User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

How to Identify Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia

Debunking Psoriasis Myths: Psoriasis Is More Than Skin Deep

Myth: Psoriasis Is Only a Skin Problem

Psoriasis is predominantly regarded as a skin disease because of the outward clinical presentation of the condition. However, psoriasis is a disorder of the immune system and its damage may be more than skin deep.

Psoriasis commonly presents on the skin and nails, but a growing body of evidence has suggested that psoriasis is associated with systemic comorbidities. Up to 25% of psoriasis patients develop joint inflammation, and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) may precede skin involvement. There also is a risk for cardiovascular complications. Because of the emotional distress caused by psoriasis, patients may develop psychosocial disorders. Other conditions in patients with psoriasis include diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, Crohn disease, and the metabolic syndrome.

Results from surveys conducted by the National Psoriasis Foundation from 2003 to 2011 found that the diagnosis of psoriasis preceded PsA in the majority of patients by a mean period of 14.6 years. Patients with moderate to severe psoriasis were more likely to develop PsA than patients with mild psoriasis. Furthermore, patients with severe psoriasis were more likely to develop diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease.

In a Cutis editorial, Dr. Jeffrey Weinberg emphasizes that the role of the dermatologist “is to identify and educate patients with psoriasis who are at risk of systemic complications and ensure appropriate follow-up for their treatment and overall health.” An infographic created by the American Academy of Dermatology illustrates areas of the body that may be impacted by psoriasis beyond the skin; for example, patients may develop eye problems, weight gain, or mood changes. Consider distributing this infographic to patients to show how psoriasis can affect more than their skin.

More Cutis content is available on psoriasis comorbidities:

- Armstrong AW, Schupp C, Bebo B. Psoriasis comorbidities: results from the National Psoriasis Foundation surveys 2003 to 2011. Dermatology. 2012;225:121-126.

- Can psoriasis affect more than my skin? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/psoriasis-signs-and-symptoms/can-psoriasis-affect-more-than-my-skin. Accessed December 10, 2018.

- Psoriasis: more than skin deep. Harv Mens Health Watch. 2010;14:4-5. https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/psoriasis-more-than-skin-deep. Accessed December 10, 2018.

- Weinberg JM. More than skin deep. Cutis. 2008;82:175.

Myth: Psoriasis Is Only a Skin Problem

Psoriasis is predominantly regarded as a skin disease because of the outward clinical presentation of the condition. However, psoriasis is a disorder of the immune system and its damage may be more than skin deep.

Psoriasis commonly presents on the skin and nails, but a growing body of evidence has suggested that psoriasis is associated with systemic comorbidities. Up to 25% of psoriasis patients develop joint inflammation, and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) may precede skin involvement. There also is a risk for cardiovascular complications. Because of the emotional distress caused by psoriasis, patients may develop psychosocial disorders. Other conditions in patients with psoriasis include diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, Crohn disease, and the metabolic syndrome.

Results from surveys conducted by the National Psoriasis Foundation from 2003 to 2011 found that the diagnosis of psoriasis preceded PsA in the majority of patients by a mean period of 14.6 years. Patients with moderate to severe psoriasis were more likely to develop PsA than patients with mild psoriasis. Furthermore, patients with severe psoriasis were more likely to develop diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease.

In a Cutis editorial, Dr. Jeffrey Weinberg emphasizes that the role of the dermatologist “is to identify and educate patients with psoriasis who are at risk of systemic complications and ensure appropriate follow-up for their treatment and overall health.” An infographic created by the American Academy of Dermatology illustrates areas of the body that may be impacted by psoriasis beyond the skin; for example, patients may develop eye problems, weight gain, or mood changes. Consider distributing this infographic to patients to show how psoriasis can affect more than their skin.

More Cutis content is available on psoriasis comorbidities:

Myth: Psoriasis Is Only a Skin Problem

Psoriasis is predominantly regarded as a skin disease because of the outward clinical presentation of the condition. However, psoriasis is a disorder of the immune system and its damage may be more than skin deep.

Psoriasis commonly presents on the skin and nails, but a growing body of evidence has suggested that psoriasis is associated with systemic comorbidities. Up to 25% of psoriasis patients develop joint inflammation, and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) may precede skin involvement. There also is a risk for cardiovascular complications. Because of the emotional distress caused by psoriasis, patients may develop psychosocial disorders. Other conditions in patients with psoriasis include diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, Crohn disease, and the metabolic syndrome.

Results from surveys conducted by the National Psoriasis Foundation from 2003 to 2011 found that the diagnosis of psoriasis preceded PsA in the majority of patients by a mean period of 14.6 years. Patients with moderate to severe psoriasis were more likely to develop PsA than patients with mild psoriasis. Furthermore, patients with severe psoriasis were more likely to develop diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease.

In a Cutis editorial, Dr. Jeffrey Weinberg emphasizes that the role of the dermatologist “is to identify and educate patients with psoriasis who are at risk of systemic complications and ensure appropriate follow-up for their treatment and overall health.” An infographic created by the American Academy of Dermatology illustrates areas of the body that may be impacted by psoriasis beyond the skin; for example, patients may develop eye problems, weight gain, or mood changes. Consider distributing this infographic to patients to show how psoriasis can affect more than their skin.

More Cutis content is available on psoriasis comorbidities:

- Armstrong AW, Schupp C, Bebo B. Psoriasis comorbidities: results from the National Psoriasis Foundation surveys 2003 to 2011. Dermatology. 2012;225:121-126.

- Can psoriasis affect more than my skin? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/psoriasis-signs-and-symptoms/can-psoriasis-affect-more-than-my-skin. Accessed December 10, 2018.

- Psoriasis: more than skin deep. Harv Mens Health Watch. 2010;14:4-5. https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/psoriasis-more-than-skin-deep. Accessed December 10, 2018.

- Weinberg JM. More than skin deep. Cutis. 2008;82:175.

- Armstrong AW, Schupp C, Bebo B. Psoriasis comorbidities: results from the National Psoriasis Foundation surveys 2003 to 2011. Dermatology. 2012;225:121-126.

- Can psoriasis affect more than my skin? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/psoriasis-signs-and-symptoms/can-psoriasis-affect-more-than-my-skin. Accessed December 10, 2018.

- Psoriasis: more than skin deep. Harv Mens Health Watch. 2010;14:4-5. https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/psoriasis-more-than-skin-deep. Accessed December 10, 2018.

- Weinberg JM. More than skin deep. Cutis. 2008;82:175.

Id Reaction Associated With Red Tattoo Ink

To the Editor:

Although relatively uncommon, hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos.1 Multiple adverse events have been described in association with tattoos, including inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic responses.2 An id reaction (also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization) develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. We describe a unique case of an id reaction and subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink.

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the New York University Skin and Cancer Unit (New York, New York) for evaluation of a pruritic eruption arising on and near sites of tattooed skin on the right foot and right upper arm of 8 months’ duration. The patient reported that she had obtained a polychromatic tattoo on the right dorsal foot 9 months prior to the current presentation. Approximately 1 month later, she developed pruritic papulonodular lesions localized to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo. Concomitantly, the patient developed a similar eruption confined to areas of red pigment in a polychromatic tattoo on the right upper arm that she had obtained 10 years prior. She was treated with intralesional triamcinolone to several of the lesions on the right dorsal foot with some benefit; however, a few days later she developed a generalized, erythematous, pruritic eruption on the back, abdomen, arms, and legs. Her medical history was remarkable only for mild iron-deficiency anemia. She had no known drug allergies or history of atopy and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the eruption.

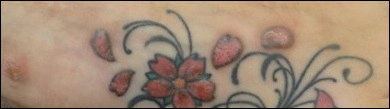

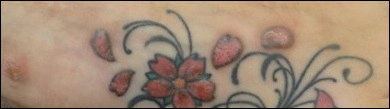

Skin examination revealed multiple, well-demarcated, eczematous papulonodules with surrounding erythema confined to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the right dorsal foot, with several similar lesions on the surrounding nontattooed skin (Figure 1). Linear, well-demarcated, eczematous, hyperpigmented plaques also were noted on the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the patient’s right upper arm (Figure 2). Eczematous plaques and scattered excoriations were noted on the back, abdomen, flanks, arms, and legs.

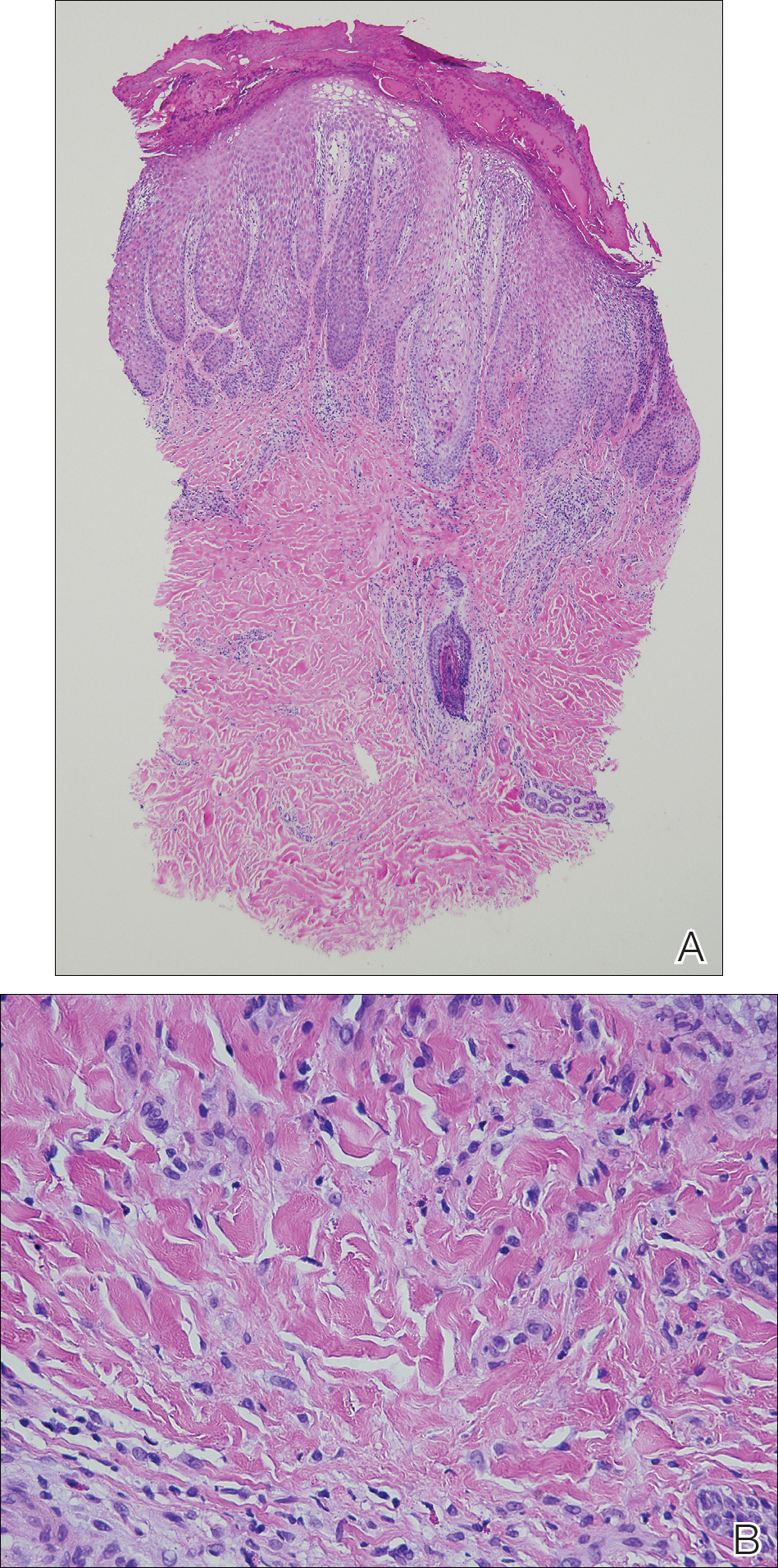

Patch testing with the North American Standard Series, metal series, and samples of the red pigments used in the tattoo on the foot were negative. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the dorsal right foot showed a psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining with diastase failed to reveal fungal hyphae. The histologic findings were consistent with allergic contact dermatitis. A punch biopsy of the eczematous reaction on nontattooed skin on the trunk demonstrated a perivascular dermatitis with eosinophils and subtle spongiosis consistent with an id reaction.

The patient was treated with fluocinonide ointment for several months with no effect. Subsequently, she received several short courses of oral prednisone, after which the affected areas of the tattoo on the arm and foot flattened and the id reaction resolved; however, after several months, the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the foot again became elevated and pruritic, and the patient developed widespread prurigo nodules on nontattooed skin on the trunk, arms, and legs. She was subsequently referred to a laser specialist for a trial of fractional laser treatment to cautiously remove the red tattoo pigment. After 2 treatments, the pruritus improved and the papular lesions appeared slightly flatter; however, the prurigo nodules remained. The tattoo on the patient’s foot was surgically removed; however, the prurigo nodules remained. Ultimately, the lesions cleared with a several-month course of mycophenolate mofetil.

Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity. An id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. Although the pathogenesis of this reaction is not certain, it has been hypothesized that autoimmunity to skin antigens might play a role.3 Autologous epidermal cells are thought to become antigenic in the presence of acute inflammation at the primary cutaneous site. These antigenic autologous epidermal cells are postulated to enter the circulation and cause secondary eczematous lesions at distant sites. This proposed mechanism is supported by the development of positive skin reactions to autologous extracts of epidermal scaling in patients with active id reaction.3

Hematogenous dissemination of cytokines has been implicated in id reactions.4 Keratinocytes produce cytokines in response to conditions that are known to trigger id reactions.5 Epidermal cytokines released from the primary site of sensitization are thought to heighten sensitivity at distant skin areas.4 These cytokines regulate both cell-mediated and humoral cutaneous immune responses. Increased levels of activated HLA-DR isotype–positive T cells in patients with active autoeczemization favors a cellular-mediated immune mechanism. The presence of activated antigen-specific T cells also supports the role of allergic contact dermatitis in triggering id reactions.6

Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common hypersensitivity reaction to tattoo ink, with red pigments representing the most common cause of tattoo-related allergic contact dermatitis. Historically, cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) has been the most common red pigment to cause allergic contact dermatitis.7 More recently, mercury-free organic pigments (eg, azo dyes) have been used in polychromatic tattoos due to their ability to retain color over long periods of time8; however, these organic red tattoo pigments also have been implicated in allergic reactions.8-11 The composition of these new organic red tattoo pigments varies, but chemical analysis has revealed a mixture of aromatic azo compounds (eg, quinacridone),10 heavy metals (eg, aluminum, lead, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, iron, titanium),9,12 and intermediate reactive compounds (eg, naphthalene, 2-naphthol, chlorobenzene, benzene).8 Allergic contact dermatitis to red tattoo ink is well documented8,13; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms tattoo and dermatitis, tattoo and allergy, tattoo and autosensitization, tattoo and id reaction, and tattoo and autoeczematization yielded only 3 other reports of a concomitant id reaction.11,14,15

The diagnosis of id reaction associated with allergic contact dermatitis is made on the basis of clinical history, physical examination, and histopathology. Patch testing usually is not positive in cases of tattoo allergy; it is thought that the allergen is a tattoo ink byproduct possibly caused by photoinduced or metabolic change of the tattoo pigment and a haptenization process.1,8,16 Histologically, variable reaction patterns, including eczematous, lichenoid, granulomatous, and pseudolymphomatous reactions have been reported in association with delayed-type inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigments, but the lichenoid pattern is most commonly observed.8

Treatment options for allergic contact dermatitis to tattoo ink include topical, intralesional, and oral steroids; topical calcineurin inhibitors; and surgical excision of the tattoo. Q-switched lasers—ruby, Nd:YAG, and alexandrite—are the gold standard for removing tattoo pigments17; however, these lasers remove tattoo pigment by selective photothermolysis, resulting in extracellular extravasation of pigment, which can precipitate a heightened immune response that can lead to localized and generalized allergic reactions.18 Therefore, Q-switched lasers should be avoided in the setting of an allergic reaction to tattoo ink. Fractional ablative laser resurfacing may be a safer alternative for removal of tattoos in the setting of an allergic reaction.17 Further studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of this modality for allergic tattoo ink removal.17,18

Our case illustrates a rare cause of id reaction and the subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink. We present this case to raise awareness of the potential health and iatrogenic risks associated with tattoo placement. Further investigation of these color additives is warranted to better elucidate ink components responsible for these cutaneous allergic reactions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Vitaly Terushkin, MD (West Orange, New Jersey, and New York, New York), and Arielle Kauvar, MD (New York, New York), for their contributions to the patient’s clinical care.

- Vasold R, Engel E, Konig B, et al. Health risks of tattoo colors. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:9-13.

- Swigost AJ, Peltola J, Jacobson-Dunlop E, et al. Tattoo-related squamous proliferations: a specturm of reactive hyperplasia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:728-732.

- Cormia FE, Esplin BM. Autoeczematization; preliminary report. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;61:931-945.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Uchi H, Terao H, Koga T, et al. Cytokines and chemokines in the epidermis. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24(suppl 1):S29-S38.

- Kasteler JS, Petersen MJ, Vance JE, et al. Circulating activated T lymphocytes in autoeczematization. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:795-798.

- Mortimer NJ, Chave TA, Johnston GA. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Garcovich S, Carbone T, Avitabile S, et al. Lichenoid red tattoo reaction: histological and immunological perspectives. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:93-96.

- Sowden JM, Byrne JP, Smith AG, et al. Red tattoo reactions: x-ray microanalysis and patch-test studies. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:576-580.

- Bendsoe N, Hansson C, Sterner O. Inflammatory reactions from organic pigments in red tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:70-73.

- Greve B, Chytry R, Raulin C. Contact dermatitis from red tattoo pigment (quinacridone) with secondary spread. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:265-266.

- Cristaudo A, Forte G, Bocca B, et al. Permanent tattoos: evidence of pseudolymphoma in three patients and metal composition of the dyes. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:776-780.

- Wenzel SM, Welzel J, Hafner C, et al. Permanent make-up colorants may cause severe skin reactions. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:223-227.

- Goldberg HM. Tattoo allergy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1315-1316.

- Gamba CS, Smith FL, Wisell J, et al. Tattoo reactions in an HIV patient: autoeczematization and progressive allergic reaction to red ink after antiretroviral therapy initiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:395-398.

- Serup J, Hutton Carlsen K. Patch test study of 90 patients with tattoo reactions: negative outcome of allergy patch test to baseline batteries and culprit inks suggests allergen(s) are generated in the skin through haptenization. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:255-263.

- Ibrahimi OA, Syed Z, Sakamoto FH, et al. Treatment of tattoo allergy with ablative fractional resurfacing: a novel paradigm for tattoo removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1111-1114.

- Harper J, Losch AE, Otto SG, et al. New insight into the pathophysiology of tattoo reactions following laser tattoo removal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:313e-314e.

To the Editor:

Although relatively uncommon, hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos.1 Multiple adverse events have been described in association with tattoos, including inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic responses.2 An id reaction (also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization) develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. We describe a unique case of an id reaction and subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink.

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the New York University Skin and Cancer Unit (New York, New York) for evaluation of a pruritic eruption arising on and near sites of tattooed skin on the right foot and right upper arm of 8 months’ duration. The patient reported that she had obtained a polychromatic tattoo on the right dorsal foot 9 months prior to the current presentation. Approximately 1 month later, she developed pruritic papulonodular lesions localized to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo. Concomitantly, the patient developed a similar eruption confined to areas of red pigment in a polychromatic tattoo on the right upper arm that she had obtained 10 years prior. She was treated with intralesional triamcinolone to several of the lesions on the right dorsal foot with some benefit; however, a few days later she developed a generalized, erythematous, pruritic eruption on the back, abdomen, arms, and legs. Her medical history was remarkable only for mild iron-deficiency anemia. She had no known drug allergies or history of atopy and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the eruption.

Skin examination revealed multiple, well-demarcated, eczematous papulonodules with surrounding erythema confined to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the right dorsal foot, with several similar lesions on the surrounding nontattooed skin (Figure 1). Linear, well-demarcated, eczematous, hyperpigmented plaques also were noted on the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the patient’s right upper arm (Figure 2). Eczematous plaques and scattered excoriations were noted on the back, abdomen, flanks, arms, and legs.

Patch testing with the North American Standard Series, metal series, and samples of the red pigments used in the tattoo on the foot were negative. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the dorsal right foot showed a psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining with diastase failed to reveal fungal hyphae. The histologic findings were consistent with allergic contact dermatitis. A punch biopsy of the eczematous reaction on nontattooed skin on the trunk demonstrated a perivascular dermatitis with eosinophils and subtle spongiosis consistent with an id reaction.

The patient was treated with fluocinonide ointment for several months with no effect. Subsequently, she received several short courses of oral prednisone, after which the affected areas of the tattoo on the arm and foot flattened and the id reaction resolved; however, after several months, the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the foot again became elevated and pruritic, and the patient developed widespread prurigo nodules on nontattooed skin on the trunk, arms, and legs. She was subsequently referred to a laser specialist for a trial of fractional laser treatment to cautiously remove the red tattoo pigment. After 2 treatments, the pruritus improved and the papular lesions appeared slightly flatter; however, the prurigo nodules remained. The tattoo on the patient’s foot was surgically removed; however, the prurigo nodules remained. Ultimately, the lesions cleared with a several-month course of mycophenolate mofetil.

Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity. An id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. Although the pathogenesis of this reaction is not certain, it has been hypothesized that autoimmunity to skin antigens might play a role.3 Autologous epidermal cells are thought to become antigenic in the presence of acute inflammation at the primary cutaneous site. These antigenic autologous epidermal cells are postulated to enter the circulation and cause secondary eczematous lesions at distant sites. This proposed mechanism is supported by the development of positive skin reactions to autologous extracts of epidermal scaling in patients with active id reaction.3

Hematogenous dissemination of cytokines has been implicated in id reactions.4 Keratinocytes produce cytokines in response to conditions that are known to trigger id reactions.5 Epidermal cytokines released from the primary site of sensitization are thought to heighten sensitivity at distant skin areas.4 These cytokines regulate both cell-mediated and humoral cutaneous immune responses. Increased levels of activated HLA-DR isotype–positive T cells in patients with active autoeczemization favors a cellular-mediated immune mechanism. The presence of activated antigen-specific T cells also supports the role of allergic contact dermatitis in triggering id reactions.6

Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common hypersensitivity reaction to tattoo ink, with red pigments representing the most common cause of tattoo-related allergic contact dermatitis. Historically, cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) has been the most common red pigment to cause allergic contact dermatitis.7 More recently, mercury-free organic pigments (eg, azo dyes) have been used in polychromatic tattoos due to their ability to retain color over long periods of time8; however, these organic red tattoo pigments also have been implicated in allergic reactions.8-11 The composition of these new organic red tattoo pigments varies, but chemical analysis has revealed a mixture of aromatic azo compounds (eg, quinacridone),10 heavy metals (eg, aluminum, lead, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, iron, titanium),9,12 and intermediate reactive compounds (eg, naphthalene, 2-naphthol, chlorobenzene, benzene).8 Allergic contact dermatitis to red tattoo ink is well documented8,13; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms tattoo and dermatitis, tattoo and allergy, tattoo and autosensitization, tattoo and id reaction, and tattoo and autoeczematization yielded only 3 other reports of a concomitant id reaction.11,14,15

The diagnosis of id reaction associated with allergic contact dermatitis is made on the basis of clinical history, physical examination, and histopathology. Patch testing usually is not positive in cases of tattoo allergy; it is thought that the allergen is a tattoo ink byproduct possibly caused by photoinduced or metabolic change of the tattoo pigment and a haptenization process.1,8,16 Histologically, variable reaction patterns, including eczematous, lichenoid, granulomatous, and pseudolymphomatous reactions have been reported in association with delayed-type inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigments, but the lichenoid pattern is most commonly observed.8

Treatment options for allergic contact dermatitis to tattoo ink include topical, intralesional, and oral steroids; topical calcineurin inhibitors; and surgical excision of the tattoo. Q-switched lasers—ruby, Nd:YAG, and alexandrite—are the gold standard for removing tattoo pigments17; however, these lasers remove tattoo pigment by selective photothermolysis, resulting in extracellular extravasation of pigment, which can precipitate a heightened immune response that can lead to localized and generalized allergic reactions.18 Therefore, Q-switched lasers should be avoided in the setting of an allergic reaction to tattoo ink. Fractional ablative laser resurfacing may be a safer alternative for removal of tattoos in the setting of an allergic reaction.17 Further studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of this modality for allergic tattoo ink removal.17,18

Our case illustrates a rare cause of id reaction and the subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink. We present this case to raise awareness of the potential health and iatrogenic risks associated with tattoo placement. Further investigation of these color additives is warranted to better elucidate ink components responsible for these cutaneous allergic reactions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Vitaly Terushkin, MD (West Orange, New Jersey, and New York, New York), and Arielle Kauvar, MD (New York, New York), for their contributions to the patient’s clinical care.

To the Editor:

Although relatively uncommon, hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos.1 Multiple adverse events have been described in association with tattoos, including inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic responses.2 An id reaction (also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization) develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. We describe a unique case of an id reaction and subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink.

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the New York University Skin and Cancer Unit (New York, New York) for evaluation of a pruritic eruption arising on and near sites of tattooed skin on the right foot and right upper arm of 8 months’ duration. The patient reported that she had obtained a polychromatic tattoo on the right dorsal foot 9 months prior to the current presentation. Approximately 1 month later, she developed pruritic papulonodular lesions localized to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo. Concomitantly, the patient developed a similar eruption confined to areas of red pigment in a polychromatic tattoo on the right upper arm that she had obtained 10 years prior. She was treated with intralesional triamcinolone to several of the lesions on the right dorsal foot with some benefit; however, a few days later she developed a generalized, erythematous, pruritic eruption on the back, abdomen, arms, and legs. Her medical history was remarkable only for mild iron-deficiency anemia. She had no known drug allergies or history of atopy and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the eruption.

Skin examination revealed multiple, well-demarcated, eczematous papulonodules with surrounding erythema confined to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the right dorsal foot, with several similar lesions on the surrounding nontattooed skin (Figure 1). Linear, well-demarcated, eczematous, hyperpigmented plaques also were noted on the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the patient’s right upper arm (Figure 2). Eczematous plaques and scattered excoriations were noted on the back, abdomen, flanks, arms, and legs.

Patch testing with the North American Standard Series, metal series, and samples of the red pigments used in the tattoo on the foot were negative. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the dorsal right foot showed a psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining with diastase failed to reveal fungal hyphae. The histologic findings were consistent with allergic contact dermatitis. A punch biopsy of the eczematous reaction on nontattooed skin on the trunk demonstrated a perivascular dermatitis with eosinophils and subtle spongiosis consistent with an id reaction.

The patient was treated with fluocinonide ointment for several months with no effect. Subsequently, she received several short courses of oral prednisone, after which the affected areas of the tattoo on the arm and foot flattened and the id reaction resolved; however, after several months, the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the foot again became elevated and pruritic, and the patient developed widespread prurigo nodules on nontattooed skin on the trunk, arms, and legs. She was subsequently referred to a laser specialist for a trial of fractional laser treatment to cautiously remove the red tattoo pigment. After 2 treatments, the pruritus improved and the papular lesions appeared slightly flatter; however, the prurigo nodules remained. The tattoo on the patient’s foot was surgically removed; however, the prurigo nodules remained. Ultimately, the lesions cleared with a several-month course of mycophenolate mofetil.

Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity. An id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. Although the pathogenesis of this reaction is not certain, it has been hypothesized that autoimmunity to skin antigens might play a role.3 Autologous epidermal cells are thought to become antigenic in the presence of acute inflammation at the primary cutaneous site. These antigenic autologous epidermal cells are postulated to enter the circulation and cause secondary eczematous lesions at distant sites. This proposed mechanism is supported by the development of positive skin reactions to autologous extracts of epidermal scaling in patients with active id reaction.3

Hematogenous dissemination of cytokines has been implicated in id reactions.4 Keratinocytes produce cytokines in response to conditions that are known to trigger id reactions.5 Epidermal cytokines released from the primary site of sensitization are thought to heighten sensitivity at distant skin areas.4 These cytokines regulate both cell-mediated and humoral cutaneous immune responses. Increased levels of activated HLA-DR isotype–positive T cells in patients with active autoeczemization favors a cellular-mediated immune mechanism. The presence of activated antigen-specific T cells also supports the role of allergic contact dermatitis in triggering id reactions.6

Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common hypersensitivity reaction to tattoo ink, with red pigments representing the most common cause of tattoo-related allergic contact dermatitis. Historically, cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) has been the most common red pigment to cause allergic contact dermatitis.7 More recently, mercury-free organic pigments (eg, azo dyes) have been used in polychromatic tattoos due to their ability to retain color over long periods of time8; however, these organic red tattoo pigments also have been implicated in allergic reactions.8-11 The composition of these new organic red tattoo pigments varies, but chemical analysis has revealed a mixture of aromatic azo compounds (eg, quinacridone),10 heavy metals (eg, aluminum, lead, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, iron, titanium),9,12 and intermediate reactive compounds (eg, naphthalene, 2-naphthol, chlorobenzene, benzene).8 Allergic contact dermatitis to red tattoo ink is well documented8,13; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms tattoo and dermatitis, tattoo and allergy, tattoo and autosensitization, tattoo and id reaction, and tattoo and autoeczematization yielded only 3 other reports of a concomitant id reaction.11,14,15

The diagnosis of id reaction associated with allergic contact dermatitis is made on the basis of clinical history, physical examination, and histopathology. Patch testing usually is not positive in cases of tattoo allergy; it is thought that the allergen is a tattoo ink byproduct possibly caused by photoinduced or metabolic change of the tattoo pigment and a haptenization process.1,8,16 Histologically, variable reaction patterns, including eczematous, lichenoid, granulomatous, and pseudolymphomatous reactions have been reported in association with delayed-type inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigments, but the lichenoid pattern is most commonly observed.8

Treatment options for allergic contact dermatitis to tattoo ink include topical, intralesional, and oral steroids; topical calcineurin inhibitors; and surgical excision of the tattoo. Q-switched lasers—ruby, Nd:YAG, and alexandrite—are the gold standard for removing tattoo pigments17; however, these lasers remove tattoo pigment by selective photothermolysis, resulting in extracellular extravasation of pigment, which can precipitate a heightened immune response that can lead to localized and generalized allergic reactions.18 Therefore, Q-switched lasers should be avoided in the setting of an allergic reaction to tattoo ink. Fractional ablative laser resurfacing may be a safer alternative for removal of tattoos in the setting of an allergic reaction.17 Further studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of this modality for allergic tattoo ink removal.17,18

Our case illustrates a rare cause of id reaction and the subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink. We present this case to raise awareness of the potential health and iatrogenic risks associated with tattoo placement. Further investigation of these color additives is warranted to better elucidate ink components responsible for these cutaneous allergic reactions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Vitaly Terushkin, MD (West Orange, New Jersey, and New York, New York), and Arielle Kauvar, MD (New York, New York), for their contributions to the patient’s clinical care.

- Vasold R, Engel E, Konig B, et al. Health risks of tattoo colors. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:9-13.

- Swigost AJ, Peltola J, Jacobson-Dunlop E, et al. Tattoo-related squamous proliferations: a specturm of reactive hyperplasia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:728-732.

- Cormia FE, Esplin BM. Autoeczematization; preliminary report. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;61:931-945.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Uchi H, Terao H, Koga T, et al. Cytokines and chemokines in the epidermis. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24(suppl 1):S29-S38.

- Kasteler JS, Petersen MJ, Vance JE, et al. Circulating activated T lymphocytes in autoeczematization. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:795-798.

- Mortimer NJ, Chave TA, Johnston GA. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Garcovich S, Carbone T, Avitabile S, et al. Lichenoid red tattoo reaction: histological and immunological perspectives. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:93-96.

- Sowden JM, Byrne JP, Smith AG, et al. Red tattoo reactions: x-ray microanalysis and patch-test studies. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:576-580.

- Bendsoe N, Hansson C, Sterner O. Inflammatory reactions from organic pigments in red tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:70-73.

- Greve B, Chytry R, Raulin C. Contact dermatitis from red tattoo pigment (quinacridone) with secondary spread. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:265-266.

- Cristaudo A, Forte G, Bocca B, et al. Permanent tattoos: evidence of pseudolymphoma in three patients and metal composition of the dyes. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:776-780.

- Wenzel SM, Welzel J, Hafner C, et al. Permanent make-up colorants may cause severe skin reactions. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:223-227.

- Goldberg HM. Tattoo allergy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1315-1316.

- Gamba CS, Smith FL, Wisell J, et al. Tattoo reactions in an HIV patient: autoeczematization and progressive allergic reaction to red ink after antiretroviral therapy initiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:395-398.

- Serup J, Hutton Carlsen K. Patch test study of 90 patients with tattoo reactions: negative outcome of allergy patch test to baseline batteries and culprit inks suggests allergen(s) are generated in the skin through haptenization. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:255-263.

- Ibrahimi OA, Syed Z, Sakamoto FH, et al. Treatment of tattoo allergy with ablative fractional resurfacing: a novel paradigm for tattoo removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1111-1114.

- Harper J, Losch AE, Otto SG, et al. New insight into the pathophysiology of tattoo reactions following laser tattoo removal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:313e-314e.

- Vasold R, Engel E, Konig B, et al. Health risks of tattoo colors. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:9-13.

- Swigost AJ, Peltola J, Jacobson-Dunlop E, et al. Tattoo-related squamous proliferations: a specturm of reactive hyperplasia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:728-732.

- Cormia FE, Esplin BM. Autoeczematization; preliminary report. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;61:931-945.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Uchi H, Terao H, Koga T, et al. Cytokines and chemokines in the epidermis. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24(suppl 1):S29-S38.

- Kasteler JS, Petersen MJ, Vance JE, et al. Circulating activated T lymphocytes in autoeczematization. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:795-798.

- Mortimer NJ, Chave TA, Johnston GA. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Garcovich S, Carbone T, Avitabile S, et al. Lichenoid red tattoo reaction: histological and immunological perspectives. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:93-96.

- Sowden JM, Byrne JP, Smith AG, et al. Red tattoo reactions: x-ray microanalysis and patch-test studies. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:576-580.

- Bendsoe N, Hansson C, Sterner O. Inflammatory reactions from organic pigments in red tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:70-73.

- Greve B, Chytry R, Raulin C. Contact dermatitis from red tattoo pigment (quinacridone) with secondary spread. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:265-266.

- Cristaudo A, Forte G, Bocca B, et al. Permanent tattoos: evidence of pseudolymphoma in three patients and metal composition of the dyes. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:776-780.

- Wenzel SM, Welzel J, Hafner C, et al. Permanent make-up colorants may cause severe skin reactions. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:223-227.

- Goldberg HM. Tattoo allergy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1315-1316.

- Gamba CS, Smith FL, Wisell J, et al. Tattoo reactions in an HIV patient: autoeczematization and progressive allergic reaction to red ink after antiretroviral therapy initiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:395-398.

- Serup J, Hutton Carlsen K. Patch test study of 90 patients with tattoo reactions: negative outcome of allergy patch test to baseline batteries and culprit inks suggests allergen(s) are generated in the skin through haptenization. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:255-263.

- Ibrahimi OA, Syed Z, Sakamoto FH, et al. Treatment of tattoo allergy with ablative fractional resurfacing: a novel paradigm for tattoo removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1111-1114.

- Harper J, Losch AE, Otto SG, et al. New insight into the pathophysiology of tattoo reactions following laser tattoo removal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:313e-314e.

Practice Points

- Hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos. Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity.

- Id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization.

- Further investigation of color additives in tattoo pigments is warranted to better elucidate the components responsible for cutaneous allergic reactions associated with tattoo ink.

Primary Cutaneous Cryptococcosis in an Immunocompetent Iraq War Veteran

To the Editor:

Disseminated cryptococcosis is a well-known opportunistic infection in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, but it is not frequently seen as a primary infection of the skin in immunocompetent hosts. We report a case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) of the lower legs in an immunocompetent Iraq War veteran.

A 28-year-old female service member presented to the dermatology clinic with progressively enlarging plaquelike lesions on the shins of 6 months’ duration. The patient had resided and worked as a deployed soldier in the lower level of a bullet hole–laden, pigeon-infested observation tower in southern Iraq 9 months prior to the current presentation. During her 7-month deployment, she reported daily exposure to pigeon excreta on equipment and frequently sustained superficial abrasions and lacerations to the legs due to the cramped and hazardous working environment. The patient noticed intensely pruritic, bugbitelike papular lesions on the shins and calves 1 month after residing in the observation tower. She sought medical treatment and was given hydrocortisone cream 1% and calamine lotion for a presumed irritant dermatitis. Over the ensuing 3 months, the pruritus worsened, and the primary lesions coalesced into annular erythematous plaques (Figure).

After returning to the United States, the patient presented again for medical care and was given ketoconazole cream 1% for presumed tinea corporis, which resulted in no improvement. A dermatologic consultation and evaluation ensued with subsequent microbial workup showing no bacterial growth on wound culture and no fungal elements on a potassium hydroxide preparation. Hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining did not demonstrate any organisms. Tissue cultures for bacteria and acid-fast bacilli showed no growth. A fungal tissue culture ultimately confirmed the presence of Cryptococcus neoformans. A lumbar puncture showed no evidence of Cryptococcus on DNA probe testing. Serologic testing for HIV was negative, and brain magnetic resonance imaging showed no lesions. Sputum culture and staining showed no fungal elements, and a chest radiograph was normal. A diagnosis of PCC was made and therapy with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily was initiated, with the intention of completing a 6-month course. During the treatment, the pruritus resolved within 3 weeks and the lesions involuted over 3 months. From the time of onset of the lesions throughout treatment, the patient showed no pulmonary, neurologic, or other systemic symptoms. She currently is healthy with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis mainly affects individuals with underlying immunosuppression, most commonly due to advanced HIV, prolonged treatment with immunosuppressive medications, or organ transplantation.1 The most common route of inoculation is by inhalation of Cryptococcus spores with subsequent hematogenous dissemination.2 Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis with skin lesions and no concomitant systemic involvement has rarely been reported, and

Due to the worldwide deployment of US military service members, exotic cutaneous infectious diseases such as PCC may be encountered in dermatology practice. Prompt clinical and histologic diagnosis is imperative to assess for systemic disease and avoid cutaneous spread and morbidity in US service members and travelers returning home from the Middle East.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Mirza SA, Phelan M, Rimland D, et al. The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: an update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1992-2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:789-94.

- Kielstein P, Hotzel H, Schmalreck A, et al. Occurrence of Cryptococcus spp. in excreta of pigeons and pet birds. Mycoses. 2000;43:7-15.

- Leão CA, Ferreira-Paim K, Andrade-Silva L, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii in an immunocompetent host [published online October 28, 2010]. Med Mycol. 2011;49:352-355.

- Zorman JV, Zupanc TL, Parac Z, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a renal transplant recipient: case report. Mycoses. 2010;53:535-537.

To the Editor:

Disseminated cryptococcosis is a well-known opportunistic infection in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, but it is not frequently seen as a primary infection of the skin in immunocompetent hosts. We report a case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) of the lower legs in an immunocompetent Iraq War veteran.

A 28-year-old female service member presented to the dermatology clinic with progressively enlarging plaquelike lesions on the shins of 6 months’ duration. The patient had resided and worked as a deployed soldier in the lower level of a bullet hole–laden, pigeon-infested observation tower in southern Iraq 9 months prior to the current presentation. During her 7-month deployment, she reported daily exposure to pigeon excreta on equipment and frequently sustained superficial abrasions and lacerations to the legs due to the cramped and hazardous working environment. The patient noticed intensely pruritic, bugbitelike papular lesions on the shins and calves 1 month after residing in the observation tower. She sought medical treatment and was given hydrocortisone cream 1% and calamine lotion for a presumed irritant dermatitis. Over the ensuing 3 months, the pruritus worsened, and the primary lesions coalesced into annular erythematous plaques (Figure).

After returning to the United States, the patient presented again for medical care and was given ketoconazole cream 1% for presumed tinea corporis, which resulted in no improvement. A dermatologic consultation and evaluation ensued with subsequent microbial workup showing no bacterial growth on wound culture and no fungal elements on a potassium hydroxide preparation. Hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining did not demonstrate any organisms. Tissue cultures for bacteria and acid-fast bacilli showed no growth. A fungal tissue culture ultimately confirmed the presence of Cryptococcus neoformans. A lumbar puncture showed no evidence of Cryptococcus on DNA probe testing. Serologic testing for HIV was negative, and brain magnetic resonance imaging showed no lesions. Sputum culture and staining showed no fungal elements, and a chest radiograph was normal. A diagnosis of PCC was made and therapy with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily was initiated, with the intention of completing a 6-month course. During the treatment, the pruritus resolved within 3 weeks and the lesions involuted over 3 months. From the time of onset of the lesions throughout treatment, the patient showed no pulmonary, neurologic, or other systemic symptoms. She currently is healthy with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis mainly affects individuals with underlying immunosuppression, most commonly due to advanced HIV, prolonged treatment with immunosuppressive medications, or organ transplantation.1 The most common route of inoculation is by inhalation of Cryptococcus spores with subsequent hematogenous dissemination.2 Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis with skin lesions and no concomitant systemic involvement has rarely been reported, and

Due to the worldwide deployment of US military service members, exotic cutaneous infectious diseases such as PCC may be encountered in dermatology practice. Prompt clinical and histologic diagnosis is imperative to assess for systemic disease and avoid cutaneous spread and morbidity in US service members and travelers returning home from the Middle East.

To the Editor:

Disseminated cryptococcosis is a well-known opportunistic infection in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, but it is not frequently seen as a primary infection of the skin in immunocompetent hosts. We report a case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) of the lower legs in an immunocompetent Iraq War veteran.

A 28-year-old female service member presented to the dermatology clinic with progressively enlarging plaquelike lesions on the shins of 6 months’ duration. The patient had resided and worked as a deployed soldier in the lower level of a bullet hole–laden, pigeon-infested observation tower in southern Iraq 9 months prior to the current presentation. During her 7-month deployment, she reported daily exposure to pigeon excreta on equipment and frequently sustained superficial abrasions and lacerations to the legs due to the cramped and hazardous working environment. The patient noticed intensely pruritic, bugbitelike papular lesions on the shins and calves 1 month after residing in the observation tower. She sought medical treatment and was given hydrocortisone cream 1% and calamine lotion for a presumed irritant dermatitis. Over the ensuing 3 months, the pruritus worsened, and the primary lesions coalesced into annular erythematous plaques (Figure).

After returning to the United States, the patient presented again for medical care and was given ketoconazole cream 1% for presumed tinea corporis, which resulted in no improvement. A dermatologic consultation and evaluation ensued with subsequent microbial workup showing no bacterial growth on wound culture and no fungal elements on a potassium hydroxide preparation. Hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining did not demonstrate any organisms. Tissue cultures for bacteria and acid-fast bacilli showed no growth. A fungal tissue culture ultimately confirmed the presence of Cryptococcus neoformans. A lumbar puncture showed no evidence of Cryptococcus on DNA probe testing. Serologic testing for HIV was negative, and brain magnetic resonance imaging showed no lesions. Sputum culture and staining showed no fungal elements, and a chest radiograph was normal. A diagnosis of PCC was made and therapy with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily was initiated, with the intention of completing a 6-month course. During the treatment, the pruritus resolved within 3 weeks and the lesions involuted over 3 months. From the time of onset of the lesions throughout treatment, the patient showed no pulmonary, neurologic, or other systemic symptoms. She currently is healthy with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis mainly affects individuals with underlying immunosuppression, most commonly due to advanced HIV, prolonged treatment with immunosuppressive medications, or organ transplantation.1 The most common route of inoculation is by inhalation of Cryptococcus spores with subsequent hematogenous dissemination.2 Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis with skin lesions and no concomitant systemic involvement has rarely been reported, and

Due to the worldwide deployment of US military service members, exotic cutaneous infectious diseases such as PCC may be encountered in dermatology practice. Prompt clinical and histologic diagnosis is imperative to assess for systemic disease and avoid cutaneous spread and morbidity in US service members and travelers returning home from the Middle East.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Mirza SA, Phelan M, Rimland D, et al. The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: an update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1992-2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:789-94.

- Kielstein P, Hotzel H, Schmalreck A, et al. Occurrence of Cryptococcus spp. in excreta of pigeons and pet birds. Mycoses. 2000;43:7-15.

- Leão CA, Ferreira-Paim K, Andrade-Silva L, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii in an immunocompetent host [published online October 28, 2010]. Med Mycol. 2011;49:352-355.

- Zorman JV, Zupanc TL, Parac Z, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a renal transplant recipient: case report. Mycoses. 2010;53:535-537.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Mirza SA, Phelan M, Rimland D, et al. The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: an update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1992-2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:789-94.

- Kielstein P, Hotzel H, Schmalreck A, et al. Occurrence of Cryptococcus spp. in excreta of pigeons and pet birds. Mycoses. 2000;43:7-15.

- Leão CA, Ferreira-Paim K, Andrade-Silva L, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii in an immunocompetent host [published online October 28, 2010]. Med Mycol. 2011;49:352-355.

- Zorman JV, Zupanc TL, Parac Z, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a renal transplant recipient: case report. Mycoses. 2010;53:535-537.

Practice Points

- Disseminated cryptococcosis is not commonly seen as a primary cutaneous infection in immunocompetent hosts.

- When encountered, primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) usually is associated with environments that predispose patients to skin wounds with simultaneous exposure to soil or vegetative debris contaminated with bird excreta.

- The variable presentation of PCC can cause clinical confusion and diagnostic delay; therefore, a high index of suspicion is required for timely diagnosis, particularly in US service members and travelers returning home from endemic areas.

Erythematous Pruritic Plaque on the Cheek

The Diagnosis: Tinea Faciei

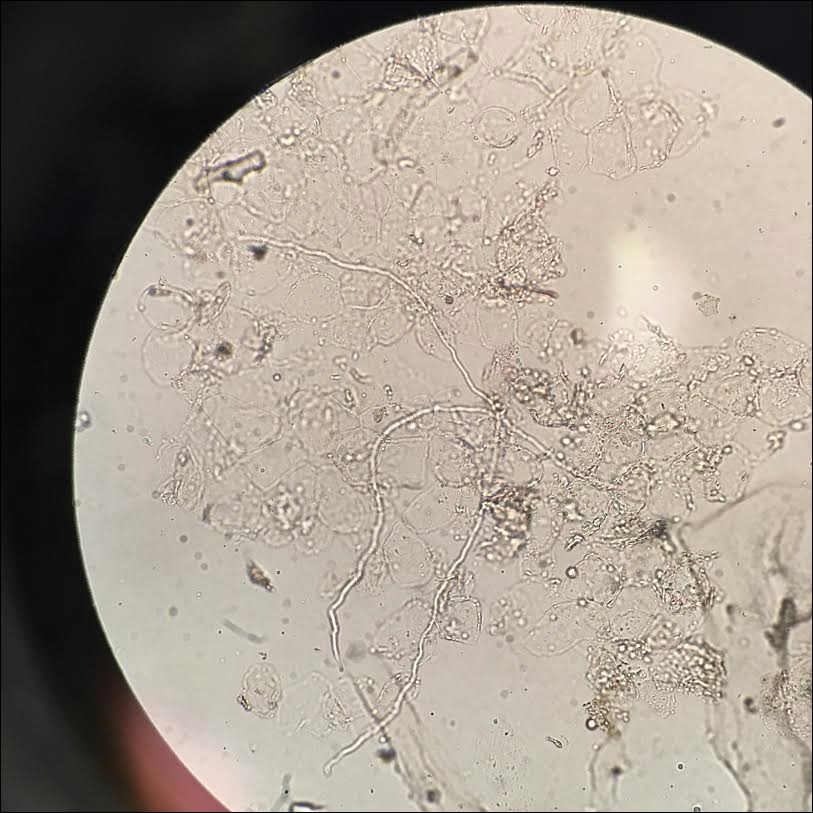

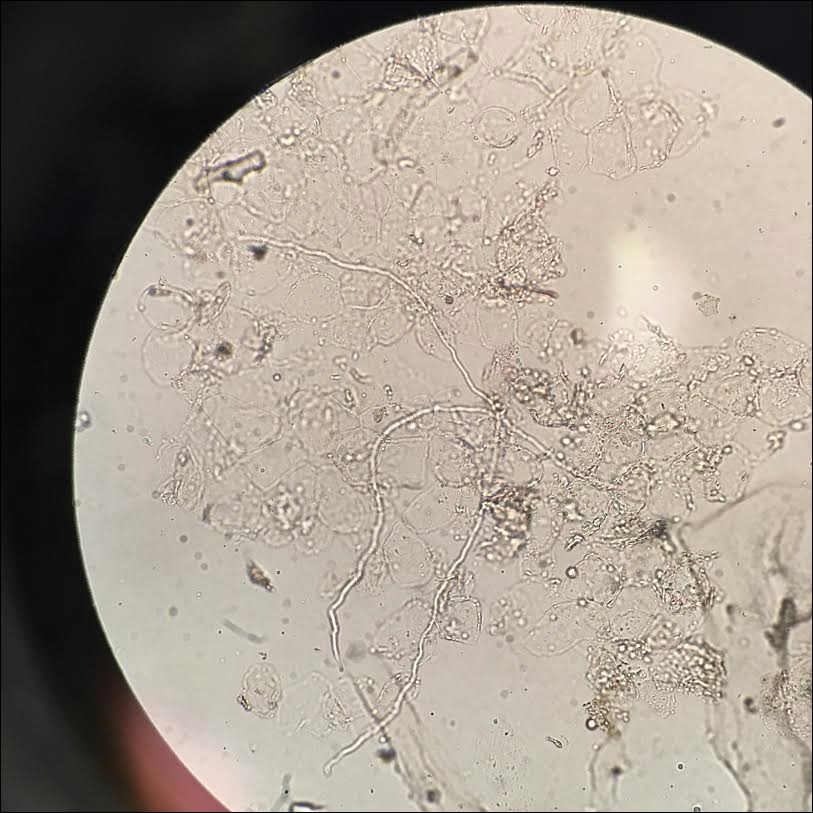

Given the morphology of the plaque, a potassium hydroxide preparation was performed and was positive for hyphal elements consistent with dermatophyte infection (Figure).

Tinea faciei is a fungal infection of the face caused by a dermatophyte that invades the stratum corneum.1 It is transmitted through direct contact with an infected individual or fomite.2 Infections typically are characterized by annular or serpiginous erythematous plaques with a scaly appearance and advancing edge. There may be associated vesicles, papules, or pustules with crusting around the advancing border.3 Tinea faciei can occur concomitantly with other dermatophytic infections and frequently presents atypically due to different characteristics of facial anatomy when compared to other tinea infections. As a result, it often is misdiagnosed.1

Tinea faciei represents roughly 19% of all superficial fungal infections and occurs more commonly in temperate humid regions.4 It can occur at any age but has bimodal peaks in incidence during childhood and early adulthood.5 The most common causative dermatophytes are Trichophyton tonsurans, Microsporum canis, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton rubrum.1 Transmission is mainly through direct contact with infected individuals, animals, or soil, which likely occurred during the close quarters and exercises our patient experienced during basic training in the military.

Tinea faciei often is misdiagnosed and treated with topical corticosteroids. The steroids can give a false impression that the rash is resolving by initially decreasing the inflammatory component and reducing scale, which is referred to as tinea incognito. Once the steroid is stopped, however, the fungal infection often returns worse than the original presentation. The differential diagnosis includes subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, periorificial dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, rosacea, erythema annulare centrifugum, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, and contact dermatitis.1,3,6

Diagnosis of tinea faciei is best made with skin scraping of the active border of the lesion. The scraping is treated with potassium hydroxide 10%. Visualizing branching or curving hyphae confirms the diagnosis. Fungal speciation often is not performed due to the long time needed to culture. Wood lamp may fluoresce blue-green if tinea faciei is caused by Microsporum species; however, diagnosis in this manner is limited because other common species do not fluoresce.7

Options for treatment of tinea faciei include topical antifungals for 2 to 6 weeks for localized disease or oral antifungals for more extensive or unresponsive infections for 1 to 8 weeks depending on the agent that is used. If fungal folliculitis is present, oral medication should be given.1 Our patient was treated with oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks with follow-up after that time to ensure resolution.

- Lin RL, Szepietowski JC, Schwartz RA. Tinea faciei, an often deceptive facial eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:437-440.

- Raimer SS, Beightler EL, Hebert AA, et al. Tinea faciei in infants caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:452-454.

- Shapiro L, Cohen HJ. Tinea faciei simulating other dermatoses. JAMA. 1971;215:2106-2107.

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(suppl 4):2-15.

- Jorquera E, Moreno JC, Camacho F. Tinea faciei: epidemiology. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1991;119:101-104.

- Hsu S, Le EH, Khoshevis MR. Differential diagnosis of annular lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:289-296.

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

The Diagnosis: Tinea Faciei

Given the morphology of the plaque, a potassium hydroxide preparation was performed and was positive for hyphal elements consistent with dermatophyte infection (Figure).

Tinea faciei is a fungal infection of the face caused by a dermatophyte that invades the stratum corneum.1 It is transmitted through direct contact with an infected individual or fomite.2 Infections typically are characterized by annular or serpiginous erythematous plaques with a scaly appearance and advancing edge. There may be associated vesicles, papules, or pustules with crusting around the advancing border.3 Tinea faciei can occur concomitantly with other dermatophytic infections and frequently presents atypically due to different characteristics of facial anatomy when compared to other tinea infections. As a result, it often is misdiagnosed.1

Tinea faciei represents roughly 19% of all superficial fungal infections and occurs more commonly in temperate humid regions.4 It can occur at any age but has bimodal peaks in incidence during childhood and early adulthood.5 The most common causative dermatophytes are Trichophyton tonsurans, Microsporum canis, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton rubrum.1 Transmission is mainly through direct contact with infected individuals, animals, or soil, which likely occurred during the close quarters and exercises our patient experienced during basic training in the military.

Tinea faciei often is misdiagnosed and treated with topical corticosteroids. The steroids can give a false impression that the rash is resolving by initially decreasing the inflammatory component and reducing scale, which is referred to as tinea incognito. Once the steroid is stopped, however, the fungal infection often returns worse than the original presentation. The differential diagnosis includes subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, periorificial dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, rosacea, erythema annulare centrifugum, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, and contact dermatitis.1,3,6

Diagnosis of tinea faciei is best made with skin scraping of the active border of the lesion. The scraping is treated with potassium hydroxide 10%. Visualizing branching or curving hyphae confirms the diagnosis. Fungal speciation often is not performed due to the long time needed to culture. Wood lamp may fluoresce blue-green if tinea faciei is caused by Microsporum species; however, diagnosis in this manner is limited because other common species do not fluoresce.7

Options for treatment of tinea faciei include topical antifungals for 2 to 6 weeks for localized disease or oral antifungals for more extensive or unresponsive infections for 1 to 8 weeks depending on the agent that is used. If fungal folliculitis is present, oral medication should be given.1 Our patient was treated with oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks with follow-up after that time to ensure resolution.

The Diagnosis: Tinea Faciei

Given the morphology of the plaque, a potassium hydroxide preparation was performed and was positive for hyphal elements consistent with dermatophyte infection (Figure).

Tinea faciei is a fungal infection of the face caused by a dermatophyte that invades the stratum corneum.1 It is transmitted through direct contact with an infected individual or fomite.2 Infections typically are characterized by annular or serpiginous erythematous plaques with a scaly appearance and advancing edge. There may be associated vesicles, papules, or pustules with crusting around the advancing border.3 Tinea faciei can occur concomitantly with other dermatophytic infections and frequently presents atypically due to different characteristics of facial anatomy when compared to other tinea infections. As a result, it often is misdiagnosed.1

Tinea faciei represents roughly 19% of all superficial fungal infections and occurs more commonly in temperate humid regions.4 It can occur at any age but has bimodal peaks in incidence during childhood and early adulthood.5 The most common causative dermatophytes are Trichophyton tonsurans, Microsporum canis, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton rubrum.1 Transmission is mainly through direct contact with infected individuals, animals, or soil, which likely occurred during the close quarters and exercises our patient experienced during basic training in the military.

Tinea faciei often is misdiagnosed and treated with topical corticosteroids. The steroids can give a false impression that the rash is resolving by initially decreasing the inflammatory component and reducing scale, which is referred to as tinea incognito. Once the steroid is stopped, however, the fungal infection often returns worse than the original presentation. The differential diagnosis includes subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, periorificial dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, rosacea, erythema annulare centrifugum, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, and contact dermatitis.1,3,6

Diagnosis of tinea faciei is best made with skin scraping of the active border of the lesion. The scraping is treated with potassium hydroxide 10%. Visualizing branching or curving hyphae confirms the diagnosis. Fungal speciation often is not performed due to the long time needed to culture. Wood lamp may fluoresce blue-green if tinea faciei is caused by Microsporum species; however, diagnosis in this manner is limited because other common species do not fluoresce.7

Options for treatment of tinea faciei include topical antifungals for 2 to 6 weeks for localized disease or oral antifungals for more extensive or unresponsive infections for 1 to 8 weeks depending on the agent that is used. If fungal folliculitis is present, oral medication should be given.1 Our patient was treated with oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks with follow-up after that time to ensure resolution.

- Lin RL, Szepietowski JC, Schwartz RA. Tinea faciei, an often deceptive facial eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:437-440.

- Raimer SS, Beightler EL, Hebert AA, et al. Tinea faciei in infants caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:452-454.

- Shapiro L, Cohen HJ. Tinea faciei simulating other dermatoses. JAMA. 1971;215:2106-2107.

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(suppl 4):2-15.

- Jorquera E, Moreno JC, Camacho F. Tinea faciei: epidemiology. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1991;119:101-104.

- Hsu S, Le EH, Khoshevis MR. Differential diagnosis of annular lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:289-296.

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

- Lin RL, Szepietowski JC, Schwartz RA. Tinea faciei, an often deceptive facial eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:437-440.

- Raimer SS, Beightler EL, Hebert AA, et al. Tinea faciei in infants caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:452-454.

- Shapiro L, Cohen HJ. Tinea faciei simulating other dermatoses. JAMA. 1971;215:2106-2107.

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(suppl 4):2-15.

- Jorquera E, Moreno JC, Camacho F. Tinea faciei: epidemiology. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1991;119:101-104.

- Hsu S, Le EH, Khoshevis MR. Differential diagnosis of annular lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:289-296.

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

A 19-year-old man with a medical history of keloids presented with a slowly enlarging, red, itchy plaque on the left cheek of 1 year's duration that first began to develop during basic training in the military. The patient denied other pain, pruritus, or separate dermatitis. He initially was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%, which he used for 8 days prior to referral to the dermatology department. The patient denied other acute concerns. On physical examination, multiple erythematous papules coalescing into a large, 10-cm, papulosquamous, arciform plaque were noted on the left preauricular cheek.

Oral Bowenoid Papulosis

To the Editor:

A 22-year-old Somali woman presented to our institution with oral lesions of 2 years’ duration. The lesions started as small papules in the corners of the mouth that gradually continued to spread to the mucosal lips and gums. The lesions did not drain any material. The patient reported that they were not painful and had not regressed. She was concerned about the cosmetic appearance of the lesions. The patient believed the lesions had developed from working in a chicken factory and was concerned that they appeared possibly due to contact with a substance in the factory. Additionally, she noted that her voice had become hoarse. She was otherwise healthy and denied any sexual contact or ever having a blood transfusion.

Physical examination revealed 10 to 15 flesh-colored papules measuring 2 to 3 mm in diameter on the vermilion, mucosal surfaces of the lips, and upper and lower gingivae (Figure 1). No lesions were seen on the hard and soft palate, tongue, buccal mucosa, or posterior pharynx.

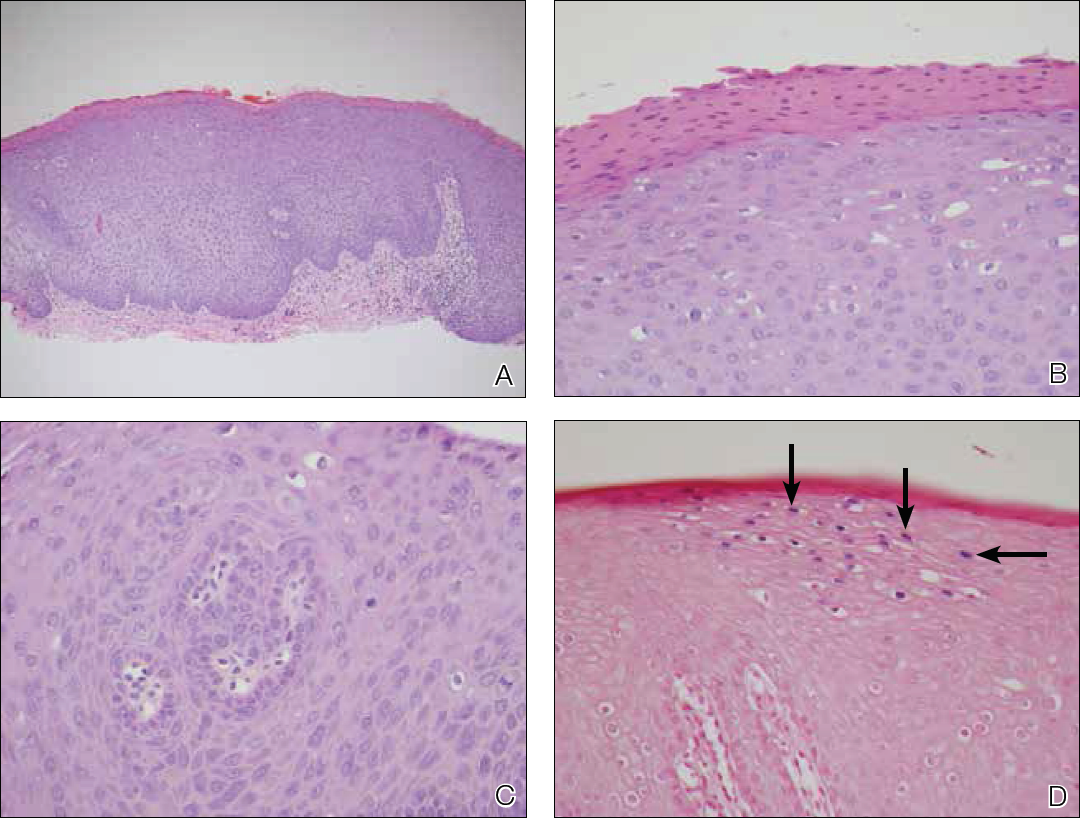

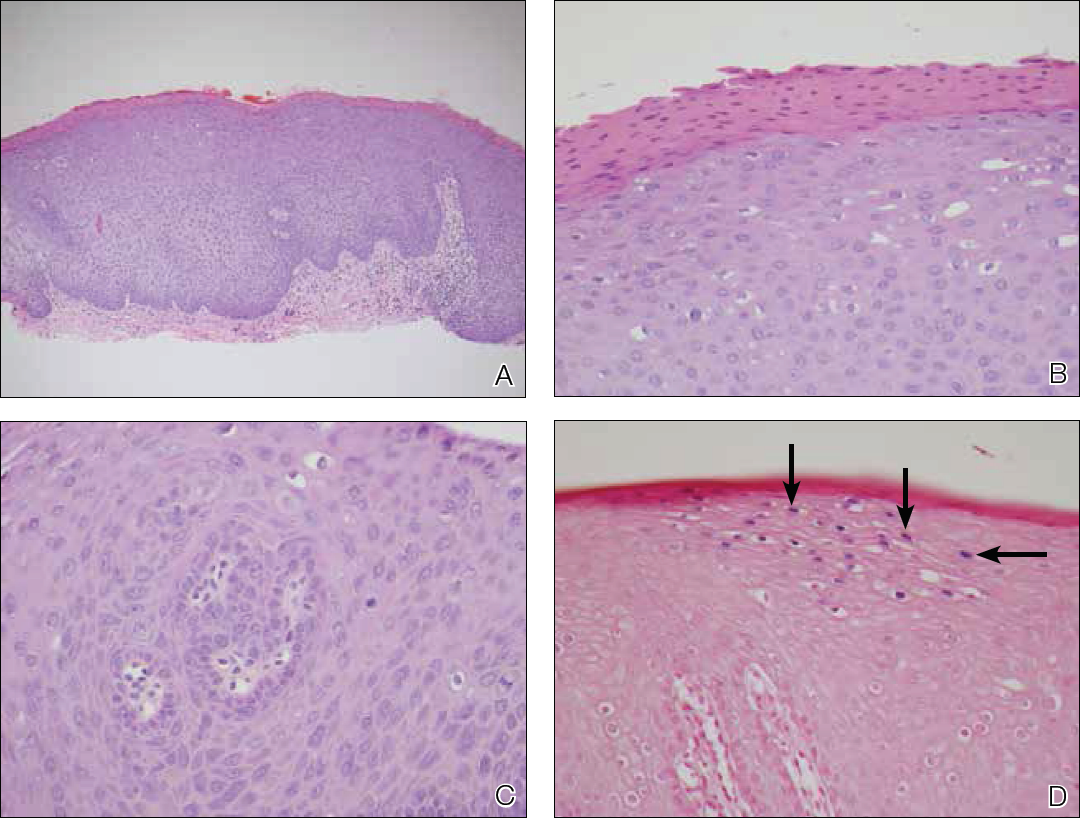

Skin biopsy of the left lower mucosal lip revealed parakeratosis, acanthosis, superficial koilocytes, and atypical keratinocytes with frequent mitoses (Figures 2A–2C). In situ hybridization testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) was negative for low-risk types 6 and 11 but positive for high-risk types 16 and 18 (Figure 2D). Laboratory investigations including complete blood cell count, electrolyte panel, and liver function studies were normal, and serum was negative for syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus antibodies.

The combined clinical and histologic findings were diagnostic of oral bowenoid papulosis. Gynecologic evaluation showed that the patient had undergone female circumcision, and she had a normal Papanicolaou test. The patient was referred to both the ear, nose, and throat clinic as well as the dermatologic surgery department to discuss treatment options, but she was lost to follow-up.

Bowenoid papulosis is triggered by HPV infection and manifests clinically as solitary or multiple verrucous papules and plaques that are usually located on the genitalia.1 Only a few cases of bowenoid papulosis have been reported in the oral cavity.1-5 Because this disease is sexually transmitted, the mean age of onset of bowenoid papulosis is 31 years.2 There is a small risk (2%–3%) of developing invasive carcinoma in bowenoid papulosis.1-3,6 Most lesions are associated with HPV type 16; however, bowenoid papulosis also has been associated with HPV types 18, 31, 32, 35, and 39.2

Some investigators consider bowenoid papulosis and Bowen disease (a type of squamous cell carcinoma [SCC] in situ) to be histologically identical1,6; however, some histologic differences have been reported.1-3,6 Bowenoid papulosis has more dilated and tortuous dermal capillaries and less atypia and dyskeratosis than Bowen disease.1,6 In contrast to bowenoid papulosis, Bowen disease is characterized clinically as well-defined scaly plaques on sun-exposed areas of the skin in older adults. Invasive SCC can be seen in 5% of skin lesions and 30% of penile lesions associated with Bowen disease.2 Risk factors for Bowen disease include sun exposure; arsenic poisoning; and infection with HPV types 2, 16, 18, 31, 33, 52, and 67.1,6

Oral bowenoid papulosis is rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term oral bowenoid papulosis yielded 7 additional cases, which are summarized in the Table. In 1987 Lookingbill et al2 described one of the first reported cases of oral disease in a 33-year-old immunosuppressed man receiving prednisone therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus who had both mouth and genital lesions. All lesions were positive for HPV type 16. The patient subsequently developed SCC of the tongue.2

The risk for progression of oral bowenoid papulosis to invasive SCC is not known. Our search yielded only 1 case of this occurrence.2

Two of 3 cases of solitary lip lesions in oral bowenoid papulosis were treated with surgical excision.1 Other treatment options include CO2 laser therapy, cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin, intralesional interferon alfa, and imiquimod.1-3,5,6

Our case represents a rare report of oral bowenoid papulosis. Recognition of this unusual presentation is important for the diagnosis and management of this disease.

- Daley T, Birek C, Wysocki GP. Oral bowenoid lesions: differential diagnosis and pathogenetic insights. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:466-473.

- Lookingbill DP, Kreider JW, Howett MK, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 in bowenoid papulosis, intraoral papillomas, and squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:363-368.

- Kratochvil FJ, Cioffi GA, Auclair PL, et al. Virus-associated dysplasia (bowenoid papulosis?) of the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:312-316.

- Degener AM, Latino L, Pierangeli A, et al. Human papilloma virus-32-positive extragenital bowenoid papulosis in a HIV patient with typical genital bowenoid papulosis localization. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:619-622.

- Rinaggio J, Glick M, Lambert WC. Oral bowenoid papulosis in an HIV-positive male [published online October 14, 2005]. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:328-332.

- Regezi JA, Dekker NP, Ramos DM, et al. Proliferation and invasion factors in HIV-associated dysplastic and nondysplastic oral warts and in oral squamous cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and RT-PCR evaluation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:724-731.

To the Editor:

A 22-year-old Somali woman presented to our institution with oral lesions of 2 years’ duration. The lesions started as small papules in the corners of the mouth that gradually continued to spread to the mucosal lips and gums. The lesions did not drain any material. The patient reported that they were not painful and had not regressed. She was concerned about the cosmetic appearance of the lesions. The patient believed the lesions had developed from working in a chicken factory and was concerned that they appeared possibly due to contact with a substance in the factory. Additionally, she noted that her voice had become hoarse. She was otherwise healthy and denied any sexual contact or ever having a blood transfusion.

Physical examination revealed 10 to 15 flesh-colored papules measuring 2 to 3 mm in diameter on the vermilion, mucosal surfaces of the lips, and upper and lower gingivae (Figure 1). No lesions were seen on the hard and soft palate, tongue, buccal mucosa, or posterior pharynx.

Skin biopsy of the left lower mucosal lip revealed parakeratosis, acanthosis, superficial koilocytes, and atypical keratinocytes with frequent mitoses (Figures 2A–2C). In situ hybridization testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) was negative for low-risk types 6 and 11 but positive for high-risk types 16 and 18 (Figure 2D). Laboratory investigations including complete blood cell count, electrolyte panel, and liver function studies were normal, and serum was negative for syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus antibodies.

The combined clinical and histologic findings were diagnostic of oral bowenoid papulosis. Gynecologic evaluation showed that the patient had undergone female circumcision, and she had a normal Papanicolaou test. The patient was referred to both the ear, nose, and throat clinic as well as the dermatologic surgery department to discuss treatment options, but she was lost to follow-up.

Bowenoid papulosis is triggered by HPV infection and manifests clinically as solitary or multiple verrucous papules and plaques that are usually located on the genitalia.1 Only a few cases of bowenoid papulosis have been reported in the oral cavity.1-5 Because this disease is sexually transmitted, the mean age of onset of bowenoid papulosis is 31 years.2 There is a small risk (2%–3%) of developing invasive carcinoma in bowenoid papulosis.1-3,6 Most lesions are associated with HPV type 16; however, bowenoid papulosis also has been associated with HPV types 18, 31, 32, 35, and 39.2

Some investigators consider bowenoid papulosis and Bowen disease (a type of squamous cell carcinoma [SCC] in situ) to be histologically identical1,6; however, some histologic differences have been reported.1-3,6 Bowenoid papulosis has more dilated and tortuous dermal capillaries and less atypia and dyskeratosis than Bowen disease.1,6 In contrast to bowenoid papulosis, Bowen disease is characterized clinically as well-defined scaly plaques on sun-exposed areas of the skin in older adults. Invasive SCC can be seen in 5% of skin lesions and 30% of penile lesions associated with Bowen disease.2 Risk factors for Bowen disease include sun exposure; arsenic poisoning; and infection with HPV types 2, 16, 18, 31, 33, 52, and 67.1,6

Oral bowenoid papulosis is rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term oral bowenoid papulosis yielded 7 additional cases, which are summarized in the Table. In 1987 Lookingbill et al2 described one of the first reported cases of oral disease in a 33-year-old immunosuppressed man receiving prednisone therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus who had both mouth and genital lesions. All lesions were positive for HPV type 16. The patient subsequently developed SCC of the tongue.2

The risk for progression of oral bowenoid papulosis to invasive SCC is not known. Our search yielded only 1 case of this occurrence.2