User login

COAPT 5-year results ‘remarkable,’ but patient selection issues remain

It remained an open question in 2018, on the unveiling of the COAPT trial’s 2-year primary results, whether the striking reductions in mortality and heart-failure (HF) hospitalization observed for transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER) with the MitraClip (Abbott) would be durable with longer follow-up.

The trial had enrolled an especially sick population of symptomatic patients with mitral regurgitation (MR) secondary to HF.

As it turns out, the therapy’s benefits at 2 years were indeed durable, at least out to 5 years, investigators reported March 5 at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The results were simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

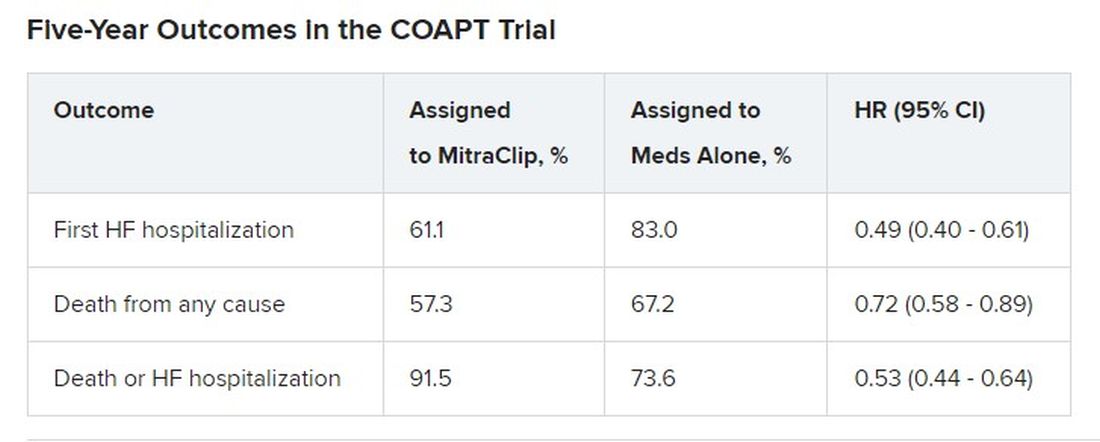

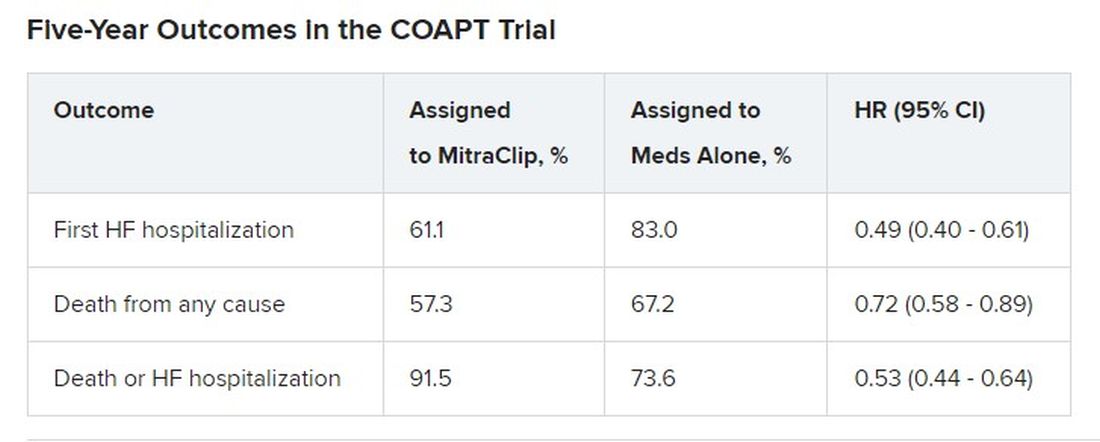

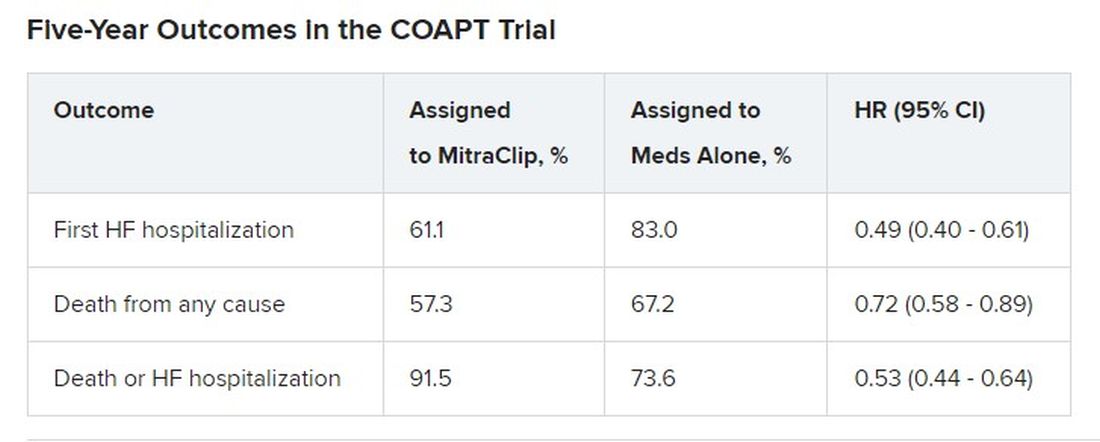

Patients who received the MitraClip on top of intensive medical therapy, compared with a group assigned to medical management alone, benefited significantly at 5 years with risk reductions of 51% for HF hospitalization, 28% for death from any cause, and 47% for the composite of the two events.

Still, mortality at 5 years among the 614 randomized patients was steep at 57.3% in the MitraClip group and 67.2% for those assigned to meds only, underscoring the need for early identification of patients appropriate for the device therapy, Gregg W. Stone, MD, said during his presentation.

Dr. Stone, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, is a COAPT co-principal investigator and lead author of the 5-year outcomes publication.

Outcomes were consistent across all prespecified patient subgroups, including by age, sex, MR, left ventricular (LV) function and volume, cardiomyopathy etiology, and degree of surgical risk, the researchers reported.

Symptom status, as measured by New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, improved throughout the 5-year follow-up for patients assigned to the MitraClip group, compared with the control group, and the intervention group was significantly more likely to be in NYHA class 1 or 2, the authors noted.

The relative benefits in terms of clinical outcomes of MitraClip therapy narrowed after 2-3 years, Dr. Stone said, primarily because at 2 years, patients who had been assigned to meds only were eligible to undergo TEER. Indeed, he noted, 45% of the 138 patients in the control group who were eligible for TEER at 2 years “crossed over” to receive a MitraClip. Those patients benefited despite their delay in undergoing the procedure, he observed.

However, nearly half of the control patients died before becoming eligible for crossover at 2 years. “We have to identify the appropriate patients for treatment and treat them early because the mortality is very high in this population,” Dr. Stone said.

“We need to do more because the MitraClip doesn’t do anything directly to the underlying left ventricular dysfunction, which is the cause of the patient’s disease,” he said. “We need advanced therapies to address the underlying left ventricular dysfunction” in this high-risk population.

Exclusions based on LV dimension

The COAPT trial included 614 patients with HF and symptomatic MR despite guideline-directed medical therapy. They were required to have moderate to severe (3+) or severe (4+) MR confirmed by an echocardiographic core laboratory and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 20%-50%.

Among the exclusion criteria were an LV end-systolic diameter greater than 70 mm, severe pulmonary hypertension, and moderate to severe symptomatic right ventricular failure.

The systolic LV dimension exclusion helped address the persistent question of whether “severe mitral regurgitation is a marker of a bad left ventricle or ... contributes to the pathophysiology” of MR and its poor outcomes, Dr. Stone said.

The 51% reduction in risk for time-to-first HF hospitalization among patients assigned to TEER “accrued very early,” Dr. Stone pointed out. “You can see the curves start to separate almost immediately after you reduce left atrial pressure and volume overload with the MitraClip.”

The curves stopped diverging after about 3 years because of crossover from the control group, he said. Still, “we had shown a substantial absolute 17% reduction in mortality at 2 years” with MitraClip. “That has continued out to 5 years, with a statistically significant 28% relative reduction,” he continued, and the absolute risk reduction reaching 10%.

Patients in the control group who crossed over “basically assumed the death and heart failure hospitalization rate of the MitraClip group,” Dr. Stone said. That wasn’t surprising “because most of the patients enrolled in the trial originally had chronic heart failure.” It’s “confirmation of the principal results of the trial.”

Comparison With MITRA-FR

“We know that MITRA-FR was a negative trial,” observed Wayne B. Batchelor, MD, an invited discussant following Dr. Stone’s presentation, referring to an earlier similar trial that showed no advantage for MitraClip. Compared with MITRA-FR, COAPT “has created an entirely different story.”

The marked reductions in mortality and risk for adverse events and low number-needed-to-treat with MitraClip are “really remarkable,” said Dr. Batchelor, who is with the Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, Va.

But the high absolute mortality for patients in the COAPT control group “speaks volumes to me and tells us that we’ve got to identify our patients well early,” he agreed, and to “implement transcatheter edge-to-edge therapy in properly selected patients on guideline-directed medical therapy in order to avoid that.”

The trial findings “suggest that we’re reducing HF hospitalization,” he said, “so this is an extremely potent therapy, potentially.

“The dramatic difference between the treated arm and the medical therapy arm in this trial makes me feel that this therapy is here to stay,” Dr. Batchelor concluded. “We just have to figure out how to deploy it properly in the right patients.”

The COAPT trial presents “a practice-changing paradigm,” said Suzanne J. Baron, MD, of Lahey Hospital & Medical Center, Burlington, Mass., another invited discussant.

The crossover data “really jumped out,” she added. “Waiting to treat patients with TEER may be harmful, so if we’re going to consider treating earlier, how do we identify the right patient?” Dr. Baron asked, especially given the negative MITRA-FR results.

MITRA-FR didn’t follow patients beyond 2 years, Dr. Stone noted. Still, “we do think that the main difference was that COAPT enrolled a patient population with more severe MR and slightly less LV dysfunction, at least in terms of the LV not being as dilated, so they didn’t have end-stage LV disease. Whereas in MITRA-FR, more of the patients had only moderate mitral regurgitation.” And big dilated left ventricles “are less likely to benefit.”

There were also differences between the studies in technique and background medical therapies, he added.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved – and payers are paying – for the treatment of patients who meet the COAPT criteria, “in whom we can be very confident they have a benefit,” Dr. Stone said.

“The real question is: Where are the edges where we should consider this? LVEF slightly less than 20% or slightly greater than 50%? Or primary atrial functional mitral regurgitation? There are registry data to suggest that they would benefit,” he said, but “we need more data.”

COAPT was supported by Abbott. Dr. Stone disclosed receiving speaker honoraria from Abbott and consulting fees or equity from Neovasc, Ancora, Valfix, and Cardiac Success; and that Mount Sinai receives research funding from Abbott. Disclosures for the other authors are available at nejm.org. Dr. Batchelor has disclosed receiving consultant fees or honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Idorsia, and V-Wave Medical, and having other ties with Medtronic. Dr. Baron has disclosed receiving consultant fees or honoraria from Abiomed, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Shockwave, and Zoll Medical, and conducting research or receiving research grants from Abiomed and Boston Scientific.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

It remained an open question in 2018, on the unveiling of the COAPT trial’s 2-year primary results, whether the striking reductions in mortality and heart-failure (HF) hospitalization observed for transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER) with the MitraClip (Abbott) would be durable with longer follow-up.

The trial had enrolled an especially sick population of symptomatic patients with mitral regurgitation (MR) secondary to HF.

As it turns out, the therapy’s benefits at 2 years were indeed durable, at least out to 5 years, investigators reported March 5 at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The results were simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Patients who received the MitraClip on top of intensive medical therapy, compared with a group assigned to medical management alone, benefited significantly at 5 years with risk reductions of 51% for HF hospitalization, 28% for death from any cause, and 47% for the composite of the two events.

Still, mortality at 5 years among the 614 randomized patients was steep at 57.3% in the MitraClip group and 67.2% for those assigned to meds only, underscoring the need for early identification of patients appropriate for the device therapy, Gregg W. Stone, MD, said during his presentation.

Dr. Stone, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, is a COAPT co-principal investigator and lead author of the 5-year outcomes publication.

Outcomes were consistent across all prespecified patient subgroups, including by age, sex, MR, left ventricular (LV) function and volume, cardiomyopathy etiology, and degree of surgical risk, the researchers reported.

Symptom status, as measured by New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, improved throughout the 5-year follow-up for patients assigned to the MitraClip group, compared with the control group, and the intervention group was significantly more likely to be in NYHA class 1 or 2, the authors noted.

The relative benefits in terms of clinical outcomes of MitraClip therapy narrowed after 2-3 years, Dr. Stone said, primarily because at 2 years, patients who had been assigned to meds only were eligible to undergo TEER. Indeed, he noted, 45% of the 138 patients in the control group who were eligible for TEER at 2 years “crossed over” to receive a MitraClip. Those patients benefited despite their delay in undergoing the procedure, he observed.

However, nearly half of the control patients died before becoming eligible for crossover at 2 years. “We have to identify the appropriate patients for treatment and treat them early because the mortality is very high in this population,” Dr. Stone said.

“We need to do more because the MitraClip doesn’t do anything directly to the underlying left ventricular dysfunction, which is the cause of the patient’s disease,” he said. “We need advanced therapies to address the underlying left ventricular dysfunction” in this high-risk population.

Exclusions based on LV dimension

The COAPT trial included 614 patients with HF and symptomatic MR despite guideline-directed medical therapy. They were required to have moderate to severe (3+) or severe (4+) MR confirmed by an echocardiographic core laboratory and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 20%-50%.

Among the exclusion criteria were an LV end-systolic diameter greater than 70 mm, severe pulmonary hypertension, and moderate to severe symptomatic right ventricular failure.

The systolic LV dimension exclusion helped address the persistent question of whether “severe mitral regurgitation is a marker of a bad left ventricle or ... contributes to the pathophysiology” of MR and its poor outcomes, Dr. Stone said.

The 51% reduction in risk for time-to-first HF hospitalization among patients assigned to TEER “accrued very early,” Dr. Stone pointed out. “You can see the curves start to separate almost immediately after you reduce left atrial pressure and volume overload with the MitraClip.”

The curves stopped diverging after about 3 years because of crossover from the control group, he said. Still, “we had shown a substantial absolute 17% reduction in mortality at 2 years” with MitraClip. “That has continued out to 5 years, with a statistically significant 28% relative reduction,” he continued, and the absolute risk reduction reaching 10%.

Patients in the control group who crossed over “basically assumed the death and heart failure hospitalization rate of the MitraClip group,” Dr. Stone said. That wasn’t surprising “because most of the patients enrolled in the trial originally had chronic heart failure.” It’s “confirmation of the principal results of the trial.”

Comparison With MITRA-FR

“We know that MITRA-FR was a negative trial,” observed Wayne B. Batchelor, MD, an invited discussant following Dr. Stone’s presentation, referring to an earlier similar trial that showed no advantage for MitraClip. Compared with MITRA-FR, COAPT “has created an entirely different story.”

The marked reductions in mortality and risk for adverse events and low number-needed-to-treat with MitraClip are “really remarkable,” said Dr. Batchelor, who is with the Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, Va.

But the high absolute mortality for patients in the COAPT control group “speaks volumes to me and tells us that we’ve got to identify our patients well early,” he agreed, and to “implement transcatheter edge-to-edge therapy in properly selected patients on guideline-directed medical therapy in order to avoid that.”

The trial findings “suggest that we’re reducing HF hospitalization,” he said, “so this is an extremely potent therapy, potentially.

“The dramatic difference between the treated arm and the medical therapy arm in this trial makes me feel that this therapy is here to stay,” Dr. Batchelor concluded. “We just have to figure out how to deploy it properly in the right patients.”

The COAPT trial presents “a practice-changing paradigm,” said Suzanne J. Baron, MD, of Lahey Hospital & Medical Center, Burlington, Mass., another invited discussant.

The crossover data “really jumped out,” she added. “Waiting to treat patients with TEER may be harmful, so if we’re going to consider treating earlier, how do we identify the right patient?” Dr. Baron asked, especially given the negative MITRA-FR results.

MITRA-FR didn’t follow patients beyond 2 years, Dr. Stone noted. Still, “we do think that the main difference was that COAPT enrolled a patient population with more severe MR and slightly less LV dysfunction, at least in terms of the LV not being as dilated, so they didn’t have end-stage LV disease. Whereas in MITRA-FR, more of the patients had only moderate mitral regurgitation.” And big dilated left ventricles “are less likely to benefit.”

There were also differences between the studies in technique and background medical therapies, he added.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved – and payers are paying – for the treatment of patients who meet the COAPT criteria, “in whom we can be very confident they have a benefit,” Dr. Stone said.

“The real question is: Where are the edges where we should consider this? LVEF slightly less than 20% or slightly greater than 50%? Or primary atrial functional mitral regurgitation? There are registry data to suggest that they would benefit,” he said, but “we need more data.”

COAPT was supported by Abbott. Dr. Stone disclosed receiving speaker honoraria from Abbott and consulting fees or equity from Neovasc, Ancora, Valfix, and Cardiac Success; and that Mount Sinai receives research funding from Abbott. Disclosures for the other authors are available at nejm.org. Dr. Batchelor has disclosed receiving consultant fees or honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Idorsia, and V-Wave Medical, and having other ties with Medtronic. Dr. Baron has disclosed receiving consultant fees or honoraria from Abiomed, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Shockwave, and Zoll Medical, and conducting research or receiving research grants from Abiomed and Boston Scientific.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

It remained an open question in 2018, on the unveiling of the COAPT trial’s 2-year primary results, whether the striking reductions in mortality and heart-failure (HF) hospitalization observed for transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER) with the MitraClip (Abbott) would be durable with longer follow-up.

The trial had enrolled an especially sick population of symptomatic patients with mitral regurgitation (MR) secondary to HF.

As it turns out, the therapy’s benefits at 2 years were indeed durable, at least out to 5 years, investigators reported March 5 at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The results were simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Patients who received the MitraClip on top of intensive medical therapy, compared with a group assigned to medical management alone, benefited significantly at 5 years with risk reductions of 51% for HF hospitalization, 28% for death from any cause, and 47% for the composite of the two events.

Still, mortality at 5 years among the 614 randomized patients was steep at 57.3% in the MitraClip group and 67.2% for those assigned to meds only, underscoring the need for early identification of patients appropriate for the device therapy, Gregg W. Stone, MD, said during his presentation.

Dr. Stone, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, is a COAPT co-principal investigator and lead author of the 5-year outcomes publication.

Outcomes were consistent across all prespecified patient subgroups, including by age, sex, MR, left ventricular (LV) function and volume, cardiomyopathy etiology, and degree of surgical risk, the researchers reported.

Symptom status, as measured by New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, improved throughout the 5-year follow-up for patients assigned to the MitraClip group, compared with the control group, and the intervention group was significantly more likely to be in NYHA class 1 or 2, the authors noted.

The relative benefits in terms of clinical outcomes of MitraClip therapy narrowed after 2-3 years, Dr. Stone said, primarily because at 2 years, patients who had been assigned to meds only were eligible to undergo TEER. Indeed, he noted, 45% of the 138 patients in the control group who were eligible for TEER at 2 years “crossed over” to receive a MitraClip. Those patients benefited despite their delay in undergoing the procedure, he observed.

However, nearly half of the control patients died before becoming eligible for crossover at 2 years. “We have to identify the appropriate patients for treatment and treat them early because the mortality is very high in this population,” Dr. Stone said.

“We need to do more because the MitraClip doesn’t do anything directly to the underlying left ventricular dysfunction, which is the cause of the patient’s disease,” he said. “We need advanced therapies to address the underlying left ventricular dysfunction” in this high-risk population.

Exclusions based on LV dimension

The COAPT trial included 614 patients with HF and symptomatic MR despite guideline-directed medical therapy. They were required to have moderate to severe (3+) or severe (4+) MR confirmed by an echocardiographic core laboratory and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 20%-50%.

Among the exclusion criteria were an LV end-systolic diameter greater than 70 mm, severe pulmonary hypertension, and moderate to severe symptomatic right ventricular failure.

The systolic LV dimension exclusion helped address the persistent question of whether “severe mitral regurgitation is a marker of a bad left ventricle or ... contributes to the pathophysiology” of MR and its poor outcomes, Dr. Stone said.

The 51% reduction in risk for time-to-first HF hospitalization among patients assigned to TEER “accrued very early,” Dr. Stone pointed out. “You can see the curves start to separate almost immediately after you reduce left atrial pressure and volume overload with the MitraClip.”

The curves stopped diverging after about 3 years because of crossover from the control group, he said. Still, “we had shown a substantial absolute 17% reduction in mortality at 2 years” with MitraClip. “That has continued out to 5 years, with a statistically significant 28% relative reduction,” he continued, and the absolute risk reduction reaching 10%.

Patients in the control group who crossed over “basically assumed the death and heart failure hospitalization rate of the MitraClip group,” Dr. Stone said. That wasn’t surprising “because most of the patients enrolled in the trial originally had chronic heart failure.” It’s “confirmation of the principal results of the trial.”

Comparison With MITRA-FR

“We know that MITRA-FR was a negative trial,” observed Wayne B. Batchelor, MD, an invited discussant following Dr. Stone’s presentation, referring to an earlier similar trial that showed no advantage for MitraClip. Compared with MITRA-FR, COAPT “has created an entirely different story.”

The marked reductions in mortality and risk for adverse events and low number-needed-to-treat with MitraClip are “really remarkable,” said Dr. Batchelor, who is with the Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, Va.

But the high absolute mortality for patients in the COAPT control group “speaks volumes to me and tells us that we’ve got to identify our patients well early,” he agreed, and to “implement transcatheter edge-to-edge therapy in properly selected patients on guideline-directed medical therapy in order to avoid that.”

The trial findings “suggest that we’re reducing HF hospitalization,” he said, “so this is an extremely potent therapy, potentially.

“The dramatic difference between the treated arm and the medical therapy arm in this trial makes me feel that this therapy is here to stay,” Dr. Batchelor concluded. “We just have to figure out how to deploy it properly in the right patients.”

The COAPT trial presents “a practice-changing paradigm,” said Suzanne J. Baron, MD, of Lahey Hospital & Medical Center, Burlington, Mass., another invited discussant.

The crossover data “really jumped out,” she added. “Waiting to treat patients with TEER may be harmful, so if we’re going to consider treating earlier, how do we identify the right patient?” Dr. Baron asked, especially given the negative MITRA-FR results.

MITRA-FR didn’t follow patients beyond 2 years, Dr. Stone noted. Still, “we do think that the main difference was that COAPT enrolled a patient population with more severe MR and slightly less LV dysfunction, at least in terms of the LV not being as dilated, so they didn’t have end-stage LV disease. Whereas in MITRA-FR, more of the patients had only moderate mitral regurgitation.” And big dilated left ventricles “are less likely to benefit.”

There were also differences between the studies in technique and background medical therapies, he added.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved – and payers are paying – for the treatment of patients who meet the COAPT criteria, “in whom we can be very confident they have a benefit,” Dr. Stone said.

“The real question is: Where are the edges where we should consider this? LVEF slightly less than 20% or slightly greater than 50%? Or primary atrial functional mitral regurgitation? There are registry data to suggest that they would benefit,” he said, but “we need more data.”

COAPT was supported by Abbott. Dr. Stone disclosed receiving speaker honoraria from Abbott and consulting fees or equity from Neovasc, Ancora, Valfix, and Cardiac Success; and that Mount Sinai receives research funding from Abbott. Disclosures for the other authors are available at nejm.org. Dr. Batchelor has disclosed receiving consultant fees or honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Idorsia, and V-Wave Medical, and having other ties with Medtronic. Dr. Baron has disclosed receiving consultant fees or honoraria from Abiomed, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Shockwave, and Zoll Medical, and conducting research or receiving research grants from Abiomed and Boston Scientific.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACC 2023

Like mother, like daughter? Moms pass obesity risk to girls

Girls between 4 and 9 years old were more likely to have high fat mass and a high body mass index if their mothers had excess adiposity – but this relationship was not seen between mothers and sons, or between fathers and sons or daughters, in a new study.

The researchers measured fat mass, lean mass, and BMI in the sons and daughters when they were age 4 (before a phenomenon known as “adiposity rebound”), ages 6-7 (around the adiposity rebound), and ages 8-9 (before or at the onset of puberty).

They also obtained measurements from the mothers and fathers when the offspring were ages 8-9.

The group found “a strong association between the fat mass of mothers and their daughters but not their sons,” Rebecca J. Moon, BM, PhD, and colleagues report.

“It would be important to establish persistence through puberty,” according to the researchers, “but nonetheless, these findings are clinically important, highlighting girls who are born to mothers with high BMI and excess adiposity are at high risk of themselves of becoming overweight/obese or having unfavorable body composition early in childhood.”

The mother-daughter relationship for fat mass appears to be established by age 4 years, note Dr. Moon, of the MRC Lifecourse Epidemiology Centre, University of Southampton (England), and colleagues.

Therefore, “early awareness and intervention is needed in mothers with excess adiposity, and potentially beginning even in the periconception and in utero period.”

Because 97% of the mothers and fathers were White, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations, they caution.

The results, from the Southampton Women’s Survey prospective cohort study, were published online in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

One of the first studies to look at fat mass, not just BMI

Children with overweight or obesity are more likely to have excess weight in adulthood that puts them at risk of developing type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and osteoarthritis. Previous research has reported that children with overweight or obesity were more likely to have mothers with adiposity.

However, most prior studies have looked at BMI alone and did not measure fat mass, and it was not known how a father’s obesity might affect offspring or how risk may differ in boy versus girl children.

Researchers analyzed data from a subset of participants in the Southampton Women’s Survey of 3,158 women who were aged 20-34 in 1998-2002 and delivered a liveborn infant.

The current study included 240 mother-father-offspring trios who had data for BMI and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans (whole body less head).

Mothers were a mean age of 31 years at delivery and had a median pre-pregnancy BMI of 23.7 kg/m2.

The offspring were 129 boys (54%) and 111 girls.

The offspring had DXA scans at ages 4, 6-7, and 8-9 years, and the mothers and fathers had a DXA scan at the last time point.

At ages 6-7 and ages 8-9, BMI and fat mass of the girls reflected that of their mothers (a significant association).

At age 4, BMI and fat mass of the daughters tended to be associated with that of their mothers, but the 95% confidence interval crossed zero.

There were no significant mother-son, father-son, or father-daughter associations for BMI or fat mass at each of the three studied ages.

The study received funding from the Medical Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, the National Institute for Health and Care Research Southampton Biomedical Research Centre, the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, the Seventh Framework Program, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Horizon 2020 Framework Program, and the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Moon has reported receiving travel bursaries from Kyowa Kirin unrelated to the current study. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the article.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Girls between 4 and 9 years old were more likely to have high fat mass and a high body mass index if their mothers had excess adiposity – but this relationship was not seen between mothers and sons, or between fathers and sons or daughters, in a new study.

The researchers measured fat mass, lean mass, and BMI in the sons and daughters when they were age 4 (before a phenomenon known as “adiposity rebound”), ages 6-7 (around the adiposity rebound), and ages 8-9 (before or at the onset of puberty).

They also obtained measurements from the mothers and fathers when the offspring were ages 8-9.

The group found “a strong association between the fat mass of mothers and their daughters but not their sons,” Rebecca J. Moon, BM, PhD, and colleagues report.

“It would be important to establish persistence through puberty,” according to the researchers, “but nonetheless, these findings are clinically important, highlighting girls who are born to mothers with high BMI and excess adiposity are at high risk of themselves of becoming overweight/obese or having unfavorable body composition early in childhood.”

The mother-daughter relationship for fat mass appears to be established by age 4 years, note Dr. Moon, of the MRC Lifecourse Epidemiology Centre, University of Southampton (England), and colleagues.

Therefore, “early awareness and intervention is needed in mothers with excess adiposity, and potentially beginning even in the periconception and in utero period.”

Because 97% of the mothers and fathers were White, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations, they caution.

The results, from the Southampton Women’s Survey prospective cohort study, were published online in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

One of the first studies to look at fat mass, not just BMI

Children with overweight or obesity are more likely to have excess weight in adulthood that puts them at risk of developing type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and osteoarthritis. Previous research has reported that children with overweight or obesity were more likely to have mothers with adiposity.

However, most prior studies have looked at BMI alone and did not measure fat mass, and it was not known how a father’s obesity might affect offspring or how risk may differ in boy versus girl children.

Researchers analyzed data from a subset of participants in the Southampton Women’s Survey of 3,158 women who were aged 20-34 in 1998-2002 and delivered a liveborn infant.

The current study included 240 mother-father-offspring trios who had data for BMI and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans (whole body less head).

Mothers were a mean age of 31 years at delivery and had a median pre-pregnancy BMI of 23.7 kg/m2.

The offspring were 129 boys (54%) and 111 girls.

The offspring had DXA scans at ages 4, 6-7, and 8-9 years, and the mothers and fathers had a DXA scan at the last time point.

At ages 6-7 and ages 8-9, BMI and fat mass of the girls reflected that of their mothers (a significant association).

At age 4, BMI and fat mass of the daughters tended to be associated with that of their mothers, but the 95% confidence interval crossed zero.

There were no significant mother-son, father-son, or father-daughter associations for BMI or fat mass at each of the three studied ages.

The study received funding from the Medical Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, the National Institute for Health and Care Research Southampton Biomedical Research Centre, the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, the Seventh Framework Program, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Horizon 2020 Framework Program, and the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Moon has reported receiving travel bursaries from Kyowa Kirin unrelated to the current study. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the article.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Girls between 4 and 9 years old were more likely to have high fat mass and a high body mass index if their mothers had excess adiposity – but this relationship was not seen between mothers and sons, or between fathers and sons or daughters, in a new study.

The researchers measured fat mass, lean mass, and BMI in the sons and daughters when they were age 4 (before a phenomenon known as “adiposity rebound”), ages 6-7 (around the adiposity rebound), and ages 8-9 (before or at the onset of puberty).

They also obtained measurements from the mothers and fathers when the offspring were ages 8-9.

The group found “a strong association between the fat mass of mothers and their daughters but not their sons,” Rebecca J. Moon, BM, PhD, and colleagues report.

“It would be important to establish persistence through puberty,” according to the researchers, “but nonetheless, these findings are clinically important, highlighting girls who are born to mothers with high BMI and excess adiposity are at high risk of themselves of becoming overweight/obese or having unfavorable body composition early in childhood.”

The mother-daughter relationship for fat mass appears to be established by age 4 years, note Dr. Moon, of the MRC Lifecourse Epidemiology Centre, University of Southampton (England), and colleagues.

Therefore, “early awareness and intervention is needed in mothers with excess adiposity, and potentially beginning even in the periconception and in utero period.”

Because 97% of the mothers and fathers were White, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations, they caution.

The results, from the Southampton Women’s Survey prospective cohort study, were published online in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

One of the first studies to look at fat mass, not just BMI

Children with overweight or obesity are more likely to have excess weight in adulthood that puts them at risk of developing type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and osteoarthritis. Previous research has reported that children with overweight or obesity were more likely to have mothers with adiposity.

However, most prior studies have looked at BMI alone and did not measure fat mass, and it was not known how a father’s obesity might affect offspring or how risk may differ in boy versus girl children.

Researchers analyzed data from a subset of participants in the Southampton Women’s Survey of 3,158 women who were aged 20-34 in 1998-2002 and delivered a liveborn infant.

The current study included 240 mother-father-offspring trios who had data for BMI and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans (whole body less head).

Mothers were a mean age of 31 years at delivery and had a median pre-pregnancy BMI of 23.7 kg/m2.

The offspring were 129 boys (54%) and 111 girls.

The offspring had DXA scans at ages 4, 6-7, and 8-9 years, and the mothers and fathers had a DXA scan at the last time point.

At ages 6-7 and ages 8-9, BMI and fat mass of the girls reflected that of their mothers (a significant association).

At age 4, BMI and fat mass of the daughters tended to be associated with that of their mothers, but the 95% confidence interval crossed zero.

There were no significant mother-son, father-son, or father-daughter associations for BMI or fat mass at each of the three studied ages.

The study received funding from the Medical Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, the National Institute for Health and Care Research Southampton Biomedical Research Centre, the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, the Seventh Framework Program, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Horizon 2020 Framework Program, and the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Moon has reported receiving travel bursaries from Kyowa Kirin unrelated to the current study. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the article.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Do artificial sweeteners alter postmeal glucose, hunger hormones?

Drinking a sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB), however, had a different effect on postprandial levels of glucose and the hormones insulin, glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), peptide YY (PYY), ghrelin, leptin, and glucagon.

These findings are from a new meta-analysis by Roselyn Zhang and colleagues, supported by the nonprofit organization Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences. The study was published recently in Nutrients.

“Nonnutritive sweeteners have no acute metabolic or endocrine effects and they are similar to water in that respect, and they show a different response from caloric sweeteners,” study author Tauseef Khan, MBBS, PhD, summarized in an interview following a press briefing from the IAFNS.

“Our study supports that nonnutritive sweeteners are a healthier alternative to sugar-sweetened beverages or caloric beverages,” said Dr. Khan, an epidemiologist in the department of nutritional sciences, University of Toronto.

Most participants in the 36 trials included in the meta-analysis were healthy, he noted. However, for certain types of NNS beverages, “we had enough studies for type 2 diabetes to also assess that separately, and the results were the same: Nonnutritive sweeteners were no different from water; however, they were different from caloric sweeteners.”

Of note, none of the studies included erythritol – a sugar alcohol (polyol) increasingly used as an artificial sweetener in keto and other types of foods – which was associated with a risk for adverse cardiac events in a paper in Nature Medicine.

Are these NNS drinks largely inert?

“This [meta-analysis] implies that sweeteners are largely inert,” in terms of acute postprandial glucose and hormone response, but the review did not include newer reports that differ, Duane Mellor, PhD, RD, RNutr, who was not involved with the research, noted in an email.

“This is possibly,” he said, because the study “only reviewed the literature up until January 2022 and therefore it missed the World Health Organization review ‘Health Effects of the Use of Non-Sugar Sweeteners’ published in April [2022], and a study published in August 2022 in the journal Cell suggesting that some nonnutritive sweeteners may have a minor effect on gut microbiome and glucose response.

“Although there is a place of nonnutritive sweeteners as a way to reduce sugar intake, they are a small part of dietary pattern and lifestyle which can help reduce risk of disease,” said Dr. Mellor, a registered dietitian and senior teaching fellow at Aston University, Birmingham, England.

“So, although we are clear we need to reduce our intake of sugar-sweetened beverages, switching to non-nutritive sweetened beverages (such as diet sodas) is not necessarily the healthiest option, as unlike water, it seems that some nonnutritive sweeteners may influence glucose responses and levels of related hormones in more recent studies.”

NNS beverages ‘are similar to water’

Dr. Khan pointed out that the meta-analysis addressed two major concerns about NNS beverages.

First, the “sweet uncoupling hypothesis” proposes that low-calorie sweeteners affect sweet taste by separating sweet taste from calories. “The body is confused, and then there is hormonal change. Our study shows that actually that’s not true, and [NNS beverages] are similar to water.”

Second, when no-calorie or low-calorie sweeteners are taken with calories (coupling), a concern is that “then you eat more somehow, or your response is different. However, the results [in this meta-analysis] also show that that is not the case for glucose response, insulin response, and other hormonal markers.”

“The strength is not that low-calorie sweeteners have some benefit per se,” he elaborated. “The advantage is that they replace caloric beverages.

“We are not saying that anybody who is not taking low-calorie sweeteners should start taking [them],” he continued. “What we are saying is somebody who is taking sugar-sweetened beverages and has a problem of taking excess calories, if you replace those calories with low-calorie sweetener, replacement of calories itself may be beneficial, and also they should not be concerned of any [acute] issues with a moderate amount of low-calorie sweeteners.”

Postprandial effect of NNS beverages, SSBs, water

Eight NNS are currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration: aspartame, acesulfame potassium (ace-K), luo han guo (monkfruit) extract, neotame, saccharin, stevia, sucralose, and advantame, the researchers noted.

Ms. Zhang and colleagues searched the literature up until Jan. 15, 2022, for studies of NNS beverages and acute postprandial glycemic and endocrine responses.

Trials were excluded if they involved sugar alcohols (eg, erythritol) or rare sugars (eg, allulose), or if they were shorter than 2 hours, lacked a comparator arm, or did not provide suitable endpoint data.

They identified 36 randomized and nonrandomized clinical trials of 472 predominantly healthy participants: 21 trials (15 reports, n = 266) with NNS consumed alone (uncoupled), 3 trials (3 reports, n = 27) with NNS consumed in a solution containing a carbohydrate (coupled), and 12 trials (7 reports, n = 179) with NNS consumed up to 15 minutes before oral glucose carbohydrate load (delayed coupling).

The four types of beverages were single NNS (ace-K, aspartame, cyclamate, saccharin, stevia, and sucralose), NNS blends (ace-K + aspartame; ace-K + sucralose; ace-K + aspartame + cyclamate; and ace-K + aspartame + sucralose), SSBs (glucose, sucrose, and fructose), and water (control).

In the uncoupled interventions, NNS beverages (single or blends) had no effect on postprandial glucose, insulin, GLP-1, GIP, PYY, ghrelin, and glucagon, with responses similar to water.

In the uncoupled interventions, SSBs sweetened with caloric sugars (glucose and sucrose) increased postprandial glucose, insulin, GLP-1, and GIP responses, with no differences in postprandial ghrelin and glucagon responses.

In the coupled and delayed coupling interventions, NNS beverages had no postprandial glucose and endocrine effects, with responses similar to water.

The studies generally had low to moderate confidence.

The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from IAFNS. Dr. Khan has received research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the International Life Sciences Institute, and the National Honey Board. He has received honorariums for lectures from the International Food Information Council and the IAFNS. Dr. Mellor has no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Drinking a sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB), however, had a different effect on postprandial levels of glucose and the hormones insulin, glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), peptide YY (PYY), ghrelin, leptin, and glucagon.

These findings are from a new meta-analysis by Roselyn Zhang and colleagues, supported by the nonprofit organization Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences. The study was published recently in Nutrients.

“Nonnutritive sweeteners have no acute metabolic or endocrine effects and they are similar to water in that respect, and they show a different response from caloric sweeteners,” study author Tauseef Khan, MBBS, PhD, summarized in an interview following a press briefing from the IAFNS.

“Our study supports that nonnutritive sweeteners are a healthier alternative to sugar-sweetened beverages or caloric beverages,” said Dr. Khan, an epidemiologist in the department of nutritional sciences, University of Toronto.

Most participants in the 36 trials included in the meta-analysis were healthy, he noted. However, for certain types of NNS beverages, “we had enough studies for type 2 diabetes to also assess that separately, and the results were the same: Nonnutritive sweeteners were no different from water; however, they were different from caloric sweeteners.”

Of note, none of the studies included erythritol – a sugar alcohol (polyol) increasingly used as an artificial sweetener in keto and other types of foods – which was associated with a risk for adverse cardiac events in a paper in Nature Medicine.

Are these NNS drinks largely inert?

“This [meta-analysis] implies that sweeteners are largely inert,” in terms of acute postprandial glucose and hormone response, but the review did not include newer reports that differ, Duane Mellor, PhD, RD, RNutr, who was not involved with the research, noted in an email.

“This is possibly,” he said, because the study “only reviewed the literature up until January 2022 and therefore it missed the World Health Organization review ‘Health Effects of the Use of Non-Sugar Sweeteners’ published in April [2022], and a study published in August 2022 in the journal Cell suggesting that some nonnutritive sweeteners may have a minor effect on gut microbiome and glucose response.

“Although there is a place of nonnutritive sweeteners as a way to reduce sugar intake, they are a small part of dietary pattern and lifestyle which can help reduce risk of disease,” said Dr. Mellor, a registered dietitian and senior teaching fellow at Aston University, Birmingham, England.

“So, although we are clear we need to reduce our intake of sugar-sweetened beverages, switching to non-nutritive sweetened beverages (such as diet sodas) is not necessarily the healthiest option, as unlike water, it seems that some nonnutritive sweeteners may influence glucose responses and levels of related hormones in more recent studies.”

NNS beverages ‘are similar to water’

Dr. Khan pointed out that the meta-analysis addressed two major concerns about NNS beverages.

First, the “sweet uncoupling hypothesis” proposes that low-calorie sweeteners affect sweet taste by separating sweet taste from calories. “The body is confused, and then there is hormonal change. Our study shows that actually that’s not true, and [NNS beverages] are similar to water.”

Second, when no-calorie or low-calorie sweeteners are taken with calories (coupling), a concern is that “then you eat more somehow, or your response is different. However, the results [in this meta-analysis] also show that that is not the case for glucose response, insulin response, and other hormonal markers.”

“The strength is not that low-calorie sweeteners have some benefit per se,” he elaborated. “The advantage is that they replace caloric beverages.

“We are not saying that anybody who is not taking low-calorie sweeteners should start taking [them],” he continued. “What we are saying is somebody who is taking sugar-sweetened beverages and has a problem of taking excess calories, if you replace those calories with low-calorie sweetener, replacement of calories itself may be beneficial, and also they should not be concerned of any [acute] issues with a moderate amount of low-calorie sweeteners.”

Postprandial effect of NNS beverages, SSBs, water

Eight NNS are currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration: aspartame, acesulfame potassium (ace-K), luo han guo (monkfruit) extract, neotame, saccharin, stevia, sucralose, and advantame, the researchers noted.

Ms. Zhang and colleagues searched the literature up until Jan. 15, 2022, for studies of NNS beverages and acute postprandial glycemic and endocrine responses.

Trials were excluded if they involved sugar alcohols (eg, erythritol) or rare sugars (eg, allulose), or if they were shorter than 2 hours, lacked a comparator arm, or did not provide suitable endpoint data.

They identified 36 randomized and nonrandomized clinical trials of 472 predominantly healthy participants: 21 trials (15 reports, n = 266) with NNS consumed alone (uncoupled), 3 trials (3 reports, n = 27) with NNS consumed in a solution containing a carbohydrate (coupled), and 12 trials (7 reports, n = 179) with NNS consumed up to 15 minutes before oral glucose carbohydrate load (delayed coupling).

The four types of beverages were single NNS (ace-K, aspartame, cyclamate, saccharin, stevia, and sucralose), NNS blends (ace-K + aspartame; ace-K + sucralose; ace-K + aspartame + cyclamate; and ace-K + aspartame + sucralose), SSBs (glucose, sucrose, and fructose), and water (control).

In the uncoupled interventions, NNS beverages (single or blends) had no effect on postprandial glucose, insulin, GLP-1, GIP, PYY, ghrelin, and glucagon, with responses similar to water.

In the uncoupled interventions, SSBs sweetened with caloric sugars (glucose and sucrose) increased postprandial glucose, insulin, GLP-1, and GIP responses, with no differences in postprandial ghrelin and glucagon responses.

In the coupled and delayed coupling interventions, NNS beverages had no postprandial glucose and endocrine effects, with responses similar to water.

The studies generally had low to moderate confidence.

The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from IAFNS. Dr. Khan has received research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the International Life Sciences Institute, and the National Honey Board. He has received honorariums for lectures from the International Food Information Council and the IAFNS. Dr. Mellor has no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Drinking a sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB), however, had a different effect on postprandial levels of glucose and the hormones insulin, glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), peptide YY (PYY), ghrelin, leptin, and glucagon.

These findings are from a new meta-analysis by Roselyn Zhang and colleagues, supported by the nonprofit organization Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences. The study was published recently in Nutrients.

“Nonnutritive sweeteners have no acute metabolic or endocrine effects and they are similar to water in that respect, and they show a different response from caloric sweeteners,” study author Tauseef Khan, MBBS, PhD, summarized in an interview following a press briefing from the IAFNS.

“Our study supports that nonnutritive sweeteners are a healthier alternative to sugar-sweetened beverages or caloric beverages,” said Dr. Khan, an epidemiologist in the department of nutritional sciences, University of Toronto.

Most participants in the 36 trials included in the meta-analysis were healthy, he noted. However, for certain types of NNS beverages, “we had enough studies for type 2 diabetes to also assess that separately, and the results were the same: Nonnutritive sweeteners were no different from water; however, they were different from caloric sweeteners.”

Of note, none of the studies included erythritol – a sugar alcohol (polyol) increasingly used as an artificial sweetener in keto and other types of foods – which was associated with a risk for adverse cardiac events in a paper in Nature Medicine.

Are these NNS drinks largely inert?

“This [meta-analysis] implies that sweeteners are largely inert,” in terms of acute postprandial glucose and hormone response, but the review did not include newer reports that differ, Duane Mellor, PhD, RD, RNutr, who was not involved with the research, noted in an email.

“This is possibly,” he said, because the study “only reviewed the literature up until January 2022 and therefore it missed the World Health Organization review ‘Health Effects of the Use of Non-Sugar Sweeteners’ published in April [2022], and a study published in August 2022 in the journal Cell suggesting that some nonnutritive sweeteners may have a minor effect on gut microbiome and glucose response.

“Although there is a place of nonnutritive sweeteners as a way to reduce sugar intake, they are a small part of dietary pattern and lifestyle which can help reduce risk of disease,” said Dr. Mellor, a registered dietitian and senior teaching fellow at Aston University, Birmingham, England.

“So, although we are clear we need to reduce our intake of sugar-sweetened beverages, switching to non-nutritive sweetened beverages (such as diet sodas) is not necessarily the healthiest option, as unlike water, it seems that some nonnutritive sweeteners may influence glucose responses and levels of related hormones in more recent studies.”

NNS beverages ‘are similar to water’

Dr. Khan pointed out that the meta-analysis addressed two major concerns about NNS beverages.

First, the “sweet uncoupling hypothesis” proposes that low-calorie sweeteners affect sweet taste by separating sweet taste from calories. “The body is confused, and then there is hormonal change. Our study shows that actually that’s not true, and [NNS beverages] are similar to water.”

Second, when no-calorie or low-calorie sweeteners are taken with calories (coupling), a concern is that “then you eat more somehow, or your response is different. However, the results [in this meta-analysis] also show that that is not the case for glucose response, insulin response, and other hormonal markers.”

“The strength is not that low-calorie sweeteners have some benefit per se,” he elaborated. “The advantage is that they replace caloric beverages.

“We are not saying that anybody who is not taking low-calorie sweeteners should start taking [them],” he continued. “What we are saying is somebody who is taking sugar-sweetened beverages and has a problem of taking excess calories, if you replace those calories with low-calorie sweetener, replacement of calories itself may be beneficial, and also they should not be concerned of any [acute] issues with a moderate amount of low-calorie sweeteners.”

Postprandial effect of NNS beverages, SSBs, water

Eight NNS are currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration: aspartame, acesulfame potassium (ace-K), luo han guo (monkfruit) extract, neotame, saccharin, stevia, sucralose, and advantame, the researchers noted.

Ms. Zhang and colleagues searched the literature up until Jan. 15, 2022, for studies of NNS beverages and acute postprandial glycemic and endocrine responses.

Trials were excluded if they involved sugar alcohols (eg, erythritol) or rare sugars (eg, allulose), or if they were shorter than 2 hours, lacked a comparator arm, or did not provide suitable endpoint data.

They identified 36 randomized and nonrandomized clinical trials of 472 predominantly healthy participants: 21 trials (15 reports, n = 266) with NNS consumed alone (uncoupled), 3 trials (3 reports, n = 27) with NNS consumed in a solution containing a carbohydrate (coupled), and 12 trials (7 reports, n = 179) with NNS consumed up to 15 minutes before oral glucose carbohydrate load (delayed coupling).

The four types of beverages were single NNS (ace-K, aspartame, cyclamate, saccharin, stevia, and sucralose), NNS blends (ace-K + aspartame; ace-K + sucralose; ace-K + aspartame + cyclamate; and ace-K + aspartame + sucralose), SSBs (glucose, sucrose, and fructose), and water (control).

In the uncoupled interventions, NNS beverages (single or blends) had no effect on postprandial glucose, insulin, GLP-1, GIP, PYY, ghrelin, and glucagon, with responses similar to water.

In the uncoupled interventions, SSBs sweetened with caloric sugars (glucose and sucrose) increased postprandial glucose, insulin, GLP-1, and GIP responses, with no differences in postprandial ghrelin and glucagon responses.

In the coupled and delayed coupling interventions, NNS beverages had no postprandial glucose and endocrine effects, with responses similar to water.

The studies generally had low to moderate confidence.

The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from IAFNS. Dr. Khan has received research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the International Life Sciences Institute, and the National Honey Board. He has received honorariums for lectures from the International Food Information Council and the IAFNS. Dr. Mellor has no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NUTRIENTS

NUDGE-FLU: Electronic ‘nudges’ boost flu shot uptake in seniors

Two types of electronically delivered letter strategies – a letter highlighting potential cardiovascular benefits of influenza vaccination and a repeat reminder letter – increased flu shot uptake, compared with usual care alone, in a national study of seniors in Denmark.

And in a prespecified subanalysis focusing on older adults with cardiovascular disease, these two strategies were also effective in boosting vaccine uptake in those with or without CVD.

The findings are from the Nationwide Utilization of Danish Government Electronic Letter System for Increasing Influenza Vaccine Uptake (NUDGE-FLU) trial, which compared usual care alone with one of nine different electronic letter “behavioral nudge” strategies during the 2022-2023 flu season in people aged 65 years and older.

Niklas Dyrby Johansen, MD, Hospital–Herlev and Gentofte and Copenhagen University, presented the main study findings in a late-breaking clinical trial session at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation, and the article was simultaneously published in The Lancet

The subanalysis in patients with CVD was published online March 5 in Circulation.

“Despite modest effect sizes, the results may have important implications when translated to a population level,” Dr. Dyrby Johansen concluded during his presentation. Still, the authors write, “the low-touch (no person-to-person interaction), inexpensive, and highly scalable nature of these electronic letters might have important population-level public health implications.”

They note that, among approximately 63 million Medicare beneficiaries in the United States, a 0.89–percentage point absolute increase in vaccination rate achieved through the most successful electronic letter in NUDGE-FLU, the one highlighting cardiovascular gain, would be expected to lead to 500,000 additional vaccinations and potentially prevent 7,849 illnesses, 4,395 medical visits, 714 hospitalizations, and 66 deaths each year.

Electronic letter systems similar to the one used in this trial are already in place in several European countries, including Sweden, Norway, and Ireland, the researchers note.

In countries such as the United States, where implementing a nationwide government electronic letter system might not be feasible, nudges could be done via email, text message, or other systems, but whether this would be as effective remains to be seen.

Commenting on the findings, David Cho, MD, UCLA Health and chair of the ACC Health Care Innovation Council, commended the researchers on engaging patients with more than a million separate nudges sent out during one flu season, and randomly assigning participants to 10 different types of nudges, calling it “impressive.”

“I think the concept that the nudge is to plant an idea that leads to an action is pretty much the basis of a lot of these health care interventions, which seems like a small way to have a big impact at outcome,” Dr. Cho noted. “The behavioral science aspects of the nudges are also fascinating to me personally, and I think to a lot of the cardiologists in the audience – about how you actually get people to act. I think it’s been a lifelong question for people in general, how do you get people to follow through on an action?”

“So I found the fact that secondary gain from a cardiovascular health standpoint, but also the repeated nudges were sort of simple ways that you could have people take ownership and get their flu vaccination,” he said.

“This is ACC, this is a cardiovascular conference, but the influence of vaccine is not just a primary care problem, it is also directly affecting cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Cho concluded.

‘Small but important effect’

In an accompanying editorial (Lancet. 2023 Mar 5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00453-1), Melissa Stockwell, MD, Columbia University, New York, writes, “The study by Johansen and colleagues highlights the small but still important effect of scalable, digital interventions across an entire at-risk population.”

A difference of 0.89% in the entire study population of over 960,000 adults age 65 years or older would be more than 8,500 additional adults protected, she notes. “That increase is important for a scalable intervention that has a low cost per letter.”

Moreover, “that the cardiovascular gain–framed messages worked best in those who had not been vaccinated in the previous season further highlights the potential impact on a more vaccine-hesitant population,” Dr. Stockwell notes.

However, with the mandatory government electronic notification system in Denmark, “notifications are sent via regular email and SMS message, and recipients log in through a portal or smartphone app to view the letter.” Similar studies in the United States that included this extra step of needing to sign in online have not been effective in older populations.

Another limitation is that the intervention may have a different effect in populations for which there is a digital divide between people with or without Internet access of sufficient data on their mobile phones.

First-of-its kind, nationwide pragmatic trial

The NUDGE-FLU protocol was previously published in the American Heart Journal. NUDGE-FLU is a first-of-its kind nationwide, pragmatic, registry-based, cluster-randomized implementation trial of electronically delivered nudges to increase influenza vaccination uptake, the researchers note.

They identified 964,870 individuals who were 65 years or older (or would turn 65 by Jan. 15, 2023) who lived in one of 691,820 households in Denmark.

This excluded individuals who lived in a nursing home or were exempt from the government’s mandatory electronic letter system that is used for official communications.

Households were randomly assigned 9:1:1:1:1:1:1:1:1:1 to receive usual care alone or to one of nine electronic letter strategies based on different behavioral science approaches to encourage influenza vaccination uptake:

- Standard electronic letter

- Standard electronic letter sent at randomization and again 14 days later (repeated letter)

- Depersonalized letter without the recipient’s name

- Gain-framing nudge (“Vaccinations help end pandemics, like COVID-19 and the flu. Protect yourself and your loved ones.”)

- Loss-framing nudge (“When too few people get vaccinated, pandemics from diseases like COVID-19 and the flu can spread and place you and your loved ones at risk.”)

- Collective-goal nudge (“78% of Danes 65 and above were vaccinated against influenza last year. Help us achieve an even higher goal this year.”)

- Active choice or implementation-intention prompt (“We encourage you to record your appointment time here.”)

- Cardiovascular gain–framing nudge (“In addition to its protection against influenza infection, influenza vaccination also seems to protect against cardiovascular disease such as heart attacks and heart failure.”)

- Expert-authority statement (“I recommend everyone over the age of 65 years to get vaccinated against influenza – Tyra Grove Krause, Executive Vice President, Statens Serum Institut.”)

The electronic letters were sent out Sept. 16, 2022, and the primary endpoint was vaccine receipt on or before Jan. 1, 2023.

All individuals received an informative vaccination encouragement letter from the Danish Health Authority (usual care) delivered via the same electronic letter system during Sept. 17 through Sept. 21, 2022.

The individuals had a mean age of 73.8 years, 51.5% were women, and 27.4% had chronic cardiovascular disease.

The analyses were done in one randomly selected individual per household.

Influenza vaccination rates were significantly higher in the cardiovascular gain–framing nudge group vs. usual care (81.00% vs. 80.12%; difference, 0.89 percentage points; P < .0001) and in the repeat-letter group vs. usual care (80.85% vs 80.12%; difference, 0.73 percentage points; P = .0006).

These two strategies also improved vaccination rates across major subgroups.

The cardiovascular gain–framed letter was particularly effective among participants who had not been vaccinated for influenza in the previous season.

The seven other letter strategies did not increase flu shot uptake.

Subanalysis in CVD

In the prespecified subanalysis of the NUDGE-FLU trial of patients aged 65 and older that focused on patients with CVD, Daniel Modin, MB, and colleagues report that 83.1% of patients with CVD vs. 79.2% of patients without CVD received influenza vaccination within the requested time (P < .0001).

The two nudging strategies – a letter highlighting potential cardiovascular benefits of influenza vaccination or a repeat letter – that were effective in boosting flu shot rates in the main analysis were also effective in all major CVD subgroups (ischemic heart disease, pulmonary heart disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, cerebrovascular disease, atherosclerotic CVD, embolic or thrombotic disease, and congenital heart disease).

Despite strong guideline endorsement, “influenza vaccination rates remain suboptimal in patients with high-risk cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Morin and colleagues write, possibly because of “insufficient knowledge among patients and providers of potential clinical benefits, concerns about vaccine safety, and other forms of vaccine hesitancy.”

Their findings suggest that “select digital behaviorally informed nudges delivered in advance of vaccine availability might be utilized to increase influenza vaccinate uptake in individuals with cardiovascular disease.”

NUDGE-HF was funded by Sanofi. Dr. Johansen and Dr. Modin have no disclosures. The disclosures of the other authors are listed with the articles. Dr. Stockwell has no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two types of electronically delivered letter strategies – a letter highlighting potential cardiovascular benefits of influenza vaccination and a repeat reminder letter – increased flu shot uptake, compared with usual care alone, in a national study of seniors in Denmark.

And in a prespecified subanalysis focusing on older adults with cardiovascular disease, these two strategies were also effective in boosting vaccine uptake in those with or without CVD.

The findings are from the Nationwide Utilization of Danish Government Electronic Letter System for Increasing Influenza Vaccine Uptake (NUDGE-FLU) trial, which compared usual care alone with one of nine different electronic letter “behavioral nudge” strategies during the 2022-2023 flu season in people aged 65 years and older.

Niklas Dyrby Johansen, MD, Hospital–Herlev and Gentofte and Copenhagen University, presented the main study findings in a late-breaking clinical trial session at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation, and the article was simultaneously published in The Lancet

The subanalysis in patients with CVD was published online March 5 in Circulation.

“Despite modest effect sizes, the results may have important implications when translated to a population level,” Dr. Dyrby Johansen concluded during his presentation. Still, the authors write, “the low-touch (no person-to-person interaction), inexpensive, and highly scalable nature of these electronic letters might have important population-level public health implications.”

They note that, among approximately 63 million Medicare beneficiaries in the United States, a 0.89–percentage point absolute increase in vaccination rate achieved through the most successful electronic letter in NUDGE-FLU, the one highlighting cardiovascular gain, would be expected to lead to 500,000 additional vaccinations and potentially prevent 7,849 illnesses, 4,395 medical visits, 714 hospitalizations, and 66 deaths each year.

Electronic letter systems similar to the one used in this trial are already in place in several European countries, including Sweden, Norway, and Ireland, the researchers note.

In countries such as the United States, where implementing a nationwide government electronic letter system might not be feasible, nudges could be done via email, text message, or other systems, but whether this would be as effective remains to be seen.

Commenting on the findings, David Cho, MD, UCLA Health and chair of the ACC Health Care Innovation Council, commended the researchers on engaging patients with more than a million separate nudges sent out during one flu season, and randomly assigning participants to 10 different types of nudges, calling it “impressive.”

“I think the concept that the nudge is to plant an idea that leads to an action is pretty much the basis of a lot of these health care interventions, which seems like a small way to have a big impact at outcome,” Dr. Cho noted. “The behavioral science aspects of the nudges are also fascinating to me personally, and I think to a lot of the cardiologists in the audience – about how you actually get people to act. I think it’s been a lifelong question for people in general, how do you get people to follow through on an action?”

“So I found the fact that secondary gain from a cardiovascular health standpoint, but also the repeated nudges were sort of simple ways that you could have people take ownership and get their flu vaccination,” he said.

“This is ACC, this is a cardiovascular conference, but the influence of vaccine is not just a primary care problem, it is also directly affecting cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Cho concluded.

‘Small but important effect’

In an accompanying editorial (Lancet. 2023 Mar 5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00453-1), Melissa Stockwell, MD, Columbia University, New York, writes, “The study by Johansen and colleagues highlights the small but still important effect of scalable, digital interventions across an entire at-risk population.”

A difference of 0.89% in the entire study population of over 960,000 adults age 65 years or older would be more than 8,500 additional adults protected, she notes. “That increase is important for a scalable intervention that has a low cost per letter.”

Moreover, “that the cardiovascular gain–framed messages worked best in those who had not been vaccinated in the previous season further highlights the potential impact on a more vaccine-hesitant population,” Dr. Stockwell notes.

However, with the mandatory government electronic notification system in Denmark, “notifications are sent via regular email and SMS message, and recipients log in through a portal or smartphone app to view the letter.” Similar studies in the United States that included this extra step of needing to sign in online have not been effective in older populations.

Another limitation is that the intervention may have a different effect in populations for which there is a digital divide between people with or without Internet access of sufficient data on their mobile phones.

First-of-its kind, nationwide pragmatic trial

The NUDGE-FLU protocol was previously published in the American Heart Journal. NUDGE-FLU is a first-of-its kind nationwide, pragmatic, registry-based, cluster-randomized implementation trial of electronically delivered nudges to increase influenza vaccination uptake, the researchers note.

They identified 964,870 individuals who were 65 years or older (or would turn 65 by Jan. 15, 2023) who lived in one of 691,820 households in Denmark.

This excluded individuals who lived in a nursing home or were exempt from the government’s mandatory electronic letter system that is used for official communications.

Households were randomly assigned 9:1:1:1:1:1:1:1:1:1 to receive usual care alone or to one of nine electronic letter strategies based on different behavioral science approaches to encourage influenza vaccination uptake:

- Standard electronic letter

- Standard electronic letter sent at randomization and again 14 days later (repeated letter)

- Depersonalized letter without the recipient’s name

- Gain-framing nudge (“Vaccinations help end pandemics, like COVID-19 and the flu. Protect yourself and your loved ones.”)

- Loss-framing nudge (“When too few people get vaccinated, pandemics from diseases like COVID-19 and the flu can spread and place you and your loved ones at risk.”)

- Collective-goal nudge (“78% of Danes 65 and above were vaccinated against influenza last year. Help us achieve an even higher goal this year.”)

- Active choice or implementation-intention prompt (“We encourage you to record your appointment time here.”)

- Cardiovascular gain–framing nudge (“In addition to its protection against influenza infection, influenza vaccination also seems to protect against cardiovascular disease such as heart attacks and heart failure.”)

- Expert-authority statement (“I recommend everyone over the age of 65 years to get vaccinated against influenza – Tyra Grove Krause, Executive Vice President, Statens Serum Institut.”)

The electronic letters were sent out Sept. 16, 2022, and the primary endpoint was vaccine receipt on or before Jan. 1, 2023.

All individuals received an informative vaccination encouragement letter from the Danish Health Authority (usual care) delivered via the same electronic letter system during Sept. 17 through Sept. 21, 2022.

The individuals had a mean age of 73.8 years, 51.5% were women, and 27.4% had chronic cardiovascular disease.

The analyses were done in one randomly selected individual per household.

Influenza vaccination rates were significantly higher in the cardiovascular gain–framing nudge group vs. usual care (81.00% vs. 80.12%; difference, 0.89 percentage points; P < .0001) and in the repeat-letter group vs. usual care (80.85% vs 80.12%; difference, 0.73 percentage points; P = .0006).

These two strategies also improved vaccination rates across major subgroups.

The cardiovascular gain–framed letter was particularly effective among participants who had not been vaccinated for influenza in the previous season.

The seven other letter strategies did not increase flu shot uptake.

Subanalysis in CVD

In the prespecified subanalysis of the NUDGE-FLU trial of patients aged 65 and older that focused on patients with CVD, Daniel Modin, MB, and colleagues report that 83.1% of patients with CVD vs. 79.2% of patients without CVD received influenza vaccination within the requested time (P < .0001).

The two nudging strategies – a letter highlighting potential cardiovascular benefits of influenza vaccination or a repeat letter – that were effective in boosting flu shot rates in the main analysis were also effective in all major CVD subgroups (ischemic heart disease, pulmonary heart disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, cerebrovascular disease, atherosclerotic CVD, embolic or thrombotic disease, and congenital heart disease).

Despite strong guideline endorsement, “influenza vaccination rates remain suboptimal in patients with high-risk cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Morin and colleagues write, possibly because of “insufficient knowledge among patients and providers of potential clinical benefits, concerns about vaccine safety, and other forms of vaccine hesitancy.”

Their findings suggest that “select digital behaviorally informed nudges delivered in advance of vaccine availability might be utilized to increase influenza vaccinate uptake in individuals with cardiovascular disease.”

NUDGE-HF was funded by Sanofi. Dr. Johansen and Dr. Modin have no disclosures. The disclosures of the other authors are listed with the articles. Dr. Stockwell has no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two types of electronically delivered letter strategies – a letter highlighting potential cardiovascular benefits of influenza vaccination and a repeat reminder letter – increased flu shot uptake, compared with usual care alone, in a national study of seniors in Denmark.

And in a prespecified subanalysis focusing on older adults with cardiovascular disease, these two strategies were also effective in boosting vaccine uptake in those with or without CVD.

The findings are from the Nationwide Utilization of Danish Government Electronic Letter System for Increasing Influenza Vaccine Uptake (NUDGE-FLU) trial, which compared usual care alone with one of nine different electronic letter “behavioral nudge” strategies during the 2022-2023 flu season in people aged 65 years and older.

Niklas Dyrby Johansen, MD, Hospital–Herlev and Gentofte and Copenhagen University, presented the main study findings in a late-breaking clinical trial session at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation, and the article was simultaneously published in The Lancet

The subanalysis in patients with CVD was published online March 5 in Circulation.

“Despite modest effect sizes, the results may have important implications when translated to a population level,” Dr. Dyrby Johansen concluded during his presentation. Still, the authors write, “the low-touch (no person-to-person interaction), inexpensive, and highly scalable nature of these electronic letters might have important population-level public health implications.”