User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

The Evolution of the Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology Fellowship

Originating in 1968, the dermatologic surgery fellowship is as young as many dermatologists in practice today. Not surprisingly, the blossoming fellowship has undergone its fair share of both growth and growing pains over the last 5 decades.

A Brief History

The first dermatologic surgery fellowship was born in 1968 when Dr. Perry Robins established a program at the New York University Medical Center for training in chemosurgery.1 The fellowship quickly underwent notable change with the rising popularity of the fresh tissue technique, which was first performed by Dr. Fred Mohs in 1953 and made popular following publication of a series of landmark articles on the technique by Drs. Sam Stegman and Theodore Tromovitch in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The fellowship correspondingly saw a rise in fresh tissue technique training, accompanied by a decline in chemosurgery training. In 1974, Dr. Daniel Jones coined the term micrographic surgery to describe the favored technique, and at the 1985 annual meeting of the American College of Chemosurgery, the name of the technique was changed to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

By 1995, the fellowship was officially named Procedural Dermatology, and programs were exclusively accredited by the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). A 1-year Procedural Dermatology fellowship gained accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in 2003.2 Beginning in July 2013, all fellowship programs in the United States fell under the governance of the ACGME; however, the ACMS has remained the sponsor of the matching process.3 In 2014, the ACGME changed the name of the fellowship to Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology (MSDO).2 Fellowship training today is centered on the core elements of cutaneous oncologic surgery, cutaneous reconstructive surgery, and dermatologic oncology; however, the scope of training in technologies and techniques offered has continued to broaden.4 Many programs now offer additional training in cosmetic and other procedural dermatology. To date, there are 76 accredited MSDO fellowship training programs in the United States and more than 1500 fellowship-trained micrographic surgeons.2,4

Trends in Program and Match Statistics

As the role of dermatologic surgery within the field of dermatology continues to expand, the MSDO fellowship has become increasingly popular over the last decade. From 2005 to 2018, applicants participating in the fellowship match increased by 34%.3 Despite the fellowship’s growing popularity, programs participating in the match have remained largely stable from 2005 to 2018, with 50 positions offered in 2005 and 58 in 2018. The match rate has correspondingly decreased from 66.2% in 2005 to 61.1% in 2018.3

Changes in the Match Process

The fellowship match is processed by the SF Match and sponsored by the ACMS. Over the last decade, programs have increasingly opted for exemptions from participation in the SF Match. In 2005, there were 8 match exemptions. In 2018, there were 20.4 Despite the increasing popularity of match exemptions, in October 2018 the ACMS Board of Directors approved a new policy that eliminated match exemptions, with the exception of applicants on active military duty and international (non-Canadian) applicants. All other applicants applying for a fellowship position for the 2020-2021 academic year must participate in the match.4 This new policy attempts to ensure a fair match process, especially for applicants who have trained at a program without an affiliated MSDO fellowship.

The Road to Board Certification

Further growth during the fellowship’s mid-adult years centered on the long-contested debate on subspecialty board certification. In 2009, an American Society for Dermatologic Surgery membership survey demonstrated an overwhelming majority in opposition. In 2014, the debate resurfaced. At the 2016 American Society for Dermatologic Surgery annual meeting, former American Academy of Dermatology presidents Brett Coldiron, MD, and Darrell S. Rigel, MD, MS, conveyed opposing positions, after which an audience survey demonstrated a 69% opposition rate. Proponents continued to argue that board certification would decrease divisiveness in the specialty, create a better brand, help to obtain a Medicare specialty designation that could help prevent exclusion of Mohs surgeons from insurance networks, give allopathic dermatologists the same opportunity for certification as osteopathic counterparts, and demonstrate competence to the public. Those in opposition argued that the term dermatologic oncology erroneously suggests general dermatologists are not experts in the treatment of skin cancers, practices may be restricted by carriers misusing the new credential, and subspecialty certification would actually create division among practicing dermatologists.5

Following years of debate, the American Board of Dermatology’s proposal to offer subspecialty certification in Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery was submitted to the American Board of Medical Specialties and approved on October 26, 2018. The name of the new subspecialty (Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery) is different than that of the fellowship (Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology), a decision reached in response to diplomats indicating discomfort with the term oncology potentially misleading the public that general dermatologists do not treat skin cancer. Per the American Board of Dermatology official website, the first certification examination likely will take place in about 2 years. A maintenance of certification examination for the subspecialty will be required every 10 years.6

Final Thoughts

During its short history, the MSDO fellowship has undergone a notable evolution in recognition, popularity among residents, match process, and board certification, which attests to its adaptability over time and growing prominence.

- Robins P, Ebede TL, Hale EK. The evolution of Mohs micrographic surgery. Skin Cancer Foundation website. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/mohs-surgery/evolution-of-mohs. Updated July 13, 2016. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-surgery-and-dermatologic-oncology.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology Fellowship. San Francisco Match website. https://sfmatch.org/SpecialtyInsideAll.aspx?id=10&typ=1&name=Micrographic%20Surgery%20and%20Dermatologic%20Oncology. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ACMS fellowship training. American College of Mohs Surgery website. https://www.mohscollege.org/fellowship-training. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Should the ABD offer a Mohs surgery sub-certification? Dermatology World. April 26, 2017. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-weekly/should-the-abd-offer-a-mohs-surgery-sub-certification. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ABD Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery (MDS) subspecialty certification. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-dermatologic-surgery-mds-questions-and-answers-1.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

Originating in 1968, the dermatologic surgery fellowship is as young as many dermatologists in practice today. Not surprisingly, the blossoming fellowship has undergone its fair share of both growth and growing pains over the last 5 decades.

A Brief History

The first dermatologic surgery fellowship was born in 1968 when Dr. Perry Robins established a program at the New York University Medical Center for training in chemosurgery.1 The fellowship quickly underwent notable change with the rising popularity of the fresh tissue technique, which was first performed by Dr. Fred Mohs in 1953 and made popular following publication of a series of landmark articles on the technique by Drs. Sam Stegman and Theodore Tromovitch in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The fellowship correspondingly saw a rise in fresh tissue technique training, accompanied by a decline in chemosurgery training. In 1974, Dr. Daniel Jones coined the term micrographic surgery to describe the favored technique, and at the 1985 annual meeting of the American College of Chemosurgery, the name of the technique was changed to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

By 1995, the fellowship was officially named Procedural Dermatology, and programs were exclusively accredited by the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). A 1-year Procedural Dermatology fellowship gained accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in 2003.2 Beginning in July 2013, all fellowship programs in the United States fell under the governance of the ACGME; however, the ACMS has remained the sponsor of the matching process.3 In 2014, the ACGME changed the name of the fellowship to Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology (MSDO).2 Fellowship training today is centered on the core elements of cutaneous oncologic surgery, cutaneous reconstructive surgery, and dermatologic oncology; however, the scope of training in technologies and techniques offered has continued to broaden.4 Many programs now offer additional training in cosmetic and other procedural dermatology. To date, there are 76 accredited MSDO fellowship training programs in the United States and more than 1500 fellowship-trained micrographic surgeons.2,4

Trends in Program and Match Statistics

As the role of dermatologic surgery within the field of dermatology continues to expand, the MSDO fellowship has become increasingly popular over the last decade. From 2005 to 2018, applicants participating in the fellowship match increased by 34%.3 Despite the fellowship’s growing popularity, programs participating in the match have remained largely stable from 2005 to 2018, with 50 positions offered in 2005 and 58 in 2018. The match rate has correspondingly decreased from 66.2% in 2005 to 61.1% in 2018.3

Changes in the Match Process

The fellowship match is processed by the SF Match and sponsored by the ACMS. Over the last decade, programs have increasingly opted for exemptions from participation in the SF Match. In 2005, there were 8 match exemptions. In 2018, there were 20.4 Despite the increasing popularity of match exemptions, in October 2018 the ACMS Board of Directors approved a new policy that eliminated match exemptions, with the exception of applicants on active military duty and international (non-Canadian) applicants. All other applicants applying for a fellowship position for the 2020-2021 academic year must participate in the match.4 This new policy attempts to ensure a fair match process, especially for applicants who have trained at a program without an affiliated MSDO fellowship.

The Road to Board Certification

Further growth during the fellowship’s mid-adult years centered on the long-contested debate on subspecialty board certification. In 2009, an American Society for Dermatologic Surgery membership survey demonstrated an overwhelming majority in opposition. In 2014, the debate resurfaced. At the 2016 American Society for Dermatologic Surgery annual meeting, former American Academy of Dermatology presidents Brett Coldiron, MD, and Darrell S. Rigel, MD, MS, conveyed opposing positions, after which an audience survey demonstrated a 69% opposition rate. Proponents continued to argue that board certification would decrease divisiveness in the specialty, create a better brand, help to obtain a Medicare specialty designation that could help prevent exclusion of Mohs surgeons from insurance networks, give allopathic dermatologists the same opportunity for certification as osteopathic counterparts, and demonstrate competence to the public. Those in opposition argued that the term dermatologic oncology erroneously suggests general dermatologists are not experts in the treatment of skin cancers, practices may be restricted by carriers misusing the new credential, and subspecialty certification would actually create division among practicing dermatologists.5

Following years of debate, the American Board of Dermatology’s proposal to offer subspecialty certification in Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery was submitted to the American Board of Medical Specialties and approved on October 26, 2018. The name of the new subspecialty (Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery) is different than that of the fellowship (Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology), a decision reached in response to diplomats indicating discomfort with the term oncology potentially misleading the public that general dermatologists do not treat skin cancer. Per the American Board of Dermatology official website, the first certification examination likely will take place in about 2 years. A maintenance of certification examination for the subspecialty will be required every 10 years.6

Final Thoughts

During its short history, the MSDO fellowship has undergone a notable evolution in recognition, popularity among residents, match process, and board certification, which attests to its adaptability over time and growing prominence.

Originating in 1968, the dermatologic surgery fellowship is as young as many dermatologists in practice today. Not surprisingly, the blossoming fellowship has undergone its fair share of both growth and growing pains over the last 5 decades.

A Brief History

The first dermatologic surgery fellowship was born in 1968 when Dr. Perry Robins established a program at the New York University Medical Center for training in chemosurgery.1 The fellowship quickly underwent notable change with the rising popularity of the fresh tissue technique, which was first performed by Dr. Fred Mohs in 1953 and made popular following publication of a series of landmark articles on the technique by Drs. Sam Stegman and Theodore Tromovitch in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The fellowship correspondingly saw a rise in fresh tissue technique training, accompanied by a decline in chemosurgery training. In 1974, Dr. Daniel Jones coined the term micrographic surgery to describe the favored technique, and at the 1985 annual meeting of the American College of Chemosurgery, the name of the technique was changed to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

By 1995, the fellowship was officially named Procedural Dermatology, and programs were exclusively accredited by the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). A 1-year Procedural Dermatology fellowship gained accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in 2003.2 Beginning in July 2013, all fellowship programs in the United States fell under the governance of the ACGME; however, the ACMS has remained the sponsor of the matching process.3 In 2014, the ACGME changed the name of the fellowship to Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology (MSDO).2 Fellowship training today is centered on the core elements of cutaneous oncologic surgery, cutaneous reconstructive surgery, and dermatologic oncology; however, the scope of training in technologies and techniques offered has continued to broaden.4 Many programs now offer additional training in cosmetic and other procedural dermatology. To date, there are 76 accredited MSDO fellowship training programs in the United States and more than 1500 fellowship-trained micrographic surgeons.2,4

Trends in Program and Match Statistics

As the role of dermatologic surgery within the field of dermatology continues to expand, the MSDO fellowship has become increasingly popular over the last decade. From 2005 to 2018, applicants participating in the fellowship match increased by 34%.3 Despite the fellowship’s growing popularity, programs participating in the match have remained largely stable from 2005 to 2018, with 50 positions offered in 2005 and 58 in 2018. The match rate has correspondingly decreased from 66.2% in 2005 to 61.1% in 2018.3

Changes in the Match Process

The fellowship match is processed by the SF Match and sponsored by the ACMS. Over the last decade, programs have increasingly opted for exemptions from participation in the SF Match. In 2005, there were 8 match exemptions. In 2018, there were 20.4 Despite the increasing popularity of match exemptions, in October 2018 the ACMS Board of Directors approved a new policy that eliminated match exemptions, with the exception of applicants on active military duty and international (non-Canadian) applicants. All other applicants applying for a fellowship position for the 2020-2021 academic year must participate in the match.4 This new policy attempts to ensure a fair match process, especially for applicants who have trained at a program without an affiliated MSDO fellowship.

The Road to Board Certification

Further growth during the fellowship’s mid-adult years centered on the long-contested debate on subspecialty board certification. In 2009, an American Society for Dermatologic Surgery membership survey demonstrated an overwhelming majority in opposition. In 2014, the debate resurfaced. At the 2016 American Society for Dermatologic Surgery annual meeting, former American Academy of Dermatology presidents Brett Coldiron, MD, and Darrell S. Rigel, MD, MS, conveyed opposing positions, after which an audience survey demonstrated a 69% opposition rate. Proponents continued to argue that board certification would decrease divisiveness in the specialty, create a better brand, help to obtain a Medicare specialty designation that could help prevent exclusion of Mohs surgeons from insurance networks, give allopathic dermatologists the same opportunity for certification as osteopathic counterparts, and demonstrate competence to the public. Those in opposition argued that the term dermatologic oncology erroneously suggests general dermatologists are not experts in the treatment of skin cancers, practices may be restricted by carriers misusing the new credential, and subspecialty certification would actually create division among practicing dermatologists.5

Following years of debate, the American Board of Dermatology’s proposal to offer subspecialty certification in Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery was submitted to the American Board of Medical Specialties and approved on October 26, 2018. The name of the new subspecialty (Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery) is different than that of the fellowship (Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology), a decision reached in response to diplomats indicating discomfort with the term oncology potentially misleading the public that general dermatologists do not treat skin cancer. Per the American Board of Dermatology official website, the first certification examination likely will take place in about 2 years. A maintenance of certification examination for the subspecialty will be required every 10 years.6

Final Thoughts

During its short history, the MSDO fellowship has undergone a notable evolution in recognition, popularity among residents, match process, and board certification, which attests to its adaptability over time and growing prominence.

- Robins P, Ebede TL, Hale EK. The evolution of Mohs micrographic surgery. Skin Cancer Foundation website. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/mohs-surgery/evolution-of-mohs. Updated July 13, 2016. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-surgery-and-dermatologic-oncology.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology Fellowship. San Francisco Match website. https://sfmatch.org/SpecialtyInsideAll.aspx?id=10&typ=1&name=Micrographic%20Surgery%20and%20Dermatologic%20Oncology. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ACMS fellowship training. American College of Mohs Surgery website. https://www.mohscollege.org/fellowship-training. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Should the ABD offer a Mohs surgery sub-certification? Dermatology World. April 26, 2017. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-weekly/should-the-abd-offer-a-mohs-surgery-sub-certification. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ABD Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery (MDS) subspecialty certification. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-dermatologic-surgery-mds-questions-and-answers-1.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Robins P, Ebede TL, Hale EK. The evolution of Mohs micrographic surgery. Skin Cancer Foundation website. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/mohs-surgery/evolution-of-mohs. Updated July 13, 2016. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-surgery-and-dermatologic-oncology.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology Fellowship. San Francisco Match website. https://sfmatch.org/SpecialtyInsideAll.aspx?id=10&typ=1&name=Micrographic%20Surgery%20and%20Dermatologic%20Oncology. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ACMS fellowship training. American College of Mohs Surgery website. https://www.mohscollege.org/fellowship-training. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Should the ABD offer a Mohs surgery sub-certification? Dermatology World. April 26, 2017. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-weekly/should-the-abd-offer-a-mohs-surgery-sub-certification. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ABD Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery (MDS) subspecialty certification. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-dermatologic-surgery-mds-questions-and-answers-1.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

Resident Pearl

- Residents should be aware of recent changes to the Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology fellowship: the elimination of fellowship match exemptions for most applicants for the upcoming 2019-2020 academic year, the American Board of Medical Specialties approval of subspecialty certification in Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery, and the likelihood of the first subspecialty certification examination in the next 2 years.

Sunscreen Regulations and Advice for Your Patients

If by now you have not had a patient ask, “Doctor, what sunscreen should I use NOW?” you will soon.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently published a press release detailing a proposed rule on how manufacturers will be required to test and label sunscreens in the United States.1,2 Although the press release was complicated and contained much information, the media specifically latched onto the FDA’s consideration of only 2 active sunscreen ingredients—zinc oxide and titanium dioxide—as generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE). In response, some patients may assume that most sunscreens on the market are dangerous.

How did this new proposed rule come about? To understand the process, it takes some explanation of the history of the FDA’s regulation of sunscreens.

How are sunscreens regulated by the FDA?

The regulatory process for sunscreens in the United States is complicated. The FDA regulates sunscreens as over-the-counter (OTC) drugs rather than as cosmetics, which is how they are regulated in most of the rest of the world.

The US sunscreen regulation process began in 1978 with an advance notice of proposed rulemaking from the FDA that included recommendations from an advisory review panel on the safe and effective use of OTC sunscreen products.3 At that time, 21 active sunscreen ingredients and their maximum use concentrations were listed and determined to be safe, or GRASE. It also gave manufacturers guidance on how to test for efficacy with the methodology for determining the sun protection factor (SPF) as well as various labeling requirements. Over the years, the FDA has issued a number of other sunscreen guidelines, such as removing padimate A and adding avobenzone and zinc oxide to the list of GRASE ingredients in the 1990s.4,5

In 1999, the FDA issued a final rule that listed 16 active sunscreen ingredients and concentrations as GRASE.6 There were some restrictions as to certain combinations of ingredients that could not be used in a finished product. Labeling requirements, including a maximum SPF of 30, also were put in place. This final rule established a final sunscreen monograph that was supposed to have been effective by 2002; however, in 2001 the agency delayed the effective date indefinitely because they had not yet established broad-spectrum (UVA) protection testing and labeling.7

The FDA published a proposed rule in 2007 as well as a final rule in 2011 that again listed the same 16 ingredients as GRASE and specified labeling and testing methods for establishing SPF, broad-spectrum protection, and water-resistance claims.8,9 The final rule limited product labels to a maximum SPF of 50+; provided directions for use with regard to other labeling elements (eg, warnings); and identified specific claims that would not be allowed on product labels, such as “waterproof” and “all-day protection.”9

Nevertheless, an effective final OTC monograph for sunscreen products has not yet been published.

What is the Sunscreen Innovation Act?

In 2014, the US Congress enacted the Sunscreen Innovation Act10 primarily to mandate that the FDA develop a more efficient way to determine the safety and efficacy of new active sunscreen ingredients that were commonly used in Europe and other parts of the world at the time. Many of these agents were thought to be more protective in the UVA and/or UVB spectrum, and if added to the list of GRASE ingredients available to US manufacturers, they would lead to the development of products that would improve the protection offered by sunscreens marketed to US consumers. The time and extent application (TEA) was established, a method that allowed manufacturers to apply for FDA approval of specific agents. The TEA also suggested allowing data generated in other countries where these agents were already in use for years to be considered in the FDA’s evaluation of the agents as GRASE. In addition, Congress mandated that a final monograph on OTC sunscreens be published by the end of 2019. A number of manufacturers have submitted TEAs for new active sunscreen ingredients, and so far, all have been rejected.

Why is the FDA interested in more safety data?

Since then, the FDA has become concerned not only with the safety and efficacy of newly proposed agents through the TEA but also with the original 16 active sunscreen ingredients listed as GRASE in the 2011 final rule. In the 1970s and 1980s, sunscreen use was limited to beach vacations or outdoor sporting events, but sun-protective behaviors have changed dramatically since that time, with health care providers now becoming cognizant of the growing threats of skin cancer and melanoma as well as the cosmetic concerns of photoaging, thereby recommending daily sunscreen use to their patients. In addition, the science behind sunscreens with higher concentrations of active ingredients intended to achieve higher and higher SPFs and their respective penetration of the skin has evolved, leading to new concerns about systemic toxicity. Early limited research frequently touted by the lay media has suggested that some of these agents might lead to hormonal changes, reproductive toxicity, and carcinogenicity.

In November 2016, the FDA issued a guidance for manufacturers that outlined the safety data that would be required to establish an OTC sunscreen active ingredient as GRASE.11 It also provided detailed information about both clinical and nonclinical safety testing, including human irritation and sensitization studies as well as human photosafety studies. In vitro dermal and systemic carcinogenicity studies and animal developmental and reproductive toxicity studies also were required as well studies regarding safety in children.

Many of these recommendations were already being utilized by manufacturers; however, one important change was the requirement for human absorption studies by a maximal usage trial, which more accurately addresses the absorption of sunscreen agents according to actual use. Such studies will be required at the highest allowable concentration of an agent in multiple vehicles and over large body surface areas for considerable exposure times.

This guidance to sunscreen manufacturers was announced to the public in a press release in May 2018.12

What are the new regulations?

All of this has culminated in the recent proposed rule, which includes several important proposals2:

- Of the 16 currently marketed active sunscreen ingredients, only 2—zinc oxide and titanium dioxide—are considered GRASE. Two ingredients—trolamine salicylate and para-aminobenzoic acid—are considered non-GRASE, but there is not enough information at this time to determine if the remaining 12 ingredients are GRASE. The FDA is working with manufacturers to obtain sufficient information to make this determination.

- Approved dosage formulations include sprays, oils, lotions, creams, gels, butters, pastes, ointments, and sticks. Further information is needed regarding powders before they can be considered.

- The maximum SPF will be increased from 50+ to 60+.

- Sunscreens with an SPF of 15 or higher are required to provide broad-spectrum protection commensurate with the SPF, expanding on critical wavelength testing.

- There are new labeling changes, including a requirement that active ingredients be listed on the front of the packaging.

- Sunscreen products that contain insect repellents are considered non-GRASE.

What’s next?

The process for the proposed final rule has now entered a 90-day public comment period that will end on May 27, 2019; however, it is unlikely that a final monograph as mandated by Congress will be produced by the end of this year.

Sunscreen manufacturers currently are coordinating a response to the proposed rule through the Personal Care Products Council and the Consumer Healthcare Products Association Sunscreen Task Force. It is likely that the new required testing will be costly, with estimates exceeding tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. In all likelihood, the number of active ingredients that the industry will agree to support with costly testing will be fewer than the 12 that are now on the list. It also is likely that this process will lead to fewer sunscreen products for consumers to choose from and almost certainly at a higher cost.

What do we tell patients in the meantime?

According to the FDA’s rules, it was necessary that this process was made public, but it will almost certainly concern our patients as to the safety of the sunscreen products they have been using. We should be concerned that some of our patients may limit their use of sunscreens because of safety concerns.

There is no question that, as physicians, we want to “first, do no harm,” so we should all be interested in assuring our patients that our sunscreen recommendations are safe and we support the FDA proposal for additional data. The good news is that when this process is completed, a large number of agents will likely be found to be GRASE. When the FDA finally gives its imprimatur to sunscreens, it will hopefully help to silence those naysayers who report that sunscreens are dangerous for consumers; however, it has been suggested by some in industry that the new testing required may take at least 5 years.

What should dermatologists do when we are asked, “What sunscreen should I use NOW?” For most patients, I would explain the regulatory process and assure them that the risk-benefit ratio at this point suggests they should continue using the same sunscreens that they are currently using. For special situations such as pregnant women and children, it may be best to suggest products that contain only the 2 GRASE inorganic agents.

- FDA advances new proposed regulation to make sure that sunscreens are safe and effective [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; February 21, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm631736.htm. Accessed April 4, 2019.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Registr. 2019;84(38):6204-6275. To be codified at 21 CFR §201, 310, 347, and 352.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Registr. 1978;43(166):38206-38269. To be codified at 21 CFR §352.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; amendment to the tentative final monograph. Fed Registr. 1996;60(180):48645-48655. To be codified at 21 CFR §352.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; amendment to the tentative final monograph; enforcement policy. Fed Registr. 1998;63(204):56584-56589. To be codified at 21 CFR §352.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; final monograph. Fed Registr. 1999;64(98):27666-27693. To be codified at 21 CFR §310, 352, 700, and 740.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; final monograph; partial stay; final rule. Fed Registr. 2001;66:67485-67487. To be codified at 21 CFR §352.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; proposed amendment of final monograph. Fed Registr. 2007;72(165):49069-49122. To be codified at 21 CFR §347 and 352.

- Labeling and effectiveness testing; sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Registr. 2011;76(117):35619-35665. To be codified at 21 CFR §201 and 310.

- Sunscreen Innovation Act, S 2141, 113th Cong, 2nd Sess (2014).

- Nonprescription sunscreen drug products-safety and effectiveness data; guidance for industry; availability. Fed Registr. 2016;81(226):84594-84595.

- Statement from Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, on new FDA actions to keep consumers safe from the harmful effects of sun exposure, and ensure the long-term safety and benefits of sunscreens [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; May 22, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm608499.htm. Accessed April 5, 2019.

If by now you have not had a patient ask, “Doctor, what sunscreen should I use NOW?” you will soon.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently published a press release detailing a proposed rule on how manufacturers will be required to test and label sunscreens in the United States.1,2 Although the press release was complicated and contained much information, the media specifically latched onto the FDA’s consideration of only 2 active sunscreen ingredients—zinc oxide and titanium dioxide—as generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE). In response, some patients may assume that most sunscreens on the market are dangerous.

How did this new proposed rule come about? To understand the process, it takes some explanation of the history of the FDA’s regulation of sunscreens.

How are sunscreens regulated by the FDA?

The regulatory process for sunscreens in the United States is complicated. The FDA regulates sunscreens as over-the-counter (OTC) drugs rather than as cosmetics, which is how they are regulated in most of the rest of the world.

The US sunscreen regulation process began in 1978 with an advance notice of proposed rulemaking from the FDA that included recommendations from an advisory review panel on the safe and effective use of OTC sunscreen products.3 At that time, 21 active sunscreen ingredients and their maximum use concentrations were listed and determined to be safe, or GRASE. It also gave manufacturers guidance on how to test for efficacy with the methodology for determining the sun protection factor (SPF) as well as various labeling requirements. Over the years, the FDA has issued a number of other sunscreen guidelines, such as removing padimate A and adding avobenzone and zinc oxide to the list of GRASE ingredients in the 1990s.4,5

In 1999, the FDA issued a final rule that listed 16 active sunscreen ingredients and concentrations as GRASE.6 There were some restrictions as to certain combinations of ingredients that could not be used in a finished product. Labeling requirements, including a maximum SPF of 30, also were put in place. This final rule established a final sunscreen monograph that was supposed to have been effective by 2002; however, in 2001 the agency delayed the effective date indefinitely because they had not yet established broad-spectrum (UVA) protection testing and labeling.7

The FDA published a proposed rule in 2007 as well as a final rule in 2011 that again listed the same 16 ingredients as GRASE and specified labeling and testing methods for establishing SPF, broad-spectrum protection, and water-resistance claims.8,9 The final rule limited product labels to a maximum SPF of 50+; provided directions for use with regard to other labeling elements (eg, warnings); and identified specific claims that would not be allowed on product labels, such as “waterproof” and “all-day protection.”9

Nevertheless, an effective final OTC monograph for sunscreen products has not yet been published.

What is the Sunscreen Innovation Act?

In 2014, the US Congress enacted the Sunscreen Innovation Act10 primarily to mandate that the FDA develop a more efficient way to determine the safety and efficacy of new active sunscreen ingredients that were commonly used in Europe and other parts of the world at the time. Many of these agents were thought to be more protective in the UVA and/or UVB spectrum, and if added to the list of GRASE ingredients available to US manufacturers, they would lead to the development of products that would improve the protection offered by sunscreens marketed to US consumers. The time and extent application (TEA) was established, a method that allowed manufacturers to apply for FDA approval of specific agents. The TEA also suggested allowing data generated in other countries where these agents were already in use for years to be considered in the FDA’s evaluation of the agents as GRASE. In addition, Congress mandated that a final monograph on OTC sunscreens be published by the end of 2019. A number of manufacturers have submitted TEAs for new active sunscreen ingredients, and so far, all have been rejected.

Why is the FDA interested in more safety data?

Since then, the FDA has become concerned not only with the safety and efficacy of newly proposed agents through the TEA but also with the original 16 active sunscreen ingredients listed as GRASE in the 2011 final rule. In the 1970s and 1980s, sunscreen use was limited to beach vacations or outdoor sporting events, but sun-protective behaviors have changed dramatically since that time, with health care providers now becoming cognizant of the growing threats of skin cancer and melanoma as well as the cosmetic concerns of photoaging, thereby recommending daily sunscreen use to their patients. In addition, the science behind sunscreens with higher concentrations of active ingredients intended to achieve higher and higher SPFs and their respective penetration of the skin has evolved, leading to new concerns about systemic toxicity. Early limited research frequently touted by the lay media has suggested that some of these agents might lead to hormonal changes, reproductive toxicity, and carcinogenicity.

In November 2016, the FDA issued a guidance for manufacturers that outlined the safety data that would be required to establish an OTC sunscreen active ingredient as GRASE.11 It also provided detailed information about both clinical and nonclinical safety testing, including human irritation and sensitization studies as well as human photosafety studies. In vitro dermal and systemic carcinogenicity studies and animal developmental and reproductive toxicity studies also were required as well studies regarding safety in children.

Many of these recommendations were already being utilized by manufacturers; however, one important change was the requirement for human absorption studies by a maximal usage trial, which more accurately addresses the absorption of sunscreen agents according to actual use. Such studies will be required at the highest allowable concentration of an agent in multiple vehicles and over large body surface areas for considerable exposure times.

This guidance to sunscreen manufacturers was announced to the public in a press release in May 2018.12

What are the new regulations?

All of this has culminated in the recent proposed rule, which includes several important proposals2:

- Of the 16 currently marketed active sunscreen ingredients, only 2—zinc oxide and titanium dioxide—are considered GRASE. Two ingredients—trolamine salicylate and para-aminobenzoic acid—are considered non-GRASE, but there is not enough information at this time to determine if the remaining 12 ingredients are GRASE. The FDA is working with manufacturers to obtain sufficient information to make this determination.

- Approved dosage formulations include sprays, oils, lotions, creams, gels, butters, pastes, ointments, and sticks. Further information is needed regarding powders before they can be considered.

- The maximum SPF will be increased from 50+ to 60+.

- Sunscreens with an SPF of 15 or higher are required to provide broad-spectrum protection commensurate with the SPF, expanding on critical wavelength testing.

- There are new labeling changes, including a requirement that active ingredients be listed on the front of the packaging.

- Sunscreen products that contain insect repellents are considered non-GRASE.

What’s next?

The process for the proposed final rule has now entered a 90-day public comment period that will end on May 27, 2019; however, it is unlikely that a final monograph as mandated by Congress will be produced by the end of this year.

Sunscreen manufacturers currently are coordinating a response to the proposed rule through the Personal Care Products Council and the Consumer Healthcare Products Association Sunscreen Task Force. It is likely that the new required testing will be costly, with estimates exceeding tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. In all likelihood, the number of active ingredients that the industry will agree to support with costly testing will be fewer than the 12 that are now on the list. It also is likely that this process will lead to fewer sunscreen products for consumers to choose from and almost certainly at a higher cost.

What do we tell patients in the meantime?

According to the FDA’s rules, it was necessary that this process was made public, but it will almost certainly concern our patients as to the safety of the sunscreen products they have been using. We should be concerned that some of our patients may limit their use of sunscreens because of safety concerns.

There is no question that, as physicians, we want to “first, do no harm,” so we should all be interested in assuring our patients that our sunscreen recommendations are safe and we support the FDA proposal for additional data. The good news is that when this process is completed, a large number of agents will likely be found to be GRASE. When the FDA finally gives its imprimatur to sunscreens, it will hopefully help to silence those naysayers who report that sunscreens are dangerous for consumers; however, it has been suggested by some in industry that the new testing required may take at least 5 years.

What should dermatologists do when we are asked, “What sunscreen should I use NOW?” For most patients, I would explain the regulatory process and assure them that the risk-benefit ratio at this point suggests they should continue using the same sunscreens that they are currently using. For special situations such as pregnant women and children, it may be best to suggest products that contain only the 2 GRASE inorganic agents.

If by now you have not had a patient ask, “Doctor, what sunscreen should I use NOW?” you will soon.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently published a press release detailing a proposed rule on how manufacturers will be required to test and label sunscreens in the United States.1,2 Although the press release was complicated and contained much information, the media specifically latched onto the FDA’s consideration of only 2 active sunscreen ingredients—zinc oxide and titanium dioxide—as generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE). In response, some patients may assume that most sunscreens on the market are dangerous.

How did this new proposed rule come about? To understand the process, it takes some explanation of the history of the FDA’s regulation of sunscreens.

How are sunscreens regulated by the FDA?

The regulatory process for sunscreens in the United States is complicated. The FDA regulates sunscreens as over-the-counter (OTC) drugs rather than as cosmetics, which is how they are regulated in most of the rest of the world.

The US sunscreen regulation process began in 1978 with an advance notice of proposed rulemaking from the FDA that included recommendations from an advisory review panel on the safe and effective use of OTC sunscreen products.3 At that time, 21 active sunscreen ingredients and their maximum use concentrations were listed and determined to be safe, or GRASE. It also gave manufacturers guidance on how to test for efficacy with the methodology for determining the sun protection factor (SPF) as well as various labeling requirements. Over the years, the FDA has issued a number of other sunscreen guidelines, such as removing padimate A and adding avobenzone and zinc oxide to the list of GRASE ingredients in the 1990s.4,5

In 1999, the FDA issued a final rule that listed 16 active sunscreen ingredients and concentrations as GRASE.6 There were some restrictions as to certain combinations of ingredients that could not be used in a finished product. Labeling requirements, including a maximum SPF of 30, also were put in place. This final rule established a final sunscreen monograph that was supposed to have been effective by 2002; however, in 2001 the agency delayed the effective date indefinitely because they had not yet established broad-spectrum (UVA) protection testing and labeling.7

The FDA published a proposed rule in 2007 as well as a final rule in 2011 that again listed the same 16 ingredients as GRASE and specified labeling and testing methods for establishing SPF, broad-spectrum protection, and water-resistance claims.8,9 The final rule limited product labels to a maximum SPF of 50+; provided directions for use with regard to other labeling elements (eg, warnings); and identified specific claims that would not be allowed on product labels, such as “waterproof” and “all-day protection.”9

Nevertheless, an effective final OTC monograph for sunscreen products has not yet been published.

What is the Sunscreen Innovation Act?

In 2014, the US Congress enacted the Sunscreen Innovation Act10 primarily to mandate that the FDA develop a more efficient way to determine the safety and efficacy of new active sunscreen ingredients that were commonly used in Europe and other parts of the world at the time. Many of these agents were thought to be more protective in the UVA and/or UVB spectrum, and if added to the list of GRASE ingredients available to US manufacturers, they would lead to the development of products that would improve the protection offered by sunscreens marketed to US consumers. The time and extent application (TEA) was established, a method that allowed manufacturers to apply for FDA approval of specific agents. The TEA also suggested allowing data generated in other countries where these agents were already in use for years to be considered in the FDA’s evaluation of the agents as GRASE. In addition, Congress mandated that a final monograph on OTC sunscreens be published by the end of 2019. A number of manufacturers have submitted TEAs for new active sunscreen ingredients, and so far, all have been rejected.

Why is the FDA interested in more safety data?

Since then, the FDA has become concerned not only with the safety and efficacy of newly proposed agents through the TEA but also with the original 16 active sunscreen ingredients listed as GRASE in the 2011 final rule. In the 1970s and 1980s, sunscreen use was limited to beach vacations or outdoor sporting events, but sun-protective behaviors have changed dramatically since that time, with health care providers now becoming cognizant of the growing threats of skin cancer and melanoma as well as the cosmetic concerns of photoaging, thereby recommending daily sunscreen use to their patients. In addition, the science behind sunscreens with higher concentrations of active ingredients intended to achieve higher and higher SPFs and their respective penetration of the skin has evolved, leading to new concerns about systemic toxicity. Early limited research frequently touted by the lay media has suggested that some of these agents might lead to hormonal changes, reproductive toxicity, and carcinogenicity.

In November 2016, the FDA issued a guidance for manufacturers that outlined the safety data that would be required to establish an OTC sunscreen active ingredient as GRASE.11 It also provided detailed information about both clinical and nonclinical safety testing, including human irritation and sensitization studies as well as human photosafety studies. In vitro dermal and systemic carcinogenicity studies and animal developmental and reproductive toxicity studies also were required as well studies regarding safety in children.

Many of these recommendations were already being utilized by manufacturers; however, one important change was the requirement for human absorption studies by a maximal usage trial, which more accurately addresses the absorption of sunscreen agents according to actual use. Such studies will be required at the highest allowable concentration of an agent in multiple vehicles and over large body surface areas for considerable exposure times.

This guidance to sunscreen manufacturers was announced to the public in a press release in May 2018.12

What are the new regulations?

All of this has culminated in the recent proposed rule, which includes several important proposals2:

- Of the 16 currently marketed active sunscreen ingredients, only 2—zinc oxide and titanium dioxide—are considered GRASE. Two ingredients—trolamine salicylate and para-aminobenzoic acid—are considered non-GRASE, but there is not enough information at this time to determine if the remaining 12 ingredients are GRASE. The FDA is working with manufacturers to obtain sufficient information to make this determination.

- Approved dosage formulations include sprays, oils, lotions, creams, gels, butters, pastes, ointments, and sticks. Further information is needed regarding powders before they can be considered.

- The maximum SPF will be increased from 50+ to 60+.

- Sunscreens with an SPF of 15 or higher are required to provide broad-spectrum protection commensurate with the SPF, expanding on critical wavelength testing.

- There are new labeling changes, including a requirement that active ingredients be listed on the front of the packaging.

- Sunscreen products that contain insect repellents are considered non-GRASE.

What’s next?

The process for the proposed final rule has now entered a 90-day public comment period that will end on May 27, 2019; however, it is unlikely that a final monograph as mandated by Congress will be produced by the end of this year.

Sunscreen manufacturers currently are coordinating a response to the proposed rule through the Personal Care Products Council and the Consumer Healthcare Products Association Sunscreen Task Force. It is likely that the new required testing will be costly, with estimates exceeding tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. In all likelihood, the number of active ingredients that the industry will agree to support with costly testing will be fewer than the 12 that are now on the list. It also is likely that this process will lead to fewer sunscreen products for consumers to choose from and almost certainly at a higher cost.

What do we tell patients in the meantime?

According to the FDA’s rules, it was necessary that this process was made public, but it will almost certainly concern our patients as to the safety of the sunscreen products they have been using. We should be concerned that some of our patients may limit their use of sunscreens because of safety concerns.

There is no question that, as physicians, we want to “first, do no harm,” so we should all be interested in assuring our patients that our sunscreen recommendations are safe and we support the FDA proposal for additional data. The good news is that when this process is completed, a large number of agents will likely be found to be GRASE. When the FDA finally gives its imprimatur to sunscreens, it will hopefully help to silence those naysayers who report that sunscreens are dangerous for consumers; however, it has been suggested by some in industry that the new testing required may take at least 5 years.

What should dermatologists do when we are asked, “What sunscreen should I use NOW?” For most patients, I would explain the regulatory process and assure them that the risk-benefit ratio at this point suggests they should continue using the same sunscreens that they are currently using. For special situations such as pregnant women and children, it may be best to suggest products that contain only the 2 GRASE inorganic agents.

- FDA advances new proposed regulation to make sure that sunscreens are safe and effective [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; February 21, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm631736.htm. Accessed April 4, 2019.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Registr. 2019;84(38):6204-6275. To be codified at 21 CFR §201, 310, 347, and 352.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Registr. 1978;43(166):38206-38269. To be codified at 21 CFR §352.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; amendment to the tentative final monograph. Fed Registr. 1996;60(180):48645-48655. To be codified at 21 CFR §352.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; amendment to the tentative final monograph; enforcement policy. Fed Registr. 1998;63(204):56584-56589. To be codified at 21 CFR §352.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; final monograph. Fed Registr. 1999;64(98):27666-27693. To be codified at 21 CFR §310, 352, 700, and 740.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; final monograph; partial stay; final rule. Fed Registr. 2001;66:67485-67487. To be codified at 21 CFR §352.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; proposed amendment of final monograph. Fed Registr. 2007;72(165):49069-49122. To be codified at 21 CFR §347 and 352.

- Labeling and effectiveness testing; sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Registr. 2011;76(117):35619-35665. To be codified at 21 CFR §201 and 310.

- Sunscreen Innovation Act, S 2141, 113th Cong, 2nd Sess (2014).

- Nonprescription sunscreen drug products-safety and effectiveness data; guidance for industry; availability. Fed Registr. 2016;81(226):84594-84595.

- Statement from Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, on new FDA actions to keep consumers safe from the harmful effects of sun exposure, and ensure the long-term safety and benefits of sunscreens [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; May 22, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm608499.htm. Accessed April 5, 2019.

- FDA advances new proposed regulation to make sure that sunscreens are safe and effective [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; February 21, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm631736.htm. Accessed April 4, 2019.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Registr. 2019;84(38):6204-6275. To be codified at 21 CFR §201, 310, 347, and 352.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Registr. 1978;43(166):38206-38269. To be codified at 21 CFR §352.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; amendment to the tentative final monograph. Fed Registr. 1996;60(180):48645-48655. To be codified at 21 CFR §352.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; amendment to the tentative final monograph; enforcement policy. Fed Registr. 1998;63(204):56584-56589. To be codified at 21 CFR §352.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; final monograph. Fed Registr. 1999;64(98):27666-27693. To be codified at 21 CFR §310, 352, 700, and 740.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; final monograph; partial stay; final rule. Fed Registr. 2001;66:67485-67487. To be codified at 21 CFR §352.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; proposed amendment of final monograph. Fed Registr. 2007;72(165):49069-49122. To be codified at 21 CFR §347 and 352.

- Labeling and effectiveness testing; sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Registr. 2011;76(117):35619-35665. To be codified at 21 CFR §201 and 310.

- Sunscreen Innovation Act, S 2141, 113th Cong, 2nd Sess (2014).

- Nonprescription sunscreen drug products-safety and effectiveness data; guidance for industry; availability. Fed Registr. 2016;81(226):84594-84595.

- Statement from Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, on new FDA actions to keep consumers safe from the harmful effects of sun exposure, and ensure the long-term safety and benefits of sunscreens [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; May 22, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm608499.htm. Accessed April 5, 2019.

Role of Diet in Treating Skin Conditions

Nail Irregularities Associated With Sézary Syndrome

Sézary syndrome (SS) is an advanced leukemic form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) that is characterized by generalized erythroderma and T-cell leukemia. Skin changes can include erythroderma, keratosis pilaris–like lesions, keratoderma, ectropion, alopecia, and nail changes.1 Nail changes in SS patients frequently are overlooked and underreported; they vary greatly from patient to patient, and their incidence has not been widely evaluated in the literature.

In this retrospective study, we reviewed medical records from a previously collected CTCL clinic database at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, Texas) and found nail abnormalities in 36 of 83 (43.4%) patients with a diagnosis of SS. Findings for 2 select cases are described in more detail; they were compared to prior case reports from the literature to establish a comprehensive list of nail irregularities that have been associated with SS.

Methods

We examined records from a previously collected CTCL clinic database at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. This database was part of an institutional review board–approved protocol to prospectively collect data from patients with CTCL. Our search yielded 83 patients with SS who were seen between 2007 and 2014.

Results

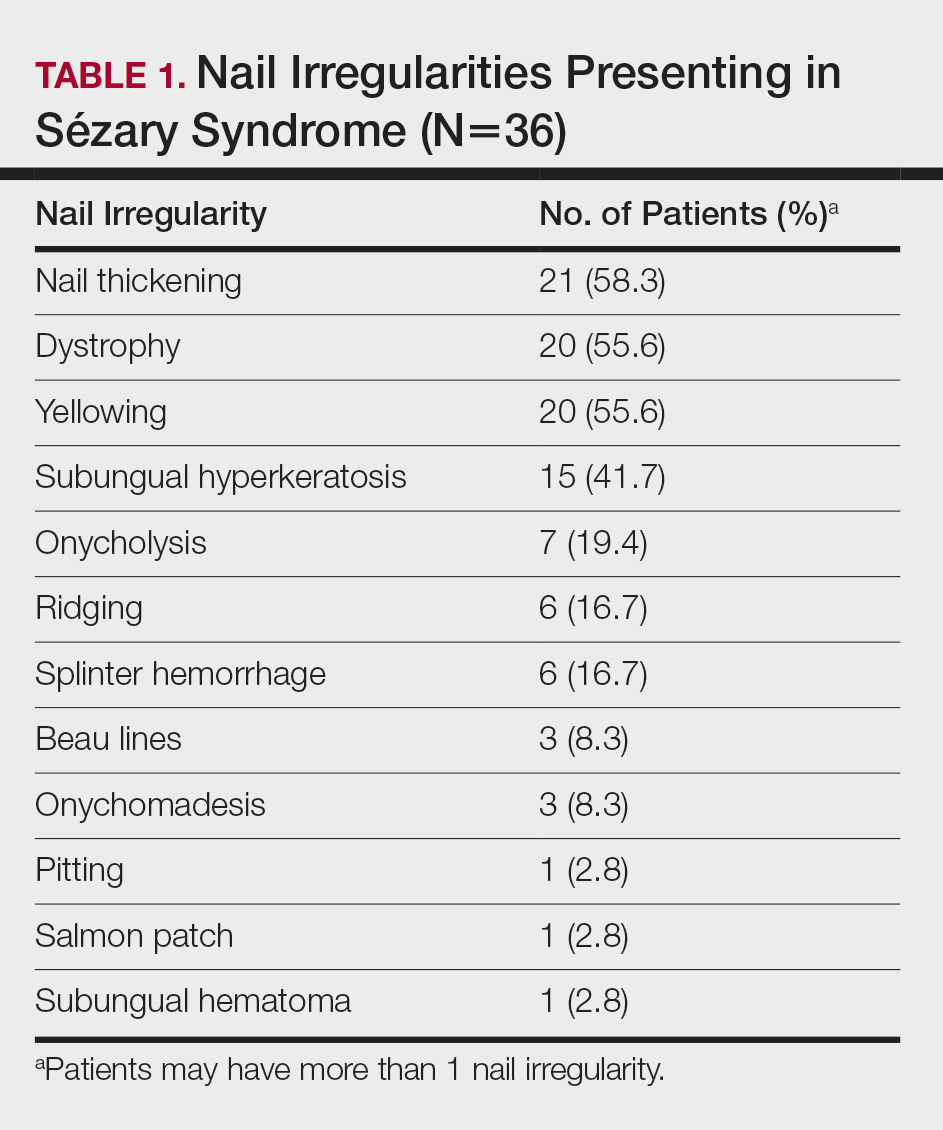

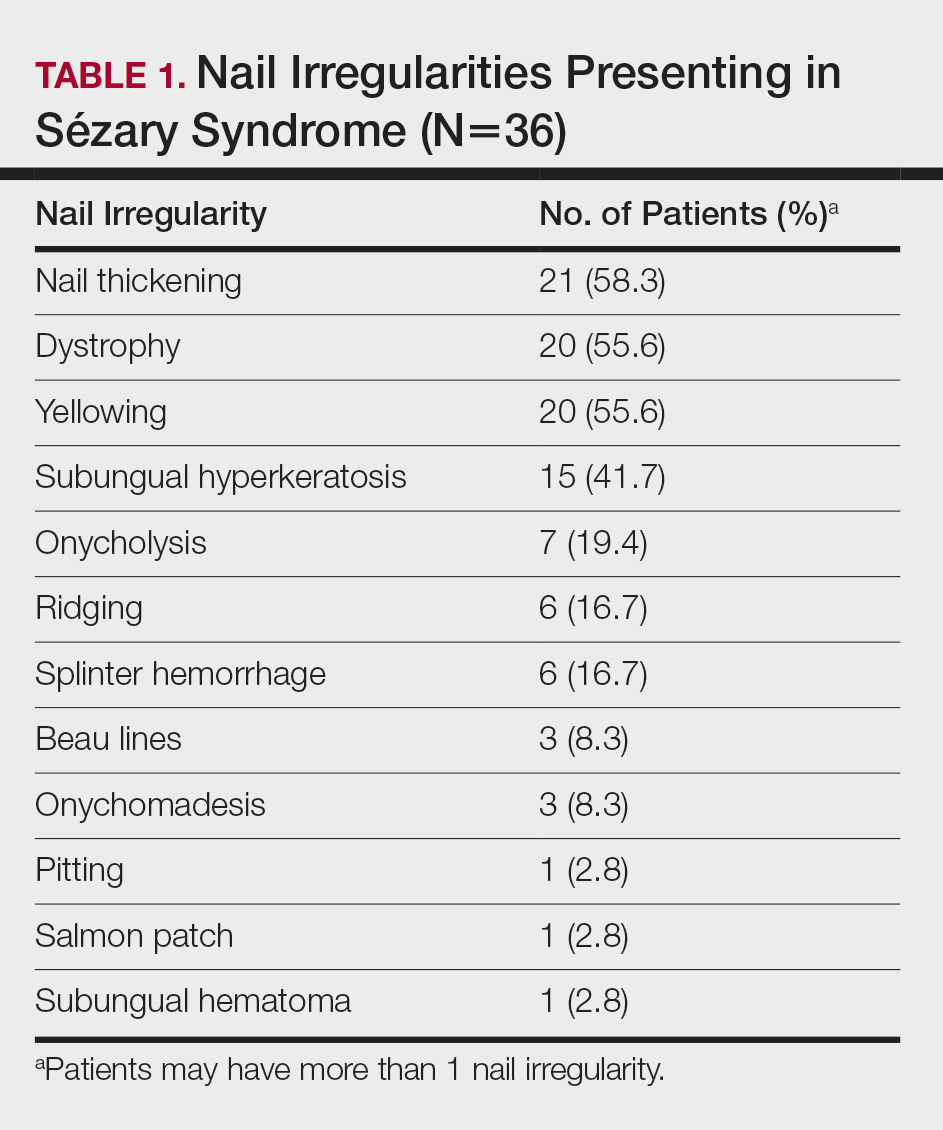

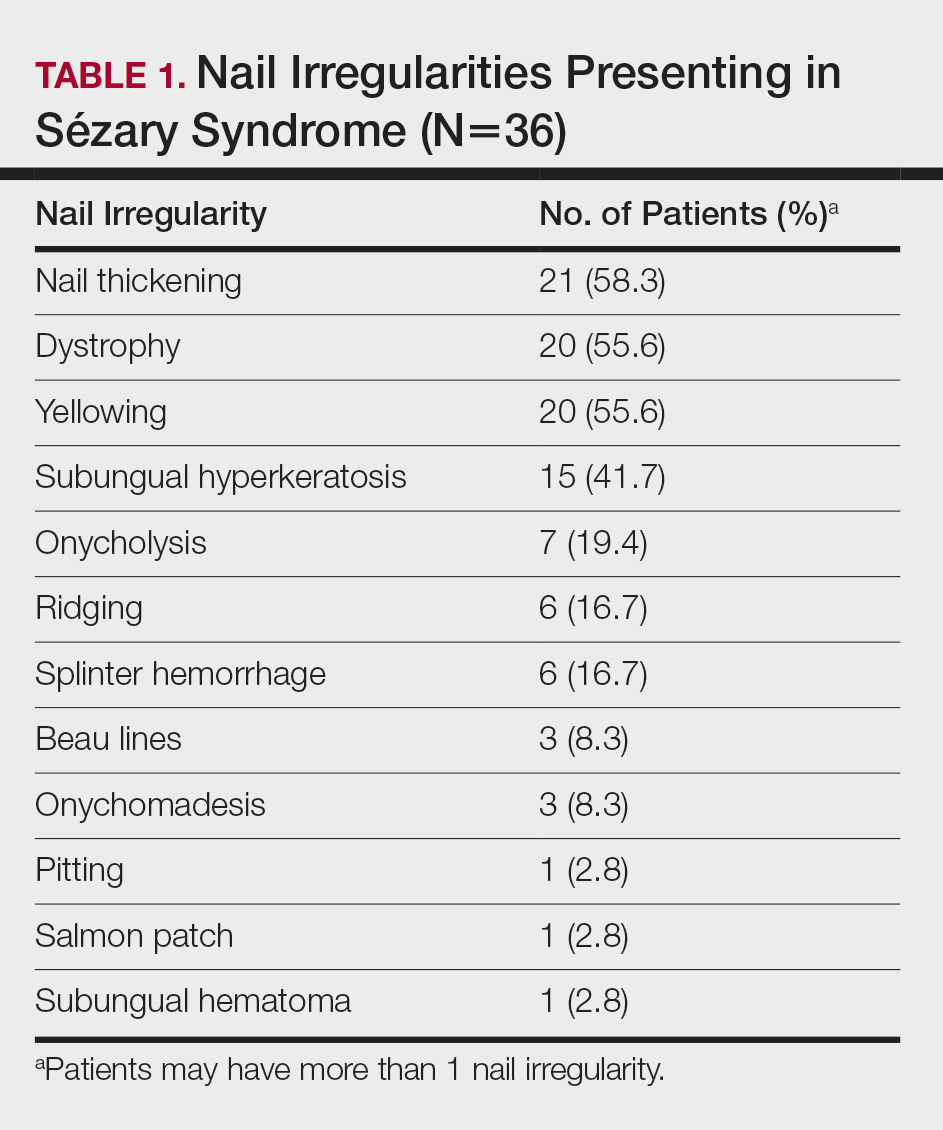

Of the 83 cases reviewed from the CTCL database, 36 (43.4%) SS patients reported at least 1 nail abnormality on the fingernails or toenails. Patients ranged in age from 59 to 85 years and included 27 (75%) men and 9 (25%) women. Nail irregularities noted on physical examination are summarized in Table 1. More than half of the patients presented with nail thickening (58.3% [21/36]), dystrophy (55.6% [20/36]), or yellowing (55.6% [20/36]) of 1 or more nails. Other findings included 15 (41.7%) patients with subungual hyperkeratosis, 3 (8.3%) with Beau lines, and 1 (2.8%) with multiple oil spots consistent with salmon patches. Five (13.9%) patients had only 1 reported nail irregularity, and 1 (2.8%) patient had 6 irregularities. The average number of nail abnormalities per patient was 2.88 (range, 1–6). We selected 2 patients with extensive nail findings who represent the spectrum of nail findings in patients with SS.

Patient 1

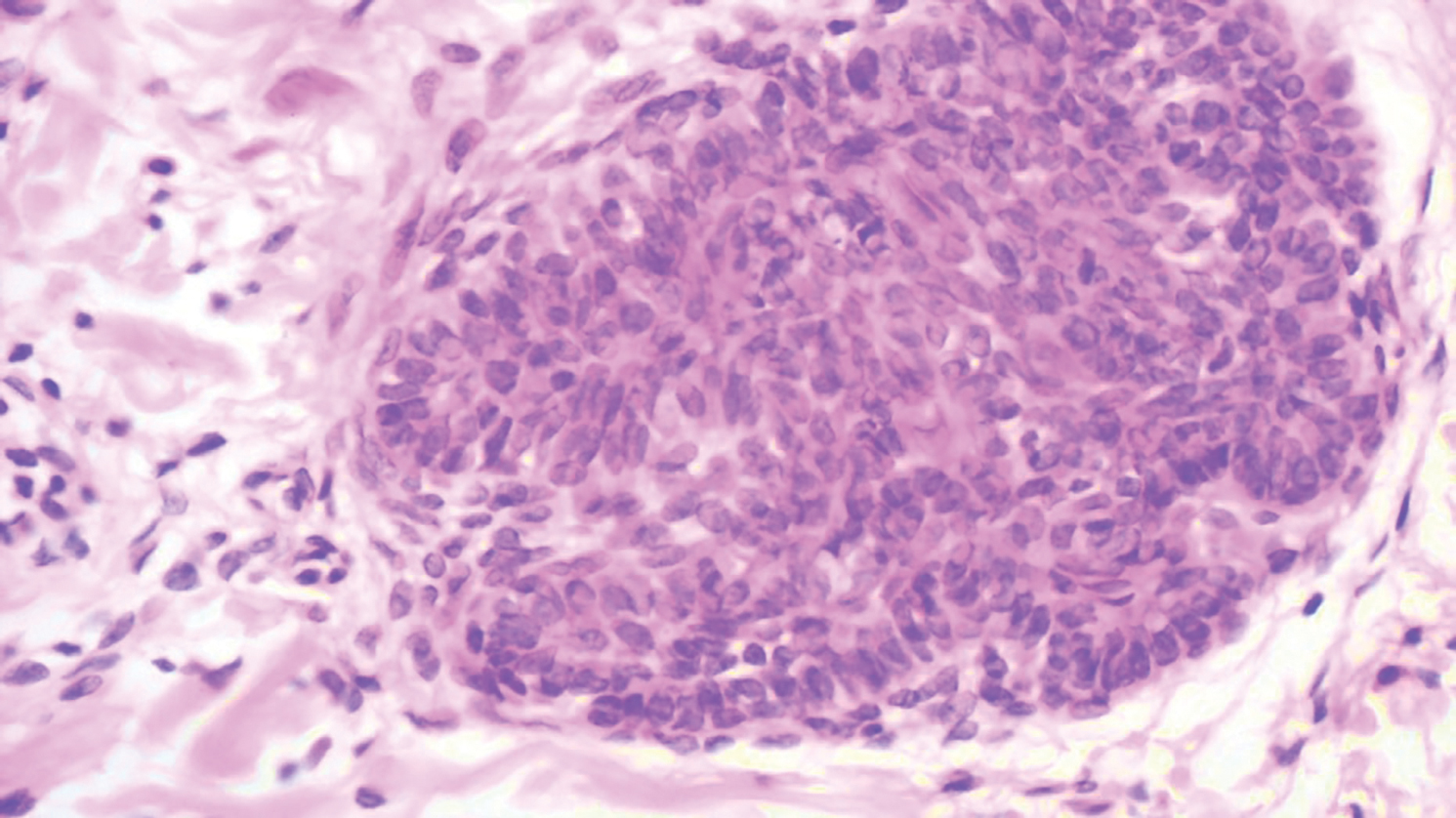

A 71-year-old white man presented with a papular rash of 30 years’ duration. The eruption first occurred on the soles of the feet but progressed to generalized erythroderma. He was found to be colonized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Over the next 9 months, the patient was diagnosed with SS at an outside institution and was treated with cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, gemcitabine, etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, cisplatin, topical steroids, and intravenous methotrexate with no apparent improvement. At presentation to our institution, physical examination revealed pruritus; alopecia; generalized lymphadenopathy; erythroderma; and irregular nail findings, including yellowing, thickened fingernails and toenails with subungual debris, and splinter hemorrhage (Figure 1). A thick plaque with perioral distribution as well as erosions on the face and feet were noted. The total body surface area (BSA) affected was 100% (patches, 91%; plaques, 9%).

At diagnosis at our institution, the patient’s white blood cell (WBC) count was 17,800/µL (reference range, 4000–11,000/µL), with 11% Sézary cells noted. Biopsy of a lymph node from the inguinal area indicated T-cell lymphoma with clonal T-cell receptor (TCR) β gene rearrangement. Biopsy of lesional skin in the right groin area showed an atypical T-cell lymphocytic infiltrate with a CD4:CD8 ratio of 2.9:1 and partial loss of CD7 expression, consistent with mycosis fungoides (MF)/SS stage IVA. At presentation to our institution, the WBC count was 12,700/µL with a neutrophil count of 47% (reference range, 42%–66%), lymphocyte count of 36% (reference range, 24%–44%), monocyte count of 4% (reference range, 2%–7%), platelet count of 427,000/µL (reference range, 150,000–350,000/µL), hemoglobin of 9.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), and lactate dehydrogenase of 733 U/L (reference range, 135–214 U/L). Lymphocytes were positive for CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD25, CD52, TCRα, TCRβ, and TCR VB17; partial for CD26; and negative for CD7, CD8, and CD57. At follow-up 1 month later, the CD4+CD26− T-cell population was 56%, which was consistent with SS T-cell lymphoma.

Skin scrapings from the generalized keratoderma on the patient’s feet were positive for fungal hyphae under potassium hydroxide examination. Nail clippings showed compact keratin with periodic acid–Schiff–positive small yeast forms admixed with bacterial organisms, consistent with onychomycosis. At our institution, the patient received extracorporeal photopheresis, whirlpool therapy (a type of hydrotherapy), steroid wet wraps, and intravenous vancomycin for methicillin-resistant S aureus. He also received bexarotene, levothyroxine sodium, and fenofibrate. After antibiotics and 2 sessions of photopheresis, the total BSA improved from 100% to 33%. The feet and nails were treated with ciclopirox gel and terbinafine, but neither the keratoderma nor the nails improved.

Patient 2

An 84-year-old white man with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia also was diagnosed with SS at an outside institution. One year later, he presented to our institution with mild pruritus and swelling of the lower left leg, which was diagnosed as deep vein thrombosis. There was bilateral scaling of the palms, with fissures present on the left palm. The fingernails showed dystrophy with Beau lines, and the toenails were dystrophic with onycholysis on the bilateral great toes (Figure 2). Patches were noted on most of the body, including the feet, with plaques limited to the hands; the total BSA affected was 80%. Flow cytometry showed an elevated Sézary cell count (CD4+CD26−) of 4700 cells/µL. Complete blood cell count with differential included a hemoglobin level of 11.4 g/dL, hematocrit level of 35.3% (reference range, 37%–47%), a platelet count of 217,000/µL, and a WBC count of 17,7

the bilateral great toes.

Comment

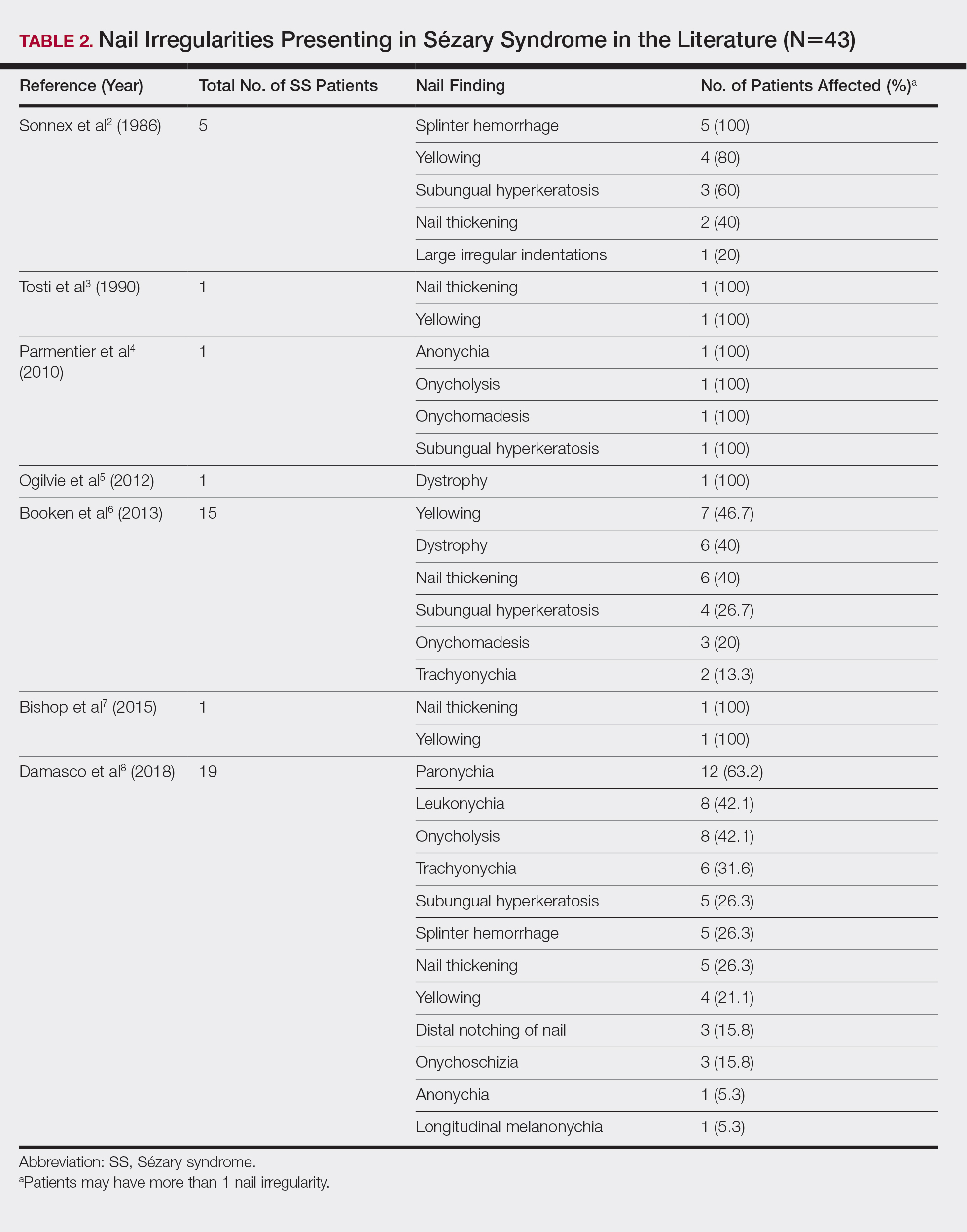

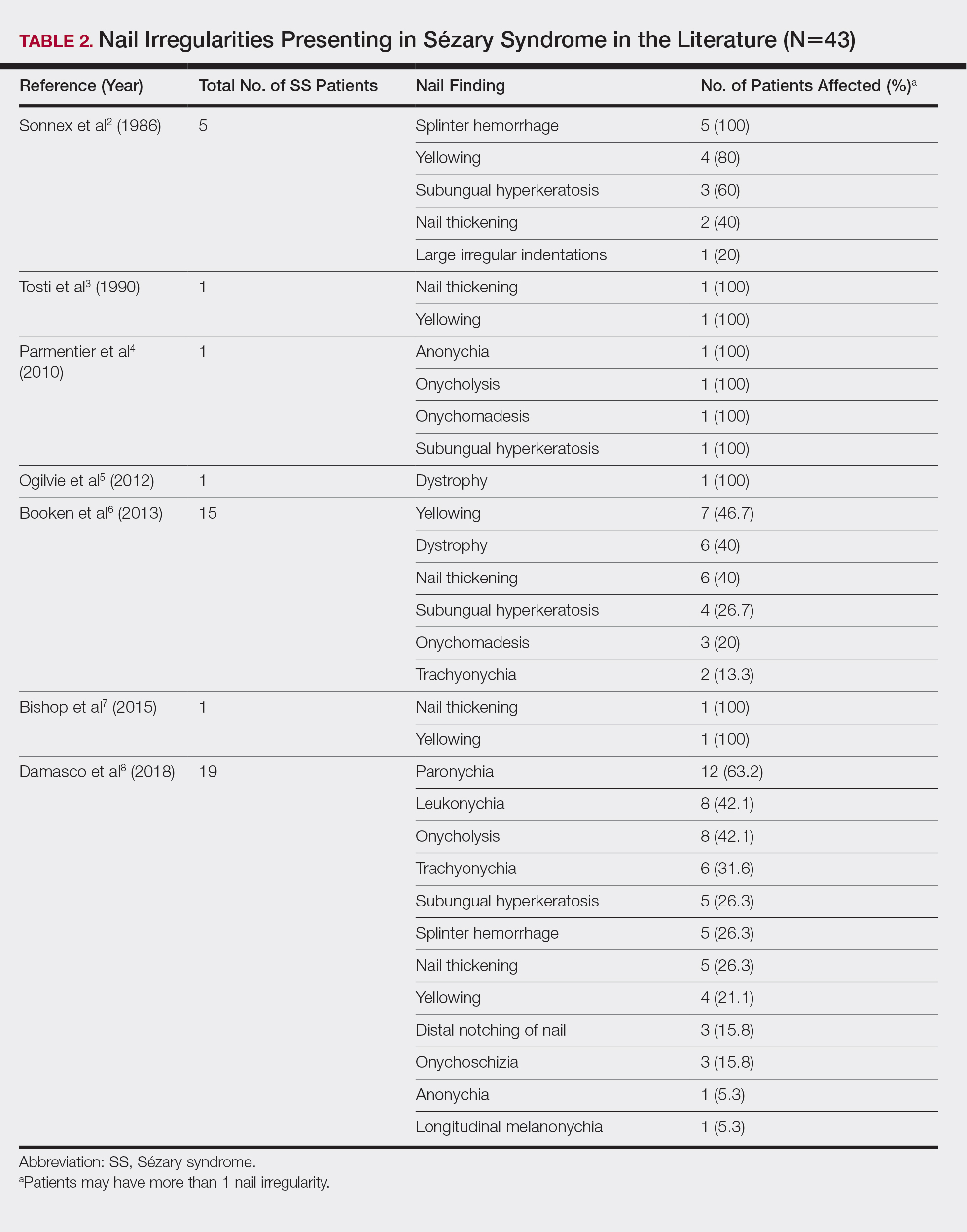

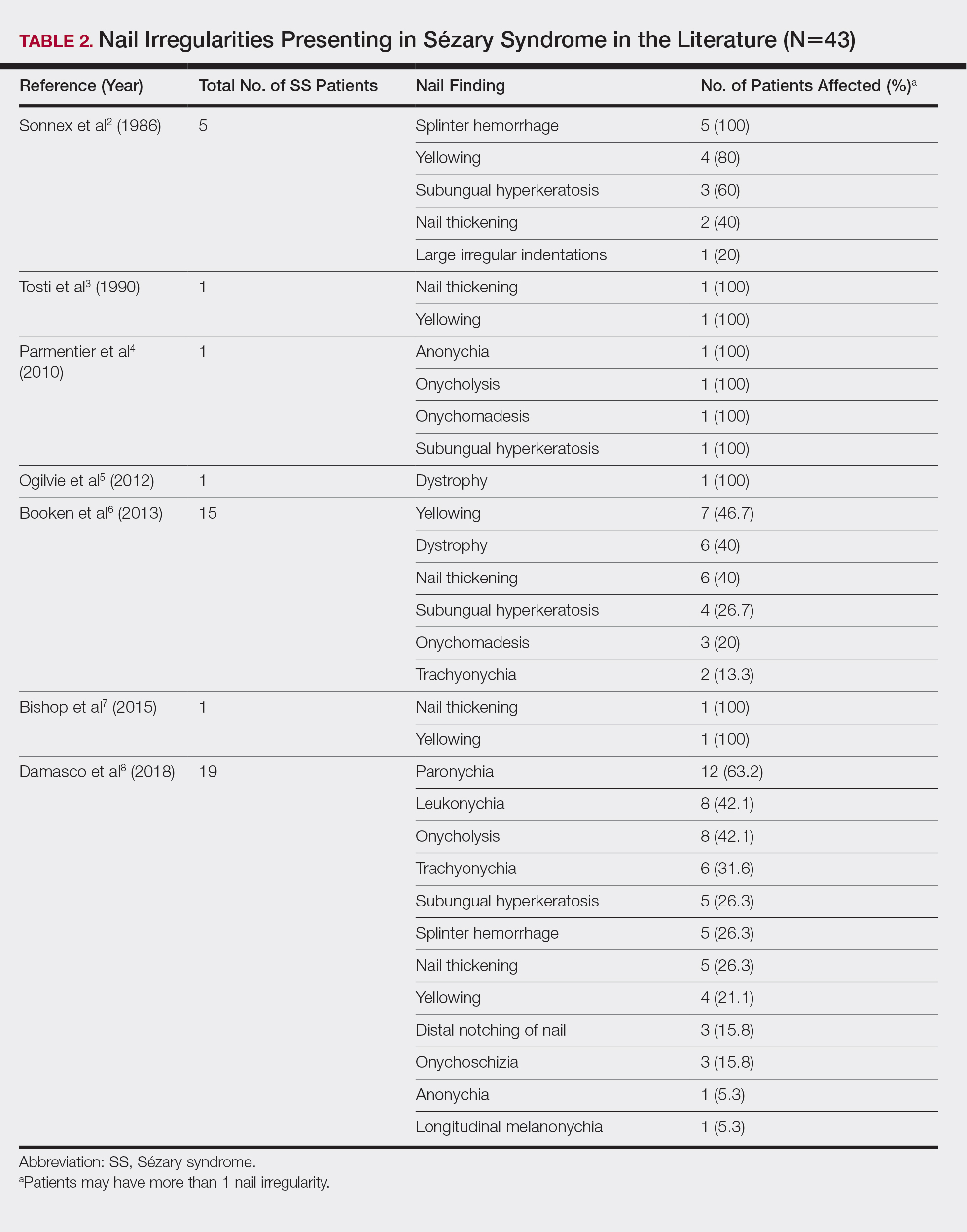

Nail changes are found in many cases of advanced-stage SS but rarely have been reported in the literature. A literature review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the search terms Sézary, nail, onychodystrophy, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and CTCL. All results were reviewed for original reported cases of SS with at least 1 reported nail finding. A total of 7 reports2-8 met these requirements with a total of 43 SS patients with reported nail findings, which are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Our findings are generally consistent with those previously described in the literature. Nail thickening, yellowing, subungual hyperkeratosis, dystrophy, and onycholysis are consistently some of the most common nail findings in patients with SS. In 2012, Martin and Duvic9 found that 52.9% (45/85) of SS patients with keratoderma on physical examination were positive for dermatophyte hyphae when skin scrapings were done under potassium hydroxide examination, a considerably greater incidence than in the general population (10%–20%). The nail changes seen in our SS patients were identical to those found in dermatophyte infections, including discoloration, subungual debris, nail thickening, onycholysis, and dystrophy.10 In patient 1, nail clippings were positive for onychomycosis, a common nail condition that is especially prevalent in older or immunocompromised patients.9,10

Interestingly, findings not observed in the literature included salmon patches and Beau lines. Beau lines are horizontal depressions in the nail plate and often are indicative of temporary interruption of nail growth, such as due to an underlying disease process, severe illness, and/or chemotherapy.11,12 In our review, patient 2 had clinical findings of Beau lines. Because the average time for fingernail regrowth is 3 to 6 months,13 it is reasonable to assume that physical findings associated with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab chemotherapy treatment would no longer be demonstrated 11 months after completion of therapy. On the other hand, paronychia was frequently observed by Damasco et al8 (63.2% [12/19] of their cases), yet it was not found in our database or the other literature reports we reviewed. Perhaps these differences are due to differences in patient populations and/or available therapies, lack of documentation, or small sample size and limited reports in the literature.

A common question is: Are the nail irregularities caused by the physical symptoms of advanced CTCL or by the underlying disease process in response to the atypical T cells? Erythroderma has been speculated to cause many of the clinical findings of nail abnormalities found in CTCL patients.2,3 However, Fleming et al14 described an MF patient who experienced onychomadesis without erythroderma, which suggests that a different mechanism may cause these nail changes. The wide range of nail abnormalities in CTCL can cause problems with diagnosing the specific cause underlying the nail alteration.

To further complicate the issue, numerous therapies for CTCL also may cause nail changes, such as the previously described Beau lines. In 2010, Parmentier et al4 reported a patient with nail alterations that had been present for more than 1 year, with 9 of 10 fingernails demonstrating anonychia, onychomadesis, subungual distal hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis. In this case report, the authors were able to exclude phototherapy as the cause of onycholysis (visible separation of the nail plate from the nail bed) and other clinical nail findings in the SS patient based on the onset of nail changes prior to beginning psoralen plus UVA therapy and complete sparing of 1 finger.4 The findings in our patient 1, who had no history of psoralen plus UVA therapy at the time the irregular nail findings presented, supports this observation. Total skin electron beam therapy for MF also has been reported to cause temporary nail stasis and thus must be taken into account when considering nail changes in patients with MF/SS.15

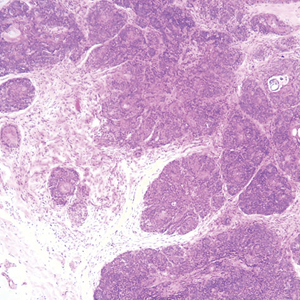

A nail matrix biopsy may provide clues to the definitive cause of the clinically observed nail changes; however, this procedure typically is not performed due to patient concerns of postoperative complications including pain and nail dystrophy.16 Histopathology features were similar in reported nail biopsies of 2 SS patients.3,4 Tosti et al3 reported that longitudinal biopsy showed a dense lymphocytic infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes with involuted nuclei and notable epidermotropism. Parmentier et al4 reported a longitudinal nail biopsy in an SS patient that presented with atypical lymphocytes, epidermotropism, and Pautrier microabscess formation. Immunostaining showed CD3 positivity within the distal nail matrix, nail bed, and hyponychium. One-third of the cells stained positive for CD4, while the majority stained positive for CD8. Most notably, the skin, nails, and blood showed identical clonal rearrangement of TCRγ.4 Nail matrix biopsies in MF patients rarely have been reported in the literature, but those that are available show similar features to those seen in SS patients. Harland et al17 summarized the findings of 4 case reports of CTCL patients that included nail biopsies by stating, “[a]ll histopathologic findings from nail biopsies showed a dense subepithelial infiltrate of lymphocytes with marked epitheliotropism.” These histopathologic abnormalities are akin to skin biopsies in MF patients, thus providing an essential link to the disease state of MF and the nail abnormalities found within SS patients.

Treatment of the nail problems found within SS is challenging due to limited research. Parmentier et al4 noted an SS patient who was treated with topical mechlorethamine applied directly to the nail. In this case, topical mechlorethamine was effective at treating onychomadesis, subungual distal hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis within 6 months.4 Another SS patient, who presented with thickening and yellowing of the nail, had reported a proximal nail plate that resolved after chemotherapy. The patient did not survive long enough to note complete improvement of the nail.3 In our study, patient 1 was treated with ciclopirox gel and terbinafine, which did not result in nail improvement. Nail treatments in SS patients have yet to show much improvement and thus need more research and focus in the literature.

Conclusion

Sézary syndrome is a rare CTCL that can present with clinical features that may be mistaken for other diseases. Nail abnormalities in SS patients may be related to fungal involvement, medical therapy, or the underlying disease process of SS. We report one of the largest populations of SS patients with specific reported nail abnormalities, thus expanding the possibilities of nail changes that accompany the disease. Continued research and studies involving SS can provide a better understanding of nail involvement and successful treatment of these clinical findings.

- Willemz e R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Sonnex TS, Dawber RP, Zachary CB, et al. The nails in adult type 1 pityriasis rubra pilaris. a comparison with Sézary syndrome and psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(5 pt 1):956-960.

- Tosti A, Fanti PA, Varotti C. Massive lymphomatous nail involvement in Sézary syndrome. Dermatologica. 1990;181:162-164.

- Parmentier L, Durr C, Vassella E, et al. Specific nail alterations in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: successful treatment with topical mechlorethamine. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1287-1291.

- Ogilvie C, Jackson R, Leach M, et al. Sézary syndrome: diagnosis and management. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2012;42:317-321.

- Booken N, Nicolay JP, Weiss C, et al. Cutaneous tumor cell load correlates with survival in patients with Sézary syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:67-79.

- Bishop BE, Wulkan A, Kerdel F, et al. Nail alterations in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a case series and review of nail manifestations. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015;1:82-86.

- Damasco FM, Geskin L, Akilov OE. Onychodystrophy in Sézary syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:972-973.

- Martin SJ, Duvic M. Prevalence and treatment of palmoplantar keratoderma and tinea pedis in patients with Sézary syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1195-1198.

- Mayo TT, Cantrell W. Putting onychomycosis under the microscope. Nurse Pract. 2014;39:8-11.

- Singh M, Kaur S. Chemotherapy-induced multiple Beau’s lines. Int J Dermatol. 1986;25:590-591.

- Tully AS, Trayes KP, Studdiford JS. Evaluation of nail abnormalities. Am Family Physician. 2012;85:779-787.

- Shirwaikar AA, Thomas T, Shirwaikar A, et al. Treatment of onychomycosis: an update. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2008;70:710-714.

- Fleming CJ, Hunt MJ, Barnetson RS. Mycosis fungoides with onychomadesis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:1012-1013.

- Jones GW, Kacinski BM, Wilson LD, et al. Total skin electron radiation in the management of mycosis fungoides: consensus of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Cutaneous Lymphoma Project Group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:364-370.

- Haneke E. Advanced nail surgery. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2011;4:167-175.

- Harland E, Dalle S, Balme B, et al. Ungueotropic T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1071-1073.

Sézary syndrome (SS) is an advanced leukemic form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) that is characterized by generalized erythroderma and T-cell leukemia. Skin changes can include erythroderma, keratosis pilaris–like lesions, keratoderma, ectropion, alopecia, and nail changes.1 Nail changes in SS patients frequently are overlooked and underreported; they vary greatly from patient to patient, and their incidence has not been widely evaluated in the literature.

In this retrospective study, we reviewed medical records from a previously collected CTCL clinic database at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, Texas) and found nail abnormalities in 36 of 83 (43.4%) patients with a diagnosis of SS. Findings for 2 select cases are described in more detail; they were compared to prior case reports from the literature to establish a comprehensive list of nail irregularities that have been associated with SS.

Methods

We examined records from a previously collected CTCL clinic database at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. This database was part of an institutional review board–approved protocol to prospectively collect data from patients with CTCL. Our search yielded 83 patients with SS who were seen between 2007 and 2014.

Results

Of the 83 cases reviewed from the CTCL database, 36 (43.4%) SS patients reported at least 1 nail abnormality on the fingernails or toenails. Patients ranged in age from 59 to 85 years and included 27 (75%) men and 9 (25%) women. Nail irregularities noted on physical examination are summarized in Table 1. More than half of the patients presented with nail thickening (58.3% [21/36]), dystrophy (55.6% [20/36]), or yellowing (55.6% [20/36]) of 1 or more nails. Other findings included 15 (41.7%) patients with subungual hyperkeratosis, 3 (8.3%) with Beau lines, and 1 (2.8%) with multiple oil spots consistent with salmon patches. Five (13.9%) patients had only 1 reported nail irregularity, and 1 (2.8%) patient had 6 irregularities. The average number of nail abnormalities per patient was 2.88 (range, 1–6). We selected 2 patients with extensive nail findings who represent the spectrum of nail findings in patients with SS.

Patient 1

A 71-year-old white man presented with a papular rash of 30 years’ duration. The eruption first occurred on the soles of the feet but progressed to generalized erythroderma. He was found to be colonized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Over the next 9 months, the patient was diagnosed with SS at an outside institution and was treated with cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, gemcitabine, etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, cisplatin, topical steroids, and intravenous methotrexate with no apparent improvement. At presentation to our institution, physical examination revealed pruritus; alopecia; generalized lymphadenopathy; erythroderma; and irregular nail findings, including yellowing, thickened fingernails and toenails with subungual debris, and splinter hemorrhage (Figure 1). A thick plaque with perioral distribution as well as erosions on the face and feet were noted. The total body surface area (BSA) affected was 100% (patches, 91%; plaques, 9%).