User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Innovations in Dermatology: Laboratory Monitoring With Isotretinoin

DRESS Syndrome Induced by Telaprevir: A Potentially Fatal Adverse Event in Chronic Hepatitis C Therapy

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hyperprolactinemia and gastrointestinal angiodysplasia presented to the dermatology department with a generalized skin rash of 3 weeks’ duration. She did not have a history of toxic habits. She had a history of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b (IL-28B locus) with severe hepatic fibrosis (stage 4) as assessed by ultrasound-based elastography. Due to lack of response, plasma HCV RNA was still detectable at week 12 of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (RIB) therapy, and triple therapy with pegylated interferon, RIB, and telaprevir was initiated.

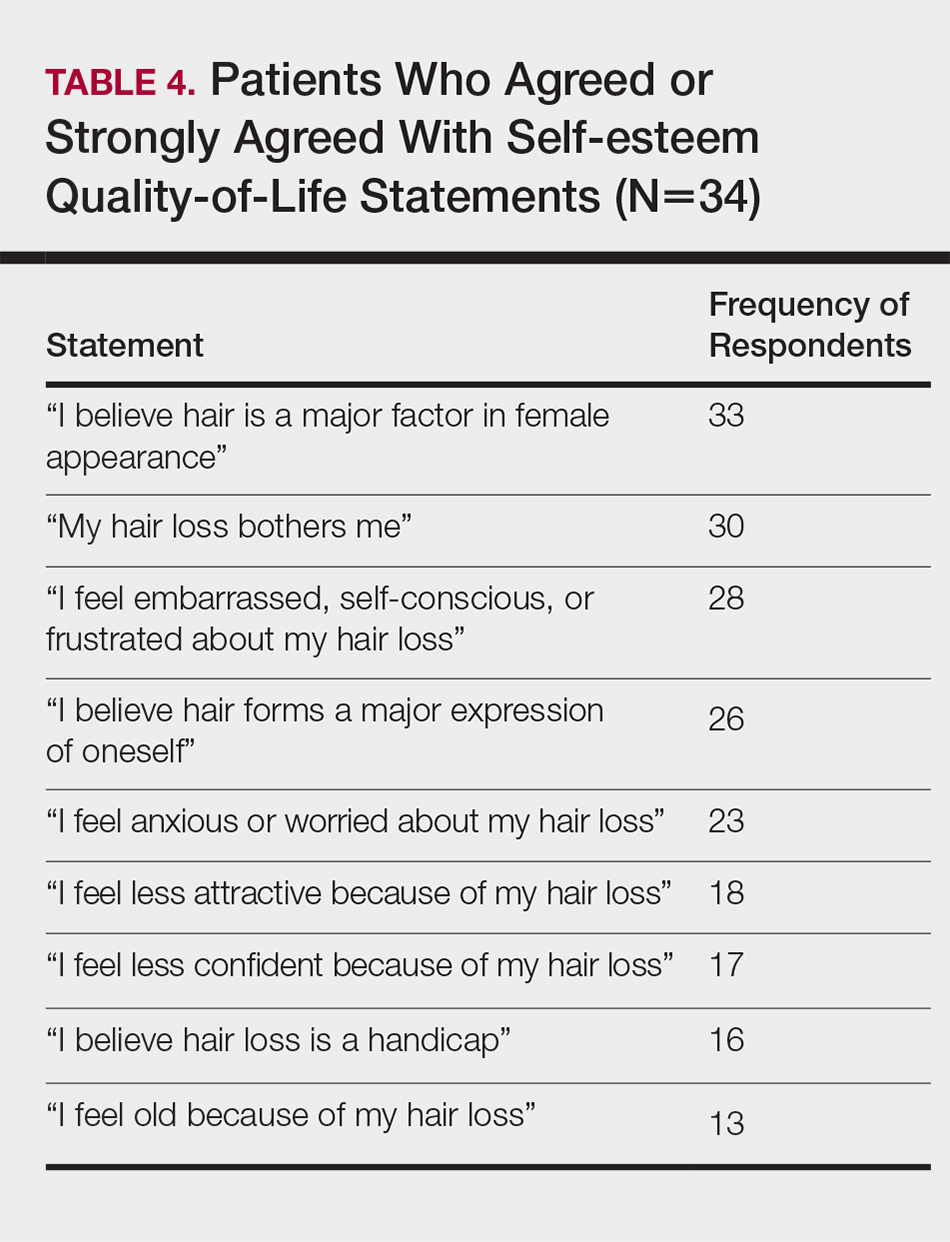

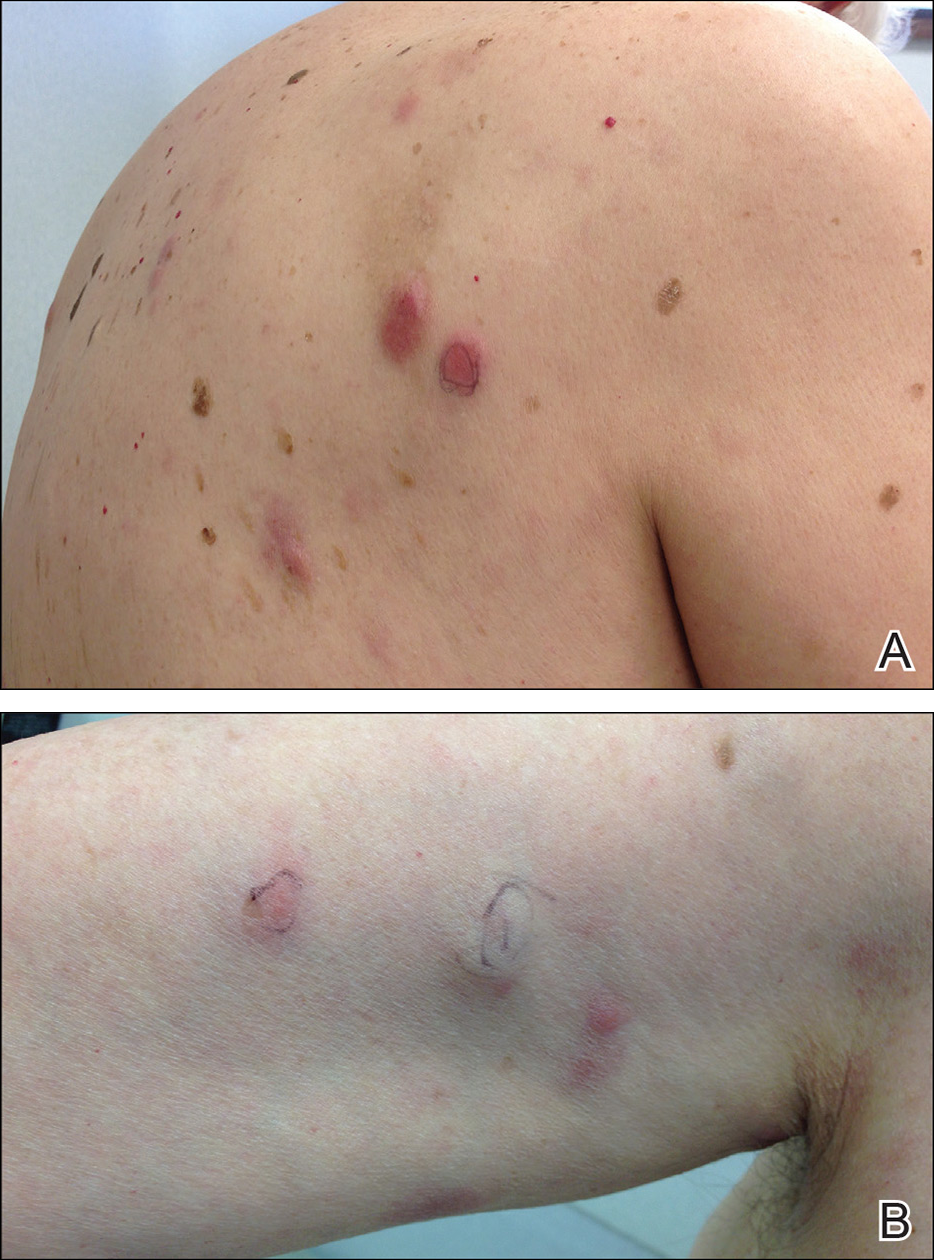

Two months later, she was admitted to the hospital after developing a generalized cutaneous rash that covered 90% of the body surface area (BSA) along with fever (temperature, 38.5°C). Laboratory blood tests showed an elevated absolute eosinophil count (2000 cells/µL [reference range, 0–500 cells/µL]), anemia (hemoglobin, 6.5 g/dL [reference range, 12–16 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (26×103/µL [reference range, 150–400×103/µL]), and altered liver function tests (serum alanine aminotransferase, 60 U/L [reference range, 0–45 U/L]; aspartate aminotransferase, 80 U/L [reference range, 0–40 U/L]). Plasma HCV RNA was undetectable at this visit. On physical examination a generalized exanthema with coalescing plaques was observed, as well as crusted vesicles covering the arms, legs, chest, abdomen, and back. Palmoplantar papules (Figure, A) and facial swelling (Figure, B) also were present. A skin biopsy specimen taken from a papule on the left arm showed superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with dermal edema. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. Application of the Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale1 in our patient (total score of 5) suggested that DRESS syndrome was a moderate adverse event likely related to the use of telaprevir.

After diagnosis of DRESS syndrome, telaprevir was discontinued, and the doses of RIB and pegylated interferon were reduced to 200 mg and 180 µg weekly, respectively. Laboratory test values including liver function tests normalized within 3 weeks and remained normal on follow-up. Plasma HCV RNA continued to be undetectable.

Hepatitis C virus is relatively common with an incidence of 3% worldwide.2 It may present as an acute hepatitis or, more frequently, as asymptomatic chronic hepatitis. The acute process is self-limited and rarely causes hepatic failure. It usually leads to a chronic infection, which can result in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and the need for liver transplantation. The aim of treatment is eradication of HCV RNA, which is predicted by the attainment of a sustained virologic response. The latter is defined by the absence of HCV RNA by a polymerase chain reaction within 3 to 6 months after cessation of treatment.

Treatment of chronic HCV was based on the combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2a or -2b with RIB until 2015. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HCV infection have been published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.2 These guidelines include new protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir, in the therapeutic approach of these patients. The main limitation of both drugs is the cutaneous toxicity.

Factors to be considered when treating HCV include viral genotype, if the patient is naïve or pretreated, the degree of fibrosis, established cirrhosis, and the treatment response. For patients with genotype 1,2 as in our case, combination therapy with 3 drugs is recommended: pegylated interferon 180 µg subcutaneous injection weekly, RIB 15 mg/kg daily, and telaprevir 2250 mg or boceprevir 2400 mg daily. Triple therapy has been shown to achieve a successful response in 75% of naïve patients and in 50% of patients refractory to standard therapy.3

Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for treatment of chronic HCV infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. In phase 2 clinical trials, 41% to 61% of patients treated with telaprevir developed cutaneous reactions, of which 5% to 8% required cessation of treatment.4 The predicting risk factors for developing a secondary rash to telaprevir include age older than 45 years, body mass index less than 30, Caucasian ethnicity, and receiving HCV therapy for the first time.4

This cutaneous side effect is managed depending on the extension of the lesions, the presence of systemic symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities.5 Therefore, the severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages4,5: (1) grade I or mild, defined as a localized rash with no systemic signs or mucosal involvement; (2) grade II or moderate, a maximum of 50% BSA involvement without epidermal detachment, and inflammation of the mucous membranes may be present without ulcers, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, arthralgia, or eosinophilia; (3) grade III or severe, skin lesions affecting more than 50% BSA or less if any of the following lesions are present: vesicles or blisters, ulcers, epidermal detachment, palpable purpura, or erythema that does not blanch under pressure; (4) grade IV or life-threatening, when the clinical picture is consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, DRESS syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

DRESS syndrome is a condition clinically characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests. Cutaneous histopathologic examination may be unspecific, though atypical lymphocytes with a marked epidermotropism mimicking fungoid mycosis also have been described.6 In addition, human herpesvirus 6 serology may be negative, despite infection with this herpesvirus subtype having been associated with the development of DRESS syndrome. The pathophysiologic mechanism of DRESS syndrome is not completely understood; however, one theory ascribes an immunologic activation due to drug metabolite formation as the main mechanism.1

Eleven patients7 with possible DRESS syndrome have been reported in clinical trials (less than 5% of the total of patients), with an addition of 1 more by Montaudié et al.8 No notable differences were found between telaprevir levels in these patients with respect to those of the control group.

For the management of DRESS syndrome, the occurrence of early signs of a severe acute skin reaction requires the immediate cessation of the drug, telaprevir in this case. The withdrawal of the dual therapy will depend on the short-term clinical course, according to the general condition of the patient, as well as the analytical abnormalities observed.9

In conclusion, telaprevir is a promising novel therapy for the treatment of HCV infection, but its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. HCV Guidelines website. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed August 11, 2018.

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Roujeau JC, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan SR, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- De Vriese AS, Philippe J, Van Renterghem DM, et al. Carbamazepine hypersensitivity syndrome: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74:144-151.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review [published online May 17, 2011]. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

- Montaudié H, Passeron T, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to telaprevir. Dermatology. 2010;221:303-305.

- Tas S, Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology. 2003;206:353-356.

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hyperprolactinemia and gastrointestinal angiodysplasia presented to the dermatology department with a generalized skin rash of 3 weeks’ duration. She did not have a history of toxic habits. She had a history of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b (IL-28B locus) with severe hepatic fibrosis (stage 4) as assessed by ultrasound-based elastography. Due to lack of response, plasma HCV RNA was still detectable at week 12 of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (RIB) therapy, and triple therapy with pegylated interferon, RIB, and telaprevir was initiated.

Two months later, she was admitted to the hospital after developing a generalized cutaneous rash that covered 90% of the body surface area (BSA) along with fever (temperature, 38.5°C). Laboratory blood tests showed an elevated absolute eosinophil count (2000 cells/µL [reference range, 0–500 cells/µL]), anemia (hemoglobin, 6.5 g/dL [reference range, 12–16 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (26×103/µL [reference range, 150–400×103/µL]), and altered liver function tests (serum alanine aminotransferase, 60 U/L [reference range, 0–45 U/L]; aspartate aminotransferase, 80 U/L [reference range, 0–40 U/L]). Plasma HCV RNA was undetectable at this visit. On physical examination a generalized exanthema with coalescing plaques was observed, as well as crusted vesicles covering the arms, legs, chest, abdomen, and back. Palmoplantar papules (Figure, A) and facial swelling (Figure, B) also were present. A skin biopsy specimen taken from a papule on the left arm showed superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with dermal edema. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. Application of the Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale1 in our patient (total score of 5) suggested that DRESS syndrome was a moderate adverse event likely related to the use of telaprevir.

After diagnosis of DRESS syndrome, telaprevir was discontinued, and the doses of RIB and pegylated interferon were reduced to 200 mg and 180 µg weekly, respectively. Laboratory test values including liver function tests normalized within 3 weeks and remained normal on follow-up. Plasma HCV RNA continued to be undetectable.

Hepatitis C virus is relatively common with an incidence of 3% worldwide.2 It may present as an acute hepatitis or, more frequently, as asymptomatic chronic hepatitis. The acute process is self-limited and rarely causes hepatic failure. It usually leads to a chronic infection, which can result in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and the need for liver transplantation. The aim of treatment is eradication of HCV RNA, which is predicted by the attainment of a sustained virologic response. The latter is defined by the absence of HCV RNA by a polymerase chain reaction within 3 to 6 months after cessation of treatment.

Treatment of chronic HCV was based on the combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2a or -2b with RIB until 2015. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HCV infection have been published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.2 These guidelines include new protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir, in the therapeutic approach of these patients. The main limitation of both drugs is the cutaneous toxicity.

Factors to be considered when treating HCV include viral genotype, if the patient is naïve or pretreated, the degree of fibrosis, established cirrhosis, and the treatment response. For patients with genotype 1,2 as in our case, combination therapy with 3 drugs is recommended: pegylated interferon 180 µg subcutaneous injection weekly, RIB 15 mg/kg daily, and telaprevir 2250 mg or boceprevir 2400 mg daily. Triple therapy has been shown to achieve a successful response in 75% of naïve patients and in 50% of patients refractory to standard therapy.3

Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for treatment of chronic HCV infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. In phase 2 clinical trials, 41% to 61% of patients treated with telaprevir developed cutaneous reactions, of which 5% to 8% required cessation of treatment.4 The predicting risk factors for developing a secondary rash to telaprevir include age older than 45 years, body mass index less than 30, Caucasian ethnicity, and receiving HCV therapy for the first time.4

This cutaneous side effect is managed depending on the extension of the lesions, the presence of systemic symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities.5 Therefore, the severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages4,5: (1) grade I or mild, defined as a localized rash with no systemic signs or mucosal involvement; (2) grade II or moderate, a maximum of 50% BSA involvement without epidermal detachment, and inflammation of the mucous membranes may be present without ulcers, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, arthralgia, or eosinophilia; (3) grade III or severe, skin lesions affecting more than 50% BSA or less if any of the following lesions are present: vesicles or blisters, ulcers, epidermal detachment, palpable purpura, or erythema that does not blanch under pressure; (4) grade IV or life-threatening, when the clinical picture is consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, DRESS syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

DRESS syndrome is a condition clinically characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests. Cutaneous histopathologic examination may be unspecific, though atypical lymphocytes with a marked epidermotropism mimicking fungoid mycosis also have been described.6 In addition, human herpesvirus 6 serology may be negative, despite infection with this herpesvirus subtype having been associated with the development of DRESS syndrome. The pathophysiologic mechanism of DRESS syndrome is not completely understood; however, one theory ascribes an immunologic activation due to drug metabolite formation as the main mechanism.1

Eleven patients7 with possible DRESS syndrome have been reported in clinical trials (less than 5% of the total of patients), with an addition of 1 more by Montaudié et al.8 No notable differences were found between telaprevir levels in these patients with respect to those of the control group.

For the management of DRESS syndrome, the occurrence of early signs of a severe acute skin reaction requires the immediate cessation of the drug, telaprevir in this case. The withdrawal of the dual therapy will depend on the short-term clinical course, according to the general condition of the patient, as well as the analytical abnormalities observed.9

In conclusion, telaprevir is a promising novel therapy for the treatment of HCV infection, but its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hyperprolactinemia and gastrointestinal angiodysplasia presented to the dermatology department with a generalized skin rash of 3 weeks’ duration. She did not have a history of toxic habits. She had a history of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b (IL-28B locus) with severe hepatic fibrosis (stage 4) as assessed by ultrasound-based elastography. Due to lack of response, plasma HCV RNA was still detectable at week 12 of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (RIB) therapy, and triple therapy with pegylated interferon, RIB, and telaprevir was initiated.

Two months later, she was admitted to the hospital after developing a generalized cutaneous rash that covered 90% of the body surface area (BSA) along with fever (temperature, 38.5°C). Laboratory blood tests showed an elevated absolute eosinophil count (2000 cells/µL [reference range, 0–500 cells/µL]), anemia (hemoglobin, 6.5 g/dL [reference range, 12–16 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (26×103/µL [reference range, 150–400×103/µL]), and altered liver function tests (serum alanine aminotransferase, 60 U/L [reference range, 0–45 U/L]; aspartate aminotransferase, 80 U/L [reference range, 0–40 U/L]). Plasma HCV RNA was undetectable at this visit. On physical examination a generalized exanthema with coalescing plaques was observed, as well as crusted vesicles covering the arms, legs, chest, abdomen, and back. Palmoplantar papules (Figure, A) and facial swelling (Figure, B) also were present. A skin biopsy specimen taken from a papule on the left arm showed superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with dermal edema. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. Application of the Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale1 in our patient (total score of 5) suggested that DRESS syndrome was a moderate adverse event likely related to the use of telaprevir.

After diagnosis of DRESS syndrome, telaprevir was discontinued, and the doses of RIB and pegylated interferon were reduced to 200 mg and 180 µg weekly, respectively. Laboratory test values including liver function tests normalized within 3 weeks and remained normal on follow-up. Plasma HCV RNA continued to be undetectable.

Hepatitis C virus is relatively common with an incidence of 3% worldwide.2 It may present as an acute hepatitis or, more frequently, as asymptomatic chronic hepatitis. The acute process is self-limited and rarely causes hepatic failure. It usually leads to a chronic infection, which can result in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and the need for liver transplantation. The aim of treatment is eradication of HCV RNA, which is predicted by the attainment of a sustained virologic response. The latter is defined by the absence of HCV RNA by a polymerase chain reaction within 3 to 6 months after cessation of treatment.

Treatment of chronic HCV was based on the combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2a or -2b with RIB until 2015. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HCV infection have been published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.2 These guidelines include new protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir, in the therapeutic approach of these patients. The main limitation of both drugs is the cutaneous toxicity.

Factors to be considered when treating HCV include viral genotype, if the patient is naïve or pretreated, the degree of fibrosis, established cirrhosis, and the treatment response. For patients with genotype 1,2 as in our case, combination therapy with 3 drugs is recommended: pegylated interferon 180 µg subcutaneous injection weekly, RIB 15 mg/kg daily, and telaprevir 2250 mg or boceprevir 2400 mg daily. Triple therapy has been shown to achieve a successful response in 75% of naïve patients and in 50% of patients refractory to standard therapy.3

Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for treatment of chronic HCV infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. In phase 2 clinical trials, 41% to 61% of patients treated with telaprevir developed cutaneous reactions, of which 5% to 8% required cessation of treatment.4 The predicting risk factors for developing a secondary rash to telaprevir include age older than 45 years, body mass index less than 30, Caucasian ethnicity, and receiving HCV therapy for the first time.4

This cutaneous side effect is managed depending on the extension of the lesions, the presence of systemic symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities.5 Therefore, the severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages4,5: (1) grade I or mild, defined as a localized rash with no systemic signs or mucosal involvement; (2) grade II or moderate, a maximum of 50% BSA involvement without epidermal detachment, and inflammation of the mucous membranes may be present without ulcers, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, arthralgia, or eosinophilia; (3) grade III or severe, skin lesions affecting more than 50% BSA or less if any of the following lesions are present: vesicles or blisters, ulcers, epidermal detachment, palpable purpura, or erythema that does not blanch under pressure; (4) grade IV or life-threatening, when the clinical picture is consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, DRESS syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

DRESS syndrome is a condition clinically characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests. Cutaneous histopathologic examination may be unspecific, though atypical lymphocytes with a marked epidermotropism mimicking fungoid mycosis also have been described.6 In addition, human herpesvirus 6 serology may be negative, despite infection with this herpesvirus subtype having been associated with the development of DRESS syndrome. The pathophysiologic mechanism of DRESS syndrome is not completely understood; however, one theory ascribes an immunologic activation due to drug metabolite formation as the main mechanism.1

Eleven patients7 with possible DRESS syndrome have been reported in clinical trials (less than 5% of the total of patients), with an addition of 1 more by Montaudié et al.8 No notable differences were found between telaprevir levels in these patients with respect to those of the control group.

For the management of DRESS syndrome, the occurrence of early signs of a severe acute skin reaction requires the immediate cessation of the drug, telaprevir in this case. The withdrawal of the dual therapy will depend on the short-term clinical course, according to the general condition of the patient, as well as the analytical abnormalities observed.9

In conclusion, telaprevir is a promising novel therapy for the treatment of HCV infection, but its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. HCV Guidelines website. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed August 11, 2018.

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Roujeau JC, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan SR, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- De Vriese AS, Philippe J, Van Renterghem DM, et al. Carbamazepine hypersensitivity syndrome: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74:144-151.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review [published online May 17, 2011]. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

- Montaudié H, Passeron T, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to telaprevir. Dermatology. 2010;221:303-305.

- Tas S, Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology. 2003;206:353-356.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. HCV Guidelines website. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed August 11, 2018.

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Roujeau JC, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan SR, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- De Vriese AS, Philippe J, Van Renterghem DM, et al. Carbamazepine hypersensitivity syndrome: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74:144-151.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review [published online May 17, 2011]. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

- Montaudié H, Passeron T, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to telaprevir. Dermatology. 2010;221:303-305.

- Tas S, Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology. 2003;206:353-356.

Practice Points

- DRESS syndrome is characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests.

- Severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages; in the third and fourth stages, adequate patient monitoring is necessary.

- Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved for treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. Its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

Eumycetoma Pedis in an Albanian Farmer

To the Editor:

Mycetoma is a noncontagious chronic infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by exogenous fungi or bacteria that can involve deeper structures such as the fasciae, muscles, and bones. Clinically it is characterized by increased swelling of the affected area, fibrosis, nodules, tumefaction, formation of draining sinuses, and abscesses that drain pus-containing grains through fistulae.1 The initiation of the infection is related to local trauma and can involve muscle, underlying bone, and adjacent organs. The feet are the most commonly affected region, and the incubation period is variable. Patients rarely report prior trauma to the affected area and only seek medical consultation when the nodules and draining sinuses become evident. The etiopathogenesis of mycetoma is associated with aerobic actinomycetes (ie, Nocardia, Actinomadura, Streptomyces), known as actinomycetoma, and fungal infections, known as eumycetomas.1

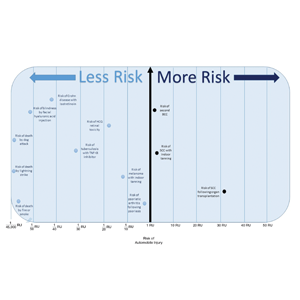

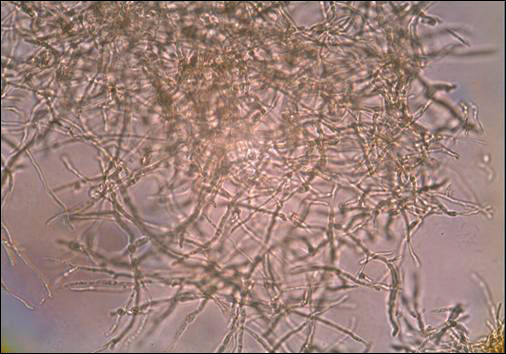

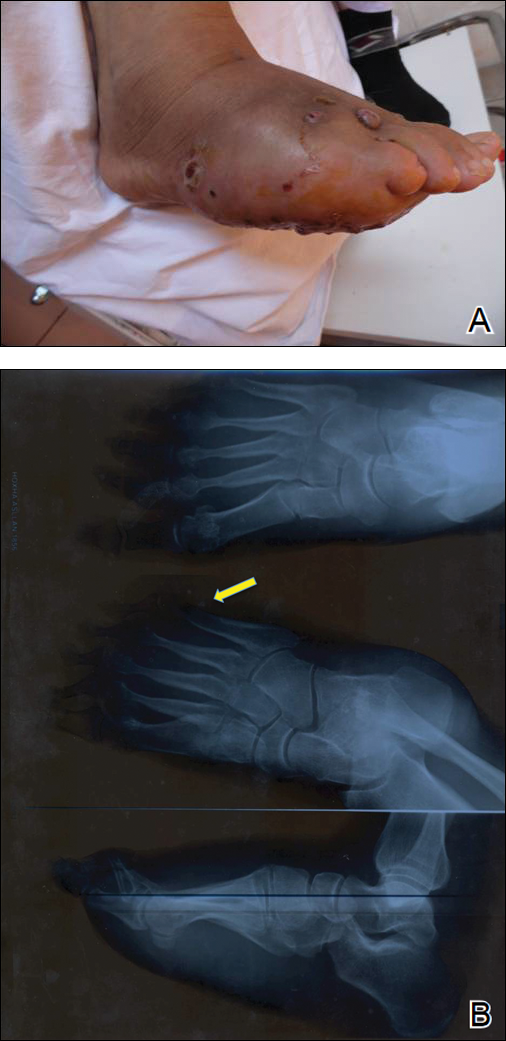

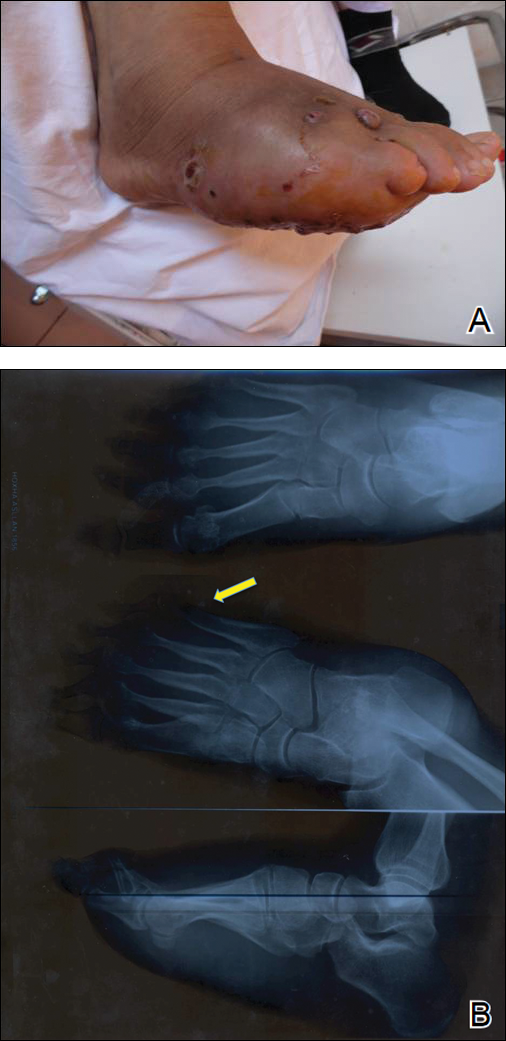

We report the case of a 57-year-old Albanian man who was referred to the outpatient clinic of our dermatology department for diagnosis and treatment of a chronic, suppurative, subcutaneous infection on the right foot presenting as abscesses and draining sinuses. The patient was a farmer and reported that the condition appeared 4 years prior following a laceration he sustained while at work. Dermatologic examination revealed local tumefaction, fistulated nodules, and abscesses discharging a serohemorrhagic fluid on the right foot (Figure 1). Perilesional erythema and subcutaneous swelling were evident. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. Standard laboratory examination was normal. Radiography of the right foot showed no osteolytic lesions or evidence of osteomyelitis.

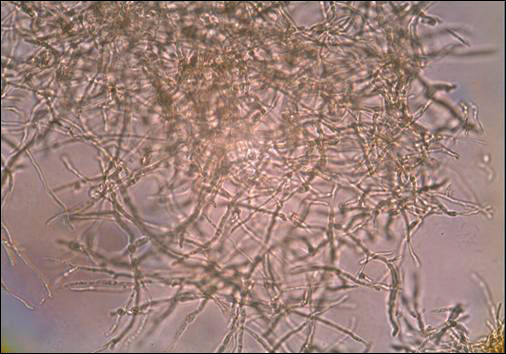

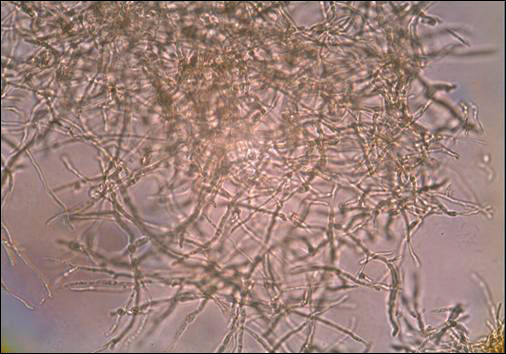

A skin biopsy from a lesion on the right foot was performed, and identification of the possible etiologic agent was based on direct microscopic examination of the granules, culture isolation of the agent, and fungal microscopic morphology.2 Granules were studied under direct examination with potassium hydroxide solution 20% and showed septate branching hyphae (Figure 2). The culture produced colonies that were white, yellow, and brown. Colonies were comprised of dense mycelium with melanin pigment and were grown at 37°C. A lactose tolerance test was positive.2 Therefore, the strain was identified as Madurella mycetomatis, and a diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was made.

The patient was hospitalized for 2 weeks and treated with intravenous fluconazole, then treatment with oral itraconazole 200 mg once daily was initiated. At 4-month follow-up, he had self-discontinued treatment but demonstrated partial improvement of the tumefaction, healing of sinus tracts, and functional recovery of the right foot.

One year following the initial presentation, the patient’s clinical condition worsened (Figure 3A). Radiography of the right foot showed osteolytic lesions on bones in the right foot (Figure 3B), and a repeat culture showed the presence of Staphylococcus aureus; thus, treatment with itraconazole 200 mg once daily along with antibiotics (cefuroxime and gentamicin) was started immediately. Surgical treatment was recommended, but the patient refused treatment.

Mycetomas are rare in Albania but are common in countries of tropical and subtropical regions. K

Clinical features of eumycetoma include lesions with clear margins, few sinuses, black grains, slow progression, and long-term involvement of bone. The grains represent an aggregate of hyphae produced by fungi; thus, the characteristic feature of eumycetoma is the formation of large granules that can involve bone.1 A critical diagnostic step is to distinguish between eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. If possible, it is important to culture the organism because treatment varies depending on the cause of the infection.

Fungal identification is crucial in the diagnosis of mycetoma. In our case, diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was based on clinical examination and detection of fungal species by microscopic examination and culture. The color of small granules (black grains) is a parameter used to identify different pathogens on histology but is not sufficient for diagnosis.5 The examination by potassium hydroxide preparation is helpful to identify the hyphae; however, culture is necessary.2

Therapeutic management of eumycetoma needs a combined strategy that includes systemic treatment and surgical therapy. Eumycetomas generally are more difficult to treat then actinomycetomas. Some authors recommend a high dose of amphotericin B as the treatment of choice for eumycetoma,6,7 but there are some that emphasize that amphotericin B is partially effective.8,9 There also is evidence in the literature of resistance of eumycetoma to ketoconazole treatment10,11 and successful treatment with fluconazole and itraconazole.10-13 For this reason, we treated our patient with the latter agents. In cases of osteolysis, amputation often is required.

In conclusion, eumycetoma pedis is a rare deep fungal infection that can cause considerable morbidity. P

- Rook A, Burns T. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

- Balows A, Hausler WJ, eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1991.

- Carter HV. On a new striking form of fungus disease principally affecting the foot and prevailing endemically in many parts of India. Trans Med Phys Soc Bombay. 1860;6:104-142.

- Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennet JE. Medical Mycology. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1992.

- Venugopal PV, Venugopal TV. Pale grain eumycetomas in Madras. Australas J Dermatol. 1995;36:149-151.

- Guarro J, Gams W, Pujol I, et al. Acremonium species: new emerging fungal opportunists—in vitro antifungal susceptibilities and review. Clin Infec Dis. 1997;25:1222-1229.

- Lau YL, Yuen KY, Lee CW, et al. Invasive Acremonium falciforme infection in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:197-198.

- Fincher RM, Fisher JF, Lovell RD, et al. Infection due to the fungus Acremonium (cephalosporium). Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:398-409.

- Milburn PB, Papayanopulos DM, Pomerantz BM. Mycetoma due to Acremonium falciforme. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:408-410.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodriguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Cur Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Restrepo A. Treatment of tropical mycoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:S91-S102.

- Gugnani HC, Ezeanolue BC, Khalil M, et al. Fluconazole in the therapy of tropical deep mycoses. Mycoses. 1995;38:485-488.

- Welsh O. Mycetoma. current concepts in treatment. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:387-398.

To the Editor:

Mycetoma is a noncontagious chronic infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by exogenous fungi or bacteria that can involve deeper structures such as the fasciae, muscles, and bones. Clinically it is characterized by increased swelling of the affected area, fibrosis, nodules, tumefaction, formation of draining sinuses, and abscesses that drain pus-containing grains through fistulae.1 The initiation of the infection is related to local trauma and can involve muscle, underlying bone, and adjacent organs. The feet are the most commonly affected region, and the incubation period is variable. Patients rarely report prior trauma to the affected area and only seek medical consultation when the nodules and draining sinuses become evident. The etiopathogenesis of mycetoma is associated with aerobic actinomycetes (ie, Nocardia, Actinomadura, Streptomyces), known as actinomycetoma, and fungal infections, known as eumycetomas.1

We report the case of a 57-year-old Albanian man who was referred to the outpatient clinic of our dermatology department for diagnosis and treatment of a chronic, suppurative, subcutaneous infection on the right foot presenting as abscesses and draining sinuses. The patient was a farmer and reported that the condition appeared 4 years prior following a laceration he sustained while at work. Dermatologic examination revealed local tumefaction, fistulated nodules, and abscesses discharging a serohemorrhagic fluid on the right foot (Figure 1). Perilesional erythema and subcutaneous swelling were evident. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. Standard laboratory examination was normal. Radiography of the right foot showed no osteolytic lesions or evidence of osteomyelitis.

A skin biopsy from a lesion on the right foot was performed, and identification of the possible etiologic agent was based on direct microscopic examination of the granules, culture isolation of the agent, and fungal microscopic morphology.2 Granules were studied under direct examination with potassium hydroxide solution 20% and showed septate branching hyphae (Figure 2). The culture produced colonies that were white, yellow, and brown. Colonies were comprised of dense mycelium with melanin pigment and were grown at 37°C. A lactose tolerance test was positive.2 Therefore, the strain was identified as Madurella mycetomatis, and a diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was made.

The patient was hospitalized for 2 weeks and treated with intravenous fluconazole, then treatment with oral itraconazole 200 mg once daily was initiated. At 4-month follow-up, he had self-discontinued treatment but demonstrated partial improvement of the tumefaction, healing of sinus tracts, and functional recovery of the right foot.

One year following the initial presentation, the patient’s clinical condition worsened (Figure 3A). Radiography of the right foot showed osteolytic lesions on bones in the right foot (Figure 3B), and a repeat culture showed the presence of Staphylococcus aureus; thus, treatment with itraconazole 200 mg once daily along with antibiotics (cefuroxime and gentamicin) was started immediately. Surgical treatment was recommended, but the patient refused treatment.

Mycetomas are rare in Albania but are common in countries of tropical and subtropical regions. K

Clinical features of eumycetoma include lesions with clear margins, few sinuses, black grains, slow progression, and long-term involvement of bone. The grains represent an aggregate of hyphae produced by fungi; thus, the characteristic feature of eumycetoma is the formation of large granules that can involve bone.1 A critical diagnostic step is to distinguish between eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. If possible, it is important to culture the organism because treatment varies depending on the cause of the infection.

Fungal identification is crucial in the diagnosis of mycetoma. In our case, diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was based on clinical examination and detection of fungal species by microscopic examination and culture. The color of small granules (black grains) is a parameter used to identify different pathogens on histology but is not sufficient for diagnosis.5 The examination by potassium hydroxide preparation is helpful to identify the hyphae; however, culture is necessary.2

Therapeutic management of eumycetoma needs a combined strategy that includes systemic treatment and surgical therapy. Eumycetomas generally are more difficult to treat then actinomycetomas. Some authors recommend a high dose of amphotericin B as the treatment of choice for eumycetoma,6,7 but there are some that emphasize that amphotericin B is partially effective.8,9 There also is evidence in the literature of resistance of eumycetoma to ketoconazole treatment10,11 and successful treatment with fluconazole and itraconazole.10-13 For this reason, we treated our patient with the latter agents. In cases of osteolysis, amputation often is required.

In conclusion, eumycetoma pedis is a rare deep fungal infection that can cause considerable morbidity. P

To the Editor:

Mycetoma is a noncontagious chronic infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by exogenous fungi or bacteria that can involve deeper structures such as the fasciae, muscles, and bones. Clinically it is characterized by increased swelling of the affected area, fibrosis, nodules, tumefaction, formation of draining sinuses, and abscesses that drain pus-containing grains through fistulae.1 The initiation of the infection is related to local trauma and can involve muscle, underlying bone, and adjacent organs. The feet are the most commonly affected region, and the incubation period is variable. Patients rarely report prior trauma to the affected area and only seek medical consultation when the nodules and draining sinuses become evident. The etiopathogenesis of mycetoma is associated with aerobic actinomycetes (ie, Nocardia, Actinomadura, Streptomyces), known as actinomycetoma, and fungal infections, known as eumycetomas.1

We report the case of a 57-year-old Albanian man who was referred to the outpatient clinic of our dermatology department for diagnosis and treatment of a chronic, suppurative, subcutaneous infection on the right foot presenting as abscesses and draining sinuses. The patient was a farmer and reported that the condition appeared 4 years prior following a laceration he sustained while at work. Dermatologic examination revealed local tumefaction, fistulated nodules, and abscesses discharging a serohemorrhagic fluid on the right foot (Figure 1). Perilesional erythema and subcutaneous swelling were evident. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. Standard laboratory examination was normal. Radiography of the right foot showed no osteolytic lesions or evidence of osteomyelitis.

A skin biopsy from a lesion on the right foot was performed, and identification of the possible etiologic agent was based on direct microscopic examination of the granules, culture isolation of the agent, and fungal microscopic morphology.2 Granules were studied under direct examination with potassium hydroxide solution 20% and showed septate branching hyphae (Figure 2). The culture produced colonies that were white, yellow, and brown. Colonies were comprised of dense mycelium with melanin pigment and were grown at 37°C. A lactose tolerance test was positive.2 Therefore, the strain was identified as Madurella mycetomatis, and a diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was made.

The patient was hospitalized for 2 weeks and treated with intravenous fluconazole, then treatment with oral itraconazole 200 mg once daily was initiated. At 4-month follow-up, he had self-discontinued treatment but demonstrated partial improvement of the tumefaction, healing of sinus tracts, and functional recovery of the right foot.

One year following the initial presentation, the patient’s clinical condition worsened (Figure 3A). Radiography of the right foot showed osteolytic lesions on bones in the right foot (Figure 3B), and a repeat culture showed the presence of Staphylococcus aureus; thus, treatment with itraconazole 200 mg once daily along with antibiotics (cefuroxime and gentamicin) was started immediately. Surgical treatment was recommended, but the patient refused treatment.

Mycetomas are rare in Albania but are common in countries of tropical and subtropical regions. K

Clinical features of eumycetoma include lesions with clear margins, few sinuses, black grains, slow progression, and long-term involvement of bone. The grains represent an aggregate of hyphae produced by fungi; thus, the characteristic feature of eumycetoma is the formation of large granules that can involve bone.1 A critical diagnostic step is to distinguish between eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. If possible, it is important to culture the organism because treatment varies depending on the cause of the infection.

Fungal identification is crucial in the diagnosis of mycetoma. In our case, diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was based on clinical examination and detection of fungal species by microscopic examination and culture. The color of small granules (black grains) is a parameter used to identify different pathogens on histology but is not sufficient for diagnosis.5 The examination by potassium hydroxide preparation is helpful to identify the hyphae; however, culture is necessary.2

Therapeutic management of eumycetoma needs a combined strategy that includes systemic treatment and surgical therapy. Eumycetomas generally are more difficult to treat then actinomycetomas. Some authors recommend a high dose of amphotericin B as the treatment of choice for eumycetoma,6,7 but there are some that emphasize that amphotericin B is partially effective.8,9 There also is evidence in the literature of resistance of eumycetoma to ketoconazole treatment10,11 and successful treatment with fluconazole and itraconazole.10-13 For this reason, we treated our patient with the latter agents. In cases of osteolysis, amputation often is required.

In conclusion, eumycetoma pedis is a rare deep fungal infection that can cause considerable morbidity. P

- Rook A, Burns T. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

- Balows A, Hausler WJ, eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1991.

- Carter HV. On a new striking form of fungus disease principally affecting the foot and prevailing endemically in many parts of India. Trans Med Phys Soc Bombay. 1860;6:104-142.

- Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennet JE. Medical Mycology. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1992.

- Venugopal PV, Venugopal TV. Pale grain eumycetomas in Madras. Australas J Dermatol. 1995;36:149-151.

- Guarro J, Gams W, Pujol I, et al. Acremonium species: new emerging fungal opportunists—in vitro antifungal susceptibilities and review. Clin Infec Dis. 1997;25:1222-1229.

- Lau YL, Yuen KY, Lee CW, et al. Invasive Acremonium falciforme infection in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:197-198.

- Fincher RM, Fisher JF, Lovell RD, et al. Infection due to the fungus Acremonium (cephalosporium). Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:398-409.

- Milburn PB, Papayanopulos DM, Pomerantz BM. Mycetoma due to Acremonium falciforme. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:408-410.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodriguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Cur Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Restrepo A. Treatment of tropical mycoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:S91-S102.

- Gugnani HC, Ezeanolue BC, Khalil M, et al. Fluconazole in the therapy of tropical deep mycoses. Mycoses. 1995;38:485-488.

- Welsh O. Mycetoma. current concepts in treatment. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:387-398.

- Rook A, Burns T. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

- Balows A, Hausler WJ, eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1991.

- Carter HV. On a new striking form of fungus disease principally affecting the foot and prevailing endemically in many parts of India. Trans Med Phys Soc Bombay. 1860;6:104-142.

- Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennet JE. Medical Mycology. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1992.

- Venugopal PV, Venugopal TV. Pale grain eumycetomas in Madras. Australas J Dermatol. 1995;36:149-151.

- Guarro J, Gams W, Pujol I, et al. Acremonium species: new emerging fungal opportunists—in vitro antifungal susceptibilities and review. Clin Infec Dis. 1997;25:1222-1229.

- Lau YL, Yuen KY, Lee CW, et al. Invasive Acremonium falciforme infection in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:197-198.

- Fincher RM, Fisher JF, Lovell RD, et al. Infection due to the fungus Acremonium (cephalosporium). Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:398-409.

- Milburn PB, Papayanopulos DM, Pomerantz BM. Mycetoma due to Acremonium falciforme. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:408-410.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodriguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Cur Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Restrepo A. Treatment of tropical mycoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:S91-S102.

- Gugnani HC, Ezeanolue BC, Khalil M, et al. Fluconazole in the therapy of tropical deep mycoses. Mycoses. 1995;38:485-488.

- Welsh O. Mycetoma. current concepts in treatment. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:387-398.

Practice Points

- A critical step in the diagnosis of mycetomas is to distinguish between eumycetoma and actinomycetoma.

- Potassium hydroxide preparation is helpful to identify fungal infection.

- Eumycetomas generally are more difficult to treat and require a combined strategy including systemic treatment and surgical therapy.

Postirradiation Morphea: Unique Presentation on the Breast

To the Editor:

Postirradiation morphea (PIM) is a rare but well-documented phenomenon that primarily occurs in breast cancer patients who have received radiation therapy; however, it also has been reported in patients who have received radiation therapy for lymphoma as well as endocervical, endometrial, and gastric carcinomas.1 Importantly, clinicians must be able to recognize and differentiate this condition from other causes of new-onset induration and erythema of the breast, such as cancer recurrence, a new primary malignancy, or inflammatory etiologies (eg, radiation or contact dermatitis). Typically, PIM presents months to years after radiation therapy as an erythematous patch within the irradiated area that progressively becomes indurated. We report an unusual case of PIM with a reticulated appearance occurring 3 weeks after radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgery for an infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the left breast.

A 62-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with a stage IIA, lymph node–negative, estrogen and progesterone receptor–negative, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the left breast. She was treated with a partial mastectomy of the left breast followed by external beam radiotherapy to the entire left breast in combination with chemotherapy (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel). The patient received 15 fractions of 270 cGy (4050 cGy total) with a weekly 600-cGy boost over 21 days without any complications.

Three weeks after finishing radiation therapy, the patient developed redness and swelling of the left breast that did not encompass the entire radiation field. There was no associated pain or pruritus. She was treated by her surgical oncologist with topical calendula and 3 courses of cephalexin for suspected mastitis with only modest improvement, then was referred to dermatology 3 months later.

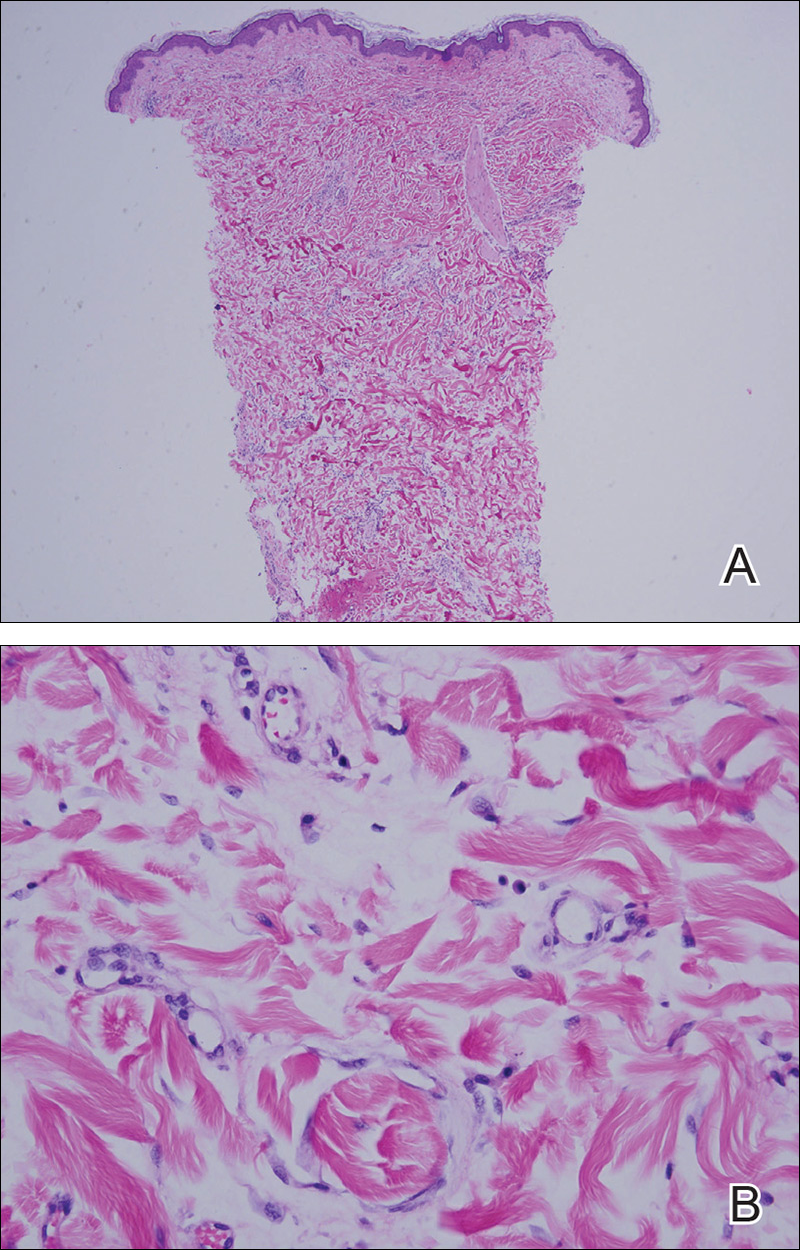

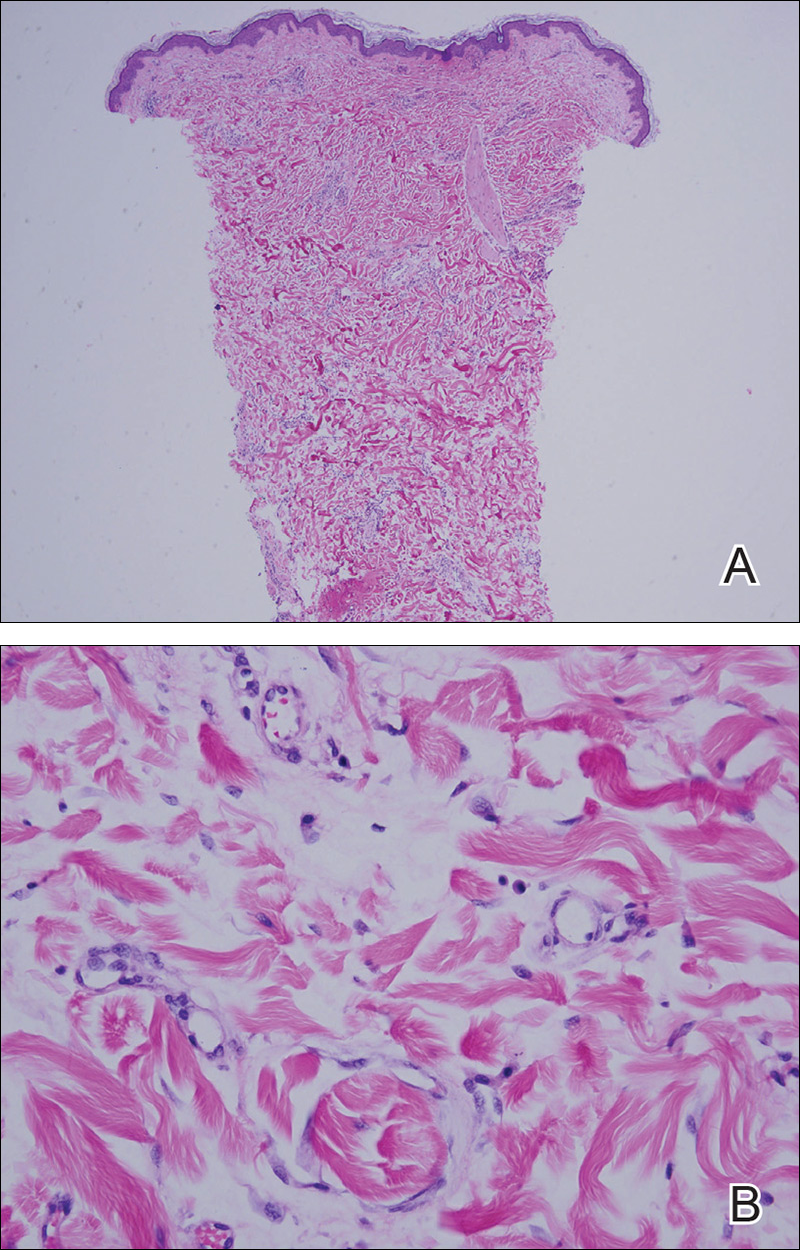

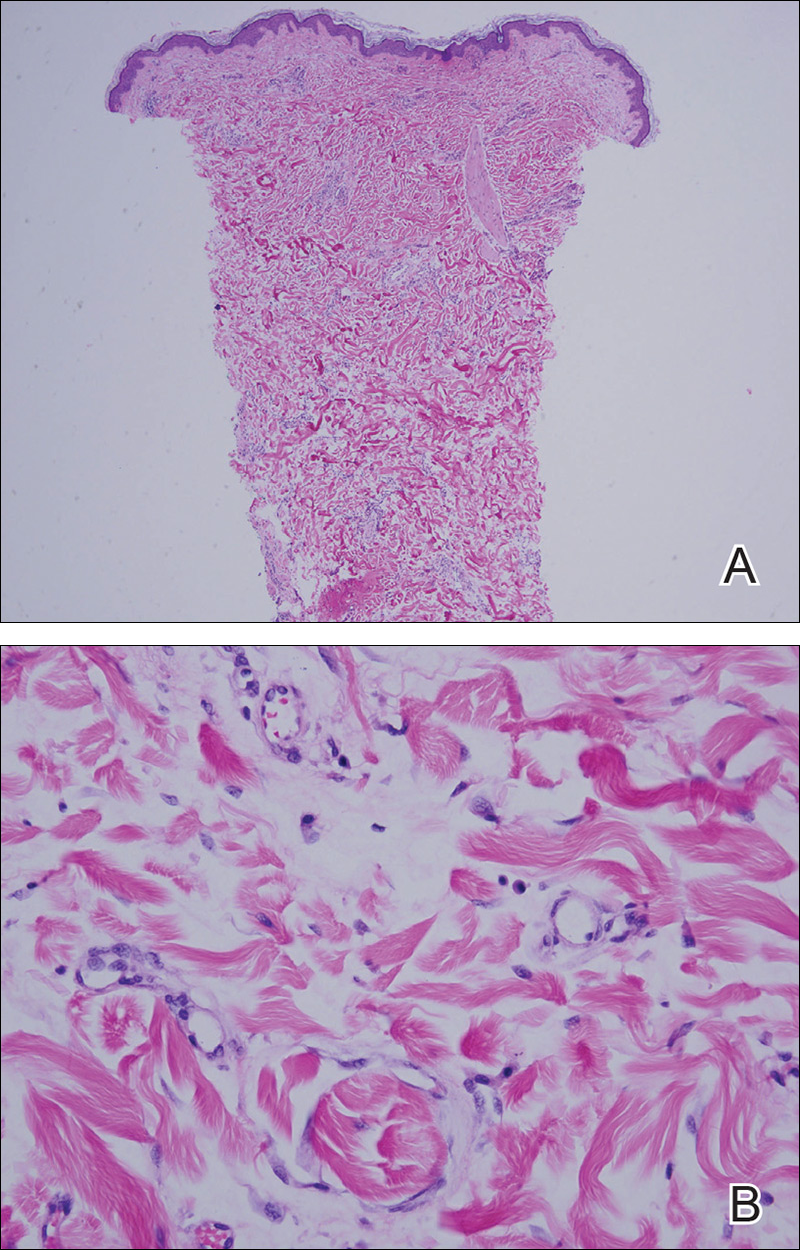

At the initial dermatology evaluation, the patient reported little improvement after antibiotics and topical calendula. On physical examination, there were erythematous, reticulated, dusky, indurated patches on the entire left breast. The area of most pronounced induration surrounded the surgical scar on the left superior breast. Punch biopsy for hematoxylin and eosin staining and tissue cultures was obtained at this appointment. The patient was started on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and was instructed to apply triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily to the affected area. After 1 month of therapy, she reported slight improvement in the degree of erythema with this regimen, but the involved area continued to extend outside of the radiation field to the central chest wall and medial right breast (Figure 1). Two additional biopsies—one from the central chest and another from the right breast—were then taken over the course of 4 months, given the consistently inconclusive clinicopathologic nature and failure of the eruption to respond to antibiotics plus topical corticosteroids.

Punch biopsy from the central chest revealed a sparse perivascular infiltrate comprised predominantly of lymphocytes with occasional eosinophils (Figure 2). There were foci suggestive of early dermal sclerosis, an increased number of small blood vessels in the dermis, and scattered enlarged fibroblasts. Metastatic carcinoma was not identified. Although the histologic findings were not entirely specific, the changes were most suggestive of PIM, for which the patient was started on pentoxifylline (400 mg 3 times daily) and oral vitamin E supplementation (400 IU daily). At subsequent follow-up appointments, she showed markedly decreased skin erythema and induration.

Morphea, also known as localized scleroderma, is an inflammatory skin condition characterized by sclerosis of the dermis and subcutis leading to scarlike tissue formation. Worldwide incidence ranges from 0.4 to 2.7 cases per 100,000 individuals with a predilection for white women.2 Unlike systemic scleroderma, morphea patients lack Raynaud phenomenon and visceral involvement.3,4

There are several clinical subtypes of morphea, including plaque, linear, generalized, and pansclerotic morphea. Lesions may vary in appearance based on configuration, stage of development, and depth of involvement.4 During the earliest phases, morphea lesions are asymptomatic, asymmetrically distributed, erythematous to violaceous patches or subtly indurated plaques expanding centrifugally with a lilac ring. Central sclerosis with loss of follicles and sweat glands is a later finding associated with advanced disease. Moreover, some reports of early-stage morphea have suggested a reticulated or geographic vascular morphology that may be misdiagnosed for other conditions such as a port-wine stain.5

Local skin exposures have long been hypothesized to contribute to development of morphea, including infection, especially Borrelia burgdorferi; trauma; chronic venous insufficiency; cosmetic surgery; medications; and exposure to toxic cooking oils, silicones, silica, pesticides, organic solvents, and vinyl chloride.2,6,7

Radiation therapy is an often overlooked cause of morphea. It was first described in 1905 but then rarely discussed until a 1989 case series of 9 patients, 7 of whom had received irradiation for breast cancer.8,9 Today, the increasing popularity of lumpectomy plus radiation therapy for treatment of early-stage breast cancer has led to a rise in PIM incidence.10

In contrast to other radiation-induced skin conditions, development of PIM is independent of the presence or absence of adjuvant chemotherapy, type of radiation therapy, or the total radiation dose or fractionation number, with reported doses ranging from less than 20.0 Gy to up to 59.4 Gy and dose fractions ranging from 10 to 30. In 20% to 30% of cases, PIM extends beyond the radiation field, sometimes involving distant sites never exposed to high-energy rays.1,10,11 This observation suggests a mechanism reliant on more widespread cascade rather than solely local tissue damage.

Prominent culture-negative, lymphoplasmacytic inflammation is another important diagnostic clue. Radiation dermatitis and fibrosis do not have the marked erythematous to violaceous hue seen in early morphea plaques. This color seen in early morphea plaques may be intense enough and in a geographic pattern, emulating a vascular lesion.

There is no standardized treatment of PIM, but traditional therapies for morphea may provide some benefit. Several randomized controlled clinical trials have shown success with pentoxifylline and oral vitamin E supplementation to treat or prevent radiation-induced breast fibrosis.12 Extrapolating from this data, our patient was started on this combination therapy and showed marked improvement in skin color and texture.

- Morganroth PA, Dehoratius D, Curry H, et al. Postirradiation morphea: a case report with a review of the literature and summary of the clinicopathologic differential diagnosis [published online October 4, 2013]. Am J

Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181cb3fdd. - Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228; quiz 229-230.

- Noh JW, Kim J, Kim JW. Localized scleroderma: a clinical study at a single center in Korea. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:437-441.

- Vasquez R, Sendejo C, Jacobe H. Morphea and other localized forms of scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:685-693.

- Nijhawan RI, Bard S, Blyumin M, et al. Early localized morphea mimicking an acquired port-wine stain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:779-782.

- Haustein UF, Ziegler V. Environmentally induced systemic sclerosis-like disorders. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:147-151.

- Mora GF. Systemic sclerosis: environmental factors. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2383-2396.

- Colver GB, Rodger A, Mortimer PS, et al. Post-irradiation morphoea. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:831-835.

- Crocker HR. Diseases of the Skin: Their Description, Pathology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston Son & Co; 1905.

- Laetsch B, Hofer T, Lombriser N, et al. Irradiation-induced morphea: x-rays as triggers of autoimmunity. Dermatology. 2011;223:9-12.

- Shetty G, Lewis F, Thrush S. Morphea of the breast: case reports and review of literature. Breast J. 2007;13:302-304.

- Jacobson G, Bhatia S, Smith BJ, et al. Randomized trial of pentoxifylline and vitamin E vs standard follow-up after breast irradiation to prevent breast fibrosis, evaluated by tissue compliance meter. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:604-608.

To the Editor:

Postirradiation morphea (PIM) is a rare but well-documented phenomenon that primarily occurs in breast cancer patients who have received radiation therapy; however, it also has been reported in patients who have received radiation therapy for lymphoma as well as endocervical, endometrial, and gastric carcinomas.1 Importantly, clinicians must be able to recognize and differentiate this condition from other causes of new-onset induration and erythema of the breast, such as cancer recurrence, a new primary malignancy, or inflammatory etiologies (eg, radiation or contact dermatitis). Typically, PIM presents months to years after radiation therapy as an erythematous patch within the irradiated area that progressively becomes indurated. We report an unusual case of PIM with a reticulated appearance occurring 3 weeks after radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgery for an infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the left breast.

A 62-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with a stage IIA, lymph node–negative, estrogen and progesterone receptor–negative, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the left breast. She was treated with a partial mastectomy of the left breast followed by external beam radiotherapy to the entire left breast in combination with chemotherapy (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel). The patient received 15 fractions of 270 cGy (4050 cGy total) with a weekly 600-cGy boost over 21 days without any complications.

Three weeks after finishing radiation therapy, the patient developed redness and swelling of the left breast that did not encompass the entire radiation field. There was no associated pain or pruritus. She was treated by her surgical oncologist with topical calendula and 3 courses of cephalexin for suspected mastitis with only modest improvement, then was referred to dermatology 3 months later.

At the initial dermatology evaluation, the patient reported little improvement after antibiotics and topical calendula. On physical examination, there were erythematous, reticulated, dusky, indurated patches on the entire left breast. The area of most pronounced induration surrounded the surgical scar on the left superior breast. Punch biopsy for hematoxylin and eosin staining and tissue cultures was obtained at this appointment. The patient was started on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and was instructed to apply triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily to the affected area. After 1 month of therapy, she reported slight improvement in the degree of erythema with this regimen, but the involved area continued to extend outside of the radiation field to the central chest wall and medial right breast (Figure 1). Two additional biopsies—one from the central chest and another from the right breast—were then taken over the course of 4 months, given the consistently inconclusive clinicopathologic nature and failure of the eruption to respond to antibiotics plus topical corticosteroids.

Punch biopsy from the central chest revealed a sparse perivascular infiltrate comprised predominantly of lymphocytes with occasional eosinophils (Figure 2). There were foci suggestive of early dermal sclerosis, an increased number of small blood vessels in the dermis, and scattered enlarged fibroblasts. Metastatic carcinoma was not identified. Although the histologic findings were not entirely specific, the changes were most suggestive of PIM, for which the patient was started on pentoxifylline (400 mg 3 times daily) and oral vitamin E supplementation (400 IU daily). At subsequent follow-up appointments, she showed markedly decreased skin erythema and induration.

Morphea, also known as localized scleroderma, is an inflammatory skin condition characterized by sclerosis of the dermis and subcutis leading to scarlike tissue formation. Worldwide incidence ranges from 0.4 to 2.7 cases per 100,000 individuals with a predilection for white women.2 Unlike systemic scleroderma, morphea patients lack Raynaud phenomenon and visceral involvement.3,4

There are several clinical subtypes of morphea, including plaque, linear, generalized, and pansclerotic morphea. Lesions may vary in appearance based on configuration, stage of development, and depth of involvement.4 During the earliest phases, morphea lesions are asymptomatic, asymmetrically distributed, erythematous to violaceous patches or subtly indurated plaques expanding centrifugally with a lilac ring. Central sclerosis with loss of follicles and sweat glands is a later finding associated with advanced disease. Moreover, some reports of early-stage morphea have suggested a reticulated or geographic vascular morphology that may be misdiagnosed for other conditions such as a port-wine stain.5

Local skin exposures have long been hypothesized to contribute to development of morphea, including infection, especially Borrelia burgdorferi; trauma; chronic venous insufficiency; cosmetic surgery; medications; and exposure to toxic cooking oils, silicones, silica, pesticides, organic solvents, and vinyl chloride.2,6,7

Radiation therapy is an often overlooked cause of morphea. It was first described in 1905 but then rarely discussed until a 1989 case series of 9 patients, 7 of whom had received irradiation for breast cancer.8,9 Today, the increasing popularity of lumpectomy plus radiation therapy for treatment of early-stage breast cancer has led to a rise in PIM incidence.10

In contrast to other radiation-induced skin conditions, development of PIM is independent of the presence or absence of adjuvant chemotherapy, type of radiation therapy, or the total radiation dose or fractionation number, with reported doses ranging from less than 20.0 Gy to up to 59.4 Gy and dose fractions ranging from 10 to 30. In 20% to 30% of cases, PIM extends beyond the radiation field, sometimes involving distant sites never exposed to high-energy rays.1,10,11 This observation suggests a mechanism reliant on more widespread cascade rather than solely local tissue damage.

Prominent culture-negative, lymphoplasmacytic inflammation is another important diagnostic clue. Radiation dermatitis and fibrosis do not have the marked erythematous to violaceous hue seen in early morphea plaques. This color seen in early morphea plaques may be intense enough and in a geographic pattern, emulating a vascular lesion.

There is no standardized treatment of PIM, but traditional therapies for morphea may provide some benefit. Several randomized controlled clinical trials have shown success with pentoxifylline and oral vitamin E supplementation to treat or prevent radiation-induced breast fibrosis.12 Extrapolating from this data, our patient was started on this combination therapy and showed marked improvement in skin color and texture.

To the Editor:

Postirradiation morphea (PIM) is a rare but well-documented phenomenon that primarily occurs in breast cancer patients who have received radiation therapy; however, it also has been reported in patients who have received radiation therapy for lymphoma as well as endocervical, endometrial, and gastric carcinomas.1 Importantly, clinicians must be able to recognize and differentiate this condition from other causes of new-onset induration and erythema of the breast, such as cancer recurrence, a new primary malignancy, or inflammatory etiologies (eg, radiation or contact dermatitis). Typically, PIM presents months to years after radiation therapy as an erythematous patch within the irradiated area that progressively becomes indurated. We report an unusual case of PIM with a reticulated appearance occurring 3 weeks after radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgery for an infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the left breast.

A 62-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with a stage IIA, lymph node–negative, estrogen and progesterone receptor–negative, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the left breast. She was treated with a partial mastectomy of the left breast followed by external beam radiotherapy to the entire left breast in combination with chemotherapy (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel). The patient received 15 fractions of 270 cGy (4050 cGy total) with a weekly 600-cGy boost over 21 days without any complications.

Three weeks after finishing radiation therapy, the patient developed redness and swelling of the left breast that did not encompass the entire radiation field. There was no associated pain or pruritus. She was treated by her surgical oncologist with topical calendula and 3 courses of cephalexin for suspected mastitis with only modest improvement, then was referred to dermatology 3 months later.

At the initial dermatology evaluation, the patient reported little improvement after antibiotics and topical calendula. On physical examination, there were erythematous, reticulated, dusky, indurated patches on the entire left breast. The area of most pronounced induration surrounded the surgical scar on the left superior breast. Punch biopsy for hematoxylin and eosin staining and tissue cultures was obtained at this appointment. The patient was started on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and was instructed to apply triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily to the affected area. After 1 month of therapy, she reported slight improvement in the degree of erythema with this regimen, but the involved area continued to extend outside of the radiation field to the central chest wall and medial right breast (Figure 1). Two additional biopsies—one from the central chest and another from the right breast—were then taken over the course of 4 months, given the consistently inconclusive clinicopathologic nature and failure of the eruption to respond to antibiotics plus topical corticosteroids.

Punch biopsy from the central chest revealed a sparse perivascular infiltrate comprised predominantly of lymphocytes with occasional eosinophils (Figure 2). There were foci suggestive of early dermal sclerosis, an increased number of small blood vessels in the dermis, and scattered enlarged fibroblasts. Metastatic carcinoma was not identified. Although the histologic findings were not entirely specific, the changes were most suggestive of PIM, for which the patient was started on pentoxifylline (400 mg 3 times daily) and oral vitamin E supplementation (400 IU daily). At subsequent follow-up appointments, she showed markedly decreased skin erythema and induration.

Morphea, also known as localized scleroderma, is an inflammatory skin condition characterized by sclerosis of the dermis and subcutis leading to scarlike tissue formation. Worldwide incidence ranges from 0.4 to 2.7 cases per 100,000 individuals with a predilection for white women.2 Unlike systemic scleroderma, morphea patients lack Raynaud phenomenon and visceral involvement.3,4

There are several clinical subtypes of morphea, including plaque, linear, generalized, and pansclerotic morphea. Lesions may vary in appearance based on configuration, stage of development, and depth of involvement.4 During the earliest phases, morphea lesions are asymptomatic, asymmetrically distributed, erythematous to violaceous patches or subtly indurated plaques expanding centrifugally with a lilac ring. Central sclerosis with loss of follicles and sweat glands is a later finding associated with advanced disease. Moreover, some reports of early-stage morphea have suggested a reticulated or geographic vascular morphology that may be misdiagnosed for other conditions such as a port-wine stain.5

Local skin exposures have long been hypothesized to contribute to development of morphea, including infection, especially Borrelia burgdorferi; trauma; chronic venous insufficiency; cosmetic surgery; medications; and exposure to toxic cooking oils, silicones, silica, pesticides, organic solvents, and vinyl chloride.2,6,7

Radiation therapy is an often overlooked cause of morphea. It was first described in 1905 but then rarely discussed until a 1989 case series of 9 patients, 7 of whom had received irradiation for breast cancer.8,9 Today, the increasing popularity of lumpectomy plus radiation therapy for treatment of early-stage breast cancer has led to a rise in PIM incidence.10

In contrast to other radiation-induced skin conditions, development of PIM is independent of the presence or absence of adjuvant chemotherapy, type of radiation therapy, or the total radiation dose or fractionation number, with reported doses ranging from less than 20.0 Gy to up to 59.4 Gy and dose fractions ranging from 10 to 30. In 20% to 30% of cases, PIM extends beyond the radiation field, sometimes involving distant sites never exposed to high-energy rays.1,10,11 This observation suggests a mechanism reliant on more widespread cascade rather than solely local tissue damage.

Prominent culture-negative, lymphoplasmacytic inflammation is another important diagnostic clue. Radiation dermatitis and fibrosis do not have the marked erythematous to violaceous hue seen in early morphea plaques. This color seen in early morphea plaques may be intense enough and in a geographic pattern, emulating a vascular lesion.

There is no standardized treatment of PIM, but traditional therapies for morphea may provide some benefit. Several randomized controlled clinical trials have shown success with pentoxifylline and oral vitamin E supplementation to treat or prevent radiation-induced breast fibrosis.12 Extrapolating from this data, our patient was started on this combination therapy and showed marked improvement in skin color and texture.

- Morganroth PA, Dehoratius D, Curry H, et al. Postirradiation morphea: a case report with a review of the literature and summary of the clinicopathologic differential diagnosis [published online October 4, 2013]. Am J

Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181cb3fdd. - Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228; quiz 229-230.

- Noh JW, Kim J, Kim JW. Localized scleroderma: a clinical study at a single center in Korea. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:437-441.

- Vasquez R, Sendejo C, Jacobe H. Morphea and other localized forms of scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:685-693.

- Nijhawan RI, Bard S, Blyumin M, et al. Early localized morphea mimicking an acquired port-wine stain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:779-782.

- Haustein UF, Ziegler V. Environmentally induced systemic sclerosis-like disorders. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:147-151.

- Mora GF. Systemic sclerosis: environmental factors. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2383-2396.

- Colver GB, Rodger A, Mortimer PS, et al. Post-irradiation morphoea. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:831-835.

- Crocker HR. Diseases of the Skin: Their Description, Pathology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston Son & Co; 1905.

- Laetsch B, Hofer T, Lombriser N, et al. Irradiation-induced morphea: x-rays as triggers of autoimmunity. Dermatology. 2011;223:9-12.

- Shetty G, Lewis F, Thrush S. Morphea of the breast: case reports and review of literature. Breast J. 2007;13:302-304.

- Jacobson G, Bhatia S, Smith BJ, et al. Randomized trial of pentoxifylline and vitamin E vs standard follow-up after breast irradiation to prevent breast fibrosis, evaluated by tissue compliance meter. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:604-608.

- Morganroth PA, Dehoratius D, Curry H, et al. Postirradiation morphea: a case report with a review of the literature and summary of the clinicopathologic differential diagnosis [published online October 4, 2013]. Am J

Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181cb3fdd. - Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228; quiz 229-230.

- Noh JW, Kim J, Kim JW. Localized scleroderma: a clinical study at a single center in Korea. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:437-441.

- Vasquez R, Sendejo C, Jacobe H. Morphea and other localized forms of scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:685-693.

- Nijhawan RI, Bard S, Blyumin M, et al. Early localized morphea mimicking an acquired port-wine stain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:779-782.

- Haustein UF, Ziegler V. Environmentally induced systemic sclerosis-like disorders. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:147-151.

- Mora GF. Systemic sclerosis: environmental factors. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2383-2396.

- Colver GB, Rodger A, Mortimer PS, et al. Post-irradiation morphoea. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:831-835.

- Crocker HR. Diseases of the Skin: Their Description, Pathology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston Son & Co; 1905.

- Laetsch B, Hofer T, Lombriser N, et al. Irradiation-induced morphea: x-rays as triggers of autoimmunity. Dermatology. 2011;223:9-12.

- Shetty G, Lewis F, Thrush S. Morphea of the breast: case reports and review of literature. Breast J. 2007;13:302-304.

- Jacobson G, Bhatia S, Smith BJ, et al. Randomized trial of pentoxifylline and vitamin E vs standard follow-up after breast irradiation to prevent breast fibrosis, evaluated by tissue compliance meter. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:604-608.

Practice Points

- Radiation therapy is an often overlooked cause of morphea.

- The increasing popularity of lumpectomy plus radiation therapy for treatment of early-stage breast cancer has led to a rise in postirradiation morphea incidence.

- Tissue changes occur as early as weeks or as late as 32 years after radiation treatment.

- Postirradiation morphea may extend beyond the radiation field.

Allergy Testing in Dermatology and Beyond

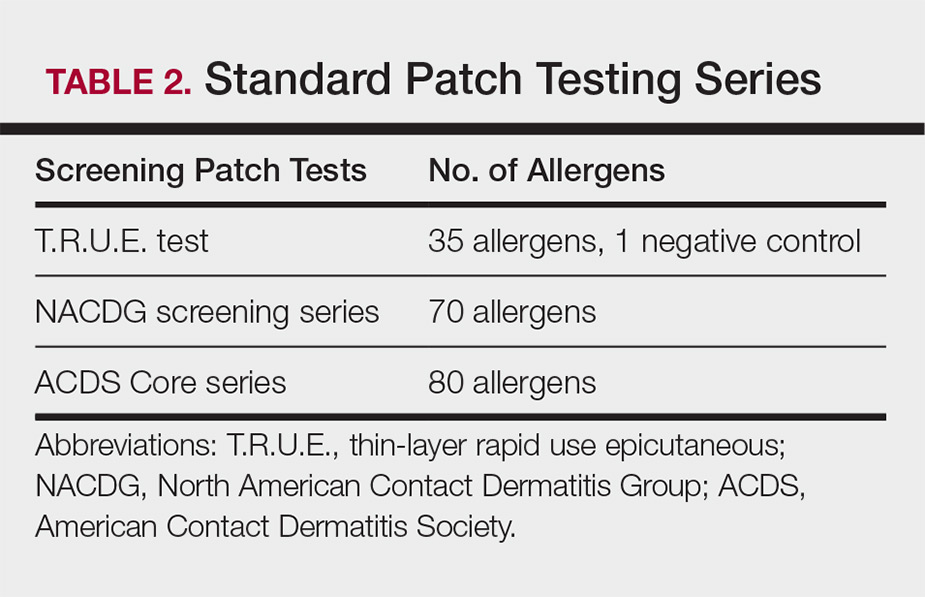

Allergy testing typically refers to evaluation of a patient for suspected type I or type IV hypersensitivity.1,2 The possibility of type I hypersensitivity is raised in patients presenting with food allergies, allergic rhinitis, asthma, and immediate adverse reactions to medications, whereas type IV hypersensitivity is suspected in patients with eczematous eruptions, delayed adverse cutaneous reactions to medications, and failure of metallic implants (eg, metal joint replacements, cardiac stents) in conjunction with overlying skin rashes (Table 1).1-5 Type II (eg, pemphigus vulgaris) and type III (eg, IgA vasculitis) hypersensitivities are not evaluated with screening allergy tests.

Type I Sensitization

Type I hypersensitivity is an immediate hypersensitivity mediated predominantly by IgE activation of mast cells in the skin as well as the respiratory and gastric mucosa.1 Sensitization of an individual patient occurs when antigen-presenting cells induce a helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response leading to B-cell class switching and allergen-specific IgE production. Upon repeat exposure to the allergen, circulating antibodies then bind to high-affinity receptors on mast cells and basophils and initiate an allergic inflammatory response, leading to a clinical presentation of allergic rhinitis, urticaria, or immediate drug reactions. Confirming type I sensitization may be performed via serologic (in vitro) or skin testing (in vivo).5,6

Serologic Testing (In Vitro)

Serologic testing is a blood test that detects circulating IgE levels against specific allergens.5 The first such test, the radioallergosorbent test, was introduced in the 1970s but is not quantitative and is no longer used. Although common, it is inaccurate to describe current serum IgE (s-IgE) testing as radioallergosorbent testing. There are several US Food and Drug Administration-approved s-IgE assays in common use, and these tests may be helpful in elucidating relevant allergens and for tailoring therapy appropriately, which may consist of avoidance of certain foods or environmental agents and/or allergen immunotherapy.

Skin Testing (In Vivo)

Skin testing can be performed percutaneously (eg, percutaneous skin testing) or intradermally (eg, intradermal testing).6 Percutaneous skin testing is performed by placing a drop of allergen extract on the skin, after which a lancet is used to lightly scratch the skin; intradermal testing is performed by injecting a small amount of allergen extract into the dermis. In both cases, the skin is evaluated after 15 to 20 minutes for the presence and size of a cutaneous wheal. Medications with antihistaminergic activity must be discontinued prior to testing. Both s-IgE and skin testing assess for type I hypersensitivity, and factors such as extensive rash, concern for anaphylaxis, or inability to discontinue antihistamines may favor s-IgE testing versus skin testing. False-positive results can occur with both tests, and for this reason, test results should always be interpreted in conjunction with clinical examination and patient history to determine relevant allergies.

Type IV Sensitization

Type IV hypersensitivity is a delayed hypersensitivity mediated primarily by lymphocytes.2 Sensitization occurs when haptens bind to host proteins and are presented by epidermal and dermal dendritic cells to T lymphocytes in the skin. These lymphocytes then migrate to regional lymph nodes where antigen-specific T lymphocytes are produced and home back to the skin. Upon reexposure to the allergen, these memory T lymphocytes become activated and incite a delayed allergic response. Confirming type IV hypersensitivity primarily is accomplished via patch testing, though other testing modalities exist.

Skin Biopsy