User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Basal Cell Carcinoma Masquerading as a Dermoid Cyst and Bursitis of the Knee

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequently diagnosed skin cancer in the United States. It develops most often on sun-exposed skin, including the face and neck. Although BCCs are slow-growing tumors that rarely metastasize, they can cause notable local destruction with disfigurement if neglected or inadequately treated. Basal cell carcinoma arising on the legs is relatively uncommon.1,2 We present an interesting case of delayed diagnosis of BCC on the left knee due to earlier misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man with no history of skin cancer presented with a painful growing tumor on the left knee of approximately 2 years’ duration. The patient’s primary care physician as well as a general surgeon initially diagnosed it as a dermoid cyst and bursitis. The nodule failed to respond to conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and continued to grow until it began to ulcerate. Concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, the patient’s primary care physician referred him to the emergency department. He was subsequently sent to the dermatology clinic.

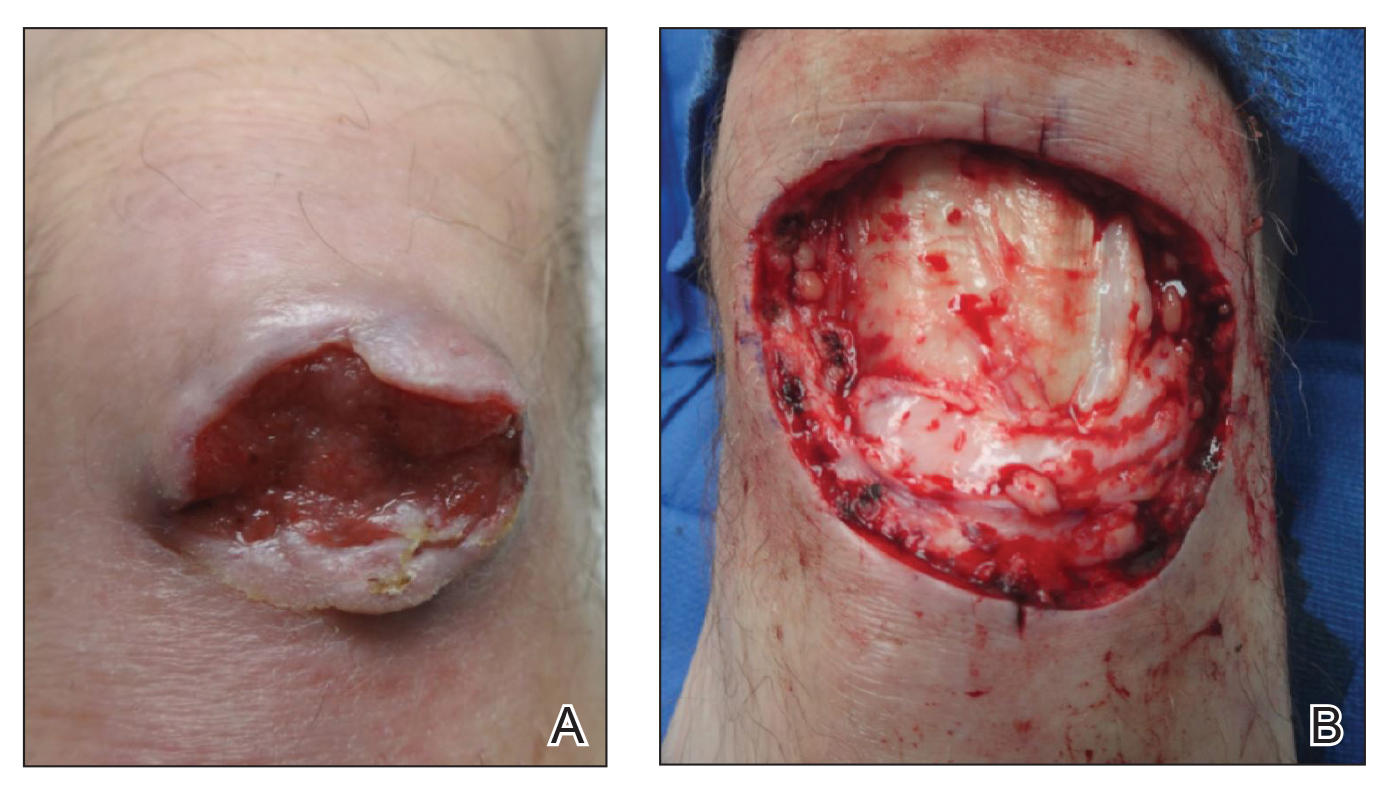

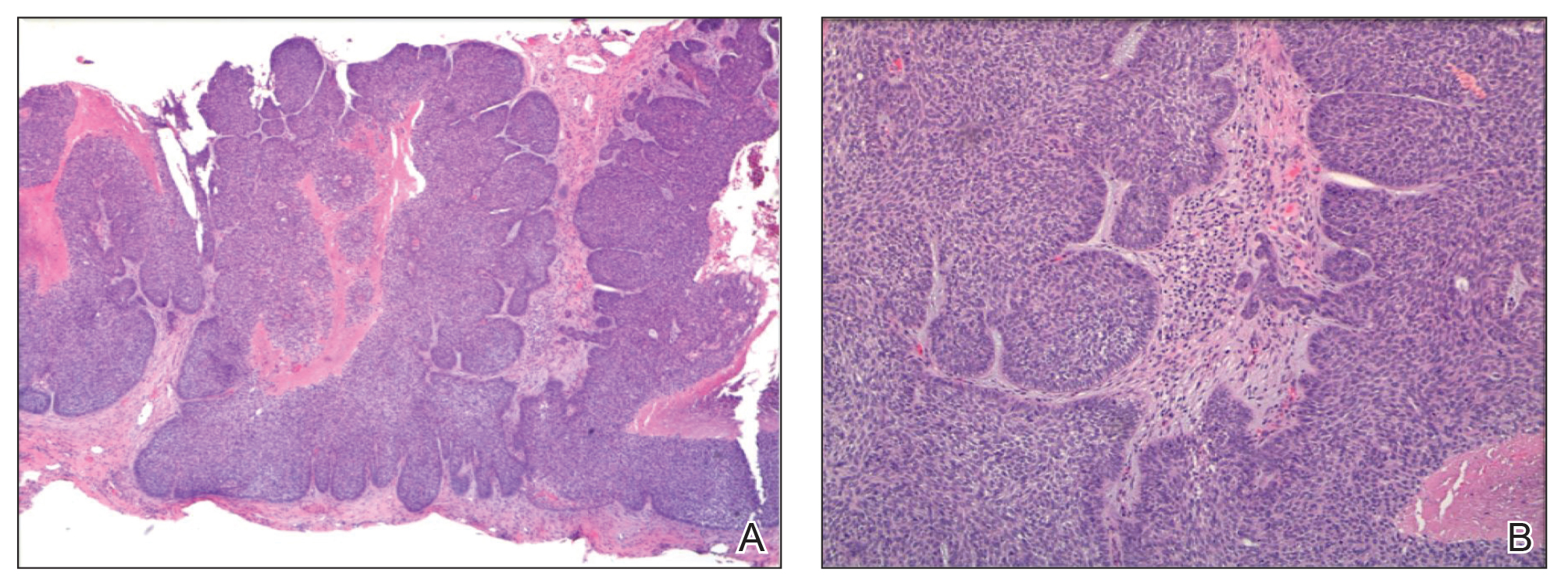

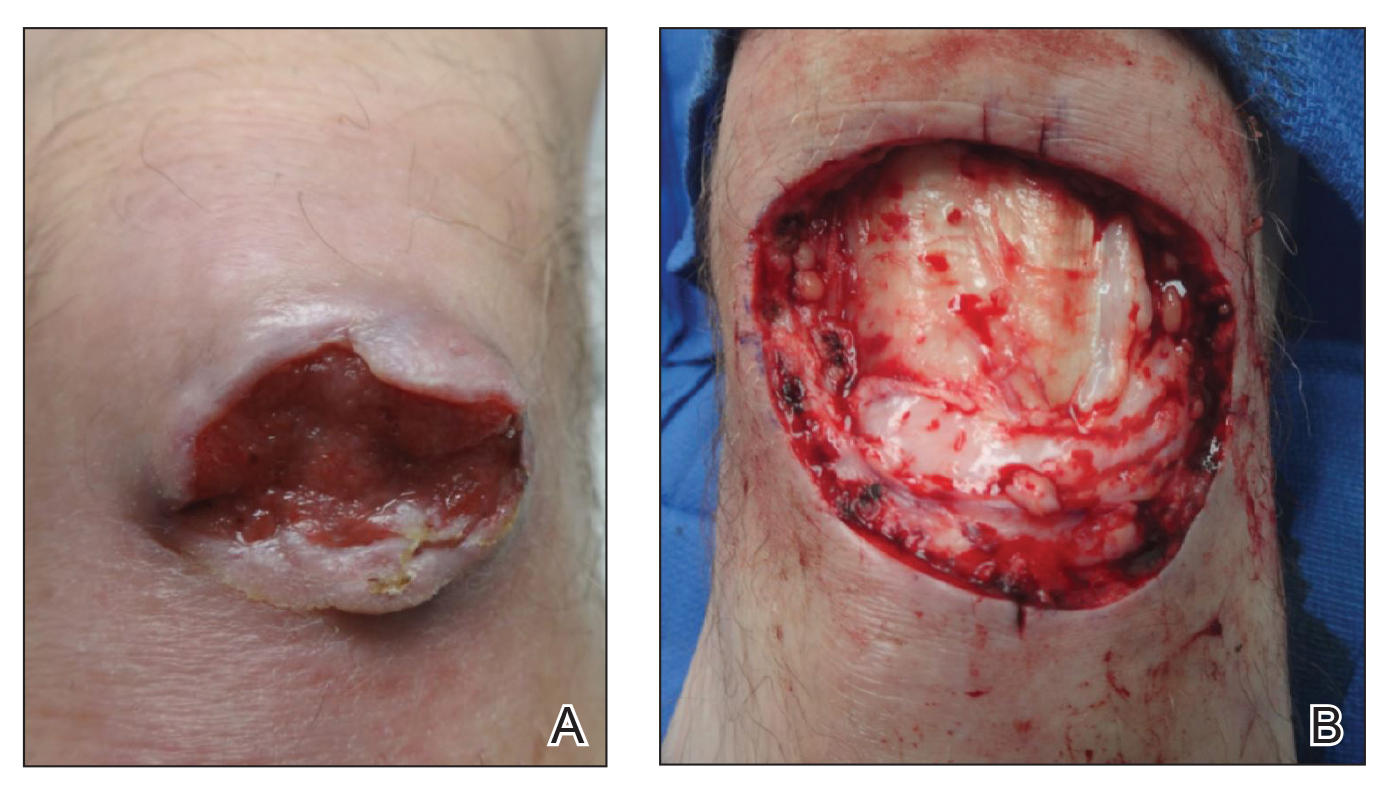

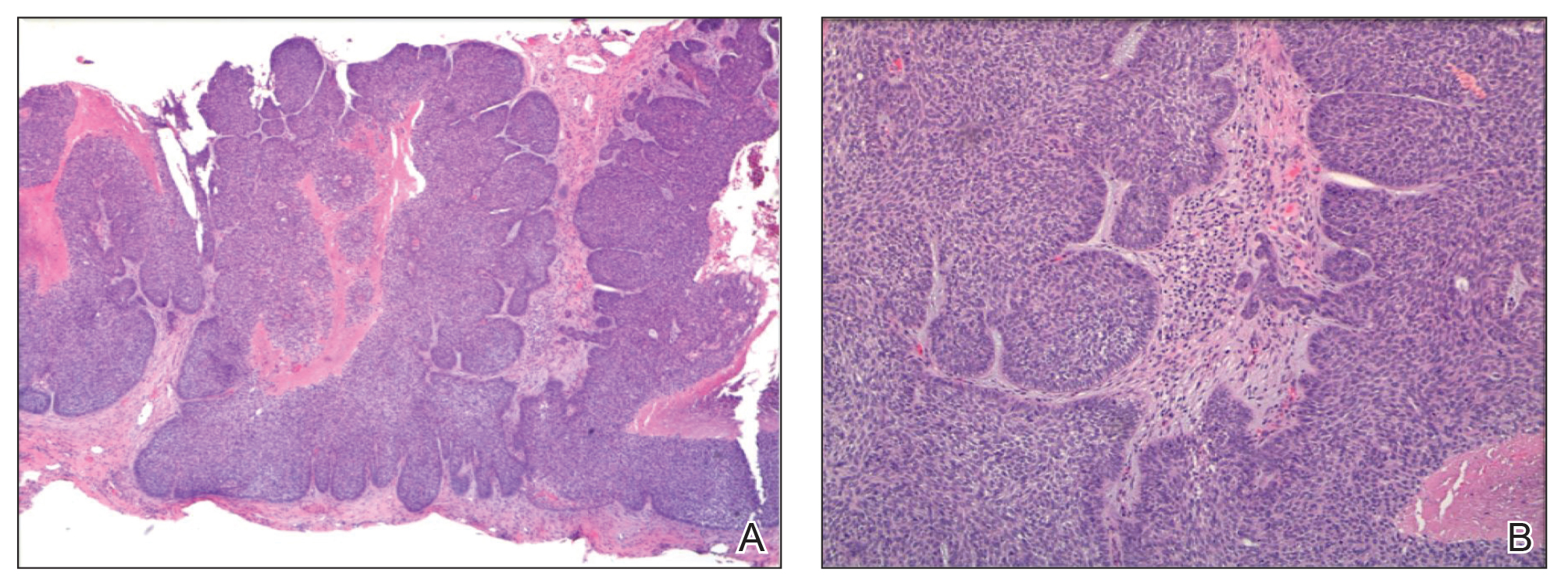

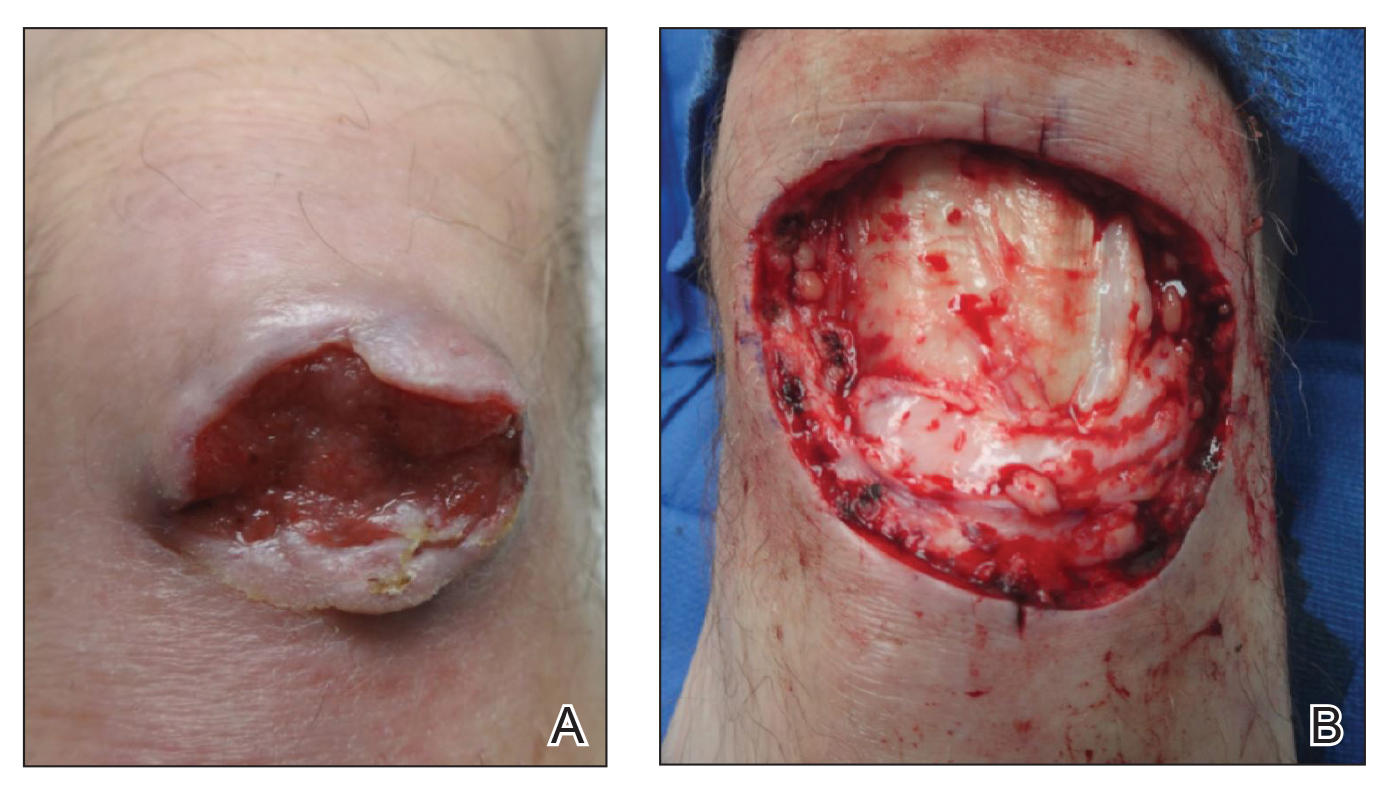

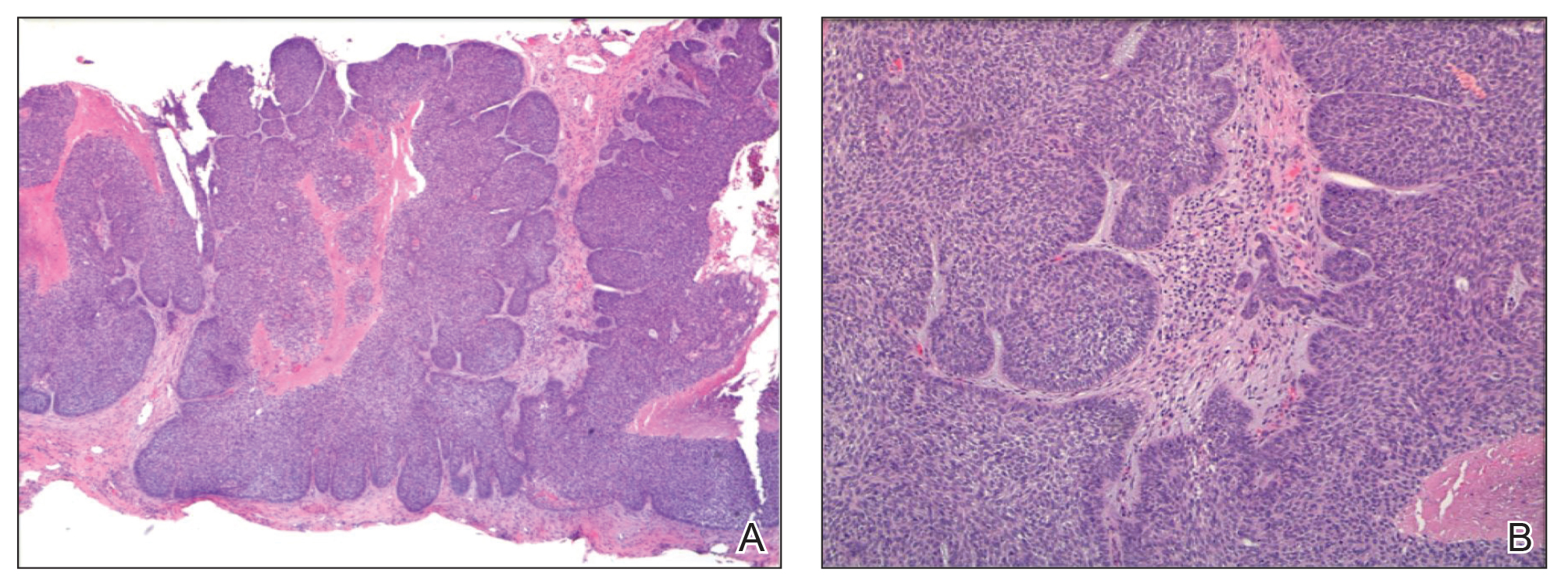

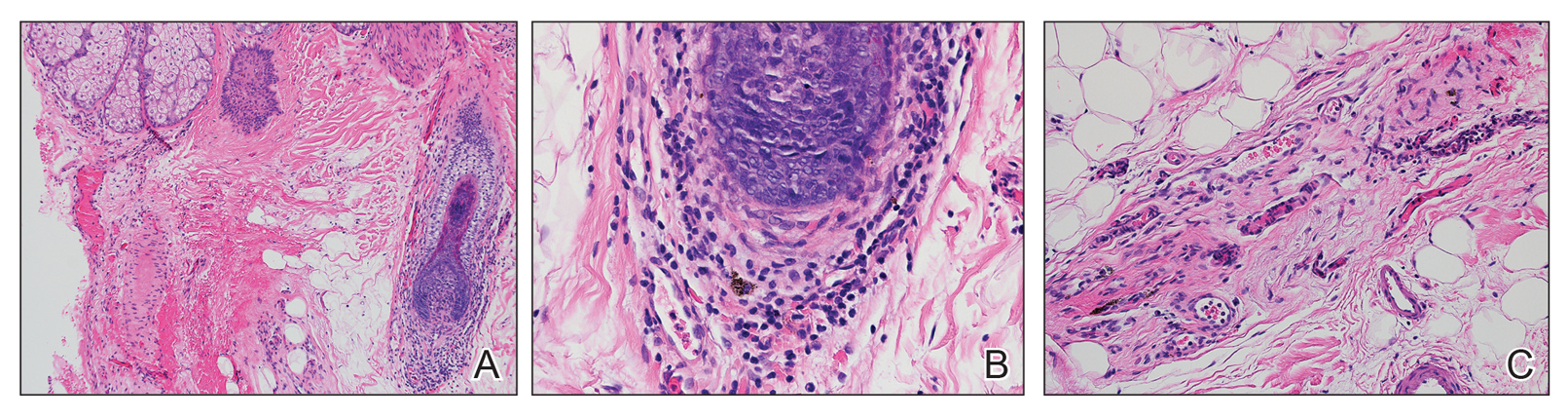

On examination by dermatology, a 6.3×4.4-cm, tender, mobile, ulcerated nodule was noted on the left knee (Figure 1A). No popliteal or inguinal lymph nodes were palpable. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or atypical infection (eg, Leishmania, deep fungal, mycobacterial) was suspected clinically. The patient underwent a diagnostic skin biopsy; hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lobular proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and central tumoral necrosis, consistent with primary BCC (Figure 2).

Given the size of the tumor, the patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and eventual reconstruction by a plastic surgeon. The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs surgery, with a final wound size of 7.7×5.4 cm (Figure 1B). Plastic surgery later performed a gastrocnemius muscle flap with a split-thickness skin graft (175 cm2) to repair the wound.

Comment

Exposure to UV radiation is the primary causative agent of most BCCs, accounting for the preferential distribution of these tumors on sun-exposed areas of the body. Approximately 80% of BCCs are located on the head and neck, 10% occur on the trunk, and only 8% are found on the lower extremities.1

Giant BCC, the finding in this case, is defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as a tumor larger than 5 cm in diameter. Fewer than 1% of all BCCs achieve this size; they appear more commonly on the back where they can go unnoticed.2 Neglect and inadequate treatment of the primary tumor are the most important contributing factors to the size of giant BCCs. Giant BCCs also have more aggressive biologic behavior, with an increased risk for local invasion and metastasis.3 In this case, the lesion was larger than 5 cm in diameter and occurred on the lower extremity rather than on the trunk.

This case is unusual because delayed diagnosis of BCC was the result of misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis, with a diagnostic skin biopsy demonstrating BCC almost 2 years later. It should be emphasized that early diagnosis and treatment could prevent tumor expansion. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion for BCC, especially when a dermoid cyst and knee bursitis fail to respond to conservative management.

- Pearson G, King LE, Boyd AS. Basal cell carcinoma of the lower extremities. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:852-854.

- Arnaiz J, Gallardo E, Piedra T, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma on the lower leg: MRI findings. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1167-1168.

- Randle HW. Giant basal cell carcinoma [letter]. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:222-223.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequently diagnosed skin cancer in the United States. It develops most often on sun-exposed skin, including the face and neck. Although BCCs are slow-growing tumors that rarely metastasize, they can cause notable local destruction with disfigurement if neglected or inadequately treated. Basal cell carcinoma arising on the legs is relatively uncommon.1,2 We present an interesting case of delayed diagnosis of BCC on the left knee due to earlier misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man with no history of skin cancer presented with a painful growing tumor on the left knee of approximately 2 years’ duration. The patient’s primary care physician as well as a general surgeon initially diagnosed it as a dermoid cyst and bursitis. The nodule failed to respond to conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and continued to grow until it began to ulcerate. Concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, the patient’s primary care physician referred him to the emergency department. He was subsequently sent to the dermatology clinic.

On examination by dermatology, a 6.3×4.4-cm, tender, mobile, ulcerated nodule was noted on the left knee (Figure 1A). No popliteal or inguinal lymph nodes were palpable. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or atypical infection (eg, Leishmania, deep fungal, mycobacterial) was suspected clinically. The patient underwent a diagnostic skin biopsy; hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lobular proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and central tumoral necrosis, consistent with primary BCC (Figure 2).

Given the size of the tumor, the patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and eventual reconstruction by a plastic surgeon. The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs surgery, with a final wound size of 7.7×5.4 cm (Figure 1B). Plastic surgery later performed a gastrocnemius muscle flap with a split-thickness skin graft (175 cm2) to repair the wound.

Comment

Exposure to UV radiation is the primary causative agent of most BCCs, accounting for the preferential distribution of these tumors on sun-exposed areas of the body. Approximately 80% of BCCs are located on the head and neck, 10% occur on the trunk, and only 8% are found on the lower extremities.1

Giant BCC, the finding in this case, is defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as a tumor larger than 5 cm in diameter. Fewer than 1% of all BCCs achieve this size; they appear more commonly on the back where they can go unnoticed.2 Neglect and inadequate treatment of the primary tumor are the most important contributing factors to the size of giant BCCs. Giant BCCs also have more aggressive biologic behavior, with an increased risk for local invasion and metastasis.3 In this case, the lesion was larger than 5 cm in diameter and occurred on the lower extremity rather than on the trunk.

This case is unusual because delayed diagnosis of BCC was the result of misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis, with a diagnostic skin biopsy demonstrating BCC almost 2 years later. It should be emphasized that early diagnosis and treatment could prevent tumor expansion. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion for BCC, especially when a dermoid cyst and knee bursitis fail to respond to conservative management.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequently diagnosed skin cancer in the United States. It develops most often on sun-exposed skin, including the face and neck. Although BCCs are slow-growing tumors that rarely metastasize, they can cause notable local destruction with disfigurement if neglected or inadequately treated. Basal cell carcinoma arising on the legs is relatively uncommon.1,2 We present an interesting case of delayed diagnosis of BCC on the left knee due to earlier misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man with no history of skin cancer presented with a painful growing tumor on the left knee of approximately 2 years’ duration. The patient’s primary care physician as well as a general surgeon initially diagnosed it as a dermoid cyst and bursitis. The nodule failed to respond to conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and continued to grow until it began to ulcerate. Concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, the patient’s primary care physician referred him to the emergency department. He was subsequently sent to the dermatology clinic.

On examination by dermatology, a 6.3×4.4-cm, tender, mobile, ulcerated nodule was noted on the left knee (Figure 1A). No popliteal or inguinal lymph nodes were palpable. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or atypical infection (eg, Leishmania, deep fungal, mycobacterial) was suspected clinically. The patient underwent a diagnostic skin biopsy; hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lobular proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and central tumoral necrosis, consistent with primary BCC (Figure 2).

Given the size of the tumor, the patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and eventual reconstruction by a plastic surgeon. The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs surgery, with a final wound size of 7.7×5.4 cm (Figure 1B). Plastic surgery later performed a gastrocnemius muscle flap with a split-thickness skin graft (175 cm2) to repair the wound.

Comment

Exposure to UV radiation is the primary causative agent of most BCCs, accounting for the preferential distribution of these tumors on sun-exposed areas of the body. Approximately 80% of BCCs are located on the head and neck, 10% occur on the trunk, and only 8% are found on the lower extremities.1

Giant BCC, the finding in this case, is defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as a tumor larger than 5 cm in diameter. Fewer than 1% of all BCCs achieve this size; they appear more commonly on the back where they can go unnoticed.2 Neglect and inadequate treatment of the primary tumor are the most important contributing factors to the size of giant BCCs. Giant BCCs also have more aggressive biologic behavior, with an increased risk for local invasion and metastasis.3 In this case, the lesion was larger than 5 cm in diameter and occurred on the lower extremity rather than on the trunk.

This case is unusual because delayed diagnosis of BCC was the result of misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis, with a diagnostic skin biopsy demonstrating BCC almost 2 years later. It should be emphasized that early diagnosis and treatment could prevent tumor expansion. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion for BCC, especially when a dermoid cyst and knee bursitis fail to respond to conservative management.

- Pearson G, King LE, Boyd AS. Basal cell carcinoma of the lower extremities. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:852-854.

- Arnaiz J, Gallardo E, Piedra T, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma on the lower leg: MRI findings. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1167-1168.

- Randle HW. Giant basal cell carcinoma [letter]. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:222-223.

- Pearson G, King LE, Boyd AS. Basal cell carcinoma of the lower extremities. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:852-854.

- Arnaiz J, Gallardo E, Piedra T, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma on the lower leg: MRI findings. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1167-1168.

- Randle HW. Giant basal cell carcinoma [letter]. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:222-223.

Practice Points

- This case highlights an unusual presentation of basal cell carcinoma masquerading as bursitis.

- Clinicians should be aware of confirmation bias, especially when multiple physicians and specialists are involved in a case.

- When the initial clinical impression is not corroborated by objective data or the condition is not responding to conventional therapy, it is important for clinicians to revisit the possibility of an inaccurate diagnosis.

Quantity and Characteristics of Flap or Graft Repairs for Skin Cancer on the Nose or Ears: A Comparison Between Mohs Micrographic Surgery and Plastic Surgery

The incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) is steadily increasing, and it accounts for more annual cancer diagnoses than all other malignancies combined.1,2 For NMSCs of the head and neck, Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has become a preferred technique because of its high cure rates, intraprocedural margin control, and improved tissue preservation in cosmetically sensitive areas.3 The nose and ears are especially sensitive anatomic locations given their prominent positions and relative lack of skin reservoir and laxity compared to other areas of the head and neck. For the nose and ears, both patients and referring providers may question who is best suited to surgically remove a malignancy and repair the defect with positive functional and cosmetic results, as a large portion of the defects following tumor extirpation will require a flap or graft for repair.

The notion of plastic surgery is strongly associated with supreme cosmesis for many patients and providers, as the specialty trains in several surgical and nonsurgical elective techniques to preserve and improve appearance. Consequently, patients commonly ask dermatologists if they should be referred to a plastic surgeon for skin cancer removal in cosmetically sensitive areas, especially areas that may require more complex surgical repairs. However, recent Medicare data indicate that dermatologists perform the vast majority of reconstructive skin surgeries, with more than 15 times the number of intermediate and complex closures and more than 4 times the number of flaps and grafts as the next closest specialty.4 Earlier studies using Medicare data revealed similar findings, with dermatologic surgeons performing more reconstructions of head and neck skin than both plastic surgeons and otorhinolaryngologists.5 However, these studies did not address the characteristics of the tumor, defects, or repairs performed by the specialties for comparison.

We sought to compare the quantity and characteristics of flaps or grafts performed for skin cancer on the nose or ears by fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons and plastic surgeons at 1 academic institution.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review of all skin cancer surgeries requiring a flap or graft on the nose or ears at Baylor Scott & White Health (Temple, Texas) from October 1, 2016, to October 1, 2017. This study was approved by the Baylor Scott & White Health institutional review board.

Data Collection

The analysis included full-time, fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons and all full-time plastic surgeons who accepted skin cancer surgery patient referrals as part of their practice and performed all procedures within our hospital system. We reviewed individual provider schedules for both outpatient consultation and operating room notes to capture each procedure performed. To ensure we captured all procedures for both Mohs and plastic surgeons, we used billing codes for any flap or graft repair done on the nose or ears to cross-reference and confirm the cases found by chart review. The total number of flaps or grafts on the nose or ears were collected. Data also were collected regarding the anatomic location of the skin cancer, final defect size prior to the repair, skin tumor type, repair type (flap or graft), and flap (transposition vs advancement) or graft (full thickness vs partial thickness) type. All surgical data were collected from operative notes. Demographic data, including age, race, and sex, also were collected. We also collected data on the specialty of the physicians who referred patients for surgical management of biopsy-proven skin malignancy.

Statistical Analysis

Sample characteristics were described using descriptive statistics. Frequencies and percentages were used to describe categorical variables. Medians and ranges were used to describe continuous variables due to nonsymmetrically distributed data. χ2 tests (or Fisher exact tests when low cell counts were present) for categorical variables and Wilcoxon signed rank tests for continuous variables were used to test for associations in bivariate comparisons between MMS and plastic surgery.

Results

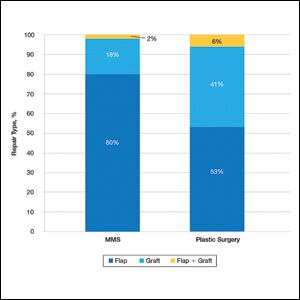

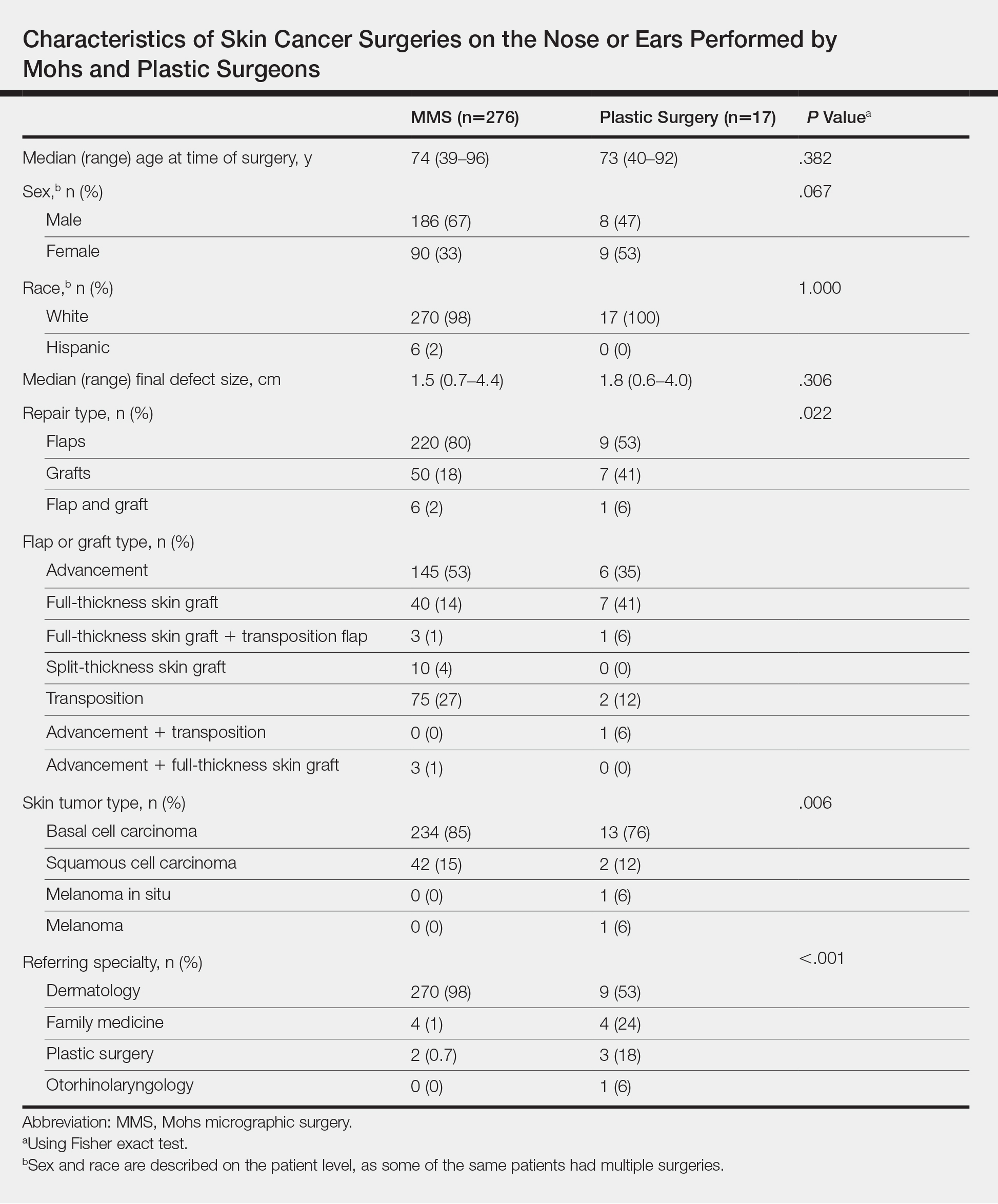

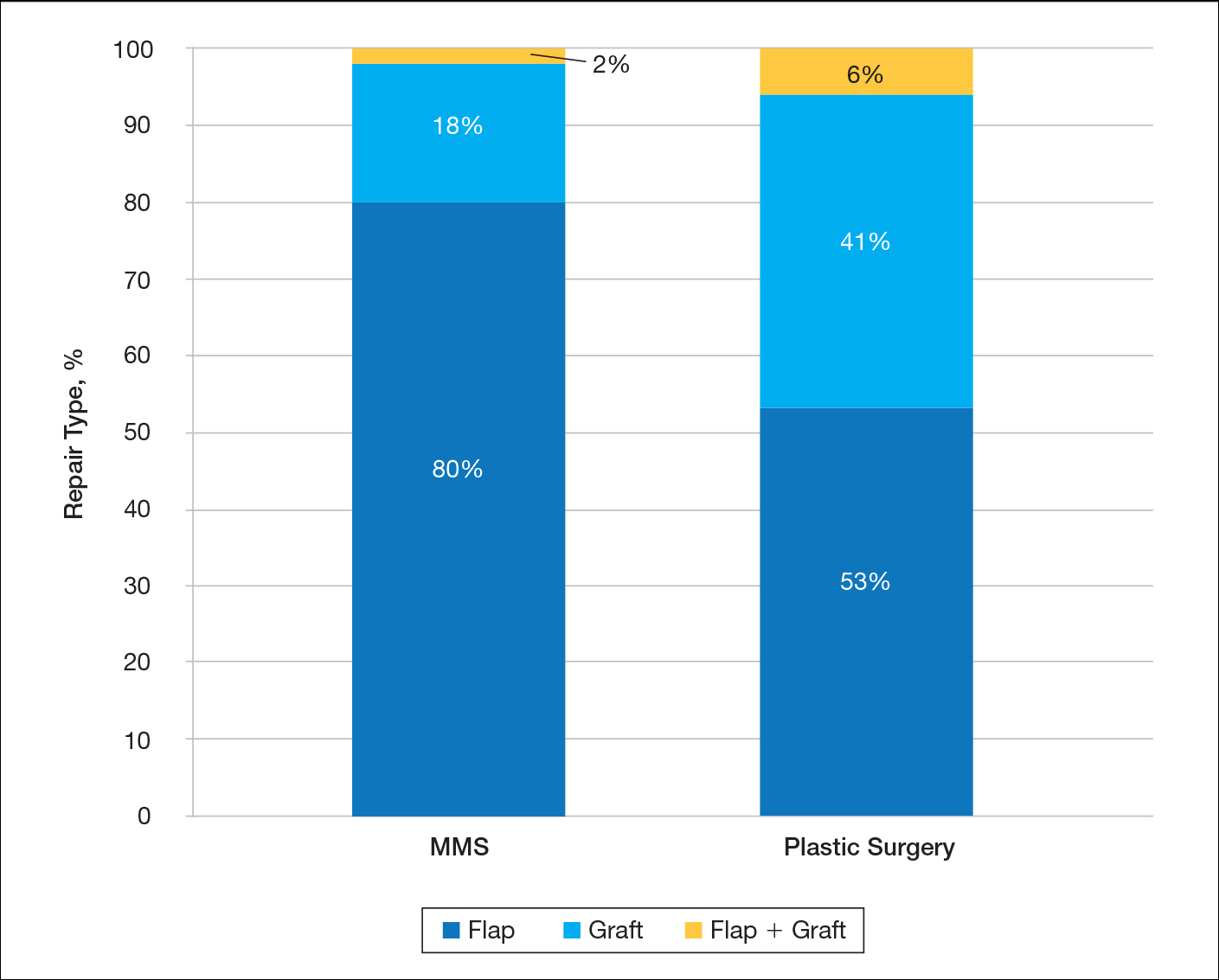

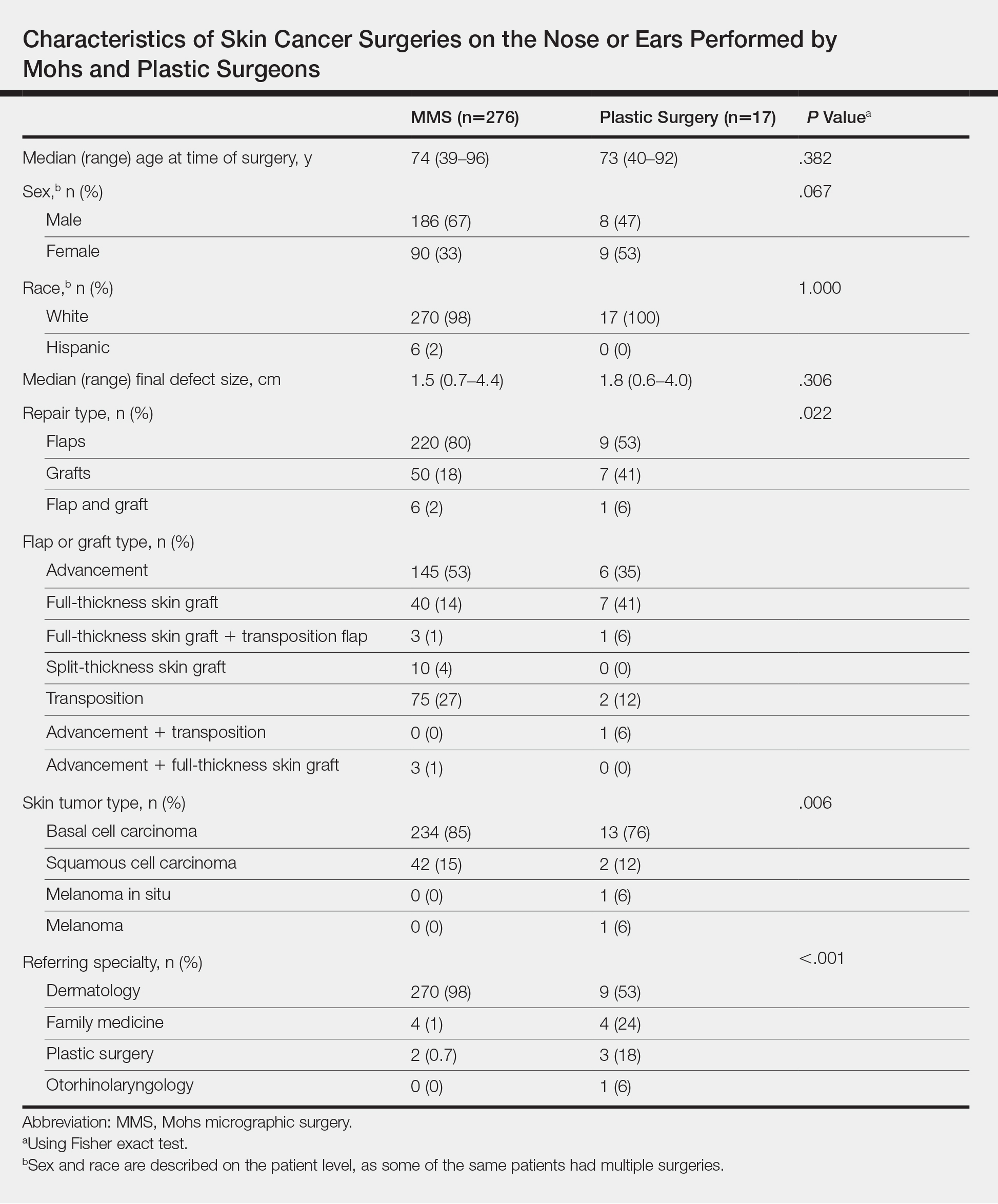

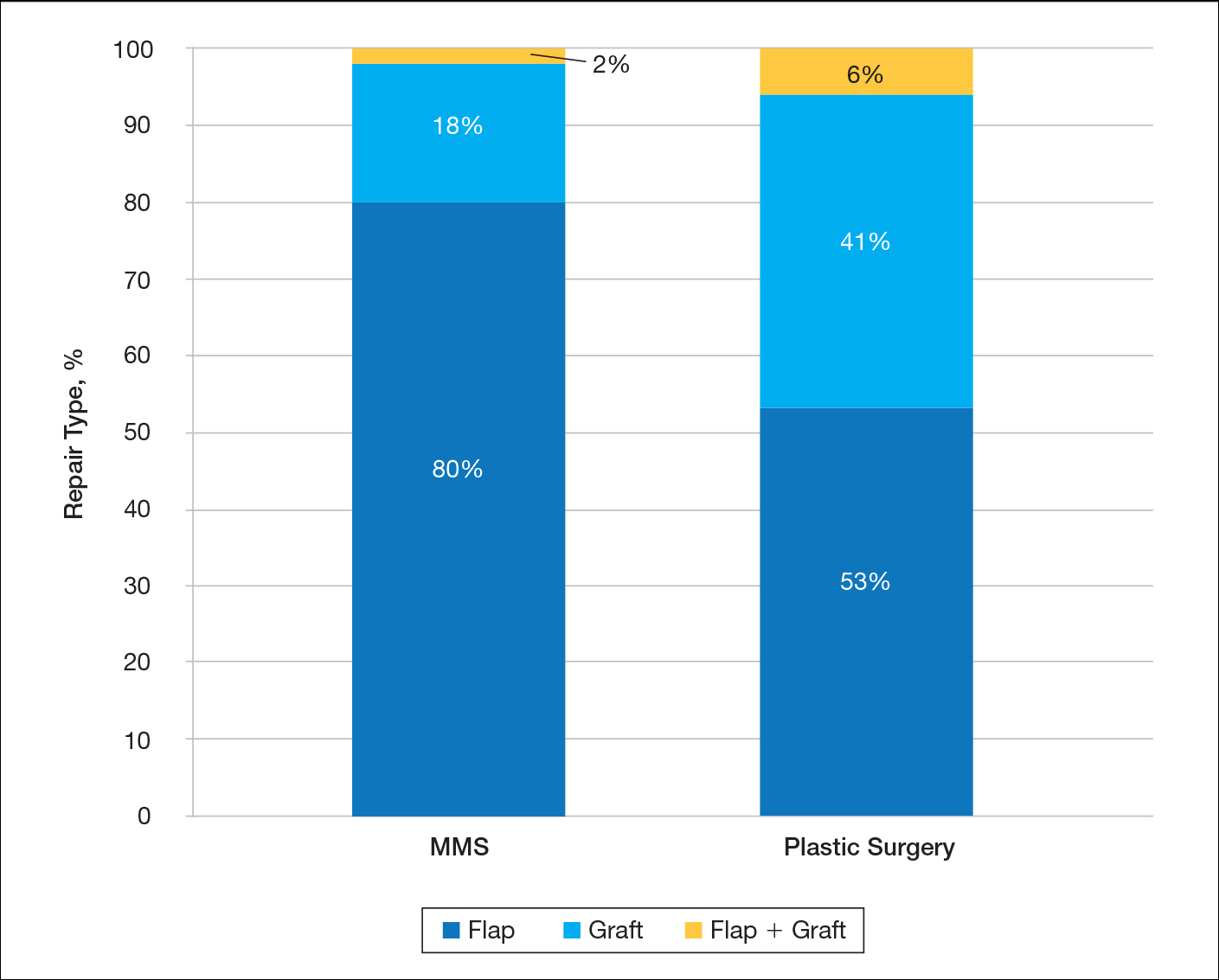

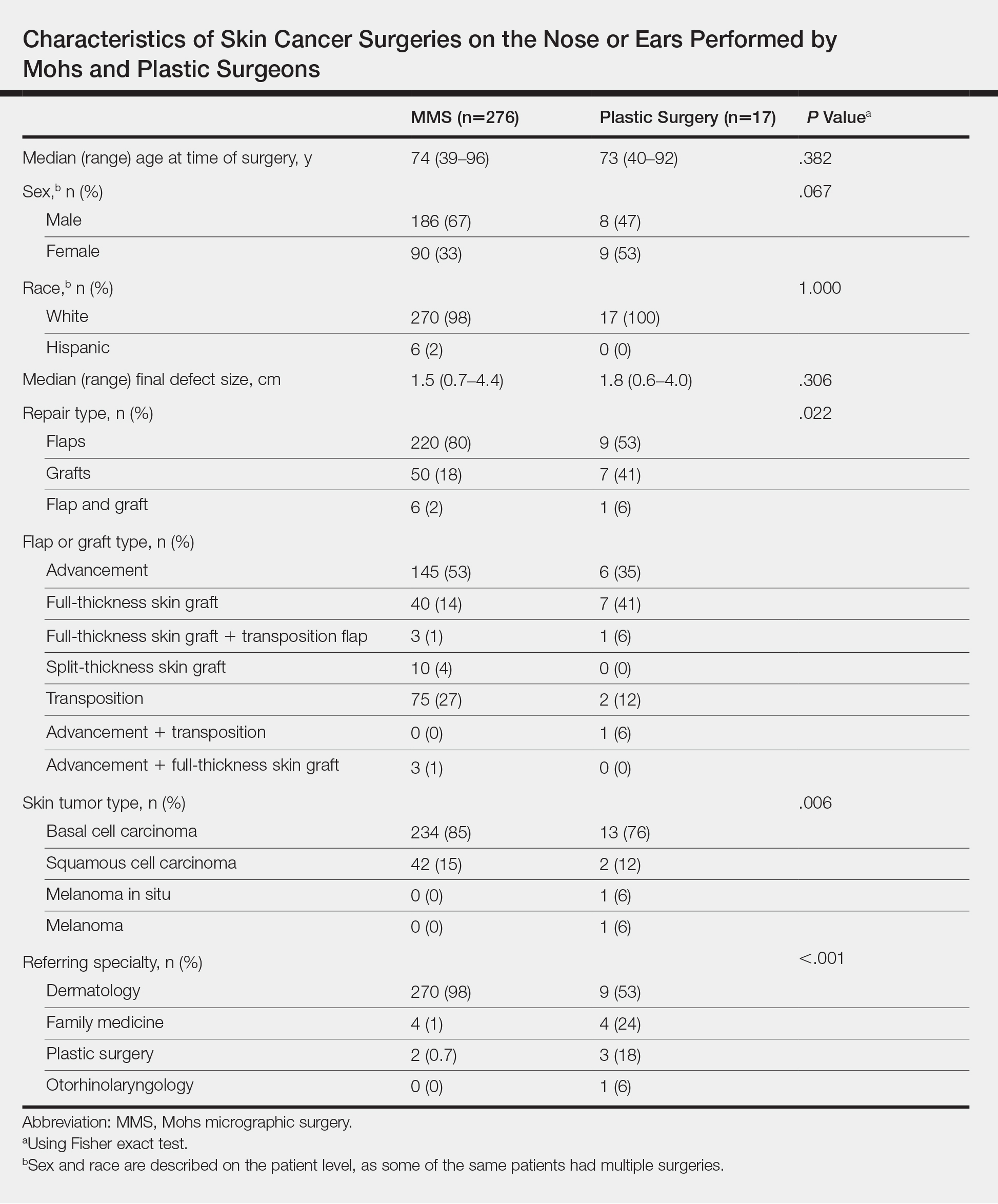

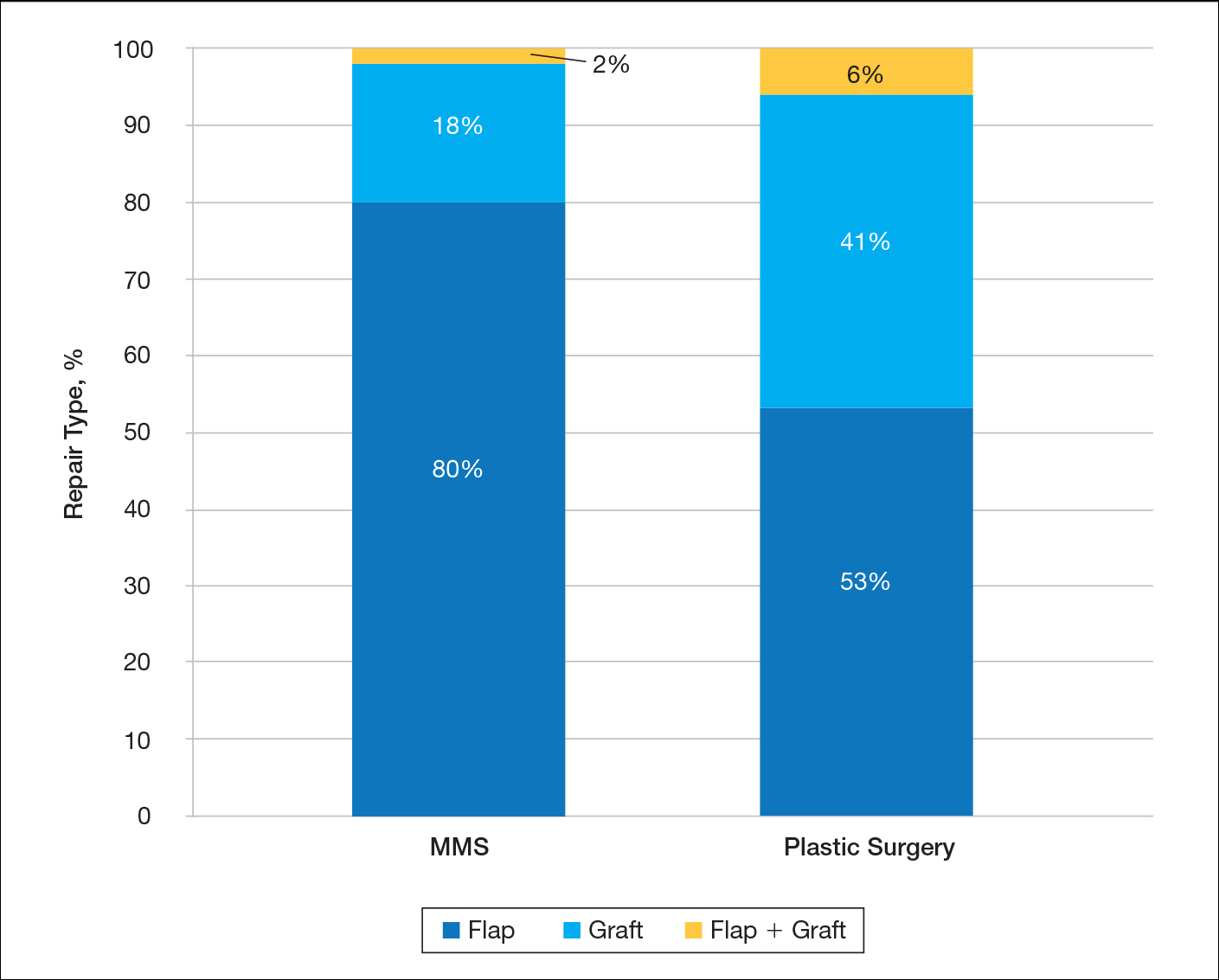

A total of 7 physicians (1 fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon and 6 plastic surgeons) at our institution met the inclusion criteria. The Mohs surgeon performed a significantly higher number of flaps and grafts (n=276) than the plastic surgeons (n=17 combined; average per plastic surgeon, 2.83) on the nose or ears in a 12-month period (P<.05)(Table). The median final defect size was not significantly different between MMS (1.5 cm) and plastic surgery (1.8 cm)(P=.306). Flap repairs were more common in patients undergoing MMS (80%) vs plastic surgery (53%)(P=.022)(Figure). For flap repair, advancement flaps were used more commonly (MMS, 53%; plastic surgery, 35%) than transposition flaps (MMS, 27%; plastic surgery, 12%) by both specialties.

Patient age was similar between MMS (median, 74 years) and plastic surgery (median, 73 years) patients (P=.382), but a greater percentage of women were treated by plastic surgeons (53%) compared with Mohs surgeons (33%). The predominant skin tumor type for both specialties was basal cell carcinoma (MMS, 85%; plastic surgery, 76%). Dermatology was the largest referring specialty to both MMS (98%) and plastic surgery (53%). Family medicine referrals comprised a much larger percentage of cases for plastic surgery (24%) compared to MMS (1%).

Comment

This study supports and adds to recent studies and data regarding the utilization of MMS for the treatment of NMSCs. Although the percentage of all skin cancer surgery is increasing for dermatology, little has been reported on more complex repairs. This study highlights the volume and complexity of skin surgery performed by Mohs surgeons compared to our colleagues in plastic surgery.

Defect Size

The defect sizes prior to repair were not statistically different between the 2 types of surgeries, though the median size was slightly larger for plastic surgery (1.8 cm) compared to MMS (1.5 cm). These non–statistically significant differences may be explained by potentially larger tumors requiring repair by plastic surgeons in an operating room. Plastic surgeons, however, may be more likely to take a larger margin of clinically unaffected tissue as part of the initial layer. Plastic surgeons also may be less likely to curette the lesion prior to excision to obtain more clear tumor margins, possibly leading to more stages and a subsequently larger defect. Knowing the clinical sizes of these NMSCs prior to biopsy would have been beneficial to our study, but these data often were not available from the referring providers.

Repair Type

Most patients who underwent MMS had surgical defects repaired with a flap vs a graft, and a much higher percentage of patients who had undergone MMS vs surgical excision with plastic surgery had their defects repaired with flaps. Using a visual analog scale score and Hollander Wound Evaluation Scale, Jacobs et al6 found flaps to be cosmetically superior to grafts following tumor extirpation on the nose. The more frequent use of grafts by plastic surgeons could be at least partially explained by larger defect size or by a few outlier larger lesions among an otherwise small sample size. Larger studies may be needed to see if a true discrepancy in repair preferences exists between the specialties.

Referring Specialty

Primary care physician referral comprised a much larger percentage of cases sent for treatment with plastic surgery (24%) compared to MMS (1%). This statistic may represent a practice gap in the perception of MMS and its benefits among our primary care colleagues, particularly among female patients, as a much higher percentage of women were treated with plastic surgery. Important potential benefits of MMS, particularly tissue conservation, cure rates for skin cancer, and the volume of repairs performed by Mohs surgeons, may need to be emphasized.

Scope of Practice

Our colleagues in plastic surgery are extremely gifted and perform numerous repairs outside the scope of most Mohs surgeons. They are vital to multidisciplinary approaches to patients with skin cancer. Although Mohs surgeons focus on treating skin cancers that arise in a narrower range of anatomic locations, the breadth and variety of surgical procedures performed by plastic surgeons is more diverse. Skin cancer surgery may account for a smaller portion of procedures in a plastic surgery practice.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. We did not compare cosmesis or wound healing in patients treated by MMS or plastic surgery. The sample size, particularly with plastic surgery, was small and did not allow for a larger, more powerful comparison of data between the 2 specialties. Finally, our study only represents 1 institution over the course of 1 year.

Conclusion

To provide the best care possible, it is imperative for referring physicians to possess an accurate understanding of the volume of cases and the types of repairs that treating specialties perform on a regular basis for NMSCs. This knowledge is particularly important when there is a treatment overlap among specialties. Our data show Mohs surgeons are performing more complex repairs and reconstructions on even the most cosmetically sensitive areas; therefore, primary care physicians and other specialists may be more likely to involve dermatology in the care of skin cancer.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the united states, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283-287.

- Mansouri B, Bicknell LM, Hill D, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for the management of cutaneous malignancies. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2017;25:291-301.

- Kantor J. Dermatologists perform more reconstructive surgery in the Medicare population than any other specialist group: a cross-sectional individual-level analysis of Medicare volume and specialist type in cutaneous and reconstructive surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:171-173.e1.

- Donaldson MR, Coldiron BM. Dermatologists perform the majority of cutaneous reconstructions in the Medicare population: numbers and trends from 2004 to 2009. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:803-808.

- Jacobs MA, Christenson LJ, Weaver AL, et al. Clinical outcome of cutaneous flaps versus full-thickness skin grafts after Mohs surgery on the nose. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:23-30.

The incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) is steadily increasing, and it accounts for more annual cancer diagnoses than all other malignancies combined.1,2 For NMSCs of the head and neck, Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has become a preferred technique because of its high cure rates, intraprocedural margin control, and improved tissue preservation in cosmetically sensitive areas.3 The nose and ears are especially sensitive anatomic locations given their prominent positions and relative lack of skin reservoir and laxity compared to other areas of the head and neck. For the nose and ears, both patients and referring providers may question who is best suited to surgically remove a malignancy and repair the defect with positive functional and cosmetic results, as a large portion of the defects following tumor extirpation will require a flap or graft for repair.

The notion of plastic surgery is strongly associated with supreme cosmesis for many patients and providers, as the specialty trains in several surgical and nonsurgical elective techniques to preserve and improve appearance. Consequently, patients commonly ask dermatologists if they should be referred to a plastic surgeon for skin cancer removal in cosmetically sensitive areas, especially areas that may require more complex surgical repairs. However, recent Medicare data indicate that dermatologists perform the vast majority of reconstructive skin surgeries, with more than 15 times the number of intermediate and complex closures and more than 4 times the number of flaps and grafts as the next closest specialty.4 Earlier studies using Medicare data revealed similar findings, with dermatologic surgeons performing more reconstructions of head and neck skin than both plastic surgeons and otorhinolaryngologists.5 However, these studies did not address the characteristics of the tumor, defects, or repairs performed by the specialties for comparison.

We sought to compare the quantity and characteristics of flaps or grafts performed for skin cancer on the nose or ears by fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons and plastic surgeons at 1 academic institution.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review of all skin cancer surgeries requiring a flap or graft on the nose or ears at Baylor Scott & White Health (Temple, Texas) from October 1, 2016, to October 1, 2017. This study was approved by the Baylor Scott & White Health institutional review board.

Data Collection

The analysis included full-time, fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons and all full-time plastic surgeons who accepted skin cancer surgery patient referrals as part of their practice and performed all procedures within our hospital system. We reviewed individual provider schedules for both outpatient consultation and operating room notes to capture each procedure performed. To ensure we captured all procedures for both Mohs and plastic surgeons, we used billing codes for any flap or graft repair done on the nose or ears to cross-reference and confirm the cases found by chart review. The total number of flaps or grafts on the nose or ears were collected. Data also were collected regarding the anatomic location of the skin cancer, final defect size prior to the repair, skin tumor type, repair type (flap or graft), and flap (transposition vs advancement) or graft (full thickness vs partial thickness) type. All surgical data were collected from operative notes. Demographic data, including age, race, and sex, also were collected. We also collected data on the specialty of the physicians who referred patients for surgical management of biopsy-proven skin malignancy.

Statistical Analysis

Sample characteristics were described using descriptive statistics. Frequencies and percentages were used to describe categorical variables. Medians and ranges were used to describe continuous variables due to nonsymmetrically distributed data. χ2 tests (or Fisher exact tests when low cell counts were present) for categorical variables and Wilcoxon signed rank tests for continuous variables were used to test for associations in bivariate comparisons between MMS and plastic surgery.

Results

A total of 7 physicians (1 fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon and 6 plastic surgeons) at our institution met the inclusion criteria. The Mohs surgeon performed a significantly higher number of flaps and grafts (n=276) than the plastic surgeons (n=17 combined; average per plastic surgeon, 2.83) on the nose or ears in a 12-month period (P<.05)(Table). The median final defect size was not significantly different between MMS (1.5 cm) and plastic surgery (1.8 cm)(P=.306). Flap repairs were more common in patients undergoing MMS (80%) vs plastic surgery (53%)(P=.022)(Figure). For flap repair, advancement flaps were used more commonly (MMS, 53%; plastic surgery, 35%) than transposition flaps (MMS, 27%; plastic surgery, 12%) by both specialties.

Patient age was similar between MMS (median, 74 years) and plastic surgery (median, 73 years) patients (P=.382), but a greater percentage of women were treated by plastic surgeons (53%) compared with Mohs surgeons (33%). The predominant skin tumor type for both specialties was basal cell carcinoma (MMS, 85%; plastic surgery, 76%). Dermatology was the largest referring specialty to both MMS (98%) and plastic surgery (53%). Family medicine referrals comprised a much larger percentage of cases for plastic surgery (24%) compared to MMS (1%).

Comment

This study supports and adds to recent studies and data regarding the utilization of MMS for the treatment of NMSCs. Although the percentage of all skin cancer surgery is increasing for dermatology, little has been reported on more complex repairs. This study highlights the volume and complexity of skin surgery performed by Mohs surgeons compared to our colleagues in plastic surgery.

Defect Size

The defect sizes prior to repair were not statistically different between the 2 types of surgeries, though the median size was slightly larger for plastic surgery (1.8 cm) compared to MMS (1.5 cm). These non–statistically significant differences may be explained by potentially larger tumors requiring repair by plastic surgeons in an operating room. Plastic surgeons, however, may be more likely to take a larger margin of clinically unaffected tissue as part of the initial layer. Plastic surgeons also may be less likely to curette the lesion prior to excision to obtain more clear tumor margins, possibly leading to more stages and a subsequently larger defect. Knowing the clinical sizes of these NMSCs prior to biopsy would have been beneficial to our study, but these data often were not available from the referring providers.

Repair Type

Most patients who underwent MMS had surgical defects repaired with a flap vs a graft, and a much higher percentage of patients who had undergone MMS vs surgical excision with plastic surgery had their defects repaired with flaps. Using a visual analog scale score and Hollander Wound Evaluation Scale, Jacobs et al6 found flaps to be cosmetically superior to grafts following tumor extirpation on the nose. The more frequent use of grafts by plastic surgeons could be at least partially explained by larger defect size or by a few outlier larger lesions among an otherwise small sample size. Larger studies may be needed to see if a true discrepancy in repair preferences exists between the specialties.

Referring Specialty

Primary care physician referral comprised a much larger percentage of cases sent for treatment with plastic surgery (24%) compared to MMS (1%). This statistic may represent a practice gap in the perception of MMS and its benefits among our primary care colleagues, particularly among female patients, as a much higher percentage of women were treated with plastic surgery. Important potential benefits of MMS, particularly tissue conservation, cure rates for skin cancer, and the volume of repairs performed by Mohs surgeons, may need to be emphasized.

Scope of Practice

Our colleagues in plastic surgery are extremely gifted and perform numerous repairs outside the scope of most Mohs surgeons. They are vital to multidisciplinary approaches to patients with skin cancer. Although Mohs surgeons focus on treating skin cancers that arise in a narrower range of anatomic locations, the breadth and variety of surgical procedures performed by plastic surgeons is more diverse. Skin cancer surgery may account for a smaller portion of procedures in a plastic surgery practice.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. We did not compare cosmesis or wound healing in patients treated by MMS or plastic surgery. The sample size, particularly with plastic surgery, was small and did not allow for a larger, more powerful comparison of data between the 2 specialties. Finally, our study only represents 1 institution over the course of 1 year.

Conclusion

To provide the best care possible, it is imperative for referring physicians to possess an accurate understanding of the volume of cases and the types of repairs that treating specialties perform on a regular basis for NMSCs. This knowledge is particularly important when there is a treatment overlap among specialties. Our data show Mohs surgeons are performing more complex repairs and reconstructions on even the most cosmetically sensitive areas; therefore, primary care physicians and other specialists may be more likely to involve dermatology in the care of skin cancer.

The incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) is steadily increasing, and it accounts for more annual cancer diagnoses than all other malignancies combined.1,2 For NMSCs of the head and neck, Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has become a preferred technique because of its high cure rates, intraprocedural margin control, and improved tissue preservation in cosmetically sensitive areas.3 The nose and ears are especially sensitive anatomic locations given their prominent positions and relative lack of skin reservoir and laxity compared to other areas of the head and neck. For the nose and ears, both patients and referring providers may question who is best suited to surgically remove a malignancy and repair the defect with positive functional and cosmetic results, as a large portion of the defects following tumor extirpation will require a flap or graft for repair.

The notion of plastic surgery is strongly associated with supreme cosmesis for many patients and providers, as the specialty trains in several surgical and nonsurgical elective techniques to preserve and improve appearance. Consequently, patients commonly ask dermatologists if they should be referred to a plastic surgeon for skin cancer removal in cosmetically sensitive areas, especially areas that may require more complex surgical repairs. However, recent Medicare data indicate that dermatologists perform the vast majority of reconstructive skin surgeries, with more than 15 times the number of intermediate and complex closures and more than 4 times the number of flaps and grafts as the next closest specialty.4 Earlier studies using Medicare data revealed similar findings, with dermatologic surgeons performing more reconstructions of head and neck skin than both plastic surgeons and otorhinolaryngologists.5 However, these studies did not address the characteristics of the tumor, defects, or repairs performed by the specialties for comparison.

We sought to compare the quantity and characteristics of flaps or grafts performed for skin cancer on the nose or ears by fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons and plastic surgeons at 1 academic institution.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review of all skin cancer surgeries requiring a flap or graft on the nose or ears at Baylor Scott & White Health (Temple, Texas) from October 1, 2016, to October 1, 2017. This study was approved by the Baylor Scott & White Health institutional review board.

Data Collection

The analysis included full-time, fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons and all full-time plastic surgeons who accepted skin cancer surgery patient referrals as part of their practice and performed all procedures within our hospital system. We reviewed individual provider schedules for both outpatient consultation and operating room notes to capture each procedure performed. To ensure we captured all procedures for both Mohs and plastic surgeons, we used billing codes for any flap or graft repair done on the nose or ears to cross-reference and confirm the cases found by chart review. The total number of flaps or grafts on the nose or ears were collected. Data also were collected regarding the anatomic location of the skin cancer, final defect size prior to the repair, skin tumor type, repair type (flap or graft), and flap (transposition vs advancement) or graft (full thickness vs partial thickness) type. All surgical data were collected from operative notes. Demographic data, including age, race, and sex, also were collected. We also collected data on the specialty of the physicians who referred patients for surgical management of biopsy-proven skin malignancy.

Statistical Analysis

Sample characteristics were described using descriptive statistics. Frequencies and percentages were used to describe categorical variables. Medians and ranges were used to describe continuous variables due to nonsymmetrically distributed data. χ2 tests (or Fisher exact tests when low cell counts were present) for categorical variables and Wilcoxon signed rank tests for continuous variables were used to test for associations in bivariate comparisons between MMS and plastic surgery.

Results

A total of 7 physicians (1 fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon and 6 plastic surgeons) at our institution met the inclusion criteria. The Mohs surgeon performed a significantly higher number of flaps and grafts (n=276) than the plastic surgeons (n=17 combined; average per plastic surgeon, 2.83) on the nose or ears in a 12-month period (P<.05)(Table). The median final defect size was not significantly different between MMS (1.5 cm) and plastic surgery (1.8 cm)(P=.306). Flap repairs were more common in patients undergoing MMS (80%) vs plastic surgery (53%)(P=.022)(Figure). For flap repair, advancement flaps were used more commonly (MMS, 53%; plastic surgery, 35%) than transposition flaps (MMS, 27%; plastic surgery, 12%) by both specialties.

Patient age was similar between MMS (median, 74 years) and plastic surgery (median, 73 years) patients (P=.382), but a greater percentage of women were treated by plastic surgeons (53%) compared with Mohs surgeons (33%). The predominant skin tumor type for both specialties was basal cell carcinoma (MMS, 85%; plastic surgery, 76%). Dermatology was the largest referring specialty to both MMS (98%) and plastic surgery (53%). Family medicine referrals comprised a much larger percentage of cases for plastic surgery (24%) compared to MMS (1%).

Comment

This study supports and adds to recent studies and data regarding the utilization of MMS for the treatment of NMSCs. Although the percentage of all skin cancer surgery is increasing for dermatology, little has been reported on more complex repairs. This study highlights the volume and complexity of skin surgery performed by Mohs surgeons compared to our colleagues in plastic surgery.

Defect Size

The defect sizes prior to repair were not statistically different between the 2 types of surgeries, though the median size was slightly larger for plastic surgery (1.8 cm) compared to MMS (1.5 cm). These non–statistically significant differences may be explained by potentially larger tumors requiring repair by plastic surgeons in an operating room. Plastic surgeons, however, may be more likely to take a larger margin of clinically unaffected tissue as part of the initial layer. Plastic surgeons also may be less likely to curette the lesion prior to excision to obtain more clear tumor margins, possibly leading to more stages and a subsequently larger defect. Knowing the clinical sizes of these NMSCs prior to biopsy would have been beneficial to our study, but these data often were not available from the referring providers.

Repair Type

Most patients who underwent MMS had surgical defects repaired with a flap vs a graft, and a much higher percentage of patients who had undergone MMS vs surgical excision with plastic surgery had their defects repaired with flaps. Using a visual analog scale score and Hollander Wound Evaluation Scale, Jacobs et al6 found flaps to be cosmetically superior to grafts following tumor extirpation on the nose. The more frequent use of grafts by plastic surgeons could be at least partially explained by larger defect size or by a few outlier larger lesions among an otherwise small sample size. Larger studies may be needed to see if a true discrepancy in repair preferences exists between the specialties.

Referring Specialty

Primary care physician referral comprised a much larger percentage of cases sent for treatment with plastic surgery (24%) compared to MMS (1%). This statistic may represent a practice gap in the perception of MMS and its benefits among our primary care colleagues, particularly among female patients, as a much higher percentage of women were treated with plastic surgery. Important potential benefits of MMS, particularly tissue conservation, cure rates for skin cancer, and the volume of repairs performed by Mohs surgeons, may need to be emphasized.

Scope of Practice

Our colleagues in plastic surgery are extremely gifted and perform numerous repairs outside the scope of most Mohs surgeons. They are vital to multidisciplinary approaches to patients with skin cancer. Although Mohs surgeons focus on treating skin cancers that arise in a narrower range of anatomic locations, the breadth and variety of surgical procedures performed by plastic surgeons is more diverse. Skin cancer surgery may account for a smaller portion of procedures in a plastic surgery practice.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. We did not compare cosmesis or wound healing in patients treated by MMS or plastic surgery. The sample size, particularly with plastic surgery, was small and did not allow for a larger, more powerful comparison of data between the 2 specialties. Finally, our study only represents 1 institution over the course of 1 year.

Conclusion

To provide the best care possible, it is imperative for referring physicians to possess an accurate understanding of the volume of cases and the types of repairs that treating specialties perform on a regular basis for NMSCs. This knowledge is particularly important when there is a treatment overlap among specialties. Our data show Mohs surgeons are performing more complex repairs and reconstructions on even the most cosmetically sensitive areas; therefore, primary care physicians and other specialists may be more likely to involve dermatology in the care of skin cancer.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the united states, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283-287.

- Mansouri B, Bicknell LM, Hill D, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for the management of cutaneous malignancies. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2017;25:291-301.

- Kantor J. Dermatologists perform more reconstructive surgery in the Medicare population than any other specialist group: a cross-sectional individual-level analysis of Medicare volume and specialist type in cutaneous and reconstructive surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:171-173.e1.

- Donaldson MR, Coldiron BM. Dermatologists perform the majority of cutaneous reconstructions in the Medicare population: numbers and trends from 2004 to 2009. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:803-808.

- Jacobs MA, Christenson LJ, Weaver AL, et al. Clinical outcome of cutaneous flaps versus full-thickness skin grafts after Mohs surgery on the nose. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:23-30.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the united states, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283-287.

- Mansouri B, Bicknell LM, Hill D, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for the management of cutaneous malignancies. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2017;25:291-301.

- Kantor J. Dermatologists perform more reconstructive surgery in the Medicare population than any other specialist group: a cross-sectional individual-level analysis of Medicare volume and specialist type in cutaneous and reconstructive surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:171-173.e1.

- Donaldson MR, Coldiron BM. Dermatologists perform the majority of cutaneous reconstructions in the Medicare population: numbers and trends from 2004 to 2009. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:803-808.

- Jacobs MA, Christenson LJ, Weaver AL, et al. Clinical outcome of cutaneous flaps versus full-thickness skin grafts after Mohs surgery on the nose. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:23-30.

Practice Points

- Patients and nondermatologist physicians may be unaware of how frequently Mohs surgeons perform complex surgical repairs compared to other specialists.

- Compared to plastic surgeons, Mohs surgeons performed a larger number of complex skin cancer repairs on the nose or ears with similar-sized defects.

- Primary care physicians and other specialists may be more likely to involve dermatology in the care of skin cancer through awareness of this type of data.

Dermoscopic Patterns of Acral Melanocytic Lesions in Skin of Color

Acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM) is a rare subtype of melanoma that occurs on the palms, soles, and nail apparatus. Unlike more common types of melanoma, ALM occurs on sun-protected areas of the skin and has distinct clinical, histologic, and genetic features. Acral lentiginous melanoma accounts for a larger proportion of melanomas in individuals with skin of color and has a worse prognosis and recurrence rate than other forms of melanoma.

Population Trends in Skin of Color

Much of the literature on malignant melanoma historically has involved non-Hispanic white patients, but the incidence in lighter-skinned populations has been increasing steadily over the last few decades.1 Although ALM can occur in any race, it disproportionately affects skin of color populations; ALM accounts for only 0.8% to 1% of all melanomas in white populations, but it constitutes 4% to 58% of melanomas in ethnic populations and is the most common melanoma subtype among black Americans.2-5 Acral lentiginous melanoma also is associated with a worse prognosis compared to other subtypes, which may indicate a more aggressive biological nature6 but also may point toward socioeconomic and cultural barriers (eg, low income or education levels, lack of insurance, lower health literacy), leading to disparities in access to care and diagnosis at advanced stages.5

Similarly, the distribution of acral melanocytic nevi appears to demonstrate an association with ethnicity and skin pigmentation. Although skin of color patients have fewer nevi than non-Hispanic whites, the proportion of acral melanocytic nevi tends to be greater.6,7 Given its grim prognosis, accurately differentiating ALM from acral nevi is of utmost importance.

Diagnostic Challenges of Acral Lesions

Due to the unique nature of the surfaces of acral sites, melanocytic lesions on the palms, soles, and nail apparatus present many diagnostic challenges. It can be difficult to distinguish acral melanoma from benign lesions using the naked eye alone. Volar surfaces are characterized by the presence of dermatoglyphics, and pigment deposition along ridges and furrows create particular dermoscopic patterns exclusive to these sites.8 Thus, dermoscopy can be useful on acral surfaces, but the dermoscopic features are different from those on the rest of the body and must be learned separately.

In addition, nearly half of patients are unaware of their acral lesions.6 Acral surfaces may not always be examined by clinicians during total-body skin examinations, leading to further possibility of overlooking a lesion. Obtaining biopsies on glabrous skin or nails also is challenging because they can be more painful and hemostasis can be more difficult, especially in the nail. Acral melanomas also may be amelanotic, including those at subungual sites.

Dermoscopic Patterns of Acral Volar Skin

Dermoscopy is a useful noninvasive tool for distinguishing between benign and malignant acral melanocytic lesions, and its efficacy in improving diagnostic accuracy and decreasing unnecessary biopsies is well-established in the literature.13,14 Acral dermoscopy allows for visualization of pigment along the dermatoglyphics that constitute the characteristic dermoscopic patterns.

Acral Lentiginous Melanoma

The hallmark dermoscopic pattern and most important finding of ALM is the parallel ridge pattern, characterized by parallel linear pigmentation along the ridges of dermatoglyphics. In the early phases of malignancy, the pattern appears light brown and involves most of the lesion; as the tumor develops, increasing melanin production results in focal areas of the parallel ridge pattern with darker bands.15,16 The sensitivity and specificity of a parallel ridge pattern for diagnosing early ALM has been shown to be 86% and 99%, respectively.15,16

A pattern of irregular diffuse pigmentation also can be observed in more advanced ALM. Dermoscopy may reveal a structureless pattern (ie, lack of identifiable structures or patterns) in a background of tan-black coloration due to more exuberant melanocyte proliferation along the epidermis.15 Sensitivity and specificity of this dermoscopic finding for invasive lesions is high at 94% and 97%, respectively.16,17 Interestingly, once ALM lesions have advanced even further, conventional melanoma-associated structures (ie, blue-white veil, polymorphous blood vessels, ulceration, irregular dots/globules or streaks) or atypical forms of typically benign acral dermoscopic patterns may be observed.15

Per a 3-step diagnostic algorithm created by Koga and Saida,18 a suspected acral lesion should first be evaluated for a parallel ridge pattern to determine the need for biopsy, as it is seen in approximately two-thirds of ALMs.19 If no parallel ridge pattern is observed, the lesion should then be checked for any of the typical dermoscopic patterns seen in benign acral nevi (eg, parallel furrow, latticelike, or fibrillar patterns).18 The maximum diameter should be measured only if the lesion does not exhibit any of the typical dermoscopic patterns. If the lesion’s diameter is greater than 7 mm in diameter, it should be biopsied; if the diameter is less than 7 mm, it should have regular clinical and dermoscopic follow-up.18

In 2015, Lallas et al20 developed the BRAAFF checklist, a scoring system of 6 variables: blotches, ridge pattern, asymmetry of structures, asymmetry of colors, parallel furrow pattern, and fibrillar pattern. The checklist also was shown to substantially improve diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy for ALM, with sensitivity and specificity at 93.1% and 86.7%, respectively.20

Acquired Acral Nevi

Three classic dermoscopic patterns are associated with acquired acral nevi: parallel furrow pattern, latticelike pattern, and fibrillar pattern.15,21 Approximately three-quarters of all acquired acral nevi exhibit one of these patterns, roughly half exhibiting parallel furrow with tan-brown bandlike pigmentation along dermatoglyphic grooves.16,17

Latticelike patterns also are characterized by brown parallel lines along the sulci of dermatoglyphics but additionally have multiple intersecting lines. Thus, this pattern can be considered a variant of the parallel furrow pattern.15 The crisscross markings can be predominantly found in the plantar arch.22 This dermoscopic pattern comprises 15% to 25% of all acral nevi.21

Fibrillar pattern accounts for 10% to 20% of all acral melanocytic nevi.21 Dermoscopically, these lesions demonstrate parallel filamentous streaks that cross dermatoglyphics obliquely. The fibrillar pattern is predominantly found on weight-bearing areas of the sole,22 which likely is explained by pressure causing slanting of melanin columns in the horny layer.23 The fibrillar pattern has been shown to be the benign acral dermoscopic pattern that is most commonly misdiagnosed, with higher reported rates of biopsy.24

Acral Congenital Melanocytic Nevi

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) present at birth or appear during the first few weeks of life. Congenital melanocytic nevi can vary widely in size, shape, and color, and they are occasionally biopsied in cases of larger diameter or dermoscopic atypia to differentiate from melanoma.25 Congenital melanocytic nevi also can occur on acral volar surfaces. Possible dermoscopic patterns include parallel furrow or fibrillar patterns as well as a crista dotted pattern, defined as evenly spaced dots/globules on the ridges near the openings of eccrine ducts.26 A more commonly observed dermoscopic pattern in acral CMN is a combination of the crista dotted and parallel furrow patterns, known as the peas-in-a-pod pattern. Changes in the clinical appearance and dermoscopic features of an acral CMN are possible over time; some lesions also may fade with age.26

Final Thoughts

Acral lentiginous melanoma is a rare but potentially aggressive melanoma subtype that accounts for a larger proportion of melanomas in patients with skin of color than in white patients. Dermoscopy of acral volar skin provides invaluable diagnostic information and allows for better management of acral melanocytic lesions. Dermoscopic patterns such as the parallel ridge, parallel furrow, latticelike, fibrillar, and peas-in-a-pod patterns are unique to acral sites and can be used to differentiate between ALMs, acquired nevi, or CMNs.

- Whiteman DC, Green AC, Olsen CM. The growing burden of invasive melanoma: projections of incidence rates and numbers of new cases in six susceptible populations through 2031. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:1161-1171.

- Bradford PT, Goldstein AM, McMaster ML, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1986-2005. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:427-434.

- Nakamura Y, Fujisawa Y. Diagnosis and management of acral lentiginous melanoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:42.

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914.

- Wang Y, Zhao Y, Ma S. Racial differences in six major subtypes of melanoma: descriptive epidemiology. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:691.

- Madankumar R, Gumaste PV, Martires K, et al. Acral melanocytic lesions in the United States: prevalence, awareness, and dermoscopic patterns in skin-of-color and non-Hispanic white patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:724.e1-730.e1.

- Palicka GA, Rhodes AR. Acral melanocytic nevi: prevalence and distribution of gross morphologic features in white and black adults. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1085-1094.

- Thomas L, Phan A, Pralong P, et al. Special locations dermoscopy: facial, acral, and nail. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31:615-624.

- Gong HZ, Zheng HY, Li J. Amelanotic melanoma [published online January 21, 2019]. Melanoma Res. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000571.

- Ise M, Yasuda F, Konohana I, et al. Acral melanoma with hyperkeratosis mimicking a pigmented wart. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:37-39.

- Serarslan G, Akçaly CM, Atik E. Acral lentiginous melanoma misdiagnosed as tinea pedis: a case report. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:37-38.

- Gumaste P, Penn L, Cohen N, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma of the foot misdiagnosed as a traumatic ulcer. a cautionary case. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2015;105:189-194.

- Carli P, de Giorgi V, Chiarugi A, et al. Addition of dermoscopy to conventional naked-eye examination in melanoma screening: a randomized study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:683-689.

- Carli P, de Giorgi V, Crocetti E, et al. Improvement of malignant/benign ratio in excised melanocytic lesions in the ‘dermoscopy era’: a retrospective study 1997-2001. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:687-692.

- Saida T, Koga H, Uhara H. Key points in dermoscopic differentiation between early acral melanoma and acral nevus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:25-34.

- Ishihara Y, Saida T, Miyazaki A, et al. Early acral melanoma in situ: correlation between the parallel ridge pattern on dermoscopy and microscopic features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:21-27.

- Saida T, Miyazaki A, Oguchi S, et al. Significance of dermoscopic patterns in detecting malignant melanoma on acral volar skin: results of a multicenter study in Japan. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1233-1238.

- Koga H, Saida T. Revised 3-step dermoscopic algorithm for the management of acral melanocytic lesions. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:741-743.

- Lallas A, Sgouros D, Zalaudek I, et al. Palmar and plantar melanomas differ for sex prevalence and tumor thickness but not for dermoscopic patterns. Melanoma Res. 2014;24:83-87.

- Lallas A, Kyrgidis A, Koga H, et al. The BRAAFF checklist: a new dermoscopic algorithm for diagnosing acral melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1041-1049.

- Saida T, Koga H. Dermoscopic patterns of acral melanocytic nevi: their variations, changes, and significance. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1423-1426.

- Miyazaki A, Saida T, Koga H, et al. Anatomical and histopathological correlates of the dermoscopic patterns seen in melanocytic nevi on the sole: a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:230-236.

- Watanabe S, Sawada M, Ishizaki S, et al. Comparison of dermatoscopic images of acral lentiginous melanoma and acral melanocytic nevus occurring on body weight-bearing areas. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:47-50.

- Costello CM, Ghanavatian S, Temkit M, et al. Educational and practice gaps in the management of volar melanocytic lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1450-1455.

- Alikhan A, Ibrahimi OA, Eisen DB. Congenital melanocytic nevi: where are we now? part I. clinical presentation, epidemiology, pathogenesis, histology, malignant transformation, and neurocutaneous melanosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:495.e1-495.e17; quiz 512-514.

- Minagawa A, Koga H, Saida T. Dermoscopic characteristics of congenital melanocytic nevi affecting acral volar skin. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:809-813.

Acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM) is a rare subtype of melanoma that occurs on the palms, soles, and nail apparatus. Unlike more common types of melanoma, ALM occurs on sun-protected areas of the skin and has distinct clinical, histologic, and genetic features. Acral lentiginous melanoma accounts for a larger proportion of melanomas in individuals with skin of color and has a worse prognosis and recurrence rate than other forms of melanoma.

Population Trends in Skin of Color

Much of the literature on malignant melanoma historically has involved non-Hispanic white patients, but the incidence in lighter-skinned populations has been increasing steadily over the last few decades.1 Although ALM can occur in any race, it disproportionately affects skin of color populations; ALM accounts for only 0.8% to 1% of all melanomas in white populations, but it constitutes 4% to 58% of melanomas in ethnic populations and is the most common melanoma subtype among black Americans.2-5 Acral lentiginous melanoma also is associated with a worse prognosis compared to other subtypes, which may indicate a more aggressive biological nature6 but also may point toward socioeconomic and cultural barriers (eg, low income or education levels, lack of insurance, lower health literacy), leading to disparities in access to care and diagnosis at advanced stages.5

Similarly, the distribution of acral melanocytic nevi appears to demonstrate an association with ethnicity and skin pigmentation. Although skin of color patients have fewer nevi than non-Hispanic whites, the proportion of acral melanocytic nevi tends to be greater.6,7 Given its grim prognosis, accurately differentiating ALM from acral nevi is of utmost importance.

Diagnostic Challenges of Acral Lesions

Due to the unique nature of the surfaces of acral sites, melanocytic lesions on the palms, soles, and nail apparatus present many diagnostic challenges. It can be difficult to distinguish acral melanoma from benign lesions using the naked eye alone. Volar surfaces are characterized by the presence of dermatoglyphics, and pigment deposition along ridges and furrows create particular dermoscopic patterns exclusive to these sites.8 Thus, dermoscopy can be useful on acral surfaces, but the dermoscopic features are different from those on the rest of the body and must be learned separately.

In addition, nearly half of patients are unaware of their acral lesions.6 Acral surfaces may not always be examined by clinicians during total-body skin examinations, leading to further possibility of overlooking a lesion. Obtaining biopsies on glabrous skin or nails also is challenging because they can be more painful and hemostasis can be more difficult, especially in the nail. Acral melanomas also may be amelanotic, including those at subungual sites.

Dermoscopic Patterns of Acral Volar Skin

Dermoscopy is a useful noninvasive tool for distinguishing between benign and malignant acral melanocytic lesions, and its efficacy in improving diagnostic accuracy and decreasing unnecessary biopsies is well-established in the literature.13,14 Acral dermoscopy allows for visualization of pigment along the dermatoglyphics that constitute the characteristic dermoscopic patterns.

Acral Lentiginous Melanoma

The hallmark dermoscopic pattern and most important finding of ALM is the parallel ridge pattern, characterized by parallel linear pigmentation along the ridges of dermatoglyphics. In the early phases of malignancy, the pattern appears light brown and involves most of the lesion; as the tumor develops, increasing melanin production results in focal areas of the parallel ridge pattern with darker bands.15,16 The sensitivity and specificity of a parallel ridge pattern for diagnosing early ALM has been shown to be 86% and 99%, respectively.15,16

A pattern of irregular diffuse pigmentation also can be observed in more advanced ALM. Dermoscopy may reveal a structureless pattern (ie, lack of identifiable structures or patterns) in a background of tan-black coloration due to more exuberant melanocyte proliferation along the epidermis.15 Sensitivity and specificity of this dermoscopic finding for invasive lesions is high at 94% and 97%, respectively.16,17 Interestingly, once ALM lesions have advanced even further, conventional melanoma-associated structures (ie, blue-white veil, polymorphous blood vessels, ulceration, irregular dots/globules or streaks) or atypical forms of typically benign acral dermoscopic patterns may be observed.15

Per a 3-step diagnostic algorithm created by Koga and Saida,18 a suspected acral lesion should first be evaluated for a parallel ridge pattern to determine the need for biopsy, as it is seen in approximately two-thirds of ALMs.19 If no parallel ridge pattern is observed, the lesion should then be checked for any of the typical dermoscopic patterns seen in benign acral nevi (eg, parallel furrow, latticelike, or fibrillar patterns).18 The maximum diameter should be measured only if the lesion does not exhibit any of the typical dermoscopic patterns. If the lesion’s diameter is greater than 7 mm in diameter, it should be biopsied; if the diameter is less than 7 mm, it should have regular clinical and dermoscopic follow-up.18

In 2015, Lallas et al20 developed the BRAAFF checklist, a scoring system of 6 variables: blotches, ridge pattern, asymmetry of structures, asymmetry of colors, parallel furrow pattern, and fibrillar pattern. The checklist also was shown to substantially improve diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy for ALM, with sensitivity and specificity at 93.1% and 86.7%, respectively.20

Acquired Acral Nevi

Three classic dermoscopic patterns are associated with acquired acral nevi: parallel furrow pattern, latticelike pattern, and fibrillar pattern.15,21 Approximately three-quarters of all acquired acral nevi exhibit one of these patterns, roughly half exhibiting parallel furrow with tan-brown bandlike pigmentation along dermatoglyphic grooves.16,17

Latticelike patterns also are characterized by brown parallel lines along the sulci of dermatoglyphics but additionally have multiple intersecting lines. Thus, this pattern can be considered a variant of the parallel furrow pattern.15 The crisscross markings can be predominantly found in the plantar arch.22 This dermoscopic pattern comprises 15% to 25% of all acral nevi.21

Fibrillar pattern accounts for 10% to 20% of all acral melanocytic nevi.21 Dermoscopically, these lesions demonstrate parallel filamentous streaks that cross dermatoglyphics obliquely. The fibrillar pattern is predominantly found on weight-bearing areas of the sole,22 which likely is explained by pressure causing slanting of melanin columns in the horny layer.23 The fibrillar pattern has been shown to be the benign acral dermoscopic pattern that is most commonly misdiagnosed, with higher reported rates of biopsy.24

Acral Congenital Melanocytic Nevi

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) present at birth or appear during the first few weeks of life. Congenital melanocytic nevi can vary widely in size, shape, and color, and they are occasionally biopsied in cases of larger diameter or dermoscopic atypia to differentiate from melanoma.25 Congenital melanocytic nevi also can occur on acral volar surfaces. Possible dermoscopic patterns include parallel furrow or fibrillar patterns as well as a crista dotted pattern, defined as evenly spaced dots/globules on the ridges near the openings of eccrine ducts.26 A more commonly observed dermoscopic pattern in acral CMN is a combination of the crista dotted and parallel furrow patterns, known as the peas-in-a-pod pattern. Changes in the clinical appearance and dermoscopic features of an acral CMN are possible over time; some lesions also may fade with age.26

Final Thoughts

Acral lentiginous melanoma is a rare but potentially aggressive melanoma subtype that accounts for a larger proportion of melanomas in patients with skin of color than in white patients. Dermoscopy of acral volar skin provides invaluable diagnostic information and allows for better management of acral melanocytic lesions. Dermoscopic patterns such as the parallel ridge, parallel furrow, latticelike, fibrillar, and peas-in-a-pod patterns are unique to acral sites and can be used to differentiate between ALMs, acquired nevi, or CMNs.

Acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM) is a rare subtype of melanoma that occurs on the palms, soles, and nail apparatus. Unlike more common types of melanoma, ALM occurs on sun-protected areas of the skin and has distinct clinical, histologic, and genetic features. Acral lentiginous melanoma accounts for a larger proportion of melanomas in individuals with skin of color and has a worse prognosis and recurrence rate than other forms of melanoma.

Population Trends in Skin of Color

Much of the literature on malignant melanoma historically has involved non-Hispanic white patients, but the incidence in lighter-skinned populations has been increasing steadily over the last few decades.1 Although ALM can occur in any race, it disproportionately affects skin of color populations; ALM accounts for only 0.8% to 1% of all melanomas in white populations, but it constitutes 4% to 58% of melanomas in ethnic populations and is the most common melanoma subtype among black Americans.2-5 Acral lentiginous melanoma also is associated with a worse prognosis compared to other subtypes, which may indicate a more aggressive biological nature6 but also may point toward socioeconomic and cultural barriers (eg, low income or education levels, lack of insurance, lower health literacy), leading to disparities in access to care and diagnosis at advanced stages.5

Similarly, the distribution of acral melanocytic nevi appears to demonstrate an association with ethnicity and skin pigmentation. Although skin of color patients have fewer nevi than non-Hispanic whites, the proportion of acral melanocytic nevi tends to be greater.6,7 Given its grim prognosis, accurately differentiating ALM from acral nevi is of utmost importance.

Diagnostic Challenges of Acral Lesions

Due to the unique nature of the surfaces of acral sites, melanocytic lesions on the palms, soles, and nail apparatus present many diagnostic challenges. It can be difficult to distinguish acral melanoma from benign lesions using the naked eye alone. Volar surfaces are characterized by the presence of dermatoglyphics, and pigment deposition along ridges and furrows create particular dermoscopic patterns exclusive to these sites.8 Thus, dermoscopy can be useful on acral surfaces, but the dermoscopic features are different from those on the rest of the body and must be learned separately.

In addition, nearly half of patients are unaware of their acral lesions.6 Acral surfaces may not always be examined by clinicians during total-body skin examinations, leading to further possibility of overlooking a lesion. Obtaining biopsies on glabrous skin or nails also is challenging because they can be more painful and hemostasis can be more difficult, especially in the nail. Acral melanomas also may be amelanotic, including those at subungual sites.

Dermoscopic Patterns of Acral Volar Skin

Dermoscopy is a useful noninvasive tool for distinguishing between benign and malignant acral melanocytic lesions, and its efficacy in improving diagnostic accuracy and decreasing unnecessary biopsies is well-established in the literature.13,14 Acral dermoscopy allows for visualization of pigment along the dermatoglyphics that constitute the characteristic dermoscopic patterns.

Acral Lentiginous Melanoma

The hallmark dermoscopic pattern and most important finding of ALM is the parallel ridge pattern, characterized by parallel linear pigmentation along the ridges of dermatoglyphics. In the early phases of malignancy, the pattern appears light brown and involves most of the lesion; as the tumor develops, increasing melanin production results in focal areas of the parallel ridge pattern with darker bands.15,16 The sensitivity and specificity of a parallel ridge pattern for diagnosing early ALM has been shown to be 86% and 99%, respectively.15,16

A pattern of irregular diffuse pigmentation also can be observed in more advanced ALM. Dermoscopy may reveal a structureless pattern (ie, lack of identifiable structures or patterns) in a background of tan-black coloration due to more exuberant melanocyte proliferation along the epidermis.15 Sensitivity and specificity of this dermoscopic finding for invasive lesions is high at 94% and 97%, respectively.16,17 Interestingly, once ALM lesions have advanced even further, conventional melanoma-associated structures (ie, blue-white veil, polymorphous blood vessels, ulceration, irregular dots/globules or streaks) or atypical forms of typically benign acral dermoscopic patterns may be observed.15

Per a 3-step diagnostic algorithm created by Koga and Saida,18 a suspected acral lesion should first be evaluated for a parallel ridge pattern to determine the need for biopsy, as it is seen in approximately two-thirds of ALMs.19 If no parallel ridge pattern is observed, the lesion should then be checked for any of the typical dermoscopic patterns seen in benign acral nevi (eg, parallel furrow, latticelike, or fibrillar patterns).18 The maximum diameter should be measured only if the lesion does not exhibit any of the typical dermoscopic patterns. If the lesion’s diameter is greater than 7 mm in diameter, it should be biopsied; if the diameter is less than 7 mm, it should have regular clinical and dermoscopic follow-up.18

In 2015, Lallas et al20 developed the BRAAFF checklist, a scoring system of 6 variables: blotches, ridge pattern, asymmetry of structures, asymmetry of colors, parallel furrow pattern, and fibrillar pattern. The checklist also was shown to substantially improve diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy for ALM, with sensitivity and specificity at 93.1% and 86.7%, respectively.20

Acquired Acral Nevi

Three classic dermoscopic patterns are associated with acquired acral nevi: parallel furrow pattern, latticelike pattern, and fibrillar pattern.15,21 Approximately three-quarters of all acquired acral nevi exhibit one of these patterns, roughly half exhibiting parallel furrow with tan-brown bandlike pigmentation along dermatoglyphic grooves.16,17

Latticelike patterns also are characterized by brown parallel lines along the sulci of dermatoglyphics but additionally have multiple intersecting lines. Thus, this pattern can be considered a variant of the parallel furrow pattern.15 The crisscross markings can be predominantly found in the plantar arch.22 This dermoscopic pattern comprises 15% to 25% of all acral nevi.21

Fibrillar pattern accounts for 10% to 20% of all acral melanocytic nevi.21 Dermoscopically, these lesions demonstrate parallel filamentous streaks that cross dermatoglyphics obliquely. The fibrillar pattern is predominantly found on weight-bearing areas of the sole,22 which likely is explained by pressure causing slanting of melanin columns in the horny layer.23 The fibrillar pattern has been shown to be the benign acral dermoscopic pattern that is most commonly misdiagnosed, with higher reported rates of biopsy.24

Acral Congenital Melanocytic Nevi

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) present at birth or appear during the first few weeks of life. Congenital melanocytic nevi can vary widely in size, shape, and color, and they are occasionally biopsied in cases of larger diameter or dermoscopic atypia to differentiate from melanoma.25 Congenital melanocytic nevi also can occur on acral volar surfaces. Possible dermoscopic patterns include parallel furrow or fibrillar patterns as well as a crista dotted pattern, defined as evenly spaced dots/globules on the ridges near the openings of eccrine ducts.26 A more commonly observed dermoscopic pattern in acral CMN is a combination of the crista dotted and parallel furrow patterns, known as the peas-in-a-pod pattern. Changes in the clinical appearance and dermoscopic features of an acral CMN are possible over time; some lesions also may fade with age.26

Final Thoughts

Acral lentiginous melanoma is a rare but potentially aggressive melanoma subtype that accounts for a larger proportion of melanomas in patients with skin of color than in white patients. Dermoscopy of acral volar skin provides invaluable diagnostic information and allows for better management of acral melanocytic lesions. Dermoscopic patterns such as the parallel ridge, parallel furrow, latticelike, fibrillar, and peas-in-a-pod patterns are unique to acral sites and can be used to differentiate between ALMs, acquired nevi, or CMNs.

- Whiteman DC, Green AC, Olsen CM. The growing burden of invasive melanoma: projections of incidence rates and numbers of new cases in six susceptible populations through 2031. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:1161-1171.

- Bradford PT, Goldstein AM, McMaster ML, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1986-2005. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:427-434.

- Nakamura Y, Fujisawa Y. Diagnosis and management of acral lentiginous melanoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:42.

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914.

- Wang Y, Zhao Y, Ma S. Racial differences in six major subtypes of melanoma: descriptive epidemiology. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:691.

- Madankumar R, Gumaste PV, Martires K, et al. Acral melanocytic lesions in the United States: prevalence, awareness, and dermoscopic patterns in skin-of-color and non-Hispanic white patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:724.e1-730.e1.

- Palicka GA, Rhodes AR. Acral melanocytic nevi: prevalence and distribution of gross morphologic features in white and black adults. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1085-1094.

- Thomas L, Phan A, Pralong P, et al. Special locations dermoscopy: facial, acral, and nail. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31:615-624.

- Gong HZ, Zheng HY, Li J. Amelanotic melanoma [published online January 21, 2019]. Melanoma Res. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000571.

- Ise M, Yasuda F, Konohana I, et al. Acral melanoma with hyperkeratosis mimicking a pigmented wart. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:37-39.

- Serarslan G, Akçaly CM, Atik E. Acral lentiginous melanoma misdiagnosed as tinea pedis: a case report. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:37-38.

- Gumaste P, Penn L, Cohen N, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma of the foot misdiagnosed as a traumatic ulcer. a cautionary case. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2015;105:189-194.

- Carli P, de Giorgi V, Chiarugi A, et al. Addition of dermoscopy to conventional naked-eye examination in melanoma screening: a randomized study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:683-689.

- Carli P, de Giorgi V, Crocetti E, et al. Improvement of malignant/benign ratio in excised melanocytic lesions in the ‘dermoscopy era’: a retrospective study 1997-2001. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:687-692.

- Saida T, Koga H, Uhara H. Key points in dermoscopic differentiation between early acral melanoma and acral nevus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:25-34.

- Ishihara Y, Saida T, Miyazaki A, et al. Early acral melanoma in situ: correlation between the parallel ridge pattern on dermoscopy and microscopic features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:21-27.

- Saida T, Miyazaki A, Oguchi S, et al. Significance of dermoscopic patterns in detecting malignant melanoma on acral volar skin: results of a multicenter study in Japan. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1233-1238.

- Koga H, Saida T. Revised 3-step dermoscopic algorithm for the management of acral melanocytic lesions. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:741-743.

- Lallas A, Sgouros D, Zalaudek I, et al. Palmar and plantar melanomas differ for sex prevalence and tumor thickness but not for dermoscopic patterns. Melanoma Res. 2014;24:83-87.