User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Solitary Nodule on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Ruptured Molluscum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is caused by a DNA virus (MC virus) belonging to the poxvirus family. Molluscum contagiosum is common and predominantly seen in children and young adults. In sexually active adults, the lesions commonly occur in the genital region, abdomen, and inner thighs. In immunocompromised individuals, including those with AIDS, the lesions are more extensive and may cause disfigurement.1 Molluscum contagiosum involving epidermoid cysts has been reported.2

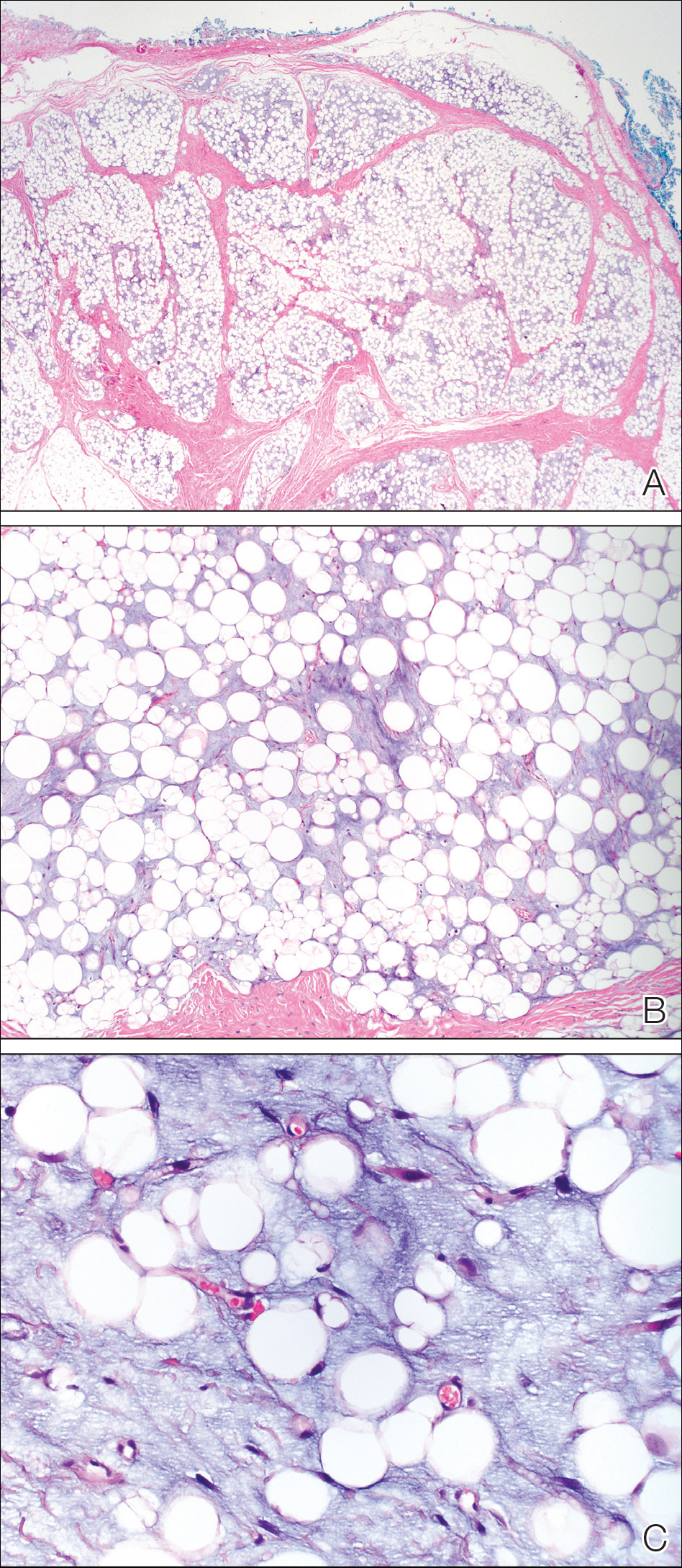

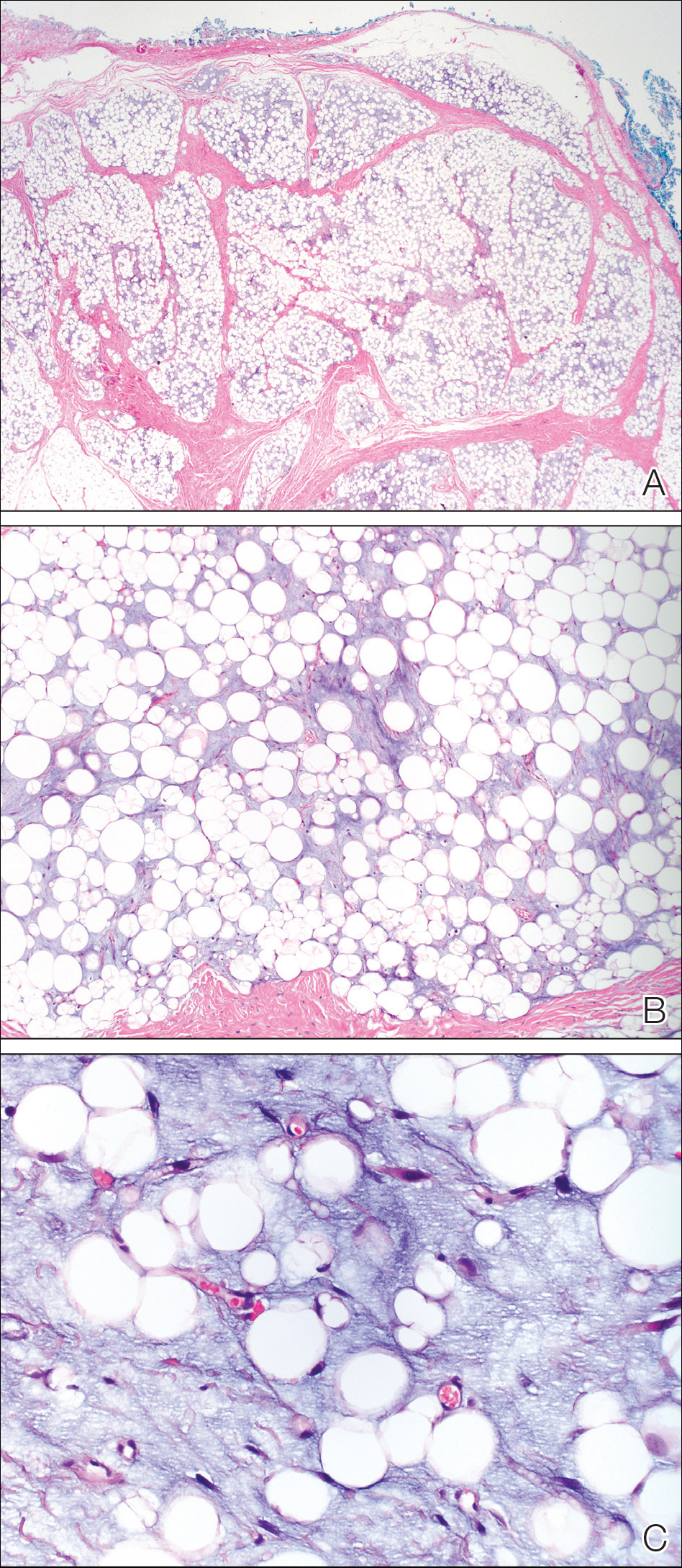

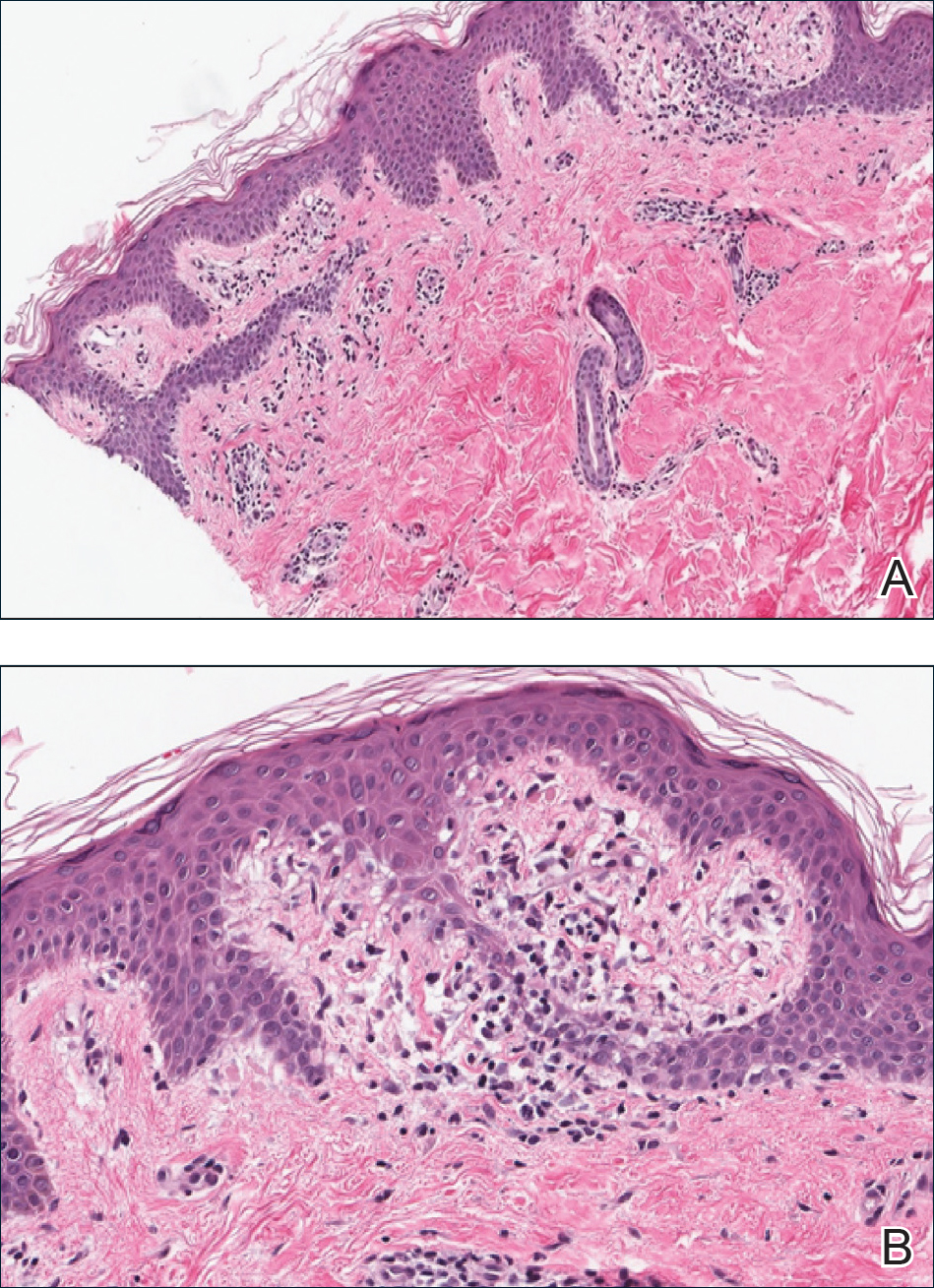

Histopathologically, MC can be classified as noninflammatory or inflammatory. In noninflamed lesions, multiple large, intracytoplasmic, eosinophilic inclusions (Henderson-Paterson bodies) appear within the lobulated endophytic and hyperplastic epidermis. Ultrastructurally, these bodies show membrane-bound collections of MC virus.1 Replicating Henderson-Paterson bodies can result in rupture and inflammation. This case demonstrates a palisading granuloma containing keratin with few Henderson-Paterson bodies (quiz image) due to prior rupture of a molluscum or molluscoid cyst.

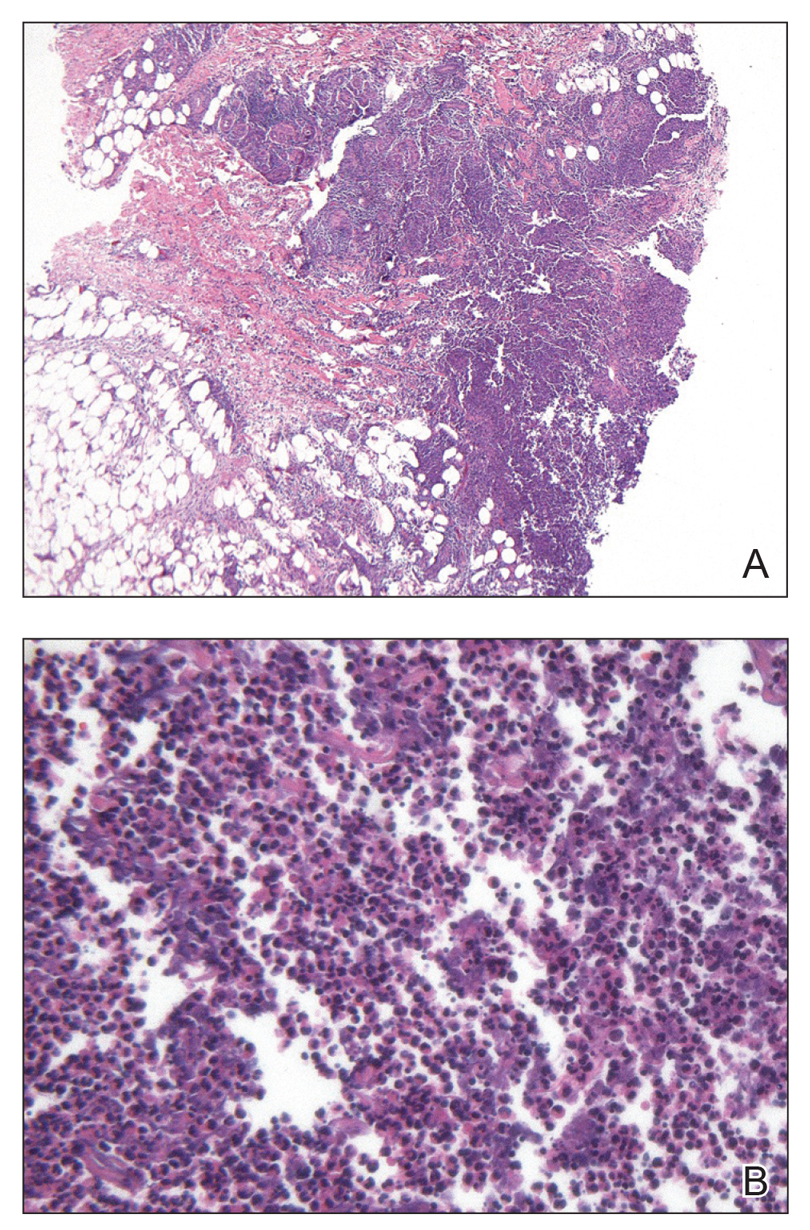

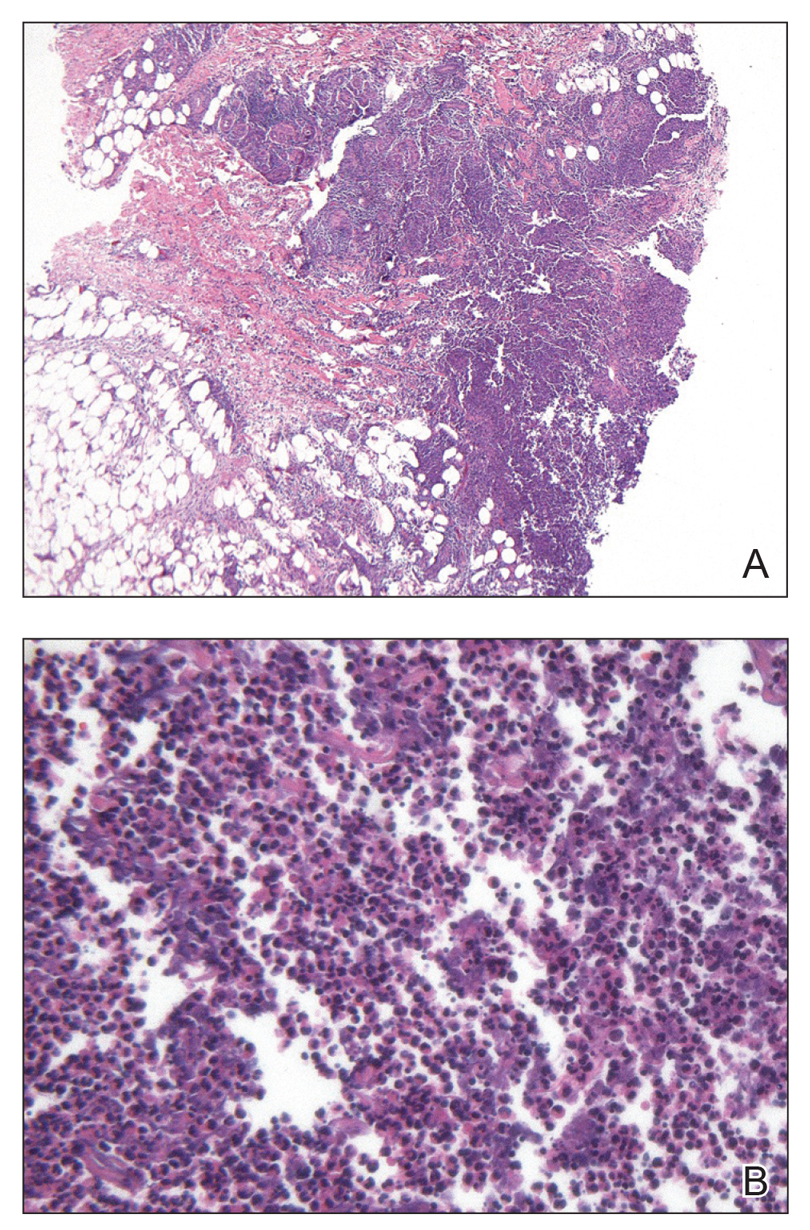

Rheumatoid nodules, the most characteristic histopathologic lesions of rheumatoid arthritis, are most commonly found in the subcutis at points of pressure and may occur in connective tissue of numerous organs. Rheumatoid nodules are firm, nontender, and mobile within the subcutaneous tissue but may be fixed to underlying structures including the periosteum, tendons, or bursae.3,4 Occasionally, superficial nodules may perforate the epidermis.5 The inner central necrobiotic zone appears as intensely eosinophilic, amorphous fibrin and other cellular debris. This central area is surrounded by histiocytes in a palisaded configuration (Figure 1). Multinucleated foreign body giant cells also may be present. Occasionally, mast cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils are present.6,7

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei presents with multiple discrete, smooth, yellow-brown to red, dome-shaped papules. The lesions typically are located on the central and lateral sides of the face and infrequently involve the neck. Other sites including the axillae, arms, hands, legs, and groin occasionally can be involved. Diascopy may reveal an apple jelly color.8,9 The histopathologic hallmark of lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is an epithelioid cell granuloma with central necrosis (Figure 2).

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a soft tissue tumor with a known propensity for local recurrence, regional lymph node involvement, sporotrichoid spread, and distant metastases.10 The name was coined by Enzinger11 in 1970 during a review of 62 cases of a “peculiar form of sarcoma that has repeatedly been confused with a chronic inflammatory process, a necrotizing granuloma, and a squamous cell carcinoma.” Epithelioid sarcoma tends to grow slowly in a nodular or multinodular manner along fascial structures and tendons, often with central necrosis and ulceration of the overlying skin. Histopathologically, classic ES shows nodular masses of uniform plump epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent central necrosis. A biphasic pattern is typical with spindle cells merging with epithelioid cells. Cellular atypia is relatively mild and mitoses are rare (Figure 3). Recurrent or metastatic lesions can show a greater degree of pleomorphism.12 Given the low-grade atypia in early lesions, this sarcoma is easily misdiagnosed as granulomatous dermatitis. Immunohistochemically, the majority of ES cases are positive for cytokeratins and epithelial membrane antigen; SMARCB1/INI-1 expression is characteristically lost.13

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis) is an autoimmune vasculitis highly associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Clinical manifestations include systemic necrotizing vasculitis; necrotizing glomerulonephritis; and granulomatous inflammation, which predominantly involves the upper respiratory tract, skin, and mucosa.14,15 Skin involvement may be the initial manifestation of the disease and consists of palpable purpura, papules, ulcerations, vesicles, subcutaneous nodules, necrotizing ulcerations, papulonecrotic lesions, and petechiae. None of the findings are pathognomonic. The cutaneous histopathologic spectrum includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, extravascular palisading granulomas, and granulomatous vasculitis.16 In the acute lesions of granulomatosis with polyangiitis, the predominant pattern of inflammation is not granulomatous but purulent with the appearance of an abscess. As it evolves, it develops a central zone of necrosis with extensive karyorrhectic debris and palisades of macrophages with scattered multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4).17

1. Nandhini G, Rajkumar K, Kanth KS, et al. Molluscum contagiosum in a 12-year-old child—report of a case and review of literature. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:63-66.

2. Phelps A, Murphy M, Elaba Z, et al. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection in benign cutaneous epithelial cystic lesions-report of 2 cases with different pathogenesis? Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:740-742.

3. Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-192.

4. Sibbitt WL Jr, Williams RC Jr. Cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:563-572.

5. Barzilai A, Huszar M, Shpiro D, et al. Pseudorheumatoid nodules in adults: a juxta-articular form of nodular granuloma annulare. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:1-5.

6. Garcia-Patos V. Rheumatoid nodule. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:100-107.

7. Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare. a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.

8. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Aggarwal AK, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei part II: an overview. Skinmed. 2005;4:234-238.

9. Cymerman R, Rosenstein R, Shvartsbeyn M, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt6b83q5gp.

10. Sobanko JF, Meijer L, Nigra TP. Epithelioid sarcoma: a review and update. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:49-54.

11. Enzinger FM. Epitheloid sarcoma. a sarcoma simulating a granuloma or a carcinoma. Cancer. 1970;26:1029-1041.

12. Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:114-121.

13. Miettinen M, Fanburg-Smith JC, Virolainen M, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: an immunohistochemical analysis of 112 classical and variant cases and a discussion of the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:934-942.

14. Lutalo PM, D’Cruz DP. Diagnosis and classification of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (aka Wegener’s granulomatosis)[published online January 29, 2014]. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:94-98.

15. Frances C, Du LT, Piette JC, et al. Wegener’s granulomatosis. dermatological manifestations in 75 cases with clinicopathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:861-867.

16. Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener’s granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

17. Jennette JC. Nomenclature and classification of vasculitis: lessons learned from granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis). Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;164 (suppl 1):7-10.

The Diagnosis: Ruptured Molluscum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is caused by a DNA virus (MC virus) belonging to the poxvirus family. Molluscum contagiosum is common and predominantly seen in children and young adults. In sexually active adults, the lesions commonly occur in the genital region, abdomen, and inner thighs. In immunocompromised individuals, including those with AIDS, the lesions are more extensive and may cause disfigurement.1 Molluscum contagiosum involving epidermoid cysts has been reported.2

Histopathologically, MC can be classified as noninflammatory or inflammatory. In noninflamed lesions, multiple large, intracytoplasmic, eosinophilic inclusions (Henderson-Paterson bodies) appear within the lobulated endophytic and hyperplastic epidermis. Ultrastructurally, these bodies show membrane-bound collections of MC virus.1 Replicating Henderson-Paterson bodies can result in rupture and inflammation. This case demonstrates a palisading granuloma containing keratin with few Henderson-Paterson bodies (quiz image) due to prior rupture of a molluscum or molluscoid cyst.

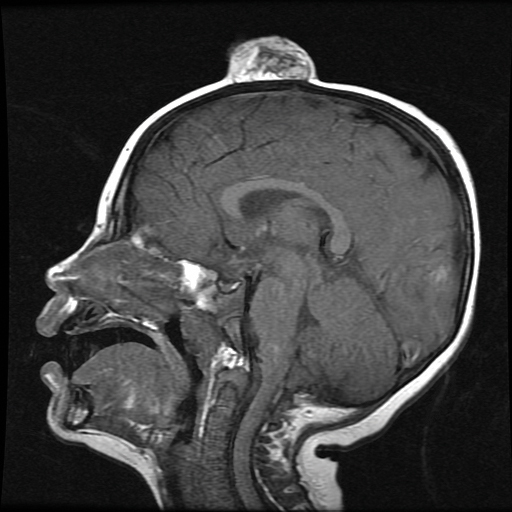

Rheumatoid nodules, the most characteristic histopathologic lesions of rheumatoid arthritis, are most commonly found in the subcutis at points of pressure and may occur in connective tissue of numerous organs. Rheumatoid nodules are firm, nontender, and mobile within the subcutaneous tissue but may be fixed to underlying structures including the periosteum, tendons, or bursae.3,4 Occasionally, superficial nodules may perforate the epidermis.5 The inner central necrobiotic zone appears as intensely eosinophilic, amorphous fibrin and other cellular debris. This central area is surrounded by histiocytes in a palisaded configuration (Figure 1). Multinucleated foreign body giant cells also may be present. Occasionally, mast cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils are present.6,7

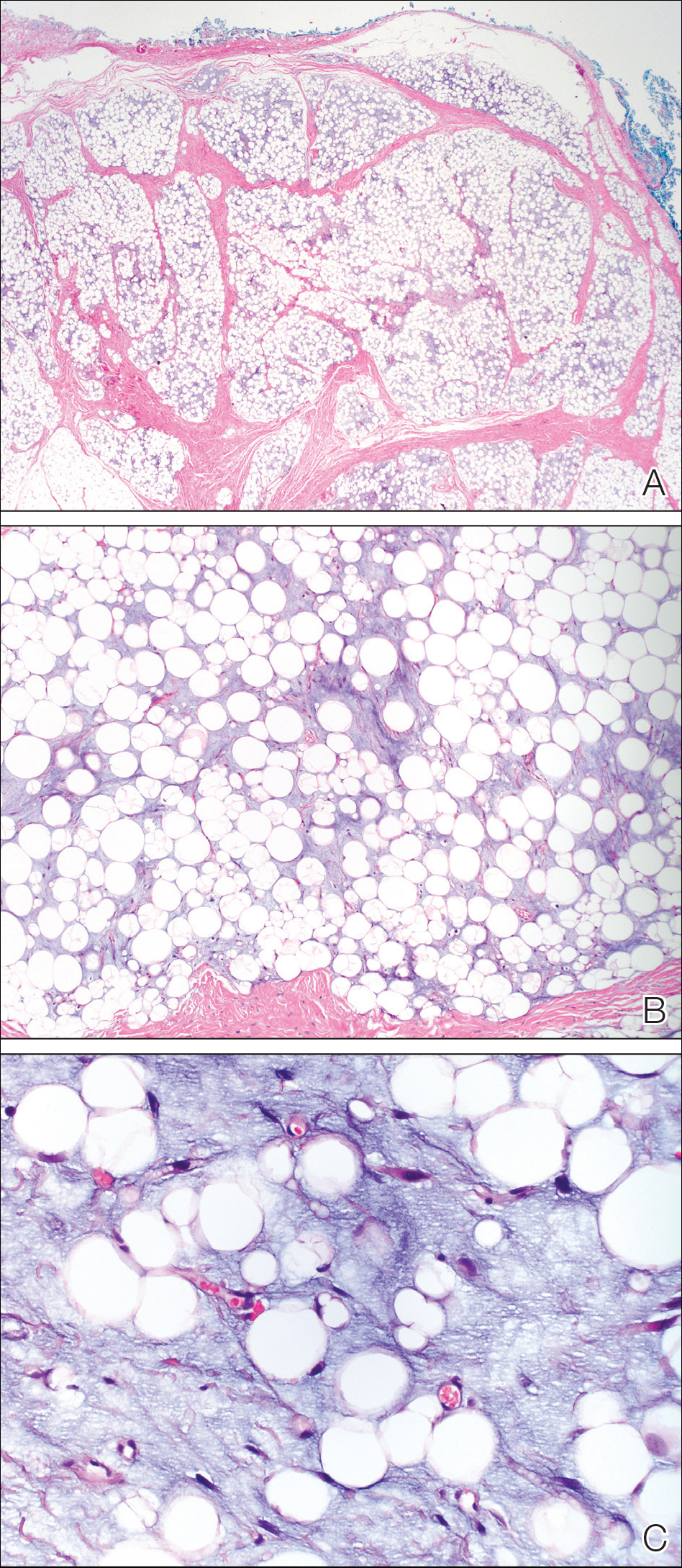

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei presents with multiple discrete, smooth, yellow-brown to red, dome-shaped papules. The lesions typically are located on the central and lateral sides of the face and infrequently involve the neck. Other sites including the axillae, arms, hands, legs, and groin occasionally can be involved. Diascopy may reveal an apple jelly color.8,9 The histopathologic hallmark of lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is an epithelioid cell granuloma with central necrosis (Figure 2).

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a soft tissue tumor with a known propensity for local recurrence, regional lymph node involvement, sporotrichoid spread, and distant metastases.10 The name was coined by Enzinger11 in 1970 during a review of 62 cases of a “peculiar form of sarcoma that has repeatedly been confused with a chronic inflammatory process, a necrotizing granuloma, and a squamous cell carcinoma.” Epithelioid sarcoma tends to grow slowly in a nodular or multinodular manner along fascial structures and tendons, often with central necrosis and ulceration of the overlying skin. Histopathologically, classic ES shows nodular masses of uniform plump epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent central necrosis. A biphasic pattern is typical with spindle cells merging with epithelioid cells. Cellular atypia is relatively mild and mitoses are rare (Figure 3). Recurrent or metastatic lesions can show a greater degree of pleomorphism.12 Given the low-grade atypia in early lesions, this sarcoma is easily misdiagnosed as granulomatous dermatitis. Immunohistochemically, the majority of ES cases are positive for cytokeratins and epithelial membrane antigen; SMARCB1/INI-1 expression is characteristically lost.13

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis) is an autoimmune vasculitis highly associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Clinical manifestations include systemic necrotizing vasculitis; necrotizing glomerulonephritis; and granulomatous inflammation, which predominantly involves the upper respiratory tract, skin, and mucosa.14,15 Skin involvement may be the initial manifestation of the disease and consists of palpable purpura, papules, ulcerations, vesicles, subcutaneous nodules, necrotizing ulcerations, papulonecrotic lesions, and petechiae. None of the findings are pathognomonic. The cutaneous histopathologic spectrum includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, extravascular palisading granulomas, and granulomatous vasculitis.16 In the acute lesions of granulomatosis with polyangiitis, the predominant pattern of inflammation is not granulomatous but purulent with the appearance of an abscess. As it evolves, it develops a central zone of necrosis with extensive karyorrhectic debris and palisades of macrophages with scattered multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4).17

The Diagnosis: Ruptured Molluscum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is caused by a DNA virus (MC virus) belonging to the poxvirus family. Molluscum contagiosum is common and predominantly seen in children and young adults. In sexually active adults, the lesions commonly occur in the genital region, abdomen, and inner thighs. In immunocompromised individuals, including those with AIDS, the lesions are more extensive and may cause disfigurement.1 Molluscum contagiosum involving epidermoid cysts has been reported.2

Histopathologically, MC can be classified as noninflammatory or inflammatory. In noninflamed lesions, multiple large, intracytoplasmic, eosinophilic inclusions (Henderson-Paterson bodies) appear within the lobulated endophytic and hyperplastic epidermis. Ultrastructurally, these bodies show membrane-bound collections of MC virus.1 Replicating Henderson-Paterson bodies can result in rupture and inflammation. This case demonstrates a palisading granuloma containing keratin with few Henderson-Paterson bodies (quiz image) due to prior rupture of a molluscum or molluscoid cyst.

Rheumatoid nodules, the most characteristic histopathologic lesions of rheumatoid arthritis, are most commonly found in the subcutis at points of pressure and may occur in connective tissue of numerous organs. Rheumatoid nodules are firm, nontender, and mobile within the subcutaneous tissue but may be fixed to underlying structures including the periosteum, tendons, or bursae.3,4 Occasionally, superficial nodules may perforate the epidermis.5 The inner central necrobiotic zone appears as intensely eosinophilic, amorphous fibrin and other cellular debris. This central area is surrounded by histiocytes in a palisaded configuration (Figure 1). Multinucleated foreign body giant cells also may be present. Occasionally, mast cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils are present.6,7

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei presents with multiple discrete, smooth, yellow-brown to red, dome-shaped papules. The lesions typically are located on the central and lateral sides of the face and infrequently involve the neck. Other sites including the axillae, arms, hands, legs, and groin occasionally can be involved. Diascopy may reveal an apple jelly color.8,9 The histopathologic hallmark of lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is an epithelioid cell granuloma with central necrosis (Figure 2).

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a soft tissue tumor with a known propensity for local recurrence, regional lymph node involvement, sporotrichoid spread, and distant metastases.10 The name was coined by Enzinger11 in 1970 during a review of 62 cases of a “peculiar form of sarcoma that has repeatedly been confused with a chronic inflammatory process, a necrotizing granuloma, and a squamous cell carcinoma.” Epithelioid sarcoma tends to grow slowly in a nodular or multinodular manner along fascial structures and tendons, often with central necrosis and ulceration of the overlying skin. Histopathologically, classic ES shows nodular masses of uniform plump epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent central necrosis. A biphasic pattern is typical with spindle cells merging with epithelioid cells. Cellular atypia is relatively mild and mitoses are rare (Figure 3). Recurrent or metastatic lesions can show a greater degree of pleomorphism.12 Given the low-grade atypia in early lesions, this sarcoma is easily misdiagnosed as granulomatous dermatitis. Immunohistochemically, the majority of ES cases are positive for cytokeratins and epithelial membrane antigen; SMARCB1/INI-1 expression is characteristically lost.13

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis) is an autoimmune vasculitis highly associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Clinical manifestations include systemic necrotizing vasculitis; necrotizing glomerulonephritis; and granulomatous inflammation, which predominantly involves the upper respiratory tract, skin, and mucosa.14,15 Skin involvement may be the initial manifestation of the disease and consists of palpable purpura, papules, ulcerations, vesicles, subcutaneous nodules, necrotizing ulcerations, papulonecrotic lesions, and petechiae. None of the findings are pathognomonic. The cutaneous histopathologic spectrum includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, extravascular palisading granulomas, and granulomatous vasculitis.16 In the acute lesions of granulomatosis with polyangiitis, the predominant pattern of inflammation is not granulomatous but purulent with the appearance of an abscess. As it evolves, it develops a central zone of necrosis with extensive karyorrhectic debris and palisades of macrophages with scattered multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4).17

1. Nandhini G, Rajkumar K, Kanth KS, et al. Molluscum contagiosum in a 12-year-old child—report of a case and review of literature. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:63-66.

2. Phelps A, Murphy M, Elaba Z, et al. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection in benign cutaneous epithelial cystic lesions-report of 2 cases with different pathogenesis? Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:740-742.

3. Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-192.

4. Sibbitt WL Jr, Williams RC Jr. Cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:563-572.

5. Barzilai A, Huszar M, Shpiro D, et al. Pseudorheumatoid nodules in adults: a juxta-articular form of nodular granuloma annulare. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:1-5.

6. Garcia-Patos V. Rheumatoid nodule. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:100-107.

7. Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare. a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.

8. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Aggarwal AK, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei part II: an overview. Skinmed. 2005;4:234-238.

9. Cymerman R, Rosenstein R, Shvartsbeyn M, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt6b83q5gp.

10. Sobanko JF, Meijer L, Nigra TP. Epithelioid sarcoma: a review and update. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:49-54.

11. Enzinger FM. Epitheloid sarcoma. a sarcoma simulating a granuloma or a carcinoma. Cancer. 1970;26:1029-1041.

12. Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:114-121.

13. Miettinen M, Fanburg-Smith JC, Virolainen M, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: an immunohistochemical analysis of 112 classical and variant cases and a discussion of the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:934-942.

14. Lutalo PM, D’Cruz DP. Diagnosis and classification of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (aka Wegener’s granulomatosis)[published online January 29, 2014]. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:94-98.

15. Frances C, Du LT, Piette JC, et al. Wegener’s granulomatosis. dermatological manifestations in 75 cases with clinicopathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:861-867.

16. Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener’s granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

17. Jennette JC. Nomenclature and classification of vasculitis: lessons learned from granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis). Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;164 (suppl 1):7-10.

1. Nandhini G, Rajkumar K, Kanth KS, et al. Molluscum contagiosum in a 12-year-old child—report of a case and review of literature. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:63-66.

2. Phelps A, Murphy M, Elaba Z, et al. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection in benign cutaneous epithelial cystic lesions-report of 2 cases with different pathogenesis? Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:740-742.

3. Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-192.

4. Sibbitt WL Jr, Williams RC Jr. Cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:563-572.

5. Barzilai A, Huszar M, Shpiro D, et al. Pseudorheumatoid nodules in adults: a juxta-articular form of nodular granuloma annulare. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:1-5.

6. Garcia-Patos V. Rheumatoid nodule. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:100-107.

7. Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare. a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.

8. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Aggarwal AK, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei part II: an overview. Skinmed. 2005;4:234-238.

9. Cymerman R, Rosenstein R, Shvartsbeyn M, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt6b83q5gp.

10. Sobanko JF, Meijer L, Nigra TP. Epithelioid sarcoma: a review and update. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:49-54.

11. Enzinger FM. Epitheloid sarcoma. a sarcoma simulating a granuloma or a carcinoma. Cancer. 1970;26:1029-1041.

12. Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:114-121.

13. Miettinen M, Fanburg-Smith JC, Virolainen M, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: an immunohistochemical analysis of 112 classical and variant cases and a discussion of the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:934-942.

14. Lutalo PM, D’Cruz DP. Diagnosis and classification of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (aka Wegener’s granulomatosis)[published online January 29, 2014]. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:94-98.

15. Frances C, Du LT, Piette JC, et al. Wegener’s granulomatosis. dermatological manifestations in 75 cases with clinicopathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:861-867.

16. Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener’s granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

17. Jennette JC. Nomenclature and classification of vasculitis: lessons learned from granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis). Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;164 (suppl 1):7-10.

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented with a discrete nodule on the thigh.

Nonhealing Eroded Plaque on an Interdigital Web Space of the Foot

The Diagnosis: Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome

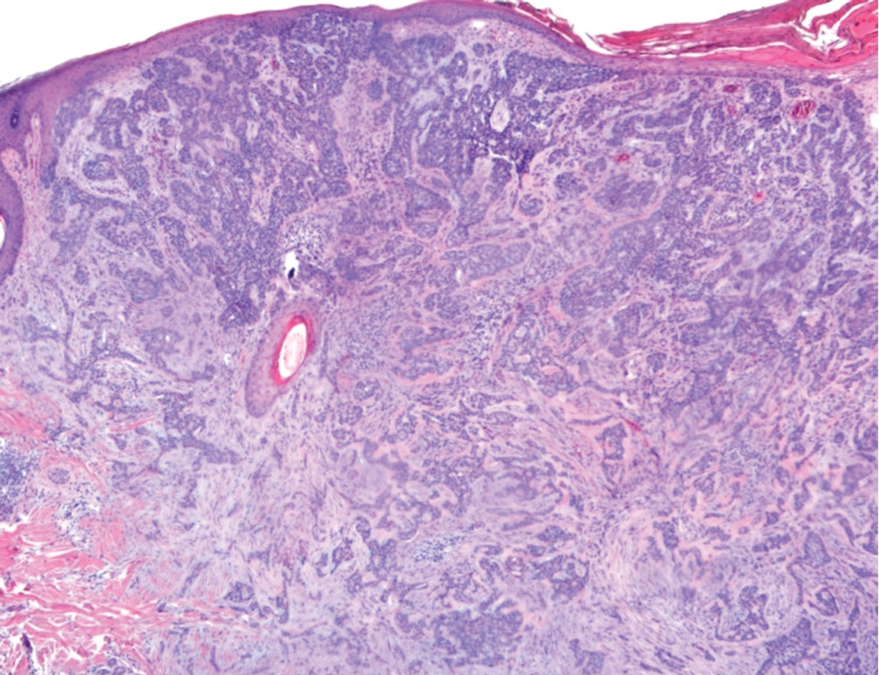

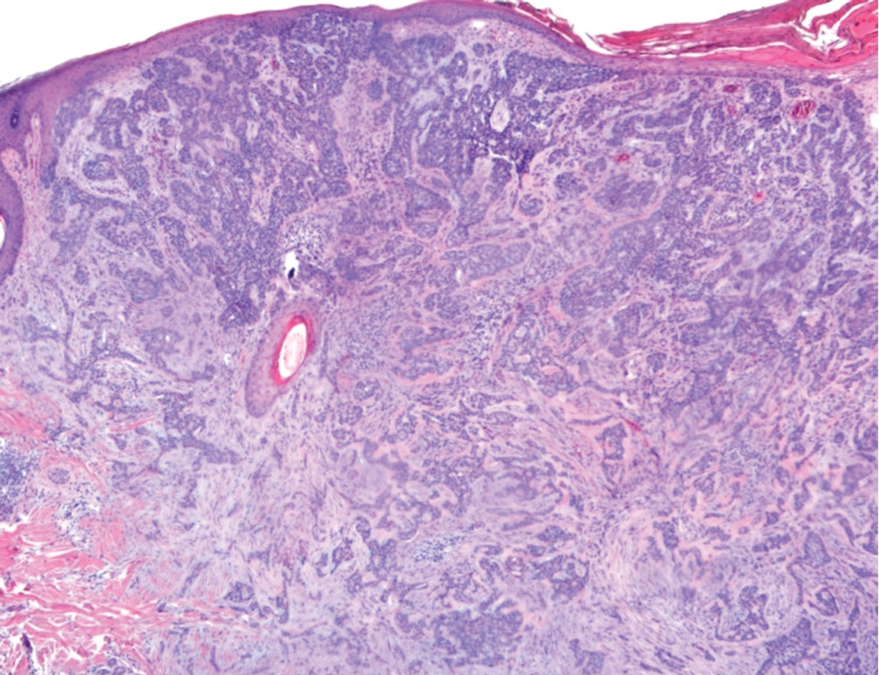

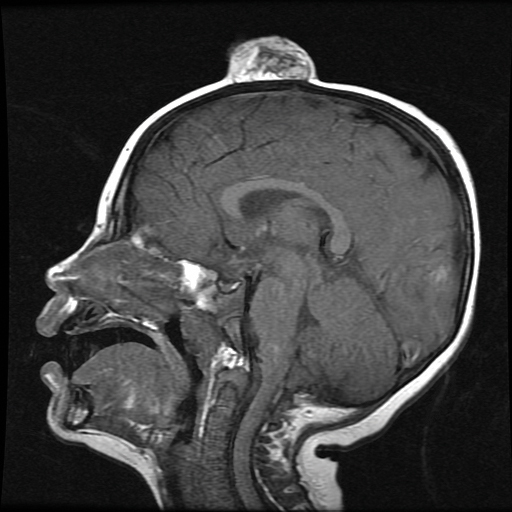

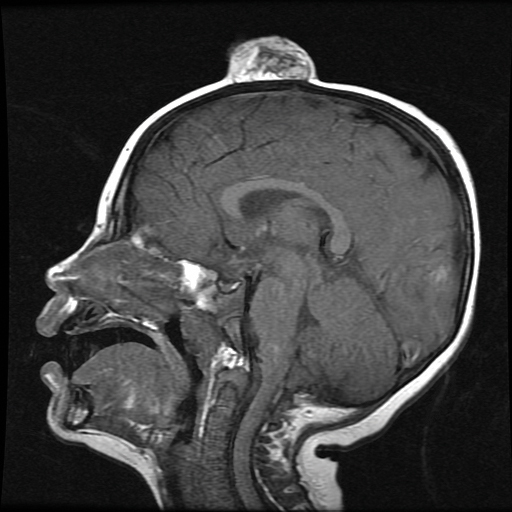

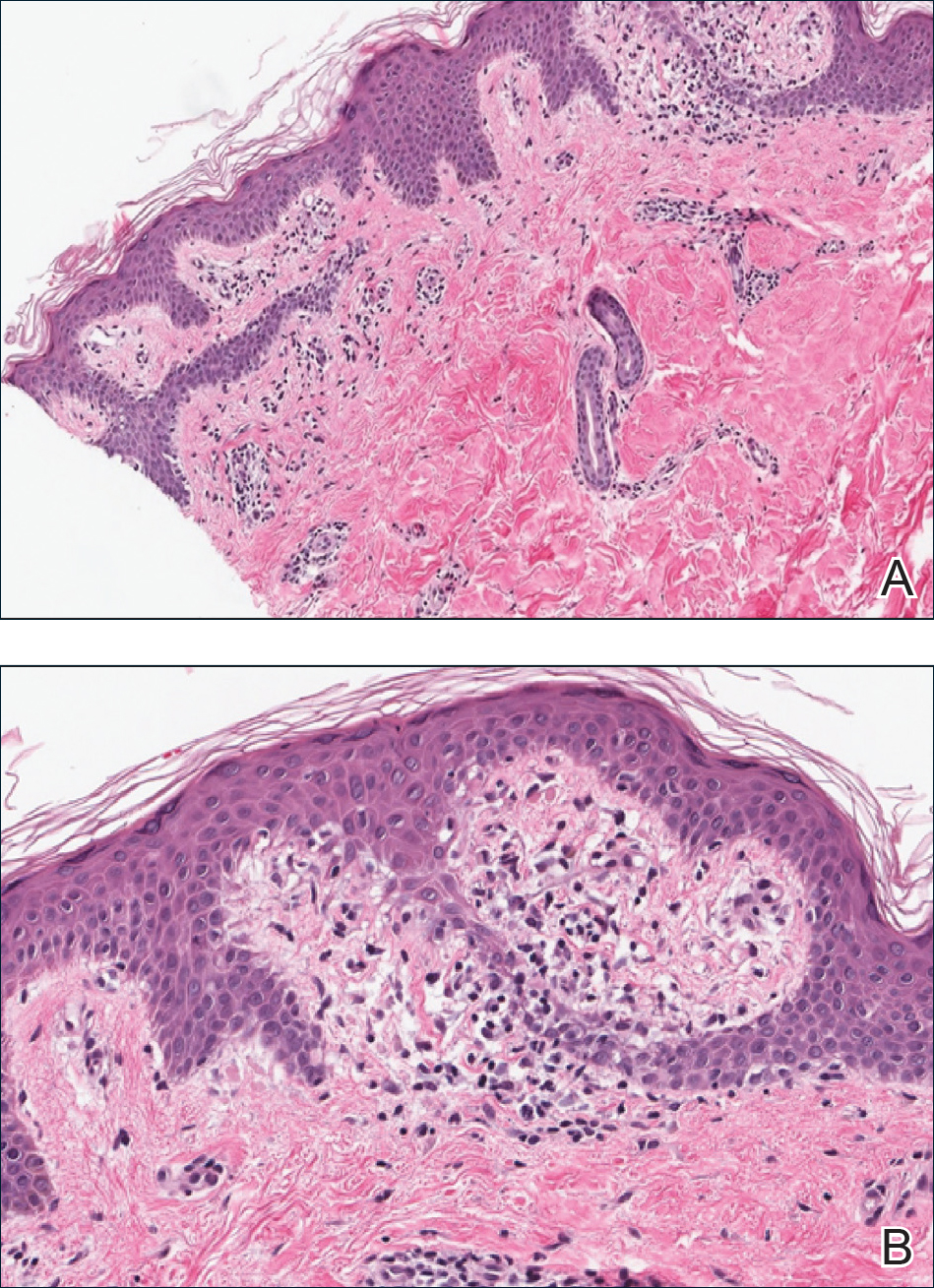

Given the patient’s history of numerous basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), odontogenic keratocysts, palmar pits, and a nonhealing ulcer, the clinical presentation was highly suggestive of interdigital BCC in the setting of basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS). A shave biopsy was performed revealing islands of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and a retraction artifact surrounded by fibromyxoid stroma, consistent with nodular and infiltrative BCC (Figure 1).

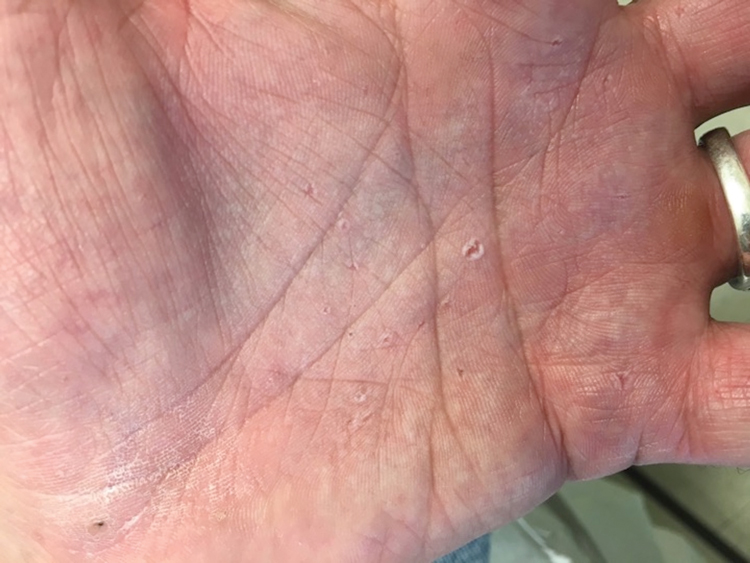

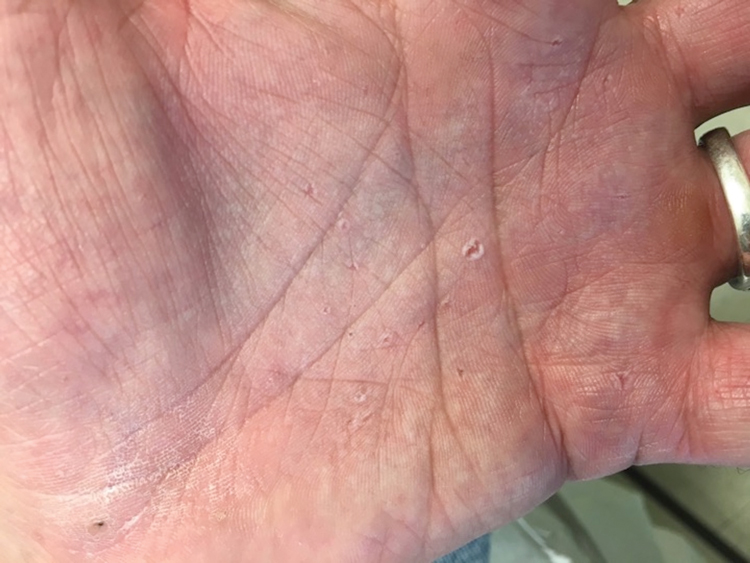

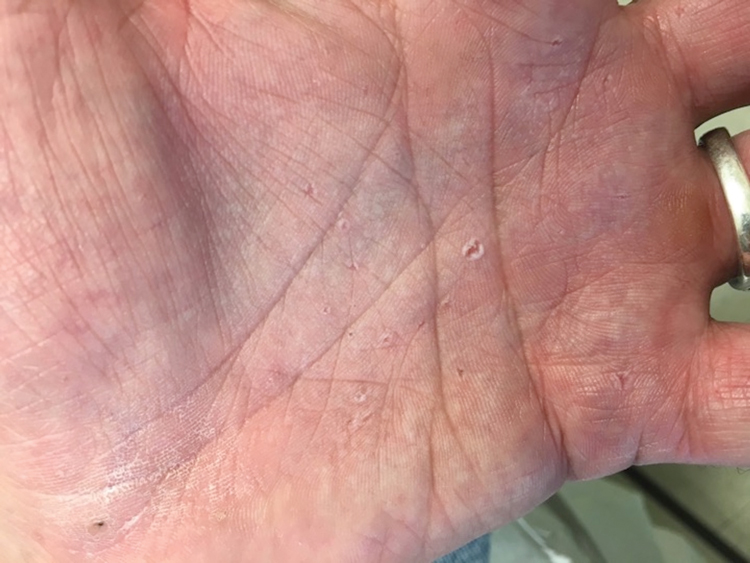

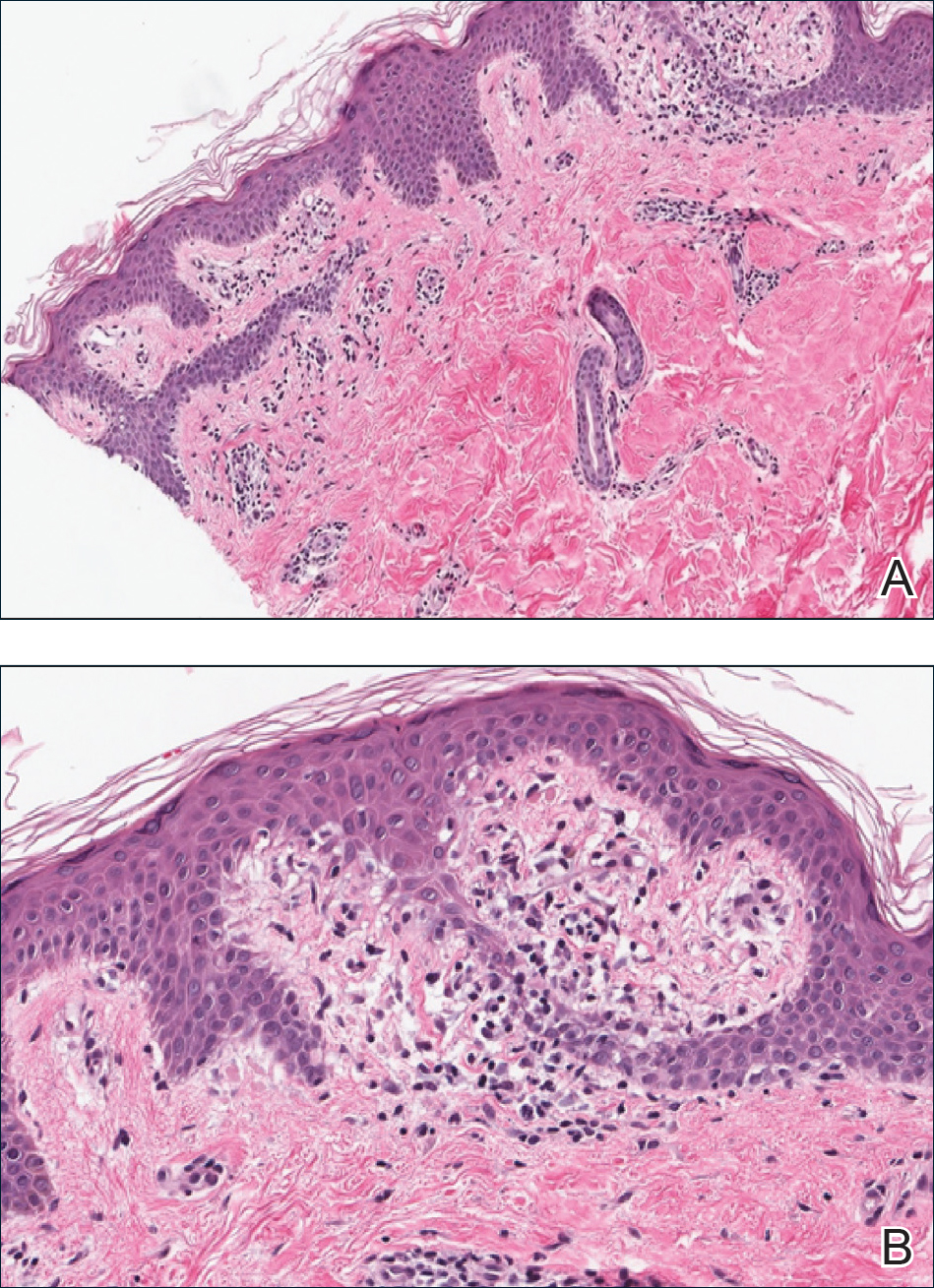

Basal cell nevus syndrome (also known as Gorlin syndrome) is a rare neurocutaneous syndrome that manifests with multiple BCCs; palmar and plantar pits (Figure 2); central nervous system tumors; and skeletal anomalies including jaw cysts, macrocephaly, frontal bossing, and bifid ribs.1 It is an autosomal-dominant condition caused by mutations in the PTCH1 gene, a tumor suppressor gene involved in the Hedgehog signaling pathway.2 Basal cell carcinoma is the most distinctive feature of BCNS, causing notable morbidity. Tumors typically present between puberty and 35 years of age, and patients can have anywhere from a few to thousands of tumors. They rarely become locally aggressive; however, with radiation therapy, proliferation and local invasion may occur within a few years. Therefore, radiotherapy should be avoided in these patients.1

Although the most common sites for BCCs in BCNS are the head, neck, and back, there is a higher rate of occurrence on sun-protected areas in BCNS compared to the general population.3 Our patient presented with interdigital BCC of the foot, which is an extremely rare occurrence. PubMed and Ovid searches using the terms basal cell carcinoma, BCC, foot, interdigital, and nonmelanoma skin cancer revealed only 3 cases of interdigital BCC of the foot. One case was associated with prior surgical trauma, the second presented as a junctional nevus, and the third did not appear to have any associated inciting factors.4-6 Dermatologists need to have a low threshold for biopsy for any unusual nonhealing lesions, especially in the setting of BCNS. Basal cell carcinomas in BCNS cannot be histologically differentiated from sporadic BCCs, and management largely depends on the size, location, recurrence, and number of lesions. Treatment methods range from topical agents to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

Nonhealing lesions of the foot may give an initial clinical impression of infection overlying peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus with the possibility of associated osteomyelitis. Our patient had no clinical history to suggest peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus, and he had palpable dorsalis pedis pulses as well as a normal neurologic examination. Clinicians also may consider fungal infection in the differential diagnosis. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica is a superficial yeast infection described as a well-defined, red, shiny plaque found in chronically wet areas, usually affecting the third or fourth interdigital spaces of the fingers.7 However, the lack of improvement with antibiotics and antifungals argued against bacterial or fungal infection in our patient. Although BCC also is a common feature of Bazex Dupré-Christol syndrome, it also is characterized by follicular atrophoderma, milia, hypohidrosis, and hypotrichosis,8 which were not evident in our patient. Pseudomonas hot foot syndrome is characterized by painful, plantar, erythematous nodules after exposure to ontaminated water that typically is self-limited but does respond to antibiotics for Pseudomonas.9

Our patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery with a complex repair utilizing a full-thickness skin graft. There were no signs of recurrence at 3-month follow-up, and he was counseled on the importance of sun-protective behaviors along with regular dermatologic follow-up.

1. Gorlin RJ. Nevoid basal cell (Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med. 2004; 6:530-539.

2. Bale A. The nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: genetics and mechanism of carcinogenesis. Cancer Invest. 1997;15:180-186.

3. Goldstein AM, Bale SJ, Peck GL, et al. Sun exposure and basal cell carcinomas in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:34-41.

4. Silvers SH. Interdigital pedal basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1983;31:199-200.

5. Weitzner S. Basal cell carcinoma of toeweb presenting as a junctional nevus. Southwest Med. 1968;49:175.

6. Niwa A, Pimentel E. Basal cell carcinoma in unusual locations. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:281-284.

7. Mitchell JH. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1922;6:675-679.

8. Kidd A, Carson L, Gregory DW, et al. A Scottish family with Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome: follicular atrophoderma, congenital hypotrichosis, and basal cell carcinoma. J Med Genet. 1996;33:493-497.

9. Yu Y, Cheng AS, Wang L, et al. Hot tub folliculitis or hot hand-foot syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:596-600.

The Diagnosis: Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome

Given the patient’s history of numerous basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), odontogenic keratocysts, palmar pits, and a nonhealing ulcer, the clinical presentation was highly suggestive of interdigital BCC in the setting of basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS). A shave biopsy was performed revealing islands of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and a retraction artifact surrounded by fibromyxoid stroma, consistent with nodular and infiltrative BCC (Figure 1).

Basal cell nevus syndrome (also known as Gorlin syndrome) is a rare neurocutaneous syndrome that manifests with multiple BCCs; palmar and plantar pits (Figure 2); central nervous system tumors; and skeletal anomalies including jaw cysts, macrocephaly, frontal bossing, and bifid ribs.1 It is an autosomal-dominant condition caused by mutations in the PTCH1 gene, a tumor suppressor gene involved in the Hedgehog signaling pathway.2 Basal cell carcinoma is the most distinctive feature of BCNS, causing notable morbidity. Tumors typically present between puberty and 35 years of age, and patients can have anywhere from a few to thousands of tumors. They rarely become locally aggressive; however, with radiation therapy, proliferation and local invasion may occur within a few years. Therefore, radiotherapy should be avoided in these patients.1

Although the most common sites for BCCs in BCNS are the head, neck, and back, there is a higher rate of occurrence on sun-protected areas in BCNS compared to the general population.3 Our patient presented with interdigital BCC of the foot, which is an extremely rare occurrence. PubMed and Ovid searches using the terms basal cell carcinoma, BCC, foot, interdigital, and nonmelanoma skin cancer revealed only 3 cases of interdigital BCC of the foot. One case was associated with prior surgical trauma, the second presented as a junctional nevus, and the third did not appear to have any associated inciting factors.4-6 Dermatologists need to have a low threshold for biopsy for any unusual nonhealing lesions, especially in the setting of BCNS. Basal cell carcinomas in BCNS cannot be histologically differentiated from sporadic BCCs, and management largely depends on the size, location, recurrence, and number of lesions. Treatment methods range from topical agents to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

Nonhealing lesions of the foot may give an initial clinical impression of infection overlying peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus with the possibility of associated osteomyelitis. Our patient had no clinical history to suggest peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus, and he had palpable dorsalis pedis pulses as well as a normal neurologic examination. Clinicians also may consider fungal infection in the differential diagnosis. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica is a superficial yeast infection described as a well-defined, red, shiny plaque found in chronically wet areas, usually affecting the third or fourth interdigital spaces of the fingers.7 However, the lack of improvement with antibiotics and antifungals argued against bacterial or fungal infection in our patient. Although BCC also is a common feature of Bazex Dupré-Christol syndrome, it also is characterized by follicular atrophoderma, milia, hypohidrosis, and hypotrichosis,8 which were not evident in our patient. Pseudomonas hot foot syndrome is characterized by painful, plantar, erythematous nodules after exposure to ontaminated water that typically is self-limited but does respond to antibiotics for Pseudomonas.9

Our patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery with a complex repair utilizing a full-thickness skin graft. There were no signs of recurrence at 3-month follow-up, and he was counseled on the importance of sun-protective behaviors along with regular dermatologic follow-up.

The Diagnosis: Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome

Given the patient’s history of numerous basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), odontogenic keratocysts, palmar pits, and a nonhealing ulcer, the clinical presentation was highly suggestive of interdigital BCC in the setting of basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS). A shave biopsy was performed revealing islands of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and a retraction artifact surrounded by fibromyxoid stroma, consistent with nodular and infiltrative BCC (Figure 1).

Basal cell nevus syndrome (also known as Gorlin syndrome) is a rare neurocutaneous syndrome that manifests with multiple BCCs; palmar and plantar pits (Figure 2); central nervous system tumors; and skeletal anomalies including jaw cysts, macrocephaly, frontal bossing, and bifid ribs.1 It is an autosomal-dominant condition caused by mutations in the PTCH1 gene, a tumor suppressor gene involved in the Hedgehog signaling pathway.2 Basal cell carcinoma is the most distinctive feature of BCNS, causing notable morbidity. Tumors typically present between puberty and 35 years of age, and patients can have anywhere from a few to thousands of tumors. They rarely become locally aggressive; however, with radiation therapy, proliferation and local invasion may occur within a few years. Therefore, radiotherapy should be avoided in these patients.1

Although the most common sites for BCCs in BCNS are the head, neck, and back, there is a higher rate of occurrence on sun-protected areas in BCNS compared to the general population.3 Our patient presented with interdigital BCC of the foot, which is an extremely rare occurrence. PubMed and Ovid searches using the terms basal cell carcinoma, BCC, foot, interdigital, and nonmelanoma skin cancer revealed only 3 cases of interdigital BCC of the foot. One case was associated with prior surgical trauma, the second presented as a junctional nevus, and the third did not appear to have any associated inciting factors.4-6 Dermatologists need to have a low threshold for biopsy for any unusual nonhealing lesions, especially in the setting of BCNS. Basal cell carcinomas in BCNS cannot be histologically differentiated from sporadic BCCs, and management largely depends on the size, location, recurrence, and number of lesions. Treatment methods range from topical agents to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

Nonhealing lesions of the foot may give an initial clinical impression of infection overlying peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus with the possibility of associated osteomyelitis. Our patient had no clinical history to suggest peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus, and he had palpable dorsalis pedis pulses as well as a normal neurologic examination. Clinicians also may consider fungal infection in the differential diagnosis. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica is a superficial yeast infection described as a well-defined, red, shiny plaque found in chronically wet areas, usually affecting the third or fourth interdigital spaces of the fingers.7 However, the lack of improvement with antibiotics and antifungals argued against bacterial or fungal infection in our patient. Although BCC also is a common feature of Bazex Dupré-Christol syndrome, it also is characterized by follicular atrophoderma, milia, hypohidrosis, and hypotrichosis,8 which were not evident in our patient. Pseudomonas hot foot syndrome is characterized by painful, plantar, erythematous nodules after exposure to ontaminated water that typically is self-limited but does respond to antibiotics for Pseudomonas.9

Our patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery with a complex repair utilizing a full-thickness skin graft. There were no signs of recurrence at 3-month follow-up, and he was counseled on the importance of sun-protective behaviors along with regular dermatologic follow-up.

1. Gorlin RJ. Nevoid basal cell (Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med. 2004; 6:530-539.

2. Bale A. The nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: genetics and mechanism of carcinogenesis. Cancer Invest. 1997;15:180-186.

3. Goldstein AM, Bale SJ, Peck GL, et al. Sun exposure and basal cell carcinomas in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:34-41.

4. Silvers SH. Interdigital pedal basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1983;31:199-200.

5. Weitzner S. Basal cell carcinoma of toeweb presenting as a junctional nevus. Southwest Med. 1968;49:175.

6. Niwa A, Pimentel E. Basal cell carcinoma in unusual locations. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:281-284.

7. Mitchell JH. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1922;6:675-679.

8. Kidd A, Carson L, Gregory DW, et al. A Scottish family with Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome: follicular atrophoderma, congenital hypotrichosis, and basal cell carcinoma. J Med Genet. 1996;33:493-497.

9. Yu Y, Cheng AS, Wang L, et al. Hot tub folliculitis or hot hand-foot syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:596-600.

1. Gorlin RJ. Nevoid basal cell (Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med. 2004; 6:530-539.

2. Bale A. The nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: genetics and mechanism of carcinogenesis. Cancer Invest. 1997;15:180-186.

3. Goldstein AM, Bale SJ, Peck GL, et al. Sun exposure and basal cell carcinomas in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:34-41.

4. Silvers SH. Interdigital pedal basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1983;31:199-200.

5. Weitzner S. Basal cell carcinoma of toeweb presenting as a junctional nevus. Southwest Med. 1968;49:175.

6. Niwa A, Pimentel E. Basal cell carcinoma in unusual locations. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:281-284.

7. Mitchell JH. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1922;6:675-679.

8. Kidd A, Carson L, Gregory DW, et al. A Scottish family with Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome: follicular atrophoderma, congenital hypotrichosis, and basal cell carcinoma. J Med Genet. 1996;33:493-497.

9. Yu Y, Cheng AS, Wang L, et al. Hot tub folliculitis or hot hand-foot syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:596-600.

A 53-year-old man with a history of numerous basal cell carcinomas and odontogenic keratocysts presented with a nonhealing erosion between the left second and third toes of several months’ duration. He was treated empirically with multiple courses of topical and systemic antibiotics as well as antifungals with minimal improvement. Physical examination revealed a 1.2×0.6-cm eroded plaque with rolled borders on the left second toe web; bilateral palmar pits; diffuse actinic damage; and several well-healed surgical scars on the head, neck, and back. Neurologic examination was normal, and dorsalis pedis pulses were equal and palpable bilaterally.

Ascending Erythematous Nodules on the Arm

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis

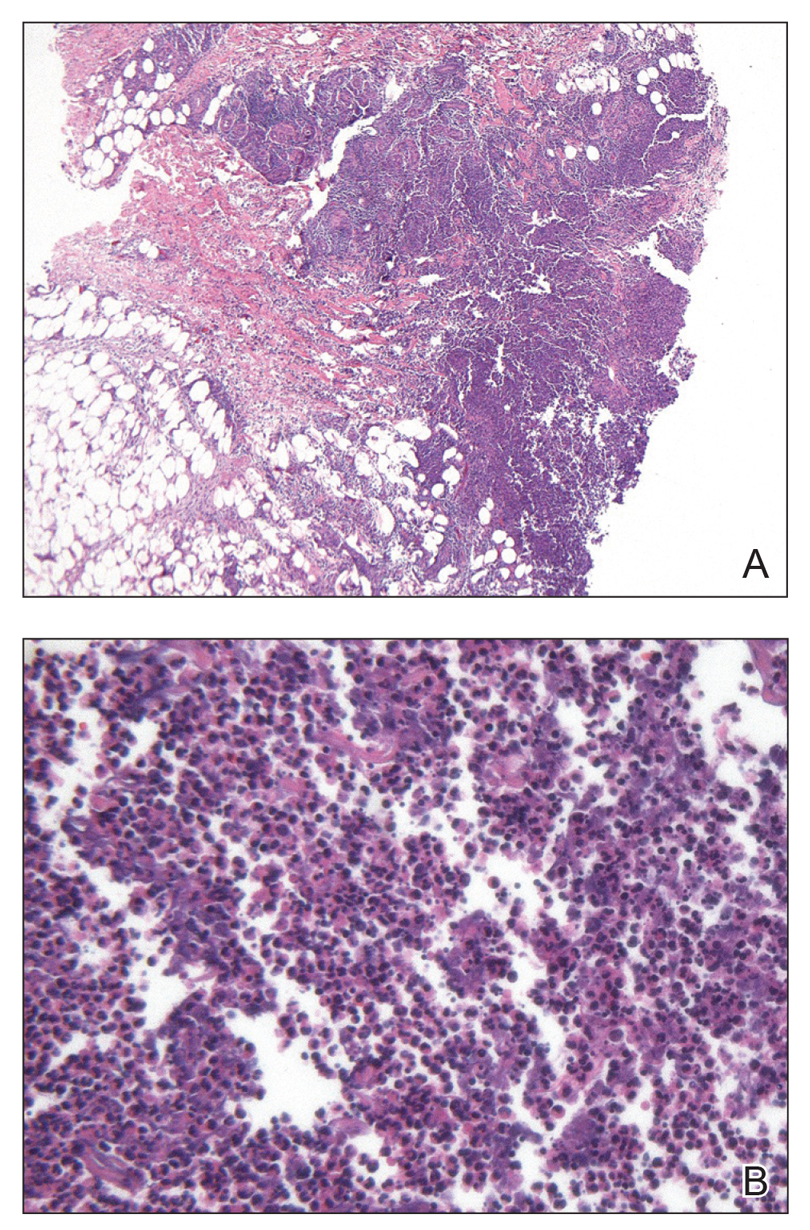

Comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count were unremarkable; human immunodeficiency virus screening was nonreactive. Punch biopsies were obtained for histopathology, as well as bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures. Histopathologic examination of a 4-mm punch biopsy of the forearm nodule showed a dermal abscess with neutrophilic infiltration in the dermis (Figure 1). No organisms were seen on Gram, methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, or acid-fast bacteria stains. Given the clinical suspicion for lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis, the patient was started on itraconazole. She reported modest improvement but subsequently developed a morbilliform eruption necessitating medication discontinuation.

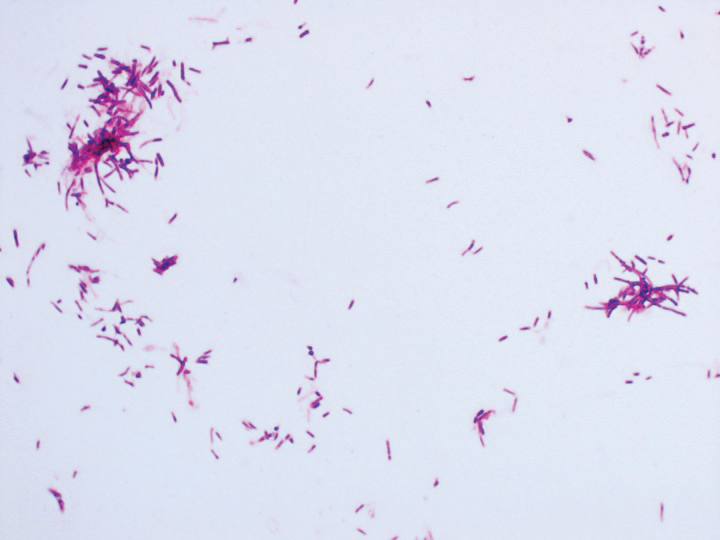

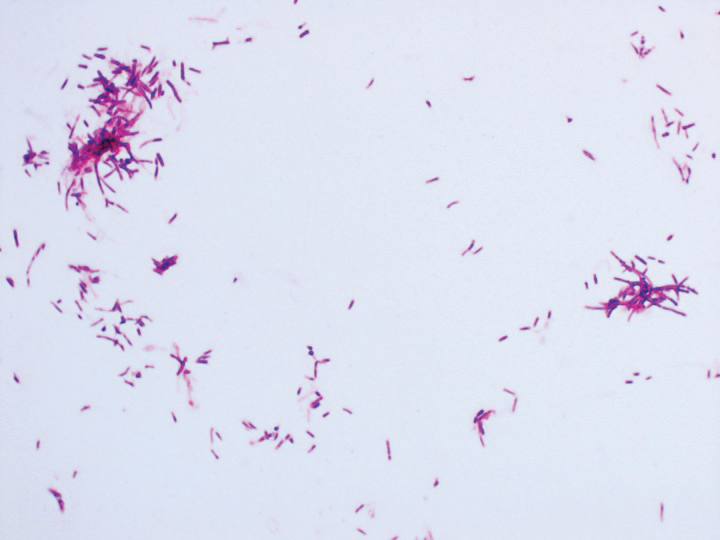

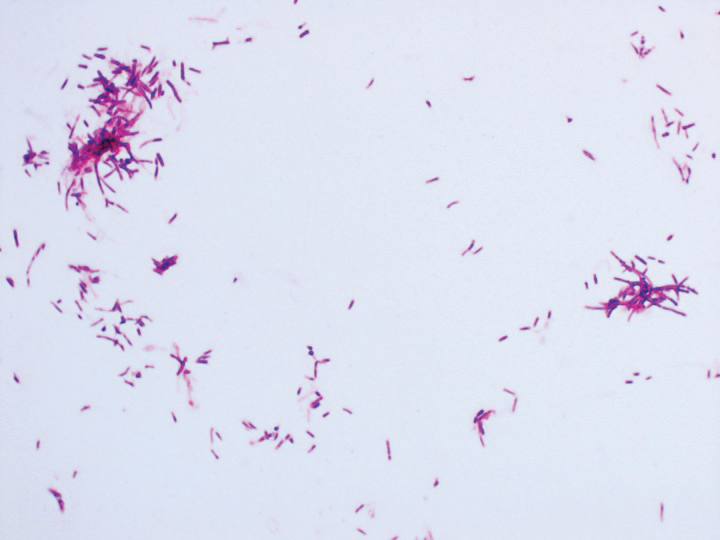

Eighteen days after obtaining the tissue culture, acid-fast organisms grew in culture. These organisms were subcultured on Middlebrook 7H11 agar (Sigma-Aldrich) with growth noted at 30°C and 37°C. Gram stain revealed filamentous gram-variable bacteria (Figure 2) that were identified as Nocardia brasiliensis by 16S ribosomal DNA analysis. Given the patient’s sulfonamide allergy, she started oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily. She responded to the therapy and subsequent testing confirmed susceptibility.

Nocardia brasiliensis, isolated from subculture on Gram stain (original

magnification ×1000).

The genus Nocardia consists of more than 50 species of gram-positive, weakly acid-fast, aerobic actinomycetes that can cause primary cutaneous infection via percutaneous inoculation. Nocardia brasiliensis is the leading cause (approximately 80% of cases) of primary cutaneous or subcutaneous nocardiosis and is found ubiquitously in soil and decaying vegetation.1 The clinical presentation varies, rendering definitive diagnosis a challenge without histopathologic and microbiologic testing.2 Patients presenting with nocardial cellulitis often are suspected to have Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus infections. The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with nocardial nodular lymphangitis, also known as lymphocutaneous syndrome, includes atypical mycobacterial infections, leishmaniasis, and lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis.2

Histologic examination of nocardial nodules typically shows granulomatous or neutrophilic inflammation, and organisms may appear in small collections resembling sulfur granules.2 The organism itself is weakly positive on acid-fast stain, and useful stains include acid-fast bacteria, methenamine silver, and periodic acid–Schiff.2 Tissue culture often provides the definitive diagnosis, as the histology is nonspecific and organisms may not be visualized.

Oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 2.5 to 10 mg/kg and 12.5 to 50 mg/kg, respectively, twice daily is the treatment of choice for primary cutaneous nocardiosis. Minocycline 100 to 200 mg twice daily is an accepted alternative in case of sulfonamide allergy, as in our patient. Antibiotics should be tailored according to the susceptibility profile of the isolated organism.3

This case highlights the importance of forming a broad differential diagnosis for patients presenting with lymphocutaneous syndrome. The incidence and prevalence of N brasiliensis infection is difficult to determine due to its nonspecific clinical presentation and a lack of recent epidemiologic studies. Although primary cutaneous nocardiosis in the United States often is diagnosed in the South or Southwest, cases have been reported in other regions.4-6 Traumatic inoculation of contaminated soil, plants, and other organic matter, a well-known method of Sporothrix schenckii transmission, also is a method of N brasiliensis transmission. Because this organism may not be detected on histologic examination, empiric treatment should be considered if the diagnosis is suspected.

1. Brown-Eliot BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:259-282.

2. Smego RA Jr, Castiglia M, Asperilla MO. Lymphocutaneous syndrome: a review of non-sporothrix causes. Medicine. 1999;78:38-63.

3. Lerner P. Nocardiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:891-903.

4. Smego RA Jr, Gallis HA. The clinical spectrum of Nocardia brasiliensis infection in the United States. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6:164-180.

5. Fukuda H, Saotome A, Usami N, et al. Lymphocutaneous type of nocardiosis caused by Nocardia brasiliensis: a case report and review of primary cutaneous nocardiosis caused by N. brasiliensis reported in Japan. J Dermatol. 2008;35:346-353.

6. Kil EH, Tsai CL, Kwark EH, et al. A case of nocardiosis with an uncharacteristically long incubation period. Cutis. 2005;76:33-36.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis

Comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count were unremarkable; human immunodeficiency virus screening was nonreactive. Punch biopsies were obtained for histopathology, as well as bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures. Histopathologic examination of a 4-mm punch biopsy of the forearm nodule showed a dermal abscess with neutrophilic infiltration in the dermis (Figure 1). No organisms were seen on Gram, methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, or acid-fast bacteria stains. Given the clinical suspicion for lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis, the patient was started on itraconazole. She reported modest improvement but subsequently developed a morbilliform eruption necessitating medication discontinuation.

Eighteen days after obtaining the tissue culture, acid-fast organisms grew in culture. These organisms were subcultured on Middlebrook 7H11 agar (Sigma-Aldrich) with growth noted at 30°C and 37°C. Gram stain revealed filamentous gram-variable bacteria (Figure 2) that were identified as Nocardia brasiliensis by 16S ribosomal DNA analysis. Given the patient’s sulfonamide allergy, she started oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily. She responded to the therapy and subsequent testing confirmed susceptibility.

Nocardia brasiliensis, isolated from subculture on Gram stain (original

magnification ×1000).

The genus Nocardia consists of more than 50 species of gram-positive, weakly acid-fast, aerobic actinomycetes that can cause primary cutaneous infection via percutaneous inoculation. Nocardia brasiliensis is the leading cause (approximately 80% of cases) of primary cutaneous or subcutaneous nocardiosis and is found ubiquitously in soil and decaying vegetation.1 The clinical presentation varies, rendering definitive diagnosis a challenge without histopathologic and microbiologic testing.2 Patients presenting with nocardial cellulitis often are suspected to have Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus infections. The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with nocardial nodular lymphangitis, also known as lymphocutaneous syndrome, includes atypical mycobacterial infections, leishmaniasis, and lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis.2

Histologic examination of nocardial nodules typically shows granulomatous or neutrophilic inflammation, and organisms may appear in small collections resembling sulfur granules.2 The organism itself is weakly positive on acid-fast stain, and useful stains include acid-fast bacteria, methenamine silver, and periodic acid–Schiff.2 Tissue culture often provides the definitive diagnosis, as the histology is nonspecific and organisms may not be visualized.

Oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 2.5 to 10 mg/kg and 12.5 to 50 mg/kg, respectively, twice daily is the treatment of choice for primary cutaneous nocardiosis. Minocycline 100 to 200 mg twice daily is an accepted alternative in case of sulfonamide allergy, as in our patient. Antibiotics should be tailored according to the susceptibility profile of the isolated organism.3

This case highlights the importance of forming a broad differential diagnosis for patients presenting with lymphocutaneous syndrome. The incidence and prevalence of N brasiliensis infection is difficult to determine due to its nonspecific clinical presentation and a lack of recent epidemiologic studies. Although primary cutaneous nocardiosis in the United States often is diagnosed in the South or Southwest, cases have been reported in other regions.4-6 Traumatic inoculation of contaminated soil, plants, and other organic matter, a well-known method of Sporothrix schenckii transmission, also is a method of N brasiliensis transmission. Because this organism may not be detected on histologic examination, empiric treatment should be considered if the diagnosis is suspected.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis

Comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count were unremarkable; human immunodeficiency virus screening was nonreactive. Punch biopsies were obtained for histopathology, as well as bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures. Histopathologic examination of a 4-mm punch biopsy of the forearm nodule showed a dermal abscess with neutrophilic infiltration in the dermis (Figure 1). No organisms were seen on Gram, methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, or acid-fast bacteria stains. Given the clinical suspicion for lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis, the patient was started on itraconazole. She reported modest improvement but subsequently developed a morbilliform eruption necessitating medication discontinuation.

Eighteen days after obtaining the tissue culture, acid-fast organisms grew in culture. These organisms were subcultured on Middlebrook 7H11 agar (Sigma-Aldrich) with growth noted at 30°C and 37°C. Gram stain revealed filamentous gram-variable bacteria (Figure 2) that were identified as Nocardia brasiliensis by 16S ribosomal DNA analysis. Given the patient’s sulfonamide allergy, she started oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily. She responded to the therapy and subsequent testing confirmed susceptibility.

Nocardia brasiliensis, isolated from subculture on Gram stain (original

magnification ×1000).

The genus Nocardia consists of more than 50 species of gram-positive, weakly acid-fast, aerobic actinomycetes that can cause primary cutaneous infection via percutaneous inoculation. Nocardia brasiliensis is the leading cause (approximately 80% of cases) of primary cutaneous or subcutaneous nocardiosis and is found ubiquitously in soil and decaying vegetation.1 The clinical presentation varies, rendering definitive diagnosis a challenge without histopathologic and microbiologic testing.2 Patients presenting with nocardial cellulitis often are suspected to have Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus infections. The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with nocardial nodular lymphangitis, also known as lymphocutaneous syndrome, includes atypical mycobacterial infections, leishmaniasis, and lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis.2

Histologic examination of nocardial nodules typically shows granulomatous or neutrophilic inflammation, and organisms may appear in small collections resembling sulfur granules.2 The organism itself is weakly positive on acid-fast stain, and useful stains include acid-fast bacteria, methenamine silver, and periodic acid–Schiff.2 Tissue culture often provides the definitive diagnosis, as the histology is nonspecific and organisms may not be visualized.

Oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 2.5 to 10 mg/kg and 12.5 to 50 mg/kg, respectively, twice daily is the treatment of choice for primary cutaneous nocardiosis. Minocycline 100 to 200 mg twice daily is an accepted alternative in case of sulfonamide allergy, as in our patient. Antibiotics should be tailored according to the susceptibility profile of the isolated organism.3

This case highlights the importance of forming a broad differential diagnosis for patients presenting with lymphocutaneous syndrome. The incidence and prevalence of N brasiliensis infection is difficult to determine due to its nonspecific clinical presentation and a lack of recent epidemiologic studies. Although primary cutaneous nocardiosis in the United States often is diagnosed in the South or Southwest, cases have been reported in other regions.4-6 Traumatic inoculation of contaminated soil, plants, and other organic matter, a well-known method of Sporothrix schenckii transmission, also is a method of N brasiliensis transmission. Because this organism may not be detected on histologic examination, empiric treatment should be considered if the diagnosis is suspected.

1. Brown-Eliot BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:259-282.

2. Smego RA Jr, Castiglia M, Asperilla MO. Lymphocutaneous syndrome: a review of non-sporothrix causes. Medicine. 1999;78:38-63.

3. Lerner P. Nocardiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:891-903.

4. Smego RA Jr, Gallis HA. The clinical spectrum of Nocardia brasiliensis infection in the United States. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6:164-180.

5. Fukuda H, Saotome A, Usami N, et al. Lymphocutaneous type of nocardiosis caused by Nocardia brasiliensis: a case report and review of primary cutaneous nocardiosis caused by N. brasiliensis reported in Japan. J Dermatol. 2008;35:346-353.

6. Kil EH, Tsai CL, Kwark EH, et al. A case of nocardiosis with an uncharacteristically long incubation period. Cutis. 2005;76:33-36.

1. Brown-Eliot BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:259-282.

2. Smego RA Jr, Castiglia M, Asperilla MO. Lymphocutaneous syndrome: a review of non-sporothrix causes. Medicine. 1999;78:38-63.

3. Lerner P. Nocardiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:891-903.

4. Smego RA Jr, Gallis HA. The clinical spectrum of Nocardia brasiliensis infection in the United States. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6:164-180.

5. Fukuda H, Saotome A, Usami N, et al. Lymphocutaneous type of nocardiosis caused by Nocardia brasiliensis: a case report and review of primary cutaneous nocardiosis caused by N. brasiliensis reported in Japan. J Dermatol. 2008;35:346-353.

6. Kil EH, Tsai CL, Kwark EH, et al. A case of nocardiosis with an uncharacteristically long incubation period. Cutis. 2005;76:33-36.

A 54-year-old woman called her primary care provider to report a painful pink nodule on the left wrist 1 week after sustaining thorn injuries while weeding in her garden. She started cephalexin and noted a pink streak with additional nodules extending up the arm over the next 2 days. She

was admitted to an outside hospital for incision and drainage of the wrist nodule and a 3-day course of intravenous vancomycin. Bacterial culture was negative, and she was discharged on oral clindamycin and doxycycline. Two days later, she presented to our emergency department with pain in the left axilla. Physical examination revealed 3 tender erythematous nodules in a linear distribution on the left arm with crusting at the incision and drainage site and painful left axillary lymphadenopathy. The patient was afebrile and otherwise asymptomatic.

Pityriasis Amiantacea Following Bone Marrow Transplant

Pityriasis amiantacea (PA) is characterized by adherence of hair shafts proximally.1 It has been associated with dermatologic conditions and rarely with medications. We describe a woman who developed PA following a bone marrow transplant with melphalan conditioning. We also review drug-induced PA and disorders that have been linked to this condition.

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman with a history of multiple myeloma was treated with 7 courses of chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, prednisone). One month later, the patient underwent a bone marrow transplant with melphalan conditioning due to residual plasma cell myeloma. Following the transplant, she developed complete scalp alopecia. Prior to and following transplant, the patient’s hair care regimen included washing her hair and scalp every other day with over-the-counter “natural” shampoos. During drug-induced alopecia, the hair washing became less frequent.

The patient left the hospital 4 weeks posttransplant; her hair had started to regrow, but its appearance was altered. Posttransplant, the patient was maintained on bortezomib every other week and zoledronate once per month. She continued to develop multiple lesions in the scalp hairs during the following 4 months.

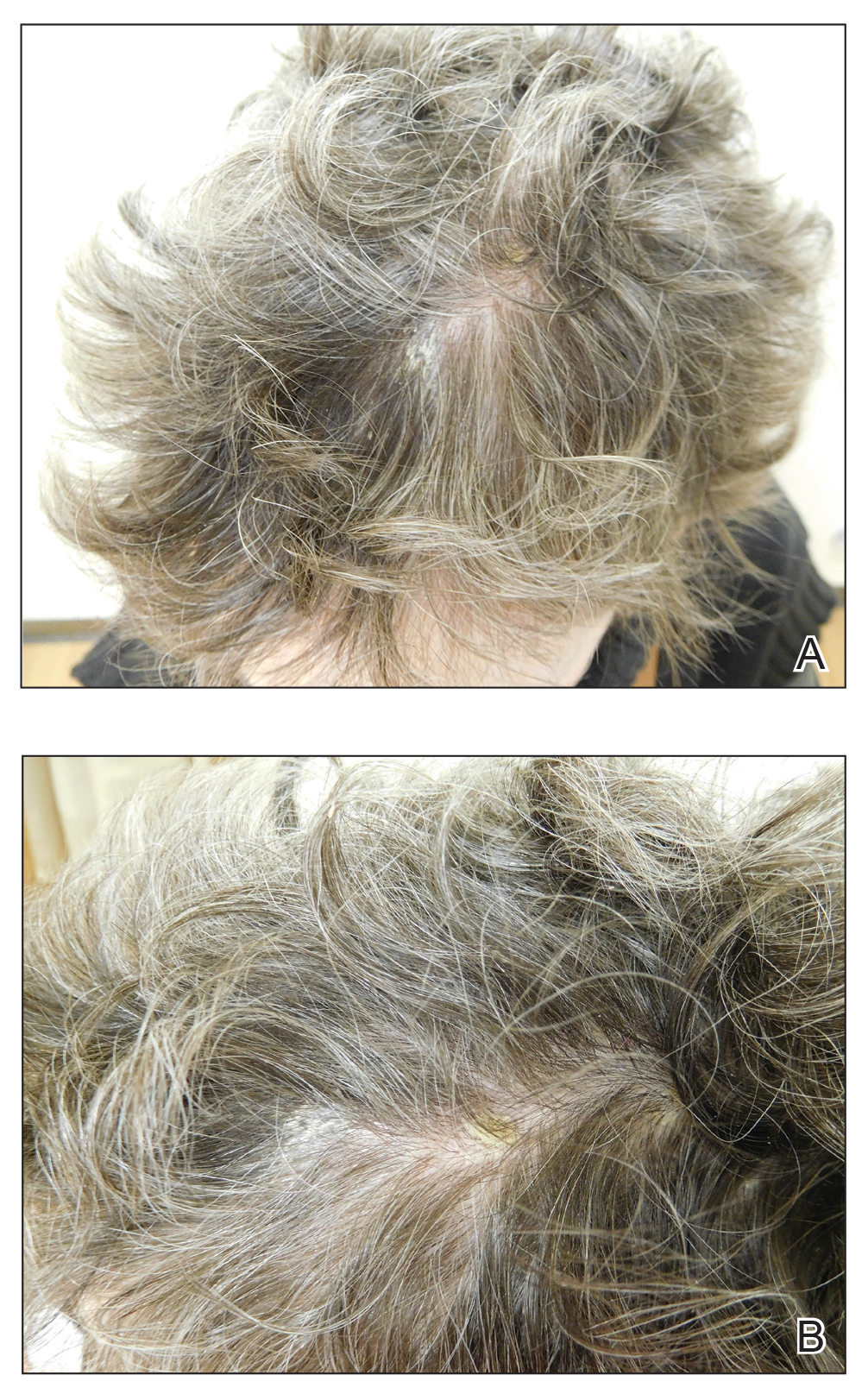

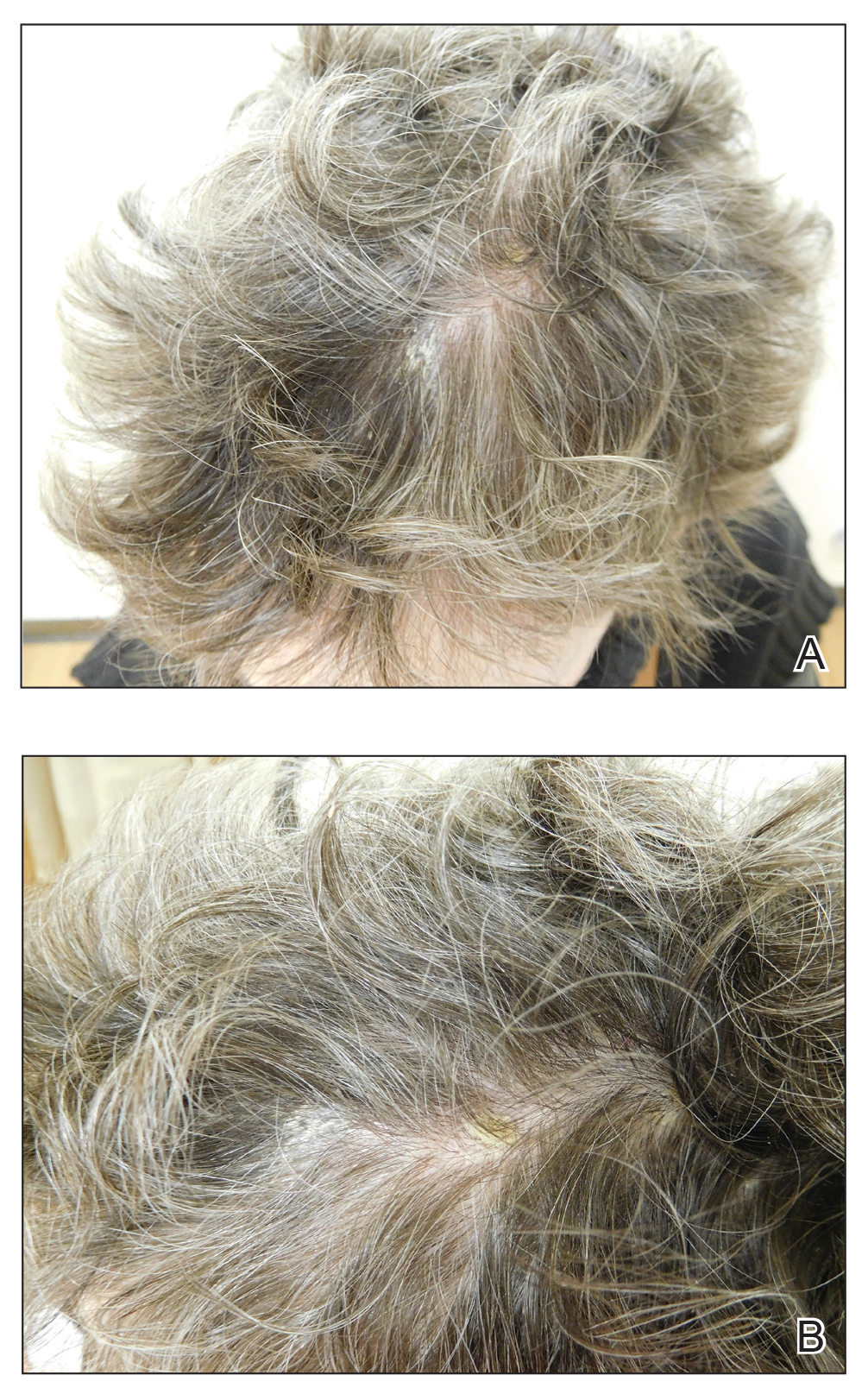

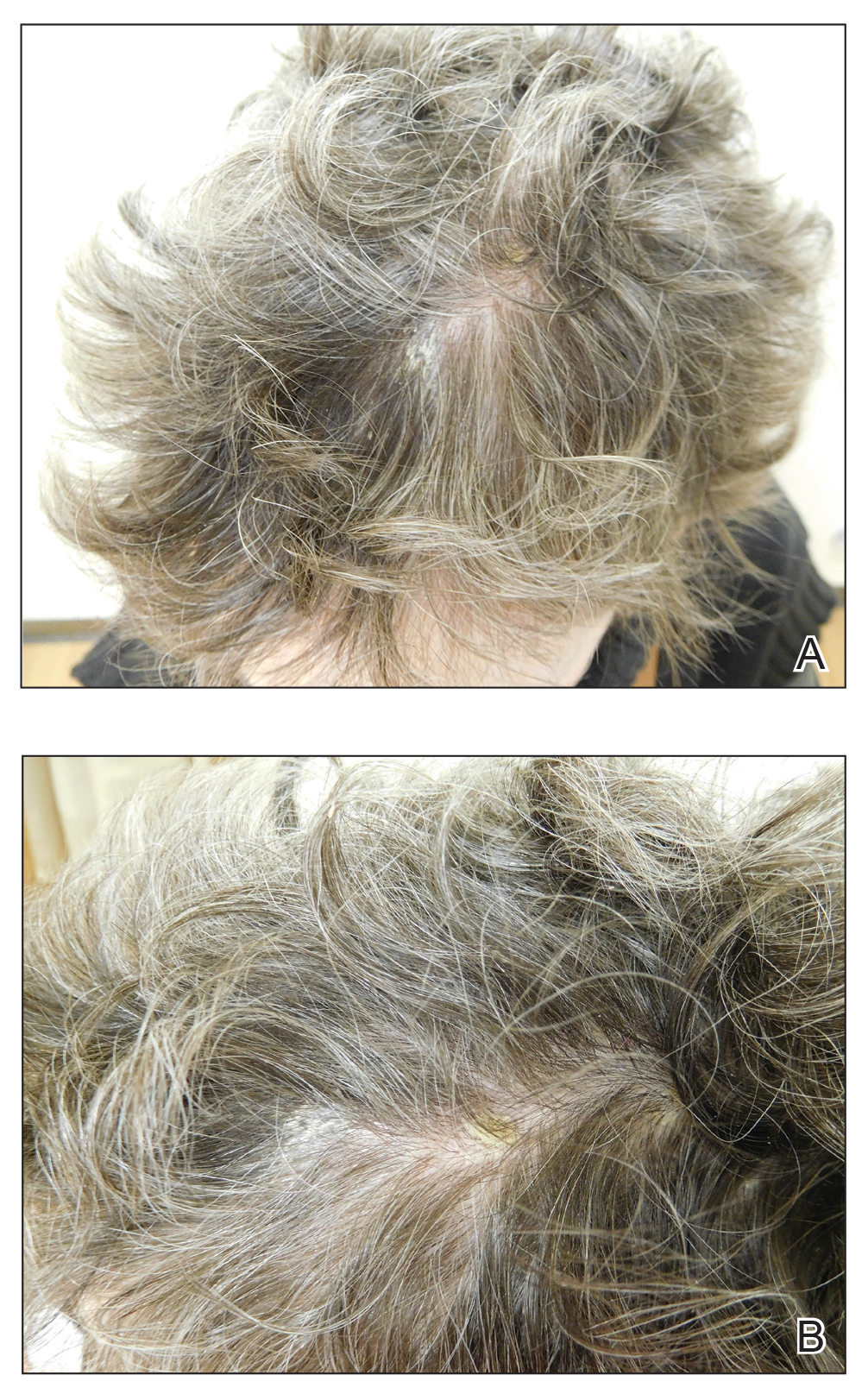

Eight months posttransplant she presented for evaluation of the scalp hair. Clinical examination showed hairs that were entwined together proximally, resulting in matting of the hair (Figure 1). A diagnosis of PA was established based on the clinical examination.

Treatment included mineral oil application to the scalp under occlusion each evening, followed by morning washing with coal tar 0.5%, salicylic acid 6%, or ketoconazole 2% shampoo in a repeating sequential manner. Within 1 month there was complete resolution of the scalp condition (Figure 2).

Comment

Clinical Presentation

Pityriasis amiantacea is characterized by thick excessive scale of the scalp1; it was initially described by Alibert2 in 1832. He described the gross appearance of the scales as resembling the feathers of young birds, which naturalists dub “amiante” or asbestoslike.1,2 In 1917, Gougerot3 explored infectious etiologies of this condition by describing cases of impetigo that transitioned into PA.1 Later, in 1929, Photinos4 described fungal origins of PA, giving credence to “tinea amiantacea.”1 However, more recent analyses failed to isolate fungus.5-7 As such, pityriasis (scaling) amiantacea is the more appropriate term, as emphasized by Brown8 in 1948. The cause of PA remains unclear; it is hypothesized that the condition is a reaction to underlying inflammatory dermatoses, though concurrent bacterial or fungal infection may be present.5,9

Prevalence

Pityriasis amiantacea is considered to be most prevalent in pediatric patients and young adults; it is more common in females.1,9,10 In a review of 85 PA patients, more than 80% were women (n=69), and the mean age at presentation was 23.8 years. Approximately half of these patients had widespread scalp lesions (n=42); however, focal localized lesions were common.9 No hereditary patterns have been described, though 3 pairs of the 10 patients with PA in Ring and Kaplan’s7 review were siblings.

Clinical Findings

Clinically, lesions of PA present as matted hairs.1 Thick scales encompass multiple hair shafts, binding down tufts of hair.1,6,11 Patients are asymptomatic, though the lesions may be accompanied by pruritus. The hairs enclosed by the scales in some cases may be easily pulled out.6 Notably, alopecia often accompanies PA; it often is reversible, but in some cases, it is permanent and can lead to scarring.9,12

Histopathology

Submission of hair specimens to histopathology usually is not performed since the diagnosis often is established based on the clinical presentation.5 However, submitted specimens have demonstrated spongiosis and parakeratosis along with reduction in the size of the sebaceous glands.1,9 Additionally, follicular keratosis that surrounds the hair shafts with a sheath of horn is present.9 Acanthosis and migration of lymphocytes into the epidermis also have been found.1 Often, Staphylococcus aureus isolates are detected.9,13

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnosis of PA includes hair casts,11 pediculosis,14 and tinea capitis.12 In PA, thick scales surround hair shafts and thus bind down tufts of hair.9 In patients with pediculosis, nits are attached to the hair shaft at an angle and do not entirely envelop the hair shaft.14 In addition, PA may be complicated by impetiginization; bacteria often are found in the keratin surrounding the hair shaft and represent either normal flora or secondary infection.1,15 It has been speculated that microbial biofilms from S aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis promote agglomeration of hair shafts and adherent scale.16 Bona fide dermatophyte infection of the scalp also may be concurrently present.12

Treatment

Our treatment included occlusion with mineral oil to loosen the scales from the scalp in tandem with shampoos traditionally used in patients with seborrheic dermatitis or psoriasis. Timely treatment is important to prevent scarring alopecia.13,17 Pityriasis amiantacea may be treatment resistant, and there are no specific therapeutic guidelines; rather, therapy should be targeted at the suspected underlying condition.17 Treatment generally includes keratolytic agents, such as salicylic acid.18 These agents allow enhanced penetration of other topical agents.19 Topical antifungal shampoos such as ketoconazole and ciclopirox are recommended,18 though other topical agents, such as coal tar and zinc pyrithione, also may benefit patients.13 Topical corticosteroids may be used if the condition is linked with psoriasis.13 Systemic antibiotics are added if S aureus superinfection is suspected.9

A single report described successful management of a patient with severe refractory PA who was treated with the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibitor infliximab.13 A 47-year-old woman presented with thick adherent scale on the scalp. She was treated with coal tar for 18 months but showed no improvement; the patient was subsequently prescribed salicylic acid 10%, clobetasol solution, and coal tar shampoo. After 3 months, when no improvement was observed, the patient was offered infliximab but declined. For 6 years the patient was treated with salicylic acid 20%, clobetasol (foam, lotion, shampoo, and solution), and coal tar shampoo without improvement. She then consented to infliximab therapy; after 3 infusions at weeks 0, 2, and 6, she demonstrated notable improvement. The patient was maintained on infliximab every 8 weeks.13

Pathogenesis

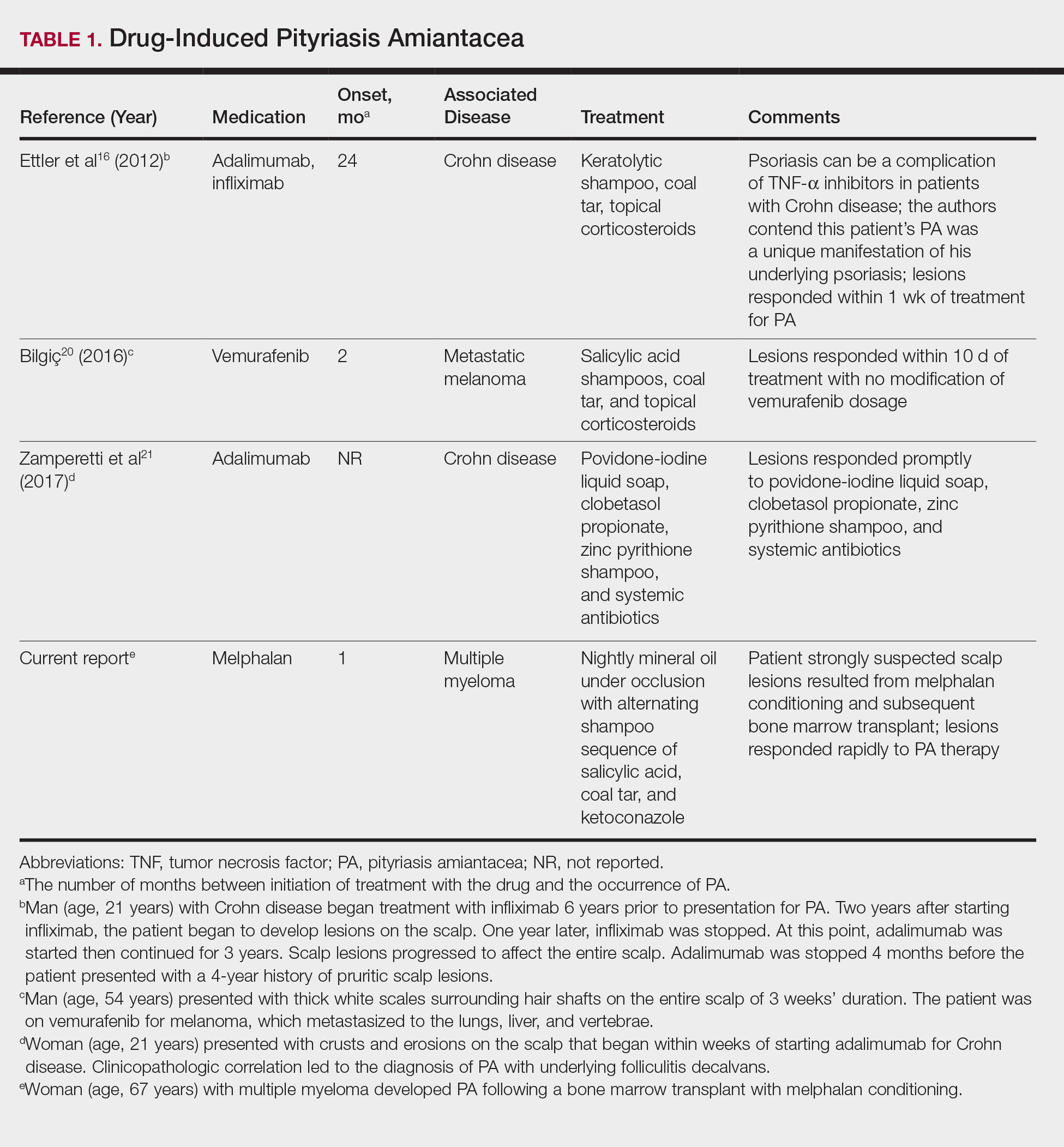

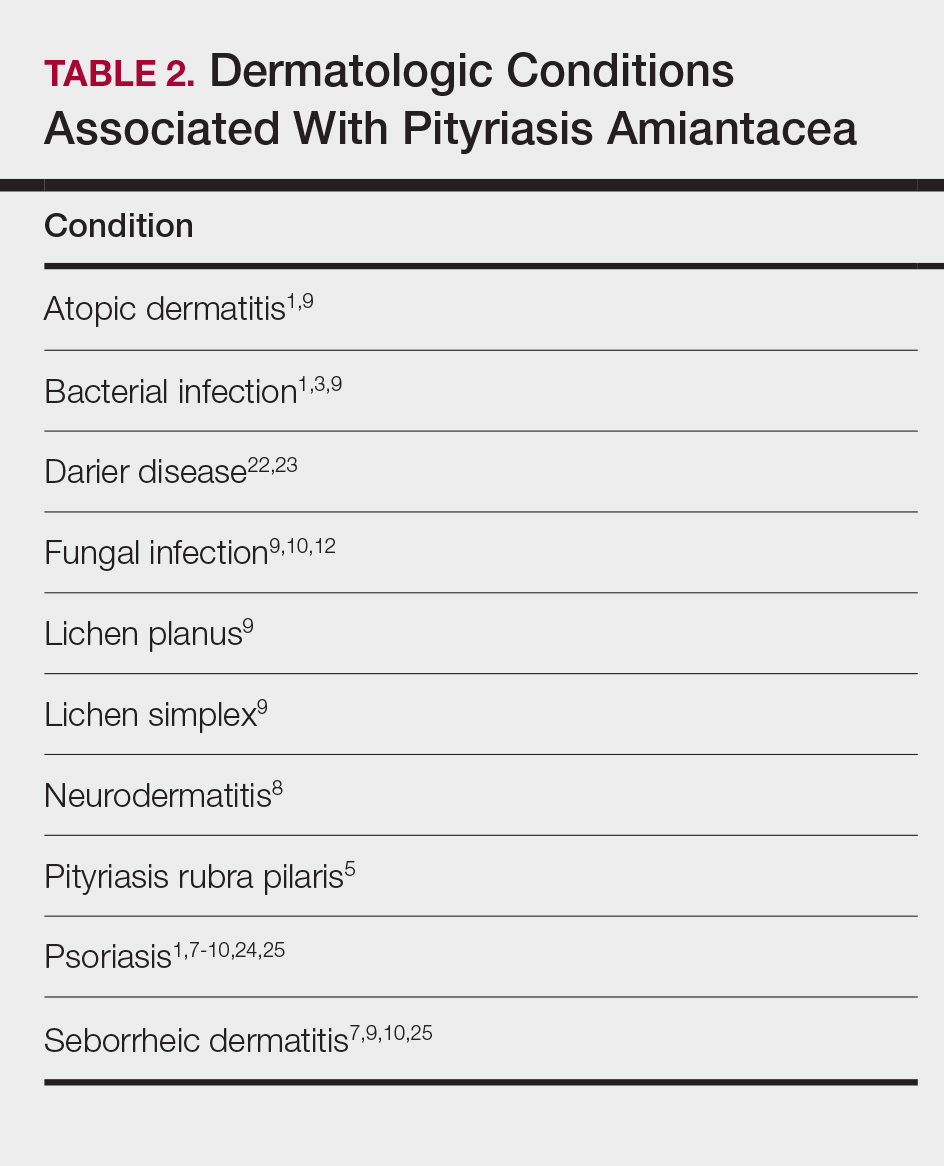

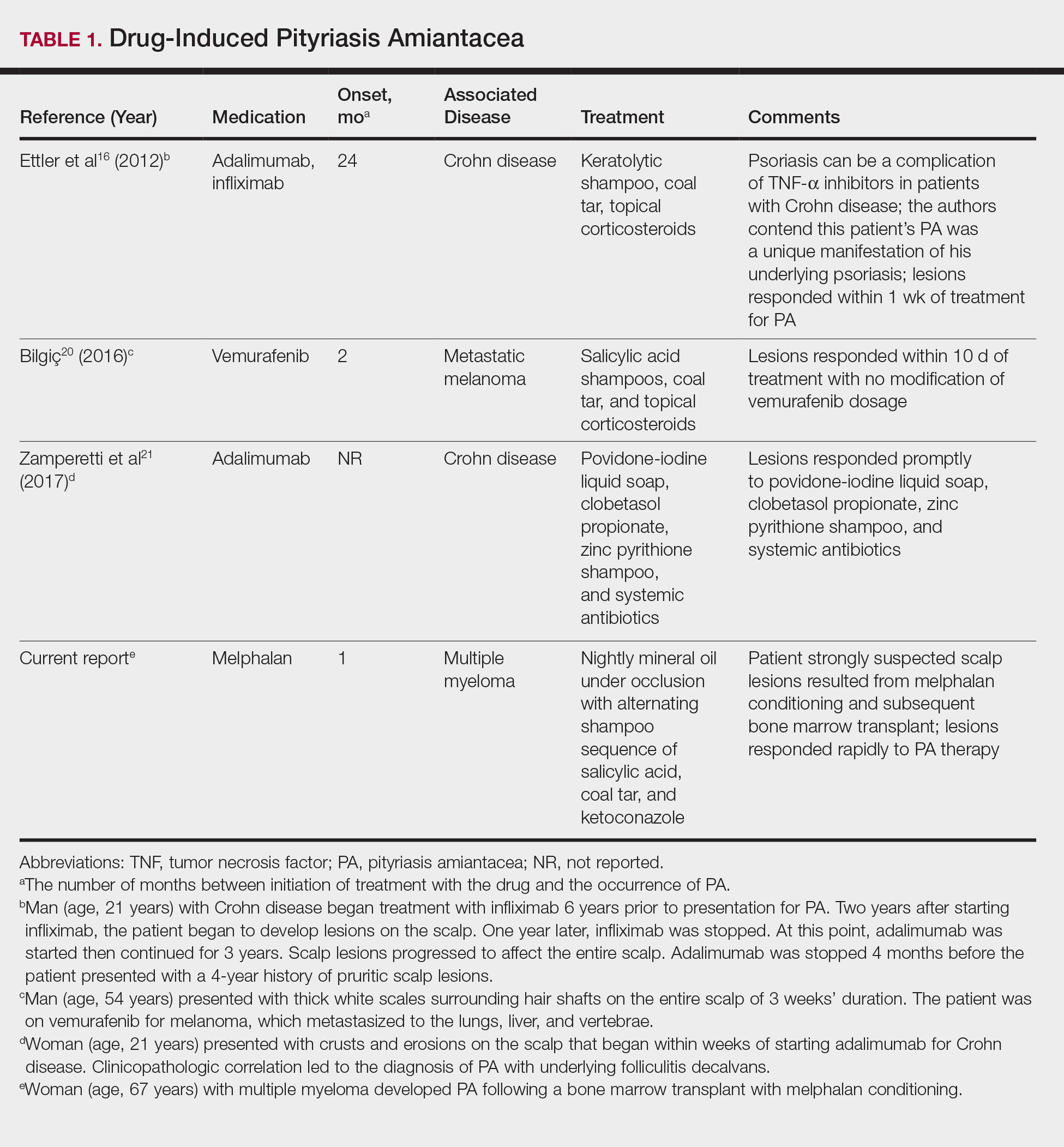

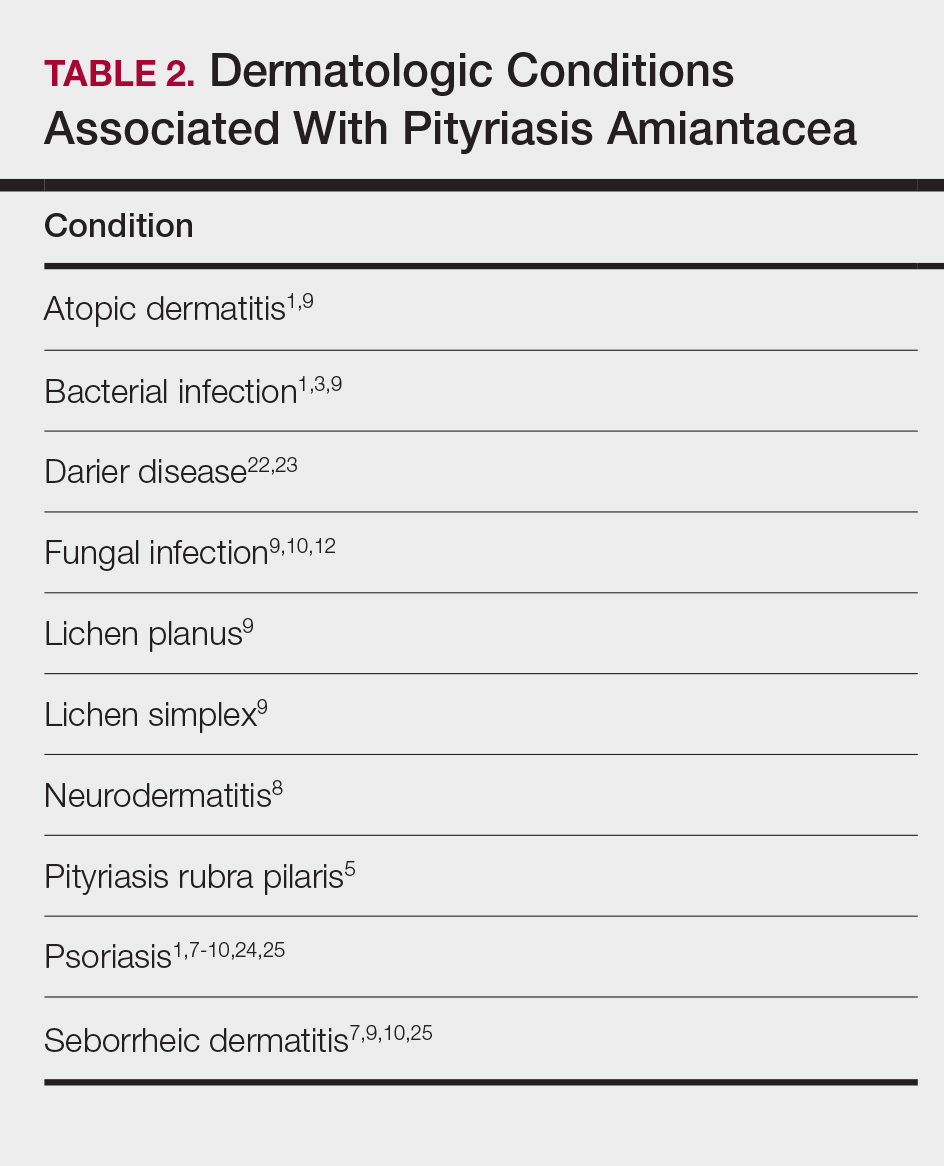

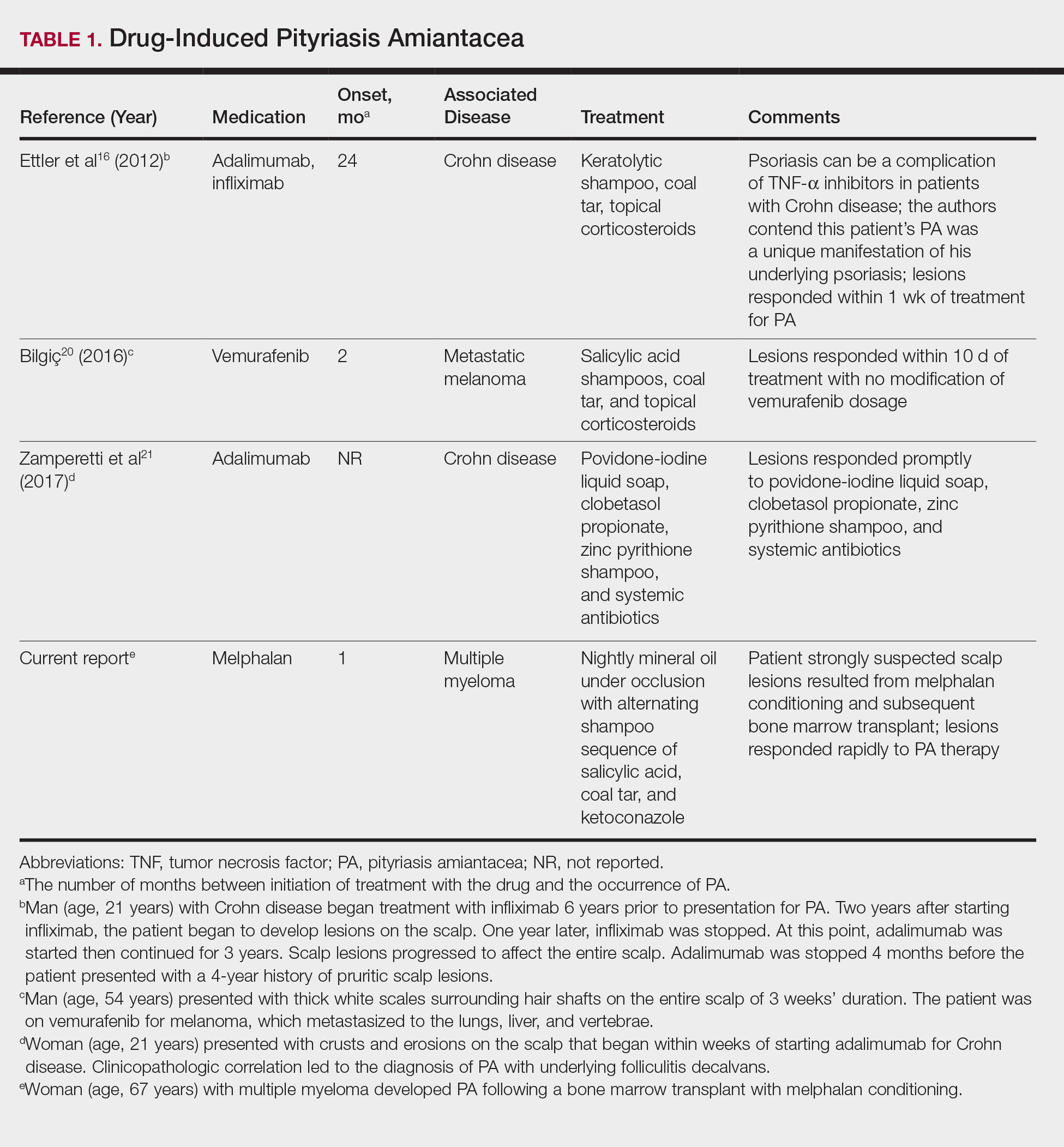

The pathogenesis of PA has yet to be definitively established, and the condition is usually idiopathic. In addition to bacterial or fungal etiologies,3,4 PA has been linked to medications (Table 1)16,20,21 and systemic conditions (Table 2).1,3,5,7-10,12,22-25

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms amiantacea, bone, drug, hair marrow, malignancy, melphalan, pityriasis, tinea, and transplant yielded 4 patients—2 men and 2 women (including our patient)—with possible drug-induced PA (Table 1)16,20,21; however, the onset after 2 years of medication (TNF-α inhibitors) or resolution while still receiving the agent (vemurafenib) makes the drug-induced linkage weak. The patients ranged in age from 21 to 67 years, with the median age being 37.5 years. Medications included melphalan, TNF-α inhibitors (adalimumab, infliximab),16,21 and vemurafenib20; it is interesting that infliximab was the medication associated with eliciting PA in 1 patient yet was an effective therapy in another patient with treatment-resistant PA. The onset of PA occurred between 1 month (melphalan) and 24 months (TNF-α inhibitors) after drug initiation. The patients’ associated diseases included Crohn disease,16,21 metastatic melanoma,20 and multiple myeloma.

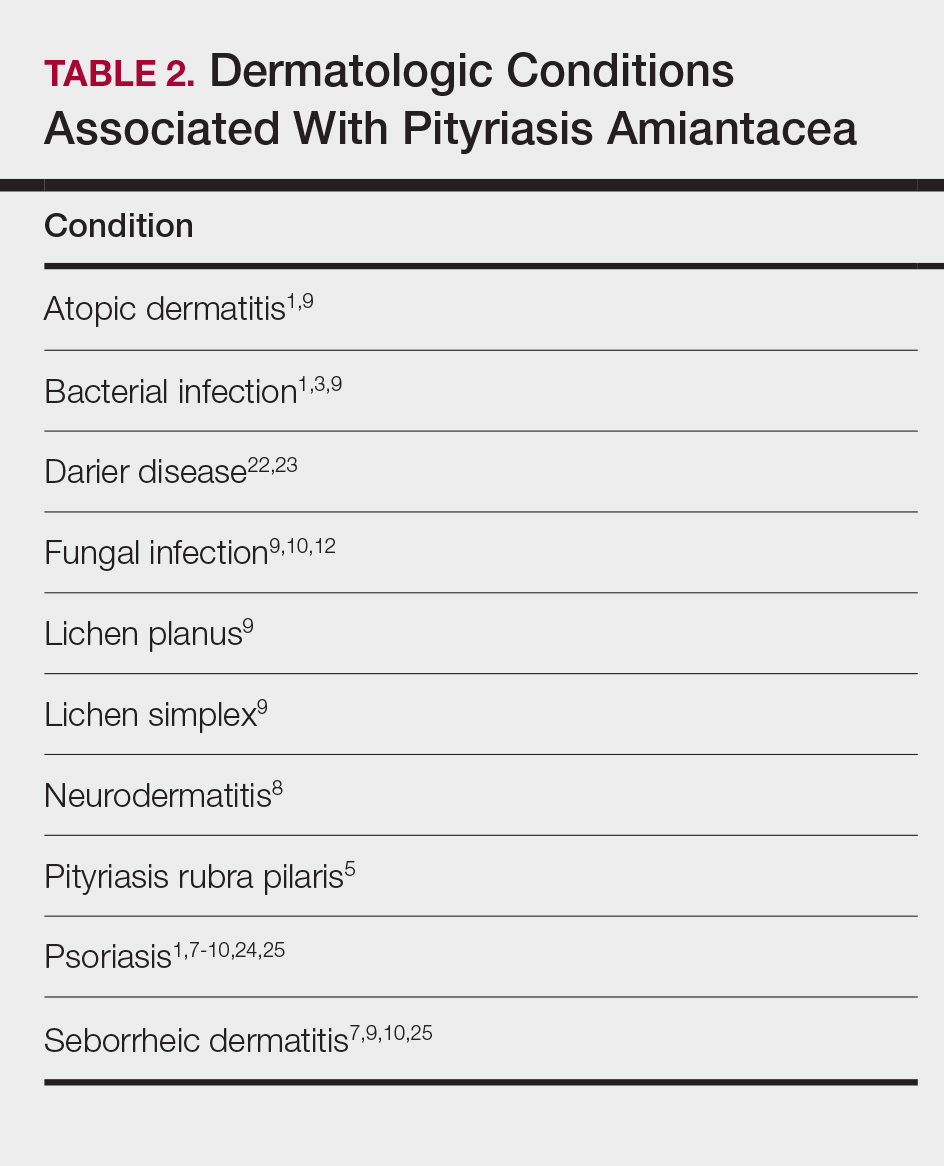

Other conditions have been described in patients with PA (Table 2). Indeed, PA may be a manifestation of an underlying inflammatory skin disease.9 In addition to dermatologic conditions, procedures or malignancy may be associated with the disease, as demonstrated in our patient. Most commonly, PA is seen in association with psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis; atopic dermatitis, bacterial infection, fungal infection, lichen planus, and neurodermatitis also have been associated with PA.1,3,5,7-10,12,18,22-25

Conclusion

Pityriasis amiantacea is a benign condition affecting the scalp hair. Albeit uncommon, it may appear in patients treated with medications such as melphalan, TNF-α inhibitors, and vemurafenib. In addition, it has been described in individuals with dermatologic conditions, systemic procedures, or underlying malignancy. Our patient developed PA following a bone marrow transplant after receiving conditioning with melphalan.

- Knight AG. Pityriasis amiantacea: a clinical and histopathological investigation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1977;2:137-143.

- Alibert JL. De la porrigine amiantacée. In: Monographie des Dermatoses. Paris, France: Baillère; 1832:293-295.

- Gougerot H. La teigne amiantacee D’Alibert. Progres Medical. 1917;13:101-104.

- Photinos P. Recherches sur la fausse teigne amiantacée. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr. 1929;10:743-758.

- Verardino GC, Azulay-Abulafia L, Macedo PM, et al. Pityriasis amiantacea: clinical-dermatoscopic features and microscopy of hair tufts. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:142-145.

- Keipert JA. Greasy scaling pityriasis amiantacea and alopecia: a syndrome in search of a cause. Australas J Dermatol. 1985;26:41-44.

- Ring DS, Kaplan DL. Pityriasis amiantacea: a report of 10 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:913-914.

- Brown WH. Some observations on neurodermatitis of the scalp, with particular reference to tinea amiantacea. Br J Dermatol Syph. 1948;60:81-90.

- Abdel-Hamid IA, Agha SA, Moustafa YM, et al. Pityriasis amiantacea: a clinical and etiopathologic study of 85 patients. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:260-264.

- Becker SW, Muir KB. Tinea amiantacea. Arch Dermatol Syphil. 1929;20:45-53.

- Dawber RP. Hair casts. Br J Dermatol. 1979;100:417-421.

- Ginarte M, Pereiro M, Fernández-Redondo V, et al. Case reports. pityriasis amiantacea as manifestation of tinea capitis due to Microsporum canis. Mycoses. 2000;43:93-96.

- Pham RK, Chan CS, Hsu S. Treatment of pityriasis amiantacea with infliximab. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:13.

- Roberts RJ. Clinical practice. Head lice. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1645-1650.

- Mcginley KJ, Leyden JJ, Marples RR, et al. Quantitative microbiology of the scalp in non-dandruff, dandruff, and seborrheic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 1975;64:401-405.

- Ettler J, Wetter DA, Pittelkow MR. Pityriasis amiantacea: a distinctive presentation of psoriasis associated with tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitor therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:639-641.

- Mannino G, McCaughey C, Vanness E. A case of pityriasis amiantacea with rapid response to treatment. WMJ. 2014;113:119-120.

- Jamil A, Muthupalaniappen L. Scales on the scalp. Malays Fam Physician. 2013;8:48-49.

- Gupta LK, Khare AK, Masatkar V, et al. Pityriasis amiantacea. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(suppl 1):S63-S64.

- Bilgiç Ö. Vemurafenib-induced pityriasis amiantacea: a case report. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2016;35:329-331.

- Zamperetti M, Zelger B, Höpfl R. Pityriasis amiantacea and folliculitis decalvans: an unusual manifestation associated with antitumor necrosis factor-α therapy. Hautarzt. 2017;68:1007-1010.

- Udayashankar C, Nath AK, Anuradha P. Extensive Darier’s disease with pityriasis amiantacea, alopecia and congenital facial nerve palsy. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18574.

- Hussain W, Coulson IH, Salman WD. Pityriasis amiantacea as the sole manifestation of Darier’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:554-556.

- Hansted B, Lindskov R. Pityriasis amiantacea and psoriasis. a follow-up study. Dermatologica. 1983;166:314-315.

- Hersle K, Lindholm A, Mobacken H, et al. Relationship of pityriasis amiantacea to psoriasis. a follow-up study. Dermatologica. 1979;159:245-250.

Pityriasis amiantacea (PA) is characterized by adherence of hair shafts proximally.1 It has been associated with dermatologic conditions and rarely with medications. We describe a woman who developed PA following a bone marrow transplant with melphalan conditioning. We also review drug-induced PA and disorders that have been linked to this condition.

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman with a history of multiple myeloma was treated with 7 courses of chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, prednisone). One month later, the patient underwent a bone marrow transplant with melphalan conditioning due to residual plasma cell myeloma. Following the transplant, she developed complete scalp alopecia. Prior to and following transplant, the patient’s hair care regimen included washing her hair and scalp every other day with over-the-counter “natural” shampoos. During drug-induced alopecia, the hair washing became less frequent.

The patient left the hospital 4 weeks posttransplant; her hair had started to regrow, but its appearance was altered. Posttransplant, the patient was maintained on bortezomib every other week and zoledronate once per month. She continued to develop multiple lesions in the scalp hairs during the following 4 months.

Eight months posttransplant she presented for evaluation of the scalp hair. Clinical examination showed hairs that were entwined together proximally, resulting in matting of the hair (Figure 1). A diagnosis of PA was established based on the clinical examination.

Treatment included mineral oil application to the scalp under occlusion each evening, followed by morning washing with coal tar 0.5%, salicylic acid 6%, or ketoconazole 2% shampoo in a repeating sequential manner. Within 1 month there was complete resolution of the scalp condition (Figure 2).

Comment

Clinical Presentation

Pityriasis amiantacea is characterized by thick excessive scale of the scalp1; it was initially described by Alibert2 in 1832. He described the gross appearance of the scales as resembling the feathers of young birds, which naturalists dub “amiante” or asbestoslike.1,2 In 1917, Gougerot3 explored infectious etiologies of this condition by describing cases of impetigo that transitioned into PA.1 Later, in 1929, Photinos4 described fungal origins of PA, giving credence to “tinea amiantacea.”1 However, more recent analyses failed to isolate fungus.5-7 As such, pityriasis (scaling) amiantacea is the more appropriate term, as emphasized by Brown8 in 1948. The cause of PA remains unclear; it is hypothesized that the condition is a reaction to underlying inflammatory dermatoses, though concurrent bacterial or fungal infection may be present.5,9

Prevalence

Pityriasis amiantacea is considered to be most prevalent in pediatric patients and young adults; it is more common in females.1,9,10 In a review of 85 PA patients, more than 80% were women (n=69), and the mean age at presentation was 23.8 years. Approximately half of these patients had widespread scalp lesions (n=42); however, focal localized lesions were common.9 No hereditary patterns have been described, though 3 pairs of the 10 patients with PA in Ring and Kaplan’s7 review were siblings.

Clinical Findings

Clinically, lesions of PA present as matted hairs.1 Thick scales encompass multiple hair shafts, binding down tufts of hair.1,6,11 Patients are asymptomatic, though the lesions may be accompanied by pruritus. The hairs enclosed by the scales in some cases may be easily pulled out.6 Notably, alopecia often accompanies PA; it often is reversible, but in some cases, it is permanent and can lead to scarring.9,12

Histopathology

Submission of hair specimens to histopathology usually is not performed since the diagnosis often is established based on the clinical presentation.5 However, submitted specimens have demonstrated spongiosis and parakeratosis along with reduction in the size of the sebaceous glands.1,9 Additionally, follicular keratosis that surrounds the hair shafts with a sheath of horn is present.9 Acanthosis and migration of lymphocytes into the epidermis also have been found.1 Often, Staphylococcus aureus isolates are detected.9,13

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnosis of PA includes hair casts,11 pediculosis,14 and tinea capitis.12 In PA, thick scales surround hair shafts and thus bind down tufts of hair.9 In patients with pediculosis, nits are attached to the hair shaft at an angle and do not entirely envelop the hair shaft.14 In addition, PA may be complicated by impetiginization; bacteria often are found in the keratin surrounding the hair shaft and represent either normal flora or secondary infection.1,15 It has been speculated that microbial biofilms from S aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis promote agglomeration of hair shafts and adherent scale.16 Bona fide dermatophyte infection of the scalp also may be concurrently present.12

Treatment

Our treatment included occlusion with mineral oil to loosen the scales from the scalp in tandem with shampoos traditionally used in patients with seborrheic dermatitis or psoriasis. Timely treatment is important to prevent scarring alopecia.13,17 Pityriasis amiantacea may be treatment resistant, and there are no specific therapeutic guidelines; rather, therapy should be targeted at the suspected underlying condition.17 Treatment generally includes keratolytic agents, such as salicylic acid.18 These agents allow enhanced penetration of other topical agents.19 Topical antifungal shampoos such as ketoconazole and ciclopirox are recommended,18 though other topical agents, such as coal tar and zinc pyrithione, also may benefit patients.13 Topical corticosteroids may be used if the condition is linked with psoriasis.13 Systemic antibiotics are added if S aureus superinfection is suspected.9

A single report described successful management of a patient with severe refractory PA who was treated with the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibitor infliximab.13 A 47-year-old woman presented with thick adherent scale on the scalp. She was treated with coal tar for 18 months but showed no improvement; the patient was subsequently prescribed salicylic acid 10%, clobetasol solution, and coal tar shampoo. After 3 months, when no improvement was observed, the patient was offered infliximab but declined. For 6 years the patient was treated with salicylic acid 20%, clobetasol (foam, lotion, shampoo, and solution), and coal tar shampoo without improvement. She then consented to infliximab therapy; after 3 infusions at weeks 0, 2, and 6, she demonstrated notable improvement. The patient was maintained on infliximab every 8 weeks.13

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of PA has yet to be definitively established, and the condition is usually idiopathic. In addition to bacterial or fungal etiologies,3,4 PA has been linked to medications (Table 1)16,20,21 and systemic conditions (Table 2).1,3,5,7-10,12,22-25

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms amiantacea, bone, drug, hair marrow, malignancy, melphalan, pityriasis, tinea, and transplant yielded 4 patients—2 men and 2 women (including our patient)—with possible drug-induced PA (Table 1)16,20,21; however, the onset after 2 years of medication (TNF-α inhibitors) or resolution while still receiving the agent (vemurafenib) makes the drug-induced linkage weak. The patients ranged in age from 21 to 67 years, with the median age being 37.5 years. Medications included melphalan, TNF-α inhibitors (adalimumab, infliximab),16,21 and vemurafenib20; it is interesting that infliximab was the medication associated with eliciting PA in 1 patient yet was an effective therapy in another patient with treatment-resistant PA. The onset of PA occurred between 1 month (melphalan) and 24 months (TNF-α inhibitors) after drug initiation. The patients’ associated diseases included Crohn disease,16,21 metastatic melanoma,20 and multiple myeloma.

Other conditions have been described in patients with PA (Table 2). Indeed, PA may be a manifestation of an underlying inflammatory skin disease.9 In addition to dermatologic conditions, procedures or malignancy may be associated with the disease, as demonstrated in our patient. Most commonly, PA is seen in association with psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis; atopic dermatitis, bacterial infection, fungal infection, lichen planus, and neurodermatitis also have been associated with PA.1,3,5,7-10,12,18,22-25

Conclusion

Pityriasis amiantacea is a benign condition affecting the scalp hair. Albeit uncommon, it may appear in patients treated with medications such as melphalan, TNF-α inhibitors, and vemurafenib. In addition, it has been described in individuals with dermatologic conditions, systemic procedures, or underlying malignancy. Our patient developed PA following a bone marrow transplant after receiving conditioning with melphalan.

Pityriasis amiantacea (PA) is characterized by adherence of hair shafts proximally.1 It has been associated with dermatologic conditions and rarely with medications. We describe a woman who developed PA following a bone marrow transplant with melphalan conditioning. We also review drug-induced PA and disorders that have been linked to this condition.

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman with a history of multiple myeloma was treated with 7 courses of chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, prednisone). One month later, the patient underwent a bone marrow transplant with melphalan conditioning due to residual plasma cell myeloma. Following the transplant, she developed complete scalp alopecia. Prior to and following transplant, the patient’s hair care regimen included washing her hair and scalp every other day with over-the-counter “natural” shampoos. During drug-induced alopecia, the hair washing became less frequent.

The patient left the hospital 4 weeks posttransplant; her hair had started to regrow, but its appearance was altered. Posttransplant, the patient was maintained on bortezomib every other week and zoledronate once per month. She continued to develop multiple lesions in the scalp hairs during the following 4 months.

Eight months posttransplant she presented for evaluation of the scalp hair. Clinical examination showed hairs that were entwined together proximally, resulting in matting of the hair (Figure 1). A diagnosis of PA was established based on the clinical examination.

Treatment included mineral oil application to the scalp under occlusion each evening, followed by morning washing with coal tar 0.5%, salicylic acid 6%, or ketoconazole 2% shampoo in a repeating sequential manner. Within 1 month there was complete resolution of the scalp condition (Figure 2).

Comment

Clinical Presentation

Pityriasis amiantacea is characterized by thick excessive scale of the scalp1; it was initially described by Alibert2 in 1832. He described the gross appearance of the scales as resembling the feathers of young birds, which naturalists dub “amiante” or asbestoslike.1,2 In 1917, Gougerot3 explored infectious etiologies of this condition by describing cases of impetigo that transitioned into PA.1 Later, in 1929, Photinos4 described fungal origins of PA, giving credence to “tinea amiantacea.”1 However, more recent analyses failed to isolate fungus.5-7 As such, pityriasis (scaling) amiantacea is the more appropriate term, as emphasized by Brown8 in 1948. The cause of PA remains unclear; it is hypothesized that the condition is a reaction to underlying inflammatory dermatoses, though concurrent bacterial or fungal infection may be present.5,9

Prevalence

Pityriasis amiantacea is considered to be most prevalent in pediatric patients and young adults; it is more common in females.1,9,10 In a review of 85 PA patients, more than 80% were women (n=69), and the mean age at presentation was 23.8 years. Approximately half of these patients had widespread scalp lesions (n=42); however, focal localized lesions were common.9 No hereditary patterns have been described, though 3 pairs of the 10 patients with PA in Ring and Kaplan’s7 review were siblings.

Clinical Findings