User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitors in the Treatment of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

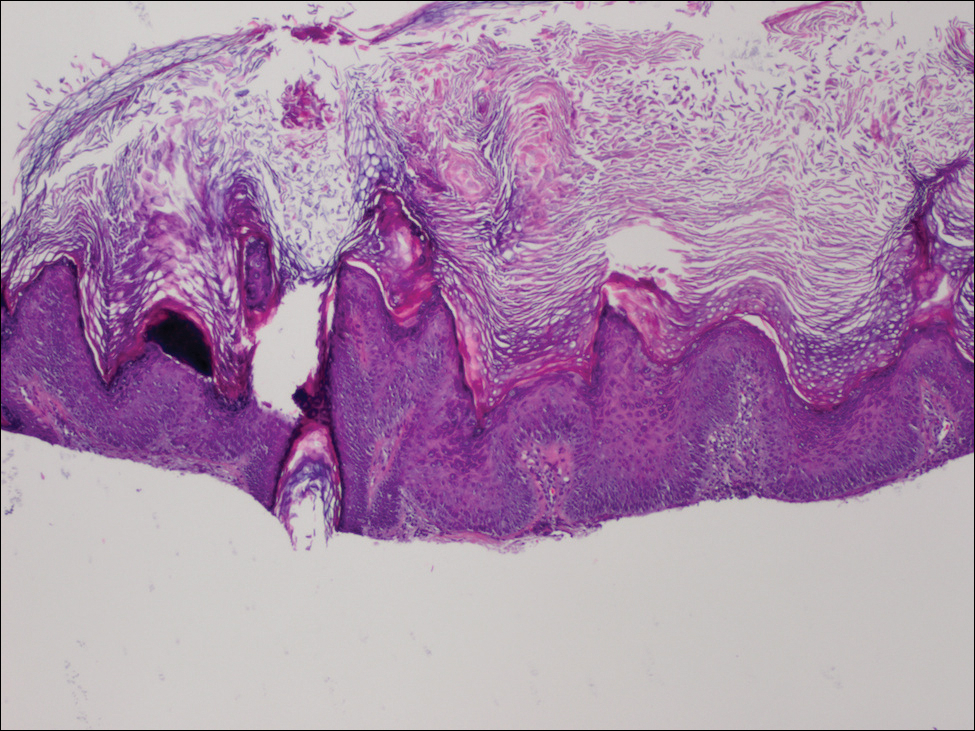

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a rare, life-threatening adverse drug reaction with an estimated incidence of 0.4 to 1.9 cases per million persons per year worldwide and an estimated mortality rate of 25% to 35%.1,2 This dermatologic emergency is characterized by extensive detachment of the epidermis and erosions of the mucous membranes secondary to massive keratinocyte cell death via apoptosis, evolving quickly into full-thickness epidermal necrosis.

Primary treatment of TEN includes (1) prompt discontinuation of the suspected medication; (2) rapid transfer to an intensive care unit, burn center, or other specialty unit; and (3) supportive care, including wound care, fluid and electrolyte maintenance, and treatment of infections. Aside from the primary treatment, controversy remains over the most effective adjunctive therapy for TEN, as none has proven consistent superiority over well-conducted primary treatment alone. Therefore, established therapeutic guidelines do not exist.1-3

The use of adjunctive systemic therapy in TEN (eg, corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin [IVIG], cyclosporine, plasmapheresis, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor) is based primarily on theories of pathogenesis, which unfortunately remain unclear. Activated CD8+ T cells are thought to increase the expression and production of granulysin, granzyme B, and perforins, leading to keratinocyte apoptosis. Fas ligand and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) also are implicated as secondary mediators of cell death via the inducible nitric oxide synthase pathway.1,4-6

Since TNF-α was found to be elevated in serum and blister fluid in patients with TEN,7,8 medications aimed at decreasing the TNF-α concentration, such as pentoxifylline (PTX) and thalidomide, have been attempted for treatment.9,10 Biologic inhibitors of TNF-α, such as infliximab and etanercept, are novel therapeutic options in the treatment of TEN, as numerous reports document their successful use in the treatment of this disease.11-24 The purpose of this study is to systematically review the current literature on the use of TNF-α antagonists in the treatment of TEN.

METHODS

A PubMed search of all available articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms toxic epidermal necrolysis and TNF-alpha and pentoxifylline or thalidomide or infliximab or etanercept or adalimumab was conducted.

RESULTS

Sixteen articles published between 1994 and 2014 were retrieved from PubMed and reviewed.9-24 Fourteen articles were case reports and case series involving the use of TNF-α inhibitors as either monotherapy, second-line agents, or in combination with other medications in the treatment of TEN, providing a total of 28 patients.9,11-23 Two articles were prospective trials, one evaluating the efficacy of thalidomide10 and the other infliximab24 in treating TEN. All studies implemented primary treatment (ie, prompt discontinuation of the suspected medication and aggressive supportive care) in addition to TNF-α inhibition.

Pentoxifylline

The first case report describing the use of an anti–TNF-α inhibitor for TEN was with PTX in 1994.9 Pentoxifylline, a vasoactive drug with immunomodulatory properties including the downregulation of TNF-α synthesis, was used to treat a 26-year-old woman with TEN on phenylhydantoin 15 days following resection of a grade II astrocytoma. The patient initially received intravenous N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (9 g once daily) and S-adenosyl-L-methionine (100 mg once daily) for antioxidant effects. On the second day of treatment, intravenous PTX (900 mg once daily) was added for TNF-α inhibition. Following PTX administration, the investigators reported quick stabilization of the eruption and achievement of reepithelialization after 7 days of therapy. Upon cessation of PTX therapy, a recurrence of generalized erythema occurred, suggesting a relapse of TEN; therefore, PTX was reinitiated for an additional 3 days, and the patient’s skin remained clear.9

Thalidomide

The earliest prospective trial we reviewed using anti–TNF-α therapy in TEN occurred in 1998 with thalidomide, a moderate inhibitor of TNF-α.10 In this randomized controlled trial, 22 TEN patients received either a 5-day course of thalidomide (400 mg once daily) or placebo. There was increased mortality in the thalidomide group (10/12 [83.3%]) versus the placebo group (3/10 [30.0%]). Additionally, the plasma TNF-α concentrations in the thalidomide group were higher than the control group. This study was stopped prematurely due to the excess mortality in the thalidomide group.10

Biologic TNF-α Antagonists

Following the PTX case report and the thalidomide trial, there was increased interest in using newer-generation TNF-α inhibitors, such as the monoclonal antibody infliximab or the fusion protein etanercept, in the treatment of TEN. To date, there are 10 known published case reports,11,12,15-21,23 3 case series,13,14,22 and 1 trial24 describing the use of these agents; however, treatment protocols vary. Categories of treatment protocols include the use of TNF-α inhibitors as monotherapy, following failure of other systemic agents, and in combination with other systemic therapies.

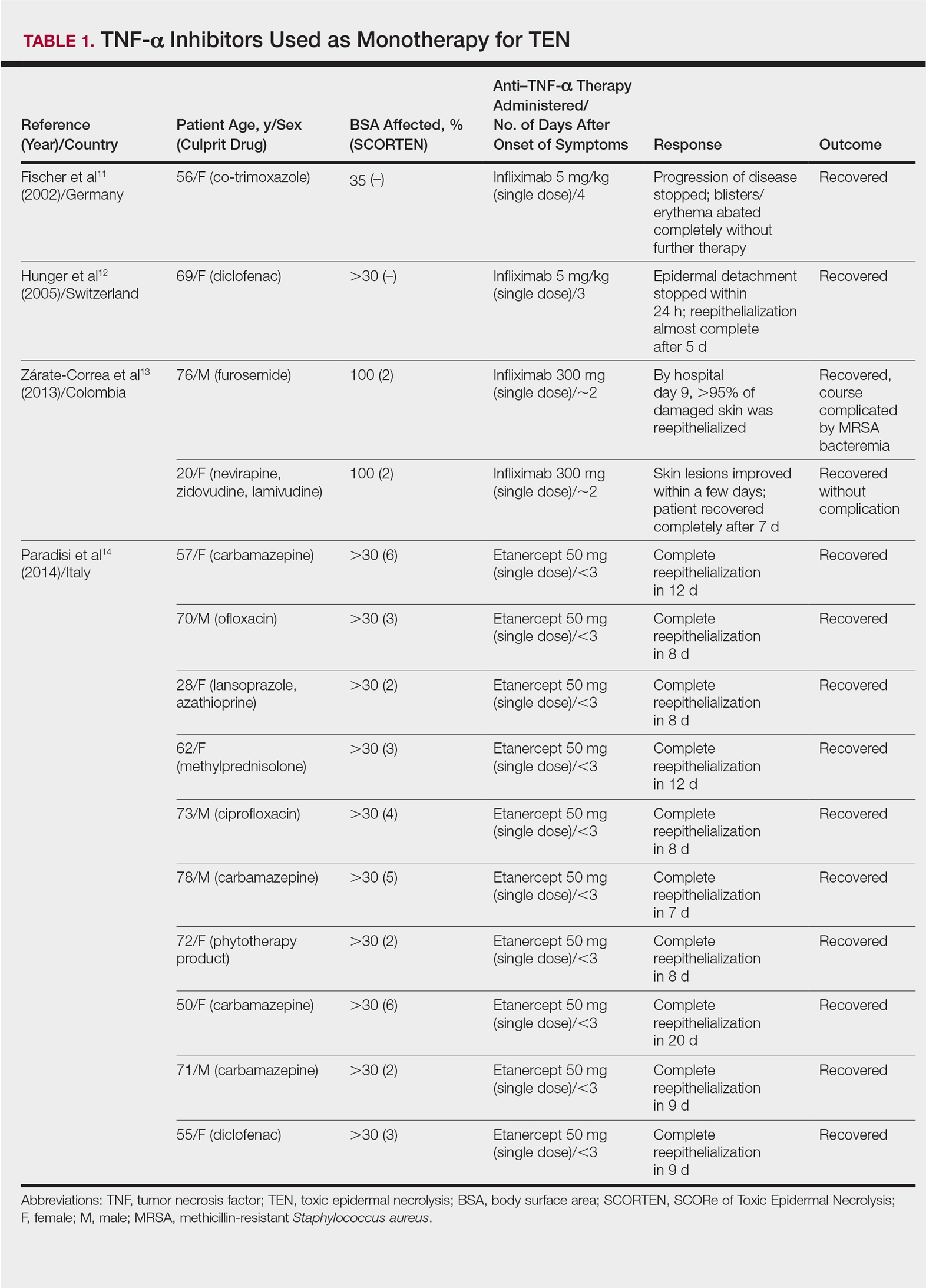

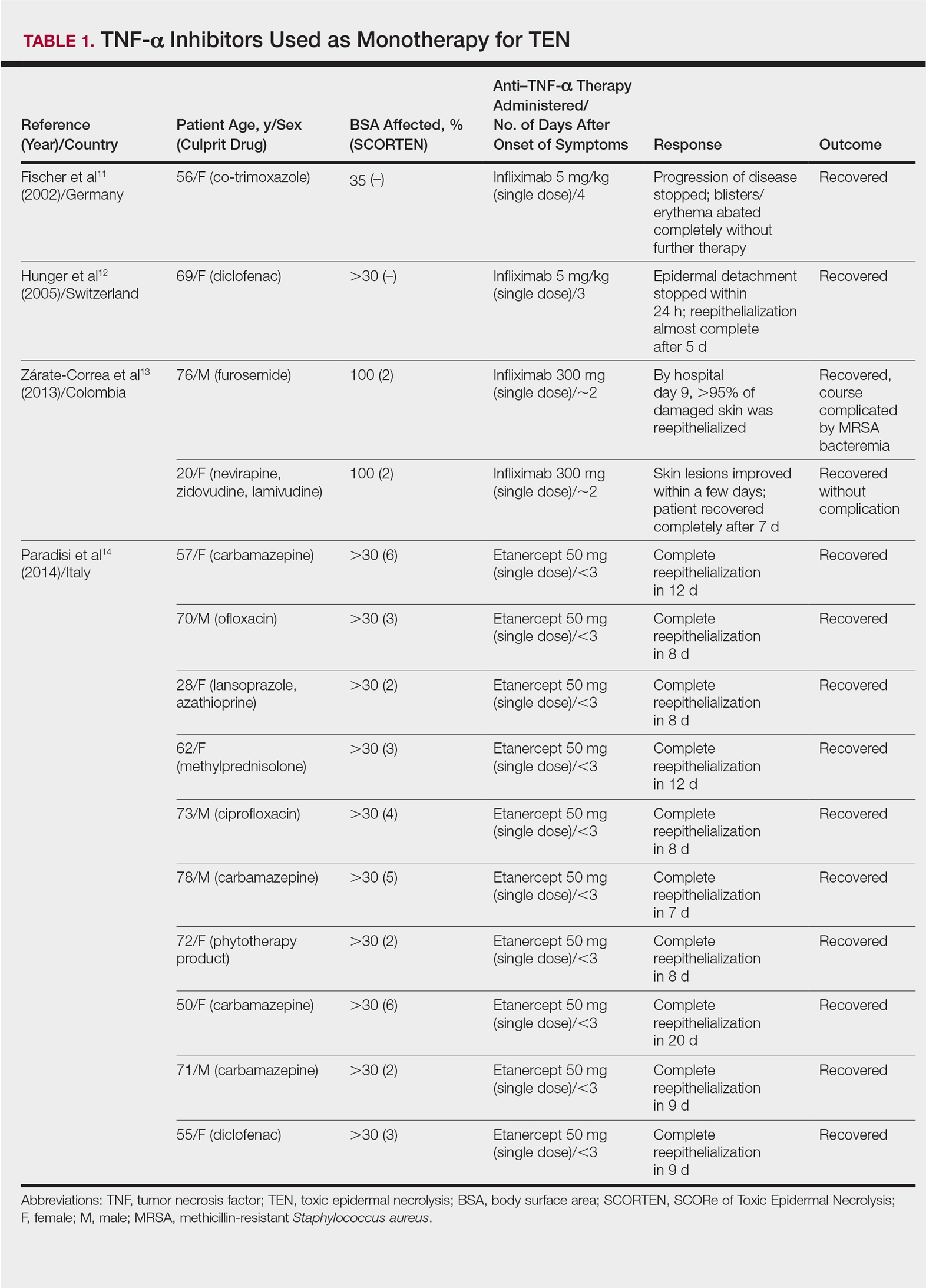

TNF-α Inhibitors as Monotherapy

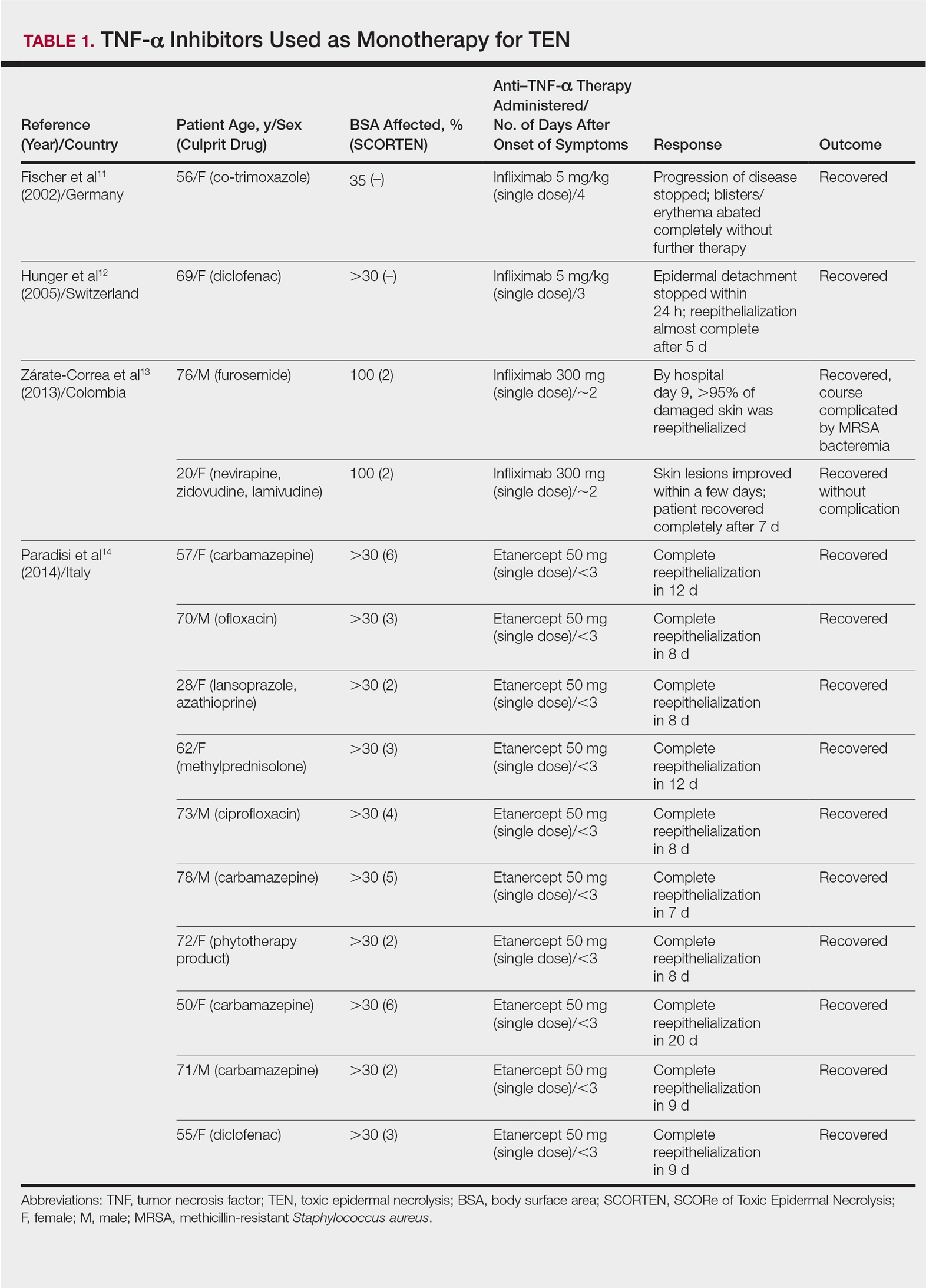

Review of the literature yielded 2 case reports using infliximab monotherapy11,12 and 2 case series using infliximab or etanercept monotherapy13,14 with a total of 14 patients (Table 1). Fischer et al11 was the first of these reports to describe a patient successfully treated with supportive care and a single dose of infliximab 5 mg/kg. The dose was given 4 days after the onset of symptoms, and the rapid progression of the disease was stopped, with complete recovery in less than 4 weeks.11 Hunger et al12 also described the successful treatment of a patient using a similar protocol: a single dose of infliximab 5 mg/kg given 3 days after symptom onset. Epidermal detachment was abated within 24 hours and the patient had almost complete reepithelialization within 5 days.12 In a case series published by Zárate-Correa et al,13 2 patients with near 100% body surface area involvement were successfully treated with a single dose of infliximab 300 mg. Although both of these patients experienced fairly rapid recoveries, one patient’s course was complicated by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia.13 Paradisi et al14 described 10 consecutive patients treated with a single dose of etanercept 50 mg given within 6 hours of hospital admission and within 72 hours of symptom onset. The SCORTEN (SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis) scale—a severity-of-illness assessment for TEN based on body surface area involvement, comorbidities, and metabolic abnormalities—was used to predict mortality in these patients. The investigators reported an expected mortality of 46.9%; however, the observed mortality was 0%, and there were no reported infections.14

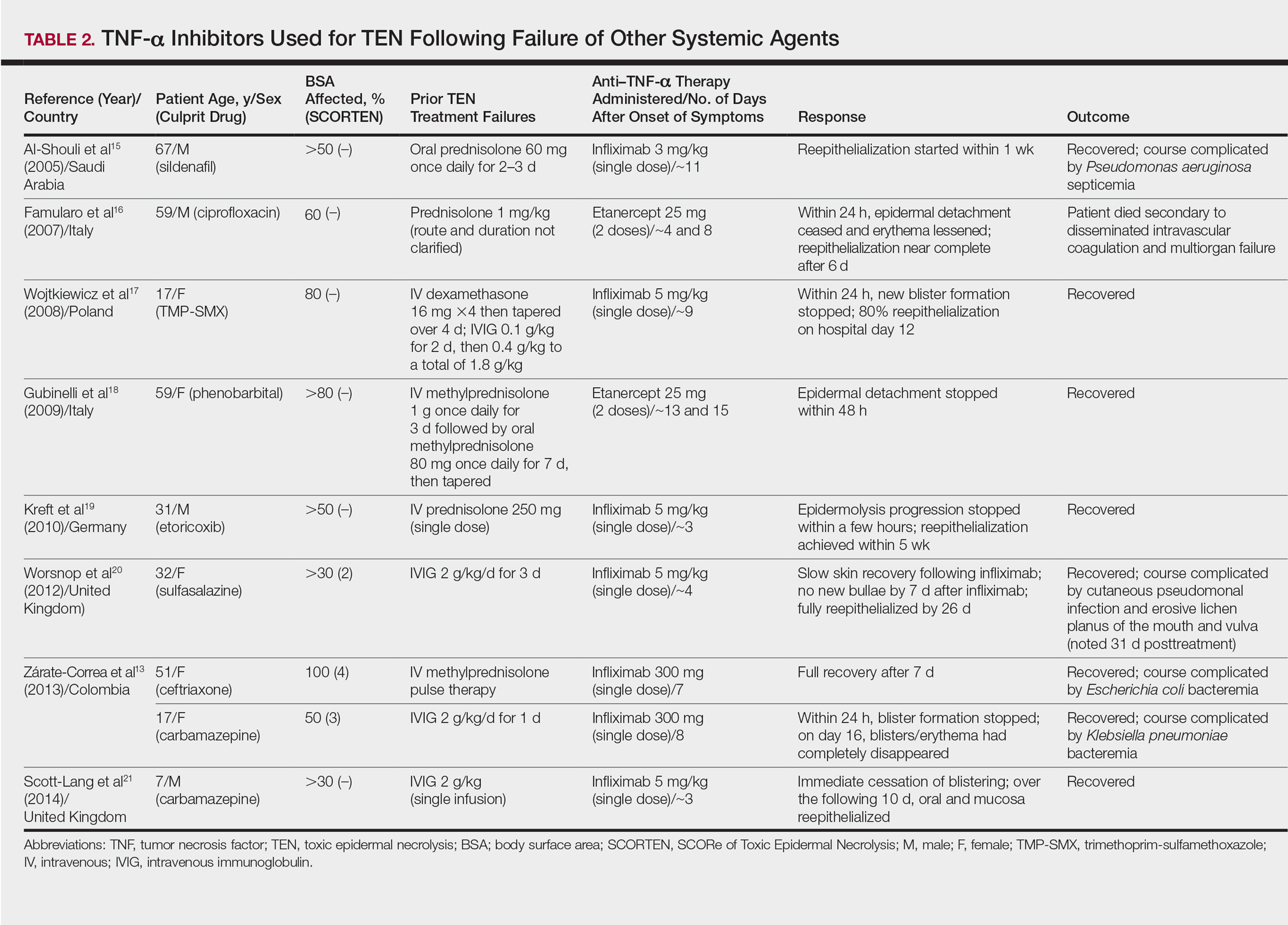

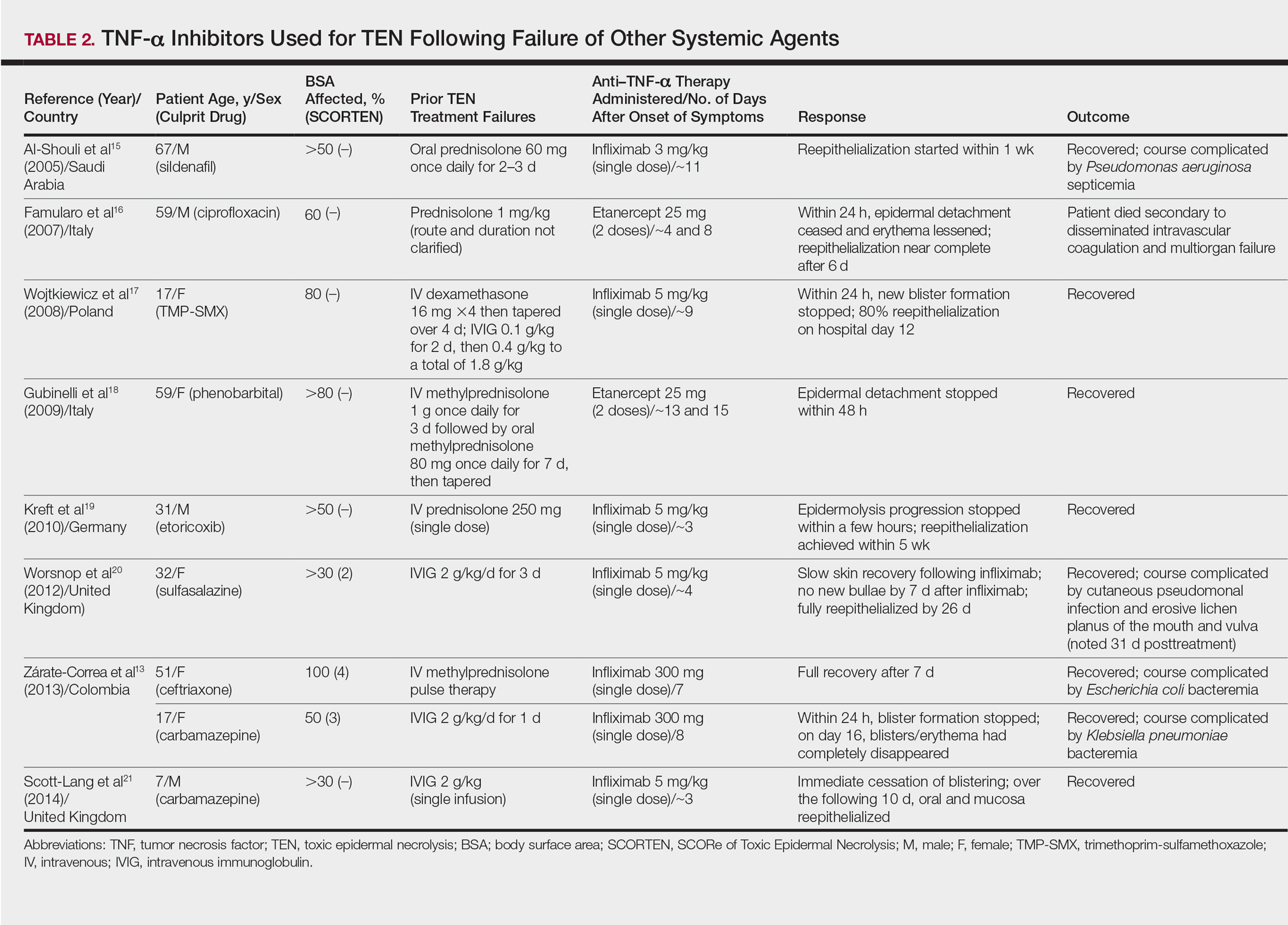

TNF-α Inhibitors Following Failure of Other Systemic Agents in TEN

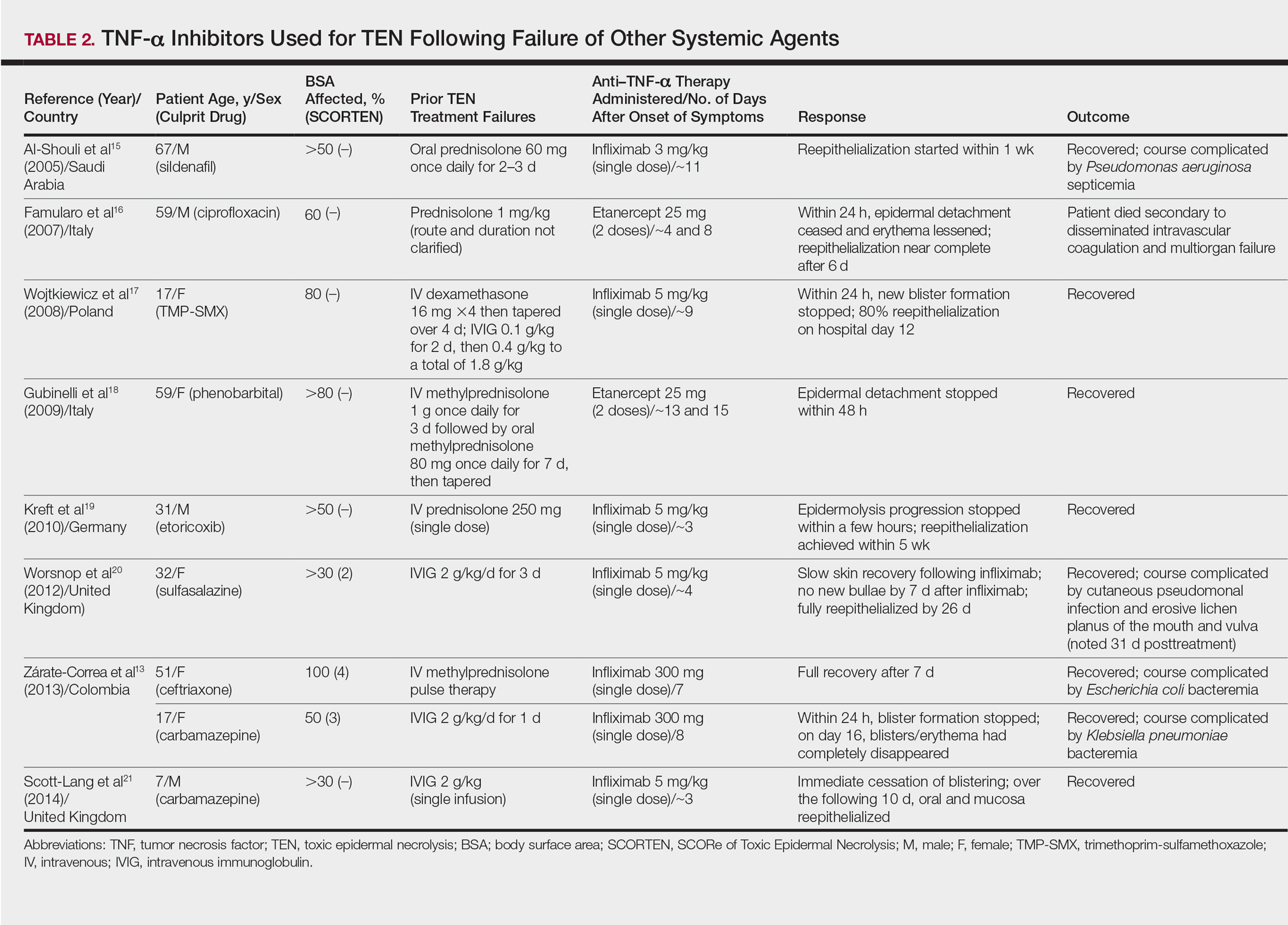

Seven case reports and 1 case series using anti–TNF-α therapy following failure of other systemic agents were reviewed for a total of 9 patients (3 pediatric/adolescent patients, 6 adult patients)(Table 2).13,15-21 Seven patients were treated with infliximab,13,15,17,19-21 and the remaining 2 patients were treated with etanercept.16,18 All patients were treated initially with corticosteroids and/or IVIG. In each case, anti–TNF-α therapy was introduced when prior treatment failed to halt the progression of TEN. Most reports claimed a rapid and beneficial response to anti–TNF-α therapy. Eight of 9 (88.9%) patients recovered.13,15,17-21 Famularo et al16 described 1 patient who was treated with 2 doses of etanercept following prednisolone but died on the tenth day of hospitalization secondary to disseminated intravascular coagulation and multiorgan failure; however, the patient reportedly had near-complete reepithelialization of the skin on the sixth day of the hospital course.16 Of the 8 surviving patients, 3 (37.5%) experienced hospital courses complicated by nosocomial gram-negative bacteremia, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae.13,15 Interestingly, a patient described by Worsnop et al20 developed erosive lichen planus of the mouth and vulva 31 days after infliximab infusion.

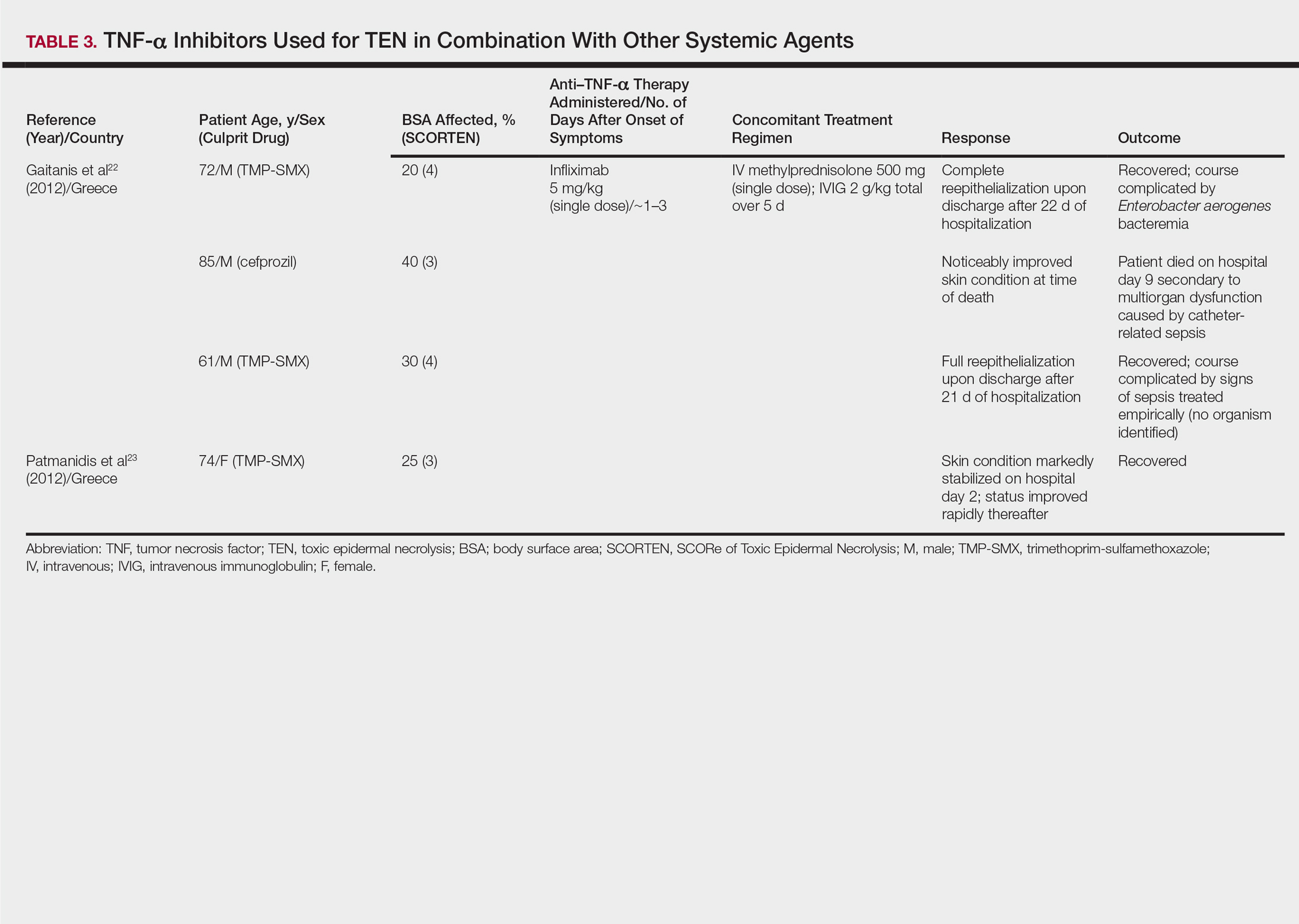

Combination of TNF-α Inhibitor With Other Systemic Agents in TEN

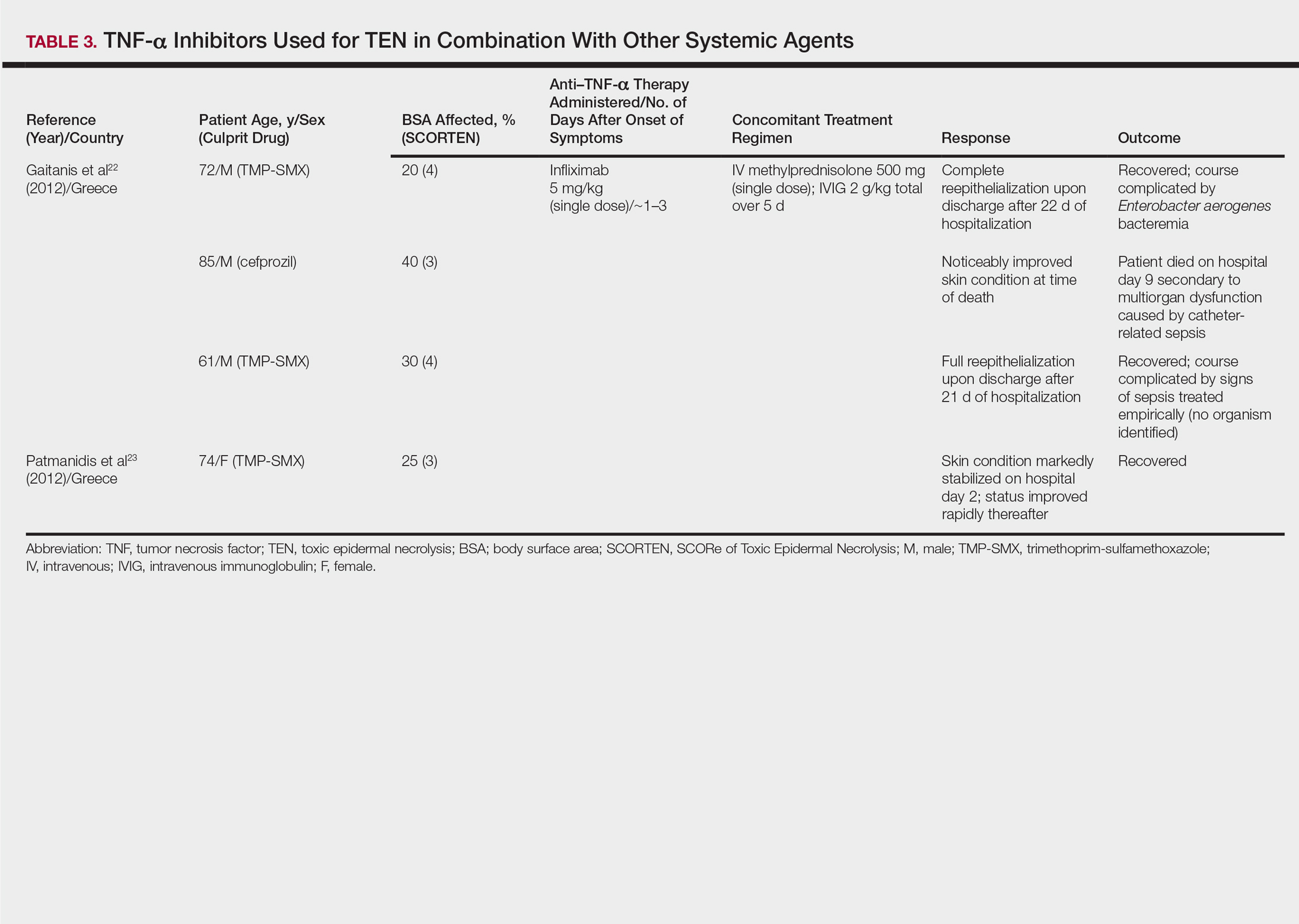

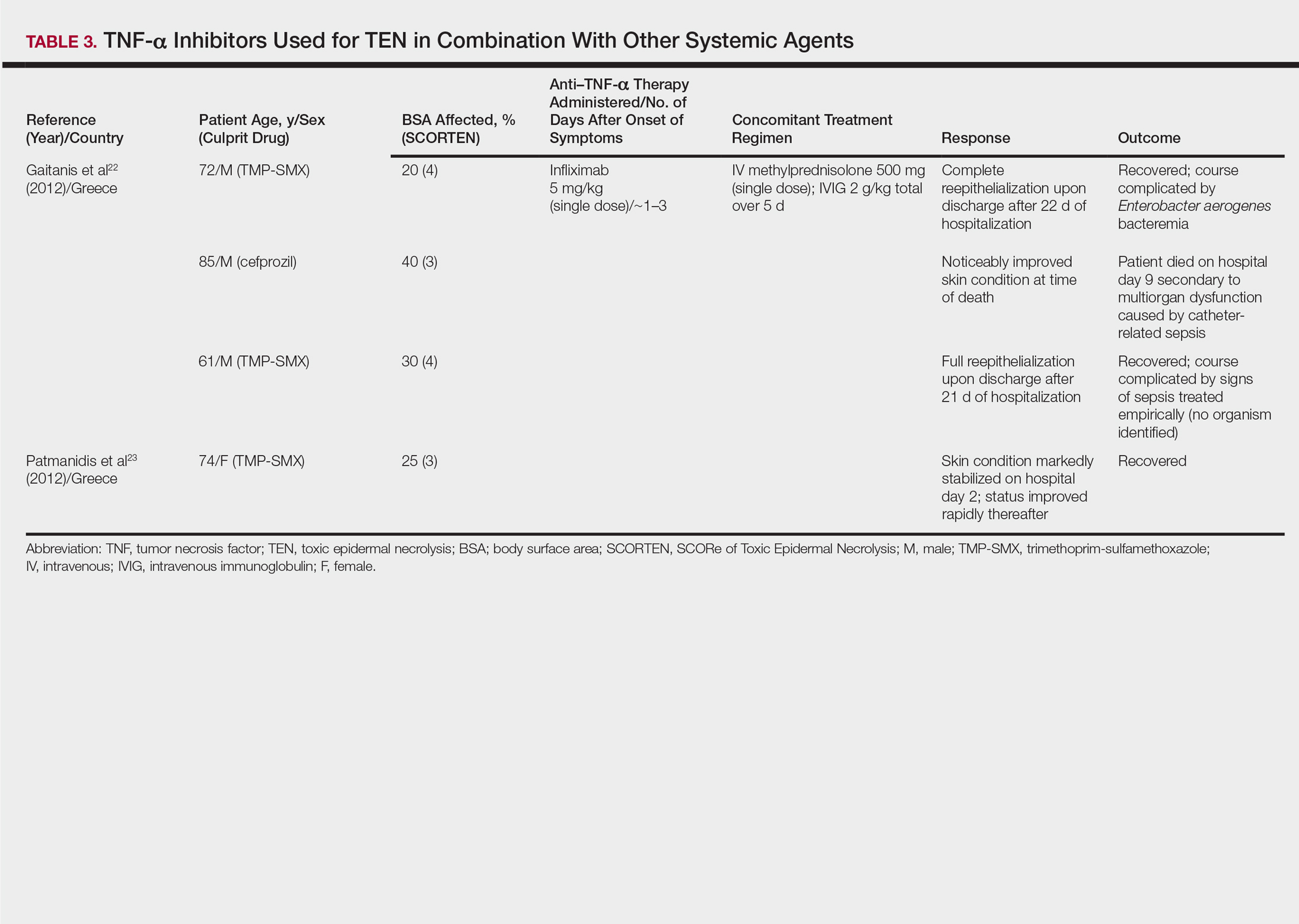

One case series22 and 1 case report23 using infliximab in combination with other systemic therapies were reviewed with a total of 4 patients (Table 3). Both reports utilized the same treatment protocol, which consisted of a single bolus of intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg followed by a single dose of infliximab 5 mg/kg and then IVIG 2 g/kg over 5 days. Three of 4 (75%) patients recovered.22,23 Gaitanis et al22 reported a patient who died on the ninth day of hospitalization secondary to multiorgan dysfunction caused by a catheter-related bacteremia. Similar to the patient described by Famularo et al,16 this patient also was noted to have remarkably improved skin prior to death. Two of the other 3 patients that survived had their hospital course complicated by infection, requiring antibiotics.22 In the Gaitanis et al22 series, the average predicted mortality according to a SCORTEN assessment was 50.8%; however, mortality was observed in 33.3% (1/3) of patients in the case series.

N-Acetylcysteine and Infliximab

The combination of NAC and infliximab was studied in a randomized controlled trial using TNF-α inhibition in TEN.24 In this study, 10 patients were admitted to a burn unit and treated with either 3 doses of intravenous NAC (150 mg/kg per dose) plus 1 dose of infliximab 5 mg/kg or NAC alone. Unlike some of the previously described articles, Paquet et al24 utilized an illness auxiliary score (IAS), which predicts both disease duration and mortality. An IAS was taken at admission and again 48 hours after completion of NAC and/or infliximab administration. The mean clinical IAS score was reported to have remained unchanged at treatment completion in the NAC group and slightly worsened in the NAC-infliximab group. One patient died in the NAC group and 2 patients died in the NAC-infliximab group, each due to infection. These fatalities corresponded to a mean mortality of 20% in the NAC-treated group and 40% for the NAC-infliximab group. To compare, the predicted mortalities based on the IAS were 20.4% and 21.4%, respectively.24

COMMENT

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibition in the treatment of TEN was first utilized in the 1990s with PTX and thalidomide.9,10 In 1994, PTX in addition to antioxidant therapy was found to successfully treat a 26-year-old woman with TEN attributed to anticonvulsant therapy.9 Other reports of PTX in the treatment of TEN were not found; however, there is a case series describing the successful treatment of 2 pediatric patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and SJS-TEN overlap with PTX.25 Thalidomide, however, proved detrimental to patients with TEN as evidenced by an increased mortality in the 1998 trial.10 Paradoxically, the treatment group was found to have increased rather than decreased TNF-α concentrations, which was hypothesized to be the cause of increased mortality. This finding furthered the theory that TNF-α is an important mediator in TEN pathogenesis and a potential novel target in disease management.10

Since the PTX case report and the thalidomide trial, many physicians have reported the beneficial effects of biologic TNF-α inhibitors in the course of TEN; however, most of the literature is composed of case reports and case series describing a small number of patients. Therefore, the beneficial effects of anti–TNF-α therapy in TEN cannot be conclusively derived. Furthermore, cases using TNF-α inhibitors in combination with or after other systemic agents complicate the effects of TNF-α inhibitors themselves. Most of these case reports and case series describe the beneficial effects of TNF-α inhibitors in TEN; however, it is important to remember that cases in which these agents were ineffective are less likely to be published. The strongest evidence for TNF-α inhibitor use in the treatment TEN comes from the Paradisi et al14 case series, which showed a decrease in expected mortality with etanercept monotherapy in a relatively large cohort of patients. However, when evaluated prospectively by Paquet et al,24 there was no benefit seen by adding infliximab to NAC therapy and possibly an increased mortality in the group treated with both agents.

In the cases reviewed, a total of 32 patients were treated with infliximab or etanercept, and of these patients there were 4 deaths (12.5%).16,22,24 Three deaths were attributed to infection and 1 was attributed to disseminated intravascular coagulation. Furthermore, infection complicated the hospital course of 9 (28.1%) patients.13,15,22,24 The bacteria cultured from these patients included methicillin-resistant S aureus, P aeruginosa, E coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, and K pneumoniae. Patients who received TNF-α antagonists in combination with or after other systemic immunosuppressants appeared to have a higher incidence of infections. All patients treated with TNF-α antagonists in TEN should undergo careful evaluation and monitoring for infections due to the immunosuppressant effect of these drugs.

In our review, a total of 3 pediatric/adolescent patients received a TNF-α inhibitor for the treatment of TEN.13,17,21 Two patients received infliximab as a second-line medication after failure of IVIG to arrest progression of disease13,17 and one patient received infliximab as a second-line medication after dexamethasone.21 Each of these patients recovered without any reported infections or long-term complications.

Although excluded from this review, both infliximab and etanercept have been reported to show benefit in acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis/TEN overlap.26,27 Interestingly, in postmarketing surveillance, rare reports have implicated both infliximab and etanercept in causing both SJS and TEN.28 Also, there have been case reports of adalimumab causing SJS, but no cases of it causing TEN were identified.29,30

CONCLUSION

Rapid discontinuation of the culprit drug and aggressive supportive care remain the primary treatment of TEN. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors as monotherapy or as second-line agents show promise in the treatment of this complex disease state in both the adult and pediatric populations. The risks of these potent immunosuppressants must be weighed, and if administered, patients must be closely monitored for infections. Additional studies are needed to further characterize the role of TNF-α inhibition in the treatment of TEN.

- Schwartz R, McDonough P, Lee B. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part I. introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:173-186.

- Schwartz R, McDonough P, Lee B. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part II. prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:187-203.

- Fernando S. The management of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;55:165-171.

- Paquet P, Paquet F, Saleh W, et al. Immunoregulatory effector cells in drug-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:413-417.

- Nassif A, Moslehi H, Le Gouvello S, et al. Evaluation of the potential role of cytokines in toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:850-855.

- Viard-Leveugle I, Gaide O, Jankovic D, et al. TNF-α and INF-γ are potential inducers of Fas-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis thought activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase in toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:489-498.

- Paquet P, Pierard G. Soluble fractions of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6 and of their receptors in toxic epidermal necrolysis: a comparison with second-degree burns. Int J Mol Med. 1998;1:459-462.

- Correia O, Delgado L, Barbosa I, et al. Increased interleukin 10, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin 6 levels in blister fluid of toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:58-62.

- Redondo P, Rutz de Erenchun F, Iglesias M, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis. treatment with pentoxifylline. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:688-689.

- Wolkenstein P, Latarjet J, Roujeau J, et al. Randomised comparison of thalidomide versus placebo in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Lancet. 1998;352:1586-1589.

- Fischer M, Fiedler E, Marsch W, et al. Antitumour necrosis factor-alpha antibodies (infliximab) in the treatment of a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:707-708.

- Hunger R, Hunziker T, Buettiker U, et al. Rapid resolution of toxic epidermal necrolysis with anti-TNF-alpha treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:923-924.

- Zárate-Correa LC, Carrillo-Gómez DC, Ramírez-Escobar AF, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis successfully treated with infliximab. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2013;23:61-63.

- Paradisi A, Abeni D, Bergamo F, et al. Etanercept therapy for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:278-283.

- Al-Shouli S, Bogusz M, Al Tufail M, et al. Toxic epidermal necrosis associated with high intake of sildenafil and its response to infliximab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85:534-553.

- Famularo G, Di Dona B, Canzona F, et al. Etanercept for toxic epidermal necrolysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1083-1084.

- Wojtkiewicz A, Wysocki M, Fortuna J, et al. Beneficial and rapid effect of infliximab on the course of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:420-421.

- Gubinelli E, Canzona F, Tonanzi T, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis successfully treated with etanercept. J Dermatol. 2009;36:150-153.

- Kreft B, Wohlrab J, Bramsiepe I, et al. Etoricoxib-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis: successful treatment with infliximab. J Dermatol. 2010;37:904-906.

- Worsnop F, Wee J, Moosa Y, et al. Reaction to biological drugs: infliximab for the treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis subsequently triggering erosive lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:879-881.

- Scott-Lang V, Tidman M, McKay D. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in a child successfully treated with infliximab. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:532-534.

- Gaitanis G, Spyridonos P, Patmanidis K, et al. Treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis with the combination of infliximab and high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins. Dermatology. 2012;224:134-139.

- Patmanidis K, Sidiras A, Dolianitis K, et al. Combination of infliximab and high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin for toxic epidermal necrolysis: successful treatment of an elderly patient. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2012;2012:915314.

- Paquet P, Jennes S, Rousseua A, et al. Effect of N-acetylcysteine combined with infliximab on toxic epidermal necrolysis: a proof-of-concept study. Burns. 2014;1:1-6.

- Sanclemente G, De le Rouche C, Escobar C, et al. Pentoxifylline in toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 1998;38:878-879.

- Meiss F, Helmbold P, Meykadeh N, et al. Overlap of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and toxic epidermal necrolysis: response to antitumor necrosis factor-alpha antibody infliximab: report of three cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:717-719.

- Sadighha A. Etanercept in the treatment of a patient with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis/toxic epidermal necrolysis: definition of a new model based on translational research. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:913-914.

- Borras-Blasco J, Navarro-Ruiz A, Borras C, et al. Adverse cutaneous reactions induced by TNF-α antagonist therapy. South Med J. 2009;102:1133-1140.

- Muna S, Lawrance I. Stevens-Johnson syndrome complicating adalimumab therapy in Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4449-4452.

- Mounach A, Rezgi A, Nouijai A, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome complicating adalimumab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis disease. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:1351-1353.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a rare, life-threatening adverse drug reaction with an estimated incidence of 0.4 to 1.9 cases per million persons per year worldwide and an estimated mortality rate of 25% to 35%.1,2 This dermatologic emergency is characterized by extensive detachment of the epidermis and erosions of the mucous membranes secondary to massive keratinocyte cell death via apoptosis, evolving quickly into full-thickness epidermal necrosis.

Primary treatment of TEN includes (1) prompt discontinuation of the suspected medication; (2) rapid transfer to an intensive care unit, burn center, or other specialty unit; and (3) supportive care, including wound care, fluid and electrolyte maintenance, and treatment of infections. Aside from the primary treatment, controversy remains over the most effective adjunctive therapy for TEN, as none has proven consistent superiority over well-conducted primary treatment alone. Therefore, established therapeutic guidelines do not exist.1-3

The use of adjunctive systemic therapy in TEN (eg, corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin [IVIG], cyclosporine, plasmapheresis, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor) is based primarily on theories of pathogenesis, which unfortunately remain unclear. Activated CD8+ T cells are thought to increase the expression and production of granulysin, granzyme B, and perforins, leading to keratinocyte apoptosis. Fas ligand and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) also are implicated as secondary mediators of cell death via the inducible nitric oxide synthase pathway.1,4-6

Since TNF-α was found to be elevated in serum and blister fluid in patients with TEN,7,8 medications aimed at decreasing the TNF-α concentration, such as pentoxifylline (PTX) and thalidomide, have been attempted for treatment.9,10 Biologic inhibitors of TNF-α, such as infliximab and etanercept, are novel therapeutic options in the treatment of TEN, as numerous reports document their successful use in the treatment of this disease.11-24 The purpose of this study is to systematically review the current literature on the use of TNF-α antagonists in the treatment of TEN.

METHODS

A PubMed search of all available articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms toxic epidermal necrolysis and TNF-alpha and pentoxifylline or thalidomide or infliximab or etanercept or adalimumab was conducted.

RESULTS

Sixteen articles published between 1994 and 2014 were retrieved from PubMed and reviewed.9-24 Fourteen articles were case reports and case series involving the use of TNF-α inhibitors as either monotherapy, second-line agents, or in combination with other medications in the treatment of TEN, providing a total of 28 patients.9,11-23 Two articles were prospective trials, one evaluating the efficacy of thalidomide10 and the other infliximab24 in treating TEN. All studies implemented primary treatment (ie, prompt discontinuation of the suspected medication and aggressive supportive care) in addition to TNF-α inhibition.

Pentoxifylline

The first case report describing the use of an anti–TNF-α inhibitor for TEN was with PTX in 1994.9 Pentoxifylline, a vasoactive drug with immunomodulatory properties including the downregulation of TNF-α synthesis, was used to treat a 26-year-old woman with TEN on phenylhydantoin 15 days following resection of a grade II astrocytoma. The patient initially received intravenous N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (9 g once daily) and S-adenosyl-L-methionine (100 mg once daily) for antioxidant effects. On the second day of treatment, intravenous PTX (900 mg once daily) was added for TNF-α inhibition. Following PTX administration, the investigators reported quick stabilization of the eruption and achievement of reepithelialization after 7 days of therapy. Upon cessation of PTX therapy, a recurrence of generalized erythema occurred, suggesting a relapse of TEN; therefore, PTX was reinitiated for an additional 3 days, and the patient’s skin remained clear.9

Thalidomide

The earliest prospective trial we reviewed using anti–TNF-α therapy in TEN occurred in 1998 with thalidomide, a moderate inhibitor of TNF-α.10 In this randomized controlled trial, 22 TEN patients received either a 5-day course of thalidomide (400 mg once daily) or placebo. There was increased mortality in the thalidomide group (10/12 [83.3%]) versus the placebo group (3/10 [30.0%]). Additionally, the plasma TNF-α concentrations in the thalidomide group were higher than the control group. This study was stopped prematurely due to the excess mortality in the thalidomide group.10

Biologic TNF-α Antagonists

Following the PTX case report and the thalidomide trial, there was increased interest in using newer-generation TNF-α inhibitors, such as the monoclonal antibody infliximab or the fusion protein etanercept, in the treatment of TEN. To date, there are 10 known published case reports,11,12,15-21,23 3 case series,13,14,22 and 1 trial24 describing the use of these agents; however, treatment protocols vary. Categories of treatment protocols include the use of TNF-α inhibitors as monotherapy, following failure of other systemic agents, and in combination with other systemic therapies.

TNF-α Inhibitors as Monotherapy

Review of the literature yielded 2 case reports using infliximab monotherapy11,12 and 2 case series using infliximab or etanercept monotherapy13,14 with a total of 14 patients (Table 1). Fischer et al11 was the first of these reports to describe a patient successfully treated with supportive care and a single dose of infliximab 5 mg/kg. The dose was given 4 days after the onset of symptoms, and the rapid progression of the disease was stopped, with complete recovery in less than 4 weeks.11 Hunger et al12 also described the successful treatment of a patient using a similar protocol: a single dose of infliximab 5 mg/kg given 3 days after symptom onset. Epidermal detachment was abated within 24 hours and the patient had almost complete reepithelialization within 5 days.12 In a case series published by Zárate-Correa et al,13 2 patients with near 100% body surface area involvement were successfully treated with a single dose of infliximab 300 mg. Although both of these patients experienced fairly rapid recoveries, one patient’s course was complicated by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia.13 Paradisi et al14 described 10 consecutive patients treated with a single dose of etanercept 50 mg given within 6 hours of hospital admission and within 72 hours of symptom onset. The SCORTEN (SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis) scale—a severity-of-illness assessment for TEN based on body surface area involvement, comorbidities, and metabolic abnormalities—was used to predict mortality in these patients. The investigators reported an expected mortality of 46.9%; however, the observed mortality was 0%, and there were no reported infections.14

TNF-α Inhibitors Following Failure of Other Systemic Agents in TEN

Seven case reports and 1 case series using anti–TNF-α therapy following failure of other systemic agents were reviewed for a total of 9 patients (3 pediatric/adolescent patients, 6 adult patients)(Table 2).13,15-21 Seven patients were treated with infliximab,13,15,17,19-21 and the remaining 2 patients were treated with etanercept.16,18 All patients were treated initially with corticosteroids and/or IVIG. In each case, anti–TNF-α therapy was introduced when prior treatment failed to halt the progression of TEN. Most reports claimed a rapid and beneficial response to anti–TNF-α therapy. Eight of 9 (88.9%) patients recovered.13,15,17-21 Famularo et al16 described 1 patient who was treated with 2 doses of etanercept following prednisolone but died on the tenth day of hospitalization secondary to disseminated intravascular coagulation and multiorgan failure; however, the patient reportedly had near-complete reepithelialization of the skin on the sixth day of the hospital course.16 Of the 8 surviving patients, 3 (37.5%) experienced hospital courses complicated by nosocomial gram-negative bacteremia, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae.13,15 Interestingly, a patient described by Worsnop et al20 developed erosive lichen planus of the mouth and vulva 31 days after infliximab infusion.

Combination of TNF-α Inhibitor With Other Systemic Agents in TEN

One case series22 and 1 case report23 using infliximab in combination with other systemic therapies were reviewed with a total of 4 patients (Table 3). Both reports utilized the same treatment protocol, which consisted of a single bolus of intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg followed by a single dose of infliximab 5 mg/kg and then IVIG 2 g/kg over 5 days. Three of 4 (75%) patients recovered.22,23 Gaitanis et al22 reported a patient who died on the ninth day of hospitalization secondary to multiorgan dysfunction caused by a catheter-related bacteremia. Similar to the patient described by Famularo et al,16 this patient also was noted to have remarkably improved skin prior to death. Two of the other 3 patients that survived had their hospital course complicated by infection, requiring antibiotics.22 In the Gaitanis et al22 series, the average predicted mortality according to a SCORTEN assessment was 50.8%; however, mortality was observed in 33.3% (1/3) of patients in the case series.

N-Acetylcysteine and Infliximab

The combination of NAC and infliximab was studied in a randomized controlled trial using TNF-α inhibition in TEN.24 In this study, 10 patients were admitted to a burn unit and treated with either 3 doses of intravenous NAC (150 mg/kg per dose) plus 1 dose of infliximab 5 mg/kg or NAC alone. Unlike some of the previously described articles, Paquet et al24 utilized an illness auxiliary score (IAS), which predicts both disease duration and mortality. An IAS was taken at admission and again 48 hours after completion of NAC and/or infliximab administration. The mean clinical IAS score was reported to have remained unchanged at treatment completion in the NAC group and slightly worsened in the NAC-infliximab group. One patient died in the NAC group and 2 patients died in the NAC-infliximab group, each due to infection. These fatalities corresponded to a mean mortality of 20% in the NAC-treated group and 40% for the NAC-infliximab group. To compare, the predicted mortalities based on the IAS were 20.4% and 21.4%, respectively.24

COMMENT

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibition in the treatment of TEN was first utilized in the 1990s with PTX and thalidomide.9,10 In 1994, PTX in addition to antioxidant therapy was found to successfully treat a 26-year-old woman with TEN attributed to anticonvulsant therapy.9 Other reports of PTX in the treatment of TEN were not found; however, there is a case series describing the successful treatment of 2 pediatric patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and SJS-TEN overlap with PTX.25 Thalidomide, however, proved detrimental to patients with TEN as evidenced by an increased mortality in the 1998 trial.10 Paradoxically, the treatment group was found to have increased rather than decreased TNF-α concentrations, which was hypothesized to be the cause of increased mortality. This finding furthered the theory that TNF-α is an important mediator in TEN pathogenesis and a potential novel target in disease management.10

Since the PTX case report and the thalidomide trial, many physicians have reported the beneficial effects of biologic TNF-α inhibitors in the course of TEN; however, most of the literature is composed of case reports and case series describing a small number of patients. Therefore, the beneficial effects of anti–TNF-α therapy in TEN cannot be conclusively derived. Furthermore, cases using TNF-α inhibitors in combination with or after other systemic agents complicate the effects of TNF-α inhibitors themselves. Most of these case reports and case series describe the beneficial effects of TNF-α inhibitors in TEN; however, it is important to remember that cases in which these agents were ineffective are less likely to be published. The strongest evidence for TNF-α inhibitor use in the treatment TEN comes from the Paradisi et al14 case series, which showed a decrease in expected mortality with etanercept monotherapy in a relatively large cohort of patients. However, when evaluated prospectively by Paquet et al,24 there was no benefit seen by adding infliximab to NAC therapy and possibly an increased mortality in the group treated with both agents.

In the cases reviewed, a total of 32 patients were treated with infliximab or etanercept, and of these patients there were 4 deaths (12.5%).16,22,24 Three deaths were attributed to infection and 1 was attributed to disseminated intravascular coagulation. Furthermore, infection complicated the hospital course of 9 (28.1%) patients.13,15,22,24 The bacteria cultured from these patients included methicillin-resistant S aureus, P aeruginosa, E coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, and K pneumoniae. Patients who received TNF-α antagonists in combination with or after other systemic immunosuppressants appeared to have a higher incidence of infections. All patients treated with TNF-α antagonists in TEN should undergo careful evaluation and monitoring for infections due to the immunosuppressant effect of these drugs.

In our review, a total of 3 pediatric/adolescent patients received a TNF-α inhibitor for the treatment of TEN.13,17,21 Two patients received infliximab as a second-line medication after failure of IVIG to arrest progression of disease13,17 and one patient received infliximab as a second-line medication after dexamethasone.21 Each of these patients recovered without any reported infections or long-term complications.

Although excluded from this review, both infliximab and etanercept have been reported to show benefit in acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis/TEN overlap.26,27 Interestingly, in postmarketing surveillance, rare reports have implicated both infliximab and etanercept in causing both SJS and TEN.28 Also, there have been case reports of adalimumab causing SJS, but no cases of it causing TEN were identified.29,30

CONCLUSION

Rapid discontinuation of the culprit drug and aggressive supportive care remain the primary treatment of TEN. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors as monotherapy or as second-line agents show promise in the treatment of this complex disease state in both the adult and pediatric populations. The risks of these potent immunosuppressants must be weighed, and if administered, patients must be closely monitored for infections. Additional studies are needed to further characterize the role of TNF-α inhibition in the treatment of TEN.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a rare, life-threatening adverse drug reaction with an estimated incidence of 0.4 to 1.9 cases per million persons per year worldwide and an estimated mortality rate of 25% to 35%.1,2 This dermatologic emergency is characterized by extensive detachment of the epidermis and erosions of the mucous membranes secondary to massive keratinocyte cell death via apoptosis, evolving quickly into full-thickness epidermal necrosis.

Primary treatment of TEN includes (1) prompt discontinuation of the suspected medication; (2) rapid transfer to an intensive care unit, burn center, or other specialty unit; and (3) supportive care, including wound care, fluid and electrolyte maintenance, and treatment of infections. Aside from the primary treatment, controversy remains over the most effective adjunctive therapy for TEN, as none has proven consistent superiority over well-conducted primary treatment alone. Therefore, established therapeutic guidelines do not exist.1-3

The use of adjunctive systemic therapy in TEN (eg, corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin [IVIG], cyclosporine, plasmapheresis, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor) is based primarily on theories of pathogenesis, which unfortunately remain unclear. Activated CD8+ T cells are thought to increase the expression and production of granulysin, granzyme B, and perforins, leading to keratinocyte apoptosis. Fas ligand and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) also are implicated as secondary mediators of cell death via the inducible nitric oxide synthase pathway.1,4-6

Since TNF-α was found to be elevated in serum and blister fluid in patients with TEN,7,8 medications aimed at decreasing the TNF-α concentration, such as pentoxifylline (PTX) and thalidomide, have been attempted for treatment.9,10 Biologic inhibitors of TNF-α, such as infliximab and etanercept, are novel therapeutic options in the treatment of TEN, as numerous reports document their successful use in the treatment of this disease.11-24 The purpose of this study is to systematically review the current literature on the use of TNF-α antagonists in the treatment of TEN.

METHODS

A PubMed search of all available articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms toxic epidermal necrolysis and TNF-alpha and pentoxifylline or thalidomide or infliximab or etanercept or adalimumab was conducted.

RESULTS

Sixteen articles published between 1994 and 2014 were retrieved from PubMed and reviewed.9-24 Fourteen articles were case reports and case series involving the use of TNF-α inhibitors as either monotherapy, second-line agents, or in combination with other medications in the treatment of TEN, providing a total of 28 patients.9,11-23 Two articles were prospective trials, one evaluating the efficacy of thalidomide10 and the other infliximab24 in treating TEN. All studies implemented primary treatment (ie, prompt discontinuation of the suspected medication and aggressive supportive care) in addition to TNF-α inhibition.

Pentoxifylline

The first case report describing the use of an anti–TNF-α inhibitor for TEN was with PTX in 1994.9 Pentoxifylline, a vasoactive drug with immunomodulatory properties including the downregulation of TNF-α synthesis, was used to treat a 26-year-old woman with TEN on phenylhydantoin 15 days following resection of a grade II astrocytoma. The patient initially received intravenous N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (9 g once daily) and S-adenosyl-L-methionine (100 mg once daily) for antioxidant effects. On the second day of treatment, intravenous PTX (900 mg once daily) was added for TNF-α inhibition. Following PTX administration, the investigators reported quick stabilization of the eruption and achievement of reepithelialization after 7 days of therapy. Upon cessation of PTX therapy, a recurrence of generalized erythema occurred, suggesting a relapse of TEN; therefore, PTX was reinitiated for an additional 3 days, and the patient’s skin remained clear.9

Thalidomide

The earliest prospective trial we reviewed using anti–TNF-α therapy in TEN occurred in 1998 with thalidomide, a moderate inhibitor of TNF-α.10 In this randomized controlled trial, 22 TEN patients received either a 5-day course of thalidomide (400 mg once daily) or placebo. There was increased mortality in the thalidomide group (10/12 [83.3%]) versus the placebo group (3/10 [30.0%]). Additionally, the plasma TNF-α concentrations in the thalidomide group were higher than the control group. This study was stopped prematurely due to the excess mortality in the thalidomide group.10

Biologic TNF-α Antagonists

Following the PTX case report and the thalidomide trial, there was increased interest in using newer-generation TNF-α inhibitors, such as the monoclonal antibody infliximab or the fusion protein etanercept, in the treatment of TEN. To date, there are 10 known published case reports,11,12,15-21,23 3 case series,13,14,22 and 1 trial24 describing the use of these agents; however, treatment protocols vary. Categories of treatment protocols include the use of TNF-α inhibitors as monotherapy, following failure of other systemic agents, and in combination with other systemic therapies.

TNF-α Inhibitors as Monotherapy

Review of the literature yielded 2 case reports using infliximab monotherapy11,12 and 2 case series using infliximab or etanercept monotherapy13,14 with a total of 14 patients (Table 1). Fischer et al11 was the first of these reports to describe a patient successfully treated with supportive care and a single dose of infliximab 5 mg/kg. The dose was given 4 days after the onset of symptoms, and the rapid progression of the disease was stopped, with complete recovery in less than 4 weeks.11 Hunger et al12 also described the successful treatment of a patient using a similar protocol: a single dose of infliximab 5 mg/kg given 3 days after symptom onset. Epidermal detachment was abated within 24 hours and the patient had almost complete reepithelialization within 5 days.12 In a case series published by Zárate-Correa et al,13 2 patients with near 100% body surface area involvement were successfully treated with a single dose of infliximab 300 mg. Although both of these patients experienced fairly rapid recoveries, one patient’s course was complicated by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia.13 Paradisi et al14 described 10 consecutive patients treated with a single dose of etanercept 50 mg given within 6 hours of hospital admission and within 72 hours of symptom onset. The SCORTEN (SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis) scale—a severity-of-illness assessment for TEN based on body surface area involvement, comorbidities, and metabolic abnormalities—was used to predict mortality in these patients. The investigators reported an expected mortality of 46.9%; however, the observed mortality was 0%, and there were no reported infections.14

TNF-α Inhibitors Following Failure of Other Systemic Agents in TEN

Seven case reports and 1 case series using anti–TNF-α therapy following failure of other systemic agents were reviewed for a total of 9 patients (3 pediatric/adolescent patients, 6 adult patients)(Table 2).13,15-21 Seven patients were treated with infliximab,13,15,17,19-21 and the remaining 2 patients were treated with etanercept.16,18 All patients were treated initially with corticosteroids and/or IVIG. In each case, anti–TNF-α therapy was introduced when prior treatment failed to halt the progression of TEN. Most reports claimed a rapid and beneficial response to anti–TNF-α therapy. Eight of 9 (88.9%) patients recovered.13,15,17-21 Famularo et al16 described 1 patient who was treated with 2 doses of etanercept following prednisolone but died on the tenth day of hospitalization secondary to disseminated intravascular coagulation and multiorgan failure; however, the patient reportedly had near-complete reepithelialization of the skin on the sixth day of the hospital course.16 Of the 8 surviving patients, 3 (37.5%) experienced hospital courses complicated by nosocomial gram-negative bacteremia, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae.13,15 Interestingly, a patient described by Worsnop et al20 developed erosive lichen planus of the mouth and vulva 31 days after infliximab infusion.

Combination of TNF-α Inhibitor With Other Systemic Agents in TEN

One case series22 and 1 case report23 using infliximab in combination with other systemic therapies were reviewed with a total of 4 patients (Table 3). Both reports utilized the same treatment protocol, which consisted of a single bolus of intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg followed by a single dose of infliximab 5 mg/kg and then IVIG 2 g/kg over 5 days. Three of 4 (75%) patients recovered.22,23 Gaitanis et al22 reported a patient who died on the ninth day of hospitalization secondary to multiorgan dysfunction caused by a catheter-related bacteremia. Similar to the patient described by Famularo et al,16 this patient also was noted to have remarkably improved skin prior to death. Two of the other 3 patients that survived had their hospital course complicated by infection, requiring antibiotics.22 In the Gaitanis et al22 series, the average predicted mortality according to a SCORTEN assessment was 50.8%; however, mortality was observed in 33.3% (1/3) of patients in the case series.

N-Acetylcysteine and Infliximab

The combination of NAC and infliximab was studied in a randomized controlled trial using TNF-α inhibition in TEN.24 In this study, 10 patients were admitted to a burn unit and treated with either 3 doses of intravenous NAC (150 mg/kg per dose) plus 1 dose of infliximab 5 mg/kg or NAC alone. Unlike some of the previously described articles, Paquet et al24 utilized an illness auxiliary score (IAS), which predicts both disease duration and mortality. An IAS was taken at admission and again 48 hours after completion of NAC and/or infliximab administration. The mean clinical IAS score was reported to have remained unchanged at treatment completion in the NAC group and slightly worsened in the NAC-infliximab group. One patient died in the NAC group and 2 patients died in the NAC-infliximab group, each due to infection. These fatalities corresponded to a mean mortality of 20% in the NAC-treated group and 40% for the NAC-infliximab group. To compare, the predicted mortalities based on the IAS were 20.4% and 21.4%, respectively.24

COMMENT

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibition in the treatment of TEN was first utilized in the 1990s with PTX and thalidomide.9,10 In 1994, PTX in addition to antioxidant therapy was found to successfully treat a 26-year-old woman with TEN attributed to anticonvulsant therapy.9 Other reports of PTX in the treatment of TEN were not found; however, there is a case series describing the successful treatment of 2 pediatric patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and SJS-TEN overlap with PTX.25 Thalidomide, however, proved detrimental to patients with TEN as evidenced by an increased mortality in the 1998 trial.10 Paradoxically, the treatment group was found to have increased rather than decreased TNF-α concentrations, which was hypothesized to be the cause of increased mortality. This finding furthered the theory that TNF-α is an important mediator in TEN pathogenesis and a potential novel target in disease management.10

Since the PTX case report and the thalidomide trial, many physicians have reported the beneficial effects of biologic TNF-α inhibitors in the course of TEN; however, most of the literature is composed of case reports and case series describing a small number of patients. Therefore, the beneficial effects of anti–TNF-α therapy in TEN cannot be conclusively derived. Furthermore, cases using TNF-α inhibitors in combination with or after other systemic agents complicate the effects of TNF-α inhibitors themselves. Most of these case reports and case series describe the beneficial effects of TNF-α inhibitors in TEN; however, it is important to remember that cases in which these agents were ineffective are less likely to be published. The strongest evidence for TNF-α inhibitor use in the treatment TEN comes from the Paradisi et al14 case series, which showed a decrease in expected mortality with etanercept monotherapy in a relatively large cohort of patients. However, when evaluated prospectively by Paquet et al,24 there was no benefit seen by adding infliximab to NAC therapy and possibly an increased mortality in the group treated with both agents.

In the cases reviewed, a total of 32 patients were treated with infliximab or etanercept, and of these patients there were 4 deaths (12.5%).16,22,24 Three deaths were attributed to infection and 1 was attributed to disseminated intravascular coagulation. Furthermore, infection complicated the hospital course of 9 (28.1%) patients.13,15,22,24 The bacteria cultured from these patients included methicillin-resistant S aureus, P aeruginosa, E coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, and K pneumoniae. Patients who received TNF-α antagonists in combination with or after other systemic immunosuppressants appeared to have a higher incidence of infections. All patients treated with TNF-α antagonists in TEN should undergo careful evaluation and monitoring for infections due to the immunosuppressant effect of these drugs.

In our review, a total of 3 pediatric/adolescent patients received a TNF-α inhibitor for the treatment of TEN.13,17,21 Two patients received infliximab as a second-line medication after failure of IVIG to arrest progression of disease13,17 and one patient received infliximab as a second-line medication after dexamethasone.21 Each of these patients recovered without any reported infections or long-term complications.

Although excluded from this review, both infliximab and etanercept have been reported to show benefit in acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis/TEN overlap.26,27 Interestingly, in postmarketing surveillance, rare reports have implicated both infliximab and etanercept in causing both SJS and TEN.28 Also, there have been case reports of adalimumab causing SJS, but no cases of it causing TEN were identified.29,30

CONCLUSION

Rapid discontinuation of the culprit drug and aggressive supportive care remain the primary treatment of TEN. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors as monotherapy or as second-line agents show promise in the treatment of this complex disease state in both the adult and pediatric populations. The risks of these potent immunosuppressants must be weighed, and if administered, patients must be closely monitored for infections. Additional studies are needed to further characterize the role of TNF-α inhibition in the treatment of TEN.

- Schwartz R, McDonough P, Lee B. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part I. introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:173-186.

- Schwartz R, McDonough P, Lee B. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part II. prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:187-203.

- Fernando S. The management of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;55:165-171.

- Paquet P, Paquet F, Saleh W, et al. Immunoregulatory effector cells in drug-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:413-417.

- Nassif A, Moslehi H, Le Gouvello S, et al. Evaluation of the potential role of cytokines in toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:850-855.

- Viard-Leveugle I, Gaide O, Jankovic D, et al. TNF-α and INF-γ are potential inducers of Fas-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis thought activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase in toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:489-498.

- Paquet P, Pierard G. Soluble fractions of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6 and of their receptors in toxic epidermal necrolysis: a comparison with second-degree burns. Int J Mol Med. 1998;1:459-462.

- Correia O, Delgado L, Barbosa I, et al. Increased interleukin 10, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin 6 levels in blister fluid of toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:58-62.

- Redondo P, Rutz de Erenchun F, Iglesias M, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis. treatment with pentoxifylline. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:688-689.

- Wolkenstein P, Latarjet J, Roujeau J, et al. Randomised comparison of thalidomide versus placebo in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Lancet. 1998;352:1586-1589.

- Fischer M, Fiedler E, Marsch W, et al. Antitumour necrosis factor-alpha antibodies (infliximab) in the treatment of a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:707-708.

- Hunger R, Hunziker T, Buettiker U, et al. Rapid resolution of toxic epidermal necrolysis with anti-TNF-alpha treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:923-924.

- Zárate-Correa LC, Carrillo-Gómez DC, Ramírez-Escobar AF, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis successfully treated with infliximab. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2013;23:61-63.

- Paradisi A, Abeni D, Bergamo F, et al. Etanercept therapy for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:278-283.

- Al-Shouli S, Bogusz M, Al Tufail M, et al. Toxic epidermal necrosis associated with high intake of sildenafil and its response to infliximab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85:534-553.

- Famularo G, Di Dona B, Canzona F, et al. Etanercept for toxic epidermal necrolysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1083-1084.

- Wojtkiewicz A, Wysocki M, Fortuna J, et al. Beneficial and rapid effect of infliximab on the course of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:420-421.

- Gubinelli E, Canzona F, Tonanzi T, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis successfully treated with etanercept. J Dermatol. 2009;36:150-153.

- Kreft B, Wohlrab J, Bramsiepe I, et al. Etoricoxib-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis: successful treatment with infliximab. J Dermatol. 2010;37:904-906.

- Worsnop F, Wee J, Moosa Y, et al. Reaction to biological drugs: infliximab for the treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis subsequently triggering erosive lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:879-881.

- Scott-Lang V, Tidman M, McKay D. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in a child successfully treated with infliximab. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:532-534.

- Gaitanis G, Spyridonos P, Patmanidis K, et al. Treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis with the combination of infliximab and high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins. Dermatology. 2012;224:134-139.

- Patmanidis K, Sidiras A, Dolianitis K, et al. Combination of infliximab and high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin for toxic epidermal necrolysis: successful treatment of an elderly patient. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2012;2012:915314.

- Paquet P, Jennes S, Rousseua A, et al. Effect of N-acetylcysteine combined with infliximab on toxic epidermal necrolysis: a proof-of-concept study. Burns. 2014;1:1-6.

- Sanclemente G, De le Rouche C, Escobar C, et al. Pentoxifylline in toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 1998;38:878-879.

- Meiss F, Helmbold P, Meykadeh N, et al. Overlap of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and toxic epidermal necrolysis: response to antitumor necrosis factor-alpha antibody infliximab: report of three cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:717-719.

- Sadighha A. Etanercept in the treatment of a patient with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis/toxic epidermal necrolysis: definition of a new model based on translational research. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:913-914.

- Borras-Blasco J, Navarro-Ruiz A, Borras C, et al. Adverse cutaneous reactions induced by TNF-α antagonist therapy. South Med J. 2009;102:1133-1140.

- Muna S, Lawrance I. Stevens-Johnson syndrome complicating adalimumab therapy in Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4449-4452.

- Mounach A, Rezgi A, Nouijai A, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome complicating adalimumab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis disease. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:1351-1353.

- Schwartz R, McDonough P, Lee B. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part I. introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:173-186.

- Schwartz R, McDonough P, Lee B. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part II. prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:187-203.

- Fernando S. The management of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;55:165-171.

- Paquet P, Paquet F, Saleh W, et al. Immunoregulatory effector cells in drug-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:413-417.

- Nassif A, Moslehi H, Le Gouvello S, et al. Evaluation of the potential role of cytokines in toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:850-855.

- Viard-Leveugle I, Gaide O, Jankovic D, et al. TNF-α and INF-γ are potential inducers of Fas-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis thought activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase in toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:489-498.

- Paquet P, Pierard G. Soluble fractions of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6 and of their receptors in toxic epidermal necrolysis: a comparison with second-degree burns. Int J Mol Med. 1998;1:459-462.

- Correia O, Delgado L, Barbosa I, et al. Increased interleukin 10, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin 6 levels in blister fluid of toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:58-62.

- Redondo P, Rutz de Erenchun F, Iglesias M, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis. treatment with pentoxifylline. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:688-689.

- Wolkenstein P, Latarjet J, Roujeau J, et al. Randomised comparison of thalidomide versus placebo in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Lancet. 1998;352:1586-1589.

- Fischer M, Fiedler E, Marsch W, et al. Antitumour necrosis factor-alpha antibodies (infliximab) in the treatment of a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:707-708.

- Hunger R, Hunziker T, Buettiker U, et al. Rapid resolution of toxic epidermal necrolysis with anti-TNF-alpha treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:923-924.

- Zárate-Correa LC, Carrillo-Gómez DC, Ramírez-Escobar AF, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis successfully treated with infliximab. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2013;23:61-63.

- Paradisi A, Abeni D, Bergamo F, et al. Etanercept therapy for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:278-283.

- Al-Shouli S, Bogusz M, Al Tufail M, et al. Toxic epidermal necrosis associated with high intake of sildenafil and its response to infliximab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85:534-553.

- Famularo G, Di Dona B, Canzona F, et al. Etanercept for toxic epidermal necrolysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1083-1084.

- Wojtkiewicz A, Wysocki M, Fortuna J, et al. Beneficial and rapid effect of infliximab on the course of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:420-421.

- Gubinelli E, Canzona F, Tonanzi T, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis successfully treated with etanercept. J Dermatol. 2009;36:150-153.

- Kreft B, Wohlrab J, Bramsiepe I, et al. Etoricoxib-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis: successful treatment with infliximab. J Dermatol. 2010;37:904-906.

- Worsnop F, Wee J, Moosa Y, et al. Reaction to biological drugs: infliximab for the treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis subsequently triggering erosive lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:879-881.

- Scott-Lang V, Tidman M, McKay D. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in a child successfully treated with infliximab. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:532-534.

- Gaitanis G, Spyridonos P, Patmanidis K, et al. Treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis with the combination of infliximab and high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins. Dermatology. 2012;224:134-139.

- Patmanidis K, Sidiras A, Dolianitis K, et al. Combination of infliximab and high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin for toxic epidermal necrolysis: successful treatment of an elderly patient. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2012;2012:915314.

- Paquet P, Jennes S, Rousseua A, et al. Effect of N-acetylcysteine combined with infliximab on toxic epidermal necrolysis: a proof-of-concept study. Burns. 2014;1:1-6.

- Sanclemente G, De le Rouche C, Escobar C, et al. Pentoxifylline in toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 1998;38:878-879.

- Meiss F, Helmbold P, Meykadeh N, et al. Overlap of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and toxic epidermal necrolysis: response to antitumor necrosis factor-alpha antibody infliximab: report of three cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:717-719.

- Sadighha A. Etanercept in the treatment of a patient with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis/toxic epidermal necrolysis: definition of a new model based on translational research. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:913-914.

- Borras-Blasco J, Navarro-Ruiz A, Borras C, et al. Adverse cutaneous reactions induced by TNF-α antagonist therapy. South Med J. 2009;102:1133-1140.

- Muna S, Lawrance I. Stevens-Johnson syndrome complicating adalimumab therapy in Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4449-4452.

- Mounach A, Rezgi A, Nouijai A, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome complicating adalimumab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis disease. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:1351-1353.

Practice Points

- Controversy remains over the most effective adjunctive therapy for toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), as none have consistently displayed superiority over rapid discontinuation of the culprit drug and aggressive supportive care alone.

- Since tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) was implicated in the pathogenesis of TEN, TNF-α inhibition has been attempted in treatment of the disease. These medications have shown positive outcomes.

- The risks of these potent immunosuppressants must be weighed, and if administered, patients must be closely monitored for infections.

What Do You Want to Be When You Grow Up? Pearls for Postresidency Planning

Dermatology residency training can feel endless at the outset; an arduous intern year followed by 3 years of specialized training. However, I have realized that, within residency, time moves quickly. As I look ahead to postresidency life, I realize that residents are all facing the same question: What do you want to be when you grow up?

You may think you have answered that question already; however, there are many different careers within the field of dermatology and no amount of studying or reading will help you choose the right one. In an attempt to make sense of these choices, I have spoken to many recent dermatology graduates over the last several months to get a sense of how they made their postresidency decisions, and I want to share their pearls.

Pearl: Explore Fellowship Opportunities Early

The first decision is whether or not to pursue a fellowship after residency. There currently are 2 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–approved fellowships after dermatology residency: dermatopathology and micrographic surgery. Pediatric dermatology is another board-certified fellowship. A list of these training programs and the requirements can be found on the American Board of Dermatology website (www.abderm.org). There also are several nonaccredited fellowships including pediatrics, cosmetics, complex medical dermatology, cutaneous oncology, and rheumatology.

Even if you are not completely committed to pursuing a fellowship, it is beneficial to explore any fellowship options early in residency. Spend extra time in any field you are considering for fellowship and consider research in the field. If there is a fellowship position at your institution, try to rotate there early in residency. Rotations at other institutions can demonstrate your interest and enthusiasm while also helping you to network within your chosen subspecialty. Several of the dermatology interest groups even sponsor rotations at outside institutions, if extra funding is needed. If recent graduates from your program have matched in fellowship, it is always a good idea to reach out to them to get program-specific advice. It takes a lot of time, confidence, and persistence to organize the opportunities that will help you maximize your fellowship potential, but it is well worth the effort.

Fellowships can occur through an official “match,” similar to residency, or can be accepted on a rolling basis. For example, many dermatopathology fellowships can begin accepting applications as early as the summer between the first and second year of residency (www.abderm.org). It is important to get this information early so that you do not miss any application deadlines.

Pearl: Prioritize Where You Want to Practice

If you have decided that fellowship is not for you, then it is time to apply for your first job as a physician. There are several big factors that help narrow the search. It is best to start the search early to allow yourself time and different options. According to the 2016 American Academy of Dermatology database, there currently are approximately 3.4 dermatologists per 100,000 Americans; however, they are unevenly distributed throughout the country. In this study, the researchers found the highest density of dermatologists on the Upper East Side of Manhattan (41.8 per 100,000 dermatologists) compared to Swainsboro, Georgia (0.45 per 100,000 dermatologists).1

With more competition for jobs in areas with a higher concentration of dermatologists, compensation often is lower. There also are many personal factors that contribute to where you want to live and work, and if you prioritize them, it will lead to greater overall satisfaction in postresidency life.

Another large factor to consider is private practice versus academic dermatology. Academic dermatology can provide opportunities for research as well as the opportunity to work with students and residents. As part of a larger hospital system, there often is the opportunity for benefits, such as 401(k) matching, that might be less accessible in small practices.

Pearl: Get Recruiter Recommendations From Your Peers

There are many recruiting services that can help put you in touch with practices that are hiring. These services can be helpful but also can be overwhelming at times, with many emails and telephone calls. In my experience, recent graduates had mixed feelings about recruiting services. Those who had been the happiest with their recruiting experience had often gotten the name of a specific recruiter from someone else in their program who had a positive experience. Mentors at your training institution or beyond also can be a good source of information for job opportunities. It can be helpful to get involved early in the various dermatologic societies and network at academic conferences throughout your training.

Pearl: Talk to Partners and Nonpartners About the Practice’s Philosophy

When picking a private practice for your first job, make sure you get a sense of the philosophy of the practice, including the partners’ goals for the office, the patient population, and the dynamic of the office staff. If there is a cosmetic component, it is important to know what devices are available and which products are sold. It is important to talk to nonpartners at a practice and get a sense of their satisfaction. If you sign the employment contract, you will be in their shoes soon!

Pearl: Have an Attorney Review Your Contract

There are many important topics in your employment contract. After years of medical school loans and resident salary, it is easy to focus only on compensation. However, pay attention to the other aspects of reimbursement including bonuses, benefits, noncompete clauses, and call schedules. Also consider the termination policies. The general advice I have received is to have a lawyer look at your contract. Although it may be tempting to skip the lawyer’s fee and review it yourself, you may actually end up negotiating a contract that benefits you more in the long-run or avoid signing a contract that will limit you.

- Glazer AM, Farberg AS, Winkelmann RR, et al. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution and density of US dermatologists. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:322-325.

Dermatology residency training can feel endless at the outset; an arduous intern year followed by 3 years of specialized training. However, I have realized that, within residency, time moves quickly. As I look ahead to postresidency life, I realize that residents are all facing the same question: What do you want to be when you grow up?

You may think you have answered that question already; however, there are many different careers within the field of dermatology and no amount of studying or reading will help you choose the right one. In an attempt to make sense of these choices, I have spoken to many recent dermatology graduates over the last several months to get a sense of how they made their postresidency decisions, and I want to share their pearls.

Pearl: Explore Fellowship Opportunities Early

The first decision is whether or not to pursue a fellowship after residency. There currently are 2 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–approved fellowships after dermatology residency: dermatopathology and micrographic surgery. Pediatric dermatology is another board-certified fellowship. A list of these training programs and the requirements can be found on the American Board of Dermatology website (www.abderm.org). There also are several nonaccredited fellowships including pediatrics, cosmetics, complex medical dermatology, cutaneous oncology, and rheumatology.

Even if you are not completely committed to pursuing a fellowship, it is beneficial to explore any fellowship options early in residency. Spend extra time in any field you are considering for fellowship and consider research in the field. If there is a fellowship position at your institution, try to rotate there early in residency. Rotations at other institutions can demonstrate your interest and enthusiasm while also helping you to network within your chosen subspecialty. Several of the dermatology interest groups even sponsor rotations at outside institutions, if extra funding is needed. If recent graduates from your program have matched in fellowship, it is always a good idea to reach out to them to get program-specific advice. It takes a lot of time, confidence, and persistence to organize the opportunities that will help you maximize your fellowship potential, but it is well worth the effort.

Fellowships can occur through an official “match,” similar to residency, or can be accepted on a rolling basis. For example, many dermatopathology fellowships can begin accepting applications as early as the summer between the first and second year of residency (www.abderm.org). It is important to get this information early so that you do not miss any application deadlines.

Pearl: Prioritize Where You Want to Practice

If you have decided that fellowship is not for you, then it is time to apply for your first job as a physician. There are several big factors that help narrow the search. It is best to start the search early to allow yourself time and different options. According to the 2016 American Academy of Dermatology database, there currently are approximately 3.4 dermatologists per 100,000 Americans; however, they are unevenly distributed throughout the country. In this study, the researchers found the highest density of dermatologists on the Upper East Side of Manhattan (41.8 per 100,000 dermatologists) compared to Swainsboro, Georgia (0.45 per 100,000 dermatologists).1

With more competition for jobs in areas with a higher concentration of dermatologists, compensation often is lower. There also are many personal factors that contribute to where you want to live and work, and if you prioritize them, it will lead to greater overall satisfaction in postresidency life.

Another large factor to consider is private practice versus academic dermatology. Academic dermatology can provide opportunities for research as well as the opportunity to work with students and residents. As part of a larger hospital system, there often is the opportunity for benefits, such as 401(k) matching, that might be less accessible in small practices.

Pearl: Get Recruiter Recommendations From Your Peers

There are many recruiting services that can help put you in touch with practices that are hiring. These services can be helpful but also can be overwhelming at times, with many emails and telephone calls. In my experience, recent graduates had mixed feelings about recruiting services. Those who had been the happiest with their recruiting experience had often gotten the name of a specific recruiter from someone else in their program who had a positive experience. Mentors at your training institution or beyond also can be a good source of information for job opportunities. It can be helpful to get involved early in the various dermatologic societies and network at academic conferences throughout your training.

Pearl: Talk to Partners and Nonpartners About the Practice’s Philosophy

When picking a private practice for your first job, make sure you get a sense of the philosophy of the practice, including the partners’ goals for the office, the patient population, and the dynamic of the office staff. If there is a cosmetic component, it is important to know what devices are available and which products are sold. It is important to talk to nonpartners at a practice and get a sense of their satisfaction. If you sign the employment contract, you will be in their shoes soon!

Pearl: Have an Attorney Review Your Contract

There are many important topics in your employment contract. After years of medical school loans and resident salary, it is easy to focus only on compensation. However, pay attention to the other aspects of reimbursement including bonuses, benefits, noncompete clauses, and call schedules. Also consider the termination policies. The general advice I have received is to have a lawyer look at your contract. Although it may be tempting to skip the lawyer’s fee and review it yourself, you may actually end up negotiating a contract that benefits you more in the long-run or avoid signing a contract that will limit you.

Dermatology residency training can feel endless at the outset; an arduous intern year followed by 3 years of specialized training. However, I have realized that, within residency, time moves quickly. As I look ahead to postresidency life, I realize that residents are all facing the same question: What do you want to be when you grow up?

You may think you have answered that question already; however, there are many different careers within the field of dermatology and no amount of studying or reading will help you choose the right one. In an attempt to make sense of these choices, I have spoken to many recent dermatology graduates over the last several months to get a sense of how they made their postresidency decisions, and I want to share their pearls.

Pearl: Explore Fellowship Opportunities Early

The first decision is whether or not to pursue a fellowship after residency. There currently are 2 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–approved fellowships after dermatology residency: dermatopathology and micrographic surgery. Pediatric dermatology is another board-certified fellowship. A list of these training programs and the requirements can be found on the American Board of Dermatology website (www.abderm.org). There also are several nonaccredited fellowships including pediatrics, cosmetics, complex medical dermatology, cutaneous oncology, and rheumatology.

Even if you are not completely committed to pursuing a fellowship, it is beneficial to explore any fellowship options early in residency. Spend extra time in any field you are considering for fellowship and consider research in the field. If there is a fellowship position at your institution, try to rotate there early in residency. Rotations at other institutions can demonstrate your interest and enthusiasm while also helping you to network within your chosen subspecialty. Several of the dermatology interest groups even sponsor rotations at outside institutions, if extra funding is needed. If recent graduates from your program have matched in fellowship, it is always a good idea to reach out to them to get program-specific advice. It takes a lot of time, confidence, and persistence to organize the opportunities that will help you maximize your fellowship potential, but it is well worth the effort.

Fellowships can occur through an official “match,” similar to residency, or can be accepted on a rolling basis. For example, many dermatopathology fellowships can begin accepting applications as early as the summer between the first and second year of residency (www.abderm.org). It is important to get this information early so that you do not miss any application deadlines.

Pearl: Prioritize Where You Want to Practice

If you have decided that fellowship is not for you, then it is time to apply for your first job as a physician. There are several big factors that help narrow the search. It is best to start the search early to allow yourself time and different options. According to the 2016 American Academy of Dermatology database, there currently are approximately 3.4 dermatologists per 100,000 Americans; however, they are unevenly distributed throughout the country. In this study, the researchers found the highest density of dermatologists on the Upper East Side of Manhattan (41.8 per 100,000 dermatologists) compared to Swainsboro, Georgia (0.45 per 100,000 dermatologists).1

With more competition for jobs in areas with a higher concentration of dermatologists, compensation often is lower. There also are many personal factors that contribute to where you want to live and work, and if you prioritize them, it will lead to greater overall satisfaction in postresidency life.

Another large factor to consider is private practice versus academic dermatology. Academic dermatology can provide opportunities for research as well as the opportunity to work with students and residents. As part of a larger hospital system, there often is the opportunity for benefits, such as 401(k) matching, that might be less accessible in small practices.

Pearl: Get Recruiter Recommendations From Your Peers