User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Cyanosis of the Foot

The Diagnosis: Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome

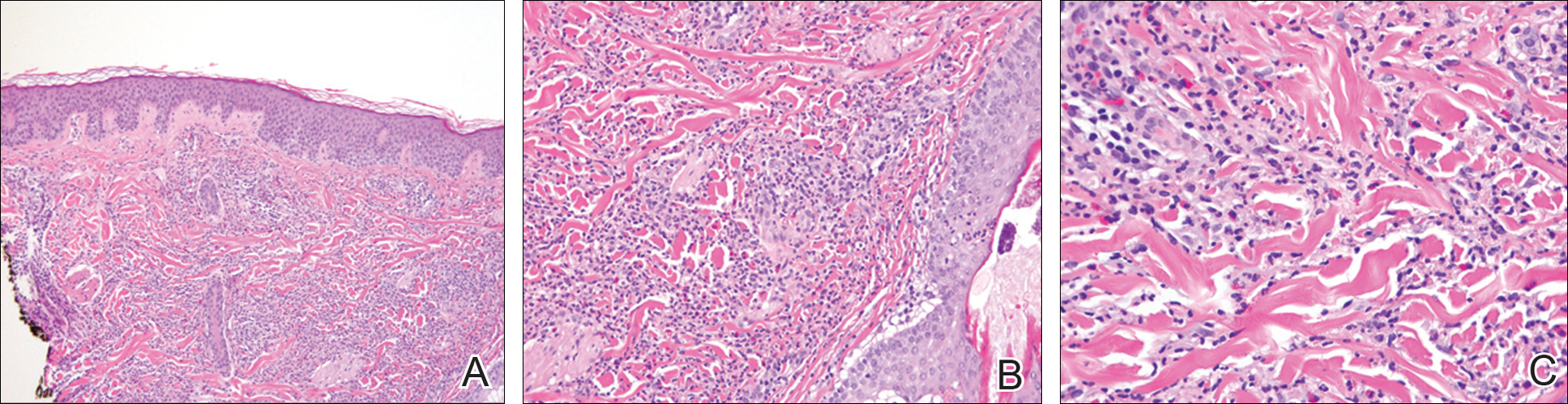

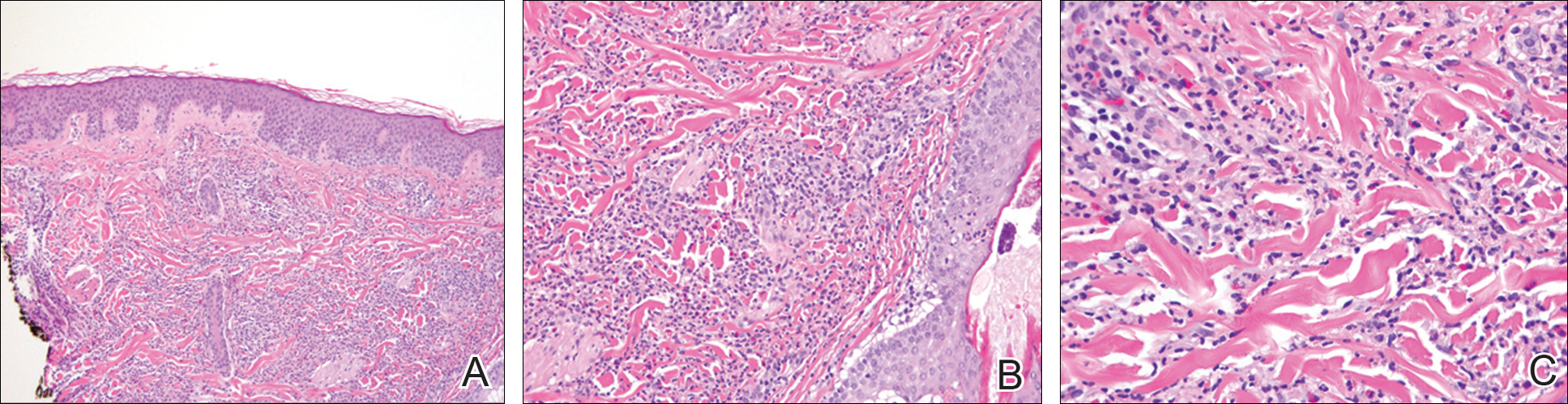

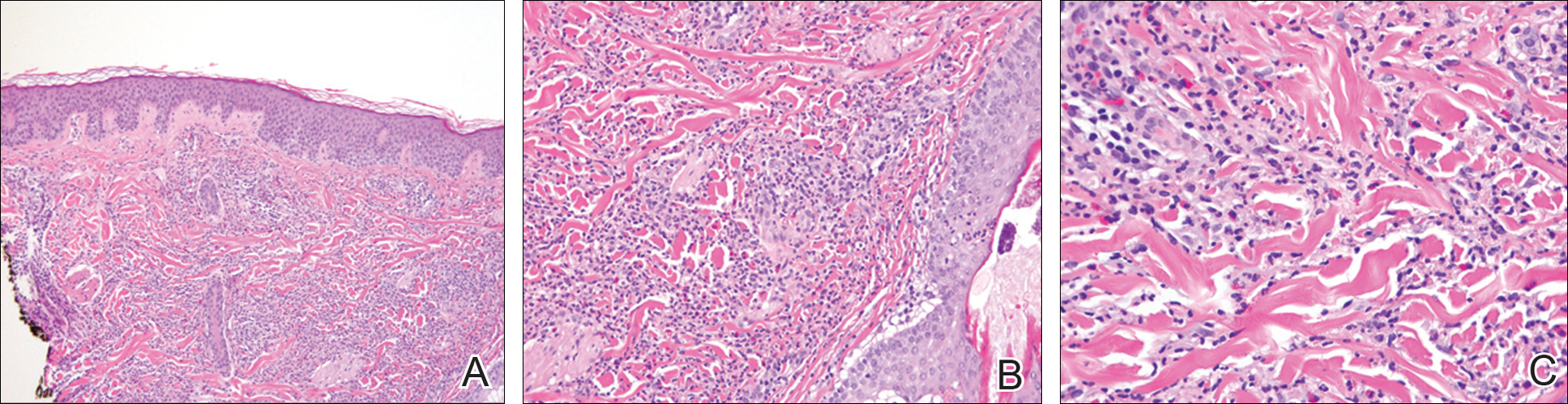

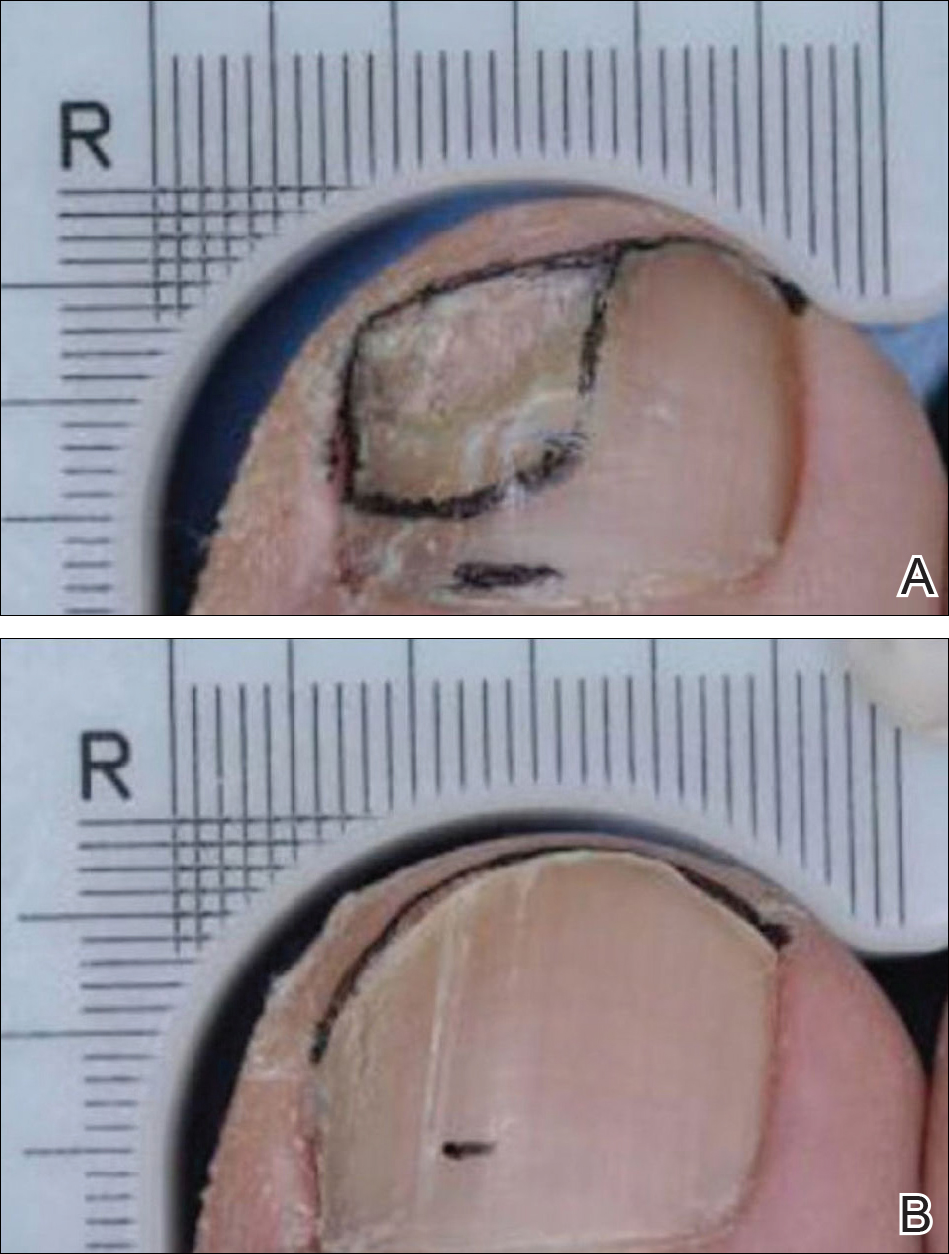

A biopsy demonstrated scattered intravascular thrombi in the dermis and subcutis, intact vascular walls, and scant lymphocytic inflammation in a background of stasis (Figure 1). A periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungal elements and highlighted the intravascular thrombi. Histologic findings were consistent with thrombotic vasculopathy. On further laboratory workup, lupus anticoagulant studies, including a mixing study, diluted Russell viper venom test, and hexagonal phase phospholipid neutralization test, were abnormal. Titers of anticardiolipin and β2-glycoprotein I antibodies were elevated (anticardiolipin IgG, 137.7 calculated units [normal, <15 calculated units]; β2-glycoprotein I IgG, 256.4 calculated units [normal, <20 calculated units]). Tissue cultures showed no growth of microorganisms and studies for cryoglobulinemia were negative.

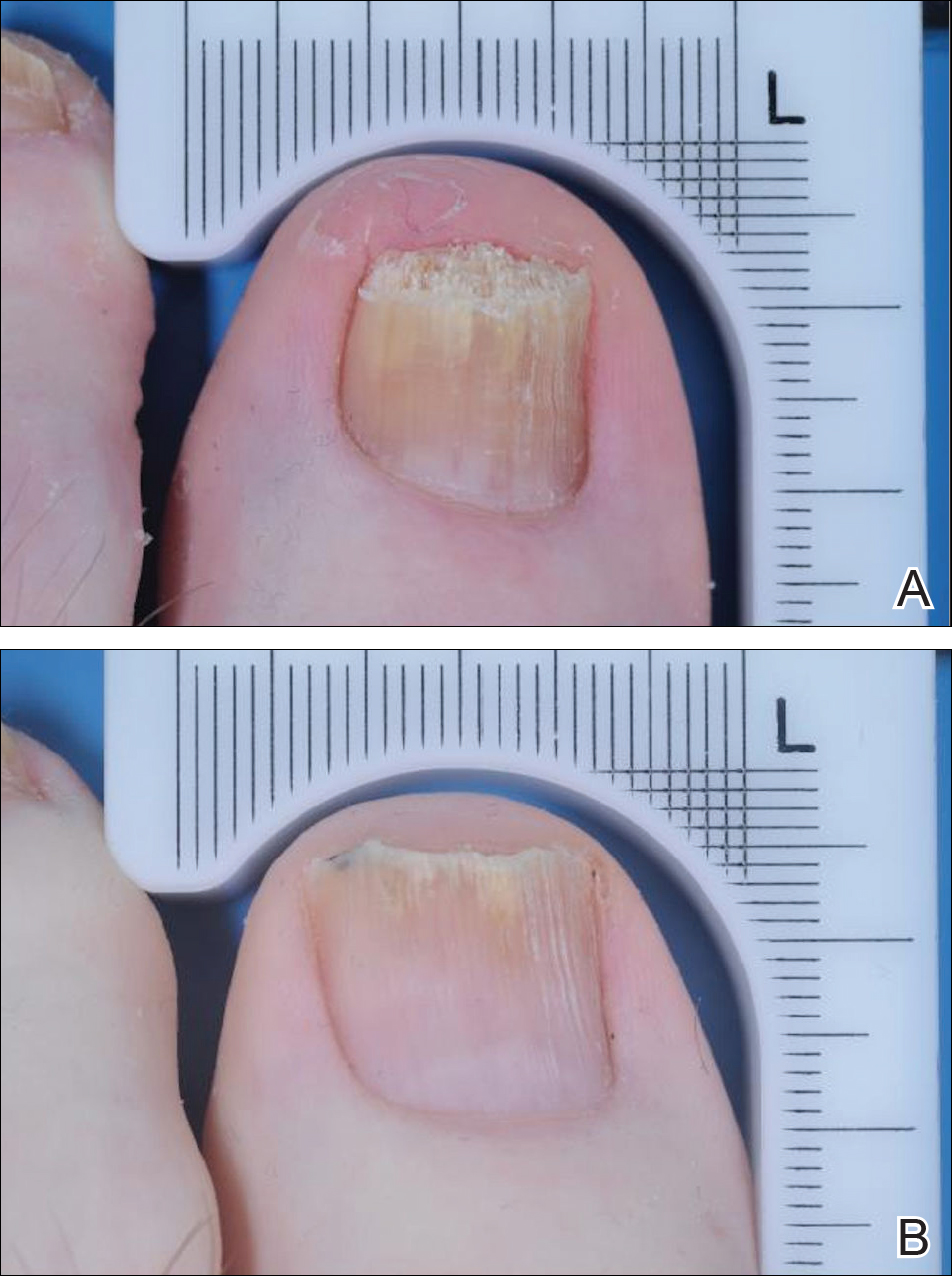

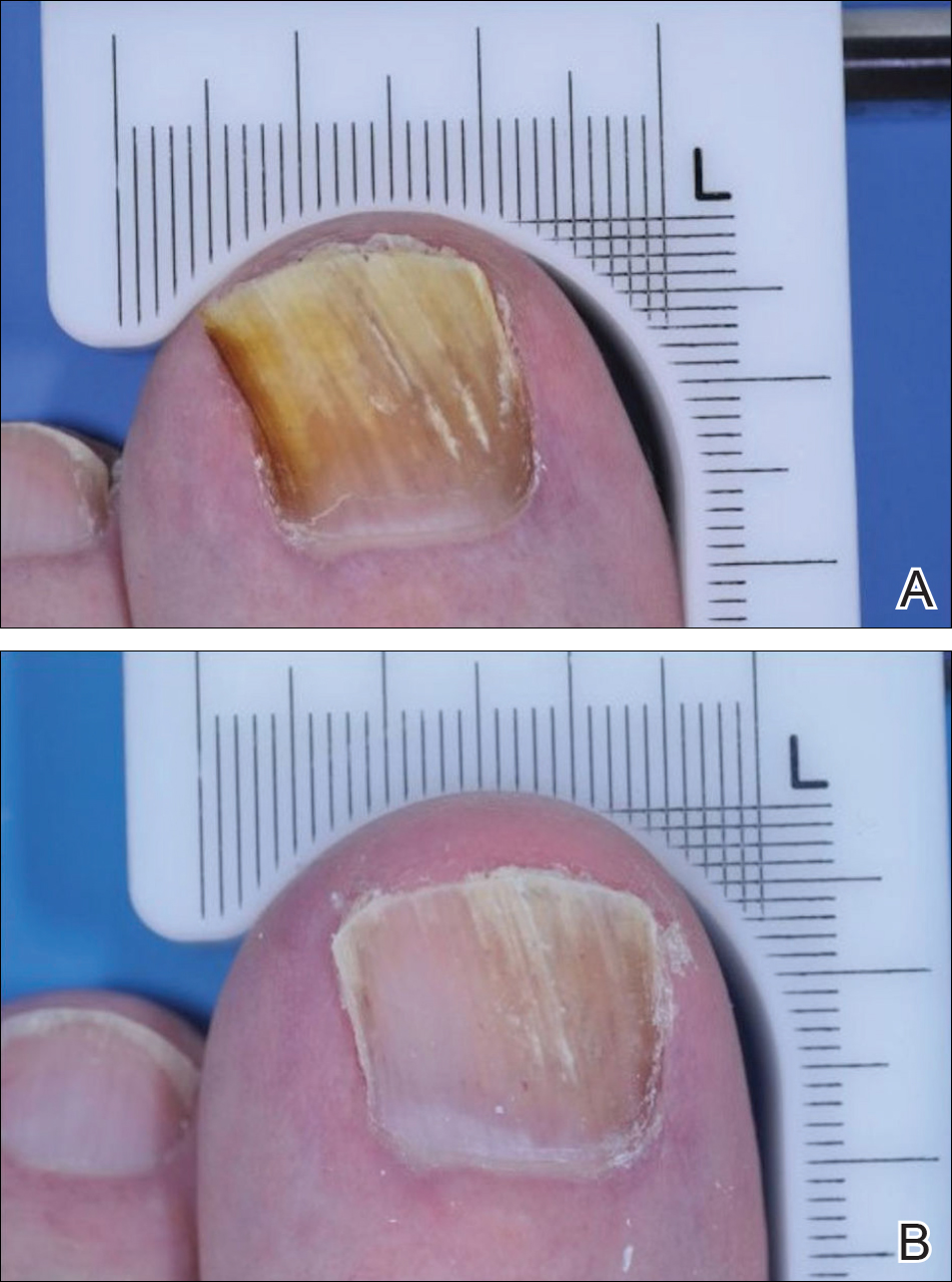

The patient was diagnosed with primary antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). He remained on anticoagulation therapy with fondaparinux as an inpatient and was treated with pulse-dose intravenous (IV) corticosteroids followed by a slow oral taper, daily plasmapheresis for 1 week, IV immunoglobulin (0.5 g/kg) for 3 doses, and 4 weekly doses of rituximab (375 mg/m2). His cutaneous findings slowly improved over the next several weeks (Figure 2).

Antiphospholipid syndrome is an autoimmune disorder characterized by thrombotic events and the presence of autoantibodies. The syndrome is defined by 2 major criteria: (1) the occurrence of at least 1 clinical feature of either an episode of vascular thrombosis or pregnancy morbidity such as unexplained fetal death beyond 10 weeks of gestation or recurrent unexplained pregnancy losses; and (2) the presence of at least 1 type of autoantibody, including lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, or β2-glycoprotein antibodies, on 2 separate occasions at least 12 weeks apart.1 Antiphospholipid syndrome can either be primary with no identifiable associated rheumatologic disease or secondary to another autoimmune disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus. Cutaneous manifestations are common and frequently are the first sign of disease in 30% to 40% of patients.2 The most common skin finding is persistent livedo reticularis, which can be seen in 20% to 25% of patients. Patients also may develop skin necrosis, ulcerations, digital gangrene, splinter hemorrhages, and livedoid vasculopathy.2 Systemic manifestations of APS include thrombocytopenia, nephropathy, cognitive dysfunction, and cardiac valve abnormalities.

The exact pathogenesis of APS remains unknown. It is thought to be due to the combination of an inflammatory stimulus that has yet to be characterized in conjunction with autoantibodies that affect multiple target cells including monocytes, platelets, and endothelial cells, which results in activation of the complement system and clotting cascade.3 In rare cases, the disorder can progress to catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS), which requires fulfillment of 4 criteria: (1) evidence of involvement of 3 organs, tissues, or systems; (2) development of manifestations simultaneously or in less than 1 week; (3) laboratory confirmation of the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies; and (4) confirmation by histopathology of small vessel occlusion.4 Probable CAPS is diagnosed when 3 of 4 criteria are present. Our patient met criteria for probable CAPS, as his antibody titers remained elevated 15 weeks after initial presentation. Precipitating factors that can lead to CAPS are thought to include infection, surgical procedures, medications, or discontinuation of anticoagulation drugs.2 Although the mainstay of management of APS is anticoagulation therapy with warfarin and antiplatelet agents such as aspirin, first-line treatment of CAPS involves high-dose systemic glucocorticoids and plasma exchange. Intravenous immunoglobulin also may be employed in treatment. Data from the CAPS registry demonstrate a role for rituximab, an anti-CD20 antibody, at 375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 weeks (the regimen described in our case) or 1 g every 14 days for 2 sessions.5 A majority of the registry patients treated with rituximab recovered (75% [15/20]) and had no recurrent thrombosis (87% [13/15]) at follow-up.5 Data also are emerging on the role of eculizumab, an anti-C5 antibody that inhibits the terminal complement cascade, as a therapy in difficult-to-treat or refractory CAPS.6-8 The prognosis for CAPS patients without treatment is poor, and mortality has been reported in up to 44% of patients. However, with intervention mortality is reduced by more than 2-fold.9,10

It is important to recognize that acral cyanosis with persistent livedo reticularis and digital gangrene can be a presenting manifestation of APS. These cutaneous manifestations should prompt histologic evaluation for thrombotic vasculopathy in addition to serologic tests for APS autoantibodies. Although APS may be treated with anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents, CAPS may require more aggressive therapy with systemic steroids, plasma exchange, IV immunoglobulin, rituximab, and/or eculizumab.

- Wilson WA, Gharavi AE, Koike T, et al. International consensus statement on preliminary classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome: report of an international workshop. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1309-1311.

- Pinto-Almeida T, Caetano M, Sanches M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome: a review of the clinical features, diagnosis and management. Acta Reumatol Port. 2013;38:10-18.

- Meroni PL, Chighizola CB, Rovelli F, et al. Antiphospholipid syndrome in 2014: more clinical manifestations, novel pathogenic players and emerging biomarkers. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:209.

- Asherson RA, Cervera R, de Grott PG, et al; Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome Registry Project Group. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines. Lupus. 2003;12:530-534.

- Berman H, Rodríguez-Pintó I, Cervera R, et al. Rituximab use in the catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: descriptive analysis of the CAPS registry patients receiving rituximab [published online June 15, 2013]. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:1085-1090.

- Shapira I, Andrade D, Allen SL, et al. Brief report: induction of sustained remission in recurrent catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome via inhibition of terminal complement with eculizumab. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2719-2723.

- Strakhan M, Hurtado-Sbordoni M, Galeas N, et al. 36-year-old female with catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome treated with eculizumab: a case report and review of literature. Case Rep Hematol. 2014;2014:704371.

- Lonze BE, Zachary AA, Magro CM, et al. Eculizumab prevents recurrent antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and enables successful renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:459-465.

- Bucciarelli S, Espinosa G, Cervera R, et al. Mortality in the catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: causes of death and prognostic factors in a series of 250 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2568-2576.

- Asherson RA, Cervera R, Piette JC, et al. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. clinical and laboratory features of 50 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1998;77:195-207.

The Diagnosis: Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome

A biopsy demonstrated scattered intravascular thrombi in the dermis and subcutis, intact vascular walls, and scant lymphocytic inflammation in a background of stasis (Figure 1). A periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungal elements and highlighted the intravascular thrombi. Histologic findings were consistent with thrombotic vasculopathy. On further laboratory workup, lupus anticoagulant studies, including a mixing study, diluted Russell viper venom test, and hexagonal phase phospholipid neutralization test, were abnormal. Titers of anticardiolipin and β2-glycoprotein I antibodies were elevated (anticardiolipin IgG, 137.7 calculated units [normal, <15 calculated units]; β2-glycoprotein I IgG, 256.4 calculated units [normal, <20 calculated units]). Tissue cultures showed no growth of microorganisms and studies for cryoglobulinemia were negative.

The patient was diagnosed with primary antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). He remained on anticoagulation therapy with fondaparinux as an inpatient and was treated with pulse-dose intravenous (IV) corticosteroids followed by a slow oral taper, daily plasmapheresis for 1 week, IV immunoglobulin (0.5 g/kg) for 3 doses, and 4 weekly doses of rituximab (375 mg/m2). His cutaneous findings slowly improved over the next several weeks (Figure 2).

Antiphospholipid syndrome is an autoimmune disorder characterized by thrombotic events and the presence of autoantibodies. The syndrome is defined by 2 major criteria: (1) the occurrence of at least 1 clinical feature of either an episode of vascular thrombosis or pregnancy morbidity such as unexplained fetal death beyond 10 weeks of gestation or recurrent unexplained pregnancy losses; and (2) the presence of at least 1 type of autoantibody, including lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, or β2-glycoprotein antibodies, on 2 separate occasions at least 12 weeks apart.1 Antiphospholipid syndrome can either be primary with no identifiable associated rheumatologic disease or secondary to another autoimmune disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus. Cutaneous manifestations are common and frequently are the first sign of disease in 30% to 40% of patients.2 The most common skin finding is persistent livedo reticularis, which can be seen in 20% to 25% of patients. Patients also may develop skin necrosis, ulcerations, digital gangrene, splinter hemorrhages, and livedoid vasculopathy.2 Systemic manifestations of APS include thrombocytopenia, nephropathy, cognitive dysfunction, and cardiac valve abnormalities.

The exact pathogenesis of APS remains unknown. It is thought to be due to the combination of an inflammatory stimulus that has yet to be characterized in conjunction with autoantibodies that affect multiple target cells including monocytes, platelets, and endothelial cells, which results in activation of the complement system and clotting cascade.3 In rare cases, the disorder can progress to catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS), which requires fulfillment of 4 criteria: (1) evidence of involvement of 3 organs, tissues, or systems; (2) development of manifestations simultaneously or in less than 1 week; (3) laboratory confirmation of the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies; and (4) confirmation by histopathology of small vessel occlusion.4 Probable CAPS is diagnosed when 3 of 4 criteria are present. Our patient met criteria for probable CAPS, as his antibody titers remained elevated 15 weeks after initial presentation. Precipitating factors that can lead to CAPS are thought to include infection, surgical procedures, medications, or discontinuation of anticoagulation drugs.2 Although the mainstay of management of APS is anticoagulation therapy with warfarin and antiplatelet agents such as aspirin, first-line treatment of CAPS involves high-dose systemic glucocorticoids and plasma exchange. Intravenous immunoglobulin also may be employed in treatment. Data from the CAPS registry demonstrate a role for rituximab, an anti-CD20 antibody, at 375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 weeks (the regimen described in our case) or 1 g every 14 days for 2 sessions.5 A majority of the registry patients treated with rituximab recovered (75% [15/20]) and had no recurrent thrombosis (87% [13/15]) at follow-up.5 Data also are emerging on the role of eculizumab, an anti-C5 antibody that inhibits the terminal complement cascade, as a therapy in difficult-to-treat or refractory CAPS.6-8 The prognosis for CAPS patients without treatment is poor, and mortality has been reported in up to 44% of patients. However, with intervention mortality is reduced by more than 2-fold.9,10

It is important to recognize that acral cyanosis with persistent livedo reticularis and digital gangrene can be a presenting manifestation of APS. These cutaneous manifestations should prompt histologic evaluation for thrombotic vasculopathy in addition to serologic tests for APS autoantibodies. Although APS may be treated with anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents, CAPS may require more aggressive therapy with systemic steroids, plasma exchange, IV immunoglobulin, rituximab, and/or eculizumab.

The Diagnosis: Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome

A biopsy demonstrated scattered intravascular thrombi in the dermis and subcutis, intact vascular walls, and scant lymphocytic inflammation in a background of stasis (Figure 1). A periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungal elements and highlighted the intravascular thrombi. Histologic findings were consistent with thrombotic vasculopathy. On further laboratory workup, lupus anticoagulant studies, including a mixing study, diluted Russell viper venom test, and hexagonal phase phospholipid neutralization test, were abnormal. Titers of anticardiolipin and β2-glycoprotein I antibodies were elevated (anticardiolipin IgG, 137.7 calculated units [normal, <15 calculated units]; β2-glycoprotein I IgG, 256.4 calculated units [normal, <20 calculated units]). Tissue cultures showed no growth of microorganisms and studies for cryoglobulinemia were negative.

The patient was diagnosed with primary antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). He remained on anticoagulation therapy with fondaparinux as an inpatient and was treated with pulse-dose intravenous (IV) corticosteroids followed by a slow oral taper, daily plasmapheresis for 1 week, IV immunoglobulin (0.5 g/kg) for 3 doses, and 4 weekly doses of rituximab (375 mg/m2). His cutaneous findings slowly improved over the next several weeks (Figure 2).

Antiphospholipid syndrome is an autoimmune disorder characterized by thrombotic events and the presence of autoantibodies. The syndrome is defined by 2 major criteria: (1) the occurrence of at least 1 clinical feature of either an episode of vascular thrombosis or pregnancy morbidity such as unexplained fetal death beyond 10 weeks of gestation or recurrent unexplained pregnancy losses; and (2) the presence of at least 1 type of autoantibody, including lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, or β2-glycoprotein antibodies, on 2 separate occasions at least 12 weeks apart.1 Antiphospholipid syndrome can either be primary with no identifiable associated rheumatologic disease or secondary to another autoimmune disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus. Cutaneous manifestations are common and frequently are the first sign of disease in 30% to 40% of patients.2 The most common skin finding is persistent livedo reticularis, which can be seen in 20% to 25% of patients. Patients also may develop skin necrosis, ulcerations, digital gangrene, splinter hemorrhages, and livedoid vasculopathy.2 Systemic manifestations of APS include thrombocytopenia, nephropathy, cognitive dysfunction, and cardiac valve abnormalities.

The exact pathogenesis of APS remains unknown. It is thought to be due to the combination of an inflammatory stimulus that has yet to be characterized in conjunction with autoantibodies that affect multiple target cells including monocytes, platelets, and endothelial cells, which results in activation of the complement system and clotting cascade.3 In rare cases, the disorder can progress to catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS), which requires fulfillment of 4 criteria: (1) evidence of involvement of 3 organs, tissues, or systems; (2) development of manifestations simultaneously or in less than 1 week; (3) laboratory confirmation of the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies; and (4) confirmation by histopathology of small vessel occlusion.4 Probable CAPS is diagnosed when 3 of 4 criteria are present. Our patient met criteria for probable CAPS, as his antibody titers remained elevated 15 weeks after initial presentation. Precipitating factors that can lead to CAPS are thought to include infection, surgical procedures, medications, or discontinuation of anticoagulation drugs.2 Although the mainstay of management of APS is anticoagulation therapy with warfarin and antiplatelet agents such as aspirin, first-line treatment of CAPS involves high-dose systemic glucocorticoids and plasma exchange. Intravenous immunoglobulin also may be employed in treatment. Data from the CAPS registry demonstrate a role for rituximab, an anti-CD20 antibody, at 375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 weeks (the regimen described in our case) or 1 g every 14 days for 2 sessions.5 A majority of the registry patients treated with rituximab recovered (75% [15/20]) and had no recurrent thrombosis (87% [13/15]) at follow-up.5 Data also are emerging on the role of eculizumab, an anti-C5 antibody that inhibits the terminal complement cascade, as a therapy in difficult-to-treat or refractory CAPS.6-8 The prognosis for CAPS patients without treatment is poor, and mortality has been reported in up to 44% of patients. However, with intervention mortality is reduced by more than 2-fold.9,10

It is important to recognize that acral cyanosis with persistent livedo reticularis and digital gangrene can be a presenting manifestation of APS. These cutaneous manifestations should prompt histologic evaluation for thrombotic vasculopathy in addition to serologic tests for APS autoantibodies. Although APS may be treated with anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents, CAPS may require more aggressive therapy with systemic steroids, plasma exchange, IV immunoglobulin, rituximab, and/or eculizumab.

- Wilson WA, Gharavi AE, Koike T, et al. International consensus statement on preliminary classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome: report of an international workshop. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1309-1311.

- Pinto-Almeida T, Caetano M, Sanches M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome: a review of the clinical features, diagnosis and management. Acta Reumatol Port. 2013;38:10-18.

- Meroni PL, Chighizola CB, Rovelli F, et al. Antiphospholipid syndrome in 2014: more clinical manifestations, novel pathogenic players and emerging biomarkers. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:209.

- Asherson RA, Cervera R, de Grott PG, et al; Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome Registry Project Group. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines. Lupus. 2003;12:530-534.

- Berman H, Rodríguez-Pintó I, Cervera R, et al. Rituximab use in the catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: descriptive analysis of the CAPS registry patients receiving rituximab [published online June 15, 2013]. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:1085-1090.

- Shapira I, Andrade D, Allen SL, et al. Brief report: induction of sustained remission in recurrent catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome via inhibition of terminal complement with eculizumab. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2719-2723.

- Strakhan M, Hurtado-Sbordoni M, Galeas N, et al. 36-year-old female with catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome treated with eculizumab: a case report and review of literature. Case Rep Hematol. 2014;2014:704371.

- Lonze BE, Zachary AA, Magro CM, et al. Eculizumab prevents recurrent antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and enables successful renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:459-465.

- Bucciarelli S, Espinosa G, Cervera R, et al. Mortality in the catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: causes of death and prognostic factors in a series of 250 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2568-2576.

- Asherson RA, Cervera R, Piette JC, et al. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. clinical and laboratory features of 50 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1998;77:195-207.

- Wilson WA, Gharavi AE, Koike T, et al. International consensus statement on preliminary classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome: report of an international workshop. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1309-1311.

- Pinto-Almeida T, Caetano M, Sanches M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome: a review of the clinical features, diagnosis and management. Acta Reumatol Port. 2013;38:10-18.

- Meroni PL, Chighizola CB, Rovelli F, et al. Antiphospholipid syndrome in 2014: more clinical manifestations, novel pathogenic players and emerging biomarkers. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:209.

- Asherson RA, Cervera R, de Grott PG, et al; Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome Registry Project Group. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines. Lupus. 2003;12:530-534.

- Berman H, Rodríguez-Pintó I, Cervera R, et al. Rituximab use in the catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: descriptive analysis of the CAPS registry patients receiving rituximab [published online June 15, 2013]. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:1085-1090.

- Shapira I, Andrade D, Allen SL, et al. Brief report: induction of sustained remission in recurrent catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome via inhibition of terminal complement with eculizumab. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2719-2723.

- Strakhan M, Hurtado-Sbordoni M, Galeas N, et al. 36-year-old female with catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome treated with eculizumab: a case report and review of literature. Case Rep Hematol. 2014;2014:704371.

- Lonze BE, Zachary AA, Magro CM, et al. Eculizumab prevents recurrent antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and enables successful renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:459-465.

- Bucciarelli S, Espinosa G, Cervera R, et al. Mortality in the catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: causes of death and prognostic factors in a series of 250 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2568-2576.

- Asherson RA, Cervera R, Piette JC, et al. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. clinical and laboratory features of 50 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1998;77:195-207.

A man in his 50s with a medical history of arterial thrombosis of the right arm, multiple deep vein thromboses (DVTs) of the legs on long-term warfarin, ischemic stroke, atrial fibrillation, and peripheral arterial disease presented with discoloration of the right foot and increasing tenderness of 1 month's duration. There was no history of trauma or recent change in outpatient medications. A family history was notable for an aunt and 2 cousins with DVTs and protein S deficiency. Physical examination revealed livedo reticularis on the sole and lateral aspect of the right foot. There was violaceous discoloration of the volar aspects of all 5 toes and a focal area of ulceration on the fifth toe. Pulses were palpable bilaterally. Initial laboratory evaluation was notable for thrombocytopenia, and preliminary blood cultures revealed no growth of bacterial or fungal organisms. Imaging studies revealed increased arterial stenosis of the right leg as well as DVT of the right great saphenous vein. A punch biopsy of the right medial foot was performed for hematoxylin and eosin stain as well as tissue culture.

Assessing the Effectiveness of Knowledge-Based Interventions in Increasing Skin Cancer Awareness, Knowledge, and Protective Behaviors in Skin of Color Populations

Malignant melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma account for approximately 40% of all neoplasms among the white population in the United States. Skin cancer is the most common malignancy in the United States.1 However, despite this occurrence, there are limited data regarding skin cancer in individuals with skin of color (SOC). The 5-year survival rates for melanoma are 58.2% for black individuals, 69.7% for Hispanics, and 70.9% for Asians compared to 79.8% for white individuals in the United States.2 Even though SOC populations have lower incidences of skin cancer—melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma—they exhibit higher death rates.3-7 Nonetheless, no specific guidelines exist to address sun exposure and safety habits in SOC populations.6,8 Furthermore, current demographics suggest that by the year 2050, approximately half of the US population will be nonwhite.4 Paradoxically, despite having increased sun protection from greater amounts of melanin in their skin, black individuals are more likely to present with advanced-stage melanoma (eg, stage III/IV) compared to white individuals.8-12 Furthermore, those of nonwhite populations are more likely to present with more advanced stages of acral lentiginous melanomas than white individuals.13,14 Hispanics also face an increasing incidence of more invasive acral lentiginous melanomas.15 Overall, SOC patients have the poorest skin cancer prognosis, and the data suggest that the reason for this paradox is delayed diagnosis.1

Although skin cancer is largely a preventable condition, the literature suggests that lack of awareness of melanoma among ethnic minorities is one of the main reasons for their poor skin cancer prognosis.16 This lack of awareness decreases the likelihood that an SOC patient would be alert to early detection of cancerous changes.17 Because educating at-risk SOC populations is key to decreasing skin cancer risk, this study focused on determining the efficacy of major knowledge-based interventions conducted to date.1 Overall, we sought to answer the question, do knowledge-based interventions increase skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behavior among people of color?

Methods

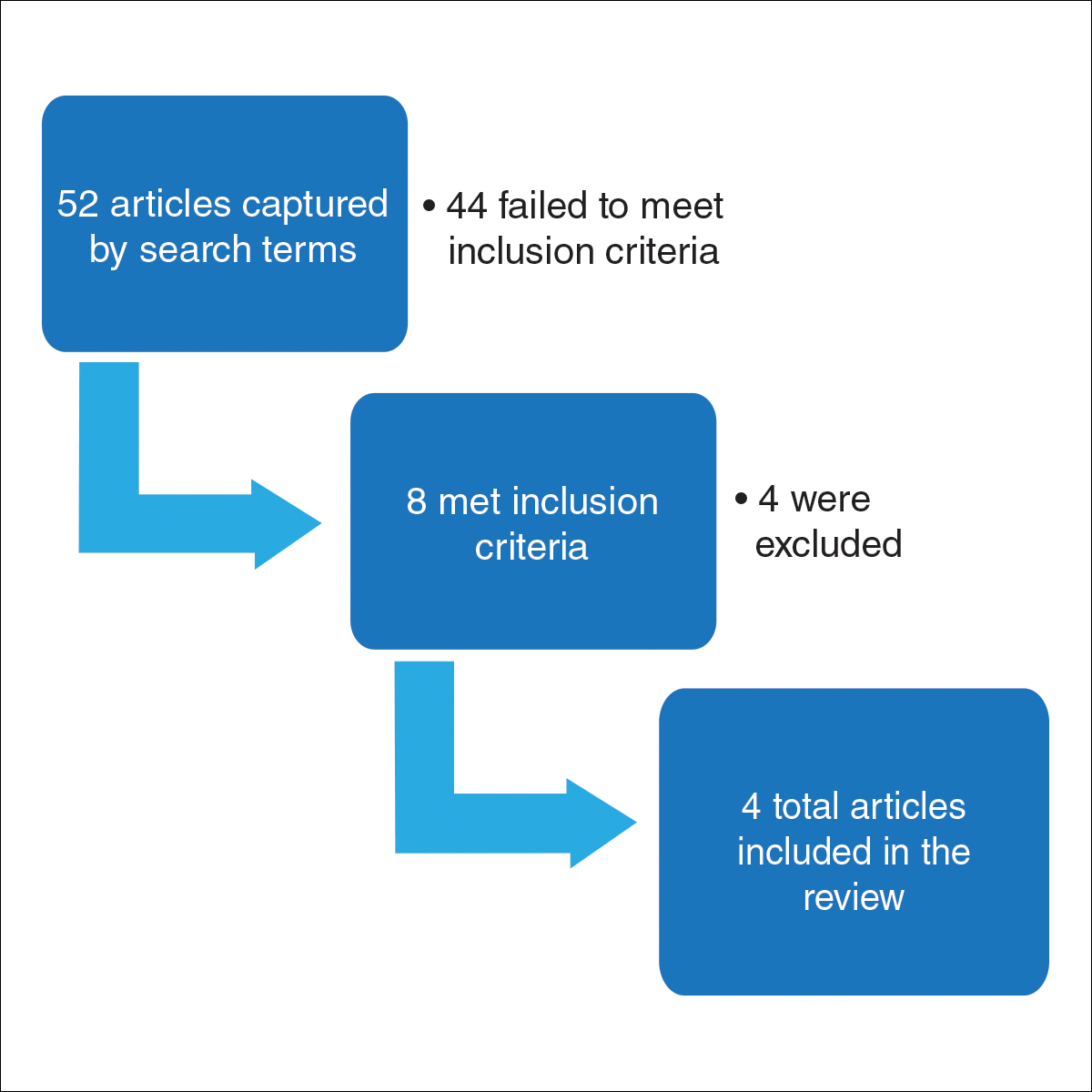

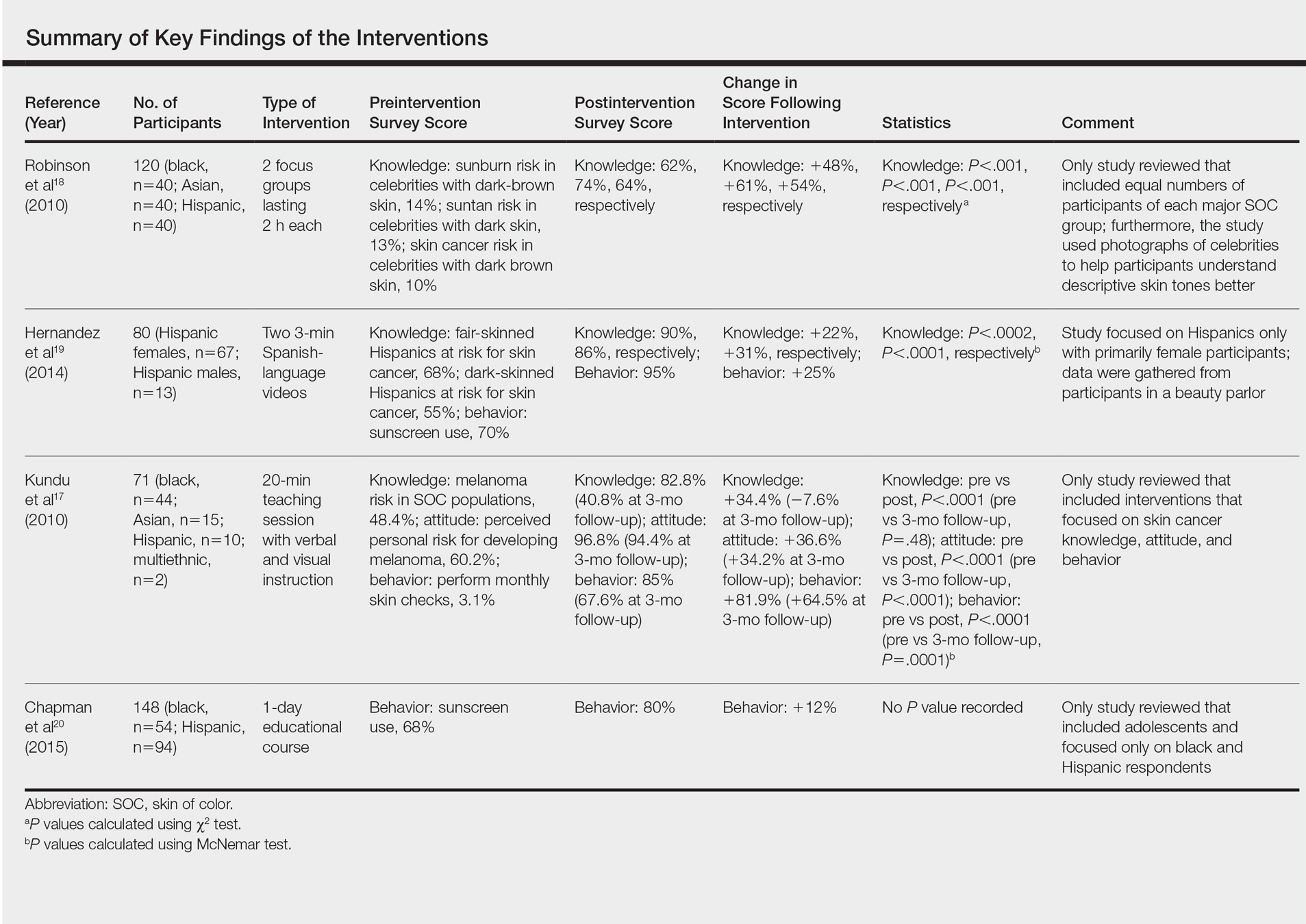

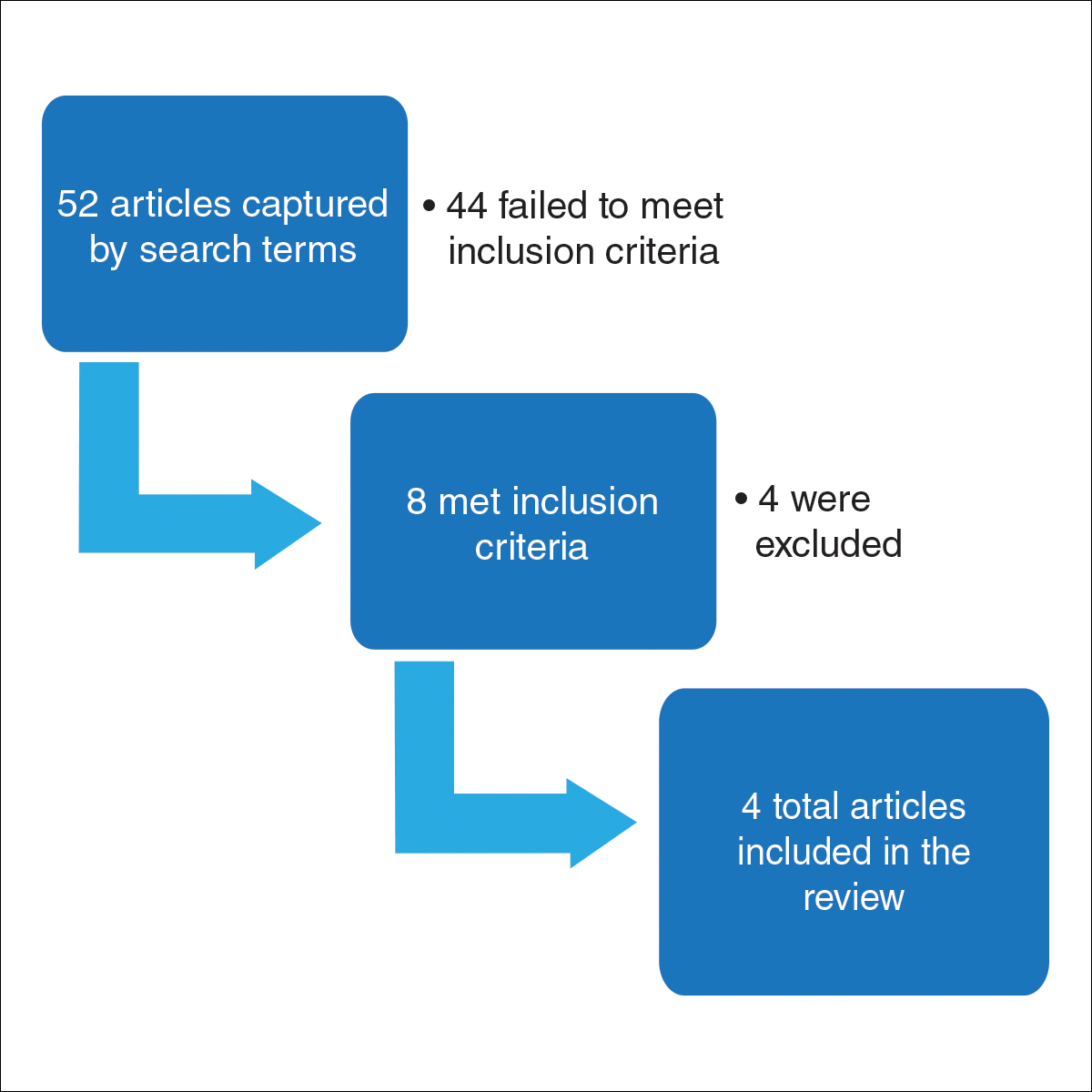

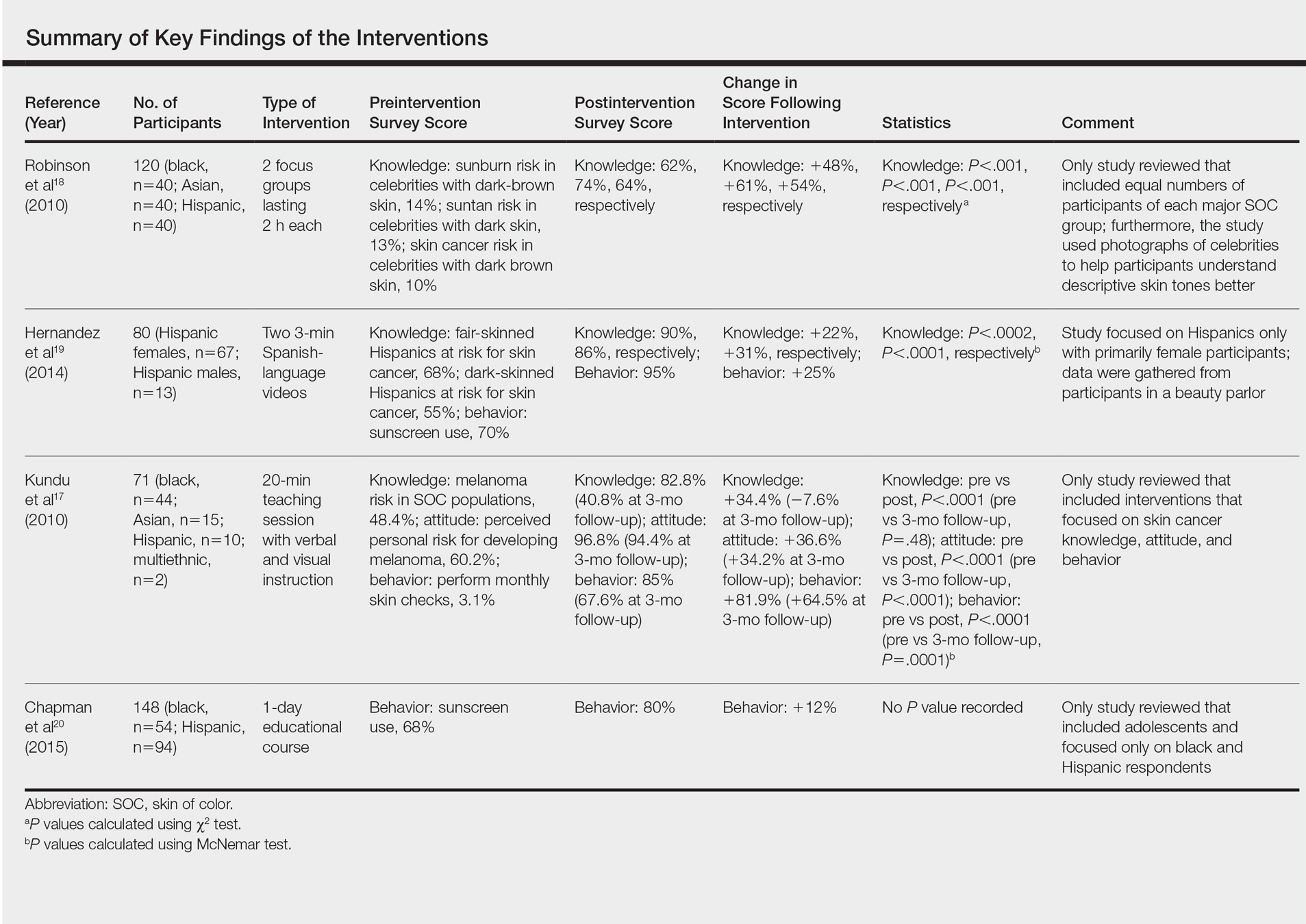

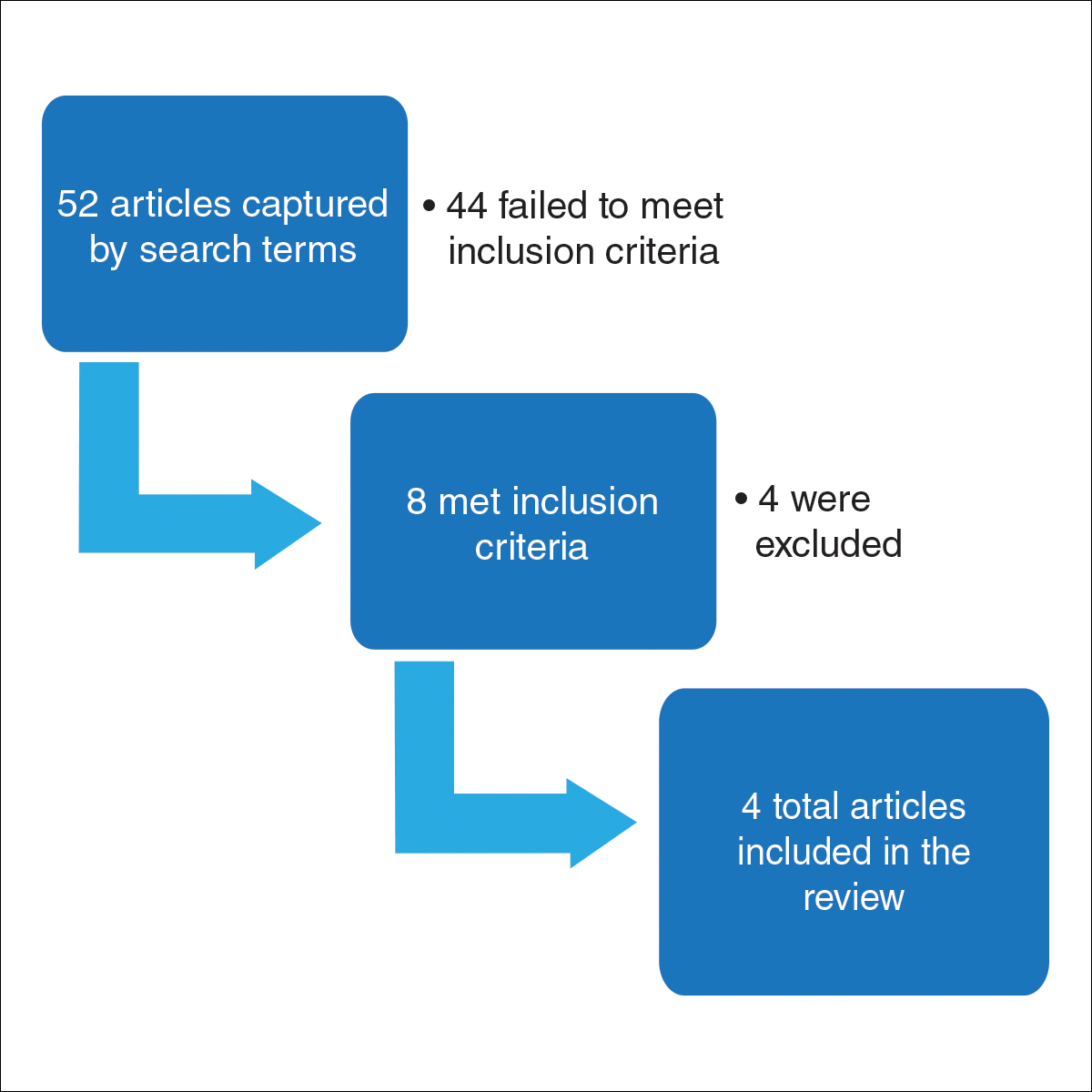

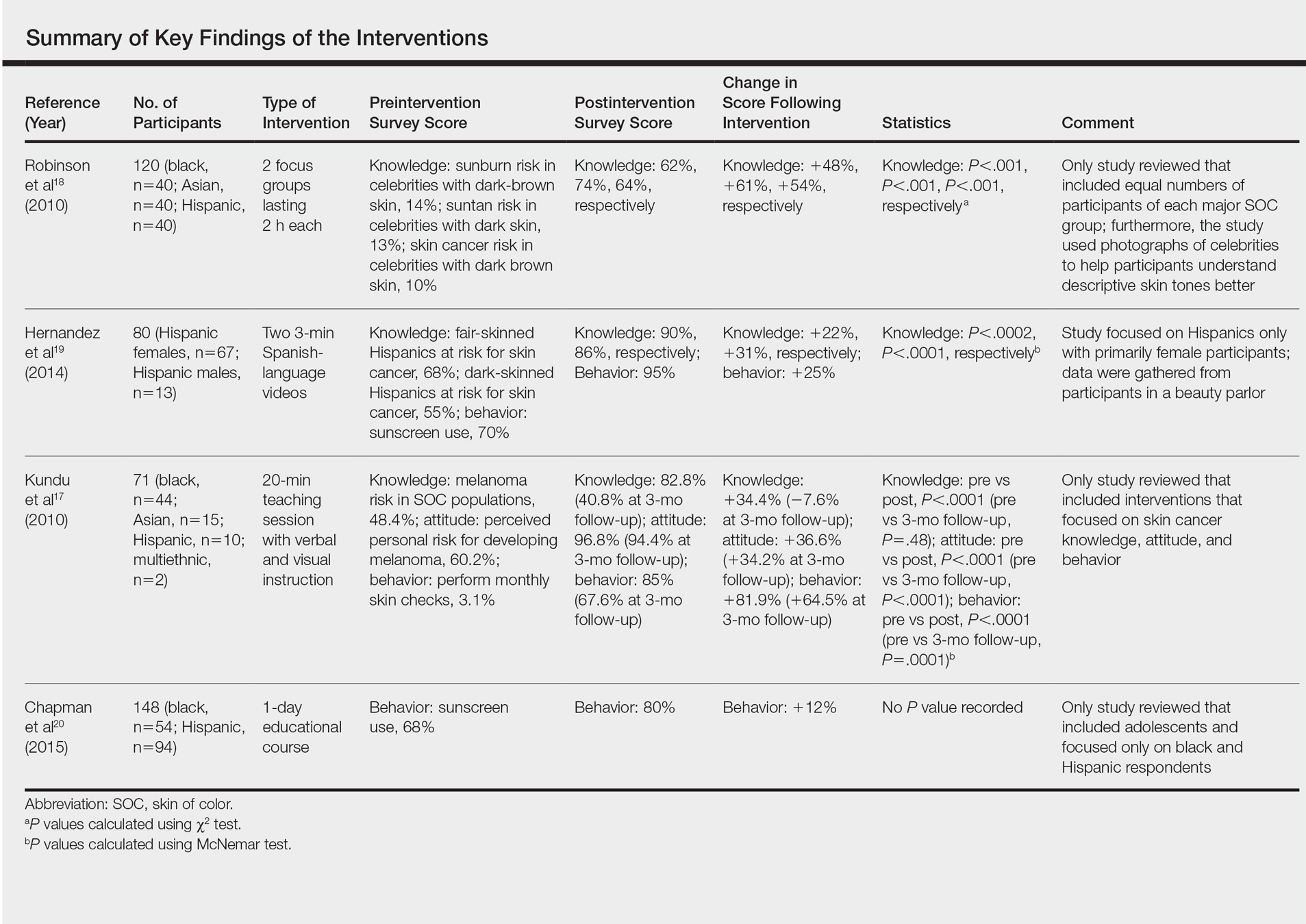

For this review, the Cochrane method of analysis was used to conduct a thorough search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE (1994-2016), as well as a search of CINAHL (1997-2016), PsycINFO (1999-2016), and Web of Science (1965-2016), using a combination of more than 100 search terms including but not limited to skin cancer, skin of color, intervention, and ethnic skin. The search yielded a total of 52 articles (Figure). Following review, only 8 articles met inclusion criteria, which were as follows: (1) study was related to skin cancer in SOC patients, which included an intervention to increase skin cancer awareness and knowledge; (2) study included adult participants or adolescents aged 12 to 18 years; (3) study was written in English; and (4) study was published in a peer-reviewed journal. Of the remaining 8 articles, 4 were excluded due to the following criteria: (1) study failed to provide both preintervention and postintervention data, (2) study failed to provide quantitative data, and (3) study included participants who worked as health care professionals or ancillary staff. As a result, a total of 4 articles were analyzed and discussed in this review (Table).

Results

Robinson et al18 conducted 12 focus groups with 120 total participants (40 black, 40 Asian, and 40 Hispanic patients). Participants engaged in a 2-hour tape-recorded focus group with a moderator guide on melanoma and skin cancer. Furthermore, they also were asked to assess skin cancer risk in 5 celebrities with different skin tones. The statistically significant preintervention results of the study (χ2=4.6, P<.001) were as follows: only 2%, 4%, and 14% correctly reported that celebrities with a very fair skin type, a fair skin type, and very dark skin type, respectively, could get sunburn, compared to 75%, 76%, and 62% post-intervention. Additionally, prior to intervention, 14% of the study population believed that dark brown skin type could get sunburn compared to 62% of the same group postintervention. This study demonstrated that the intervention helped SOC patients better identify their ability to get sunburn and identify their skin cancer risk.18

Hernandez et al19 used a video-based intervention in a Hispanic community, which was in contrast to the multiracial focus group intervention conducted by Robinson et al.18 Eighty Hispanic individuals were recruited from beauty salons to participate in the study. Participants watched two 3-minute videos in Spanish and completed a preintervention and postintervention survey. The first video emphasized the photoaging benefits of sun protection, while the second focused on skin cancer prevention. Preintervention surveys indicated that only 54 (68%) participants believed that fair-skinned Hispanics were at risk for skin cancer, which improved to 72 (90%) participants postintervention. Furthermore, initially only 44 (55%) participants thought those with darker skin types could develop skin cancer, but this number increased to 69 (86%) postintervention. For both questions regarding fair and dark skin, the agreement proportion was significantly different between the preeducation and posteducation videos (P<.0002 for the fair skin question and P<.0001 for the dark skin question). This study greatly increased awareness of skin cancer risk among Hispanics,19 similar to the Robinson et al18 study.

In contrast to 2-hour focus groups or 3-minute video–based interventions, a study by Kundu et al17 employed a 20-minute educational class-based intervention with both verbal and visual instruction. This study assessed the efficacy of an educational tutorial on improving awareness and early detection of melanoma in SOC individuals. Photographs were used to help participants recognize the ABCDEs of melanoma and to show examples of acral lentiginous melanomas in white individuals. A total of 71 participants completed a preintervention questionnaire, participated in a 20-minute class, and completed a postintervention questionnaire immediately after and 3 months following the class. The study population included 44 black, 15 Asian, 10 Hispanic, and 2 multiethnic participants. Knowledge that melanoma is a skin cancer increased from 83.9% to 100% immediately postintervention (P=.0001) and 97.2% at 3 months postintervention (P=.0075). Additionally, knowledge that people of color are at risk for melanoma increased from 48.4% preintervention to 82.8% immediately postintervention (P<.0001). However, only 40.8% of participants retained this knowledge at 3 months postintervention. Because only 1 participant reported a family history of skin cancer, the authors hypothesized that the reason for this loss of knowledge was that most participants were not personally affected by friends or family members with melanoma. A future study with an appropriate control group would be needed to support this claim. This study shed light on the potential of class-based interventions to increase both awareness and knowledge of skin cancer in SOC populations.17

A study by Chapman et al20 examined the effects of a sun protection educational program on increasing awareness of skin cancer in Hispanic and black middle school students in southern Los Angeles, California. It was the only study we reviewed that focused primarily on adolescents. Furthermore, it included the largest sample size (N=148) analyzed here. Students were given a preintervention questionnaire to evaluate their awareness of skin cancer and current sun-protection practices. Based on these results, the investigators devised a set of learning goals and incorporated them into an educational pamphlet. The intervention, called “Skin Teaching Day,” was a 1-day program discussing skin cancer and the importance of sun protection. Prior to the intervention, 68% of participants reported that they used sunscreen. Three months after completing the program, 80% of participants reported sunscreen use, an increase of 12% prior to the intervention. The results of this study demonstrated the unique effectiveness and potential of pamphlets in increasing sunscreen use.20

Comment

Overall, various methods of interventions such as focus groups, videos, pamphlets, and lectures improved knowledge of skin cancer risk and sun-protection behaviors in SOC populations. Furthermore, the unique differences of each study provided important insights into the successful design of an intervention.

An important characteristic of the Robinson et al18 study was the addition of photographs, which allowed participants not only to visualize different skin tones but also provided them with the opportunity to relate themselves to the photographs; by doing so, participants could effectively pick out the skin tone that best suited them. Written SOC scales are limited to mere descriptions and thus make it more difficult for participants to accurately identify the tone that best fits them. Kundu et al17 used photographs to teach skin self-examination and ABCDEs for detection of melanoma. Additionally, both studies used photographs to demonstrate examples of skin cancer.17,18 Recent evidence suggests the use of visuals can be efficacious for improving skin cancer knowledge and awareness; a study in 16 SOC kidney transplant recipients found that the addition of photographs of squamous cell carcinoma in various skin tones to a sun-protection educational pamphlet was more effective than the original pamphlet without photographs.21

In contrast to the Robinson et al18 study and Hernandez et al19 study, the Kundu et al17 study showed photographs of acral lentiginous melanomas in white patients rather than SOC patients. However, SOC populations may be less likely to relate to or identify skin changes in skin types that are different from their own. This technique was still beneficial, as acral lentiginous melanoma is the most common type of melanoma in SOC populations. Another benefit of the study was that it was the only study reviewed that included a follow-up postintervention questionnaire. Such data is useful, as it demonstrates how muchinformation is retained by participants and may be more likely to predict compliance with skin cancer protective behaviors.17

The Hernandez et al19 study is unique in that it was the only one to include an educational intervention entirely in Spanish, which is important to consider, as language may be a hindrance to participants’ understanding in the other studies, particularly Hispanics, possibly leading to a lack of information retention regarding sun-protective behaviors. Furthermore, it also was the only study to utilize videos as a method for interventions. The 3-minute videos demonstrated that interventions could be efficient as compared to the 2-hour in-class intervention used by Robinson et al18 and the 20-minute intervention used by Kundu et al.17 Additionally, videos also could be more cost-effective, as incentives for large focus groups would no longer be needed. Furthermore, in the Hernandez et al19 study, there was minimal to no disruption in the participants’ daily routine, as the participants were getting cosmetic services while watching the videos, perhaps allowing them to be more attentive. In contrast, both the Robinson et al18 and Kundu et al17 studies required time out from the participants’ daily schedules. In addition, these studies were notably longer than the Hernandez et al19 study. The 8-hour intervention in the Chapman et al20 study also may not be feasible for the general population because of its excessive length. However, the intervention was successful among the adolescent participants, which suggested that shorter durations are effective in the adult population and longer interventions may be more appropriate for adolescents because they benefit from peer activity.

Despite the success of the educational interventions as outlined in the 4 studies described here, a major epidemiologic flaw is that these interventions included only a small percentage of the target population. The largest total number of adults surveyed and undergoing an intervention in any of the populations was only 120.17 By failing to reach a substantial proportion of the population at risk, the number of preventable deaths likely will not decrease. The authors believe a larger-scale intervention would provide meaningful change. Australia’s SunSmart campaign to increase skin cancer awareness in the Australian population is an example of one such large-scale national intervention. The campaign focused on massive television advertisements in the summer to educate participants about the dangers of skin cancer and the importance of protective behaviors. Telephone surveys conducted from 1987 to 2011 demonstrated that more exposure to the advertisements in the SunSmart campaign meant that individuals were more likely to use sunscreen and avoid sun exposure.22 In the United States, a similar intervention would be of great benefit in educating SOC populations regarding skin cancer risk. Additionally, dermatology residents need to be adequately trained to educate patients of color about the risk for skin cancer, as survey data indicated more than 80% of Australian dermatologists desired more SOC teaching during their training and 50% indicated that they would have time to learn it during their training if offered.23 Furthermore, one study suggested that future interventions must include primary-, secondary-, and tertiary-prevention methods to effectively reduce skin cancer risk among patients of color.24 Primary prevention involves sun avoidance, secondary prevention involves detecting cancerous lesions, and tertiary prevention involves undergoing treatment of skin malignancies. However, increased knowledge does not necessarily mean increased preventative action will be employed (eg, sunscreen use, wearing sun-protective clothing and sunglasses, avoiding tanning beds and excessive sun exposure). Additional studies that demonstrate a notable increase in sun-protective behaviors related to increased knowledge are needed.

Because retention of skin cancer knowledge decreased in several postintervention surveys, there also is a dire need for continuing skin cancer education in patients of color, which may be accomplished through a combination effort of television advertisement campaigns, pamphlets, social media, community health departments, or even community members. For example, a pilot program found that Hispanic lay health workers who are educated about skin cancer may serve as a bridge between medical providers and the Hispanic community by encouraging individuals in this population to get regular skin examinations from a physician.25 Overall, there are currently gaps in the understanding and treatment of skin cancer in people of color.26 Identifying the advantages and disadvantages of all relevant skin cancer interventions conducted in the SOC population will hopefully guide future studies to help close these gaps by allowing others to design the best possible intervention. By doing so, researchers can generate an intervention that is precise, well-informed, and effective in decreasing mortality rates from skin cancer among SOC populations.

Conclusion

All of the studies reviewed demonstrated that instructional and educational interventions are promising methods for improving either knowledge, awareness, or safe skin practices and sun-protective behaviors in SOC populations to differing degrees (Table). Although each of the 4 interventions employed their own methods, they all increased 1 or more of the 3 aforementioned concepts—knowledge, awareness, or safe skin practices and sun-protective behaviors—when comparing postsurvey to presurvey data. However, the critically important message derived from this research is that there is a tremendous need for a substantial large-scale educational intervention to increase knowledge regarding skin cancer in SOC populations.

- Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748-762.

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914.

- Gloster HM Jr, Neal K. Skin cancer in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:741-760.

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991.

- Byrd KM, Wilson DC, Hoyler SS, et al. Advanced presentation of melanoma in African Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:21-24.

- Hu S, Parmet Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites, Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1369-1374.

- Wu XC, Eide MJ, King J, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in incidence and survival of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 1999-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5, suppl 1):S26-S37.

- Byrd-Miles K, Toombs EL, Peck GL. Skin cancer in individuals of African, Asian, Latin-American, and American-Indian descent: differences in incidence, clinical presentation, and survival compared to Caucasians. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:10-16.

- Hu S, Soza-Vento RM, Parker DF, et al. Comparison of stage at diagnosis of melanoma among Hispanic, black, and white patients in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:704-708.

- Hu S, Parker DF, Thomas AG, et al. Advanced presentation of melanoma in African Americans: the Miami-Dade County experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;5:1031-1032.

- Bellows CF, Belafsky P, Fortgang IS, et al. Melanoma in African-Americans: trends in biological behavior and clinical characteristics over two decades. J Surg Oncol. 2001;78:10-16.

- Pritchett EN, Doyle A, Shaver CM, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in nonwhite organ transplant recipients. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1348-1353.

- Shin S, Palis BE, Phillips JL, et al. Cutaneous melanoma in Asian-Americans. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:114-118.

- Stubblefield J, Kelly B. Melanoma in non-caucasian populations. Surg Clin North Am. 2014;94:1115-1126.

- Bradford PT, Goldstein AM, McMaster ML, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1986-2005. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:427-434.

- Pichon LC, Corral I, Landrine H, et al. Perceived skin cancer risk and sunscreen use among African American adults. J Health Psychol. 2010;15:1181-1189.

- Kundu RV, Kamaria M, Ortiz S, et al. Effectiveness of a knowledge-based intervention for melanoma among those with ethnic skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:777-784.

- Robinson JK, Joshi KM, Ortiz S, et al. Melanoma knowledge, perception, and awareness in ethnic minorities in Chicago: recommendations regarding education. Psychooncology. 2010;20:313-320.

- Hernandez C, Wang S, Abraham I, et al. Evaluation of educational videos to increase skin cancer risk awareness and sun safe behaviors among adult Hispanics. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29:563-569.

- Chapman LW, Ochoa A, Tenconi F, et al. Dermatologic health literacy in underserved communities: a case report of south Los Angeles middle schools. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt8671p40n.

- Yanina G, Gaber R, Clayman ML, et al. Sun protection education for diverse audiences: need for skin cancer pictures. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30:187-189.

- Dobbinson SJ, Volkov A, Wakefield MA. Continued impact of sunsmart advertising on youth and adults’ behaviors. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:20-28.

- Rodrigues MA, Ross AL, Gilmore S, et al. Australian dermatologists’ perspective on skin of colour: results of a national survey [published online December 9, 2016]. Australas J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ajd.12556.

- Jacobsen A, Galvan A, Lachapelle CC, et al. Defining the need for skin cancer prevention education in uninsured, minority, and immigrant communities. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1342-1347.

- Hernandez C, Kim H, Mauleon G, et al. A pilot program in collaboration with community centers to increase awareness and participation in skin cancer screening among Latinos in Chicago. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28:342-345.

- Kailas A, Solomon JA, Mostow EN, et al. Gaps in the understanding and treatment of skin cancer in people of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:144-149.

Malignant melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma account for approximately 40% of all neoplasms among the white population in the United States. Skin cancer is the most common malignancy in the United States.1 However, despite this occurrence, there are limited data regarding skin cancer in individuals with skin of color (SOC). The 5-year survival rates for melanoma are 58.2% for black individuals, 69.7% for Hispanics, and 70.9% for Asians compared to 79.8% for white individuals in the United States.2 Even though SOC populations have lower incidences of skin cancer—melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma—they exhibit higher death rates.3-7 Nonetheless, no specific guidelines exist to address sun exposure and safety habits in SOC populations.6,8 Furthermore, current demographics suggest that by the year 2050, approximately half of the US population will be nonwhite.4 Paradoxically, despite having increased sun protection from greater amounts of melanin in their skin, black individuals are more likely to present with advanced-stage melanoma (eg, stage III/IV) compared to white individuals.8-12 Furthermore, those of nonwhite populations are more likely to present with more advanced stages of acral lentiginous melanomas than white individuals.13,14 Hispanics also face an increasing incidence of more invasive acral lentiginous melanomas.15 Overall, SOC patients have the poorest skin cancer prognosis, and the data suggest that the reason for this paradox is delayed diagnosis.1

Although skin cancer is largely a preventable condition, the literature suggests that lack of awareness of melanoma among ethnic minorities is one of the main reasons for their poor skin cancer prognosis.16 This lack of awareness decreases the likelihood that an SOC patient would be alert to early detection of cancerous changes.17 Because educating at-risk SOC populations is key to decreasing skin cancer risk, this study focused on determining the efficacy of major knowledge-based interventions conducted to date.1 Overall, we sought to answer the question, do knowledge-based interventions increase skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behavior among people of color?

Methods

For this review, the Cochrane method of analysis was used to conduct a thorough search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE (1994-2016), as well as a search of CINAHL (1997-2016), PsycINFO (1999-2016), and Web of Science (1965-2016), using a combination of more than 100 search terms including but not limited to skin cancer, skin of color, intervention, and ethnic skin. The search yielded a total of 52 articles (Figure). Following review, only 8 articles met inclusion criteria, which were as follows: (1) study was related to skin cancer in SOC patients, which included an intervention to increase skin cancer awareness and knowledge; (2) study included adult participants or adolescents aged 12 to 18 years; (3) study was written in English; and (4) study was published in a peer-reviewed journal. Of the remaining 8 articles, 4 were excluded due to the following criteria: (1) study failed to provide both preintervention and postintervention data, (2) study failed to provide quantitative data, and (3) study included participants who worked as health care professionals or ancillary staff. As a result, a total of 4 articles were analyzed and discussed in this review (Table).

Results

Robinson et al18 conducted 12 focus groups with 120 total participants (40 black, 40 Asian, and 40 Hispanic patients). Participants engaged in a 2-hour tape-recorded focus group with a moderator guide on melanoma and skin cancer. Furthermore, they also were asked to assess skin cancer risk in 5 celebrities with different skin tones. The statistically significant preintervention results of the study (χ2=4.6, P<.001) were as follows: only 2%, 4%, and 14% correctly reported that celebrities with a very fair skin type, a fair skin type, and very dark skin type, respectively, could get sunburn, compared to 75%, 76%, and 62% post-intervention. Additionally, prior to intervention, 14% of the study population believed that dark brown skin type could get sunburn compared to 62% of the same group postintervention. This study demonstrated that the intervention helped SOC patients better identify their ability to get sunburn and identify their skin cancer risk.18

Hernandez et al19 used a video-based intervention in a Hispanic community, which was in contrast to the multiracial focus group intervention conducted by Robinson et al.18 Eighty Hispanic individuals were recruited from beauty salons to participate in the study. Participants watched two 3-minute videos in Spanish and completed a preintervention and postintervention survey. The first video emphasized the photoaging benefits of sun protection, while the second focused on skin cancer prevention. Preintervention surveys indicated that only 54 (68%) participants believed that fair-skinned Hispanics were at risk for skin cancer, which improved to 72 (90%) participants postintervention. Furthermore, initially only 44 (55%) participants thought those with darker skin types could develop skin cancer, but this number increased to 69 (86%) postintervention. For both questions regarding fair and dark skin, the agreement proportion was significantly different between the preeducation and posteducation videos (P<.0002 for the fair skin question and P<.0001 for the dark skin question). This study greatly increased awareness of skin cancer risk among Hispanics,19 similar to the Robinson et al18 study.

In contrast to 2-hour focus groups or 3-minute video–based interventions, a study by Kundu et al17 employed a 20-minute educational class-based intervention with both verbal and visual instruction. This study assessed the efficacy of an educational tutorial on improving awareness and early detection of melanoma in SOC individuals. Photographs were used to help participants recognize the ABCDEs of melanoma and to show examples of acral lentiginous melanomas in white individuals. A total of 71 participants completed a preintervention questionnaire, participated in a 20-minute class, and completed a postintervention questionnaire immediately after and 3 months following the class. The study population included 44 black, 15 Asian, 10 Hispanic, and 2 multiethnic participants. Knowledge that melanoma is a skin cancer increased from 83.9% to 100% immediately postintervention (P=.0001) and 97.2% at 3 months postintervention (P=.0075). Additionally, knowledge that people of color are at risk for melanoma increased from 48.4% preintervention to 82.8% immediately postintervention (P<.0001). However, only 40.8% of participants retained this knowledge at 3 months postintervention. Because only 1 participant reported a family history of skin cancer, the authors hypothesized that the reason for this loss of knowledge was that most participants were not personally affected by friends or family members with melanoma. A future study with an appropriate control group would be needed to support this claim. This study shed light on the potential of class-based interventions to increase both awareness and knowledge of skin cancer in SOC populations.17

A study by Chapman et al20 examined the effects of a sun protection educational program on increasing awareness of skin cancer in Hispanic and black middle school students in southern Los Angeles, California. It was the only study we reviewed that focused primarily on adolescents. Furthermore, it included the largest sample size (N=148) analyzed here. Students were given a preintervention questionnaire to evaluate their awareness of skin cancer and current sun-protection practices. Based on these results, the investigators devised a set of learning goals and incorporated them into an educational pamphlet. The intervention, called “Skin Teaching Day,” was a 1-day program discussing skin cancer and the importance of sun protection. Prior to the intervention, 68% of participants reported that they used sunscreen. Three months after completing the program, 80% of participants reported sunscreen use, an increase of 12% prior to the intervention. The results of this study demonstrated the unique effectiveness and potential of pamphlets in increasing sunscreen use.20

Comment

Overall, various methods of interventions such as focus groups, videos, pamphlets, and lectures improved knowledge of skin cancer risk and sun-protection behaviors in SOC populations. Furthermore, the unique differences of each study provided important insights into the successful design of an intervention.

An important characteristic of the Robinson et al18 study was the addition of photographs, which allowed participants not only to visualize different skin tones but also provided them with the opportunity to relate themselves to the photographs; by doing so, participants could effectively pick out the skin tone that best suited them. Written SOC scales are limited to mere descriptions and thus make it more difficult for participants to accurately identify the tone that best fits them. Kundu et al17 used photographs to teach skin self-examination and ABCDEs for detection of melanoma. Additionally, both studies used photographs to demonstrate examples of skin cancer.17,18 Recent evidence suggests the use of visuals can be efficacious for improving skin cancer knowledge and awareness; a study in 16 SOC kidney transplant recipients found that the addition of photographs of squamous cell carcinoma in various skin tones to a sun-protection educational pamphlet was more effective than the original pamphlet without photographs.21

In contrast to the Robinson et al18 study and Hernandez et al19 study, the Kundu et al17 study showed photographs of acral lentiginous melanomas in white patients rather than SOC patients. However, SOC populations may be less likely to relate to or identify skin changes in skin types that are different from their own. This technique was still beneficial, as acral lentiginous melanoma is the most common type of melanoma in SOC populations. Another benefit of the study was that it was the only study reviewed that included a follow-up postintervention questionnaire. Such data is useful, as it demonstrates how muchinformation is retained by participants and may be more likely to predict compliance with skin cancer protective behaviors.17

The Hernandez et al19 study is unique in that it was the only one to include an educational intervention entirely in Spanish, which is important to consider, as language may be a hindrance to participants’ understanding in the other studies, particularly Hispanics, possibly leading to a lack of information retention regarding sun-protective behaviors. Furthermore, it also was the only study to utilize videos as a method for interventions. The 3-minute videos demonstrated that interventions could be efficient as compared to the 2-hour in-class intervention used by Robinson et al18 and the 20-minute intervention used by Kundu et al.17 Additionally, videos also could be more cost-effective, as incentives for large focus groups would no longer be needed. Furthermore, in the Hernandez et al19 study, there was minimal to no disruption in the participants’ daily routine, as the participants were getting cosmetic services while watching the videos, perhaps allowing them to be more attentive. In contrast, both the Robinson et al18 and Kundu et al17 studies required time out from the participants’ daily schedules. In addition, these studies were notably longer than the Hernandez et al19 study. The 8-hour intervention in the Chapman et al20 study also may not be feasible for the general population because of its excessive length. However, the intervention was successful among the adolescent participants, which suggested that shorter durations are effective in the adult population and longer interventions may be more appropriate for adolescents because they benefit from peer activity.

Despite the success of the educational interventions as outlined in the 4 studies described here, a major epidemiologic flaw is that these interventions included only a small percentage of the target population. The largest total number of adults surveyed and undergoing an intervention in any of the populations was only 120.17 By failing to reach a substantial proportion of the population at risk, the number of preventable deaths likely will not decrease. The authors believe a larger-scale intervention would provide meaningful change. Australia’s SunSmart campaign to increase skin cancer awareness in the Australian population is an example of one such large-scale national intervention. The campaign focused on massive television advertisements in the summer to educate participants about the dangers of skin cancer and the importance of protective behaviors. Telephone surveys conducted from 1987 to 2011 demonstrated that more exposure to the advertisements in the SunSmart campaign meant that individuals were more likely to use sunscreen and avoid sun exposure.22 In the United States, a similar intervention would be of great benefit in educating SOC populations regarding skin cancer risk. Additionally, dermatology residents need to be adequately trained to educate patients of color about the risk for skin cancer, as survey data indicated more than 80% of Australian dermatologists desired more SOC teaching during their training and 50% indicated that they would have time to learn it during their training if offered.23 Furthermore, one study suggested that future interventions must include primary-, secondary-, and tertiary-prevention methods to effectively reduce skin cancer risk among patients of color.24 Primary prevention involves sun avoidance, secondary prevention involves detecting cancerous lesions, and tertiary prevention involves undergoing treatment of skin malignancies. However, increased knowledge does not necessarily mean increased preventative action will be employed (eg, sunscreen use, wearing sun-protective clothing and sunglasses, avoiding tanning beds and excessive sun exposure). Additional studies that demonstrate a notable increase in sun-protective behaviors related to increased knowledge are needed.

Because retention of skin cancer knowledge decreased in several postintervention surveys, there also is a dire need for continuing skin cancer education in patients of color, which may be accomplished through a combination effort of television advertisement campaigns, pamphlets, social media, community health departments, or even community members. For example, a pilot program found that Hispanic lay health workers who are educated about skin cancer may serve as a bridge between medical providers and the Hispanic community by encouraging individuals in this population to get regular skin examinations from a physician.25 Overall, there are currently gaps in the understanding and treatment of skin cancer in people of color.26 Identifying the advantages and disadvantages of all relevant skin cancer interventions conducted in the SOC population will hopefully guide future studies to help close these gaps by allowing others to design the best possible intervention. By doing so, researchers can generate an intervention that is precise, well-informed, and effective in decreasing mortality rates from skin cancer among SOC populations.

Conclusion

All of the studies reviewed demonstrated that instructional and educational interventions are promising methods for improving either knowledge, awareness, or safe skin practices and sun-protective behaviors in SOC populations to differing degrees (Table). Although each of the 4 interventions employed their own methods, they all increased 1 or more of the 3 aforementioned concepts—knowledge, awareness, or safe skin practices and sun-protective behaviors—when comparing postsurvey to presurvey data. However, the critically important message derived from this research is that there is a tremendous need for a substantial large-scale educational intervention to increase knowledge regarding skin cancer in SOC populations.

Malignant melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma account for approximately 40% of all neoplasms among the white population in the United States. Skin cancer is the most common malignancy in the United States.1 However, despite this occurrence, there are limited data regarding skin cancer in individuals with skin of color (SOC). The 5-year survival rates for melanoma are 58.2% for black individuals, 69.7% for Hispanics, and 70.9% for Asians compared to 79.8% for white individuals in the United States.2 Even though SOC populations have lower incidences of skin cancer—melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma—they exhibit higher death rates.3-7 Nonetheless, no specific guidelines exist to address sun exposure and safety habits in SOC populations.6,8 Furthermore, current demographics suggest that by the year 2050, approximately half of the US population will be nonwhite.4 Paradoxically, despite having increased sun protection from greater amounts of melanin in their skin, black individuals are more likely to present with advanced-stage melanoma (eg, stage III/IV) compared to white individuals.8-12 Furthermore, those of nonwhite populations are more likely to present with more advanced stages of acral lentiginous melanomas than white individuals.13,14 Hispanics also face an increasing incidence of more invasive acral lentiginous melanomas.15 Overall, SOC patients have the poorest skin cancer prognosis, and the data suggest that the reason for this paradox is delayed diagnosis.1

Although skin cancer is largely a preventable condition, the literature suggests that lack of awareness of melanoma among ethnic minorities is one of the main reasons for their poor skin cancer prognosis.16 This lack of awareness decreases the likelihood that an SOC patient would be alert to early detection of cancerous changes.17 Because educating at-risk SOC populations is key to decreasing skin cancer risk, this study focused on determining the efficacy of major knowledge-based interventions conducted to date.1 Overall, we sought to answer the question, do knowledge-based interventions increase skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behavior among people of color?

Methods

For this review, the Cochrane method of analysis was used to conduct a thorough search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE (1994-2016), as well as a search of CINAHL (1997-2016), PsycINFO (1999-2016), and Web of Science (1965-2016), using a combination of more than 100 search terms including but not limited to skin cancer, skin of color, intervention, and ethnic skin. The search yielded a total of 52 articles (Figure). Following review, only 8 articles met inclusion criteria, which were as follows: (1) study was related to skin cancer in SOC patients, which included an intervention to increase skin cancer awareness and knowledge; (2) study included adult participants or adolescents aged 12 to 18 years; (3) study was written in English; and (4) study was published in a peer-reviewed journal. Of the remaining 8 articles, 4 were excluded due to the following criteria: (1) study failed to provide both preintervention and postintervention data, (2) study failed to provide quantitative data, and (3) study included participants who worked as health care professionals or ancillary staff. As a result, a total of 4 articles were analyzed and discussed in this review (Table).

Results

Robinson et al18 conducted 12 focus groups with 120 total participants (40 black, 40 Asian, and 40 Hispanic patients). Participants engaged in a 2-hour tape-recorded focus group with a moderator guide on melanoma and skin cancer. Furthermore, they also were asked to assess skin cancer risk in 5 celebrities with different skin tones. The statistically significant preintervention results of the study (χ2=4.6, P<.001) were as follows: only 2%, 4%, and 14% correctly reported that celebrities with a very fair skin type, a fair skin type, and very dark skin type, respectively, could get sunburn, compared to 75%, 76%, and 62% post-intervention. Additionally, prior to intervention, 14% of the study population believed that dark brown skin type could get sunburn compared to 62% of the same group postintervention. This study demonstrated that the intervention helped SOC patients better identify their ability to get sunburn and identify their skin cancer risk.18

Hernandez et al19 used a video-based intervention in a Hispanic community, which was in contrast to the multiracial focus group intervention conducted by Robinson et al.18 Eighty Hispanic individuals were recruited from beauty salons to participate in the study. Participants watched two 3-minute videos in Spanish and completed a preintervention and postintervention survey. The first video emphasized the photoaging benefits of sun protection, while the second focused on skin cancer prevention. Preintervention surveys indicated that only 54 (68%) participants believed that fair-skinned Hispanics were at risk for skin cancer, which improved to 72 (90%) participants postintervention. Furthermore, initially only 44 (55%) participants thought those with darker skin types could develop skin cancer, but this number increased to 69 (86%) postintervention. For both questions regarding fair and dark skin, the agreement proportion was significantly different between the preeducation and posteducation videos (P<.0002 for the fair skin question and P<.0001 for the dark skin question). This study greatly increased awareness of skin cancer risk among Hispanics,19 similar to the Robinson et al18 study.

In contrast to 2-hour focus groups or 3-minute video–based interventions, a study by Kundu et al17 employed a 20-minute educational class-based intervention with both verbal and visual instruction. This study assessed the efficacy of an educational tutorial on improving awareness and early detection of melanoma in SOC individuals. Photographs were used to help participants recognize the ABCDEs of melanoma and to show examples of acral lentiginous melanomas in white individuals. A total of 71 participants completed a preintervention questionnaire, participated in a 20-minute class, and completed a postintervention questionnaire immediately after and 3 months following the class. The study population included 44 black, 15 Asian, 10 Hispanic, and 2 multiethnic participants. Knowledge that melanoma is a skin cancer increased from 83.9% to 100% immediately postintervention (P=.0001) and 97.2% at 3 months postintervention (P=.0075). Additionally, knowledge that people of color are at risk for melanoma increased from 48.4% preintervention to 82.8% immediately postintervention (P<.0001). However, only 40.8% of participants retained this knowledge at 3 months postintervention. Because only 1 participant reported a family history of skin cancer, the authors hypothesized that the reason for this loss of knowledge was that most participants were not personally affected by friends or family members with melanoma. A future study with an appropriate control group would be needed to support this claim. This study shed light on the potential of class-based interventions to increase both awareness and knowledge of skin cancer in SOC populations.17

A study by Chapman et al20 examined the effects of a sun protection educational program on increasing awareness of skin cancer in Hispanic and black middle school students in southern Los Angeles, California. It was the only study we reviewed that focused primarily on adolescents. Furthermore, it included the largest sample size (N=148) analyzed here. Students were given a preintervention questionnaire to evaluate their awareness of skin cancer and current sun-protection practices. Based on these results, the investigators devised a set of learning goals and incorporated them into an educational pamphlet. The intervention, called “Skin Teaching Day,” was a 1-day program discussing skin cancer and the importance of sun protection. Prior to the intervention, 68% of participants reported that they used sunscreen. Three months after completing the program, 80% of participants reported sunscreen use, an increase of 12% prior to the intervention. The results of this study demonstrated the unique effectiveness and potential of pamphlets in increasing sunscreen use.20

Comment

Overall, various methods of interventions such as focus groups, videos, pamphlets, and lectures improved knowledge of skin cancer risk and sun-protection behaviors in SOC populations. Furthermore, the unique differences of each study provided important insights into the successful design of an intervention.

An important characteristic of the Robinson et al18 study was the addition of photographs, which allowed participants not only to visualize different skin tones but also provided them with the opportunity to relate themselves to the photographs; by doing so, participants could effectively pick out the skin tone that best suited them. Written SOC scales are limited to mere descriptions and thus make it more difficult for participants to accurately identify the tone that best fits them. Kundu et al17 used photographs to teach skin self-examination and ABCDEs for detection of melanoma. Additionally, both studies used photographs to demonstrate examples of skin cancer.17,18 Recent evidence suggests the use of visuals can be efficacious for improving skin cancer knowledge and awareness; a study in 16 SOC kidney transplant recipients found that the addition of photographs of squamous cell carcinoma in various skin tones to a sun-protection educational pamphlet was more effective than the original pamphlet without photographs.21

In contrast to the Robinson et al18 study and Hernandez et al19 study, the Kundu et al17 study showed photographs of acral lentiginous melanomas in white patients rather than SOC patients. However, SOC populations may be less likely to relate to or identify skin changes in skin types that are different from their own. This technique was still beneficial, as acral lentiginous melanoma is the most common type of melanoma in SOC populations. Another benefit of the study was that it was the only study reviewed that included a follow-up postintervention questionnaire. Such data is useful, as it demonstrates how muchinformation is retained by participants and may be more likely to predict compliance with skin cancer protective behaviors.17

The Hernandez et al19 study is unique in that it was the only one to include an educational intervention entirely in Spanish, which is important to consider, as language may be a hindrance to participants’ understanding in the other studies, particularly Hispanics, possibly leading to a lack of information retention regarding sun-protective behaviors. Furthermore, it also was the only study to utilize videos as a method for interventions. The 3-minute videos demonstrated that interventions could be efficient as compared to the 2-hour in-class intervention used by Robinson et al18 and the 20-minute intervention used by Kundu et al.17 Additionally, videos also could be more cost-effective, as incentives for large focus groups would no longer be needed. Furthermore, in the Hernandez et al19 study, there was minimal to no disruption in the participants’ daily routine, as the participants were getting cosmetic services while watching the videos, perhaps allowing them to be more attentive. In contrast, both the Robinson et al18 and Kundu et al17 studies required time out from the participants’ daily schedules. In addition, these studies were notably longer than the Hernandez et al19 study. The 8-hour intervention in the Chapman et al20 study also may not be feasible for the general population because of its excessive length. However, the intervention was successful among the adolescent participants, which suggested that shorter durations are effective in the adult population and longer interventions may be more appropriate for adolescents because they benefit from peer activity.

Despite the success of the educational interventions as outlined in the 4 studies described here, a major epidemiologic flaw is that these interventions included only a small percentage of the target population. The largest total number of adults surveyed and undergoing an intervention in any of the populations was only 120.17 By failing to reach a substantial proportion of the population at risk, the number of preventable deaths likely will not decrease. The authors believe a larger-scale intervention would provide meaningful change. Australia’s SunSmart campaign to increase skin cancer awareness in the Australian population is an example of one such large-scale national intervention. The campaign focused on massive television advertisements in the summer to educate participants about the dangers of skin cancer and the importance of protective behaviors. Telephone surveys conducted from 1987 to 2011 demonstrated that more exposure to the advertisements in the SunSmart campaign meant that individuals were more likely to use sunscreen and avoid sun exposure.22 In the United States, a similar intervention would be of great benefit in educating SOC populations regarding skin cancer risk. Additionally, dermatology residents need to be adequately trained to educate patients of color about the risk for skin cancer, as survey data indicated more than 80% of Australian dermatologists desired more SOC teaching during their training and 50% indicated that they would have time to learn it during their training if offered.23 Furthermore, one study suggested that future interventions must include primary-, secondary-, and tertiary-prevention methods to effectively reduce skin cancer risk among patients of color.24 Primary prevention involves sun avoidance, secondary prevention involves detecting cancerous lesions, and tertiary prevention involves undergoing treatment of skin malignancies. However, increased knowledge does not necessarily mean increased preventative action will be employed (eg, sunscreen use, wearing sun-protective clothing and sunglasses, avoiding tanning beds and excessive sun exposure). Additional studies that demonstrate a notable increase in sun-protective behaviors related to increased knowledge are needed.

Because retention of skin cancer knowledge decreased in several postintervention surveys, there also is a dire need for continuing skin cancer education in patients of color, which may be accomplished through a combination effort of television advertisement campaigns, pamphlets, social media, community health departments, or even community members. For example, a pilot program found that Hispanic lay health workers who are educated about skin cancer may serve as a bridge between medical providers and the Hispanic community by encouraging individuals in this population to get regular skin examinations from a physician.25 Overall, there are currently gaps in the understanding and treatment of skin cancer in people of color.26 Identifying the advantages and disadvantages of all relevant skin cancer interventions conducted in the SOC population will hopefully guide future studies to help close these gaps by allowing others to design the best possible intervention. By doing so, researchers can generate an intervention that is precise, well-informed, and effective in decreasing mortality rates from skin cancer among SOC populations.

Conclusion

All of the studies reviewed demonstrated that instructional and educational interventions are promising methods for improving either knowledge, awareness, or safe skin practices and sun-protective behaviors in SOC populations to differing degrees (Table). Although each of the 4 interventions employed their own methods, they all increased 1 or more of the 3 aforementioned concepts—knowledge, awareness, or safe skin practices and sun-protective behaviors—when comparing postsurvey to presurvey data. However, the critically important message derived from this research is that there is a tremendous need for a substantial large-scale educational intervention to increase knowledge regarding skin cancer in SOC populations.

- Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748-762.

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914.

- Gloster HM Jr, Neal K. Skin cancer in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:741-760.

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991.

- Byrd KM, Wilson DC, Hoyler SS, et al. Advanced presentation of melanoma in African Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:21-24.

- Hu S, Parmet Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites, Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1369-1374.

- Wu XC, Eide MJ, King J, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in incidence and survival of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 1999-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5, suppl 1):S26-S37.

- Byrd-Miles K, Toombs EL, Peck GL. Skin cancer in individuals of African, Asian, Latin-American, and American-Indian descent: differences in incidence, clinical presentation, and survival compared to Caucasians. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:10-16.

- Hu S, Soza-Vento RM, Parker DF, et al. Comparison of stage at diagnosis of melanoma among Hispanic, black, and white patients in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:704-708.