User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Atypical Herpes Zoster Presentation in a Healthy Vaccinated Pediatric Patient

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is a neurotropic human herpesvirus that causes varicella (chicken pox) and herpes zoster (shingles). During infection, the virus invades the dorsal root ganglia and establishes permanent latency. It can later reactivate and travel through sensory nerves to the skin where localized viral replication causes herpes zoster (HZ), which manifests with pain in a unilateral dermatomal distribution followed closely by an eruption of grouped macules and papules that evolve into vesicles on an erythematous base.1 These lesions form pustules and crusts over 7 to 10 days and heal completely within 4 weeks. Although postherpetic neuralgia is rare in children, the pain associated with HZ can last months or years.1,2

Universal childhood vaccination against VZV has existed in the United States since 1995, with a 2-dose vaccine regimen recommended by the CDC since 2007. Consequently, primary varicella infection in children is uncommon, and the majority of cases now occur in the vaccinated population.3 However, breakthrough varicella infection and postvaccination HZ are rare due to the long-lasting immunity and low virulence of the attenuated vaccine strain. We recount the case of a 6-year-old vaccinated girl with a unique presentation of HZ with no known primary varicella infection.

Case Report

A healthy 6-year-old girl presented with a stabbing burning pain in the left thigh extending down the calf of 4 days’ duration. The intense pain made walking difficult and responded minimally to ibuprofen and naproxen. Poor appetite, nausea, colicky abdominal pain, and fever (temperature, 38°C) accompanied the pain. Three days after the pain began she developed a pruritic rash on the same leg. Notably, she reported falling on a rosebush and sustaining a thorn prick in the left thigh 3 days prior to the onset of pain. Before presenting to our dermatology clinic, she was seen by a pediatrician, an emergency department physician, and an infectious disease specialist. The initial workup included a complete blood cell count, C-reactive protein test, erythrocyte sedimentation rate test, and hip and femur radiograph, which were all unremarkable. She was referred to dermatology with a differential diagnosis of sporotrichosis, contact dermatitis, reactive arthritis, viral myalgia, and Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease.

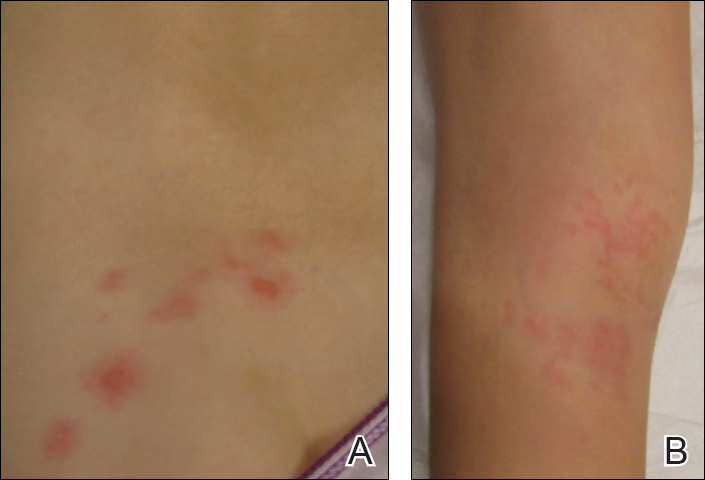

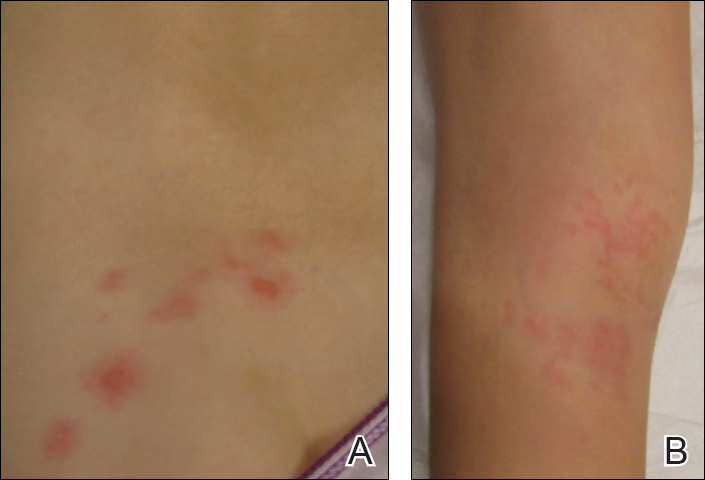

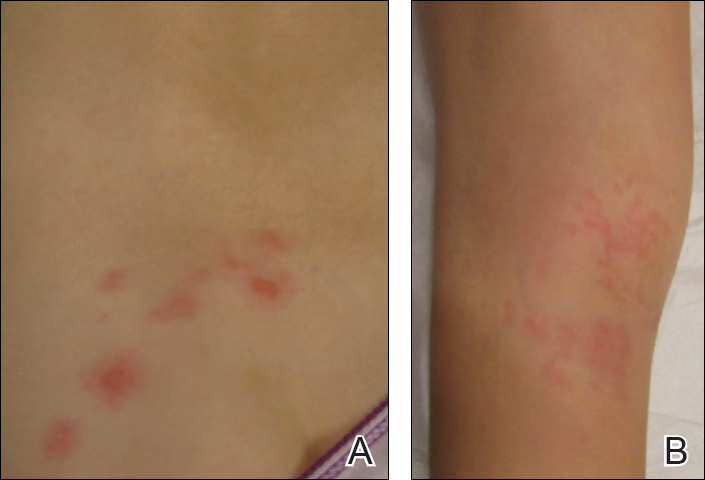

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing child with pink eczematous patches and plaques extending from the left side of the lower back to the mid shin in an L5 distribution (Figure). The left thigh was tender to palpation, and nontender left inguinal lymphadenopathy was present. A single isolated 2-mm vesicle was found on the anterior aspect of the left lower leg. Direct fluorescent antibody testing of vesicle fluid was positive for VZV antigen, confirming the diagnosis of HZ.

The patient’s mother confirmed that she had no obvious history of VZV. She had received VZV vaccinations in the left leg and arm at 1 and 4 years of age, respectively. She was treated with acyclovir (80 mg/kg daily at 6-hour intervals for 5 days) with immediate improvement in symptoms and resolution of the rash by day 5 of treatment. She experienced intermittent burning pain in the leg throughout the course of treatment, which resolved shortly thereafter.

Comment

Herpes zoster is rare in young healthy children, and its incidence has decreased since the introduction of universal varicella vaccination.4 Reported incidence rates in vaccinated children vary from approximately 15 to 93 per 100,000 person-years,5,6 and the reported relative risk is 0.08 to 0.36 in vaccinated compared to unvaccinated children.6,7 No correlations with gender, race, or ethnicity and postvaccination HZ have been observed.5,8 Reported intervals between vaccination and HZ presentation are as short as 3 months and as long as 11 years.9 Although HZ is uncommon in immunocompetent children, the diagnosis of HZ itself is not an indication for formal workup for an underlying immunodeficiency or malignancy.10

Both wild-type and vaccine-strain VZV establish latent infection and can cause HZ in vaccinated children. Direct fluorescent antibody testing or polymerase chain reaction of HZ lesions can be used to identify VZV. Genotyping can distinguish the wild-type versus the vaccine strain but is not required for clinical management.3 In previously vaccinated children with HZ, approximately half present with wild-type and half with vaccine-strain VZV. In approximately half of wild-type cases, prior clinical varicella infection also occurred.8

Regardless of virus strain, vaccinated children typically present with the characteristic painful, vesicular, dermatomal HZ rash.8,9 This presentation can be milder with less pain and fewer vesicles than with unvaccinated cases.6 When vaccine-strain HZ occurs, the rash often presents at or near the site of initial vaccination, which typically is the arm or thigh.3,4,6,9 The vaccine strain has lower virulence than the wild-type virus. Eight cases of vaccine-strain zoster severe enough to cause neurological complications such as meningitis or encephalitis have been reported in children, with 6 cases reported in healthy children.9,11-17 Antiviral drugs hasten the healing of the HZ rash and shorten the duration of associated pain.1

Although pediatric HZ is uncommon, all physicians should be aware of possible atypical presentations in healthy vaccinated children to appropriately and quickly manage treatment.

- Sampathkumar P, Drage LA, Martin DP. Herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:274-280.

- Hillebrand K, Bricout H, Schulze-Rath R, et al. Incidence of herpes zoster and its complications in Germany, 2005-2009. J Infect. 2015;70:178-186.

- Lopez A, Schmid S, Bialek S. Varicella. In: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Manual for the Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. 5th ed. 2011:1-16.

- Tanuseputroa P, Zagorskia B, Chanc KJ, et al. Population-based incidence of herpes zoster after introduction of a publicly funded varicella vaccination program. Vaccine. 2011;29:8580- 8584.

- Wen SY, Liu WL. Epidemiology of pediatric herpes zoster after varicella infection: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2015;135:565-571.

- Civen R, Chaves SS, Jumaan A, et al. The incidence and clinical characteristics of herpes zoster among children and adolescents after implementation of varicella vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:954-959.

- Stein M, Cohen R, Bromberg M, et al. Herpes zoster in a partially vaccinated pediatric population in Central Israel. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:906-909.

- Weinmann S, Chun C, Schmid DS, et al. Incidence and clinical characteristics of herpes zoster among children in the varicella vaccine era, 2005-2009. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1859-1868.

- Horien C, Grose C. Neurovirulence of varicella and the live attenuated varicella vaccine virus. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2012;19:124-129.

- Petursson G, Helgason S, Gudmundsson S, et al. Herpes zoster in children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:905-908.

- Levin MJ, Dahl KM, Weinberg A, et al. Development of resistance to acyclovir during chronic infection with the Oka vaccine strain of varicella-zoster virus in an immunosuppressed child. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:954-959.

- Chaves SS, Haber P, Walton K, et al. Safety of varicella vaccine after licensure in the United States: experience from reports to the vaccine adverse event reporting system, 1995-2005. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(suppl 2):S170-S177.

- Levin MJ, DeBiasi RL, Bostik V, et al. Herpes zoster with skin lesions and meningitis caused by 2 different genotypes of the Oka varicella zoster virus vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1444-1447.

- Iyer S, Mittal MK, Hodinka RL. Herpes zoster and meningitis resulting from reactivation of varicella vaccine virus in an immunocompetent child. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:792-795.

- Chouliaras G, Spoulou V, Quinlivan M, et al. Vaccine-associated herpes zoster ophthalmicus and encephalitis in an immunocompetent child. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e969-e972.

- Pahud BA, Glaser CA, Dekker CL, et al. Varicella zoster disease of the central nervous system: epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory features 10 years after the introduction of the varicella vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:316-323.

- Han JY, Hanson DC, Way SS. Herpes zoster and meningitis due to reactivation of varicella vaccine virus in an immunocompetent child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:266-268.

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is a neurotropic human herpesvirus that causes varicella (chicken pox) and herpes zoster (shingles). During infection, the virus invades the dorsal root ganglia and establishes permanent latency. It can later reactivate and travel through sensory nerves to the skin where localized viral replication causes herpes zoster (HZ), which manifests with pain in a unilateral dermatomal distribution followed closely by an eruption of grouped macules and papules that evolve into vesicles on an erythematous base.1 These lesions form pustules and crusts over 7 to 10 days and heal completely within 4 weeks. Although postherpetic neuralgia is rare in children, the pain associated with HZ can last months or years.1,2

Universal childhood vaccination against VZV has existed in the United States since 1995, with a 2-dose vaccine regimen recommended by the CDC since 2007. Consequently, primary varicella infection in children is uncommon, and the majority of cases now occur in the vaccinated population.3 However, breakthrough varicella infection and postvaccination HZ are rare due to the long-lasting immunity and low virulence of the attenuated vaccine strain. We recount the case of a 6-year-old vaccinated girl with a unique presentation of HZ with no known primary varicella infection.

Case Report

A healthy 6-year-old girl presented with a stabbing burning pain in the left thigh extending down the calf of 4 days’ duration. The intense pain made walking difficult and responded minimally to ibuprofen and naproxen. Poor appetite, nausea, colicky abdominal pain, and fever (temperature, 38°C) accompanied the pain. Three days after the pain began she developed a pruritic rash on the same leg. Notably, she reported falling on a rosebush and sustaining a thorn prick in the left thigh 3 days prior to the onset of pain. Before presenting to our dermatology clinic, she was seen by a pediatrician, an emergency department physician, and an infectious disease specialist. The initial workup included a complete blood cell count, C-reactive protein test, erythrocyte sedimentation rate test, and hip and femur radiograph, which were all unremarkable. She was referred to dermatology with a differential diagnosis of sporotrichosis, contact dermatitis, reactive arthritis, viral myalgia, and Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease.

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing child with pink eczematous patches and plaques extending from the left side of the lower back to the mid shin in an L5 distribution (Figure). The left thigh was tender to palpation, and nontender left inguinal lymphadenopathy was present. A single isolated 2-mm vesicle was found on the anterior aspect of the left lower leg. Direct fluorescent antibody testing of vesicle fluid was positive for VZV antigen, confirming the diagnosis of HZ.

The patient’s mother confirmed that she had no obvious history of VZV. She had received VZV vaccinations in the left leg and arm at 1 and 4 years of age, respectively. She was treated with acyclovir (80 mg/kg daily at 6-hour intervals for 5 days) with immediate improvement in symptoms and resolution of the rash by day 5 of treatment. She experienced intermittent burning pain in the leg throughout the course of treatment, which resolved shortly thereafter.

Comment

Herpes zoster is rare in young healthy children, and its incidence has decreased since the introduction of universal varicella vaccination.4 Reported incidence rates in vaccinated children vary from approximately 15 to 93 per 100,000 person-years,5,6 and the reported relative risk is 0.08 to 0.36 in vaccinated compared to unvaccinated children.6,7 No correlations with gender, race, or ethnicity and postvaccination HZ have been observed.5,8 Reported intervals between vaccination and HZ presentation are as short as 3 months and as long as 11 years.9 Although HZ is uncommon in immunocompetent children, the diagnosis of HZ itself is not an indication for formal workup for an underlying immunodeficiency or malignancy.10

Both wild-type and vaccine-strain VZV establish latent infection and can cause HZ in vaccinated children. Direct fluorescent antibody testing or polymerase chain reaction of HZ lesions can be used to identify VZV. Genotyping can distinguish the wild-type versus the vaccine strain but is not required for clinical management.3 In previously vaccinated children with HZ, approximately half present with wild-type and half with vaccine-strain VZV. In approximately half of wild-type cases, prior clinical varicella infection also occurred.8

Regardless of virus strain, vaccinated children typically present with the characteristic painful, vesicular, dermatomal HZ rash.8,9 This presentation can be milder with less pain and fewer vesicles than with unvaccinated cases.6 When vaccine-strain HZ occurs, the rash often presents at or near the site of initial vaccination, which typically is the arm or thigh.3,4,6,9 The vaccine strain has lower virulence than the wild-type virus. Eight cases of vaccine-strain zoster severe enough to cause neurological complications such as meningitis or encephalitis have been reported in children, with 6 cases reported in healthy children.9,11-17 Antiviral drugs hasten the healing of the HZ rash and shorten the duration of associated pain.1

Although pediatric HZ is uncommon, all physicians should be aware of possible atypical presentations in healthy vaccinated children to appropriately and quickly manage treatment.

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is a neurotropic human herpesvirus that causes varicella (chicken pox) and herpes zoster (shingles). During infection, the virus invades the dorsal root ganglia and establishes permanent latency. It can later reactivate and travel through sensory nerves to the skin where localized viral replication causes herpes zoster (HZ), which manifests with pain in a unilateral dermatomal distribution followed closely by an eruption of grouped macules and papules that evolve into vesicles on an erythematous base.1 These lesions form pustules and crusts over 7 to 10 days and heal completely within 4 weeks. Although postherpetic neuralgia is rare in children, the pain associated with HZ can last months or years.1,2

Universal childhood vaccination against VZV has existed in the United States since 1995, with a 2-dose vaccine regimen recommended by the CDC since 2007. Consequently, primary varicella infection in children is uncommon, and the majority of cases now occur in the vaccinated population.3 However, breakthrough varicella infection and postvaccination HZ are rare due to the long-lasting immunity and low virulence of the attenuated vaccine strain. We recount the case of a 6-year-old vaccinated girl with a unique presentation of HZ with no known primary varicella infection.

Case Report

A healthy 6-year-old girl presented with a stabbing burning pain in the left thigh extending down the calf of 4 days’ duration. The intense pain made walking difficult and responded minimally to ibuprofen and naproxen. Poor appetite, nausea, colicky abdominal pain, and fever (temperature, 38°C) accompanied the pain. Three days after the pain began she developed a pruritic rash on the same leg. Notably, she reported falling on a rosebush and sustaining a thorn prick in the left thigh 3 days prior to the onset of pain. Before presenting to our dermatology clinic, she was seen by a pediatrician, an emergency department physician, and an infectious disease specialist. The initial workup included a complete blood cell count, C-reactive protein test, erythrocyte sedimentation rate test, and hip and femur radiograph, which were all unremarkable. She was referred to dermatology with a differential diagnosis of sporotrichosis, contact dermatitis, reactive arthritis, viral myalgia, and Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease.

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing child with pink eczematous patches and plaques extending from the left side of the lower back to the mid shin in an L5 distribution (Figure). The left thigh was tender to palpation, and nontender left inguinal lymphadenopathy was present. A single isolated 2-mm vesicle was found on the anterior aspect of the left lower leg. Direct fluorescent antibody testing of vesicle fluid was positive for VZV antigen, confirming the diagnosis of HZ.

The patient’s mother confirmed that she had no obvious history of VZV. She had received VZV vaccinations in the left leg and arm at 1 and 4 years of age, respectively. She was treated with acyclovir (80 mg/kg daily at 6-hour intervals for 5 days) with immediate improvement in symptoms and resolution of the rash by day 5 of treatment. She experienced intermittent burning pain in the leg throughout the course of treatment, which resolved shortly thereafter.

Comment

Herpes zoster is rare in young healthy children, and its incidence has decreased since the introduction of universal varicella vaccination.4 Reported incidence rates in vaccinated children vary from approximately 15 to 93 per 100,000 person-years,5,6 and the reported relative risk is 0.08 to 0.36 in vaccinated compared to unvaccinated children.6,7 No correlations with gender, race, or ethnicity and postvaccination HZ have been observed.5,8 Reported intervals between vaccination and HZ presentation are as short as 3 months and as long as 11 years.9 Although HZ is uncommon in immunocompetent children, the diagnosis of HZ itself is not an indication for formal workup for an underlying immunodeficiency or malignancy.10

Both wild-type and vaccine-strain VZV establish latent infection and can cause HZ in vaccinated children. Direct fluorescent antibody testing or polymerase chain reaction of HZ lesions can be used to identify VZV. Genotyping can distinguish the wild-type versus the vaccine strain but is not required for clinical management.3 In previously vaccinated children with HZ, approximately half present with wild-type and half with vaccine-strain VZV. In approximately half of wild-type cases, prior clinical varicella infection also occurred.8

Regardless of virus strain, vaccinated children typically present with the characteristic painful, vesicular, dermatomal HZ rash.8,9 This presentation can be milder with less pain and fewer vesicles than with unvaccinated cases.6 When vaccine-strain HZ occurs, the rash often presents at or near the site of initial vaccination, which typically is the arm or thigh.3,4,6,9 The vaccine strain has lower virulence than the wild-type virus. Eight cases of vaccine-strain zoster severe enough to cause neurological complications such as meningitis or encephalitis have been reported in children, with 6 cases reported in healthy children.9,11-17 Antiviral drugs hasten the healing of the HZ rash and shorten the duration of associated pain.1

Although pediatric HZ is uncommon, all physicians should be aware of possible atypical presentations in healthy vaccinated children to appropriately and quickly manage treatment.

- Sampathkumar P, Drage LA, Martin DP. Herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:274-280.

- Hillebrand K, Bricout H, Schulze-Rath R, et al. Incidence of herpes zoster and its complications in Germany, 2005-2009. J Infect. 2015;70:178-186.

- Lopez A, Schmid S, Bialek S. Varicella. In: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Manual for the Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. 5th ed. 2011:1-16.

- Tanuseputroa P, Zagorskia B, Chanc KJ, et al. Population-based incidence of herpes zoster after introduction of a publicly funded varicella vaccination program. Vaccine. 2011;29:8580- 8584.

- Wen SY, Liu WL. Epidemiology of pediatric herpes zoster after varicella infection: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2015;135:565-571.

- Civen R, Chaves SS, Jumaan A, et al. The incidence and clinical characteristics of herpes zoster among children and adolescents after implementation of varicella vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:954-959.

- Stein M, Cohen R, Bromberg M, et al. Herpes zoster in a partially vaccinated pediatric population in Central Israel. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:906-909.

- Weinmann S, Chun C, Schmid DS, et al. Incidence and clinical characteristics of herpes zoster among children in the varicella vaccine era, 2005-2009. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1859-1868.

- Horien C, Grose C. Neurovirulence of varicella and the live attenuated varicella vaccine virus. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2012;19:124-129.

- Petursson G, Helgason S, Gudmundsson S, et al. Herpes zoster in children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:905-908.

- Levin MJ, Dahl KM, Weinberg A, et al. Development of resistance to acyclovir during chronic infection with the Oka vaccine strain of varicella-zoster virus in an immunosuppressed child. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:954-959.

- Chaves SS, Haber P, Walton K, et al. Safety of varicella vaccine after licensure in the United States: experience from reports to the vaccine adverse event reporting system, 1995-2005. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(suppl 2):S170-S177.

- Levin MJ, DeBiasi RL, Bostik V, et al. Herpes zoster with skin lesions and meningitis caused by 2 different genotypes of the Oka varicella zoster virus vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1444-1447.

- Iyer S, Mittal MK, Hodinka RL. Herpes zoster and meningitis resulting from reactivation of varicella vaccine virus in an immunocompetent child. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:792-795.

- Chouliaras G, Spoulou V, Quinlivan M, et al. Vaccine-associated herpes zoster ophthalmicus and encephalitis in an immunocompetent child. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e969-e972.

- Pahud BA, Glaser CA, Dekker CL, et al. Varicella zoster disease of the central nervous system: epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory features 10 years after the introduction of the varicella vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:316-323.

- Han JY, Hanson DC, Way SS. Herpes zoster and meningitis due to reactivation of varicella vaccine virus in an immunocompetent child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:266-268.

- Sampathkumar P, Drage LA, Martin DP. Herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:274-280.

- Hillebrand K, Bricout H, Schulze-Rath R, et al. Incidence of herpes zoster and its complications in Germany, 2005-2009. J Infect. 2015;70:178-186.

- Lopez A, Schmid S, Bialek S. Varicella. In: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Manual for the Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. 5th ed. 2011:1-16.

- Tanuseputroa P, Zagorskia B, Chanc KJ, et al. Population-based incidence of herpes zoster after introduction of a publicly funded varicella vaccination program. Vaccine. 2011;29:8580- 8584.

- Wen SY, Liu WL. Epidemiology of pediatric herpes zoster after varicella infection: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2015;135:565-571.

- Civen R, Chaves SS, Jumaan A, et al. The incidence and clinical characteristics of herpes zoster among children and adolescents after implementation of varicella vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:954-959.

- Stein M, Cohen R, Bromberg M, et al. Herpes zoster in a partially vaccinated pediatric population in Central Israel. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:906-909.

- Weinmann S, Chun C, Schmid DS, et al. Incidence and clinical characteristics of herpes zoster among children in the varicella vaccine era, 2005-2009. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1859-1868.

- Horien C, Grose C. Neurovirulence of varicella and the live attenuated varicella vaccine virus. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2012;19:124-129.

- Petursson G, Helgason S, Gudmundsson S, et al. Herpes zoster in children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:905-908.

- Levin MJ, Dahl KM, Weinberg A, et al. Development of resistance to acyclovir during chronic infection with the Oka vaccine strain of varicella-zoster virus in an immunosuppressed child. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:954-959.

- Chaves SS, Haber P, Walton K, et al. Safety of varicella vaccine after licensure in the United States: experience from reports to the vaccine adverse event reporting system, 1995-2005. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(suppl 2):S170-S177.

- Levin MJ, DeBiasi RL, Bostik V, et al. Herpes zoster with skin lesions and meningitis caused by 2 different genotypes of the Oka varicella zoster virus vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1444-1447.

- Iyer S, Mittal MK, Hodinka RL. Herpes zoster and meningitis resulting from reactivation of varicella vaccine virus in an immunocompetent child. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:792-795.

- Chouliaras G, Spoulou V, Quinlivan M, et al. Vaccine-associated herpes zoster ophthalmicus and encephalitis in an immunocompetent child. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e969-e972.

- Pahud BA, Glaser CA, Dekker CL, et al. Varicella zoster disease of the central nervous system: epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory features 10 years after the introduction of the varicella vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:316-323.

- Han JY, Hanson DC, Way SS. Herpes zoster and meningitis due to reactivation of varicella vaccine virus in an immunocompetent child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:266-268.

Practice Points

- Both wild-type and vaccine-strain varicella-zoster virus (VZV) can establish latency in dorsal root ganglia and can cause herpes zoster (HZ) in vaccinated children.

- When HZ due to a vaccine strain of VZV occurs, the rash often presents near the site of initial vaccination.

- Although most cases of HZ in vaccinated children present with a characteristic HZ rash, physicians should be aware of the possibility for atypical presentations.

Nominate a Colleague or Patient for a NORD Rare Impact Award

Nominations are now open for the 2018 NORD Rare Impact Awards. These awards honor individuals who have made a positive impact on the rare disease community through research, patient care, advocacy, or other areas of involvement.

Awards are presented in May each year at NORD’s annual Rare Impact Celebration. Nominations may be submitted online. The deadline is January 12, 2018.

In recognition of the 35th anniversaries of NORD and the Orphan Drug Act in 2018, the awards will be presented in four categories representing the four pillars of NORD’s mission: Advocacy, Education, Research, and Patient Assistance.

Honorees from previous years have included members of Congress, staff and senior officials from NIH and FDA, medical researchers and clinicians, patient organization leaders, and individual patients and caregivers. The awards honor those who have helped to improve the lives of those affected by rare diseases.

Nominations are now open for the 2018 NORD Rare Impact Awards. These awards honor individuals who have made a positive impact on the rare disease community through research, patient care, advocacy, or other areas of involvement.

Awards are presented in May each year at NORD’s annual Rare Impact Celebration. Nominations may be submitted online. The deadline is January 12, 2018.

In recognition of the 35th anniversaries of NORD and the Orphan Drug Act in 2018, the awards will be presented in four categories representing the four pillars of NORD’s mission: Advocacy, Education, Research, and Patient Assistance.

Honorees from previous years have included members of Congress, staff and senior officials from NIH and FDA, medical researchers and clinicians, patient organization leaders, and individual patients and caregivers. The awards honor those who have helped to improve the lives of those affected by rare diseases.

Nominations are now open for the 2018 NORD Rare Impact Awards. These awards honor individuals who have made a positive impact on the rare disease community through research, patient care, advocacy, or other areas of involvement.

Awards are presented in May each year at NORD’s annual Rare Impact Celebration. Nominations may be submitted online. The deadline is January 12, 2018.

In recognition of the 35th anniversaries of NORD and the Orphan Drug Act in 2018, the awards will be presented in four categories representing the four pillars of NORD’s mission: Advocacy, Education, Research, and Patient Assistance.

Honorees from previous years have included members of Congress, staff and senior officials from NIH and FDA, medical researchers and clinicians, patient organization leaders, and individual patients and caregivers. The awards honor those who have helped to improve the lives of those affected by rare diseases.

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on Men’s Moisturizers

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on men’s moisturizers. Consideration must be given to:

- Clinique For Men Oil Control Mattifying Moisturizer

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

“I recommend this product for men with oily or combination skin. It’s very lightweight and provides good hydration benefits without leaving the skin shiny.”—Jeannette Graf, MD, Great Neck, New York

- Facial Fuel Energizing Moisture Treatment for Men

Kiehl’s

“I commonly recommend this moisturizer. The Facial Fuel line is great for most skin types and the products are moderately priced.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Neutrogena Men Triple Protect Face Lotion With Sunscreen

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc

“This is a light, daily moisturizer with broad-spectrum UV protection.”—Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

- Triple Lipid Restore 2:4:2

SkinCeuticals

“This moisturizer has the precise lipid content needed by the skin.”— Jerome Potozkin, MD, Danville, California

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Wet skin moisturizer, lip plumper, and pigment corrector will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on men’s moisturizers. Consideration must be given to:

- Clinique For Men Oil Control Mattifying Moisturizer

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

“I recommend this product for men with oily or combination skin. It’s very lightweight and provides good hydration benefits without leaving the skin shiny.”—Jeannette Graf, MD, Great Neck, New York

- Facial Fuel Energizing Moisture Treatment for Men

Kiehl’s

“I commonly recommend this moisturizer. The Facial Fuel line is great for most skin types and the products are moderately priced.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Neutrogena Men Triple Protect Face Lotion With Sunscreen

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc

“This is a light, daily moisturizer with broad-spectrum UV protection.”—Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

- Triple Lipid Restore 2:4:2

SkinCeuticals

“This moisturizer has the precise lipid content needed by the skin.”— Jerome Potozkin, MD, Danville, California

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Wet skin moisturizer, lip plumper, and pigment corrector will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on men’s moisturizers. Consideration must be given to:

- Clinique For Men Oil Control Mattifying Moisturizer

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

“I recommend this product for men with oily or combination skin. It’s very lightweight and provides good hydration benefits without leaving the skin shiny.”—Jeannette Graf, MD, Great Neck, New York

- Facial Fuel Energizing Moisture Treatment for Men

Kiehl’s

“I commonly recommend this moisturizer. The Facial Fuel line is great for most skin types and the products are moderately priced.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Neutrogena Men Triple Protect Face Lotion With Sunscreen

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc

“This is a light, daily moisturizer with broad-spectrum UV protection.”—Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

- Triple Lipid Restore 2:4:2

SkinCeuticals

“This moisturizer has the precise lipid content needed by the skin.”— Jerome Potozkin, MD, Danville, California

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Wet skin moisturizer, lip plumper, and pigment corrector will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

Debunking Acne Myths: Does Back Acne Need to Be Treated?

Myth: Back acne will clear on its own

Patients with back acne may not seek treatment options because they assume it will clear on its own; however, deep painful lesions typically require treatment by a dermatologist. Mild to moderate cases may respond to less aggressive over-the-counter treatments but also may benefit from a combination of topical and systemic antibiotic therapies. According to James Q. Del Rosso, MD, a dermatologist in Las Vegas, Nevada, “Many dermatologists believe that truncal acne vulgaris warrants use of systemic antibiotic therapy, which may not necessarily be the case, especially in patients presenting with mild to moderate acne severity.” Cases of deep inflammatory acne on the back often warrant using systemic therapies such as oral isotretinoin. These severe cases may be less responsive to standard therapies and may require repeated treatment.

Although back acne is not as cosmetically visible as facial acne, it has been associated with sexual and bodily self-consciousness in both males and females. Preliminary data from one study showed that 78% of patients with truncal acne (n=141) on the back and/or chest indicated they were definitely interested in treatment, but truncal acne was not mentioned by these patients without direct inquiry from a physician. As a result, it may be beneficial for dermatologists to ask acne patients about lesions presenting on the back and inform them that treatment options are available.

Treatment application also is a consideration for back acne. Benzoyl peroxide cleanser/wash formulations are convenient, and the foam formulation of clindamycin phosphate allows for easy use due to its spreadability, rapid penetration, and lack of residue and fabric bleaching.

It is important to inform patients that back acne can flare even during active treatment. Patients should be instructed to wear loose-fitting clothes made of cotton or other sweat-wicking fabrics when working out and to shower and change clothes immediately after. Sheets and pillowcases should be changed regularly to avoid exposure to dead skin cells and bacteria, which can exacerbate acne on the back. Backpacks and handbags also can rub against the skin on the back, causing acne to flare. As an alternative, patients should be encouraged to carry handheld bags or bags with shoulder straps to avoid irritation of the skin on the back.

Back acne: how to see clearer skin. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/back-acne-how-to-see-clearer-skin. Accessed October 30, 2017.

Del Rosso JQ. Management of truncal acne vulgaris: current perspectives on treatment. Cutis. 2006;77:285-289.

Dunn LK, O’Neill JL, Feldman SR. Acne in adolescents: quality of life, self-esteem, mood, and psychological disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

Hassan J, Grogan S, Clark-Carter D, et al. The individual health burden of acne: appearance-related distress in male and female adolescents and adults with back, chest and facial acne. J Health Psychol. 2009;14:1105-11118.

Myth: Back acne will clear on its own

Patients with back acne may not seek treatment options because they assume it will clear on its own; however, deep painful lesions typically require treatment by a dermatologist. Mild to moderate cases may respond to less aggressive over-the-counter treatments but also may benefit from a combination of topical and systemic antibiotic therapies. According to James Q. Del Rosso, MD, a dermatologist in Las Vegas, Nevada, “Many dermatologists believe that truncal acne vulgaris warrants use of systemic antibiotic therapy, which may not necessarily be the case, especially in patients presenting with mild to moderate acne severity.” Cases of deep inflammatory acne on the back often warrant using systemic therapies such as oral isotretinoin. These severe cases may be less responsive to standard therapies and may require repeated treatment.

Although back acne is not as cosmetically visible as facial acne, it has been associated with sexual and bodily self-consciousness in both males and females. Preliminary data from one study showed that 78% of patients with truncal acne (n=141) on the back and/or chest indicated they were definitely interested in treatment, but truncal acne was not mentioned by these patients without direct inquiry from a physician. As a result, it may be beneficial for dermatologists to ask acne patients about lesions presenting on the back and inform them that treatment options are available.

Treatment application also is a consideration for back acne. Benzoyl peroxide cleanser/wash formulations are convenient, and the foam formulation of clindamycin phosphate allows for easy use due to its spreadability, rapid penetration, and lack of residue and fabric bleaching.

It is important to inform patients that back acne can flare even during active treatment. Patients should be instructed to wear loose-fitting clothes made of cotton or other sweat-wicking fabrics when working out and to shower and change clothes immediately after. Sheets and pillowcases should be changed regularly to avoid exposure to dead skin cells and bacteria, which can exacerbate acne on the back. Backpacks and handbags also can rub against the skin on the back, causing acne to flare. As an alternative, patients should be encouraged to carry handheld bags or bags with shoulder straps to avoid irritation of the skin on the back.

Myth: Back acne will clear on its own

Patients with back acne may not seek treatment options because they assume it will clear on its own; however, deep painful lesions typically require treatment by a dermatologist. Mild to moderate cases may respond to less aggressive over-the-counter treatments but also may benefit from a combination of topical and systemic antibiotic therapies. According to James Q. Del Rosso, MD, a dermatologist in Las Vegas, Nevada, “Many dermatologists believe that truncal acne vulgaris warrants use of systemic antibiotic therapy, which may not necessarily be the case, especially in patients presenting with mild to moderate acne severity.” Cases of deep inflammatory acne on the back often warrant using systemic therapies such as oral isotretinoin. These severe cases may be less responsive to standard therapies and may require repeated treatment.

Although back acne is not as cosmetically visible as facial acne, it has been associated with sexual and bodily self-consciousness in both males and females. Preliminary data from one study showed that 78% of patients with truncal acne (n=141) on the back and/or chest indicated they were definitely interested in treatment, but truncal acne was not mentioned by these patients without direct inquiry from a physician. As a result, it may be beneficial for dermatologists to ask acne patients about lesions presenting on the back and inform them that treatment options are available.

Treatment application also is a consideration for back acne. Benzoyl peroxide cleanser/wash formulations are convenient, and the foam formulation of clindamycin phosphate allows for easy use due to its spreadability, rapid penetration, and lack of residue and fabric bleaching.

It is important to inform patients that back acne can flare even during active treatment. Patients should be instructed to wear loose-fitting clothes made of cotton or other sweat-wicking fabrics when working out and to shower and change clothes immediately after. Sheets and pillowcases should be changed regularly to avoid exposure to dead skin cells and bacteria, which can exacerbate acne on the back. Backpacks and handbags also can rub against the skin on the back, causing acne to flare. As an alternative, patients should be encouraged to carry handheld bags or bags with shoulder straps to avoid irritation of the skin on the back.

Back acne: how to see clearer skin. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/back-acne-how-to-see-clearer-skin. Accessed October 30, 2017.

Del Rosso JQ. Management of truncal acne vulgaris: current perspectives on treatment. Cutis. 2006;77:285-289.

Dunn LK, O’Neill JL, Feldman SR. Acne in adolescents: quality of life, self-esteem, mood, and psychological disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

Hassan J, Grogan S, Clark-Carter D, et al. The individual health burden of acne: appearance-related distress in male and female adolescents and adults with back, chest and facial acne. J Health Psychol. 2009;14:1105-11118.

Back acne: how to see clearer skin. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/back-acne-how-to-see-clearer-skin. Accessed October 30, 2017.

Del Rosso JQ. Management of truncal acne vulgaris: current perspectives on treatment. Cutis. 2006;77:285-289.

Dunn LK, O’Neill JL, Feldman SR. Acne in adolescents: quality of life, self-esteem, mood, and psychological disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

Hassan J, Grogan S, Clark-Carter D, et al. The individual health burden of acne: appearance-related distress in male and female adolescents and adults with back, chest and facial acne. J Health Psychol. 2009;14:1105-11118.

What’s Eating You? Scabies in the Developing World

Scabies is caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis.1 It is in the arthropod class Arachnida, subclass Acari, and family Sarcoptidae.2 Historically, scabies was first described in the Old Testament and by Aristotle,2 but the causative organism was not identified until 1687 using a light microscope.3 Scabies affects all age groups, races, and social classes and is globally widespread. It is most prevalent in developing tropical countries.1 It is estimated that 300 million individuals worldwide are infested with scabies mites annually, with the highest burden in young children.4-7 In industrialized societies, infections often are seen in young adults and in institutional settings such as nursing homes.8 Scabies disproportionately impacts impoverished communities with crowded living conditions, poor hygiene and nutrition, and substandard housing.5,9 Controlling the spread of the disease in these communities presents challenges but is important because of the connection between scabies and chronic kidney disease.10 As such, scabies represents a major health problem in the developing world and has been the focus of major health initiatives.1,11

Identifying Characteristics

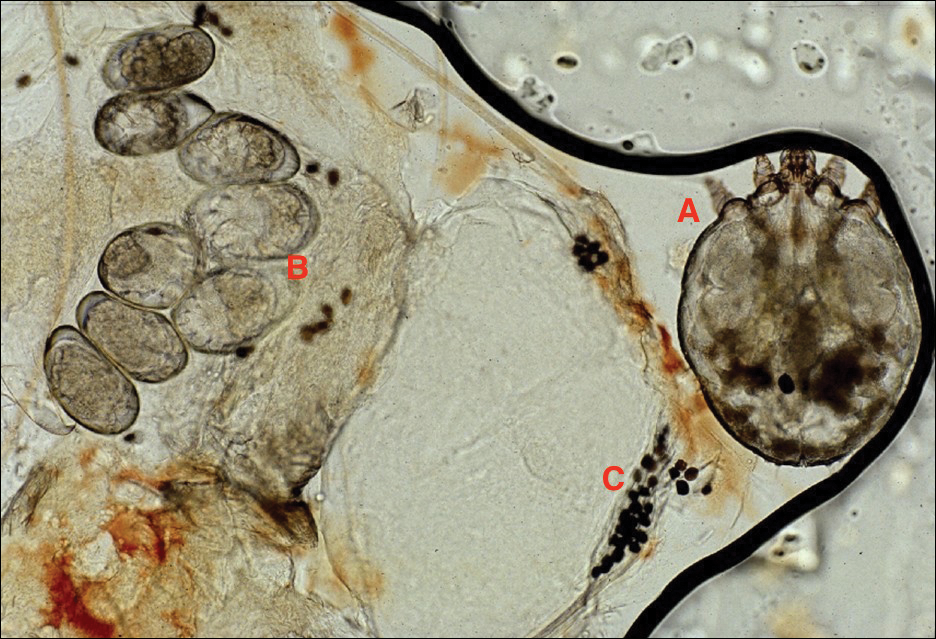

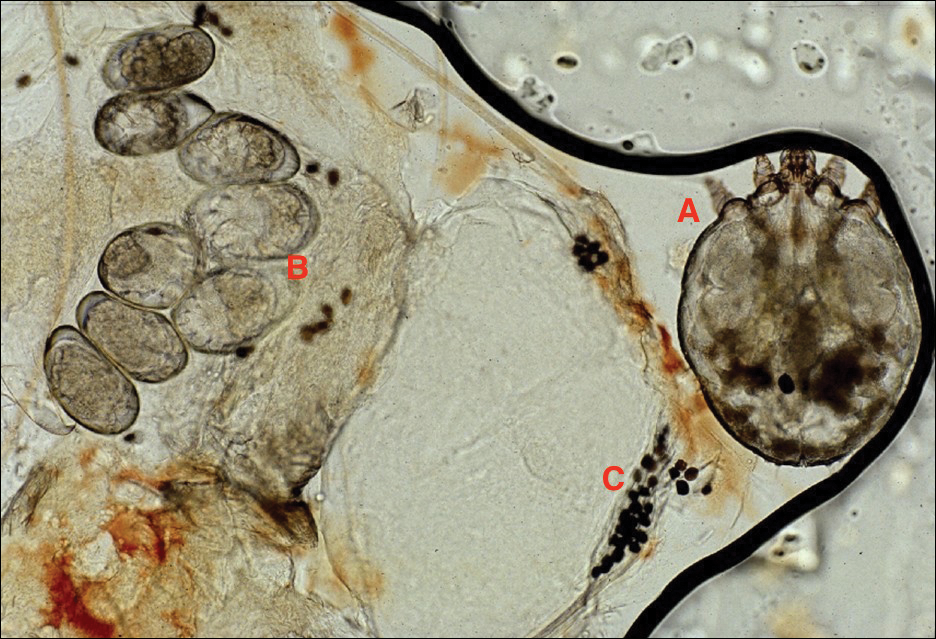

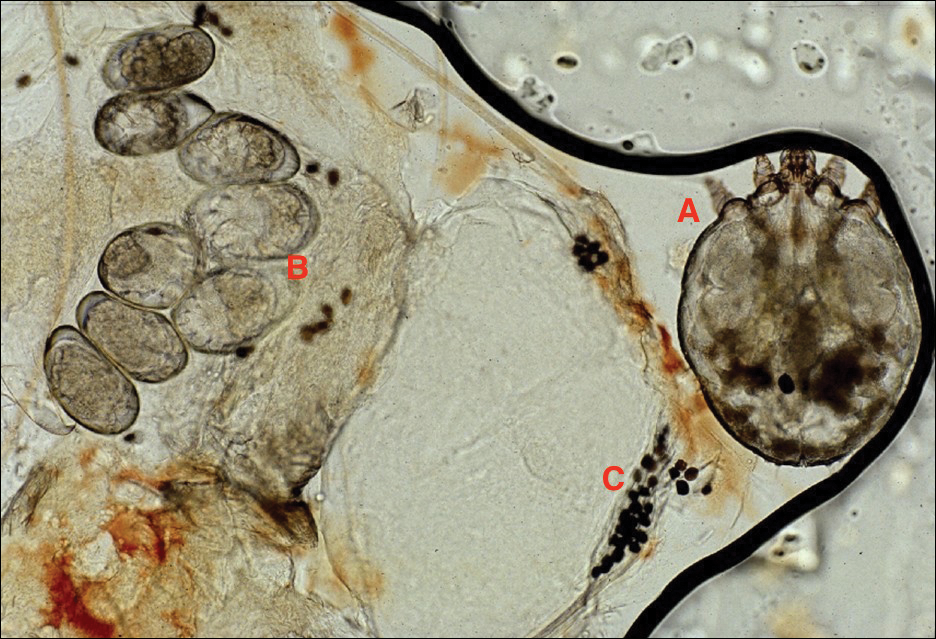

Adult females are 0.4-mm long and 0.3-mm wide, with males being smaller. Adult nymphs have 8 legs and larvae have 6 legs. Scabies mites are distinguishable from other arachnids by the position of a distinct gnathosoma and the lack of a division between the abdomen and cephalothorax.12 They are ovoid with a small anterior cephalic and caudal thoracoabdominal portion with hairlike projections coming off from the rudimentary legs. They can crawl as fast as 2.5 cm per minute on warm skin.2 The life cycle of the mite begins after mating: the male mite dies, and the female lays up to 3 eggs per day, which hatch in 3 to 4 days,2 in skin burrows within the stratum granulosum.12 Maturation from larva to adult takes 10 to 14 days.12 A female mite can live for 4 to 6 weeks and can produce up to 40 ova (Figure 1).

Disease Transmission

Without a host, mites are able to survive and remain capable of infestation for 24 to 36 hours at 21°C and 40% to 80% relative humidity. Lower temperatures and higher humidity prolong survival, but infectivity decreases the longer they are without a host.13

An adult human with ordinary scabies will have an average of 12 adult female mites on the body surface at a given time.14 However, hundreds of mites can be found in neglected children in underprivileged communities and millions in patients with crusted scabies.13 Transmission of typical scabies requires close direct skin-to-skin contact for 15 to 20 minutes.2,8 Transmission from clothing or fomites are an unlikely source of infestation with the exception of patients who are heavily infested such as in crusted scabies.12 In adults, sexual contact is an important method of transmission,12 and patients with scabies should be screened for other sexually transmitted diseases.8

Clinical Manifestations

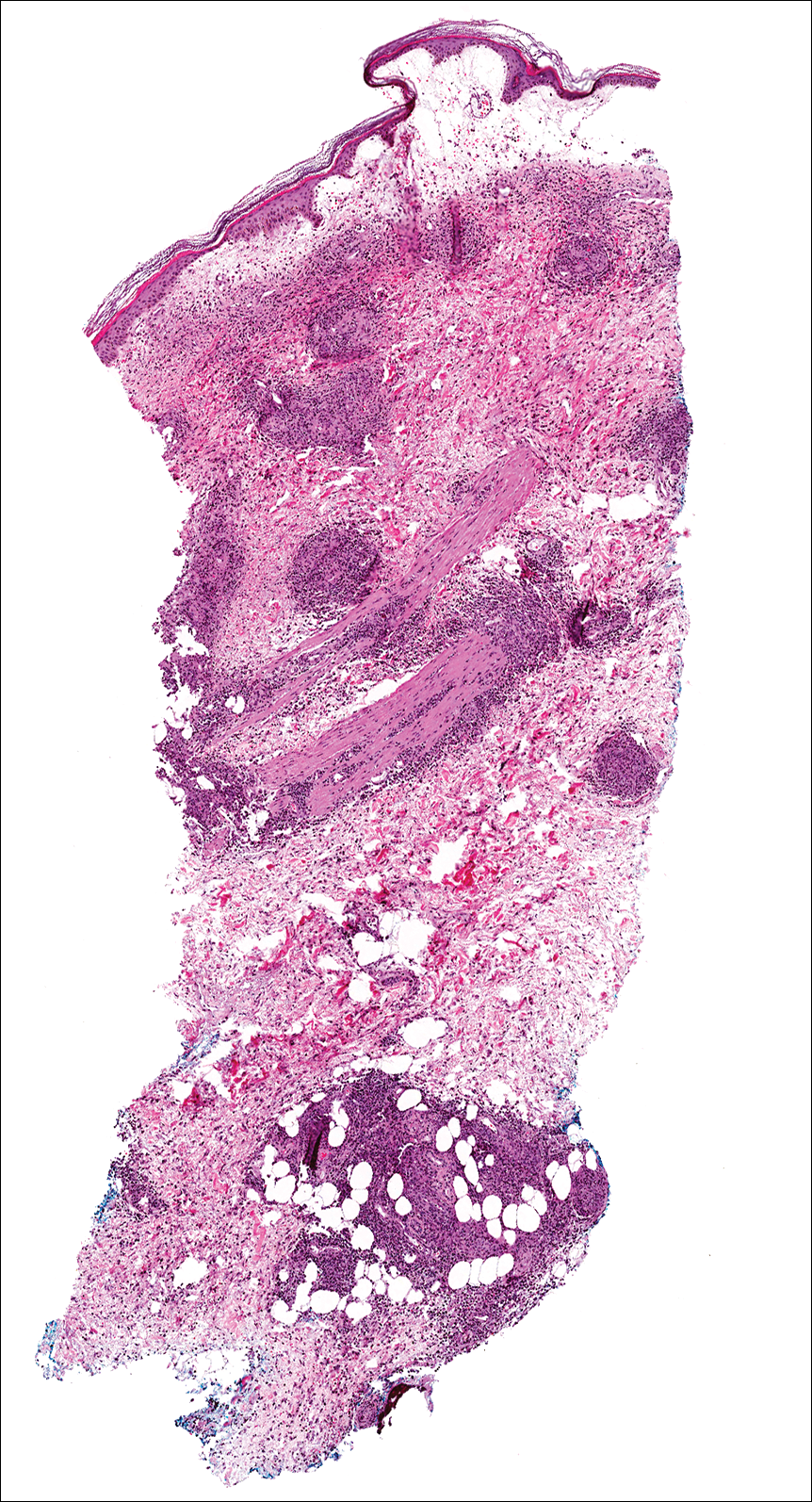

Signs of scabies on the skin include burrows, erythematous papules, and generalized pruritus (Figure 2).12 The scalp, face, and neck frequently are involved in infants and children,2 and the hands, wrists, elbows, genitalia, axillae, umbilicus, belt line, nipples, and buttocks commonly are involved in adults.12 Itching is characteristically worse at night.8 In tropical climates, patients with scabies are predisposed to secondary bacterial skin infections, particularly Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococci). The association between scabies and pyoderma caused by group A streptococci has been well established.15,16 Mika et al10 suggested that local complement inhibition plays an important role in the development of pyoderma in scabies-infested skin.

Prevention and Control in the Developing World

Low-cost diagnostic equipment can play a key role in the definitive diagnosis and management of scabies outbreaks in the developing world. Micali et al28 found that a $30 videomicroscope was as effective in scabies diagnosis as a $20,000 videodermatoscope. Because of the low cost of benzyl benzoate, it is commonly used as a first-line drug in many parts of the world,13 whereas permethrin cream 5% is the standard treatment in the developed world.29 Recognition of the role of scabies in patients with pyoderma is key, and one study indicated clinically apparent scabies went unnoticed by physicians in 52% of patients presenting with skin lesions.30 Drug shortages also can contribute to a high prevalence of scabies infestation in the community.31 Mass treatment with ivermectin has proven to be an effective means of reducing the prevalence of many parasitic diseases,1,32,33 and it shows great promise for crusted scabies, institutional outbreaks, and mass administration in highly endemic communites.8 However, there is evidence of ivermectin tolerance among mites, which could undermine the success of mass drug administration.34 Another important consideration is population mobility and the risk for rapid reintroduction of scabies infection across regions.35

Complicating disease control are the socioeconomic factors associated with scabies in the developing world. Families with scabies infestation typically do not own their homes, are less likely to have constant electricity, have a lower monthly income, and live in substandard housing.20 Families can spend a substantial part of their household income on treatment, impacting what they can spend on food.8,11 In addition to medication, control of scabies requires community education and involvement, along with access to primary care and attention to living conditions and environmental factors.34,36

- Romani L, Whitfeld MJ, Koroivueta J, et al. Mass drug administration for scabies control in a population with endemic disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2305-2313.

- Hicks MI, Elston DM. Scabies. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:279-292.

- Ramos-e-Silva M. Giovan Cosimo Bonomo (1663-1696): discoverer of the etiology of scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:625-630.

- Chung SD, Wang KH, Huang CC, et al. Scabies increased the risk of chronic kidney disease: a 5-year follow-up study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:286-292.

- Wong SS, Poon RW, Chau S, et al. Development of conventional and real-time quantitative PCR assays for diagnosis and monitoring of scabies. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2095-2102.

- Kearns TM, Speare R, Cheng AC, et al. Impact of an ivermectin mass drug administration on scabies prevalence in a remote Australian aboriginal community. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004151.

- Gilmore SJ. Control strategies for endemic childhood scabies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15990.

- Hay RJ, Steer AC, Engelman D, Walton S. Scabies in the developing world—its prevalence, complications, and management. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:313-323.

- Hoy WE, White AV, Dowling A, et al. Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis is a strong risk factor for chronic kidney disease in later life. Kidney Int. 2012;81:1026-1032.

- Mika A, Reynolds SL, Pickering D, et al. Complement inhibitors from scabies mites promote streptococcal growth—a novel mechanism in infected epidermis? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1563.

- McLean FE. The elimination of scabies: a task for our generation. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1215-1223.

- Hengge UR, Currie BJ, Jäger G, et al. Scabies: a ubiquitous neglected skin disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:769-779.

- Heukelbach J, Feldmeier H. Scabies. Lancet. 2006;367:1767-1774.

- Johnston G, Sladden M. Scabies: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ. 2005;331:619-622.

- Yeoh DK, Bowen AC, Carapetis JR. Impetigo and scabies—disease burden and modern treatment strategies [published online May 11, 2016]. J Infect. 2016;(72 suppl):S61-S67.

- Bowen AC, Mahé A, Hay RJ, et al. The global epidemiology of impetigo: a systematic review of the population prevalence of impetigo and pyoderma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136789.

- Bowen AC, Tong SY, Chatfield MD, et al. The microbiology of impetigo in indigenous children: associations between Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, scabies, and nasal carriage. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:727.

- Sesso R, Pinto SW. Five-year follow-up of patients with epidemic glomerulonephritis due to Streptococcus zooepidemicus. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1808-1812.

- Singh GR. Glomerulonephritis and managing the risks of chronic renal disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:1363-1382.

- La Vincente S, Kearns T, Connors C, et al. Community management of endemic scabies in remote aboriginal communities of northern Australia: low treatment uptake and high ongoing acquisition. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e444.

- Clucas DB, Carville KS, Connors C, et al. Disease burden and health-care clinic attendances for young children in remote aboriginal communities of northern Australia. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:275-281.

- Stanton B, Khanam S, Nazrul H, et al. Scabies in urban Bangladesh. J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;90:219-226.

- Heukelbach J, de Oliveira FA, Feldmeier H. Ecoparasitoses and public health in Brazil: challenges for control [in Portuguese]. Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19:1535-1540.

- Edison L, Beaudoin A, Goh L, et al. Scabies and bacterial superinfection among American Samoan children, 2011-2012. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139336.

- Steer AC, Jenney AW, Kado J, et al. High burden of impetigo and scabies in a tropical country. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e467.

- Romani L, Steer AC, Whitfeld MJ, et al. Prevalence of scabies and impetigo worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:960-967.

- Romani L, Koroivueta J, Steer AC, et al. Scabies and impetigo prevalence and risk factors in Fiji: a national survey. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003452.

- Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Verzì AE, et al. Low-cost equipment for diagnosis and management of endemic scabies outbreaks in underserved populations. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:327-329.

- Pasay C, Walton S, Fischer K, et al. PCR-based assay to survey for knockdown resistance to pyrethroid acaricides in human scabies mites (Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:649-657.

- Heukelbach J, van Haeff E, Rump B, et al. Parasitic skin diseases: health care-seeking in a slum in north-east Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:368-373.

- Potter EV, Mayon-White R, Poon-King T, et al. Acute glomerulonephritis as a complication of scabies. In: Orkin M, Maibach HI, eds. Cutaneous Infestations and Insect Bites. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1985.

- Mahé A. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1689.

- Steer AC, Romani L, Kaldor JM. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1690.

- Mounsey KE, Holt DC, McCarthy JS, et al. Longitudinal evidence of increasing in vitro tolerance of scabies mites to ivermectin in scabies-endemic communities. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:840-841.

- Currie BJ. Scabies and global control of neglected tropical diseases. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2371-2372.

- O’Donnell V, Morris S, Ward J. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1689-1690.

Scabies is caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis.1 It is in the arthropod class Arachnida, subclass Acari, and family Sarcoptidae.2 Historically, scabies was first described in the Old Testament and by Aristotle,2 but the causative organism was not identified until 1687 using a light microscope.3 Scabies affects all age groups, races, and social classes and is globally widespread. It is most prevalent in developing tropical countries.1 It is estimated that 300 million individuals worldwide are infested with scabies mites annually, with the highest burden in young children.4-7 In industrialized societies, infections often are seen in young adults and in institutional settings such as nursing homes.8 Scabies disproportionately impacts impoverished communities with crowded living conditions, poor hygiene and nutrition, and substandard housing.5,9 Controlling the spread of the disease in these communities presents challenges but is important because of the connection between scabies and chronic kidney disease.10 As such, scabies represents a major health problem in the developing world and has been the focus of major health initiatives.1,11

Identifying Characteristics

Adult females are 0.4-mm long and 0.3-mm wide, with males being smaller. Adult nymphs have 8 legs and larvae have 6 legs. Scabies mites are distinguishable from other arachnids by the position of a distinct gnathosoma and the lack of a division between the abdomen and cephalothorax.12 They are ovoid with a small anterior cephalic and caudal thoracoabdominal portion with hairlike projections coming off from the rudimentary legs. They can crawl as fast as 2.5 cm per minute on warm skin.2 The life cycle of the mite begins after mating: the male mite dies, and the female lays up to 3 eggs per day, which hatch in 3 to 4 days,2 in skin burrows within the stratum granulosum.12 Maturation from larva to adult takes 10 to 14 days.12 A female mite can live for 4 to 6 weeks and can produce up to 40 ova (Figure 1).

Disease Transmission

Without a host, mites are able to survive and remain capable of infestation for 24 to 36 hours at 21°C and 40% to 80% relative humidity. Lower temperatures and higher humidity prolong survival, but infectivity decreases the longer they are without a host.13

An adult human with ordinary scabies will have an average of 12 adult female mites on the body surface at a given time.14 However, hundreds of mites can be found in neglected children in underprivileged communities and millions in patients with crusted scabies.13 Transmission of typical scabies requires close direct skin-to-skin contact for 15 to 20 minutes.2,8 Transmission from clothing or fomites are an unlikely source of infestation with the exception of patients who are heavily infested such as in crusted scabies.12 In adults, sexual contact is an important method of transmission,12 and patients with scabies should be screened for other sexually transmitted diseases.8

Clinical Manifestations

Signs of scabies on the skin include burrows, erythematous papules, and generalized pruritus (Figure 2).12 The scalp, face, and neck frequently are involved in infants and children,2 and the hands, wrists, elbows, genitalia, axillae, umbilicus, belt line, nipples, and buttocks commonly are involved in adults.12 Itching is characteristically worse at night.8 In tropical climates, patients with scabies are predisposed to secondary bacterial skin infections, particularly Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococci). The association between scabies and pyoderma caused by group A streptococci has been well established.15,16 Mika et al10 suggested that local complement inhibition plays an important role in the development of pyoderma in scabies-infested skin.

Prevention and Control in the Developing World

Low-cost diagnostic equipment can play a key role in the definitive diagnosis and management of scabies outbreaks in the developing world. Micali et al28 found that a $30 videomicroscope was as effective in scabies diagnosis as a $20,000 videodermatoscope. Because of the low cost of benzyl benzoate, it is commonly used as a first-line drug in many parts of the world,13 whereas permethrin cream 5% is the standard treatment in the developed world.29 Recognition of the role of scabies in patients with pyoderma is key, and one study indicated clinically apparent scabies went unnoticed by physicians in 52% of patients presenting with skin lesions.30 Drug shortages also can contribute to a high prevalence of scabies infestation in the community.31 Mass treatment with ivermectin has proven to be an effective means of reducing the prevalence of many parasitic diseases,1,32,33 and it shows great promise for crusted scabies, institutional outbreaks, and mass administration in highly endemic communites.8 However, there is evidence of ivermectin tolerance among mites, which could undermine the success of mass drug administration.34 Another important consideration is population mobility and the risk for rapid reintroduction of scabies infection across regions.35

Complicating disease control are the socioeconomic factors associated with scabies in the developing world. Families with scabies infestation typically do not own their homes, are less likely to have constant electricity, have a lower monthly income, and live in substandard housing.20 Families can spend a substantial part of their household income on treatment, impacting what they can spend on food.8,11 In addition to medication, control of scabies requires community education and involvement, along with access to primary care and attention to living conditions and environmental factors.34,36

Scabies is caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis.1 It is in the arthropod class Arachnida, subclass Acari, and family Sarcoptidae.2 Historically, scabies was first described in the Old Testament and by Aristotle,2 but the causative organism was not identified until 1687 using a light microscope.3 Scabies affects all age groups, races, and social classes and is globally widespread. It is most prevalent in developing tropical countries.1 It is estimated that 300 million individuals worldwide are infested with scabies mites annually, with the highest burden in young children.4-7 In industrialized societies, infections often are seen in young adults and in institutional settings such as nursing homes.8 Scabies disproportionately impacts impoverished communities with crowded living conditions, poor hygiene and nutrition, and substandard housing.5,9 Controlling the spread of the disease in these communities presents challenges but is important because of the connection between scabies and chronic kidney disease.10 As such, scabies represents a major health problem in the developing world and has been the focus of major health initiatives.1,11

Identifying Characteristics

Adult females are 0.4-mm long and 0.3-mm wide, with males being smaller. Adult nymphs have 8 legs and larvae have 6 legs. Scabies mites are distinguishable from other arachnids by the position of a distinct gnathosoma and the lack of a division between the abdomen and cephalothorax.12 They are ovoid with a small anterior cephalic and caudal thoracoabdominal portion with hairlike projections coming off from the rudimentary legs. They can crawl as fast as 2.5 cm per minute on warm skin.2 The life cycle of the mite begins after mating: the male mite dies, and the female lays up to 3 eggs per day, which hatch in 3 to 4 days,2 in skin burrows within the stratum granulosum.12 Maturation from larva to adult takes 10 to 14 days.12 A female mite can live for 4 to 6 weeks and can produce up to 40 ova (Figure 1).

Disease Transmission

Without a host, mites are able to survive and remain capable of infestation for 24 to 36 hours at 21°C and 40% to 80% relative humidity. Lower temperatures and higher humidity prolong survival, but infectivity decreases the longer they are without a host.13

An adult human with ordinary scabies will have an average of 12 adult female mites on the body surface at a given time.14 However, hundreds of mites can be found in neglected children in underprivileged communities and millions in patients with crusted scabies.13 Transmission of typical scabies requires close direct skin-to-skin contact for 15 to 20 minutes.2,8 Transmission from clothing or fomites are an unlikely source of infestation with the exception of patients who are heavily infested such as in crusted scabies.12 In adults, sexual contact is an important method of transmission,12 and patients with scabies should be screened for other sexually transmitted diseases.8

Clinical Manifestations

Signs of scabies on the skin include burrows, erythematous papules, and generalized pruritus (Figure 2).12 The scalp, face, and neck frequently are involved in infants and children,2 and the hands, wrists, elbows, genitalia, axillae, umbilicus, belt line, nipples, and buttocks commonly are involved in adults.12 Itching is characteristically worse at night.8 In tropical climates, patients with scabies are predisposed to secondary bacterial skin infections, particularly Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococci). The association between scabies and pyoderma caused by group A streptococci has been well established.15,16 Mika et al10 suggested that local complement inhibition plays an important role in the development of pyoderma in scabies-infested skin.

Prevention and Control in the Developing World

Low-cost diagnostic equipment can play a key role in the definitive diagnosis and management of scabies outbreaks in the developing world. Micali et al28 found that a $30 videomicroscope was as effective in scabies diagnosis as a $20,000 videodermatoscope. Because of the low cost of benzyl benzoate, it is commonly used as a first-line drug in many parts of the world,13 whereas permethrin cream 5% is the standard treatment in the developed world.29 Recognition of the role of scabies in patients with pyoderma is key, and one study indicated clinically apparent scabies went unnoticed by physicians in 52% of patients presenting with skin lesions.30 Drug shortages also can contribute to a high prevalence of scabies infestation in the community.31 Mass treatment with ivermectin has proven to be an effective means of reducing the prevalence of many parasitic diseases,1,32,33 and it shows great promise for crusted scabies, institutional outbreaks, and mass administration in highly endemic communites.8 However, there is evidence of ivermectin tolerance among mites, which could undermine the success of mass drug administration.34 Another important consideration is population mobility and the risk for rapid reintroduction of scabies infection across regions.35

Complicating disease control are the socioeconomic factors associated with scabies in the developing world. Families with scabies infestation typically do not own their homes, are less likely to have constant electricity, have a lower monthly income, and live in substandard housing.20 Families can spend a substantial part of their household income on treatment, impacting what they can spend on food.8,11 In addition to medication, control of scabies requires community education and involvement, along with access to primary care and attention to living conditions and environmental factors.34,36

- Romani L, Whitfeld MJ, Koroivueta J, et al. Mass drug administration for scabies control in a population with endemic disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2305-2313.

- Hicks MI, Elston DM. Scabies. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:279-292.

- Ramos-e-Silva M. Giovan Cosimo Bonomo (1663-1696): discoverer of the etiology of scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:625-630.

- Chung SD, Wang KH, Huang CC, et al. Scabies increased the risk of chronic kidney disease: a 5-year follow-up study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:286-292.

- Wong SS, Poon RW, Chau S, et al. Development of conventional and real-time quantitative PCR assays for diagnosis and monitoring of scabies. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2095-2102.

- Kearns TM, Speare R, Cheng AC, et al. Impact of an ivermectin mass drug administration on scabies prevalence in a remote Australian aboriginal community. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004151.

- Gilmore SJ. Control strategies for endemic childhood scabies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15990.

- Hay RJ, Steer AC, Engelman D, Walton S. Scabies in the developing world—its prevalence, complications, and management. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:313-323.

- Hoy WE, White AV, Dowling A, et al. Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis is a strong risk factor for chronic kidney disease in later life. Kidney Int. 2012;81:1026-1032.

- Mika A, Reynolds SL, Pickering D, et al. Complement inhibitors from scabies mites promote streptococcal growth—a novel mechanism in infected epidermis? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1563.

- McLean FE. The elimination of scabies: a task for our generation. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1215-1223.

- Hengge UR, Currie BJ, Jäger G, et al. Scabies: a ubiquitous neglected skin disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:769-779.

- Heukelbach J, Feldmeier H. Scabies. Lancet. 2006;367:1767-1774.

- Johnston G, Sladden M. Scabies: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ. 2005;331:619-622.

- Yeoh DK, Bowen AC, Carapetis JR. Impetigo and scabies—disease burden and modern treatment strategies [published online May 11, 2016]. J Infect. 2016;(72 suppl):S61-S67.

- Bowen AC, Mahé A, Hay RJ, et al. The global epidemiology of impetigo: a systematic review of the population prevalence of impetigo and pyoderma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136789.

- Bowen AC, Tong SY, Chatfield MD, et al. The microbiology of impetigo in indigenous children: associations between Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, scabies, and nasal carriage. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:727.

- Sesso R, Pinto SW. Five-year follow-up of patients with epidemic glomerulonephritis due to Streptococcus zooepidemicus. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1808-1812.

- Singh GR. Glomerulonephritis and managing the risks of chronic renal disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:1363-1382.

- La Vincente S, Kearns T, Connors C, et al. Community management of endemic scabies in remote aboriginal communities of northern Australia: low treatment uptake and high ongoing acquisition. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e444.

- Clucas DB, Carville KS, Connors C, et al. Disease burden and health-care clinic attendances for young children in remote aboriginal communities of northern Australia. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:275-281.

- Stanton B, Khanam S, Nazrul H, et al. Scabies in urban Bangladesh. J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;90:219-226.

- Heukelbach J, de Oliveira FA, Feldmeier H. Ecoparasitoses and public health in Brazil: challenges for control [in Portuguese]. Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19:1535-1540.

- Edison L, Beaudoin A, Goh L, et al. Scabies and bacterial superinfection among American Samoan children, 2011-2012. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139336.

- Steer AC, Jenney AW, Kado J, et al. High burden of impetigo and scabies in a tropical country. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e467.

- Romani L, Steer AC, Whitfeld MJ, et al. Prevalence of scabies and impetigo worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:960-967.

- Romani L, Koroivueta J, Steer AC, et al. Scabies and impetigo prevalence and risk factors in Fiji: a national survey. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003452.

- Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Verzì AE, et al. Low-cost equipment for diagnosis and management of endemic scabies outbreaks in underserved populations. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:327-329.

- Pasay C, Walton S, Fischer K, et al. PCR-based assay to survey for knockdown resistance to pyrethroid acaricides in human scabies mites (Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:649-657.

- Heukelbach J, van Haeff E, Rump B, et al. Parasitic skin diseases: health care-seeking in a slum in north-east Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:368-373.

- Potter EV, Mayon-White R, Poon-King T, et al. Acute glomerulonephritis as a complication of scabies. In: Orkin M, Maibach HI, eds. Cutaneous Infestations and Insect Bites. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1985.

- Mahé A. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1689.

- Steer AC, Romani L, Kaldor JM. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1690.

- Mounsey KE, Holt DC, McCarthy JS, et al. Longitudinal evidence of increasing in vitro tolerance of scabies mites to ivermectin in scabies-endemic communities. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:840-841.

- Currie BJ. Scabies and global control of neglected tropical diseases. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2371-2372.

- O’Donnell V, Morris S, Ward J. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1689-1690.

- Romani L, Whitfeld MJ, Koroivueta J, et al. Mass drug administration for scabies control in a population with endemic disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2305-2313.

- Hicks MI, Elston DM. Scabies. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:279-292.

- Ramos-e-Silva M. Giovan Cosimo Bonomo (1663-1696): discoverer of the etiology of scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:625-630.

- Chung SD, Wang KH, Huang CC, et al. Scabies increased the risk of chronic kidney disease: a 5-year follow-up study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:286-292.

- Wong SS, Poon RW, Chau S, et al. Development of conventional and real-time quantitative PCR assays for diagnosis and monitoring of scabies. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2095-2102.

- Kearns TM, Speare R, Cheng AC, et al. Impact of an ivermectin mass drug administration on scabies prevalence in a remote Australian aboriginal community. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004151.

- Gilmore SJ. Control strategies for endemic childhood scabies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15990.

- Hay RJ, Steer AC, Engelman D, Walton S. Scabies in the developing world—its prevalence, complications, and management. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:313-323.

- Hoy WE, White AV, Dowling A, et al. Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis is a strong risk factor for chronic kidney disease in later life. Kidney Int. 2012;81:1026-1032.

- Mika A, Reynolds SL, Pickering D, et al. Complement inhibitors from scabies mites promote streptococcal growth—a novel mechanism in infected epidermis? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1563.

- McLean FE. The elimination of scabies: a task for our generation. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1215-1223.

- Hengge UR, Currie BJ, Jäger G, et al. Scabies: a ubiquitous neglected skin disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:769-779.

- Heukelbach J, Feldmeier H. Scabies. Lancet. 2006;367:1767-1774.

- Johnston G, Sladden M. Scabies: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ. 2005;331:619-622.

- Yeoh DK, Bowen AC, Carapetis JR. Impetigo and scabies—disease burden and modern treatment strategies [published online May 11, 2016]. J Infect. 2016;(72 suppl):S61-S67.

- Bowen AC, Mahé A, Hay RJ, et al. The global epidemiology of impetigo: a systematic review of the population prevalence of impetigo and pyoderma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136789.

- Bowen AC, Tong SY, Chatfield MD, et al. The microbiology of impetigo in indigenous children: associations between Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, scabies, and nasal carriage. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:727.

- Sesso R, Pinto SW. Five-year follow-up of patients with epidemic glomerulonephritis due to Streptococcus zooepidemicus. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1808-1812.

- Singh GR. Glomerulonephritis and managing the risks of chronic renal disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:1363-1382.

- La Vincente S, Kearns T, Connors C, et al. Community management of endemic scabies in remote aboriginal communities of northern Australia: low treatment uptake and high ongoing acquisition. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e444.

- Clucas DB, Carville KS, Connors C, et al. Disease burden and health-care clinic attendances for young children in remote aboriginal communities of northern Australia. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:275-281.

- Stanton B, Khanam S, Nazrul H, et al. Scabies in urban Bangladesh. J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;90:219-226.

- Heukelbach J, de Oliveira FA, Feldmeier H. Ecoparasitoses and public health in Brazil: challenges for control [in Portuguese]. Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19:1535-1540.

- Edison L, Beaudoin A, Goh L, et al. Scabies and bacterial superinfection among American Samoan children, 2011-2012. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139336.

- Steer AC, Jenney AW, Kado J, et al. High burden of impetigo and scabies in a tropical country. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e467.

- Romani L, Steer AC, Whitfeld MJ, et al. Prevalence of scabies and impetigo worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:960-967.

- Romani L, Koroivueta J, Steer AC, et al. Scabies and impetigo prevalence and risk factors in Fiji: a national survey. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003452.

- Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Verzì AE, et al. Low-cost equipment for diagnosis and management of endemic scabies outbreaks in underserved populations. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:327-329.

- Pasay C, Walton S, Fischer K, et al. PCR-based assay to survey for knockdown resistance to pyrethroid acaricides in human scabies mites (Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:649-657.

- Heukelbach J, van Haeff E, Rump B, et al. Parasitic skin diseases: health care-seeking in a slum in north-east Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:368-373.

- Potter EV, Mayon-White R, Poon-King T, et al. Acute glomerulonephritis as a complication of scabies. In: Orkin M, Maibach HI, eds. Cutaneous Infestations and Insect Bites. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1985.

- Mahé A. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1689.

- Steer AC, Romani L, Kaldor JM. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1690.

- Mounsey KE, Holt DC, McCarthy JS, et al. Longitudinal evidence of increasing in vitro tolerance of scabies mites to ivermectin in scabies-endemic communities. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:840-841.

- Currie BJ. Scabies and global control of neglected tropical diseases. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2371-2372.

- O’Donnell V, Morris S, Ward J. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1689-1690.

Practice Points

- Scabies infestation is one of the world’s leading causes of chronic kidney disease.