User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Follow-Up Outcomes Data Often Missing for FDA Drug Approvals Based on Surrogate Markers

Over the past few decades, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has increasingly relied on surrogate measures such as blood tests instead of clinical outcomes for medication approvals. But critics say the agency lacks consistent standards to ensure the surrogate aligns with clinical outcomes that matter to patients — things like improvements in symptoms and gains in function.

Sometimes those decisions backfire. Consider: In July 2021, the FDA approved aducanumab for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, bucking the advice of an advisory panel for the agency that questioned the effectiveness of the medication. Regulators relied on data from the drugmaker, Biogen, showing the monoclonal antibody could reduce levels of amyloid beta plaques in blood — a surrogate marker officials hoped would translate to clinical benefit.

The FDA’s decision triggered significant controversy, and Biogen in January announced it is pulling it from the market this year, citing disappointing sales.

Although the case of aducanumab might seem extreme, given the stakes — Alzheimer’s remains a disease without an effective treatment — it’s far from unusual.

“When we prescribe a drug, there is an underlying assumption that the FDA has done its due diligence to confirm the drug is safe and of benefit,” said Reshma Ramachandran, MD, MPP, MHS, a researcher at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, and a coauthor of a recent review of surrogate outcomes. “In fact, we found either no evidence or low-quality evidence.” Such markers are associated with clinical outcomes. “We just don’t know if they work meaningfully to treat the patient’s condition. The results were pretty shocking for us,” she said.

The FDA in 2018 released an Adult Surrogate Endpoint Table listing markers that can be used as substitutes for clinical outcomes to more quickly test, review, and approve new therapies. The analysis found the majority of these endpoints lacked subsequent confirmations, defined as published meta-analyses of clinical studies to validate the association between the marker and a clinical outcome important to patients.

In a paper published in JAMA, Dr. Ramachandran and her colleagues looked at 37 surrogate endpoints for nearly 3 dozen nononcologic diseases in the table.

Approval with surrogate markers implies responsibility for postapproval or validation studies — not just lab measures or imaging findings but mortality, morbidity, or improved quality of life, said Joshua D. Wallach, PhD, MS, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology at the Emory Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta and lead author of the JAMA review.

Dr. Wallach said surrogate markers are easier to measure and do not require large and long trials. But the FDA has not provided clear rules for what makes a surrogate marker valid in clinical trials.

“They’ve said that at a minimum, it requires meta-analytical evidence from studies that have looked at the correlation or the association between the surrogate and the clinical outcome,” Dr. Wallach said. “Our understanding was that if that’s a minimum expectation, we should be able to find those studies in the literature. And the reality is that we were unable to find evidence from those types of studies supporting the association between the surrogate and the clinical outcome.”

Physicians generally do not receive training about the FDA approval process and the difference between biomarkers, surrogate markers, and clinical endpoints, Dr. Ramachandran said. “Our study shows that things are much more uncertain than we thought when it comes to the prescribing of new drugs,” she said.

Surrogate Markers on the Rise

Dr. Wallach’s group looked for published meta-analyses compiling randomized controlled trials reporting surrogate endpoints for more than 3 dozen chronic nononcologic conditions, including type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s, kidney disease, HIV, gout, and lupus. They found no meta-analyses at all for 59% of the surrogate markers, while for those that were studied, few reported high-strength evidence of an association with clinical outcomes.

The findings echo previous research. In a 2020 study in JAMA Network Open, researchers tallied primary endpoints for all FDA approvals of new drugs and therapies during three 3-year periods: 1995-1997, 2005-2007, and 2015-2017. The proportion of products whose approvals were based on the use of clinical endpoints decreased from 43.8% in 1995-1997 to 28.4% in 2005-2007 to 23.3% in 2015-2017. The share based on surrogate endpoints rose from 43.3% to roughly 60% over the same interval.

A 2017 study in the Journal of Health Economics found the use of “imperfect” surrogate endpoints helped support the approval of an average of 16 new drugs per year between 2010 and 2014 compared with six per year from 1998 to 2008.

Similar concerns about weak associations between surrogate markers and drugs used to treat cancer have been documented before, including in a 2020 study published in eClinicalMedicine. The researchers found the surrogate endpoints in the FDA table either were not tested or were tested but proven to be weak surrogates.

“And yet the FDA considered these as good enough not only for accelerated approval but also for regular approval,” said Bishal Gyawali, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of oncology at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, who led the group.

The use of surrogate endpoints is also increasing in Europe, said Huseyin Naci, MHS, PhD, associate professor of health policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science in England. He cited a cohort study of 298 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) in JAMA Oncology suggesting “contemporary oncology RCTs now largely measure putative surrogate endpoints.” Dr. Wallach called the FDA’s surrogate table “a great first step toward transparency. But a key column is missing from that table, telling us what is the basis for which the FDA allows drug companies to use the recognized surrogate markers. What is the evidence they are considering?”

If the agency allows companies the flexibility to validate surrogate endpoints, postmarketing studies designed to confirm the clinical utility of those endpoints should follow.

“We obviously want physicians to be guided by evidence when they’re selecting treatments, and they need to be able to interpret the clinical benefits of the drug that they’re prescribing,” he said. “This is really about having the research consumer, patients, and physicians, as well as industry, understand why certain markers are considered and not considered.”

Dr. Wallach reported receiving grants from the FDA (through the Yale University — Mayo Clinic Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (1K01AA028258), and Johnson & Johnson (through the Yale University Open Data Access Project); and consulting fees from Hagens Berman Sobol Shapiro LLP and Dugan Law Firm APLC outside the submitted work. Dr. Ramachandran reported receiving grants from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation and FDA; receiving consulting fees from ReAct Action on Antibiotic Resistance strategy policy program outside the submitted work; and serving in an unpaid capacity as chair of the FDA task force for the nonprofit organization Doctors for America and in an unpaid capacity as board president for Universities Allied for Essential Medicines North America.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Over the past few decades, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has increasingly relied on surrogate measures such as blood tests instead of clinical outcomes for medication approvals. But critics say the agency lacks consistent standards to ensure the surrogate aligns with clinical outcomes that matter to patients — things like improvements in symptoms and gains in function.

Sometimes those decisions backfire. Consider: In July 2021, the FDA approved aducanumab for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, bucking the advice of an advisory panel for the agency that questioned the effectiveness of the medication. Regulators relied on data from the drugmaker, Biogen, showing the monoclonal antibody could reduce levels of amyloid beta plaques in blood — a surrogate marker officials hoped would translate to clinical benefit.

The FDA’s decision triggered significant controversy, and Biogen in January announced it is pulling it from the market this year, citing disappointing sales.

Although the case of aducanumab might seem extreme, given the stakes — Alzheimer’s remains a disease without an effective treatment — it’s far from unusual.

“When we prescribe a drug, there is an underlying assumption that the FDA has done its due diligence to confirm the drug is safe and of benefit,” said Reshma Ramachandran, MD, MPP, MHS, a researcher at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, and a coauthor of a recent review of surrogate outcomes. “In fact, we found either no evidence or low-quality evidence.” Such markers are associated with clinical outcomes. “We just don’t know if they work meaningfully to treat the patient’s condition. The results were pretty shocking for us,” she said.

The FDA in 2018 released an Adult Surrogate Endpoint Table listing markers that can be used as substitutes for clinical outcomes to more quickly test, review, and approve new therapies. The analysis found the majority of these endpoints lacked subsequent confirmations, defined as published meta-analyses of clinical studies to validate the association between the marker and a clinical outcome important to patients.

In a paper published in JAMA, Dr. Ramachandran and her colleagues looked at 37 surrogate endpoints for nearly 3 dozen nononcologic diseases in the table.

Approval with surrogate markers implies responsibility for postapproval or validation studies — not just lab measures or imaging findings but mortality, morbidity, or improved quality of life, said Joshua D. Wallach, PhD, MS, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology at the Emory Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta and lead author of the JAMA review.

Dr. Wallach said surrogate markers are easier to measure and do not require large and long trials. But the FDA has not provided clear rules for what makes a surrogate marker valid in clinical trials.

“They’ve said that at a minimum, it requires meta-analytical evidence from studies that have looked at the correlation or the association between the surrogate and the clinical outcome,” Dr. Wallach said. “Our understanding was that if that’s a minimum expectation, we should be able to find those studies in the literature. And the reality is that we were unable to find evidence from those types of studies supporting the association between the surrogate and the clinical outcome.”

Physicians generally do not receive training about the FDA approval process and the difference between biomarkers, surrogate markers, and clinical endpoints, Dr. Ramachandran said. “Our study shows that things are much more uncertain than we thought when it comes to the prescribing of new drugs,” she said.

Surrogate Markers on the Rise

Dr. Wallach’s group looked for published meta-analyses compiling randomized controlled trials reporting surrogate endpoints for more than 3 dozen chronic nononcologic conditions, including type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s, kidney disease, HIV, gout, and lupus. They found no meta-analyses at all for 59% of the surrogate markers, while for those that were studied, few reported high-strength evidence of an association with clinical outcomes.

The findings echo previous research. In a 2020 study in JAMA Network Open, researchers tallied primary endpoints for all FDA approvals of new drugs and therapies during three 3-year periods: 1995-1997, 2005-2007, and 2015-2017. The proportion of products whose approvals were based on the use of clinical endpoints decreased from 43.8% in 1995-1997 to 28.4% in 2005-2007 to 23.3% in 2015-2017. The share based on surrogate endpoints rose from 43.3% to roughly 60% over the same interval.

A 2017 study in the Journal of Health Economics found the use of “imperfect” surrogate endpoints helped support the approval of an average of 16 new drugs per year between 2010 and 2014 compared with six per year from 1998 to 2008.

Similar concerns about weak associations between surrogate markers and drugs used to treat cancer have been documented before, including in a 2020 study published in eClinicalMedicine. The researchers found the surrogate endpoints in the FDA table either were not tested or were tested but proven to be weak surrogates.

“And yet the FDA considered these as good enough not only for accelerated approval but also for regular approval,” said Bishal Gyawali, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of oncology at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, who led the group.

The use of surrogate endpoints is also increasing in Europe, said Huseyin Naci, MHS, PhD, associate professor of health policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science in England. He cited a cohort study of 298 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) in JAMA Oncology suggesting “contemporary oncology RCTs now largely measure putative surrogate endpoints.” Dr. Wallach called the FDA’s surrogate table “a great first step toward transparency. But a key column is missing from that table, telling us what is the basis for which the FDA allows drug companies to use the recognized surrogate markers. What is the evidence they are considering?”

If the agency allows companies the flexibility to validate surrogate endpoints, postmarketing studies designed to confirm the clinical utility of those endpoints should follow.

“We obviously want physicians to be guided by evidence when they’re selecting treatments, and they need to be able to interpret the clinical benefits of the drug that they’re prescribing,” he said. “This is really about having the research consumer, patients, and physicians, as well as industry, understand why certain markers are considered and not considered.”

Dr. Wallach reported receiving grants from the FDA (through the Yale University — Mayo Clinic Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (1K01AA028258), and Johnson & Johnson (through the Yale University Open Data Access Project); and consulting fees from Hagens Berman Sobol Shapiro LLP and Dugan Law Firm APLC outside the submitted work. Dr. Ramachandran reported receiving grants from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation and FDA; receiving consulting fees from ReAct Action on Antibiotic Resistance strategy policy program outside the submitted work; and serving in an unpaid capacity as chair of the FDA task force for the nonprofit organization Doctors for America and in an unpaid capacity as board president for Universities Allied for Essential Medicines North America.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Over the past few decades, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has increasingly relied on surrogate measures such as blood tests instead of clinical outcomes for medication approvals. But critics say the agency lacks consistent standards to ensure the surrogate aligns with clinical outcomes that matter to patients — things like improvements in symptoms and gains in function.

Sometimes those decisions backfire. Consider: In July 2021, the FDA approved aducanumab for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, bucking the advice of an advisory panel for the agency that questioned the effectiveness of the medication. Regulators relied on data from the drugmaker, Biogen, showing the monoclonal antibody could reduce levels of amyloid beta plaques in blood — a surrogate marker officials hoped would translate to clinical benefit.

The FDA’s decision triggered significant controversy, and Biogen in January announced it is pulling it from the market this year, citing disappointing sales.

Although the case of aducanumab might seem extreme, given the stakes — Alzheimer’s remains a disease without an effective treatment — it’s far from unusual.

“When we prescribe a drug, there is an underlying assumption that the FDA has done its due diligence to confirm the drug is safe and of benefit,” said Reshma Ramachandran, MD, MPP, MHS, a researcher at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, and a coauthor of a recent review of surrogate outcomes. “In fact, we found either no evidence or low-quality evidence.” Such markers are associated with clinical outcomes. “We just don’t know if they work meaningfully to treat the patient’s condition. The results were pretty shocking for us,” she said.

The FDA in 2018 released an Adult Surrogate Endpoint Table listing markers that can be used as substitutes for clinical outcomes to more quickly test, review, and approve new therapies. The analysis found the majority of these endpoints lacked subsequent confirmations, defined as published meta-analyses of clinical studies to validate the association between the marker and a clinical outcome important to patients.

In a paper published in JAMA, Dr. Ramachandran and her colleagues looked at 37 surrogate endpoints for nearly 3 dozen nononcologic diseases in the table.

Approval with surrogate markers implies responsibility for postapproval or validation studies — not just lab measures or imaging findings but mortality, morbidity, or improved quality of life, said Joshua D. Wallach, PhD, MS, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology at the Emory Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta and lead author of the JAMA review.

Dr. Wallach said surrogate markers are easier to measure and do not require large and long trials. But the FDA has not provided clear rules for what makes a surrogate marker valid in clinical trials.

“They’ve said that at a minimum, it requires meta-analytical evidence from studies that have looked at the correlation or the association between the surrogate and the clinical outcome,” Dr. Wallach said. “Our understanding was that if that’s a minimum expectation, we should be able to find those studies in the literature. And the reality is that we were unable to find evidence from those types of studies supporting the association between the surrogate and the clinical outcome.”

Physicians generally do not receive training about the FDA approval process and the difference between biomarkers, surrogate markers, and clinical endpoints, Dr. Ramachandran said. “Our study shows that things are much more uncertain than we thought when it comes to the prescribing of new drugs,” she said.

Surrogate Markers on the Rise

Dr. Wallach’s group looked for published meta-analyses compiling randomized controlled trials reporting surrogate endpoints for more than 3 dozen chronic nononcologic conditions, including type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s, kidney disease, HIV, gout, and lupus. They found no meta-analyses at all for 59% of the surrogate markers, while for those that were studied, few reported high-strength evidence of an association with clinical outcomes.

The findings echo previous research. In a 2020 study in JAMA Network Open, researchers tallied primary endpoints for all FDA approvals of new drugs and therapies during three 3-year periods: 1995-1997, 2005-2007, and 2015-2017. The proportion of products whose approvals were based on the use of clinical endpoints decreased from 43.8% in 1995-1997 to 28.4% in 2005-2007 to 23.3% in 2015-2017. The share based on surrogate endpoints rose from 43.3% to roughly 60% over the same interval.

A 2017 study in the Journal of Health Economics found the use of “imperfect” surrogate endpoints helped support the approval of an average of 16 new drugs per year between 2010 and 2014 compared with six per year from 1998 to 2008.

Similar concerns about weak associations between surrogate markers and drugs used to treat cancer have been documented before, including in a 2020 study published in eClinicalMedicine. The researchers found the surrogate endpoints in the FDA table either were not tested or were tested but proven to be weak surrogates.

“And yet the FDA considered these as good enough not only for accelerated approval but also for regular approval,” said Bishal Gyawali, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of oncology at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, who led the group.

The use of surrogate endpoints is also increasing in Europe, said Huseyin Naci, MHS, PhD, associate professor of health policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science in England. He cited a cohort study of 298 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) in JAMA Oncology suggesting “contemporary oncology RCTs now largely measure putative surrogate endpoints.” Dr. Wallach called the FDA’s surrogate table “a great first step toward transparency. But a key column is missing from that table, telling us what is the basis for which the FDA allows drug companies to use the recognized surrogate markers. What is the evidence they are considering?”

If the agency allows companies the flexibility to validate surrogate endpoints, postmarketing studies designed to confirm the clinical utility of those endpoints should follow.

“We obviously want physicians to be guided by evidence when they’re selecting treatments, and they need to be able to interpret the clinical benefits of the drug that they’re prescribing,” he said. “This is really about having the research consumer, patients, and physicians, as well as industry, understand why certain markers are considered and not considered.”

Dr. Wallach reported receiving grants from the FDA (through the Yale University — Mayo Clinic Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (1K01AA028258), and Johnson & Johnson (through the Yale University Open Data Access Project); and consulting fees from Hagens Berman Sobol Shapiro LLP and Dugan Law Firm APLC outside the submitted work. Dr. Ramachandran reported receiving grants from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation and FDA; receiving consulting fees from ReAct Action on Antibiotic Resistance strategy policy program outside the submitted work; and serving in an unpaid capacity as chair of the FDA task force for the nonprofit organization Doctors for America and in an unpaid capacity as board president for Universities Allied for Essential Medicines North America.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

FDA Approves Tarlatamab for Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer

Tarlatamab is a first-in-class bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE) that binds delta-like ligand 3 on the surface of cells, including tumor cells, and CD3 expressed on the surface of T cells. It causes T-cell activation, release of inflammatory cytokines, and lysis of DLL3-expressing cells, according to labeling.

Approval was based on data from 99 patients in the DeLLphi-301 trial with relapsed/refractory extensive-stage SCLC who had progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy. Patients with symptomatic brain metastases, interstitial lung disease, noninfectious pneumonitis, and active immunodeficiency were excluded.

The overall response rate was 40%, and median duration of response 9.7 months. The overall response rate was 52% in 27 patients with platinum-resistant SCLC and 31% in 42 with platinum-sensitive disease.

Continued approval may depend on verification of clinical benefit in a confirmatory trial.

Labeling includes a box warning of serious or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome and neurologic toxicity, including immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome.

The most common adverse events, occurring in 20% or more of patients, were cytokine release syndrome, fatigue, pyrexia, dysgeusia, decreased appetite, musculoskeletal pain, constipation, anemia, and nausea.

The most common grade 3 or 4 laboratory abnormalities included decreased lymphocytes, decreased sodium, increased uric acid, decreased total neutrophils, decreased hemoglobin, increased activated partial thromboplastin time, and decreased potassium.

The starting dose is 1 mg given intravenously over 1 hour on the first day of the first cycle followed by 10 mg on day 8 and day 15 of the first cycle, then every 2 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

M. Alexander Otto is a physician assistant with a master’s degree in medical science and a journalism degree from Newhouse. He is an award-winning medical journalist who worked for several major news outlets before joining Medscape. Alex is also an MIT Knight Science Journalism fellow. Email: [email protected]

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Tarlatamab is a first-in-class bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE) that binds delta-like ligand 3 on the surface of cells, including tumor cells, and CD3 expressed on the surface of T cells. It causes T-cell activation, release of inflammatory cytokines, and lysis of DLL3-expressing cells, according to labeling.

Approval was based on data from 99 patients in the DeLLphi-301 trial with relapsed/refractory extensive-stage SCLC who had progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy. Patients with symptomatic brain metastases, interstitial lung disease, noninfectious pneumonitis, and active immunodeficiency were excluded.

The overall response rate was 40%, and median duration of response 9.7 months. The overall response rate was 52% in 27 patients with platinum-resistant SCLC and 31% in 42 with platinum-sensitive disease.

Continued approval may depend on verification of clinical benefit in a confirmatory trial.

Labeling includes a box warning of serious or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome and neurologic toxicity, including immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome.

The most common adverse events, occurring in 20% or more of patients, were cytokine release syndrome, fatigue, pyrexia, dysgeusia, decreased appetite, musculoskeletal pain, constipation, anemia, and nausea.

The most common grade 3 or 4 laboratory abnormalities included decreased lymphocytes, decreased sodium, increased uric acid, decreased total neutrophils, decreased hemoglobin, increased activated partial thromboplastin time, and decreased potassium.

The starting dose is 1 mg given intravenously over 1 hour on the first day of the first cycle followed by 10 mg on day 8 and day 15 of the first cycle, then every 2 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

M. Alexander Otto is a physician assistant with a master’s degree in medical science and a journalism degree from Newhouse. He is an award-winning medical journalist who worked for several major news outlets before joining Medscape. Alex is also an MIT Knight Science Journalism fellow. Email: [email protected]

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Tarlatamab is a first-in-class bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE) that binds delta-like ligand 3 on the surface of cells, including tumor cells, and CD3 expressed on the surface of T cells. It causes T-cell activation, release of inflammatory cytokines, and lysis of DLL3-expressing cells, according to labeling.

Approval was based on data from 99 patients in the DeLLphi-301 trial with relapsed/refractory extensive-stage SCLC who had progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy. Patients with symptomatic brain metastases, interstitial lung disease, noninfectious pneumonitis, and active immunodeficiency were excluded.

The overall response rate was 40%, and median duration of response 9.7 months. The overall response rate was 52% in 27 patients with platinum-resistant SCLC and 31% in 42 with platinum-sensitive disease.

Continued approval may depend on verification of clinical benefit in a confirmatory trial.

Labeling includes a box warning of serious or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome and neurologic toxicity, including immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome.

The most common adverse events, occurring in 20% or more of patients, were cytokine release syndrome, fatigue, pyrexia, dysgeusia, decreased appetite, musculoskeletal pain, constipation, anemia, and nausea.

The most common grade 3 or 4 laboratory abnormalities included decreased lymphocytes, decreased sodium, increased uric acid, decreased total neutrophils, decreased hemoglobin, increased activated partial thromboplastin time, and decreased potassium.

The starting dose is 1 mg given intravenously over 1 hour on the first day of the first cycle followed by 10 mg on day 8 and day 15 of the first cycle, then every 2 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

M. Alexander Otto is a physician assistant with a master’s degree in medical science and a journalism degree from Newhouse. He is an award-winning medical journalist who worked for several major news outlets before joining Medscape. Alex is also an MIT Knight Science Journalism fellow. Email: [email protected]

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Chatbots Seem More Empathetic Than Docs in Cancer Discussions

Large language models (LLM) such as ChatGPT have shown mixed results in the quality of their responses to consumer questions about cancer.

One recent study found AI chatbots to churn out incomplete, inaccurate, or even nonsensical cancer treatment recommendations, while another found them to generate largely accurate — if technical — responses to the most common cancer questions.

While researchers have seen success with purpose-built chatbots created to address patient concerns about specific cancers, the consensus to date has been that the generalized models like ChatGPT remain works in progress and that physicians should avoid pointing patients to them, for now.

Yet new findings suggest that these chatbots may do better than individual physicians, at least on some measures, when it comes to answering queries about cancer. For research published May 16 in JAMA Oncology (doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2024.0836), David Chen, a medical student at the University of Toronto, and his colleagues, isolated a random sample of 200 questions related to cancer care addressed to doctors on the public online forum Reddit. They then compared responses from oncologists with responses generated by three different AI chatbots. The blinded responses were rated for quality, readability, and empathy by six physicians, including oncologists and palliative and supportive care specialists.

Mr. Chen and colleagues’ research was modeled after a 2023 study that measured the quality of physician responses compared with chatbots for general medicine questions addressed to doctors on Reddit. That study found that the chatbots produced more empathetic-sounding answers, something Mr. Chen’s study also found. : quality, empathy, and readability.

Q&A With Author of New Research

Mr. Chen discussed his new study’s implications during an interview with this news organization.

Question: What is novel about this study?

Mr. Chen: We’ve seen many evaluations of chatbots that test for medical accuracy, but this study occurs in the domain of oncology care, where there are unique psychosocial and emotional considerations that are not precisely reflected in a general medicine setting. In effect, this study is putting these chatbots through a harder challenge.

Question: Why would chatbot responses seem more empathetic than those of physicians?

Mr. Chen: With the physician responses that we observed in our sample data set, we saw that there was very high variation of amount of apparent effort [in the physician responses]. Some physicians would put in a lot of time and effort, thinking through their response, and others wouldn’t do so as much. These chatbots don’t face fatigue the way humans do, or burnout. So they’re able to consistently provide responses with less variation in empathy.

Question: Do chatbots just seem empathetic because they are chattier?

Mr. Chen: We did think of verbosity as a potential confounder in this study. So we set a word count limit for the chatbot responses to keep it in the range of the physician responses. That way, verbosity was no longer a significant factor.

Question: How were quality and empathy measured by the reviewers?

Mr. Chen: For our study we used two teams of readers, each team composed of three physicians. In terms of the actual metrics we used, they were pilot metrics. There are no well-defined measurement scales or checklists that we could use to measure empathy. This is an emerging field of research. So we came up by consensus with our own set of ratings, and we feel that this is an area for the research to define a standardized set of guidelines.

Another novel aspect of this study is that we separated out different dimensions of quality and empathy. A quality response didn’t just mean it was medically accurate — quality also had to do with the focus and completeness of the response.

With empathy there are cognitive and emotional dimensions. Cognitive empathy uses critical thinking to understand the person’s emotions and thoughts and then adjusting a response to fit that. A patient may not want the best medically indicated treatment for their condition, because they want to preserve their quality of life. The chatbot may be able to adjust its recommendation with consideration of some of those humanistic elements that the patient is presenting with.

Emotional empathy is more about being supportive of the patient’s emotions by using expressions like ‘I understand where you’re coming from.’ or, ‘I can see how that makes you feel.’

Question: Why would physicians, not patients, be the best evaluators of empathy?

Mr. Chen: We’re actually very interested in evaluating patient ratings of empathy. We are conducting a follow-up study that evaluates patient ratings of empathy to the same set of chatbot and physician responses,to see if there are differences.

Question: Should cancer patients go ahead and consult chatbots?

Mr. Chen: Although we did observe increases in all of the metrics compared with physicians, this is a very specialized evaluation scenario where we’re using these Reddit questions and responses.

Naturally, we would need to do a trial, a head to head randomized comparison of physicians versus chatbots.

This pilot study does highlight the promising potential of these chatbots to suggest responses. But we can’t fully recommend that they should be used as standalone clinical tools without physicians.

This Q&A was edited for clarity.

Large language models (LLM) such as ChatGPT have shown mixed results in the quality of their responses to consumer questions about cancer.

One recent study found AI chatbots to churn out incomplete, inaccurate, or even nonsensical cancer treatment recommendations, while another found them to generate largely accurate — if technical — responses to the most common cancer questions.

While researchers have seen success with purpose-built chatbots created to address patient concerns about specific cancers, the consensus to date has been that the generalized models like ChatGPT remain works in progress and that physicians should avoid pointing patients to them, for now.

Yet new findings suggest that these chatbots may do better than individual physicians, at least on some measures, when it comes to answering queries about cancer. For research published May 16 in JAMA Oncology (doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2024.0836), David Chen, a medical student at the University of Toronto, and his colleagues, isolated a random sample of 200 questions related to cancer care addressed to doctors on the public online forum Reddit. They then compared responses from oncologists with responses generated by three different AI chatbots. The blinded responses were rated for quality, readability, and empathy by six physicians, including oncologists and palliative and supportive care specialists.

Mr. Chen and colleagues’ research was modeled after a 2023 study that measured the quality of physician responses compared with chatbots for general medicine questions addressed to doctors on Reddit. That study found that the chatbots produced more empathetic-sounding answers, something Mr. Chen’s study also found. : quality, empathy, and readability.

Q&A With Author of New Research

Mr. Chen discussed his new study’s implications during an interview with this news organization.

Question: What is novel about this study?

Mr. Chen: We’ve seen many evaluations of chatbots that test for medical accuracy, but this study occurs in the domain of oncology care, where there are unique psychosocial and emotional considerations that are not precisely reflected in a general medicine setting. In effect, this study is putting these chatbots through a harder challenge.

Question: Why would chatbot responses seem more empathetic than those of physicians?

Mr. Chen: With the physician responses that we observed in our sample data set, we saw that there was very high variation of amount of apparent effort [in the physician responses]. Some physicians would put in a lot of time and effort, thinking through their response, and others wouldn’t do so as much. These chatbots don’t face fatigue the way humans do, or burnout. So they’re able to consistently provide responses with less variation in empathy.

Question: Do chatbots just seem empathetic because they are chattier?

Mr. Chen: We did think of verbosity as a potential confounder in this study. So we set a word count limit for the chatbot responses to keep it in the range of the physician responses. That way, verbosity was no longer a significant factor.

Question: How were quality and empathy measured by the reviewers?

Mr. Chen: For our study we used two teams of readers, each team composed of three physicians. In terms of the actual metrics we used, they were pilot metrics. There are no well-defined measurement scales or checklists that we could use to measure empathy. This is an emerging field of research. So we came up by consensus with our own set of ratings, and we feel that this is an area for the research to define a standardized set of guidelines.

Another novel aspect of this study is that we separated out different dimensions of quality and empathy. A quality response didn’t just mean it was medically accurate — quality also had to do with the focus and completeness of the response.

With empathy there are cognitive and emotional dimensions. Cognitive empathy uses critical thinking to understand the person’s emotions and thoughts and then adjusting a response to fit that. A patient may not want the best medically indicated treatment for their condition, because they want to preserve their quality of life. The chatbot may be able to adjust its recommendation with consideration of some of those humanistic elements that the patient is presenting with.

Emotional empathy is more about being supportive of the patient’s emotions by using expressions like ‘I understand where you’re coming from.’ or, ‘I can see how that makes you feel.’

Question: Why would physicians, not patients, be the best evaluators of empathy?

Mr. Chen: We’re actually very interested in evaluating patient ratings of empathy. We are conducting a follow-up study that evaluates patient ratings of empathy to the same set of chatbot and physician responses,to see if there are differences.

Question: Should cancer patients go ahead and consult chatbots?

Mr. Chen: Although we did observe increases in all of the metrics compared with physicians, this is a very specialized evaluation scenario where we’re using these Reddit questions and responses.

Naturally, we would need to do a trial, a head to head randomized comparison of physicians versus chatbots.

This pilot study does highlight the promising potential of these chatbots to suggest responses. But we can’t fully recommend that they should be used as standalone clinical tools without physicians.

This Q&A was edited for clarity.

Large language models (LLM) such as ChatGPT have shown mixed results in the quality of their responses to consumer questions about cancer.

One recent study found AI chatbots to churn out incomplete, inaccurate, or even nonsensical cancer treatment recommendations, while another found them to generate largely accurate — if technical — responses to the most common cancer questions.

While researchers have seen success with purpose-built chatbots created to address patient concerns about specific cancers, the consensus to date has been that the generalized models like ChatGPT remain works in progress and that physicians should avoid pointing patients to them, for now.

Yet new findings suggest that these chatbots may do better than individual physicians, at least on some measures, when it comes to answering queries about cancer. For research published May 16 in JAMA Oncology (doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2024.0836), David Chen, a medical student at the University of Toronto, and his colleagues, isolated a random sample of 200 questions related to cancer care addressed to doctors on the public online forum Reddit. They then compared responses from oncologists with responses generated by three different AI chatbots. The blinded responses were rated for quality, readability, and empathy by six physicians, including oncologists and palliative and supportive care specialists.

Mr. Chen and colleagues’ research was modeled after a 2023 study that measured the quality of physician responses compared with chatbots for general medicine questions addressed to doctors on Reddit. That study found that the chatbots produced more empathetic-sounding answers, something Mr. Chen’s study also found. : quality, empathy, and readability.

Q&A With Author of New Research

Mr. Chen discussed his new study’s implications during an interview with this news organization.

Question: What is novel about this study?

Mr. Chen: We’ve seen many evaluations of chatbots that test for medical accuracy, but this study occurs in the domain of oncology care, where there are unique psychosocial and emotional considerations that are not precisely reflected in a general medicine setting. In effect, this study is putting these chatbots through a harder challenge.

Question: Why would chatbot responses seem more empathetic than those of physicians?

Mr. Chen: With the physician responses that we observed in our sample data set, we saw that there was very high variation of amount of apparent effort [in the physician responses]. Some physicians would put in a lot of time and effort, thinking through their response, and others wouldn’t do so as much. These chatbots don’t face fatigue the way humans do, or burnout. So they’re able to consistently provide responses with less variation in empathy.

Question: Do chatbots just seem empathetic because they are chattier?

Mr. Chen: We did think of verbosity as a potential confounder in this study. So we set a word count limit for the chatbot responses to keep it in the range of the physician responses. That way, verbosity was no longer a significant factor.

Question: How were quality and empathy measured by the reviewers?

Mr. Chen: For our study we used two teams of readers, each team composed of three physicians. In terms of the actual metrics we used, they were pilot metrics. There are no well-defined measurement scales or checklists that we could use to measure empathy. This is an emerging field of research. So we came up by consensus with our own set of ratings, and we feel that this is an area for the research to define a standardized set of guidelines.

Another novel aspect of this study is that we separated out different dimensions of quality and empathy. A quality response didn’t just mean it was medically accurate — quality also had to do with the focus and completeness of the response.

With empathy there are cognitive and emotional dimensions. Cognitive empathy uses critical thinking to understand the person’s emotions and thoughts and then adjusting a response to fit that. A patient may not want the best medically indicated treatment for their condition, because they want to preserve their quality of life. The chatbot may be able to adjust its recommendation with consideration of some of those humanistic elements that the patient is presenting with.

Emotional empathy is more about being supportive of the patient’s emotions by using expressions like ‘I understand where you’re coming from.’ or, ‘I can see how that makes you feel.’

Question: Why would physicians, not patients, be the best evaluators of empathy?

Mr. Chen: We’re actually very interested in evaluating patient ratings of empathy. We are conducting a follow-up study that evaluates patient ratings of empathy to the same set of chatbot and physician responses,to see if there are differences.

Question: Should cancer patients go ahead and consult chatbots?

Mr. Chen: Although we did observe increases in all of the metrics compared with physicians, this is a very specialized evaluation scenario where we’re using these Reddit questions and responses.

Naturally, we would need to do a trial, a head to head randomized comparison of physicians versus chatbots.

This pilot study does highlight the promising potential of these chatbots to suggest responses. But we can’t fully recommend that they should be used as standalone clinical tools without physicians.

This Q&A was edited for clarity.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

CPAP Underperforms: The Sequel

A few months ago, I posted a column on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with the title, “CPAP Oversells and Underperforms.” To date, it has 299 likes and 90 comments, which are almost all negative. I’m glad to see that it’s generated interest, and I’d like to address some of the themes expressed in the posts.

Most comments were personal testimonies to the miracles of CPAP. These are important, and the point deserves emphasis. CPAP can provide significant improvements in daytime sleepiness and quality of life. I closed the original piece by acknowledging this important fact. Readers can be forgiven for missing it given that the title and text were otherwise disparaging of CPAP.

But several comments warrant a more in-depth discussion. The original piece focuses on CPAP and cardiovascular (CV) outcomes but made no mention of atrial fibrillation (AF) or ejection fraction (EF). The effects of CPAP on each are touted by cardiologists and PAP-pushers alike and are drivers of frequent referrals. It›s my fault for omitting them from the discussion.

AF is easy. The data is identical to all other things CPAP and CV. Based on biologic plausibility alone, the likelihood of a relationship between AF and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is similar to the odds that the Celtics raise an 18th banner come June. There’s hypoxia, intrathoracic pressure swings, sympathetic surges, and sleep state disruptions. It’s easy to get from there to arrhythmogenesis. There’s lots of observational noise, too, but no randomized proof that CPAP alters this relationship.

I found four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that tested CPAP’s effect on AF. I’ll save you the suspense; they were all negative. One even found a signal for more adverse events in the CPAP group. These studies have several positive qualities: They enrolled patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea and high oxygen desaturation indices, adherence averaged more than 4 hours across all groups in all trials, and the methods for assessing the AF outcomes differed slightly. There’s also a lot not to like: The sample sizes were small, only one trial enrolled “sleepy” patients (as assessed by the Epworth Sleepiness Score), and follow-up was short.

To paraphrase Carl Sagan, “absence of evidence does not equal evidence of absence.” As a statistician would say, type II error cannot be excluded by these RCTs. In medicine, however, the burden of proof falls on demonstrating efficacy. If we treat before concluding that a therapy works, we risk wasting time, money, medical resources, and the most precious of patient commodities: the energy required for behavior change. In their response to letters to the editor, the authors of the third RCT summarize the CPAP, AF, and CV disease data far better than I ever could. They sound the same words of caution and come out against screening patients with AF for OSA.

The story for CPAP’s effects on EF is similar though muddier. The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for heart failure cite a meta-analysis showing that CPAP improves left ventricular EF. In 2019, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) CPAP guidelines included a systematic review and meta-analysis that found that CPAP has no effect on left ventricular EF in patients with or without heart failure.

There are a million reasons why two systematic reviews on the same topic might come to different conclusions. In this case, the included studies only partially overlap, and broadly speaking, it appears the authors made trade-offs. The review cited by the ACC/AHA had broader inclusion and significantly more patients and paid for it in heterogeneity (I2 in the 80%-90% range). The AASM analysis achieved 0% heterogeneity but limited inclusion to fewer than 100 patients. Across both, the improvement in EF was 2%- 5% at a minimally clinically important difference of 4%. Hardly convincing.

In summary, the road to negative trials and patient harm has always been paved with observational signal and biologic plausibility. Throw in some intellectual and academic bias, and you’ve created the perfect storm of therapeutic overconfidence.

Dr. Holley is a professor in the department of medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland, and a physician at Pulmonary/Sleep and Critical Care Medicine, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington. He disclosed ties to Metapharm Inc., CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

A few months ago, I posted a column on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with the title, “CPAP Oversells and Underperforms.” To date, it has 299 likes and 90 comments, which are almost all negative. I’m glad to see that it’s generated interest, and I’d like to address some of the themes expressed in the posts.

Most comments were personal testimonies to the miracles of CPAP. These are important, and the point deserves emphasis. CPAP can provide significant improvements in daytime sleepiness and quality of life. I closed the original piece by acknowledging this important fact. Readers can be forgiven for missing it given that the title and text were otherwise disparaging of CPAP.

But several comments warrant a more in-depth discussion. The original piece focuses on CPAP and cardiovascular (CV) outcomes but made no mention of atrial fibrillation (AF) or ejection fraction (EF). The effects of CPAP on each are touted by cardiologists and PAP-pushers alike and are drivers of frequent referrals. It›s my fault for omitting them from the discussion.

AF is easy. The data is identical to all other things CPAP and CV. Based on biologic plausibility alone, the likelihood of a relationship between AF and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is similar to the odds that the Celtics raise an 18th banner come June. There’s hypoxia, intrathoracic pressure swings, sympathetic surges, and sleep state disruptions. It’s easy to get from there to arrhythmogenesis. There’s lots of observational noise, too, but no randomized proof that CPAP alters this relationship.

I found four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that tested CPAP’s effect on AF. I’ll save you the suspense; they were all negative. One even found a signal for more adverse events in the CPAP group. These studies have several positive qualities: They enrolled patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea and high oxygen desaturation indices, adherence averaged more than 4 hours across all groups in all trials, and the methods for assessing the AF outcomes differed slightly. There’s also a lot not to like: The sample sizes were small, only one trial enrolled “sleepy” patients (as assessed by the Epworth Sleepiness Score), and follow-up was short.

To paraphrase Carl Sagan, “absence of evidence does not equal evidence of absence.” As a statistician would say, type II error cannot be excluded by these RCTs. In medicine, however, the burden of proof falls on demonstrating efficacy. If we treat before concluding that a therapy works, we risk wasting time, money, medical resources, and the most precious of patient commodities: the energy required for behavior change. In their response to letters to the editor, the authors of the third RCT summarize the CPAP, AF, and CV disease data far better than I ever could. They sound the same words of caution and come out against screening patients with AF for OSA.

The story for CPAP’s effects on EF is similar though muddier. The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for heart failure cite a meta-analysis showing that CPAP improves left ventricular EF. In 2019, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) CPAP guidelines included a systematic review and meta-analysis that found that CPAP has no effect on left ventricular EF in patients with or without heart failure.

There are a million reasons why two systematic reviews on the same topic might come to different conclusions. In this case, the included studies only partially overlap, and broadly speaking, it appears the authors made trade-offs. The review cited by the ACC/AHA had broader inclusion and significantly more patients and paid for it in heterogeneity (I2 in the 80%-90% range). The AASM analysis achieved 0% heterogeneity but limited inclusion to fewer than 100 patients. Across both, the improvement in EF was 2%- 5% at a minimally clinically important difference of 4%. Hardly convincing.

In summary, the road to negative trials and patient harm has always been paved with observational signal and biologic plausibility. Throw in some intellectual and academic bias, and you’ve created the perfect storm of therapeutic overconfidence.

Dr. Holley is a professor in the department of medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland, and a physician at Pulmonary/Sleep and Critical Care Medicine, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington. He disclosed ties to Metapharm Inc., CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

A few months ago, I posted a column on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with the title, “CPAP Oversells and Underperforms.” To date, it has 299 likes and 90 comments, which are almost all negative. I’m glad to see that it’s generated interest, and I’d like to address some of the themes expressed in the posts.

Most comments were personal testimonies to the miracles of CPAP. These are important, and the point deserves emphasis. CPAP can provide significant improvements in daytime sleepiness and quality of life. I closed the original piece by acknowledging this important fact. Readers can be forgiven for missing it given that the title and text were otherwise disparaging of CPAP.

But several comments warrant a more in-depth discussion. The original piece focuses on CPAP and cardiovascular (CV) outcomes but made no mention of atrial fibrillation (AF) or ejection fraction (EF). The effects of CPAP on each are touted by cardiologists and PAP-pushers alike and are drivers of frequent referrals. It›s my fault for omitting them from the discussion.

AF is easy. The data is identical to all other things CPAP and CV. Based on biologic plausibility alone, the likelihood of a relationship between AF and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is similar to the odds that the Celtics raise an 18th banner come June. There’s hypoxia, intrathoracic pressure swings, sympathetic surges, and sleep state disruptions. It’s easy to get from there to arrhythmogenesis. There’s lots of observational noise, too, but no randomized proof that CPAP alters this relationship.

I found four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that tested CPAP’s effect on AF. I’ll save you the suspense; they were all negative. One even found a signal for more adverse events in the CPAP group. These studies have several positive qualities: They enrolled patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea and high oxygen desaturation indices, adherence averaged more than 4 hours across all groups in all trials, and the methods for assessing the AF outcomes differed slightly. There’s also a lot not to like: The sample sizes were small, only one trial enrolled “sleepy” patients (as assessed by the Epworth Sleepiness Score), and follow-up was short.

To paraphrase Carl Sagan, “absence of evidence does not equal evidence of absence.” As a statistician would say, type II error cannot be excluded by these RCTs. In medicine, however, the burden of proof falls on demonstrating efficacy. If we treat before concluding that a therapy works, we risk wasting time, money, medical resources, and the most precious of patient commodities: the energy required for behavior change. In their response to letters to the editor, the authors of the third RCT summarize the CPAP, AF, and CV disease data far better than I ever could. They sound the same words of caution and come out against screening patients with AF for OSA.

The story for CPAP’s effects on EF is similar though muddier. The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for heart failure cite a meta-analysis showing that CPAP improves left ventricular EF. In 2019, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) CPAP guidelines included a systematic review and meta-analysis that found that CPAP has no effect on left ventricular EF in patients with or without heart failure.

There are a million reasons why two systematic reviews on the same topic might come to different conclusions. In this case, the included studies only partially overlap, and broadly speaking, it appears the authors made trade-offs. The review cited by the ACC/AHA had broader inclusion and significantly more patients and paid for it in heterogeneity (I2 in the 80%-90% range). The AASM analysis achieved 0% heterogeneity but limited inclusion to fewer than 100 patients. Across both, the improvement in EF was 2%- 5% at a minimally clinically important difference of 4%. Hardly convincing.

In summary, the road to negative trials and patient harm has always been paved with observational signal and biologic plausibility. Throw in some intellectual and academic bias, and you’ve created the perfect storm of therapeutic overconfidence.

Dr. Holley is a professor in the department of medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland, and a physician at Pulmonary/Sleep and Critical Care Medicine, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington. He disclosed ties to Metapharm Inc., CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Aquagenic Wrinkling Among Skin-Related Signs of Cystic Fibrosis

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Patients with CF, caused by a mutation in the CF Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) gene, can develop diverse dermatologic manifestations.

- Researchers reviewed the literature and provided their own clinical experience regarding dermatologic manifestations of CF.

- They also reviewed the cutaneous side effects of CFTR modulators and antibiotics used to treat CF.

TAKEAWAY:

- Aquagenic wrinkling of the palm is common in individuals with CF, affecting up to 80% of patients (and 25% of CF gene carriers), and can be an early manifestation of CF. Treatments include topical medications (such as aluminum chloride, corticosteroids, and salicylic acid), botulinum toxin injections, and recently, CFTR-modulating treatments.

- CF nutrient deficiency dermatitis, often in a diaper distribution, usually appears in infancy and, before newborn screening was available, was sometimes the first sign of CF in some cases. It usually resolves with an adequate diet, pancreatic enzymes, and/or nutritional supplements. Zinc and essential fatty acid deficiencies can lead to acrodermatitis enteropathica–like symptoms and psoriasiform rashes, respectively.

- CF is also associated with vascular disorders, including cutaneous and, rarely, systemic vasculitis. Treatment includes topical and oral steroids and immune-modulating therapies.

- CFTR modulators, now the most common and highly effective treatment for CF, are associated with several skin reactions, which can be managed with treatments that include topical steroids and oral antihistamines. Frequent antibiotic treatment can also trigger skin reactions.

IN PRACTICE:

“Recognition and familiarity with dermatologic clinical manifestations of CF are important for multidisciplinary care” for patients with CF, the authors wrote, adding that “dermatology providers may play a significant role in the diagnosis and management of CF cutaneous comorbidities.”

SOURCE:

Aaron D. Smith, BS, from the University of Virginia (UVA) School of Medicine, Charlottesville, and coauthors were from the departments of dermatology and pulmonology/critical care medicine at UVA. The study was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors did not make a comment about the limitations of their review.

DISCLOSURES:

No funding was received for the review. The authors had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Patients with CF, caused by a mutation in the CF Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) gene, can develop diverse dermatologic manifestations.

- Researchers reviewed the literature and provided their own clinical experience regarding dermatologic manifestations of CF.

- They also reviewed the cutaneous side effects of CFTR modulators and antibiotics used to treat CF.

TAKEAWAY:

- Aquagenic wrinkling of the palm is common in individuals with CF, affecting up to 80% of patients (and 25% of CF gene carriers), and can be an early manifestation of CF. Treatments include topical medications (such as aluminum chloride, corticosteroids, and salicylic acid), botulinum toxin injections, and recently, CFTR-modulating treatments.

- CF nutrient deficiency dermatitis, often in a diaper distribution, usually appears in infancy and, before newborn screening was available, was sometimes the first sign of CF in some cases. It usually resolves with an adequate diet, pancreatic enzymes, and/or nutritional supplements. Zinc and essential fatty acid deficiencies can lead to acrodermatitis enteropathica–like symptoms and psoriasiform rashes, respectively.

- CF is also associated with vascular disorders, including cutaneous and, rarely, systemic vasculitis. Treatment includes topical and oral steroids and immune-modulating therapies.

- CFTR modulators, now the most common and highly effective treatment for CF, are associated with several skin reactions, which can be managed with treatments that include topical steroids and oral antihistamines. Frequent antibiotic treatment can also trigger skin reactions.

IN PRACTICE:

“Recognition and familiarity with dermatologic clinical manifestations of CF are important for multidisciplinary care” for patients with CF, the authors wrote, adding that “dermatology providers may play a significant role in the diagnosis and management of CF cutaneous comorbidities.”

SOURCE:

Aaron D. Smith, BS, from the University of Virginia (UVA) School of Medicine, Charlottesville, and coauthors were from the departments of dermatology and pulmonology/critical care medicine at UVA. The study was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors did not make a comment about the limitations of their review.

DISCLOSURES:

No funding was received for the review. The authors had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Patients with CF, caused by a mutation in the CF Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) gene, can develop diverse dermatologic manifestations.

- Researchers reviewed the literature and provided their own clinical experience regarding dermatologic manifestations of CF.

- They also reviewed the cutaneous side effects of CFTR modulators and antibiotics used to treat CF.

TAKEAWAY:

- Aquagenic wrinkling of the palm is common in individuals with CF, affecting up to 80% of patients (and 25% of CF gene carriers), and can be an early manifestation of CF. Treatments include topical medications (such as aluminum chloride, corticosteroids, and salicylic acid), botulinum toxin injections, and recently, CFTR-modulating treatments.

- CF nutrient deficiency dermatitis, often in a diaper distribution, usually appears in infancy and, before newborn screening was available, was sometimes the first sign of CF in some cases. It usually resolves with an adequate diet, pancreatic enzymes, and/or nutritional supplements. Zinc and essential fatty acid deficiencies can lead to acrodermatitis enteropathica–like symptoms and psoriasiform rashes, respectively.

- CF is also associated with vascular disorders, including cutaneous and, rarely, systemic vasculitis. Treatment includes topical and oral steroids and immune-modulating therapies.

- CFTR modulators, now the most common and highly effective treatment for CF, are associated with several skin reactions, which can be managed with treatments that include topical steroids and oral antihistamines. Frequent antibiotic treatment can also trigger skin reactions.

IN PRACTICE:

“Recognition and familiarity with dermatologic clinical manifestations of CF are important for multidisciplinary care” for patients with CF, the authors wrote, adding that “dermatology providers may play a significant role in the diagnosis and management of CF cutaneous comorbidities.”

SOURCE:

Aaron D. Smith, BS, from the University of Virginia (UVA) School of Medicine, Charlottesville, and coauthors were from the departments of dermatology and pulmonology/critical care medicine at UVA. The study was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors did not make a comment about the limitations of their review.

DISCLOSURES:

No funding was received for the review. The authors had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Why Cardiac Biomarkers Don’t Help Predict Heart Disease

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s the counterintuitive stuff in epidemiology that always really interests me. One intuition many of us have is that if a risk factor is significantly associated with an outcome, knowledge of that risk factor would help to predict that outcome. Makes sense. Feels right.

But it’s not right. Not always.

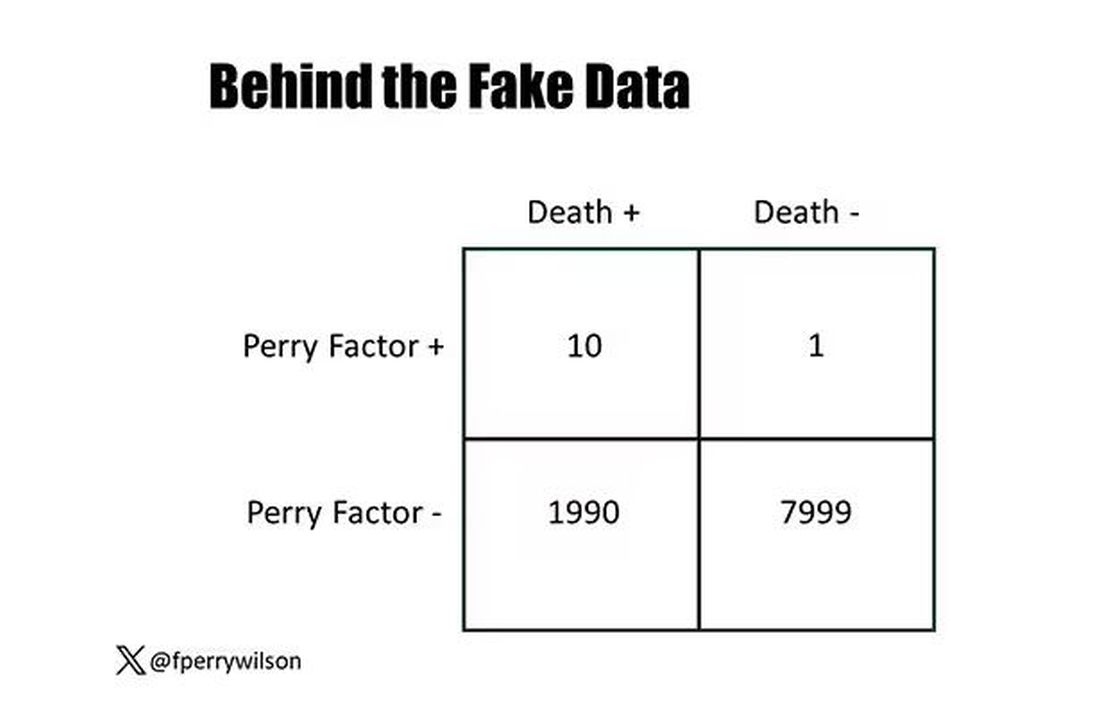

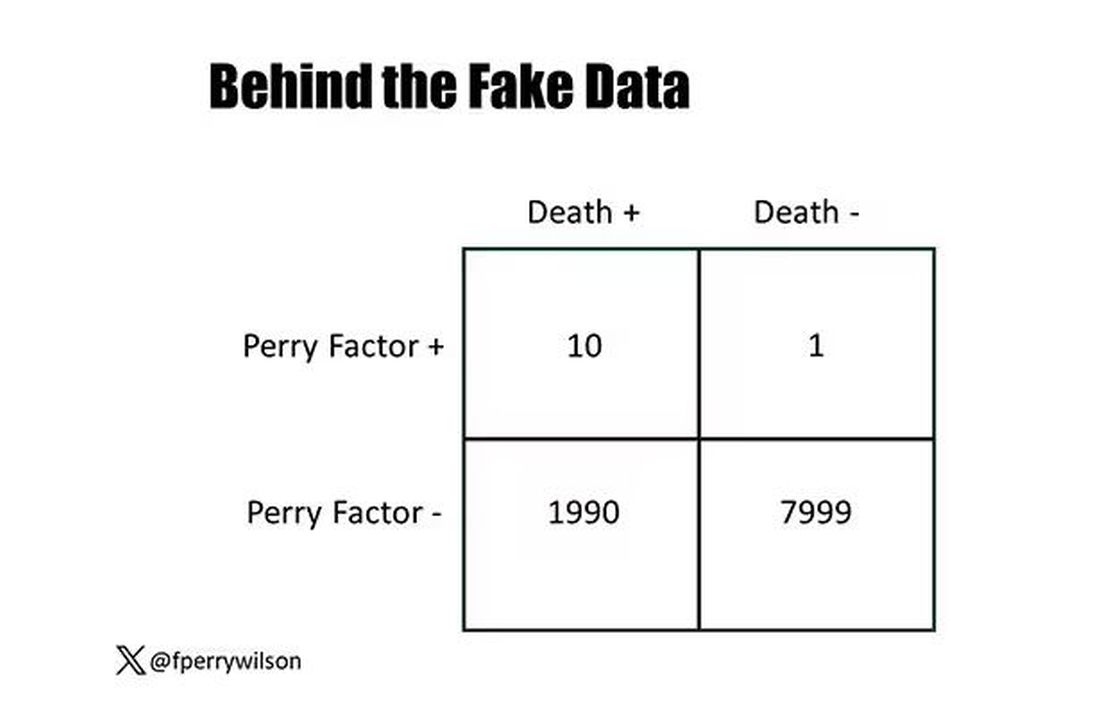

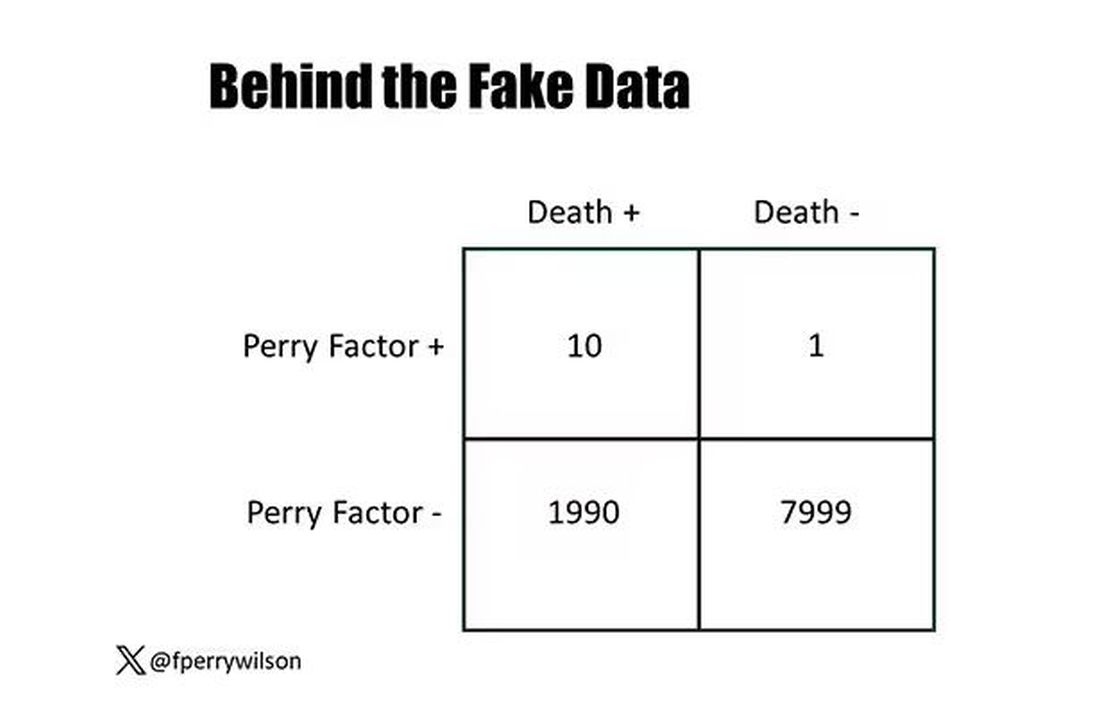

Here’s a fake example to illustrate my point. Let’s say we have 10,000 individuals who we follow for 10 years and 2000 of them die. (It’s been a rough decade.) At baseline, I measured a novel biomarker, the Perry Factor, in everyone. To keep it simple, the Perry Factor has only two values: 0 or 1.

I then do a standard associational analysis and find that individuals who are positive for the Perry Factor have a 40-fold higher odds of death than those who are negative for it. I am beginning to reconsider ascribing my good name to this biomarker. This is a highly statistically significant result — a P value <.001.

Clearly, knowledge of the Perry Factor should help me predict who will die in the cohort. I evaluate predictive power using a metric called the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC, referred to as the C-statistic in time-to-event studies). It tells you, given two people — one who dies and one who doesn’t — how frequently you “pick” the right person, given the knowledge of their Perry Factor.

A C-statistic of 0.5, or 50%, would mean the Perry Factor gives you no better results than a coin flip; it’s chance. A C-statistic of 1 is perfect prediction. So, what will the C-statistic be, given the incredibly strong association of the Perry Factor with outcomes? 0.9? 0.95?

0.5024. Almost useless.

Let’s figure out why strength of association and usefulness for prediction are not always the same thing.

I constructed my fake Perry Factor dataset quite carefully to illustrate this point. Let me show you what happened. What you see here is a breakdown of the patients in my fake study. You can see that just 11 of them were Perry Factor positive, but 10 of those 11 ended up dying.

That’s quite unlikely by chance alone. It really does appear that if you have Perry Factor, your risk for death is much higher. But the reason that Perry Factor is a bad predictor is because it is so rare in the population. Sure, you can use it to correctly predict the outcome of 10 of the 11 people who have it, but the vast majority of people don’t have Perry Factor. It’s useless to distinguish who will die vs who will live in that population.

Why have I spent so much time trying to reverse our intuition that strength of association and strength of predictive power must be related? Because it helps to explain this paper, “Prognostic Value of Cardiovascular Biomarkers in the Population,” appearing in JAMA, which is a very nice piece of work trying to help us better predict cardiovascular disease.

I don’t need to tell you that cardiovascular disease is the number-one killer in this country and most of the world. I don’t need to tell you that we have really good preventive therapies and lifestyle interventions that can reduce the risk. But it would be nice to know in whom, specifically, we should use those interventions.

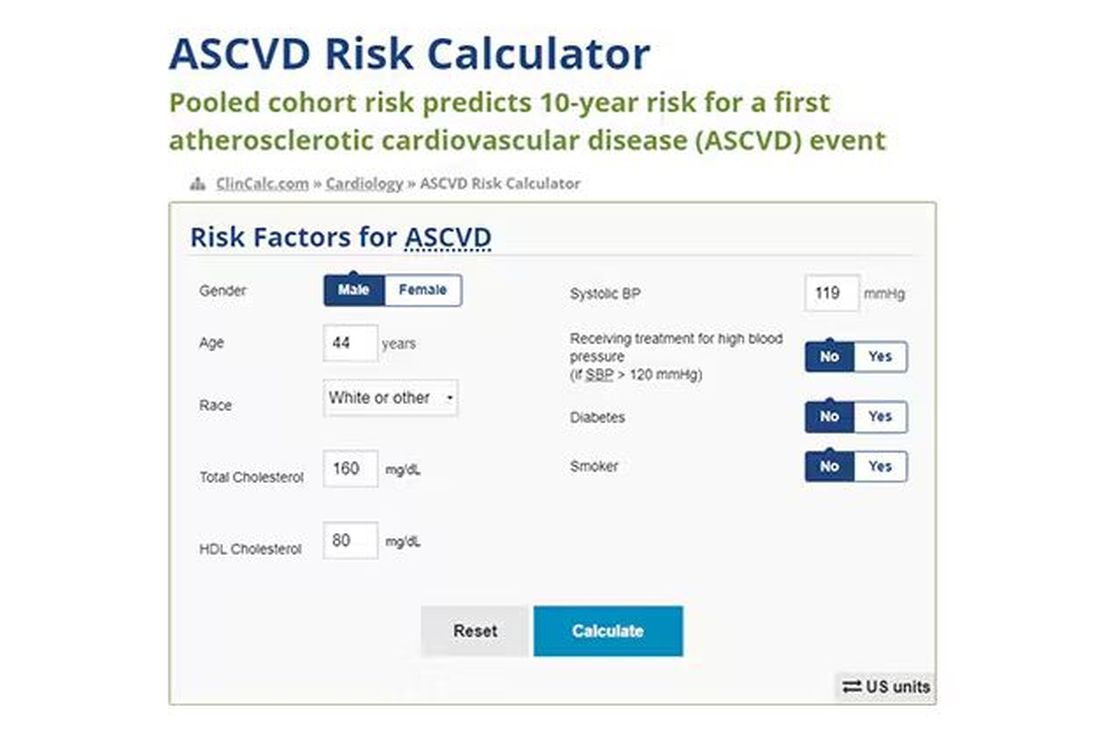

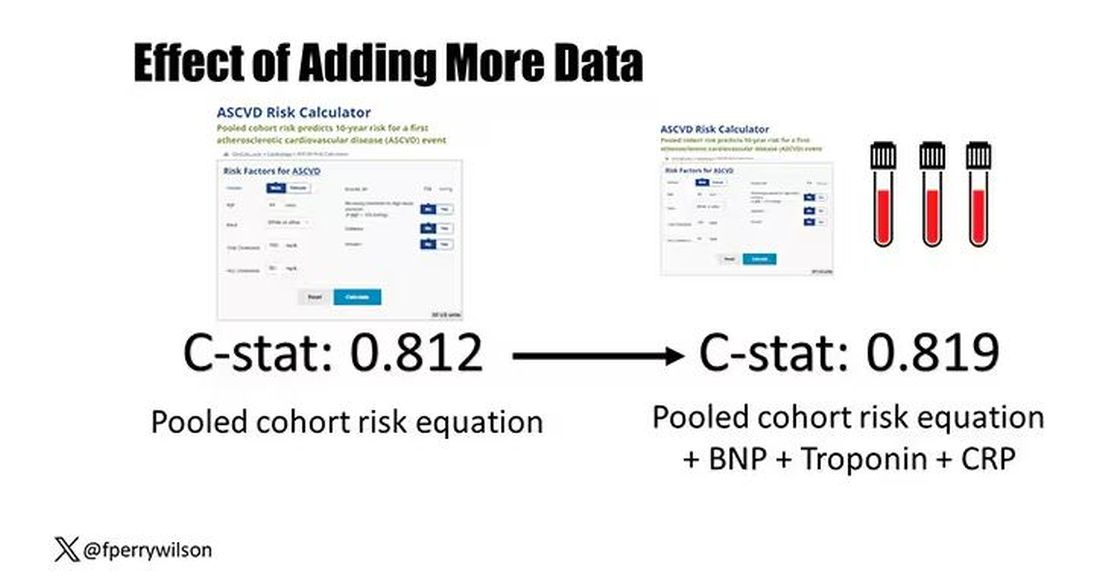

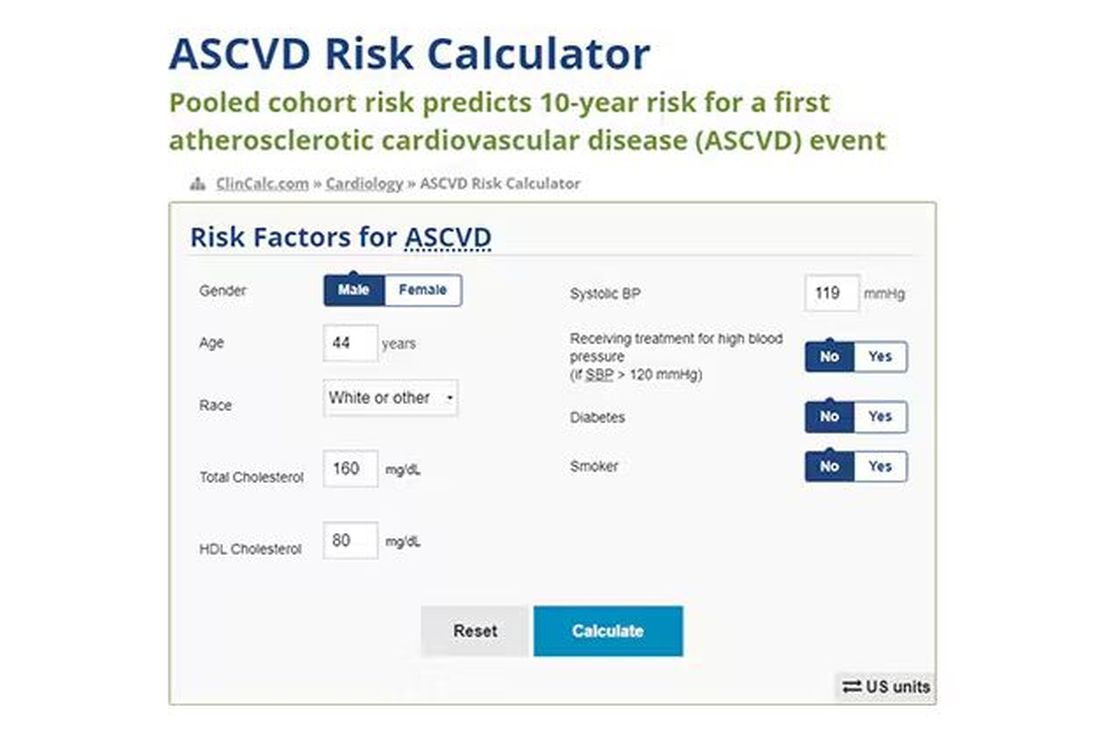

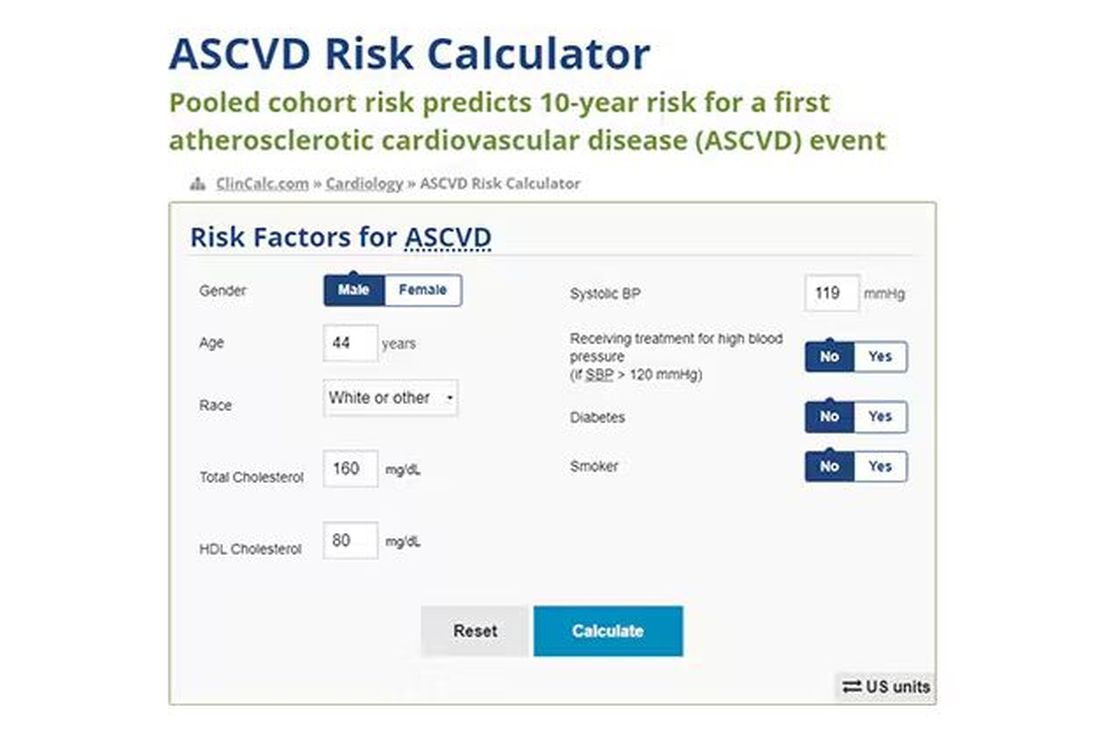

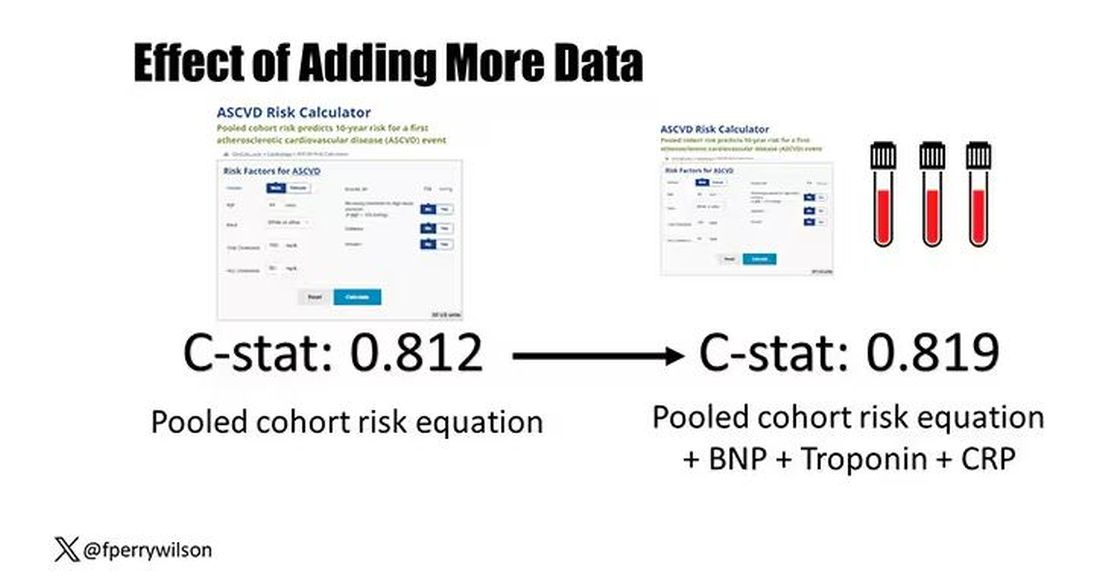

Cardiovascular risk scores, to date, are pretty simple. The most common one in use in the United States, the pooled cohort risk equation, has nine variables, two of which require a cholesterol panel and one a blood pressure test. It’s easy and it’s pretty accurate.

Using the score from the pooled cohort risk calculator, you get a C-statistic as high as 0.82 when applied to Black women, a low of 0.71 when applied to Black men. Non-Black individuals are in the middle. Not bad. But, clearly, not perfect.

And aren’t we in the era of big data, the era of personalized medicine? We have dozens, maybe hundreds, of quantifiable biomarkers that are associated with subsequent heart disease. Surely, by adding these biomarkers into the risk equation, we can improve prediction. Right?

The JAMA study includes 164,054 patients pooled from 28 cohort studies from 12 countries. All the studies measured various key biomarkers at baseline and followed their participants for cardiovascular events like heart attack, stroke, coronary revascularization, and so on.

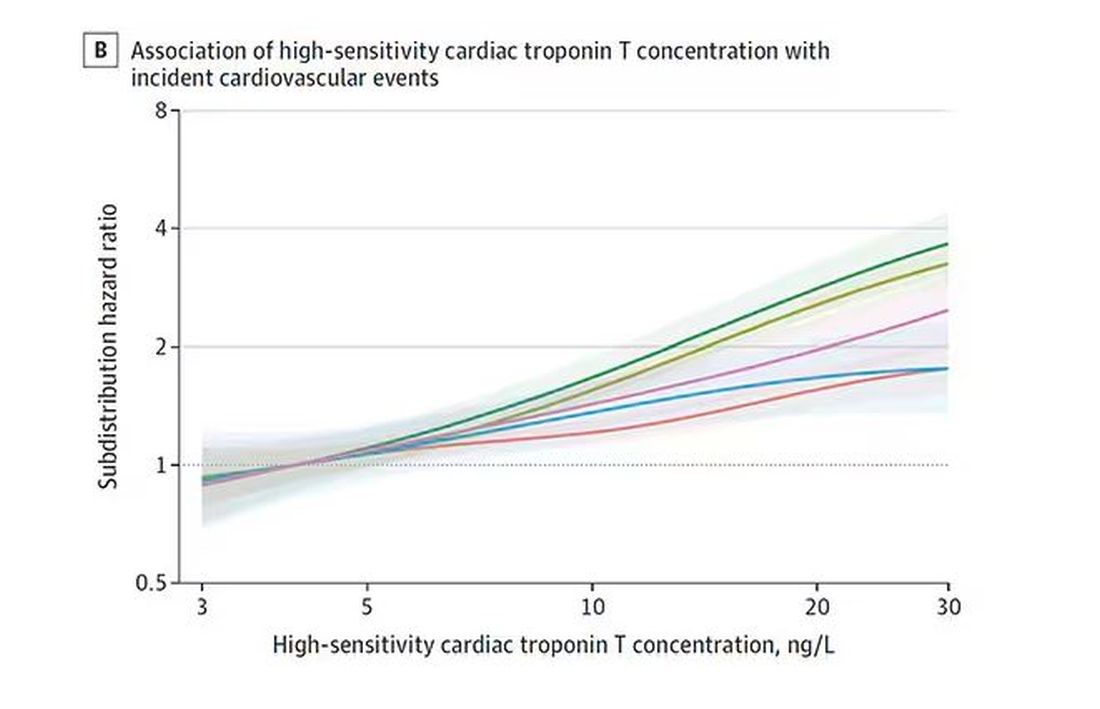

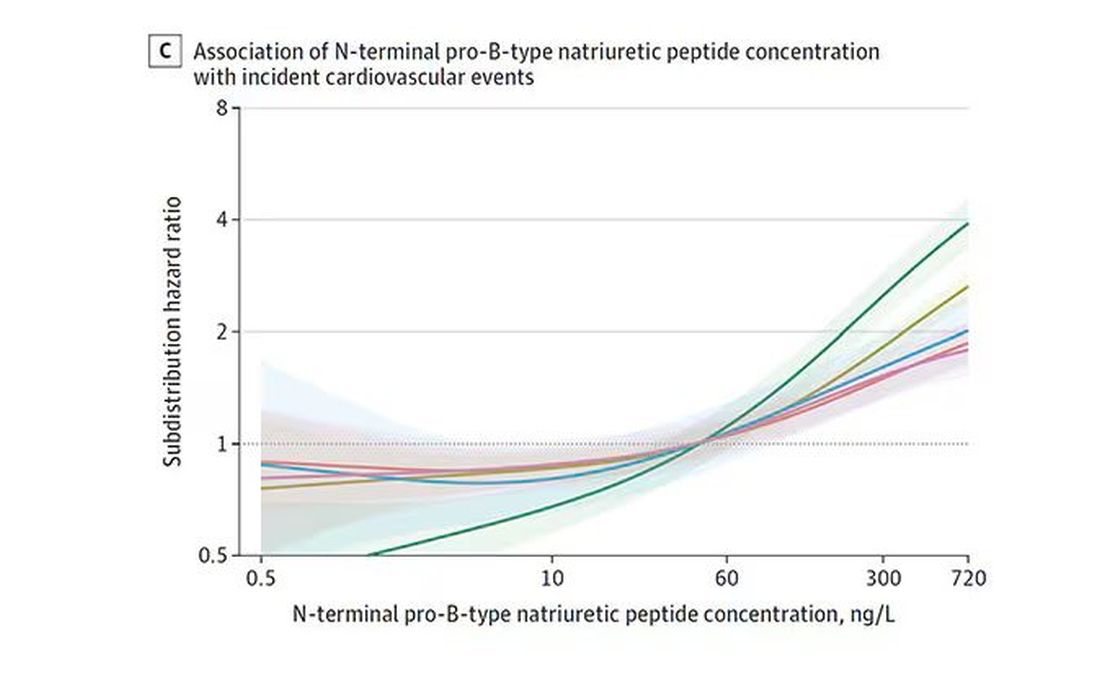

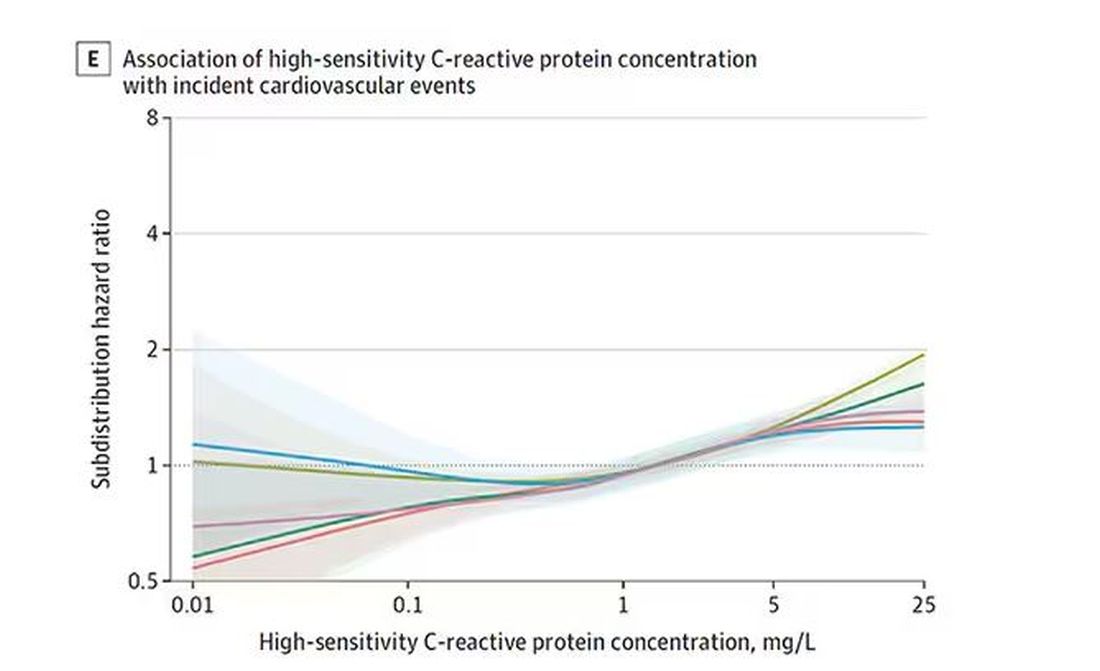

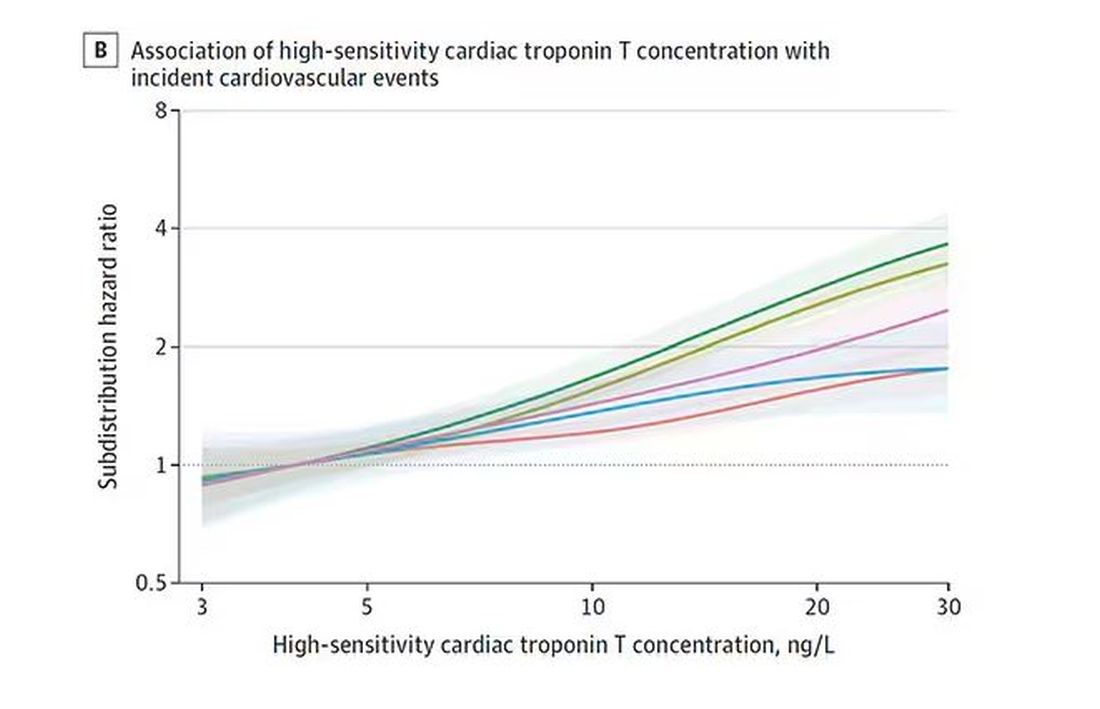

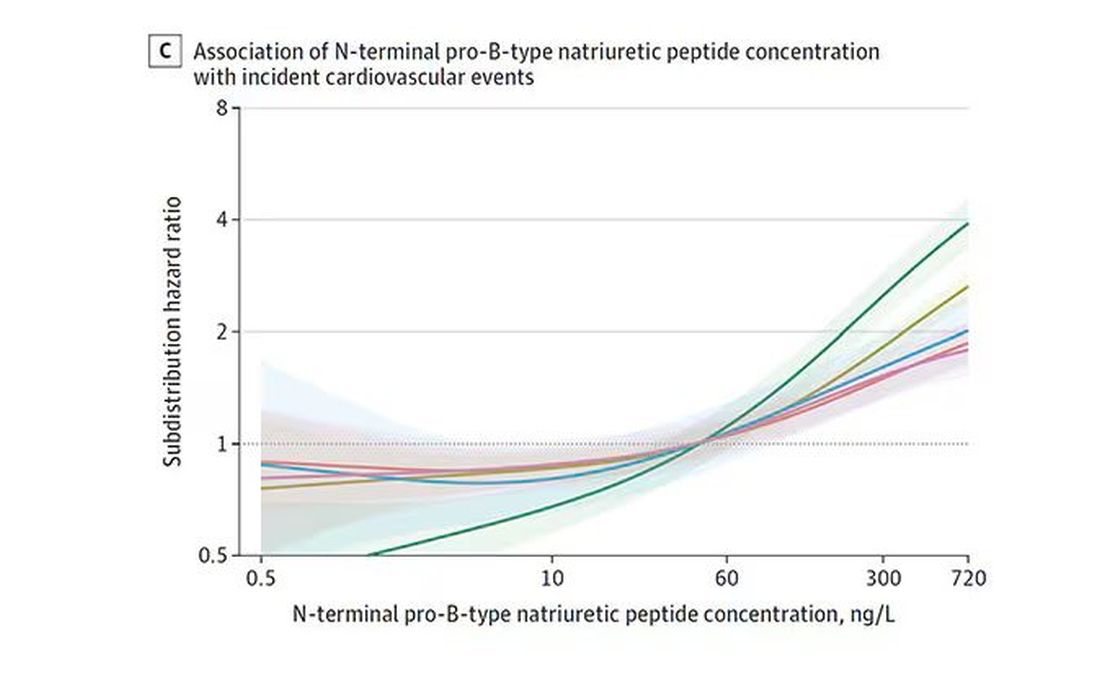

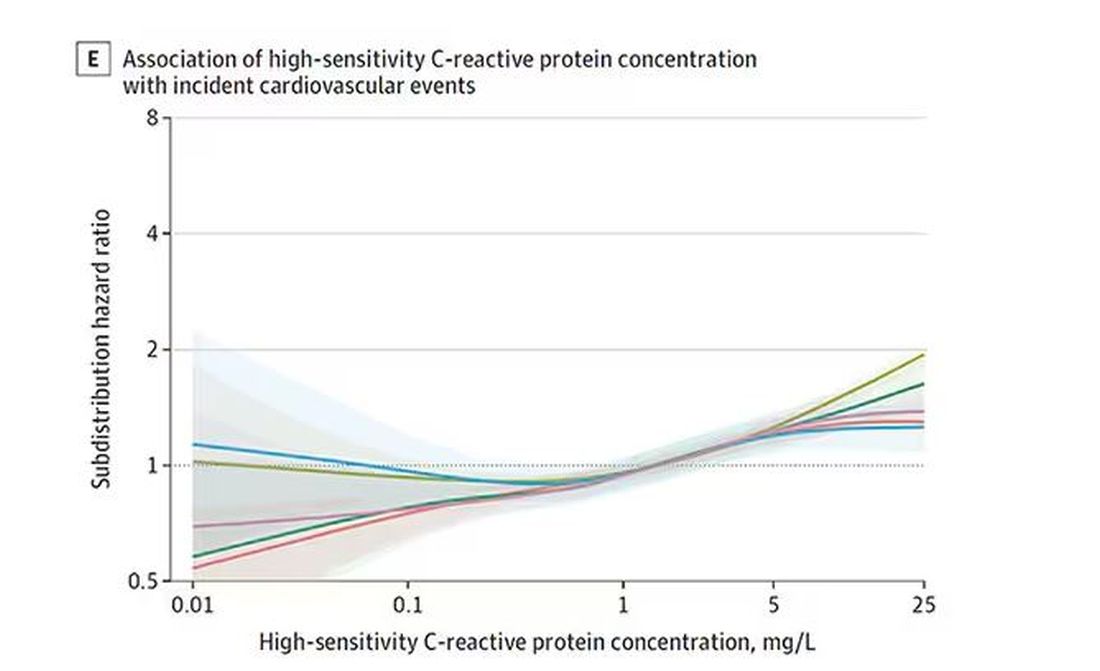

The biomarkers in question are really the big guns in this space: troponin, a marker of stress on the heart muscle; NT-proBNP, a marker of stretch on the heart muscle; and C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation. In every case, higher levels of these markers at baseline were associated with a higher risk for cardiovascular disease in the future.

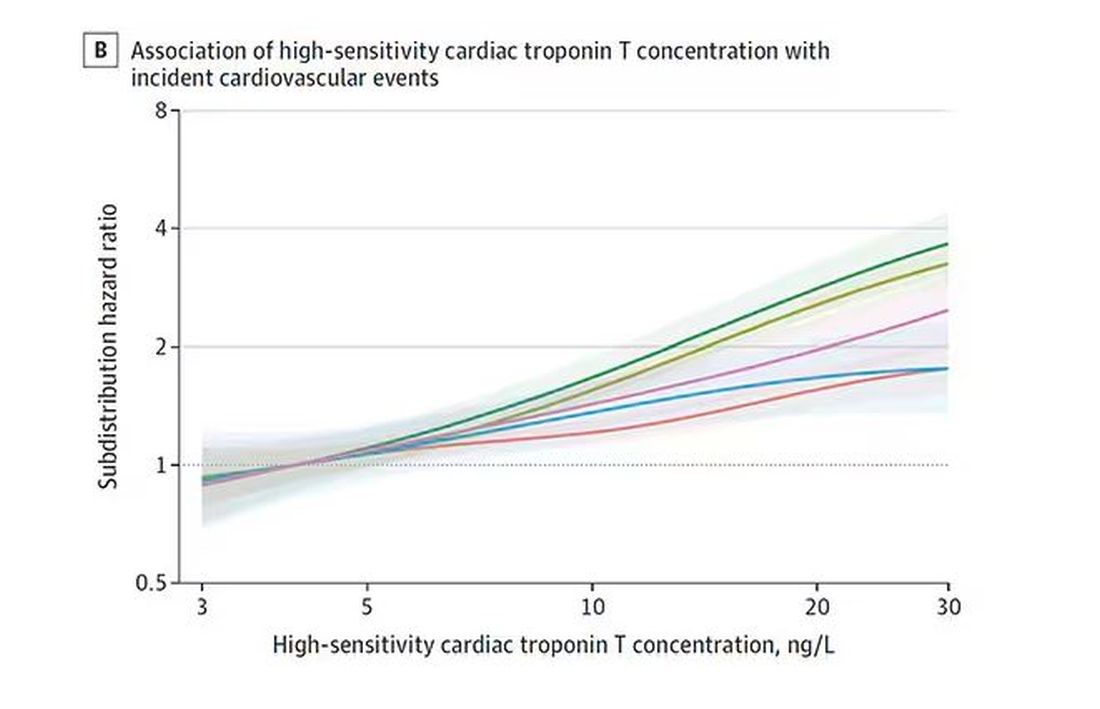

Troponin T, shown here, has a basically linear risk with subsequent cardiovascular disease.

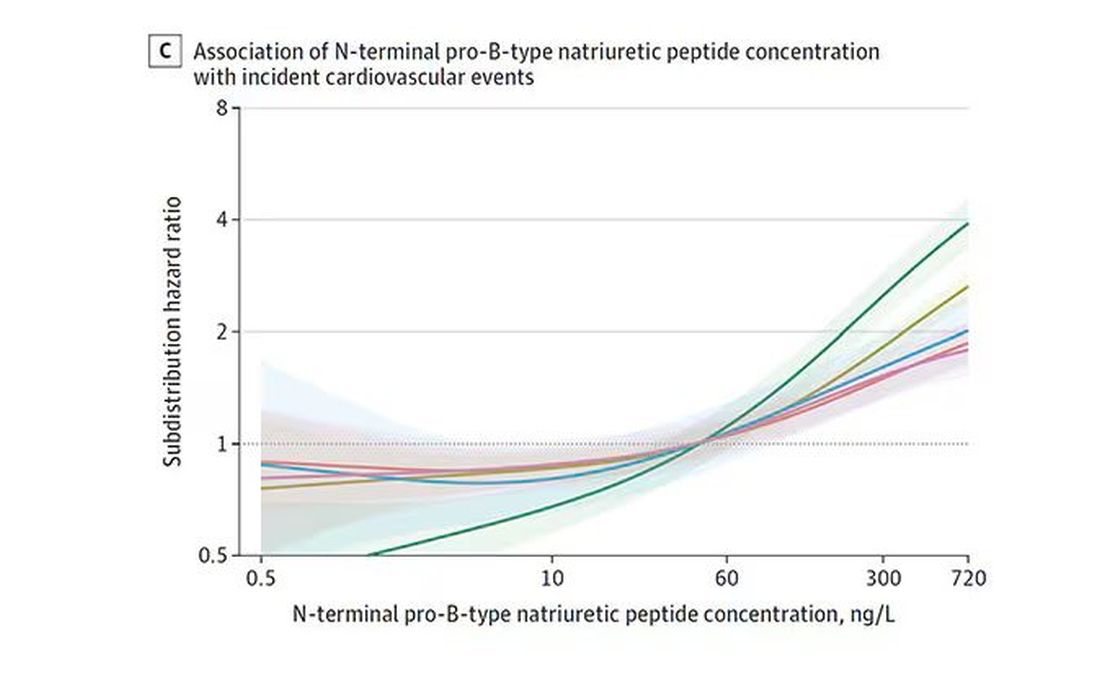

BNP seems to demonstrate more of a threshold effect, where levels above 60 start to associate with problems.

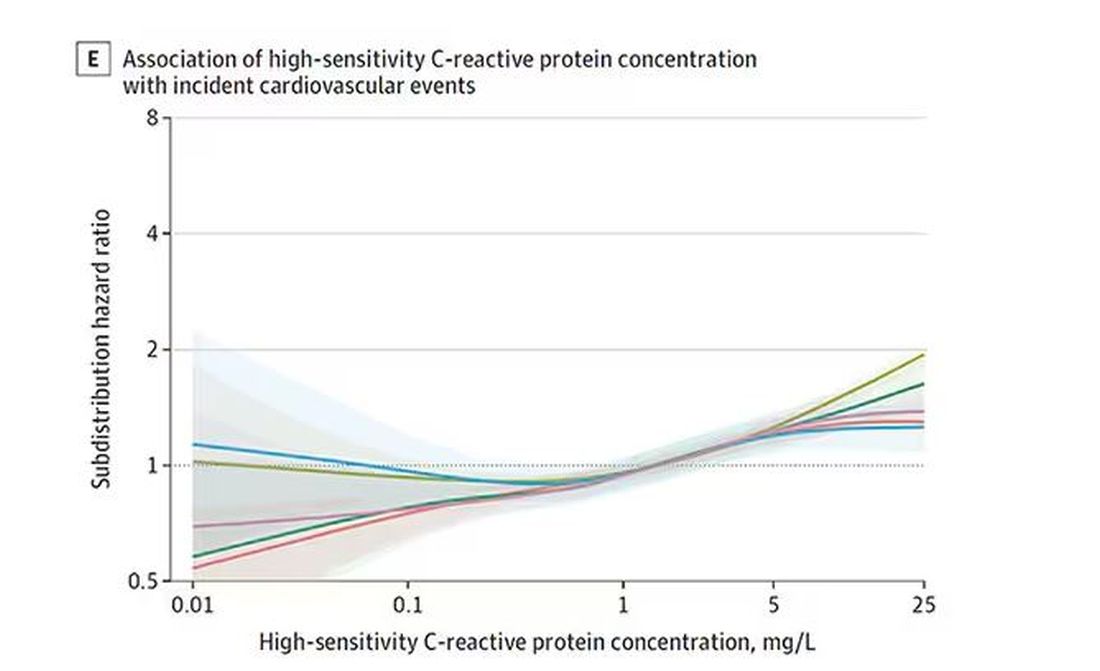

And CRP does a similar thing, with levels above 1.

All of these findings were statistically significant. If you have higher levels of one or more of these biomarkers, you are more likely to have cardiovascular disease in the future.

Of course, our old friend the pooled cohort risk equation is still here — in the background — requiring just that one blood test and measurement of blood pressure. Let’s talk about predictive power.

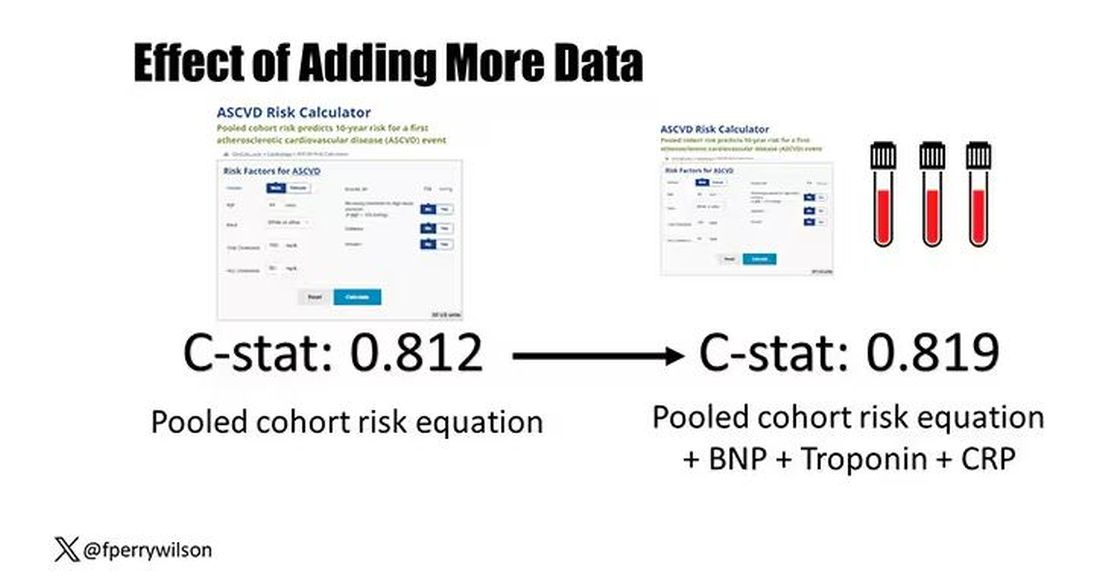

The pooled cohort risk equation score, in this study, had a C-statistic of 0.812.

By adding troponin, BNP, and CRP to the equation, the new C-statistic is 0.819. Barely any change.

Now, the authors looked at different types of prediction here. The greatest improvement in the AUC was seen when they tried to predict heart failure within 1 year of measurement; there the AUC improved by 0.04. But the presence of BNP as a biomarker and the short time window of 1 year makes me wonder whether this is really prediction at all or whether they were essentially just diagnosing people with existing heart failure.

Why does this happen? Why do these promising biomarkers, clearly associated with bad outcomes, fail to improve our ability to predict the future? I already gave one example, which has to do with how the markers are distributed in the population. But even more relevant here is that the new markers will only improve prediction insofar as they are not already represented in the old predictive model.

Of course, BNP, for example, wasn’t in the old model. But smoking was. Diabetes was. Blood pressure was. All of that data might actually tell you something about the patient’s BNP through their mutual correlation. And improvement in prediction requires new information.

This is actually why I consider this a really successful study. We need to do studies like this to help us find what those new sources of information might be.

We will never get to a C-statistic of 1. Perfect prediction is the domain of palm readers and astrophysicists. But better prediction is always possible through data. The big question, of course, is which data?

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s the counterintuitive stuff in epidemiology that always really interests me. One intuition many of us have is that if a risk factor is significantly associated with an outcome, knowledge of that risk factor would help to predict that outcome. Makes sense. Feels right.

But it’s not right. Not always.

Here’s a fake example to illustrate my point. Let’s say we have 10,000 individuals who we follow for 10 years and 2000 of them die. (It’s been a rough decade.) At baseline, I measured a novel biomarker, the Perry Factor, in everyone. To keep it simple, the Perry Factor has only two values: 0 or 1.

I then do a standard associational analysis and find that individuals who are positive for the Perry Factor have a 40-fold higher odds of death than those who are negative for it. I am beginning to reconsider ascribing my good name to this biomarker. This is a highly statistically significant result — a P value <.001.

Clearly, knowledge of the Perry Factor should help me predict who will die in the cohort. I evaluate predictive power using a metric called the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC, referred to as the C-statistic in time-to-event studies). It tells you, given two people — one who dies and one who doesn’t — how frequently you “pick” the right person, given the knowledge of their Perry Factor.

A C-statistic of 0.5, or 50%, would mean the Perry Factor gives you no better results than a coin flip; it’s chance. A C-statistic of 1 is perfect prediction. So, what will the C-statistic be, given the incredibly strong association of the Perry Factor with outcomes? 0.9? 0.95?

0.5024. Almost useless.

Let’s figure out why strength of association and usefulness for prediction are not always the same thing.

I constructed my fake Perry Factor dataset quite carefully to illustrate this point. Let me show you what happened. What you see here is a breakdown of the patients in my fake study. You can see that just 11 of them were Perry Factor positive, but 10 of those 11 ended up dying.

That’s quite unlikely by chance alone. It really does appear that if you have Perry Factor, your risk for death is much higher. But the reason that Perry Factor is a bad predictor is because it is so rare in the population. Sure, you can use it to correctly predict the outcome of 10 of the 11 people who have it, but the vast majority of people don’t have Perry Factor. It’s useless to distinguish who will die vs who will live in that population.

Why have I spent so much time trying to reverse our intuition that strength of association and strength of predictive power must be related? Because it helps to explain this paper, “Prognostic Value of Cardiovascular Biomarkers in the Population,” appearing in JAMA, which is a very nice piece of work trying to help us better predict cardiovascular disease.

I don’t need to tell you that cardiovascular disease is the number-one killer in this country and most of the world. I don’t need to tell you that we have really good preventive therapies and lifestyle interventions that can reduce the risk. But it would be nice to know in whom, specifically, we should use those interventions.

Cardiovascular risk scores, to date, are pretty simple. The most common one in use in the United States, the pooled cohort risk equation, has nine variables, two of which require a cholesterol panel and one a blood pressure test. It’s easy and it’s pretty accurate.

Using the score from the pooled cohort risk calculator, you get a C-statistic as high as 0.82 when applied to Black women, a low of 0.71 when applied to Black men. Non-Black individuals are in the middle. Not bad. But, clearly, not perfect.