User login

Examining Moral Injury in Legal-Involved Veterans: Psychometric Properties of the Moral Injury Events Scale

Following exposure to potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs), some individuals may experience moral injury, which represents negative psychological, social, behavioral, and occasionally spiritual impacts.1 The consequences of PMIE exposure and moral injury are well documented. Individuals may begin to question the goodness and trustworthiness of oneself, others, or the world.1 Examples of other sequelae include guilt, demoralization, spiritual pain, loss of trust in the self or others, and difficulties with forgiveness.2-6 In addition, prior studies have found that moral injury is associated with an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, spiritual distress, and interpersonal difficulties.7-11

Moral injury was first conceptualized in relation to combat trauma. However in recent years it has been examined in other groups such as health care practitioners, educators, refugees, and law enforcement personnel.12-17 Furthermore, there has been a recent call for the study of moral injury in other understudied groups. One such group is legal-involved individuals, defined as those who are currently involved or previously involved in the criminal justice system (ie, arrests, incarceration, parole, and probation).1,18-22

Many veterans are also involved with the legal system. Specifically, veterans currently comprise about 8% of the incarcerated US population, with an estimated > 180,000 veterans in prisons or jails and even more on parole or probation.23,24 Legal-involved veterans may be at heightened risk for homelessness, suicide, unemployment, and high prevalence rates of psychiatric diagnoses.25-28

Limited research has explored exposure to PMIEs as part of the legal process and the resulting expression of moral injury. The circumstances leading to incarceration, interactions with the US legal system, the environment of prison itself, and the subsequent challenges faced by legal-involved individuals after release all provide ample opportunity for PMIEs to occur.18 For example, engaging in a criminal act may represent a PMIE, particularly in violent offenses that involve harm to another individual. Moreover, the process of being convicted and charged with an offense may serve as a powerful reminder of the PMIE and tie this event to the individual’s identity and future. Furthermore, the physical and social environment of prison itself (eg, being surrounded by other offenders, witnessing the perpetration of violence, participating in violence for survival) presents a myriad of opportunities for PMIEs to occur.18

The consequences of PMIEs in the context of legal involvement may also have bearing on a touchstone of moral injury: changes in one’s schema of the self and world.4 At a societal level, legal-involved individuals are, by definition, deemed “guilty” and held culpable for their offense, which may reinforce a negative change in one’s view of self and the world.29 In line with identity theory, external negative appraisals about legal-involved individuals (eg, they are a danger to society, they cannot be trusted to do the right thing) may influence their self-perception.30 Furthermore, the affective characteristics often found in the context of moral injury (eg, guilt, shame, anger, contempt) may be exacerbated by legal involvement.29 Personal feelings of guilt and shame may be reinforced by receiving a verdict and sentence, as well as the negative perceptions of individuals around them (eg, disapproval from prior sources of social support). Additionally, feelings of betrayal and distrust towards the legal system may arise.

In sum, legal-involved veterans incur increased risk of moral injury due to the potential for exposure to PMIEs across multiple time points (eg, prior to military service, during military service, during arrest/sentencing, during imprisonment, and postincarceration). The stigma that accompanies legal involvement may limit access to treatment or a willingness to seek treatment for distress related to moral injury.29 Additionally, repeated exposure to PMIEs and resulting moral injury may compound over time, potentially exacerbating psychosocial functioning and increasing the risk for psychosocial stressors (eg, homelessness, unemployment) and mental health disorders (eg, depression, substance misuse).31

Although numerous measures of moral injury have been developed, most require that respondents consider a specific context (eg, military experiences).32 Therefore, study of legal-related moral injury requires adaptation of existing instruments to the legal context. The original and most commonly used scale of moral injury is the Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES).33 The MIES scales was originally developed to measure moral injury in military-related contexts but has since been adapted as a measure of exposure to context-specific PMIEs.34

Unfortunately, there are no validated measures for assessing legal-related moral injury. Such a gap in understanding is problematic, as it may impact measurement of the prevalence of PMIEs in both clinical and research settings for this at-risk population. The goal of this study was to conduct a psychometric evaluation of an adapted version of the MIES for legal-involved persons (MIES-LIP).

METHODS

A total of 177 veterans from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) North Texas Health Care System were contacted for study enrollment between November 2020 and June 2021, yielding a final sample of 100 legal-involved veteran participants. Adults aged ≥ 18 years who were US military veterans and had ≥ 1 prior felony conviction resulting in incarceration were included. Participants were excluded if they had symptoms of psychosis that would preclude meaningful participation.

The study collected data on participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics using a semistructured survey instrument. Each participant completed an instructor-led questionnaire in a session that lasted about 1.5 hours. Participants who completed the visit in person received a $50 cash voucher for their time. Participants who were unable to meet with the study coordinator in person were able to complete the visit via telephone and received a $25 digital gift card. Of the total 100 participants, 79 participants completed the interview in person, and 21 completed by telephone. No significant differences were found in assessment measures between administration methods. Written informed consent was obtained during all in-person visits. For those completing via telephone, a waiver of written informed consent was obtained. This study was approved by the VA North Texas Health Care System’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES) is a 9-item self-report measure that assesses exposure to PMIEs.33 Respondents rate their agreement with each item on a 6-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater moral injury. The MIES has a 2-factor structure: Factor 1 has 6 items on perceived transgressions and Factor 2 has 3 items on perceived betrayals.33

Creation of Legal-Involved Moral Injury Measure. To create the MIES-LIP, items and instructions from the MIES were modified to address moral injury in the context of legal involvement.33 Adaptations were finalized following consultation and approval by the authors of the original measure. Specifically, the instructions were changed to: “Please respond to these items based specifically in the context of your involvement with the legal system.” The instructions clarified that legal involvement could include experiences related to committing an offense, legal proceedings and sentencing, incarceration, or transitioning out of the legal system. This differs from the original measure, which focused on military experiences, with instructions stating: “Please respond to these items based specifically in the context of your military service (ie, events and experiences during enlistment, deployment, combat, etc).”

Other measures. The study collected data on demographic characteristics including sex, race and ethnicity, marital status, military service, combat experience, and legal involvement. PTSD symptom severity, based on the criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), was assessed using the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5).35,36 The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure in which item scores are summed to create a total score. The PCL-5 has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including good internal consistency, test-retest reliability convergent validity, and discriminant validity.37,38

Depressive symptom severity was measured using the Personal Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).39 The PHQ-9 is a 9-item self-report measure where item scores summed to create a total score. The PHQ-9 has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including internal consistency and test-retest reliability.39

STATISTICAL METHODS

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation for continuous variables; frequencies and percentages for categorical variables) were used to describe the study sample. Factor analysis was conducted to evaluate the psychometric properties of the MIES-LIP. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to determine whether the MEIS-LIP had a similar factor structure to the MIES.40 Criteria for fit indices used for CFA include the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; values of > 0.95 suggest good fit), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; values of > 0.95 suggest a good fit), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; values of ≥ 0.06 suggest good fit), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; values of ≥ 0.08 suggest good fit). With insufficient fit, subsequent exploratory factor analysis was conducted using maximum likelihood estimation with an Oblimin rotation. The Kaiser rule and a scree plot were considered when defining the factor structure. Reliability was evaluated using the McDonald omega coefficient test. Convergent validity was assessed through the association between adapted measures and other clinical measures (ie, PCL-5, PHQ-9). In addition, associations between the PCL-5 and PHQ-9 were examined as they related to the MIES and MIES-LIP.

RESULTS

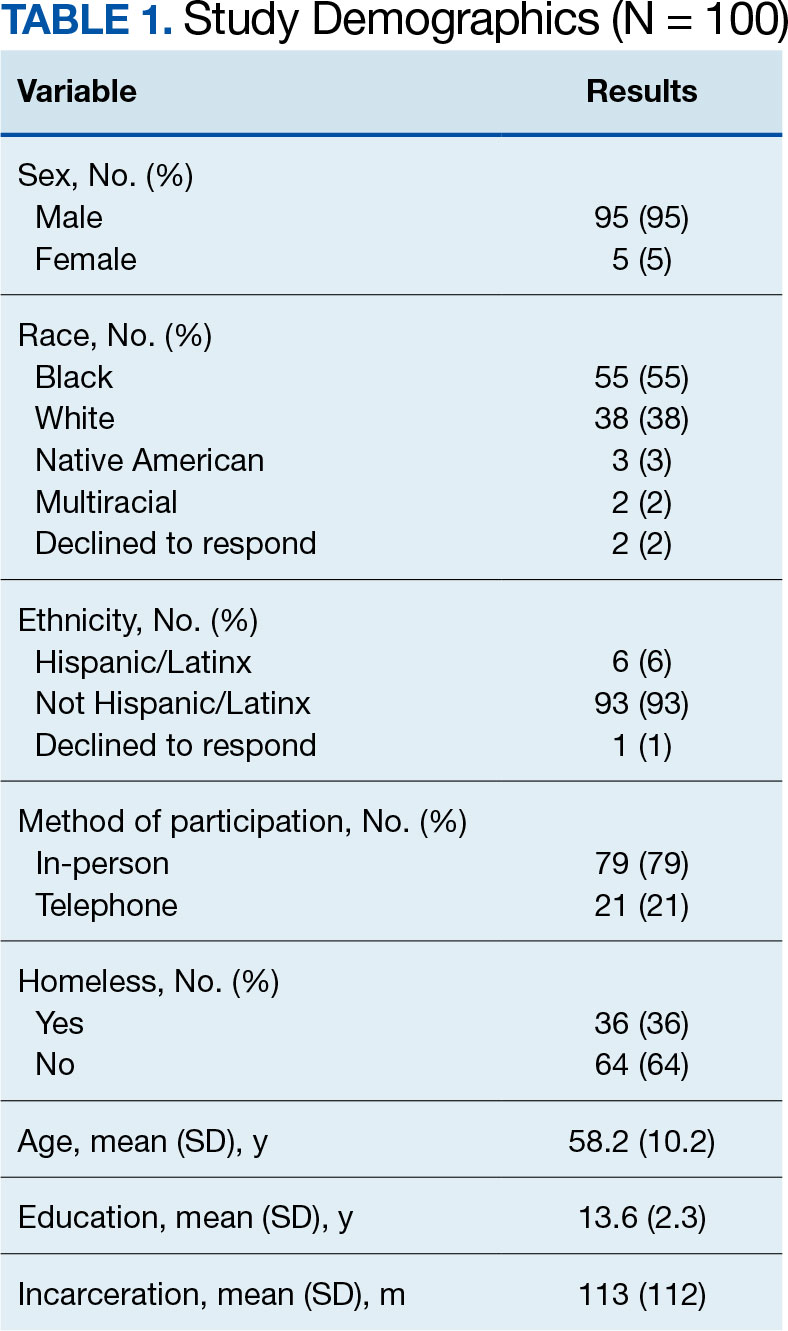

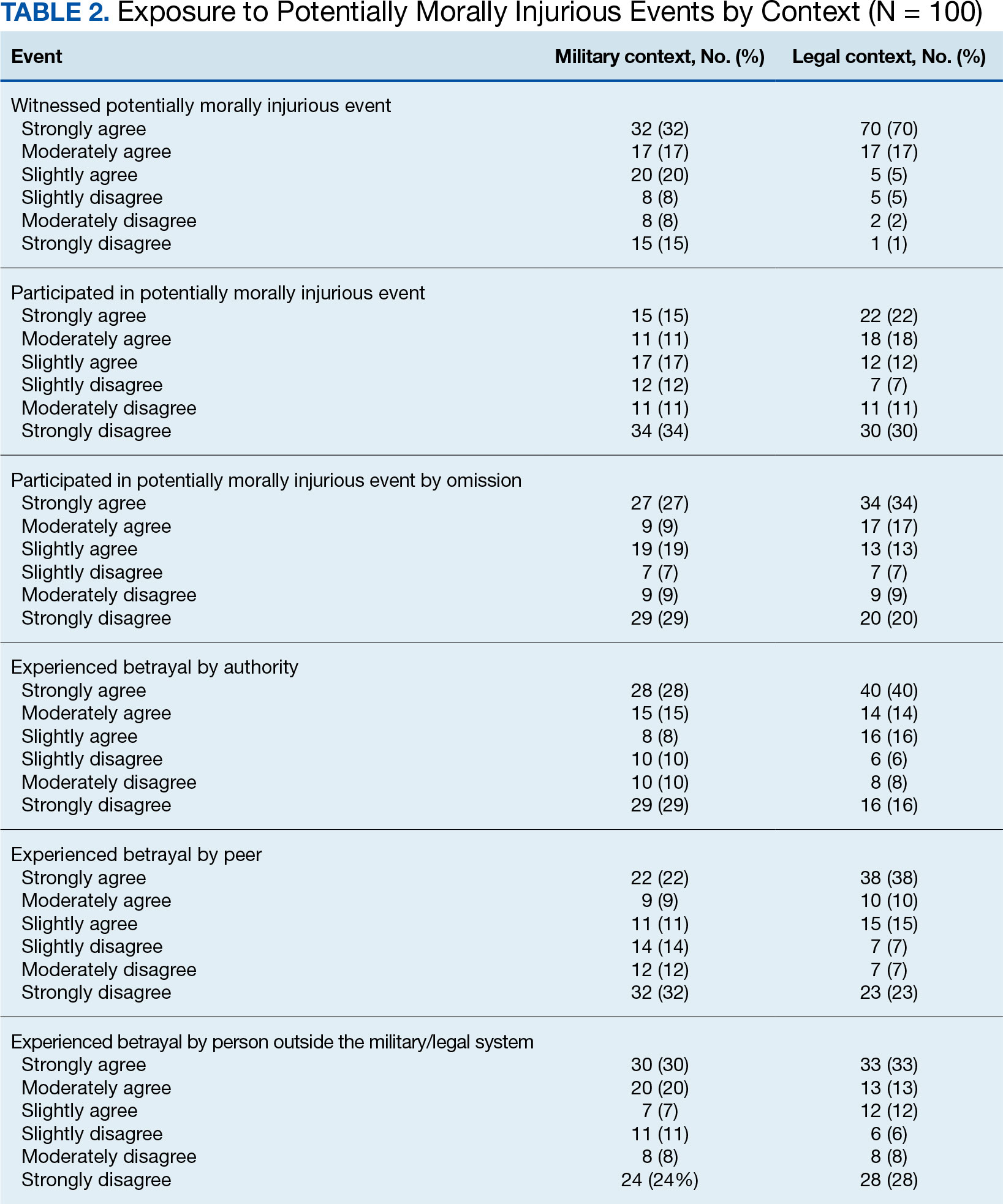

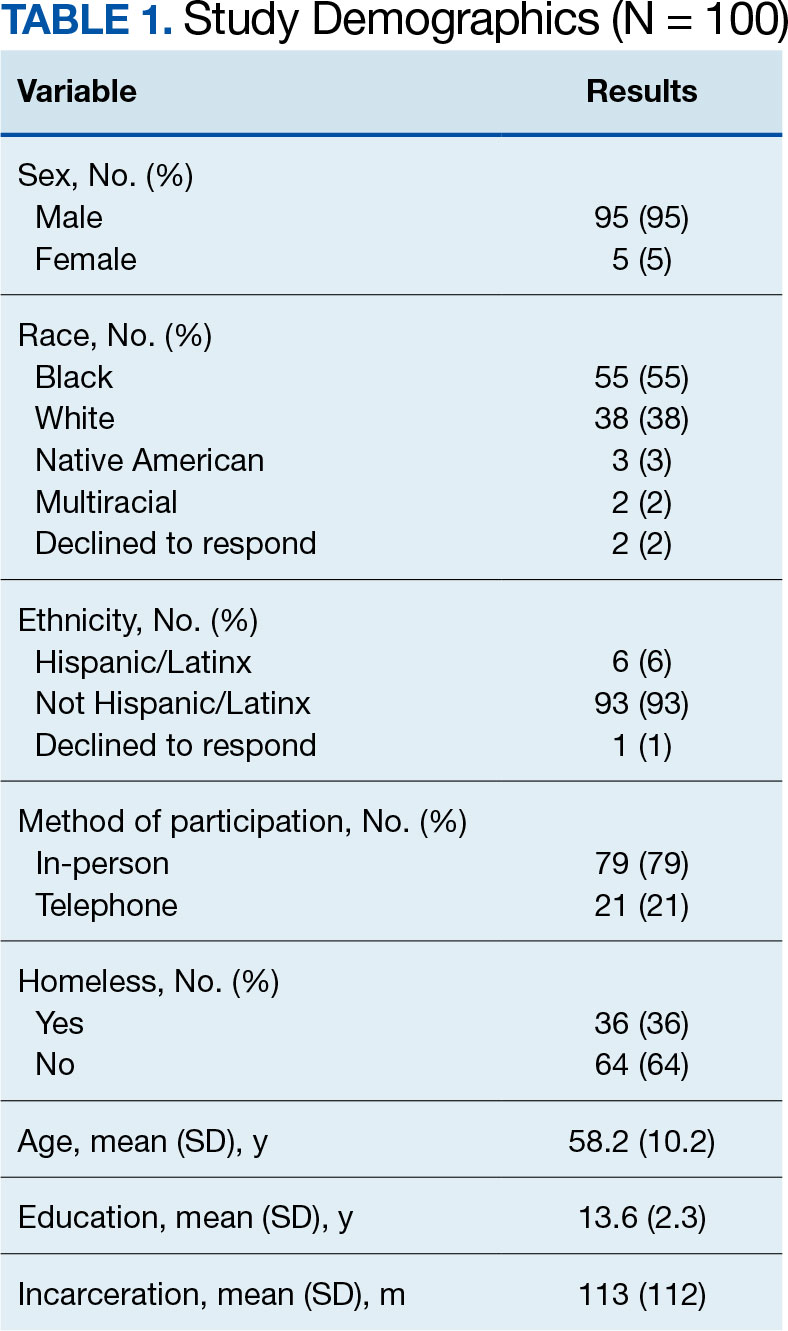

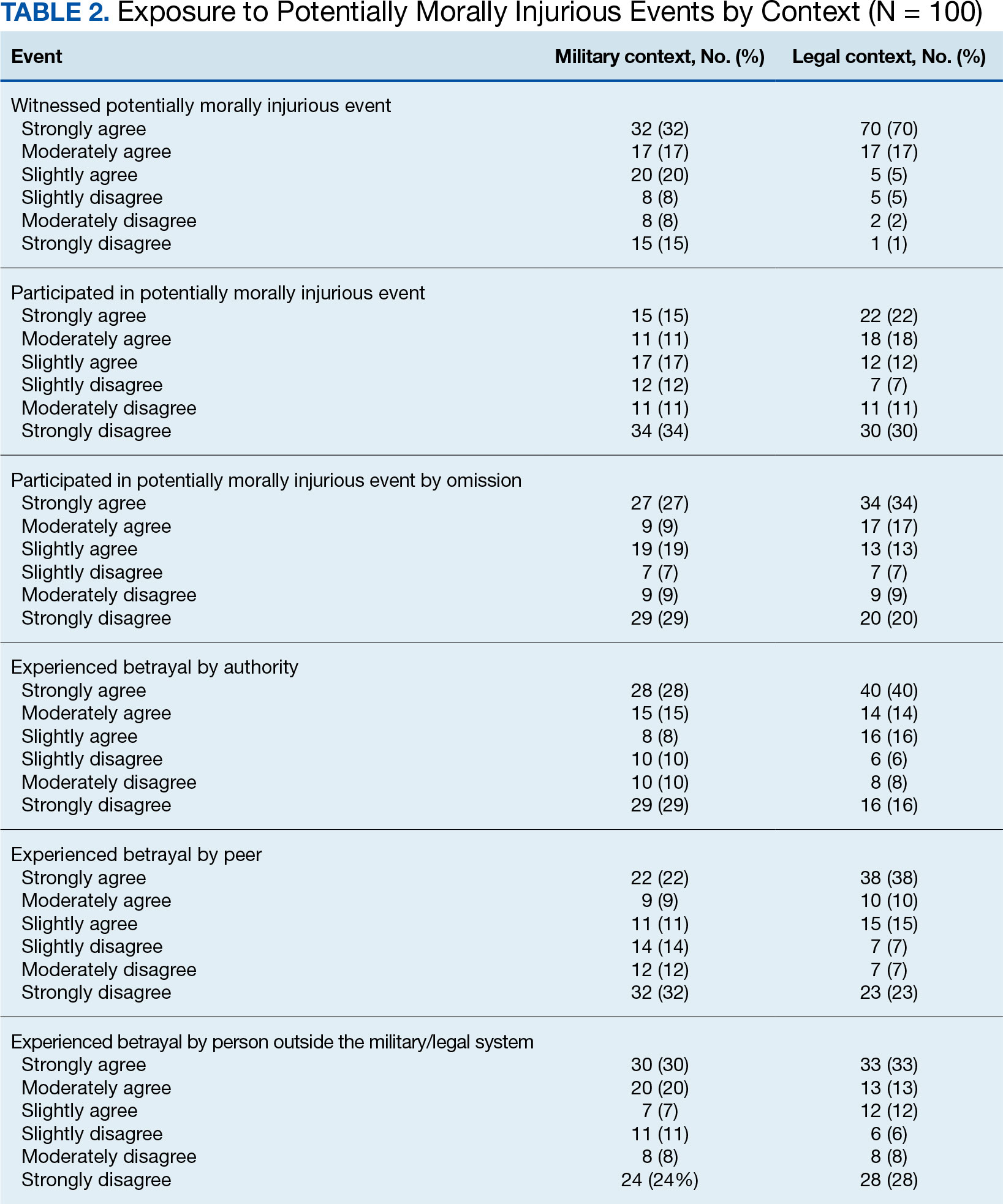

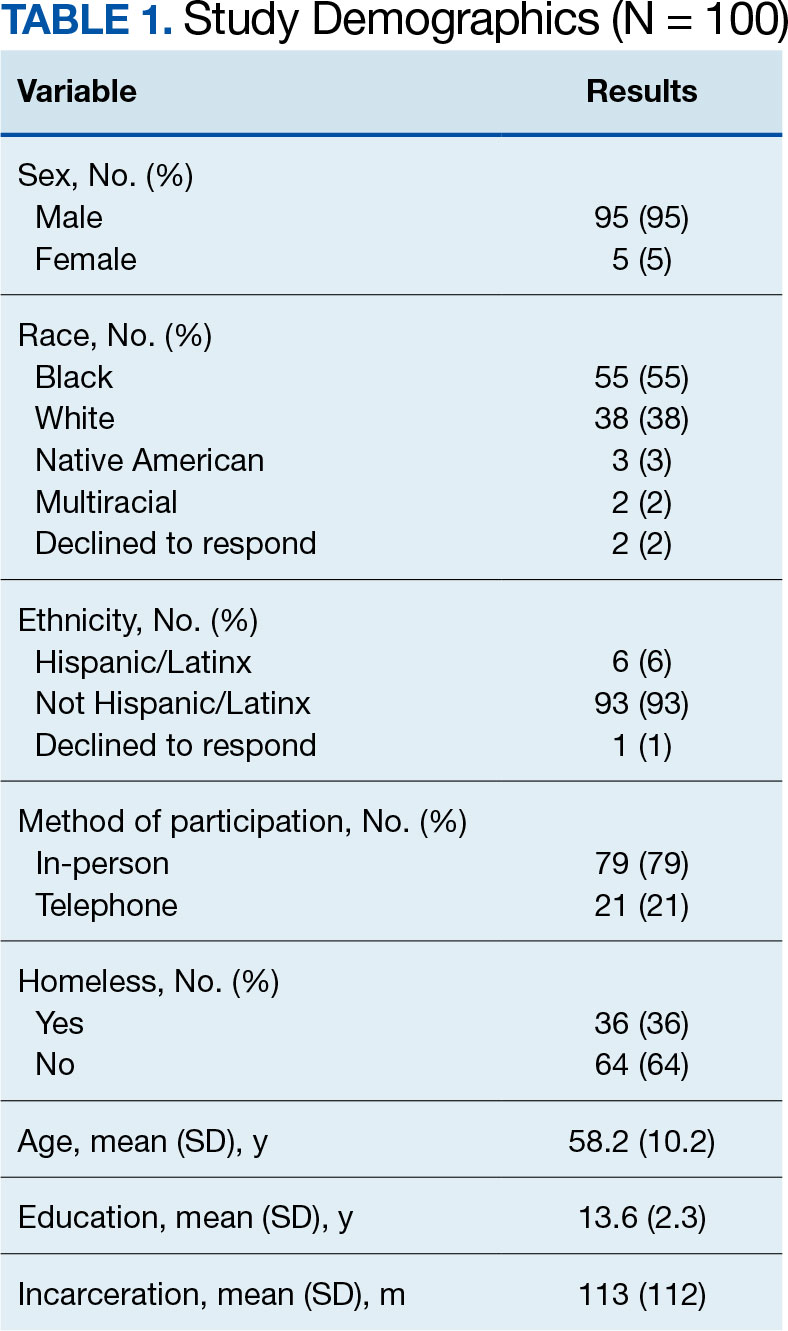

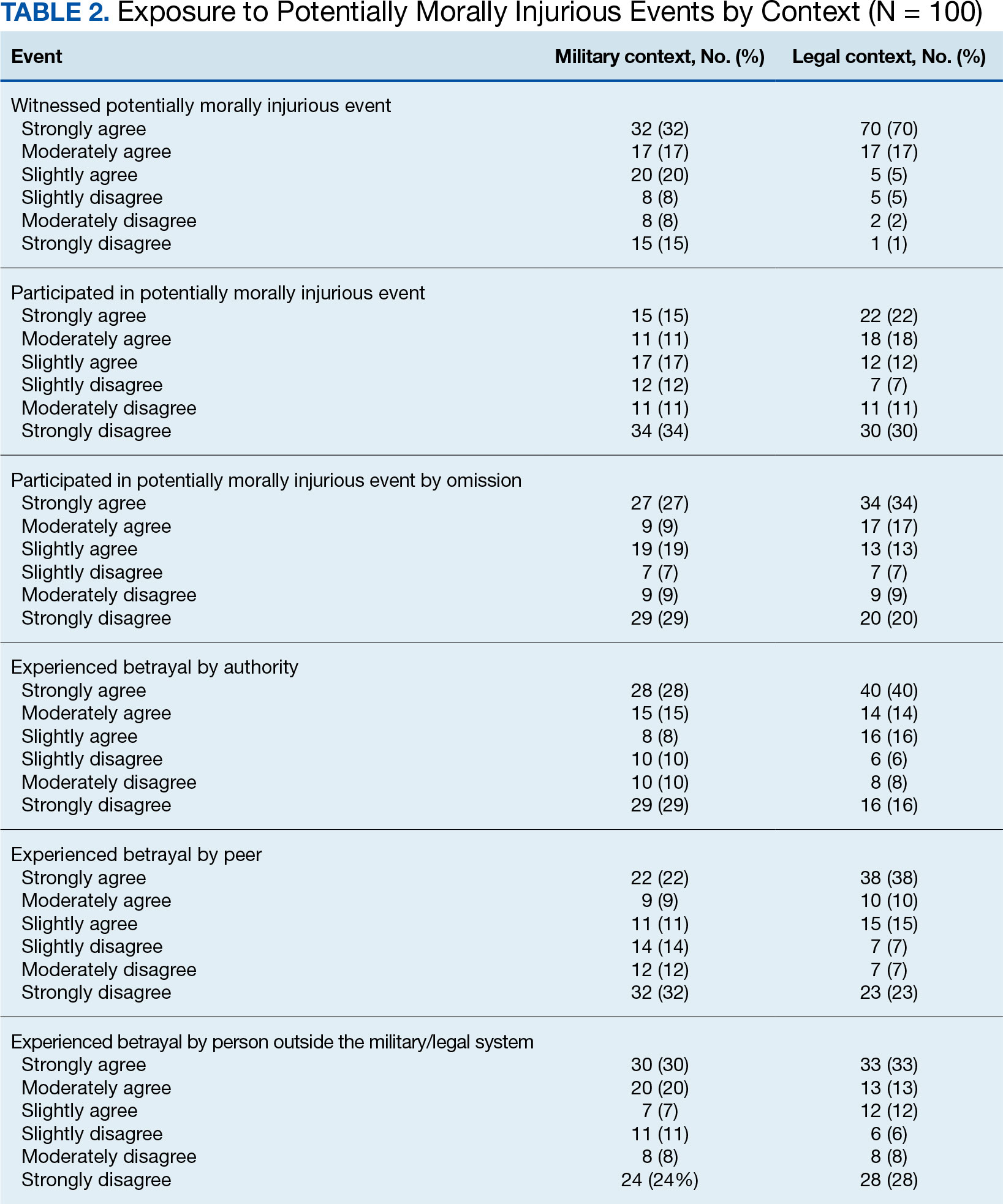

Table 1 describes demographic characteristics of the study sample. Rates of potentially morally injurious experiences and the expression of moral injury in the legal context are presented in Table 2. Witnessing PMIEs while in the legal system was nearly ubiquitous, with > 90% of the sample endorsing this experience. More than half of the sample also endorsed engaging in morally injurious behavior by commission or omission, as well as experiencing betrayal while involved with the legal system.

Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was utilized to test the factor structure of the adapted MIES-LIP in our sample compared to the published factor structures of the MIES.33 Results did not support the established factor structure. Analysis yielded unacceptable CFI (0.79), TLI (0.70), SRMR (0.14), and RMSEA (0.21). The unsatisfactory results of CFA warranted follow-up exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to examine the factor structure of the moral injury scales in this sample.

EFA of MIES-LIP

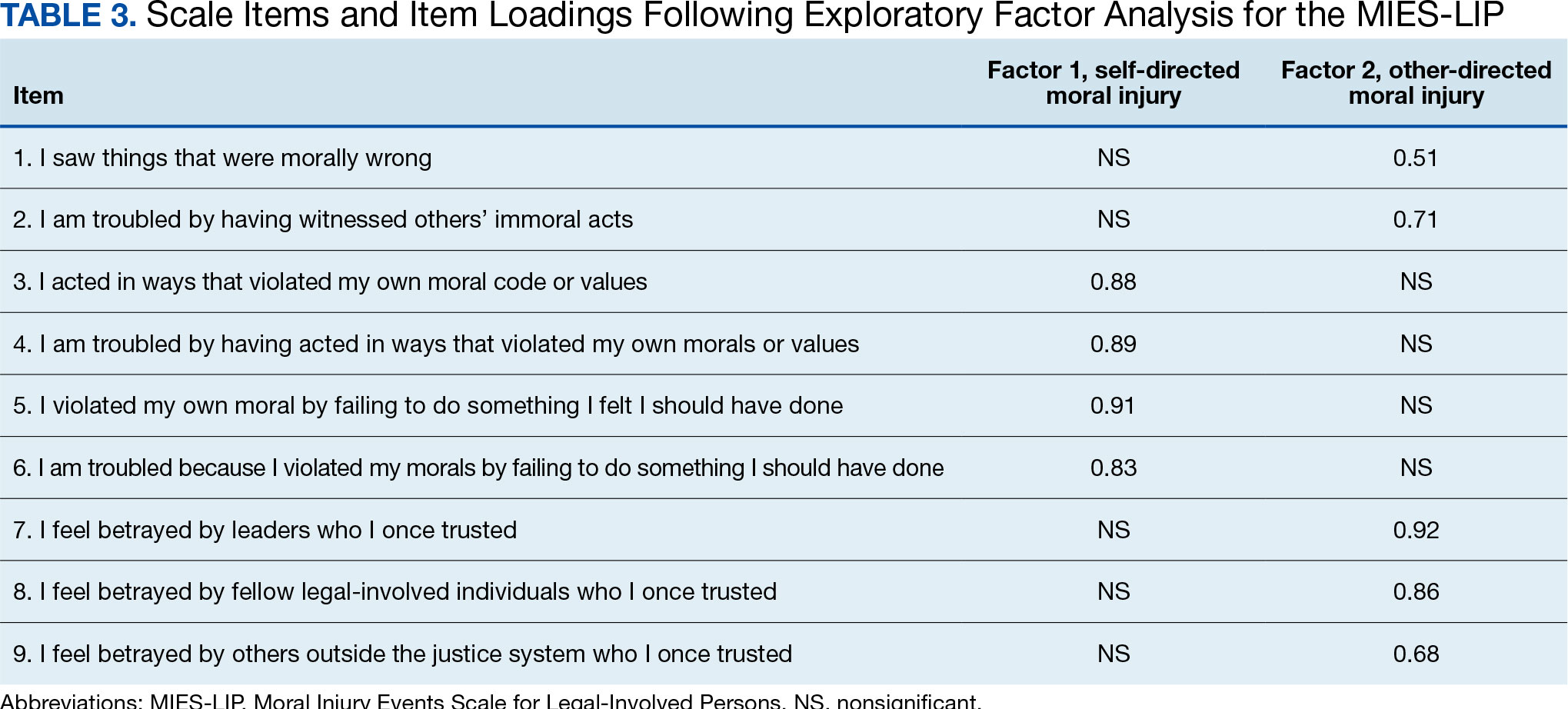

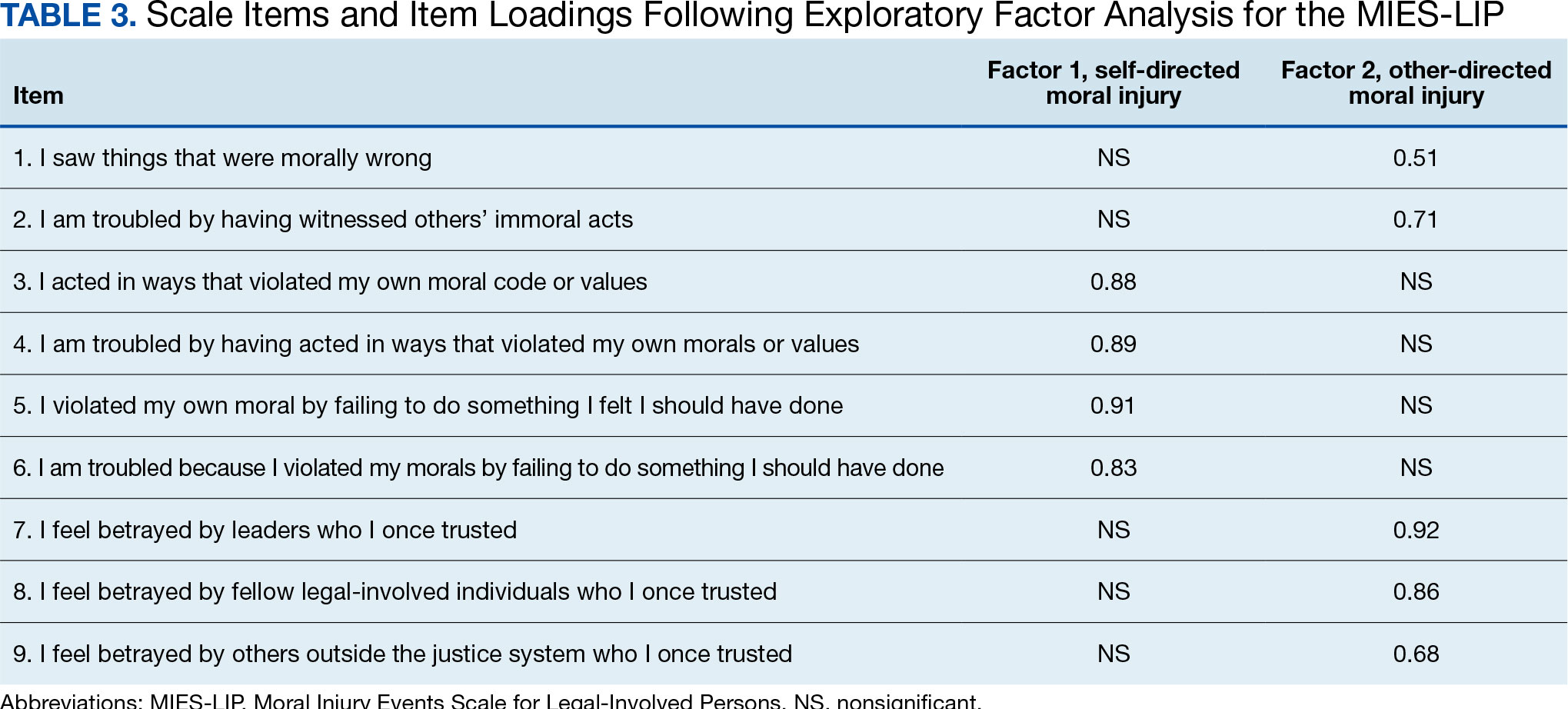

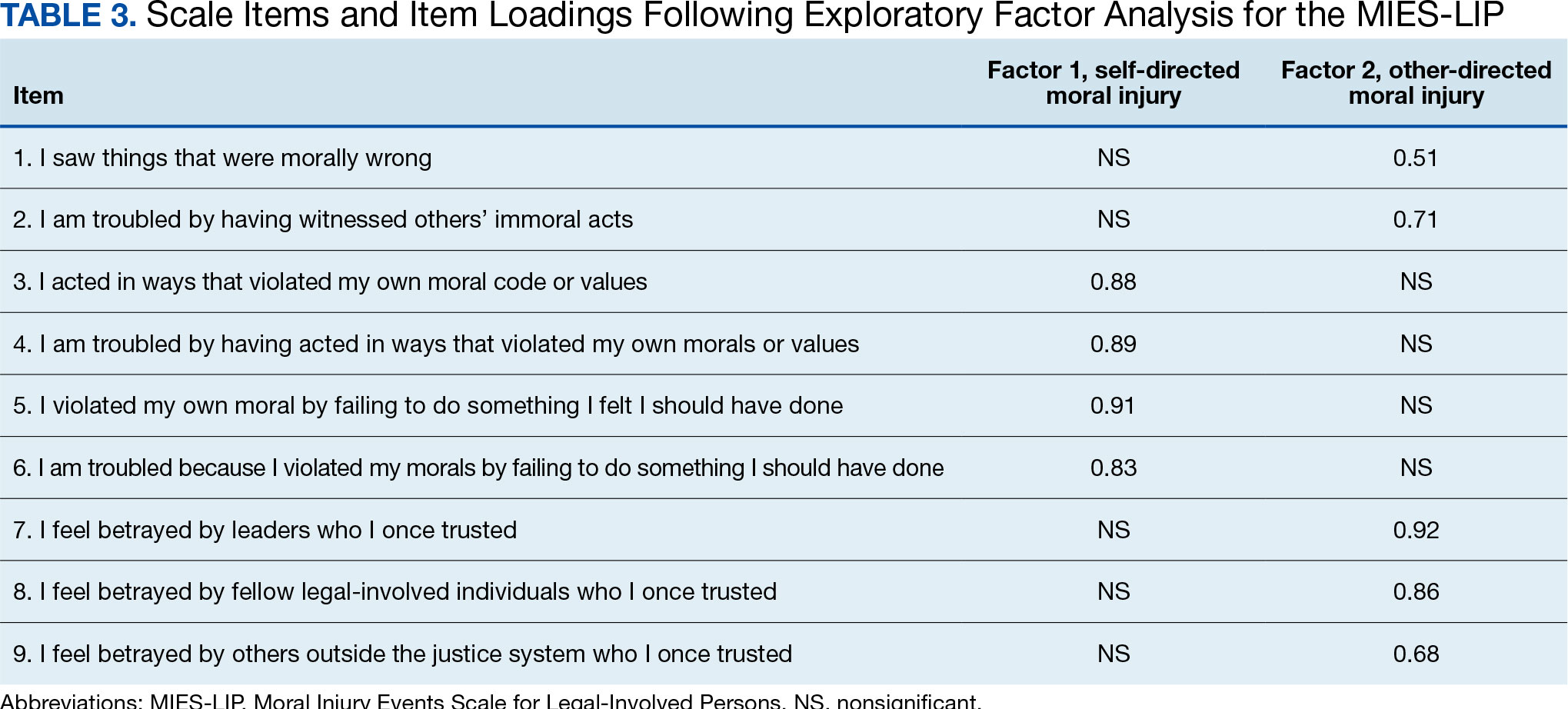

The factor structure of the MIES-LIP was examined using EFA. The factorability of the data was examined using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO value = 0.75) and Bartlett Test of Sphericity (X2 = 525.41; P < .001), both of which suggested that the data were appropriate for factor analysis. The number of factors to retain was selected based on the Kaiser criterion.41 After extraction, an Oblimin rotation was applied, given that we expected factors to be correlated. A 2-factor solution was found, explaining 65.76% of the common variance. All 9 items were retained as they had factor loadings > 0.30. Factor 1, comprised self-directed moral injury questions (3-6). Factor 2 comprised other directed moral injury questions (1, 2, 7-9) (Table 3). The factor correlation coefficient between Factor 1 and Factor 2 was 0.34, which supports utilizing an oblique rotation.

Reliability. We examined the reliability of the adapted MIES-LIP using measures of internal consistency, with both MIES-LIP factors demonstrating good reliability. The internal consistency of both factors of the MIES-LIP were found to be good (self-directed moral injury: Ω = 0.89; other-directed moral injury: Ω = 0.83).

Convergent Validity

Association between moral injury scales. A significant, moderate correlation was observed between all subscales of the MIES and MIES-LIP. Specifically, the self-directed moral injury factor of the MIES-LIP was associated with both the perceived transgressions (r = 0.41, P < .001) and the MIES perceived betrayals factors (r = 0.25, P < .05). Similarly, the other-directed moral injury factor of the MIES-LIP was associated with both the MIES perceived transgressions (r = 0.45, P < .001) and the MIES perceived betrayals factors (r = 0.45, P < .001).

Association with PTSD symptoms. All subscales of both the MIES and MIES-LIP were associated with PTSD symptom severity. The MIES perceived transgressions factor (r = 0.43, P < .001) and the perceived betrayals factor of the MIES (r = 0.39, P < .001) were moderately associated with the PCL-5. Mirroring this, the “self-directed moral injury” factor of the MIESLIP (r = 0.44, P < .001) and the “other-directed moral injury” factor of the MIES-LIP (r = 0.42, P < .001) were also positively associated with PCL-5.

Association with depression symptoms. All subscales of the MIES and MIES-LIP were also associated with depressive symptoms. The MIES perceived transgressions factor (r = 0.27, P < .01) and the MIES perceived betrayals factor (r = 0.23, P < .05) had a small association with the PHQ-9. In addition, the self-directed moral injury factor of the MIES-LIP (r = 0.40, P < .001) and the other-directed moral injury factor of the MIES-LIP (r = 0.31, P < .01) had small to moderate associations with the PCL-5.

DISCUSSION

Potentially morally injurious events appear to be a salient factor affecting legal-involved veterans. Among our sample, the vast majority of legal-involved veterans endorsed experiencing both legal- and military-related PMIEs. Witnessing or participating in a legal-related PMIE appears to be widespread among those who have experienced incarceration. The MIES-LIP yielded a 2-factor structure: self-directed moral injury and other-directed moral injury, in the evaluated population. The MIES-LIP showed similar psychometric performance to the MIES in our sample. Specifically, the MIES-LIP had good reliability and adequate convergent validity. While CFA did not confirm the anticipated factor structure of the MIES-LIP within our sample, EFA showed similarities in factor structure between the original and adapted measures. While further research and validation are needed, preliminary results show promise of the MIES-LIP in assessing legal-related moral injury.

Originally, the MIES was found to have a 2-factor structure, defined by perceived transgressions and perceived betrayals.33 However, additional research has identified a 3-factor structure, where the betrayal factor is maintained, and the transgressions factor is divided into transgressions by others and by self.8 The factor structure of the MIES-LIP was more closely related to the factor structure, with transgressions by others and betrayal mapped onto the same factor (ie, other-directed moral injury).8 While further research is needed, it is possible that the nature of morally injurious events experienced in legal contexts are experienced more in terms of self vs other, compared to morally injurious events experienced by veterans or active-duty service members.

Accurately identifying the types of moral injury experienced in a legal context may be important for determining the differences in drivers of legal-related moral injury compared to military-related moral injury. For example, self-directed moral injury in legal contexts may include a variety of actions the individual initiated that led to conviction and incarceration (eg, a criminal offense), as well as behaviors performed or witnessed while incarcerated (eg, engaging in violence). Inconsistent with military populations where other-directed moral injury clusters with self-directed moral injury, other-directed moral injury clustered with betrayal in legal contexts in our sample. This discrepancy may result from differences in identification with the military vs legal system. When veterans witness fellow service members engaging in PMIEs (eg, physical violence towards civilians in a military setting), this may be similar to self-directed moral injury due to the veteran’s identification with the same military system as the perpetrator.42 When legal-involved veterans witness other incarcerated individuals engaging in PMIEs (eg, physical violence toward other inmates), this may be experienced as similar to betrayal due to lack of personal identification with the criminal-legal system. Additional research is needed to better understand how self- and other-related moral injury are associated with betrayal in legal contexts.

Another potential driver of legal-related moral injury may be culpability. In order for moral injury to occur, an individual must perceive that something has taken place that deeply violated their sense of right and wrong.1 In terms of criminal offenses or even engaging in violent behavior while incarcerated, the potential for moral injury may differ based on whether an individual views themselves as culpable for the act(s).29 This may further distinguish between self-directed and other-directed moral injury in legal contexts. In situations where the individual views themselves as culpable, self-directed moral injury may be higher. In situations where the individual does not view themselves as culpable, other-directed moral injury may be higher based on the perception that the legal system is unfairly punishing them. Further research is needed to clarify how an individual’s view of their culpability relates to moral injury, as well as to elucidate which aspects of military service and legal involvement are most closely associated with moral injury among legal-involved veterans.

While this study treated legal-related and military-related moral injury as distinct, it is possible moral injury may have a cumulative effect over time with individuals experiencing morally injurious events across different contexts (eg, military, legal involvement). This, in turn, may compound risk for moral injury. These cumulative experiences may result in increased negative outcomes such as exacerbated psychiatric symptoms, substance misuse, and elevated suicide risk. Future studies should examine differences between groups who have experienced moral injury in differing contexts, as well as those with multiple sources of moral injury.

Limitations

The sample for this study included only veterans. The number of veterans incarcerated is large and the focus on veterans also allowed for a more robust comparison of moral injury related to the legal system and the more traditional military-related moral injury. However, the generalizability of the findings to nonveterans cannot be assured. The study used a relatively small sample (N = 100), which was overwhelmingly male. Although the PCL-5 was utilized to examine traumatic stress symptoms, this measure was not anchored to a specific criterion A trauma nor was it anchored specifically to a morally injurious experience. For all participants, their most recent military service preceded their most recent legal involvement which could affect the associations between variables. Furthermore, while all participants endorsed prior legal involvement, many participants reported no combat exposure.

CONCLUSIONS

This study resulted in several key findings. First, legal-involved veterans endorsed high rates of experiencing legal-related morally injurious experiences. Second, our adapted measure displayed adequate psychometric strength and suggests that legal-related moral injury is a salient and distinct phenomenon affecting legal-involved veterans. These items may not capture all the nuances of legal-related moral injury. Qualitative interviews with legal-involved persons may help identify relevant areas of legal-related moral injury not reflected in the current instrument. The MIES-LIP represents a practical measure that may help clinicians identify and address legal-related moral injury when working with legal-involved veterans. Given the high prevalence of PMIEs among legal-involved veterans, further examination of whether current interventions for moral injury and novel treatments being developed are effective for this population is needed.

- Griffin BJ, Purcell N, Burkman K, et al. Moral injury: an integrative review. J Trauma Stress. 2019;32(3):350-362. doi:10.1002/jts.22362

- Currier JM, Holland JM, Malott J. Moral injury, meaning making, and mental health in returning veterans. J Clin Psychol. 2015;71(3):229-240. doi:10.1002/jclp.22134

- Jinkerson JD. Defining and assessing moral injury: a syndrome perspective. Traumatology. 2016;22(2):122-130. doi:10.1037/trm0000069

- Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695-706. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

- Maguen S, Litz B. Moral injury in veterans of war. PTSD Res Q. 2012;23(1):1-6. www.vva1071.org/uploads/3/4/4/6/34460116/moral_injury_in_veterans_of_war.pdf

- Drescher KD, Foy DW, Kelly C, Leshner A, Schutz K, Litz B. An exploration of the viability and usefulness of the construct of moral injury in war veterans. Traumatology. 2011;17(1):8-13. doi:10.1177/1534765610395615

- Wisco BE, Marx BP, May CL, et al. Moral injury in U.S. combat veterans: results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. Depress Anxiety. 2017; 34(4):340-347. doi:10.1002/da.22614

- Bryan CJ, Bryan AO, Anestis MD, et al. Measuring moral injury: psychometric properties of the moral injury events scale in two military samples. Assessment. 2016;23(5):557- 570. doi:10.1177/1073191115590855

- Currier JM, Smith PN, Kuhlman S. Assessing the unique role of religious coping in suicidal behavior among U.S. Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2017;9(1):118-123. doi:10.1037/rel0000055

- Kopacz MS, Connery AL, Bishop TM, et al. Moral injury: a new challenge for complementary and alternative medicine. Complement Ther Med. 2016;24:29-33. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2015.11.003

- Vargas AF, Hanson T, Kraus D, Drescher K, Foy D. Moral injury themes in combat veterans’ narrative responses from the national vietnam veterans’ readjustment study. Traumatology. 2013;19(3):243-250. doi:10.1177/1534765613476099

- Borges LM, Barnes SM, Farnsworth JK, Bahraini NH, Brenner LA. A commentary on moral injury among health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(S1):S138-S140. doi:10.1037/tra0000698

- Borges LM, Holliday R, Barnes SM, et al. A longitudinal analysis of the role of potentially morally injurious events on COVID-19-related psychosocial functioning among healthcare providers. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0260033. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260033

- Currier JM, Holland JM, Rojas-Flores L, Herrera S, Foy D. Morally injurious experiences and meaning in Salvadorian teachers exposed to violence. Psychol Trauma. 2015;7(1):24-33. doi:10.1037/a0034092

- Nickerson A, Schnyder U, Bryant RA, Schick M, Mueller J, Morina N. Moral injury in traumatized refugees. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(2):122-123. doi:10.1159/000369353

- Papazoglou K, Chopko B. The role of moral suffering (moral distress and moral injury) in police compassion fatigue and PTSD: An unexplored topic. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1999. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01999

- Papazoglou K, Blumberg DM, Chiongbian VB, et al. The role of moral injury in PTSD among law enforcement officers: a brief report. Front Psychol. 2020;11:310. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00310

- Martin WB, Holliday R, LePage JP. Trauma and diversity: moral injury among justice involved veterans: an understudied clinical concern. Stresspoints. 2020;33(5).

- Currier JM, Drescher KD, Nieuwsma J. Future directions for addressing moral injury in clinical practice: concluding comments. In: Currier JM, Drescher KD, Nieuwsma J, eds. Addressing Moral Injury in Clinical Practice. American Psychological Association; 2021:261-271. doi:10.1037/0000204-015

- Alexander AR, Mendez L, Kerig PK. Moral injury as a transdiagnostic risk factor for mental health problems in detained youth. Crim Justice Behav. 2023;51(2):194-212. doi:10.1177/00938548231208203

- DeCaro JB, Straka K, Malek N, Zalta AK. Sentenced to shame: moral injury exposure in former lifers. Psychol Trauma. 2024; 15(5):722-730. doi:10.1037/tra0001400

- Orak U, Kelton K, Vaughn MG, Tsai J, Pietrzak RH. Homelessness and contact with the criminal legal system among U.S. combat veterans: an exploration of potential mediating factors. Crim Justice Behav. 2022;50(3):392-409. doi:10.1177/00938548221140352

- Bronson J, Carson EA, Noonan M. Veterans in Prison and Jail, 2011-12. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Published December 2015. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/vpj1112.pdf

- Maruschak LM, Bronson J, Alper M. Veterans in Prison: Survey of Prison Inmates, 2016. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; March 2021. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://bjs.ojp.gov/redirect-legacy/content/pub/pdf/vpspi16st.pdf

- Blodgett JC, Avoundjian T, Finlay AK, et al. Prevalence of mental health disorders among justiceinvolved veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:163-176. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxu003

- Finlay AK, Owens MD, Taylor E, et al. A scoping review of military veterans involved in the criminal justice system and their health and healthcare. Health Justice. 2019;7(1):6. doi:10.1186/s40352-019-0086-9

- Holliday R, Martin WB, Monteith LL, Clark SC, LePage JP. Suicide among justice-involved veterans: a brief overview of extant research, theoretical conceptualization, and recommendations for future research. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2020;30(1):41-49. doi:10.1080/10530789.2019.1711306

- Wortzel HS, Binswanger IA, Anderson CA, Adler LE. Suicide among incarcerated veterans. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2009;37(1):82-91.

- Desai A, Holliday R, Borges LM, et al. Facilitating successful reentry among justice-involved veterans: the role of veteran and offender identity. J Psychiatr Pract. 2021;27(1):52-60. doi:10.1097/PRA.0000000000000520

- Asencio EK, Burke PJ. Does incarceration change the criminal identity? A synthesis of labeling and identity theory perspectives on identity change. Sociol Perspect. 2011;54(2):163-182. doi:10.1525/sop.2011.54.2.163

- Borges LM, Desai A, Barnes SM, Johnson JPS. The role of social determinants of health in moral injury: implications and future directions. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2022;9(3):202-214. doi:10.1007/s40501-022-00272-4

- Houle SA, Ein N, Gervasio J, et al. Measuring moral distress and moral injury: a systematic review and content analysis of existing scales. Clin Psychol Rev. 2024;108:102377. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102377

- Nash WP, Marino Carper TL, Mills MA, Au T, Goldsmith A, Litz BT. Psychometric evaluation of the moral injury events scale. Mil Med. 2013;178(6):646-652. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00017

- Zerach G, Ben-Yehuda A, Levi-Belz Y. Prospective associations between psychological factors, potentially morally injurious events, and psychiatric symptoms among Israeli combatants: the roles of ethical leadership and ethical preparation. Psychol Trauma. 2023;15(8):1367-1377. doi:10.1037/tra0001466

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmeri PA, Marx BP. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). National Center for PTSD. Accessed March 4, 2025. www.ptsd.va.gov

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, et al. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol Assess. 2016;28(11):1379-1391. doi:10.1037/pas0000254

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The osttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL- 5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):489-498. doi:10.1002/jts.22059

- Kroenke K, Spi tzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Brown TA. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; 2015.

- Kaiser HF. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20(1):141-151. doi:10.1177/001316446002000116

- Schorr Y, Stein NR, Maguen S, Barnes JB, Bosch J, Litz BT. Sources of moral injury among war veterans: a qualitative evaluation. J Clin Psychol. 2018;74(12):2203-2218. doi:10.1002/jclp.22660

Following exposure to potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs), some individuals may experience moral injury, which represents negative psychological, social, behavioral, and occasionally spiritual impacts.1 The consequences of PMIE exposure and moral injury are well documented. Individuals may begin to question the goodness and trustworthiness of oneself, others, or the world.1 Examples of other sequelae include guilt, demoralization, spiritual pain, loss of trust in the self or others, and difficulties with forgiveness.2-6 In addition, prior studies have found that moral injury is associated with an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, spiritual distress, and interpersonal difficulties.7-11

Moral injury was first conceptualized in relation to combat trauma. However in recent years it has been examined in other groups such as health care practitioners, educators, refugees, and law enforcement personnel.12-17 Furthermore, there has been a recent call for the study of moral injury in other understudied groups. One such group is legal-involved individuals, defined as those who are currently involved or previously involved in the criminal justice system (ie, arrests, incarceration, parole, and probation).1,18-22

Many veterans are also involved with the legal system. Specifically, veterans currently comprise about 8% of the incarcerated US population, with an estimated > 180,000 veterans in prisons or jails and even more on parole or probation.23,24 Legal-involved veterans may be at heightened risk for homelessness, suicide, unemployment, and high prevalence rates of psychiatric diagnoses.25-28

Limited research has explored exposure to PMIEs as part of the legal process and the resulting expression of moral injury. The circumstances leading to incarceration, interactions with the US legal system, the environment of prison itself, and the subsequent challenges faced by legal-involved individuals after release all provide ample opportunity for PMIEs to occur.18 For example, engaging in a criminal act may represent a PMIE, particularly in violent offenses that involve harm to another individual. Moreover, the process of being convicted and charged with an offense may serve as a powerful reminder of the PMIE and tie this event to the individual’s identity and future. Furthermore, the physical and social environment of prison itself (eg, being surrounded by other offenders, witnessing the perpetration of violence, participating in violence for survival) presents a myriad of opportunities for PMIEs to occur.18

The consequences of PMIEs in the context of legal involvement may also have bearing on a touchstone of moral injury: changes in one’s schema of the self and world.4 At a societal level, legal-involved individuals are, by definition, deemed “guilty” and held culpable for their offense, which may reinforce a negative change in one’s view of self and the world.29 In line with identity theory, external negative appraisals about legal-involved individuals (eg, they are a danger to society, they cannot be trusted to do the right thing) may influence their self-perception.30 Furthermore, the affective characteristics often found in the context of moral injury (eg, guilt, shame, anger, contempt) may be exacerbated by legal involvement.29 Personal feelings of guilt and shame may be reinforced by receiving a verdict and sentence, as well as the negative perceptions of individuals around them (eg, disapproval from prior sources of social support). Additionally, feelings of betrayal and distrust towards the legal system may arise.

In sum, legal-involved veterans incur increased risk of moral injury due to the potential for exposure to PMIEs across multiple time points (eg, prior to military service, during military service, during arrest/sentencing, during imprisonment, and postincarceration). The stigma that accompanies legal involvement may limit access to treatment or a willingness to seek treatment for distress related to moral injury.29 Additionally, repeated exposure to PMIEs and resulting moral injury may compound over time, potentially exacerbating psychosocial functioning and increasing the risk for psychosocial stressors (eg, homelessness, unemployment) and mental health disorders (eg, depression, substance misuse).31

Although numerous measures of moral injury have been developed, most require that respondents consider a specific context (eg, military experiences).32 Therefore, study of legal-related moral injury requires adaptation of existing instruments to the legal context. The original and most commonly used scale of moral injury is the Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES).33 The MIES scales was originally developed to measure moral injury in military-related contexts but has since been adapted as a measure of exposure to context-specific PMIEs.34

Unfortunately, there are no validated measures for assessing legal-related moral injury. Such a gap in understanding is problematic, as it may impact measurement of the prevalence of PMIEs in both clinical and research settings for this at-risk population. The goal of this study was to conduct a psychometric evaluation of an adapted version of the MIES for legal-involved persons (MIES-LIP).

METHODS

A total of 177 veterans from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) North Texas Health Care System were contacted for study enrollment between November 2020 and June 2021, yielding a final sample of 100 legal-involved veteran participants. Adults aged ≥ 18 years who were US military veterans and had ≥ 1 prior felony conviction resulting in incarceration were included. Participants were excluded if they had symptoms of psychosis that would preclude meaningful participation.

The study collected data on participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics using a semistructured survey instrument. Each participant completed an instructor-led questionnaire in a session that lasted about 1.5 hours. Participants who completed the visit in person received a $50 cash voucher for their time. Participants who were unable to meet with the study coordinator in person were able to complete the visit via telephone and received a $25 digital gift card. Of the total 100 participants, 79 participants completed the interview in person, and 21 completed by telephone. No significant differences were found in assessment measures between administration methods. Written informed consent was obtained during all in-person visits. For those completing via telephone, a waiver of written informed consent was obtained. This study was approved by the VA North Texas Health Care System’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES) is a 9-item self-report measure that assesses exposure to PMIEs.33 Respondents rate their agreement with each item on a 6-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater moral injury. The MIES has a 2-factor structure: Factor 1 has 6 items on perceived transgressions and Factor 2 has 3 items on perceived betrayals.33

Creation of Legal-Involved Moral Injury Measure. To create the MIES-LIP, items and instructions from the MIES were modified to address moral injury in the context of legal involvement.33 Adaptations were finalized following consultation and approval by the authors of the original measure. Specifically, the instructions were changed to: “Please respond to these items based specifically in the context of your involvement with the legal system.” The instructions clarified that legal involvement could include experiences related to committing an offense, legal proceedings and sentencing, incarceration, or transitioning out of the legal system. This differs from the original measure, which focused on military experiences, with instructions stating: “Please respond to these items based specifically in the context of your military service (ie, events and experiences during enlistment, deployment, combat, etc).”

Other measures. The study collected data on demographic characteristics including sex, race and ethnicity, marital status, military service, combat experience, and legal involvement. PTSD symptom severity, based on the criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), was assessed using the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5).35,36 The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure in which item scores are summed to create a total score. The PCL-5 has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including good internal consistency, test-retest reliability convergent validity, and discriminant validity.37,38

Depressive symptom severity was measured using the Personal Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).39 The PHQ-9 is a 9-item self-report measure where item scores summed to create a total score. The PHQ-9 has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including internal consistency and test-retest reliability.39

STATISTICAL METHODS

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation for continuous variables; frequencies and percentages for categorical variables) were used to describe the study sample. Factor analysis was conducted to evaluate the psychometric properties of the MIES-LIP. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to determine whether the MEIS-LIP had a similar factor structure to the MIES.40 Criteria for fit indices used for CFA include the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; values of > 0.95 suggest good fit), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; values of > 0.95 suggest a good fit), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; values of ≥ 0.06 suggest good fit), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; values of ≥ 0.08 suggest good fit). With insufficient fit, subsequent exploratory factor analysis was conducted using maximum likelihood estimation with an Oblimin rotation. The Kaiser rule and a scree plot were considered when defining the factor structure. Reliability was evaluated using the McDonald omega coefficient test. Convergent validity was assessed through the association between adapted measures and other clinical measures (ie, PCL-5, PHQ-9). In addition, associations between the PCL-5 and PHQ-9 were examined as they related to the MIES and MIES-LIP.

RESULTS

Table 1 describes demographic characteristics of the study sample. Rates of potentially morally injurious experiences and the expression of moral injury in the legal context are presented in Table 2. Witnessing PMIEs while in the legal system was nearly ubiquitous, with > 90% of the sample endorsing this experience. More than half of the sample also endorsed engaging in morally injurious behavior by commission or omission, as well as experiencing betrayal while involved with the legal system.

Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was utilized to test the factor structure of the adapted MIES-LIP in our sample compared to the published factor structures of the MIES.33 Results did not support the established factor structure. Analysis yielded unacceptable CFI (0.79), TLI (0.70), SRMR (0.14), and RMSEA (0.21). The unsatisfactory results of CFA warranted follow-up exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to examine the factor structure of the moral injury scales in this sample.

EFA of MIES-LIP

The factor structure of the MIES-LIP was examined using EFA. The factorability of the data was examined using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO value = 0.75) and Bartlett Test of Sphericity (X2 = 525.41; P < .001), both of which suggested that the data were appropriate for factor analysis. The number of factors to retain was selected based on the Kaiser criterion.41 After extraction, an Oblimin rotation was applied, given that we expected factors to be correlated. A 2-factor solution was found, explaining 65.76% of the common variance. All 9 items were retained as they had factor loadings > 0.30. Factor 1, comprised self-directed moral injury questions (3-6). Factor 2 comprised other directed moral injury questions (1, 2, 7-9) (Table 3). The factor correlation coefficient between Factor 1 and Factor 2 was 0.34, which supports utilizing an oblique rotation.

Reliability. We examined the reliability of the adapted MIES-LIP using measures of internal consistency, with both MIES-LIP factors demonstrating good reliability. The internal consistency of both factors of the MIES-LIP were found to be good (self-directed moral injury: Ω = 0.89; other-directed moral injury: Ω = 0.83).

Convergent Validity

Association between moral injury scales. A significant, moderate correlation was observed between all subscales of the MIES and MIES-LIP. Specifically, the self-directed moral injury factor of the MIES-LIP was associated with both the perceived transgressions (r = 0.41, P < .001) and the MIES perceived betrayals factors (r = 0.25, P < .05). Similarly, the other-directed moral injury factor of the MIES-LIP was associated with both the MIES perceived transgressions (r = 0.45, P < .001) and the MIES perceived betrayals factors (r = 0.45, P < .001).

Association with PTSD symptoms. All subscales of both the MIES and MIES-LIP were associated with PTSD symptom severity. The MIES perceived transgressions factor (r = 0.43, P < .001) and the perceived betrayals factor of the MIES (r = 0.39, P < .001) were moderately associated with the PCL-5. Mirroring this, the “self-directed moral injury” factor of the MIESLIP (r = 0.44, P < .001) and the “other-directed moral injury” factor of the MIES-LIP (r = 0.42, P < .001) were also positively associated with PCL-5.

Association with depression symptoms. All subscales of the MIES and MIES-LIP were also associated with depressive symptoms. The MIES perceived transgressions factor (r = 0.27, P < .01) and the MIES perceived betrayals factor (r = 0.23, P < .05) had a small association with the PHQ-9. In addition, the self-directed moral injury factor of the MIES-LIP (r = 0.40, P < .001) and the other-directed moral injury factor of the MIES-LIP (r = 0.31, P < .01) had small to moderate associations with the PCL-5.

DISCUSSION

Potentially morally injurious events appear to be a salient factor affecting legal-involved veterans. Among our sample, the vast majority of legal-involved veterans endorsed experiencing both legal- and military-related PMIEs. Witnessing or participating in a legal-related PMIE appears to be widespread among those who have experienced incarceration. The MIES-LIP yielded a 2-factor structure: self-directed moral injury and other-directed moral injury, in the evaluated population. The MIES-LIP showed similar psychometric performance to the MIES in our sample. Specifically, the MIES-LIP had good reliability and adequate convergent validity. While CFA did not confirm the anticipated factor structure of the MIES-LIP within our sample, EFA showed similarities in factor structure between the original and adapted measures. While further research and validation are needed, preliminary results show promise of the MIES-LIP in assessing legal-related moral injury.

Originally, the MIES was found to have a 2-factor structure, defined by perceived transgressions and perceived betrayals.33 However, additional research has identified a 3-factor structure, where the betrayal factor is maintained, and the transgressions factor is divided into transgressions by others and by self.8 The factor structure of the MIES-LIP was more closely related to the factor structure, with transgressions by others and betrayal mapped onto the same factor (ie, other-directed moral injury).8 While further research is needed, it is possible that the nature of morally injurious events experienced in legal contexts are experienced more in terms of self vs other, compared to morally injurious events experienced by veterans or active-duty service members.

Accurately identifying the types of moral injury experienced in a legal context may be important for determining the differences in drivers of legal-related moral injury compared to military-related moral injury. For example, self-directed moral injury in legal contexts may include a variety of actions the individual initiated that led to conviction and incarceration (eg, a criminal offense), as well as behaviors performed or witnessed while incarcerated (eg, engaging in violence). Inconsistent with military populations where other-directed moral injury clusters with self-directed moral injury, other-directed moral injury clustered with betrayal in legal contexts in our sample. This discrepancy may result from differences in identification with the military vs legal system. When veterans witness fellow service members engaging in PMIEs (eg, physical violence towards civilians in a military setting), this may be similar to self-directed moral injury due to the veteran’s identification with the same military system as the perpetrator.42 When legal-involved veterans witness other incarcerated individuals engaging in PMIEs (eg, physical violence toward other inmates), this may be experienced as similar to betrayal due to lack of personal identification with the criminal-legal system. Additional research is needed to better understand how self- and other-related moral injury are associated with betrayal in legal contexts.

Another potential driver of legal-related moral injury may be culpability. In order for moral injury to occur, an individual must perceive that something has taken place that deeply violated their sense of right and wrong.1 In terms of criminal offenses or even engaging in violent behavior while incarcerated, the potential for moral injury may differ based on whether an individual views themselves as culpable for the act(s).29 This may further distinguish between self-directed and other-directed moral injury in legal contexts. In situations where the individual views themselves as culpable, self-directed moral injury may be higher. In situations where the individual does not view themselves as culpable, other-directed moral injury may be higher based on the perception that the legal system is unfairly punishing them. Further research is needed to clarify how an individual’s view of their culpability relates to moral injury, as well as to elucidate which aspects of military service and legal involvement are most closely associated with moral injury among legal-involved veterans.

While this study treated legal-related and military-related moral injury as distinct, it is possible moral injury may have a cumulative effect over time with individuals experiencing morally injurious events across different contexts (eg, military, legal involvement). This, in turn, may compound risk for moral injury. These cumulative experiences may result in increased negative outcomes such as exacerbated psychiatric symptoms, substance misuse, and elevated suicide risk. Future studies should examine differences between groups who have experienced moral injury in differing contexts, as well as those with multiple sources of moral injury.

Limitations

The sample for this study included only veterans. The number of veterans incarcerated is large and the focus on veterans also allowed for a more robust comparison of moral injury related to the legal system and the more traditional military-related moral injury. However, the generalizability of the findings to nonveterans cannot be assured. The study used a relatively small sample (N = 100), which was overwhelmingly male. Although the PCL-5 was utilized to examine traumatic stress symptoms, this measure was not anchored to a specific criterion A trauma nor was it anchored specifically to a morally injurious experience. For all participants, their most recent military service preceded their most recent legal involvement which could affect the associations between variables. Furthermore, while all participants endorsed prior legal involvement, many participants reported no combat exposure.

CONCLUSIONS

This study resulted in several key findings. First, legal-involved veterans endorsed high rates of experiencing legal-related morally injurious experiences. Second, our adapted measure displayed adequate psychometric strength and suggests that legal-related moral injury is a salient and distinct phenomenon affecting legal-involved veterans. These items may not capture all the nuances of legal-related moral injury. Qualitative interviews with legal-involved persons may help identify relevant areas of legal-related moral injury not reflected in the current instrument. The MIES-LIP represents a practical measure that may help clinicians identify and address legal-related moral injury when working with legal-involved veterans. Given the high prevalence of PMIEs among legal-involved veterans, further examination of whether current interventions for moral injury and novel treatments being developed are effective for this population is needed.

Following exposure to potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs), some individuals may experience moral injury, which represents negative psychological, social, behavioral, and occasionally spiritual impacts.1 The consequences of PMIE exposure and moral injury are well documented. Individuals may begin to question the goodness and trustworthiness of oneself, others, or the world.1 Examples of other sequelae include guilt, demoralization, spiritual pain, loss of trust in the self or others, and difficulties with forgiveness.2-6 In addition, prior studies have found that moral injury is associated with an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, spiritual distress, and interpersonal difficulties.7-11

Moral injury was first conceptualized in relation to combat trauma. However in recent years it has been examined in other groups such as health care practitioners, educators, refugees, and law enforcement personnel.12-17 Furthermore, there has been a recent call for the study of moral injury in other understudied groups. One such group is legal-involved individuals, defined as those who are currently involved or previously involved in the criminal justice system (ie, arrests, incarceration, parole, and probation).1,18-22

Many veterans are also involved with the legal system. Specifically, veterans currently comprise about 8% of the incarcerated US population, with an estimated > 180,000 veterans in prisons or jails and even more on parole or probation.23,24 Legal-involved veterans may be at heightened risk for homelessness, suicide, unemployment, and high prevalence rates of psychiatric diagnoses.25-28

Limited research has explored exposure to PMIEs as part of the legal process and the resulting expression of moral injury. The circumstances leading to incarceration, interactions with the US legal system, the environment of prison itself, and the subsequent challenges faced by legal-involved individuals after release all provide ample opportunity for PMIEs to occur.18 For example, engaging in a criminal act may represent a PMIE, particularly in violent offenses that involve harm to another individual. Moreover, the process of being convicted and charged with an offense may serve as a powerful reminder of the PMIE and tie this event to the individual’s identity and future. Furthermore, the physical and social environment of prison itself (eg, being surrounded by other offenders, witnessing the perpetration of violence, participating in violence for survival) presents a myriad of opportunities for PMIEs to occur.18

The consequences of PMIEs in the context of legal involvement may also have bearing on a touchstone of moral injury: changes in one’s schema of the self and world.4 At a societal level, legal-involved individuals are, by definition, deemed “guilty” and held culpable for their offense, which may reinforce a negative change in one’s view of self and the world.29 In line with identity theory, external negative appraisals about legal-involved individuals (eg, they are a danger to society, they cannot be trusted to do the right thing) may influence their self-perception.30 Furthermore, the affective characteristics often found in the context of moral injury (eg, guilt, shame, anger, contempt) may be exacerbated by legal involvement.29 Personal feelings of guilt and shame may be reinforced by receiving a verdict and sentence, as well as the negative perceptions of individuals around them (eg, disapproval from prior sources of social support). Additionally, feelings of betrayal and distrust towards the legal system may arise.

In sum, legal-involved veterans incur increased risk of moral injury due to the potential for exposure to PMIEs across multiple time points (eg, prior to military service, during military service, during arrest/sentencing, during imprisonment, and postincarceration). The stigma that accompanies legal involvement may limit access to treatment or a willingness to seek treatment for distress related to moral injury.29 Additionally, repeated exposure to PMIEs and resulting moral injury may compound over time, potentially exacerbating psychosocial functioning and increasing the risk for psychosocial stressors (eg, homelessness, unemployment) and mental health disorders (eg, depression, substance misuse).31

Although numerous measures of moral injury have been developed, most require that respondents consider a specific context (eg, military experiences).32 Therefore, study of legal-related moral injury requires adaptation of existing instruments to the legal context. The original and most commonly used scale of moral injury is the Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES).33 The MIES scales was originally developed to measure moral injury in military-related contexts but has since been adapted as a measure of exposure to context-specific PMIEs.34

Unfortunately, there are no validated measures for assessing legal-related moral injury. Such a gap in understanding is problematic, as it may impact measurement of the prevalence of PMIEs in both clinical and research settings for this at-risk population. The goal of this study was to conduct a psychometric evaluation of an adapted version of the MIES for legal-involved persons (MIES-LIP).

METHODS

A total of 177 veterans from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) North Texas Health Care System were contacted for study enrollment between November 2020 and June 2021, yielding a final sample of 100 legal-involved veteran participants. Adults aged ≥ 18 years who were US military veterans and had ≥ 1 prior felony conviction resulting in incarceration were included. Participants were excluded if they had symptoms of psychosis that would preclude meaningful participation.

The study collected data on participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics using a semistructured survey instrument. Each participant completed an instructor-led questionnaire in a session that lasted about 1.5 hours. Participants who completed the visit in person received a $50 cash voucher for their time. Participants who were unable to meet with the study coordinator in person were able to complete the visit via telephone and received a $25 digital gift card. Of the total 100 participants, 79 participants completed the interview in person, and 21 completed by telephone. No significant differences were found in assessment measures between administration methods. Written informed consent was obtained during all in-person visits. For those completing via telephone, a waiver of written informed consent was obtained. This study was approved by the VA North Texas Health Care System’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES) is a 9-item self-report measure that assesses exposure to PMIEs.33 Respondents rate their agreement with each item on a 6-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater moral injury. The MIES has a 2-factor structure: Factor 1 has 6 items on perceived transgressions and Factor 2 has 3 items on perceived betrayals.33

Creation of Legal-Involved Moral Injury Measure. To create the MIES-LIP, items and instructions from the MIES were modified to address moral injury in the context of legal involvement.33 Adaptations were finalized following consultation and approval by the authors of the original measure. Specifically, the instructions were changed to: “Please respond to these items based specifically in the context of your involvement with the legal system.” The instructions clarified that legal involvement could include experiences related to committing an offense, legal proceedings and sentencing, incarceration, or transitioning out of the legal system. This differs from the original measure, which focused on military experiences, with instructions stating: “Please respond to these items based specifically in the context of your military service (ie, events and experiences during enlistment, deployment, combat, etc).”

Other measures. The study collected data on demographic characteristics including sex, race and ethnicity, marital status, military service, combat experience, and legal involvement. PTSD symptom severity, based on the criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), was assessed using the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5).35,36 The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure in which item scores are summed to create a total score. The PCL-5 has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including good internal consistency, test-retest reliability convergent validity, and discriminant validity.37,38

Depressive symptom severity was measured using the Personal Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).39 The PHQ-9 is a 9-item self-report measure where item scores summed to create a total score. The PHQ-9 has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including internal consistency and test-retest reliability.39

STATISTICAL METHODS

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation for continuous variables; frequencies and percentages for categorical variables) were used to describe the study sample. Factor analysis was conducted to evaluate the psychometric properties of the MIES-LIP. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to determine whether the MEIS-LIP had a similar factor structure to the MIES.40 Criteria for fit indices used for CFA include the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; values of > 0.95 suggest good fit), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; values of > 0.95 suggest a good fit), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; values of ≥ 0.06 suggest good fit), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; values of ≥ 0.08 suggest good fit). With insufficient fit, subsequent exploratory factor analysis was conducted using maximum likelihood estimation with an Oblimin rotation. The Kaiser rule and a scree plot were considered when defining the factor structure. Reliability was evaluated using the McDonald omega coefficient test. Convergent validity was assessed through the association between adapted measures and other clinical measures (ie, PCL-5, PHQ-9). In addition, associations between the PCL-5 and PHQ-9 were examined as they related to the MIES and MIES-LIP.

RESULTS

Table 1 describes demographic characteristics of the study sample. Rates of potentially morally injurious experiences and the expression of moral injury in the legal context are presented in Table 2. Witnessing PMIEs while in the legal system was nearly ubiquitous, with > 90% of the sample endorsing this experience. More than half of the sample also endorsed engaging in morally injurious behavior by commission or omission, as well as experiencing betrayal while involved with the legal system.

Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was utilized to test the factor structure of the adapted MIES-LIP in our sample compared to the published factor structures of the MIES.33 Results did not support the established factor structure. Analysis yielded unacceptable CFI (0.79), TLI (0.70), SRMR (0.14), and RMSEA (0.21). The unsatisfactory results of CFA warranted follow-up exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to examine the factor structure of the moral injury scales in this sample.

EFA of MIES-LIP

The factor structure of the MIES-LIP was examined using EFA. The factorability of the data was examined using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO value = 0.75) and Bartlett Test of Sphericity (X2 = 525.41; P < .001), both of which suggested that the data were appropriate for factor analysis. The number of factors to retain was selected based on the Kaiser criterion.41 After extraction, an Oblimin rotation was applied, given that we expected factors to be correlated. A 2-factor solution was found, explaining 65.76% of the common variance. All 9 items were retained as they had factor loadings > 0.30. Factor 1, comprised self-directed moral injury questions (3-6). Factor 2 comprised other directed moral injury questions (1, 2, 7-9) (Table 3). The factor correlation coefficient between Factor 1 and Factor 2 was 0.34, which supports utilizing an oblique rotation.

Reliability. We examined the reliability of the adapted MIES-LIP using measures of internal consistency, with both MIES-LIP factors demonstrating good reliability. The internal consistency of both factors of the MIES-LIP were found to be good (self-directed moral injury: Ω = 0.89; other-directed moral injury: Ω = 0.83).

Convergent Validity

Association between moral injury scales. A significant, moderate correlation was observed between all subscales of the MIES and MIES-LIP. Specifically, the self-directed moral injury factor of the MIES-LIP was associated with both the perceived transgressions (r = 0.41, P < .001) and the MIES perceived betrayals factors (r = 0.25, P < .05). Similarly, the other-directed moral injury factor of the MIES-LIP was associated with both the MIES perceived transgressions (r = 0.45, P < .001) and the MIES perceived betrayals factors (r = 0.45, P < .001).

Association with PTSD symptoms. All subscales of both the MIES and MIES-LIP were associated with PTSD symptom severity. The MIES perceived transgressions factor (r = 0.43, P < .001) and the perceived betrayals factor of the MIES (r = 0.39, P < .001) were moderately associated with the PCL-5. Mirroring this, the “self-directed moral injury” factor of the MIESLIP (r = 0.44, P < .001) and the “other-directed moral injury” factor of the MIES-LIP (r = 0.42, P < .001) were also positively associated with PCL-5.

Association with depression symptoms. All subscales of the MIES and MIES-LIP were also associated with depressive symptoms. The MIES perceived transgressions factor (r = 0.27, P < .01) and the MIES perceived betrayals factor (r = 0.23, P < .05) had a small association with the PHQ-9. In addition, the self-directed moral injury factor of the MIES-LIP (r = 0.40, P < .001) and the other-directed moral injury factor of the MIES-LIP (r = 0.31, P < .01) had small to moderate associations with the PCL-5.

DISCUSSION

Potentially morally injurious events appear to be a salient factor affecting legal-involved veterans. Among our sample, the vast majority of legal-involved veterans endorsed experiencing both legal- and military-related PMIEs. Witnessing or participating in a legal-related PMIE appears to be widespread among those who have experienced incarceration. The MIES-LIP yielded a 2-factor structure: self-directed moral injury and other-directed moral injury, in the evaluated population. The MIES-LIP showed similar psychometric performance to the MIES in our sample. Specifically, the MIES-LIP had good reliability and adequate convergent validity. While CFA did not confirm the anticipated factor structure of the MIES-LIP within our sample, EFA showed similarities in factor structure between the original and adapted measures. While further research and validation are needed, preliminary results show promise of the MIES-LIP in assessing legal-related moral injury.

Originally, the MIES was found to have a 2-factor structure, defined by perceived transgressions and perceived betrayals.33 However, additional research has identified a 3-factor structure, where the betrayal factor is maintained, and the transgressions factor is divided into transgressions by others and by self.8 The factor structure of the MIES-LIP was more closely related to the factor structure, with transgressions by others and betrayal mapped onto the same factor (ie, other-directed moral injury).8 While further research is needed, it is possible that the nature of morally injurious events experienced in legal contexts are experienced more in terms of self vs other, compared to morally injurious events experienced by veterans or active-duty service members.

Accurately identifying the types of moral injury experienced in a legal context may be important for determining the differences in drivers of legal-related moral injury compared to military-related moral injury. For example, self-directed moral injury in legal contexts may include a variety of actions the individual initiated that led to conviction and incarceration (eg, a criminal offense), as well as behaviors performed or witnessed while incarcerated (eg, engaging in violence). Inconsistent with military populations where other-directed moral injury clusters with self-directed moral injury, other-directed moral injury clustered with betrayal in legal contexts in our sample. This discrepancy may result from differences in identification with the military vs legal system. When veterans witness fellow service members engaging in PMIEs (eg, physical violence towards civilians in a military setting), this may be similar to self-directed moral injury due to the veteran’s identification with the same military system as the perpetrator.42 When legal-involved veterans witness other incarcerated individuals engaging in PMIEs (eg, physical violence toward other inmates), this may be experienced as similar to betrayal due to lack of personal identification with the criminal-legal system. Additional research is needed to better understand how self- and other-related moral injury are associated with betrayal in legal contexts.

Another potential driver of legal-related moral injury may be culpability. In order for moral injury to occur, an individual must perceive that something has taken place that deeply violated their sense of right and wrong.1 In terms of criminal offenses or even engaging in violent behavior while incarcerated, the potential for moral injury may differ based on whether an individual views themselves as culpable for the act(s).29 This may further distinguish between self-directed and other-directed moral injury in legal contexts. In situations where the individual views themselves as culpable, self-directed moral injury may be higher. In situations where the individual does not view themselves as culpable, other-directed moral injury may be higher based on the perception that the legal system is unfairly punishing them. Further research is needed to clarify how an individual’s view of their culpability relates to moral injury, as well as to elucidate which aspects of military service and legal involvement are most closely associated with moral injury among legal-involved veterans.

While this study treated legal-related and military-related moral injury as distinct, it is possible moral injury may have a cumulative effect over time with individuals experiencing morally injurious events across different contexts (eg, military, legal involvement). This, in turn, may compound risk for moral injury. These cumulative experiences may result in increased negative outcomes such as exacerbated psychiatric symptoms, substance misuse, and elevated suicide risk. Future studies should examine differences between groups who have experienced moral injury in differing contexts, as well as those with multiple sources of moral injury.

Limitations

The sample for this study included only veterans. The number of veterans incarcerated is large and the focus on veterans also allowed for a more robust comparison of moral injury related to the legal system and the more traditional military-related moral injury. However, the generalizability of the findings to nonveterans cannot be assured. The study used a relatively small sample (N = 100), which was overwhelmingly male. Although the PCL-5 was utilized to examine traumatic stress symptoms, this measure was not anchored to a specific criterion A trauma nor was it anchored specifically to a morally injurious experience. For all participants, their most recent military service preceded their most recent legal involvement which could affect the associations between variables. Furthermore, while all participants endorsed prior legal involvement, many participants reported no combat exposure.

CONCLUSIONS

This study resulted in several key findings. First, legal-involved veterans endorsed high rates of experiencing legal-related morally injurious experiences. Second, our adapted measure displayed adequate psychometric strength and suggests that legal-related moral injury is a salient and distinct phenomenon affecting legal-involved veterans. These items may not capture all the nuances of legal-related moral injury. Qualitative interviews with legal-involved persons may help identify relevant areas of legal-related moral injury not reflected in the current instrument. The MIES-LIP represents a practical measure that may help clinicians identify and address legal-related moral injury when working with legal-involved veterans. Given the high prevalence of PMIEs among legal-involved veterans, further examination of whether current interventions for moral injury and novel treatments being developed are effective for this population is needed.

- Griffin BJ, Purcell N, Burkman K, et al. Moral injury: an integrative review. J Trauma Stress. 2019;32(3):350-362. doi:10.1002/jts.22362

- Currier JM, Holland JM, Malott J. Moral injury, meaning making, and mental health in returning veterans. J Clin Psychol. 2015;71(3):229-240. doi:10.1002/jclp.22134

- Jinkerson JD. Defining and assessing moral injury: a syndrome perspective. Traumatology. 2016;22(2):122-130. doi:10.1037/trm0000069

- Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695-706. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

- Maguen S, Litz B. Moral injury in veterans of war. PTSD Res Q. 2012;23(1):1-6. www.vva1071.org/uploads/3/4/4/6/34460116/moral_injury_in_veterans_of_war.pdf

- Drescher KD, Foy DW, Kelly C, Leshner A, Schutz K, Litz B. An exploration of the viability and usefulness of the construct of moral injury in war veterans. Traumatology. 2011;17(1):8-13. doi:10.1177/1534765610395615

- Wisco BE, Marx BP, May CL, et al. Moral injury in U.S. combat veterans: results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. Depress Anxiety. 2017; 34(4):340-347. doi:10.1002/da.22614

- Bryan CJ, Bryan AO, Anestis MD, et al. Measuring moral injury: psychometric properties of the moral injury events scale in two military samples. Assessment. 2016;23(5):557- 570. doi:10.1177/1073191115590855

- Currier JM, Smith PN, Kuhlman S. Assessing the unique role of religious coping in suicidal behavior among U.S. Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2017;9(1):118-123. doi:10.1037/rel0000055

- Kopacz MS, Connery AL, Bishop TM, et al. Moral injury: a new challenge for complementary and alternative medicine. Complement Ther Med. 2016;24:29-33. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2015.11.003

- Vargas AF, Hanson T, Kraus D, Drescher K, Foy D. Moral injury themes in combat veterans’ narrative responses from the national vietnam veterans’ readjustment study. Traumatology. 2013;19(3):243-250. doi:10.1177/1534765613476099

- Borges LM, Barnes SM, Farnsworth JK, Bahraini NH, Brenner LA. A commentary on moral injury among health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(S1):S138-S140. doi:10.1037/tra0000698

- Borges LM, Holliday R, Barnes SM, et al. A longitudinal analysis of the role of potentially morally injurious events on COVID-19-related psychosocial functioning among healthcare providers. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0260033. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260033

- Currier JM, Holland JM, Rojas-Flores L, Herrera S, Foy D. Morally injurious experiences and meaning in Salvadorian teachers exposed to violence. Psychol Trauma. 2015;7(1):24-33. doi:10.1037/a0034092

- Nickerson A, Schnyder U, Bryant RA, Schick M, Mueller J, Morina N. Moral injury in traumatized refugees. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(2):122-123. doi:10.1159/000369353

- Papazoglou K, Chopko B. The role of moral suffering (moral distress and moral injury) in police compassion fatigue and PTSD: An unexplored topic. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1999. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01999

- Papazoglou K, Blumberg DM, Chiongbian VB, et al. The role of moral injury in PTSD among law enforcement officers: a brief report. Front Psychol. 2020;11:310. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00310

- Martin WB, Holliday R, LePage JP. Trauma and diversity: moral injury among justice involved veterans: an understudied clinical concern. Stresspoints. 2020;33(5).

- Currier JM, Drescher KD, Nieuwsma J. Future directions for addressing moral injury in clinical practice: concluding comments. In: Currier JM, Drescher KD, Nieuwsma J, eds. Addressing Moral Injury in Clinical Practice. American Psychological Association; 2021:261-271. doi:10.1037/0000204-015

- Alexander AR, Mendez L, Kerig PK. Moral injury as a transdiagnostic risk factor for mental health problems in detained youth. Crim Justice Behav. 2023;51(2):194-212. doi:10.1177/00938548231208203

- DeCaro JB, Straka K, Malek N, Zalta AK. Sentenced to shame: moral injury exposure in former lifers. Psychol Trauma. 2024; 15(5):722-730. doi:10.1037/tra0001400

- Orak U, Kelton K, Vaughn MG, Tsai J, Pietrzak RH. Homelessness and contact with the criminal legal system among U.S. combat veterans: an exploration of potential mediating factors. Crim Justice Behav. 2022;50(3):392-409. doi:10.1177/00938548221140352

- Bronson J, Carson EA, Noonan M. Veterans in Prison and Jail, 2011-12. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Published December 2015. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/vpj1112.pdf

- Maruschak LM, Bronson J, Alper M. Veterans in Prison: Survey of Prison Inmates, 2016. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; March 2021. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://bjs.ojp.gov/redirect-legacy/content/pub/pdf/vpspi16st.pdf

- Blodgett JC, Avoundjian T, Finlay AK, et al. Prevalence of mental health disorders among justiceinvolved veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:163-176. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxu003

- Finlay AK, Owens MD, Taylor E, et al. A scoping review of military veterans involved in the criminal justice system and their health and healthcare. Health Justice. 2019;7(1):6. doi:10.1186/s40352-019-0086-9

- Holliday R, Martin WB, Monteith LL, Clark SC, LePage JP. Suicide among justice-involved veterans: a brief overview of extant research, theoretical conceptualization, and recommendations for future research. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2020;30(1):41-49. doi:10.1080/10530789.2019.1711306

- Wortzel HS, Binswanger IA, Anderson CA, Adler LE. Suicide among incarcerated veterans. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2009;37(1):82-91.

- Desai A, Holliday R, Borges LM, et al. Facilitating successful reentry among justice-involved veterans: the role of veteran and offender identity. J Psychiatr Pract. 2021;27(1):52-60. doi:10.1097/PRA.0000000000000520

- Asencio EK, Burke PJ. Does incarceration change the criminal identity? A synthesis of labeling and identity theory perspectives on identity change. Sociol Perspect. 2011;54(2):163-182. doi:10.1525/sop.2011.54.2.163

- Borges LM, Desai A, Barnes SM, Johnson JPS. The role of social determinants of health in moral injury: implications and future directions. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2022;9(3):202-214. doi:10.1007/s40501-022-00272-4

- Houle SA, Ein N, Gervasio J, et al. Measuring moral distress and moral injury: a systematic review and content analysis of existing scales. Clin Psychol Rev. 2024;108:102377. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102377

- Nash WP, Marino Carper TL, Mills MA, Au T, Goldsmith A, Litz BT. Psychometric evaluation of the moral injury events scale. Mil Med. 2013;178(6):646-652. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00017

- Zerach G, Ben-Yehuda A, Levi-Belz Y. Prospective associations between psychological factors, potentially morally injurious events, and psychiatric symptoms among Israeli combatants: the roles of ethical leadership and ethical preparation. Psychol Trauma. 2023;15(8):1367-1377. doi:10.1037/tra0001466

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmeri PA, Marx BP. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). National Center for PTSD. Accessed March 4, 2025. www.ptsd.va.gov

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, et al. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol Assess. 2016;28(11):1379-1391. doi:10.1037/pas0000254