User login

Renewed Concern for Navy Conditions Following Suicides

Eight Navy sailors have died by suicide in less than a year. The most recent death was on January 23. Three sailors who died in the past 2 months have more than suicide in common: They were all stationed aboard Navy aircraft carriers undergoing refits: the USS George Washington and the USS Theodore Roosevelt.

These deaths come only a month after the Navy released a report on 3 deaths by suicide on the George Washington, all of which happened in a single week last April. Military.com reported that the ship’s commander, Capt. Brent Gaut, had said 10 sailors had died by suicide in under a year.

In November and December 2022, at least 4 sailors assigned to the Mid-Atlantic Regional Maintenance Center (MARMC) in Virginia died by suicide, multiplying concerns about a fleetwide mental health crisis. “I was inundated with the amount of hopelessness at that command,” Kayla Arestivo, a counselor brought in to help, told nbcnews.com. Sailors spoke of being overworked, undervalued, and not getting the mental health help they needed. “Part of it is toxic leadership. The sailors immediately pointed that out,” Arestivo said.

She noted that many of the people assigned to MARMC are on limited duty due to mental or physical disabilities or have personal stressors that prevent them from full unrestricted duty. Electronics technician Kody Lee Decker, for instance, was on limited duty due to mental health issues when he died by suicide on October 29, 2022, according to a friend. Those people, Arestivo suggested, should have been provided help earlier.

Disabilities are not the only potential risk factors, though. Sailors living aboard the George Washington from April 2021 until April 2022 reported difficult and noisy living conditions with shortages of power, running water, and heat, and poor ventilation. Sailors would sleep in their cars or rent rooms in town rather than stay on board.

The George Washington has been docked at Newport News [Virginia] Shipbuilding for a major overhaul and repairs since 2017 (expected to extend into 2023, nearly 2 years later than the original deadline). The Navy investigation acknowledged “overwhelming” stress and noted that the living conditions created by an “intense and complex” maintenance process were posing hardships for the sailors, including sleep deprivation. (The Theodore Roosevelt has been at the Puget Sound shipyard since August 2021, although none of the sailors live onboard.)

However, the Navy investigation concluded that the 3 April suicide deaths were not directly connected to living conditions. According to the US Fleet Forces Command, “each Sailor was experiencing unique and individualized life stressors, which were contributing factors leading to their deaths.” The 3 suicide deaths were deemed independent events, with no direct correlation among them.

But the report also charged that leaders were oblivious to the problems, and the mental health care the Navy offered was insufficient: “Multiple command members knew or should have known that MASR Mitchell-Sandor [who died by suicide] was experiencing displeasure with Navy life and could have intervened to help him better cope or seek out available support services.”

In the official response to the Navy report, Rear Adm. John Meier, Commander, Naval Air Force Atlantic, noted that he had convened a “second and broader investigation” to assess quality of life issues and other systemic issues for aircraft carriers undergoing extensive maintenance or construction in the Newport News shipyard. “It is safe to say,” he wrote, that “generations of Navy leaders had become accustomed to the reduced quality of life in the shipyard, and accepted the status quo as par for the course…”

He agreed that the general stress of the environment was not the root cause of the deaths but was “certainly a contributing factor” in at least one case. The report, he said, placed too much emphasis on the sailor’s personal decisions to not improve his own living conditions (he was offered the opportunity to change berthing) and thus placed “too much burden on him for his situation.” Senior enlisted leadership knew that the sailor was sleeping in his car and counseled him, but Meier found no evidence of follow-through. More senior sailors or an assigned mentor should have been there to support the sailor, Meier said, and help him make decisions that were in his best interests. “This was a time for intrusive leadership.”

Adm. Daryl Caudle, Commander, US Fleet Forces Command, advised revising the wording in the report to say “No one at the command knew, or had a reason to know, of MASR [Xavier] Mitchell-Sandor’s previous suicidal ideations.” He also advised modifying the wording with: “Had the Navy been aware of MASR Mitchell-Sandor’s previous suicidal ideations, existing programs and procedures were in place that make it likely that he would have been placed in a ‘do not arm’ status and received necessary care.”

Vice Admiral Kenneth Whitesell, Commander, Naval Air Force, US Pacific Fleet, also endorsed the report findings with some revisions, saying, “We cannot assume these issues are isolated to a single ship, or to shipyards alone. Rather, these 3 tragic losses brought to light the ultimate need to remain laser-focused on providing care and guidance to our sailors.”

The Navy is providing mental health support to sailors, including an embedded mental health team and 2 civilian resiliency counselors who work on the George Washington. According to an action update in the report, Commander, Naval Air Force directed all CVNs and Naval Aviation Units to have a minimum of 1 safeTALK (Suicide Alertness For Everyone; Tell, Ask, Listen and KeepSafe) trained member onboard, and 2 to 3 safeTALK trained personnel in each division no later than December 31, 2022.

At MARMC, Arestivo was brought in for several mandatory suicide prevention sessions but without systemic changes, she said, “We’re putting Band-Aids on bullet holes.”

She said she told MARMC’s commanding officer, “You will have another one.” The fourth sailor died by suicide 10 days later.

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, call or text 988 to reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline or contact the Veterans Crisis Line.

Eight Navy sailors have died by suicide in less than a year. The most recent death was on January 23. Three sailors who died in the past 2 months have more than suicide in common: They were all stationed aboard Navy aircraft carriers undergoing refits: the USS George Washington and the USS Theodore Roosevelt.

These deaths come only a month after the Navy released a report on 3 deaths by suicide on the George Washington, all of which happened in a single week last April. Military.com reported that the ship’s commander, Capt. Brent Gaut, had said 10 sailors had died by suicide in under a year.

In November and December 2022, at least 4 sailors assigned to the Mid-Atlantic Regional Maintenance Center (MARMC) in Virginia died by suicide, multiplying concerns about a fleetwide mental health crisis. “I was inundated with the amount of hopelessness at that command,” Kayla Arestivo, a counselor brought in to help, told nbcnews.com. Sailors spoke of being overworked, undervalued, and not getting the mental health help they needed. “Part of it is toxic leadership. The sailors immediately pointed that out,” Arestivo said.

She noted that many of the people assigned to MARMC are on limited duty due to mental or physical disabilities or have personal stressors that prevent them from full unrestricted duty. Electronics technician Kody Lee Decker, for instance, was on limited duty due to mental health issues when he died by suicide on October 29, 2022, according to a friend. Those people, Arestivo suggested, should have been provided help earlier.

Disabilities are not the only potential risk factors, though. Sailors living aboard the George Washington from April 2021 until April 2022 reported difficult and noisy living conditions with shortages of power, running water, and heat, and poor ventilation. Sailors would sleep in their cars or rent rooms in town rather than stay on board.

The George Washington has been docked at Newport News [Virginia] Shipbuilding for a major overhaul and repairs since 2017 (expected to extend into 2023, nearly 2 years later than the original deadline). The Navy investigation acknowledged “overwhelming” stress and noted that the living conditions created by an “intense and complex” maintenance process were posing hardships for the sailors, including sleep deprivation. (The Theodore Roosevelt has been at the Puget Sound shipyard since August 2021, although none of the sailors live onboard.)

However, the Navy investigation concluded that the 3 April suicide deaths were not directly connected to living conditions. According to the US Fleet Forces Command, “each Sailor was experiencing unique and individualized life stressors, which were contributing factors leading to their deaths.” The 3 suicide deaths were deemed independent events, with no direct correlation among them.

But the report also charged that leaders were oblivious to the problems, and the mental health care the Navy offered was insufficient: “Multiple command members knew or should have known that MASR Mitchell-Sandor [who died by suicide] was experiencing displeasure with Navy life and could have intervened to help him better cope or seek out available support services.”

In the official response to the Navy report, Rear Adm. John Meier, Commander, Naval Air Force Atlantic, noted that he had convened a “second and broader investigation” to assess quality of life issues and other systemic issues for aircraft carriers undergoing extensive maintenance or construction in the Newport News shipyard. “It is safe to say,” he wrote, that “generations of Navy leaders had become accustomed to the reduced quality of life in the shipyard, and accepted the status quo as par for the course…”

He agreed that the general stress of the environment was not the root cause of the deaths but was “certainly a contributing factor” in at least one case. The report, he said, placed too much emphasis on the sailor’s personal decisions to not improve his own living conditions (he was offered the opportunity to change berthing) and thus placed “too much burden on him for his situation.” Senior enlisted leadership knew that the sailor was sleeping in his car and counseled him, but Meier found no evidence of follow-through. More senior sailors or an assigned mentor should have been there to support the sailor, Meier said, and help him make decisions that were in his best interests. “This was a time for intrusive leadership.”

Adm. Daryl Caudle, Commander, US Fleet Forces Command, advised revising the wording in the report to say “No one at the command knew, or had a reason to know, of MASR [Xavier] Mitchell-Sandor’s previous suicidal ideations.” He also advised modifying the wording with: “Had the Navy been aware of MASR Mitchell-Sandor’s previous suicidal ideations, existing programs and procedures were in place that make it likely that he would have been placed in a ‘do not arm’ status and received necessary care.”

Vice Admiral Kenneth Whitesell, Commander, Naval Air Force, US Pacific Fleet, also endorsed the report findings with some revisions, saying, “We cannot assume these issues are isolated to a single ship, or to shipyards alone. Rather, these 3 tragic losses brought to light the ultimate need to remain laser-focused on providing care and guidance to our sailors.”

The Navy is providing mental health support to sailors, including an embedded mental health team and 2 civilian resiliency counselors who work on the George Washington. According to an action update in the report, Commander, Naval Air Force directed all CVNs and Naval Aviation Units to have a minimum of 1 safeTALK (Suicide Alertness For Everyone; Tell, Ask, Listen and KeepSafe) trained member onboard, and 2 to 3 safeTALK trained personnel in each division no later than December 31, 2022.

At MARMC, Arestivo was brought in for several mandatory suicide prevention sessions but without systemic changes, she said, “We’re putting Band-Aids on bullet holes.”

She said she told MARMC’s commanding officer, “You will have another one.” The fourth sailor died by suicide 10 days later.

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, call or text 988 to reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline or contact the Veterans Crisis Line.

Eight Navy sailors have died by suicide in less than a year. The most recent death was on January 23. Three sailors who died in the past 2 months have more than suicide in common: They were all stationed aboard Navy aircraft carriers undergoing refits: the USS George Washington and the USS Theodore Roosevelt.

These deaths come only a month after the Navy released a report on 3 deaths by suicide on the George Washington, all of which happened in a single week last April. Military.com reported that the ship’s commander, Capt. Brent Gaut, had said 10 sailors had died by suicide in under a year.

In November and December 2022, at least 4 sailors assigned to the Mid-Atlantic Regional Maintenance Center (MARMC) in Virginia died by suicide, multiplying concerns about a fleetwide mental health crisis. “I was inundated with the amount of hopelessness at that command,” Kayla Arestivo, a counselor brought in to help, told nbcnews.com. Sailors spoke of being overworked, undervalued, and not getting the mental health help they needed. “Part of it is toxic leadership. The sailors immediately pointed that out,” Arestivo said.

She noted that many of the people assigned to MARMC are on limited duty due to mental or physical disabilities or have personal stressors that prevent them from full unrestricted duty. Electronics technician Kody Lee Decker, for instance, was on limited duty due to mental health issues when he died by suicide on October 29, 2022, according to a friend. Those people, Arestivo suggested, should have been provided help earlier.

Disabilities are not the only potential risk factors, though. Sailors living aboard the George Washington from April 2021 until April 2022 reported difficult and noisy living conditions with shortages of power, running water, and heat, and poor ventilation. Sailors would sleep in their cars or rent rooms in town rather than stay on board.

The George Washington has been docked at Newport News [Virginia] Shipbuilding for a major overhaul and repairs since 2017 (expected to extend into 2023, nearly 2 years later than the original deadline). The Navy investigation acknowledged “overwhelming” stress and noted that the living conditions created by an “intense and complex” maintenance process were posing hardships for the sailors, including sleep deprivation. (The Theodore Roosevelt has been at the Puget Sound shipyard since August 2021, although none of the sailors live onboard.)

However, the Navy investigation concluded that the 3 April suicide deaths were not directly connected to living conditions. According to the US Fleet Forces Command, “each Sailor was experiencing unique and individualized life stressors, which were contributing factors leading to their deaths.” The 3 suicide deaths were deemed independent events, with no direct correlation among them.

But the report also charged that leaders were oblivious to the problems, and the mental health care the Navy offered was insufficient: “Multiple command members knew or should have known that MASR Mitchell-Sandor [who died by suicide] was experiencing displeasure with Navy life and could have intervened to help him better cope or seek out available support services.”

In the official response to the Navy report, Rear Adm. John Meier, Commander, Naval Air Force Atlantic, noted that he had convened a “second and broader investigation” to assess quality of life issues and other systemic issues for aircraft carriers undergoing extensive maintenance or construction in the Newport News shipyard. “It is safe to say,” he wrote, that “generations of Navy leaders had become accustomed to the reduced quality of life in the shipyard, and accepted the status quo as par for the course…”

He agreed that the general stress of the environment was not the root cause of the deaths but was “certainly a contributing factor” in at least one case. The report, he said, placed too much emphasis on the sailor’s personal decisions to not improve his own living conditions (he was offered the opportunity to change berthing) and thus placed “too much burden on him for his situation.” Senior enlisted leadership knew that the sailor was sleeping in his car and counseled him, but Meier found no evidence of follow-through. More senior sailors or an assigned mentor should have been there to support the sailor, Meier said, and help him make decisions that were in his best interests. “This was a time for intrusive leadership.”

Adm. Daryl Caudle, Commander, US Fleet Forces Command, advised revising the wording in the report to say “No one at the command knew, or had a reason to know, of MASR [Xavier] Mitchell-Sandor’s previous suicidal ideations.” He also advised modifying the wording with: “Had the Navy been aware of MASR Mitchell-Sandor’s previous suicidal ideations, existing programs and procedures were in place that make it likely that he would have been placed in a ‘do not arm’ status and received necessary care.”

Vice Admiral Kenneth Whitesell, Commander, Naval Air Force, US Pacific Fleet, also endorsed the report findings with some revisions, saying, “We cannot assume these issues are isolated to a single ship, or to shipyards alone. Rather, these 3 tragic losses brought to light the ultimate need to remain laser-focused on providing care and guidance to our sailors.”

The Navy is providing mental health support to sailors, including an embedded mental health team and 2 civilian resiliency counselors who work on the George Washington. According to an action update in the report, Commander, Naval Air Force directed all CVNs and Naval Aviation Units to have a minimum of 1 safeTALK (Suicide Alertness For Everyone; Tell, Ask, Listen and KeepSafe) trained member onboard, and 2 to 3 safeTALK trained personnel in each division no later than December 31, 2022.

At MARMC, Arestivo was brought in for several mandatory suicide prevention sessions but without systemic changes, she said, “We’re putting Band-Aids on bullet holes.”

She said she told MARMC’s commanding officer, “You will have another one.” The fourth sailor died by suicide 10 days later.

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, call or text 988 to reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline or contact the Veterans Crisis Line.

Why Did Nonventilator-Associated HAP Peak During the Pandemic?

Cases of nonventilator-associated hospital-acquired pneumonia (NV-HAP) declined by 32% between 2015 and 2020. Then, of course, COVID-19 changed the trajectory and rates began to rise. After February 2020, the incidence rate rose by 25% among veterans without COVID-19—but by 108% among those who had COVID-19.

Those are findings from a study by researchers at Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center, Aurora, Colorado. They studied data on 1,567,275 veterans admitted to 135 VA facilities in acute care settings between October 2015 and March 2021, with a stay of at least 48 hours.

They say, to their knowledge, this is the first published report of changes in NV-HAP risk associated with the onset of COVID-19 among all hospitalized veterans in a national health care system.

The questions for the researchers were: What drove the increase in NV-HAP rates? Was it the elevated risk among veterans with COVID-19, reduced NV-HAP prevention measures during the extreme pandemic-related stress on the system, and/or increased patient acuity among hospitalized veterans?

They concluded that the observed increase in NV-HAP risk among all patients during the COVID-19 pandemic is “likely multifactorial.” The stresses on clinical workload may have hampered fundamental preventive nursing care, such as early mobility programs, consistent oral care, and aspiration precautions. The researchers also cite barriers including wearing personal protective equipment, which affected communication and the ability to get needed supplies to the bedside without cross-contamination.

Among patients with COVID-19 infections, the greater NV-HAP risk could be due to changes in the lower respiratory tract microbiome, disruption of the immune response, and synergism seen with COVID-19 infection. Moreover, they note, placing patients in a prone position to improve oxygenation might have raised the risk of NV-HAP.

The hospitalized veterans in the study also had a high burden of clinical comorbidities. Those with COVID-19 were more likely to have documented diagnosis of dementia in the previous year, compared with COVID-19-negative veterans or those hospitalized before the pandemic began. The researchers point out that dementia increased the risk of microaspiration, which can lead to secondary bacterial pneumonia.

In addition to reinforcing prevention efforts, the researchers suggest that NV-HAP monitoring via automated electronic surveillance could “serve as a cornerstone of a strong infection prevention program.” A system like that, installed before the pandemic, they say, might have identified the NV-HAP risk sooner.

Most importantly, they add, strategies to reduce NV-HAP risk “should be designed with resilience to significant system stress such as the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Cases of nonventilator-associated hospital-acquired pneumonia (NV-HAP) declined by 32% between 2015 and 2020. Then, of course, COVID-19 changed the trajectory and rates began to rise. After February 2020, the incidence rate rose by 25% among veterans without COVID-19—but by 108% among those who had COVID-19.

Those are findings from a study by researchers at Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center, Aurora, Colorado. They studied data on 1,567,275 veterans admitted to 135 VA facilities in acute care settings between October 2015 and March 2021, with a stay of at least 48 hours.

They say, to their knowledge, this is the first published report of changes in NV-HAP risk associated with the onset of COVID-19 among all hospitalized veterans in a national health care system.

The questions for the researchers were: What drove the increase in NV-HAP rates? Was it the elevated risk among veterans with COVID-19, reduced NV-HAP prevention measures during the extreme pandemic-related stress on the system, and/or increased patient acuity among hospitalized veterans?

They concluded that the observed increase in NV-HAP risk among all patients during the COVID-19 pandemic is “likely multifactorial.” The stresses on clinical workload may have hampered fundamental preventive nursing care, such as early mobility programs, consistent oral care, and aspiration precautions. The researchers also cite barriers including wearing personal protective equipment, which affected communication and the ability to get needed supplies to the bedside without cross-contamination.

Among patients with COVID-19 infections, the greater NV-HAP risk could be due to changes in the lower respiratory tract microbiome, disruption of the immune response, and synergism seen with COVID-19 infection. Moreover, they note, placing patients in a prone position to improve oxygenation might have raised the risk of NV-HAP.

The hospitalized veterans in the study also had a high burden of clinical comorbidities. Those with COVID-19 were more likely to have documented diagnosis of dementia in the previous year, compared with COVID-19-negative veterans or those hospitalized before the pandemic began. The researchers point out that dementia increased the risk of microaspiration, which can lead to secondary bacterial pneumonia.

In addition to reinforcing prevention efforts, the researchers suggest that NV-HAP monitoring via automated electronic surveillance could “serve as a cornerstone of a strong infection prevention program.” A system like that, installed before the pandemic, they say, might have identified the NV-HAP risk sooner.

Most importantly, they add, strategies to reduce NV-HAP risk “should be designed with resilience to significant system stress such as the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Cases of nonventilator-associated hospital-acquired pneumonia (NV-HAP) declined by 32% between 2015 and 2020. Then, of course, COVID-19 changed the trajectory and rates began to rise. After February 2020, the incidence rate rose by 25% among veterans without COVID-19—but by 108% among those who had COVID-19.

Those are findings from a study by researchers at Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center, Aurora, Colorado. They studied data on 1,567,275 veterans admitted to 135 VA facilities in acute care settings between October 2015 and March 2021, with a stay of at least 48 hours.

They say, to their knowledge, this is the first published report of changes in NV-HAP risk associated with the onset of COVID-19 among all hospitalized veterans in a national health care system.

The questions for the researchers were: What drove the increase in NV-HAP rates? Was it the elevated risk among veterans with COVID-19, reduced NV-HAP prevention measures during the extreme pandemic-related stress on the system, and/or increased patient acuity among hospitalized veterans?

They concluded that the observed increase in NV-HAP risk among all patients during the COVID-19 pandemic is “likely multifactorial.” The stresses on clinical workload may have hampered fundamental preventive nursing care, such as early mobility programs, consistent oral care, and aspiration precautions. The researchers also cite barriers including wearing personal protective equipment, which affected communication and the ability to get needed supplies to the bedside without cross-contamination.

Among patients with COVID-19 infections, the greater NV-HAP risk could be due to changes in the lower respiratory tract microbiome, disruption of the immune response, and synergism seen with COVID-19 infection. Moreover, they note, placing patients in a prone position to improve oxygenation might have raised the risk of NV-HAP.

The hospitalized veterans in the study also had a high burden of clinical comorbidities. Those with COVID-19 were more likely to have documented diagnosis of dementia in the previous year, compared with COVID-19-negative veterans or those hospitalized before the pandemic began. The researchers point out that dementia increased the risk of microaspiration, which can lead to secondary bacterial pneumonia.

In addition to reinforcing prevention efforts, the researchers suggest that NV-HAP monitoring via automated electronic surveillance could “serve as a cornerstone of a strong infection prevention program.” A system like that, installed before the pandemic, they say, might have identified the NV-HAP risk sooner.

Most importantly, they add, strategies to reduce NV-HAP risk “should be designed with resilience to significant system stress such as the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Periorbital Orange Spots

The Diagnosis: Orange Palpebral Spots

The clinical presentation of our patient was consistent with a diagnosis of orange palpebral spots (OPSs), an uncommon discoloration that most often appears in White patients in the fifth or sixth decades of life. Orange palpebral spots were first described in 2008 by Assouly et al1 in 27 patients (23 females and 4 males). In 2015, Belliveau et al2 expanded the designation to yellow-orange palpebral spots because they felt the term more fully expressed the color variations depicted in their patients; however, this term more frequently is used in ophthalmology.

Orange palpebral spots commonly appear as asymptomatic, yellow-orange, symmetric lesions with a predilection for the recessed areas of the superior eyelids but also can present on the canthi and inferior eyelids. The discolorations are more easily visible on fair skin and have been reported to measure from 10 to 15 mm in the long axis.3 Assouly et al1 described the orange spots as having indistinct margins, with borders similar to “sand on a sea shore.” Orange palpebral spots can be a persistent discoloration, and there are no reports of spontaneous regression. No known association with malignancy or systemic illness has been reported.

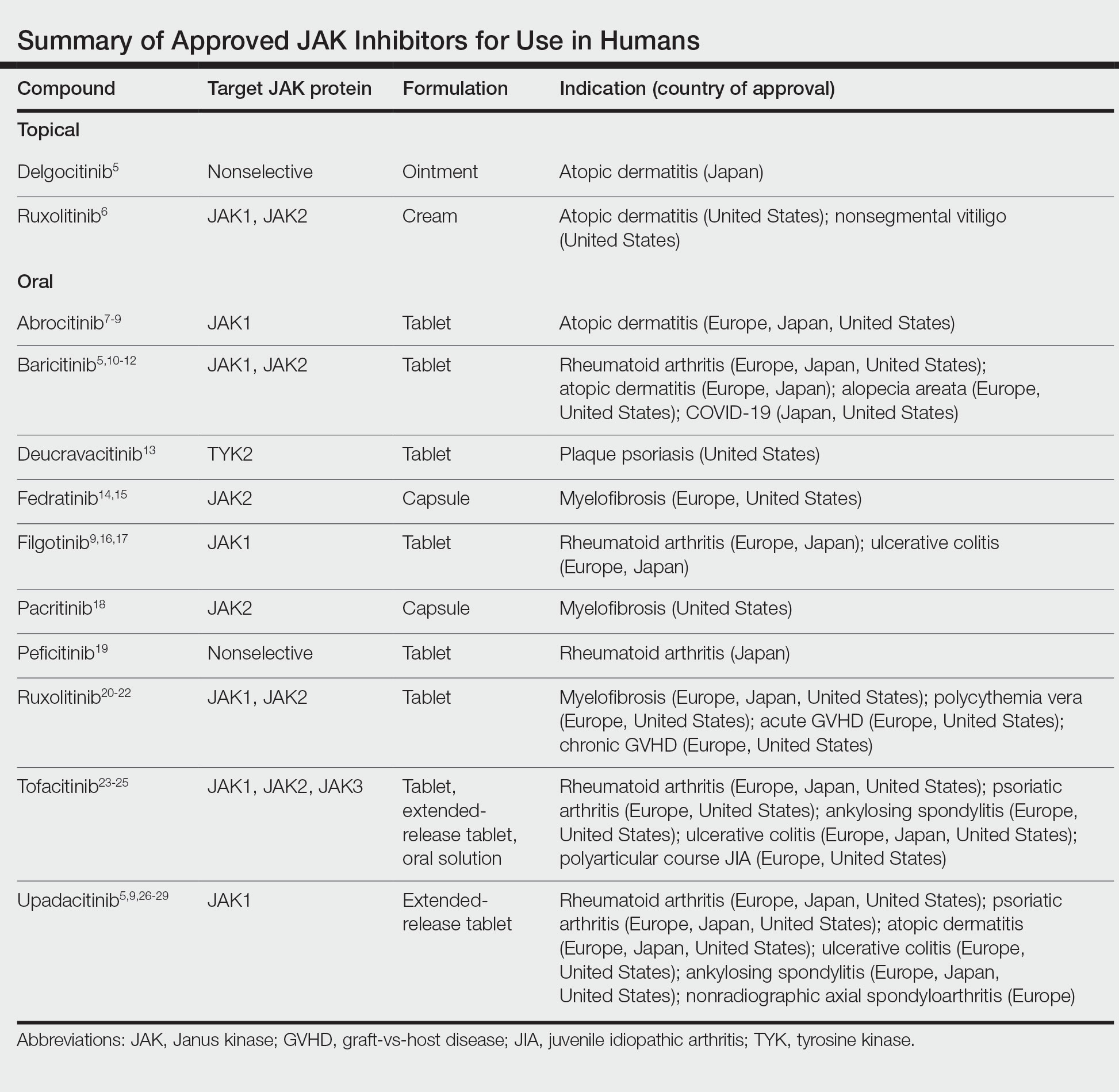

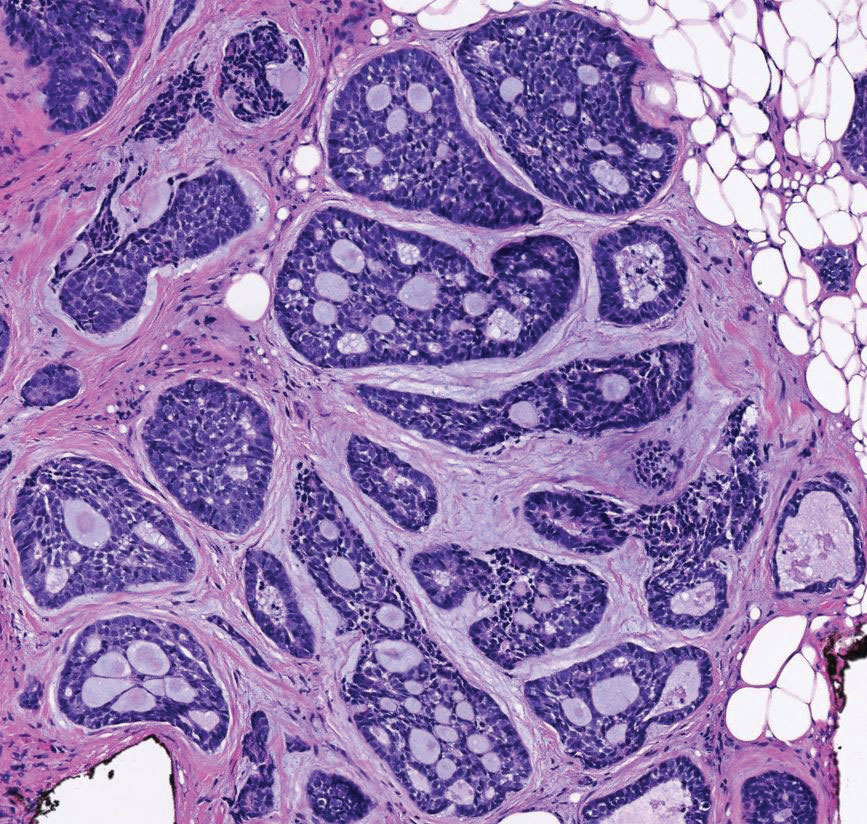

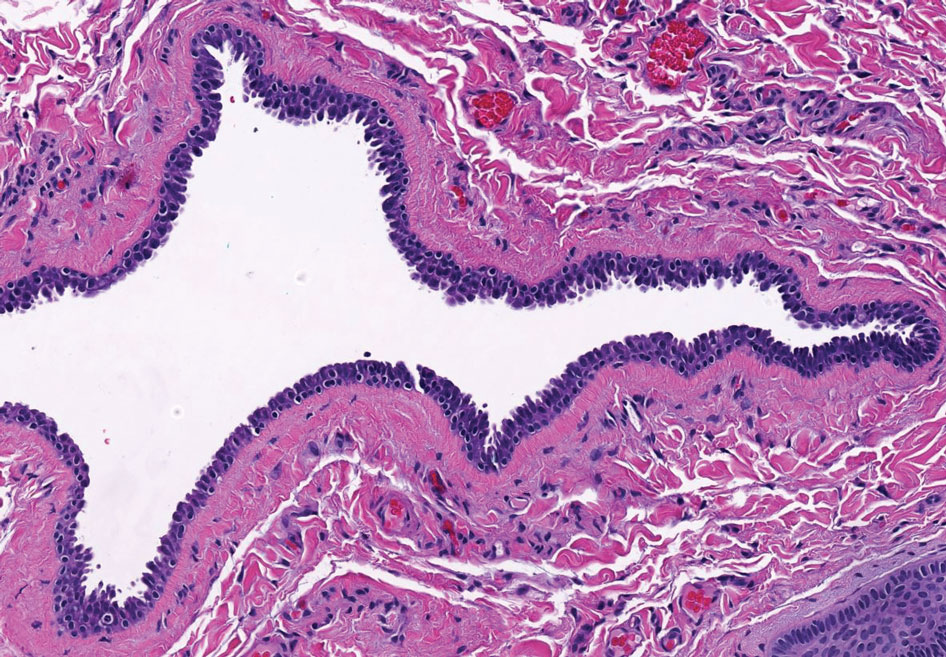

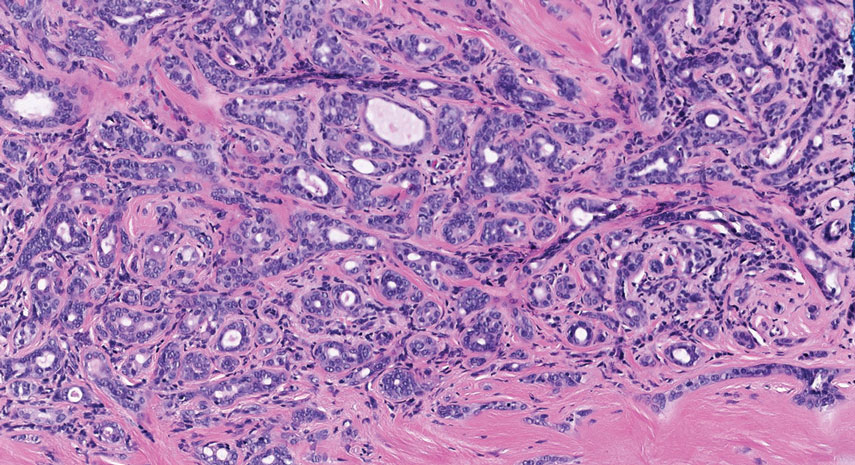

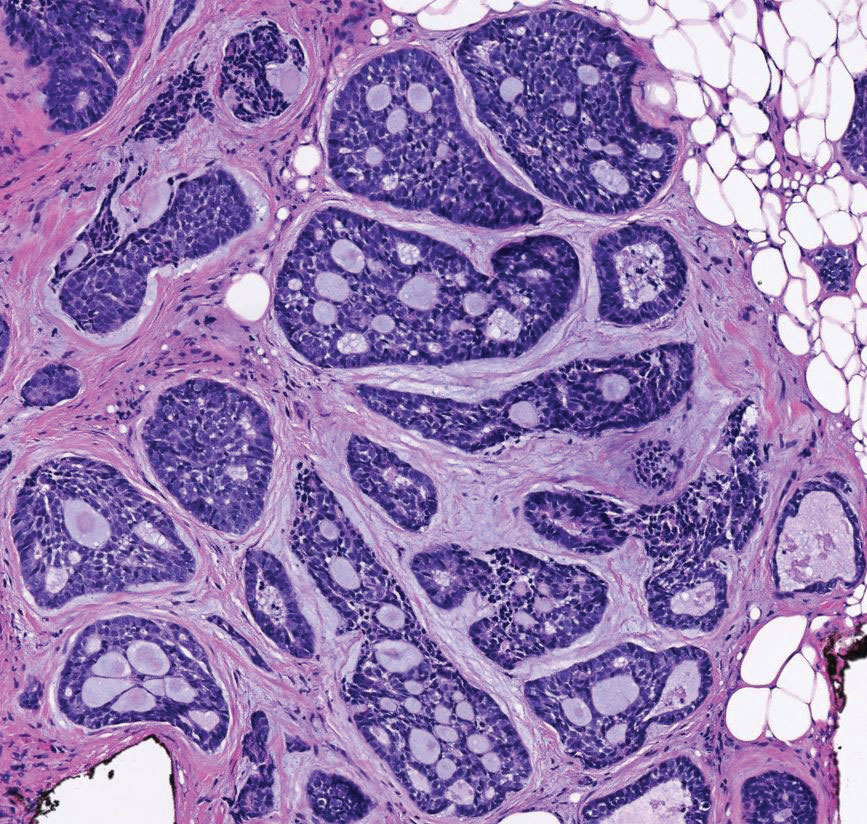

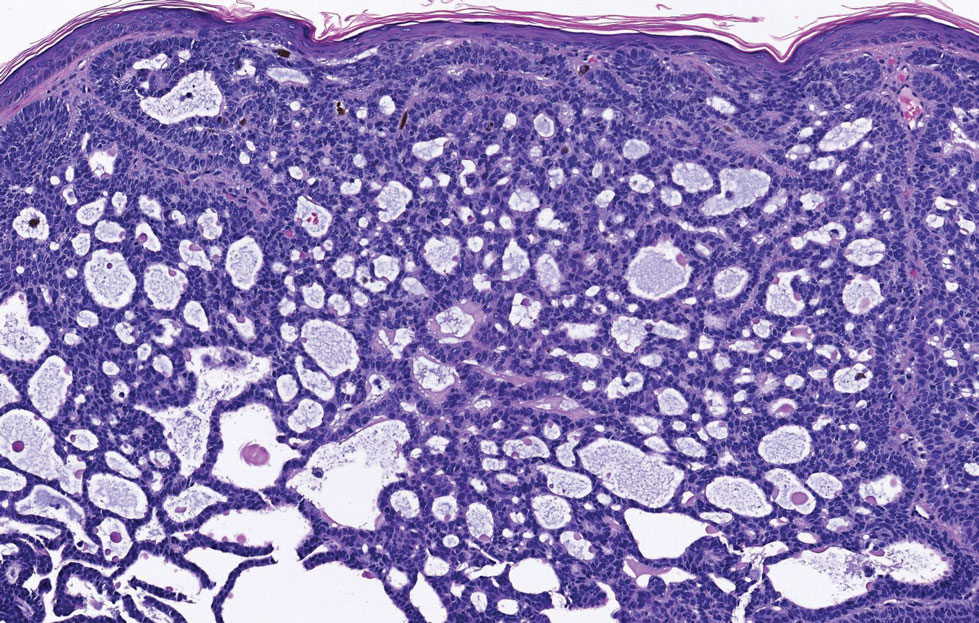

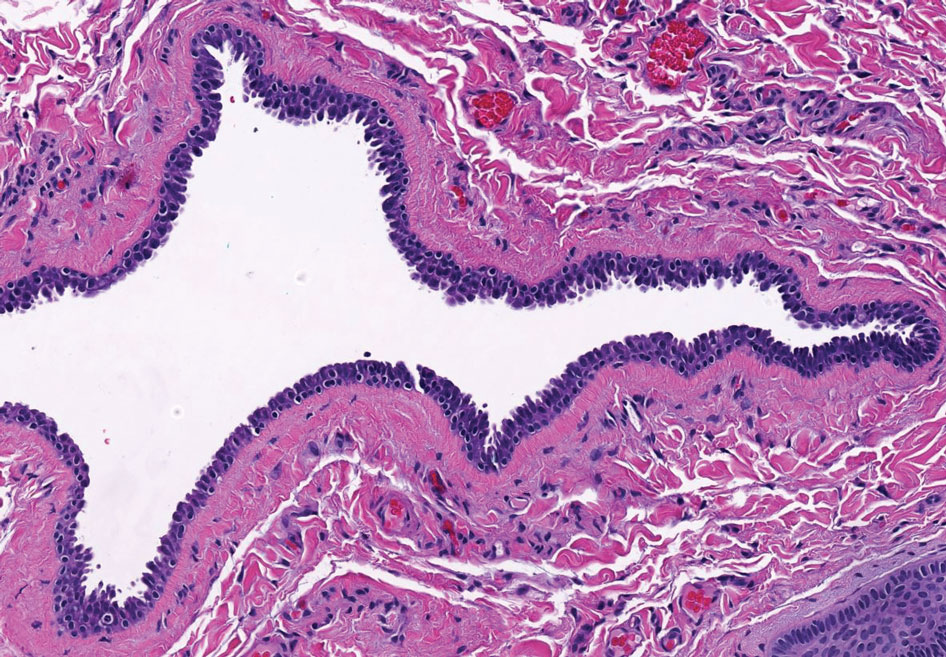

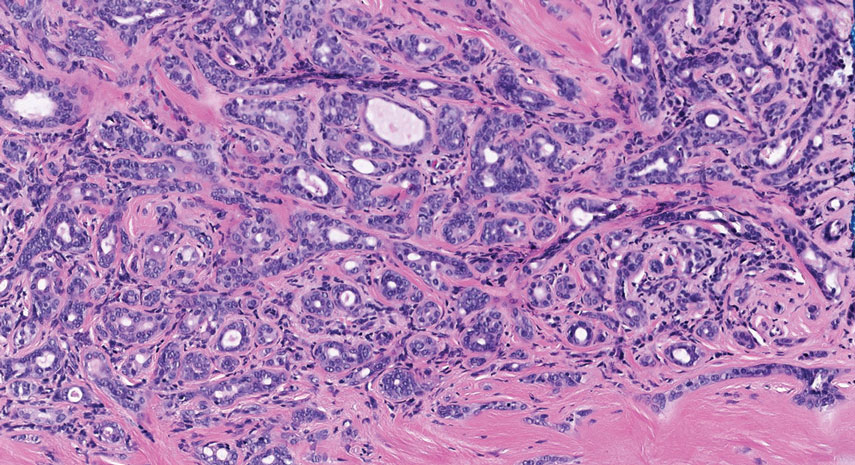

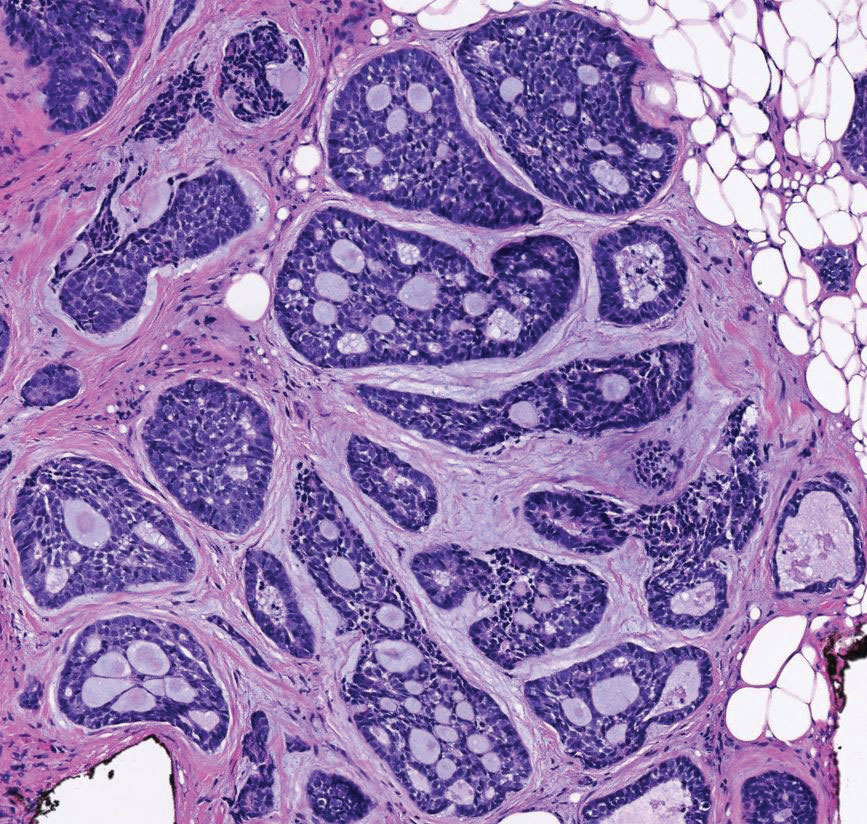

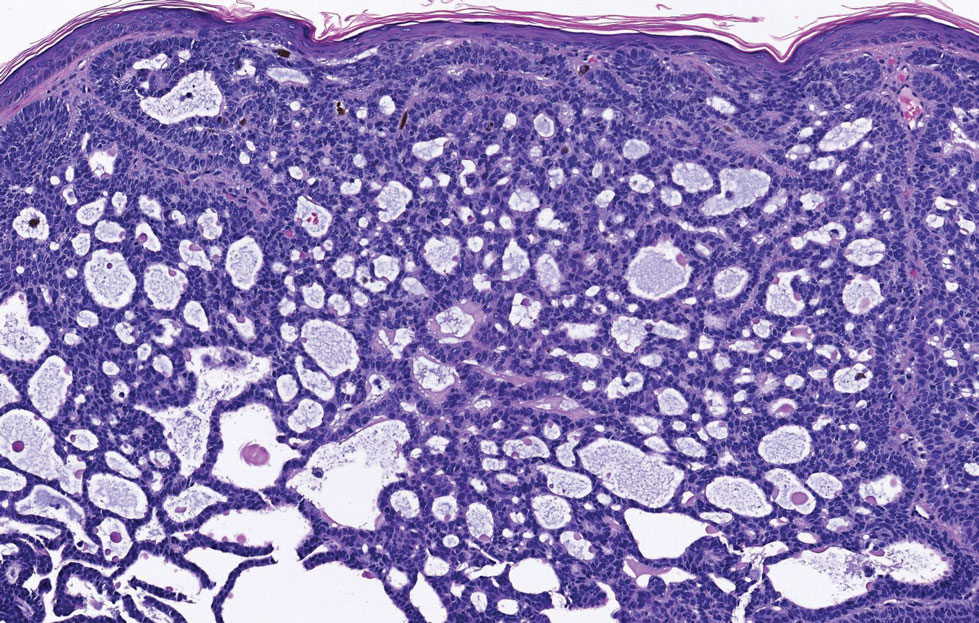

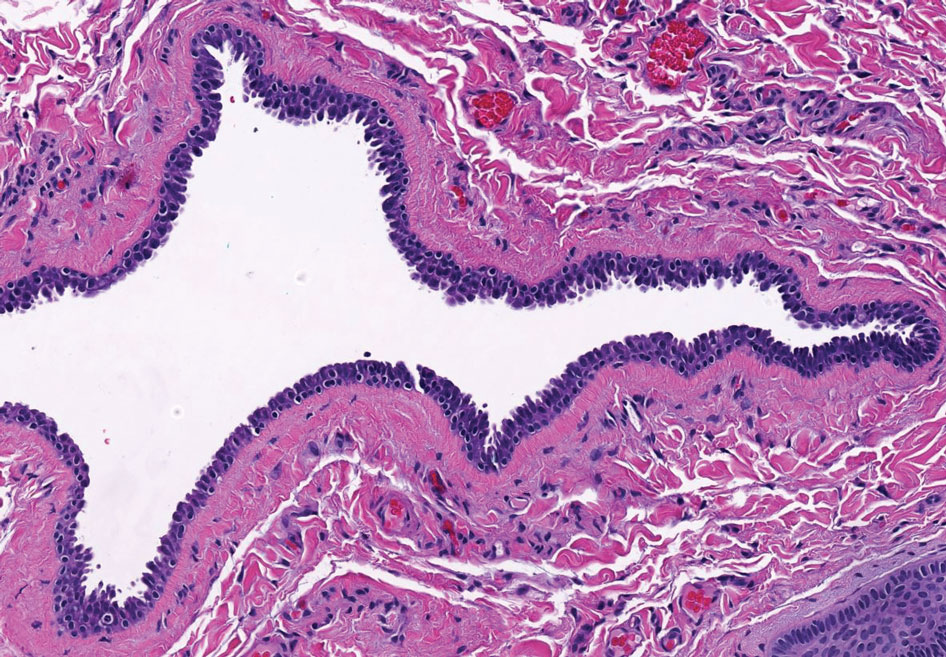

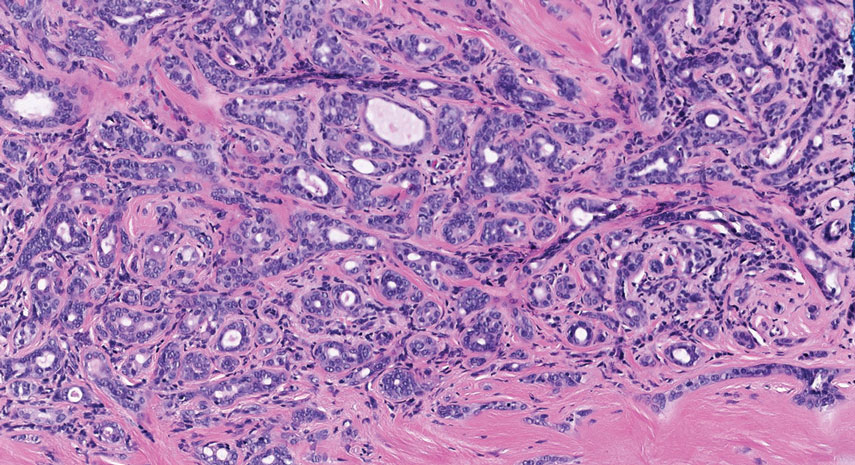

Case reports of OPSs describe histologic similarities between specimens, including increased adipose tissue and pigment-laden macrophages in the superficial dermis.2 The pigmented deposits sometimes may be found in the basal keratinocytes of the epidermis and turn black with Fontana-Masson stain.1 No inflammatory infiltrates, necrosis, or xanthomization are characteristically found. Stains for iron, mucin, and amyloid also have been negative.2

The cause of pigmentation in OPSs is unknown; however, lipofuscin deposits and high-situated adipocytes in the reticular dermis colored by carotenoids have been proposed as possible mechanisms.1 No unifying cause for pigmentation in the serum (eg, cholesterol, triglycerides, thyroid-stimulating hormone, free retinol, vitamin E, carotenoids) was found in 11 of 27 patients with OPSs assessed by Assouly et al.1 In one case, lipofuscin, a degradation product of lysosomes, was detected by microscopic autofluorescence in the superficial dermis. However, lipofuscin typically is a breakdown product associated with aging, and OPSs have been present in patients as young as 28 years.1 Local trauma related to eye rubbing is another theory that has been proposed due to the finding of melanin in the superficial dermis. However, the absence of hemosiderin deposits as well as the extensive duration of the discolorations makes local trauma a less likely explanation for the etiology of OPSs.2

The clinical differential diagnosis for OPSs includes xanthelasma, jaundice, and carotenoderma. Xanthelasma presents as elevated yellow plaques usually found over the medial aspect of the eyes. In contrast, OPSs are nonelevated with both orange and yellow hues typically present. Histologic samples of xanthelasma are characterized by lipid-laden macrophages (foam cells) in the dermis in contrast to the adipose tissue seen in OPSs that has not been phagocytized.1,2 The lack of scleral icterus made jaundice an unlikely diagnosis in our patient. Bilirubin elevations substantial enough to cause skin discoloration also would be expected to discolor the conjunctiva. In carotenoderma, carotenoids are deposited in the sweat and sebum of the stratum corneum with the orange pigmentation most prominent in regions of increased sweating such as the palms, soles, and nasolabial folds.4 Our patient’s lack of discoloration in places other than the periorbital region made carotenoderma less likely.

In the study by Assouly et al,1 10 of 11 patients who underwent laboratory analysis self-reported eating a diet rich in fruit and vegetables, though no standardized questionnaire was given. One patient was found to have an elevated vitamin E level, and in 5 cases there was an elevated level of β-cryptoxanthin. The significance of these elevations in such a small minority is unknown, and increased β-cryptoxanthin has been attributed to increased consumption of citrus fruits during the winter season. Our patient reported ingesting a daily oral supplement rich in carotenoids that constituted 60% of the daily value of vitamin E including mixed tocopherols as well as 90% of the daily value of vitamin A with many sources of carotenoids including beta-carotenes, lutein/zeaxanthin, lycopene, and astaxanthin. An invasive biopsy was not taken in this case, as OPSs largely are diagnosed clinically. Greater awareness and recognition of OPSs may help to identify common underlying causes for this unique diagnosis.

- Assouly P, Cavelier-Balloy B, Dupré T. Orange palpebral spots. Dermatology. 2008;216:166-170.

- Belliveau MJ, Odashiro AN, Harvey JT. Yellow-orange palpebral spots. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2139-2140.

- Kluger N, Guillot B. Bilateral orange discoloration of the upper eyelids: a quiz. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:211-212.

- Maharshak N, Shapiro J, Trau H. Carotenoderma—a review of the current literature. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:178-181.

The Diagnosis: Orange Palpebral Spots

The clinical presentation of our patient was consistent with a diagnosis of orange palpebral spots (OPSs), an uncommon discoloration that most often appears in White patients in the fifth or sixth decades of life. Orange palpebral spots were first described in 2008 by Assouly et al1 in 27 patients (23 females and 4 males). In 2015, Belliveau et al2 expanded the designation to yellow-orange palpebral spots because they felt the term more fully expressed the color variations depicted in their patients; however, this term more frequently is used in ophthalmology.

Orange palpebral spots commonly appear as asymptomatic, yellow-orange, symmetric lesions with a predilection for the recessed areas of the superior eyelids but also can present on the canthi and inferior eyelids. The discolorations are more easily visible on fair skin and have been reported to measure from 10 to 15 mm in the long axis.3 Assouly et al1 described the orange spots as having indistinct margins, with borders similar to “sand on a sea shore.” Orange palpebral spots can be a persistent discoloration, and there are no reports of spontaneous regression. No known association with malignancy or systemic illness has been reported.

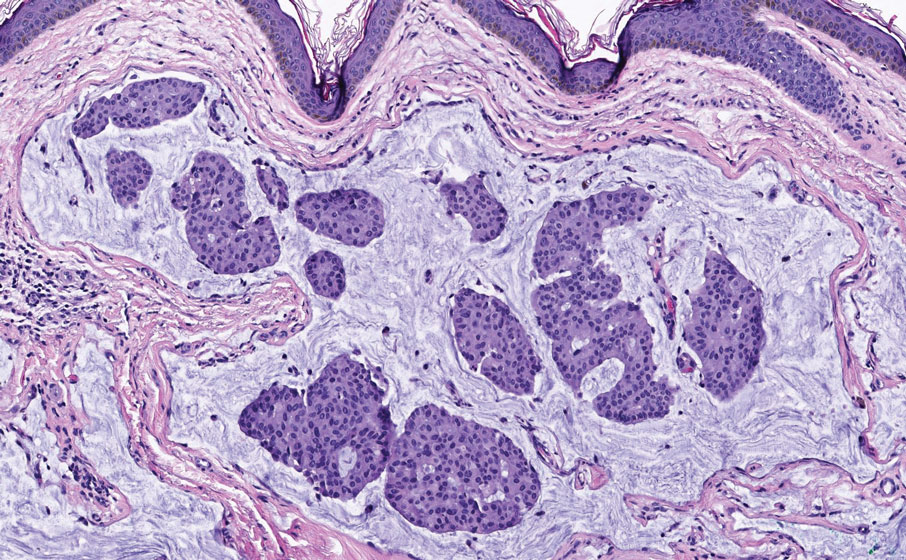

Case reports of OPSs describe histologic similarities between specimens, including increased adipose tissue and pigment-laden macrophages in the superficial dermis.2 The pigmented deposits sometimes may be found in the basal keratinocytes of the epidermis and turn black with Fontana-Masson stain.1 No inflammatory infiltrates, necrosis, or xanthomization are characteristically found. Stains for iron, mucin, and amyloid also have been negative.2

The cause of pigmentation in OPSs is unknown; however, lipofuscin deposits and high-situated adipocytes in the reticular dermis colored by carotenoids have been proposed as possible mechanisms.1 No unifying cause for pigmentation in the serum (eg, cholesterol, triglycerides, thyroid-stimulating hormone, free retinol, vitamin E, carotenoids) was found in 11 of 27 patients with OPSs assessed by Assouly et al.1 In one case, lipofuscin, a degradation product of lysosomes, was detected by microscopic autofluorescence in the superficial dermis. However, lipofuscin typically is a breakdown product associated with aging, and OPSs have been present in patients as young as 28 years.1 Local trauma related to eye rubbing is another theory that has been proposed due to the finding of melanin in the superficial dermis. However, the absence of hemosiderin deposits as well as the extensive duration of the discolorations makes local trauma a less likely explanation for the etiology of OPSs.2

The clinical differential diagnosis for OPSs includes xanthelasma, jaundice, and carotenoderma. Xanthelasma presents as elevated yellow plaques usually found over the medial aspect of the eyes. In contrast, OPSs are nonelevated with both orange and yellow hues typically present. Histologic samples of xanthelasma are characterized by lipid-laden macrophages (foam cells) in the dermis in contrast to the adipose tissue seen in OPSs that has not been phagocytized.1,2 The lack of scleral icterus made jaundice an unlikely diagnosis in our patient. Bilirubin elevations substantial enough to cause skin discoloration also would be expected to discolor the conjunctiva. In carotenoderma, carotenoids are deposited in the sweat and sebum of the stratum corneum with the orange pigmentation most prominent in regions of increased sweating such as the palms, soles, and nasolabial folds.4 Our patient’s lack of discoloration in places other than the periorbital region made carotenoderma less likely.

In the study by Assouly et al,1 10 of 11 patients who underwent laboratory analysis self-reported eating a diet rich in fruit and vegetables, though no standardized questionnaire was given. One patient was found to have an elevated vitamin E level, and in 5 cases there was an elevated level of β-cryptoxanthin. The significance of these elevations in such a small minority is unknown, and increased β-cryptoxanthin has been attributed to increased consumption of citrus fruits during the winter season. Our patient reported ingesting a daily oral supplement rich in carotenoids that constituted 60% of the daily value of vitamin E including mixed tocopherols as well as 90% of the daily value of vitamin A with many sources of carotenoids including beta-carotenes, lutein/zeaxanthin, lycopene, and astaxanthin. An invasive biopsy was not taken in this case, as OPSs largely are diagnosed clinically. Greater awareness and recognition of OPSs may help to identify common underlying causes for this unique diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Orange Palpebral Spots

The clinical presentation of our patient was consistent with a diagnosis of orange palpebral spots (OPSs), an uncommon discoloration that most often appears in White patients in the fifth or sixth decades of life. Orange palpebral spots were first described in 2008 by Assouly et al1 in 27 patients (23 females and 4 males). In 2015, Belliveau et al2 expanded the designation to yellow-orange palpebral spots because they felt the term more fully expressed the color variations depicted in their patients; however, this term more frequently is used in ophthalmology.

Orange palpebral spots commonly appear as asymptomatic, yellow-orange, symmetric lesions with a predilection for the recessed areas of the superior eyelids but also can present on the canthi and inferior eyelids. The discolorations are more easily visible on fair skin and have been reported to measure from 10 to 15 mm in the long axis.3 Assouly et al1 described the orange spots as having indistinct margins, with borders similar to “sand on a sea shore.” Orange palpebral spots can be a persistent discoloration, and there are no reports of spontaneous regression. No known association with malignancy or systemic illness has been reported.

Case reports of OPSs describe histologic similarities between specimens, including increased adipose tissue and pigment-laden macrophages in the superficial dermis.2 The pigmented deposits sometimes may be found in the basal keratinocytes of the epidermis and turn black with Fontana-Masson stain.1 No inflammatory infiltrates, necrosis, or xanthomization are characteristically found. Stains for iron, mucin, and amyloid also have been negative.2

The cause of pigmentation in OPSs is unknown; however, lipofuscin deposits and high-situated adipocytes in the reticular dermis colored by carotenoids have been proposed as possible mechanisms.1 No unifying cause for pigmentation in the serum (eg, cholesterol, triglycerides, thyroid-stimulating hormone, free retinol, vitamin E, carotenoids) was found in 11 of 27 patients with OPSs assessed by Assouly et al.1 In one case, lipofuscin, a degradation product of lysosomes, was detected by microscopic autofluorescence in the superficial dermis. However, lipofuscin typically is a breakdown product associated with aging, and OPSs have been present in patients as young as 28 years.1 Local trauma related to eye rubbing is another theory that has been proposed due to the finding of melanin in the superficial dermis. However, the absence of hemosiderin deposits as well as the extensive duration of the discolorations makes local trauma a less likely explanation for the etiology of OPSs.2

The clinical differential diagnosis for OPSs includes xanthelasma, jaundice, and carotenoderma. Xanthelasma presents as elevated yellow plaques usually found over the medial aspect of the eyes. In contrast, OPSs are nonelevated with both orange and yellow hues typically present. Histologic samples of xanthelasma are characterized by lipid-laden macrophages (foam cells) in the dermis in contrast to the adipose tissue seen in OPSs that has not been phagocytized.1,2 The lack of scleral icterus made jaundice an unlikely diagnosis in our patient. Bilirubin elevations substantial enough to cause skin discoloration also would be expected to discolor the conjunctiva. In carotenoderma, carotenoids are deposited in the sweat and sebum of the stratum corneum with the orange pigmentation most prominent in regions of increased sweating such as the palms, soles, and nasolabial folds.4 Our patient’s lack of discoloration in places other than the periorbital region made carotenoderma less likely.

In the study by Assouly et al,1 10 of 11 patients who underwent laboratory analysis self-reported eating a diet rich in fruit and vegetables, though no standardized questionnaire was given. One patient was found to have an elevated vitamin E level, and in 5 cases there was an elevated level of β-cryptoxanthin. The significance of these elevations in such a small minority is unknown, and increased β-cryptoxanthin has been attributed to increased consumption of citrus fruits during the winter season. Our patient reported ingesting a daily oral supplement rich in carotenoids that constituted 60% of the daily value of vitamin E including mixed tocopherols as well as 90% of the daily value of vitamin A with many sources of carotenoids including beta-carotenes, lutein/zeaxanthin, lycopene, and astaxanthin. An invasive biopsy was not taken in this case, as OPSs largely are diagnosed clinically. Greater awareness and recognition of OPSs may help to identify common underlying causes for this unique diagnosis.

- Assouly P, Cavelier-Balloy B, Dupré T. Orange palpebral spots. Dermatology. 2008;216:166-170.

- Belliveau MJ, Odashiro AN, Harvey JT. Yellow-orange palpebral spots. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2139-2140.

- Kluger N, Guillot B. Bilateral orange discoloration of the upper eyelids: a quiz. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:211-212.

- Maharshak N, Shapiro J, Trau H. Carotenoderma—a review of the current literature. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:178-181.

- Assouly P, Cavelier-Balloy B, Dupré T. Orange palpebral spots. Dermatology. 2008;216:166-170.

- Belliveau MJ, Odashiro AN, Harvey JT. Yellow-orange palpebral spots. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2139-2140.

- Kluger N, Guillot B. Bilateral orange discoloration of the upper eyelids: a quiz. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:211-212.

- Maharshak N, Shapiro J, Trau H. Carotenoderma—a review of the current literature. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:178-181.

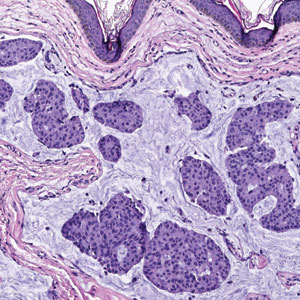

A 63-year-old White man with a history of melanoma presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of gradually worsening yellow discoloration around the eyes of 2 years’ duration. Physical examination revealed periorbital yellow-orange patches (top). The discolorations were nonelevated and nonpalpable. Dermoscopy revealed yellow blotches with sparing of the hair follicles (bottom). The remainder of the skin examination was unremarkable.

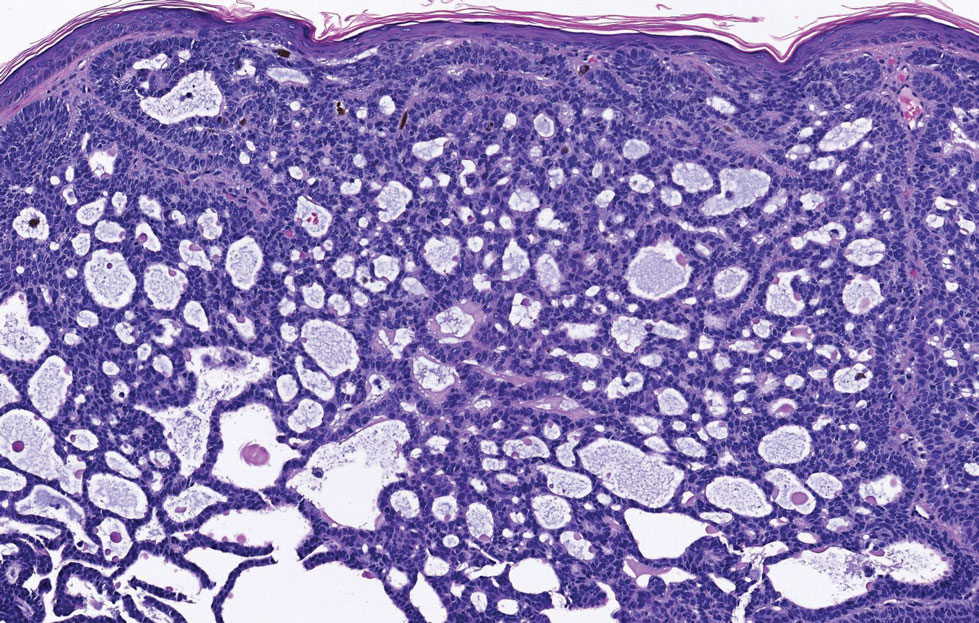

Pruritic rash on arms and legs

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic, inflammatory skin diseases encountered by dermatologists. AD is characterized by pruritus and a chronic course of exacerbations and remissions. AD is thought to involve the interplay of genetic predisposition, immune dysregulation, and environmental factors. It is also associated with other allergic conditions, including asthma.

Although AD typically presents with pruritus as the hallmark symptom in all patients, the appearance of skin lesions may vary among different skin types. In individuals with light-colored skin, AD often appears as erythematous patches and plaques. It also more commonly affects the flexor surfaces of the skin. In individuals with darker skin tones, AD may more often result in follicularly centered papules, lichenification, and pigmentary changes. Lesions may also present on extensor surfaces rather than the typical flexure surfaces. Erythema in darker skin types may appear reddish-brown, have a violaceous hue, or be an ashen gray or darker brown color rather than bright red. Because erythema is more difficult to detect in darker skin types, clinicians may mistakenly minimize the severity of AD.

Clinical severity may also differ between ethnicities. Black patients have an increased tendency toward hyperlinearity of the palms, periorbital dark circles, Dennie-Morgan lines, and diffuse xerosis. Compared with White patients, Black patients with AD are also more likely to develop prurigo nodularis and lichenification. In contrast, Asian patients with AD often experience psoriasiform features, with lesions having more well-defined borders and increased scaling and lichenification.

Beyond differences in clinical appearance, AD may appear molecularly and histologically distinct in ethnic skin. One study suggests that Black patients with AD may have decreased Th1 and Th17 but share similar upregulation of Th2 and Th22 as seen in White patients. Another study showed that Asian patients may have higher Th17 and Th22 and lower Th1/interferon compared with White patients.

Regardless of skin type, treatment goals remain the same. Treatment goals aim to repair and improve the function of the skin barrier while preventing and managing flares. Clinical studies have shown that skincare regimens incorporating ceramide-containing moisturizers may improve AD by increasing the lipid content in the skin. This may offer clinical benefit in patients with skin of color. However, some treatments often used for AD may lead to other skin issues in skin in color. For example, long-term use of topical steroids may worsen hypopigmentation in darker skin types. Management strategies should take into account the unique clinical and genetic features of AD among different patient demographic groups.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic, inflammatory skin diseases encountered by dermatologists. AD is characterized by pruritus and a chronic course of exacerbations and remissions. AD is thought to involve the interplay of genetic predisposition, immune dysregulation, and environmental factors. It is also associated with other allergic conditions, including asthma.

Although AD typically presents with pruritus as the hallmark symptom in all patients, the appearance of skin lesions may vary among different skin types. In individuals with light-colored skin, AD often appears as erythematous patches and plaques. It also more commonly affects the flexor surfaces of the skin. In individuals with darker skin tones, AD may more often result in follicularly centered papules, lichenification, and pigmentary changes. Lesions may also present on extensor surfaces rather than the typical flexure surfaces. Erythema in darker skin types may appear reddish-brown, have a violaceous hue, or be an ashen gray or darker brown color rather than bright red. Because erythema is more difficult to detect in darker skin types, clinicians may mistakenly minimize the severity of AD.

Clinical severity may also differ between ethnicities. Black patients have an increased tendency toward hyperlinearity of the palms, periorbital dark circles, Dennie-Morgan lines, and diffuse xerosis. Compared with White patients, Black patients with AD are also more likely to develop prurigo nodularis and lichenification. In contrast, Asian patients with AD often experience psoriasiform features, with lesions having more well-defined borders and increased scaling and lichenification.

Beyond differences in clinical appearance, AD may appear molecularly and histologically distinct in ethnic skin. One study suggests that Black patients with AD may have decreased Th1 and Th17 but share similar upregulation of Th2 and Th22 as seen in White patients. Another study showed that Asian patients may have higher Th17 and Th22 and lower Th1/interferon compared with White patients.

Regardless of skin type, treatment goals remain the same. Treatment goals aim to repair and improve the function of the skin barrier while preventing and managing flares. Clinical studies have shown that skincare regimens incorporating ceramide-containing moisturizers may improve AD by increasing the lipid content in the skin. This may offer clinical benefit in patients with skin of color. However, some treatments often used for AD may lead to other skin issues in skin in color. For example, long-term use of topical steroids may worsen hypopigmentation in darker skin types. Management strategies should take into account the unique clinical and genetic features of AD among different patient demographic groups.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic, inflammatory skin diseases encountered by dermatologists. AD is characterized by pruritus and a chronic course of exacerbations and remissions. AD is thought to involve the interplay of genetic predisposition, immune dysregulation, and environmental factors. It is also associated with other allergic conditions, including asthma.

Although AD typically presents with pruritus as the hallmark symptom in all patients, the appearance of skin lesions may vary among different skin types. In individuals with light-colored skin, AD often appears as erythematous patches and plaques. It also more commonly affects the flexor surfaces of the skin. In individuals with darker skin tones, AD may more often result in follicularly centered papules, lichenification, and pigmentary changes. Lesions may also present on extensor surfaces rather than the typical flexure surfaces. Erythema in darker skin types may appear reddish-brown, have a violaceous hue, or be an ashen gray or darker brown color rather than bright red. Because erythema is more difficult to detect in darker skin types, clinicians may mistakenly minimize the severity of AD.

Clinical severity may also differ between ethnicities. Black patients have an increased tendency toward hyperlinearity of the palms, periorbital dark circles, Dennie-Morgan lines, and diffuse xerosis. Compared with White patients, Black patients with AD are also more likely to develop prurigo nodularis and lichenification. In contrast, Asian patients with AD often experience psoriasiform features, with lesions having more well-defined borders and increased scaling and lichenification.

Beyond differences in clinical appearance, AD may appear molecularly and histologically distinct in ethnic skin. One study suggests that Black patients with AD may have decreased Th1 and Th17 but share similar upregulation of Th2 and Th22 as seen in White patients. Another study showed that Asian patients may have higher Th17 and Th22 and lower Th1/interferon compared with White patients.

Regardless of skin type, treatment goals remain the same. Treatment goals aim to repair and improve the function of the skin barrier while preventing and managing flares. Clinical studies have shown that skincare regimens incorporating ceramide-containing moisturizers may improve AD by increasing the lipid content in the skin. This may offer clinical benefit in patients with skin of color. However, some treatments often used for AD may lead to other skin issues in skin in color. For example, long-term use of topical steroids may worsen hypopigmentation in darker skin types. Management strategies should take into account the unique clinical and genetic features of AD among different patient demographic groups.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 27-year-old student presents with a pruritic rash on his hands and in the bends of his arms and legs. He recently started clinical rotations in a nursing facility and has been using hand sanitizer multiple times per day, which has exacerbated the rash on his hands, causing them to ooze and sting. He describes the rash as itchy, especially at night. At times he reports that the itching causes difficulty sleeping. In addition, his skin has little cracks that frequently bleed. He notes that he has experienced similar symptoms in the past, which resolved with moisturizers and topical cream from the drugstore. He has tried over-the-counter hydrocortisone during this episode, with minimal improvement in symptoms. He denies any change in laundry detergents or use of new household products.

Physical examination reveals large erythematous plaques on the hands and flexure surfaces of his neck, antecubital fossa, and behind the knees with scattered excoriations. Erythematous, slightly lichenified coalescing papules are noted on the proximal arms. His face is clear. General skin pigmentation is brown and free of masses and lumps.

Product updates and reviews

HEGENBERGER RETRACTOR: IS IT HELPFUL FOR PERINEAL REPAIR?

The Hegenberger Retractor, manufactured by Hegenberger Medical (Abingdon, United Kingdom) is available for purchase in the United States through Rocket Medical. A video that I find particularly useful for explaining its use is available here: https://www.youtube.com /watch?v=p-jilXgXZLY

Background. About 85% of women having a vaginal birth experience some form of perineal trauma, and 60% to 70% receive stitches for those spontaneous tears or intentional incisions. As such, repairing perineal lacerations is a requisite skill for all obstetricians and midwives, and every provider has developed exposure techniques to perform their suturing with the goals of good tissue re-approximation, efficiency, minimized patient discomfort, reduced blood loss, and safety from needle sticks. For several millennia, the most commonly used tissue retractor for these repairs has been one’s own fingers, or those of a colleague. While cost-effective and readily available, fingers do have drawbacks as a vaginal retractor. First, their use as a retractor precludes their use for other tasks. Second, their frequent need to be inserted and replaced (see drawback #1) can be uncomfortable for patients. Third, their limited surface area is often insufficient to appropriately provide adequate tissue retraction for optimal surgical site visualization. Finally, they get tired and typically do not appreciate being stuck with needles. Given all this, it is surprising that so many centuries have passed with so little innovation for this ubiquitous procedure. Fortunately, Danish midwife Malene Hegenberger thought now was a good time to change the status quo.

Design/Functionality. The Hegenberger Retractor is brilliant in its simplicity. Its unique molded plastic design is smooth, ergonomic, nonconductive, and packaged as a single-use sterile device. Amazingly, it has a near-perfect pliability balance, making it simultaneously easy to compress for insertion while providing enough retraction tension for good visualization once it has been reexpanded. The subtle ridges on the compression points are just enough to allow for a good grip, and the notches on the sides are a convenient addition for holding extra suture if needed. The device has been cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a Class 1 device and is approved for sale in the United States. In my experience with its use, I thought it was easy to place and provided excellent exposure for the repairs I was doing. In fact, I thought it provided as good if not better exposure than what I would expect from a Gelpi retractor without any of the trauma the Gelpi adds with its pointed ends. Smile emoji!

Innovation. In the early 1800s, French midwifery pioneer Marie Boivin introduced a novel pelvimeter and a revolutionary 2-part speculum to the technology of the day. Why it took more than 200 years for the ideas of another cutting-edge midwife to breach the walls of the obstetric technological establishment remains a mystery, but fortunately it has been done. While seemingly obvious, the Hegenberger Retractor is the culmination of years of work and 88 prototypes. It looks simple, but the secret to its functionality is the precision with which each dimension and every curve was designed. The device has been cleared by the FDA as a Class 1 device and is approved for sale in the United States.

Summary. There are a lot of reasons to like the Hegenberger Retractor. I like it for its simplicity; I like it for its functionality; I like it for its ability to fill a real need. On the downside, I do not like that it is a single-use plastic device, and I am not happy about adding cost to obstetric care. Most of all, I hate that I did not invent it.

Is the Hegenberger Retractor going to be needed to repair every obstetric laceration? No. Will it provide perfect exposure to repair every obstetric laceration? Of course not. But it is an incredibly clever device that will be very helpful in many situations, and I suspect it will soon become a mainstay on most maternity units as it gains recognition.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.rocketmedical.com

- McCandlish R, Bowler U, van Asten H, et al. A randomised controlled trial of care of the perineum during second stage of normal labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:1262-1272.

- Ferry G. Marie Boivin: from midwife to gynaecologist. Lancet. 2019;393:2192-2193. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31188-2.

HEGENBERGER RETRACTOR: IS IT HELPFUL FOR PERINEAL REPAIR?

The Hegenberger Retractor, manufactured by Hegenberger Medical (Abingdon, United Kingdom) is available for purchase in the United States through Rocket Medical. A video that I find particularly useful for explaining its use is available here: https://www.youtube.com /watch?v=p-jilXgXZLY

Background. About 85% of women having a vaginal birth experience some form of perineal trauma, and 60% to 70% receive stitches for those spontaneous tears or intentional incisions. As such, repairing perineal lacerations is a requisite skill for all obstetricians and midwives, and every provider has developed exposure techniques to perform their suturing with the goals of good tissue re-approximation, efficiency, minimized patient discomfort, reduced blood loss, and safety from needle sticks. For several millennia, the most commonly used tissue retractor for these repairs has been one’s own fingers, or those of a colleague. While cost-effective and readily available, fingers do have drawbacks as a vaginal retractor. First, their use as a retractor precludes their use for other tasks. Second, their frequent need to be inserted and replaced (see drawback #1) can be uncomfortable for patients. Third, their limited surface area is often insufficient to appropriately provide adequate tissue retraction for optimal surgical site visualization. Finally, they get tired and typically do not appreciate being stuck with needles. Given all this, it is surprising that so many centuries have passed with so little innovation for this ubiquitous procedure. Fortunately, Danish midwife Malene Hegenberger thought now was a good time to change the status quo.

Design/Functionality. The Hegenberger Retractor is brilliant in its simplicity. Its unique molded plastic design is smooth, ergonomic, nonconductive, and packaged as a single-use sterile device. Amazingly, it has a near-perfect pliability balance, making it simultaneously easy to compress for insertion while providing enough retraction tension for good visualization once it has been reexpanded. The subtle ridges on the compression points are just enough to allow for a good grip, and the notches on the sides are a convenient addition for holding extra suture if needed. The device has been cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a Class 1 device and is approved for sale in the United States. In my experience with its use, I thought it was easy to place and provided excellent exposure for the repairs I was doing. In fact, I thought it provided as good if not better exposure than what I would expect from a Gelpi retractor without any of the trauma the Gelpi adds with its pointed ends. Smile emoji!

Innovation. In the early 1800s, French midwifery pioneer Marie Boivin introduced a novel pelvimeter and a revolutionary 2-part speculum to the technology of the day. Why it took more than 200 years for the ideas of another cutting-edge midwife to breach the walls of the obstetric technological establishment remains a mystery, but fortunately it has been done. While seemingly obvious, the Hegenberger Retractor is the culmination of years of work and 88 prototypes. It looks simple, but the secret to its functionality is the precision with which each dimension and every curve was designed. The device has been cleared by the FDA as a Class 1 device and is approved for sale in the United States.

Summary. There are a lot of reasons to like the Hegenberger Retractor. I like it for its simplicity; I like it for its functionality; I like it for its ability to fill a real need. On the downside, I do not like that it is a single-use plastic device, and I am not happy about adding cost to obstetric care. Most of all, I hate that I did not invent it.

Is the Hegenberger Retractor going to be needed to repair every obstetric laceration? No. Will it provide perfect exposure to repair every obstetric laceration? Of course not. But it is an incredibly clever device that will be very helpful in many situations, and I suspect it will soon become a mainstay on most maternity units as it gains recognition.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.rocketmedical.com

HEGENBERGER RETRACTOR: IS IT HELPFUL FOR PERINEAL REPAIR?

The Hegenberger Retractor, manufactured by Hegenberger Medical (Abingdon, United Kingdom) is available for purchase in the United States through Rocket Medical. A video that I find particularly useful for explaining its use is available here: https://www.youtube.com /watch?v=p-jilXgXZLY

Background. About 85% of women having a vaginal birth experience some form of perineal trauma, and 60% to 70% receive stitches for those spontaneous tears or intentional incisions. As such, repairing perineal lacerations is a requisite skill for all obstetricians and midwives, and every provider has developed exposure techniques to perform their suturing with the goals of good tissue re-approximation, efficiency, minimized patient discomfort, reduced blood loss, and safety from needle sticks. For several millennia, the most commonly used tissue retractor for these repairs has been one’s own fingers, or those of a colleague. While cost-effective and readily available, fingers do have drawbacks as a vaginal retractor. First, their use as a retractor precludes their use for other tasks. Second, their frequent need to be inserted and replaced (see drawback #1) can be uncomfortable for patients. Third, their limited surface area is often insufficient to appropriately provide adequate tissue retraction for optimal surgical site visualization. Finally, they get tired and typically do not appreciate being stuck with needles. Given all this, it is surprising that so many centuries have passed with so little innovation for this ubiquitous procedure. Fortunately, Danish midwife Malene Hegenberger thought now was a good time to change the status quo.

Design/Functionality. The Hegenberger Retractor is brilliant in its simplicity. Its unique molded plastic design is smooth, ergonomic, nonconductive, and packaged as a single-use sterile device. Amazingly, it has a near-perfect pliability balance, making it simultaneously easy to compress for insertion while providing enough retraction tension for good visualization once it has been reexpanded. The subtle ridges on the compression points are just enough to allow for a good grip, and the notches on the sides are a convenient addition for holding extra suture if needed. The device has been cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a Class 1 device and is approved for sale in the United States. In my experience with its use, I thought it was easy to place and provided excellent exposure for the repairs I was doing. In fact, I thought it provided as good if not better exposure than what I would expect from a Gelpi retractor without any of the trauma the Gelpi adds with its pointed ends. Smile emoji!

Innovation. In the early 1800s, French midwifery pioneer Marie Boivin introduced a novel pelvimeter and a revolutionary 2-part speculum to the technology of the day. Why it took more than 200 years for the ideas of another cutting-edge midwife to breach the walls of the obstetric technological establishment remains a mystery, but fortunately it has been done. While seemingly obvious, the Hegenberger Retractor is the culmination of years of work and 88 prototypes. It looks simple, but the secret to its functionality is the precision with which each dimension and every curve was designed. The device has been cleared by the FDA as a Class 1 device and is approved for sale in the United States.

Summary. There are a lot of reasons to like the Hegenberger Retractor. I like it for its simplicity; I like it for its functionality; I like it for its ability to fill a real need. On the downside, I do not like that it is a single-use plastic device, and I am not happy about adding cost to obstetric care. Most of all, I hate that I did not invent it.

Is the Hegenberger Retractor going to be needed to repair every obstetric laceration? No. Will it provide perfect exposure to repair every obstetric laceration? Of course not. But it is an incredibly clever device that will be very helpful in many situations, and I suspect it will soon become a mainstay on most maternity units as it gains recognition.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.rocketmedical.com

- McCandlish R, Bowler U, van Asten H, et al. A randomised controlled trial of care of the perineum during second stage of normal labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:1262-1272.

- Ferry G. Marie Boivin: from midwife to gynaecologist. Lancet. 2019;393:2192-2193. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31188-2.

- McCandlish R, Bowler U, van Asten H, et al. A randomised controlled trial of care of the perineum during second stage of normal labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:1262-1272.

- Ferry G. Marie Boivin: from midwife to gynaecologist. Lancet. 2019;393:2192-2193. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31188-2.

COMMENT & CONTROVERSY

Should treatment be initiated for mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy to improve outcomes?

JAIMEY M. PAULI, MD (JUNE 2022)

Consider this, when it comes to treating chronic hypertension

I welcome the article by Dr. Jaimey Pauli, which focuses on initiating treatment for mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy to reach a goal blood pressure (BP) of <140/90 mm Hg to prevent adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.1 I would like to offer 3 additional thoughts for your consideration. First, it is known that there is a physiological decrease in BP during the second trimester, which results in a normotensive presentation. Thus, it would be beneficial to see if pregnant women with high-normal BP levels before the third trimester be administered a lower dose of antihypertensives. However, there is also a concern that decreased maternal BP may compromise uteroplacental perfusion and fetal circulation, which also could be evaluated.2

Second, I would like to see how comorbidities affect the initiation of antihypertensives for mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Research incorporating pregnant women with borderline hypertension and comorbidities such as obesity, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM) is likely to yield informative results. This is especially beneficial since, for example, chronic hypertension and DM are independent risk factors for adverse maternal and fetal outcomes; therefore, a mother with both these conditions may have additive effects on obstetric outcomes.3

Lastly, I would suggest you include a brief conversation about prepregnancy ways to manage women with chronic hypertension. Because many women who enter pregnancy with chronic hypertension have hypertension of unknown origin, it would be beneficial to optimize antihypertensive regimens before conception.4 Also, it should be further evaluated whether initiation of lifestyle modifications, such as weight reduction and the DASH diet before pregnancy, for women with chronic hypertension improves pregnancy outcomes.

Cassandra Maafoh, MD

Macon, Georgia

References

- Pauli JM. Should treatment be initiated for mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy to improve outcomes? OBG Manag. 2022;34:14-15.

- Brown CM, Garovic VD. Drug treatment of hypertension in pregnancy. Drugs. 2014;74:283-296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-014-0187-7.

- Yanit KE, Snowden JM, Cheng YW, et al. The impact of chronic hypertension and pregestational diabetes on pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.066.

- Seely EW, Ecker J. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Circulation. 2014;129:1254-1261. https:// doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.113.003904.

BARBARA LEVY, MD (AUGUST 2022)

Are these new and rare syndromes’ pathophysiological mechanisms related?

I read with great interest Dr. Barbara Levy’s UPDATE in the August 2022 issue on testosterone therapy for women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), as well as her comments on persistent genital arousal disorder/genito-pelvic dysesthesia (PGAD/GPD) that was recently so coined by the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) as a 2-component syndrome.1 The new syndrome, explains Dr. Levy, presents with “the perception of genital arousal that is involuntary, unrelated to sexual desire, without any identified cause, not relieved with orgasm, and distressing to the patient (the PGAD component),” combined with “itching, burning, tingling, or pain” (the GPD component).

Although agreeing with ISSWSH that diagnosis and management require a multidisciplinary biopsychosocial approach, in her practical advice, Dr. Levy mentioned: “neuropathic signaling” with “aberrant sensory processing” as the syndrome’s possible main pathophysiology. Interestingly, there are 2 other rare, chronic, and “poorly recognized source(s) of major distress to a small but significant group of patients.” Persistent idiopathic oro-facial pain (PIFP) disorder2 after dental interventions and burning mouth syndrome (BMS),3 defined by the absence of any local or systemic contributing etiology, also present with continuous local burning and pain (as in GPD). Consequently, PGAD/GPD may indeed have the same pathophysiological explanation—as Dr. Levy suggested—of being a (genital) peripheral chronic neuropathic pain condition.

A potentially promising new therapeutic approach for PGAD/GPD would then be to use the same, or similar, antineuropathic medications (Clonazepam, Nortriptyline, Pregabalin, etc.) in the form of topical vaginal swishing solutions similar to the presently recommended antiepileptic and/or antidepressant oral swishing treatment for PIFP and BMS. As the topical approach works well for oral neuropathic pain, vaginal swishing could potentially be the answer for PGAD/GPD peripheral neuropathic pain. Moreover, such a novel topical approach would significantly increase patient motivation for treatment by avoiding the adverse effects of ingested antiepileptic or antidepressant drugs.

This is the first time that anticonvulsant and/or antidepressant vaginal swishing is proposed as topical therapy for GPD peripheral neuropathic pain, still pending scientific/clinical validation. ●

Zwi Hoch, MD

Newton, Massachusetts

- Goldstein I, Komisaruk BR, Pukall CF, et al. International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) Review of Epidemiology and Pathophysiology, and a Consensus Nomenclature and Process of Care for the Management of Persistent Genital Arousal Disorder/Genito-Pelvic Dysesthesia (PGAD/GPD). J Sex Med. 2021;18:665-697.

- Baad-Hansen L, Benoliel R. Neuropathic orofacial pain: facts and fiction. Cephalgia. 2017;37:670-679.

- Kuten-Shorer M, Treister NS, Stock S, et al. Safety and tolerability of topical clonazepam solution for management of oral dysesthesia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2017;124: 146-151.

Should treatment be initiated for mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy to improve outcomes?

JAIMEY M. PAULI, MD (JUNE 2022)

Consider this, when it comes to treating chronic hypertension

I welcome the article by Dr. Jaimey Pauli, which focuses on initiating treatment for mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy to reach a goal blood pressure (BP) of <140/90 mm Hg to prevent adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.1 I would like to offer 3 additional thoughts for your consideration. First, it is known that there is a physiological decrease in BP during the second trimester, which results in a normotensive presentation. Thus, it would be beneficial to see if pregnant women with high-normal BP levels before the third trimester be administered a lower dose of antihypertensives. However, there is also a concern that decreased maternal BP may compromise uteroplacental perfusion and fetal circulation, which also could be evaluated.2

Second, I would like to see how comorbidities affect the initiation of antihypertensives for mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Research incorporating pregnant women with borderline hypertension and comorbidities such as obesity, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM) is likely to yield informative results. This is especially beneficial since, for example, chronic hypertension and DM are independent risk factors for adverse maternal and fetal outcomes; therefore, a mother with both these conditions may have additive effects on obstetric outcomes.3

Lastly, I would suggest you include a brief conversation about prepregnancy ways to manage women with chronic hypertension. Because many women who enter pregnancy with chronic hypertension have hypertension of unknown origin, it would be beneficial to optimize antihypertensive regimens before conception.4 Also, it should be further evaluated whether initiation of lifestyle modifications, such as weight reduction and the DASH diet before pregnancy, for women with chronic hypertension improves pregnancy outcomes.

Cassandra Maafoh, MD

Macon, Georgia

References

- Pauli JM. Should treatment be initiated for mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy to improve outcomes? OBG Manag. 2022;34:14-15.

- Brown CM, Garovic VD. Drug treatment of hypertension in pregnancy. Drugs. 2014;74:283-296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-014-0187-7.

- Yanit KE, Snowden JM, Cheng YW, et al. The impact of chronic hypertension and pregestational diabetes on pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.066.

- Seely EW, Ecker J. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Circulation. 2014;129:1254-1261. https:// doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.113.003904.

BARBARA LEVY, MD (AUGUST 2022)

Are these new and rare syndromes’ pathophysiological mechanisms related?

I read with great interest Dr. Barbara Levy’s UPDATE in the August 2022 issue on testosterone therapy for women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), as well as her comments on persistent genital arousal disorder/genito-pelvic dysesthesia (PGAD/GPD) that was recently so coined by the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) as a 2-component syndrome.1 The new syndrome, explains Dr. Levy, presents with “the perception of genital arousal that is involuntary, unrelated to sexual desire, without any identified cause, not relieved with orgasm, and distressing to the patient (the PGAD component),” combined with “itching, burning, tingling, or pain” (the GPD component).

Although agreeing with ISSWSH that diagnosis and management require a multidisciplinary biopsychosocial approach, in her practical advice, Dr. Levy mentioned: “neuropathic signaling” with “aberrant sensory processing” as the syndrome’s possible main pathophysiology. Interestingly, there are 2 other rare, chronic, and “poorly recognized source(s) of major distress to a small but significant group of patients.” Persistent idiopathic oro-facial pain (PIFP) disorder2 after dental interventions and burning mouth syndrome (BMS),3 defined by the absence of any local or systemic contributing etiology, also present with continuous local burning and pain (as in GPD). Consequently, PGAD/GPD may indeed have the same pathophysiological explanation—as Dr. Levy suggested—of being a (genital) peripheral chronic neuropathic pain condition.

A potentially promising new therapeutic approach for PGAD/GPD would then be to use the same, or similar, antineuropathic medications (Clonazepam, Nortriptyline, Pregabalin, etc.) in the form of topical vaginal swishing solutions similar to the presently recommended antiepileptic and/or antidepressant oral swishing treatment for PIFP and BMS. As the topical approach works well for oral neuropathic pain, vaginal swishing could potentially be the answer for PGAD/GPD peripheral neuropathic pain. Moreover, such a novel topical approach would significantly increase patient motivation for treatment by avoiding the adverse effects of ingested antiepileptic or antidepressant drugs.

This is the first time that anticonvulsant and/or antidepressant vaginal swishing is proposed as topical therapy for GPD peripheral neuropathic pain, still pending scientific/clinical validation. ●

Zwi Hoch, MD

Newton, Massachusetts