User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Hair Loss in Skin of Color Patients

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

All patients, regardless of race, gender, or age, are afraid of an alopecia diagnosis. Often, the first thing a patient may say when I enter the examination room is, "Please don't tell me I have alopecia."

The first step to a successful initial visit for hair loss is addressing the angst around the word alopecia, which helps to manage the patient's hair-induced anxiety. The next priority is setting expectations for the journey including what to expect during the diagnosis process, treatment, and beyond.

Next is data collection. An extensive hair care practice investigation can begin with a survey that the patient fills out before the visit. Dive into and expand on hair loss history questions, including medical history as well as hair care practices (eg, history of use, frequency, number of years, maintenance for that particular hairstyle) such as braids (eg, individual braids, cornrow braids, with or without added synthetic or human hair), locs (eg, length of locs), chemical relaxers (eg, number of years, frequency, professionally applied or applied at home), hair color, weaves (eg, glued in, sewn in, combination), and more.1 Include a family history of hair loss, both maternal and paternal.

The hair loss investigation almost always includes a scalp biopsy, hair-pull test, dermoscopy, photographs, and even blood work, if applicable. Scalp biopsies may reveal more than one type of alopecia diagnosis, which may impact the treatment plan.2 Sending the scalp biopsy specimen to a dermatopathologist specializing in alopecia along with clinical information about the patient is preferred.

What are your go-to treatments?

My go-to treatments for patients with skin of color (SOC) and hair loss really depend on the specific diagnosis. Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials focusing on treatment are lacking in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia and traction alopecia, which holds true for many other types of alopecia.

For black patients with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, I often address the inflammatory component of the disease with oral doxycycline and either a topical corticosteroid, such as clobetasol, or intralesional triamcinolone. Adding minoxidil-containing products later in the treatment process can be helpful. Various treatment protocols exist but are mainly based on anecdotal evidence.1

For those with traction alopecia, modification of offending hairstyle practices is a must.3 Also, treatment of inflammation is key. Typically, I gravitate to topical or intralesional corticosteroids, followed by minoxidil-containing products. However, a challenge of treating traction alopecia is changing the hair care practices that cause tight pulling, friction, or pressure on the scalp, such as from the band of a tightly fitted wig.

It is important to discuss potential side effects of any treatment with the patient. For the most common side effects, discuss how to best prevent them. For example, because of the photosensitivity potential of doxycycline, I ask patients to wear sunscreen daily. To prevent nausea, I recommend that they avoid taking doxycycline on an empty stomach, drink plenty of fluids, and avoid laying down within a few hours after taking the medication.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Dermatologists should try to understand their patients' hair. A study of 200 black women demonstrated that 68% of the patients did not think their physician understood their hair,4 which likely impacts patients' perceptions of their physician, confidence in the treatment plan, and even compliance with the plan. Attempting to understand the nuances of tightly coiled hair in those of African descent is the first step in the journey of diagnosing and treating hair loss in partnership with the patient.

Setting the goal is a crucial step toward patient compliance. It may be going out in public without a wig or weave and feeling confident, providing more coverage so affected areas do not show as much, improving scalp tenderness, and/or preventing further progression of the condition. These are all reasonable outcomes and each goal is uniquely tailored to each patient.

Familiarize yourself with various hair types, hairstyles, and preferred medication vehicles by attending continuing medical education lectures on alopecia in patients with SOC and on nuances to diagnosis and treatment, reading textbooks focusing on SOC, or seeking out mentorship from a dermatologist who is a hair expert in the types of alopecia most commonly affecting patients with SOC.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information

For patients with scarring alopecia, the Cicatricial Alopecia Research Foundation (http://www.carfintl.org/) is a great resource for medical information and support groups. Also, the Skin of Color Society has dermatology patient education information (http://skinofcolorsociety.org/).

For patients who are extremely distressed by hair loss, I encourage them to see a mental health professional. The mental health impact of alopecia, despite the extent of disease, is likely underestimated. Patients sometimes need our permission to seek help, especially in many SOC communities where even seeking mental health care often is frowned upon.

- Taylor SC, Barbosa V, Burgess C, et al. Hair and scalp disorders in adult and pediatric skin of color patients: bootcamp discussion. Cutis. 2017;100:31-35.

- Wohltmann WE, Sperling L. Histopathologic diagnosis of multifactorial alopecia. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:483-491.

- Haskin A, Aguh C. All hairstyles are not created equal: what the dermatologist needs to know about black hairstyling practices and the risk of traction alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:606-611.

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African American women, hair care and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

All patients, regardless of race, gender, or age, are afraid of an alopecia diagnosis. Often, the first thing a patient may say when I enter the examination room is, "Please don't tell me I have alopecia."

The first step to a successful initial visit for hair loss is addressing the angst around the word alopecia, which helps to manage the patient's hair-induced anxiety. The next priority is setting expectations for the journey including what to expect during the diagnosis process, treatment, and beyond.

Next is data collection. An extensive hair care practice investigation can begin with a survey that the patient fills out before the visit. Dive into and expand on hair loss history questions, including medical history as well as hair care practices (eg, history of use, frequency, number of years, maintenance for that particular hairstyle) such as braids (eg, individual braids, cornrow braids, with or without added synthetic or human hair), locs (eg, length of locs), chemical relaxers (eg, number of years, frequency, professionally applied or applied at home), hair color, weaves (eg, glued in, sewn in, combination), and more.1 Include a family history of hair loss, both maternal and paternal.

The hair loss investigation almost always includes a scalp biopsy, hair-pull test, dermoscopy, photographs, and even blood work, if applicable. Scalp biopsies may reveal more than one type of alopecia diagnosis, which may impact the treatment plan.2 Sending the scalp biopsy specimen to a dermatopathologist specializing in alopecia along with clinical information about the patient is preferred.

What are your go-to treatments?

My go-to treatments for patients with skin of color (SOC) and hair loss really depend on the specific diagnosis. Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials focusing on treatment are lacking in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia and traction alopecia, which holds true for many other types of alopecia.

For black patients with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, I often address the inflammatory component of the disease with oral doxycycline and either a topical corticosteroid, such as clobetasol, or intralesional triamcinolone. Adding minoxidil-containing products later in the treatment process can be helpful. Various treatment protocols exist but are mainly based on anecdotal evidence.1

For those with traction alopecia, modification of offending hairstyle practices is a must.3 Also, treatment of inflammation is key. Typically, I gravitate to topical or intralesional corticosteroids, followed by minoxidil-containing products. However, a challenge of treating traction alopecia is changing the hair care practices that cause tight pulling, friction, or pressure on the scalp, such as from the band of a tightly fitted wig.

It is important to discuss potential side effects of any treatment with the patient. For the most common side effects, discuss how to best prevent them. For example, because of the photosensitivity potential of doxycycline, I ask patients to wear sunscreen daily. To prevent nausea, I recommend that they avoid taking doxycycline on an empty stomach, drink plenty of fluids, and avoid laying down within a few hours after taking the medication.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Dermatologists should try to understand their patients' hair. A study of 200 black women demonstrated that 68% of the patients did not think their physician understood their hair,4 which likely impacts patients' perceptions of their physician, confidence in the treatment plan, and even compliance with the plan. Attempting to understand the nuances of tightly coiled hair in those of African descent is the first step in the journey of diagnosing and treating hair loss in partnership with the patient.

Setting the goal is a crucial step toward patient compliance. It may be going out in public without a wig or weave and feeling confident, providing more coverage so affected areas do not show as much, improving scalp tenderness, and/or preventing further progression of the condition. These are all reasonable outcomes and each goal is uniquely tailored to each patient.

Familiarize yourself with various hair types, hairstyles, and preferred medication vehicles by attending continuing medical education lectures on alopecia in patients with SOC and on nuances to diagnosis and treatment, reading textbooks focusing on SOC, or seeking out mentorship from a dermatologist who is a hair expert in the types of alopecia most commonly affecting patients with SOC.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information

For patients with scarring alopecia, the Cicatricial Alopecia Research Foundation (http://www.carfintl.org/) is a great resource for medical information and support groups. Also, the Skin of Color Society has dermatology patient education information (http://skinofcolorsociety.org/).

For patients who are extremely distressed by hair loss, I encourage them to see a mental health professional. The mental health impact of alopecia, despite the extent of disease, is likely underestimated. Patients sometimes need our permission to seek help, especially in many SOC communities where even seeking mental health care often is frowned upon.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

All patients, regardless of race, gender, or age, are afraid of an alopecia diagnosis. Often, the first thing a patient may say when I enter the examination room is, "Please don't tell me I have alopecia."

The first step to a successful initial visit for hair loss is addressing the angst around the word alopecia, which helps to manage the patient's hair-induced anxiety. The next priority is setting expectations for the journey including what to expect during the diagnosis process, treatment, and beyond.

Next is data collection. An extensive hair care practice investigation can begin with a survey that the patient fills out before the visit. Dive into and expand on hair loss history questions, including medical history as well as hair care practices (eg, history of use, frequency, number of years, maintenance for that particular hairstyle) such as braids (eg, individual braids, cornrow braids, with or without added synthetic or human hair), locs (eg, length of locs), chemical relaxers (eg, number of years, frequency, professionally applied or applied at home), hair color, weaves (eg, glued in, sewn in, combination), and more.1 Include a family history of hair loss, both maternal and paternal.

The hair loss investigation almost always includes a scalp biopsy, hair-pull test, dermoscopy, photographs, and even blood work, if applicable. Scalp biopsies may reveal more than one type of alopecia diagnosis, which may impact the treatment plan.2 Sending the scalp biopsy specimen to a dermatopathologist specializing in alopecia along with clinical information about the patient is preferred.

What are your go-to treatments?

My go-to treatments for patients with skin of color (SOC) and hair loss really depend on the specific diagnosis. Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials focusing on treatment are lacking in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia and traction alopecia, which holds true for many other types of alopecia.

For black patients with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, I often address the inflammatory component of the disease with oral doxycycline and either a topical corticosteroid, such as clobetasol, or intralesional triamcinolone. Adding minoxidil-containing products later in the treatment process can be helpful. Various treatment protocols exist but are mainly based on anecdotal evidence.1

For those with traction alopecia, modification of offending hairstyle practices is a must.3 Also, treatment of inflammation is key. Typically, I gravitate to topical or intralesional corticosteroids, followed by minoxidil-containing products. However, a challenge of treating traction alopecia is changing the hair care practices that cause tight pulling, friction, or pressure on the scalp, such as from the band of a tightly fitted wig.

It is important to discuss potential side effects of any treatment with the patient. For the most common side effects, discuss how to best prevent them. For example, because of the photosensitivity potential of doxycycline, I ask patients to wear sunscreen daily. To prevent nausea, I recommend that they avoid taking doxycycline on an empty stomach, drink plenty of fluids, and avoid laying down within a few hours after taking the medication.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Dermatologists should try to understand their patients' hair. A study of 200 black women demonstrated that 68% of the patients did not think their physician understood their hair,4 which likely impacts patients' perceptions of their physician, confidence in the treatment plan, and even compliance with the plan. Attempting to understand the nuances of tightly coiled hair in those of African descent is the first step in the journey of diagnosing and treating hair loss in partnership with the patient.

Setting the goal is a crucial step toward patient compliance. It may be going out in public without a wig or weave and feeling confident, providing more coverage so affected areas do not show as much, improving scalp tenderness, and/or preventing further progression of the condition. These are all reasonable outcomes and each goal is uniquely tailored to each patient.

Familiarize yourself with various hair types, hairstyles, and preferred medication vehicles by attending continuing medical education lectures on alopecia in patients with SOC and on nuances to diagnosis and treatment, reading textbooks focusing on SOC, or seeking out mentorship from a dermatologist who is a hair expert in the types of alopecia most commonly affecting patients with SOC.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information

For patients with scarring alopecia, the Cicatricial Alopecia Research Foundation (http://www.carfintl.org/) is a great resource for medical information and support groups. Also, the Skin of Color Society has dermatology patient education information (http://skinofcolorsociety.org/).

For patients who are extremely distressed by hair loss, I encourage them to see a mental health professional. The mental health impact of alopecia, despite the extent of disease, is likely underestimated. Patients sometimes need our permission to seek help, especially in many SOC communities where even seeking mental health care often is frowned upon.

- Taylor SC, Barbosa V, Burgess C, et al. Hair and scalp disorders in adult and pediatric skin of color patients: bootcamp discussion. Cutis. 2017;100:31-35.

- Wohltmann WE, Sperling L. Histopathologic diagnosis of multifactorial alopecia. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:483-491.

- Haskin A, Aguh C. All hairstyles are not created equal: what the dermatologist needs to know about black hairstyling practices and the risk of traction alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:606-611.

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African American women, hair care and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Taylor SC, Barbosa V, Burgess C, et al. Hair and scalp disorders in adult and pediatric skin of color patients: bootcamp discussion. Cutis. 2017;100:31-35.

- Wohltmann WE, Sperling L. Histopathologic diagnosis of multifactorial alopecia. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:483-491.

- Haskin A, Aguh C. All hairstyles are not created equal: what the dermatologist needs to know about black hairstyling practices and the risk of traction alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:606-611.

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African American women, hair care and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

April 2019 Highlights

Scientific Abstracts; Skin Disease Education Foundation’s 43rd Annual Hawaii Dermatology Seminar

Bothersome Blisters: Localized Epidermolysis Bullosa Simplex

To the Editor:

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) was first described in 1886, with the first classification scheme proposed in 1962 utilizing transmission electron microscopy (TEM) findings to delineate categories: epidermolytic (EB simplex [EBS]), lucidolytic (junctional EB), and dermolytic (dystrophic EB).1 Localized EBS (EBS-loc) is an autosomal-dominant disorder caused by negative mutations in keratin-5 and keratin-14, proteins expressed in the intermediate filaments of basal keratinocytes, which result in fragility of the skin in response to minor trauma.2 The incidence of EBS-loc is approximately 10 to 30 cases per million live births, with the age of presentation typically between the first and third decades of life.3,4 Because EBS-loc is the most common and often mildest form of EB, not all patients present for medical evaluation and true prevalence may be underestimated.4 We report a case of EBS-loc.

A 26-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of skin blisters that had been intermittently present since infancy. The blisters primarily occurred on the feet, but she did occasionally develop blisters on the hands, knees, and elbows and at sites of friction or trauma (eg, bra line, medial thighs) following exercise. The blisters were worsened by heat and tight-fitting shoes. Because of the painful nature of the blisters, she would lance them with a needle. On the medial thighs, she utilized nonstick and gauze bandage roll dressings to minimize friction. A review of systems was positive for hyperhidrosis. Her family history revealed multiple family members with blisters involving the feet and areas of friction or trauma for 4 generations with no known diagnosis.

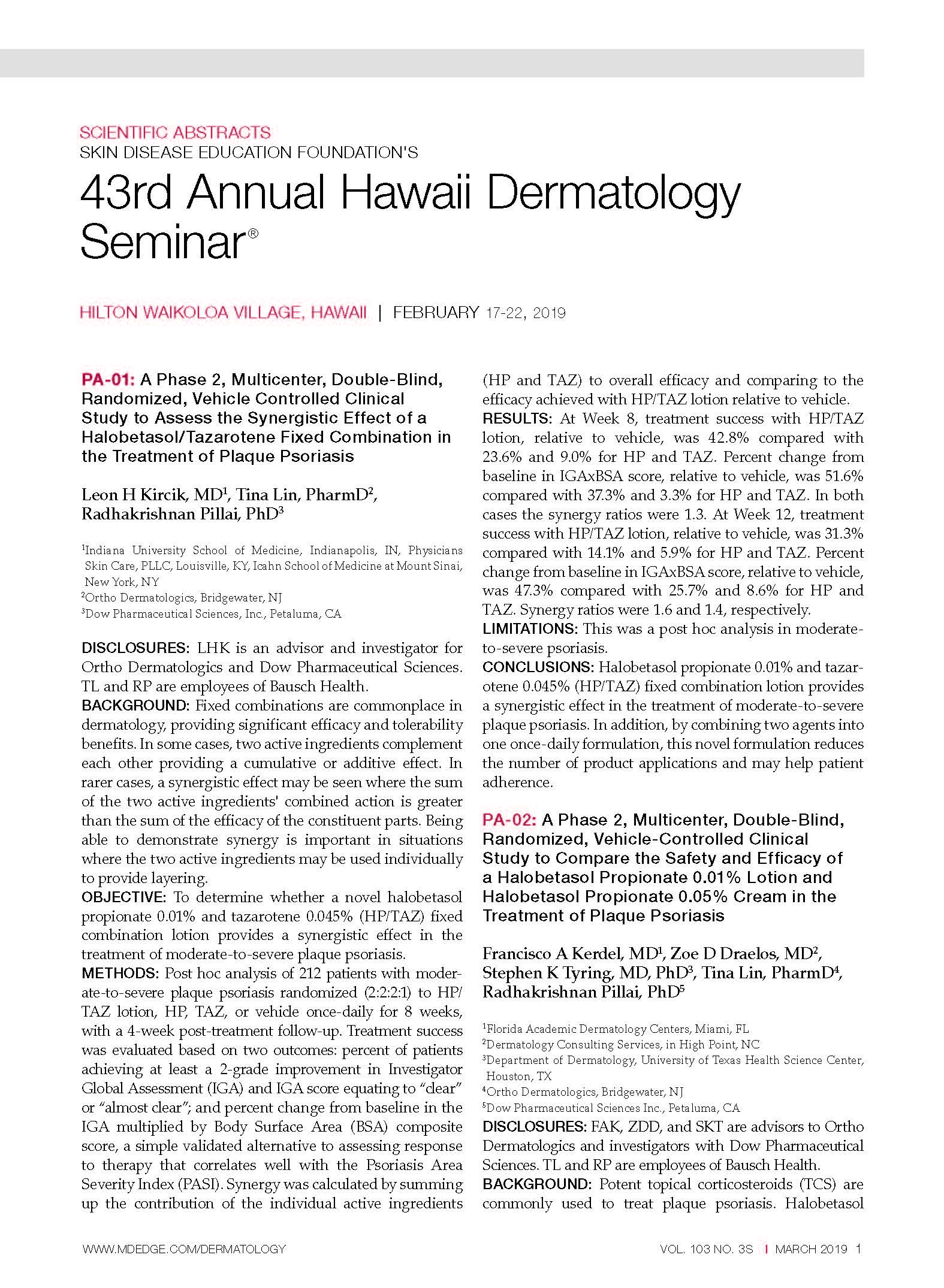

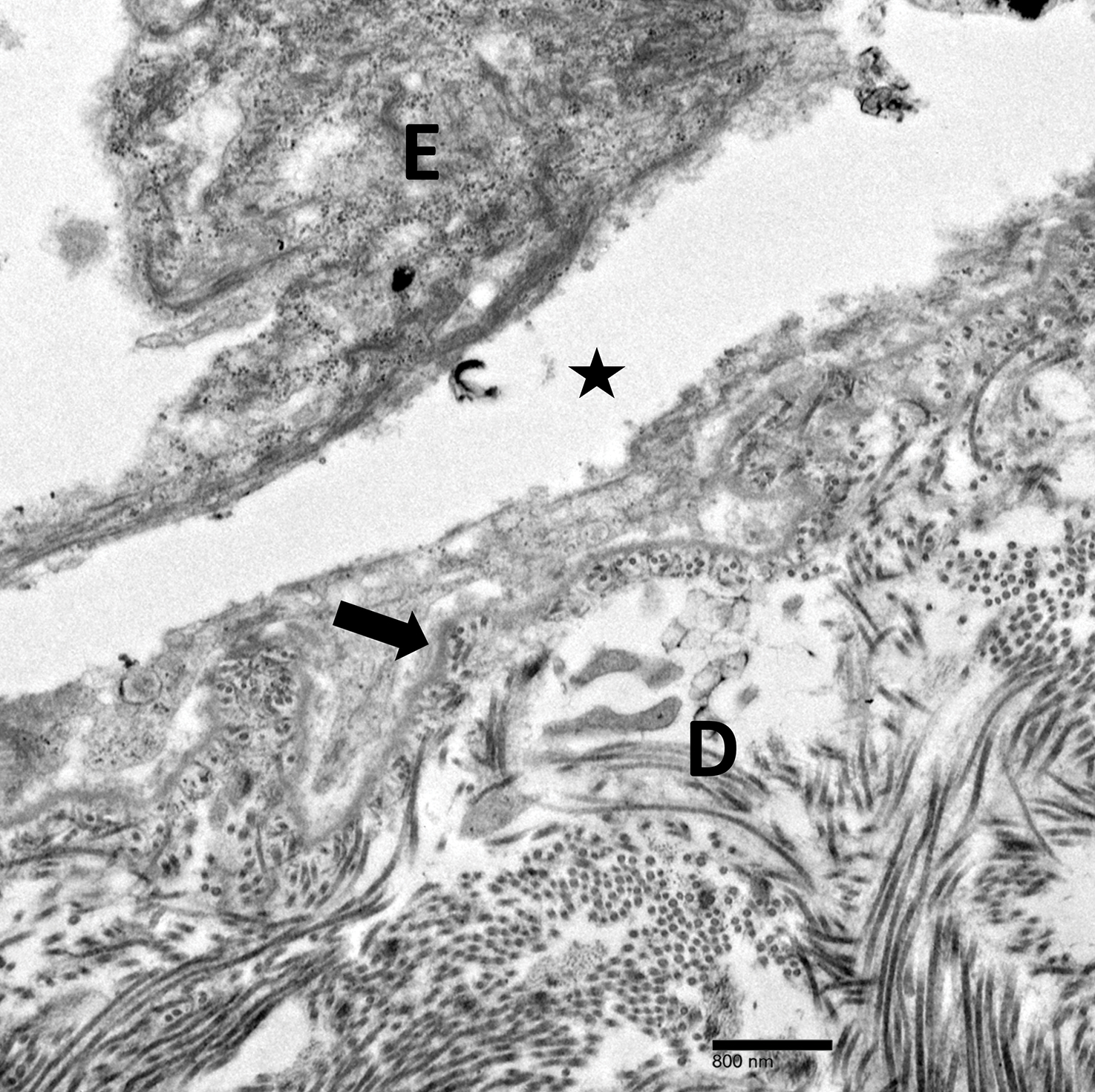

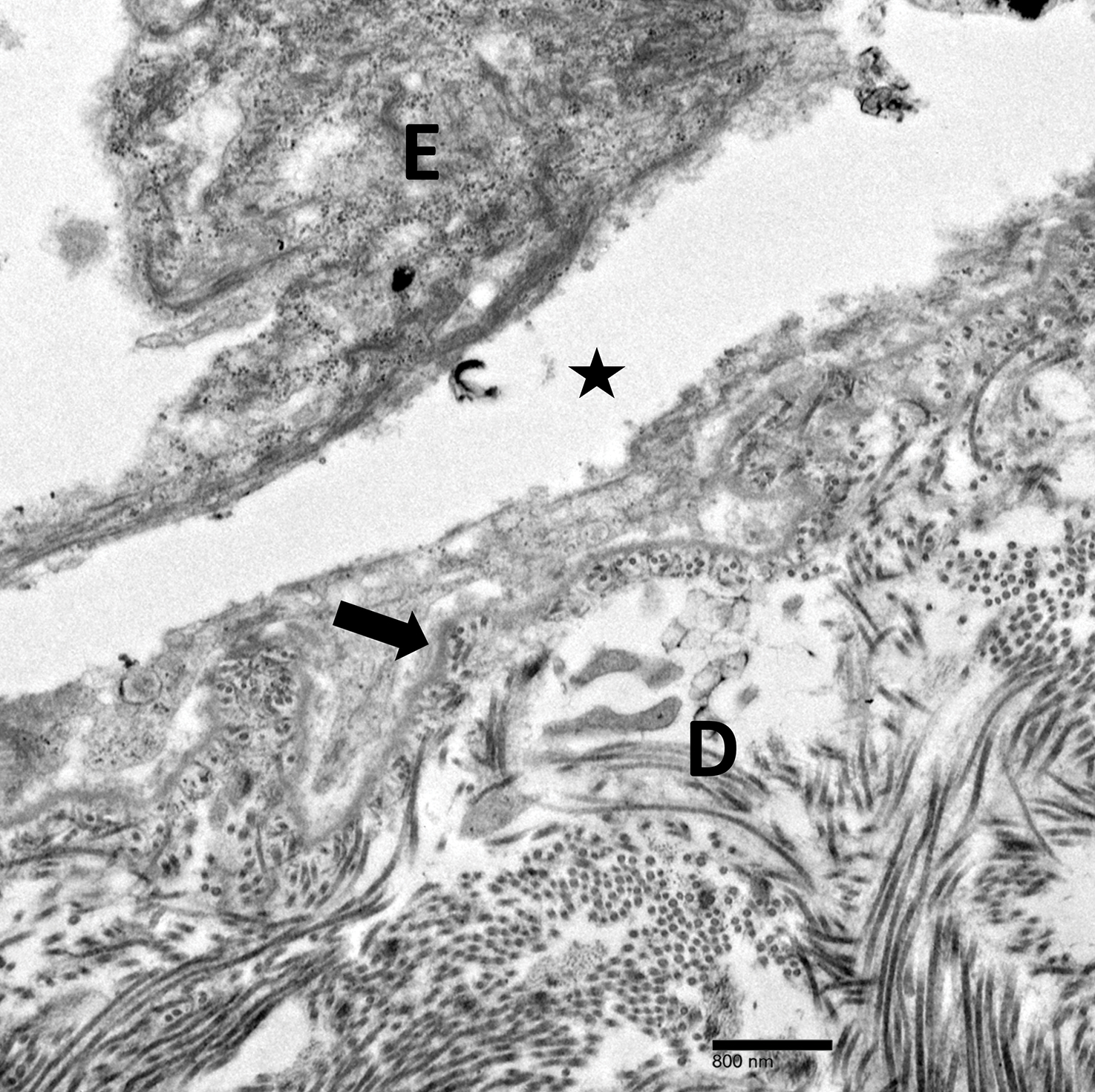

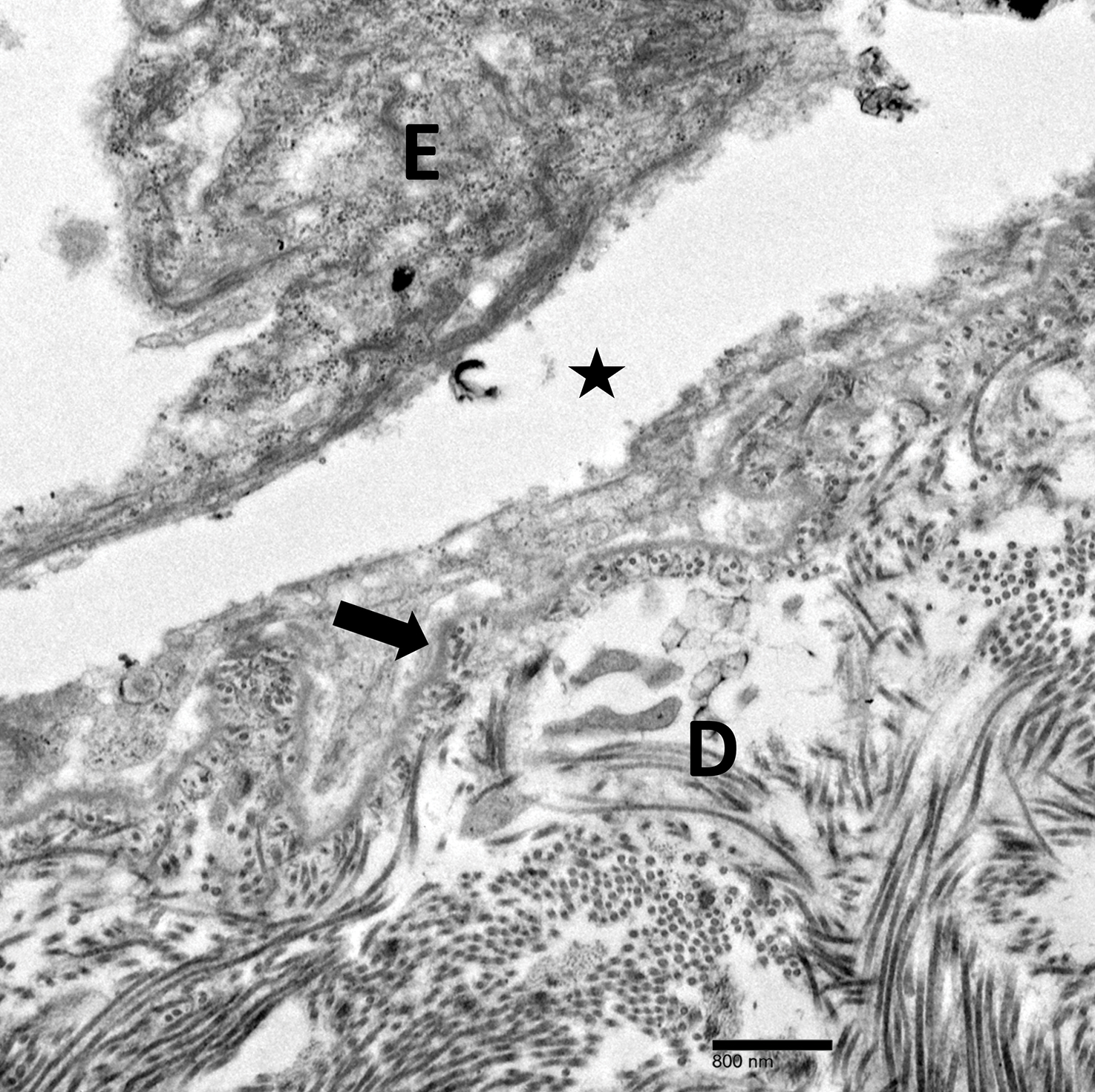

Physical examination revealed multiple tense bullae and calluses scattered over the bilateral plantar and distal dorsal feet with a few healing, superficially eroded, erythematous papules and plaques on the bilateral medial thighs (Figure 1). A biopsy from an induced blister on the right dorsal second toe was performed and sent in glutaraldehyde to the Epidermolysis Bullosa Clinic at Stanford University (Redwood City, California) for electron microscopy, which revealed lysis within the basal keratinocytes through the tonofilaments with continuous and intact lamina densa and lamina lucida (Figure 2). In this clinical context with the relevant family history, the findings were consistent with the diagnosis of EBS-loc (formerly Weber-Cockayne syndrome).2

Skin manifestations of EBS-loc typically consist of friction-induced blisters, erosions, and calluses primarily on the palms and soles, often associated with hyperhidrosis and worsening of symptoms in summer months and hot temperatures.3 Milia, atrophic scarring, and dystrophic nails are uncommon.1 Extracutaneous involvement is rare with the exception of oral cavity erosions, which typically are asymptomatic and usually are only seen during infancy.1

Light microscopy does not have a notable role in diagnosis of classic forms of inherited EB unless another autoimmune blistering disorder is suspected.2,5 Both TEM and immunofluorescence mapping are used to diagnose EB.1 DNA mutational analysis is not considered a first-line diagnostic test for EB given it is a costly labor-intensive technique with limited access at present, but it may be considered in settings of prenatal diagnosis or in vitro fertilization.1 Biopsy of a freshly induced blister should be performed, as early reepithelialization of an existing blister makes it difficult to establish the level of cleavage.5 Applying firm pressure using a pencil eraser and rotating it on intact skin induces a subclinical blister. Two punch biopsies (4 mm) at the edge of the blister with one-third lesional and two-thirds perilesional skin should be obtained, with one biopsy sent for immunofluorescence mapping in Michel fixative and the other for TEM in glutaraldehyde.3,5 Transmission electron microscopy of an induced blister in EBS-loc shows cleavage within the most inferior portion of the basilar keratinocyte.2 Immunofluorescence mapping with anti–epidermal basement membrane monoclonal antibodies can distinguish between EB subtypes and assess expression of specific skin-associated proteins on both a qualitative or semiquantitative basis, providing insight on which structural protein is mutated.1,5

No specific treatments are available for EBS-loc. Mainstays of treatment include prevention of mechanical trauma and secondary infection. Hyperhidrosis of thepalms and soles may be treated with topical aluminum chloride hexahydrate or injections of botulinum toxin type A.2,6 Patients have normal life expectancy, though some cases may have complications with substantial morbidity.1 Awareness of this disease, its clinical course, and therapeutic options will allow physicians to more appropriately counsel patients on the disease process.

Localized EBS may be more common than previously thought, as not all patients seek medical care. Given its impact on patient quality of life, it is important for clinicians to recognize EBS-loc. Although no specific treatments are available, wound care counseling and explanation of the genetics of the disease should be provided to patients.

- Fine JD, Eady RA, Bauer EA, et al. The classification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa (EB): report of the Third International Consensus Meeting on Diagnosis and Classification of EB. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:931-950.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2012.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, Mathes EF, et al, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015.

- Spitz JL. Genodermatoses: A Clinical Guide to Genetic Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

- Epidermolysis bullosa. Stanford Medicine website. http://med.stanford.edu/dermatopathology/dermpath-services/epiderm.html. Accessed April 3, 2019.

- Abitbol RJ, Zhou LH. Treatment of epidermolysis bullosa simplex, Weber-Cockayne type, with botulinum toxin type A. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:13-15.

To the Editor:

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) was first described in 1886, with the first classification scheme proposed in 1962 utilizing transmission electron microscopy (TEM) findings to delineate categories: epidermolytic (EB simplex [EBS]), lucidolytic (junctional EB), and dermolytic (dystrophic EB).1 Localized EBS (EBS-loc) is an autosomal-dominant disorder caused by negative mutations in keratin-5 and keratin-14, proteins expressed in the intermediate filaments of basal keratinocytes, which result in fragility of the skin in response to minor trauma.2 The incidence of EBS-loc is approximately 10 to 30 cases per million live births, with the age of presentation typically between the first and third decades of life.3,4 Because EBS-loc is the most common and often mildest form of EB, not all patients present for medical evaluation and true prevalence may be underestimated.4 We report a case of EBS-loc.

A 26-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of skin blisters that had been intermittently present since infancy. The blisters primarily occurred on the feet, but she did occasionally develop blisters on the hands, knees, and elbows and at sites of friction or trauma (eg, bra line, medial thighs) following exercise. The blisters were worsened by heat and tight-fitting shoes. Because of the painful nature of the blisters, she would lance them with a needle. On the medial thighs, she utilized nonstick and gauze bandage roll dressings to minimize friction. A review of systems was positive for hyperhidrosis. Her family history revealed multiple family members with blisters involving the feet and areas of friction or trauma for 4 generations with no known diagnosis.

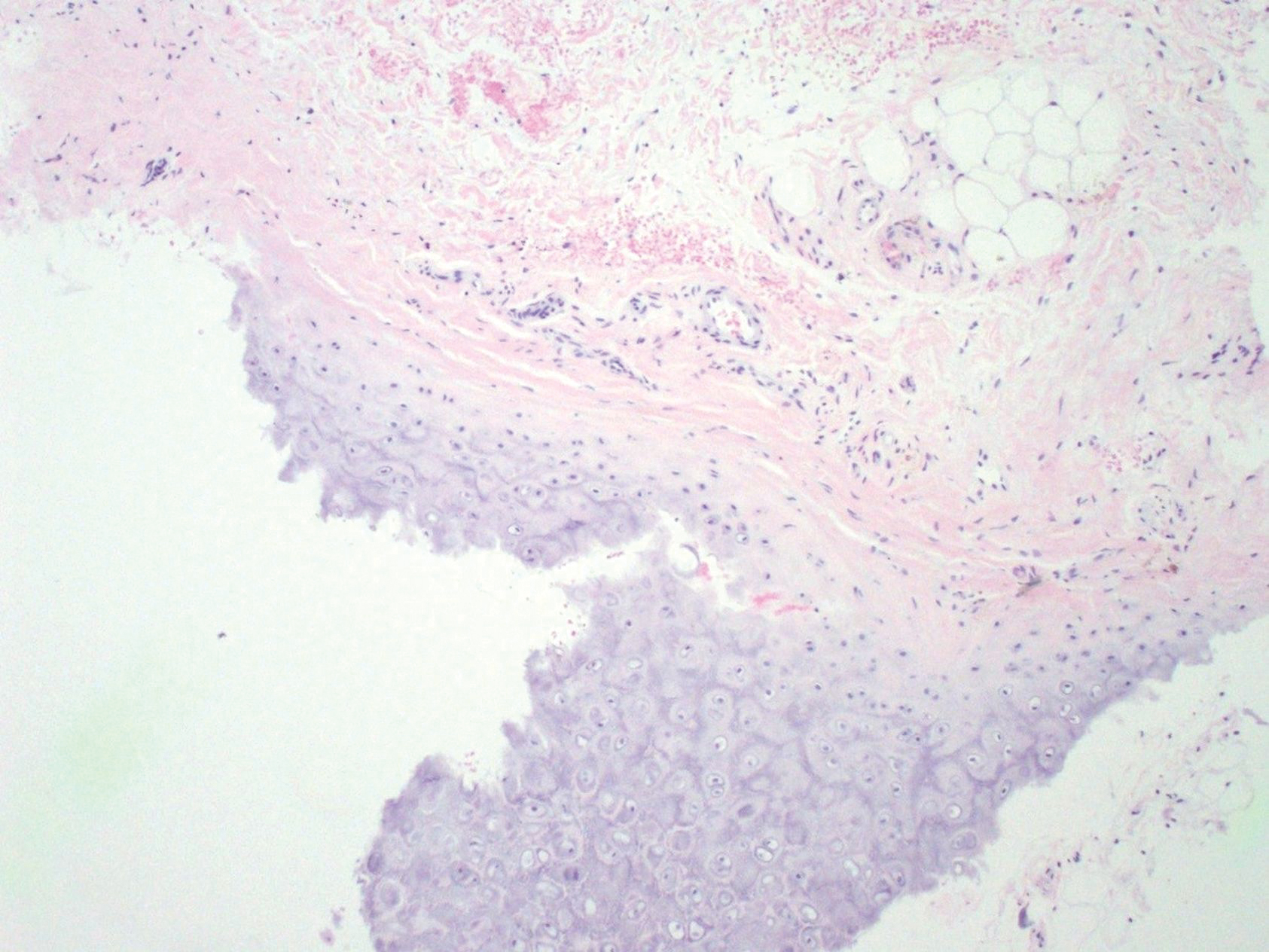

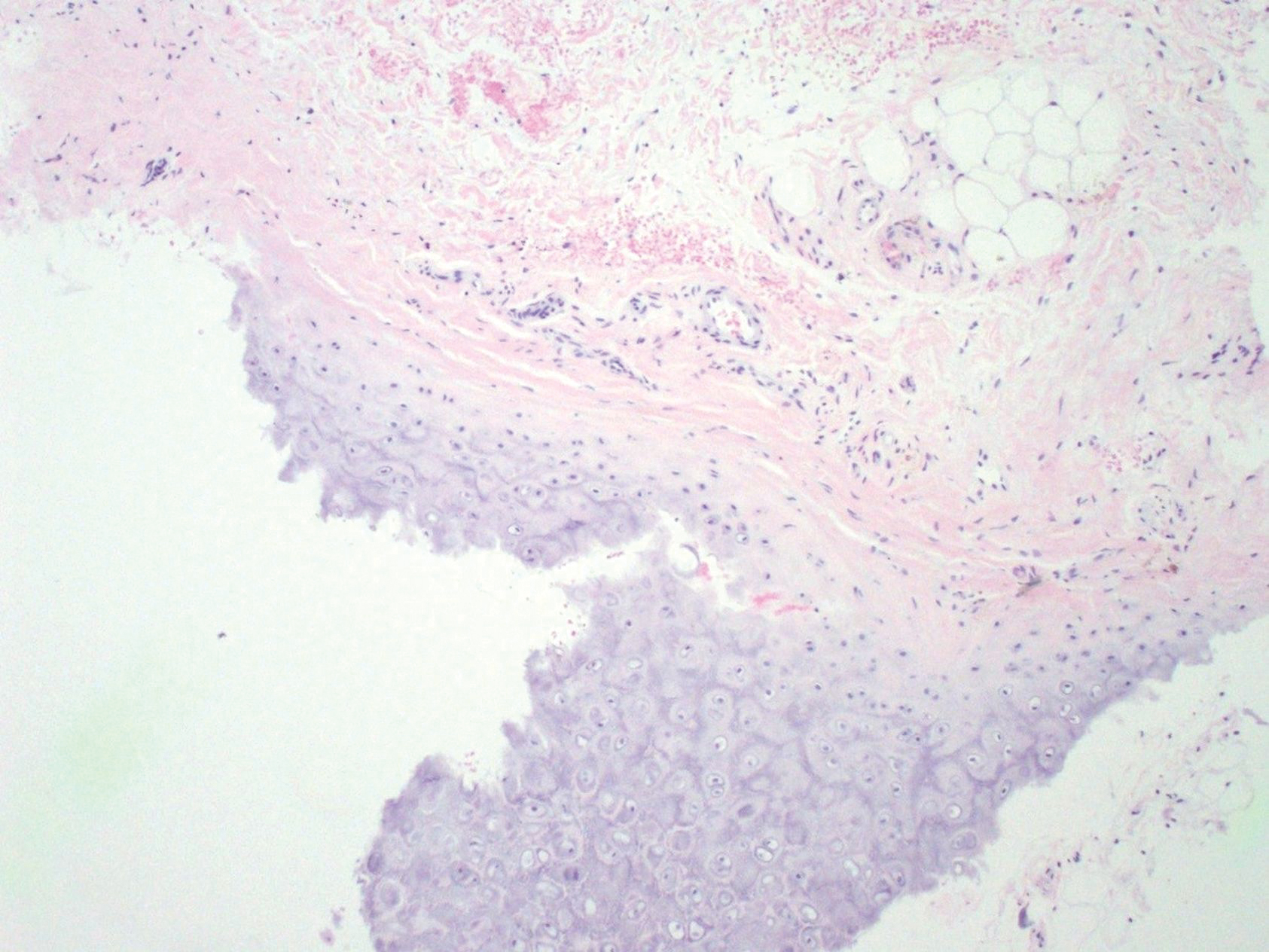

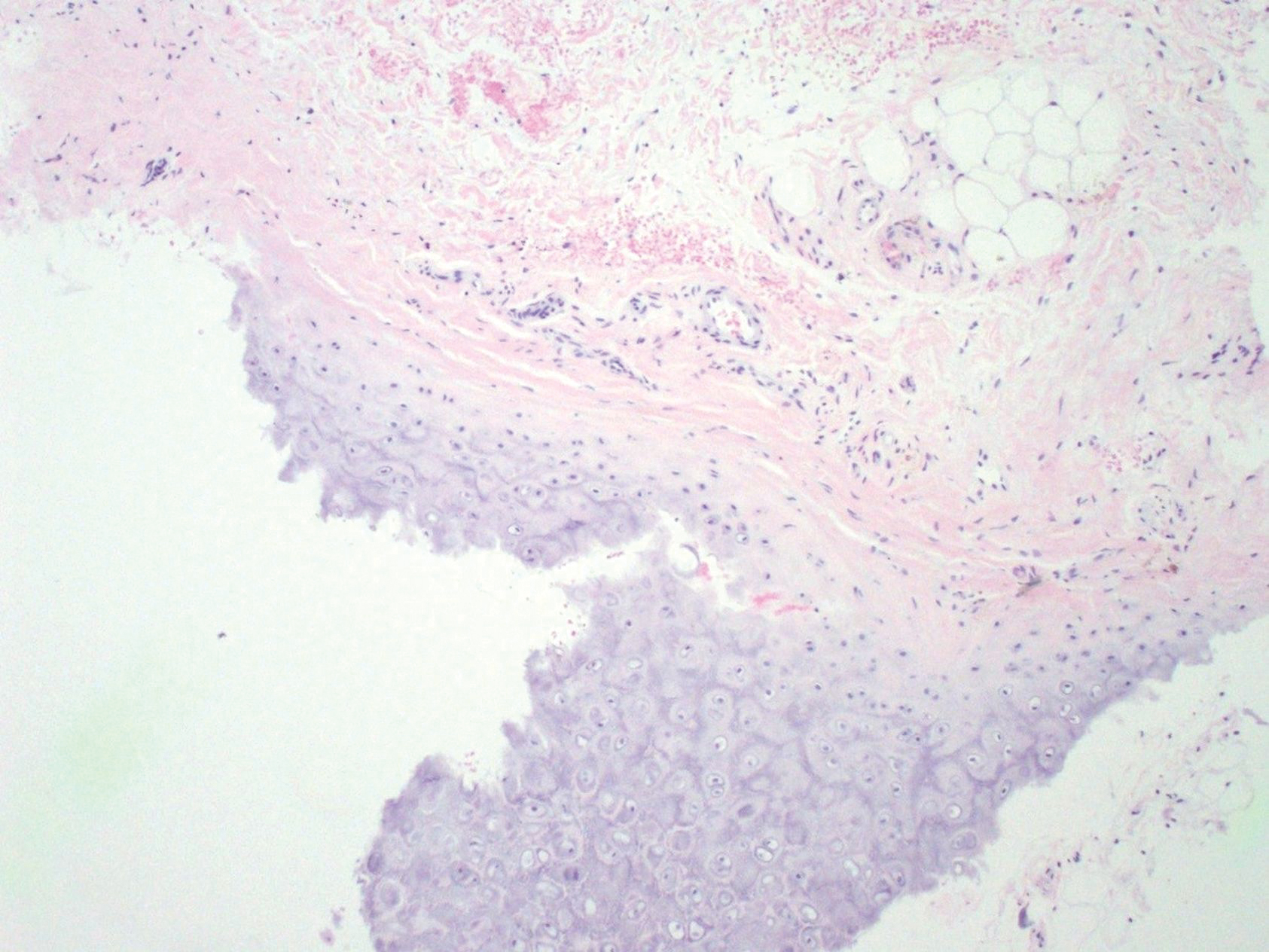

Physical examination revealed multiple tense bullae and calluses scattered over the bilateral plantar and distal dorsal feet with a few healing, superficially eroded, erythematous papules and plaques on the bilateral medial thighs (Figure 1). A biopsy from an induced blister on the right dorsal second toe was performed and sent in glutaraldehyde to the Epidermolysis Bullosa Clinic at Stanford University (Redwood City, California) for electron microscopy, which revealed lysis within the basal keratinocytes through the tonofilaments with continuous and intact lamina densa and lamina lucida (Figure 2). In this clinical context with the relevant family history, the findings were consistent with the diagnosis of EBS-loc (formerly Weber-Cockayne syndrome).2

Skin manifestations of EBS-loc typically consist of friction-induced blisters, erosions, and calluses primarily on the palms and soles, often associated with hyperhidrosis and worsening of symptoms in summer months and hot temperatures.3 Milia, atrophic scarring, and dystrophic nails are uncommon.1 Extracutaneous involvement is rare with the exception of oral cavity erosions, which typically are asymptomatic and usually are only seen during infancy.1

Light microscopy does not have a notable role in diagnosis of classic forms of inherited EB unless another autoimmune blistering disorder is suspected.2,5 Both TEM and immunofluorescence mapping are used to diagnose EB.1 DNA mutational analysis is not considered a first-line diagnostic test for EB given it is a costly labor-intensive technique with limited access at present, but it may be considered in settings of prenatal diagnosis or in vitro fertilization.1 Biopsy of a freshly induced blister should be performed, as early reepithelialization of an existing blister makes it difficult to establish the level of cleavage.5 Applying firm pressure using a pencil eraser and rotating it on intact skin induces a subclinical blister. Two punch biopsies (4 mm) at the edge of the blister with one-third lesional and two-thirds perilesional skin should be obtained, with one biopsy sent for immunofluorescence mapping in Michel fixative and the other for TEM in glutaraldehyde.3,5 Transmission electron microscopy of an induced blister in EBS-loc shows cleavage within the most inferior portion of the basilar keratinocyte.2 Immunofluorescence mapping with anti–epidermal basement membrane monoclonal antibodies can distinguish between EB subtypes and assess expression of specific skin-associated proteins on both a qualitative or semiquantitative basis, providing insight on which structural protein is mutated.1,5

No specific treatments are available for EBS-loc. Mainstays of treatment include prevention of mechanical trauma and secondary infection. Hyperhidrosis of thepalms and soles may be treated with topical aluminum chloride hexahydrate or injections of botulinum toxin type A.2,6 Patients have normal life expectancy, though some cases may have complications with substantial morbidity.1 Awareness of this disease, its clinical course, and therapeutic options will allow physicians to more appropriately counsel patients on the disease process.

Localized EBS may be more common than previously thought, as not all patients seek medical care. Given its impact on patient quality of life, it is important for clinicians to recognize EBS-loc. Although no specific treatments are available, wound care counseling and explanation of the genetics of the disease should be provided to patients.

To the Editor:

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) was first described in 1886, with the first classification scheme proposed in 1962 utilizing transmission electron microscopy (TEM) findings to delineate categories: epidermolytic (EB simplex [EBS]), lucidolytic (junctional EB), and dermolytic (dystrophic EB).1 Localized EBS (EBS-loc) is an autosomal-dominant disorder caused by negative mutations in keratin-5 and keratin-14, proteins expressed in the intermediate filaments of basal keratinocytes, which result in fragility of the skin in response to minor trauma.2 The incidence of EBS-loc is approximately 10 to 30 cases per million live births, with the age of presentation typically between the first and third decades of life.3,4 Because EBS-loc is the most common and often mildest form of EB, not all patients present for medical evaluation and true prevalence may be underestimated.4 We report a case of EBS-loc.

A 26-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of skin blisters that had been intermittently present since infancy. The blisters primarily occurred on the feet, but she did occasionally develop blisters on the hands, knees, and elbows and at sites of friction or trauma (eg, bra line, medial thighs) following exercise. The blisters were worsened by heat and tight-fitting shoes. Because of the painful nature of the blisters, she would lance them with a needle. On the medial thighs, she utilized nonstick and gauze bandage roll dressings to minimize friction. A review of systems was positive for hyperhidrosis. Her family history revealed multiple family members with blisters involving the feet and areas of friction or trauma for 4 generations with no known diagnosis.

Physical examination revealed multiple tense bullae and calluses scattered over the bilateral plantar and distal dorsal feet with a few healing, superficially eroded, erythematous papules and plaques on the bilateral medial thighs (Figure 1). A biopsy from an induced blister on the right dorsal second toe was performed and sent in glutaraldehyde to the Epidermolysis Bullosa Clinic at Stanford University (Redwood City, California) for electron microscopy, which revealed lysis within the basal keratinocytes through the tonofilaments with continuous and intact lamina densa and lamina lucida (Figure 2). In this clinical context with the relevant family history, the findings were consistent with the diagnosis of EBS-loc (formerly Weber-Cockayne syndrome).2

Skin manifestations of EBS-loc typically consist of friction-induced blisters, erosions, and calluses primarily on the palms and soles, often associated with hyperhidrosis and worsening of symptoms in summer months and hot temperatures.3 Milia, atrophic scarring, and dystrophic nails are uncommon.1 Extracutaneous involvement is rare with the exception of oral cavity erosions, which typically are asymptomatic and usually are only seen during infancy.1

Light microscopy does not have a notable role in diagnosis of classic forms of inherited EB unless another autoimmune blistering disorder is suspected.2,5 Both TEM and immunofluorescence mapping are used to diagnose EB.1 DNA mutational analysis is not considered a first-line diagnostic test for EB given it is a costly labor-intensive technique with limited access at present, but it may be considered in settings of prenatal diagnosis or in vitro fertilization.1 Biopsy of a freshly induced blister should be performed, as early reepithelialization of an existing blister makes it difficult to establish the level of cleavage.5 Applying firm pressure using a pencil eraser and rotating it on intact skin induces a subclinical blister. Two punch biopsies (4 mm) at the edge of the blister with one-third lesional and two-thirds perilesional skin should be obtained, with one biopsy sent for immunofluorescence mapping in Michel fixative and the other for TEM in glutaraldehyde.3,5 Transmission electron microscopy of an induced blister in EBS-loc shows cleavage within the most inferior portion of the basilar keratinocyte.2 Immunofluorescence mapping with anti–epidermal basement membrane monoclonal antibodies can distinguish between EB subtypes and assess expression of specific skin-associated proteins on both a qualitative or semiquantitative basis, providing insight on which structural protein is mutated.1,5

No specific treatments are available for EBS-loc. Mainstays of treatment include prevention of mechanical trauma and secondary infection. Hyperhidrosis of thepalms and soles may be treated with topical aluminum chloride hexahydrate or injections of botulinum toxin type A.2,6 Patients have normal life expectancy, though some cases may have complications with substantial morbidity.1 Awareness of this disease, its clinical course, and therapeutic options will allow physicians to more appropriately counsel patients on the disease process.

Localized EBS may be more common than previously thought, as not all patients seek medical care. Given its impact on patient quality of life, it is important for clinicians to recognize EBS-loc. Although no specific treatments are available, wound care counseling and explanation of the genetics of the disease should be provided to patients.

- Fine JD, Eady RA, Bauer EA, et al. The classification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa (EB): report of the Third International Consensus Meeting on Diagnosis and Classification of EB. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:931-950.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2012.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, Mathes EF, et al, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015.

- Spitz JL. Genodermatoses: A Clinical Guide to Genetic Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

- Epidermolysis bullosa. Stanford Medicine website. http://med.stanford.edu/dermatopathology/dermpath-services/epiderm.html. Accessed April 3, 2019.

- Abitbol RJ, Zhou LH. Treatment of epidermolysis bullosa simplex, Weber-Cockayne type, with botulinum toxin type A. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:13-15.

- Fine JD, Eady RA, Bauer EA, et al. The classification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa (EB): report of the Third International Consensus Meeting on Diagnosis and Classification of EB. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:931-950.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2012.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, Mathes EF, et al, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015.

- Spitz JL. Genodermatoses: A Clinical Guide to Genetic Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

- Epidermolysis bullosa. Stanford Medicine website. http://med.stanford.edu/dermatopathology/dermpath-services/epiderm.html. Accessed April 3, 2019.

- Abitbol RJ, Zhou LH. Treatment of epidermolysis bullosa simplex, Weber-Cockayne type, with botulinum toxin type A. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:13-15.

Practice Points

- Localized epidermolysis bullosa simplex (formerly Weber-Cockayne syndrome) presents with flaccid bullae and erosions predominantly on the hands and feet, most commonly related to mechanical friction and heat.

- It is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion with defects in keratin-5 and keratin-14.

- Biopsy of a freshly induced blister should be examined by transmission electron microscopy or immunofluorescence mapping.

- Treatment is focused on wound management and infection control of the blisters.

Nivolumab-Induced Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Nivolumab, an immune checkpoint modulator, acts by binding to the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) receptor on T cells, which blocks the inhibition of T cells. Nivolumab ultimately leads to stimulation of the T-cell response1 and overcomes evasive adaptations of certain cancers. Cutaneous adverse events (AEs) have been reported in approximately 20% to 40% of patients treated with the anti–PD-1 class of drugs, including nivolumab.2-4 The most common cutaneous AEs include pruritus; vitiligo; and various forms of rash, such as lichenoid dermatitis, psoriasiform eruptions, and bullous pemphigoid.1-3,5-7 We report a patient with non–small cell lung cancer being treated with nivolumab who developed a bullous lichenoid eruption consistent with the diagnosis of lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP).

Case Report

An 87-year-old woman presented with a pruritic rash on the trunk and extremities of 3 weeks’ duration. Her medical history included stage IV non–small cell lung cancer, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, and hypertension. Her long-term medications were ipratropium-albuterol, alendronate, amlodipine, aspirin, carvedilol, colesevelam, probiotic granules, and bumetanide. She was previously treated with carboplatin and docetaxel, which were discontinued secondary to fatigue, diarrhea, poor appetite, loss of taste, and a nonspecific rash. Six months later (approximately 3 months prior to the onset of cutaneous symptoms), she was started on nivolumab monotherapy every 14 days for a total of 9 infusions.

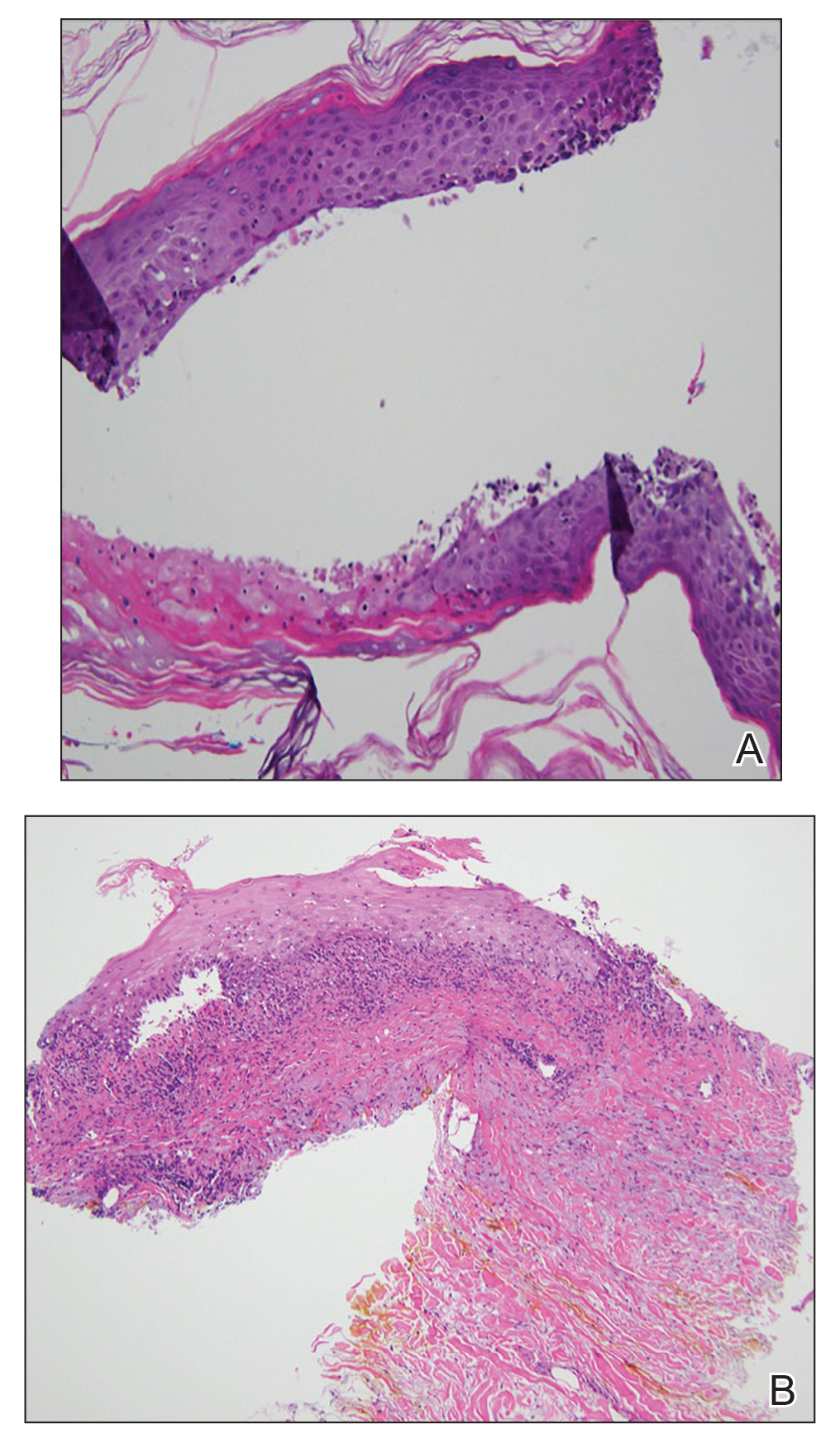

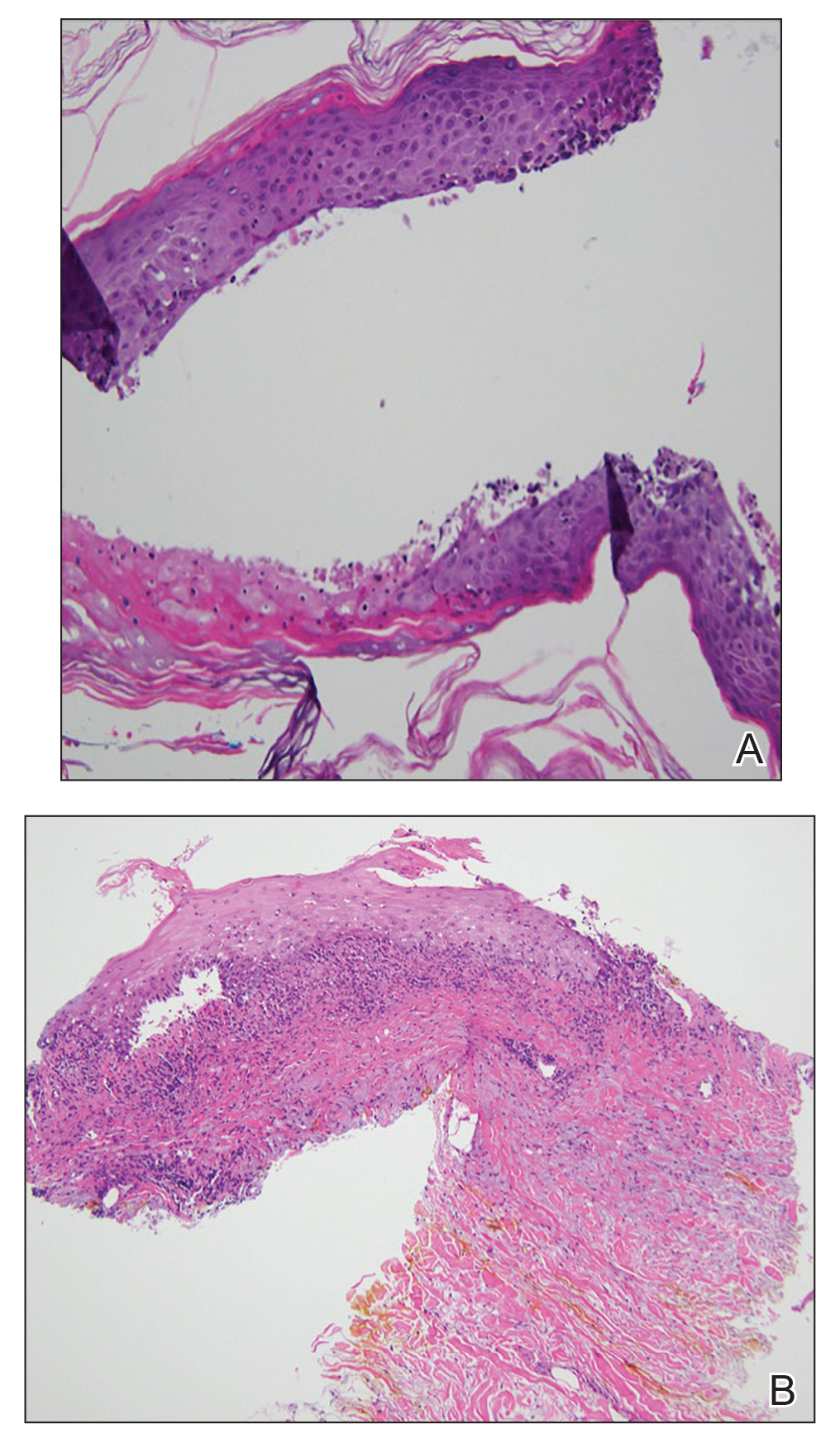

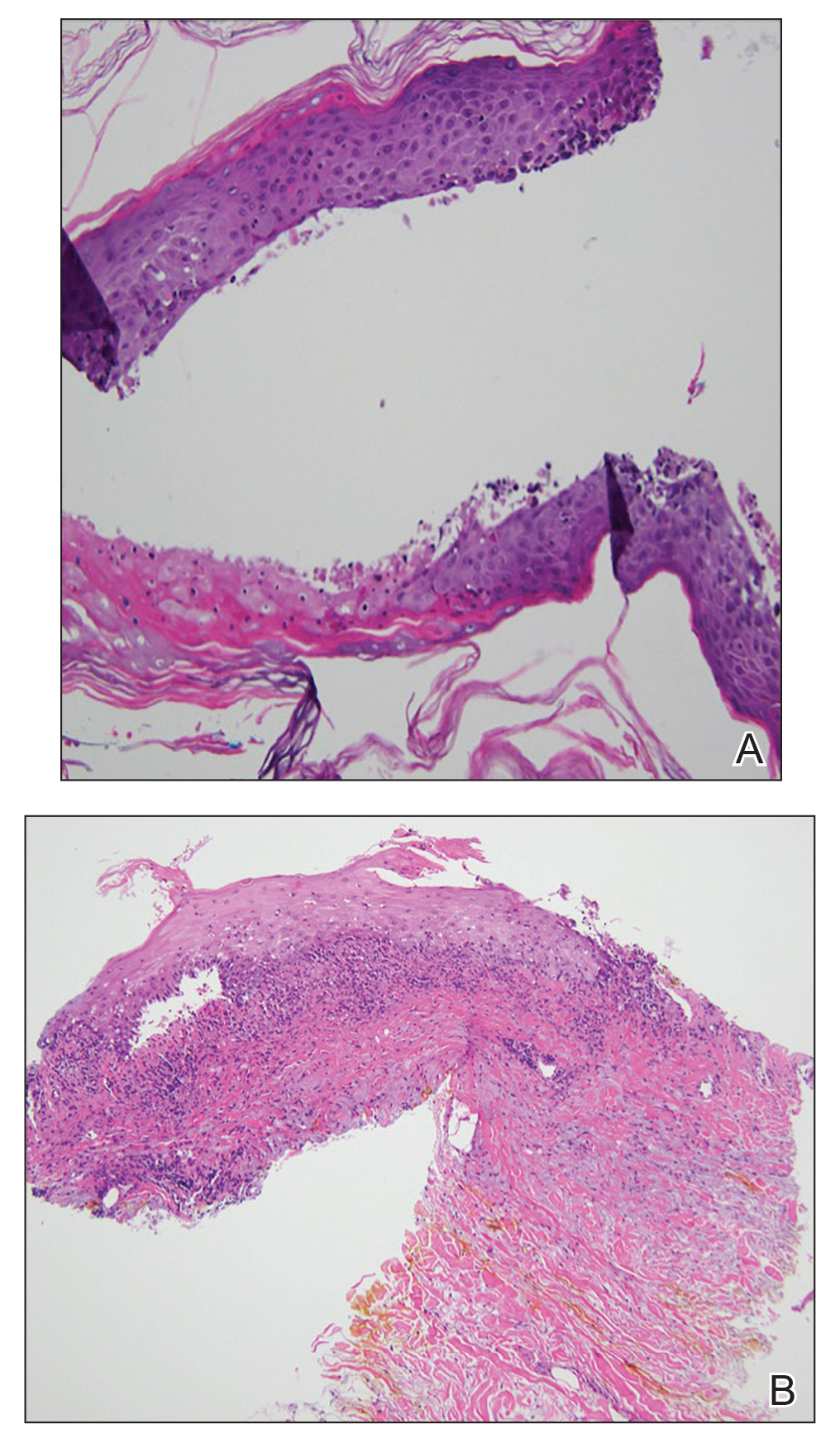

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed erythematous crusted erosions on the trunk and extremities and 1 flaccid bulla on the back. A punch biopsy revealed lichenoid dermatitis. The patient returned 2 weeks later with worsening of cutaneous manifestations, including more blisters and erosions. Figure 1 shows the clinical appearance of the eruption on the patient’s leg. At this time, additional biopsies revealed a subepidermal bullous lichenoid eruption with eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was negative; however, indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) revealed weak linear staining for IgG antibodies along the basement membrane zone on monkey esophagus substrate. Examination of salt-split skin was noncontributory. The patient improved with a 2-week oral prednisone taper (starting at 40 mg daily). The dose was decreased incrementally over the course of 2 weeks from 40 mg to 20 mg to 0 mg. Because of the presumed grade 3 (severe) cutaneous drug eruption linked to nivolumab and further discussion with the medical oncology team, the patient decided to cease therapy. Since cessation of therapy, she has been seen twice for follow-up. At 2-month follow-up, she presented with drastic improvement of the eruption, and at 1 year she has continued to forego any further treatment for the stable and nonprogressing malignancy.

Widespread coalescent lesions with crusted and hemorrhagic bullae were present on the thigh and knee.

Comment

Immunotherapy

The interaction between the PD-1 receptor and its ligands, programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and programmed death ligand 2, is an immune checkpoint.8,9 Under normal physiologic conditions, this checkpoint serves to prevent autoimmunity.10 When the PD-1 receptor is left unbound, T cells are more inclined to mount an immune response. If the receptor is ligand bound, the response of T cells is suppressed via mechanisms such as anergy or apoptosis.8 Tumor cells are known to produce PD-L1 as an adaptive resistance mechanism to evade immunity.8 Nivolumab is a human monoclonal antibody that targets the PD-1 receptor, thereby preventing the interaction with its ligand and allowing for unsuppressed activity of T cells.10 This therapy ultimately blocks the tumor’s local immune suppression mechanisms, which allows T cells to recognize cancer antigens.10

Adverse Events

Dermatologic AEs are among the most common with nivolumab treatment. In a pooled retrospective analysis of melanoma patients, Weber et al9 found that 34% of 576 patients experience cutaneous any-grade AEs associated with nivolumab treatment, most commonly pruritus. It has been well documented that anti–PD-1 therapy AEs of the skin as well as other organ systems have a delayed onset of at least 1 month.9 The average time of onset for bullous eruptions associated with anti–PD-1 therapy has been reported to be approximately 12 weeks, with a range of 7 to 16.1 weeks.11 Our patient had a bullous eruption with an onset of 12 weeks following initiation of treatment.

Although lichenoid reactions appear to be relatively common AEs of anti–PD-1 therapy,2,5,6 only a small number of cases of bullous pemphigoid eruptions have been reported.7 It has been hypothesized that blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway increases production of hemidesmosomal protein BP180 autoantibody, which is involved in the pathogenesis of LPP.7 Bullous eruptions have not been reported in the use of anticytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 agents, which could indicate that such eruptions are specific to the anti–PD-1 class of drugs.7

Diagnosis

Our patient represents a rare drug reaction involving both lichenoid and bullous components. Our differential diagnosis included drug-induced bullous lichen planus (BLP) and drug-induced LPP. Differentiation of these diagnoses can be difficult. In fact, in 2017 Fujii et al12 found reason to reprise the hypothesis that BLP is a transitional step toward LPP. The histologic evaluation of LPP differs depending on the type of lesion biopsied and can be indistinguishable from BLP as well as bullous pemphigoid. Therefore, clinical history and immunofluorescence should be used to make a diagnosis. Lichen planus pemphigoides typically will have linear IgG deposition along the basement membrane zone on both DIF and IIF, findings that will be negative in patients with BLP.13 Direct immunofluorescence findings in BLP include shaggy deposits of fibrin along the basement membrane zone. In this patient, DIF was negative, which may have been caused by variability among lesions in LPP, but IIF was positive. Given the clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of LPP was made. Further studies, such as immunoblot and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, also can be used to aid diagnosis.

A similar presentation has been documented in a patient with metastatic melanoma.14 The diagnosis in this patient was LPP induced by pembrolizumab, which is another agent within the anti–PD-1 class. The Naranjo probability scale scored our patient’s eruption as a possible adverse drug reaction.15 Thus, other etiologies, such as a paraneoplastic process, cannot be completely ruled out. However, our patient has not had recurrence after 1 year, and the timing of the eruption appeared to be related to drug therapy, making alternative etiologies less likely.

Management

Cessation of nivolumab therapy and a short course of oral corticosteroid therapy led to marked improvement of symptoms. Given the emergent treatment of our patient, the resolution of her symptoms cannot be solely attributed to the cessation of nivolumab or to treatment with prednisone. Oral rather than topical corticosteroids were chosen because of the severity of the eruption. Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines can provide relief in less severe cases of bullous reactions to anti–PD-1 therapy.7,11 This regimen also has proven to be effective in lichenoid dermatitis induced by anti–PD-1.2

Conclusion

We hope this case report will contribute to the growing body of evidence regarding recognition and management of unique reactions to cancer immunotherapies.

- Macdonald JB, Macdonald B, Golitz LE, et al. Cutaneous adverse effects of targeted therapies: part II: inhibitors of intracellular molecular signaling pathways. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:221-236; quiz 237-238.

- Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25.

- Abdel-Rahman O, El Halawani H, Fouad M. Risk of cutaneous toxicities in patients with solid tumors treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Future Oncol. 2015;11:2471-2484.

- Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443-2454.

- Hwang SJ, Carlos G, Wakade D, et al. Cutaneous adverse events (AEs) of anti-programmed cell death (PD)-1 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma: a single-institution cohort [published online January 12, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:455-461.e1.

- Sibaud V, Meyer N, Lamant L, et al. Dermatologic complications of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28:254-263.

- Naidoo J, Schindler K, Querfeld C, et al. Autoimmune bullous skin disorders with immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1 and PD-L1. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:383-389.

- Zou W, Wolchok JD, Chen L. PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:328rv4.

- Weber JS, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, et al. Safety profile of nivolumab monotherapy: a pooled analysis of patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:785-792.

- Mamalis A, Garcha M, Jagdeo J. Targeting the PD-1 pathway: a promising future for the treatment of melanoma. Arch Dermatol Res. 2014;306:511-519.

- Jour G, Glitza IC, Ellis RM, et al. Autoimmune dermatologic toxicities from immune checkpoint blockade with anti-PD-1 antibody therapy: a report on bullous skin eruptions. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:688-696.

- Fujii M, Takahashi I, Honma M, et al. Bullous lichen planus accompanied by elevation of serum anti-BP180 autoantibody: a possible transitional mechanism to lichen planus pemphigoides. J Dermatol. 2017;44:E124-E125.

- Arbache ST, Nogueira TG, Delgado L, et al. Immunofluorescence testing in the diagnosis of autoimmune blistering diseases: overview of 10-year experience. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:885-889.

- Schmidgen MI, Butsch F, Schadmand-Fischer S, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced lichen planus pemphigoides in a patient with metastatic melanoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:742-745.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

Nivolumab, an immune checkpoint modulator, acts by binding to the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) receptor on T cells, which blocks the inhibition of T cells. Nivolumab ultimately leads to stimulation of the T-cell response1 and overcomes evasive adaptations of certain cancers. Cutaneous adverse events (AEs) have been reported in approximately 20% to 40% of patients treated with the anti–PD-1 class of drugs, including nivolumab.2-4 The most common cutaneous AEs include pruritus; vitiligo; and various forms of rash, such as lichenoid dermatitis, psoriasiform eruptions, and bullous pemphigoid.1-3,5-7 We report a patient with non–small cell lung cancer being treated with nivolumab who developed a bullous lichenoid eruption consistent with the diagnosis of lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP).

Case Report

An 87-year-old woman presented with a pruritic rash on the trunk and extremities of 3 weeks’ duration. Her medical history included stage IV non–small cell lung cancer, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, and hypertension. Her long-term medications were ipratropium-albuterol, alendronate, amlodipine, aspirin, carvedilol, colesevelam, probiotic granules, and bumetanide. She was previously treated with carboplatin and docetaxel, which were discontinued secondary to fatigue, diarrhea, poor appetite, loss of taste, and a nonspecific rash. Six months later (approximately 3 months prior to the onset of cutaneous symptoms), she was started on nivolumab monotherapy every 14 days for a total of 9 infusions.

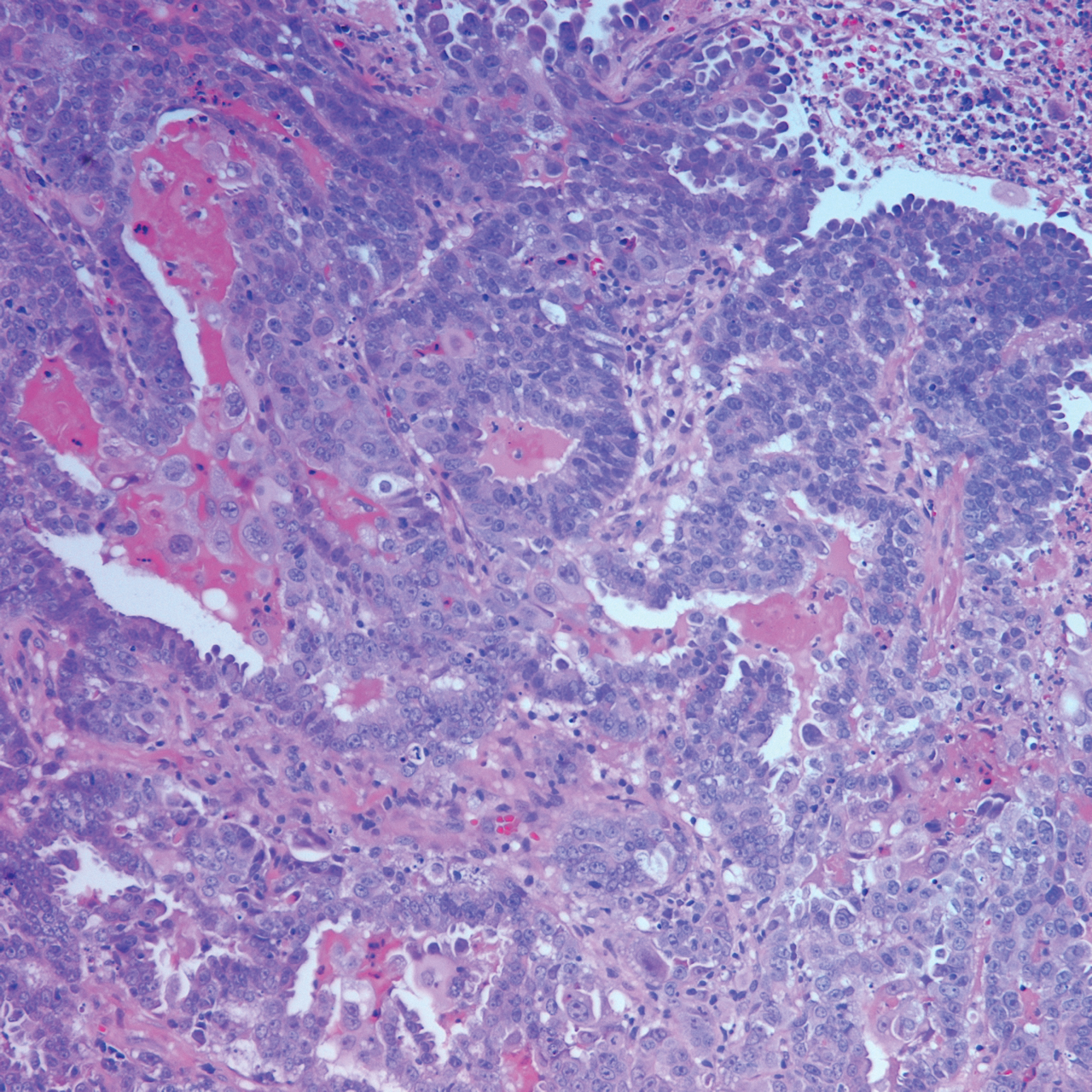

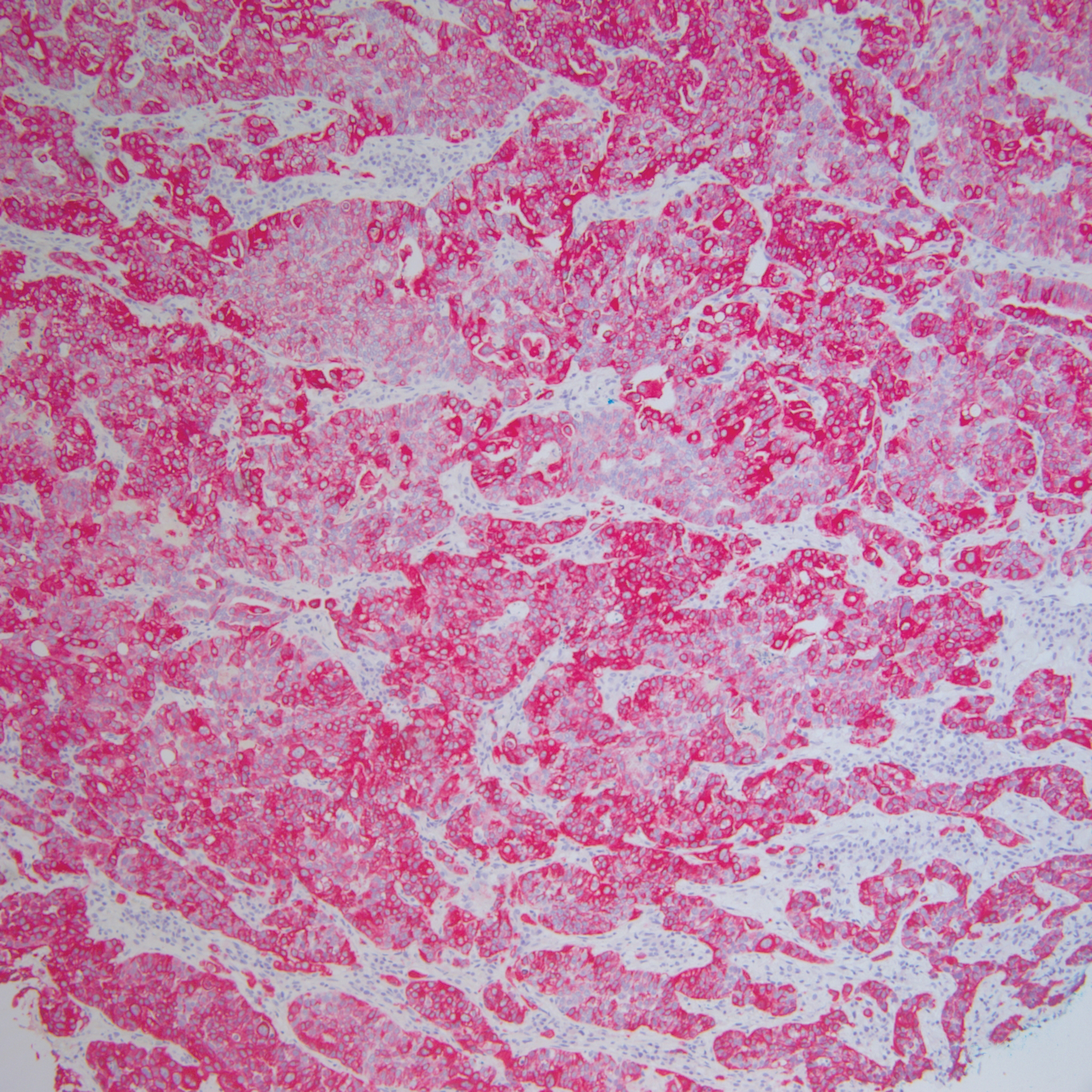

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed erythematous crusted erosions on the trunk and extremities and 1 flaccid bulla on the back. A punch biopsy revealed lichenoid dermatitis. The patient returned 2 weeks later with worsening of cutaneous manifestations, including more blisters and erosions. Figure 1 shows the clinical appearance of the eruption on the patient’s leg. At this time, additional biopsies revealed a subepidermal bullous lichenoid eruption with eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was negative; however, indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) revealed weak linear staining for IgG antibodies along the basement membrane zone on monkey esophagus substrate. Examination of salt-split skin was noncontributory. The patient improved with a 2-week oral prednisone taper (starting at 40 mg daily). The dose was decreased incrementally over the course of 2 weeks from 40 mg to 20 mg to 0 mg. Because of the presumed grade 3 (severe) cutaneous drug eruption linked to nivolumab and further discussion with the medical oncology team, the patient decided to cease therapy. Since cessation of therapy, she has been seen twice for follow-up. At 2-month follow-up, she presented with drastic improvement of the eruption, and at 1 year she has continued to forego any further treatment for the stable and nonprogressing malignancy.

Widespread coalescent lesions with crusted and hemorrhagic bullae were present on the thigh and knee.

Comment

Immunotherapy

The interaction between the PD-1 receptor and its ligands, programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and programmed death ligand 2, is an immune checkpoint.8,9 Under normal physiologic conditions, this checkpoint serves to prevent autoimmunity.10 When the PD-1 receptor is left unbound, T cells are more inclined to mount an immune response. If the receptor is ligand bound, the response of T cells is suppressed via mechanisms such as anergy or apoptosis.8 Tumor cells are known to produce PD-L1 as an adaptive resistance mechanism to evade immunity.8 Nivolumab is a human monoclonal antibody that targets the PD-1 receptor, thereby preventing the interaction with its ligand and allowing for unsuppressed activity of T cells.10 This therapy ultimately blocks the tumor’s local immune suppression mechanisms, which allows T cells to recognize cancer antigens.10

Adverse Events

Dermatologic AEs are among the most common with nivolumab treatment. In a pooled retrospective analysis of melanoma patients, Weber et al9 found that 34% of 576 patients experience cutaneous any-grade AEs associated with nivolumab treatment, most commonly pruritus. It has been well documented that anti–PD-1 therapy AEs of the skin as well as other organ systems have a delayed onset of at least 1 month.9 The average time of onset for bullous eruptions associated with anti–PD-1 therapy has been reported to be approximately 12 weeks, with a range of 7 to 16.1 weeks.11 Our patient had a bullous eruption with an onset of 12 weeks following initiation of treatment.

Although lichenoid reactions appear to be relatively common AEs of anti–PD-1 therapy,2,5,6 only a small number of cases of bullous pemphigoid eruptions have been reported.7 It has been hypothesized that blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway increases production of hemidesmosomal protein BP180 autoantibody, which is involved in the pathogenesis of LPP.7 Bullous eruptions have not been reported in the use of anticytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 agents, which could indicate that such eruptions are specific to the anti–PD-1 class of drugs.7

Diagnosis

Our patient represents a rare drug reaction involving both lichenoid and bullous components. Our differential diagnosis included drug-induced bullous lichen planus (BLP) and drug-induced LPP. Differentiation of these diagnoses can be difficult. In fact, in 2017 Fujii et al12 found reason to reprise the hypothesis that BLP is a transitional step toward LPP. The histologic evaluation of LPP differs depending on the type of lesion biopsied and can be indistinguishable from BLP as well as bullous pemphigoid. Therefore, clinical history and immunofluorescence should be used to make a diagnosis. Lichen planus pemphigoides typically will have linear IgG deposition along the basement membrane zone on both DIF and IIF, findings that will be negative in patients with BLP.13 Direct immunofluorescence findings in BLP include shaggy deposits of fibrin along the basement membrane zone. In this patient, DIF was negative, which may have been caused by variability among lesions in LPP, but IIF was positive. Given the clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of LPP was made. Further studies, such as immunoblot and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, also can be used to aid diagnosis.

A similar presentation has been documented in a patient with metastatic melanoma.14 The diagnosis in this patient was LPP induced by pembrolizumab, which is another agent within the anti–PD-1 class. The Naranjo probability scale scored our patient’s eruption as a possible adverse drug reaction.15 Thus, other etiologies, such as a paraneoplastic process, cannot be completely ruled out. However, our patient has not had recurrence after 1 year, and the timing of the eruption appeared to be related to drug therapy, making alternative etiologies less likely.

Management

Cessation of nivolumab therapy and a short course of oral corticosteroid therapy led to marked improvement of symptoms. Given the emergent treatment of our patient, the resolution of her symptoms cannot be solely attributed to the cessation of nivolumab or to treatment with prednisone. Oral rather than topical corticosteroids were chosen because of the severity of the eruption. Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines can provide relief in less severe cases of bullous reactions to anti–PD-1 therapy.7,11 This regimen also has proven to be effective in lichenoid dermatitis induced by anti–PD-1.2

Conclusion

We hope this case report will contribute to the growing body of evidence regarding recognition and management of unique reactions to cancer immunotherapies.

Nivolumab, an immune checkpoint modulator, acts by binding to the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) receptor on T cells, which blocks the inhibition of T cells. Nivolumab ultimately leads to stimulation of the T-cell response1 and overcomes evasive adaptations of certain cancers. Cutaneous adverse events (AEs) have been reported in approximately 20% to 40% of patients treated with the anti–PD-1 class of drugs, including nivolumab.2-4 The most common cutaneous AEs include pruritus; vitiligo; and various forms of rash, such as lichenoid dermatitis, psoriasiform eruptions, and bullous pemphigoid.1-3,5-7 We report a patient with non–small cell lung cancer being treated with nivolumab who developed a bullous lichenoid eruption consistent with the diagnosis of lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP).

Case Report

An 87-year-old woman presented with a pruritic rash on the trunk and extremities of 3 weeks’ duration. Her medical history included stage IV non–small cell lung cancer, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, and hypertension. Her long-term medications were ipratropium-albuterol, alendronate, amlodipine, aspirin, carvedilol, colesevelam, probiotic granules, and bumetanide. She was previously treated with carboplatin and docetaxel, which were discontinued secondary to fatigue, diarrhea, poor appetite, loss of taste, and a nonspecific rash. Six months later (approximately 3 months prior to the onset of cutaneous symptoms), she was started on nivolumab monotherapy every 14 days for a total of 9 infusions.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed erythematous crusted erosions on the trunk and extremities and 1 flaccid bulla on the back. A punch biopsy revealed lichenoid dermatitis. The patient returned 2 weeks later with worsening of cutaneous manifestations, including more blisters and erosions. Figure 1 shows the clinical appearance of the eruption on the patient’s leg. At this time, additional biopsies revealed a subepidermal bullous lichenoid eruption with eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was negative; however, indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) revealed weak linear staining for IgG antibodies along the basement membrane zone on monkey esophagus substrate. Examination of salt-split skin was noncontributory. The patient improved with a 2-week oral prednisone taper (starting at 40 mg daily). The dose was decreased incrementally over the course of 2 weeks from 40 mg to 20 mg to 0 mg. Because of the presumed grade 3 (severe) cutaneous drug eruption linked to nivolumab and further discussion with the medical oncology team, the patient decided to cease therapy. Since cessation of therapy, she has been seen twice for follow-up. At 2-month follow-up, she presented with drastic improvement of the eruption, and at 1 year she has continued to forego any further treatment for the stable and nonprogressing malignancy.

Widespread coalescent lesions with crusted and hemorrhagic bullae were present on the thigh and knee.

Comment

Immunotherapy

The interaction between the PD-1 receptor and its ligands, programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and programmed death ligand 2, is an immune checkpoint.8,9 Under normal physiologic conditions, this checkpoint serves to prevent autoimmunity.10 When the PD-1 receptor is left unbound, T cells are more inclined to mount an immune response. If the receptor is ligand bound, the response of T cells is suppressed via mechanisms such as anergy or apoptosis.8 Tumor cells are known to produce PD-L1 as an adaptive resistance mechanism to evade immunity.8 Nivolumab is a human monoclonal antibody that targets the PD-1 receptor, thereby preventing the interaction with its ligand and allowing for unsuppressed activity of T cells.10 This therapy ultimately blocks the tumor’s local immune suppression mechanisms, which allows T cells to recognize cancer antigens.10

Adverse Events

Dermatologic AEs are among the most common with nivolumab treatment. In a pooled retrospective analysis of melanoma patients, Weber et al9 found that 34% of 576 patients experience cutaneous any-grade AEs associated with nivolumab treatment, most commonly pruritus. It has been well documented that anti–PD-1 therapy AEs of the skin as well as other organ systems have a delayed onset of at least 1 month.9 The average time of onset for bullous eruptions associated with anti–PD-1 therapy has been reported to be approximately 12 weeks, with a range of 7 to 16.1 weeks.11 Our patient had a bullous eruption with an onset of 12 weeks following initiation of treatment.

Although lichenoid reactions appear to be relatively common AEs of anti–PD-1 therapy,2,5,6 only a small number of cases of bullous pemphigoid eruptions have been reported.7 It has been hypothesized that blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway increases production of hemidesmosomal protein BP180 autoantibody, which is involved in the pathogenesis of LPP.7 Bullous eruptions have not been reported in the use of anticytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 agents, which could indicate that such eruptions are specific to the anti–PD-1 class of drugs.7

Diagnosis

Our patient represents a rare drug reaction involving both lichenoid and bullous components. Our differential diagnosis included drug-induced bullous lichen planus (BLP) and drug-induced LPP. Differentiation of these diagnoses can be difficult. In fact, in 2017 Fujii et al12 found reason to reprise the hypothesis that BLP is a transitional step toward LPP. The histologic evaluation of LPP differs depending on the type of lesion biopsied and can be indistinguishable from BLP as well as bullous pemphigoid. Therefore, clinical history and immunofluorescence should be used to make a diagnosis. Lichen planus pemphigoides typically will have linear IgG deposition along the basement membrane zone on both DIF and IIF, findings that will be negative in patients with BLP.13 Direct immunofluorescence findings in BLP include shaggy deposits of fibrin along the basement membrane zone. In this patient, DIF was negative, which may have been caused by variability among lesions in LPP, but IIF was positive. Given the clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of LPP was made. Further studies, such as immunoblot and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, also can be used to aid diagnosis.

A similar presentation has been documented in a patient with metastatic melanoma.14 The diagnosis in this patient was LPP induced by pembrolizumab, which is another agent within the anti–PD-1 class. The Naranjo probability scale scored our patient’s eruption as a possible adverse drug reaction.15 Thus, other etiologies, such as a paraneoplastic process, cannot be completely ruled out. However, our patient has not had recurrence after 1 year, and the timing of the eruption appeared to be related to drug therapy, making alternative etiologies less likely.

Management

Cessation of nivolumab therapy and a short course of oral corticosteroid therapy led to marked improvement of symptoms. Given the emergent treatment of our patient, the resolution of her symptoms cannot be solely attributed to the cessation of nivolumab or to treatment with prednisone. Oral rather than topical corticosteroids were chosen because of the severity of the eruption. Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines can provide relief in less severe cases of bullous reactions to anti–PD-1 therapy.7,11 This regimen also has proven to be effective in lichenoid dermatitis induced by anti–PD-1.2

Conclusion

We hope this case report will contribute to the growing body of evidence regarding recognition and management of unique reactions to cancer immunotherapies.

- Macdonald JB, Macdonald B, Golitz LE, et al. Cutaneous adverse effects of targeted therapies: part II: inhibitors of intracellular molecular signaling pathways. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:221-236; quiz 237-238.

- Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25.

- Abdel-Rahman O, El Halawani H, Fouad M. Risk of cutaneous toxicities in patients with solid tumors treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Future Oncol. 2015;11:2471-2484.

- Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443-2454.

- Hwang SJ, Carlos G, Wakade D, et al. Cutaneous adverse events (AEs) of anti-programmed cell death (PD)-1 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma: a single-institution cohort [published online January 12, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:455-461.e1.

- Sibaud V, Meyer N, Lamant L, et al. Dermatologic complications of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28:254-263.

- Naidoo J, Schindler K, Querfeld C, et al. Autoimmune bullous skin disorders with immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1 and PD-L1. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:383-389.

- Zou W, Wolchok JD, Chen L. PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:328rv4.

- Weber JS, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, et al. Safety profile of nivolumab monotherapy: a pooled analysis of patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:785-792.

- Mamalis A, Garcha M, Jagdeo J. Targeting the PD-1 pathway: a promising future for the treatment of melanoma. Arch Dermatol Res. 2014;306:511-519.

- Jour G, Glitza IC, Ellis RM, et al. Autoimmune dermatologic toxicities from immune checkpoint blockade with anti-PD-1 antibody therapy: a report on bullous skin eruptions. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:688-696.

- Fujii M, Takahashi I, Honma M, et al. Bullous lichen planus accompanied by elevation of serum anti-BP180 autoantibody: a possible transitional mechanism to lichen planus pemphigoides. J Dermatol. 2017;44:E124-E125.

- Arbache ST, Nogueira TG, Delgado L, et al. Immunofluorescence testing in the diagnosis of autoimmune blistering diseases: overview of 10-year experience. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:885-889.

- Schmidgen MI, Butsch F, Schadmand-Fischer S, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced lichen planus pemphigoides in a patient with metastatic melanoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:742-745.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- Macdonald JB, Macdonald B, Golitz LE, et al. Cutaneous adverse effects of targeted therapies: part II: inhibitors of intracellular molecular signaling pathways. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:221-236; quiz 237-238.

- Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25.

- Abdel-Rahman O, El Halawani H, Fouad M. Risk of cutaneous toxicities in patients with solid tumors treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Future Oncol. 2015;11:2471-2484.

- Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443-2454.

- Hwang SJ, Carlos G, Wakade D, et al. Cutaneous adverse events (AEs) of anti-programmed cell death (PD)-1 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma: a single-institution cohort [published online January 12, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:455-461.e1.

- Sibaud V, Meyer N, Lamant L, et al. Dermatologic complications of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28:254-263.

- Naidoo J, Schindler K, Querfeld C, et al. Autoimmune bullous skin disorders with immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1 and PD-L1. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:383-389.

- Zou W, Wolchok JD, Chen L. PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:328rv4.

- Weber JS, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, et al. Safety profile of nivolumab monotherapy: a pooled analysis of patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:785-792.

- Mamalis A, Garcha M, Jagdeo J. Targeting the PD-1 pathway: a promising future for the treatment of melanoma. Arch Dermatol Res. 2014;306:511-519.

- Jour G, Glitza IC, Ellis RM, et al. Autoimmune dermatologic toxicities from immune checkpoint blockade with anti-PD-1 antibody therapy: a report on bullous skin eruptions. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:688-696.

- Fujii M, Takahashi I, Honma M, et al. Bullous lichen planus accompanied by elevation of serum anti-BP180 autoantibody: a possible transitional mechanism to lichen planus pemphigoides. J Dermatol. 2017;44:E124-E125.

- Arbache ST, Nogueira TG, Delgado L, et al. Immunofluorescence testing in the diagnosis of autoimmune blistering diseases: overview of 10-year experience. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:885-889.

- Schmidgen MI, Butsch F, Schadmand-Fischer S, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced lichen planus pemphigoides in a patient with metastatic melanoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:742-745.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be aware that lichen planus pemphigoides is within the spectrum of toxicity for patients treated with nivolumab.

- Bullous eruptions related to anti–programmed cell death 1 agents tend to appear 4 months after initiation of therapy.

- A severe cutaneous toxicity of a checkpoint inhibitor should be managed using oral corticosteroids with consideration of withdrawing the offending agent.

Relapsing Polychondritis in Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is a recurrent inflammatory condition involving primarily cartilaginous structures. The disease, first described as a clinical entity in 1960 by Pearson et al,1 is rare with an estimated incidence of 3.5 cases per 1 million individuals.2 The pathogenesis of RP is widely accepted as being autoimmune in nature, largely due to the identification of circulating autoantibodies seen in the sera of patients with similar clinical pictures.3

Although in most patients the primary process involves inflammation of cartilage, a subset of patients experience involvement of noncartilaginous sites.4 The degree of systemic involvement varies from none to notable, affecting the cardiovascular and respiratory systems and potentially leading to life-threatening complications, including cardiac valve compromise and airway collapse. Relapsing polychondritis is considered to be a progressive disease with the ultimate potential to be life-threatening.5

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection leads to a profound state of immune dysregulation, affecting innate, adaptive, and natural killer components of the immune system.6 There is variability in the development of autoimmune disease in HIV patients depending on the stage of infection. The frequency of rheumatologic disease in HIV patients might be as high as 60%.6 Relapsing polychondritis is rare in patients with HIV.7-9 Of 4 reported cases, 2 patients had other coexisting autoimmune disease—sarcoidosis and Behçet disease.8,9

Case Report

A 36-year-old man presented to the clinic with a concern of recurrent ear pain and swelling of approximately 2 years’ duration. Onset was sudden without inciting event. Symptoms initially involved the right ear with eventual progression to both ears. Additional symptoms included an auditory perception of underwater submersion, intermittent vertigo, and 3 episodes of throat closure sensation.

The patient’s medical history was notable for asthma; gastritis; depression; and HIV infection, which was diagnosed 4 years earlier and adequately managed with highly active antiretroviral therapy. His family history was notable for systemic lupus erythematosus in his mother, maternal aunt, and maternal cousin.

At presentation, the patient’s CD4 count was 799 cells/mm3 with an undetectable viral load. Medications included abacavir-dolutegravir-lamivudine, hydroxyzine, meclizine, mometasone, and quetiapine. Physical examination showed erythema, swelling, and tenderness of the left and right auricles with sparing of the earlobe that was more noticeable on the left ear (Figure 1). Bacterial culture from the external auditory meatus was positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Biopsy revealed chronic inflammatory perichondritis with mild to moderate fibrosis and chronic lymphocytic inflammation at the dermal cartilaginous junction (Figure 2). A direct immunofluorescent biopsy was unremarkable, but subsequent type II collagen antibodies were positive (35.5 endotoxin units/mL [reference range, <20 endotoxin units/mL]).

Comment

Relapsing polychondritis is an uncommon progressive disease characterized by recurrent inflammatory insults to cartilaginous and proteoglycan-rich structures.4 The most consistent clinical features of RP are ear inflammation that involves the auricle and spares the lobe, nasal chondritis, and arthralgia.10 Laryngotracheal compromise may occur from tracheal cartilage inflammation. The involvement of these specific structures is due to commonality between their component collagens.5 Although any organ system can be affected, as many as 50% of patients have respiratory tract involvement, which may affect any portion of the respiratory tree.11 If involving the larynx, this inflammation can lead to severe edema warranting intubation. Cardiovascular involvement is present in 24% to 52% of patients,10 which most commonly manifests as valvular impairment affecting the aortic valve more frequently than the mitral valve.5

Pathogenesis

Although the etiology of RP remains undetermined, multiple hypotheses have been proposed. One is that a certain subset of patients is predisposed to autoimmunity, and a secondary triggering event in the form of infection, malignancy, or medication catalyzes development of RP. A second hypothesis is that mechanical trauma to cartilage exposes the immune system to certain antigens that would have otherwise remained hidden, prompting autosensitization.12,13

Regardless of cause, an autoimmune pathogenesis is favored based on the following observations: RP is frequently associated with other autoimmune diseases in the same patient, glucocorticosteroids and other immunosuppressive therapies are effective for treatment, and histopathologic findings include an infiltrate of CD4+ T lymphocytes with detection of immunoglobulins and plasma cells in different lesions.5 The detection of autoantibodies against collagen in the serum of patients with RP further supports an autoimmune pathogenesis.3 The earliest identified autoantibodies in patients with RP were against type II collagen. Subsequent studies have identified autoantibodies against type IV and type XI collagens as well as other cartilage-related proteins such as matrilin 114 and cartilage oligomeric matrix proteins.15 Although circulating antibodies to type II collagen are present in a variable number of patients with the disease (30%–70%), levels likely correlate with disease activity and are highest at times of acute inflammation.3 Additionally, titers of type II collagen antibodies have been shown to decrease upon institution of immunosuppressive therapy.16

Although a humoral response dominates the picture of RP, there also is an associated T cell–mediated response.13 Histopathologically, biopsy of an active lesion of auricular cartilage shows a mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed primarily of lymphocytes, with variable numbers of polymorphonuclear cells, monocytes, and plasma cells. Loss of basophilia of the cartilage matrix can be observed, thought to be the result of proteoglycan depletion.13 Later, lesions classically display apoptosis of chondrocytes, focal calcification, or fibrosis.5

Diagnosis

Relapsing polychondritis acts classically as an autoimmune disease with a variable presentation, making diagnosis a challenge. Many sets of diagnostic criteria have been proposed. The most referenced remains the original criteria described by McAdam et al.17 In 2012, the Relapsing Polychondritis Disease Activity Index modified criteria set forth by Michet et al18 and might serve as the standard for diagnosis going forward.19

McAdam et al17 proposed that 3 of 6 clinical features are necessary for diagnosis: bilateral auricular chondritis, nonerosive seronegative inflammatory polyarthritis, nasal chondritis, ocular inflammation, respiratory tract chondritis, and audiovestibular damage. Michet et al18 proposed that 1 of 2 conditions are necessary for diagnosis of RP: (1) proven inflammation in 2 of 3 of the auricular, nasal, or laryngotracheal cartilages; or (2) proven inflammation in 1 of 3 of the auricular, nasal, or laryngotracheal cartilages, plus 2 other signs, including ocular inflammation, vestibular dysfunction, seronegative inflammatory arthritis, and hearing loss.

These criteria were proposed originally in 197617 and modified in 1986.18 No further updates have been offered since then. As such, serologic findings, such as antibodies against type II collagen, are not included in the diagnostic criteria. Additionally, these antibodies are not specific for RP and can be seen in other conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis.20

More recently, imaging analysis has been employed in conjunction with clinical and serologic data to diagnose the disease and evaluate its severity. The use of imaging modalities for these purposes is most beneficial in patients with notable disease and respiratory involvement.21