areas also was noted. Immunohistochemical studies with S-100 and neurofilament stains allowed insight into the pathomechanism of the clinically observed anesthesia, as nerve fibers were identified showing different stages of damage elicited by the granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Fite staining was positive for occasional bacilli within histiocytes (Figure 3A inset). Despite the clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical evidence, the patient had no known exposure to leprosy; consequently, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay was ordered for confirmation of the diagnosis. Surprisingly, the PCR was positive for Mycobacterium leprae DNA. These findings were consistent with borderline tuberculoid leprosy.

The case was reported to the National Hansen’s Disease Program (Baton Rouge, Louisiana). The patient was started on rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 6 months. The lesions exhibited marked improvement after completion of therapy (Figure 1B).

Comment

Disease Transmission

Hansen disease, also known as leprosy, is a chronic granulomatous infectious disease that is caused by M leprae, an obligate intracellular bacillus aerobe.1 The mechanism of spread of M leprae is not clear. It is thought to be transmitted via respiratory droplets, though it may occur through injured skin.2 Studies have suggested that in addition to humans, nine-banded armadillos are a source of infection.2,3 Exposure to infected individuals, particularly multibacillary patients, increases the likelihood of contracting leprosy.2

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 81 cases of Hansen disease were diagnosed in the United States in 2013,4 compared to 178 cases registered in 2015.5 Cases from Hawaii, Texas, California, Louisiana, New York, and Florida made up 72% (129/178) of the reported cases. There was an increase from 34 cases to 49 cases in Florida from 2014 to 2015.5 The spread of leprosy throughout Florida may be from the merge of 2 armadillo populations, an M leprae–infected population migrating east from Texas and one from south central Florida that historically had not been infected with M leprae until recently.3,6 Our patient did not have any known exposures to armadillos.

Classification and Presentation

The clinical presentation of Hansen disease is widely variable, as it can present at any point along a spectrum ranging from tuberculoid leprosy to lepromatous leprosy with borderline conditions in between, according to the Ridley-Jopling critera.7 The World Health Organization also classifies leprosy based on the number of acid-fast bacilli seen in a skin smear as either paucibacillary or multibacillary.2 The paucibacillary classification correlates with tuberculoid, borderline tuberculoid, and indeterminate leprosy, and multibacillary correlates with borderline lepromatous and lepromatous leprosy. Paucibacillary leprosy usually presents with a less dramatic clinical picture than multibacillary leprosy. The clinical presentation is dependent on the magnitude of immune response to M leprae.2

Paucibacillary infection occurs when the body generates a strong cell-mediated immune response against the bacteria,8 which causes the activation and proliferation of CD4 and CD8 T cells, limiting the spread of the mycobacterium. Subsequently, the patient typically presents with a mild clinical picture with few skin lesions and limited nerve involvement.8 The skin lesions are papules or plaques with raised borders that are usually hypopigmented on dark skin and erythematous on light skin. Nerve involvement in paucibacillary forms of leprosy include sensory impairment and anhidrosis within the lesions. Nerve enlargement usually affects superficial nerves, with the posterior tibial nerve being most commonly affected.

Multibacillary leprosy presents with systemic involvement due to a weak cell-mediated immune response. Patients generally present with diffuse, poorly defined nodules; greater nerve impairment; and other systemic symptoms such as blindness, swelling of the fingers and toes, and testicular atrophy (in men). Additionally, enlargement of the earlobes and widening of the nasal bridge may contribute to the appearance of leonine facies. Nerve impairment in multibacillary forms of leprosy may be more severe, including more diffuse sensory involvement (eg, stocking glove–pattern neuropathy, nerve-trunk palsies), which ultimately may lead to foot drop, claw toe, and lagophthalmos.8

In addition to the clinical presentation, the histology of the paucibacillary and multibacillary types differ. Multibacillary leprosy shows diffuse histiocytes without granulomas and multiple bacilli seen on Fite staining.8 In the paucibacillary form, there are well-formed granulomas with Langerhans giant cells and a perineural lymphocytic infiltrate seen on hematoxylin and eosin staining with rare acid-fast bacilli seen on Fite staining.

To diagnose leprosy, at least one of the following 3 clinical signs must be present: (1) a hypopigmented or erythematous lesion with loss of sensation, (2) thickened peripheral nerve, or (3) acid-fast bacilli on slit-skin smear.2

Management

The World Health Organization guidelines involve multidrug therapy over an extended period of time.2 For adults, the paucibacillary regimen includes rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 6 months. The adult regimen for multibacillary leprosy includes clofazimine 300 mg once monthly and 50 mg once daily, in addition to rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 12 months. If classification cannot be determined, it is recommended the patient be treated for multibacillary disease.2

Reversal Reactions

During the course of the disease, patients may upgrade (to a less severe form) or downgrade (to a more severe form) between the tuberculoid, borderline, and lepromatous forms.8 The patient’s clinical picture also may change with complications of leprosy, which include type 1 and type 2 reactions. Type 1 reaction is a reversal reaction seen in 15% to 30% of patients at risk, usually those with borderline forms of leprosy.9 Reversal reactions usually manifest as erythema and edema of current skin lesions, formation of new tumid lesions, and tenderness of peripheral nerves with loss of nerve function.8 Treatment of reversal reactions involves systemic corticosteroids.10 Type 2 reaction is classified as erythema nodosum leprosum. It presents within the first 2 years of treatment in approximately 20% of lepromatous patients and approximately 10% of borderline lepromatous patients but is rare in paucibacillary infections.11 It presents with fever and crops of pink nodules and may include iritis, neuritis, lymphadenitis, orchitis, dactylitis, arthritis, and proteinuria.8 Treatment options for erythema nodosum leprosum include corticosteroids, clofazimine, and thalidomide.12,13

Conclusion

Hansen disease is a rare condition in the United States. This case is unique because, to our knowledge, it is the first known PCR-confirmed case of Hansen disease in Okeechobee County, Florida. Additionally, the patient had no known exposure to M leprae. Exposure is increasing due to the increased geographical range of infected armadillos. Infection rates also may rise due to travel to endemic countries. Initially lesions may appear as innocuous erythematous plaques. When they do not respond to standard therapy, infectious agents such as M leprae should be part of the differential diagnosis. Because hematoxylin and eosin staining does not always yield results, if clinical suspicion is present, PCR should be performed. If a patient meets the clinical and histological diagnosis, the case should be reported to the National Hansen’s Disease Program.

After completion of treatment, our patient has shown excellent results. He has not yet demonstrated a reversal reaction; however, he may still be at risk, as it most commonly presents 2 months after starting treatment but can present years after treatment has been initiated.8 Cutaneous leprosy must be considered in the differential diagnosis for steroid-nonresponsive skin lesions, particularly in states such as Florida with a documented increase in incidence.

Acknowledgment

We thank Sharon Barrineau, ARNP (Okeechobee, Florida), for her acumen, contributions, and support on this case.

- Britton WJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Lancet. 2004;363:1209-1219.

- World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy, 8th Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Truman RW, Singh P, Sharma R, et al. Probable zoonotic leprosy in the southern United States. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1626-1633.

- Adams DA, Fullerton K, Jajosky R, et al; Division of Notifiable Diseases and Healthcare Information, Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, CDC. Summary of notifiable diseases—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;62:1-122.

- A summary of Hansen’s disease in the United States—2015. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Hansen’s Disease Program. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hansensdisease/pdfs/hansens2015report.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2017.

- Loughry WJ, Truman RW, McDonough CM, et al. Is leprosy spreading among nine-banded armadillos in the southeastern United States? J Wildl Dis. 2009;45:144-152.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity: a five group system. Int J Lepr. 1966;34:225-273.

- Lee DJ, Rea TH, Modlin RL. Leprosy. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Scollard DM, Adams LB, Gillis TP, et al. The continuing challenges of leprosy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:338-381.

- Britton WJ. The management of leprosy reversal reactions. Lepr Rev. 1998;69:225-234.

- Manandhar R, LeMaster JW, Roche PW. Risk factors for erythema nodosum leprosum. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1999;67:270-278.

- Lockwood DN. The management of erythema nodosum leprosum: current and future options. Lepr Rev. 1996;67:253-259.

- Jakeman P, Smith WC. Thalidomide in leprosy reaction. Lancet. 1994;343:432-433.

- Britton WJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Lancet. 2004;363:1209-1219.

- World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy, 8th Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Truman RW, Singh P, Sharma R, et al. Probable zoonotic leprosy in the southern United States. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1626-1633.

- Adams DA, Fullerton K, Jajosky R, et al; Division of Notifiable Diseases and Healthcare Information, Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, CDC. Summary of notifiable diseases—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;62:1-122.

- A summary of Hansen’s disease in the United States—2015. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Hansen’s Disease Program. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hansensdisease/pdfs/hansens2015report.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2017.

- Loughry WJ, Truman RW, McDonough CM, et al. Is leprosy spreading among nine-banded armadillos in the southeastern United States? J Wildl Dis. 2009;45:144-152.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity: a five group system. Int J Lepr. 1966;34:225-273.

- Lee DJ, Rea TH, Modlin RL. Leprosy. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Scollard DM, Adams LB, Gillis TP, et al. The continuing challenges of leprosy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:338-381.

- Britton WJ. The management of leprosy reversal reactions. Lepr Rev. 1998;69:225-234.

- Manandhar R, LeMaster JW, Roche PW. Risk factors for erythema nodosum leprosum. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1999;67:270-278.

- Lockwood DN. The management of erythema nodosum leprosum: current and future options. Lepr Rev. 1996;67:253-259.

- Jakeman P, Smith WC. Thalidomide in leprosy reaction. Lancet. 1994;343:432-433.

Practice Points

- A majority of leprosy cases in the United States have been reported in Florida, California, Texas, Louisiana, Hawaii, and New York.

- Leprosy should be included in the differential diagnosis for annular plaques, particularly those not responding to traditional treatment.

Atypical Disseminated Herpes Zoster: Management Guidelines in Immunocompromised Patients

Well-known for its typical presentation, classic herpes zoster (HZ) presents as a dermatomal eruption of painful erythematous papules that evolve into grouped vesicles or bullae.1,2 Thereafter, the lesions can become pustular or hemorrhagic.1 Although the diagnosis most often is made clinically, confirmatory techniques for diagnosis include viral culture, direct fluorescent antibody testing, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay.1,3

The main risk factor for HZ is advanced age, most commonly affecting elderly patients.4 It is hypothesized that a physiological decline in varicella-zoster virus (VZV)–specific cell-mediated immunity among elderly individuals helps trigger reactivation of the virus within the dorsal root ganglion.1,5 Similarly affected are immunocompromised individuals, including those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, due to suppression of T cells immune to VZV,1,5 as well as immunosuppressed transplant recipients who have diminished VZV-specific cellular responses and VZV IgG antibody avidity.6

Secondary complications of VZV infection (eg, postherpetic neuralgia, bacterial superinfection progressing to cellulitis) lead to increased morbidity.7,8 Disseminated cutaneous HZ is another grave complication of VZV infection and almost exclusively occurs with immunosuppression.1,8 It manifests as an eruption of at least 20 widespread vesiculobullous lesions outside the primary and adjacent dermatomes.6 Immunocompromised patients also are at increased risk for visceral involvement of VZV infection, which may affect vital organs such as the brain, liver, or lungs.7,8 Given the atypical presentation of VZV infection among some immunocompromised individuals, these patients are at increased risk for diagnostic delay and morbidity in the absence of high clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 52-year-old man developed a painless nonpruritic rash on the left leg of 4 days’ duration. It initially appeared as an erythematous maculopapular rash on the medial aspect of the left knee without any prodromal symptoms. Over the next 4 days, erythematous vesicles developed that progressed to pustules, and the rash spread both proximally and distally along the left leg. Shortly following hospital admission, he developed a fever (temperature, 38.4°C). His medical history included alcoholic liver cirrhosis and AIDS, with a CD4 count of 174 cells/µL (reference range, 500–1500 cells/µL). He had been taking antiretroviral therapy (abacavir-lamivudine and dolutegravir) and prophylaxis against opportunistic infections (dapsone and itraconazole).

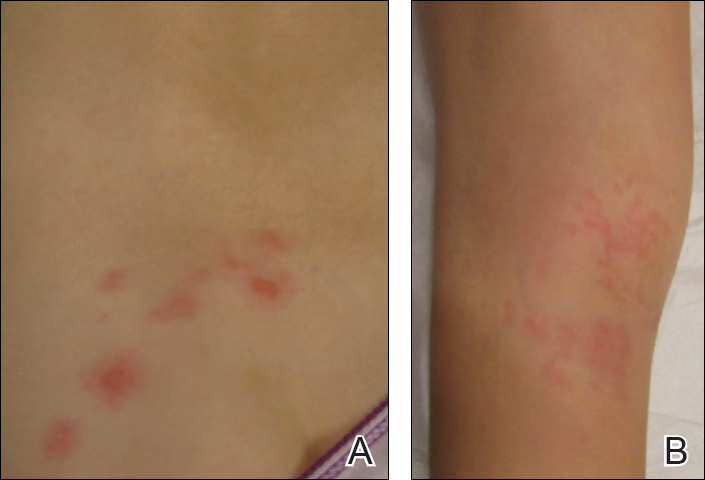

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of multiple 1-cm clusters of approximately 40 pustules each scattered in a nondermatomal distribution along the left leg (Figure 1). Many of the vesicles were confluent with an erythematous base and were in different stages of evolution with some crusted and others emanating a thin liquid exudate. The lesions were nontender and without notable induration. The leg was warm and edematous.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis included disseminated HZ with bacterial superinfection, Vibrio vulnificus infection, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. The patient was treated with intravenous vancomycin, levofloxacin, and acyclovir, and no new lesions developed throughout the course of treatment. On this regimen, his fever resolved after 1 day, the active lesions began to crust, and the edema and erythema diminished. Results of bacterial cultures and plasma PCR and IgM for HSV types 1 and 2 were negative. Viral culture results were negative, but a PCR assay for VZV was positive, reflective of acute reactivation of VZV.

Patient 2

A 63-year-old man developed a pruritic burning rash involving the face, trunk, arms, and legs of 6 days’ duration. His medical history included a heart transplant 6 months prior to presentation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. He was taking antirejection therapy with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), prednisone, and tacrolimus.

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of clusters of 1- to 2-mm vesicles scattered in a nondermatomal pattern. Isolated vesicles involved the forehead, nose, and left ear, and diffuse vesicles with a relatively symmetric distribution were scattered across the back, chest, and proximal and distal arms and legs (Figure 2). Many of the vesicles had an associated overlying crust with hemorrhage. Some of the vesicles coalesced with central necrotic plaques.

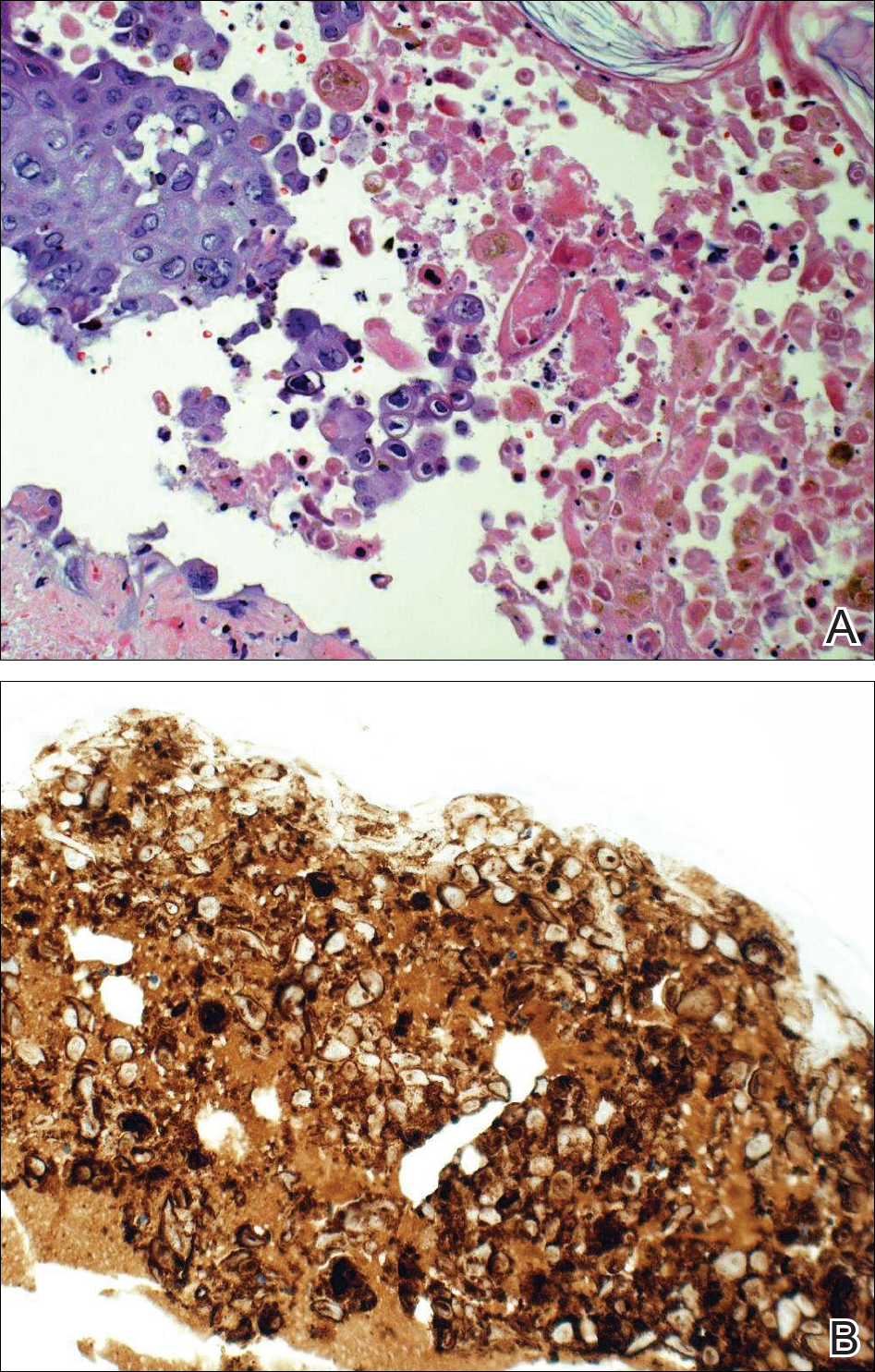

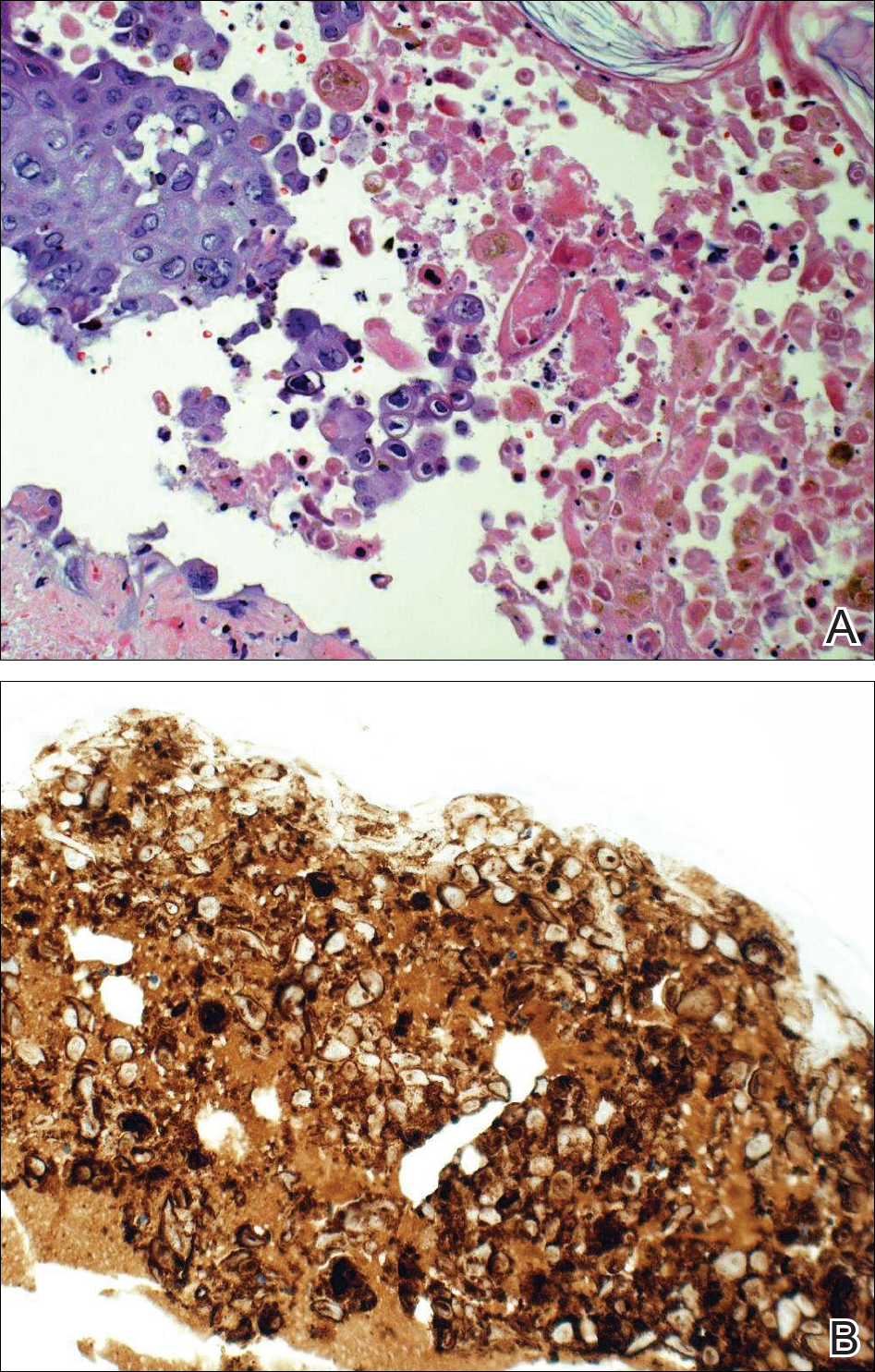

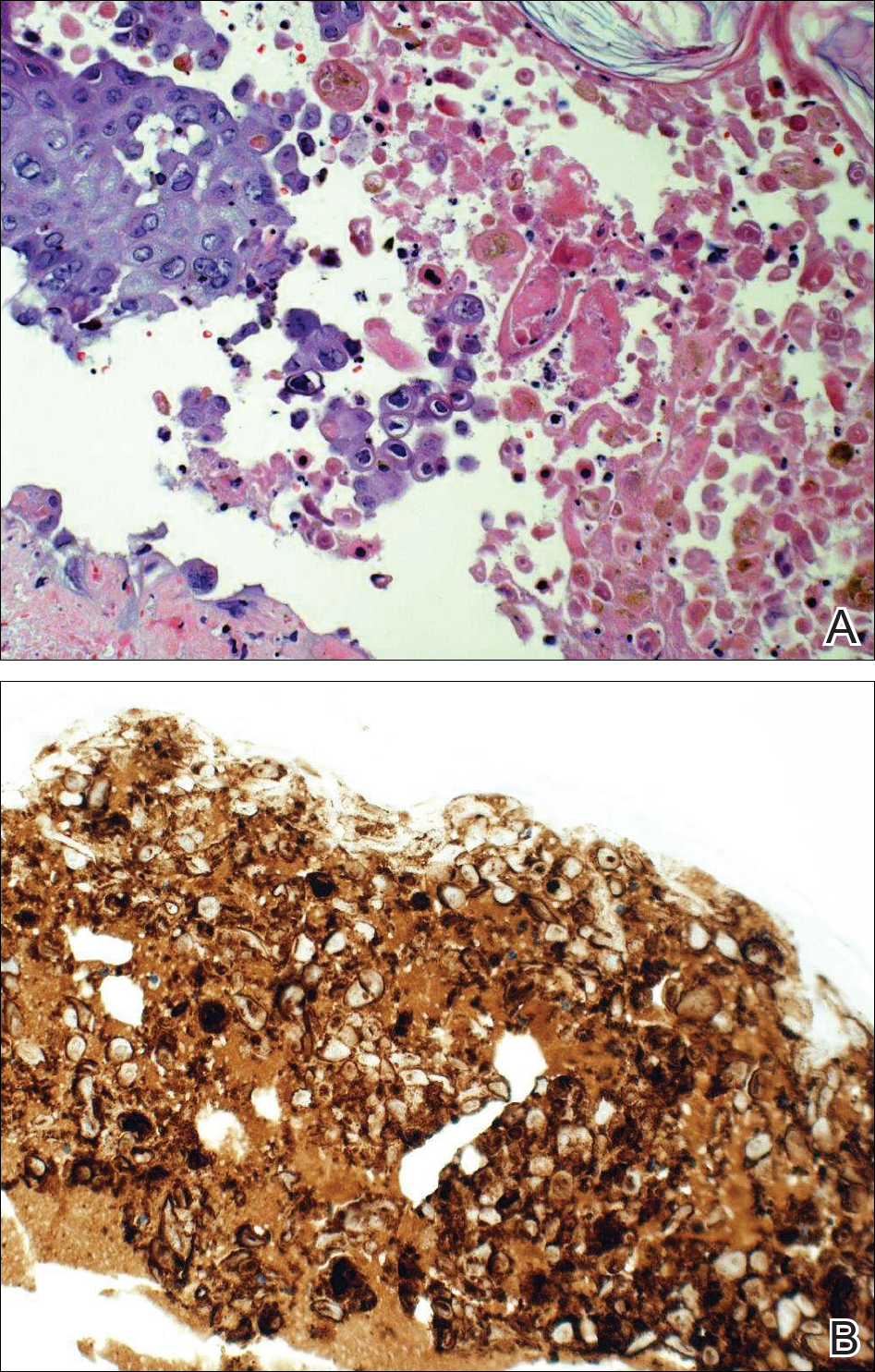

Given a clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ, therapy with oral valacyclovir was initiated. Two punch biopsies were consistent with herpesvirus cytopathic changes. Multiple sections demonstrated ulceration as well as acantholysis and necrosis of keratinocytes with multinucleation and margination of chromatin. There was an intense lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. Immunohistochemistry staining was positive for VZV and negative for HSV, indicating acute reactivation of VZV (Figure 3). Upon completion of an antiviral regimen, the patient returned to clinic with healed crusted lesions.

Comment

Frequently, the clinical features of HZ in immunocompromised patients mirror those in immunocompetent hosts.8 However, each of our 2 patients developed an unusual presentation of atypical generalized HZ.7 In this clinical variant, lesions develop along a single dermatome, then a diffuse vesicular eruption subsequently develops without dermatomal localization. These lesions can be chronic, persisting for months or years.7

The classic clinical presentation of HZ is distinct and often is readily diagnosed by visual inspection.7 However, atypical presentations and their associated complications can pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.7 Painless HZ lesions in a nondermatomal pattern were described in a patient who also had AIDS.9 Interestingly, multiple reports have found that patients with a severe but painless rash are less likely to have experienced a viral prodrome consisting of hyperesthesia, paresthesia, or pruritus.2,10 This observation suggests that lack of a prodrome, as in the case of patient 1 in our report, may aid in the recognition of painless HZ. Because of these atypical presentations, laboratory testing is even more important than in immunocompetent hosts, as diagnosis may be more difficult to establish on clinical presentation alone.

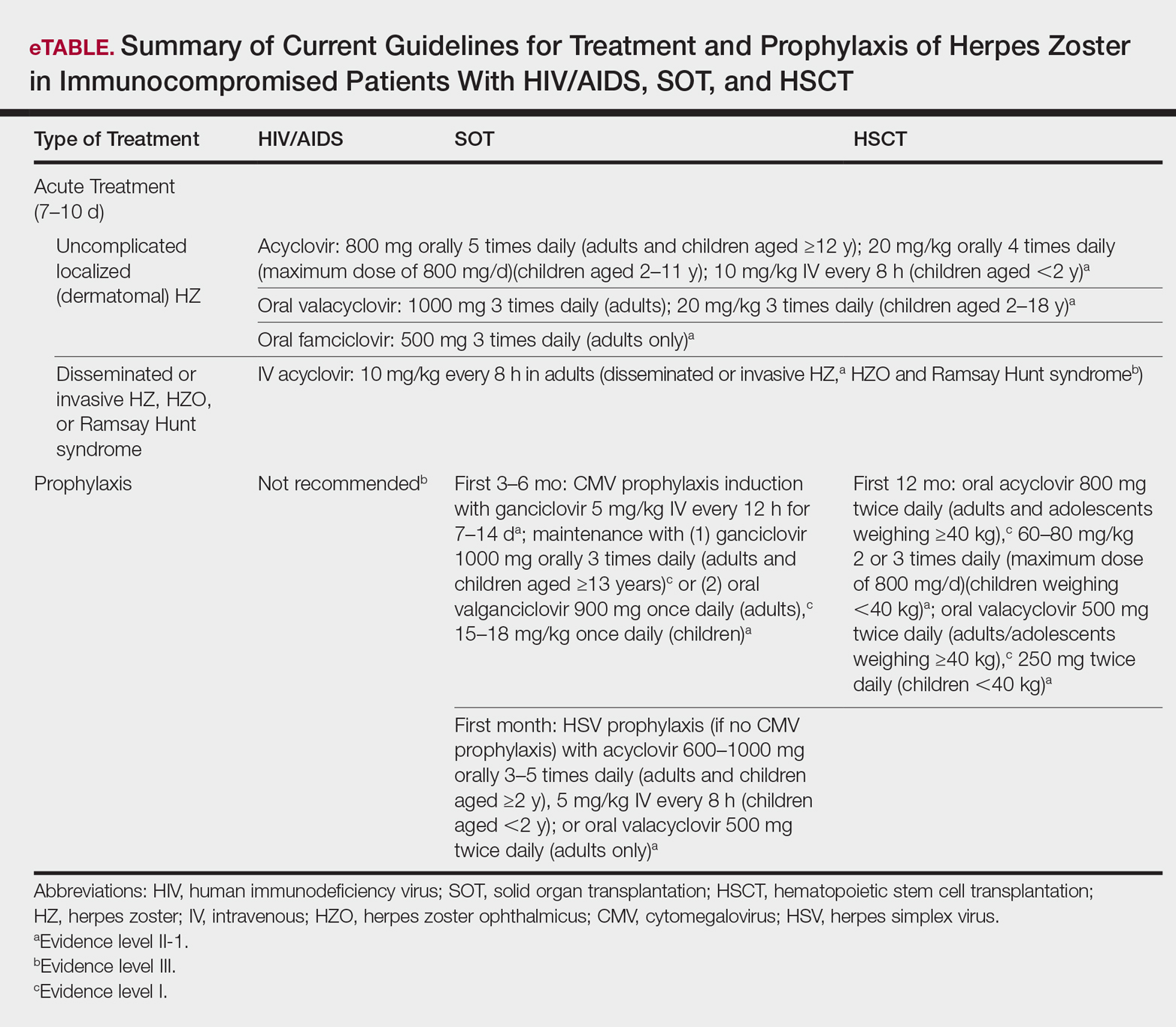

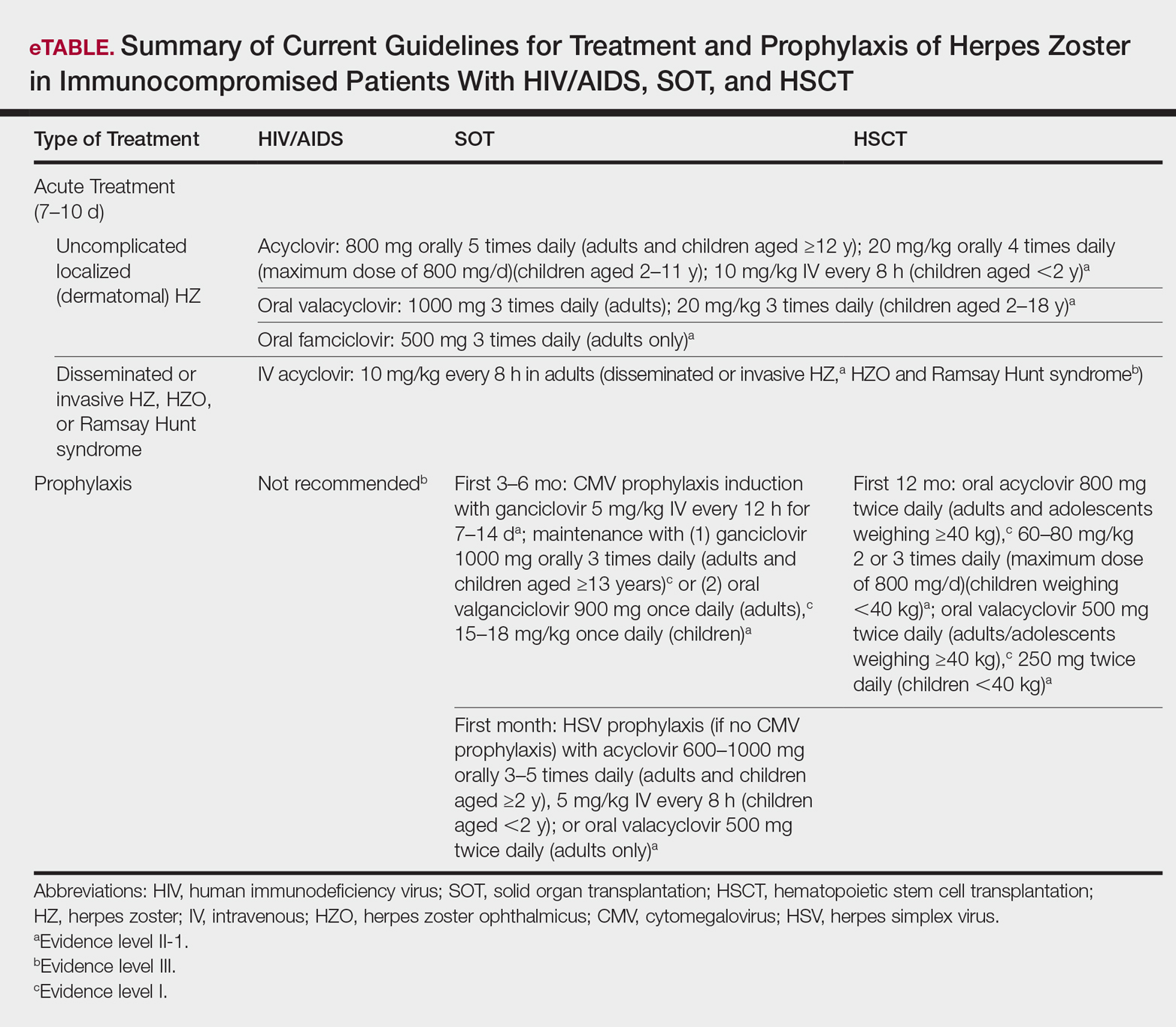

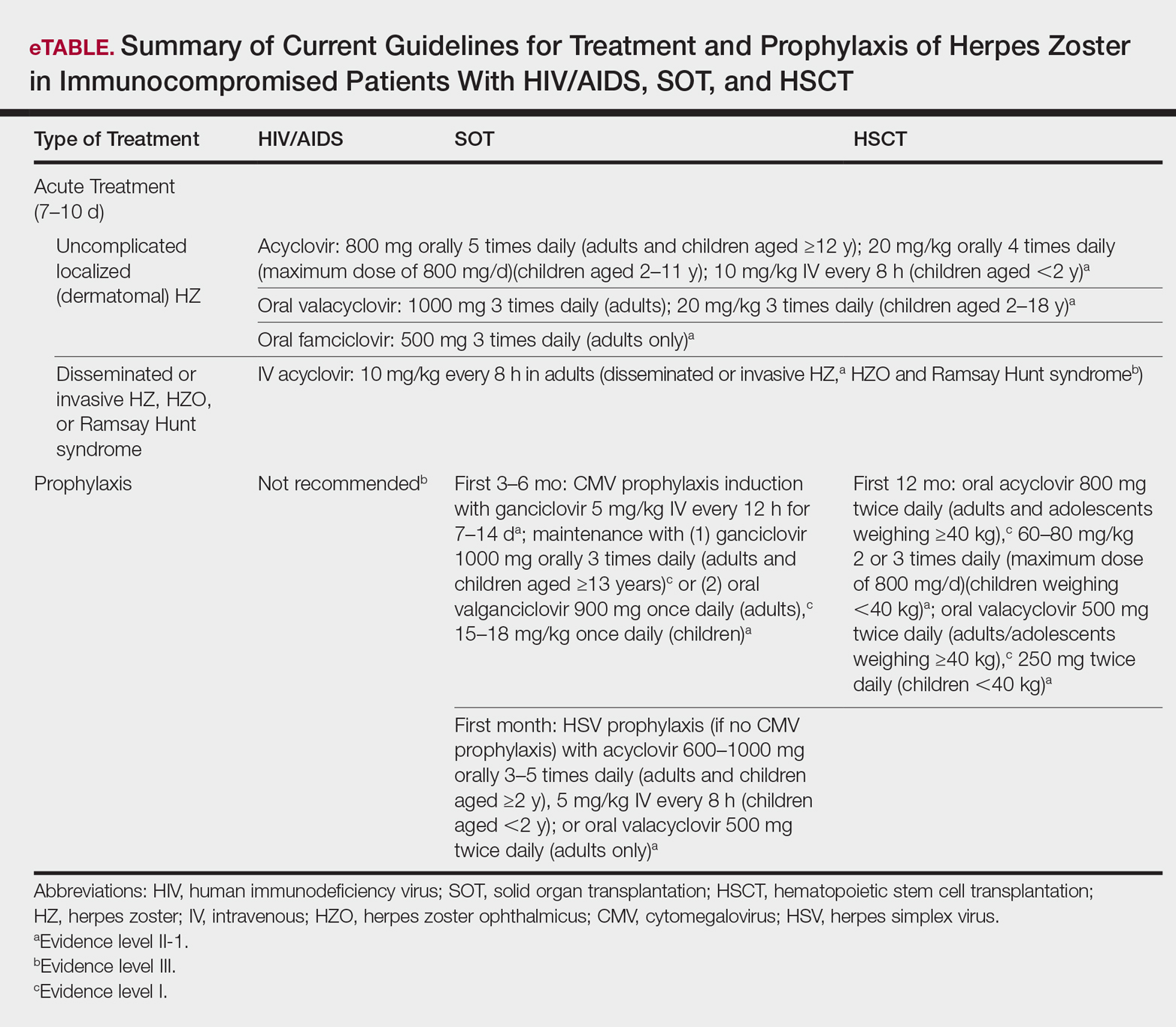

Several studies11-32 have evaluated modalities for treatment and prophylaxis for disseminated HZ in immunocompromised hosts, given its increased risk and potentially fatal complications in this population. The current guidelines in patients with HIV/AIDS, solid organ transplantation (SOT), and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are summarized in the eTable.

HIV/AIDS Patients

Given their efficacy and low rate of toxicity, oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir are recommended treatment options for HIV patients with localized, mild, dermatomal HZ.11 Two exceptions include HZ ophthalmicus and Ramsay Hunt syndrome for which some experts recommend intravenous acyclovir given the risk for vision loss and facial palsy, respectively. Intravenous acyclovir often is the drug of choice for treating complicated, disseminated, or severe HZ in HIV-infected patients, though prospective efficacy data remain limited.11

With regard to prevention of infection, a large randomized trial in 2016 found that acyclovir prophylaxis resulted in a 68% reduction in HZ over 2 years among HIV patients.12 Despite data that acyclovir may be effective for this purpose, long-term antiviral prophylaxis is not routinely recommended for HZ,11,13 as it has been linked to rare cases of acyclovir-resistant HZ in HIV patients.14,15 However, antiviral prophylaxis against HSV type 2 reactivation in HIV patients also confers protection against VZV reactivation.11,12

Solid Organ Transplantation

Localized, mild to moderately severe dermatomal HZ can be treated with oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir. As in HIV patients, SOT patients with severe, disseminated, or complicated HZ should receive IV acyclovir.11 In the first 3 to 6 months following the procedure, SOT patients receive cytomegalovirus prophylaxis with ganciclovir or valgan-ciclovir, which also provides protection against HZ.13-18 For patients not receiving cytomegalovirus prophylaxis, HSV prophylaxis with oral acyclovir or valacyclovir is given for at least the first month after transplantation, which also confers protection against HZ.16,19 Antiviral therapy is critical during the early posttransplantation period when patients are most severely immunosuppressed and thus have the highest risk for VZV-associated complications.20 Although immunosuppression is lifelong in most SOT recipients, there is insufficient evidence for extending prophylaxis beyond 6 months.16,21

As a possible risk factor for HZ,22 MMF use is another consideration among SOT patients, similar to patient 2 in our report. A 2003 observational study supported withdrawal of MMF therapy during active VZV infection due to clinical observation of an association with HZ.23 However, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial reported no cases of HZ in renal transplant recipients on MMF.24 Additionally, MMF has been observed to enhance the antiviral activity of acyclovir, at least in vitro.25 Given the lack of evidence of MMF as a risk factor for HZ, there is insufficient evidence for cessation of use during VZVreactivation in SOT patients.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

The preferred agents for treatment of localized mild dermatomal HZ are oral acyclovir or valacyclovir, as data on the safety and efficacy of famciclovir among HSCT recipients are limited.13,26 Patients should receive antiviral prophylaxis with one of these agents during the first year following allogeneic or autologous HSCT. This 1-year course has proven highly effective in reducing HZ in the first year following transplantation when most severe cases occur,21,26-29 and it has been associated with a persistently decreased risk for HZ even after discontinuation.21 Prophylaxis may be continued beyond 1 year in allogeneic HSCT recipients experiencing graft-versus-host disease who should receive acyclovir until 6 months after the end of immunosuppressive therapy.21,26

Vaccination remains a potential strategy to reduce the incidence of HZ in this patient population. A heat-inactivated vaccine administered within the first 3 months after the procedure has been shown to be safe among autologous and allogeneic HSCT patients.30,31 The vaccine notably reduced the incidence of HZ in patients who underwent autologous HSCT,32 but no known data are available on its clinical efficacy in allogeneic HSCT patients. Accordingly, there are no known official recommendations to date regarding vaccine use in these patient populations.26

Conclusion

It is incumbent upon clinicians to recognize the spectrum of atypical presentations of HZ and maintain a low threshold for performing appropriate diagnostic or confirmatory studies among at-risk patients with impaired immune function. Disseminated HZ can have potentially life-threatening visceral complications such as encephalitis, hepatitis, or pneumonitis.7,8 As such, an understanding of prevention and treatment modalities for VZV infection among immunocompromised patients is critical. Because the morbidity associated with complications of VZV infection is substantial and the risks associated with antiviral agents are minimal, antiviral prophylaxis is recommended for 6 months following SOT or 1 year following HSCT, and prompt treatment is warranted in cases of reasonable clinical suspicion for HZ.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generosity of our patients in permitting photography of their skin findings for the furthering of medical education.

- McCrary ML, Severson J, Tyring SK. Varicella zoster virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:1-16.

- Nagasako EM, Johnson RW, Griffin DR, et al. Rash severity in herpes zoster: correlates and relationship to postherpetic neuralgia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:834-839.

- Leung J, Harpaz R, Baughman AL, et al. Evaluation of laboratory methods for diagnosis of varicella. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:23-32.

- Herpes Zoster and Functional Decline Consortium. Functional decline and herpes zoster in older people: an interplay of multiple factors. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27:757-765.

- Weinberg A, Levin MJ. VZV T cell-mediated immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;342:341-357.

- Prelog M, Schonlaub J, Jeller V, et al. Reduced varicella-zoster-virus (VZV)-specific lymphocytes and IgG antibody avidity in solid organ transplant recipients. Vaccine. 2013;31:2420-2426.

- Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(suppl 1):S91-S98.

- Glesby MJ, Moore RD, Chaisson RE. Clinical spectrum of herpes zoster in adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:370-375.

- Blankenship W, Herchline T, Hockley A. Asymptomatic vesicles in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. disseminated varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1193, 1196.

- Katz J, Cooper EM, Walther RR, et al. Acute pain in herpes zoster and its impact on health-related quality of life. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:342-348.

- Gnann JW. Antiviral therapy of varicella-zoster virus infections. In: Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, et al, eds. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2007:1175-1191.

- Barnabas RV, Baeten JM, Lingappa JR, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis reduces the incidence of herpes zoster among HIV-infected individuals: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:551-555.

- Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, et al. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 1):S1-S26.

- Jacobson MA, Berger TG, Fikrig S, et al. Acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus infection after chronic oral acyclovir therapy in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:187-191.

- Linnemann CC Jr, Biron KK, Hoppenjans WG, et al. Emergence of acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus in an AIDS patient on prolonged acyclovir therapy. AIDS. 1990;4:577-579.

- Pergam SA, Limaye AP; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S108-S115.

- Preiksaitis JK, Brennan DC, Fishman J, et al. Canadian society of transplantation consensus workshop on cytomegalovirus management in solid organ transplantation final report. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:218-227.

- Fishman JA, Doran MT, Volpicelli SA, et al. Dosing of intravenous ganciclovir for the prophylaxis and treatment of cytomegalovirus infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2000;69:389-394.

- Zuckerman R, Wald A; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Herpes simplex virus infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S104-S107.

- Arness T, Pedersen R, Dierkhising R, et al. Varicella zoster virus-associated disease in adult kidney transplant recipients: incidence and risk-factor analysis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10:260-268.

- Erard V, Guthrie KA, Varley C, et al. One-year acyclovir prophylaxis for preventing varicella-zoster virus disease after hematopoietic cell transplantation: no evidence of rebound varicella-zoster virus disease after drug discontinuation. Blood. 2007;110:3071-3077.

- Rothwell WS, Gloor JM, Morgenstern BZ, et al. Disseminated varicella infection in pediatric renal transplant recipients treated with mycophenolate mofetil. Transplantation. 1999;68:158-161.

- Lauzurica R, Bayés B, Frías C, et al. Disseminated varicella infection in adult renal allograft recipients: role of mycophenolate mofetil. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1758-1759.

- A blinded, randomized clinical trial of mycophenolate mofetil for the prevention of acute rejection in cadaveric renal transplantation. TheTricontinental Mycophenolate Mofetil Renal Transplantation Study Group. Transplantation. 1996;61:1029-1037.

- Neyts J, De Clercq E. Mycophenolate mofetil strongly potentiates the anti-herpesvirus activity of acyclovir. Antiviral Res. 1998;40:53-56.

- Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H, et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1143-1238.

- Boeckh M, Kim HW, Flowers ME, et al. Long-term acyclovir for prevention of varicella zoster virus disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation—a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Blood. 2006;107:1800-1805.

- Kawamura K, Hayakawa J, Akahoshi Y, et al. Low-dose acyclovir prophylaxis for the prevention of herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus diseases after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2015;102:230-237.

- Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance. Long-term follow-up after hematopoietic stem cell transplant general guidelines for referring physicians. Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center website. https://www.fredhutch.org/content/dam/public/Treatment-Suport/Long-Term-Follow-Up/physician.pdf. Published July 17, 2014. Accessed October 19, 2017.

- Kussmaul SC, Horn BN, Dvorak CC, et al. Safety of the live, attenuated varicella vaccine in pediatric recipients of hematopoietic SCTs. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:1602-1606.

- Hata A, Asanuma H, Rinki M, et al. Use of an inactivated varicella vaccine in recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:26-34.

- Issa NC, Marty FM, Leblebjian H, et al. Live attenuated varicella-zoster vaccine in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:285-287.

Well-known for its typical presentation, classic herpes zoster (HZ) presents as a dermatomal eruption of painful erythematous papules that evolve into grouped vesicles or bullae.1,2 Thereafter, the lesions can become pustular or hemorrhagic.1 Although the diagnosis most often is made clinically, confirmatory techniques for diagnosis include viral culture, direct fluorescent antibody testing, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay.1,3

The main risk factor for HZ is advanced age, most commonly affecting elderly patients.4 It is hypothesized that a physiological decline in varicella-zoster virus (VZV)–specific cell-mediated immunity among elderly individuals helps trigger reactivation of the virus within the dorsal root ganglion.1,5 Similarly affected are immunocompromised individuals, including those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, due to suppression of T cells immune to VZV,1,5 as well as immunosuppressed transplant recipients who have diminished VZV-specific cellular responses and VZV IgG antibody avidity.6

Secondary complications of VZV infection (eg, postherpetic neuralgia, bacterial superinfection progressing to cellulitis) lead to increased morbidity.7,8 Disseminated cutaneous HZ is another grave complication of VZV infection and almost exclusively occurs with immunosuppression.1,8 It manifests as an eruption of at least 20 widespread vesiculobullous lesions outside the primary and adjacent dermatomes.6 Immunocompromised patients also are at increased risk for visceral involvement of VZV infection, which may affect vital organs such as the brain, liver, or lungs.7,8 Given the atypical presentation of VZV infection among some immunocompromised individuals, these patients are at increased risk for diagnostic delay and morbidity in the absence of high clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 52-year-old man developed a painless nonpruritic rash on the left leg of 4 days’ duration. It initially appeared as an erythematous maculopapular rash on the medial aspect of the left knee without any prodromal symptoms. Over the next 4 days, erythematous vesicles developed that progressed to pustules, and the rash spread both proximally and distally along the left leg. Shortly following hospital admission, he developed a fever (temperature, 38.4°C). His medical history included alcoholic liver cirrhosis and AIDS, with a CD4 count of 174 cells/µL (reference range, 500–1500 cells/µL). He had been taking antiretroviral therapy (abacavir-lamivudine and dolutegravir) and prophylaxis against opportunistic infections (dapsone and itraconazole).

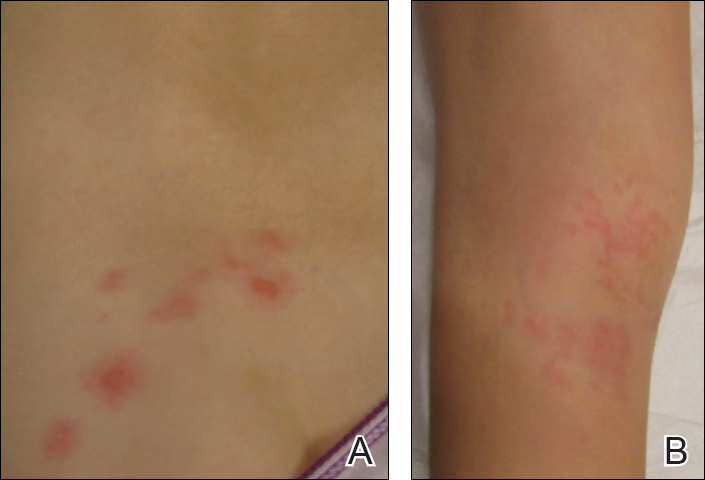

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of multiple 1-cm clusters of approximately 40 pustules each scattered in a nondermatomal distribution along the left leg (Figure 1). Many of the vesicles were confluent with an erythematous base and were in different stages of evolution with some crusted and others emanating a thin liquid exudate. The lesions were nontender and without notable induration. The leg was warm and edematous.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis included disseminated HZ with bacterial superinfection, Vibrio vulnificus infection, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. The patient was treated with intravenous vancomycin, levofloxacin, and acyclovir, and no new lesions developed throughout the course of treatment. On this regimen, his fever resolved after 1 day, the active lesions began to crust, and the edema and erythema diminished. Results of bacterial cultures and plasma PCR and IgM for HSV types 1 and 2 were negative. Viral culture results were negative, but a PCR assay for VZV was positive, reflective of acute reactivation of VZV.

Patient 2

A 63-year-old man developed a pruritic burning rash involving the face, trunk, arms, and legs of 6 days’ duration. His medical history included a heart transplant 6 months prior to presentation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. He was taking antirejection therapy with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), prednisone, and tacrolimus.

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of clusters of 1- to 2-mm vesicles scattered in a nondermatomal pattern. Isolated vesicles involved the forehead, nose, and left ear, and diffuse vesicles with a relatively symmetric distribution were scattered across the back, chest, and proximal and distal arms and legs (Figure 2). Many of the vesicles had an associated overlying crust with hemorrhage. Some of the vesicles coalesced with central necrotic plaques.

Given a clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ, therapy with oral valacyclovir was initiated. Two punch biopsies were consistent with herpesvirus cytopathic changes. Multiple sections demonstrated ulceration as well as acantholysis and necrosis of keratinocytes with multinucleation and margination of chromatin. There was an intense lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. Immunohistochemistry staining was positive for VZV and negative for HSV, indicating acute reactivation of VZV (Figure 3). Upon completion of an antiviral regimen, the patient returned to clinic with healed crusted lesions.

Comment

Frequently, the clinical features of HZ in immunocompromised patients mirror those in immunocompetent hosts.8 However, each of our 2 patients developed an unusual presentation of atypical generalized HZ.7 In this clinical variant, lesions develop along a single dermatome, then a diffuse vesicular eruption subsequently develops without dermatomal localization. These lesions can be chronic, persisting for months or years.7

The classic clinical presentation of HZ is distinct and often is readily diagnosed by visual inspection.7 However, atypical presentations and their associated complications can pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.7 Painless HZ lesions in a nondermatomal pattern were described in a patient who also had AIDS.9 Interestingly, multiple reports have found that patients with a severe but painless rash are less likely to have experienced a viral prodrome consisting of hyperesthesia, paresthesia, or pruritus.2,10 This observation suggests that lack of a prodrome, as in the case of patient 1 in our report, may aid in the recognition of painless HZ. Because of these atypical presentations, laboratory testing is even more important than in immunocompetent hosts, as diagnosis may be more difficult to establish on clinical presentation alone.

Several studies11-32 have evaluated modalities for treatment and prophylaxis for disseminated HZ in immunocompromised hosts, given its increased risk and potentially fatal complications in this population. The current guidelines in patients with HIV/AIDS, solid organ transplantation (SOT), and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are summarized in the eTable.

HIV/AIDS Patients

Given their efficacy and low rate of toxicity, oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir are recommended treatment options for HIV patients with localized, mild, dermatomal HZ.11 Two exceptions include HZ ophthalmicus and Ramsay Hunt syndrome for which some experts recommend intravenous acyclovir given the risk for vision loss and facial palsy, respectively. Intravenous acyclovir often is the drug of choice for treating complicated, disseminated, or severe HZ in HIV-infected patients, though prospective efficacy data remain limited.11

With regard to prevention of infection, a large randomized trial in 2016 found that acyclovir prophylaxis resulted in a 68% reduction in HZ over 2 years among HIV patients.12 Despite data that acyclovir may be effective for this purpose, long-term antiviral prophylaxis is not routinely recommended for HZ,11,13 as it has been linked to rare cases of acyclovir-resistant HZ in HIV patients.14,15 However, antiviral prophylaxis against HSV type 2 reactivation in HIV patients also confers protection against VZV reactivation.11,12

Solid Organ Transplantation

Localized, mild to moderately severe dermatomal HZ can be treated with oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir. As in HIV patients, SOT patients with severe, disseminated, or complicated HZ should receive IV acyclovir.11 In the first 3 to 6 months following the procedure, SOT patients receive cytomegalovirus prophylaxis with ganciclovir or valgan-ciclovir, which also provides protection against HZ.13-18 For patients not receiving cytomegalovirus prophylaxis, HSV prophylaxis with oral acyclovir or valacyclovir is given for at least the first month after transplantation, which also confers protection against HZ.16,19 Antiviral therapy is critical during the early posttransplantation period when patients are most severely immunosuppressed and thus have the highest risk for VZV-associated complications.20 Although immunosuppression is lifelong in most SOT recipients, there is insufficient evidence for extending prophylaxis beyond 6 months.16,21

As a possible risk factor for HZ,22 MMF use is another consideration among SOT patients, similar to patient 2 in our report. A 2003 observational study supported withdrawal of MMF therapy during active VZV infection due to clinical observation of an association with HZ.23 However, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial reported no cases of HZ in renal transplant recipients on MMF.24 Additionally, MMF has been observed to enhance the antiviral activity of acyclovir, at least in vitro.25 Given the lack of evidence of MMF as a risk factor for HZ, there is insufficient evidence for cessation of use during VZVreactivation in SOT patients.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

The preferred agents for treatment of localized mild dermatomal HZ are oral acyclovir or valacyclovir, as data on the safety and efficacy of famciclovir among HSCT recipients are limited.13,26 Patients should receive antiviral prophylaxis with one of these agents during the first year following allogeneic or autologous HSCT. This 1-year course has proven highly effective in reducing HZ in the first year following transplantation when most severe cases occur,21,26-29 and it has been associated with a persistently decreased risk for HZ even after discontinuation.21 Prophylaxis may be continued beyond 1 year in allogeneic HSCT recipients experiencing graft-versus-host disease who should receive acyclovir until 6 months after the end of immunosuppressive therapy.21,26

Vaccination remains a potential strategy to reduce the incidence of HZ in this patient population. A heat-inactivated vaccine administered within the first 3 months after the procedure has been shown to be safe among autologous and allogeneic HSCT patients.30,31 The vaccine notably reduced the incidence of HZ in patients who underwent autologous HSCT,32 but no known data are available on its clinical efficacy in allogeneic HSCT patients. Accordingly, there are no known official recommendations to date regarding vaccine use in these patient populations.26

Conclusion

It is incumbent upon clinicians to recognize the spectrum of atypical presentations of HZ and maintain a low threshold for performing appropriate diagnostic or confirmatory studies among at-risk patients with impaired immune function. Disseminated HZ can have potentially life-threatening visceral complications such as encephalitis, hepatitis, or pneumonitis.7,8 As such, an understanding of prevention and treatment modalities for VZV infection among immunocompromised patients is critical. Because the morbidity associated with complications of VZV infection is substantial and the risks associated with antiviral agents are minimal, antiviral prophylaxis is recommended for 6 months following SOT or 1 year following HSCT, and prompt treatment is warranted in cases of reasonable clinical suspicion for HZ.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generosity of our patients in permitting photography of their skin findings for the furthering of medical education.

Well-known for its typical presentation, classic herpes zoster (HZ) presents as a dermatomal eruption of painful erythematous papules that evolve into grouped vesicles or bullae.1,2 Thereafter, the lesions can become pustular or hemorrhagic.1 Although the diagnosis most often is made clinically, confirmatory techniques for diagnosis include viral culture, direct fluorescent antibody testing, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay.1,3

The main risk factor for HZ is advanced age, most commonly affecting elderly patients.4 It is hypothesized that a physiological decline in varicella-zoster virus (VZV)–specific cell-mediated immunity among elderly individuals helps trigger reactivation of the virus within the dorsal root ganglion.1,5 Similarly affected are immunocompromised individuals, including those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, due to suppression of T cells immune to VZV,1,5 as well as immunosuppressed transplant recipients who have diminished VZV-specific cellular responses and VZV IgG antibody avidity.6

Secondary complications of VZV infection (eg, postherpetic neuralgia, bacterial superinfection progressing to cellulitis) lead to increased morbidity.7,8 Disseminated cutaneous HZ is another grave complication of VZV infection and almost exclusively occurs with immunosuppression.1,8 It manifests as an eruption of at least 20 widespread vesiculobullous lesions outside the primary and adjacent dermatomes.6 Immunocompromised patients also are at increased risk for visceral involvement of VZV infection, which may affect vital organs such as the brain, liver, or lungs.7,8 Given the atypical presentation of VZV infection among some immunocompromised individuals, these patients are at increased risk for diagnostic delay and morbidity in the absence of high clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 52-year-old man developed a painless nonpruritic rash on the left leg of 4 days’ duration. It initially appeared as an erythematous maculopapular rash on the medial aspect of the left knee without any prodromal symptoms. Over the next 4 days, erythematous vesicles developed that progressed to pustules, and the rash spread both proximally and distally along the left leg. Shortly following hospital admission, he developed a fever (temperature, 38.4°C). His medical history included alcoholic liver cirrhosis and AIDS, with a CD4 count of 174 cells/µL (reference range, 500–1500 cells/µL). He had been taking antiretroviral therapy (abacavir-lamivudine and dolutegravir) and prophylaxis against opportunistic infections (dapsone and itraconazole).

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of multiple 1-cm clusters of approximately 40 pustules each scattered in a nondermatomal distribution along the left leg (Figure 1). Many of the vesicles were confluent with an erythematous base and were in different stages of evolution with some crusted and others emanating a thin liquid exudate. The lesions were nontender and without notable induration. The leg was warm and edematous.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis included disseminated HZ with bacterial superinfection, Vibrio vulnificus infection, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. The patient was treated with intravenous vancomycin, levofloxacin, and acyclovir, and no new lesions developed throughout the course of treatment. On this regimen, his fever resolved after 1 day, the active lesions began to crust, and the edema and erythema diminished. Results of bacterial cultures and plasma PCR and IgM for HSV types 1 and 2 were negative. Viral culture results were negative, but a PCR assay for VZV was positive, reflective of acute reactivation of VZV.

Patient 2

A 63-year-old man developed a pruritic burning rash involving the face, trunk, arms, and legs of 6 days’ duration. His medical history included a heart transplant 6 months prior to presentation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. He was taking antirejection therapy with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), prednisone, and tacrolimus.

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of clusters of 1- to 2-mm vesicles scattered in a nondermatomal pattern. Isolated vesicles involved the forehead, nose, and left ear, and diffuse vesicles with a relatively symmetric distribution were scattered across the back, chest, and proximal and distal arms and legs (Figure 2). Many of the vesicles had an associated overlying crust with hemorrhage. Some of the vesicles coalesced with central necrotic plaques.

Given a clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ, therapy with oral valacyclovir was initiated. Two punch biopsies were consistent with herpesvirus cytopathic changes. Multiple sections demonstrated ulceration as well as acantholysis and necrosis of keratinocytes with multinucleation and margination of chromatin. There was an intense lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. Immunohistochemistry staining was positive for VZV and negative for HSV, indicating acute reactivation of VZV (Figure 3). Upon completion of an antiviral regimen, the patient returned to clinic with healed crusted lesions.

Comment

Frequently, the clinical features of HZ in immunocompromised patients mirror those in immunocompetent hosts.8 However, each of our 2 patients developed an unusual presentation of atypical generalized HZ.7 In this clinical variant, lesions develop along a single dermatome, then a diffuse vesicular eruption subsequently develops without dermatomal localization. These lesions can be chronic, persisting for months or years.7

The classic clinical presentation of HZ is distinct and often is readily diagnosed by visual inspection.7 However, atypical presentations and their associated complications can pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.7 Painless HZ lesions in a nondermatomal pattern were described in a patient who also had AIDS.9 Interestingly, multiple reports have found that patients with a severe but painless rash are less likely to have experienced a viral prodrome consisting of hyperesthesia, paresthesia, or pruritus.2,10 This observation suggests that lack of a prodrome, as in the case of patient 1 in our report, may aid in the recognition of painless HZ. Because of these atypical presentations, laboratory testing is even more important than in immunocompetent hosts, as diagnosis may be more difficult to establish on clinical presentation alone.

Several studies11-32 have evaluated modalities for treatment and prophylaxis for disseminated HZ in immunocompromised hosts, given its increased risk and potentially fatal complications in this population. The current guidelines in patients with HIV/AIDS, solid organ transplantation (SOT), and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are summarized in the eTable.

HIV/AIDS Patients

Given their efficacy and low rate of toxicity, oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir are recommended treatment options for HIV patients with localized, mild, dermatomal HZ.11 Two exceptions include HZ ophthalmicus and Ramsay Hunt syndrome for which some experts recommend intravenous acyclovir given the risk for vision loss and facial palsy, respectively. Intravenous acyclovir often is the drug of choice for treating complicated, disseminated, or severe HZ in HIV-infected patients, though prospective efficacy data remain limited.11

With regard to prevention of infection, a large randomized trial in 2016 found that acyclovir prophylaxis resulted in a 68% reduction in HZ over 2 years among HIV patients.12 Despite data that acyclovir may be effective for this purpose, long-term antiviral prophylaxis is not routinely recommended for HZ,11,13 as it has been linked to rare cases of acyclovir-resistant HZ in HIV patients.14,15 However, antiviral prophylaxis against HSV type 2 reactivation in HIV patients also confers protection against VZV reactivation.11,12

Solid Organ Transplantation

Localized, mild to moderately severe dermatomal HZ can be treated with oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir. As in HIV patients, SOT patients with severe, disseminated, or complicated HZ should receive IV acyclovir.11 In the first 3 to 6 months following the procedure, SOT patients receive cytomegalovirus prophylaxis with ganciclovir or valgan-ciclovir, which also provides protection against HZ.13-18 For patients not receiving cytomegalovirus prophylaxis, HSV prophylaxis with oral acyclovir or valacyclovir is given for at least the first month after transplantation, which also confers protection against HZ.16,19 Antiviral therapy is critical during the early posttransplantation period when patients are most severely immunosuppressed and thus have the highest risk for VZV-associated complications.20 Although immunosuppression is lifelong in most SOT recipients, there is insufficient evidence for extending prophylaxis beyond 6 months.16,21

As a possible risk factor for HZ,22 MMF use is another consideration among SOT patients, similar to patient 2 in our report. A 2003 observational study supported withdrawal of MMF therapy during active VZV infection due to clinical observation of an association with HZ.23 However, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial reported no cases of HZ in renal transplant recipients on MMF.24 Additionally, MMF has been observed to enhance the antiviral activity of acyclovir, at least in vitro.25 Given the lack of evidence of MMF as a risk factor for HZ, there is insufficient evidence for cessation of use during VZVreactivation in SOT patients.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

The preferred agents for treatment of localized mild dermatomal HZ are oral acyclovir or valacyclovir, as data on the safety and efficacy of famciclovir among HSCT recipients are limited.13,26 Patients should receive antiviral prophylaxis with one of these agents during the first year following allogeneic or autologous HSCT. This 1-year course has proven highly effective in reducing HZ in the first year following transplantation when most severe cases occur,21,26-29 and it has been associated with a persistently decreased risk for HZ even after discontinuation.21 Prophylaxis may be continued beyond 1 year in allogeneic HSCT recipients experiencing graft-versus-host disease who should receive acyclovir until 6 months after the end of immunosuppressive therapy.21,26

Vaccination remains a potential strategy to reduce the incidence of HZ in this patient population. A heat-inactivated vaccine administered within the first 3 months after the procedure has been shown to be safe among autologous and allogeneic HSCT patients.30,31 The vaccine notably reduced the incidence of HZ in patients who underwent autologous HSCT,32 but no known data are available on its clinical efficacy in allogeneic HSCT patients. Accordingly, there are no known official recommendations to date regarding vaccine use in these patient populations.26

Conclusion

It is incumbent upon clinicians to recognize the spectrum of atypical presentations of HZ and maintain a low threshold for performing appropriate diagnostic or confirmatory studies among at-risk patients with impaired immune function. Disseminated HZ can have potentially life-threatening visceral complications such as encephalitis, hepatitis, or pneumonitis.7,8 As such, an understanding of prevention and treatment modalities for VZV infection among immunocompromised patients is critical. Because the morbidity associated with complications of VZV infection is substantial and the risks associated with antiviral agents are minimal, antiviral prophylaxis is recommended for 6 months following SOT or 1 year following HSCT, and prompt treatment is warranted in cases of reasonable clinical suspicion for HZ.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generosity of our patients in permitting photography of their skin findings for the furthering of medical education.

- McCrary ML, Severson J, Tyring SK. Varicella zoster virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:1-16.

- Nagasako EM, Johnson RW, Griffin DR, et al. Rash severity in herpes zoster: correlates and relationship to postherpetic neuralgia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:834-839.

- Leung J, Harpaz R, Baughman AL, et al. Evaluation of laboratory methods for diagnosis of varicella. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:23-32.

- Herpes Zoster and Functional Decline Consortium. Functional decline and herpes zoster in older people: an interplay of multiple factors. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27:757-765.

- Weinberg A, Levin MJ. VZV T cell-mediated immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;342:341-357.

- Prelog M, Schonlaub J, Jeller V, et al. Reduced varicella-zoster-virus (VZV)-specific lymphocytes and IgG antibody avidity in solid organ transplant recipients. Vaccine. 2013;31:2420-2426.