User login

Postop RT: Meaningful survival improvement in N2 lung cancer

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Mark Kris from Memorial Sloan Kettering, speaking today about a topic that’s become quite controversial, which is

Data from clinical trials and data from a SEER study showed approximately 7% improvement in overall survival in patients with N2 disease who received PORT. There has been a very clear demonstration of an improved local control rate in every trial that’s ever looked at PORT.

However, there was a randomized trial, the Lung ART trial, where patients were randomized to get PORT or not. PORT was delivered in a way that is not routinely used now. In that trial, the benefit of PORT was found in terms of local control, almost doubling control within the mediastinum.

The difference in overall survival was less than 12%. Again, I’m not surprised to see that because the improvement in overall survival is probably somewhere between 5% and 10%. They also found an excess of deaths, probably due to cardiac causes from the radiation in the radiation arm.

However, the trial used a type of radiation not used at this point – it used conformal, but now we would use 3D. And its ability at the time of the trial to estimate and lower cardiac risk was not what it is today. Owing to the design of the trial, it was not a significant difference and has largely been interpreted as saying that the PORT doesn’t work.

First, let’s please go to the guidelines. I’m going to the ASCO guidelines, which say that patients with mediastinal disease should not routinely get PORT, but they should be routinely referred to a radiation oncologist for consideration of PORT. I don’t think anything that’s been published so far changes that.

I think each case needs to be individualized and requires the specialty care of a radiation oncologist to weigh the pros and cons of PORT. It also depends upon the treatment plan. Can the heart be spared? Are there radiation techniques available that would eliminate or lessen heart exposure, such as using protons? The point is that PORT is still needed.

When we look at the trials of patients receiving adjuvant therapy – and I’m looking particularly at the ADAURA trial where patients received adjuvant osimertinib – the greatest number of failures now is in the chest. We have to look for good ways to cut down on failure in the chest. Unfortunately, failure in the chest means ultimately failure and lack of cure, and we have to do a better job at that. I think PORT can play a role there.

Please, when you have patients with N2 disease, after the completion of systemic therapies, think about the use of PORT and get the advice of a radiation oncologist to meet with the patient, review their clinical situation, and assess whether or not PORT could be useful for that patient.

That is following the NCCN guidelines, which were not changed on the basis of the Lung ART paper. I think we owe it to our patients to make sure that those who could benefit from this additional therapy receive it.

I’ll put it to you that radiation delivered in the most innovative way – taking very careful account of the effects on the heart – can improve local control. There’s no question about that. I think PORT has the ability to improve survival by a small amount – probably less than 12%, which I will agree the Lung ART trial showed – but still an important amount for patients with this condition.

Mark G. Kris, MD, is chief of the thoracic oncology service and the William and Joy Ruane Chair in Thoracic Oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. He reported conflicts of interest with Arial Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, PUMA, and Roche/Genentech. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Mark Kris from Memorial Sloan Kettering, speaking today about a topic that’s become quite controversial, which is

Data from clinical trials and data from a SEER study showed approximately 7% improvement in overall survival in patients with N2 disease who received PORT. There has been a very clear demonstration of an improved local control rate in every trial that’s ever looked at PORT.

However, there was a randomized trial, the Lung ART trial, where patients were randomized to get PORT or not. PORT was delivered in a way that is not routinely used now. In that trial, the benefit of PORT was found in terms of local control, almost doubling control within the mediastinum.

The difference in overall survival was less than 12%. Again, I’m not surprised to see that because the improvement in overall survival is probably somewhere between 5% and 10%. They also found an excess of deaths, probably due to cardiac causes from the radiation in the radiation arm.

However, the trial used a type of radiation not used at this point – it used conformal, but now we would use 3D. And its ability at the time of the trial to estimate and lower cardiac risk was not what it is today. Owing to the design of the trial, it was not a significant difference and has largely been interpreted as saying that the PORT doesn’t work.

First, let’s please go to the guidelines. I’m going to the ASCO guidelines, which say that patients with mediastinal disease should not routinely get PORT, but they should be routinely referred to a radiation oncologist for consideration of PORT. I don’t think anything that’s been published so far changes that.

I think each case needs to be individualized and requires the specialty care of a radiation oncologist to weigh the pros and cons of PORT. It also depends upon the treatment plan. Can the heart be spared? Are there radiation techniques available that would eliminate or lessen heart exposure, such as using protons? The point is that PORT is still needed.

When we look at the trials of patients receiving adjuvant therapy – and I’m looking particularly at the ADAURA trial where patients received adjuvant osimertinib – the greatest number of failures now is in the chest. We have to look for good ways to cut down on failure in the chest. Unfortunately, failure in the chest means ultimately failure and lack of cure, and we have to do a better job at that. I think PORT can play a role there.

Please, when you have patients with N2 disease, after the completion of systemic therapies, think about the use of PORT and get the advice of a radiation oncologist to meet with the patient, review their clinical situation, and assess whether or not PORT could be useful for that patient.

That is following the NCCN guidelines, which were not changed on the basis of the Lung ART paper. I think we owe it to our patients to make sure that those who could benefit from this additional therapy receive it.

I’ll put it to you that radiation delivered in the most innovative way – taking very careful account of the effects on the heart – can improve local control. There’s no question about that. I think PORT has the ability to improve survival by a small amount – probably less than 12%, which I will agree the Lung ART trial showed – but still an important amount for patients with this condition.

Mark G. Kris, MD, is chief of the thoracic oncology service and the William and Joy Ruane Chair in Thoracic Oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. He reported conflicts of interest with Arial Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, PUMA, and Roche/Genentech. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Mark Kris from Memorial Sloan Kettering, speaking today about a topic that’s become quite controversial, which is

Data from clinical trials and data from a SEER study showed approximately 7% improvement in overall survival in patients with N2 disease who received PORT. There has been a very clear demonstration of an improved local control rate in every trial that’s ever looked at PORT.

However, there was a randomized trial, the Lung ART trial, where patients were randomized to get PORT or not. PORT was delivered in a way that is not routinely used now. In that trial, the benefit of PORT was found in terms of local control, almost doubling control within the mediastinum.

The difference in overall survival was less than 12%. Again, I’m not surprised to see that because the improvement in overall survival is probably somewhere between 5% and 10%. They also found an excess of deaths, probably due to cardiac causes from the radiation in the radiation arm.

However, the trial used a type of radiation not used at this point – it used conformal, but now we would use 3D. And its ability at the time of the trial to estimate and lower cardiac risk was not what it is today. Owing to the design of the trial, it was not a significant difference and has largely been interpreted as saying that the PORT doesn’t work.

First, let’s please go to the guidelines. I’m going to the ASCO guidelines, which say that patients with mediastinal disease should not routinely get PORT, but they should be routinely referred to a radiation oncologist for consideration of PORT. I don’t think anything that’s been published so far changes that.

I think each case needs to be individualized and requires the specialty care of a radiation oncologist to weigh the pros and cons of PORT. It also depends upon the treatment plan. Can the heart be spared? Are there radiation techniques available that would eliminate or lessen heart exposure, such as using protons? The point is that PORT is still needed.

When we look at the trials of patients receiving adjuvant therapy – and I’m looking particularly at the ADAURA trial where patients received adjuvant osimertinib – the greatest number of failures now is in the chest. We have to look for good ways to cut down on failure in the chest. Unfortunately, failure in the chest means ultimately failure and lack of cure, and we have to do a better job at that. I think PORT can play a role there.

Please, when you have patients with N2 disease, after the completion of systemic therapies, think about the use of PORT and get the advice of a radiation oncologist to meet with the patient, review their clinical situation, and assess whether or not PORT could be useful for that patient.

That is following the NCCN guidelines, which were not changed on the basis of the Lung ART paper. I think we owe it to our patients to make sure that those who could benefit from this additional therapy receive it.

I’ll put it to you that radiation delivered in the most innovative way – taking very careful account of the effects on the heart – can improve local control. There’s no question about that. I think PORT has the ability to improve survival by a small amount – probably less than 12%, which I will agree the Lung ART trial showed – but still an important amount for patients with this condition.

Mark G. Kris, MD, is chief of the thoracic oncology service and the William and Joy Ruane Chair in Thoracic Oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. He reported conflicts of interest with Arial Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, PUMA, and Roche/Genentech. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The way I see it

I’ve worn glasses since I was 8, when a routine school vision test showed I was nearsighted. Except for an ill-fated 3-month attempt at contact lenses when I was 16, glasses have been just another part of my daily routine.

The last time I got new ones was in 2018, and my vision always seemed “off” after that. I took them back to the store a few times and was told I’d adjust to them and that things would be fine, So after a few weeks of doggedly wearing them I adjusted to them. I still felt like something was slightly off, but then I was busy, and then came the pandemic, and then my eye doctor retired and I had to find a new one ... so going to get my glasses prescription rechecked kept getting pushed back.

As so many of us do over time, I’ve gotten used to taking my glasses off to read things up close, like a book, or to do a detailed jigsaw puzzle. This has gotten worse over time, and so finally I made an appointment with a new eye doctor.

I handed him my previous prescription. He did a reading off the lenses, looked at the prescription again, gave me a perplexed look, and started the usual eye exam, asking me to read different lines as he switched lenses around. This went on for 10-15 minutes.

“The right lens wasn’t made correctly,” he told me. “You’ve been working off your left eye for the last 5 years.”

He returned my glasses and I put them on. He covered my left eye and showed me how, without realizing it, I was tilting my head back to bring distant items into focus on the right – the opposite of what I should be doing – and with both eyes would adjust my position to use the left eye.

The next morning, while working at my desk, I realized for the first time that I had my head turned slightly right to bring the left eye a tad closer to the screen. In a job where we’re trained to look for such minutiae in patients I’d missed it on myself. A friend even suggested I submit my story as a case report – “An unusual cause of a head-tilt in a middle-aged male” – to a journal.

It’s an interesting commentary on how adaptable the brain is at handling vision changes. It was several hundred million years ago when the brain figured out how to invert images that were seen upside down, and it continues to find ways to compensate for field cuts, cranial nerve palsies, and other lesions. Including flawed spectacles.

When my new eyeglasses arrive, my brain will have to readjust. This time, though, I’m curious and will try to pay better attention to my own reactions. If I can.

so we don’t notice an issue.

Amazing stuff if you think about it.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’ve worn glasses since I was 8, when a routine school vision test showed I was nearsighted. Except for an ill-fated 3-month attempt at contact lenses when I was 16, glasses have been just another part of my daily routine.

The last time I got new ones was in 2018, and my vision always seemed “off” after that. I took them back to the store a few times and was told I’d adjust to them and that things would be fine, So after a few weeks of doggedly wearing them I adjusted to them. I still felt like something was slightly off, but then I was busy, and then came the pandemic, and then my eye doctor retired and I had to find a new one ... so going to get my glasses prescription rechecked kept getting pushed back.

As so many of us do over time, I’ve gotten used to taking my glasses off to read things up close, like a book, or to do a detailed jigsaw puzzle. This has gotten worse over time, and so finally I made an appointment with a new eye doctor.

I handed him my previous prescription. He did a reading off the lenses, looked at the prescription again, gave me a perplexed look, and started the usual eye exam, asking me to read different lines as he switched lenses around. This went on for 10-15 minutes.

“The right lens wasn’t made correctly,” he told me. “You’ve been working off your left eye for the last 5 years.”

He returned my glasses and I put them on. He covered my left eye and showed me how, without realizing it, I was tilting my head back to bring distant items into focus on the right – the opposite of what I should be doing – and with both eyes would adjust my position to use the left eye.

The next morning, while working at my desk, I realized for the first time that I had my head turned slightly right to bring the left eye a tad closer to the screen. In a job where we’re trained to look for such minutiae in patients I’d missed it on myself. A friend even suggested I submit my story as a case report – “An unusual cause of a head-tilt in a middle-aged male” – to a journal.

It’s an interesting commentary on how adaptable the brain is at handling vision changes. It was several hundred million years ago when the brain figured out how to invert images that were seen upside down, and it continues to find ways to compensate for field cuts, cranial nerve palsies, and other lesions. Including flawed spectacles.

When my new eyeglasses arrive, my brain will have to readjust. This time, though, I’m curious and will try to pay better attention to my own reactions. If I can.

so we don’t notice an issue.

Amazing stuff if you think about it.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’ve worn glasses since I was 8, when a routine school vision test showed I was nearsighted. Except for an ill-fated 3-month attempt at contact lenses when I was 16, glasses have been just another part of my daily routine.

The last time I got new ones was in 2018, and my vision always seemed “off” after that. I took them back to the store a few times and was told I’d adjust to them and that things would be fine, So after a few weeks of doggedly wearing them I adjusted to them. I still felt like something was slightly off, but then I was busy, and then came the pandemic, and then my eye doctor retired and I had to find a new one ... so going to get my glasses prescription rechecked kept getting pushed back.

As so many of us do over time, I’ve gotten used to taking my glasses off to read things up close, like a book, or to do a detailed jigsaw puzzle. This has gotten worse over time, and so finally I made an appointment with a new eye doctor.

I handed him my previous prescription. He did a reading off the lenses, looked at the prescription again, gave me a perplexed look, and started the usual eye exam, asking me to read different lines as he switched lenses around. This went on for 10-15 minutes.

“The right lens wasn’t made correctly,” he told me. “You’ve been working off your left eye for the last 5 years.”

He returned my glasses and I put them on. He covered my left eye and showed me how, without realizing it, I was tilting my head back to bring distant items into focus on the right – the opposite of what I should be doing – and with both eyes would adjust my position to use the left eye.

The next morning, while working at my desk, I realized for the first time that I had my head turned slightly right to bring the left eye a tad closer to the screen. In a job where we’re trained to look for such minutiae in patients I’d missed it on myself. A friend even suggested I submit my story as a case report – “An unusual cause of a head-tilt in a middle-aged male” – to a journal.

It’s an interesting commentary on how adaptable the brain is at handling vision changes. It was several hundred million years ago when the brain figured out how to invert images that were seen upside down, and it continues to find ways to compensate for field cuts, cranial nerve palsies, and other lesions. Including flawed spectacles.

When my new eyeglasses arrive, my brain will have to readjust. This time, though, I’m curious and will try to pay better attention to my own reactions. If I can.

so we don’t notice an issue.

Amazing stuff if you think about it.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Is there still a role for tubal surgery in the modern world of IVF?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Preventions, in 2019 2.1% of all infants born in the United States were conceived by assisted reproductive technology (ART). Now 45 years old, ART, namely in vitro fertilization (IVF), is offered in nearly 500 clinics in the United States, contributing to over 300,000 treatment cycles per year.

A tubal factor is responsible for 30% of female infertility and may involve proximal and/or distal tubal occlusion, irrespective of pelvic adhesions.1 Before the advent of IVF, the sole approach to the treatment of a tubal factor had been surgery. Given its success and minimal invasiveness, IVF is increasingly being offered to circumvent a tubal factor for infertility. This month we examine the utility of surgical treatment of tubal factor infertility. The options for fertility with a history of bilateral tubal ligation was covered in a prior Reproductive Rounds column.

Tubal disease and pelvic adhesions prevent the normal transport of the oocyte and sperm through the fallopian tube. The primary etiology of tubal factor infertility is pelvic inflammatory disease, mainly caused by chlamydia or gonorrhea. Other conditions that may interfere with tubal transport include severe endometriosis, adhesions from previous surgery, or nontubal infection (for example, appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease), pelvic tuberculosis, and salpingitis isthmica nodosa (that is, diverticulosis of the fallopian tube).

Proximal tubal occlusion

During a hysterosalpingogram (HSG), transient uterine cornual spasm can result if a woman experiences significant uterine cramping, thereby resulting in a false-positive diagnosis of proximal tubal occlusion. When a repeat HSG is gently performed with slow instillation of contrast, uterine cramping is less likely, and the tubal patency rate is 60%. PTO may also result from plugs of mucus and amorphous debris, but this is not true occlusion.2 In cases with unilateral PTO, controlled ovarian hyperstimulation with intrauterine insemination has resulted in pregnancy rates similar to those in patients with unexplained infertility.3

Reconstructive surgery for bilateral PTO has limited effectiveness and the risk of subsequent ectopic pregnancy is as high as 20%.4 A more successful option is fluoroscopic tubal catheterization (FTC), an outpatient procedure performed in a radiology or infertility center. FTC uses a coaxial catheter system where the outer catheter is guided through the tubal ostium and an inner catheter is atraumatically advanced to overcome the blockage. This procedure is 85% successful for tubal patency with 50% of patients conceiving in the first 12 months; one-third of time the tubes reocclude. After the reestablishment of patency with FTC, the chance of achieving a live birth is 22% and the risk of ectopic pregnancy is 4%.5

Treatment of distal tubal occlusion – the hydrosalpinx

Surgery for treating tubal factor infertility is most successful in women with distal tubal obstruction (DTO), often caused by a hydrosalpinx. Fimbrioplasty is the lysis of fimbrial adhesions or dilatation of fimbrial strictures; the tube is patent, but there are adhesive bands that surround the terminal end with preserved tubal rugae. Gentle introduction of an alligator laparoscopic forceps into the tubal ostium followed by opening and withdrawal of the forceps helps to stretch the tube and release minor degrees of fimbrial agglutination.6

A hydrosalpinx is diagnosed by DTO with dilation and intraluminal fluid accumulation along with the reduction/loss of endothelial cilia. Left untreated, a hydrosalpinx can lead to a 50% reduction in IVF pregnancy rates.7 Tube-sparing treatment involves neosalpingostomy to create a new tubal opening. A nonsurgical approach, ultrasound-guided aspiration of hydrosalpinges, has not been shown to significantly increase the rate of clinical pregnancy. Efficacy for improving fertility is generally poor, but depends upon tubal wall thickness, ampullary dilation, presence of mucosal folds, percentage of ciliated cells in the fimbrial end, and peritubal adhesions.8

Evidence supports that laparoscopic salpingectomy in women with hydrosalpinges improves the outcomes of IVF treatment, compared with no surgical intervention.9 The improvement in pregnancy and live birth rates likely stems from the elimination of the retrograde flow of embryotoxic fluid that disrupts implantation. Endometrial receptivity markers (endometrial cell adhesion molecules, integrins, and HOXA10) have been shown to be reduced in the presence of hydrosalpinx.10 A small, randomized trial demonstrated that bipolar diathermy prior to IVF improved pregnancy outcomes.11 PTO was not more effective than salpingectomy. Conceptions, without IVF, have been reported following salpingectomy for unilateral hydrosalpinx.12

In a series including 434 patients with DTO who underwent laparoscopic fimbrioplasty (enlargement of the ostium) or neosalpingostomy (creation of a new ostium) by a single surgeon, 5-year actuarial delivery rates decreased as the severity of tubal occlusion increased; the ectopic rate was stable at approximately 15%.13 A prospective study reported that the relative increase in the pregnancy rate after salpingectomy was greatest in women with a large hydrosalpinx visible on ultrasound.14

Because of the possible risks of decreased ovarian reserve secondary to interruption of ovarian blood supply, salpingectomy should be done with minimal thermal injury and very close to the fallopian tube.

Summary

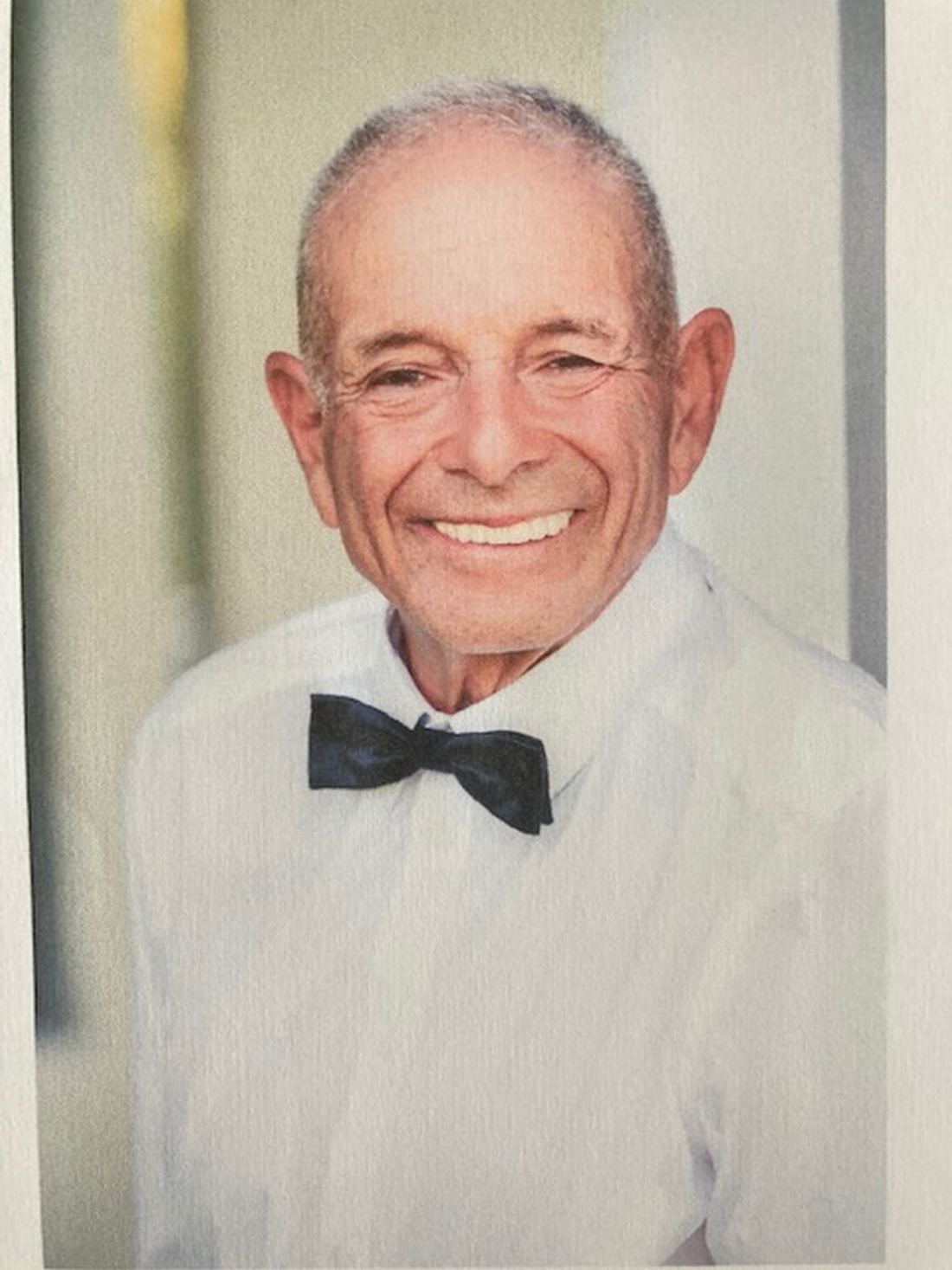

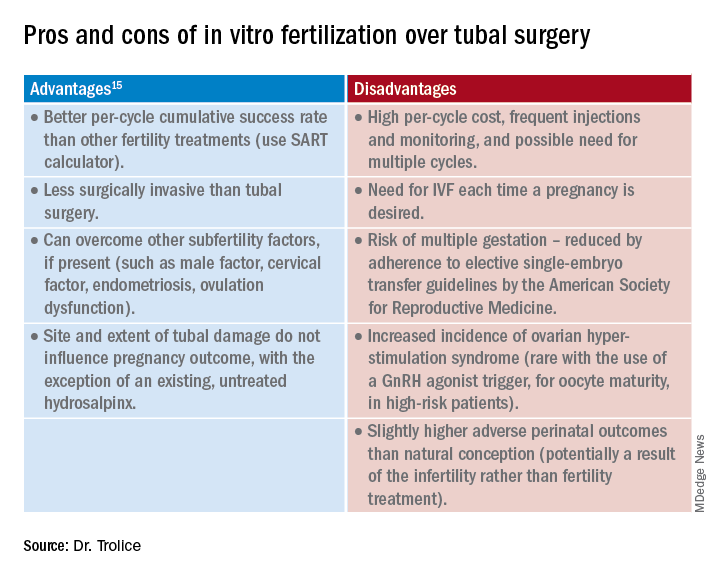

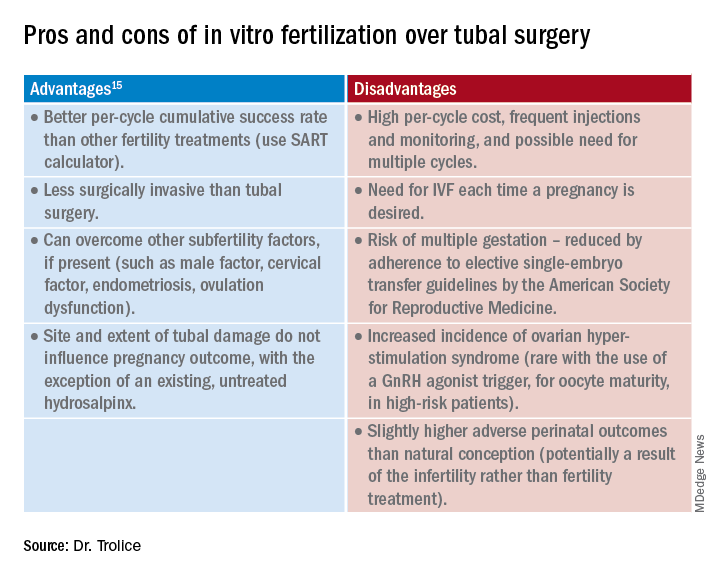

Surgery may be considered for young women with mild distal tubal disease as one surgical procedure can lead to several pregnancies whereas IVF must be performed each time pregnancy is desired. IVF is more likely than surgery to be successful in women with bilateral hydrosalpinx, in those with pelvic adhesions, in older reproductive aged women, and for both proximal and distal tubal occlusion.15 An online prediction calculator from the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) can be helpful in counseling patients on personalized expectations for IVF pregnancy outcomes.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Ambildhuke K et al. Cureus. 2022;1:14(11):e30990.

2. Fatemeh Z et al. Br J Radiol. 2021 Jun 1;94(1122):20201386.

3. Farhi J et al. Fertil Steril. 2007 Aug;88(2):396.

4. Honoré GM et al. Fertil Steril. 1999;71(5):785.

5. De Silva PM et al. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(4):836.

6. Namnoum A and Murphy A. “Diagnostic and Operative Laparoscopy,” in Te Linde’s Operative Gynecology, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997, pp. 389.

7. Camus E et al.Hum Reprod. 1999;14(5):1243.

8. Marana R et al. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(12):2991-5.

9. Johnson N et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Jan 20;2010(1):CD002125.

10. Savaris RF et al. Fertil Steril. 2006 Jan;85(1):188.

11. Kontoravdis A et al. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(6):1642.

12. Sagoskin AW et al. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(12):2634.

13. Audebert A et al. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(4):1203.

14. Bildirici I et al. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(11):2422.

15. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(3):539.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Preventions, in 2019 2.1% of all infants born in the United States were conceived by assisted reproductive technology (ART). Now 45 years old, ART, namely in vitro fertilization (IVF), is offered in nearly 500 clinics in the United States, contributing to over 300,000 treatment cycles per year.

A tubal factor is responsible for 30% of female infertility and may involve proximal and/or distal tubal occlusion, irrespective of pelvic adhesions.1 Before the advent of IVF, the sole approach to the treatment of a tubal factor had been surgery. Given its success and minimal invasiveness, IVF is increasingly being offered to circumvent a tubal factor for infertility. This month we examine the utility of surgical treatment of tubal factor infertility. The options for fertility with a history of bilateral tubal ligation was covered in a prior Reproductive Rounds column.

Tubal disease and pelvic adhesions prevent the normal transport of the oocyte and sperm through the fallopian tube. The primary etiology of tubal factor infertility is pelvic inflammatory disease, mainly caused by chlamydia or gonorrhea. Other conditions that may interfere with tubal transport include severe endometriosis, adhesions from previous surgery, or nontubal infection (for example, appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease), pelvic tuberculosis, and salpingitis isthmica nodosa (that is, diverticulosis of the fallopian tube).

Proximal tubal occlusion

During a hysterosalpingogram (HSG), transient uterine cornual spasm can result if a woman experiences significant uterine cramping, thereby resulting in a false-positive diagnosis of proximal tubal occlusion. When a repeat HSG is gently performed with slow instillation of contrast, uterine cramping is less likely, and the tubal patency rate is 60%. PTO may also result from plugs of mucus and amorphous debris, but this is not true occlusion.2 In cases with unilateral PTO, controlled ovarian hyperstimulation with intrauterine insemination has resulted in pregnancy rates similar to those in patients with unexplained infertility.3

Reconstructive surgery for bilateral PTO has limited effectiveness and the risk of subsequent ectopic pregnancy is as high as 20%.4 A more successful option is fluoroscopic tubal catheterization (FTC), an outpatient procedure performed in a radiology or infertility center. FTC uses a coaxial catheter system where the outer catheter is guided through the tubal ostium and an inner catheter is atraumatically advanced to overcome the blockage. This procedure is 85% successful for tubal patency with 50% of patients conceiving in the first 12 months; one-third of time the tubes reocclude. After the reestablishment of patency with FTC, the chance of achieving a live birth is 22% and the risk of ectopic pregnancy is 4%.5

Treatment of distal tubal occlusion – the hydrosalpinx

Surgery for treating tubal factor infertility is most successful in women with distal tubal obstruction (DTO), often caused by a hydrosalpinx. Fimbrioplasty is the lysis of fimbrial adhesions or dilatation of fimbrial strictures; the tube is patent, but there are adhesive bands that surround the terminal end with preserved tubal rugae. Gentle introduction of an alligator laparoscopic forceps into the tubal ostium followed by opening and withdrawal of the forceps helps to stretch the tube and release minor degrees of fimbrial agglutination.6

A hydrosalpinx is diagnosed by DTO with dilation and intraluminal fluid accumulation along with the reduction/loss of endothelial cilia. Left untreated, a hydrosalpinx can lead to a 50% reduction in IVF pregnancy rates.7 Tube-sparing treatment involves neosalpingostomy to create a new tubal opening. A nonsurgical approach, ultrasound-guided aspiration of hydrosalpinges, has not been shown to significantly increase the rate of clinical pregnancy. Efficacy for improving fertility is generally poor, but depends upon tubal wall thickness, ampullary dilation, presence of mucosal folds, percentage of ciliated cells in the fimbrial end, and peritubal adhesions.8

Evidence supports that laparoscopic salpingectomy in women with hydrosalpinges improves the outcomes of IVF treatment, compared with no surgical intervention.9 The improvement in pregnancy and live birth rates likely stems from the elimination of the retrograde flow of embryotoxic fluid that disrupts implantation. Endometrial receptivity markers (endometrial cell adhesion molecules, integrins, and HOXA10) have been shown to be reduced in the presence of hydrosalpinx.10 A small, randomized trial demonstrated that bipolar diathermy prior to IVF improved pregnancy outcomes.11 PTO was not more effective than salpingectomy. Conceptions, without IVF, have been reported following salpingectomy for unilateral hydrosalpinx.12

In a series including 434 patients with DTO who underwent laparoscopic fimbrioplasty (enlargement of the ostium) or neosalpingostomy (creation of a new ostium) by a single surgeon, 5-year actuarial delivery rates decreased as the severity of tubal occlusion increased; the ectopic rate was stable at approximately 15%.13 A prospective study reported that the relative increase in the pregnancy rate after salpingectomy was greatest in women with a large hydrosalpinx visible on ultrasound.14

Because of the possible risks of decreased ovarian reserve secondary to interruption of ovarian blood supply, salpingectomy should be done with minimal thermal injury and very close to the fallopian tube.

Summary

Surgery may be considered for young women with mild distal tubal disease as one surgical procedure can lead to several pregnancies whereas IVF must be performed each time pregnancy is desired. IVF is more likely than surgery to be successful in women with bilateral hydrosalpinx, in those with pelvic adhesions, in older reproductive aged women, and for both proximal and distal tubal occlusion.15 An online prediction calculator from the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) can be helpful in counseling patients on personalized expectations for IVF pregnancy outcomes.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Ambildhuke K et al. Cureus. 2022;1:14(11):e30990.

2. Fatemeh Z et al. Br J Radiol. 2021 Jun 1;94(1122):20201386.

3. Farhi J et al. Fertil Steril. 2007 Aug;88(2):396.

4. Honoré GM et al. Fertil Steril. 1999;71(5):785.

5. De Silva PM et al. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(4):836.

6. Namnoum A and Murphy A. “Diagnostic and Operative Laparoscopy,” in Te Linde’s Operative Gynecology, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997, pp. 389.

7. Camus E et al.Hum Reprod. 1999;14(5):1243.

8. Marana R et al. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(12):2991-5.

9. Johnson N et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Jan 20;2010(1):CD002125.

10. Savaris RF et al. Fertil Steril. 2006 Jan;85(1):188.

11. Kontoravdis A et al. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(6):1642.

12. Sagoskin AW et al. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(12):2634.

13. Audebert A et al. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(4):1203.

14. Bildirici I et al. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(11):2422.

15. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(3):539.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Preventions, in 2019 2.1% of all infants born in the United States were conceived by assisted reproductive technology (ART). Now 45 years old, ART, namely in vitro fertilization (IVF), is offered in nearly 500 clinics in the United States, contributing to over 300,000 treatment cycles per year.

A tubal factor is responsible for 30% of female infertility and may involve proximal and/or distal tubal occlusion, irrespective of pelvic adhesions.1 Before the advent of IVF, the sole approach to the treatment of a tubal factor had been surgery. Given its success and minimal invasiveness, IVF is increasingly being offered to circumvent a tubal factor for infertility. This month we examine the utility of surgical treatment of tubal factor infertility. The options for fertility with a history of bilateral tubal ligation was covered in a prior Reproductive Rounds column.

Tubal disease and pelvic adhesions prevent the normal transport of the oocyte and sperm through the fallopian tube. The primary etiology of tubal factor infertility is pelvic inflammatory disease, mainly caused by chlamydia or gonorrhea. Other conditions that may interfere with tubal transport include severe endometriosis, adhesions from previous surgery, or nontubal infection (for example, appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease), pelvic tuberculosis, and salpingitis isthmica nodosa (that is, diverticulosis of the fallopian tube).

Proximal tubal occlusion

During a hysterosalpingogram (HSG), transient uterine cornual spasm can result if a woman experiences significant uterine cramping, thereby resulting in a false-positive diagnosis of proximal tubal occlusion. When a repeat HSG is gently performed with slow instillation of contrast, uterine cramping is less likely, and the tubal patency rate is 60%. PTO may also result from plugs of mucus and amorphous debris, but this is not true occlusion.2 In cases with unilateral PTO, controlled ovarian hyperstimulation with intrauterine insemination has resulted in pregnancy rates similar to those in patients with unexplained infertility.3

Reconstructive surgery for bilateral PTO has limited effectiveness and the risk of subsequent ectopic pregnancy is as high as 20%.4 A more successful option is fluoroscopic tubal catheterization (FTC), an outpatient procedure performed in a radiology or infertility center. FTC uses a coaxial catheter system where the outer catheter is guided through the tubal ostium and an inner catheter is atraumatically advanced to overcome the blockage. This procedure is 85% successful for tubal patency with 50% of patients conceiving in the first 12 months; one-third of time the tubes reocclude. After the reestablishment of patency with FTC, the chance of achieving a live birth is 22% and the risk of ectopic pregnancy is 4%.5

Treatment of distal tubal occlusion – the hydrosalpinx

Surgery for treating tubal factor infertility is most successful in women with distal tubal obstruction (DTO), often caused by a hydrosalpinx. Fimbrioplasty is the lysis of fimbrial adhesions or dilatation of fimbrial strictures; the tube is patent, but there are adhesive bands that surround the terminal end with preserved tubal rugae. Gentle introduction of an alligator laparoscopic forceps into the tubal ostium followed by opening and withdrawal of the forceps helps to stretch the tube and release minor degrees of fimbrial agglutination.6

A hydrosalpinx is diagnosed by DTO with dilation and intraluminal fluid accumulation along with the reduction/loss of endothelial cilia. Left untreated, a hydrosalpinx can lead to a 50% reduction in IVF pregnancy rates.7 Tube-sparing treatment involves neosalpingostomy to create a new tubal opening. A nonsurgical approach, ultrasound-guided aspiration of hydrosalpinges, has not been shown to significantly increase the rate of clinical pregnancy. Efficacy for improving fertility is generally poor, but depends upon tubal wall thickness, ampullary dilation, presence of mucosal folds, percentage of ciliated cells in the fimbrial end, and peritubal adhesions.8

Evidence supports that laparoscopic salpingectomy in women with hydrosalpinges improves the outcomes of IVF treatment, compared with no surgical intervention.9 The improvement in pregnancy and live birth rates likely stems from the elimination of the retrograde flow of embryotoxic fluid that disrupts implantation. Endometrial receptivity markers (endometrial cell adhesion molecules, integrins, and HOXA10) have been shown to be reduced in the presence of hydrosalpinx.10 A small, randomized trial demonstrated that bipolar diathermy prior to IVF improved pregnancy outcomes.11 PTO was not more effective than salpingectomy. Conceptions, without IVF, have been reported following salpingectomy for unilateral hydrosalpinx.12

In a series including 434 patients with DTO who underwent laparoscopic fimbrioplasty (enlargement of the ostium) or neosalpingostomy (creation of a new ostium) by a single surgeon, 5-year actuarial delivery rates decreased as the severity of tubal occlusion increased; the ectopic rate was stable at approximately 15%.13 A prospective study reported that the relative increase in the pregnancy rate after salpingectomy was greatest in women with a large hydrosalpinx visible on ultrasound.14

Because of the possible risks of decreased ovarian reserve secondary to interruption of ovarian blood supply, salpingectomy should be done with minimal thermal injury and very close to the fallopian tube.

Summary

Surgery may be considered for young women with mild distal tubal disease as one surgical procedure can lead to several pregnancies whereas IVF must be performed each time pregnancy is desired. IVF is more likely than surgery to be successful in women with bilateral hydrosalpinx, in those with pelvic adhesions, in older reproductive aged women, and for both proximal and distal tubal occlusion.15 An online prediction calculator from the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) can be helpful in counseling patients on personalized expectations for IVF pregnancy outcomes.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Ambildhuke K et al. Cureus. 2022;1:14(11):e30990.

2. Fatemeh Z et al. Br J Radiol. 2021 Jun 1;94(1122):20201386.

3. Farhi J et al. Fertil Steril. 2007 Aug;88(2):396.

4. Honoré GM et al. Fertil Steril. 1999;71(5):785.

5. De Silva PM et al. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(4):836.

6. Namnoum A and Murphy A. “Diagnostic and Operative Laparoscopy,” in Te Linde’s Operative Gynecology, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997, pp. 389.

7. Camus E et al.Hum Reprod. 1999;14(5):1243.

8. Marana R et al. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(12):2991-5.

9. Johnson N et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Jan 20;2010(1):CD002125.

10. Savaris RF et al. Fertil Steril. 2006 Jan;85(1):188.

11. Kontoravdis A et al. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(6):1642.

12. Sagoskin AW et al. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(12):2634.

13. Audebert A et al. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(4):1203.

14. Bildirici I et al. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(11):2422.

15. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(3):539.

What’s new in brain health?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dear colleagues, I am Christoph Diener from the medical faculty of the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany.

Treatment of tension-type headache

I would like to start with headache. You are all aware that we have several new studies regarding the prevention of migraine, but very few studies involving nondrug treatments for tension-type headache.

A working group in Göttingen, Germany, conducted a study in people with frequent episodic and chronic tension-type headache. The first of the four randomized groups received traditional Chinese acupuncture for 3 months. The second group received physical therapy and exercise for 1 hour per week for 12 weeks. The third group received a combination of acupuncture and exercise. The last was a control group that received only standard care.

The outcome parameters of tension-type headache were evaluated after 6 months and again after 12 months. Previously, these same researchers published that the intensity but not the frequency of tension-type headache was reduced by active therapy.

In Cephalalgia, they published the outcome for the endpoints of depression, anxiety, and quality of life. Acupuncture, exercise, and the combination of the two improved depression, anxiety, and quality of life. This shows that nonmedical treatment is effective in people with frequent episodic and chronic tension-type headache.

Headache after COVID-19

The next study was published in Headache and discusses headache after COVID-19. In this review of published studies, more than 50% of people with COVID-19 develop headache. It is more frequent in young patients and people with preexisting primary headaches, such as migraine and tension-type headache. Prognosis is usually good, but some patients develop new, daily persistent headache, which is a major problem because treatment is unclear. We desperately need studies investigating how to treat this new, daily persistent headache after COVID-19.

SSRIs during COVID-19 infection

The next study also focuses on COVID-19. We have conflicting results from several studies suggesting that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors might be effective in people with mild COVID-19 infection. This hypothesis was tested in a study in Brazil and was published in JAMA, The study included 1,288 outpatients with mild COVID-19 who either received 50 mg of fluvoxamine twice daily for 10 days or placebo. There was no benefit of the treatment for any outcome.

Preventing dementia with antihypertensive treatment

The next study was published in the European Heart Journal and addresses the question of whether effective antihypertensive treatment in elderly persons can prevent dementia. This is a meta-analysis of five placebo-controlled trials with more than 28,000 patients. The meta-analysis clearly shows that treating hypertension in elderly patients does prevent dementia. The benefit is higher if the blood pressure is lowered by a larger amount which also stays true for elderly patients. There is no negative impact of lowering blood pressure in this population.

Antiplatelet therapy

The next study was published in Stroke and reexamines whether resumption of antiplatelet therapy should be early or late in people who had an intracerebral hemorrhage while on antiplatelet therapy. In the Taiwanese Health Registry, this was studied in 1,584 patients. The researchers divided participants into groups based on whether antiplatelet therapy was resumed within 30 days or after 30 days. In 1 year, the rate of recurrent intracerebral hemorrhage was 3.2%. There was no difference whether antiplatelet therapy was resumed early or late.

Regular exercise in Parkinson’s disease

The final study is a review of nonmedical therapy. This meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials looked at the benefit of regular exercise in patients with Parkinson’s disease and depression. The analysis clearly showed that rigorous and moderate exercise improved depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease. This is very important because exercise improves not only the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease but also comorbid depression while presenting no serious adverse events or side effects.

Dr. Diener is a professor in the department of neurology at Stroke Center–Headache Center, University Duisburg-Essen, Germany. He disclosed ties with Abbott, Addex Pharma, Alder, Allergan, Almirall, Amgen, Autonomic Technology, AstraZeneca, Bayer Vital, Berlin Chemie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chordate, CoAxia, Corimmun, Covidien, Coherex, CoLucid, Daiichi Sankyo, D-Pharm, Electrocore, Fresenius, GlaxoSmithKline, Grunenthal, Janssen-Cilag, Labrys Biologics Lilly, La Roche, Lundbeck, 3M Medica, MSD, Medtronic, Menarini, MindFrame, Minster, Neuroscore, Neurobiological Technologies, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Johnson & Johnson, Knoll, Paion, Parke-Davis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer Inc, Schaper and Brummer, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, Servier, Solvay, St. Jude, Talecris, Thrombogenics, WebMD Global, Weber and Weber, Wyeth, and Yamanouchi. Dr. Diener has served as editor of Aktuelle Neurologie, Arzneimitteltherapie, Kopfschmerz News, Stroke News, and the Treatment Guidelines of the German Neurological Society; as co-editor of Cephalalgia; and on the editorial board of The Lancet Neurology, Stroke, European Neurology, and Cerebrovascular Disorders. The department of neurology in Essen is supported by the German Research Council, the German Ministry of Education and Research, European Union, National Institutes of Health, Bertelsmann Foundation, and Heinz Nixdorf Foundation. Dr. Diener has no ownership interest and does not own stocks in any pharmaceutical company. A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dear colleagues, I am Christoph Diener from the medical faculty of the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany.

Treatment of tension-type headache

I would like to start with headache. You are all aware that we have several new studies regarding the prevention of migraine, but very few studies involving nondrug treatments for tension-type headache.

A working group in Göttingen, Germany, conducted a study in people with frequent episodic and chronic tension-type headache. The first of the four randomized groups received traditional Chinese acupuncture for 3 months. The second group received physical therapy and exercise for 1 hour per week for 12 weeks. The third group received a combination of acupuncture and exercise. The last was a control group that received only standard care.

The outcome parameters of tension-type headache were evaluated after 6 months and again after 12 months. Previously, these same researchers published that the intensity but not the frequency of tension-type headache was reduced by active therapy.

In Cephalalgia, they published the outcome for the endpoints of depression, anxiety, and quality of life. Acupuncture, exercise, and the combination of the two improved depression, anxiety, and quality of life. This shows that nonmedical treatment is effective in people with frequent episodic and chronic tension-type headache.

Headache after COVID-19

The next study was published in Headache and discusses headache after COVID-19. In this review of published studies, more than 50% of people with COVID-19 develop headache. It is more frequent in young patients and people with preexisting primary headaches, such as migraine and tension-type headache. Prognosis is usually good, but some patients develop new, daily persistent headache, which is a major problem because treatment is unclear. We desperately need studies investigating how to treat this new, daily persistent headache after COVID-19.

SSRIs during COVID-19 infection

The next study also focuses on COVID-19. We have conflicting results from several studies suggesting that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors might be effective in people with mild COVID-19 infection. This hypothesis was tested in a study in Brazil and was published in JAMA, The study included 1,288 outpatients with mild COVID-19 who either received 50 mg of fluvoxamine twice daily for 10 days or placebo. There was no benefit of the treatment for any outcome.

Preventing dementia with antihypertensive treatment

The next study was published in the European Heart Journal and addresses the question of whether effective antihypertensive treatment in elderly persons can prevent dementia. This is a meta-analysis of five placebo-controlled trials with more than 28,000 patients. The meta-analysis clearly shows that treating hypertension in elderly patients does prevent dementia. The benefit is higher if the blood pressure is lowered by a larger amount which also stays true for elderly patients. There is no negative impact of lowering blood pressure in this population.

Antiplatelet therapy

The next study was published in Stroke and reexamines whether resumption of antiplatelet therapy should be early or late in people who had an intracerebral hemorrhage while on antiplatelet therapy. In the Taiwanese Health Registry, this was studied in 1,584 patients. The researchers divided participants into groups based on whether antiplatelet therapy was resumed within 30 days or after 30 days. In 1 year, the rate of recurrent intracerebral hemorrhage was 3.2%. There was no difference whether antiplatelet therapy was resumed early or late.

Regular exercise in Parkinson’s disease

The final study is a review of nonmedical therapy. This meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials looked at the benefit of regular exercise in patients with Parkinson’s disease and depression. The analysis clearly showed that rigorous and moderate exercise improved depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease. This is very important because exercise improves not only the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease but also comorbid depression while presenting no serious adverse events or side effects.

Dr. Diener is a professor in the department of neurology at Stroke Center–Headache Center, University Duisburg-Essen, Germany. He disclosed ties with Abbott, Addex Pharma, Alder, Allergan, Almirall, Amgen, Autonomic Technology, AstraZeneca, Bayer Vital, Berlin Chemie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chordate, CoAxia, Corimmun, Covidien, Coherex, CoLucid, Daiichi Sankyo, D-Pharm, Electrocore, Fresenius, GlaxoSmithKline, Grunenthal, Janssen-Cilag, Labrys Biologics Lilly, La Roche, Lundbeck, 3M Medica, MSD, Medtronic, Menarini, MindFrame, Minster, Neuroscore, Neurobiological Technologies, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Johnson & Johnson, Knoll, Paion, Parke-Davis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer Inc, Schaper and Brummer, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, Servier, Solvay, St. Jude, Talecris, Thrombogenics, WebMD Global, Weber and Weber, Wyeth, and Yamanouchi. Dr. Diener has served as editor of Aktuelle Neurologie, Arzneimitteltherapie, Kopfschmerz News, Stroke News, and the Treatment Guidelines of the German Neurological Society; as co-editor of Cephalalgia; and on the editorial board of The Lancet Neurology, Stroke, European Neurology, and Cerebrovascular Disorders. The department of neurology in Essen is supported by the German Research Council, the German Ministry of Education and Research, European Union, National Institutes of Health, Bertelsmann Foundation, and Heinz Nixdorf Foundation. Dr. Diener has no ownership interest and does not own stocks in any pharmaceutical company. A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dear colleagues, I am Christoph Diener from the medical faculty of the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany.

Treatment of tension-type headache

I would like to start with headache. You are all aware that we have several new studies regarding the prevention of migraine, but very few studies involving nondrug treatments for tension-type headache.

A working group in Göttingen, Germany, conducted a study in people with frequent episodic and chronic tension-type headache. The first of the four randomized groups received traditional Chinese acupuncture for 3 months. The second group received physical therapy and exercise for 1 hour per week for 12 weeks. The third group received a combination of acupuncture and exercise. The last was a control group that received only standard care.

The outcome parameters of tension-type headache were evaluated after 6 months and again after 12 months. Previously, these same researchers published that the intensity but not the frequency of tension-type headache was reduced by active therapy.

In Cephalalgia, they published the outcome for the endpoints of depression, anxiety, and quality of life. Acupuncture, exercise, and the combination of the two improved depression, anxiety, and quality of life. This shows that nonmedical treatment is effective in people with frequent episodic and chronic tension-type headache.

Headache after COVID-19

The next study was published in Headache and discusses headache after COVID-19. In this review of published studies, more than 50% of people with COVID-19 develop headache. It is more frequent in young patients and people with preexisting primary headaches, such as migraine and tension-type headache. Prognosis is usually good, but some patients develop new, daily persistent headache, which is a major problem because treatment is unclear. We desperately need studies investigating how to treat this new, daily persistent headache after COVID-19.

SSRIs during COVID-19 infection

The next study also focuses on COVID-19. We have conflicting results from several studies suggesting that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors might be effective in people with mild COVID-19 infection. This hypothesis was tested in a study in Brazil and was published in JAMA, The study included 1,288 outpatients with mild COVID-19 who either received 50 mg of fluvoxamine twice daily for 10 days or placebo. There was no benefit of the treatment for any outcome.

Preventing dementia with antihypertensive treatment

The next study was published in the European Heart Journal and addresses the question of whether effective antihypertensive treatment in elderly persons can prevent dementia. This is a meta-analysis of five placebo-controlled trials with more than 28,000 patients. The meta-analysis clearly shows that treating hypertension in elderly patients does prevent dementia. The benefit is higher if the blood pressure is lowered by a larger amount which also stays true for elderly patients. There is no negative impact of lowering blood pressure in this population.

Antiplatelet therapy

The next study was published in Stroke and reexamines whether resumption of antiplatelet therapy should be early or late in people who had an intracerebral hemorrhage while on antiplatelet therapy. In the Taiwanese Health Registry, this was studied in 1,584 patients. The researchers divided participants into groups based on whether antiplatelet therapy was resumed within 30 days or after 30 days. In 1 year, the rate of recurrent intracerebral hemorrhage was 3.2%. There was no difference whether antiplatelet therapy was resumed early or late.

Regular exercise in Parkinson’s disease

The final study is a review of nonmedical therapy. This meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials looked at the benefit of regular exercise in patients with Parkinson’s disease and depression. The analysis clearly showed that rigorous and moderate exercise improved depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease. This is very important because exercise improves not only the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease but also comorbid depression while presenting no serious adverse events or side effects.

Dr. Diener is a professor in the department of neurology at Stroke Center–Headache Center, University Duisburg-Essen, Germany. He disclosed ties with Abbott, Addex Pharma, Alder, Allergan, Almirall, Amgen, Autonomic Technology, AstraZeneca, Bayer Vital, Berlin Chemie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chordate, CoAxia, Corimmun, Covidien, Coherex, CoLucid, Daiichi Sankyo, D-Pharm, Electrocore, Fresenius, GlaxoSmithKline, Grunenthal, Janssen-Cilag, Labrys Biologics Lilly, La Roche, Lundbeck, 3M Medica, MSD, Medtronic, Menarini, MindFrame, Minster, Neuroscore, Neurobiological Technologies, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Johnson & Johnson, Knoll, Paion, Parke-Davis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer Inc, Schaper and Brummer, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, Servier, Solvay, St. Jude, Talecris, Thrombogenics, WebMD Global, Weber and Weber, Wyeth, and Yamanouchi. Dr. Diener has served as editor of Aktuelle Neurologie, Arzneimitteltherapie, Kopfschmerz News, Stroke News, and the Treatment Guidelines of the German Neurological Society; as co-editor of Cephalalgia; and on the editorial board of The Lancet Neurology, Stroke, European Neurology, and Cerebrovascular Disorders. The department of neurology in Essen is supported by the German Research Council, the German Ministry of Education and Research, European Union, National Institutes of Health, Bertelsmann Foundation, and Heinz Nixdorf Foundation. Dr. Diener has no ownership interest and does not own stocks in any pharmaceutical company. A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A doctor must go to extremes to save a choking victim

Some time ago I was invited to join a bipartisan congressional task force on valley fever, also known as coccidioidomycosis. A large and diverse crowd attended the task force’s first meeting in Bakersfield, Calif. – a meeting for everyone: the medical profession, the public, it even included veterinarians.

The whole thing was a resounding success. Francis Collins was there, the just-retired director of the NIH. Tom Frieden, then-director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was there, as were several congresspeople and also my college roommate, a retired Navy medical corps captain. I was enjoying it.

Afterward, we had a banquet dinner at a restaurant in downtown Bakersfield. One of the people there was a woman I knew well – her husband was a physician friend. The restaurant served steak and salmon, and this woman made the mistake of ordering the steak.

Not long after the entrees were served, I heard a commotion at the table just behind me. I turned around and saw that woman in distress. A piece of steak had wedged in her trachea and she couldn’t breathe.

Almost immediately, the chef showed up. I don’t know how he got there. The chef at this restaurant was a big guy. I mean, probably 6 feet, 5 inches tall and 275 pounds. He tried the Heimlich maneuver. It didn’t work.

At that point, I jumped up. I thought, “Well, maybe I know how to do this better than him.” Probably not, actually. I tried and couldn’t make it work either. So I knew we were going to have to do something.

Paul Krogstad, my friend and research partner who is a pediatric infectious disease physician, stepped up and tried to put his finger in her throat and dig it out. He couldn’t get it. The patient had lost consciousness.

So, I’m thinking, okay, there’s really only one choice. You have to get an airway surgically.

I said, “We have to put her down on the floor.” And then I said, “Knife!”

I was looking at the steak knives on the table and they weren’t to my liking for doing a procedure. My college roommate – the retired Navy man – whipped out this very good pocketknife.

I had never done this in my life.

While I was making the incision, somebody gave Paul a ballpoint pen and he broke it into pieces to make a tracheostomy tube. Once I’d made the little incision, I put the tube in. She wasn’t breathing, but she still had a pulse.

I leaned forward and blew into the tube and inflated her lungs. I could see her lungs balloon up. It was a nice feeling, because I knew I was clearly in the right place.

I can’t quite explain it, but while I was doing this, I was enormously calm and totally focused. I knew there was a crowd of people around me, all looking at me, but I wasn’t conscious of that.

It was really just the four of us: Paul and Tom and me and our patient. Those were the only people that I was really cognizant of. Paul and Tom were not panic stricken at all. I remember somebody shouting, “We have to start CPR!” and Frieden said, “No. We don’t.”

Moments later, she woke up, sat up, coughed, and shot the piece of steak across the room.

She was breathing on her own, but we still taped that tube into place. Somebody had already summoned an ambulance; they were there not very long after we completed this procedure. I got in the ambulance with her and we rode over to the emergency room at Mercy Truxtun.

She was stable and doing okay. I sat with her until a thoracic surgeon showed up. He checked out the situation and decided we didn’t need that tube and took it out. I didn’t want to take that out until I had a surgeon there who could do a formal tracheostomy.

They kept her in the hospital for 3 or 4 days. Now, this woman had always had difficulties swallowing, so steak may not have been the best choice. She still had trouble swallowing afterward but recovered.

I’ve known her and her husband a long time, so it was certainly rewarding to be able to provide this service. Years later, though, when her husband died, I spoke at his funeral. When she was speaking to the gathering, she said, “And oh, by the way, Royce, thanks for saving my life.”

That surprised me. I didn’t think we were going to go there.

I’d never tried to practice medicine “at the roadside” before. But that’s part of the career.

Royce Johnson, MD, is the chief of the division of infectious disease among other leadership positions at Kern Medical in Bakersfield, Calif., and the medical director of the Valley Fever Institute.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some time ago I was invited to join a bipartisan congressional task force on valley fever, also known as coccidioidomycosis. A large and diverse crowd attended the task force’s first meeting in Bakersfield, Calif. – a meeting for everyone: the medical profession, the public, it even included veterinarians.

The whole thing was a resounding success. Francis Collins was there, the just-retired director of the NIH. Tom Frieden, then-director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was there, as were several congresspeople and also my college roommate, a retired Navy medical corps captain. I was enjoying it.

Afterward, we had a banquet dinner at a restaurant in downtown Bakersfield. One of the people there was a woman I knew well – her husband was a physician friend. The restaurant served steak and salmon, and this woman made the mistake of ordering the steak.

Not long after the entrees were served, I heard a commotion at the table just behind me. I turned around and saw that woman in distress. A piece of steak had wedged in her trachea and she couldn’t breathe.

Almost immediately, the chef showed up. I don’t know how he got there. The chef at this restaurant was a big guy. I mean, probably 6 feet, 5 inches tall and 275 pounds. He tried the Heimlich maneuver. It didn’t work.

At that point, I jumped up. I thought, “Well, maybe I know how to do this better than him.” Probably not, actually. I tried and couldn’t make it work either. So I knew we were going to have to do something.

Paul Krogstad, my friend and research partner who is a pediatric infectious disease physician, stepped up and tried to put his finger in her throat and dig it out. He couldn’t get it. The patient had lost consciousness.

So, I’m thinking, okay, there’s really only one choice. You have to get an airway surgically.

I said, “We have to put her down on the floor.” And then I said, “Knife!”

I was looking at the steak knives on the table and they weren’t to my liking for doing a procedure. My college roommate – the retired Navy man – whipped out this very good pocketknife.

I had never done this in my life.

While I was making the incision, somebody gave Paul a ballpoint pen and he broke it into pieces to make a tracheostomy tube. Once I’d made the little incision, I put the tube in. She wasn’t breathing, but she still had a pulse.

I leaned forward and blew into the tube and inflated her lungs. I could see her lungs balloon up. It was a nice feeling, because I knew I was clearly in the right place.

I can’t quite explain it, but while I was doing this, I was enormously calm and totally focused. I knew there was a crowd of people around me, all looking at me, but I wasn’t conscious of that.

It was really just the four of us: Paul and Tom and me and our patient. Those were the only people that I was really cognizant of. Paul and Tom were not panic stricken at all. I remember somebody shouting, “We have to start CPR!” and Frieden said, “No. We don’t.”

Moments later, she woke up, sat up, coughed, and shot the piece of steak across the room.

She was breathing on her own, but we still taped that tube into place. Somebody had already summoned an ambulance; they were there not very long after we completed this procedure. I got in the ambulance with her and we rode over to the emergency room at Mercy Truxtun.

She was stable and doing okay. I sat with her until a thoracic surgeon showed up. He checked out the situation and decided we didn’t need that tube and took it out. I didn’t want to take that out until I had a surgeon there who could do a formal tracheostomy.

They kept her in the hospital for 3 or 4 days. Now, this woman had always had difficulties swallowing, so steak may not have been the best choice. She still had trouble swallowing afterward but recovered.

I’ve known her and her husband a long time, so it was certainly rewarding to be able to provide this service. Years later, though, when her husband died, I spoke at his funeral. When she was speaking to the gathering, she said, “And oh, by the way, Royce, thanks for saving my life.”

That surprised me. I didn’t think we were going to go there.

I’d never tried to practice medicine “at the roadside” before. But that’s part of the career.

Royce Johnson, MD, is the chief of the division of infectious disease among other leadership positions at Kern Medical in Bakersfield, Calif., and the medical director of the Valley Fever Institute.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some time ago I was invited to join a bipartisan congressional task force on valley fever, also known as coccidioidomycosis. A large and diverse crowd attended the task force’s first meeting in Bakersfield, Calif. – a meeting for everyone: the medical profession, the public, it even included veterinarians.

The whole thing was a resounding success. Francis Collins was there, the just-retired director of the NIH. Tom Frieden, then-director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was there, as were several congresspeople and also my college roommate, a retired Navy medical corps captain. I was enjoying it.

Afterward, we had a banquet dinner at a restaurant in downtown Bakersfield. One of the people there was a woman I knew well – her husband was a physician friend. The restaurant served steak and salmon, and this woman made the mistake of ordering the steak.

Not long after the entrees were served, I heard a commotion at the table just behind me. I turned around and saw that woman in distress. A piece of steak had wedged in her trachea and she couldn’t breathe.

Almost immediately, the chef showed up. I don’t know how he got there. The chef at this restaurant was a big guy. I mean, probably 6 feet, 5 inches tall and 275 pounds. He tried the Heimlich maneuver. It didn’t work.

At that point, I jumped up. I thought, “Well, maybe I know how to do this better than him.” Probably not, actually. I tried and couldn’t make it work either. So I knew we were going to have to do something.

Paul Krogstad, my friend and research partner who is a pediatric infectious disease physician, stepped up and tried to put his finger in her throat and dig it out. He couldn’t get it. The patient had lost consciousness.

So, I’m thinking, okay, there’s really only one choice. You have to get an airway surgically.

I said, “We have to put her down on the floor.” And then I said, “Knife!”

I was looking at the steak knives on the table and they weren’t to my liking for doing a procedure. My college roommate – the retired Navy man – whipped out this very good pocketknife.

I had never done this in my life.

While I was making the incision, somebody gave Paul a ballpoint pen and he broke it into pieces to make a tracheostomy tube. Once I’d made the little incision, I put the tube in. She wasn’t breathing, but she still had a pulse.

I leaned forward and blew into the tube and inflated her lungs. I could see her lungs balloon up. It was a nice feeling, because I knew I was clearly in the right place.

I can’t quite explain it, but while I was doing this, I was enormously calm and totally focused. I knew there was a crowd of people around me, all looking at me, but I wasn’t conscious of that.

It was really just the four of us: Paul and Tom and me and our patient. Those were the only people that I was really cognizant of. Paul and Tom were not panic stricken at all. I remember somebody shouting, “We have to start CPR!” and Frieden said, “No. We don’t.”

Moments later, she woke up, sat up, coughed, and shot the piece of steak across the room.

She was breathing on her own, but we still taped that tube into place. Somebody had already summoned an ambulance; they were there not very long after we completed this procedure. I got in the ambulance with her and we rode over to the emergency room at Mercy Truxtun.

She was stable and doing okay. I sat with her until a thoracic surgeon showed up. He checked out the situation and decided we didn’t need that tube and took it out. I didn’t want to take that out until I had a surgeon there who could do a formal tracheostomy.

They kept her in the hospital for 3 or 4 days. Now, this woman had always had difficulties swallowing, so steak may not have been the best choice. She still had trouble swallowing afterward but recovered.

I’ve known her and her husband a long time, so it was certainly rewarding to be able to provide this service. Years later, though, when her husband died, I spoke at his funeral. When she was speaking to the gathering, she said, “And oh, by the way, Royce, thanks for saving my life.”

That surprised me. I didn’t think we were going to go there.

I’d never tried to practice medicine “at the roadside” before. But that’s part of the career.

Royce Johnson, MD, is the chief of the division of infectious disease among other leadership positions at Kern Medical in Bakersfield, Calif., and the medical director of the Valley Fever Institute.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Can medication management smooth the journey for families of autistic children?

Caring for a child with autism is a long haul for families and not often a smooth ride. Medications can help improve child functioning and family quality of life but the evidence may require our careful consideration.

Although I am discussing medication treatment here, the best evidence-based treatments for autism symptoms such as poor social communication and repetitive restricted behavior (RRB) are behavioral (for example, applied behavior analysis), cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and parent training. These modalities also augment the effectiveness of medications in many cases. Educational adjustments and specific therapies, when indicated, such as speech-language, occupational, and physical therapy are also beneficial.

Autism symptoms change with age from early regression, later to RRB, then depression, and they are complicated by coexisting conditions. Not surprisingly then, studying the effectiveness and side effects of medications is complex and guidance is in flux as reliable data emerge.

Because of the shortage of specialists and increasing prevalence of autism, we need to be prepared to manage, monitor, and sometimes start medications for our autistic patients. With great individual differences and the hopes and fears of distressed parents making them desperate for help, we need to be as evidence-based as possible to avoid serious side effects or delay effective behavioral treatments.

Our assistance is mainly to address the many co-occurring symptoms in autism: 37%-85% ADHD, 50% anxiety, 7.3% bipolar disorder, and 54.1% depression (by age 30). Many autistic children have problematic irritability, explosive episodes, repetitive or rigid routines, difficulty with social engagement, or trouble sleeping.

We need to be clear with families about the evidence and, whenever possible, use our own time-limited trials with placebos and objective measures that target symptoms and goals for improvement. This is complicated by that fact that the child may have trouble communicating about how they feel, have hypo- or hypersensitivity to feelings, as well as confounding coexisting conditions.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the atypical antipsychotics risperidone (ages 5-16) and aripiprazole (ages 6-17) for reducing symptoms of irritability by 25%-50% – such as agitation, stereotypy, anger outbursts, self-injurious behavior, and hyperactivity within 8 weeks. The Aberrant Behavior Checklist can be used for monitoring. These benefits are largest with behavior therapy and at doses of 1.25-1.75 mg/day (risperidone) or 2-15 mg/day (aripiprazole). Unfortunately, side effects of these medications include somnolence, increased appetite and weight gain (average of 5.1 kg), abnormal blood lipids and glucose, dyskinesia, and elevated prolactin (sometimes galactorrhea). Aripiprazole is equivalent to risperidone for irritability, has less prolactin and fewer metabolic effects, but sometimes has extrapyramidal symptoms. Other second-generation atypical antipsychotics have less evidence but may have fewer side effects. With careful monitoring, these medications can make a major difference in child behavior.

ADHD symptoms often respond to methylphenidate within 4 weeks but at a lower dose and with more side effects of irritability, social withdrawal, and emotional outbursts than for children with ADHD without autism. Formulations such as liquid (short or long acting) or dermal patch may facilitate the important small-dose adjustments and slow ramp-up we should use with checklist monitoring (for example, Vanderbilt Assessment). Atomoxetine also reduces hyperactivity, especially when used with parent training, but has associated nausea, anorexia, early awakening, and rare unpredictable liver failure. Mixed amphetamine salts have not been studied. Clonidine (oral or patch) and guanfacine extended release have also shown some effectiveness for hyperarousal, social interaction, and sleep although they can cause drowsiness/hypotension.

Sleep issues such as sleep onset, duration, and disruptions can improve with melatonin, especially combined with CBT, and it can even sometimes help with anxiety, rigidity, and communication. Use a certified brand and prevent accidental ingestion of gummy forms. Note that obstructive sleep apnea is significantly more common in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and should be evaluated if there are signs. The Childhood Sleep Questionnaire can be used to monitor.

There aren’t data available for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treating depression and anxiety in autistic children but CBT may help. Buspirone improved RRB (at 2.5 mg b.i.d.) but did not help mood. Mood-stabilizing antiepileptics have had mixed results (valproate reduced irritability but with serious side effects), no benefits (lamotrigine and levetiracetam), or no trials (lithium, oxcarbazepine, and topiramate). In spite of this, a Cochrane report recommends antidepressants “on a case by case basis” for children with ASD, keeping in mind the higher risks of behavioral activation (consider comorbid bipolar disorder), irritability, akathisia, and sleep disturbance. We can monitor with Short Moods and Feelings Questionnaire and Problem Behavior Checklist.

NMDA and GABA receptors are implicated in the genesis of ASD. Bumetanide, a GABA modulator, at 1 mg b.i.d., improved social communication and restricted interests, but had dose-related hypokalemia, increased urination, dehydration, loss of appetite, and asthenia. Donepezil (cholinesterase inhibitor) in small studies improved autism scores and expressive/receptive language. N-acetylcysteine, D-cycloserine, and arbaclofen did not show efficacy.

Currently, 64% of children with ASD are prescribed one psychotropic medication, 35% more than two classes, and 15% more than three. While we may look askance at polypharmacy, several medications not effective as monotherapy for children with ASD have significant effects in combination with risperidone; notably memantine, riluzole, N-acetylcysteine, amantadine, topiramate, and buspirone, compared with placebo. Memantine alone has shown benefits in 60% of autistic patients on social, language, and self-stimulatory behaviors at 2.5-30 mg; effective enough that 80% chose continuation.