User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Graft-versus-host Disease Presenting Along Blaschko Lines: Cutaneous Mosaicism

To the Editor:

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a common and serious complication seen most often with bone marrow transplantation and peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. With these therapies, functional lymphoid cells are transferred from an immunocompetent donor into a nongenetically identical recipient, or "host." Because of the allogeneic nature of these transplants, the transplanted lymphoid cells have a high potential to recognize and treat the host's cells as foreign, and the resultant clinical and pathologic picture is that of GVHD. The primary organ systems affected in this immune response are the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and hepatobiliary system.1,2 Cutaneous manifestations are by far the most common.3

Although notable gains have been made in elucidating the causes, risk factors, and mechanisms that result in the clinical picture of GVHD, gaps in our knowledge and understanding still exist. Our patient represents a unique case of unilateral GVHD occurring along Blaschko lines, which has important implications for both recognizing and understanding the pathogenesis of GVHD.

A 35-year-old woman was diagnosed with stage IV follicular lymphoma and received various chemotherapy regimens over the next 4 years. Unfortunately, her disease progressed despite treatment. At 39 years of age, she underwent a nonmyeloablative allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation from a single HLA-mismatched sibling. She was placed on prednisone and cyclosporine for immunosuppression. High-dose acyclovir prophylaxis also was initiated given her history of zoster affecting the right C3 dermatome. Successful engraftment was achieved, with molecular studies showing 100% of cells following transplantation were of donor origin. Restaging at 1 and 2 years following transplantation found her to be in complete remission.

At 2 years following transplantation, she began a slow taper of immunosuppressive medications. She was successfully weaned off prednisone and continued to gradually reduce the cyclosporine dose. Toward the end of the cyclosporine taper 3 months later, she developed a pruritic eruption on the left proximal arm.

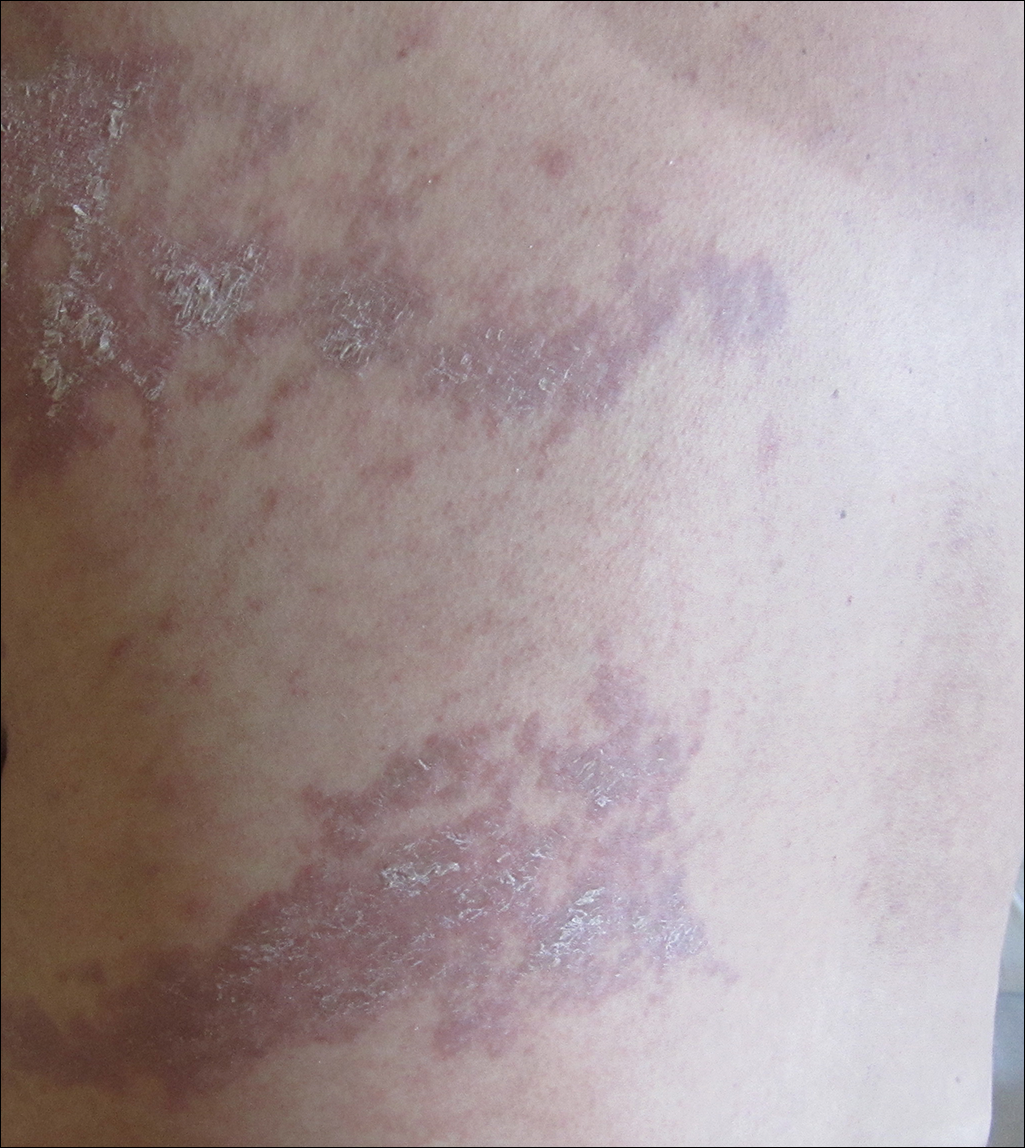

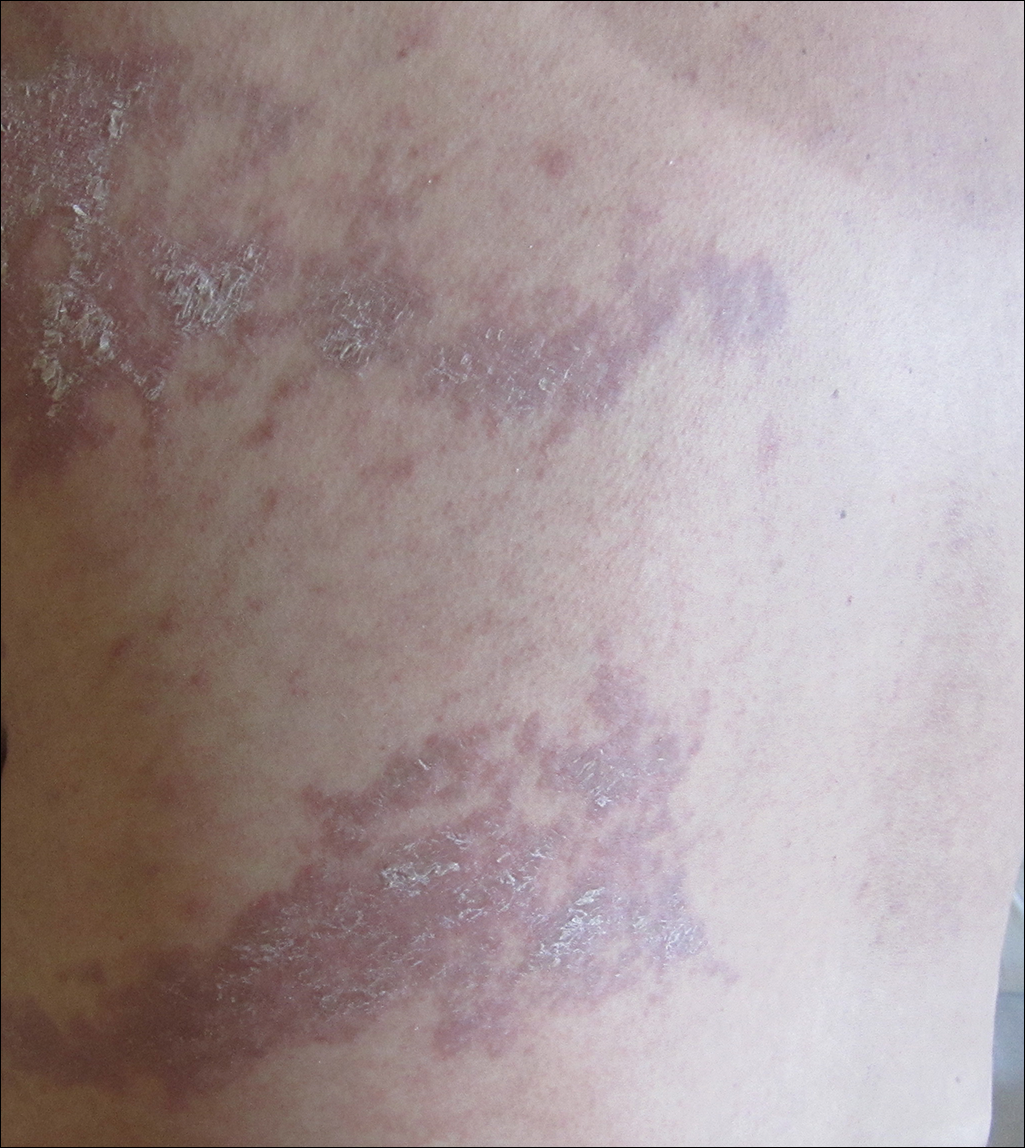

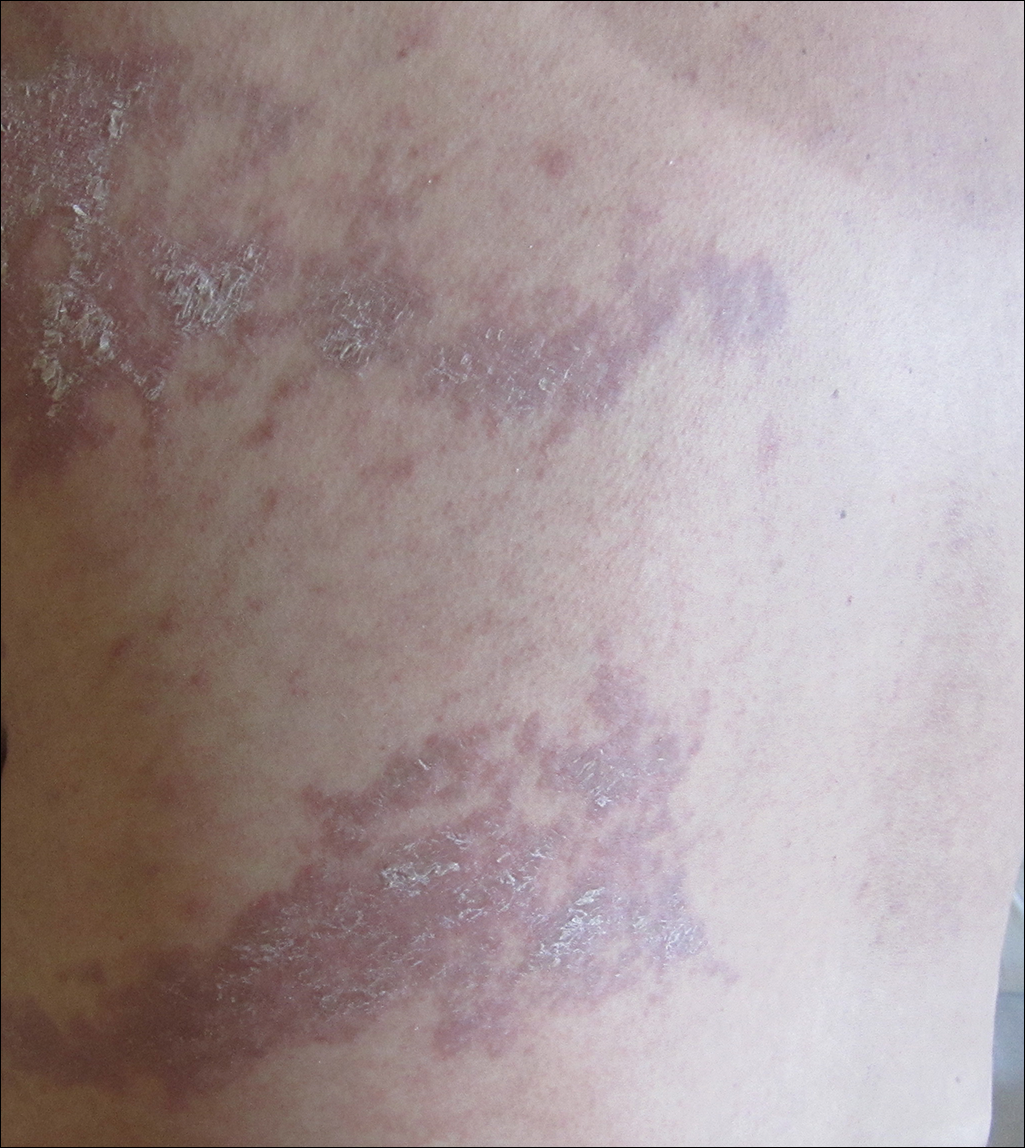

She was seen in a bone marrow transplant clinic 4 weeks after the rash developed. On examination, she had multiple, violaceous, lichenoid papules coalescing into linear bandlike plaques. One plaque extended along the left upper arm and 2 others encircled the left hemithorax, respecting the midline. She was treated empirically for zoster with valacyclovir 1 g 3 times daily based on the presumed dermatomal distribution of the eruption. Despite treatment, the rash progressed, and she developed fever. Eight days later, she was admitted with concern for disseminated zoster (Figure). Viral tissue cultures and polymerase chain reaction analysis of the lesions were negative for varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2. Biopsies of skin lesions on the arm and trunk were both consistent with GVHD.

Given the clinical history, characteristic lesion morphology, and distinct linear distribution along with histopathological confirmation, a diagnosis of GVHD along Blaschko lines was made. Recognizing the cause to be immunogenic rather than infectious, immunosuppressive medications were started. In addition to increasing the prednisone and cyclosporine back to therapeutic levels, she received weekly methylprednisolone. With treatment, she showed gradual but marked improvement.

Six cases of linear GVHD have occurred as an isotopic response along dermatomes previously affected by varicella-zoster virus.4-8 These cases give credence to the idea that a cutaneous viral infection may alter the skin through unknown mechanisms, predisposing it to become affected by GVHD. Notably, this phenomenon occurred despite absence of a persistent viral genome when assessed using polymerase chain reaction analysis.4

An additional 3 cases of GVHD occurring in a dermatomal distribution without any prior infections in those areas have been reported.9,10 Of note, 2 of 3 patients did have episodes of zoster occur at other sites following transplantation and did not develop GVHD symptoms in any of those locations.9 Interestingly, controversy exists as to whether the distribution of these lesions was dermatomal or followed Blaschko lines.11

Two cases of linear GVHD have been reported in which lesions were identified as occurring along Blaschko lines.12,13 The lines of Blaschko, first described in 1901, correspond to cellular migration patterns during embryological development.14 Postzygotic mutations causing epidermal cell mosaicism may result in skin disorders occurring in segmental areas defined by the Blaschko lines.15-17 Accordingly, the Blaschko-linear pattern in GVHD suggests cellular mosaicism as the etiology in this case. Although the host's immune system develops immunotolerance to both cellular lineages during maturation, transplanted lymphoid cells from a nongenetically identical sibling may identify just one of the cell lines as nonself, producing a selective pattern of GVHD18 confined to the distribution of the genetically disparate cell line, which occurs along the lines of Blaschko in the skin. Candidate genes for mutations that would produce a mosaic following transplant GVHD include any of the 25 to 30 known minor histocompatibility antigens (or any of the several hundred yet to be found).19 Although well established for monogenic dominant disorders, in 2007 it was recognized that a postzygotic mutation can cause many complex polygenetic disorders, including GVHD, to manifest in a limited segmental pattern. This understanding, along with retrospective case review, has brought into question previously reported "dermatomal" or "zosteriform" presentations of GVHD, asserting that the linear patterns were misidentified and thus inappropriately attributed to a postviral response.20 Recognition of the Blaschko-linear distribution holds significance in both identifying lesion etiology and understanding disease pathogenesis and treatment.

Our patient illustrates a case of a Blaschko-linear GVHD. The distinctive pattern of her physical findings strongly favored epidermal cell mosaicism as the etiology of her disease. More than just a phenotypically unique case, it provided further insight into the complex etiology underlying GVHD and iterated the basic concepts of Blaschko lines and genetic alterations in development.

- Thomas ED, Storb R, Clift RA, et al. Bone-marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:895-902.

- Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:215-233.

- Johnson ML, Farmer ER. Graft versus host reactions in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:369-384.

- Baselga E, Drolet BA, Segura AD, et al. Dermatomal lichenoid chronic graft-vs-host disease following varicella-zoster infection despite absence of viral genome. J Cutan Pathol. 1996;23:576-581.

- Lacour JP, Sirvent N, Monpoux F, et al. Dermatomal chronic cutaneous graft versus host disease at the site of prior herpes zoster. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:587-589.

- Cordoba S, Fraga J, Bartolome B, et al. Giant cell lichenoid dermatitis within herpes zoster scars in a bone marrow recipient. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:255-257.

- Sanli H, Anadolu R, Arat M, et al. Dermatomal lichenoid graft-versus-host disease within herpes zoster scars. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:562-564.

- Martires KJ, Baird K, Citrin DE, et al. Localization of sclerotic-type chronic graft-versus-host disease to sites of skin injury: potential insight into the mechanism of isomorphic and isotopic responses. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1081-1086.

- Freemer CS, Farmer ER, Corio RL, et al. Lichenoid chronic graft-vs-host disease occurring in a dermatomal distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:70-72.

- Cohen PR, Hymes SR. Linear and dermatomal cutaneous graft-versus-host disease. South Med J. 1994;87:758-761.

- Reisfeld PL. Linear lichenoid graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1207-1208.

- Beers B, Kalish RS, Kaye VN, et al. Unilateral linear lichenoid eruption after bone marrow transplantation: an unmasking of tolerance to an abnormal keratinocyte clone? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(5, pt 2):888-892.

- Wilson BB, Lockman DW. Linear lichenoid graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1206-1207.

- Goldberg I, Sprecher E. Patterned disorders in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:498-503.

- Colman SD, Rasmussen SA, Ho VT, et al. Somatic mosaicism in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:484-490.

- Munro CS, Wilkie AO. Epidermal mosaicism producing localised acne: somatic mutation in FGFR2. Lancet. 1998;352:704-705.

- Sakuntabhai A, Dhitavat J, Burge S, et al. Mosaicism for ATP2A2 mutations causes segmental Darier's disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1144-1147.

- Dickinson AM, Wang XN, Sviland L, et al. In situ dissection of the graft-versus-host activities of cytotoxic T cells specific for minor histocompatibility antigens. Nat Med. 2002;8:410-414.

- Hansen JA, Chien JW, Warren EH, et al. Defining genetic risk for graft- versus-host disease and mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17:483-492.

- Happle R. Superimposed segmental manifestation of polygenic skin disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:690-699.

To the Editor:

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a common and serious complication seen most often with bone marrow transplantation and peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. With these therapies, functional lymphoid cells are transferred from an immunocompetent donor into a nongenetically identical recipient, or "host." Because of the allogeneic nature of these transplants, the transplanted lymphoid cells have a high potential to recognize and treat the host's cells as foreign, and the resultant clinical and pathologic picture is that of GVHD. The primary organ systems affected in this immune response are the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and hepatobiliary system.1,2 Cutaneous manifestations are by far the most common.3

Although notable gains have been made in elucidating the causes, risk factors, and mechanisms that result in the clinical picture of GVHD, gaps in our knowledge and understanding still exist. Our patient represents a unique case of unilateral GVHD occurring along Blaschko lines, which has important implications for both recognizing and understanding the pathogenesis of GVHD.

A 35-year-old woman was diagnosed with stage IV follicular lymphoma and received various chemotherapy regimens over the next 4 years. Unfortunately, her disease progressed despite treatment. At 39 years of age, she underwent a nonmyeloablative allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation from a single HLA-mismatched sibling. She was placed on prednisone and cyclosporine for immunosuppression. High-dose acyclovir prophylaxis also was initiated given her history of zoster affecting the right C3 dermatome. Successful engraftment was achieved, with molecular studies showing 100% of cells following transplantation were of donor origin. Restaging at 1 and 2 years following transplantation found her to be in complete remission.

At 2 years following transplantation, she began a slow taper of immunosuppressive medications. She was successfully weaned off prednisone and continued to gradually reduce the cyclosporine dose. Toward the end of the cyclosporine taper 3 months later, she developed a pruritic eruption on the left proximal arm.

She was seen in a bone marrow transplant clinic 4 weeks after the rash developed. On examination, she had multiple, violaceous, lichenoid papules coalescing into linear bandlike plaques. One plaque extended along the left upper arm and 2 others encircled the left hemithorax, respecting the midline. She was treated empirically for zoster with valacyclovir 1 g 3 times daily based on the presumed dermatomal distribution of the eruption. Despite treatment, the rash progressed, and she developed fever. Eight days later, she was admitted with concern for disseminated zoster (Figure). Viral tissue cultures and polymerase chain reaction analysis of the lesions were negative for varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2. Biopsies of skin lesions on the arm and trunk were both consistent with GVHD.

Given the clinical history, characteristic lesion morphology, and distinct linear distribution along with histopathological confirmation, a diagnosis of GVHD along Blaschko lines was made. Recognizing the cause to be immunogenic rather than infectious, immunosuppressive medications were started. In addition to increasing the prednisone and cyclosporine back to therapeutic levels, she received weekly methylprednisolone. With treatment, she showed gradual but marked improvement.

Six cases of linear GVHD have occurred as an isotopic response along dermatomes previously affected by varicella-zoster virus.4-8 These cases give credence to the idea that a cutaneous viral infection may alter the skin through unknown mechanisms, predisposing it to become affected by GVHD. Notably, this phenomenon occurred despite absence of a persistent viral genome when assessed using polymerase chain reaction analysis.4

An additional 3 cases of GVHD occurring in a dermatomal distribution without any prior infections in those areas have been reported.9,10 Of note, 2 of 3 patients did have episodes of zoster occur at other sites following transplantation and did not develop GVHD symptoms in any of those locations.9 Interestingly, controversy exists as to whether the distribution of these lesions was dermatomal or followed Blaschko lines.11

Two cases of linear GVHD have been reported in which lesions were identified as occurring along Blaschko lines.12,13 The lines of Blaschko, first described in 1901, correspond to cellular migration patterns during embryological development.14 Postzygotic mutations causing epidermal cell mosaicism may result in skin disorders occurring in segmental areas defined by the Blaschko lines.15-17 Accordingly, the Blaschko-linear pattern in GVHD suggests cellular mosaicism as the etiology in this case. Although the host's immune system develops immunotolerance to both cellular lineages during maturation, transplanted lymphoid cells from a nongenetically identical sibling may identify just one of the cell lines as nonself, producing a selective pattern of GVHD18 confined to the distribution of the genetically disparate cell line, which occurs along the lines of Blaschko in the skin. Candidate genes for mutations that would produce a mosaic following transplant GVHD include any of the 25 to 30 known minor histocompatibility antigens (or any of the several hundred yet to be found).19 Although well established for monogenic dominant disorders, in 2007 it was recognized that a postzygotic mutation can cause many complex polygenetic disorders, including GVHD, to manifest in a limited segmental pattern. This understanding, along with retrospective case review, has brought into question previously reported "dermatomal" or "zosteriform" presentations of GVHD, asserting that the linear patterns were misidentified and thus inappropriately attributed to a postviral response.20 Recognition of the Blaschko-linear distribution holds significance in both identifying lesion etiology and understanding disease pathogenesis and treatment.

Our patient illustrates a case of a Blaschko-linear GVHD. The distinctive pattern of her physical findings strongly favored epidermal cell mosaicism as the etiology of her disease. More than just a phenotypically unique case, it provided further insight into the complex etiology underlying GVHD and iterated the basic concepts of Blaschko lines and genetic alterations in development.

To the Editor:

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a common and serious complication seen most often with bone marrow transplantation and peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. With these therapies, functional lymphoid cells are transferred from an immunocompetent donor into a nongenetically identical recipient, or "host." Because of the allogeneic nature of these transplants, the transplanted lymphoid cells have a high potential to recognize and treat the host's cells as foreign, and the resultant clinical and pathologic picture is that of GVHD. The primary organ systems affected in this immune response are the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and hepatobiliary system.1,2 Cutaneous manifestations are by far the most common.3

Although notable gains have been made in elucidating the causes, risk factors, and mechanisms that result in the clinical picture of GVHD, gaps in our knowledge and understanding still exist. Our patient represents a unique case of unilateral GVHD occurring along Blaschko lines, which has important implications for both recognizing and understanding the pathogenesis of GVHD.

A 35-year-old woman was diagnosed with stage IV follicular lymphoma and received various chemotherapy regimens over the next 4 years. Unfortunately, her disease progressed despite treatment. At 39 years of age, she underwent a nonmyeloablative allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation from a single HLA-mismatched sibling. She was placed on prednisone and cyclosporine for immunosuppression. High-dose acyclovir prophylaxis also was initiated given her history of zoster affecting the right C3 dermatome. Successful engraftment was achieved, with molecular studies showing 100% of cells following transplantation were of donor origin. Restaging at 1 and 2 years following transplantation found her to be in complete remission.

At 2 years following transplantation, she began a slow taper of immunosuppressive medications. She was successfully weaned off prednisone and continued to gradually reduce the cyclosporine dose. Toward the end of the cyclosporine taper 3 months later, she developed a pruritic eruption on the left proximal arm.

She was seen in a bone marrow transplant clinic 4 weeks after the rash developed. On examination, she had multiple, violaceous, lichenoid papules coalescing into linear bandlike plaques. One plaque extended along the left upper arm and 2 others encircled the left hemithorax, respecting the midline. She was treated empirically for zoster with valacyclovir 1 g 3 times daily based on the presumed dermatomal distribution of the eruption. Despite treatment, the rash progressed, and she developed fever. Eight days later, she was admitted with concern for disseminated zoster (Figure). Viral tissue cultures and polymerase chain reaction analysis of the lesions were negative for varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2. Biopsies of skin lesions on the arm and trunk were both consistent with GVHD.

Given the clinical history, characteristic lesion morphology, and distinct linear distribution along with histopathological confirmation, a diagnosis of GVHD along Blaschko lines was made. Recognizing the cause to be immunogenic rather than infectious, immunosuppressive medications were started. In addition to increasing the prednisone and cyclosporine back to therapeutic levels, she received weekly methylprednisolone. With treatment, she showed gradual but marked improvement.

Six cases of linear GVHD have occurred as an isotopic response along dermatomes previously affected by varicella-zoster virus.4-8 These cases give credence to the idea that a cutaneous viral infection may alter the skin through unknown mechanisms, predisposing it to become affected by GVHD. Notably, this phenomenon occurred despite absence of a persistent viral genome when assessed using polymerase chain reaction analysis.4

An additional 3 cases of GVHD occurring in a dermatomal distribution without any prior infections in those areas have been reported.9,10 Of note, 2 of 3 patients did have episodes of zoster occur at other sites following transplantation and did not develop GVHD symptoms in any of those locations.9 Interestingly, controversy exists as to whether the distribution of these lesions was dermatomal or followed Blaschko lines.11

Two cases of linear GVHD have been reported in which lesions were identified as occurring along Blaschko lines.12,13 The lines of Blaschko, first described in 1901, correspond to cellular migration patterns during embryological development.14 Postzygotic mutations causing epidermal cell mosaicism may result in skin disorders occurring in segmental areas defined by the Blaschko lines.15-17 Accordingly, the Blaschko-linear pattern in GVHD suggests cellular mosaicism as the etiology in this case. Although the host's immune system develops immunotolerance to both cellular lineages during maturation, transplanted lymphoid cells from a nongenetically identical sibling may identify just one of the cell lines as nonself, producing a selective pattern of GVHD18 confined to the distribution of the genetically disparate cell line, which occurs along the lines of Blaschko in the skin. Candidate genes for mutations that would produce a mosaic following transplant GVHD include any of the 25 to 30 known minor histocompatibility antigens (or any of the several hundred yet to be found).19 Although well established for monogenic dominant disorders, in 2007 it was recognized that a postzygotic mutation can cause many complex polygenetic disorders, including GVHD, to manifest in a limited segmental pattern. This understanding, along with retrospective case review, has brought into question previously reported "dermatomal" or "zosteriform" presentations of GVHD, asserting that the linear patterns were misidentified and thus inappropriately attributed to a postviral response.20 Recognition of the Blaschko-linear distribution holds significance in both identifying lesion etiology and understanding disease pathogenesis and treatment.

Our patient illustrates a case of a Blaschko-linear GVHD. The distinctive pattern of her physical findings strongly favored epidermal cell mosaicism as the etiology of her disease. More than just a phenotypically unique case, it provided further insight into the complex etiology underlying GVHD and iterated the basic concepts of Blaschko lines and genetic alterations in development.

- Thomas ED, Storb R, Clift RA, et al. Bone-marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:895-902.

- Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:215-233.

- Johnson ML, Farmer ER. Graft versus host reactions in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:369-384.

- Baselga E, Drolet BA, Segura AD, et al. Dermatomal lichenoid chronic graft-vs-host disease following varicella-zoster infection despite absence of viral genome. J Cutan Pathol. 1996;23:576-581.

- Lacour JP, Sirvent N, Monpoux F, et al. Dermatomal chronic cutaneous graft versus host disease at the site of prior herpes zoster. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:587-589.

- Cordoba S, Fraga J, Bartolome B, et al. Giant cell lichenoid dermatitis within herpes zoster scars in a bone marrow recipient. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:255-257.

- Sanli H, Anadolu R, Arat M, et al. Dermatomal lichenoid graft-versus-host disease within herpes zoster scars. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:562-564.

- Martires KJ, Baird K, Citrin DE, et al. Localization of sclerotic-type chronic graft-versus-host disease to sites of skin injury: potential insight into the mechanism of isomorphic and isotopic responses. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1081-1086.

- Freemer CS, Farmer ER, Corio RL, et al. Lichenoid chronic graft-vs-host disease occurring in a dermatomal distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:70-72.

- Cohen PR, Hymes SR. Linear and dermatomal cutaneous graft-versus-host disease. South Med J. 1994;87:758-761.

- Reisfeld PL. Linear lichenoid graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1207-1208.

- Beers B, Kalish RS, Kaye VN, et al. Unilateral linear lichenoid eruption after bone marrow transplantation: an unmasking of tolerance to an abnormal keratinocyte clone? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(5, pt 2):888-892.

- Wilson BB, Lockman DW. Linear lichenoid graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1206-1207.

- Goldberg I, Sprecher E. Patterned disorders in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:498-503.

- Colman SD, Rasmussen SA, Ho VT, et al. Somatic mosaicism in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:484-490.

- Munro CS, Wilkie AO. Epidermal mosaicism producing localised acne: somatic mutation in FGFR2. Lancet. 1998;352:704-705.

- Sakuntabhai A, Dhitavat J, Burge S, et al. Mosaicism for ATP2A2 mutations causes segmental Darier's disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1144-1147.

- Dickinson AM, Wang XN, Sviland L, et al. In situ dissection of the graft-versus-host activities of cytotoxic T cells specific for minor histocompatibility antigens. Nat Med. 2002;8:410-414.

- Hansen JA, Chien JW, Warren EH, et al. Defining genetic risk for graft- versus-host disease and mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17:483-492.

- Happle R. Superimposed segmental manifestation of polygenic skin disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:690-699.

- Thomas ED, Storb R, Clift RA, et al. Bone-marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:895-902.

- Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:215-233.

- Johnson ML, Farmer ER. Graft versus host reactions in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:369-384.

- Baselga E, Drolet BA, Segura AD, et al. Dermatomal lichenoid chronic graft-vs-host disease following varicella-zoster infection despite absence of viral genome. J Cutan Pathol. 1996;23:576-581.

- Lacour JP, Sirvent N, Monpoux F, et al. Dermatomal chronic cutaneous graft versus host disease at the site of prior herpes zoster. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:587-589.

- Cordoba S, Fraga J, Bartolome B, et al. Giant cell lichenoid dermatitis within herpes zoster scars in a bone marrow recipient. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:255-257.

- Sanli H, Anadolu R, Arat M, et al. Dermatomal lichenoid graft-versus-host disease within herpes zoster scars. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:562-564.

- Martires KJ, Baird K, Citrin DE, et al. Localization of sclerotic-type chronic graft-versus-host disease to sites of skin injury: potential insight into the mechanism of isomorphic and isotopic responses. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1081-1086.

- Freemer CS, Farmer ER, Corio RL, et al. Lichenoid chronic graft-vs-host disease occurring in a dermatomal distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:70-72.

- Cohen PR, Hymes SR. Linear and dermatomal cutaneous graft-versus-host disease. South Med J. 1994;87:758-761.

- Reisfeld PL. Linear lichenoid graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1207-1208.

- Beers B, Kalish RS, Kaye VN, et al. Unilateral linear lichenoid eruption after bone marrow transplantation: an unmasking of tolerance to an abnormal keratinocyte clone? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(5, pt 2):888-892.

- Wilson BB, Lockman DW. Linear lichenoid graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1206-1207.

- Goldberg I, Sprecher E. Patterned disorders in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:498-503.

- Colman SD, Rasmussen SA, Ho VT, et al. Somatic mosaicism in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:484-490.

- Munro CS, Wilkie AO. Epidermal mosaicism producing localised acne: somatic mutation in FGFR2. Lancet. 1998;352:704-705.

- Sakuntabhai A, Dhitavat J, Burge S, et al. Mosaicism for ATP2A2 mutations causes segmental Darier's disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1144-1147.

- Dickinson AM, Wang XN, Sviland L, et al. In situ dissection of the graft-versus-host activities of cytotoxic T cells specific for minor histocompatibility antigens. Nat Med. 2002;8:410-414.

- Hansen JA, Chien JW, Warren EH, et al. Defining genetic risk for graft- versus-host disease and mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17:483-492.

- Happle R. Superimposed segmental manifestation of polygenic skin disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:690-699.

Practice Points

- Recognizing the characteristic manners in which different linear dermatoses present can aid in correctly identifying disorders that most commonly present in either a dermatomal or Blaschko-linear-type distribution.

- A blaschkoid-type distribution is the result of cutaneous mosaicism that occurs during embryological development and therefore subsequently produces a unique phenotypical presentation for various genetically influenced skin disorders, including graft-versus-host disease.

Debunking Acne Myths: Do Patients Need to Worry About Acne After Adolescence?

Myth: Acne only occurs in teenagers

Acne typically is associated with teenagers and puberty, and many adult patients may not be aware that acne can persist beyond adolescence or even develop for the first time in adulthood. As the prevalence of adults with acne increases, it is important to educate this population about factors associated with postadolescent acne development and let them know that effective treatments are available.

There are 2 types of adult acne: persistent acne, which refers to adolescent acne that continues beyond 25 years of age, and late-onset acne, which develops for the first time after 25 years of age. Adult acne generally is mild to moderate in severity and may be refractory to treatment. Unlike adolescent acne, which is more prominent in adolescent boys and manifests as the more severe forms of the disease, adult acne primarily affects women and is more inflammatory in nature, making these patients more susceptible to scarring. In one study, acne prevalence among 1055 adult participants (age range, 20–60 years) was estimated at 61.5%; however, only 36.8% were aware of their condition and only 25% sought treatment. The most commonly affected area was the malar region, which differs from acne seen in teenagers. In addition to the cheeks, adult acne generally is more prominent on the lower chin, jawline, and neck, and lesions more commonly present as closed comedones.

Fluctuating hormone levels are a common cause of adult acne, particularly in women during menses or pregnancy, menopause, or perimenopause; women also may experience breakouts after starting or discontinuing birth control pills. Acne flare-ups in adults also have been linked to chronic stress, family history, hair and skin care products, medication side effects, undiagnosed medical conditions, steroid use, increased calorie intake, whole and fat-reduced milk consumption, and tobacco smoking. Adult acne also has been found to be associated with other dermatologic conditions including hirsutism, alopecia, and seborrhea.

Early diagnosis and treatment of adult acne is crucial to ensure good cosmetic outcomes and minimize disease burden. When treating adult acne, particularly in women, dermatologists should consider a variety of factors that set this condition apart from adolescent acne, including the predisposition of older skin to irritation, possible slow response to treatment, a high likelihood of good adherence to treatment, and the psychosocial impact of acne in the adult population. In adult women, it also is important to consider whether patients are of childbearing age when selecting a treatment. Patients also should be encouraged to read the labels on their personal care products to ensure they are noncomedogenic and will not clog pores.

Adult acne. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/adult-acne. Accessed January 9, 2018.

Dréno B, Layton A, Zouboulis CC, et al. Adult female acne: a new paradigm [published online January 10, 2013]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1063-1070.

Khunger N, Kumar C. A clinic-epidemiological study of adult acne: is it different from adolescent acne? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:335-341.

Semedo D, Ladeiro F, Ruivo M, et al. Adult acne: prevalence and portrayal in primary healthcare patients, in the Great Porto Area, Portugal [published online September 30, 2016]. Acta Med Port. 2016;29:507-513.

Myth: Acne only occurs in teenagers

Acne typically is associated with teenagers and puberty, and many adult patients may not be aware that acne can persist beyond adolescence or even develop for the first time in adulthood. As the prevalence of adults with acne increases, it is important to educate this population about factors associated with postadolescent acne development and let them know that effective treatments are available.

There are 2 types of adult acne: persistent acne, which refers to adolescent acne that continues beyond 25 years of age, and late-onset acne, which develops for the first time after 25 years of age. Adult acne generally is mild to moderate in severity and may be refractory to treatment. Unlike adolescent acne, which is more prominent in adolescent boys and manifests as the more severe forms of the disease, adult acne primarily affects women and is more inflammatory in nature, making these patients more susceptible to scarring. In one study, acne prevalence among 1055 adult participants (age range, 20–60 years) was estimated at 61.5%; however, only 36.8% were aware of their condition and only 25% sought treatment. The most commonly affected area was the malar region, which differs from acne seen in teenagers. In addition to the cheeks, adult acne generally is more prominent on the lower chin, jawline, and neck, and lesions more commonly present as closed comedones.

Fluctuating hormone levels are a common cause of adult acne, particularly in women during menses or pregnancy, menopause, or perimenopause; women also may experience breakouts after starting or discontinuing birth control pills. Acne flare-ups in adults also have been linked to chronic stress, family history, hair and skin care products, medication side effects, undiagnosed medical conditions, steroid use, increased calorie intake, whole and fat-reduced milk consumption, and tobacco smoking. Adult acne also has been found to be associated with other dermatologic conditions including hirsutism, alopecia, and seborrhea.

Early diagnosis and treatment of adult acne is crucial to ensure good cosmetic outcomes and minimize disease burden. When treating adult acne, particularly in women, dermatologists should consider a variety of factors that set this condition apart from adolescent acne, including the predisposition of older skin to irritation, possible slow response to treatment, a high likelihood of good adherence to treatment, and the psychosocial impact of acne in the adult population. In adult women, it also is important to consider whether patients are of childbearing age when selecting a treatment. Patients also should be encouraged to read the labels on their personal care products to ensure they are noncomedogenic and will not clog pores.

Myth: Acne only occurs in teenagers

Acne typically is associated with teenagers and puberty, and many adult patients may not be aware that acne can persist beyond adolescence or even develop for the first time in adulthood. As the prevalence of adults with acne increases, it is important to educate this population about factors associated with postadolescent acne development and let them know that effective treatments are available.

There are 2 types of adult acne: persistent acne, which refers to adolescent acne that continues beyond 25 years of age, and late-onset acne, which develops for the first time after 25 years of age. Adult acne generally is mild to moderate in severity and may be refractory to treatment. Unlike adolescent acne, which is more prominent in adolescent boys and manifests as the more severe forms of the disease, adult acne primarily affects women and is more inflammatory in nature, making these patients more susceptible to scarring. In one study, acne prevalence among 1055 adult participants (age range, 20–60 years) was estimated at 61.5%; however, only 36.8% were aware of their condition and only 25% sought treatment. The most commonly affected area was the malar region, which differs from acne seen in teenagers. In addition to the cheeks, adult acne generally is more prominent on the lower chin, jawline, and neck, and lesions more commonly present as closed comedones.

Fluctuating hormone levels are a common cause of adult acne, particularly in women during menses or pregnancy, menopause, or perimenopause; women also may experience breakouts after starting or discontinuing birth control pills. Acne flare-ups in adults also have been linked to chronic stress, family history, hair and skin care products, medication side effects, undiagnosed medical conditions, steroid use, increased calorie intake, whole and fat-reduced milk consumption, and tobacco smoking. Adult acne also has been found to be associated with other dermatologic conditions including hirsutism, alopecia, and seborrhea.

Early diagnosis and treatment of adult acne is crucial to ensure good cosmetic outcomes and minimize disease burden. When treating adult acne, particularly in women, dermatologists should consider a variety of factors that set this condition apart from adolescent acne, including the predisposition of older skin to irritation, possible slow response to treatment, a high likelihood of good adherence to treatment, and the psychosocial impact of acne in the adult population. In adult women, it also is important to consider whether patients are of childbearing age when selecting a treatment. Patients also should be encouraged to read the labels on their personal care products to ensure they are noncomedogenic and will not clog pores.

Adult acne. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/adult-acne. Accessed January 9, 2018.

Dréno B, Layton A, Zouboulis CC, et al. Adult female acne: a new paradigm [published online January 10, 2013]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1063-1070.

Khunger N, Kumar C. A clinic-epidemiological study of adult acne: is it different from adolescent acne? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:335-341.

Semedo D, Ladeiro F, Ruivo M, et al. Adult acne: prevalence and portrayal in primary healthcare patients, in the Great Porto Area, Portugal [published online September 30, 2016]. Acta Med Port. 2016;29:507-513.

Adult acne. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/adult-acne. Accessed January 9, 2018.

Dréno B, Layton A, Zouboulis CC, et al. Adult female acne: a new paradigm [published online January 10, 2013]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1063-1070.

Khunger N, Kumar C. A clinic-epidemiological study of adult acne: is it different from adolescent acne? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:335-341.

Semedo D, Ladeiro F, Ruivo M, et al. Adult acne: prevalence and portrayal in primary healthcare patients, in the Great Porto Area, Portugal [published online September 30, 2016]. Acta Med Port. 2016;29:507-513.

A Peek at Our January 2018 Issue

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NIH Undiagnosed Diseases Network to Offer Grand Rounds Webinar Series

The NIH Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN) will launch a webinar series on March 8, 2018 (1–2 p.m. ET) that will feature descriptions of clinical phenotype and diagnostic evaluations of UDN patients. Webinar participants will be able to ask questions and offer insights on the presented cases. Registration is free but required using this link. This activity has been approved for free AMA PRA Category 1 Credit. Contact [email protected] with questions.

The NIH Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN) will launch a webinar series on March 8, 2018 (1–2 p.m. ET) that will feature descriptions of clinical phenotype and diagnostic evaluations of UDN patients. Webinar participants will be able to ask questions and offer insights on the presented cases. Registration is free but required using this link. This activity has been approved for free AMA PRA Category 1 Credit. Contact [email protected] with questions.

The NIH Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN) will launch a webinar series on March 8, 2018 (1–2 p.m. ET) that will feature descriptions of clinical phenotype and diagnostic evaluations of UDN patients. Webinar participants will be able to ask questions and offer insights on the presented cases. Registration is free but required using this link. This activity has been approved for free AMA PRA Category 1 Credit. Contact [email protected] with questions.

FDA Issues Guidance for More Efficient Approach to Drug Development for Rare Pediatric Diseases

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has released a draft guidance describing a possible new approach for companies to collaborate and test multiple drug products in the same clinical trials. Public comment is welcomed.

FDA also has issued a guidance on clarification of orphan designation of drugs and biologics for pediatric subpopulations of common diseases.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has released a draft guidance describing a possible new approach for companies to collaborate and test multiple drug products in the same clinical trials. Public comment is welcomed.

FDA also has issued a guidance on clarification of orphan designation of drugs and biologics for pediatric subpopulations of common diseases.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has released a draft guidance describing a possible new approach for companies to collaborate and test multiple drug products in the same clinical trials. Public comment is welcomed.

FDA also has issued a guidance on clarification of orphan designation of drugs and biologics for pediatric subpopulations of common diseases.

NORD Provides Update on Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passed by Congress and signed into law by President Trump includes a reduction of the Orphan Drug Tax Credit (ODTC), a repeal of the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate, and a temporary bolstering of the Medical Expense Deduction. While NORD supports the temporary strengthening of the Medical Expense Deduction, it opposed the repeal of the individual mandate and the reduction of the ODTC. Thanks to the work of rare disease advocates joining NORD in support for the ODTC, the tax credit was not repealed entirely, as was initially suggested, but rather was cut in half. NORD is grateful for the support it received on this issue and will continue to work to preserve the important orphan drug incentives in 2018.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passed by Congress and signed into law by President Trump includes a reduction of the Orphan Drug Tax Credit (ODTC), a repeal of the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate, and a temporary bolstering of the Medical Expense Deduction. While NORD supports the temporary strengthening of the Medical Expense Deduction, it opposed the repeal of the individual mandate and the reduction of the ODTC. Thanks to the work of rare disease advocates joining NORD in support for the ODTC, the tax credit was not repealed entirely, as was initially suggested, but rather was cut in half. NORD is grateful for the support it received on this issue and will continue to work to preserve the important orphan drug incentives in 2018.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passed by Congress and signed into law by President Trump includes a reduction of the Orphan Drug Tax Credit (ODTC), a repeal of the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate, and a temporary bolstering of the Medical Expense Deduction. While NORD supports the temporary strengthening of the Medical Expense Deduction, it opposed the repeal of the individual mandate and the reduction of the ODTC. Thanks to the work of rare disease advocates joining NORD in support for the ODTC, the tax credit was not repealed entirely, as was initially suggested, but rather was cut in half. NORD is grateful for the support it received on this issue and will continue to work to preserve the important orphan drug incentives in 2018.

NORD Launches Year-Long 35th Anniversary Observance

2018 marks the 35th anniversary of the Orphan Drug Act (ODA) and of NORD. The ODA was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan on January 4, 1983. Exactly four months later, NORD was formally established by the patient organization leaders who had provided advocacy for the ODA. The ODA provides critically important financial incentives to encourage development of treatments for rare diseases. Major events during the anniversary year will include NORD’s Rare Impact Awards in May and Rare Summit in October. Visit the NORD website often this year for information about those and other anniversary activities.

2018 marks the 35th anniversary of the Orphan Drug Act (ODA) and of NORD. The ODA was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan on January 4, 1983. Exactly four months later, NORD was formally established by the patient organization leaders who had provided advocacy for the ODA. The ODA provides critically important financial incentives to encourage development of treatments for rare diseases. Major events during the anniversary year will include NORD’s Rare Impact Awards in May and Rare Summit in October. Visit the NORD website often this year for information about those and other anniversary activities.

2018 marks the 35th anniversary of the Orphan Drug Act (ODA) and of NORD. The ODA was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan on January 4, 1983. Exactly four months later, NORD was formally established by the patient organization leaders who had provided advocacy for the ODA. The ODA provides critically important financial incentives to encourage development of treatments for rare diseases. Major events during the anniversary year will include NORD’s Rare Impact Awards in May and Rare Summit in October. Visit the NORD website often this year for information about those and other anniversary activities.

Visit NORD’s Website to Learn About Current or Future Research Funding Opportunities

NORD research grant opportunities are posted throughout the year as funds become available for research on specific rare diseases. Researchers should visit the website periodically to learn whether any new requests for proposals (RFPs) have been posted. Information about the NORD Research Program and current RFPs may be found here.

NORD research grant opportunities are posted throughout the year as funds become available for research on specific rare diseases. Researchers should visit the website periodically to learn whether any new requests for proposals (RFPs) have been posted. Information about the NORD Research Program and current RFPs may be found here.

NORD research grant opportunities are posted throughout the year as funds become available for research on specific rare diseases. Researchers should visit the website periodically to learn whether any new requests for proposals (RFPs) have been posted. Information about the NORD Research Program and current RFPs may be found here.

NORD Awards Five Research Grants

NORD has awarded research grants to the following scientists and institutions:

- Arun Pradhan, PhD, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio

- J. Silvio Gutkind, PhD, University of California, San Diego, California

- D. Scott Merrell, PhD, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland

- Marc Pocard, MD, PhD, Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (Inserm), Paris

- Traci L. Testerman, PhD, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Columbia, South Carolina

These grants are for studies of alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of the pulmonary veins (with support from the David Ashwell Foundation, Alveolar Capillary Dysplasia Association and William Akers Jr. and Georgia O. Akers Private Foundation) and appendix cancer pseudomyxoma peritonei (with support from the Appendix Cancer Pseudomyxoma Peritonei Research Foundation).

NORD has awarded research grants to the following scientists and institutions:

- Arun Pradhan, PhD, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio

- J. Silvio Gutkind, PhD, University of California, San Diego, California

- D. Scott Merrell, PhD, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland

- Marc Pocard, MD, PhD, Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (Inserm), Paris

- Traci L. Testerman, PhD, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Columbia, South Carolina

These grants are for studies of alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of the pulmonary veins (with support from the David Ashwell Foundation, Alveolar Capillary Dysplasia Association and William Akers Jr. and Georgia O. Akers Private Foundation) and appendix cancer pseudomyxoma peritonei (with support from the Appendix Cancer Pseudomyxoma Peritonei Research Foundation).

NORD has awarded research grants to the following scientists and institutions:

- Arun Pradhan, PhD, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio

- J. Silvio Gutkind, PhD, University of California, San Diego, California

- D. Scott Merrell, PhD, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland

- Marc Pocard, MD, PhD, Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (Inserm), Paris

- Traci L. Testerman, PhD, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Columbia, South Carolina

These grants are for studies of alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of the pulmonary veins (with support from the David Ashwell Foundation, Alveolar Capillary Dysplasia Association and William Akers Jr. and Georgia O. Akers Private Foundation) and appendix cancer pseudomyxoma peritonei (with support from the Appendix Cancer Pseudomyxoma Peritonei Research Foundation).

January 12 Is Deadline for Rare Impact Awards Nominations

Nominate a colleague, patient, caregiver, or organization for a NORD Rare Impact Award online by January 12, 2018. These awards honor individuals or organizations for improving the lives of those affected by rare diseases. The awards are presented at NORD’s Rare Impact Awards event in Washington, DC in May. Over the years, those honored have included members of Congress, senior officials from FDA and NIH, clinicians, researchers, medical societies, patient organizations, and others whose work has had a beneficial impact on the community. More info.

Nominate a colleague, patient, caregiver, or organization for a NORD Rare Impact Award online by January 12, 2018. These awards honor individuals or organizations for improving the lives of those affected by rare diseases. The awards are presented at NORD’s Rare Impact Awards event in Washington, DC in May. Over the years, those honored have included members of Congress, senior officials from FDA and NIH, clinicians, researchers, medical societies, patient organizations, and others whose work has had a beneficial impact on the community. More info.

Nominate a colleague, patient, caregiver, or organization for a NORD Rare Impact Award online by January 12, 2018. These awards honor individuals or organizations for improving the lives of those affected by rare diseases. The awards are presented at NORD’s Rare Impact Awards event in Washington, DC in May. Over the years, those honored have included members of Congress, senior officials from FDA and NIH, clinicians, researchers, medical societies, patient organizations, and others whose work has had a beneficial impact on the community. More info.