User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Imaging Overview: Report From the Mount Sinai Fall Symposium

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Update on Lasers and Radiofrequency: Report From the Mount Sinai Fall Symposium

Skin Cancer in Military Pilots: A Special Population With Special Risk Factors

Military dermatologists are charged with caring for a diverse population of active-duty members, civilian dependents, and military retirees. Although certain risk factors for cutaneous malignancies are common in all of these groups, the active-duty population experiences unique exposures to be considered when determining their risk for skin cancer. One subset that may be at a higher risk is military pilots who fly at high altitudes on irregular schedules in austere environments. Through the unparalleled comradeship inherent in many military units, pilots “hear” from their fellow pilots that they are at increased risk for skin cancer. Do their occupational exposures translate into increased risk for cutaneous malignancy? This article will survey the literature pertaining to pilots and skin cancer so that all dermatologists may better care for this unique population.

Epidemiology

Anecdotally, we have observed basal cell carcinoma in pilots in their 20s and early 30s, earlier than would be expected in an otherwise healthy prescreened military population.1 Woolley and Hughes2 published a case report of skin cancer in a young military aviator. The patient was a 32-year-old male helicopter pilot with Fitzpatrick skin type II and no personal or family history of skin cancer who was diagnosed with a periocular nodular basal cell carcinoma. He deployed to locations with high UV radiation (UVR) indices, and his vacation time also was spent in such areas.2 UV radiation exposure and Fitzpatrick skin type are known risk factors across occupations, but are there special exposures that come with military aviation service?

To better understand the risk for malignancy in this special population, the US Air Force examined the rates of all cancer types among a cohort of flying versus nonflying officers.3 Aviation personnel showed increased incidence of testicular, bladder, and all-site cancers combined. Noticeably absent was a statistically significant increased risk for malignant melanoma (MM) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC). Other epidemiological studies examined the incidence rates of MM in the US Armed Forces compared with age- and race-matched civilian populations and showed mixed results: 2 studies showed increased risk,4,5 while a third showed decreased risk.6 Despite finding opposite results of MM rates in military members versus the civilian population, 2 of these studies showed US Air Force members to have higher rates of MM than those in the US Army or Navy.4,6 Interestingly, the air force has the highest number of pilots among all the services, with 4000 more pilots than the army and navy.7 Further studies are needed to determine if the higher air force MM rates occur in pilots.

Although there are mixed and limited data pertaining to military flight crews, there is more robust literature concerning civilian flight personnel. One meta-analysis pooled studies related to cancer risk in cabin crews and civil and military pilots.8 In military pilots, they found a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.43 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09-1.87) for MM and 1.80 (95% CI, 1.25-2.80) for NMSC. The SIRs were higher for male cabin attendants (3.42 and 7.46, respectively) and civil pilots (2.18 and 1.88, respectively). They also found the most common cause of mortality in civilian cabin crews was AIDS, possibly explaining the higher SIRs for all types of malignancy in that population.8 In the United States, many civilian pilots previously were military pilots9 who likely served in the military for at least 10 years.10 A 2015 meta-analysis of 19 studies of more than 266,000 civil pilots and aircrew members found an SIR for MM of 2.22 (95% CI, 1.67-2.93) for civil pilots and 2.09 (95% CI, 1.67-2.62) for aircrews, stating the risk for MM is at least twice that of the general population.11

Risk Factors

UV Radiation

These studies suggest flight duties increase the risk for cutaneous malignancy. UV radiation is a known risk factor for skin cancer.12 The main body of the aircraft may protect the cabin’s crew and passengers from UVR, but pilots are exposed to more UVR, especially in aircraft with larger windshields. A government study in 2007 examined the transmittance of UVR through windscreens of 8 aircraft: 3 commercial jets, 2 commercial propeller planes, 1 private jet, and 2 small propeller planes.13 UVB was attenuated by all the windscreens (<1% transmittance), but 43% to 54% of UVA was transmitted, with plastic windshields attenuating more than glass. Sanlorenzo et al14 measured UVA irradiance at the pilot’s seat of a turboprop aircraft at 30,000-ft altitude. They compared this exposure to a UVA tanning bed and estimated that 57 minutes of flight at 30,000-ft altitude was equivalent to 20 minutes inside a UVA tanning booth, a startling finding.14

Cosmic Radiation

Cosmic radiation consists of neutrons and gamma rays that originate outside Earth’s atmosphere. Pilots are exposed to higher doses of cosmic radiation than nonpilots, but the health effects are difficult to study. Boice et al15 described how factors such as altitude, latitude, and flight time determine pilots’ cumulative exposure. With longer flight times at higher altitudes, a pilot’s exposure to cosmic radiation is increasing over the years.15 A 2012 review found that aircrews have low-level cosmic radiation exposure. Despite increases in MM and NMSC in pilots and increased rates of breast cancer in female aircrew, overall cancer-related mortality was lower in flying versus nonflying controls.16 Thus, cosmic radiation may not be as onerous of an occupational hazard for pilots as has been postulated.

Altered Circadian Rhythms

Aviation duties, especially in the military, require irregular work schedules that repeatedly interfere with normal sleep-wake cycles, disrupt circadian rhythms, and lead to reduced melatonin levels.8 Evidence suggests that low levels of melatonin could increase the risk for breast and prostate cancer—both cancers that occur more frequently in female aircrew and male pilots, respectively—by reducing melatonin’s natural protective role in such malignancies.17,18 A World Health Organization working group categorized shift work as “probably carcinogenic” and cited alterations of melatonin levels, changes in other circadian rhythm–related gene pathways, and relative immunosuppression as likely causative factors.19 In a 2011 study, exposing mice to UVR during times when nucleotide excision repair mechanisms were at their lowest activity caused an increased rate of skin cancers.20 A 2014 review discussed how epidemiological studies of shift workers such as nurses, firefighters, pilots, and flight crews found contradictory data, but molecular studies show that circadian rhythm–linked repair and tumorigenesis mechanisms are altered by aberrations in the normal sleep-wake cycle.21

Cockpit Instrumentation

Electromagnetic energy from the flight instruments in the cockpit also could influence malignancy risk. Nicholas et al22 found magnetic field measurements within the cockpit to be 2 to 10 times that experienced within the home or office. However, no studies examining the health effects of cockpit flight instruments and magnetic fields were found.

Final Thoughts

It is important to counsel pilots on the generally recognized, nonaviation-specific risk factors of family history, skin type, and UVR exposure in the development of skin cancer. Additionally, it is important to explain the possible role of exposure to UVR at higher altitudes, cosmic radiation, and electromagnetic energy from cockpit instruments, as well as altered sleep-wake cycles. A pilot’s risk for MM may be twice that of matched controls, and the risk for NMSC could be higher.8,11 Although the literature lacks specific recommendations for pilots, it is reasonable to screen pilots once per year to better assess their individual risk and encourage diligent use of sunscreen and sun-protective measures when flying. It also may be important to advocate for the development of engineering controls that decrease UVR transmittance through windscreens, particularly for aircraft flying at higher altitudes for longer flights. More research is needed to determine if changes in circadian rhythm and decreases in melatonin increase skin cancer risk, which could impact how pilots’ schedules are managed. Together, we can ensure adequate surveillance, diagnosis, and treatment in this at-risk population.

- Roewert‐Huber J, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Stockfleth E, et al. Epidemiology and aetiology of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):47-51.

- Woolley SD, Hughes C. A young military pilot presents with a periocular basal cell carcinoma: a case report. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2013;11:435-437.

- Grayson JK, Lyons TJ. Cancer incidence in United States Air Force aircrew, 1975-89. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1996;67:101-104.

- Lea CS, Efird JT, Toland AE, et al. Melanoma incidence rates in active duty military personnel compared with a population-based registry in the United States, 2000-2007. Mil Med. 2014;179:247-253.

- Garland FC, White MR, Garland CF, et al. Occupational sunlight exposure and melanoma in the US Navy. Arc Environ Health. 1990;45:261-267.

- Zhou J, Enewold L, Zahm SH, et al. Melanoma incidence rates among whites in the US military. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:318-323.

- Active Duty Master Personnel File: Active Duty Tactical Operations Officers. Seaside, CA: Defense Manpower Data Center; August 31, 2017. Accessed September 22, 2017.

- Buja A, Lange JH, Perissinotto E, et al. Cancer incidence among male military and civil pilots and flight attendants: an analysis on published data. Toxicol Ind Health. 2005;21:273-282.

- Jansen HS, Oster CV, eds. Taking Flight: Education and Training for Aviation Careers. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997.

- About AFROTC Service Commitment. US Air Force ROTC website. https://www.afrotc.com/about/service. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- Sanlorenzo M, Wehner MR, Linos E, et al. The risk of melanoma in airline pilots and cabin crew: a meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:51-58.

- Ananthaswamy HN, Pierceall WE. Molecular mechanisms of ultraviolet radiation carcinogenesis. Photochem Photobiol. 1990;52:1119-1136.

- Nakagawara VB, Montgomery RW, Marshall WJ. Optical Radiation Transmittance of Aircraft Windscreens and Pilot Vision. Oklahoma City, OK: Federal Aviation Administration; 2007.

- Sanlorenzo M, Vujic I, Posch C, et al. The risk of melanoma in pilots and cabin crew: UV measurements in flying airplanes. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:450-452.

- Boice JD, Blettner M, Auvinen A. Epidemiologic studies of pilots and aircrew. Health Phys. 2000;79:576-584.

- Zeeb H, Hammer GP, Blettner M. Epidemiological investigations of aircrew: an occupational group with low-level cosmic radiation exposure [published online March 6, 2012]. J Radiol Prot. 2012;32:N15-N19.

- Stevens RG. Circadian disruption and breast cancer: from melatonin to clock genes. Epidemiology. 2005;16:254-258.

- Siu SW, Lau KW, Tam PC, et al. Melatonin and prostate cancer cell proliferation: interplay with castration, epidermal growth factor, and androgen sensitivity. Prostate. 2002;52:106-122.

- IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Painting, Firefighting, and Shiftwork. Lyon, France: World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010.

- Gaddameedhi S, Selby CP, Kaufmann WK, et al. Control of skin cancer by the circadian rhythm. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:18790-18795.

- Markova-Car EP, Jurišic´ D, Ilic´ N, et al. Running for time: circadian rhythms and melanoma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:8359-8368.

- Nicholas JS, Lackland DT, Butler GC, et al. Cosmic radiation and magnetic field exposure to airline flight crews. Am J Ind Med. 1998;34:574-580.

Military dermatologists are charged with caring for a diverse population of active-duty members, civilian dependents, and military retirees. Although certain risk factors for cutaneous malignancies are common in all of these groups, the active-duty population experiences unique exposures to be considered when determining their risk for skin cancer. One subset that may be at a higher risk is military pilots who fly at high altitudes on irregular schedules in austere environments. Through the unparalleled comradeship inherent in many military units, pilots “hear” from their fellow pilots that they are at increased risk for skin cancer. Do their occupational exposures translate into increased risk for cutaneous malignancy? This article will survey the literature pertaining to pilots and skin cancer so that all dermatologists may better care for this unique population.

Epidemiology

Anecdotally, we have observed basal cell carcinoma in pilots in their 20s and early 30s, earlier than would be expected in an otherwise healthy prescreened military population.1 Woolley and Hughes2 published a case report of skin cancer in a young military aviator. The patient was a 32-year-old male helicopter pilot with Fitzpatrick skin type II and no personal or family history of skin cancer who was diagnosed with a periocular nodular basal cell carcinoma. He deployed to locations with high UV radiation (UVR) indices, and his vacation time also was spent in such areas.2 UV radiation exposure and Fitzpatrick skin type are known risk factors across occupations, but are there special exposures that come with military aviation service?

To better understand the risk for malignancy in this special population, the US Air Force examined the rates of all cancer types among a cohort of flying versus nonflying officers.3 Aviation personnel showed increased incidence of testicular, bladder, and all-site cancers combined. Noticeably absent was a statistically significant increased risk for malignant melanoma (MM) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC). Other epidemiological studies examined the incidence rates of MM in the US Armed Forces compared with age- and race-matched civilian populations and showed mixed results: 2 studies showed increased risk,4,5 while a third showed decreased risk.6 Despite finding opposite results of MM rates in military members versus the civilian population, 2 of these studies showed US Air Force members to have higher rates of MM than those in the US Army or Navy.4,6 Interestingly, the air force has the highest number of pilots among all the services, with 4000 more pilots than the army and navy.7 Further studies are needed to determine if the higher air force MM rates occur in pilots.

Although there are mixed and limited data pertaining to military flight crews, there is more robust literature concerning civilian flight personnel. One meta-analysis pooled studies related to cancer risk in cabin crews and civil and military pilots.8 In military pilots, they found a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.43 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09-1.87) for MM and 1.80 (95% CI, 1.25-2.80) for NMSC. The SIRs were higher for male cabin attendants (3.42 and 7.46, respectively) and civil pilots (2.18 and 1.88, respectively). They also found the most common cause of mortality in civilian cabin crews was AIDS, possibly explaining the higher SIRs for all types of malignancy in that population.8 In the United States, many civilian pilots previously were military pilots9 who likely served in the military for at least 10 years.10 A 2015 meta-analysis of 19 studies of more than 266,000 civil pilots and aircrew members found an SIR for MM of 2.22 (95% CI, 1.67-2.93) for civil pilots and 2.09 (95% CI, 1.67-2.62) for aircrews, stating the risk for MM is at least twice that of the general population.11

Risk Factors

UV Radiation

These studies suggest flight duties increase the risk for cutaneous malignancy. UV radiation is a known risk factor for skin cancer.12 The main body of the aircraft may protect the cabin’s crew and passengers from UVR, but pilots are exposed to more UVR, especially in aircraft with larger windshields. A government study in 2007 examined the transmittance of UVR through windscreens of 8 aircraft: 3 commercial jets, 2 commercial propeller planes, 1 private jet, and 2 small propeller planes.13 UVB was attenuated by all the windscreens (<1% transmittance), but 43% to 54% of UVA was transmitted, with plastic windshields attenuating more than glass. Sanlorenzo et al14 measured UVA irradiance at the pilot’s seat of a turboprop aircraft at 30,000-ft altitude. They compared this exposure to a UVA tanning bed and estimated that 57 minutes of flight at 30,000-ft altitude was equivalent to 20 minutes inside a UVA tanning booth, a startling finding.14

Cosmic Radiation

Cosmic radiation consists of neutrons and gamma rays that originate outside Earth’s atmosphere. Pilots are exposed to higher doses of cosmic radiation than nonpilots, but the health effects are difficult to study. Boice et al15 described how factors such as altitude, latitude, and flight time determine pilots’ cumulative exposure. With longer flight times at higher altitudes, a pilot’s exposure to cosmic radiation is increasing over the years.15 A 2012 review found that aircrews have low-level cosmic radiation exposure. Despite increases in MM and NMSC in pilots and increased rates of breast cancer in female aircrew, overall cancer-related mortality was lower in flying versus nonflying controls.16 Thus, cosmic radiation may not be as onerous of an occupational hazard for pilots as has been postulated.

Altered Circadian Rhythms

Aviation duties, especially in the military, require irregular work schedules that repeatedly interfere with normal sleep-wake cycles, disrupt circadian rhythms, and lead to reduced melatonin levels.8 Evidence suggests that low levels of melatonin could increase the risk for breast and prostate cancer—both cancers that occur more frequently in female aircrew and male pilots, respectively—by reducing melatonin’s natural protective role in such malignancies.17,18 A World Health Organization working group categorized shift work as “probably carcinogenic” and cited alterations of melatonin levels, changes in other circadian rhythm–related gene pathways, and relative immunosuppression as likely causative factors.19 In a 2011 study, exposing mice to UVR during times when nucleotide excision repair mechanisms were at their lowest activity caused an increased rate of skin cancers.20 A 2014 review discussed how epidemiological studies of shift workers such as nurses, firefighters, pilots, and flight crews found contradictory data, but molecular studies show that circadian rhythm–linked repair and tumorigenesis mechanisms are altered by aberrations in the normal sleep-wake cycle.21

Cockpit Instrumentation

Electromagnetic energy from the flight instruments in the cockpit also could influence malignancy risk. Nicholas et al22 found magnetic field measurements within the cockpit to be 2 to 10 times that experienced within the home or office. However, no studies examining the health effects of cockpit flight instruments and magnetic fields were found.

Final Thoughts

It is important to counsel pilots on the generally recognized, nonaviation-specific risk factors of family history, skin type, and UVR exposure in the development of skin cancer. Additionally, it is important to explain the possible role of exposure to UVR at higher altitudes, cosmic radiation, and electromagnetic energy from cockpit instruments, as well as altered sleep-wake cycles. A pilot’s risk for MM may be twice that of matched controls, and the risk for NMSC could be higher.8,11 Although the literature lacks specific recommendations for pilots, it is reasonable to screen pilots once per year to better assess their individual risk and encourage diligent use of sunscreen and sun-protective measures when flying. It also may be important to advocate for the development of engineering controls that decrease UVR transmittance through windscreens, particularly for aircraft flying at higher altitudes for longer flights. More research is needed to determine if changes in circadian rhythm and decreases in melatonin increase skin cancer risk, which could impact how pilots’ schedules are managed. Together, we can ensure adequate surveillance, diagnosis, and treatment in this at-risk population.

Military dermatologists are charged with caring for a diverse population of active-duty members, civilian dependents, and military retirees. Although certain risk factors for cutaneous malignancies are common in all of these groups, the active-duty population experiences unique exposures to be considered when determining their risk for skin cancer. One subset that may be at a higher risk is military pilots who fly at high altitudes on irregular schedules in austere environments. Through the unparalleled comradeship inherent in many military units, pilots “hear” from their fellow pilots that they are at increased risk for skin cancer. Do their occupational exposures translate into increased risk for cutaneous malignancy? This article will survey the literature pertaining to pilots and skin cancer so that all dermatologists may better care for this unique population.

Epidemiology

Anecdotally, we have observed basal cell carcinoma in pilots in their 20s and early 30s, earlier than would be expected in an otherwise healthy prescreened military population.1 Woolley and Hughes2 published a case report of skin cancer in a young military aviator. The patient was a 32-year-old male helicopter pilot with Fitzpatrick skin type II and no personal or family history of skin cancer who was diagnosed with a periocular nodular basal cell carcinoma. He deployed to locations with high UV radiation (UVR) indices, and his vacation time also was spent in such areas.2 UV radiation exposure and Fitzpatrick skin type are known risk factors across occupations, but are there special exposures that come with military aviation service?

To better understand the risk for malignancy in this special population, the US Air Force examined the rates of all cancer types among a cohort of flying versus nonflying officers.3 Aviation personnel showed increased incidence of testicular, bladder, and all-site cancers combined. Noticeably absent was a statistically significant increased risk for malignant melanoma (MM) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC). Other epidemiological studies examined the incidence rates of MM in the US Armed Forces compared with age- and race-matched civilian populations and showed mixed results: 2 studies showed increased risk,4,5 while a third showed decreased risk.6 Despite finding opposite results of MM rates in military members versus the civilian population, 2 of these studies showed US Air Force members to have higher rates of MM than those in the US Army or Navy.4,6 Interestingly, the air force has the highest number of pilots among all the services, with 4000 more pilots than the army and navy.7 Further studies are needed to determine if the higher air force MM rates occur in pilots.

Although there are mixed and limited data pertaining to military flight crews, there is more robust literature concerning civilian flight personnel. One meta-analysis pooled studies related to cancer risk in cabin crews and civil and military pilots.8 In military pilots, they found a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.43 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09-1.87) for MM and 1.80 (95% CI, 1.25-2.80) for NMSC. The SIRs were higher for male cabin attendants (3.42 and 7.46, respectively) and civil pilots (2.18 and 1.88, respectively). They also found the most common cause of mortality in civilian cabin crews was AIDS, possibly explaining the higher SIRs for all types of malignancy in that population.8 In the United States, many civilian pilots previously were military pilots9 who likely served in the military for at least 10 years.10 A 2015 meta-analysis of 19 studies of more than 266,000 civil pilots and aircrew members found an SIR for MM of 2.22 (95% CI, 1.67-2.93) for civil pilots and 2.09 (95% CI, 1.67-2.62) for aircrews, stating the risk for MM is at least twice that of the general population.11

Risk Factors

UV Radiation

These studies suggest flight duties increase the risk for cutaneous malignancy. UV radiation is a known risk factor for skin cancer.12 The main body of the aircraft may protect the cabin’s crew and passengers from UVR, but pilots are exposed to more UVR, especially in aircraft with larger windshields. A government study in 2007 examined the transmittance of UVR through windscreens of 8 aircraft: 3 commercial jets, 2 commercial propeller planes, 1 private jet, and 2 small propeller planes.13 UVB was attenuated by all the windscreens (<1% transmittance), but 43% to 54% of UVA was transmitted, with plastic windshields attenuating more than glass. Sanlorenzo et al14 measured UVA irradiance at the pilot’s seat of a turboprop aircraft at 30,000-ft altitude. They compared this exposure to a UVA tanning bed and estimated that 57 minutes of flight at 30,000-ft altitude was equivalent to 20 minutes inside a UVA tanning booth, a startling finding.14

Cosmic Radiation

Cosmic radiation consists of neutrons and gamma rays that originate outside Earth’s atmosphere. Pilots are exposed to higher doses of cosmic radiation than nonpilots, but the health effects are difficult to study. Boice et al15 described how factors such as altitude, latitude, and flight time determine pilots’ cumulative exposure. With longer flight times at higher altitudes, a pilot’s exposure to cosmic radiation is increasing over the years.15 A 2012 review found that aircrews have low-level cosmic radiation exposure. Despite increases in MM and NMSC in pilots and increased rates of breast cancer in female aircrew, overall cancer-related mortality was lower in flying versus nonflying controls.16 Thus, cosmic radiation may not be as onerous of an occupational hazard for pilots as has been postulated.

Altered Circadian Rhythms

Aviation duties, especially in the military, require irregular work schedules that repeatedly interfere with normal sleep-wake cycles, disrupt circadian rhythms, and lead to reduced melatonin levels.8 Evidence suggests that low levels of melatonin could increase the risk for breast and prostate cancer—both cancers that occur more frequently in female aircrew and male pilots, respectively—by reducing melatonin’s natural protective role in such malignancies.17,18 A World Health Organization working group categorized shift work as “probably carcinogenic” and cited alterations of melatonin levels, changes in other circadian rhythm–related gene pathways, and relative immunosuppression as likely causative factors.19 In a 2011 study, exposing mice to UVR during times when nucleotide excision repair mechanisms were at their lowest activity caused an increased rate of skin cancers.20 A 2014 review discussed how epidemiological studies of shift workers such as nurses, firefighters, pilots, and flight crews found contradictory data, but molecular studies show that circadian rhythm–linked repair and tumorigenesis mechanisms are altered by aberrations in the normal sleep-wake cycle.21

Cockpit Instrumentation

Electromagnetic energy from the flight instruments in the cockpit also could influence malignancy risk. Nicholas et al22 found magnetic field measurements within the cockpit to be 2 to 10 times that experienced within the home or office. However, no studies examining the health effects of cockpit flight instruments and magnetic fields were found.

Final Thoughts

It is important to counsel pilots on the generally recognized, nonaviation-specific risk factors of family history, skin type, and UVR exposure in the development of skin cancer. Additionally, it is important to explain the possible role of exposure to UVR at higher altitudes, cosmic radiation, and electromagnetic energy from cockpit instruments, as well as altered sleep-wake cycles. A pilot’s risk for MM may be twice that of matched controls, and the risk for NMSC could be higher.8,11 Although the literature lacks specific recommendations for pilots, it is reasonable to screen pilots once per year to better assess their individual risk and encourage diligent use of sunscreen and sun-protective measures when flying. It also may be important to advocate for the development of engineering controls that decrease UVR transmittance through windscreens, particularly for aircraft flying at higher altitudes for longer flights. More research is needed to determine if changes in circadian rhythm and decreases in melatonin increase skin cancer risk, which could impact how pilots’ schedules are managed. Together, we can ensure adequate surveillance, diagnosis, and treatment in this at-risk population.

- Roewert‐Huber J, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Stockfleth E, et al. Epidemiology and aetiology of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):47-51.

- Woolley SD, Hughes C. A young military pilot presents with a periocular basal cell carcinoma: a case report. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2013;11:435-437.

- Grayson JK, Lyons TJ. Cancer incidence in United States Air Force aircrew, 1975-89. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1996;67:101-104.

- Lea CS, Efird JT, Toland AE, et al. Melanoma incidence rates in active duty military personnel compared with a population-based registry in the United States, 2000-2007. Mil Med. 2014;179:247-253.

- Garland FC, White MR, Garland CF, et al. Occupational sunlight exposure and melanoma in the US Navy. Arc Environ Health. 1990;45:261-267.

- Zhou J, Enewold L, Zahm SH, et al. Melanoma incidence rates among whites in the US military. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:318-323.

- Active Duty Master Personnel File: Active Duty Tactical Operations Officers. Seaside, CA: Defense Manpower Data Center; August 31, 2017. Accessed September 22, 2017.

- Buja A, Lange JH, Perissinotto E, et al. Cancer incidence among male military and civil pilots and flight attendants: an analysis on published data. Toxicol Ind Health. 2005;21:273-282.

- Jansen HS, Oster CV, eds. Taking Flight: Education and Training for Aviation Careers. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997.

- About AFROTC Service Commitment. US Air Force ROTC website. https://www.afrotc.com/about/service. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- Sanlorenzo M, Wehner MR, Linos E, et al. The risk of melanoma in airline pilots and cabin crew: a meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:51-58.

- Ananthaswamy HN, Pierceall WE. Molecular mechanisms of ultraviolet radiation carcinogenesis. Photochem Photobiol. 1990;52:1119-1136.

- Nakagawara VB, Montgomery RW, Marshall WJ. Optical Radiation Transmittance of Aircraft Windscreens and Pilot Vision. Oklahoma City, OK: Federal Aviation Administration; 2007.

- Sanlorenzo M, Vujic I, Posch C, et al. The risk of melanoma in pilots and cabin crew: UV measurements in flying airplanes. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:450-452.

- Boice JD, Blettner M, Auvinen A. Epidemiologic studies of pilots and aircrew. Health Phys. 2000;79:576-584.

- Zeeb H, Hammer GP, Blettner M. Epidemiological investigations of aircrew: an occupational group with low-level cosmic radiation exposure [published online March 6, 2012]. J Radiol Prot. 2012;32:N15-N19.

- Stevens RG. Circadian disruption and breast cancer: from melatonin to clock genes. Epidemiology. 2005;16:254-258.

- Siu SW, Lau KW, Tam PC, et al. Melatonin and prostate cancer cell proliferation: interplay with castration, epidermal growth factor, and androgen sensitivity. Prostate. 2002;52:106-122.

- IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Painting, Firefighting, and Shiftwork. Lyon, France: World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010.

- Gaddameedhi S, Selby CP, Kaufmann WK, et al. Control of skin cancer by the circadian rhythm. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:18790-18795.

- Markova-Car EP, Jurišic´ D, Ilic´ N, et al. Running for time: circadian rhythms and melanoma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:8359-8368.

- Nicholas JS, Lackland DT, Butler GC, et al. Cosmic radiation and magnetic field exposure to airline flight crews. Am J Ind Med. 1998;34:574-580.

- Roewert‐Huber J, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Stockfleth E, et al. Epidemiology and aetiology of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):47-51.

- Woolley SD, Hughes C. A young military pilot presents with a periocular basal cell carcinoma: a case report. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2013;11:435-437.

- Grayson JK, Lyons TJ. Cancer incidence in United States Air Force aircrew, 1975-89. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1996;67:101-104.

- Lea CS, Efird JT, Toland AE, et al. Melanoma incidence rates in active duty military personnel compared with a population-based registry in the United States, 2000-2007. Mil Med. 2014;179:247-253.

- Garland FC, White MR, Garland CF, et al. Occupational sunlight exposure and melanoma in the US Navy. Arc Environ Health. 1990;45:261-267.

- Zhou J, Enewold L, Zahm SH, et al. Melanoma incidence rates among whites in the US military. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:318-323.

- Active Duty Master Personnel File: Active Duty Tactical Operations Officers. Seaside, CA: Defense Manpower Data Center; August 31, 2017. Accessed September 22, 2017.

- Buja A, Lange JH, Perissinotto E, et al. Cancer incidence among male military and civil pilots and flight attendants: an analysis on published data. Toxicol Ind Health. 2005;21:273-282.

- Jansen HS, Oster CV, eds. Taking Flight: Education and Training for Aviation Careers. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997.

- About AFROTC Service Commitment. US Air Force ROTC website. https://www.afrotc.com/about/service. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- Sanlorenzo M, Wehner MR, Linos E, et al. The risk of melanoma in airline pilots and cabin crew: a meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:51-58.

- Ananthaswamy HN, Pierceall WE. Molecular mechanisms of ultraviolet radiation carcinogenesis. Photochem Photobiol. 1990;52:1119-1136.

- Nakagawara VB, Montgomery RW, Marshall WJ. Optical Radiation Transmittance of Aircraft Windscreens and Pilot Vision. Oklahoma City, OK: Federal Aviation Administration; 2007.

- Sanlorenzo M, Vujic I, Posch C, et al. The risk of melanoma in pilots and cabin crew: UV measurements in flying airplanes. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:450-452.

- Boice JD, Blettner M, Auvinen A. Epidemiologic studies of pilots and aircrew. Health Phys. 2000;79:576-584.

- Zeeb H, Hammer GP, Blettner M. Epidemiological investigations of aircrew: an occupational group with low-level cosmic radiation exposure [published online March 6, 2012]. J Radiol Prot. 2012;32:N15-N19.

- Stevens RG. Circadian disruption and breast cancer: from melatonin to clock genes. Epidemiology. 2005;16:254-258.

- Siu SW, Lau KW, Tam PC, et al. Melatonin and prostate cancer cell proliferation: interplay with castration, epidermal growth factor, and androgen sensitivity. Prostate. 2002;52:106-122.

- IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Painting, Firefighting, and Shiftwork. Lyon, France: World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010.

- Gaddameedhi S, Selby CP, Kaufmann WK, et al. Control of skin cancer by the circadian rhythm. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:18790-18795.

- Markova-Car EP, Jurišic´ D, Ilic´ N, et al. Running for time: circadian rhythms and melanoma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:8359-8368.

- Nicholas JS, Lackland DT, Butler GC, et al. Cosmic radiation and magnetic field exposure to airline flight crews. Am J Ind Med. 1998;34:574-580.

Practice Points

- Military and civilian pilots have an increased risk for melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer, likely due to unique occupational exposures.

- We recommend annual skin cancer screening for all pilots to help assess their individual risk.

- Pilots should be educated on their increased risk for skin cancer and encouraged to use sun-protective measures during their flying duties and leisure activities.

Major Changes in the American Board of Dermatology’s Certification Examination

Older dermatologists may recall (or may have expunged from memory) taking the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) certification examination at the Holiday Inn in Rosemont, Illinois. I remember schlepping a borrowed microscope from Denver, Colorado; penciling in answers to questions about slides projected on a screen; and having a proctor escort me to the bathroom. On the flight home, the pilot kept my microscope in the cockpit for safekeeping.

Much has changed since then. Today’s examination takes 1 day instead of 2, is in July instead of October, and airline security would never allow me to stow a microscope in the pilot’s cabin. The content of the examination also has evolved. No longer does one have to identify yeasts and fungi in culture—a subject I spotted the ABD and hoped for the best—and surgery is a much more prominent part of the examination.

Nevertheless, over the years the examination continued to emphasize book knowledge and visual pattern recognition. Although they are essential components of being an effective dermatologist, there are other important factors. Many of these can be classified under the term clinical judgment, the ability to make good decisions that take into account the individual patient and situation.

In 2013, the ABD Board of Directors began the process of making fundamental changes in the certification examination with the goal of making it a better test of clinical competence. The process has included matters such as finding the correct technical consultant for examination development and psychometrics, writing and vetting new types of questions, gathering input from program directors, and building the electronic infrastructure to support these changes.

The structure of the new examination is based on a natural progression of learning, from mastering the basics, to acquiring more advanced knowledge, to applying that knowledge in clinical situations. It consists of the following:

- BASIC Exam, a test of fundamentals obtained during the first year of dermatology residency

- CORE Exam, a modular examination emphasizing the more comprehensive knowledge base obtained during the second and third years of residency

- APPLIED Exam, a case-based examination testing ability to apply knowledge appropriately in clinical situations

These new examinations will replace the In-Training Exam and the current certification examination, beginning with the cohort of residents entering dermatology training in July 2017.

The BASIC Exam is designed to test fundamentals such as visual recognition of common diseases, management of uncomplicated conditions, and familiarity with standard procedures. The purposes of the examination are to measure progress, to identify residents who are having difficulty, and to ensure that residents actually master the basics that we sometimes take for granted that they know. It is not a pass/fail examination and thus technically is not part of certification. A detailed content outline for the BASIC Exam can be found on the ABD website.1 Because it is a new examination, it is anticipated that the content will be modified as we gain experience with it and obtain feedback from program directors as to how its usefulness may be improved.

The CORE Exam is designed to test a more advanced, clinically relevant knowledge base. It is part of the certification

The APPLIED Exam is the centerpiece of the new examinations and tests the ability to apply knowledge appropriately in clinical situations. It is case based and ranges from straightforward (most likely diagnosis based on examination) to complex (how to manage pemphigus not responding to the initial treatment in a patient with multiple comorbidities). It is designed to test skills such as knowing when additional information is needed and when it is not, recognizing when referral is indicated, modifying management depending on response to therapy, and recognizing and managing complications. The unique characteristics of an individual patient including patient preferences, ability to comprehend and communicate, comorbidities, financial considerations, and other concerns, will need to be taken into account. The APPLIED Exam will be given in July following completion of residency.

Writing knowledge-based questions with straightforward answers in a psychometrically valid format is actually rather challenging, as first-time question writers discover. Writing items (questions) that test clinical judgment is considerably more difficult. One of the challenges is ensuring that there truly is agreement about the answers. To ensure that there is consensus, we have initiated a new process in item vetting. Rather than sit around a table and come to consensus, a process that could be dominated by experts in a particular area or those with the strongest opinions, committees first vet new questions through a blinded review. Each committee member takes the “test” from home without knowledge of what is supposed to be the correct answer. The responses are anonymous, so members feel free to respond candidly. Then, at the in-person meeting, the anonymous blinded review responses are evaluated and the items are discussed. We have found the blinded review to be invaluable, not just for items testing judgment but for all items.

An enormous amount of work has been put into preparing for the new examinations. Item-writing committees have been working enthusiastically to develop questions. There also is a great deal of work that goes on beyond the ABD. The ABD must contract with vendors for the electronic item bank, editing, psychometrics quality control and scoring, electronic publishing of the examination, virtual dermatopathology, website software for examination registration and reporting, and proctoring. Although developing new examinations is a costly enterprise, the ABD is committed not to increase the financial burden for residents and can use reserve funds to defray new examination development expenses. To keep expenses low during training, we will not charge residents an examination fee for the CORE modules, though they will pay a modest proctoring fee to the proctoring vendor. Also, instead of traveling to Tampa, Florida, in July, candidates will take the APPLIED Exam at a nearby Pearson VUE test center.

It will be the end of an era. Perhaps some of us will feel a little nostalgia for the Rosemont Holiday Inn and the fungal cultures, but I doubt it. Sample items for the 3 examinations, content overviews, frequently asked questions, and more information about the Exam of the Future can be found on the ABD website.2

- Exam of the Future: content outline and blueprint for BASIC exam. American Board of Dermatology website. https://dlpgnf31z4a6s.cloudfront.net/media/151102/basic-exam-content-outline-08132017.pdf. Updated August 13, 2017. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- Exam of the Future information center. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/exam-of-the-future-information-center.aspx. Accessed September 12, 2017.

Older dermatologists may recall (or may have expunged from memory) taking the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) certification examination at the Holiday Inn in Rosemont, Illinois. I remember schlepping a borrowed microscope from Denver, Colorado; penciling in answers to questions about slides projected on a screen; and having a proctor escort me to the bathroom. On the flight home, the pilot kept my microscope in the cockpit for safekeeping.

Much has changed since then. Today’s examination takes 1 day instead of 2, is in July instead of October, and airline security would never allow me to stow a microscope in the pilot’s cabin. The content of the examination also has evolved. No longer does one have to identify yeasts and fungi in culture—a subject I spotted the ABD and hoped for the best—and surgery is a much more prominent part of the examination.

Nevertheless, over the years the examination continued to emphasize book knowledge and visual pattern recognition. Although they are essential components of being an effective dermatologist, there are other important factors. Many of these can be classified under the term clinical judgment, the ability to make good decisions that take into account the individual patient and situation.

In 2013, the ABD Board of Directors began the process of making fundamental changes in the certification examination with the goal of making it a better test of clinical competence. The process has included matters such as finding the correct technical consultant for examination development and psychometrics, writing and vetting new types of questions, gathering input from program directors, and building the electronic infrastructure to support these changes.

The structure of the new examination is based on a natural progression of learning, from mastering the basics, to acquiring more advanced knowledge, to applying that knowledge in clinical situations. It consists of the following:

- BASIC Exam, a test of fundamentals obtained during the first year of dermatology residency

- CORE Exam, a modular examination emphasizing the more comprehensive knowledge base obtained during the second and third years of residency

- APPLIED Exam, a case-based examination testing ability to apply knowledge appropriately in clinical situations

These new examinations will replace the In-Training Exam and the current certification examination, beginning with the cohort of residents entering dermatology training in July 2017.

The BASIC Exam is designed to test fundamentals such as visual recognition of common diseases, management of uncomplicated conditions, and familiarity with standard procedures. The purposes of the examination are to measure progress, to identify residents who are having difficulty, and to ensure that residents actually master the basics that we sometimes take for granted that they know. It is not a pass/fail examination and thus technically is not part of certification. A detailed content outline for the BASIC Exam can be found on the ABD website.1 Because it is a new examination, it is anticipated that the content will be modified as we gain experience with it and obtain feedback from program directors as to how its usefulness may be improved.

The CORE Exam is designed to test a more advanced, clinically relevant knowledge base. It is part of the certification

The APPLIED Exam is the centerpiece of the new examinations and tests the ability to apply knowledge appropriately in clinical situations. It is case based and ranges from straightforward (most likely diagnosis based on examination) to complex (how to manage pemphigus not responding to the initial treatment in a patient with multiple comorbidities). It is designed to test skills such as knowing when additional information is needed and when it is not, recognizing when referral is indicated, modifying management depending on response to therapy, and recognizing and managing complications. The unique characteristics of an individual patient including patient preferences, ability to comprehend and communicate, comorbidities, financial considerations, and other concerns, will need to be taken into account. The APPLIED Exam will be given in July following completion of residency.

Writing knowledge-based questions with straightforward answers in a psychometrically valid format is actually rather challenging, as first-time question writers discover. Writing items (questions) that test clinical judgment is considerably more difficult. One of the challenges is ensuring that there truly is agreement about the answers. To ensure that there is consensus, we have initiated a new process in item vetting. Rather than sit around a table and come to consensus, a process that could be dominated by experts in a particular area or those with the strongest opinions, committees first vet new questions through a blinded review. Each committee member takes the “test” from home without knowledge of what is supposed to be the correct answer. The responses are anonymous, so members feel free to respond candidly. Then, at the in-person meeting, the anonymous blinded review responses are evaluated and the items are discussed. We have found the blinded review to be invaluable, not just for items testing judgment but for all items.

An enormous amount of work has been put into preparing for the new examinations. Item-writing committees have been working enthusiastically to develop questions. There also is a great deal of work that goes on beyond the ABD. The ABD must contract with vendors for the electronic item bank, editing, psychometrics quality control and scoring, electronic publishing of the examination, virtual dermatopathology, website software for examination registration and reporting, and proctoring. Although developing new examinations is a costly enterprise, the ABD is committed not to increase the financial burden for residents and can use reserve funds to defray new examination development expenses. To keep expenses low during training, we will not charge residents an examination fee for the CORE modules, though they will pay a modest proctoring fee to the proctoring vendor. Also, instead of traveling to Tampa, Florida, in July, candidates will take the APPLIED Exam at a nearby Pearson VUE test center.

It will be the end of an era. Perhaps some of us will feel a little nostalgia for the Rosemont Holiday Inn and the fungal cultures, but I doubt it. Sample items for the 3 examinations, content overviews, frequently asked questions, and more information about the Exam of the Future can be found on the ABD website.2

Older dermatologists may recall (or may have expunged from memory) taking the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) certification examination at the Holiday Inn in Rosemont, Illinois. I remember schlepping a borrowed microscope from Denver, Colorado; penciling in answers to questions about slides projected on a screen; and having a proctor escort me to the bathroom. On the flight home, the pilot kept my microscope in the cockpit for safekeeping.

Much has changed since then. Today’s examination takes 1 day instead of 2, is in July instead of October, and airline security would never allow me to stow a microscope in the pilot’s cabin. The content of the examination also has evolved. No longer does one have to identify yeasts and fungi in culture—a subject I spotted the ABD and hoped for the best—and surgery is a much more prominent part of the examination.

Nevertheless, over the years the examination continued to emphasize book knowledge and visual pattern recognition. Although they are essential components of being an effective dermatologist, there are other important factors. Many of these can be classified under the term clinical judgment, the ability to make good decisions that take into account the individual patient and situation.

In 2013, the ABD Board of Directors began the process of making fundamental changes in the certification examination with the goal of making it a better test of clinical competence. The process has included matters such as finding the correct technical consultant for examination development and psychometrics, writing and vetting new types of questions, gathering input from program directors, and building the electronic infrastructure to support these changes.

The structure of the new examination is based on a natural progression of learning, from mastering the basics, to acquiring more advanced knowledge, to applying that knowledge in clinical situations. It consists of the following:

- BASIC Exam, a test of fundamentals obtained during the first year of dermatology residency

- CORE Exam, a modular examination emphasizing the more comprehensive knowledge base obtained during the second and third years of residency

- APPLIED Exam, a case-based examination testing ability to apply knowledge appropriately in clinical situations

These new examinations will replace the In-Training Exam and the current certification examination, beginning with the cohort of residents entering dermatology training in July 2017.

The BASIC Exam is designed to test fundamentals such as visual recognition of common diseases, management of uncomplicated conditions, and familiarity with standard procedures. The purposes of the examination are to measure progress, to identify residents who are having difficulty, and to ensure that residents actually master the basics that we sometimes take for granted that they know. It is not a pass/fail examination and thus technically is not part of certification. A detailed content outline for the BASIC Exam can be found on the ABD website.1 Because it is a new examination, it is anticipated that the content will be modified as we gain experience with it and obtain feedback from program directors as to how its usefulness may be improved.

The CORE Exam is designed to test a more advanced, clinically relevant knowledge base. It is part of the certification

The APPLIED Exam is the centerpiece of the new examinations and tests the ability to apply knowledge appropriately in clinical situations. It is case based and ranges from straightforward (most likely diagnosis based on examination) to complex (how to manage pemphigus not responding to the initial treatment in a patient with multiple comorbidities). It is designed to test skills such as knowing when additional information is needed and when it is not, recognizing when referral is indicated, modifying management depending on response to therapy, and recognizing and managing complications. The unique characteristics of an individual patient including patient preferences, ability to comprehend and communicate, comorbidities, financial considerations, and other concerns, will need to be taken into account. The APPLIED Exam will be given in July following completion of residency.

Writing knowledge-based questions with straightforward answers in a psychometrically valid format is actually rather challenging, as first-time question writers discover. Writing items (questions) that test clinical judgment is considerably more difficult. One of the challenges is ensuring that there truly is agreement about the answers. To ensure that there is consensus, we have initiated a new process in item vetting. Rather than sit around a table and come to consensus, a process that could be dominated by experts in a particular area or those with the strongest opinions, committees first vet new questions through a blinded review. Each committee member takes the “test” from home without knowledge of what is supposed to be the correct answer. The responses are anonymous, so members feel free to respond candidly. Then, at the in-person meeting, the anonymous blinded review responses are evaluated and the items are discussed. We have found the blinded review to be invaluable, not just for items testing judgment but for all items.

An enormous amount of work has been put into preparing for the new examinations. Item-writing committees have been working enthusiastically to develop questions. There also is a great deal of work that goes on beyond the ABD. The ABD must contract with vendors for the electronic item bank, editing, psychometrics quality control and scoring, electronic publishing of the examination, virtual dermatopathology, website software for examination registration and reporting, and proctoring. Although developing new examinations is a costly enterprise, the ABD is committed not to increase the financial burden for residents and can use reserve funds to defray new examination development expenses. To keep expenses low during training, we will not charge residents an examination fee for the CORE modules, though they will pay a modest proctoring fee to the proctoring vendor. Also, instead of traveling to Tampa, Florida, in July, candidates will take the APPLIED Exam at a nearby Pearson VUE test center.

It will be the end of an era. Perhaps some of us will feel a little nostalgia for the Rosemont Holiday Inn and the fungal cultures, but I doubt it. Sample items for the 3 examinations, content overviews, frequently asked questions, and more information about the Exam of the Future can be found on the ABD website.2

- Exam of the Future: content outline and blueprint for BASIC exam. American Board of Dermatology website. https://dlpgnf31z4a6s.cloudfront.net/media/151102/basic-exam-content-outline-08132017.pdf. Updated August 13, 2017. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- Exam of the Future information center. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/exam-of-the-future-information-center.aspx. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- Exam of the Future: content outline and blueprint for BASIC exam. American Board of Dermatology website. https://dlpgnf31z4a6s.cloudfront.net/media/151102/basic-exam-content-outline-08132017.pdf. Updated August 13, 2017. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- Exam of the Future information center. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/exam-of-the-future-information-center.aspx. Accessed September 12, 2017.

Melanotrichoblastoma: A Rare Pigmented Variant of Trichoblastoma

Trichoblastomas are rare cutaneous tumors that recapitulate the germinative hair bulb and the surrounding mesenchyme. Although benign, they can present diagnostic difficulties for both the clinician and pathologist because of their rarity and overlap both clinically and microscopically with other follicular neoplasms as well as basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Several classification schemes for hair follicle neoplasms have been established based on the relative proportions of epithelial and mesenchymal components as well as stromal inductive change, but nomenclature continues to be problematic, as individual neoplasms show varying degrees of differentiation that do not always uniformly fit within these categories.1,2 One of these established categories is a pigmented trichoblastoma.3 An exceedingly rare variant of a pigmented trichoblastoma referred to as melanotrichoblastoma was first described in 20024 and has only been documented in 3 cases, according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term melanotrichoblastoma.4-6 We report another case of this rare tumor and review the literature on this unique group of tumors.

Case Report

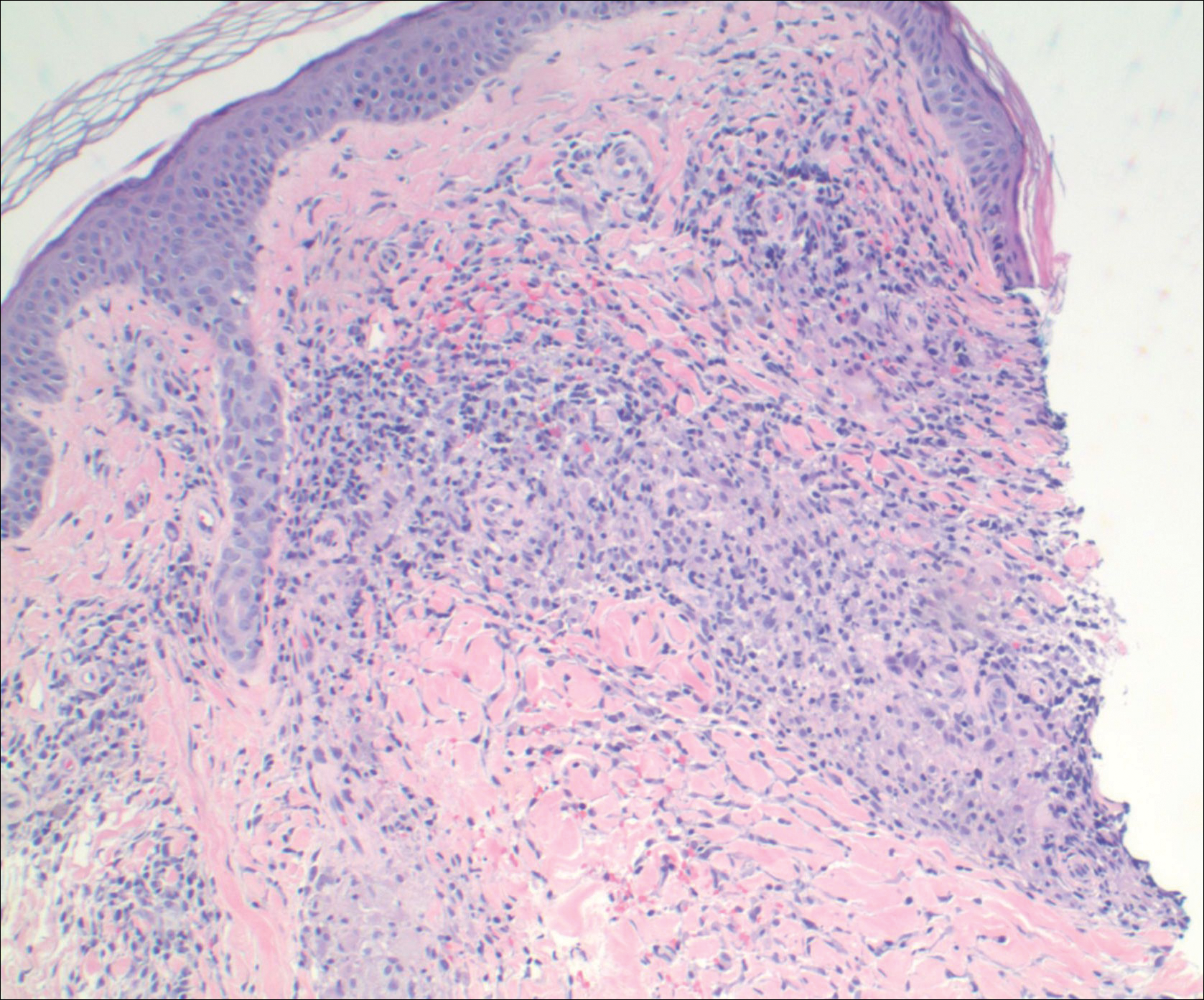

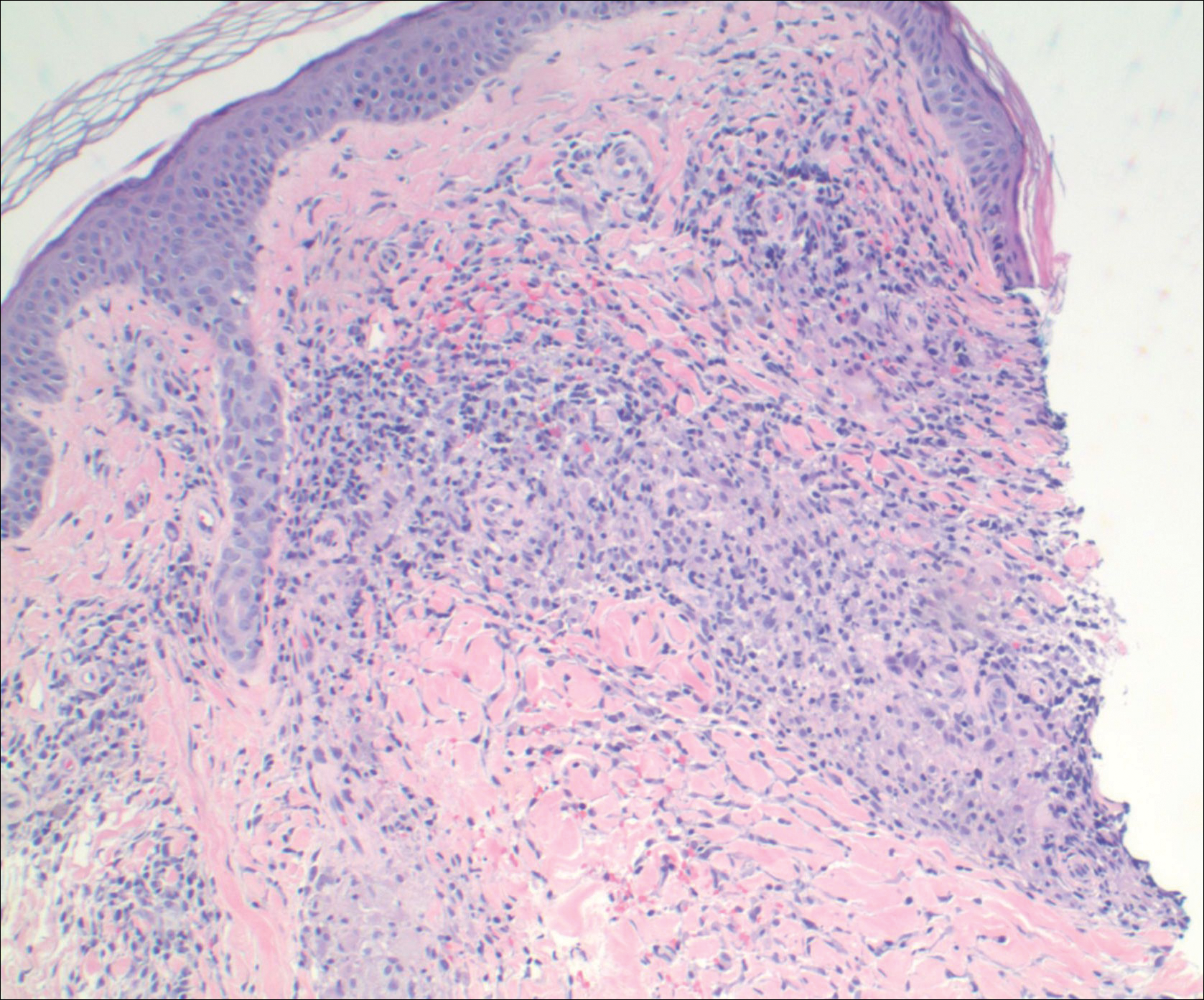

A 25-year-old white woman with a medical history of chronic migraines, myofascial syndrome, and Arnold-Chiari malformation type I presented to dermatology with a 1.5-cm, pedunculated, well-circumscribed tumor on the left side of the scalp (Figure 1). The tumor was grossly flesh colored with heterogeneous areas of dark pigmentation. Microscopic examination demonstrated that within the superficial and deep dermis were variable-sized nests of basaloid cells. Some of the nests had large central cystic spaces with brown pigment within some of these spaces and focal pigmentation of the basaloid cells (Figure 2A). Focal areas of keratinization were present. Mitotic figures were easily identified; however, no atypical mitotic figures were present. Areas of peripheral palisading were present but there was no retraction artifact. Connection to the overlying epidermis was not identified. Surrounding the basaloid nodules was a mildly cellular proliferation of cytologically bland spindle cells. Occasional pigment-laden macrophages were present in the dermis. Focal areas suggestive of papillary mesenchymal body formation were present (Figure 2B). Immunohistochemical staining for Melan-A was performed and demonstrated the presence of a prominent number of melanocytes in some of the nests (Figure 3) and minimal to no melanocytes in other nests. There was no evidence of a melanocytic lesion involving the overlying epidermis. Features of nevus sebaceus were not present. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin (CK) 20 was performed and demonstrated no notable number of Merkel cells within the lesion.

Comment

Overview of Trichoblastomas

Trichoblastomas most often present as solitary, flesh-colored, well-circumscribed, slow-growing tumors that usually progress in size over months to years. Although they may be present at any age, they most commonly occur in adults in the fifth to seventh decades of life and are equally distributed between males and females.7,8 They most often occur on the head and neck with a predilection for the scalp. Although they behave in a benign fashion, cases of malignant trichoblastomas have been reported.9

Histopathology

Histologically, these tumors are well circumscribed but unencapsulated and usually located within the deep dermis, often with extension into the subcutaneous tissue. An epidermal connection is not identified. The tumor typically is composed of variable-sized nests of basaloid cells surrounded by a variable cellular stromal component. Although peripheral palisading is present in the basaloid component, retraction artifact is not present. Several histologic variants of trichoblastomas have been reported including cribriform, racemiform, retiform, pigmented, giant, subcutaneous, rippled pattern, and clear cell.5 Pigmented trichoblastomas are histologically similar to typical trichoblastomas, except for the presence of large amounts of melanin deposited within and around the tumor nests.6 A melanotrichoblastoma is a rare variant of a pigmented trichoblastoma; pigment is present in the lesion and melanocytes are identified within the basaloid nests.

The stromal component of trichoblastomas may show areas of condensation associated with some of the basaloid cells, resembling an attempt at hair bulb formation. Staining for CD10 will be positive in these areas of papillary mesenchymal bodies.10

In an immunohistochemical study of 13 cases of trichoblastomas, there was diffuse positive staining for CK14 and CK17 in all cases (similar to BCC) and positive staining for CK19 in 70% (9/13) of cases compared to 21% (4/19) of BCC cases. Staining for CK8 and CK20 demonstrated the presence of numerous Merkel cells in all trichoblastomas but in none of the 19 cases of BCC tested.11 However, other studies have reported the presence of Merkel cells in only 42% to 70% of trichoblastomas.12,13 Despite the lack of Merkel cells in our case, the lesion was interpreted as a melanotrichoblastoma based on the histologic features in conjunction with the presence of the melanocytes.

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical and histologic differential diagnosis of trichoblastomas includes both trichoepithelioma and BCC. Clinically, all 3 lesions often are slow growing, dome shaped, and small in size (several millimeters), and are observed in the same anatomic distribution of the head and neck region. Furthermore, they often affect middle-aged to older individuals and those of Caucasian descent, though other ethnicities can be affected. Histologic evaluation often is necessary to differentiate between these 3 entities.

Histologically, trichoepitheliomas are composed of nodules of basaloid cells encircled by stromal spindle cells. Although there can be histologic overlap between trichoepitheliomas and trichoblastoma, trichoepitheliomas typically will display obvious features of hair follicle differentiation with the presence of small keratinous cysts and hair bulb structures, while trichoblastomas tend to display minimal changes suggestive of its hair follicle origin. Similar to trichoblastomas, BCC is composed of nests of basaloid cells; however, BCCs often demonstrate retraction artifact and connection to the overlying epidermis. In addition, BCCs typically demonstrate a fibromucinous stromal component that is distinct from the cellular stroma of trichoblastic tumors. Immunoperoxidase staining for androgen receptors has been reported to be positive in 78% (25/32) of BCCs and negative in trichoblastic tumors.14

Melanotrichoblastoma Differentiating Characteristics

An exceedingly rare variant of pigmented trichoblastoma is the melanotrichoblastoma. There are clinical and histologic similarities and differences between the reported cases. The first case, described by Kanitakis et al,4 reported a 32-year-old black woman with a 2-cm scalp mass that slowly enlarged over the course of 2 years. The second case, presented by Kim et al,5 described a 51-year-old Korean man with a subcutaneous 6-cm mass on the back that had been present and slowly enlarging over the course of 5 years. The third case, reported by Hung et al,6 described a 34-year-old Taiwanese man with a 1-cm, left-sided, temporal scalp mass present for 3 years, arising from a nevus sebaceous. Comparing these clinical findings with our case of a 25-year-old white woman with a 1.5-cm mass on the left side of the scalp, melanotrichoblastomas demonstrate a relatively similar age of onset in the early to middle-aged adult years. All 4 tumors were slow growing. Additionally, 3 of 4 cases demonstrated a predilection for the head, particularly the scalp, and grossly showed well-circumscribed lesions with notable pigmentation. Although age, size, location, and gross appearance were similar, a comparable ethnic and gender demographic was not identified.

Microscopic similarities between the 4 cases were present. Each case was characterized by a large, well-circumscribed, unencapsulated, basaloid tumor present in the lower dermis, with only 1 case having tumor cells occasionally reaching the undersurface of the epidermis. The tumor cells were monomorphic round-ovoid in appearance with scant cytoplasm. There was melanin pigment in the basaloid nests. The basaloid nests were surrounded by a proliferation of stromal cells. The mitotic rate was sparse in 2 cases, brisk in 1 case, and not discussed in 1 case. Melanocytes were identified in the basaloid nests in all 4 cases; however, in the current case, the melanocytes were seen in only some of the nests. None of the cases exhibited an overlying junctional melanocytic lesion, which would argue against a possible collision tumor or colonization of an epithelial lesion by a melanocytic lesion.

Although the histologic features of our cases are consistent with prior reports of melanotrichoblastoma, there is some question as to whether it represents a true variant of a pigmented trichoblastoma. There are relatively few articles in the literature that describe pigmented trichoblastomas, and of those, immunohistochemistry staining for melanocytes is uncommon. In one of the earliest descriptions of a pigmented trichoblastoma, dendritic melanocytes were present within the tumor lobules; however, the lesion was reported as a pigmented trichoblastoma and not a melanotrichoblastoma.3 It is possible that all pigmented trichoblastomas may contain some number of dendritic melanocytes, thus negating the existence of a melanotrichoblastoma as a true subtype of pigmented trichoblastomas. Additional study looking at multiple examples of pigmented trichoblastomas would be required to more definitively classify melanotrichoblastomas. It is important to appreciate that at least some cases of pigmented trichoblastomas may contain melanocytes and not to confuse the lesion as representing an example of colonization or collision tumor. A rare case of melanoma possibly arising from these dendritic melanocytes has been reported.15

Conclusion

Trichoblastomas are uncommon tumors of germinative hair bulb origin that can have several histologic variants. A well-documented subtype of trichoblastoma characterized by melanin deposits within and around tumor nests has been identified and classified as a pigmented trichoblastoma. Four cases of melanotrichoblastoma have been reported and represent a variant of a pigmented trichoblastoma characterized by the presence of melanocytes within the lesion. Whether they represent a true variant is of some debate and additional study is required. Although these tumors are exceedingly rare, it is important for the clinician and pathologist to be aware of this entity to prevent confusion with other similarly appearing follicular lesions, most notably BCCs, because of the difference in treatment and follow-up.

- Headington JT. Tumors of the hair follicle: a review. Am J Pathol. 1976; 85 : 479- 514 .

- Wong TY, Reed JA, Suster S, et al. Benign trichogenic tumors: a report of two cases supporting a simplified nomenclature. Histopathology. 1993;22:575-580.

- Aloi F, Tomasini C, Pippione M. Pigmented trichoblastoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:345-349.

- Kanitakis J, Brutzkus A, Butnaru AC, et al. Melanotrichoblastoma: immunohistochemical study of a variant of pigmented trichoblastoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:498-501.

- Kim DW, Lee JH, Kim I. Giant melanotrichoblastoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:E37-E40.

- Hung CT, Chiang CP, Gao HW, et al. Ripple-pattern melanotrichoblastoma arising within nevus sebaceous. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:665.

- Sau P, Lupton GP, Graham JH. Trichogerminoma: report of 14 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:357-365.

- Johnson TV, Wojno TH, Grossniklaus HE. Trichoblastoma of the eyelid. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27:E148-E149.

- Schulz T, Proske S, Hartschuh W, et al. High-grade trichoblasticcarcinoma arising in trichoblastoma: a rare adnexal neoplasm often showing metastatic spread. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:9-16.

- Aslani FS, Akbarzadeh-Jahromi M, Jowkar F. Value of CD10 expression in differentiating cutaneous basal from squamous cell carcinomas and basal cell carcinoma from trichoepithelioma. Iran J Med Sci. 2013;38:100-106.

- Kurzen H, Esposito L, Langbein L, et al. Cytokeratins as markers of follicular differentiation: an immunohistochemical study of trichoblastoma and basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:501-509.

- Schulz T, Hartschuh W. Merkel cells are absent in basal cell carcinoma but frequently found in trichoblastomas. an immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 1997;24:14-24.

- McNiff JM, Eisen RN, Glusac EJ. Immunohistochemical comparison of cutaneous lymphadenoma, trichoblastoma, and basal cell carcinoma: support for classification of lymphadenoma as a variant of trichoblastoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:119-124.

- Izikson L, Bhan A, Zembowicz A. Androgen receptor expression helps to differentiate basal cell carcinoma from benign trichoblastic tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:91-95.

- Benaim G, Castillo C, Houang M, et al. Melanoma arising from a long standing pigmented trichoblastoma: clinicopathologic study with complementary aCGH/mutation analysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:E146-E151.

Trichoblastomas are rare cutaneous tumors that recapitulate the germinative hair bulb and the surrounding mesenchyme. Although benign, they can present diagnostic difficulties for both the clinician and pathologist because of their rarity and overlap both clinically and microscopically with other follicular neoplasms as well as basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Several classification schemes for hair follicle neoplasms have been established based on the relative proportions of epithelial and mesenchymal components as well as stromal inductive change, but nomenclature continues to be problematic, as individual neoplasms show varying degrees of differentiation that do not always uniformly fit within these categories.1,2 One of these established categories is a pigmented trichoblastoma.3 An exceedingly rare variant of a pigmented trichoblastoma referred to as melanotrichoblastoma was first described in 20024 and has only been documented in 3 cases, according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term melanotrichoblastoma.4-6 We report another case of this rare tumor and review the literature on this unique group of tumors.

Case Report

A 25-year-old white woman with a medical history of chronic migraines, myofascial syndrome, and Arnold-Chiari malformation type I presented to dermatology with a 1.5-cm, pedunculated, well-circumscribed tumor on the left side of the scalp (Figure 1). The tumor was grossly flesh colored with heterogeneous areas of dark pigmentation. Microscopic examination demonstrated that within the superficial and deep dermis were variable-sized nests of basaloid cells. Some of the nests had large central cystic spaces with brown pigment within some of these spaces and focal pigmentation of the basaloid cells (Figure 2A). Focal areas of keratinization were present. Mitotic figures were easily identified; however, no atypical mitotic figures were present. Areas of peripheral palisading were present but there was no retraction artifact. Connection to the overlying epidermis was not identified. Surrounding the basaloid nodules was a mildly cellular proliferation of cytologically bland spindle cells. Occasional pigment-laden macrophages were present in the dermis. Focal areas suggestive of papillary mesenchymal body formation were present (Figure 2B). Immunohistochemical staining for Melan-A was performed and demonstrated the presence of a prominent number of melanocytes in some of the nests (Figure 3) and minimal to no melanocytes in other nests. There was no evidence of a melanocytic lesion involving the overlying epidermis. Features of nevus sebaceus were not present. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin (CK) 20 was performed and demonstrated no notable number of Merkel cells within the lesion.

Comment

Overview of Trichoblastomas

Trichoblastomas most often present as solitary, flesh-colored, well-circumscribed, slow-growing tumors that usually progress in size over months to years. Although they may be present at any age, they most commonly occur in adults in the fifth to seventh decades of life and are equally distributed between males and females.7,8 They most often occur on the head and neck with a predilection for the scalp. Although they behave in a benign fashion, cases of malignant trichoblastomas have been reported.9

Histopathology

Histologically, these tumors are well circumscribed but unencapsulated and usually located within the deep dermis, often with extension into the subcutaneous tissue. An epidermal connection is not identified. The tumor typically is composed of variable-sized nests of basaloid cells surrounded by a variable cellular stromal component. Although peripheral palisading is present in the basaloid component, retraction artifact is not present. Several histologic variants of trichoblastomas have been reported including cribriform, racemiform, retiform, pigmented, giant, subcutaneous, rippled pattern, and clear cell.5 Pigmented trichoblastomas are histologically similar to typical trichoblastomas, except for the presence of large amounts of melanin deposited within and around the tumor nests.6 A melanotrichoblastoma is a rare variant of a pigmented trichoblastoma; pigment is present in the lesion and melanocytes are identified within the basaloid nests.

The stromal component of trichoblastomas may show areas of condensation associated with some of the basaloid cells, resembling an attempt at hair bulb formation. Staining for CD10 will be positive in these areas of papillary mesenchymal bodies.10

In an immunohistochemical study of 13 cases of trichoblastomas, there was diffuse positive staining for CK14 and CK17 in all cases (similar to BCC) and positive staining for CK19 in 70% (9/13) of cases compared to 21% (4/19) of BCC cases. Staining for CK8 and CK20 demonstrated the presence of numerous Merkel cells in all trichoblastomas but in none of the 19 cases of BCC tested.11 However, other studies have reported the presence of Merkel cells in only 42% to 70% of trichoblastomas.12,13 Despite the lack of Merkel cells in our case, the lesion was interpreted as a melanotrichoblastoma based on the histologic features in conjunction with the presence of the melanocytes.

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical and histologic differential diagnosis of trichoblastomas includes both trichoepithelioma and BCC. Clinically, all 3 lesions often are slow growing, dome shaped, and small in size (several millimeters), and are observed in the same anatomic distribution of the head and neck region. Furthermore, they often affect middle-aged to older individuals and those of Caucasian descent, though other ethnicities can be affected. Histologic evaluation often is necessary to differentiate between these 3 entities.