User login

Upadacitinib for Treatment of Severe Atopic Dermatitis in a Child

Upadacitinib for Treatment of Severe Atopic Dermatitis in a Child

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases and is characterized by age-related morphology and distribution of lesions. Although AD can manifest at any age, it often develops during childhood, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 15% to 25% in children and 1% to 10% in adults.1 Clinical manifestation includes chronic or recurrent xerosis, pruritic eczematous lesions involving the flexural and extensor areas, and cutaneous infections. Immediate skin test reactivity and elevated total IgE levels can be found in up to 80% of patients.2

Although the pathogenesis of AD is complex, multifactorial, and not completely understood, some studies have highlighted the central role of a type 2 immune response, resulting in skin barrier dysfunction, cutaneous inflammation, and neuroimmune dysregulation.3,4 The primary goals of treatment are to mitigate these factors through improvement of symptoms and long-term disease control. Topical emollients are used to repair the epidermal barrier, and topical anti-inflammatory therapy with corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors might be applied during flares; however, systemic treatment is essential for patients with moderate to severe AD that is not controlled with topical treatment or phototherapy.5

Until recently, systemic immunosuppressant agents such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and methotrexate were the only systemic treatment options for severe AD; however, their effectiveness is limited and they may cause serious long-term adverse events, limiting their regular usage, especially in children.6

Therapies that target type 2 immune responses include anti–IL-4/IL-13, anti–IL-13, and anti–IL-31 biologics. Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the type 2 immune response. This biologic directly binds to IL-4Rα,which prevents signaling by both the IL-4 and IL-13 pathways. Dupilumab was the first biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe AD, with demonstrated efficacy and a favorable safety profile.5

In addition to biologics, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors belong to the small-molecule class. These drugs block the JAK/STAT intracellular signaling pathway, leading to inhibition of downstream effects triggered by several cytokines related to AD pathogenesis. Upadacitinib is an oral JAK inhibitor that was approved by the FDA in 2022 for treatment of severe AD in adults and children aged 12 years and older. This drug promotes a selective and reversible JAK-1 inhibition and has demonstrated rapid onset of action and a sustained reduction in the signs and symptoms of AD.7 We report the case of a child with recalcitrant severe AD that showed significant clinical improvement following off-label treatment with upadacitinib after showing a poor clinical response to dupilumab.

A 9-year-old girl presented to our pediatrics department with progressive worsening of severe AD over the previous 2 years. The patient had been diagnosed with AD at 6 months old, at which time she was treated with several prescribed moisturizers, topical and systemic corticosteroids, and calcineurin inhibitors with no clinical improvement.

The patient initially presented to us for evaluation of severe pruritus and associated sleep loss at age 7 years; physical examination revealed severe xerosis and disseminated pruritic eczematous lesions. Her SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) score was 70 (range, 0-103), and laboratory testing showed a high eosinophil count (1.5×103/μL [range, 0-0.6×103], 13%) and IgE level (1686 κU/L [range, 0-90]); a skin prick test on the forearm was positive for Blomia tropicalis.

Following her presentation with severe AD at 7 years old, the patient was prescribed systemic treatments including methotrexate and cyclosporine. During treatment with these agents, she presented to our department with several bacterial skin infections that required oral and intravenous antibiotics for treatment. These agents ultimately were discontinued after 12 months due to the adverse effects and poor clinical improvement. At age 8 years, the patient received an initial 600-mg dose of dupilumab followed by 300 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks for 6 months along with topical corticosteroids and emollients. During treatment with dupilumab, the patient showed no clinical improvement (SCORAD score, 62). Therefore, we decided to change the dose to 200 mg every 2 weeks. The patient still showed no improvement and presented at age 9 years with moderate conjunctivitis and oculocutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus, which required treatment with oral acyclovir (Figure 1).

Considering the severe and refractory clinical course and the poor response to the recommended treatments for the patient’s age, oral upadacitinib was administered off label at a dose of 15 mg once daily after informed consent was obtained from her parents. She returned for follow-up once weekly for 1 month. Three days after starting treatment with upadacitinib, she showed considerable improvement in itch, and her SCORAD score decreased from 62 to 31 after 15 days. After 2 months of treatment, she reported no pruritus or sleep loss, and her SCORAD score was 4.5 (Figure 2). The results of a complete blood count, coagulation function test, and liver and kidney function tests were normal at 6-month and 12-month follow-up during upadacitinib therapy. No adverse effects were observed. The patient currently has completed 18 months of treatment, and the disease remains in complete remission.

Atopic dermatitis is highly prevalent in children. According to the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, the prevalence of eczema in 2009 was 8.2% among children aged 6 to 7 years and 5% among adolescents aged between 13 and 14 years in Brazil; severe AD was present in 1.5% of children in both age groups.8

The main systemic therapies currently available for patients with severe AD are immunosuppressants, biologics, and small-molecule drugs. The considerable adverse effects of immunosuppressants limit their application. Dupilumab is considered the first-line treatment for children with severe AD. Clinical trials and case reports have demonstrated that dupilumab is effective in patients with AD, promoting notable improvement of pruritic eczematous lesions and quality-of-life scores.9 Dupilumab has been approved by the FDA for children older than 6 months, and some studies have shown up to a 49% reduction of pruritus in this age group.9 The main reported adverse effects were mild conjunctivitis and oral herpes simplex virus infection.9,10

Upadacitinib is a reversible and selective JAK-1 inhibitor approved by the FDA for treatment of severe AD in patients aged 12 years and older. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated adolescents (12-17 years) and adults (18-75 years) with moderate to severe AD who were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive upadacitinib 15 mg, upadacitinib 30 mg, or placebo once daily for 16 weeks.11 A higher proportion of patients achieved an Eczema Area and Severity Index score of 75 at week 16 with both upadacitinib 15 mg daily (70%) and 30 mg daily (80%) compared to placebo. Improvements also were observed in both SCORAD and pruritus scores. The most commonly reported adverse events were acne, lipid profile abnormalities, and herpes zoster infection.11

Our patient was a child with severe refractory AD that demonstrated a poor treatment response to dupilumab. When switched to off-label upadacitinib, her disease was effectively controlled; the treatment also was well tolerated with no adverse effects. Reports of upadacitinib used to treat AD in patients younger than 12 years are limited in the literature. One case report described a 9-year-old child with concurrent alopecia areata and severe AD who was successfully treated off label with upadacitinib.12 A clinical trial also has evaluated the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of upadacitinib in children aged 2 to 12 years with severe AD (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03646604); although the trial was completed in 2024, at the time of this review (July 2025), the results have not been published.

Interestingly, there have been a few reports of adults with severe AD that failed to respond to treatment with immunosuppressants and dupilumab but showed notable clinical improvement when therapy was switched to upadacitinib,13,14 as we noticed with our patient. These findings suggest that the JAK-STAT intracellular signaling pathway plays an important role in the pathogenesis of AD.

Continued development of safe and efficient targeted treatment for children with severe AD is critical. Upadacitinib was a safe and effective option for treatment of refractory and severe AD in our patient; however, further studies are needed to confirm both the efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in this age group.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387:1109-1122.

- Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A, et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema Task Force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 :2717-2744.

- Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venererol. 1980;92:44-47.

- Nakahara T, Kido-Nakahara M, Tsuji G, et al. Basics and recent advances in the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2021;48:130-139.

- Wollenberg A, Kinberger M, Arents B, et al. European guideline (EuroGuiDerm) on atopic eczema: part I—systemic therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:1409-1431.

- Chu DK, Schneider L, Asiniwasis RN, et al. Atopic dermatitis (eczema) guidelines: 2023 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters GRADE– and Institute of Medicine–based recommendations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024;132:274-312.

- Rick JW, Lio P, Atluri S, et al. Atopic dermatitis: a guide to transitioning to janus kinase inhibitors. Dermatitis. 2023;34:297-300.

- Prado E, Pastorino AC, Harari DK, et al. Severe atopic dermatitis: a practical treatment guide from the Brazilian Association of Allergy and Immunology and the Brazilian Society of Pediatrics. Arq Asma Alerg Imunol. 2022;6:432-467.

- Paller AS, Simpson EL, Siegfried EC, et al. Dupilumab in children aged 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400:908-919.

- Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021 ;397:2151-2168.

- Yu D, Ren Y. Upadacitinib for successful treatment of alopecia universalis in a child: a case report and literature review. Acta Derm Venererol. 2023;103:adv5578.

- Cantelli M, Martora F, Patruno C, et al. Upadacitinib improved alopecia areata in a patient with atopic dermatitis: a case report. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15346.

- Gambardella A, Licata G, Calabrese G, et al. Dual efficacy of upadacitinib in 2 patients with concomitant severe atopic dermatitis and alopecia areata. Dermatitis. 2021;32:E85-E86.

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases and is characterized by age-related morphology and distribution of lesions. Although AD can manifest at any age, it often develops during childhood, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 15% to 25% in children and 1% to 10% in adults.1 Clinical manifestation includes chronic or recurrent xerosis, pruritic eczematous lesions involving the flexural and extensor areas, and cutaneous infections. Immediate skin test reactivity and elevated total IgE levels can be found in up to 80% of patients.2

Although the pathogenesis of AD is complex, multifactorial, and not completely understood, some studies have highlighted the central role of a type 2 immune response, resulting in skin barrier dysfunction, cutaneous inflammation, and neuroimmune dysregulation.3,4 The primary goals of treatment are to mitigate these factors through improvement of symptoms and long-term disease control. Topical emollients are used to repair the epidermal barrier, and topical anti-inflammatory therapy with corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors might be applied during flares; however, systemic treatment is essential for patients with moderate to severe AD that is not controlled with topical treatment or phototherapy.5

Until recently, systemic immunosuppressant agents such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and methotrexate were the only systemic treatment options for severe AD; however, their effectiveness is limited and they may cause serious long-term adverse events, limiting their regular usage, especially in children.6

Therapies that target type 2 immune responses include anti–IL-4/IL-13, anti–IL-13, and anti–IL-31 biologics. Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the type 2 immune response. This biologic directly binds to IL-4Rα,which prevents signaling by both the IL-4 and IL-13 pathways. Dupilumab was the first biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe AD, with demonstrated efficacy and a favorable safety profile.5

In addition to biologics, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors belong to the small-molecule class. These drugs block the JAK/STAT intracellular signaling pathway, leading to inhibition of downstream effects triggered by several cytokines related to AD pathogenesis. Upadacitinib is an oral JAK inhibitor that was approved by the FDA in 2022 for treatment of severe AD in adults and children aged 12 years and older. This drug promotes a selective and reversible JAK-1 inhibition and has demonstrated rapid onset of action and a sustained reduction in the signs and symptoms of AD.7 We report the case of a child with recalcitrant severe AD that showed significant clinical improvement following off-label treatment with upadacitinib after showing a poor clinical response to dupilumab.

A 9-year-old girl presented to our pediatrics department with progressive worsening of severe AD over the previous 2 years. The patient had been diagnosed with AD at 6 months old, at which time she was treated with several prescribed moisturizers, topical and systemic corticosteroids, and calcineurin inhibitors with no clinical improvement.

The patient initially presented to us for evaluation of severe pruritus and associated sleep loss at age 7 years; physical examination revealed severe xerosis and disseminated pruritic eczematous lesions. Her SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) score was 70 (range, 0-103), and laboratory testing showed a high eosinophil count (1.5×103/μL [range, 0-0.6×103], 13%) and IgE level (1686 κU/L [range, 0-90]); a skin prick test on the forearm was positive for Blomia tropicalis.

Following her presentation with severe AD at 7 years old, the patient was prescribed systemic treatments including methotrexate and cyclosporine. During treatment with these agents, she presented to our department with several bacterial skin infections that required oral and intravenous antibiotics for treatment. These agents ultimately were discontinued after 12 months due to the adverse effects and poor clinical improvement. At age 8 years, the patient received an initial 600-mg dose of dupilumab followed by 300 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks for 6 months along with topical corticosteroids and emollients. During treatment with dupilumab, the patient showed no clinical improvement (SCORAD score, 62). Therefore, we decided to change the dose to 200 mg every 2 weeks. The patient still showed no improvement and presented at age 9 years with moderate conjunctivitis and oculocutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus, which required treatment with oral acyclovir (Figure 1).

Considering the severe and refractory clinical course and the poor response to the recommended treatments for the patient’s age, oral upadacitinib was administered off label at a dose of 15 mg once daily after informed consent was obtained from her parents. She returned for follow-up once weekly for 1 month. Three days after starting treatment with upadacitinib, she showed considerable improvement in itch, and her SCORAD score decreased from 62 to 31 after 15 days. After 2 months of treatment, she reported no pruritus or sleep loss, and her SCORAD score was 4.5 (Figure 2). The results of a complete blood count, coagulation function test, and liver and kidney function tests were normal at 6-month and 12-month follow-up during upadacitinib therapy. No adverse effects were observed. The patient currently has completed 18 months of treatment, and the disease remains in complete remission.

Atopic dermatitis is highly prevalent in children. According to the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, the prevalence of eczema in 2009 was 8.2% among children aged 6 to 7 years and 5% among adolescents aged between 13 and 14 years in Brazil; severe AD was present in 1.5% of children in both age groups.8

The main systemic therapies currently available for patients with severe AD are immunosuppressants, biologics, and small-molecule drugs. The considerable adverse effects of immunosuppressants limit their application. Dupilumab is considered the first-line treatment for children with severe AD. Clinical trials and case reports have demonstrated that dupilumab is effective in patients with AD, promoting notable improvement of pruritic eczematous lesions and quality-of-life scores.9 Dupilumab has been approved by the FDA for children older than 6 months, and some studies have shown up to a 49% reduction of pruritus in this age group.9 The main reported adverse effects were mild conjunctivitis and oral herpes simplex virus infection.9,10

Upadacitinib is a reversible and selective JAK-1 inhibitor approved by the FDA for treatment of severe AD in patients aged 12 years and older. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated adolescents (12-17 years) and adults (18-75 years) with moderate to severe AD who were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive upadacitinib 15 mg, upadacitinib 30 mg, or placebo once daily for 16 weeks.11 A higher proportion of patients achieved an Eczema Area and Severity Index score of 75 at week 16 with both upadacitinib 15 mg daily (70%) and 30 mg daily (80%) compared to placebo. Improvements also were observed in both SCORAD and pruritus scores. The most commonly reported adverse events were acne, lipid profile abnormalities, and herpes zoster infection.11

Our patient was a child with severe refractory AD that demonstrated a poor treatment response to dupilumab. When switched to off-label upadacitinib, her disease was effectively controlled; the treatment also was well tolerated with no adverse effects. Reports of upadacitinib used to treat AD in patients younger than 12 years are limited in the literature. One case report described a 9-year-old child with concurrent alopecia areata and severe AD who was successfully treated off label with upadacitinib.12 A clinical trial also has evaluated the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of upadacitinib in children aged 2 to 12 years with severe AD (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03646604); although the trial was completed in 2024, at the time of this review (July 2025), the results have not been published.

Interestingly, there have been a few reports of adults with severe AD that failed to respond to treatment with immunosuppressants and dupilumab but showed notable clinical improvement when therapy was switched to upadacitinib,13,14 as we noticed with our patient. These findings suggest that the JAK-STAT intracellular signaling pathway plays an important role in the pathogenesis of AD.

Continued development of safe and efficient targeted treatment for children with severe AD is critical. Upadacitinib was a safe and effective option for treatment of refractory and severe AD in our patient; however, further studies are needed to confirm both the efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in this age group.

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases and is characterized by age-related morphology and distribution of lesions. Although AD can manifest at any age, it often develops during childhood, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 15% to 25% in children and 1% to 10% in adults.1 Clinical manifestation includes chronic or recurrent xerosis, pruritic eczematous lesions involving the flexural and extensor areas, and cutaneous infections. Immediate skin test reactivity and elevated total IgE levels can be found in up to 80% of patients.2

Although the pathogenesis of AD is complex, multifactorial, and not completely understood, some studies have highlighted the central role of a type 2 immune response, resulting in skin barrier dysfunction, cutaneous inflammation, and neuroimmune dysregulation.3,4 The primary goals of treatment are to mitigate these factors through improvement of symptoms and long-term disease control. Topical emollients are used to repair the epidermal barrier, and topical anti-inflammatory therapy with corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors might be applied during flares; however, systemic treatment is essential for patients with moderate to severe AD that is not controlled with topical treatment or phototherapy.5

Until recently, systemic immunosuppressant agents such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and methotrexate were the only systemic treatment options for severe AD; however, their effectiveness is limited and they may cause serious long-term adverse events, limiting their regular usage, especially in children.6

Therapies that target type 2 immune responses include anti–IL-4/IL-13, anti–IL-13, and anti–IL-31 biologics. Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the type 2 immune response. This biologic directly binds to IL-4Rα,which prevents signaling by both the IL-4 and IL-13 pathways. Dupilumab was the first biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe AD, with demonstrated efficacy and a favorable safety profile.5

In addition to biologics, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors belong to the small-molecule class. These drugs block the JAK/STAT intracellular signaling pathway, leading to inhibition of downstream effects triggered by several cytokines related to AD pathogenesis. Upadacitinib is an oral JAK inhibitor that was approved by the FDA in 2022 for treatment of severe AD in adults and children aged 12 years and older. This drug promotes a selective and reversible JAK-1 inhibition and has demonstrated rapid onset of action and a sustained reduction in the signs and symptoms of AD.7 We report the case of a child with recalcitrant severe AD that showed significant clinical improvement following off-label treatment with upadacitinib after showing a poor clinical response to dupilumab.

A 9-year-old girl presented to our pediatrics department with progressive worsening of severe AD over the previous 2 years. The patient had been diagnosed with AD at 6 months old, at which time she was treated with several prescribed moisturizers, topical and systemic corticosteroids, and calcineurin inhibitors with no clinical improvement.

The patient initially presented to us for evaluation of severe pruritus and associated sleep loss at age 7 years; physical examination revealed severe xerosis and disseminated pruritic eczematous lesions. Her SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) score was 70 (range, 0-103), and laboratory testing showed a high eosinophil count (1.5×103/μL [range, 0-0.6×103], 13%) and IgE level (1686 κU/L [range, 0-90]); a skin prick test on the forearm was positive for Blomia tropicalis.

Following her presentation with severe AD at 7 years old, the patient was prescribed systemic treatments including methotrexate and cyclosporine. During treatment with these agents, she presented to our department with several bacterial skin infections that required oral and intravenous antibiotics for treatment. These agents ultimately were discontinued after 12 months due to the adverse effects and poor clinical improvement. At age 8 years, the patient received an initial 600-mg dose of dupilumab followed by 300 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks for 6 months along with topical corticosteroids and emollients. During treatment with dupilumab, the patient showed no clinical improvement (SCORAD score, 62). Therefore, we decided to change the dose to 200 mg every 2 weeks. The patient still showed no improvement and presented at age 9 years with moderate conjunctivitis and oculocutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus, which required treatment with oral acyclovir (Figure 1).

Considering the severe and refractory clinical course and the poor response to the recommended treatments for the patient’s age, oral upadacitinib was administered off label at a dose of 15 mg once daily after informed consent was obtained from her parents. She returned for follow-up once weekly for 1 month. Three days after starting treatment with upadacitinib, she showed considerable improvement in itch, and her SCORAD score decreased from 62 to 31 after 15 days. After 2 months of treatment, she reported no pruritus or sleep loss, and her SCORAD score was 4.5 (Figure 2). The results of a complete blood count, coagulation function test, and liver and kidney function tests were normal at 6-month and 12-month follow-up during upadacitinib therapy. No adverse effects were observed. The patient currently has completed 18 months of treatment, and the disease remains in complete remission.

Atopic dermatitis is highly prevalent in children. According to the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, the prevalence of eczema in 2009 was 8.2% among children aged 6 to 7 years and 5% among adolescents aged between 13 and 14 years in Brazil; severe AD was present in 1.5% of children in both age groups.8

The main systemic therapies currently available for patients with severe AD are immunosuppressants, biologics, and small-molecule drugs. The considerable adverse effects of immunosuppressants limit their application. Dupilumab is considered the first-line treatment for children with severe AD. Clinical trials and case reports have demonstrated that dupilumab is effective in patients with AD, promoting notable improvement of pruritic eczematous lesions and quality-of-life scores.9 Dupilumab has been approved by the FDA for children older than 6 months, and some studies have shown up to a 49% reduction of pruritus in this age group.9 The main reported adverse effects were mild conjunctivitis and oral herpes simplex virus infection.9,10

Upadacitinib is a reversible and selective JAK-1 inhibitor approved by the FDA for treatment of severe AD in patients aged 12 years and older. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated adolescents (12-17 years) and adults (18-75 years) with moderate to severe AD who were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive upadacitinib 15 mg, upadacitinib 30 mg, or placebo once daily for 16 weeks.11 A higher proportion of patients achieved an Eczema Area and Severity Index score of 75 at week 16 with both upadacitinib 15 mg daily (70%) and 30 mg daily (80%) compared to placebo. Improvements also were observed in both SCORAD and pruritus scores. The most commonly reported adverse events were acne, lipid profile abnormalities, and herpes zoster infection.11

Our patient was a child with severe refractory AD that demonstrated a poor treatment response to dupilumab. When switched to off-label upadacitinib, her disease was effectively controlled; the treatment also was well tolerated with no adverse effects. Reports of upadacitinib used to treat AD in patients younger than 12 years are limited in the literature. One case report described a 9-year-old child with concurrent alopecia areata and severe AD who was successfully treated off label with upadacitinib.12 A clinical trial also has evaluated the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of upadacitinib in children aged 2 to 12 years with severe AD (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03646604); although the trial was completed in 2024, at the time of this review (July 2025), the results have not been published.

Interestingly, there have been a few reports of adults with severe AD that failed to respond to treatment with immunosuppressants and dupilumab but showed notable clinical improvement when therapy was switched to upadacitinib,13,14 as we noticed with our patient. These findings suggest that the JAK-STAT intracellular signaling pathway plays an important role in the pathogenesis of AD.

Continued development of safe and efficient targeted treatment for children with severe AD is critical. Upadacitinib was a safe and effective option for treatment of refractory and severe AD in our patient; however, further studies are needed to confirm both the efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in this age group.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387:1109-1122.

- Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A, et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema Task Force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 :2717-2744.

- Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venererol. 1980;92:44-47.

- Nakahara T, Kido-Nakahara M, Tsuji G, et al. Basics and recent advances in the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2021;48:130-139.

- Wollenberg A, Kinberger M, Arents B, et al. European guideline (EuroGuiDerm) on atopic eczema: part I—systemic therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:1409-1431.

- Chu DK, Schneider L, Asiniwasis RN, et al. Atopic dermatitis (eczema) guidelines: 2023 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters GRADE– and Institute of Medicine–based recommendations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024;132:274-312.

- Rick JW, Lio P, Atluri S, et al. Atopic dermatitis: a guide to transitioning to janus kinase inhibitors. Dermatitis. 2023;34:297-300.

- Prado E, Pastorino AC, Harari DK, et al. Severe atopic dermatitis: a practical treatment guide from the Brazilian Association of Allergy and Immunology and the Brazilian Society of Pediatrics. Arq Asma Alerg Imunol. 2022;6:432-467.

- Paller AS, Simpson EL, Siegfried EC, et al. Dupilumab in children aged 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400:908-919.

- Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021 ;397:2151-2168.

- Yu D, Ren Y. Upadacitinib for successful treatment of alopecia universalis in a child: a case report and literature review. Acta Derm Venererol. 2023;103:adv5578.

- Cantelli M, Martora F, Patruno C, et al. Upadacitinib improved alopecia areata in a patient with atopic dermatitis: a case report. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15346.

- Gambardella A, Licata G, Calabrese G, et al. Dual efficacy of upadacitinib in 2 patients with concomitant severe atopic dermatitis and alopecia areata. Dermatitis. 2021;32:E85-E86.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387:1109-1122.

- Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A, et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema Task Force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 :2717-2744.

- Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venererol. 1980;92:44-47.

- Nakahara T, Kido-Nakahara M, Tsuji G, et al. Basics and recent advances in the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2021;48:130-139.

- Wollenberg A, Kinberger M, Arents B, et al. European guideline (EuroGuiDerm) on atopic eczema: part I—systemic therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:1409-1431.

- Chu DK, Schneider L, Asiniwasis RN, et al. Atopic dermatitis (eczema) guidelines: 2023 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters GRADE– and Institute of Medicine–based recommendations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024;132:274-312.

- Rick JW, Lio P, Atluri S, et al. Atopic dermatitis: a guide to transitioning to janus kinase inhibitors. Dermatitis. 2023;34:297-300.

- Prado E, Pastorino AC, Harari DK, et al. Severe atopic dermatitis: a practical treatment guide from the Brazilian Association of Allergy and Immunology and the Brazilian Society of Pediatrics. Arq Asma Alerg Imunol. 2022;6:432-467.

- Paller AS, Simpson EL, Siegfried EC, et al. Dupilumab in children aged 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400:908-919.

- Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021 ;397:2151-2168.

- Yu D, Ren Y. Upadacitinib for successful treatment of alopecia universalis in a child: a case report and literature review. Acta Derm Venererol. 2023;103:adv5578.

- Cantelli M, Martora F, Patruno C, et al. Upadacitinib improved alopecia areata in a patient with atopic dermatitis: a case report. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15346.

- Gambardella A, Licata G, Calabrese G, et al. Dual efficacy of upadacitinib in 2 patients with concomitant severe atopic dermatitis and alopecia areata. Dermatitis. 2021;32:E85-E86.

Upadacitinib for Treatment of Severe Atopic Dermatitis in a Child

Upadacitinib for Treatment of Severe Atopic Dermatitis in a Child

PRACTICE POINTS

- Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases in pediatric patients.

- Dupilumab is the first-line treatment for severe AD in children and is approved for use in patients aged 6 months and older. Janus kinase inhibitors are approved only for patients aged 12 years and older.

- Upadacitinib may be a safe treatment option for severe AD in children, even those younger than 12 years.

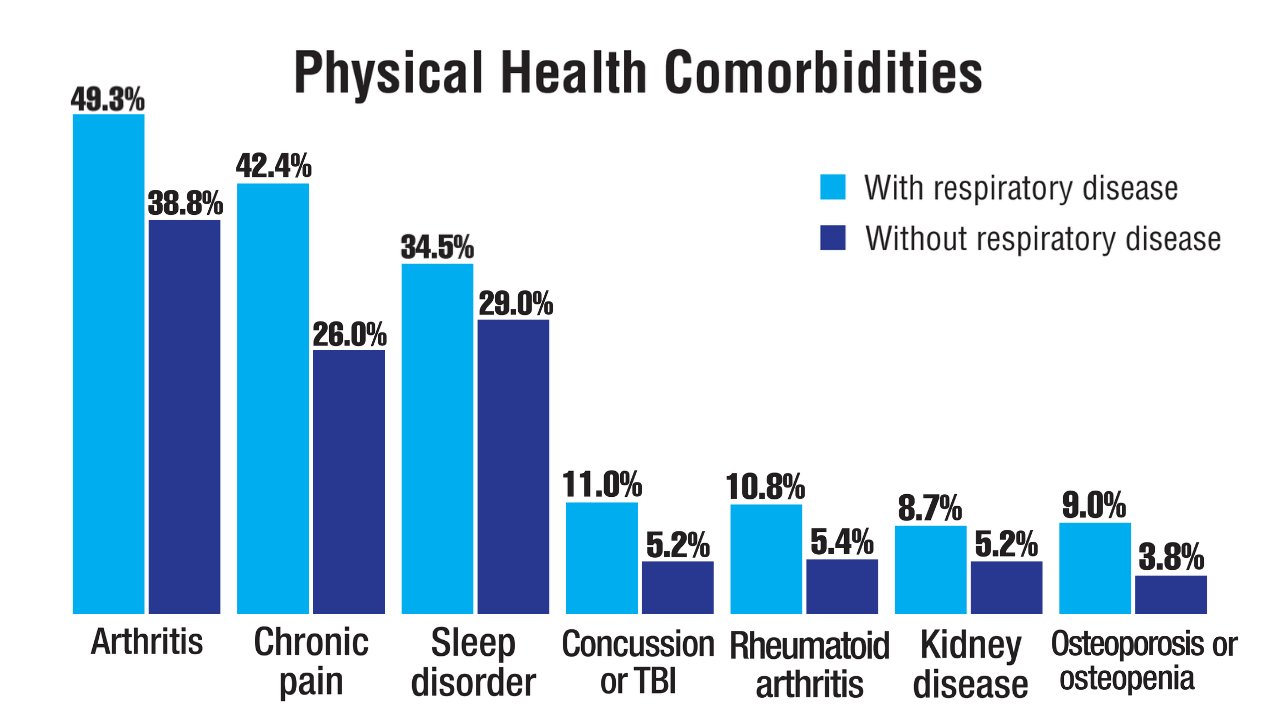

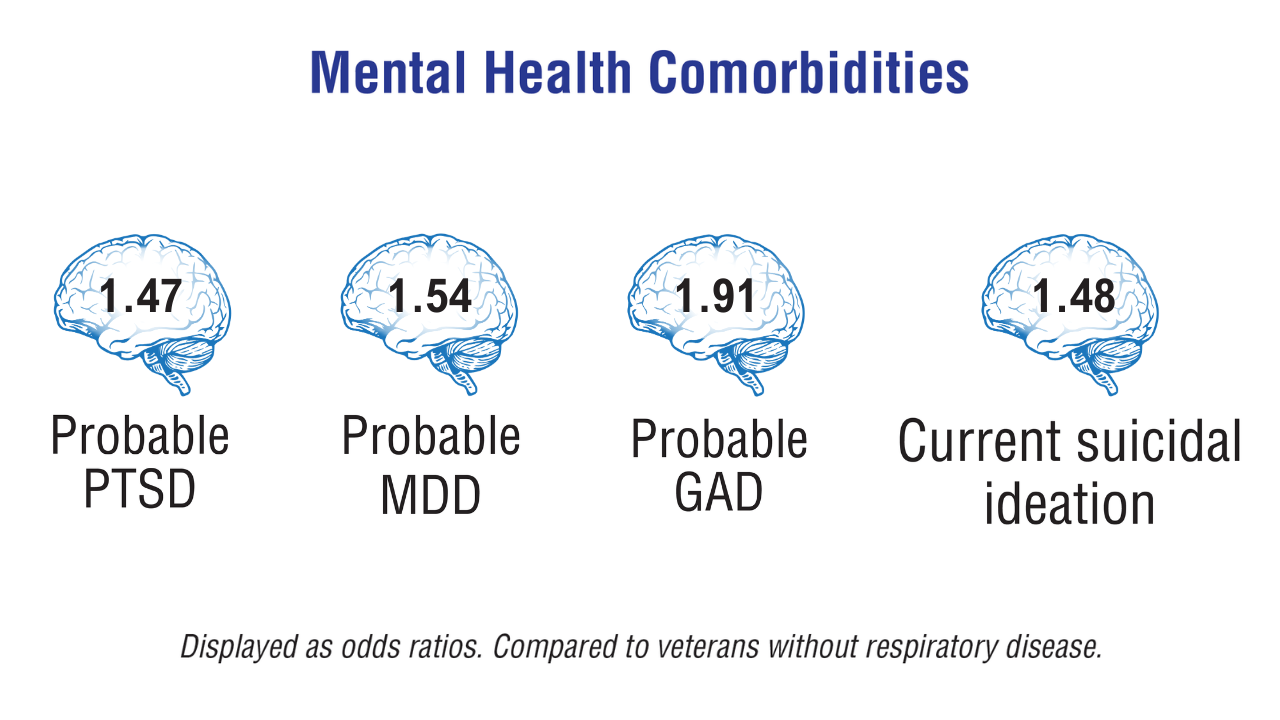

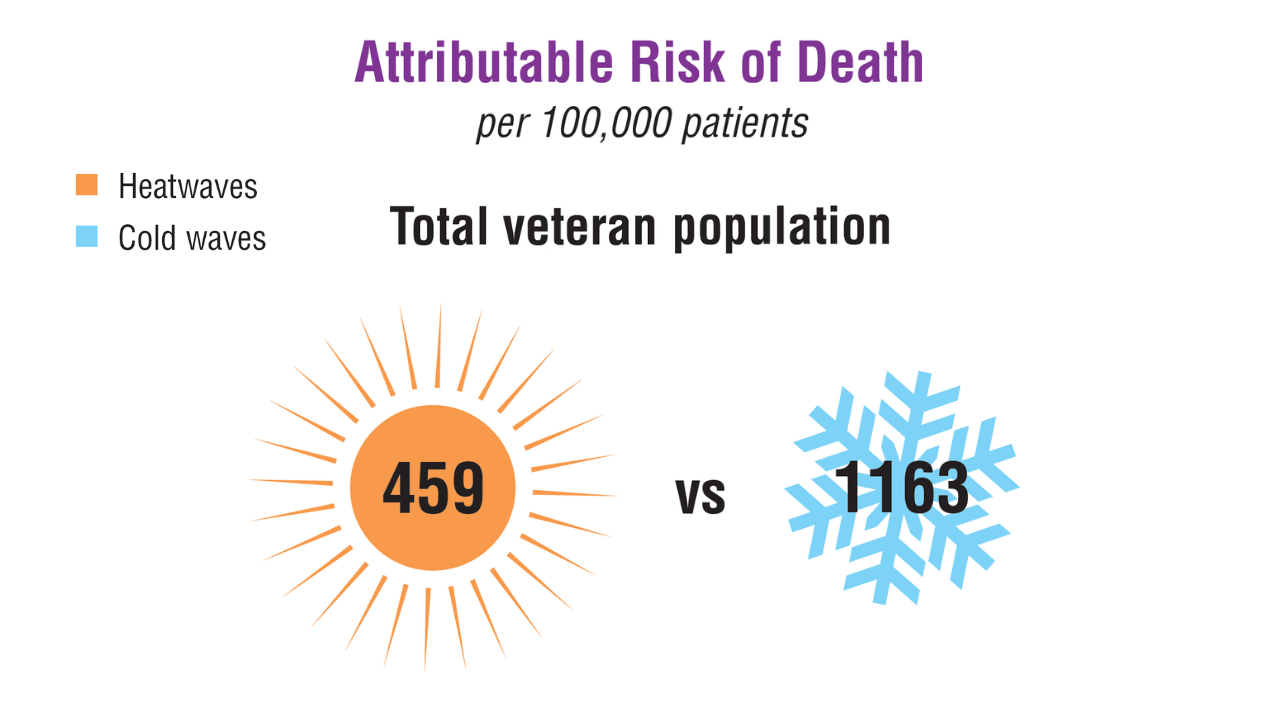

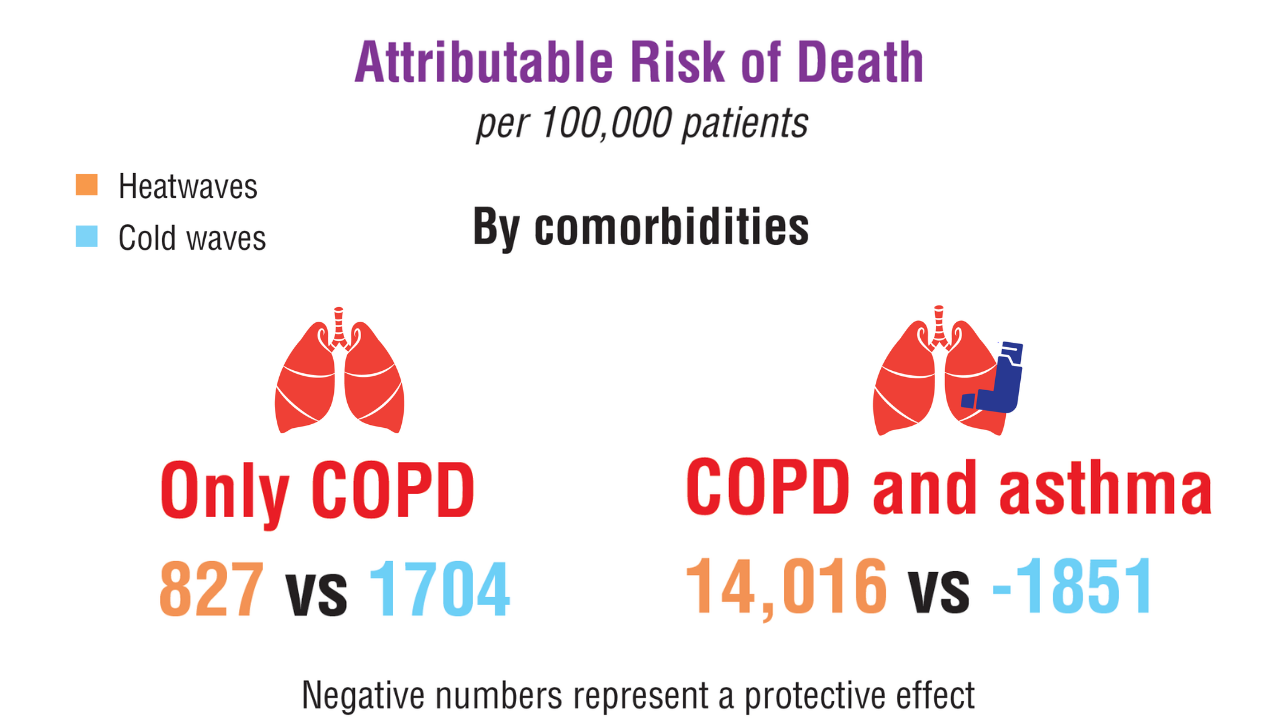

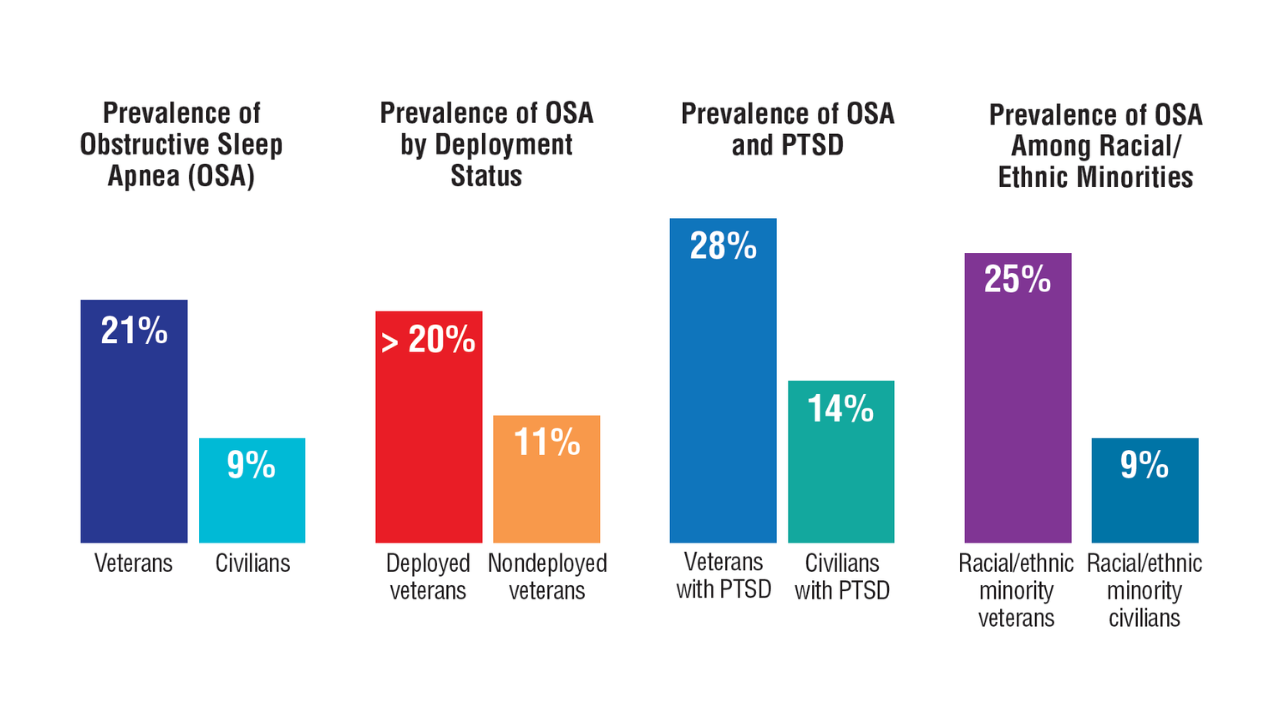

Data Trends 2025: Pulmonology

Data Trends 2025: Pulmonology

Click to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Bozick R, Neil R. Respiratory health among US veterans across age and over time. RAND Corporation;2024. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1363-13.html

- Kaul B, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206(6):750-757. doi:10.1164/rccm.202112-2724OC

- Garshick E, Blanc PD. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2023;29(2):83-89. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000946

- Bamonti PM, et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2024;176:140-147. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.05.053

- Bamonti PM, et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1269-1283. doi:10.2147/COPD.S339323

- Goldstein LA, et al. Am J Health Promot. 2025;39(2):215-223. doi:10.1177/08901171241273443

- Leng Y, et al. Neurology. 2021;96(13):e1792-e1799. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000011656

- Rau A, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2025;22(2):200-207. doi:10.1513/AnnalATS.202312-1089OC

Click to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

Click to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Bozick R, Neil R. Respiratory health among US veterans across age and over time. RAND Corporation;2024. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1363-13.html

- Kaul B, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206(6):750-757. doi:10.1164/rccm.202112-2724OC

- Garshick E, Blanc PD. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2023;29(2):83-89. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000946

- Bamonti PM, et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2024;176:140-147. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.05.053

- Bamonti PM, et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1269-1283. doi:10.2147/COPD.S339323

- Goldstein LA, et al. Am J Health Promot. 2025;39(2):215-223. doi:10.1177/08901171241273443

- Leng Y, et al. Neurology. 2021;96(13):e1792-e1799. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000011656

- Rau A, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2025;22(2):200-207. doi:10.1513/AnnalATS.202312-1089OC

- Bozick R, Neil R. Respiratory health among US veterans across age and over time. RAND Corporation;2024. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1363-13.html

- Kaul B, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206(6):750-757. doi:10.1164/rccm.202112-2724OC

- Garshick E, Blanc PD. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2023;29(2):83-89. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000946

- Bamonti PM, et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2024;176:140-147. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.05.053

- Bamonti PM, et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1269-1283. doi:10.2147/COPD.S339323

- Goldstein LA, et al. Am J Health Promot. 2025;39(2):215-223. doi:10.1177/08901171241273443

- Leng Y, et al. Neurology. 2021;96(13):e1792-e1799. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000011656

- Rau A, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2025;22(2):200-207. doi:10.1513/AnnalATS.202312-1089OC

Data Trends 2025: Pulmonology

Data Trends 2025: Pulmonology

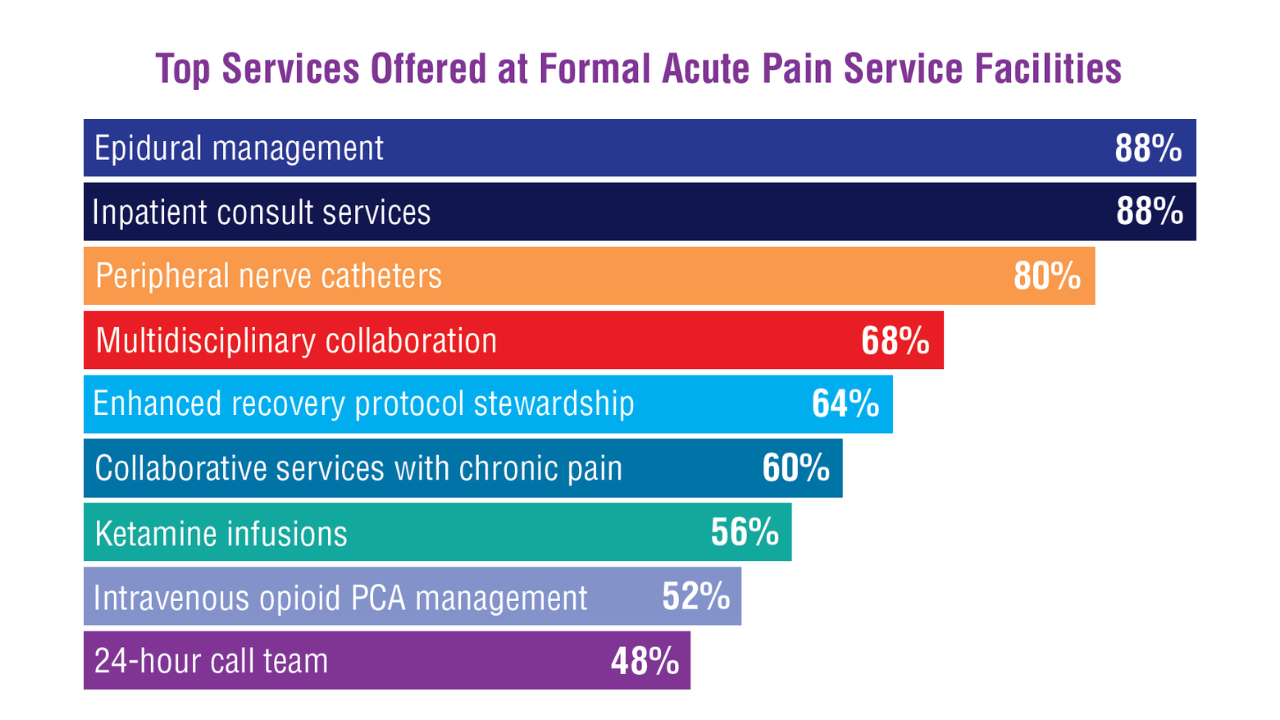

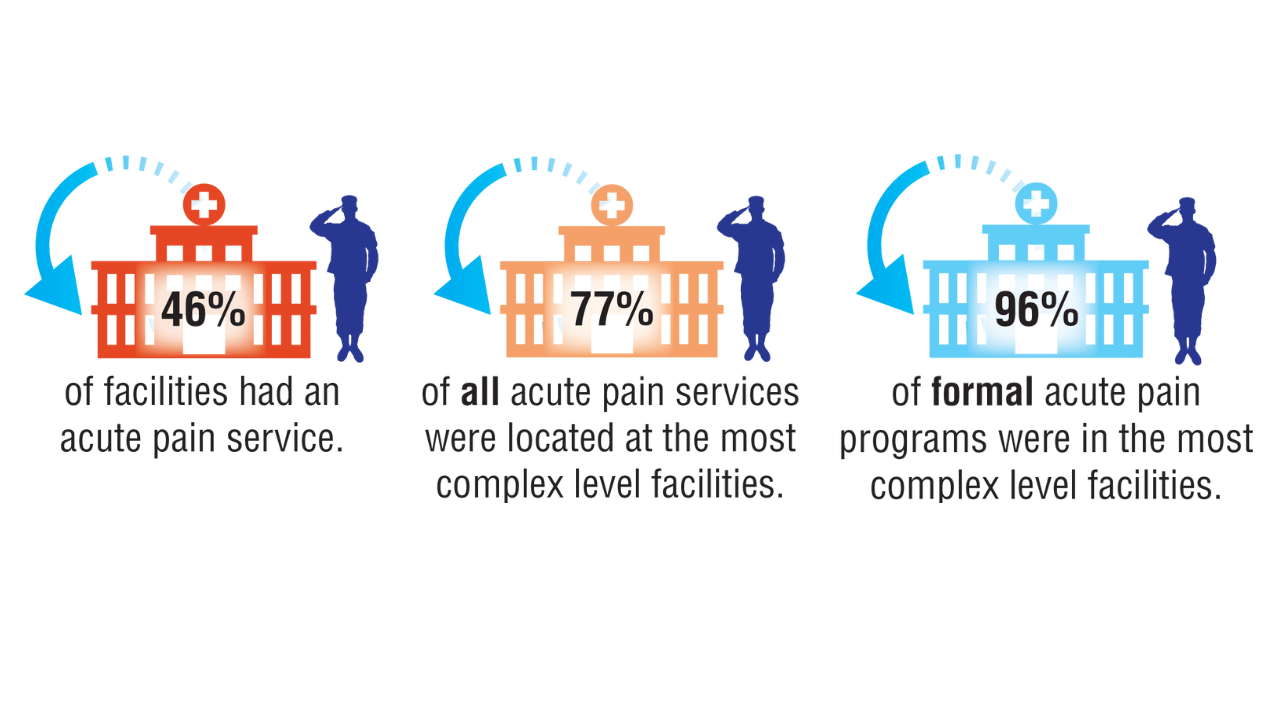

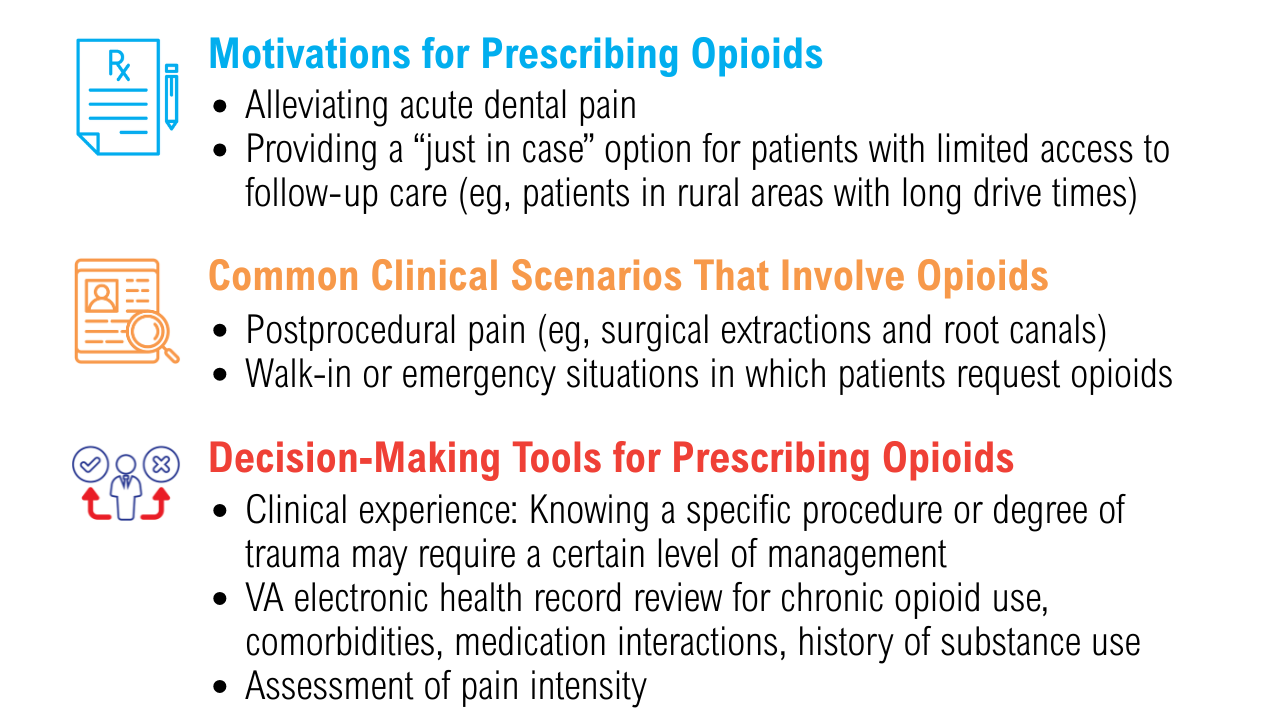

Data Trends 2025: Acute Pain

Data Trends 2025: Acute Pain

Click to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Baumann L, et al. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2023;27(9):437-444. doi:10.1007/s11916-023-01127-0

- Reif S, et al. Mil Med. 2018;183(9-10):e330-e337. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx200

- Sharp LK, e t a l . Pain. 2023;164( 4 ) : 749-757. doi:10.1097/j .pain.0000000000002759

- Dalton MK, et al. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;91(2S Suppl 2):S213-S220. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000003133

- Mahyar L, et al. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2024;49(2):117-121. doi:10.1136/rapm-2023-104610

- Gupta K, et al. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2025;51(1):103. doi:10.1007/s00068-025-02778-x

- Mariano ER, et al. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2022;47(2):118-127. doi:10.1136/rapm-2021-103083

Click to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

Click to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Baumann L, et al. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2023;27(9):437-444. doi:10.1007/s11916-023-01127-0

- Reif S, et al. Mil Med. 2018;183(9-10):e330-e337. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx200

- Sharp LK, e t a l . Pain. 2023;164( 4 ) : 749-757. doi:10.1097/j .pain.0000000000002759

- Dalton MK, et al. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;91(2S Suppl 2):S213-S220. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000003133

- Mahyar L, et al. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2024;49(2):117-121. doi:10.1136/rapm-2023-104610

- Gupta K, et al. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2025;51(1):103. doi:10.1007/s00068-025-02778-x

- Mariano ER, et al. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2022;47(2):118-127. doi:10.1136/rapm-2021-103083

- Baumann L, et al. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2023;27(9):437-444. doi:10.1007/s11916-023-01127-0

- Reif S, et al. Mil Med. 2018;183(9-10):e330-e337. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx200

- Sharp LK, e t a l . Pain. 2023;164( 4 ) : 749-757. doi:10.1097/j .pain.0000000000002759

- Dalton MK, et al. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;91(2S Suppl 2):S213-S220. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000003133

- Mahyar L, et al. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2024;49(2):117-121. doi:10.1136/rapm-2023-104610

- Gupta K, et al. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2025;51(1):103. doi:10.1007/s00068-025-02778-x

- Mariano ER, et al. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2022;47(2):118-127. doi:10.1136/rapm-2021-103083

Data Trends 2025: Acute Pain

Data Trends 2025: Acute Pain

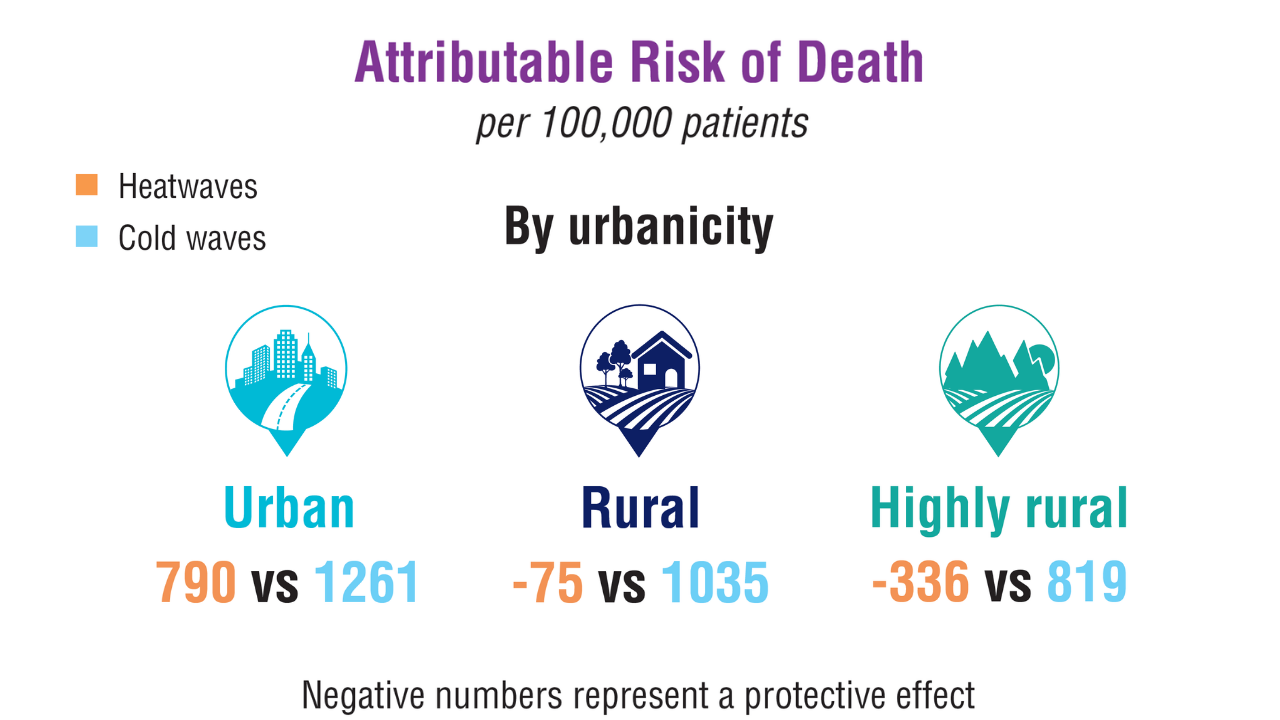

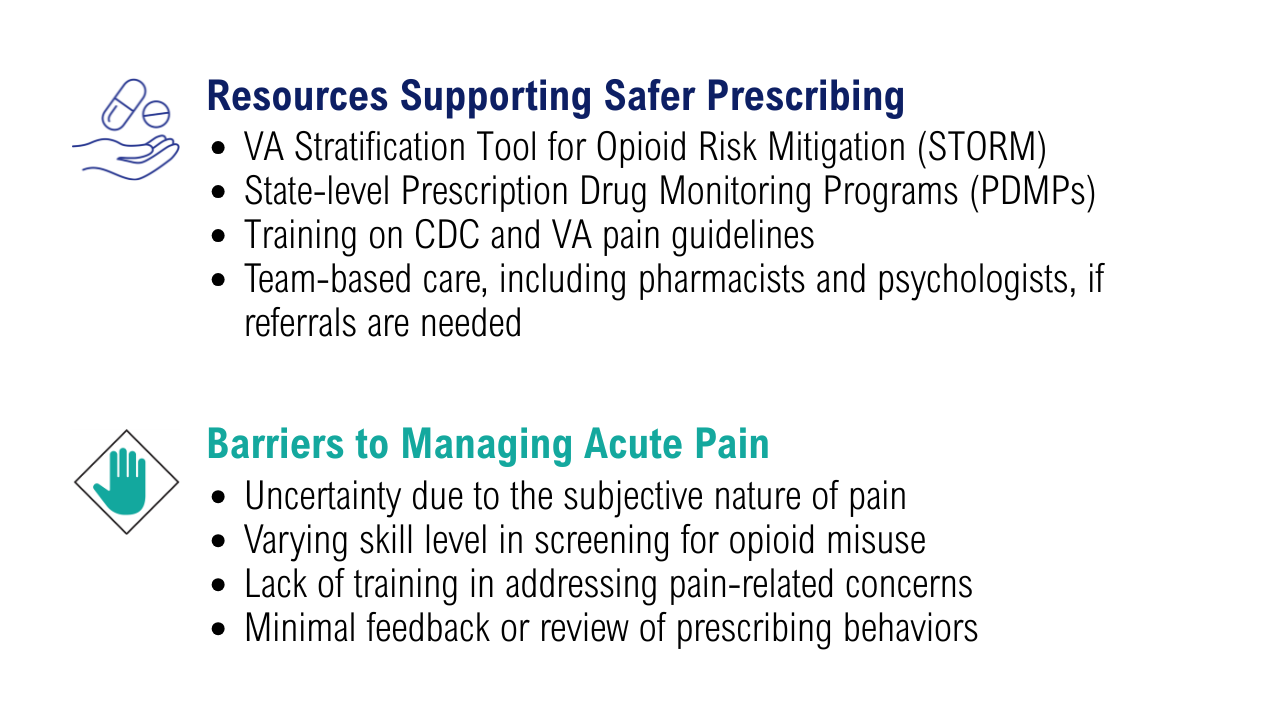

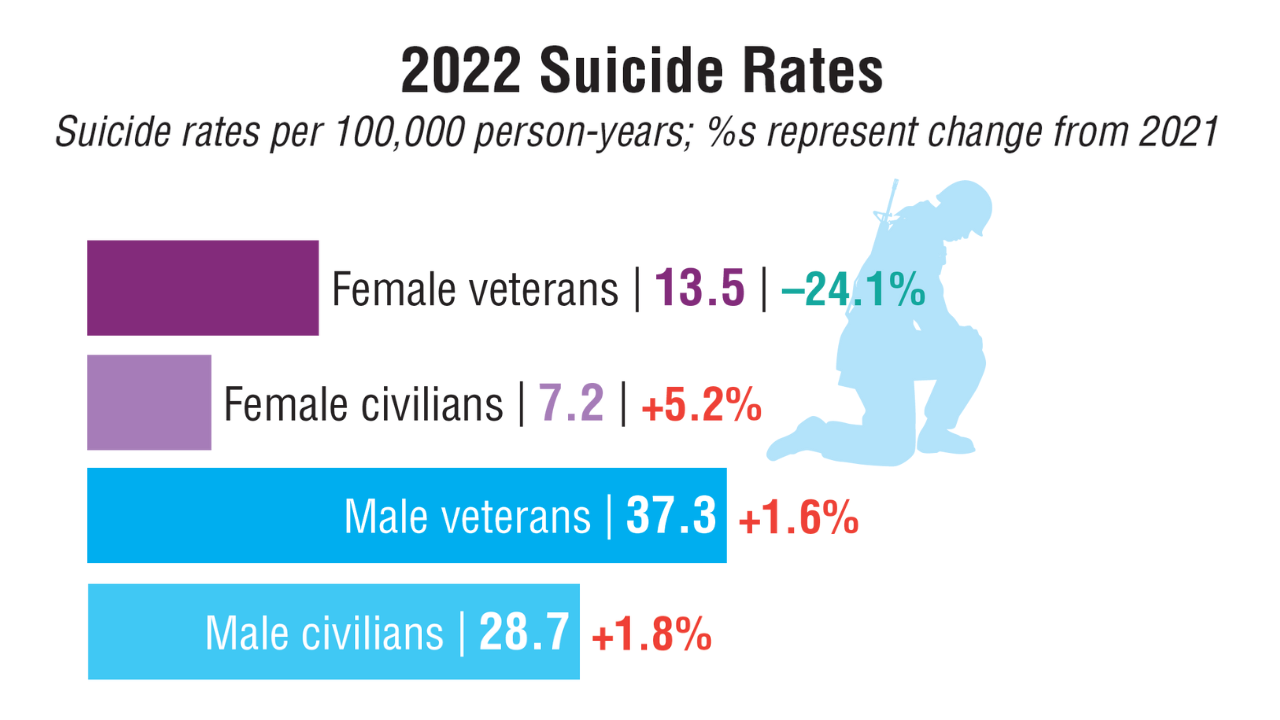

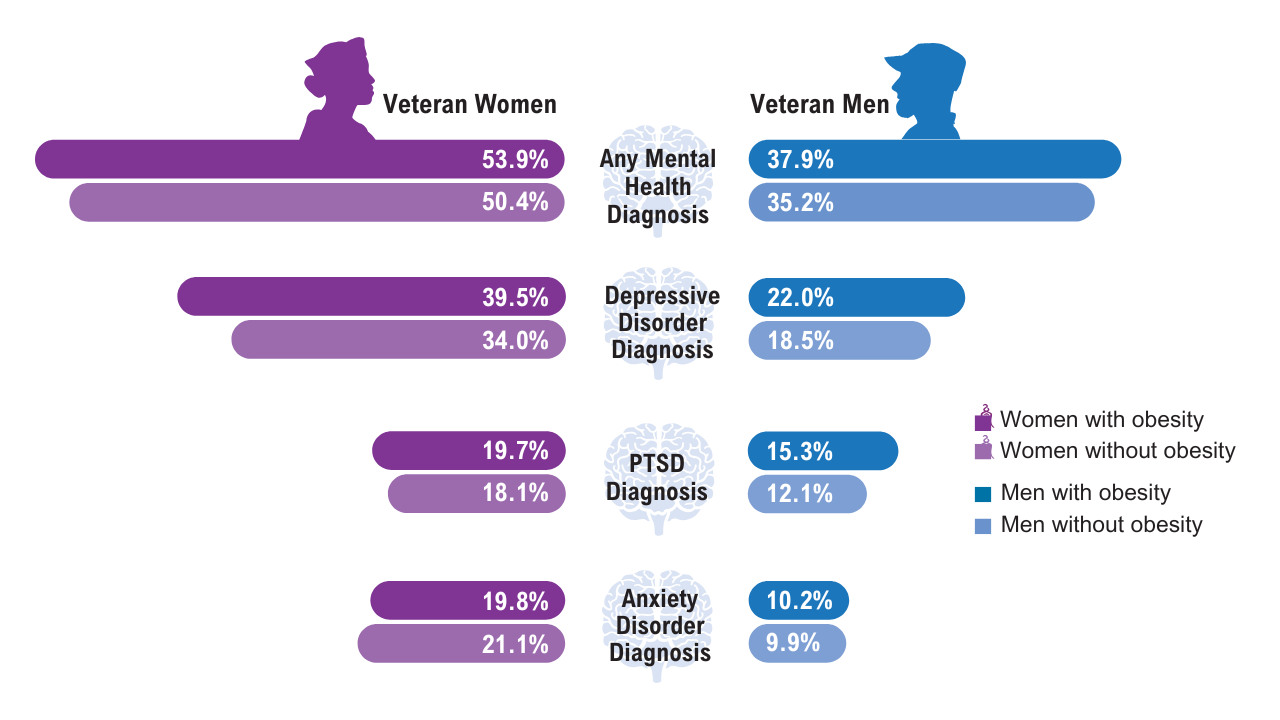

Data Trends 2025: Mental Health

Data Trends 2025: Mental Health

Click to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Suicide Prevention. 2024 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. 2024. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/data.asp.

- Tenso K, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(11):e2443054. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.43054

- Saulnier KG, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(12):e2452144. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.52144

- Elser H, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 2025;194(2):123-132. doi:10.1093/aje/kwaf002

Click to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

Click to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Suicide Prevention. 2024 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. 2024. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/data.asp.

- Tenso K, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(11):e2443054. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.43054

- Saulnier KG, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(12):e2452144. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.52144

- Elser H, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 2025;194(2):123-132. doi:10.1093/aje/kwaf002

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Suicide Prevention. 2024 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. 2024. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/data.asp.

- Tenso K, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(11):e2443054. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.43054

- Saulnier KG, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(12):e2452144. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.52144

- Elser H, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 2025;194(2):123-132. doi:10.1093/aje/kwaf002

Data Trends 2025: Mental Health

Data Trends 2025: Mental Health

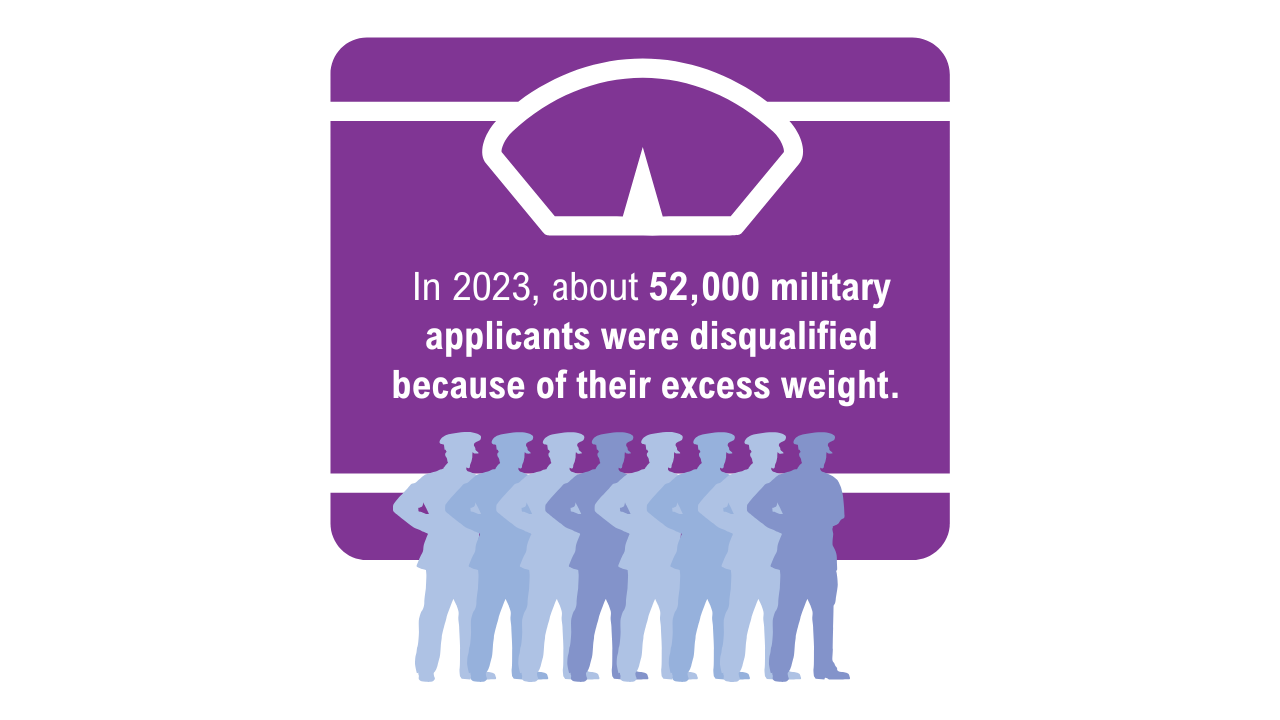

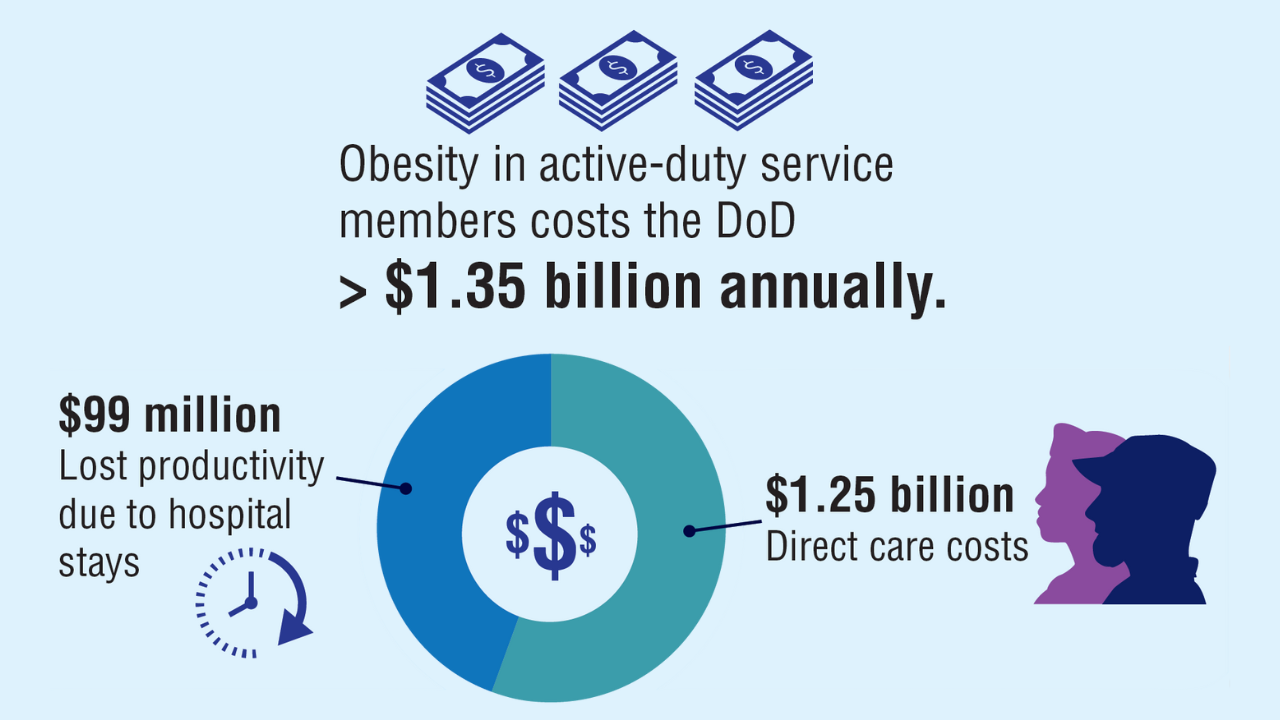

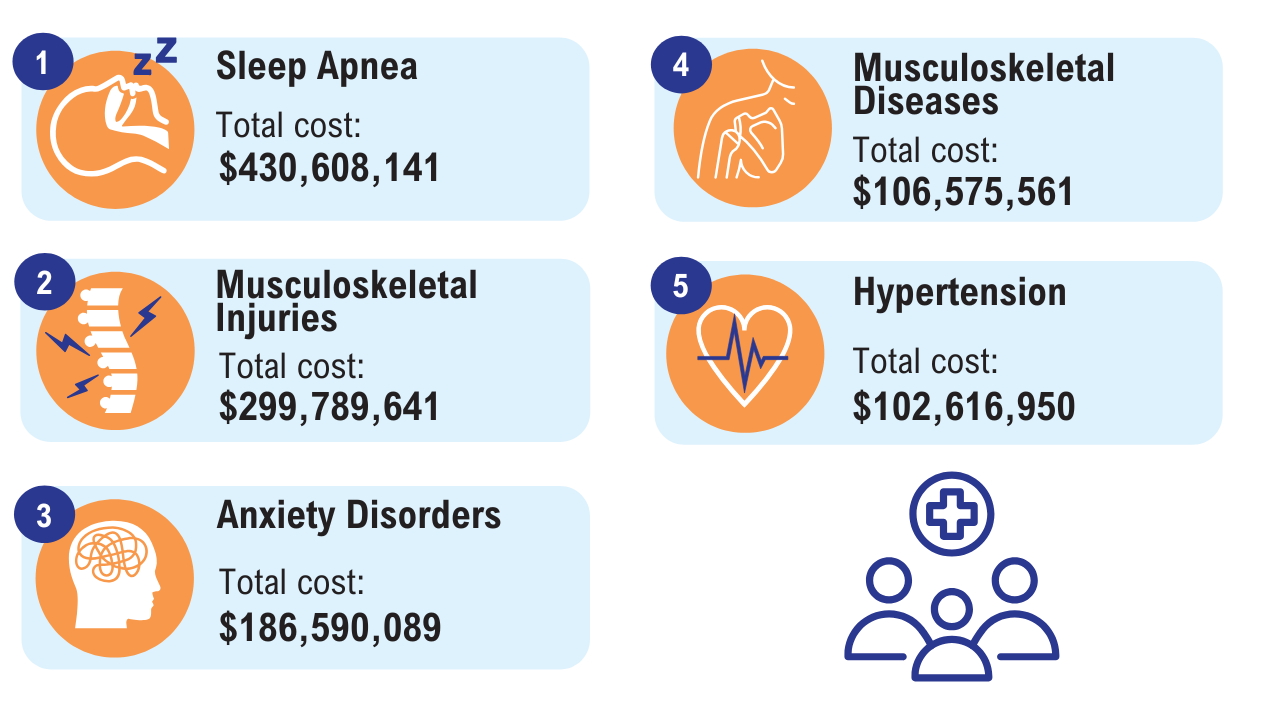

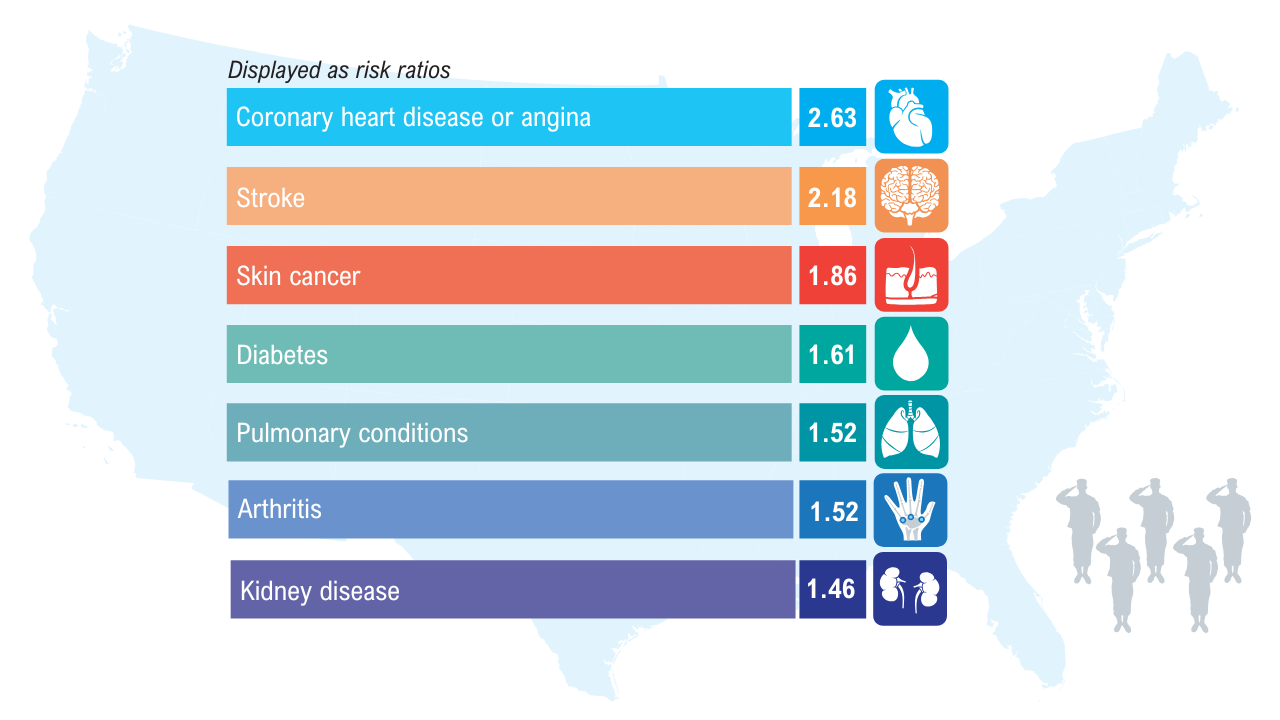

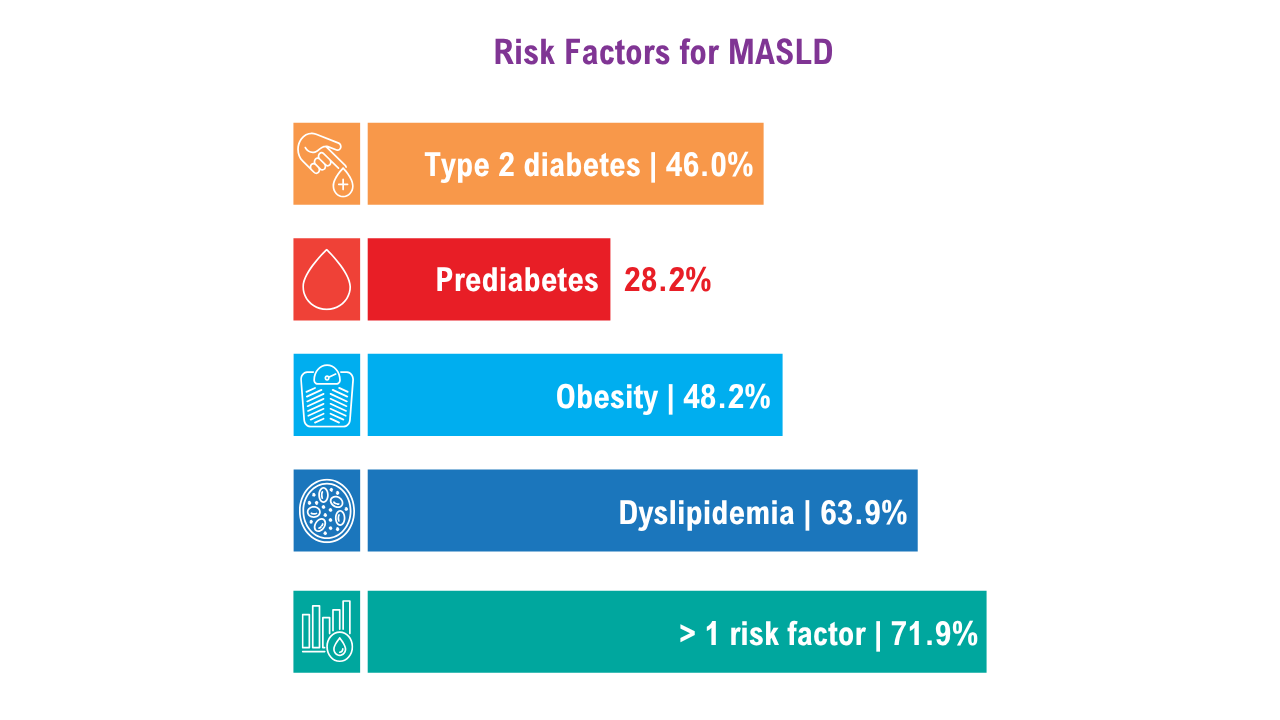

Data Trends 2025: Obesity

Obesity

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

1. GBD 2021 US Obesity Forecasting Collaborators. National-level and state-level prevalence of overweight and obesity among children, adolescents, and adults in the USA, 1990-2021, and forecasts up to 2050. Lancet. 2024;404(10469):2278-2298. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01548-4

2. Breland JY, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(Suppl 1):11-17. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3962-1

3. American Security Project. Costs and consequences: obesity’s compounding impact on the Military Health System. September 2024. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.americansecurityproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Ref-0295-Costs-and-Consequences-Obesitys-Compounding-Impact-on-the-Military-Health-System.pdf

4. Baser O, et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(11):1529. doi:10.3390/healthcare11111529

5. Maclin-Akinyemi C, et al. Mil Med. 2017;182(9):e1816-e1823. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00380.

6. Yang D, et al. Mil Med. 2022;187(7-8):e948-e954. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab292

7. American Security Project. Ready the Reserve: obesity’s impacts on National Guard and Reserve readiness. April 2025. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.americansecurityproject.org/white-paper-ready-the-reserve-obesitys-impacts-onnational-guard-and-reserve-readiness/

8. Betancourt JA, et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(3):191. doi:10.3390/healthcare8030191

9. Breland JY, et al. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;1;71(5):506-509. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201900078

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

1. GBD 2021 US Obesity Forecasting Collaborators. National-level and state-level prevalence of overweight and obesity among children, adolescents, and adults in the USA, 1990-2021, and forecasts up to 2050. Lancet. 2024;404(10469):2278-2298. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01548-4

2. Breland JY, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(Suppl 1):11-17. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3962-1

3. American Security Project. Costs and consequences: obesity’s compounding impact on the Military Health System. September 2024. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.americansecurityproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Ref-0295-Costs-and-Consequences-Obesitys-Compounding-Impact-on-the-Military-Health-System.pdf

4. Baser O, et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(11):1529. doi:10.3390/healthcare11111529

5. Maclin-Akinyemi C, et al. Mil Med. 2017;182(9):e1816-e1823. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00380.

6. Yang D, et al. Mil Med. 2022;187(7-8):e948-e954. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab292

7. American Security Project. Ready the Reserve: obesity’s impacts on National Guard and Reserve readiness. April 2025. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.americansecurityproject.org/white-paper-ready-the-reserve-obesitys-impacts-onnational-guard-and-reserve-readiness/

8. Betancourt JA, et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(3):191. doi:10.3390/healthcare8030191

9. Breland JY, et al. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;1;71(5):506-509. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201900078

1. GBD 2021 US Obesity Forecasting Collaborators. National-level and state-level prevalence of overweight and obesity among children, adolescents, and adults in the USA, 1990-2021, and forecasts up to 2050. Lancet. 2024;404(10469):2278-2298. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01548-4

2. Breland JY, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(Suppl 1):11-17. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3962-1

3. American Security Project. Costs and consequences: obesity’s compounding impact on the Military Health System. September 2024. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.americansecurityproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Ref-0295-Costs-and-Consequences-Obesitys-Compounding-Impact-on-the-Military-Health-System.pdf

4. Baser O, et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(11):1529. doi:10.3390/healthcare11111529

5. Maclin-Akinyemi C, et al. Mil Med. 2017;182(9):e1816-e1823. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00380.

6. Yang D, et al. Mil Med. 2022;187(7-8):e948-e954. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab292

7. American Security Project. Ready the Reserve: obesity’s impacts on National Guard and Reserve readiness. April 2025. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.americansecurityproject.org/white-paper-ready-the-reserve-obesitys-impacts-onnational-guard-and-reserve-readiness/

8. Betancourt JA, et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(3):191. doi:10.3390/healthcare8030191

9. Breland JY, et al. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;1;71(5):506-509. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201900078

Obesity

Obesity

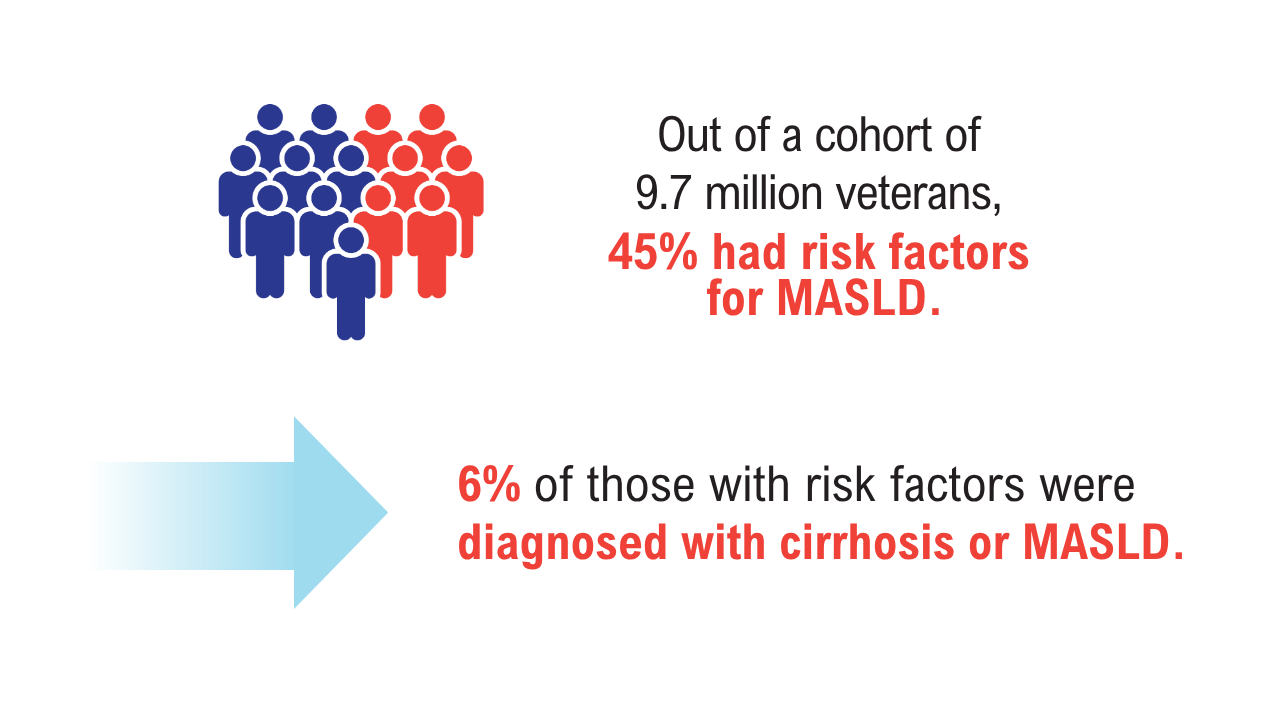

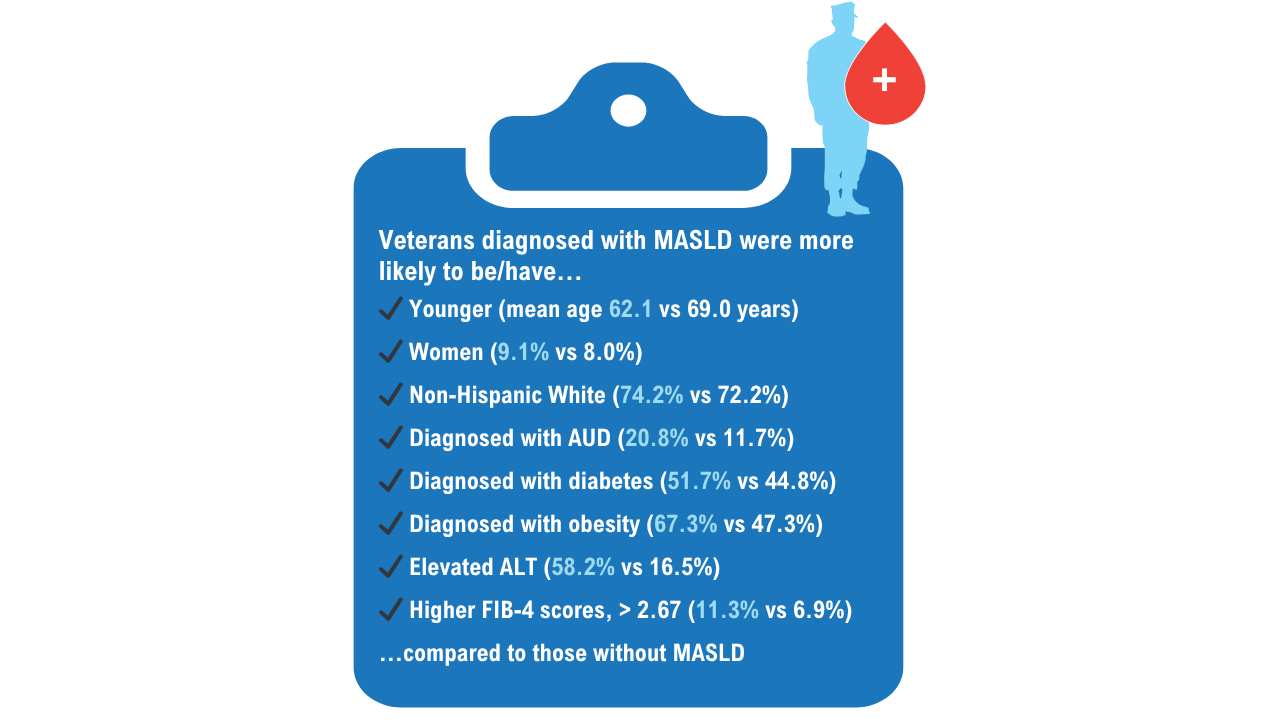

Data Trends 2025: Hepatology

Data Trends 2025: Hepatology

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

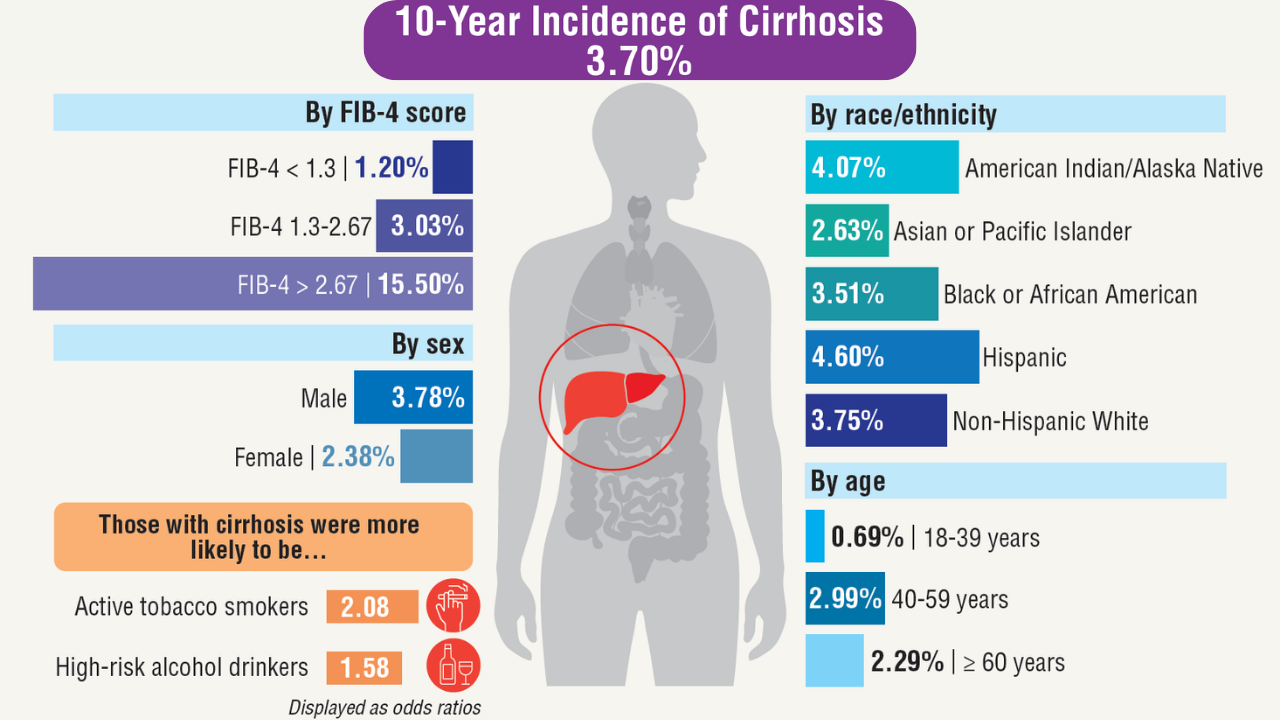

- Niezen S, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. Published online January 7, 2025. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000003312

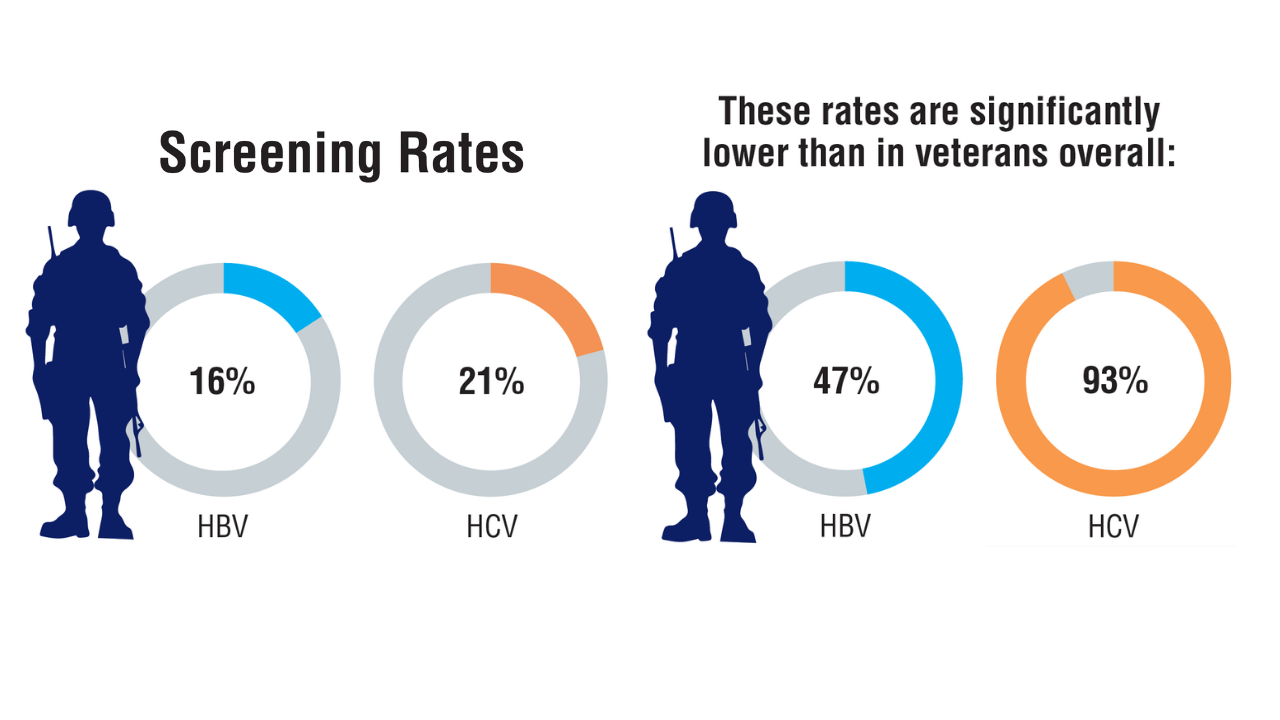

- Beydoun HA, Tsai J. J Viral Hepat. 2024;31(10):601-613. doi:10.1111/jvh.13981

- Yeoh A, et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2024;58(7):718-725. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001921

- Varley CD, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;78(6):1571-1579. doi:10.1093/cid/ciae025

- Njei B, et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2025;70(2):802-813. doi:10.1007/s10620-024-08764-4

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Niezen S, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. Published online January 7, 2025. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000003312

- Beydoun HA, Tsai J. J Viral Hepat. 2024;31(10):601-613. doi:10.1111/jvh.13981

- Yeoh A, et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2024;58(7):718-725. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001921

- Varley CD, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;78(6):1571-1579. doi:10.1093/cid/ciae025

- Njei B, et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2025;70(2):802-813. doi:10.1007/s10620-024-08764-4

- Niezen S, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. Published online January 7, 2025. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000003312

- Beydoun HA, Tsai J. J Viral Hepat. 2024;31(10):601-613. doi:10.1111/jvh.13981

- Yeoh A, et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2024;58(7):718-725. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001921

- Varley CD, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;78(6):1571-1579. doi:10.1093/cid/ciae025

- Njei B, et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2025;70(2):802-813. doi:10.1007/s10620-024-08764-4

Data Trends 2025: Hepatology

Data Trends 2025: Hepatology

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025

Federal Health Care Data Trends is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, showcasing the latest research in health care for veterans and active-duty military members via compelling infographics.

Topics include:

Federal Health Care Data Trends is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, showcasing the latest research in health care for veterans and active-duty military members via compelling infographics.

Topics include:

Federal Health Care Data Trends is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, showcasing the latest research in health care for veterans and active-duty military members via compelling infographics.

Topics include:

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025

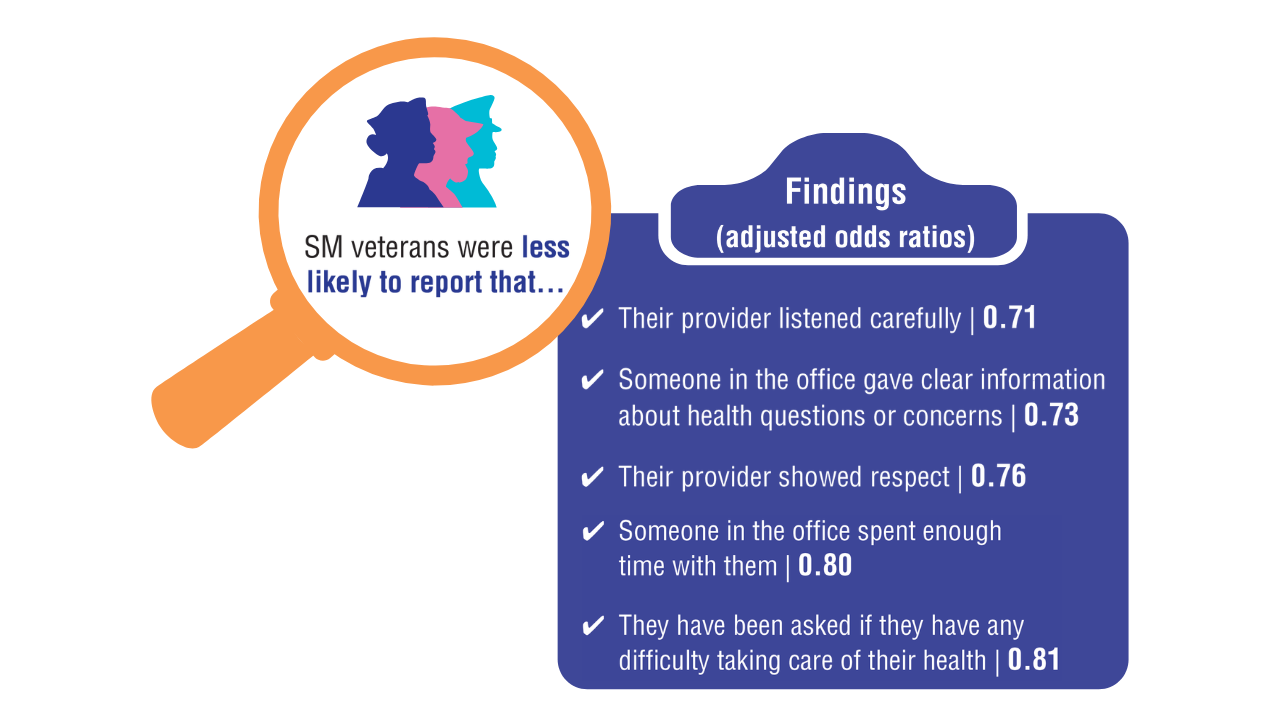

Data Trends 2025: LGBTQ+ Care

Data Trends 2025: LGBTQ+ Care

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Meadows SO, et al. 2018 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS): Sexual Orientation, Transgender, and Health Among US Active-Duty Service Members. RAND Corporation; 2018. Accessed May 13, 2025. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR4222.html

- Singh RS, et al. Front Public Health. 2024;11:1251565. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1251565

- Livingston NA, et al. LGBT Health. 2022;9(2):136-144. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2021.0069

- Lamda, et al. LGBT Health. 2024;11(6). doi:10.1089/lgbt.2023.0224

- Shipherd JC, et al. LGBT Health. 2018;5(5):303-311. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2017.0179

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Health Equity. Health Disparities Among LGBT Veterans. Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs; Updated July 21, 2020. Accessed February 13, 2025. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Health_Disparities_Among_LGBT_Veterans.asp

- McGirr J, et al. Chartbook on the Health of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Veterans. Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Health Equity, Veterans Health Administration; 2021. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/docs/LGB_Veteran_Health_Chartbook_Final.pdf

Livingston NA. Trauma, minority stress, and disproportionate health burden among LGBTQ+ people. PTSD Research Quarterly. 2023;34(4):1050-1835. Accessed April10, 2025. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/publications/rq_docs/V34N4.pdf

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Meadows SO, et al. 2018 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS): Sexual Orientation, Transgender, and Health Among US Active-Duty Service Members. RAND Corporation; 2018. Accessed May 13, 2025. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR4222.html

- Singh RS, et al. Front Public Health. 2024;11:1251565. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1251565

- Livingston NA, et al. LGBT Health. 2022;9(2):136-144. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2021.0069

- Lamda, et al. LGBT Health. 2024;11(6). doi:10.1089/lgbt.2023.0224

- Shipherd JC, et al. LGBT Health. 2018;5(5):303-311. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2017.0179

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Health Equity. Health Disparities Among LGBT Veterans. Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs; Updated July 21, 2020. Accessed February 13, 2025. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Health_Disparities_Among_LGBT_Veterans.asp

- McGirr J, et al. Chartbook on the Health of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Veterans. Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Health Equity, Veterans Health Administration; 2021. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/docs/LGB_Veteran_Health_Chartbook_Final.pdf

Livingston NA. Trauma, minority stress, and disproportionate health burden among LGBTQ+ people. PTSD Research Quarterly. 2023;34(4):1050-1835. Accessed April10, 2025. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/publications/rq_docs/V34N4.pdf

- Meadows SO, et al. 2018 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS): Sexual Orientation, Transgender, and Health Among US Active-Duty Service Members. RAND Corporation; 2018. Accessed May 13, 2025. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR4222.html

- Singh RS, et al. Front Public Health. 2024;11:1251565. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1251565

- Livingston NA, et al. LGBT Health. 2022;9(2):136-144. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2021.0069

- Lamda, et al. LGBT Health. 2024;11(6). doi:10.1089/lgbt.2023.0224

- Shipherd JC, et al. LGBT Health. 2018;5(5):303-311. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2017.0179

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Health Equity. Health Disparities Among LGBT Veterans. Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs; Updated July 21, 2020. Accessed February 13, 2025. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Health_Disparities_Among_LGBT_Veterans.asp

- McGirr J, et al. Chartbook on the Health of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Veterans. Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Health Equity, Veterans Health Administration; 2021. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/docs/LGB_Veteran_Health_Chartbook_Final.pdf

Livingston NA. Trauma, minority stress, and disproportionate health burden among LGBTQ+ people. PTSD Research Quarterly. 2023;34(4):1050-1835. Accessed April10, 2025. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/publications/rq_docs/V34N4.pdf

Data Trends 2025: LGBTQ+ Care

Data Trends 2025: LGBTQ+ Care

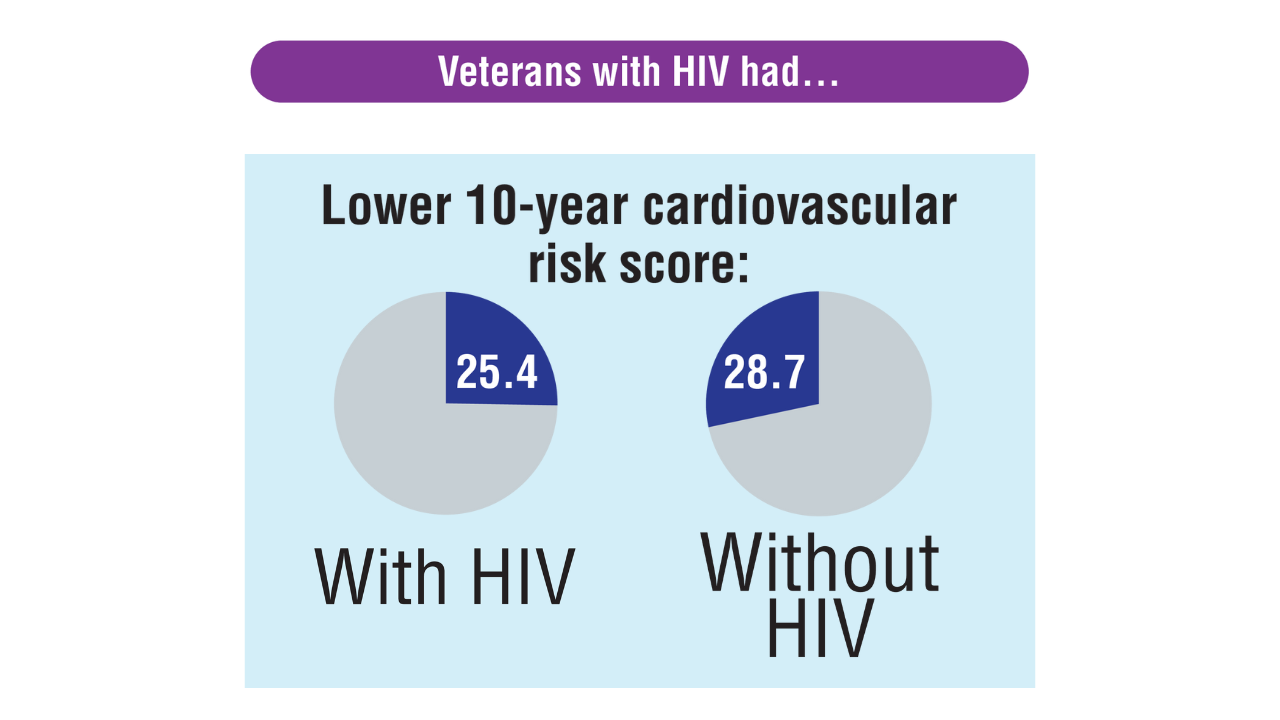

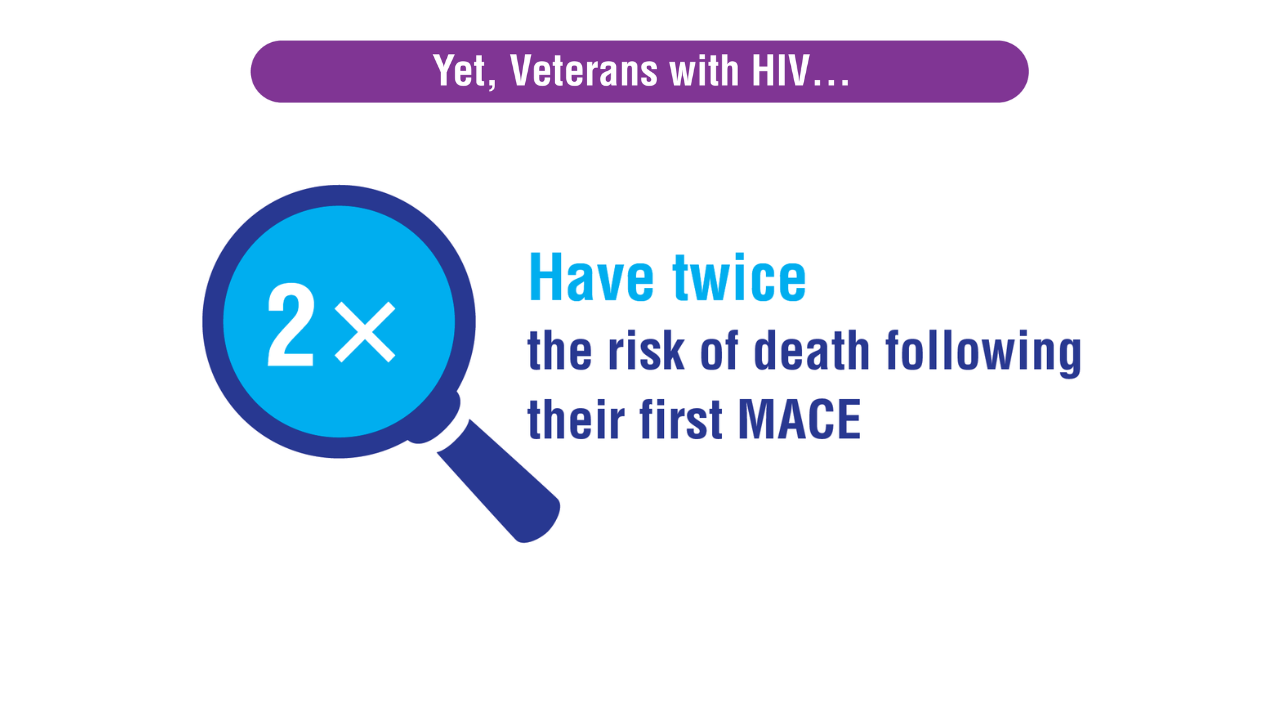

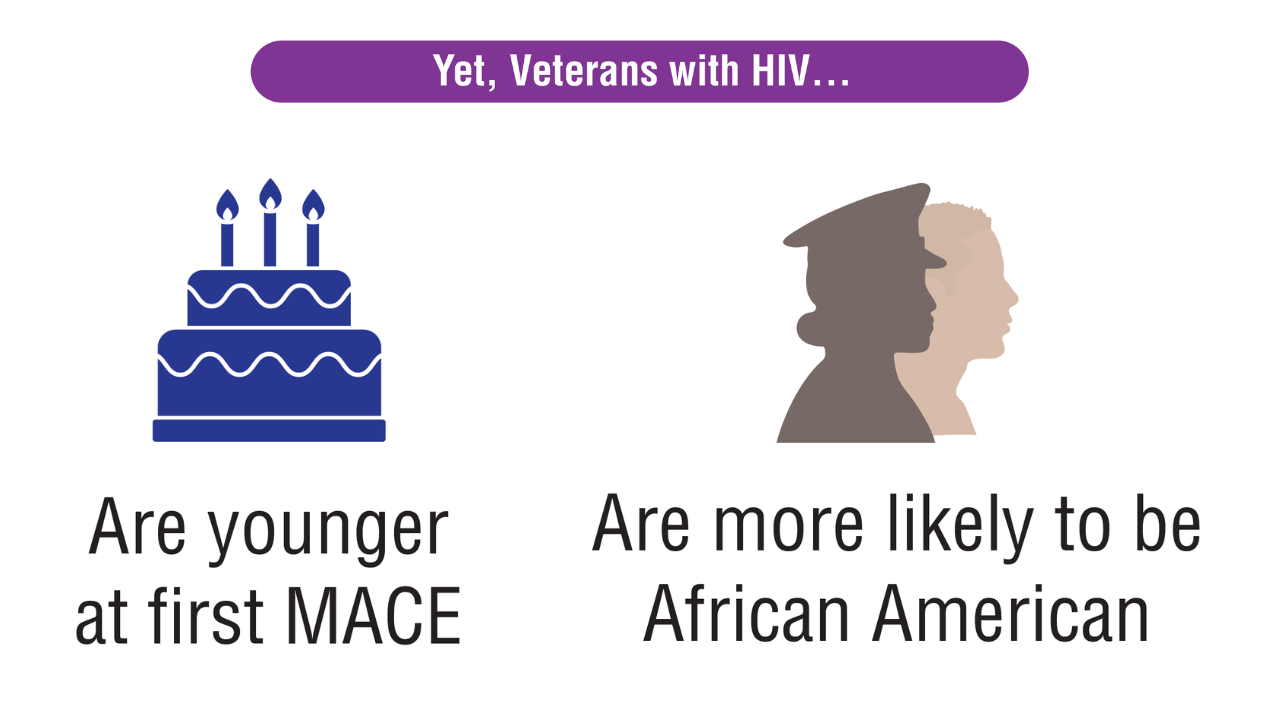

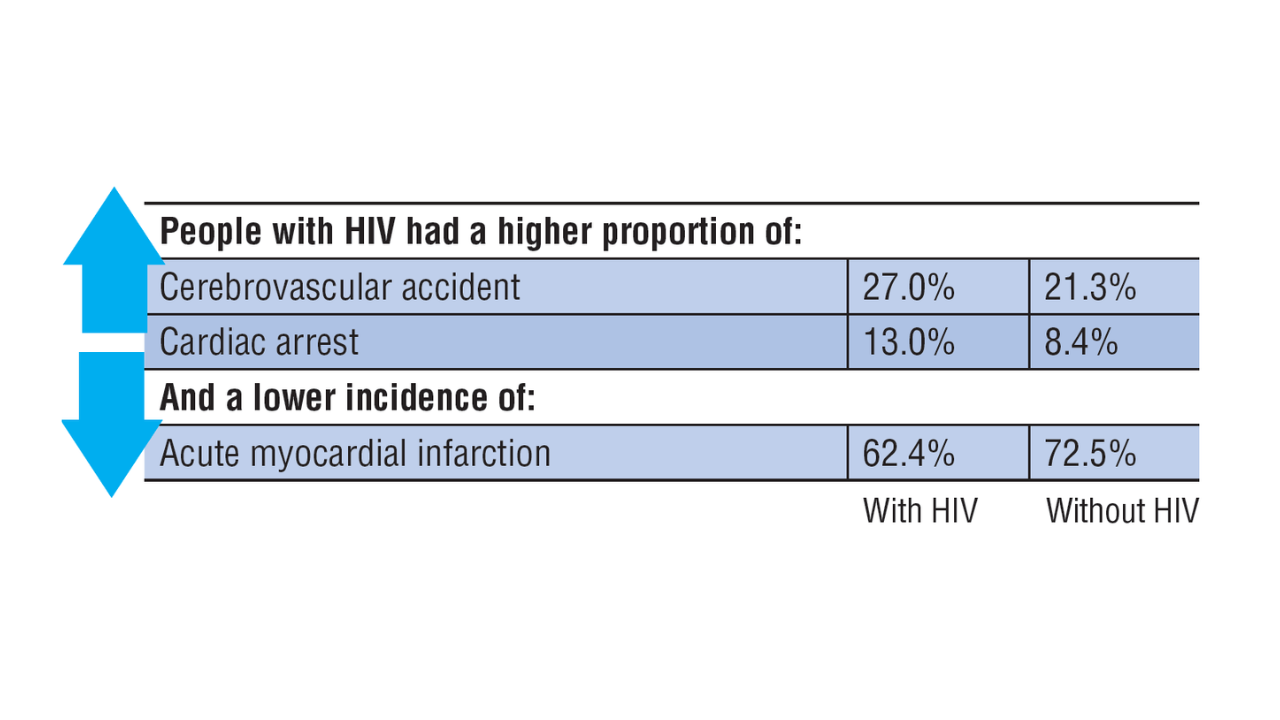

Data Trends 2025: HIV

Data Trends 2025: HIV

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Varley CD, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;78(6):1571-1579. doi:10.1093/cid/

ciae025 Hicks WL, et al. HIV Med. 2025;26(2):218-229. doi:10.1111/hiv.13724

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Varley CD, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;78(6):1571-1579. doi:10.1093/cid/

ciae025 Hicks WL, et al. HIV Med. 2025;26(2):218-229. doi:10.1111/hiv.13724

- Varley CD, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;78(6):1571-1579. doi:10.1093/cid/

ciae025 Hicks WL, et al. HIV Med. 2025;26(2):218-229. doi:10.1111/hiv.13724

Data Trends 2025: HIV

Data Trends 2025: HIV

Pedunculated Pink Papule on the Nose

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pedunculated Lipofibroma

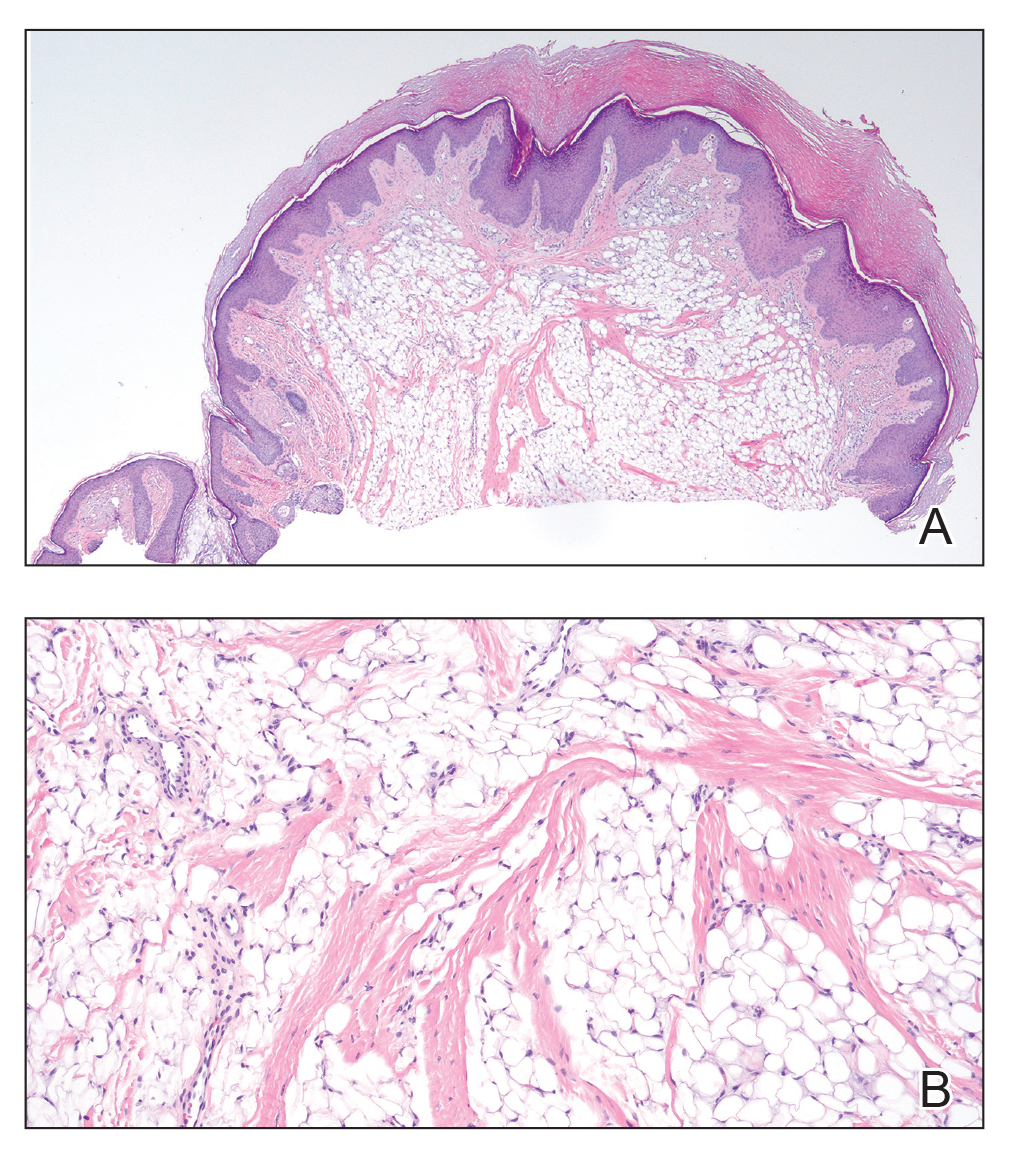

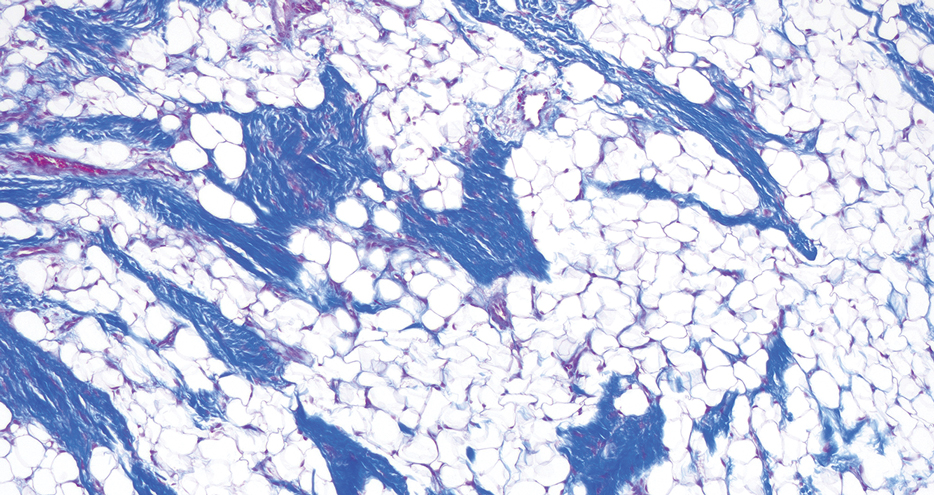

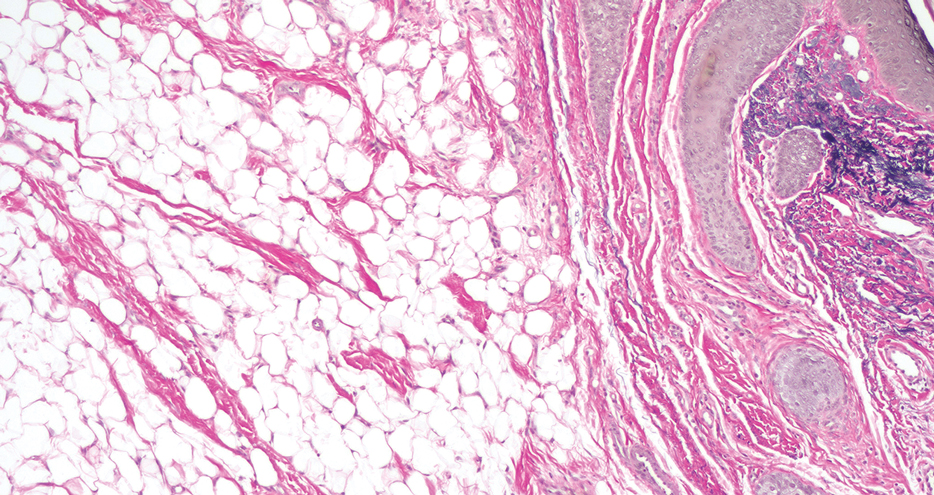

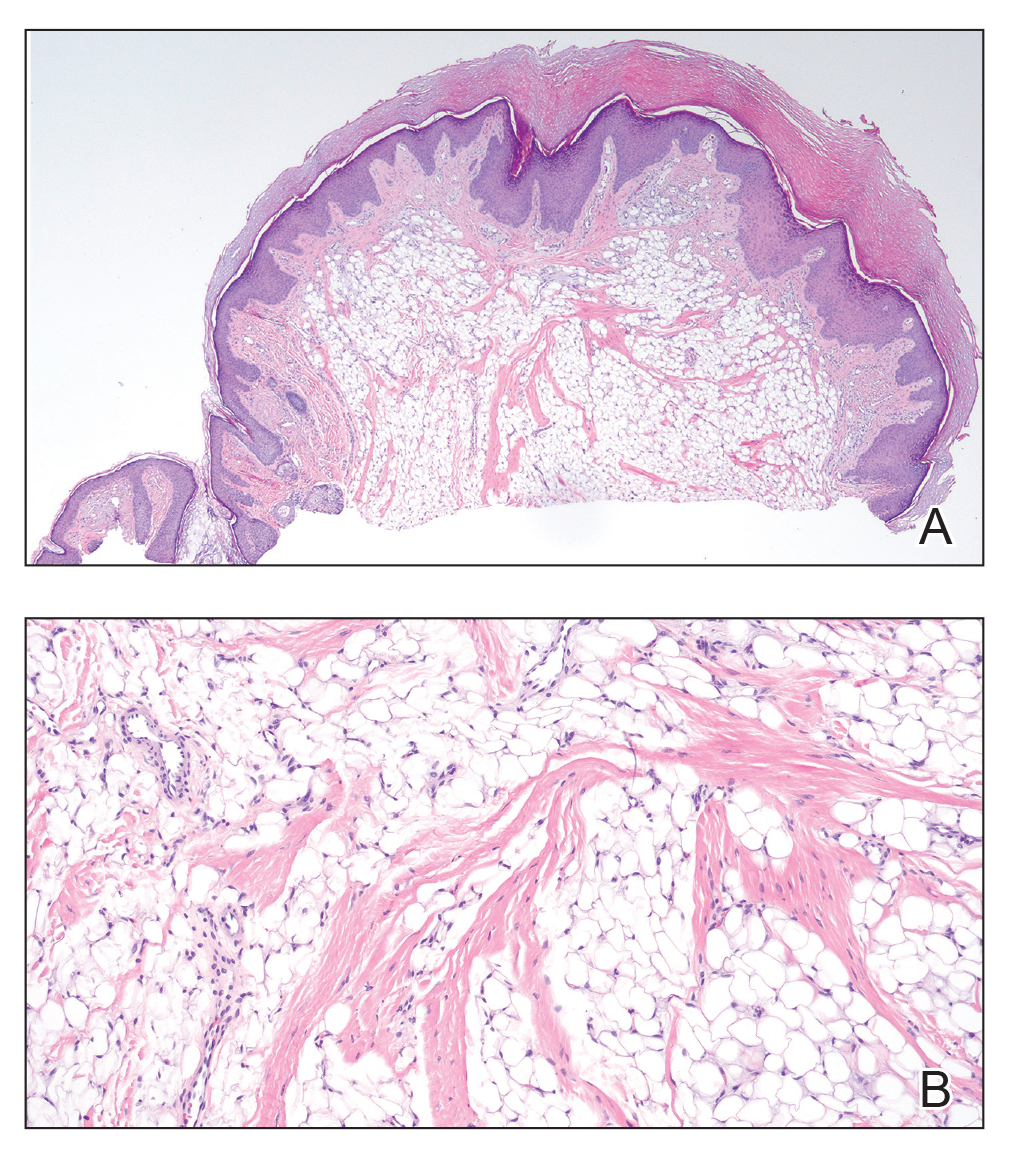

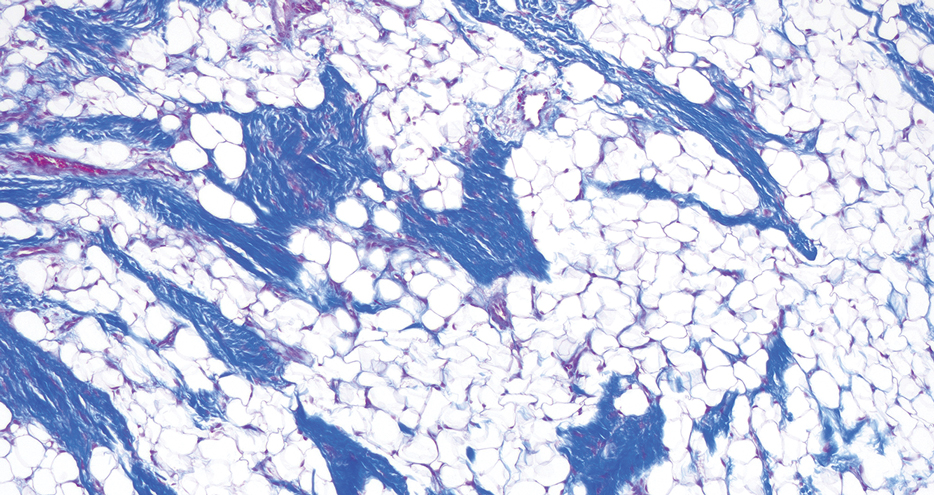

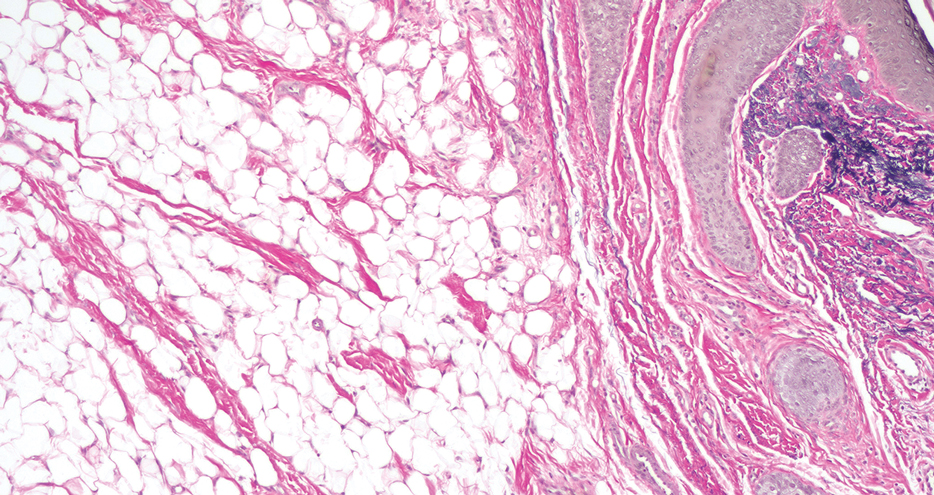

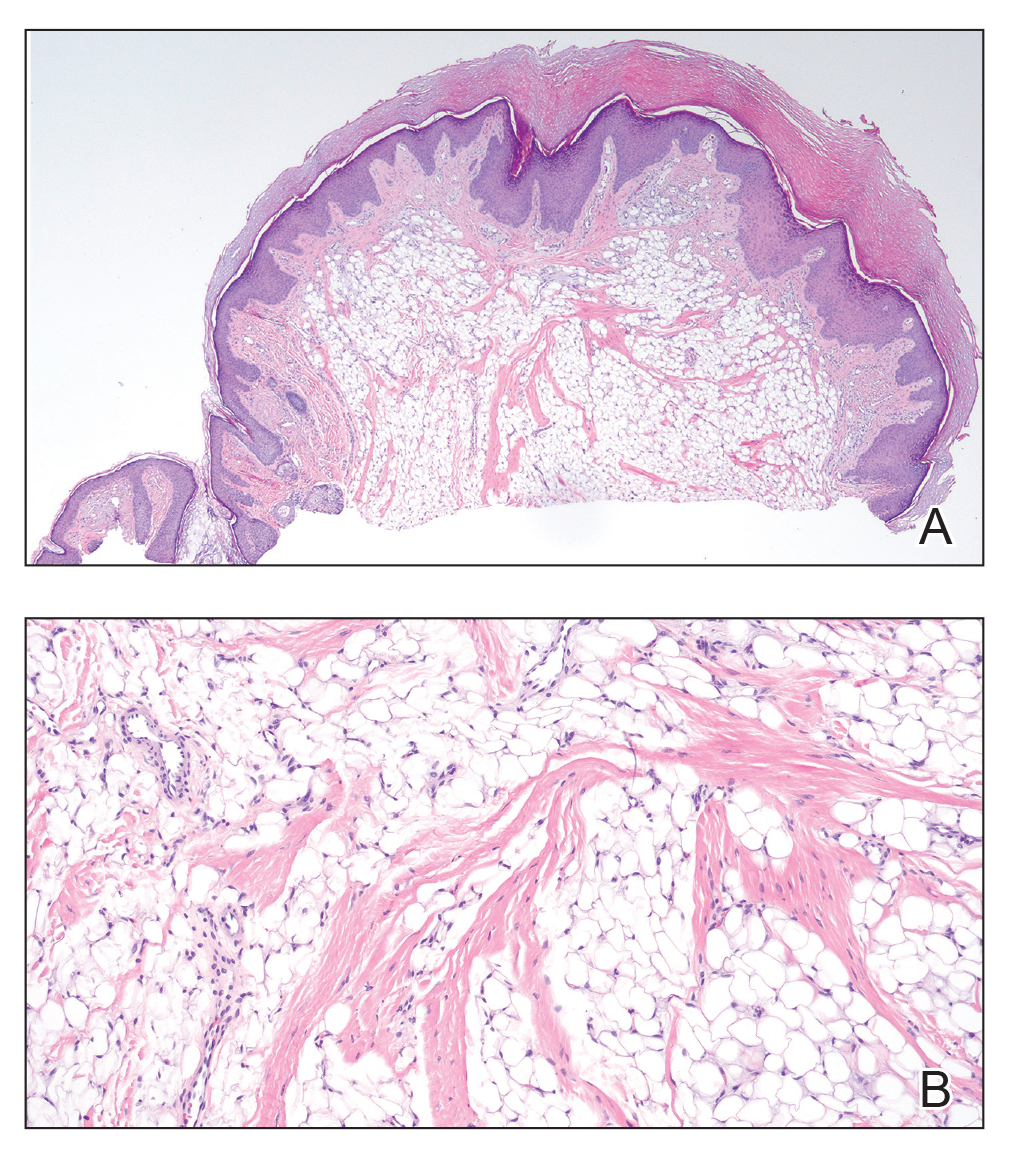

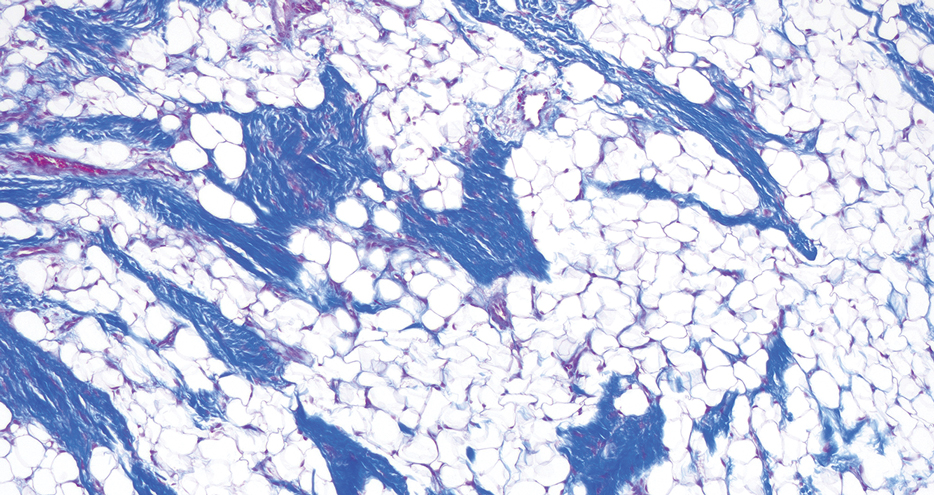

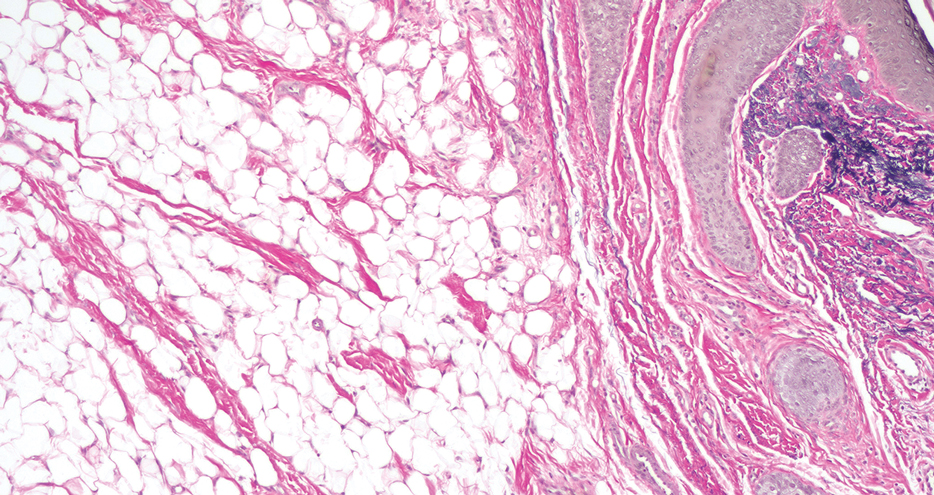

Histopathology confirmed a pedunculated/polypoid lesion with intradermal lobules of adipocytes/mature adipose tissue admixed with connective tissue bundles and vascular ectasias. Overlying epidermal acanthosis with slight papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis was present (Figure 1). Masson trichrome staining highlighted admixed collagen bundles (Figure 2). Verhoeff–van Gieson staining showed marked reduction in elastic fibers (Figure 3). Immunostaining was negative for smooth muscle actin and desmin. A diagnosis of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose was made based on both clinical and histopathologic findings.

Pedunculated lipofibroma (or solitary lipofibroma) is the solitary form of nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (NLCS).7 First described by Hoffmann and Zurhelle1 in 1921, NLCS is an uncommon benign hamartomatous cutaneous lesion/connective tissue nevus that also has a classic multiple form.1-13 The etiology of NLCS remains unclear, but several theories have been proposed to explain its pathogenesis, including deposition of adipocytes secondary to degenerative changes in dermal connective tissue, focal/local heterotopic development of adipose tissue, and derivation from differentiating lipoblasts (preadipose tissue) originating from precursor vascular or perivascular cells.2-13

Pedunculated lipofibroma usually develops during the third to sixth decades of life and manifests as a single cutaneous lesion with a smooth surface, often on a non–pelvic girdle location.7-13 No particular predilection sites are noted, with lesions reported on the arm, axilla, back, upper thigh, knee, and sole.5,12 There are rare reports of this type of NLCS on the ear, scalp, forehead, or eyelid.7-11

In the classic form of NLCS, multiple cutaneous lesions are present at birth or develop within the first 2 to 3 decades of life.2-6 Lesions consist of soft, nontender, pedunculated, flesh-colored or yellowish papules and nodules with a verrucoid or cerebriform surface that may later coalesce to form plaques.2-6 Predilection sites include the pelvic girdle, buttocks, sacral and coccygeal regions, and upper posterior thighs, with a linear or zosteriform pattern of distribution.2-6 Rarely, the classic form can arise in elderly patients and/or at an atypical anatomic location (eg, clitoris,3 shoulder,5 thorax,5 abdomen5) and can demonstrate extension of lesions across the midline.4 Rare cases of classic NLCS on the scalp2 and face3-6 have been reported, including lesions localized to the nose3 and chin4 and others extending from the right mandible to the neck5 and right lower lip to the submandibular/posteriorateral cervical region.6 In some cases, lesions clinically resemble plane xanthoma4 and localized scleroderma.6

Adotama et al13 proposed a set of clinical features to differentiate classic NLCS, pedunculated lipofibroma (solitary NLCS), and fibroepithelial polyp with adipocytes (distinguished by their furrowed surface, hyperpigmentation, and anatomic predilection for the neck and axilla). Lesions are asymptomatic in both forms of NLCS.2-13 Family history or predominant sex involvement have not been reported in either clinical type.2-13 Reported associations with NLCS include a number of endocrinologic conditions including diabetes.7 Other coexisting skin findings can include café-au-lait macules, leukodermic (white) spots, overlying hypertrichosis, comedolike alterations, angiokeratoma, hemangioma, and folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma.4 None of these were evident in our patient.

Lesions from both types of NLCS are indistinguishable on histopathology, characterized by the presence of a central core of ectopic mature adipocytes in the papillary/reticular dermis.2-13 Additional light microscopic features (some seen in our case) have been described, including thickened collagen bundles, reduction of elastic fibers, increased numbers of fibroblasts and/or mast cells, increased (small-vessel) vascularity, focal mucin deposition/myxoid degeneration, a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, attenuation of adnexal structures, and abnormalities of the epidermis (eg, surface ulceration).2-13

Prior to biopsy, the differential diagnosis in our patient included angiofibroma, pyogenic granuloma, and basal cell carcinoma given the exophytic, pink, papular appearance of the lesion; however, the histopathologic differential diagnosis included angiofibroma, angiomyolipoma, lymphangioma, nevus sebaceus, and spindle cell lipoma (SCL). In angiofibroma, a dermal proliferation of stellate fibroblasts, dilated blood vessels, and collagenous stroma are seen. Cutaneous angiomyolipoma demonstrates smooth muscle bundles in addition to thickened blood vessels and variable proportions of mature adipocytes. Lymphangioma is characterized by dilated lymph channels lined by flat endothelial cells. Nevus sebaceus shows superficial immature and abnormally formed pilosebaceous units, with epidermal papillomatosis.

Rare cases of SCL on the nose have been described.14 Similar to pedunculated lipofibroma, reported examples demonstrate mature univacuolar adipocytes with thick collagen fibers and bland uniform spindle cells. Unlike the lesion seen in our patient, nasal SCL may be clinically mobile and typically is localized to the subcutaneous tissue, although dermal tumors also occur.14 Variably reported histopathologic findings in nasal SCL include circumscription/encapsulation, spindle cells arranged in short fascicles with nuclear palisading, a myxoid/mucinous interstitial matrix, and/or multinucleated giant cells—all light microscopic features that were not identified in our case; however, variable proportions of adipocytic, fibrous, and myxoid components among reported examples of SCL on the nose14 can make distinction from pedunculated lipofibroma difficult, as both are benign lipomatous tumor variants.

Clinically, pedunculated lipofibroma may be confused with more common benign cutaneous lesions and must be distinguished from other fibrolipomatous lesions on the nose. Specifically, the differential diagnosis includes benign cutaneous papillomas such as acrochordon, angiofibroma, melanocytic nevi, neurofibroma, nevus sebaceus, lymphangioma, and eccrine poroma.7-13 These all can be readily excluded on histopathology. Pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose, as in our patient, must be distinguished from fibrolipoma15 and dendritic myxofibrolipoma.16 Fibrolipoma is a subcutaneous proliferation of mature adipose tissue and fibrous tissue and comprises 1.6% of all facial lipomas reported worldwide.15 Dendritic myxofibrolipoma is a recently described benign soft-tissue tumor characterized by an admixture of mature adipose tissue, spindle and stellate cells, and an abundant myxoid stroma with prominent collagenization.16

Treatment of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose is not indicated except for cosmetic reasons, in which case simple surgical excision would be considered satisfactory. Following biopsy, no further treatment was pursued in our patient.

- Hoffmann E, Zurhelle E. Uber einen naevus lipomatodes cutaneous superficialis der linken Glutaalgegend. Arch Derm Syph. 1921;130:327-333.

- Chanoki M, Isukos S, Suzuki S, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis of the scalp. Cutis. 1989;43:143-144.

- Sáez Rodríguez M, Rodríguez-Martin M, Carnerero A, et al. Naevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis on the nose. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:751-752.

- Hassab-El-Naby HMM, Rageh MA. Adult-onset nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis mimicking plane xanthoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:10-11.

- Park HJ, Park CJ, Yi JY, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis on the face. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:435-437.

- Ioannidou DJ, Stefanidou MP, Panayiotides JG, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (Hoffman-Zurhelle) with localized scleroderma like appearance. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:54-57.

- Nogita T, Wong TY, Hidano A, et al. Pedunculated lipofibroma. a clinicopathologic study of thirty-two cases supporting a simplified nomenclature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2 pt 1):235-240.

- Sawada Y. Solitary nevus lipomatosus superficialis on the forehead. Ann Plast Surg. 1986;16:356-358.

- Knoth W. Uber Naevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis Hoffmann-Zurhelle und uber Naevus naevocellularis partim lipomatodes. Dermatologica. 1962;125:161.

- Weitzner S. Solitary naevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis of scalp. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:540-542.

- Kaw P, Carlson A, Meyer DR. Nevus lipomatosus (pedunculated lipofibroma) of the eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;21:74-76.

- Vano-Galvan S, Moreno C, Vano-Galvan E, et al. Solitary naevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis on the sole. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:353-354.

- Adotama P, Hutson SD, Rieder EA, et al. Revisiting solitary pedunculated lipofibromas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;156:954-957.

- Kubin ME, Lantto U, Lindgren O, et al. A rare, recurrent spindle cell lipoma of the nose. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00571.

- Jung SN, Shin JW, Kwon H, et al. Fibrolipoma of the tip of the nose. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:555-556.

- Han XC, Zheng LQ, Shang XL. Dendritic fibromyxolipoma on the nasal tip in an old patient. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7064-7067.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pedunculated Lipofibroma

Histopathology confirmed a pedunculated/polypoid lesion with intradermal lobules of adipocytes/mature adipose tissue admixed with connective tissue bundles and vascular ectasias. Overlying epidermal acanthosis with slight papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis was present (Figure 1). Masson trichrome staining highlighted admixed collagen bundles (Figure 2). Verhoeff–van Gieson staining showed marked reduction in elastic fibers (Figure 3). Immunostaining was negative for smooth muscle actin and desmin. A diagnosis of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose was made based on both clinical and histopathologic findings.

Pedunculated lipofibroma (or solitary lipofibroma) is the solitary form of nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (NLCS).7 First described by Hoffmann and Zurhelle1 in 1921, NLCS is an uncommon benign hamartomatous cutaneous lesion/connective tissue nevus that also has a classic multiple form.1-13 The etiology of NLCS remains unclear, but several theories have been proposed to explain its pathogenesis, including deposition of adipocytes secondary to degenerative changes in dermal connective tissue, focal/local heterotopic development of adipose tissue, and derivation from differentiating lipoblasts (preadipose tissue) originating from precursor vascular or perivascular cells.2-13

Pedunculated lipofibroma usually develops during the third to sixth decades of life and manifests as a single cutaneous lesion with a smooth surface, often on a non–pelvic girdle location.7-13 No particular predilection sites are noted, with lesions reported on the arm, axilla, back, upper thigh, knee, and sole.5,12 There are rare reports of this type of NLCS on the ear, scalp, forehead, or eyelid.7-11

In the classic form of NLCS, multiple cutaneous lesions are present at birth or develop within the first 2 to 3 decades of life.2-6 Lesions consist of soft, nontender, pedunculated, flesh-colored or yellowish papules and nodules with a verrucoid or cerebriform surface that may later coalesce to form plaques.2-6 Predilection sites include the pelvic girdle, buttocks, sacral and coccygeal regions, and upper posterior thighs, with a linear or zosteriform pattern of distribution.2-6 Rarely, the classic form can arise in elderly patients and/or at an atypical anatomic location (eg, clitoris,3 shoulder,5 thorax,5 abdomen5) and can demonstrate extension of lesions across the midline.4 Rare cases of classic NLCS on the scalp2 and face3-6 have been reported, including lesions localized to the nose3 and chin4 and others extending from the right mandible to the neck5 and right lower lip to the submandibular/posteriorateral cervical region.6 In some cases, lesions clinically resemble plane xanthoma4 and localized scleroderma.6

Adotama et al13 proposed a set of clinical features to differentiate classic NLCS, pedunculated lipofibroma (solitary NLCS), and fibroepithelial polyp with adipocytes (distinguished by their furrowed surface, hyperpigmentation, and anatomic predilection for the neck and axilla). Lesions are asymptomatic in both forms of NLCS.2-13 Family history or predominant sex involvement have not been reported in either clinical type.2-13 Reported associations with NLCS include a number of endocrinologic conditions including diabetes.7 Other coexisting skin findings can include café-au-lait macules, leukodermic (white) spots, overlying hypertrichosis, comedolike alterations, angiokeratoma, hemangioma, and folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma.4 None of these were evident in our patient.

Lesions from both types of NLCS are indistinguishable on histopathology, characterized by the presence of a central core of ectopic mature adipocytes in the papillary/reticular dermis.2-13 Additional light microscopic features (some seen in our case) have been described, including thickened collagen bundles, reduction of elastic fibers, increased numbers of fibroblasts and/or mast cells, increased (small-vessel) vascularity, focal mucin deposition/myxoid degeneration, a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, attenuation of adnexal structures, and abnormalities of the epidermis (eg, surface ulceration).2-13

Prior to biopsy, the differential diagnosis in our patient included angiofibroma, pyogenic granuloma, and basal cell carcinoma given the exophytic, pink, papular appearance of the lesion; however, the histopathologic differential diagnosis included angiofibroma, angiomyolipoma, lymphangioma, nevus sebaceus, and spindle cell lipoma (SCL). In angiofibroma, a dermal proliferation of stellate fibroblasts, dilated blood vessels, and collagenous stroma are seen. Cutaneous angiomyolipoma demonstrates smooth muscle bundles in addition to thickened blood vessels and variable proportions of mature adipocytes. Lymphangioma is characterized by dilated lymph channels lined by flat endothelial cells. Nevus sebaceus shows superficial immature and abnormally formed pilosebaceous units, with epidermal papillomatosis.

Rare cases of SCL on the nose have been described.14 Similar to pedunculated lipofibroma, reported examples demonstrate mature univacuolar adipocytes with thick collagen fibers and bland uniform spindle cells. Unlike the lesion seen in our patient, nasal SCL may be clinically mobile and typically is localized to the subcutaneous tissue, although dermal tumors also occur.14 Variably reported histopathologic findings in nasal SCL include circumscription/encapsulation, spindle cells arranged in short fascicles with nuclear palisading, a myxoid/mucinous interstitial matrix, and/or multinucleated giant cells—all light microscopic features that were not identified in our case; however, variable proportions of adipocytic, fibrous, and myxoid components among reported examples of SCL on the nose14 can make distinction from pedunculated lipofibroma difficult, as both are benign lipomatous tumor variants.

Clinically, pedunculated lipofibroma may be confused with more common benign cutaneous lesions and must be distinguished from other fibrolipomatous lesions on the nose. Specifically, the differential diagnosis includes benign cutaneous papillomas such as acrochordon, angiofibroma, melanocytic nevi, neurofibroma, nevus sebaceus, lymphangioma, and eccrine poroma.7-13 These all can be readily excluded on histopathology. Pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose, as in our patient, must be distinguished from fibrolipoma15 and dendritic myxofibrolipoma.16 Fibrolipoma is a subcutaneous proliferation of mature adipose tissue and fibrous tissue and comprises 1.6% of all facial lipomas reported worldwide.15 Dendritic myxofibrolipoma is a recently described benign soft-tissue tumor characterized by an admixture of mature adipose tissue, spindle and stellate cells, and an abundant myxoid stroma with prominent collagenization.16

Treatment of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose is not indicated except for cosmetic reasons, in which case simple surgical excision would be considered satisfactory. Following biopsy, no further treatment was pursued in our patient.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pedunculated Lipofibroma

Histopathology confirmed a pedunculated/polypoid lesion with intradermal lobules of adipocytes/mature adipose tissue admixed with connective tissue bundles and vascular ectasias. Overlying epidermal acanthosis with slight papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis was present (Figure 1). Masson trichrome staining highlighted admixed collagen bundles (Figure 2). Verhoeff–van Gieson staining showed marked reduction in elastic fibers (Figure 3). Immunostaining was negative for smooth muscle actin and desmin. A diagnosis of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose was made based on both clinical and histopathologic findings.

Pedunculated lipofibroma (or solitary lipofibroma) is the solitary form of nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (NLCS).7 First described by Hoffmann and Zurhelle1 in 1921, NLCS is an uncommon benign hamartomatous cutaneous lesion/connective tissue nevus that also has a classic multiple form.1-13 The etiology of NLCS remains unclear, but several theories have been proposed to explain its pathogenesis, including deposition of adipocytes secondary to degenerative changes in dermal connective tissue, focal/local heterotopic development of adipose tissue, and derivation from differentiating lipoblasts (preadipose tissue) originating from precursor vascular or perivascular cells.2-13

Pedunculated lipofibroma usually develops during the third to sixth decades of life and manifests as a single cutaneous lesion with a smooth surface, often on a non–pelvic girdle location.7-13 No particular predilection sites are noted, with lesions reported on the arm, axilla, back, upper thigh, knee, and sole.5,12 There are rare reports of this type of NLCS on the ear, scalp, forehead, or eyelid.7-11

In the classic form of NLCS, multiple cutaneous lesions are present at birth or develop within the first 2 to 3 decades of life.2-6 Lesions consist of soft, nontender, pedunculated, flesh-colored or yellowish papules and nodules with a verrucoid or cerebriform surface that may later coalesce to form plaques.2-6 Predilection sites include the pelvic girdle, buttocks, sacral and coccygeal regions, and upper posterior thighs, with a linear or zosteriform pattern of distribution.2-6 Rarely, the classic form can arise in elderly patients and/or at an atypical anatomic location (eg, clitoris,3 shoulder,5 thorax,5 abdomen5) and can demonstrate extension of lesions across the midline.4 Rare cases of classic NLCS on the scalp2 and face3-6 have been reported, including lesions localized to the nose3 and chin4 and others extending from the right mandible to the neck5 and right lower lip to the submandibular/posteriorateral cervical region.6 In some cases, lesions clinically resemble plane xanthoma4 and localized scleroderma.6

Adotama et al13 proposed a set of clinical features to differentiate classic NLCS, pedunculated lipofibroma (solitary NLCS), and fibroepithelial polyp with adipocytes (distinguished by their furrowed surface, hyperpigmentation, and anatomic predilection for the neck and axilla). Lesions are asymptomatic in both forms of NLCS.2-13 Family history or predominant sex involvement have not been reported in either clinical type.2-13 Reported associations with NLCS include a number of endocrinologic conditions including diabetes.7 Other coexisting skin findings can include café-au-lait macules, leukodermic (white) spots, overlying hypertrichosis, comedolike alterations, angiokeratoma, hemangioma, and folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma.4 None of these were evident in our patient.

Lesions from both types of NLCS are indistinguishable on histopathology, characterized by the presence of a central core of ectopic mature adipocytes in the papillary/reticular dermis.2-13 Additional light microscopic features (some seen in our case) have been described, including thickened collagen bundles, reduction of elastic fibers, increased numbers of fibroblasts and/or mast cells, increased (small-vessel) vascularity, focal mucin deposition/myxoid degeneration, a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, attenuation of adnexal structures, and abnormalities of the epidermis (eg, surface ulceration).2-13

Prior to biopsy, the differential diagnosis in our patient included angiofibroma, pyogenic granuloma, and basal cell carcinoma given the exophytic, pink, papular appearance of the lesion; however, the histopathologic differential diagnosis included angiofibroma, angiomyolipoma, lymphangioma, nevus sebaceus, and spindle cell lipoma (SCL). In angiofibroma, a dermal proliferation of stellate fibroblasts, dilated blood vessels, and collagenous stroma are seen. Cutaneous angiomyolipoma demonstrates smooth muscle bundles in addition to thickened blood vessels and variable proportions of mature adipocytes. Lymphangioma is characterized by dilated lymph channels lined by flat endothelial cells. Nevus sebaceus shows superficial immature and abnormally formed pilosebaceous units, with epidermal papillomatosis.

Rare cases of SCL on the nose have been described.14 Similar to pedunculated lipofibroma, reported examples demonstrate mature univacuolar adipocytes with thick collagen fibers and bland uniform spindle cells. Unlike the lesion seen in our patient, nasal SCL may be clinically mobile and typically is localized to the subcutaneous tissue, although dermal tumors also occur.14 Variably reported histopathologic findings in nasal SCL include circumscription/encapsulation, spindle cells arranged in short fascicles with nuclear palisading, a myxoid/mucinous interstitial matrix, and/or multinucleated giant cells—all light microscopic features that were not identified in our case; however, variable proportions of adipocytic, fibrous, and myxoid components among reported examples of SCL on the nose14 can make distinction from pedunculated lipofibroma difficult, as both are benign lipomatous tumor variants.

Clinically, pedunculated lipofibroma may be confused with more common benign cutaneous lesions and must be distinguished from other fibrolipomatous lesions on the nose. Specifically, the differential diagnosis includes benign cutaneous papillomas such as acrochordon, angiofibroma, melanocytic nevi, neurofibroma, nevus sebaceus, lymphangioma, and eccrine poroma.7-13 These all can be readily excluded on histopathology. Pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose, as in our patient, must be distinguished from fibrolipoma15 and dendritic myxofibrolipoma.16 Fibrolipoma is a subcutaneous proliferation of mature adipose tissue and fibrous tissue and comprises 1.6% of all facial lipomas reported worldwide.15 Dendritic myxofibrolipoma is a recently described benign soft-tissue tumor characterized by an admixture of mature adipose tissue, spindle and stellate cells, and an abundant myxoid stroma with prominent collagenization.16