User login

Bone Wax as a Physical Hemostatic Agent

Practice Gap

Hemostasis after cutaneous surgery typically can be aided by mechanical occlusion with petrolatum and gauze known as a pressure bandage. However, in certain scenarios such as bone bleeding or irregularly shaped areas (eg, conchal bowl), difficulty applying a pressure bandage necessitates alternative hemostatic measures.1 In those instances, physical hemostatic agents, such as gelatin, oxidized cellulose, microporous polysaccharide spheres, hydrophilic polymers with potassium salts, microfibrillar collagen, and chitin, also can be used.2 However, those agents are expensive and often adhere to wound edges, inducing repeat trauma with removal. To avoid such concerns, we propose the use of bone wax as an effective hemostatic technique.

The Technique

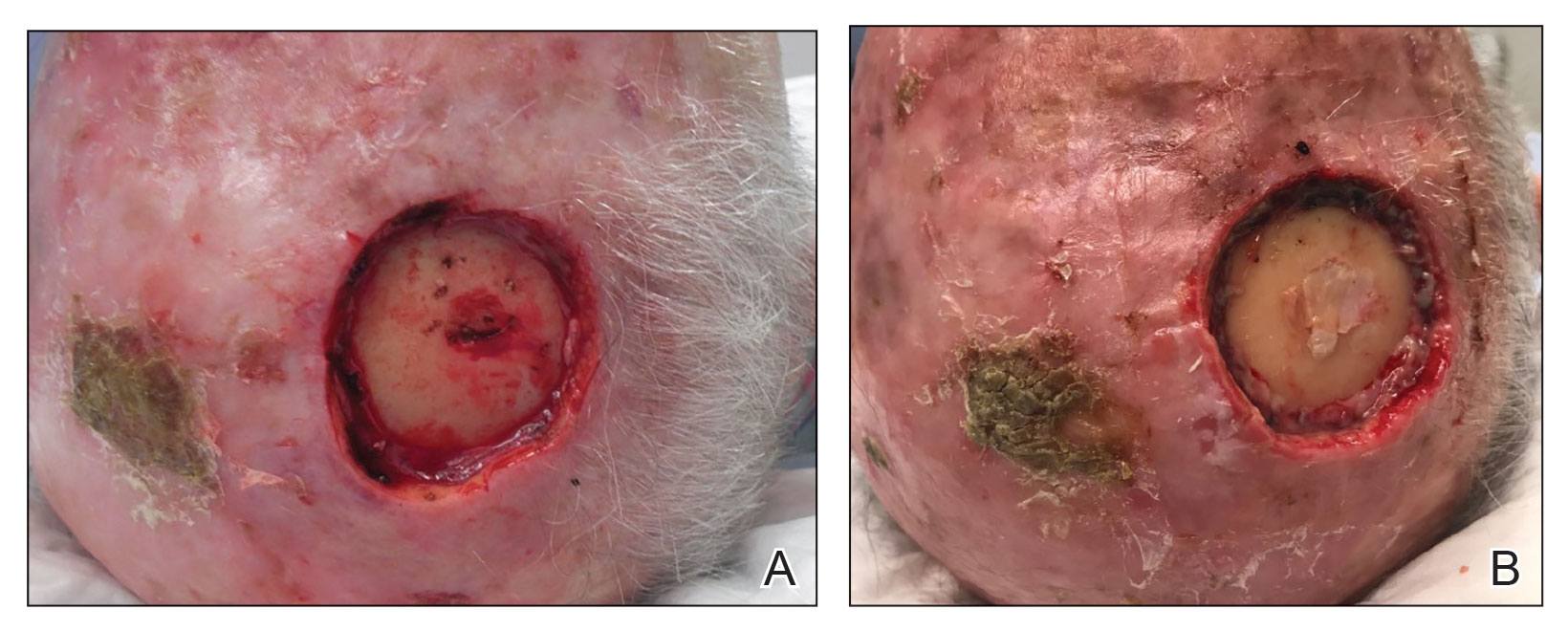

When secondary intention healing is chosen or a temporary bandage needs to be placed, we offer the use of bone wax as an alternative to help achieve hemostasis. Bone wax—a combination of beeswax, isopropyl palmitate, and a stabilizing agent such as almond oils or sterilized salicylic acid3—helps achieve hemostasis by purely mechanical means. It is malleable and can be easily adapted to the architecture of the surgical site (Figure 1). The bone wax can be applied immediately following surgery and removed during bandage change.

Practice Implications

Use of bone wax as a physical hemostatic agent provides a practical alternative to other options commonly used in dermatologic surgery for deep wounds or irregular surfaces. It offers several advantages.

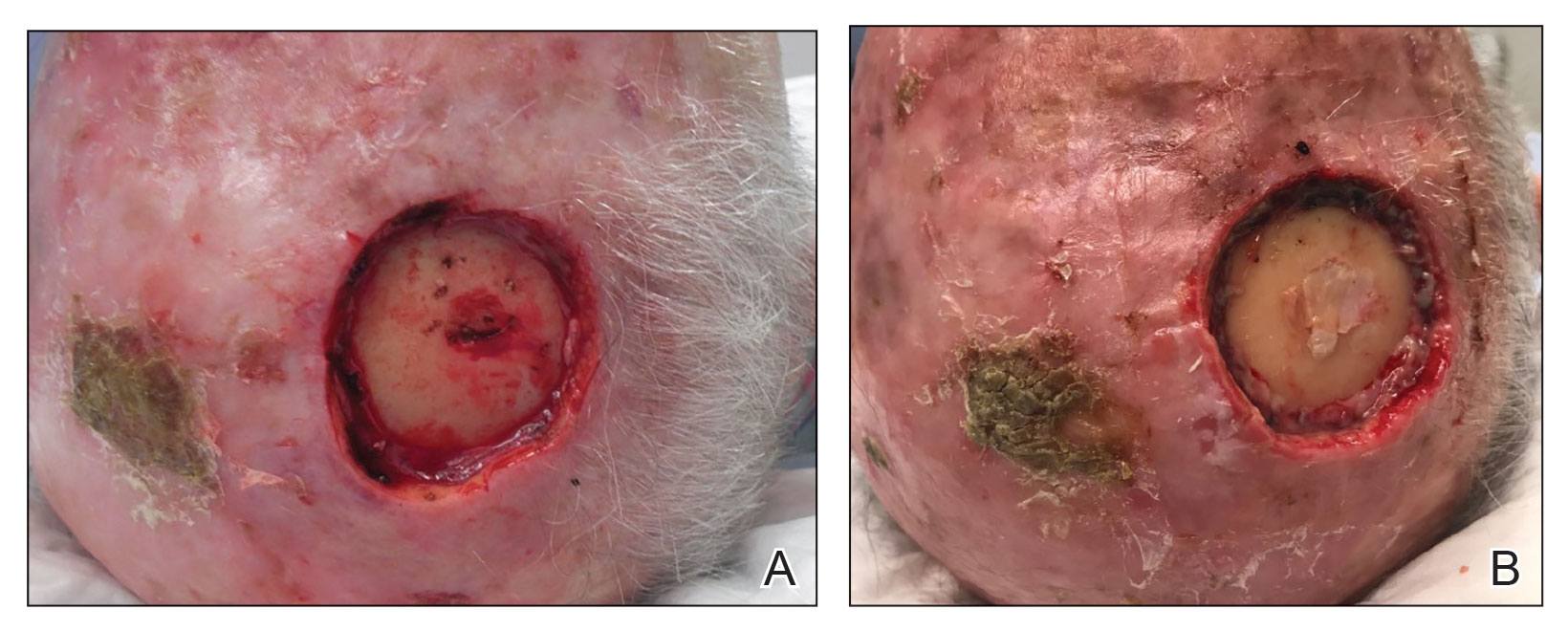

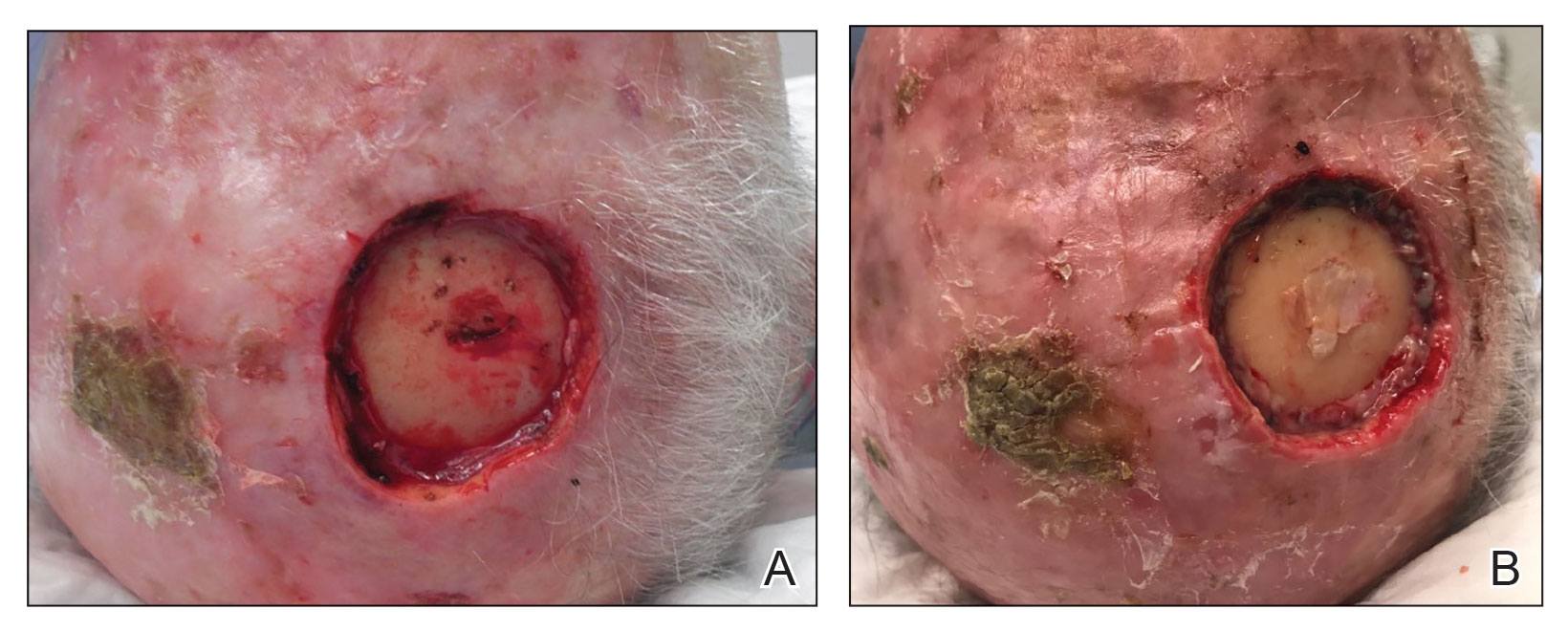

Bone wax is not absorbed and does not adhere to wound surfaces, which makes removal easy and painless. Furthermore, bone wax allows for excellent growth of granulation tissue2 (Figure 2), most likely due to the healing and emollient properties of the beeswax and the moist occlusive environment created by the bone wax.

Additional advantages are its low cost, especially compared to other hemostatic agents, and long shelf-life (approximately 5 years).2 Furthermore, in scenarios when cutaneous tumors extend into the calvarium, bone wax can prevent air emboli from entering noncollapsible emissary veins.4

When bone wax is used as a temporary measure in a dermatologic setting, complications inherent to its use in bone healing (eg, granulomatous reaction, infection)—for which it is left in place indefinitely—are avoided.

- Perandones-González H, Fernández-Canga P, Rodríguez-Prieto MA. Bone wax as an ideal dressing for auricle concha. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:e75-e76. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.002

- Palm MD, Altman JS. Topical hemostatic agents: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:431-445. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34090.x

- Alegre M, Garcés JR, Puig L. Bone wax in dermatologic surgery. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:299-303. doi:10.1016/j.adengl.2013.03.001

- Goldman G, Altmayer S, Sambandan P, et al. Development of cerebral air emboli during Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1414-1421. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01250.x

Practice Gap

Hemostasis after cutaneous surgery typically can be aided by mechanical occlusion with petrolatum and gauze known as a pressure bandage. However, in certain scenarios such as bone bleeding or irregularly shaped areas (eg, conchal bowl), difficulty applying a pressure bandage necessitates alternative hemostatic measures.1 In those instances, physical hemostatic agents, such as gelatin, oxidized cellulose, microporous polysaccharide spheres, hydrophilic polymers with potassium salts, microfibrillar collagen, and chitin, also can be used.2 However, those agents are expensive and often adhere to wound edges, inducing repeat trauma with removal. To avoid such concerns, we propose the use of bone wax as an effective hemostatic technique.

The Technique

When secondary intention healing is chosen or a temporary bandage needs to be placed, we offer the use of bone wax as an alternative to help achieve hemostasis. Bone wax—a combination of beeswax, isopropyl palmitate, and a stabilizing agent such as almond oils or sterilized salicylic acid3—helps achieve hemostasis by purely mechanical means. It is malleable and can be easily adapted to the architecture of the surgical site (Figure 1). The bone wax can be applied immediately following surgery and removed during bandage change.

Practice Implications

Use of bone wax as a physical hemostatic agent provides a practical alternative to other options commonly used in dermatologic surgery for deep wounds or irregular surfaces. It offers several advantages.

Bone wax is not absorbed and does not adhere to wound surfaces, which makes removal easy and painless. Furthermore, bone wax allows for excellent growth of granulation tissue2 (Figure 2), most likely due to the healing and emollient properties of the beeswax and the moist occlusive environment created by the bone wax.

Additional advantages are its low cost, especially compared to other hemostatic agents, and long shelf-life (approximately 5 years).2 Furthermore, in scenarios when cutaneous tumors extend into the calvarium, bone wax can prevent air emboli from entering noncollapsible emissary veins.4

When bone wax is used as a temporary measure in a dermatologic setting, complications inherent to its use in bone healing (eg, granulomatous reaction, infection)—for which it is left in place indefinitely—are avoided.

Practice Gap

Hemostasis after cutaneous surgery typically can be aided by mechanical occlusion with petrolatum and gauze known as a pressure bandage. However, in certain scenarios such as bone bleeding or irregularly shaped areas (eg, conchal bowl), difficulty applying a pressure bandage necessitates alternative hemostatic measures.1 In those instances, physical hemostatic agents, such as gelatin, oxidized cellulose, microporous polysaccharide spheres, hydrophilic polymers with potassium salts, microfibrillar collagen, and chitin, also can be used.2 However, those agents are expensive and often adhere to wound edges, inducing repeat trauma with removal. To avoid such concerns, we propose the use of bone wax as an effective hemostatic technique.

The Technique

When secondary intention healing is chosen or a temporary bandage needs to be placed, we offer the use of bone wax as an alternative to help achieve hemostasis. Bone wax—a combination of beeswax, isopropyl palmitate, and a stabilizing agent such as almond oils or sterilized salicylic acid3—helps achieve hemostasis by purely mechanical means. It is malleable and can be easily adapted to the architecture of the surgical site (Figure 1). The bone wax can be applied immediately following surgery and removed during bandage change.

Practice Implications

Use of bone wax as a physical hemostatic agent provides a practical alternative to other options commonly used in dermatologic surgery for deep wounds or irregular surfaces. It offers several advantages.

Bone wax is not absorbed and does not adhere to wound surfaces, which makes removal easy and painless. Furthermore, bone wax allows for excellent growth of granulation tissue2 (Figure 2), most likely due to the healing and emollient properties of the beeswax and the moist occlusive environment created by the bone wax.

Additional advantages are its low cost, especially compared to other hemostatic agents, and long shelf-life (approximately 5 years).2 Furthermore, in scenarios when cutaneous tumors extend into the calvarium, bone wax can prevent air emboli from entering noncollapsible emissary veins.4

When bone wax is used as a temporary measure in a dermatologic setting, complications inherent to its use in bone healing (eg, granulomatous reaction, infection)—for which it is left in place indefinitely—are avoided.

- Perandones-González H, Fernández-Canga P, Rodríguez-Prieto MA. Bone wax as an ideal dressing for auricle concha. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:e75-e76. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.002

- Palm MD, Altman JS. Topical hemostatic agents: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:431-445. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34090.x

- Alegre M, Garcés JR, Puig L. Bone wax in dermatologic surgery. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:299-303. doi:10.1016/j.adengl.2013.03.001

- Goldman G, Altmayer S, Sambandan P, et al. Development of cerebral air emboli during Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1414-1421. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01250.x

- Perandones-González H, Fernández-Canga P, Rodríguez-Prieto MA. Bone wax as an ideal dressing for auricle concha. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:e75-e76. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.002

- Palm MD, Altman JS. Topical hemostatic agents: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:431-445. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34090.x

- Alegre M, Garcés JR, Puig L. Bone wax in dermatologic surgery. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:299-303. doi:10.1016/j.adengl.2013.03.001

- Goldman G, Altmayer S, Sambandan P, et al. Development of cerebral air emboli during Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1414-1421. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01250.x

Dermatology Articles in Preprint Servers: A Cross-sectional Study

To the Editor:

Preprint servers allow researchers to post manuscripts before publication in peer-reviewed journals. As of January 2022, 41 public preprint servers accepted medicine/science submissions.1 We sought to analyze characteristics of dermatology manuscripts in preprint servers and assess preprint publication policies in top dermatology journals.

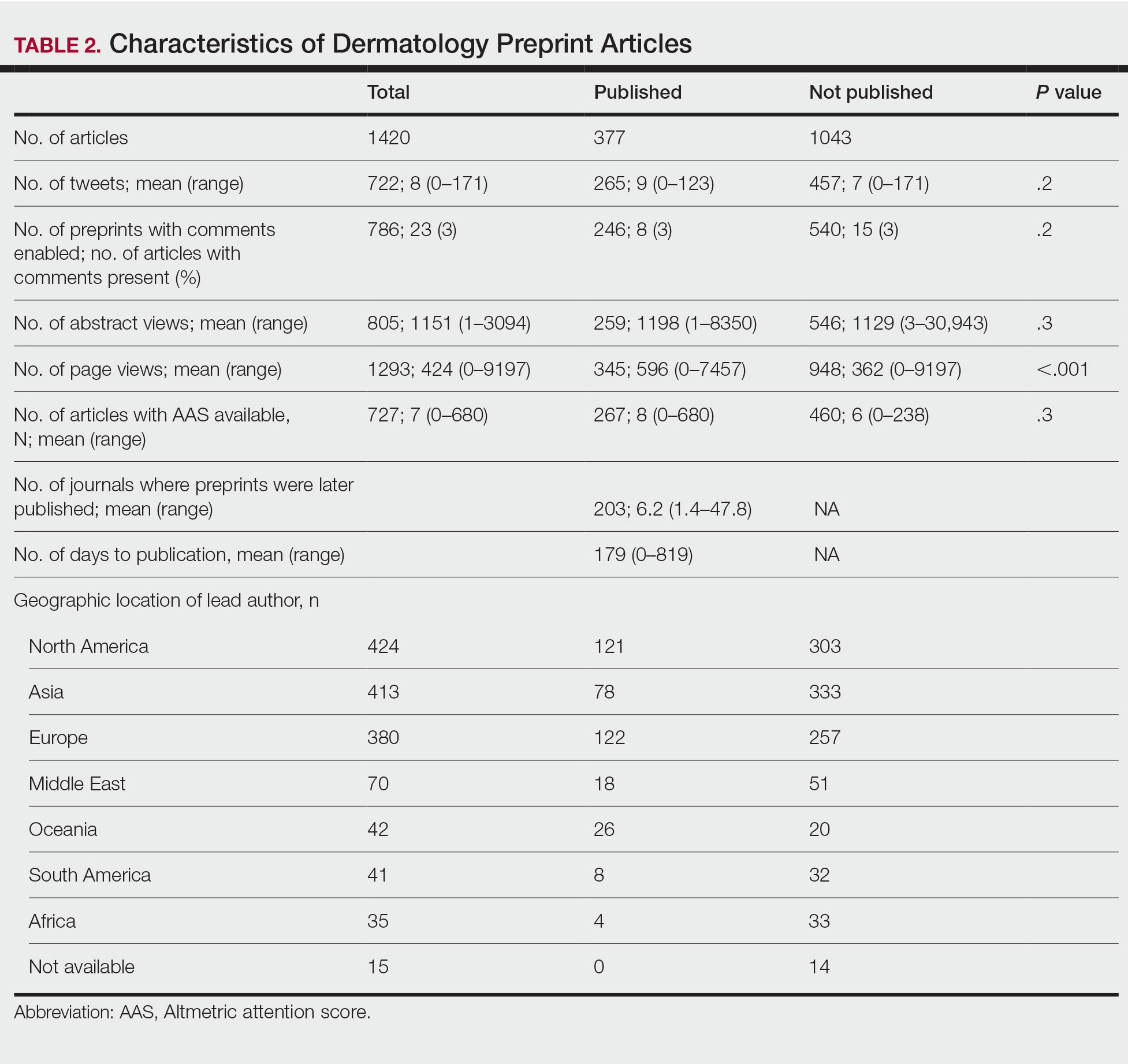

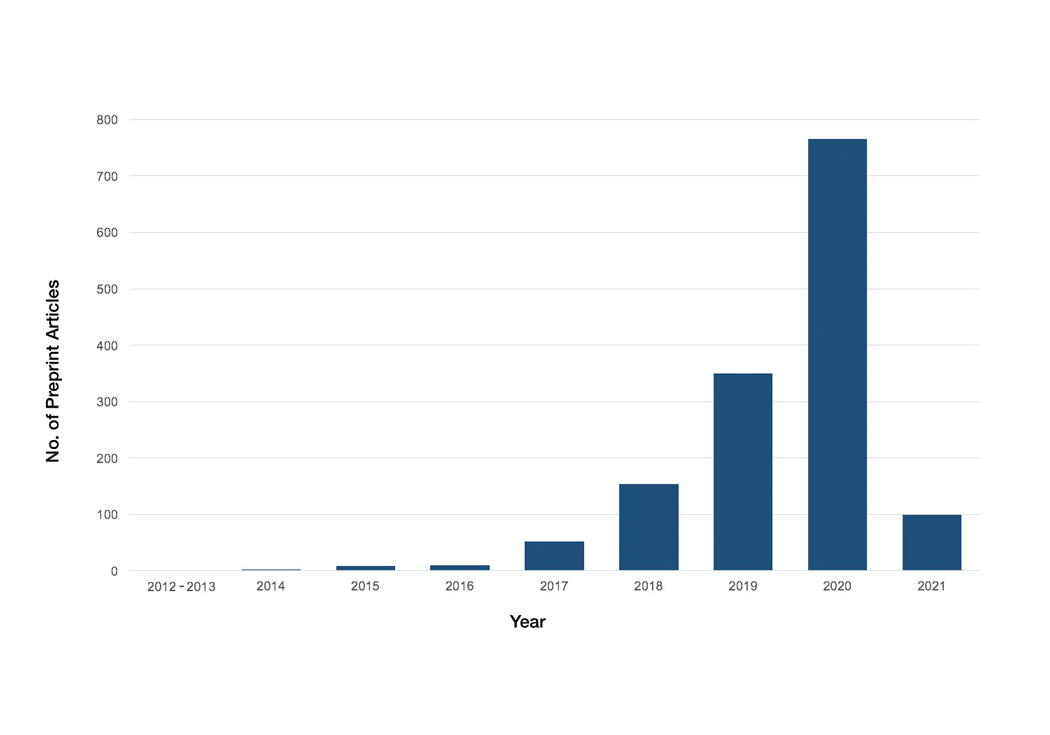

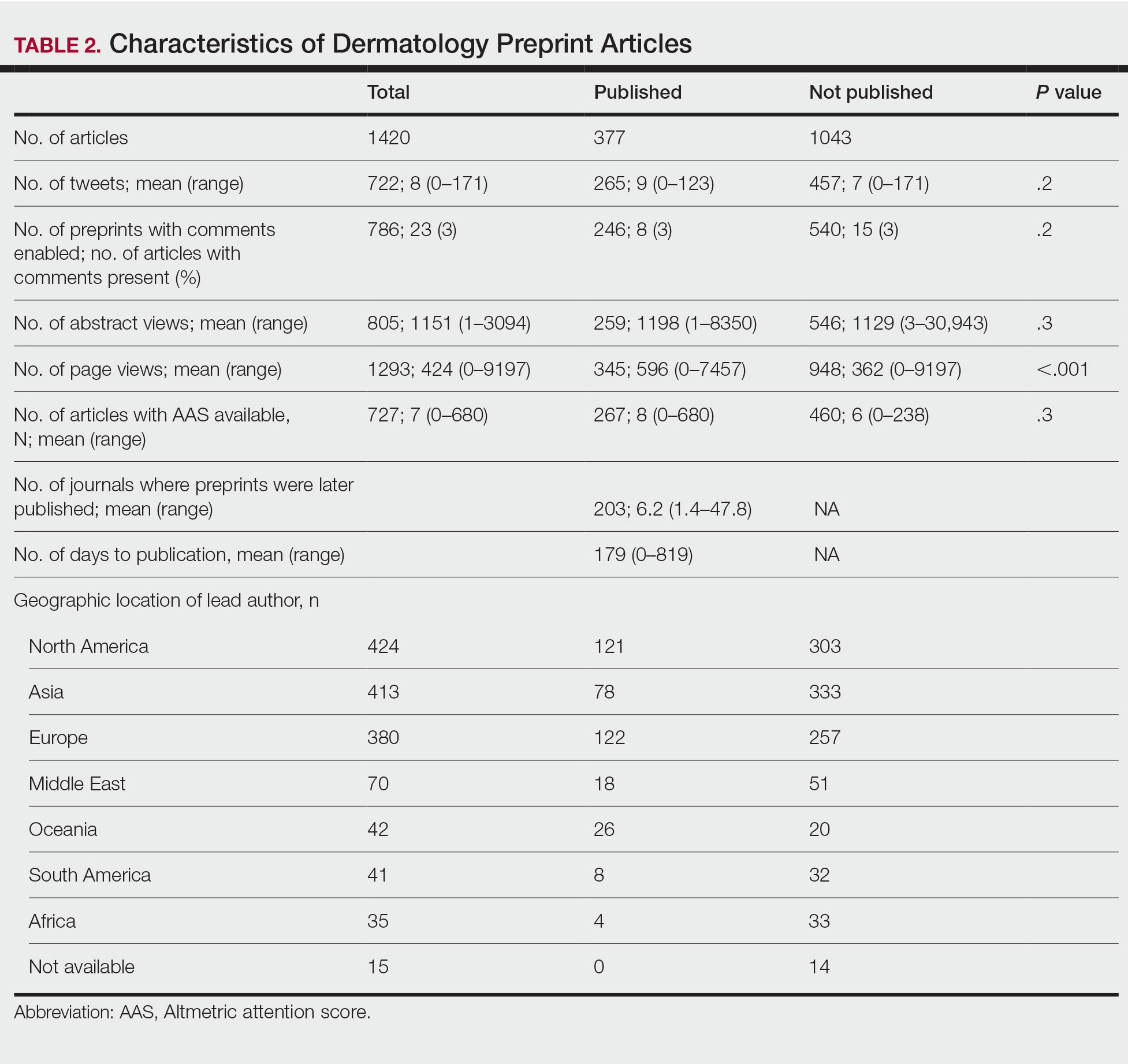

Thirty-five biology/health sciences preprint servers1 were searched (March 3 to March 24, 2021) with keywords dermatology, skin, and cutaneous. Preprint server, preprint post date, location, metrics, journal, impact factor (IF), and journal publication date were recorded. Preprint policies of the top 20 dermatology journals—determined by impact factor of the journal (https://www.scimagojr.com/)—were reviewed. Two-tailed t tests and χ2 tests were performed (P<.05).

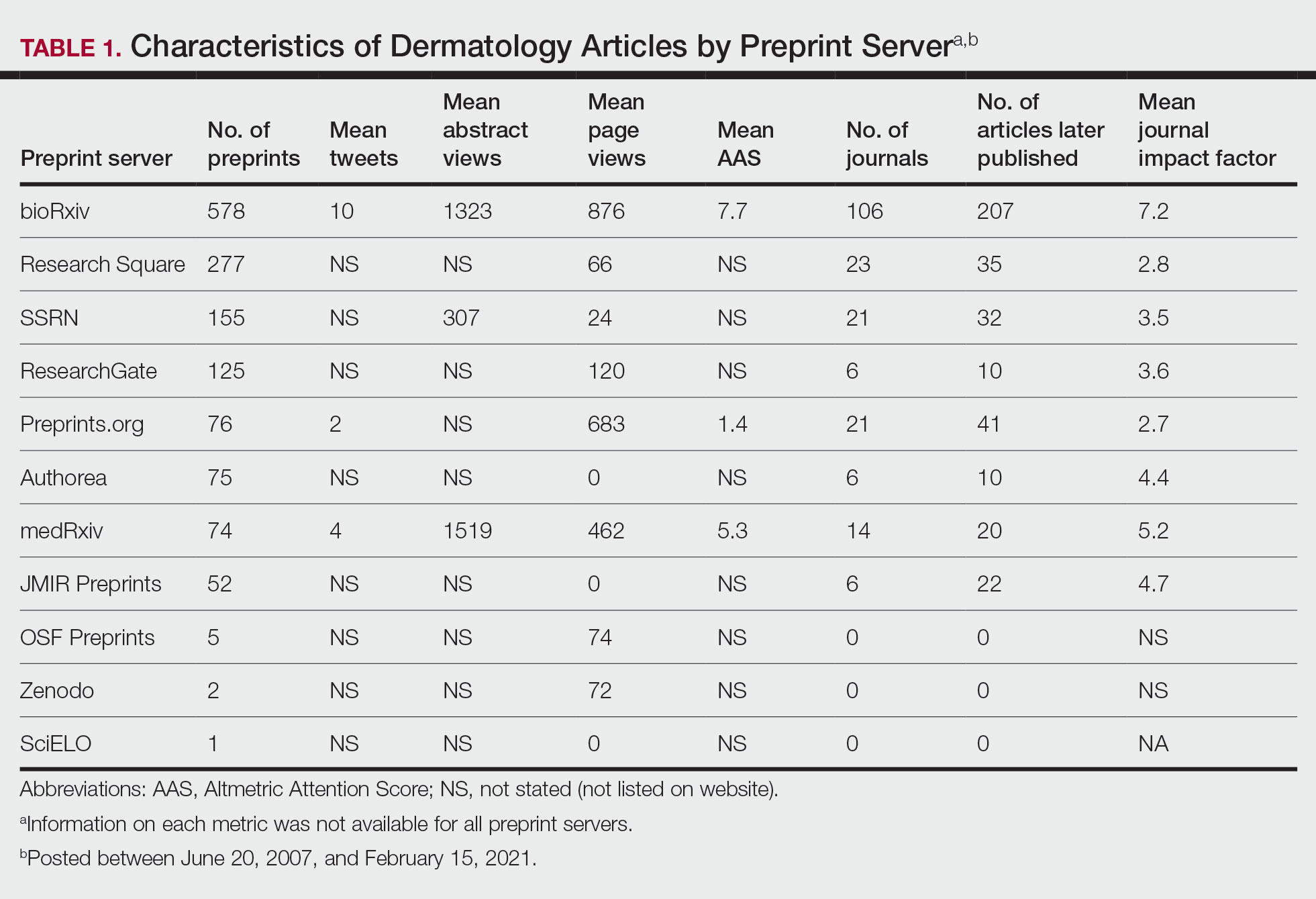

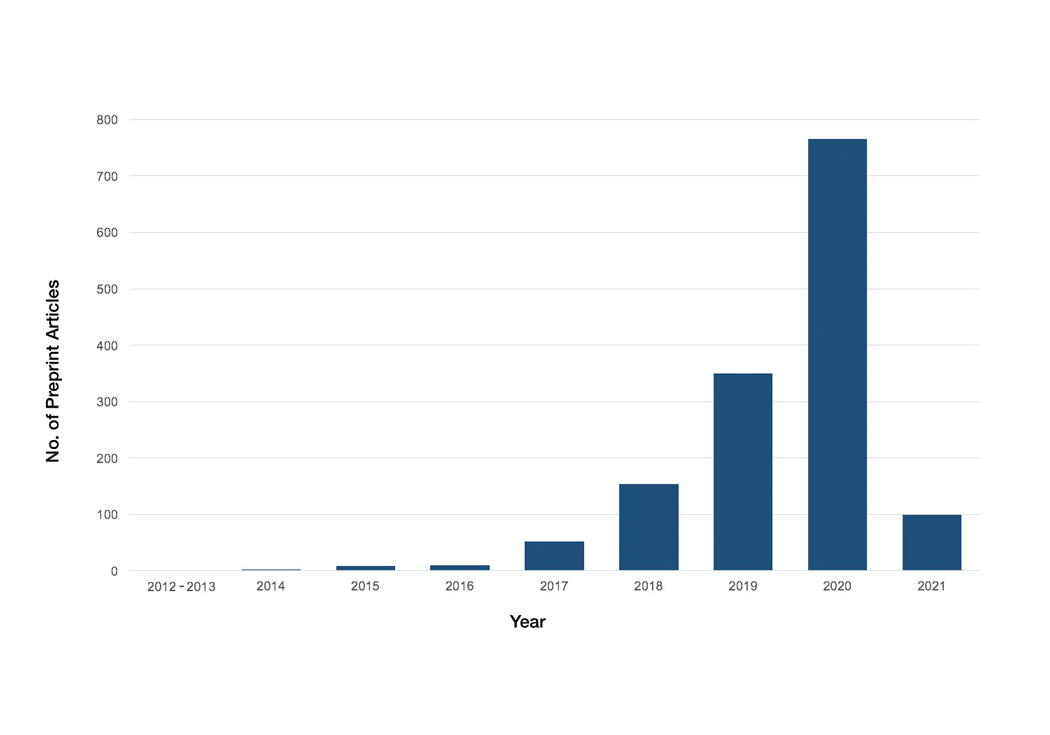

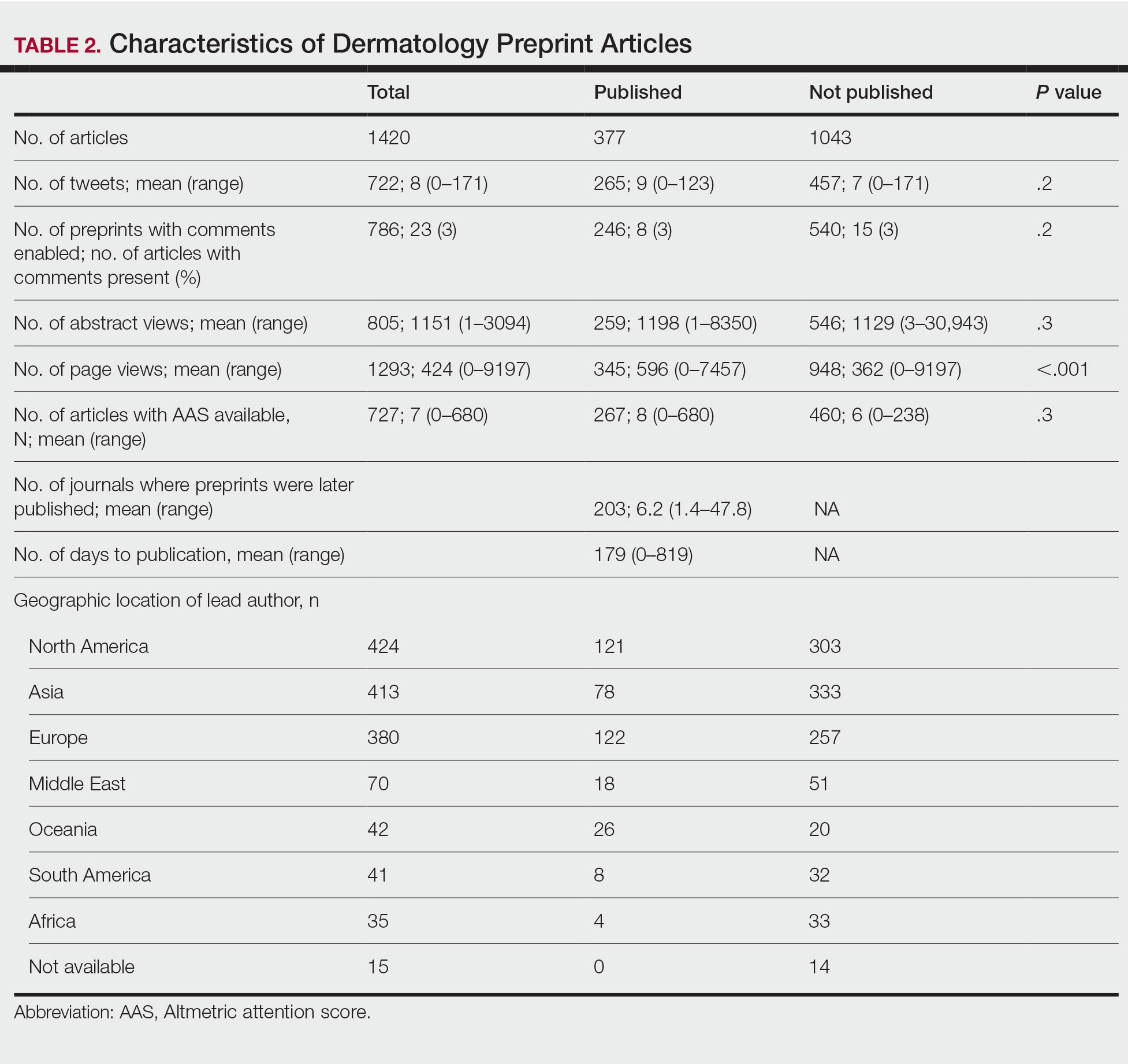

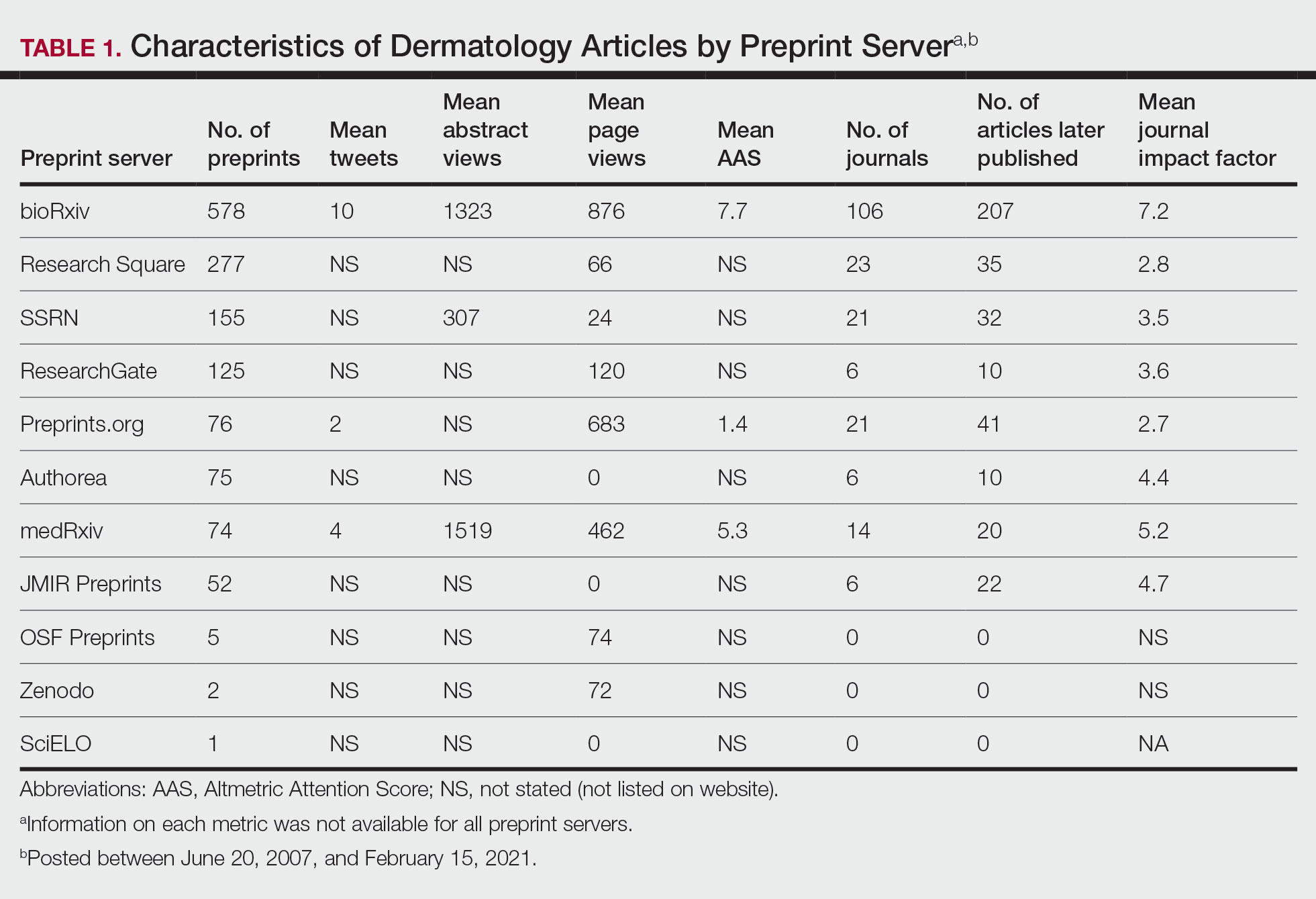

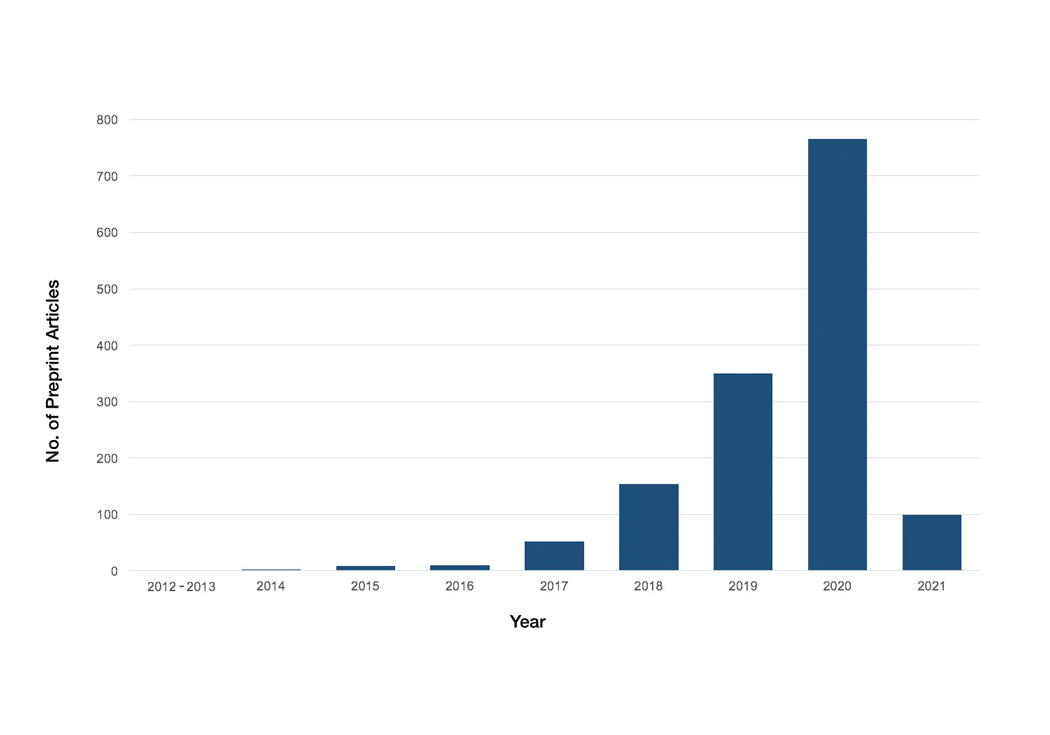

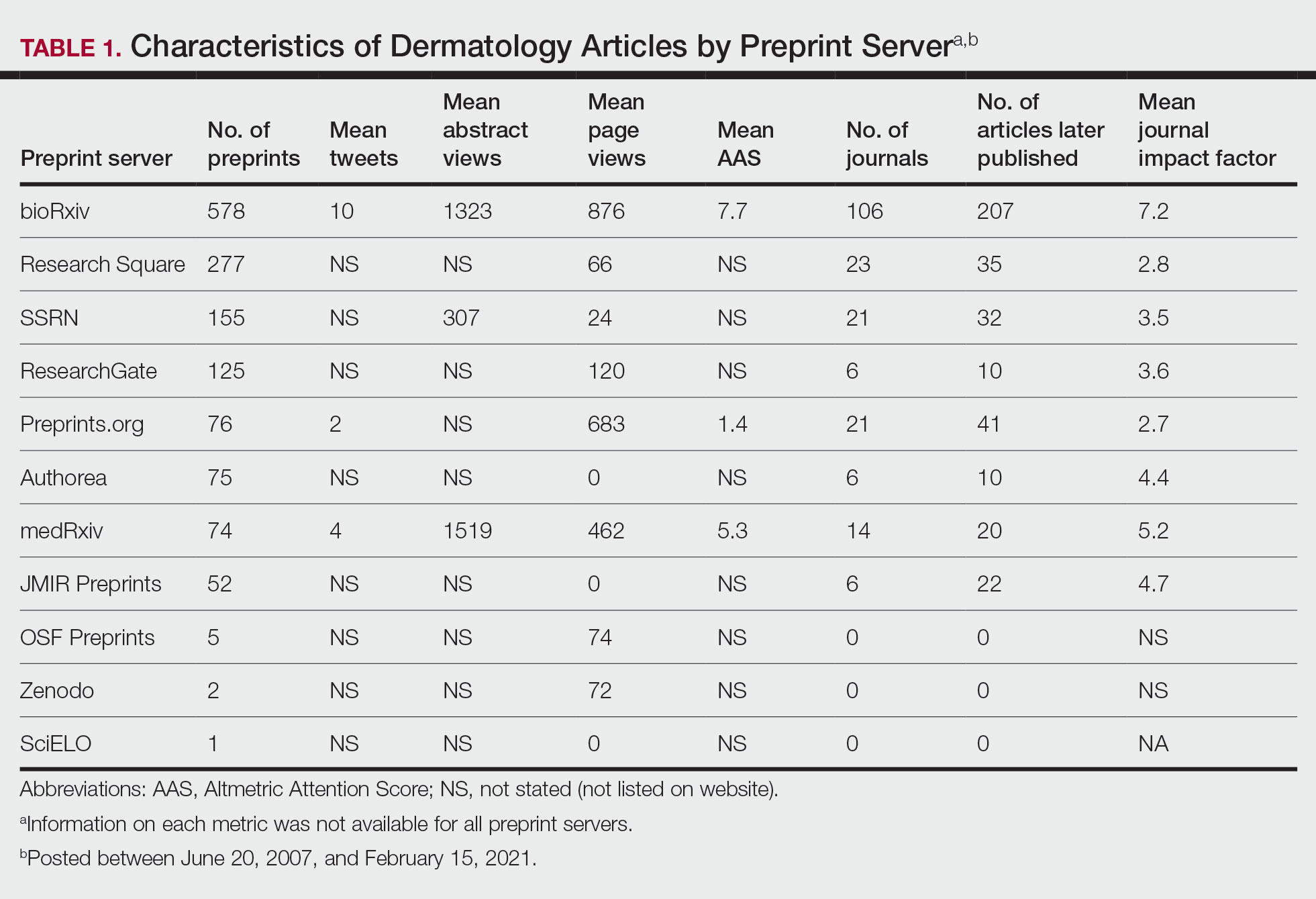

A total of 1420 articles were posted to 11 preprint servers between June 20, 2007, and February 15, 2021 (Table 1); 377 (27%) were published in peer-reviewed journals, with 350 (93%) of those published within 1 year of preprint post. Preprints were published in 203 journals with a mean IF of 6.2. Growth in preprint posts by year (2007-2020) was exponential (R2=0.78)(Figure). On average, preprints were viewed 424 times (Table 2), with published preprints viewed more often than unpublished preprints (596 vs 362 views)(P<.001). Only 23 of 786 (3%) preprints with comments enabled had feedback. Among the top 20 dermatology journals, 18 (90%) allowed preprints, 1 (5%) evaluated case by case, and 1 (5%) prohibited preprints.

Our study showed exponential growth in dermatology preprints, a low proportion published in peer-reviewed journals with high IFs, and a substantial number of page views for both published and unpublished preprints. Very few preprints had feedback. We found that most of the top 20 dermatology journals accept preprints. An analysis of 61 dermatology articles in medRxiv found only 51% (31/61) of articles were subsequently published.2 The low rate of publication may be due to the quality of preprints that do not meet criteria to be published following peer review.

Preprint servers are fairly novel, with a majority launched within the last 5 years.1 The goal of preprints is to claim conception of an idea, solicit feedback prior to submission for peer review, and expedite research distribution.3 Because preprints are uploaded without peer review, manuscripts may lack quality and accuracy. An analysis of 57 of thelargest preprint servers found that few provided guidelines on authorship, image manipulation, or reporting of study limitations; however, most preprint servers do perform some screening.4 medRxiv requires full scientific research reports and absence of obscenity, plagiarism, and patient identifiers. In its first year, medRxiv rejected 34% of 176 submissios; reasons were not disclosed.5

The low rate of on-site comments suggests that preprint servers may not be effective for obtaining feedback to improve dermatology manuscripts prior to journal submission. Almost all of the top 20 dermatologyjournals accept preprints. Therefore, dermatologists may use these preprint servers to assert project ideas and disseminate research quickly and freely but may not receive constructive criticism.

Our study is subject to several limitations. Although our search was extensive, it is possible manuscripts were missed. Article metrics also were not available on all servers, and we could not account for accepted articles that were not yet indexed.

There has been a surge in posting of dermatology preprints in recent years. Preprints have not been peer reviewed, and data should be corroborated before incorporating new diagnostics or treatments into clinical practice. Utilization of preprint servers by dermatologists is increasing, but because the impact is still unknown, further studies on accuracy and reliability of preprints are warranted.

1. List of preprint servers: policies and practices across platforms. ASAPbio website. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://asapbio.org/preprint-servers

2. Jia JL, Hua VJ, Sarin KY. Journal attitudes and outcomes of preprints in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:230-232.

3. Chiarelli A, Johnson R, Richens E, et al. Accelerating scholarly communication: the transformative role of preprints. Copyright, Fair Use, Scholarly Communication, etc. 127. September 20, 2019. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1128&context=scholcom

4. Malicki M, Jeroncic A, Riet GT, et al. Preprint servers’ policies, submission requirements, and transparency in reporting and research integrity recommendations. JAMA. 2020;324:1901-1903.

5. Krumholz HM, Bloom T, Sever R, et al. Submissions and downloads of preprints in the first year of medRxiv. JAMA. 2020;324:1903-1905.

To the Editor:

Preprint servers allow researchers to post manuscripts before publication in peer-reviewed journals. As of January 2022, 41 public preprint servers accepted medicine/science submissions.1 We sought to analyze characteristics of dermatology manuscripts in preprint servers and assess preprint publication policies in top dermatology journals.

Thirty-five biology/health sciences preprint servers1 were searched (March 3 to March 24, 2021) with keywords dermatology, skin, and cutaneous. Preprint server, preprint post date, location, metrics, journal, impact factor (IF), and journal publication date were recorded. Preprint policies of the top 20 dermatology journals—determined by impact factor of the journal (https://www.scimagojr.com/)—were reviewed. Two-tailed t tests and χ2 tests were performed (P<.05).

A total of 1420 articles were posted to 11 preprint servers between June 20, 2007, and February 15, 2021 (Table 1); 377 (27%) were published in peer-reviewed journals, with 350 (93%) of those published within 1 year of preprint post. Preprints were published in 203 journals with a mean IF of 6.2. Growth in preprint posts by year (2007-2020) was exponential (R2=0.78)(Figure). On average, preprints were viewed 424 times (Table 2), with published preprints viewed more often than unpublished preprints (596 vs 362 views)(P<.001). Only 23 of 786 (3%) preprints with comments enabled had feedback. Among the top 20 dermatology journals, 18 (90%) allowed preprints, 1 (5%) evaluated case by case, and 1 (5%) prohibited preprints.

Our study showed exponential growth in dermatology preprints, a low proportion published in peer-reviewed journals with high IFs, and a substantial number of page views for both published and unpublished preprints. Very few preprints had feedback. We found that most of the top 20 dermatology journals accept preprints. An analysis of 61 dermatology articles in medRxiv found only 51% (31/61) of articles were subsequently published.2 The low rate of publication may be due to the quality of preprints that do not meet criteria to be published following peer review.

Preprint servers are fairly novel, with a majority launched within the last 5 years.1 The goal of preprints is to claim conception of an idea, solicit feedback prior to submission for peer review, and expedite research distribution.3 Because preprints are uploaded without peer review, manuscripts may lack quality and accuracy. An analysis of 57 of thelargest preprint servers found that few provided guidelines on authorship, image manipulation, or reporting of study limitations; however, most preprint servers do perform some screening.4 medRxiv requires full scientific research reports and absence of obscenity, plagiarism, and patient identifiers. In its first year, medRxiv rejected 34% of 176 submissios; reasons were not disclosed.5

The low rate of on-site comments suggests that preprint servers may not be effective for obtaining feedback to improve dermatology manuscripts prior to journal submission. Almost all of the top 20 dermatologyjournals accept preprints. Therefore, dermatologists may use these preprint servers to assert project ideas and disseminate research quickly and freely but may not receive constructive criticism.

Our study is subject to several limitations. Although our search was extensive, it is possible manuscripts were missed. Article metrics also were not available on all servers, and we could not account for accepted articles that were not yet indexed.

There has been a surge in posting of dermatology preprints in recent years. Preprints have not been peer reviewed, and data should be corroborated before incorporating new diagnostics or treatments into clinical practice. Utilization of preprint servers by dermatologists is increasing, but because the impact is still unknown, further studies on accuracy and reliability of preprints are warranted.

To the Editor:

Preprint servers allow researchers to post manuscripts before publication in peer-reviewed journals. As of January 2022, 41 public preprint servers accepted medicine/science submissions.1 We sought to analyze characteristics of dermatology manuscripts in preprint servers and assess preprint publication policies in top dermatology journals.

Thirty-five biology/health sciences preprint servers1 were searched (March 3 to March 24, 2021) with keywords dermatology, skin, and cutaneous. Preprint server, preprint post date, location, metrics, journal, impact factor (IF), and journal publication date were recorded. Preprint policies of the top 20 dermatology journals—determined by impact factor of the journal (https://www.scimagojr.com/)—were reviewed. Two-tailed t tests and χ2 tests were performed (P<.05).

A total of 1420 articles were posted to 11 preprint servers between June 20, 2007, and February 15, 2021 (Table 1); 377 (27%) were published in peer-reviewed journals, with 350 (93%) of those published within 1 year of preprint post. Preprints were published in 203 journals with a mean IF of 6.2. Growth in preprint posts by year (2007-2020) was exponential (R2=0.78)(Figure). On average, preprints were viewed 424 times (Table 2), with published preprints viewed more often than unpublished preprints (596 vs 362 views)(P<.001). Only 23 of 786 (3%) preprints with comments enabled had feedback. Among the top 20 dermatology journals, 18 (90%) allowed preprints, 1 (5%) evaluated case by case, and 1 (5%) prohibited preprints.

Our study showed exponential growth in dermatology preprints, a low proportion published in peer-reviewed journals with high IFs, and a substantial number of page views for both published and unpublished preprints. Very few preprints had feedback. We found that most of the top 20 dermatology journals accept preprints. An analysis of 61 dermatology articles in medRxiv found only 51% (31/61) of articles were subsequently published.2 The low rate of publication may be due to the quality of preprints that do not meet criteria to be published following peer review.

Preprint servers are fairly novel, with a majority launched within the last 5 years.1 The goal of preprints is to claim conception of an idea, solicit feedback prior to submission for peer review, and expedite research distribution.3 Because preprints are uploaded without peer review, manuscripts may lack quality and accuracy. An analysis of 57 of thelargest preprint servers found that few provided guidelines on authorship, image manipulation, or reporting of study limitations; however, most preprint servers do perform some screening.4 medRxiv requires full scientific research reports and absence of obscenity, plagiarism, and patient identifiers. In its first year, medRxiv rejected 34% of 176 submissios; reasons were not disclosed.5

The low rate of on-site comments suggests that preprint servers may not be effective for obtaining feedback to improve dermatology manuscripts prior to journal submission. Almost all of the top 20 dermatologyjournals accept preprints. Therefore, dermatologists may use these preprint servers to assert project ideas and disseminate research quickly and freely but may not receive constructive criticism.

Our study is subject to several limitations. Although our search was extensive, it is possible manuscripts were missed. Article metrics also were not available on all servers, and we could not account for accepted articles that were not yet indexed.

There has been a surge in posting of dermatology preprints in recent years. Preprints have not been peer reviewed, and data should be corroborated before incorporating new diagnostics or treatments into clinical practice. Utilization of preprint servers by dermatologists is increasing, but because the impact is still unknown, further studies on accuracy and reliability of preprints are warranted.

1. List of preprint servers: policies and practices across platforms. ASAPbio website. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://asapbio.org/preprint-servers

2. Jia JL, Hua VJ, Sarin KY. Journal attitudes and outcomes of preprints in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:230-232.

3. Chiarelli A, Johnson R, Richens E, et al. Accelerating scholarly communication: the transformative role of preprints. Copyright, Fair Use, Scholarly Communication, etc. 127. September 20, 2019. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1128&context=scholcom

4. Malicki M, Jeroncic A, Riet GT, et al. Preprint servers’ policies, submission requirements, and transparency in reporting and research integrity recommendations. JAMA. 2020;324:1901-1903.

5. Krumholz HM, Bloom T, Sever R, et al. Submissions and downloads of preprints in the first year of medRxiv. JAMA. 2020;324:1903-1905.

1. List of preprint servers: policies and practices across platforms. ASAPbio website. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://asapbio.org/preprint-servers

2. Jia JL, Hua VJ, Sarin KY. Journal attitudes and outcomes of preprints in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:230-232.

3. Chiarelli A, Johnson R, Richens E, et al. Accelerating scholarly communication: the transformative role of preprints. Copyright, Fair Use, Scholarly Communication, etc. 127. September 20, 2019. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1128&context=scholcom

4. Malicki M, Jeroncic A, Riet GT, et al. Preprint servers’ policies, submission requirements, and transparency in reporting and research integrity recommendations. JAMA. 2020;324:1901-1903.

5. Krumholz HM, Bloom T, Sever R, et al. Submissions and downloads of preprints in the first year of medRxiv. JAMA. 2020;324:1903-1905.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Preprint servers allow researchers to post manuscripts before publication in peer-reviewed journals.

- The low rate of on-site comments suggests that preprint servers may not be effective for obtaining feedback to improve dermatology manuscripts prior to journal submission; therefore, dermatologists may use these servers to disseminate research quickly and freely but may not receive constructive criticism.

- Preprints have not been peer reviewed, and data should be corroborated before incorporating new diagnostics or treatments into clinical practice.

Commentary: Glucocorticoid use and progression in RA, February 2023

Several recent studies have assessed the use of glucocorticoids, a frequent companion to disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) and biologic therapy. Many patients are treated with glucocorticoids early in their disease course as a bridging therapy to long-term treatment, and others receive glucocorticoid therapy chronically or intermittently for flares. Van Ouwerkerk and colleagues performed a combined analysis of seven clinical trials, identified in a systematic literature review, that included a glucocorticoid taper protocol for the treatment of newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis (RA), undifferentiated arthritis, or "high-risk profile for persistent arthritis." These studies encompassed intravenous, intramuscular, and oral glucocorticoid regimens, and the continued use of glucocorticoids after bridging. These regimens, including cumulative doses, were examined and found to result in a low probability of ongoing use, especially in patients with lower initial doses and shorter bridging schedules. However, though reassuring as to the early use of glucocorticoids in clinical practice, this finding can be affected by patient characteristics not examined in detail in the aggregated results, including whether the patients were classified as having RA, undifferentiated arthritis, or a "high-risk profile."

Adami and colleagues also looked at tapering of glucocorticoids in patients with RA (though not necessarily early RA) in order to determine risk for flare associated with different tapering schedules. They examined the characteristics of patients with RA experiencing a flare (defined as an increase in Disease Activity Score 28 for Rheumatoid Arthritis with C-reactive protein [DAS28-CRP] > 1.2) and their glucocorticoid therapy in the preceding 6 months and found that tapering to a prednisone equivalent ≤ 2.5 mg daily was associated with a higher risk for flare but that doses > 2.5 mg daily were not. Though this finding is perhaps expected, it does not provide further insight into a strategy to minimize the associated adverse effects of glucocorticoid therapy.

Adding further weight to this point is a study performed in Denmark by Dieperink and colleagues examining risk for Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) using a nation-wide registry of over 30,000 patients with RA. They found 180 cases of SAB and examined the patient characteristics. Patients who were currently using or previously used a biologic DMARD had an increased risk for SAB as well as those with moderate to high RA disease activity. Study participants who were currently using a prednisone-equivalent of ≤ 7.5 mg daily had an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 2.2 and those using > 7.5 mg daily had an aOR of 9.5 for SAB. This concerning finding suggests that even a relatively "low" dose of prednisone use is not benign for patients with RA, and these studies bring to light the need to research optimal strategies for disease control and balancing immunosuppression with the risk for infection and other adverse events.

Heckert and colleagues looked at another aspect of RA disease control, namely, local progression in a single affected joint. Their prior work has suggested that patients with RA may be prone to recurrent inflammation in a single joint despite systemic treatment, a finding that aligns with common clinical observations. This study evaluates radiographic progression in susceptible joints via post hoc analysis using data from the BeSt study including tender and swollen joints, hand and foot radiographs, and disease activity scores. Despite systemic treatment to a target low disease activity or remission state (as per the BeSt protocol), the study found an association between recurrent joint inflammation and radiographic progression (ie, erosions). However, because they only looked at hand and foot joints, the strength of this association in other joints is unknown, as is the use of local treatment, such as steroid injection to minimize inflammation, though both questions may be difficult to evaluate in a small prospective study.

Several recent studies have assessed the use of glucocorticoids, a frequent companion to disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) and biologic therapy. Many patients are treated with glucocorticoids early in their disease course as a bridging therapy to long-term treatment, and others receive glucocorticoid therapy chronically or intermittently for flares. Van Ouwerkerk and colleagues performed a combined analysis of seven clinical trials, identified in a systematic literature review, that included a glucocorticoid taper protocol for the treatment of newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis (RA), undifferentiated arthritis, or "high-risk profile for persistent arthritis." These studies encompassed intravenous, intramuscular, and oral glucocorticoid regimens, and the continued use of glucocorticoids after bridging. These regimens, including cumulative doses, were examined and found to result in a low probability of ongoing use, especially in patients with lower initial doses and shorter bridging schedules. However, though reassuring as to the early use of glucocorticoids in clinical practice, this finding can be affected by patient characteristics not examined in detail in the aggregated results, including whether the patients were classified as having RA, undifferentiated arthritis, or a "high-risk profile."

Adami and colleagues also looked at tapering of glucocorticoids in patients with RA (though not necessarily early RA) in order to determine risk for flare associated with different tapering schedules. They examined the characteristics of patients with RA experiencing a flare (defined as an increase in Disease Activity Score 28 for Rheumatoid Arthritis with C-reactive protein [DAS28-CRP] > 1.2) and their glucocorticoid therapy in the preceding 6 months and found that tapering to a prednisone equivalent ≤ 2.5 mg daily was associated with a higher risk for flare but that doses > 2.5 mg daily were not. Though this finding is perhaps expected, it does not provide further insight into a strategy to minimize the associated adverse effects of glucocorticoid therapy.

Adding further weight to this point is a study performed in Denmark by Dieperink and colleagues examining risk for Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) using a nation-wide registry of over 30,000 patients with RA. They found 180 cases of SAB and examined the patient characteristics. Patients who were currently using or previously used a biologic DMARD had an increased risk for SAB as well as those with moderate to high RA disease activity. Study participants who were currently using a prednisone-equivalent of ≤ 7.5 mg daily had an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 2.2 and those using > 7.5 mg daily had an aOR of 9.5 for SAB. This concerning finding suggests that even a relatively "low" dose of prednisone use is not benign for patients with RA, and these studies bring to light the need to research optimal strategies for disease control and balancing immunosuppression with the risk for infection and other adverse events.

Heckert and colleagues looked at another aspect of RA disease control, namely, local progression in a single affected joint. Their prior work has suggested that patients with RA may be prone to recurrent inflammation in a single joint despite systemic treatment, a finding that aligns with common clinical observations. This study evaluates radiographic progression in susceptible joints via post hoc analysis using data from the BeSt study including tender and swollen joints, hand and foot radiographs, and disease activity scores. Despite systemic treatment to a target low disease activity or remission state (as per the BeSt protocol), the study found an association between recurrent joint inflammation and radiographic progression (ie, erosions). However, because they only looked at hand and foot joints, the strength of this association in other joints is unknown, as is the use of local treatment, such as steroid injection to minimize inflammation, though both questions may be difficult to evaluate in a small prospective study.

Several recent studies have assessed the use of glucocorticoids, a frequent companion to disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) and biologic therapy. Many patients are treated with glucocorticoids early in their disease course as a bridging therapy to long-term treatment, and others receive glucocorticoid therapy chronically or intermittently for flares. Van Ouwerkerk and colleagues performed a combined analysis of seven clinical trials, identified in a systematic literature review, that included a glucocorticoid taper protocol for the treatment of newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis (RA), undifferentiated arthritis, or "high-risk profile for persistent arthritis." These studies encompassed intravenous, intramuscular, and oral glucocorticoid regimens, and the continued use of glucocorticoids after bridging. These regimens, including cumulative doses, were examined and found to result in a low probability of ongoing use, especially in patients with lower initial doses and shorter bridging schedules. However, though reassuring as to the early use of glucocorticoids in clinical practice, this finding can be affected by patient characteristics not examined in detail in the aggregated results, including whether the patients were classified as having RA, undifferentiated arthritis, or a "high-risk profile."

Adami and colleagues also looked at tapering of glucocorticoids in patients with RA (though not necessarily early RA) in order to determine risk for flare associated with different tapering schedules. They examined the characteristics of patients with RA experiencing a flare (defined as an increase in Disease Activity Score 28 for Rheumatoid Arthritis with C-reactive protein [DAS28-CRP] > 1.2) and their glucocorticoid therapy in the preceding 6 months and found that tapering to a prednisone equivalent ≤ 2.5 mg daily was associated with a higher risk for flare but that doses > 2.5 mg daily were not. Though this finding is perhaps expected, it does not provide further insight into a strategy to minimize the associated adverse effects of glucocorticoid therapy.

Adding further weight to this point is a study performed in Denmark by Dieperink and colleagues examining risk for Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) using a nation-wide registry of over 30,000 patients with RA. They found 180 cases of SAB and examined the patient characteristics. Patients who were currently using or previously used a biologic DMARD had an increased risk for SAB as well as those with moderate to high RA disease activity. Study participants who were currently using a prednisone-equivalent of ≤ 7.5 mg daily had an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 2.2 and those using > 7.5 mg daily had an aOR of 9.5 for SAB. This concerning finding suggests that even a relatively "low" dose of prednisone use is not benign for patients with RA, and these studies bring to light the need to research optimal strategies for disease control and balancing immunosuppression with the risk for infection and other adverse events.

Heckert and colleagues looked at another aspect of RA disease control, namely, local progression in a single affected joint. Their prior work has suggested that patients with RA may be prone to recurrent inflammation in a single joint despite systemic treatment, a finding that aligns with common clinical observations. This study evaluates radiographic progression in susceptible joints via post hoc analysis using data from the BeSt study including tender and swollen joints, hand and foot radiographs, and disease activity scores. Despite systemic treatment to a target low disease activity or remission state (as per the BeSt protocol), the study found an association between recurrent joint inflammation and radiographic progression (ie, erosions). However, because they only looked at hand and foot joints, the strength of this association in other joints is unknown, as is the use of local treatment, such as steroid injection to minimize inflammation, though both questions may be difficult to evaluate in a small prospective study.

NSCLC Medications

The Ins and Outs of Transferring Residency Programs

Transferring from one residency program to another is rare but not unheard of. According to the most recent Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Data Resource Book, there were 1020 residents who transferred residency programs in the 2020-2021 academic year.1 With a total of 126,759 active residents in specialty programs, the percentage of transferring residents was less than 1%. The specialties with the highest number of transferring residents included psychiatry, general surgery, internal medicine, and family medicine. In dermatology programs, there were only 2 resident transfers during the 2019-2020 academic year and 6 transfers in the 2020-2021 academic year.1,2 A resident contemplating transferring training programs must carefully consider the advantages and disadvantages before undertaking the uncertain transfer process, but transferring residency programs can be achieved successfully with planning and luck.

Deciding to Transfer

The decision to transfer residency programs may be a difficult one that is wrought with anxiety. There are many reasons why a trainee may wish to pursue transferring training programs. A transfer to another geographic area may be necessary for personal or family reasons, such as to reunite with a spouse and children or to care for a sick family member. A resident may find their program to be a poor fit and may wish to train in a different educational environment. Occasionally, a program can lose its accreditation, and its residents will be tasked with finding a new position elsewhere. A trainee also may realize that the specialty they matched into initially does not align with their true passions. It is important for the potential transfer applicant to be levelheaded about their decision. Residency is a demanding period for every trainee; switching programs may not be the best solution for every problem and should only be considered if essential.

Transfer Timing

A trainee may have thoughts of leaving a program soon after starting residency or perhaps even before starting if their National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) Match result was a disappointment; however, there are certain rules related to transfer timing. The NRMP Match represents a binding commitment for both the applicant and program. If for any reason an applicant will not honor the binding commitment, the NRMP requires the applicant to initiate a waiver review, which can be requested for unanticipated serious and extreme hardship, change of specialty, or ineligibility. According to the NRMP rules and regulations, applicants cannot apply for, discuss, interview for, or accept a position in another program until a waiver has been granted.3 Waivers based on change of specialty must be requested by mid-January prior to the start of training, which means most applicants who match to positions that begin in the same year of the Match do not qualify for change of specialty waivers. However, those who matched to an advanced position and are doing a preliminary year position may consider this option if they have a change of heart during their internship. The NRMP may consider a 1-year deferral to delay training if mutually agreed upon by both the matched applicant and the program.3 The binding commitment is in place for the first 45 days of training, and applicants who resign within 45 days or a program that tries to solicit the transfer of a resident prior to that date could be in violation of the Match and can face consequences such as being barred from entering the matching process in future cycles. Of the 1020 transfers that occurred among residents in specialty programs during the 2020-2021 academic year, 354 (34.7%) occurred during the first year of the training program; 228 (22.4%) occurred during the second year; 389 (38.1%) occurred during the third year; and 49 (4.8%) occurred in the fourth, fifth, or sixth year of the program.1 Unlike other jobs/occupations in which one can simply give notice, in medical training even if a transfer position is accepted, the transition date between programs must be mutually agreed upon. Often, this may coincide with the start of the new academic year.

The Transfer Process

Transferring residency programs is a substantial undertaking. Unlike the Match, a trainee seeking to transfer programs does so without a standardized application system or structured support through the process; the transfer applicant must be prepared to navigate the transfer process on their own. The first step after making the decision to transfer is for the resident to meet with the program leadership (ie, program director[s], coordinator, designated official) at their home program to discuss the decision—a nerve-wracking but imperative first step. A receiving program may not favor an applicant secretly applying to a new program without the knowledge of their home program and often will require the home program’s blessing to proceed. The receiving program also would want to ensure the applicant is in good standing and not leaving due to misconduct. Once given the go-ahead, the process is largely in the hands of the applicant. The transfer applicant should identify locations or programs of interest and then take initiative to reach out to potential programs. FREIDA (Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database Access) is the American Medical Association’s residency and fellowship database that allows vacant position listings to be posted online.4 Additionally, the Association of American Medical Colleges’ FindAResident website is a year-round search tool designed to help find open residency and fellowship positions.5 Various specialties also may have program director listserves that communicate vacant positions. On occasion, there are spots in the main NRMP Match that are reserved positions (“R”). These are postgraduate year 2 positions in specialty programs that begin in the year of the Match and are reserved for physicians with prior graduate medical education; these also are known as “Physician Positions.”6 Ultimately, advertisements for vacancies may be few and far between, requiring the resident to send unsolicited emails with curriculum vitae attached to the program directors at programs of interest to inquire about any vacancies and hope for a favorable response. Even if the transfer applicant is qualified, luck that the right spot will be available at the right time may be the deciding factor in transferring programs.

The next step is interviewing for the position. There likely will be fewer candidates interviewing for an open spot but that does not make the process less competitive. The candidate should highlight their strengths and achievements and discuss why the new program would be a great fit both personally and professionally. Even if an applicant is seeking a transfer due to discontent with a prior program, it is best to act graciously and not speak poorly about another training program.

Prior to selection, the candidate may be asked to provide information such as diplomas, US Medical Licensing Examination Step and residency in-service training examination scores, and academic reviews from their current residency program. The interview process may take several weeks as the graduate medical education office often will need to officially approve of an applicant before a formal offer to transfer is extended.

Finally, once an offer is made and accepted, there still is a great amount of paperwork to complete before the transition. The applicant should stay on track with all off-boarding and on-boarding requirements, such as signing a contract, obtaining background checks, and applying for a new license to ensure the switch is not delayed.

Disadvantages of Transferring Programs

The transfer process is not easy to navigate and can be a source of stress for the applicant. It is natural to fear resentment from colleagues and co-residents. Although transferring programs might be in the best interest of the trainee, it may leave a large gap in the program that they are leaving, which can place a burden on the remaining residents.

There are many adjustments to be made after transferring programs. The transferring resident will again start from scratch, needing to learn the ropes and adapt to the growing pains of being at a new institution. This may require learning a completely new electronic medical record, adapting to a new culture, and in many cases stepping in as a senior resident without fully knowing the ins and outs of the program.

Advantages of Transferring Programs

Successfully transferring programs is something to celebrate. There may be great benefits to transferring to a program that is better suited to the trainee—either personally or professionally. Ameliorating the adversity that led to the decision to transfer such as reuniting a long-distance family or realizing one’s true passion can allow the resident to thrive as a trainee and maximize their potential. Transferring programs can give a resident a more well-rounded training experience, as different programs may have different strengths, patient populations, and practice settings. Working with different faculty members with varied niches and practice styles can create a more comprehensive residency experience.

Final Thoughts

Ultimately, transferring residency programs is not easy but also is not impossible. Successfully switching residency programs can be a rewarding experience providing greater well-being and fulfillment.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book, Academic Year 2021-2022. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2021-2022_acgme__databook_document.pdf

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book, Academic Year 2020-2021. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2020-2021_acgme_databook_document.pdf

- After the Match. National Resident Matching Program website. Accessed January 23, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/fellowship-applicants/after-the-match/

- FREIDA vacant position listings. American Medical Association website. Accessed January 23, 2023. https://freida.ama-assn.org/vacant-position

- FindAResident. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed January 23, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/findaresident/findaresident

- What are the types of program positions in the main residency match? National Resident Matching Program website. Published August 5, 2021. Accessed January 23, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/help/item/what-types-of-programs-participate-in-the-main-residency-match/

Transferring from one residency program to another is rare but not unheard of. According to the most recent Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Data Resource Book, there were 1020 residents who transferred residency programs in the 2020-2021 academic year.1 With a total of 126,759 active residents in specialty programs, the percentage of transferring residents was less than 1%. The specialties with the highest number of transferring residents included psychiatry, general surgery, internal medicine, and family medicine. In dermatology programs, there were only 2 resident transfers during the 2019-2020 academic year and 6 transfers in the 2020-2021 academic year.1,2 A resident contemplating transferring training programs must carefully consider the advantages and disadvantages before undertaking the uncertain transfer process, but transferring residency programs can be achieved successfully with planning and luck.

Deciding to Transfer

The decision to transfer residency programs may be a difficult one that is wrought with anxiety. There are many reasons why a trainee may wish to pursue transferring training programs. A transfer to another geographic area may be necessary for personal or family reasons, such as to reunite with a spouse and children or to care for a sick family member. A resident may find their program to be a poor fit and may wish to train in a different educational environment. Occasionally, a program can lose its accreditation, and its residents will be tasked with finding a new position elsewhere. A trainee also may realize that the specialty they matched into initially does not align with their true passions. It is important for the potential transfer applicant to be levelheaded about their decision. Residency is a demanding period for every trainee; switching programs may not be the best solution for every problem and should only be considered if essential.

Transfer Timing

A trainee may have thoughts of leaving a program soon after starting residency or perhaps even before starting if their National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) Match result was a disappointment; however, there are certain rules related to transfer timing. The NRMP Match represents a binding commitment for both the applicant and program. If for any reason an applicant will not honor the binding commitment, the NRMP requires the applicant to initiate a waiver review, which can be requested for unanticipated serious and extreme hardship, change of specialty, or ineligibility. According to the NRMP rules and regulations, applicants cannot apply for, discuss, interview for, or accept a position in another program until a waiver has been granted.3 Waivers based on change of specialty must be requested by mid-January prior to the start of training, which means most applicants who match to positions that begin in the same year of the Match do not qualify for change of specialty waivers. However, those who matched to an advanced position and are doing a preliminary year position may consider this option if they have a change of heart during their internship. The NRMP may consider a 1-year deferral to delay training if mutually agreed upon by both the matched applicant and the program.3 The binding commitment is in place for the first 45 days of training, and applicants who resign within 45 days or a program that tries to solicit the transfer of a resident prior to that date could be in violation of the Match and can face consequences such as being barred from entering the matching process in future cycles. Of the 1020 transfers that occurred among residents in specialty programs during the 2020-2021 academic year, 354 (34.7%) occurred during the first year of the training program; 228 (22.4%) occurred during the second year; 389 (38.1%) occurred during the third year; and 49 (4.8%) occurred in the fourth, fifth, or sixth year of the program.1 Unlike other jobs/occupations in which one can simply give notice, in medical training even if a transfer position is accepted, the transition date between programs must be mutually agreed upon. Often, this may coincide with the start of the new academic year.

The Transfer Process

Transferring residency programs is a substantial undertaking. Unlike the Match, a trainee seeking to transfer programs does so without a standardized application system or structured support through the process; the transfer applicant must be prepared to navigate the transfer process on their own. The first step after making the decision to transfer is for the resident to meet with the program leadership (ie, program director[s], coordinator, designated official) at their home program to discuss the decision—a nerve-wracking but imperative first step. A receiving program may not favor an applicant secretly applying to a new program without the knowledge of their home program and often will require the home program’s blessing to proceed. The receiving program also would want to ensure the applicant is in good standing and not leaving due to misconduct. Once given the go-ahead, the process is largely in the hands of the applicant. The transfer applicant should identify locations or programs of interest and then take initiative to reach out to potential programs. FREIDA (Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database Access) is the American Medical Association’s residency and fellowship database that allows vacant position listings to be posted online.4 Additionally, the Association of American Medical Colleges’ FindAResident website is a year-round search tool designed to help find open residency and fellowship positions.5 Various specialties also may have program director listserves that communicate vacant positions. On occasion, there are spots in the main NRMP Match that are reserved positions (“R”). These are postgraduate year 2 positions in specialty programs that begin in the year of the Match and are reserved for physicians with prior graduate medical education; these also are known as “Physician Positions.”6 Ultimately, advertisements for vacancies may be few and far between, requiring the resident to send unsolicited emails with curriculum vitae attached to the program directors at programs of interest to inquire about any vacancies and hope for a favorable response. Even if the transfer applicant is qualified, luck that the right spot will be available at the right time may be the deciding factor in transferring programs.

The next step is interviewing for the position. There likely will be fewer candidates interviewing for an open spot but that does not make the process less competitive. The candidate should highlight their strengths and achievements and discuss why the new program would be a great fit both personally and professionally. Even if an applicant is seeking a transfer due to discontent with a prior program, it is best to act graciously and not speak poorly about another training program.

Prior to selection, the candidate may be asked to provide information such as diplomas, US Medical Licensing Examination Step and residency in-service training examination scores, and academic reviews from their current residency program. The interview process may take several weeks as the graduate medical education office often will need to officially approve of an applicant before a formal offer to transfer is extended.

Finally, once an offer is made and accepted, there still is a great amount of paperwork to complete before the transition. The applicant should stay on track with all off-boarding and on-boarding requirements, such as signing a contract, obtaining background checks, and applying for a new license to ensure the switch is not delayed.

Disadvantages of Transferring Programs

The transfer process is not easy to navigate and can be a source of stress for the applicant. It is natural to fear resentment from colleagues and co-residents. Although transferring programs might be in the best interest of the trainee, it may leave a large gap in the program that they are leaving, which can place a burden on the remaining residents.

There are many adjustments to be made after transferring programs. The transferring resident will again start from scratch, needing to learn the ropes and adapt to the growing pains of being at a new institution. This may require learning a completely new electronic medical record, adapting to a new culture, and in many cases stepping in as a senior resident without fully knowing the ins and outs of the program.

Advantages of Transferring Programs

Successfully transferring programs is something to celebrate. There may be great benefits to transferring to a program that is better suited to the trainee—either personally or professionally. Ameliorating the adversity that led to the decision to transfer such as reuniting a long-distance family or realizing one’s true passion can allow the resident to thrive as a trainee and maximize their potential. Transferring programs can give a resident a more well-rounded training experience, as different programs may have different strengths, patient populations, and practice settings. Working with different faculty members with varied niches and practice styles can create a more comprehensive residency experience.

Final Thoughts

Ultimately, transferring residency programs is not easy but also is not impossible. Successfully switching residency programs can be a rewarding experience providing greater well-being and fulfillment.

Transferring from one residency program to another is rare but not unheard of. According to the most recent Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Data Resource Book, there were 1020 residents who transferred residency programs in the 2020-2021 academic year.1 With a total of 126,759 active residents in specialty programs, the percentage of transferring residents was less than 1%. The specialties with the highest number of transferring residents included psychiatry, general surgery, internal medicine, and family medicine. In dermatology programs, there were only 2 resident transfers during the 2019-2020 academic year and 6 transfers in the 2020-2021 academic year.1,2 A resident contemplating transferring training programs must carefully consider the advantages and disadvantages before undertaking the uncertain transfer process, but transferring residency programs can be achieved successfully with planning and luck.

Deciding to Transfer

The decision to transfer residency programs may be a difficult one that is wrought with anxiety. There are many reasons why a trainee may wish to pursue transferring training programs. A transfer to another geographic area may be necessary for personal or family reasons, such as to reunite with a spouse and children or to care for a sick family member. A resident may find their program to be a poor fit and may wish to train in a different educational environment. Occasionally, a program can lose its accreditation, and its residents will be tasked with finding a new position elsewhere. A trainee also may realize that the specialty they matched into initially does not align with their true passions. It is important for the potential transfer applicant to be levelheaded about their decision. Residency is a demanding period for every trainee; switching programs may not be the best solution for every problem and should only be considered if essential.

Transfer Timing

A trainee may have thoughts of leaving a program soon after starting residency or perhaps even before starting if their National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) Match result was a disappointment; however, there are certain rules related to transfer timing. The NRMP Match represents a binding commitment for both the applicant and program. If for any reason an applicant will not honor the binding commitment, the NRMP requires the applicant to initiate a waiver review, which can be requested for unanticipated serious and extreme hardship, change of specialty, or ineligibility. According to the NRMP rules and regulations, applicants cannot apply for, discuss, interview for, or accept a position in another program until a waiver has been granted.3 Waivers based on change of specialty must be requested by mid-January prior to the start of training, which means most applicants who match to positions that begin in the same year of the Match do not qualify for change of specialty waivers. However, those who matched to an advanced position and are doing a preliminary year position may consider this option if they have a change of heart during their internship. The NRMP may consider a 1-year deferral to delay training if mutually agreed upon by both the matched applicant and the program.3 The binding commitment is in place for the first 45 days of training, and applicants who resign within 45 days or a program that tries to solicit the transfer of a resident prior to that date could be in violation of the Match and can face consequences such as being barred from entering the matching process in future cycles. Of the 1020 transfers that occurred among residents in specialty programs during the 2020-2021 academic year, 354 (34.7%) occurred during the first year of the training program; 228 (22.4%) occurred during the second year; 389 (38.1%) occurred during the third year; and 49 (4.8%) occurred in the fourth, fifth, or sixth year of the program.1 Unlike other jobs/occupations in which one can simply give notice, in medical training even if a transfer position is accepted, the transition date between programs must be mutually agreed upon. Often, this may coincide with the start of the new academic year.

The Transfer Process

Transferring residency programs is a substantial undertaking. Unlike the Match, a trainee seeking to transfer programs does so without a standardized application system or structured support through the process; the transfer applicant must be prepared to navigate the transfer process on their own. The first step after making the decision to transfer is for the resident to meet with the program leadership (ie, program director[s], coordinator, designated official) at their home program to discuss the decision—a nerve-wracking but imperative first step. A receiving program may not favor an applicant secretly applying to a new program without the knowledge of their home program and often will require the home program’s blessing to proceed. The receiving program also would want to ensure the applicant is in good standing and not leaving due to misconduct. Once given the go-ahead, the process is largely in the hands of the applicant. The transfer applicant should identify locations or programs of interest and then take initiative to reach out to potential programs. FREIDA (Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database Access) is the American Medical Association’s residency and fellowship database that allows vacant position listings to be posted online.4 Additionally, the Association of American Medical Colleges’ FindAResident website is a year-round search tool designed to help find open residency and fellowship positions.5 Various specialties also may have program director listserves that communicate vacant positions. On occasion, there are spots in the main NRMP Match that are reserved positions (“R”). These are postgraduate year 2 positions in specialty programs that begin in the year of the Match and are reserved for physicians with prior graduate medical education; these also are known as “Physician Positions.”6 Ultimately, advertisements for vacancies may be few and far between, requiring the resident to send unsolicited emails with curriculum vitae attached to the program directors at programs of interest to inquire about any vacancies and hope for a favorable response. Even if the transfer applicant is qualified, luck that the right spot will be available at the right time may be the deciding factor in transferring programs.

The next step is interviewing for the position. There likely will be fewer candidates interviewing for an open spot but that does not make the process less competitive. The candidate should highlight their strengths and achievements and discuss why the new program would be a great fit both personally and professionally. Even if an applicant is seeking a transfer due to discontent with a prior program, it is best to act graciously and not speak poorly about another training program.

Prior to selection, the candidate may be asked to provide information such as diplomas, US Medical Licensing Examination Step and residency in-service training examination scores, and academic reviews from their current residency program. The interview process may take several weeks as the graduate medical education office often will need to officially approve of an applicant before a formal offer to transfer is extended.

Finally, once an offer is made and accepted, there still is a great amount of paperwork to complete before the transition. The applicant should stay on track with all off-boarding and on-boarding requirements, such as signing a contract, obtaining background checks, and applying for a new license to ensure the switch is not delayed.

Disadvantages of Transferring Programs

The transfer process is not easy to navigate and can be a source of stress for the applicant. It is natural to fear resentment from colleagues and co-residents. Although transferring programs might be in the best interest of the trainee, it may leave a large gap in the program that they are leaving, which can place a burden on the remaining residents.

There are many adjustments to be made after transferring programs. The transferring resident will again start from scratch, needing to learn the ropes and adapt to the growing pains of being at a new institution. This may require learning a completely new electronic medical record, adapting to a new culture, and in many cases stepping in as a senior resident without fully knowing the ins and outs of the program.

Advantages of Transferring Programs

Successfully transferring programs is something to celebrate. There may be great benefits to transferring to a program that is better suited to the trainee—either personally or professionally. Ameliorating the adversity that led to the decision to transfer such as reuniting a long-distance family or realizing one’s true passion can allow the resident to thrive as a trainee and maximize their potential. Transferring programs can give a resident a more well-rounded training experience, as different programs may have different strengths, patient populations, and practice settings. Working with different faculty members with varied niches and practice styles can create a more comprehensive residency experience.

Final Thoughts

Ultimately, transferring residency programs is not easy but also is not impossible. Successfully switching residency programs can be a rewarding experience providing greater well-being and fulfillment.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book, Academic Year 2021-2022. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2021-2022_acgme__databook_document.pdf

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book, Academic Year 2020-2021. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2020-2021_acgme_databook_document.pdf

- After the Match. National Resident Matching Program website. Accessed January 23, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/fellowship-applicants/after-the-match/

- FREIDA vacant position listings. American Medical Association website. Accessed January 23, 2023. https://freida.ama-assn.org/vacant-position

- FindAResident. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed January 23, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/findaresident/findaresident

- What are the types of program positions in the main residency match? National Resident Matching Program website. Published August 5, 2021. Accessed January 23, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/help/item/what-types-of-programs-participate-in-the-main-residency-match/

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book, Academic Year 2021-2022. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2021-2022_acgme__databook_document.pdf

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book, Academic Year 2020-2021. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2020-2021_acgme_databook_document.pdf

- After the Match. National Resident Matching Program website. Accessed January 23, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/fellowship-applicants/after-the-match/

- FREIDA vacant position listings. American Medical Association website. Accessed January 23, 2023. https://freida.ama-assn.org/vacant-position

- FindAResident. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed January 23, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/findaresident/findaresident

- What are the types of program positions in the main residency match? National Resident Matching Program website. Published August 5, 2021. Accessed January 23, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/help/item/what-types-of-programs-participate-in-the-main-residency-match/

RESIDENT PEARL

- Transferring residency programs is difficult but possible. The decision to transfer residencies may be anxiety producing, but with substantial motives, the rewards of transferring can be worthwhile.

Severe Asthma Guidelines

Hemorrhagic Lacrimation and Epistaxis: Rare Findings in Acute Hemorrhagic Edema of Infancy

To the Editor:

Hemorrhagic lacrimation and epistaxis are dramatic presentations with a narrow differential diagnosis. It rarely has been reported to present alongside the more typical features of acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI), which is a benign self-limited leukocytoclastic vasculitis most often seen in children aged 4 months to 2 years. Extracutaneous involvement rarely is seen in AHEI, though joint, gastrointestinal tract, and renal involvement have been reported.1 Most patients present with edematous, annular, or cockade purpuric vasculitic lesions classically involving the face and distal extremities with relative sparing of the trunk. We present a case of a well-appearing, 10-month-old infant boy with hemorrhagic vasculitic lesions, acral edema, and an associated episode of hemorrhagic lacrimation and epistaxis.

A 10-month-old infant boy who was otherwise healthy presented to the emergency department (ED) with an acute-onset, progressively worsening cutaneous eruption of 2 days’ duration. A thorough history revealed that the eruption initially had presented as several small, bright-red papules on the thighs. The eruption subsequently spread to involve the buttocks, legs, and arms (Figures 1 and 2). The parents also noted that the patient had experienced an episode of bloody tears and epistaxis that lasted a few minutes at the pediatrician’s office earlier that morning, a finding that prompted the urgent referral to the ED.

Dermatology was then consulted. A review of systems was notable for rhinorrhea and diarrhea during the week leading to the eruption. The patient’s parents denied fevers, decreased oral intake, or a recent course of antibiotics. The patient’s medical history was notable only for atopic dermatitis treated with emollients and occasional topical steroids. The parents denied recent travel or vaccinations. Physical examination showed an afebrile, well-appearing infant with multiple nontender, slightly edematous, circular, purpuric papules and plaques scattered on the buttocks and extremities with edema on the dorsal feet. The remainder of the patient’s workup in the ED was notable for mild elevations in C-reactive protein levels (1.4 mg/dL [reference range, 0–1.2 mg/dL]) and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (22 mm/h [reference range, 2–12 mm/h]). A complete blood cell count; liver function tests; urinalysis; and coagulation studies, including prothrombin, partial thromboplastin time, and international normalized ratio, were unremarkable. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy was diagnosed based on the clinical manifestations.

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (also known as Finkelstein disease, medallionlike purpura, Seidemayer syndrome, infantile postinfectious irislike purpura and edema, and purpura en cocarde avec oedeme) is believed to result from an immune complex–related reaction, often in the setting of an upper respiratory tract infection; medications, especially antibiotics; or vaccinations. The condition previously was considered a benign form of Henoch-Schönlein purpura; however, it is now recognized as its own clinical entity. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy commonly affects children between the ages of 4 months and 2 years. The incidence peaks in the winter months, and males tend to be more affected than females.1

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is clinically characterized by a triad of large purpuric lesions, low-grade fever, and peripheral acral edema. Edema can develop on the hands, feet, and genitalia. Importantly, facial edema has been noted to precede skin lesions.2 Coin-shaped or targetoid hemorrhagic and purpuric lesions in a cockade or rosette pattern with scalloped margins typically begin on the distal extremities and tend to spread proximally. The lesions are variable in size but have been reported to be as large as 5 cm in diameter. Although joint pain, bloody diarrhea, hematuria, and proteinuria can accompany AHEI, most cases are devoid of systemic symptoms.3 Hemorrhagic lacrimation and epistaxis—both present in our patient—are rare findings with AHEI. It is likely that most providers, including dermatologists, may be unfamiliar with these striking clinical findings. Although the pathophysiology of hemorrhagic lacrimation and epistaxis has not been formally investigated, we postulate that it likely is related to the formation of immune complexes that lead to small vessel vasculitis, underpinning the characteristic findings in AHEI.4,5 This reasoning is supported by the complete resolution of symptoms corresponding with clinical clearance of the cutaneous vasculitis in 2 prior cases4,5 as well as in our patient who did not have a relapse of symptoms following cessation of the cutaneous eruption at a pediatric follow-up appointment 2 weeks later.

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is a clinical diagnosis; however, a skin biopsy can be performed to confirm the clinical suspicion and rule out more serious conditions. Histopathologic examination reveals a leukocytoclastic vasculitis involving the capillaries and postcapillary venules of the upper and mid dermis. Laboratory test results usually are nonspecific but can help distinguish AHEI from more serious diseases. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level may be slightly elevated in infants with AHEI. Urinalysis and stool guaiac tests also can be performed to evaluate for any renal or gastrointestinal involvement.6

The differential diagnosis includes IgA vasculitis, erythema multiforme, acute meningococcemia, urticarial vasculitis, Kawasaki disease, and child abuse. IgA vasculitis often presents with more systemic involvement, with abdominal pain, vomiting, hematemesis, diarrhea, and hematochezia occurring in up to 50% of patients. The cutaneous findings of erythema multiforme classically are confined to the limbs and face, and edema of the extremities typically is not seen. Patients with acute meningococcemia appear toxic with high fevers, malaise, and possible septic shock.5

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is a self-limited condition typically lasting 1 to 3 weeks and requires only supportive care.7 Antibiotics should be given to treat concurrent bacterial infections, and antihistamines and steroids may be useful for symptomatic relief. Importantly, however, systemic corticosteroids do not appear to conclusively alter the disease course.8

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is a rare benign leukocytoclastic vasculitis with a striking presentation often seen following an upper respiratory tract infection or course of antibiotics. Our case demonstrates that on rare occasions, AHEI may be accompanied by hemorrhagic lacrimation and epistaxis—findings that can be quite alarming to both parents and medical providers. Nonetheless, patients and their caretakers should be assured that the condition is self-limited and resolves without permanent sequalae.

- Emerich PS, Prebianchi PA, Motta LL, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy: report of three cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1181-1184.

- Avhad G, Ghuge P, Jerajani H. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:356-357.

- Krause I, Lazarov A, Rachmel A, et al. Acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy, a benign variant of leucocytoclastic vasculitis. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:114-117.

- Sneller H, Vega C, Zemel L, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy with associated hemorrhagic lacrimation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37:E70-E72. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001542

- Mreish S, Al-Tatari H. Hemorrhagic lacrimation and epistaxis in acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Case Rep Pediatr. 2016;2016:9762185. doi:10.1155/2016/9762185

- Savino F, Lupica MM, Tarasco V, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy: a troubling cutaneous presentation with a self-limiting course. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E149-E152.

- Fiore E, Rizzi M, Ragazzi M, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of young children (cockade purpura and edema): a case series and systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:684-695.

- Acute hemorrhagic edema of young children: a concise narrative review. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:1507-1511.

To the Editor:

Hemorrhagic lacrimation and epistaxis are dramatic presentations with a narrow differential diagnosis. It rarely has been reported to present alongside the more typical features of acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI), which is a benign self-limited leukocytoclastic vasculitis most often seen in children aged 4 months to 2 years. Extracutaneous involvement rarely is seen in AHEI, though joint, gastrointestinal tract, and renal involvement have been reported.1 Most patients present with edematous, annular, or cockade purpuric vasculitic lesions classically involving the face and distal extremities with relative sparing of the trunk. We present a case of a well-appearing, 10-month-old infant boy with hemorrhagic vasculitic lesions, acral edema, and an associated episode of hemorrhagic lacrimation and epistaxis.

A 10-month-old infant boy who was otherwise healthy presented to the emergency department (ED) with an acute-onset, progressively worsening cutaneous eruption of 2 days’ duration. A thorough history revealed that the eruption initially had presented as several small, bright-red papules on the thighs. The eruption subsequently spread to involve the buttocks, legs, and arms (Figures 1 and 2). The parents also noted that the patient had experienced an episode of bloody tears and epistaxis that lasted a few minutes at the pediatrician’s office earlier that morning, a finding that prompted the urgent referral to the ED.