User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

High obesity rates in Southern states magnify COVID threats

In January, as Mississippi health officials planned for their incoming shipments of COVID-19 vaccine, they assessed the state’s most vulnerable: health care workers, of course, and elderly people in nursing homes. But among those who needed urgent protection from the virus ripping across the Magnolia State were 1 million Mississippians with obesity.

Obesity and weight-related illnesses have been deadly liabilities in the COVID era. A report released this month by the World Obesity Federation found that increased body weight is the second-greatest predictor of COVID-related hospitalization and death across the globe, trailing only old age as a risk factor.

As a fixture of life in the American South – home to 9 of the nation’s 12 heaviest states – obesity is playing a role not only in COVID outcomes, but in the calculus of the vaccination rollout. Mississippi was one of the first states to add a body mass index of 30 or more (a rough gauge of obesity tied to height and weight) to the list of qualifying medical conditions for a shot. About 40% of the state’s adults meet that definition, according to federal health survey data, and combined with the risk group already eligible for vaccination – residents 65 and older – that means fully half of Mississippi’s adults are entitled to vie for a restricted allotment of shots.

At least 29 states have green-lighted obesity for inclusion in the first phases of the vaccine rollout, according to KFF – a vast widening of eligibility that has the potential to overwhelm government efforts and heighten competition for scarce doses.

“We have a lifesaving intervention, and we don’t have enough of it,” said Jen Kates, PhD, director of global health and HIV policy for Kaiser Family Foundation. “Hard choices are being made about who should go first, and there is no right answer.”

The sheer prevalence of obesity in the nation – two in three Americans exceed what is considered a healthy weight – was a public health concern well before the pandemic. But COVID-19 dramatically fast-tracked the discussion from warnings about the long-term damage excess fat tissue can pose to heart, lung and metabolic functions to far more immediate threats.

In the United Kingdom, for example, overweight COVID patients were 67% more likely to require intensive care, and obese patients three times likelier, according to the World Obesity Federation report. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study released Monday found a similar trend among U.S. patients and noted that the risk of COVID-related hospitalization, ventilation and death increased with patients’ obesity level.

The counties that hug the southern Mississippi River are home to some of the most concentrated pockets of extreme obesity in the United States. Coronavirus infections began surging in Southern states early last summer, and hospitalizations rose in step.

Deaths in rural stretches of Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee have been overshadowed by the sheer number of deaths in metropolitan areas like New York, Los Angeles, and Essex County, N.J. But as a share of the population, the coronavirus has been similarly unsparing in many Southern communities. In sparsely populated Claiborne County, Miss., on the floodplains of the Mississippi River, 30 residents – about 1 in 300 – had died as of early March. In East Feliciana Parish, La., north of Baton Rouge, with 106 deaths, about 1 in 180 had died by then.

“It’s just math. If the population is more obese and obesity clearly contributes to worse outcomes, then neighborhoods, cities, states and countries that are more obese will have a greater toll from COVID,” said Dr. James de Lemos, MD, a professor of internal medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas who led a study of hospitalized COVID patients published in the medical journal Circulation.

And, because in the U.S. obesity rates tend to be relatively high among African Americans and Latinos who are poor, with diminished access to health care, “it’s a triple whammy,” Dr. de Lemos said. “All these things intersect.”

Poverty and limited access to medical care are common features in the South, where residents like Michelle Antonyshyn, a former registered nurse and mother of seven in Salem, Ark., say they are afraid of the virus. Ms. Antonyshyn, 49, has obesity and debilitating pain in her knees and back, though she does not have high blood pressure or diabetes, two underlying conditions that federal health officials have determined are added risk factors for severe cases of COVID-19.

Still, she said, she “was very concerned just knowing that being obese puts you more at risk for bad outcomes such as being on a ventilator and death.” As a precaution, Ms. Antonyshyn said, she and her large brood locked down early and stopped attending church services in person, watching online instead.

“It’s not the same as having fellowship, but the risk for me was enough,” said Ms. Antonyshyn.

Governors throughout the South seem to recognize that weight can contribute to COVID-19 complications and have pushed for vaccine eligibility rules that prioritize obesity. But on the ground, local health officials are girding for having to tell newly eligible people who qualify as obese that there aren’t enough shots to go around.

In Port Gibson, Miss., Mheja Williams, MD, medical director of the Claiborne County Family Health Center, has been receiving barely enough doses to inoculate the health workers and oldest seniors in her county of 9,600. One week in early February, she received 100 doses.

Obesity and extreme obesity are endemic in Claiborne County, and health officials say the “normalization” of obesity means people often don’t register their weight as a risk factor, whether for COVID or other health issues. The risks are exacerbated by a general flouting of pandemic etiquette: Dr. Williams said that middle-aged and younger residents are not especially vigilant about physical distancing and that mask use is rare.

The rise of obesity in the United States is well documented over the past half-century, as the nation turned from a diet of fruits, vegetables and limited meats to one laden with ultra-processed foods and rich with salt, fat, sugar, and flavorings, along with copious amounts of meat, fast food, and soda. The U.S. has generally led the global obesity race, setting records as even toddlers and young children grew implausibly, dangerously overweight.

Well before COVID, obesity was a leading cause of preventable death in the United States. The National Institutes of Health declared it a disease in 1998, one that fosters heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and breast, colon, and other cancers.

Researchers say it is no coincidence that nations like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Italy, with relatively high obesity rates, have proved particularly vulnerable to the novel coronavirus.

They believe the virus may exploit underlying metabolic and physiological impairments that often exist in concert with obesity. Extra fat can lead to a cascade of metabolic disruptions, chronic systemic inflammation, and hormonal dysregulation that may thwart the body’s response to infection.

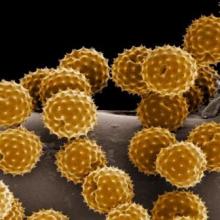

Other respiratory viruses, like influenza and SARS, which appeared in China in 2002, rely on cholesterol to spread enveloped RNA virus to neighboring cells, and researchers have proposed that a similar mechanism may play a role in the spread of the novel coronavirus.

There are also practical problems for coronavirus patients with obesity admitted to the hospital. They can be more difficult to intubate because of excess central weight pressing down on the diaphragm, making breathing with infected lungs even more difficult.

Physicians who specialize in treating patients with obesity say public health officials need to be more forthright and urgent in their messaging, telegraphing the risks of this COVID era.

“It should be explicit and direct,” said Fatima Stanford, MD, an obesity medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and a Harvard Medical School instructor.

Dr. Stanford denounces the fat-shaming and bullying that people with obesity often experience. But telling patients – and the public – that obesity increases the risk of hospitalization and death is crucial, she said.

“I don’t think it’s stigmatizing,” she said. “If you tell them in that way, it’s not to scare you, it’s just giving information. Sometimes people are just unaware.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

In January, as Mississippi health officials planned for their incoming shipments of COVID-19 vaccine, they assessed the state’s most vulnerable: health care workers, of course, and elderly people in nursing homes. But among those who needed urgent protection from the virus ripping across the Magnolia State were 1 million Mississippians with obesity.

Obesity and weight-related illnesses have been deadly liabilities in the COVID era. A report released this month by the World Obesity Federation found that increased body weight is the second-greatest predictor of COVID-related hospitalization and death across the globe, trailing only old age as a risk factor.

As a fixture of life in the American South – home to 9 of the nation’s 12 heaviest states – obesity is playing a role not only in COVID outcomes, but in the calculus of the vaccination rollout. Mississippi was one of the first states to add a body mass index of 30 or more (a rough gauge of obesity tied to height and weight) to the list of qualifying medical conditions for a shot. About 40% of the state’s adults meet that definition, according to federal health survey data, and combined with the risk group already eligible for vaccination – residents 65 and older – that means fully half of Mississippi’s adults are entitled to vie for a restricted allotment of shots.

At least 29 states have green-lighted obesity for inclusion in the first phases of the vaccine rollout, according to KFF – a vast widening of eligibility that has the potential to overwhelm government efforts and heighten competition for scarce doses.

“We have a lifesaving intervention, and we don’t have enough of it,” said Jen Kates, PhD, director of global health and HIV policy for Kaiser Family Foundation. “Hard choices are being made about who should go first, and there is no right answer.”

The sheer prevalence of obesity in the nation – two in three Americans exceed what is considered a healthy weight – was a public health concern well before the pandemic. But COVID-19 dramatically fast-tracked the discussion from warnings about the long-term damage excess fat tissue can pose to heart, lung and metabolic functions to far more immediate threats.

In the United Kingdom, for example, overweight COVID patients were 67% more likely to require intensive care, and obese patients three times likelier, according to the World Obesity Federation report. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study released Monday found a similar trend among U.S. patients and noted that the risk of COVID-related hospitalization, ventilation and death increased with patients’ obesity level.

The counties that hug the southern Mississippi River are home to some of the most concentrated pockets of extreme obesity in the United States. Coronavirus infections began surging in Southern states early last summer, and hospitalizations rose in step.

Deaths in rural stretches of Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee have been overshadowed by the sheer number of deaths in metropolitan areas like New York, Los Angeles, and Essex County, N.J. But as a share of the population, the coronavirus has been similarly unsparing in many Southern communities. In sparsely populated Claiborne County, Miss., on the floodplains of the Mississippi River, 30 residents – about 1 in 300 – had died as of early March. In East Feliciana Parish, La., north of Baton Rouge, with 106 deaths, about 1 in 180 had died by then.

“It’s just math. If the population is more obese and obesity clearly contributes to worse outcomes, then neighborhoods, cities, states and countries that are more obese will have a greater toll from COVID,” said Dr. James de Lemos, MD, a professor of internal medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas who led a study of hospitalized COVID patients published in the medical journal Circulation.

And, because in the U.S. obesity rates tend to be relatively high among African Americans and Latinos who are poor, with diminished access to health care, “it’s a triple whammy,” Dr. de Lemos said. “All these things intersect.”

Poverty and limited access to medical care are common features in the South, where residents like Michelle Antonyshyn, a former registered nurse and mother of seven in Salem, Ark., say they are afraid of the virus. Ms. Antonyshyn, 49, has obesity and debilitating pain in her knees and back, though she does not have high blood pressure or diabetes, two underlying conditions that federal health officials have determined are added risk factors for severe cases of COVID-19.

Still, she said, she “was very concerned just knowing that being obese puts you more at risk for bad outcomes such as being on a ventilator and death.” As a precaution, Ms. Antonyshyn said, she and her large brood locked down early and stopped attending church services in person, watching online instead.

“It’s not the same as having fellowship, but the risk for me was enough,” said Ms. Antonyshyn.

Governors throughout the South seem to recognize that weight can contribute to COVID-19 complications and have pushed for vaccine eligibility rules that prioritize obesity. But on the ground, local health officials are girding for having to tell newly eligible people who qualify as obese that there aren’t enough shots to go around.

In Port Gibson, Miss., Mheja Williams, MD, medical director of the Claiborne County Family Health Center, has been receiving barely enough doses to inoculate the health workers and oldest seniors in her county of 9,600. One week in early February, she received 100 doses.

Obesity and extreme obesity are endemic in Claiborne County, and health officials say the “normalization” of obesity means people often don’t register their weight as a risk factor, whether for COVID or other health issues. The risks are exacerbated by a general flouting of pandemic etiquette: Dr. Williams said that middle-aged and younger residents are not especially vigilant about physical distancing and that mask use is rare.

The rise of obesity in the United States is well documented over the past half-century, as the nation turned from a diet of fruits, vegetables and limited meats to one laden with ultra-processed foods and rich with salt, fat, sugar, and flavorings, along with copious amounts of meat, fast food, and soda. The U.S. has generally led the global obesity race, setting records as even toddlers and young children grew implausibly, dangerously overweight.

Well before COVID, obesity was a leading cause of preventable death in the United States. The National Institutes of Health declared it a disease in 1998, one that fosters heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and breast, colon, and other cancers.

Researchers say it is no coincidence that nations like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Italy, with relatively high obesity rates, have proved particularly vulnerable to the novel coronavirus.

They believe the virus may exploit underlying metabolic and physiological impairments that often exist in concert with obesity. Extra fat can lead to a cascade of metabolic disruptions, chronic systemic inflammation, and hormonal dysregulation that may thwart the body’s response to infection.

Other respiratory viruses, like influenza and SARS, which appeared in China in 2002, rely on cholesterol to spread enveloped RNA virus to neighboring cells, and researchers have proposed that a similar mechanism may play a role in the spread of the novel coronavirus.

There are also practical problems for coronavirus patients with obesity admitted to the hospital. They can be more difficult to intubate because of excess central weight pressing down on the diaphragm, making breathing with infected lungs even more difficult.

Physicians who specialize in treating patients with obesity say public health officials need to be more forthright and urgent in their messaging, telegraphing the risks of this COVID era.

“It should be explicit and direct,” said Fatima Stanford, MD, an obesity medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and a Harvard Medical School instructor.

Dr. Stanford denounces the fat-shaming and bullying that people with obesity often experience. But telling patients – and the public – that obesity increases the risk of hospitalization and death is crucial, she said.

“I don’t think it’s stigmatizing,” she said. “If you tell them in that way, it’s not to scare you, it’s just giving information. Sometimes people are just unaware.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

In January, as Mississippi health officials planned for their incoming shipments of COVID-19 vaccine, they assessed the state’s most vulnerable: health care workers, of course, and elderly people in nursing homes. But among those who needed urgent protection from the virus ripping across the Magnolia State were 1 million Mississippians with obesity.

Obesity and weight-related illnesses have been deadly liabilities in the COVID era. A report released this month by the World Obesity Federation found that increased body weight is the second-greatest predictor of COVID-related hospitalization and death across the globe, trailing only old age as a risk factor.

As a fixture of life in the American South – home to 9 of the nation’s 12 heaviest states – obesity is playing a role not only in COVID outcomes, but in the calculus of the vaccination rollout. Mississippi was one of the first states to add a body mass index of 30 or more (a rough gauge of obesity tied to height and weight) to the list of qualifying medical conditions for a shot. About 40% of the state’s adults meet that definition, according to federal health survey data, and combined with the risk group already eligible for vaccination – residents 65 and older – that means fully half of Mississippi’s adults are entitled to vie for a restricted allotment of shots.

At least 29 states have green-lighted obesity for inclusion in the first phases of the vaccine rollout, according to KFF – a vast widening of eligibility that has the potential to overwhelm government efforts and heighten competition for scarce doses.

“We have a lifesaving intervention, and we don’t have enough of it,” said Jen Kates, PhD, director of global health and HIV policy for Kaiser Family Foundation. “Hard choices are being made about who should go first, and there is no right answer.”

The sheer prevalence of obesity in the nation – two in three Americans exceed what is considered a healthy weight – was a public health concern well before the pandemic. But COVID-19 dramatically fast-tracked the discussion from warnings about the long-term damage excess fat tissue can pose to heart, lung and metabolic functions to far more immediate threats.

In the United Kingdom, for example, overweight COVID patients were 67% more likely to require intensive care, and obese patients three times likelier, according to the World Obesity Federation report. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study released Monday found a similar trend among U.S. patients and noted that the risk of COVID-related hospitalization, ventilation and death increased with patients’ obesity level.

The counties that hug the southern Mississippi River are home to some of the most concentrated pockets of extreme obesity in the United States. Coronavirus infections began surging in Southern states early last summer, and hospitalizations rose in step.

Deaths in rural stretches of Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee have been overshadowed by the sheer number of deaths in metropolitan areas like New York, Los Angeles, and Essex County, N.J. But as a share of the population, the coronavirus has been similarly unsparing in many Southern communities. In sparsely populated Claiborne County, Miss., on the floodplains of the Mississippi River, 30 residents – about 1 in 300 – had died as of early March. In East Feliciana Parish, La., north of Baton Rouge, with 106 deaths, about 1 in 180 had died by then.

“It’s just math. If the population is more obese and obesity clearly contributes to worse outcomes, then neighborhoods, cities, states and countries that are more obese will have a greater toll from COVID,” said Dr. James de Lemos, MD, a professor of internal medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas who led a study of hospitalized COVID patients published in the medical journal Circulation.

And, because in the U.S. obesity rates tend to be relatively high among African Americans and Latinos who are poor, with diminished access to health care, “it’s a triple whammy,” Dr. de Lemos said. “All these things intersect.”

Poverty and limited access to medical care are common features in the South, where residents like Michelle Antonyshyn, a former registered nurse and mother of seven in Salem, Ark., say they are afraid of the virus. Ms. Antonyshyn, 49, has obesity and debilitating pain in her knees and back, though she does not have high blood pressure or diabetes, two underlying conditions that federal health officials have determined are added risk factors for severe cases of COVID-19.

Still, she said, she “was very concerned just knowing that being obese puts you more at risk for bad outcomes such as being on a ventilator and death.” As a precaution, Ms. Antonyshyn said, she and her large brood locked down early and stopped attending church services in person, watching online instead.

“It’s not the same as having fellowship, but the risk for me was enough,” said Ms. Antonyshyn.

Governors throughout the South seem to recognize that weight can contribute to COVID-19 complications and have pushed for vaccine eligibility rules that prioritize obesity. But on the ground, local health officials are girding for having to tell newly eligible people who qualify as obese that there aren’t enough shots to go around.

In Port Gibson, Miss., Mheja Williams, MD, medical director of the Claiborne County Family Health Center, has been receiving barely enough doses to inoculate the health workers and oldest seniors in her county of 9,600. One week in early February, she received 100 doses.

Obesity and extreme obesity are endemic in Claiborne County, and health officials say the “normalization” of obesity means people often don’t register their weight as a risk factor, whether for COVID or other health issues. The risks are exacerbated by a general flouting of pandemic etiquette: Dr. Williams said that middle-aged and younger residents are not especially vigilant about physical distancing and that mask use is rare.

The rise of obesity in the United States is well documented over the past half-century, as the nation turned from a diet of fruits, vegetables and limited meats to one laden with ultra-processed foods and rich with salt, fat, sugar, and flavorings, along with copious amounts of meat, fast food, and soda. The U.S. has generally led the global obesity race, setting records as even toddlers and young children grew implausibly, dangerously overweight.

Well before COVID, obesity was a leading cause of preventable death in the United States. The National Institutes of Health declared it a disease in 1998, one that fosters heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and breast, colon, and other cancers.

Researchers say it is no coincidence that nations like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Italy, with relatively high obesity rates, have proved particularly vulnerable to the novel coronavirus.

They believe the virus may exploit underlying metabolic and physiological impairments that often exist in concert with obesity. Extra fat can lead to a cascade of metabolic disruptions, chronic systemic inflammation, and hormonal dysregulation that may thwart the body’s response to infection.

Other respiratory viruses, like influenza and SARS, which appeared in China in 2002, rely on cholesterol to spread enveloped RNA virus to neighboring cells, and researchers have proposed that a similar mechanism may play a role in the spread of the novel coronavirus.

There are also practical problems for coronavirus patients with obesity admitted to the hospital. They can be more difficult to intubate because of excess central weight pressing down on the diaphragm, making breathing with infected lungs even more difficult.

Physicians who specialize in treating patients with obesity say public health officials need to be more forthright and urgent in their messaging, telegraphing the risks of this COVID era.

“It should be explicit and direct,” said Fatima Stanford, MD, an obesity medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and a Harvard Medical School instructor.

Dr. Stanford denounces the fat-shaming and bullying that people with obesity often experience. But telling patients – and the public – that obesity increases the risk of hospitalization and death is crucial, she said.

“I don’t think it’s stigmatizing,” she said. “If you tell them in that way, it’s not to scare you, it’s just giving information. Sometimes people are just unaware.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

COVID-19 virus reinfections rare; riskiest after age 65

When researchers analyzed test results of 4 million people in Denmark, they found that less than 1% of those who tested positive experienced reinfection.

Initial infection was associated with about 80% protection overall against getting SARS-CoV-2 again. However, among those older than 65, the protection plummeted to 47%.

“Not everybody is protected against reinfection after a first infection. Older people are at higher risk of catching it again,” co–lead author Daniela Michlmayr, PhD, said in an interview. “Our findings emphasize the importance of policies to protect the elderly and of adhering to infection control measures and restrictions, even if previously infected with COVID-19.”

Verifying the need for vaccination

“The findings also highlight the need to vaccinate people who had COVID-19 before, as natural immunity to infection – especially among the elderly 65 and older – cannot be relied upon,” added Dr. Michlmayr, a researcher in the department of bacteria, parasites, and fungi at the Staten Serums Institut, Copenhagen.

The population-based observational study was published online March 17 in The Lancet.

“The findings make sense, as patients who are immunocompromised or of advanced age may not mount an immune response that is as long-lasting,” David Hirschwerk, MD, said in an interview. “It does underscore the importance of vaccination for people of more advanced age, even if they previously were infected with COVID.

“For those who were infected last spring and have not yet been vaccinated, this helps to support the value of still pursuing the vaccine,” added Dr. Hirschwerk, an infectious disease specialist at Northwell Health in Manhasset, N.Y.

Evidence on reinfection risk was limited prior to this study. “Little is known about protection against SARS-CoV-2 repeat infections, but two studies in the UK have found that immunity could last at least 5 to 6 months after infection,” the authors noted.

Along with co–lead author Christian Holm Hansen, PhD, Dr. Michlmayr and colleagues found that 2.11% of 525,339 individuals tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during the first surge in Denmark from March to May 2020. Within this group, 0.65% tested positive during a second surge from September to December.

By the end of 2020, more than 10 million people had undergone free polymerase chain reaction testing by the Danish government or through the national TestDenmark program.

“My overall take is that it is great to have such a big dataset looking at this question,” E. John Wherry, PhD, said in an interview. The findings support “what we’ve seen in previous, smaller studies.”

Natural protection against reinfection of approximately 80% “is not as good as the vaccines, but not bad,” added Dr. Wherry, director of the Institute for Immunology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Age alters immunity?

“Our finding that older people were more likely than younger people to test positive again if they had already tested positive could be explained by natural age-related changes in the immune system of older adults, also referred to as immune senescence,” the authors noted.

The investigators found no significant differences in reinfection rates between women and men.

As with the previous research, this study also indicates that an initial bout with SARS-CoV-2 infection appears to confer protection for at least 6 months. The researchers found no significant differences between people who were followed for 3-6 months and those followed for 7 months or longer.

Variants not included

To account for possible bias among people who got tested repeatedly, Dr. Michlmayr and colleagues performed a sensitivity analysis in a subgroup. They assessed reinfection rates among people who underwent testing frequently and routinely – nurses, doctors, social workers, and health care assistants – and found that 1.2% tested positive a second time during the second surge.

A limitation of the study was the inability to correlate symptoms with risk for reinfection. Also, the researchers did not account for SARS-CoV-2 variants, noting that “during the study period, such variants were not yet established in Denmark; although into 2021 this pattern is changing.”

Asked to speculate whether the results would be different had the study accounted for variants, Dr. Hirschwerk said, “It depends upon the variant, but certainly for the B.1.351 variant, there already has been data clearly demonstrating risk of reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 despite prior infection with the original strain of virus.”

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern that could escape natural and vaccine-related immunity “complicates matters further,” Rosemary J. Boyton, MBBS, and Daniel M. Altmann, PhD, both of Imperial College London, wrote in an accompanying comment in The Lancet.

“Emerging variants of concern might shift immunity below a protective margin, prompting the need for updated vaccines. Interestingly, vaccine responses even after single dose are substantially enhanced in individuals with a history of infection with SARS-CoV-2,” they added.

The current study confirms that “the hope of protective immunity through natural infections might not be within our reach, and a global vaccination program with high efficacy vaccines is the enduring solution,” Dr. Boyton and Dr. Altmann noted.

Cause for alarm?

Despite evidence that reinfection is relatively rare, “many will find the data reported by Hansen and colleagues about protection through natural infection relatively alarming,” Dr. Boyton and Dr. Altmann wrote in their commentary. The 80% protection rate from reinfection in general and the 47% rate among people aged 65 and older “are more concerning figures than offered by previous studies.”

Vaccines appear to provide better quality, quantity, and durability of protection against repeated infection – measured in terms of neutralizing antibodies and T cells – compared with previous infection with SARS-CoV-2, Dr. Boyton and Dr. Altmann wrote.

More research needed

The duration of natural protection against reinfection remains an unanswered question, the researchers noted, “because too little time has elapsed since the beginning of the pandemic.”

Future prospective and longitudinal cohort studies coupled with molecular surveillance are needed to characterize antibody titers and waning of protection against repeat infections, the authors noted. Furthermore, more answers are needed regarding how some virus variants might contribute to reinfection risk.

No funding for the study has been reported. Dr. Michlmayr, Dr. Hirschwerk, Dr. Wherry, Dr. Boyton, and Dr. Altmann have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When researchers analyzed test results of 4 million people in Denmark, they found that less than 1% of those who tested positive experienced reinfection.

Initial infection was associated with about 80% protection overall against getting SARS-CoV-2 again. However, among those older than 65, the protection plummeted to 47%.

“Not everybody is protected against reinfection after a first infection. Older people are at higher risk of catching it again,” co–lead author Daniela Michlmayr, PhD, said in an interview. “Our findings emphasize the importance of policies to protect the elderly and of adhering to infection control measures and restrictions, even if previously infected with COVID-19.”

Verifying the need for vaccination

“The findings also highlight the need to vaccinate people who had COVID-19 before, as natural immunity to infection – especially among the elderly 65 and older – cannot be relied upon,” added Dr. Michlmayr, a researcher in the department of bacteria, parasites, and fungi at the Staten Serums Institut, Copenhagen.

The population-based observational study was published online March 17 in The Lancet.

“The findings make sense, as patients who are immunocompromised or of advanced age may not mount an immune response that is as long-lasting,” David Hirschwerk, MD, said in an interview. “It does underscore the importance of vaccination for people of more advanced age, even if they previously were infected with COVID.

“For those who were infected last spring and have not yet been vaccinated, this helps to support the value of still pursuing the vaccine,” added Dr. Hirschwerk, an infectious disease specialist at Northwell Health in Manhasset, N.Y.

Evidence on reinfection risk was limited prior to this study. “Little is known about protection against SARS-CoV-2 repeat infections, but two studies in the UK have found that immunity could last at least 5 to 6 months after infection,” the authors noted.

Along with co–lead author Christian Holm Hansen, PhD, Dr. Michlmayr and colleagues found that 2.11% of 525,339 individuals tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during the first surge in Denmark from March to May 2020. Within this group, 0.65% tested positive during a second surge from September to December.

By the end of 2020, more than 10 million people had undergone free polymerase chain reaction testing by the Danish government or through the national TestDenmark program.

“My overall take is that it is great to have such a big dataset looking at this question,” E. John Wherry, PhD, said in an interview. The findings support “what we’ve seen in previous, smaller studies.”

Natural protection against reinfection of approximately 80% “is not as good as the vaccines, but not bad,” added Dr. Wherry, director of the Institute for Immunology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Age alters immunity?

“Our finding that older people were more likely than younger people to test positive again if they had already tested positive could be explained by natural age-related changes in the immune system of older adults, also referred to as immune senescence,” the authors noted.

The investigators found no significant differences in reinfection rates between women and men.

As with the previous research, this study also indicates that an initial bout with SARS-CoV-2 infection appears to confer protection for at least 6 months. The researchers found no significant differences between people who were followed for 3-6 months and those followed for 7 months or longer.

Variants not included

To account for possible bias among people who got tested repeatedly, Dr. Michlmayr and colleagues performed a sensitivity analysis in a subgroup. They assessed reinfection rates among people who underwent testing frequently and routinely – nurses, doctors, social workers, and health care assistants – and found that 1.2% tested positive a second time during the second surge.

A limitation of the study was the inability to correlate symptoms with risk for reinfection. Also, the researchers did not account for SARS-CoV-2 variants, noting that “during the study period, such variants were not yet established in Denmark; although into 2021 this pattern is changing.”

Asked to speculate whether the results would be different had the study accounted for variants, Dr. Hirschwerk said, “It depends upon the variant, but certainly for the B.1.351 variant, there already has been data clearly demonstrating risk of reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 despite prior infection with the original strain of virus.”

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern that could escape natural and vaccine-related immunity “complicates matters further,” Rosemary J. Boyton, MBBS, and Daniel M. Altmann, PhD, both of Imperial College London, wrote in an accompanying comment in The Lancet.

“Emerging variants of concern might shift immunity below a protective margin, prompting the need for updated vaccines. Interestingly, vaccine responses even after single dose are substantially enhanced in individuals with a history of infection with SARS-CoV-2,” they added.

The current study confirms that “the hope of protective immunity through natural infections might not be within our reach, and a global vaccination program with high efficacy vaccines is the enduring solution,” Dr. Boyton and Dr. Altmann noted.

Cause for alarm?

Despite evidence that reinfection is relatively rare, “many will find the data reported by Hansen and colleagues about protection through natural infection relatively alarming,” Dr. Boyton and Dr. Altmann wrote in their commentary. The 80% protection rate from reinfection in general and the 47% rate among people aged 65 and older “are more concerning figures than offered by previous studies.”

Vaccines appear to provide better quality, quantity, and durability of protection against repeated infection – measured in terms of neutralizing antibodies and T cells – compared with previous infection with SARS-CoV-2, Dr. Boyton and Dr. Altmann wrote.

More research needed

The duration of natural protection against reinfection remains an unanswered question, the researchers noted, “because too little time has elapsed since the beginning of the pandemic.”

Future prospective and longitudinal cohort studies coupled with molecular surveillance are needed to characterize antibody titers and waning of protection against repeat infections, the authors noted. Furthermore, more answers are needed regarding how some virus variants might contribute to reinfection risk.

No funding for the study has been reported. Dr. Michlmayr, Dr. Hirschwerk, Dr. Wherry, Dr. Boyton, and Dr. Altmann have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When researchers analyzed test results of 4 million people in Denmark, they found that less than 1% of those who tested positive experienced reinfection.

Initial infection was associated with about 80% protection overall against getting SARS-CoV-2 again. However, among those older than 65, the protection plummeted to 47%.

“Not everybody is protected against reinfection after a first infection. Older people are at higher risk of catching it again,” co–lead author Daniela Michlmayr, PhD, said in an interview. “Our findings emphasize the importance of policies to protect the elderly and of adhering to infection control measures and restrictions, even if previously infected with COVID-19.”

Verifying the need for vaccination

“The findings also highlight the need to vaccinate people who had COVID-19 before, as natural immunity to infection – especially among the elderly 65 and older – cannot be relied upon,” added Dr. Michlmayr, a researcher in the department of bacteria, parasites, and fungi at the Staten Serums Institut, Copenhagen.

The population-based observational study was published online March 17 in The Lancet.

“The findings make sense, as patients who are immunocompromised or of advanced age may not mount an immune response that is as long-lasting,” David Hirschwerk, MD, said in an interview. “It does underscore the importance of vaccination for people of more advanced age, even if they previously were infected with COVID.

“For those who were infected last spring and have not yet been vaccinated, this helps to support the value of still pursuing the vaccine,” added Dr. Hirschwerk, an infectious disease specialist at Northwell Health in Manhasset, N.Y.

Evidence on reinfection risk was limited prior to this study. “Little is known about protection against SARS-CoV-2 repeat infections, but two studies in the UK have found that immunity could last at least 5 to 6 months after infection,” the authors noted.

Along with co–lead author Christian Holm Hansen, PhD, Dr. Michlmayr and colleagues found that 2.11% of 525,339 individuals tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during the first surge in Denmark from March to May 2020. Within this group, 0.65% tested positive during a second surge from September to December.

By the end of 2020, more than 10 million people had undergone free polymerase chain reaction testing by the Danish government or through the national TestDenmark program.

“My overall take is that it is great to have such a big dataset looking at this question,” E. John Wherry, PhD, said in an interview. The findings support “what we’ve seen in previous, smaller studies.”

Natural protection against reinfection of approximately 80% “is not as good as the vaccines, but not bad,” added Dr. Wherry, director of the Institute for Immunology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Age alters immunity?

“Our finding that older people were more likely than younger people to test positive again if they had already tested positive could be explained by natural age-related changes in the immune system of older adults, also referred to as immune senescence,” the authors noted.

The investigators found no significant differences in reinfection rates between women and men.

As with the previous research, this study also indicates that an initial bout with SARS-CoV-2 infection appears to confer protection for at least 6 months. The researchers found no significant differences between people who were followed for 3-6 months and those followed for 7 months or longer.

Variants not included

To account for possible bias among people who got tested repeatedly, Dr. Michlmayr and colleagues performed a sensitivity analysis in a subgroup. They assessed reinfection rates among people who underwent testing frequently and routinely – nurses, doctors, social workers, and health care assistants – and found that 1.2% tested positive a second time during the second surge.

A limitation of the study was the inability to correlate symptoms with risk for reinfection. Also, the researchers did not account for SARS-CoV-2 variants, noting that “during the study period, such variants were not yet established in Denmark; although into 2021 this pattern is changing.”

Asked to speculate whether the results would be different had the study accounted for variants, Dr. Hirschwerk said, “It depends upon the variant, but certainly for the B.1.351 variant, there already has been data clearly demonstrating risk of reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 despite prior infection with the original strain of virus.”

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern that could escape natural and vaccine-related immunity “complicates matters further,” Rosemary J. Boyton, MBBS, and Daniel M. Altmann, PhD, both of Imperial College London, wrote in an accompanying comment in The Lancet.

“Emerging variants of concern might shift immunity below a protective margin, prompting the need for updated vaccines. Interestingly, vaccine responses even after single dose are substantially enhanced in individuals with a history of infection with SARS-CoV-2,” they added.

The current study confirms that “the hope of protective immunity through natural infections might not be within our reach, and a global vaccination program with high efficacy vaccines is the enduring solution,” Dr. Boyton and Dr. Altmann noted.

Cause for alarm?

Despite evidence that reinfection is relatively rare, “many will find the data reported by Hansen and colleagues about protection through natural infection relatively alarming,” Dr. Boyton and Dr. Altmann wrote in their commentary. The 80% protection rate from reinfection in general and the 47% rate among people aged 65 and older “are more concerning figures than offered by previous studies.”

Vaccines appear to provide better quality, quantity, and durability of protection against repeated infection – measured in terms of neutralizing antibodies and T cells – compared with previous infection with SARS-CoV-2, Dr. Boyton and Dr. Altmann wrote.

More research needed

The duration of natural protection against reinfection remains an unanswered question, the researchers noted, “because too little time has elapsed since the beginning of the pandemic.”

Future prospective and longitudinal cohort studies coupled with molecular surveillance are needed to characterize antibody titers and waning of protection against repeat infections, the authors noted. Furthermore, more answers are needed regarding how some virus variants might contribute to reinfection risk.

No funding for the study has been reported. Dr. Michlmayr, Dr. Hirschwerk, Dr. Wherry, Dr. Boyton, and Dr. Altmann have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New guidelines dispel myths about COVID-19 treatment

Recommendations, as well as conspiracy theories about COVID-19, have changed at distressing rates over the past year. No disease has ever been more politicized, or more polarizing.

Experts, as well as the least educated, take a stand on what they believe is the most important way to prevent and treat this virus.

Just recently, a study was published revealing that ivermectin is not effective as a COVID-19 treatment while people continue to claim it works. It has never been more important for doctors, and especially family physicians, to have accurate and updated guidelines.

The NIH and CDC have been publishing recommendations and guidelines for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic. Like any new disease, these have been changing to keep up as new knowledge related to the disease becomes available.

NIH updates treatment guidelines

A recent update to the NIH COVID-19 treatment guidelines was published on March 5, 2021. While the complete guidelines are quite extensive, spanning over 200 pages, it’s most important to understand the most recent updates in them.

Since preventative medicine is an integral part of primary care, it is important to note that no medications have been advised to prevent infection with COVID-19. In fact, taking drugs for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEp) is not recommended even in the highest-risk patients, such as health care workers.

In the updated guidelines, tocilizumab in a single IV dose of 8 mg/kg up to a maximum of 800 mg can be given only in combination with dexamethasone (or equivalent corticosteroid) in certain hospitalized patients exhibiting rapid respiratory decompensation. These patients include recently hospitalized patients who have been admitted to the ICU within the previous 24 hours and now require mechanical ventilation or high-flow oxygen via nasal cannula. Those not in the ICU who require rapidly increasing oxygen levels and have significantly increased levels of inflammatory markers should also receive this therapy. In the new guidance, the NIH recommends treating other hospitalized patients who require oxygen with remdesivir, remdesivir + dexamethasone, or dexamethasone alone.

In outpatients, those who have mild to moderate infection and are at increased risk of developing severe disease and/or hospitalization can be treated with bamlanivimab 700 mg + etesevimab 1,400 mg. This should be started as soon as possible after a confirmed diagnosis and within 10 days of symptom onset, according to the NIH recommendations. There is no evidence to support its use in patients hospitalized because of infection. However, it can be used in patients hospitalized for other reasons who have mild to moderate infection, but should be reserved – because of limited supply – for those with the highest risk of complications.

Hydroxychloroquine and casirivimab + imdevimab

One medication that has been touted in the media as a tool to treat COVID-19 has been hydroxychloroquine. Past guidelines recommended against this medication as a treatment because it lacked efficacy and posed risks for no therapeutic benefit. The most recent guidelines also recommend against the use of hydroxychloroquine for pre- and postexposure prophylaxis.

Casirivimab + imdevimab has been another talked about therapy. However, current guidelines recommend against its use in hospitalized patients. In addition, it is advised that hospitalized patients be enrolled in a clinical trial to receive it.

Since the pandemic began, the world has seen more than 120 million infections and more than 2 million deaths. Family physicians have a vital role to play as we are often the first ones patients turn to for treatment and advice. It is imperative we stay current with the guidelines and follow the most recent updates as research data are published.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at [email protected].

Recommendations, as well as conspiracy theories about COVID-19, have changed at distressing rates over the past year. No disease has ever been more politicized, or more polarizing.

Experts, as well as the least educated, take a stand on what they believe is the most important way to prevent and treat this virus.

Just recently, a study was published revealing that ivermectin is not effective as a COVID-19 treatment while people continue to claim it works. It has never been more important for doctors, and especially family physicians, to have accurate and updated guidelines.

The NIH and CDC have been publishing recommendations and guidelines for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic. Like any new disease, these have been changing to keep up as new knowledge related to the disease becomes available.

NIH updates treatment guidelines

A recent update to the NIH COVID-19 treatment guidelines was published on March 5, 2021. While the complete guidelines are quite extensive, spanning over 200 pages, it’s most important to understand the most recent updates in them.

Since preventative medicine is an integral part of primary care, it is important to note that no medications have been advised to prevent infection with COVID-19. In fact, taking drugs for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEp) is not recommended even in the highest-risk patients, such as health care workers.

In the updated guidelines, tocilizumab in a single IV dose of 8 mg/kg up to a maximum of 800 mg can be given only in combination with dexamethasone (or equivalent corticosteroid) in certain hospitalized patients exhibiting rapid respiratory decompensation. These patients include recently hospitalized patients who have been admitted to the ICU within the previous 24 hours and now require mechanical ventilation or high-flow oxygen via nasal cannula. Those not in the ICU who require rapidly increasing oxygen levels and have significantly increased levels of inflammatory markers should also receive this therapy. In the new guidance, the NIH recommends treating other hospitalized patients who require oxygen with remdesivir, remdesivir + dexamethasone, or dexamethasone alone.

In outpatients, those who have mild to moderate infection and are at increased risk of developing severe disease and/or hospitalization can be treated with bamlanivimab 700 mg + etesevimab 1,400 mg. This should be started as soon as possible after a confirmed diagnosis and within 10 days of symptom onset, according to the NIH recommendations. There is no evidence to support its use in patients hospitalized because of infection. However, it can be used in patients hospitalized for other reasons who have mild to moderate infection, but should be reserved – because of limited supply – for those with the highest risk of complications.

Hydroxychloroquine and casirivimab + imdevimab

One medication that has been touted in the media as a tool to treat COVID-19 has been hydroxychloroquine. Past guidelines recommended against this medication as a treatment because it lacked efficacy and posed risks for no therapeutic benefit. The most recent guidelines also recommend against the use of hydroxychloroquine for pre- and postexposure prophylaxis.

Casirivimab + imdevimab has been another talked about therapy. However, current guidelines recommend against its use in hospitalized patients. In addition, it is advised that hospitalized patients be enrolled in a clinical trial to receive it.

Since the pandemic began, the world has seen more than 120 million infections and more than 2 million deaths. Family physicians have a vital role to play as we are often the first ones patients turn to for treatment and advice. It is imperative we stay current with the guidelines and follow the most recent updates as research data are published.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at [email protected].

Recommendations, as well as conspiracy theories about COVID-19, have changed at distressing rates over the past year. No disease has ever been more politicized, or more polarizing.

Experts, as well as the least educated, take a stand on what they believe is the most important way to prevent and treat this virus.

Just recently, a study was published revealing that ivermectin is not effective as a COVID-19 treatment while people continue to claim it works. It has never been more important for doctors, and especially family physicians, to have accurate and updated guidelines.

The NIH and CDC have been publishing recommendations and guidelines for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic. Like any new disease, these have been changing to keep up as new knowledge related to the disease becomes available.

NIH updates treatment guidelines

A recent update to the NIH COVID-19 treatment guidelines was published on March 5, 2021. While the complete guidelines are quite extensive, spanning over 200 pages, it’s most important to understand the most recent updates in them.

Since preventative medicine is an integral part of primary care, it is important to note that no medications have been advised to prevent infection with COVID-19. In fact, taking drugs for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEp) is not recommended even in the highest-risk patients, such as health care workers.

In the updated guidelines, tocilizumab in a single IV dose of 8 mg/kg up to a maximum of 800 mg can be given only in combination with dexamethasone (or equivalent corticosteroid) in certain hospitalized patients exhibiting rapid respiratory decompensation. These patients include recently hospitalized patients who have been admitted to the ICU within the previous 24 hours and now require mechanical ventilation or high-flow oxygen via nasal cannula. Those not in the ICU who require rapidly increasing oxygen levels and have significantly increased levels of inflammatory markers should also receive this therapy. In the new guidance, the NIH recommends treating other hospitalized patients who require oxygen with remdesivir, remdesivir + dexamethasone, or dexamethasone alone.

In outpatients, those who have mild to moderate infection and are at increased risk of developing severe disease and/or hospitalization can be treated with bamlanivimab 700 mg + etesevimab 1,400 mg. This should be started as soon as possible after a confirmed diagnosis and within 10 days of symptom onset, according to the NIH recommendations. There is no evidence to support its use in patients hospitalized because of infection. However, it can be used in patients hospitalized for other reasons who have mild to moderate infection, but should be reserved – because of limited supply – for those with the highest risk of complications.

Hydroxychloroquine and casirivimab + imdevimab

One medication that has been touted in the media as a tool to treat COVID-19 has been hydroxychloroquine. Past guidelines recommended against this medication as a treatment because it lacked efficacy and posed risks for no therapeutic benefit. The most recent guidelines also recommend against the use of hydroxychloroquine for pre- and postexposure prophylaxis.

Casirivimab + imdevimab has been another talked about therapy. However, current guidelines recommend against its use in hospitalized patients. In addition, it is advised that hospitalized patients be enrolled in a clinical trial to receive it.

Since the pandemic began, the world has seen more than 120 million infections and more than 2 million deaths. Family physicians have a vital role to play as we are often the first ones patients turn to for treatment and advice. It is imperative we stay current with the guidelines and follow the most recent updates as research data are published.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at [email protected].

Some with long COVID see relief after vaccination

Several weeks after getting his second dose of an mRNA vaccine, Aaron Goyang thinks his long bout with COVID-19 has finally come to an end.

Mr. Goyang, who is 33 and is a radiology technician in Austin, Tex., thinks he got COVID-19 from some of the coughing, gasping patients he treated last spring.

At the time, testing was scarce, and by the time he was tested – several weeks into his illness – it came back negative. He fought off the initial symptoms but experienced relapse a week later.

Mr. Goyang says that, for the next 8 or 9 months, he was on a roller coaster with extreme shortness of breath and chest tightness that could be so severe it would send him to the emergency department. He had to use an inhaler to get through his workdays.

“Even if I was just sitting around, it would come and take me,” he says. “It almost felt like someone was bear-hugging me constantly, and I just couldn’t get in a good enough breath.”

On his best days, he would walk around his neighborhood, being careful not to overdo it. He tried running once, and it nearly sent him to the hospital.

“Very honestly, I didn’t know if I would ever be able to do it again,” he says.

But Mr. Goyang says that, several weeks after getting the Pfizer vaccine, he was able to run a mile again with no problems. “I was very thankful for that,” he says.

Mr. Goyang is not alone. Some social media groups are dedicated to patients who are living with a condition that’s been known as long COVID and that was recently termed postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These patients are sometimes referred to as long haulers.

On social media, patients with PASC are eagerly and anxiously quizzing each other about the vaccines and their effects.

Survivor Corps, which has a public Facebook group with 159,000 members, recently took a poll to see whether there was any substance to rumors that those with long COVID were feeling better after being vaccinated.

“Out of 400 people, 36% showed an improvement in symptoms, anywhere between a mild improvement to complete resolution of symptoms,” said Diana Berrent, a long-COVID patient who founded the group. Survivor Corps has become active in patient advocacy and is a resource for researchers studying the new condition.

Ms. Berrent has become such a trusted voice during the pandemic. She interviewed Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, last October.

“The implications are huge,” she says.

“Some of this damage is permanent damage. It’s not going to cure the scarring of your heart tissue, it’s not going to cure the irreparable damage to your lungs, but if it’s making people feel better, then that’s an indication there’s viral persistence going on,” says Ms. Berrent.

“I’ve been saying for months and months, we shouldn’t be calling this postacute anything,” she adds.

Patients report improvement

Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, is equally excited. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, New York. He says about one in five patients he treated for COVID-19 last year never got better. Many of them, such as Mr. Goyang, were health care workers.

“I don’t know if people actually catch this, but a lot of our coworkers are either permanently disabled or died,” Dr. Griffin says.

Health care workers were also among the first to be vaccinated. Dr. Griffin says many of his patients began reaching out to him about a week or two after being vaccinated “and saying, ‘You know, I actually feel better.’ And some of them were saying, ‘I feel all better,’ after being sick – a lot of them – for a year.”

Then he was getting calls and texts from other doctors, asking, “Hey, are you seeing this?”

The benefits of vaccination for some long-haulers came as a surprise. Dr. Griffin says that, before the vaccines came out, many of his patients were worried that getting vaccinated might overstimulate their immune systems and cause symptoms to get worse.

Indeed, a small percentage of people – about 3%-5%, based on informal polls on social media – report that they do experience worsening of symptoms after getting the shot. It’s not clear why.

Dr. Griffin estimates that between 30% and 50% of patients’ symptoms improve after they receive the mRNA vaccines. “I’m seeing this chunk of people – they tell me their brain fog has improved, their fatigue is gone, the fevers that wouldn’t resolve have now gone,” he says. “I’m seeing that personally, and I’m hearing it from my colleagues.”

Dr. Griffin says the observation has launched several studies and that there are several theories about how the vaccines might be affecting long COVID.

An immune system boost?

One possibility is that the virus continues to stimulate the immune system, which continues to fight the virus for months. If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be giving the immune system the boost it needs to finally clear the virus away.

Donna Farber, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, has heard the stories, too.

“It is possible that the persisting virus in long COVID-19 may be at a low level – not enough to stimulate a potent immune response to clear the virus, but enough to cause symptoms. Activating the immune response therefore is therapeutic in directing viral clearance,” she says.

Dr. Farber explains that long COVID may be a bit like Lyme disease. Some patients with Lyme disease must take antibiotics for months before their symptoms disappear.

Dr. Griffin says there’s another possibility. Several studies have now shown that people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms develop autoantibodies. There’s a theory that SARS-CoV-2 may create an autoimmune condition that leads to long-term symptoms.

If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be helping the body to reset its tolerance to itself, “so maybe now you’re getting a healthy immune response.”

More studies are needed to know for sure.

Either way, the vaccines are a much-needed bit of hope for the long-COVID community, and Dr. Griffin tells his patients who are still worried that, at the very least, they’ll be protected from another SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Several weeks after getting his second dose of an mRNA vaccine, Aaron Goyang thinks his long bout with COVID-19 has finally come to an end.

Mr. Goyang, who is 33 and is a radiology technician in Austin, Tex., thinks he got COVID-19 from some of the coughing, gasping patients he treated last spring.

At the time, testing was scarce, and by the time he was tested – several weeks into his illness – it came back negative. He fought off the initial symptoms but experienced relapse a week later.

Mr. Goyang says that, for the next 8 or 9 months, he was on a roller coaster with extreme shortness of breath and chest tightness that could be so severe it would send him to the emergency department. He had to use an inhaler to get through his workdays.

“Even if I was just sitting around, it would come and take me,” he says. “It almost felt like someone was bear-hugging me constantly, and I just couldn’t get in a good enough breath.”

On his best days, he would walk around his neighborhood, being careful not to overdo it. He tried running once, and it nearly sent him to the hospital.

“Very honestly, I didn’t know if I would ever be able to do it again,” he says.

But Mr. Goyang says that, several weeks after getting the Pfizer vaccine, he was able to run a mile again with no problems. “I was very thankful for that,” he says.

Mr. Goyang is not alone. Some social media groups are dedicated to patients who are living with a condition that’s been known as long COVID and that was recently termed postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These patients are sometimes referred to as long haulers.

On social media, patients with PASC are eagerly and anxiously quizzing each other about the vaccines and their effects.

Survivor Corps, which has a public Facebook group with 159,000 members, recently took a poll to see whether there was any substance to rumors that those with long COVID were feeling better after being vaccinated.

“Out of 400 people, 36% showed an improvement in symptoms, anywhere between a mild improvement to complete resolution of symptoms,” said Diana Berrent, a long-COVID patient who founded the group. Survivor Corps has become active in patient advocacy and is a resource for researchers studying the new condition.

Ms. Berrent has become such a trusted voice during the pandemic. She interviewed Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, last October.

“The implications are huge,” she says.

“Some of this damage is permanent damage. It’s not going to cure the scarring of your heart tissue, it’s not going to cure the irreparable damage to your lungs, but if it’s making people feel better, then that’s an indication there’s viral persistence going on,” says Ms. Berrent.

“I’ve been saying for months and months, we shouldn’t be calling this postacute anything,” she adds.

Patients report improvement

Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, is equally excited. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, New York. He says about one in five patients he treated for COVID-19 last year never got better. Many of them, such as Mr. Goyang, were health care workers.

“I don’t know if people actually catch this, but a lot of our coworkers are either permanently disabled or died,” Dr. Griffin says.

Health care workers were also among the first to be vaccinated. Dr. Griffin says many of his patients began reaching out to him about a week or two after being vaccinated “and saying, ‘You know, I actually feel better.’ And some of them were saying, ‘I feel all better,’ after being sick – a lot of them – for a year.”

Then he was getting calls and texts from other doctors, asking, “Hey, are you seeing this?”

The benefits of vaccination for some long-haulers came as a surprise. Dr. Griffin says that, before the vaccines came out, many of his patients were worried that getting vaccinated might overstimulate their immune systems and cause symptoms to get worse.

Indeed, a small percentage of people – about 3%-5%, based on informal polls on social media – report that they do experience worsening of symptoms after getting the shot. It’s not clear why.

Dr. Griffin estimates that between 30% and 50% of patients’ symptoms improve after they receive the mRNA vaccines. “I’m seeing this chunk of people – they tell me their brain fog has improved, their fatigue is gone, the fevers that wouldn’t resolve have now gone,” he says. “I’m seeing that personally, and I’m hearing it from my colleagues.”

Dr. Griffin says the observation has launched several studies and that there are several theories about how the vaccines might be affecting long COVID.

An immune system boost?

One possibility is that the virus continues to stimulate the immune system, which continues to fight the virus for months. If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be giving the immune system the boost it needs to finally clear the virus away.

Donna Farber, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, has heard the stories, too.

“It is possible that the persisting virus in long COVID-19 may be at a low level – not enough to stimulate a potent immune response to clear the virus, but enough to cause symptoms. Activating the immune response therefore is therapeutic in directing viral clearance,” she says.

Dr. Farber explains that long COVID may be a bit like Lyme disease. Some patients with Lyme disease must take antibiotics for months before their symptoms disappear.

Dr. Griffin says there’s another possibility. Several studies have now shown that people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms develop autoantibodies. There’s a theory that SARS-CoV-2 may create an autoimmune condition that leads to long-term symptoms.

If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be helping the body to reset its tolerance to itself, “so maybe now you’re getting a healthy immune response.”

More studies are needed to know for sure.

Either way, the vaccines are a much-needed bit of hope for the long-COVID community, and Dr. Griffin tells his patients who are still worried that, at the very least, they’ll be protected from another SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Several weeks after getting his second dose of an mRNA vaccine, Aaron Goyang thinks his long bout with COVID-19 has finally come to an end.

Mr. Goyang, who is 33 and is a radiology technician in Austin, Tex., thinks he got COVID-19 from some of the coughing, gasping patients he treated last spring.

At the time, testing was scarce, and by the time he was tested – several weeks into his illness – it came back negative. He fought off the initial symptoms but experienced relapse a week later.

Mr. Goyang says that, for the next 8 or 9 months, he was on a roller coaster with extreme shortness of breath and chest tightness that could be so severe it would send him to the emergency department. He had to use an inhaler to get through his workdays.

“Even if I was just sitting around, it would come and take me,” he says. “It almost felt like someone was bear-hugging me constantly, and I just couldn’t get in a good enough breath.”

On his best days, he would walk around his neighborhood, being careful not to overdo it. He tried running once, and it nearly sent him to the hospital.

“Very honestly, I didn’t know if I would ever be able to do it again,” he says.

But Mr. Goyang says that, several weeks after getting the Pfizer vaccine, he was able to run a mile again with no problems. “I was very thankful for that,” he says.

Mr. Goyang is not alone. Some social media groups are dedicated to patients who are living with a condition that’s been known as long COVID and that was recently termed postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These patients are sometimes referred to as long haulers.

On social media, patients with PASC are eagerly and anxiously quizzing each other about the vaccines and their effects.

Survivor Corps, which has a public Facebook group with 159,000 members, recently took a poll to see whether there was any substance to rumors that those with long COVID were feeling better after being vaccinated.

“Out of 400 people, 36% showed an improvement in symptoms, anywhere between a mild improvement to complete resolution of symptoms,” said Diana Berrent, a long-COVID patient who founded the group. Survivor Corps has become active in patient advocacy and is a resource for researchers studying the new condition.

Ms. Berrent has become such a trusted voice during the pandemic. She interviewed Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, last October.

“The implications are huge,” she says.

“Some of this damage is permanent damage. It’s not going to cure the scarring of your heart tissue, it’s not going to cure the irreparable damage to your lungs, but if it’s making people feel better, then that’s an indication there’s viral persistence going on,” says Ms. Berrent.

“I’ve been saying for months and months, we shouldn’t be calling this postacute anything,” she adds.

Patients report improvement

Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, is equally excited. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, New York. He says about one in five patients he treated for COVID-19 last year never got better. Many of them, such as Mr. Goyang, were health care workers.

“I don’t know if people actually catch this, but a lot of our coworkers are either permanently disabled or died,” Dr. Griffin says.

Health care workers were also among the first to be vaccinated. Dr. Griffin says many of his patients began reaching out to him about a week or two after being vaccinated “and saying, ‘You know, I actually feel better.’ And some of them were saying, ‘I feel all better,’ after being sick – a lot of them – for a year.”

Then he was getting calls and texts from other doctors, asking, “Hey, are you seeing this?”

The benefits of vaccination for some long-haulers came as a surprise. Dr. Griffin says that, before the vaccines came out, many of his patients were worried that getting vaccinated might overstimulate their immune systems and cause symptoms to get worse.

Indeed, a small percentage of people – about 3%-5%, based on informal polls on social media – report that they do experience worsening of symptoms after getting the shot. It’s not clear why.

Dr. Griffin estimates that between 30% and 50% of patients’ symptoms improve after they receive the mRNA vaccines. “I’m seeing this chunk of people – they tell me their brain fog has improved, their fatigue is gone, the fevers that wouldn’t resolve have now gone,” he says. “I’m seeing that personally, and I’m hearing it from my colleagues.”

Dr. Griffin says the observation has launched several studies and that there are several theories about how the vaccines might be affecting long COVID.

An immune system boost?

One possibility is that the virus continues to stimulate the immune system, which continues to fight the virus for months. If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be giving the immune system the boost it needs to finally clear the virus away.

Donna Farber, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, has heard the stories, too.

“It is possible that the persisting virus in long COVID-19 may be at a low level – not enough to stimulate a potent immune response to clear the virus, but enough to cause symptoms. Activating the immune response therefore is therapeutic in directing viral clearance,” she says.

Dr. Farber explains that long COVID may be a bit like Lyme disease. Some patients with Lyme disease must take antibiotics for months before their symptoms disappear.

Dr. Griffin says there’s another possibility. Several studies have now shown that people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms develop autoantibodies. There’s a theory that SARS-CoV-2 may create an autoimmune condition that leads to long-term symptoms.

If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be helping the body to reset its tolerance to itself, “so maybe now you’re getting a healthy immune response.”

More studies are needed to know for sure.