User login

Joint effort: CBD not just innocent bystander in weed

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I visited a legal cannabis dispensary in Massachusetts a few years ago, mostly to see what the hype was about. There I was, knowing basically nothing about pot, as the gentle stoner behind the counter explained to me the differences between the various strains. Acapulco Gold is buoyant and energizing; Purple Kush is sleepy, relaxed, dissociative. Here’s a strain that makes you feel nostalgic; here’s one that helps you focus. It was as complicated and as oddly specific as a fancy wine tasting – and, I had a feeling, about as reliable.

It’s a plant, after all, and though delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical responsible for its euphoric effects, it is far from the only substance in there.

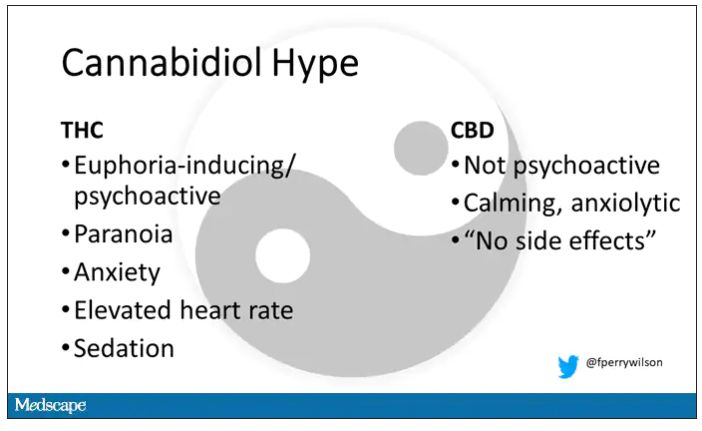

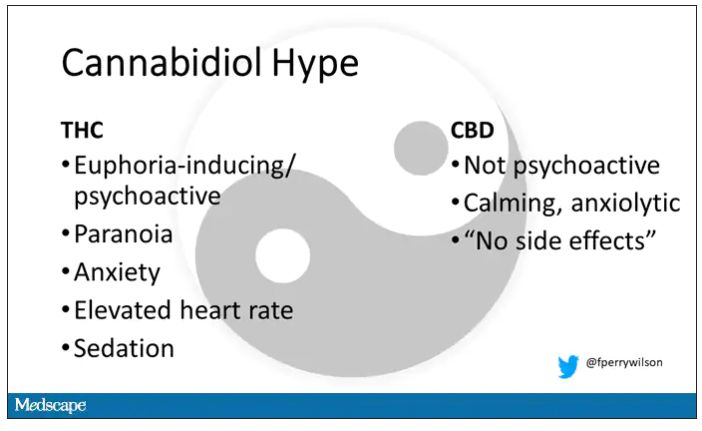

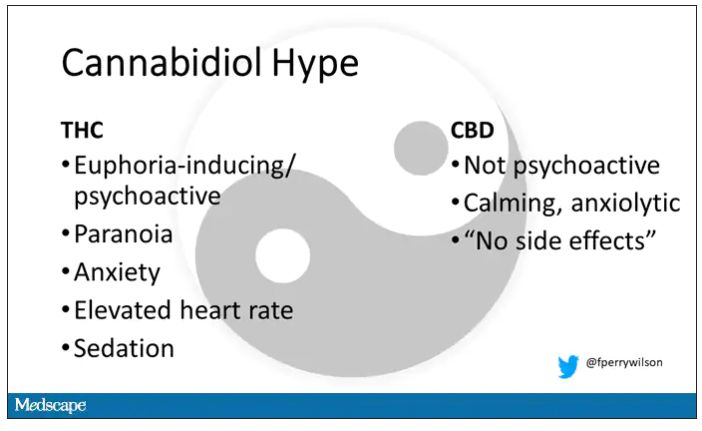

The second most important compound in cannabis is cannabidiol, and most people will tell you that CBD is the gentle yin to THC’s paranoiac yang. Hence your local ganja barista reminding you that, if you don›t want all those anxiety-inducing side effects of THC, grab a strain with a nice CBD balance.

But is it true? A new study appearing in JAMA Network Open suggests, in fact, that it’s quite the opposite. This study is from Austin Zamarripa and colleagues, who clearly sit at the researcher cool kids table.

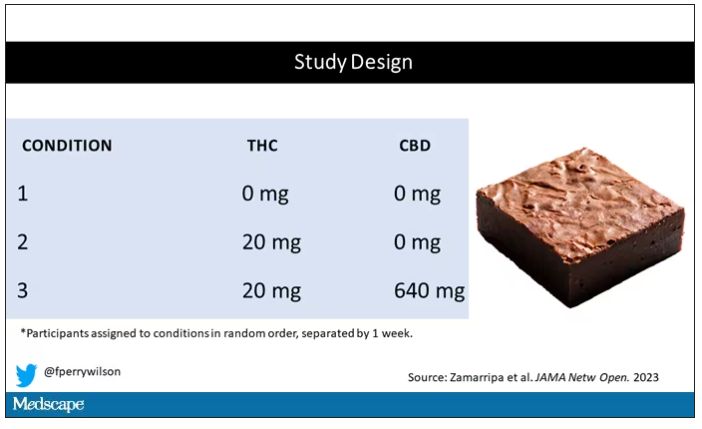

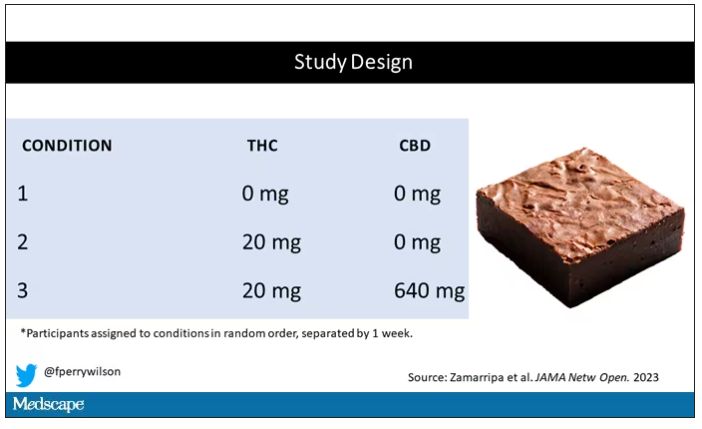

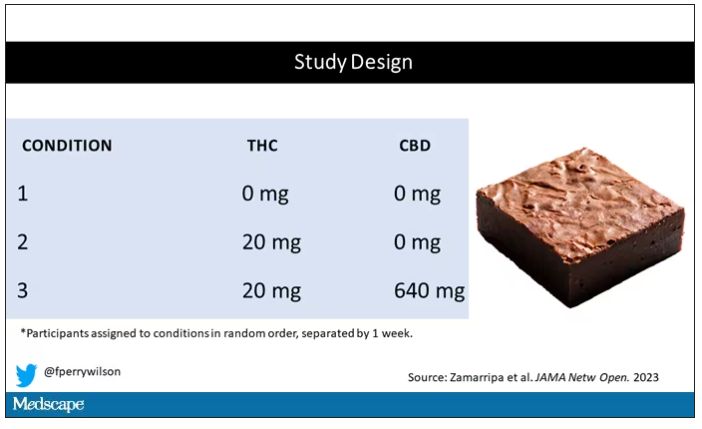

Eighteen adults who had abstained from marijuana use for at least a month participated in this trial (which is way more fun than anything we do in my lab at Yale). In random order, separated by at least a week, they ate some special brownies.

Condition one was a control brownie, condition two was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC, and condition three was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC and 640 mg of CBD. Participants were assigned each condition in random order, separated by at least a week.

A side note on doses for those of you who, like me, are not totally weed literate. A dose of 20 mg of THC is about a third of what you might find in a typical joint these days (though it’s about double the THC content of a joint in the ‘70s – I believe the technical term is “doobie”). And 640 mg of CBD is a decent dose, as 5 mg per kilogram is what some folks start with to achieve therapeutic effects.

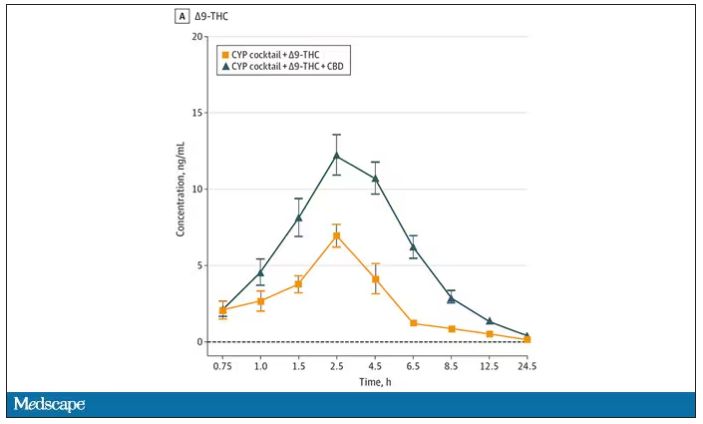

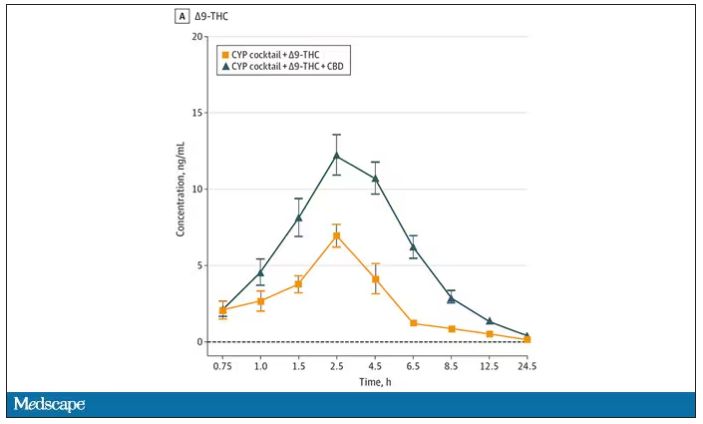

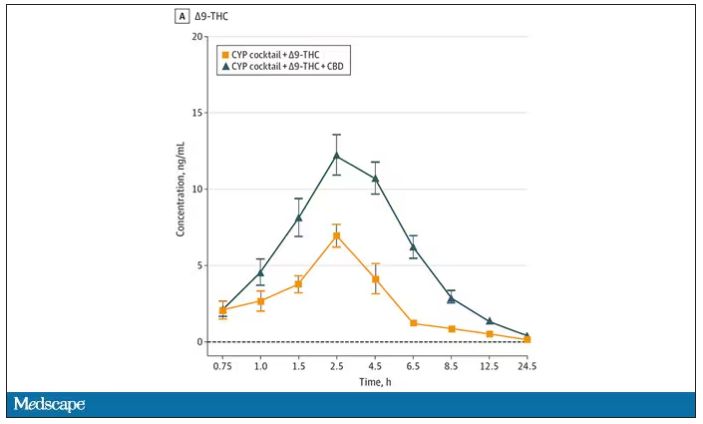

Both THC and CBD interact with the cytochrome p450 system in the liver. This matters when you’re ingesting them instead of smoking them because you have first-pass metabolism to contend with. And, because of that p450 inhibition, it’s possible that CBD might actually increase the amount of THC that gets into your bloodstream from the brownie, or gummy, or pizza sauce, or whatever.

Let’s get to the results, starting with blood THC concentration. It’s not subtle. With CBD on board the THC concentration rises higher faster, with roughly double the area under the curve.

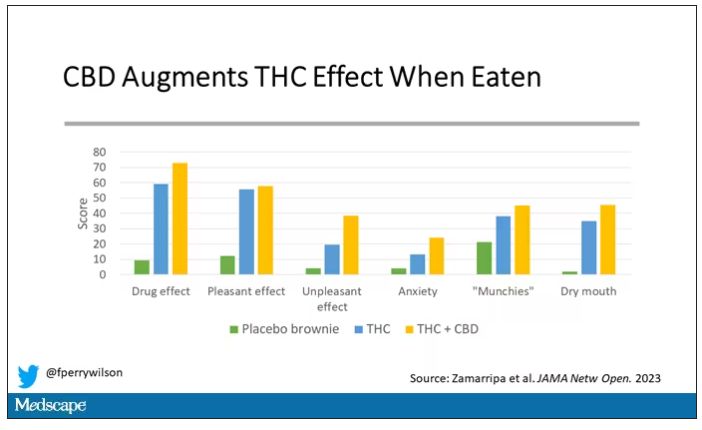

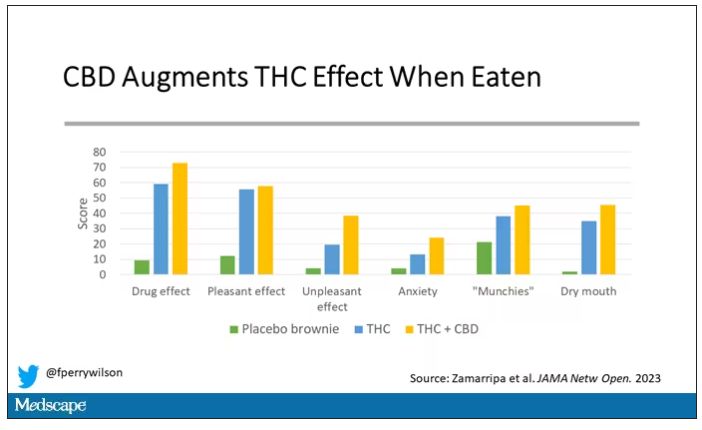

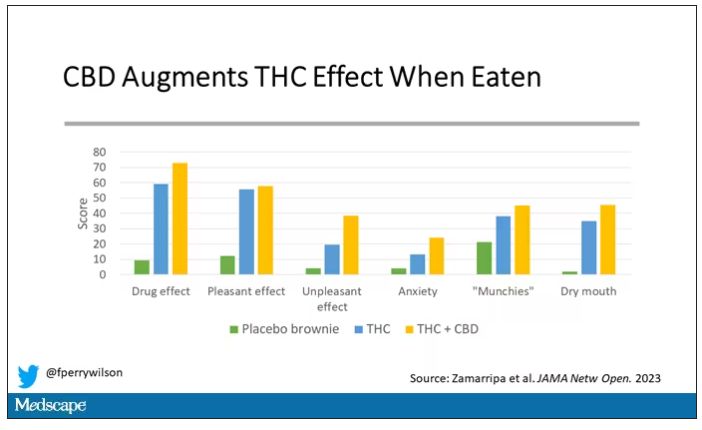

And, unsurprisingly, the subjective experience correlated with those higher levels. Individuals rated the “drug effect” higher with the combo. But, interestingly, the “pleasant” drug effect didn’t change much, while the unpleasant effects were substantially higher. No mitigation of THC anxiety here – quite the opposite. CBD made the anxiety worse.

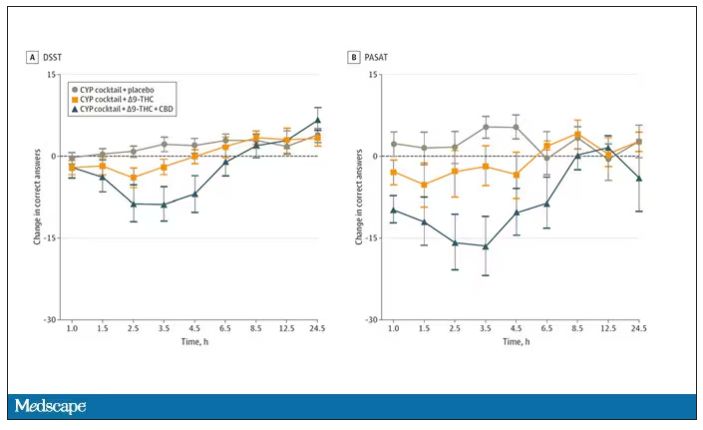

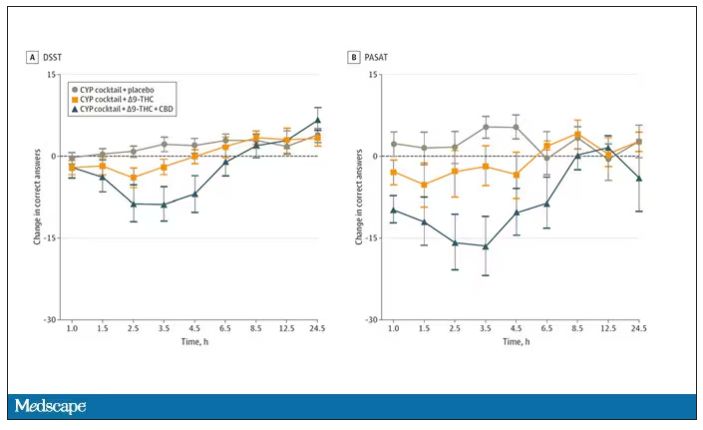

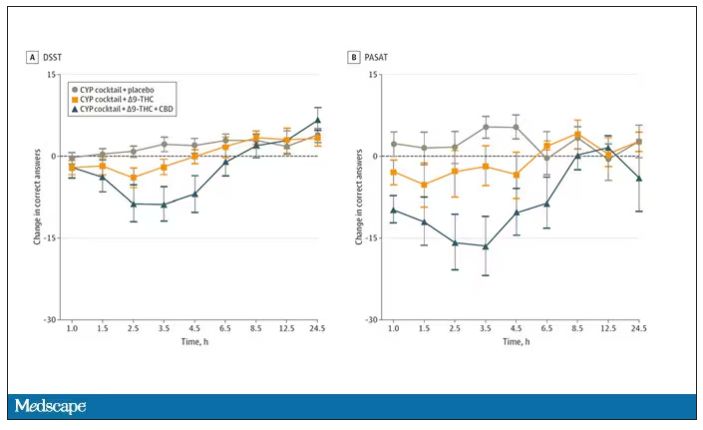

Cognitive effects were equally profound. Scores on a digit symbol substitution test and a paced serial addition task were all substantially worse when CBD was mixed with THC.

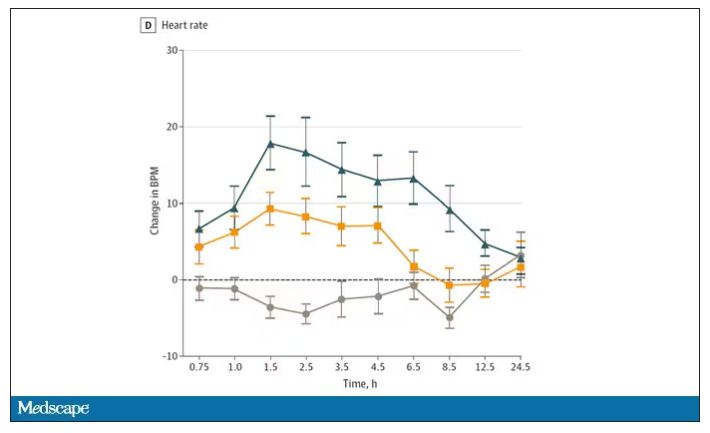

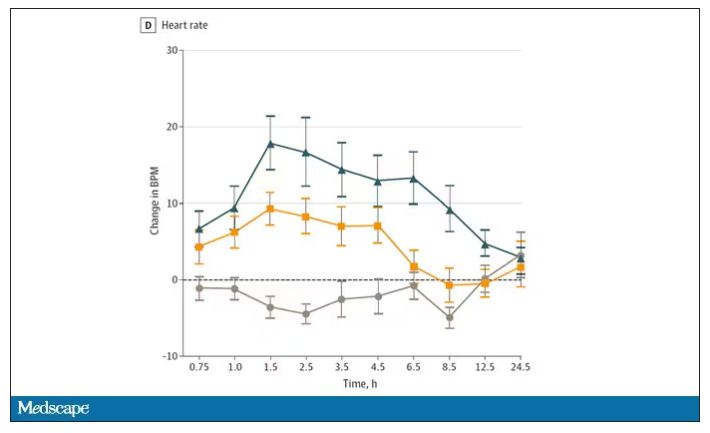

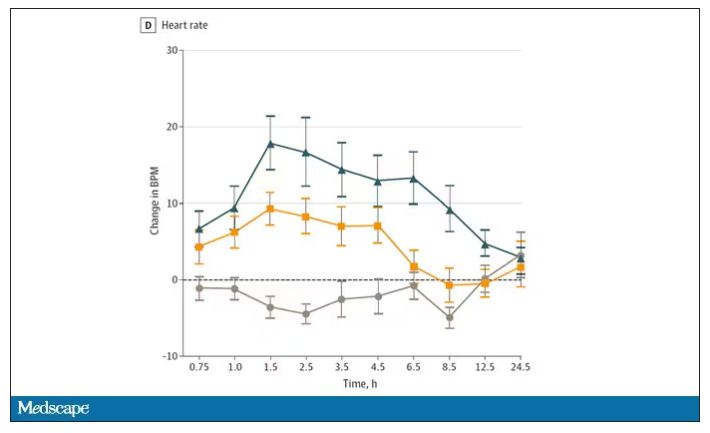

And for those of you who want some more objective measures, check out the heart rate. Despite the purported “calming” nature of CBD, heart rates were way higher when individuals were exposed to both chemicals.

The picture here is quite clear, though the mechanism is not. At least when talking edibles, CBD enhances the effects of THC, and not necessarily for the better. It may be that CBD is competing with some of the proteins that metabolize THC, thus prolonging its effects. CBD may also directly inhibit those enzymes. But whatever the case, I think we can safely say the myth that CBD makes the effects of THC more mild or more tolerable is busted.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I visited a legal cannabis dispensary in Massachusetts a few years ago, mostly to see what the hype was about. There I was, knowing basically nothing about pot, as the gentle stoner behind the counter explained to me the differences between the various strains. Acapulco Gold is buoyant and energizing; Purple Kush is sleepy, relaxed, dissociative. Here’s a strain that makes you feel nostalgic; here’s one that helps you focus. It was as complicated and as oddly specific as a fancy wine tasting – and, I had a feeling, about as reliable.

It’s a plant, after all, and though delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical responsible for its euphoric effects, it is far from the only substance in there.

The second most important compound in cannabis is cannabidiol, and most people will tell you that CBD is the gentle yin to THC’s paranoiac yang. Hence your local ganja barista reminding you that, if you don›t want all those anxiety-inducing side effects of THC, grab a strain with a nice CBD balance.

But is it true? A new study appearing in JAMA Network Open suggests, in fact, that it’s quite the opposite. This study is from Austin Zamarripa and colleagues, who clearly sit at the researcher cool kids table.

Eighteen adults who had abstained from marijuana use for at least a month participated in this trial (which is way more fun than anything we do in my lab at Yale). In random order, separated by at least a week, they ate some special brownies.

Condition one was a control brownie, condition two was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC, and condition three was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC and 640 mg of CBD. Participants were assigned each condition in random order, separated by at least a week.

A side note on doses for those of you who, like me, are not totally weed literate. A dose of 20 mg of THC is about a third of what you might find in a typical joint these days (though it’s about double the THC content of a joint in the ‘70s – I believe the technical term is “doobie”). And 640 mg of CBD is a decent dose, as 5 mg per kilogram is what some folks start with to achieve therapeutic effects.

Both THC and CBD interact with the cytochrome p450 system in the liver. This matters when you’re ingesting them instead of smoking them because you have first-pass metabolism to contend with. And, because of that p450 inhibition, it’s possible that CBD might actually increase the amount of THC that gets into your bloodstream from the brownie, or gummy, or pizza sauce, or whatever.

Let’s get to the results, starting with blood THC concentration. It’s not subtle. With CBD on board the THC concentration rises higher faster, with roughly double the area under the curve.

And, unsurprisingly, the subjective experience correlated with those higher levels. Individuals rated the “drug effect” higher with the combo. But, interestingly, the “pleasant” drug effect didn’t change much, while the unpleasant effects were substantially higher. No mitigation of THC anxiety here – quite the opposite. CBD made the anxiety worse.

Cognitive effects were equally profound. Scores on a digit symbol substitution test and a paced serial addition task were all substantially worse when CBD was mixed with THC.

And for those of you who want some more objective measures, check out the heart rate. Despite the purported “calming” nature of CBD, heart rates were way higher when individuals were exposed to both chemicals.

The picture here is quite clear, though the mechanism is not. At least when talking edibles, CBD enhances the effects of THC, and not necessarily for the better. It may be that CBD is competing with some of the proteins that metabolize THC, thus prolonging its effects. CBD may also directly inhibit those enzymes. But whatever the case, I think we can safely say the myth that CBD makes the effects of THC more mild or more tolerable is busted.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I visited a legal cannabis dispensary in Massachusetts a few years ago, mostly to see what the hype was about. There I was, knowing basically nothing about pot, as the gentle stoner behind the counter explained to me the differences between the various strains. Acapulco Gold is buoyant and energizing; Purple Kush is sleepy, relaxed, dissociative. Here’s a strain that makes you feel nostalgic; here’s one that helps you focus. It was as complicated and as oddly specific as a fancy wine tasting – and, I had a feeling, about as reliable.

It’s a plant, after all, and though delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical responsible for its euphoric effects, it is far from the only substance in there.

The second most important compound in cannabis is cannabidiol, and most people will tell you that CBD is the gentle yin to THC’s paranoiac yang. Hence your local ganja barista reminding you that, if you don›t want all those anxiety-inducing side effects of THC, grab a strain with a nice CBD balance.

But is it true? A new study appearing in JAMA Network Open suggests, in fact, that it’s quite the opposite. This study is from Austin Zamarripa and colleagues, who clearly sit at the researcher cool kids table.

Eighteen adults who had abstained from marijuana use for at least a month participated in this trial (which is way more fun than anything we do in my lab at Yale). In random order, separated by at least a week, they ate some special brownies.

Condition one was a control brownie, condition two was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC, and condition three was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC and 640 mg of CBD. Participants were assigned each condition in random order, separated by at least a week.

A side note on doses for those of you who, like me, are not totally weed literate. A dose of 20 mg of THC is about a third of what you might find in a typical joint these days (though it’s about double the THC content of a joint in the ‘70s – I believe the technical term is “doobie”). And 640 mg of CBD is a decent dose, as 5 mg per kilogram is what some folks start with to achieve therapeutic effects.

Both THC and CBD interact with the cytochrome p450 system in the liver. This matters when you’re ingesting them instead of smoking them because you have first-pass metabolism to contend with. And, because of that p450 inhibition, it’s possible that CBD might actually increase the amount of THC that gets into your bloodstream from the brownie, or gummy, or pizza sauce, or whatever.

Let’s get to the results, starting with blood THC concentration. It’s not subtle. With CBD on board the THC concentration rises higher faster, with roughly double the area under the curve.

And, unsurprisingly, the subjective experience correlated with those higher levels. Individuals rated the “drug effect” higher with the combo. But, interestingly, the “pleasant” drug effect didn’t change much, while the unpleasant effects were substantially higher. No mitigation of THC anxiety here – quite the opposite. CBD made the anxiety worse.

Cognitive effects were equally profound. Scores on a digit symbol substitution test and a paced serial addition task were all substantially worse when CBD was mixed with THC.

And for those of you who want some more objective measures, check out the heart rate. Despite the purported “calming” nature of CBD, heart rates were way higher when individuals were exposed to both chemicals.

The picture here is quite clear, though the mechanism is not. At least when talking edibles, CBD enhances the effects of THC, and not necessarily for the better. It may be that CBD is competing with some of the proteins that metabolize THC, thus prolonging its effects. CBD may also directly inhibit those enzymes. But whatever the case, I think we can safely say the myth that CBD makes the effects of THC more mild or more tolerable is busted.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The 5-year survival rate for pancreatic cancer is increasing

John Whyte, MD: Hello, I’m Dr. John Whyte, the Chief Medical Officer of WebMD. One of those cancers was pancreatic cancer, which historically has had a very low survival rate. What’s going on here? Are we doing better with diagnosis, treatment, a combination?

Joining me today is Dr. Lynn Matrisian. She is PanCAN’s chief science officer. Dr. Matrisian, thanks for joining me today. It’s great to see you.

Lynn Matrisian, PhD, MBA: Great to be here. Thank you.

Dr. Whyte: Well, tell me what your first reaction was when you saw the recent data from the American Cancer Society. What one word would you use?

Dr. Matrisian: Hopeful. I think hopeful in general that survival rates are increasing, not for all cancers, but for many cancers. We continue to make progress. Research is making a difference. And we’re making progress against cancer in general.

Dr. Whyte: You’re passionate, as our viewers know, about pancreatic cancer. And that’s been one of the hardest cancers to treat, and one of the lowest survival rates. But there’s some encouraging news that we saw, didn’t we?

Dr. Matrisian: Yes. So the 5-year survival rate for pancreatic cancer went up a whole percentage. It’s at 12% now. And what’s really good is it was at 11% last year. It was at 10% the year before. So that’s 2 years in a row that we’ve had an increase in the 5-year survival rate for pancreatic cancer. So we’re hopeful that’s a trajectory that we can really capitalize on is how fast we’re making progress in this disease.

Dr. Whyte: I want to put it into context, Lynn. Because some people might be thinking, 1%? Like you’re excited about 1%? That doesn’t seem that much. But correct me if I’m wrong. A one percentage point increase means 641 more loved ones will enjoy life’s moments, as you put it, 5 years after their diagnosis that otherwise wouldn’t have. What does that practically mean to viewers?

Dr. Matrisian: That means that more than 600 people in the United States will hug a loved one 5 years after that diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. It is a very deadly disease. But we’re going to, by continuing to make progress, it gives those moments to those people. And it means that we’re making progress against the disease in general.

Dr. Whyte: So even 1%, and 1% each year, does have value.

Dr. Matrisian: It has a lot of value.

Dr. Whyte: What’s driving this improvement? Is it better screening? And we’re not so great still in screening a pancreatic cancer. Is it the innovation in cancer treatments? What do you think is accounting for what we hope is this trajectory of increases in 5-year survival?

Dr. Matrisian: Right, so the nice thing the reason that we like looking at 5-year survival rates is because it takes into account all of those things. And we have actually made progress in all of those things. So by looking at those that are diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in general as a whole, and looking at their survival, we are looking at better treatments. People who are getting pancreatic cancer later are living longer as a result of better treatments.

But it’s not just that. It’s also, if you’re diagnosed earlier, your 5-year survival rate is higher. More people who are diagnosed early live to five years than those that are diagnosed later. So within that statistic, there are more people who are diagnosed earlier. And those people also live longer. So it takes into account all of those things, which is why we really like to look at that five-year survival rate for a disease like pancreatic cancer.

Dr. Whyte: Where are we on screening? Because we always want to catch people early. That gives them that greatest chance of survival. Have we made much improvements there? And if we have, what are they?

Dr. Matrisian: Well we have made improvements there are more people that are now diagnosed with localized disease than there were 20 years ago. So that is increasing. And we’re still doing it really by being aware of the symptoms right now. Being aware that kind of chronic indigestion, lower back pain that won’t go away, these are signs and symptoms. And especially things like jaundice ...

Dr. Whyte: That yellow color that they might see.

Dr. Matrisian: Yes, that yellow colors in your eye, that’s a really important symptom that would certainly send people to the doctor in order to look at this. So some of it is being more aware and finding the disease earlier. But what we’re really hoping for is some sort of blood test or some sort of other way of looking through medical records and identifying those people that need to go and be checked.

Dr. Whyte: Now we chatted about that almost two years ago. So tell me the progress that we’ve made. How are we doing?

Dr. Matrisian: Yeah, well there’s a number of companies now that have blood tests that are available. They still need more work. They still need more studies to really understand how good they are at finding pancreatic cancer early. But we didn’t have them a couple of years ago. And so it’s really a very exciting time in the field, that there’s companies that were taking advantage of research for many years and actually turning it into a commercial product that is available for people to check.

Dr. Whyte: And then what about treatments? More treatment options today than there were just a few years ago, but still a lot of progress to be made. So when we talk about even 12% 5-year survival, we’d love to see it much more. And you talk about, I don’t want to misquote, so correct me if I’m wrong. Your goal is 20%. Five-year survival by 2030. That’s not too far. So, Lynn, how are we going to get there?

Dr. Matrisian: Okay, well this is our mission. And that’s exactly our goal, 20% by 2030. So we’ve got some work to do. And we are working at both fronts. You’re right, we need better treatments. And so we’ve set up a clinical trial platform where we can look at a lot of different treatments much more efficiently, much faster, kind of taking advantage of an infrastructure to do that. And that’s called Precision Promise. And we’re excited about that as a way to get new treatments for advanced pancreatic cancer.

And then we’re also working on the early detection end. We think an important symptom of pancreatic cancer that isn’t often recognized is new onset diabetes, sudden diabetes in those over 50 where that person did not have diabetes before. So it’s new, looks like type 2 diabetes, but it’s actually caused by pancreatic cancer.

And so we have an initiative, The Early Detection Initiative, that is taking advantage of that. And seeing if we image people right away based on that symptom, can we find pancreatic cancer early? So we think it’s important to look both at trying to diagnose it earlier, as well as trying to treat it better for advanced disease.

Dr. Whyte: Yeah. You know, at WebMD we’re always trying to empower people with better information so they can also become advocates for their health. You’re an expert in advocacy on pancreatic cancer. So what’s your advice to listeners as to how they become good advocates for themselves or advocates in general for loved ones who have pancreatic cancer?

Dr. Matrisian: Yeah. Yeah. Well certainly, knowledge is power. And so the real thing to do is to call the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network. This is what we do. We stay up on the most current information. We have very experienced case managers who can help navigate the complexities of pancreatic cancer at every stage of the journey.

Or if you have questions about pancreatic cancer, call PanCAN. Go to PanCAN.org and give us a call. Because it’s really that knowledge, knowing what it is that you need to get more knowledge about, how to advocate for yourself is very important in a disease, in any disease, but in particular a disease like pancreatic cancer.

Dr. Whyte: And I don’t want to dismiss the progress that we’ve made, that you’ve just referenced in terms of the increased survival. But there’s still a long way to go. We need a lot more dollars for research. We need a lot more clinical trials to take place. What’s your message to a viewer who’s been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer or a loved one? What’s your message, Lynn, today for them?

Dr. Matrisian: Well, first, get as much knowledge as you can. Call PanCAN, and let us help you help your loved one. But then help us. Let’s do research. Let’s do more research. Let’s understand this disease better so we can make those kinds of progress in both treatment and early detection.

And PanCAN works very hard at understanding the disease and setting up research programs that are going to make a difference, that are going to get us to that aggressive goal of 20% survival by 2030. So there is a lot of things that can be done, raise awareness to your friends and neighbors about the disease, lots of things that will help this whole field.

Dr. Whyte: What’s your feeling on second opinions? Given that this can be a difficult cancer to treat, given that there’s emerging therapies that are always developing, when you have a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, is it important to consider getting a second opinion?

Dr. Matrisian: Yes. Yes, it is. And our case managers will help with that process. We do think it’s important.

Dr. Whyte: Because sometimes, Lynn, people just want to get started, right? Get it out of me. Get treatment. And sometimes getting a second opinion, doing some genomic testing can take time. So what’s your response to that?

Dr. Matrisian: Yeah. Yeah. Well we say, your care team is very important. Who is on your care team, and it may take a little time to find the right people on your care team. But that is an incredibly important step. Sometimes it’s not just one person. Sometimes you need more than one doctor, more than one nurse, more than one type of specialty to help you deal with this. And taking the time to do that is incredibly important.

Yes, you need to – you do need to act. But act smart. And do it with knowledge. Do it really understanding what your options are, and advocate for yourself.

Dr. Whyte: And surround yourself as you reference with that right care team for you, because that’s the most important thing when you have any type of cancer diagnosis. Dr. Lynn Matrisian, I want to thank you for taking time today.

Dr. Matrisian: Thank you so much, John.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

John Whyte, MD: Hello, I’m Dr. John Whyte, the Chief Medical Officer of WebMD. One of those cancers was pancreatic cancer, which historically has had a very low survival rate. What’s going on here? Are we doing better with diagnosis, treatment, a combination?

Joining me today is Dr. Lynn Matrisian. She is PanCAN’s chief science officer. Dr. Matrisian, thanks for joining me today. It’s great to see you.

Lynn Matrisian, PhD, MBA: Great to be here. Thank you.

Dr. Whyte: Well, tell me what your first reaction was when you saw the recent data from the American Cancer Society. What one word would you use?

Dr. Matrisian: Hopeful. I think hopeful in general that survival rates are increasing, not for all cancers, but for many cancers. We continue to make progress. Research is making a difference. And we’re making progress against cancer in general.

Dr. Whyte: You’re passionate, as our viewers know, about pancreatic cancer. And that’s been one of the hardest cancers to treat, and one of the lowest survival rates. But there’s some encouraging news that we saw, didn’t we?

Dr. Matrisian: Yes. So the 5-year survival rate for pancreatic cancer went up a whole percentage. It’s at 12% now. And what’s really good is it was at 11% last year. It was at 10% the year before. So that’s 2 years in a row that we’ve had an increase in the 5-year survival rate for pancreatic cancer. So we’re hopeful that’s a trajectory that we can really capitalize on is how fast we’re making progress in this disease.

Dr. Whyte: I want to put it into context, Lynn. Because some people might be thinking, 1%? Like you’re excited about 1%? That doesn’t seem that much. But correct me if I’m wrong. A one percentage point increase means 641 more loved ones will enjoy life’s moments, as you put it, 5 years after their diagnosis that otherwise wouldn’t have. What does that practically mean to viewers?

Dr. Matrisian: That means that more than 600 people in the United States will hug a loved one 5 years after that diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. It is a very deadly disease. But we’re going to, by continuing to make progress, it gives those moments to those people. And it means that we’re making progress against the disease in general.

Dr. Whyte: So even 1%, and 1% each year, does have value.

Dr. Matrisian: It has a lot of value.

Dr. Whyte: What’s driving this improvement? Is it better screening? And we’re not so great still in screening a pancreatic cancer. Is it the innovation in cancer treatments? What do you think is accounting for what we hope is this trajectory of increases in 5-year survival?

Dr. Matrisian: Right, so the nice thing the reason that we like looking at 5-year survival rates is because it takes into account all of those things. And we have actually made progress in all of those things. So by looking at those that are diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in general as a whole, and looking at their survival, we are looking at better treatments. People who are getting pancreatic cancer later are living longer as a result of better treatments.

But it’s not just that. It’s also, if you’re diagnosed earlier, your 5-year survival rate is higher. More people who are diagnosed early live to five years than those that are diagnosed later. So within that statistic, there are more people who are diagnosed earlier. And those people also live longer. So it takes into account all of those things, which is why we really like to look at that five-year survival rate for a disease like pancreatic cancer.

Dr. Whyte: Where are we on screening? Because we always want to catch people early. That gives them that greatest chance of survival. Have we made much improvements there? And if we have, what are they?

Dr. Matrisian: Well we have made improvements there are more people that are now diagnosed with localized disease than there were 20 years ago. So that is increasing. And we’re still doing it really by being aware of the symptoms right now. Being aware that kind of chronic indigestion, lower back pain that won’t go away, these are signs and symptoms. And especially things like jaundice ...

Dr. Whyte: That yellow color that they might see.

Dr. Matrisian: Yes, that yellow colors in your eye, that’s a really important symptom that would certainly send people to the doctor in order to look at this. So some of it is being more aware and finding the disease earlier. But what we’re really hoping for is some sort of blood test or some sort of other way of looking through medical records and identifying those people that need to go and be checked.

Dr. Whyte: Now we chatted about that almost two years ago. So tell me the progress that we’ve made. How are we doing?

Dr. Matrisian: Yeah, well there’s a number of companies now that have blood tests that are available. They still need more work. They still need more studies to really understand how good they are at finding pancreatic cancer early. But we didn’t have them a couple of years ago. And so it’s really a very exciting time in the field, that there’s companies that were taking advantage of research for many years and actually turning it into a commercial product that is available for people to check.

Dr. Whyte: And then what about treatments? More treatment options today than there were just a few years ago, but still a lot of progress to be made. So when we talk about even 12% 5-year survival, we’d love to see it much more. And you talk about, I don’t want to misquote, so correct me if I’m wrong. Your goal is 20%. Five-year survival by 2030. That’s not too far. So, Lynn, how are we going to get there?

Dr. Matrisian: Okay, well this is our mission. And that’s exactly our goal, 20% by 2030. So we’ve got some work to do. And we are working at both fronts. You’re right, we need better treatments. And so we’ve set up a clinical trial platform where we can look at a lot of different treatments much more efficiently, much faster, kind of taking advantage of an infrastructure to do that. And that’s called Precision Promise. And we’re excited about that as a way to get new treatments for advanced pancreatic cancer.

And then we’re also working on the early detection end. We think an important symptom of pancreatic cancer that isn’t often recognized is new onset diabetes, sudden diabetes in those over 50 where that person did not have diabetes before. So it’s new, looks like type 2 diabetes, but it’s actually caused by pancreatic cancer.

And so we have an initiative, The Early Detection Initiative, that is taking advantage of that. And seeing if we image people right away based on that symptom, can we find pancreatic cancer early? So we think it’s important to look both at trying to diagnose it earlier, as well as trying to treat it better for advanced disease.

Dr. Whyte: Yeah. You know, at WebMD we’re always trying to empower people with better information so they can also become advocates for their health. You’re an expert in advocacy on pancreatic cancer. So what’s your advice to listeners as to how they become good advocates for themselves or advocates in general for loved ones who have pancreatic cancer?

Dr. Matrisian: Yeah. Yeah. Well certainly, knowledge is power. And so the real thing to do is to call the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network. This is what we do. We stay up on the most current information. We have very experienced case managers who can help navigate the complexities of pancreatic cancer at every stage of the journey.

Or if you have questions about pancreatic cancer, call PanCAN. Go to PanCAN.org and give us a call. Because it’s really that knowledge, knowing what it is that you need to get more knowledge about, how to advocate for yourself is very important in a disease, in any disease, but in particular a disease like pancreatic cancer.

Dr. Whyte: And I don’t want to dismiss the progress that we’ve made, that you’ve just referenced in terms of the increased survival. But there’s still a long way to go. We need a lot more dollars for research. We need a lot more clinical trials to take place. What’s your message to a viewer who’s been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer or a loved one? What’s your message, Lynn, today for them?

Dr. Matrisian: Well, first, get as much knowledge as you can. Call PanCAN, and let us help you help your loved one. But then help us. Let’s do research. Let’s do more research. Let’s understand this disease better so we can make those kinds of progress in both treatment and early detection.

And PanCAN works very hard at understanding the disease and setting up research programs that are going to make a difference, that are going to get us to that aggressive goal of 20% survival by 2030. So there is a lot of things that can be done, raise awareness to your friends and neighbors about the disease, lots of things that will help this whole field.

Dr. Whyte: What’s your feeling on second opinions? Given that this can be a difficult cancer to treat, given that there’s emerging therapies that are always developing, when you have a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, is it important to consider getting a second opinion?

Dr. Matrisian: Yes. Yes, it is. And our case managers will help with that process. We do think it’s important.

Dr. Whyte: Because sometimes, Lynn, people just want to get started, right? Get it out of me. Get treatment. And sometimes getting a second opinion, doing some genomic testing can take time. So what’s your response to that?

Dr. Matrisian: Yeah. Yeah. Well we say, your care team is very important. Who is on your care team, and it may take a little time to find the right people on your care team. But that is an incredibly important step. Sometimes it’s not just one person. Sometimes you need more than one doctor, more than one nurse, more than one type of specialty to help you deal with this. And taking the time to do that is incredibly important.

Yes, you need to – you do need to act. But act smart. And do it with knowledge. Do it really understanding what your options are, and advocate for yourself.

Dr. Whyte: And surround yourself as you reference with that right care team for you, because that’s the most important thing when you have any type of cancer diagnosis. Dr. Lynn Matrisian, I want to thank you for taking time today.

Dr. Matrisian: Thank you so much, John.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

John Whyte, MD: Hello, I’m Dr. John Whyte, the Chief Medical Officer of WebMD. One of those cancers was pancreatic cancer, which historically has had a very low survival rate. What’s going on here? Are we doing better with diagnosis, treatment, a combination?

Joining me today is Dr. Lynn Matrisian. She is PanCAN’s chief science officer. Dr. Matrisian, thanks for joining me today. It’s great to see you.

Lynn Matrisian, PhD, MBA: Great to be here. Thank you.

Dr. Whyte: Well, tell me what your first reaction was when you saw the recent data from the American Cancer Society. What one word would you use?

Dr. Matrisian: Hopeful. I think hopeful in general that survival rates are increasing, not for all cancers, but for many cancers. We continue to make progress. Research is making a difference. And we’re making progress against cancer in general.

Dr. Whyte: You’re passionate, as our viewers know, about pancreatic cancer. And that’s been one of the hardest cancers to treat, and one of the lowest survival rates. But there’s some encouraging news that we saw, didn’t we?

Dr. Matrisian: Yes. So the 5-year survival rate for pancreatic cancer went up a whole percentage. It’s at 12% now. And what’s really good is it was at 11% last year. It was at 10% the year before. So that’s 2 years in a row that we’ve had an increase in the 5-year survival rate for pancreatic cancer. So we’re hopeful that’s a trajectory that we can really capitalize on is how fast we’re making progress in this disease.

Dr. Whyte: I want to put it into context, Lynn. Because some people might be thinking, 1%? Like you’re excited about 1%? That doesn’t seem that much. But correct me if I’m wrong. A one percentage point increase means 641 more loved ones will enjoy life’s moments, as you put it, 5 years after their diagnosis that otherwise wouldn’t have. What does that practically mean to viewers?

Dr. Matrisian: That means that more than 600 people in the United States will hug a loved one 5 years after that diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. It is a very deadly disease. But we’re going to, by continuing to make progress, it gives those moments to those people. And it means that we’re making progress against the disease in general.

Dr. Whyte: So even 1%, and 1% each year, does have value.

Dr. Matrisian: It has a lot of value.

Dr. Whyte: What’s driving this improvement? Is it better screening? And we’re not so great still in screening a pancreatic cancer. Is it the innovation in cancer treatments? What do you think is accounting for what we hope is this trajectory of increases in 5-year survival?

Dr. Matrisian: Right, so the nice thing the reason that we like looking at 5-year survival rates is because it takes into account all of those things. And we have actually made progress in all of those things. So by looking at those that are diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in general as a whole, and looking at their survival, we are looking at better treatments. People who are getting pancreatic cancer later are living longer as a result of better treatments.

But it’s not just that. It’s also, if you’re diagnosed earlier, your 5-year survival rate is higher. More people who are diagnosed early live to five years than those that are diagnosed later. So within that statistic, there are more people who are diagnosed earlier. And those people also live longer. So it takes into account all of those things, which is why we really like to look at that five-year survival rate for a disease like pancreatic cancer.

Dr. Whyte: Where are we on screening? Because we always want to catch people early. That gives them that greatest chance of survival. Have we made much improvements there? And if we have, what are they?

Dr. Matrisian: Well we have made improvements there are more people that are now diagnosed with localized disease than there were 20 years ago. So that is increasing. And we’re still doing it really by being aware of the symptoms right now. Being aware that kind of chronic indigestion, lower back pain that won’t go away, these are signs and symptoms. And especially things like jaundice ...

Dr. Whyte: That yellow color that they might see.

Dr. Matrisian: Yes, that yellow colors in your eye, that’s a really important symptom that would certainly send people to the doctor in order to look at this. So some of it is being more aware and finding the disease earlier. But what we’re really hoping for is some sort of blood test or some sort of other way of looking through medical records and identifying those people that need to go and be checked.

Dr. Whyte: Now we chatted about that almost two years ago. So tell me the progress that we’ve made. How are we doing?

Dr. Matrisian: Yeah, well there’s a number of companies now that have blood tests that are available. They still need more work. They still need more studies to really understand how good they are at finding pancreatic cancer early. But we didn’t have them a couple of years ago. And so it’s really a very exciting time in the field, that there’s companies that were taking advantage of research for many years and actually turning it into a commercial product that is available for people to check.

Dr. Whyte: And then what about treatments? More treatment options today than there were just a few years ago, but still a lot of progress to be made. So when we talk about even 12% 5-year survival, we’d love to see it much more. And you talk about, I don’t want to misquote, so correct me if I’m wrong. Your goal is 20%. Five-year survival by 2030. That’s not too far. So, Lynn, how are we going to get there?

Dr. Matrisian: Okay, well this is our mission. And that’s exactly our goal, 20% by 2030. So we’ve got some work to do. And we are working at both fronts. You’re right, we need better treatments. And so we’ve set up a clinical trial platform where we can look at a lot of different treatments much more efficiently, much faster, kind of taking advantage of an infrastructure to do that. And that’s called Precision Promise. And we’re excited about that as a way to get new treatments for advanced pancreatic cancer.

And then we’re also working on the early detection end. We think an important symptom of pancreatic cancer that isn’t often recognized is new onset diabetes, sudden diabetes in those over 50 where that person did not have diabetes before. So it’s new, looks like type 2 diabetes, but it’s actually caused by pancreatic cancer.

And so we have an initiative, The Early Detection Initiative, that is taking advantage of that. And seeing if we image people right away based on that symptom, can we find pancreatic cancer early? So we think it’s important to look both at trying to diagnose it earlier, as well as trying to treat it better for advanced disease.

Dr. Whyte: Yeah. You know, at WebMD we’re always trying to empower people with better information so they can also become advocates for their health. You’re an expert in advocacy on pancreatic cancer. So what’s your advice to listeners as to how they become good advocates for themselves or advocates in general for loved ones who have pancreatic cancer?

Dr. Matrisian: Yeah. Yeah. Well certainly, knowledge is power. And so the real thing to do is to call the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network. This is what we do. We stay up on the most current information. We have very experienced case managers who can help navigate the complexities of pancreatic cancer at every stage of the journey.

Or if you have questions about pancreatic cancer, call PanCAN. Go to PanCAN.org and give us a call. Because it’s really that knowledge, knowing what it is that you need to get more knowledge about, how to advocate for yourself is very important in a disease, in any disease, but in particular a disease like pancreatic cancer.

Dr. Whyte: And I don’t want to dismiss the progress that we’ve made, that you’ve just referenced in terms of the increased survival. But there’s still a long way to go. We need a lot more dollars for research. We need a lot more clinical trials to take place. What’s your message to a viewer who’s been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer or a loved one? What’s your message, Lynn, today for them?

Dr. Matrisian: Well, first, get as much knowledge as you can. Call PanCAN, and let us help you help your loved one. But then help us. Let’s do research. Let’s do more research. Let’s understand this disease better so we can make those kinds of progress in both treatment and early detection.

And PanCAN works very hard at understanding the disease and setting up research programs that are going to make a difference, that are going to get us to that aggressive goal of 20% survival by 2030. So there is a lot of things that can be done, raise awareness to your friends and neighbors about the disease, lots of things that will help this whole field.

Dr. Whyte: What’s your feeling on second opinions? Given that this can be a difficult cancer to treat, given that there’s emerging therapies that are always developing, when you have a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, is it important to consider getting a second opinion?

Dr. Matrisian: Yes. Yes, it is. And our case managers will help with that process. We do think it’s important.

Dr. Whyte: Because sometimes, Lynn, people just want to get started, right? Get it out of me. Get treatment. And sometimes getting a second opinion, doing some genomic testing can take time. So what’s your response to that?

Dr. Matrisian: Yeah. Yeah. Well we say, your care team is very important. Who is on your care team, and it may take a little time to find the right people on your care team. But that is an incredibly important step. Sometimes it’s not just one person. Sometimes you need more than one doctor, more than one nurse, more than one type of specialty to help you deal with this. And taking the time to do that is incredibly important.

Yes, you need to – you do need to act. But act smart. And do it with knowledge. Do it really understanding what your options are, and advocate for yourself.

Dr. Whyte: And surround yourself as you reference with that right care team for you, because that’s the most important thing when you have any type of cancer diagnosis. Dr. Lynn Matrisian, I want to thank you for taking time today.

Dr. Matrisian: Thank you so much, John.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Forced hospitalization for mental illness not a permanent solution

I met Eleanor when I was writing a book on involuntary psychiatric treatment. She was very ill when she presented to an emergency department in Northern California. She was looking for help and would have signed herself in, but after waiting 8 hours with no food or medical attention, she walked out and went to another hospital.

At this point, she was agitated and distressed and began screaming uncontrollably. The physician in the second ED did not offer her the option of signing in, and she was placed on a 72-hour hold and subsequently held in the hospital for 3 weeks after a judge committed her.

Like so many issues, involuntary psychiatric care is highly polarized. Some groups favor legislation to make involuntary treatment easier, while patient advocacy and civil rights groups vehemently oppose such legislation.

We don’t hear from these combatants as much as we hear from those who trumpet their views on abortion or gun control, yet this battlefield exists. It is not surprising that when New York City Mayor Eric Adams announced a plan to hospitalize homeless people with mental illnesses – involuntarily if necessary, and at the discretion of the police – people were outraged.

New York City is not the only place using this strategy to address the problem of mental illness and homelessness; California has enacted similar legislation, and every major city has homeless citizens.

Eleanor was not homeless, and fortunately, she recovered and returned to her family. However, she remained distressed and traumatized by her hospitalization for years. “It sticks with you,” she told me. “I would rather die than go in again.”

I wish I could tell you that Eleanor is unique in saying that she would rather die than go to a hospital unit for treatment, but it is not an uncommon sentiment for patients. Some people who are charged with crimes and end up in the judicial system will opt to go to jail rather than to a psychiatric hospital. It is also not easy to access outpatient psychiatric treatment.

Barriers to care

Many psychiatrists don’t participate with insurance networks, and publicly funded clinics may have long waiting lists, so illnesses escalate until there is a crisis and hospitalization is necessary. For many, stigma and fear of potential professional repercussions are significant barriers to care.

What are the issues that legislation attempts to address? The first is the standard for hospitalizing individuals against their will. In some states, the patient must be dangerous, while in others there is a lower standard of “gravely disabled,” and finally there are those that promote a standard of a “need for treatment.”

The second is related to medicating people against their will, a process that can be rightly perceived as an assault if the patient refuses to take oral medications and must be held down for injections. Next, the use of outpatient civil commitment – legally requiring people to get treatment if they are not in the hospital – has been increasingly invoked as a way to prevent mass murders and random violence against strangers.

All but four states have some legislation for outpatient commitment, euphemistically called Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT), yet these laws are difficult to enforce and expensive to enact. They are also not fully effective.

In New York City, Kendra’s Law has not eliminated subway violence by people with psychiatric disturbances, and the shooter who killed 32 people and wounded 17 others at Virginia Tech in 2007 had previously been ordered by a judge to go to outpatient treatment, but he simply never showed up for his appointment.

Finally, the battle includes the right of patients to refuse to have their psychiatric information released to their caretakers under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 – a measure that many families believe would help them to get loved ones to take medications and go to appointments.

The concern about how to negotiate the needs of society and the civil rights of people with psychiatric disorders has been with us for centuries. There is a strong antipsychiatry movement that asserts that psychotropic medications are ineffective or harmful and refers to patients as “psychiatric survivors.” We value the right to medical autonomy, and when there is controversy over the validity of a treatment, there is even more controversy over forcing it upon people.

Psychiatric medications are very effective and benefit many people, but they don’t help everyone, and some people experience side effects. Also, we can’t deny that involuntary care can go wrong; the conservatorship of Britney Spears for 13 years is a very public example.

Multiple stakeholders

Many have a stake in how this plays out. There are the patients, who may be suffering and unable to recognize that they are ill, who may have valid reasons for not wanting the treatments, and who ideally should have the right to refuse care.

There are the families who watch their loved ones suffer, deteriorate, and miss the opportunities that life has to offer; who do not want their children to be homeless or incarcerated; and who may be at risk from violent behavior.

There are the mental health professionals who want to do what’s in the best interest of their patients while following legal and ethical mandates, who worry about being sued for tragic outcomes, and who can’t meet the current demand for services.

There is the taxpayer who foots the bill for disability payments, lost productivity, and institutionalization. There is our society that worries that people with psychiatric disorders will commit random acts of violence.

Finally, there are the insurers, who want to pay for as little care as possible and throw up constant hurdles in the treatment process. We must acknowledge that resources used for involuntary treatment are diverted away from those who want care.

Eleanor had many advantages that unhoused people don’t have: a supportive family, health insurance, and the financial means to pay a psychiatrist who respected her wishes to wean off her medications. She returned to a comfortable home and to personal and occupational success.

It is tragic that we have people living on the streets because of a psychiatric disorder, addiction, poverty, or some combination of these. No one should be unhoused. If the rationale of hospitalization is to decrease violence, I am not hopeful. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study shows that people with psychiatric disorders are responsible for only 4% of all violence.

The logistics of determining which people living on the streets have psychiatric disorders, transporting them safely to medical facilities, and then finding the resources to provide for compassionate and thoughtful care in meaningful and sustained ways are very challenging.

If we don’t want people living on the streets, we need to create supports, including infrastructure to facilitate housing, access to mental health care, and addiction treatment before we resort to involuntary hospitalization.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I met Eleanor when I was writing a book on involuntary psychiatric treatment. She was very ill when she presented to an emergency department in Northern California. She was looking for help and would have signed herself in, but after waiting 8 hours with no food or medical attention, she walked out and went to another hospital.

At this point, she was agitated and distressed and began screaming uncontrollably. The physician in the second ED did not offer her the option of signing in, and she was placed on a 72-hour hold and subsequently held in the hospital for 3 weeks after a judge committed her.

Like so many issues, involuntary psychiatric care is highly polarized. Some groups favor legislation to make involuntary treatment easier, while patient advocacy and civil rights groups vehemently oppose such legislation.

We don’t hear from these combatants as much as we hear from those who trumpet their views on abortion or gun control, yet this battlefield exists. It is not surprising that when New York City Mayor Eric Adams announced a plan to hospitalize homeless people with mental illnesses – involuntarily if necessary, and at the discretion of the police – people were outraged.

New York City is not the only place using this strategy to address the problem of mental illness and homelessness; California has enacted similar legislation, and every major city has homeless citizens.

Eleanor was not homeless, and fortunately, she recovered and returned to her family. However, she remained distressed and traumatized by her hospitalization for years. “It sticks with you,” she told me. “I would rather die than go in again.”

I wish I could tell you that Eleanor is unique in saying that she would rather die than go to a hospital unit for treatment, but it is not an uncommon sentiment for patients. Some people who are charged with crimes and end up in the judicial system will opt to go to jail rather than to a psychiatric hospital. It is also not easy to access outpatient psychiatric treatment.

Barriers to care

Many psychiatrists don’t participate with insurance networks, and publicly funded clinics may have long waiting lists, so illnesses escalate until there is a crisis and hospitalization is necessary. For many, stigma and fear of potential professional repercussions are significant barriers to care.

What are the issues that legislation attempts to address? The first is the standard for hospitalizing individuals against their will. In some states, the patient must be dangerous, while in others there is a lower standard of “gravely disabled,” and finally there are those that promote a standard of a “need for treatment.”

The second is related to medicating people against their will, a process that can be rightly perceived as an assault if the patient refuses to take oral medications and must be held down for injections. Next, the use of outpatient civil commitment – legally requiring people to get treatment if they are not in the hospital – has been increasingly invoked as a way to prevent mass murders and random violence against strangers.

All but four states have some legislation for outpatient commitment, euphemistically called Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT), yet these laws are difficult to enforce and expensive to enact. They are also not fully effective.

In New York City, Kendra’s Law has not eliminated subway violence by people with psychiatric disturbances, and the shooter who killed 32 people and wounded 17 others at Virginia Tech in 2007 had previously been ordered by a judge to go to outpatient treatment, but he simply never showed up for his appointment.

Finally, the battle includes the right of patients to refuse to have their psychiatric information released to their caretakers under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 – a measure that many families believe would help them to get loved ones to take medications and go to appointments.

The concern about how to negotiate the needs of society and the civil rights of people with psychiatric disorders has been with us for centuries. There is a strong antipsychiatry movement that asserts that psychotropic medications are ineffective or harmful and refers to patients as “psychiatric survivors.” We value the right to medical autonomy, and when there is controversy over the validity of a treatment, there is even more controversy over forcing it upon people.

Psychiatric medications are very effective and benefit many people, but they don’t help everyone, and some people experience side effects. Also, we can’t deny that involuntary care can go wrong; the conservatorship of Britney Spears for 13 years is a very public example.

Multiple stakeholders

Many have a stake in how this plays out. There are the patients, who may be suffering and unable to recognize that they are ill, who may have valid reasons for not wanting the treatments, and who ideally should have the right to refuse care.

There are the families who watch their loved ones suffer, deteriorate, and miss the opportunities that life has to offer; who do not want their children to be homeless or incarcerated; and who may be at risk from violent behavior.

There are the mental health professionals who want to do what’s in the best interest of their patients while following legal and ethical mandates, who worry about being sued for tragic outcomes, and who can’t meet the current demand for services.

There is the taxpayer who foots the bill for disability payments, lost productivity, and institutionalization. There is our society that worries that people with psychiatric disorders will commit random acts of violence.

Finally, there are the insurers, who want to pay for as little care as possible and throw up constant hurdles in the treatment process. We must acknowledge that resources used for involuntary treatment are diverted away from those who want care.

Eleanor had many advantages that unhoused people don’t have: a supportive family, health insurance, and the financial means to pay a psychiatrist who respected her wishes to wean off her medications. She returned to a comfortable home and to personal and occupational success.

It is tragic that we have people living on the streets because of a psychiatric disorder, addiction, poverty, or some combination of these. No one should be unhoused. If the rationale of hospitalization is to decrease violence, I am not hopeful. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study shows that people with psychiatric disorders are responsible for only 4% of all violence.

The logistics of determining which people living on the streets have psychiatric disorders, transporting them safely to medical facilities, and then finding the resources to provide for compassionate and thoughtful care in meaningful and sustained ways are very challenging.

If we don’t want people living on the streets, we need to create supports, including infrastructure to facilitate housing, access to mental health care, and addiction treatment before we resort to involuntary hospitalization.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I met Eleanor when I was writing a book on involuntary psychiatric treatment. She was very ill when she presented to an emergency department in Northern California. She was looking for help and would have signed herself in, but after waiting 8 hours with no food or medical attention, she walked out and went to another hospital.

At this point, she was agitated and distressed and began screaming uncontrollably. The physician in the second ED did not offer her the option of signing in, and she was placed on a 72-hour hold and subsequently held in the hospital for 3 weeks after a judge committed her.

Like so many issues, involuntary psychiatric care is highly polarized. Some groups favor legislation to make involuntary treatment easier, while patient advocacy and civil rights groups vehemently oppose such legislation.

We don’t hear from these combatants as much as we hear from those who trumpet their views on abortion or gun control, yet this battlefield exists. It is not surprising that when New York City Mayor Eric Adams announced a plan to hospitalize homeless people with mental illnesses – involuntarily if necessary, and at the discretion of the police – people were outraged.

New York City is not the only place using this strategy to address the problem of mental illness and homelessness; California has enacted similar legislation, and every major city has homeless citizens.

Eleanor was not homeless, and fortunately, she recovered and returned to her family. However, she remained distressed and traumatized by her hospitalization for years. “It sticks with you,” she told me. “I would rather die than go in again.”

I wish I could tell you that Eleanor is unique in saying that she would rather die than go to a hospital unit for treatment, but it is not an uncommon sentiment for patients. Some people who are charged with crimes and end up in the judicial system will opt to go to jail rather than to a psychiatric hospital. It is also not easy to access outpatient psychiatric treatment.

Barriers to care

Many psychiatrists don’t participate with insurance networks, and publicly funded clinics may have long waiting lists, so illnesses escalate until there is a crisis and hospitalization is necessary. For many, stigma and fear of potential professional repercussions are significant barriers to care.

What are the issues that legislation attempts to address? The first is the standard for hospitalizing individuals against their will. In some states, the patient must be dangerous, while in others there is a lower standard of “gravely disabled,” and finally there are those that promote a standard of a “need for treatment.”

The second is related to medicating people against their will, a process that can be rightly perceived as an assault if the patient refuses to take oral medications and must be held down for injections. Next, the use of outpatient civil commitment – legally requiring people to get treatment if they are not in the hospital – has been increasingly invoked as a way to prevent mass murders and random violence against strangers.

All but four states have some legislation for outpatient commitment, euphemistically called Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT), yet these laws are difficult to enforce and expensive to enact. They are also not fully effective.

In New York City, Kendra’s Law has not eliminated subway violence by people with psychiatric disturbances, and the shooter who killed 32 people and wounded 17 others at Virginia Tech in 2007 had previously been ordered by a judge to go to outpatient treatment, but he simply never showed up for his appointment.

Finally, the battle includes the right of patients to refuse to have their psychiatric information released to their caretakers under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 – a measure that many families believe would help them to get loved ones to take medications and go to appointments.

The concern about how to negotiate the needs of society and the civil rights of people with psychiatric disorders has been with us for centuries. There is a strong antipsychiatry movement that asserts that psychotropic medications are ineffective or harmful and refers to patients as “psychiatric survivors.” We value the right to medical autonomy, and when there is controversy over the validity of a treatment, there is even more controversy over forcing it upon people.

Psychiatric medications are very effective and benefit many people, but they don’t help everyone, and some people experience side effects. Also, we can’t deny that involuntary care can go wrong; the conservatorship of Britney Spears for 13 years is a very public example.

Multiple stakeholders

Many have a stake in how this plays out. There are the patients, who may be suffering and unable to recognize that they are ill, who may have valid reasons for not wanting the treatments, and who ideally should have the right to refuse care.

There are the families who watch their loved ones suffer, deteriorate, and miss the opportunities that life has to offer; who do not want their children to be homeless or incarcerated; and who may be at risk from violent behavior.

There are the mental health professionals who want to do what’s in the best interest of their patients while following legal and ethical mandates, who worry about being sued for tragic outcomes, and who can’t meet the current demand for services.

There is the taxpayer who foots the bill for disability payments, lost productivity, and institutionalization. There is our society that worries that people with psychiatric disorders will commit random acts of violence.

Finally, there are the insurers, who want to pay for as little care as possible and throw up constant hurdles in the treatment process. We must acknowledge that resources used for involuntary treatment are diverted away from those who want care.

Eleanor had many advantages that unhoused people don’t have: a supportive family, health insurance, and the financial means to pay a psychiatrist who respected her wishes to wean off her medications. She returned to a comfortable home and to personal and occupational success.

It is tragic that we have people living on the streets because of a psychiatric disorder, addiction, poverty, or some combination of these. No one should be unhoused. If the rationale of hospitalization is to decrease violence, I am not hopeful. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study shows that people with psychiatric disorders are responsible for only 4% of all violence.

The logistics of determining which people living on the streets have psychiatric disorders, transporting them safely to medical facilities, and then finding the resources to provide for compassionate and thoughtful care in meaningful and sustained ways are very challenging.

If we don’t want people living on the streets, we need to create supports, including infrastructure to facilitate housing, access to mental health care, and addiction treatment before we resort to involuntary hospitalization.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An 11-year-old boy presents with small itchy bumps on the wrists, face, arms, and legs

The patient was diagnosed with lichen nitidus, given the characteristic clinical presentation.

Lichen nitidus is a rare chronic inflammatory condition of the skin that most commonly presents in children and young adults and does not seem to be restricted to any sex or race. The classic lesions are described as asymptomatic to slightly pruritic, small (1 mm), skin-colored to hypopigmented flat-topped papules.

Koebner phenomenon is usually seen in which the skin lesions appear in areas of traumatized healthy skin. The extremities, abdomen, chest, and penis are common locations for the lesions to occur. Rarely, the oral mucosa or nails can be involved. It has been described in patients with a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, Niemann-Pick disease, Down syndrome, and HIV. The rare, generalized purpuric variant has been reported in a few cases associated with interferon and ribavirin treatment for hepatitis C infection and nivolumab treatment for cancer. The pathophysiology of lichen nitidus is unknown.

Lichen nitidus can occur in the presence of other skin conditions like lichen planus, atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, erythema nodosum, and lichen spinulosus. Histopathologic characteristics of lichen nitidus are described as a “ball and claw” of epidermal rete around a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Parakeratosis overlying epidermal atrophy and focal basal liquefaction degeneration is also seen.

The differential diagnosis of lichen nitidus includes flat warts, which can present as clusters of small flat-topped papules that can show a pseudo-Koebner phenomenon (where the virus is seeded in traumatized skin). The morphological difference between the condition is that lichen nitidus lesions are usually monomorphic, compared with flat warts, which usually present with different sizes and shapes.

Patients with a history of allergic contact dermatitis may present with a generalized monomorphic eruption of skin-colored papules (known as ID reaction) that can sometimes be very similar to lichen nitidus. Allergic contact dermatitis tends to respond fairly quickly to topical or systemic corticosteroids, unlike lichen nitidus. There are a few reports that consider lichen nitidus to be a variant of lichen planus, although they have different histopathologic findings. Lichen planus lesions are described as polygonal, pruritic, purple to pink papules most commonly seen on the wrists, lower back, and ankles. Lichen planus can be seen in patients with hepatitis C and may also occur secondary to medication.

Milia are small keratin cysts on the skin that are commonly seen in babies as primary milia and can be seen in older children secondary to trauma (commonly on the eyelids) or medications. Given their size and monomorphic appearance, they can sometimes be confused with lichen nitidus.

Lichen nitidus is often asymptomatic and the lesions resolve within a few months to years. Topical corticosteroids can be helpful to alleviate the symptoms in patients who present with pruritus. In more persistent and generalized cases, phototherapy, systemic corticosteroids, acitretin, isotretinoin, or cyclosporine can be considered.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Chu J and Lam JM. CMAJ. 2014 Dec 9;186(18):E688.

Lestringant G et al. Dermatology 1996;192:171-3.

Peterson JA et al. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2021 Aug 25;35(1):70-2.

Schwartz C and Goodman MB. “Lichen nitidus,” in StatPearls. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

The patient was diagnosed with lichen nitidus, given the characteristic clinical presentation.

Lichen nitidus is a rare chronic inflammatory condition of the skin that most commonly presents in children and young adults and does not seem to be restricted to any sex or race. The classic lesions are described as asymptomatic to slightly pruritic, small (1 mm), skin-colored to hypopigmented flat-topped papules.

Koebner phenomenon is usually seen in which the skin lesions appear in areas of traumatized healthy skin. The extremities, abdomen, chest, and penis are common locations for the lesions to occur. Rarely, the oral mucosa or nails can be involved. It has been described in patients with a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, Niemann-Pick disease, Down syndrome, and HIV. The rare, generalized purpuric variant has been reported in a few cases associated with interferon and ribavirin treatment for hepatitis C infection and nivolumab treatment for cancer. The pathophysiology of lichen nitidus is unknown.

Lichen nitidus can occur in the presence of other skin conditions like lichen planus, atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, erythema nodosum, and lichen spinulosus. Histopathologic characteristics of lichen nitidus are described as a “ball and claw” of epidermal rete around a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Parakeratosis overlying epidermal atrophy and focal basal liquefaction degeneration is also seen.

The differential diagnosis of lichen nitidus includes flat warts, which can present as clusters of small flat-topped papules that can show a pseudo-Koebner phenomenon (where the virus is seeded in traumatized skin). The morphological difference between the condition is that lichen nitidus lesions are usually monomorphic, compared with flat warts, which usually present with different sizes and shapes.

Patients with a history of allergic contact dermatitis may present with a generalized monomorphic eruption of skin-colored papules (known as ID reaction) that can sometimes be very similar to lichen nitidus. Allergic contact dermatitis tends to respond fairly quickly to topical or systemic corticosteroids, unlike lichen nitidus. There are a few reports that consider lichen nitidus to be a variant of lichen planus, although they have different histopathologic findings. Lichen planus lesions are described as polygonal, pruritic, purple to pink papules most commonly seen on the wrists, lower back, and ankles. Lichen planus can be seen in patients with hepatitis C and may also occur secondary to medication.

Milia are small keratin cysts on the skin that are commonly seen in babies as primary milia and can be seen in older children secondary to trauma (commonly on the eyelids) or medications. Given their size and monomorphic appearance, they can sometimes be confused with lichen nitidus.

Lichen nitidus is often asymptomatic and the lesions resolve within a few months to years. Topical corticosteroids can be helpful to alleviate the symptoms in patients who present with pruritus. In more persistent and generalized cases, phototherapy, systemic corticosteroids, acitretin, isotretinoin, or cyclosporine can be considered.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Chu J and Lam JM. CMAJ. 2014 Dec 9;186(18):E688.

Lestringant G et al. Dermatology 1996;192:171-3.

Peterson JA et al. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2021 Aug 25;35(1):70-2.

Schwartz C and Goodman MB. “Lichen nitidus,” in StatPearls. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

The patient was diagnosed with lichen nitidus, given the characteristic clinical presentation.

Lichen nitidus is a rare chronic inflammatory condition of the skin that most commonly presents in children and young adults and does not seem to be restricted to any sex or race. The classic lesions are described as asymptomatic to slightly pruritic, small (1 mm), skin-colored to hypopigmented flat-topped papules.

Koebner phenomenon is usually seen in which the skin lesions appear in areas of traumatized healthy skin. The extremities, abdomen, chest, and penis are common locations for the lesions to occur. Rarely, the oral mucosa or nails can be involved. It has been described in patients with a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, Niemann-Pick disease, Down syndrome, and HIV. The rare, generalized purpuric variant has been reported in a few cases associated with interferon and ribavirin treatment for hepatitis C infection and nivolumab treatment for cancer. The pathophysiology of lichen nitidus is unknown.

Lichen nitidus can occur in the presence of other skin conditions like lichen planus, atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, erythema nodosum, and lichen spinulosus. Histopathologic characteristics of lichen nitidus are described as a “ball and claw” of epidermal rete around a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Parakeratosis overlying epidermal atrophy and focal basal liquefaction degeneration is also seen.

The differential diagnosis of lichen nitidus includes flat warts, which can present as clusters of small flat-topped papules that can show a pseudo-Koebner phenomenon (where the virus is seeded in traumatized skin). The morphological difference between the condition is that lichen nitidus lesions are usually monomorphic, compared with flat warts, which usually present with different sizes and shapes.

Patients with a history of allergic contact dermatitis may present with a generalized monomorphic eruption of skin-colored papules (known as ID reaction) that can sometimes be very similar to lichen nitidus. Allergic contact dermatitis tends to respond fairly quickly to topical or systemic corticosteroids, unlike lichen nitidus. There are a few reports that consider lichen nitidus to be a variant of lichen planus, although they have different histopathologic findings. Lichen planus lesions are described as polygonal, pruritic, purple to pink papules most commonly seen on the wrists, lower back, and ankles. Lichen planus can be seen in patients with hepatitis C and may also occur secondary to medication.

Milia are small keratin cysts on the skin that are commonly seen in babies as primary milia and can be seen in older children secondary to trauma (commonly on the eyelids) or medications. Given their size and monomorphic appearance, they can sometimes be confused with lichen nitidus.

Lichen nitidus is often asymptomatic and the lesions resolve within a few months to years. Topical corticosteroids can be helpful to alleviate the symptoms in patients who present with pruritus. In more persistent and generalized cases, phototherapy, systemic corticosteroids, acitretin, isotretinoin, or cyclosporine can be considered.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Chu J and Lam JM. CMAJ. 2014 Dec 9;186(18):E688.

Lestringant G et al. Dermatology 1996;192:171-3.

Peterson JA et al. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2021 Aug 25;35(1):70-2.

Schwartz C and Goodman MB. “Lichen nitidus,” in StatPearls. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

An 11-year-old male with a prior history of atopic dermatitis as a young child, presents with 6 months of slightly itchy, small bumps on the wrists, face, arms, and legs. Has been treated with fluocinolone oil and hydrocortisone 2.5% for a month with no change in the lesions. Besides the use of topical corticosteroids, he has not been taking any other medications.

On physical examination he has multiple skin-colored, flat-topped papules that coalesce into plaques on the arms, legs, chest, and back (Photo 1). Koebner phenomenon was also seen on the knees and arms. There were no lesions in the mouth or on the nails.

Scams

It’s amazing how many phone calls I get from different agencies and groups:

The Drug Enforcement Administration – A car rented in your name was found with fentanyl in the trunk.

The Maricopa County Sheriff’s Department – There is a warrant for your arrest due to failure to show up for jury duty and/or as an expert witness.

Doctors Without Borders – We treated one of your patients while they were overseas and need payment for the supplies used.

The Arizona Medical Board – Your license has been suspended.

The Department of Health & Human Services – Your patient database has been posted on the dark web.