User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

A Peek at Our October 2017 Issue

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Levofloxacin-Induced Purpura Annularis Telangiectodes of Majocchi

To the Editor:

Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi (PATM) is a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD). Patients present with nonblanchable, annular, symmetric, purpuric, and telangiectatic patches, often on the legs, with histology revealing a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes.1,2 A variety of medications have been linked to the development of PPD. We describe a case of levofloxacin-induced PATM.

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Changes Associated With Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

A 42-year-old man presented with a rash on the arms, trunk, abdomen, and legs of 1 month’s duration. He reported no associated itching, bleeding, or pain, and no history of a similar rash. He had a history of hypothyroidism and had been taking levothyroxine for years. He had no known allergies and no history of childhood eczema, asthma, or allergic rhinitis. Notably, the rash started shortly after the patient finished a 2-week course of levofloxacin, an antibiotic he had not taken in the past. The patient resided with his wife, 3 children, and a pet dog, and no family members had the rash. Prior to presentation, the patient had tried econazole cream and then triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.5% without any clinical improvement.

A complete review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed scattered, reddish brown, annular, nonscaly patches on the back, abdomen (Figure 1), arms, and legs with nonblanching petechiae within the patches.

A punch biopsy of the left inner thigh demonstrated patchy interface dermatitis, superficial perivascular inflammation, and numerous extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). The histologic features were compatible with the clinical impression of PATM. The patient presented for a follow-up visit 2 weeks later with no new lesions and the old lesions were rapidly fading (Figure 3).

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses are a group of conditions that have different clinical morphologies but similar histopathologic examinations.2 All PPDs are characterized by nonblanching, nonpalpable, purpuric lesions that often are bilaterally symmetrical and present on the legs.2,3 Although the precise etiology of these conditions is not known, most cases include a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate along with the presence of extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposition in the dermis.2 Of note, PATM often is idiopathic and patients usually present with no associated comorbidities.3 The currently established PPDs include progressive pigmentary dermatosis (Schamberg disease), PATM, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis.2,4

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

The lesions of PATM are symmetrically distributed on the bilateral legs and may be symptomatic in most cases, with severe pruritus being reported in several drug-induced PATM cases.3,5 Although the exact etiology of PPDs currently is unknown, some contributing factors that are thought to play a role include exercise, venous stasis, gravitational dependence, capillary fragility, hypertension, drugs, chemical exposure or ingestions, and contact allergy to dyes.3 Some of the drugs known to cause drug-induced PPDs fall into the class of sedatives, stimulants, antibiotics, cardiovascular drugs, vitamins, and nutritional supplements.3,6 Some medications that have been reported to cause PPDs include acetaminophen, aspirin, carbamazepine, diltiazem, furosemide, glipizide, hydralazine, infliximab, isotretinoin, lorazepam, minocycline, nitroglycerine, and sildenafil.3,7-15

Although the mechanism of drug-induced PPD is not completely understood, it is thought that the ingested substance leads to an immunologic response in the capillary endothelium, which results in a cell-mediated immune response causing vascular damage.3 The ingested substance may act as a hapten, stimulating antibody formation and immune-mediated injury, leading to the clinical presentation of nonblanching, symmetric, purpuric, telangiectatic, and atrophic patches at the site of injury.1,3

Levofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that has activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. It inhibits the enzymes DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, preventing bacteria from undergoing proper DNA synthesis.16 Our patient’s rash began shortly after a 2-week course of levofloxacin and faded within a few weeks of discontinuing the drug; the clinical presentation, time course, and histologic appearance of the lesions were consistent with the diagnosis of drug-induced PPD. Of note, solar capillaritis has been reported following a phototoxic reaction induced by levofloxacin.17 Our case differs in that our patient had annular lesions on both photoprotected and photoexposed skin.

The first-line interventions for the treatment of PPDs are nonpharmacologic, such as discontinuation of an offending drug or allergen or wearing supportive stockings if there are signs of venous stasis. Other interventions include the use of a medium- or high-potency topical corticosteroid once to twice daily to affected areas for 4 to 6 weeks.18 Some case series also have shown improvement with narrowband UVB treatment after 24 to 28 treatment sessions or with psoralen plus UVA phototherapy within 7 to 20 treatments.19,20 If the above measures are unsuccessful in resolving symptoms, other treatment alternatives may include pentoxifylline, griseofulvin, colchicine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. The potential benefit of treatment must be weighed against the side-effect profile of these medications.2,21-24 Of note, oral rutoside (50 mg twice daily) and ascorbic acid (500 mg twice daily) were administered to 3 patients with chronic progressive pigmented purpura. At the end of the 4-week treatment period, complete clearance of skin lesions was seen in all patients with no adverse reactions noted.25

Despite these treatment options, PATM does not necessitate treatment given its benign course and often self-resolving nature.26 In cases of drug-induced PPD such as in our patient, discontinuation of the offending drug often may lead to resolution.

In summary, PATM is a PPD that has been associated with different etiologic factors. If PATM is suspected to be caused by a drug, discontinuation of the offending agent usually results in resolution of symptoms, as it did in our case with fading of lesions within a few weeks after the patient was no longer taking levofloxacin.

- Hale EK. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:17.

- Hoesly FJ, Huerter CJ, Shehan JM. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1129-1133.

- Kaplan R, Meehan SA, Leger M. A case of isotretinoin-induced purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi and review of substance-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:182-184.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Ratnam KV, Su WP, Peters MS. Purpura simplex (inflammatory purpura without vasculitis): a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:642-647.

- Pang BK, Su D, Ratnam KV. Drug-induced purpura simplex: clinical and histological characteristics. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1993;22:870-872.

- Abeck D, Gross GE, Kuwert C, et al. Acetaminophen-induced progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:123-124.

- Lipsker D, Cribier B, Heid E, et al. Cutaneous lymphoma manifesting as pigmented, purpuric capillaries [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;126:321-326.

- Peterson WC Jr, Manick KP. Purpuric eruptions associated with use of carbromal and meprobamate. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:40-42.

- Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

- Voelter WW. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis-like reaction to topical fluorouracil. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:875-876.

- Adams BB, Gadenne AS. Glipizide-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5, pt 2):827-829.

- Tsao H, Lerner LH. Pigmented purpuric eruption associated with injection medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 1):308-310.

- Koçak AY, Akay BN, Heper AO. Sildenafil-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:91-92.

- Nishioka K, Sarashi C, Katayama I. Chronic pigmented purpura induced by chemical substances. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:213-218.

- Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377-392.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Fathy H, Abdelgaber S. Treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatoses with narrow-band UVB: a report of six cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:603-606.

- Krizsa J, Hunyadi J, Dobozy A. PUVA treatment of pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis (Gougerot-Blum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(5, pt 1):778-780.

- Panda S, Malakar S, Lahiri K. Oral pentoxifylline vs topical betamethasone in Schamberg disease: a comparative randomized investigator-blinded parallel-group trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:491-493.

- Tamaki K, Yasaka N, Osada A, et al. Successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with griseofulvin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:159-160.

- Geller M. Benefit of colchicine in the treatment of Schamberg’s disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:246.

- Okada K, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y. Purpura pigmentosa chronica successfully treated with oral cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:180-181.

- Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 1):207-208.

- Wang A, Shuja F, Chan A, et al. Unilateral purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi in an elderly male: an atypical presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19263.

To the Editor:

Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi (PATM) is a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD). Patients present with nonblanchable, annular, symmetric, purpuric, and telangiectatic patches, often on the legs, with histology revealing a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes.1,2 A variety of medications have been linked to the development of PPD. We describe a case of levofloxacin-induced PATM.

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Changes Associated With Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

A 42-year-old man presented with a rash on the arms, trunk, abdomen, and legs of 1 month’s duration. He reported no associated itching, bleeding, or pain, and no history of a similar rash. He had a history of hypothyroidism and had been taking levothyroxine for years. He had no known allergies and no history of childhood eczema, asthma, or allergic rhinitis. Notably, the rash started shortly after the patient finished a 2-week course of levofloxacin, an antibiotic he had not taken in the past. The patient resided with his wife, 3 children, and a pet dog, and no family members had the rash. Prior to presentation, the patient had tried econazole cream and then triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.5% without any clinical improvement.

A complete review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed scattered, reddish brown, annular, nonscaly patches on the back, abdomen (Figure 1), arms, and legs with nonblanching petechiae within the patches.

A punch biopsy of the left inner thigh demonstrated patchy interface dermatitis, superficial perivascular inflammation, and numerous extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). The histologic features were compatible with the clinical impression of PATM. The patient presented for a follow-up visit 2 weeks later with no new lesions and the old lesions were rapidly fading (Figure 3).

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses are a group of conditions that have different clinical morphologies but similar histopathologic examinations.2 All PPDs are characterized by nonblanching, nonpalpable, purpuric lesions that often are bilaterally symmetrical and present on the legs.2,3 Although the precise etiology of these conditions is not known, most cases include a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate along with the presence of extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposition in the dermis.2 Of note, PATM often is idiopathic and patients usually present with no associated comorbidities.3 The currently established PPDs include progressive pigmentary dermatosis (Schamberg disease), PATM, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis.2,4

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

The lesions of PATM are symmetrically distributed on the bilateral legs and may be symptomatic in most cases, with severe pruritus being reported in several drug-induced PATM cases.3,5 Although the exact etiology of PPDs currently is unknown, some contributing factors that are thought to play a role include exercise, venous stasis, gravitational dependence, capillary fragility, hypertension, drugs, chemical exposure or ingestions, and contact allergy to dyes.3 Some of the drugs known to cause drug-induced PPDs fall into the class of sedatives, stimulants, antibiotics, cardiovascular drugs, vitamins, and nutritional supplements.3,6 Some medications that have been reported to cause PPDs include acetaminophen, aspirin, carbamazepine, diltiazem, furosemide, glipizide, hydralazine, infliximab, isotretinoin, lorazepam, minocycline, nitroglycerine, and sildenafil.3,7-15

Although the mechanism of drug-induced PPD is not completely understood, it is thought that the ingested substance leads to an immunologic response in the capillary endothelium, which results in a cell-mediated immune response causing vascular damage.3 The ingested substance may act as a hapten, stimulating antibody formation and immune-mediated injury, leading to the clinical presentation of nonblanching, symmetric, purpuric, telangiectatic, and atrophic patches at the site of injury.1,3

Levofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that has activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. It inhibits the enzymes DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, preventing bacteria from undergoing proper DNA synthesis.16 Our patient’s rash began shortly after a 2-week course of levofloxacin and faded within a few weeks of discontinuing the drug; the clinical presentation, time course, and histologic appearance of the lesions were consistent with the diagnosis of drug-induced PPD. Of note, solar capillaritis has been reported following a phototoxic reaction induced by levofloxacin.17 Our case differs in that our patient had annular lesions on both photoprotected and photoexposed skin.

The first-line interventions for the treatment of PPDs are nonpharmacologic, such as discontinuation of an offending drug or allergen or wearing supportive stockings if there are signs of venous stasis. Other interventions include the use of a medium- or high-potency topical corticosteroid once to twice daily to affected areas for 4 to 6 weeks.18 Some case series also have shown improvement with narrowband UVB treatment after 24 to 28 treatment sessions or with psoralen plus UVA phototherapy within 7 to 20 treatments.19,20 If the above measures are unsuccessful in resolving symptoms, other treatment alternatives may include pentoxifylline, griseofulvin, colchicine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. The potential benefit of treatment must be weighed against the side-effect profile of these medications.2,21-24 Of note, oral rutoside (50 mg twice daily) and ascorbic acid (500 mg twice daily) were administered to 3 patients with chronic progressive pigmented purpura. At the end of the 4-week treatment period, complete clearance of skin lesions was seen in all patients with no adverse reactions noted.25

Despite these treatment options, PATM does not necessitate treatment given its benign course and often self-resolving nature.26 In cases of drug-induced PPD such as in our patient, discontinuation of the offending drug often may lead to resolution.

In summary, PATM is a PPD that has been associated with different etiologic factors. If PATM is suspected to be caused by a drug, discontinuation of the offending agent usually results in resolution of symptoms, as it did in our case with fading of lesions within a few weeks after the patient was no longer taking levofloxacin.

To the Editor:

Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi (PATM) is a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD). Patients present with nonblanchable, annular, symmetric, purpuric, and telangiectatic patches, often on the legs, with histology revealing a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes.1,2 A variety of medications have been linked to the development of PPD. We describe a case of levofloxacin-induced PATM.

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Changes Associated With Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

A 42-year-old man presented with a rash on the arms, trunk, abdomen, and legs of 1 month’s duration. He reported no associated itching, bleeding, or pain, and no history of a similar rash. He had a history of hypothyroidism and had been taking levothyroxine for years. He had no known allergies and no history of childhood eczema, asthma, or allergic rhinitis. Notably, the rash started shortly after the patient finished a 2-week course of levofloxacin, an antibiotic he had not taken in the past. The patient resided with his wife, 3 children, and a pet dog, and no family members had the rash. Prior to presentation, the patient had tried econazole cream and then triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.5% without any clinical improvement.

A complete review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed scattered, reddish brown, annular, nonscaly patches on the back, abdomen (Figure 1), arms, and legs with nonblanching petechiae within the patches.

A punch biopsy of the left inner thigh demonstrated patchy interface dermatitis, superficial perivascular inflammation, and numerous extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). The histologic features were compatible with the clinical impression of PATM. The patient presented for a follow-up visit 2 weeks later with no new lesions and the old lesions were rapidly fading (Figure 3).

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses are a group of conditions that have different clinical morphologies but similar histopathologic examinations.2 All PPDs are characterized by nonblanching, nonpalpable, purpuric lesions that often are bilaterally symmetrical and present on the legs.2,3 Although the precise etiology of these conditions is not known, most cases include a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate along with the presence of extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposition in the dermis.2 Of note, PATM often is idiopathic and patients usually present with no associated comorbidities.3 The currently established PPDs include progressive pigmentary dermatosis (Schamberg disease), PATM, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis.2,4

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

The lesions of PATM are symmetrically distributed on the bilateral legs and may be symptomatic in most cases, with severe pruritus being reported in several drug-induced PATM cases.3,5 Although the exact etiology of PPDs currently is unknown, some contributing factors that are thought to play a role include exercise, venous stasis, gravitational dependence, capillary fragility, hypertension, drugs, chemical exposure or ingestions, and contact allergy to dyes.3 Some of the drugs known to cause drug-induced PPDs fall into the class of sedatives, stimulants, antibiotics, cardiovascular drugs, vitamins, and nutritional supplements.3,6 Some medications that have been reported to cause PPDs include acetaminophen, aspirin, carbamazepine, diltiazem, furosemide, glipizide, hydralazine, infliximab, isotretinoin, lorazepam, minocycline, nitroglycerine, and sildenafil.3,7-15

Although the mechanism of drug-induced PPD is not completely understood, it is thought that the ingested substance leads to an immunologic response in the capillary endothelium, which results in a cell-mediated immune response causing vascular damage.3 The ingested substance may act as a hapten, stimulating antibody formation and immune-mediated injury, leading to the clinical presentation of nonblanching, symmetric, purpuric, telangiectatic, and atrophic patches at the site of injury.1,3

Levofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that has activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. It inhibits the enzymes DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, preventing bacteria from undergoing proper DNA synthesis.16 Our patient’s rash began shortly after a 2-week course of levofloxacin and faded within a few weeks of discontinuing the drug; the clinical presentation, time course, and histologic appearance of the lesions were consistent with the diagnosis of drug-induced PPD. Of note, solar capillaritis has been reported following a phototoxic reaction induced by levofloxacin.17 Our case differs in that our patient had annular lesions on both photoprotected and photoexposed skin.

The first-line interventions for the treatment of PPDs are nonpharmacologic, such as discontinuation of an offending drug or allergen or wearing supportive stockings if there are signs of venous stasis. Other interventions include the use of a medium- or high-potency topical corticosteroid once to twice daily to affected areas for 4 to 6 weeks.18 Some case series also have shown improvement with narrowband UVB treatment after 24 to 28 treatment sessions or with psoralen plus UVA phototherapy within 7 to 20 treatments.19,20 If the above measures are unsuccessful in resolving symptoms, other treatment alternatives may include pentoxifylline, griseofulvin, colchicine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. The potential benefit of treatment must be weighed against the side-effect profile of these medications.2,21-24 Of note, oral rutoside (50 mg twice daily) and ascorbic acid (500 mg twice daily) were administered to 3 patients with chronic progressive pigmented purpura. At the end of the 4-week treatment period, complete clearance of skin lesions was seen in all patients with no adverse reactions noted.25

Despite these treatment options, PATM does not necessitate treatment given its benign course and often self-resolving nature.26 In cases of drug-induced PPD such as in our patient, discontinuation of the offending drug often may lead to resolution.

In summary, PATM is a PPD that has been associated with different etiologic factors. If PATM is suspected to be caused by a drug, discontinuation of the offending agent usually results in resolution of symptoms, as it did in our case with fading of lesions within a few weeks after the patient was no longer taking levofloxacin.

- Hale EK. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:17.

- Hoesly FJ, Huerter CJ, Shehan JM. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1129-1133.

- Kaplan R, Meehan SA, Leger M. A case of isotretinoin-induced purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi and review of substance-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:182-184.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Ratnam KV, Su WP, Peters MS. Purpura simplex (inflammatory purpura without vasculitis): a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:642-647.

- Pang BK, Su D, Ratnam KV. Drug-induced purpura simplex: clinical and histological characteristics. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1993;22:870-872.

- Abeck D, Gross GE, Kuwert C, et al. Acetaminophen-induced progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:123-124.

- Lipsker D, Cribier B, Heid E, et al. Cutaneous lymphoma manifesting as pigmented, purpuric capillaries [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;126:321-326.

- Peterson WC Jr, Manick KP. Purpuric eruptions associated with use of carbromal and meprobamate. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:40-42.

- Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

- Voelter WW. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis-like reaction to topical fluorouracil. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:875-876.

- Adams BB, Gadenne AS. Glipizide-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5, pt 2):827-829.

- Tsao H, Lerner LH. Pigmented purpuric eruption associated with injection medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 1):308-310.

- Koçak AY, Akay BN, Heper AO. Sildenafil-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:91-92.

- Nishioka K, Sarashi C, Katayama I. Chronic pigmented purpura induced by chemical substances. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:213-218.

- Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377-392.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Fathy H, Abdelgaber S. Treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatoses with narrow-band UVB: a report of six cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:603-606.

- Krizsa J, Hunyadi J, Dobozy A. PUVA treatment of pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis (Gougerot-Blum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(5, pt 1):778-780.

- Panda S, Malakar S, Lahiri K. Oral pentoxifylline vs topical betamethasone in Schamberg disease: a comparative randomized investigator-blinded parallel-group trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:491-493.

- Tamaki K, Yasaka N, Osada A, et al. Successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with griseofulvin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:159-160.

- Geller M. Benefit of colchicine in the treatment of Schamberg’s disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:246.

- Okada K, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y. Purpura pigmentosa chronica successfully treated with oral cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:180-181.

- Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 1):207-208.

- Wang A, Shuja F, Chan A, et al. Unilateral purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi in an elderly male: an atypical presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19263.

- Hale EK. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:17.

- Hoesly FJ, Huerter CJ, Shehan JM. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1129-1133.

- Kaplan R, Meehan SA, Leger M. A case of isotretinoin-induced purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi and review of substance-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:182-184.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Ratnam KV, Su WP, Peters MS. Purpura simplex (inflammatory purpura without vasculitis): a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:642-647.

- Pang BK, Su D, Ratnam KV. Drug-induced purpura simplex: clinical and histological characteristics. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1993;22:870-872.

- Abeck D, Gross GE, Kuwert C, et al. Acetaminophen-induced progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:123-124.

- Lipsker D, Cribier B, Heid E, et al. Cutaneous lymphoma manifesting as pigmented, purpuric capillaries [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;126:321-326.

- Peterson WC Jr, Manick KP. Purpuric eruptions associated with use of carbromal and meprobamate. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:40-42.

- Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

- Voelter WW. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis-like reaction to topical fluorouracil. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:875-876.

- Adams BB, Gadenne AS. Glipizide-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5, pt 2):827-829.

- Tsao H, Lerner LH. Pigmented purpuric eruption associated with injection medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 1):308-310.

- Koçak AY, Akay BN, Heper AO. Sildenafil-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:91-92.

- Nishioka K, Sarashi C, Katayama I. Chronic pigmented purpura induced by chemical substances. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:213-218.

- Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377-392.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Fathy H, Abdelgaber S. Treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatoses with narrow-band UVB: a report of six cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:603-606.

- Krizsa J, Hunyadi J, Dobozy A. PUVA treatment of pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis (Gougerot-Blum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(5, pt 1):778-780.

- Panda S, Malakar S, Lahiri K. Oral pentoxifylline vs topical betamethasone in Schamberg disease: a comparative randomized investigator-blinded parallel-group trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:491-493.

- Tamaki K, Yasaka N, Osada A, et al. Successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with griseofulvin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:159-160.

- Geller M. Benefit of colchicine in the treatment of Schamberg’s disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:246.

- Okada K, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y. Purpura pigmentosa chronica successfully treated with oral cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:180-181.

- Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 1):207-208.

- Wang A, Shuja F, Chan A, et al. Unilateral purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi in an elderly male: an atypical presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19263.

Practice Point

- Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis, may on occasion be triggered by a medication; therefore, a careful medication history may prove to be an important part of the workup for this eruption.

Chromoblastomycosis Infection From a House Plant

To the Editor:

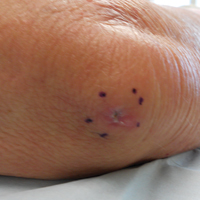

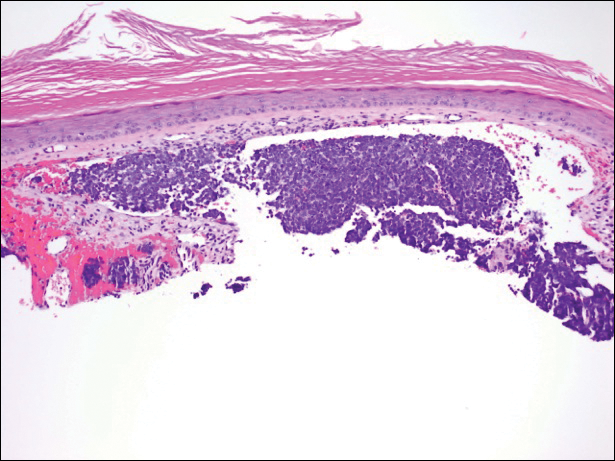

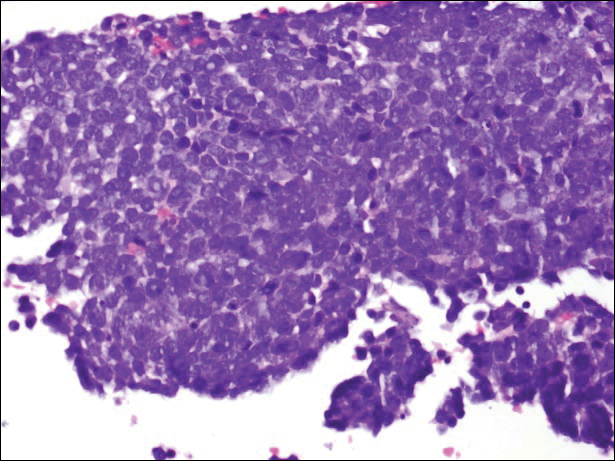

A 69-year-old woman with no history of immunodeficiency presented 1 month after a thorn from her locally grown Madagascar palm plant (Pachypodium lamerei) pierced the skin. The patient developed a painful nodule at the site on the left elbow (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy by an outside dermatologist was performed, which showed granulomatous inflammation within the dermis with epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of golden brown spherules (medlar bodies). The diagnosis was a dermal fungal infection consistent with chromoblastomycosis. A curative surgical excision was performed, and medlar bodies were seen adjacent to a polarizable foreign body consistent with plant material on histology (Figure 2). Because the lesion was localized, adjuvant medical treatment was not deemed necessary. The patient has not had any recurrence in the last 1.5 years since the resection.

The categorization of chromoblastomycosis includes a chronic fungal infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi. This definition is such that there are a multitude of organisms that can be the primary cause of this diagnosis. Generally, infection follows a traumatic permeation of the skin by a foreign body contaminated by the causative organism in agricultural workers. The most common dematiaceous pathogens are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, and Cladosporium carrionii; however, the specific causative organism varies heavily on geographic location. With inoculation by a foreign body, a small papule develops at the site of the lesion. Several years after the primary infection, nodules and verrucous erythematous plaques develop in the same area, and patients present with concerns of pain and pruritus.1 Lesions usually are localized to the initial area of inoculation, generally a break in the skin by the offending foreign body, on the legs, arms, or hands, but hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination with distant transmission due to scratching also can occur. Ulceration due to secondary bacterial infection is another possible manifestation, resulting in a foul odor and less commonly lymphedema. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma is a complication.2

RELATED ARTICLE: Fungal Foes: Presentations of Chromoblastomycosis Post–Hurricane Ike

On histopathology, thick-walled sclerotic bodies termed medlar bodies or copper pennies are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis and represent the fungal elements. Grossly, black dots can be seen on the skin in the affected areas from the transepidermal elimination of the fungi.1,2 However, there is no specificity for determining the causative organism in this manner, or even with culture, as it is difficult to differentiate the species morphologically. More advanced tests can help, such as polymerase chain reaction or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, where available.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain also shows epidermal hyperplasia and dermal mononuclear infiltrate.

Treatment modalities include surgical excision, cryotherapy, pharmacologic treatment, and combination therapy. Localized lesions often can be resected, but more severe infections can require pharmacologic treatment. Unfortunately, there tends to be a high risk for relapse with most antifungal modalities. The combination of itraconazole and terbinafine has been shown to offer the best medical therapy with lower risk for refractoriness to treatment by producing a synergistic effect between the 2 antifungals.2,3 Many surgical treatments often are combined with oral antifungals to try to attain complete eradication in deep or extensive lesions, as seen in a case in which oral terbinafine was used prior to surgery to reduce the size of the lesion, followed by complete resection.4 With localized lesions that are resectable, a wide and deep incision often can be curative. Cryotherapy also may be coupled with surgical excision or pharmacologic therapy. Most literature suggests that cryotherapy or the use of antifungals prior to excision offers improved outcomes.2,5 Prognosis tends to be good for chromoblastomycoses, particularly with smaller lesions. Complete eradication varies greatly on the size and depth of the lesion, independent of the causative pathogen.

Our patient’s presentation with chromoblastomycosis is unique because of the source of infection, which was a plant grown from seeds in a local nursery in South Florida and then sold to the patient. The majority of chromoblastomycosis infections occur in agricultural workers, typically in tropical climates such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico.1,2 Historically, infections in the United States have been uncommon, with the majority presenting in patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy or with other immunosuppressive conditions.6,7

- Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

- Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

- Zhang J, Xi L, Lu C, et al. Successful treatment for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea monophora: a report of three cases in Guangdong, China. Mycoses. 2009;52:176-181.

- Tamura K, Matsuyama T, Yahagi E, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by surgical therapy combined with preceded oral administration of terbinafine to reduce the size of the lesion. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:6-10.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Basílio FM, Hammerschmidt M, Mukai MM, et al. Mucormycosis and chromoblastomycosis occurring in a patient with leprosy type 2 reaction under prolonged corticosteroid and thalidomide therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:767-771.

- Parente JN, Talhari C, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in immunocompetent patients: two new cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses. 2001;54:265-269.

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman with no history of immunodeficiency presented 1 month after a thorn from her locally grown Madagascar palm plant (Pachypodium lamerei) pierced the skin. The patient developed a painful nodule at the site on the left elbow (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy by an outside dermatologist was performed, which showed granulomatous inflammation within the dermis with epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of golden brown spherules (medlar bodies). The diagnosis was a dermal fungal infection consistent with chromoblastomycosis. A curative surgical excision was performed, and medlar bodies were seen adjacent to a polarizable foreign body consistent with plant material on histology (Figure 2). Because the lesion was localized, adjuvant medical treatment was not deemed necessary. The patient has not had any recurrence in the last 1.5 years since the resection.

The categorization of chromoblastomycosis includes a chronic fungal infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi. This definition is such that there are a multitude of organisms that can be the primary cause of this diagnosis. Generally, infection follows a traumatic permeation of the skin by a foreign body contaminated by the causative organism in agricultural workers. The most common dematiaceous pathogens are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, and Cladosporium carrionii; however, the specific causative organism varies heavily on geographic location. With inoculation by a foreign body, a small papule develops at the site of the lesion. Several years after the primary infection, nodules and verrucous erythematous plaques develop in the same area, and patients present with concerns of pain and pruritus.1 Lesions usually are localized to the initial area of inoculation, generally a break in the skin by the offending foreign body, on the legs, arms, or hands, but hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination with distant transmission due to scratching also can occur. Ulceration due to secondary bacterial infection is another possible manifestation, resulting in a foul odor and less commonly lymphedema. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma is a complication.2

RELATED ARTICLE: Fungal Foes: Presentations of Chromoblastomycosis Post–Hurricane Ike

On histopathology, thick-walled sclerotic bodies termed medlar bodies or copper pennies are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis and represent the fungal elements. Grossly, black dots can be seen on the skin in the affected areas from the transepidermal elimination of the fungi.1,2 However, there is no specificity for determining the causative organism in this manner, or even with culture, as it is difficult to differentiate the species morphologically. More advanced tests can help, such as polymerase chain reaction or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, where available.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain also shows epidermal hyperplasia and dermal mononuclear infiltrate.

Treatment modalities include surgical excision, cryotherapy, pharmacologic treatment, and combination therapy. Localized lesions often can be resected, but more severe infections can require pharmacologic treatment. Unfortunately, there tends to be a high risk for relapse with most antifungal modalities. The combination of itraconazole and terbinafine has been shown to offer the best medical therapy with lower risk for refractoriness to treatment by producing a synergistic effect between the 2 antifungals.2,3 Many surgical treatments often are combined with oral antifungals to try to attain complete eradication in deep or extensive lesions, as seen in a case in which oral terbinafine was used prior to surgery to reduce the size of the lesion, followed by complete resection.4 With localized lesions that are resectable, a wide and deep incision often can be curative. Cryotherapy also may be coupled with surgical excision or pharmacologic therapy. Most literature suggests that cryotherapy or the use of antifungals prior to excision offers improved outcomes.2,5 Prognosis tends to be good for chromoblastomycoses, particularly with smaller lesions. Complete eradication varies greatly on the size and depth of the lesion, independent of the causative pathogen.

Our patient’s presentation with chromoblastomycosis is unique because of the source of infection, which was a plant grown from seeds in a local nursery in South Florida and then sold to the patient. The majority of chromoblastomycosis infections occur in agricultural workers, typically in tropical climates such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico.1,2 Historically, infections in the United States have been uncommon, with the majority presenting in patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy or with other immunosuppressive conditions.6,7

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman with no history of immunodeficiency presented 1 month after a thorn from her locally grown Madagascar palm plant (Pachypodium lamerei) pierced the skin. The patient developed a painful nodule at the site on the left elbow (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy by an outside dermatologist was performed, which showed granulomatous inflammation within the dermis with epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of golden brown spherules (medlar bodies). The diagnosis was a dermal fungal infection consistent with chromoblastomycosis. A curative surgical excision was performed, and medlar bodies were seen adjacent to a polarizable foreign body consistent with plant material on histology (Figure 2). Because the lesion was localized, adjuvant medical treatment was not deemed necessary. The patient has not had any recurrence in the last 1.5 years since the resection.

The categorization of chromoblastomycosis includes a chronic fungal infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi. This definition is such that there are a multitude of organisms that can be the primary cause of this diagnosis. Generally, infection follows a traumatic permeation of the skin by a foreign body contaminated by the causative organism in agricultural workers. The most common dematiaceous pathogens are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, and Cladosporium carrionii; however, the specific causative organism varies heavily on geographic location. With inoculation by a foreign body, a small papule develops at the site of the lesion. Several years after the primary infection, nodules and verrucous erythematous plaques develop in the same area, and patients present with concerns of pain and pruritus.1 Lesions usually are localized to the initial area of inoculation, generally a break in the skin by the offending foreign body, on the legs, arms, or hands, but hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination with distant transmission due to scratching also can occur. Ulceration due to secondary bacterial infection is another possible manifestation, resulting in a foul odor and less commonly lymphedema. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma is a complication.2

RELATED ARTICLE: Fungal Foes: Presentations of Chromoblastomycosis Post–Hurricane Ike

On histopathology, thick-walled sclerotic bodies termed medlar bodies or copper pennies are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis and represent the fungal elements. Grossly, black dots can be seen on the skin in the affected areas from the transepidermal elimination of the fungi.1,2 However, there is no specificity for determining the causative organism in this manner, or even with culture, as it is difficult to differentiate the species morphologically. More advanced tests can help, such as polymerase chain reaction or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, where available.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain also shows epidermal hyperplasia and dermal mononuclear infiltrate.

Treatment modalities include surgical excision, cryotherapy, pharmacologic treatment, and combination therapy. Localized lesions often can be resected, but more severe infections can require pharmacologic treatment. Unfortunately, there tends to be a high risk for relapse with most antifungal modalities. The combination of itraconazole and terbinafine has been shown to offer the best medical therapy with lower risk for refractoriness to treatment by producing a synergistic effect between the 2 antifungals.2,3 Many surgical treatments often are combined with oral antifungals to try to attain complete eradication in deep or extensive lesions, as seen in a case in which oral terbinafine was used prior to surgery to reduce the size of the lesion, followed by complete resection.4 With localized lesions that are resectable, a wide and deep incision often can be curative. Cryotherapy also may be coupled with surgical excision or pharmacologic therapy. Most literature suggests that cryotherapy or the use of antifungals prior to excision offers improved outcomes.2,5 Prognosis tends to be good for chromoblastomycoses, particularly with smaller lesions. Complete eradication varies greatly on the size and depth of the lesion, independent of the causative pathogen.

Our patient’s presentation with chromoblastomycosis is unique because of the source of infection, which was a plant grown from seeds in a local nursery in South Florida and then sold to the patient. The majority of chromoblastomycosis infections occur in agricultural workers, typically in tropical climates such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico.1,2 Historically, infections in the United States have been uncommon, with the majority presenting in patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy or with other immunosuppressive conditions.6,7

- Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

- Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

- Zhang J, Xi L, Lu C, et al. Successful treatment for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea monophora: a report of three cases in Guangdong, China. Mycoses. 2009;52:176-181.

- Tamura K, Matsuyama T, Yahagi E, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by surgical therapy combined with preceded oral administration of terbinafine to reduce the size of the lesion. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:6-10.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Basílio FM, Hammerschmidt M, Mukai MM, et al. Mucormycosis and chromoblastomycosis occurring in a patient with leprosy type 2 reaction under prolonged corticosteroid and thalidomide therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:767-771.

- Parente JN, Talhari C, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in immunocompetent patients: two new cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses. 2001;54:265-269.

- Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

- Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

- Zhang J, Xi L, Lu C, et al. Successful treatment for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea monophora: a report of three cases in Guangdong, China. Mycoses. 2009;52:176-181.

- Tamura K, Matsuyama T, Yahagi E, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by surgical therapy combined with preceded oral administration of terbinafine to reduce the size of the lesion. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:6-10.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Basílio FM, Hammerschmidt M, Mukai MM, et al. Mucormycosis and chromoblastomycosis occurring in a patient with leprosy type 2 reaction under prolonged corticosteroid and thalidomide therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:767-771.

- Parente JN, Talhari C, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in immunocompetent patients: two new cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses. 2001;54:265-269.

Practice Points

- Chromoblastomycosis is an uncommon fungal infection that should be considered in cases of traumatic injuries to the skin.

- Biopsies of growing or nonhealing nodules will demonstrate characteristic golden brown spherules (medlar bodies).

- In localized cases, surgical excision may be curative.

Debunking Actinic Keratosis Myths: Are Patients With Darker Skin At Risk for Actinic Keratoses?

Myth: Actinic keratoses are only seen in patients with lighter skin

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are precancerous lesions that may turn into squamous cell carcinoma if left untreated. UV rays cause AKs, either from outdoor sun exposure or tanning beds. According to the American Academy of Dermatology, AKs are more likely to develop in patients 40 years or older with fair skin; hair color that is naturally blonde or red; eye color that is naturally blue, green, or hazel; skin that freckles or burns when in the sun; a weakened immune system; and occupations involving substances that contain polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as coal or tar.

A 2007 study compared the most common diagnoses among patients of different racial and ethnic groups in New York City. Alexis et al found that AK was in the top 10 diagnoses in white patients but not for black patients. They postulated that photoprotective factors in darkly pigmented skin such as larger and more numerous melanosomes that contain more melanin and are more dispersed throughout the epidermis result in a lower incidence of skin cancers in the skin of color (SOC) population.

RELATED ARTICLE: Common Dermatologic Disorders in Skin of Color: A Comparative Practice Survey

However, a recent skin cancer awareness study in Cutis reported that even though SOC populations have lower incidences of skin cancer such as melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma, they exhibit higher death rates. Furthermore, black individuals are more likely to present with advanced-stage melanoma and acral lentiginous melanomas compared to white individuals. Kailas et al stated, “Overall, SOC patients have the poorest skin cancer prognosis, and the data suggest that the reason for this paradox is delayed diagnosis.” They evaluated several knowledge-based interventions for increasing skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behaviors in SOC populations, including the use of visuals such as photographs to allow SOC patients to visualize different skin tones, educational interventions in another language, and pamphlets.

Dermatologists should be aware that education of SOC patients is important to eradicate the common misconception that these patients do not have to worry about AKs and other skin cancers. Remind these patients that they need to protect their skin from the sun, just as patients with fair skin do. Further research in the dermatology community should focus on educational interventions that will help increase knowledge regarding skin cancer in SOC populations.

Expert Commentary

Although more common in patients with lighter skin, actinic keratosis and skin cancer can be seen in patients of all skin types. Many patients are unaware of this risk and do not use sunscreen and other sun-protective measures. We, as a specialty, have to educate our patients and the public of the risk for actinic keratosis and skin cancer in all skin types.

—Gary Goldenberg, MD (New York, New York)

Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

American Academy of Dermatology. Actinic keratosis. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/actinic-keratosis. Accessed October 17, 2017.

Kailas A, Botwin AL, Pritchett EN, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of knowledge-based interventions in increasing skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behaviors in skin of color populations. Cutis. 2017;100:235-240.

Myth: Actinic keratoses are only seen in patients with lighter skin

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are precancerous lesions that may turn into squamous cell carcinoma if left untreated. UV rays cause AKs, either from outdoor sun exposure or tanning beds. According to the American Academy of Dermatology, AKs are more likely to develop in patients 40 years or older with fair skin; hair color that is naturally blonde or red; eye color that is naturally blue, green, or hazel; skin that freckles or burns when in the sun; a weakened immune system; and occupations involving substances that contain polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as coal or tar.

A 2007 study compared the most common diagnoses among patients of different racial and ethnic groups in New York City. Alexis et al found that AK was in the top 10 diagnoses in white patients but not for black patients. They postulated that photoprotective factors in darkly pigmented skin such as larger and more numerous melanosomes that contain more melanin and are more dispersed throughout the epidermis result in a lower incidence of skin cancers in the skin of color (SOC) population.

RELATED ARTICLE: Common Dermatologic Disorders in Skin of Color: A Comparative Practice Survey

However, a recent skin cancer awareness study in Cutis reported that even though SOC populations have lower incidences of skin cancer such as melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma, they exhibit higher death rates. Furthermore, black individuals are more likely to present with advanced-stage melanoma and acral lentiginous melanomas compared to white individuals. Kailas et al stated, “Overall, SOC patients have the poorest skin cancer prognosis, and the data suggest that the reason for this paradox is delayed diagnosis.” They evaluated several knowledge-based interventions for increasing skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behaviors in SOC populations, including the use of visuals such as photographs to allow SOC patients to visualize different skin tones, educational interventions in another language, and pamphlets.

Dermatologists should be aware that education of SOC patients is important to eradicate the common misconception that these patients do not have to worry about AKs and other skin cancers. Remind these patients that they need to protect their skin from the sun, just as patients with fair skin do. Further research in the dermatology community should focus on educational interventions that will help increase knowledge regarding skin cancer in SOC populations.

Expert Commentary

Although more common in patients with lighter skin, actinic keratosis and skin cancer can be seen in patients of all skin types. Many patients are unaware of this risk and do not use sunscreen and other sun-protective measures. We, as a specialty, have to educate our patients and the public of the risk for actinic keratosis and skin cancer in all skin types.

—Gary Goldenberg, MD (New York, New York)

Myth: Actinic keratoses are only seen in patients with lighter skin

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are precancerous lesions that may turn into squamous cell carcinoma if left untreated. UV rays cause AKs, either from outdoor sun exposure or tanning beds. According to the American Academy of Dermatology, AKs are more likely to develop in patients 40 years or older with fair skin; hair color that is naturally blonde or red; eye color that is naturally blue, green, or hazel; skin that freckles or burns when in the sun; a weakened immune system; and occupations involving substances that contain polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as coal or tar.

A 2007 study compared the most common diagnoses among patients of different racial and ethnic groups in New York City. Alexis et al found that AK was in the top 10 diagnoses in white patients but not for black patients. They postulated that photoprotective factors in darkly pigmented skin such as larger and more numerous melanosomes that contain more melanin and are more dispersed throughout the epidermis result in a lower incidence of skin cancers in the skin of color (SOC) population.

RELATED ARTICLE: Common Dermatologic Disorders in Skin of Color: A Comparative Practice Survey

However, a recent skin cancer awareness study in Cutis reported that even though SOC populations have lower incidences of skin cancer such as melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma, they exhibit higher death rates. Furthermore, black individuals are more likely to present with advanced-stage melanoma and acral lentiginous melanomas compared to white individuals. Kailas et al stated, “Overall, SOC patients have the poorest skin cancer prognosis, and the data suggest that the reason for this paradox is delayed diagnosis.” They evaluated several knowledge-based interventions for increasing skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behaviors in SOC populations, including the use of visuals such as photographs to allow SOC patients to visualize different skin tones, educational interventions in another language, and pamphlets.

Dermatologists should be aware that education of SOC patients is important to eradicate the common misconception that these patients do not have to worry about AKs and other skin cancers. Remind these patients that they need to protect their skin from the sun, just as patients with fair skin do. Further research in the dermatology community should focus on educational interventions that will help increase knowledge regarding skin cancer in SOC populations.

Expert Commentary

Although more common in patients with lighter skin, actinic keratosis and skin cancer can be seen in patients of all skin types. Many patients are unaware of this risk and do not use sunscreen and other sun-protective measures. We, as a specialty, have to educate our patients and the public of the risk for actinic keratosis and skin cancer in all skin types.

—Gary Goldenberg, MD (New York, New York)

Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

American Academy of Dermatology. Actinic keratosis. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/actinic-keratosis. Accessed October 17, 2017.

Kailas A, Botwin AL, Pritchett EN, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of knowledge-based interventions in increasing skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behaviors in skin of color populations. Cutis. 2017;100:235-240.

Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

American Academy of Dermatology. Actinic keratosis. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/actinic-keratosis. Accessed October 17, 2017.

Kailas A, Botwin AL, Pritchett EN, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of knowledge-based interventions in increasing skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behaviors in skin of color populations. Cutis. 2017;100:235-240.

Debunking Acne Myths: Does Popping Pimples Resolve Acne Faster?

Myth: Popping pimples resolves acne faster

Acne patients may be compelled to squeeze or pop their pimples at home thinking it will clear their acne faster, but they should be advised that doing so without using the proper technique can actually make the condition worse.

When over-the-counter or prescription acne medications take too long to work, some patients may use their fingernails or even a physical instrument (eg, tweezers) to clear the contents of the pimple; however, this process often produces lesions that are inflamed and far more visible, slower to heal, and more likely to scar than lesions progressing through the natural disease course. According to the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), unwanted side effects of popping pimples can include permanent acne scars, more noticeable and/or painful acne lesions, and infection from bacteria on the hands.

The AAD promotes that dermatologists know how to remove bothersome acne lesions safely. Also, the AAD guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris reported that comedo removal may be helpful for lesions resistant to other therapies. Acne extraction may be offered when standard treatments fail and involves the use of sterile instruments to clear comedones and microcomedones. For single lesions that are particularly painful, dermatologists may opt to inject the lesion with a corticosteroid to reduce inflammation, speed healing, and decrease the risk of scarring; the strength of this recommendation is level C, according to the AAD acne guidelines work group. Finally, incision and drainage using a sterile needle or surgical blade can be used to open and clear the contents of large or painful pimples, nodules, and cysts.

These procedures are not first-line acne therapies. To minimize the appearance of acne lesions and promote clearance while waiting to see results from prescribed treatment regimens, patients should be advised to keep their hands away from their face and avoid picking at lesions, to apply ice to painful lesions to reduce inflammation and relieve pain, and to be patient with the acne treatment prescribed by a dermatologist. If patients are prone to picking their acne lesions, a more aggressive approach to treatment may be necessary, as a reduced number of inflammatory lesions leaves the patient with fewer spots to manipulate.

Pimple popping: why only a dermatologist should do it. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/pimple-popping-why-only-a-dermatologist-should-do-it. Accessed October 11, 2017.

Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.

Myth: Popping pimples resolves acne faster

Acne patients may be compelled to squeeze or pop their pimples at home thinking it will clear their acne faster, but they should be advised that doing so without using the proper technique can actually make the condition worse.

When over-the-counter or prescription acne medications take too long to work, some patients may use their fingernails or even a physical instrument (eg, tweezers) to clear the contents of the pimple; however, this process often produces lesions that are inflamed and far more visible, slower to heal, and more likely to scar than lesions progressing through the natural disease course. According to the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), unwanted side effects of popping pimples can include permanent acne scars, more noticeable and/or painful acne lesions, and infection from bacteria on the hands.

The AAD promotes that dermatologists know how to remove bothersome acne lesions safely. Also, the AAD guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris reported that comedo removal may be helpful for lesions resistant to other therapies. Acne extraction may be offered when standard treatments fail and involves the use of sterile instruments to clear comedones and microcomedones. For single lesions that are particularly painful, dermatologists may opt to inject the lesion with a corticosteroid to reduce inflammation, speed healing, and decrease the risk of scarring; the strength of this recommendation is level C, according to the AAD acne guidelines work group. Finally, incision and drainage using a sterile needle or surgical blade can be used to open and clear the contents of large or painful pimples, nodules, and cysts.

These procedures are not first-line acne therapies. To minimize the appearance of acne lesions and promote clearance while waiting to see results from prescribed treatment regimens, patients should be advised to keep their hands away from their face and avoid picking at lesions, to apply ice to painful lesions to reduce inflammation and relieve pain, and to be patient with the acne treatment prescribed by a dermatologist. If patients are prone to picking their acne lesions, a more aggressive approach to treatment may be necessary, as a reduced number of inflammatory lesions leaves the patient with fewer spots to manipulate.

Myth: Popping pimples resolves acne faster

Acne patients may be compelled to squeeze or pop their pimples at home thinking it will clear their acne faster, but they should be advised that doing so without using the proper technique can actually make the condition worse.

When over-the-counter or prescription acne medications take too long to work, some patients may use their fingernails or even a physical instrument (eg, tweezers) to clear the contents of the pimple; however, this process often produces lesions that are inflamed and far more visible, slower to heal, and more likely to scar than lesions progressing through the natural disease course. According to the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), unwanted side effects of popping pimples can include permanent acne scars, more noticeable and/or painful acne lesions, and infection from bacteria on the hands.

The AAD promotes that dermatologists know how to remove bothersome acne lesions safely. Also, the AAD guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris reported that comedo removal may be helpful for lesions resistant to other therapies. Acne extraction may be offered when standard treatments fail and involves the use of sterile instruments to clear comedones and microcomedones. For single lesions that are particularly painful, dermatologists may opt to inject the lesion with a corticosteroid to reduce inflammation, speed healing, and decrease the risk of scarring; the strength of this recommendation is level C, according to the AAD acne guidelines work group. Finally, incision and drainage using a sterile needle or surgical blade can be used to open and clear the contents of large or painful pimples, nodules, and cysts.

These procedures are not first-line acne therapies. To minimize the appearance of acne lesions and promote clearance while waiting to see results from prescribed treatment regimens, patients should be advised to keep their hands away from their face and avoid picking at lesions, to apply ice to painful lesions to reduce inflammation and relieve pain, and to be patient with the acne treatment prescribed by a dermatologist. If patients are prone to picking their acne lesions, a more aggressive approach to treatment may be necessary, as a reduced number of inflammatory lesions leaves the patient with fewer spots to manipulate.

Pimple popping: why only a dermatologist should do it. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/pimple-popping-why-only-a-dermatologist-should-do-it. Accessed October 11, 2017.

Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.

Pimple popping: why only a dermatologist should do it. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/pimple-popping-why-only-a-dermatologist-should-do-it. Accessed October 11, 2017.

Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.

Painless Telangiectatic Lesion on the Wrist

The Diagnosis: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

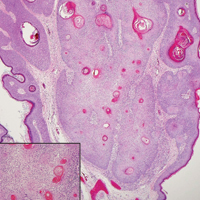

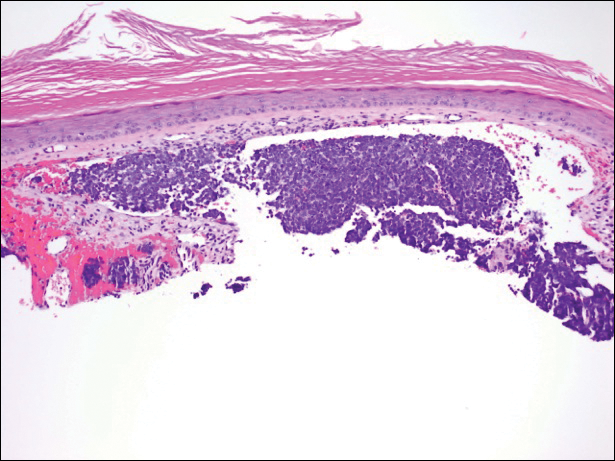

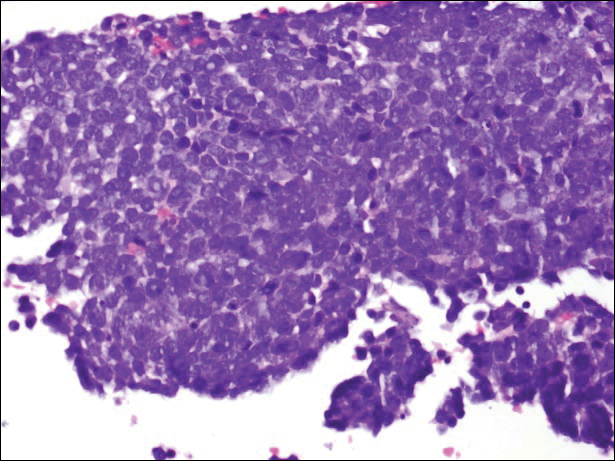

A partial biopsy was performed during the dermatology examination. Histopathology demonstrated a dense dermal infiltrate of small, dark blue, pleomorphic cells (Figure 1). On high power, the individual cells were noted to have vesicular nuclei with finely granular and dusty chromatin (Figure 2). Numerous mitotic figures were present. Immunohistochemical stains were performed and revealed positive staining for cytokeratin 20 (with a perinuclear dot pattern), synaptophysin, and chromogranin.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an uncommon carcinoma of the epidermal neuroendocrine cells with approximately 1500 cases a year in the United States.1 Merkel cell carcinoma has a poor prognosis with approximately one-third of cases resulting in death within 5 years and with a survival rate strongly dependent on the stage of disease at presentation.2 A complete surgical excision with histologically verified clear margins is the main form of treatment of the primary cancer.3 Although the effectiveness of adjuvant therapy for MCC has been debated,4 retrospective analysis has shown that the high local recurrence rate of the primary tumor can be reduced by combining surgical excision with a form of radiation therapy.5

A systematic cohort study of 195 patients diagnosed with MCC summarized its most clinical factors with the acronym AEIOU: asymptomatic, expanding rapidly, immunosuppression, older than 50 years of age, and UV-exposed site on a fair-skinned individual.6 The role of immune function in MCC was highlighted by a 16-fold overrepresentation of immunosuppressed patients in the studied cohort as compared to the general US population. The immunosuppressed patients included individuals with human immunodeficiency virus, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and iatrogenic suppression secondary to solid organ transplantation.6

In 2008, Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) was found in 80% (8/10) of MCC tumors tested.7 Since then, many different studies have suggested that MCPyV is an etiologic agent of MCC.8-10 A natural component of skin flora, MCPyV only becomes tumorigenic after integration into the host DNA and with mutations to the viral genome.11 Although there currently is no difference in treatment of MCPyV-positive and MCPyV-negative MCC,12 research is being done to determine how the discovery of the MCPyV could impact the treatment of MCC.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:20-27.

- Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309.

- Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al. A comprehensive review of the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2007;30:624-636.

- Beenken SW, Urist MM. Treatment options for Merkel cell carcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2004;2:89-92.

- Decker RH, Wilson LD. Role of radiotherapy in the management of Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006;4:713-718.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the "AEIOU" features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, et al. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096-1100.

- Duncavage EJ, Zehnbauer BA, Pfeifer JD. Prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:516-521.

- Sastre-Garau X, Peter M, Avril MF, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: pathological and molecular evidence for a causative role of MCV in oncogenesis. J Pathol. 2009;218:48-56.

- Varga E, Kiss M, Szabó K, et al. Detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA in Merkel cell carcinomas. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:930-932.

- Wendzicki JA, Moore PS, Chang Y. Large T and small T antigens of Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Virol. 2015;11:38-43.

- Duprat JP, Landman G, Salvajoli JV, et al. A review of the epidemiology and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66:1817-1823.

The Diagnosis: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

A partial biopsy was performed during the dermatology examination. Histopathology demonstrated a dense dermal infiltrate of small, dark blue, pleomorphic cells (Figure 1). On high power, the individual cells were noted to have vesicular nuclei with finely granular and dusty chromatin (Figure 2). Numerous mitotic figures were present. Immunohistochemical stains were performed and revealed positive staining for cytokeratin 20 (with a perinuclear dot pattern), synaptophysin, and chromogranin.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an uncommon carcinoma of the epidermal neuroendocrine cells with approximately 1500 cases a year in the United States.1 Merkel cell carcinoma has a poor prognosis with approximately one-third of cases resulting in death within 5 years and with a survival rate strongly dependent on the stage of disease at presentation.2 A complete surgical excision with histologically verified clear margins is the main form of treatment of the primary cancer.3 Although the effectiveness of adjuvant therapy for MCC has been debated,4 retrospective analysis has shown that the high local recurrence rate of the primary tumor can be reduced by combining surgical excision with a form of radiation therapy.5

A systematic cohort study of 195 patients diagnosed with MCC summarized its most clinical factors with the acronym AEIOU: asymptomatic, expanding rapidly, immunosuppression, older than 50 years of age, and UV-exposed site on a fair-skinned individual.6 The role of immune function in MCC was highlighted by a 16-fold overrepresentation of immunosuppressed patients in the studied cohort as compared to the general US population. The immunosuppressed patients included individuals with human immunodeficiency virus, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and iatrogenic suppression secondary to solid organ transplantation.6

In 2008, Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) was found in 80% (8/10) of MCC tumors tested.7 Since then, many different studies have suggested that MCPyV is an etiologic agent of MCC.8-10 A natural component of skin flora, MCPyV only becomes tumorigenic after integration into the host DNA and with mutations to the viral genome.11 Although there currently is no difference in treatment of MCPyV-positive and MCPyV-negative MCC,12 research is being done to determine how the discovery of the MCPyV could impact the treatment of MCC.

The Diagnosis: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

A partial biopsy was performed during the dermatology examination. Histopathology demonstrated a dense dermal infiltrate of small, dark blue, pleomorphic cells (Figure 1). On high power, the individual cells were noted to have vesicular nuclei with finely granular and dusty chromatin (Figure 2). Numerous mitotic figures were present. Immunohistochemical stains were performed and revealed positive staining for cytokeratin 20 (with a perinuclear dot pattern), synaptophysin, and chromogranin.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an uncommon carcinoma of the epidermal neuroendocrine cells with approximately 1500 cases a year in the United States.1 Merkel cell carcinoma has a poor prognosis with approximately one-third of cases resulting in death within 5 years and with a survival rate strongly dependent on the stage of disease at presentation.2 A complete surgical excision with histologically verified clear margins is the main form of treatment of the primary cancer.3 Although the effectiveness of adjuvant therapy for MCC has been debated,4 retrospective analysis has shown that the high local recurrence rate of the primary tumor can be reduced by combining surgical excision with a form of radiation therapy.5